Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

From Nature to Innovation: Exploring the Functional Properties and Multifaceted Applications of Seed Mucilage

1 Department of Food Technology and Nutrition, School of Agriculture, Lovely Professional University, Phagwara, 144411, India

2 Fruit Trees and Vine Research Program, National Institute for Agricultural Research (INRA), Regional Center of Meknes, Meknes, BO 578, Morocco

3 Laboratory of Biotechnology, Conservation and Valorisation of Bioresources (LBCVB), Faculty of Sciences Dhar El Mehraz, Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University, Fez, BP 1796, Morocco

* Corresponding Authors: Nouha Haoudi. Email: ; Sonia Morya. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Vegetable Resources, Sustainable Plant Protection and Adaptation Strategies to Climate Change)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(9), 2669-2700. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.065058

Received 02 March 2025; Accepted 17 June 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

The trends of consuming or using eco-friendly, biodegradable products due to the change in the lifestyle of the people have led to the exploration of new sources from plants or animals. Seed mucilage (SeM) is an underexplored component of plants that can be brought into play to deal with such problems. Mucilage, a viscous polysaccharide that can be obtained when seeds like chia, flax, garden cress, and tomato get hydrated and form a slimy, gel-like substance around the seed coat, can be utilized due to its unique characteristics. It has been used in developing many products such as bio-based films, plant-based dressing wounds with antibacterial effects, a medium for oral drug delivery, edible coatings, etc. Primarily composed of soluble fiber, it exhibits effects on human health, including blood glucose management, cholesterol, weight reduction, antioxidant (AOx), and antimicrobial activity. It offers a range of functional properties, including emulsification, stabilization, foam formation, fat replacement, encapsulating agent, flocculation, coagulation, and medium for drug release. These attributes make SeM a suitable component for applications in various sectors like food and pharmacy. Further study in this field may open more opportunities to address environmental problems and contribute to sustainability. This review explores aspects of SeM, emphasizing its functional properties and highlighting its current as well as potential applications across various sectors.Keywords

Mucilage is a lipophilic polysaccharide comprised of monosaccharides, uronic acids, glycoproteins, and different types of bioactive compounds. This plant-derived polysaccharide becomes an enticing choice for a shift towards sustainable and biodegradable polymers in various sectors, including food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries, with applications such as emulsifier, gelling agent, fat-replacer, and thickener [1]. Given its strong film-forming ability, it has also been utilized to create bio-based films [2]. Polysaccharide-based films are regarded as superior amongst the emerging sustainable coating/packaging materials [3]. In addition, mucilage acts as an additive and an encapsulating agent, providing anti-inflammatory, anti-hypercholesterolemic, laxative, and antibacterial effects [4].

Mucopolysaccharides are obtained from living organisms, including plants, bacteria, fungi, and animals. Compared to the mucilage obtained from the green algae and phytoplankton, which is typically created under stress conditions, the ones sourced from plants are readily available and formed as an integral part of the plant cells. They are considered to be safe, bio-based products, economical, and eco-friendly [5,6]. Mucilage generally consists of two major fractions of polysaccharides, specifically hemicellulose (made up mostly of arabinoxylans, AXY) and pectin (arising from rhamnogalacturonan I, RHG-I) [5,7]. Neutral sugars such as D-xylose, D-galactose, and L-arabinose are spotted. Additionally, glycosidic linkages bind uronic acid residues to methyl pentose, pentose, and galactose. Biologically active compounds, including steroids, alkaloids, tannins, and phenolic compounds, are also found. Depending on the plant species, the functional properties and chemical composition vary greatly. Besides, agronomic variations related to climate, soil, and hydration conditions have a significant impact on the chemical composition of the mucilage. The physiological and morphological characteristics of the plants and the extraction methods employed consequently affect the nutritional value and the yield of the mucilage [4,5,8].

The secretion or the production of mucilage from various parts of the plants, including roots, leaves, stems, and seeds, helps in withstanding any changes in the environmental conditions. Especially in the seeds, it acts as a protective layer and promotes germination, seed dispersal, and seed coat formation. The capacity to generate mucilage by the fruit pericarp or seed coat upon imbibition is named myxodiaspory. The outer cell layer of the fruit that has the potential to produce mucopolysaccharides is termed myxocarpy [9]. The specific type of plant undergoes myxospermy, a significant feature of the plant having the capacity to produce mucilage by commencing the differentiation of the seed coat epidermis upon fertilization. This leads to the formation of mucilage in the Golgi Apparatus, which is then secreted into the apoplastic compartment through secretory vesicles [4,10]. Furthermore, it forms a gel-like clear covering around the seed and acts as a protective covering, along with functional benefits like moisture retention, protection against harsh environmental conditions, and protection from the attack of pathogenic microorganisms. SeM is primarily composed of cellulose, pectin, and hemicellulose [11]. Seed-derived mucilage, synthesized by plants including Arabidopsis thaliana, basil, clary sage, and flaxseed, possesses hydrophilic properties, offering diverse applications and functional properties. The potential of the seed mucilage extends beyond the food sector. It has been used in the pharmaceutical and cosmetic sectors for peroral delivery and stabilizers, respectively [4,12,13]. This review focuses on the applications and functional properties of some selected seed mucilage sources such as tomato, fenugreek, balangu, sicklepod, basil, tamarind, garden cress, broadleaf plantain, sage, and quince. It further highlights the factors affecting the seed-derived mucilage, limitations, and prospects. Research findings on the new applications of the selected seed-derived mucilage sources have been elucidated and consolidated. For instance, novel biodegradable films from tomato SeM and gelatin at different ratios by incorporating plasticizers like polyethylene, glycerol, and sorbitol were prepared. Although it is a good option for food packaging, it was observed to be inferior to synthetic ones in terms of barrier properties and not scalable at the industrial level [14]. Carboxymethylated and thiolated sicklepod SeM developed for drug delivery was observed to improve the disintegration property in the carboxymethylated one and the bio-adhesive property in the thiolated one [15]. Additionally, the review expects further exploration in future research regarding the unknown applications and improvement in its extraction and uses in various industries. Table 1 shows the composition, benefits, and applications of mucilage from various plants.

Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) processing produces an enormous amount of waste which mostly comprises seed and peel, with seeds making up 60% and peel 40% of the total waste [18,54]. A beneficial polysaccharide called mucilage primarily consists of arabinose, rhamnose, xylose, glucose, and galactose. Glucose and rhamnose surround the tomato seeds, whereas xylose forms the majority of the tomato SeM [2,55]. Owing to its polysaccharide composition, tomato SeM possesses film-forming ability, which can be used as edible packaging. It has been observed that the addition of titanium dioxide to the film increased its antibacterial activity against certain Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [14]. A study reported the use of tomato SeM incorporated with shallot essential oil as an active coating to reduce the rate of physical, microbial, chemical, and color changes in Oncorhynchus mykiss fillet [56]. Besides, tomato SeM also finds its applications in the formulation of edible coatings and encapsulation to improve sensory properties and keep the quality of ketchup [57]. Polysaccharides extracted from black tomato pomace showed significantly higher emulsifying capacity compared to acid-extracted potato, apple, and citrus pectins. These polysaccharides may be utilized as emulsifiers and stabilizers in the food sector [58].

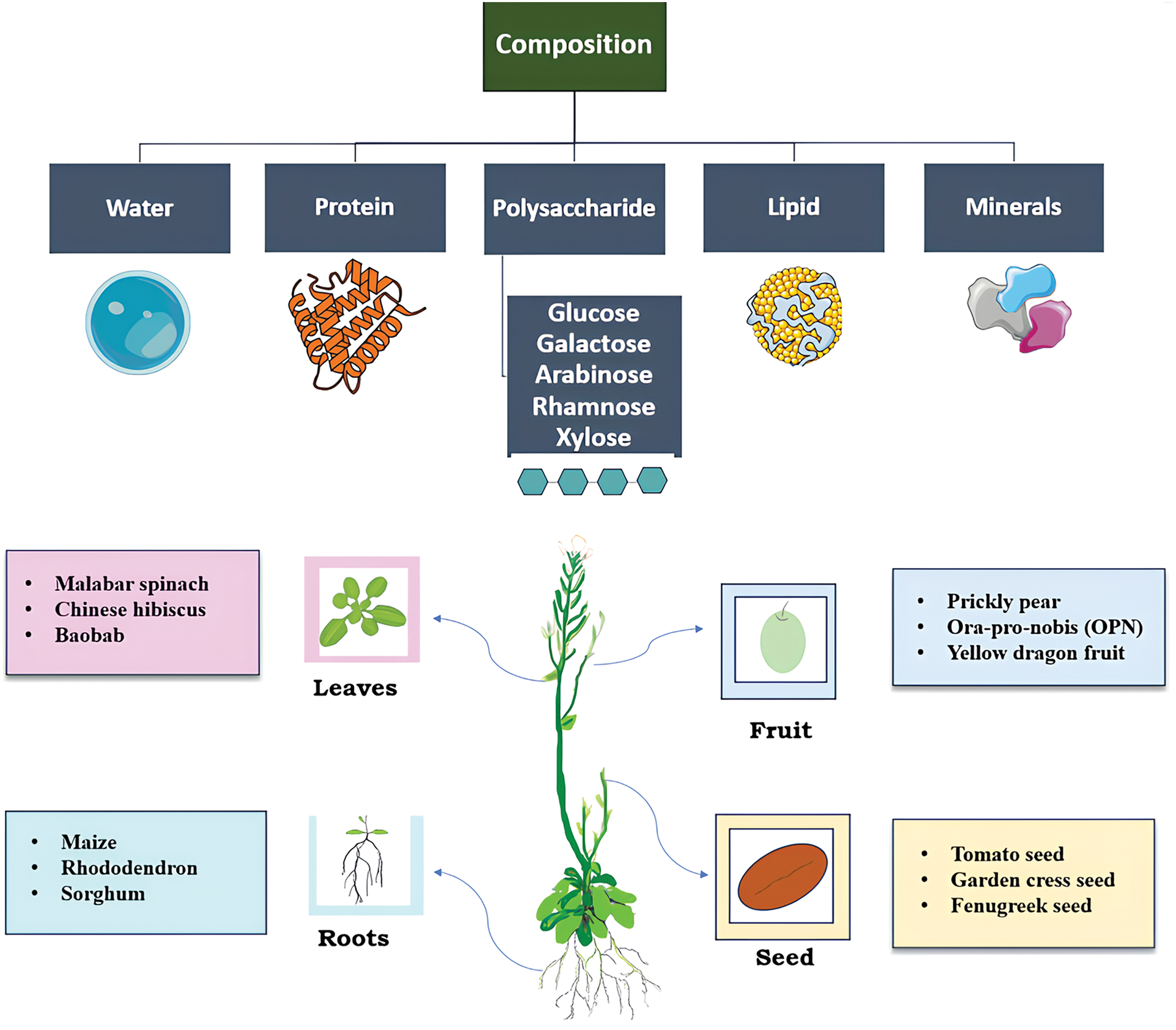

Trigonella foenum-graecum, which is commonly known as fenugreek, belongs to the leguminous family Fabaceae. It is widely cultivated in Western Asia, Europe, the Mediterranean, and Asia for culinary and medicinal purposes. The seeds of the fenugreek add flavor to the food. The ripe seeds of the fenugreek are comprised of bioactive substances that offer a great deal in the food industry and medicine [52]. Fenugreek SeM, which is naturally available in fenugreek, helps in facilitating the hydration and germination of the seeds. It is considered to be biocompatible, non-irritating, and non-toxic biomolecules. The mucilage content is high in the fenugreek seed and exhibits antidiabetic properties [53]. Fenugreek SeM is comprised of polysaccharides along with other bioactive molecules like steroids, amino acids, alkaloids, saponins, and flavonoids. It has 45%–60% carbohydrates, out of which around 30% is soluble fiber and 20% is insoluble fiber [52,59]. The general composition of plant mucilage and its sources are shown in Fig. 1. Fenugreek SeM acts as a gelling agent and thickener (suspending agent) in the food industry [60]. The film-forming ability of the SeM enables its application in food packaging, pharmaceuticals, and various industries with great opportunities for the development of sustainable and bio-based materials [3]. It has good water solubility [61]. In pharmaceutical industries, it is used as a mucoadhesive gelling agent, binding agent, and disintegrating agent, providing great potential as an absorbent for capturing substances from the aqueous solution [52]. Recently, Hussain et al. [62] prepared a pH-responsive colloidal gel system from fenugreek SeM for better oral availability of methotrexate. Moreover, fenugreek SeM is considered to be a promising medium for oral drug delivery.

Figure 1: Various sources of plant mucilage and their composition

Balangu (Lallemantia royleana) is an annual herb belonging to the family Lamiaceae. The mucilage of balangu seed is a high molecular weight polysaccharide, resulting in its many functional properties. This plant is commonly grown in Iran, Turkey, and India. The seed forms mucilage when it comes in contact with water. Traditionally, its seeds are used for many purposes, including the treatment of ailments, including inflammation and cough, as a sexual stimulant, as well as seed oil for medicinal purposes [48,49]. Balangu SeM finds its applications in various sectors due to its beneficial properties [63]. Balangu SeM is majorly composed of carbohydrates, consisting of arabinose, galactose, xylose, glucose, and rhamnose. Apart from this, balangu SeM composition includes around 9.9% ash, 9.4% moisture, 3.8% protein, and 82.56 µg GAE/mg total phenolic content [47].

Owing to its high molecular weight, balangu SeM can be used as a foam stabilizer. The SeM offers a wide range of functional properties. Given its potential to develop edible films with improved mechanical and barrier properties, it is ideal for food packaging [64]. When used in combination with cumin essential oil as an edible coating, it showed improved shelf life, reduced lipid oxidation, and microbial spoilage [48]. The SeM has antibacterial and AOx effects due to the presence of active compounds. Because of its high uronic acid and protein content, the supernatant fraction of its water-soluble polysaccharides exhibits the best emulsifying performance when fractionated according to molecular weight [49].

Cassia obtusifolia L, commonly known as sicklepod or Chinese senna, is an annual herb that belongs to the Leguminosae family. It is extensively found in Brazil and is native to West India and Central and tropical America. Cassia obtusifolia has many health-boosting properties like reducing hypertension, enhancing eyesight, reducing blood glucose levels, and immunomodulatory effects [50,51]. The mucilage of sicklepod seed has been found to have polysaccharides which are useful in film formation for drug delivery and have properties like swelling capacity, mucoadhesive property, and flexibility [15,65]. The sicklepod SeM primarily consists of polysaccharides, which make up approximately 68% of its composition. The mucilage lacks steroids, starch, glycosides, tannins, and alkaloids [50]. Different fractions of sicklepod SeM have varying compositions. The fraction obtained using 30% ethanol majorly consists of branched galactomannan. On the other hand, the fraction obtained using 40% ethanol has a high concentration of xylose and a low concentration of galactose and mannose [66].

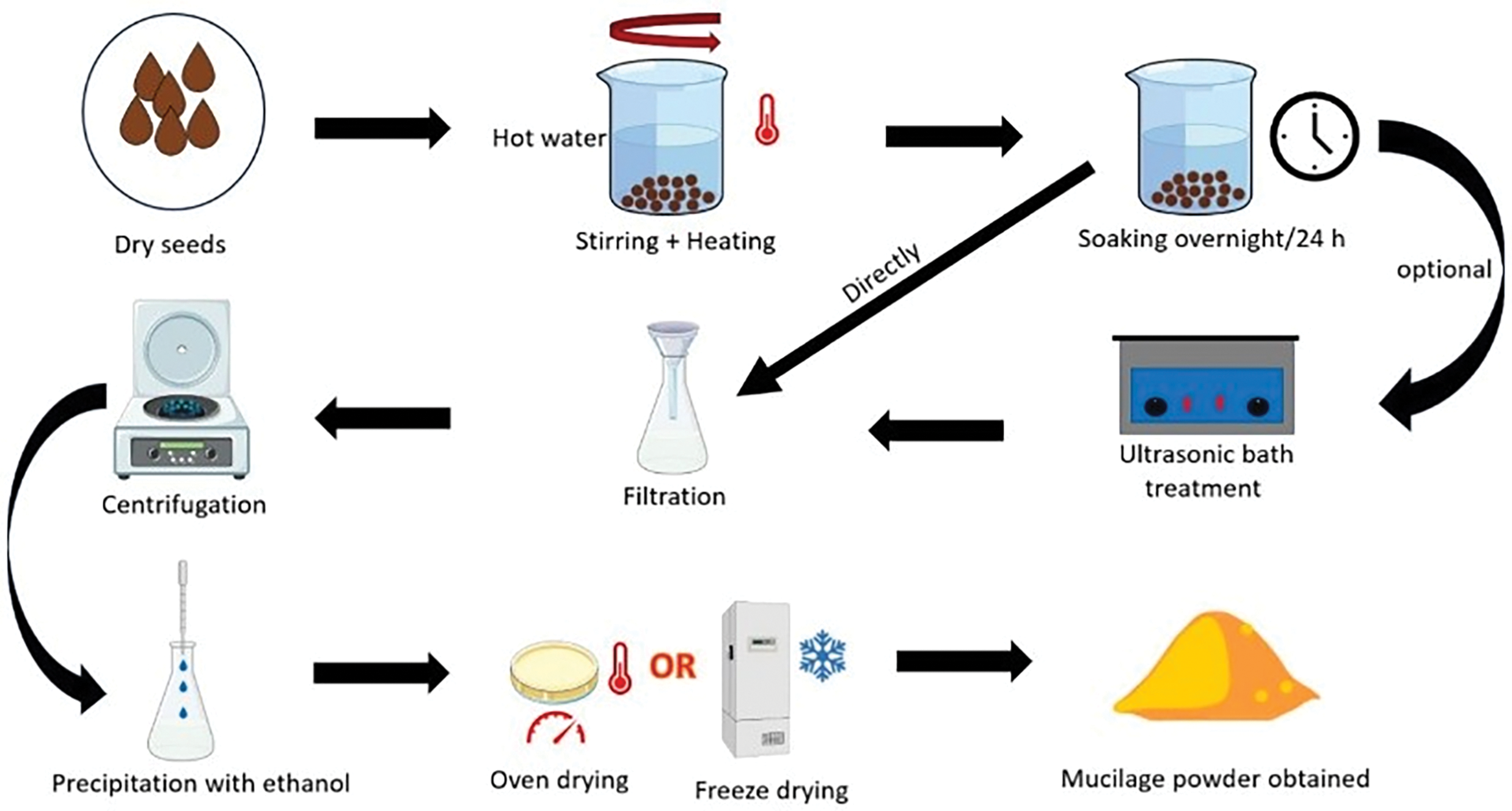

The SeM can be extracted using hot water, followed by purification and drying to get a free-flowing powder. The general method for the extraction of SeM is given in Fig. 2. Sickle pod SeM has several functional properties. The film formed using the mucilage is flexible, non-irritating, chemically stable, has good tensile strength, and mucoadhesive properties. Carboxylation and thiolation of sicklepod SeM result in the improvement of bio-adhesive properties and lower the disintegrating time for drug delivery [15,50]. The mucilage has immunomodulatory activity, showing a stimulating effect on macrophages [64]. Carboxymethyl-substituted sicklepod SeM shows improved swelling properties, flow behavior, degree of crystallinity, and reduced viscosity of aqueous dispersion [65].

Figure 2: General extraction method of Seed mucilage

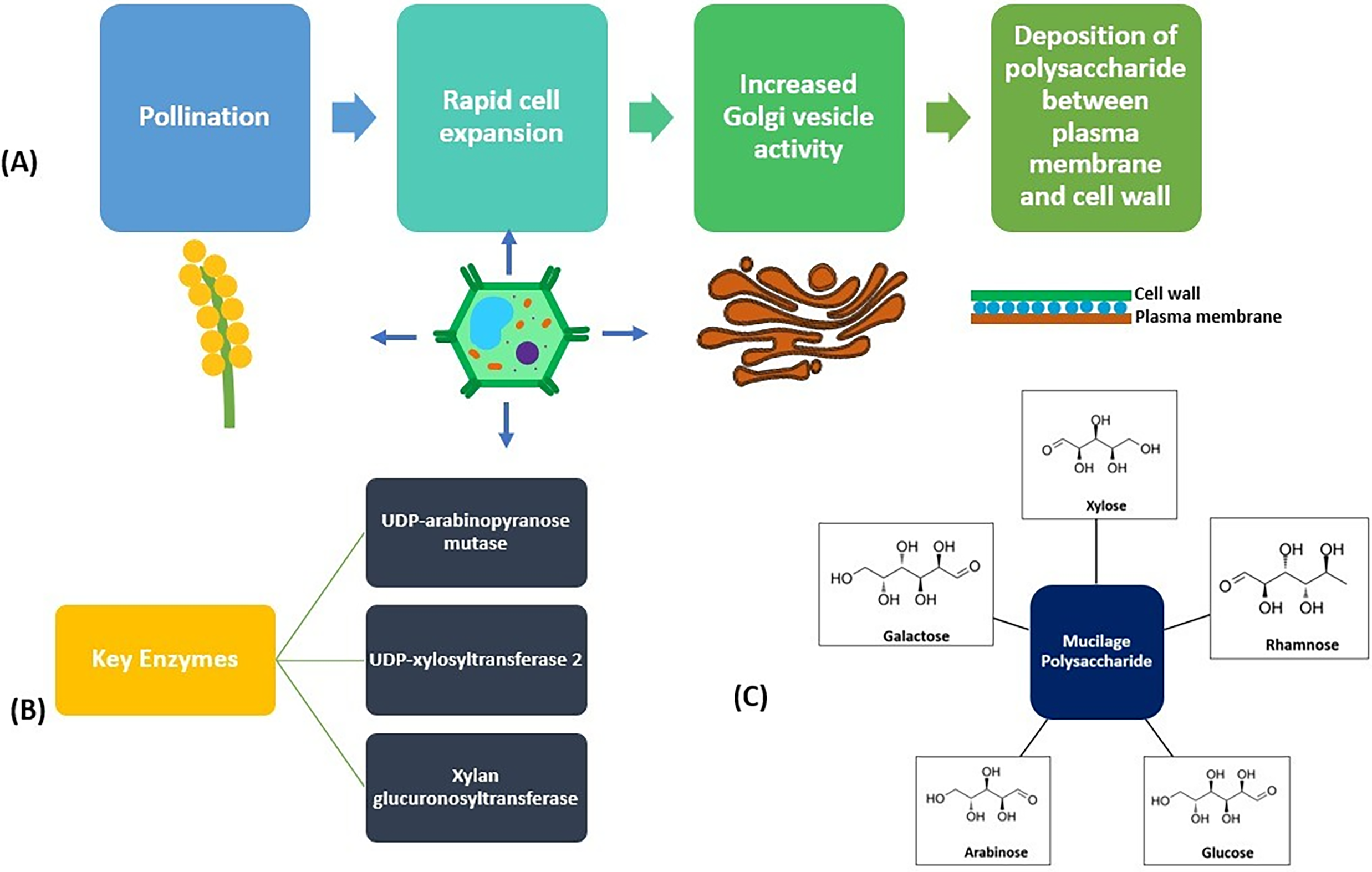

Ocimum basilicum L., which is commonly known as basil, comes under the family of Lamiaceae. It has been predominantly grown in the Himalayan region of Jammu and Kashmir, India. Upon hydration, mucilaginous substances are eventually formed around the seeds [24]. Approximately, basil SeM is comprised of carbohydrates (79.6%), lipids (9.7%), moisture (8.1%), ash (3.3%), protein (1.6%), and starch (1.53%). It consists of two major fractions, one of which is acid-stable glucomannan with a ratio of glucose to mannose of 10:2, and the other one is xylan, which has (1, 4) glycosidic linkages having acidic side chains at C-2 and C-3 at the xylosyl part. Moreover, there is also a minor portion of glucan, constituting 2.31%, and a highly branched arabinogalactan [67]. The carbohydrates of the basil SeM consist of glucose, galacturonic acid, rhamnose, mannose, glucuronic acid, arabinose, and galactose in the ratio of 3.54:2.56:1.56:0.46:0.99:0.21: 0.12 M accordingly [23]. Fig. 3 depicts the structure, synthesis pathway of mucilage, and key enzymes involved in its formation.

Figure 3: Depiction of structure, key steps, and enzymes involved in seed mucilage formation. (A) shows the key steps involved in mucilage synthesis. The key enzymes involved in mucilage synthesis are depicted in (B). (C) shows the structure of major polysaccharides present in seed mucilage

The highly viscous nature of basil SeM contributes to its good foaming properties [24]. Due to its low production cost, biocompatibility, eco-friendliness, and great rheological properties, basil SeM has shown great potential as a film-forming agent [68]. It has also been used in man-made heart coatings, skin operations, bio-detection systems, contact lenses, edible films, drug delivery systems, etc. [23]. According to the study conducted by Hasheminya [69], films developed from basil SeM with the incorporation of zinc oxide nanoparticles have been shown to have an effect with varying concentrations of zinc oxide nanoparticles. With the increase in the concentration of zinc oxide nanomaterials, the films are observed to have lower oxygen permeability, moisture content, water vapor permeability, water solubility, and a rise in tensile strength.

Tamarindus indica, also known as tamarind or Indian date, belongs to the leguminous family Fabaceae. It is predominantly grown in Asian countries like India, Thailand, Malaysia, Myanmar, and Bangladesh, and other countries like South America and Africa. India is the largest producer and exporter of tamarind. Tamarind seed is obtained as a by-product during tamarind processing. Mucilage can be extracted from these seeds, which could significantly reduce waste generation and would help in increasing the economies of the producer [70–72].

It has been found that tamarind seed contains ~72% mucilage. Tamarind SeM is composed of galactose, glucose, and xylose as the primary polysaccharides in a ratio of ~1:3:2, with a molecular weight ranging from 700–880 kDa. Essential amino acids such as valine, phenylalanine, leucine, lysine, methionine, and isoleucine are present in high concentrations [71]. Tamarind SeM comprises ash content (2.45%–3.30%), proteins (12.77%–15.40%), carbohydrates (61%–72.2%), and fat (3%–7.5%) [41]. It is made up of β-(1,4)-D-D-glucan backbone replaced with side chains of α-(1,4)-D-xylopy-ranose and (1,6) linked [β-D-galactopyranosyl-(1,2)-α-D-xylopyranosyl] to glucose residues [70]. It has been found that tamarind SeM has high stability (>82%). Its particles are thermostable until 175°C [72]. It is chemically stable, biocompatible, non-toxic, edible, eco-friendly, and non-carcinogenic. Due to its high viscosity and pH tolerance across a wide range of pH and temperature conditions, and other functional properties, it is a biomaterial that is a good choice for conservation [41].

Lepidium sativum L., commonly known as garden cress, is an annual herb (family Brassicaceae). It is a fast-growing herb that originated from Asia and Egypt [73]. When the seed is immersed in water, the mucilage on its coat swells up and envelopes the entire seed, creating a clear, colorless layer [74,75]. Its seeds give mucilage owing to their high polysaccharide content. The mucilage can be extracted by using hot water as the solvent. The seeds have properties like radical scavenging activity and egg re-placement [25,27]. The protein content of garden cress SeM ranges from 31.2% to 34.1%. Ash content ranges from 11.43% to 13.46%. The mucilage shows high AOx activity [25]. The polysaccharide content of garden cress is approximately 18.3%, which includes galacturonic acid, glucose, rhamnose, arabinose, and galactose. It also consists of cellulose and uronic acid [28].

Garden cress SeM has many functional properties which are useful in industry. The mucilage extracted using an ultrasonic bath showed high AOx activity (DPPH 88.9%). As compared to Butylated Hydroxytoluene, garden cress SeM showed more radical scavenging activity [25]. Microcapsules prepared from garden cress mucilage showed good retention of phenolic content. In simulated intestinal fluid, it showed high bio-accessibility of garden cress phenolic-rich extract as well as good storage stability [76]. Biopolymer extract of garden cress SeM contains functional groups like meth-oxy, carbonyl, carboxyl, and hydroxyl. The biopolymer’s anionic behavior was shown by its zeta potential. These properties make the biopolymer a good coagulating and flocculating agent that can be used for the removal of turbidity from wastewater [77]. Because of its reactive oxygen species scavenging potential, it shows a high antimicrobial effect, especially against Staphylococcus aureus. The polysaccharides extracted from garden cress seeds also showed diminishing growth effects against cancer cell lines. It also showed an anti-mutagenic effect, possibly due to its radical scavenging activity [26].

Plantago major (broadleaf plantain), belonging to the family Plantaginaceae, is a perennial herb widely distributed across the globe with various potential pharmaceutical and functional applications. Historically, it has been used in countless civilizations for wound healing, respiratory, and digestive ailments [78,79]. Mucilage from broadleaf plantain is primarily composed of high molecular weight polysaccharides. The seed’s outer coat (known as the seed coat) has polysaccharides that swell when they come in contact with water, creating a densely viscous mucilage. The polysaccharides obtained from the seeds with cold water consist of arabinose, xylose, and galacturonic acid; when re-extracting the remaining material with hot water, xylose, arabinose, galactose, and galacturonic acid were obtained [30].

Broadleaf plantain SeM is a useful natural polymer that may be used for multiple purposes as an abundant polysaccharide containing functional properties. The extracts of this plant show numerous biological activities, which make them potential components for therapeutic applications. They aid in wound healing by improving tissue regeneration and reducing recovery time. These remedies demonstrate anti-inflammatory and pain-reducing effects that enable a reduction in swelling and discomfort. Additionally, their AOx characteristics safeguard cells against oxidative harm, supporting overall well-being. These extracts also have immunomodulatory properties that regulate the immune system response, and their antiulcerogenic effect protects the stomach, thus reducing the risk of ulcers [79]. Plantago major SeM combined with Citrus limon essential oil coat for buffalo meat effectively reduced lipid oxidation for 10 days of storage at 4°C without affecting meat sensory characteristics [80]. Markers such as 25 inter-simple sequence repeat ISSR (Inter Simple Sequence Repeat) primers showed genetic diversity among Plantago species. P. amplexicaulis and P. psyllium showed the greatest variation of high levels of polymorphism (>80%) in thirty-one Plantago accessions from eight different species. The highest number of polymorphic bands and marker index were produced by ISSR-9, whereas the highest polymorphic information content values of ISSR-9 and IS01 indicate their effectiveness in genetic diversity assessment [81]. Another study evaluated drought risk index and marker-trait associations using ISSR and simple sequence repeats markers across multiple environments. Particularly in drought-stressed conditions, ISSRs found strong, consistent correlations with seed and mucilage characteristics and SSR markers connected to genes specific to drought. About 86% of 30 Plantago accessions performed better for mucilage under drought stress [82].

Wild sage seed, also known as Salvia macrosiphon (Lamiaceae family), has round and small seeds that form mucilage when the seeds come in contact with water [83]. It is an herbaceous plant with having strong lemon-like scent. It has high AOx as well as anti-inflammatory effects. It has about 30% uronic acid content with polysaccharides comprising mannose and galactose [46]. It consists of about 0.85% lipid, 8.17% ash, 6.72% moisture, 2.84% protein, and 1.67% crude fiber, along with 79.75% carbohydrate content [84]. It is widely utilized in the food and pharmaceutical industries. According to certain research, sage mucilage has a lot of potential as a thickening agent in food items. It also exhibits pseudoplastic properties. When Lactobacillus casei was encapsulated with sage SeM, its growth was enhanced [85]. The viability of Lactobacillus rhamnosus under stress and heat was increased by encapsulating it in this mucilage. Wild sage mucilage is utilized in a variety of applications, including as a class 1 preservative for fish, meat, poultry, and sauces. It also has antibacterial qualities, which make it a useful plant [46]. Wild sage seed gum has high-yield stress, viscosity, and strong shear-thinning characteristics [83].

Quince (Cydonia oblonga) is a fruit seed plant known for its high mucilage content. Quince SeM has been researched for application in the food and pharmaceutical industries due to its functional properties. Quince SeM is a water-soluble polysaccharide composed of glucuronic acid and glucu-ronoxylan-based substances [32,86]. Quince SeM’s highly cross-linked structure endows it with a superior thickening capability compared to many other seed gums, enabling it to form viscous colloidal suspensions with aqueous solutions. Its complex yet precise macromolecular architecture is responsible for its utility as a valued source of hydrocolloids, combining cellulosic fibers and water-soluble polysaccharides, prized for numerous industrial and culinary applications requiring a high degree of viscosity [87–89]. This mucilage can be extracted using various techniques as depicted in Table 2. The water holding capacity, which includes hydrodynamic water, physically bound water, and linked water, was measured at 92.50 ± 1.63, while the oil holding capacity, indicating oil absorption capacity, was measured at 19.30 ± 0.59 [31]. The plant has been used and prescribed in traditional Iranian medicine to treat health problems. The sedative leaves and the dysentery fruits. The seed also acts as a soothing agent for the throat and as an emulsifier for inhair-setting lotion formulations lotions [88]. Aghmiuni et al. [32] prepared a quince SeM-based scaffold, which was able to promote the adhesion of human adipose stem cells as well as the growth of fibroblasts, showing its potential application in wound dressings.

3 Research Studies Elucidation

Mucilage from tomato seeds, sage, and fenugreek has shown extensive applications in the food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic sectors. A study investigated the use of tomato SeM as a suitable material for the formation of biodegradable films. It mainly focused on the use and effects of glycerol and cellulose nanofibers on film properties. With the addition of 5% glycerol and 10% cellulose nanofibres, the thermal stability, mechanical strength, and barrier properties improved. Water and oxygen resistance was accelerated with the addition of cellulose nanofibers. The films formed had strong AOx and antimicrobial properties along with a UV-blocking effect [2]. A pH-responsive hydrogel was formed using fenugreek SeM to increase the oral bioavailability of methotrexate. The hydrogels were swollen maximum of around 384.7% at pH 7.4 and provided controlled methotrexate release for up to 24 h. Toxicity tests were performed, which did not show any harmful effects on normal cells or animal cells, and the hydrogels were less toxic to cancer cells compared to free methotrexate [62]. Sickle pods can be used as an additive form of drug delivery. A biodegradable film was formed, which showed a smooth surface on scanning electron microscopy, and X-ray diffraction showed an amorphous structure. In vitro degradation, simulated body fluids, and oral acute toxicity showed that the sicklepod mucilage is a safe additive for drug delivery [50]. The antibacterial activity of basil SeM, a green wound dressing, was increased with the addition of aloe vera extract. The mucilage was cross-linked using malonic acid, which increased the stiffness and decreased porosity, swelling, and water retention to improve dimensional stability. The sponge cytotoxicity, mechanical characteristics, and hydrophilicity were unaffected by the addition of aloe vera extract. It considerably increased the antibacterial activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus [97].

Tamarind SeM was used as a wall material for the encapsulation of sesame oil using the spray drying technology. Two distinct wall-to-core ratios (1:1 and 1:2) were evaluated, which further revealed that both kinds of microcapsules exhibited good encapsulation efficiency and free-flowing characteristics (91.05% for the 1:1 ratio and 81.22% for the 1:2 ratio) [72]. Garden cress SeM was used as a natural nutraceutical for protection against enterocolitis. The mucilage that was extracted using the ultrasonication technique showed strong AOx activity. Rats that were pre-treated with the mucilage before receiving indomethacin showed lower levels of intestinal TNF-α, plasma LDH, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) than rats that were not treated. The intestinal malondialdehyde (MDA) showed lower levels, whereas intestinal reduced glutathione (GSH) was high [25]. The mucilage extracted from Plantago major L. seed was used as a natural cosmetic ingredient. The maximum yield of 18.4% mucilage was achieved under ideal circumstances at conditions of 140.5 min, a 0.0284 solvent-to-seed mass ratio, and a temperature of 80.2°C after the mucilage was removed and dried. The dried substance showed a structure resembling carbohydrates that was thermally stable. The mucilage showed a pseudoplastic rheological profile when it was gelled, re-sembling commercial polymers such as xanthan gum [96]. The addition of quince SeM to yogurt resulted in enhanced sensory properties. The addition of mucilage powder at 0.05% and 0.1% was considered acceptable by the panelists in terms of mouthfeel, flavor, and odor scores, however, increased amounts of SeM resulted in a decline in sensory qualities [98]. Table 3 shows potential applications of seed mucilage as per different studies.

4 Factors Affecting the Yield of Seed Mucilage

Based on the study undertaken, it has been reported that factors such as time, temperature, and water/seed ratio have a significant impact on the extraction yield of SeM. The highest yield (20.5 g/100 g) of basil SeM using an aqueous extraction method has been observed at a temperature of 50–65°C and an extraction time (2–3 h). The yield also increased with the increase in water/seed ratio (30:1) [95]. A study utilizing response surface methodology for the extraction of Plantago major SeM found that maintaining a pH of 6.8, a seed-to-water ratio of 1:60, and a temperature of 75°C resulted in a maximum yield of 15.18%. It also affected the functional properties, including foam stability, water absorption capacity, emulsion stability, and solubility [105]. In the case of the extraction of mucilage from Ximenia americana seed, the optimum conditions to attain the highest yield of 17.31% were a water/seed ratio of 37.62:1 v/w, a temperature of 65.06°C, and an extraction time of around 1.5 h [106]. Besides these factors, the extraction methods employed also play an important role in determining the yield of mucilage. Extraction methods like ultrasound and microwave are considered green technology. They are less time-consuming, requiring little to no use of organic solvents and full automation as compared to traditional extraction methods. The use of organic solvents and pressing in the ultrasound technique increases the yield but produces organic solvent residues. It has been found that an increase in the stirring time of the raw material increases the yield of mucilage [107]. As stated in the study conducted by Shiehnezhad et al. [108], it has been reported that mucilage recovery is slightly higher in the case of microwave-assisted extraction (17± 0.14%) than the conventional extraction (14.53 ± 0.25%) when both were provided with optimum conditions.

The films that were developed using seed mucilage with the incorporation of plasticizers are not scalable as they are inferior in terms of barrier and mechanical properties compared to synthetic ones [17]. In addition, the lipophilic nature of mucilage is also one of the factors limiting its uses in industries [2]. Microwave-assisted extraction is known for high-yield extraction (approx. 31.8%). However, it has been found to reduce the apparent viscosity and molecular weight, leading to the degradation of the mucopolysaccharides. Although ultrasound-assisted extraction has been used predominantly for the extraction, it still degrades the quality of the mucilage [13]. Extraction of mucilage (chia seed) using the conventional method reduces the extraction yield due to the partial removal of mucilage from the sources [109].

A decrease in the phenolic content occurs during the process of encapsulation. It can be due to the drying method that was employed [76]. Particle size influences the film-forming ability of the mucilage. The larger the particle size, the more it is prone to microbial attacks [56]. Although seed mucilage is packed with diverse applications that promote sustainability, further studies regarding the effect of antimicrobial activity on a large number of microbes and sensory aspects need to be carried out [52]. Titanium dioxide (0%, 0.5%, and 1%) nanoparticles were incorporated with different proportions of tomato SeM and gelatin. As the proportion of tomato SeM increased, changes such as an increase in color differences and yellowness index were observed. Contrarily, a decrease in lightness and whiteness index was observed. Significant inhibitory and deadly effects against a variety of bacteria were noted when the concentration of titanium dioxide was increased to 1% [17]. During the extraction of mucilage from chia seeds, incomplete removal or detachment occurs, which reduces its yield. The yield and quality of chia mucilage are influenced by extraction parameters such as temperature, duration, and water-to-seed ratio [109].

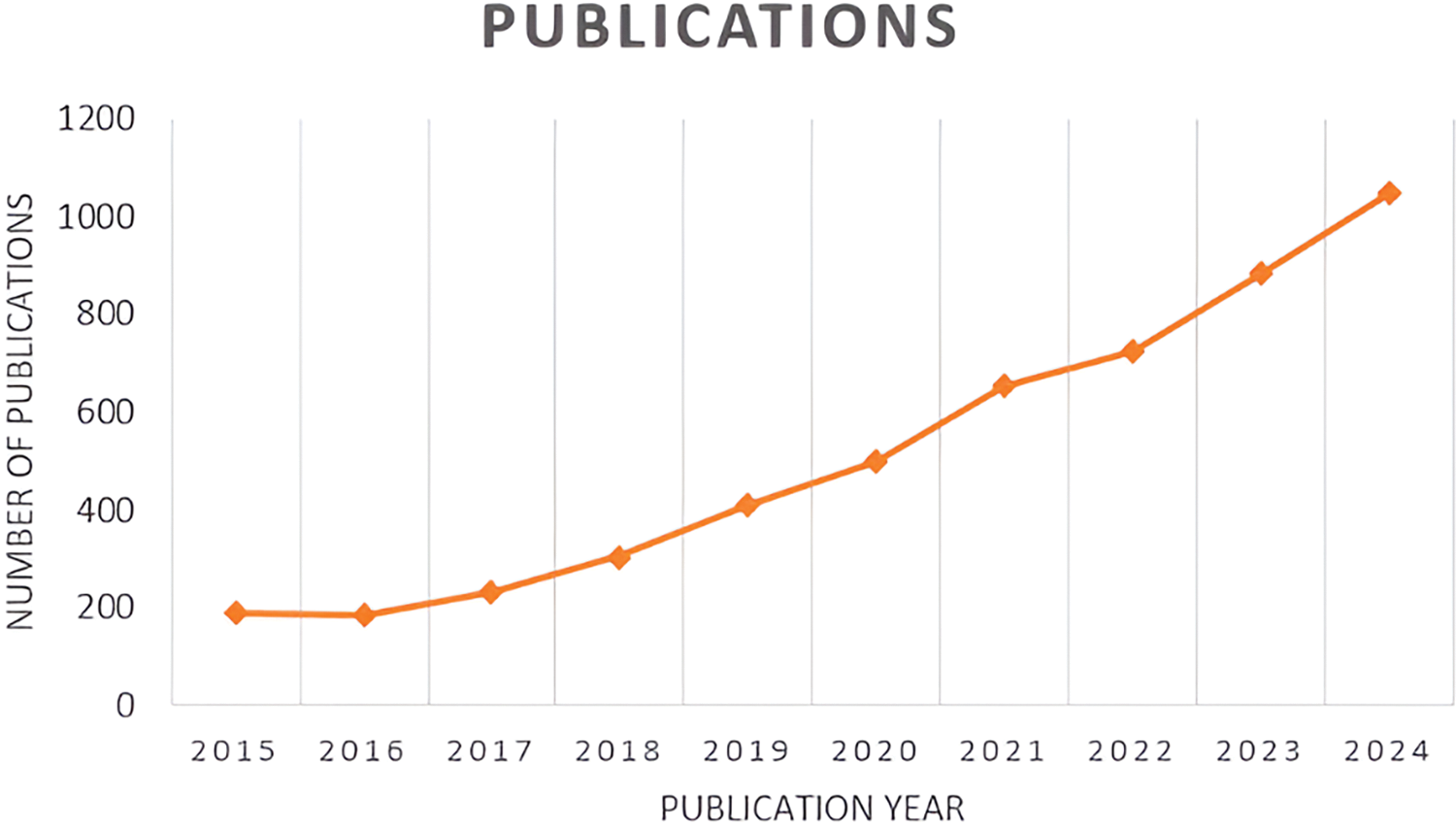

Seed mucilage has great potential for use in various industries. The functional properties of seed mucilage can be enhanced by blending it with other natural polymers. More research can be done on making stimuli-responsive hydrogels which can be used for smart drug delivery in response to factors such as temperature, pH, and pressure. Nanoparticles can be used as a seed coating for improved seed hydration which can lead to better seed germination, they can also act as a carrier for fertilizers, and the coating which contains antimicrobial properties can act as a barrier that can protect the seeds from pathogens and other bacterial growth. Research is required for the commercialization of products that can be made using seed mucilage. It can completely replace synthetic stabilizers, thickeners, and emulsifiers in food products. It can be used in plant-based meat alternatives such as gelatin or egg substitutes. It can replace synthetic polymers as bio-based adhesives and gels. The seed mucilage being hydrating, can be used to produce natural and biodegradable cosmetic products such as hair gels, and skin-care products. It can also have a thriving future in the nutraceutical industry. The mucilage obtained from different seeds can also act as a natural flocculant to purify water. Fig. 4 depicts a graph showing the approximate number of papers related to seed mucilage published each year from 2015 to 2024 (data taken from the Scopus database using search terms “seed mucilage” and “plant seed mucilage” while excluding the papers published before 2015 and after 2024).

Figure 4: A line graph illustrating the approximate number of seed mucilage-related papers published annually between 2015 and 2024 as per Scopus database

Seed mucilage has become a promising biomaterial that is sustainable and biodegradable. From the food and pharmaceutical industries to the environmental and cosmetic fields, mucilage utilization has increased in the past few years. Seed mucilage possesses many important functional properties that can pave the way for its extensive use, such as film-forming ability, water retention, and antioxidant potential, making it an ideal component for developing eco-friendly products. Being biodegradable, it can serve as a possible replacement for various artificial additives, contributing to sustainability and environmental protection. Despite its promising applications in various sectors, a few challenges need to be addressed, such as optimization of its mechanical and barrier properties, such as low tensile strength, high moisture sensitivity, inconsistent permeability, water and moisture resistance, and oil permeability. Seed mucilage is not only a biodegradable alternative to synthetic polymer but also a sustainable solution to many environmental problems. Many of these seeds come under the waste category, and if they are used to produce mucilage, they can act as a profitable by-product of industries. A few mucilage-rich seeds have been explored; however, it is clear that more research is required to uncover the full potential of the mucilage of these seeds and for them to be effectively used in industries.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank the academics, researchers, and scientists whose work has been referenced in this manuscript.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Sonia Morya; data collection: Livanshee Gupta, Lanjelina Oinam, Ananya Mahajan; analysis and interpretation of results: Sonia Morya, Nouha Haoudi; draft manuscript preparation: Livanshee Gupta, Lanjelina Oinam, Ananya Mahajan. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Cakmak H, Ilyasoglu-Buyukkestelli H, Sogut E, Ozyurt VH, Gumus-Bonacina CE, Simsek S. A review on recent advances of plant mucilages and their applications in food industry: extraction, functional properties and health benefits. Food Hydrocoll. 2023;3(7):100131. doi:10.1016/j.fhfh.2023.100131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Ghadiri Alamdari N, Salmasi S, Almasi H. Tomato seed mucilage as a new source of biodegradable film-forming material: effect of glycerol and cellulose nanofibers on the characteristics of resultant films. Food Bioproc Tech. 2021;14(12):2380–400. doi:10.1007/s11947-021-02721-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Mishra A, Mohite AM, Sharma N. Influence of particle size on physical, mechanical, thermal, and morphological properties of tamarind-fenugreek mucilage biodegradable films. Polym Bull. 2023;80(3):3119–33. doi:10.1007/s00289-022-04378-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Kučka M, Ražná K, Harenčár L, Kolarovičová T. Plant seed mucilage—great potential for sticky matter. Nutraceuticals. 2022;2(4):253–69. doi:10.3390/nutraceuticals2040020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Goksen G, Demir D, Dhama K, Kumar M, Shao P, Xie F, et al. Mucilage polysaccharide as a plant secretion: potential trends in food and biomedical applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;230(1):123146. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.123146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Waghmare R, R P, Moses JA, Anandharamakrishnan C. Mucilages: sources, extraction methods, and characteristics for their use as encapsulation agents. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022;62(15):4186–207. doi:10.1080/10408398.2021.1880362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Soukoulis C, Gaiani C, Hoffmann L. Plant seed mucilage as emerging biopolymer in food industry applications. Curr Opin Food Sci. 2018;22:28–42. doi:10.1016/j.cofs.2018.01.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Dybka-Stępień K, Otlewska A, Góźdź P, Piotrowska M. The renaissance of plant mucilage in health promotion and industrial applications: a review. Nutrients. 2021;13(10):3354. doi:10.3390/nu13103354. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Viudes S, Burlat V, Dunand C. Seed mucilage evolution: diverse molecular mechanisms generate versatile ecological functions for particular environments. Plant Cell Environ. 2020;43(12):2857–70. doi:10.1111/pce.13861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Huang D, Wang C, Yuan J, Cao J, Lan H. Differentiation of the seed coat and composition of the mucilage of Lepidium perfoliatum L.: a desert annual with typical myxospermy. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin. 2015;47(10):775–87. doi:10.1093/abbs/gmv078. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Tsai AYL, McGee R, Dean GH, Haughn GW, Sawa S. Seed mucilage: biological functions and potential applications in biotechnology. Plant Cell Physiol. 2021;62(12):1847–57. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcab133. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Kreitschitz A, Gorb SN. The micro- and nanoscale spatial architecture of the seed mucilage-comparative study of selected plant species. PLoS One. 2018;13(7):e0200522. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0200522. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Liu Y, Liu Z, Zhu X, Hu X, Zhang H, Guo Q, et al. Seed coat mucilages: structural, functional/bioactive properties, and genetic information. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2021;20(3):2534–59. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12742. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Davoudi S, Zandi M, Ganjloo A. Fabrication and characterization of novel biodegradable films based on tomato seed mucilage and gelatin plasticized with polyol mixtures. Food Bioprod Process. 2024;148:187–97. doi:10.1016/j.fbp.2024.03.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Deore UV, Mahajan HS, Surana SJ, Wagh RD. Thiolated and carboxymethylated Cassia obtusifolia seed mucilage as novel excipient for drug delivery: development and characterisation. Mater Technol. 2020;36(14):857. doi:10.1080/10667857.2020.1819302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Hovjecki M, Radovanovic M, Levic SM, Mirkovic M, Peric I, Miloradovic Z, et al. Chia seed mucilage as a functional ingredient to improve quality of goat milk yoghurt: effects on rheology, texture, microstructure and sensory properties. Fermentation. 2024;10(8):382. doi:10.3390/fermentation10080382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Davoudi S, Zandi M, Ganjloo A. Characterization of nanocomposite films based on tomato seed mucilage, gelatin and TiO2 nanoparticles. Prog Org Coat. 2024;192:108507. doi:10.1016/j.porgcoat.2024.108507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Kumar M, Tomar M, Bhuyan DJ, Punia S, Grasso S, Sá AGA, et al. Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) seed: a review on bioactives and biomedical activities. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;142(1):112018. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Kučka M, Harenčár Ľ, Ražná K, Nôžková J, Kowalczewski PŁ, Deyholos M, et al. Great potential of flaxseed mucilage. Eur Food Res Technol. 2024;250(3):877–93. doi:10.1007/s00217-023-04429-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Morya S, Menaa F, Jiménez-López C, Lourenço-Lopes C, BinMowyna MN, Alqahtani A. Nutraceutical and pharmaceutical behavior of bioactive compounds of miracle oilseeds: an overview. Foods. 2022;11(13):1824. doi:10.3390/foods11131824. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Troshchynska Y, Bleha R, Synytsya A, Štětina J. Chemical composition and rheological properties of seed mucilages of various yellow- and brown-seeded flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) cultivars. Polymers. 2022 Jan;14(10):2040. doi:10.3390/polym14102040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Gao X, Sharma M, Bains A, Chawla P, Goksen G, Zou J, et al. Application of seed mucilage as functional biopolymer in meat product processing and preservation. Carbohydr Polym. 2024;339(5):122228. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2024.122228. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Maqsood H, Uroos M, Muazzam R, Naz S, Muhammad N. Extraction of basil seed mucilage using ionic liquid and preparation of AuNps/mucilage nanocomposite for catalytic degradation of dye. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;164(4):1847–57. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.08.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Nazir S, Wani IA. Functional characterization of basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) seed mucilage. Bioact Carbohydr Diet Fibre. 2021;25(1):100266. doi:10.1016/j.bcdf.2021.100266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Akl EM. Characterization of garden cress mucilage and its prophylactic effect against indomethacin-induced enter-colitis in rats. Biointerface Res Appl Chem. 2021;12(6):7298–309. doi:10.33263/BRIAC126.72987309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Alkahtani J, Soliman Elshikh M, Almaary KS, Ali S, Imtiyaz Z, Bilal Ahmad S. Anti-bacterial, anti-scavenging and cytotoxic activity of garden cress polysaccharides. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2020;27(11):2929–35. doi:10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.07.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Sharma M, Bains A, Goksen G, Ali N, Rehman MZ, Chawla P. Arabinogalactans-rich microwave-assisted nanomucilage originated from garden cress seeds as an egg replacement in the production of cupcakes: market orientation and in vitro digestibility. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;282:136929. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.136929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Sharma S, Agarwal N. Nourishing and healing prowess of garden cress (Lepidium sativum Linn.)—a review. Int J Pharm Life Sci. 2011;2(4):742–52. [Google Scholar]

29. Niknam R, Ghanbarzadeh B, Ayaseh A, Rezagholi F. Barhang (Plantago major L.) seed gum: ultrasound-assisted extraction optimization, characterization, and biological activities. J Food Process Preserv. 2020;44(10):e14750. doi:10.1111/jfpp.14750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Niknam R, Ghanbarzadeh B, Ayaseh A, Adun P. Comprehensive study of intrinsic viscosity, steady and oscillatory shear rheology of Barhang seed hydrocolloid in aqueous dispersions. J Food Process Eng. 2019;42(4):e13047. doi:10.1111/jfpe.13047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Yousuf S, Maktedar SS. Utilization of quince (Cydonia oblonga) seeds for production of mucilage: functional, thermal and rheological characterization. Sustain Food Technol. 2023;1(1):107–15. doi:10.1039/D2FB00047H. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Izadyari Aghmiuni A, Heidari Keshel S, Sefat F, Akbarzadeh Khiyavi A. Quince seed mucilage-based scaffold as a smart biological substrate to mimic mechanobiological behavior of skin and promote fibroblasts proliferation and h-ASCs differentiation into keratinocytes. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;142(1):668–79. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.10.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Bakr RO, Amer RI, Attia D, Abdelhafez MM, Al-Mokaddem AK, El-Gendy AENG, et al. In-vivo wound healing activity of a novel composite sponge loaded with mucilage and lipoidal matter of Hibiscus species. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;135:111225. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Dantas TL, Alonso Buriti FC, Florentino ER. Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L.) as a potential functional food source of mucilage and bioactive compounds with technological applications and health benefits. Plants. 2021;10(8):1683. doi:10.3390/plants10081683. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Elkhalifa AEO, Alshammari E, Adnan M, Alcantara JC, Awadelkareem AM, Eltoum NE, et al. Okra (Abelmoschus Esculentus) as a potential dietary medicine with nutraceutical importance for sustainable health applications. Molecules. 2021;26(3):696. doi:10.3390/molecules26030696. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Santos FSD, de Figueirêdo RMF, de Queiroz AJM, Paiva YF, Moura HV, de Silva ETV, et al. Influence of dehydration temperature on obtaining chia and okra powder mucilage. Foods. 2023;12(3):569. doi:10.3390/foods12030569. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Fatima M, Rakha A, Altemimi AB, Van Bockstaele F, Khan AI, Ayyub M, et al. Okra: mucilage extraction, composition, applications, and potential health benefits. Eur Polym J. 2024;215(1):113193. doi:10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2024.113193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Garg SS, Gupta J. Guar gum-based nanoformulations: implications for improving drug delivery. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;229:476–85. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.12.252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Kazachenko AS, Akman F, Sagaama A, Issaoui N, Malyar YN, Vasilieva NY, et al. Theoretical and experimental study of guar gum sulfation. J Mol Model. 2021;27(1):5. doi:10.1007/s00894-020-04616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Khakimova B, Atkhamova S, Ruzmetova D, Kurambaev S, Samandarov A, Masharipova M, et al. Study on the acid polysaccharide from the purslane plant Portulaca olerácea. E3S Web Conf. 2023;434(11):03023. doi:10.1051/e3sconf/202343403023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. González-Martínez DA, Carrillo-Navas H, Barrera-Díaz CE, Martínez-Vargas SL, Alvarez-Ramírez J, Pérez-Alonso C. Characterization of a novel complex coacervate based on whey protein isolate-tamarind seed mucilage. Food Hydrocoll. 2017;72(5):115–26. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2017.05.035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Lin HC, Lin JY. Characterization of guava (Psidium guajava Linn) seed polysaccharides with an immunomodulatory activity. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;154(5):511–20. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.03.125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Martin AA, de Freitas RA, Sassaki GL, Evangelista PHL, Sierakowski MR. Chemical structure and physical-chemical properties of mucilage from the leaves of Pereskia aculeata. Food Hydrocoll. 2017;70(2):20–8. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2017.03.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Silva SH, Neves ICO, Oliveira NL, de Oliveira ACF, Lago AMT, de Oliveira Giarola TM, et al. Extraction processes and characterization of the mucilage obtained from green fruits of Pereskia aculeata Miller. Ind Crops Prod. 2019;140:111716. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.111716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Hosseini AR, Zahabi N. Fabrication and rheological properties of a novel interpenetrating network hydrogel based on sage seed hydrocolloid and globulin from the hydrocolloid extraction by-product. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;253(2):127452. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.127452. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Saadi MA, Sekhavatizadeh SS, Barzegar H, Behbahani BA, Mehrnia MA. Date yogurt supplemented with Lactobacillus rhamnosus (ATCC 53103) encapsulated in wild sage (Salvia macrosiphon) mucilage and sodium alginate by extrusion: the survival and viability against the gastrointestinal condition, cold storage, heat, and salt with low pH. Food Sci Nutr. 2024;12(10):7630–43. doi:10.1002/fsn3.4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Behbahani BA, Fooladi AAI. Shirazi balangu (Lallemantia royleana) seed mucilage: chemical composition, molecular weight, biological activity and its evaluation as edible coating on beefs. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;114(10):882–9. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.07.175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Behbahani BA, Imani Fooladi AA. Improving oxidative and microbial stability of beef using shahri balangu seed mucilage loaded with cumin essential oil as a bioactive edible coating. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2020;24(3):101563. doi:10.1016/j.bcab.2020.101563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Sardarodiyan M, Arianfar A, Sani AM, Naji-Tabasi S. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of water-soluble polysaccharide isolated from Balangu seed (Lallemantia royleana) gum. J Anal Sci Technol. 2019;10(1):17. doi:10.1186/s40543-019-0176-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Deore UV, Mahajan HS. Isolation and characterization of natural polysaccharide from Cassia Obtustifolia seed mucilage as film forming material for drug delivery. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;115:1071–8. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.04.174. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Wu DT, Liu W, Han QH, Wang P, Xiang XR, Ding Y, et al. Extraction optimization, structural characterization, and antioxidant activities of polysaccharides from cassia seed (Cassia obtusifolia). Molecules. 2019;24(15):2817. doi:10.3390/molecules24152817. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Lindi AM, Gorgani L, Mohammadi M, Hamedi S, Darzi GN, Cerruti P, et al. Fenugreek seed mucilage-based active edible films for extending fresh fruit shelf life: antimicrobial and physicochemical properties. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;269:132186. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.132186. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Tayel AA, Ebaid AM, Otian AM, Mahrous H, El Rabey HA, Salem MF. Application of edible nanocomposites from chitosan/fenugreek seed mucilage/selenium nanoparticles for protecting lemon from green mold. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;273(3):133109. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.133109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Solaberrieta I, Mellinas C, Jiménez A, Garrigós MC. Recovery of antioxidants from tomato seed industrial wastes by microwave-assisted and ultrasound-assisted extraction. Foods. 2022;11(19):3068. doi:10.3390/foods11193068. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Nascimento GE, Baggio CH, de Werner MFP, Iacomini M, Cordeiro LMC. Arabinoxylan from mucilage of tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum L.structure and antinociceptive effect in mouse models. J Agric Food Chem. 2016;64(6):1239–44. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.5b05734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Izadi H, Zandi M, Rafeiee G, Bimakr M. Effect of tomato seed mucilage coating enriched with shallot essential oil on frozen rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) fillet quality. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2024;57(9):103082. doi:10.1016/j.bcab.2024.103082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Ganje M, Sekhavatizadeh SS, Hejazi SJ, Mehrpooya R. Effect of encapsulation of Lactobacillus reuteri (ATCC 23272) in sodium alginate and tomato seed mucilage on properties of ketchup sauce. Carbohydr Polym Technol Appl. 2024;7(3):100486. doi:10.1016/j.carpta.2024.100486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Kumar M, Chandran D, Tomar M, Bhuyan DJ, Grasso S, Sá AGA, et al. Valorization potential of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) seed: nutraceutical quality, food properties, safety aspects, and application as a health-promoting ingredient in foods. Horticulturae. 2022;8(3):265. doi:10.3390/horticulturae8030265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Amiri S, Nabizadeh F, Rezazad Bari L. A novel source of food hydrocolloids from Trigonella elliptica seeds: extraction of mucilage and comprehensive characterization. J Sci Food Agric. 2022;102(15):7144–54. doi:10.1002/jsfa.12080. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Mr. Gorakhnath GS, Dr. Hingane LD. Characterization of fenugreek seeds mucilage and its evaluation as suspending agent. Int J Res Appl Sci Eng Technol. 2022;10(6):4382–6. doi:10.22214/ijraset.2022.44934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Gupta K. Formulation and evaluation of metformin using fenugreek seed mucilage used as a natural polymer. Int J Adv Pharm Sci Res. 2024;4(4):35–41. [Google Scholar]

62. Hussain HR, Bashir S, Mahmood A, Sarfraz RM, Kanwal M, Ahmad N, et al. Fenugreek seed mucilage grafted poly methacrylate pH-responsive hydrogel: a promising tool to enhance the oral bioavailability of methotrexate. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;202:1156–66. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.03.158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Sardarodiyan M, Arianfar A, Mohamadi Sani A, Naji-Tabasi S. Physicochemical properties and surface activity characterization of water-soluble polysaccharide isolated from Balangu seed (Lallemantia royleana) gum. J Food Meas Charact. 2020;14(6):3625–32. doi:10.1007/s11694-020-00552-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Sadeghi-Varkani A, Emam-Djomeh Z, Askari G. Physicochemical and microstructural properties of a novel edible film synthesized from Balangu seed mucilage. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;108(204):1110–9. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.11.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Verma S, Rimpy, Ahuja M. Carboxymethyl modification of Cassia obtusifolia galactomannan and its evaluation as sustained release carrier. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;164(2):3823–34. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.08.231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Feng L, Yin J, Nie S, Wan Y, Xie M. Fractionation, physicochemical property and immunological activity of polysaccharides from Cassia obtusifolia. Int J Biol Macromol. 2016;91:946–53. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.06.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Zhou D, Barney JN, Welbaum GE. Production, composition, and ecological function of sweet-basil-seed mucilage during hydration. Horticulturae. 2022;8(4):327. doi:10.3390/horticulturae8040327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Thessrimuang N, Prachayawarakorn J. Development, modification and characterization of new biodegradable film from basil seed (Ocimum basilicum L.) mucilage. J Sci Food Agric. 2019;99(12):5508–15. doi:10.1002/jsfa.9820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Hasheminya S, Dehghannya J, Ehsani A. Development of basil seed mucilage (a heteropolysaccharide)—polyvinyl alcohol biopolymers incorporating zinc oxide nanoparticles. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;253(10):127342. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.127342. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Alpizar-Reyes E, Varela-Guerrero V, Cruz-Olivares J, Carrillo-Navas H, Alvarez-Ramirez J, Pérez-Alonso C. Microencapsulation of sesame seed oil by tamarind seed mucilage. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;145(8):207–15. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.12.234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Geethalaxmi M, Sunil CK, Venkatachalapathy N. Tamarind seed polysaccharides, proteins, and mucilage: extraction, modification of properties, and their application in food. Sustain Food Technol. 2024;2(6):1670–85. doi:10.1039/d4fb00224e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Alpizar-Reyes E, Carrillo-Navas H, Gallardo-Rivera R, Varela-Guerrero V, Alvarez-Ramirez J, Pérez-Alonso C. Functional properties and physicochemical characteristics of tamarind (Tamarindus indica L.) seed mucilage powder as a novel hydrocolloid. J Food Eng. 2017;209:68–75. doi:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2017.04.026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Pignattelli S, Broccoli A, Renzi M. Physiological responses of garden cress (Lepidium sativum) to different types of microplastics. Sci Total Environ. 2020;727(9):138609. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138609. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Jain T, Grover K. A comprehensive review on the nutritional and nutraceutical aspects of garden cress (Lepidium sativum Linn.). Proc Natl Acad Sci India B Biol Sci. 2018;88(3):829–36. doi:10.1007/s40011-016-0780-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Tufail T, Khan T, Bader Ul Ain H, Morya S, Shah MA. Garden cress seeds: a review on nutritional composition, therapeutic potential, and industrial utilization. Food Sci Nutr. 2024;12(6):3834–48. doi:10.1002/fsn3.4018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Abdel-Aty AM, Barakat AZ, Mohamed SA. Garden cress gum and maltodextrin as microencapsulation coats for entrapment of garden cress phenolic-rich extract: improved thermal stability, storage stability, antioxidant and antibacterial activities. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2022;32(1):47–58. doi:10.1007/s10068-022-01171-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Lim BC, Lim JW, Ho YC. Garden cress mucilage as a potential emerging biopolymer for improving turbidity removal in water treatment. Process Saf Environ Prot. 2018;119(5):233–41. doi:10.1016/j.psep.2018.08.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Rahamouz-Haghighi S, Bagheri K, Sharafi A. Antibacterial activities and chemical compounds of Plantago lanceolata (Ribwort Plantain) and Plantago major (Broadleaf Plantain) leaf extracts. Pharma Biomed Res. 2023;9(3):183–200. doi:10.18502/pbr.v9i3.13624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Samuelsen AB. The traditional uses, chemical constituents and biological activities of Plantago major L. A review. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;71(1–2):1–21. doi:10.1016/S0378-8741(00)00212-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Noshad M, Alizadeh Behbahani B, Jooyandeh H, Rahmati-Joneidabad M, Hemmati Kaykha ME, Ghodsi Sheikhjan M. Utilization of Plantago major seed mucilage containing Citrus limon essential oil as an edible coating to improve shelf-life of buffalo meat under refrigeration conditions. Food Sci Nutr. 2021;9(3):1625–39. doi:10.1002/fsn3.2137. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Bagheri M, Heidari B, Dadkhodaie A, Heidari Z, Daneshnia N, Richards CM. Analysis of genetic diversity in a collection of Plantago species: application of ISSR markers. J Crop Sci Biotechnol. 2021;25(1):1–8. doi:10.1007/s12892-021-00107-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Sharirari Z, Heidari B, Salami M, Richards CM. Analysis of drought risk index (DRI) and marker-trait associations (MTAs) for grain and mucilage traits in diverse Plantago species: comparative analysis of MTAs by arithmetic and BLUP means. Ind Crops Prod. 2024;222(25):119699. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2024.119699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Razavi SMA, Mohammadi Moghaddam T, Emadzadeh B, Salehi F. Dilute solution properties of wild sage (Salvia macrosiphon) seed gum. Food Hydrocoll. 2012;(1):29. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2012.02.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Mohammadzadeh H, Koocheki A, Kadkhodaee R, Razavi SMA. Physical and flow properties of d-limonene-in-water emulsions stabilized with whey protein concentrate and wild sage (Salvia macrosiphon) seed gum. Food Res Int. 2013;53(1):312–8. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2013.05.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Nasiri H, Golestan L, Shahidi SA, Darjani P. Encapsulation of Lactobacillus casei in sodium alginate microcapsules: improvement of the bacterial viability under simulated gastrointestinal conditions using wild sage seed mucilage. J Food Meas Charact. 2021;15(5):4726–34. doi:10.1007/s11694-021-01022-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Hussain MA, Muhammad G, Haseeb MT, Tahir MN. Quince seed mucilage: a stimuli-responsive/smart biopolymer. In: Jafar Mazumder MA, Sheardown H, Al-Ahmed A, editors. Funct biopolymers. Cham, Swizerland: Springer; 2019. p. 1–22. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-92066-5_19-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

87. Erkaya Kotan T, Gürbüz Z, Dağdemir E, Şengül M. Utilization of edible coating based on quince seed mucilage loaded with thyme essential oil: shelf life, quality, and ACE-inhibitory activity efficiency in Kaşar cheese. Food Biosci. 2023;54(7):102895. doi:10.1016/j.fbio.2023.102895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

88. Jouki M, Tabatabaei Yazdi F, Mortazavi SA, Koocheki A. Quince seed mucilage films incorporated with oregano essential oil: physical, thermal, barrier, antioxidant and antibacterial properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2014;36(16):9–19. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2013.08.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

89. Trigueros L, Pérez-Alvarez JA, Viuda-Martos M, Sendra E. Production of low-fat yogurt with quince (Cydonia oblonga Mill.) scalding water. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2011;44(6):1388–95. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2010.12.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

90. Izadi H, Zandi M, Rafeiee G, Bimakr M. Tomato seed mucilage-whey protein isolate coating enriched with shallot essential oil: effect on quality changes of the trout fish fillet during cold storage. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2024;58(9):103149. doi:10.1016/j.bcab.2024.103149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

91. Raham M, Houshang N, Yousef A. Improving yield, mucilage and seed oil of the Balangu (Lallemantia spp.) landraces in dryland conditions. J Agric Sci Eng. 2022;4(1):13–9. [Google Scholar]

92. Kozlu A, Elmacı Y. Quince seed mucilage as edible coating for mandarin fruit; determination of the quality characteristics during storage. J Food Process Preserv. 2020;44(11):e14854. doi:10.1111/jfpp.14854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

93. Şimşek E, Karaca B, Arslan YE. Bioengineered three-dimensional physical constructs from quince seed mucilage for human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. J Bioact Compat Polym. 2020;35(3):240–53. doi:10.1177/0883911520912702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

94. Ghadermazi R, Khosrowshahi Asl A, Tamjidi F. Optimization of whey protein isolate-quince seed mucilage complex coacervation. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;131(2):368–77. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.03.096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

95. Nazir S, Wani IA, Masoodi FA. Extraction optimization of mucilage from Basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) seeds using response surface methodology. J Adv Res. 2017;8(3):235–44. doi:10.1016/j.jare.2016.12.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

96. Rocha MEB, Kakuda L, Souto EB, Oliveira WP. Extraction and characterization of Plantago major L. mucilage as a potential natural alternative over synthetic polymers for pharmaceutical formulations. Sustain Chem Pharm. 2024;42(4):101764. doi:10.1016/j.scp.2024.101764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

97. Seeharaj P, Siriwat P, Phonrat A, Prachayawarakorn J. Natural wound dressing from acid-modified basil seed mucilage containing aloe vera extract. Green Mater. 2024;1–12. doi:10.1680/jgrma.24.00003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

98. Gürbüz Z, Erkaya-Kotan T, Şengül M. Evaluation of physicochemical, microbiological, texture and microstructure characteristics of set-style yoghurt supplemented with quince seed mucilage powder as a novel natural stabiliser. Int Dairy J. 2020;114:104938. doi:10.1016/j.idairyj.2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

99. Tantiwatcharothai S, Prachayawarakorn J. Characterization of an antibacterial wound dressing from basil seed (Ocimum basilicum L.) mucilage-ZnO nanocomposite. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;135:133–40. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.05.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

100. Nourozi F, Sayyari M. Enrichment of Aloe vera gel with basil seed mucilage preserve bioactive compounds and postharvest quality of apricot fruits. Sci Hortic. 2020;262:109041. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2019.109041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

101. Ali MR, Parmar A, Niedbała G, Wojciechowski T, Abou El-Yazied A, El-Gawad HGA, et al. Improved shelf-life and consumer acceptance of fresh-cut and fried potato strips by an edible coating of garden cress seed mucilage. Foods. 2021;10(7):1536. doi:10.3390/foods10071536. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Falahati MT, Ghoreishi SM. Preparation of Balangu (Lallemantia royleana) seed mucilage aerogels loaded with paracetamol: evaluation of drug loading via response surface methodology. J Supercrit Fluids. 2019;150:1–10. doi:10.1016/j.supflu.2019.04.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

103. Yousefi M, Khanniri E, Khorshidian N. Effect of Plantago major L. seed mucilage on physicochemical, rheological, textural and sensory properties of non-fat yogurt. Appl Food Res. 2025;5(1):100687. doi:10.1016/j.afres.2025.100687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

104. Mensah EO, Oludipe EO, Gebremeskal YH, Nadtochii LA, Baranenko D. Evaluation of extraction techniques for chia seed mucilage; a review on the structural composition, physicochemical properties and applications. Food Hydrocoll. 2024;153(8):110051. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2024.110051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

105. Behbahani BA, Yazdi FT, Shahidi F, Hesarinejad MA, Mortazavi SA, Mohebbi M. Plantago major seed mucilage: optimization of extraction and some physicochemical and rheological aspects. Carbohydr Polym. 2016;155(3):68–77. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.08.051. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

106. Bazezew AM, Emire SA, Sisay MT, Teshome PG. Optimization of mucilage extraction from Ximenia americana seed using response surface methodology. Heliyon. 2022;8(1):e08781. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e08781. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

107. Silva L, Sinnecker P, Cavalari A, Sato A, Perrechil F. Extraction of chia seed mucilage: effect of ultrasound application. Food Chem Adv. 2022;1:100024. doi:10.1016/j.focha.2022.100024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

108. Shiehnezhad M, Zarringhalami S, Malekjani N. Optimization of microwave-assisted extraction of mucilage from Ocimum basilicum var. album (L.) seed. J Food Process Preserv. 2023;2023:1–15. doi:10.1155/2023/5524621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

109. Niknam R, Ghanbarzadeh B, Ayaseh A, Rezagholi F. The hydrocolloid extracted from Plantago major seed: effects on emulsifying and foaming properties. J Dispers Sci Technol. 2020;41(5):667–73. doi:10.1080/01932691.2019.1583182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools