Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Metabolic Profile Analysis and Key Metabolic Pathways Identification in Different Embryo Parts Regulating Dormancy and Germination in Pinus koraiensis

1 Department of Health Management, Guiyang Institute of Information Science and Technology, Guiyang, 550025, China

2 College of Eco-Environmental Engineering, Guizhou Minzu University, Guiyang, 550025, China

* Corresponding Author: Yuan Song. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Seed Dormancy, Germination and Ecology: Mechanisms, Regulation, and Applications)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(8), 2499-2513. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.067104

Received 25 April 2025; Accepted 29 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Pinus koraiensis is the dominant and constructive species of the zonal vegetation in Northeast China, known as the mixed broadleaf-Korean pine forest. Although carbohydrate metabolism pathways in the seed embryo are known to play crucial roles during seed dormancy and germination in P. koraiensis, it remains unclear whether these metabolic pathways function differentially across tissues. P. koraiensis seeds that had undergone different durations of moist chilling in their natural environment, yielding seeds with relatively deeper primary physiological dormancy (DDS) and seeds with released primary physiological dormancy (RDS). A non-targeted metabolomic analysis was conducted on the radicle and hypocotyl-cotyledon portions of both DDS and RDS, before and after a two-week incubation under favorable conditions. Under germination conditions, RDS and DDS showed divergent metabolic profiles, especially regarding carbohydrate metabolism. Specifically, RDS seeds showed significantly reduced substrates of respiratory metabolic pathways in both radicles and hypocotyl-cotyledons. Conversely, the intermediates of the carbohydrate metabolism pathway (particularly the tricarboxylic acid cycle) accumulating in radicles of DDS seeds under germination conditions. Moreover, in RDS, the carbohydrate metabolic pathways were more prevalent in the hypocotyl-cotyledon, while lysine degradation and ascorbate and aldarate metabolism were the dominant metabolic pathways in radicles. In contrast, the tricarboxylic acid cycle showed higher activity in DDS radicles compared to hypocotyl-cotyledons. We further demonstrated that carbohydrate metabolic pathways continue to play a dominant role in both dormancy maintenance and germination processes of P. koraiensis seeds. Notably, the carbohydrate metabolism in radicles likely exerts more critical regulatory functions in these two physiological processes compared to that in cotyledon and hypocotyl tissues.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileTrees play an essential role in determining the species composition, abundance, diversity, and functioning of ecosystems, acting as constructive or dominant species. However, many tree species in the temperate zone exhibit seed dormancy phenomena, which affects forest regeneration. Studies have shown that the seeds of numerous temperate tree species, such as Korean pine [1], European beech (Fagus sylvatica) [2–4], Norway maple (Acer platanoides) [5,6], and sycamore maple (Acer pseudoplatanus) [7,8], enter deeper dormancy when dispersed in autumn at maturity. These seeds over dormancy through exposure to moist chilling conditions in winter and then germinate the following spring [9]. In nurseries, moist chilling has long been utilized as a standard method to break seed dormancy. Understanding the mechanism of dormancy release regulated by moist chilling, particularly under natural conditions, is crucial for successful forest regeneration.

In fact, although seed germination does not occur in the winter immediately following seed dispersal, the release of seed dormancy induced by moist chilling during winter is a major prerequisite for subsequent seed germination in spring. Seed germination relies heavily on metabolic pathways that mobilize reserves, providing necessary energy, carbon, and other building blocks in the absence of mineral uptake and photosynthesis [10]. Omics studies have demonstrated that moist chilling triggers multiple changes contributing to dormancy release, including the mobilization of seed reserves such as starch, oils, and proteins [11], the activation of energy production metabolic pathways (i.e., glycolysis and gluconeogenesis, the TCA (tricarboxylic acid) cycle, the pentose phosphate pathway, and oxidative phosphorylation) [9,12], protein degradation and biosynthesis [9], the reduction in abscisic acid (ABA, which is required for seed dormancy induction and maintenance) and ABA sensitivity [13–15], and the accumulation of gibberellins (GA, which are required for seed germination) along with enhanced GA sensitivity [15,16].

However, to our knowledge, several studies have indicated that moist chilling alone does not dramatically reduce ABA levels or increase the concentrations of TCA cycle metabolites, such as citrate, malate, and succinate [17,18]. In contrast, once moist stratified seeds were transferred to standard germination conditions, a sharp decline in ABA levels and an accumulation of TCA cycle metabolites were observed [17,18]. Furthermore, some researchers have reported that the relative levels of three TCA cycle intermediates rapidly decrease upon radicle emergence [19]. Similarly, proteins associated with the TCA cycle were found to decrease in non-dormant seeds under favorable germination conditions [20]. Along with six TCA cycle-related metabolites (citrate, succinate acid, malate acid, fumarate acid, and alpha-ketoglutarate), two phosphorylated sugars (D-glucose-6-phosphate and fructose-6-phosphate) and 3-phosphoglyceric acid, a key intermediate in glycolysis, showed significant reduction in the embryos of non-dormant Korean pine seeds compared to dormant seeds under germination conditions [21]. Similar findings were reported by Song et al. (2021) in a comparative metabolome analysis of dormant Korean pine seeds incubated for 4 weeks vs non-dormant seeds with ruptured seed coat [22].

An endospermic seed consists of a seed coat, endosperm, and embryo; the embryo includes the cotyledon, shoot apex, hypocotyl, and radicle [23]. Different seed parts exhibit distinct physiological functions: starch-degrading enzymes are localized in the endosperm, while proteins associated with energy generation and protein synthesis are enriched in the embryo [24,25]. The abundance of some proteins involved in glycolysis and the TCA cycle increases in the embryo but decreases in the endosperm during seed dormancy in rice seeds [26]. The embryo may serve as a major metabolic control point for seed dormancy breaking and germination. In Arabidopsis thaliana dormant seeds induced by ABA treatment, recent studies have revealed that glucose availability is limited in the lower hypocotyl of the embryo, but not in the cotyledon or radicle [27]. Previous studies have also demonstrated differences in free radicals production and antioxidant molecules activities between embryo axes and cotyledons [28]. Therefore, comprehensive understanding of tissue-specific differences in metabolic regulation among the cotyledon, hypocotyl, and radicle in response to seed dormancy release treatment is essential.

Korean pine is the dominant tree species in mixed-broadleaved Korean pine forests (MBKPF) of Northeast China, where the climate is continental [1]. We previously demonstrated that Korean pine seeds exhibit morphophysiological dormancy after dispersal in early autumn, and release their physiological dormancy under cold, moist conditions during autumn and winter [29]. It has been confirmed that carbohydrate metabolism occurring in the embryo (rather than in the megagametophyte) of Korean pine seeds plays a crucial regulatory role in either dormancy maintenance or germination [22]. The metabolite contents in both glycolysis and TCA cycle pathways exhibited opposite trends in dormant vs non-dormant seed embryos, with increases observed in dormant seeds and decreases in non-dormant seeds [21,22]. All these studies used dormant dry seeds collected at autumn maturity with approximately 10% moisture content to determine the metabolic changes occurring in seed tissues during incubation under favorable germination conditions. However, to what extent are these metabolic changes caused by water absorption in dry seeds? Therefore, comparative analysis between seeds with relatively deeper dormancy (collected from cold, moist natural environments during autumn and winter when primary dormancy is not yet fully released) and seeds with completely released dormancy (collected from natural environments in late spring) may yield more precise conclusions by eliminating variations in seed water content. This would further verify whether the opposite patterns of carbohydrate metabolism persist in embryos of seeds with different dormancy depths during incubation, and whether these metabolic changes show tissue-specific differences among radicle, cotyledons and hypocotyl. Korean pine seeds with relatively deeper primary physiological dormancy (abbreviated DDS) and seeds with released primary physiological dormancy (abbreviated RDS) were used as study subjects in the present study. A non-targeted metabolome analysis was conducted on the radicle and hypocotyl-cotyledon of DDS and RDS both before and after 2 weeks of incubation under favorable conditions, to determine whether differences in metabolic profiles, particularly in carbohydrate metabolism, occur in either radicle or hypocotyl-cotyledon. The results of this study will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the metabolic regulation network involved in seed dormancy release and germination.

Fresh Korean pine (Pinus koraiensis Siebold & Zucc.) seeds were collected from at least 50 individuals within the same Korean pine population in MBKPF at Liangshui National Nature Reserves in Heilongjiang Province, northeastern China (47°6′49″ N–47°16′10″ N, 128°47′8″ E–128°57′19″ E), during autumn 2020 (late September). The region has a temperate continental monsoon climate characterized by short, warm, and moist summers and long, cold, dry winters [30]. The Korean pine seeds had a moisture content below 10% (dry weight basis). These dried seeds were stored at −20°C to maintain their primary physiological dormancy.

2.2 Acquisition of DDS and RDS

Our previous research revealed that fresh Korean pine seeds exhibit primary morphophysiological dormancy shortly after dispersal in early autumn and gradually release their primary physiological dormancy under moist, cold conditions during late autumn and winter [29]. Accordingly, fresh Korean pine seeds were buried between litter and soil layers in the MBKPF in early October (early autumn). The seeds were retrieved in late October of the first year to obtain DDS, and in late May of the following year to obtain RDS. Additionally, the germination capacity of both DDS and RDS was assessed under laboratory conditions using four temperature regimes simulating the approximate mean maximum and minimum seasonal temperatures in the Liangshui region: 10/5°C (mid-spring/late-autumn), 20/10°C (late-spring/early-autumn), 25/15°C (early-summer), and 30/20°C (mid-summer). Specifically, three locations in MBKPF were selected as seed burial sites. At each site, one fine-mesh nylon bag containing a mixture of 5000 seeds and soil from MBKPF was buried as a replicate. The germination tests were conducted in plant growth chambers (MGC-350HP-2, manufactured by Bluepard, Shanghai, China) located in the Plant Physiological Ecology and Silviculture Laboratory at the Colleage of Ecological and Environmental Engineering, Guizhou Minzu University. The growth chambers were programmed with a 14-h light/10-h dark photoperiod, maintaining a light intensity of 200 μmol m−2·s−1 and 70% relative humidity. For each temperature regime, three replicates of 20 seeds each were used. Seeds were moistened with distilled water as needed during germination checks performed every two days over an eight-week period. Radicle emergence exceeding 2 mm was considered successful germination. After eight weeks, non-germinated seeds were dissected for viability assessment. Seeds with firm and white embryos were deemed viable and included in the germination percentage calculation. The seed germination rate was calculated as the ratio of germinated seeds to the sum of germinated seeds and viable non-germinated seeds remaining in the petri dish at the end of the experiment.

2.3 Acquisition of DDS and RDS Incubating for 2 Weeks

For both DDS and RDS, three replicates were prepared, each containing approximately 200 seeds. The seeds were initially placed in sterile plastic container (26.2 cm × 21 cm × 4 cm) lined with moistened sterile medical cotton pads. They were then incubated in growth chambers (MGC-350HP-2, manufactured by Bluepard, Shanghai, China) under optimal temperature of 25/15°C (day/night) with a 14-h photoperiod (200 μmol·m−2·s−1 light intensity; 14 h light/10 h dark cycle) in the Plant Physiological Ecology and Silviculture Laboratory at the Colleage of Ecological and Environmental Engineering, Guizhou Minzu University. After 14 days of incubation, at the time when the first seed germinated, non-germinated but still viable DDS or RDS were collected for metabolomic analysis [31].

The four types of seeds including DDS, DDS incubated for 2 weeks (abbreviated as DDS2), RDS, and RDS incubated for 2 weeks (abbreviated as RDS2) were used for metabolomic analysis. Radicles and the hypocotyl along with cotyledon (defined as hypocotyl-cotyledon) were collected from each seed type. The excised radicle and hypocotyl-cotyledon samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for about one week until further processing. The procedures of metabolite extraction, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis, and data processing were completed at Applied Protein Technology Corporation in Shanghai, China.

After slow thawing at 4°C, each sample was treated with a pre-cooled methanol (cat. no. A452-4, Fisher Chemical, Waltham, MA, USA), acetonitrile (cat. no. 1499230-935, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and aqueous solution (2:2:1, v/v/v). The sample-extraction solution mixture was vortexed for 1 min, then subjected to 30-min of cryogenic sonication. After standing at −20°C for 10 min, the samples were centrifuged (14,000× g, 4°C, 20 min) to collect the supernatant. The supernatant was then lyophilized and stored at −80°C until analysis. For chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis, the freeze-dried powder was reconstituted in 100 μL acetonitrile and water (1:1, v/v), vortexed, and centrifuged (14,000× g, 4°C, 15 min) before collecting the supernatant for LC-MS analysis.

LC-MS analysis was performed using an Agilent 1290 Infinity Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) coupled to a Triple TOF 6600 time-of-flight mass spectrometer (AB SCIEX, Framingham, MA, USA). Analyte separation was achieved on a hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) column (ACQUITY UPLC BEH Amide, 2.1 mm × 100 mm, with an internal diameter of 1.7 mm, manufactured by Waters, Wexford, Ireland) maintained at 25°C with a 0.5 mL min−1 flow rate. The sample injection volume was 2 μL. The mobile phase consisted of: (A) 25 mM aqueous ammonium acetate (cat. no. 70221, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 25 mM ammonia in water and (B) acetonitrile (cat. no. 1499230–935, Merck). The optimized gradient elution program for separation was as follows: 0–0.5 min, 95% B; 0.5–7 min, 95% to 65% B; 7–8 min, 65% to 40% B; 8–9 min, 40% B held constant; 9–9.1 min, 40% to 95% B; 9.1–12 min, 95% B held constant. Samples were maintained at 4°C in the autosampler throughout analysis. Mass spectrometry analysis was performed using an AB Sciex TripleTOF 6600 system (Sciex, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for acquisition of both primary (MS1) and secondary (MS2) spectra. Following HILIC separation, the electrospray ionization (ESI) source operation parameters were set as follows: ion source gas 1 (Gas1) at 60, ion source gas 2 (Gas2) at 60, curtain gas (CUR) at 30, source temperature at 600°C, IonSpray Voltage Floating (ISVF) at ±5500 V (for both positive and negative ion modes), TOF MS scan m/z range from 60 to 1000 Da, product ion scan m/z range from 25 to 1000 Da, TOF MS scan accumulation time of 0.20 s per spectrum, and product ion scan accumulation time of 0.05 s per spectrum. MS-MS data was acquired using information-dependent acquisition (IDA) in high sensitivity mode. The parameters were configured as follows: the collision energy (CE) was set at a fixed value of 35 ± 15 eV, the declustering potential (DP) was ±60 V for both positive and negative ion modes, isotopes within a 4 Da window were excluded, and 10 candidate ions were monitored per cycle.

The raw data (wiff. scan files) were converted into mzXML format using ProteoWizard‘s msConvert tool (version 3.0.6428). Peak alignment, retention time correction, and peak area extraction were conducted with XCMS software. Metabolite identification was achieved by matching measured m/z values (mass accuracy < 25 ppm) and MS-MS fragmentation patterns against a self-constructed database.

Principal component analysis (PCA) of the complete metabolomic dataset was performed using MetaboAnalyst 5.0 online software to reveal metabolite profiles differences across samples types, including: the hypocotyl-cotyledon of DDS (DDS-HC), the hypocotyl-cotyledon of DDS2 (DDS2-HC), the radicle of DDS (DDS-R), the radicle of DDS2 (DDS2-R), the hypocotyl-cotyledon of RDS (RDS-HC), the hypocotyl-cotyledon of RDS2 (RDS2-HC), the radicle of RDS (RDS-R), and the radicle of RDS2 (RDS2-R). The metabolomics data were normalized prior to PCA using Pareto scaling (mean-centered and then divided by the square root of the standard deviation of each variable), auto scaling (mean-centered and then divided by the standard deviation of each variable), or logarithm transformation. Partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) was conducted using MetaboAnalyst 5.0 online software to identify metabolites significantly contributing to sample discrimination, comparing the following pairs: DDS-HC vs DDS2-HC, DDS-R vs DDS2-R, DDS2-R vs DDS2-HC, RDS-HC vs RDS2-HC, RDS-R vs RDS2-R, and RDS2-R vs RDS2-HC. The metabolic data were normalized using the methods described above prior to conducting PLS-DA. The selection criteria for metabolites significantly contributing to metabolic profile differences across these six sample pairs were: variable importance in projection (VIP) score ≥ 1.0 and p-value < 0.05. Subsequently, MetaboAnalyst 5.0 online software was employed to calculate fold changes between the corresponding sample pairs and identify significantly enriched metabolic pathways for these metabolites. The corresponding parameters for pathway analysis were configured as described in reference [21].

3.1 Germination of DDS and RDS

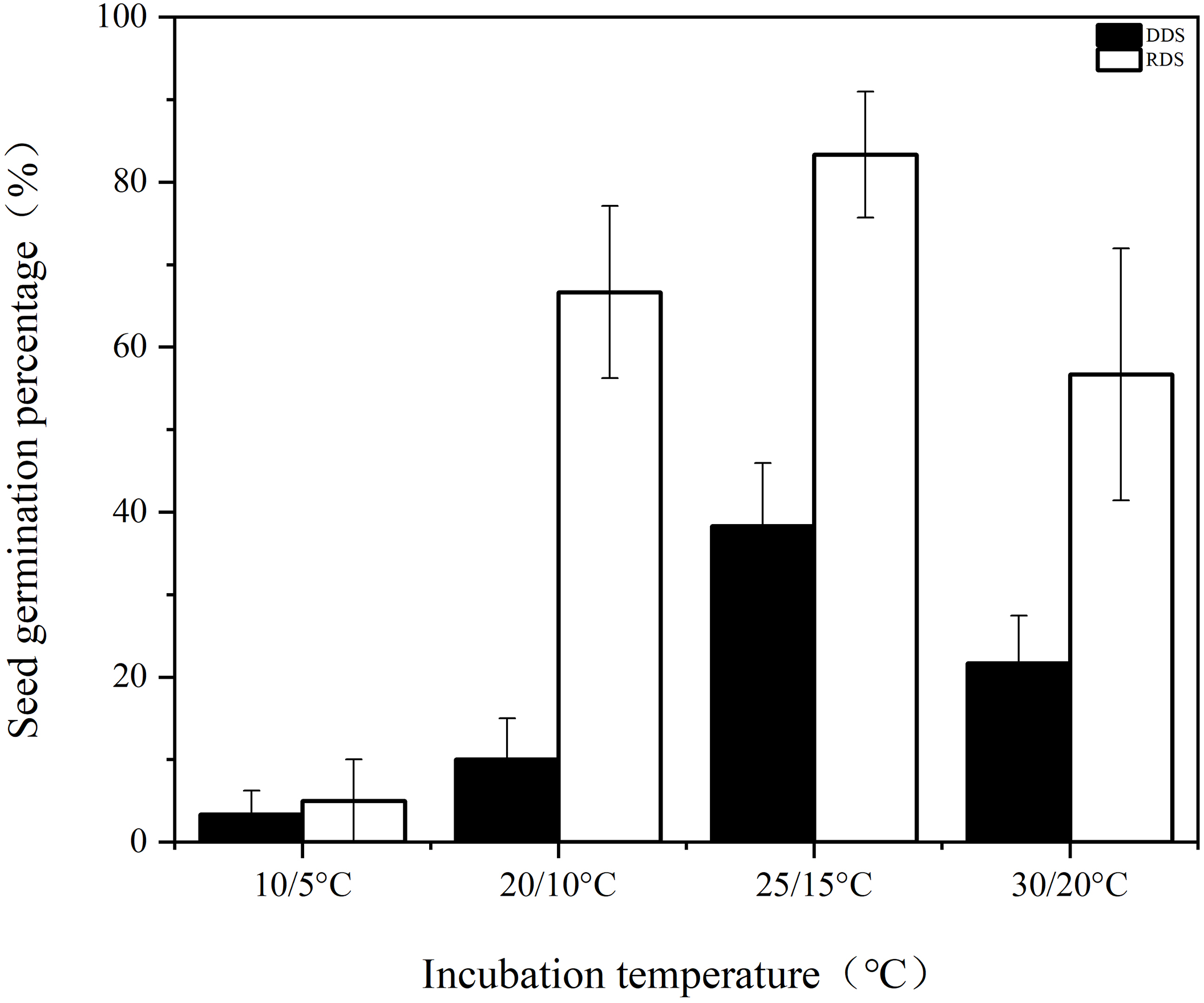

The germination rates of DDS were consistently low across all four incubation temperatures, with the highest rate of 38.33% observed only at 25/15°C (Fig. 1). In contrast, RDS exhibited significantly higher germination percentages of 66.67 ± 10.41%, 83.33 ± 7.64%, and 56.67 ± 15.28% under the same temperature regimes.

Figure 1: Germination percentage of seeds with deeper physiological dormancy (DDS) and seeds with released primary physiological dormancy (RDS) under four incubation temperatures

3.2 PCA of Metabolites in the Radicle and Hypocotyl-Cotyledon of DDS and RDS

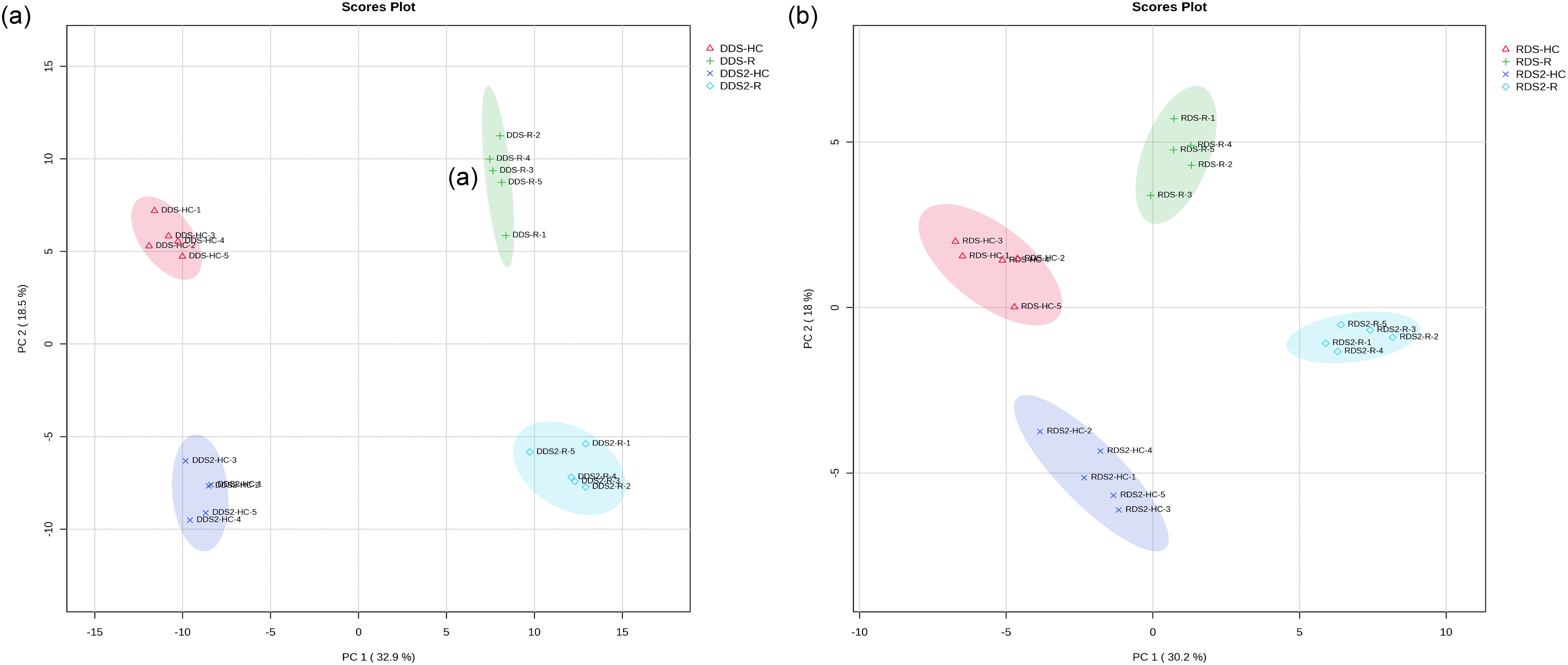

The PCA score plot explains 51.4% of the variance in metabolite profiles in DDS, with PC1 accounting for 32.9% of the variance and PC2 accounting for 18.5% (Fig. 2a). The radicle samples are primarily separated from the hypocotyl-cotyledon samples along the first principal component. Both radicle and hypocotyl-cotyledon exhibit a distinct separation after 2 weeks of incubation along the second dimension of this PCA.

Figure 2: Principal component analysis of metabolites relative contents in the hypocotyl-cotyledon (HC) and radicle (R) of (a) seeds with deeper physiological dormancy (DDS) and DDS after 2-week incubation (DDS2), and (b) seeds with released primary physiological dormancy (RDS) and RDS after 2-week incubation (RDS2)

The first component, accounting for 30.2% of the total variance, separated the radicle samples distinctly from the hypocotyl-cotyledon samples of RDS (Fig. 2b). For the metabolic profiles of both the radicle and hypocotyl-cotyledon, an apparent separation was observed along the second component (which explains 18.0% of the total variation) before and after 2 weeks of incubation.

3.3 Fold Changes in Metabolites That Underwent Significant Changes in the Hypocotyl-Cotyledon and Radicle of DDS after 2 Weeks of Incubation

Of the 32 metabolites with increased relative contents, the majority were amino acids, peptides, and their analogues, including D-aspartic acid, L-aspartate, L-isoleucine, L-pyroglutamic acid, L-glutamine, L-asparagine, acetylglycine, L-serine, L-tryptophan and L-glutamate (Table S1). Among them, D-aspartic acid and L-aspartate increased by 10.67-fold and 9.73-fold, respectively. Seven of the 13 metabolites with decreased relative contents were carbohydrates and carbohydrate conjugates, including .alpha.-D-(+)-talose, raffinose, 3.alpha.-mannobiose, D-(+)-melibiose, stachyose, myo-inositol and galactinol (Table S1). Additionally, O-phosphoethanolamine, a phosphoethanolamine, showed the largest decrease (3.53-fold).

A total of 35 metabolites exhibited significantly different relative content in the radicle of DDS after 2 weeks of incubation (Table S2). Among them, the most abundant metabolites were organic acids and derivatives, followed by organic oxygen compounds, and lipids and lipid-like molecules. Among the 17 organic acids and their derivatives, 13 showed increased levels (Table S2). These included 10 amino acids, peptides, and their analogues, along with two tricarboxylic acids and derivatives (homocitrate and citrate), and one beta-hydroxy acid and derivative (L-malic acid). Of the 10 organic oxygen compounds, all except one (an alcohol and polyol) belonged to carbohydrates and carbohydrate conjugates (Table S2). Specifically, the levels of four monosaccharides and their sugar alcohol derivatives (2′-deoxy-D-ribose, L-sorbose, D-sorbitol, L-fucose, and D-mannose) increased, while the concentrations of two oligosaccharides (3.alpha.-mannobiose and D-(+)-melibiose) decreased. All lipids and lipid-like molecules exhibited approximately a 2-fold decrease in abundance (Table S2).

3.4 Fold Changes of Metabolites between the Hypocotyl-Cotyledon and Radicle of DDS with 2 Weeks of Incubation

The levels of lipid and lipid-like molecules in the hypocotyl-cotyledon are higher than those in the radicles (Table S3). Most noticeably were the respective 23.60-, 16.96-, 7.10-, and 5.47-fold higher levels of glycerophosphocholine, isopimaric acid, 1-palmitoyl-2-linoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate, and linoleic acid. Additionally, D-aspartic acid and L-aspartate showed nearly 10-fold higher levels (Table S3). In contrast, six organic acids and their derivatives, comprising four amino acids (L-histidine, argininosuccinic acid, L-pyroglutamic acid, and L-glutamate), one beta-hydroxy acid and its derivative (L-malic acid), one tricarboxylic acid and its derivative (citrate), as well as nine organic oxygen compounds (mainly carbohydrates and carbohydrate conjugates), showed higher concentrations in radicles than in the hypocotyl-cotyledon (Table S3). Furthermore, 16.95-fold and 142.86-fold higher levels of two phenylpropanoids and polyketides, (-)-epicatechin and 2-hydroxy-5-methoxybenzoic acid, were observed in radicles, respectively.

3.5 Fold Changes in Metabolites That Underwent Significant Changes in the Hypocotyl-Cotyledon and Radicle of RDS after 2 Weeks of Incubation

During the cultivation period, significant changes were observed in the levels of three major compound categories: organic acids and their derivatives (33 in total), organic oxygen compounds (29 in total), and lipids and lipid-like molecules (26 in total) (Table S4). Approximately 90% of amino acids, peptides, and analogues, along with 62% of lipids and lipid-like molecules showed increased accumulation. In contrast, about 71% of carbohydrates and carbohydrate conjugates decreased, including monosaccharides, oligosaccharides, sugar derivatives, and phosphorylated sugars. Additionally, all six detected phenylpropanoids and polyketides exhibited elevated levels, with apigenin and (+)-catechin showing approximately 3.8-fold increases (Table S4).

In the radicle, 74% of amino acids, peptides, and analogues (19 in total) showed increased contents, while 71% of carbohydrates and carbohydrate conjugates (24 in total) exhibited decreased contents, primarily including monosaccharides, phosphorylated monosaccharides, sugar alcohols, disaccharides, oligosaccharides, and glycoside derivatives (Table S5). Among the 16 analyzed lipids and lipid-like molecules, reduced contents were detected in 10 compounds, among which all cis-(6,9,12)-linolenic acid was found to be decreased by 6.89-fold (Table S5). All 8 benzenoids and 8 phenylpropanoids and polyketides demonstrated increased accumulation, particularly three phenylpropanoids and polyketides—apigenin, (+)-catechin, and procyanidin B2—which increased by 67.24-fold, 17.99-fold and 6.39-fold, respectively (Table S5). Furthermore, substantial content reductions were recorded in 14 out of 15 nucleosides, nucleotides, and analogues (Table S5).

3.6 Fold Changes of Metabolites between the Hypocotyl-Cotyledon and Radicle of RDS with 2 Weeks of Incubation

The hypocotyl-cotyledon contained more hexoses, sugar acids and derivatives, pentose phosphates, hexose phosphates, and monosaccharide phosphates (Table S6). In contrast, the relative contents of sugar alcohols, monosaccharides, and oligosaccharides were higher in the radicle. The derivatives of amino acids, intermediates or end-products of amino acid metabolism accumulate in the radicle, while free amino acids predominantly exist in the hypocotyl-cotyledon (Table S6). An abundant accumulation of lipids and lipid-like molecules (approximately 65%) was observed in the hypocotyl-cotyledon (Table S6). Notably, the contents of eicosapentaenoic acid, PC(20:5(5Z,8Z,11Z,14Z,17Z)/20:5(5Z,8Z,11Z,14Z,17Z)), and dehydroabietic acid in the hypocotyl-cotyledon were 16.74-fold, 12.75-fold, and 11.64-fold higher than those in the radicle, respectively. All six phenylpropanoids and polyketides showed significant accumulation in the radicle, with (+)-catechin and apiin exhibiting 10.20-fold and 41.27-fold higher contents respectively compared to those in the hypocotyl-cotyledon (Table S6).

3.7 Significantly Enriched Metabolic Pathways in the Hypocotyl-Cotyledon and Radicle of DDS after 2 Weeks of Incubation

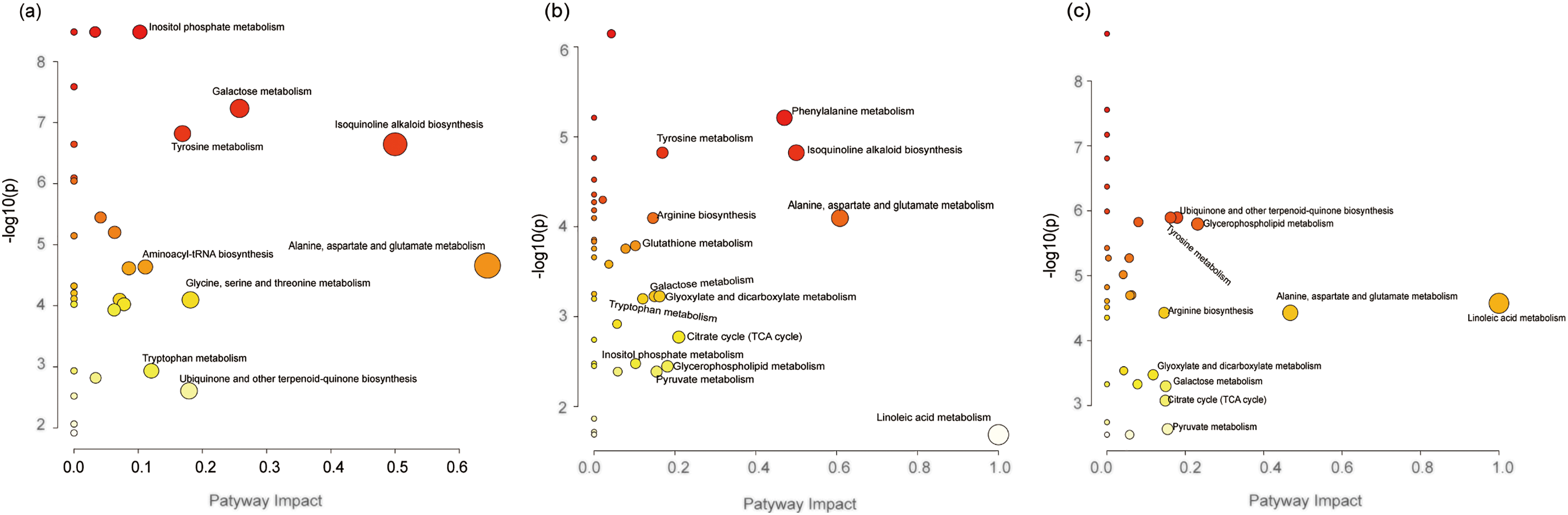

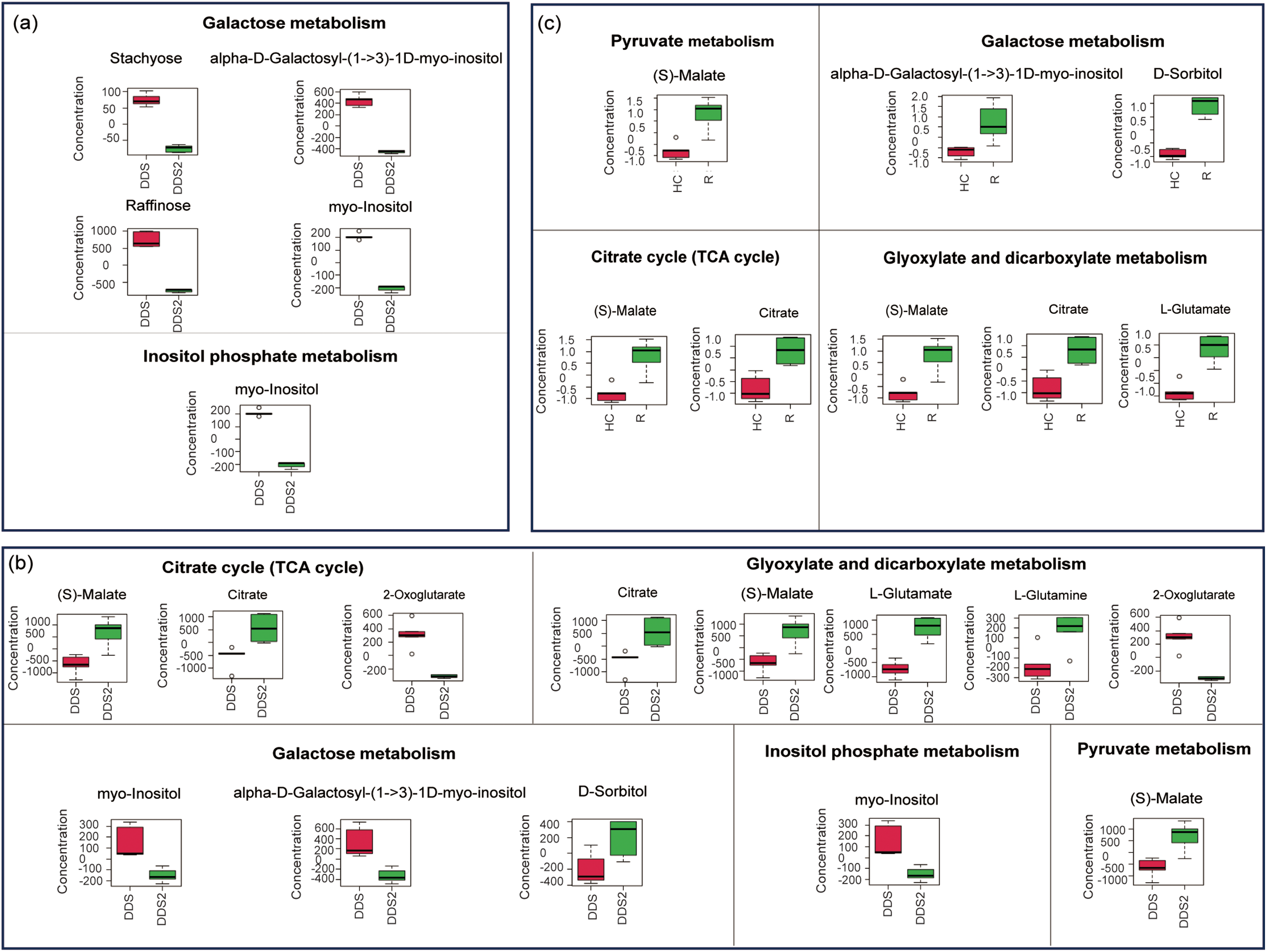

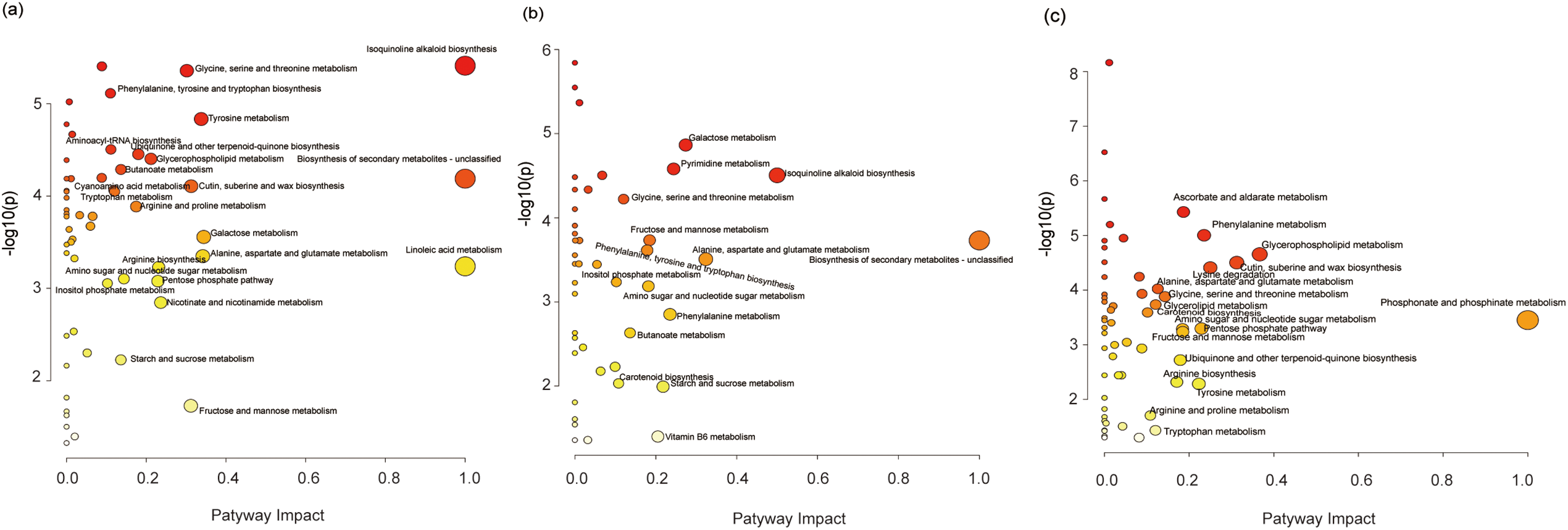

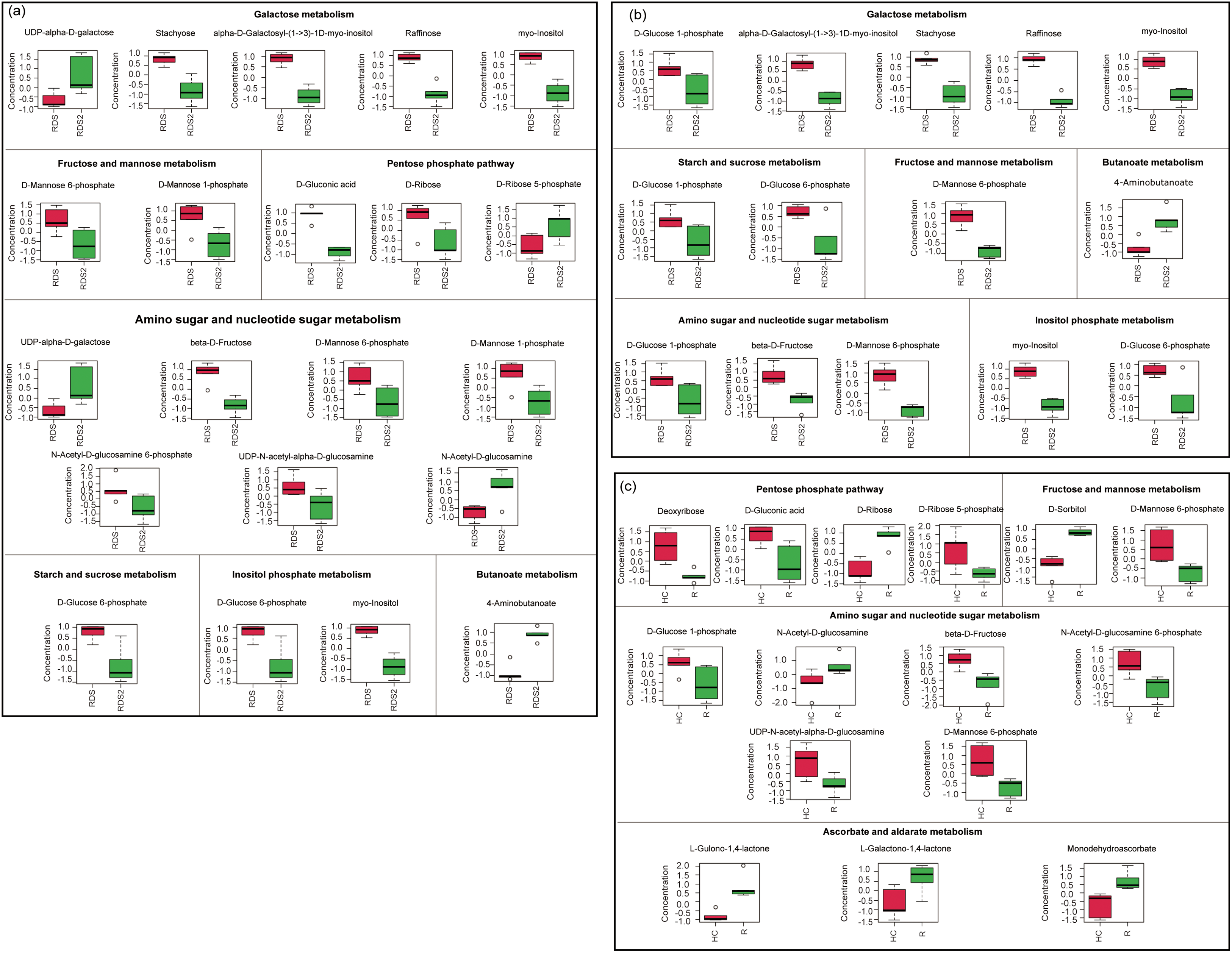

Most of the differentially expressed metabolites were significantly enriched in nine metabolic pathways in the hypocotyl-cotyledon and 14 metabolic pathways in the radicle of DDS, respectively (Fig. 3a,b). More metabolic pathways were classified under amino acid metabolism, carbohydrate metabolism, and lipid metabolism (Table S7, Fig. 4). During incubation, most metabolites in amino acid metabolism accumulated, except for four metabolites (e.g., stachyose, alpha-D-Galactosyl-(1->3)-1D-myo-inositol, raffinose and myo-inositol) in galactose and inositol phosphate metabolism, which decreased in the hypocotyl-cotyledon (Table S7, Fig. 4a). In the radicle, intermediates of amino acid metabolism, carbohydrate metabolism (including the TCA cycle, glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism, and pyruvate metabolism), and glutathione metabolism generally increased (Table S7, Fig. 4b). Conversely, four lipids involved in linoleic acid and glycerophospholipid metabolism, including linoleate, sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, phosphatide and choline phosphate, showed significant declines (Table S7). Metabolic pathways with significant differences between the hypocotyl-cotyledon and radicle mainly involved amino acid, carbohydrate, and lipid metabolism (Table S7, Fig. 3c). Metabolites in linoleic acid and glycerophospholipid metabolism were more abundant in the hypocotyl-cotyledon, whereas those linked to carbohydrate metabolism pathways, including (S)-malate, alpha-D-galactosyl-(1->3)-1D-myo-inositol, D-sorbitol, citrate and L-glutamate, showed higher concentrations in the radicle (Table S7, Fig. 4c).

Figure 3: Metabolome view of the altered metabolic pathways between (a) the hypocotyl-cotyledon of seeds with deeper physiological dormancy (DDS) and DDS after 2-week incubation (DDS2), (b) the radicle of DDS and DDS2, and (c) the radicle and hypocotyl-cotyledon of DDS2. Dark red, large circles in the top-right corner of the metabolome view represent the main altered pathways, in contrast to the yellow, small circles on the left side of the graphs

Figure 4: Differentially expressed metabolites related to carbohydrate metabolism between (a) the hypocotyl-cotyledon (HC) of seeds with deeper physiological dormancy (DDS) and DDS after 2-week incubation (DDS2), (b) the radicle (R) of DDS and DDS2, and (c) between the HC and R of DDS2

3.8 Significantly Enriched Metabolic Pathways in the Hypocotyl-Cotyledon and Radicle of RDS after 2 Weeks of Incubation

Significantly altered metabolites were enriched in 23 (hypocotyl-cotyledon) and 15 (radicle) metabolic pathways (Fig. 5a,b). These pathways fell into eight categories: amino acid, carbohydrate, and lipid metabolism; other amino acid metabolism; nucleotide metabolism; cofactor and vitamin metabolism; secondary metabolite biosynthesis; and terpenoid and polyketide metabolism (Table S8, Fig. 6). Amino acids generally accumulated in both tissues during incubation (Table S8, Fig. 6). Conversely, carbohydrate metabolism metabolites, particularly in galactose, fructose and mannose, pentose phosphate, amino and nucleotide sugar, inositol phosphate, and starch and sucrose pathways, showed significant decreases (Fig. 6a,b). Metabolites showing significant differences between hypocotyl-cotyledon and radicle were primarily enriched in lipid, carbohydrate, amino acid, and phosphonate and phosphinate metabolism (Table S8, Fig. 5c). These metabolites were generally more abundant in hypocotyl-cotyledon than radicle (Table S8). In contrast, the radicle showed higher levels of metabolites involved in lysine degradation (N6-(L-1,3-dicarboxypropyl)-L-lysine, L-pipecolate), carotenoid biosynthesis (Beta-carotene), ascorbate and aldarate metabolism (L-gulono-1,4-lactone, L-galactono-1,4-lactone, and monodehydroascorbate), and ubiquinone and terpenoid-quinone biosynthesis (homogentisate) (Table S8, Fig. 6c).

Figure 5: Metabolome view of the altered metabolic pathways between (a) the hypocotyl-cotyledon of seeds with released physiological dormancy (RDS) and RDS after 2-week incubation (RDS2), (b) the radicle of RDS and RDS2, and (c) the radicle and hypocotyl-cotyledon of RDS2. Dark red, large circles in the top-right corner of the metabolome view represent the main altered pathways, in contrast to the yellow, small circles on the left side of the graphs

Figure 6: Differentially expressed metabolites related to carbohydrate metabolism between (a) the hypocotyl-cotyledon (HC) of seeds with released physiological dormancy (RDS) and RDS after 2-week incubation (RDS2), (b) the radicle (R) of RDS and RDS2, and (c) the HC and R of RDS2

Compared to seeds with deep dormancy buried for 1 month (DDS), approximately 83% of the shallow dormant seeds buried for 8 months (RDS) germinated when incubated at the optimal temperature of 25/16°C (Fig. 1). Notably, they also achieved germination rates of 67% and 57% under suboptimal temperatures of 20/10°C and 30/20°C, respectively (Fig. 1). These results demonstrate that Korean pine seeds dispersed in autumn not only exhibited enhanced germination capacity but also broader temperature tolerance for germination after experiencing low temperatures throughout autumn, winter, and early spring. This finding is consistent with previous research [29], providing compelling evidence that primary physiological dormancy was gradually released through moist chilling during autumn and winter. We observed that after transfer to favorable conditions, amino acid metabolism and carbohydrate metabolism were more active in both the hypocotyl-cotyledon and radicle of RDS (Table S8, Fig. 6a,b). The relative levels of amino acid metabolism-associated metabolites were higher in both the hypocotyl-cotyledon and radicle after two weeks of RDS incubation (Table S8). A similar trend in amino acid metabolism-related metabolites was also observed in DDS, suggesting that amino acid metabolism may not be differentially upregulated. However, compared to DDS under germination conditions, carbohydrate metabolism in both the hypocotyl-cotyledon and radicle of RDS exhibited a distinct change pattern. Although most carbohydrate metabolism-related metabolites showed significantly reduced levels in both the hypocotyl-cotyledon of RDS and DDS, RDS contained not only raffinose, stachyose, and myo-inositol (compounds exclusively detected in DDS) but also multiple phosphorylated sugars (D-mannose 6-phosphate, D-mannose 1-phosphate, D-ribose 5-phosphate, and D-glucose 6-phosphate) and glucosamine (N-Acetyl-D-glucosamine 6-phosphate, UDP-N-acetyl-alpha-D-glucosamine, and N-Acetyl-D-glucosamine) (Figs. 4a and 6a). The relative levels of carbohydrate metabolism-associated metabolites, particularly those participating in starch and sucrose metabolism (D-glucose 1-phosphate and D-glucose 6-phosphate), fructose and mannose metabolism (D-mannose 6-phosphate), amino sugar and nucleotide metabolism (D-glucose 1-phosphate, beta-D-fructose and D-mannose 6-phosphate), and inositol phosphate metabolism (myo-inositol and D-glucose 6-phosphate), were decreased in RDS radicles (Fig. 6b). In contrast, metabolites related to pyruvate metabolism ((S)-malate), the TCA cycle ((S)-malate and citrate), and glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism ((S)-malate, citrate and L-glutamate) showed increased levels in DDS radicles (Fig. 4b). This further confirms previous findings that Korean pine seeds at different dormancy depths exhibit distinct patterns in carbohydrate metabolism during incubation under favorable germination conditions. Specifically, the carbohydrate metabolic pathway appears more active in deeply dormant seeds but relatively weaker in non-dormant seeds, particularly within radicle tissues.

Our results demonstrated that under favorable germination conditions, respiratory pathway substrates in RDS, particularly D-gluconic acid, D-ribose, β-D-fructose, D-mannose-6-phosphate, D-mannose-1-phosphate, D-glucose-1-phosphate, and D-glucose-6-phosphate, showed significant decrease in both radicles and hypocotyl-cotyledon (Fig. 4a,b). Conversely, DDS radicles exhibited 1.36-fold and 1.75-fold increase in malate and citrate levels, respectively. These metabolites participate in carbohydrate metabolism pathways including pyruvate metabolism, the TCA cycle, and glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism (Fig. 4b). This suggests that TCA cycle activity in the radicle may be enhanced. Why might the TCA cycle be enhanced in DDS while respiratory metabolic pathways are weakened in RDS. The reducing power generated through the TCA cycle is subsequently channeled to the mitochondria electron transport chain (etc) for adenosine triphosphate (ATP) regeneration, enabling efficient electron transport while minimizing superoxide (O2−) production [32]. However, under oxygen-limited conditions, electron leakage from the etc and subsequent transfer to molecular oxygen may result in reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation [32,33]. Although ROS function as crucial physiological regulators and signaling molecules [34], overaccumulation causes oxidative stress. To minimize ROS production, mitochondria can both exchange (or modify) etc subunits and reduce electron flow through metabolic adjustments, including TCA cycle activity downregulation [32]. Therefore, we speculate that the opposite changing characteristics observed in the radicles of seeds at different dormancy depths may be primarily related to ROS generation, which consequently play an important role in the maintenance of dormancy or the initiation of germination. However, further verification is still needed.

The comparison of metabolic profiles between radicle and hypocotyl-cotyledon in RDS and DDS after two weeks of incubation revealed that the radicles of RDS showed lower relative levels of carbohydrate metabolism intermediates (e.g., D-gluconic acid, D-ribose 5-phosphate, deoxyribose, D-mannose-6-phosphate, and D-glucose 1-phosphate) than those in hypocotyl-cotyledons (Fig. 6c). Conversely, the radicles of DDS exhibited significantly higher relative level of TCA cycle intermediates (malate and citrate) compared to the hypocotyl-cotyledons (Fig. 4c). Given the TCA cycle-ROS production relationship, DDS radicles likely accumulate more ROS than RDS radicles. It has also been reported that significant ROS over-accumulation occurs at the root tips of Arabidopsis thaliana seeds with low germination capacity [35], and that excessive ROS production inhibits root growth [36]. Additionally, the predominance of ascorbate and aldarate metabolism in radicles compared to hypocotyl-cotyledons further supports the documented stronger antioxidant capacity in RDS radicles (Fig. 6c). Similarly, multiple lines of evidence suggest that radicles of germinating seeds are more susceptible to hypoxia stress and activate antioxidative systems more readily than cotyledons. For instance, previous studies on lupine (Lupinus luteus) seed germination demonstrated more pronounced accumulation of free radicals, hydrogen peroxide, and two antioxidative enzymes (superoxide dismutase and catalase) in the radicle and hypocotyl compared to cotyledons [28]. A similar pattern was observed in germinating pea (Pisum sativum) seeds and Brassica parachinensis seeds, where radicle and hypocotyl showed relatively greater increases in free radical levels and the antioxidant molecule ascorbate compared to cotyledons [37,38].

In natural environments, the moist chilling conditions during autumn and winter facilitate the release of primary physiological dormancy in Korean pine seeds. When seeds that had undergone eight months and one month of moist chilling treatment, respectively, were transferred to germination conditions, these seeds with different dormancy depths displayed distinct metabolic patterns, particularly in carbohydrate metabolism. An opposite trend in carbohydrate metabolism was observed, characterized by a significant decrease in respiratory pathway substrates in both the radicles and hypocotyl-cotyledons of RDS, in contrast to the accumulation of TCA cycle intermediates in DDS radicles. The radicle showed significantly distinct metabolic profiles compared to the hypocotyl-cotyledon. Lysine degradation and ascorbate-aldarate metabolism were the key metabolic pathways in RDS radicles, while carbohydrate metabolism predominated in hypocotyl-cotyledon. However, compared to the hypocotyl-cotyledon, the TCA cycle was more active in DDS radicles. We thus concluded that the carbohydrate metabolic pathways in the embryonic radicle, rather than in other tissues, may play a crucial role in the dormancy and germination of Korean pine seeds. Future research should focus on investigating carbohydrate metabolic pathways in radicle tissues to elucidate the mechanisms underlying seed dormancy and germination in Korean pine or other Pinus species.

Acknowledgement: Many thanks to Chuanzhao Liu from the Liangshui National Nature Reserves in Northeastern China for his field support.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31901300).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Xinghuan Li, Binxi Hao, Shimin Cheng, Ju Zhang, Yuan Song; data collection: Xinghuan Li, Binxi Hao; analysis and interpretation of results: Shimin Cheng, Ju Zhang, Yuan Song; draft manuscript preparation: Xinghuan Li. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.067104/s1.

References

1. Song Y, Li X, Zhang M, Xia G, Xiong C. Effect of cold stratification on the temperature range for germination of Pinus koraiensis. J For Res. 2023;34(1):221–31. doi:10.1007/s11676-022-01540-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Vondrakova Z, Pesek B, Malbeck J, Bezdeckova L, Vondrak T, Fischerova L, et al. Dormancy breaking in Fagus sylvatica seeds is linked to formation of abscisic acid-glucosyl ester. New For. 2020;51(4):671–88. doi:10.1007/s11056-019-09751-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Elisovetcaia D, Ivanova R, Mascenco N, Brindza J. Improvement of seed germination and seedling resistance of beech (Fagus sylvatica) by growth regulators. Agrofor Int J. 2022;7(1):90–7. doi:10.7251/AGRENG2201090E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Vannini A, Carbognani M, Chiari G, Forte TGW, Lumiero F, Malcevschi A, et al. Effects of wood-derived biochar on germination, physiology, and growth of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) and Turkey oak (Quercus cerris L.). Plants. 2022;11(23):3254. doi:10.3390/plants11233254. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Kalemba EM, Dufour S, Gevaert K, Impens F, Meimoun P. Proteomics- and metabolomics-based analysis of the regulation of germination in Norway maple and sycamore embryonic axes. Tree Physiol. 2025;45(2):tpaf003. doi:10.1093/treephys/tpaf003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Kijowska-Oberc J, Staszak AM, Wawrzyniak MK, Ratajczak E. Changes in proline levels during seed development of orthodox and recalcitrant seeds of genus Acer in a climate change scenario. Forests. 2020;11(12):1362. doi:10.3390/f11121362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Alipour S, Bilska K, Stolarska E, Wojciechowska N, Kalemba EM. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotides are associated with distinct redox control of germination in Acer seeds with contrasting physiology. PLoS One. 2021;16(1):e0245635. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0245635. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Wojciechowska N, Alipour S, Stolarska E, Bilska K, Rey P, Kalemba EM. Involvement of the MetO/Msr system in two Acer species that display contrasting characteristics during germination. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(23):9197. doi:10.3390/ijms21239197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Pawłowski TA. Proteomic approach to analyze dormancy breaking of tree seeds. Plant Mol Biol. 2010;73(1–2):15–25. doi:10.1007/s11103-010-9623-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Ali AS, Elozeiri AA. Metabolic processes during seed germination. In: Jimenez-Lopez JC, editor. Advances in seed biology. London, UK: IntechOpen; 2017. p. 141–66. doi:10.5772/intechopen.70653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhang J, Qian JY, Bian YH, Liu X, Wang CL. Transcriptome and metabolite conjoint analysis reveals the seed dormancy release process in callery pear. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(4):2186. doi:10.3390/ijms23042186. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Gao Y, Xue K, Huang T, Sun L, Zhu M, Wang Y, et al. PFK1-mediated metabolic shifts facilitate cold stratification-induced dormancy release in Cercis chinensis seeds. Ind Crops Prod. 2025;225(2):120552. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2025.120552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Wu Y, Deng ZY, Wang MZ, Liu LY, Shen YB. Effect of gibberellic acid treatment and cold stratification on breaking combined (physiological + mechanical) dormancy and germination in Sassafras tzumu (Hemsl.) Hemsl seeds. J Appl Res Med Aromat Plants. 2025;44(1):100606. doi:10.1016/j.jarmap.2024.100606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Vishal B, Kumar PP. Regulation of seed germination and abiotic stresses by gibberellins and abscisic acid. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:838. doi:10.3389/fpls.2018.00838. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Tuttle KM, Martinez SA, Schramm EC, Takebayashi Y, Seo M, Steber CM. Grain dormancy loss is associated with changes in ABA and GA sensitivity and hormone accumulation in bread wheat, Triticum aestivum (L.). Seed Sci Res. 2015;25(2):179–93. doi:10.1017/s0960258515000057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Mursaliyeva V, Imanbayeva A, Parkhatova R. Seed germination of Allochrusa Gypsophiloides (Caryophyllaceaean endemic species from Central Asia and Kazakhstan. Seed Sci Technol. 2020;48(2):289–95. doi:10.15258/sst.2020.48.2.15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Corbineau F, Bianco J, Garello G, Côme D. Breakage of Pseudotsuga menziesii seed dormancy by cold treatment as related to changes in seed ABA sensitivity and ABA levels. Physiol Plant. 2002;114(2):313–9. doi:10.1034/j.1399-3054.2002.1140218.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Angelovici R, Fait A, Fernie AR, Galili G. A seed high-lysine trait is negatively associated with the TCA cycle and slows down Arabidopsis seed germination. New Phytol. 2011;189(1):148–59. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03478.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Qu C, Chen J, Cao L, Teng X, Li J, Yang C, et al. Non-targeted metabolomics reveals patterns of metabolic changes during poplar seed germination. Forests. 2019;10(8):659. doi:10.3390/f10080659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Hou L, Wang M, Wang H, Zhang WH, Mao P. Physiological and proteomic analyses for seed dormancy and release in the perennial grass of Leymus chinensis. Environ Exp Bot. 2019;162(5):95–102. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2019.02.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Song Y, Zhu J. The roles of metabolic pathways in maintaining primary dormancy of Pinus koraiensis seeds. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19(1):550. doi:10.1186/s12870-019-2167-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Song Y, Gao X, Wu Y. Key metabolite differences between Korean pine (Pinus koraiensis) seeds with primary physiological dormancy and no-dormancy. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:767108. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.767108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. El-Maarouf-Bouteau H. The seed and the metabolism regulation. Biology. 2022;11(2):168. doi:10.3390/biology11020168. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Sano N, Lounifi I, Cueff G, Collet B, Clément G, Balzergue S, et al. Multi-omics approaches unravel specific features of embryo and endosperm in rice seed germination. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:867263. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.867263. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Galland M, He D, Lounifi I, Arc E, Clément G, Balzergue S, et al. An integrated multi-omics comparison of embryo and endosperm tissue-specific features and their impact on rice seed quality. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1984. doi:10.3389/fpls.2017.01984. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Xu HH, Liu SJ, Song SH, Wang WQ, Møller IM, Song SQ. Proteome changes associated with dormancy release of Dongxiang wild rice seeds. J Plant Physiol. 2016;206:68–86. doi:10.1016/j.jplph.2016.08.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Xue X, Yu YC, Wu Y, Xue H, Chen LQ. Locally restricted glucose availability in the embryonic hypocotyl determines seed germination under abscisic acid treatment. New Phytol. 2021;231(5):1832–44. doi:10.1111/nph.17513. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Verma G, Mishra S, Sangwan N, Sharma S. Reactive oxygen species mediate axis-cotyledon signaling to induce reserve mobilization during germination and seedling establishment in Vigna radiata. J Plant Physiol. 2015;184(1):79–88. doi:10.1016/j.jplph.2015.07.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Song Y, Zhang M, Guo Y, Gao X. Change in seed dormancy status controls seasonal timing of seed germination in Korean pine (Pinus koraiensis). J Plant Ecol. 2023;16(2):rtac067. doi:10.1093/jpe/rtac067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Wang YF, Duan WB, Qu MX, Chen LX, Lan HY, Yang XF, et al. Differences of carbon and nitrogen stoichiometry between different habitats in two natural Korean pine forests in Northeast China’s mountainous areas. J Mt Sci. 2022;19(5):1324–35. doi:10.1007/s11629-021-6774-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Song Y, Zhu JJ. How does moist cold stratification under field conditions affect the dormancy release of Korean pine seed (Pinus koraiensis)? Seed Sci Technol. 2016;44(1):27–42. doi:10.15258/sst.2016.44.1.06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Fuhrmann DC, Brüne B. Mitochondrial composition and function under the control of hypoxia. Redox Biol. 2017;12:208–15. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2017.02.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Hendrix S, Vanbuel I, Colemont J, Bos Calderó L, Hamzaoui MA, Kunnen K, et al. Jack of all trades: reactive oxygen species in plant responses to stress combinations and priming-induced stress tolerance. J Exp Bot. 2025;24:eraf065. doi:10.1093/jxb/eraf065. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Farooq MA, Zhang X, Zafar MM, Ma W, Zhao J. Roles of reactive oxygen species and mitochondria in seed germination. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:781734. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.781734. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Gong C, Yin X, Ye T, Liu X, Yu M, Dong T, et al. The F-Box/DUF295 Brassiceae specific 2 is involved in ABA-inhibited seed germination and seedling growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Sci. 2022;323:111369. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2022.111369. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Xu N, Chu Y, Chen H, Li X, Wu Q, Jin L, et al. Rice transcription factor OsMADS25 modulates root growth and confers salinity tolerance via the ABA-mediated regulatory pathway and ROS scavenging. PLoS Genet. 2018;14(10):e1007662. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1007662. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Wojtyla Ł, Garnczarska M, Zalewski T, Bednarski W, Ratajczak L, Jurga S. A comparative study of water distribution, free radical production and activation of antioxidative metabolism in germinating pea seeds. J Plant Physiol. 2006;163(12):1207–20. doi:10.1016/j.jplph.2006.06.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Chen BX, Peng YX, Yang XQ, Liu J. Delayed germination of Brassica parachinensis seeds by coumarin involves decreased GA4 production and a consequent reduction of ROS accumulation. Seed Sci Res. 2021;31(3):224–35. doi:10.1017/s0960258521000167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools