Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Effects of Microplastics on Growth Pattern of Pinus massoniana and Schima uperba

1 Institute for Forest Resources and Environment of Guizhou, Guizhou University, Guiyang, 550025, China

2 Guizhou Key Laboratory of Forest Cultivation in Plateau Mountain, Guizhou University, Guiyang, 550025, China

3 College of Forestry, Guizhou University, Guiyang, 550025, China

4 Guizhou Liping Rocky Desertification Ecosystem National Observation and Research Station, Guizhou Academy of Forestry, Guiyang, 550000, China

* Corresponding Author: Honglang Duan. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Plant Responses to Abiotic Stress Mechanisms)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(9), 2855-2871. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.065683

Received 19 March 2025; Accepted 11 June 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

As ubiquitous environmental contaminants, microplastics (MPs) have garnered global concern due to their persistence, bioaccumulation potential, and multifaceted threats to ecosystem health. These particles threaten terrestrial ecosystems via soil contamination; however, research on their phytotoxicity remains predominantly focused on herbaceous plants. The responses of woody plants to MPs and their interspecific differences are severely unexplored. Here, two important ecological and economical tree species in southern China, Pinus massoniana (P. massoniana) and Schima superba (S. superba), were selected to explore the ecotoxicity effects of polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP) MPs (the two most abundant species in the soil) on seedling growth characteristics, specific leaf area (SLA) and biomass allocation at 0%, 1%, 5% and 10% concentration gradients in the 120-day potted experiment. The results showed that the inhibition effect of MPs was concentration and tree species-dependent. Seedling height, basal diameter, and total biomass of P. massoniana decreased significantly with increased concentration, while S. superba showed a non-significant growth effect at 1% concentration. The SLA was generally increased, revealing that plants enhanced their light capture ability through leaf morphological plasticity to compensate for the loss of carbon assimilation. There were interspecific differences in root investment strategies: the root-shoot ratio of P. massoniana was significantly reduced by 48.43% under 10% PP treatment. In comparison, the root-shoot ratio of S. superba was significantly reduced by maintaining a higher root-shoot ratio (65.26% higher than that of P. massoniana on average) and phased resource allocation (5% concentration biomass is higher than 10%) partially alleviated the toxic pressure. Collectively, our results indicate that the ecotoxicity of MPs was mainly driven by concentration and was not correlated with type (PE/PP), while the differences in tree species response were closely related to their resource allocation strategies and morphological plasticity. These findings imply that MPs contamination can differently impact the growth and development of dominant tree species, potentially altering the structure, diversity, and function of forest ecosystems. This study systematically revealed the growth response mechanism of native common tree species to MPs pollution and provided a theoretical basis for sustainable management of plantations and toxicological risk assessment of forest ecosystems.Keywords

Current evaluations confirm global plastic production has exceeded hundreds of million tons annually [1]. Projections suggest future outputs may rise by orders of magnitude within three decades, while recycling rates remain below 10% [2,3]. Discarded plastics undergo physicochemical degradation in the environment, progressively fragmenting into smaller particulate matter. Particles with diameters below 5 mm are operationally classified as microplastics (MPs). Their nanoscale dimensions and persistent molecular configuration facilitate uptake by vascular plants [2,4,5]. Plastic film use, tire abrasion, and atmospheric deposition generate microplastics (MPs) in forest ecosystems, where hydrological processes (surface runoff/rainfall) mediate their flux into soil compartments. Their proliferation threatens tree growth, forest productivity, and agroforestry sustainability, particularly in urban forests impacted by human activities [8–10]. Therefore, quantifying the largely unexplored effects of MPs on tree growth will aid in predicting tree performance in environments polluted by MPs. However, most existing studies focus on herbaceous plants, and there is still a significant knowledge gap in the response mechanism of woody plants. This paucity fundamentally impedes accurate prediction of forest ecosystem dynamics and resilience under anthropogenically altered environments.

A line of evidence indicates that experimental microplastics influence plant growth trajectories, though substantial variability persists across experimental systems [11–13]. This heterogeneity effect is mainly controlled by two key factors: MPs concentration and type. In terms of the concentration effect, studies showed that when the concentrations of PP, PLA, and PE MPs reached 0.1–1 g kg−1, wheat plant height and growth rate were significantly suppressed [14]; PVC did not significantly affect maize seedlings at 0.54 g kg−1, however, PVC at concentrations exceeding 1.62 g kg−1 significantly suppressed maize seedling growth, with the magnitude of growth inhibition demonstrating a dose-response relationship characterized by progressively intensified phytotoxic effects at elevated MPs concentrations [15]. However, PE MPs promoted soybean stem root development at 0.1% concentration, but lost the significant effect at 1% concentration [15]. MPs types differentially impact plant physiology: PLA induced significantly stronger phytotoxicity than PE in maize at 10% concentration [16]. Organ-specific response variations to distinct MPs (PET, PVC, PP, PE) were observed in gourd seedlings [17]; whereas soybean exhibited concentration-dependent sensitivity thresholds to both PE and PLA [15].

Current research categorizes the phytotoxic effects of MPs into indirect and direct pathways. The indirect mechanisms primarily involve MPs-induced alterations in soil physicochemical properties, suppression of soil faunal activity, and modifications to microbial community structure and abundance, ultimately exerting downward cascading effects on plant performance [18–22]. Direct phytotoxicity manifests through three principal mechanisms: (i) MPs can block root aerenchyma pores and narrow xylem conduits, thereby reducing hydraulic conductivity. For instance, the adhesion of MPs to xylem walls (similar to capillary action in polar surfaces) disrupts the cohesion-tension mechanism critical for water transport [23,24], (ii) disruption of plant biochemical processes, and (iii) leaching of chemical additives from MPs polymers, collectively impacting plant morphology, growth physiology, and grain nutritional quality [7,25]. For instance, MPs accumulation in the micropyle regions of Lepidium sativum seeds significantly reduced water through pore blockage, consequently delaying seed germination [26]. In rice (Oryza sativa) seedlings, direct root-surface adsorption of MPs decreased root vitality indices by 23%–41%, while microfiber entanglement induced mechanical stress that impaired root architecture development [27]. Consensus findings center on herbaceous plants, whereas woody species’ microplastic response mechanisms constitute a critical research frontier. Despite documented MPs accumulation in birch roots [28] and Ginkgo biloba growth suppression at elevated exposures [29], inter-specific variations among woody plants and their dose-response relationships remain unelucidated.

Pinus massoniana Lamb, functioning as an ecological pioneer and principal timber species in southern China’s afforestation programs, exhibits significant ecological-economic values [30]. Schima superba, as a common subtropical tree species and one of the main co-current species in P. massoniana mixed forests, is widely distributed in the vast mountainous areas from central to southern China, and is both good timber and beautiful ornamental species [31]. However, in agroforestry, management practices like artificial fertilization and understory plastic film mulching have exacerbated the accumulation of MPs in the mixed forests of P. massoniana and S. superba. Against the backdrop of large-scale global plastic production and disposal, soil MPs pollution poses a potential threat to the growth of P. massoniana and S. superba. This, in turn, may undermine the carbon sequestration capacity of forests and jeopardize the stability of forest ecosystems. Yet there are few studies on the response of woody plants to MPs [32,33]. Therefore, we selected one-year-old P. massoniana and S. superba as model species, systematically observed the growth parameters and biomass allocation patterns of seedlings by conducting a control experiment of different MPs types and concentrations. Researching the effects of MPs on P. massoniana and S. superba contributes to clarifying their impacts on the growth and development of these species. This study can provide a theoretical basis for optimizing cultivation and management practices of P. massoniana and S. superba under global MPs contamination, as well as informing species selection in MPs-polluted regions. Furthermore, it offers scientific references for ecotoxicological risk assessment of MPs pollution in forest ecosystems.

Based on previous investigations of herbaceous species’ responses to environmental stressors, this study extends the research framework to woody plants, specifically focusing on P. massoniana and S. superba. The primary objectives of this investigation are: (1) to study the stress responses of P. massoniana and S. superba to MPs, and (2) to clarify the effects of MPs on the growth and development of these species. Accordingly, the following scientific hypotheses have been formulated: (H1) The addition of MPs can inhibit plant growth, which would vary between tree species; (H2) The inhibitory effect of MPs addition on seedlings would be related to the concentration and type of MPs.

2.1 Plant Materials and Experimental Design

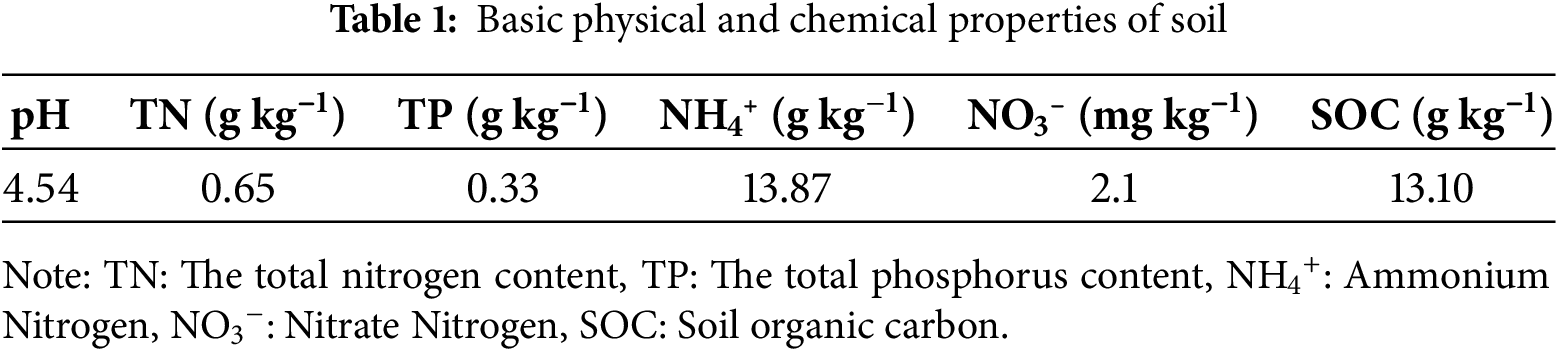

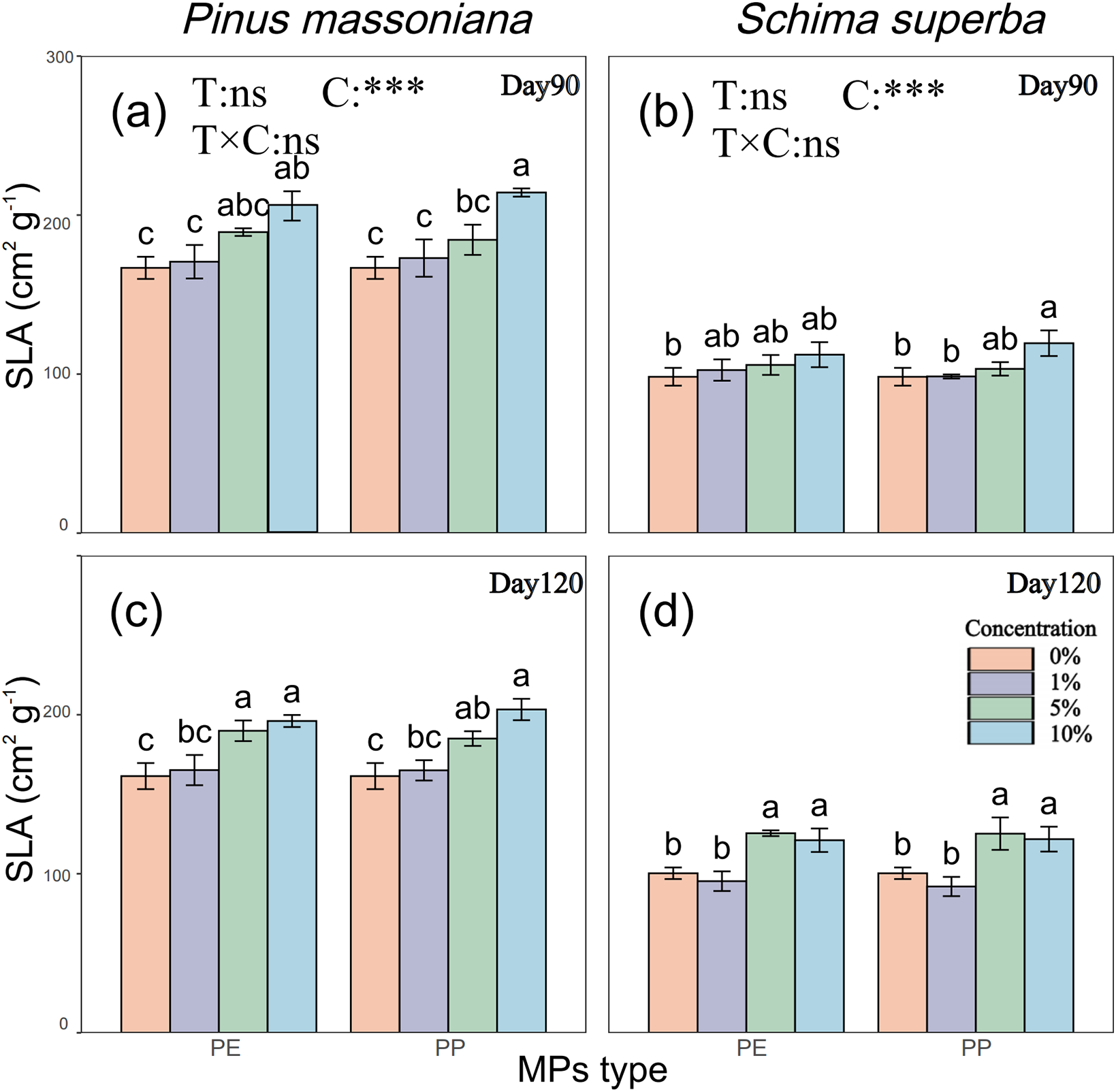

The two most abundant MPs in soil (polyethene (PE) and polypropylene (PP)) were purchased from a company (Dongguan Zhangmutou Ruixiang Polymer Materials Business Co., Ltd., Dongguan, China). To ensure that shape, particle size distribution, and surface treatment do not introduce additional confounding effects in our experiments, we used uniformly sized (45–50 μm diameter) and untreated MPs beads. The soil utilized in this experiment was collected from a soil region in a P. massoniana plantation located in Guiyang, Guizhou Province, China. The soil was naturally air-dried. Initially, the pH of the soil was 4.54, and the physical and chemical properties of the soil are detailed in the Table 1. To examine the interactive effects of MPs types and species on seedlings, a Four-factor experimental design was implemented. The fixed factors included the types of MPs (PE and PP), their respective concentrations (0%, 1%, 5% and 10% w/w). We selected two of the most common types of MPs found in soil [34]. The concentration gradients were designed based on previous research experience and existing literature. This experimental setup aims to simulate the current state of soil MPs pollution and predict potential impacts under more severe pollution scenarios in the future [35]. Consequently, a total of 14 treatments were established: a control group (CK), PE MPs (0%, 1%, 5%, 10%) and PP MPs (0%, 1%, 5%, 10%). Each experimental pot contained 2 kg of soil. MPs were incorporated into the soil at the designated proportions according to the specified concentrations, subsequently kept for 60 days to rebalance the soil system.

A total of 64 one-year-old P. massoniana (height is 30 ± 2 cm, basal diameter is 4.9 ± 0.2 mm) and S. superba (height is 37 ± 2 cm, basal diameter is 5.3 ± 0.3 mm) seedlings exhibiting uniform and healthy growth were then transplanted into soil added with MPs. All the processing is now shown in Table 2. Throughout the experimental period, the soil was maintained at field capacity. All pots were positioned within a polytunnel and rotated weekly. After 90 and 120 days of growth, the plants were harvested, and growth traits of the seedlings were measured.

2.2 Height and Basal Diameter Measurements

At harvest, the height and basal diameter of seedlings were recorded using a tape (0.1 cm) and a electronic calliper (0.01 mm), with three replicates per treatment.

2.3 Specific Leaf Area (SLA) Measurements

Ten fresh leaves of P. massoniana and one leaf of S. superba were collected for scanning with a scanning system (Epson Scanner, Shanghai Zequan Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), one leaf of and the leaf area was subsequently determined, with three replicates per treatment. Then, the SLA will be calculated by:

2.4 Biomass and Biomass Allocation Measurements

The harvested seedlings were separated into leaves, stems, and roots, with the seedlings being washed free of soil using tap water. To terminate metabolic processes, fresh samples underwent thermal deactivation (105°C, 30 min) prior to dehydration in a forced-air oven (65°C, 72 h) until reaching constant mass. The dry mass was then recorded. Subsequently, the dry weight of each organ was measured using an electronic balance, with three replicates per treatment. Next, the variables R/S, root mass ratio, stem mass ratio, and leaf mass ratio will be calculated using the following equations

All statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS 26.0 (IBM, USA). We ensured that homoscedasticity and normality requirements were met before all statistical analyses. The data were categorized by tree species, and a three-way ANOVA (analysis of variance) was conducted to determine the main effects of MPs concentration, MPs type, and treatment duration. Subsequently, one-way ANOVA was performed separately for MPs concentration and MPs type, with a Duncan post-hoc test applied to assess significant differences among MPs treatments. Results were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. The correlation heatmap between plant growth indicators was created using the “ggcorrplot” package in the R software.

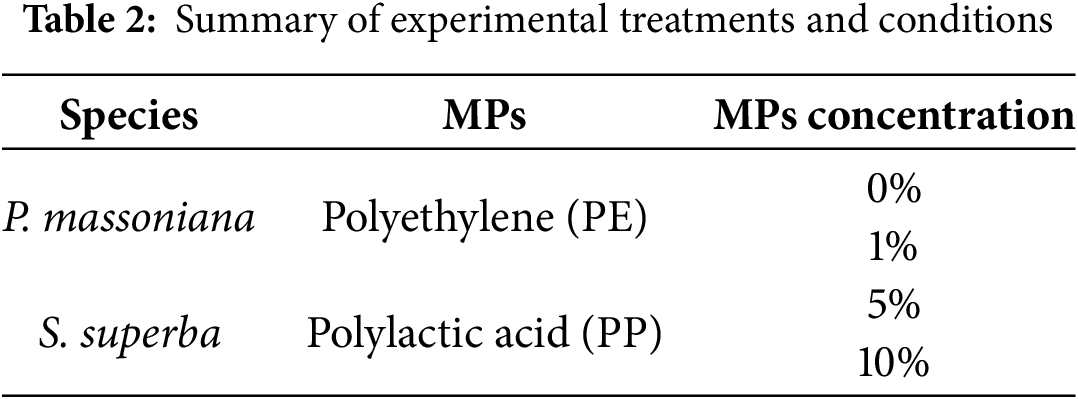

3.1 Effects of MPs on Seedling Height and Basal Diameter

The ANOVA results demonstrated that P. massoniana seedling height was significantly influenced by the concentration of MPs. By day 120, no significant difference in seedling height was observed at the 1% MPs concentration; however, significant reductions were recorded at 5% and 10% concentrations (Fig. 1a). Notably, the 10% concentration exhibited a more pronounced inhibitory effect on seedling height compared to the 5% concentrations of PE and PP. Relative to the control group, the 5% PE, 5% PP, 10% PE, and 10% PP treatments resulted in reductions of 24.46%, 32.52%, 38.10%, and 43.15%, respectively. In contrast, MPs had a non-significant promotive effect on S. superba seedling height at the 1% concentration (Fig. 1b). While no significant differences were observed between the 5% PE and PP treatments and the control group, the 10% PE and PP treatments significantly reduced seedling height by 18.10% and 14.17%, respectively.

Figure 1: Effects of PE and PP on height and basal diameter of P. massoniana and S. superba seedlings. The lower-case letters indicate significant differences in concentrations of PE and PP on day 90; uppercase letters indicate the difference on day 120 (p < 0.05). Each value represents the mean ± Standard Error (n = 3). *, ***, and ns represent significant levels of 0.05, 0.001, and a nonsignificant effect, respectively. T: MPs type; C: MPs concentration. (a): P. massoniana seedling height; (b): P. massoniana seedling basal diameter; (c): S. superba seedling height; (d): S. superba seedling basal diameter

Similarly, by day 120, P. massoniana basal diameter decreased progressively with increasing MPs concentrations, showing significant reductions at 5% and 10% concentrations of PE and PP, although no significant difference was observed between these two concentrations (Fig. 1c). Compared to the control, the reductions in basal diameter were 26.19%, 21.02%, 27.66%, and 29.03% for the 5% PE, 5% PP, 10% PE, and 10% PP treatments, respectively. For S. superba, the basal diameter showed no significant differences at 1% and 5% concentrations of PE and PP compared to the control. However, the 10% PE and PP treatments significantly reduced the ground basal diameter by 24.30% and 21.16%, respectively (Fig. 1d). Both species’ height was found to be dependent on MPs concentration and tree species rather than the type of MPs.

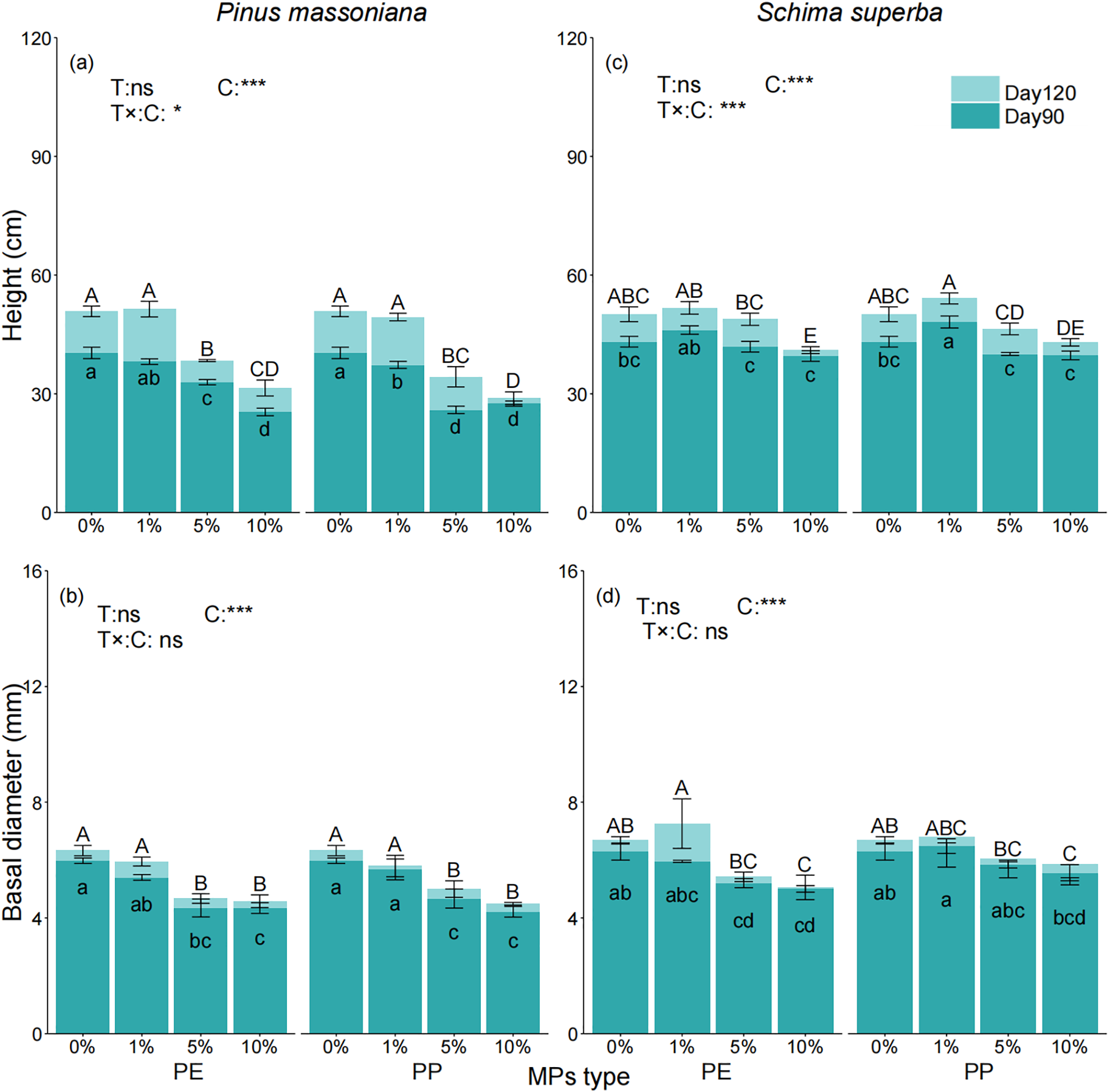

3.2 Effects of MPs on Seedling SLA

The SLA of P. massoniana and S. superba increased gradually with rising MPs concentrations (Fig. 2a–d). By day 120, no significant difference in SLA was observed for P. massoniana at the 1% concentration compared to the control group. However, significant increases of 17.65%, 14.62%, 21.47%, and 25.95% were recorded at higher concentrations (Fig. 2c). For S. superba, with no significant difference at the 1% concentration but significant increases of 25.11%, 24.84%, 20.69%, and 21.39% at 5% PE, 5% PP, 10% PE, and 10% PP, respectively (Fig. 2d). The SLA of both species was influenced by MPs concentration and tree species but not by the type or exposure time of MPs.

Figure 2: Effects of PE and PP on SLA of P. massoniana and S. superba seedlings. The left bars represent PE treatment, and the right bars represent PP treatment. The lower-case letters indicate significant differences in concentrations of PE and PP (p < 0.05). Each value represents the mean ± Standard Error (n = 3). ***, and ns represent significant levels of 0.001, and a nonsignificant effect, respectively. T: MPs type; C: MPs concentration. SLA: specific leaf area. The same applies hereinafter. (a): P. massoniana seedling SLA at Day 90; (b): S. superba seedling SLA at Day 90; (c): P. massoniana seedling SLA at Day 120; (d): S. superba seedling SLA at Day 120

3.3 Effects of MPs on Seedling Biomass and Its Allocation

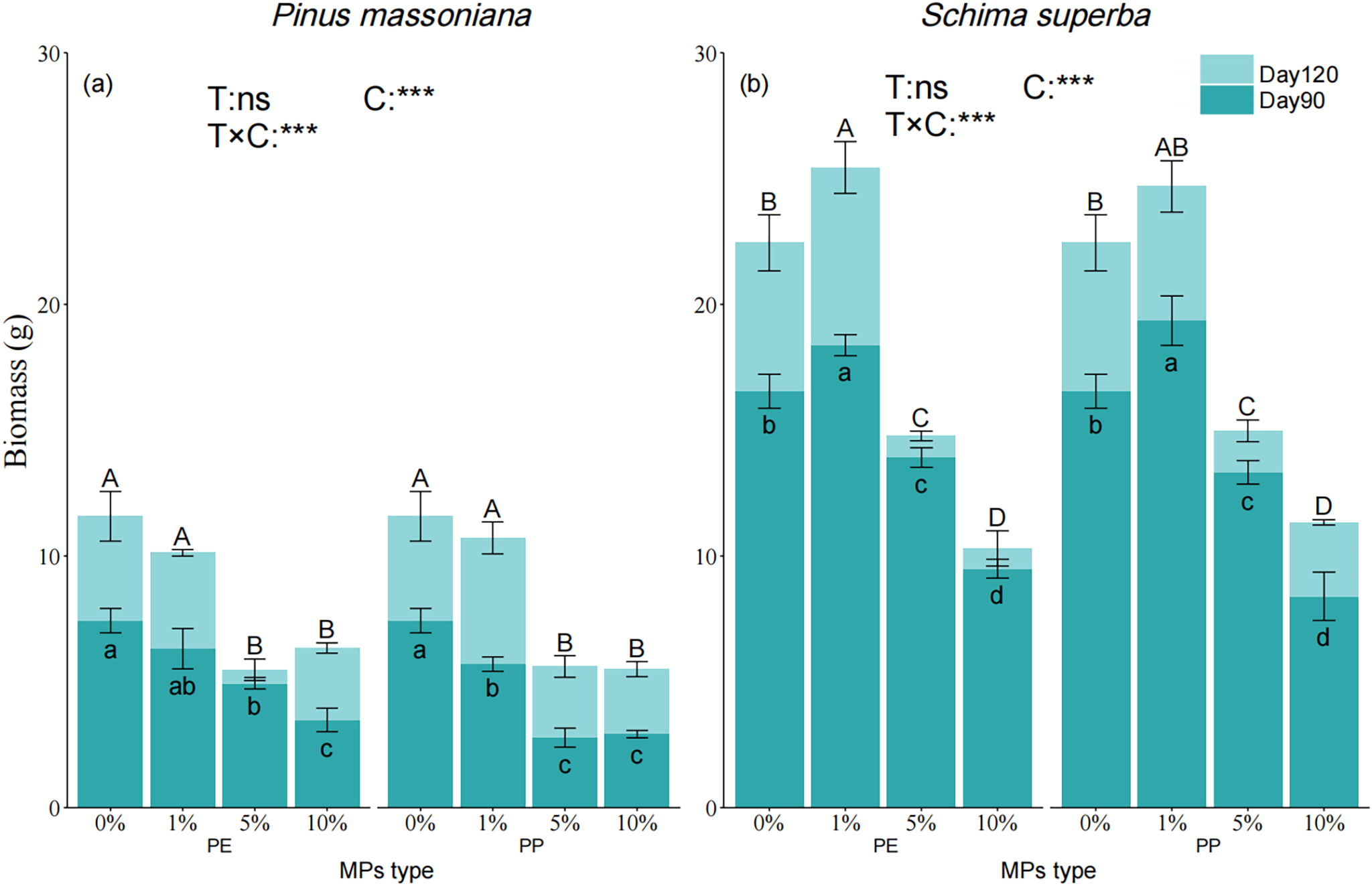

The biomass of P. massoniana and S. superba was significantly affected by MPs concentrations (Fig. 3a–d). By day 120, P. massoniana biomass was significantly reduced by 52.69%, 51.56%, 45.21%, and 52.46% for the 5% PE, 5% PP, 10% PE, and 10% PP treatments, respectively, compared to the control group (Fig. 3a). Similarly, S. superba biomass was significantly lower than the control group by 34.19%, 33.29%, 54.10%, and 50.98% at the same concentrations (Fig. 3b). Unlike P. massoniana, S. superba biomass at 5% PE and PP was significantly higher than at other concentrations. Both species’ biomass correlated with MPs concentration, tree species, and time stage but not with the type of MPs (Fig. 3c,d).

Figure 3: Effects of PE and PP on biomass of P. massoniana and S. superba seedlings. The lower-case letters indicate significant differences in concentrations of PE and PP on day 90; uppercase letters indicate the difference on day 120 (p < 0.05). Each value represents the mean ± Standard Error (n = 3). ***, and ns represent significant levels of 0.001, and a nonsignificant effect, respectively. T: MPs type; C: MPs concentration. (a): P. massoniana seedling biomass; (b): S. superba seedling biomass

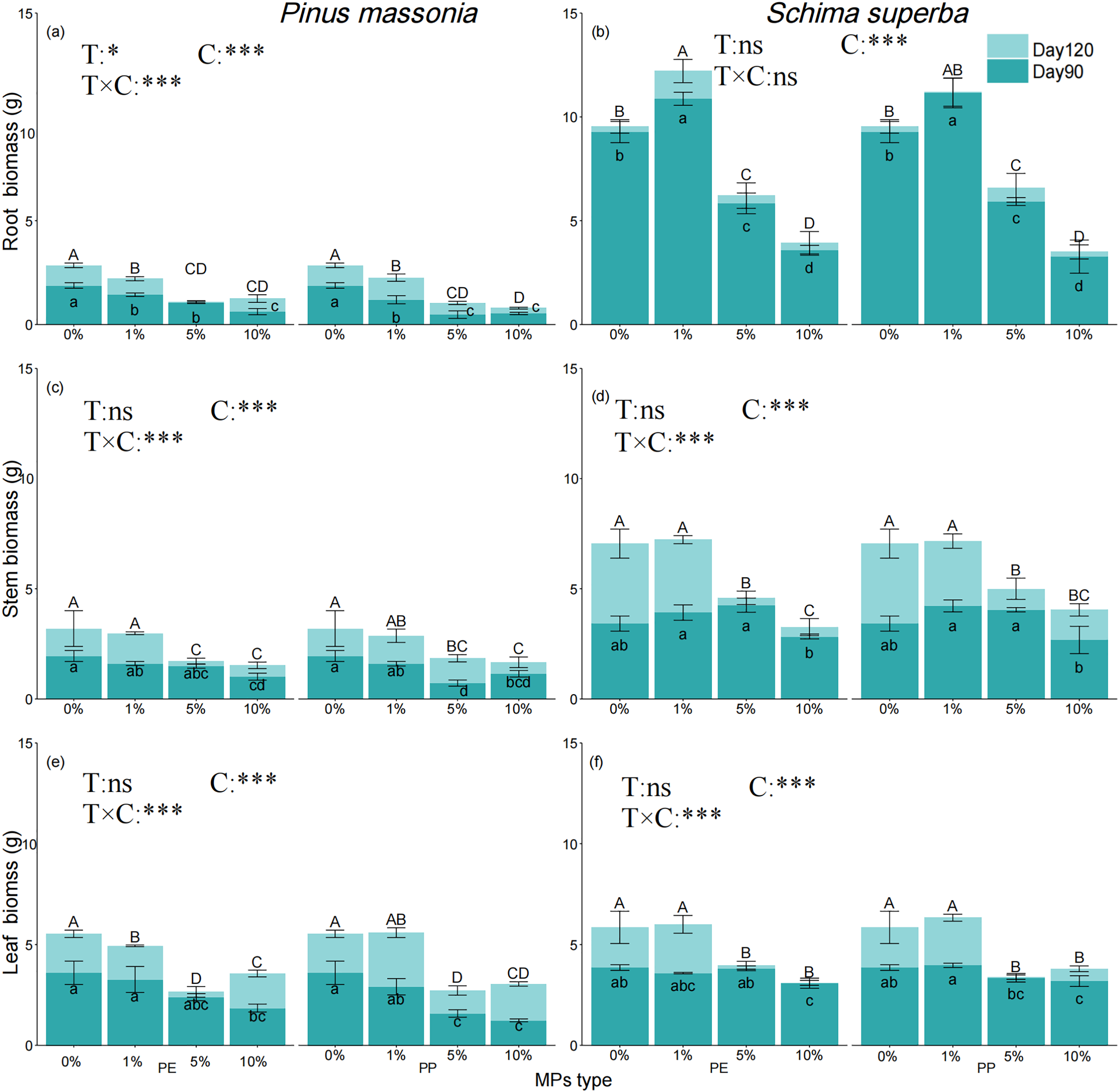

The ANOVA results further indicated that MPs concentration significantly affected the biomass of roots, stems, and leaves of both species (Fig. 4a–f). By day 120, P. massoniana biomass decreased significantly with increasing MPs concentration, with no significant difference between 5% and 10% PE and PP treatments. For S. superba, root biomass increased significantly at the 1% concentration by day 90, but by day 120, only the 1% PE treatment remained significantly higher than the control (Fig. 4b). At 5% and 10% concentrations, S. superba root biomass was significantly lower than the control, with the 10% concentration showing a more pronounced reduction than the 5%. P. massoniana stem biomass decreased significantly at 5% and 10% concentrations, while S. superba exhibited no significant reduction at 1% but significant decreases at 5% and 10%. P. massoniana leaf biomass showed no significant difference at 1% but decreased significantly at 5% and 10%, with the 10% concentration resulting in higher leaf biomass than 5. For S. superba, leaf biomass increased slightly at 1% but decreased significantly at 5% and 10%. The biomass of roots, stems, and leaves was influenced by tree species, MPs concentration, and time but not by the type of MPs.

Figure 4: Effects of PE and PP on Root/Stem/Leaf biomass of P. massoniana and S. superba seedlings. The lower-case letters indicate significant differences in concentrations of PE and PP on day 90; uppercase letters indicate the difference on day 120 (p < 0.05). Each value represents the mean ± Standard Error (n = 3). *, ***, and ns represent significant levels of 0.05, 0.001, and a nonsignificant effect, respectively. T: MPs type; C: MPs concentration. (a): P. massoniana seedling root biomass; (b): S. superba seedling root biomass; (c): P. massoniana seedling stem biomass; (d): S. superba seedling stem biomass; (e): P. massoniana seedling leaf biomass; (f): S. superba seedling leaf biomass

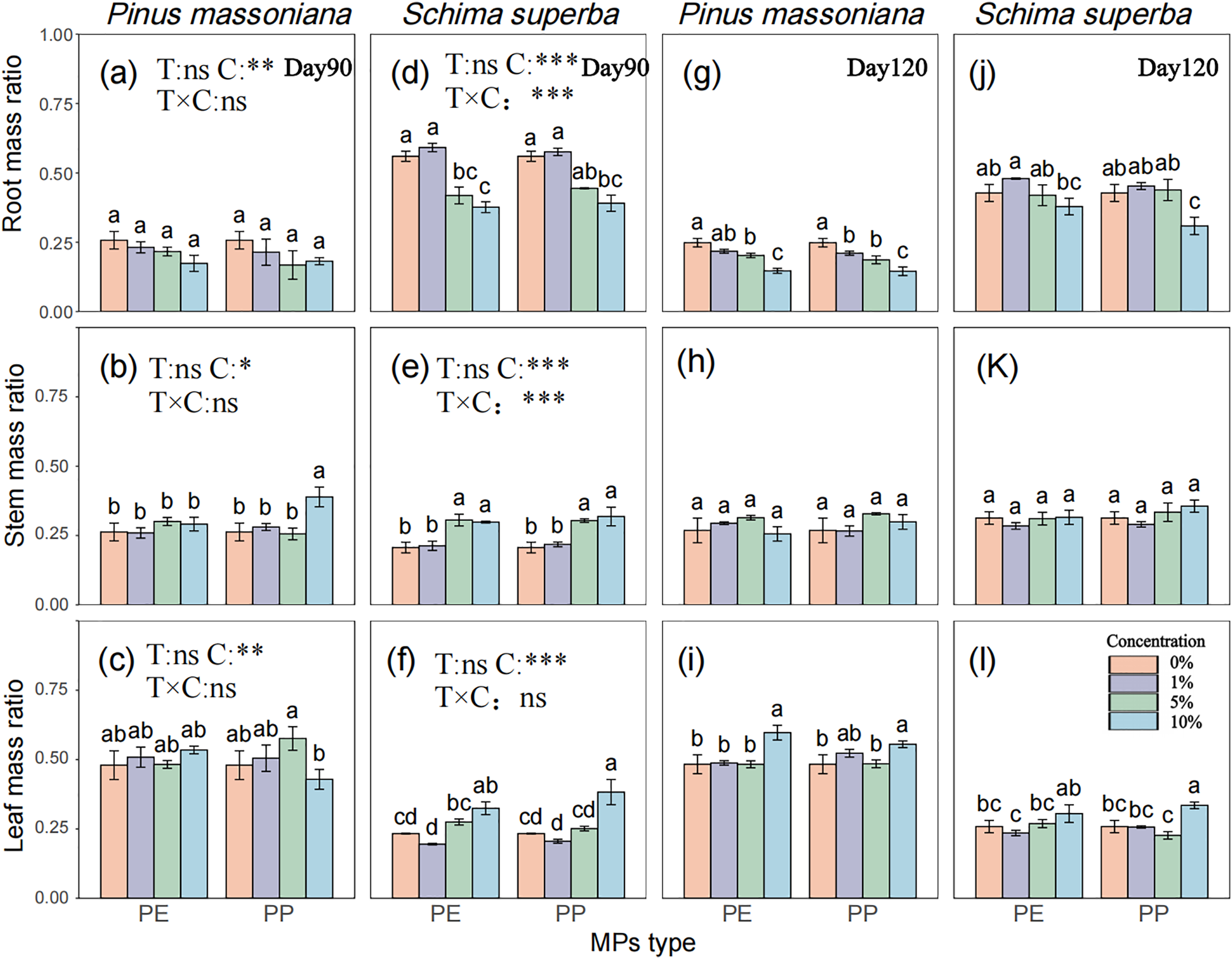

P. massoniana proportion of root biomass decreased progressively with increasing MPs concentration (Fig. 5a–l), with reductions of 18.49% to 41.44% at 5% and 10% PE and PP by day 120 (Fig. 5g). In contrast, S. superba proportion of root biomass initially increased and then decreased, with a 27.82% reduction at 10% PP. No significant differences were observed in stem biomass proportion for either species compared to the control (Fig. 5h). P. massoniana proportion of leaf biomass was generally higher than that of S. superba, showing an upward trend with increasing MPs concentration, with significant increases of 16.48% and 14.89% at 10% PE and PP, respectively (Fig. 5i). For S. superba, leaf biomass increased significantly by 29.51% at 10% PP (Fig. 5l).

Figure 5: Effects of PE and PP on Root/Stem/Leaf mass ratio of P. massoniana and S. superba seedlings. The left bars represent PE treatment, and the right bars represent PP treatment. The lower-case letters indicate significant differences in concentrations of PE and PP (p < 0.05). Each value represents the mean ± Standard Error (n = 3). *, **, ***, and ns represent significant levels of 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, and a nonsignificant effect, respectively. T: MPs type; C: MPs concentration. (a): P. massoniana seedling root mass ratio at Day 90; (b): P. massoniana seedling stem mass ratio at Day 90; (c): P. massoniana seedling leaf mass ratio at Day 90; (d): S. superba seedling root mass ratio at Day 90; (e): S. superba seedling stem mass ratio at Day 90; (f): S. superba seedling leaf mass ratio at Day 90; (g): P. massoniana seedling root mass ratio at Day 120; (h): P. massoniana seedling stem mass ratio at Day 120; (i): P. massoniana seedling leaf mass ratio at Day 120; (j): S. superba seedling root mass ratio at Day 120; (k): S. superba seedling stem mass ratio at Day 120; (l): S. superba seedling leaf mass ratio at Day 120

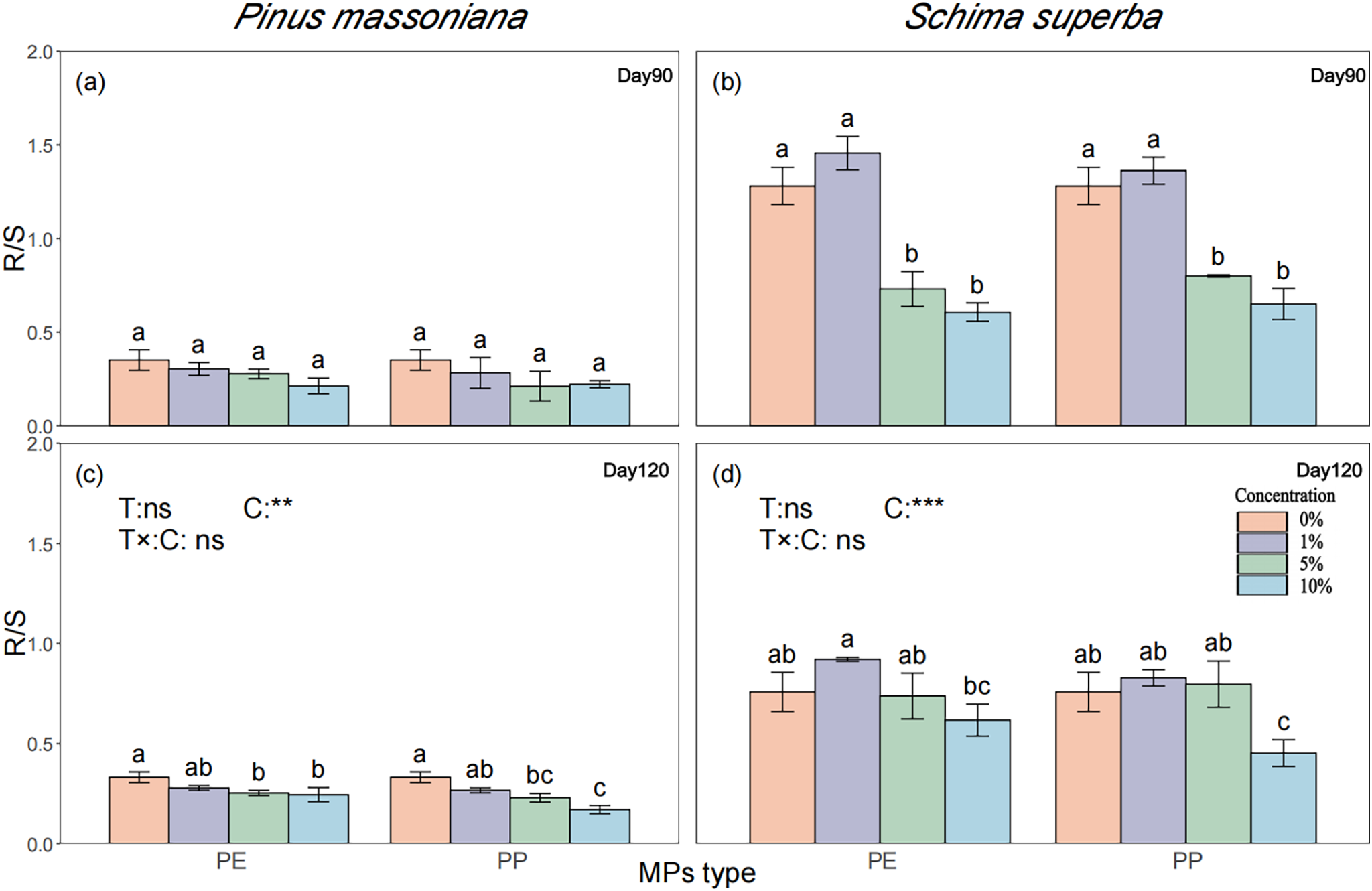

P. massoniana and S. superba root/shoot ratios were significantly affected by MPs concentration by day 120. While no significant differences were observed at day 90 (Fig. 6a), P. massoniana root/shoot ratios at 5% PE, 5% PP, 10% PE, and 10% PP were significantly lower than the control by 23.36%, 30.59%, 25.98%, and 48.43%, respectively, with the 10% PP treatment showing a more pronounced reduction than 10% PE (Fig. 6b). For S. superba, only the 10% PP treatment exhibited a significant decrease of 31.74% compared to the control. P. massoniana root/shoot ratios were influenced by MPs concentration but not by time stage, while that of S. superba was dependent on both concentration and time stage but not on the type of MPs (Fig. 6c,d). Overall, the root/shoot ratio varied significantly between tree species, with S. superba exhibiting higher values than P. massoniana.

Figure 6: Effects of PE and PP on root-shoot ratio of P. massoniana and S. superba seedlings. The left bars represent PE treatment, and the right bars represent PP treatment. The lower-case letters indicate significant differences in concentrations of PE and PP (p < 0.05). Each value represents the mean ± Standard Error (n = 3). **, ***, and ns represent significant levels of 0.01, 0.001, and a nonsignificant effect, respectively. T: MPs type; C: MPs concentration. R/S: Root shoot ratio. (a): P. massoniana seedling root-shoot ratio at Day 90; (b): S. superba seedling root-shoot ratio at Day 90; (c): P. massoniana seedling root-shoot ratio at Day 120; (d): S. superba seedling root-shoot ratio at Day 120

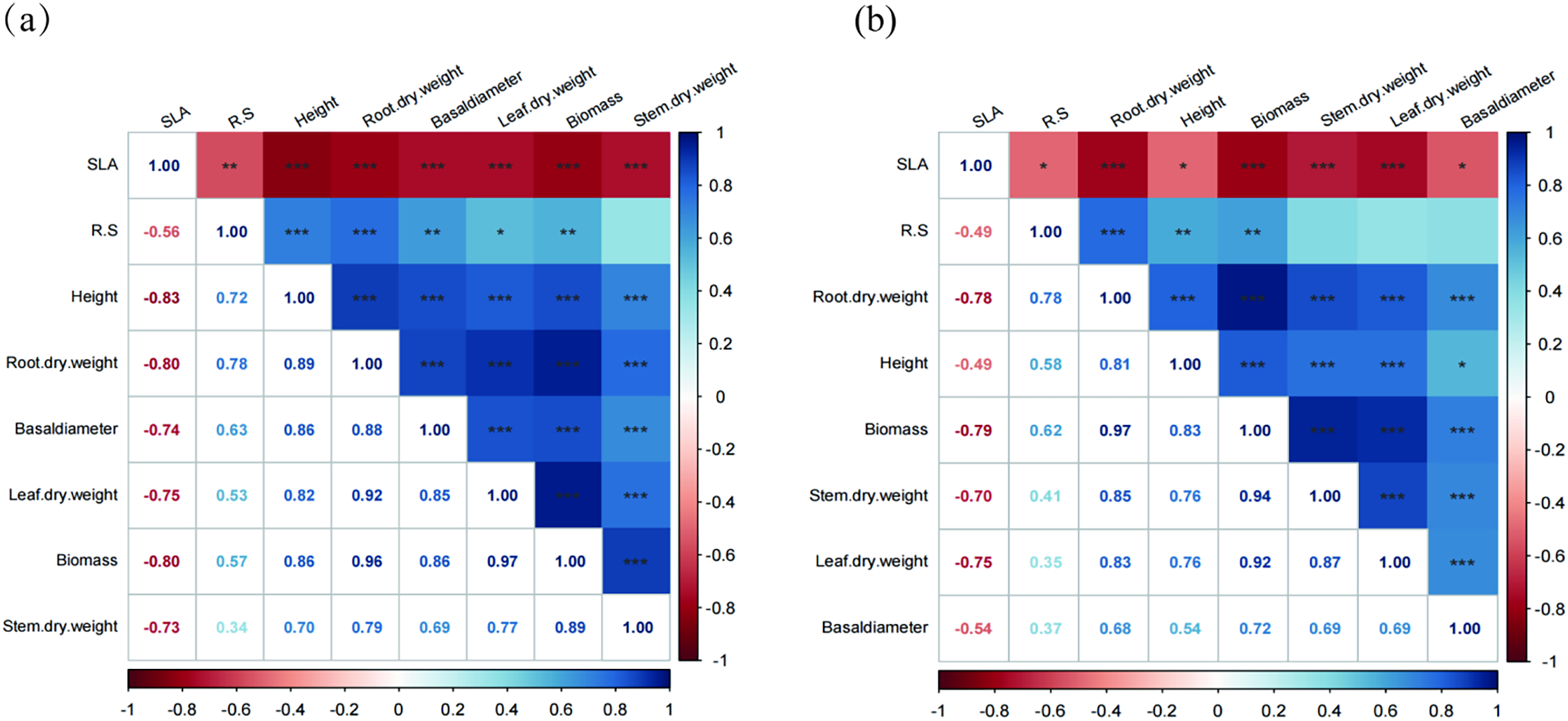

The results of correlation analysis showed that P. massoniana and S. superba biomass were significantly positively correlated with seedling height, root/shoot ratio, and negatively correlated with SLA (Fig. 7a,b).

Figure 7: The correlation plant indicators were shown as P. massoniana (a) and S. superba (b) seedlings. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05. SLA: specific leaf area, R.S: Root shoot ratio, Root.dry.weight: Root biomass, Basaldiameter: Basal diameter, Leaf.dry.weight: Leaf biomass, Stem.dry.weight: Stem biomass. Heatmap of correlation between different variables based on Pearson correlation coefficients. (a): The correlation plant indicators were shown as P. massoniana, (b): The correlation plant indicators were shown as S. superba

4.1 MPs Addition Inhibits Plant Growth, and the Effect Is Dependent on Tree Species and Time

There are substantial differences between woody and herbaceous plants in terms of root structure, growth cycle, and resource allocation. Woody plants possess intricate root systems, exhibit slow growth, and allocate a large proportion of their resources to the construction of structural tissues. In contrast, herbaceous plants generally have relatively simple root systems, rapid growth rates, and prioritize resource allocation for reproductive purposes [36]. These distinctions may account for the divergence in the response mechanisms of woody plants to MPs. The results of this study support the hypothesis that MPs addition generally inhibits plant growth, with the extent of inhibition varying significantly between tree species and over time. For P. massoniana, seedling height and basal diameter were significantly reduced at higher MPs concentrations (5% and 10%), with reductions of up to 43.15% and 29.03%, respectively, by day 120. This aligns with previous studies demonstrating that MPs can physically obstruct root development and nutrient uptake, leading to stunted growth [7]. In contrast, S. superba exhibited a more nuanced response, with non-significant promotion at 1% MPs concentration but significant inhibition at 10%, suggesting species-specific tolerance thresholds (Figs. 3 and 4). These findings are consistent with the work of Jiang (2023), who reported that plant species respond variably to MPs stress [37].

The temporal aspect of MPs effects was also evident. For instance, S. superba root biomass increased at 1% concentration by day 90 but decreased by day 120, indicating that prolonged exposure exacerbates MPs-induced stress. Similarly, P. massoniana root/shoot ratio showed significant reductions by day 120 but not at day 90, further underscoring the time-dependent nature of MPs impacts (Fig. 6b). This temporal variability may be attributed to the cumulative physical and chemical effects of MPs, such as the gradual release of additives or the accumulation of MPs in root zones [6].

4.2 The Inhibitory Effects of MPs Are Concentration-Dependent but not Type-Dependent

The second hypothesis, that the inhibitory effects of MPs are concentration-dependent but not type-dependent, is also supported by the data. For both P. massoniana and S. superba, higher MPs concentrations (5% and 10%) consistently resulted in greater reductions in seedling height, basal diameter, and biomass compared to the CK. For example, P. massoniana biomass was reduced by 52.69% and 45.21% at 5% and 10% PE, respectively, while S. superba exhibited reductions of 54.10% and 50.98% at the same concentrations (Fig. 3a,b). Nevertheless, at the MPs concentration of 1%, the growth of P. massoniana was not significantly inhibited, and some growth indicators of S. superba even showed promotion. This might be attributed to the differences in root structure and physiological functions between the two species. Possibly, the root system of S. superba, with its more developed root hairs, can still effectively absorb nutrients under low-MPs concentration conditions, maintaining the normal physiological functions of the roots and thus promoting the increase of certain growth indicators. These findings align with the concentration-response relationships observed in other studies [16], where higher MPs loads were shown to exacerbate physical barriers to root growth and nutrient absorption [34].

Notably, the type of MPs (PE vs. PP) did not significantly influence plant growth parameters, as both polymers elicited similar responses at equivalent concentrations. For instance, P. massoniana height was reduced by 24.46% and 32.52% at 5% PE and PP, respectively, with no significant difference between the two types (Figs. 3 and 4). This study reveals that PE and PP had no significant impact on plant growth. This is likely because there are no substantial differences in their chemical properties. In terms of surface charge, PE and PP have similar electrical properties [38]. When interacting with plant roots, they have a similar degree of interference on root nutrient absorption. As for the release of additives, the types and amounts of additives released by these two materials may not be sufficient to cause obvious differences in plant growth. However, although no significant impacts have been observed currently, these chemical property differences may still have potential effects on root nutrient absorption and soil microbial communities under long-term conditions or specific environmental conditions, and further longer-term research is warranted. In the future, we will also consider analyzing the impact of microplastic additives in our research to further explore their ecological toxicity.

This finding is inconsistent with the results of previous studies [39,40], which suggest that there are differences among different types of MPs. It is possible that the experimental conditions, plant species, or MPs characteristics in our study differed from those in previous research, leading to this discrepancy. Future studies are needed to systematically compare these factors to better understand the complex mechanisms underlying the effects of MPs on plant growth. However, some studies have suggested that MPs types significantly influence plant growth. Notably, Wang et al. (2020) reported that PLA induced greater phytotoxicity to maize than PE, whereas our findings revealed that PE and PP exhibited polymer-independent effects on plant growth. A plausible explanation is that conventional non-degradable MPs (e.g., PE) undergo slower fragmentation, while biodegradable MPs (e.g., PLA) rapidly degrade into smaller particles. These MPs may more effectively clog root systems, thereby impairing water and nutrient uptake, ultimately exacerbating growth inhibition in maize [16]. Intriguingly, both MPs investigated in our study were non-degradable polymers, which might primarily account for the observed polymer-independent ecotoxicological effects on plant development.

However, SLA and biomass allocation patterns revealed subtle differences in plant responses to MPs. While SLA increased significantly at higher MPs concentrations for both species, P. massoniana leaf biomass proportion showed an upward trend, whereas S. superba exhibited a decline at 10% PP (Figs. 2c,d and 5i,l). This divergence may reflect species-specific strategies for resource allocation under stress to optimize survival under adverse conditions [41]. The SLA-mediated adjustment of mesophyll cell light energy allocation potentially influences carbon assimilation by regulating the photosynthetic-respiratory metabolic balance, which may elucidate the coordinated decline in light-saturated net photosynthetic rate (Asat) (47.49%–60.43%) and dark respiration rate (Rd) (105.20%–116.56%) observed in P. massoniana under high-concentration MPs (>5%), as well as the species-specific response in Schima superba characterized by Asat reduction (30.77%–42.83%) concomitant with Rd transition from stimulation (↑17.19%) at 1% concentration to collapse (↓95.95%) under high concentrations.

Collectively, P. massoniana and S. superba exhibited concentration-time-species dependent growth inhibition under MPs stress, with divergent adaptive strategies—leaf plasticity (SLA↑25%) vs. root investment, highlighting niche-specific responses. These woody species’ physical obstruction-driven tolerance suggests long-lifecycle adaptations critical for predicting forest resilience to MPs. Future research should prioritize (1) multi-year exposure trials to assess cumulative effects, (2) mechanistic disentanglement of physical vs. chemical MPs impacts via xylem transport analysis, (3) development of species sensitivity indices using functional trait databases, and (4) evaluation of mycorrhizal mediation in MPs detoxification. Addressing these gaps will enable predictive modelling of forest resilience under global plastic proliferation. (5) In the future, more in-depth exploration can be carried out from the molecular level to further reveal the mechanism of the impact of MPs on plants.

Our study systematically elucidates the differential responses of P. massoniana and S. superba seedlings to PE and PP MPs contamination, revealing concentration-dependent phytotoxicity and species-specific adaptation strategies. Our findings demonstrate that MPs at elevated concentrations (5–10% w/w) significantly inhibited seedling height, basal diameter, biomass accumulation, and root-shoot ratio in both species, with suppression intensity escalating proportionally to MPs concentration. Notably, S. superba exhibited transient growth stimulation under low MPs exposure (1%), while this response was absent in P. massoniana. The universal elevation in SLA implied a compensatory mechanism through leaf morphological plasticity to enhance light capture efficiency under carbon assimilation constraints. However, this acclimatization failed to offset biomass losses, underscoring the irreversible metabolic costs imposed by MPs stress. P. massoniana suffered severe root-shoot ratio reductions, reflecting compromised root functionality and prioritized aboveground carbon investment. In contrast, S. superba maintained higher root-shoot ratios across treatments, coupled with staged biomass allocation (5% > 10% MPs), indicative of dynamic resource rebalancing to alleviate rhizospheric toxicity. Crucially, MPs-induced ecotoxicity was governed by concentrations rather than type (PE vs. PP). The strong negative correlations between SLA and biomass (p < 0.05) further validated that morphological adjustments inadequately counterbalanced physiological impairments under prolonged MPs exposure. Based on the above-mentioned findings, in regions at risk of MPs pollution, it is strongly recommended to prioritize the selection of S. superba as a tree species for ecological restoration and afforestation. Owing to its remarkable tolerance to pollutants, S. superba can effectively guarantee the ecological benefits of vegetation reconstruction. This conclusion offers a crucial theoretical foundation for the tree-species selection in the establishment of subtropical plantation forests. Moreover, the findings advocate for MPs concentration thresholds in silvicultural practices and underscore the urgency of incorporating MPs resilience into afforestation species selection, particularly in pollution-prone regions. Collectively, this study provides critical insights into MPs threats to forest regeneration, highlighting species-specific vulnerabilities in economically vital trees. While this investigation has specifically examined the influence of MPs on seedling growth, subsequent studies should employ an integrated approach combining soil biogeochemical analysis with plant metabolic profiling to comprehensively assess MPs impacts on plant development.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Natural Science Talent Funding of Guizhou University (202132, 202318) and the Innovative Talent Team Project of Seedling Breeding and plantation cultivation for Precious Tree Species in Guizhou (Qiankehe Platform Talents-CXTD [2023]006).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Honglang Duan; methodology, Keke Zhang, Liqing Yang, Yuxin Wang and Yao Fang; formal analysis, Keke Zhang; investigation, Keke Zhang, Liqing Yang, Yuxin Wang and Yao Fang; writing—original draft preparation, Keke Zhang; writing—review and editing, Yong Cui, Changchang Shao, Hua Zhou, Jie Wang and Honglang Duan; supervision, Honglang Duan; project administration, Honglang Duan; funding acquisition, Honglang Duan. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Honglang Duan, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Plastics Europe. Plastics-the fast Facts 2023 [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 May 1]. Available from: https://plasticseurope.org/knowledge-hub/plastics-the-fast-facts-2023. [Google Scholar]

2. Geyer R, Jambeck JR, Law KL. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci Adv. 2017;3(7):e1700782. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1700782. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Maes T, McGlade J, Fahim IS, Green DS, Landrigan P, Andrady AL, et al. From pollution to solution: a global assessment of marine litter and plastic pollution [Internet]. [cited 2022 Dec 14]. Available from: https://www.unep.org/resources/pollution-solution-global-assessment-marine-litter-and-plastic-pollution. [Google Scholar]

4. Thompson RC, Olsen Y, Mitchell RP, Davis A, Rowland SJ, John AWG, et al. Lost at sea: where is all the plastic? Science. 2004;304:838. doi:10.1126/science.1094559. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Rillig MC. Microplastic in terrestrial ecosystems and the soil? Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46(12):6453–4. doi:10.1021/es302011r. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. de Souza Machado AA, Lau CW, Kloas W, Bergmann J, Bachelier JB, Faltin E, et al. Microplastics can change soil properties and affect plant performance. Environ Sci Technol. 2019;53(10):6044–52. doi:10.1021/acs.est.9b01339. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Rillig MC, Lehmann A, de Souza Machado AA, Yang G. Microplastic effects on plants. New Phytol. 2019;223(3):1066–70. doi:10.1111/nph.15794. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Goßmann I, Herzke D, Held A, Schulz J, Nikiforov V, Georgi C, et al. Occurrence and backtracking of microplastic mass loads including tire wear particles in northern Atlantic air. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):3707. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-39340-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Parashar N, Hait S. Plastic rain—atmospheric microplastics deposition in urban and peri-urban areas of Patna City, Bihar, India: distribution, characteristics, transport, and source analysis. J Hazard Mater. 2023;458:131883. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.131883. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Allen S, Allen D, Phoenix VR, Le Roux G, Jiménez PD, Simonneau A, et al. Author correction: atmospheric transport and deposition of microplastics in a remote mountain catchment. Nat Geosci. 2019;12(8):679. doi:10.1038/s41561-019-0409-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Bonet A, Lelu Walter MA, Faugeron C, Gloaguen V, Saladin G. Physiological responses of the hybrid larch (Larix × eurolepis Henry) to cadmium exposure and distribution of cadmium in plantlets. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2016;23(9):8617–26. doi:10.1007/s11356-016-6094-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Lian JP, Wu JN, Zeb A, Zheng SN, Ma T, Peng F, et al. Do polystyrene nanoplastics affect the toxicity of cadmium to wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)? Environ Pollut. 2020;263(5):114498. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114498. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Sun HD, Bai JR, Liu R, Zhao ZM, Li W, Mao H, et al. Polyethylene microplastic and nano ZnO Co-exposure: effects on peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) growth and rhizosphere bacterial community. J Clean Prod. 2024;445(1):141368. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.141368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Sun H, Lei C, Xu J, Li R. Foliar uptake and leaf-to-root translocation of nanoplastics with different coating charge in maize plants. J Hazard Mater. 2021;416:125854. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.125854. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Lian YH, Liu WT, Shi Y, Zeb A, Wang Q, Li JT, et al. Effects of polyethylene and polylactic acid microplastics on plant growth and bacterial community in the soil. J Hazard Mater. 2022;436:129057. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.129057. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Wang FY, Zhang XQ, Zhang SQ, Zhang SW, Sun YH. Interactions of microplastics and cadmium on plant growth and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities in an agricultural soil. Chemosphere. 2020;254:126791. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.126791. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Colzi I, Renna L, Bianchi E, Castellani MB, Coppi A, Pignattelli S, et al. Impact of microplastics on growth, photosynthesis and essential elements in Cucurbita pepo L. J Hazard Mater. 2022;423(7):127238. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127238. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Hernández Arenas R, Beltrán Sanahuja A, Navarro Quirant P, Sanz Lazaro C. The effect of sewage sludge containing microplastics on growth and fruit development of tomato plants. Environ Pollut. 2021;268:115779. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115779. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Lozano YM, Lehnert T, Linck LT, Lehmann A, Rillig MC. Microplastic shape, polymer type, and concentration affect soil properties and plant biomass. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12(12):616645. doi:10.1101/2020.07.27.223768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zhang ZQ, Li Y, Qiu TY, Duan CJ, Chen L, Zhao SL, et al. Microplastics addition reduced the toxicity and uptake of cadmium to Brassica chinensis L. Sci Total Environ. 2022;852:158353. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158353. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Rehman A, Zhong S, Du D, Zheng X, Arif MS, Ijaz S, et al. Unveiling the microplastics degradation and its transformative effects on soil nutrient dynamics and plant health—a systematic review. Sustain Prod Consum. 2025;54:25–42. doi:10.1016/j.spc.2024.12.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Iqbal B, Zhao T, Yin W, Zhao X, Xie Q, Khan KY, et al. Impacts of soil microplastics on crops: a review. Appl Soil Ecol. 2023;181(1):104680. doi:10.1016/j.apsoil.2022.104680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ranathunge K, Kotula L, Steudle E, Lafitte R. Water permeability and reflection coefficient of the outer part of young rice roots are differently affected by closure of water channels (aquaporins) or blockage of apoplastic pores. J Exp Bot. 2004;55:433–47. doi:10.1093/jxb/erh041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Venturas MD, Sperry JS, Hacke UG. Plant xylem hydraulics: what we understand, current research, and future challenges. J Integr Plant Biol. 2017;59(6):356–89. doi:10.1111/jipb.12534. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Pignattelli S, Broccoli A, Renzi M. Physiological responses of garden cress (Lepidium sativum) to different types of microplastics. Sci Total Environ. 2020;727(9):138609. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138609. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Bosker T, Bouwman LJ, Brun NR, Behrens P, Vijver MG. Microplastics accumulate on pores in seed capsule and delay germination and root growth of the terrestrial vascular plant Lepidium sativum. Chemosphere. 2019;226:774–81. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.03.163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Gan Q. Effects of microplastics on growth, physiological biochemistry, and transcriptional regulation of Ginkgo biloba seedlings [dissertation]. Yangzhou, China: Yangzhou University; 2023. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

28. Ding GJ, Zhou ZC, Wang ZR. Cultivation and utilization of Pinus massoniana lamb for pulpwood. Beijing, China: China Forestry Publishing House; 2006. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

29. Brown RW, Chadwick DR, Zang HD, Graf M, Liu XJ, Wang K, et al. Bioplastic (PHBV) addition to soil alters microbial community structure and negatively affects plant-microbial metabolic functioning in maize. J Hazard Mater. 2023;441(65):129959. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.129959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Gu C, Ma J, Zhu G, Yang H, Zhang K, Wang Y. Partitioning evapotranspiration using an optimized satellite-based ET model across biomes. Agric For Meteorol. 2018;259(17):355–63. doi:10.1016/j.agrformet.2018.05.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhou ZC, Zhang R, Fan HH, Chinese Schima. Beijing, China: Science and Technology Press; 2020. p. 1–6. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

32. Huang X, Lai J, Liu Y, Zheng L, Fang X, Song W, et al. Biogenic volatile organic compound emissions from Pinus massoniana and Schima superba seedlings: their responses to foliar and soil application of nitrogen. Sci Total Environ. 2020;705:135761. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135761. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Zhu L, Fu T, Du J, Hu W, Li Y, Zhao X, et al. Hydraulic role in differential stomatal behaviors at two contrasting elevations in three dominant tree species of a mixed coniferous and broad-leaved forest in low subtropical China. For Ecosyst. 2023;10:100095. doi:10.1016/j.fecs.2023.100095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Qi R, Jones DL, Li Z, Liu Q, Yan C. Behavior of microplastics and plastic film residues in the soil environment: a critical review. Sci Total Environ. 2020;703(5):134722. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134722. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Fuller S, Gautam A. A procedure for measuring microplastics using pressurized fluid extraction. Environ Sci Technol. 2016;50(11):5774–80. doi:10.1021/acs.est.6b00816. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Šímová I, Violle C, Svenning J, Kattge J, Engemann K, Sandel B, et al. Spatial patterns and climate relationships of major plant traits in the New World differ between woody and herbaceous species. J Biogeogr. 2018;45(4):895–916. doi:10.1111/jbi.13171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Jiang JT. Effects of microplastics on the growth and physiological-ecological characteristics of three northern crops [dissertation]. Shenyang, China: Shenyang University; 2022. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

38. Zhang YW, Zhao H, Li ZE, Zheng FH, An ZH. Comparison of space charge injection characteristics in polyethylene and polypropylene. High Volt Eng. 2014;40:2613–8. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

39. Hasan MM, Jho EH. Effect of different types and shapes of microplastics on the growth of lettuce. Chemosphere. 2023;339:139660. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.139660. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Sun HR, Shi YL, Zhao P, Long GQ, Li C, Wang J, et al. Effects of polyethylene and biodegradable microplastics on photosynthesis, antioxidant defense systems, and arsenic accumulation in maize (Zea mays L.) seedlings grown in arsenic-contaminated soils. Sci Total Environ. 2023;868(11):161557. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.161557. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Poorter H, Niklas KJ, Reich PB, Oleksyn J, Poot P, Mommer L. Biomass allocation to leaves, stems and roots: meta-analyses of interspecific variation and environmental control. New Phytol. 2012;193(1):30–50. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03952.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools