Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Citric Acid Optimizes Lead (Pb) Phytoextraction in Mung Bean (Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek) by Regulating Nutrient Uptake and Photosynthesis

1 Department of Botany, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, 38040, Pakistan

2 Institute of Botany, Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, 60800, Pakistan

3 Department of Botany, Govt. Sadiq College Women University, Bahawalpur, 53100, Pakistan

4 Department of Plant Production, College of Food and Agriculture Sciences, King Saud University, P.O. Box 2460, Riyadh, 11451, Saudi Arabia

5 College of Pastoral Agriculture Science and Technology, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, 730020, China

6 Department of Plant Science, McGill University, Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, Montreal, QC H9X 3V9, Canada

7 Department of Field Crops, Faculty of Agriculture, Siirt University, Siirt, 56100, Türkiye

* Corresponding Authors: Hafiza Saima Gul. Email: ; Ayman El Sabagh. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Crop Plants: Physio-biochemical and Molecular Mechanisms)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(9), 2893-2909. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.058816

Received 22 September 2024; Accepted 06 March 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

The low efficiency of phytoextraction of lead (Pb) from agricultural fields poses a significant agricultural challenge. Organic chelating agents can influence Pb bioavailability in soil, affecting its uptake, transport, and toxicity in plants. This study aimed to assess the impact of citric acid (CA) and diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) on chelate-assisted phytoextraction of Pb and its effect on growth and physiology of two cultivars (07001; 07002) of mung bean (Vigna radiata). The cultivars of mung bean were exposed to 60 mg·L−1 lead chloride (PbCl2) solution, with or without the addition of 300 mg·L−1 CA or 500 mg·L−1 DTPA, until maturity. The exposure of plants to Pb stress increased the accumulation of Pb in roots (49% of control), stems (58% of control), leaves (67% of control), and seeds (61% of control). Maximum accumulation of Pb was observed in roots and the least accumulation was found in seeds of both mung bean cultivars. The extent of Pb accumulation in different plant parts correlated positively with Pb toxicity and reduced growth of both mung bean cultivars (33% to 40%). The cultivar cv 07001 was more susceptible to Pb stress. The addition of CA and DTPA increased the accumulation of Pb in plant parts of mung bean cultivars-phytoextraction (10.8% to 21.5%). However, the addition of CA partitioned Pb in vegetative parts, i.e., root, stem thus mitigated the toxic effects of Pb on the growth of mung bean cultivars (6.25%–10.5%). In contrast, the addition of DTPA had adverse effects on the growth of mung bean cultivars. The addition of CA facilitated a greater uptake and accumulation of nitrogen, phosphorous, and potassium in the roots and leaves of mung bean cultivars. In addition, CA also improved the photosynthetic pigments (11%–14%) and photosynthetic rate (5%–12%) under both control and Pb stress conditions. The ameliorative effect of CA on the photosynthetic capacity of mung bean cultivars was likely associated with photosynthetic metabolic factors rather than stomatal factors. Furthermore, cv 07002 was found to be more tolerant to Pb stress and showed better performance in CA application. Overall, the application of CA demonstrated significant potential as a chelating agent for remediating Pb-contaminated soil.Keywords

The toxic heavy metals, resulting from human activities and industrial processes, are often released or leached into the environment, causing detrimental effects to the ecosystems [1,2]. Among these heavy metals, lead (Pb) is particularly hazardous as it hinders metabolic processes, impedes plant growth, and reduces productivity [1,3,4]. In mungbean and other plant species, Pb toxicity reduces plant height, root-to-shoot ratio, dry weight, number of nodules per plant, and chlorophyll content [5] due to the inhibition of cell division and differentiation [6]. The Pb toxicity disrupts water balance, mineral nutrition, and membrane structure while impeding photosynthetic process and enzyme activity and inhibiting cell division [7–10]. Additionally, Pb presents significant health hazards to both children and adults through the transmission of contaminated food chains [11].

Plants have developed a range of tolerance strategies to Pb stress, including mechanisms for Pb exclusion from the cytosol, reduction of Pb uptake, and the chelating or binding of Pb to various thiol compounds in the cytosol, such as glutathione, phytochelatins, and metallothioneins [2,12]. These compounds are subsequently sequestered into inactive organelles. Plants also detoxify the Pb-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) to mitigate the detrimental effects [2].

Various strategies have been proposed for improving or restoring soil contamination with Pb, including physical, chemical, and biological strategies. Phytoremediation is a biological strategy in which hyperaccumulator plants of heavy metals are used, which is a feasible, and and cost-effectiveness strategy. The effectiveness of phytoremediation is limited by several factors [13,14]. For instance, plant biology restricts the remediation process primarily to the rhizosphere at shallow depths. Moreover, the concentration of heavy metals in the soil should be maintained at non-excessive levels due to their toxicity and limited bioavailability [15]. The exploration of alternative approaches to enhance phytoremediation is necessary due to the limitations of traditional methods. These limitations include long remediation times, variations in soil pH that influence the concentration and bioavailability of metal ions, limited understanding of plant behavior and their potential in phytoremediation, and challenges in managing plant crops [1,2,13,15].

Recent studies highlighted the significance of enhancing phytoremediation efficiency by utilizing chelating agents to improve metal removal across different plant species [2,16]. Chelating agents, such as ethylene diamine disuccinic acid (EDDS), ethylene diamine tetraacetate (EDTA), diethelene tri-amine penta-acetic acid (DTPA) and nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA), promote the uptake of heavy metals in plants by increasing their solubility [17,18]. It is important to carefully regulate the application rate of chelating agents to monitor and mitigate potential environmental risks [19]. Furthermore, the promoting effect of EDTA exhibits selectivity towards certain metal elements [17,18]. For instance, EDTA exhibits high complexation constants with metals such as Cu, Ni, Pb, Zn, and Cd, thereby facilitating the activation of heavy metals in the soil [17]. Similarly, the addition of EDTA in the growth medium increases the concentration of water-soluble Cd and Pb in soil, facilitating their uptake by rapeseed, corn, and wheat [2,17,20]. However, high concentrations of EDTA-Pb complex were found to reduce the transpiration rate of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea L.) and shoot water content, attributed to the presence of free protonated EDTA (H-EDTA) [21–23]. Moreover, EDTA poses environmental concerns due to its poor biodegradability and potential soil-related risks. Among naturally occurring organic acids, CA has been extensively used in chemically enhanced phytoextraction processes and is considered a potential alternative to EDTA [24–26]. Similarly, Evangelou et al. [20] also supported the use of EDTA alternatives but biodegradable chelating agents for enhancing the phytoremediation capacity of plants. However, the comparative performance of different chelating agents in different plant species for phytoextraction of Pb is poorly understood. Additionally, the potential environmental risks associated with the use of these agents require further investigation. Therefore, it is imperative to understand the mechanisms of CA- or EDTA-assisted changes in Pb uptake by plants.

Mung bean is an important pulse crop for resource-poor farmers due to its potential ability to enhance soil fertility through symbiotic nitrogen fixation [27]. Mung bean has a short growing period, and it is important in intensive crop production. Given the economic importance of mung bean and the role of chelating agents in enhancing phytoremediation, we hypothesized that different chelating agents with a leguminous crop of mung bean have distinct effects on Pb phytoextraction. The role of CA and EDTA in facilitating Pb uptake through roots and its subsequent transport to different parts of plants of mung beans needs to be assessed. Therefore, the present study aimed to assess and compare the effectiveness of chelating agents (DPTA and citric acid) in enhancing phytoextraction of Pb in mung bean. In addition, the secondary objective of the study was to evaluate the extent to which DTPA and CA modulate the different physiological and biochemical processes, thereby affecting the growth and yield of mung bean. This study will help in the development of effective and environmentally sustainable remediation strategies for heavy metal-contaminated soils.

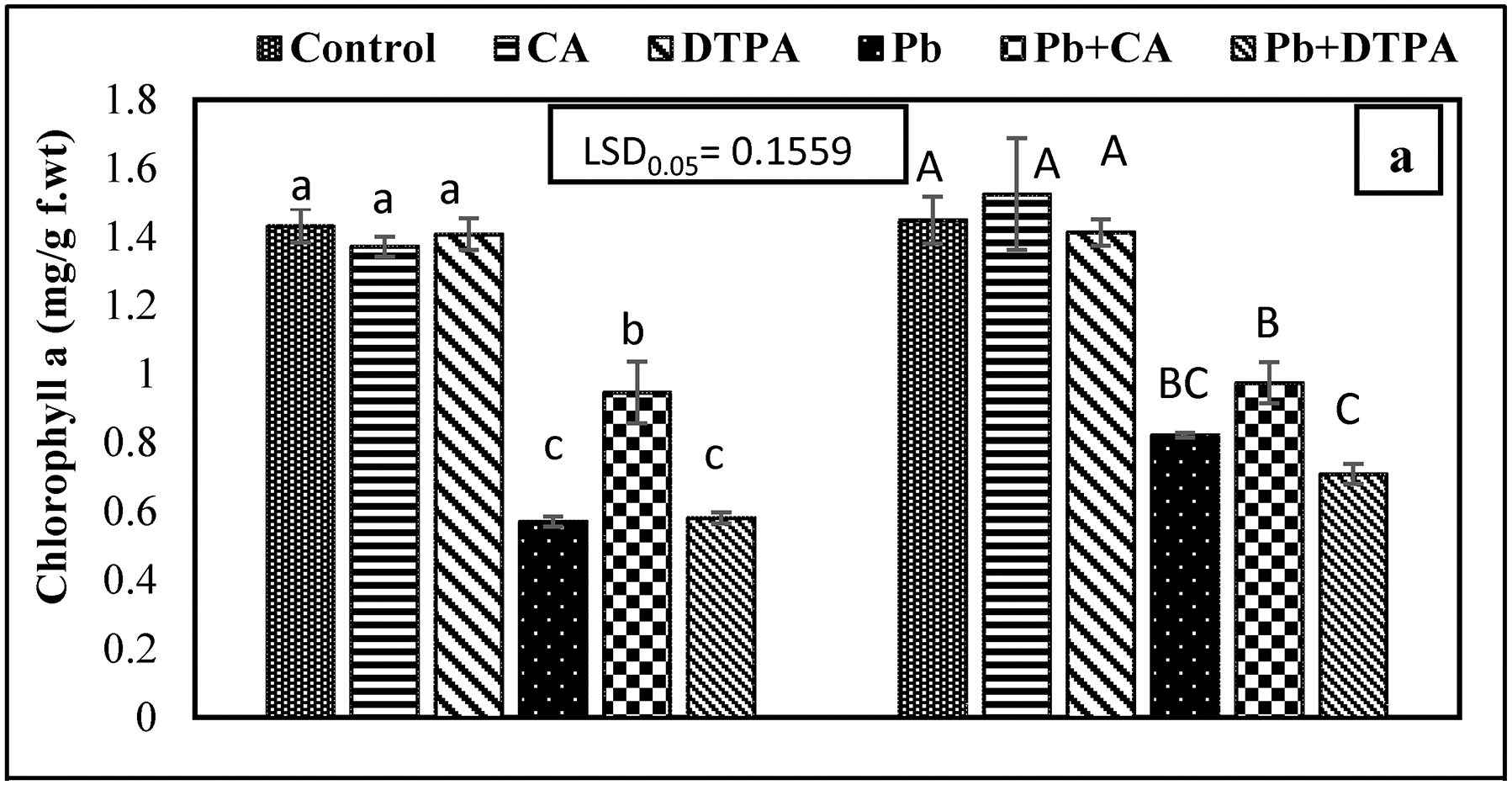

A pot experiment was conducted to evaluate the potential of two chelating agents (DTPA) and Citric acid (CA) in reducing Pb toxicity in two cultivars of mung bean (Vigna radiata) (07001; 07002). This experiment was carried out in the net house at the Botanical Garden of the University of Agriculture, Faisalabad. Seeds of two cultivars of mung bean were obtained from Ayub Agriculture Research Institute (AARI), Faisalabad. Ten seeds of each cultivar were sown in each pot lined with polyethylene bags (15 cm × 20 cm; diameter × depth) filled with 11 kg soil containing ¼ of green manure. After one week of seed germination, seedlings were thinned to five seedlings per pot. Selected seedlings were equal in size and equally placed in pots. This experiment was laid out in a Completely Randomized Design (CRD) with three replicates. The application of lead and chelating agents was carried out four weeks after seed germination. There were the following six treatments details of which are given below in Table 1.

Two liters of each treatment solution were applied to the respective treatment pot. Plants were allowed to grow for a further three weeks. Three plants from each pot were harvested, separated into shoots and roots and their fresh weights were recorded. Plant parts were oven-dried at 70°C for 48 h and their dry biomass was recorded. Two plants of each cultivar in each pot were allowed to grow till yield and yield attributes, i.e., number of pods per plant, number of seeds per plant, and 1000-seed weight were determined. Before harvesting plants, the following physiological attributes were measured.

The chlorophyll a, b, a/b, and carotenoid contents were calculated according to the method of Arnon [28]. The fresh leaves (0.1 g) of each plant were ground in 5 mL of 80% acetone and centrifuged at 6000× g. The absorbance of supernatant was measured at 645, 663, and 480 nm using a spectrophotometer (Hitachi U-2900, Tokyo, Japan). The chlorophyll a, b, chlorophyll a/b ratio, and carotenoids were calculated [28].

2.2 Assessment of Photosynthetic Capacity Using an Infrared Gas Analyzer

The photosynthetic capacity of mung bean plants was recorded using a portable infrared gas analyzer (LCA-4, Analytical Development Company, Hoddesdon, UK) on the youngest but fully developed leaves of mung bean. All data was recorded at a uniform light intensity from 11:00 am to 1:00 pm to avoid major fluctuations in light while measuring photosynthesis. Following gas exchange attributes were recorded, photosynthetic rate (A) (μmol CO2 m−2·s−1), stomatal conductance (gs) (mmol m−2·s−1), transpiration rate (E) (mmol H2O m−2·s−1) and water use efficiency (mmol CO2·mol−1 H2O).

2.3 Accumulation of Mineral Nutrients in Root, Stem, and Leaves

Oven-dried root, stem, and leaf material of each sample were ground to a fine powder and digested in sulfuric acid at a moderate temperature. Oven-dried material (0.1 g) was placed in digestion tubes, and 2 mL of H2SO4 was added and left overnight. On the next morning, digestion tubes containing 0.1 g oven-dried material and 2 mL of H2SO4 were placed on hot plates, and digested the plant samples at 250°C. After one hour, 1 mL of perchloric acid was added and heated again on a hot plate till a clear digested solution was obtained. The digested samples were diluted with distilled water and made the volume up to 50 mL. The content of Na+ and K+ in digested and diluted samples of roots, stems and leaves was measured by using a flame photometer (Model PFP7, Jenway, Staffordshire, UK). Phosphorous content was measured by treating 1 mL of diluted digested samples with 4 mL of Barton’s reagent and the absorbance was taken at 470 nm. Total nitrogen was estimated by Kjeldahl’s apparatus [29]. Lead ions were determined with the help of an Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer (Model AAnalyst 100, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

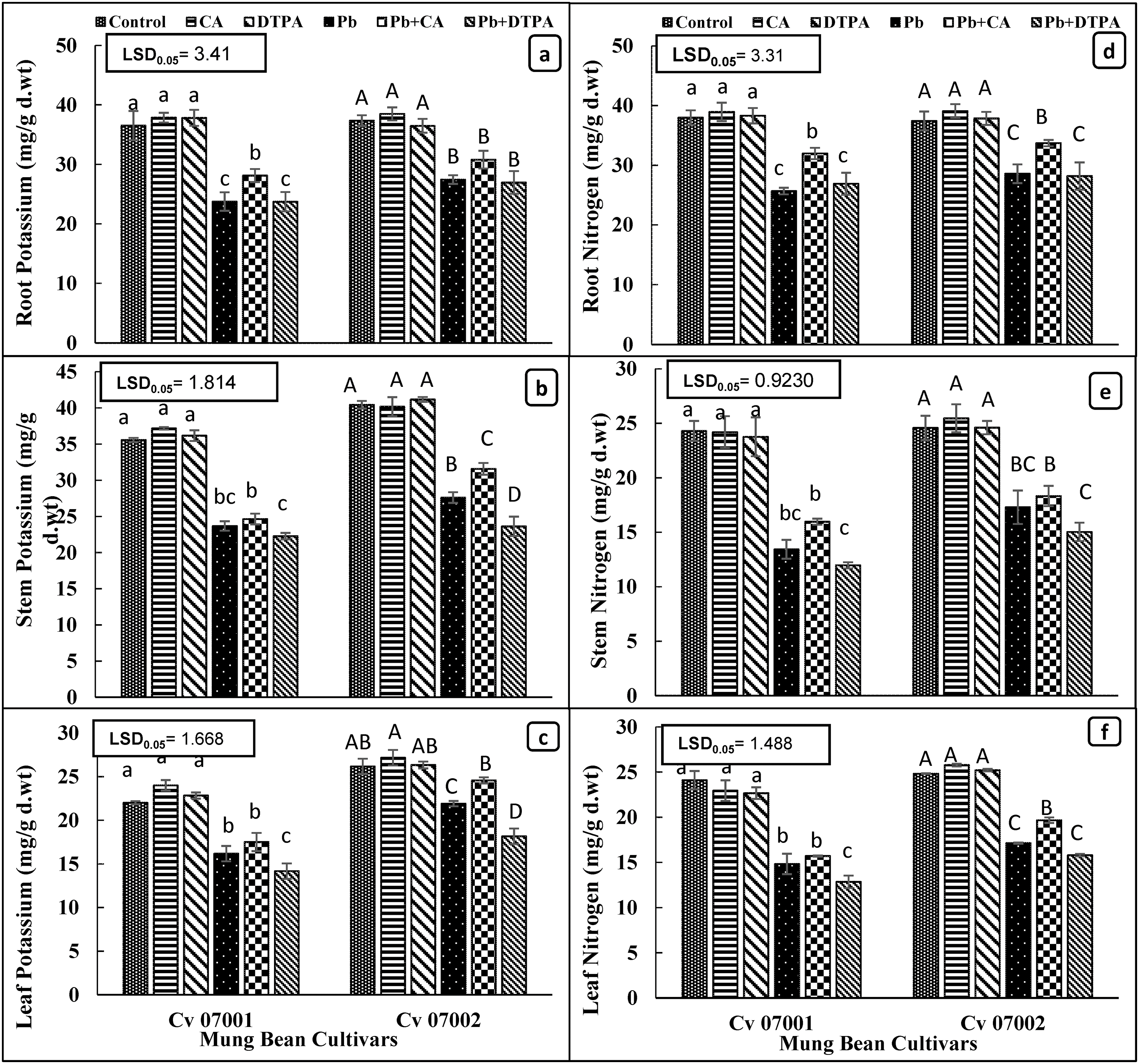

To assess the effects of lead (Pb) stress and organic chelating agents (Citric acid, CA; DPTA) on different morpho-physiological attributes of mung bean cultivars, a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with completely randomized design (CRD) was conducted using statistical computer package CoStat v. 6.4 (CoHort, Berkley, CA, USA). Before analyzing data, the assumptions of normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test and homogeneity of variance using Levene’s test were tested. The results indicated that both assumptions were met (p > 0.05). Treatment means were compared by the least significant differences (LSD) test at 0.05 probability level following Steel and Torrie [30].

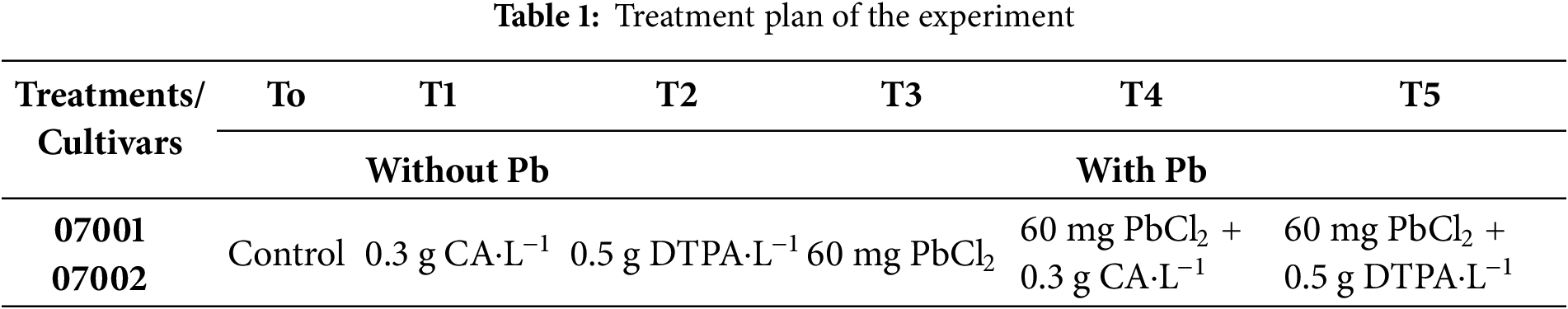

Application of Pb caused a considerable reduction in growth, shoot length, root length, fresh biomass, and number of leaves. The addition of Pb reduced the shoot fresh weight (63.63% & 58.82%), root fresh weight (52.77% & 33.33%), shoot dry weight (40% & 37.5%), and root dry weight (54.8% & 33%) of both mung bean cultivars cv 07001 and cv 07002, respectively (Fig. 1). The Pb-induced reduction in fresh and dry weights of shoot and root was greater in mung bean cultivar 07001. In addition, the application of CA had an increasing effect on the shoot fresh weight (11% & 9%), shoot dry weight (10.5% & 6.25%), and root fresh weight (7.14% and 11.1%) of both cultivars. However, the application of DPTA in Pb-stressed plants (Pb + DPTA) did not alleviate the adverse effect of Pb stress and it caused a further reduction in 40% & 37.5% in shoot dry weight, and 54.8% & 33% in root dry weights of both mung bean cultivars (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Growth attributes of two Mungbean cultivars (Vigna radiata) when subjected to Pb, CA, and DTPA treatments. (a) Shoot fresh weight (g/plant) (b) root fresh weight (g/plant) (c) shoot dry weight (g/plant) and (d) root dry weight (g/plant) of n = 3. The bars denoted by different letters (a to c) are significantly different for the 07001 cultivar while (A to C) are significantly different for the 07002 cultivar at p ≤ 0.05

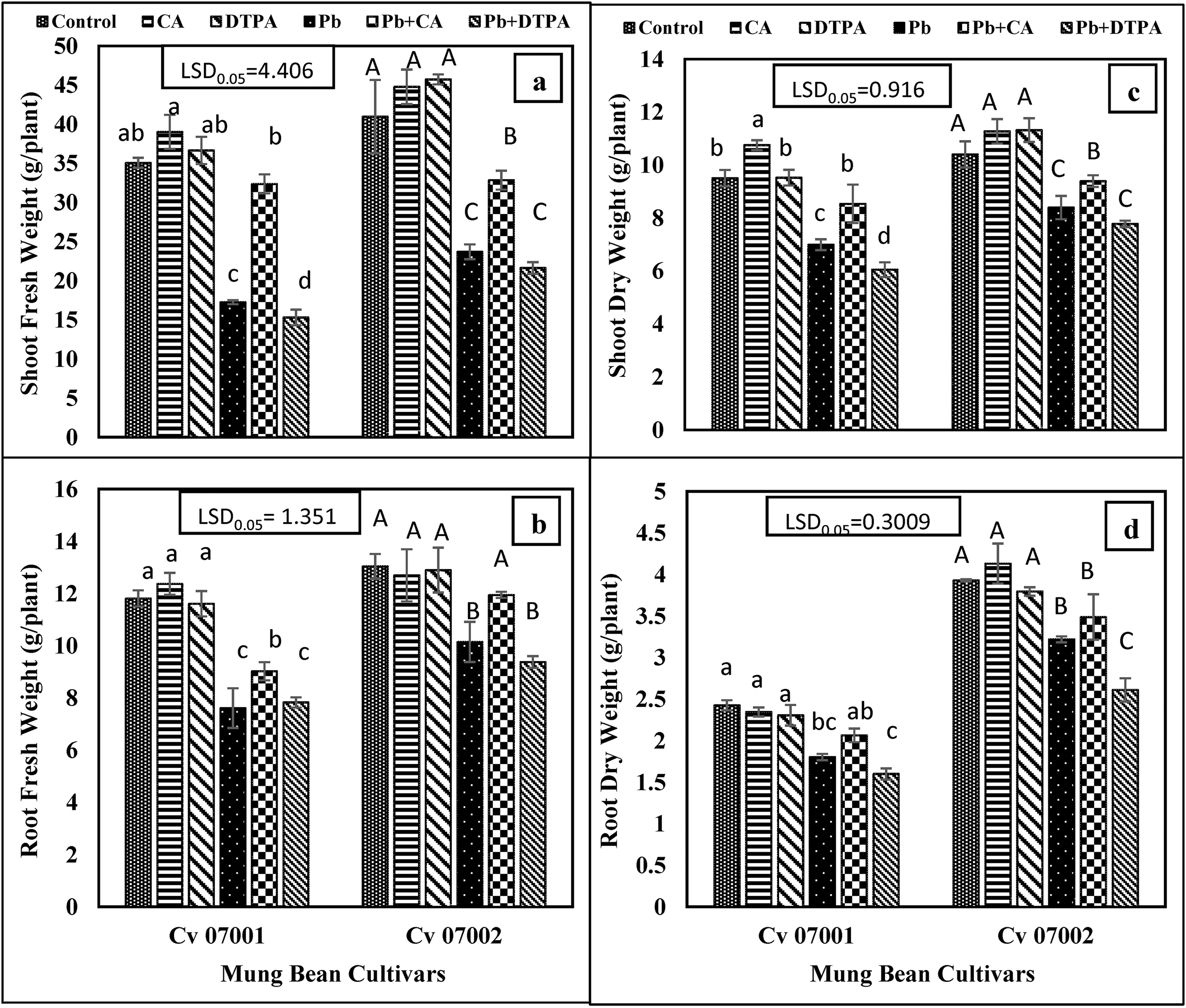

The addition of DTPA to Pb-stressed plants of mung bean cultivars caused a reduction in shoot and root length (Fig. 2). The effect of DTPA on reducing shoot and root length was more obvious in cultivar 07001 than in 07002. However, the application of CA to Pb-stressed plants minimized the adverse effect of Pb on these growth attributes, particularly in root length in cultivar 07002. The addition of Pb and DTPA alone or in combination reduced the number of leaves in both mung bean cultivars (Fig. 2), whereas the application of CA alone or in combination with Pb increased the number of leaves in both mung bean cultivars.

Figure 2: Changes in shoot and root length, and number of leaves per plant of two mungbean cultivars (Vigna radiata) when subjected to Pb, CA, and DTPA treatments. (a) Shoot length (cm) (b) root length (cm) and (c) no. of leaves. n = 3. The bars denoted by different letters (a to e) are significantly different for the 07001 cultivar while (A to D) are significantly different for the 07002 cultivar at p ≤ 0.05

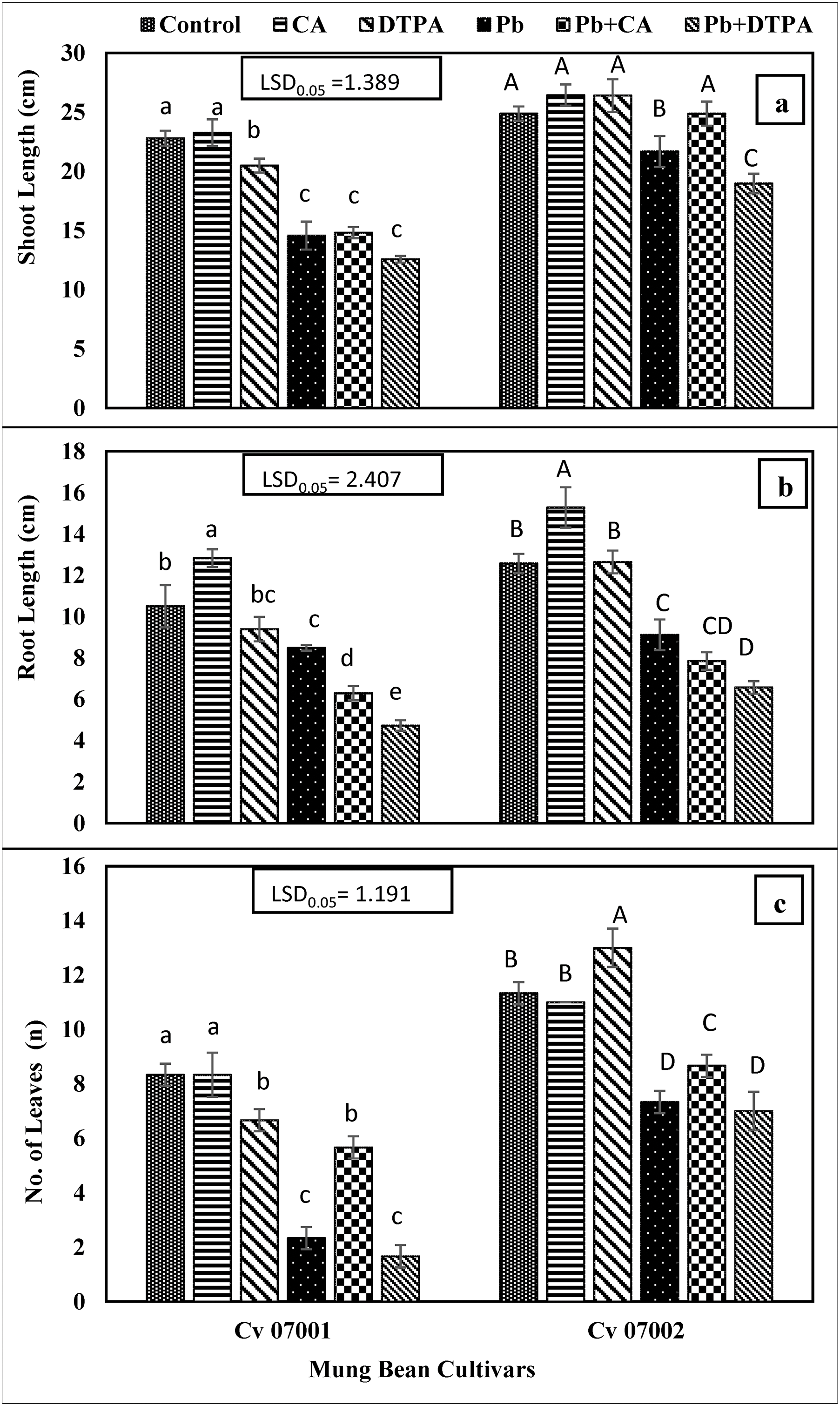

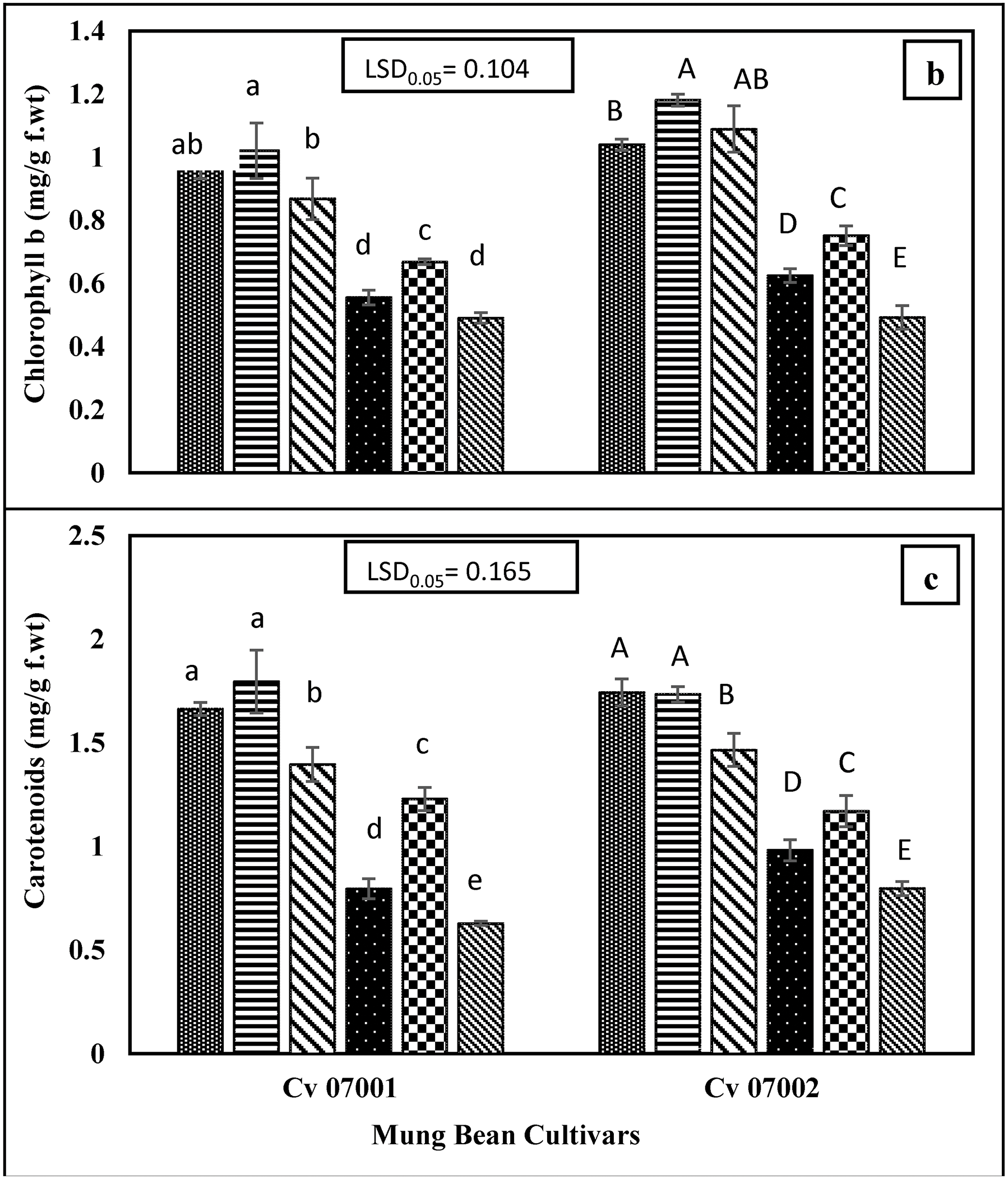

The Pb stress caused a significant decrease in chlorophyll “a”, chlorophyll “b” and carotenoid contents in the leaves of mung bean cultivars. The addition of DPTA did not show any significant effect on mitigating the toxic effect of Pb stress on photosynthetic pigments. However, CA application increased the chlorophyll “a”, chlorophyll “b” and carotenoid content in leaves of mung bean cultivars (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Photosynthetic pigments of two Mungbean cultivars (Vigna radiata) when subjected to Pb, CA, and DTPA treatments. (a) chlorophyll a (mg/g f.wt) (b) chlorophyll b (mg/g f.wt) (c) carotenoids (mg/g f.wt). n = 3. The bars denoted by different letters (a to d) are significantly different for the 07001 cultivar while (A to E) are significantly different for the 07002 cultivar at p ≤ 0.05

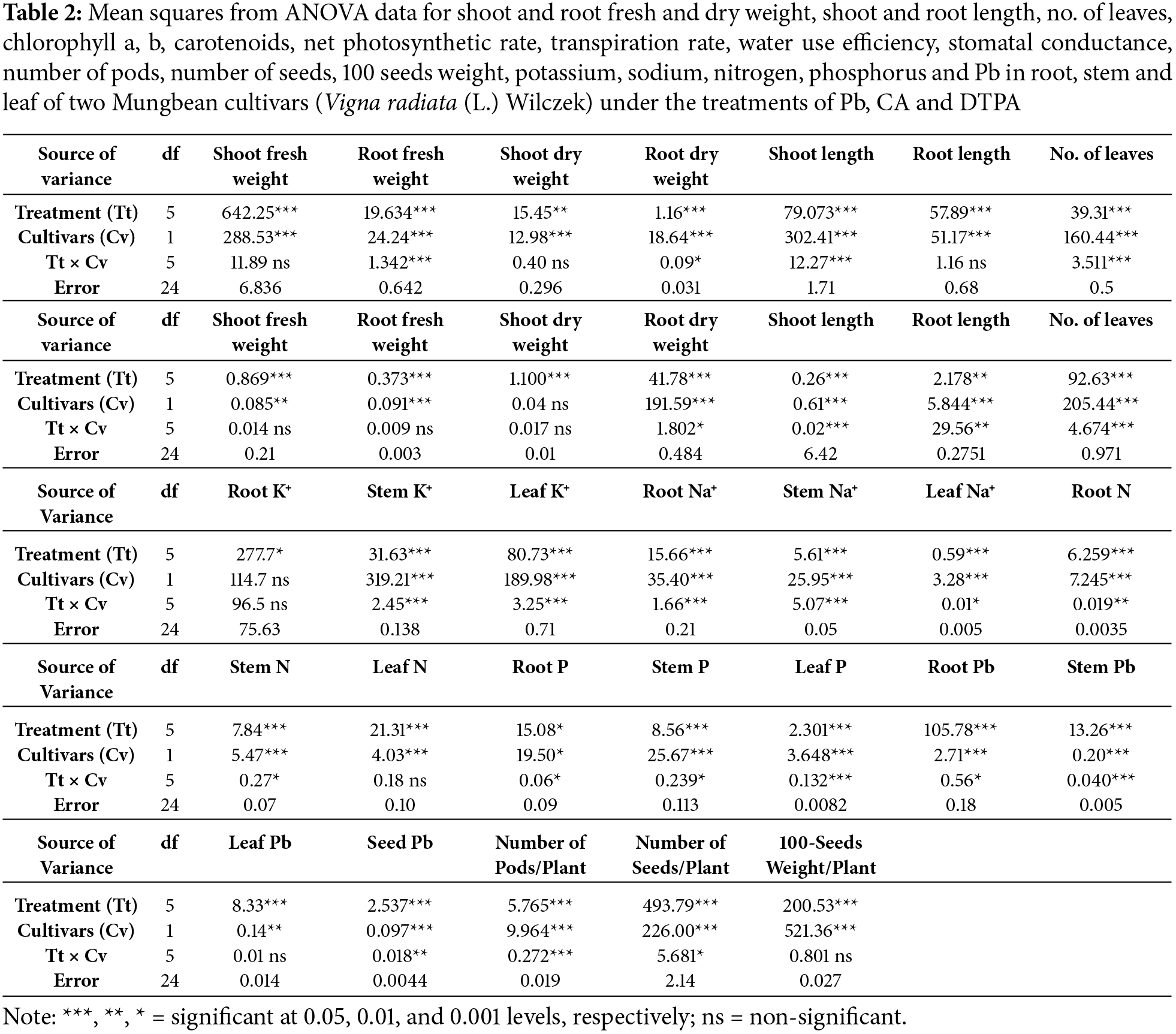

The Pb stress reduced the photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance, and transpiration rate of the two cultivars of mung bean (Table 2 and Fig. 4a–d). Application of CA improved photosynthetic rate and stomatal conductance of both mung bean cultivars but did not affect the transpiration rate of both mung bean cultivars. However, DTPA caused a significant reduction in photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance, and transpiration rate in the Pb stress-07001 cultivar, but the transpiration rate in the 07002 cultivars remained the same as in Pb stressed plants. The comparison of the two cultivars indicated that 07002 had a significantly higher photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance, and transpiration rate than cultivar 07001. The application of CA to Pb-stressed plants of both mung bean cultivars increased water use efficiency, whereas the application of DTPA increased the water use efficiency of cultivar 07001, whereas the opposite effect was observed in cultivar 07002.

Figure 4: Gas exchange traits as photosynthetic capacity attributes of two Mungbean cultivars (Vigna radiata) when subjected to Pb, CA, and DTPA treatments. (a) Net photosynthetic rate (μmol/m2/s) (b) stomatal conductance (mmol/m2/s) (c) transpiration rate (mmol/m2/s) and (d) water use efficiency (μmol CO2/mmol H2O). n = 3. The bars denoted by different letters (a to c) are significantly different for the 07001 cultivar while (A to D) are significantly different for the 07002 cultivar at p ≤ 0.05

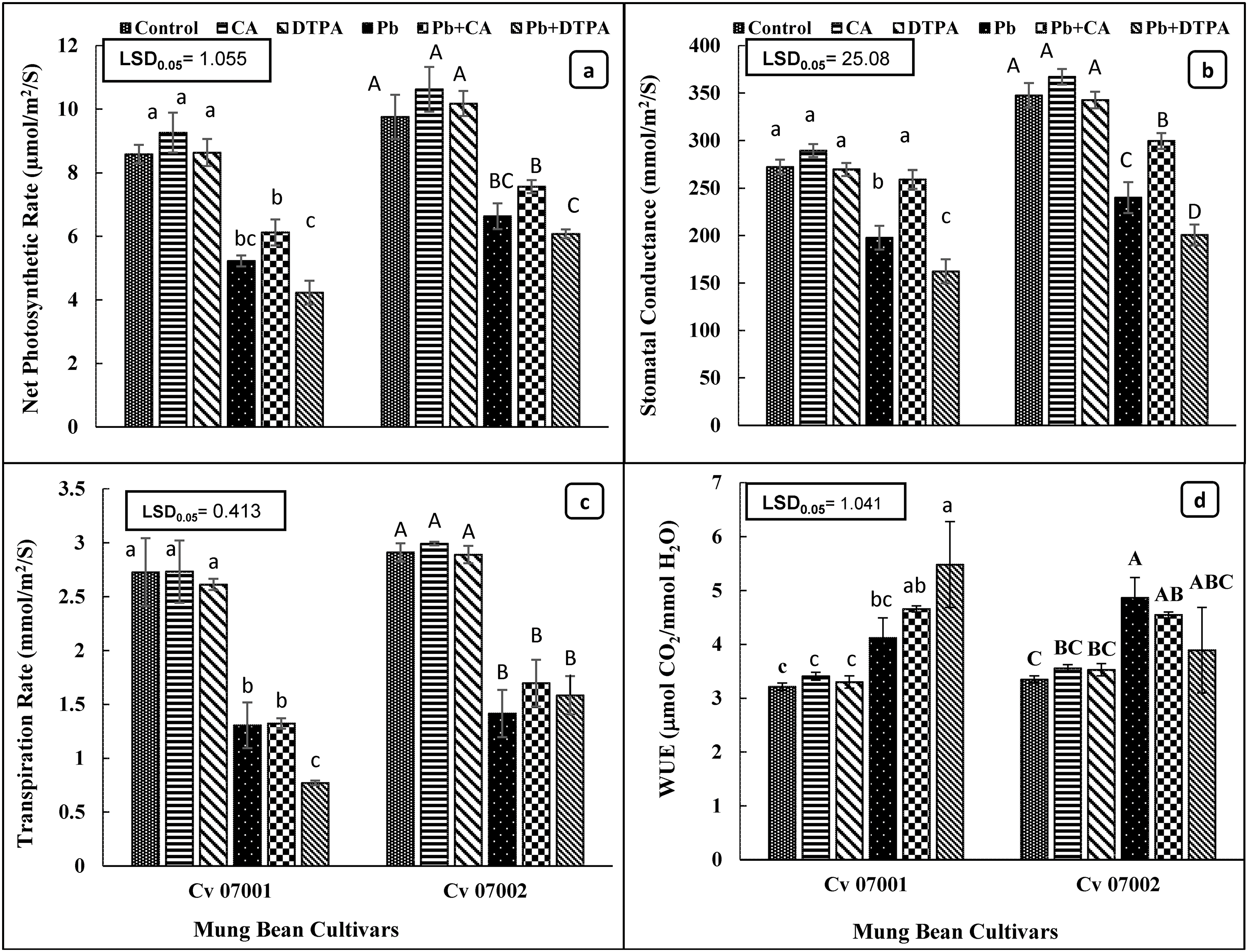

3.2.2 Mineral Nutrient Accumulation

Accumulation of potassium in the leaf, stem, and roots of two mung bean cultivars reduced due to Pb stress. Application of CA improved the accumulation of potassium in the root, stem, and leaves of both mung bean cultivars. Application of DPTA did not change the accumulation of potassium in the roots and stem of both mung bean cultivars, whereas in the leaves of both cultivars DPTA application caused a further reduction in the accumulation of potassium (Table 1; Fig. 5a–c).

Figure 5: Accumulation of potassium and nitrogen in roots stems and leaves of two mungbean cultivars (Vigna radiata) when subjected to Pb, CA, and DTPA treatments. And Potassium content (mg/g dry wt.) in (a) root (b) stem (c) leaf and Nitrogen content (mg/g dry wt.) in (d) root (e) stem (f) leaf. n = 3. The bars denoted by different letters (a to c) are significantly different for the 07001 cultivar while (A to D) are significantly different for the 07002 cultivar at p ≤ 0.05

Nitrogen content in the roots, stem and leaves of both mung bean cultivars decreased due to Pb treatment. Application of Pb chelating agents CA and DTPA did not change the nitrogen contents in the roots, stem, and leaves of both mung bean cultivars. However, under Pb stress conditions, application of CA improved (39.54%) the nitrogen contents in roots, stems, and leaves of both mung bean cultivars (Table 1; Fig. 5d–f). However, the improving effects of CA on the accumulation of nitrogen content were greater in roots than in stems and leaves. Both mung bean cultivars had similar nitrogen contents in roots but cultivar 07002 had greater nitrogen content in stem and leaves than in 07001.

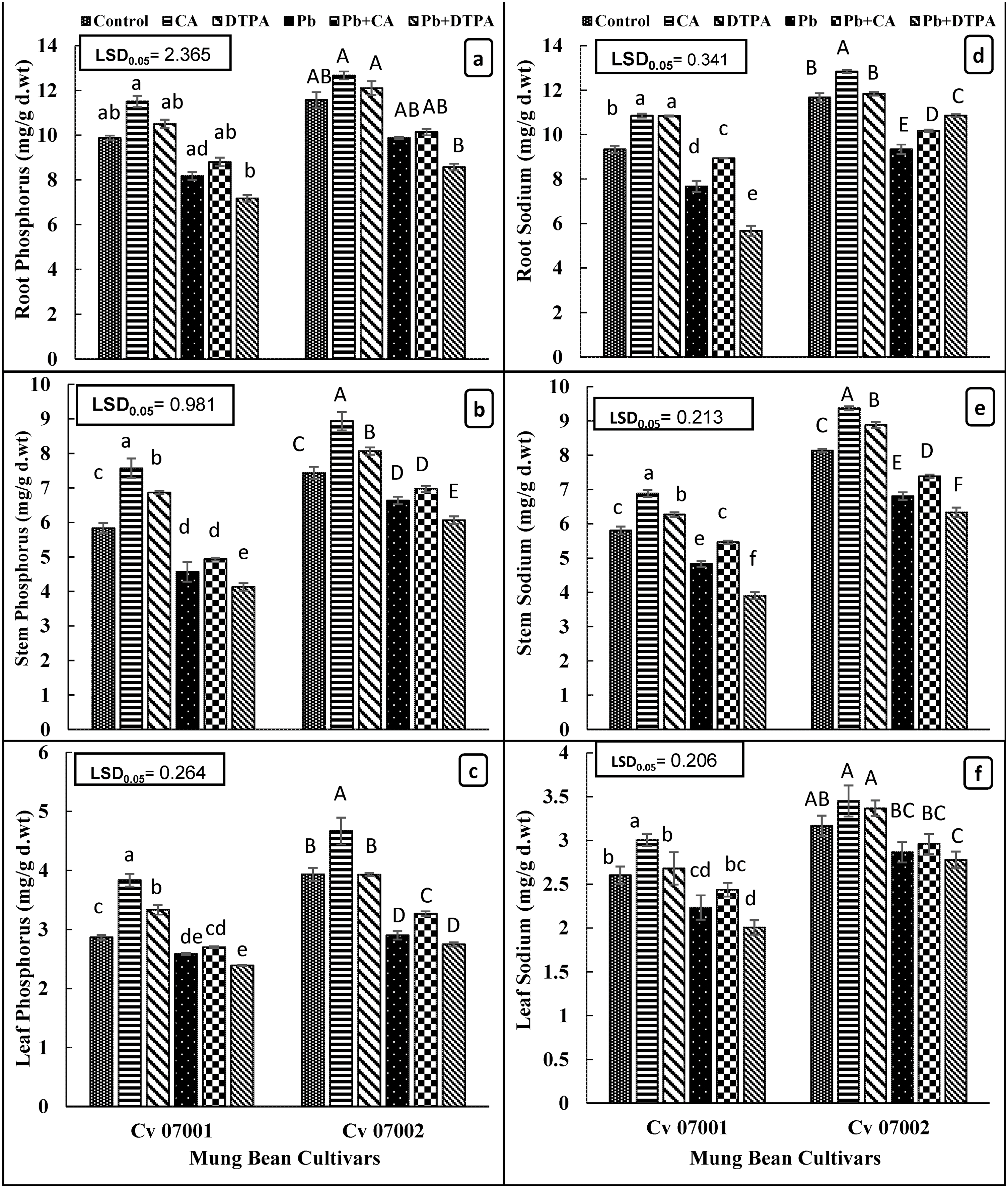

Accumulation of phosphorous in roots, stems and leaves of two cultivars of mung bean reduced significantly due to Pb stress (Table 1; Fig. 6a–c). This reducing effect of Pb was more in mung bean cultivar 07001 than in 07002. However, the accumulation of phosphorous in roots and stems was greater in cultivar 07002 than in 07001 (Fig. 6a,b). Application of CA caused a significant increase in the accumulation of phosphorous in roots (11.42%), stems, and leaves of both mung bean cultivars under both control and Pb stress conditions. Although the application of DPTA improved the accumulation of phosphorous in roots, stems, and leaves of both cultivars under control conditions, it did not improve the phosphorous accumulation in roots, stems, and leaves of both mung bean cultivars. However, DTPA caused a significant reduction (26.96%) in root phosphorus content of mung bean cultivar 07002 under Pb stress conditions.

Figure 6: Accumulation of phosphorus and sodium in roots stem, and leaves of two mungbean cultivars (Vigna radiata) when subjected to Pb, CA, and DTPA treatments. Phosphorus content (mg/g dry wt.) in (a) root (b) stem (c) leaf and Sodium content in (d) root (e) stem (f) leaf. n = 3. The bars denoted by different letters (a to f) are significantly different for the 07001 cultivar while (A to F) are significantly different for the 07002 cultivar at p ≤ 0.05

Accumulation of sodium exhibited a slight yet significant decrease in all plant parts of both mung bean cultivars (Table 1; Fig. 6d–f). Application of CA improved the accumulation of sodium in roots, stems, and leaves of both mung bean cultivars, whereas application of DPTA had no effect on the accumulation of sodium in all plant parts. Roots of both cultivars exhibited higher sodium accumulation compared to stems and leaves. Cultivar 07002 exhibited higher sodium accumulation across all plant parts compared to cultivar 07001.

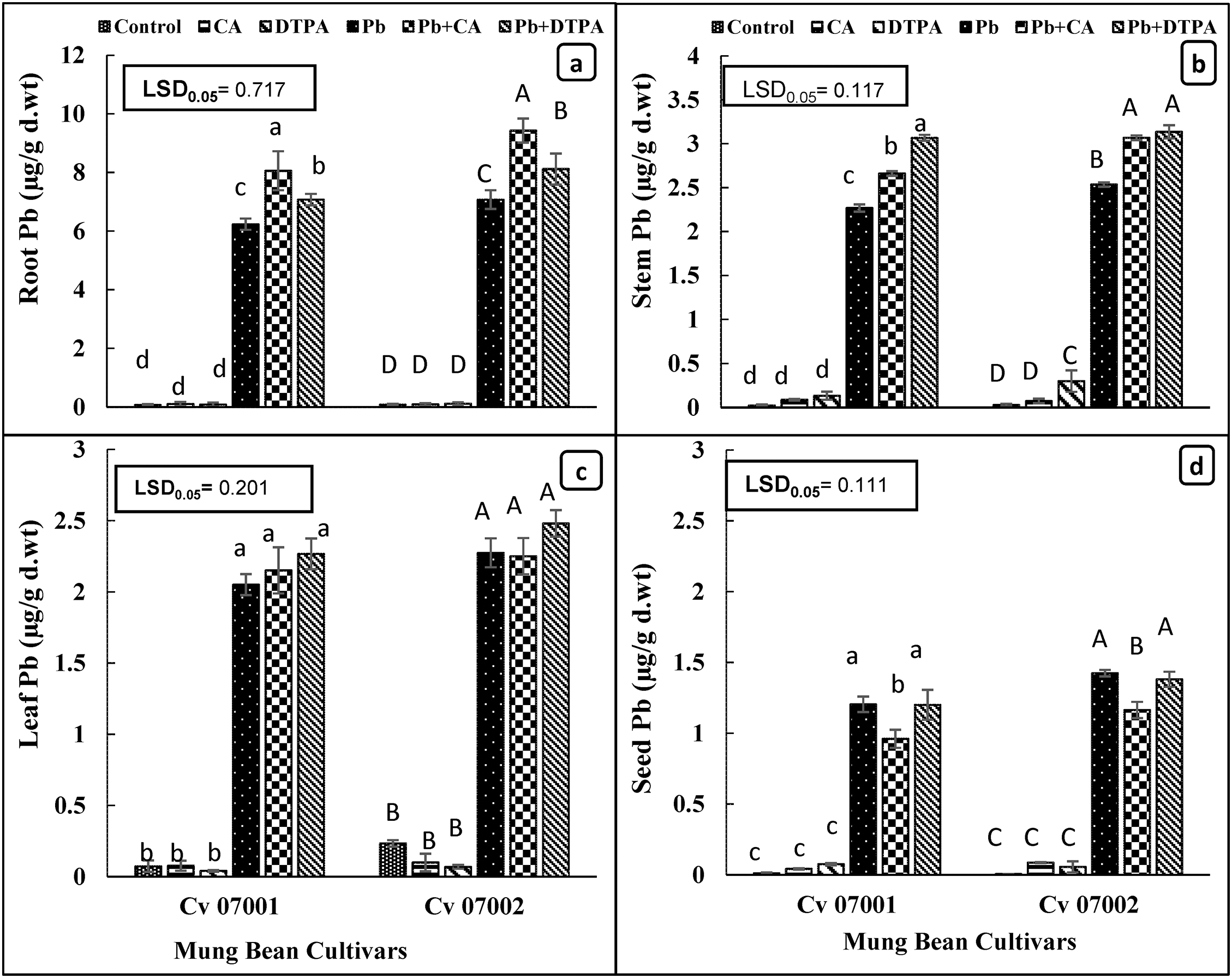

Accumulation of Pb in roots, stems, leaves, and seeds of both mung bean cultivars significantly increased as a result of Pb stress (Table 1; Fig. 7a–d). Accumulation of Pb was highest in the roots of both mung bean cultivars, whereas the Pb accumulation was the lowest in the seeds. Although both mung bean cultivars exhibited similar levels of Pb accumulation in stems, leaves, and seeds, cultivar 07002 had greater Pb accumulation in roots than cultivar 07001. Application of CA and DTPA significantly increased Pb accumulation in roots and stems, while no significant changes were observed in the leaves of both mung bean cultivars. Nonetheless, the application of only CA reduced the accumulation of Pb in the seeds of both mung bean cultivars.

Figure 7: Uptake and accumulation of lead (Pb) in roots, stem, leaves, and seeds of two mungbean cultivars (Vigna radiata) when subjected to Pb, CA, and DTPA treatments. Pb content (μg/g dry wt.) in (a) root (b) stem (c) leaf and (d) seed. n = 3. The bars denoted by different letters (a to d) are significantly different for the 07001 cultivar while (A to D) are significantly different for the 07002 cultivar at p ≤ 0.05

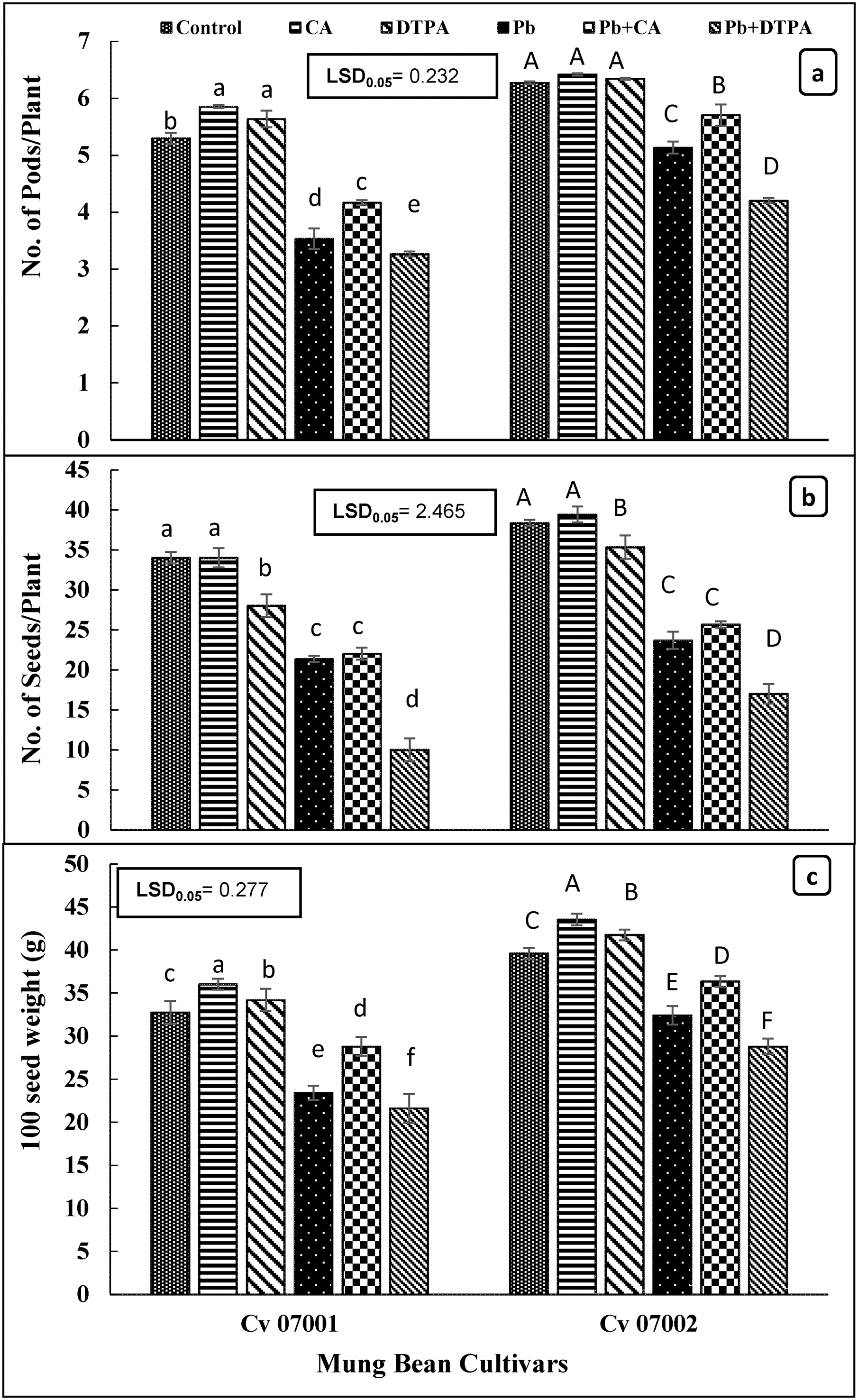

The Pb stress significantly reduced the number of pods per plant, the number of seeds per plant, and the 1000 seed weight (Table 1; Fig. 8a–c). The mung bean cultivars exhibited significant differences in yield attributes, with cultivar 07002 demonstrating a greater number of pods (7.16%), number of seeds, and 1000-seed weight compared to cultivar 07001. Application of CA increased the number of pods and 1000-seed weight in both mung bean cultivars, particularly under Pb stress conditions (by 35.22% and 20.51%; Fig. 5a). The effect of DTPA on yield attributes of both mung bean cultivars was inconsistent. Application of DTPA decreased the number of seeds per plant in cultivar 07001 under Pb stress, while the number of pods and 1000-seed yield remained unchanged. Nonetheless, DTPA application resulted in a further decrease in the number of pods, number of seeds, and 1000 seed weight of mung bean cultivar 07002 under Pb stress conditions.

Figure 8: Yield and yield attributes of two Mungbean cultivars (Vigna radiata) when subjected to Pb, CA, and DTPA treatments. (a) Number of pods/plant (b) number of seeds/plant and (c) 100 seeds weight (g). n = 3. The bars denoted by different letters (a to f) are significantly different for the 07001 cultivar while (A to F) are significantly different for the 07002 cultivar at p ≤ 0.05

The Pb toxicity poses a significant threat to plant growth and crop yield, leading to detrimental effects on final agricultural productivity. The severity of lead toxicity differs among various crop species, with certain crops exhibiting higher tolerance or resistance compared to others. The current study demonstrates that the addition of Pb in the growth medium inhibited the growth of both cultivars of mung bean (Vigna radiata), which is consistent with findings from previous research on different crops [31,32]. Exogenous application of chelating agents has been found to enhance plant capabilities in phytoextraction of heavy metals by improving ion mobility, solubility, and bioavailability during soil solution and root uptake [19,21,24,33]. The present study indicates that the addition of DTPA in Pb-contaminated soil (60 mg Pb + 0.5 g DTPA·L−1) resulted in decreased plant growth and photosynthetic pigments in both mung bean cultivars. Moreover, the adverse effect of DTPA application was more pronounced in mung bean plants compared to those treated only with 60 mg Pb·L−1, which indicates that the addition of DTPA did not enhance the phytoextraction capacity of mung bean cultivars. These results are in contrast with a previous study that reported enhancement of phytoextraction capacity in plants through the use of DPTA as a chelator [34]. The application of DTPA resulted in a 9.5 times increase in Pb accumulation in the shoots of maize plants [35]. Similarly, the addition of DTPA enhanced a 2.09-fold increase in Pb accumulation in the leaves of Lolium perenne [36]. The detrimental impact of DPTA on the growth of both mung bean cultivars can be attributed to the high mobilization of Pb in the soil induced by DPTA, which resulted in decreased plant growth and phytoextraction efficiency [34,36].

Natural organic chelating agents such as citric acid (CA) are biodegradable in soil and can form complexes with metals of varying stability. This property enhances plant tolerance to heavy metals, making them preferable to synthetic chelators for assisted phytoremediation initiatives. In this study, CA application improved the growth and chlorophyll content in both mung bean cultivars. The 07002 cultivars showed better growth compared to that of the 07001 cultivars as a result of CA treatments under Pb stress conditions. These results align with the findings of Ghnaya et al. [37], who demonstrated that CA has the potential to translocate and accumulate metals in the shoot, suggesting its potential for for remediating Pb-polluted soils. In addition, growth improvement and enhancement in chlorophyll content of mung bean cultivars is attributed to the antioxidant properties of CA, which helps in mitigating oxidative stress [38].

Heavy metal stress, particularly Pb stress reduces plant growth and yield by affecting key physiological processes such as photosynthesis. The photosynthetic capacity of plants can be assessed as net CO2 assimilation rate, stomatal conductance, transpiration rate, and chlorophyll biosynthesis. In the present study, Pb stress reduced gas exchange attributes, including net CO2 assimilation rate, stomatal conductance, transpiration rate, and water use efficiency in the leaves of both mung bean cultivars. Similar results were reported in a previous study [39]. The net assimilation rate of CO2 decreased in both mung bean cultivars under pb stress; however, the addition of CA alleviated the adverse effects of Pb, resulting in higher net CO2 assimilation rates. The addition of CA enhanced the stomatal conductance in both mung bean cultivars under Pb stress, thereby increasing the CO2 fixation, as previously observed in wheat [40,41].

The mineral nutrition is essential for the normal growth and development of plants. These minerals play crucial roles in essential physiological and biochemical processes, such as photosynthesis, respiration, protein synthesis, and hormone regulation. The Pb stress causes excessive accumulation of Pb in roots, stems, and leaves, which disrupts the uptake and transport of essential mineral nutrients such as K+ and Ca2+. This disruption results in nutrient imbalances and deficiencies [1,3,4,12]. In the present study, Pb stress reduced the nutrient uptake and accumulation in all plant parts including roots, stems, and leaves. The addition of CA in the growth medium significantly enhanced the mineral nutrition status of both mung bean cultivars. However, the addition of DPTA had minor effects on the mineral nutrition status of both mung bean cultivars. These findings are similar to those of previous studies indicating that Pb stress reduced the concentration of potassium and phosphorus in cowpea, rice, and maize, while the presence of DTPA or CA increased the uptake of Pb in barley shoots, leaves, and stems [42–44].

Grejtovský et al. [45] observed that the presence of DTPA significantly increased the concentration of Pb in barley shoots, leaves, and stems, while the absence of DTPA resulted in a minimal effect of Pb. It was concluded that chelating agents can increase the transfer of Pb to plants and increase its uptake. In mung bean plants, Pb toxicity reduced the physiological and biochemical physio-biochemical activities of plants, such as photosynthetic pigments [46]; however, CA application improved it in Helianthus annuus under similar conditions [47].

The yield and yield attributes of mung bean are important indicators of its productivity. Pb stress reduced the mung bean yield by impairing various yield attributes associated with physiological processes such as floral development, fertilization, number of pods, number of seeds per pod, and size of seeds. In this study, Pb stress reduced the yield of both mung bean cultivars. However, the addition of CA enhanced the yield and yield attributes in mung bean cultivars. However, the application of DPTA to mung bean plants grown in Pb-contaminated soil caused a further decrease in yield. The observed yield reduction was positively associated with a high accumulation of Pb in leaves reduced amount of photosynthetic pigments and lower rate of CO2 assimilation rates. High concentrations of Pb have been associated with reduced photosynthesis and a significant decline in all yield parameters of rice and other crops, as reported by various earlier studies [1–3,20,46]. Understanding the mechanisms underlying the negative impact of Pb on mung bean is essential for developing strategies to mitigate the harmful effects of Pb stress and improve the yield potential of mung bean crops.

Lead (Pb) stress caused a significant increase in Pb accumulation in all plant parts which caused a reduction in growth and yield. Application of CA modulated the uptake and transport of Pb in seeds and leaves. Application of CA alleviated the Pb toxicity on plant growth of mung bean plants by having a positive effect on nutrient uptake (N, P, and K), photosynthetic pigments, and photosynthetic rate by regulation of stomatal conductance and transpiration rate. However, the application of DTPA showed a more toxic effect on mung bean as it poorly regulates the nutrient uptake and photosynthesis of plants. The cv. 07001 is more susceptible to Pb stress. In addition, cv. 07002 was found to be more tolerant to Pb stress and showed better performance in the CA application. The application of CA can be considered as a potential chelating agent for the remediation of Pb-contaminated soil.

Acknowledgement: The work presented in this manuscript is original research conducted by Hafiza Saima Gul as part of her M.Phil. thesis and acknowledges the technical support from Department of Botany, University of Agriculture Faisalabad. The authors received funding from the Ongoing Research Funding program, ORF-2025-298, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding Statement: The authors received funding from the Ongoing Research Funding program, ORF-2025-298, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Hafiza Saima Gul, Mumtaz Hussain; data collection: Hafiza Saima Gul, Tayyaba Sanaullah; analysis and interpretation of results: Hafiza Saima Gul, Habib-ur-Rehman Athar, Muhammad Kamran; draft manuscript preparation, revision of the manuscript: Habib-ur-Rehman Athar, Ibrahim Al-Ashkar, Muhammad Kamran, Mohammed Antar, Ayman El Sabagh. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data used or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Kamran M, Wang D, Alhaithloul HA, Alghanem SM, Aftab T, Xie K, et al. Jasmonic acid-mediated enhanced regulation of oxidative, glyoxalase defense system and reduced chromium uptake contributes to alleviation of chromium (VI) toxicity in choysum (Brassica parachinensis L.). Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021;208:111758. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.111758. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Gavrilescu M. Enhancing phytoremediation of soils polluted with heavy metals. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2022;74:21–31. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2021.10.024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Aslam M, Aslam A, Sheraz M, Ali B, Ulhassan Z, Najeeb U, et al. Lead toxicity in cereals: mechanistic insight into toxicity, mode of action, and management. Front Plant Sci. 2021;11:587785. doi:10.3389/fpls.2020.587785. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Kumar A, Prasad MNV. Plant-lead interactions: transport, toxicity, tolerance, and detoxification mechanisms. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2018;166:401–18. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.09.113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Gashi B, Buqaj L, Vataj R, Tuna M. Chlorophyll biosynthesis suppression, oxidative level and cell cycle arrest caused by Ni, Cr and Pb stress in maize exposed to treated soil from the Ferronikel smelter in Drenas. Kosovo Plant Stress. 2024;11(7):100379. doi:10.1016/j.stress.2024.100379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Ilyas MZ, Sa KJ, Ali MW, Lee JK. Toxic effects of lead on plants: integrating multi-omics with bioinformatics to develop Pb-tolerant crops. Planta. 2023;259(1):18. doi:10.1007/s00425-023-04296-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Romanowska E, Wasilewska W, Fristedt R, Vener AV, Zienkiewicz M. Phosphorylation of PSII proteins in maize thylakoids in the presence of Pb ions. J Plant Physiol. 2012;169(4):345–52. doi:10.1016/j.jplph.2011.10.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Fan T, Yang L, Wu X, Ni J, Jiang H, Zhang Q, et al. The PSE1 gene modulates lead tolerance in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2016;67(15):4685–95. doi:10.1093/jxb/erw251. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Pourrut B, Shahid M, Dumat C, Winterton P, Pinelli E. Lead uptake, toxicity, and detoxification in plants. In: Whitacre DM, editor. Reviews of environmental contamination and toxicology. Vol. 213. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2011. p. 113–36 doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-9860-6_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Li X. The role of funneliformis mosseae symbiosis on cotton plants under lead toxicity: molecular and physiological aspects. Russ J Plant Physiol. 2024;71(3):83. doi:10.1134/s1021443724604129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Collin MS, Venkatraman SK, Vijayakumar N, Kanimozhi V, Arbaaz SM, Stacey RGS, et al. Bioaccumulation of lead (Pb) and its effects on human: a review. J Hazard Mater Adv. 2022;7(2):100094. doi:10.1016/j.hazadv.2022.100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zafari S, Sharifi M, Ahmadian Chashmi N, Mur LAJ. Modulation of Pb-induced stress in Prosopis shoots through an interconnected network of signaling molecules, phenolic compounds and amino acids. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2016;99(1):11–20. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2015.12.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Cameselle C, Gouveia S, Urréjola S. Benefits of phytoremediation amended with DC electric field. Application to soils contaminated with heavy metals. Chemosphere. 2019;229:481–8. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.04.222. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Diaconu M, Pavel LV, Hlihor RM, Rosca M, Fertu DI, Lenz M, et al. Characterization of heavy metal toxicity in some plants and microorganisms—a preliminary approach for environmental bioremediation. New Biotechnol. 2020;56:130–9. doi:10.1016/j.nbt.2020.01.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Manoj SR, Karthik C, Kadirvelu K, Arulselvi PI, Shanmugasundaram T, Bruno B, et al. Understanding the molecular mechanisms for the enhanced phytoremediation of heavy metals through plant growth promoting rhizobacteria: a review. J Environ Manag. 2020;254(9–10):109779. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109779. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Cheraghi M, Lorestani B, Khorasani N, Yousefi N, Karami M. Findings on the phytoextraction and phytostabilization of soils contaminated with heavy metals. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2011;144(1):1133–41. doi:10.1007/s12011-009-8359-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Chauhan G, Pant KK, Nigam KDP. Chelation technology: a promising green approach for resource management and waste minimization. Environ Sci Process Impacts. 2015;17(1):12–40. doi:10.1039/c4em00559g. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Attinti R, Barrett KR, Datta R, Sarkar D. Ethylenediaminedisuccinic acid (EDDS) enhances phytoextraction of lead by vetiver grass from contaminated residential soils in a panel study in the field. Environ Pollut. 2017;225(5):524–33. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2017.01.088. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Li FL, Qiu Y, Xu X, Yang F, Wang Z, Feng J, et al. EDTA-enhanced phytoremediation of heavy metals from sludge soil by Italian ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2020;191:110185. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Evangelou MWH, Ebel M, Schaeffer A. Chelate assisted phytoextraction of heavy metals from soil. Effect, mechanism, toxicity, and fate of chelating agents. Chemosphere. 2007;68(6):989–1003. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.01.062. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Vassil AD, Kapulnik Y, Raskin I, Salt DE. The role of EDTA in lead transport and accumulation by Indian mustard. Plant Physiol. 1998;117(2):447–53. doi:10.1104/pp.117.2.447. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Nakbanpote W, Kutrasaeng N, Jitto P, Prasad MNV. Chapter 9—Potential of ornamental plants for phytoremediation and income generation. In: Prasad MNV, editor Bioremediation and Bioeconomy. 2nd ed. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2024. p. 211–56. doi:10.1016/b978-0-443-16120-9.00017-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Arshad M, Naqvi N, Gul I, Yaqoob K, Bilal M, Kallerhoff J. Lead phytoextraction by Pelargonium hortorum: comparative assessment of EDTA and DIPA for Pb mobility and toxicity. Sci Total Environ. 2020;748(2):141496. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141496. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Meers E, Ruttens A, Hopgood MJ, Samson D, Tack FM. Comparison of EDTA and EDDS as potential soil amendments for enhanced phytoextraction of heavy metals. Chemosphere. 2005;58(8):1011–22. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2004.09.047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Liphadzi MS, Kirkham MB. Availability and plant uptake of heavy metals in EDTA-assisted phytoremediation of soil and composted biosolids. S Afr J Bot. 2006;72(3):391–7. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2005.10.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Wang Y, Xu Y, Qin X, Zhao L, Huang Q, Liang X. Effects of S,S-ethylenediamine disuccinic acid on the phytoextraction efficiency of Solanum nigrum L. and soil quality in Cd-contaminated alkaline wheat soil. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2021;28(31):42959–74. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-13764-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Kaur R, Bains TS, Bindumadhava H, Nayyar H. Responses of mungbean (Vigna radiata L.) genotypes to heat stress: effects on reproductive biology, leaf function and yield traits. Sci Hort. 2015;197:527–41. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2015.10.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Arnon DI. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts—polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris L. Plant Physiol. 1949;24(1):1–15. doi:10.1104/pp.24.1.1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Bremner JM, Mulvaney CS. Nitrogen—total. In: Page AL, Miller RH, Keeney DR, editors. Methods of soil analysis: part 2 chemical and microbiological properties. Madison, WI, USA: American Society of Agronomy; 1983. p. 595–624. [Google Scholar]

30. Steel RGD, Torrie JH. Principles and procedures of statistics: a biometrical approach. 2nd ed. New York, NY, USA: McGraw-Hill; 1984. 633 p. [Google Scholar]

31. Sengar RS, Gautam M, Garg SK, Chaudhary R, Sengar K. Effect of lead on seed germination, seedling growth, chlorophyll content and nitrate reductase activity in mung bean (Vigna radiata). Res J Phytochem. 2008;2(2):61–8. doi:10.3923/rjphyto.2008.61.68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Khan ZI, Ahmad K, Bibi HF, Ahmad I, Muhammad FG, Ashfaq A, et al. Heavy metals and proximate analysis of Sihar (Rhazya stricta Decne) collected from different sites of Warcha salt mine, Salt Range, Pakistan. Int J Appl Exp Biol. 2023;2(1):47–57. doi:10.56612/ijaeb.v2i1.46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Li H, Liu Y, Zeng G, Zhou L, Wang X, Wang Y, et al. Enhanced efficiency of cadmium removal by Boehmeria nivea (L.) Gaud. in the presence of exogenous citric and oxalic acids. J Environ Sci. 2014;26(12):2508–16. doi:10.1016/j.jes.2014.05.031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Nörtemann B. Biodegradation of chelating agents: EDTA, DTPA, PDTA, NTA, and EDDS. In: Biogeochemistry of chelating agents. Washington, WA, USA: American Chemical Society; 2005. p. 150–70. [Google Scholar]

35. Yang X, Yang J, Huang Z, Xu L. Influence of chelators application on the growth and lead accumulation of maize seedlings in Pb-contaminated soils. J Agro-Environ Sci. 2007;26:482–6. [Google Scholar]

36. Zhao S, Shen Z, Duo L. Heavy metal uptake and leaching from polluted soil using permeable barrier in DTPA-assisted phytoextraction. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2015;22(7):5263–70. doi:10.1007/s11356-014-3751-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Ghnaya T, Zaier H, Baioui R, Sghaier S, Lucchini G, Sacchi GA, et al. Implication of organic acids in the long-distance transport and the accumulation of lead in Sesuvium portulacastrum and Brassica juncea. Chemosphere. 2013;90(4):1449–54. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.08.061. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Arsenov D, Župunski M, Borišev M, Nikolić N, Pilipovic A, Orlovic S, et al. Citric acid as soil amendment in cadmium removal by Salix viminalis L., alterations on biometric attributes and photosynthesis. Int J Phytoremediat. 2020;22(1):29–39. doi:10.1080/15226514.2019.1633999. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Ali MA, Ashraf M, Athar HR. Influence of nickel stress on growth and some important physiological/biochemical attributes in some diverse canola (Brassica napus L.) cultivars. J Hazard Mater. 2009;172(2–3):964–9. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.07.077. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Athar HUR, Khan A, Ashraf M. Exogenously applied ascorbic acid alleviates salt-induced oxidative stress in wheat. Environ Exp Bot. 2008;63(1–3):224–31. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2007.10.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Athar HUR, Khan A, Ashraf M. Inducing salt tolerance in wheat by exogenously applied ascorbic acid through different modes. J Plant Nutr. 2009;32(11):1799–817. doi:10.1080/01904160903242334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Kibria M, Islam M, Osman K. Effects of lead on growth and mineral nutrition of Amaranthus gangeticus L. and Amaranthus oleracea L. Soil Environ. 2009;28(1):1–6. [Google Scholar]

43. Kopittke PM, Asher CJ, Kopittke RA, Menzies NW. Toxic effects of Pb2+ on growth of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata). Environ Pollut. 2007;150(2):280–7. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2007.01.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Bhardwaj P, Chaturvedi A, Pratti P. Effect of enhanced lead and cadmium in soil on physiological and biochemical attributes of Phaseolus vulgaris L. Nat Sci. 2009;7:63–75. [Google Scholar]

45. Grejtovský A, Markušová K, Nováková L. Lead uptake by Matricaria chamomilla L. Plant Soil Environ. 2008;54(2):47–54. doi:10.17221/2784-pse. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Ashraf U, Kanu AS, Deng Q, Mo Z, Pan S, Tian H, et al. Lead (Pb) toxicity; physio-biochemical mechanisms, grain yield, quality, and Pb distribution proportions in scented rice. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:259. doi:10.3389/fpls.2017.00259. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Turgut C, Katie Pepe M, Cutright TJ. The effect of EDTA and citric acid on phytoremediation of Cd, Cr, and Ni from soil using Helianthus annuus. Environ Pollut. 2004;131(1):147–54. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2004.01.017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools