Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Genome-Wide Identification of the APETALA2/Ethylene-Responsive Factor (AP2/ERF) Gene Family in Acer paxii and Transcriptional Expression Analysis at Different Leaf Coloration Stages

1 School of Horticulture, Anhui Agricultural University, Hefei, 230036, China

2 College of Urban Construction, Zhejiang Shuren University, Shaoxing, 312028, China

3 Agriculture Mechanization and Engineering Research Institute, Anhui Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Hefei, 230031, China

* Corresponding Authors: Hongfei Zhao. Email: ; Jie Ren. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Ornamental Plants: Traits, Flowering, Aroma, Molecular Mechanisms, Postharvest Handling, and Application)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(9), 2927-2947. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.067310

Received 29 April 2025; Accepted 05 August 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Acer paxii belongs to the evergreen species of Acer, but it exhibits a unique feature of reddish leaves in fall in subtropical regions. Although the association of AP2/ERF transcription factors with color change has been well-documented in prior research, molecular investigations focusing on AP2/ERF remain notably lacking in Acer paxii. This research focuses on performing an extensive genome-wide investigation to identify and characterize the AP2/ERF gene family in Acer paxii. As a result, 123 ApAP2/ERFs were obtained. Phylogenetic analyses categorized the ApAP2/ERF family members into 15 subfamilies. The evolutionary traits of the ApAP2/ERFs were investigated by analyzing their chromosomal locations, conserved protein motifs, and gene duplication events. Moreover, investigating gene promoters revealed their potential involvement in developmental regulation, physiological processes, and stress adaptation mechanisms. Measurements of anthocyanin content revealed a notable increase in red leaves during autumn. Utilizing transcriptome data, transcriptomic profiling revealed that the majority of AP2/ERF genes in Acer paxii displayed significant differential expression between red and green leaves during the color-changing period. Furthermore, through qRT-PCR analysis, it was found that the gene expression levels of ApERF006, ApERF014, ApERF048, ApERF097, and ApERF107 were significantly elevated in red leaves. This indicates their potential participation in leaf pigmentation processes. These findings offer significant insights into the biological significance of ApAP2/ERF transcription factors and lay the groundwork for subsequent investigations into their regulatory mechanisms underlying leaf pigmentation in Acer paxii.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileAcer paxii is an evergreen tree classified under the genus Acer within the family Sapindaceae, and it is endemic to China. It is primarily distributed in Yunnan Province, including the Kunming region. This species thrives in the natural environment of Kunming, adapting well to the local climate and soil conditions. The evergreen nature of Acer paxii allows it to add greenery to the landscape throughout all four seasons, making it highly valuable for ornamental and ecological purposes [1]. Acer paxii is highly resistant, with dense foliage and branches, and is often planted in gardens as avenue trees and shade trees. After being transplanted to Hefei, Anhui Province, Acer paxii leaves turn red in the fall, which is highly ornamental and very suitable for cities, gardens, and road beautification [2].

Several studies have systematically examined and quantified the pigmentation and physiological indicators of leaves in colorful foliage plants, revealing the mechanisms of leaf color change [3]. Anthocyanins play a direct role in influencing the key mechanisms of leaf color transition to purple or red hues [4]. Anthocyanins, a group of naturally occurring compounds classified under the flavonoid group, are produced via the phenylpropanoid biosynthetic pathway in plants [5]. These naturally occurring pigments, displaying diverse hues spanning crimson, violet, and indigo, are extensively present in multiple plant structures such as blossoms, berries, foliage, and root systems [6]. The production of anthocyanins in plant cells is governed by an intricate regulatory network, in which critical enzymes play a central role in coordinating this process. Within the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway, these enzymes are indispensable for driving precise biochemical transformations. The biosynthesis of anthocyanins begins with the action of chalcone synthase (CHS), which catalyzes the formation of chalcones from phenylpropanoid precursors. These chalcones are then isomerized by chalcone isomerase (CHI) to produce flavanones. Flavanone 3-hydroxylase (F3H) further modifies these intermediates, and dihydroflavonoid 4-reductase (DFR) catalyzes the reduction of dihydroflavonols to leucoanthocyanidins. Finally, anthocyanidin synthase (ANS) plays a pivotal role in converting leucoanthocyanidins into colored anthocyanidins, which are subsequently stabilized into anthocyanins. These enzymatic steps collectively ensure the biosynthesis of anthocyanins. The compounds are responsible for the striking colors of plant tissues and significantly contribute to the regulation of pigment biosynthesis and diversity in plants [7].

Beyond enzymatic catalysis, anthocyanin biosynthesis is precisely orchestrated via the regulatory influence of specific transcriptional activators [8]. Transcription factors not only indirectly influence the accumulation of anthocyanin by modulating the transcriptional activity of genes involved in the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway (such as CHS, DFR, and ANS), but also directly participate in modulating critical steps within the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway. For example, in apples (Malus × domestica), MdERF1B regulates anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin biosynthesis [9]. MdLNC499 connects the functions of MdWRKY1 and MdERF109, playing a crucial part in the modulation of anthocyanin accumulation in apple fruit [10]. Besides, MYB can function independently or in a ternary complex with two other Transcription Factors (bHLH and WD40, called MBW) [11]. In poplar, metabolic changes induced by the activation of PdCHS and PdANS via PdMYB113 present a key mechanism for coloration in ornamental species [12]. In the red autumn leaves of toothed oak (Quercus dentata), the transcription factor QdNAC regulates anthocyanin accumulation by interacting directly with QdMYB [13]. A genome-wide study of Pelargonium lanceolatum identified 158 R2R3-MYB transcription factors, with MYB113 specifically linked to anthocyanin biosynthesis [14]. Additionally, transcriptome analysis conducted when the leaves of Populus euramericana ‘Zhonghuahongye’ were changing color, from the initial reddish-purple through an intermediate stage to the final greenish-purple phase, showed that bHLH35 and bHLH63 serve as negative regulators of anthocyanin synthesis [15].

The AP2/ERF superfamily, also known as AP2/ethylene-responsive element binding factors, constitutes a major and highly conserved group of transcriptional regulators in plants [16]. Each member of the AP2/ERF family has a conserved AP2 domain [17], which is responsible for DNA binding and typically comprises 60 to 70 amino acids [18]. Based on the number of conserved AP2/ERF domains and variations in their structural organization, the AP2/ERF TFs are classified into five distinct subgroups AP2 (APETALA2), DREB (dehydration-responsive element binding proteins), ERF (ethylene-responsive factors), RAV (related to ABI3/VP1), and Soloist [19]. Structural characterization revealed distinct domain organizations among subfamilies: the AP2 group contains dual AP2/ERF domains, whereas ERF members feature a single AP2 domain. Notably, RAV proteins are characterized by the presence of both an AP2 domain and a unique B3 DNA-binding motif [20]. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that both DREB and ERF subgroups diverged into six distinct clades, with DREB lineages categorized as B1-B6 and ERF lineages grouped into A1-A6 clusters [21].

The AP2/ERF transcription factors regulate multiple aspects of plant biology, including developmental processes, hormonal signaling pathways [22]. The AP2/ERF transcription factors have been reported to be involved in Arabidopsis thaliana flower development [23]. PsERF1 controls the ripening of plum fruit by means of the ethylene pathway [24]. The AP2/ERF family gene MaERF11 in bananas plays a crucial role in ethylene-mediated fruit ripening through its function as a transcriptional repressor of the MaACO1 and MaACS1 promoters, thereby modulating the ripening process [25]. Throughout apple fruit maturation, MdERF2 functions as an inhibitory factor in ethylene production by downregulating MdACS1 expression, consequently modulating ripening progression [26]. Several AP2/ERF TFs have emerged as crucial regulators in enhancing plant adaptation to environmental stresses [27]. The AP2/ERF superfamily has been characterized on a genomic scale among various species. In Arabidopsis thaliana 147 gene members were identified [28]. A total of 163 gene members have been reported in Oryza sativa [29]. In Populus trichocarpa, the literature has documented the identification and characterization of 202 gene homologs in prior research [30]. In Pinus massoniana, 88 AP2/ERF members were identified [31]. In Actinidia eriantha, 158 AP2/ERFs were identified [32]. In Citrus reticulata, 126 AP2/ERFs were identified [33]. Vitis vinifera has 149 AP2/ERF members [34].

Accumulating evidence has demonstrated that AP2/ERF transcription factors play a regulatory role in the biosynthesis of anthocyanins. In Arabidopsis thaliana mutants, mutations in AtERF4 and AtERF8, reduce the rate and extent of anthocyanin production [35]. In ‘Zaosu’ pear, PbERF22 has been shown to positively regulate anthocyanin synthesis [36]. In ‘RedZaosu’ pearfruits, the control of anthocyanin buildup is mediated through the interaction between ethylene-responsive factors Pp4ERF24 and Pp12ERF96 with MYB114 [37]. The transcription factor ZbERF3 enhances anthocyanin biosynthesis in Zanthoxylum bungeanum when induced by ethylene [38]. In Litchi chinensis Sonn, ethylene enhances anthocyanin accumulation by activating positive regulators of anthocyanin biosynthesis, such as LcERF1/22/25/37, or by suppressing the negative regulator LcERF64 [39]. In Lily (Lilium spp.), LhERF4 has been identified as a negative regulator of anthocyanin accumulation, functioning through the suppression of LhMYBSPLATTER expression, a key player in the anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway [40]. These investigations indicate that AP2/ERF transcription factors could significantly influence the regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis.

Current understanding of AP2/ERF-mediated regulation of anthocyanin accumulation in leaf pigmentation is still incomplete. Through genome-wide analysis of the Acer paxii genome, a number of 123 ApAP2/ERF genes were identified. We systematically investigated their evolutionary relationships and structural organization, and putative regulatory elements. And we measured pigment levels in green and red leaves of Acer paxii, conducting transcriptome sequencing, and performing qRT-PCR. These findings establish the foundation for subsequent explorations concerning the functional responsibilities and underlying mechanisms of AP2/ERF members within Acer paxii.

2.1 Research Materials and Sample Collection

All plant material was grown under natural growing conditions in Hefei, Anhui Province, China, and field management followed standard agricultural practices. At the the autumn discoloration period in 2024, green and red leaves of the same plant were selected as the test materials, with all samples collected within a two-week timeframe. Right after collection, all samples were promptly plunged into liquid nitrogen for rapid freezing. Subsequently, they were transferred to a −80°C refrigerator for storage. These samples were designated for the determination of pigmentation content, extraction of total RNA for transcriptome sequencing, and gene expression analysis.

2.2 Determination of Leaf Pigment Content

To 0.2 g of sample was added 10 mL of 1 mol/L ethanol hydrochloride. Three replicates were taken for each treatment and six samples were hydrolyzed in a water bath at 55°C for 2 h. The supernatant was taken as a sample extract. The anthocyanin content was measured using spectrophotometry, with the optical densities of the extracts recorded at 530, 620, and 650 nm, using a 1 mol/L hydrochloric acid ethanol solution as the reference (Supplementary Material S1).

The corrected absorbance was calculated as:

ODλ: the corrected absorbance; ε: 4.62 ∗ 104 (the molar extinction coefficient of the major anthocyanin); V: total volume of the extract (ml); m: quality of the sample (g); M: 287.24 (the molecular weight of the major anthocyanin-cyanidin) [41].

2.3 Identification of the ApAP2/ERF Gene Family

We performed sequencing on the Acer paxii genome database with data generated by Dr. Ren’s team (Supplementary Material S2). The ApAP2/ERF sequences of Arabidopsis thaliana were obtained from the TAIR database (https://www.arabidopsis.org/, accessed on 04 August 2025). Moreover, we carried out supplementary analysis using Pfam [42]. Domain architecture verification using NCBI-CDD confirmed the presence of complete AP2/ERF domains in all identified proteins (Supplementary Material S3). Computational characterization employing TBtools enabled comprehensive profiling of key molecular parameters (Supplementary Material S4).

2.4 Phylogenetic Evolutionary Tree on ApAP2/ERFs

Using the MUSCLE tool, we conducted pairwise and multiple sequence alignments under default settings to examine the complete protein sequences of AP2/ERFs from Acer paxii and Arabidopsis thaliana. After the alignment process, in MEGA 7, we generated a phylogenetic tree via the neighbor-joining approach. Bootstrap analysis was carried out over 1000 iterations during this phylogenetic tree construction [43]. Subsequently, the phylogenetic tree generated from the analysis was presented visually using the ITOLS platform (http://itol.embl.de, accessed on 04 August 2025). The AP2/ERF genes identified in Acer paxii were classified into distinct subgroups according to the number of AP2 and B3 conserved domains [44].

2.5 Gene Structure, Conserved Structural Domains, Motifs and Cis-Acting Elements

We utilized the Pfam database and the NCBI CD search tool (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/, accessed on 01 January 2025) to identify the conserved AP2/ERF structural domain in the Acer paxii AP2/ERF proteins. For analyzing the architecture and features of the ApAP2/ERF genes, we applied TBtools. Additionally, to detect conserved motifs within the gene, we used MEME software version 5.0.5 (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme, accessed on 01 January 2025). The motif findings from MEME were subsequently visualized in XML format using TBtools [45]. Finally, the PlantCARE database (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/, accessed on 01 January 2025) was employed to analyze cis-regulatory elements (Supplementary Material S5) in the 2-kb upstream promoter region [46].

2.6 Chromosomal Location, Gene Duplication and Colinearity Analyses of the ApAP2/ERF Gene Family

TBtools was utilized to visualize the genomic positions (Supplementary Material S6) of all potential ApAP2/ERFs [47]. The inter-species duplication events (Supplementary Material S7) in Acer paxii were evaluated using the Multiple Collinearity Scan tool (MCScanX). Genomic data for Populus trichocarpa, Citrus reticulata, Vitis vinifera, and Arabidopsis thaliana were obtained from the NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, accessed on 04 August 2025). Using TBtools, the syntenic gene relationships between Acer paxii and these four species were analyzed and visualized.

2.7 Transcriptome Analysis of ApAP2/ERF Gene Family

In this study, green and red leaf samples of Acer paxii were collected during the autumn leaf color transition period. Transcriptome sequencing was conducted by the research team, and gene expression heatmaps were generated and visualized using TBtools (Supplementary Material S8).

2.8 RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the samples using the thermal boric acid method, with all reagents obtained from Zoonbio Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China). The integrity and concentration of the isolated RNA were assessed following standard protocols. The reverse transcription process employed the Hifair® II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix for qPCR (gDNA digester plus) (11123ES10; Yeasen Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) as the primary reagent for cDNA synthesis.

Then the amplification reaction was carried out on a Fluorescence Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction Detection System (FQD-48A); BIOER, Hangzhou, China). The reaction conditions were set as follows: 95°C for 5 min pre-denaturation; 95°C for 10 s, 60°C for 30 s, cycling 40 times, and 72°C for single-point detection of signals; and the lysis curve was programmed as 95°C for 0 s, 65°C for 15 s, and 95°C for 0 s, with continuous detection of signals. The primer sequences were designed by Primer Premier 5 software, in which ACTIN was used as the internal reference gene (Supplementary Material S9).

In this experiment, samples were used, each with 3 biological replicates. The relative quantification of gene expression levels was performed using the 2−ΔΔCt approach established by Livak & Schmittgen [48]. Bar graph were created with GraphPad Prism 8.4.5. Statistical significance was assessed using Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05, n = 3), where different letters in the figures indicate significant differences.

2.9 Protein Interaction Network of ApAP2/ERF Gene Family

The ApAP2/ERF sequences were analyzed using the STRING platform (version 11.0, http://string-db.org, accessed on 04 August 2025), employing Arabidopsis thaliana as the reference species from the provided options (Supplementary Material S10). To elucidate the relationships between proteins, the ApAP2/ERF protein interaction network was analyzed [49].

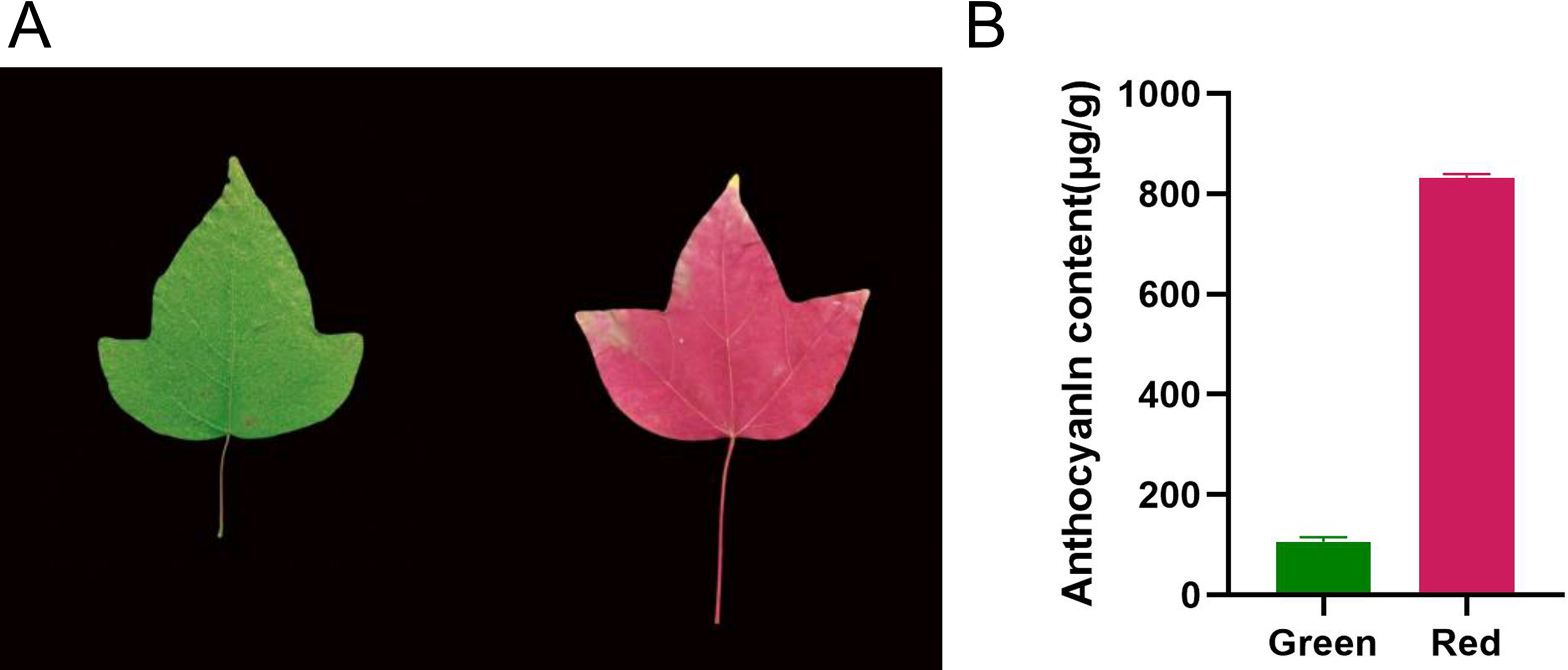

3.1 Detection of Anthocyanin Pigments in Acer paxii Leaf Blades

Measurements of anthocyanin content revealed that green and red Acer paxii leaves contained 106.66 μg/g and 831.08 μg/g of anthocyanins, respectively. During the discoloration period, the anthocyanin content in the red leaves increased significantly, reaching levels 8 times higher than those observed in the green period (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Observed color transformation and detected color parameters of Acer paxii leaves. (A) Color of Acer paxii leaf blades in the discoloration period. (B) Anthocyanin content of Acer paxii green leaves in the discoloration period

3.2 Comprehensive Genomic Analysis of AP2/ERF Genes in Acer paxii

To identify the AP2/ERF family members in Acer paxii, a Hidden Markov Model (HMM) search was executed, with a focus on the AP2 structural domain (PF00847). After domain screening, this search resulted in the discovery of 123 AP2/ERF genes. Following the identification of candidate AP2/ERF proteins in Acer paxii, we used Pfam and NCBI-CDD, to confirm they had intact AP2/ERF structural domains. Then, We designated the genes ApERF1 to ApERF123 based on chromosomal location distribution across the chromosomes for subsequent phylogenetic and functional analyses.

Furthermore, we conducted a comprehensive characterization of 123 AP2/ERF genes in Acer paxii, employing TBtools for computational analysis of their sequence features. This included the determination of molecular mass, theoretical isoelectric points, protein stability indices, and overall hydrophobicity profiles. The ApAP2/ERF-encoded proteins exhibit amino acid lengths varying from 122 to 1170, molecular weights between 14.05 and 128.90 kD, and isoelectric points (pIs) spanning from 4.55 to 10.56 (Supplementary Material S4). The overall hydrophilicity of the proteins is below zero, indicating that they are hydrophobic in nature.

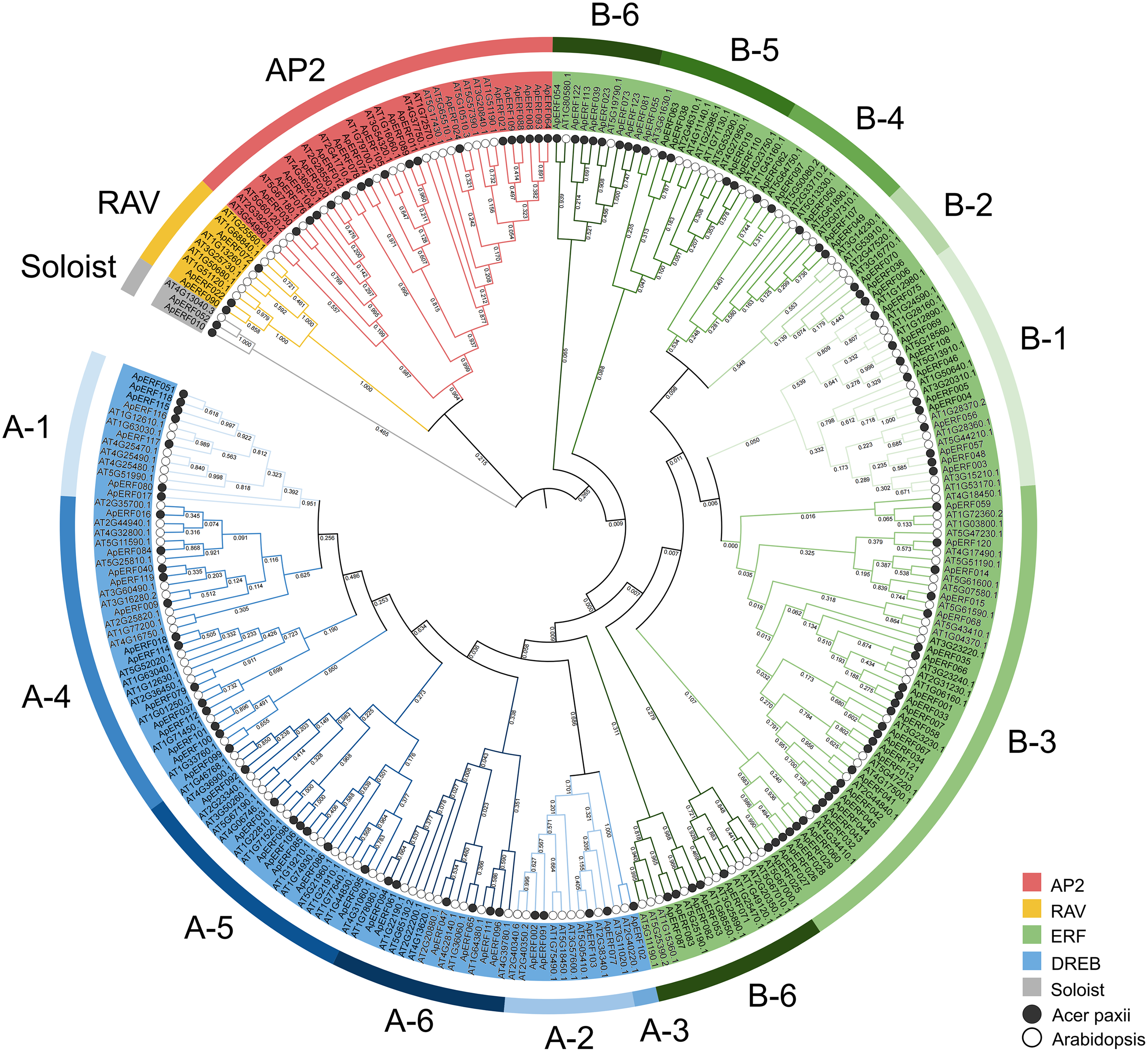

3.3 Phylogenetic Evolutionary Analysis of the Acer paxii AP2/ERF Gene Family

To elucidate the evolutionary connections among members of the AP2/ERF gene family in Acer paxii, a phylogenetic analysis was performed by aligning 123 AP2/ERF proteins from Acer paxii with 147 counterparts from Arabidopsis thaliana, resulting in the generation of a phylogenetic tree (Fig. 2). The phylogenetic analysis revealed that the 123 ApAP2/ERF genes clustered into five major evolutionary groups, including ERF (with its DREB subgroup), AP2, RAV, and Soloist. The DREB and ERF subfamilies, which are key components of the AP2/ERF family, have been further subdivided into 12 distinct groups based on the Arabidopsis thaliana classification framework [50]. Within these 12 groups, A1 to A6 were part of the DREB subfamily, consisting of 7, 4, 1, 14, 7, and 6 members, respectively. On the other hand, the remaining six groups (B1 to B6) were classified under the ERF subfamily, with 10, 3, 27, 5, 5, and 13 members, respectively.

Figure 2: Phylogenetic relationships of 123 ApAP2/ERF family members in Acer paxii. An unrooted phylogenetic tree was generated using the aligned amino acid sequences of the 123 ApAP2/ERFs along with 1000 bootstrap replicate sequences. The classification of each subgroup is indicated by colored boxes

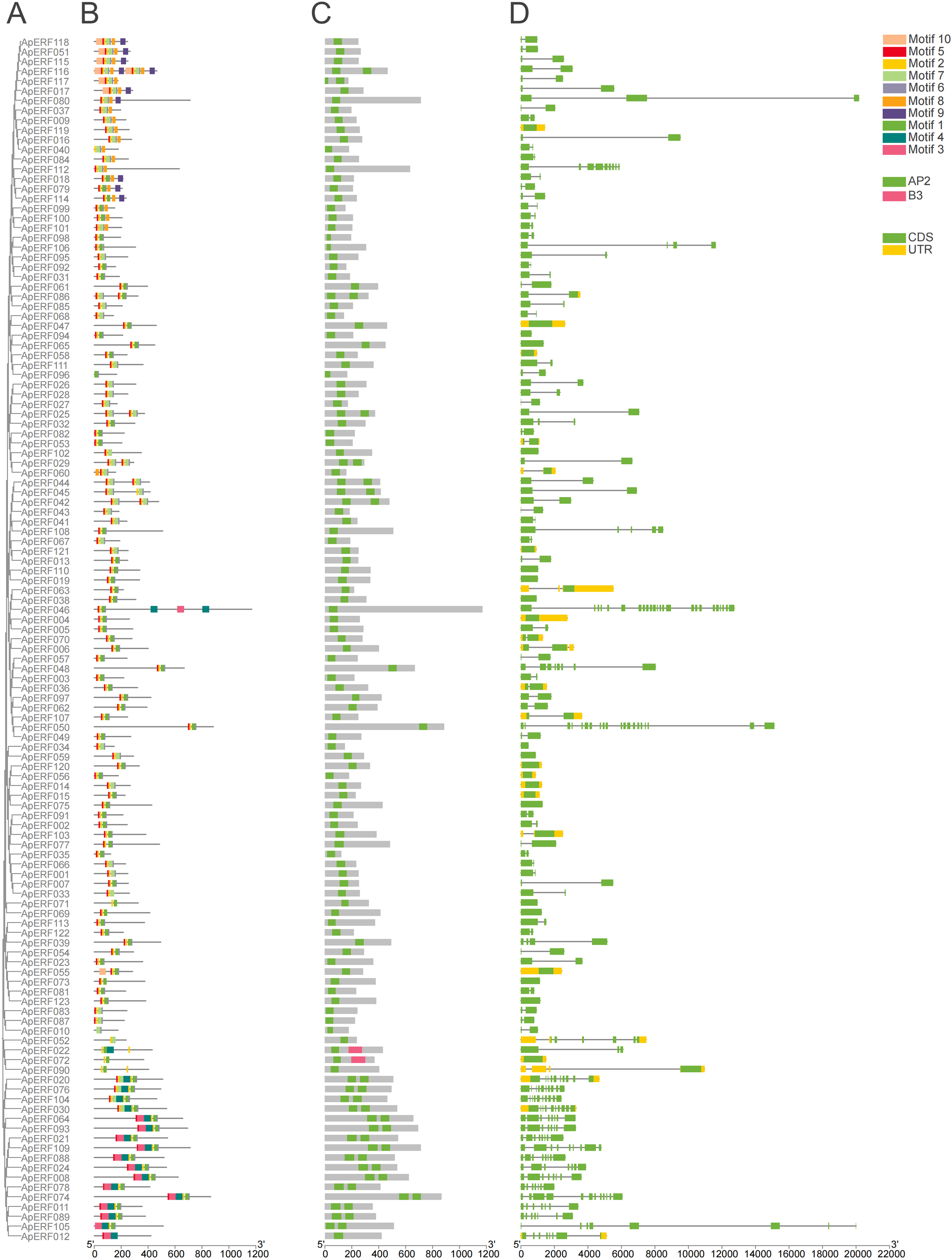

3.4 Conserved Motifs, Structural Domains and Gene Structure Analysis of the ApAP2/ERF Gene Family

To provide evolutionary context, a gene phylogenetic tree was included on the left side (Fig. 3A), facilitating comparison between genetic relationships and conserved motifs, structural domains, and gene structure. Analysis of conserved motifs in the Acer paxii AP2/ERF transcription factors revealed that the majority of gene family members simultaneously possess four motifs (motif 1, motif 2, motif 5, motif 6). Using the MEME online tool, the 10 conserved motifs in the AP2/ERF genes of Acer paxii were identified. It was discovered that the number of motifs harbored by different members varied from 2 to 7 (Fig. 3B). This finding implies that motifs 1, 2, 5, and 6 are the main constituents of the AP2 structural domain. Motif 4 was detected in all AP2 subfamily members. Most DREB subfamily genes contained motif 2 and motif 5. In the ERF subfamily, the majority of genes were found to contain motifs 1, 2, and 6.

Figure 3: Visualization of motifs, conserved domains and gene structures of Acer paxii AP2/ERF family genes. (A) The unrooted phylogenetic tree of 123 AP2/ERF genes. (B) Protein motifs of the Acer paxii AP2/ERF family. (C) Protein structural domains of the Acer paxii AP2/ERF family. (D) Gene structure of Acer paxii AP2/ERF. The X-axis in this figure is measured in base pairs (bp)

In the process of identifying AP2/ERF members in Acer paxii, we took 147 AP2/ERF protein sequences from Arabidopsis thaliana. With the help of TBtools software, we conducted a search within the protein database of Acer paxii. Consequently, the search resulted in the discovery of 123 ApAP2/ERFs in Acer paxii. Drawing from the reference study, we analyzed the domain configurations of the AP2/ERF gene family proteins in Acer paxii. Every protein features at least one such domain. Members of the ERF and AP2 subfamilies possess either one or two, whereas proteins in the RAV subfamily (Fig. 3C) include an additional B3-binding domain, potentially influencing gene regulation.

Analyzing introns and exons can provide deeper insights into gene expression patterns. It is worth noting that the quantity of exons and introns in the AP2/ERF genes varies considerably. Specifically, the ERF and AP2 subfamilies exhibit a higher number of exons compared to the DREB subfamily. Moreover, the ERF subfamily exhibits a higher number of untranslated regions (UTRs) compared to the other subfamilies (Fig. 3D). Typically, closely related members within each subfamily exhibit conserved gene architecture, maintaining consistent patterns of intron-exon organization.

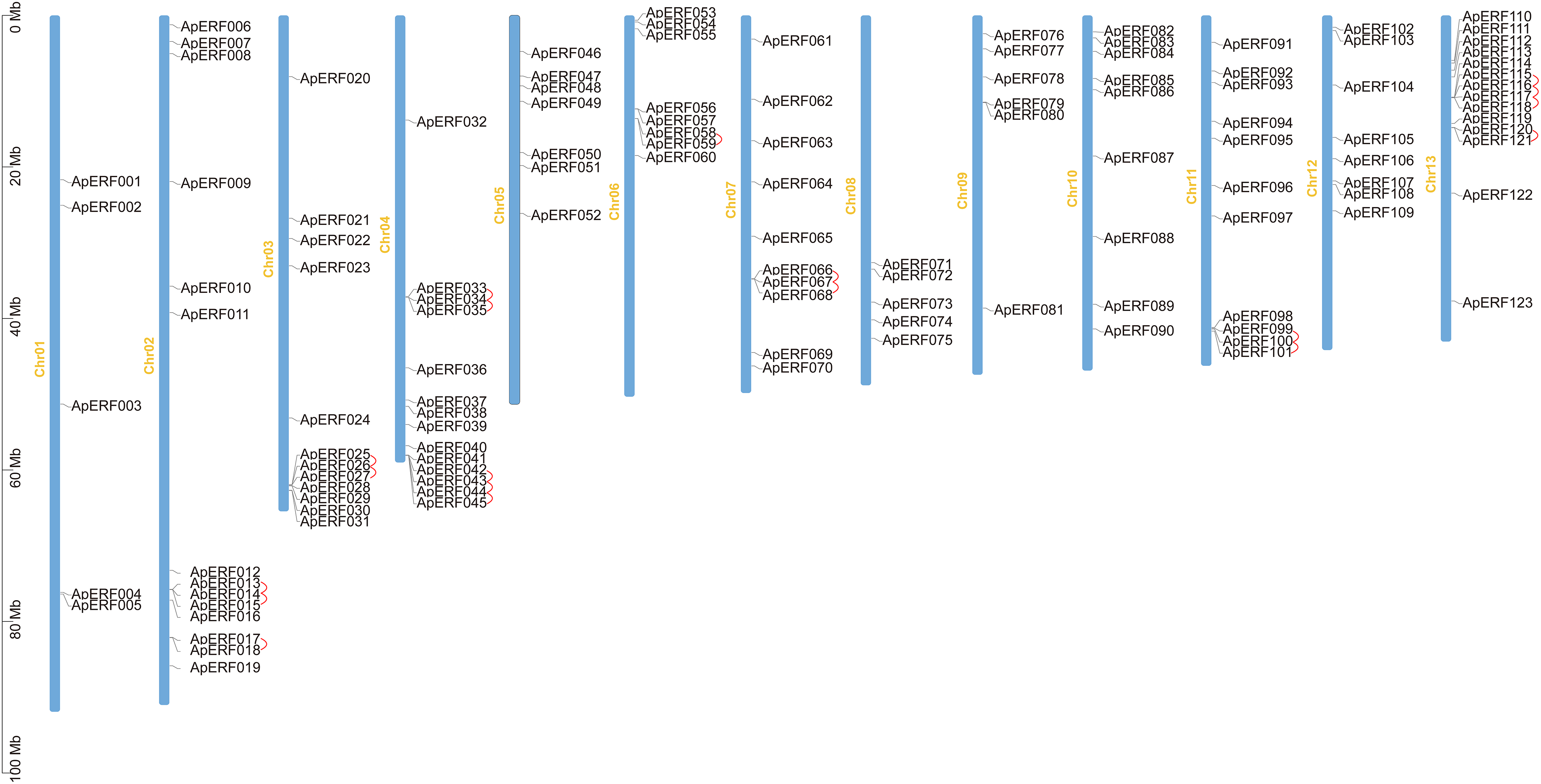

3.5 Chromosomal Location and Replication Events of the ApAP2/ERF Gene Family

The examination indicated that the 123 ApERFs were dispersed unevenly among the 13 chromosomes of Acer paxii, with a range of 5 to 14 genes present on each chromosome (Fig. 4). Chromosomes 2, 4, and 13 exhibited the highest gene counts, each with 14 ApERFs. Chromosome 3 followed with 12 genes, while chromosomes 1 and 8 had the fewest, with only 5 genes each. The remaining genes were unevenly distributed across the other chromosomes.

Figure 4: Distribution of chromosomal locations for the 123 ApAP2/ERFs. The scale bar on the left indicates the chromosome length in Mb. Red lines denote duplicated ApAP2/ERF gene pairs. Use TBTools software to generate the chromosome location map.

Tandem and segmental duplications in genes have contributed to the formation of gene families over the course of biological evolution [51]. To explore the potential for duplication-driven amplification within the ApERF gene family, the analysis of duplication events was conducted. The findings indicated that 31% (38/123) of the ApAP2/ERFs were part of tandem duplication sequences and 24 segmental duplicattion paris distributed across chromosomes (Fig. 4). Furthermore, MCScanX covariance analysis highlighted segmental duplication events, identifying 27 pairs of genes segmental duplicated across different chromosomes (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Duplication analysis of AP2/ERFs in Acer paxii. Gray lines represent all syntenic blocks in the Acer paxii genome and red lines indicate homozygous gene pairs in the AP2/ERF gene family. Lines along rectangles, heatmaps, and histograms indicate gene density on chromosomes

3.6 Colinearity Analysis of AP2/ERFs of the Acer paxii with Genes from Other Species

Based on the previous studies, the evolutionary connections within the AP2/ERF gene families in several species were explored. We analyzed gene duplication events and genetic differentiation of homologous AP2/ERFs across Arabidopsis thaliana, Vitis vinifera, Citrus reticulata, Populus trichocarpa, and Acer paxii (Fig. 6) to gain insights into their evolutionary patterns. The analysis revealed 243 homologous gene pairs between Acer paxii and Populus trichocarpa. Additionally, 144 homologous pairs were identified between Acer paxii and Citrus reticulata. Furthermore, 141 and 131 homologous gene pairs were detected between Acer paxii and Vitis vinifera, and Acer paxii and Arabidopsis thaliana, respectively.

Figure 6: Colinearity analysis of AP2/ERFs between Acer paxii and Populus trichocarpa, Citrus reticulata, Vitis vinifera, and Arabidopsis thaliana. Gray lines represent collinear blocks between the Acer paxii and other plant genomes, and red lines denote syntenic AP2/ERF gene pairs

3.7 Identification of Cis-Acting Elements of the ApAP2/ERF Gene Family

The regulation of plant adaptation mechanisms under diverse environmental conditions hinges significantly on transcription factors. The promoter regions of these factors harbor numerous cis-regulatory elements that are vital for gene expression regulation. Analysis of ApAP2/ERFs identified numerous cis-acting elements, including those responsive to phytohormones, light, and both abiotic and biotic stresses (Fig. 7). The study found 123 elements responsive to light, 101 to abscisic acid, 93 to MeJA, 61 to gibberellin, 56 to growth hormones, 47 to defense and stress, and 36 to low temperatures. Our study identified several key AP2/ERF genes, including ApERF006, ApERF014, ApERF048, ApERF097, and ApERF107. ApERF048 and ApERF097 contain 10–13 light-responsive elements and ApERF097 exhibits 3 gibberellin and 2 MeJA responsive elements. While ABA-responsive elements are present in ApERF048 and ApERF097 each containing 1 ABRE, their prevalence does not show significant enrichment compared to other genes.

Figure 7: Cis-acting element analysis of 123 ApAP2/ERF gene promoters. Nine distinct colored columns are used to represent various elementslight, meristem induction, specific activation elements, as well as those related to GA, ABA, MeJA, SA, IAA, anaerobic conditions, defense, wounding, and low-temperature responses. The horizontal coordinates signify the lengths of the genes. The X-axis in this figure is measured in base pairs (bp)

3.8 Expression Analysis of the ApAP2/ERF Gene Family

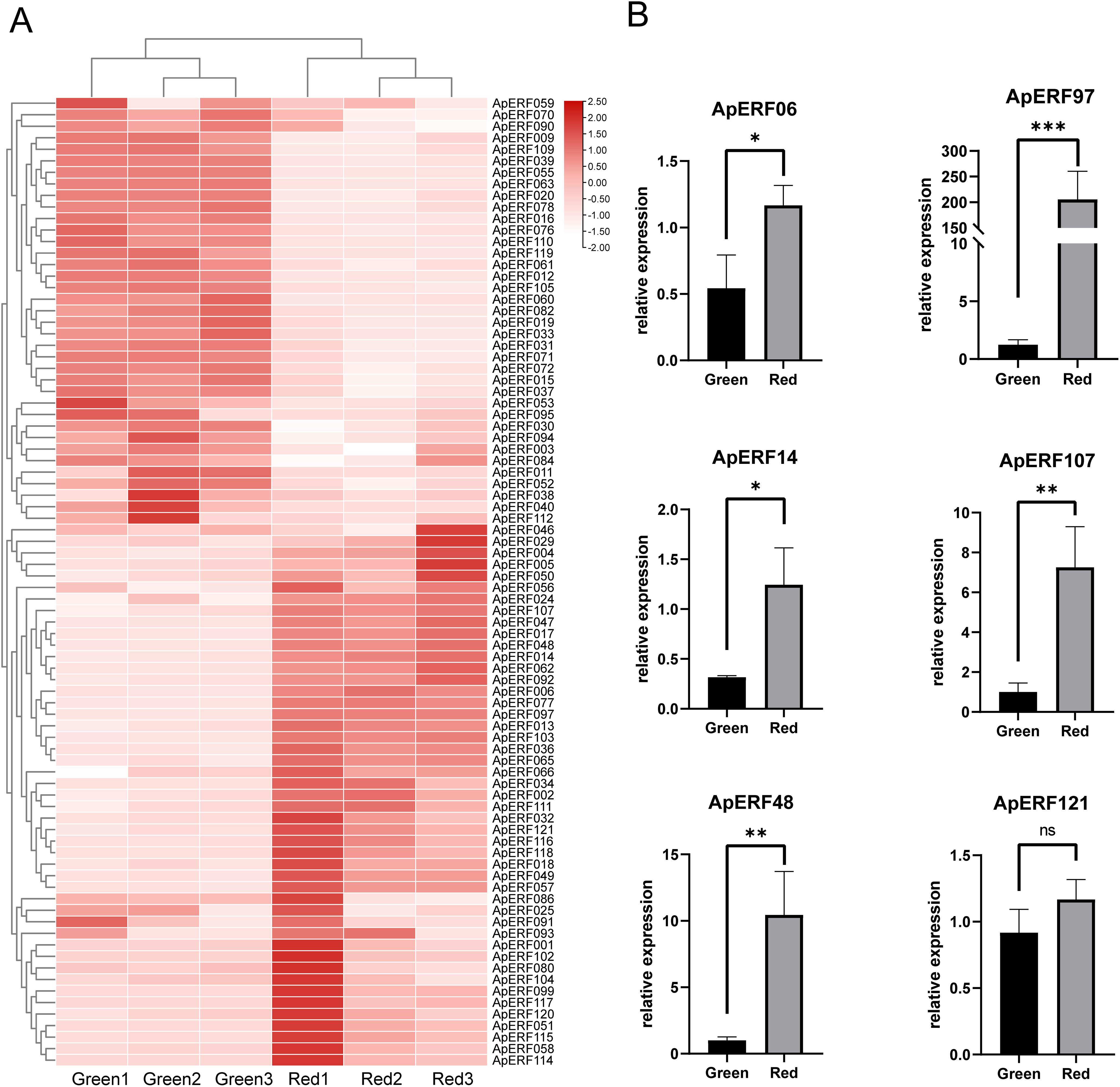

Transcriptome sequencing data were analyzed, and a heatmap illustrating the expression profiles based on raw FPKM values was generated (Fig. 8A). The expression profiles of 123 ApAP2/ERFs were analyzed in 2 different leaf color stages in green and red. Analysis revealed that certain genes exhibited increased expression levels during the color transition of Acer paxii leaves. In total, 44 genes were upregulated. Specifically, ApERF006, ApERF048, and ApERF097 displayed upregulation in red leaves.

Figure 8: 123 ApAP2/ERF gene expression profiles based on transcriptomic data at different color stages of leaves. (A) Expression of ApAP2/ERFs in heat map. (B) Expression patterns of ApAP2/ERF in qRT-PCR for different leaf colors (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001, ns: not significant)

A heat map of ApAP2/ERF expression was constructed from the transcriptome data, and six highly expressed ApAP2/ERFs were screened out (Fig. 8B). Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was conducted to investigate the tissue expression patterns of these six ApAP2/ERF genes in leaves collected during the green and red stages. Comparative analysis revealed differential expression patterns among five ApAP2/ERF genes (p < 0.05). Relative quantification showed that the expression of ApERF06, ApERF14, ApERF48, ApERF97, and ApERF107 was elevated in red leaves compared to green leaves, while ApERF121 showed no significant change. The experimental outcomes showed strong concordance with the transcriptome analysis, supporting the robustness of the sequencing dataset.

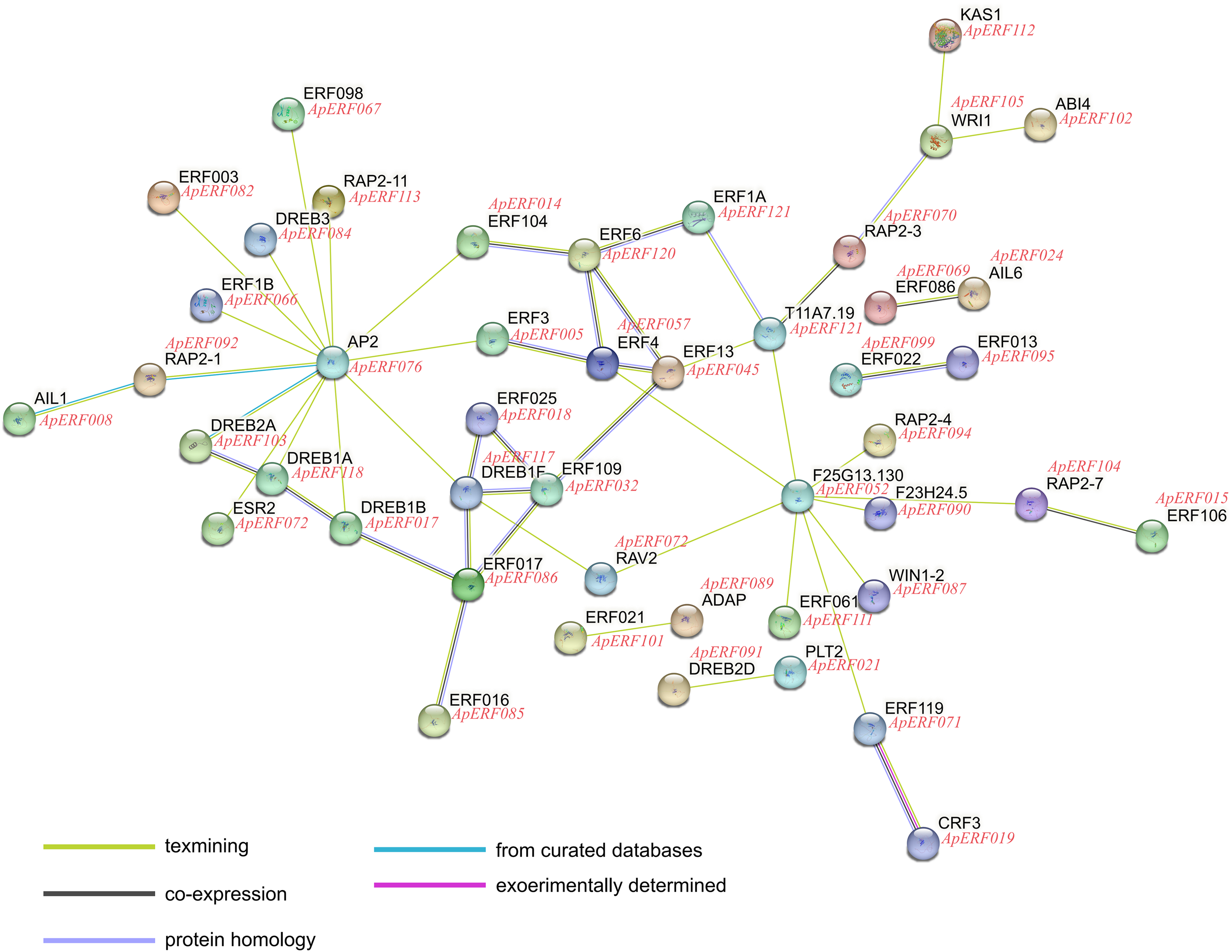

3.9 Predicting Interactions in ApAP2/ERF Proteins

The functional relationships and co-expression patterns between 123 ApAP2/ERF proteins and Arabidopsis thaliana were predicted using the STRING protein-protein interaction database, as illustrated in the interaction network diagram (Fig. 9), the connected genes may have some kind of tight functional link. ApERF076 was functionally similar to the floral homeotic protein AP2 and was identified as a probable transcriptional activator that promoted early floral meristem identity. ApERF52 was functionally similar to the ethylene-responsive transcription factor-like protein F25G13.130. It probably functioned as a transcriptional activator, potentially playing a role in modulating gene expression in reaction to stress factors and elements of stress signal transduction pathways. The AtDREB1F homolog, ApERF117, exhibited numerous interactions with other genes. It bound to the C-repeat/DRE element and mediated cold or dehydration-inducible transcription. The AtERF4 homolog ApERF057 demonstrated extensive regulatory interactions with multiple genes.

Figure 9: Predicted ApAP2/ERF proteins function connects networks. The network utilizes colored spheres to visually distinguish between various input proteins and their predicted interaction partners

The AP2/ERFs represent a major class of regulatory proteins in plant systems, extensively present across multiple biological processes. These molecular regulators are involved in developmental regulation and environmental adaptation mechanisms in plants [52,53]. Through comprehensive genomic analysis, a total of 123 ApAP2/ERFs were identified in Acer paxii, showing a comparatively reduced quantity when contrasted with certain plant species such as Erianthus fulvus (145) [54], Actinidia eriantha (158) [32] and Solanum tuberosum L. (181) [55]. Through phylogenetic and structural domain analysis, the 123 ApAP2/ERF genes were categorized into five groups, and the ERF subgroup emerged as the most predominant cluster, comprising 63 sequences that represent approximately 51.2% of the complete set. This classification pattern demonstrates consistency with the genomic organization observed across various plant species, including Myrica rubra [56], Rhododendron [57], and Coptis chinensis Franch [58]. Subfamilies such as DREB, ERF, and AP2 evolved distinct roles in stress responses, hormone signaling, and development, influenced by lineage-specific selective pressures [59]. Structural conservation of the AP2 domain contrasts with functional divergence in flanking regions, enabling varied cis-element recognition [60].

Gene duplication plays a critical role in driving the adaptive expansion and functional specialization of gene lineages [61]. Gene replication, including whole-genome duplication, tandem duplication, and segment duplication, etc., significantly impacts the functional diversity of gene families by providing raw genetic material for evolutionary innovation. For example, in the ERF subfamily, whole-genome duplication events in Brassicaceae and Poaceae led to the retention of duplicated genes, enabling functional divergence in stress responses and development. Tandem duplications, particularly in Subgroup IX, contributed to over half of its gene copies, with ancient events giving rise to functionally distinct clades like IXb from IXa [62].

The AP2/ERF transcription factor family has undergone significant functional differentiation and evolutionary expansion, driven by gene duplication. We analyzed duplicated genes based on their cis-regulatory elements and transcriptome data. Conserved gene pairs share more than 80% motif similarity in light-responsive, MYB binding, and ABA-responsive elements. This high conservation suggests these pairs maintain ancestral functions through gene dosage effects, with purifying selection acting to preserve their regulatory architecture [63]. Divergent gene pairs like ApERF019 and ApERF110 exhibit striking differences in their regulatory elements. While ApERF110 contains 20 light-responsive elements, ApERF019 possesses 78, along with distinct ABA-responsive motifs. This regulatory divergence suggests potential subfunctionalization, with ApERF019 showing enhanced light-responsive regulatory capacity compared to its duplicate ApERF110, which retains other ancestral functions.

Tandem duplicates show significantly greater motif conservation than segmental pairs. RNA-seq analysis revealed that among the 19 tandem-duplicated AP2/ERF gene pairs, the 16 pairs (84.2%) exhibited similar expression patterns in red and green leaves, suggesting potential functional redundancy. However, three pairs (15.8%) showed significant divergence, including ApERF0121 (highly expressed in red leaves) and its tandem duplicate ApERF120 (lowly expressed), indicating possible subfunctionalization or neofunctionalization after duplication. Similarly, among 27 segmentally duplicated pairs, 20 (74.1%) maintained similar expression patterns whereas 7 (25.9%) showed differential expression, exemplified by ApERF048 (red-leaf enriched) and its duplicate ApERF056 (red-leaf suppressed). This pattern of expression divergence aligns closely with the findings from studies on the AP2/ERF family in Solanaceae [64]. These observations together indicate that changes in expression patterns following gene duplication events are a significant driver of gene functional divergence.

Traditionally, conserved motifs in transcription factors have been associated with roles like protein interactions, DNA binding, and transcriptional regulation [65]. Motif analysis in the present research demonstrated that motifs 1, 2, 5, and 6 are predominantly linked to the AP2 domain within the ApAP2/ERF gene family. Specifically, motif 2 shows a connection with the subfamilies of ERF and DREB. These findings suggest that while the motifs in the AP2/ERF gene family exhibit significant evolutionary stability, the newly identified motifs may be linked with unique functional roles in plants, warranting further investigation. Introns boost gene expression by enhancing transcription, mRNA stability, and translation efficiency. They enable alternative splicing, allowing single genes to produce multiple protein variants. Evolutionarily, introns provide recombination sites that drive genetic innovation [66]. In our study, we observed that Acer paxii AP2/ERF members, particularly those in the AP2 subfamily, predominantly retain introns, which is a striking contrast to other species where AP2/ERF genes often exhibit fewer introns [43,56]. This divergence may reflect lineage-specific evolutionary dynamics.

Cis-acting elements are crucial for controlling gene expression [67]. AP2/ERF transcription factors are known to broadly modulate gene expression and are potentially involved in multiple signaling pathways, such as those regulated by SA, JA/ET, and ABA [68]. Numerous phytohormone-responsive and light-responsive elements, along with elements associated with stress responses, are present within the promoter zone of the ApAP2/ERF genes. Our study identified several key AP2/ERF genes, including ApERF006, ApERF014, ApERF048, ApERF097, and ApERF107, these genes show significantly elevated expression in red leaves which contain various light-responsive and phytohormone-responsive cis-elements and suggest that these genes may integrate environmental light signals with hormonal pathways to regulate leaf discoloration. Additionally, cis-acting elements within the ApAP2/ERF gene family were identified to contain numerous MYB binding sites, which often through formation of MBW complexes with bHLH and WD40 partners. Given the involvement of MYB transcription factors in anthocyanin biosynthesis [11]. For the high-expression genes during red leaf development, our data shows that ApERF048 and ApERF097 contain both MYB binding sites, suggesting that they may bind to MYB sites and be involved in anthocyanin-related pathways, potentially influencing color variation in plants.

Homologous lineage analysis with other species showed a certain number of homologous gene pairs between Acer paxii and Citrus reticulata, Populus trichocarpa, Vitis vinifera, and Arabidopsis thaliana. In this analysis, the ApAP2/ERF genes exhibited strong sequence similarity with Populus trichocarpa but showed relatively lower conservation when compared to Arabidopsis thaliana. These analyses shed light on the genetic divergence and duplication events of the Acer paxii AP2/ERF family, offering valuable insights into its evolutionary history and functional diversification.

Changes in anthocyanin content are an important cause of color change in Acer paxii leaf blades. Due to constraints in experimental resources, we initially focused on the two most representative stages (green and red) to identify genes potentially associated with the initiation and completion of discoloration. The experimental data showed an 8-fold enhancement in anthocyanin accumulation in red leaves relative to green leaves, reflecting pronounced seasonal differences in pigment production. Transcriptomic profiling combined with qRT-PCR verification revealed increased expression levels of certain ApAP2/ERF genes in the red foliage of autumn leaves, such as ApERF006, ApERF014, ApERF048, ApERF97, and ApERF107, and it is worth noting that ApERF048 is homologous to AtERF8, AtERF4, and AtERF8 participated in the anthocyanin production process [35], thus, it is hypothesized that ApERF048 likely exhibits analogous functional roles. Research across various species has demonstrated that AP2/ERF family members regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis [9,69–71]. Based on transcriptome analysis and previous studies, it is speculated that the ApAP2/ERF genes may play a role in regulating anthocyanin biosynthesis in Acer paxii leaves, contributing to their color variation. In future studies, we plan to conduct functional validations including ethylene and ABA treatments, light quality experiments, tobacco overexpression assays, and virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS). These experiments will systematically examine whether the candidate genes regulate leaf color transition through light signaling and hormone response pathways, thereby providing deeper mechanistic insights into this biological process.

In this study, through a genome-wide screening approach, 123 ApAP2/ERF genes were detected in Acer paxii. A series of in-depth bioinformatics analyses were performed to investigate their molecular characteristics, evolutionary connections, structural organization of genes, genomic locations, duplication events, regulatory elements, and transcriptional profiles. The results demonstrate that tandem duplication serves as a major mechanism driving the expansion of ApAP2/ERF genes, likely contributing significantly to organismal development and environmental adaptation. Additionally, differential expression of certain ApAP2/ERF genes was observed during leaf discoloration, accompanied by a significant rise in anthocyanin levels in red leaves during autumn. The study proposed that genes such as ApERF006, ApERF014, ApERF048, ApERF097, and ApERF107 could be crucial in regulating anthocyanin synthesis and leaf coloration in Acer paxii. However, the functional analysis of these transcription factors in Acer paxii remains unexplored, and the molecular mechanisms underlying their control of anthocyanin biosynthesis during color development are yet to be elucidated. Future experiments are planned to validate these gene functions. This research establishes a foundational framework for elucidating the molecular regulatory networks mediated by AP2/ERF transcription factors in Acer paxii, while offering novel perspectives on the genetic mechanisms underlying color variation in ornamental species.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant numbers 32271914 and 32301660] and the Quality Engineering Project of Anhui Provincial Department of Education [grant number 2023zygzts007].

Author Contributions: Zhong Ren performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, and approved the final draft. Shuiming Zhang conceived and designed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, and approved the final draft. Yuzhi Fei analyzed the data, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper. Zhu Chen analyzed the data, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft. Yue Zhao analyzed the data, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper. Xin Meng analyzed the data, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft. Hongfei Zhao conceived and designed the experiments, and approved the final draft. Jie Ren conceived and designed the experiments, and funding acquisition. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All the data supporting the findings of this study are included in this article and its supplementary materials.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declared no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: Supplementary Material S1: Determination of anthocyanin content; Supplementary Material S2: Sequence Data of Acer paxii; Supplementary Material S3: Basic information on Acer paxii AP2/ERF transcription factor; Supplementary Material S4: Physicochemical property of ApAP2/ERFs; Supplementary Material S5: Details of gene segmental-duplication of ApAP2/ERFs; Supplementary Material S6: Details of gene tandem-duplication of ApAP2/ERFs; Supplementary Material S7: Cis-acting regulatory element analysis of ApAP2/ERFs; Supplementary Material S8: Transcriptome data of ApERFs during Acer paxii leaf discoloration; Supplementary Material S9: Primer used for qRT-PCR analysis of ApAP2/ERFs; Supplementary Material S10: Coexpression network analysis in ApAP2/ERFs. The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.067310/s1.

References

1. Dong PB, Wang RN, Afzal N, Liu ML, Yue M, Liu JN, et al. Phylogenetic relationships and molecular evolution of woody forest tree family Aceraceae based on plastid phylogenomics and nuclear gene variations. Genomics. 2021;113(4):2365–76. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2021.03.037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Yang J, Wang X-R, Zhao Y. Leaf color attributes of urban colored-leaf plants. Open Geosci. 2022;14(1):1591–605. doi:10.1515/geo-2022-0433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Lo Piccolo E, Landi M, Massai R, Remorini D, Guidi L. Girled-induced anthocyanin accumulation in red-leafed Prunus cerasifera: effect on photosynthesis, photoprotection and sugar metabolism. Plant Sci. 2020;294:110456. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2020.110456. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Liu GH, Gu H, Cai HY, Guo CC, Chen Y, Wang LG, et al. Integrated transcriptome and biochemical analysis provides new insights into the leaf color change in Acer fabri. Forests. 2023;14(8):1638. doi:10.3390/f14081638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wu Y, Han T, Lyu L, Li W, Wu W. Research progress in understanding the biosynthesis and regulation of plant anthocyanins. Sci Hortic. 2023;321(3):112374. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2023.112374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Tanaka Y, Sasaki N, Ohmiya A. Biosynthesis of plant pigments: anthocyanins, betalains and carotenoids. Plant J. 2008;54(4):733–49. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313x.2008.03447.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Chen X, Wang P, Zheng Y, Gu M, Lin X, Wang S, et al. Comparison of metabolome and transcriptome of flavonoid biosynthesis pathway in a purple-leaf tea germplasm Jinmingzao and a green-leaf tea germplasm Huangdan reveals their relationship with genetic mechanisms of color formation. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(11):4167. doi:10.3390/ijms21114167. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Gao Y-F, Zhao D-H, Zhang J-Q, Chen J-S, Li J-L, Weng Z, et al. De novo transcriptome sequencing and anthocyanin metabolite analysis reveals leaf color of Acer pseudosieboldianum in autumn. BMC Genom. 2021;22(1):383. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-53463/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhang J, Xu H, Wang N, Jiang S, Fang H, Zhang Z, et al. The ethylene response factor MdERF1B regulates anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in apple. Plant Mol Biol. 2018;98(3):205–18. doi:10.1007/s11103-018-0770-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Ma H, Yang T, Li Y, Zhang J, Wu T, Song T, et al. The long noncoding RNA MdLNC499 bridges MdWRKY1 and MdERF109 function to regulate early-stage light-induced anthocyanin accumulation in apple fruit. Plant Cell. 2021;33(10):3309–30. doi:10.1093/plcell/koab188. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Li CX, Yu WJ, Xu JR, Lu XF, Liu YZ. Anthocyanin biosynthesis induced by MYB transcription factors in plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(19):11701. doi:10.3390/ijms231911701. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Li W, Li Q, Che J, Ren J, Wang A, Chen J. A key R2R3-MYB transcription factor activates anthocyanin biosynthesis and leads to leaf reddening in Poplar Mutants. Plant Cell Env. 2024;48(3):2067–82. doi:10.1111/pce.15276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Wang WB, He XF, Yan XM, Ma B, Lu CF, Wu J, et al. Chromosome-scale genome assembly and insights into the metabolome and gene regulation of leaf color transition in an important oak species, Quercus dentata. New Phytol. 2023;238(5):2016–32. doi:10.1111/nph.18814. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Song X, Yang Q, Liu Y, Li J, Chang X, Xian L, et al. Genome-wide identification of pistacia R2R3-MYB gene family and function characterization of PcMYB113 during autumn leaf coloration in pistacia chinensis. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;192:16–27. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.09.092. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Chen MJ, Li H, Zhang W, Huang L, Zhu JL. Transcriptomic analysis of the differences in leaf color formation during stage transitions in Populus x euramericana ‘Zhonghuahongye’. Agronomy. 2022;12(10):2396. doi:10.3390/agronomy12102396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Licausi F, Ohme-Takagi M, Perata P. APETALA/Ethylene Responsive Factor (AP2/ERF) transcription factors: mediators of stress responses and developmental programs. New Phytol. 2013;199(3):639–49. doi:10.1111/nph.12291. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Xie Z, Yang C, Liu S, Li M, Gu L, Peng X, et al. Identification of AP2/ERF transcription factors in Tetrastigma hemsleyanum revealed the specific roles of ERF46 under cold stress. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:936602. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.936602. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Park S, Shi A, Meinhardt LW, Mou B. Genome-wide characterization and evolutionary analysis of the AP2/ERF gene family in lettuce (Lactuca sativa). Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):21990. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-3292841/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Xu W, Li F, Ling L, Liu A. Genome-wide survey and expression profiles of the AP2/ERF family in castor bean (Ricinus communis L.). BMC Genom. 2013;14(1):785. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-14-785. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Zhang CH, Shangguan LF, Ma RJ, Sun X, Tao R, Guo L, et al. Genome-wide analysis of the AP2/ERF superfamily in peach (Prunus persica). Genet Mol Res. 2012;11(4):4789–809. doi:10.4238/2012.october.17.6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Yang F, Han S, Zhang Y, Chen X, Gai W, Zhao T. Phylogenomic analysis and functional characterization of the APETALA2/Ethylene-responsive factor transcription factor across solanaceae. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(20):11247. doi:10.3390/ijms252011247. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Feng K, Hou X-L, Xing G-M, Liu J-X, Duan A-Q, Xu Z-S, et al. Advances in AP2/ERF super-family transcription factors in plant. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2020;40(6):750–76. doi:10.1080/07388551.2020.1768509. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Jofuku KD, Omidyar PK, Gee Z, Okamuro JK. Control of seed mass and seed yield by the floral homeotic gene APETALA2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(8):3117–22. doi:10.1073/pnas.0409893102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. El-Sharkawy I, Sherif S, Mila I, Bouzayen M, Jayasankar S. Molecular characterization of seven genes encoding ethylene-responsive transcriptional factors during plum fruit development and ripening. J Exp Bot. 2009;60(3):907–22. doi:10.1093/jxb/ern354. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Xiao Y-Y, Chen J-Y, Kuang J-F, Shan W, Xie H, Jiang Y-M, et al. Banana ethylene response factors are involved in fruit ripening through their interactions with ethylene biosynthesis genes. J Exp Bot. 2013;64(8):2499–510. doi:10.1093/jxb/ert108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Li T, Jiang Z, Zhang L, Tan D, Wei Y, Yuan H, et al. Apple (Malus domestica) MdERF2 negatively affects ethylene biosynthesis during fruit ripening by suppressing MdACS1 transcription. Plant J. 2016;88(5):735–48. doi:10.1111/tpj.13289. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Rehman S, Mahmood T. Functional role of DREB and ERF transcription factors: regulating stress-responsive network in plants. Acta Physiol Plant. 2015;37(9):178. doi:10.1007/s11738-015-1929-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Marsch-Martinez N, Greco R, Becker JD, Dixit S, Bergervoet JHW, Karaba A, et al. BOLITA, an Arabidopsis AP2/ERF-like transcription factor that affects cell expansion and proliferation/differentiation pathways. Plant Mol Biol. 2006;62(6):825–43. doi:10.1007/s11103-006-9059-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Sharoni AM, Nuruzzaman M, Satoh K, Shimizu T, Kondoh H, Sasaya T, et al. Gene structures, classification and expression models of the AP2/EREBP transcription factor family in rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 2011;52(2):344–60. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcq196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Zhuang J, Cai B, Peng R-H, Zhu B, Jin X-F, Xue Y, et al. Genome-wide analysis of the AP2/ERF gene family in Populus trichocarpa. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;371(3):468–74. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhu P, Chen Y, Zhang J, Wu F, Wang X, Pan T, et al. Identification, classification, and characterization of AP2/ERF superfamily genes in Masson pine (Pinus massoniana Lamb.). Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):5441. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-84855-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Jiang Q, Wang Z, Hu G, Yao X. Genome-wide identification and characterization of AP2/ERF gene superfamily during flower development in Actinidia eriantha. BMC Genom. 2022;23(1):650. doi:10.1186/s12864-022-08871-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Xie X-L, Shen S-L, Yin X-R, Xu Q, Sun C-D, Grierson D, et al. Isolation, classification and transcription profiles of the AP2/ERF transcription factor superfamily in citrus. Mol Biol Rep. 2014;41(7):4261–71. doi:10.1007/s11033-014-3297-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Zhuang J, Peng R-H, Cheng Z-M, Zhang J, Cai B, Zhang Z, et al. Genome-wide analysis of the putative AP2/ERF family genes in Vitis vinifera. Sci Hortic. 2009;123(1):73–81. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2009.08.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Koyama T, Sato F. The function of ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR genes in the light-induced anthocyanin production of Arabidopsis thaliana leaves. Plant Biotechnol. 2018;35(1):87–91. doi:10.5511/plantbiotechnology.18.0122b. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Wu T, Liu H-T, Zhao G-P, Song J-X, Wang X-L, Yang C-Q, et al. Jasmonate and ethylene-regulated ethylene response factor 22 promotes lanolin-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis in ‘Zaosu’ pear (Pyrus bretschneideri Rehd.) fruit. Biomolecules. 2020;10(2):278. doi:10.3390/biom10020278. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Ni J, Bai S, Zhao Y, Qian M, Tao R, Yin L, et al. Ethylene response factors Pp4ERF24 and Pp12ERF96 regulate blue light-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis in ‘Red Zaosu’ pear fruits by interacting with MYB114. Plant Mol Biol. 2019;99(1):67–78. doi:10.1007/s11103-018-0802-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Zhang S, Liu S, Ren Y, Zhang J, Han N, Wang C, et al. The ERF transcription factor ZbERF3 promotes ethylene-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis in Zanthoxylum bungeanum. Plant Sci. 2024;349(2):112264. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2024.112264. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Zhuo M-G, Wang T-Y, Huang X-M, Hu G-B, Zhou B-Y, Wang H-C, et al. ERF transcription factors govern anthocyanin biosynthesis in litchi pericarp by modulating the expression of anthocyanin biosynthesis genes. Sci Hortic. 2024;337(1):113464. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2024.113464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Cao Y-W, Song M, Bi M-M, Yang P-P, He G-R, Wang J, et al. Lily (Lilium spp.) LhERF4 negatively affects anthocyanin biosynthesis by suppressing LhMYBSPLATTER transcription. Plant Sci. 2024;342:112026. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2024.112026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Chen Z, Lu X, Xuan Y, Tang F, Wang J, Shi D, et al. Transcriptome analysis based on a combination of sequencing platforms provides insights into leaf pigmentation in Acer rubrum. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19(1):240. doi:10.1186/s12870-019-1850-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Mistry J, Chuguransky S, Williams L, Qureshi M, Salazar GA, Sonnhammer ELL, et al. Pfam: the protein families database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(D1):D412–9. doi:10.1093/nar/gkaa913. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Zhang H, Wang S, Zhao X, Dong S, Chen J, Sun Y, et al. Genome-wide identification and comprehensive analysis of the AP2/ERF gene family in Prunus sibirica under low-temperature stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2024;24(1):883. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-4451430/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024;52(W1):78–82. doi:10.1093/nar/gkae268. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Bailey TL, Boden M, Buske FA, Frith M, Grant CE, Clementi L, et al. MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W202–8. doi:10.1093/nar/gkp335. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Liu X, Yu F, Yang G, Liu X, Peng S. Identification of TIFY gene family in walnut and analysis of its expression under abiotic stresses. BMC Genom. 2022;23(1):190. doi:10.1186/s12864-022-08416-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Wang Y, Tang H, DeBarry JD, Tan X, Li J, Wang X, et al. MCScanX: a toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(7):e49. doi:10.1093/nar/gkr1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–8. doi:10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Lyon D, Junge A, Wyder S, Huerta-Cepas J, et al. STRING v11: protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D607–13. doi:10.1093/nar/gky1131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Nakano T, Suzuki K, Fujimura T, Shinshi H. Genome-wide analysis of the ERF gene family in Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Physiol. 2006;140(2):411–32. doi:10.1104/pp.105.073783. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Kent WJ, Baertsch R, Hinrichs A, Miller W, Haussler D. Evolution’s cauldron: duplication, deletion, and rearrangement in the mouse and human genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(20):11484–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.1932072100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Wang Z, Song G, Zhang F, Shu X, Wang N. Functional characterization of AP2/ERF transcription factors during flower development and anthocyanin biosynthesis related candidate genes in Lycoris. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(19):14464. doi:10.3390/ijms241914464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Cui M, Haider MS, Chai P, Guo J, Du P, Li H, et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of AP2/ERF transcription factor related to drought stress in cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Front Genet. 2021;12:750761. doi:10.3389/fgene.2021.750761. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Qian Z, Rao X, Zhang R, Gu S, Shen Q, Wu H, et al. Genome-Wide identification, evolution, and expression analyses of AP2/ERF family transcription factors in Erianthus fulvus. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(8):7102. doi:10.3390/ijms24087102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Charfeddine M, Saidi MN, Charfeddine S, Hammami A, Bouzid RG. Genome-wide analysis and expression profiling of the ERF transcription factor family in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Mol Biotechnol. 2015;57(4):348–58. doi:10.1007/s12033-014-9828-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Liu Y, Cai L, Zhu J, Lin Y, Chen M, Zhang H, et al. Genome-wide identification, structural characterization and expression profiling of AP2/ERF gene family in bayberry (Myrica rubra). BMC Plant Biol. 2024;24(1):1139. doi:10.1186/s12870-024-05847-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Guo Z, He L, Sun X, Li C, Su J, Zhou H, et al. Genome-wide analysis of the Rhododendron AP2/ERF gene family: identification and expression profiles in response to cold, salt and drought stress. Plants. 2023;12(5):994. doi:10.3390/plants12050994. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Zhang M, Lu P, Zheng Y, Huang X, Liu J, Yan H, et al. Genome-wide identification of AP2/ERF gene family in Coptis Chinensis Franch reveals its role in tissue-specific accumulation of benzylisoquinoline alkaloids. BMC Genom. 2024;25(1):972. doi:10.1186/s12864-024-10883-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Abiri R, Shaharuddin NA, Maziah M, Yusof ZNB, Atabaki N, Sahebi M, et al. Role of ethylene and the APETALA 2/ethylene response factor superfamily in rice under various abiotic and biotic stress conditions. Env Exp Bot. 2017;134(5757):33–44. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2016.10.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Paul P, Singh SK, Patra B, Liu X, Pattanaik S, Yuan L. Mutually regulated AP2/ERF gene clusters modulate biosynthesis of specialized metabolites in plants. Plant Physiol. 2020;182(2):840–56. doi:10.1104/pp.19.00772. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Yang L, Zhang S, Chu D, Wang X. Exploring the evolution of CHS gene family in plants. Front Genet. 2024;15:1368358. doi:10.3389/fgene.2024.1368358. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Zhu X-G, Hutang G-R, Gao L-Z. Ancient Duplication and lineage-specific transposition determine evolutionary trajectory of ERF subfamily across angiosperms. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(7):3941. doi:10.3390/ijms25073941. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Veitia RA, Bottani S, Birchler JA. Gene dosage effects: nonlinearities, genetic interactions, and dosage compensation. Trends Genet. 2013;29(7):385–93. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2013.04.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Choi JW, Choi HH, Park YS, Jang MJ, Kim S. Comparative and expression analyses of AP2/ERF genes reveal copy number expansion and potential functions of ERF genes in Solanaceae. BMC Plant Biol. 2023;23(1):48. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-2136792/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Liu L, White MJ, MacRae TH. Transcription factors and their genes in higher plants functional domains, evolution and regulation. Eur J Biochem. 1999;262(2):247–57. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00349.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Shaul O. How introns enhance gene expression. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2017;91:145–55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

67. Shi J, Feng Z, Song Q, Wang F, Zhang Z, Liu J, et al. Structural and functional insights into transcription activation of the essential LysR-type transcriptional regulators. Protein Sci. 2024;33(6):e5012. doi:10.1002/pro.5012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Zhang J-Y, Wang Q-J, Guo Z-R. Progresses on plant AP2/ERF transcription factors. Yi Chuan Hered. 2012;34(7):835–47. doi:10.3724/sp.j.1005.2012.00835. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Yang Y, Bi M, Luo K, Cao Y, Wang J, Yang P, et al. Lily (Lilium spp.) LhERF061 suppresses anthocyanin biosynthesis by inhibiting LhMYBSPLATTER and LhDFR expression and interacting with LhMYBSPLATTER. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2025;219:109496. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2025.109496. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Jia H, Zuo Q, Sadeghnezhad E, Zheng T, Chen X, Dong T, et al. HDAC19 recruits ERF4 to the MYB5a promoter and diminishes anthocyanin accumulation during grape ripening. Plant J. 2023;113(1):127–44. doi:10.1111/tpj.16040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Xu Y, Liu Y, Yue L, Zhang S, Wei J, Zhang Y, et al. MsERF17 promotes ethylene-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis under drought conditions in Malus spectabilis leaves. Plant Cell Env. 2025;48(3):1890–902. doi:10.1111/pce.15271. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools