Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Evaluation of Seaweeds as Stimulators to Alleviate Salinity-Induced Stress on Some Agronomic Traits of Different Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) Cultivars

Department of Field Crops, Faculty of Agriculture, Ankara University, Ankara, 06110, Türkiye

* Corresponding Author: Nilüfer Kocak Sahin. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Abiotic Stress in Agricultural Crops)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(8), 2399-2421. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.067880

Received 15 May 2025; Accepted 14 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Peanut (Arachis hypogaea) is of international importance as a source of oil and protein. Soil salinity is one of the most significant abiotic stress factors affecting the yield and quality of peanuts. This study evaluated the potential of a seaweed-based biostimulant to enhance emergence and seedling growth of four peanut cultivars (‘Ayse Hanım’, ‘Halis Bey’, ‘NC-7’, and ‘Albenek’) under increasing salinity levels. The experiment was conducted under greenhouse conditions using a randomized complete block design with four replicates. Seeds were sown in trays and treated with two doses of seaweed extract (0 and 5 g L−1) applied directly to the seedbed. Salinity stress was induced by dissolving NaCl in distilled water used for weekly irrigation over six weeks, with salinity levels set at: S0: Control, S1: 50 mM NaCl, S2: 100 mM NaCl, S3: 150 mM NaCl, and S4: 200 mM NaCl. Emergence percentage, mean emergence time, shoot and root length, fresh and dry biomass, chlorophyll content, proline, crude protein, and macro- and micronutrient concentrations (Ca, K, P, Mg, Zn, Mn, Cu, and Fe) were measured. The results revealed significant differences between treatments. Seaweed applications showed notable improvements in measured parameters of each variety compared to the salt treated and un-treated control plants of each variety. As salinity stress increased, the emergence percentage, root and shoot length, fresh and dry weight of the plants, crude protein content percentage, leaf chlorophyll contents, Ca, K, P, Mg, Zn, Mn, Cu, and Fe decreased. Similarly, the mean emergence time, and proline contents also decreased with each increase in Na concentration. The best outcomes were obtained in seedlings treated with seaweed under no salinity (0 mM NaCl) and mild salinity (50 mM NaCl) conditions. These findings suggest that seaweeds is an effective biostimulant for improving early-stage growth and stress resilience in peanuts under saline conditions.Keywords

Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) holds an important place in the Turkish economy and agriculture. It can replenish soil by fixing N and adding carbon reserves by contributing positively to crop production [1]. It contains a high amount of protein, which can help overcome the country’s protein shortage, in the food industry [2]. Additionally, peanut production adds value to the national economy through its contributions to both domestic consumption and exports [3].

Soil salinity negatively affects plant yield and quality. Salt-affected agricultural lands are rapidly increasing due to global warming and climate change. Over 33% of irrigated lands worldwide are saline, with an annual increase of 1–2 million hectares of arable land. It is projected that 50% of arable land will be saline, posing a significant threat to agriculture and food security by 2050 [4]. High salinity in agricultural areas makes it difficult for plants to absorb water and nutrients, reduces productivity, and threatens the sustainability of agriculture [5]. Soil salinity problems are present in almost all irrigated areas of the world [6]. Inadequate drainage and inappropriate irrigation techniques cause an increase in soil salinity, thus negatively affecting crop productivity in arid and semi-arid regions [7]. High soil salinity makes it difficult for plants to absorb water through their roots [8]. High salt concentrations in soil cause osmotic stress, which inhibits root growth, reduces cell water content, disrupts plant water balance, creates nutrient imbalances, and leads to physiological drought [9]. Under extreme salinity conditions, plants can synthesize some osmotic regulators (such as proline and sugars) to maintain osmotic balance and protect cell membranes up to a certain threshold level [10]. Organic matters are important component of soil and they could be found with in natural aquatic, terrestrial and engineered, environments. Generally organic compounds are made up of decomposed plant and animal residues. They are composed of lignin, cutin, tannin, cellulose, etc., and various other carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids. They help nutrient movement and water retention in the soil. They help in the nutrient movement and retention of water in the soil [11]. The agricultural sector is grappling with reduced fertile soil availability and water scarcity due to climate change. To address this, soil amendments are being developed to increase water retention, protect crops from drought stress, control soil pH, and supply plant nutrients. Overuse of commercial fertilizers and slow-release fertilizers can cause water pollution. Alginate-based hydrogels, produced from natural carbohydrate alginate, can increase water retention and help maintain soil moisture during drought stress. However, limited research exists on using alginate hydrogels for fertilizer release [12]. Potassium leaching is common in lighter soils, and due to reduced fertilization and decreasing manure content, crop yield and quality are decreasing. Assessing if a crop needs extra potassium is crucial, as it reduces susceptibility to drought, frost, and fungi [12].

Peanut production adds value to the national economy through its contributions to both domestic consumption and exports [3]. Seaweeds are natural resources used as biostimulants in agriculture [13]. These extracts contain beneficial components such as growth-regulating hormones, minerals, vitamins, amino acids, and polysaccharides [14,15]. These also act as root growth promoters and help in water uptake, enhancing plant resilience to salinity stress [16]. Seaweeds contain minerals such as calcium, magnesium, potassium, and trace elements [17]. The antioxidants and osmoregulators contained in seaweeds strengthen the defense mechanism of plants against salinity stress [18]. They also protect cell membranes and protein structures from the harmful effects of salts. Seaweeds can improve the soil’s physical structure, increasing its water-holding capacity. This can provide more water to the root system of plants under saline conditions, increasing the plant’s resistance to drought and salinity [19].

Peanut is a crop of significant economic importance in agricultural production and is cultivated across diverse geographical regions [20]. However, environmental challenges such as climate change, increasing soil salinity, and water scarcity continue to adversely affect crop productivity. Biological additives such as seaweeds (algae) have been increasingly utilized to enhance plant tolerance to abiotic stress factors particularly salinity and to improve overall yield performance [21].

Meng et al. (2022) [22] demonstrated that peanut fertilized with seaweed liquid fertilizer exhibited superior growth performance compared to those without the use of any seaweed fertilizer in the control group. In particular, physiological and morphological parameters such as rate of photosynthesis, leaf chlorophyll contents, main stem height, lateral branch length, and dry matter accumulation were significantly higher in plants treated with seaweed fertilizer compared to untreated controls.

Numerous studies have also reported the beneficial effects of seaweed extracts on various crops, including legumes such as peanut [23]. Seaweed applications have been shown to alleviate salinity-induced water stress by improving the water use efficiency (WUE) of many plant species [24]. This effect is especially critical in regions where water resources are limited and soil salinity levels are high [18]. Research has indicated that under saline conditions, seaweed-treated plants tend to produce higher fruit and better crop yield [15,21].

According to Cruz et al., 2021 [25], the salinity threshold for peanut plants is 3.2 dS m−1. It is well known that the peanut plant is sensitive to salinity [26]. Seaweed has shown promising effects on plants grown under salt stress conditions. Particularly in the context of abiotic stress, the use of seaweed extracts has demonstrated positive results. For example, positive outcomes have been reported in tomato [27], rice [28], pepper [29], maize and cowpea [30], sugarcane [31], and soybean [32]. However, studies investigating the potential of seaweed applications to mitigate abiotic stress in peanut cultivation remain limited.

Salinity impacts legume productivity and distribution with legumes being sensitive or moderately resistant [33]. These stresses cause water deficit, oxidative stress, and reduced growth. Plants have a multilevel antioxidant system, and salt stress induces proline accumulation [34]. This study investigates abiotic stress responses in peanuts under different levels of salt stress and damage amelioration using seaweed extracts never studied earlier.

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the role of seaweed treatment in modulating the effects of varying salinity levels on the emergence and growth performance of four distinct peanut cultivars and focused on understanding how seaweed treatments can enhance plant resilience and development under salt-stress conditions.

Four different peanut varieties, ‘Ayse Hanım’, ‘Halis Bey’, ‘NC-7’, and ‘Albenek’ were tested in this study. These varieties were obtained from the Eastern Mediterranean Agricultural Research Institute Adana, Türkiye. The experiment was conducted under controlled conditions. This study was carried out in the greenhouses of the Department of Field Crops, Faculty of Agriculture, Ankara University.

The experiment had four replications and was conducted using five doses of NaCl. During the 6-week period, NaCl (Merck, Germany) solution was used as;

S0: Control (0 g L−1),

S1: 50 mmol NaCl (2.92 g L−1, EC = 4.39 mS cm−1),

S2: 100 mmol NaCl (5.84 g L−1, EC = 9.51 mS cm−1),

S3: 150 mmol NaCl (8.76 g L−1, EC = 14.85 mS cm−1),

S4: 200 mmol NaCl (11.68 g L−1, EC = 19.61 mS cm−1) was applied for irrigation once.

The commercial solid seaweed (SW) preparation, (L Ocean Premium Agricultura, Antalya, Türkiye) was used as a biostimulant. In the experiment, 5 g L−1 seaweed was applied to the seedbeds during sowing as a biostimulant by uniform manual mixing it to facilitate seed hydration; which contained 45% organic matter, 2% alginic acid, 15% water soluble K2O at pH of 7–9.

Seaweeds treatment:

Seaweed0: Non-treated (Control group),

Seaweed1: 5 g L−1 (EC = 2.044 mS cm−1).

Four replications were conducted, with twenty-five seeds sown at a depth of 2 cm in each tray (60 × 40 × 10 cm) filled with peat in a controlled greenhouse. Each plastic tray was irrigated with 2000 mL of distilled water ever week to manage the loss of water without affecting concentration of salt in the peat substrate. Loss of water through evapotranspiration from plants was also managed by spray of aspirin (Acetyl salicylic acid) on the plants [35]. The greenhouse temperature was set at 24 ± 1°C, with relative humidity of 50%. The photoperiod was set to 16 h of light and 8 h of darkness, with a light intensity of 45 μmol m−1 s−1.

Mean Emergence Time (MET): This was calculated following Day and Koçak-Şahin [36]:

Emergence Percentage (EP): This was calculated as described by Day and Koçak-Şahin [36]:

2.2 Measurement of Morphological Parameters

The response of peanut cultivars to seaweeds and salinity during early growth was measured from 15 randomly selected plants. After 42 days in the greenhouse, the shoot, root, and plant fresh weights, as well as plant dry weight, were measured from 15 randomly selected plants. Plant fresh weights were recorded immediately after the experiment to avoid any weight loss [37]. Plant dry weight was determined after drying the plants at 72°C for 72 h [38].

2.3 Chlorophyll Contents (SPAD-Unit)

The chlorophyll was measured using the SPAD-502 Plus (Konica Minolta) apparatus on five plant leaves from each plant [38].

2.4 Crude Protein Ratio (CPR %)

Crude protein (CP) analyses were performed by the Dumas method according to AACCI method 46–30, employing a Velp brand NDA-701 model automatic nitrogen analyzer [39].

2.5 Determination of Proline (μg/g Dw)

The method used by Karabal et al. [40] was used with modifications for determining the amount of proline. 0.05 g of dried leaf samples was crushed by a mortar using 5 mL of 3% sulfosalicylic acid solution. The extract was then centrifuged at 15,000× g for 10 min at room temperature. Two millilitres of the supernatant was added to each tube in duplicate, followed by the addition of 2 mL of glacial acetic acid, and 2 mL of a solution of acetic acid, phosphoric acid, and ninhydrin. The tubes were then mixed. The tubes were boiled for one hour, after which they were cooled suddenly. Thereafter, 4 mL of toluene was added to the samples, which were then mixed. The toluene layer was transferred to a glass cuvette and read at 520 nm. Standard solutions were prepared to determine the proline concentration. The absorbencies of the diluted stock solutions were measured using spectrophotometer. The resulting graph was used as a reference, and the concentration was calculated using the equation of this line.

The mineral content (Sodium, Calcium, Magnesium, Potassium, Phosphorus, Iron, Manganese, Zinc, Copper) of the plant samples was determined using an ICP-OES (Inductively Coupled Plasma Spectrophotometer) (PerkinElmer Optima 2100 DV ICP/OES, Shelton, CT 06484-4794, USA) after wet digestion with nitric acid and perchloric acid [41,42].

The data were evaluated using the analysis of variance technique in a two-factorial split-plot design with four replicates, and significant differences were determined using the Duncan’s Multiple Range Test. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 17.0 (Chicago, IL, USA), and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The salt stress treatment doses (0, 50, 100, 150, and 200 mM) were assigned to the main plots as the first factor, and the seaweed treatment (0 and 5 g L−1) was allocated to the subplots (split plots) as the second factor. Salt applications (n = 5) in peanut varieties (n = 4) and Seaweed application (n = 2) were visualized using a heatmap. The heatmap was plotted using the ‘pheatmap’ R package (version 1.0.12) [43]. The correlations between parameters were visualized using the ‘ggcorrplot’ R package (version 0.1.4.1) [44].

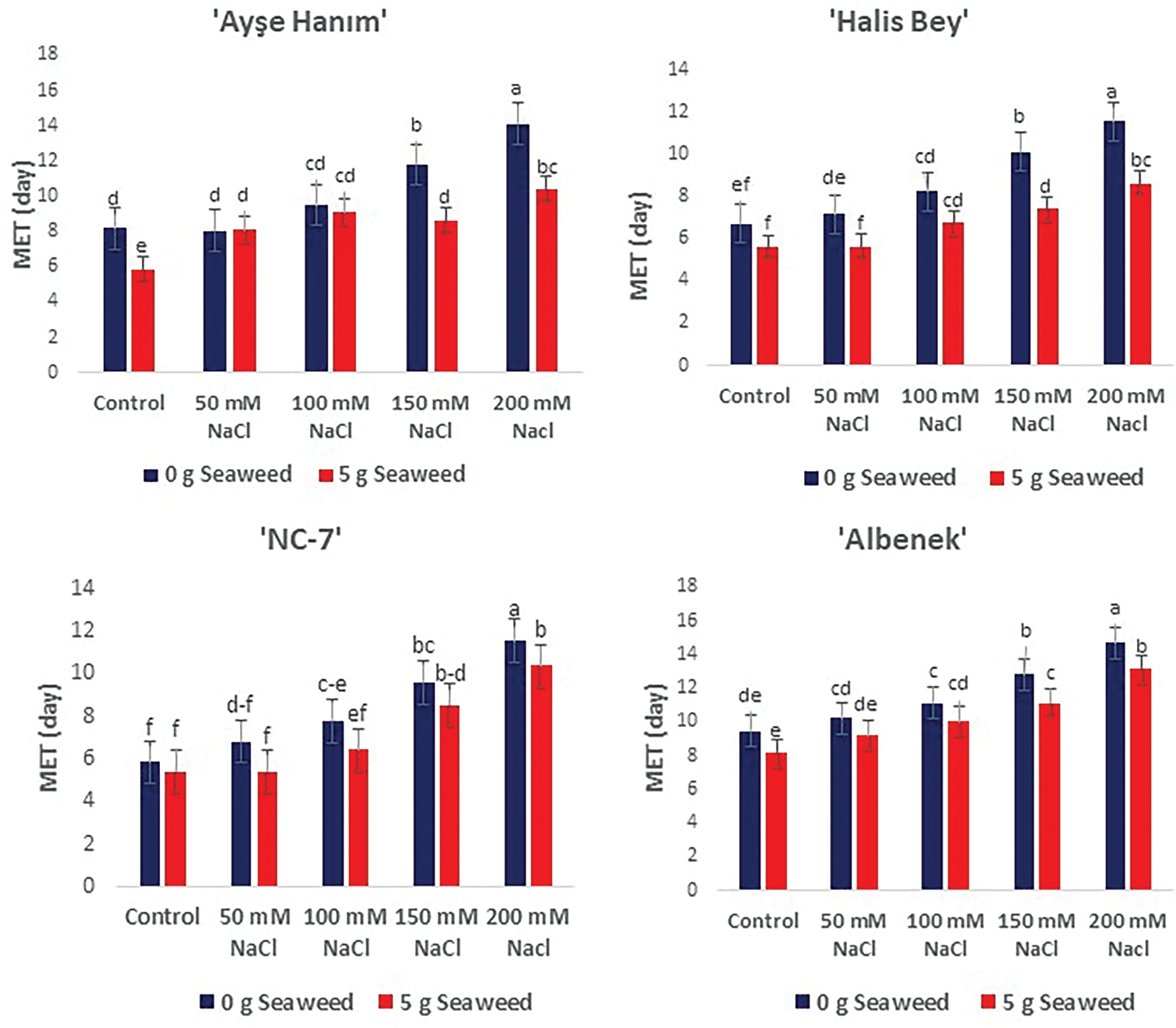

The effect of seaweed application on the emergence parameters of peanut seeds subjected to salinity stress is illustrated in Fig. 1. Significant differences (p < 0.05) were observed in the mean emergence time (days) of the four cultivars studied regarding the ameliorative effect of seaweed on salinity stress. All cultivars experienced delayed emergence as salinity stress increased. However, seaweed-treated seeds emerged earlier than the Control groups, even under stress conditions.

Figure 1: The effects of seaweed treatment on the mean emergence time (MET) (days) of 4 peanut varieties (‘Ayse Hanım’, ‘Halis Bey’, ‘NC-7’, and ‘Albenek’) under different levels of salt stress. Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences among treatments, as determined by Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (p < 0.05). Error bars represent standard errors of means (n = 4)

The fastest emergence was observed in the cv. ‘NC-7’, cv. ‘Halis Bey’, cv. ‘Ayse Hanım’, and cv. ‘Albenek’ treated with 0 mM NaCl × 5 g L−1 seaweed application, while the slowest germination occurred in the cv. ‘Albenek’, cv. ‘Ayse Hanım’, cv. ‘Halis Bey’, and cv. ‘NC-7’ under 200 mM salinity stress, respectively.

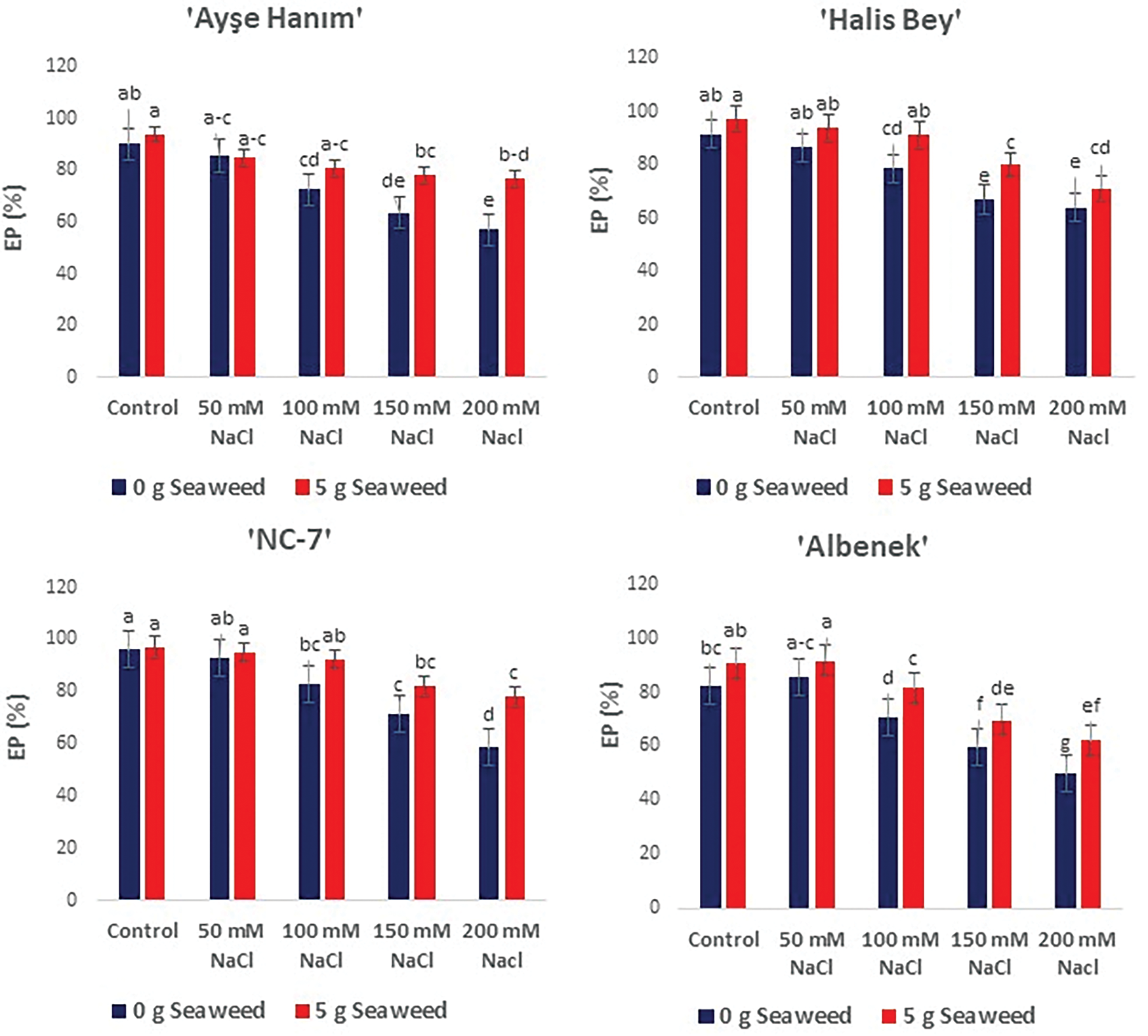

Significant differences (p < 0.05) were observed in the mean emergence percentage (%) of the four cultivars studied to find the the ameliorative effect of seaweed on salinity stress. All cultivars experienced reduced emergence percentage as salinity stress increased. However, seaweed-treated seeds showed higher emergence compared to the non sea weed treated seeds, even under stress conditions (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: The effects of seaweed treatment on the mean emergence percenage (EP) (%) of 4 peanut varieties varieties (‘Ayşe Hanım’, ‘Halis Bey’, ‘NC-7’, and ‘Albenek’) under different levels of salt stress. Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences between treatments, as determined by Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05). Error bars represent standard errors of means (n = 4)

When comparing peanut seeds treated with seaweed and non-treated seeds; the ‘Ayse Hanım’, ‘Halis Bey’, ‘NC-7’, and ‘Albenek’ increased by 4.0, 6.5, 1.1, and 9.8%, respectively, under the controlled (0 mM NaCl) conditions. When compared with the performance of 200 mM salt treated and untreated peanut seeds of the Ayse Hanım showed improvement by 34.7%, Similarly, Halis Bey had improvement of 11.5%. Whereas, ‘NC-7 and ‘Albenek had improvement of 33.3%, and 24.9%, respectively (Fig. 2).

3.3 Measurement of Morphological Parameters

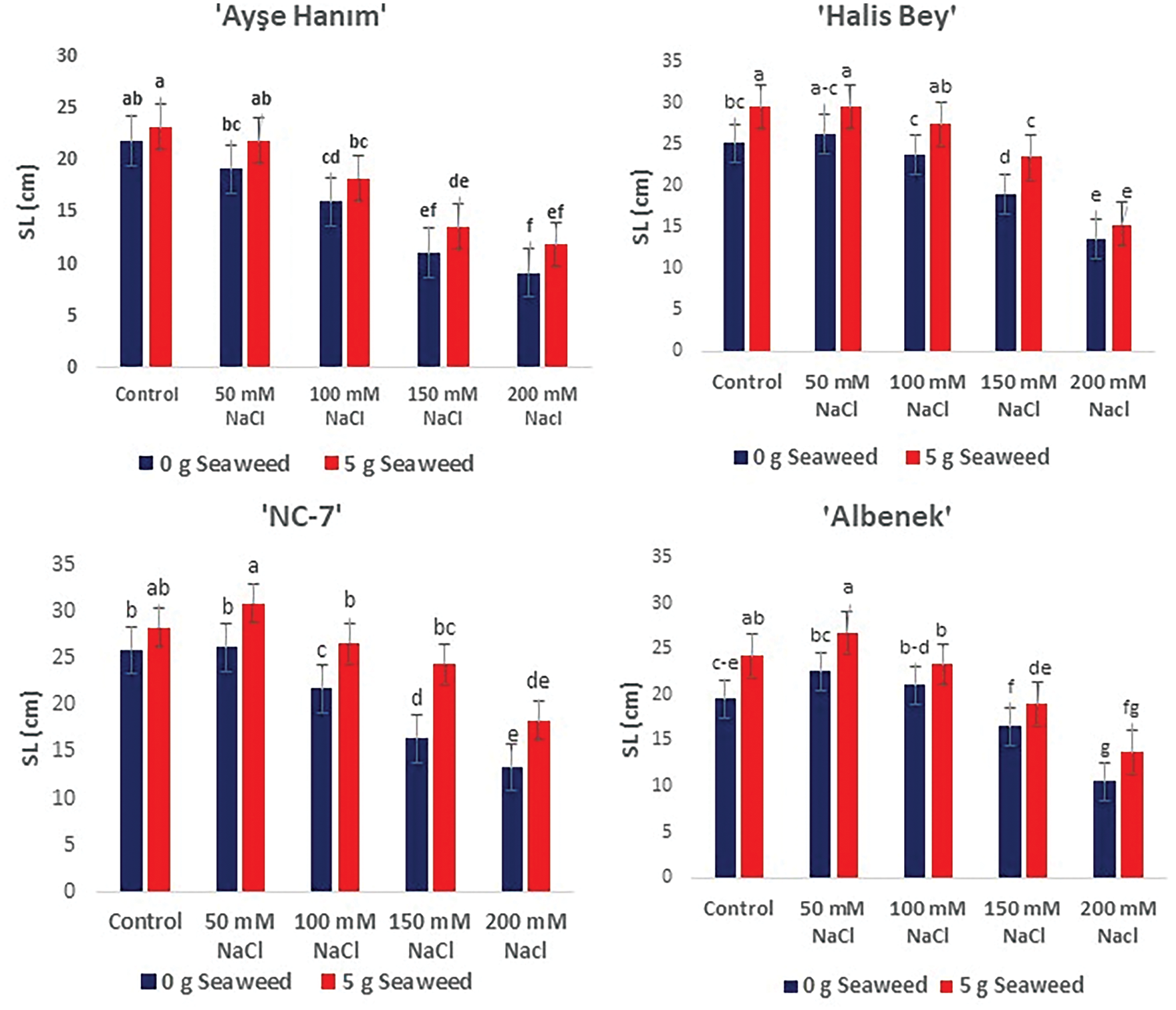

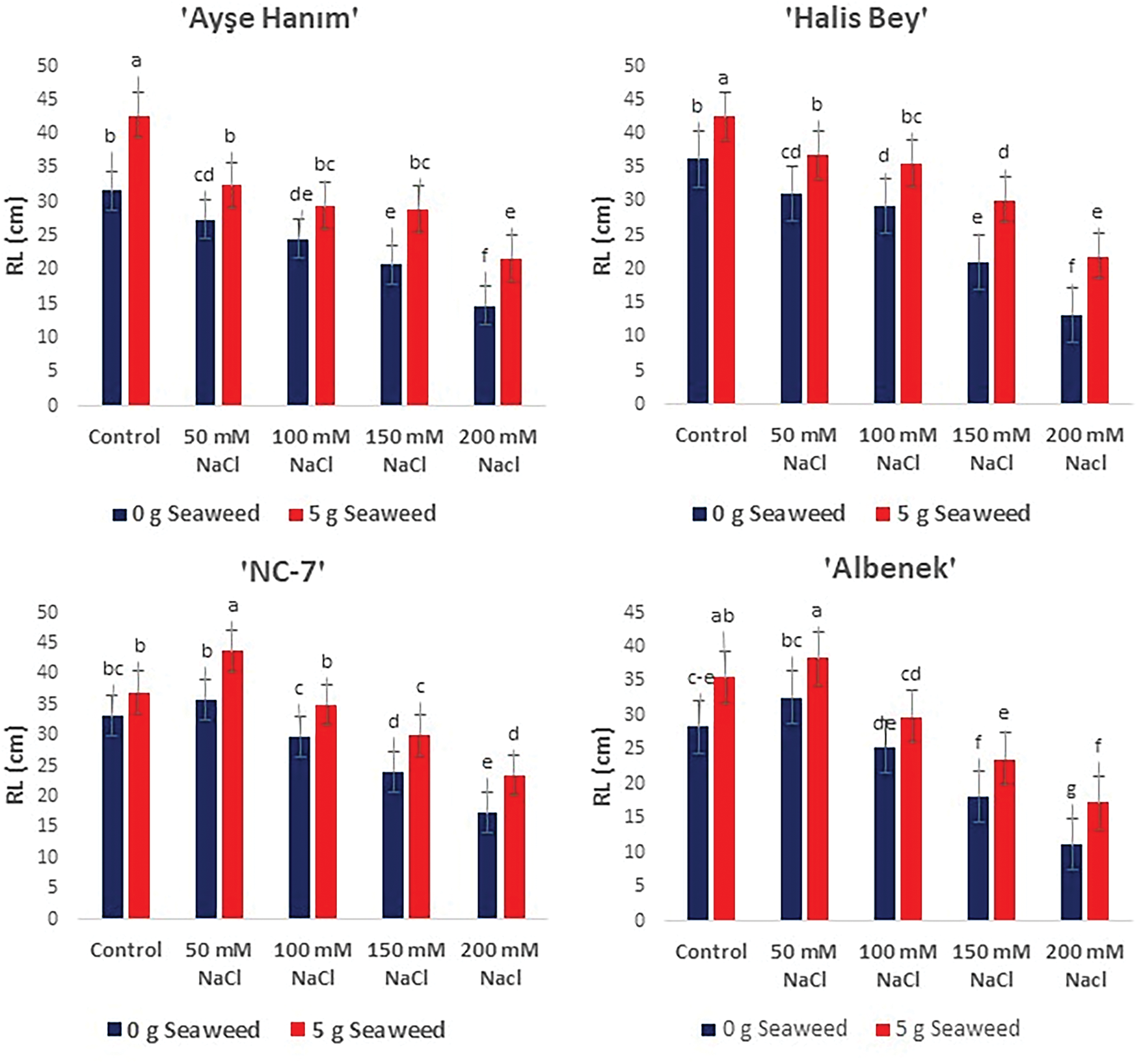

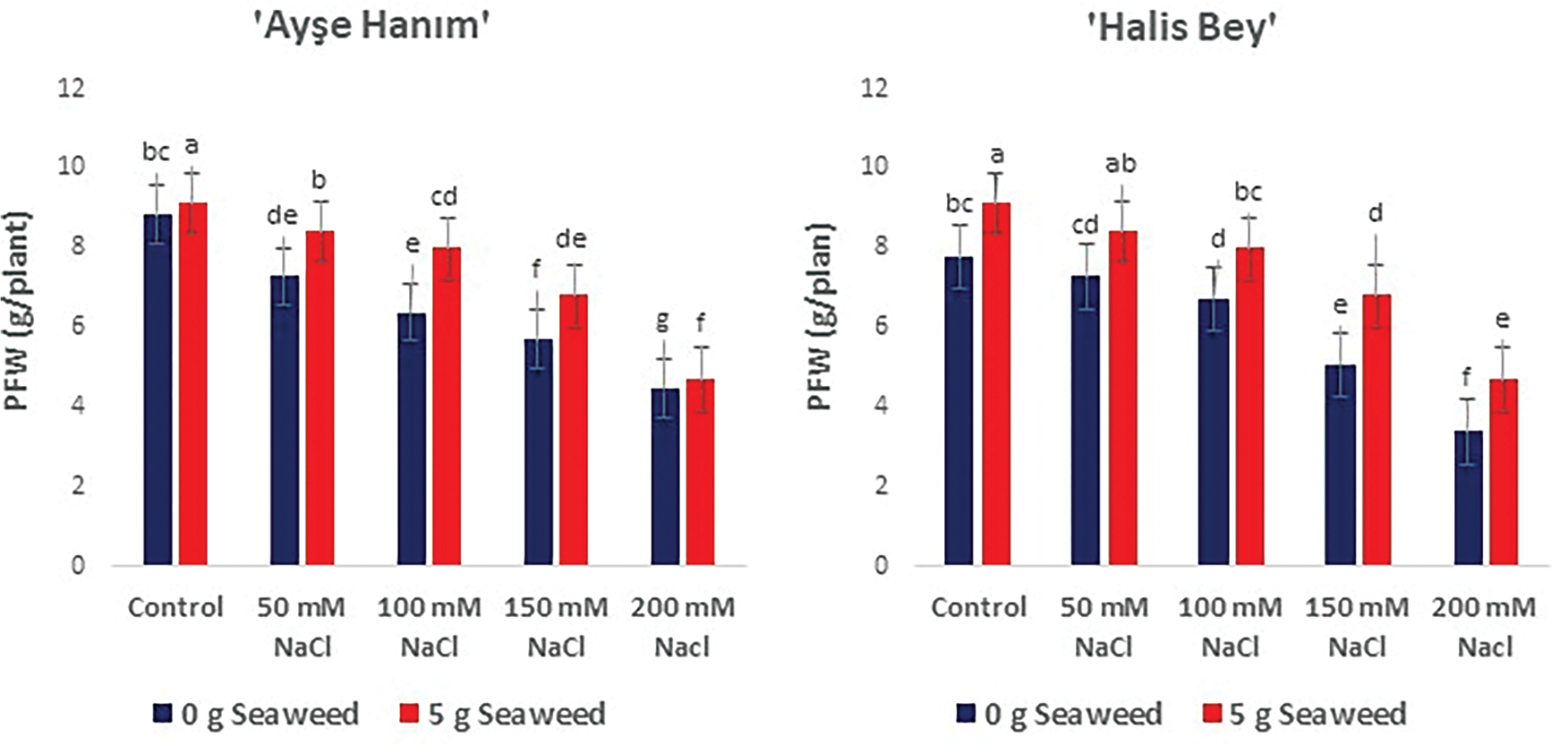

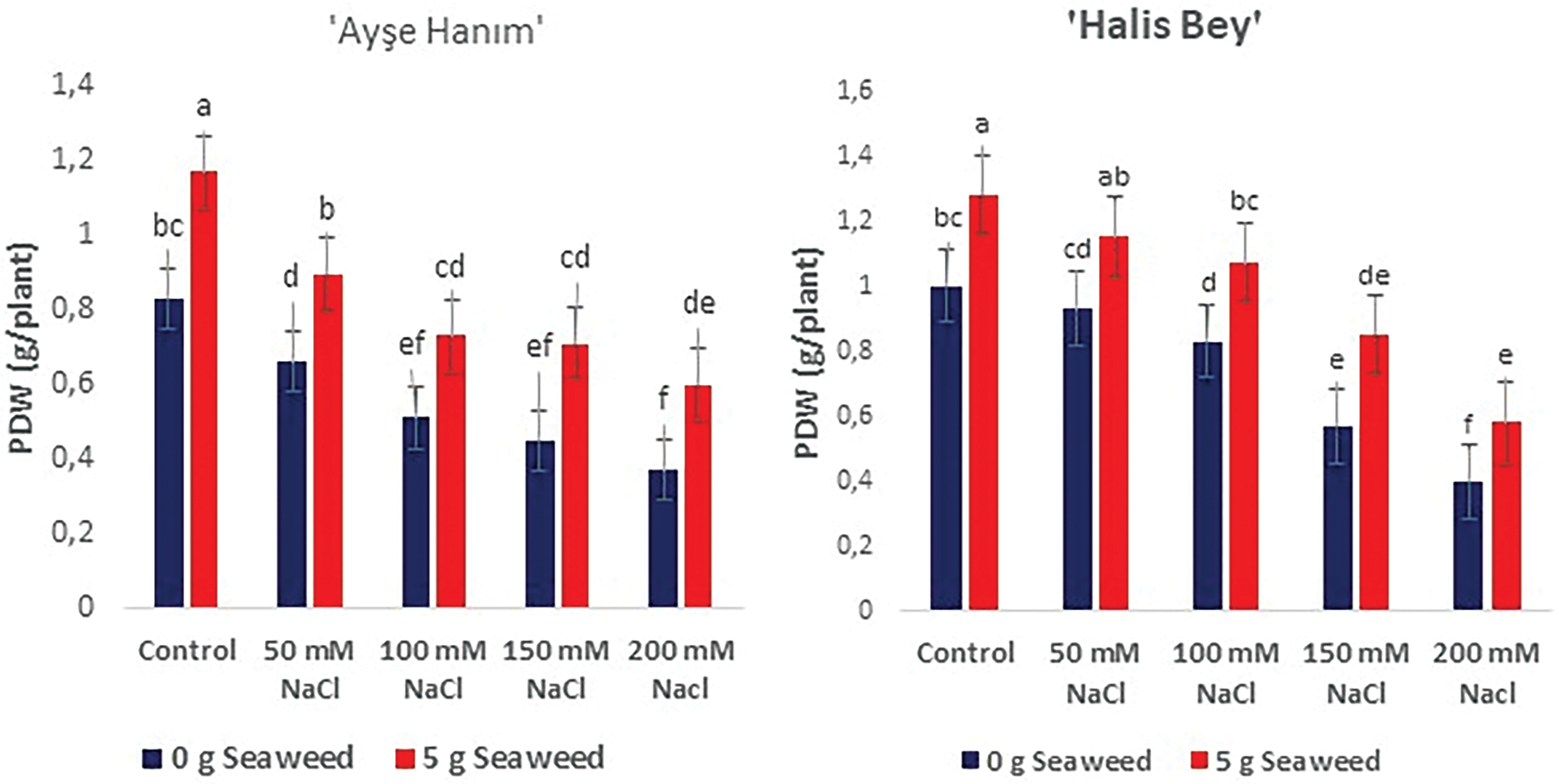

As given in Figs. 3–5, shoot/root length, and plant fresh weight decreased significantly (p < 0.05) with increasing salinity stress. Under non stress conditions, seaweed-treated seeds had higher shoot/root length, and plant fresh weight compared to salt treated seeds. When the results obtained were compared within the treatments, the minimum shoot/root length (cm) and plant fresh weight (g plant−1) were noted from the 200 mM NaCl treatment in all varieties, the maximum shoot/root length (cm) and plant fresh weight (g plant−1) were exhibited from the 50 mM NaCl × Sw treatment in the ‘NC-7’ and ‘Albenek’ varieties, and the 0 mM NaCl (Control) × 5 g L−1 Sw treatment in the ‘Ayse Hanım’ and ‘Halis Bey’ varieties, respectively.

Figure 3: The effects of seaweed treatment on shoot length (cm) of 4 peanut varieties (‘Ayşe Hanım’, ‘Halis Bey’, ‘NC-7’, and ‘Albenek’) under different levels of salt stress. Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences between treatments, as determined by Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05). Error bars represent standard errors of means (n = 4)

Figure 4: The effects of seaweed treatment on the mean root length (cm) of 4 peanut varieties (‘Ayşe Hanım’, ‘Halis Bey’, ‘NC-7’, and ‘Albenek’) under different levels of salt stress. Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences between treatments, as determined by Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05). Error bars represent standard errors of means (n = 4)

Figure 5: The effects of seaweed treatment on the plant fresh weight (g plant−1) of 4 peanut (‘Ayse Hanım’, ‘Halis Bey’, ‘NC-7’, and ‘Albenek’) under different levels of salt stress. Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences between treatments, as determined by Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05). Error bars represent standard errors of means (n = 4)

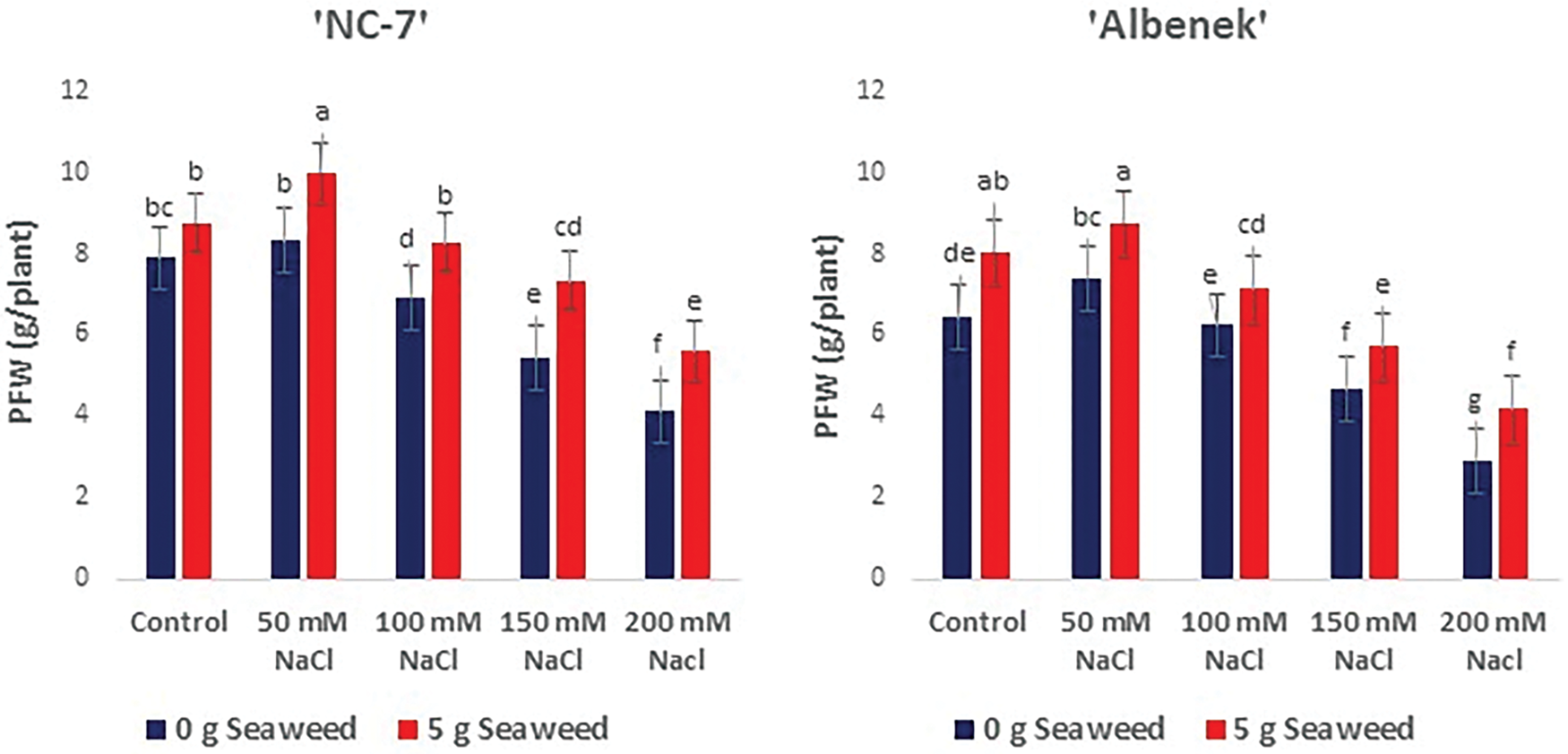

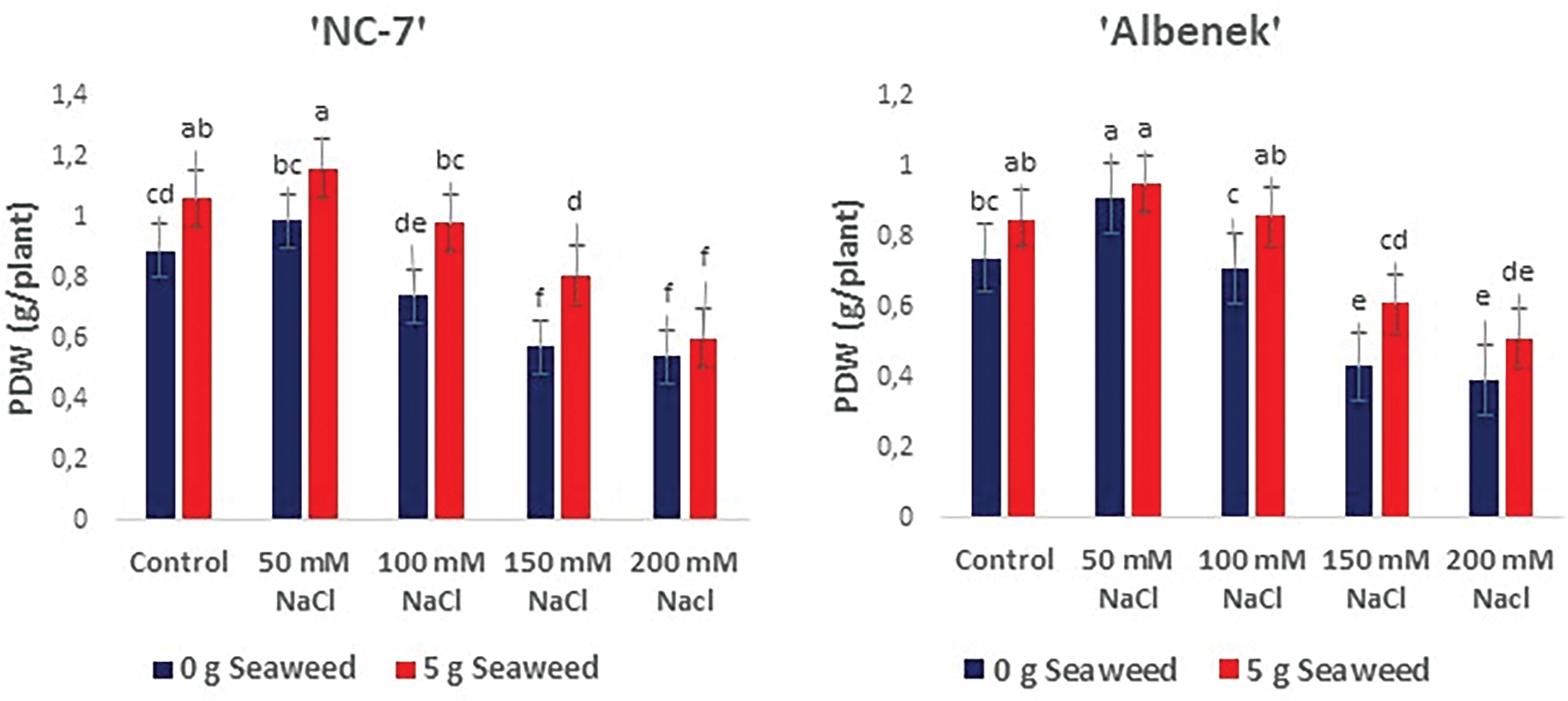

Seaweed treatment improved dry weights (g plant−1) under the same stress conditions. The obtained plant dry weight data were statistically affected (p < 0.05) by seaweed treatment under the same salinity conditions. The maximum plant dry weight (g plant−1) was recorded from 50 mM NaCl × 5 g L−1 treatment in cv. ‘NC-7’ and cv. ‘Albenek’, while it was noted from 0 mM NaCl (Control) × 5 g L−1 treatment in cv. ‘Ayse Hanım’ and cv. ‘Halis Bey’ (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: The effects of seaweed treatment on the plant dry weight (g plant−1) of peanut varieties (‘Ayse Hanım’, ‘Halis Bey’, ‘NC-7’, and ‘Albenek’) under Salt stress. Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences between treatments, as determined by Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05). Error bars represent standard errors of means (n = 4)

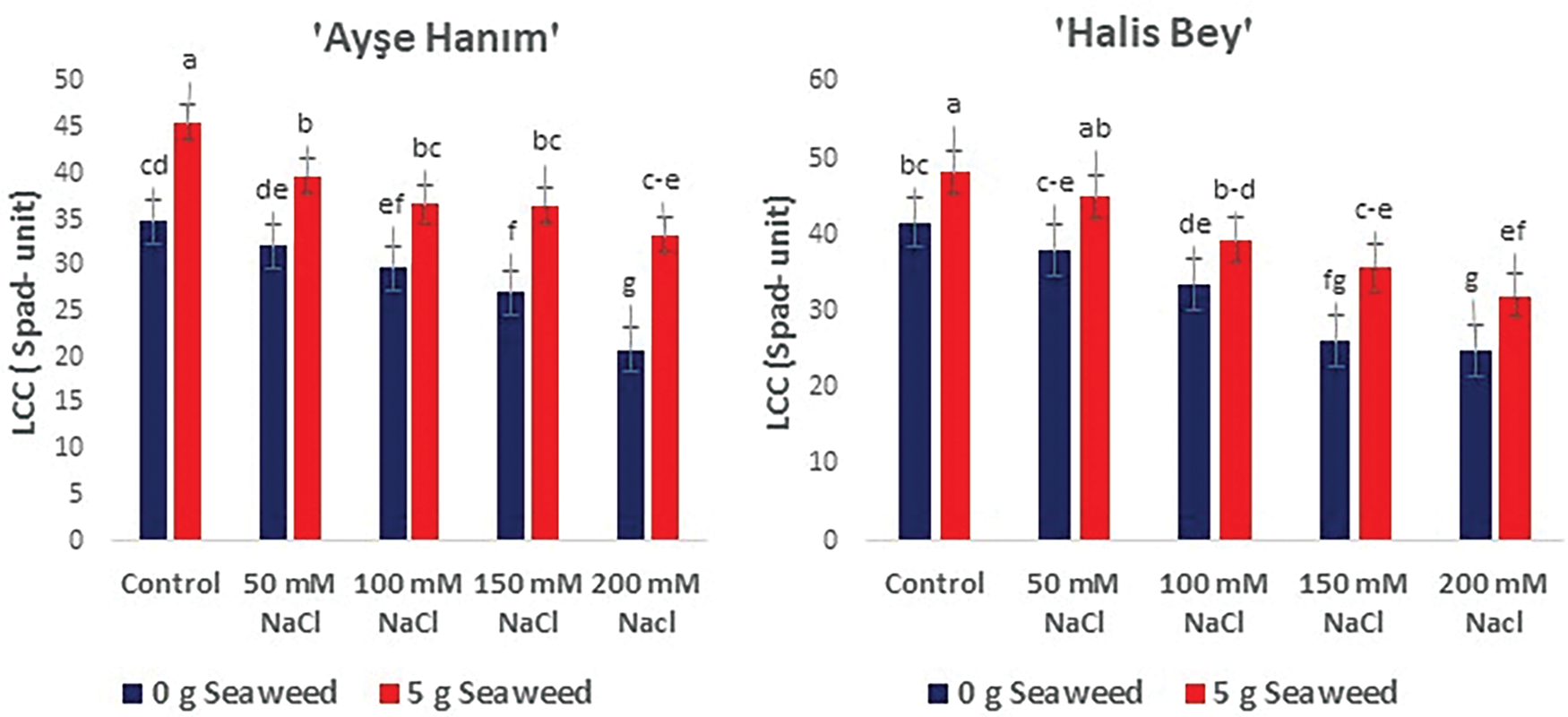

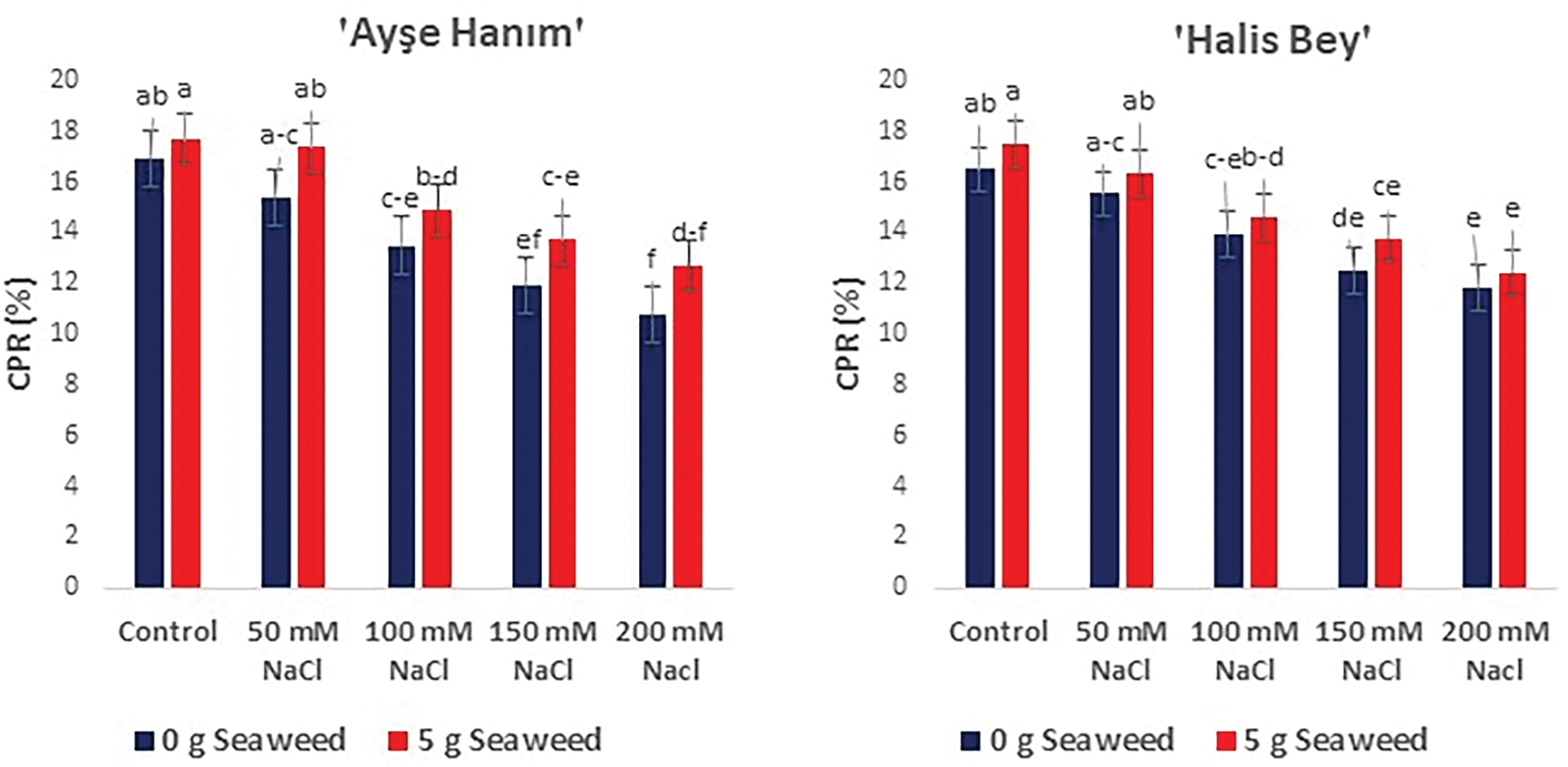

3.4 Chlorophyll Contents (LCC) (SPAD-Unit)

The analysis of variance revealed that the interaction between salinity and seaweed had a significant effect on the content of chlorophyll in the leaves (p < 0.05). In all cultivars, the amount of chlorophyll in the leaves reduced as the salinity increased. However, applying seaweed increased the amount of chlorophyll contained in the leaves. The highest leaf chlorophyll measurement was obtained from 0 mM NaCl (Control) ×5 g L−1 seaweed treatment in cv. ‘NC-7’, in cv. ‘Halis Bey’, and in cv. ‘Ayse Hanım’, but cv. ‘Albenek’ was noted with 50 mM NaCl (Control) × 5 g L−1 seaweed. The lowest leaf chlorophyll measurements were exhibited from 200 mM NaCl treatment, and cv. ‘Ayse Hanım’ was followed by cv. ‘Albenek’, cv. ‘NC-7’, and cv. ‘Halis Bey’ (Fig. 7).

Figure 7: The effects of seaweed treatment on the plant leaf chlorophyll content of peanut varieties (‘Ayse Hanım’, ‘Halis Bey’, ‘NC-7’, and ‘Albenek’) under Salt stress. Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences between treatments, as determined by Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05). Error bars represent standard errors of means (n = 4)

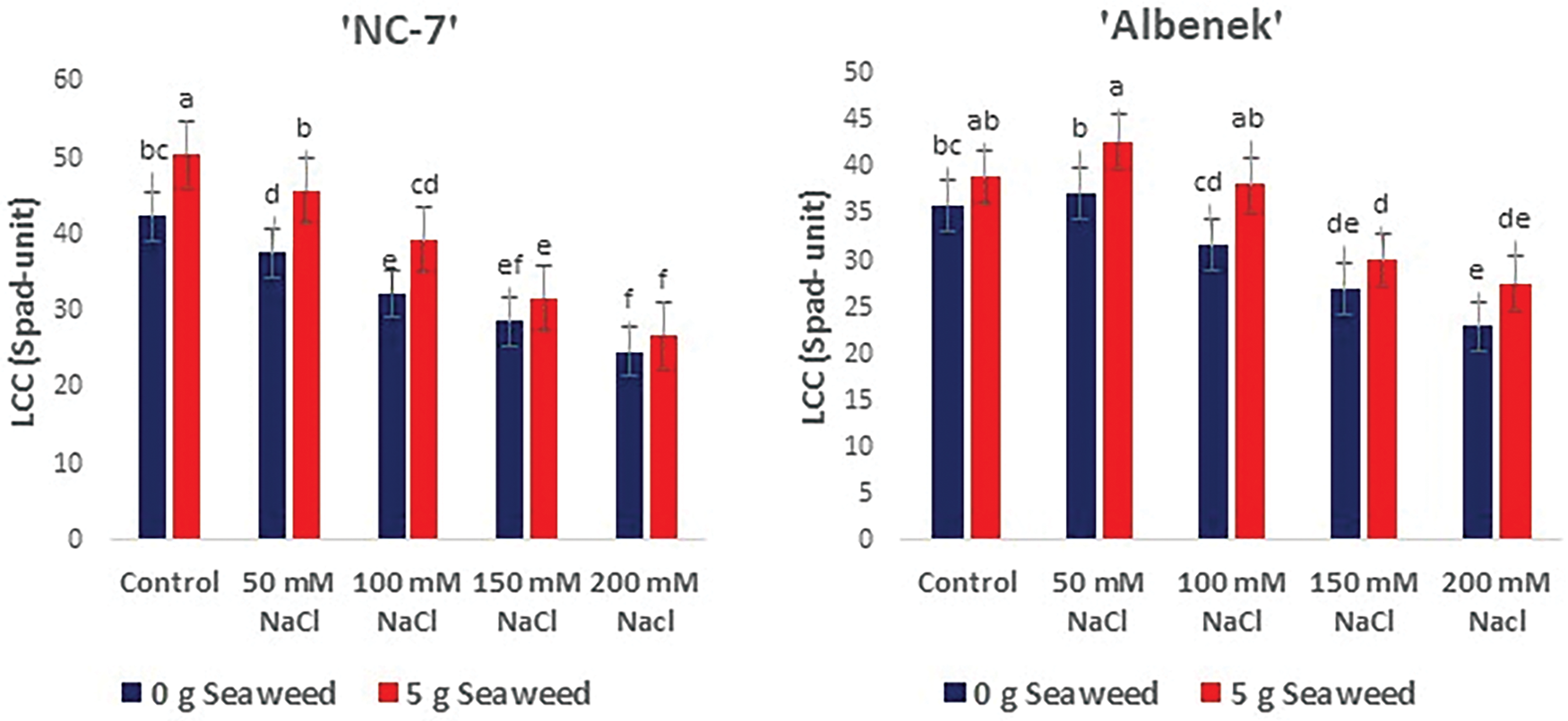

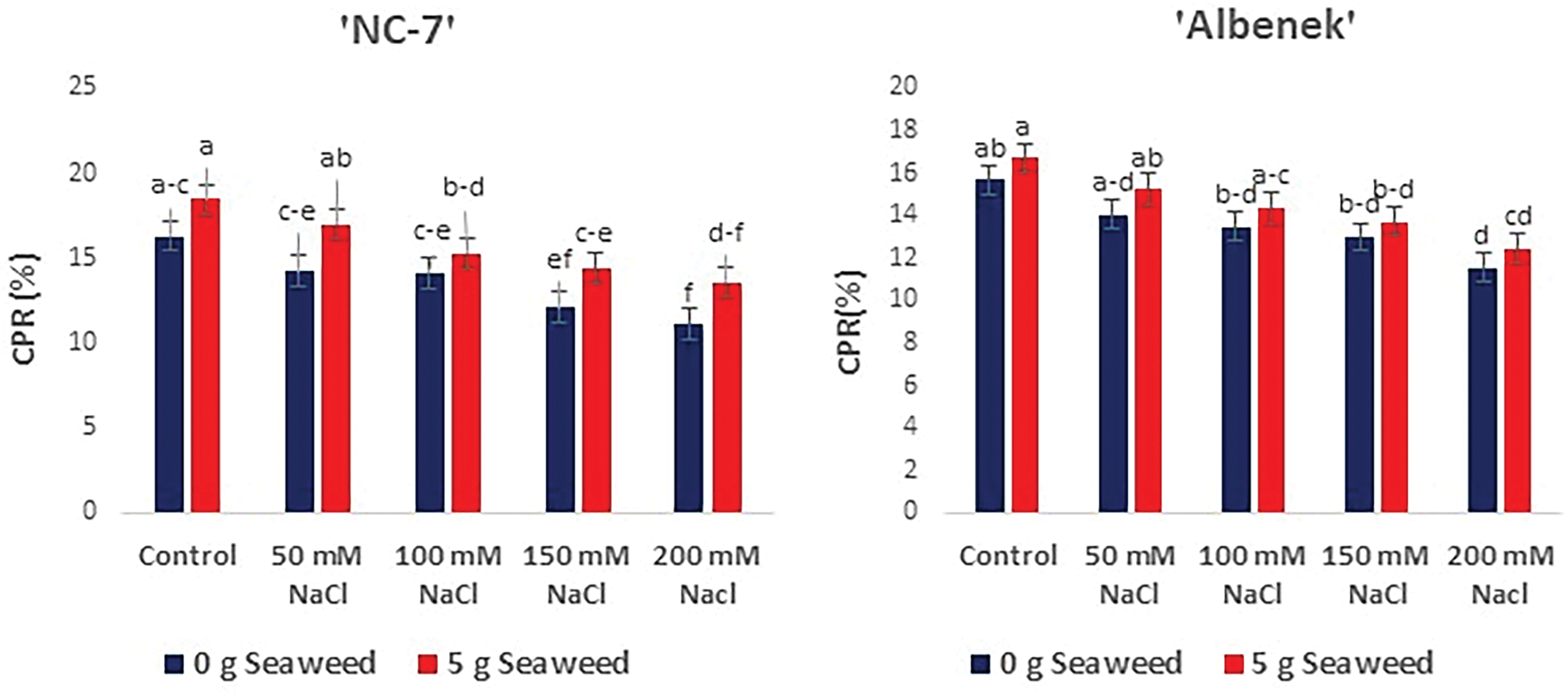

3.5 Crude Protein Ratio (CPR) (%)

ANOVA revealed that increasing salt stress had a detrimental effect on the crude protein content (%) of the leaves; however, seaweed application mitigated this effect (p < 0.05) (Fig. 8). The maximum crude protein content was obtained in cv. ‘NC-7’ under 0 mM NaCl (Control) × 5 g L−1 seaweed treatment, followed by cv. ‘Ayse Hanım’ cv. ‘Halis Bey’ and cv. ‘Albenek’, respectively. The minimum crude protein content was recorded under 200 mM NaCl stress in all varieties.

Figure 8: The effects of seaweed treatment on the crude protein ratio (CPR) (%) of peanut varieties (‘Ayse Hanım’, ‘Halis Bey’, ‘NC-7’, and ‘Albenek’) under salt stress. Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences between treatments, as determined by Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05). Error bars represent standard errors of means (n = 4)

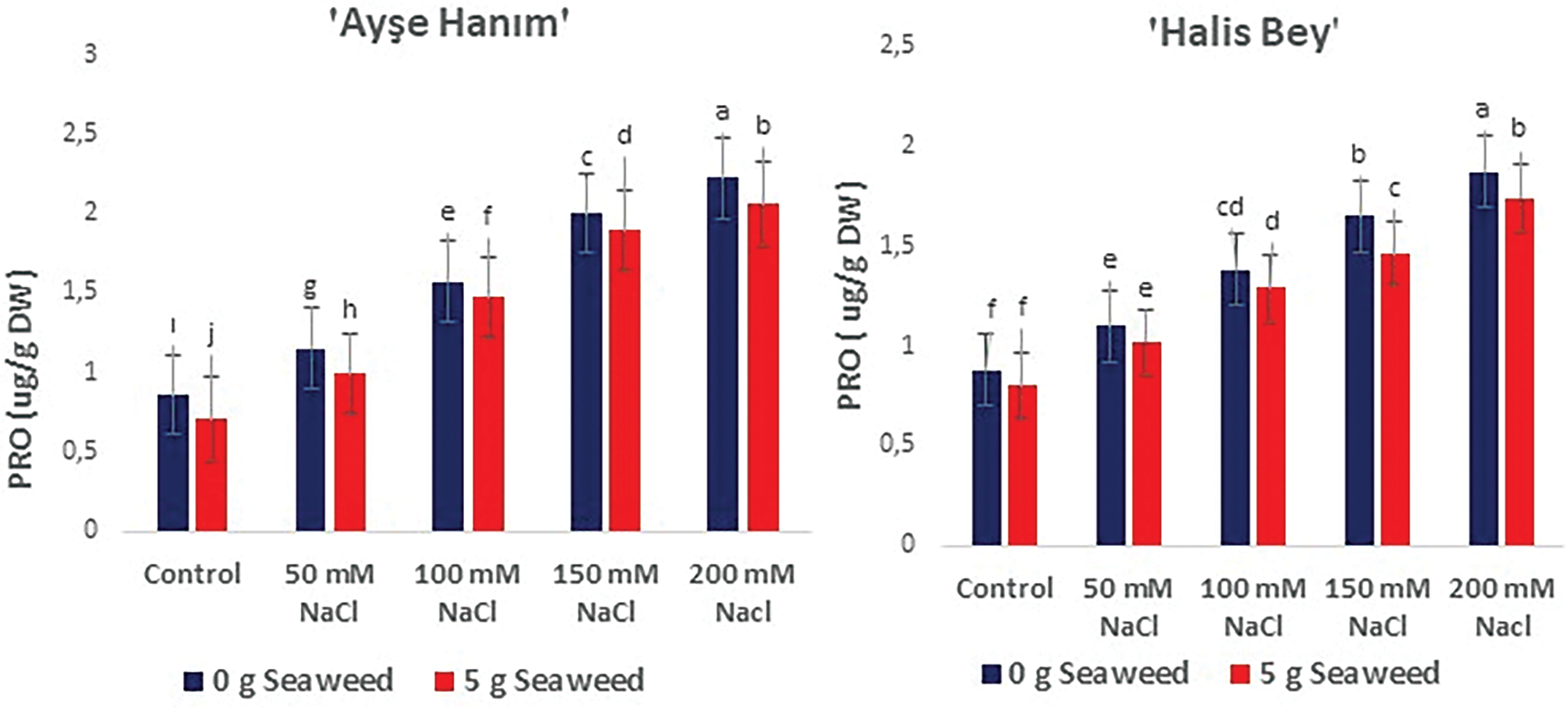

3.6 Determination of Proline (PRO) (μg−1 DW)

The impact of seaweed treatment on proline (μg g−1 DW) levels in peanut plants subjected to Salt stress is presented in Fig. 9. Proline concentration in the leaves increased with escalating salinity stress (50, 100, 150, and 200 mM); however, this detrimental effect was mitigated by seaweed treatment (p < 0.05). The highest proline content was recorded in all varieties under 200 mM NaCl salinity conditions. The ameliorative effect of seaweed application under the same stress conditions is clearly visible in Fig. 9. The lowest proline content was obtained in cv. ‘NC-7’, followed by cv. ‘Ayse Hanım’ and cv. ‘Halis Bey’, and cv. ‘Albenek’ under 0 mM NaCl (control) × 5 g L−1 seaweed treatment.

Figure 9: The effects of seaweed treatment on the proline (PRO) (μg g−1 Dw) of peanut varieties (‘Ayse Hanım’, ‘Halis Bey’, ‘NC-7’, and ‘Albenek’) under Salt stress. Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences between treatments, as determined by Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05). Error bars represent standard errors of means (n = 4)

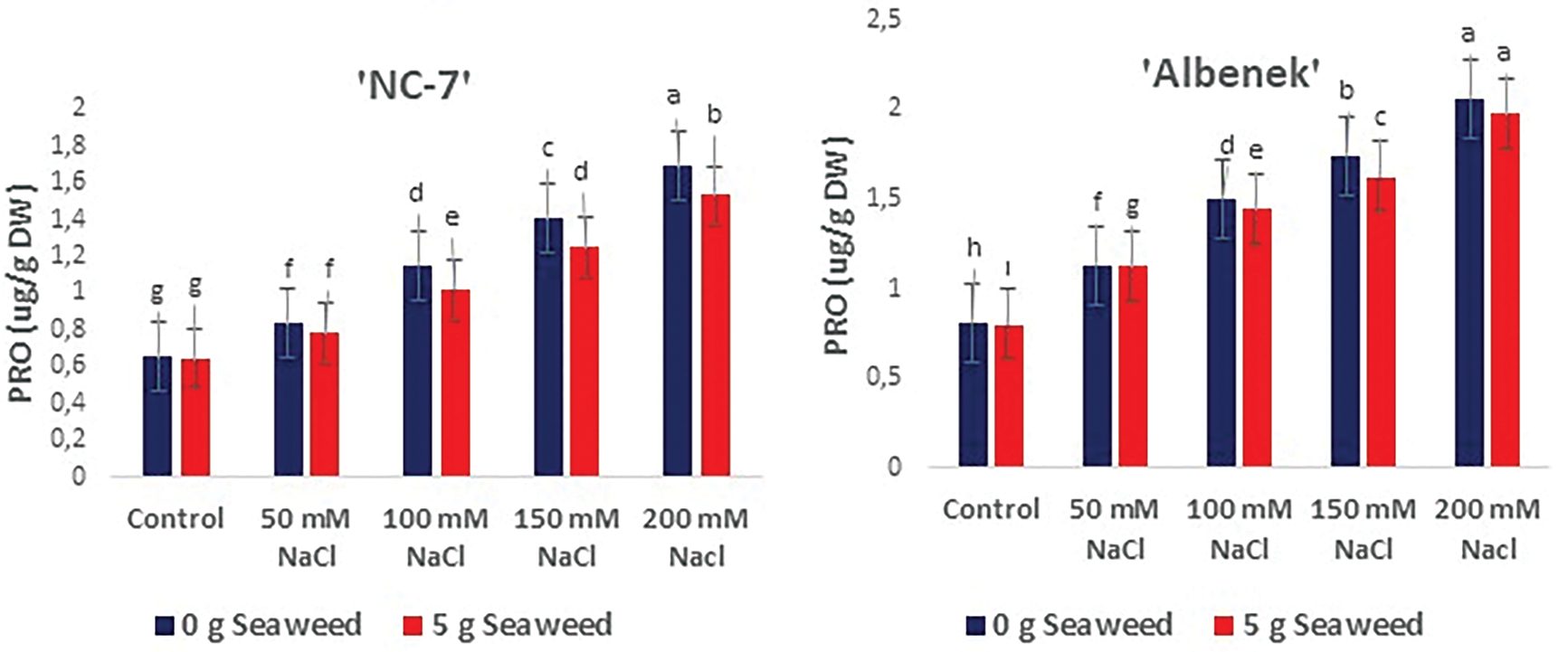

The effects of seaweed application on the mineral contents of peanut cultivars under salinity stress are given in detail in Table 1. The results showed that the leaf mineral concentrations (Na, Ca, K, P, Mg, Zn, Mn, Cu, Fe) of peanut cultivars was affected in statistically significant manner (p < 0.05) by increasing salinity stress. In four varieties, the application of seaweed had a statistically significant and positive impact, particularly on potassium (p < 0.05). The impact of seaweed on other mineral contents was also found to be statistically significant (p < 0.05) for iron and magnesium in the cv. ‘Halis Bey’, phosphorus in the cv. ‘NC-7’, manganese and zinc in the cv. ‘Ayse Hanım’, and iron in the cv. ‘Albenek’. When the interaction between seaweed treatment and salinity was analyzed, the effects could be statistically distinguished and sharp differences could be noted across different varieties. In the Ayşe Hanım variety, the interaction had a significant effect on leaf copper contents. In the cv. ‘Halis Bey’, significant effects were obtained for magnesium, copper, and iron contents. For the cv. ‘NC-7’, the interaction significantly influenced potassium and copper levels, whereas in the cv. ‘Albenek’, a significant effect was observed only for iron contents.

The highest Na content was observed in the 200 mM NaCl × 5 g L−1 treatment in cv. ‘Albenek’, fol-lowed by cv. ‘Halis Bey’, cv. ‘NC-7’, and cv. ‘Ayşe Hanım’, respectively. The maximum Ca content was recorded from the Control × 5 g L−1 treatment in cv. ‘NC-7’, followed by cv. ‘Halis Bey’, cv. ‘Albenek’, and cv. ‘Ayşe Hanım’, respectively. The highest K content was noted in the 0 mM NaCl (Control) × 5 g L−1 treatment in cv. ‘Ayşe Hanım’, followed by cv. ‘Halis Bey’ and cv. ‘Albenek’, while the treatment also yielded notable K content in cv. ‘NC-7’. The maximum Mg content was obtained from the 0 mM NaCl (Control) treatment in cv. ‘Halis Bey’ and cv. ‘Ayşe Hanım’, whereas the 0 mM NaCl (Control) × 5 g L−1 treatment produced the highest Mg content in cv. ‘NC-7’ and cv. ‘Albenek’. The highest P content was noted in the 0 mM NaCl (Control) treatment in cv. ‘NC-7’, cv. ‘Ayşe Hanım’, and cv. ‘Albenek’, while it was also recorded from the 0 mM NaCl (Control) × 5 g L−1 treatment in cv. ‘NC-7’. The highest Zn con-tent was recorded in the 0 mM NaCl (Control) × 5 g L−1 treatment in cv. ‘Ayşe Hanım’, cv. ‘Halis Bey’, and cv. ‘Albenek’, while it was also observed in cv. ‘NC-7’ under the same treatment. The highest Mn content was obtained from the 50 mM NaCl × 5 g L−1 treatment in cv. ‘NC-7’, followed by cv. ‘Halis Bey’, cv. ‘Ayşe Hanım’, and cv. ‘Albenek’, respectively. The maximum Cu content was observed in the 0 mM NaCl (Control) treatment across all varieties. The highest Fe content was recorded in the 0 mM NaCl (Control) × 5 g L−1 treatment in cv. ‘Ayşe Hanım’, while the highest Fe content in cv. ‘NC-7’, cv. ‘Al-benek’, and cv. ‘Halis Bey’ was obtained from the 0 mM NaCl (Control) treatment.

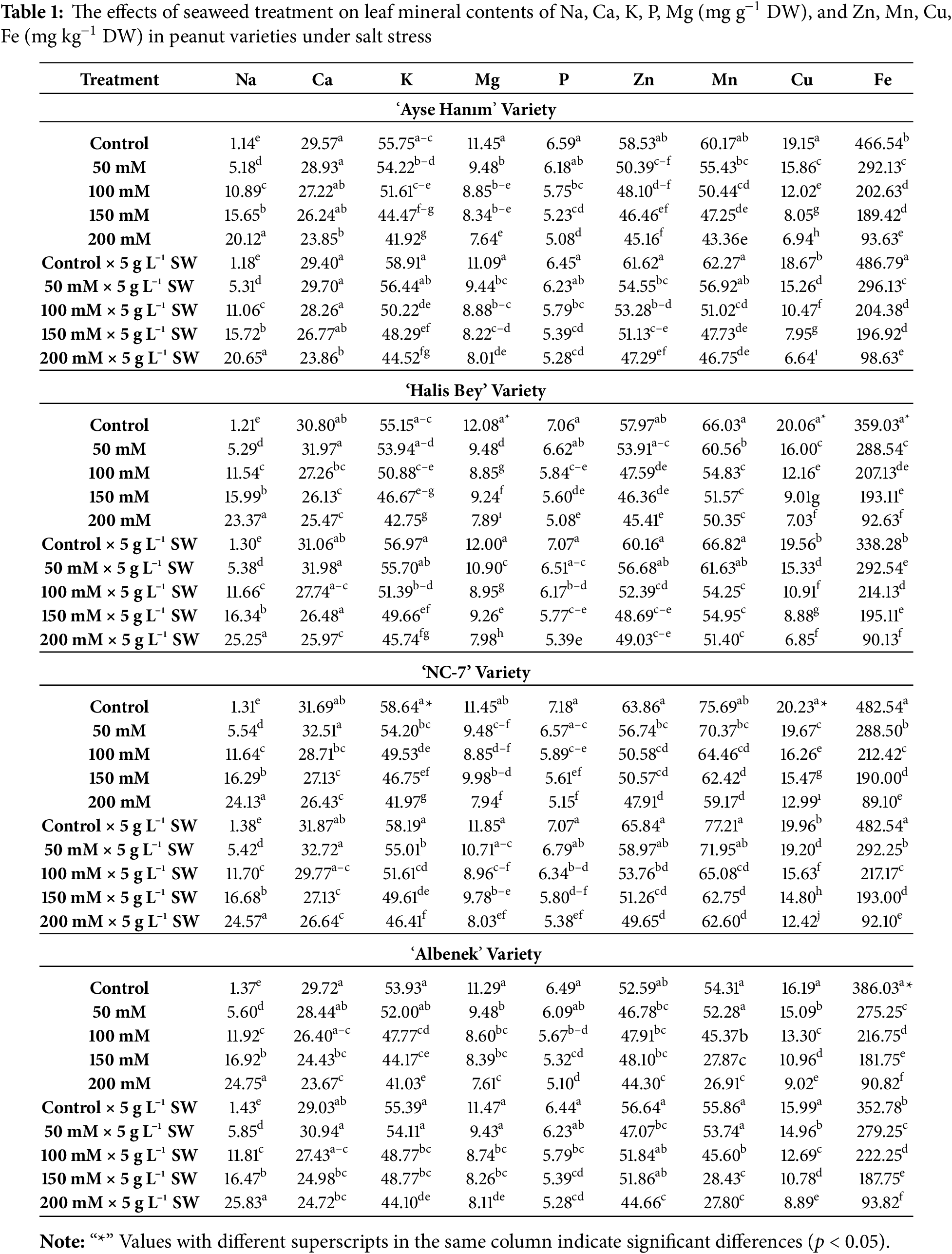

The heatmap visualization of the parameters of the peanut varieties is partitioned in Fig. 10. Heatmap showing z-score normalized values of physiological and biochemical traits measured in four peanut varieties under different salinity levels (S0–S4) with seaweed treatment (SW0–SW1). The color scale represents z-score-based normalization: red tones indicate low values (negative z-scores), blue tones indicate high values (positive z-scores). Under 100 and 150 mM salinity stress, even when seaweed was applied, a light-dark-red color intensity with negative values is observed in all studied traits. At 200 mM salinity, mean emergence time, proline and Na showed a dark blue color intensity, whereas at Control and 50 mM salinity a light to dark blue color intensity was detected, indicating positive values for the other parameters.

Figure 10: Heat map of parameters for peanut varieties ‘Ayşe Hanım’, ‘Halis Bey’, ‘NC-7’, ‘Albenek’, after treatment with 0 g L−1 and 5 g L−1 seed weed each along with 0, 50, 100, 150, and 200 mM NaCl

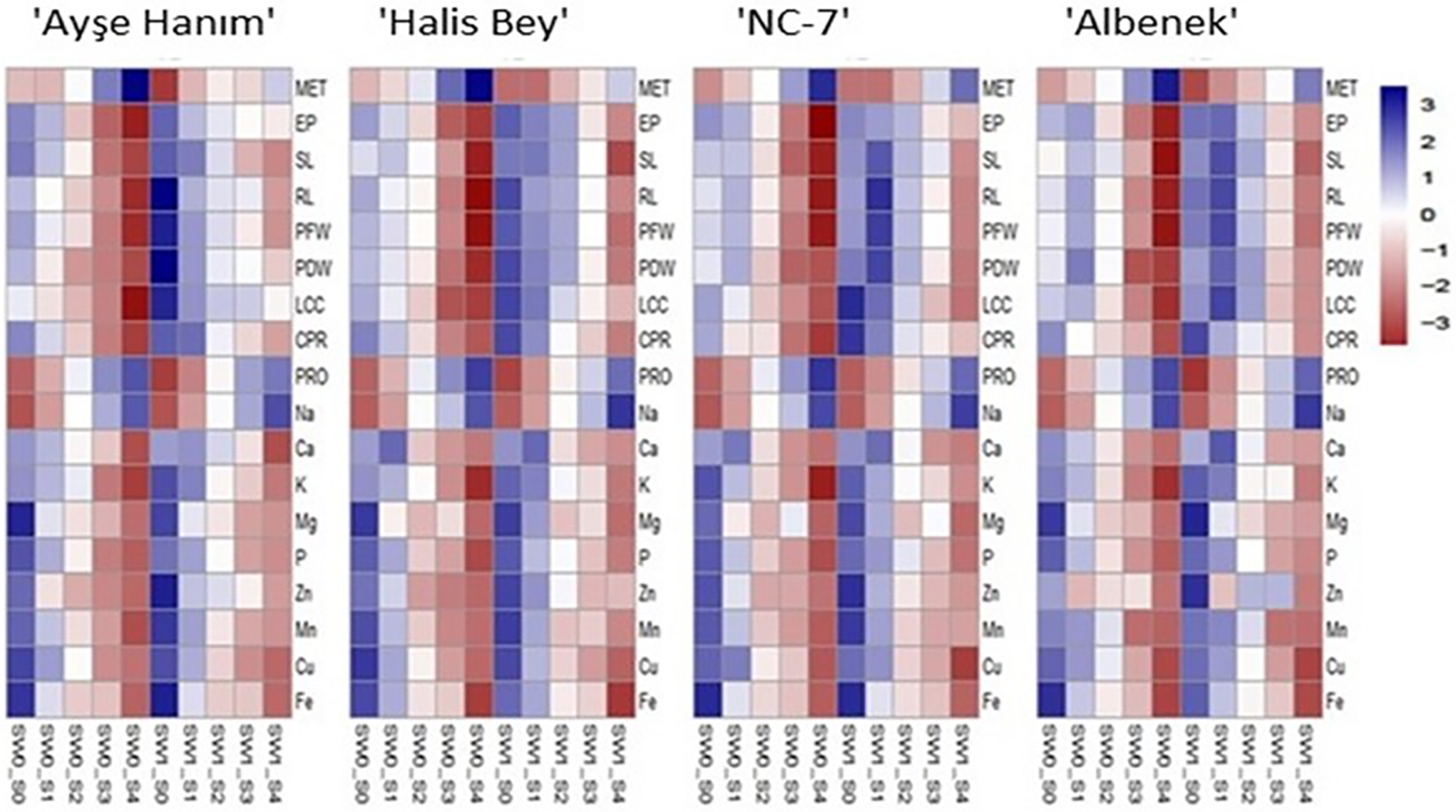

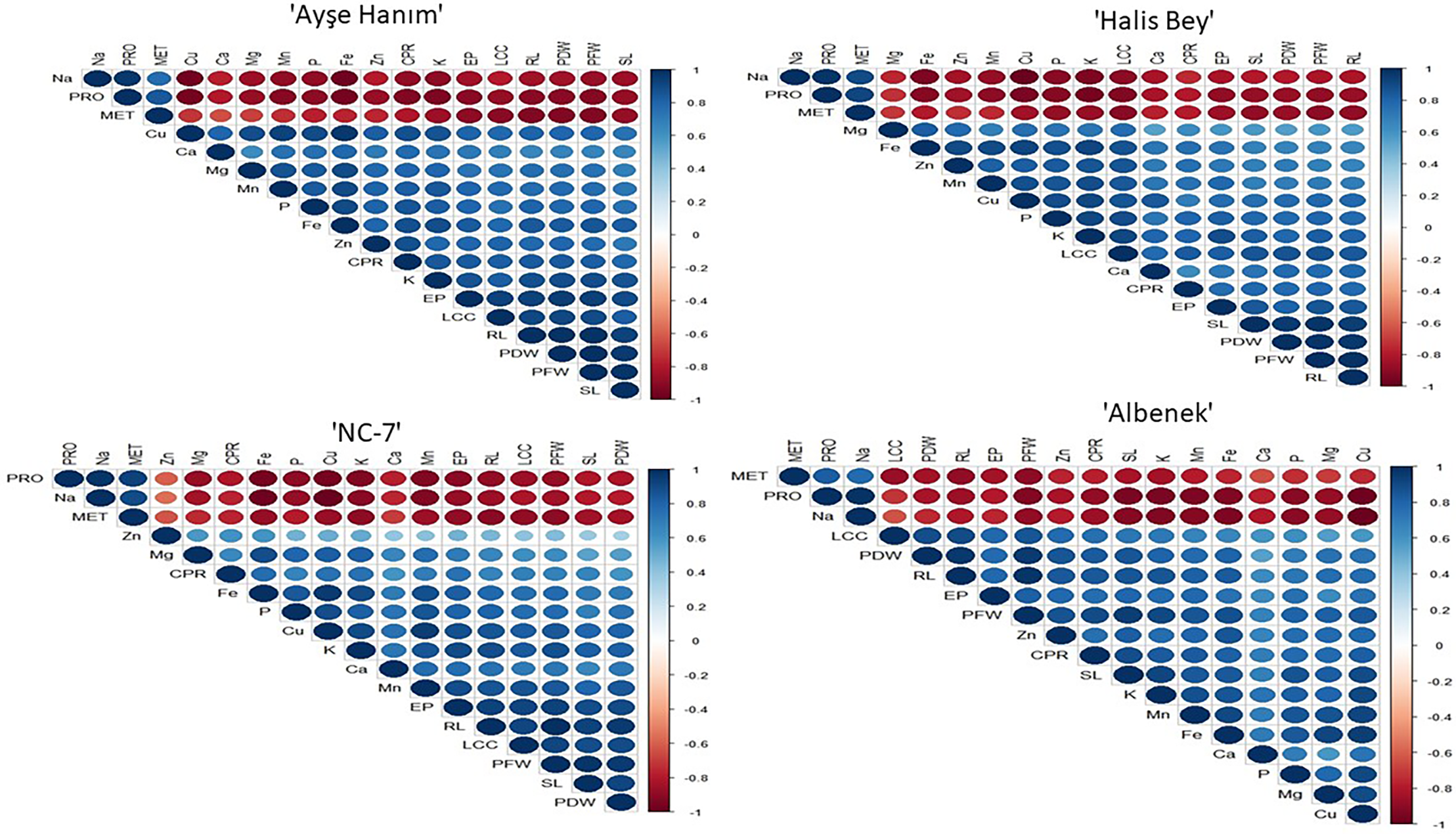

Visualization of the correlations between variables of peanut varieties is given in Fig. 11. There is a positive correlation between mean emergence time, Na content and proline levels. The mean emergence time showed a negative correlation with emergence percentage, shoot length, root length, plant fresh and dry weight, leaf chlorophyll contents, crude protein contents, and the concentrations of Zn, Mg, Fe, P, Cu, K, Ca, and Mn.

Figure 11: Visualization of the correlations between variables of peanut varieties (Variety-1: ‘Ayşe Hanım’, Variety-2: ‘Halis Bey’, Variety-3: ‘NC-7’, Variety-4: ‘Albenek’)

Organic matters are important components of soil [11]. Organic matter, composed of decomposed plant and animal residues, is crucial for soil health and nutrient movement. Climate change is reducing fertility of soils and water holding capacity of soils. Soil amendments are being developed to increase water retention, protect crops from drought stress, control soil pH, and supply plant nutrients. Both organic matter and alginate-based hydrogels can increase water retention and maintain soil moisture during salt stress. Moreover, the soils are continuously affected with Potassium leaching in the soil and decreased organic matters in the soil. Therefore using seaweeds with rich organic matter, alginic acids and K2O could help improve soil qualities for better vegetative growth of plants [45]. Seaweed were used to assess their stimulatory effects on seed germination and other growth parameters to improve seedling formation in crops grown under salt stress conditions, and determine the extent of interaction between salinity and seaweed extracts.

According to the results, seaweed treatments had a positive effect on the tested parameters in the study using four different peanut cultivars under salinity stress. Fig. 1 indicated the emergence time of the peanuts was extended under increasing salinity; however, seaweed treatments ameliorated and improved the negative effects of stress. The percentage of seed emergence increased, and earlier emergence was observed in all peanut cultivars treated with seaweed extracts. A previous study by Carvalho et al. (2013) [46] indicated that seaweed treatment improved the emergence percentage, which is economically important for farmers, as it can potentially lead to a germination of a higher number of plants per sown area and high germination percentage. Delays in emergence from the soil, and decrease in emergence rates was observed with increasing salt doses. Delayed germination of peanut seeds, decreased or delayed germination emergence, with decreased plant and root lengths [47,48].

Seaweed extracts alleviated a variety of abiotic stresses, including salinity, and have beneficial effects on shoot growth and crop yield [49]. The negative impact of salinity on plant growth may be related to its influence on factors involved in plant metabolism, nutrient uptake, protein and nucleic acid synthesis, and inadequate water supply to the cells, which impaired plant growth [50]. Seaweeds, as biostimulants, also reduced the negative effects of salinity on seedlings growth [51,52].

It was further observed that the seedlings after seaweed treatment exhibited longer shoots and roots, resulting in higher fresh and dry matter compared to non-seaweed treated seedlings. Studies conducted on various plants using seaweed, such as milkweed [51], tomato [18], and common wheat [53], confirmed that the presence of macro and microelements in plants enhance plant growth performance, is consistent with this research. These results align with those of Munns and Rawson (1999) [54], who reported that salt stress reduced shoot and root growth. Roots are in direct contact with the soil and absorb water from it, while shoots supply water to the rest of the plant, making root shoot length as the most important parameter to measure salt stress [55]. Desheva et al. (2020) [48] highlighted that peanut cultivars exhibited strong inhibition with increasing salinity, especially at high salinity (150 and 200 mM) levels. This is consistent with reports that NaCl reduces a plant’s ability to take up water, leading to slow growth. Subsequently, excessive amounts of salt entering the transpiration stream will eventually damage cells in the transpiring leaves, which can further reduce growth [56]. These studies emphasized that salinity stress significantly affects other plant growth parameters, such as plant and root fresh weight, with high leaf Na+ concentration and reduce CO2 assimilation due to ionic toxicity. Growth inhibition and morphological changes are related to leaf area and plant height [57] and are related to the initial effects of osmotic stress [58].

According to results of the current study, salinity significantly affected the chlorophyll content in the leaves of peanut plants, which was also confirmed using SPAD instruments to evaluate chlorophyll levels [59]. Wang et al. (2024) [60] reported that salinity stress, resulting from high NaCl concentrations, causes osmotic stress in plants, thereby limiting chlorophyll synthesis. Furthermore, Covaş et al. (2023) [61] noted that excess salinity increases oxidative stress by producing reactive oxygen species, which can degrade chlorophyll and other cellular components. The use of seaweed fertilizer has been reported to increase chlorophyll contents in plant leaves [22], and seaweed extracts, which increased the net photosynthesis rate in grape plants [46]. However, chlorophyll content decreased in cotton as salt stress increased [62]. Salt stress not only affected growth parameters in plants but also negatively impacted photosynthesis parameters [63]. Biostimulants have demonstrated the potential to reduce chlorophyll degradation in salt-stressed plants, such as maize [64], lettuce [65], and tomato [66]. Our findings are consistent with the studies described above.

Plants under salinity stress must produce low molecular weight non-enzymatic antioxidants, such as proline, to protect their cells and tissues from oxidative damage and hyperosmotic stress [67]. Proline is an osmolyte that accumulates in plants and plays a role in stress tolerance [68]. Plant mitochondria and chloroplasts are the main sites where proline catabolism occurs [69]. In our study conducted to evaluate seaweed in alleviating salinity-induced stress in peanut seeds. The significant increase in proline content observed in this study is consistent with that previously reported for rapeseed (Brassica napus) [70]. Covaş et al. (2023) [61] emphasized that biostimulant application to tomato plants grown under salinity stress positively affected the increased proline concentration with salinity. It appears that salt stress prompts the activation of protection mechanisms in plants, leading to proline accumulation, which provides defense against salinity [71]. A possible reason for this could be that seaweed contains phytohormones that increase the plant’s ability to cope with osmotic stress and reduce the need for high proline levels as a defense tactic by reducing oxidative damage [72].

Plants decompose proteins to generate amino acids, such as proline, to modulate their osmotic pressure in response to salinity when nitrogen is diminished or inadequately absorbed. Due to the regulation of osmotic pressure by nitrogen intake and proline synthesis during stress, protein degradation was necessary [73]. This explains the higher protein level observed in the seaweed treatment under the same stress conditions in our study. The researchers noted that the crude protein ratio in leaves decreased with increasing salinity, but the crude protein ratio in leaves increased with the application of biostimulants (e.g., halotolerant PGPR) in wheat under the same salinity stress [74]. This finding is consistent with our study.

It was observed that salinity stress affected the mineral matter content in leaves for the four cultivars used. Notably, Na accumulation in the leaves increased significantly under increasing NaCl stress. Potassium is a vital element in protein synthesis, glycolytic enzymes, and photosynthesis; it serves as an osmoticum that regulates cell expansion and turgor-driven motions, and it competes with Na+ in saline environments [75]. Under NaCl stress, there is an opposite relationship between sodium ions and potassium ions. In all four cultivars, K+ decreased as Na ions increased in the leaves. However, the seaweed biostimulant used increased some K+ in leaves under the same stress condition. A high concentration of Na+ ions has an antagonistic effect on K+ ions, as reported by Xie et al. (2021) [76], supporting our findings. Calcium is essential for regulating many physiological processes that influence both growth and the responses to various ecological conditions [77]. Aha and Özkutlu (2023) [78] reported that salinity stress reduced calcium content in leaves in their study on wheat (both bread and durum). According to the results obtained, Ca content decreased in peanut leaves. Mg, P, Zn, Mn, Cu, and Fe levels decreased with salinity in our study. However, it has been reported reported that the accumulation of beneficial ions decreased primarily under salinity [79], while seaweed application provided some benefit [80]. In the study, each cultivar has specific physico chemical characteristics in terms of mineral contents, which determine its adaptability and likes for consumption. This is the reason why each cultivar showed different elemental properties in agreement with Gebreegziabher and Tsegay (2020) [45].

Heatmap analysis is one of the most commonly used multivariate statistical methods, allowing the visualization of relationships between genotypes and the traits examined in the study [81]. The comparisons presented in this way define the relationship between the practices [82]. The heatmap analysis also groups various traits between genotypes [83]. Heat map analysis is widely preferred for comparing traits in many plants. For example, it is successfully used in alfalfa [84] and field crops such as mung beans [82].

The study found that seaweed extracts significantly improved agronomic performance in four peanut ‘Ayse Hanım’, ‘Halis Bey’, ‘NC-7’, and ‘Albenek’ varieties under salinity stress. In terms of the parameters examined, the best results were obtained from cv. NC-7 under control (0 mM NaCl) and 50 mM NaCl salinity conditions following seaweed application.

The study aimed to assess the effects of seaweed on seed germination and other growth parameters in crops grown under salt stress conditions. The results showed that seaweed treatments had a positive effect on the tested parameters, including seed emergence time, shoot growth, crop yield, and chlorophyll content. Seaweed extracts alleviated various abiotic stresses, including salinity, and have beneficial effects on shoot growth and crop yield. Seaweed treatment also resulted in longer shoots and roots, resulting in higher fresh and dry matter compared to non-seaweed treated seedlings. Salinity significantly affected chlorophyll content in the leaves of peanut plants, which was confirmed using SPAD instruments to evaluate chlorophyll levels, which increased the net photosynthesis rate seaweed treated plants. Proline accumulation, an osmolyte that accumulates in plants and plays a role in stress tolerance, was observed in the seaweed treated plants under the same stress conditions in this study. The crude protein ratio in leaves decreased with increasing salinity, but increased with the application of biostimulants under the same salinity stress. Salinity stress affected the mineral matter content in leaves for the four cultivars used. Na accumulation in the leaves increased significantly under increasing NaCl stress, while calcium content decreased in peanut leaves. Heatmap analysis also confirmed the above-mentioned results. These seaweed treatments are easy to apply, cost-effective, and indispensable in reducing abiotic stress, thereby positively impacting quantitative agricultural production. The use of seaweed extracts should be expanded, and scientific research should focus on optimum dosage and application time of seaweed extracts to mitigate the negative effects of salinity on peanut production.

Acknowledgement: The author would like to express his sincere gratitude to Onur Okumuş for his valuable support and contributions to this study.

Funding Statement: The author received no specific funding for this study.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Cui F, Li Q, Shang S, Hou X, Miao H, Chen X. Effects of cotton peanut rotation on crop yield soil nutrients and microbial diversity. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):28072. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-75309-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Arya SS, Salve AR, Chauhan S. Peanuts as functional food: a review. J Food Sci Technol. 2016;53:31–41. doi:10.1007/s13197-015-2007-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Özalp B, Ören MN. Political economy of input-output markets of peanut: a case from the peanut value chain of Turkey. J Agrar Change. 2024;24(2):e12568. doi:10.1111/joac.12568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Shalaby OA. Using Bacillus megaterium as a bio-fertilizer alleviates salt stress, improves phosphorus nutrition, and increases cauliflower yield. J Plant Nutr. 2023;47(6):926–39. doi:10.1080/01904167.2023.2291022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Singh A. Soil salinity: a global threat to sustainable development. Soil Use Manage. 2022;38(1):39–67. doi:10.1111/sum.12772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Nithila S, Durga Devi D, Velu G, Amutha R, Rangaraju G. Physiological evaluation of peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) cultivars for salt tolerance and amelioration of salt stress. Res J Agric Sci. 2013;2320:6063. [Google Scholar]

7. Akça E, Aydin M, Kapur S, Kume T, Nagano T, Watanabe T, et al. Long-term monitoring of soil salinity in a semi-arid environment of Türkiye. Catena. 2020;193:104614. doi:10.1016/j.catena.2020.104614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Xu Q, Liu H, Li M, Ping G, Li P, Xu Y, et al. Effects of water-nitrogen coupling on water and salt environment and root distribution in Suaeda salsa. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15:1342725. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1342725. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Shalaby OA, Ramadan MES. Mycorrhizal colonization and calcium spraying modulate physiological and antioxidant responses to improve pepper growth and yield under salinity stress. Rhizosphere. 2024;29:100852. doi:10.1016/j.rhisph.2024.100852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Singh M, Kumar J, Singh S, Singh VP, Prasad SM. Roles of osmoprotectants in improving salinity and drought tolerance in plants: a review. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol. 2015;14:407–26. doi:10.1007/s11157-015-9372-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Sejian V, Bhatta R, Soren NM, Malik PK, Ravindra JP, Prasad CS, et al. Introduction to concepts of climate change impact on livestock and its adaptation and mitigation. In: Climate change impact on livestock: adaptation and mitigation. New Delhi, India: Springer; 2015. p. 1–23. doi:10.1007/978-81-322-2265-1_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Ishra MI, Nishadani BSS, Jayawickrama MT, Manthilaka MMMGPG. Recent advances in organic nanofillers-derived polymer hydrogels. In: Nanofillers. 1st. ed. CRC Press; 2023. p. 173–97. [Google Scholar]

13. Rouphael Y, Colla G. Biostimulants in agriculture. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

14. Chaturvedi S, Kulshrestha S, Bhardwaj K. Role of seaweeds in plant growth promotion and disease management. In: New and future developments in microbial biotechnology and bioengineering. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2022. p. 217–38. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-85579-2.00007-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ali O, Ramsubhag A, Jayaraman J. Biostimulant properties of seaweed extracts in plants: implications towards sustainable crop production. Plants. 2021;10(3):531. doi:10.3390/plants10030531. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Zou Y, Zhang Y, Testerink C. Root dynamic growth strategies in response to salinity. Plant Cell Environ. 2022;45(3):695–704. doi:10.1111/pce.14205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Xavier J, Jose J. Study of mineral and nutritional composition of some seaweeds found along the coast of the gulf of Mannar, India. Plant Sci Today. 2020;7(4):631–7. doi:10.14719/pst.2020.7.4.912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Hernández-Herrera RM, Sánchez-Hernández CV, Palmeros-Suárez PA, Ocampo-Alvarez H, Santacruz-Ruvalcaba F, Meza-Canales ID, et al. Seaweed extract improves the growth and productivity of tomato plants under salinity stress. Agronomy. 2022;12(10):2495. doi:10.3390/agronomy12102495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Lakhdar A, Trigui M, Montemurro F. An overview of biostimulants’ effects in saline soils. Agronomy. 2023;13(8):2092. doi:10.3390/agronomy13082092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Krapovickas A. The origin, variability and spread of the peanut (Arachis hypogaea). In: The domestication and exploitation of plants and animals. London, UK: Routledge; 2017. p. 427–42. [Google Scholar]

21. Jalali P, Roosta H, Khodadadi M, Mohammadi Torkashvand A, Ghanbari Jahromi M. Foliar application of seaweed extract, silicon and selenium improve growth characteristics and yield of tomatoes in different hydroponic substrates. Hortic Plants Nutr. 2022;4(2):1–12. [Google Scholar]

22. Meng C, Gu X, Liang H, Wu M, Wu Q, Yang L, et al. Optimized preparation and high-efficient application of seaweed fertilizer on peanut. J Agric Food Res. 2022;7:100275. doi:10.1016/j.jafr.2022.100275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Kumari R, Bhatnagar S, Mehla N, Vashistha A. Potential of organic amendments (AM fungi, PGPR, Vermicompost and Seaweeds) in combating salt stress: a review. Plant Stress. 2022;6:100111. doi:10.1016/j.stress.2022.100111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Rouphael Y, De Micco V, Arena C, Raimondi G, Colla G, De Pascale S. Effect of Ecklonia maxima seaweed extract on yield, mineral composition, gas exchange, and leaf anatomy of zucchini squash grown under saline conditions. J Appl Phycol. 2017;29:459–70. doi:10.1007/s10811-016-0937-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Cruz RIF, Silva GFD, Silva MMD, Silva AHS, Santos Junior JA, França E, et al. Productivity of irrigated peanut plants under pulse and continuous dripping irrigation with brackish water1 2. Rev Caatinga. 2021;34:208–18. doi:10.1590/1983-21252021v34n121rc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Meena HN, Ajay BC, Reddy KK, Meena MD, Mishra JP. Enhancing peanut (Arachis hypogaea) productivity and biochemical traits: a comparison of straw mulch and polythene mulch under prolonged salinity stress. J Agron Crop Sci. 2024;210(5):e12739. doi:10.1111/jac.12739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Hussain HI, Kasinadhuni N, Arioli T. The effect of seaweed extract on tomato plant growth, productivity and soil. J Appl Phycol. 2021;33(2):1305–14. doi:10.1007/s10811-021-02387-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Chanthini KMP, Senthil-Nathan S, Pavithra GS, Malarvizhi P, Murugan P, Deva-Andrews A, et al. Aqueous seaweed extract alleviates salinity-induced toxicities in rice plants (Oryza sativa L.) by modulating their physiology and biochemistry. Agriculture. 2022;12(12):2049. doi:10.3390/agriculture12122049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Pal SC, Hossain MB, Mallick D, Bushra F, Abdullah SR, Dash PK, et al. Combined use of seaweed extract and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi for alleviating salt stress in bell pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Sci Hortic. 2024;325:112597. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2023.112597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Hussein MH, Eltanahy E, Al Bakry AF, Elsafty N, Elshamy MM. Seaweed extracts as prospective plant growth bio-stimulant and salinity stress alleviator for Vigna sinensis and Zea mays. J Appl Phycol. 2021;33:1273–91. doi:10.1007/s10811-020-02330-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Jacomassi LM, Viveiros JDO, Oliveira MP, Momesso L, de Siqueira GF, Crusciol CAC. A seaweed extract-based biostimulant mitigates drought stress in sugarcane. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:865291. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.865291. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Shukla PS, Shotton K, Norman E, Neily W, Critchley AT, Prithiviraj B. Seaweed extract improve drought tolerance of soybean by regulating stress-response genes. AoB Plants. 2018;10(1):plx051. doi:10.1093/aobpla/plx051. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Kirova E, Kocheva K. Physiological effects of salinity on nitrogen fixation in legumes—a review. J Plant Nutr. 2021;44(17):2653–62. doi:10.1080/01904167.2021.1921204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zulfiqar F, Ashraf M. Proline alleviates abiotic stress induced oxidative stress in plants. J Plant Growth Regul. 2023;42(8):4629–51. doi:10.1007/s00344-022-10839-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Senaratna T, Touchell D, Bunn E, Dixon K. Acetyl salicylic acid (Aspirin) and salicylic acid induce multiple stress tolerance in bean and tomato plants. Plant Growth Regul. 2000;30(2):157–61. [Google Scholar]

36. Day S, Kocak-Sahin N. Determination of seed size properties of soybean cultivars and their response under salinity during early growth. Legume Res. 2024;47(6):945–51. doi:10.18805/lrf-780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Yildiz M, Ozcan S, Telci C, Day S, Ozat H. The effect of drying and submersion pretreatment on adventitious shoot regeneration from hypocotyl explants of flax (Linum usitatissimum L.). Turk J Bot. 2010;34(4):323–8. doi:10.1016/j.nbt.2012.08.070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Day S, Cikili Y, Aasim M. Screening of three safflower (Carthamus tinctorius L.) cultivars under boron stress. Acta Sci Pol Hortorum Cultus. 2017;16:109–16. doi:10.24326/asphc.2017.5.11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. AACC. Official methods of analysis of the association of official analytical chemist [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jul 13]. Available from: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=tr&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=39.%09AACC.+%282000%29.+Official+methods+of+analysis.+15th+Edition%2C+Association+of+Official+Analytical+Chemist%2C+Washington+DC.&btnG=. [Google Scholar]

40. Karabal E, Yücel M, Öktem HA. Antioxidant responses of tolerant and sensitive barley cultivars to boron toxicity. Plant Sci. 2003;164(6):925–33. doi:10.1016/S0168-9452(03)00067-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Mertens D. AOAC official method 922.02. In: Horwitz W, Latimer GW, editors. Plants preparation of laboratory sample. Official methods of analysis. 18th ed. Gaitherburg, MD, USA: AOAC-International Suite; 2005. p. 20877–2417. [Google Scholar]

42. Mertens D. AOAC official method 975.03. In: Horwitz W, Latimer GW, editors. Metal in plants and pet foods. Official methods of analysis. 18th ed. Gaitherburg, MD, USA: AOAC-International Suite; 2005. p. 3–4. [Google Scholar]

43. Kolde R. Pheatmap: pretty heatmaps. R package version 1.2 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jul 13]. Available from: https://CRAN.Rproject.org/package=pheatmap. [Google Scholar]

44. Kassambara A, Kassambara MA. Package ‘ggcorrplot’. R package version 0.1. [cited 2025 Jul 13]. Available from: https://cloud.r-project.org/web/packages/ggcorrplot/ggcorrplot.pdf. [Google Scholar]

45. Gebreegziabher BG, Tsegay BA. Proximate and mineral composition of Ethiopian pea (Pisum sativum var. abyssinicum A. Braun) landraces vary across altitudinal ecosystems. Cogent Food Agric. 2020;6(1):1789421. doi:10.1080/23311932.2020.1789421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Carvalho RPD, Pasqual M, de Oliveira Silveira HR, de Melo PC, Bispo DFA, Laredo RR, et al. Niágara Rosada table grape cultivated with seaweed extracts: physiological, nutritional, and yielding behavior. J Appl Phycol. 2019;31:2053–64. doi:10.1007/s10811-018-1724-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Steiner F, Zuffo AM, Busch A, Sousa TDO, Zoz T. Does seed size affect the germination rate and seedling growth of peanut under salinity and water stress? Pesqui Agropecuária. 2019;49:e54353. doi:10.1590/1983-40632019v4954353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Desheva G, Desheva GN, Stamatov SK. Germination and early seedling growth characteristics of Arachis hypogaea L. under Salinity (NaCl) stress. Agric Conspec Sci. 2020;85(2):113–21. [Google Scholar]

49. Craigie JS. Seaweed extract stimuli in plant science and agriculture. J Appl Phycol. 2011;23(3):371–93. doi:10.1007/s10811-010-9560-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Shahid MA, Sarkhosh A, Khan N, Balal RM, Ali S, Rossi L, et al. Insights into the physiological and biochemical impacts of salt stress on plant growth and development. Agronomy. 2020;10(7):938. doi:10.3390/agronomy10070938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Bahmani Jafarlou M, Pilehvar B, Modaresi M, Mohammadi M. Seaweed liquid extract as an alternative biostimulant for the amelioration of salt-stress effects in Calotropis procera (Aiton) WT. J Plant Growth Regul. 2023;42(1):449–64. doi:10.1007/s00344-021-10566-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Rakkammal K, Maharajan T, Ceasar SA, Ramesh M. Biostimulants and their role in improving plant growth under drought and salinity. Cereal Res Commun. 2023;51(1):61–74. doi:10.1007/s42976-022-00299-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Hamouda MM, Saad-Allah KM, Gad D. The potential of seaweed extract on growth, physiological, cytological and biochemical parameters of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seedlings. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2022;22(2):1818–31. doi:10.1007/s42729-022-00774-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Munns R, Rawson HM. Effect of salinity on salt accumulation and reproductive development in the apical meristem of wheat and barley. Funct Plant Biol. 1999;26(5):459–64. doi:10.1071/pp99049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Anwar T, Munwwar F, Qureshi H, Siddiqi EH, Hanif A, Anwaar S, et al. Synergistic effect of biochar-based compounds from vegetable wastes and gibberellic acid on wheat growth under salinity stress. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):19024. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-46487-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Munns R, James RA, Läuchli A. Approaches to increasing the salt tolerance of wheat and other cereals. J Exp Bot. 2006;57:1025–43. doi:10.1093/jxb/erj100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Chen TT, Zeng RE, Wang XY, Zhang JL, Ci DW, Chen Y, et al. Growth and physiological responses of peanut seedling to salt stress. Int J Agric Biol. 2019;22(5):1181–6. [Google Scholar]

58. Thameur A, Lachiheband B, Ferchichi A. Drought effect on growth, gas exchange and yield, in two strains of local barely Ardhaoui, under water difict conditions in southern Tunisia. J Environ Manage. 2012;113:495–500. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.05.026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Ling Q, Huang W, Jarvis P. Use of a SPAD-502 meter to measure leaf chlorophyll concentration in Arabidopsis thaliana. Photosynth Res. 2011;107:209–14. doi:10.1007/s11120-010-9606-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Wang X, Chen Z, Sui N. Sensitivity and responses of chloroplasts to salt stress in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15:1374086. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1374086. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Covasa M, Slabu C, Marta AE, Jităreanu CD. Increasing the salt stress tolerance of some tomato cultivars under the influence of growth regulators. Plants. 2023;12(2):363. doi:10.3390/plants12020363. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Saleh B. Effect of salt stress on growth and chlorophyll content of some cultivated cotton varieties grown in Syria. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal. 2012;43(15):1976–83. doi:10.1080/00103624.2012.693229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Hameed M, Ashraf M, Naz N, Nawaz T, Batool R, Ahmad MSA, et al. Anatomical adaptations of Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers. from the salt range (Pakistan) to salinity stress. II. Leaf anatomy. Pak J Bot. 2013;45(S1):133–42. doi:10.1016/j.flora.2007.11.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. D’Amato R, Del Buono D. Use of a biostimulant to mitigate salt stress in maize plants. Agronomy. 2021;11(9):1755. doi:10.3390/agronomy11091755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Lucini L, Rouphael Y, Cardarelli M, Canaguier R, Kumar P, Colla G. The effect of a plant-derived biostimulant on metabolic profiling and crop performance of lettuce grown under saline conditions. Sci Hortic. 2015;182:124–33. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2014.11.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Gedeon S, Ioannou A, Balestrini R, Fotopoulos V, Antoniou C. Application of biostimulants in tomato plants (Solanum lycopersicum) to enhance plant growth and salt stress tolerance. Plants. 2022;11(22):3082. doi:10.3390/plants11223082. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Singh M, Kumar J, Singh VP, Prasad SM. Proline and salinity tolerance in plants. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;3(6):10–4172. doi:10.4172/2167-0501.1000e170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Manonmani S, Senthilkumar S, Manivannan S. Multilevel functionality of biostimulants in sustainable horticulture for modern era. Pharma Innov J. 2022;11:1283–8. [Google Scholar]

69. Day S, Koçak N, Önol B. Hemp seed priming via different agents to alleviate temperature stress. J Agric Sci. 2024;30(3):562–9. [Google Scholar]

70. Gürsoy M. Alone or combined effect of seaweed and humic acid applications on rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) under salinity stress. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2024;24:3364–76. doi:10.1007/s42729-024-01759-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Hao S, Wang Y, Yan Y, Liu Y, Wang J, Chen S. A review on plant responses to salt stress and their mechanisms of salt resistance. Horticulturae. 2021;7(6):132. doi:10.3390/horticulturae7060132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Afeeza KLG, Dilipan E. Enhancing salt stress tolerance in black gram (Vigna mungo L.) through the exogenous application of seaweed liquid fertilizer derived from Sargassum sp. Algal Res. 2024;81:103588. doi:10.1016/j.algal.2024.103588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Dos Santos TB, Ribas AF, de Souza SGH, Budzinski IGF, Domingues DS. Physiological responses to drought, salinity, and heat stress in plants: a review. Stresses. 2022;2(1):113–35. doi:10.3390/stresses2010009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Hajiabadi AA, Arani AM, Ghasemi S, Rad MH, Etesami H, Manshadi SS, et al. Mining the rhizosphere of halophytic rangeland plants for halotolerant bacteria to improve growth and yield of salinity-stressed wheat. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2021;163:139–53. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.03.059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Khalil R, Elsayed N, Khan TA, Yusuf M. Potassium: a potent modulator of plant responses under changing environment. In: Role of potassium in abiotic stress. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2022. p. 221–47. doi:10.1007/978-981-16-4461-0_11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Xie K, Cakmak I, Wang S, Zhang F, Guo S. Synergistic and antagonistic interactions between potassium and magnesium in higher plants. Crop J. 2021;9(2):249–56. doi:10.1016/j.cj.2020.10.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Khan F, Siddique AB, Shabala S, Zhou M, Zhao C. Phosphorus plays key roles in regulating plants’ physiological responses to abiotic stresses. Plants. 2023;12(15):2861. doi:10.3390/plants12152861. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Aha FD, Özkutlu F. Tuzlu koşullarda bentonit uygulamasının makarnalık ve ekmeklik buğdayların kuru madde verimi ve mineral besin elementleri üzerine etkisi. Ordu Üniversitesi Bilim Ve Teknol Derg. 2023;13(1):71–8. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

79. Hussain T, Li J, Feng X, Asrar H, Gul B, Liu X. Salinity induced alterations in photosynthetic and oxidative regulation are ameliorated as a function of salt secretion. J Plant Res. 2021;134:779–96. doi:10.1007/s10265-021-01285-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Kumari R, Kaur I, Bhatnagar AK. Effect of aqueous extract of Sargassum Johnstonii Setchell & gardner on growth, yield and quality of Lycopersicon esculentum mill. J Appl Phycol. 2011;23:623–33. [Google Scholar]

81. Erkek B, Yaman M, Sümbül A, Demirel S, Demirel F, Çoskun Ö.F, et al. Natural diversity of crataegus monogyna Jacq. In Northeastern Türkiye encompassing morphological, biochemical, and molecular features. Horticulturae. 2025;11(3):238. doi:10.3390/horticulturae11030238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Islam R, Hossain J, Huda S, Azam MG, Hossain F, Zaman AU, et al. Assessment of drought tolerance in mung bean [Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek] through phenology, growth, protein yield, and cluster heatmap analysis. Philipp Agric Sci. 2024;107(4):6. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-60129-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Sakınah A, Musa Y, Farıd M, Anshorı MF, Arıfuddın M, Laraswati A. Cluster heatmap for screening the drought tolerant rice through hydroponic culture. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. 2021;807:042045. [Google Scholar]

84. Wang F, Wu H, Yang M, Xu W, Zhao W, Qiu R, et al. Unveiling salt tolerance mechanisms and hub genes in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) through transcriptomic and WGCNA analysis. Plants. 2024;13:3141. doi:10.3390/plants13223141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools