Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Moderate Grazing Disturbance Can Promote the Leymus chinensis Grasslands’ Recovery through the Existing Bud Banks in Northern China

1 Institute of Applied Ecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shenyang, 110016, China

2 School of Life Science, Taizhou University, Taizhou, 318000, China

* Corresponding Authors: Wei Liang. Email: ; Jing Wu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Plant and Environments)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(7), 2183-2194. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.067807

Received 13 May 2025; Accepted 24 June 2025; Issue published 31 July 2025

Abstract

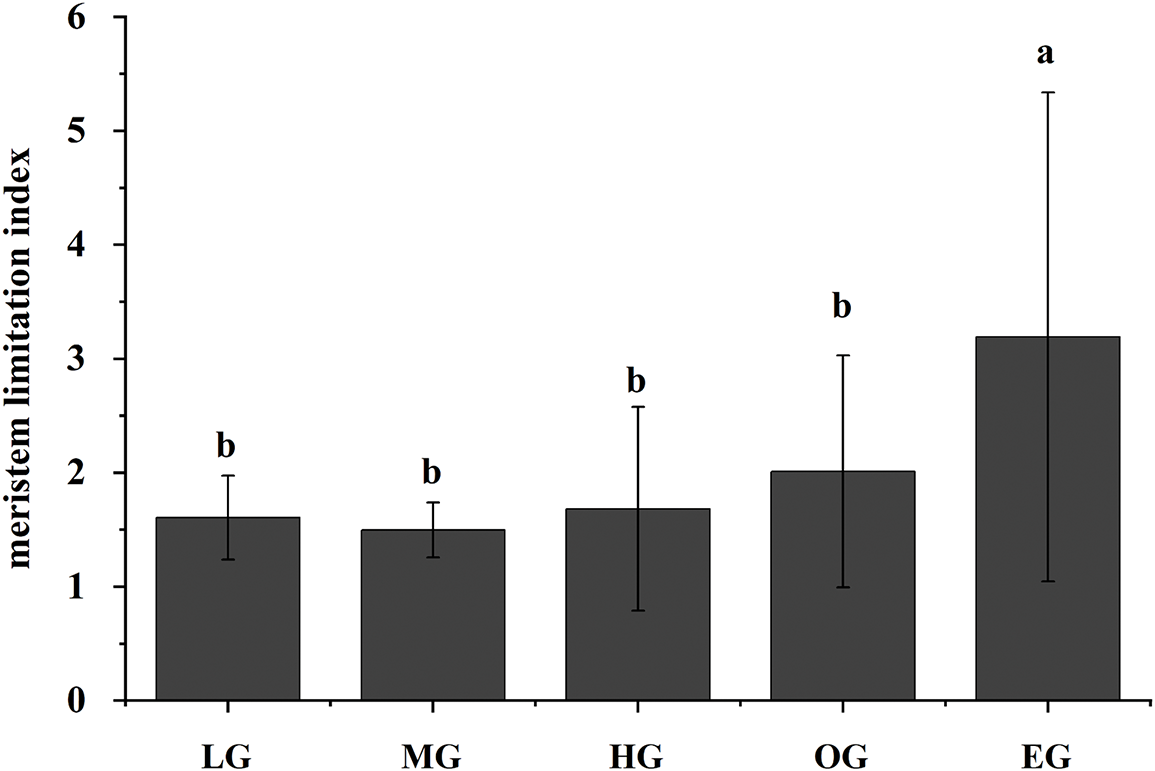

The Leymus chinensis grassland is one of the most widely distributed associations in the warm temperate grassland and due to overgrazing in recent years, it has experienced varying degrees of degradation. Vegetative regeneration via bud banks serves as the primary way of vegetation reproduction in the L. chinensis grassland ecosystem. However, the role of the bud bank in the vegetation regeneration of grazing grassland remains unclear. Based on the relationship between the under-ground bud bank and above-ground vegetation of L. chinensis grassland under different grazing stages, this study aimed to explore whether the grazing grassland could self-recover through the existing bud bank. The findings revealed that the bud density initially increased and then decreased with increasing grazing intensity, indicating that appropriate grazing promoted vegetation renewal. Moreover, grazing significantly influenced the composition of the bud bank: during the early grazing stage, the rhizome buds accounted for the main part, and tiller buds dominated during the mid-stage grazing; while during the late-stage grazing, root-sprouting buds prevailed. The meristem restriction index for light, moderate, and heavy grazing grasslands was close to one; conversely, overgrazing and extreme overgrazing grasslands exhibited the higher meristem restriction index (2.00, 3.19), suggesting that plant regeneration was constrained by bud banks under light-grazing conditions where regenerate rates failed to meet above-ground modular’s recovery requirements following overgrazing and extreme overgrazing events. Consequently, moderate grazing grasslands could achieve natural community recovery by continuously adjusting their vegetative regeneration strategies. Understanding the role of bud banks in vegetative regeneration in grazing grassland will not only supply theoretical support for the ecological succession process of degraded grassland but also provide practical experience for the sustainable management of the L. chinensis grassland ecosystem.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileThe Leymus chinensis grasslands are one of the most widely distributed associations in the warm temperate grassland, with a total area of 420,000 km2, half of which was located in China. The largest natural L. chinensis grassland of China was in Inner Mongolia, covering approximately 108,700 km2. However, in recent years, excessive grazing has led to severe consumption of L. chinensis and other palatable species, disrupting the renewal and succession of grazing grasslands and initiating a unique successional process of L. chinensis grasslands [1]. The maintenance and renewal of the plant population are influenced by grazing, as it impacts the growth and reproduction of individual plants, and drives community succession. Grassland grazing succession depends on grazing intensity, habitat type, animals, and grazing season. According to the grazing intensity, the grazing succession can be divided into light, moderate, heavy, overgrazing stage, and extremely overgrazing stage. Each stage has a certain dominant species as the indicator, and the corresponding stage is miscellaneous grass, bunch grass, Festuca, bluegrass, and Atriplex plant [2–5].

Grazing induces community succession by altering biological factors such as plant growth rate, phenology, seed and bud banks, and abiotic factors [6]. Population regeneration through belowground meristems (bud banks) significantly contributes to population recruitment and community dynamics in perennial grasslands [7]. For instance, over 99% of aboveground shoots are recruited from belowground bud banks in the tallgrass prairies of North America. The L. chinensis grasslands are dominated by perennial herbs (L. chinensis, Poa sphondylodes, Cleistogenes squarrosa, Stipa baicalensi), and vegetative regeneration via bud banks serves as the primary way of perennials’ vegetation regeneration after disturbance, influencing the resilience and stability of plant communities [8]. As minor disturbances primarily impact aboveground shoot populations, the presence of buds serves as a potential population that enables plant survival during moderate disturbances and acts as a buffer against land degradation processes [9,10]. Grazing promotes the emergence of belowground buds into aboveground shoots, resulting in a decrease in bud density on grazed sites [11,12]. Grasslands with larger bud banks dominated by a balanced composition are more conducive to successful restoration and ecosystem stability [13]. However, the contribution of bud banks to community succession in L. chinensis grasslands remains unclear. Understanding how the bud banks respond to different grazing stages is not only essential for plant adaptation and evolution but also aids predictions regarding vegetation responses to numerous disturbances.

Different types of bud banks may possess distinct functions and contribute differently to population regeneration and community dynamics [14]. The composition in bud banks reflects different vegetative regeneration processes and plant adaptive abilities, as well as their varied responses to disturbance intensity, which is crucial for understanding the regulation of community succession by bud banks. In resource-rich habitats, plants consist of diverse types of buds, including tiller buds, root-sprouting buds, and rhizome buds, while under resource-poor ecosystems plants have single-type buds [10,15]. Grazing increased the bud density of Cyperaceae, which of Gramineae were not affected [16].

At a community scale, changes in bud bank composition in response to grazing will most likely influence population regeneration and subsequent community composition. Differential activation of buds at different positions contributes to its grazing tolerance or avoidance strategies and ensures long-term persistence within grazed grasslands. High grazing tolerance may be achieved through demographic mechanisms such as output from a below-ground dormant bud bank [17]. The proportion of shoots to buds, which determines the degree of impacts of below-ground buds on above-ground population recruitment/regeneration (meristem imitation) [14,18,19], plays a key role in resistance to disturbance and recovery post-disturbance of perennial grasslands [13]. Therefore, this study investigated the composition of above-ground and below-ground modules at different stages of grazing-induced succession to determine whether existing underground bud banks can facilitate natural renewal and restoration in L. chinensis grasslands. Additionally, it seeks to provide a theoretical basis for L. chinensis grassland management in northern China.

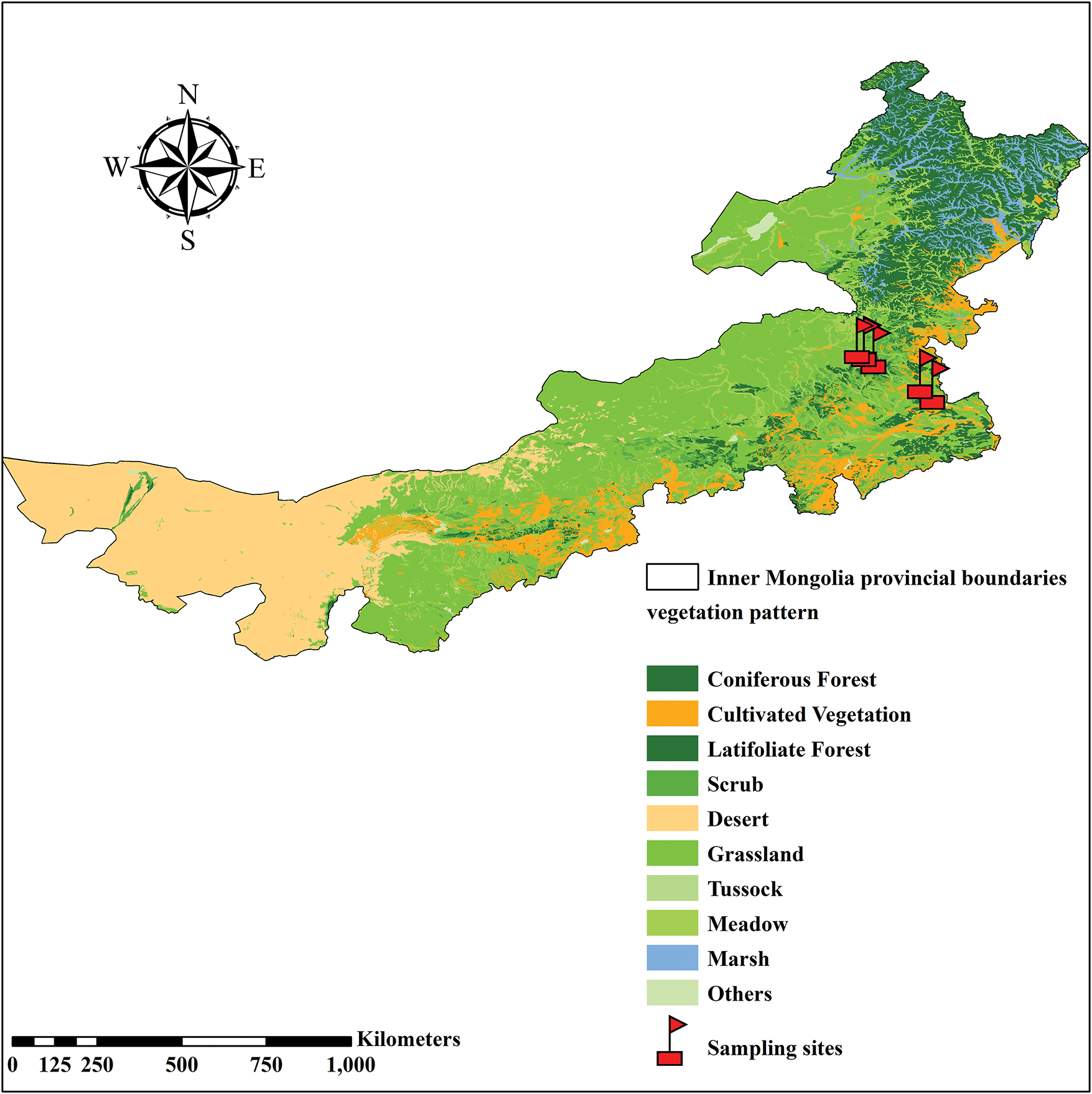

The study area was established in L. chinensis grasslands located in the east of Inner Mongolia, northeastern China. The grassland used to be mixed grazing by house, sheep, and goats for more than 50 years and for now is grazing exclusion all year round. Based on the community composition and characteristic species of different stages in the study area (Table S1) [2–5], five grazing stages were selected in the L. chinensis grasslands in Inner Mongolia: Light grazing, moderate grazing, heavy grazing, overgrazing, and extreme grazing, to investigate the plant community composition and bud bank (Fig. 1). During the light grazing stage, the community was dominated solely by L. chinensis. Due to the minimal grazing disturbance, highly palatable species such as L. chinensis retain a competitive advantage, characterized by high productivity and vegetation coverage ranging from 60% to 80%. The vertical structure of the community is complex during this phase; In the moderate grazing stage, the L. chinensis-dominated community becomes invaded by Agropyron cristatum, Carex korshinskyi, and a small proportion of leguminous plants; During the heavy grazing stage, the community was still dominated by L. chinensis to some extent, but palatable plant species were markedly suppressed due to frequent grazing and trampling pressures. While less preferred species, such as Potentilla anserina and a few halophytes, gained prominence. Vegetation coverage declined significantly, typically not exceeding 40%, with a corresponding decrease in productivity. In the overgrazing stage, the soil and vegetation environment deteriorated further. The L. chinensis lost its dominant position, and the community structure suffered noticeable changes. Species such as Carex korshinskyi, Chloris virgata, Elymus nutans, and Artemisia ordosica increased substantially, leading to a sharp decline in productivity. Finally, during the extremely heavy grazing stage, the population of L. chinensis diminished significantly or may even vanish, being replaced by alternative community types, i.e., degraded indicator species with low palatability. At this point, the grassland became largely unsuitable for grazing. A plot (50 m × 50 m) was set up at each grazing stage, and 10 bud bank quadrats (30 cm × 30 cm × 30 cm) were randomly selected in each plot. Both the above-ground and underground parts of the quadrats were excavated together, and the connection between them was kept intact during the sampling process, to facilitate the species identification. Samples are placed in sealed plastic bags and taken back to the laboratory for counting and investigation. The species name, type of bud bank, and number of each species in each quadrat were recorded. Three vegetation quadrats (1 m × 1 m) were set up in each plot to investigate the species names and abundance in the quadrat.

Figure 1: The sampling sites in Inner Mongolia. The red flags represented the sampling sites at different grazing stages

The relationship between the under-ground bud bank and above-ground vegetation was analyzed, and the type and density of the bud bank in each investigation stage were calculated. The bud bank density is the density per unit area, that is, the number of each type of bud per square meter. The ratio of bud density to shoot density (bud density/shoot density) is the plant meristem limitation index, which indicates whether the replacement of the above-ground plant is limited by the bud bank [20]. If the index is less than one, or only slightly larger than one, then the replacement of the above-ground plant is limited by the bud bank. If the index is much greater than one, then the replacement of the above-ground plant is not restricted by the bud bank. The species-abundance curve was used to describe the effects of different grazing stages on the above-ground vegetation distribution.

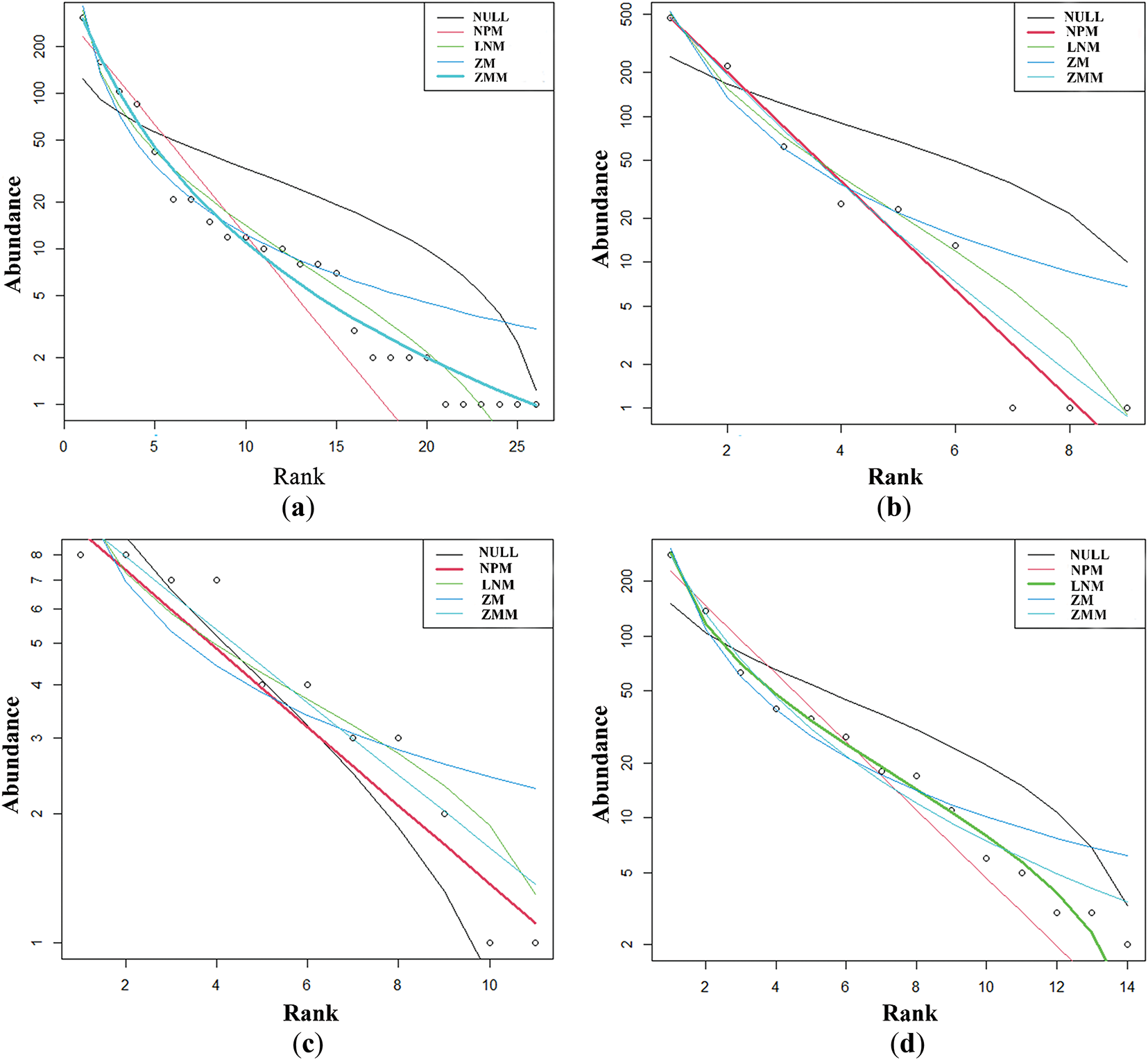

Species abundance patterns effectively reflect community structure, describing the distribution of different species within a population. Within the same community, multiple species interact with one another, and their mutual influences result in diverse species abundance patterns. Compared with traditional diversity indices, species abundance patterns provide a more comprehensive reflection of interspecific relationships and underlying mechanisms within the community. This study fit the community species abundance models to explore vegetation distribution patterns during different grazing stages, thereby elucidating the mechanisms driving above and below-ground population changes throughout the community transformation and succession process. In this study, species abundance distribution models (statistical model and mechanism model) were selected. The statistical model included lognormal model; Niche models included the NULL model, the Lognormal model (LNM), Niche Preemption model (NPM), Zipf model (ZM), Zipf-Mandelbrot model (ZMM). The AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) was employed to determine the optimal model for elucidating changes in the distribution pattern of community species abundance with grazing stages, as well as to investigate the ecological processes underlying community species composition and structure.

NULL models are often used to examine whether the composition of a biome or the distribution of species is affected by a particular ecological process or mechanism. Specifically, in niche models, NULL models often assume that species distributions or interactions between species are random, with no specific ecological processes or mechanisms at work. Then, by comparing it with the observed data, it is possible to assess whether the actual observed pattern deviates significantly from the expectations of the NULL model.

Lognormal model (LNM) was proposed by Preston [21], this model holds that the logarithm of the individual number (N) of each species in the community is normally distributed, and the abundance Pi of the species i in the community can be expressed as:

where Pi is the abundance of the species i; μ and σ are the mean and variance of the normal distribution, respectively.

Niche Preemption model (NPM) was also known as geometric series model [22]. NPM reflects the allocation of resources and niches within a community by species. The model assumes that the first specie accounts for k portion of the total niche resources, the second species accounts for k(1 − k) of the remaining resources, and N is the total niche resources, so the expected value Pi of the abundance of the species i can be calculated:

Zipf model (ZM) assumed that the colonization of species in a community is dependent on the previous environment and existing species. The colonization of pioneer species pays a lower price, and that of later succeeding species pays a higher price. The abundance Pi of the species i in the community can be expressed as:

where α is the parameter; P1 is the abundance of the species with the largest abundance; Pi is the theoretical abundance of the species i; J is the total abundance in the community.

Zipf-Mandelbrot model (ZMM) was improved based on the Zipf model. ZMM replaces P1 (the proportion of abundance of the most abundant species predicted by the model) with the nonsensical parameter c, and the added parameter β can be understood as ecological environmental potential diversity, such as niche diversity. The abundance Pi of the species i in the community can be expressed as:

One-way ANOVA was applied to analyze the effects of grazing stages on bud bank density and meristem limitation. When ANOVA revealed significant effects, Tukey’s honestly significant difference post hoc test (p < 0.05) was performed to compare the difference in bud density among different sites. RDA was conducted using CANOCO 4.5. Difference was considered significant at the level of p < 0.05. Data analysis was completed with R4.2.3 and Excel 2016. R4.2.3, OriginPro 9.0 and Arcgis 10.2 was used for plotting.

3.1 Species Abundance Distribution at Different Grazing Stages

The NPM had the best simulation effect for the MG, HG, and EG stages (AIC: 66.69, 124.48, 38.61). The ZMM was the best for LG simulation (AIC: 124.95). The LNM was the best for OG simulation (AIC: 77.85; Table S2). Through the comparison of species abundance patterns in different grazing stages, it was found that with the increase of grazing degree, rare species decreased first and then increased, and the proportion of single individuals was increasing, but the proportion of common species decreased. In the light grazing stage, most species concentrated in the high abundance area, while in the excessive and extreme grazing stage, the species concentrated in the low abundance area (Fig. 2a–e).

Figure 2: Species abundance distribution models at different grazing stages. (a–e) represented the species distribution models at light grazing, moderate grazing, heavy grazing, overgrazing and extremely overgrazing stage, respectively. The y-axis represented the abundance of communities and the x-axis represented the species rank. NULL-NULL model, NPM-Niche Preemption model, LNM-Lognormal model, ZM-Zipf model, ZMM-Zipf Mandelbrot model

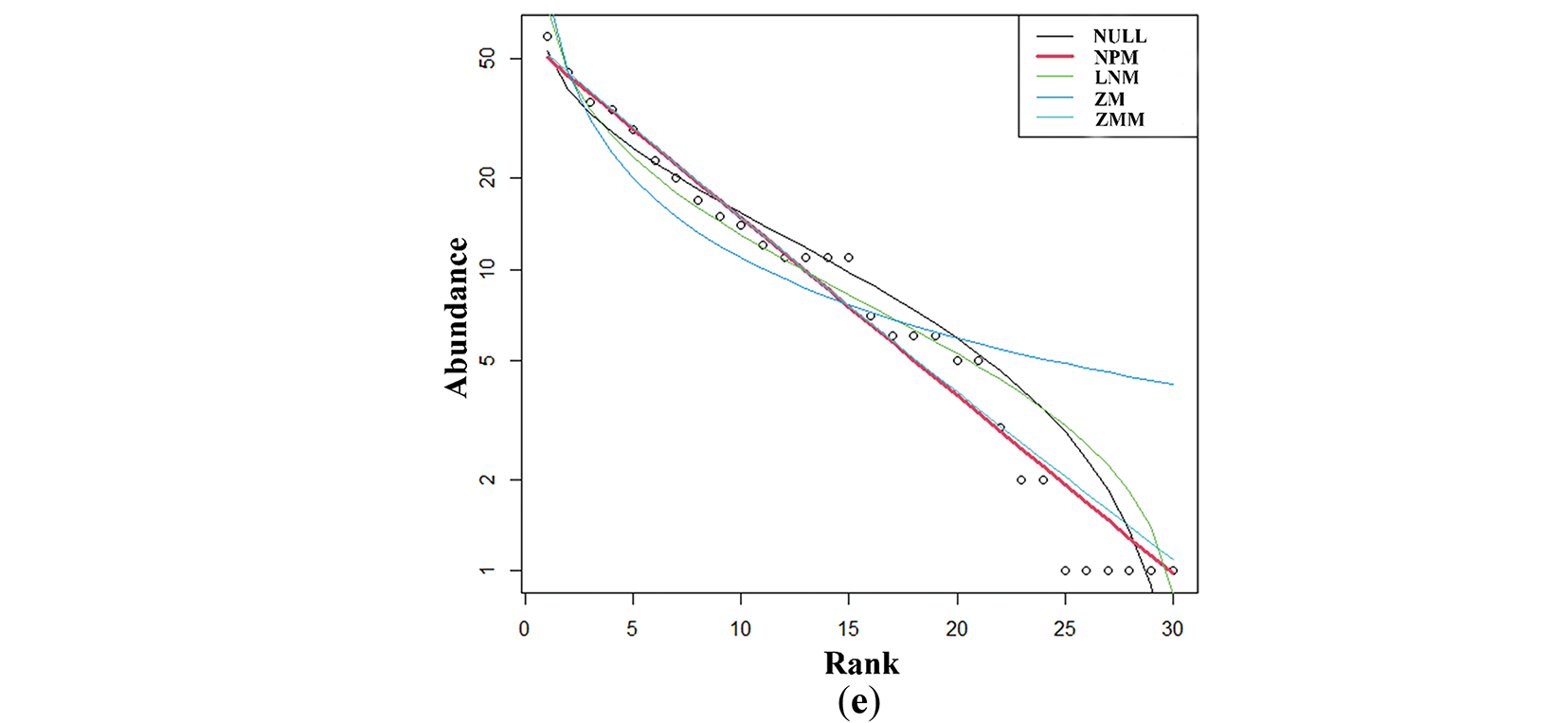

3.2 The Bud Bank Density and Composition among Different Grazing Stage

In general, the total densities of bud bank in the early grazing stages (LG, MG) were significantly higher than those in the late grazing stages (HG, OG and EG). The total density of bud bank was the highest in the moderate grazing stage. The bud bank types included tiller bud, rhizome bud and root-sprouting bud. There were significant differences among the types of bud banks among different grazing stages. In the early stage of grazing, the main type was rhizome bud, in the middle stage was tiller bud, and in the late stage of grazing, the main contents were root-sprouting bud (p < 0.05). The densities of tiller and rhizome buds firstly increased and then decreased with grazing stages. The density of root-sprouting bud increased along the grazing stages, which was dominant under extremely overgrazing condition (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: The bud bank density and composition among different grazing stages. The x-axis represented the grazing stages. LG-light grazing, MG-moderate grazing, HG-heavy grazing, OG-overgrazing, EG-extremely overgrazing. “abc/AB” represented the significance test. Different letters indicated the density of same bud type showed significant differences among different grazing stages (p < 0.05), while the same letter indicated no significant differences

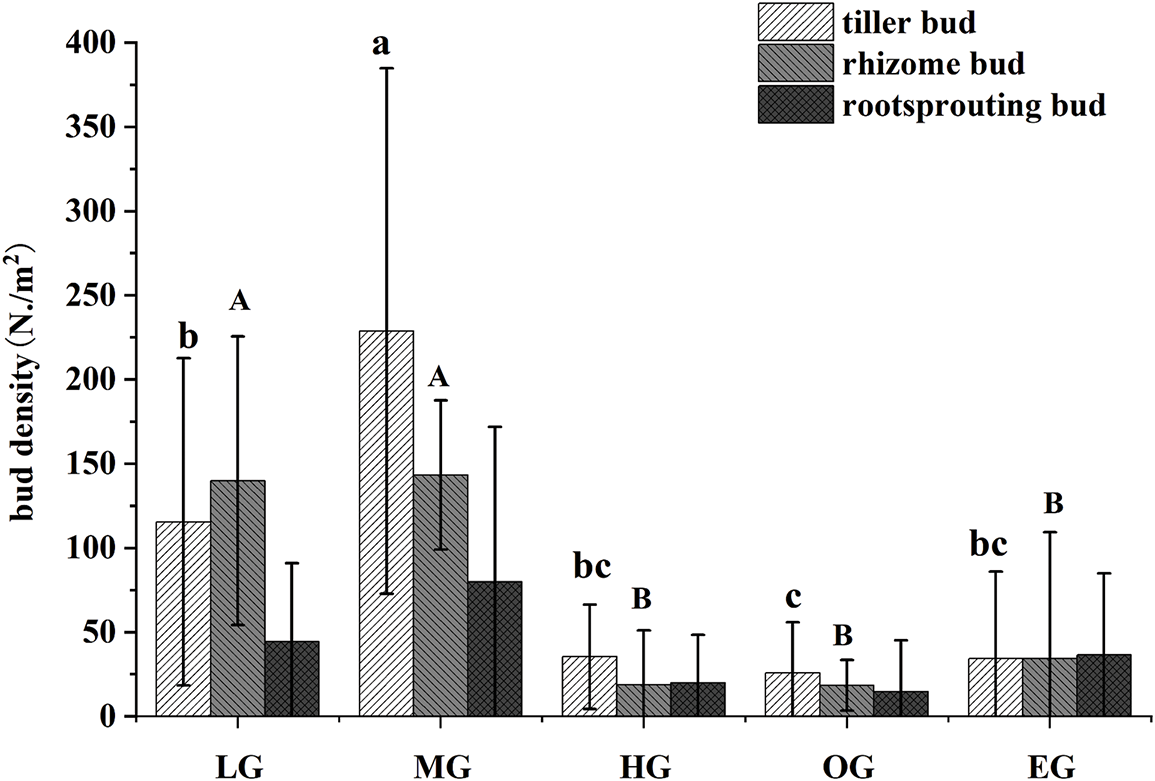

3.3 The Meristem Limitation Index at Different Grazing Stages

The meristem limitation index increased with the grazing stages, while the stem density decreased with the grazing stages. In LG, MG and HG stages, the restriction index was close to 1, while in the HG and EG, the restriction index was 2.0 and 3.9 (Fig. 4), respectively, indicating that meristem restriction was not limited in earlier grazing stages, and the recovery and regeneration of aboveground shoot could be carried out by bud bank, except for heavy and extremely heavy grazing.

Figure 4: The meristem limitation index among different grazing stages. The x-axis represented the grazing stages. LG-light grazing, MG-moderate grazing, HG-heavygrazing, OG-overgrazing, EG-extremely overgrazing. “ab” represented the significance test. Different letters indicated the meristem limitation index showed significant differences among different grazing stages (p < 0.05), while the same letter indicated no significant differences

4.1 Effects of Different Grazing Stages on the Size and Type of Bud Bank

The demography of belowground bud bank was likely to be the main underlying mechanism for explaining how perennial grassland plants respond to disturbance in grassland ecosystems [10]. Contrary to previous studies that grasslands with larger bud banks were more resistant to disturbance, this study indicated that the total bud density of plants in different grazing succession stages in the same area was inevitably related to the species and abundance of the community, and the adaptation mechanisms and abilities of communities with different bud bank types to disturbances and environmental changes were different in L. chinensis grasslands. Different buds allowed plants to prefer either an expansive or conservative strategy to respond to environmental disturbances and the availability of resources [6,10]. In the early stage of grazing, the habitat conditions were better, and the clonal integration of rhizome plants enabled the offspring shoots to maintain the most vigorous vitality. To a certain extent, the intense competition between the offspring tillers was avoided, which could also make the daughter ramets escape from grazing and trampling [23]. Therefore, nutrients, energy and resources were more efficiently allocated, and the space for growth or expansion was more fully occupied. At the same time, the new aboveground shoot based on the rhizome buds could become a new reproductive mother and produce more rhizome buds to maintain their capacity to occupy resources. Although it was found in previous studies that the growth of dominant grasses was inhibited under moderate grazing by domestic animals, moderate disturbance also stimulated the germination of underground bud banks. On the other hand, the excretion of livestock also provided necessary nutrients for plant growth [24]. Moderate grazing was beneficial to improve the potential and intensity of soil fertilizer supply. Tiller buds of tussock grasses tended to be more tolerance to environmental stresses than other types of buds [25]. As a result, more tiller buds were produced during moderate to heavy grazing, the increased tiller buds around the mother plant, which quickly sprouted as daughter plants. It allowed plants to effectively take advantage of the available resources, expand their population and occupy the existing habitat to resist the invasion of alien plants, which was consistent with previous study on sand ecosystem [9]. However, there may be a threshold effect on the disturbance of rhizome buds to grazing. When the grazing intensity was large enough, that is, in the later stage of grazing, the rhizomes of surface plants were heavily damaged by nibbling and trampling, and rhizome clones were difficult to maintain clonal integration. The new buds in the tiller node close to the soil surface for bunchgrass were particularly easily damaged or eaten by grazers. At the moment, plant shoots with rhizome and tiller buds were sparse and the bud bank size was small, and plants didn’t not fully occupy the grassland [8]. So damaged tillers were unable to promptly accumulate enough nutrients to produce new buds, and a significant reduction in grass aboveground biomass accumulation may reduce bud production in grazing grasslands. Conversely, the root-sprouting plants were usually buried deeper than rhizome plants, and they were more likely to sprout adventitious buds after disturbance [9], which could adapt to the stage of heavy grazing disturbance. In grazing grasslands, plants responded to grazing disturbance by changing bud banks of different types. During these processes, more desirable (i.e., preferred, palatable and high nutrient) perennial grasses were replaced by less-desirable or non-desirable ones (i.e., non-preferred, unpalatable and low nutrient) [26].

4.2 Relationship between Belowground Bud Bank and Succession of Above-Ground Vegetation

The capacity of L. chinensis grassland ecosystems to respond rapidly to disturbance might be linked to the potential for compensatory regrowth, mainly from bud banks. Perennial grasslands with a large reserve bud bank may be the most responsive to grazing [8]. Our study indicated that grasslands at earlier grazing stages all had enough buds present in the bud bank during the growing season to completely supply the above-ground population. In addition, long-term grazing exclusion would improve the ability to respond to resource pulses, rates of clonal population recovery, and productivity after disturbance by increasing below-ground bud bank density. The effects of different grazing stages on plant communities were obviously reflected in the changes in population composition in L. chinensis grassland. Fencing could greatly improve the above-ground biomass, height, and coverage of grassland vegetation, and had relatively little effect on the underground biomass. However, fencing would greatly reduce the diversity of grassland vegetation. This was because the grazing of domestic animals was avoided, and the grassland vegetation obtained a relatively favorable environment for growth, which was conducive to the improvement of the coverage, height, and biomass of grassland vegetation [27]. This was roughly consistent with the findings of Zhang et al. (2020) [28]. In the case of moderate grazing, although the above-ground biomass of grassland vegetation decreased, the diversity of grassland vegetation increased significantly which is consistent with de Villalobos & Long (2024) [29]. In the extreme grazing stage, the quantity of L. chinensis was less and even disappeared. At the same time, with the increase of grazing, species abundance and richness decreased, but after the extreme stage, species were more concentrated in the low abundance area. The population of high-quality perennial grasses gradually declined, and finally was replaced by annual halophytes, the community structure tended to be simplified, and the soil environment tended to be poor. However, under extreme grazing conditions, the habitat conditions gradually deteriorated, and different plant groups in the community also differentiated, and each selected the most suitable habitat to form a new plant community, leading to the degradation and succession of plant communities in L. chinensis grassland.

With the increase in grazing, different types of bud banks showed different response trends. In the light grazing stage, the offspring tillers of L. chinensis maintained the most vigorous vitality through the clonal integration of rhizomes. And to a certain extent, the intense competition among the offspring ramets could be avoided. Thus nutrients, energy, and resources were more effectively distributed, and the growth space or expansion space could be fully occupied. At the moderate grazing stage, the environmental conditions became complicated, the habitat heterogeneity increased, the dominance of rhizome type bud bank decreased, and the tiller bud bank remained relatively stable, resulting in a diversified community structure. With the increase in grazing intensity, the competitiveness between individuals decreased, and the species abundance was mainly determined by the species’ choice of habitat. Grazing also influenced the composition of functional groups, with grazing-avoiding species being more prevalent in heavily grazed areas [29]. The dominant species occupied a larger ecological niche and had more available resources, while the other species had less available resources, so the species abundance was less and the clumping of small grasses increased significantly. In the extreme grazing stage, the soil habitat gradually deteriorated, the rhizome buds, tiller buds, and perennial herbs gradually decreased or disappeared, and the root-sprouting plants gradually increased. The population dominance of L. chinensis decreased rapidly, such as Potentilla chinensis, which appeared in the extreme grazing stage. Therefore, the responses of bud bank types at different grazing stages affected the species composition and structure of the community in L. chinensis grassland.

The findings revealed that appropriate grazing promoted vegetation renewal in L. chinensis grassland. Plant regeneration was constrained by bud banks under light-grazing conditions where regenerate rates failed to meet above-ground plant recovery requirements following overgrazing and extreme overgrazing events. Consequently, mildly disturbed L. chinensis grasslands could achieve natural community recovery by continuously adjusting their vegetative regeneration strategies. Understanding the mechanism of grazing on vegetative regeneration in L. chinensis grassland will not only supply theoretical support for the ecological restoration process of grazing grassland but also provide practical experience for the sustainable management of the L. chinensis grassland ecosystem in northern China.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This study is financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42377458 and 41907411).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Qun Ma and Zhimin Liu; methodology, Qun Ma; software, Wei Liang; validation, Qun Ma, Wei Liang, and Jing Wu; formal analysis, Qun Ma; investigation, Qun Ma, Wei Liang, and Jing Wu; data curation, Qun Ma; writing—original draft preparation, Qun Ma; writing—review and editing, Qun Ma; visualization, Qun Ma; supervision, Zhimin Liu and Quanlai Zhou; project administration, Zhimin Liu and Quanlai Zhou; funding acquisition, Qun Ma. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Authors, Wei Liang and Jing Wu, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.067807/s1.

References

1. Chen ZZ, Wang SP. Typical grassland ecosystem in China. Beijing, China: Science Press; 2000. 412 p. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

2. Li SY, Xiao YF. Preliminary division of grazing succession stage of Leymus chinensis grassland in Modamuji area, Humeng, Inner Mongolia. Chin J Plant Ecol. 1965;2:200–17. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

3. Wang RZ, Li JD. Cluster analysis method for dividing successional stages of Leymus chinesis grassland for grazing. Chin Acta Ecol Sin. 1991;11(4):367–71. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

4. Wang Y. Vegetation dynamics of grazing succession in the Stipa baicalensis steppe in Northeastern China. Vegetatio. 1992;98(1):83–95. doi:10.1007/BF00031639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Yao ZY, Xin Y, Mu WK, Zhang QM, Yang L, Zhao LQ. Community characteristics of Leymus chinensis steppe in Nei Mongol. China Chin J Plant Ecol. 2024;48(10):1385–92. (In Chinese). doi:10.17521/cjpe.2023.0235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Klimesova J, Klimeš L. Bud banks and their role in vegetative regeneration—a literature review and proposal for simple classification and assessment. Perspect Plant Ecol Evol Syst. 2007;8(3):115–29. doi:10.1016/j.ppees.2006.10.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Harper JL. Population biology of plants. London, UK: Academic Press; 1977. 892 p. [Google Scholar]

8. Zhao LP, Wang D, Liang FH, Liu Y, Wu GL. Grazing exclusion promotes grasses functional group dominance via increasing of bud banks in steppe community. J Environ Manage. 2019;251:109589. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109589. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Ma Q, Qian J, Tian L, Liu Z. Responses of belowground bud bank to disturbance and stress in the sand dune ecosystem. Ecol Indic. 2019;106(6):105521. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2019.105521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Ma Q, Qian J, Shi X, Qin X, Tian L, Liu Z. Temperature-related factors are the better determinants of belowground bud density, while moisture-related factors are the better determinants of belowground bud diversity at the regional scale. Land Degrad Dev. 2023;34(4):1145–58. doi:10.1002/ldr.4522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Busso CA, Mueller RJ, Richards JH. Effects of drought and defoliation on bud viability in two caespitose grasses. Ann Bot. 1989;63(4):477–85. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a087768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Qian J, Wang Z, Klimešová J, Lü X, Zhang C. Belowground bud bank and its relationship with aboveground vegetation under watering and nitrogen addition in temperate semiarid steppe. Ecol Indic. 2021;125(7005):107520. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.107520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Luo W, Muraina TO, Griffin-Nolan RJ, Te N, Qian J, Yu Q, et al. High below-ground bud abundance increases ecosystem recovery from drought across arid and semiarid grasslands. J Ecol. 2023;111(9):2038–48. doi:10.1111/1365-2745.14160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Klimešová J, Herben T. Belowground morphology as a clue for plant response to disturbance and productivity in a temperate flora. New Phytol. 2024;242(1):61–76. doi:10.1111/nph.19584. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Klimešová J, Klimeš L. Clonal growth diversity and bud banks of plants in the Czech flora: an evaluation using the CLO-PLA3 database. Preslia. 2008;80:255–75. [Google Scholar]

16. Damhoureyeh SA, Hartnett DC. Variation in grazing tolerance among three tallgrass prairie plant species. Am J Bot. 2002;89(10):1634–43. doi:10.3732/ajb.89.10.1634. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. N’Guessan M, Hartnett DC. Differential responses to defoliation frequency in little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) in tallgrass prairie: implications for herbivory tolerance and avoidance. Plant Ecol. 2011;212(8):1275–85. doi:10.1007/s11258-011-9904-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Benson EJ, Hartnett DC, Mann KH. Belowground bud banks and meristem limitation in tallgrass prairieplant populations. Am J Bot. 2004;91(3):416–21. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.3.416. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Knapp AK, Smith MD. Variation among biomes in temporal dynamics of aboveground primary production. Science. 2001;291(5503):481–4. doi:10.1126/science.291.5503.481. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Dalgleish HJ, Hartnett DC. Below-ground bud banks increase along a precipitation gradient of the North American Great Plains: a test of the meristem limitation hypothesis. New Phytol. 2006;171(1):81–9. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01739.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Preston FW. The commonness, and rarity, of species. Ecology. 1948;29(3):254–83. doi:10.2307/1930989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Whittaker RH. Evolution and measurement of species diversity. Taxon. 1972;21(2–3):213–51. doi:10.2307/1218190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ding X, Su P, Zhou Z, Shi R, Yang J. Responses of plant bud bank characteristics to the enclosure in different desertified grasslands on the Tibetan Plateau. Plants. 2021;10(1):141. doi:10.3390/plants10010141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Dong M, Qiao J, Ye X, Liu G, Chu Y. Plant functional types across dune fixation stages in the Chinese steppe zone and their applicability for restoration of the desertified land. In: Werger MJA, Van Staalduinen MA, editors. Eurasian steppes. Ecological problems and livelihoods in a changing world. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2012. p. 321–34. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-3886-7_11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Qian J, Wang Z, Liu Z, Busso CA. Belowground bud bank responses to grazing intensity in the inner-Mongolia steppe. China Land Degrad Dev. 2017;28(3):822–32. doi:10.1002/ldr.2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Distel RA, Bóo RM. Vegetation states and transitions in temperate semiarid rangelands of Argentina. In: Proceedings of the Fifth International Rangeland Congress Rangelands in a Sustainable Biosphere; 1995 Jul 23–28; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. [Google Scholar]

27. Cepeda C, Oliva G, Ferrante D. Experimental exclusion of guanaco grazing increases cover, diversity, land function and plant recruitment in Patagonia. Phyton-Int J Exp Bot. 2024;93(7):1383–401. doi:10.32604/phyton.2024.052534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhang F, Nilsson C, Xu Z, Zhou G. Evaluation of restoration approaches on the Inner Mongolian steppe based on criteria of the society for ecological restoration. Land Degrad Dev. 2020;31(3):285–96. doi:10.1002/ldr.3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. de Villalobos AE, Long MA. Grasslands response to livestock grazing intensity in the austral pampas (Argentinatesting the intermediate disturbance hypothesis. Phyton-Int J Exp Bot. 2024;93(8):2037–50. doi:10.32604/phyton.2024.053928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools