Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Physiological and Biochemical Responses and Non-Parametric Transcriptome Analysis for the Curcumin-Induced Improvement of Saline-Alkali Resistance in Akebia trifoliate (Thunb.) Koidz

College of Agriculture and Life Science, Kunming University, Kunming, 650214, China

* Corresponding Author: Yongfu Zhang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Plant Responses to Abiotic Stress)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(8), 2529-2550. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.066894

Received 19 April 2025; Accepted 05 August 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Soil salinization is a major abiotic stress that hampers plant development and significantly reduces agricultural productivity, posing a serious challenge to global food security. Akebia trifoliata (Thunb.) Koidz, a species within the genus Akebia Decne., is valued for its use in food, traditional medicine, oil production, and as an ornamental plant. Curcumin, widely recognized for its pharmacological properties including anti-cancer, anti-neuroinflammatory, and anti-fibrotic effects, has recently drawn interest for its potential roles in plant stress responses. However, its impact on plant tolerance to saline-alkali stress remains poorly understood. In this study, the effects of curcumin on saline-alkali resistance in A. trifoliata were examined by subjecting plants to a saline-alkali solution containing 150 mmol/L sodium ions (a mixture of Na2SO4, Na2CO3, and NaHCO3). Curcumin treatment under these stress conditions leads to anatomical improvements in leaf structure. Furthermore, A. trifoliata maintained a favorable Na+/K+ ratio through increased potassium uptake and reduced sodium accumulation. Biochemical analysis revealed elevated levels of proline, soluble sugars, and soluble proteins, along with improved activities of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and peroxidase (POD). Similarly, the concentrations of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and malondialdehyde (MDA) were significantly reduced. Transcriptome analysis under saline-alkali stress conditions showed that curcumin influenced seven key metabolic pathways annotated in the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database, with differentially expressed unigenes primarily enriched in transcription factor families such as MYB, AP2/ERF, NAC, bHLH, and C2C2. Moreover, eight differentially expressed genes (DEGs) associated with plant hormone signal transduction were linked to the auxin and brassinosteroid pathways, critical for cell elongation and plant growth. These findings indicate that curcumin increases saline-alkali stress tolerance in A. trifoliata by modulating physiological, biochemical, and transcriptional responses, ultimately supporting improved growth under adverse conditions.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileSoil degradation caused by salinization represents one of the most critical abiotic stresses limiting plant growth and agricultural productivity. Most plant species display low tolerance to saline-alkali conditions and cannot sustain normal growth in high-salinity environments [1,2]. Globally, saline-alkali soils cover an estimated 9.54 × 109 km2, and projections suggest that over 50% of arable land may be affected by salinization by 2050. This trend poses a substantial threat to crop development and the long-term sustainability of modern agriculture [2,3]. The accumulation of salts such as Na2CO3, NaHCO3, NaCl, and Na2SO4 leads to elevated soil pH and sodium ion (Na+) concentrations (≥40 mmol/L), creating saline-alkali conditions. Under such stress, plants experience multiple forms of physiological disruption, including ionic imbalance, osmotic stress, and oxidative damage, often resulting in compounded secondary injuries [4,5]. These stresses hinder root development, reduce the absorption of essential micronutrients, and manifest in visible symptoms such as chlorosis and wilting. Ultimately, such effects compromise crop quality and lead to significant yield losses [6].

Under saline-alkali stress, plants undergo a range of morphological, structural, physiological, and biochemical adjustments to adapt to adverse environmental conditions [7]. This type of stress disrupts normal metabolic activity. It adversely affects plant growth, often leading to anatomical alterations such as reduced palisade thickness and spongy mesophyll tissues, ultimately resulting in thinner leaves [8,9]. To cope with osmotic imbalances, plants activate osmoregulatory mechanisms that modulate the uptake of inorganic ions, including Na+, K+, NO3−, and Cl−, helping to reestablish cellular turgor and maintain homeostasis. Adaptation is further facilitated by synthesizing or accumulating osmoregulatory compounds such as proline, soluble proteins, sugars, and organic acids. These substances help lower osmotic potential, alleviate osmotic pressure, and mitigate damage caused by saline-alkali conditions [4,10,11]. Saline-alkali stress also disrupts numerous metabolic and systemic processes, leading to oxidative damage. In response, plants rely on an antioxidant defense system to combat accumulating reactive oxygen species (ROS). Key enzymes involved in ROS scavenging include superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and peroxidase (POD), which work together to mitigate oxidative injury. SOD activity is typically up-regulated first to neutralize superoxide radicals, followed by CAT and POD, which further detoxify hydrogen peroxide and other ROS [12–14]. Plant hormones also play a crucial role in modulating growth and orchestrating responses to abiotic stressors, including salinity and alkalinity [15]. Hormones such as abscisic acid (ABA), brassinosteroids (BRs), melatonin (MT), gibberellic acid (GA), ethylene (ET), auxin (IAA), cytokinins (CK), salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), and strigolactones (SL) contribute to various aspects of the stress response [3,16,17]. Among these, ABA is central to the plant’s response to salt stress, promoting the expression of stress-responsive genes. Saline-alkali conditions stimulate the endogenous synthesis of ABA, activating pathways that increase stress tolerance [18,19]. Other hormones also respond dynamically to stress; for instance, exposure to alkaline conditions increases ethylene levels in Arabidopsis, promoting IAA synthesis, suppressing root elongation, and enhancing [20]. Transcription factors (TFs) are essential in coordinating gene expression under saline-alkali stress. By binding to specific cis-regulatory elements in gene promoters, TFs regulate the transcription of genes involved in development, tissue differentiation, nutrient transport, metabolism, and stress adaptation [21–23]. Several TF families, such as C2H2, MYB/MYC [18], CBF/DREBl [24], zinc-finger, AP2/ERF, WRKY, bZIP, MYB [25], C2C2 [26], GRAS-[27], TIFY [28], Trihelix [29], bHLH, NAC, and FAR1 [30], have been implicated in modulating plant responses to saline-alkali stress.

Akebia trifoliata (Thunb.) Koidz is a perennial woody vine from the Akebia genus, predominantly distributed across East Asia, including China, Japan, and South Korea. Within China, it is widely found in northern and southern regions, the Yangtze River Basin, and along the southeastern coastal areas. The species holds significant value as a fruit crop, medicinal plant, oil source, and ornamental species, and it also serves as a model for investigating the evolutionary mechanisms of plant sex differentiation [31,32]. Despite its multifaceted importance, the saline-alkali tolerance of A. trifoliata has not been thoroughly studied. One effective approach to mitigating saline-alkali stress in plants involves the application of exogenous substances. Commonly used compounds include proline, betaine [33], sugars [34], organic acids, SA, IAA, humic acid, Ca2+, selenium [35], NO, γ-aminobutyric acid [36], silicon [37,38], JA [39], lanthanum [40], melatonin [41], CTK [42], 5-aminolevulinic acid [43], among others. Several of these substances, such as melatonin [44], JA and IAA [45], SA [46], humic acid [47], selenium [48], silicon [49], and GABA [50], have also been shown to influence plant stress responses by modulating DNA methylation patterns. Curcumin, the principal bioactive compound extracted from turmeric rhizomes [51], is a known inhibitor of DNA methylation [52]. It has garnered considerable attention for its therapeutic potential, including anti-cancer, anti-apoptotic, anti-neuroinflammatory, and anti-fibrotic properties [53]. In plants, curcumin has been demonstrated to reduce genome-wide DNA methylation levels in maize [53] and chrysanthemum [54], and to promote early flowering in chrysanthemum through epigenetic modulation [54]. However, its role in increasing saline-alkali stress tolerance in plants remains unexplored. This study investigated the physiological and molecular mechanisms by which curcumin confers saline-alkali resistance in A. trifoliata. This was achieved through an integrated approach combining morphological and anatomical assessments, physiological and biochemical analyses, and transcriptomic profiling of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) using non-parametric methods.

Cuttings of Akebia trifoliata were collected from Dongfeng Farm Administration in Mile City, Yunnan Province, and transplanted into nutrient bowls (25 cm in diameter × 30 cm in height) containing a standardized growth substrate. Plants were cultivated in a controlled growth chamber under a 14-h light/10-h dark photoperiod, at temperatures of 28°C (day) and 23°C (night), with relative humidity maintained at 65%. Each pot received 500 mL of Hoagland’s nutrient solution (pH 6.5) every seven days. To prepare the saline-alkali treatment, stock solutions of Na2SO4, Na2CO3, and NaHCO3 were prepared in distilled water at concentrations of 1, 1, and 2 mol/L, respectively. These were mixed in equal volumes (1:1:1) and diluted with distilled water to yield a final Na+ concentration of 150 mmol/L and a pH of 8.5, simulating saline-alkali stress conditions. Healthy and disease-free A. trifoliata cuttings were selected and transplanted into white plastic containers (120 cm × 40 cm × 30 cm; length × width × height), with four plants per container. Each nutrient bowl received 2 L of the prepared saline-alkali solution. The leaves of the treated plants were sprayed with curcumin solutions at concentrations of 0, 200, 400, or 800 μmol/L. These treatments were designated CUR0, CUR200, CUR400, and CUR800, respectively. Plants that received neither saline-alkali solution nor curcumin treatment were the negative control. All treatments were applied once every seven days. On day 28, leaves numbered 10 to 20 were harvested for analysis. Samples were either immediately used for experiments or rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. All treatments were conducted with four biological replicates.

2.2 Determination of A. trifoliate Morphological Indicators

Plant height was measured using tape, while stem diameter was recorded 2 cm above the soil surface using vernier calipers. After carefully removing the plants from the substrate, both above-ground and below-ground parts were rinsed with water and air-dried at room temperature, after which their fresh weights were determined.

2.3 Preparation of Paraffin Sections of A. trifoliate Roots, Stems, and Leaves

The middle leaflet of the tenth compound leaf from A. trifoliata plants was excised and immediately fixed in Formaldehyde-Acetic Acid-Ethanol (FAA) solution. Fixed tissues were dehydrated sequentially in increasing concentrations of ethanol (75%, 85%, 95%, and 100%) for 2 h. For tissue clearing, samples were treated successively with a 1:1 mixture of absolute ethanol and xylene (1.5 h), followed by a 1:2 ethanol: xylene solution (1.5 h), and finally with pure xylene for 5 min and then again for 1 h. The cleared tissues were infiltrated with molten paraffin wax at 58°C, embedded in fresh paraffin blocks, arranged neatly, cooled rapidly, and sectioned using a microtome. The paraffin sections were dewaxed using Environmentally Friendly Transparent Dewaxing Liquid I and II (20 min each), followed by sequential washes in absolute ethanol (15 and 5 min) and 75% ethanol (5 min). Sections were stained with toluidine blue for 2 h, briefly differentiated in a graded ethanol series (50%, 70%, and 80%) for 3–8 s each, and counterstained with solid green. The stained sections were examined under a NIKON ECLIPSE E100 light microscope (Nikon, Japan), and images were captured and analyzed using the NIKON DS-U3 imaging system.

2.4 Measurement of Physiological and Biochemical Indicators of A. trifoliate

Potassium (K+) content was determined using the Nessler reagent–sodium tetraphenylborate (TPB) spectrophotometric method. Samples were first incinerated to a white-gray ash, then soaked in 20% (v/v) aqueous ethanol for 30 min and filtered. The filtrate was diluted with double-distilled water (ddH2O) to a final volume of 50 mL. From this, 2.0 mL of the sample solution was mixed with 2.0 mL of 3% TPB, 2.0 mL of sodium tetraborate buffer (pH 9.0), and 5.0 mL of 10% glycerol. The mixture was brought to 25 mL with ddH2O, and absorbance was measured at 420 nm [55]. Sodium (Na+) content was measured using the bromocresol green spectrophotometric method. After ashing the sample to a white-gray residue, 1 mL of bromocresol green was added, followed by ddH2O to a final volume of 10 mL. Then, 5 mL of 0.4% chloroform was added, the mixture was shaken for 1 min, and the absorbance of the organic phase was read at 410 nm [56]. Proline content was assessed using the acid ninhydrin colorimetric method [57], H2O2 content using the titanium sulphate colorimetric method [57], while soluble protein content was quantified using the Coomassie Brilliant Blue assay [58]. Soluble sugar content was determined using the sulfuric acid–phenol method [59]. Antioxidant enzyme activities were evaluated as follows: SOD activity using the nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) photoreduction method, POD activity using the guaiacol—H2O2 colorimetric method, and CAT activity by UV absorption [59]. MDA content was quantified using the thiobarbituric acid (TBA) method [60].

Leaves from the control, CUR0, and CUR200 treatments were collected after 28 days for transcriptome analysis, with three biological replicates per group. Total RNA was extracted from A. trifoliata leaves using the TRIzol method. RNA concentration and purity were assessed using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer, integrity was evaluated via agarose gel electrophoresis, and RNA integrity number (RIN) values were determined with the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. Polyadenylated RNA (mRNA) was then enriched from the total RNA using oligo(dT)-conjugated magnetic beads and fragmented into approximately 300 bp fragments using a fragmentation buffer. First-strand cDNA synthesis was carried out using the fragmented mRNA as a template, followed by second-strand synthesis. The resulting double-stranded cDNA was purified, end-repaired, and A-tailed at the 3′ ends to facilitate adapter ligation. After ligation, the cDNA fragments were size-selected and amplified via PCR to construct the final libraries. Library quality was assessed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and quantified with the ABI StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System. High-throughput transcriptome sequencing was performed on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform for all treatment groups.

Raw sequencing data were pre-processed to remove low-quality reads, adaptor contamination, and reads containing excessive unknown nucleotides (high N content), resulting in high-quality clean reads. De novo transcriptome assembly was performed using Trinity, with PCR duplicates removed to improve assembly efficiency. The resulting transcripts were further clustered and de-redundantized using Tgicl to generate a set of unigenes. Functional annotation of the unigenes was conducted, and the clean reads were aligned to the reference unigene sequences using Bowtie2. Gene and transcript expression levels were estimated using RSEM, and differential expression analysis was performed across different treatment groups. Gene expression was quantified as FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads). Differentially expressed unigenes were identified using DESeq2 software [61], with a fold change threshold of ≥2.0 and a false discovery rate (FDR) cutoff of ≤0.05.

The assembled unigene sequences were annotated by aligning them against multiple public databases, including the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), Gene Ontology (GO), Non-Redundant Protein (NR), Non-Redundant Nucleotide (NT), SwissProt, Pfam, and Clusters of Orthologous Groups for Eukaryotic Complete Genomes (KOG), using BLASTx with an E-value cutoff of ≤1e−10. Alignment against the NR and NT databases provided functional protein annotations and species origin information, respectively. Functional classification of unigenes was conducted using the KOG database. Differentially expressed unigenes were further annotated and categorized into functional groups and biological pathways based on GO and KEGG annotations. Enrichment analysis of these pathways was performed using the phyper function in R. Furthermore, TF annotation and classification were conducted using the PlantTFDB database, based on conserved DNA-binding domains and motif structures within the annotated genes.

2.6 Data Processing and Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0 and Microsoft Excel. Significant differences among treatments were assessed using Duncan’s multiple range test at a significance level of p < 0.05. Graphs and visualizations were generated using Adobe Illustrator 2019 and GraphPad Prism 8.

3.1 A. trifoliate Morphology and Leaf Anatomy Following Curcumin Application under Saline-Alkali Stress

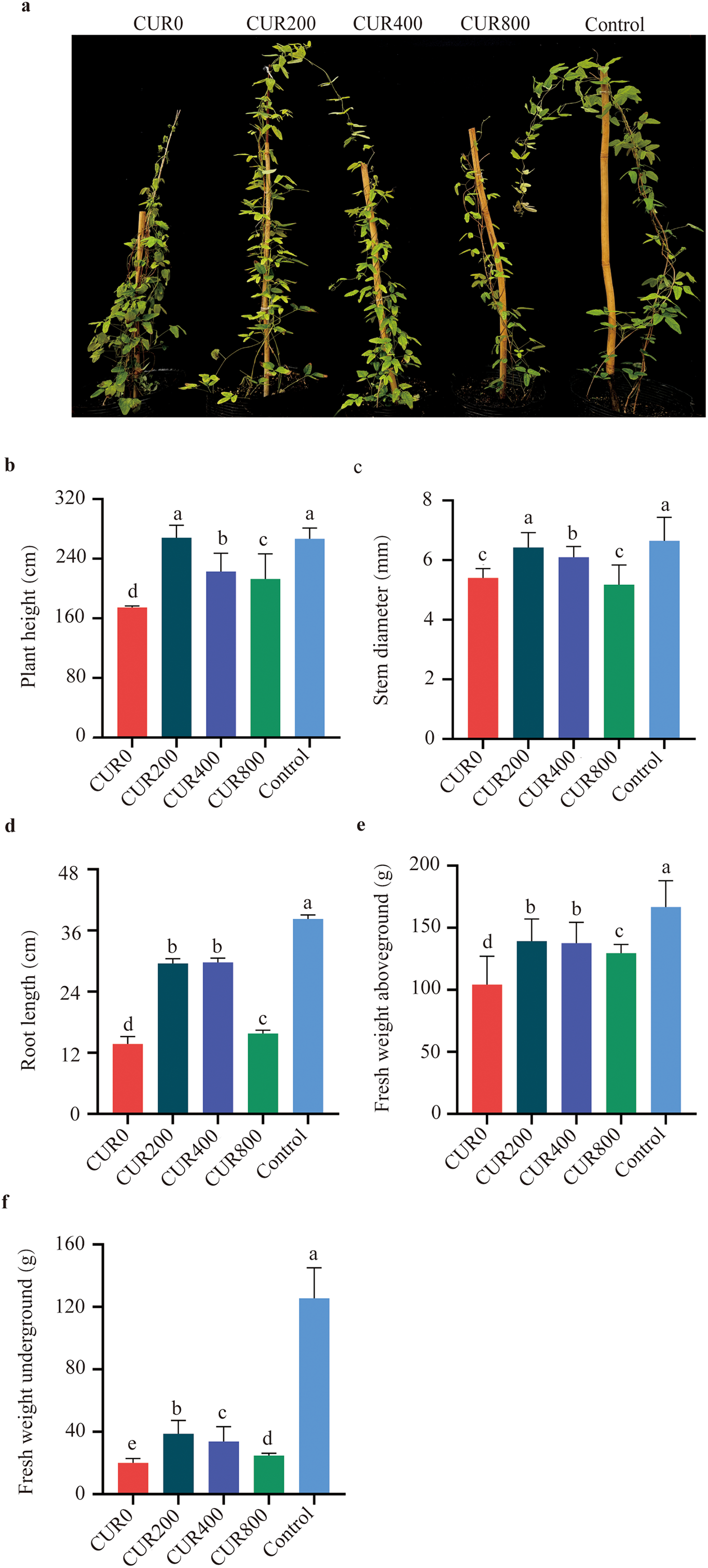

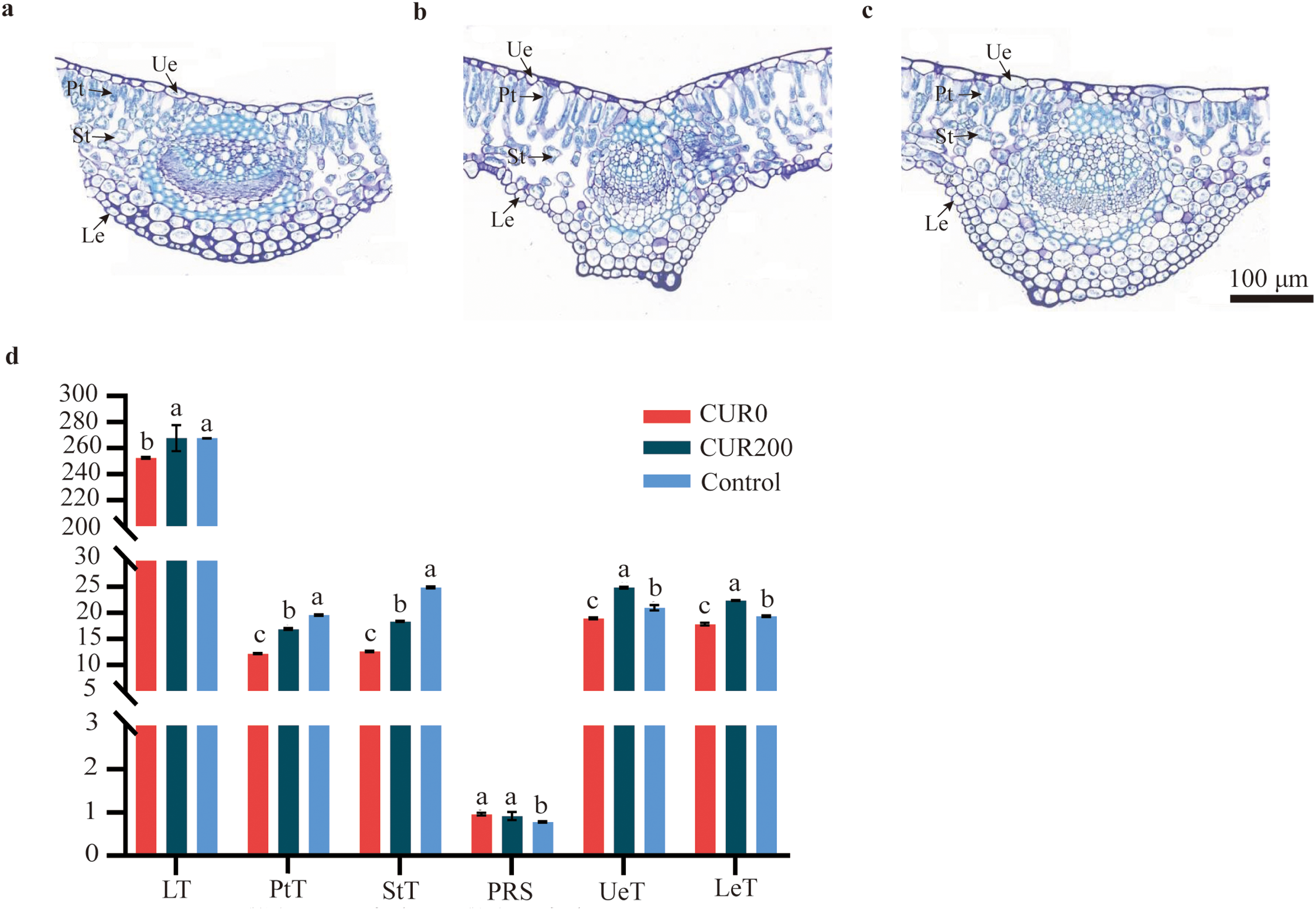

To assess the effects of curcumin on A. trifoliate under saline-alkali stress, morphological traits were examined 28 days after treatment. Compared to the control, plants in the CUR0 group (saline-alkali stress without curcumin) displayed pronounced stress symptoms, including leaf yellowing and wilting, reduced plant height, thinner stems, and shorter roots. These symptoms were alleviated to varying extents following curcumin treatment (Fig. 1a). Relative to CUR0, plant height increased by 53.72%, 27.65%, and 22.06% in the CUR200, CUR400, and CUR800 groups, respectively (Fig. 1b). Stem diameter was significantly increased in CUR200 and CUR400 by 18.98% and 12.96%, respectively. In comparison, CUR800 showed no significant change (Fig. 1c). Root length improvements were most pronounced in CUR200 and CUR400, with increases of 107.64% and 116.36%, respectively, whereas CUR800 showed only a 12.80% increase (Fig. 1d). Above-ground fresh biomass increased by 27.46%, 25.88%, and 18.54% in CUR200, CUR400, and CUR800, respectively (Fig. 1e). Below-ground fresh biomass also rose substantially, with CUR200, CUR400, and CUR800 showing increases of 93.75%, 68.75%, and 23.75%, respectively (Fig. 1f). Among the treatments, 200 μmol/L curcumin (CUR200) was the most effective in mitigating saline-alkali stress, followed by 400 μmol/L, while 800 μmol/L offered the least benefit. Based on this, a detailed anatomical analysis of leaves from the CUR200 group was conducted. Compared to the control (Fig. 2c), saline-alkali stress in CUR0 plants (Fig. 2a) led to significant reductions in total leaf thickness (5.62%), palisade tissue thickness (37.76%), spongy tissue thickness (49.48%), upper epidermis (9.76%), and lower epidermis (7.85%) (Fig. 2d). In comparison, CUR200 treatment (Fig. 2b) significantly improved these anatomical features relative to CUR0 by 5.96%, 38.52%, 46.03%, 31.19%, and 25.50%, respectively (Fig. 2d). These results suggest that curcumin enhances saline-alkali stress resistance in A. trifoliate, potentially by modulating leaf anatomical structures, through increased palisade thickness and spongy mesophyll tissues.

Figure 1: Observation and measurement of A. trifoliata morphology after spraying with curcumin under salinity-alkalinity stress. The results are shown as mean ± standard deviation. Different lowercase letters ‘a–d’ on the bar chart indicate significant differences at the p < 0:05 level. (a) Plant appearance and growth situation of CUR0, CUR200, CUR400, CUR800, and Control; (b) The plant height; (c) The plant stem diameter; (d) The plant of root length; (e) The plant of fresh weight above-ground; (f) The plant of fresh weight underground

Figure 2: Observation on the anatomical structure of leaves of A. trifoliata of CUR0, CUR200, and Control. (a) The A. trifoliata anatomical structure of CUR0; (b) The A. trifoliata anatomical structure of CUR200; (c) The A. trifoliata anatomical structure of Control; (d) The statistics of A. trifoliata anatomical characteristics. Note: Ue: Upper epidermis; Pt: Palisade tissue; St: Spong tissue; Le: Lower epidermis; LT: Leaf thickness; PtT: Palisade tissue thickness; StT: Spong tissue thickness; PRS: The ratio of palisade to spongy tissue; UeT: Upper epidermis cell thickness; LeT: Lower epidermis cell thickness. The results are shown as mean ± standard deviation. Different lowercase letters ‘a–c’ on the bar chart indicate significant differences at the p < 0:05 level

3.2 Physiological and Biochemical Indicator Levels in A. trifoliate Following Curcumin Application under Saline-Alkali Stress

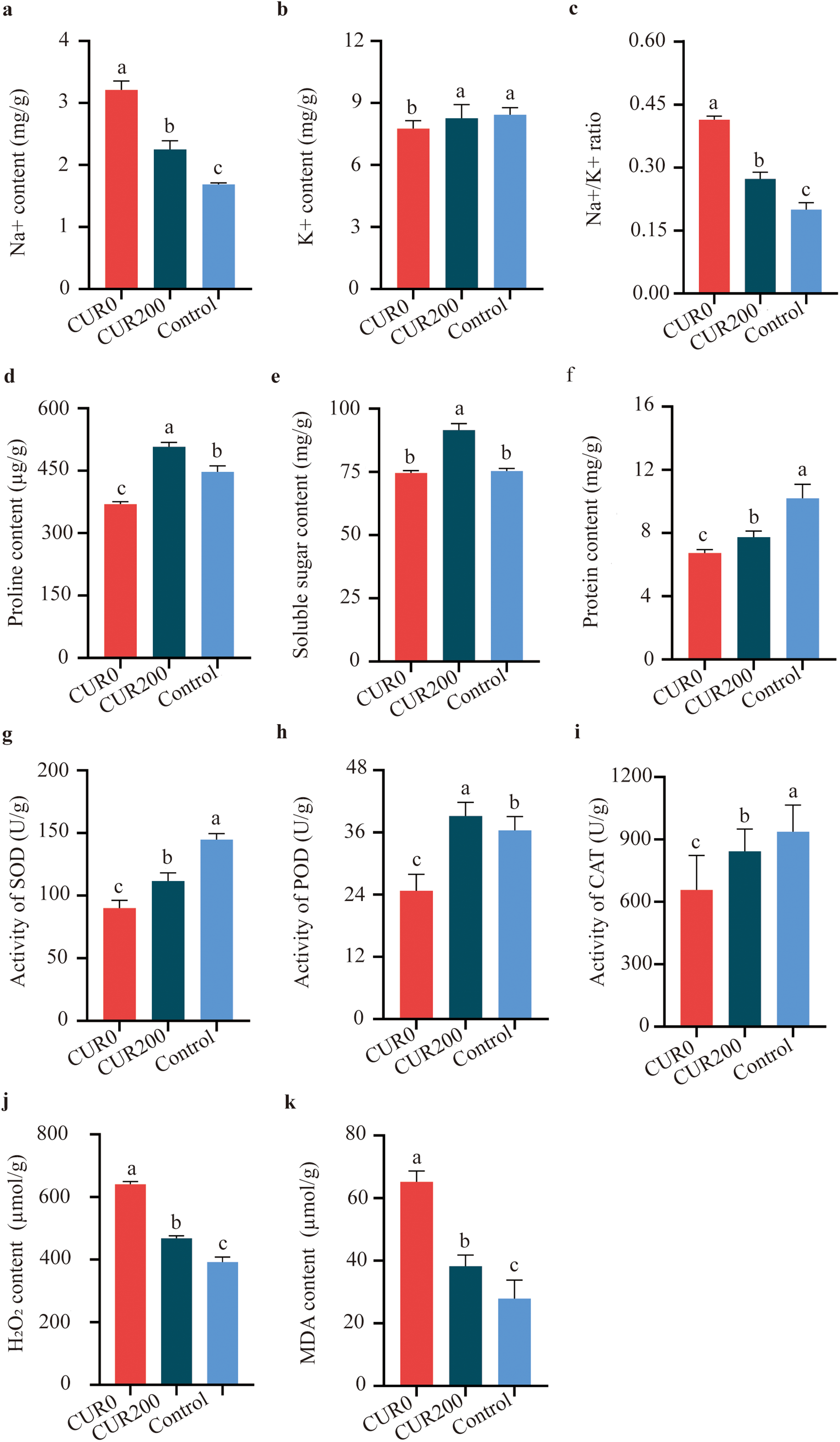

Compared to CUR0, leaves from CUR200-treated plants showed a 29.89% reduction in Na+ content (Fig. 3a), a 6.45% increase in K+ content (Fig. 3b), and a 34.14% decrease in the Na+/K+ ratio (Fig. 3c). Similarly, proline, soluble sugar, and soluble protein levels increased by 37.35% (Fig. 3d), 22.59% (Fig. 3e), and 14.85% (Fig. 3f), respectively. Antioxidant enzyme activities were also improved: SOD activity rose by 24.09% (Fig. 3g), POD by 58.33% (Fig. 3h), and CAT by 28.25% (Fig. 3i). Meanwhile, the levels of oxidative stress markers were significantly reduced in CUR200 leaves, with H2O2 and MDA contents declining by 226.93% and 41.42%, respectively (Fig. 3j,k). These findings indicate that curcumin increases the saline-alkali tolerance of A. trifoliate by modulating ion balance (via reduced Na+ accumulation and a lower Na+/K+ ratio), improving osmotic regulation (through increased proline, sugars, and proteins), and strengthening antioxidant defense (via elevated SOD, POD, and CAT activity and reduced oxidative damage). Thus, curcumin confers stress resistance through coordinated responses to ionic, osmotic, and oxidative challenges.

Figure 3: Measurement of physiological and biochemical indices of A. trifoliata leaves after spraying with curcumin under salinity-alkalinity stress. (a) The content of Na+; (b) The content of K+; (c) The ratio of Na+/K+; (d) The content of proline; (e) The content of soluble sugar; (f) The content of protein; (g) The activity of SOD; (h) The activity of POD; (i) The activity of CAT; (j) The content of H2O2; (k) The content of MDA. The results are shown as mean ± standard deviation. Different lowercase letters ‘a–c’ on the bar chart indicate significant differences at the p < 0:05 level

3.3 Non-Parametric Transcriptome Sequencing of A. trifoliate Following Curcumin Application under Saline-Alkali Stress

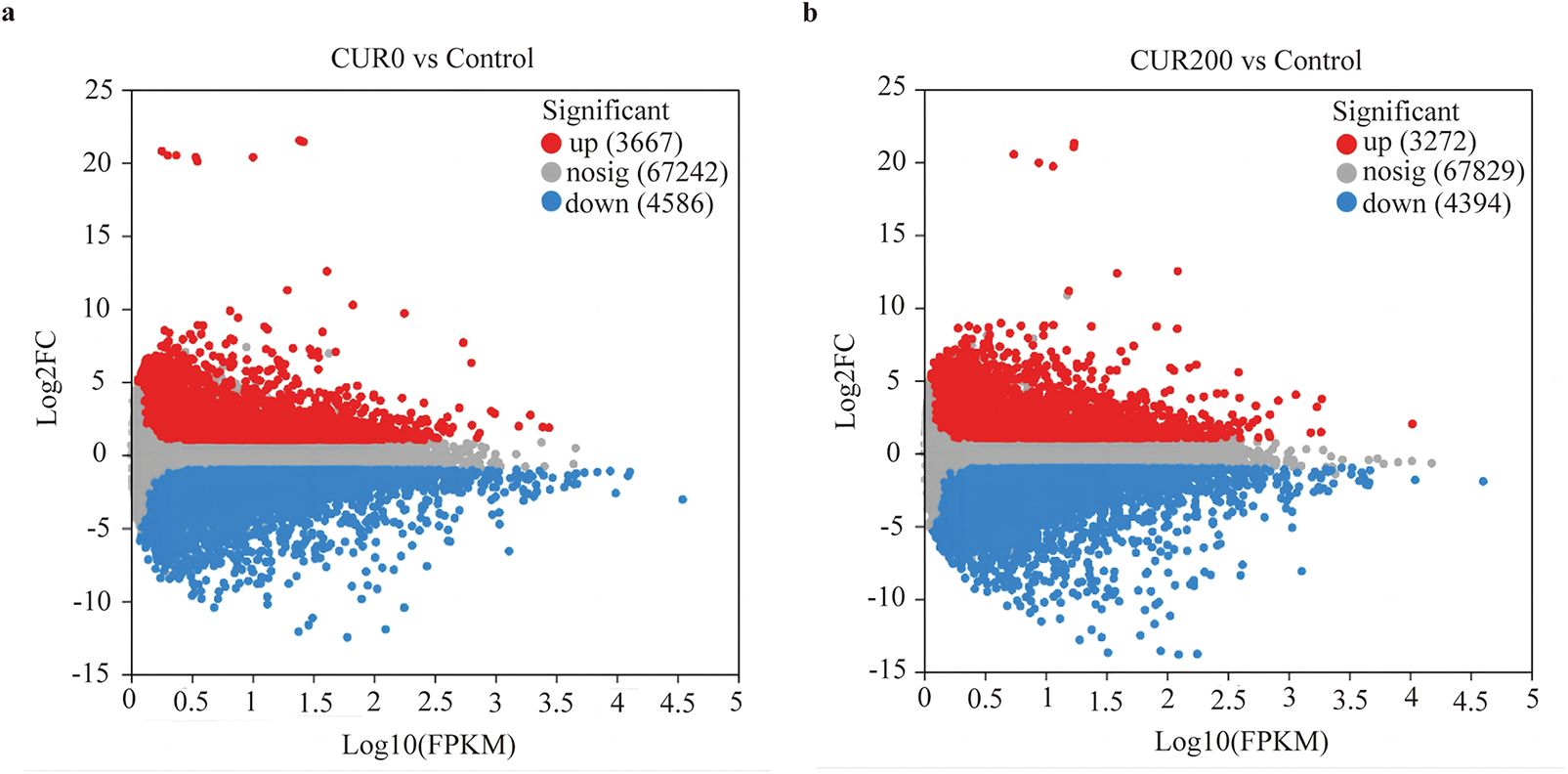

3.3.1 Sequencing Data Statistics, Expression Analysis, and Differentially Expressed Unigenes

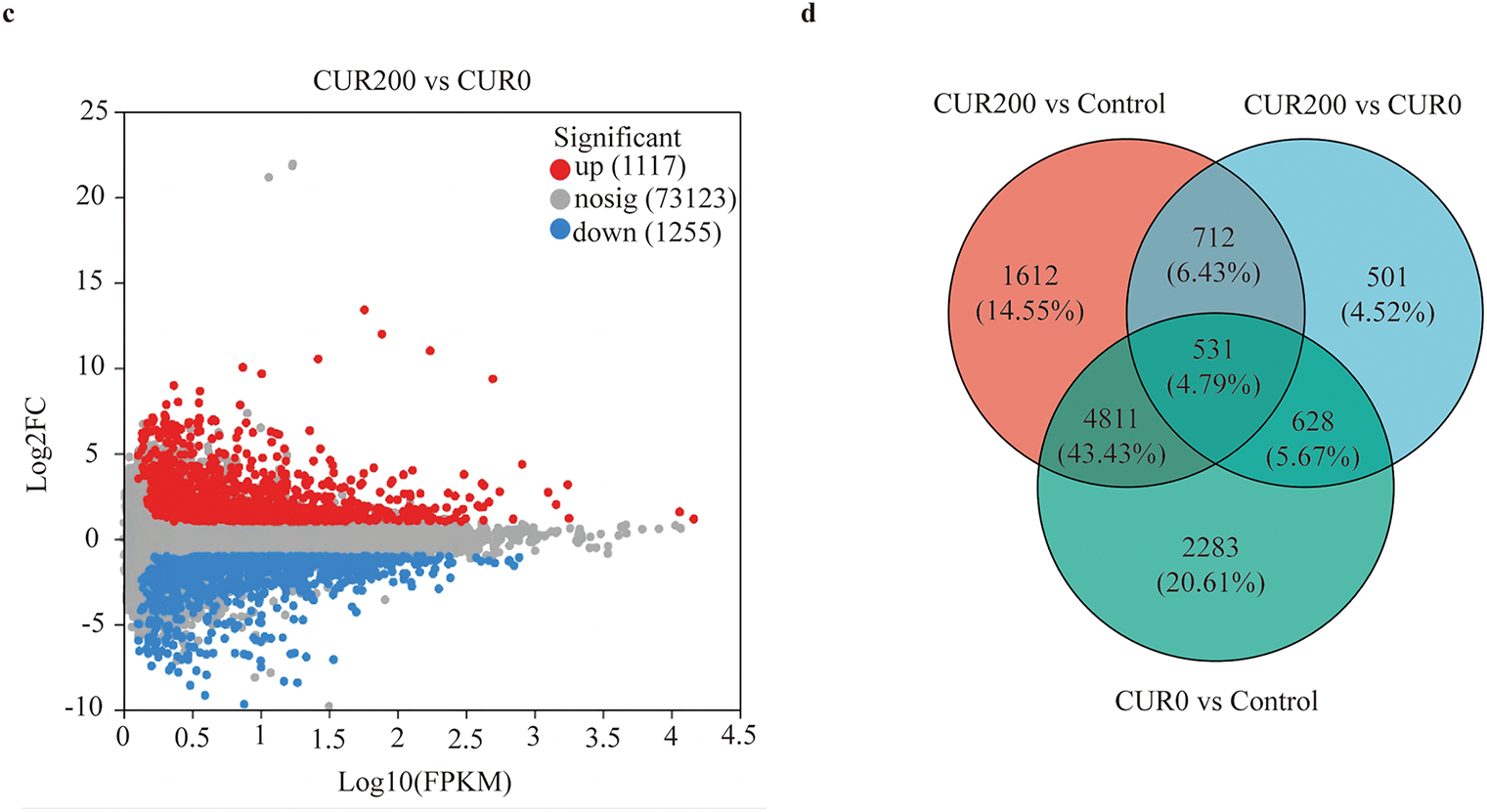

Transcriptome sequencing was conducted on three sample groups, yielding a total of 52.19 Gb of clean bases and 3.54 Gb of clean reads. Each sample produced 6.52 Gb of clean bases and 0.44 Gb of clean reads. The GC content across samples ranged from 42.97% to 44.15%, while Q20 and Q30 base percentages exceeded 97.98% and 94.32%, respectively (Table S1), indicating high sequencing quality suitable for downstream analysis. Clean reads were mapped to reference sequences assembled using Trinity, forming the basis for subsequent gene and transcript quantification. Mapping rates exceeded 83.80% across all samples (Table S2). Gene expression quantification was performed using RSEM, with transcript abundance represented as TPM. For statistical analysis, FPKM values were log10-transformed to compare gene expression among control, CUR0, and CUR200 leaf samples. Comparative transcriptome analysis revealed 8253 differentially expressed unigenes between CUR0 and the control group, with 44.43% up-regulated and 55.57% down-regulated (Fig. 4a). In the CUR200 vs. control comparison, 7666 DEGs were identified, with 42.68% up-regulated and 57.32% down-regulated (Fig. 4b). Between CUR200 and CUR0, 2373 DEGs were detected, with 47.09% up-regulated and 52.91% down-regulated (Fig. 4c). Venn diagram analysis across the three comparisons identified a shared set of 531 differentially expressed unigenes (Fig. 4d).

Figure 4: Analysis of differentially expressed unigenes between samples. (a) Volcano plot analysis of differentially expressed unigenes in CUR0 vs. Control; (b) Volcano plot analysis of differentially expressed unigenes in CUR200 vs. Control; (c) Volcano plot analysis of differentially expressed unigenes in CUR200 vs. CUR0; The red dots in the figure represent significantly up-regulated unigene/transcript, the blue dots represent significantly downregulated unigene/transcript, and the gray dots represent non significantly different unigene/transcript. (d) Venn analysis of differentially expressed unigenes among CUR0 vs. Control, CUR200 vs. Control, and CUR200 vs. CUR0

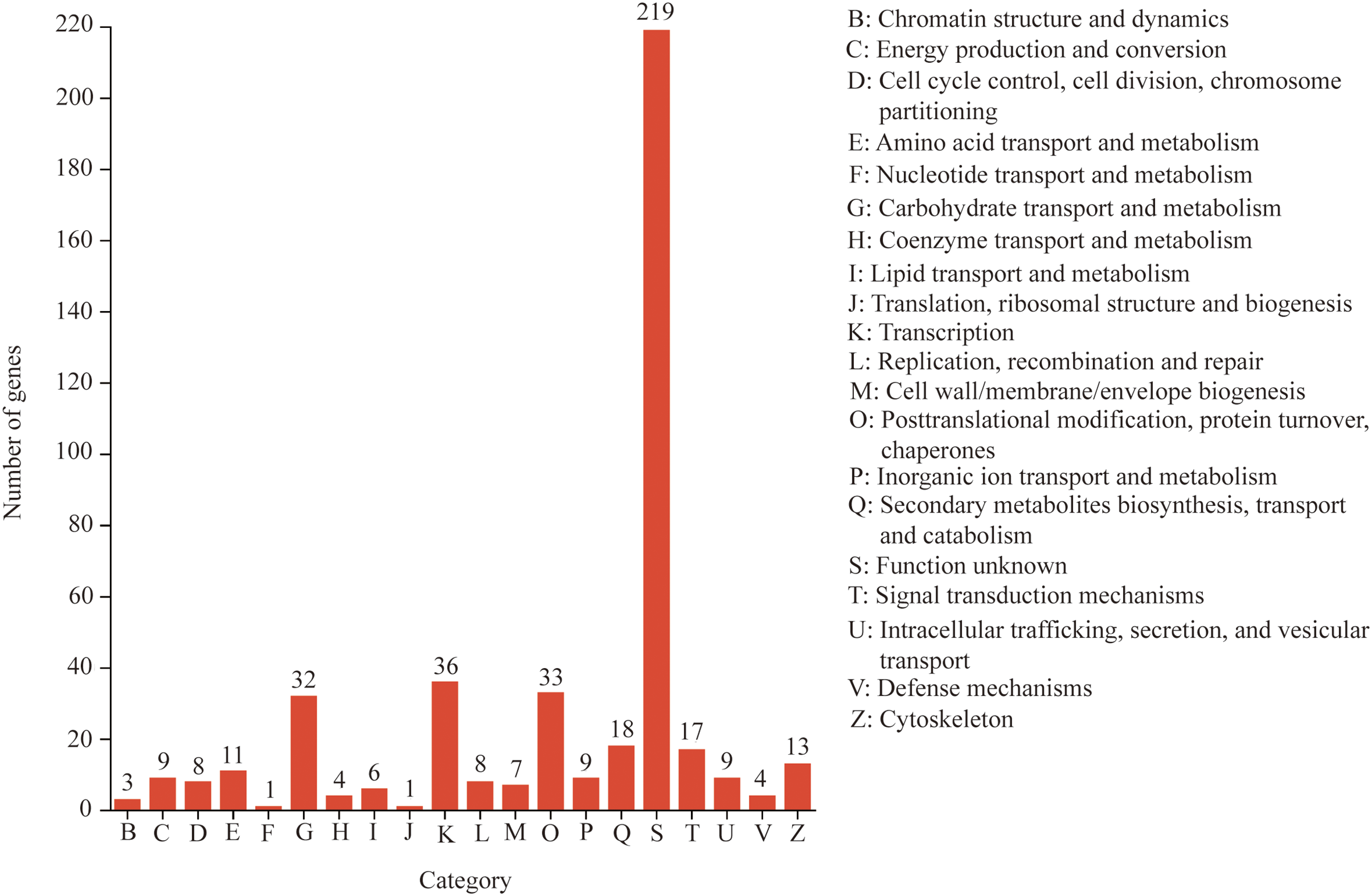

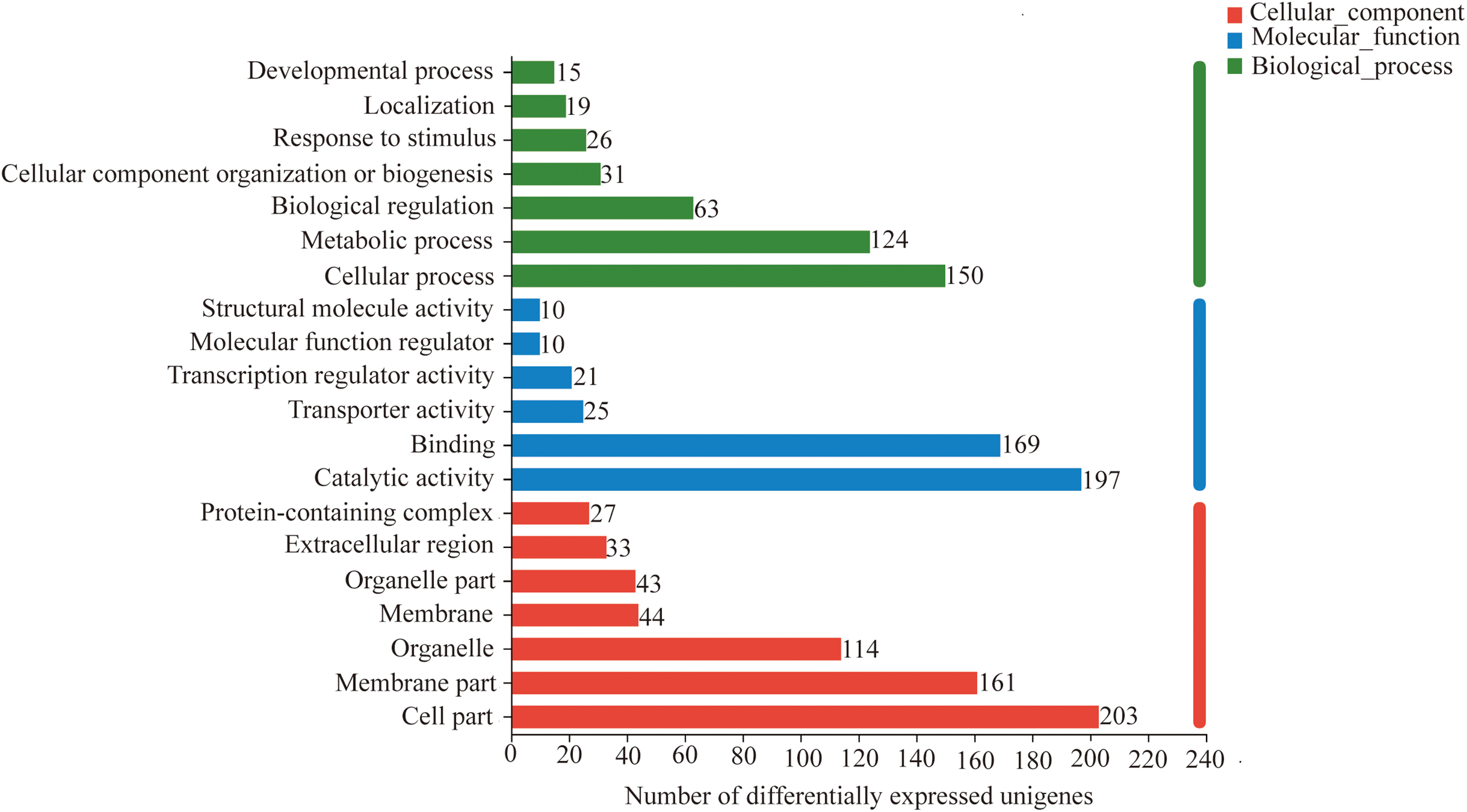

3.3.2 eggNOG and GO Functional Annotation Analysis

To further elucidate the mechanisms underlying curcumin-induced saline-alkali stress resistance in A. trifoliata, functional classification of differentially expressed unigenes was performed using eggNOG and GO analyses. The eggNOG results revealed that most DEGs were associated with unknown function, transcription, posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones, and carbohydrate transport and metabolism, comprising 219, 36, 33, and 32 unigenes, respectively (Fig. 5). GO annotation showed that in the Biological Process (BP) category, the majority of DEGs were involved in cellular processes (GO:0009987) and metabolic processes (GO:0008152), with 150 and 124 unigenes, respectively. In the Molecular Function (MF) category, catalytic activity (GO:0003824) and binding (GO:0005488) were predominant, comprising 197 and 169 unigenes, respectively. Within the Cellular Component (CC) category, most DEGs were associated with the cell part (GO:0044464), membrane part (GO:0044425), and organelle (GO:0043226), with 1203, 161, and 114 unigenes, respectively (Fig. 6).

Figure 5: eggNOG functional annotation analysis of differentially expressed unigenes

Figure 6: GO functional annotation analysis of differentially expressed unigenes

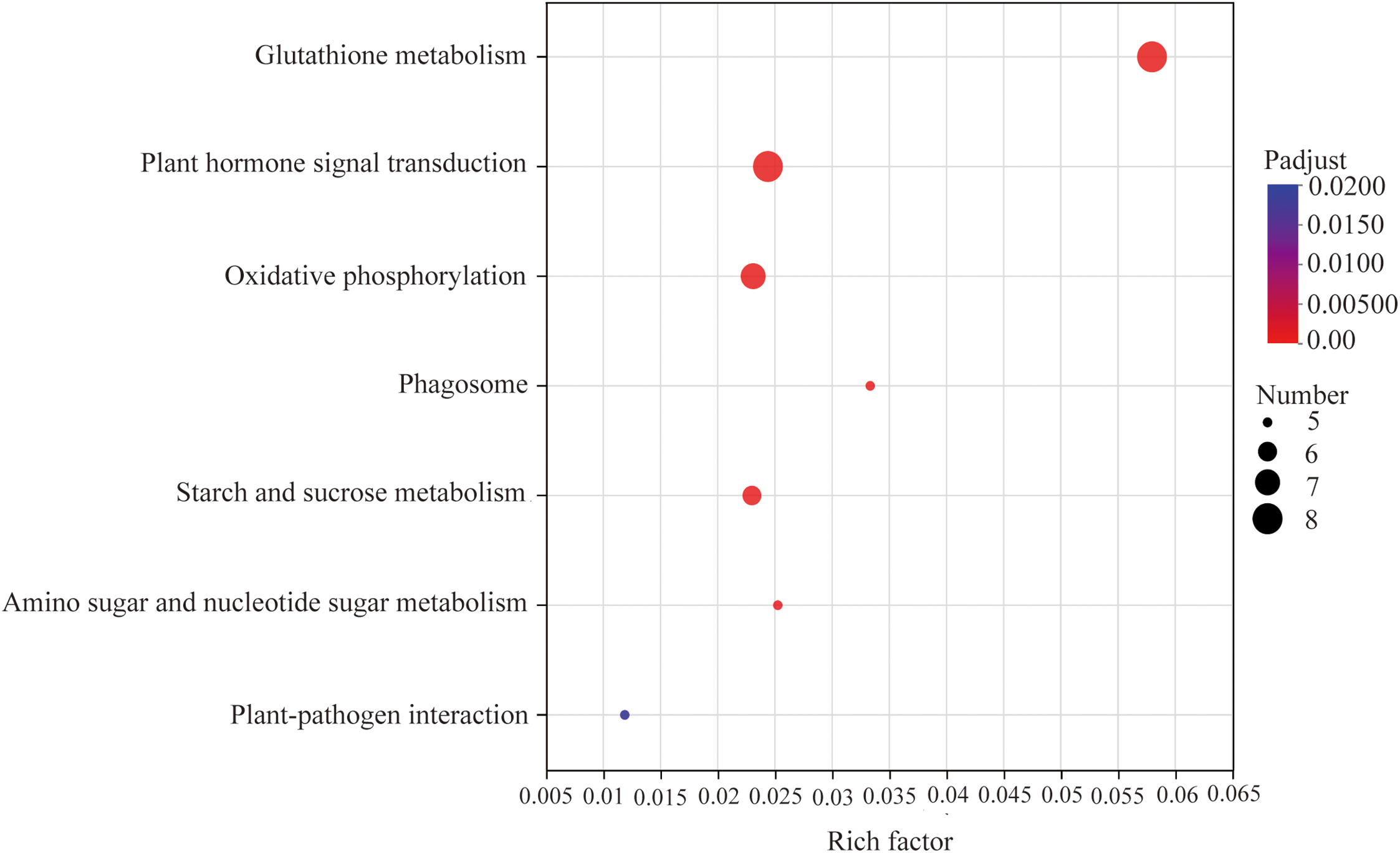

3.3.3 KEGG Functional Annotation Analysis

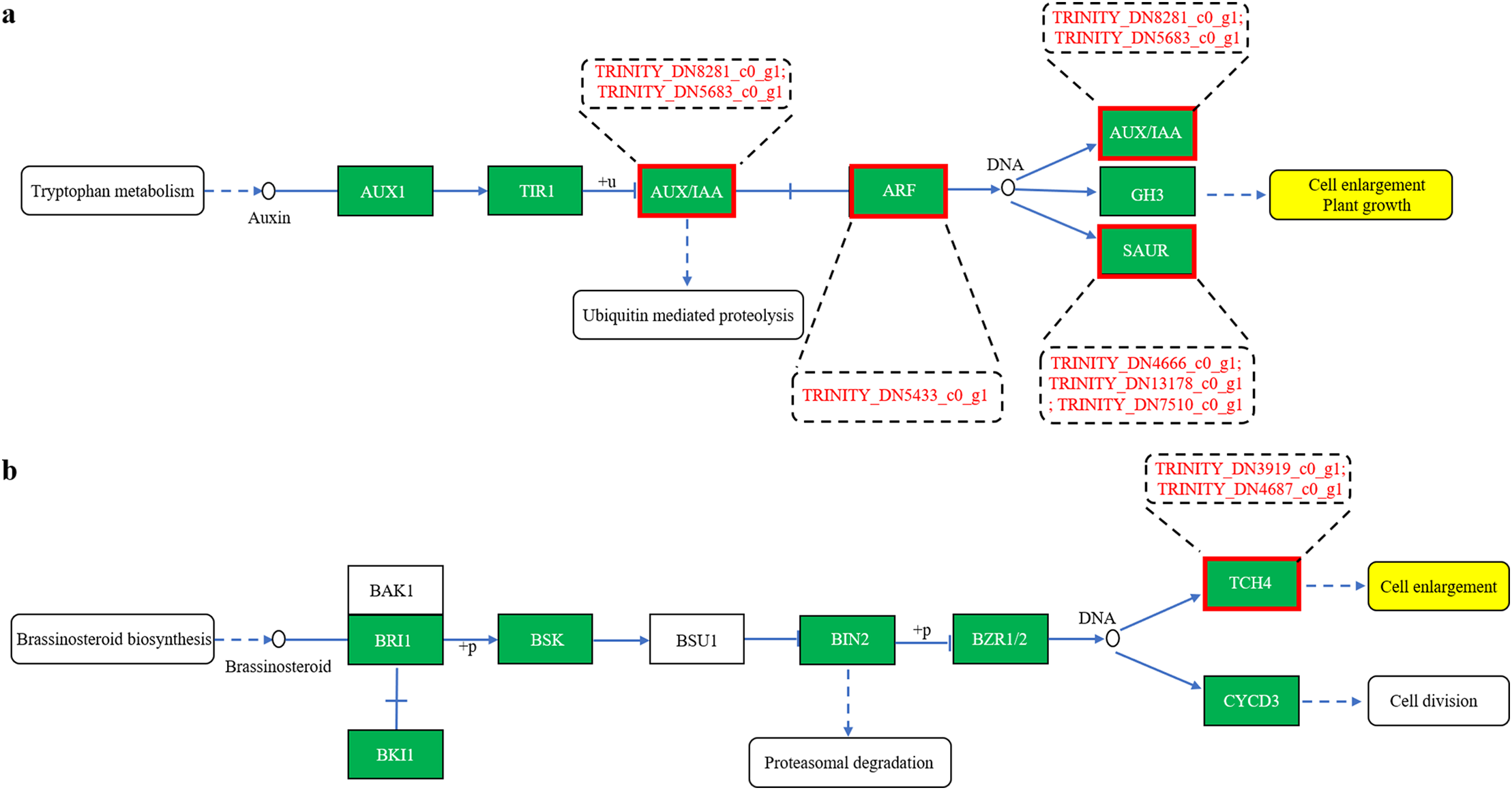

KEGG pathway analysis revealed that the differentially expressed unigenes were predominantly enriched in the Metabolism and Environmental Information Processing categories, particularly in pathways related to carbohydrate metabolism and amino acid metabolism (within Metabolism), as well as signal transduction (within Environmental Information Processing) (Fig. S1). Further examination indicated that these DEGs were mainly involved in key KEGG pathways, including plant hormone signal transduction (map04075), glutathione metabolism (map00480), oxidative phosphorylation (map00190), starch and sucrose metabolism (map00500), phagosome (map04145), plant–pathogen interaction (map04626), and amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism (map00520), encompassing 8, 8, 7, 6, 5, 5, and 5 unigenes, respectively (Fig. 7, Table S3). These results suggest that curcumin increases A. trifoliata tolerance to saline-alkali stress by modulating osmotic balance, mitigating ion toxicity, and alleviating oxidative damage. Eight DEGs were associated with auxin signal transduction, of which six were involved in auxin biosynthesis and regulation of plant cell elongation and growth. TRINITY_DN8281_c0_g1 and TRINITY_DN5683_c0_g1 encode auxin-responsive protein IAA25 and auxin-induced protein 22D (AUX/IAA family, K14484), respectively; TRINITY_DN5433_c0_g1 encodes auxin response factor 4 (ARF family, K14486); and TRINITY_DN4666_c0_g1, TRINITY_DN7510_c0_g1, and TRINITY_DN13178_c0_g1 encode auxin-responsive proteins SAUR21 and auxin-induced protein 10A5 (SAUR family, K14488) (Fig. 8a). Two DEGs were associated with brassinosteroid biosynthesis, both of which were involved in cell elongation processes. TRINITY_DN3919_c0_g1 and TRINITY_DN4687_c0_g1 encode xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase protein 24 and protein 23, respectively (TCH4 family, K14504) (Fig. 8b). These results indicate that curcumin increases the growth and saline-alkali resistance of A. trifoliata mainly through the regulation of auxin and brassinosteroid signaling pathways. These molecular findings agree with the observed morphological and anatomical improvements in A. trifoliata leaves following curcumin treatment under saline-alkali stress.

Figure 7: Functional annotation analysis of the top 7 KEGG metabolic pathways of differentially expressed unigenes. Note: The horizontal axis represents the enrichment rate; the vertical axis is −log10(p-value), and the default parameter is p-value_uncorrected. Each bubble in the figure represents a KEGG metabolic pathway. The size of bubbles is directly proportional to the number of differentially expressed unigenes enriched in KEGG metabolic pathway (p-adjust < 0.05)

Figure 8: Gene prediction in the plant hormone signal transduction pathway of differentially expressed unigenes (a–b)

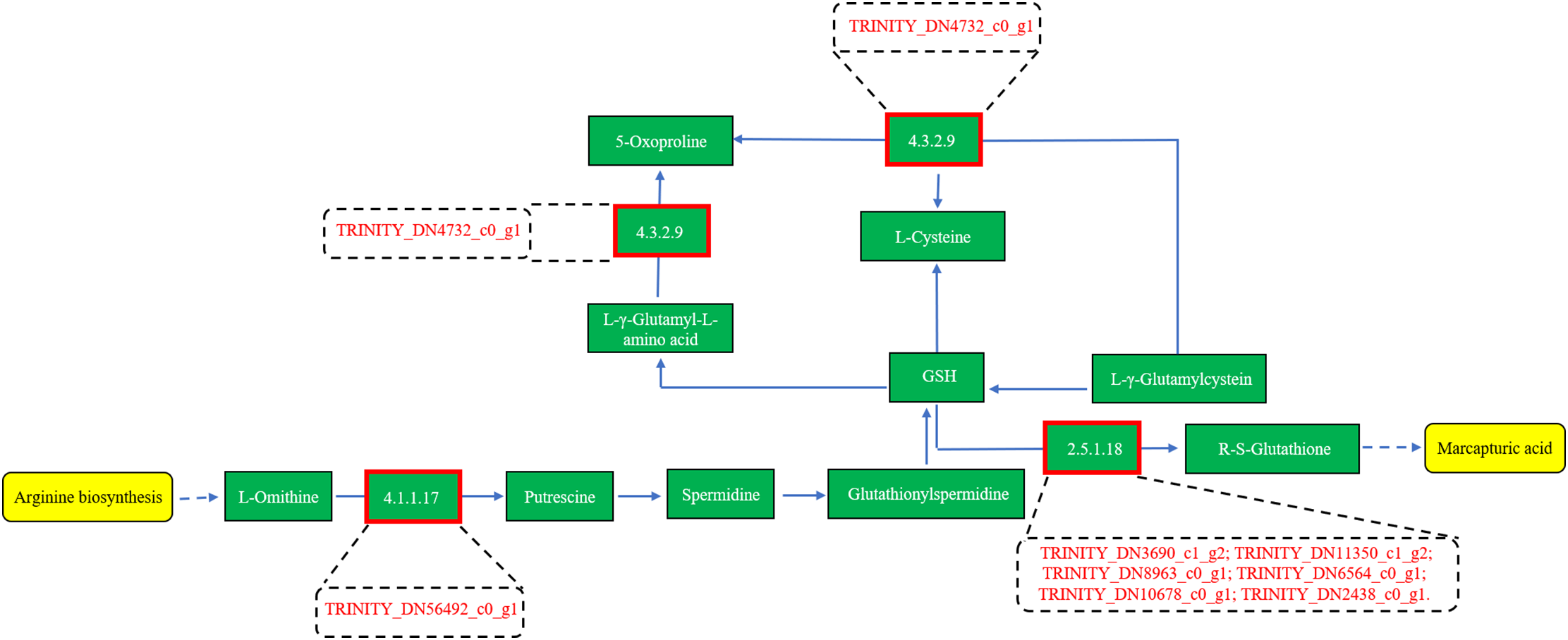

Furthermore, eight differentially expressed unigenes were identified in the glutathione metabolism pathway. Among them, six TRINITY_DN3690_c1_g2, TRINITY_DN11350_c1_g2, TRINITY_DN8963_c0_g1, TRINITY_DN6564_c0_g1, TRINITY_DN10678_c0_g1, and TRINITY_DN2438_c0_g1 encode the hypothetical protein HHK36, which corresponds to glutathione S-transferase (GST, K00799). The remaining two unigenes, TRINITY_DN56492_c0_g1 and TRINITY_DN4732_c0_g1, encode the hypothetical protein IFM89 (E4.1.1.17, K01581) and gamma-glutamylcyclotransferase 2 (GGCT, K22596), respectively (Fig. 9). Reduced glutathione (GSH) functions as a critical redox buffer, maintaining intracellular redox homeostasis. It can be enzymatically modified by glutathione S-transferase (GST) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX) to scavenge H2O2 by promoting the formation of GSH conjugates [62]. These findings suggest that curcumin enhances GST expression in A. trifoliata, contributing to H2O2 detoxification and improving salt–alkali stress tolerance. This molecular evidence aligns with the observed reduction in H2O2 levels from physiological and biochemical assays following curcumin treatment under saline-alkali conditions (Fig. 3j).

Figure 9: Gene prediction in the Glutathione metabolism of differentially expressed unigenes

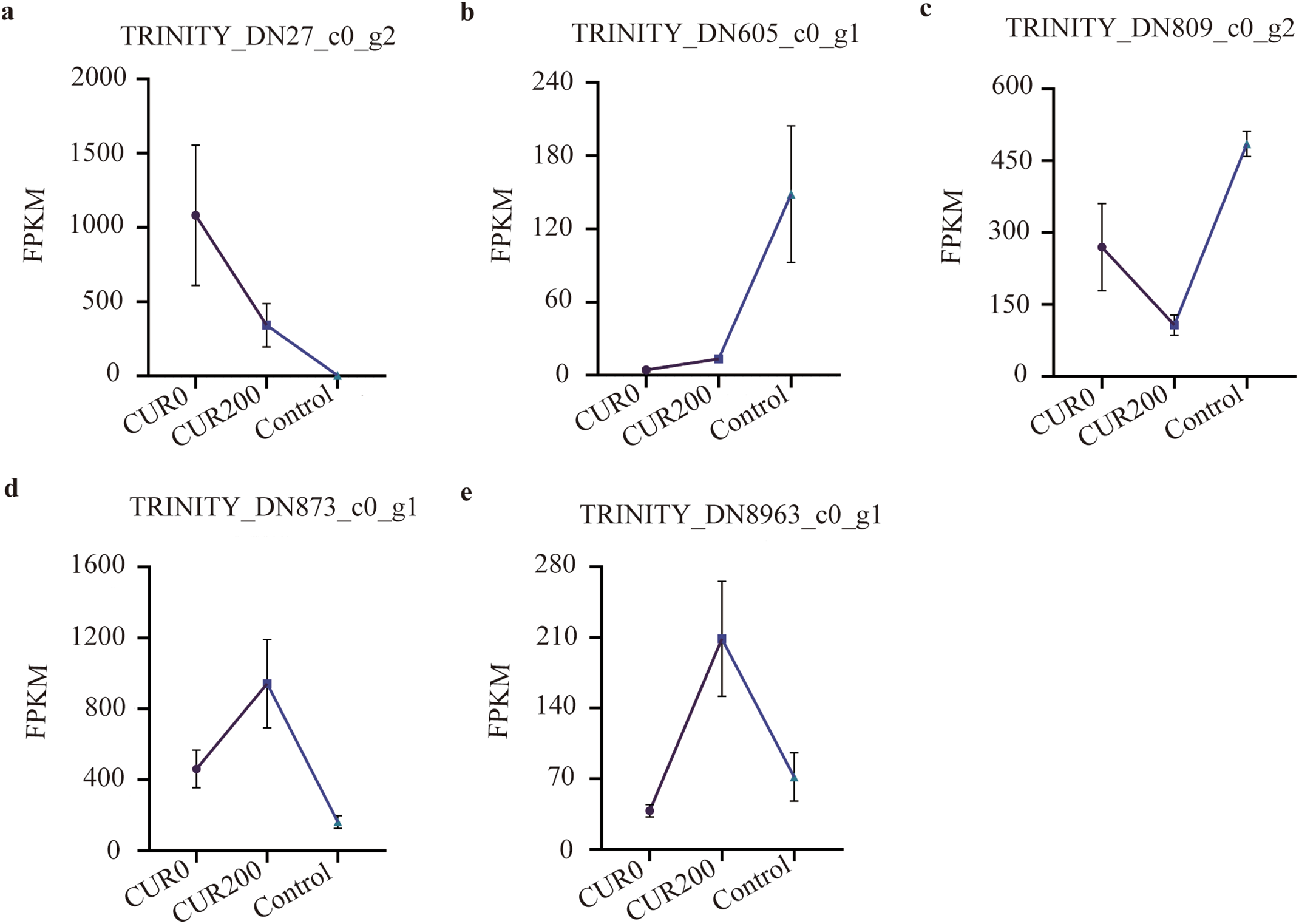

FPKM expression profiling of 44 differentially expressed unigenes involved in the seven key KEGG pathways revealed five distinct expression patterns:

(1) FPKMCUR0 > FPKMCUR200 > FPKMControl (Fig. 10a; 10 unigenes),

(2) FPKMControl > FPKMCUR200 > FPKMCUR0 (Fig. 10b; 11 unigenes),

(3) FPKMControl > FPKMCUR0 > FPKMCUR200 (Fig. 10c; 14 unigenes),

(4) FPKMCUR200 > FPKMCUR0 > FPKMControl (Fig. 10d; 4 unigenes), and

(5) FPKMCUR200 > FPKMControl > FPKMCUR0 (Fig. 10e; 2 unigenes).

Figure 10: Gene expression pattern analysis in the KEGG metabolic pathways of differentially expressed unigenes. The results are shown as mean ± standard deviation

Among these, the highest expressed genes in each model were:

• TRINITY_DN27_c0_g2 (glucose-1-phosphate adenylyltransferase large subunit 2, glgC, K00975) in Model 1 (Fig. 9a),

• TRINITY_DN605_c0_g1 (endoglucanase 6, E3.2.1.4, K01179) in Model 2 (Fig. 9b),

• TRINITY_DN809_c0_g2 (tubulin alpha-1 chain, TUBA, K07374) in Model 3 (Fig. 9c),

• TRINITY_DN873_c0_g1 (beta-amylase 1, E3.2.1.2, K01177) in Model 4 (Fig. 9d), and

• TRINITY_DN8963_c0_g1 (glutathione S-transferase, GST, K00799) in Model 5 (Fig. 9e).

Overall, the expression profiles of these unigenes indicate that curcumin regulates a complex network of genes in A. trifoliata, contributing to enhanced resistance against saline-alkali stress. The dynamic regulation of genes such as glgC, endoglucanase, TUBA, beta-amylase, and GST, along with their associated metabolic functions, provides valuable insight into the molecular mechanisms through which curcumin confers stress resilience.

The TFs in plants play crucial roles in regulating gene expression at the transcriptional level and are key mediators of responses to environmental stresses. Analysis of differentially expressed unigenes identified 29 TFs across several families, including MYB (6), AP2/ERF (6), NAC (5), bHLH (4), C2C2 (3), bZIP (1), LBD/AS2-LOB (1), B3 (1), HSF (1), and GRAS (1) (Table S4). These findings suggest that curcumin predominantly modulates TFs from the MYB, AP2/ERF, NAC, bHLH, and C2C2 families to enhance saline-alkali tolerance in A. trifoliata.

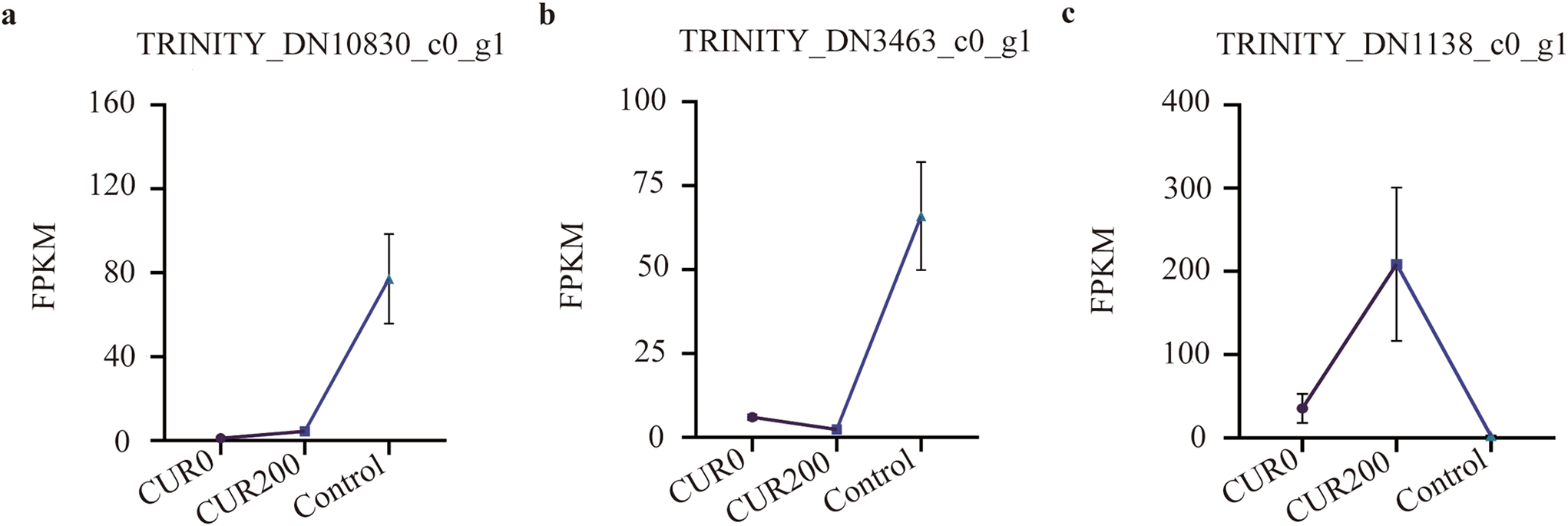

Expression pattern analysis of these 29 TFs revealed three major expression models:

(1) FPKMControl > FPKMCUR200 > FPKMCUR0 (Fig. 11a; 4 unigenes),

(2) FPKMControl > FPKMCUR0 > FPKMCUR200 (Fig. 11b; 16 unigenes), and

(3) FPKMCUR200 > FPKMCUR0 > FPKMControl (Fig. 11c; 9 unigenes).

The most highly expressed unigenes in each model were:

• TRINITY_DN10830_c0_g1 (RADIALIS-like 1) in Model 1 (Fig. 11a),

• TRINITY_DN3463_c0_g1 (bHLH63) in Model 2 (Fig. 11b), and

• TRINITY_DN1138_c0_g1 (MYB123/MYBP, K09422) in Model 3 (Fig. 11c).

Figure 11: Analysis of expression patterns of TFs. The results are shown as mean ± standard deviation

In summary, the expression profiles of RADIALIS-like 1, bHLH63, and MYB123, along with their respective transcription factor families, highlight the key regulatory roles these TFs may play in curcumin-mediated enhancement of saline-alkali resistance in A. trifoliata. Further functional characterization of these TFs could provide valuable insights into the underlying transcriptional regulatory mechanisms.

Soil salinization poses a significant global challenge as a major environmental constraint on plant growth and development. Understanding how plants respond to saline-alkali stress is essential for enhancing their resilience under such adverse conditions [63]. Saline-alkali stress typically induces ionic, osmotic, and oxidative stress, often leading to secondary damage in plant tissues [4]. While DNA methylation inhibitors like curcumin have been widely studied for their biological activities, their potential role in mitigating saline-alkali stress in plants has not yet been reported. Moreover, recent research has focused primarily on plant responses to NaCl stress, with limited attention to other salts such as Na2SO4, NaHCO3, and Na2CO3, which are also prevalent in saline-alkali soils [30]. In this study, a mixed saline-alkali solution containing Na2SO4, NaHCO3, and Na2CO3 was used to simulate stress conditions in A. trifoliata, enabling investigation into the protective mechanisms of curcumin under complex saline-alkali environments. Previous studies have shown that high salinity can negatively impact leaf structure. For example, Parida et al. [64] observed reduced epidermal and mesophyll thickness in Bruguiera parviflora under various NaCl concentrations, while Liu et al. [9] reported a significant decrease in overall leaf thickness, particularly in palisade and spongy mesophyll tissues, in Xanthoceras sorbifolium Bunge subjected to high-concentration saline-alkali stress. Consistent with these findings, our results demonstrated that saline-alkali stress significantly reduced the leaf thickness of A. trifoliata, importantly, within the palisade and spongy tissues. However, curcumin treatment significantly reversed these effects, resulting in increased leaf thickness and enhanced palisade and spongy mesophyll tissue development. This suggests that curcumin may be protective in preserving or restoring leaf anatomical integrity under saline-alkali stress.

Potassium, a key inorganic solute, plays a crucial role in lowering the osmotic potential of plant cells and maintaining water balance under saline-alkali stress. This is particularly important because excessive Na+ accumulation can damage cell membranes. To mitigate this, plants restrict Na+ entry and enhance selective K+ uptake in the cytoplasm, sustaining a low intracellular Na+/K+ ratio. Maintaining this ratio is vital for normal physiological processes and is a key determinant of plant salt tolerance [65–67]. In the present study, curcumin application under saline-alkali stress significantly reduced Na+ content and promoted K+ accumulation in A. trifoliata leaves, effectively maintaining a lower Na+/K+ ratio. This indicates that curcumin enhances ionic homeostasis and contributes to improved tolerance to saline-alkali conditions. Under stress, plants also initiate osmotic adjustment as a self-protective mechanism by synthesizing osmolytes such as soluble sugars, soluble proteins, and proline to stabilize cellular osmotic pressure and limit water loss [30]. Previous studies have shown that soluble protein levels in sorghum initially rise and then fall with increasing saline-alkali stress [68], while Carex duriuscula and Trollius chinensis Bunge exhibit elevated levels of soluble sugars and proline under similar stress conditions [30,69]. In our study, the contents of proline and soluble proteins in the CUR0 group were significantly lower than those in the control, and soluble sugar levels showed no significant change. However, treatment with curcumin (CUR200) significantly increased proline, soluble sugar, and soluble protein levels compared to CUR0. These findings suggest that curcumin enhances osmotic adjustment in A. trifoliata, helping to mitigate saline-alkali stress. In addition to osmotic regulation, enzymatic antioxidant defense plays a pivotal role in plant stress responses. The SOD, CAT, and POD are key enzymes involved in scavenging ROS under saline-alkali stress. Previous studies have reported that POD and SOD activities in alfalfa initially increase and then decline with rising stress levels [70]. At the same time, in Brassica campestris seedlings, saline-alkali stress induces increased SOD and POD activity but decreases CAT activity [71]. Consistent with these reports, our findings revealed that the activities of SOD, POD, and CAT in CUR0 leaves were lower than those in the control group. Their activities were significantly enhanced following curcumin treatment (CUR200). This suggests that curcumin may reinforce the antioxidant defense system of A. trifoliata, contributing further to its saline-alkali stress tolerance.

Genes involved in plant responses to saline-alkali stress generally fall into four major categories: (1) those associated with the biosynthesis of osmoprotective compounds [72], (2) genes encoding ion transporters [73], (3) genes related to antioxidant defense [74], and (4) genes involved in signal transduction [75]. The transcriptomic analysis in this study was consistent with these functional categories. Curcumin treatment altered the expression of genes involved in amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism, starch and sucrose metabolism, oxidative phosphorylation, glutathione metabolism, phagosome formation, auxin signaling, and plant–pathogen interactions in A. trifoliata leaves. These transcriptional changes likely contribute to enhanced saline-alkali stress resistance. Moreover, 6 out of 8 differentially expressed unigenes were associated with auxin biosynthesis and signaling within the plant hormone signal transduction pathway. This indicates that curcumin may modulate saline-alkali stress responses by affecting the auxin pathway. No differentially expressed unigenes linked to the ABA biosynthetic pathway were detected, suggesting that the ABA signaling pathway may not play a central role in the curcumin-mediated stress response in A. trifoliata. This comparison with previous findings highlights the ABA pathway as a primary regulator of plant responses to saline-alkali conditions. Supporting the current findings, Li et al. [20] reported that ethylene alleviates alkaline stress-induced root growth inhibition in Arabidopsis by enhancing the auxin biosynthesis gene AUX1 expression, thus promoting auxin accumulation. Similarly, Iglesias et al. [76] observed that the expression of auxin receptors TIR1 and AFB2 was downregulated under saline-alkali stress, while Jiang et al. [77] found that the localization of auxin transporters AUX1 and PIN1/2 was disrupted under saline conditions, further underscoring the central role of the auxin signaling pathway in plant stress adaptation. In the present study, six differentially expressed unigenes identified through transcriptome analysis were related to the auxin pathway, specifically belonging to the AUX/IAA, ARF, and SAUR gene families. These results highlight the importance of auxin signaling in mediating A. trifoliata’s response to curcumin under saline-alkali stress. The transcriptomic data also aligned with phenotypic and anatomical improvements in leaf morphology following curcumin treatment. Although curcumin is known to function as a DNA methylation inhibitor [52], capable of altering plant traits by reducing genome-wide DNA methylation levels [53,54], no differentially expressed unigenes associated with DNA methylation were detected in this study. This suggests that the enhancement of saline-alkali stress resistance in A. trifoliata by curcumin may not be mediated through epigenetic regulation via DNA demethylation but through modulation of hormone signaling pathways, particularly the auxin pathway.

The TFs bind to specific DNA sequences to regulate the transcription of genetic information from DNA to messenger RNA and play a critical role in plant responses to various environmental stresses [78]. Gao et al. [79] identified 57 TF families, including bHLH, ERF, MYB-related, NAC, C2H2, WRKY, MYB, and bZIP, implicated in the response to saline-alkali stress in Bignoniaceae species. Among these, the WRKY family is one of the largest and most extensively studied TF groups in higher plants. Evidence indicates that WRKY TFs contribute to plant tolerance to saline-alkali stress by modulating osmoprotectant accumulation, ROS scavenging, and ion homeostasis [80]. For example, Zhao et al. [81] reported that overexpression of PagWRKY75 in poplar suppressed ROS scavenging capacity and proline accumulation, negatively affecting salt and osmotic stress tolerance. In comparison, Zhu et al. [82] demonstrated that IbWRKY2 interacts with IbVQ4 in sweet potato to enhance salt tolerance by up-regulating genes associated with proline biosynthesis and antioxidant enzymes. In the present study, curcumin-induced enhancement of saline-alkali stress resistance in A. trifoliata appeared to be primarily mediated by TFs from the MYB, AP2/ERF, NAC, bHLH, and C2C2 families, while WRKY TFs did not appear to contribute significantly to this response. Previous research supports a potential association between NAC transcription factors and auxin signaling. Hao et al. [83] found that NAC enhances salt tolerance in Arabidopsis by regulating the expression of genes in the ARF family. Similarly, Ma et al. [84] reported that NAC promotes salt resistance by up-regulating genes in the IAA family. Based on these findings, it is speculated that curcumin may improve the saline-alkali stress tolerance of A. trifoliata by inducing the expression of specific transcription factors that, in turn, modulate key components of the auxin signaling pathway.

In this study, curcumin application significantly increased the growth of A. trifoliata. It mitigated osmotic stress and oxidative damage under saline-alkali conditions by modulating the expression of key stress-responsive genes. Curcumin alleviated oxidative injury by reducing MDA levels, boosting the activities of antioxidant enzymes such as CAT, SOD, and POD, activating glutathione metabolism, and lowering H2O2 content, contributing to improved tolerance to saline-alkali stress. Further, curcumin enhanced stress resilience by modulating auxin signaling pathways, promoting plant growth. Pasternak et al. [85] reported that GSH acts as a key enhancer of auxin signaling in Arabidopsis, suggesting that the glutathione metabolic pathway may similarly facilitate the growth of A. trifoliata under saline-alkali stress through its interaction with the auxin signaling cascade.

The A. trifoliata is a valuable multipurpose plant used for fruit production, medicinal applications, oil extraction, and ornamental purposes. This study demonstrated that curcumin effectively alleviates saline-alkali stress in A. trifoliata. Morphological and leaf anatomical analyses revealed that curcumin treatment under saline-alkali conditions significantly increased plant height, stem diameter, root length, above- and below-ground fresh weights, as well as the thickness of palisade and spongy mesophyll tissues. Physiological and biochemical assessments further showed that curcumin increased the accumulation of key osmoprotectants, including proline, soluble sugars, and soluble proteins. Transcriptome profiling under non-parametric analysis indicated that curcumin primarily modulated seven KEGG metabolic pathways and influenced the expression of unigenes belonging to the MYB, AP2/ERF, NAC, bHLH, and C2C2 transcription factor families. Moreover, eight differentially expressed unigenes related to plant hormone signal transduction were identified, primarily associated with the auxin and brassinosteroid pathways, known to regulate cell elongation and growth. These transcriptomic findings align with the observed morphological and anatomical improvements, supporting the conclusion that curcumin promotes growth and increases stress tolerance in A. trifoliata under saline-alkali conditions.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Number: 32060645); The Joint Special Project (Key Project) of Yunnan Province Local Undergraduate University (202101BA070001-036); The Joint Special Project (Surface Project) of Yunnan Province Local Undergraduate University (202101BA070001-172); the Science Research Fund Project for Education Department of Yunnan Province (Numbers: 2023Y0876; 2023Y0860; 2023J0828); the Basic Research Special Project for Science and Technology Department of Yunnan Provincial (Number: 202301AU070137).

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Xiaoqin Li, Yongfu Zhang and Zhen Ren; data collection: Jiao Chen, Zuqin Qiao, Xingmei Tao and Xuan Yi; analysis and interpretation of results: Xiaoqin Li, Jiao Chen, Kai Wang and Zhao Liu; draft manuscript preparation: Xiaoqin Li and Yongfu Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.066894/s1.

References

1. Munns R, Gilliham M. Salinity tolerance of crops—what is the cost? New Phytol. 2015;208(3):668–73. doi:10.1111/nph.13519. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Balasubramaniam T, Shen G, Esmaeili N, Zhang H. Plants’ response mechanisms to salinity stress. Plants. 2023;12(12):2253. doi:10.3390/plants12122253. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Liang X, Li J, Yang Y, Jiang C, Guo Y. Designing salt stress-resilient crops: current progress and future challenges. J Integr Plant Biol. 2024;66(3):303–29. doi:10.1111/jipb.13599. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Yang Y, Guo Y. Elucidating the molecular mechanisms mediating plant salt-stress responses. New Phytol. 2018;217(2):523–39. doi:10.1111/nph.14920. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Van Zelm E, Zhang Y, Testerink C. Salt tolerance mechanisms of plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2020;71:403–33. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-050718-100005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Parveen A, Ahmar S, Kamran M, Malik Z, Ali A, Riaz M, et al. Abscisic acid signaling reduced transpiration flow, regulated Na+ ion homeostasis and antioxidant enzyme activities to induce salinity tolerance in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seedlings. Environ Technol Innov. 2021;24:101808. doi:10.1016/j.eti.2021.101808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Singh A, Rajput VD, Lalotra S, Agrawal S, Ghazaryan K, Singh J, et al. Zinc oxide nanoparticles influence on plant tolerance to salinity stress: insights into physiological, biochemical, and molecular responses. Environ Geochem Health. 2024;46(5):148. doi:10.1007/s10653-024-01921-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Wang X, Yin J, Wang J, Li J. Integrative analysis of transcriptome and metabolome revealed the mechanisms by which flavonoids and phytohormones regulated the adaptation of alfalfa roots to NaCl stress. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1117868. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1117868. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Liu Y, Su M, Han Z. Effects of NaCl stress on the growth, physiological characteristics and anatomical structures of Populus talassica × Populus euphratica seedlings. Plants. 2022;11(22):3025. doi:10.3390/plants11223025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Blumwald E. Engineering salt tolerance in plants. Biotechnol Genet Eng Rev. 2003;20(1):261–76. doi:10.1080/02648725.2003.10648046. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Ullah Z, Haq SIU, Ullah A, Asghar MA, Seleiman MF, Saleem K, et al. Effect of green synthesized silver nanoparticles on growth and physiological responses of pearl millet under salinity stress. Environ Dev Sustain. 2025;27(1):625–44. doi:10.1007/s10668-024-05453-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Dutilleul C, Garmier M, Noctor G, Mathieu C, Chétrit P, Foyer CH, et al. Leaf mitochondria modulate whole cell redox homeostasis, set antioxidant capacity, and determine stress resistance through altered signaling and diurnal regulation. Plant Cell. 2003;15(5):1212–26. doi:10.1105/tpc.009464. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Dietz KJ, Mittler R, Noctor G. Recent progress in understanding the role of reactive oxygen species in plant cell signaling. Plant Physiol. 2016;171(3):1535–9. doi:10.1104/pp.16.00938. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Chen Y, Li H, Zhang S, Du S, Zhang J, Song Z, et al. Analysis of the main antioxidant enzymes in the roots of Tamarix ramosissima under NaCl stress by applying exogenous potassium (K+). Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1114266. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1114266. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Aizaz M, Lubna , Jan R, Asaf S, Bilal S, Kim KM, et al. Regulatory dynamics of plant hormones and transcription factors under salt stress. Biology. 2024;13(9):673. doi:10.3390/biology13090673. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Yang Y, Yang X, Guo X, Hu X, Dong D, Li G, et al. Exogenously applied methyl Jasmonate induces early defense related genes in response to Phytophthora infestans infection in potato plants. Hortic Plant J. 2022;8(4):511–26. doi:10.1016/j.hpj.2022.04.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Yin Y, Xu J, He X, Yang Z, Fang W, Tao J. Role of exogenous melatonin involved in phenolic acid metabolism of germinated hulless barley under NaCl stress. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2022;170:14–22. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.11.036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Wei J, Cai QA, Li Y, Shang LX, Bu XF, Yu ZJ, et al. Research progress on response mechanism of the plant to sa-line-alkali stress. Shandong Agricul Sci. 2022;54:156–64. (In Chinese). doi:10.14083/j.issn.1001-4942.2022.04.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Liu A, Yu Y, Duan X, Sun X, Duanmu H, Zhu Y. GsSKP21, a Glycine soja S-phase kinase-associated protein, mediates the regulation of plant alkaline tolerance and ABA sensitivity. Plant Mol Biol. 2015;87(1–2):111–24. doi:10.1007/s11103-014-0264-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Li J, Xu HH, Liu WC, Zhang XW, Lu YT. Ethylene inhibits root elongation during alkaline stress through AUXIN1 and associated changes in auxin accumulation. Plant Physiol. 2015;168(4):1777–91. doi:10.1104/pp.15.00523. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Farquharson KL. A domain in the bHLH transcription factor DYT1 is critical for anther development. Plant Cell. 2016;28(5):997–8. doi:10.1105/tpc.16.00331. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Zhang C, Liu J, Zhao T, Gomez A, Li C, Yu C, et al. A drought-inducible transcription factor delays reproductive timing in rice. Plant Physiol. 2016;171(1):334–43. doi:10.1104/pp.16.01691. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Zhang H, Guo J, Chen X, Zhou Y, Pei Y, Chen L, et al. Pepper bHLH transcription factor CabHLH035 contributes to salt tolerance by modulating ion homeostasis and proline biosynthesis. Hortic Res. 2022;9:uhac203. doi:10.1093/hr/uhac203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Erpen L, Devi HS, Grosser JW, Dutt M. Potential use of the DREB/ERF, MYB, NAC and WRKY transcription factors to improve abiotic and biotic stress in transgenic plants. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2018;132(1):1–25. doi:10.1007/s11240-017-1320-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Sun B, Zhao Y, Shi S, Yang M, Xiao K. TaZFP1, a C2H2 type-ZFP gene of T. aestivum, mediates salt stress tolerance of plants by modulating diverse stress-defensive physiological processes. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2019;136:127–42. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2019.01.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. İnal B, Büyük İ, İlhan E, Aras S. Genome-wide analysis of Phaseolus vulgaris C2C2-YABBY transcription factors under salt stress conditions. 3 Biotech. 2017;7(5):302. doi:10.1007/s13205-017-0933-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Ma A, Wang TJ, Wang H, Guo P, Peng X, Wang X, et al. The GRAS transcription factor OsGRAS2 negatively impacts salt tolerance in rice. Plant Cell Rep. 2024;44(1):17. doi:10.1007/s00299-024-03413-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Zhang C, Yang R, Zhang T, Zheng D, Li X, Zhang ZB, et al. ZmTIFY16, a novel maize TIFY transcription factor gene, promotes root growth and development and enhances drought and salt tolerance in Arabidopsis and Zea mays. Plant Growth Regul. 2023;100(1):149–60. doi:10.1007/s10725-022-00946-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zhang W, Cheng Y, Jian L, Wang H, Li H, Shen Z, et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the trihelix gene family in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) under salt and drought stress. J Agron Crop Sci. 2025;211(2):e70038. doi:10.1111/jac.70038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Hou R, Yang L, Wuyun T, Chen S, Zhang L. Genes related to osmoregulation and antioxidation play important roles in the response of Trollius chinensis seedlings to saline-alkali stress. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1080504. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1080504. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Kawagoe T, Suzuki N. Flower-size dimorphism avoids geitonogamous pollination in a nectarless monoecious plant Akebia quinata. Int J Plant Sci. 2003;164(6):893–7. doi:10.1086/378659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Kawagoe T, Suzuki N. Floral sexual dimorphism and flower choice by pollinators in a nectarless monoecious vine Akebia quinata (Lardizabalaceae). Ecol Res. 2002;17(3):295–303. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1703.2002.00489.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Ashraf M, Foolad MR. Roles of Glycine betaine and proline in improving plant abiotic stress resistance. Environ Exp Bot. 2007;59(2):206–16. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2005.12.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Hu M, Shi Z, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Li H. Effects of exogenous glucose on seed germination and antioxidant capacity in wheat seedlings under salt stress. Plant Growth Regul. 2012;68(2):177–88. doi:10.1007/s10725-012-9705-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Wang QZ, Liu Q, Gao YN, Liu X. Review on the mechanisms of the response to salinity-alkalinity stress in plants. Acta Ecol Sin. 2017;37(16):5565–77. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

36. Xie C, Wang P, Sun M, Gu Z, Yang R. Nitric oxide mediates γ-aminobutyric acid signaling to regulate phenolic compounds biosynthesis in soybean sprouts under NaCl stress. Food Biosci. 2021;44:101356. doi:10.1016/j.fbio.2021.101356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Liang X, Fang S, Ji W, Zheng D. The positive effects of silicon on rice seedlings under saline-alkali mixed stress. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal. 2015;46(17):2127–38. doi:10.1080/00103624.2015.1059848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Akhter MS, Noreen S, Saleem N, Saeed M, Ahmad S, Khan TM, et al. Silicon can alleviate toxic effect of NaCl stress by improving K+ and Si uptake, photosynthetic efficiency with reduced Na+ toxicity in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Silicon. 2022;14(9):4991–5000. doi:10.1007/s12633-021-01270-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Ding H, Lai J, Wu Q, Zhang S, Chen L, Dai YS, et al. Jasmonate complements the function of Arabidopsis lipoxygenase3 in salinity stress response. Plant Sci. 2016;244:1–7. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.11.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Liu RQ, Xu XJ, Wang S, Shan CJ. Lanthanum improves salt tolerance of maize seedlings. Photosynthetica. 2016;54(1):148–51. doi:10.1007/s11099-015-0157-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Zhang Y, Li Y, Liu H, Xie H, Liu J, Hua J, et al. Effect of exogenous melatonin on corn seed germination and seedling salt damage mitigation under NaCl stress. Plants. 2025;14(7):1139. doi:10.3390/plants14071139. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Ma X, Zhang J, Huang B. Cytokinin-mitigation of salt-induced leaf senescence in perennial ryegrass involving the activation of antioxidant systems and ionic balance. Environ Exp Bot. 2016;125:1–11. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2016.01.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Wang X, Yang S, Li B, Chen C, Li J, Wang Y, et al. Exogenous 5-aminolevulinic acid enhanced saline-alkali tolerance in pepper seedlings by regulating photosynthesis, oxidative damage, and glutathione metabolism. Plant Cell Rep. 2024;43(11):267. doi:10.1007/s00299-024-03352-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Lu Y, Gharib A, Chen R, Wang H, Tao T, Zuo Z, et al. Rice melatonin deficiency causes premature leaf senescence via DNA methylation regulation. Crop J. 2024;12(3):721–31. doi:10.1016/j.cj.2024.04.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Latzel V, Münzbergová Z, Skuhrovec J, Novák O, Strnad M. Effect of experimental DNA demethylation on phytohormones production and palatability of a clonal plant after induction via jasmonic acid. Oikos. 2020;129(12):1867–76. doi:10.1111/oik.07302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Ngom B, Mamati E, Goudiaby MF, Kimatu J, Sarr I, Diouf D, et al. Methylation analysis revealed salicylic acid affects pearl millet defense through external cytosine DNA demethylation. J Plant Interact. 2018;13(1):288–93. doi:10.1080/17429145.2018.1473515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Aydin M, Arslan E, Yigider E, Taspinar MS, Agar G. Protection of Phaseolus vulgaris L. from herbicide 2,4-D results from exposing seeds to humic acid. Arab J Sci Eng. 2021;46(1):163–73. doi:10.1007/s13369-020-04893-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Bocchini M, D’Amato R, Ciancaleoni S, Fontanella MC, Palmerini CA, Beone GM, et al. Soil selenium (Se) biofortification changes the physiological, biochemical and epigenetic responses to water stress in Zea mays L. by inducing a higher drought tolerance. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:389. doi:10.3389/fpls.2018.00389. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Zhang H, Shi M, Su S, Zheng S, Wang M, Lv J, et al. Whole-genome methylation analysis reveals epigenetic differences in the occurrence and recovery of hyperhydricity in Dendrobium officinale plantlets. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Plant. 2022;58(2):290–301. doi:10.1007/s11627-022-10250-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Wang SJ, Cui GP, Qin R, Liu H, Gong HY, Li G, et al. Dynamic changes of DNA methylcytosine in Arabidopsis root stem cells and their responses to γ-aminobutyric acid. Chin J Cell Biol. 2015;37(8):1109–14. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

51. Rauf A, Imran M, Orhan IE, Bawazeer S. Health perspectives of a bioactive compound curcumin: a review. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2018;74:33–45. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2018.01.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Liu Z, Xie Z, Jones W, Pavlovicz RE, Liu S, Yu J, et al. Curcumin is a potent DNA hypomethylation agent. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19(3):706–9. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.12.041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Tan MP. Analysis of DNA methylation of maize in response to osmotic and salt stress based on methylation-sensitive amplified polymorphism. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2010;48(1):21–6. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2009.10.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Kang D, Khan MA, Song P, Liu Y, Wu Y, Ai P, et al. Comparative analysis of the chrysanthemum transcriptome with DNA methylation inhibitors treatment and silencing MET1 lines. BMC Plant Biol. 2023;23(1):47. doi:10.1186/s12870-023-04036-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Yang ZQ, Xin YP, Zhao Q, Wang M, Qin YL, Hu F, et al. Research progress of rapid detection for available potassium in soil by turbidimetry. Chin Agric Sci Bull. 2024;40(9):83–8. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

56. Xi GQ, Yang XZ. Spectrophotometric determination of sodium with benzo-15-crown-5-ether and bromocresol green. Chin J Anal Chem. 1985;13(6):452–5. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

57. Yao Y, Nan L, Wang K, Xia J, Ma B, Cheng J. Integrative leaf anatomy structure, physiology, and metabolome analyses revealed the response to drought stress in sainfoin at the seedling stage. Phytochem Anal. 2024;35(5):1174–85. doi:10.1002/pca.3351. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Wu Y, Shen Y. Dormancy in Tilia miqueliana is attributable to permeability barriers and mechanical constraints in the endosperm and seed coat. Braz J Bot. 2021;44(3):725–40. doi:10.1007/s40415-021-00749-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Li HS. Principles and techniques of plant physiological and biochemical experiments. Beijing, China: Higher Education Press; 2000. p. 164–7. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

60. Turóczy Z, Kis P, Török K, Cserháti M, Lendvai A, Dudits D, et al. Overproduction of a rice aldo-keto reductase increases oxidative and heat stress tolerance by malondialdehyde and methylglyoxal detoxification. Plant Mol Biol. 2011;75(4–5):399–412. doi:10.1007/s11103-011-9735-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15(12):550. doi:10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Qian G, Wang M, Wang X, Liu K, Li Y, Bu Y, et al. Integrated transcriptome and metabolome analysis of rice leaves response to high saline-alkali stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(4):4062. doi:10.3390/ijms24044062. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Zhu JK. Regulation of ion homeostasis under salt stress. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2003;6(5):441–5. doi:10.1016/s1369-5266(03)00085-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Parida AK, Das AB, Mittra B. Effects of salt on growth, ion accumulation, photosynthesis and leaf anatomy of the mangrove, Bruguiera parviflora. Trees. 2004;18(2):167–74. doi:10.1007/s00468-003-0293-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Chang J, Wang Y, Chu J, Huang Y, Ling Y, Jiang X. Comparative salt stress responses in two turnip cultivars: insights into ion homeostasis, osmotic regulation, and antioxidant capacity. Hortic Environ Biotechnol. 2025;66(3):615–26. doi:10.1007/s13580-024-00673-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Kopittke PM. Interactions between Ca, Mg, Na and K: alleviation of toxicity in saline solutions. Plant Soil. 2012;352(1):353–62. doi:10.1007/s11104-011-1001-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Hasegawa PM. Sodium (Na+) homeostasis and salt tolerance of plants. Environ Exp Bot. 2013;92:19–31. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2013.03.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Sun J, He L, Li T. Response of seedling growth and physiology of Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench to saline-alkali stress. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0220340. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0220340. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Zhang YX, Fan F, Cui L, Du XY. Effects of saline-alkali stress on the contents of osmotic adjustment and activity of antioxidant enzymes of Carex duriuscula. Grassland Turf. 2012;32(6):48–51,61. (In Chinese). doi:10.13817/j.cnki.cyycp.2012.06.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Li B, Liu C. Effects of mixed soda saline alkali stress on soluble protein and enzyme activities of Alfalfa leaves. J Sci Teach Coll Univ. 2020;40(8):52–6. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

71. Zhu HF, Li XF, Li P, Liang ZJ, Ning DF, Liu D. Different response of non-heading Chinese cabbage seedling to saline and alkaline stress. Ecol Sci. 2022;41(6):176–82. (In Chinese). doi:10.14108/j.cnki.1008-8873.2022.06.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Li QL, Xie JH, Ma XQ, Li D. Molecular cloning of Phosphoethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PEAMT) gene and its promoter from the halophyte Suaeda liaotungensis and their response to salt stress. Acta Physiol Plant. 2016;38(2):39. doi:10.1007/s11738-016-2063-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Villicaña C, Warner N, Arce-Montoya M, Rojas M, Angulo C, Orduño A, et al. Antiporter NHX2 differentially induced in Mesembryanthemum crystallinum natural genetic variant under salt stress. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2016;124(2):361–75. doi:10.1007/s11240-015-0900-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Gong B, Wang X, Wei M, Yang F, Li Y, Shi Q. Overexpression of S-adenosylmethionine synthetase 1 enhances tomato callus tolerance to alkali stress through polyamine and hydrogen peroxide cross-linked networks. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2016;124(2):377–91. doi:10.1007/s11240-015-0901-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Luo P, Shen Y, Jin S, Huang S, Cheng X, Wang Z, et al. Overexpression of Rosa rugosa anthocyanidin reductase enhances tobacco tolerance to abiotic stress through increased ROS scavenging and modulation of ABA signaling. Plant Sci. 2016;245:35–49. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.01.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Iglesias MJ, Terrile MC, Windels D, Lombardo MC, Bartoli CG, Vazquez F, et al. MiR393 regulation of auxin signaling and redox-related components during acclimation to salinity in Arabidopsis. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e107678. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0107678. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Jiang K, Moe-Lange J, Hennet L, Feldman LJ. Salt stress affects the redox status of Arabidopsis root meristems. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:81. doi:10.3389/fpls.2016.00081. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Khan SA, Li MZ, Wang SM, Yin HJ. Revisiting the role of plant transcription factors in the battle against abiotic stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(6):1634. doi:10.3390/ijms19061634. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Gao XQ, Wang XY, Jiao W, Li N, Wang J, Zheng LY, et al. Physiological and transcriptomic analysis of Catalpa bungei seedlings in response to saline-alkali stresses. For Res. 2023;36(1):166–78. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

80. Liu T, Yu E, Hou L, Hua P, Zhao M, Wang Y, et al. Transcriptome-based identification, characterization, evolutionary analysis, and expression pattern analysis of the WRKY gene family and salt stress response in Panax ginseng. Horticulturae. 2022;8(9):756. doi:10.3390/horticulturae8090756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Zhao K, Zhang D, Lv K, Zhang X, Cheng Z, Li R, et al. Functional characterization of poplar WRKY75 in salt and osmotic tolerance. Plant Sci. 2019;289:110259. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2019.110259. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Zhu H, Zhou Y, Zhai H, He S, Zhao N, Liu Q. A novel sweetpotato WRKY transcription factor, IbWRKY2, positively regulates drought and salt tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Biomolecules. 2020;10(4):506. doi:10.3390/biom10040506. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Hao YJ, Wei W, Song QX, Chen HW, Zhang YQ, Wang F, et al. Soybean NAC transcription factors promote abiotic stress tolerance and lateral root formation in transgenic plants. Plant J. 2011;68(2):302–13. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04687.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Ma J, Wang LY, Dai JX, Wang Y, Lin D. The NAC-type transcription factor CaNAC46 regulates the salt and drought tolerance of transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 2021;21(1):11. doi:10.1186/s12870-020-02764-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Pasternak T, Palme K, Paponov IA. Glutathione enhances auxin sensitivity in Arabidopsis roots. Biomolecules. 2020;10(11):1550. doi:10.3390/biom10111550. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools