Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Hypoglycemic Lignans from Amomum tsao-ko Leaves: Their α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Mechanism Integrated In Silico and In Vivo Validation

1 State Key Laboratory of Phytochemistry and Natural Medicines, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, 650201, China

2 Key Laboratory of Structure-Based Drug Design & Discovery, Ministry of Education, and School of Traditional Chinese Materia Medica, Shenyang Pharmaceutical University, Shenyang, 110016, China

3 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, 100049, China

* Corresponding Author: Chang-An Geng. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(8), 2563-2574. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.068185

Received 22 May 2025; Accepted 23 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Twelve lignans (1–12) isolated from Amomum tsao-ko leaves were evaluated for the inhibitory effects against α-glucosidase and PTP1B. Compounds 1−4 and 10 showed inhibition on α-glucosidase with inhibitory ratios ranging from 53.8% to 90.0%, while compound 10 demonstrated 56.1% inhibition on PTP1B at 200 μM. Notably, erythro-5-methoxy-dadahol A (2) and threo-5-methoxy-dadahol A (3) displayed obvious inhibition on α-glucosidase with IC50 values of 33.3 μM and 22.1 μM, significantly outperforming acarbose (IC50 = 344.0 μM). Kinetic study revealed that compound 3 maintained a mixed-type mode, engaging with both free enzyme and enzyme-substrate complex via non-competitive and uncompetitive mechanisms. Molecular docking simulations further clarified its interactions with the key residues of Trp402, Lys400, and Gly361 in the catalytic pocket. In vivo evaluation demonstrated that oryzativol A (1) showed dose-dependent hypoglycemic effects in an oral starch tolerance test, reducing postprandial blood glucose levels (AUC) by 21.1% (20 mg/kg) and 24.9% (40 mg/kg). These results highlight the potential of lignans in A. tsao-ko as α-glucosidase inhibitors for managing type 2 diabetes, warranting further exploration of their therapeutic potential.Keywords

Diabetes mellitus, characterized by persistent hyperglycemia, is a chronic metabolic disorder resulting from impaired insulin secretion or resistance [1]. Globally, an estimated 537 million adults live with diabetes, of which over 90% suffer from type 2 diabetes [2]. Type 2 diabetes poses significant health risks, often contributing to severe complications such as cardiovascular disease, nephropathy, retinopathy, and neuropathy, all of which markedly reduce patients’ quality of life and longevity [3,4]. The etiology of diabetes involves a multifaceted interaction of genetic susceptibility, environmental influences, and lifestyle factors. Despite the availability of various therapeutic interventions, including oral and injectable medications, their effectiveness is often constrained by adverse side effects and drug resistance [3,4]. Therefore, identifying new hypoglycemic leads with distinct mechanisms remains a critical research priority.

Lignans are a structurally diverse group of natural products biosynthesized via the shikimate pathway, featuring a core structure composed of two or more phenylpropanoid units [5,6]. Their monomeric precursors encompass cinnamic acid, cinnamyl alcohol, propenyl benzene, and allylbenzene. Structurally, lignans are classified into “classical lignans” (containing β-β′/8-8′ linkages) and “neolignans” (exhibiting alternative coupling patterns) [7]. These compounds are widely distributed across the plant kingdom, particularly in families such as Lauraceae (e.g., Machilus, Ocotea, and Nectandra), Zingiberaceae, Annonaceae, Orchidaceae, Berberidaceae, and Schisandraceae [8,9]. To date, over 70 plant families have yielded hundreds of classical and neolignan derivatives, which predominantly exist as dimers, higher oligomers (e.g., trimers and tetramers), or glycosylated and hybrid forms [10]. Pharmacologically, lignans possess multifaceted therapeutic potential, including antitumor, antioxidant, antimicrobial, immunosuppressive, and antiasthmatic effects [11–14].

Amomum tsao-ko Crevost et Lemarie (commonly known as Caoguo in Chinese) is predominantly cultivated in Yunnan, Guizhou, and Guangxi provinces of China. Yunnan Province serves as the primary cultivation region of Caoguo, accounting for approximately 90% of the total production [15]. Its fruits are highly valued as a culinary spice worldwide. In China, it is documented in all editions of the Chinese Pharmacopoeia and officially recognized as a “Both Food and Medicine” substance. In traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), Caoguo is commonly used for the treatment of malaria, gastrointestinal disorders, throat infections, and hepatic abscesses [16]. Phytochemical studies on A. tsao-ko have revealed the presence of diarylheptanoids, flavonoids, terpenoids, phenolics, and bicyclic nonanes, which demonstrate neuroprotective, anti-obesity, antiproliferative, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial effects [17–21].

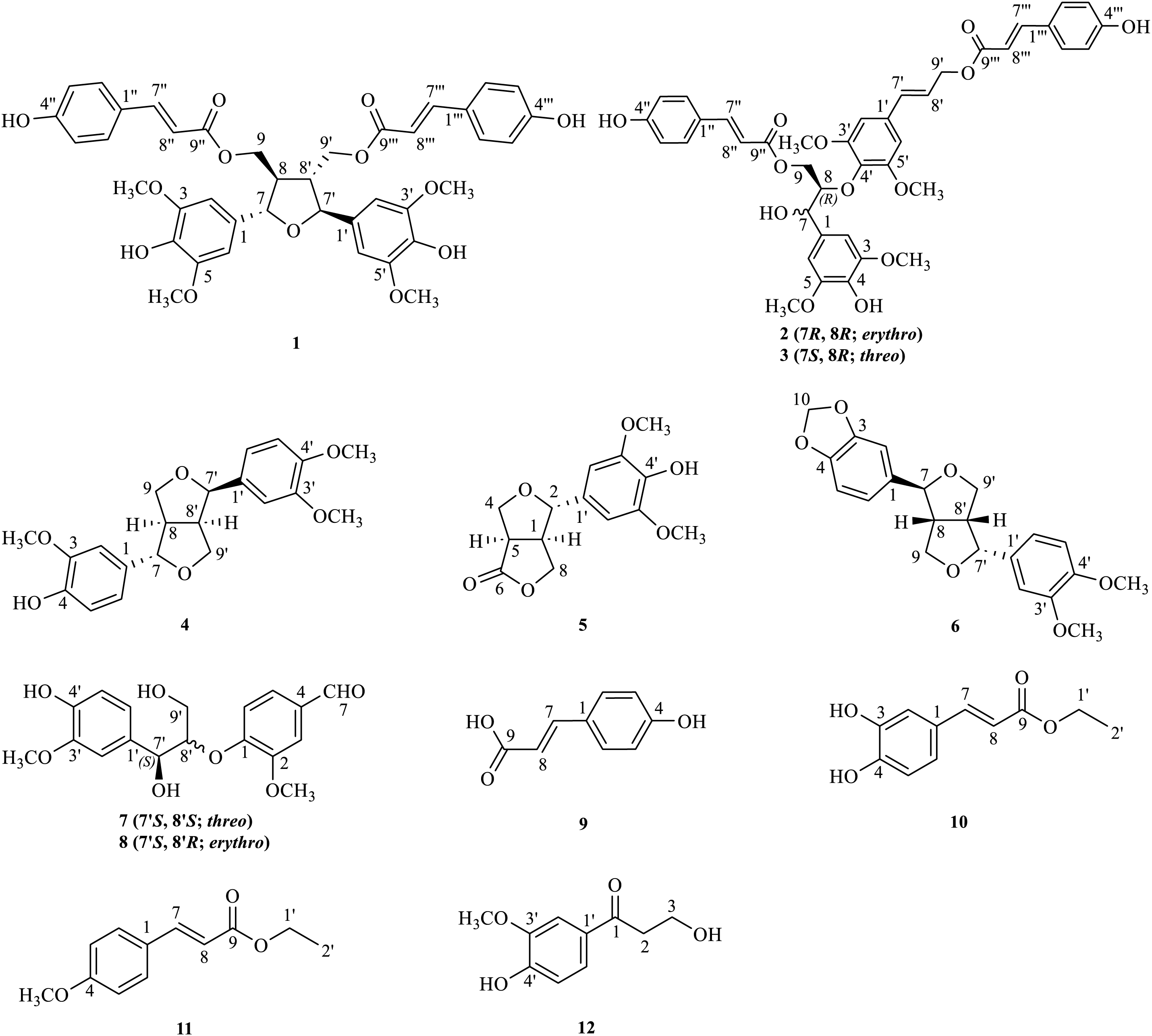

In the previous study, flavonoids, diarylheptanoids, and hydroxytetradecenals have been isolated from A. tsao-ko fruits, demonstrating activity against GPa, α-glucosidase, and PTP1B [22–26]. Although the stems and leaves of A. tsao-ko constitute the majority of the plant’s biomass, their chemical and pharmacological profiles remain underexplored [15,27]. This research focused on A. tsao-ko leaves, from which twelve lignans with antidiabetic potential were further reported (Fig. 1). We present their isolation procedure, α-glucosidase inhibitory action, and therapeutic effects on diabetes.

Figure 1: Chemical structures of 1–12

2.1 General Laboratory Procedures

A Bruker Advance III-600 spectrometer (600 MHz, Bremerhaven, Germany) and Shimadzu LC/MS-IT-TOF system (Kyoto, Japan) were applied for recording NMR and HRESIMS spectra. Column chromatography separations were achieved on silica gel (Xinnuo) (Shanghai, China) and Sephadex LH-20 gel (Amersham Bioscience) (Amersham, UK). The Xinnuo silica gel GF254 plates (Yantai, China) were used for TLC detection. A Shimadzu LC-20 system and a Huideyi Dr-Flash II system were used for HPLC and MPLC separation. Enzymes of PTP1B (10304-H07E, Sigma-Aldrich) (Burlington, MA, USA) and α-glucosidase (G5003-100UN, Sino Biological) (Beijing, China) were used for bioassay.

The aerial parts of A. tsao-ko (201808At-2) were gathered from Wenshan, China in 2018 and taxonomically identified by Dr. Jiang Zeng (Wenshan University).

The leaves (10 kg) were powdered and extracted twice with 70% aqueous ethanol, each for 72 h. The combined extracts were concentrated to remove the ethanol and extracted with EtOAc. The EtOAc-soluble portion (1.85 kg) was separated by silica gel column chromatography (CC) with a petroleum ether-acetone gradient (100:0~0:100), producing ten fractions (Frs. 1~10).

Fr. 9 (84 g) underwent sequential purification through silica gel CC (petroleum ether-acetone, from 95:5 to 10:90) and polyamide CC (MeCN-H2O, from 10:90 to 100:0) to yield six subfractions. Fr. 9-2-2 was further separated by silica gel CC (CHCl3-MeOH, from 100:0 to 0:100), MPLC (Rp-C18, MeCN-H2O, from 10:90 to 100:0), Sephadex LH-20 gel CC (CHCl3-MeOH, 1:1), and final HPLC on a C18 column (MeCN-H2O, 24:76) to obtain compounds 7 (8 mg, tR = 11.0 min) and 8 (10 mg, tR = 11.6 min). Fr. 9-2-5 (1.5 g) was processed through silica gel CC (CHCl3-MeOH, from 95:5 to 0:100) and MPLC (Rp-C18 column, MeOH-H2O, from 10:90 to 100:0) to produce five subfractions (Frs. 9-2-5-4-1~9-2-5-4-5). Fr. 9-2-5-4-1 (210 mg) was purified via silica gel CC (chloroform-acetone, from 100:0 to 0:100), Sephadex LH-20 gel CC (MeOH), and HPLC (C8 column, MeCN-H2O, 46:54) to provide compound 1 (83 mg, tR = 12.3 min). Fr. 9-2-5-4-3 (460 mg) underwent alumina CC (CHCl3-MeOH, from 100:0 to 0:100), Sephadex LH-20 gel CC (MeOH), and HPLC (C8 column, MeCN-H2O, 46:54) to yield compounds 2 (6 mg, tR = 23.5 min) and 3 (11 mg, tR = 25.0 min).

Fr. 8 (160.7 g) was fractionated by silica gel CC (petroleum ether-acetone, from 95:5 to 0:100) to afford six subfractions. Fr. 8-4 was further separated through polyamide CC (MeOH-H2O, from 10:90 to 100:0) and silica gel CC (CHCl3-MeOH, from 100:0 to 0:100) to yield six fractions (Frs. 8-4-1-1~8-4-1-6). Compound 9 (1.0 g) was recrystallized from Fr. 8-4-1-4 (11.4 g) in MeOH. Fr. 8-4-1-3 (9.9 g) was purified by Sephadex LH-20 gel CC (MeOH) and silica gel CC (CHCl3-MeOH, from 100:0 to 0:100) to give four subfractions (Frs. 8-4-1-3-2-1~8-4-1-3-2-4). Compound 5 (31 mg) was obtained from Fr. 8-4-1-3-2-1 (188 mg) upon recrystallization in MeOH. Fr. 8-4-1-3-2-2 (254 mg) was purified by Sephadex LH-20 (MeOH) and HPLC on a C18 column (MeCN-H2O, 35:65) to generated compounds 4 (50 mg, tR = 9.4 min), 6 (11 mg, tR = 10.0 min) and 12 (35 mg, tR = 11.8 min).

Fr. 7 was subjected to successive chromatographic separations involving silica gel CC (petroleum ether-acetone and CHCl3-MeOH), polyamide CC (MeOH-H2O), and Sephadex LH-20 CC (MeOH), ultimately yielding compounds 10 (13 mg) and 11 (362 mg).

The α-glucosidase (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) and PTP1B (recombinant human) inhibition assays were conducted following the established protocols [28]. Briefly, enzyme and test samples in appropriate buffer were added to 96-well plates and incubated at 37°C. The reaction was initiated by adding the respective substrate. After the designated incubation period, the reaction was stopped and measured at 405 nm using a microplate reader. Inhibition rates were calculated from triplicate measurements, and IC50 values were determined by dose-response curve fitting using GraphPad Prism 10.1.2 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA).

Kinetic analysis of α-glucosidase inhibition was performed using Lineweaver-Burk plots and secondary plots, employing p-NPG substrate (0.5~4 mM) in the presence of test compounds (0~40 μmol/L) [29].

Computational docking studies were conducted on AutoDock Vina 1.5.6, utilizing the α-glucosidase structure (PDB ID: 3a4a) from the PDB database and the 3D structure of 3 from ChemDraw and Chem3D [30,31]. The results were processed with Pymol and Discovery Studio software.

Molecular docking grid parameters: The grid box points in the x, y, and z directions were set to 86, 116, and 104, respectively, with a grid spacing of 0.664 Å. The center coordinates of the grid box were positioned at x = +26.031 Å, y = −4.630 Å, and z = +18.059 Å, with corresponding offsets of x = +4.750 Å, y = −3.861 Å, and z = −0.528 Å. All other parameters were kept at their default settings.

In this study, 24 seven-week-old male SPF Kunming mice (No. SCXK (Sichuan) 2023-0040) were provided by Sichuan VitoLihua Experimental Animal Technology. All experimental procedures received approval (License No. SYXK (Yunnan) K2024-0003) from the Animal Welfare Committee of the Kunming Institute of Botany (CAS). All mice were housed under controlled environmental conditions at 25 ± 2°C, 50 ± 10% relative humidity, and a 12-h light/dark cycle. During the one-week acclimatization period, mice were fed with a standard pellet diet and drinking water ad libitum.

2.7.2 Oral Starch Tolerance Test

Although compounds 2 and 3 exhibited potent inhibition on α-glucosidase in vitro, they were excluded from in vivo evaluation due to insufficient quantities for animal studies. Compound 1 with high activity and sufficient quantity was thus selected for further pharmacological evaluation. The experimental protocol was adapted from established methodologies with necessary modifications [25]. Twenty-four male Kunming mice were randomly grouped into four groups (n = 6): (1) blank control, (2) acarbose (20 mg/kg), (3) low-dose compound 1 (20 mg/kg), and (4) high-dose compound 1 (40 mg/kg). Compound 1 or acarbose was suspended in 0.5% CMC-Na solution. Following a 16-h fasting period with free access to water, baseline blood glucose levels were determined, showing no intergroup variations (p > 0.05). For the starch tolerance test, mice received oral administration of starch solution (3 g/kg) alone or in combination with compound 1/acarbose. Blood glucose levels were monitored at different intervals (15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min) post-administration using an Accu-Chek Instant system (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Glucose excursion was quantified by calculating the 120-min area under the curve (AUC) through trapezoidal integration.

All enzymatic data in triplicate were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Dose-response curves were analyzed by nonlinear regression to derive IC50 values. Statistical significance (p < 0.05) was assessed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s T3 test.

Twelve lignans were identified as oryzativol A (1) [32], erythro-5-methoxy-dadahol A (2) [33], threo-5-methoxy-dadahol A (3) [33], phillygenin (4) [34], zhebeiresinol (5) [35], fargesin (6) [36], threo-guaiacylglycerol 8′-vanillin ether (7) [37], erythro-guaiacylglycerol 8′-vanillin ether (8) [37], p-hydroxycinnamic acid (9) [38], ethyl caffeate (10) [39], trans-ethyl p-methoxycinnamate (11) [40], and 3-hydroxy-1-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxy-phenyl)-1-propanone (12) [41]. Twelve lignans were identified by comparing their spectroscopic data (1H-NMR, 13C-NMR, DEPT, and HRESIMS) with those previously reported in the literature.

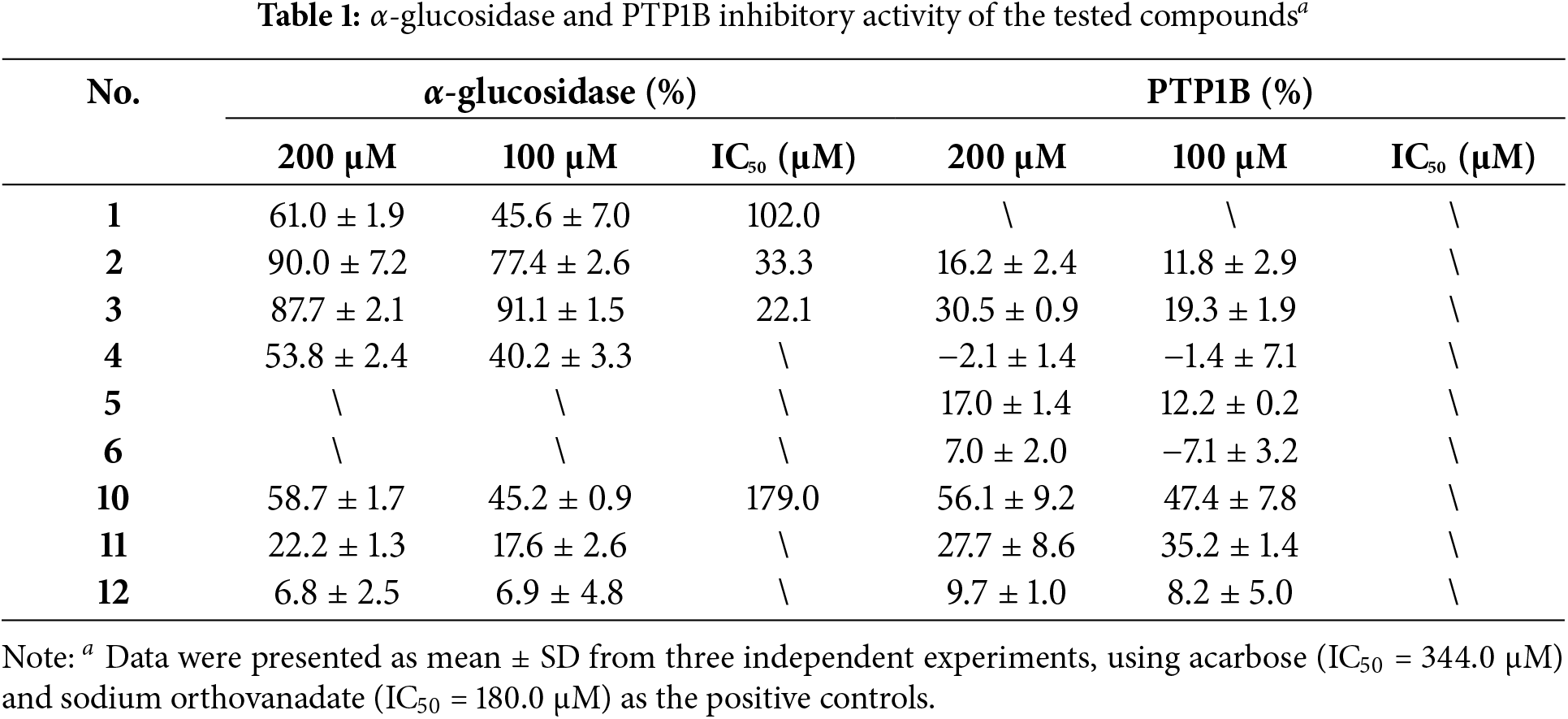

3.2 α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity

As shown in Table 1 and Fig. 2, two compounds (2 and 3) exhibited significant activity inhibiting α-glucosidase with IC50 values of 33.3 μM and 22.1 μM. Specifically, compounds 2 and 3 were approximately 10 and 15 times more active than acarbose (IC50 = 344.0 μM). Besides, compounds 1 (IC50 = 102.0 μM) and 10 (IC50 = 179.0 μM) demonstrated moderate inhibition on α-glucosidase, about 2~3 times higher activity than acarbose. The remaining compounds displayed weak activity against α-glucosidase.

Figure 2: Dose-dependent relationship of 1, 2, 3, and 10 on α-glucosidase (A–D)

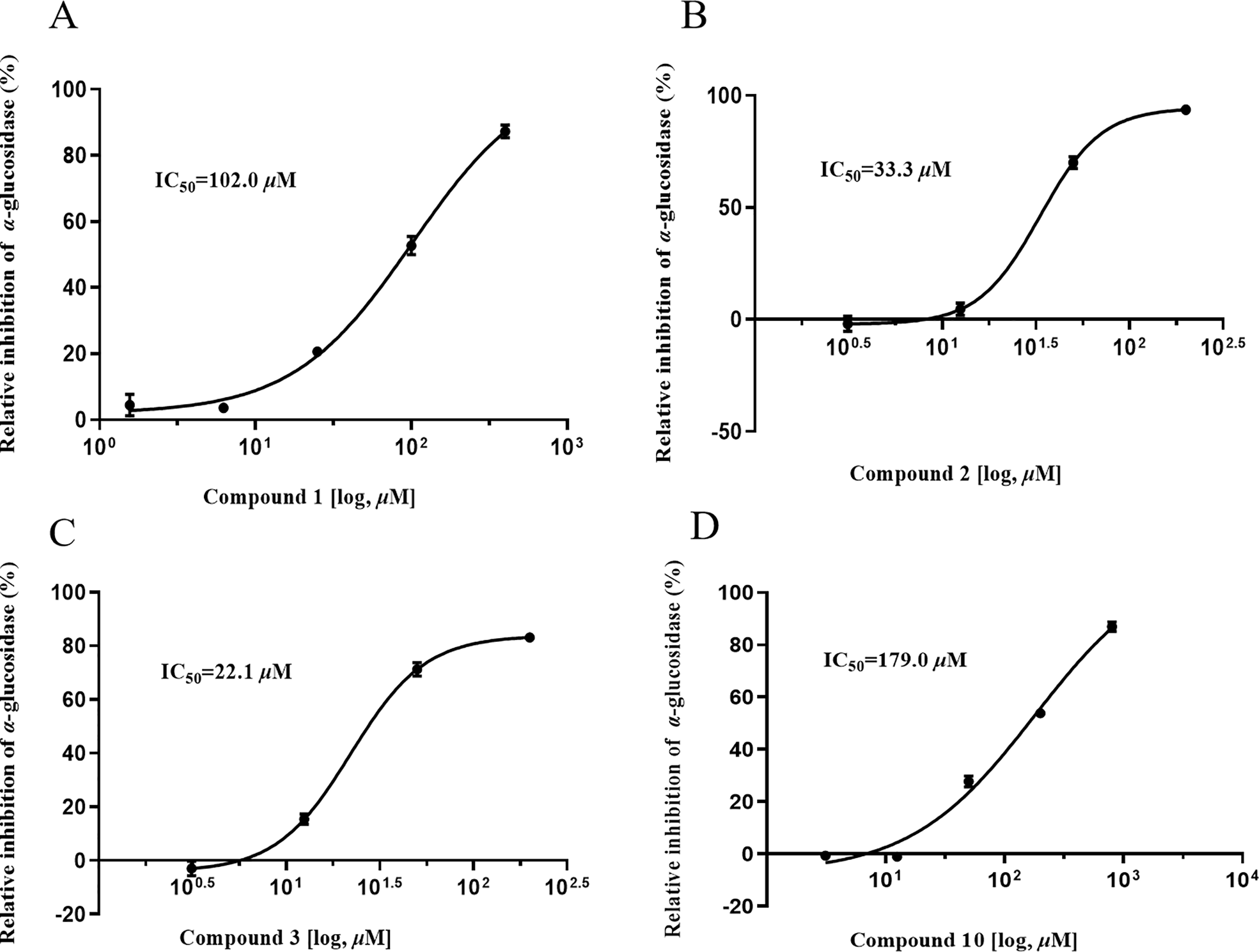

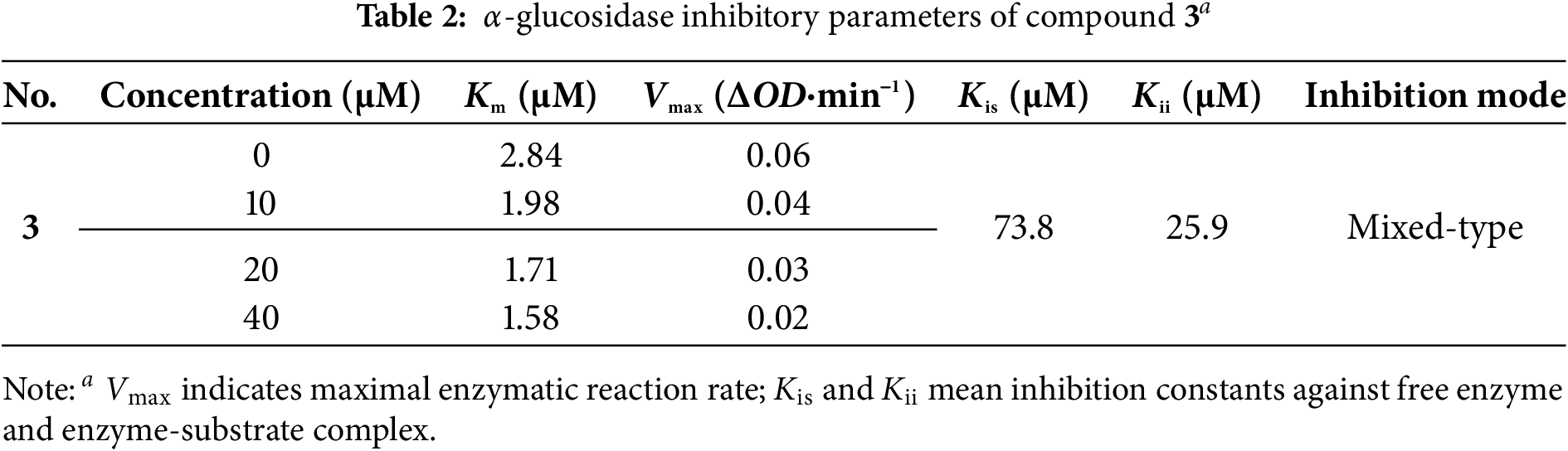

Lineweaver-Burk analysis revealed compound 3 as a mixed-type α-glucosidase inhibitor. The intersecting plots in the third quadrant demonstrated that both Km (michaelis constant) and Vmax (maximum reaction velocity) decreased with increasing concentrations of compound 3 (Fig. 3A). The inhibition constants (Kis = 73.8 μM, Kii = 25.9 μM) indicate stronger binding to the enzyme-substrate complex than free enzyme, displaying non-competitive and anti-competitive inhibition features (Table 2) [29,31].

Figure 3: Inhibition kinetics of compound 3. Lineweaver-Burk plots (A), secondary plots (B,C) of 3 against α-glucosidase

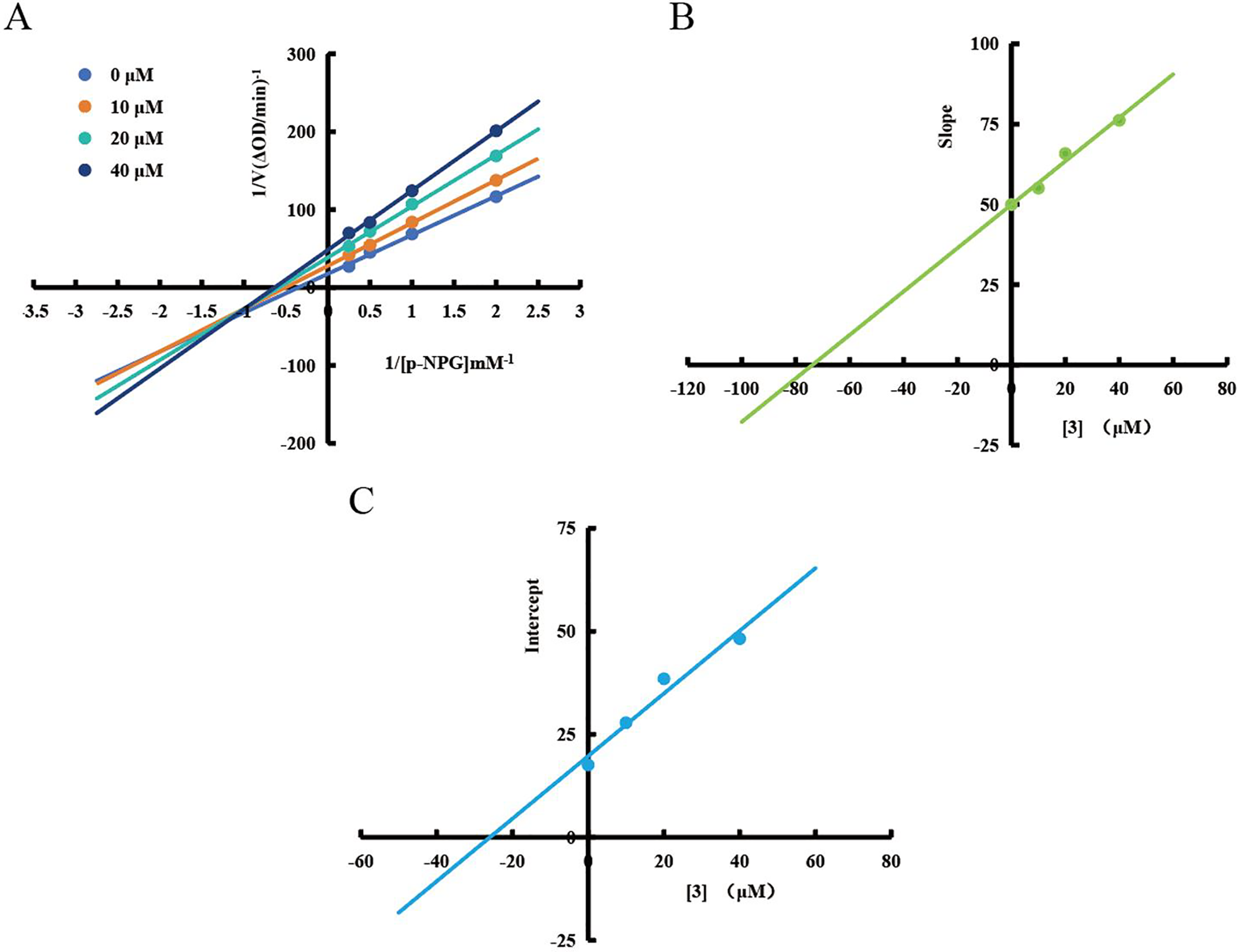

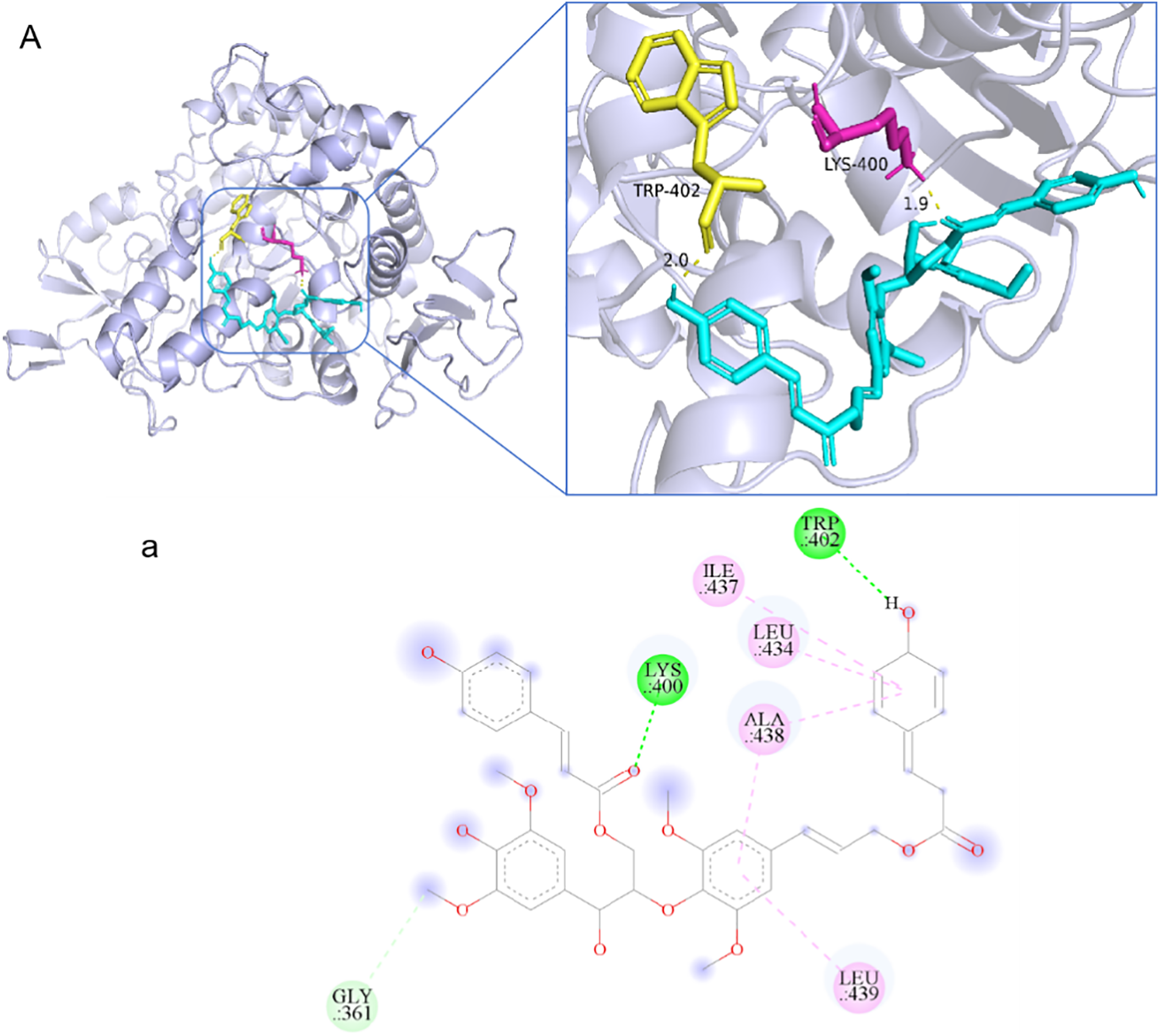

Molecular docking analyses suggested that compound 3 strongly interacted with the catalytic pocket of α-glucosidase (Fig. 4). The binding energies of compound 3 and acarbose with α-glucosidase were –2.9 and –4.5 kcal/mol, respectively. The key interactions included hydrogen bonds with Trp402, Lys400, and Gly361, as well as π-π stacking interactions with Ile437, Leu434, Ala438, and Leu439.

Figure 4: Docking analysis of 3 with α-glucosidase: (A) Overall binding conformation; (a) Key interactions (green: H-bonds; pink: π-π interactions)

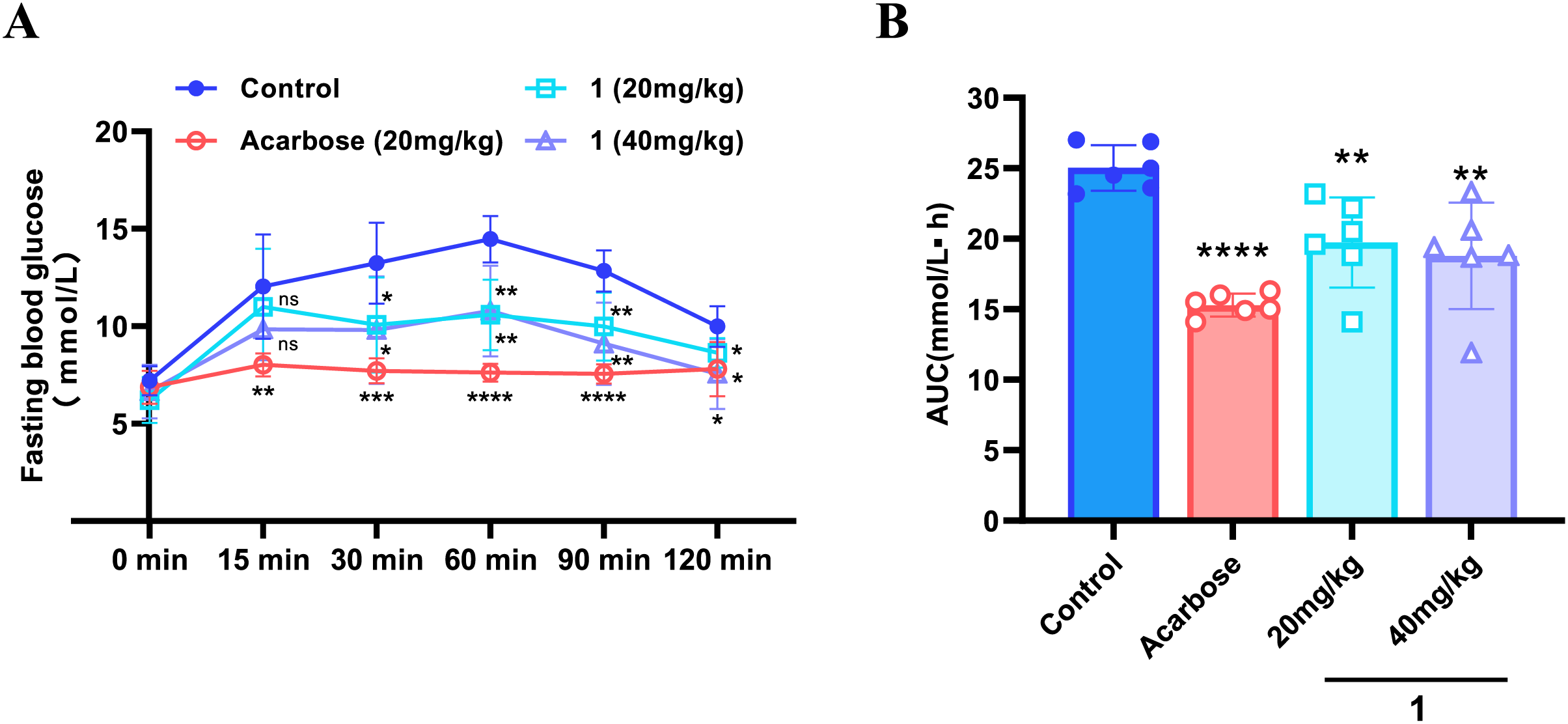

The oral starch tolerance test demonstrated significant differences in glycemic responses across the experimental groups (Fig. 5A). Following starch administration, the control group displayed a characteristic postprandial blood glucose (PBG) profile, with glucose levels peaking at 60 min. For the acarbose group, the area under the curve (AUC) was reduced by 38.9% compared to the control (p < 0.0001). Similarly, compound 1 demonstrated dose-dependent hypoglycemic effects, reducing the AUC by 24.9% at the high dose (40 mg/kg) and by 21.1% at the low dose (20 mg/kg) (Fig. 5B). The delayed and attenuated glucose peak suggests that compound 1 may slow down carbohydrate digestion and absorption, likely through α-glucosidase inhibition. Although compound 1 was less efficacious than acarbose, the improved PBG control at the high dose suggests its hypoglycemic potential by dose optimization. These findings support further investigation of compound 1 as a potential anti-diabetic agent, including studies on its precise mechanism of action, long-term safety, and synergistic effects with other medications.

Figure 5: Oral starch tolerance test (OSTT) in mice. (A) Postprandial blood glucose (PBG) levels at indicated time points; (B) Area under the curve (AUC) analysis of PBG levels during 0–120 min. Data were presented as mean ± SD from one experiment (n = 6). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, “ns” means no significant

This study identified twelve lignans from Amomum tsao-ko leaves, revealing erythro-5-methoxy-dadahol A (2) and threo-5-methoxy-dadahol A (3) as potent α-glucosidase inhibitors. Kinetic analyses and molecular docking elucidated their mechanisms of action, confirming that compound 3 acts as a mixed-type inhibitor. Furthermore, compound 1 demonstrated promising in vivo hypoglycemic effects by attenuating postprandial glucose elevation, aligning with its α-glucosidase inhibitory activity in vitro. These findings expand the phytochemical profile of A. tsao-ko and highlight the potential of its lignans as promising antidiabetic agents. The hypoglycemic effects of these lignans have only been demonstrated through in vitro experiments and in vivo OSTT. To fully evaluate their antidiabetic potential, comprehensive mechanistic studies and long-term pharmacological evaluations are required.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was financially supported by the Yunnan Major Scientific and Technological Program (202202AE090035), CAS Interdisciplinary Team of “Light of West China” Program (xbzg-zdsys-202405), the Yunnan Fundamental Research Projects (202201AV070010, 202301AS070069, 202402AA310003), Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB1230000), and the Yunnan Province Science and Technology Department (202305AH340005). We highly appreciate Dr. Jiang Zeng (Wenshan University) for providing the plant material.

Author Contributions: Investigation and wrote the original draft: Yun Wang and Xin-Yu Li; Methodology: Sheng-Li Wu and Pianchou Gongpan; Supervision: Da-Hong Li; Conceptualization, writing—review and editing, supervision, and funding acquisition: Chang-An Geng. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: All experimental procedures received approval (License No. SYXK (Yunnan) K2024-0003) from the Animal Welfare Committee of the Kunming Institute of Botany (CAS).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Abel ED, Gloyn AL, Evans-Molina C, Joseph JJ, Misra S, Pajvani UB, et al. Diabetes mellitus-Progress and opportunities in the evolving epidemic. Cell. 2024;187(15):3789–3820. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2024.06.029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Federation ID. IDF diabetes atlas. 10th ed. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes; 2021. [Google Scholar]

3. Sugandh F, Chandio M, Raveena F, Kumar L, Karishma F, Khuwaja S, et al. Advances in the management of diabetes mellitus: a focus on personalized medicine. Cureus. 2023;15(8):e43697. doi:10.7759/cureus.43697. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Wong ND, Sattar N. Cardiovascular risk in diabetes mellitus: epidemiology, assessment and prevention. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2023;20(10):685–95. doi:10.1038/s41569-023-00877-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Teponno RB, Kusari S, Spiteller M. Recent advances in research on lignans and neolignans. Nat Prod Rep. 2016;33(9):1044–92. doi:10.1039/c6np00021e. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Ayres DC, Loike JD. Lignans: chemical, biological and clinical properties. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

7. Cui QH, Du RK, Liu MM, Rong LJ. Lignans and their derivatives from plants as antivirals. Molecules. 2020;25(1):183. doi:10.3390/molecules25010183. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Wu XQ, Li W, Chen JX, Zhai JW, Xu HY, Ni L, et al. Chemical constituents and biological activity profiles on Pleione (Orchidaceae). Molecules. 2019;24(17):3195. doi:10.3390/molecules24173195. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Lu H, Liu GT. Anti-oxidant activity of dibenzocyclooctene lignans isolated from Schisandraceae. Planta Med. 1992;58(4):311–3. doi:10.1055/s-2006-961473. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Pan JY, Chen SL, Yang MH, Wu J, Sinkkonen J, Zou K. An update on lignans: natural products and synthesis. Nat Prod Rep. 2009;26(10):1251–92. doi:10.1039/b910940d. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Capilla AS, Sánchez I, Caignard DH, Renard P, Pujol MD. Antitumor agents. Synthesis and biological evaluation of new compounds related to podophyllotoxin, containing the 2,3-dihydro-1,4-benzodioxin system. Eur J Med Chem. 2001;36(4):389–93. doi:10.1016/s0223-5234(01)01231-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Kawazoe K, Yutani A, Tamemoto K, Yuasa S, Shibata H, Higuti T, et al. Phenylnaphthalene compounds from the subterranean part of Vitex rotundifolia and their antibacterial activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Nat Prod. 2001;64(5):588–91. doi:10.1021/np000307b. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Hirano T, Wakasugi A, Oohara M, Oka K, Sashida Y. Suppression of mitogen-induced proliferation of human peripheral blood lymphocytes by plant lignans. Planta Med. 1991;57(4):331–4. doi:10.1055/s-2006-960110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Iwasaki T, Kondo K, Kuroda T, Moritani Y, Yamagata S, Sugiura M, et al. Novel selective PDE IV inhibitors as antiasthmatic agents. Synthesis and biological activities of a series of 1-aryl-2,3-bis(hydroxymethyl)naphthalene lignans. J Med Chem. 1996;39(14):2696–704. doi:10.1021/jm9509096. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Wang Y, Wu SL, Li XY, Gongpan PC, Fu H, Liao XM, et al. Isospongian diterpenoids from the leaves of Amomum tsao-ko promote GLP-1 secretion via Ca2+/CaMKII and PKA pathways and inhibit DPP-4 enzyme. Chem Biodivers. 2024;21(11):e202401407. doi:10.1002/cbdv.202401407. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Yang S, Xue Y, Chen D, Wang Z. Amomum tsao-ko Crevost & Lemarié: a comprehensive review on traditional uses, botany, phytochemistry, and pharmacology. Phytochem Rev. 2022;21(5):1487–521. doi:10.1007/s11101-021-09793-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Hong SS, Lee JH, Choi YH, Jeong W, Ahn EK, Lym SH, et al. Amotsaokonal A-C, benzaldehyde and cycloterpenal from Amomum tsao-ko. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015;56(48):6681–4. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2015.10.045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Lee KY, Kim SH, Sung SH, Kim YC. Inhibitory constituents of lipopolysaccharide-induced nitric oxide production in BV2 microglia isolated from Amomum tsao-ko. Planta Med. 2008;74(8):867–9. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1074552. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Yang XZ, Küenzi P, Plitzko I, Potterat O, Hamburger M. Bicyclononane aldehydes and antiproliferative constituents from Amomum tsao-ko. Planta Med. 2009;75(5):543–6. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1185320. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Song QS, Teng RW, Liu XK, Yang CR. Tsaokoin, a new bicyclic nonane from Amomum tsao-ko. Chin Chem Lett. 2001;12(3):227–30. [Google Scholar]

21. Kim JH, Kim HY, Jin CH. Mechanistic investigation of anthocyanidin derivatives as α-glucosidase inhibitors. Bioorg Chem. 2019;87:803–9. doi:10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.01.033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. He XF, Chen JJ, Huang XY, Hu J, Zhang XK, Guo YQ, et al. The antidiabetic potency of Amomum tsao-ko and its active flavanols, as PTP1B selective and α-glucosidase dual inhibitors. Ind Crops Prod. 2021;160:112908. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2020.112908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. He XF, Chen JJ, Li TZ, Zhang XK, Guo YQ, Zhang XM, et al. Nineteen new flavanol-fatty alcohol hybrids with α-glucosidase and PTP1B dual inhibition: one unusual type of antidiabetic constituent from Amomum tsao-ko. J Agric Food Chem. 2020;68(41):11434–48. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.0c04615. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. He XF, Wang HM, Geng CA, Hu J, Zhang XM, Guo YQ, et al. Amomutsaokols A-K, diarylheptanoids from Amomum tsao-ko and their α-glucosidase inhibitory activity. Phytochemistry. 2020;177(3):112418. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2020.112418. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. He XF, Zhang XK, Geng CA, Hu J, Zhang XM, Guo YQ, et al. Tsaokopyranols A-M, 2,6-epoxydiarylheptanoids from Amomum tsao-ko and their α-glucosidase inhibitory activity. Bioorg Chem. 2020;96:103638. doi:10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.103638. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. He XF, Chen JJ, Li TZ, Hu J, Zhang XK, Guo YQ, et al. Tsaokols A and B, unusual flavanol-monoterpenoid hybrids as α-glucosidase inhibitors from Amomum tsao-ko. Chin Chem Lett. 2021;32(3):1202–5. doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2020.08.050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Wang Y, Li XY, Wu SL, Gongpan PC, Yang Y, Huang M, et al. Antidiabetic diarylheptanoids from the leaves of Amomum tsao-ko and their inhibition mechanism against α-glucosidase. Fitoterapia. 2025;183:106566. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2025.106566. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. He XF, Chen JJ, Li TZ, Hu J, Huang XY, Zhang XM, et al. Diarylheptanoid-flavanone hybrids as multiple-target antidiabetic agents from Alpinia katsumadai. Chin J Chem. 2021;39(11):3051–63. doi:10.1002/cjoc.202100469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Ge CC, Li XY, Qiao WH, Cui C, Wang J, Gongpan PC, et al. BACE1 inhibitors from the fruits of Alpinia oxyphylla have efficacy to treat T2DM-related cognitive disorder. Fitoterapia. 2024;178:106157. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2024.106157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Dong Q, Hu N, Yue H, Wang H. Inhibitory activity and mechanism investigation of hypericin as a novel α-glucosidase inhibitor. Molecules. 2021;26(15):4566. doi:10.3390/molecules26154566. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Li XY, Wang T, Wu SL, Huang XY, Ma YB, Geng CA. New C-linked diarylheptanoid dimers as potential α-glucosidase inhibitors evidenced by biological, spectral and theoretical approaches. Int J Biol Macromol. 2025;295(23):139496. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.139496. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Kang HR, Yun HS, Lee TK, Lee S, Kim SH, Moon E, et al. Chemical characterization of novel natural products from the roots of Asian Rice (Oryza sativa) that control adipocyte and osteoblast differentiation. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66(11):2677–84. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.7b05030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Yamashita A, Kishimoto T, Hamada M, Nakajima N, Urabe D. Biomimetic oxidation of monolignol acetate and p-coumarate by silver oxide in 1, 4-dioxane. J Agric Food Chem. 2020;68(7):2124–31. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.9b07682. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Kwak JH, Kang MW, Roh JH, Choi SU, Zee OP. Cytotoxic phenolic compounds from Chionanthus retusus. Arch Pharm Res. 2009;32(12):1681–7. doi:10.1007/s12272-009-2203-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Posri P, Suthiwong J, Takomthong P, Wongsa C, Chuenban C, Boonyarat C, et al. A new flavonoid from the leaves of Atalantia monophylla (L.) DC. Nat Prod Res. 2019;33(8):1115–21. doi:10.1080/14786419.2018.1457667. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Yang GZ, Hu Y, Yang B, Chen Y. Lignans from the Bark of Zanthoxylum planispinum. Helv Chim Acta. 2009;92(8):1657–64. doi:10.1002/hlca.200900055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Wang L, Li F, Yang CY, Khan AA, Liu X, Wang MK. Neolignans, lignans and glycoside from the fruits of Melia toosendan. Fitoterapia. 2014;99:92–8. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2014.09.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Goetz G, Fkyerat A, Métais N, Kunz M, Tabacchi R, Pezet R, et al. Resistance factors to grey mould in grape berries: identification of some phenolics inhibitors of Botrytis cinerea stilbene oxidase. Phytochemistry. 1999;52(5):759–67. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(99)00351-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Kisiel W, Zielinska K. Sesquiterpenoids and phenolics from Lactuca perennis. Fitoterapia. 2000;71(1):86–7. doi:10.1016/s0367-326x(99)00112-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. He ZH, Yue GGL, Lau CBS, Ge W, But PPH. Antiangiogenic effects and mechanisms of trans-ethyl p-methoxycinnamate from Kaempferia galanga L. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60(45):11309–17. doi:10.1021/jf304169j. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Karonen M, Hämäläinen M, Nieminen R, Klika KD, Loponen J, Ovcharenko VV, et al. Phenolic extractives from the bark of Pinus sylvestris L. and their effects on inflammatory mediators nitric oxide and prostaglandin E2. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52(25):7532–40. doi:10.1021/jf048948q. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools