Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Optimizing In Vitro Regeneration of Wheat via Somatic Embryogenesis Using Endosperm-Supported Mature Embryos

1 Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics, Faculty of Science, Erzurum Technical University, Erzurum, 25000, Turkey

2 Department of Agricultural Biotechnology, Faculty of Agriculture, Atatürk University, Erzurum, 25240, Turkey

3 Department of Horticulture, Faculty of Agriculture, Atatürk University, Erzurum, 25240, Turkey

* Corresponding Author: Murat Aydin. Email:

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(8), 2461-2477. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.068383

Received 27 May 2025; Accepted 06 August 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Wheat is a crucial crop for global food security, and effective in vitro plant regeneration techniques are considered a precondition for genetic engineering in wheat breeding programs. A practical approach for in vitro regeneration of the Kırik bread wheat cultivar via somatic embryogenesis was investigated using endosperm-supported mature embryos. Callus cultures were initiated from mature embryos supported by endosperm, cultured on phytagel-based Murashige and Skoog (MS) basal medium containing dicamba (12 mg/L) and indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) (0.5 mg/L) under dark conditions. This research was designed to examine the impact of putrescine (Put) (0.0 and 1.0 mM) on inducing embryonic callus and the effects of thidiazuron (TDZ) (0.0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, and 0.5 mg/L) on wheat regeneration. Adding 1.0 mM putrescine to MS medium significantly increased (p < 0.01) embryogenic callus formation, resulting in a complete (100%) induction rate. Moreover, the highest number of regenerated plants per explant (5.8) was obtained through the synergistic interaction between 1.0 mM putrescine and 0.5 mg/L TDZ. To assess the genetic homogeneity of regenerated plants, 10 different inter-simple sequence repeat (ISSR) primers were utilized, revealing a high level of genetic stability. The results of all the applications of a particular plant tissue culture technique showed a level of somaclonal variation within acceptable limits, indicating that the genetic diversity of the plant populations was protected without compromising the desired traits. These improvements offer a promising tool for wheat biotechnology, especially for genetic transformation.Keywords

Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) is a nutritionally and economically significant crop due to its widespread cultivation and use as a staple food worldwide [1]. By 2050, the global population is expected to hit 9.7 billion, leading to a 70% rise in food demand compared to 2005–2007 levels [2]. To address the rapidly increasing demand for food, plant breeders use both traditional and genetically engineered methods to improve wheat crops [3]. Tissue culture is considered a fundamental aspect of genetic engineering, providing an added advantage to crop breeding operations [4,5]. Furthermore, the success of crop genetic engineering and gene transfer research depends on the development of an effective regeneration system [6].

Somatic embryogenesis is a commonly employed regeneration pathway in tissue culture systems for plant regeneration [7–11] and has significant potential for rapid clonal reproduction of different plant species [12,13]. Additionally, somatic embryos can serve as a dependable source of material required for gene transformation in plants [14]. The main obstacle to genetic engineering programs is poor plant regeneration in various crops, including wheat. Genotype, explant source, culture medium, and their interactions are the primary determinants of wheat plant somatic embryogenesis regeneration frequency [15,16]. Although immature embryos are the most frequently utilized explant type in wheat gene transfer studies due to their high regenerative capacity [5,17,18], different studies have demonstrated that mature embryos can also be utilized [19–21]. Mature embryos can be obtained throughout the year and easily isolated from seeds, thereby maintaining the genetic stability of the regenerated plants [22].

In vitro, plant morphogenesis is governed by chemical agents, primarily plant growth regulators, present in the culture composition. Cytokinin, a cell division stimulant in in vitro tissue culture, increases the growth rate of pro-embryogenic mass [23]. In wheat tissue culture, cytokinin was used with or without auxin to stimulate callus regeneration [15,24]. Thidiazuron (TDZ) has gained interest from researchers because of its auxin and cytokinin-like properties on plant tissue culture [25,26]. TDZ also promotes the growth of somatic embryogenesis in plants [27,28].

Polyamines are essential for plant development and somatic embryo formation, just like auxins and cytokinins. Changes in polyamines and their biosynthetic enzyme levels cause hormonal responses [29,30]. Putrescine (Put), one of the polyamines, plays a role in many vital processes in plant cells, including protein synthesis, DNA replication, cell division, root development, tolerance to abiotic stress, and promoting growth and morphogenesis, such as somatic embryogenesis development in in vitro plant tissue culture [31–34]. Put has been found to positively influence embryonic development in various plant species, as reported [35–38].

Numerous studies have identified media components as the origins of typical genetic or epigenetic alterations in vitro-grown plants [39]. Genetic changes encompass alterations in DNA sequences and cytogenetic abnormalities, whereas epigenetic changes refer to modifications in gene expression that do not involve changes to the DNA sequences. Furthermore, these are known as somaclonal variations [40]. Somaclonal variation is a crucial factor to consider in selecting an effective regeneration system for genetic engineering and micropropagation [41]. Furthermore, somaclonal variation could make it more challenging to use transgenic plants to determine the function of cloned genes that lack a known purpose [42]. Therefore, somaclonal changes need to be analyzed using molecular markers. Inter Simple Sequence Repeats (ISSRs) are highly effective in assessing the genetic fidelity of regenerated plants across diverse plant species [43–45]. This method, which is inexpensive, simple, and highly discriminatory in determining the variation hidden in plants [46–48], confirmed the genetic stability of regenerated plants across several crops [49–52].

This research aims to develop a dependable and efficient in vitro regeneration system for wheat using endosperm-supported mature embryos. These embryos provide benefits like year-round access to explants and better culture responsiveness, which can improve the consistency of transformation and breeding processes. Specifically, the research focused on evaluating the effects of TDZ and Put on regeneration efficiency through somatic embryogenesis, and on assessing the genetic stability of regenerated plants, with the ultimate goal of establishing a regeneration protocol suitable for genetic engineering strategies in wheat improvement programs.

All experimental procedures were carried out in the Tissue Culture and Molecular Analysis Laboratories, which are managed by the Agricultural Biotechnology Laboratories at Atatürk University.

2.1 Plant Material and Preparation of Endosperm-Supported Mature Embryos

The Kırik bread wheat cultivar, sourced from the East Anatolian Agricultural Research Institute in Türkiye, was used as the plant material. The dry seeds were sterilized by first soaking them in 70% ethanol for 5 min, then rinsing with a 5% sodium hypochlorite solution containing 2–3 drops of Tween-20 for 30 min, and finally washed three times with sterile distilled water. The sterilized seeds were stored at +4°C in the dark for 14–16 h. The mature embryos of surface-sterilized seeds were divided into six parts without being separated from the seed, following the methodology described [15].

2.2 Callus Induction, Embryogenic Callus Formation, and Plant Regeneration

Endosperm-supported embryos were cultured in callus induction media (CIM) including MS basal medium [53], 20 g/L sucrose, 1.95 g/L MES Hydrate, 2 g/L of phytagel, 12 mg/L dicamba, and 0.5 mg/L IAA in the darkest conditions at 25 ± 1°C for 14 days. Afterward, calli were cultured on an embryogenic callus formation medium (ECM), which consisted of hormone-free CIM containing either 0.0 mM putrescine (ECM1) or 1.0 mM putrescine (ECM2), and incubated under dark conditions at 25°C for 14 days. The embryogenic callus formation rate (%) was determined before the calluses were shifted to the plant regeneration medium.

The embryogenic calli were subsequently stimulated to plant regeneration medium (RM), which consisted of the putrescine-free ECM supplemented with different concentrations of TDZ (RM1: 0.0 mg/L, RM2: 0.1 mg/L, RM3: 0.2 mg/L, RM4: 0.3 mg/L, RM5: 0.4 mg/L, and RM6: 0.5 mg/L). Cultures were maintained for 30 days under a 16/8 h light/dark photoperiod (light intensity: 62 μmol m−2 s−1) at 25 ± 2°C. Then, responsive embryogenic callus rates (%) and the number of regenerated plants per explant (PN) (number) were calculated. When the regenerated plantlets reached a height of 3–4 cm, they were transferred to magenta boxes containing hormone-free regeneration medium and cultured under the same conditions until they grew to a height of 12–14 cm. Later, the plants were transplanted into a peat-soil mixture (1:1) and acclimated in the greenhouse at 24 ± 2°C with 16 h of light. Before autoclaving at 121°C for 15 min, all media were adjusted to a pH of 5.8 ± 0.1. Since the autoclave degraded the structure of vitamins and plant growth regulators, they were introduced to the medium (~50°C–60°C) through a 0.22 µm cellulose nitrate filter (Milipor®).

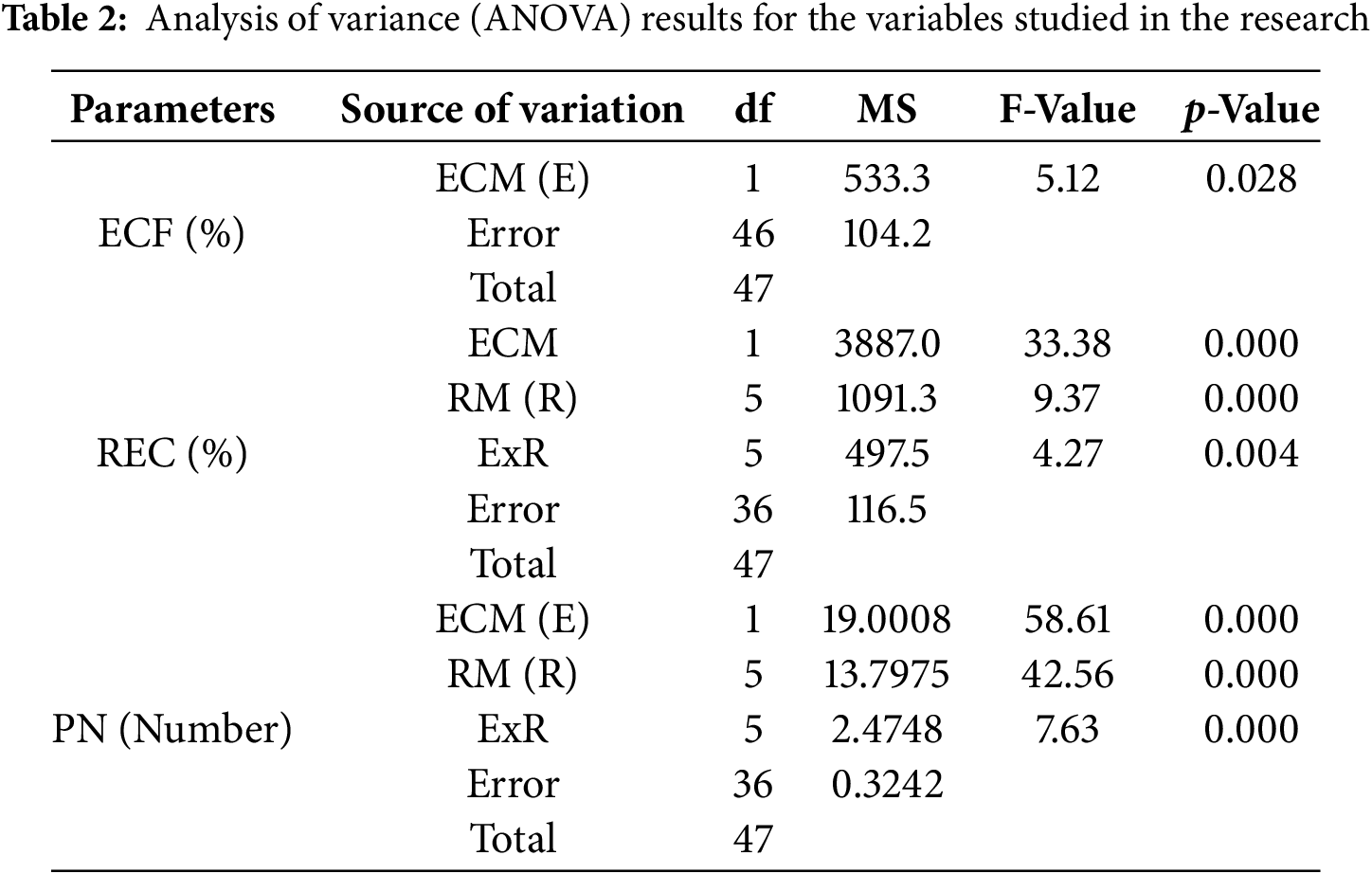

The study was conducted employing a completely randomized design. Each Petri dish was considered an individual replicate, containing 10 endosperm-supported mature embryos. For each concentration of Put, a total of 24 Petri dishes were used. From these, four dishes were randomly selected and assigned to each TDZ concentration for regeneration analysis. The data was analyzed statistically using analysis of variance (ANOVA). A one-way ANOVA was performed to evaluate the effect of Put concentrations on embryogenic callus formation. At the same time, a two-way ANOVA was used to assess the interactive effects of ECM and RM on both regeneration frequency and regeneration efficiency. Mean comparisons were conducted with the Least Significant Difference (LSD) test at a 5% significance level (p ≤ 0.05). All statistical analyses utilized SAS software (version 9.3).

The bulk DNA method was used to assess diversity in regenerated plants; ten plants were randomly sampled from each treatment. Genomic DNA (gDNA) was isolated with the CTAB method described by Cota-Sanchez et al. (2006). The DNA amount and purity of the samples were determined using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA; Multiskan Go). DNA samples were stored at −20°C until used.

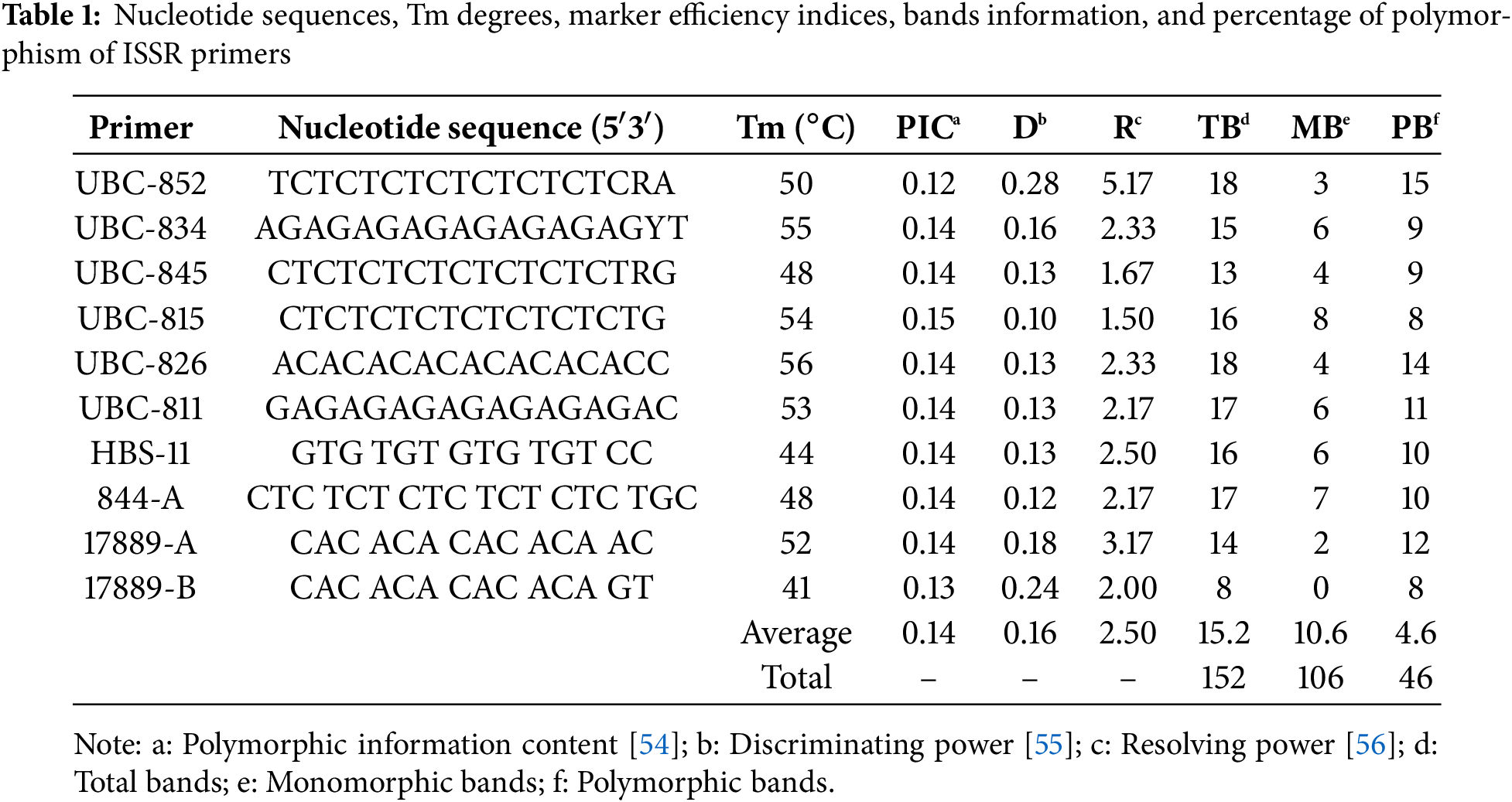

Twenty-five primers were tested in the control plant DNA, of which the ten primers displaying the highest amplification were used in ISSR analysis (Table 1). The ISSR-PCR process was performed using a thermal cycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA, Model 5020). The PCR reaction mix was prepared in a final volume of 25 μL, containing 50 ng of DNA template, 1x PCR buffer, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase, and 0.2 µM primer. The ISSR-PCR conditions were as follows: 4 min at 94°C, 35 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 35 s at 41°C–56°C (dependent on primer) (Table 1), 1 min at 72°C, ending with a final extension step of 5 min at 72°C, the program was terminated at 4°C for 10 min.

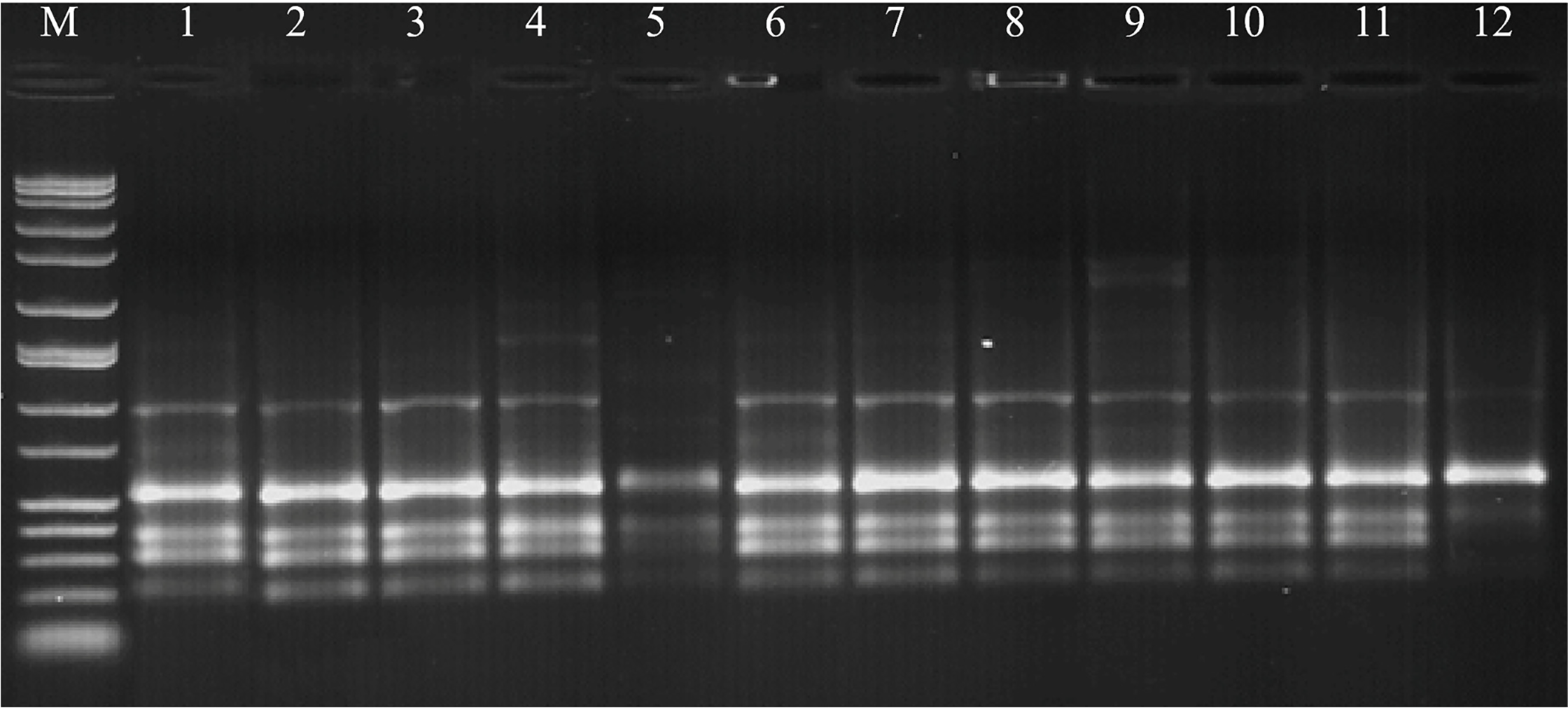

PCR products were loaded onto a 1.5% agarose gel containing 2 µL of ethidium bromide (EtBr), and electrophoresis was conducted at 90 V for 120 min in 0.5 X TBE buffer. Subsequently, the DNA band patterns were visualized and photographed under UV transillumination (Fig. 1). The amplification products (only clear band patterns) were scored as present (1) or absent (0), and the data were constructed as a binary matrix using the computer program TotalLab TL120. Discrimination power (D), polymorphism information content (PIC), marker index (MI), and resolving power (R) were evaluated for each primer based on the treatments using the online iMEC software [57]. A UPGMA dendrogram, generated from the distance matrix using Jaccard’s coefficient, was used to visualize genetic similarities.

Figure 1: ISSR pattern for primer 844-A based on 12 treatments from combinations of ECM and RM on Triticum aestivum L. M: Marker; 1: ECM1 + RM1, 2: ECM1 + RM2, 3: ECM1 + RM3, 4: ECM1 + RM4, 5: ECM1 + RM5, 6: ECM1 + RM6, 7: ECM2 + RM1, 8: ECM2 + RM2, 9: ECM2 + RM3, 10: ECM2 + RM4, 11: ECM1 + RM5, 12: ECM2 + RM6

The type of explant used is one of the most important factors influencing the success of plant tissue culture, as it directly impacts the plant’s growth and response in vitro culture conditions. In this study, endosperm-supported developed embryos were used as explants because they are available throughout the year, are structurally stable, and maintain their physiological integrity during the culture initiation process. Adding endosperm tissue creates a favorable microenvironment that facilitates the exchange of nutrients, hormone balance, and signal transmission between the embryo and surrounding tissues [19,21]. This physical and chemical connection may help maintain high natural auxin and cytokinin gradients, which are crucial for controlling dedifferentiation and somatic embryo formation [29]. The endosperm may also act as a biological support, reducing the mechanical and oxidative stress that comes from isolating the explant. This buffering action helps keep cells alive and maintain the plant’s structure, making it easier for calluses to form and the plant to recover [58]. According to [59], endosperm may also help prevent oxidative damage in the early stages of culture by changing the levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS). This will eventually lead to a more efficient conversion of somatic embryos into whole plantlets.

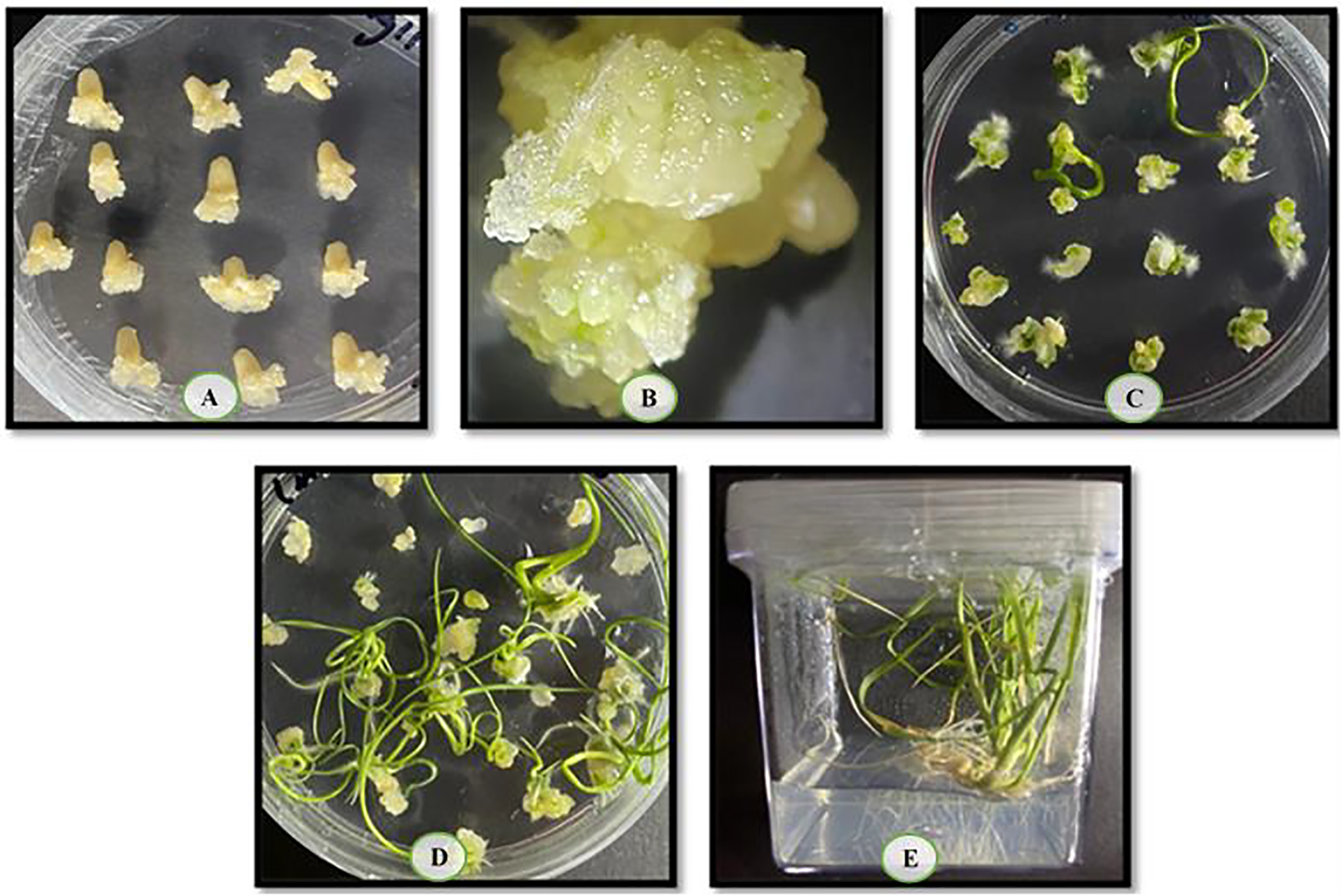

In this study, callus formation in endosperm-supported mature embryos was observed after three days of culture initiation in the callus induction medium. All the explants successfully induced well-developed calli (Fig. 2A). Plant growth regulators impact the development of somatic embryos from callus. Furthermore, the presence of plant growth regulators in the media influences each stage of the in vitro development procedure [60]. Auxin and cytokinin-based plant growth regulators are commonly employed to promote somatic embryogenesis, though other types of plant growth regulators have also been associated with this process. One of these different plant regulators is polyamines. Polyamines are widely recognized for their many roles in plant physiology, encompassing tasks such as cellular differentiation, induction of totipotency, acceleration of cell division, and facilitation of molecular signaling.

Figure 2: (A) Callus induction; (B) embryogenic callus; (C) responded embryogenic callus; (D) plant regeneration; and (E) regenerated plants in magenta boxes

Exogenous polyamine, moreover, usage increased embryogenic structure formation and produced positive results in embryogenesis [61]. Put, one of the polyamines, has a low molecular weight and plays a significant role in cellular mechanisms in plants, such as DNA replication, cell division, and protein synthesis. Furthermore, Put induces over cell division and enlargement, leading to an increase in callus growth, as well as improvements in somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration, as observed in various studies [62,63]. In this study, 14-day-old calli were transferred to an embryogenic callus formation medium containing 0 (ECM1) or 1 mM (ECM2) Put to evaluate the impact of Put on embryogenic callus development and plant regeneration. Its white colour and watery appearance distinguished the non-embryonic callus. In contrast, the embryonic callus was characterized by its light-yellow colour, friable and compact nature, and the appearance of somatic embryos (Fig. 2B). The embryogenic callus formation rate was determined 85.4% and 92.1 for 0 (ECM1) and 1 mM (ECM2) Put, respectively, and the impact of Put concentration on this parameter was important (p < 0.05) (Table 2). Parallel results were shown in Brassica napus L., Cocos nucifera L., and Guizotia abyssinica (Lf) Cass [64,65]. According to a study, 1 mM Put caused a 5-fold increase in embryogenic callus weights and a 2.5-fold rise in embryo formation rate in bitter [66]. Reference [58] found that a 1 mM dose of Put promoted plant formation from responsive embryogenic. The high frequency of somatic embryos in the indica rice variety was also observed when 1 mM putrescine (Put) was added to the growth medium [29].

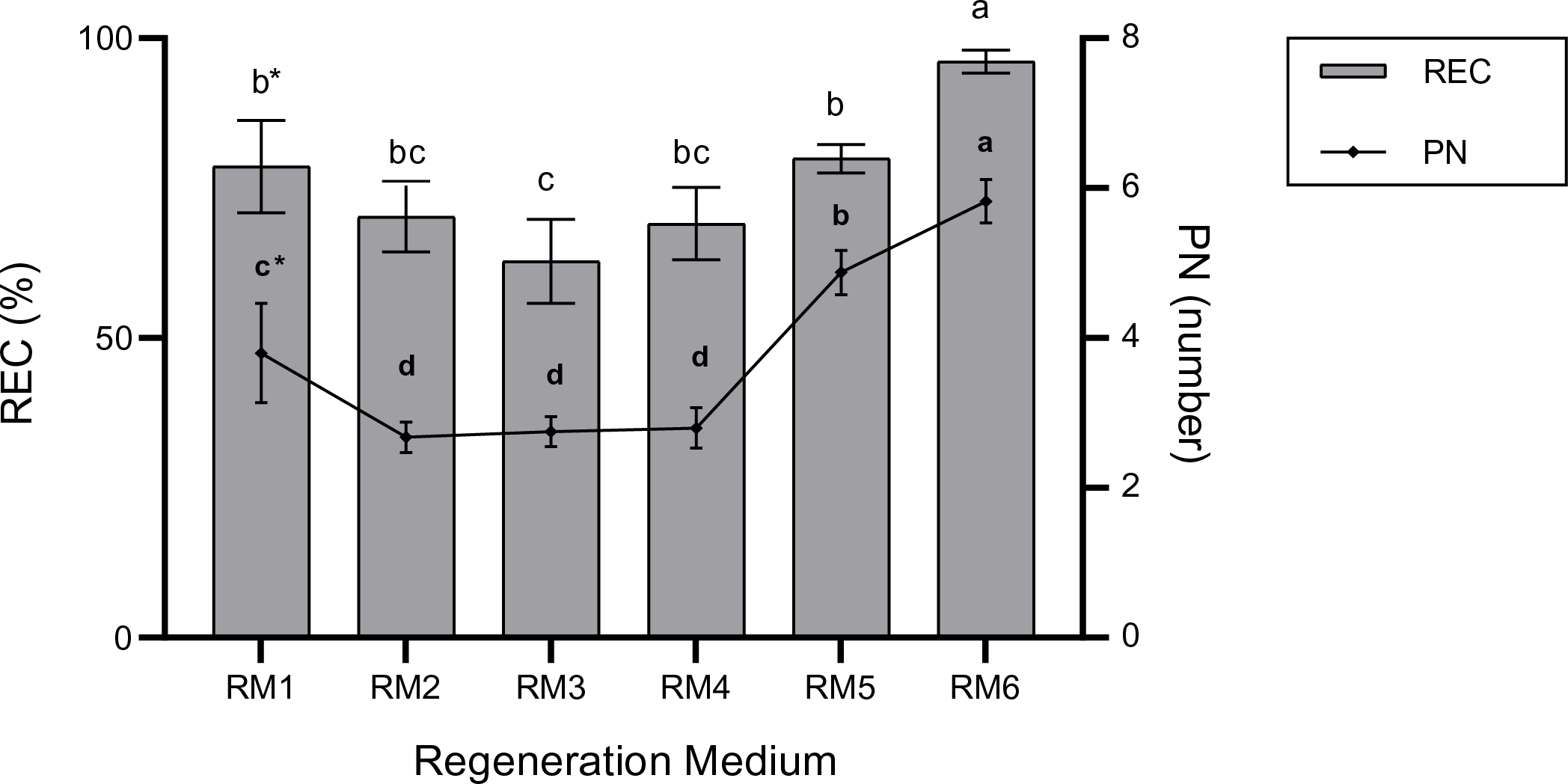

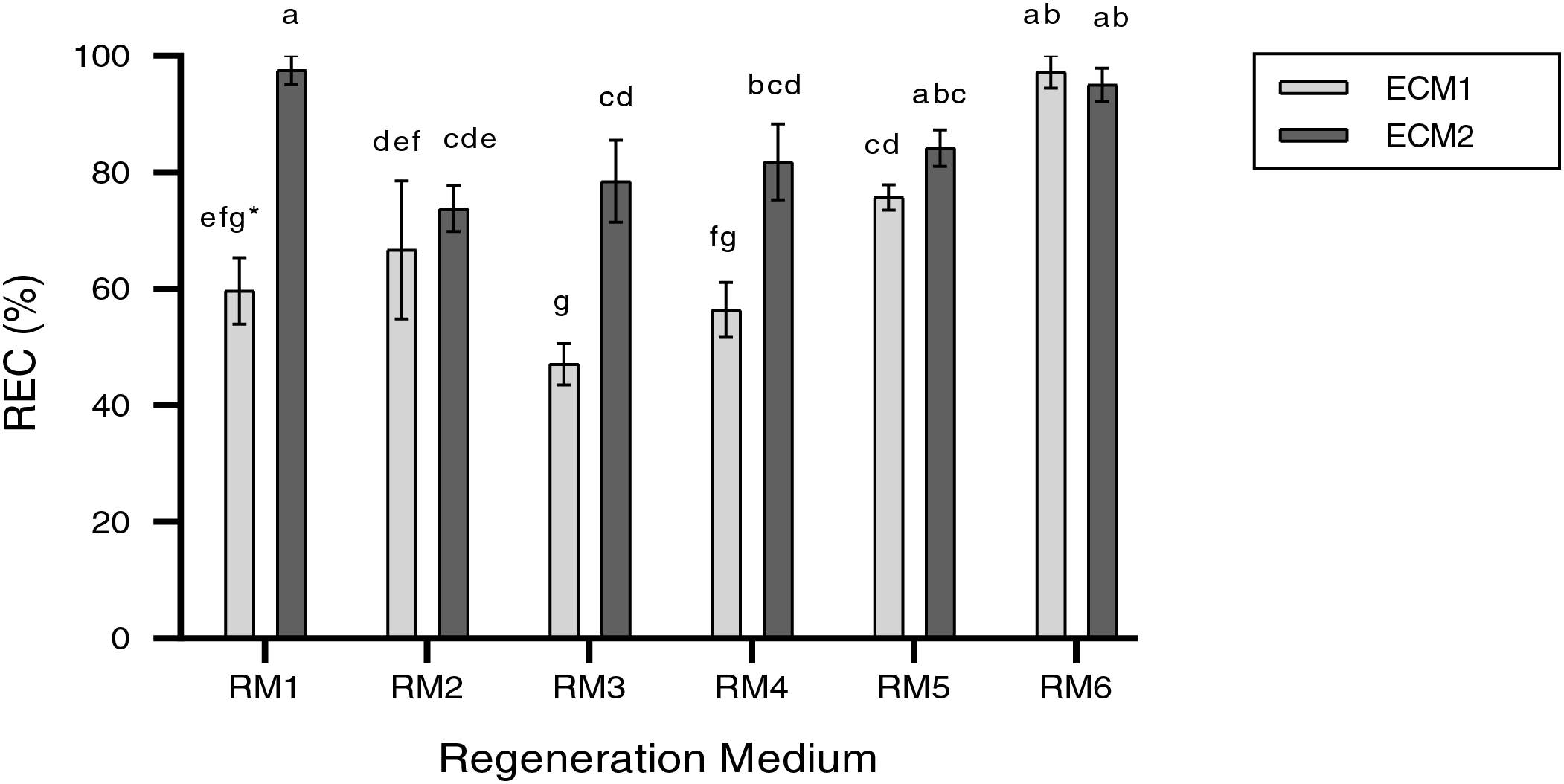

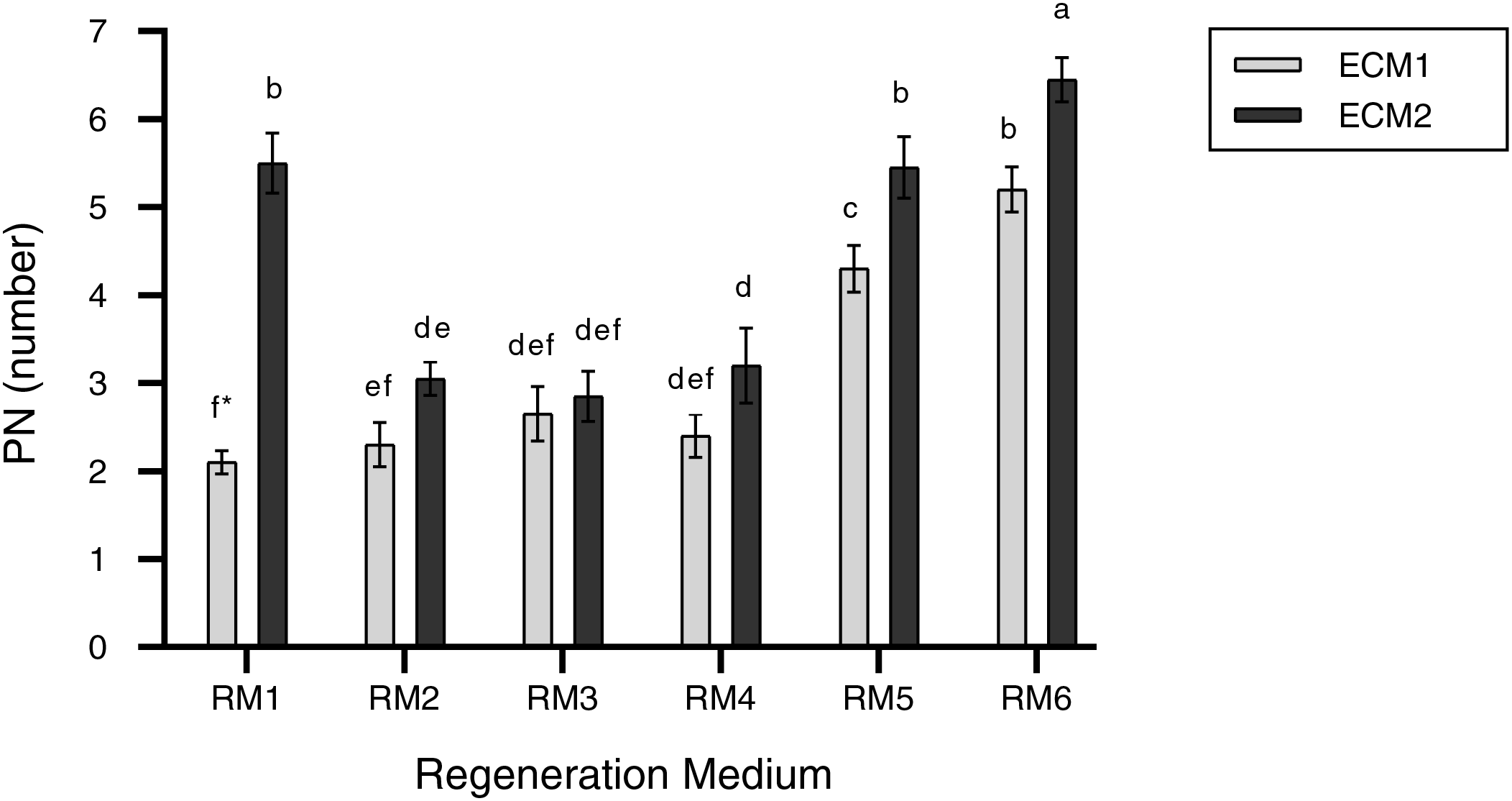

Not only is regenerative plant formation not observed in all somatic embryos in embryogenic calli, but also plant regeneration may not occur in the entire embryogenic calli. Therefore, in this study, the responsive embryonic callus was defined as calli that form plants with roots and shoots (Fig. 2C,D). The main impacts of ECM and RM on the REC rate were significant (p < 0.01) (Table 2). The REC rate (85.1%) in 1 mM Put (ECM2) was higher than 0 mM Put (ECM1) (67.1%). On the other hand, the highest REC rate of 96.1% was determined at a 0.5 mg/L TDZ concentration (RM6). In contrast, the lowest REC rate (62,8%) was observed in 0.2 mg/L TDZ concentration (RM3) (Fig. 3). Because the effects of the plant regeneration medium differed based on the embryogenic callus formation medium, the ECM × RM interaction was significant (p < 0.01) (Table 2). The highest REC ratio (97.5%) was observed using 1 mM Put as the embryogenic callus formation medium (ECM2) and 0 mg/L TDZ as the plant regeneration medium (RM1). The lowest rate (47.1%), however, was determined using a medium containing 0 mM Put for embryogenic callus formation (ECM1) and 0.2 mg/L TDZ for the regeneration medium (RM3) (Fig. 4).

Figure 3: The main impact of regeneration medium on REC (%) and PN (number). The bars represent the mean values, and standard error (mean + SE). *: Means with different letters are significantly different from each other at the 5% significance level, based on the Least Significant Difference (LSD) test

Figure 4: REC rate (%) in the regeneration media according to embryogenic callus formation media. The bars represent the mean values, and standard error (mean + SE). *: Means with different letters are significantly different from each other at the 5% significance level, based on the Least Significant Difference (LSD) test

Furthermore, the results indicated that the number of regenerated per explant was remarkably affected by the ECM and RM and their interactions (Table 2). When the main impact of the regeneration medium was evaluated, the number of regenerative plants per explant in ECM2 (1 mM Put) was higher than in ECM1 (0 mM Put). Also, when the main effect of the regeneration media was considered, the RM6 medium gave the highest number of regenerated plants per explant, which was 5.8 (Fig. 5). The average number of regenerated plants per explant (regeneration efficiency) ranged from 2.1 to 6.5 based on ECM and RM (Fig. 5). The highest number of regenerating plants (PN) (6.5) per explant was observed using ECM2 (1 mM Put) as embryogenic callus formation medium and RM6 (0.5 mg/L TDZ) as plant regeneration medium (Fig. 2E). The lowest PN (2.1) was determined in the use of ECM1 and RM1 as embryogenic callus formation and regeneration media, respectively.

Figure 5: PN (number) in the regeneration media according to embryogenic callus formation media. The bars represent the mean values, and standard error (mean + SE). *: Means with different letters are significantly different from each other at the 5% significance level, based on the Least Significant Difference (LSD) test

Previous research has demonstrated that TDZ plays a functional role in initiating somatic embryogenesis [67–71] and is also a highly effective inducer of morphogenesis, causing cell dedifferentiation and reprogramming of the cell cycle before the formation of meristematic centers, which lead to de novo morphogenesis, such as random shoot growth or somatic embryogenesis [72,73]

This action of TDZ is connected to a series of metabolic pathways, including a signaling event, the buildup and transmission of endogenous plant signals, a system of secondary messengers, and concurrent stress response mechanisms [74]. The reason for the positive impact of TDZ on plant regeneration may be due to its involvement in modulating plant endogenous growth regulators, particularly cytokinins and auxins [75,76]. The cytokinin-like activity of TDZ is implicated in the gathering of ions and enzymes in plant tissues and induces the expression of somatic embryogenesis genes [77]. Additionally, TDZ facilitates the accumulation and production of endogenous growth hormones in the plant [78]. The possible metabolism of TDZ by plant cells, oligomerization of proteins in solutions by TDZ, and improved utilization and sugar catabolism (5C and 6C) by TDZ in the medium are only a few of the numerous plausible explanations for TDZ’s excellent role [79]. The study findings indicated that the application of Put and TDZ elicited a significant enhancement in plant regeneration. Many studies have revealed the beneficial impacts of Put on somatic embryogenesis formation and plant regeneration in various plants, containing bitter melon [66], Momordica charantia [80], wheat [58], palm [81], sweet pepper [82], sugar cane [83], rice [29] and Litchi chinensis Sonn [84]. The main reason for the enhancing effect of Put on plant regeneration may be that it increases the development and formation of somatic embryos. One of the primary challenges in somatic embryogenesis is the low rate of transformation of these structures into plantlets. Reference [85] demonstrated that low conversion rates have been caused by low somatic embryo quality and a lack of maturation and desiccation tolerance in various species. Treatment is known to promote various osmotic substances, such as amino acids, soluble sugars, and proline, which contribute to drought stress tolerance and reduced reactive oxygen species (ROS) overgeneration [86]. Study [59] indicated that the amount of Put increased during the maturation stages of somatic embryos in grapevine and reported that somatic embryogenesis is linked to the accumulation of large amounts of polyamines. Furthermore, Study [58] reported that polyamines are primarily involved in the maturation of somatic embryos and may have positive effects on plant regeneration by protecting DNA from the detrimental impacts of ROSs.

A simple medium composition, minimal manufacturing phases, a predictable degree of propagation, and genetically stable products are all necessary components of an efficient regeneration system [87]. In vitro tissue culture conditions can be mutagenic, and plants regenerated from calli, organ cultures, somatic embryos, and protoplasts can exhibit phenotypic and genotypic diversity [88]. Meanwhile, although cellular organization is essential for plant growth, the loss of cellular regulation in vitro, resulting in disorderly growth, may generate somaclonal variation [89]. Moreover, somaclonal variation in tissue cultures is induced, in part, by variations in nutritional conditions, culture duration, phytohormone concentrations, and the auxin–cytokinin ratio [87]. Somaclonal variation is a serious problem when cultivating plant tissue for genetic engineering and micropropagation. Thus, regeneration systems need to be evaluated in terms of genetic fidelity. Previous research has employed PCR-based techniques utilizing various molecular markers to investigate the genetic stability and somaclonal diversity of diverse regenerated plant specimens [90–93]. The regenerated plants in the study were screened for genetic differences using the ISSR approach, which was chosen because of its cost-effectiveness, simplicity, widespread distribution throughout the genomic DNA, and more precise genetic conclusions [94].

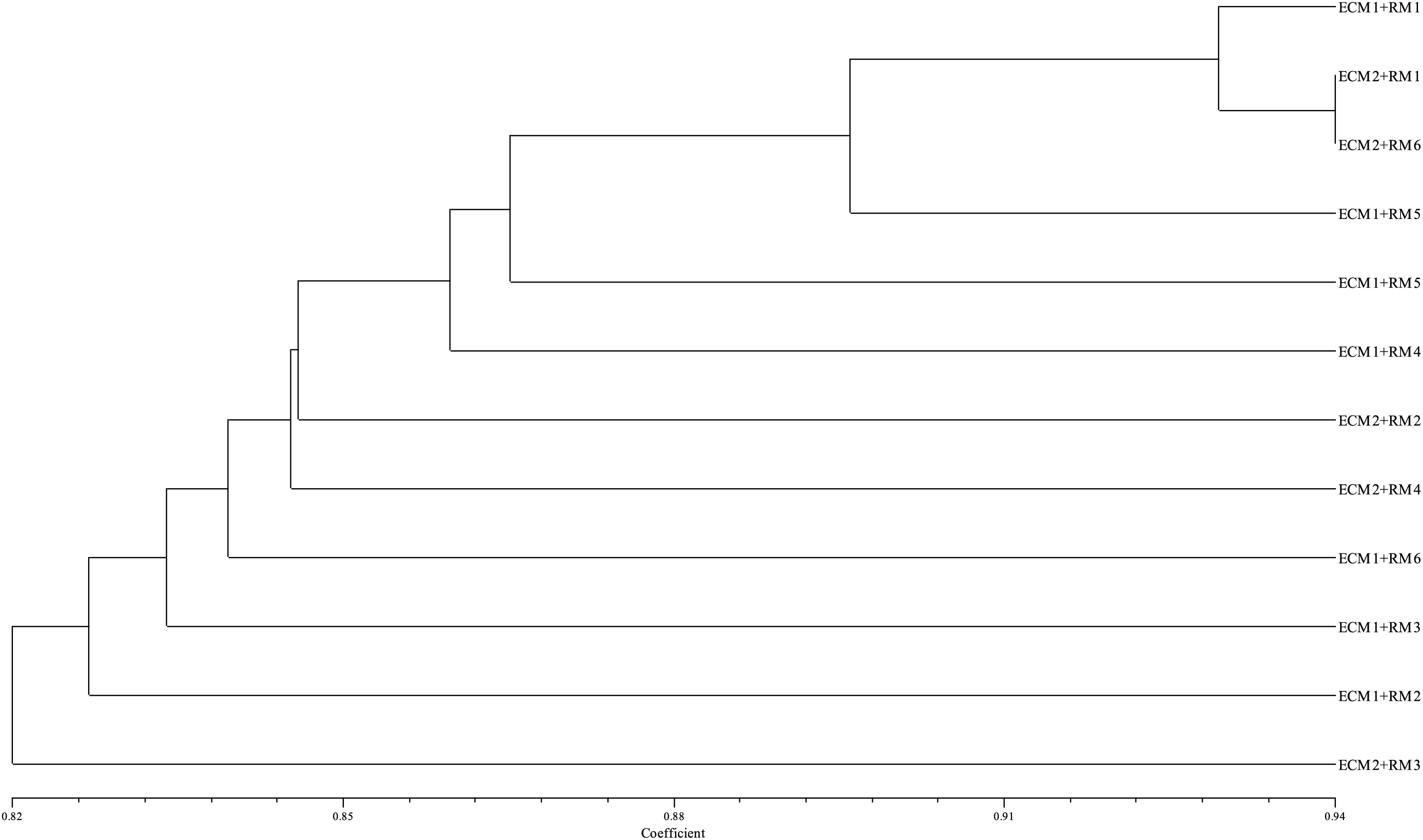

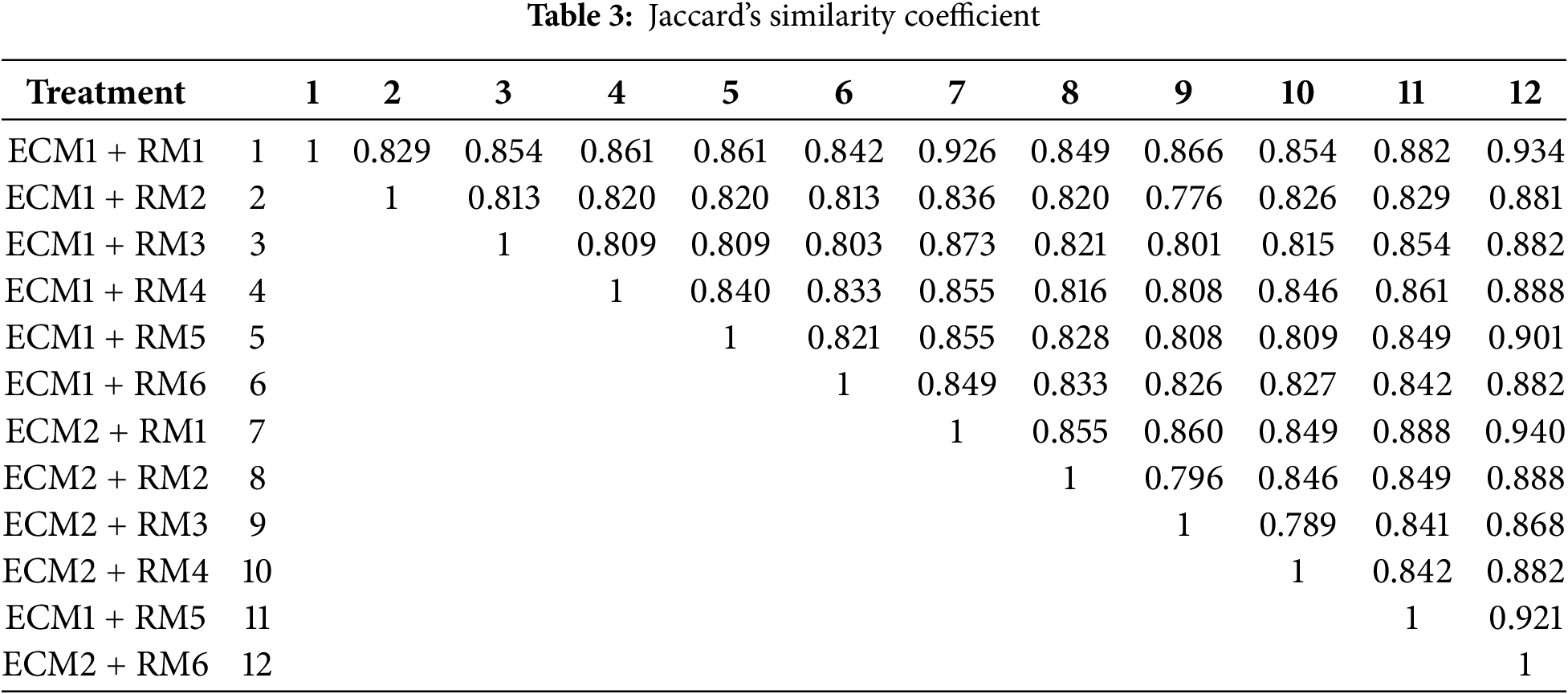

Ten ISSR primers were utilized to evaluate the genetic stability of the regenerated plants obtained from a total of 12 different treatments consisting of different embryogenic callus formation and regeneration media. A total of 152 bands were acquired, with 106 of them being polymorphic bands. The number of polymorphic bands varied between 8 and 15, and all bands of primer 17889 B were polymorphic bands (Table 1). According to the results of marker efficiency, although the highest and lowest PIC values were determined in the UBC-815 (0.15) and UBC-852 (0.12) primers, respectively, the primers were found to have similar values in general. On the other hand, regarding the resolving power (R), the UBC-852 primer showed the highest value (5.17) while primer UBC-815 showed the lowest (1.50), and the mean of the primers was determined as 2.5. In addition, the D ranged between 0.10 (primer UBC-815) and 0.28 (primer UBC-852), with a mean value of 0.16. The ISSR band patterns generally displayed an acceptable level of polymorphism induction. A dendrogram constructed using Jaccard’s similarity coefficient and the UPGMA algorithm illustrates the genetic relationships between treatments (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: Dendrogram of genetic relationship between treatments

According to the results, similarity coefficients among 12 treatments ranged from 0.776 to 0.940 with a mean of 0.845 (Table 3). Maximum similarity was observed between ECM1 + RM1 and ECM2 + RM6 (Table 3).

The potential cause of this polymorphism observed in this study may be ROS. In vitro culture conditions are stressful [95]. They also are thought to be subjected to elevated levels of oxidative stress [96]. ROSs caused genomic instability [97–99]. Moreover, genomic instability occurring in vitro has been associated with chromosomal irregularities, gene amplification, point mutation, and DNA methylation alteration [41,100–102]. The probable cause of ISSR polymorphism may have resulted from the retrotransposons’ movement. DNA methylation is essential for regulating gene expression and silencing transposons in plants [103]. Reference [104] indicated that Put gives rise to the retrotransposon’s movement. Furthermore, alterations in cellular polyamine levels have been shown to impact the level of DNA methylation [105]. No morphological changes were detected in all the regenerated plants in this study. These findings support our thinking that it should be verified in the next generation obtained from regenerated plants to wholly illuminate the cause of polymorphism determined in ISSR.

This study successfully established an efficient and reproducible in vitro regeneration system for wheat (Triticum aestivum L., cv. Kırik) through somatic embryogenesis using endosperm-supported mature embryos. The incorporation of 1.0 mM Put significantly enhanced embryogenic callus induction, while the application of TDZ, particularly at 0.5 mg/L, markedly improved regeneration efficiency. The combined application of 1.0 mM Put and 0.5 mg/L TDZ resulted in the highest regeneration rate and the greatest number of plantlets per explant, highlighting the synergistic effect of polyamines and cytokinin-like regulators in enhancing somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration. Genetic fidelity assessment using ISSR markers confirmed a high level of genetic stability among the regenerated plants, with polymorphism remaining within acceptable limits and no morphological abnormalities observed. However, observed ISSR polymorphisms in some treatments suggest potential underlying epigenetic or retrotransposon-related changes, likely triggered by in vitro stress conditions, warranting further investigation in subsequent generations. Overall, the regeneration protocol established here offers a practical and scalable platform for wheat improvement programs, especially in the context of modern breeding, genetic engineering, and biotechnological applications.

Acknowledgement: The authors are very grateful to Atatürk University.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Sumeyra Ucar, Esma Yigider, Murat Aydin; Methodology, Sumeyra Ucar, Murat Aydin, Esma Yigider; Validation, Muhammed Aldaif, Murat Aydin; Formal analysis, Sumeyra Ucar, Esma Yigider, Murat Aydin; Investigation, Esra Yaprak, Emre Ilhan, Abdulkadir Ciltas; Resources, Esra Yaprak, Muhammed Aldaif; Data curation, Esma Yigider, Emre Ilhan; Writing—original draft preparation, Sumeyra Ucar, Esma Yigider; Writing—review and editing, Murat Aydin, Ertan Yildirim, Sumeyra Ucar; Visualization, Sumeyra Ucar, Muhammed Aldaif; Supervision, Murat Aydin, Abdulkadir Ciltas, Ertan Yildirim. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report concerning the present study.

References

1. Moshawih S, Abdullah Juperi RNA, Paneerselvam GS, Ming LC, Liew KB, Goh BH, et al. General health benefits and pharmacological activities of Triticum aestivum L. Molecules. 2022;27(6):1948. doi:10.3390/molecules27061948. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Cazcarro I, López-Morales CA, Duchin F. The global economic costs of substituting dietary protein from fish with meat, grains and legumes, and dairy. J Ind Ecol. 2019;23(5):1159–71. doi:10.1111/jiec.12856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Hamdan MF, Mohd Noor SN, Abd-Aziz N, Pua TL, Tan BC. Green revolution to gene revolution: technological advances in agriculture to feed the world. Plants. 2022;11(10):1297. doi:10.3390/plants11101297. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Espinosa-Leal CA, Puente-Garza CA, Garcia-Lara S. In vitro plant tissue culture: means for production of biological active compounds. Planta. 2018;248(1):1–18. doi:10.1007/s00425-018-2910-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Kumar R, Mamrutha HM, Kaur A, Venkatesh K, Sharma D, Singh GP. Optimization of Agrobacterium-mediated transformation in spring bread wheat using mature and immature embryos. Mol Biol Rep. 2019;46(2):1845–53. doi:10.1007/s11033-019-04637-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Kumar R, Mamrutha HM, Kaur A, Venkatesh K, Grewal A, Kumar R, et al. Development of an efficient and reproducible regeneration system in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2017;23(4):945–54. doi:10.1007/s12298-017-0463-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Al Shamari M, Rihan HZ, Fuller MP. An effective protocol for the production of primary and secondary somatic embryos in cauliflower (Brassica oleraceae Var Botrytis). Agri Res Tech Open Access J. 2018;14(1):555908. [Google Scholar]

8. Cardoza V. Tissue culture: the manipulation of plant development. Plant Biotechnol Genet Princ Tech Appl. 2008:113–34. doi:10.1002/9780470282014.ch5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Sánchez-Romero C. Use of meta-topolin in somatic embryogenesis. In: Meta-topolin: a growth regulator for plant biotechnology and agriculture. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2021. p. 187–202. [Google Scholar]

10. Tomiczak K, Mikuła A, Niedziela A, Wójcik-Lewandowska A, Domżalska L, Rybczyński JJ. Somatic embryogenesis in the family gentianaceae and its biotechnological application. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:762. doi:10.3389/fpls.2019.00762. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Ucar S, Aydin M. Effects of epigenetic inhibitors on somatic embryogenesis in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Iran J Sci. 2024;49(1):1–10. doi:10.1007/s40995-024-01679-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Chen TT, Yang DJ, Fan RF, Zheng RH, Lu Y, Cheng TL, et al. γ-Aminobutyric acid a novel candidate for rapid induction in somatic embryogenesis of Liriodendron hybrid. Plant Growth Regul. 2022;96(2):293–302. doi:10.1007/s10725-021-00776-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Reddy MC, Indu K, Bhargavi C, Rajendra MP, Babu BH. A review on vegetative propagation and applications in forestry. J Plant Dev Sci. 2022;14:265–72. [Google Scholar]

14. Parimalan R, Venugopalan A, Giridhar P, Ravishankar GA. Somatic embryogenesis and Agrobacterium-mediated transformation in Bixa orellana L. Plant Cell Tiss Org. 2011;105(3):317–28. doi:10.1007/s11240-010-9870-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Aydin M, Tosun M, Haliloglu K. Plant regeneration in wheat mature embryo culture. Afr J Biotechnol. 2011;10(70):15749–55. [Google Scholar]

16. Senhaji C, Gaboun F, Abdelwahd R, Udupa SM, Douira A, Iraqi D. Development of an efficient regeneration system for bombarded calli from immature embryos of Moroccan durum wheat varieties. Agron Res. 2019;17(4):1750–60. doi:10.15159/AR.19.191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Sparks CA, Doherty A. Genetic transformation of common wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) using biolistics. Methods Mol Biol. 2020;2124:229–50. doi:10.1007/978-1-0716-0356-7_12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Tanaka J, Minkenberg B, Poddar S, Staskawicz B, Cho MJ. Improvement of gene delivery and mutation efficiency in the CRISPR-Cas9 wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genomics system via biolistics. Genes. 2022;13(7):1180. doi:10.3390/genes13071180. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Ahansal K, Abdelwahd R, Udupa SM, Aadel H, Gaboun F, Ibriz M, et al. Effect of type of mature embryo explants and acetosyringone on agrobacterium-mediated transformation of moroccan durum wheat. Biosci J. 2022;38:e38007. doi:10.14393/bj-v38n0a2022-54513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ashraf A, Amhed N, Shahid M, Zahra T, Ali Z, Hassan A, et al. Effect of different media compositions of 2,4-d, dicamba, and picloram on callus induction in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Biol Clin Sci Res J. 2022;2022(1):2022. doi:10.54112/bcsrj.v2022i1.159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Liu HY, Ma HL, Zhang W, Wang WQ, Wu JJ, Wang K, et al. Identification of three wheat near isogenic lines originated from CB037 on tissue culture and transformation capacities. Plant Cell Tiss Org. 2023;152(1):67–79. doi:10.1007/s11240-022-02389-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Ben Ali N, Benkaddour R, Rahmouni S, Boussaoudi I, Hamdoun O, Hassoun M, et al. Secondary somatic embryogenesis in Cork oak: influence of plant growth regulators. For Sci Technol. 2023;19(1):78–88. doi:10.1080/21580103.2023.2172462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Desai P, Desai S, Rafaliya R, Patil G. Plant tissue culture: somatic embryogenesis and organogenesis. In: Chandra Rai A, Kumar A, Modi A, Singh M, editors. Advances in plant tissue culture. Cambridge, MA, USA: Academic Press; 2022. p. 109–30. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-323-90795-8.00006-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Aydin M, Taspinar MS, Cakmak ZE, Dumlupinar R, Agar G. Static magnetic field induced epigenetic changes in wheat callus. Bioelectromagnetics. 2016;37(7):504–11. doi:10.1002/bem.21997. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Al-Mayahi AMW. In vitro propagation and assessment of genetic stability in date palm as affected by chitosan and thidiazuron combinations. J Genet Eng Biotechnol. 2022;20(1):165. doi:10.1186/s43141-022-00447-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Luo Y, Han Y, Wei W, Han Y, Yuan J, He N. Transcriptome and metabolome analyses reveal the efficiency of in vitro regeneration by TDZ pretreatment in mulberry. Sci Hortic-Amsterdam. 2023;310:111678. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2022.111678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Mose W, Indrianto A, Purwantoro A, Semiarti E. The influence of thidiazuron on direct somatic embryo formation from various types of explant in Phalaenopsis amabilis (L.) blume orchid. HAYATI J Biosci. 2017;24(4):201–5. doi:10.1016/j.hjb.2017.11.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Narváez I, Martín C, Jiménez-Díaz RM, Mercado JA, Pliego-Alfaro F. Plant regeneration via somatic embryogenesis in mature wild olive genotypes resistant to the defoliating pathotype of Verticillium dahliae. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:1471. doi:10.3389/fpls.2019.01471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Sundararajan S, Sivakumar HP, Nayeem S, Rajendran V, Subiramani S, Ramalingam S. Influence of exogenous polyamines on somatic embryogenesis and regeneration of fresh and long-term cultures of three elite indica rice cultivars. Cereal Res Commun. 2021;49(2):245–53. doi:10.1007/s42976-020-00098-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zeng YH, Zhang YP, Xiang J, Wu H, Chen HZ, Zhang YK, et al. Effects of chilling tolerance induced by spermidine pretreatment on antioxidative activity, endogenous hormones and ultrastructure of indica-japonica hybrid rice seedlings. J Integr Agric. 2016;15(2):295–308. doi:10.1016/s2095-3119(15)61051-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Abd Elbar OH, Farag RE, Shehata SA. Effect of putrescine application on some growth, biochemical and anatomical characteristics of Thymus vulgaris L. under drought stress. Ann Agric Sci. 2019;64(2):129–37. doi:10.1016/j.aoas.2019.10.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Alam N, Ahmad A, Ahmad N, Anis M. Polyamines mediated in vitro morphogenesis in cotyledonary node explants of Mucuna pruriens (L.) DC.: a natural source of L-Dopa. J Plant Growth Regul. 2023;42(8):5203–15. doi:10.1007/s00344-023-10917-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Aragão VPM, Sousa KRD, Oliveira TDRD, de Oliveira LF, Floh EIS, Silveira V, et al. The inhibition of putrescine synthesis affects the in vitro shoot development of Cedrela fissilis Vell. (Meliaceae) by altering endogenous polyamine metabolism and the proteomic profile. Plant Cell Tiss Org. 2022;152(2):377–92. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-2049319/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Bhardwaj S, Verma T, Thakur M, Kumar R, Kapoor D. Polyamines metabolism and their regulatory mechanism in plant development and in abiotic stress tolerance. Plant Ionomics. 2023;225:54–72. doi:10.1002/9781119803041.ch4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Hegazy AE, Aboshama HM. An efficient novel pathway discovered in date palm micropropagation. In:Proceedings of the IV International Date Palm Conference. Leuven, Belgium: International Society for Horticultural Science (ISHS); 2010. doi:10.17660/actahortic.2010.882.18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Hussein NH, Jawad HA, Saleh FF. The effect of putrescine and spermidine on somatic embryogenesis and regeneration of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) Cv. Barhee. Int J Agric Stat Sci. 2021;17(2):827–30. doi:10.63147/39y1tk23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Rajesh MK, Radha E, Sajini KK, Karun A. Polyamine-induced somatic embryogenesis and plantlet regeneration in vitro from plumular explants of dwarf cultivars of coconut (Cocos nucifera). Indian J Agric Sci. 2014;84(4):527–30. doi:10.56093/ijas.v84i4.39473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Silveira V, de Vita AM, Macedo AF, Dias MFR, Floh EIS, Santa-Catarina C. Morphological and polyamine content changes in embryogenic and non-embryogenic callus of sugarcane. Plant Cell Tiss Org. 2013;114(3):351–64. doi:10.1007/s11240-013-0330-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Orłowska R. Barley somatic embryogenesis—an attempt to modify variation induced in tissue culture. J Biol Res. 2021;28(1):9. doi:10.1186/s40709-021-00138-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Leva A, Petruccelli R, Rinaldi L. Somaclonal variation in tissue culture: a case study with olive. In: Leva A, editor. Recent advances in plant in vitro culture. London, UK: IntechOpen; 2012. doi:10.5772/50367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Aydin M, Taspinar MS, Arslan E, Sigmaz B, Agar G. Auxin effects on somaclonal variation and plant regeneration from mature embryo of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Pak J Bot. 2015;47(5):1749–57. [Google Scholar]

42. Sala F, Labra M. Tissue culture and plant breeding | somaclonal variation. In: Thomas B, editor. Encyclopedia of applied plant sciences. Oxford, UK: Elsevier; 2003. p. 1417–22. doi:10.1016/b0-12-227050-9/00195-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Faisal M, Alatar AA, Ahmad N, Anis M, Hegazy AK. Assessment of genetic fidelity in Rauvolfia serpentina plantlets grown from synthetic (encapsulated) seeds following in vitro storage at 4°C. Molecules. 2012;17(5):5050–61. doi:10.3390/molecules17055050. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Heikrujam M, Kumar D, Kumar S, Gupta SC, Agrawal V. High efficiency cyclic production of secondary somatic embryos and ISSR based assessment of genetic fidelity among the emblings in Calliandra tweedii (Benth.). Sci Hortic-Amsterdam. 2014;177:63–70. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2014.07.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Huang WJ, Ning GG, Liu GF, Bao MZ. Determination of genetic stability of long-term micropropagated plantlets of Platanus acerifolia using ISSR markers. Biol Plantarum. 2009;53(1):159–63. doi:10.1007/s10535-009-0025-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Tyagi S, Rajpurohit D, Sharma A. Genetic fidelity studies for testing true-to-type plants in some horticultural and medicinal crops using molecular markers. In: Agricultural biotechnology: latest research and trends. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore; 2021. p. 147–70. doi: 10.1007/978-981-16-2339-4_7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Vafadar Shamasbi F, Nasiri N, Shokri E. Genetic diversity of Persian ecotypes of Indian walnut (Aeluropus littoralis (Gouan) Pari.) by AFLP and ISSR markers. Cytol Genet. 2018;52:222–30. doi:10.3103/s009545271803012x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Gong SF, Fu HJ, Wang JG. ISSR analysis of M1 generation of Gladiolus hybridus Hort treated by EMS. J Northeast Agric Univ. 2010;17(2):22–6. [Google Scholar]

49. Amom T, Tikendra L, Apana N, Goutam M, Sonia P, Koijam AS, et al. Efficiency of RAPD, ISSR, iPBS, SCoT and phytochemical markers in the genetic relationship study of five native and economical important bamboos of North-East India. Phytochemistry. 2020;174:112330. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2020.112330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Faisal M, Abdel-Salam EM, Alatar AA, Qahtan AA. Induction of somatic embryogenesis in Brassica juncea L. and analysis of regenerants using ISSR-PCR and flow cytometer. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2021;28(1):1147–53. doi:10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.11.050. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Hassan FA, Ismail IA, Mazrou R, Hassan M. Applicability of inter-simple sequence repeat (ISSRstart codon targeted (SCoT) markers and ITS2 gene sequencing for genetic diversity assessment in Moringa oleifera Lam. J Appl Res Med Aromat Plants. 2020;18:100256. doi:10.1016/j.jarmap.2020.100256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Thakur M, Rakshandha, Sharma V, Chauhan A. Genetic fidelity assessment of long term shoot cultures and regenerated plants in Japanese plum cvs Santa Rosa and Frontier through RAPD, ISSR and SCoT markers. South Afr J Bot. 2021;140:428–33. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2020.11.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant. 1962;15(3):473–97. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3054.1962.tb08052.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Liu BH. Statistical genomics. 1st ed. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2017. doi:10.1201/9780203738658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Tessier C, David J, This P, Boursiquot JM, Charrier A. Optimization of the choice of molecular markers for varietal identification in Vitis vinifera L. Theor Appl Genet. 1999;98(1):171–7. doi:10.1007/s001220051054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Prevost A, Wilkinson MJ. A new system of comparing PCR primers applied to ISSR fingerprinting of potato cultivars. Theor Appl Genet. 1999;98(1):107–12. doi:10.1007/s001220051046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Amiryousefi A, Hyvönen J, Poczai P. iMEC: online marker efficiency calculator. Appl Plant Sci. 2018;6(6):e01159. doi:10.1002/aps3.1159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Aydin M, Hossein Pour A, Haliloglu K, Tosun M. Effect of polyamines on somatic embryogenesis via mature embryo in wheat. Turkish J Biol. 2016;40(6):1178–84. [Google Scholar]

59. Domínguez C, Martínez Ó., Nieto Ó., Ferradás Y, González MV, Rey M. Involvement of polyamines in the maturation of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L. ‘Mencía’) somatic embryos over a semipermeable membrane. Sci Hortic-Amsterdam. 2023;308:111537. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2022.111537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Vondráková Z, Krajňáková J, Fischerová L, Vágner M, Eliášová K. Physiology and role of plant growth regulators in somatic embryogenesis. In: Vegetative propagation of forest trees. Seoul, Republic of Korea: National Institute of Forest Science; 2016. p. 123–69. [Google Scholar]

61. Rakesh B, Sudheer WN, Nagella P. Role of polyamines in plant tissue culture: an overview. Plant Cell Tiss Org. 2021;145(3):487–506. doi:10.1007/s11240-021-02029-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Malabadi R, Nataraja K. Putrescine influences somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration in Pinus gerardiana wall. Am J Plant Physiol. 2007;2(2):107–14. doi:10.3923/ajpp.2007.107.114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Steiner N, Santa-Catarina C, Silveira V, Floh EIS, Guerra MP. Polyamine effects on growth and endogenous hormones levels in Araucaria angustifolia embryogenic cultures. Plant Cell Tiss Org. 2007;89(1):55–62. doi:10.1007/s11240-007-9216-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Ahmadi B, Shariatpanahi ME, Ojaghkandi MA, Heydari AA. Improved microspore embryogenesis induction and plantlet regeneration using putrescine, cefotaxime and vancomycin in Brassica napus L. Plant Cell Tiss Org. 2014;118(3):497–505. doi:10.1007/s11240-014-0501-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Hema BP, Murthy HN. Improvement of in vitro androgenesis in niger using amino acids and polyamines. Biol Plantarum. 2008;52(1):121–5. doi:10.1007/s10535-008-0024-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Paul A, Mitter K, Raychaudhuri SS. Effect of polyamines on in vitro somatic embryogenesis in Momordica charantia L. Plant Cell Tiss Org. 2009;97(3):303–11. doi:10.1007/s11240-009-9529-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Bhusare BP, John CK, Bhatt VP, Nikam TD. Induction of somatic embryogenesis in leaf and root explants of Digitalis lanata Ehrh.: direct and indirect method. South Afr J Bot. 2020;130:356–65. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2020.01.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Devikar SD, Naikawadi VB, Shirke HA, Aher RK, Nikam TD. Regeneration through somaticembryogenesis from zygotic embryo explant of Boswellia serrata Roxb. and detection of medicinal boswellic acid. Forthcoming 2022. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-1794177/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Dhekney SA, Li ZT, Grant TNL, Gray DJ. Somatic embryogenesis and genetic modification of vitis. In: Germana MA, Lambardi M, editors. In vitro embryogenesis in higher plants. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 2016. p. 263–77. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3061-6_11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Ghosh A, Igamberdiev AU, Debnath SC. Thidiazuron-induced somatic embryogenesis and changes of antioxidant properties in tissue cultures of half-high blueberry plants. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):16978. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-35233-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Adero MO, Syombua ED, Asande LK, Amugune NO, Mulanda ES, Macharia G. Somatic embryogenesis and regeneration of Kenyan wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genotypes from mature embryo explants. Afr J Biotechnol. 2019;18(27):689–94. [Google Scholar]

72. Gantait S, Subrahmanyeswari T, Sinniah UR. Original research leaf-based induction of protocorm-like bodies, their encapsulation, storage and post-storage germination with genetic fidelity in Mokara Sayan × Ascocenda Wangsa gold. South Afr J Bot. 2022;150:893–902. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2022.08.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Monthony AS, Baethke K, Erland LAE, Murch SJ. Tools for conservation of Balsamorhiza deltoidea and Balsamorhiza sagittata: Karrikin and thidiazuron-induced growth. In Vitro Cellul Develop Biol-Plant. 2020;56(3):398–406. doi:10.1007/s11627-019-10052-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Jones MP, Cao J, O’Brien R, Murch SJ, Saxena PK. The mode of action of thidiazuron: auxins, indoleamines, and ion channels in the regeneration of Echinacea purpurea L. Plant Cell Rep. 2007;26(9):1481–90. doi:10.1007/s00299-007-0357-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Murthy BNS, Murch SJ, Saxena PK. Thidiazuron-induced somatic embryogenesis in intact seedlings of Peanut (Arachis hypogaeaendogenous growth-regulator levels and significance of cotyledons. Physiol Plant. 1995;94(2):268–76. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3054.1995.tb05311.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Murthy BNS, Murch SJ, Saxena PK. Thidiazuron: a potent regulator of in vitro plant morphogenesis. In Vitro Cell Dev-Pl. 1998;34(4):267–75. doi:10.1007/bf02822732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Balilashaki K, Moradi S, Vahedi M, Khoddamzadeh AA. A molecular perspective on orchid development. J Hortic Sci Biotech. 2020;95(5):542–52. doi:10.1080/14620316.2020.1727782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Shu H, Sun S, Wang X, Yang C, Zhang G, Meng Y, et al. Low temperature inhibits the defoliation efficiency of thidiazuron in cotton by regulating plant hormone synthesis and the signaling pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(22):14208. doi:10.3390/ijms232214208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Erland LAE, Giebelhaus RT, Victor JMR, Murch SJ, Saxena PK. The morphoregulatory role of thidiazuron: metabolomics-guided hypothesis generation for mechanisms of activity. Biomolecules. 2020;10(9):1253. doi:10.3390/biom10091253. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Thiruvengadam M, Rekha KT, Kim EH, Praveen N, Chung IM. Effect of exogenous polyamines enhances somatic embryogenesis via suspension cultures of spine gourd (Momordica dioica Roxb. ex. Willd.). Aust J Crop Sci. 2013;7(3):446–53. [Google Scholar]

81. El-Dawayati MM, Ghazzawy HS, Munir M. Somatic embryogenesis enhancement of date palm cultivar Sewi using different types of polyamines and glutamine amino acid concentration under in-vitro solid and liquid media conditions. Int J Biol Res. 2018;12(1):149–59. [Google Scholar]

82. Heidari-Zefreh AA, Shariatpanahi ME, Mousavi A, Kalatejari S. Enhancement of microspore embryogenesis induction and plantlet regeneration of sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) using putrescine and ascorbic acid. Protoplasma. 2019;256(1):13–24. doi:10.1007/s00709-018-1268-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Sathish D, Theboral J, Vasudevan V, Pavan G, Ajithan C, Appunu C, et al. Exogenous polyamines enhance somatic embryogenesis and Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation efficiency in sugarcane (Saccharum spp. hybrid). In Vitro Cellul Develop Biol-Plant. 2019;56(1):29–40. doi:10.1007/s11627-019-10022-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Wang G, Wang J, Liu Y. Influence of exogenous putrescine on somatic embryogenesis and regeneration in litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.). Forthcoming 2022. [Google Scholar]

85. Etienne H, Montoro P, Michaux-Ferriere N, Carron MP. Effects of desiccation, medium osmolarity and abscisic-acid on the maturation of hevea-brasiliensis somatic embryos. J Exp Bot. 1993;44(267):1613–9. doi:10.1093/jxb/44.10.1613. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Shao J, Huang K, Batool M, Idrees F, Afzal R, Haroon M, et al. Versatile roles of polyamines in improving abiotic stress tolerance of plants. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:1003155. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.1003155. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Grzegorczyk-Karolak I, Hnatuszko-Konka K, Krzemińska M, Olszewska MA, Owczarek A. Cytokinin-based tissue cultures for stable medicinal plant production: regeneration and phytochemical profiling of Salvia bulleyana shoots. Biomolecules. 2021;11(10):1513. doi:10.3390/biom11101513. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Gawronski J, Dyduch-Sieminska M. Potential of in vitro culture of Scutellaria baicalensis in the formation of genetic variation confirmed by ScoT markers. Genes. 2022;13(11):2114. doi:10.3390/genes13112114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Leva A, Rinaldi LMR. Somaclonal variation. In: Thomas B, Murray BG, Murphy DJ, editors. Encyclopedia of applied plant sciences. Oxford, UK: Academic Press; 2017. p. 468–73. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-394807-6.00150-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

90. Nandhakumar N, Kumar K, Sudhakar D, Soorianathasundaram K. Plant regeneration, developmental pattern and genetic fidelity of somatic embryogenesis derived Musa spp. J Genet Eng Biotechnol. 2018;16(2):587–98. doi:10.1016/j.jgeb.2018.10.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Natarajan N, Sundararajan S, Ramalingam S, Chellakan PS. Efficient and rapid in-vitro plantlet regeneration via somatic embryogenesis in ornamental bananas (Musa spp.). Biologia. 2020;75(2):317–26. doi:10.2478/s11756-019-00358-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

92. Tippani R, Nanna RS, Mamidala P, Thammidala C. Assessment of genetic stability in somatic embryo derived plantlets of Pterocarpus marsupium Roxb. using inter-simple sequence repeat analysis. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2019;25(2):569–79. doi:10.1007/s12298-018-0602-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Uma S, Kumaravel M, Backiyarani S, Saraswathi MS, Durai P, Karthic R. Somatic embryogenesis as a tool for reproduction of genetically stable plants in banana and confirmatory field trials. Plant Cell Tiss Org. 2021;147(1):181–8. doi:10.1007/s11240-021-02108-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

94. Powell W, Machray GC, Provan J. Polymorphism revealed by simple sequence repeats. Trends Plant Sci. 1996;1(7):215–22. doi:10.1016/s1360-1385(96)86898-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

95. Joyce SM, Cassells AC, Jain SM. Stress and aberrant phenotypes in vitro culture. Plant Cell Tiss Org. 2003;74(2):103–21. [Google Scholar]

96. Lakshmanan V, Venkataramareddy SR, Neelwarne B. Molecular analysis of genetic stability in long-term micropropagated shoots of banana using RAPD and ISSR markers. Electron J Biotechn. 2007;10(1):106–13. [Google Scholar]

97. Aydin M, Arslan E, Yigider E, Taspinar MS, Agar G. Protection of Phaseolus vulgaris L. from Herbicide 2,4-D results from exposing seeds to humic acid. Arab J Sci Eng. 2020;46(1):163–73. doi:10.1007/s13369-020-04893-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

98. Kasapoğlu AG, Muslu S, Aygören AS, Öner BM, Güneş E, İlhan E, et al. Genome-wide characterization of the GPAT gene family in bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) and expression analysis under abiotic stress and melatonin. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2024;71(8):4549–69. doi:10.1007/s10722-024-01899-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

99. Turhan S, Taspinar MS, Yigider E, Aydin M, Agar G. The role of long terminal repeat (Ltr) responses to drought in selenium-treated wheat. Environ Eng Manag J. 2021;20(6):917–25. [Google Scholar]

100. Aydin M, Arslan E, Taspinar MS, Karadayi G, Agar G. Analyses of somaclonal variation in endosperm-supported mature embryo culture of rye (Secale cereale L.). Biotechnol Biotec Eq. 2016;30(6):1082–9. doi:10.1080/13102818.2016.1224980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

101. Rani V, Raina SN. Genetic fidelity of organized meristem-derived micropropagated plants: a critical reappraisal. In Vitro Cell Dev-Pl. 2000;36(5):319–30. doi:10.1007/s11627-000-0059-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

102. Saker MM, Bekheet SA, Taha HS, Fahmy AS, Moursy HA. Detection of somaclonal variations in tissue culture-derived date palm plants using isoenzyme analysis and RAPD fingerprints. Biologia Plant. 2000;43(3):347–51. doi:10.1023/a:1026755913034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

103. Yang LL, Zhang XY, Wang LY, Li YG, Li XT, Yang Y, et al. Lineage-specific amplification and epigenetic regulation of LTR-retrotransposons contribute to the structure, evolution, and function of Fabaceae species. BMC Genom. 2023;24(1):423. doi:10.1186/s12864-023-09530-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. Sigmaz B, Agar G, Arslan E, Aydin M, Taspinar MS. The role of putrescine against the long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposon polymorphisms induced by salinity stress in Triticum aestivum. Acta Physiol Plant. 2015;37(11):251. doi:10.1007/s11738-015-2002-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

105. Soda K. Overview of polyamines as nutrients for human healthy long life and effect of increased polyamine intake on DNA methylation. Cells. 2022;11(1):164. doi:10.3390/cells11010164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools