Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Evaluation of Floral Phenotypic Diversity of Kiwifruit Male Germplasm Resources

1 Key Laboratory of Coarse Cereal Processing, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, Sichuan Engineering & Technology Research Center of Coarse Cereal Industrialization, School of Food and Biological Engineering, Chengdu University, Chengdu, 610106, China

2 Sichuan Provincial Academy of Natural Resource Sciences, Sichuan Key Laboratory of Kiwifruit Breeding and Utilization, China-New Zealand Belt and Road Joint Laboratory on Kiwifruit, Chengdu, 610015, China

* Corresponding Author: Xiaoqin Zheng. Email:

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(9), 2781-2796. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.071151

Received 01 August 2025; Accepted 28 August 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Exploring the phenotypic trait variation and diversity of kiwifruit male plant resources can support selection, breeding, and genetic improvement, ultimately enhancing agricultural production. In this study, 50 kiwifruit male plants were collected from the resource nursery of Sichuan Provincial Natural Resources Bureau. The phenotypic variation of the germplasm was analyzed using 16 quantitative traits. The analysis involved coefficient of variation (CV), Shannon-Wiener index (H), principal component analysis, correlation analysis, cluster analysis, and comprehensive evaluation. The results showed that the variation range of 16 phenotypic traits in kiwifruit male germplasm resources was 1.55% to 83.71%, with an average coefficient of variation of 28.62%, and an H index of 1.265 to 2.941. The average CVs of diploid, tetraploid, and hexaploid were 22.62%, 18.99% and 18.18%, respectively, and the average CV of diploid was the largest. Indicated that the male germplasm resources of kiwifruit showed significant phenotypic diversity, and the diploid showed higher diversity characteristics. Principal component analysis (PCA) revealed that the cumulative variance contribution rate of the first seven principal components was 76.66%, which effectively captured the information from 21 traits. Cluster analysis divided the 50 kiwifruit male germplasm resources into 4 clusters; each cluster exhibited distinct phenotypic characteristics. The analysis also determined the trait characteristics and breeding value of each cluster. The results of this study provide valuable information for genetic improvement, protection, and evaluation of kiwifruit male germplasm resources.Keywords

Kiwifruit (Actinidia spp.) is a perennial dioecious vine belonging to the genus Actinidia and serves as an important economic crop worldwide. The genus comprises approximately 75 taxonomic units, with China recognized as both its center of origin and diversity, hosting 52 species—including 44 endemic varieties [1]. Kiwifruit is renowned for its high nutritional value, particularly its abundance of vitamin C, dietary fiber, and essential trace minerals, earning it the reputation as the “king of fruits” [2,3]. Research has shown that kiwifruit exhibits a notable pollen xenia effect, where the origin of pollen significantly influences fruit traits [4]. More specifically, the vitality of pollen and its compatibility in male plants are key factors in determining the rate of fruit set, size, and quality [5,6]. However, current kiwifruit breeding programs predominantly focus on female cultivar selection, while research on male germplasm resources lags significantly behind. According to statistics, as of 2021, only 14 out of 253 kiwifruit cultivars applied for protection in China were male, accounting for a mere 5.53% [7]. Therefore, systematic evaluation of male plant floral phenotypic traits and selection of superior pollinizer cultivars are of great significance for optimizing pollination combinations and improving fruit quality and yield.

Germplasm resources serve as fundamental materials for enhancing the genetics of a particular species [8]. Phenotypic characterization is the most direct and crucial method for evaluating genetic diversity within germplasm collections. A thorough understanding of the diversity within male kiwifruit germplasm is essential for the efficient conservation, utilization, and improvement of these genetic resources, thereby supporting targeted breeding programs. While extensive research has been conducted on male kiwifruit plants, particularly on key species [9–11], studies focusing on systematic floral phenotypic diversity remain limited. Previous work has primarily addressed aspects like flowering phenology [12], pollen [13,14], branches, leaves, and fruits [15,16], yet a holistic evaluation of floral traits across diverse germplasm is still lacking.

In recent years, related studies have been extensively applied to crops such as Citrus [17], Apple [18], Jujube [19], Mulberry [20], Lycium [21], and Sugar Beet [22], providing a theoretical foundation for the selection of elite germplasm. However, research on male kiwifruit germplasm resources remains relatively scarce, notably lacking systematic analyses of floral phenotypic diversity. However, despite the economic and ecological significance of kiwifruit, research on its male germplasm resources lags behind. Addressing these gaps will not only enhance germplasm conservation but also accelerate the development of improved kiwifruit cultivars. Thus, this study aims to systematically evaluate floral phenotypic diversity in male kiwifruit germplasm, providing a theoretical basis for future breeding optimization.

This study evaluated 50 male kiwifruit germplasm accessions through comprehensive analysis of floral morphological traits, flowering phenology, and their genetic variation patterns, incorporating correlation analysis, PCA, and cluster analysis. The research aims to (1) elucidate the phenotypic variation patterns in male kiwifruit flowers and (2) identify superior pollinizer germplasm with desirable pollination characteristics. The findings will provide scientific support for kiwifruit hybridization breeding and pollinizer selection, thereby enhancing the utilization efficiency of male germplasm resources and promoting sustainable industry development.

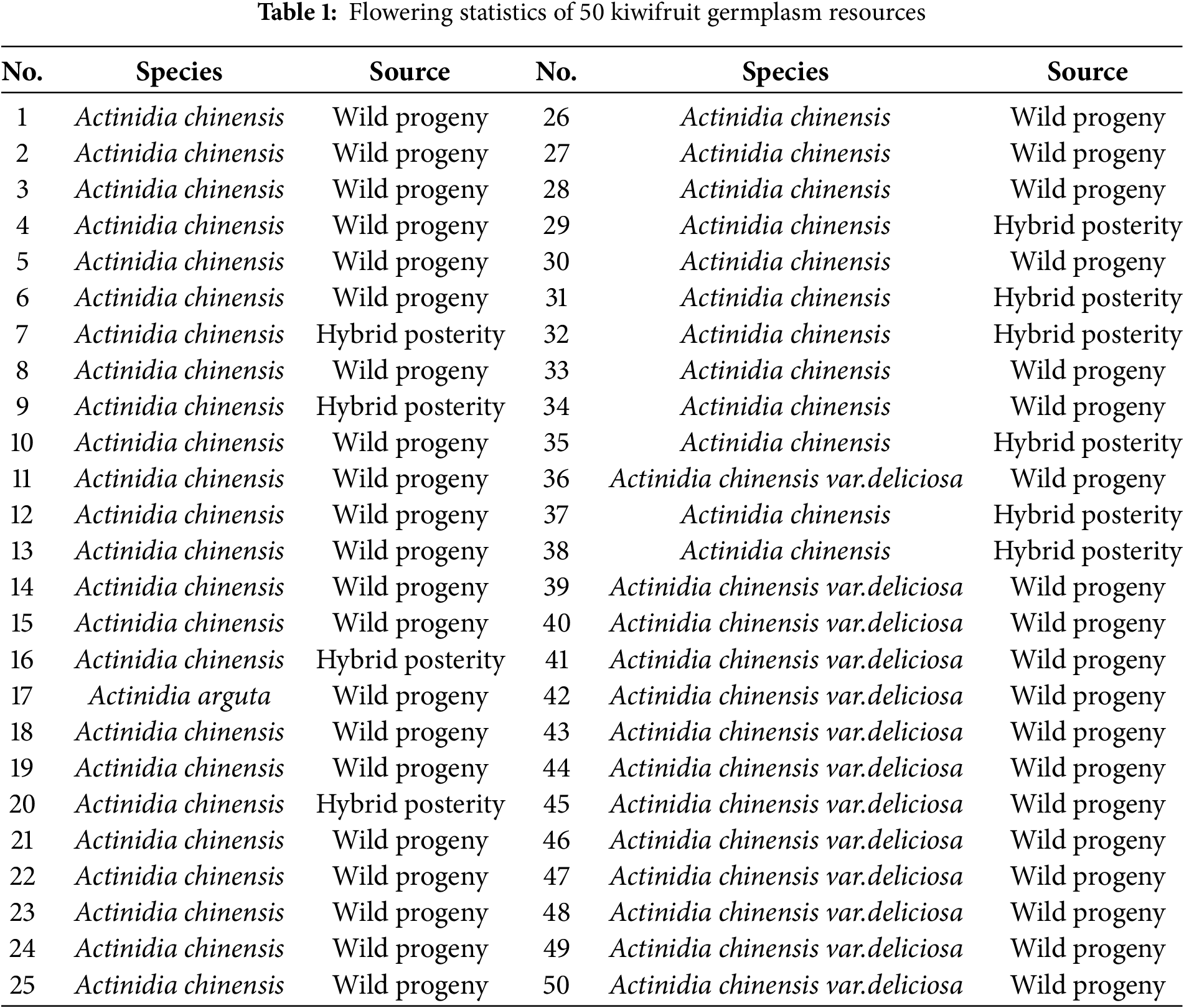

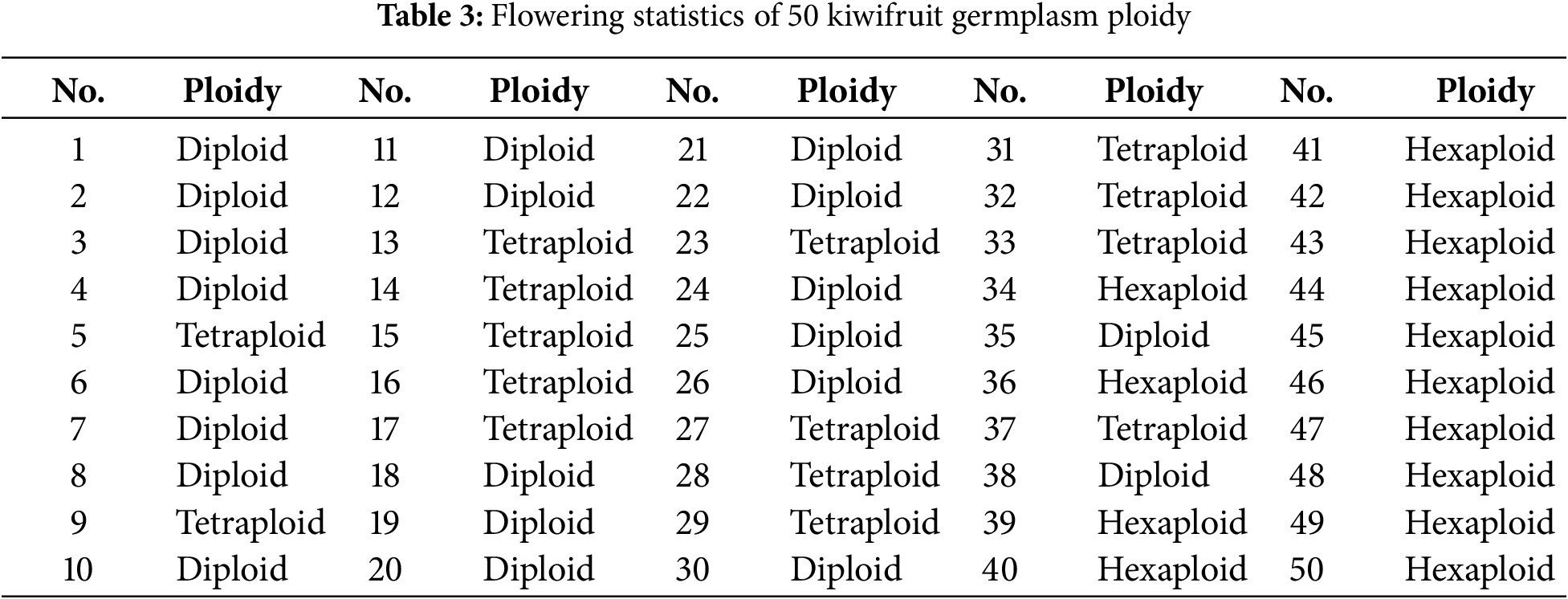

All the experimental materials were obtained from the Provincial Germplasm Resource Nursery of Kiwifruit of Sichuan Institute of Natural Resource Science, with sandy loam soil in the fruiting area, medium fertility, no flower and fruit thinning, and unified management of conventional production technology. The experimental materials involved three species: Actinidia chinensis, Actinidia argute, and Actinidia chinensis var.deliciosa, for a total of 50 male kiwifruit plants, of which 40 were field sources and 10 were hybrid progeny. The details are listed in Table 1. The flowering period of male plants was observed for two consecutive years, from 2023 to 2024. During this period, 20 young leaves, bell flowers and fully open flowers were collected and brought back to the laboratory in self-sealing bags, to be numbered and measured for the main phenotypic trait indexes.

Take about 0.5 cm2 of the sample young leaves and put them on a plane slide, add 500 μL extraction buffer, use a disposable blade to chop the leaves quickly and soak them for 30–90 s, filter them through a filter into a sample tube, then add 2 mL of DAPI staining solution, and stain them for 30~60 min away from the light, and then detect them by using FACS Celesta flow cytometer made by BD Company in the United States, in order to The diploid Chinese kiwifruit variety ‘Hong yang’ was used as reference for instrument calibration.

2.3 Determination of Phenotypic Traits

For 50 test male plant materials, three plants with consistent growth were selected for each material, and 3–5 fully open flowers were selected from branches of different orientations. selected 20 fully open flowers in total, and reference was made to the Specification for the Description of Kiwifruit Germplasm Resources (NY/T2933-2016) [23] for the observation and characterization of the kiwifruit floral apparatus. Phenotypic traits: observation of inflorescence. Phenotypic traits: observe the inflorescence type, petal shape, calyx shape, petal color, calyx color, filament color and anther color. Quantitative traits: measurements of flower diameter, calyx diameter, petal length, petal width, budding rate, annual basal roughness, annual branch internode length, number of flowering branches per unit length of the mother branch, and flowering branch rate of the test male plants were made by using electronic vernier calipers and tape measure; visual counting of flowers, number of flowers per inflorescence, number of calyxes, number of petals, and number of anthers was used.

2.4 Pollen Isolated Germination Method

According to the method of Liao [24] and improved, the optimum solid medium was: 1% sucrose + 150 mg/L boric acid + 0.7% agar. Kiwifruit pollen was dipped into a paper towel and lightly flicked to let the pollen scatter on the medium, and then placed into an incubator at 25~28°C for 2 h, after which it was observed under a microscope, and the length of pollen tubes exceeding the diameter of the pollen grains was regarded as germination, and took the photos and counted for germination rate.

Referring to the method of Li [25], a petri dish coated with pollen was placed under a microscope to observe the shape and purity of the pollen, and the total number of pollen and the total number of impurities in the field of view were counted to calculate the purity of the pollen.

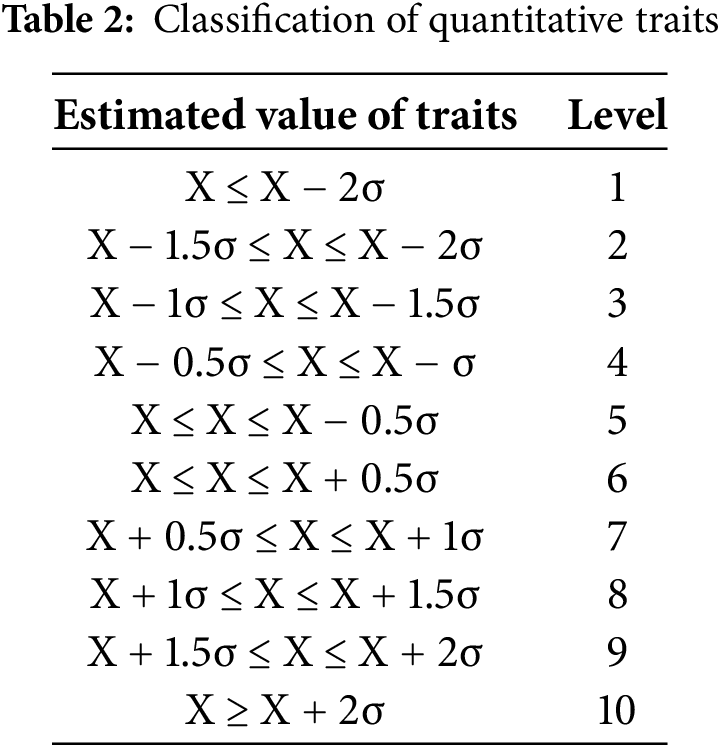

2.6 Data Processing and Analysis

Mean, maximum, minimum, standard deviation (σ), coefficient of variation (CV), and Shannon-Wiener diversity index (H) of kiwifruit male plant phenotypes were analyzed using Excel.2016 software. Categorized quantitative traits into 10 classes based on mean (X) and standard deviation (σ), where class 1 < X − 2σ and class 10 ≥ X + 2σ, with a difference of 0.5σ at each stage (Table 2). Phenotypic diversity for each trait was assessed using the Shannon-Weaver diversity index:

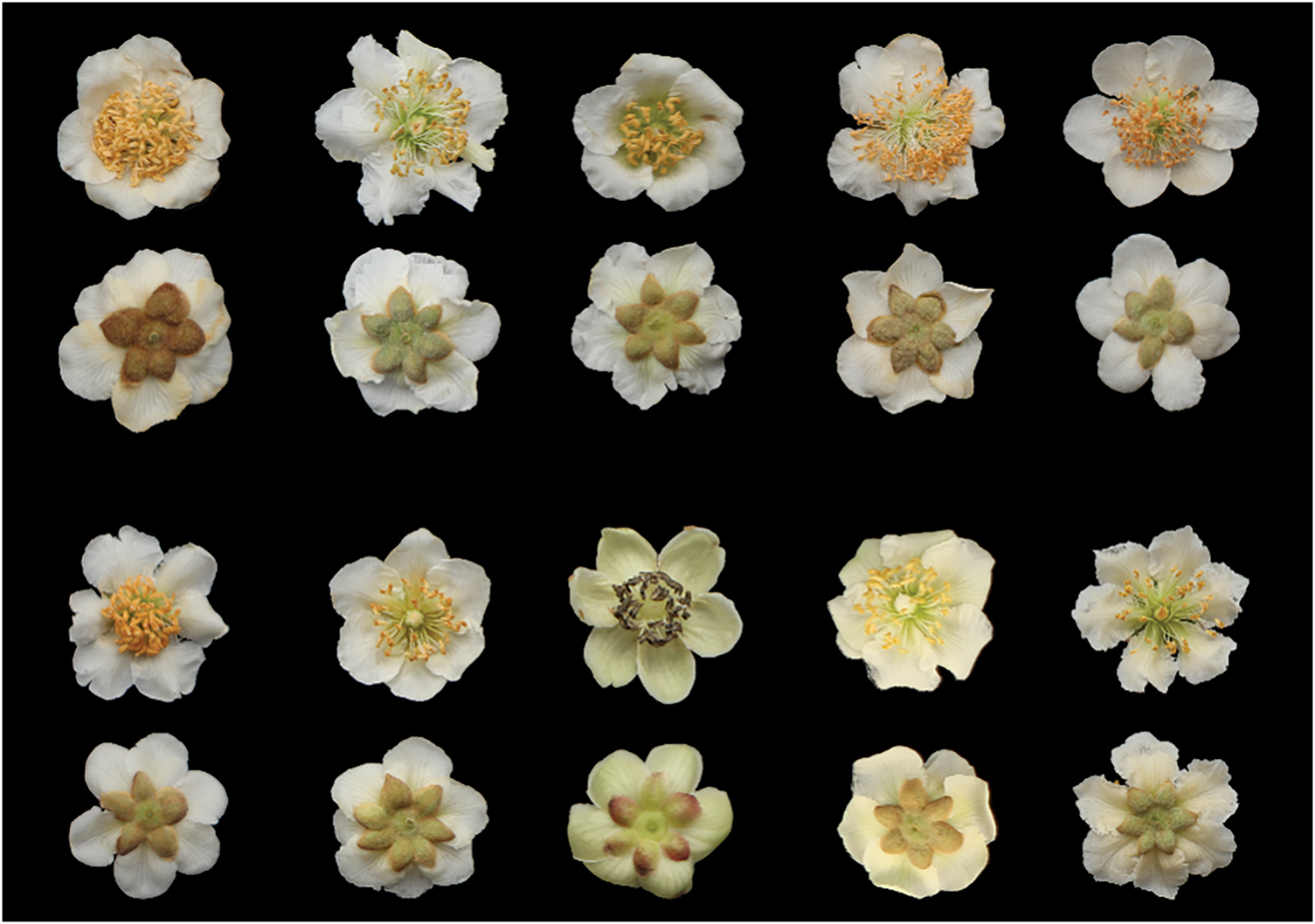

3.1 Biological Traits of Flower

Phenotypic characterization of floral organs revealed that all male accessions exhibited cymose inflorescences, with both petals and sepals displaying spatulate morphology. Petal coloration ranged from greenish-white to yellowish-white and pure white, while sepals were primarily brown or green, with occasional reddish-brown variants. Filaments appeared either white or pale green, and anthers were predominantly yellow to orange-yellow, except for accession No. 22, which uniquely exhibited black pigmentation (Fig. 1). Analysis of flowering phenology revealed that the earliest flowering occurred on April 2, while the latest commenced on April 23, with flowering duration ranging from 5 to 17 days. Flow cytometry analysis (Table 3) demonstrated that among the 50 male kiwifruit accessions, A. chinensis and A. arguta comprised both diploid and tetraploid individuals, whereas A. deliciosa accessions were exclusively hexaploid. Specifically, the collection included 21 diploids, 15 tetraploids, and 14 hexaploids.

Figure 1: Male flowers of kiwifruit with different phenotypes

3.2 Diversity Analysis of Quantitative Traits

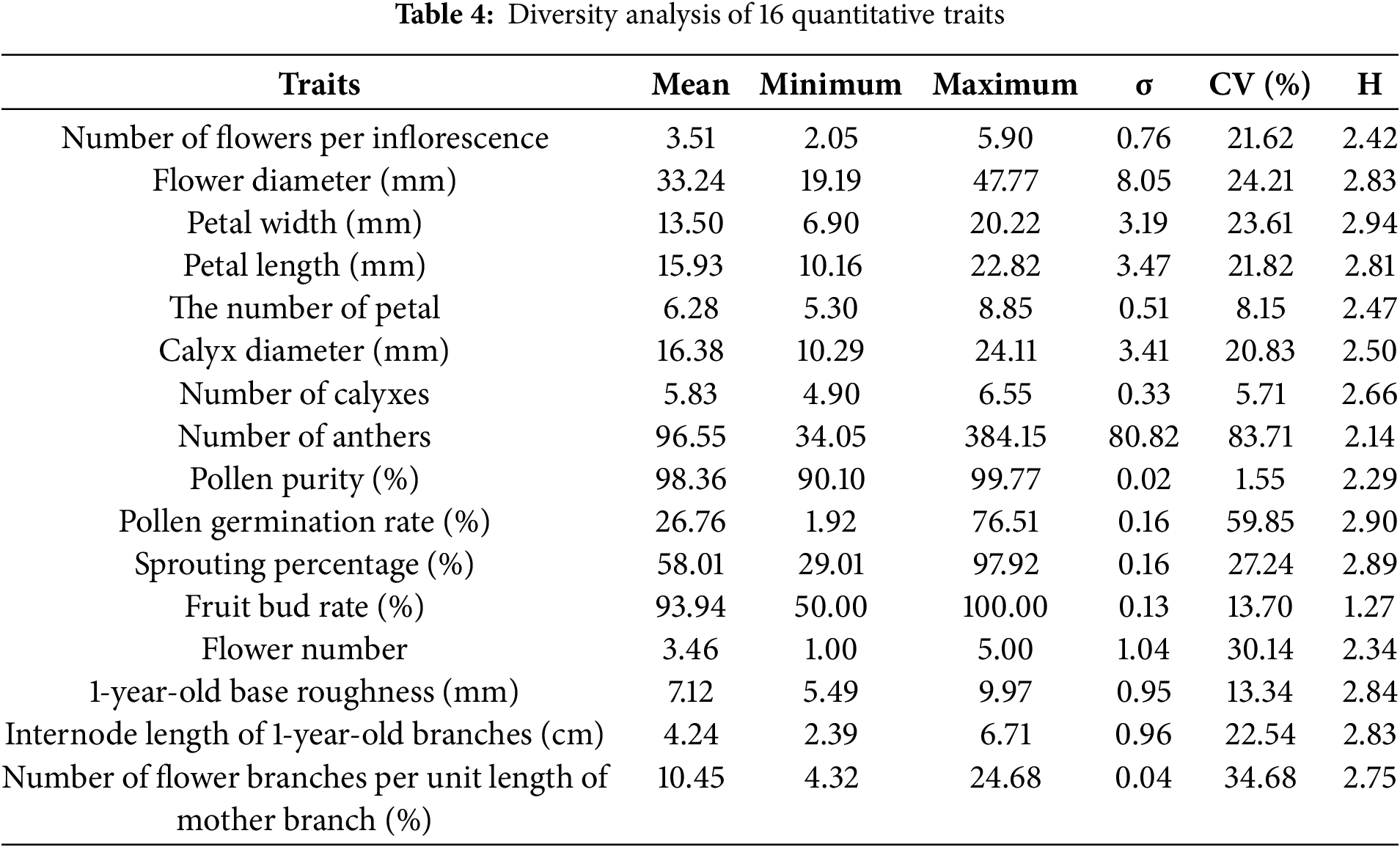

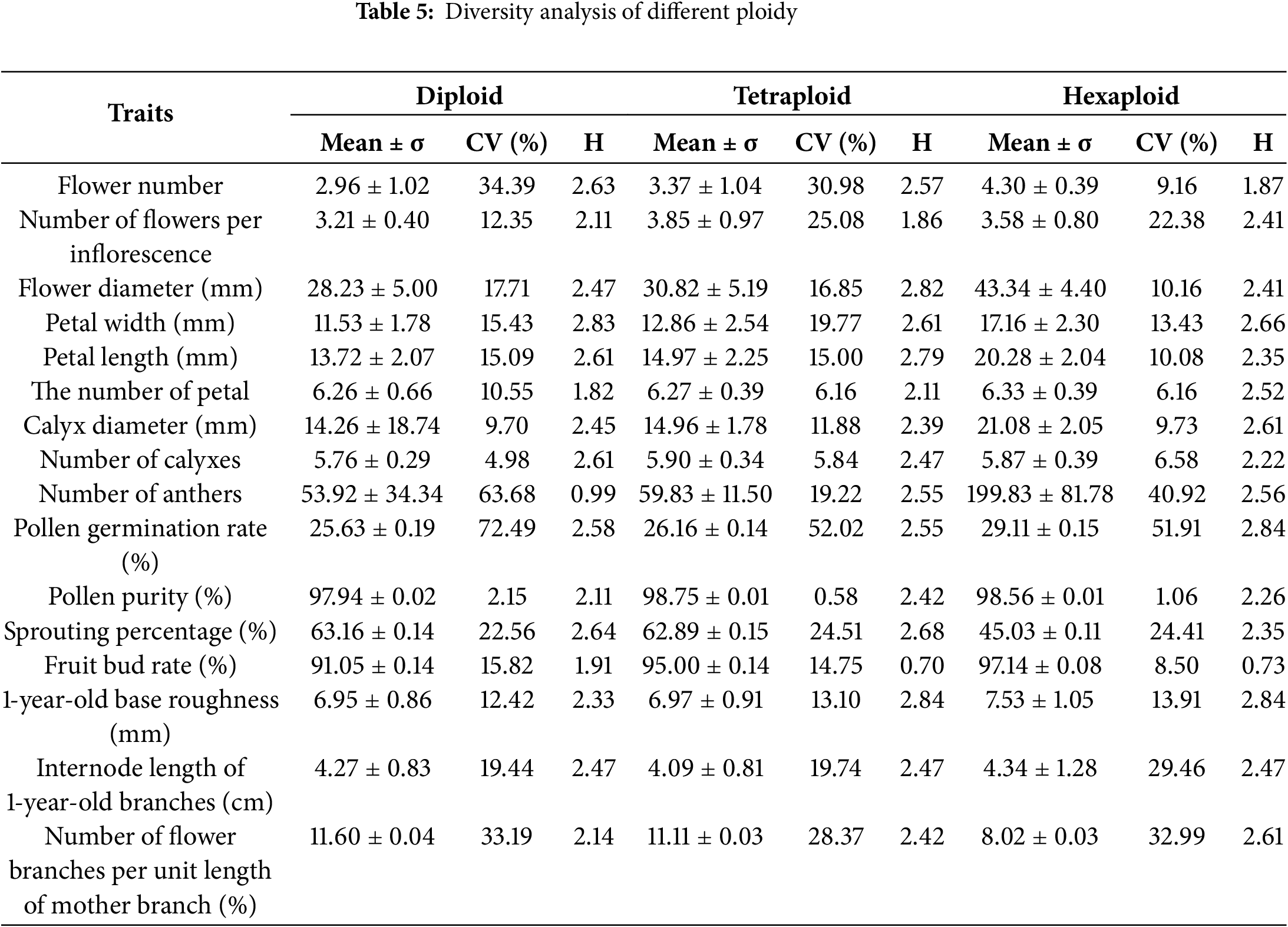

The CV of 16 numerical traits in 50 male kiwifruit plants was 1.55%–83.71% with an average of 28.62%, where H ranged from 1.27 to 2.94, indicating a significant variation and rich diversity among individual plants (Table 4). The Anther number, pollen germination rate, and number of flowering branches per unit length of the mother branch showed the highest variation, at 83.71%, 59.85%, and 34.68%, respectively. On the contrary, the lowest CV was observed for pollen purity, calyx number and petal number. They were 1.55%, 5.71% and 8.15%, respectively. H-ranking results were: petal width > pollen germination rate > germination rate > annual basal roughness > annual branch internode length > flower diameter > petal length > number of branches per unit length of parent branch > calyx number > calyx diameter > number of petals > number of flowers per inflorescence > flower volume > pollen purity > number of anthers > flower branch rate. According to the different ploidy grouping (Table 5), it was found that the average values of CVs of diploid, tetraploid and hexaploid were 22.62%, 18.99% and 18.18%, respectively, among which the average CV of diploid was the largest and rich in diversity. The CV of tetraploid and hexaploid was not large. However, its genetic diversity index was relatively large, indicating that it was relatively consistent in terms of phenotypes, but it might be high in terms of gene level.

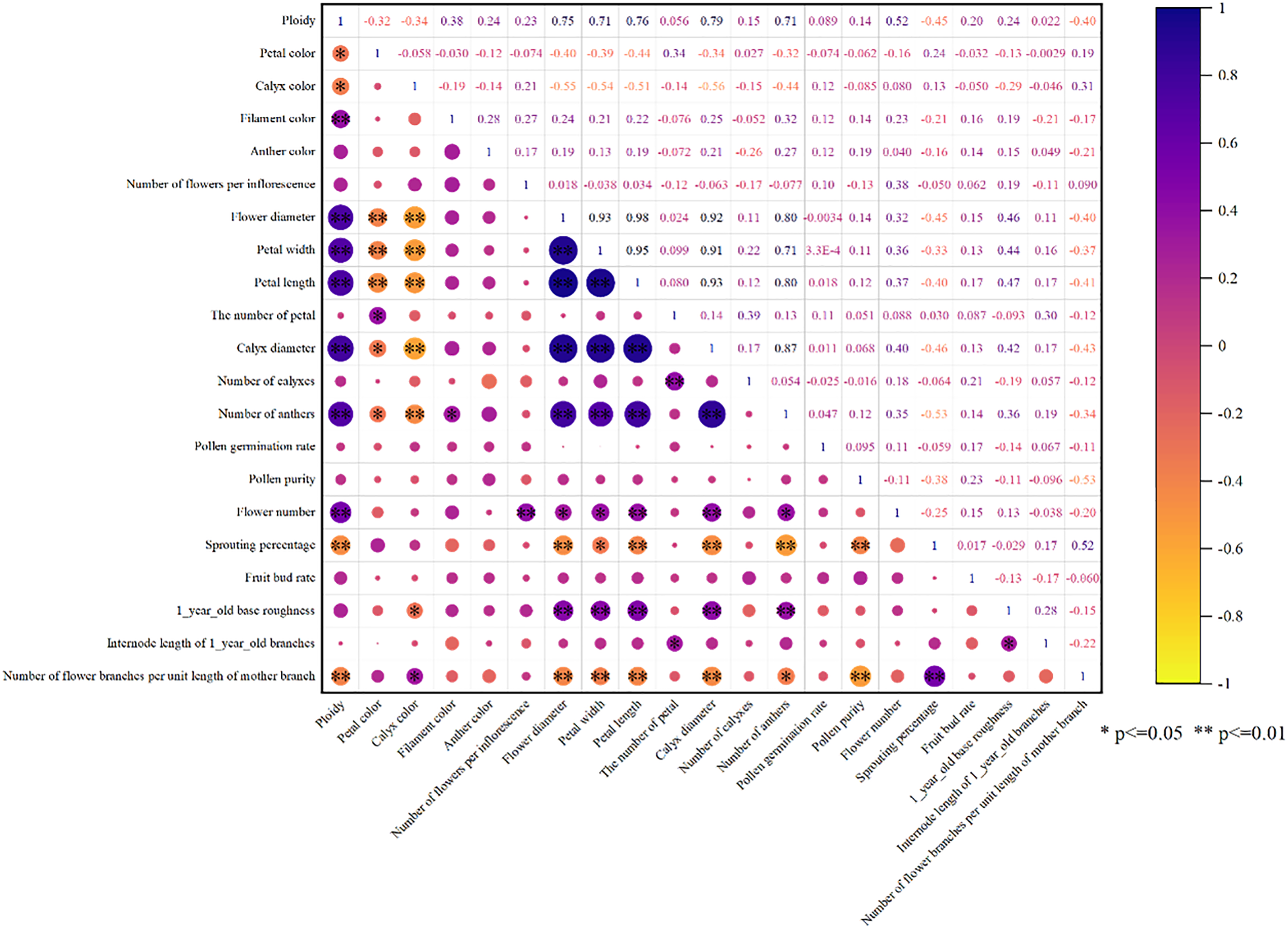

3.3 Correlation Analysis of Phenotypic Trait

Correlation analysis of 21 phenotypic traits in kiwifruit (Fig. 2) revealed strong inter-trait correlations, indicating significant mutual influences among these characteristics. Specifically, ploidy level, flower diameter, sepal diameter, petal length, petal width, and anther number showed significant positive correlations with each other, while exhibiting significant negative correlations with petal color, sepal color, bud break rate, and flower bud number per unit length of mother branch. Flower quantity demonstrated significant positive correlations with flower number per inflorescence, petal length, and sepal diameter. Additionally, basal diameter of one-year-old shoots was positively correlated with flower diameter, sepal diameter, petal length, petal width, and anther number. Other trait pairs showed no significant correlations. These findings demonstrate distinct correlation patterns among different traits, suggesting that evaluation based on single traits would be inadequate. Therefore, principal component analysis is warranted to establish comprehensive evaluation criteria for male kiwifruit germplasm resources.

Figure 2: Correlation analysis of 21 phenotypic traits. Note: Red represents positive correlation, blue represents negative correlation, and the darker the color, the greater the correlation. *significant at the 0.05 level; **significant at the 0.01 level

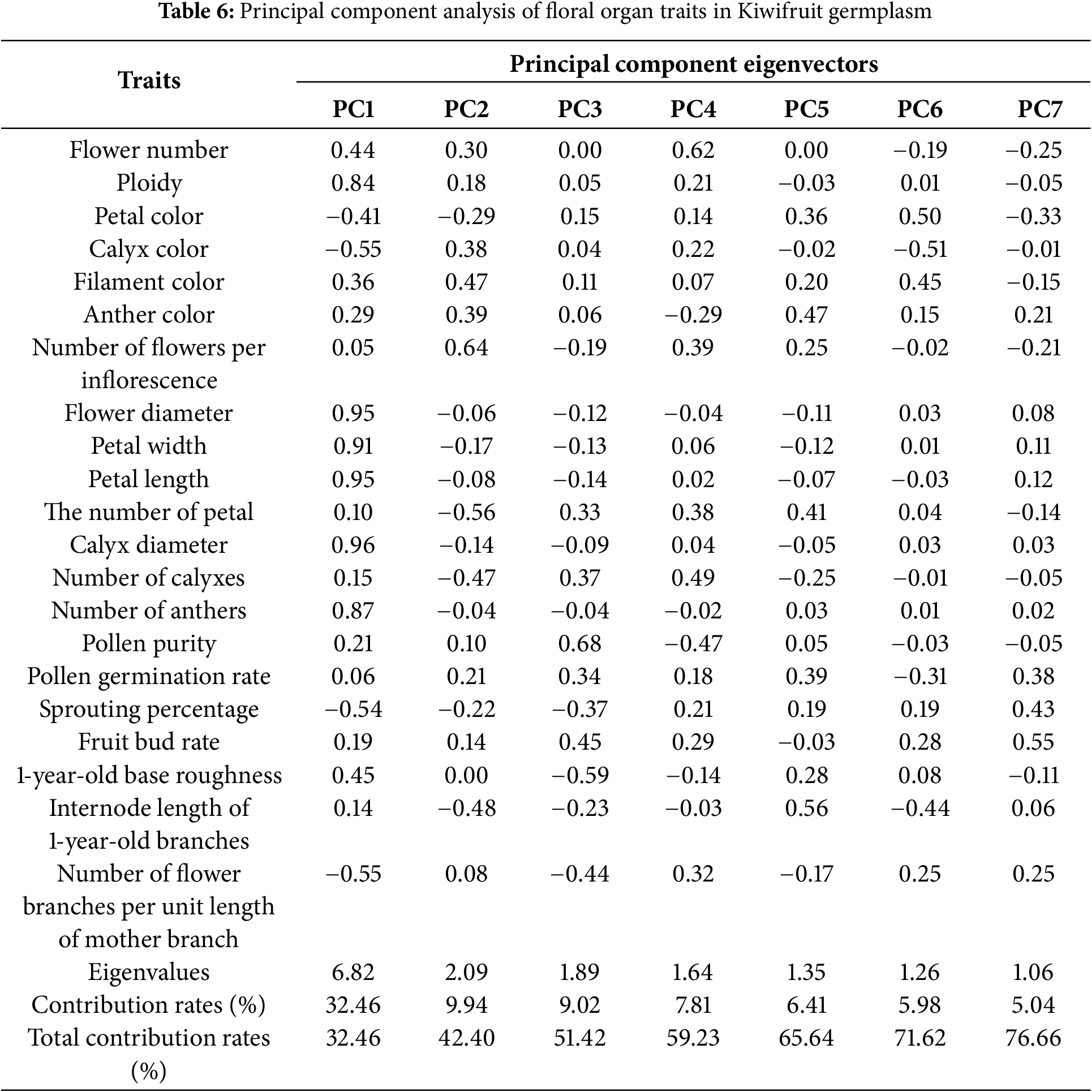

3.4 Principal Component Analysis of Phenotypic Traits

Principal component analysis can transform multiple and complex related traits into a few principal components to find out the main influencing factors. Among the 21 phenotypic traits in 50 kiwifruit samples, PCA extracted seven principal components with eigenvalues greater than 1, accounting for 76.66% of the total variance (Table 6), suggesting that these principal components can represent the main information of the phenotypes of kiwifruit male plants. Among them, PC1 had the largest contribution (32.46%), with calyx diameter, petal length, flower diameter, and petal width as the primary indexes, reflecting the comprehensive size of the flower.PC2 had a contribution of 9.94%, with the number of flowers per inflorescence, the number of petals, and the length of internodes of the 1-year old branches as the main indexes, which was mainly related to the density of inflorescence distribution. The contribution of PC3 had a contribution of 9.02%, and the traits had higher absolute values of eigenvectors. The high traits were mainly pollen purity (0.68) and 1-year branch base thickness (−0.59). The two indicators with the highest contribution rate were selected from each principal component to determine 14 representative indicators. These indicators, in descending order, were petal length, flower diameter, pollen purity, number of flowers per inflorescence, flower volume, annual branch basal roughness, annual branch internode length, number of petals, flowering branch rate, calyx color, petal color, number of calyxes, anther color, and budding rate. It is self-evident that floral traits contributed the most to the diversity of male plants in kiwifruit, followed by some of the traits of annual branches.

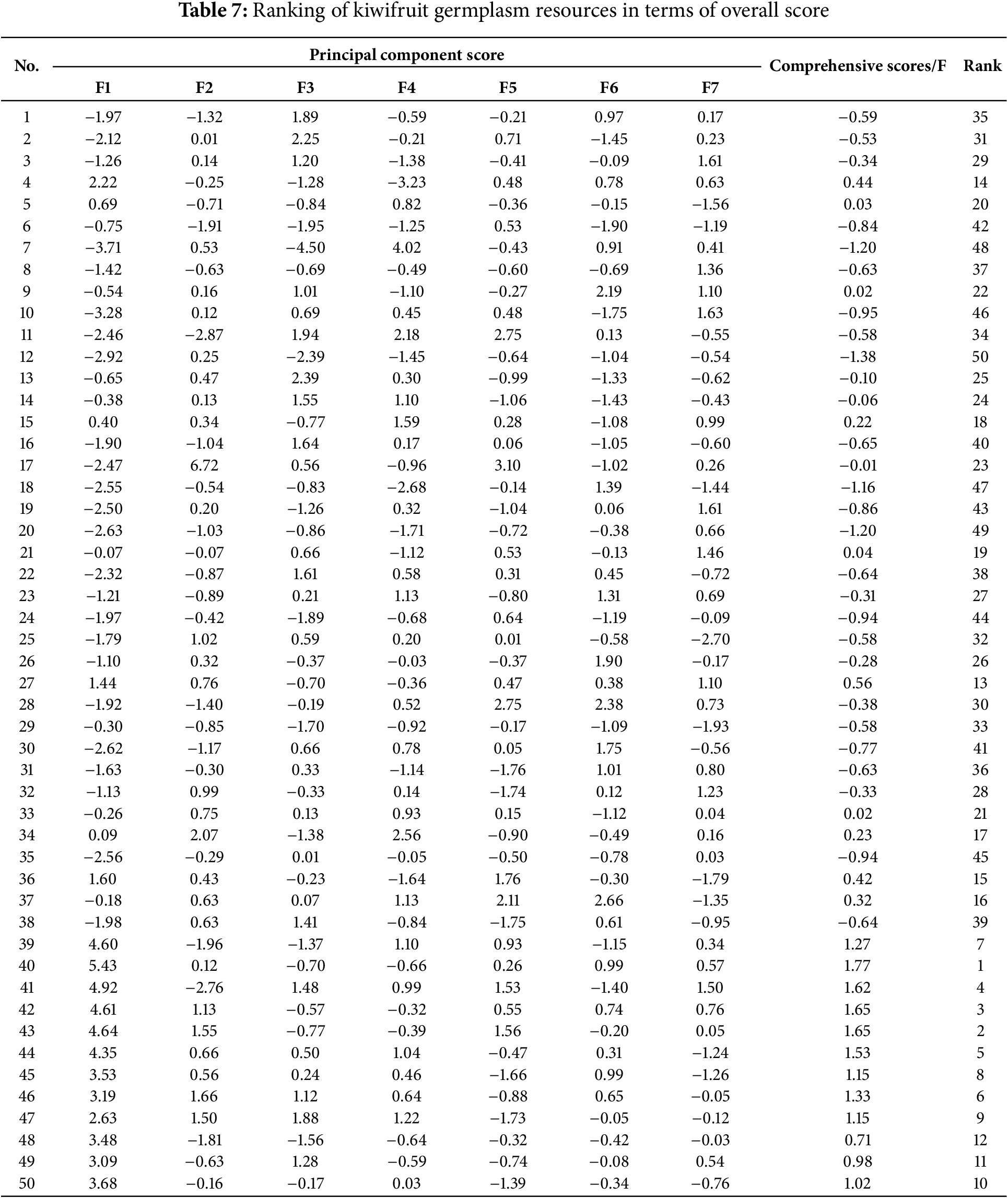

The 21 main traits of 50 male materials were standardized using the affiliation function method, and the standardized results were imported into the principal component analysis to obtain seven principal component scores for each texture, and the composite score F value was calculated based on the contribution rate of each principal component (Table 7). This composite score was comprehensively utilized and evaluated for phenotypic diversity. The F-values of the 50 samples ranged from −1.38 to 1.77, where the composite score was less than 0, indicating low phenotypic diversity. Numbers 40, 43, 42, 41 and 44 had a composite score of >1, which was much higher than the other materials, with 1.77, 1.65, 1.65, 1.62 and 1.53, respectively, indicating that they were rich in phenotypic diversity, and their phenotypic traits could effectively represent the diversity of phenotypic traits in several varieties. Therefore, the selection, development and utilization of kiwifruit male plant germplasm resources should focus on these materials.

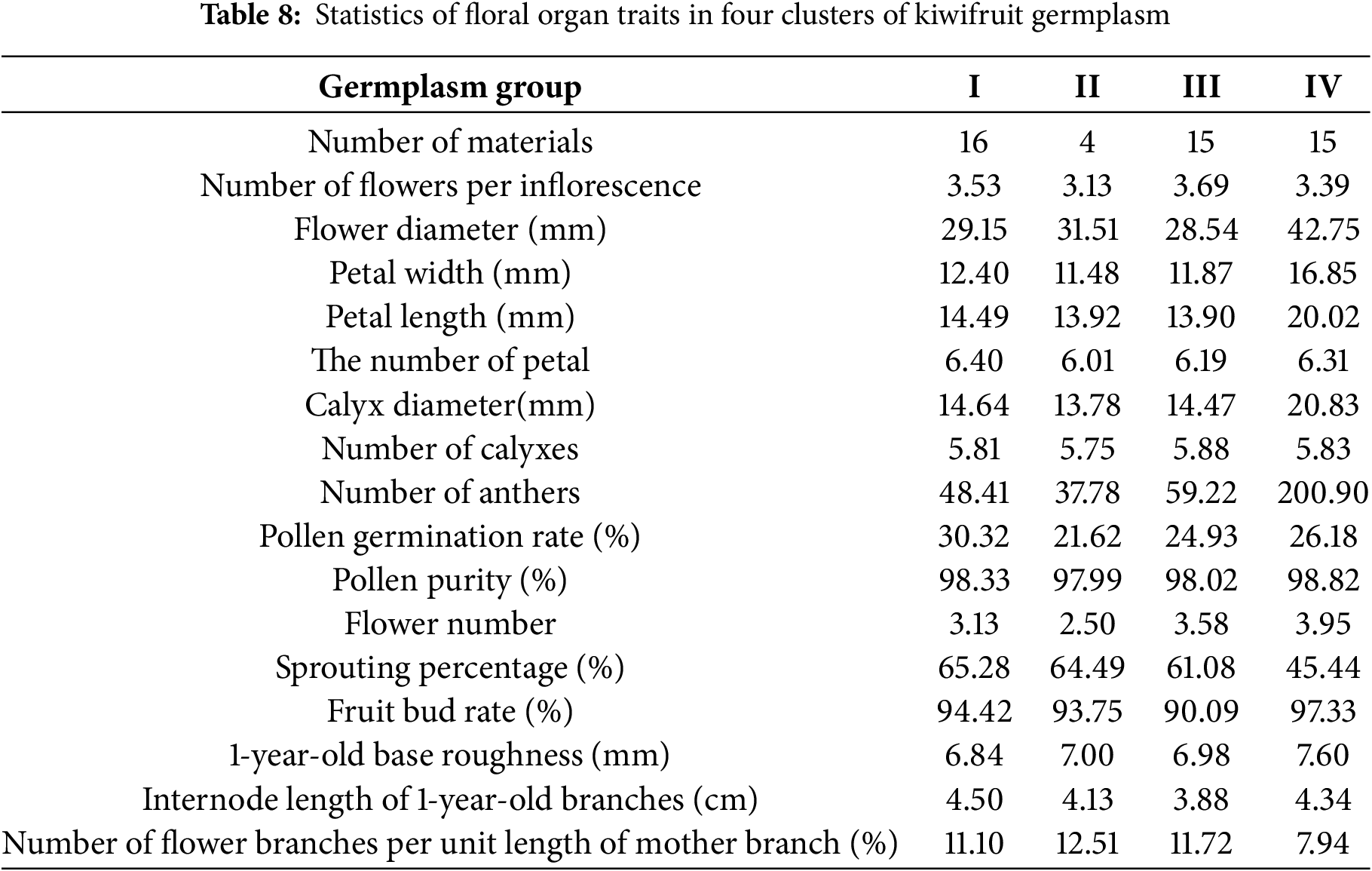

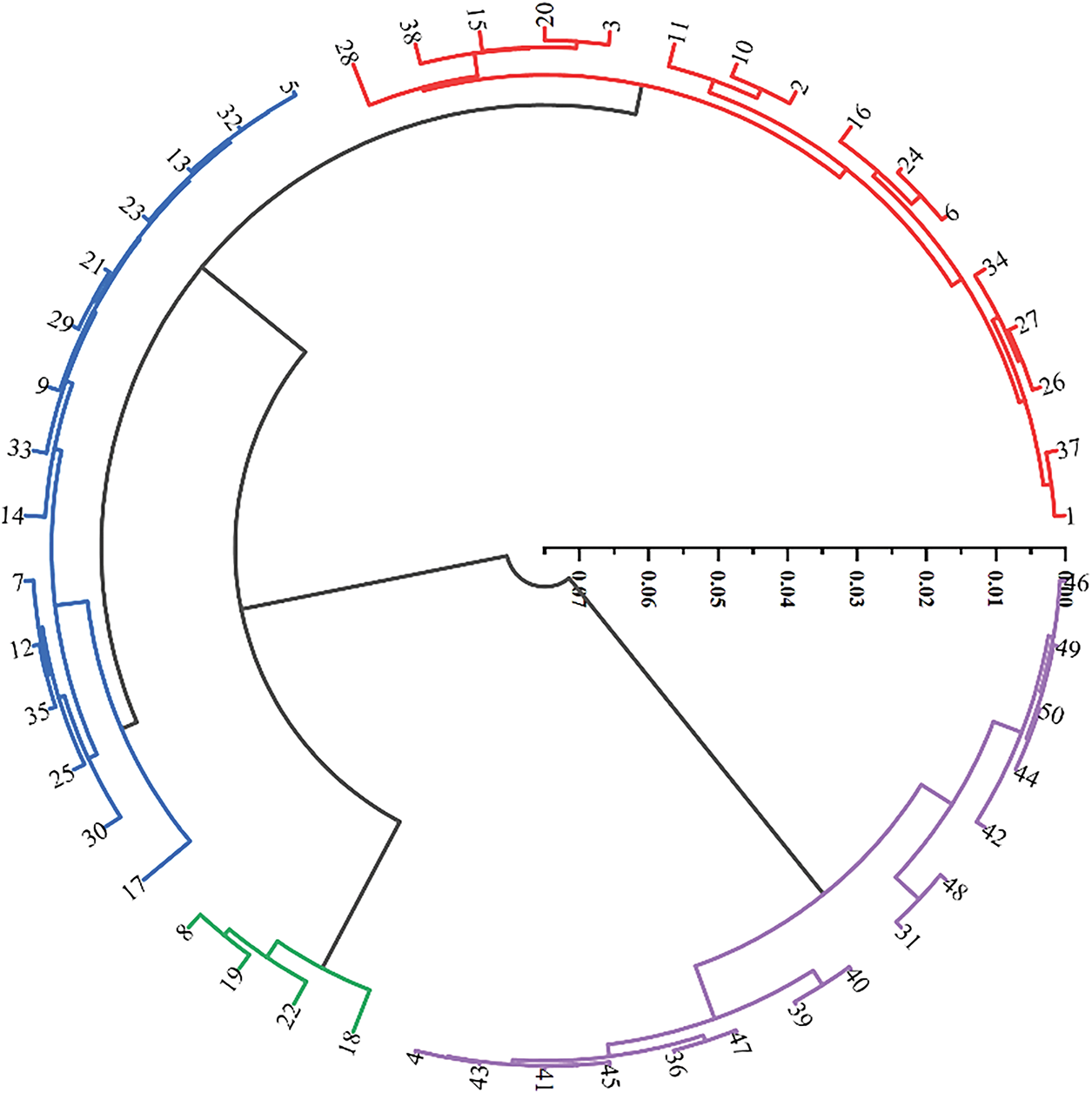

The 16 main traits of the 50 male germplasm resources for testing were clustered, and the clustering tree was drawn, which can be divided into four classes as shown in Table 8 and Fig. 3:

Figure 3: Cluster analysis of 50 kiwifruit germplasm resources

Category I includes 16 materials, with the main characteristics being the highest germination rate (65.28%) and pollen germination rate (30.32%). Category II includes 4 materials, with the main characteristics being germination rate and the number of flower branches per unit length of the mother branch, while other characteristics are at a moderately low level. Category III includes 15 materials, with all characteristic values at a moderately high level. Category IV includes 15 materials, with the best overall trait values, especially those related to floral traits. Among these, the germplasm resources in Categories I and III are mostly at an intermediate level, while those in Category II have relatively low average values for all traits. In contrast, the germplasm resources in Category IV have trait values that are significantly higher than those in the other three categories, except for the number of flowers per inflorescence and the number of flower branches per unit length of the mother branch. Overall, the germplasm resources in Group IV exhibit the best trait performance.

Phenotypic diversity, as the external morphological expression of plants resulting from the combined effects of genetic and environmental factors, provides a direct reflection of species’ genetic diversity and serves as a fundamental yet efficient approach for evaluating variation [20]. This diversity holds significant implications for breeding superior cultivars and improving agronomic traits, while also forming a crucial foundation for conserving, researching, and selecting novel germplasm resources [30]. This study conducted a systematic investigation of phenotypic traits in male kiwifruit plants, analyzing the diversity and differentiation of 21 phenotypic characteristics across 50 germplasm accessions. The results demonstrated abundant and highly diversified phenotypic variations, with quantitative traits exhibiting superior diversity indices compared to qualitative traits. The CV, which reflects the degree of dispersion traits among individuals, showed that higher CV values correspond to greater dispersion and richer phenotypic diversity [31]. In this study, the 21 phenotypic traits exhibited CV ranging from 1.55% to 83.71%, with an average of 28.62%. The highest CV was observed for anther number (83.71%), followed by pollen germination rate (59.85%), which is consistent with findings reported by Zhong [32]and Qi [33]. Correlation analysis revealed differential relationships among male kiwifruit floral traits, indicating that evaluation based on single traits would be inadequate [34]. Therefore, principal component analysis is essential to establish comprehensive evaluation criteria for floral morphological characteristics in male kiwifruit germplasm resources.

PCA can transform multiple, complexly related traits into a few principal components, identify the main influencing factors, and simplify the process of resource assessment and screening [35]. In this study, PCA identified seven principal components with a cumulative contribution rate of 76.66%. PC1 had the highest contribution rate (32.46%), with calyx diameter, petal length, flower diameter, and petal width as the main indexes, which were comprehensive reflections of flower size PC2 had a contribution rate of 9.94%, with the number of flowers per inflorescence, number of petals, and internode length of 1-year old branches as the main indexes, which were mainly related to inflorescence distribution density. The contribution of PC3 was 9.02%, and the traits with high absolute values of eigenvectors were mainly pollen purity (0.68) and 1-year branch base roughness (−0.59), revealing that these traits contributed significantly to the phenotypic diversity of agronomy. In addition, correlation analyses revealed highly significant relationships between ploidy, floral traits, and characteristics of annual branches in male kiwifruit plants. These traits could be important indicators for future evaluation and selection of kiwifruit male plant germplasm resources and should be given special attention.

This study employed phenotypic cluster analysis to classify 50 germplasm nursery samples into four distinct groups, with a preliminary characterization of the key traits for each group. This classification system will facilitate more effective exploitation and utilization of germplasm nursery resources. Group I has high germination rates and pollen germination rates, making it suitable for breeding commercial pollen kiwifruit. Group II has higher germination rates and more flower branches per unit length of mother branches, making it suitable for breeding resistant materials. Group III has larger flowers and higher flower counts, making it suitable for breeding ornamental kiwifruit. Notably, Group IV displayed several outstanding phenotypic traits, establishing this group as a valuable genetic resource for further exploitation and utilization as unique germplasm materials.

Kiwifruit is a dioecious plant, and previous studies have shown that the pollen amount and pollen germination rate of male plants have a significant effect on the pollination and fertilization of female plants and fruit quality [36,37], There is a significant phenotypic correlation between the floral organ traits of male plants (such as flower diameter, anther number, pollen viability, etc.) and fruit traits [38]. For example, correlation analysis confirmed that the flower diameter of male flowers is significantly positively correlated with the single fruit weight of female plants, which may be related to the fact that male plants with larger flower diameters have more developed anther tissue and higher pollen production [39,40]; the number of anthers in male flowers is significantly positively correlated with fruit diameter and soluble solids content, suggesting that the development of floral organs may regulate fruit development by influencing pollination efficiency [41]. Furthermore, Chen et al. [42,43] pointed out that the method of combining the principal component analysis and the subordinate function can improve the accuracy of the evaluation results of germplasm resources. Based on this, in this study, the male plant materials with the top three scores (40, 43, and 42) were screened by calculating the composite score (F value). At the same time, 16 main traits were used as indicators for cluster analysis.

In this study, we synthesized the results of principal component analysis, ranking of subordinate function scores, and clustering of traits, and obtained three excellent male plant materials by preliminary screening. Among them, No. 40 material has 4 levels of flowering, and the flowering period is from April 20 to May 1 for 12 days; No. 43 material has 4.5 levels of flowering, and the flowering period is from April 23 to May 4 for 12 days; No. 42 material has 4.5 levels of flowering, and the flowering period is from April 20 to May 2 for 13 days. After comparing the existing main plant varieties in Sichuan, found that these three male plant materials could completely meet the flowering period of the yellow-fleshed kiwifruit variety ‘Jinshi No. 1’ (flowering period around 20–28 April), and the three male plant materials could be used as the matching pollination trees of ‘Jinshi No. 1’ in the subsequent pollination experiments to study pollination. Pollination experiments were carried out to study the effects of pollination on the yield, quality and other characteristics of ‘Jinshi No. 1’ fruits, to obtain excellent matching pollinating male plants for ‘Jinshi No. 1’.

The 50 kiwifruit male germplasm resources exhibited significant phenotypic variation, with higher diversity in quantitative than qualitative traits. Flower size contributed the most to this phenotypic diversity, followed by the annual branching trait. The results of the study indicated that the kiwifruit male plant germplasm was rich in phenotypic variation and had higher diversity in quantitative traits compared to qualitative traits. In addition, highly significant correlations were found between flowering traits and ploidy in kiwifruit male plants. These traits should receive special attention as important indicators for germplasm selection in future kiwifruit male plant germplasm evaluation and breeding efforts. Principal component analysis reduced the 21 phenotypic traits to seven, capturing most of the phenotypic information. Clustering divided the 50 samples into four groups, clarifying the characteristics and breeding value of each group. The next step will be to conduct pollination experiments on Group IV materials to observe their effects on fruit characteristics. This information effectively highlights the phenotypic variation in male kiwifruit germplasm resources and provides valuable insights into their genetic improvement, conservation, and future utilization.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2023YFH0006).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization: Xiaoqin Zheng, Lihua Wang and Qian Zhang; investigation: Yuqing Wan, Qian Gao, Xin Liu and Gaomin Fan; writing—original draft preparation: Yuqing Wan; writing—review and editing: Yuqing Wan, Qian Zhang, Lihua Wang and Xiaoqin Zheng; supervision: Yan Wan; funding acquisition: Xiaoqin Zheng. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Nomenclature

| X | Mean |

| σ | Standard deviation |

| H | Shannon-Wiener diversity index |

| CV | Coefficient of variation |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

References

1. Huang HW, Gong JJ, Wang SM, He ZC, Zhang ZH, Li JQ. Genetic diversity in the genus Actinidia. Biodivers Sci. 2000;8(1):1. [Google Scholar]

2. Bano S, Scrimgeour F. The export growth and revealed comparative advantage of the New Zealand kiwifruit industry. Int Bus Res. 2012;5(2):73–82. doi:10.5539/ibr.v5n2p73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Drummond L. The composition and nutritional value of kiwifruit. In: Nutritional benefits of kiwifruit. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2013. p. 33–57. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-394294-4.00003-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Denney JO. Xenia includes metaxenia. HortScience. 1992;27(7):722–8. doi:10.21273/hortsci.27.7.722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Chai Y, Hong W, Liu H, Shi X, Liu Y, Liu Z. The pollen donor affects seed development, taste, and flavor quality in ‘Hayward’ kiwifruit. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(10):8876. doi:10.3390/ijms24108876. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Liu L, Gao BW, Li ZY, Lei H, Wang YM, Song ZJ, et al. Effects of different pollen on fruit quality of ‘Hongyang’ Actinidia chinensis. Hubei For Sci Technol. 2022;51(6):7–13. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1004-3020.2022.06.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zheng XQ, Tan ML, Wang LH, Zhang X. Progress on breeding of male varieties of kiwifruit. South China Fruits. 2023;52(4):213–6. (In Chinese). doi:10.13938/j.issn.1007-1431.20220544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Saccomani M, Stevanato P, Cagnin M, Fama G, De Biaggi M, Biancardi E. Genetic diversity for root morpho-physiological traits and productivity in sugar beet. In: American Society of Sugarbeet Technologist (ASSBT); 2005 Mar 2–5; Palm Springs, CA, USA. doi:10.5274/assbt.2005.54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Li X, Shi G, Geng J, Sun D, Wang Z, Ai J. Morphogenesis, megagametogenesis, and microgametogenesis in Actinidia arguta flower buds. Sci Hortic. 2024;336(1096):113445. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2024.113445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Caporali E, Testolin R, Pierce S, Spada A. Sex change in kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis Planch.a developmental framework for the bisexual to unisexual floral transition. Plant Reprod. 2019;32(3):323–30. doi:10.1007/s00497-019-00373-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Guo D, Wang R, Fang J, Zhong Y, Qi X. Development of sex-linked markers for gender identification of Actinidia arguta. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):12780. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-39561-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Cheng CH, Seal AG, Murphy SJ, Lowe RG. Variability and inheritance of flowering time and duration in Actinidia chinensis (kiwifruit). Euphytica. 2006;147(3):395–402. doi:10.1007/s10681-005-9036-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Chai J, Liao B, Li J, Liu H, Liu Z. Pollen donor affects the taste and aroma compounds in ‘Cuixiang’ and ‘Xuxiang’ kiwifruit. Sci Hortic. 2023;314(25):111945. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2023.111945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Liao G, Jiang Z, He Y, Zhong M, Huang C, Qu X, et al. The comprehensive evaluation analysis of the fruit quality in Actinidia eriantha pollinated with different pollen donors based on the membership function method. Erwerbs Obstbau. 2022;64(1):91–6. doi:10.1007/s10341-021-00620-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Lv Z, He Y, Jia D, Huang C, Zhong M, Liao G, et al. Genetic diversity analysis of phenotypic traits for kiwifruit germplasm resources. Acta Hortic Sin. 2022;49(7):1571–81. (In Chinese). doi:10.16420/j.issn.0513-353x.2021-0248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Chen XL, Liang H, Xie ZW, Liu SH. Cluster analysis of fruit and leaf characters from 11 species of Actinidia. J Anhui Agric Sci. 2008;36(35):15408–10. doi:10.13989/j.cnki.0517-6611.2008.35.105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Sun ZZ, Li QY, Wang XK, Zhao WT, Xue Y, Feng JY, et al. Comprehensive evaluation and phenotypic diversity analysis of germplasm resources in mandarin. Sci Agric Sin. 2017;50(22):4362–83. doi:10.3864/j.issn.0578-1752.2017.22.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Tian W, Li Z, Wang L, Sun S, Wang D, Wang K, et al. Comprehensive evaluation of apple germplasm genetic diversity on the basis of 26 phenotypic traits. Agronomy. 2024;14(6):1264. doi:10.3390/agronomy14061264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Sun YQ, Wu CY, Wang D, Wang ZQ. Multivariate statistic analysis of fruit phenotypic traits and quality of wild jujube germplasm resources. Acta Agric Jiangxi. 2015;27(12):29–32. [Google Scholar]

20. Wang ZJ, Luo GQ, Dai FW, Xiao GS, Lin S, Li ZY, et al. Genetic diversity of 569 fruit mulberry germplasm resources based on eight agronomic traits. Acta Hortic Sin. 2021;48(12):2375–84. doi:10.16420/j.issn.0513-353x.2020-0931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Yang R, Li J, Huang H, Wu X, Wu R, Bai YE. Analysis of phenotypic trait variation in germplasm resources of Lycium ruthenicum Murr. Agronomy. 2024;14(9):1930. doi:10.3390/agronomy14091930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Liu D, Wang X, Li W, Li J, Tan W, Xing W. Genetic diversity analysis of the phenotypic traits of 215 sugar beet germplasm resources. Sugar Tech. 2022;24(6):1790–800. doi:10.1007/s12355-022-01120-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Hu Z, Chen W, Li K. Descriptors and data standard for kiwifruit. Beijing, China: China Agricultural Press; 2006.(In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

24. Liao GL, Chen L, Zhong M, Wang SY, Huang CH, Tao JJ, et al. Ploidy difference and correlation analysis of pollen traits from male plants in Actinidia. China Fruits, 2018;2:13–7,22. doi:10.16626/j.cnki.issn1000-8047.2018.02.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Li X, Duan M, Shang T, Duan J. Kiwi pollen purity detection technology. Appl Technol Inf Fruit Tree. 2019;5:43–4. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

26. Omayio D, Mzungu E. Modification of Shannon-wiener diversity index towards quantitative estimation of environmental wellness and biodiversity levels under a non-comparative scenario. J Environ Earth Sci. 2019;9(9):46–57. [Google Scholar]

27. Houmanat K, Douaik A, Charafi J, Hssaini L, El Fechtali M, Nabloussi A. Appropriate statistical methods for analysis of safflower genetic diversity using agglomerative hierarchical cluster analysis through combination of phenotypic traits and molecular markers. Crop Sci. 2021;61(6):4164–80. doi:10.1002/csc2.20598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Santhy V, Rathinavel K, Saravanan M, Priyadharshini M. Genetic diversity assessment of extant cotton varieties based on Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and cluster analysis of enlisted DUS traits. Electron J Plant Breed. 2020;11(2):430–8. doi:10.37992/2020.1102.075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Uhlarik A, Ćeran M, Živanov D, Grumeza R, Skøt L, Sizer-Coverdale E, et al. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization and correlation analysis of pea (Pisum sativum L.) diversity panel. Plants. 2022;11(10):1321. doi:10.3390/plants11101321. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Peng Y, Wang G, Cao F, Fu FF. Collection and evaluation of thirty-seven pomegranate germplasm resources. Appl Biol Chem. 2020;63(1):15. doi:10.1186/s13765-020-00497-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Mahmoud AMA, Osman NH. Utilizing genetic diversity to select tomato lines tolerant of tomato yellow leaf curl virus based on genotypic coefficient of variation, heritability, genotypic correlation, and multivariate analyses. Braz J Bot. 2023;46(3):609–24. doi:10.1007/s40415-023-00908-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Zhong M, Liao GL, Li ZY, Zou LF, Huang Q, Chen L, et al. Genetic diversity of wild male kiwifruit (Actinidia eriantha Benth.) germplasms based on SSR and morphological markers. J Fruit Sci. 2018;35(6):658–67. doi:10.13925/j.cnki.gsxb.20170514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Qi X, Xu S, Zhong Y, Chen J, Lin M, Sun L, et al. Genetic differences and cluster analysis of pollens from different male kiwifruit germplasm resources. J Fruit Sci. 2016;33(10):1194–205. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

34. Diao SF, Shao WH, Jiang JM, Dong RX, Sun HG. Phenotypic diversity in natural populations of Sapindus mukorossi based on fruit and seed traits. Acta Ecol Sin. 2014;34(6):1451–60. doi:10.5846/stxb201306211756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Salem N, Hussein S. Data dimensional reduction and principal components analysis. Procedia Comput Sci. 2019;163(12):292–9. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2019.12.111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Li FF, Zhang SL, Zhang HP, Hu HJ, Tian R, Li QS. Cluster analysis for the quantity and germinating characteristics of the pollens from different pear cultivars. J Nanjing Agric Univ. 2013;36(5):27–32. [Google Scholar]

37. Yang JC, Han ZC, He MM, Luo C, Li LL, Li WJ. Effect of pollen Xenia on ‘Hongyang’ kiwifruit. China Fruits, 2021;6:7–12,109. (In Chinese). doi:10.16626/j.cnki.issn1000-8047.2021.06.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Li YW, Wang XR. Effects of pollen from different male plants on the fruit of Huayou kiwifruit. Shaanxi J Agric Sci. 2012;58(3):91–2. doi:10.3969/j.issn.0488-5368.2012.03.034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Zhang WH, Zhang BR, Li XH, Zhong YP, Li X, Zheng M, et al. Effects of the correlation between the characteristics of male flowers and pollinated fruit of kiwifruit. J Agric Resour Environ. 2020;37(3):413–8. doi:10.13254/j.jare.2019.0576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Zhang M, Tang DM, Zhong WM, Tang JW, Huang YX, Wu SF, et al. Effects of pollen donor on the fruit quality of Guichang kiwifruit. J South Agric. 2019;50(11):2504–11. doi:10.3969/j.issn.2095-1191.2019.11.17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Luo MM, Wang Z, Wang XY, Gao L, Luo X, Huang Q, et al. Variation analysis of flower traits in male lines of Jinyi kiwifruit seedling progeny. J Fruit Sci. 2024;41(11):2173–81. doi:10.13925/j.cnki.gsxb.20240483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Chen T, Liu L, Zhou Y, Zheng Q, Luo S, Xiang T, et al. Characterization and comprehensive evaluation of phenotypic characters in wild Camellia oleifera germplasm for conservation and breeding. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1052890. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1052890. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Xue X, Yu Z, Mu A, Yang F, Liu D, Zhang S, et al. Identification and evaluation of phenotypic characters and genetic diversity analysis of 1558 foxtail millet germplasm resources for conservation and breeding. Front Plant Sci. 2025;16:1624252. doi:10.3389/fpls.2025.1624252. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools