Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Effects of Seed Priming and Foliar Application of Selenite, Nanoselenium, and Microselenium on Growth, Biomolecules, and Nutrients in Cucumber Seedlings

1 Postdoctoral Program SECIHTI, Universidad Autónoma Agraria Antonio Narro, Saltillo, 25315, Coahuila, Mexico

2 SECIHTI, Universidad Autónoma Agraria Antonio Narro, Saltillo, 25315, Coahuila, Mexico

3 Macromolecular Chemistry and Nanomaterials, Centro de Investigación en Química Aplicada, Saltillo, 25294, Coahuila, Mexico

4 Robotics and Advanced Manufacturing, Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados, Unidad Saltillo, Ramos Arizpe, 25900, Coahuila, Mexico

5 Faculty of Agrotechnological Sciences, Universidad Autónoma de Chihuahua, Ciudad Universitaria Campus 1 s/n, Chihuahua, 31310, Chihuahua, Mexico

6 Faculty of Agronomy, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, General Escobedo, 66050, Nuevo León, Mexico

7 Department of Horticulture, Universidad Autónoma Agraria Antonio Narro, Saltillo, 25315, Coahuila, Mexico

* Corresponding Author: Adalberto Benavides-Mendoza. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Application of Nanomaterials in Plants)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(7), 2131-2153. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.067577

Received 07 May 2025; Accepted 20 June 2025; Issue published 31 July 2025

Abstract

Selenium (Se) is a nutrient that is considered beneficial for plants, because its improvement in growth, yield and quality helps plants to mitigate stress. The objective of this research was to evaluate the application of sodium selenite (Na2SeO3), nanoparticles (SeNPs) and microparticles (SeMPs) of Se in cucumber seedlings, via two experiments: one with seed priming and the other with foliar application of Se materials. The doses used were: 0, 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5 and 3.0 mg · L−1, for each form of Se and for each form of application. Treatment 0 consisted of the application of distilled water, which was used as a control. The results indicated that the SeMPs treatment at 3.0 mg · L−1 for seed priming had the greatest effect on stem diameter and leaf area. Foliar application of SeMPs at 1.5 mg · L−1 was the most effective at increasing the leaf area. In terms of fresh and dry biomass (aerial, root and total) for seed priming, all the treatments were superior to the control, and SeMPs at 1.5 and 3.0 mg · L−1 caused the greatest effects. With foliar application, fresh root biomass improved to a greater extent with the SeMPs treatment at 3.0 mg · L−1, and dry biomass (aerial, root and total) increased with the SeMPs at 1.0 and 3.0 mg · L−1. With respect to the photosynthetic pigments, proteins, phenols and minerals, the Se treatments, both for seed priming and foliar application, caused increases and decreases; however, reduced glutathione (GSH) increased with treatments in both forms of application. The Se concentration in the seedlings increased as the dose of Se material increased, and greater accumulation was achieved with foliar application of SeNPs and SeMPs. The results indicate that the use of Se materials is recommended, mainly the use of SeMPs, which improved the variables studied. This opens new opportunities for further studies with SeMPs, as little information is available on their application in agricultural crops.Keywords

Climate change and population growth are factors that force the search for new alternatives to improve crop yields. Therefore, rapid seed germination and high-quality seedling production are crucial to achieve these objectives. There are conventional practices such as genetic engineering; however, this method is time consuming and may not be suitable for the ecosystem, so there are practices based on the use of biostimulants [1]. A biostimulant is any substance or microorganism applied to plants with the objective of improving nutritional efficiency, stress tolerance and quality characteristics, regardless of nutrient content [2].

The use of biostimulants can take different forms, the most studied of which are seed priming and foliar application. Seed priming is a treatment that occurs prior to sowing and consists of soaking the seeds for a certain time in a solution or dispersion of one or more substances or microorganisms at a specific concentration [3]. Currently, foliar application is the fastest way for biostimulants to be absorbed and incorporated into plant metabolism [4]. These practices result in the improvement of physiological and metabolic processes that result in increased and faster seed germination, in the absorption and transport of nutrients and in the mitigation of stress, which results in increased yields and quality of harvested products [5,6].

Within the range of biostimulants that exist, inorganic compounds such as selenium (Se), iodine (I), silicon (Si), cobalt (Co), vanadium (V) and cerium (Ce), which are not essential nutrients for plants but are considered beneficial nutrients, stand out [7]. Se can induce certain beneficial effects in plants at low concentrations, stimulating growth, increasing biotic and abiotic stress tolerance and prolonging the shelf-life and quality of agricultural products [8]. Owing to their high solubility, plants can absorb Se in the form of selenite (SeO32−) through phosphate transporters and aquaporins and selenate (SeO42−) through sulfate transporters [9]. Some crops, such as those of the Crusiferae family and the Allium genus, accumulate Se; however, crops belonging to the Cucurbitaceae and Solanaceae families are nonaccumulators, and high concentrations of Se are toxic [10]. Se is chemically similar to sulfur (S) and phosphorus (P), since they share the same absorption pathways [11,12]. Accordingly, Se can be incorporated into sulfur metabolites such as reduced glutathione (GSH) and glucosinolates or form selenoamino acids such as selenomethionine (SeMet), selenocysteine (SeCys) and methylselenocysteine (MSeCys) [4,13,14].

Currently, it is common to apply Se in nanometric form (SeNPs), which has certain advantages over ionic forms. The size of these NPs is ≤100 nm; in this sense, their electrical, optical and magnetic properties allow them to enter the cell interior more easily and trigger a cascade of signaling that end in the improvement of physiological and metabolic processes of plants; however, NPs with dimensions greater than 100 nm also have very effective biostimulant properties [15,16]. In accordance with the above, El-Araby et al. [17] evaluated the application of SeNPs in pea plants under salt stress and reported that stress-induced damage to growth attributes, the mitotic index and the percentage of chromosomal abnormalities were reduced, which improved the productivity of plants under stress.

The use of inorganic compounds is not only based on the use of ionic or nanometric materials; their use is also implemented in micrometric form. There are studies on the application of microparticles (MPs) of Si and essential nutrients such as iron (Fe), zinc (Zn) and copper (Cu), which have positive effects on crops growth, yield and quality [18–21]. These MPs have physical dimensions between 1 and 1000 μm and have electrical, optical and magnetic properties that enhance seed germination, nutrient uptake, and photosynthesis and mitigate stress by activating the antioxidant system [22,23]. In this sense, de Alencar et al. [21], who applied SiMPs in the form of seed priming in cowpea, a nutrient that, like Se, is considered beneficial, reported that the harmful effects of water deficit were attenuated through osmotic adjustment and activation of the antioxidant system.

Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) is one of the most cultivated vegetables and is thus economically and food important globally. This crop has fruits rich in vitamins, phenolic compounds, carotenoids, GSH, and minerals with important functions for human health [24]. In this sense, crops are prone to different types of stress, such as fungi, bacteria, viruses, extreme temperatures, salinity, and drought [25]. Therefore, it is important to produce vigorous seedlings with a well-developed root system to ensure high-quality production. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to evaluate the effects of seed priming and foliar application of sodium selenite (Na2SeO3), SeNPs and SeMPs on the growth, biomolecules and nutrients of cucumber seedlings.

In addition, this study focused on the innovative use of SeMPs, which are compounds that have not been thoroughly explored but whose size allows for unique properties that allow for more effective interactions with plants. These particles can function as fertilizers, pesticides, and sensors and remediate contaminated soils [26,27]. The use of MPs in agriculture can contribute substantially to the sustainability of the agricultural sector through resource efficiency and reduced environmental impact. By optimizing production and reducing losses, these MPs can help improve global food security. However, their use also presents challenges, centered on the potential long-term effects they may have on human health. Therefore, it is important to continue conducting research to establish their appropriate use in agricultural systems.

2.1 Synthesis and Preparation of Selenium Materials

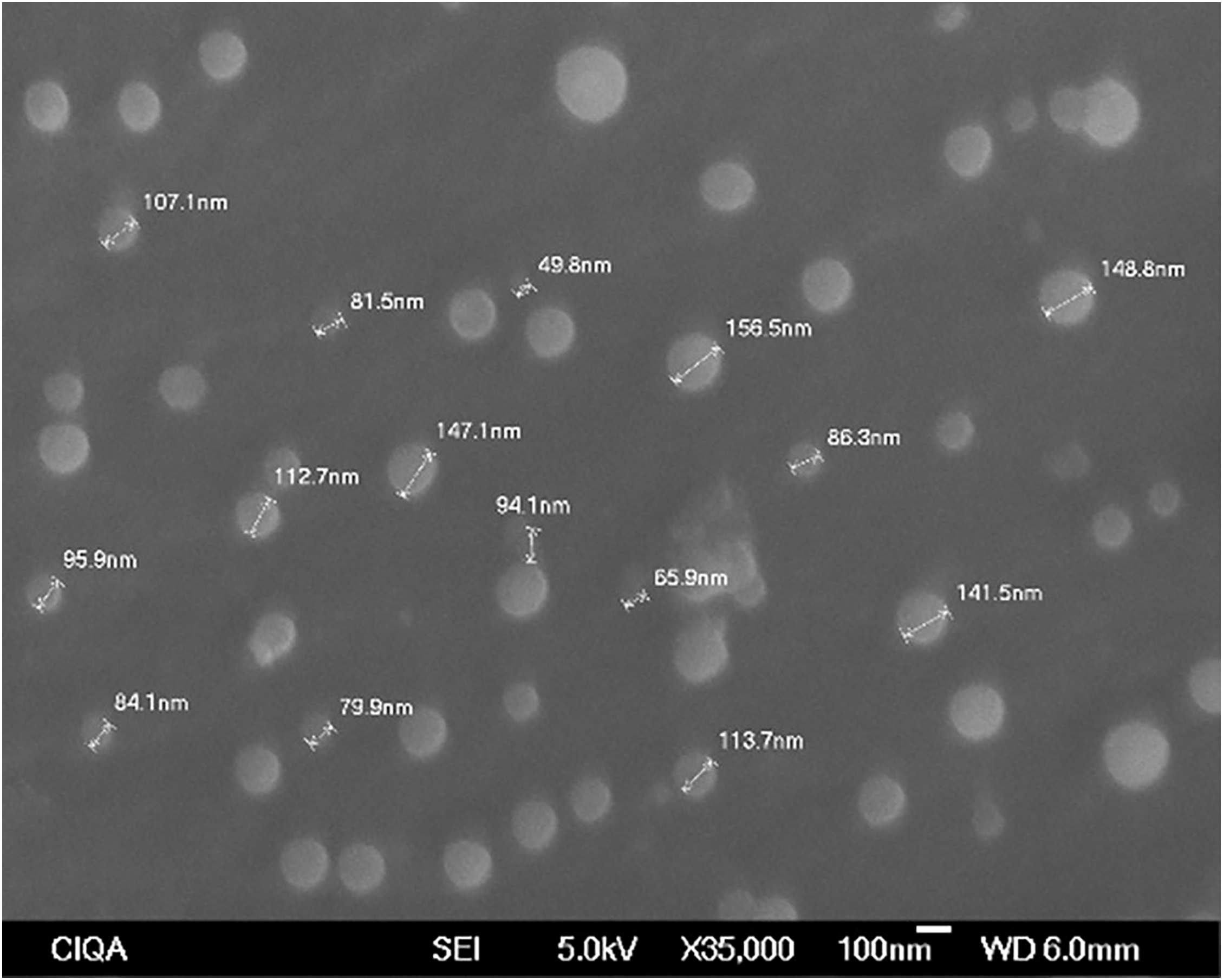

The Se materials were synthesized and prepared at the Centro de Investigación en Química Aplicada (Saltillo, Coahuila, México). For the synthesis of SeNPs, selenious acid (H2SeO3, 97.0%) (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and arabic gum (2 g L−1) were added to a glass reactor; after the solution was stirred (400 rpm at 0°C for 15 min), hydrazine hydrate (N2H4·H2O reagent grade, 50%–60%) (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to carry out the reduction. The mixture was stirred for 2 h under a nitrogen atmosphere at 0°C. Scanning electron microscopy analysis revealed that the SeNPs were 49.8–156.5 nm in size and had a spherical morphology (Fig. 1). A 2 L aqueous dispersion containing 1.1 g of SeNPs was subsequently added to the reactor with 4 mL of agricultural dispersant (dioctyl sulfosuccinate 2.3%), and the mixture was stirred for 30 min at 400 rpm. A stock dispersion was obtained, from which the concentrations used were prepared. The preparation of the SeNPs was based on that reported by Quiterio-Gutiérrez et al. [28] and Mata-Padilla et al. [29] with modifications.

Figure 1: Scanning electron microscopy of SeNPs

The SeMPs used were commercial with a size of 150 μm and a purity of 99.5% (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and were functionalized. In a glass reactor, 2 L of distilled water and 4 g of arabic gum were added, the mixture was agitated (440–500 rpm for 20 min), and then, 1.1 g of commercial SeMPs was added. The dispersion was stirred to homogenize the SeMPs (1 h), 4 mL of agricultural dispersant was added, and again, the dispersion was agitated (30 min). A stock dispersion was obtained, with which the concentrations used were prepared.

The Na2SeO3 used was 99% pure (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), which was functionalized. In a glass reactor, 0.5 L of distilled water and 3 mL of agricultural dispersant were added, after which the reactor was agitated until the agricultural dispersant was completely dissolved (440–500 rpm for 20 min). Subsequently, 0.5 L of an aqueous solution containing 1.5 g of Na2SeO3 was added. The solution was homogenized by stirring (60 min), and then 0.5 L of an aqueous solution containing 3 g of arabic gum was added and stirred again (30 min). Finally, a stock solution was obtained, with which the concentrations to be used were prepared.

2.2 Plant Material and Description of Treatments

Braga F1 cucumber seeds from Bejo (Waarmenhuizen, The Netherlands) were used. The seeds were treated with fludioxonil and had a purity of 99.9% and a germination percentage of 99%. The experiment was carried out in a growth chamber adapted with LED lights (LumiGrow PRO-650, Emeryville, CA, USA) at the Plant Physiology Laboratory of the Horticulture Department of the Universidad Autónoma Agraria Antonio Narro (Saltillo, Coahuila, México). The LED lights emitted photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) of 43 μmol m2 · s−1 and the temperature and relative humidity in the growth chamber ranged from 22–25°C and 50%–60%, respectively. The photoperiod was 12 h light per day.

Two experiments were carried out at the same time; seed priming and foliar application under the following treatments: 0, 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5 and 3.0 mg · L−1 of Na2SeO3, SeNPs and SeMPs, resulting in a total of 16 treatments for each form of application (seed priming and foliar). Treatment 0 consisted of distilled water. Each treatment had six replicates. The choice of concentrations used was based on the study by Castillo-Godina et al. [30].

Seed priming consisted of preparing the solutions and dispersions in 150 mL beakers containing the cucumber seeds and 100 mL of the treatment corresponding to the different Se forms. The seed priming treatment was carried out for 24 h at 25°C. Foliar applications of the Se treatments were performed every 10 days after seedling emergence (dae), for a total of two applications. The test lasted 23 dae. All the Se solutions and dispersions were prepared with distilled water at a pH of 6.0.

After 24 h of seed priming, the seeds were sown together with those that would later produce seedlings for foliar application. The substrate used for sowing was peat moss and perlite (1:1 v/v) in 0.5 L polystyrene containers. Seedling nutrition was carried out with a 25% Steiner [31] nutrient solution at pH 6.0.

At the end of the experiments (23 dae), the height, stem diameter, leaf area, and fresh and dry biomass of the seedlings were evaluated. Seedling tissue was then used to determine the concentrations of biomolecules and minerals. The evaluations and samplings consisted of measuring the biometric parameters of the six replicates and finally weighing the aerial parts and roots of the seedlings fresh and immediately storing them at −20°C in a refrigerator. The samples were then lyophilized at −80°C in a freeze-dryer (Labconco, model FreeZone 2.5 L, Kansas City, MO, USA) for 72 h. The lyophilized samples were weighed on an analytical balance to obtain dry weight and subsequently macerated with a porcelain mortar until a fine powder was obtained, allowing biomolecule and mineral analyses to be performed. These analyses were subsequently performed on mixed samples (shoots and roots). Fig. 2 shows images of the experiment.

Figure 2: Cucumber seedlings used in the experiment

The pigments were determined as described by Wellburn [32]. The soluble proteins were quantified as described by Bradford [33], using Coomassie brilliant blue as the reaction agent. The GSH concentration was determined via the technique of Xue et al. [34], using the DTNB dye used as the reaction agent. Total phenols were quantified via the Folin–Ciocalteu reagent following the methodology described by Singleton et al. [35].

The concentration of Se and macro- and micronutrients were determined in the mixed tissue (aerial part and root). For the digestions, the methodology described by López-Morales et al. [36] was used, which is based on digestion with a triacid mixture (1 L of concentrated HNO3, 100 mL of concentrated HCl and 25 mL of concentrated H2SO4). Quantification was performed via the plasma atomic emission spectrometry technique (ICP–OES, Perkin Elmer brand, Optima 8300 model).

2.4 Experimental Design and Data Analysis

A completely randomized design was used, with 16 treatments for each application method (seed priming and foliar) and six replicates per treatment. The growth and biomass of the six replicates were assessed, followed by three replicates for biomolecule determination and three replicates for mineral quantification. Analysis of variance and Fisher’s LSD means test (p ≤ 0.05) were performed via Infostat statistical software (v2020).

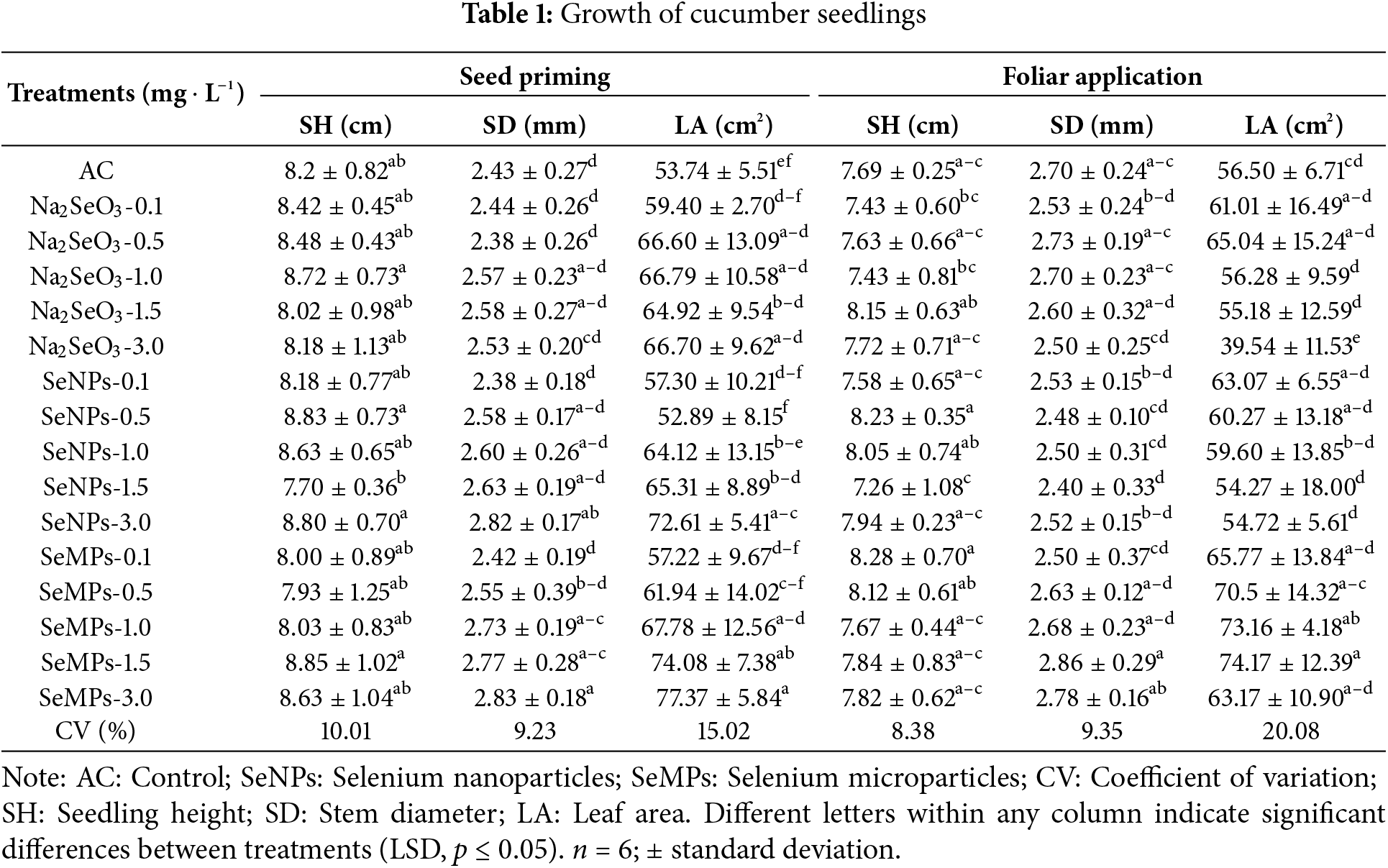

The application of the different forms of Se caused significant effects (p ≤ 0.05) in terms of seedling growth between the two types of application (Table 1). For stem diameter, with seed priming, SeMPs and SeNPs at 3.0 mg · L−1 had the best results, outperforming the control by 16.46% and 16.04%, respectively. However, SeMPs at concentrations of 1.0 and 1.5 mg · L−1 were also superior to the control. In terms of leaf area, SeMPs at concentrations of 1.5 and 3.0 mg · L−1 applied for seed priming had the greatest impact, exceeding that of the control by 37.84% and 43.97%, respectively. With respect to stem diameter, foliar application resulted in a decrease of only 11.11% with SeNPs treatment at 1.5 mg · L−1. The leaf area with foliar application presented the highest values in the SeMPs treatments at 1.0 and 1.5 mg · L−1, which exceeded those of the control by 29.48% and 31.27%, respectively. Compared with that of the control, the seedling height of both forms of Se application were not different.

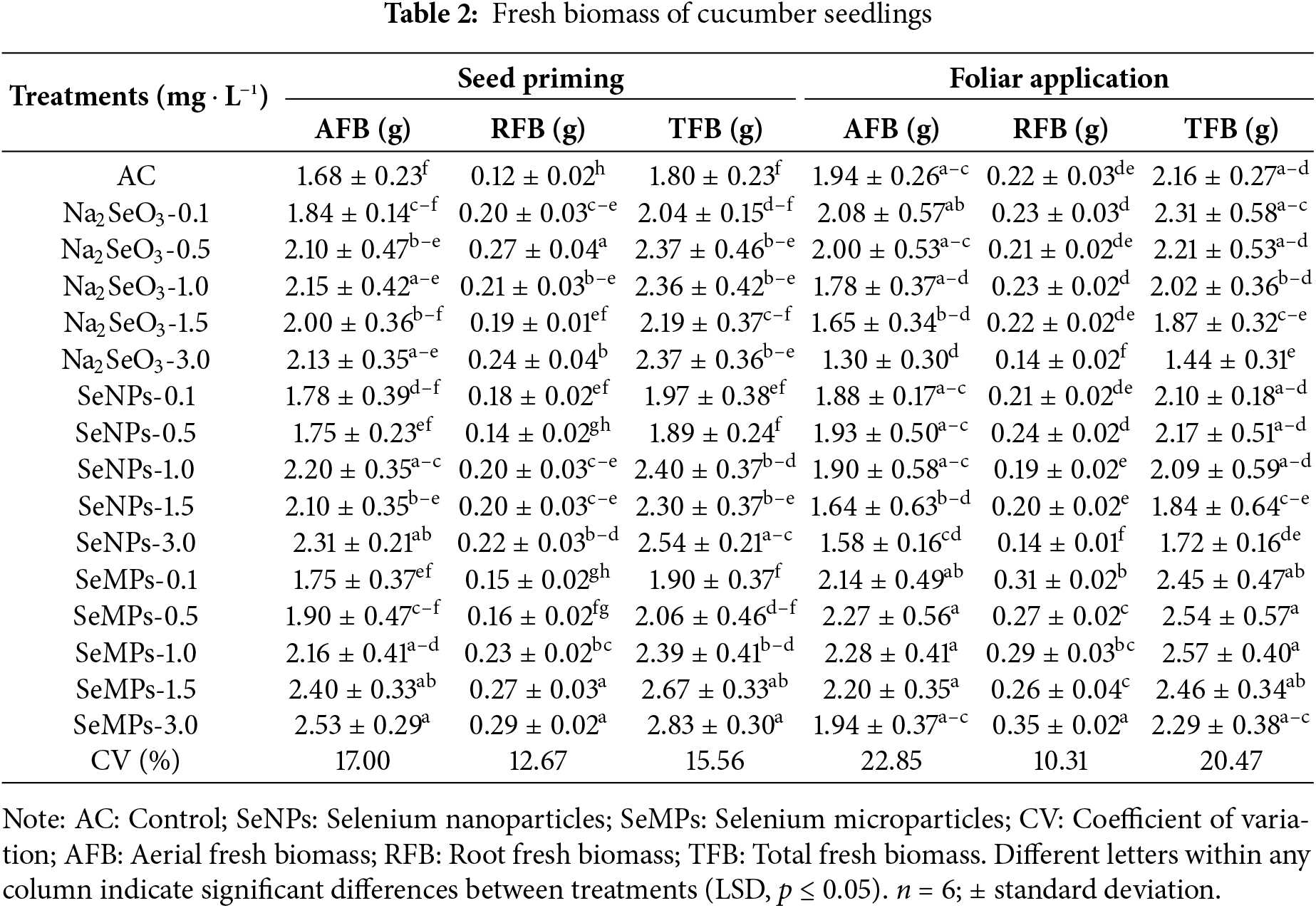

With respect to fresh biomass, the different forms of Se and both forms of application caused different responses (Table 2). In general, in terms of seed priming, the control was inferior to all the Se treatments (p ≤ 0.05), which was different from the results of foliar application, where some Se treatments were superior and inferior to the control. The SeMPs present at a concentration of 3.0 mg · L−1 during seed priming were the ones that stood out from the other treatments, and exceeded the control by 50.59%, 141.66% and 57.22% in terms of fresh aerial, root and total biomasses, respectively. Under foliar application, there was a 32.98% decrease in fresh aerial biomass with Na2SeO3 treatment at 3.0 mg · L−1. The fresh root biomass with foliar application improved only with all concentrations of SeMPs (p ≤ 0.05); however, the Na2SeO3 and SeNPs treatments at 3.0 mg · L−1 had a negative effect on the fresh root biomass. The total fresh biomass for foliar application was negatively affected by the Na2SeO3 treatment at 3.0 mg · L−1, and the remaining treatments were equal to the control.

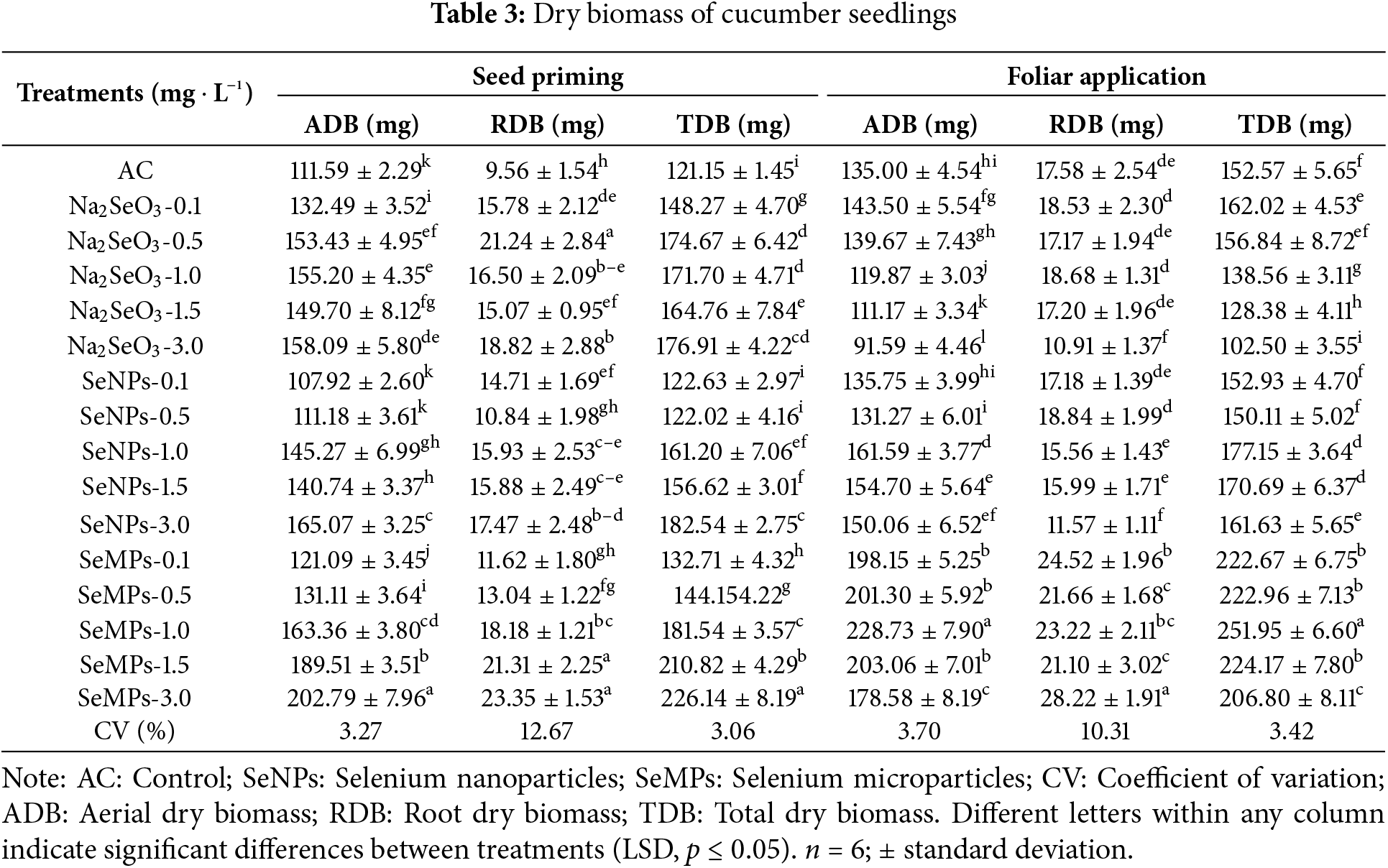

The dry biomass for seed priming indicates that the control was one of the treatments that presented the lowest values, being surpassed to a greater extent by the SeMPs at 3.0 mg · L−1 in 81.72%, 144.24% and 86.66%, for aerial, root and total dry biomass, respectively (p ≤ 0.05) (Table 3). Foliar application resulted in a trend in which all the treatments with SeMPs significantly increased aerial, root and total dry biomass, with concentrations of 1.0 and 3.0 mg · L−1 standing out (p ≤ 0.05); however, the Na2SeO3 at 1.0, 1.5 and 3.0 mg · L−1 treatments decreased aerial and total dry biomass, and the Na2SeO3 and SeNPs at 3.0 mg · L−1 decreased root dry biomass (Table 3).

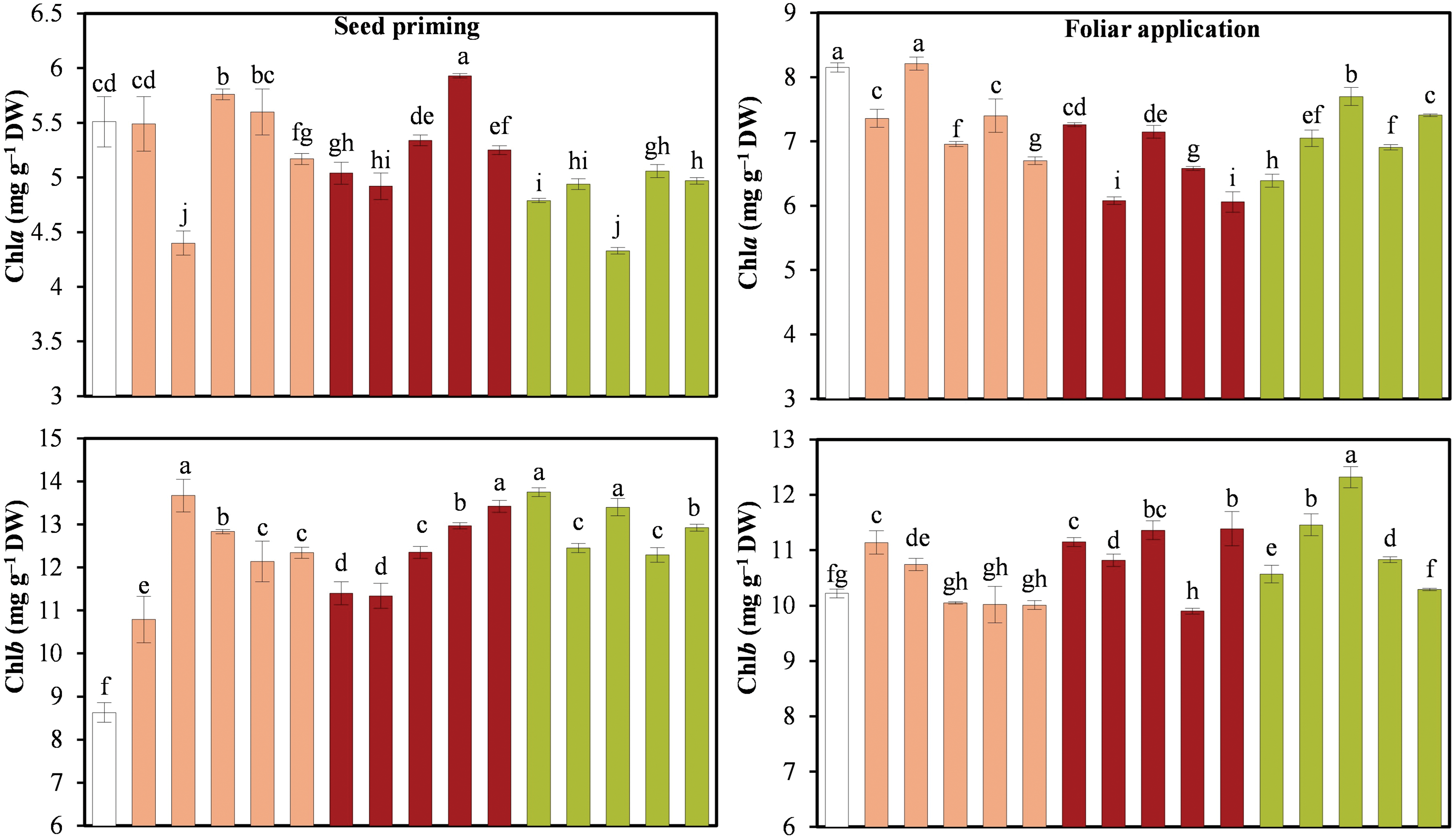

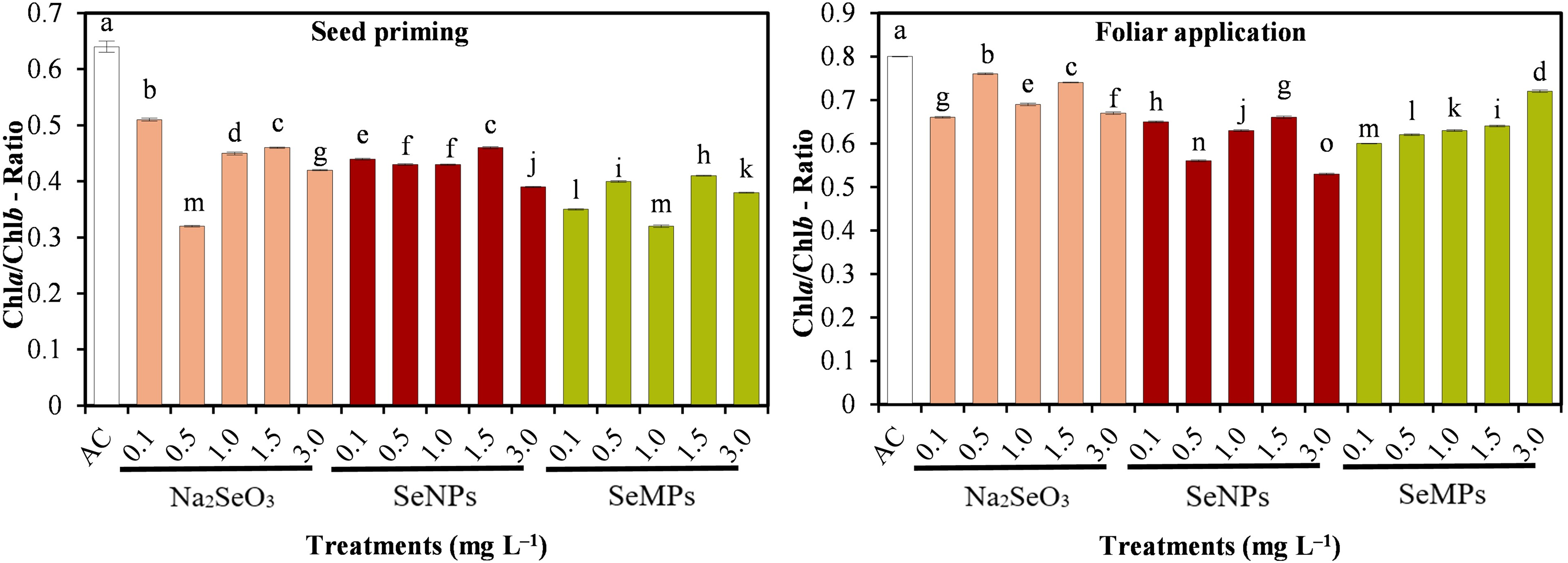

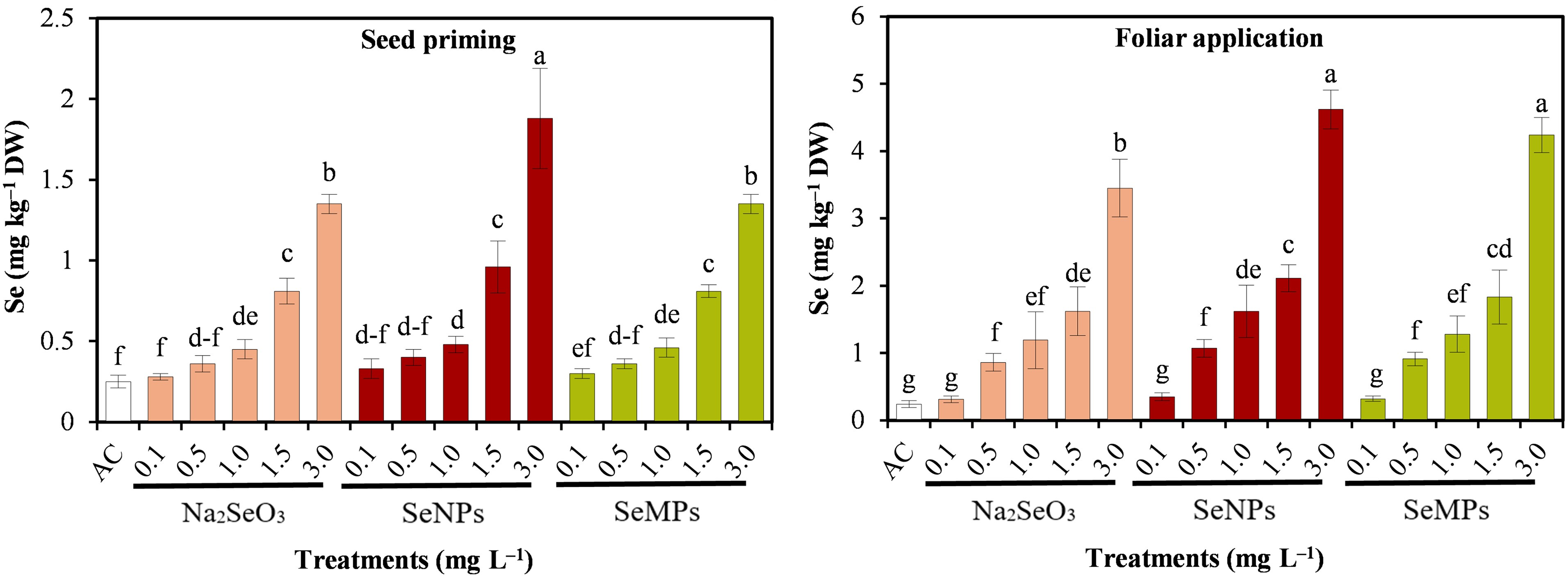

Photosynthetic pigments showed very interesting trends for both seed priming and foliar application (Fig. 3). For Chla in seed priming the treatments Na2SeO3 1.0 mg · L−1 and SeNPs 1.5 mg · L−1 was superior to the control by 4.53% and 7.62%, respectively (p ≤ 0.05), and the remaining treatments were equal to or inferior to the control. For Chlb and total Chl, all the Se treatments were statistically superior to the control (p ≤ 0.05).

Figure 3: Photosynthetic pigments of cucumber seedlings. AC: Control; SeNPs: Selenium nanoparticles; SeMPs: Selenium microparticles; Chla: Chlorophyll a; Chlb: Chlorophyll b; ChlT: Total chlorophyll; DW: Dry weight. Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments (LSD, p ≤ 0.05). n = 3; the ranges of the bars represent the standard deviation

With respect to foliar application, the Chla content decreased with all the Se treatments, except for the 0.5 mg · L−1 Na2SeO3 treatment, which was equal to that of the control. With foliar application, Chlb showed the best results with SeMPs at 0.5 and 1.0 mg · L−1, with increases of 12.13% and 20.54%, respectively, compared to the control (p ≤ 0.05). In terms of total Chl, treatments with Na2SeO3 at 0.5 mg · L−1 and SeMPs at 1.0 mg · L−1 increased its concentration by 3.21% and 9.09%, respectively, compared to the control (p ≤ 0.05).

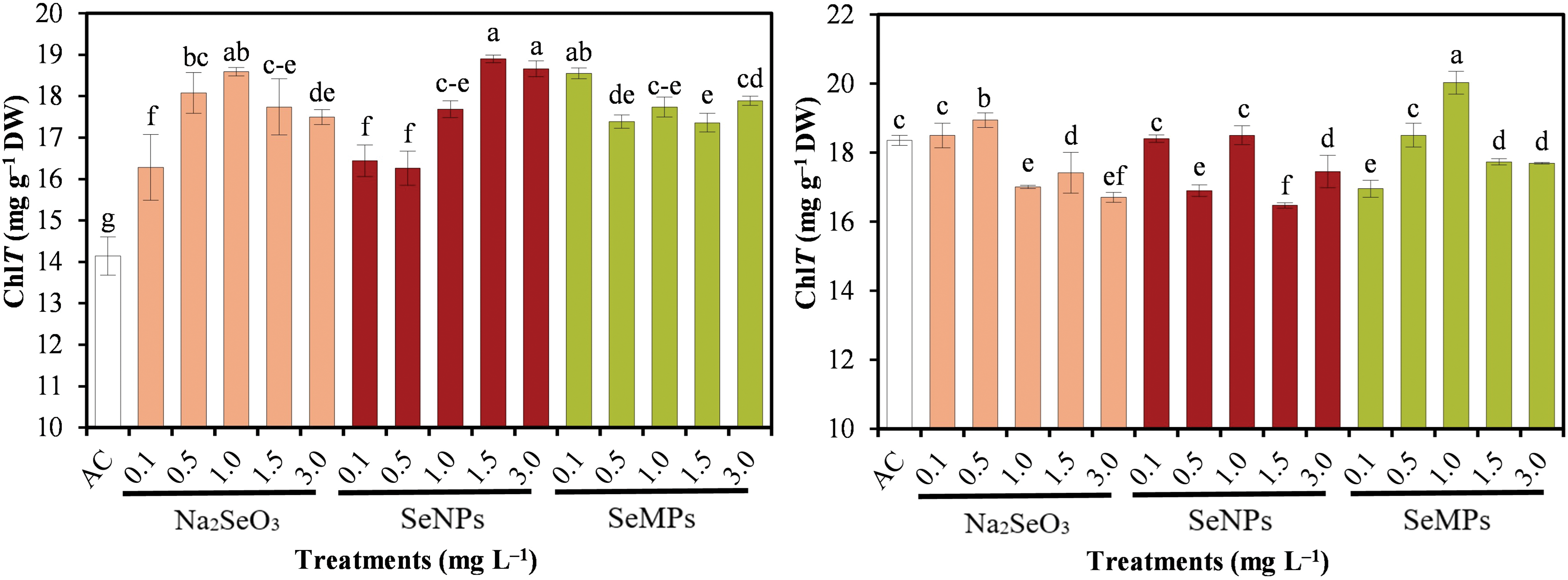

In both experiments and for all the treatments, the Chlb concentration was greater than the Chla concentration, which was reflected in a low Chla/Chlb ratio (Fig. 4). All the Se treatments resulted in a significantly lower Chla/Chlb ratio than did the control treatment.

Figure 4: Chla/Chlb ratio of cucumber seedlings. AC: Control; SeNPs: Selenium nanoparticles; SeMPs: Selenium microparticles; Chla: Chlorophyll a; Chlb: Chlorophyll b. Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments (LSD, p ≤ 0.05). n = 3; the ranges of the bars represent the standard deviation

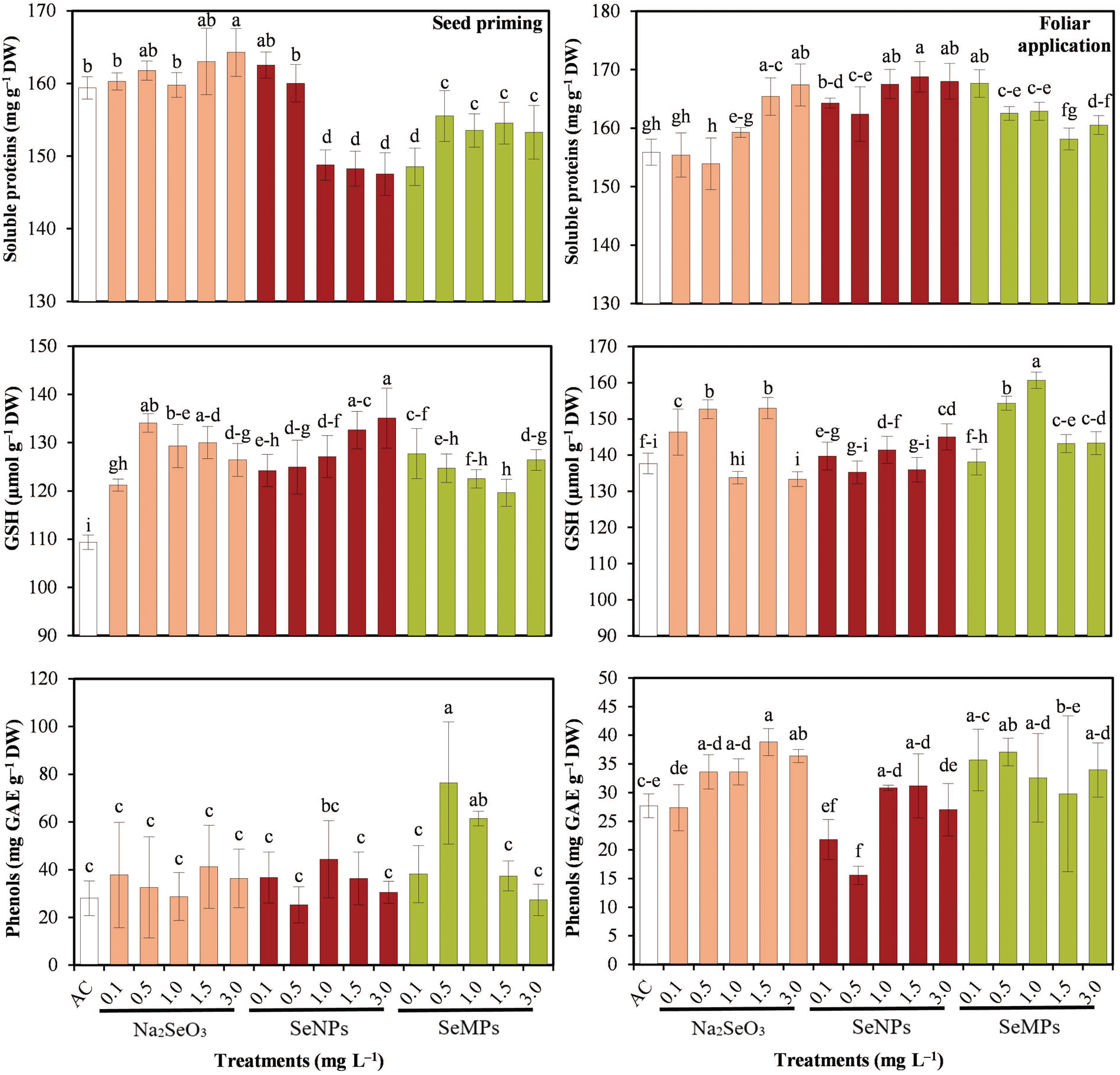

3.3 Proteins and Bioactive Compounds

The soluble protein concentration differed with respect to seed priming and foliar application of the different forms of Se (Fig. 5). In terms of seed priming, that in the Na2SeO3 at 3.0 mg · L−1 treatment was 3.06% greater than that in the control (p ≤ 0.05), and those in the other treatments were equal to or lower than those in the control. In terms of foliar application, the results of the control treatment were the lowest, with the best results occurring with Na2SeO3 at 1.5 and 3.0 mg · L−1; SeNPs at 1.0, 1.5 and 3.0 mg · L−1; and SeMPs at 0.1 mg · L−1 (p ≤ 0.05).

Figure 5: Soluble proteins and bioactive compounds of cucumber seedlings. AC: Control; SeNPs: Selenium nanoparticles; SeMPs: Selenium microparticles; GAE: Gallic acid equivalents; GSH: Reduced glutathione; DW: Dry weight. Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments (LSD, p ≤ 0.05). n = 3; the ranges of the bars represent the standard deviation

The Se materials caused interesting effects on the GSH and phenols concentrations (Fig. 5). All forms of Se significantly increased GSH in seed priming compared to the control and for phenols, only 0.5 and 1.0 mg · L−1 SeMPs were superior to the control (p ≤ 0.05). In the foliar application of Se, the control was one of the treatments that presented the lowest GSH concentrations, the most outstanding being Na2SeO3 at 0.5 and 1.5 mg · L−1 and SeMPs at 0.5 and 1.0 mg · L−1 (p ≤ 0.05). With the foliar application, phenols increased as the Na2SeO3 dose increased, SeNPs in some treatments decreased them and SeMPs at 0.5 mg · L−1 increased them (p ≤ 0.05).

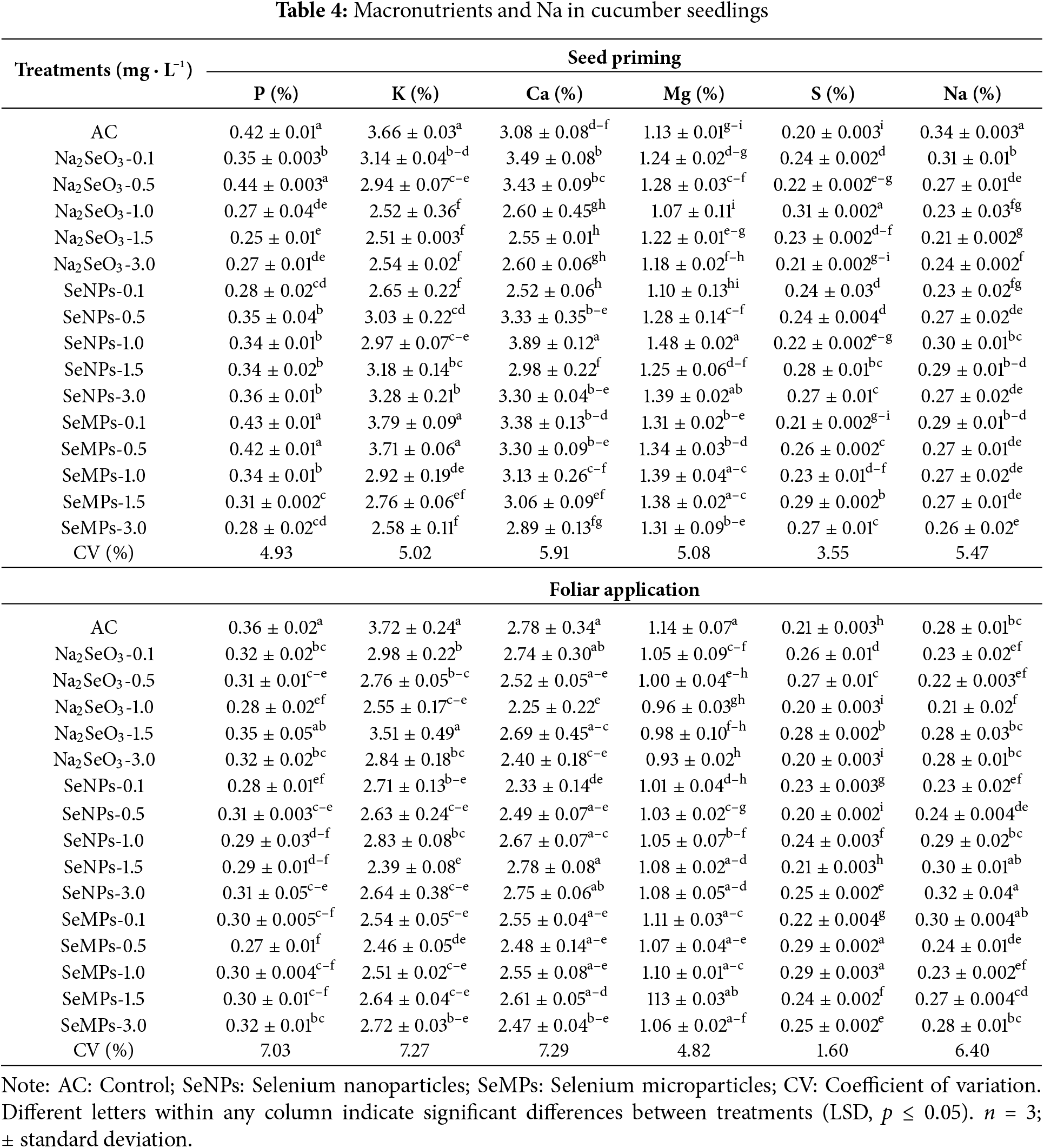

The application of Se for the two application methods resulted in some significant differences in macronutrients and sodium (Na) (p ≤ 0.05) (Table 4). For seed priming, P and potassium (K) decreased in most treatments with Se, with those in the control treatment being among the highest. With respect to calcium (Ca), some treatments with Se surpassed the control, others were equal, and others were inferior, with the best results, Na2SeO3 0.1 mg · L−1 and SeNPs 1.0 mg · L−1, resulting in increases of 13.31% and 26.29%, respectively. In terms of magnesium (Mg), the SeNPs 1.0 and 3.0 mg · L−1 treatment exceeded the control by 30.97% and 23%, respectively, with the latter being among the lowest treatments. For S, the control had the lowest values, with Na2SeO3 at 1.0 mg · L−1 (+55%) and SeMPs at 1.5 mg · L−1 (+45%) presenting the highest values. With respect to Na, the control had the greatest accumulation.

Foliar application of Se materials, for P, K, Ca and Mg caused a decrease in most of the treatments, being the control in all cases of the treatments that presented the highest values. For S, most of the treatments with Se were superior to the control, where the SeMPs at 0.5 and 1.0 mg · L−1 showed the highest values. For Na, the control showed intermediate values compared to the rest of the Se treatments.

Table 5 shows the results of micronutrients and Si in seed priming, where some significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) are observed. The amount of Fe increased in some of the treatments, with the greatest increase occurring with 0.1 mg · L−1 at Na2SeO3 (+94.75%). For Zn, the control had the highest values, and those of all the treatments with Se were lower. The amount of Cu increased only with the 0.1 mg · L−1 SeNPs treatment. For manganese (Mn), the treatments with 0.1, 0.5 and 1.0 mg · L−1 SeMPs presented the highest values compared with those of the control. Finally, Si showed very varied values, where the control presented intermediate values and the 0.5 mg · L−1 Na2SeO3 treatment presented the highest values.

Table 5 also shows the results for micronutrients and Si from foliar application, where some significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) between treatments can be observed. The SeNPs at 1.5 mg · L−1 treatment presented the highest values for Fe, exceeding those of the control by 170.50%. For Zn, Na2SeO3 (1.5 mg · L−1) and SeMPs (1.0 mg · L−1) outperformed the control by 52.78% and 51.50%, respectively. For Cu and Mn, the control was among the treatments that presented the highest values, with some treatments having equal values and others having lower values than the control. For Si, only the SeMPs concentration of 1.0 mg · L−1 was greater than that of the control.

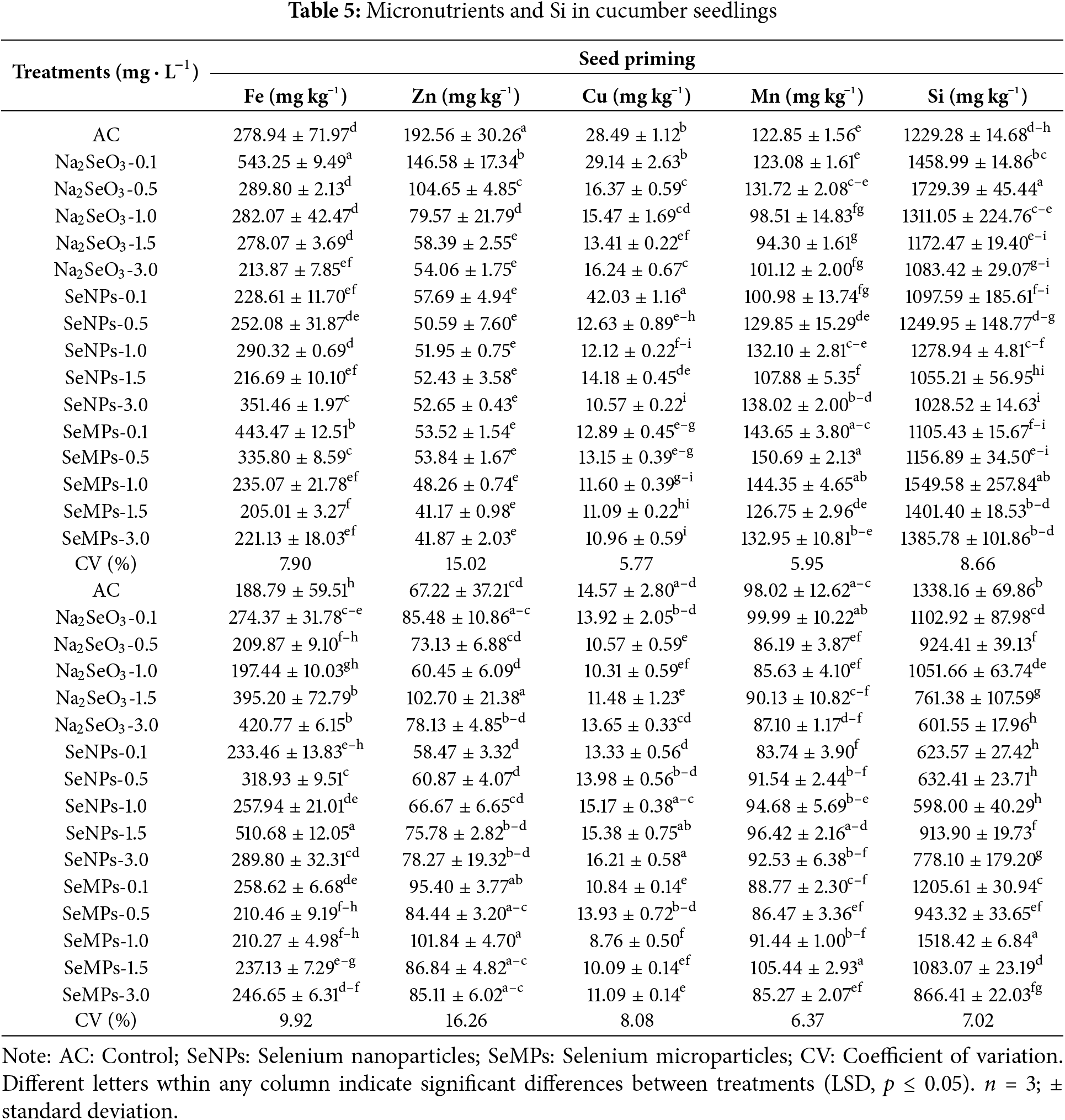

Fig. 6 shows the concentration of Se in cucumber seedlings, which shows significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) between treatments. The concentration in plant tissue increased, for all three forms of Se, as the nutrient dose was increased. On the other hand, foliar applications showed more accumulation than seed priming. In this sense, seed priming with SeNPs at 3.0 mg · L−1 showed the highest value, followed by SeMPs and Na2SeO3 at 3.0 mg · L−1. For foliar application, SeNPs at 3.0 mg · L−1 also showed the highest concentration, followed by SeMPs and Na2SeO3 at 3.0 mg · L−1.

Figure 6: Selenium concentration of cucumber seedlings. AC: Control; SeNPs: Selenium nanoparticles; SeMPs: Selenium microparticles; DW: Dry weight. Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments (LSD, p ≤ 0.05). n = 3; the ranges of the bars represent the standard deviation

The use of biostimulants in agriculture has expanded substantially in response to the resulting increases in crop growth, development and yield [37]. In this study, seed priming and foliar application of different forms of Se increased the stem diameter, leaf area and biomass of cucumber seedlings. García-Locascio et al. [38] reported that seed priming with SeNPs inhibited the germination rate in corn, but increased it in tomato, together with the vigor index, this at 10 mg · L−1. The same authors evaluated the foliar application of SeNPs and mentioned that stem length and diameter of tomato plants increased. Raza et al. [39] evaluated the seed priming of quinoa with sodium selenate (Na2SeO4) at 3, 6 and 9 mg · L−1, and show in their results that panicle length, panicle weight and 1000 grain weight were increased under standard growth conditions and drought stress. Colman et al. [22] reported that tomato seed priming with chitosan microparticles (CsMPs) improved the germination percentage and vigor and that foliar application increased the shoot and root biomass of seedlings.

The results are mainly because Se, at low concentrations, can stimulate organogenesis, amino acid synthesis and protein synthesis, which are directly involved in increasing plant biomass and growth [40,41]. In addition, the Se applied for seed priming results in the de novo synthesis of nucleic acids, proteins and ATP, in plants which subsequently benefits plant growth [41,42]. Foliar application of Se allows direct application of nutrient to organs for synthesis, such as leaves, and in this way, Se can reach chloroplasts, organelles where it can be assimilated into selenoamino acids via the S pathway [8]. With respect to SeNPs and SeMPs, owing to their magnetic, electrical and optical properties and the composition of their corona, when applied by seed priming, they create a greater number of pores in the seed coat, which facilitates the absorption of water; therefore, germination is accelerated, and the growth of the seedlings is faster [43]. The application of SeNPs and SeMPs in any application form can likely induce the mobilization of sugars in plants to the organs of demand and, therefore, improve their growth, as has been proven for AgNPs [44].

When they meet the epidermis or internal fluids of plants, SeNPs and SeMPs adsorb mainly peptides and proteins and form a corona, which is the first to come into direct contact with the receptors or components of plant cell walls and membranes [45,46]. This phenomenon stimulates plants, leading to improvements in different physiological processes involved in plant growth. One of these processes is hormonal induction as indicated by Zahedi et al. [47], who reported that the foliar application of SeNPs to strawberry plants increased the synthesis of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) and abscisic acid (ABA) in leaves, which was reflected in improved plant growth and yield. Another process in which this type of material is involved is nitrogen (N) metabolism, as shown by Colman et al. [48], who demonstrated that CsMPs positively regulate genes involved in N metabolism (NRT1.1, NRT2.1, AMT1.1, NR and GS1) in tomato seedlings. These genes encode enzymes and transporters responsible for the assimilation of N to protein amino acids. The NRT1.1 gene encodes a dual-affinity NO3− transporter protein; NRT2.1 also encodes an NO3− transporter protein, especially under conditions of low availability; the AMT1 gene is part of a family of NH4+ transporter genes; NR encodes the enzyme nitrate reductase, which carries out the reduction of NO3− to NO2−; GS1 encodes the enzyme glutamine synthetase, responsible for the conversion of NH4+ to glutamine [49–52].

Establishing a possible explanation or hypothesis of how different forms of Se improve plant growth is complicated since there are different metabolic pathways that can be activated; however, N metabolism is one of those involved and has a broad relationship with carbon metabolism (photosynthesis) and the metabolism of phytohormones, mainly with that of IAA, as mentioned above. Se, by enhancing, to a certain extent, the photosynthetic activity that results in the production of photoassimilates (mainly glucose), increases the process of glycolysis, which is due to a greater availability of glucose, metabolism from which compounds such as phosphoenolpyruvate can be obtained, which is a precursor of aromatic amino acids such as tryptophan [53]. This amino acid is a precursor of IAA, a phytohormone responsible for cell division and elongation, tissue differentiation, tropisms and root formation, which is directly related to increased plant growth [54]. In this sense, some of the effects of Se on plant growth derive from improvements in photosynthetic activity and N metabolism, which produce sugars, amino acids, proteins and phytohormones, compounds involved in plant development. Abdelsalam et al. [55] evaluated the application of Na2SeO4 and SeNPs in beans and reported that treatment with SeNPs resulted in higher concentrations of sugars, carboxylic acids and amino acids, mainly due to the increase in N, glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism.

Se is a beneficial nutrient that has direct effects on the photosynthetic system by increasing or decreasing the concentration of chlorophyll, depending on the concentration used, the form of Se and the application method [8]. In this study, for seed priming, there were increases and decreases in Chla with the Se materials, and for Chlb and total Chl, all the Se treatments were superior to the control. With respect to foliar application, the Chla, Chlb and total Chl concentrations increased and decreased, respectively, with increasing Se application. Similar results were shown by Ishtiaq et al. [56], who reported that tomato seed priming with SeNPs increased total Chl as the dose increased from 25 to 100 mg · L−1. Lin et al. [57] reported that foliar application of Na2SeO3 to strawberry plants improved the Chla, Chlb and total Chl concentrations. On the other hand, Wang et al. [19] reported that applications of CuONPs and CuOMPs at 200 and 400 mg kg−1 did not affect the concentrations of Chla and Chlb in lettuce leaves.

When Se is absorbed, it can reach chloroplasts directly, increase the activity of enzymes involved in chlorophyll synthesis, and can also be incorporated into the electron transport chain, thus improving photosynthetic activity [9]. Se can act as a prooxidant and induce the synthesis of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which cause chloroplast membrane peroxidation and affect chlorophyll synthesis [58]. SeNPs, owing to their properties, can increase the gene expression of proteins that are part of light-harvesting complexes (LHCII and LHCI) in the thylakoid membrane so that SeNPs can induce pigment synthesis and increase light absorption, water photolysis, oxygen evolution, and energy distribution between photosystems and accelerate the transformation of light energy into chemical energy [59]. This may also occur with the use of SeMPs, as they have properties similar to those of SeNPs.

Seed priming is a practice that has gained relevance because of its multiple positive effects on crop production. There is evidence that this practice can increase the accumulation of osmolytes such as proline, polyamines, and glycine-betaine. The latter can act to protect the structure of extrinsic PSII proteins. It also improves RUBISCO activity and chloroplasts stability [60,61].

In both experiments, there was a higher concentration of Chlb than Chla, which was due to the use of LED lamps with photosynthetic irradiance very different from that in open field conditions. In this sense, plants, as a mechanism to ensure greater light absorption, increase the amount of Chlb, an adaptive mechanism that allows greater absorption efficiency with lower light intensity, ensuring the photosynthetic rate [62]. The Chla/Chlb ratio indicates low ratios; however, the control treatment presented the highest value, indicating that Se possibly increased the activity of the Chla oxygenase enzyme, which is responsible for the synthesis of Chlb from Chla [63]. This reduction in the Chla/Chlb ratio and the increase in Chlb indicate a higher concentration of PSII versus PSI since Chlb is more abundant in PSII [64]. The Chla/Chlb ratio is an important determinant of the light absorption efficiency of photosynthesis, as it is an indicator of the size or concentration of the photosystems [65].

4.3 Proteins and Bioactive Compounds

Se has positive effects on the production of bioactive compounds and proteins in plant cells of different species. The results revealed some increases and decreases in soluble proteins during seed priming; however, with foliar application most of the Se treatments were superior to the control. Sardari et al. [66] demonstrated that the drench application of Na2SeO4 at low concentrations and SeNPs at high concentrations increased soluble protein accumulation in wheat. Similarly, Li et al. [67] reported increases in soluble proteins in cowpea with foliar application of Na2SeO3 and SeNPs, with SeNPs showing the greatest accumulation. This is because Se at low concentrations can stimulate the synthesis of amino acids and proteins through the selenoamino acids (SeMet and SeCys) formed, which function as precursors of protein amino acids; however, high concentrations can cause the synthesis of large amounts of selenoamino acids, which replace methionine and cysteine in proteins and affect their synthesis and functionality [8,68]. Similarly, Nauman Khan et al. [69] reported increases in soluble proteins in NaCl-stressed oilseed rape plants treated under seed priming with Se-doped carbon-doped NPs.

The results for GSH and phenols showed increases with Se treatments, which is a very common occurrence. Ishtiaq et al. [56] reported that seed priming of tomato with SeNPs increased the concentrations of GSH and ascorbic acid as the dose of SeNPs increased. Golubkina et al. [70] investigated the foliar application of Na2SeO4 to lettuce plants to evaluate seed productivity and quality. These authors reported that the antioxidant capacity of seeds was improved and that phenols were not modified. As mentioned above, Se can act as a prooxidant, increasing in the synthesis of ROS, which function as signaling agents and activate the antioxidant system of plants [71]. Currently, materials such as SeNPs and SeMPs, which are highly reactive, can directly activate the antioxidant system of plants since they can modify the membrane potential and different receptors located in cell walls and membranes [23,72]. On the other hand, the similarity of Se to S allows it to be incorporated into different sulfur metabolites, such as GSH, and as seen in the experiment, the different Se materials in both forms of application increased the GSH concentration. GSH in plants is essential for maintaining redox homeostasis through the GSH-ascorbate cycle because it scavenges ROS to protect cells from oxidative damage [73].

The use of Se in agricultural plants commonly causes changes in nutrient uptake, as shown by the results of the present study. For the macro- and micronutrients of cucumber seedlings all values were within the sufficiency ranges mentioned by Campbell [74]; however, there were some significant differences between the treatments. There were some increases in some nutrients for seed priming (Ca, Mg, S, Fe, Cu, Mn and Si) and foliar application (S, Fe, Zn and Si). de Lima Gomes et al. [75] reported that the application of Na2SeO4 to tomatoes caused increases in N, P, Ca, S, Fe and Mn in plant shoots and increases in P, S, Mn and Zn in fruits. In fruits, K and Fe were not modified. There are several explanations for why different forms of Se can increase nutrient concentrations, one of which is that Se promotes the expression of genes encoding aquaporins, proteins responsible for transporting water, minerals, and other molecules into the cell [76]. In addition, Se positively regulates the expression of sulfate transporters (SULTR3;1 and SULTR3;6) [77]. When applied to plants, SeNPs and SeMPs can be transported to different plant organs, such as the roots, where they can create a greater number of pores, promoting the diffusion of ions [78].

On the other hand, some nutrients showed no alterations or showed decreases. For example, the decrease in P for both seed priming and foliar application of Se. Se and P can act synergistically or antagonistically, depending on their concentration and plant species. To some extent, Na2SeO3 can inhibit P uptake and metabolism, as Na2SeO3 can be taken up by phosphate transporters (PHT1;1, PHT1;8, and PHT1;9) and can compete for uptake [79,80]. Jafari & Moghaddam [81] reported that the application of Na2SeO3 to mint caused a decrease in P. Santos et al. [12] reported that the application of Na2SeO3 to Vigna unguiculata L. did not affect the P concentration.

K is another nutrient that decreases with the application of Se materials in both forms of application (seed priming and foliar application of Se), which depends on factors that have not yet been fully elucidated; however, Se influences K uptake, mainly because it participates in the regulation of its transporters [82]. In contrast, Badawy et al. [83] reported that the use of SeNPs in rice leaves increased the concentration of K. Saffaryazdi et al. [84] reported that the application of Na2SeO3 to spinach caused a decrease in K as the Se dose increased.

Se can affect in different ways the absorption of Ca and Mg, in this sense, it can be seen that with seed priming some increases of these cations were achieved and with foliar application there were decreases, therefore, the interaction can be synergistic and antagonistic, which depends on the form of application, the species of Se, the dose and the plant species [85]. Mn can be negatively affected because Se can inhibit the expression of the Nramp5 transporter, which is involved in the absorption of Mn [86,87]. Wu et al. [88] reported that with the use of Na2SeO3 and Na2SeO4 in Cardamine violifolia the Mn concentration decreased. Different results were reported by Logvinenko et al. [89], who reported that the application of Na2SeO4 and SeNPs to Artemisia annua L. plants increased the concentrations of Mn, Ca and Mg in leaves. Du et al. [90] reported that the use of CuNPs and CuMPs in oregano increased Mg and Ca and reduced Mn accumulation in stems and leaves.

Compared with seed priming, foliar application of Se was more effective in terms of Se accumulation. In addition, in both cases, SeNPs and SeMPs achieved the highest accumulation. Freire et al. [91] reported that foliar application of Na2SeO3 and SeNPs increased the Se concentration in rice grains, resulting in the highest accumulation of Na2SeO3; however, in leaves and stems, the greatest accumulation was achieved with SeNPs. Similarly, García-Locascio et al. [6] reported that tomato seed priming with SeNPs increased the Se concentration in seedlings as the dose increased. The results of the present study agree with those reported in the literature, where it is common that as the dose of Se increases, the Se concentration in the tissue increases. Specifically, for both application methods, SeNPs increased the Se concentration in cucumber seedling tissue the most, followed by SeMPs and Na2SeO3. This is because SeNPs and SeMPs, owing to their optical, magnetic and electrical properties, can enter the cell interior more effectively and thus achieve greater accumulation in plant tissues [23,72]. Now, with foliar applications, more Se was accumulated in the seedlings because two applications were made, and seed priming only consists of a single application of Se materials. It is also important to mention that keeping the SeMPs dispersed is more complicated than with SeNPs, which to a certain extent makes the application of SeNPs more effective and therefore their accumulation in plant tissues may be greater, as in the present experiment for seed priming.

The results indicate that the application of the three forms of Se (mainly SeMPs) is feasible and can improve the growth, pigments, proteins, bioactive compounds and minerals of cucumber seedlings, both for seed priming and foliar application. With respect to Se accumulation in seedling tissues, foliar application of SeNPs and SeMPs at 3.0 mg · L−1 was more effective, indicating that the use of these treatments is feasible for subsequent studies on the biofortification of cucumber fruits. The results presented are promising for the use of SeMPs, since, to our knowledge, there are no studies in agricultural crops, and they may constitute an additional alternative for biostimulation and biofortification. This study has several limitations, which, in subsequent experiments, can be addressed, such as the lack of analysis of important variables related to the activity of antioxidant enzymes, phytohormones, and ROS and the expression of sulfate, phosphate and aquaporin transporters, which would facilitate a better understanding of the response of cucumber seedlings to the application of Se materials and their application methods.

Acknowledgement: Oscar Sariñana-Aldaco thanks SECIHTI for the Postdoctoral financial support with CVU number 818215. Thanks are also extended to the Universidad Autónoma Agraria Antonio Narro (UAAAN), the Centro de Investigación en Química Aplicada (CIQA) and the Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados (CINVESTAV) for collaborating in the research.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Oscar Sariñana-Aldaco and Adalberto Benavides-Mendoza; methodology, Adalberto Benavides-Mendoza; software, Susana González-Morales; validation, Gregorio Cadenas-Pliego and Marissa Pérez-Alvarez; formal analysis, Oscar Sariñana-Aldaco; investigation, Oscar Sariñana-Aldaco and Carmen Alicia Ayala-Contreras; resources, Adalberto Benavides-Mendoza and América Berenice Morales-Díaz; data curation, Oscar Sariñana-Aldaco; writing—original draft preparation, Oscar Sariñana-Aldaco; writing—review and editing, Adalberto Benavides-Mendoza; visualization, Dámaris Leopoldina Ojeda-Barrios; supervision, José Gerardo Uresti-Porras; project administration, Adalberto Benavides-Mendoza; funding acquisition, Adalberto Benavides-Mendoza. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Adalberto Benavides-Mendoza, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Kumar K, Gambhir G, Dass A, Tripathi AK, Singh A, Jha AK, et al. Genetically modified crops: current status and future prospects. Planta. 2020;251(4):91. doi:10.1007/s00425-020-03372-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. du Jardin P. Plant biostimulants: definition, concept, main categories and regulation. Sci Hortic. 2015;196:3–14. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2015.09.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Nile SH, Thiruvengadam M, Wang Y, Samynathan R, Shariati MA, Rebezov M, et al. Nano-priming as emerging seed priming technology for sustainable agriculture—recent developments and future perspectives. J Nanobiotechnology. 2022;20(1):254. doi:10.1186/s12951-022-01423-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Dima S-O, Neamţu C, Desliu-Avram M, Ghiurea M, Capra L, Radu E, et al. Plant biostimulant effects of baker’s yeast vinasse and selenium on tomatoes through foliar fertilization. Agronomy. 2020;10(1):133. doi:10.3390/agronomy10010133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wu M, Su H, Li C, Fu Z, Wu F, Yang J, et al. Effects of foliar application of single-walled carbon nanotubes on carbohydrate metabolism in crabapple plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2023;194:214–22. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2022.11.023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. García-Locascio E, Valenzuela EI, Cervantes-Avilés P. Impact of seed priming with selenium nanoparticles on germination and seedlings growth of tomato. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):6726. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-57049-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Singhal RK, Fahad S, Kumar P, Choyal P, Javed T, Jinger D, et al. Beneficial elements: new players in improving nutrient use efficiency and abiotic stress tolerance. Plant Growth Regul. 2023;100(2):237–65. doi:10.1007/s10725-022-00843-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Garduño-Zepeda AM, Márquez-Quiroz C. Application of selenium in agricultural crops. Inf Técnica Econ Agrar. 2018;114(4):327–43. (In Spanish). doi:10.12706/itea.2018.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhou X, Yang J, Kronzucker HJ, Shi W. Selenium biofortification and interaction with other elements in plants: a review. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:586421. doi:10.3389/fpls.2020.586421. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Amagova Z, Matsadze V, Kavarnakaeva Z, Golubkina N, Antoshkina M, Sękara A, et al. Joint cultivation of Allium ursinum and Armoracia rusticana under foliar sodium selenate supply. Plants. 2022;11(20):2778. doi:10.3390/plants11202778. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Guignardi Z, Schiavon M. Biochemistry of plant selenium uptake and metabolism. In: Pilon-Smits E, Winkel L, Lin ZQ, editors. Selenium in plants: molecular, physiological, ecological and evolutionary aspects. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2017. p. 21–34. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-56249-0_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Santos EF, Figueiredo CO, Rocha MAP, Lanza MGDB, Silva VM, Reis AR. Phosphorus and selenium interaction effects on agronomic biofortification of cowpea plants. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2023;23(3):4385–95. doi:10.1007/s42729-023-01357-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Abdalla MA, Meschede CAC, Mühling KH. Selenium foliar application alters patterns of glucosinolate hydrolysis products of pak choi Brassica rapa L. var. chinensis. Sci Hortic. 2020;273(9):109614. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2020.109614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zou X, Sun R, Wang C, Wang J. Study on selenium assimilation and transformation in radish sprouts cultivated using maillard reaction products. Foods. 2024;13(17):2761. doi:10.3390/foods13172761. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Morales-Díaz AB, Ortega-Ortíz H, Juárez-Maldonado A, Cadenas-Pliego G, González-Morales S, Benavides-Mendoza A. Application of nanoelements in plant nutrition and its impact in ecosystems. Adv Nat Sci Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2017;8(1):013001. doi:10.1088/2043-6254/8/1/013001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Marmiroli M, Maestri E. Special issue physiological and molecular responses of plants to engineered nanomaterials. Nanomaterials. 2024;14(2):151. doi:10.3390/nano14020151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. El-Araby HG, El-Hefnawy SFM, Nassar MA, Elsheery NI. Comparative studies between growth regulators and nanoparticles on growth and mitotic index of pea plants under salinity. Afr J Biotechnol. 2020;19(8):564–75. doi:10.5897/AJB2020.17198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Nozari Rad D, Baradaran Firouzabadi M, Makarian H, Farrokhi N, Gholami A. Effect of foliar application of nano and micro iron oxide particles with D.G ADJUVANT and RCP-5 additive material on some physiological traits of green bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Iran J Pulses Res. 2016;7:161–73. doi:10.22067/IJPR.V7I1.34475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Wang Y, Lin Y, Xu Y, Yin Y, Guo H, Du W. Divergence in response of lettuce (var. ramosa Hort.) to copper oxide nanoparticles/microparticles as potential agricultural fertilizer. Environ Pollut Bioavailab. 2019;31(1):80–4. doi:10.1080/26395940.2019.1578187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Read TL, Doolette CL, Howell NR, Kopittke PM, Cresswell T, Lombi E. Zinc accumulates in the nodes of wheat following the foliar application of 65Zn oxide nano- and microparticles. Environ Sci Technol. 2021;55(20):13523–31. doi:10.1021/acs.est.0c08544. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. de Alencar RS, Dias GF, de Araujo YML, de Vian PMO, Borborema LDA, Bonou SI, et al. Seed priming with residual silicon-glass microparticles mitigates water stress in cowpea. Sci Hortic. 2024;328(10):112933. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2024.112933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Colman SL, Salcedo MF, Mansilla AY, Iglesias MJ, Fiol DF, Martín-Saldaña S, et al. Chitosan microparticles improve tomato seedling biomass and modulate hormonal, redox and defense pathways. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2019;143(1):203–11. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2019.09.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Galogahi FM, Zhu Y, An H, Nguyen N-T. Core-shell microparticles: generation approaches and applications. J Sci-Adv Mster Dev. 2020;5(4):417–35. doi:10.1016/j.jsamd.2020.09.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Trejo-Valencia R, Sánchez-Acosta L, Fortis-Hernández M, Preciado-Rangel P, Gallegos-Robles MÁ, Antonio-Cruz RDC, et al. Effect of seaweed aqueous extracts and compost on vegetative growth, yield, and nutraceutical quality of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) fruit. Agronomy. 2018;8(11):264. doi:10.3390/agronomy8110264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Anwar S, Siddique R, Ahmad S, Haider MZ, Ali H, Sami A, et al. Genome wide identification and characterization of Bax inhibitor-1 gene family in cucumber (Cucumis sativus) under biotic and abiotic stress. BMC Genom. 2024;25(1):1032. doi:10.1186/s12864-024-10704-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Jurić S, Jurić M, Režek Jambrak A, Vinceković M. Tailoring alginate/chitosan microparticles loaded with chemical and biological agents for agricultural application and production of value-added foods. Appl Sci. 2021;11(9):4061. doi:10.3390/app11094061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Pedersen O, Revsbech NP, Shabala S. Microsensors in plant biology: in vivo visualization of inorganic analytes with high spatial and/or temporal resolution. J Exp Bot. 2020;71(14):3941–54. doi:10.1093/jxb/eraa175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Quiterio-Gutiérrez T, Ortega-Ortiz H, Cadenas-Pliego G, Hernández-Fuentes AD, Sandoval-Rangel A, Benavides-Mendoza A, et al. The application of selenium and copper nanoparticles modifies the biochemical responses of tomato plants under stress by Alternaria solani. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(8):1950. doi:10.3390/ijms20081950. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Mata-Padilla JM, Ledón-Smith JÁ, Pérez-Alvarez M, Cadenas-Pliego G, Barriga-Castro ED, Pérez-Camacho O, et al. Synthesis and superficial modification “in situ” of copper selenide (Cu2-x Se) nanoparticles and their antibacterial activity. Nanomaterials. 2024;14(13):1151. doi:10.3390/nano14131151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Castillo-Godina RG, Foroughbakhch-Pournavab R, Benavides-Mendoza A. Effect of selenium on elemental concentration and antioxidant enzymatic activity of tomato plants. J Agric Sci Technol. 2016;18:233–44. [Google Scholar]

31. Steiner AA. A universal method for preparing nutrient solutions of a certain desired composition. Plant Soil. 1961;15(2):134–54. doi:10.1007/bf01347224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Wellburn AR. The spectral determination of chlorophylls a and b, as well as total carotenoids, using various solvents with spectrophotometers of different resolution. J Plant Physiol. 1994;144(3):307–13. doi:10.1016/S0176-1617(11)81192-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72(1–2):248–54. doi:10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Xue T, Hartikainen H, Piironen V. Antioxidative and growth-promoting effect of selenium on senescing lettuce. Plant Soil. 2001;237(1):55–61. doi:10.1023/A:1013369804867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Singleton VL, Orthofer R, Lamuela-Raventós RM. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of folin-ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999;299(10):152–78. doi:10.1016/S0076-6879(99)99017-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. López-Morales D, de la Cruz-Lázaro E, Sánchez-Chávez E, Preciado-Rangel P, Márquez-Quiroz C, Osorio-Osorio R. Impact of agronomic biofortification with zinc on the nutrient content, bioactive compounds, and antioxidant capacity of cowpea bean (Vigna unguiculata L. Walpers). Agronomy. 2020;10(10):1460. doi:10.3390/agronomy10101460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Ruzzi M, Colla G, Rouphael Y. Editorial: biostimulants in agriculture II: towards a sustainable future. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15:1427283. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1427283. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. García-Locascio E, Valenzuela EI, Cervantes-Avilés P. Effects of seed priming and foliar application of Se nanoparticles in the germination, seedling growth, and reproductive stage of tomato and maize. BIO Web Conf. 2024;122:01014. doi:10.1051/bioconf/202412201014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Raza MAS, Aslam MU, Valipour M, Iqbal R, Haider I, Mustafa AEZMA, et al. Seed priming with selenium improves growth and yield of quinoa plants suffering drought. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):886. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-51371-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Domokos-Szabolcsy E, Marton L, Sztrik A, Babka B, Prokisch J, Fari M. Accumulation of red elemental selenium nanoparticles and their biological effects in Nicotinia tabacum. Plant Growth Regul. 2012;68(3):525–31. doi:10.1007/s10725-012-9735-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Zhang X, He H, Xiang J, Yin H, Hou T. Selenium-containing proteins/peptides from plants: a review on the structures and functions. J Agric Food Chem. 2020;68(51):15061–73. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.0c05594. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Aswathi KPR, Kalaji HM, Puthur JT. Seed priming of plants aiding in drought stress tolerance and faster recovery: a review. Plant Growth Regul. 2022;97(2):235–53. doi:10.1007/s10725-021-00755-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Mahakham W, Sarmah AK, Maensiri S, Theerakulpisut P. Nanopriming technology for enhancing germination and starch metabolism of aged rice seeds using phytosynthesized silver nanoparticles. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):8263. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-08669-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Acharya P, Jayaprakasha GK, Crosby KM, Jifon JL, Patil BS. Nanoparticle-mediated seed priming improves germination, growth, yield, and quality of watermelons (Citrullus lanatus) at multi-locations in Texas. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):5037. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-61696-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Juárez-Maldonado A, Ortega-Ortíz H, Morales-Díaz AB, González-Morales S, Morelos-Moreno Á., Cabrera-De la Fuente M, et al. Nanoparticles and nanomaterials as plant biostimulants. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(1):162. doi:10.3390/ijms20010162. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Weiss ACG, Krüger K, Besford QA, Schlenk M, Kempe K, Förster S, et al. In situ characterization of protein corona formation on silica microparticles using confocal laser scanning microscopy combined with microfluidics. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019;11(2):2459–69. doi:10.1021/acsami.8b14307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Zahedi SM, Abdelrahman M, Hosseini MS, Hoveizeh NF, Tran LSP. Alleviation of the effect of salinity on growth and yield of strawberry by foliar spray of selenium-nanoparticles. Environ Pollut. 2019;253:246–58. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2019.04.078. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Colman SL, Salcedo MF, Iglesias MJ, Alvarez VA, Fiol DF, Casalongué CA, et al. Chitosan microparticles mitigate nitrogen deficiency in tomato plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2024;212(12):108728. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2024.108728. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Fang XZ, Fang SQ, Ye ZQ, Liu D, Zhao KL, Jin CW. NRT1.1 dual-affinity nitrate transport/signalling and its roles in plant abiotic stress resistance. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:715694. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.715694. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Jia L, Hu D, Wang J, Liang Y, Li F, Wang Y, et al. Genome-wide identification and functional analysis of nitrate transporter genes (NPF, NRT2 and NRT3) in maize. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(16):12941. doi:10.3390/ijms241612941. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Ma C, Ban T, Yu H, Li Q, Li X, Jiang W, et al. Increased ammonium enhances suboptimal-temperature tolerance in cucumber seedlings. Plants. 2023;12(12):2243. doi:10.3390/plants12122243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Ma L, Wei A, Liu C, Liu N, Han Y, Chen Z, et al. Screening key genes related to nitrogen use efficiency in cucumber through weighted gene co-expression network analysis. Genes. 2024;15(12):1505. doi:10.3390/genes15121505. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Skrypnik L, Feduraev P, Golovin A, Maslennikov P, Styran T, Antipina M, et al. The integral boosting effect of selenium on the secondary metabolism of higher plants. Plants. 2022;11(24):3432. doi:10.3390/plants11243432. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Gull M, Sajid ZA, Aftab F. Alleviation of salt stress in Solanum tuberosum L. by exogenous application of indoleacetic acid and L-tryptophan. J Plant Growth Regul. 2023;42(5):3257–73. doi:10.1007/s00344-022-10788-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Abdelsalam A, Gharib FAEL, Boroujerdi A, Abouelhamd N, Ahmed EZ. Selenium nanoparticles enhance metabolic and nutritional profile in Phaseolus vulgaris: comparative metabolomic and pathway analysis with selenium selenate. BMC Plant Biol. 2025;25(1):119. doi:10.1186/s12870-025-06097-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Ishtiaq M, Mazhar MW, Maqbool M, Hussain T, Hussain SA, Casini R, et al. Seed priming with the selenium nanoparticles maintains the redox status in the water stressed tomato plants by modulating the antioxidant defense enzymes. Plants. 2023;12(7):1556. doi:10.3390/plants12071556. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Lin Y, Cao S, Wang X, Liu Y, Sun Z, Zhang Y, et al. Foliar application of sodium selenite affects the growth, antioxidant system, and fruit quality of strawberry. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15:1449157. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1449157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Semida WM, El-Mageed TAA, Abdelkhalik A, Hemida KA, Abdurrahman HA, Howladar SM, et al. Selenium modulates antioxidant activity, osmoprotectants, and photosynthetic efficiency of onion under saline soil conditions. Agronomy. 2021;11(5):855. doi:10.3390/agronomy11050855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Ze Y, Liu C, Wang L, Hong M, Hong F. The regulation of TiO2 nanoparticles on the expression of light-harvesting complex II and photosynthesis of chloroplasts of Arabidopsis thaliana. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2011;143(2):1131–41. doi:10.1007/s12011-010-8901-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Marthandan V, Geetha R, Kumutha K, Renganathan VG, Karthikeyan A, Ramalingam J. Seed priming: a feasible strategy to enhance drought tolerance in crop plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(21):8258. doi:10.3390/ijms21218258. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Zhu M, Li Q, Zhang Y, Zhang M, Li Z. Glycine betaine increases salt tolerance in maize (Zea mays L.) by regulating Na+ homeostasis. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:978304. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.978304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Hu X, Gu T, Khan I, Zada A, Jia T. Research progress in the interconversion, turnover and degradation of chlorophyll. Cells. 2021;10(11):3134. doi:10.3390/cells10113134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Li Q, Zhou S, Liu W, Zhai Z, Pan Y, Liu C, et al. A chlorophyll a oxygenase 1 gene ZmCAO1 contributes to grain yield and waterlogging tolerance in maize. J Exp Bot. 2021;72(8):3155–67. doi:10.1093/jxb/erab059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Lichtenthaler HK, Babani F. Contents of photosynthetic pigments and ratios of chlorophyll a/b and chlorophylls to carotenoids (a + b)/(x + c) in C4 plants as compared to C3 plants. Photosynthetica. 2022;60:3–9. doi:10.32615/ps.2021.041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Kume A, Akitsu T, Nasahara KN. Why is chlorophyll b only used in light-harvesting systems? J Plant Res. 2018;131(6):961–72. doi:10.1007/s10265-018-1052-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Sardari M, Rezayian M, Niknam V. Comparative study for the effect of selenium and nano-selenium on wheat plants grown under drought stress. Russ J Plant Physl. 2022;69(6):127. doi:10.1134/S102144372206022X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Li L, Xiong Y, Wang Y, Wu S, Xiao C, Wang S, et al. Effect of nano-selenium on nutritional quality of cowpea and response of ABCC transporter family. Molecules. 2023;28(3):1398. doi:10.3390/molecules28031398. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Yang H, Yang X, Ning Z, Kwon SY, Li ML, Tack FMG, et al. The beneficial and hazardous effects of selenium on the health of the soil-plant-human system: an overview. J Hazard Mater. 2022;422(1314):126876. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126876. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Nauman Khan M, Fu C, Liu X, Li Y, Yan J, Yue L, et al. Nanopriming with selenium doped carbon dots improved rapeseed germination and seedling salt tolerance. Crop J. 2024;12(5):1333–43. doi:10.1016/j.cj.2024.03.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Golubkina N, Kharchenko V, Moldovan A, Antoshkina M, Ushakova O, Sękara A, et al. Effect of selenium and garlic extract treatments of seed-addressed lettuce plants on biofortification level, seed productivity and mature plant yield and quality. Plants. 2024;13(9):1190. doi:10.3390/plants13091190. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Ikram M, Raja NI, Mashwani ZUR, Omar AA, Mohamed AH, Satti SH, et al. Phytogenic selenium nanoparticles elicited the physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant defense system amelioration of Huanglongbing-infected ‘kinnow’ mandarin plants. Nanomaterials. 2022;12(3):356. doi:10.3390/nano12030356. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Juárez-Maldonado A, Tortella G, Rubilar O, Fincheira P, Benavides-Mendoza A. Biostimulation and toxicity: the magnitude of the impact of nanomaterials in microorganisms and plants. J Adv Res. 2021;31:113–26. doi:10.1016/j.jare.2020.12.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Lanza MGDB, dos Reis AR. Roles of selenium in mineral plant nutrition: ROS scavenging responses against abiotic stresses. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2021;164(6):27–43. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.04.026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Campbell CR. Reference sufficiency ranges for plant analysis in the southern region of the United States. Raleigh, NC, USA: Southern Region Agricultural Experiment Station; 2000. 134 p. [Google Scholar]

75. de Lima Gomes FT, Chales AS, Borghi EJA, Ferreira ACM, de Souza BCDOQ, Nascimento VL, et al. Agronomic biofortification with selenium and zinc in tomato plants (Solanum lycopersicum L.) and their effects on nutrient content and crop production. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2025;25(2):2503–17. doi:10.1007/s42729-025-02281-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Soliman MH, Alnusairi GSH, Khan AA, Alnusaire TS, Fakhr MA, Abdulmajeed AM, et al. Biochar and selenium nanoparticles induce water transporter genes for sustaining carbon assimilation and grain production in salt-stressed wheat. J Plant Growth Regul. 2023;42(3):1522–43. doi:10.1007/s00344-022-10636-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Chauhan R, Awasthi S, Indoliya Y, Chauhan AS, Mishra S, Agrawal L, et al. Transcriptome and proteome analyses reveal selenium mediated amelioration of arsenic toxicity in rice (Oryza sativa L.). J Hazard Mater. 2020;390(1):122122. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Wang X, Xie H, Wang P, Yin H. Nanoparticles in plants: uptake, transport and physiological activity in leaf and root. Materials. 2023;16(8):3097. doi:10.3390/ma16083097. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Jiang H, Lin W, Jiao H, Liu J, Chan L, Liu X, et al. Uptake, transport, and metabolism of selenium and its protective effects against toxic metals in plants: a review. Metallomics. 2021;13(7):mfab040. doi:10.1093/mtomcs/mfab040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Hu C, Nie Z, Shi H, Peng H, Li G, Liu H, et al. Selenium uptake, translocation, subcellular distribution and speciation in winter wheat in response to phosphorus application combined with three types of selenium fertilizer. BMC Plant Biol. 2023;23(1):224. doi:10.1186/s12870-023-04227-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Jafari H, Moghaddam M. Effect of different levels of sodium selenate and selenite on morphological characteristics and nutrients concentration in peppermint. J Soil Plant Interact Isfahan Univ Technol. 2022;13(3):1–16. doi:10.47176/jspi.13.3.121011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Xu S, Zhao N, Qin D, Liu S, Jiang S, Xu L, et al. The synergistic effects of silicon and selenium on enhancing salt tolerance of maize plants. Environ Exp Bot. 2021;187(2):104482. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2021.104482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Badawy SA, Zayed BA, Bassiouni SMA, Mahdi AHA, Majrashi A, Ali EF, et al. Influence of nano silicon and nano selenium on root characters, growth, ion selectivity, yield, and yield components of rice (Oryza sativa L.) under salinity conditions. Plants. 2021;10(8):1657. doi:10.3390/plants10081657. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Saffaryazdi A, Lahouti M, Ganjeali A, Bayat H. Impact of selenium supplementation on growth and selenium accumulation on spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) plants. Not Sci Biol. 2012;4(4):95–100. doi:10.15835/nsb448029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Longchamp M, Angeli N, Castrec-Rouelle M. Effects on the accumulation of calcium, magnesium, iron, manganese, copper and zinc of adding the two inorganic forms of selenium to solution cultures of Zea mays. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2016;98:128–37. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2015.11.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Cui J, Liu T, Li Y, Li F. Selenium reduces cadmium uptake into rice suspension cells by regulating the expression of lignin synthesis and cadmium-related genes. Sci Total Environ. 2018;644:602–10. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.07.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Li J, Jia Y, Dong R, Huang R, Liu P, Li X, et al. Advances in the mechanisms of plant tolerance to manganese toxicity. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(20):5096. doi:10.3390/ijms20205096. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Wu M, Cong X, Li M, Rao S, Liu Y, Guo J, et al. Effects of different exogenous selenium on Se accumulation, nutrition quality, elements uptake, and antioxidant response in the hyperaccumulation plant Cardamine violifolia. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2020;204(18):111045. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.111045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Logvinenko L, Golubkina N, Fedotova I, Bogachuk M, Fedotov M, Kataev V, et al. Effect of foliar sodium selenate and nano selenium supply on biochemical characteristics, essential oil accumulation and mineral composition of Artemisia annua L. Molecules. 2022;27(23):8246. doi:10.3390/molecules27238246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Du W, Tan W, Yin Y, Ji R, Peralta-Videa JR, Guo H, et al. Differential effects of copper nanoparticles/microparticles in agronomic and physiological parameters of oregano (Origanum vulgare). Sci Total Environ. 2018;618(4):306–12. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.11.042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Freire BM, Lange CN, Augusto CC, Onwuatu FR, Rodrigues GDP, Pieretti JC, et al. Foliar application of SeNPs for rice biofortification: a comparative study with selenite and speciation assessment. ACS Agric Sci Technol. 2024;5(1):94–107. doi:10.1021/acsagscitech.4c00613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools