Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Seed Priming Mitigates the Salt Stress in Eggplant (Solanum melongena) by Activating Antioxidative Defense Mechanisms

Environmental Science Center, Qatar University, Doha, 2713, Qatar

* Corresponding Author: Talaat Ahmed. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Decoding Plant Resilience Under Abiotic Stresses)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(8), 2423-2439. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.068303

Received 25 May 2025; Accepted 17 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Salt stress is a major threat to crop agricultural productivity. Salinity affects plants’ physiological and biochemical functions by hampering metabolic functions and decreasing photosynthetic rates. Salinity causes hyperosmotic and hyperionic stress, directly impairing plant growth. In this study, eggplant seeds primed with moringa leaf extract (5%, 10%, and 15%), nano-titanium dioxide (0.02%, 0.04%, and 0.06%), and ascorbic acid (0.5, 1, and 2 mM) at different NaCl salt (0, 75, and 150 mM) concentration were grown. The germination attributes (final germination percentage, germination index, mean germination time, and mean germination rate) and growth (root length, shoot length, fresh biomass, and dry biomass) were enhanced in the primed seedlings by the different priming agents, more prominently in ascorbic acid primed seedlings. The accumulation of hydrogen peroxide was greater in seedlings with higher salt levels. Similarly, the activity of antioxidant enzymes (superoxide dismutase, peroxidase, and catalase) was higher in primed seedlings compared to the control. At 150 mM, the antioxidant capacity was higher than 75 mM, and the seedlings’ sodium and chloride content was higher. The results demonstrate that seedling germination, growth, and activity of the antioxidant enzymes in ascorbic acid-primed seedlings increase their tolerance to salinity. Therefore, using different ascorbic acid concentrations (0.5, 1, and 2 mM) as a priming agent to enhance germination and growth in saline conditions has proven effective.Keywords

The agricultural industry faces many challenges, from using high amounts of pesticides to depleting resources due to global climate change. With the world population expected to be approximately 10 billion by 2050, food security is a major global risk of this century. Maintaining the high food demand with global climate change affecting the environment is humongous. The effects of global climate change, such as drought and flooding, are increasing the plants’ abiotic stress and decreasing productivity [1]. Salt stress is a major factor in limiting agricultural productivity among the many abiotic stresses. The land area affected by salt is 20% and more than 50% of the irrigated agricultural land [2]. With the current trends of an increase in saline soil due to overproduction, the salt stress land is expected to increase by 30%, and by the year 2050, 50% of the agricultural land could be lost [3].

Saline soils are dominated mainly by chloride or sulfate salts; each salt affects the plant’s initial growth. Due to salt stress, the uptake of necessary ions is reduced due to high sodium (Na+) and chloride (Cl−) ion concentrations, which inhibit the uptake of Ca+ and K+ ions, negatively affecting the physiological processes and significantly reducing plant germination and seedling growth [1]. Plants are sensitive in the initial stages and more susceptible to stress. The growth inhibition is mainly caused by cytotoxicity and nutritional imbalance due to the high uptake of Na+ and Cl− ions [4]. Salinity causes hyperosmotic and hyperionic stress, which directly impair plant growth. The plant’s water absorption capacity is disturbed due to hyperosmotic stresses. Salt stress inhibits cell expansion and stomatal closure due to high ionic accumulation, leading to downregulation of metabolic processes and ultimately cell death [5].

Rapid seed germination is essential in crop production and quality under stressful conditions. The rapid growth of seedlings ensures the expansion of leaves and roots, leading to higher uptake of nutrients and biomass production. Methods to develop and boost seed germination processes to recuperate from stress in agriculture are essential [6]. Several strategies to improve plant growth, such as breeding and priming [7]. Priming has proven practical and cost-effective in remediating the risks associated with seed germination and seedling emergence by inducing metabolic activities. Seed priming treatment is done before sowing the seeds by hydrating them in a specific environment to start the germination process. Seed priming improves the seeds’ defense mechanisms to overcome the environmental stresses that hinder germination. Seed priming improves rapid germination and crop establishment under stressful conditions. The effectiveness of seed priming in saline conditions has been reported for wheat [8,9], corn [4], tomato [10], lentils [11], and maize [12].

Moringa leaf extract (MLE) is rich in plant growth-promoting hormones such as cytokinin, which stimulate several enzymes and protect plant cells from aging and the effects of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [8]. Hassanein et al. [13] reported increased plant biomass with a high photosynthetic rate and phytohormone content. Ascorbic acid has strong antioxidant potential and is a crucial factor in cell division, photosynthesis, and hormone biosynthesis, playing an essential role in the early stages of germination [14]. Seed priming with ascorbic acid has been reported to increase the speed and uniformity of germination by reducing the toxic compounds due to the antioxidant system [11]. A wide range of nanoparticles are being used in the agriculture industry for remediation purposes, elongating roots in saline conditions, and alleviating salt stress [15]. Titanium dioxide nanoparticle (TiO2) is a commonly used nanoparticle due to its stimulating effects in accelerated seed germination [16,17]. Haghighi & Teixeira da Silva [18] reported increased growth in tomatoes, onions, and radishes with the application of nano-TiO2.

Vegetables are mostly affected by salinity during production. Salinity affects the morphological, physiological, and biochemical functions during the production phase of vegetables. Eggplant (Solanum melongena L.), part of the Solanaceous family, is grown globally [19]. As a sensitive plant, its growth and yield decline under high salt levels [20]. However, different varieties respond uniquely to stress due to their physical, biochemical, and physiological traits [21]. Rich in phenolic acids, eggplants provide health benefits, spurring research into their salt tolerance in high-salinity environments [22]. This study aimed to use MLE, TiO2, and ascorbic acid as plant bio-stimulants to induce priming effects in eggplant seeds during germination and seedling development. This study encompasses the morphological observations during the growth and biochemical processes like antioxidant enzyme activity and reactive oxygen species modulation, which are essential in early growth in plants. The use of different priming agents in the current study is vital in understanding the potential of enhancing and improving the seed germination of eggplant seeds under different salt stress conditions.

All the experimental procedures were carried out in the Environmental Science Center of Qatar University. Eggplant seeds of Violetta lunga 2 from Zorzi Italy were collected for the experiment. Different concentrations of saline solutions of 0 (as control), 75, and 150 mM NaCl were prepared. Ten priming solutions were prepared: control primed with water, MLE (5%, 10%, and 15%), TiO2 (0.02%, 0.04%, and 0.06%), and ascorbic acid (0.5, 1, and 2 mM) at different NaCl salt (0, 75, and 150 mM), the concentration was selected by following the methods in previous studies [8,16,23]. The seeds were soaked in priming solutions for 12 h and dried before placing them in Petri dishes at 22°C for the germination tests. A completely randomized design (CRD) with three replications was applied in this study.

The experiment was carried out in sterilized Petri dishes with Whatman filter paper number 1 after humidifying with distilled water or NaCl solutions via spraying at 0 (S0), 75 (S1), and 150 mM (S2). Each replicated Petri dish contained ten primed seeds.

The seeds’ germination was monitored daily until the maximum germination in the control was achieved, 14 days after the start of the experiment. After the maximum elongation, the germination parameters were calculated with germination index (GI), mean germination time (MGT), mean germination rate (MGR), and final germination percentage (FGP) following Milivojević et al. [24].

where ti is the time from day one to the last day of observation, ni is the observed number of germinated seeds on each day, and k is the last germination time.

The growth parameters of seedlings under different salt stress treatments were assessed by measuring the root length, shoot length, fresh weight, and dry weight at the end of the experiment. The seedlings were dried in an oven at 65°C for dry weight estimation until a constant weight was achieved. The greenness of the leaves was measured using a SPAD meter. After the experiment, the leaves’ quantum yield (QY) was measured with a chlorophyll fluorometer (FlourPen FP-100, Photon System Instruments, Drásov, Czech Republic).

2.3 Enzymatic Assays and Hydrogen Peroxide

300 mg of fresh samples were homogenized in sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) and centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was used for the analysis of superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and peroxidase (POD) was determined by following the method of Khalid et al. [25]. The hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was estimated by homogenizing 300 mg of sample in 3 mL of trichloroacetic acid (0.1%) and centrifuging at 12,000 rpm for 15 min; the supernatant was used. The analysis was done at the end of the experiment at the early vegetative stage, 14 days after the start of the experiment.

To measure Na+ and Cl−, dry samples of plants were taken from primed eggplant seedlings. For Na+, wet digestion was completed by heating 100 mg of plant material at 350°C. The methodology of Ryan et al. [26], using a flame photometer, was used to measure Na. For Cl− analysis, 100 mg of each oven-dried leaf or root sample was placed in a muffle furnace at 400°C, and Hussain et al. [27] method was used using a chloride electrode.

The data collected was analyzed using the Statistix 8.1 (USA) software package. An analysis of variance was done to examine the significant difference between control and other treatments, and LSD tests were used to compare means at a 5% probability level. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using R. Pearson’s correlation was constructed in Excel.

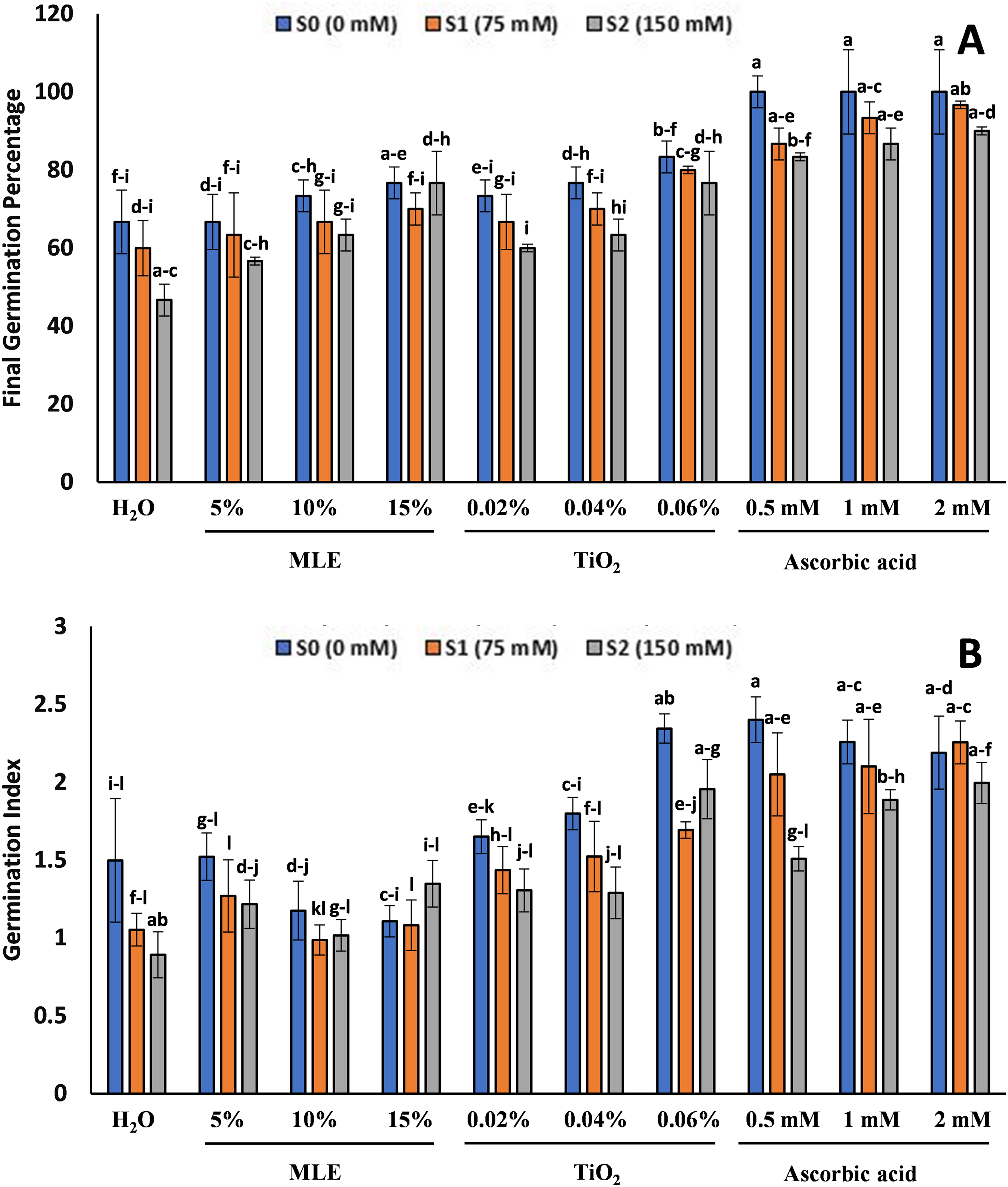

The FGP and GI showed that, with the increase in salinity, there was a decrease in FGP and GI (Fig. 1). The seedlings primed with ascorbic acid showed the highest FGP at all salt stress levels (0, 75, 150 mM). The 100% FGP at S0, 96.67% for 2 mM and 93.34% for 1 mM at S1, and 90% for 2 mM and 86.67% for 1 mM at S2. The lowest FGP at all levels was observed in control H2O, with 66.67%, 60%, and 46.67% at S0, S1, and S2. Similarly, the GI was observed to be the highest for all the treatments of ascorbic acid-primed seedlings, with 2.4 for 0.5 mM at S0, 2.25 for 2 mM at S1, and 1.99 for 2 mM at S2. The minimum GI was observed in MLE-primed seeds with 1.1 for 15% MLE at S0, 0.98 for 10% MLE at S1, and 1.01 for 10% MLE at S2.

Figure 1: Effect of salt stress on eggplant seedlings treated with control (H2O), moringa leaf extract (5%, 10%, and 15%), titanium dioxide (0.02%, 0.04%, and 0.06%), and ascorbic acid (0.5, 1, and 2 mM) on Final germination percentage (A) and Germination Index (B) (the error bars indicate standard error). The lowercase letters indicate the significant difference between data points. The level of significance is p < 0.05

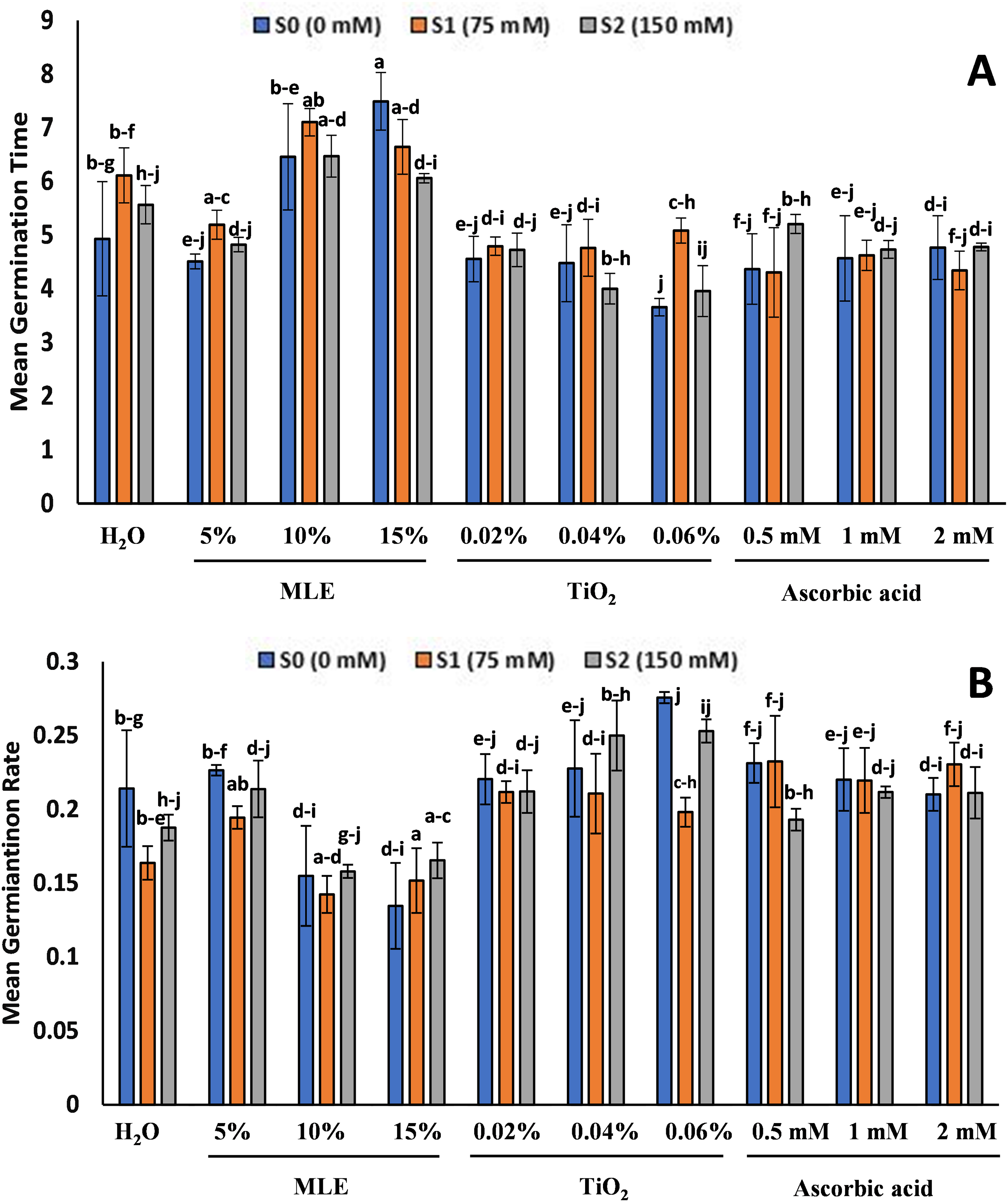

The MGT for the TiO2 primed seedlings at S0 and S2 was the lowest with 3.65 and 3.95 for 0.06% concentration, whereas at S1, the lowest was in ascorbic acid primed seedlings with 4.3 for 0.5 mM (Fig. 2). The highest MGT was in MLE with 7.49 at S0 for 10%, 7.1 at S1 for 15%, and 6.46 at S2 for 10%. The MGR was the highest in TiO2 and ascorbic acid primed seedlings with 0.27 for 0.06% TiO2 at S0, 0.232 for 0.5 mM ascorbic acid at S1, and 0.253 for 0.06% TiO2 at S2. The lowest was in MLE-primed seedlings with 0.13 at S0, 0.15 at S1, and 0.16 at S2 for the 15% treatment (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Effect of salt stress on eggplant seedlings treated with control (H2O), moringa leaf extract (5%, 10%, and 15%), titanium dioxide (0.02%, 0.04%, and 0.06%), and ascorbic acid (0.5, 1, and 2 mM) on Mean Germination Time (A) and Mean Germination Rate (B) (the error bars indicate standard error). The lowercase letters indicate the significant difference between data points. The level of significance is p < 0.05

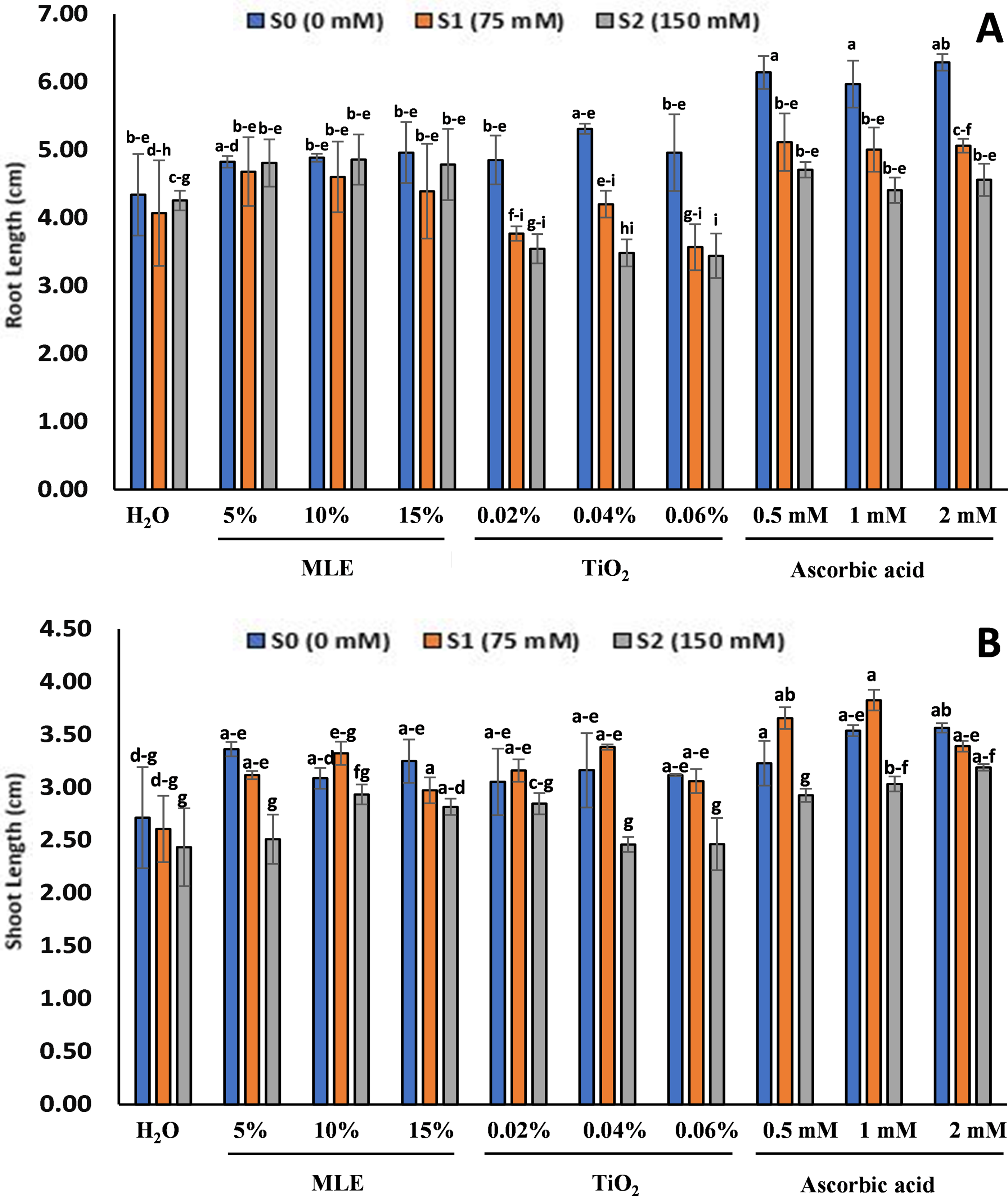

An increase in salt stress decreased the growth parameters in the seedlings of all treatments, after 14 days from the start of the experiment (vegetative stage). The primed seedlings treatments showed better growth than the control (Fig. 3). The root length for the seedlings at S0 was observed longest in ascorbic acid primed seedlings with 2 mM (6.28 cm), 0.5 mM (6.14 cm), and 1 mM (5.96 cm), and the shortest root length was observed in control (4.34 cm), 5% MLE (4.82 cm), and 0.02% TiO2 (4.85 cm). Similarly, the most extended root length at S1 was observed in ascorbic acid-primed seedlings 0.5 mM (5.11 cm), 2 mM (5.06 cm), and 1 mM (5 cm), and the shortest was observed in TiO2 0.06% (3.56 cm), 0.04% (3.76 cm) and 0.02% (4.2 cm). The longest root length for the seedlings at S2 was observed in MLE primed seedlings, 10% (4.85 cm), 5% (4.8 cm), and 15% (4.78 cm), and the shortest was observed in TiO2 primed seedlings at 0.06% (3.44 cm) and 0.04% (3.48 cm). As for the root length, being longest in ascorbic acid primed seedlings, similar results were observed with the shoot length for the seedlings at S0 with 2 mM (3.56 cm) and 1 mM (3.53 cm) having the longest shoot, and the shortest was observed in control (2.71 cm) and MLE primed seedlings 10% (3.08 cm). The most extended shoot length at S1 was observed in ascorbic acid-primed seedlings in 1 mM (3.82 cm), 0.5 mM (3.5 cm), and the shortest was observed in control (2.6 cm), and 0.02% TiO2 (3.16 cm). The shoot length for seedlings under high salt stress was observed to be the longest in ascorbic acid seedlings 2 mM (3.19 cm) and 1 mM (3.03 cm), and the shortest was observed in the control (2.43 cm) and TiO2 primed seedlings 0.04% (2.46 cm).

Figure 3: Effect of salt stress on eggplant seedlings treated with control (H2O), moringa leaf extract (5%, 10%, and 15%), titanium dioxide (0.02%, 0.04%, and 0.06%), and ascorbic acid (0.5, 1, and 2 mM) on Root length (A), Shoot length (B), at the start of the vegetative stage (the error bars indicate standard error). The lowercase letters indicate the significant difference between data points. The level of significance is p < 0.05

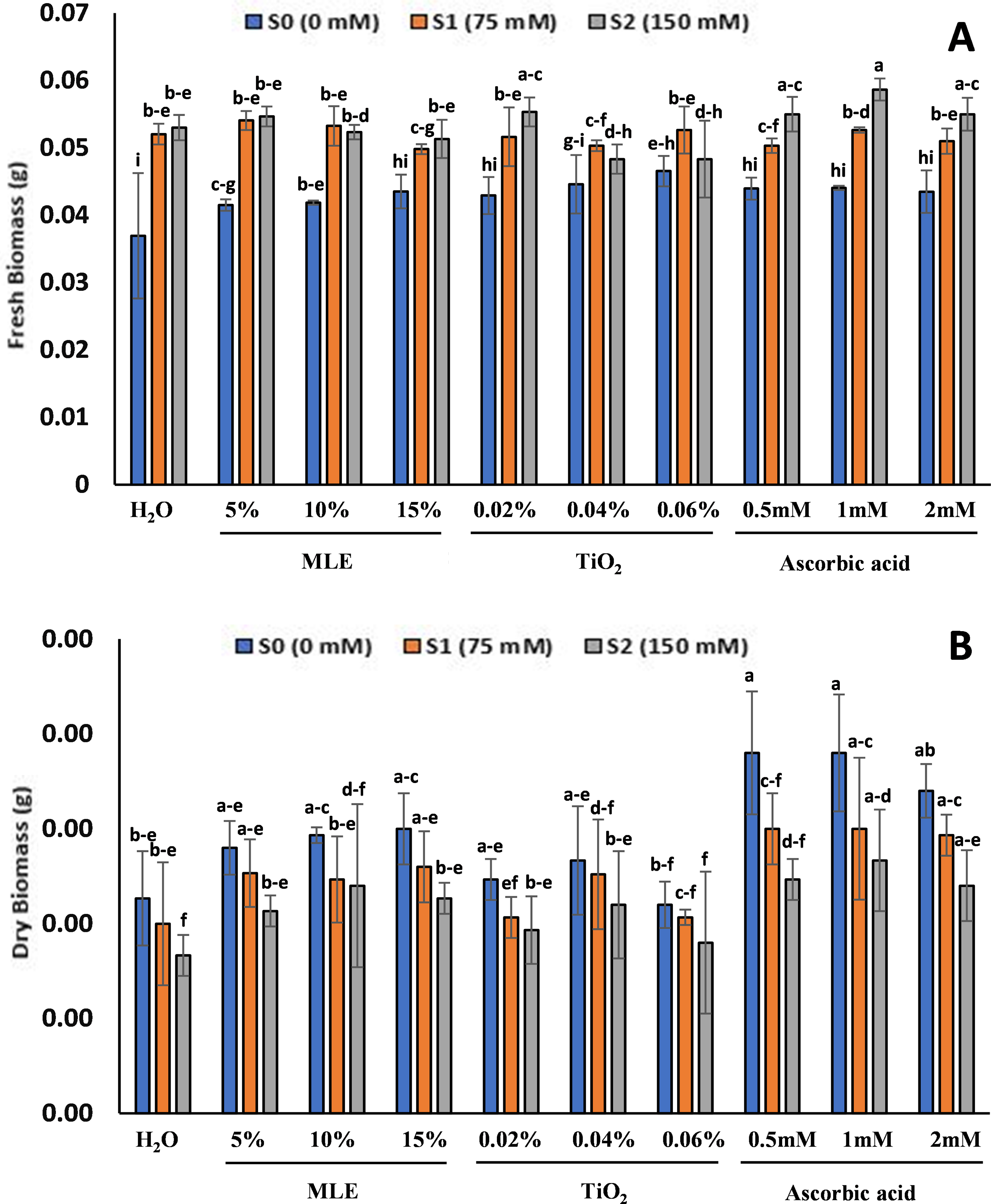

Fresh and dry biomass were observed to be higher in seedlings with high salt concentrations (Fig. 4). The seedlings at S0 with the highest fresh biomass were observed in TiO2 primed seedlings with 0.046 g for 0.06%, and the lowest was in the control at 0.036 g. Similarly, the highest fresh biomass at S1 was in TiO2-primed seedlings at 0.06% with 0.052 g, while the lowest was in MLE-primed seedlings with 0.049 g for 15%. The fresh biomass at S2 was the highest in ascorbic acid primed seedlings, 1 mM, with 0.058 g, and the lowest in T6 and T7, with 0.048 g. The dry biomass was highest for ascorbic acid-primed seedlings at S0 with 0.5 mM and 0.0019 g at 1 mM, and the minimum was in control at 0.0011 g. For the seedlings at S1, the maximum recorded dry biomass was for ascorbic acid seedlings, 0.5 and 1 mM, with 0.0015 g, and the minimum was in control with 0.001 g. The dry biomass for seedlings at S2 was maximum in ascorbic acid primed seedlings 1 mM (0.0013 g), and the minimum was recorded in the control (0.008 g).

Figure 4: Effect of salt stress on eggplant seedlings treated with control (H2O), moringa leaf extract (5%, 10%, and 15%), titanium dioxide (0.02%, 0.04%, and 0.06%), and ascorbic acid (0.5, 1, and 2 mM) on Fresh biomass (A) and Dry biomass (B), at the start of the vegetative stage (the error bars indicate standard error). The lowercase letters indicate the significant difference between data points. The level of significance is p < 0.05

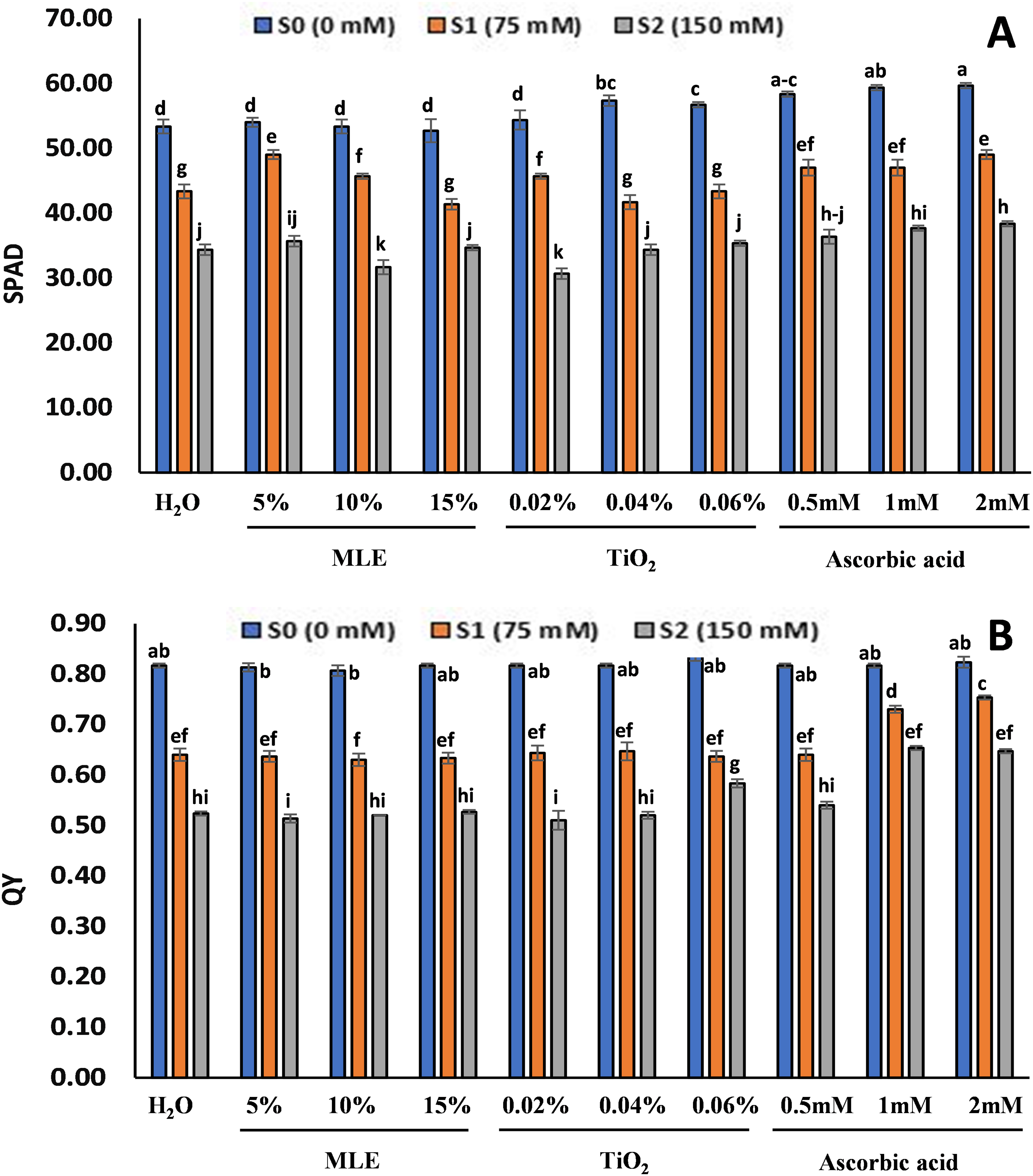

The SPAD and QY readings followed similar trends in all the treatments, with a decrease and an increase in salinity levels (Fig. 5). The highest SPAD for S0 seedlings was highest in ascorbic acid primed seedlings 2 mM (59.67) and 1 mM (59.34), while the lowest was in MLE 15% (52.67) and 10% (53.34). For the S1 seedlings, the highest SPAD was recorded in 5% MLE and 2 mM ascorbic acid (49), and the lowest was at 15% MLE (41.34) and 0.04% TiO2 (41.67). The SPAD recorded for S2 seedlings was highest in 2 mM (38.34) and 1 mM ascorbic acid (37.67), and the lowest was in 0.02% TiO2 (30.67). The QY values were higher at lower salinity levels and decreased with the increase in salinity. The highest QY value for seedlings at S0 was 0.06% TiO2 (0.83) and 2 mM ascorbic acid (0.82), while the lowest was in 10% (0.8) and 5% MLE (0.81). The highest QY values for seedlings at S1 were 2 mM (0.75) and 1 mM ascorbic acid (0.73) and the lowest in 10% (0.634) and 5% MLE (0.636). For the S2 seedlings, the highest QY was in ascorbic acid 1 mM (0.65) and 2 mM (0.64), and the lowest was in 0.02% TiO2 (0.51) and 5% MLE (0.513).

Figure 5: Effect of salt stress on eggplant seedlings treated with control (H2O), moringa leaf extract (5%, 10%, and 15%), titanium dioxide (0.02%, 0.04%, and 0.06%), and ascorbic acid (0.5, 1, and 2 mM) on SPAD (A) and QY (B), at the start of the vegetative stage (the error bars indicate standard error). The lowercase letters indicate the significant difference between data points. The level of significance is p < 0.05

3.3 Enzymatic Assays and Hydrogen Peroxide

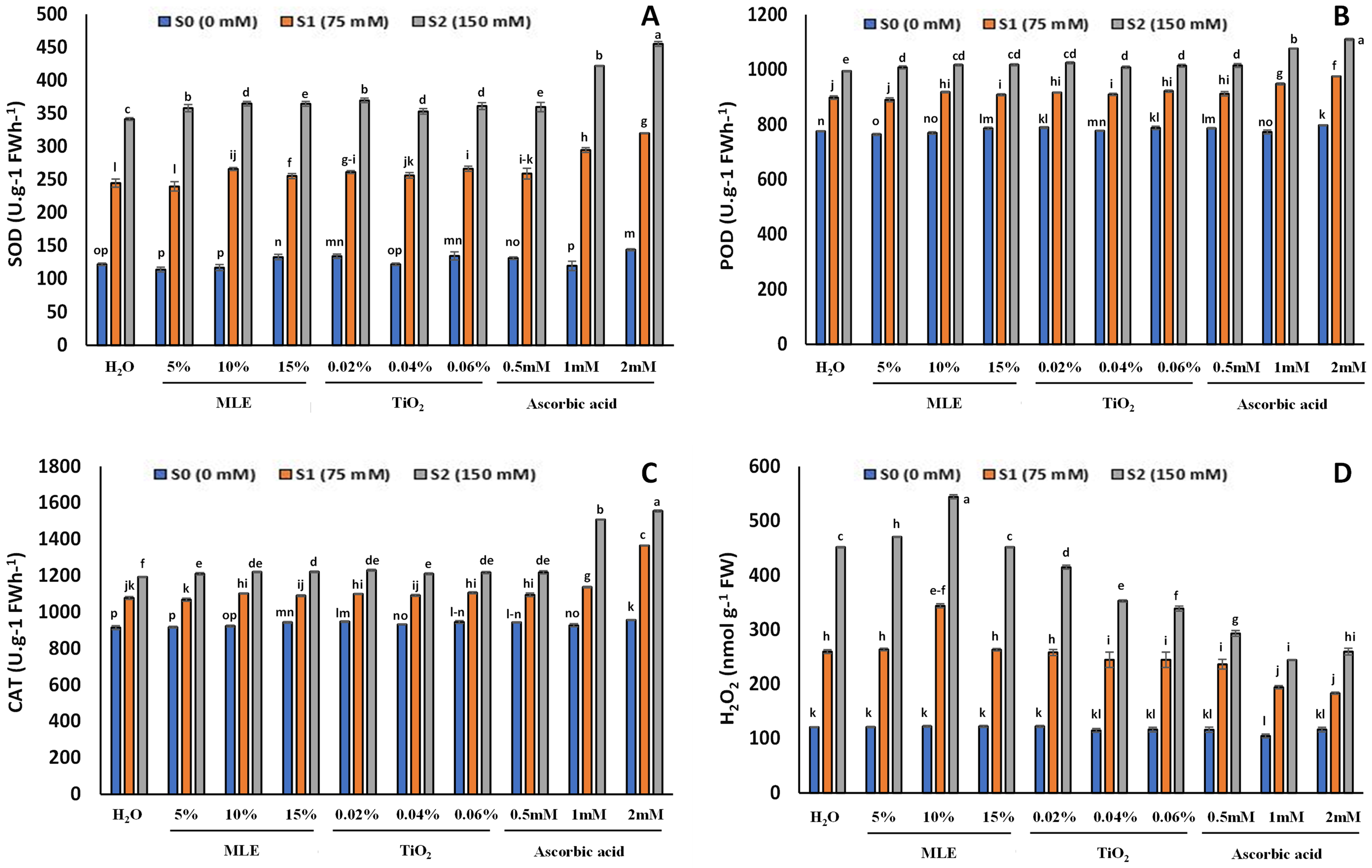

The results of SOD, POD, and CAT showed similar trends, there was an increase in antioxidant enzyme activity with an increase in salt stress with the highest observed in 150 mM NaCl concentration (Fig. 6) after 14 days from the start of the experiment (vegetative stage). The highest SOD, POD, and CAT were found to be in ascorbic acid-primed seedlings, and the lowest was observed in MLE-primed seedlings and control. The SOD for seedlings at S0 was measured highest in 2 mM ascorbic acid (144 U g−1 FWh−1) and the lowest in 5% MLE (114 U g−1 FWh−1). The SOD for seedlings at S1 was highest in 2 mM ascorbic acid (320.33 U g−1 FWh−1) and the lowest in 5% MLE (240 U g−1 FWh−1). For the seedlings at S2, the SOD was the highest in 2 mM ascorbic acid (455.33 U g−1 FWh−1) and the lowest in control (341.67 U g−1 FWh−1). The POD of the seedlings at S0 was the highest in 2 mM ascorbic acid (797.33 U g−1 min−1) and lowest in 5% MLE (764.33 U g−1 min−1). For the seedlings at S1, the POD measured was the highest in 2 mM ascorbic acid (975.33 U g−1 min−1) and the lowest in 5% MLE (890 U g−1 min−1). The POD for seedlings at S2 was the highest in 2 mM ascorbic acid (1110.33 U g−1 min−1) and the lowest in 5% MLE (1008.33 U g−1 min−1). The CAT for seedlings at S0 was highest for 2 mM ascorbic acid (956.8 U g−1 FWh−1) and the lowest in the control (915 U g−1 FWh−1). The highest CAT for seedlings at S1 was in 2 mM ascorbic acid (1365.46 U g−1 FWh−1) and the lowest in the control (1077.6 U g−1 FWh−1). The CAT for seedlings at S2 was the highest in 2 mM ascorbic acid (1554.46 U g−1 FWh−1) and the minimum in control and 0.5 mM ascorbic acid (1210 U g−1 FWh−1).

Figure 6: Effect of salt stress on eggplant seedlings treated with control (H2O), moringa leaf extract (5%, 10%, and 15%), titanium dioxide (0.02%, 0.04%, and 0.06%), and ascorbic acid (0.5, 1, and 2 mM) on SOD (A), POD (B), CAT (C) and H2O2 (D), at the start of the vegetative stage (the error bars indicate standard error). The lowercase letters indicate the significant difference between data points. The level of significance is p < 0.05

The H2O2 was higher in seedlings with the increase in salt concentration. The highest concentration of H2O2 was in MLE-primed seedlings, and the lowest was found to be in ascorbic acid (Fig. 3). In seedlings at S0, the H2O2 was the highest in 10% MLE (122.67 nmol g−1 FW) and the lowest in 1 mM ascorbic acid (105 nmol g−1 FW). For the seedlings at S1, H2O2 was highest in 5% MLE (263.66 nmol g−1 FW) and the lowest in 2 mM ascorbic acid (183.33 nmol g−1 FW). For the seedlings S2, the H2O2 was the highest in 10% MLE (544.33 nmol g−1 FW) and lowest in 1 mM ascorbic acid (244.33 nmol g−1 FW).

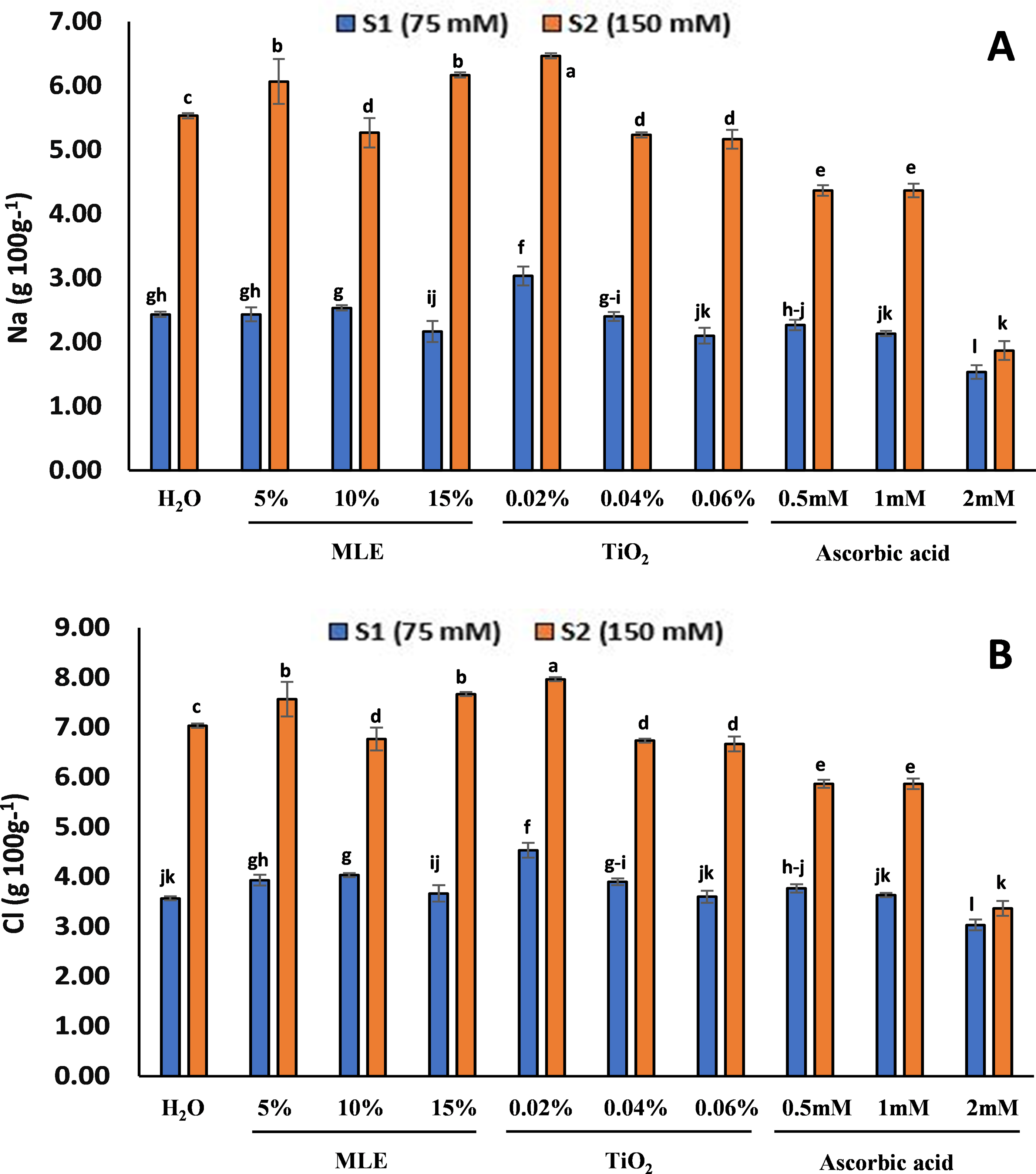

The mineral analysis of the seedlings showed the Na+ and Cl− concentration in the primed seedlings, after 14 days from the start of the experiment (vegetative stage) (Fig. 7). There was no salt treatment at S0; therefore, the concentration of Na and Cl was zero. For the seedlings at S1, the Na concentration was highest in 0.02% TiO2 (3.03 g/100 g) and the lowest in 2 mM ascorbic acid (1.53 g/100 g). In the seedlings at S2, the highest Na concentration was in 0.02% TiO2 (6.46 g/100 g) and the lowest in 2 mM ascorbic acid (1.86 g/100 g). The Cl concentration at S1 was highest in 0.02% TiO2 (4.53 g 100 g−1) and the lowest in 2 mM ascorbic acid (3.03 g/100 g). For the seedlings at S2, the highest Cl was in 0.02% TiO2 (7.96 g/100 g) and the lowest in 2 mM ascorbic acid (3.36 g/100 g).

Figure 7: Effect of salt stress on eggplant seedlings treated with control (H2O), moringa leaf extract (5%, 10%, and 15%), titanium dioxide (0.02%, 0.04%, and 0.06%), and ascorbic acid (0.5, 1, and 2 mM) on Na concentration (A) and Cl concentration (B) at S1 (75 mM), S2 (150 mM) of salt stress, at the start of the vegetative stage (the error bars indicate standard error). The lowercase letters indicate the significant difference between data points. The level of significance is p < 0.05

3.5 Principal Component Analysis

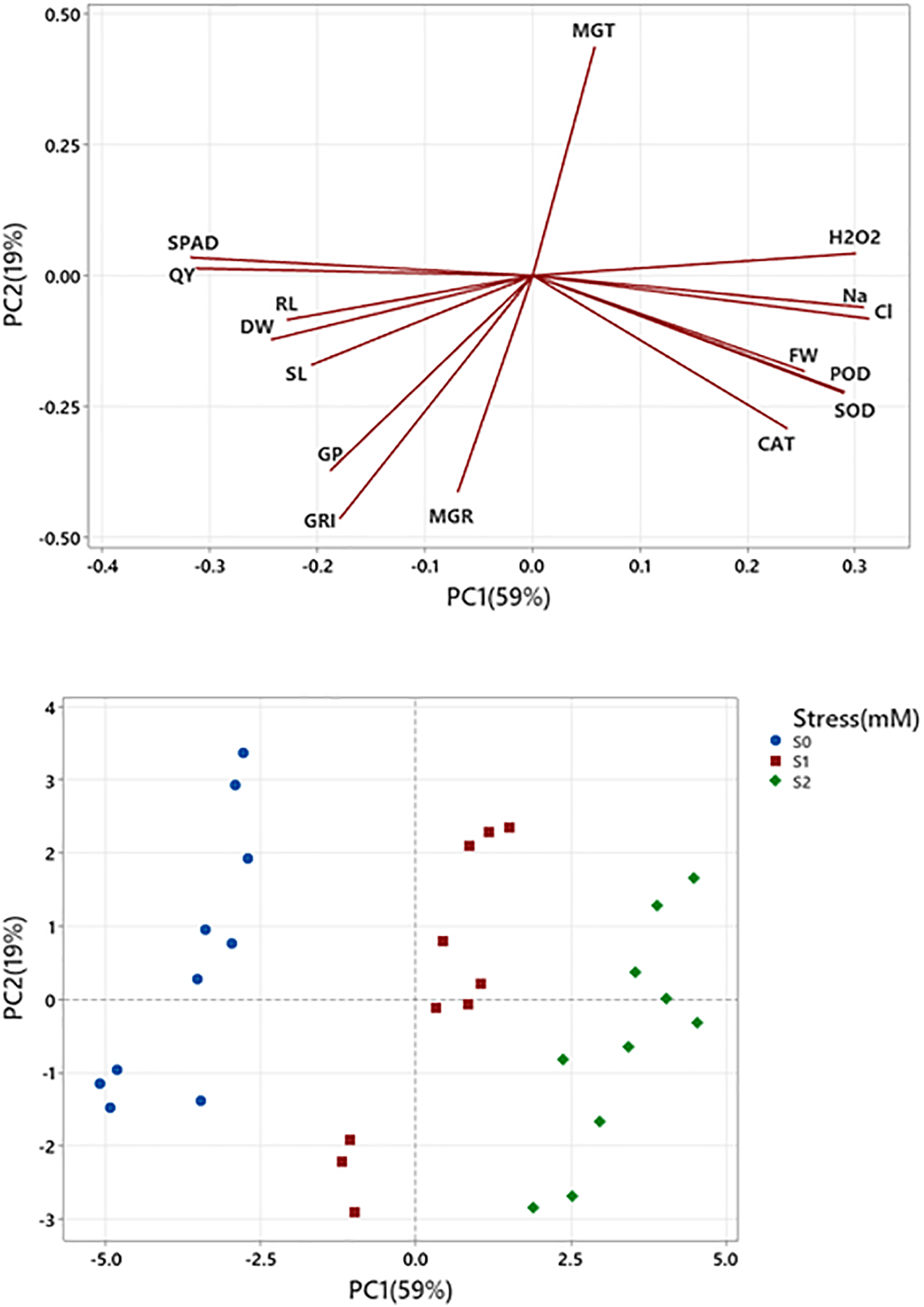

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of sixteen variables (GP, GRI, MGT, MGR, RL, SL, FW, DW, SOD, POD, CAT, H2O2, SPAD, QY, Na, and Cl) at three different levels of salt stress (0, 1, and 2 mM). The first two components (PC1 and PC2) account for 78% of the overall variance. The first principal component (PC1) has an eigenvalue of 9.43, which accounts for 59% of the variation. In contrast, the second principal component (PC2) has an eigenvalue of 3.04, which accounts for only 19% of the total variation. This suggests that PC1 accounts for more variability in the dataset than PC2. Each primary component accounts for a specific proportion of the overall variation in the dataset. Based on the loadings, it is clear that variables such as H2O2, FW, SOD, POD, CAT, Na, and Cl have a positive loading on PC1, whereas SPAD and QY have a negative loading. Regarding PC2, the factors GRI and MGR exert an adverse effect, but MGT has a positive impact (Fig. 8).

Figure 8: PCA analysis between various variables and the levels of salt stress. It represents the strong association between the high salt level (S2) and H2O2, Na, Cl, FW, POD, SOD, and CAT, while other variables are associated with low levels of salt. This chart provides insights into how different variables correlate with each other and how they distribute across varying stress levels.

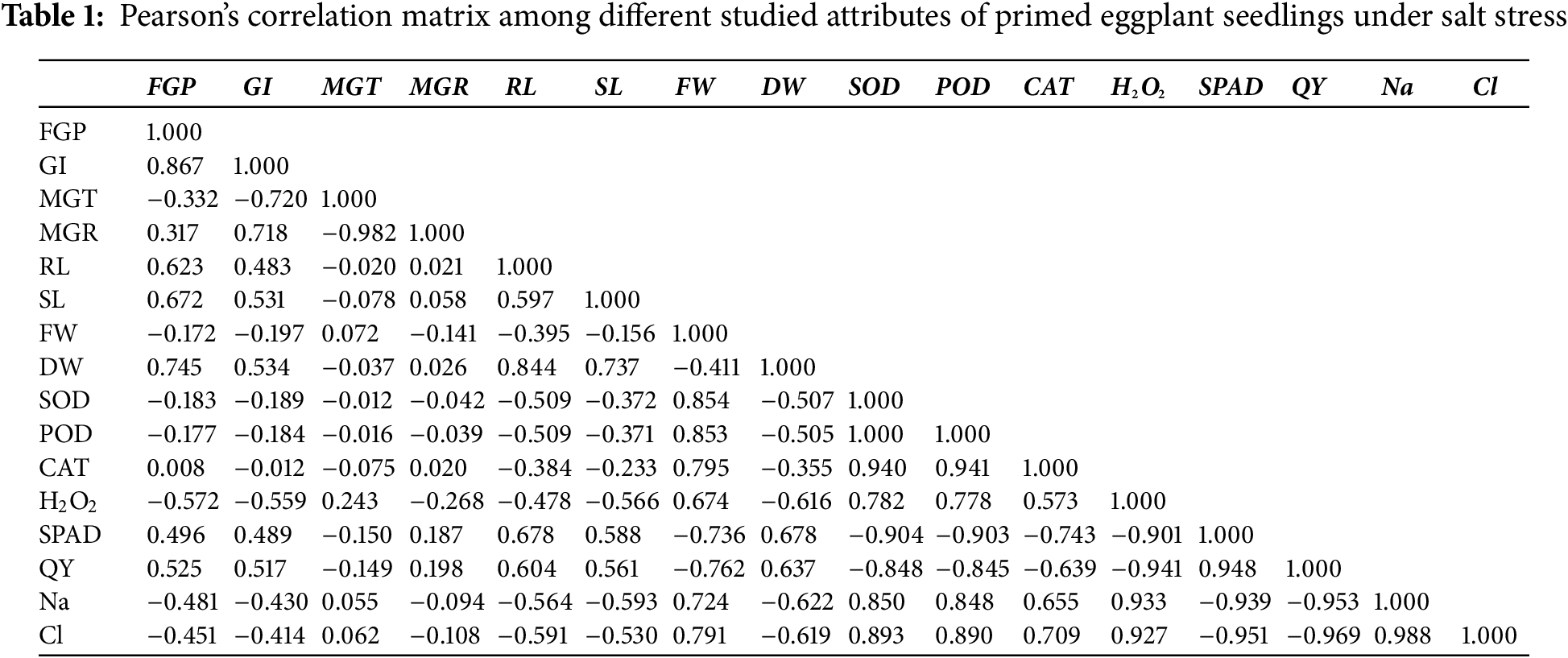

The correlation depicted that GI and FGP are positively correlated with each other (Table 1). MGT and MGR are also negatively correlated with each other. Our results also showed that increasing the concentrations of the toxic ions (Na, Cl) significantly and positively increased the concentrations of hydrogen peroxide in the cells of eggplant seedlings, which negatively correlates with the SPAD and QY values. SOD and POD are also negatively correlated with SPAD and QY values.

Salinity is a major factor in inhibiting plant growth, with the salt in the soil decreasing the water absorption capacity of the plant. Excessive salt in the plant stream injures the cells and further reduces growth [23]. In a saline environment, Na+ accumulation disrupts nutrient and ion balances, affecting physiological and biochemical processes. The essential processes, such as plant growth and biomass, are impaired due to high salt content. In this study, an increase in NaCl salt levels (0, 75, and 150 mM) caused a significant (p < 0.05) decrease in the germination parameters and plant growth in the eggplant seedlings. During the germination and seedling period, the plants are sensitive to environmental stress; any stress increase affects the growth parameters [20].

MLE effectively provides phytohormones, particularly cytokinins and zeatin, stimulating cytokinin synthesis in stressed plants. This reduces environmental stress effects, increases chlorophyll content, decreases leaf senescence, maintains photosynthetic activity, and enhances plant growth and physiological processes [8,28]. Shalaby [29] examined different methods of applying MLE and found that its concentration affected lettuce growth. Applying MLE, either through seed priming or foliar spraying, helped reduce the adverse effects of salt stress and improved lettuce growth. Similar to our study, MLE application enhanced the antioxidant activity in the plants and the growth parameters. Rady & Mohamed [30] reported using combined salicylic acid and MLE treatments in different concentrations, resulting in a higher germination rate than single treatments. Similarly, in this study, the single treatments of MLE resulted in a slower germination rate.

Nano-TiO2 induces local oxidative stress, which extends cell wall pores and enhances water flow and root elongation [31]. Moreover, nano-TiO2 can indirectly loosen cell wall structure, potentially improving cell enlargement and plant growth [32]. Gohari et al. [33] demonstrated that all agronomic traits were adversely affected by salinity, but TiO2 NPs alleviated these effects. The application of TiO2 NPs to Moldavian balm under salt stress enhanced agronomic traits and increased antioxidant enzyme activity compared to untreated plants. Additionally, nano-TiO2 significantly reduced H2O2 concentrations. The results of this study aligned with our findings, indicating that higher salt levels negatively affected germination parameters and overall plant growth in eggplant seedlings, while the application of TiO2 effectively mitigated the adverse effects of salinity and elevated antioxidant levels. Higher dosage of nano-TiO2 showed reduced levels of H2O2.

The seeds primed with ascorbic acid showed higher germination (FGP, GI, MGT, and MGR) parameters than the control and other seed priming treatments with MLE and TiO2, showing higher salt stress tolerance. Initially, a fast germination rate led to higher growth (root length and shoot length) and biomass (fresh weight and dry weight) in ascorbic acid-primed seedlings. Similar results of increased germination and growth were reported by Ghobadi et al. [11], Hassan et al. [23], and Baig et al. [34]. Plant stress inhibits radicle protrusion, which can be reversed by seed priming and leads to faster germination [7]. Ascorbic acid is an essential plant antioxidant, increasing the cellular processes during germination. Applying ascorbic acid helps in growth and physiological activities [34], as observed in this study.

Under salt stress, ROS is produced in plants, which causes oxidative injuries [35]. In this study, the physiological attributes (SPAD and QY) gradually decreased with an increase in salinity, and the decrease was noticeable in higher salt concentrations (150 mM). The ability of plants to scavenge ROS indicates high-stress resistance [35]. An indicator of oxidative damage is H2O2. When plants face salinity stress, they produce more reactive oxygen species (ROS) like O2•−, H2O2, and OH•. Plants that can better remove ROS are more resistant to oxidative damage. Salinity exposure increases ROS in plants, causing harm to nucleic acids, membranes, cellular metabolism, and metabolic processes in chloroplasts and mitochondria, ultimately leading to cell death [25]. Priming has been reported to decrease the levels of ROS in plants, which may be effective in regulating antioxidant enzyme activity [36]. In this study, the seedlings exposed to higher salinity showed higher H2O2 content. The seeds primed with ascorbic acid showed lower H2O2 content, depicting greater tolerance. Activating antioxidant enzymes in response to increased ROS is essential for the plant’s effective performance [2]. The SOD, POD, and CAT in primed seeds were higher due to higher salt concentration, and ascorbic acid primed seeds showed effective performance of the primary defense mechanism in plants under stress. The high CAT activity in the seedlings explains the lower concentration of H2O2 under higher salt stress, which removes H2O2. Similarly, POD is known to scavenge H2O2 in the chloroplast [2]. This is observed in this study, with the highest POD and CAT activity in ascorbic acid-primed seeds with the lowest H2O2 concentration. The PCA and Pearson Correlation showed a significant and positive relation with Na+ and Cl- ions, depicting an increase in Na+ concentration leading to an increased H2O2 and antioxidant enzyme activity (Fig. 8). However, applying MLE, TiO2, and ascorbic acid reduced the accumulation of H2O2 and increased enzymatic activity. Similar results were reported with MLE in wheat [7], with TiO2 NPs in grapes [37], Zea mays [38], and Moldavin Balm [39], which enhanced antioxidant enzyme activity and reduced the H2O2 accumulation.

The Na+ and Cl− content was significantly higher in all treatments under salt stress. Despite the high Na+ and Cl− accumulation, these levels were lower in seedlings primed with ascorbic acid. The increased growth under stress conditions is related to the action of ascorbic acid, mainly due to its cell division and expansion capacity through auxin level regulation [40]. Many studies have emphasized the importance of the seed priming technique due to its feasible use. Seed hydration activates metabolic processes and antioxidant mechanisms, all required in the early stages of imbibition. Salt stress can adversely affect plants by decreasing photosynthesis and increasing H2O2, which causes oxidative damage to plant cells [26].

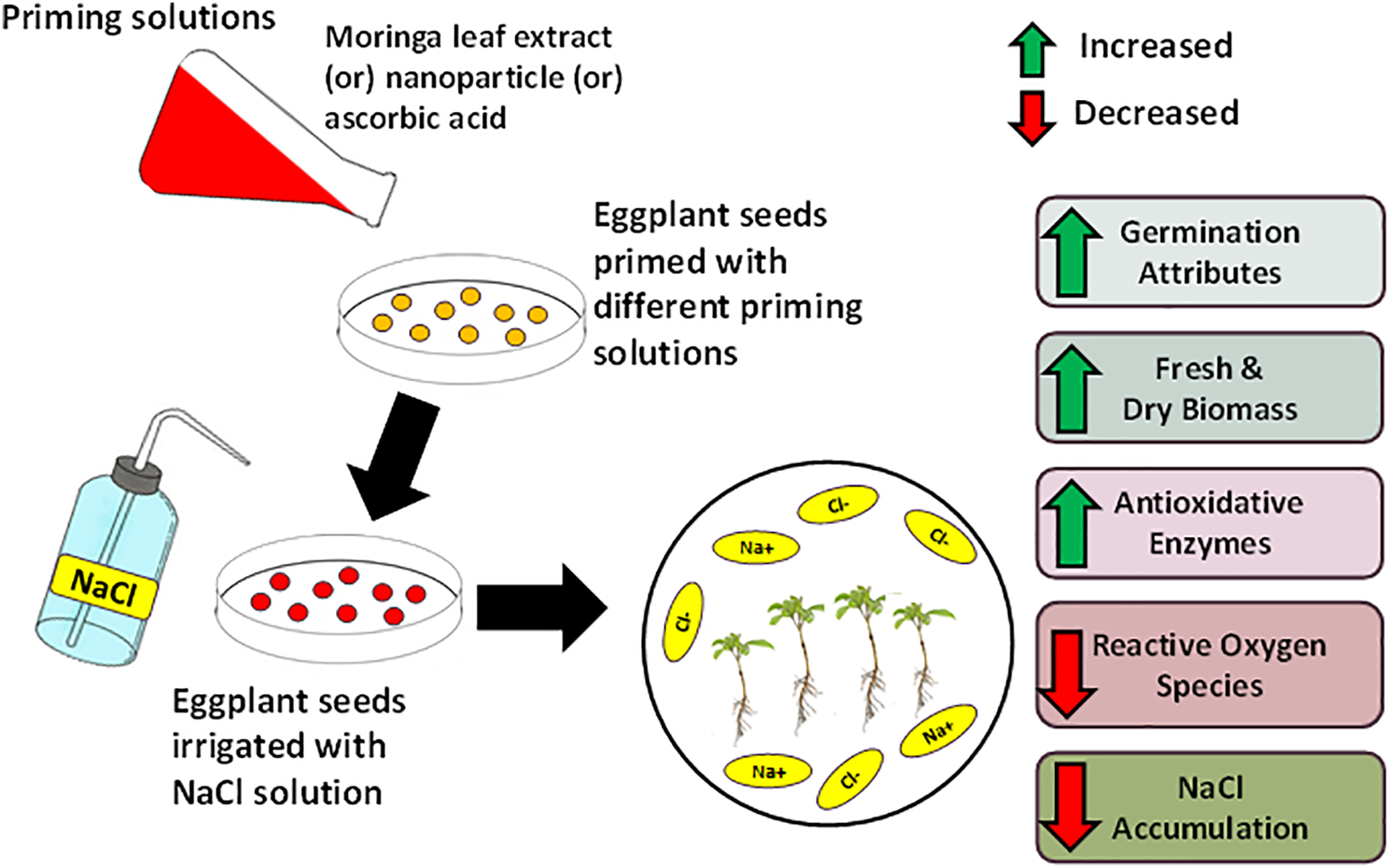

The results of the seed priming of eggplant seeds with different priming agents have shown that it is a valuable technique for coping with the adverse effects of salinity (Fig. 9). The salt stress effects can be reduced by selecting an appropriate priming solution for the conditions. All the priming treatments (moringa leaf extract, nano-titanium dioxide, and ascorbic acid) reduced the severe effects of salinity with the maximum amelioration found in ascorbic acid primed seedlings with higher germination and growth along with higher antioxidant enzyme (SOD, POD, CAT) activity. Priming with ascorbic acid in this study has shown promising results in higher antioxidant activity, leading to higher germination and growth of seedlings.

Figure 9: A schematic diagram showed the priming effect of moringa leaf extract, nanoparticles, and ascorbic acid on eggplant seeds under salt stress conditions

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Muhammad Zaid Jawaid collected the data and conducted formal analysis. Muhammad Fasih Khalid wrote and reviewed the manuscript. Ahmed Abou Elezz helped with statistical analysis. Talaat Ahmed supervised the work and helped in reviewing the article. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Mohammed Ibrahim Elsiddig A, Zhou G, Nimir NE, Yousif Adam Ali A. Effect of exogenous ascorbic acid on two sorghum varieties under different types of salt stress. Chil J Agric Res. 2022;82(1):10–20. [Google Scholar]

2. Khalid MF, Hussain S, Ahmad S, Ejaz S, Zakir I, Ali MA, et al. Impacts of abiotic stresses on growth and development of plants. In: Hasanuzzaman M, Fujita M, Oku H, Tofazzal Islam M, editors. Plant tolerance to environmental stress. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2019. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

3. Ali AY, Ibrahim ME, Zhou G, Nimir NE, Elsiddig AM, Jiao X, et al. Gibberellic acid and nitrogen efficiently protect early seedlings growth stage from salt stress damage in Sorghum. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):6672. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-84713-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Islam AT, Ullah H, Himanshu SK, Tisarum R, Cha-um S, Datta A. Effect of salicylic acid seed priming on morpho-physiological responses and yield of baby corn under salt stress. Sci Hortic. 2022;304:111304. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2022.111304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Isayenkov SV, Maathuis FJ. Plant salinity stress: many unanswered questions remain. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:80. doi:10.3389/fpls.2019.00080. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Khalid MF, Hussain S, Anjum MA, Ejaz S, Ahmad M, Jan M, et al. Hydropriming for plant growth and stress tolerance. In: Hasanuzzaman M, Fotopoulos V, editors. Priming and pretreatment of seeds and seedlings. Singapore: Springer; 2019. p.373–84 doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-8625-1_18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Pawar VA, Laware SL. Seed priming a critical review. Int J Sci Res Biol Sci. 2018;5(5):94–101. [Google Scholar]

8. Ahmed T, Abou Elezz A, Khalid MF. Hydropriming with moringa leaf extract mitigates salt stress in wheat seedlings. Agriculture. 2021;11(12):1254. doi:10.3390/agriculture11121254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Hadia E, Slama A, Romdhane L, M’Hamed CH, Fahej MA, Radhouane L, et al. Seed priming of bread wheat varieties with growth regulators and nutrients improves salt stress tolerance particularly for the local genotype. J Plant Growth Regul. 2023;42(1):304–18. doi:10.1007/s00344-021-10548-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Srinivasa C, Umesha S, Pradeep S, Ramu R, Gopinath SM, Ansari MA, et al. Salicylic acid-mediated enhancement of resistance in tomato plants against Xanthomonas perforans. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2022;29(4):2253–61. doi:10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.11.067. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Ghobadi M, Jalali Honarmand S, Mehrkish M. Improving the germination characteristics of aged lentil (Lens culinaris L.) seeds using the ascorbic acid priming method. Cent Asian J Plant Sci Innov. 2022;2(1):37–41. [Google Scholar]

12. Salam A, Khan AR, Liu L, Yang S, Azhar W, Ulhassan Z, et al. Seed priming with zinc oxide nanoparticles downplayed ultrastructural damage and improved photosynthetic apparatus in maize under cobalt stress. J Hazard Mater. 2022;423(1):127021. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Hassanein RA, Abdelkader AF, Faramawy HM. Moringa leaf extracts as biostimulants-inducing salinity tolerance in the sweet basil plant. Egypt J Bot. 2019;59(2):303–18. doi:10.21608/ejbo.2019.5989.1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Farooq M, Irfan M, Aziz T, Ahmad I, Cheema SA. Seed priming with ascorbic acid improves drought resistance of wheat. J Agron Crop Sci. 2013;199(1):12–22. doi:10.1111/j.1439-037x.2012.00521.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ye Y, Cota-Ruiz K, Hernández-Viezcas JA, Valdes C, Medina-Velo IA, Turley RS, et al. Manganese nanoparticles control salinity-modulated molecular responses in Capsicum annuum L. through priming: a sustainable approach for agriculture. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2020;8(3):1427–36. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b05615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Jafari L, Abdollahi F, Feizi H, Adl S. Improved marjoram (Origanum majorana L.) tolerance to salinity with seed priming using titanium dioxide (TiO2). Iran J Sci Technol Trans Sci. 2022;46(2):361–71. doi:10.1007/s40995-021-01249-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Khalid MF, Iqbal Khan R, Jawaid MZ, Shafqat W, Hussain S, Ahmed T, et al. Nanoparticles: the plant saviour under abiotic stresses. Nanomater. 2022;12(21):3915. doi:10.3390/nano12213915. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Haghighi M, Teixeira da Silva JA. The effect of N-TiO2 on tomato, onion, and radish seed germination. J Crop Sci Biotechnol. 2014;17(4):221–7. doi:10.1007/s12892-014-0056-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Jiang Z, Shen L, He J, Du L, Xia X, Zhang L, et al. Functional analysis of SmMYB39 in salt stress tolerance of eggplant (Solanum melongena L.). Horticulturae. 2023;9(8):848. doi:10.3390/horticulturae9080848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Hanachi S, Van Labeke MC, Mehouachi T. Application of chlorophyll fluorescence to screen eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) cultivars for salt tolerance. Photosynthetica. 2014;52(1):57–62. doi:10.1007/s11099-014-0007-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Mustafa Z, Ayyub CM, Amjad M, Ahmad R. Assessment of biochemical and ionic attributes against salt stress in eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) genotypes. J Anim Plant Sci. 2017;27(2):503–9. [Google Scholar]

22. Ekinci M, Yildirim E, Turan M. Ameliorating effects of hydrogen sulfide on growth, physiological and biochemical characteristics of eggplant seedlings under salt stress. S Afr J Bot. 2021;143(4):79–89. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2021.07.034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Hassan A, Amjad SF, Saleem MH, Yasmin H, Imran M, Riaz M, et al. Foliar application of ascorbic acid enhances salinity stress tolerance in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) through modulation of morpho-physio-biochemical attributes, ions uptake, osmo-protectants and stress response genes expression. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2021;28(8):4276–90. doi:10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.03.045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Milivojević M, Ripka Z, Petrović T. ISTA rules changes in seed germination testing at the beginning of the 21st century. J Process Energy Agric. 2018;22(1):40–5. doi:10.5937/jpea1801040m. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Khalid MF, Hussain S, Anjum MA, Ahmad S, Ali MA, Ejaz S, et al. Better salinity tolerance in tetraploid vs diploid volkamer lemon seedlings is associated with robust antioxidant and osmotic adjustment mechanisms. J Plant Physiol. 2020;244:153071. doi:10.1016/j.jplph.2019.153071. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Ryan JG, Estefan G, Rashid A. Soil-plant-analysis soil and plant analysis laboratory manual. Aleppo, Syria: International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA); 2001. p. 46–8. [Google Scholar]

27. Hussain S, Luro F, Costantino G, Ollitrault P, Morillon R. Physiological analysis of salt stress behaviour of citrus species and genera: low chloride accumulation as an indicator of salt tolerance. S Afr J Bot. 2012;81:103–12. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2012.06.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Khan S, Basra SM, Afzal I, Nawaz M, Rehman HU. Growth promoting potential of fresh and stored Moringa oleifera leaf extracts in improving seedling vigor, growth and productivity of wheat crop. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2017;24(35):27601–12. doi:10.1007/s11356-017-0336-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Shalaby OA. Moringa leaf extract increases tolerance to salt stress, promotes growth, increases yield, and reduces nitrate concentration in lettuce plants. Sci Hortic. 2024;325(12):112654. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2023.112654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Rady MM, Mohamed GF. Modulation of salt stress effects on the growth, physio-chemical attributes and yields of Phaseolus vulgaris L. plants by the combined application of salicylic acid and Moringa oleifera leaf extract. Sci Hortic. 2015;193(2):105–13. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2015.07.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Larue C, Laurette J, Herlin-Boime N, Khodja H, Fayard B, Flank AM, et al. Accumulation, translocation and impact of TiO2 nanoparticles in wheat (Triticum aestivum spp.influence of diameter and crystal phase. Sci Total Environ. 2012;431(1):197–208. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.04.073. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Karami A, Sepehri A. Nano titanium dioxide and nitric oxide alleviate salt induced changes in seedling growth, physiological and photosynthesis attributes of barley. Zemdirb Agric. 2018;105(2):123–32. doi:10.13080/z-a.2018.105.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Gohari G, Mohammadi A, Akbari A, Panahirad S, Dadpour MR, Fotopoulos V, et al. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs) promote growth and ameliorate salinity stress effects on essential oil profile and biochemical attributes of Dracocephalum moldavica. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):912. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-57794-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Baig Z, Khan N, Sahar S, Sattar S, Zehra R. Effects of seed priming with ascorbic acid to mitigate salinity stress on three wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivars. Acta Ecol Sin. 2021;41(5):491–8. doi:10.1016/j.chnaes.2021.08.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Khoshbakht D, Asghari MR, Haghighi M. Effects of foliar applications of nitric oxide and spermidine on chlorophyll fluorescence, photosynthesis and antioxidant enzyme activities of citrus seedlings under salinity stress. Photosynthetica. 2018;56(4):1313–25. doi:10.1007/s11099-018-0839-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Alves RD, Rossatto DR, da Silva JD, Checchio MV, de Oliveira KR, Oliveira FD, et al. Seed priming with ascorbic acid enhances salt tolerance in micro-tom tomato plants by modifying the antioxidant defense system components. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2021;31:101927. doi:10.1016/j.bcab.2021.101927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Mozafari AA, Ghadakchi asl A, Ghaderi N. Grape response to salinity stress and role of iron nanoparticle and potassium silicate to mitigate salt induced damage under in vitro conditions. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2018;24(1):25–35. doi:10.1007/s12298-017-0488-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Shah T, Latif S, Saeed F, Ali I, Ullah S, Alsahli AA, et al. Seed priming with titanium dioxide nanoparticles enhances seed vigor, leaf water status, and antioxidant enzyme activities in maize (Zea mays L.) under salinity stress. J King Saud Univ Sci. 2021;33(1):101207. doi:10.1016/j.jksus.2020.10.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Mohammadi MH, Panahirad S, Navai A, Bahrami MK, Kulak M, Gohari G. Cerium oxide nanoparticles (CeO2-NPs) improve growth parameters and antioxidant defense system in Moldavian Balm (Dracocephalum moldavica L.) under salinity stress. Plant Stress. 2021;1(1):100006. doi:10.1016/j.stress.2021.100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Shah T, Latif S, Khan H, Munsif F, Nie L. Ascorbic acid priming enhances seed germination and seedling growth of winter wheat under low temperature due to late sowing in Pakistan. Agronomy. 2019;9(11):757. doi:10.3390/agronomy9110757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools