Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Comparative Analyses of Physiological and Transcriptomic Responses Reveal Chive (Allium ascalonicum L.) Bolting Tolerance Mechanisms

1 Department of Horticulture, College of Agriculture, Guizhou University, Guiyang, 550025, China

2 Plant Protection Institute, Guizhou Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Guiyang, 550025, China

* Corresponding Authors: Guangdong Geng. Email: ; Suqin Zhang. Email:

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(8), 2441-2460. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.068368

Received 27 May 2025; Accepted 18 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Chive (Allium ascalonicum L.), a seeding-vernalization-type vegetable, is prone to bolting. To explore the physiological and molecular mechanisms of its bolting, bolting-prone (‘BA’) and bolting-resistant (‘WA’) chives were sampled at the vegetative growth, floral bud differentiation, and bud emergence stages. No bolting was observed in bolting-resistant ‘WA’ on the 130th day after planting, whereas the bolting reached 39.22% in bolting-prone ‘BA’, which was significantly higher than that of ‘WA’. The contents of gibberellins, abscisic acid, and zeatin riboside after floral bud differentiation in ‘WA’ were significantly less than in ‘BA’, whereas the indoleacetic acid content in ‘WA’ was significantly higher than that in ‘BA’ before and after floral bud differentiation. The soluble sugar content and nitrate reductase activity in ‘BA’ were significantly higher than those in ‘WA’ before and during floral bud differentiation periods. However, they were significantly lower in ‘BA’ compared with in ‘WA’ after bolting due to the nutrient consumption required by reproductive growth. A transcriptome analysis determined that the differentially expressed genes related to bolting tolerance were enriched in the terms ‘photoperiodism, flowering’, ‘auxin-activated signaling pathway’, ‘gibberellic acid mediated signaling pathway’, and ‘carbohydrate metabolic process’, and this was generally consistent with the physiological data. Additionally, 12 key differentially expressed genes (including isoform_203018, isoform_481005, isoform_716975, and isoform_564877) related to bolting tolerance were investigated. This research provides new information for breeding bolting-tolerant chives.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileChive (Allium ascalonicum L.) is a perennial monocotyledonous herb of Liliaceae. It is mainly used as a fresh food but is also used in processed food and as a condiment. Chives prefer cool temperatures and are not heat-tolerant. After a certain time at low temperature, they will bloom through vernalization [1,2]. After bolting, the flower stems are tough and inedible, which severely affects chive yield and quality, and the reproductive growth competes for nutrients, thereby inhibiting vegetative growth [3]. Consequently, bolting-resistance is a desired trait in chive production. Bolting requires exposure to low temperatures for vernalization, followed by floral bud differentiation. Floral bud differentiation is an important symbol of the plant’s transition from vegetative to reproductive growth, encompassing many complex physiological changes during which the plant responds to various signals [4,5]. Phytohormones are key factors in floral bud differentiation [6–8], including gibberellins (GA), abscisic acid (ABA), indoleacetic acid (IAA), and zeatin riboside (ZR), which are important mediators of floral organ formation [9]. Carbohydrates can activate key genes, such as sugar transporters and glycokinases, before flowering, thereby promoting flowering [10,11]. The levels of soluble protein in Chinese cabbage varieties with bolting-resistant genotypes are lower than those of bolting-prone genotypes [12]. Nitrate reductase (NR) is a key enzyme in plant nitrogen metabolism that catalyzes the reduction of nitrate to nitrite. Nitrite is further converted to ammonia or other nitrogenous compounds, which are important raw materials for protein synthesis [13].

In recent years, RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) technology has generated a large amount of transcriptome data, which mainly includes functional gene exploration, developmental mechanism research, molecular marker development, and gene regulatory network construction. It is an important omics and is also an important tool for analyzing genetic changes [14,15]. It has been successfully applied to bolting and flowering studies of onion and garlic [16,17].

Chive is a traditional vegetable with a rich nutritional profile. However, early bolting reduces the yield and leads to the loss of edible value. Chives can be planted all year round, but they are prone to bolting and flowering when planted in winter and spring, resulting in a significant decline in quality. However, the physiological and molecular mechanisms of bolting in chives are still unclear. Therefore, RNA-seq was performed using the leaves of bolting-resistant (‘WA’) and bolting-prone (‘BA’) chive varieties during vegetative growth, floral bud differentiation, and budding stages to analyze the physiological and molecular mechanisms of bolting and provide a theoretical basis for the breeding of bolting-resistant chives.

2.1 Plant Materials and Sampling

The materials used in this experiment were the ‘BA’ and ‘WA’ varieties, which were derived through years of single-plant selection by us. The experimental site was located at the Guizhou University farm, Huaxi District, Guiyang City, Guizhou Province (1050 m, 106°67′ E, 26°42′ N). The two chive varieties were each planted in holes, with spacings of 15 cm and three plants per hole. Conventional field management was applied. The transplanting date for the two chive varieties was 01 October 2023.

Sampling was conducted at three stages, vegetative growth (CK, control, 50 d after planting), floral bud differentiation (T1, 80 d after planting), and budding (T2, 1–2 cm flower stalks were visible when the plants were peeled off, 110 d after planting) (Fig. S1). Uniform healthy plants were selected. The outer leaves were carefully removed, and the tender leaf primordia/floral bud were observed and photographed using the VHX-700 3D microscope system (KEYENCE Corporation, Osaka, Japan). Ten plants were selected at each stage, and samples were taken from the tender leaves near the growing point. The samples were rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for physiological, transcriptomic, and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analyses. Three biological replicates, with 10 plants per replicate, were included.

2.2 Measurements of Bolting Percentage, and Physiological and Biochemical Indicators

Bolting percentage was observed on the 130th day after planting. The physiological and biochemical indicators in the leaves of the two chive varieties were measured at the CK, T1, and T2 stages. The GA (Cas No.: SY-01038P1, Spbio, Wuhan, China), ABA (Cas No.: SY-01051P1, Spbio), ZR (Cas No.: SY-01037P1, Spbio), and IAA (Cas No.: SY-01121P1, Spbio) levels were measured using the appropriate ELISA detection kit. The soluble sugar (SS) content (Cas No.: AKPL008M, Boxbio, Beijing, China) and the NR activity (Cas No.: BC0085, Solarbio, Beijing, China) were measured in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.3 RNA Extraction and RNA-Seq

Total RNA was extracted from the leaves of the two chive varieties (‘WA’ and ‘BA’) using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and then treated with TaKaRa RNase-free DNase I for 30 min in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The quantity and quality of the extracted RNA were detected using a NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer. A total of 18 cDNA libraries were constructed using RNA extracted from the leaves of the two chive varieties, after two treatments (T1 and T2) and one control (CK), with three replicates. The RNA-seq was performed on a BGISEQ-500 platform [Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI), Shenzhen, China].

2.4 Normalization and Annotation of Sequencing Data

The RNA-seq data of ‘WA’ and ‘BA’ were preprocessed using the filtering software SOAPnuke (v1.6.5, BGI) and the analysis software Trimmomatic (v0.36, BGI). The specific steps followed the method of Shen et al. [18]. Allium ascalonicum does not have a reference genome. So, the merged full-length transcriptome data of two Allium ascalonicum cultivars (AS21 and AS27) were analyzed with single-molecule real-time sequencing technology for the reference. The leaves of the two chive varieties at the CK, T1, and T2 stages were sequenced using a third-generation PacBio sequencing platform. After sequencing, the errors were corrected using second-generation sequencing data to obtain high-quality sequence data. The clean reads, the reference sequence alignment, and the expression levels of the transcripts were calculated using RSEM (v1.2.8) [19]. Statistical tests were performed on the fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped reads to detect differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between different stages [20]. Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) tests were performed to compute the false discovery rates (FDR), and an adjusted p-value (Q-value) ≤ 0.05 was established as a confidence limit for statistical significance. The screening threshold of the DEGs was |log2 fold-change| ≥ 1 and Q-value ≤ 0.05.

2.5 GO and KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analyses

Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses were performed using the GO seq R package and KOBAS software, respectively [21,22]. Length bias in the DEGs was adjusted, and a Q-value ≤ 0.05 was used to determine significantly enriched terms or pathways associated with the DEGs.

The expression levels of 12 key DEGs were analyzed using the qRT-PCR method to verify the transcriptome data. Total RNA extracted from a leaf was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the gDNA Eraser Kit (Perfect Real-Time, Takara, Dalian, China). Specific primers were designed based on the gene sequences (Table S1). TUB2 was used as the reference gene [23]. The DEG expression levels were analyzed using an ABI one-step qRT-PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The 20 μL reaction mixture included 10 μL of SYBR Green PCR SuperMix (Tiangen, Beijing, China), 0.6 μL of each forward and reverse primer, 1 μL of cDNA, and 7.8 μL of distilled water. The PCR conditions were as follows: 95°C for 2 min, 95°C for 15 s, and 60°C for 30 s, cycling 40 times. The relative expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method, including three biological replicates and three technical replicates [24].

Statistical analyses were performed using statistical software (SPSS 19.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). ANOVAs and Duncan’s multiple range tests were used to compare means and determine differences at the significance level of p < 0.05. Physiological, KEGG, and GO analysis graphs were constructed using GraphPad graphics software (Origin 2021, Northampton, MA, USA).

3.1 Bolting Percentage Identification for Two Chive Varieties

No bolting was observed in ‘WA’ on the 130th day after planting, whereas the bolting percentage reached 39.22% in ‘BA’ (Fig. 1A–C), which was significantly higher than that of ‘WA’. Thus, ‘WA’ was identified as a bolting-resistant chive, whereas ‘BA’ was a bolting-prone chive.

Figure 1: Bolting percentages of the two chive varieties. (A) ‘BA’, bolting-prone chive. (B) ‘WA’, bolting-resistant chive. (C) Bolting percentage. The ‘a’ indicates a significant difference at p < 0.05 according to ANOVA followed by Duncan’s multiple range test

3.2 Physiological Responses of Chives to Bolting

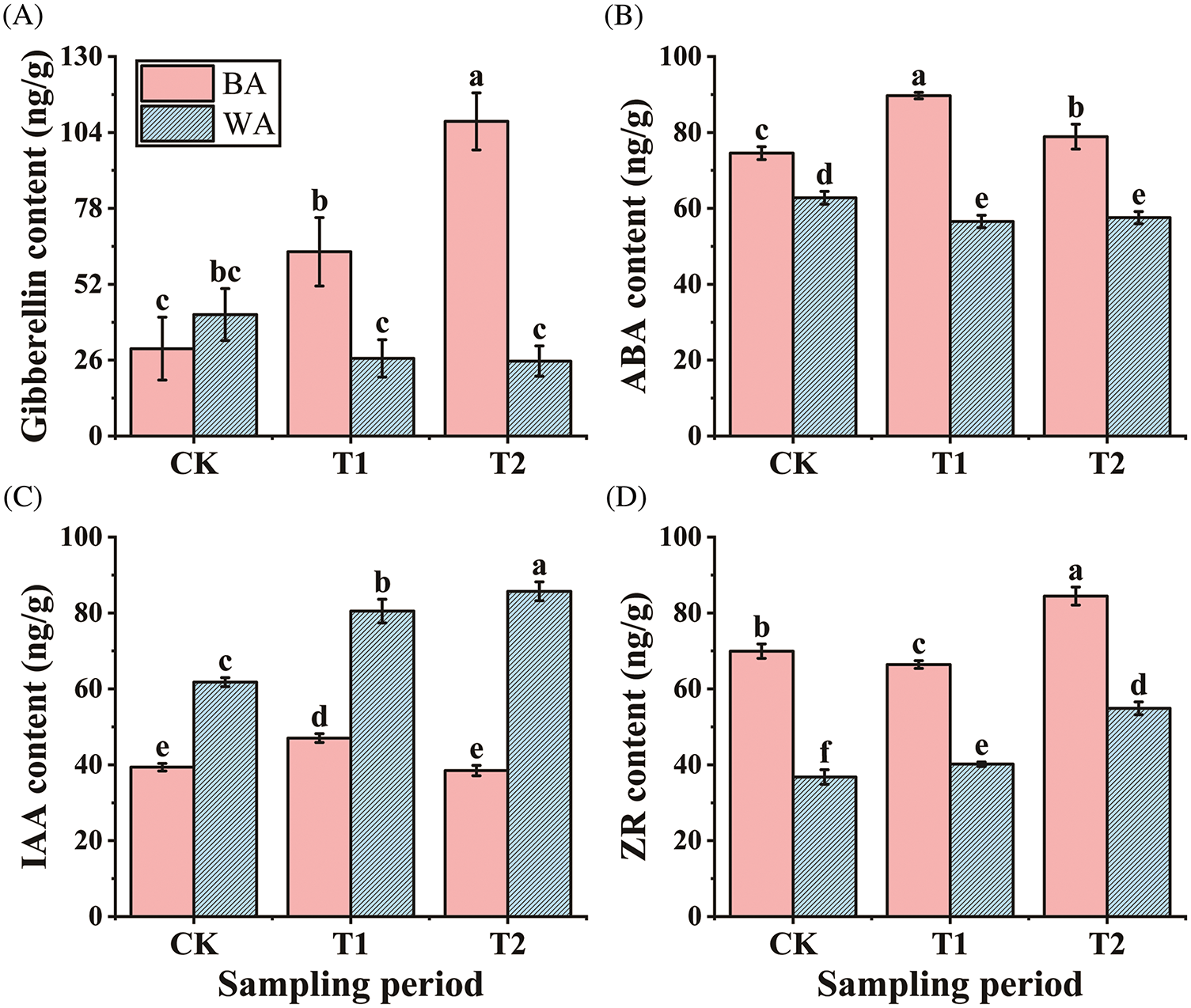

A main biological function of GA is to promote plant growth. An increase in the endogenous GA content can improve stem elongation in plants [25]. The GA content of ‘BA’ showed a strong upward trend from the CK (control) to T2 (budding) stages, being 3.59-fold that of the CK at the T2 stage. However, ‘WA’ showed a slow downward trend. At the T1 (floral bud differentiation) and T2 stages, the GA content in ‘BA’ was significantly (p < 0.05) greater than that in ‘WA’ (Fig. 2A). The high GA content may be the reason for the ‘BA’ early bolting.

Figure 2: Hormone level changes at the different bolting stages in the two chive varieties. (A) gibberellin (GA), (B) abscisic acid (ABA), (C) indoleacetic acid (IAA), and (D) zeatin riboside (ZR) contents. ‘BA’, bolting-prone chive; ‘WA’, bolting-resistant chive. CK, T1, and T2 represent vegetative growth, floral bud differentiation, and budding stages, respectively. Bars indicate means ± SDs (n = 3). Different letters ‘a–f’ indicate a significant difference at p < 0.05 according to ANOVA followed by Duncan’s multiple range test

ABA promotes bolting and bulb formation by influencing plant maturity [26]. The ABA content in ‘BA’ showed a trend of first increasing and then decreasing. At the T1 and T2 stages, the ABA content in the ‘WA’ was significantly (p < 0.05) lower than in the CK, whereas ‘BA’ had a significantly (p < 0.05) greater content than the CK in each stage. The ABA content in ‘BA’ was significantly (p < 0.05) greater than that in ‘WA’ in all three stages (Fig. 2B). The low level of ABA may have prevented maturation, leading to the ‘WA’ variety late bolting.

IAA affects plant growth, development, and floral organ formation [27]. The IAA contents at the three stages in ‘WA’ were significantly (p < 0.05) greater than in ‘BA’. From the CK to T2 stages, the IAA content in ‘WA’ gradually increased, with a significant (p < 0.05) rise of 30.31% at the T1 stage compared with the CK. In contrast, the IAA content in ‘BA’ showed an initial increase, peaked at T1 stage, and then declined (Fig. 2C). The lower IAA concentration in ‘BA’ may promote floral development, leading to early bolting.

In plants, ZR can promote floral bud differentiation [28]. The ZR content of ‘BA’ decreased slowly at the T1 stage and then increased rapidly at the T2 stage. In contrast, ‘WA’ showed a consistent upward ZR content trend. Both genotypes reached their highest levels, which were 20.76% and 49.28% higher than the CK, respectively, at the T2 stage (Fig. 2D). Thus, the overall ZR content in ‘WA’ was significantly (p < 0.05) lower than in ‘BA’, indicating that the low ZR level in ‘WA’ might have inhibited floral bud differentiation.

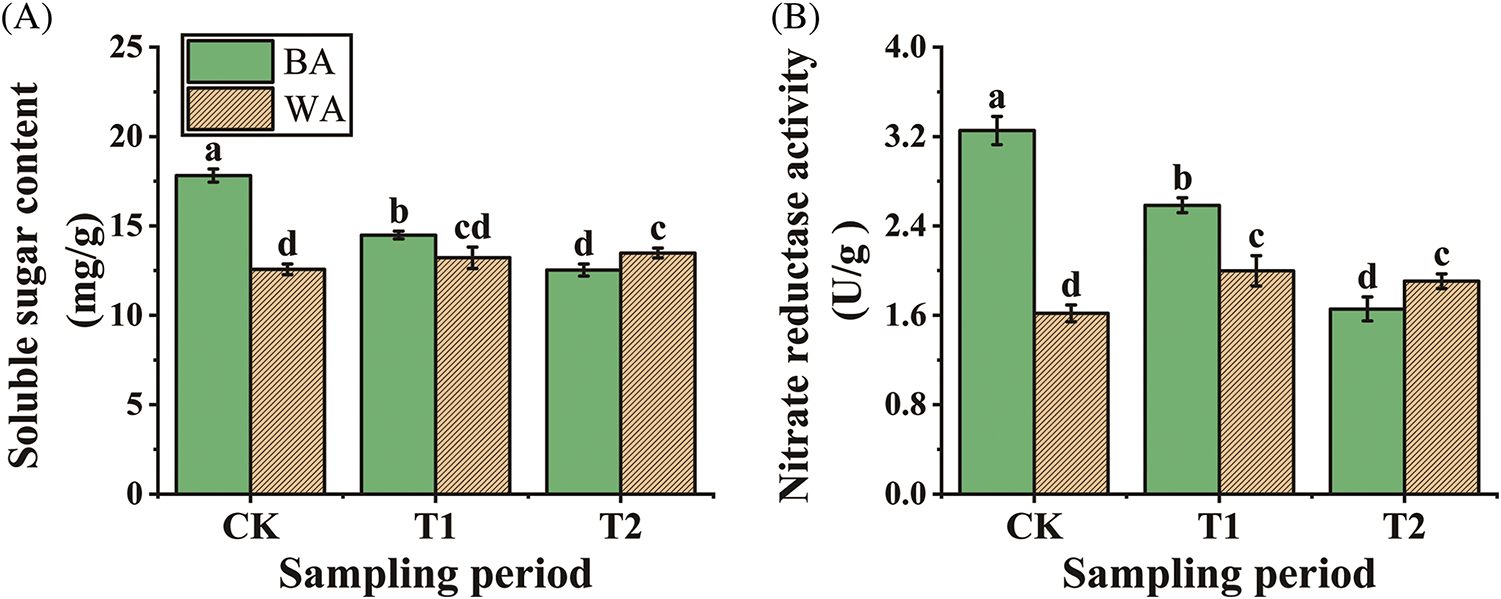

The plant flowering process requires a large amount of energy, which mostly comes from SS hydrolysis. The conditions for flowering induction cannot be met until a certain SS content has been accumulated [29]. The two chive varieties showed significant (p < 0.05) differences in SS contents at the CK stage. ‘BA’ accumulated more SS (17.81 mg/g) at the CK stage, but the content decreased after floral bud differentiation. There was a significant (p < 0.05) reduction of 18.54% at the T1 stage compared with the CK, followed by a further significant (p < 0.05) decrease of 13.79% at the T2 stage compared with the T1 stage (Fig. 3A). In contrast, ‘WA’ exhibited a slow upward trend in SS content, but it may not reach the level required for bolting and flowering.

Figure 3: Changes in the soluble sugar contents (A) and nitrate reductase activities (B) of the two chive varieties. ‘BA’, bolting-prone chive; ‘WA’, bolting-resistant chive. CK, T1, and T2 represent vegetative growth, floral bud differentiation, and budding stages, respectively. Bars indicate means ± SDs (n = 3). Different letters ‘a–d’ indicate a significant difference at p < 0.05 according to ANOVA followed by Duncan’s multiple range test

The higher the NR activity, the more nitrate nitrogen plants can absorb and utilize, which promotes plant bolting and flowering [12,30]. At the CK stage, the NR activity of ‘BA’ was approximately 2-fold that of ‘WA’, likely due to the need for a large amount of nitrogen accumulation prior to bolting. At the T1 stage, the NR activity of ‘BA’ decreased by 20.62%, whereas the NR activity of ‘WA’ increased by 23.46%. However, the NR activity of ‘BA’ was significantly (p < 0.05) higher than that of ‘WA’. At the T2 stage, the NR activity of ‘BA’ decreased significantly (p < 0.05) by 35.66% compared with the T1 stage, and it became significantly (p < 0.05) lower than that of ‘WA’ (Fig. 3B). The overall downward trend in ‘BA’ indicated that the higher NR activity before bolting enabled the accumulation of more nitrogen for bolting and flowering.

3.3 Quality Verification of RNA-Seq Data

To study the molecular mechanisms of chive bolting responses, an RNA-seq experiment was performed. A total of 18 libraries were constructed for high-throughput sequencing. The sequencing depth for each sample was 6 Gb. On average, each sample yielded 44.03 million clean reads (Table S2). These sequencing parameters were chosen to ensure adequate coverage for accurate transcript quantification and differential expression analysis. The mapping rates of the RNA-seq reads to the reference sequence were consistently high across all samples (Table S2). On average, 97.07% of the reads were successfully mapped to the reference sequence. The high mapping rates indicated the quality of the sequencing data and the suitability of the chosen reference for our analysis. The general correlation between replicates was determined based on Pearson’s correlation coefficient (Fig. S2), indicating that the quality of the sequencing results met the demands of the subsequent bioinformatics analyses.

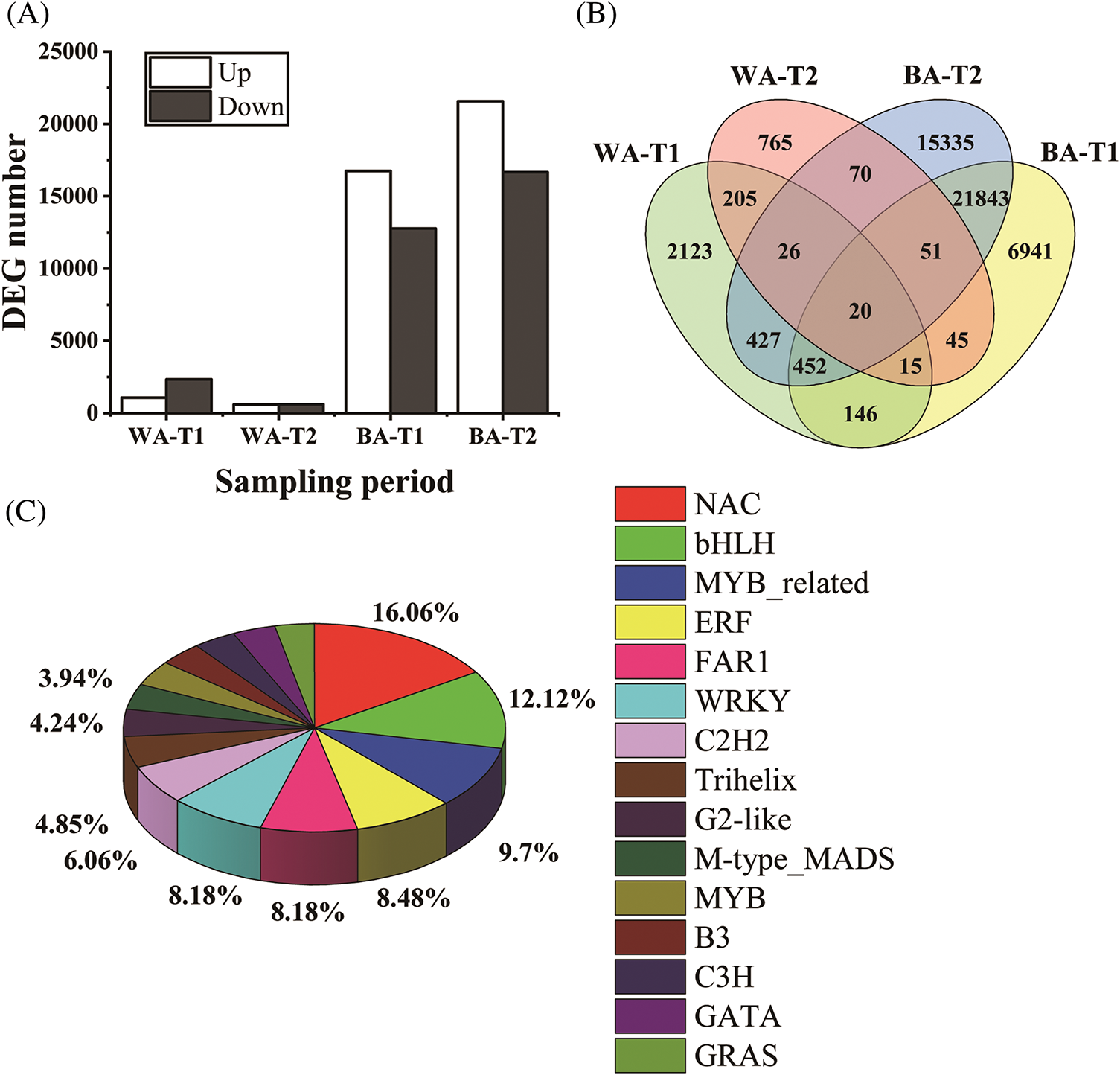

3.4 Identification of DEGs Related to Bolting

An RNA-seq analysis was performed on six samples (‘BA’-CK, ‘BA’-T1, ‘BA’-T2, ‘WA’-CK, ‘WA’-T1, and ‘WA’-T2), and a total of 72,348 DEGs were detected in four groups (‘WA’-CK vs. ‘WA’-T1, ‘WA’-CK vs. ‘WA’-T2, ‘BA’-CK vs. ‘BA’-T1, and ‘BA’-CK vs. ‘BA’-T2) (Fig. 4A). In addition, 3093 specific DEGs in ‘WA’ were identified, of which 2123 were only present at the T1 stage, 765 were only present at the T2 stage, and 205 were present at both T1 and T2 stages (Fig. 4B). These specific DEGs in ‘WA’ may be related to its strong bolting resistance.

Figure 4: DEG-related statistics and characteristics. (A) Upregulated/downregulated DEGs in the four groups. (B) Venn diagram showing the DEG numbers of the two chive varieties at the T1 and T2 stages. (C) Transcription factor distribution. ‘BA’, bolting-prone chive; ‘WA’, bolting-resistant chive. T1 and T2 represent floral bud differentiation and budding stages, respectively

Among the specific DEGs in ‘WA’, 316 DEGs with |log2FC| ≥ 10 were identified, and the number of DEGs at the T1 stage was higher than that at the T2 stage. Additionally, 438 DEGs with |log2FC| ≥ 1 were annotated as transcription factors, with NAC (16.06%), bHLH (12.12%), MYB_related (9.70%), and ERF (8.48%) being predominant (Fig. 4C).

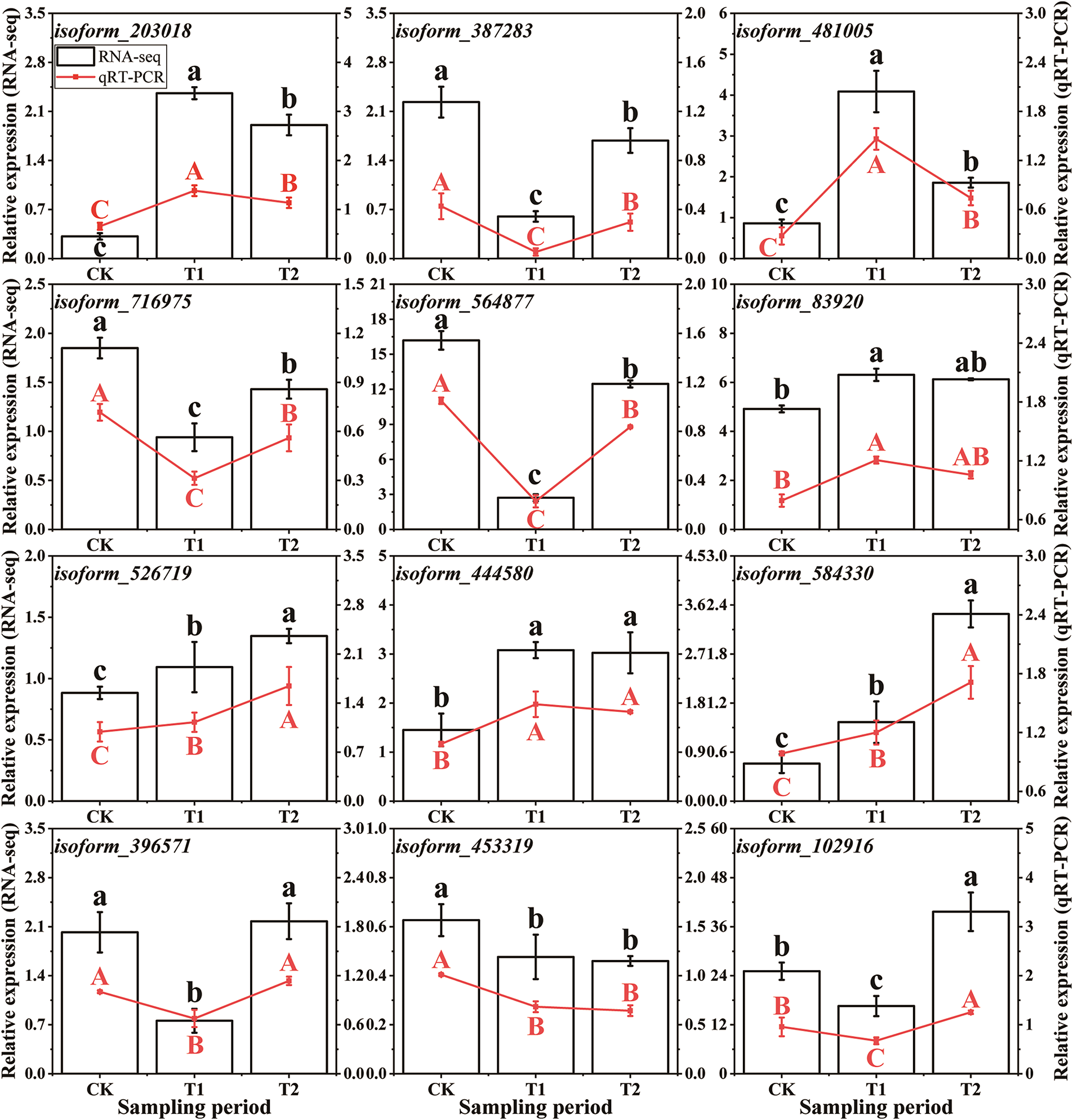

In total, 12 key DEGs were selected, and their relative expression levels at different stages were detected using qRT-PCR (Fig. 5). These DEGs (including isoform_203018, isoform_481005, isoform_716975, and isoform_564877) mainly functioned in the terms related to ‘photoperiodism, flowering’, ‘auxin-activated signaling pathway’, ‘gibberellic acid mediated signaling pathway’, and ‘carbohydrate metabolic process’. The qRT-PCR results were consistent with the RNA-seq data, with an average Pearson’s correlation coefficient r = 0.83 (Table S3), indicating that the transcriptome accurately reflected the responses of chives to bolting.

Figure 5: DEG relative expression assessed by qRT-PCR and RNA-seq analyses in bolting-resistant ‘WA’. The X-axis represents sampling period. The left and right Y-axes represent the relative expressions based on RNA-seq and qRT-PCR, respectively. The uppercase and lowercase letters represent the differences in qRT-PCR and RNA-seq results among the stages, respectively. CK, T1, and T2 represent vegetative growth, floral bud differentiation, and budding stages, respectively. Bars indicate means ± SDs (n = 3). Different letters ‘a–c’ ‘A–C’ indicate a significant difference at p < 0.05 according to ANOVA followed by Duncan’s multiple range test

3.5 GO Enrichment Analysis of ‘WA’ DEGs

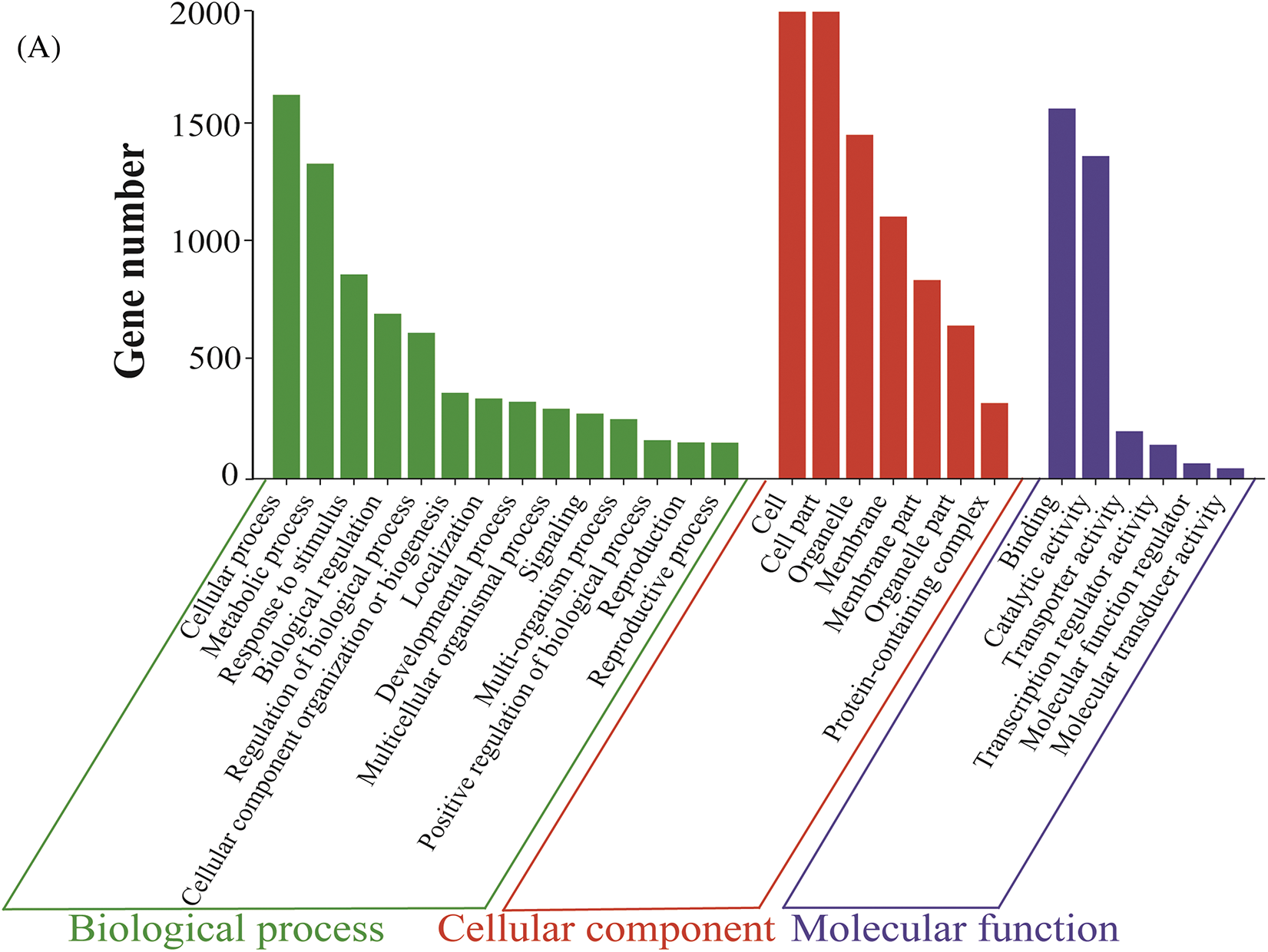

The GO functional enrichment analysis divided the main biological functions of DEGs (‘WA’-CK vs. ‘WA’-T1) into three categories: molecular function, biological process, and cellular component (Fig. 6A). In biological process, ‘WA’ DEGs were annotated to 28 GO terms, which were mainly concentrated in cellular (20.77%) and metabolic (17.04%) processes. In cellular component, ‘WA’ DEGs were annotated to 14 GO terms, with the highest abundance of the DEGs being related to cell and cell part, both accounting for 22.12%. In molecular function, ‘WA’ DEGs were annotated to 12 GO terms, with the DEGs related to binding functions (44.75%) and catalytic activities (39.02%) being the most abundant, whereas the numbers of DEGs enriched in other terms were generally small.

Figure 6: GO enrichment classification of ‘WA’ DEGs at the floral bud differentiation stage. (A) Classification chart of the GO enrichment. (B) Bubble chart of significant GO terms in the biological process category. ‘WA’, bolting-resistant chive

The terms in biological process were the most enriched. Therefore, a GO bubble chart for ‘WA’-CK vs. ‘WA’-T1 was created, with 20 terms being mainly enriched (Fig. 6B). The terms related to GA included ‘gibberellic acid mediated signaling pathway’ and ‘gibberellin biosynthetic process.’ The terms related to IAA included ‘auxin-activated signaling pathway’. The terms related to photoperiod induction included ‘circadian rhythm’, ‘photoperiodism, flowering’, ‘photomorphogenesis’, and ‘regulation of photoperiodism, flowering’. There were also the terms related to flowering, such as ‘pollen development’, ‘flower development’, ‘vegetative to reproductive phase transition of meristem’, and ‘inflorescence development’. Through the GO enrichment analysis, the DEGs were classified according to different functions, which were defined and described. This provided a theoretical basis for screening genes related to bolting resistance in chives.

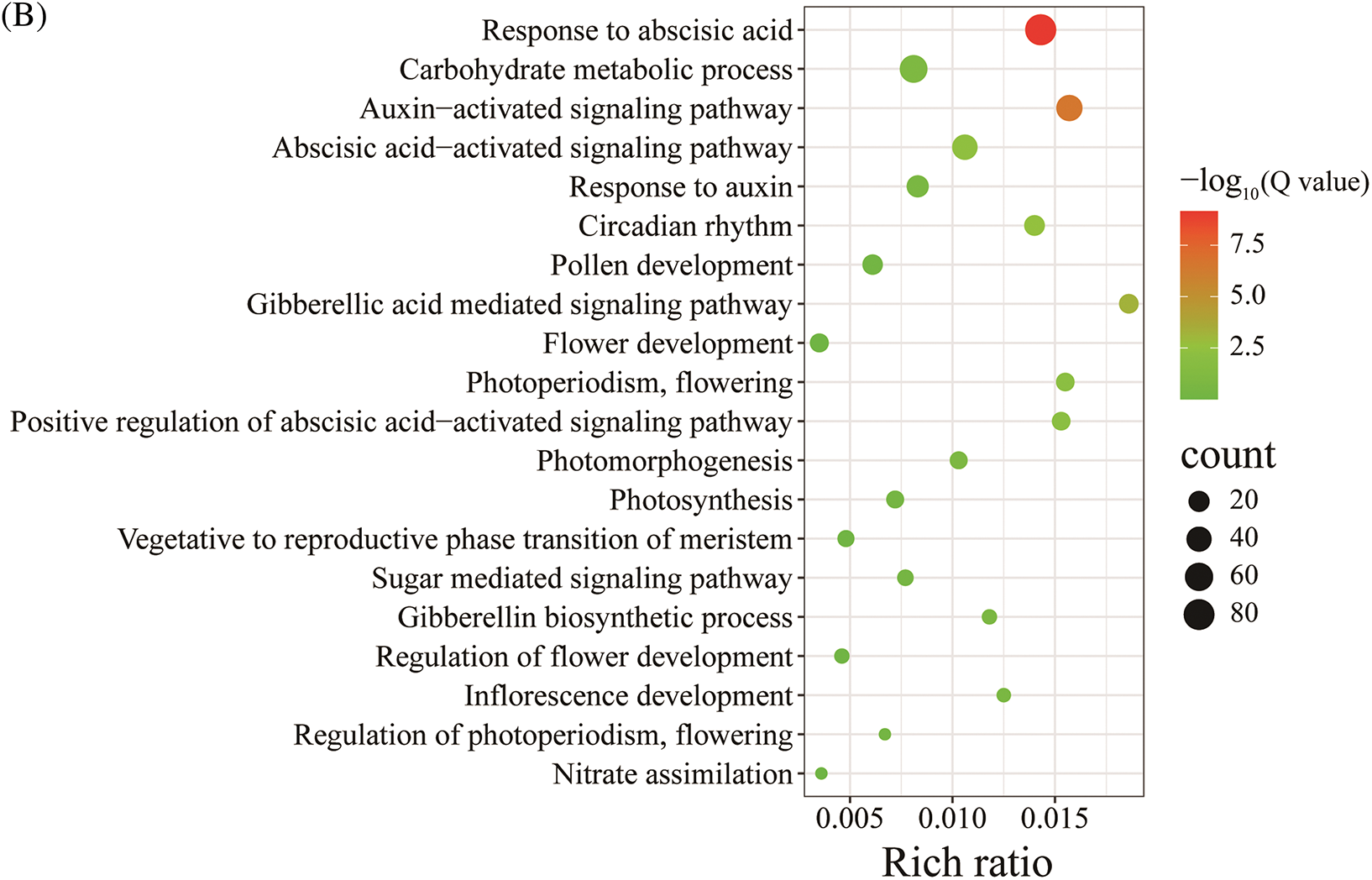

3.6 KEGG Pathway Analysis of ‘WA’ DEGs

A KEGG analysis was performed on the DEGs of ‘WA’-CK vs. ‘WA’-T1. Most of the DEGs were enriched in metabolic pathways, particularly in the ‘carbohydrate metabolic process’ pathway, with 221 DEGs. The pathways ‘folding, sorting and degradation’ and ‘environmental adaptation’ were enriched with 164 and 119 DEGs, respectively (Fig. 7A). Among the tertiary pathways enriched with ‘WA’-CK vs. ‘WA’-T1 DEGs, those related to bolting and flowering included ‘amino acid biosynthesis’ (60), ‘plant hormone signal transduction’ (56), ‘MAPK signaling pathway-plant’ (53), and ‘glycolysis and glucose metabolism synthesis’ (31) (Fig. 7B). Compared with the T2 stage of ‘WA’, ‘amino acids biosynthesis’, ‘plant hormone signal transduction’, and ‘glycolysis and sugar metabolism synthesis’ were only significantly enriched at the T1 stage. Compared with the T1 stage of ‘BA’, ‘nitrogen metabolism’ and ‘zeaxanin biosynthesis’ pathways were only significantly enriched at the T1 stage of ‘WA’. The KEGG enrichment analysis revealed the coordinated genes in metabolic pathways during floral bud differentiation, and this was conducive to further investigating the functions of related genes.

Figure 7: The KEGG pathways enriched with ‘WA’ DEGs at the floral bud differentiation stage. (A) KEGG pathways. (B) Bubble chart of significant KEGG pathways. ‘WA’, bolting-resistant chive

3.7 Key Genes Involved in the Response to Bolting

This study identified key genes involved in bolting resistance, such as isoform_203018, isoform_83920, isoform_481005, isoform_716975, and isoform_564877 (Table S4). These DEGs exhibited significant difference between the two chive varieties and were associated with the terms ‘photoperiodism, flowering’, ‘vernalization’, ‘auxin-activated signaling pathway’, ‘gibberellic acid mediated signaling pathway’, and ‘carbohydrate metabolic process’.

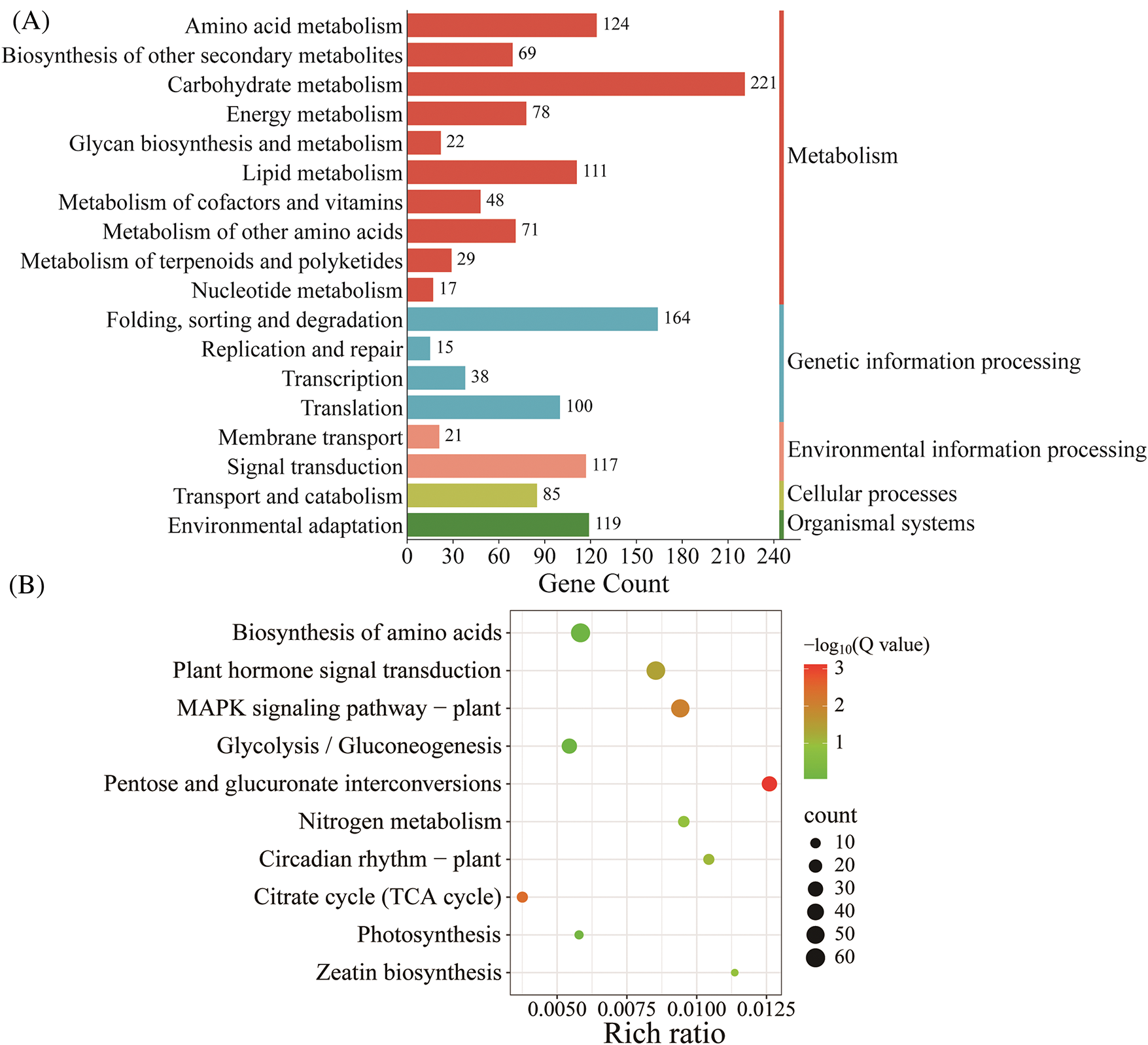

3.7.1 DEGs Related to Photoperiod and Vernalization

Flowering is often coordinated with seasonal environmental cues such as photoperiod and vernalization [31]. A total of 10 key DEGs related to photoperiod induction were enriched (Fig. 8A). At the T1 stage, isoform_203018 was upregulated (log2FC = 3.03) in ‘WA’, but showed no differential expression in ‘BA’. It had a high alignment rate with the E3 ubiquitin protein ligase COP1, which may degrade key factors involved in plant photoperiod, thereby inhibiting photomorphogenesis and delaying bolting and flowering [32]. Isoform_387283 was downregulated (log2FC = −5.90) in ‘WA’ at the T1 stage, but showed no differential expression in ‘BA’. It had a high alignment rate (95.24%) with the splicing factor U2AF small subunit B.

Figure 8: Heat map of DEGs involved in photoperiod induction (A) and vernalization (B). ‘BA’, bolting-prone chive; ‘WA’, bolting-resistant chive. T1 and T2 represent floral bud differentiation and budding stages, respectively

Here, six DEGs related to vernalization were identified (Fig. 8B). Two genes, isoform_83920 and isoform_526719, were upregulated in ‘BA’ at both stages, with log2FC values of 9.38 and 4.84, respectively, but showed no differential expression in ‘WA’. Both genes had high alignment rates (96.57%) with the flowering-promoting gene SOC1-like. SOC1 interacts with other genes to jointly regulate the timing of flowering, flower type, and floral meristem in plants [33]. These genes may be important for inhibiting bolting and flowering in ‘WA’ through photoperiod and vernalization responses.

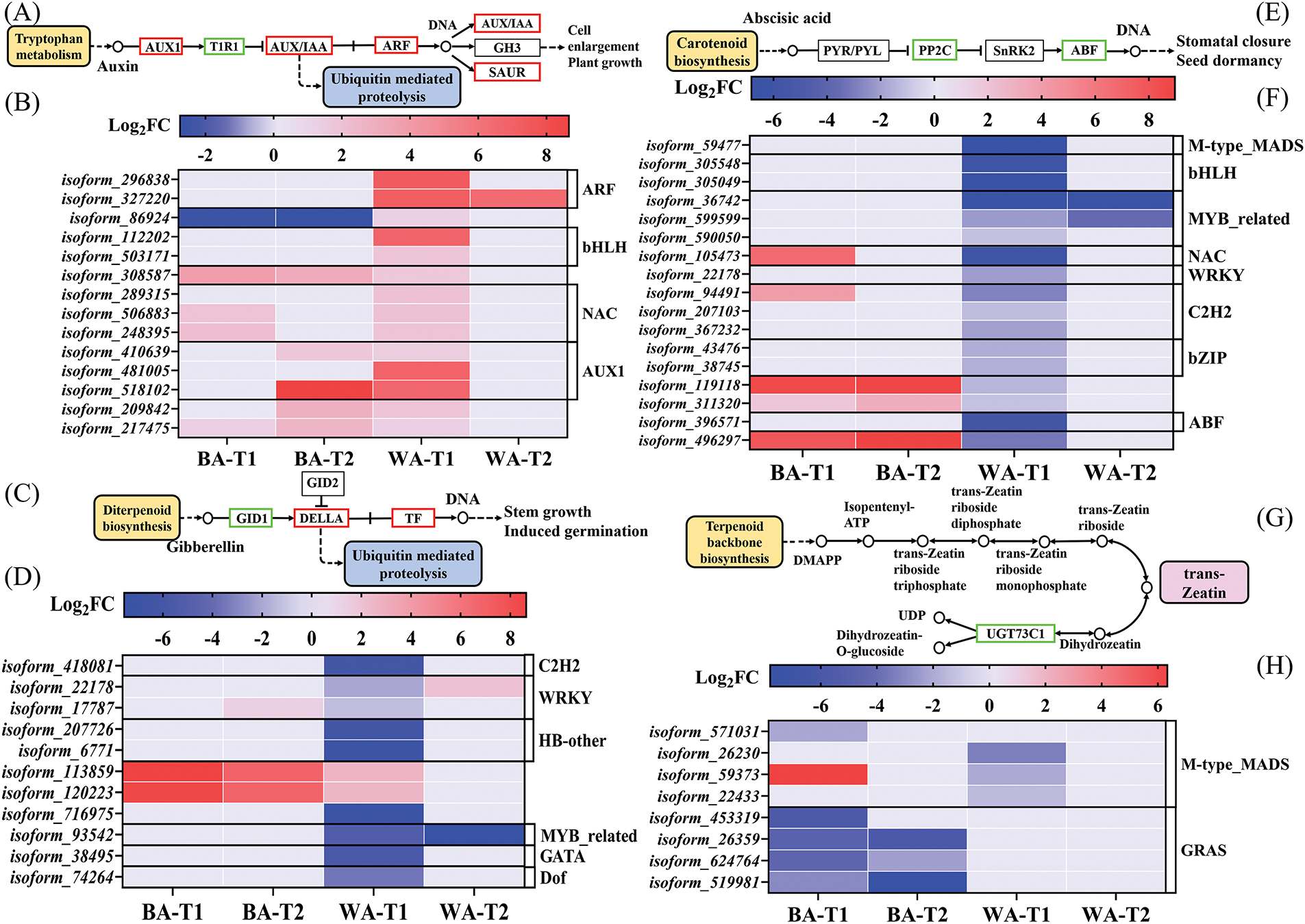

3.7.2 DEGs Related to Hormones

Plant flowering is influenced by not only external environmental factors but also various hormones. In the ‘auxin-activated signaling pathway’, AUX1 family members are the main carriers involved in auxin influx, and the significant upregulation of these genes can enhance cellular auxin uptake [34] (Fig. 9A). In ‘WA’, AUX1-related isoform_410639, isoform_481005, and isoform_518102 were upregulated at the T1 stage, thereby enhancing the auxin influx (Fig. 9B). These DEGs had high alignment rates with auxin transporter-like protein 4 and were upregulated in ‘WA’ at the T1 stage, but showed no differential expression in ‘BA’. In the ‘gibberellic acid mediated signaling pathway’, DEGs primarily affect DELLA proteins through the GID1 gene (Fig. 9C). At the T1 stage, the upregulated gene, with the greatest expression difference from in the ‘BA’, was isoform_113859 (log2FC = 2.65), whereas the most downregulated DEG, with the greatest expression difference from in the ‘WA’, was isoform_716975 (log2FC = −7.00) (Fig. 9D). Isoform_716975 and GID1b are homologous genes that act as a GA receptor. The downregulation of GID1b may inhibit the expression of flowering-related genes by weakening the transmission efficiency of GA signals [35]. The IAA can promote the stability of DELLA [9]. Therefore, isoform_481005 and isoform_716975 might affect DELLA’s stability, and so participate in flowering induction. In the ‘abscisic acid-activated signaling pathway’, the ABA-responsive element binding factor (ABF) family contains the key regulators (Fig. 9E) [36]. The DEG isoform_396571 of the ABF family was downregulated in ‘WA’, but showed no differential expression in ‘BA’, especially at the T1 stage, and it may inhibit ABA signal transduction (Fig. 9F). Its expression is completely opposite to that of isoform_481005, which may indicate the antagonistic effect between ABA and IAA. The DEGs were enriched in the ‘zeatin biosynthesis’ pathway (Fig. 9G). Members of the GRAS family, isoform_453319, isoform_26359, isoform_624764, and isoform_519981, were all downregulated in ‘BA’ and showed no differential expression in ‘WA’, which may lead to an increase in free trans-zeatin, thereby facilitating ZR accumulation (Fig. 9H). Although isoform_453319 and isoform_716975 exhibited different manifestations, they both reduced the levels of flowering-promoting hormones in WA. In summary, these DEGs might be aid in WA’s late bolting.

Figure 9: Pathways related to indole acetic acid signal transduction (A) and its heat map (B), gibberellin signal transduction (C) and its heat map (D), abscisic acid signal transduction (E) and its heat map (F), and zeatin biosynthesis (G) and its heat map (H). ‘BA’, bolting-prone chive; ‘WA’, bolting-resistant chive. T1 and T2 represent floral bud differentiation and budding stages, respectively

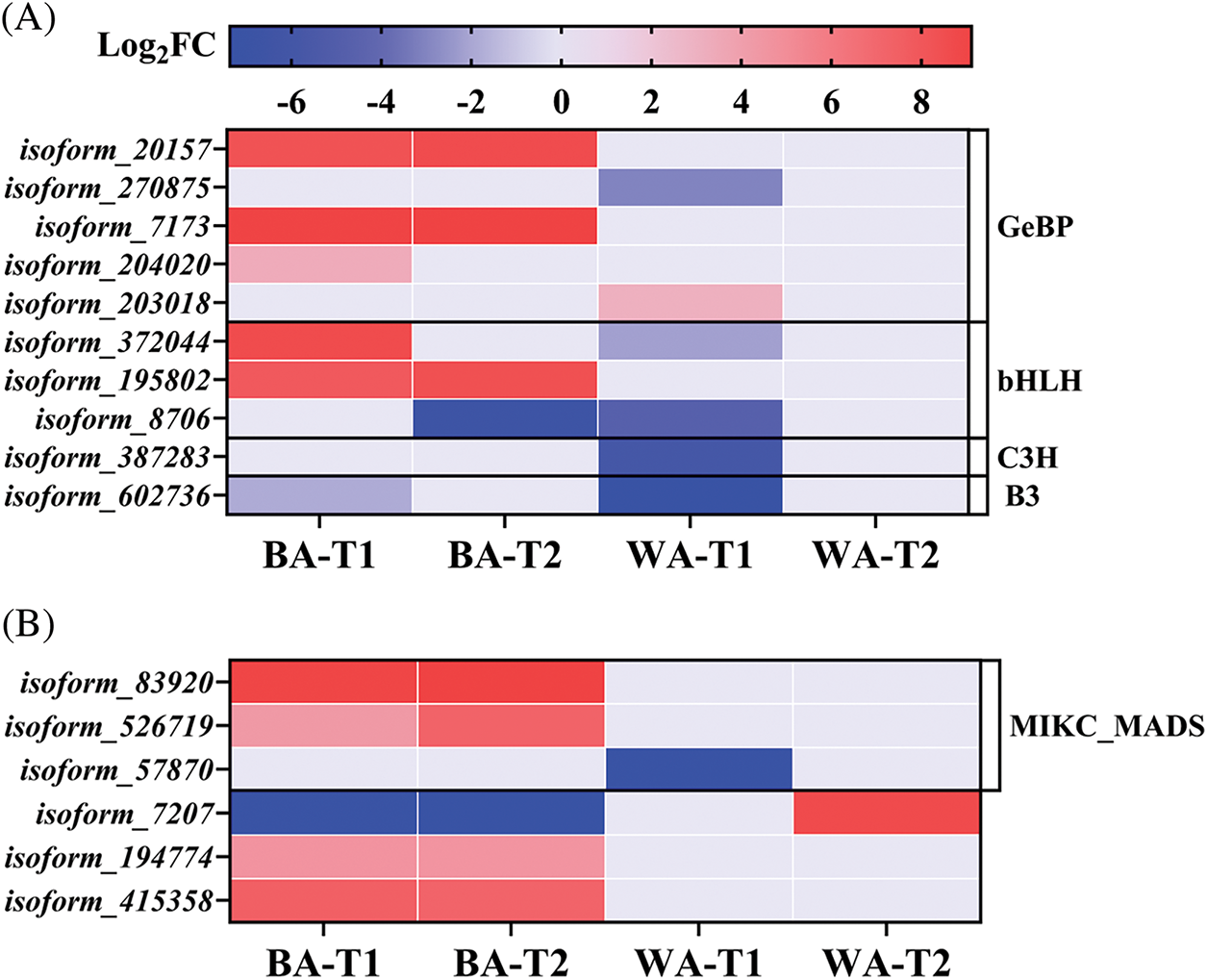

3.7.3 DEGs Related to Nutrient Metabolism

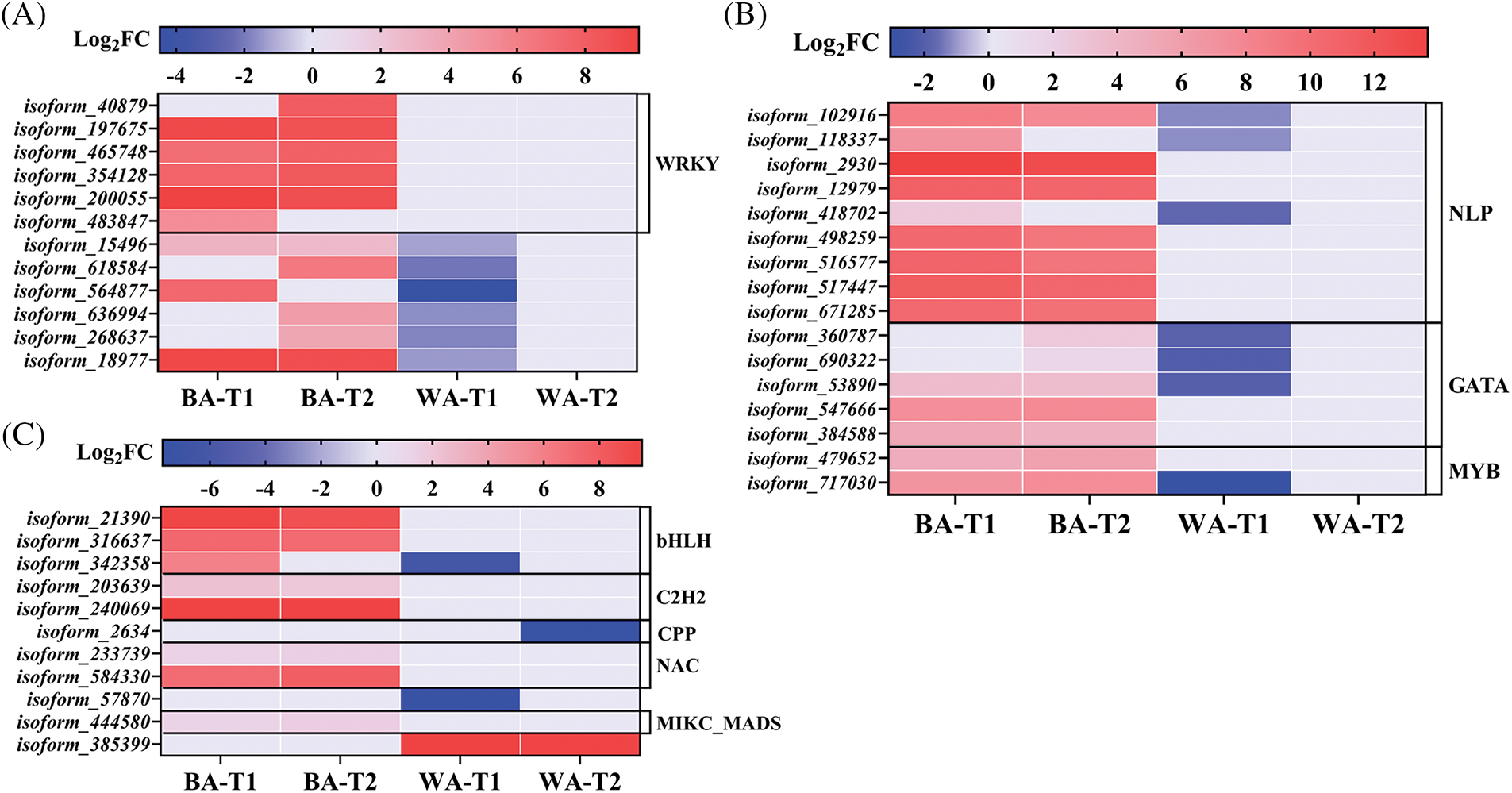

Sugar and proteins are the prerequisites for the floral bud differentiation. Twelve DEGs were enriched in the ‘carbohydrate metabolic process’ pathway (Fig. 10A). The WRKY family plays an important role in plant growth and development. Its members are also significantly differentially expressed during the transition from vegetative to reproductive growth [37]. Six DEGs were identified as members of the WRKY family, all of which showed no differential expression in ‘WA’ at the T1 stage, but they were upregulated in ‘BA’. The DEGs isoform_15496 and isoform_564877 had high similarities to β-fructofuranosidase genes. These genes were upregulated in ‘BA’ at the T1 stage but downregulated in ‘WA’. β-Fructofuranosidase catalyzes the hydrolysis of sucrose into glucose and fructose, providing nutrition for plant bolting and flowering [38].

Figure 10: Heat map of DEGs involved in carbohydrate metabolism (A), nitrate reductase synthesis (B), and flower development (C). ‘BA’, bolting-prone chive; ‘WA’, bolting-resistant chive. T1 and T2 represent floral bud differentiation and budding stages, respectively

In plants, NR can enhance the absorption and reduction of NO3−, thereby improving the ability to synthesize proteins and other nutrients [30], which is conducive to supplying nutrients for flower buds and flowering. In the ‘nitrogen metabolism’ pathway, 16 DEGs related to NR were enriched (Fig. 10B), including 9 DEGs that were annotated as members of the NLP family. The NLP is a transcription factor unique to plants that is primarily involved in nitrogen uptake, transport, and assimilation [39]. Isoform_102916, isoform_118337, and isoform_418702 were all upregulated in ‘BA’ but downregulated in ‘WA’. In addition, these three genes had high alignment rates with NADH-like protein-encoding genes. Their upregulation accelerated nitrogen signal transduction in ‘BA’, increased NR activity, enhanced nitrogen metabolism, and facilitated protein synthesis, thereby causing ‘BA’ to bolt early. Their downregulated expression might play important roles in WA’s late bolting.

3.7.4 DEGs Related to Flower Development

The ‘flower development’ term regulates the recognition and differentiation of floral organs, elongation and occurrence, as well as the formation of pedicels and calyxes. Eleven DEGs related to flower development were identified (Fig. 10C), but only two genes, isoform_342358 and isoform_57870, were downregulated in ‘WA’, with log2FC = −6.26 and −7.69, respectively. The MIKC_MADS-Box member isoform_444580 was continuously upregulated in ‘BA’, with log2FC = 1.18 and 1.48 at the T1 and T2 stages, respectively, but showed no differential expression in ‘WA’. This gene is a homolog of AcRAD21-1, which promotes mitosis in onions (alignment rate 92.97%). In the annotated NAC transcription factor family, the DEG isoform_584330 was upregulated in ‘BA’ at both stages but showed no differential expression in ‘WA’. Both the MADS and NAC families are involved in the regulation of floral organ development and the timing of bolting and flowering in plants [40]. The lack of differential expression in ‘WA’ may be related to the inhibition of bolting and flowering.

Plants can regulate the timing of bolting and flowering, based on the duration of light exposure through photoreceptors, and provide energy for bolting and flowering [41]. The photoperiod induces the production of florigens (such as GA) in leaves and stimulates the transport of GA to the apical meristem to induce floral bud differentiation. Thus, flowering is promoted under long-day conditions. It plays a crucial role in the inflorescence development of female cannabis [42]. In this experiment, the GA content of ‘BA’ was significantly higher than that of ‘WA’ at the T1 and T2 stages, and the high GA concentration encouraged early bolting in ‘BA’ (Fig. 2A). This is consistent with results seen in radish [43]. The E3 ubiquitin ligase COP1 is a key repressor of photomorphogenesis. It targets many positive regulators of light signals and degrades them in the dark [44]. The DEG isoform_203018, which had a high similarity to COP1, was upregulated in ‘WA’ at the T1 stage, inhibiting the plant’s response to light signals and thereby delaying bolting and flowering (Fig. 8A). U2AF plays a role in 3′ splice site recognition during mRNA splicing [45]. In Arabidopsis thaliana, AtU2AF is involved in the splicing of FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC; a flowering repressor) pre-mRNA. The downregulation of the U2AF homolog isoform_387283 in ‘WA’ at the T1 stage may increase FLC mRNA levels, thereby delaying bolting [46]. Thus, isoform_203018 and isoform_387283 may be key genes involved in photoperiod induction that contribute to the inhibition of bolting and flowering in ‘WA’.

Low temperature can induce the synthesis of vernalization hormones, which promote the development of flower buds and the flowering process [47]. Here, isoform_526719 and isoform_83920 enriched in the ‘vernalization’ term were SOC1-like homologous genes. SOC1 is a flowering activator and integrator in Arabidopsis [48]. In various plants, the overexpression of SOC1-like promotes early flowering [49,50]. Therefore, their upregulation in ‘BA’ promoted early bolting and flowering (Fig. 8B). Isoform_444580 in the flower development term was upregulated in ‘BA’ and might promote cell mitosis (Fig. 10C). The pollen of the rice RAD21-1 defective genotype shows mitotic arrest, indicating that RAD21-1 is essential for rice pollen development [51,52]. Overexpression of Zanthoxylum armatum ZaNAC93 in tomato led to early flowering, increased the numbers of lateral shoots and flowers [53]. The NAC isoform_584330 was upregulated in ‘BA’, it may promoted flowering. Thus, isoform_526719, isoform_83920, isoform_444580 and isoform_584330 are key genes regulating bolting and flowering in chives, and they caused ‘BA’ to be prone to bolting.

Hormones play important regulatory roles in vegetable bolting, and their contents and balance are significant factors for floral bud differentiation [54]. GA can stimulate the division and elongation of stem cells in plants and accelerate stem growth during the bolting process [55]. DELLA inhibits GA signal transduction and is regarded as an inhibitory factor of flowering. IAA can promote the DELLA stability [9], and the IAA concentration is positively correlated with vegetative growth and negatively correlated with reproductive growth [56]. Here, six DEGs (such as isoform_481005) in the ‘auxin-activated signaling pathway’ that have high similarities to auxin transporter-like protein 4 facilitated IAA accumulation at the T1 stage and promoted auxin signal transduction in ‘WA’. Additionally, the IAA contents at the three stages in ‘BA’ were significantly lower than in ‘WA’ (Fig. 2C). Therefore, IAA promoted vegetative growth and inhibit early bolting, and the genes that promoted IAA accumulation were negatively correlated with flowering, which is similar to bolting and auxin metabolism in cabbage (Fig. 2C) [55]. GA can release some flowering repressors, such as DELLA proteins, thereby allowing the expression of flowering-promoting factors [57]. Here, the homolog of GID1b (the GA receptor) isoform_716975 was identified in the ‘gibberellic acid mediated signaling pathway’ (Fig. 9D). Its downregulation may release DELLA proteins, reducing the efficiency of GA signal transduction and leading to bolting-resistance in ‘WA’. DELLA proteins promote the physical interaction between brahma and nuclear transcription factor Y subunit gamma (NF-YC) proteins, which impairs the binding of NF-YCs to SOC1, and inhibits flowering [58]. It was speculated that the down-regulation of isoform_716975 inhibited GA signal transduction in ‘WA’ at the T1 stage, resulting in its bolting resistance. ABA promotes the expression of the FT gene (a flowering-promoting gene) and accelerates the synthesis and transport of FT protein, thereby inducing early flowering in plants [59]. ABF family members can recognize and bind to ABA response elements to regulate the expression of downstream genes. In the ‘abscisic acid-activated signaling pathway’, ABF family member isoform_396571 was downregulated in ‘WA’ at the T1 stage (Fig. 9F). Its homologous gene ABI5 is the key transcription factor in the ABA signaling pathway. Plants overexpressing ABI5 have an earlier flowering phenotype [60]. Consequently, its down-regulation might inhibit ABA signal transduction in ‘WA’, which improved its bolting resistance (Fig. 2B). An increase in bud ZR content is beneficial for embryo development and promotes floral bud differentiation in black goji and apples [7,26]. ZR and trans-zeatin can transform. ZR is the nucleosylated form of trans-zeatin, and it is convenient for plant transportation or storage [61]. The DEGs isoform_453319, isoform_26359, isoform_624764, and isoform_519981 may enhance active trans-zeatin and ZR contents in ‘BA’ through downregulated expression in the ‘zeatin biosynthesis’ pathway (Fig. 9H). GA upregulates IPT genes to increase ZR levels, and ZR stimulates GA20ox expression, synergistically promoting stem growth [62]. IAA can inhibit GA signal transduction by stabilizing DELLA proteins. IAA promotes growth by suppressing ABA biosynthesis, while ABA restricts the IAA distribution [63]. Therefore, the four hormones may interact through a complex network to regulate the chive flowering process.

Nutrients, such as proteins and sugar, play an important role in promoting plant flowering [29,64]. WRKY transcription factors influence flowering by enhancing the expression of floral meristem genes, such as AP1 and AP2, which determine the morphology and development of floral organs and control the formation of inflorescence meristems [65]. This was confirmed by the upregulation of six WRKY genes in the ‘carbohydrate metabolism process’ in ‘BA’ (Fig. 10A). Cell wall invertase β-fructofuranosidase, together with monosaccharide transporters, plays an important positive role in regulating plant flower development [66]. The downregulation of isoform_15496 and isoform_564877 (similar to β-fructofuranosidase), which are key genes in bolting resistance, in ‘WA’ indicated their negative regulation of SS accumulation, leading to ‘WA’ late bolting. The NLP family in Arabidopsis is a major regulator of nitrate responses [67]. In the ‘nitrogen metabolism’, DEGs isoform_102916, isoform_118337, and isoform_418702 were NLPs (Fig. 10B). Their functions were similar to that of nitrate reductase. They were upregulated at the T1 stage, promoting protein synthesis in ‘BA’, which led to early flowering. The different expression of these genes between the two genotypes increased the SS content and NR activity at the CK stage in ‘BA’, but they decreased significantly at the T1 stage (Fig. 3). ‘WA’ showed no significant differences between the two stages. This may be because ‘BA’ required nutrients during bolting.

Although the qRT-PCR supported the RNA-seq results, further functional validation experiments are still needed to elucidate the detailed molecular mechanisms underlying their differential tolerance to bolting. In the future, we will validate the functions of the bolting-resistant genes identified through overexpression or knockdown experiments, providing a theoretical basis for the breeding of bolting-resistant chives.

After floral bud differentiation in chives, the IAA content in bolting-resistant ‘WA’ was significantly higher than that in bolting-prone ‘BA’. In contrast, the contents of GA, ABA, ZR, and SS, as well as NR activity, in ‘WA’ were all significantly lower than those in ‘BA’. Through a transcriptome analysis, 3093 ‘WA’-specific DEGs were detected after the initiation of floral bud differentiation. The functions of most bolting-resistant genes were closely related to terms such as ‘photoperiodism, flowering’, ‘auxin-activated signaling pathway’, ‘gibberellic acid mediated signaling pathway’, and ‘carbohydrate metabolic process’. New key candidate genes related to light perception, IAA and GA signaling transduction, and ‘carbohydrate metabolic process’ were identified and analyzed. Transcription factors, such as isoform_203018 (suppressing light sensing), isoform_481005 (enhancing IAA signal transduction), isoform_716975 (weakening the transmission efficiency of GA signals), and isoform_564877 (suppressing sugar accumulation), were significantly differentially expressed between the two chive varieties. The physiological data were consistent with the transcriptome results. These results provide new insights into the mechanism of bolting in chives and offer a theoretical basis for the breeding of bolting-resistant chive varieties.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the ‘National Key R&D Program Subject of China’ (No. 2021YFD1100301), the post subsidy project of National Key R&D Program, and the Guizhou Modern Agriculture Research System (GZMARS)-Plateau characteristic vegetable industry.

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Siyang Ou, Guangdong Geng; data collection: Liuyan Yang, Tingting Yuan; analysis and interpretation of results: Mutong Li, Guohui Liao, Wanping Zhang; draft manuscript preparation: Suqin Zhang, Siyang Ou. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analyzed during this study are provided in this published article and its supplementary data files, or they will be provided upon a reasonable request. The raw reads used for the transcriptomic analysis have been deposited in the NCBI database under the accession number PRJNA1265764.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: Figure S1: Bud morphology at different sampling periods in two chive genotypes. Figure S2: The correlation between replicates. Table S1: qRT-PCR primers for differentially expressed genes and the internal control gene. Table S2: The quality statistics of the filtered reads. Table S3: Pearson correlation coefficient between RNA-seq and qRT-PCR. Table S4: Key differentially expressed genes between two genotypes. The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.068368/s1.

References

1. Fukuda M, Yanai Y, Nakano Y, Higashide T. Differences in vernalisation responses in onion cultivars. J Hortic Sci Biotechnol. 2018;93(3):316–22. doi:10.1080/14620316.2017.1372111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Wu C, Wang M, Cheng Z, Meng H. Response of garlic (Allium sativum L.) bolting and bulbing to temperature and photoperiod treatments. Biol Open. 2016;5(4):507–18. doi:10.1242/bio.016444. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Wako T, Tsukazaki H, Yaguchi S, Yamashita KI, Ito SI, Shigyo M. Mapping of quantitative trait loci for bolting time in bunching onion (Allium fistulosum L.). Euphytica. 2016;209(2):537–46. doi:10.1007/s10681-016-1686-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Gazzani S, Gendall AR, Lister C, Dean C. Analysis of the molecular basis of flowering time variation in Arabidopsis accessions. Plant Physiol. 2003;132(2):1107–14. doi:10.1104/pp.103.021212. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Mouradov A, Cremer F, Coupland G. Control of flowering time: interacting pathways as a basis for diversity. Plant Cell. 2002;14(1 Suppl):S111–30. doi:10.1105/tpc.001362. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Domagalska MA, Sarnowska E, Nagy F, Davis SJ. Genetic analyses of interactions among gibberellin, abscisic acid, and brassinosteroids in the control of flowering time in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS One. 2010;5(11):e14012. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Wang J, Luo T, Zhang H, Shao J, Peng J, Sun J. Variation of endogenous hormones during flower and leaf buds development in ‘Tianhong 2’ apple. HortScience. 2020;55(11):1794–8. doi:10.21273/hortsci15288-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Du W, Ding J, Li J, Li H, Ruan C. Co-regulatory effects of hormone and mRNA-miRNA module on flower bud formation of Camellia oleifera. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1109603. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1109603. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Zou LP, Pan C, Wang MX, Cui L, Han BY. Progress on the mechanism of hormones regulating plant flower formation. Hereditas. 2020;42(8):739–51. (In Chinese). doi:10.16288/j.yczz.20-014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Kwon YS, Kim CW, Kim JS, Moon JS, Yoo KS. Effects of bolting and flower stem removal on the growth and chemical qualities of onion bulbs. Hortic Environ Biotechnol. 2016;57(2):132–8. doi:10.1007/s13580-016-0116-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. He Q, He L, Feng Z, Liu Y, Xiao Y, Liu J, et al. Role of BraSWEET12 in regulating flowering through sucrose transport in flowering Chinese cabbage. Horticulturae. 2024;10(10):1037. doi:10.3390/horticulturae10101037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Li J, Zhao X, Nishimura Y, Fukumoto Y. Correlation between bolting and physiological properties in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. pekinensis group). J Japan Soc Hort Sci. 2010;79(3):294–300. doi:10.2503/jjshs1.79.294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Weber K, Burow M. Nitrogen-essential macronutrient and signal controlling flowering time. Physiol Plant. 2018;162(2):251–60. doi:10.1111/ppl.12664. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Bian J, Zhuang Z, Ji X, Tang R, Li J, Chen J, et al. Research progress of single-cell transcriptome sequencing technology in plants. Agronomy. 2024;14(11):2530. doi:10.3390/agronomy14112530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Liu C, Li T, Cui L, Wang N, Huang G, Li R. OrangeExpDB: an integrative gene expression database for Citrus spp. BMC Genomics. 2024;25(1):521. doi:10.1186/s12864-024-10445-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Liu Y, Wang D, Yuan Y, Liu Y, Lv B, Lv H. Transcriptome profiling reveals key regulatory networks for age-dependent vernalization in Welsh onion (Allium fistulosum L.). Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(23):13159. doi:10.3390/ijms252313159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Shemesh-Mayer E, Ben-Michael T, Rotem N, Rabinowitch HD, Doron-Faigenboim A, Kosmala A, et al. Garlic (Allium sativum L.) fertility: transcriptome and proteome analyses provide insight into flower and pollen development. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:271. doi:10.3389/fpls.2015.00271. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Shen C, Yuan J, Qiao H, Wang Z, Liu Y, Ren X, et al. Transcriptomic and anatomic profiling reveal the germination process of different wheat varieties in response to waterlogging stress. BMC Genet. 2020;21(1):93. doi:10.1186/s12863-020-00901-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 2011;12(1):323. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15(12):550. doi:10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Young MD, Wakefield MJ, Smyth GK, Oshlack A. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 2010;11(2):R14. doi:10.1186/gb-2010-11-2-r14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Mao X, Cai T, Olyarchuk JG, Wei L. Automated genome annotation and pathway identification using the KEGG Orthology (KO) as a controlled vocabulary. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(19):3787–93. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bti430. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Lin Y, Liu G, Rao Y, Wang B, Tian R, Tan Y, et al. Identification and validation of reference genes for qRT-PCR analyses under different experimental conditions in Allium wallichii. J Plant Physiol. 2023;281(15):153925. doi:10.1016/j.jplph.2023.153925. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(5):511–5. doi:10.1038/nbt.1621. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Kou E, Huang X, Zhu Y, Su W, Liu H, Sun G, et al. Crosstalk between auxin and gibberellin during stalk elongation in flowering Chinese cabbage. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):3976. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-83519-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Guo Y, An L, Yu H, Yang M. Endogenous hormones and biochemical changes during flower development and florescence in the buds and leaves of Lycium ruthenicum Murr. Forests. 2022;13(5):763. doi:10.3390/f13050763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Yue J, Hu X, Huang J. Origin of plant auxin biosynthesis. Trends Plant Sci. 2014;19(12):764–70. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2014.07.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Yan B, Hou J, Cui J, He C, Li W, Chen X, et al. The effects of endogenous hormones on the flowering and fruiting of Glycyrrhiza uralensis. Plants. 2019;8(11):519. doi:10.3390/plants8110519. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Zhang W, Li J, Zhang W, Njie A, Pan X. The changes in C/N, carbohydrate, and amino acid content in leaves during female flower bud differentiation of Juglans sigillata. Acta Physiol Plant. 2022;44(2):19. doi:10.1007/s11738-021-03328-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Rehman HU, Alharby HF, Al-Zahrani HS, Bamagoos AA, Alsulami NB, Alabdallah NM, et al. Enriching urea with nitrogen inhibitors improves growth, N uptake and seed yield in quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd) affecting photochemical efficiency and nitrate reductase activity. Plants. 2022;11(3):371. doi:10.3390/plants11030371. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Ream TS, Woods DP, Schwartz CJ, Sanabria CP, Mahoy JA, Walters EM, et al. Interaction of photoperiod and vernalization determines flowering time of Brachypodium distachyon. Plant Physiol. 2014;164(2):694–709. doi:10.1104/pp.113.232678. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Hoecker U. The activities of the E3 ubiquitin ligase COP1/SPA, a key repressor in light signaling. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2017;37:63–9. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2017.03.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Jung JH, Ju Y, Seo PJ, Lee JH, Park CM. The SOC1-SPL module integrates photoperiod and gibberellic acid signals to control flowering time in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2012;69(4):577–88. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04813.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Swarup R, Bhosale R. Developmental roles of AUX1/LAX auxin influx carriers in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:1306. doi:10.3389/fpls.2019.01306. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Liu Y, Hao X, Lu Q, Zhang W, Zhang H, Wang L, et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of flowering-related genes reveal putative floral induction and differentiation mechanisms in tea plant (Camellia sinensis). Genomics. 2020;112(3):2318–26. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2020.01.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Li Z, Yang X, Li Z, Zou X, Jiang C, Zhu J, et al. Genome-wide analysis of ABF gene family in lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) reveals the negative roles of LsABF1 in thermally induced bolting. J Hortic Sci Biotechnol. 2025;100(1):53–67. doi:10.1080/14620316.2024.2360439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Shang C, Cao X, Tian T, Hou Q, Wen Z, Qiao G, et al. Cross-talk between transcriptome analysis and dynamic changes of carbohydrates identifies stage-specific genes during the flower bud differentiation process of Chinese cherry (Prunus pseudocerasus L.). Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(24):15562. doi:10.3390/ijms232415562. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Heyer AG, Raap M, Schroeer B, Marty B, Willmitzer L. Cell wall invertase expression at the apical meristem alters floral, architectural, and reproductive traits in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2004;39(2):161–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02124.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Yanagisawa S. Transcription factors involved in controlling the expression of nitrate reductase genes in higher plants. Plant Sci. 2014;229:167–71. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2014.09.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Mai Y, Diao S, Yuan J, Wang L, Suo Y, Li H, et al. Identification and analysis of MADS-box, WRKY, NAC, and SBP-box transcription factor families in Diospyros oleifera Cheng and their associations with sex differentiation. Agronomy. 2022;12(9):2100. doi:10.3390/agronomy12092100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Liu S, Lu J, Tian J, Cao P, Li S, Ge H, et al. Effect of photoperiod and gibberellin on the bolting and flowering of non-heading Chinese cabbage. Horticulturae. 2023;9(12):1349. doi:10.3390/horticulturae9121349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Alter H, Sade Y, Sood A, Carmeli-Weissberg M, Shaya F, Kamenetsky-Goldstein R, et al. Inflorescence development in female Cannabis plants is mediated by photoperiod and gibberellin. Hortic Res. 2024;11(11):uhae245. doi:10.1093/hr/uhae245. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Jung H, Jo SH, Jung WY, Park HJ, Lee A, Moon JS, et al. Gibberellin promotes bolting and flowering via the floral integrators RsFT and RsSOC1-1 under marginal vernalization in radish. Plants. 2020;9(5):594. doi:10.3390/plants9050594. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Chen H, Huang X, Gusmaroli G, Terzaghi W, Lau OS, Yanagawa Y, et al. Arabidopsis cullin4-damaged DNA binding protein 1 interacts with constitutively photomorphogenic1-suppressor of phya complexes to regulate photomorphogenesis and flowering time. Plant Cell. 2010;22(1):108–23. doi:10.1105/tpc.109.065490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Wang BB, Brendel V. Molecular characterization and phylogeny of U2AF35 homologs in plants. Plant Physiol. 2006;140(2):624–36. doi:10.1104/pp.105.073858. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Wang YY, Xiong F, Ren QP, Wang XL. Regulation of flowering transition by alternative splicing: the role of the U2 auxiliary factor. J Exp Bot. 2020;71(3):751–8. doi:10.1093/jxb/erz416. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Stinchcombe JR, Caicedo AL, Hopkins R, Mays C, Boyd EW, Purugganan MD, et al. Vernalization sensitivity in Arabidopsis thaliana (Brassicaceaethe effects of latitude and FLC variation. Am J Bot. 2005;92(10):1701–7. doi:10.3732/ajb.92.10.1701. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Lee J, Lee I. Regulation and function of SOC1, a flowering pathway integrator. J Exp Bot. 2010;61(9):2247–54. doi:10.1093/jxb/erq098. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Duan X, Liang J, Wang P. Overexpression of SOC1-like gene promotes flowering and decreases seed set in Brachypodium. Int J Agric Biol. 2019;22(2):234–42. doi:10.17957/IJAB/15.1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Ma G, Ning G, Zhang W, Zhan J, Lv H, Bao M. Overexpression of Petunia SOC1-like gene FBP21 in tobacco promotes flowering without decreasing flower or fruit quantity. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 2011;29(3):573–81. doi:10.1007/s11105-010-0263-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Suzuki G, Nishiuchi C, Tsuru A, Kako E, Li J, Yamamoto M, et al. Cellular localization of mitotic RAD21 with repetitive amino acid motifs in Allium cepa. Gene. 2013;514(2):75–81. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2012.11.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Tao J, Zhang L, Chong K, Wang T. OsRAD21-3, an orthologue of yeast RAD21, is required for pollen development in Oryza sativa. Plant J. 2007;51(5):919–30. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03190.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Tang N, Wu P, Cao Z, Liu Y, Zhang X, Lou J, et al. A NAC transcription factor ZaNAC93 confers floral initiation, fruit development, and prickle formation in Zanthoxylum armatum. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2023;201(2):107813. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2023.107813. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Chen C, Huang W, Hou K, Wu W. Bolting, an important process in plant development, two types in plants. J Plant Biol. 2019;62(3):161–9. doi:10.1007/s12374-018-0408-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Hou Y, Wang X, Zhu Z, Sun M, Li M, Hou L. Expression analysis of genes related to auxin metabolism at different growth stages of pak choi. Hortic Plant J. 2020;6(1):25–33. doi:10.1016/j.hpj.2019.12.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Wang CM, Zeng ZX, Liu ZL, Zhu JH, Su XG, Huang RM, et al. BrARR10 contributes to 6-BA-delayed leaf senescence in Chinese flowering cabbage by activating genes related to CTK GA and ABA metabolism. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2024;216:113084. doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2024.113084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Guan H, Huang X, Zhu Y, Xie B, Liu H, Song S, et al. Identification of DELLA genes and key stage for GA sensitivity in bolting and flowering of flowering Chinese cabbage. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(22):12092. doi:10.3390/ijms222212092. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Zhang C, Jian M, Li W, Yao X, Tan C, Qian Q, et al. Gibberellin signaling modulates flowering via the DELLA-BRAHMA-NF-YC module in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2023;35(9):3470–84. doi:10.1093/plcell/koad166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Martignago D, Siemiatkowska B, Lombardi A, Conti L. Abscisic acid and flowering regulation: many targets, different places. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(24):9700. doi:10.3390/ijms21249700. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Wang Y, Li L, Ye T, Lu Y, Chen X, Wu Y. The inhibitory effect of ABA on floral transition is mediated by ABI5 in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2013;64(2):675–84. doi:10.1093/jxb/ers361. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Osugi A, Kojima M, Takebayashi Y, Ueda N, Kiba T, Sakakibara H. Systemic transport of trans-zeatin and its precursor have differing roles in Arabidopsis shoots. Nat Plants. 2017;3(8):17112. doi:10.1038/nplants.2017.112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Liao R, Wu X, Zeng Z, Yin L, Gao Z. Transcriptomes of fruit cavity revealed by de novo sequence analysis in Nai plum (Prunus salicina). J Plant Growth Regul. 2018;37(3):730–44. doi:10.1007/s00344-017-9768-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Li J, Xu P, Zhang B, Song Y, Wen S, Bai Y, et al. Paclobutrazol promotes root development of difficult-to-root plants by coordinating auxin and abscisic acid signaling pathways in Phoebe bournei. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(4):3753. doi:10.3390/ijms24043753. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Xiong H, Ma H, Hu B, Zhao H, Wang J, Rennenberg H, et al. Nitrogen fertilization stimulates nitrogen assimilation and modifies nitrogen partitioning in the spring shoot leaves of Citrus (Citrus reticulata Blanco) trees. J Plant Physiol. 2021;267(3):153556. doi:10.1016/j.jplph.2021.153556. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Zhang M, Wang W, Liu Q, Zang E, Wu L, Hu G, et al. Transcriptome analysis of Saposhnikovia divaricata and mining of bolting and flowering genes. Chin Herb Med. 2023;15(4):574–87. doi:10.1016/j.chmed.2022.08.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. von Schweinichen C, Büttner M. Expression of a plant cell wall invertase in roots of Arabidopsis leads to early flowering and an increase in whole plant biomass. Plant Biol. 2005;7(5):469–75. doi:10.1055/s-2005-865894. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Konishi M, Yanagisawa S. Arabidopsis NIN-like transcription factors have a central role in nitrate signalling. Nat Commun. 2013;4(1):1617. doi:10.1038/ncomms2621. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools