Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Enhancement of Growth and Quality of Chinese Bayberry Using LED Supplemental Lighting

1 Joint Laboratory for Extreme Conditions Matter Properties, Southwest University of Science and Technology, Mianyang, 621010, China

2 School of Mathematics and Physics, Southwest University of Science and Technology, Mianyang, 621010, China

3 Key Laboratory of 3D Micro/Nano Fabrication and Characterization of Zhejiang Province, School of Engineering, Westlake University, 18 Shilongshan Road, Hangzhou, 310024, China

* Corresponding Author: Ni Tang. Email:

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(8), 2551-2562. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.070556

Received 18 July 2025; Accepted 12 August 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Supplemental lighting has emerged as a widely adopted technique in greenhouse cultivation to enhance product visibility and improve the flavor characteristics of Chinese bayberry (Myrica rubra) in the international market. While studies on lighting have predominantly focused on colorimetry, limited research has addressed the precise control of chromatic parameters and their effect on fruit quality. This study examined the effects of varying lighting conditions, specifically correlated color temperatures and illuminance, on the growth and quality of Chinese bayberry varieties “Black Charcoal” and “Dongkui” using a precision control system. The bayberry plants were exposed to a constant illuminance of 155 μmol∙m−2∙s−1 with chromatic levels ranging from 2250 to 6000 K. Black Charcoal demonstrated substantial improvements under different chromatic parameters, with fruit weight and size increasing by 40% and 14%, respectively. Furthermore, soluble solids content increased by 4% and vitamin C content rose by 142%, while organic acid content decreased by 30%. Dongkui, however, showed more modest responses under identical conditions, with fruit weight increasing by 2% and fruit size decreasing by 1%. Soluble solids and vitamin C contents showed minimal increases of 2% and 2.5%, respectively, while organic acid content decreased by 8%. The findings demonstrate that supplemental LED lighting significantly enhances both yield and quality parameters in Black Charcoal compared with Dongkui. These results provide valuable insights for optimizing Chinese bayberry cultivation, and the precise control methodology developed can be used to improve supplemental lighting strategies in other fruit and plant species.Keywords

Chinese bayberry (Myrica rubra) represents a distinctive subtropical fruit in China, highly valued by consumers for its characteristic balance of moderate sweetness and sourness, which creates a uniquely appealing flavor profile [1]. The Chinese bayberry tree exhibits extended economic viability and contributes to nitrogen fixation, establishing its reputation as both “green enterprise” and “money tree” [2]. However, the fruit’s maturation period coincides with the plum rain season, characterized by elevated humidity and substantial rainfall. This climatic convergence increases the fruit’s water content during the development and maturity stages, subsequently reducing sugar content and firmness, thereby diminishing overall fruit quality [3]. Addressing this challenge necessitates transitioning from traditional natural cultivation environments to artificially controlled greenhouse settings. This adaptation has demonstrated advantages in enhancing sugar accumulation and improving fruit firmness [4]. While greenhouse cultivation techniques have successfully increased bayberry yield and reduced fruit ripening duration, achieving significant economic efficiency [4,5], a notable compromise exists: diminished light exposure, particularly during critical color development and maturity stages, results in decreased fruit quality.

Light, a fundamental environmental factor, plays a vital role in both photomorphogenesis and photosynthesis of plants under natural and artificial conditions [6–8]. In addition to providing energy for photosynthesis, light functions as a regulatory signal, influencing plant development, morphology, and metabolism through specific signals associated with different wavelengths [8–11]. Light quality has emerged as a critical factor affecting both plant growth and fruit quality. Research demonstrates that variations in light quality ratios significantly influence the growth and development of blueberries, subsequently affecting fruit quality. Specific red–blue light ratios prove particularly effective in enhancing blueberry nutrient content and improving fruit quality, with ultraviolet light exhibiting a lesser but notable influence [12]. For Impatiens, optimal productivity of high-quality cutting requires a combination of 83% red light and 17% blue light in LED supplemental lighting [13]. However, the effect of light color on bayberry quality in controlled environments remains insufficiently studied. Currently, studies addressing the effects of supplemental lighting on bayberry are limited. Related studies have focused on rain shelter equipment, which enhances both quality and economic value of bayberry [1,14,15]. Various colored film covers have contributed significantly to understanding the effect of light quality on bayberry fruit characteristics. Treatments using different color fruit bags influence fruit quality, the red bags are conducive to the accumulation of anthocyanins and soluble sugars, while the blue bags perform the worst [16]. Furthermore, light quality under colored rainproof films significantly affects bayberry fruit development and quality. Yellow film exposure resulted in notable increases of 12.05% and 12.21% in soluble sugar and anthocyanin contents, respectively [17]. Recent studies examining supplemental light in controlled environments for bayberry, utilizing various mixed red–blue light ratios through light-emitting diodes (LEDs) and fluorescent lamps, have consistently demonstrated positive effects. Research has explored supplemental light treatments with correlated color temperatures (CCTs) of 3329 and 1531 K for their effect on bayberry flower buds. Studies examining red–blue light ratio (9:1) and (4:1) laser supplemental lighting treatments reveal superior overall fruit quality under the 9:1 red–blue light ratio [18]. Research also indicates that 8 h supplemental lighting in greenhouses optimally promotes the vegetative growth and fruit quality of Chinese bayberry [19]. In addition, blue light significantly affects sugar and cryptochrome gene expression in post-harvest bayberry while inducing anthocyanin accumulation and associated gene expression [20,21]. Meanwhile, the researchers also examined the impact of light intensity on the growth of bayberries. High temperature and intense light exposure negatively affect the photosynthetic capacity of two bayberry cultivars, ‘Dongkui’ and ‘Tanmei’ [22]. Additionally, varying treatment methods for light-transmitting bags influence both fruit quality and anthocyanin synthesis in Chinese bayberries [23]. The effect of different shading conditions on bayberry plants was also explored, revealing that 50% shading can significantly enhance growth and biomass [24].

While previous research has investigated enhancement of Chinese bayberry flower bud development and fruit quality through color film coverings and supplemental lighting, the selection of colored lights has generally been restricted to basic categories such as “red” and “white”. These broad classifications lack precise definitions within color and optics sciences, potentially compromising repeatability and stability in fruit quality and production in greenhouse environments using supplemental lighting. To address this limitation, this study introduces a digital color-coding method (DCCM) for precise management of chromatic parameters in supplemental light, specifically focusing on chromaticity coordinates or CCTs [25–27]. Precise control of supplemental lighting CCTs not only enhances Chinese bayberry yield and quality but also enables precise lighting adjustments based on plant growth stages and species characteristics, facilitating lighting plan modification and optimal environmental conditions. This study systematically evaluates the effects of these chromatic parameters on bayberry fruit quality. The implementation of DCCM, combined with a comprehensive understanding of the influence of chromatic factors on Chinese bayberry fruit quality, presents significant potential for widespread adoption in greenhouses. This methodology can transform artificial cultivation and mass production, ensuring consistent, high-quality bayberry yield across diverse markets.

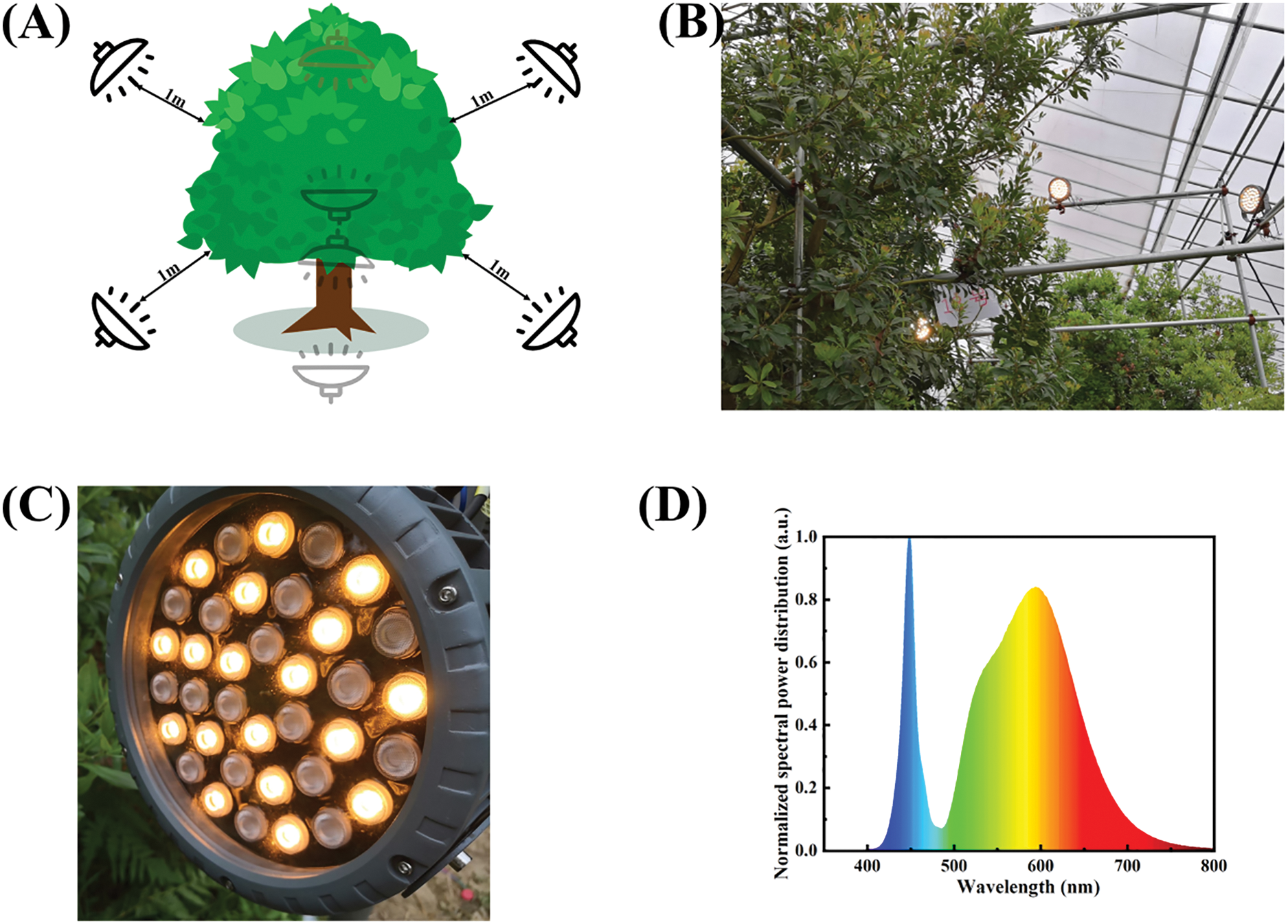

The experiment was performed in a greenhouse at Jiande Fruit and Vegetable Paradise, Old Eagle Rock Fruit Forest (29.4747° N, 119.2812° E) in Zhejiang Province, China, from May to mid-June 2023. The investigation examined two varieties of Chinese bayberry, “Black Charcoal” and “Dongkui”. The supplemental lighting arrangement is illustrated in Fig. 1A. Four supplemental lights were installed at the top of the Chinese bayberry tree, emitting light downward. The distance between the lights and tree was maintained at 1 m, with light intensity set at 155 μmol∙m−2∙s−1. Concurrently, four additional lights were positioned in the middle and lower sections of the tree, projecting light upward, with identical parameters to the top lights. This setup comprised eight supplemental lights, constituting a single illumination group. The practical arrangement of the lights is shown in Fig. 1B. Supplemental lighting utilized LED luminaires supplied by Zhejiang Light Cone Technology Co., Ltd. (Hangzhou, China). Each luminaire contained 18 “warm” white LED chips and 18 “cold” white LED chips. The terms “warm” and “cold” are conventionally used to describe light with high and low CCTs, respectively. Single-color LED chips were connected in series, while two-color LEDs were connected in parallel and operated independently. The normalized spectral power distribution and physical representation of the supplemental luminaire are shown in Fig. 1C,D.

Figure 1: Experimental conditions and materials. (A) Schematic diagram of the supplemental lighting installation for Chinese bayberry. (B) Distribution of Chinese bayberry supplemental lights. (C) A supplemental luminaire. (D) Normalized spectral power distribution of supplemental lighting

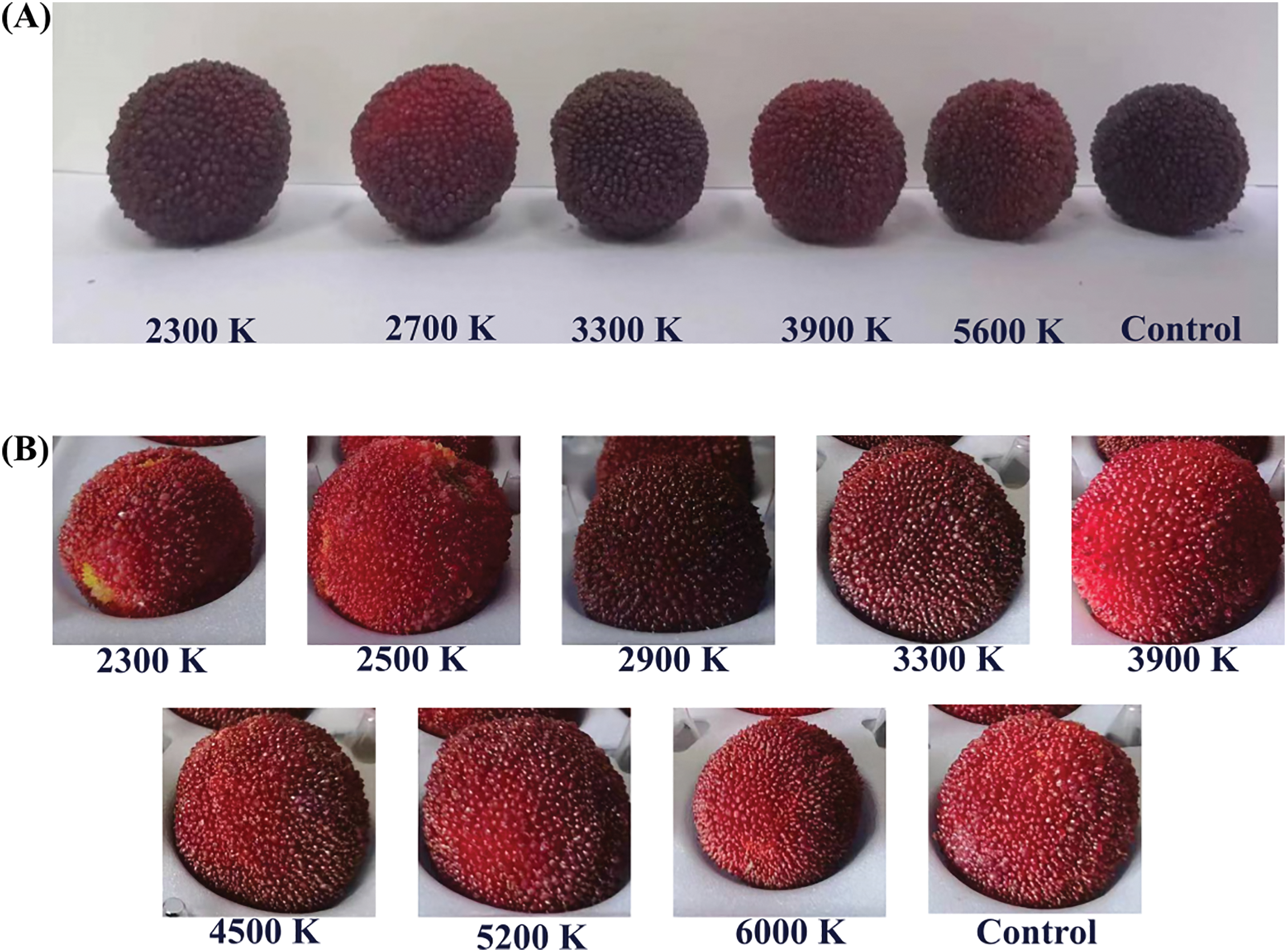

This study examines the effects of supplemental lighting on Black Charcoal and Dongkui bayberry varieties. Fig. 2 presents photographs of ripe Black Charcoal and Dongkui under various CCT conditions. Black Charcoal exhibited a decrease in size as CCT of the supplemental lighting increased, although the treated specimens remained larger than the reference (control) (Fig. 2A). No such distinct pattern of size variation was observable for Dongkui under various CCT conditions (Fig. 2B). Additional size analysis of Chinese bayberry is necessary to establish more definitive conclusions.

Figure 2: Experimental conditions and materials. (A) Photographs of Black Charcoal bayberry. (B) Photographs of Dongkui bayberry

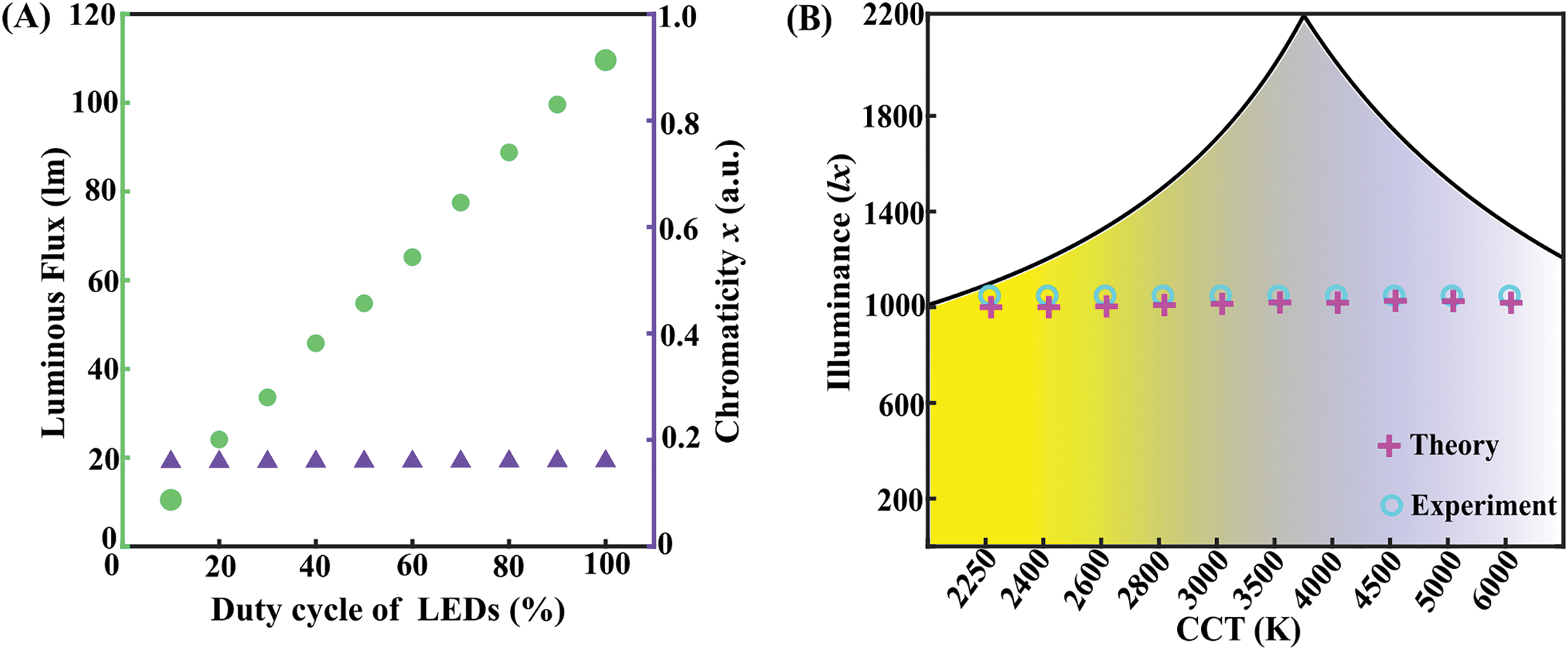

This study implements DCCM, a precise color mixing algorithm that enables accurate control of light chromaticity and luminosity within the Commission Internationale de l’Éclairage (CIE) color spaces [25–27]. The system utilizes pulse modulation signals to control “cold” and “warm” white LEDs. The algorithm maps generated pulses with specific duty cycles to corresponding mixed light color components, allowing independent adjustment of chromaticity and luminosity. The DCCM dimming principle shows constant chromaticity with linear luminosity increase relative to single-color LED duty cycles (Fig. 3A). Fig. 3B demonstrates the precise control of chromaticity (CCT) and luminosity (illuminance) through DCCM’s biprimary color mixing technique. The supplemental luminaire tested incorporates “warm” and “cold” white LEDs. During testing, the supplemental luminaire is maintained at 155 μmol∙m−2∙s−1 illuminance while CCT is varied from 2250 to 6000 K in set increments. The gradient region indicates the accessible space, representing the gamut achievable with DCCM [25–27]. The experimental results (turquoise circles) demonstrate strong alignment with theoretical predictions (plum crosses), confirming the effectiveness and precision of the DCCM approach.

Figure 3: The working principle and experimental demonstrations of precise color control of supplemental light using DCCM. (A) Chromaticity x (purple triangles) and luminous flux (cyan dots) vary with the duty cycle of single-color light-emitting diodes (LEDs). (B) Theoretical (plum crosses) and experimental (turquoise circles) illuminance and correlated color temperatures (CCTs) of biprimary color-mixed LEDs mapped in a 2D accessible space (gradient region)

The experiment maintained uniform CCTs using eight luminaires for light requirements of the experimental bayberry trees. For Black Charcoal bayberry trees, five CCT variations were tested: 2300, 2700, 3300, 3900, and 5600 K. Dongkui bayberry trees were subjected to eight CCTs: 2300, 2500, 2900, 3300, 3900, 4500, 5200, and 6000 K. The light intensity of all supplemental lights remained constant at 155 μmol∙m−2∙s−1. Two reference bayberry trees (controls) were selected from the same greenhouse and positioned at an adequate distance from the experimental trees to prevent interference from artificial light. Standard cultivation practices, including watering, topdressing, and plant management, were applied consistently to both control and experimental bayberry plants. All plants received natural sunlight exposure. The experimental bayberry plants received additional 4 h periods of programmed supplemental lighting before sunrise (3:00 a.m. to 7:00 a.m.) and after sunset (6:00 p.m. to 10:00 p.m.). This lighting schedule continued from the fruitlet stage to the picking season. During cloudy, rainy, or snowy conditions, the luminaires were activated manually from 7:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. to compensate for reduced natural light. Both automated and manual operations maintained optimal growing conditions throughout the growth and ripening period. Chinese bayberry fruits from experimental and control plants were harvested, and parameters including individual weight, horizontal diameter, longitudinal diameter, soluble solids content, organic acid content, and vitamin C content were measured.

The parameters were measured after 40 days of supplemental light exposure, corresponding to the bayberry harvest stage. Individual weight (g) was determined using an electronic balance (accuracy: 0.1 g), measuring ten randomly selected bayberries per group. Horizontal and longitudinal diameters were measured using a vernier caliper (accuracy: 0.1 mm), with three measurements per bayberry. Soluble solids content (%) was assessed using a digital sugar meter. Organic acid was evaluated by NaOH titration [28]. Bayberry juice (1 g), extracted through grinding, was dissolved in 20 mL of pure water and titrated with 0.1 mol∙L−1 NaOH until reaching pH 8.2. The results were expressed as millimoles (mmol) of citric acid per 100 g of juice, with ten bayberries tested per group. Vitamin C content was determined using the ammonium molybdate colorimetric method [29]. Ground bayberry pulp (2 g) was diluted to 10 mL with oxalic acid solution. Following reagent addition, 4 mL of ammonium molybdate solution was incorporated, mixed thoroughly, and left to stand for 15 min. The sample’s colorimetric value was then measured at the specified wavelength.

Microsoft Office LTSC Professional Plus 2021, IBM SPSS Statistics 29, and MATLAB R2022b were used for data processing, analysis, and graphing. Significant differences between treatments were determined based on the Least Significant Distance (LSD) method (p < 0.05) for multiple comparisons.

3.1 Chromatic Effect of Supplemental Light on the Individual Weight of Chinese Bayberry

The weight of bayberry significantly influences its economic value and overall fruit yield. Fig. 4 demonstrates the correlation between individual weight and CCTs of supplemental light. The individual weight of Black Charcoal was consistently higher in the experimental groups than in the control group (Fig. 4A). Particularly, at CCTs below 3300 K, bayberries attained their peak individual weight of 15 g. The mean individual fruit weight of Black Charcoal cultivated under supplemental lighting exceeded that of the control group by 40%. Exposure to varying CCTs of supplemental light (in the range of 2300 K and between 5200 and 6000 K) typically decreased the individual weight of Dongkui in the experimental groups compared with the control group (Fig. 4B). Nevertheless, under certain CCTs, the individual weight of Dongkui in the experimental groups either exceeded or remained comparable to the control group. The maximum individual weight was observed at CCT 2500 K, reaching 30.17 ± 3.42 g. The overall growth rate in Dongkui was only 2%, substantially lower than that of Black Charcoal.

Figure 4: Influence of supplemental luminaire CCT on the individual weight of Black Charcoal and Dongkui bayberry varieties. (A) Individual weight of Black Charcoal measured as a function of CCT. (B) Individual weight of Dongkui measured as a function of CCT

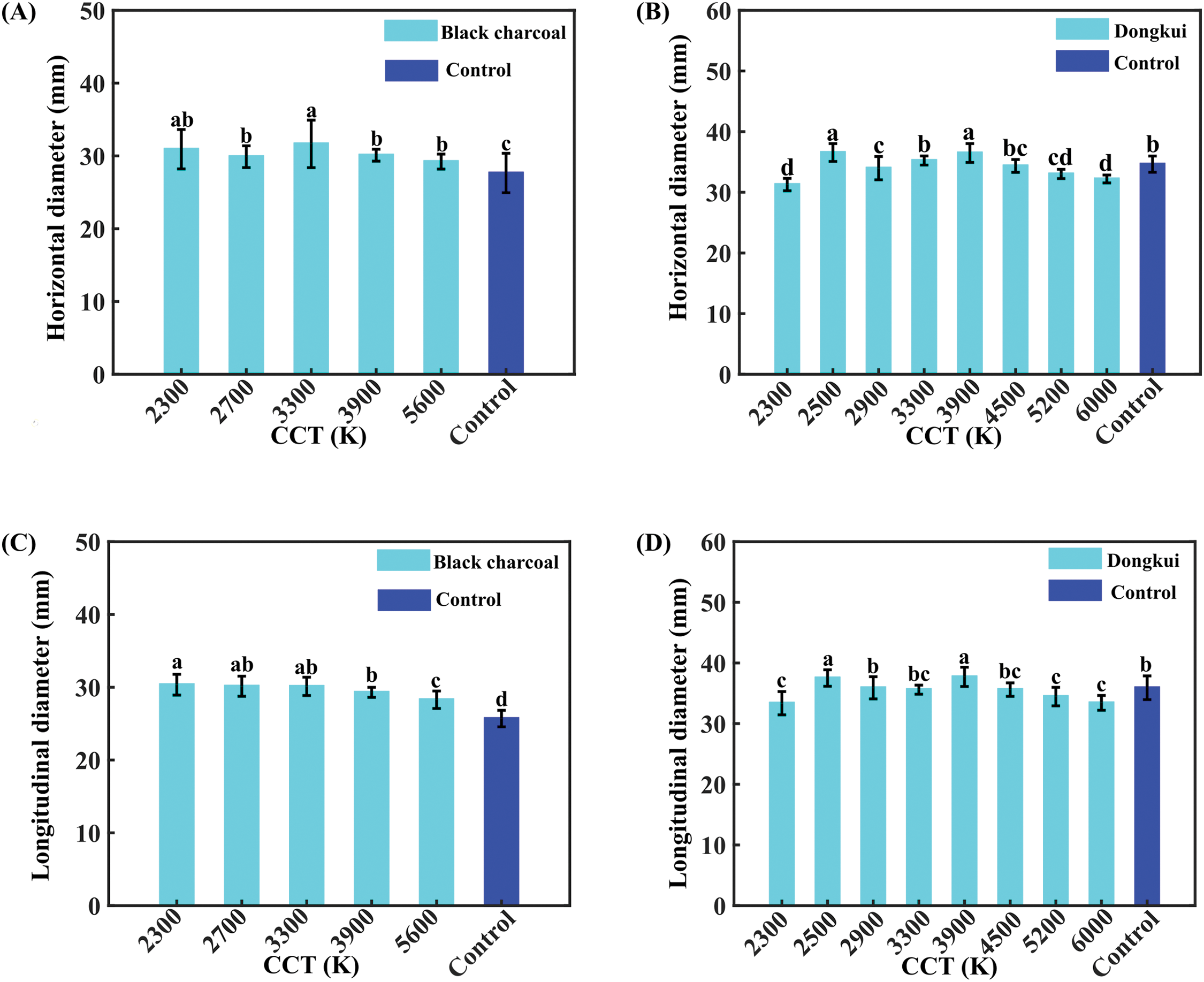

3.2 Chromatic Effect of Supplemental Light on the Fruit Size of Chinese Bayberry

The size of bayberry serves as a critical factor in determining economic value (Fig. 5). The horizontal and longitudinal diameters of Black Charcoal exceeded those of the control group, demonstrating increases of 12% and 15%, respectively, relative to the control (Fig. 5A,C). The aggregate fruit size increase amounted to 14%. Regarding horizontal diameter, bayberries reached their maximum size of 31.65 ± 3.27 mm at CCT 3300 K, while other CCTs exhibited marginally lower effects. However, the chromatic effect, characterized by varying CCTs, showed no significant effect on the longitudinal diameter of Black Charcoal, maintaining consistent fruit size. A distinct oscillating pattern was observed in both horizontal and longitudinal diameters of Dongkui (Fig. 5B,D). Peak sizes occurred at CCTs of 2500 and 3900 K, with horizontal and longitudinal diameters of 36.56 ± 1.48 mm and 37.71 ± 1.59 mm, respectively. Other dimensions remained either similar to the reference diameter or slightly below it. The overall fruit size decreased by 1%.

Figure 5: Influence of supplemental luminaire CCT on the horizontal and longitudinal diameters of Black Charcoal and Dongkui bayberry varieties. (A) Horizontal diameter of Black Charcoal measured as a function of CCT. (B) Horizontal diameter of Dongkui measured as a function of CCT. (C) Longitudinal diameter of Black Charcoal measured as a function of CCT. (D) Longitudinal diameter of Dongkui measured as a function of CCT

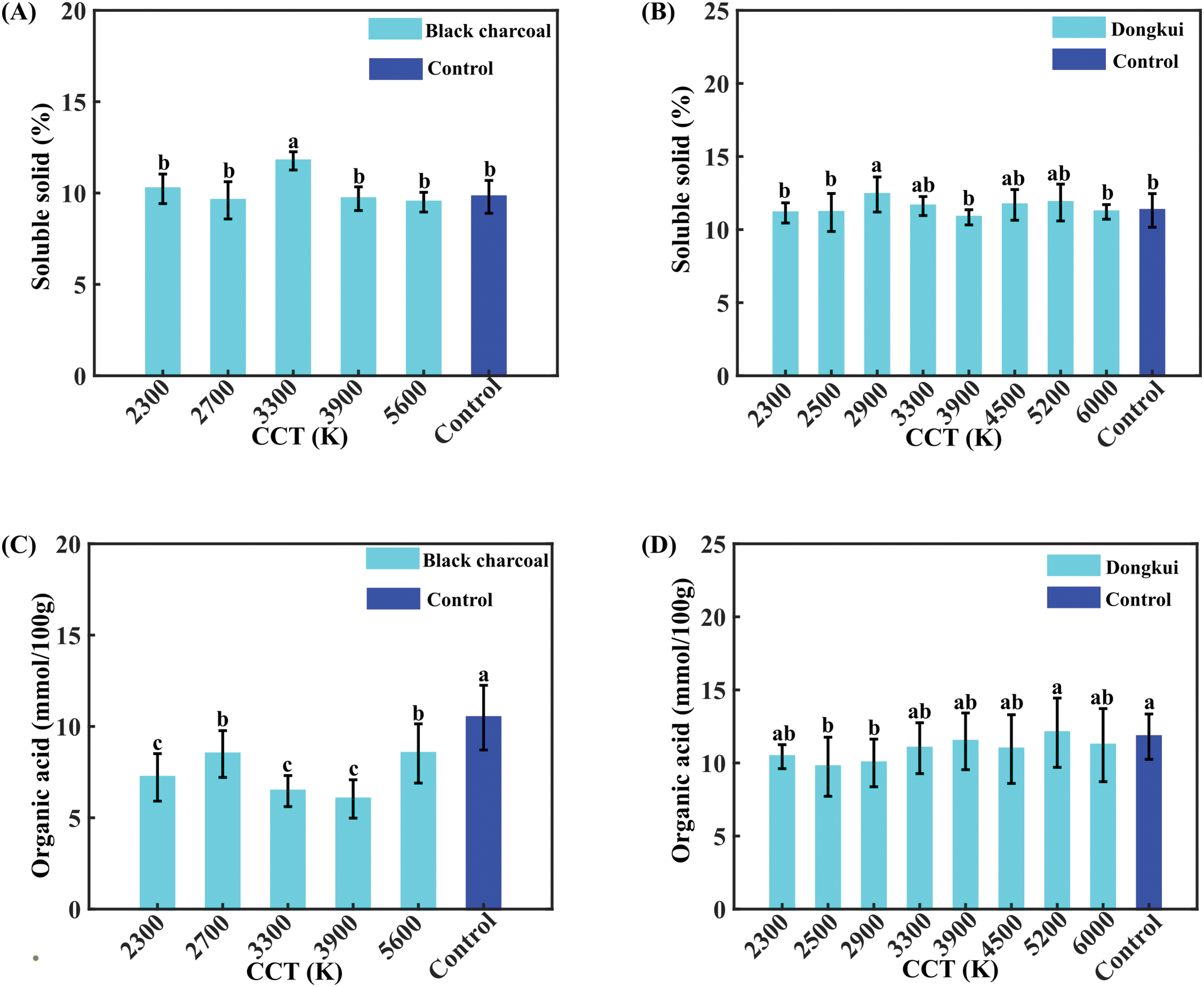

3.3 Chromatic Effect of Supplemental Light on the Soluble Solids and Organic Acid Contents of Chinese Bayberry

Soluble solids and organic acids are essential factors determining the flavor and tartness of bayberry, respectively. The soluble solids content of Black Charcoal in the experimental groups exceeded or remained comparable to that in the control group, demonstrating an overall increase of 4% (Fig. 6A). It reached its maximum in Black Charcoal at CCT 3300 K, maintaining a value of 11.8%. The organic acid content of Black Charcoal was lower in the experimental groups than in the control group, exhibiting a decrease of 30% (Fig. 6C). The organic acid content was lowest at CCTs of 3300 and 3900 K, remaining at 6.2 mmol∙100 g−1. An increased solid–acid ratio enhances the taste and flavor of bayberry. The soluble solids content of Dongkui in the experimental groups exceeded or remained consistent with that in the control group, showing a 1.5% increase (Fig. 6B,D). The maximum soluble solids content, 12.4%, occurred at CCT 2900 K. The organic acid content was lower in the experimental groups compared with the control group, with the lowest value recorded at 10 ± 1.63 mmol∙100 g−1 at CCT 2900 K (Fig. 6D). A high solid–acid ratio (a concurrent increase in soluble solids content and decrease in organic acid content) substantially improves the taste and flavor of bayberry.

Figure 6: Influence of supplemental luminaire CCT on soluble solids and organic acid contents of Black Charcoal and Dongkui bayberry varieties. (A) Soluble solids content of Black Charcoal measured as a function of CCT. (B) Soluble solids content of Dongkui measured as a function of CCT. (C) Organic acid content of Black Charcoal measured as a function of CCT. (D) Organic acid content of Dongkui measured as a function of CCT

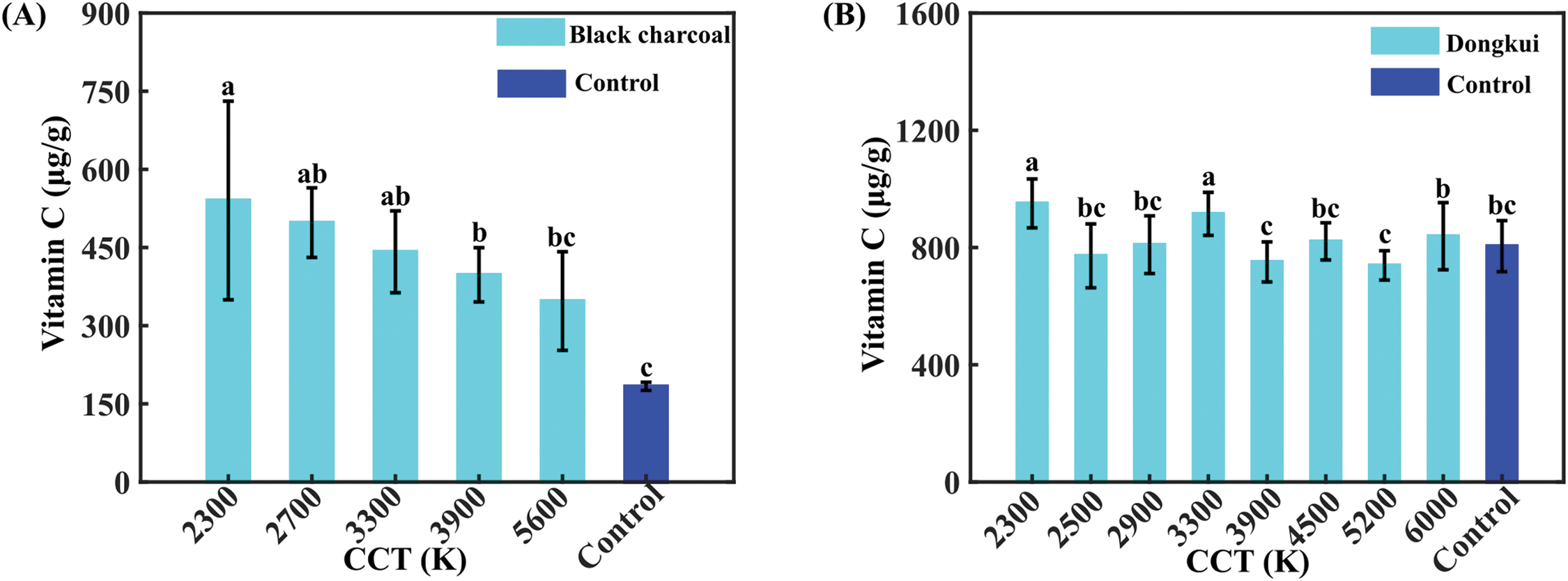

3.4 Chromatic Effect of Supplemental Light on the Vitamin C Content of Chinese Bayberry

Vitamin C serves as a critical parameter in determining fruit quality, significantly enhancing its nutritional value. The vitamin C content of Black Charcoal in the experimental groups substantially exceeded that in the control group, showing an increase of 142% (Fig. 7A). The effect of chromatic variations on vitamin C content was significant, with maximum levels reaching 540 μg∙g−1 at CCT 2300 K. However, the pattern observed in Dongkui was distinct from Black Charcoal. Vitamin C content serves as an essential metric for assessing bayberry nutritional value (Fig. 7B). The experimental groups displayed mixed results, with 50% of vitamin C content exceeding control values and 50% falling below, demonstrating a more nuanced effect of supplemental light on this nutrient, yielding a modest 2% overall increase.

Figure 7: Influence of supplemental luminaire CCT on vitamin C content of Black Charcoal and Dongkui bayberry varieties. (A) Vitamin C content of Black Charcoal measured as a function of CCT. (B) Vitamin C content of Dongkui measured as a function of CCT

In summary, supplemental lighting with precisely controlled CCTs had a more pronounced effect on Black Charcoal compared with Dongkui. This differential response may be attributed to Dongkui’s nature as an improved variety, exhibiting reduced light requirements relative to Black Charcoal. Black Charcoal, being a traditional variety, demonstrated higher light requirements.

Light quality consistently influences plant growth and development. The spectral composition of light plays a crucial role in regulating phytohormone levels through specific pigments, subsequently affecting growth, development, and yield parameters [11].

Under supplemental lighting conditions, the average individual weight of bayberry either surpassed or matched the control group. The individual weight of Black Charcoal under supplemental lighting exceeded the control group by approximately 40% (Fig. 4A). Conversely, the individual weight of Dongkui in the experimental groups remained consistent with the control group (Fig. 4B). The optimal chromatic effect for Black Charcoal occurred at 2300 K, while Dongkui responded optimally at 2500 K. Previous research indicated that laser supplemental lighting significantly enhanced individual weight of Chinese bayberry. During the color transition phase, laser supplemental lighting with a 9:1 red–blue light ratio increased Dongkui individual weight by 19.19% compared with the control group. However, during red color transition and ripening stages, neither 9:1 nor 4:1 red–blue light ratio increased individual fruit weight [18]. These findings demonstrate the significant influence of light quality on bayberry growth and fruit development.

The horizontal and longitudinal diameters of Black Charcoal and Dongkui bayberry varieties under supplemental lighting exhibited notable variations compared with naturally grown specimens. Black Charcoal displayed significantly larger horizontal and longitudinal diameters, exceeding the control group by 12% and 15%, respectively (Fig. 5A,C). The optimal supplemental light quality for Black Charcoal corresponded to CCT 3300 K. In contrast, Dongkui in the experimental groups that maintained diameters similar to the control group, with optimal supplemental light being CCT 3900 K for both diameter measurements (Fig. 5B,D). Under laser supplemental lighting with a 9:1 red–blue light ratio, Dongkui exhibited increases of 9.22% and 2.99% in longitudinal and horizontal diameters, respectively, during color transition. However, neither 9:1 nor 4:1 red–blue light ratio produced significant diameter changes during red color transition and maturity stages [18].

The soluble solids content of bayberry exhibited significant improvements with supplemental lighting across experimental groups. For Black Charcoal, it increased by 20% in the experimental groups compared with the control group under supplemental lighting with CCT 3300 K (Fig. 6A). For Dongkui, it was 9.6% higher in the experimental groups than in the control group at CCT 2900 K (Fig. 6B). These findings align with previous studies, including research involving red bags, which demonstrated significant increases in soluble sugars content of Chinese bayberry. Conversely, while blue bagging treatment negatively regulated the soluble sugars content [16]. Under laser lamp illumination during the whitening stage of Dongkui, the total sugar content remained unchanged regardless of whether the red–blue light ratio was 9:1 or 4:1. However, during the reddening stage, the total sugar content increased significantly by 29.97% with a 9:1 red–blue light ratio. In the fruit ripening stage, the increase in total sugar content was more substantial with a 4:1 red–blue light ratio [18]. Blue light treatment enhanced the total sugar content during Chinese bayberry storage [20].

Supplemental lighting demonstrated a significant effect on organic acid concentration in bayberry. Compared with the control group, Black Charcoal in the experimental groups generally exhibited lower organic acid content. Statistical analysis revealed significantly lower organic acid content of Black Charcoal, with minimal concentration observed at CCT 3300 K (Fig. 6C). Dongkui in the experimental groups displayed organic acid content either lower than or comparable to the control group, depending on conditions (Fig. 6D). Research indicates that colored rainproof significantly affected organic acid concentration in bayberry. Specifically, colored rainproof films, particularly yellow, significantly decreased organic acid content of Dongkui during late maturity [17]. During the whitening stage, laser supplemental light showed no significant effect on total acid content. However, during reddening, laser light with a 4:1 red–blue light ratio reduced the total acid content by 9.59%. The effect intensified during ripening with a 9:1 red–blue light ratio, decreasing the total acid content by 34.35% [18].

Supplemental light demonstrated a positive effect on the vitamin C content of both bayberry varieties at specific CCTs. Vitamin C content of Black Charcoal in the experimental groups was notably higher than that in the control group, reaching peak concentrations at CCT 2300 K (Fig. 7A). Similarly, Dongkui exhibited elevated vitamin C levels under supplemental light compared with the control group. Vitamin C content of Dongkui was 2.5% higher in the experimental groups than in the control group, with optimal results at CCT 2300 K (Fig. 7B). During the reddening stage of Dongkui, laser supplemental light with a 9:1 red–blue light ratio decreased vitamin C content by 3.77%, while a 4:1 ratio increased it by 61.64%. However, during the ripening period, vitamin C content significantly decreased, particularly with a 4:1 red–blue light ratio, declining by 31.58% [18].

This investigation examined the influence of supplemental light on the fruit quality of Black Charcoal and Dongkui bayberry varieties cultivated in artificially controlled greenhouses, emphasizing chromatic effects. The supplemental lighting utilized two-color white LEDs with adjustable color parameters, and DCCM facilitated precise management of CCTs. This methodology enabled a comprehensive analysis of how supplemental light affects the critical fruit quality parameters (individual weight, horizontal diameter, longitudinal diameter, soluble solids content, organic acid content, and vitamin C content) of both bayberry varieties. The findings reveal that supplemental light produced a substantial increase in the individual weight of Black Charcoal in the experimental groups, showing an increase exceeding 40% compared with the control group. The optimal individual weight occurred at CCT 2300 K. However, Dongkui demonstrated no significant variation in individual weight. Regarding dimensions, Black Charcoal in the experimental groups showed increases in both horizontal and longitudinal diameters, with 12% and 15% improvements, respectively. The maximum diameters were observed at CCT 3300 K for both measurements. Conversely, Dongkui in the experimental groups exhibited no significant diameter difference from the control group, with optimal CCT for diameter growth at 3900 K. For Black Charcoal, the solid–acid ratio in the experimental groups reached its optimum at CCT 3300 K, doubling the control value. In Dongkui, the solid–acid ratio in the experimental groups maximized at CCT 2900 K, measuring 1.3 times higher than the control. Vitamin C content, crucial for nutritional value, was 2.4 times higher for Black Charcoal in the experimental groups than in the control group, with optimal CCT at 2300 K, displaying a 2.9-fold increase. The vitamin C content of Dongkui was 2.5% higher in the experimental groups than in the control group, with optimal CCT at 2300 K, 1.2 times above the control. This research establishes that light spectral composition, determined by different CCTs, significantly influences the nutritional and physical qualities of both Black Charcoal and Dongkui bayberry varieties. These findings provide valuable insights for optimizing growing conditions to enhance specific nutritional attributes, enabling customized bayberry cultivation for diverse consumer preferences and dietary requirements.

Acknowledgement: The authors thank Zhejiang Light Cone Technology Co., Ltd. for the technical support during luminaire installation and express their gratitude to Zhilin Jiang for providing experimental fields.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Doctor Foundation of Southwest University of Science and Technology, grant number: 24zx7116.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Ni Tang; methodology, Ni Tang and Chenchun Hao; software, Ni Tang; validation, Ni Tang; formal analysis, Ni Tang and Chenchun Hao; investigation, Ni Tang and Chenchun Hao; resources, Rong Qiu; data curation, Ni Tang; writing—original draft preparation, Ni Tang and Chenchun Hao; writing—review and editing, Ni Tang, Chenchun Hao and Rong Qiu; visualization, Ni Tang, Chenchun Hao and Rong Qiu; supervision, Ni Tang, Chenchun Hao and Rong Qiu; project administration, Ni Tang, Chenchun Hao and Rong Qiu; funding acquisition, Ni Tang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wu D, Cheng H, Chen J, Ye X, Liu Y. Characteristics changes of Chinese bayberry (Myrica rubra) during different growth stages. J Food Sci Technol. 2019;56(2):654–62. doi:10.1007/s13197-018-3520-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Zhang S, Yu Z, Sun L, Ren H, Zheng X, Liang S, et al. An overview of the nutritional value, health properties, and future challenges of Chinese bayberry. PeerJ. 2022;10:e13070. doi:10.7717/peerj.13070. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Shah IH, Manzoor MA, Wu J, Li X, Hameed MK, Rehaman A, et al. Comprehensive review: effects of climate change and greenhouse gases emission relevance to environmental stress on horticultural crops and management. J Environ Manage. 2024;351:119978. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.119978. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Wu BP, Zhang C, Gao YB, Zheng WW, Xu K. Changes in sugar accumulation and related enzyme activities of red bayberry (Myrica rubra) in greenhouse cultivation. Horticulturae. 2021;7(11):429. doi:10.3390/horticulturae7110429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Sun L, Zhang SW, Yu ZP, Zheng XL, Qi XJ. Research progress on the protected cultivation and intelligent management technology of Myrica rubra. J Zhejiang Agric Sci. 2024;65(9):2119–24. (In Chinese). doi:10.16178/j.issn.0528-9017.20240527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Avercheva OV, Berkovich YA, Erokhin AN, Zhigalova TV, Pogosyan SI, Smolyanina SO. Growth and photosynthesis of Chinese cabbage plants grown under light-emitting diode-based light source. Russ J Plant Physiol. 2009;56(1):14–21. doi:10.1134/s1021443709010038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Nascimento LBS, Leal-Costa MV, Coutinho MAS, dos S Moreira N, Lage CLS, dos S.Barbi N, et al. Increased antioxidant activity and changes in phenolic profile of Kalanchoe pinnata (Lamarck) Persoon (Crassulaceae) specimens grown under supplemental blue light. Photochem Photobiol. 2013;89(2):391–9. doi:10.1111/php.12006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Rehman M, Ullah S, Bao Y, Wang B, Peng D, Liu L. Light-emitting diodes: whether an efficient source of light for indoor plants? Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2017;24(32):24743–52. doi:10.1007/s11356-017-0333-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Samuolienė G, Sirtautas R, Brazaitytė A, Duchovskis P. LED lighting and seasonality effects antioxidant properties of baby leaf lettuce. Food Chem. 2012;134(3):1494–9. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.03.061. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Xu F, Cao S, Shi L, Chen W, Su X, Yang Z. Blue light irradiation affects anthocyanin content and enzyme activities involved in postharvest strawberry fruit. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62(20):4778–83. doi:10.1021/jf501120u. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Loi M, Villani A, Paciolla F, Mulè G, Paciolla C. Challenges and opportunities of light-emitting diode (LED) as key to modulate antioxidant compounds in plants: a review. Antioxidants. 2020;10(1):42. doi:10.3390/antiox10010042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Wang JQ, He YY, Wei XT, Li YQ, Yang L, Chen WR, et al. Effects of LED supplemental light on the growth and development of blueberry in greenhouse. Acta Hortic Sin. 2020;47(6):1183–93. (In Chinese). doi:10.16420/j.issn.0513-353x.2019-0707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Kobori MMRG, da Costa Mello S, de Freitas IS, Silveira FF, Alves MC, Azevedo RA. Supplemental light with different blue and red ratios in the physiology, yield and quality of Impatiens. Sci Hortic. 2022;306:111424. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2022.111424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Yun HY, Kim H, Han SH, Yim EY. Light-shading effect on the growth performance, leaf morphological char-acteristics and chlorophyll content of Myrica rubra Seedlings. Korean J Plant Resour. 2024;37(5):547–54. [Google Scholar]

15. Chai CY, Zhou HF, Xu SQ, Fang CL, Xie GQ, Huang SW. Effect of different rainproof cultivation methods on fruit quantity of Myrica rubra in Zhejiang. J Zhejiang For Sci Technol. 2010;30(4):83–5. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

16. Li X, Li S, Yu Z, Zhang Y, Yang H, Wu Y, et al. Influence of color bagging on anthocyanin and sugar in bayberry fruit. Sci Hortic. 2025;345:114141. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2025.114141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Qi X, Zheng X, Li X, Zhang S, Ren H, Yu Z. Influence of different light quality formed by colored rainproof-films on Bayberry fruit quality during ripening. Acta Hortic Sin. 2021;48(9):1794–804. doi:10.16420/j.issn.0513-353x.2020-0835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Liang SM, Qi XJ, Yu ZP, Sun L, Xie JC, Zhang SW. Effects of laser supplementary lighting on the fruit development and quality formation of bayberry (Myrica rubra). Fruits South China. 2024;53(6):163–8. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

19. Lin XR, Zhu JX, Chen CF, Sun P, Wang J, Shen JS. Effects of different light exposure durations on the growth and fruit quality of facility-grown bayberry (Myrica rubra). Mod Agric Sci Technol. 2024;24:41–4. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

20. Shi L, Cao S, Shao J, Chen W, Yang Z, Zheng Y. Chinese bayberry fruit treated with blue light after harvest exhibit enhanced sugar production and expression of cryptochrome genes. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2016;111:197–204. doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2015.08.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Shi L, Cao S, Chen W, Yang Z. Blue light induced anthocyanin accumulation and expression of associated genes in Chinese bayberry fruit. Sci Hortic. 2014;179:98–102. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2014.09.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Gao YB, Zheng WW, Zhang C, Zhang LL, Xu K. High temperature and high light intensity induced photoinhibition of bayberry (Myrica rubra Sieb. et Zucc.) by disruption of D1 turnover in photosystem II. Sci Hortic. 2019;248:132–7. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2019.01.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Yang H, Sun L, Qi Y, Li Z, Lei K, Cheng F, et al. Integrated transcriptomic and metabolomic analysis reveals light-induced modulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in Chinese bayberry (Myrica rubra). Fruit Res. 2025;5(1):e015. doi:10.48130/frures-0025-0004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zeng G, Guo Y, Xu J, Hu M, Zheng J, Wu Z. Partial shade optimizes photosynthesis and growth in bayberry (Myrica rubra) trees. Hortic Environ Biotechnol. 2017;58(3):203–11. doi:10.1007/s13580-017-0003-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Tang N, Zhang L, Zhou J, Yu J, Chen B, Peng Y, et al. Nonlinear color space coded by additive digital pulses. Optica. 2021;8(7):977. doi:10.1364/optica.422287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Wang J, Mou T, Wang J, Tian X. A quantitative dimming method for LED based on PWM. In: Twelfth International Conference on Solid State Lighting and Fourth International Conference on White LEDs and Solid State Lighting; 2012 Aug 12–16; San Diego, CA, USA. doi:10.1117/12.970576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Tang N, Wang J, Zhang B, Chen H, Qiu M. Chromatic effects of supplemental light on the fruit quality of strawberries. Horticulturae. 2023;9(12):1333. doi:10.3390/horticulturae9121333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Maslov OY, Kolisnyk SV, Kostina TA, Shovkova ZV, Ahmedov EY, Komisarenko MA. Validation of the alkalimetry method for the quantitative determination of free organic acids in raspberry leaves. J Org Pharm Chem. 2021;19(73):53–8. doi:10.24959/ophcj.21.226278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Spínola V, Llorent-Martínez EJ, Castilho PC. Determination of vitamin C in foods: current state of method validation. J Chromatogr A. 2014;1369:2–17. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2014.09.087. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools