Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Ecological Factors Drive the Accumulation of Active Components in Codonopsis pilosula

1 College of Horticulture, University, Yantai, 264000, Shandong, China

2 Key Laboratory of Beijing for Identification and Safety Evaluation of Chinese Medicine, Institute of Chinese Materia Medica, China Academy of

Chinese Medical Sciences, Beijing, 100700, China

* Corresponding Authors: Xiaotong Guo. Email: ; Linlin Dong. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(8), 2575-2591. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.064518

Received 18 February 2025; Accepted 21 May 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Codonopsis pilosula is a major Qi-tonifying medicinal herb, and its active composition is analyzed systematically. However, the relationship between its production origins and commodity specification grades with the active composition of C. pilosula lacks systematic research. This study integrates the HPLC and UV-Vis methodologies to evaluate the quality of C. pilosula from commodity specification grades and different origins, and it explores the correlation between ecological factors and production origins with active components. Here, network pharmacology is used to determine that lobetyolin, syringin, and tangshenoside I have potential efficacy in treating pulmonary fibrosis and oxidative stress. The HPLC and UV-Vis methods were employed to quantitatively analyse the levels of five active compounds from different origins and commodity specification grades. Ecological factors were collected from the different production origins with ArcGIS, and correlation analysis was conducted between these factors and the active components of C. pilosula to identify the key ecological influences that drive the accumulation of active compounds. Results showed that network pharmacology analyses indicated that the active components of C. pilosula, including lobetyolin, syringin, and tangshenoside I, bind to targets and exhibit antioxidant and anti-pulmonary fibrosis effects. Differences in the contents of active components across three commodity specification grades were not significant. The contents of active components in C. pilosula showed differences with varying origins, with the most variation observed in soluble sugar content, and notable variations are also observed in the levels of lobetyolin, syringin, and tangshenoside I, which could serve as potential biomarkers for different origins. Additionally, ecological factors influenced the accumulation of C. pilosula’s active components. The contents of soluble sugars and tangshenoside I were positively correlated with temperature and precipitation. Our study evaluated the active components of C. pilosula, and findings show that lobetyolin, syringin, and tangshenoside I have potential efficacy in treating pulmonary fibrosis and oxidative stress. The differences in the quality of C. pilosula across varying commodity specification grades are not significant. The different contents of C. pilosula across varying origins are significant, with soluble sugars and glycosides serving as potential markers for distinguishing C. pilosula from different origins. Moreover, ecological factors drove the accumulation of C. pilosula components. Soluble sugars and tangshenoside I content were particularly influenced by temperature and precipitation. Sand content and electrical conductivity significantly correlated with syringin, whereas organic carbon negatively influenced total flavonoids. This research provides a theoretical basis for the selection of the C. pilosula growing area and lays a foundation for the study of the C. pilosula quality standard.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileCodonopsis pilosula is a prominent Chinese herbal medicine, renowned for its ability to tonify qi, blood, spleen, and lung functions [1]. It is commonly referred to as ‘small ginseng’ and has been officially included in the list of foods and medicines. C. pilosula exhibits dual therapeutic effects in both Qi tonification and fluid regeneration, demonstrating particular efficacy in managing deficiency-heat syndrome characterized by chronic thirst, xerostomia, and pharyngeal dryness resulting from prolonged Qi-Yin consumption [2]. Modern studies have shown that the active components of C. pilosula mainly include flavonoids, alkaloids, sugars, saponins, steroids, amino acids, etc., which mainly have pharmacological effects such as enhancing immune system function, improving digestive function, anti-inflammatory, regulating endocrine system, promoting hematopoietic function, regulating cardiovascular and cerebrovascular system, anti-tumor, lowering blood lipids and delaying aging [3]. Mechanistically, C. pilosula’s polysaccharides regulate energy homeostasis through hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis modulation, specifically enhancing AMPK/PGC-1α signaling pathways to restore metabolic equilibrium, as evidenced by recent in vivo studies [4]. Modern pharmacological studies have demonstrated that C. pilosula exhibits resistance to oxidative stress [5] and enhances immune function [6,7]. The soluble sugar of C. pilosula has antioxidative properties [1,8], and the total flavonoid compound of C. pilosula has an anti-hepatocarcinoma effect [9,10], which are active components for evaluating the quality of C. pilosula. Monomeric components of C. pilosula, such as lobetyolin, syringin, and tangshenoside I can regulate immunity and improve haematopoietic function [7,11]. C. pilosula is an effective drug for intervention in ulcerative colitis, with lobetyolin and atractylenolide III being the main active components involved in the treatment [12]. Importantly, decoctions of C. pilosula have a significant effect on the treatment of pulmonary fibrosis [13], and C. pilosula has many pharmacological effects, such as anti-hypoxia, anti-stress, and enhancing body immunity [14]. However, few studies have focused on the function of lobetyolin, syringin, and tangshenoside I as potential active components in the treatment of pulmonary fibrosis and oxidative stress. The potential function of the three active components needs to be analysed by using network pharmacology.

The grading standards for the commodity specification grades of Chinese medicinal materials are an important reference for evaluating the quality of Chinese medicinal materials [15]. The polysaccharide content of Dendrobii Officinalis Caulis with different specifications varied, and the data were scattered [16]. The total amino acid content of Cornu Cervi Pantotrichum from different specifications showed little variation [17]. According to the diameter and length of the root head, C. pilosula medicinal materials are divided into first class, second class, and third class in the circulation situation [18]. Research has demonstrated that the alcohol-soluble extractives and polysaccharide content in wild C. pilosula align closely with internal quality parameters and grading criteria. In contrast, for cultivated C. pilosula, the levels of tangshenoside I, codonopsis saponin, and atractylenolide III exhibit a unique pattern: second-class herbs contain higher concentrations than first-class herbs, while third-class herbs show lower levels compared to both first- and second-class herbs [18]. Additionally, the content of codonopsis saponin and atractylenolide III in white C. pilosula across various commercial specifications exhibits a negative correlation with these specifications. The grading system for commercial products of white C. pilosula in major production areas is inconsistent and fails to accurately reflect the true quality of the herb [19,20]. Consequently, further systematic investigation into the relationship between commercial grading and the intrinsic quality of C. pilosula is warranted.

The quality of C. pilosula from different origins is highly variable, with genetics and environmental factors being the primary influences [21]. The complex and diverse terrain and climate lead to differences in quality of the same Bupleurum species when grown in different locations [22]. The contents of iridoids in Gentiana scabra are significantly different in different habitats [23]. Ecological factors have a great effect on the accumulation of iridoids in G. scabra [24]. Numerous studies have explored the relationship between medicinal plants and their ecological environments [25,26]; however, published reports specifically addressing C. pilosula are rare. Researching the differences in the quality of C. pilosula from different origins is crucial for guiding the standardised cultivation of C. pilosula, improving the quality of C. pilosula, and ensuring the safety and efficacy of its clinical use.

The study aims to identify the potential active components through network pharmacology analysis, the content of active components from different origins, and commodity specification grades. Additionally, the correlation between the active components of C. pilosula and ecological factors is evaluated. This study provides a scientific basis for explaining geoherbalism and the reasonable production selection of C. pilosula.

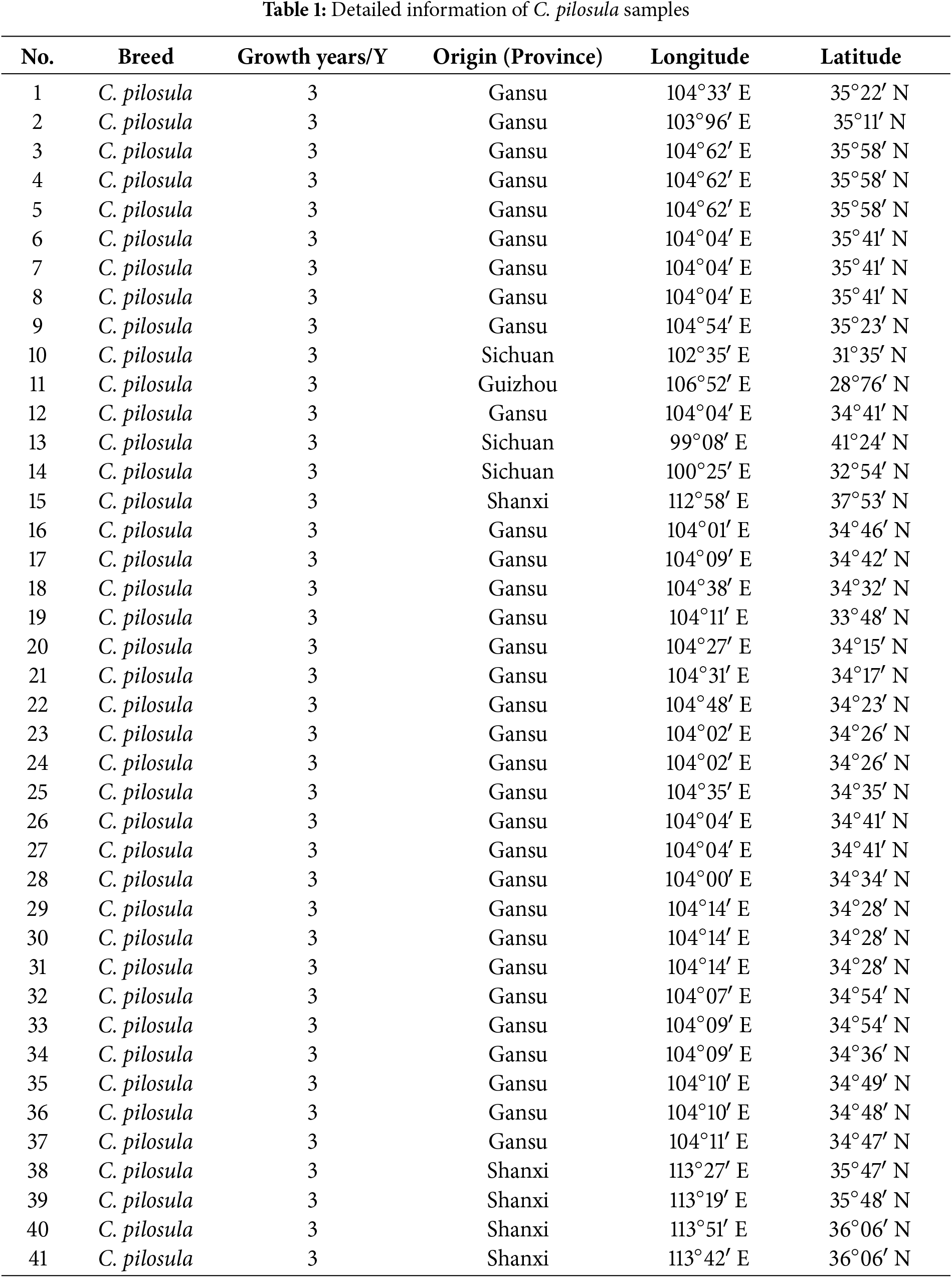

Forty-one batches of C. pilosula were obtained primarily from the main producing origins of Gansu, Guizhou, Shanxi, and Sichuan provinces in October 2022 (Table 1). All samples were from three-year-old artificially cultivated C. pilosula according to Good Agricultural Practice. Three batches of samples, each consisting of 20 plants, were collected from each site as replicates. The samples were immediately transported to the laboratory, rinsed with deionised water to remove dirt and sand. The medicinal materials were dried in a dryer [11], with a temperature range of 40°C–60°C being suitable [27]. The dried C. pilosula samples were crushed in a grinder, passed through a No. 4 sieve (200 mesh), and the resulting powder was stored in a clean sample bottle, sealed, and labeled [28].

2.2 Network Pharmacological Analysis and Molecular Docking

The canonical SMILES formulas of the active glycoside components were obtained from the PubMed (https://pub-chem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, accessed on 18 February 2025) database and imported into the Swisstarget prediction website to predict their protein targets in Homo sapiens. The active glycoside components and potential target proteins of C. pilosula were retrieved by querying the TCMSP (http://tcmspw.com/tcmsp.php, accessed on 18 February 2025) database with specific criteria for oral bioavailability (OB ≥ 30%) and drug likeness (DL ≥ 0.18). The TCMID (http://www.megabionet.org/tcmid/, accessed on 18 February 2025) database was used with ‘DANG SHEN’ as a keyword, which yielded information on the active components of C. pilosula, including lobetyolin, syringin, and tangshenoside I. After all identified targets were consolidated while the duplicates were removed, the components were screened by TCMSP and TCMID databases, and target proteins were screened after UniProt standardised protein names. PubMed, GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org, accessed on 18 February 2025), and OMIM (https://www.omim.org, accessed on 18 February 2025) were employed to collect targets related to pulmonary fibrosis and oxidative stress. Venny 2.10 (https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html, accessed on 18 February 2025) was employed to identify commonalities between drug-related targets and disease-related targets. The active glycoside targets were intersected with the pulmonary fibrosis and oxidative stress targets to construct a Venn diagram of the intersected targets. On the basis of the interaction of the lobetyolin, syringin, tangshenoside I, molecular targets, pulmonary fibrosis, and oxidative stress, a complex information network was built and visualised using Cytoscape 3.9.1 software. After these targets were imported into the STRING database to build a protein interaction network, the structure of the target was molecularly docked with the structure of the active glycoside component, and the Vina inside PyRx software was used for the docking. Finally, the result with the lowest binding energy of each protein was mapped and visualised with Pymol software.

2.3 Commodity Specification Grades of C. pilosula

By the classification standards for C. pilosula stipulated in the Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China, the Shanxi Market Supervision Bureau categorizes C. pilosula into three commercial grades [29], C. pilosula’s first class (the diameter of the root head is greater than 0.8 cm, and the length is greater than 23 cm), second class (0.8 cm > diameter ≥ 0.5 cm, 23 cm > length ≥ 18 cm) and third class (0.5 cm > diameter ≥ 0.4 cm, 18 cm > length ≥ 10 cm).

2.4 Determination of Active Components of C. pilosula

2.4.1 Determination of Lobetyolin, Syringin, and Tangshenoside I Content

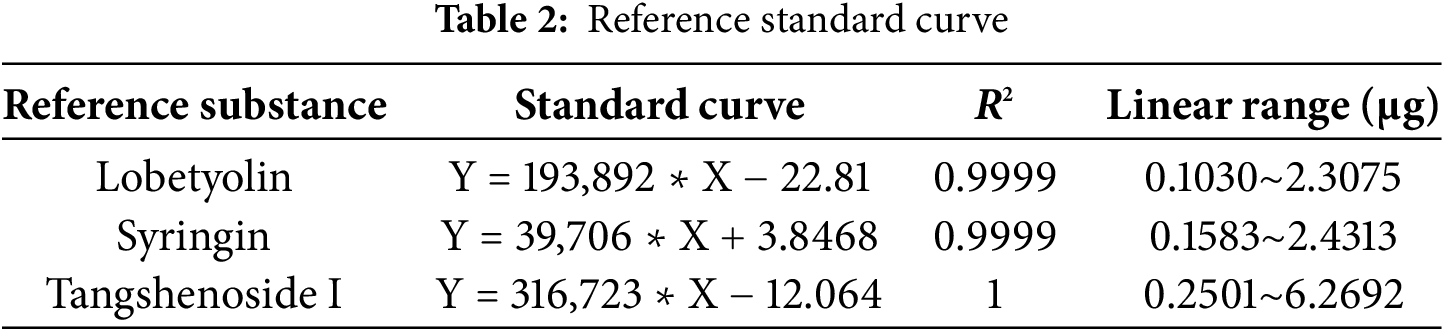

The content of lobetyolin, syringin, and tangshenoside I, and the HPLC fingerprint of C. pilosula samples were obtained as follows. An appropriate amount of lobetyolin, syringin, and tangshenoside I reference substances was accurately weighed and diluted with 80% methanol to obtain final concentrations of 0.252, 0.2, and 0.169 mg/mL, respectively. These solutions were used for retention time determination and standard curve construction (Table 2). The chromatographic column was a C18 reversed phase column (250 × 4.6 mm, i.d. 5 µm, Eclipse XDB; Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA); the mobile phase was 0.01% phosphoric acid aqueous solution (A) acetonitrile (B), gradient elution: 0–10 min for 5% B to 15% B, 10–20 min for 15% B to 20% B, 20–35 min for 20% B to 35%, 35–45 min for 35% B to 70% B, 45–48 min for 70% B to 15% and 48–58 min for 15% B. The column temperature was 25°C, the flow rate was 1.0 mL/min, the UV detection wavelength was 267 nm, and the injection volume was 10 μL. The quantitative determination of lobetyolin, syringin, and tangshenoside I samples and the establishment of HPLC fingerprint (Fig. S1) were accomplished under the above conditions.

2.4.2 Determination of Soluble Sugar Content

With its simplicity, low cost, and rapid analytical speed, the UV-Vis spectrophotometric method has become an essential screening tool for the quality control of natural drugs. It is widely employed for the determination of total component content and process optimization. In this experiment, UV-Vis spectroscopy was combined with HPLC to enable a comprehensive qualitative and quantitative analysis, ensuring a more accurate and reliable evaluation of the target compounds.

The content detection of soluble sugar of C. pilosula samples was based on the methods in the literature with slight modifications [30]. The content of soluble sugar was determined by the phenol-sulfuric acid method. Briefly, 1 mL of C. pilosula was taken for testing, and 1 mL of 50 g/L phenol solution was added. The mixture was shaken well. Next, 5 mL sulfuric acid was added quickly, and the mixture was cooled in ice, heated in a 100°C water bath for 10 min, removed, cooled in an ice bath for 20 min, and diluted to 10 mL with water. The detection wavelength of soluble sugar is 490 nm, and an 80% ethanol solution was used as a reference. Under the above conditions, the content of soluble sugar was measured. After detection and calculation, the standard curve of soluble sugar was Y = 0.2437X + 0.1016, R2 = 0.9994.

2.4.3 Determination of Total Flavonoid Content

The content detection of total flavonoids of C. pilosula samples was based on the methods in the literature with slight modifications [30]. The content of total flavone was determined by the AlCl3-NaNO2 method. First, 1 mL of C. pilosula was placed in a 10 mL tube with a plug for testing, 0.3 mL of 50 g/mL sodium nitrite solution was added successively, and the mixture was shaken. Then, 0.3 mL of 100 g/mL aluminium nitrate solution was added, and the mixture was shaken well and let stand for 6 min. Next, 5 mL of 40 g/mL sodium hydroxide solution was added, diluted with 60% ethanol solution to scale, shaken well, and stored for 10 min. The detection wavelength of total flavonoids is 510 nm, with a 60% ethanol solution as the reference. Under the above conditions, the content of total flavonoids was determined. After detection and calculation, the standard curve of total flavonoids was Y = 3.9706X + 0.3846, R2 = 0.9996.

2.5 Analysis of Multivariate Correlation between Ecological Factors and Active Components

2.5.1 Extraction of Ecological Factors

Geospatial data for all study sites were collected using GIS technology, while microclimatic parameters (temperature and humidity) were recorded using portable digital hygrometers at each location. The ecological factors were extracted from WorldClim (Table S1) and HWSD (Table S2) by GMPGIS based on geographical coordinates [31,32], including temperature, precipitation, accumulated temperature, exchangeable sodium salts, and organic carbon content index for further analysis.

2.5.2 Multivariate Correlation Analysis

The data for each climate factor was extracted separately. One layer was then removed after extraction and imported into the next layer. All the weather data were combined in a spreadsheet and processed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25. The vegan and psych packages in R version 4.1.0 were used for multivariate correlation between ecological factors and active components [33]. One-way analysis of variance was conducted using SPSS, and the ggplot2 packages in R version 4.1.0 were used for the correlation bubble diagram.

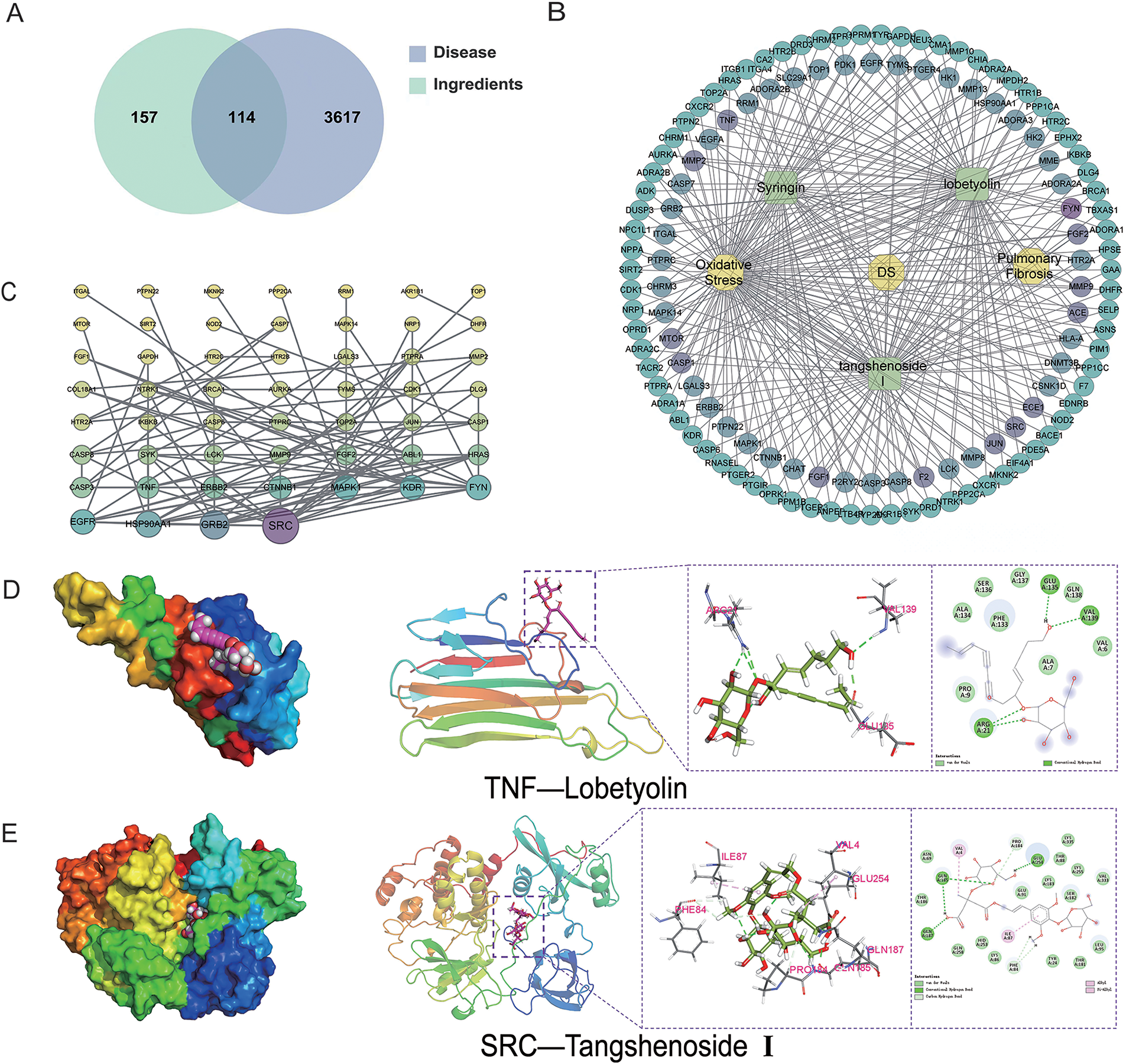

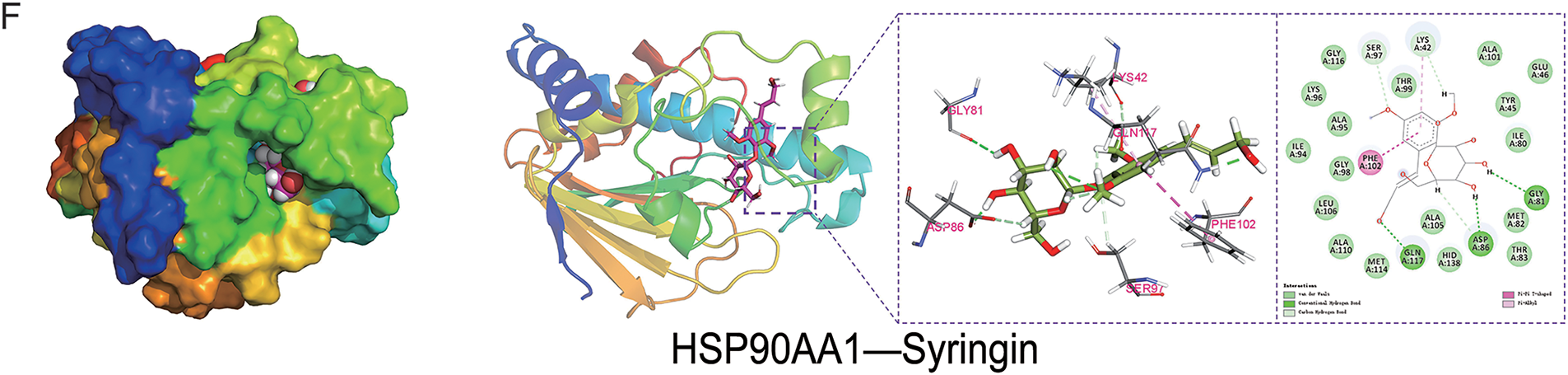

3.1 Active Components in C. pilosula Showing Anxiolytic Effects of Pulmonary Fibrosis and Oxidative Stress

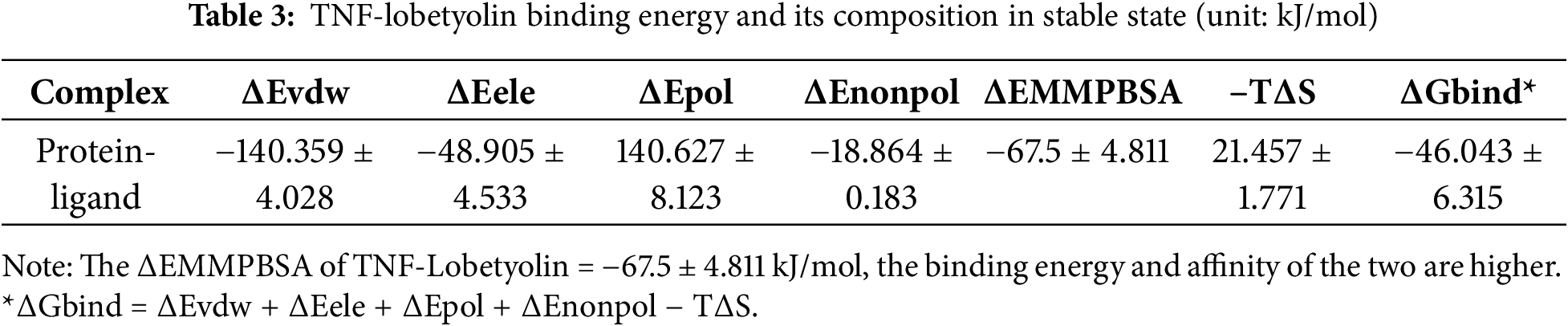

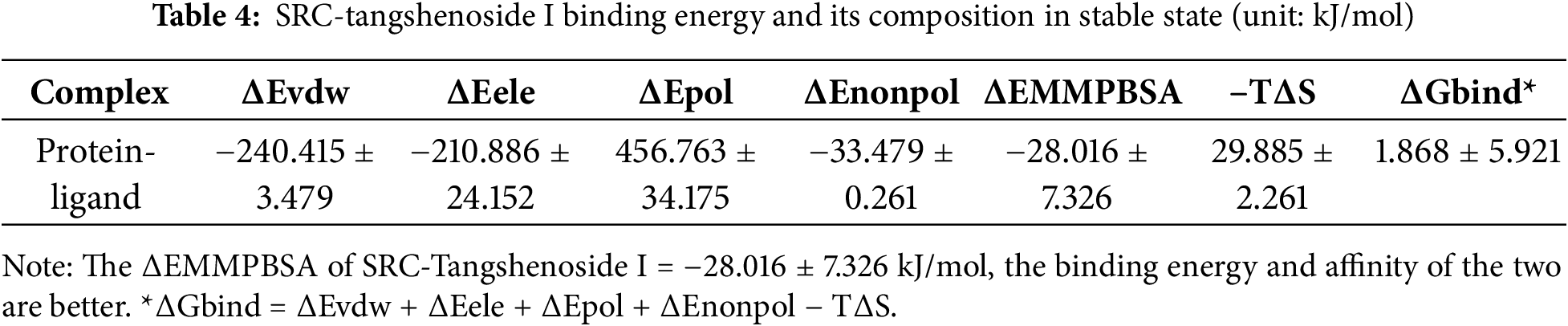

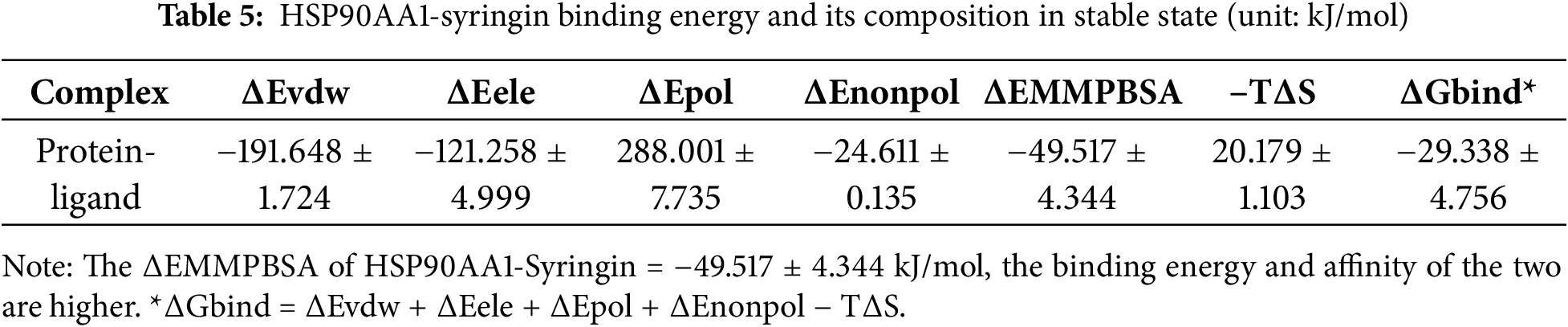

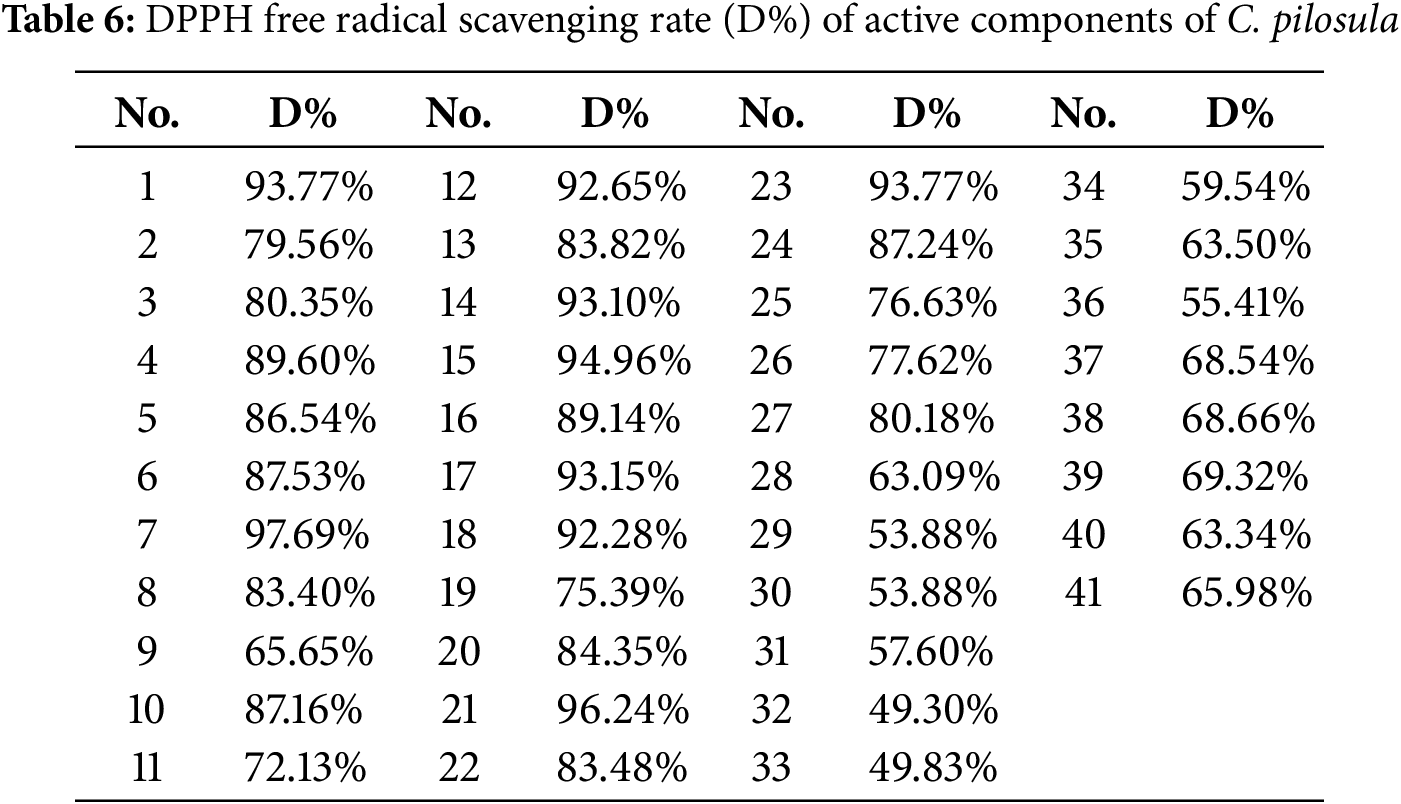

To explore the resistance effect of C. pilosula active components on pulmonary fibrosis and oxidative stress, we used network pharmacology analysis for evaluation and prediction. A total of 271 pharmacological target genes were identified as related to lobetyolin, syringin, and tangshenoside I through the Swiss Target Prediction database. A total of 3731 target genes linked to pulmonary fibrosis and oxidative stress were mined from these online databases, Gene Cards, OMIM, and DrugBank. A total of 114 common genes were found in both gene groups (Fig. 1A), suggesting that these 114 genes may be the potential targets that resist pulmonary fibrosis and oxidative stress effects. To further understand the active compound–target–disease interaction mechanism of C. pilosula, we built a network to visualise the active compound–target–disease correlations (Fig. 1B). The core genes identified through PPI analysis included SRC, GRB2, HSP90AA1, EGFR, FYN, KDR, MAPK1, CTNNB1, ERBB2 and TNF (Fig. 1C). Molecular docking was performed to visualise the interaction between these core genes and potent active compounds (Fig. 1D–F). Molecular docking analysis revealed that lobetyolin exhibited strong binding affinity to the key target TNF, tangshenoside I effectively interacted with SRC, and syringin was closely associated with HSP90AA1. These multi-target interactions suggest a synergistic therapeutic potential in mitigating pulmonary fibrosis and oxidative stress. In the composition of the binding energy (Tables 3–5), the van der Waals forces are the mutual action play a primary role, the electrostatic interaction plays a secondary role, and the hydrophobic interaction plays a supplementary role. These findings suggest that lobetyolin, syringin, and tangshenoside I may be potential active components with anti-pulmonary fibrosis and antioxidative effects by targeting multiple proteins. As shown in Table 6, the study on the DPPH radical scavenging activity of the active components in C. pilosula revealed that the DPPH radical scavenging rate ranged from 49.3% to 97.69%, which indicates that C. pilosula has strong antioxidant activity.

Figure 1: Network pharmacologic analysis of active components of C. pilosula. (A) Venn diagram of diseases and targets. (B) Network diagram of C. pilosula–diseases–ingredients–common targets. (C) PPI network of intersecting target proteins. (D) The molecular docking results of lobetyolin. (E) The molecular docking results of syringin. (F) The molecular docking results of tangshenoside I

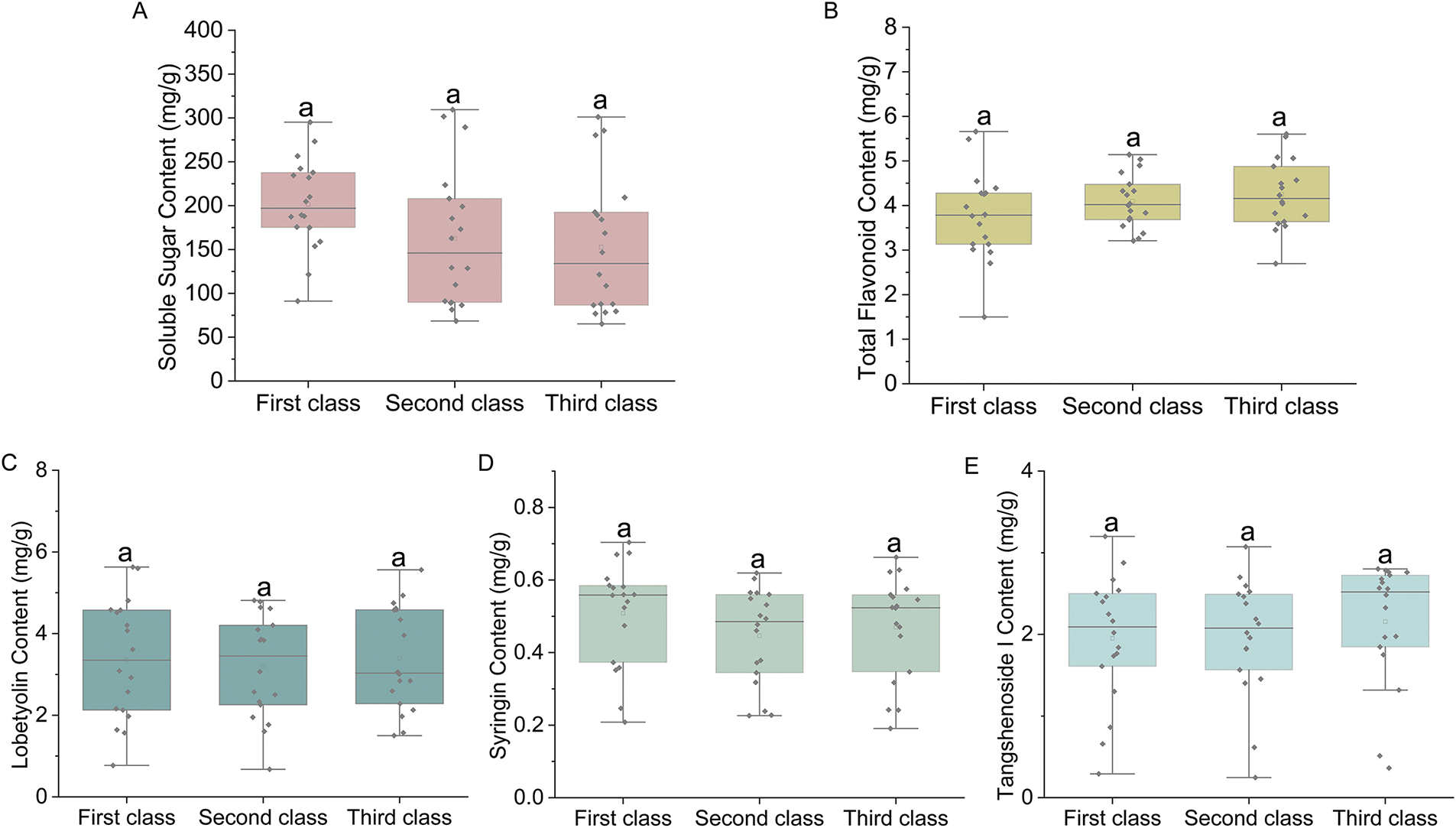

3.2 Analysis of the Active Components Content of C. pilosula among Different Specifications

The correlation between commodity specification grades and the quality of C. pilosula was studied. In terms of soluble sugar content, the first-class herb of C. pilosula exhibited higher levels than the second-class herb did, while the second-class herb showed higher levels than the third-class herb did (Fig. 2A). With regard to total flavonoid content, the third-class herb displayed higher levels than the second-class herb did, and the second-class herb had higher levels than the first-class herb did (Fig. 2B). The lobetyolin content in the third-class herb was comparable to that in the first-class herb but lower than in both first- and second-class herbs (Fig. 2C). The highest syringin content was found in the first-class herb, with comparable levels observed in both second- and third-class herbs (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, tangshenoside I content in the third-class herb surpassed that in both first- and second-class herbs, while its level in the second-class herb was similar to that of the first-class herb (Fig. 2E). These results indicate that the disparity of the composition of C. pilosula is not statistically significant among different specifications.

Figure 2: Analysis of the active components in C. pilosula from different specifications in Gansu Province. (A) Boxplot illustrating the soluble sugar content. (B) Boxplot illustrating the total flavonoid content. (C) Boxplot illustrating the lobetyolin content. (D) Boxplot illustrating the syringin content. (E) Boxplot illustrating the tangshenoside I content. Note: Containing the same letter “a” indicates that there is no significant difference between the two groups

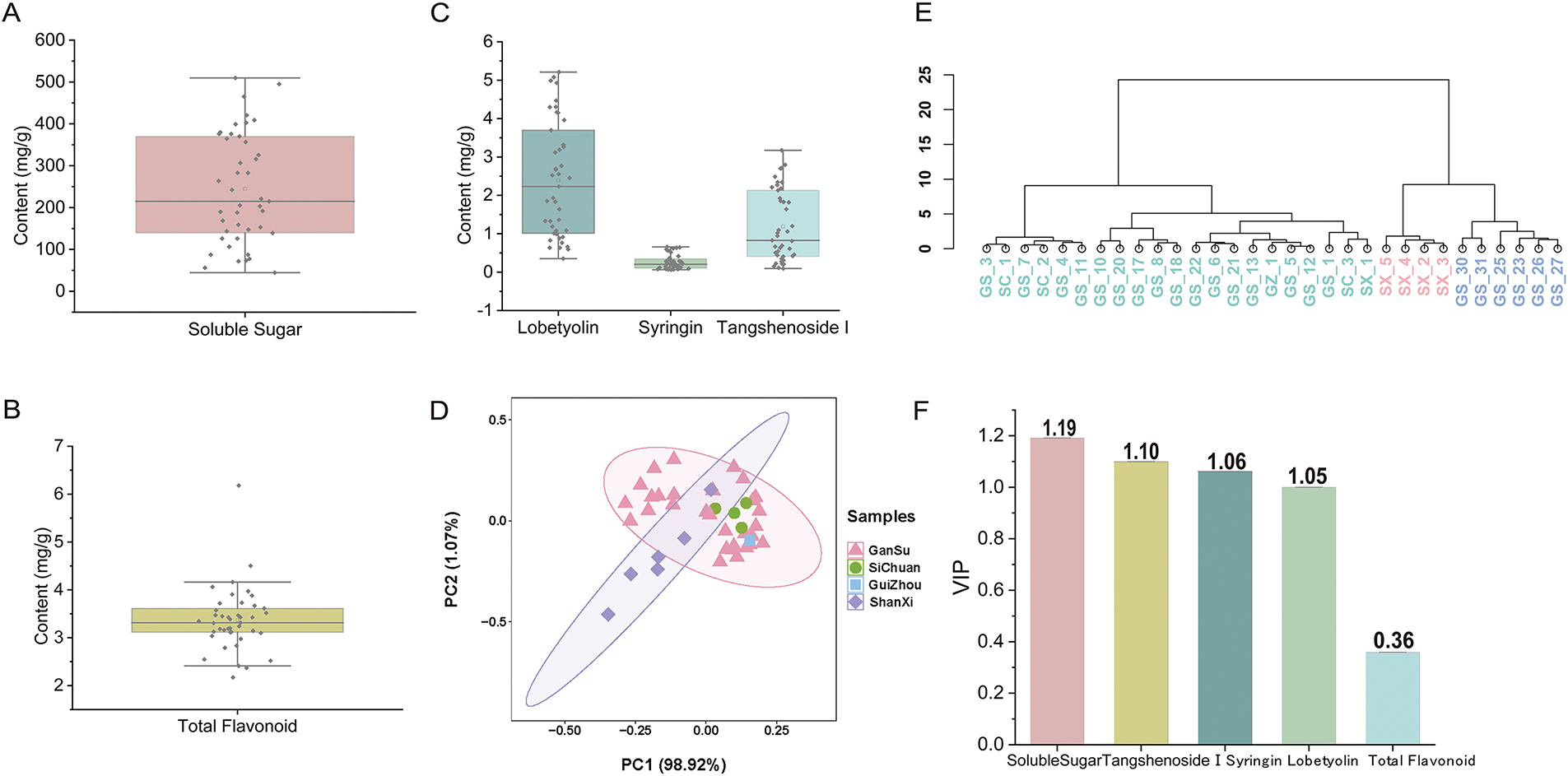

3.3 Analysis of Active Components of C. pilosula from Different Origins

Significant differences were found in the content of active components of C. pilosula among different origins. The soluble sugar content ranged from 10.78 to 49.51 mg·g−1, with an average of 24.29 mg·g−1 (Fig. 3A). The content of total flavonoids ranged from 1.33 to 4.57 mg·g−1, with an average of 2.09 mg·g−1 (Fig. 3B). The contents of lobetyolin ranged from 0.35 to 5.21 mg·g−1, with an average of 2.47 mg·g−1. The content of tangshenoside I ranged from 0.95 to 31.73 mg·g−1, with an average of 12.37 mg·g−1. The content of syringin ranged from 0.06 to 0.66 mg·g−1, with an average of 0.27 mg·g−1 (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3: Analysis of the active components in C. pilosula from different origins. (A) Boxplot illustrating the soluble sugar content. (B) Boxplot illustrating the total flavonoid content. (C) Boxplot illustrating the content of three types of glycosides. (D) PCA of the active components. (E) Cluster tree analysis of different origins. (F) VIP value analysis of active components

Principal component analysis (PCA) was employed to achieve a comprehensive differentiation. Distinct separation trends were discernible in the PCA model score plot (Fig. 3D). The samples from Gansu and Shanxi were classified into different clusters by cluster tree analysis (Fig. 3E), and a robust classification result was obtained. VIP analysis based on active components was conducted to identify potential biomarkers for distinguishing C. pilosula of different origins (Fig. 3F). Potential markers across diverse origins were selected by screening for VIP values >1 (p < 0.05). Notably, soluble sugar and three glycoside components—tangshenoside I, syringin, and lobetyolin all exhibited VIP values exceeding 1.0, indicating their potential role as markers for the quality disparities among geographically distinct varieties of C. pilosula.

3.4 Ecological Factors Contributing to the Accumulation of Active Components in C. pilosula

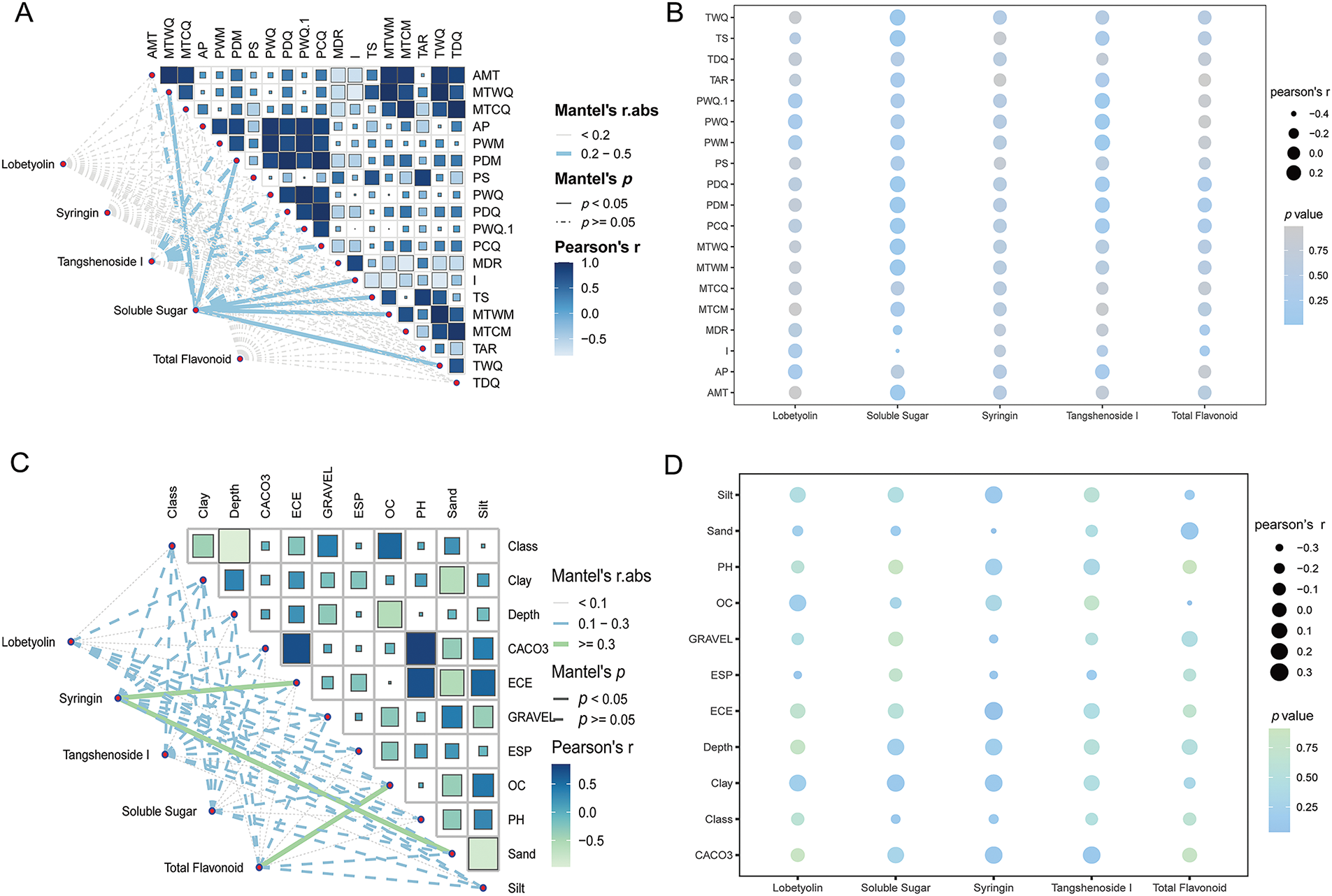

A total of 19 climatic factors (Table S3) were extracted from WorldClim based on latitude and longitude for conducting correlation analysis with the quality indicators of C. pilosula. These factors mainly include annual mean temperature, mean diurnal range, isothermality, and temperature seasonality.

Ecological factors such as temperature, rainfall, humidity, light, and soil composition index affected the accumulation of the main components of C. pilosula. The primary influencing factors are temperature and precipitation. Mantel tests revealed significant correlations of climatic factors with soluble sugar (p < 0.05) and tangshenoside I contents (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4A), while soil factors significantly affected syringin and total flavonoid levels (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4C). Further visualization of the relationship between climatic factors and the content of each active component was showed (Fig. 4B) temperature-related parameters demonstrated significant positive correlations with soluble sugar content. Conversely, precipitation metrics showed pronounced negative correlations with soluble sugar content. Annual precipitation exhibited a negative correlation with the accumulation of tangshenoside I content. Sand content and electric conductivity showed a significant correlation with syringin. Organic carbon content exhibited a significant negative correlation with total flavonoid levels (Fig. 4D and Table S4).

Figure 4: Study on the correlation between ecological factors and the accumulation of active components. (A) Correlation between climatic factors categories and active components. (B) Correlation bubble map analysis between climatic factors and active components. (C) Correlation between soil factor categories and active components. (D) Correlation bubble map analysis between soil factors and active components

Lobetyolin, syringin, and tangshenoside I are potential active components of C. pilosula in the treatment of pulmonary fibrosis and oxidative stress [6]. Lobetyolin is the primary active component in the pharmacopoeia, while syringin and tangshenoside I are essential indicators for assessing the quality of C. pilosula [7,34]. Network pharmacology contributes to the exploration of the relationships among herbs, diseases, and molecular targets [35]. Modern studies suggest that C. pilosula has various pharmacological activities, including enhancing immunity, antioxidation, anti-tumour effects, anti-inflammatory properties, and regulation of gastrointestinal function [36,37]. This study explores the resistance effects of the active components of C. pilosula on pulmonary fibrosis and oxidative stress by using network pharmacology and molecular docking techniques. The literature indicates that the flavonoids in C. pilosula can not only inhibit pulmonary inflammatory responses but also have anti-pulmonary fibrosis effects [38]. The soluble sugar in C. pilosula can improve gastric mucosal injury in CAG rats and inhibit oxidative stress, inflammatory response, and cell apoptosis [1,39]. The lobetyolin and syringin in C. pilosula can mitigate oxidative damage by regulating immune inflammation [7]. These results indicate that soluble sugar, total flavonoids, tangshenoside I, syringin, and lobetyolin are active components of C. pilosula.

No significant difference was found in the content of active components of C. pilosula between different specifications. Over the long history of traditional Chinese medicine development, a unique standard for evaluating drug quality has gradually emerged, known as ‘visual inspection for grading and pricing’ [40]. The intrinsic quality of Scale ginseng medicinal materials is related to the commodity specification grades of market segmentation [41]. A certain correlation exists between the commercial specifications and the content of ingredients in Salvia miltiorrhiza, but using this result as a conclusion is one-sided [42]. The results indicated that the intrinsic quality of cultivated C. pilosula varieties across different specifications and grades was generally consistent with the current classification standards based on morphological characteristics and origin. Notably, first- and second-class herbs exhibited higher levels of key index components, categorizing them as high-quality medicinal materials [18]. However, the contents of lobetyolin and atractylodes III in different specifications of C. pilosula sinensis were negatively correlated with the commodity grade [19]. While the study states that differences in the contents of active components across three commodity specification grades were not significant, the implication of this result has not been fully explored in previous studies. The existing grading standards for C. pilosula primarily rely on subjective morphological characteristics of the medicinal materials, while insufficiently accounting for variations in active components [43]. Furthermore, inconsistent classification criteria for major production origins have resulted in a weak correlation between commodity specification grades and actual medicinal quality [44]. This suggests that quality control based on commodity grades is insufficient for ensuring consistent bioactivity, and it reflects the robustness of the active components across grades. Therefore, it is urgent to construct a C. pilosula quality evaluation index based on core quality elements.

Notable differences were observed in the content of active components in C. pilosula from different origins. Soluble sugars, lobetyolin, syringin, and tangshenoside I serve as potential markers that distinguish the quality of C. pilosula from different origins. Significant differences exist in the content of lobetyolin across different origins [45]. The flavonoid content of C. pilosula varies significantly with different origins [1]. The content of soluble sugar, lobetyolin, atractylenolide III, and amino acids of C. pilosula from different production origins was significantly different [1,46]. Previous studies indicated that the content of soluble sugars and total flavonoids can serve as marker components for C. pilosula from different origins [47,48]. Lobetyolin and syringin serve as index components of C. pilosula [7]. Tangshenoside I and lobetyolin were identified as important differential components of C. pilosula from different origins [46,49]. These results provide valuable data for the selection of optimal production areas for C. pilosula.

Ecological factors were correlated to the accumulation of active components in C. pilosula. Ecological factors, including temperature and precipitation, exhibit distinct seasonal variations. Moreover, geographical heterogeneity significantly influences these environmental parameters, resulting in substantial variations in the quality of medicinal materials across different regions [24]. Notably, even within the same geographical location, micro-environmental differences can lead to discernible variations in medicinal material quality [50]. Among them, temperature significantly impacts the accumulation of soluble sugars, while precipitation notably affects the accumulation of tangshenoside I. Temperature fluctuations directly impact associated ecological factors such as humidity, evaporation, and soil moisture, which collectively influence plant growth, development, and yield [51]. Similarly, variations in precipitation levels alter physiological and biochemical processes in plants, modulating secondary metabolic pathways and, consequently, the accumulation of bioactive compounds [52]. Key ecological factors, including precipitation and altitude, exert significant influences on the accumulation of specific metabolites such as lobetyolin, atractylenolide III, and polysaccharides in C. pilosula plants. Consequently, pronounced regional variations in these phytochemical constituents have been observed among C. pilosula samples collected from different geographical locations [21]. The appropriate temperature range and precipitation are conducive to the normal growth of C. pilosula and to the synthesis and accumulation of its active components [32,53]. Different ecological factors had varying influences on the accumulation of active components in medicinal plants. These findings indicate that ecological factors acted as driving factors for the accumulation of active components, and they provide valuable guidance for selecting authentic production areas of C. pilosula.

The results illustrated that lobetyolin, syringin, and tangshenoside I are potential agents with anti-pulmonary fibrosis and antioxidation effects based on network pharmacological analysis. The content of active components in different specifications of C. pilosula was different but not significant. Significant differences were observed in the active component content of C. pilosula from different origins. Soluble sugars, lobetyolin, syringin, and tangshenoside I can serve as potential biomarkers for distinguishing between C. pilosula from different origins. Additionally, temperature significantly influences the accumulation of soluble sugar content, while precipitation notably affects the accumulation of tangshenoside I. Sand content and electrical conductivity were significantly correlated with syringin levels, while organic carbon content negatively influenced the association with total flavonoid concentrations. Taking climate and soil data as the core basis for planting decisions, precision and sustainability in C. pilosula cultivation can be achieved through variety adaptation, soil improvement, application of ecological technologies, and dynamic monitoring. This study can further refine regional cultivation models by integrating artificial intelligence and big data analytics, thereby driving the C. pilosula industry toward high-quality production and higher added value. Nevertheless, the sample of this study is confined to major producing areas, and its findings may not fully capture the broader regional variability. Future research should aim to elucidate the mechanisms by which additional ecological factors influence the biosynthesis of active components in C. pilosula by incorporating a larger and more diverse sample set (including wild-type specimens) and by expanding the geographical coverage. These findings demonstrate the relationship between the geographical distribution of C. pilosula herbs and their intrinsic active components, offering evidence for the traditional Chinese medicine concept of ‘Dao-di’.

Acknowledgement: Thanks to the instructor for the academic guidance and to my colleagues for the technical support and experimental assistance.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the National Key R&D Plan (2022YFC3501804), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Public Welfare Research Institutes (No. ZZ13-YQ-049) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (ZXKT22001).

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Menghan Li, Li Liu, Jia Xu and Linlin Dong; data collection: Menghan Li, Yuhui He, Changning Chen and Xiaotong Guo; analysis and interpretation of results: Menghan Li, Changning Chen, Jiahao Cao and Linlin Dong; writing original draft preparation: Menghan Li and Yuhui He; review and editing: Linlin Dong and Xiaotong Guo; funding: Linlin Dong. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.064518/s1.

References

1. Zou YF, Zhang YY, Paulsen BS, Fu YP, Huang C, Feng B, et al. Prospects of Codonopsis pilosula polysaccharides: structural features and bioactivities diversity. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2020;103(8):1–11. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2020.06.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Chen WJ, Pang WT, Wang GY, Zhang YZ, Meng LK, Zhuang M, et al. Herbalogical study on traditional Chinese medicine Dangshen (Codonopsis Radix) for tonifying Qi. J Liaoning Univ Tradit Chin Med. 2025;27(4):118–23. (In Chinese). doi:10.13194/j.issn.1673-842X.2025.04.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ji JJ, Feng Q, Sun HF, Zhang XJ, Li XX, Li JK, et al. Response of bioactive metabolite and biosynthesis related genes to methyl jasmonate elicitation in Codonopsis pilosula. Molecules. 2019;24(3):533. doi:10.3390/molecules24030533. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Yu Z, Wang W, Yang K, Gou J, Jiang Y, Yu Z. Sports and Chinese herbal medicine. Pharmacol Res-Mod Chin Med. 2023;9(1):100290. doi:10.1016/j.prmcm.2023.100290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zou Y, Yan H, Li C, Wen F, Jize X, Zhang C, et al. A pectic polysaccharide from Codonopsis pilosula alleviates inflammatory response and oxidative stress of aging mice via modulating intestinal microbiota-related gut-liver axis. Antioxidants. 2023;12(9):1781. doi:10.3390/antiox12091781. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Chu R, Zhou Y, Ye C, Pan R, Tan X. Advancements in the investigation of chemical components and pharmacological properties of Codonopsis: a review. Medicine. 2024;103(26):e38632. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000038632. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Dong J, Na Y, Hou A, Zhang S, Yu H, Zheng S, et al. A review of the botany, ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry, analysis method and quality control, processing methods, pharmacological effects, pharmacokinetics and toxicity of Codonopsis Radix. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1162036. doi:10.3389/fphar.2023.1162036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Li LX, Chen MS, Zhang ZY, Paulsen BS, Rise F, Huang C, et al. Structural features and antioxidant activities of polysaccharides from different parts of Codonopsis pilosula var. modesta (Nannf.) L. T. Shen. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:937581. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.937581. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Yu Y, Ding S, Xu X, Yan D, Fan Y, Ruan B, et al. Integrating network pharmacology and bioinformatics to explore the effects of Dangshen (Codonopsis pilosula) against hepatocellular carcinoma: validation based on the active compound luteolin. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2023;17:659–73. doi:10.2147/dddt.s386941. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang YY, Zhang YM, Xu HY. Effect of Codonopsis pilosula polysaccharides on the growth and motility of hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells by regulating β-catenin/TCF4 pathway. Int J Polym Sci. 2019;2019:1–7. doi:10.1155/2019/7068437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Gao SM, Liu JS, Wang M, Cao TT, Qi YD, Zhang BG, et al. Quantitative and HPLC fingerprint analysis combined with chemometrics for quality evaluation of Codonopsis Radix processed with different methods. Chin Herb Med. 2019;11(2):160–8. doi:10.1016/j.chmed.2018.08.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Chen B, Dong X, Zhang JL, Sun X, Zhou L, Zhao K, et al. Natural compounds target programmed cell death (PCD) signaling mechanism to treat ulcerative colitis: a review. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1333657. doi:10.3389/fphar.2024.1333657. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Zhao B, Shu X, Zhang H. Pulmonary diseases and traditional Chinese medicine. In: Zhao Y, editor. Lung biology and pathophysiology. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2024. p. 237–64. [Google Scholar]

14. He L, Zhang L, Li X, He H, Fu G, Zhu YZ, et al. “Qi-invigoration” action of Codonopsis pilosula polysaccharide through altering mitochondrial bioenergetics; 2024. doi:10.20944/preprints202410.2152.v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Chen J, Li LF, Lin ZZ, Cheng XL, Wei F, Ma SC. A quality-comprehensive-evaluation-index-based model for evaluating traditional Chinese medicine quality. Chin Med. 2023;18(1):89. doi:10.1186/s13020-023-00782-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Cao ZJ, Yip KM, Jiang YG, Ji SL, Ruan JQ, Wang C, et al. Suitability evaluation on material specifications and edible methods of Dendrobii Officinalis Caulis based on holistic polysaccharide marker. Chin Med. 2020;15(1):46. doi:10.1186/s13020-020-0300-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Zhu J, Fan S, He M, Wang N, Xu X, Pang J, et al. Quality-grade analysis of velvet antler materials using ultra-weak delayed luminescence combined with chemometrics. Qual Assur Saf Crops Foods. 2023;15(4):1–10. doi:10.15586/qas.v15i4.1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zhang X, Tong L, Wang Y, Li Z, Xi X, Wang S, et al. Quality analysis of Codonopsis pilosula with different commodity specification grades. China Pharm. 2023;34(11):1363–7. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

19. Li CY, Liu SB, Wang MW, Wei XM, Qiang ZZ, Zhang YS. Comprehensive quality evaluation of Gansu Baitiao Codonopsis Radix with different commercial grades. Chin J Inf TCM. 2016;23(5):91–5. [Google Scholar]

20. Liu SB, Li CY, Wang MW, Li S, Qiang ZZ, Wei XM. Correlation scores between commodity grade and active ingredients of Gansu real estate white tiao Codonopsis. Lishizhen Med Mater Medica Res. 2016;27(2):329–31. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

21. Fan L, Li Y, Wang X, Leng F, Li S, Zhu N, et al. Culturable endophytic fungi community structure isolated from Codonopsis pilosula roots and effect of season and geographic location on their structures. BMC Microbiol. 2023;23(1):132. doi:10.1186/s12866-023-02848-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Gong J, Liu M, Xu S, Jiang Y, Pan Y, Zhai Z, et al. Effects of light deficiency on the accumulation of saikosaponins and the ecophysiological characteristics of wild Bupleurum chinense DC. in China. Ind Crops Prod. 2017;99(3):179–88. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.01.040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Li J, Zhang J, Zhao YL, Huang HY, Wang YZ. Comprehensive quality assessment based specific chemical profiles for geographic and tissue variation in gentiana rigescens using HPLC and FTIR method combined with principal component analysis. Front Chem. 2017;5:125. doi:10.3389/fchem.2017.00125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Zhang J, Zhang Z, Wang Y, Zuo Y, Cai C. Environmental impact on the variability in quality of Gentiana rigescens, a medicinal plant in southwest China. Glob Ecol Conserv. 2020;24:e01374. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ncube B, Finnie JF, Van Staden J. Quality from the field: the impact of environmental factors as quality determinants in medicinal plants. S Afr J Bot. 2012;82:11–20. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2012.05.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zou H, Zhang B, Chen B, Duan D, Zhou X, Chen J, et al. A multi-dimensional “climate-land-quality” approach to conservation planning for medicinal plants: take Gentiana scabra Bunge in China as an example. Ind Crops Prod. 2024;211:118222. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2024.118222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Nurhaslina CR, Andi Bacho S, Mustapa AN. Review on drying methods for herbal plants. Mater Today Proc. 2022;63(4):S122–39. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2022.02.052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Commission CP, Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China. 2020 ed. Beijing, China: China Medical Science and Technology Press; 2020. 1927 p. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

29. Shanxi Market Supervision Bureau. Requirements for grading Codonopsis pilosula [Internet]. (In Chinese). [cited 2025 May 20]. Available from: https://www.ndls.org.cn/standard/detail/d7b40f00c1cf67fea33d24b65dfd6429. [Google Scholar]

30. Yue Y, Zhang Q, Wan F, Ma G, Zang Z, Xu Y, et al. Effects of different drying methods on the drying characteristics and quality of Codonopsis pilosulae slices. Foods. 2023;12(6):1323. doi:10.3390/foods12061323. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Zhang Z, Li X, Zhang Y, Yin N, Wu G, Wei G, et al. Ecological factors impacting genetic characteristics and metabolite accumulations of Gastrodia elata. Chin Herb Med. Forthcoming 2024. doi:10.1016/j.chmed.2024.09.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Tan Y, Wang X, Liu X, Zhang S, Li N, Liang J, et al. Comparison of AHP and BWM methods based on ArcGIS for ecological suitability assessment of Panax notoginseng in Yunnan Province, China. Ind Crops Prod. 2023;199(4):116737. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.116737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Liang H, Kong Y, Chen W, Wang X, Jia Z, Dai Y, et al. The quality of wild Salvia miltiorrhiza from Dao Di area in China and its correlation with soil parameters and climate factors. Phytochem Anal. 2021;32(3):318–25. doi:10.1002/pca.2978. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Liang W, Sun J, Bai G, Qiu D, Li Q, Dong P, et al. Codonopsis Radix: a review of resource utilisation, postharvest processing, quality assessment, and its polysaccharide composition. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1366556. doi:10.3389/fphar.2024.1366556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Pang Y, Yu W, Liang W, Gao Y, Yang F, Zhu Y, et al. Solid-phase microextraction/gas chromatography-time-of-flight mass spectrometry approach combined with network pharmacology analysis to evaluate the quality of agarwood from different regions against anxiety disorder. Molecules. 2024;29(2):468. doi:10.3390/molecules29020468. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Yin XL, Gu RJ, Han X. Research progress on the anti-tumor effect of Codonopsis pilosula. Pharmacol Discov. 2024;4(3):15. doi:10.53388/pd202404015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Guo H, Lou Y, Hou X, Han Q, Guo Y, Li Z, et al. A systematic review of the mechanism of action and potential medicinal value of Codonopsis pilosula in diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1415147. doi:10.3389/fphar.2024.1415147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Lin Y, Tan D, Kan Q, Xiao Z, Jiang Z. The protective effect of naringenin on airway remodeling after mycoplasma pneumoniae infection by inhibiting autophagy-mediated lung inflammation and fibrosis. Mediat Inflamm. 2018;2018:8753894. doi:10.1155/2018/8753894. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Wang Y, Chen R, Yang Z, Wen Q, Cao X, Zhao N, et al. Protective effects of polysaccharides in neurodegenerative diseases. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022;14:917629. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2022.917629. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Guo Z, Zhang M, Lee DJ, Simons T. Smart camera for quality inspection and grading of food products. Electronics. 2020;9(3):505. [Google Scholar]

41. Zhang W, Bai X, Guo J, Yang J, Yu B, Chen J, et al. Hyperspectral imaging for in situ visual assessment of industrial-scale ginseng. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2024;321:124700. doi:10.1016/j.saa.2024.124700. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Fang W, Deng A, Kang L, Nan T, Tang J, Zhang Y, et al. Research on standards of commercial grades for chinese materia medica and quality evaluation of Salviae miltiorrhizae Radix et Rhizoma. Mod Chin Med. 2020;22(2):188–201. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

43. Willer J, Zidorn C, Juan-Vicedo J. Ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry, and bioactivities of Hieracium L. and Pilosella Hill (Cichorieae, Asteraceae) species. J Ethnopharmacol. 2021;281(6):114465. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2021.114465. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Govindaraghavan S, Sucher NJ. Quality assessment of medicinal herbs and their extracts: criteria and prerequisites for consistent safety and efficacy of herbal medicines. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;52(Pt B):363–71. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.03.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Tadege G, Alebachew Y, Hymete A, Tadesse S. Identification of lobetyolin as a major antimalarial constituent of the roots of Lobelia giberroa Hemsl. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist. 2022;18:43–51. doi:10.1016/j.ijpddr.2022.01.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Yue J, Xiao Y, Chen W. Insights into Genus Codonopsis: from past achievements to future perspectives. Crit Rev Anal Chem. 2024;54(8):3345–76. doi:10.1080/10408347.2023.2242953. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Wang SS, Zhang T, Wang L, Dong S, Wang DH, Li B, et al. The dynamic changes in the main substances in Codonopsis pilosula root provide insights into the carbon flux between primary and secondary metabolism during different growth stages. Metabolites. 2023;13(3):456. doi:10.3390/metabo13030456. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Wang Y, Yuan J, Li S, Hui L, Li Y, Chen K, et al. Comparative analysis of carbon and nitrogen metabolism, antioxidant indexes, polysaccharides and lobetyolin changes of different tissues from Codonopsis pilosula co-inoculated with Trichoderma. J Plant Physiol. 2021;267(1):153546. doi:10.1016/j.jplph.2021.153546. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Zeng X, Li J, Lyu X, Chen J, Chen X, Guo S. Untargeted metabolomics reveals multiple phytometabolites in the agricultural waste materials and medicinal materials of Codonopsis pilosula. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:814011. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.814011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Jia H. Study on quality of germplasm resources of Ligusticum chuanxiong from different regions. Chengdu, China: Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine; 2007. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

51. Ding JL, Zheng K, Yu LS. Effects of light, temperature and water on the growth and development of indoor plants. Zhejiang Agric Sci. 2012;10:1458–61. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

52. Liu XL, Gao M. Effect of different water content in soil on growth and four water-soluble active components of Salvia miltiorrhiza bunge. J Agric Sci Technol. 2020;22(10):175–80. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

53. Tri C, Tuan T, Kiem T. Application of AHP-GIS model to assess the ecological suitability of Codonopsis javanica in Kon Plong District, Kon Tum Province, Viet Nam. J Ecol Eng. 2022;23(7):276–83. doi:10.12911/22998993/150027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools