Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Impacts of Fertilization and Soil Amendments on Rhizosphere Microbiota and Growth of Panax: A Meta-Analysis

1 Institute of Drug Discovery Technology, Ningbo University, Ningbo, 315211, China

2 Qian Xuesen Collaborative Research Center of Astrochemistry and Space Life Sciences, Ningbo University, Ningbo, 315211, China

3 Zhejiang Key Laboratory of Pathophysiology, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Health Science Center, Ningbo University, Ningbo, 315211, China

* Corresponding Author: Ming-Xiao Zhao. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Fungal and Bacterial Disease Management in Agricultural Crops Through Biological Control, Disease Resistance, and Transcriptomics Approaches)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2026, 95(1), 11 https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.072276

Received 23 August 2025; Accepted 02 December 2025; Issue published 30 January 2026

Abstract

Panax species are globally recognized for their high medicinal and economic value, yet large-scale cultivation is constrained by high production costs, progressive soil acidification, and persistent soil-borne diseases. Although various soil improvement strategies have been tested, a comprehensive synthesis of their comparative effectiveness has been lacking. Here, we conducted a meta-analysis of 1381 observations from 54 independent studies to evaluate the effects of conventional fertilizers, microbial fertilizers, organic amendments, and inorganic amendments on Panax cultivation. Our results demonstrate that microbial fertilizers, organic amendments, and inorganic amendments significantly increased soil pH, thereby ameliorating soil acidification. Among them, organic amendments significantly enhanced the content of soil organic carbon, available nitrogen, and available phosphorus, alongside a notable increase in microbial diversity (Chao1 and ACE indices, which increased by 9% and 17%, respectively). Moreover, our analysis revealed that while microbial fertilizers, organic amendments, and inorganic amendments (except conventional fertilizers) reduced the disease index of Panax plants, organic amendments demonstrated absolute superiority in promoting plant height, root dry weight, root fresh weight, and root length. By quantitatively integrating multi-source evidence, this study provides novel mechanistic insights and practical recommendations that extend beyond local practices, offering guidance for sustainable ginseng cultivation and broader medicinal plant production systems worldwide.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileThe genus Panax (Araliaceae family), including Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer (Asian ginseng), Panax notoginseng (Burk.) F. H. Chen (sanchi ginseng) and Panax quinquefolius L. (American ginseng) has a centuries-long history of medicinal use and remain among the most widely utilized and commercially valuable medicinal plants worldwide [1]. Among them, P. ginseng is extensively harnessed to boost physical endurance, alleviate mental stress, counteract the aging process, and elevate cognitive capabilities [2,3]. Similarly, P. notoginseng is prized for its ability to promote blood circulation, and P. quinquefolius is used for its immune-boosting and anti-inflammatory effects [4,5]. Due to these beneficial properties, Panax species are cultivated worldwide, particularly in East Asia and North America, for both their medicinal roots and high commercial value in the pharmaceutical industry.

However, the successful cultivation of Panax is often hindered by various challenges. One of the most pressing problems in Panax cultivation is continuous cropping, which can lead to nutrient imbalances, decreased microbial diversity, and increased soil-borne diseases like root rot and rusty roots [6,7]. Continuous cropping refers to the practice of planting Panax species in the same soil year after year. This practice leads to the decline of soil health, as it disrupts the soil microbial community and impairs essential nutrients [8]. In particular, the repeated planting of Panax in the same soil can result in soil acidification, which in turn leads to nutrient imbalances and impaired root function [9]. Root rot and other diseases, spurred by environmental factors, attack different plant parts, harming yield and quality [10]. To address these issues, several management strategies have been proposed. The most common approach involves the application of chemical fertilizers, which provide essential nutrients like nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) [11,12]. While chemical fertilizers can promote plant growth in the short term, their overuse has been shown to negatively impact soil health by disrupting the microbial communities in the rhizosphere, leading to soil acidification and nutrient imbalances [13]. Long-term reliance on chemical fertilizers can also result in soil erosion, reduced microbial diversity, and the occurrence of root rot, which further threatens the sustainability of Panax cultivation [14].

In contrast, more environmentally friendly substitutes, such as microbial fertilizers and soil amendments, have gained attention in recent years for their potential to improve soil health and promote plant growth without causing harm to the environment [15,16]. Microbial fertilizers, which contain beneficial microorganisms like plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), can enhance nutrient availability and suppress soil-borne pathogens [17,18]. For instance, the application of AMF biofertilizer in American ginseng cultivation can recruit beneficial rhizosphere microorganisms, including bacteria such as Bacillus, Pseudarthrobacter, and Streptomyces, and the fungus M. elongata. Meanwhile, it can inhibit harmful bacteria like Solibacter and fungal disease-related microorganisms such as F. oxysporum and F. solani, thus alleviating the continuous cropping obstacle [19]. In addition, inoculating Sphingobacterium sp. PG-1 into the ginseng continuous cropping soil can effectively reduce the content of toxic compounds and subsequently promote the growth of Panax ginseng [20]. Organic amendments, such as compost and biochar, improve soil structure, enhance water retention, and provide a slow release of nutrients that benefit plant growth over time [21,22]. For example, the application of biochar during the cultivation of P. notoginseng can enhance microbial diversity, alleviate soil acidification, and significantly improve the survival rate of P. notoginseng [23]. Meanwhile, the combined application of organic fertilizers and appropriate water deficit can significantly increase the dry yields of P. notoginseng flowers and roots, as well as the saponin content [24]. Inorganic amendments, such as lime, gypsum, and silicates, are often used to adjust soil pH and improve nutrient availability [25,26]. The application of lime and calcium magnesium phosphate can mitigate the occurrence of root rot by improving soil pH, thereby promoting the growth and enhancing the quality of P. notoginseng [27].

Diverse fertilizers and soil amendments have each demonstrated their own advantages in the cultivation of Panax. However, existing studies are often based on individual trials with limited replicability, making it difficult to draw generalizable conclusions. In particular, there has been no systematic comparison across fertilizer and amendment types that integrates evidence from multiple studies. Meta-analysis provides a powerful approach to quantitatively synthesize multi-source data and identify robust patterns, thereby overcoming the limitations of individual studies and clarifying the relative effectiveness of different cultivation practices [28]. To address this issue, this work conducted a meta-analysis to comprehensively evaluate the impacts of four distinct fertilizer and amendment types—conventional fertilizers, microbial fertilizers, organic amendments, and inorganic amendments—on the rhizosphere microorganisms, soil physicochemical properties, and plant growth of Panax. By analyzing the changes in rhizosphere microorganisms, such as the diversity and abundance of bacteria, evaluating soil chemical properties like pH and nutrient content, and monitoring plant growth parameters, including biomass, disease incidence, height, and root development. We aim to identify the most effective fertilizers or amendments for promoting the healthy growth of Panax while maintaining soil quality. Beyond the context of local cultivation, the findings of this study also provide insights for sustainable medicinal plant production systems worldwide.

2.1 Data Collection and Screening

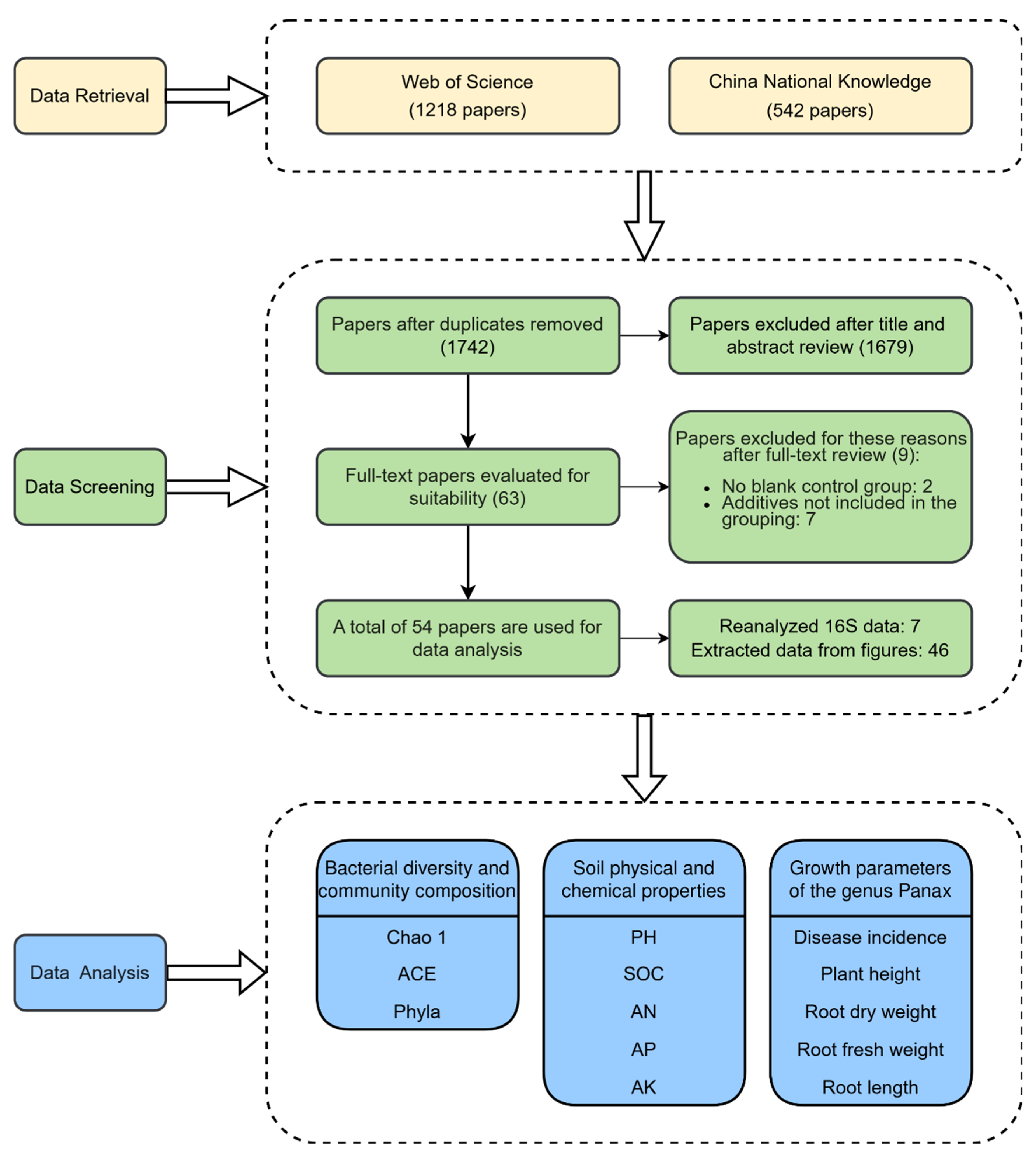

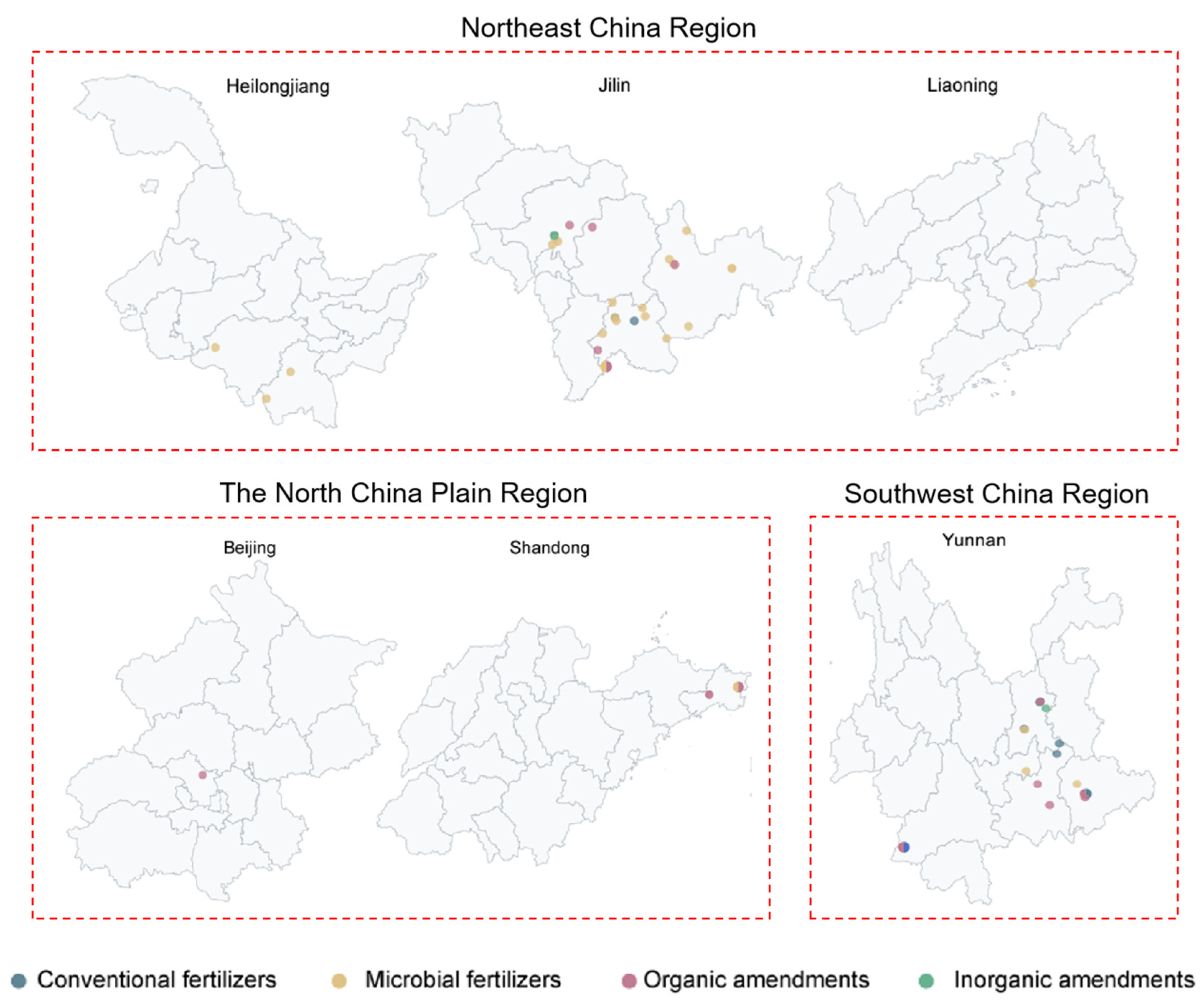

The meta-analysis dataset was developed using peer-reviewed papers published between January 2014 and December 2024. These papers were collected from two academic databases: Web of Science and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI, http://www.cnki.net/). The keywords used were (bacterium OR bacteria OR microbial community OR microbial communities) AND (soil) AND (“Panax ginseng” OR “Panax notoginseng” OR “Panax quinquefolius”). The literature selection process applied the following inclusion criteria: (1) Studies must include untreated controls and treatments with external inputs. (2) Only studies focused on plants of the Panax genus were included. (3) Data were limited to high-throughput sequencing methods, excluding studies using alternative techniques (e.g., Phospholipid fatty acid, Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis). (4) Studies requiring a minimum of three replicates per treatment were selected. (5) The additives belong to fertilizers or soil amendments. A total of 1381 observations from 54 publications were included in the dataset based on the above criteria (Fig. 1 and Table S1). These observations are distributed across 54 sampling sites spanning six provinces in China: Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning (Northeast China Region); Beijing and Shandong (North China Plain Region); and Yunnan (Southwest China Region) (Fig. 2). The observations derived from the studies we have collated predominantly encompass three pivotal dimensions. Microbial diversity and composition data, manifested through phylum-level abundance, Chao1 index, and ACE observations, offer valuable insights into the intricate microbial communities. The soil physicochemical property data, an essential component, facilitates a comprehensive understanding of the soil’s physical and chemical characteristics. Moreover, the observations of plant growth parameters serve as a means to assess the growth and developmental status of plants.

Figure 1: Flowchart of literature selection and data extraction for the meta-analysis.

Figure 2: Distribution of sampling sites classified into three geographical regions. Northeast China (Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning), North China Plain (Beijing and Shandong), and Southwest China (Yunnan).

When a single study is conducted at different stages of plant growth, data were extracted separately for each stage. When a single study includes multiple concentrations of fertilizers and amendments, each concentration is treated as a separate treatment, and data are collected accordingly. Treatments were categorized into four groups by additive type: conventional fertilizers (nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and compound fertilizers), microbial fertilizers (microbial inoculants and biofertilizers), organic amendments (manure, compost, biogas slurry, and organic carbon), and inorganic amendments (quicklime and inorganic salts) [29,30,31,32,33] (Table S2). The data collected included bacterial community composition, Chao1 and ACE diversity indices, soil physicochemical properties (pH, SOC: soil organic carbon, AN: available nitrogen, AP: available phosphorus, and AK: available potassium), and plant growth parameters (disease incidence, plant height, root length, root dry weight, and root fresh weight) (Fig. 1). Data were extracted from the text and tables in the literature. For data presented in figures, the GetData (v2.22) software was used for extraction. For each study, we recorded the means (M), standard deviations (SD), and sample sizes (n: number of replicates) of both the additive treatment and control groups. In studies where no standard errors (SE), standard deviations (SD), or confidence intervals (CI) are reported, we assigned standard deviations that are 1/10 of the means [34]. In studies where only SE were reported, SD were calculated using the formula:

2.3.1 Reanalysis of 16S rRNA Data

To supplement the data on microbial diversity and composition, we downloaded and preprocessed the raw data from several studies that provided accession numbers, following a standardized workflow. Data were downloaded from NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) and ENA (European Nucleotide Archive). The 16S sequencing data were processed according to the standard operating procedure recommended by Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology (QIIME2 2023.5) [35]. The sequences were resolved into amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) using the Deblur workflow [36]. The ASVs were assigned taxonomy using a classifier trained on the full-length 16S rRNA gene from the SILVA v138 database [37]. A detailed description of the bioinformatics pipeline can be found in the Supplementary Methods.

The effects of various fertilizers and amendments on rhizosphere microorganisms, soil physicochemical properties, and plant growth were assessed by comparing the treatment groups with their respective controls. Effect size quantification was performed using the natural logarithm-transformed response ratio (

The response ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated through MetaWin (v2.1) software. A random-effects model was constructed in MetaWin using a weighted resampling method with 9999 iterations. The total heterogeneity (

3.1 Effect of Exogenous Additives on Soil Chemical Properties

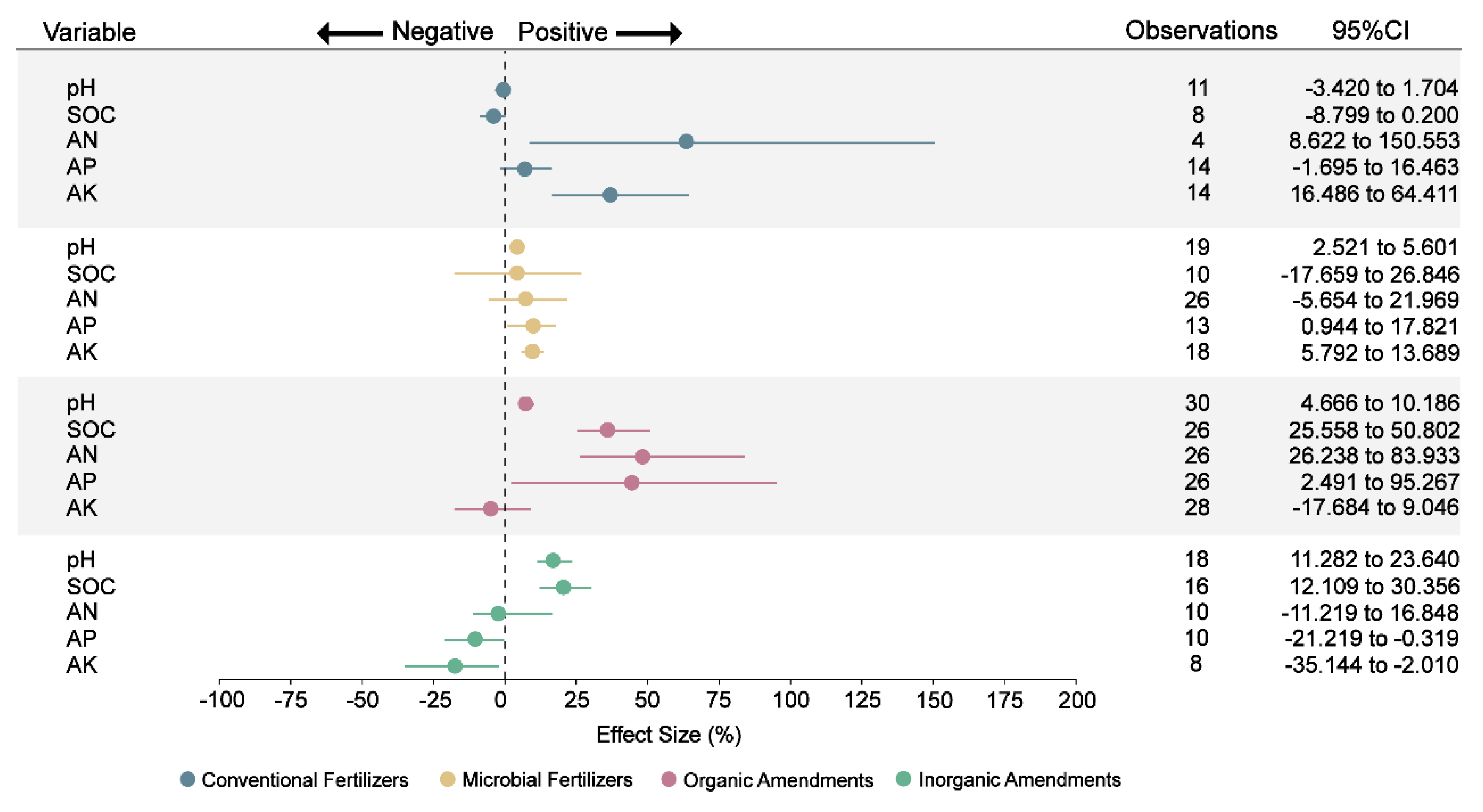

We conducted analysis of the imported additives and their chemical properties on the collected data. The analysis results showed that the application of microbial fertilizers, organic amendments, and inorganic amendments led to notable increases of 4%, 7%, and 17%, respectively—shifts that moved soil pH closer to neutral ranges and helped mitigate soil acidification (Fig. 3 and Table S3). The insignificant effect of conventional fertilizers on pH likely stems from the fact that their impact is influenced by multiple interacting factors, including fertilization rate, duration of application, soil buffering capacity, and plant-mediated processes. Previous studies have demonstrated that soil acidification induced by nitrogen fertilizers varies greatly depending on fertilizer type, application intensity, and the soil’s inherent buffering capacity [39,40]. Moreover, plants can partly mitigate acidification through nutrient uptake and rhizosphere interactions that regulate proton release and organic acid exudation [41,42]. In previous studies, lime as an inorganic amendment has been shown to be an efficient method for improving soil acidity [43]. Similarly, the application of organic amendments and microbial fertilizers can increase soil pH [44,45]. The pH increase under organic and microbial amendments may result from enhanced microbial decomposition of organic acids and elevated base cation exchange capacity, while lime-based inorganic amendments directly neutralize soil acidity [46,47]. Additionally, certain microbial activities in fertilizers can contribute to the elevation of soil pH through metabolic processes [48]. The increase in soil pH was associated with improved suitability of acidic soils and coincided with greater abundance of beneficial microbes and higher nutrient availability, suggesting a potential linkage to enhanced soil health [49,50].

Figure 3: Effect of different fertilizers and amendments on soil chemical properties. SOC: soil organic carbon, AN: soil available nitrogen, AP: soil available phosphorus, AK: soil available potassium. Points represent the mean effect size, and the error bars show the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) after bias correction. If the 95% confidence interval does not overlap with zero, then the impact of fertilizers or amendments on this variable is considered significant.

The improvement in soil pH by various amendments not only mitigated acidification but also altered soil nutrient dynamics. While conventional fertilizers significantly boosted available nitrogen and potassium by 64% and 37%, respectively, this form of nutrient supply is often prone to leaching and less efficient in plant uptake [51]. Microbial fertilizer enhanced available phosphorus (10%) and potassium (9%), primarily through microbially mediated solubilization and mobilization processes [52] (Fig. 3). Such enhancement can be attributed to microbial secretion of organic acids and phosphatases that dissolve insoluble phosphate minerals and release K+ through mineral weathering processes, thereby increasing nutrient bioavailability [53,54]. Organic amendments induced the most comprehensive improvements, elevating soil organic carbon (36%), available nitrogen (49%), and available phosphorus (45%) (Fig. 3). These gains stem from stimulated microbial activity promoting both carbon accumulation and nutrient mineralization [55], with compounds in compost and biochar further chelating nitrogen to provide slow-release availability crucial for sustained Panax uptake [56]. Inorganic amendments increased soil organic carbon (21%), likely through indirect effects on microbial turnover, but paradoxically decreased available phosphorus (10%) and potassium (17%) (Fig. 3). Research work has demonstrated that lime and gypsum improved cation exchange and reduced Al3+ toxicity, indirectly favoring SOC stabilization [57]. This pattern may be related to enhanced nutrient uptake efficiency under optimized pH conditions [58] rather than true depletion. The three approaches—activation of beneficial microbes via microbial fertilizers, improved mineralization and nutrient retention through organic amendments, and pH adjustment using inorganic amendments—address the nutrient imbalances that arise in ginseng monoculture. Together these practices promote root growth and alter root metabolic profiles (including energy-related pathways), thereby improving plant performance under continuous cropping [59,60].

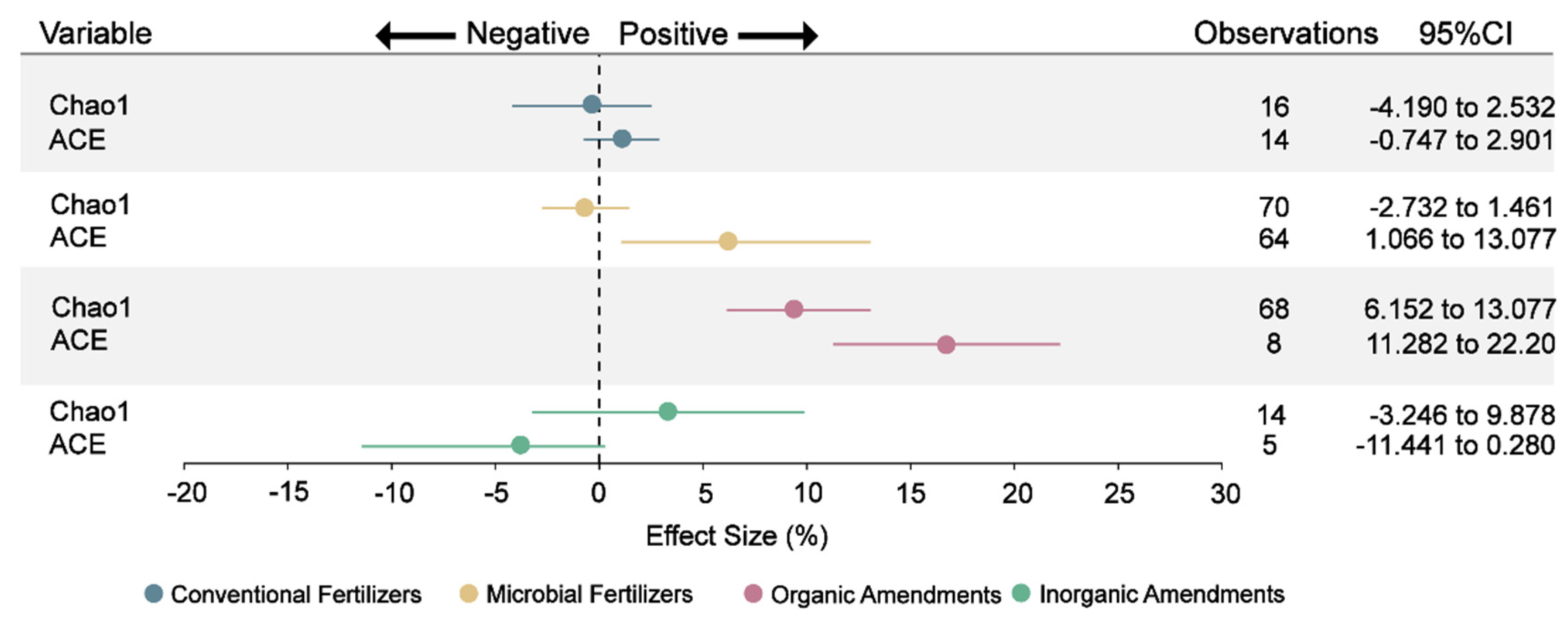

3.2 Soil Bacterial Community Responses to Exogenous Additives

Rhizosphere microorganisms are vital for plant growth and maintaining plant health [61]. Microbial diversity, a crucial indicator for gauging the functions of rhizosphere soil microorganisms, is highly susceptible to external environmental factors and anthropogenic disturbances [62,63]. Following the application of organic amendments, soil microbial diversity exhibited a notable increase. This increase is reflected in the significant rises in the Chao1 and ACE indices, which went up by 9% and 17%, respectively. (Fig. 4 and Table S3). Previous studies have confirmed that organic amendments can increase soil bacterial diversity [64]. Organic substances in organic amendments supply diverse carbon and energy sources. These sources support the growth of various soil microorganisms, thereby promoting their reproduction and enhancing microbial diversity [65]. Microbial fertilizer specifically elevated the ACE index (6%), potentially through enhancement of soil catalase activity and subsequent stimulation of microbial activity [66]. Critically, increased diversity bolsters ecosystem stability and functional diversity [67], essential for mitigating continuous cropping constraints.

Figure 4: Effect of different fertilizers and amendments on the Chao1 diversity index and ACE diversity index of soil bacteria communities. The sources of bacterial diversity data include the analysis of raw sequencing data and data derived from figures and tables in the original study. Points represent the mean effect size, and the error bars show the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) after bias correction. If the 95% confidence interval does not overlap with zero, then the impact of fertilizers or amendments on this variable is considered significant.

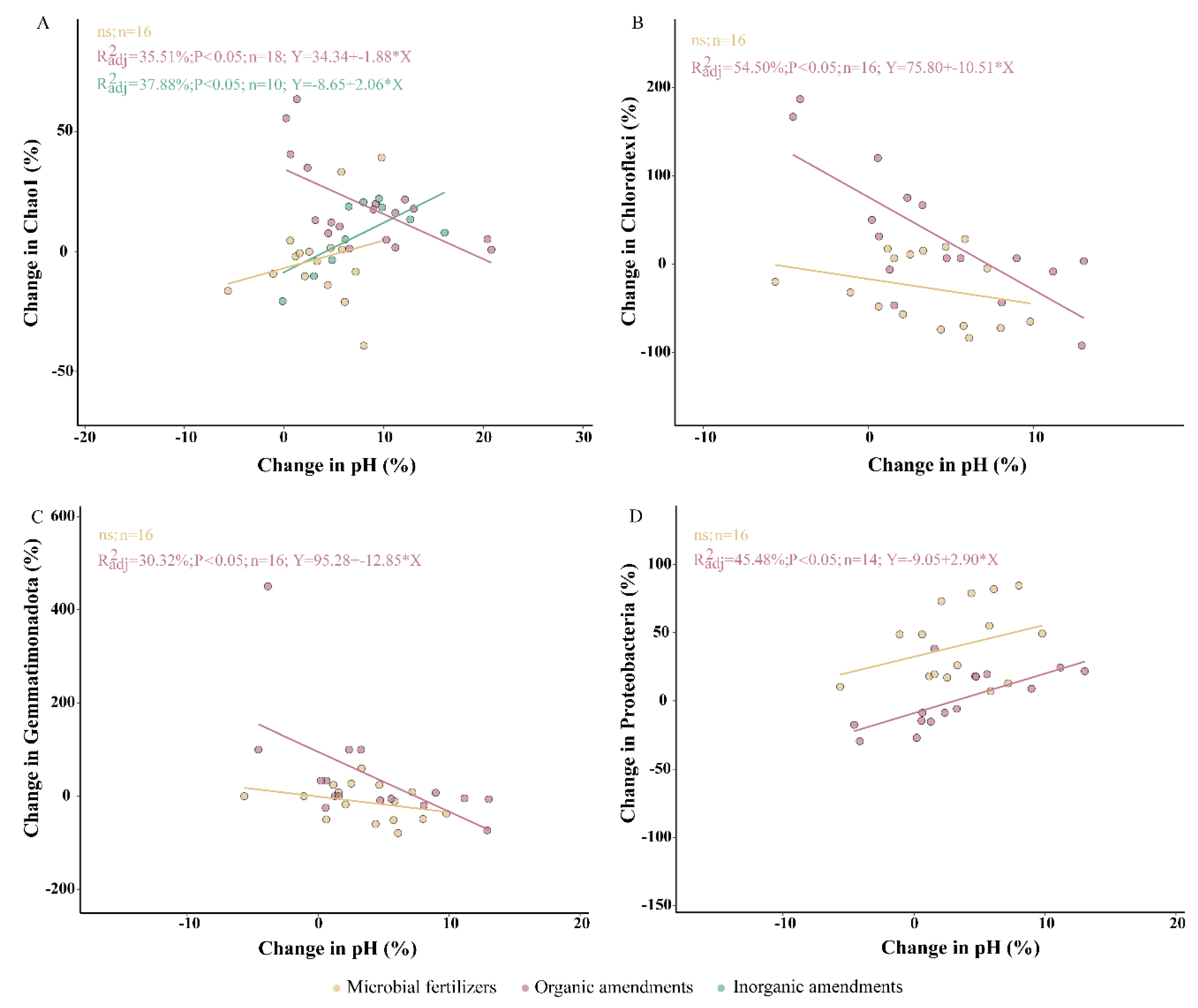

However, regression analysis further revealed that the response of microbial diversity to pH differed among amendment types (Fig. 5). Under organic amendments, a significant negative correlation was observed between pH change and Chao1 diversity (R2 = 0.36, p = 0.005), while under inorganic amendments, the correlation was positive (R2 = 0.38, p = 0.034) (Fig. 5A). Organic amendments can increase soil pH while enhancing nutrient and carbon availability. In acidic soils, the initial increase in nutrient availability promotes diversity; when pH exceeds the threshold, the inhibitory effect of pH prevails, leading to a decline in diversity [68]. In contrast, inorganic amendments mainly alter soil pH without substantial nutrient input. In acidic soils, their pH elevation relieves acidic stress, thereby increasing microbial diversity [69].

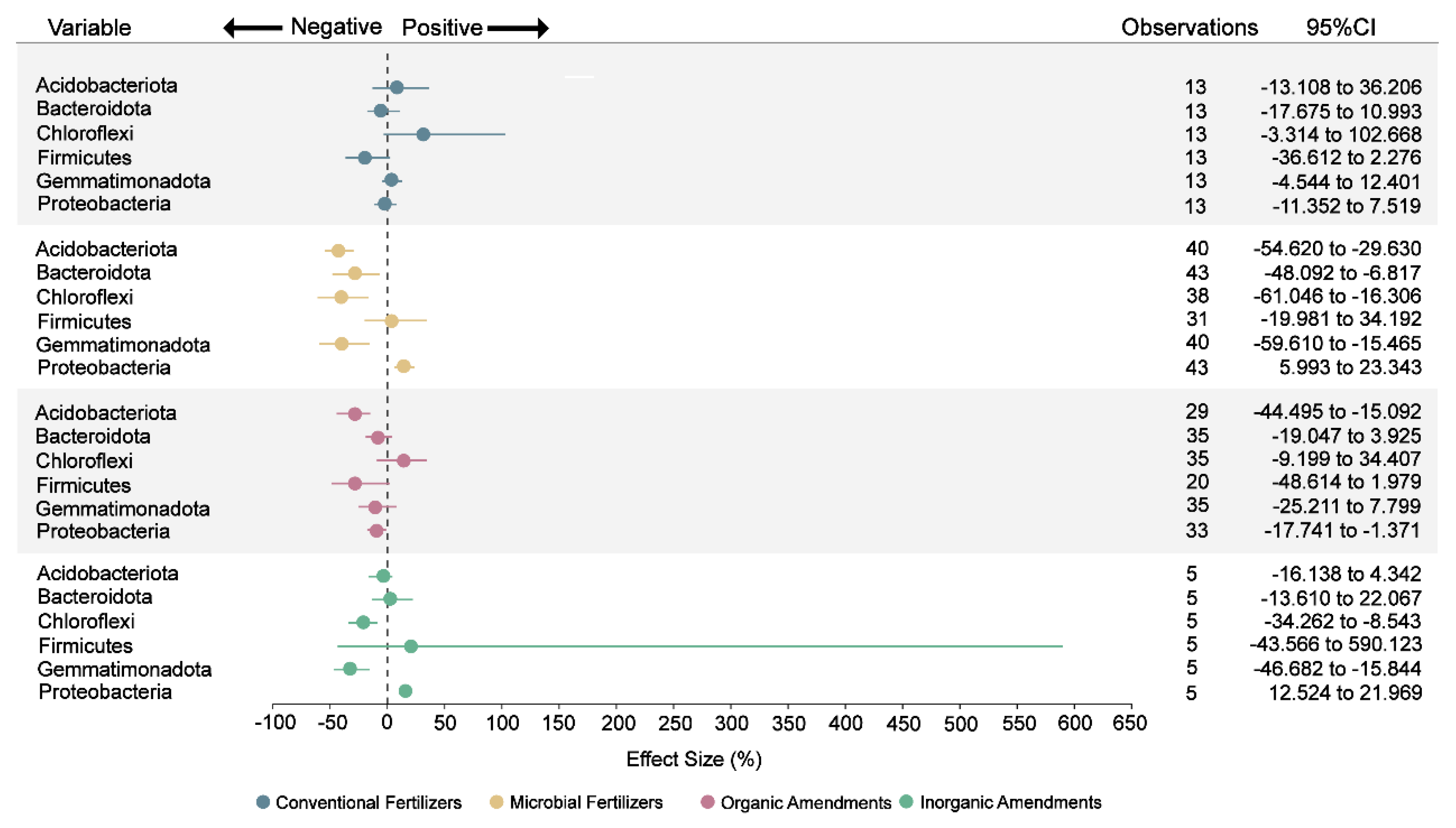

Concurrently, among the six bacterial phyla meeting Rosenthal’s fail-safe N criteria, microbial fertilizers significantly increased Proteobacteria abundance by 15% while reducing Acidobacteriota, Bacteroidota, Chloroflexi, and Gemmatimonadota by 43%, 28%, 40%, and 39%, respectively (Fig. 6 and Table S3). These microbial shifts can be interpreted through ecological selection theory, where pH and nutrient availability act as major environmental filters shaping bacterial communities. This restructuring likely results from introduced functional microorganisms altering the soil microenvironment through metabolite secretion [70,71] or competitive exclusion for nutrients [72].

Figure 5: Relationships between relative changes in soil pH and microbial community features under different exogenous amendments. (A) Chao1 index. (B) Chloroflexi. (C) Gemmatimonadota, (D) Proteobacteria. n < 5 will not include, n is the number of samples. Points rep resent paired values for individual samples under each treatment, and lines denote the linear regression for microbial fertilizers (yellow) organic amendments (pink), and inorganic amendments (green).

In contrast, inorganic amendments also increased Proteobacteria abundance (16%) but specifically reduced Chloroflexi (22%) and Gemmatimonadota (32%) (Fig. 6). This pattern may potentially be associated with their significant elevation of soil pH (17%, Fig. 3), which selectively favors neutrophilic Proteobacteria over acidophilic groups whose abundances are negatively correlated with alkaline conditions [73]. Organic amendments induced declines in Proteobacteria (9%) and Acidobacteriota (28%) (Fig. 6). Organic amendments often raise soil pH and increase labile nutrients. Acidobacteriota are typically oligotrophic and prefer acidic, low-nutrient conditions, so increases in pH and resource availability tend to reduce their relative abundance [74]. Similarly, some Proteobacteria taxa are sensitive to pH shifts and may decline if the amendment moves pH away from their local optimum [75].

Figure 6: Effect of different fertilizers and amendments on six bacterial phyla. According to the collected data, these six phyla were the only ones that met the requirements of Rosenthal’s fail-safe N method. Points represent the mean effect size, and the error bars show the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) after bias correction. If the 95% confidence interval does not overlap with zero, then the impact of fertilizers or amendments on this variable is considered significant.

These microbial compositional changes may be further explained by their relationships with soil pH. Regression analyses provided mechanistic insight into how microbial shifts correlate with pH alterations under different amendments (Fig. 5). For example, increased pH under organic amendments was significantly associated with reductions in Chloroflexi (R2 = 0.54, p < 0.001) and Gemmatimonadota (R2 = 0.30, p = 0.016) (Fig. 5B,C). Conversely, Proteobacteria abundance significantly increased with pH under organic inputs (R2 = 0.45, p = 0.005) (Fig. 5D). Although these phyla did not show significant changes in meta-analysis (except Proteobacteria) (Fig. 6), their negative correlations with pH are consistent with previous findings that Chloroflexi and Gemmatimonadota prefer slightly acidic conditions and tend to decline in abundance as pH increases [76].

These compositional changes bear functional significance. Proteobacteria enrichment enhances nitrogen fixation and phosphorus solubilization [70], while reduced Bacteroidota mitigates nutrient competition and harmful metabolite production [18]. Declines in Chloroflexi and Gemmatimonadota under higher pH could further minimize root-nutrient competition [77]. Collectively, these microbial modifications establish a functional foundation for improved soil health.

Together, these results highlight that soil chemical adjustments and microbial restructuring are tightly interlinked processes that jointly shape the rhizosphere environment. Improvements in pH balance, nutrient availability, and microbial diversity collectively enhance soil functional resilience, forming the basis for healthier root systems and more sustainable Panax cultivation.

3.3 Effect of Exogenous Additives on Ginseng Plant Growth

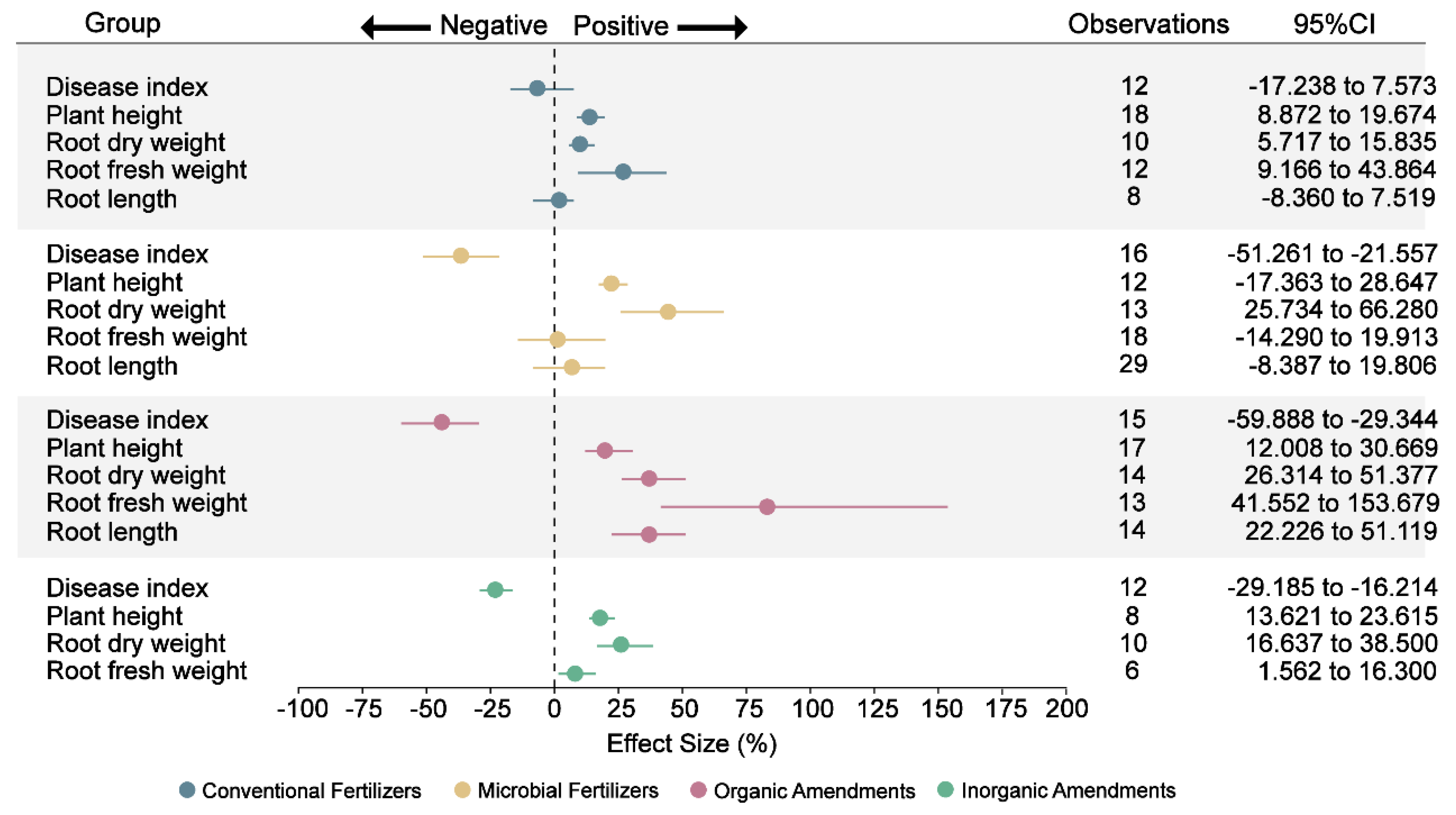

Ginseng root rot is a major limiting factor in its cultivation, leading to significant yield losses [78]. The application of conventional fertilizers showed minimal association with reducing disease incidence in Panax cultivation, with only a marginal improvement observed (Fig. 7and Table S3). In contrast, microbial fertilizers, organic amendments, and inorganic amendments were considerably more effective, reducing disease incidence by 36%, 44%, and 23%, respectively (Fig. 7 and Table S3). This is consistent with earlier findings showing that organic materials like vermicompost and biochar reduce root rot in Panax quinquefolius by enriching the soil with beneficial microbes that suppress pathogens [79,80]. Moreover, biochar may act by adsorbing allelopathic root exudates that would otherwise facilitate pathogen proliferation [81]. Inorganic amendments show a correlation with reduced root rot incidence in Panax notoginseng, coinciding with altered soil pH and improved nutrient availability that create conditions less favorable for pathogen survival [27].

Figure 7: Effect of different fertilizers and amendments on plant growth. Points represent the mean effect size, and the error bars show the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) after bias correction. If the 95% CI does not overlap zero, the effect of the fertilizer or amendment on the respective plant growth parameter is considered significant.

In terms of plant growth, all four types of fertilizers and amendments led to a notable increase in plant height, with respective gains of 14%, 23%, 20%, and 18% (Fig. 7 and Table S3). This uniform improvement suggests broad enhancements in soil conditions and nutrient uptake across treatments. Root length, however, responded specifically to organic amendments, exhibiting a substantial increase of 37% (Fig. 7 and Table S3). This elongation likely results from nutrient gradients formed by the slow mineralization of organic materials, which encourage roots to grow deeper and explore a broader soil volume [82,83].

While conventional, organic, and inorganic amendments all contributed to increases in both fresh and dry root biomass, microbial fertilizers stood out by producing the most significant improvement in dry root weight (45% increase) (Fig. 7 and Table S3). However, this improvement was not accompanied by a statistically significant change in fresh root weight. This discrepancy may be explained by microbial fertilizers’ ability to enhance water use efficiency and reduce excess water accumulation in roots, leading to denser, more nutrient-rich dry mass without a corresponding rise in water-laden fresh weight [84]. Microbial fertilizers, organic amendments, and inorganic amendments improved ginseng growth through different but related ways. They helped reduce soil-borne diseases, improved nutrient availability, and supported healthier root development. Among them, organic amendments had the most comprehensive effect by improving overall soil health and promoting deeper root growth. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that environmentally friendly amendments—particularly organic and microbial inputs—simultaneously enhance soil physicochemical balance and microbial diversity, thereby fostering healthier rhizosphere ecosystems. Such improvements contribute to the long-term sustainability and productivity of Panax cultivation by promoting nutrient cycling, disease suppression, and soil resilience.

Meta-analysis results reveal that conventional fertilizers are ineffective in addressing soil microecological imbalance and soil-borne diseases in Panax cultivation, whereas applications of microbial fertilizers, organic amendments, and inorganic amendments significantly alleviate soil degradation, reduce disease incidence, and enhance the medicinal value of plants. Specifically, organic amendments and microbial fertilizers increase soil bacterial diversity, with organic amendments uniquely promoting the biomass of medicinal plant parts. Overall, the research results of this work show that replacing conventional fertilizers with environmentally friendly and sustainable organic amendments can support healthier soils and higher-quality Panax production.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 42388101, 82403271); Natural Science Foundation of Ningbo Municipality (No. 2024J420); Ningbo Top Talent Project (No. 215-432094250).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Hong Chen and Ming-Xiao Zhao; methodology, Hong Chen; software, Runze Yang; validation, Jing Tian; formal analysis, Boyuan Xu; investigation, Hong Chen; data curation, Hong Chen and Runze Yang; writing—original draft preparation, Hong Chen; writing—review and editing, Ming-Xiao Zhao; visualization, Qiang Chen; supervision, Ming-Xiao Zhao; project administration, Ming-Xiao Zhao and Yuzong Chen; funding acquisition, Ming-Xiao Zhao. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article or its Supplementary Materials.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.072276/s1.

References

1. Qi LW , Wang CZ , Yuan CS . Isolation and analysis of ginseng: advances and challenges. Nat Prod Rep. 2011; 28( 3): 467– 95. doi:10.1039/c0np00057d. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Oliynyk S , Oh S . Actoprotective effect of ginseng: improving mental and physical performance. J Ginseng Res. 2013; 37( 2): 144– 66. doi:10.5142/jgr.2013.37.144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Xu LL , Han T , Wu JZ , Zhang QY , Zhang H , Huang BK , et al. Comparative research of chemical constituents, antifungal and antitumor properties of ether extracts of Panax ginseng and its endophytic fungus. Phytomedicine. 2009; 16( 6–7): 609– 16. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2009.03.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Yang CR . The history and origin of notoginseng. Res Pract Chin Med. 2015; 29( 6): 83– 6. (In Chinese). doi:10.13728/j.1673-6427.2015.06.026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Riaz M , Rahman NU , Zia-Ul-Haq M , Jaffar HZE , Manea R . Ginseng: a dietary supplement as immune-modulator in various diseases. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2019; 83: 12– 30. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2018.11.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Farh ME , Kim YJ , Kim YJ , Yang DC . Cylindrocarpon destructans/Ilyonectria radicicola-species complex: causative agent of ginseng root-rot disease and rusty symptoms. J Ginseng Res. 2018; 42( 1): 9– 15. doi:10.1016/j.jgr.2017.01.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Wu LJ , Zhao YH , Guan YM , Pang SF . A review on studies of the reason and control methods of succession cropping obstacle of Panax ginseng C.A. Mey. Spec Wild Econ Anim Plant Res. 2008; 2: 68– 72. [Google Scholar]

8. Ying YX , Ding WL , Zhou YQ , Li Y . Influence of Panax ginseng continuous cropping on metabolic function of soil microbial communities. Chin Herb Med. 2012; 4( 4): 329– 34. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1674-6348.2012.04.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Chen D , Lan Z , Bai X , Grace JB , Bai Y . Evidence that acidification-induced declines in plant diversity and productivity are mediated by changes in below-ground communities and soil properties in a semi-arid steppe. J Ecol. 2013; 101( 5): 1322– 34. doi:10.1111/1365-2745.12119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Lei F , Fu J , Zhou R , Wang D , Zhang A , Ma W , et al. Chemotactic response of Ginseng bacterial soft-rot to ginseng root exudates. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2017; 24( 7): 1620– 5. doi:10.1016/j.sjbs.2017.05.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zeng M , de Vries W , Bonten LTC , Zhu Q , Hao T , Liu X , et al. Model-based analysis of the long-term effects of fertilization management on cropland soil acidification. Environ Sci Technol. 2017; 51( 7): 3843– 51. doi:10.1021/acs.est.6b05491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Sun J , Luo H , Yu Q , Kou B , Jiang Y , Weng L , et al. Optimal NPK fertilizer combination increases Panax ginseng yield and quality and affects diversity and structure of rhizosphere fungal communities. Front Microbiol. 2022; 13: 919434. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2022.919434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Guo JH , Liu XJ , Zhang Y , Shen JL , Han WX , Zhang WF , et al. Significant acidification in major Chinese croplands. Science. 2010; 327( 5968): 1008– 10. doi:10.1126/science.1182570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Li Z , Luo W , Yu S . Effects of cultivating measures on root rot of Panax notoginseng. J Chin Med Mater. 2000; 23( 12): 731– 2. [Google Scholar]

15. Kätterer T , Roobroeck D , Andrén O , Kimutai G , Karltun E , Kirchmann H , et al. Biochar addition persistently increased soil fertility and yields in maize-soybean rotations over 10 years in sub-humid regions of Kenya. Field Crops Res. 2019; 235: 18– 26. doi:10.1016/j.fcr.2019.02.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Wu L , Chen J , Wu H , Qin X , Wang J , Wu Y , et al. Insights into the regulation of rhizosphere bacterial communities by application of bio-organic fertilizer in Pseudostellaria heterophylla monoculture regime. Front Microbiol. 2016; 7: 1788. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.01788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Qiu M , Zhang R , Xue C , Zhang S , Li S , Zhang N , et al. Application of bio-organic fertilizer can control Fusarium wilt of cucumber plants by regulating microbial community of rhizosphere soil. Biol Fertil Soils. 2012; 48( 7): 807– 16. doi:10.1007/s00374-012-0675-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Babalola OO . Beneficial bacteria of agricultural importance. Biotechnol Lett. 2010; 32( 11): 1559– 70. doi:10.1007/s10529-010-0347-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Liu N , Shao C , Sun H , Liu Z , Guan Y , Wu L , et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi biofertilizer improves American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius L.) growth under the continuous cropping regime. Geoderma. 2020; 363: 114155. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2019.114155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Dong L , Xu J , Li Y , Fang H , Niu W , Li X , et al. Manipulation of microbial community in the rhizosphere alleviates the replanting issues in Panax ginseng. Soil Biol Biochem. 2018; 125: 64– 74. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.06.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Karami A , Homaee M , Afzalinia S , Ruhipour H , Basirat S . Organic resource management: impacts on soil aggregate stability and other soil physico-chemical properties. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2012; 148: 22– 8. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2011.10.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Luo G , Li L , Friman VP , Guo J , Guo S , Shen Q , et al. Organic amendments increase crop yields by improving microbe-mediated soil functioning of agroecosystems: a meta-analysis. Soil Biol Biochem. 2018; 124: 105– 15. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.06.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zhao L , Xu W , Guan H , Wang K , Xiang P , Wei F , et al. Biochar increases Panax notoginseng’s survival under continuous cropping by improving soil properties and microbial diversity. Sci Total Environ. 2022; 850: 157990. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Li J , Yang Q , Shi Z , Zang Z , Liu X . Effects of deficit irrigation and organic fertilizer on yield, saponin and disease incidence in Panax notoginseng under shaded conditions. Agric Water Manag. 2021; 256: 107056. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2021.107056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Holland JE , Bennett AE , Newton AC , White PJ , McKenzie BM , George TS , et al. Liming impacts on soils, crops and biodiversity in the UK: a review. Sci Total Environ. 2018; 610–611: 316– 32. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.08.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhang S , Zhu Q , de Vries W , Ros GH , Chen X , Muneer MA , et al. Effects of soil amendments on soil acidity and crop yields in acidic soils: a world-wide meta-analysis. J Environ Manage. 2023; 345: 118531. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.118531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Deng W , Gong J , Peng W , Luan W , Liu Y , Huang H , et al. Alleviating soil acidification to suppress Panax notoginseng soil-borne disease by modifying soil properties and the microbiome. Plant Soil. 2024; 502( 1): 653– 69. doi:10.1007/s11104-024-06577-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Harrison F . Getting started with meta-analysis. Meth Ecol Evol. 2011; 2( 1): 1– 10. doi:10.1111/j.2041-210X.2010.00056.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Bossolani JW , Crusciol CAC , Merloti LF , Moretti LG , Costa NR , Tsai SM , et al. Long-term lime and gypsum amendment increase nitrogen fixation and decrease nitrification and denitrification gene abundances in the rhizosphere and soil in a tropical no-till intercropping system. Geoderma. 2020; 375: 114476. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2020.114476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Garbowski T , Bar-Michalczyk D , Charazińska S , Grabowska-Polanowska B , Kowalczyk A , Lochyński P . An overview of natural soil amendments in agriculture. Soil Tillage Res. 2023; 225: 105462. doi:10.1016/j.still.2022.105462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Aloo BN , Tripathi V , Makumba BA , Mbega ER . Plant growth-promoting rhizobacterial biofertilizers for crop production: the past, present, and future. Front Plant Sci. 2022; 13: 1002448. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.1002448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Roy RN , Finck A , Blair GJ , Tandon HLS . Plant nutrition for food security: a guide for integrated nutrient management. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2006. [Google Scholar]

33. Sadati Valojai ST , Niknejad Y , Fallah Amoli H , Barari Tari D . Response of rice yield and quality to nano-fertilizers in comparison with conventional fertilizers. J Plant Nutr. 2021; 44( 13): 1971– 81. doi:10.1080/01904167.2021.1884701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Luo Y , Hui D , Zhang D . Elevated CO2 stimulates net accumulations of carbon and nitrogen in land ecosystems: a meta-analysis. Ecology. 2006; 87( 1): 53– 63. doi:10.1890/04-1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Bolyen E , Rideout JR , Dillon MR , Bokulich NA , Abnet CC , Al Ghalith GA , et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol. 2019; 37( 8): 852– 7. [Google Scholar]

36. Amir A , McDonald D , Navas-Molina JA , Kopylova E , Morton JT , Zech Xu Z , et al. Deblur rapidly resolves single-nucleotide community sequence patterns. mSystems. 2017; 2( 2): e00191– 16. doi:10.1128/mSystems.00191-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Quast C , Pruesse E , Yilmaz P , Gerken J , Schweer T , Yarza P , et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41( D1): D590– 6. doi:10.1093/nar/gks1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Ling N , Wang T , Kuzyakov Y . Rhizosphere bacteriome structure and functions. Nat Commun. 2022; 13( 1): 836. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-28448-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Hao T , Zhu Q , Zeng M , Shen J , Shi X , Liu X , et al. Impacts of nitrogen fertilizer type and application rate on soil acidification rate under a wheat-maize double cropping system. J Environ Manage. 2020; 270: 110888. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Zhang H , Wang L , Fu W , Xu C , Zhang H , Xu X , et al. Soil acidification can be improved under different long-term fertilization regimes in a sweetpotato-wheat rotation system. Plants. 2024; 13( 13): 1740. doi:10.3390/plants13131740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Matsumoto S , Doi H , Kasuga J . Changes over the years in soil chemical properties associated with the cultivation of ginseng (Panax ginseng Meyer) on andosol soil. Agriculture. 2022; 12( 8): 1223. doi:10.3390/agriculture12081223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Chang F , Jia F , Lv R , Guan M , Jia Q , Sun Y , et al. Effects of American ginseng cultivation on bacterial community structure and responses of soil nutrients in different ecological niches. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2022; 32( 4): 419– 29. doi:10.4014/jmb.2202.02003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Goulding KWT . Soil acidification and the importance of liming agricultural soils with particular reference to the United Kingdom. Soil Use Manag. 2016; 32( 3): 390– 9. doi:10.1111/sum.12270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Siedt M , Schäffer A , Smith KEC , Nabel M , Roß-Nickoll M , van Dongen JT . Comparing straw, compost, and biochar regarding their suitability as agricultural soil amendments to affect soil structure, nutrient leaching, microbial communities, and the fate of pesticides. Sci Total Environ. 2021; 751: 141607. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Zhang K , Wei H , Chai Q , Li L , Wang Y , Sun J . Biological soil conditioner with reduced rates of chemical fertilization improves soil functionality and enhances rice production in vegetable-rice rotation. Appl Soil Ecol. 2024; 195: 105242. doi:10.1016/j.apsoil.2023.105242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Iticha B , Mosley LM , Marschner P . Combining lime and organic amendments based on titratable alkalinity for efficient amelioration of acidic soils. Soil. 2024; 10( 1): 33– 47. doi:10.5194/soil-10-33-2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Regasa A , Haile W , Abera G . Effects of lime and vermicompost application on soil physicochemical properties and phosphorus availability in acidic soils. Sci Rep. 2025; 15: 25544. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-02053-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Usero FM , Armas C , Morillo JA , Gallardo M , Thompson RB , Pugnaire FI . Effects of soil microbial communities associated to different soil fertilization practices on tomato growth in intensive greenhouse agriculture. Appl Soil Ecol. 2021; 162: 103896. doi:10.1016/j.apsoil.2021.103896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Zhang S , Liu X , Zhou L , Deng L , Zhao W , Liu Y , et al. Alleviating soil acidification could increase disease suppression of bacterial wilt by recruiting potentially beneficial rhizobacteria. Microbiol Spectr. 2022; 10( 2): e02333– 21. doi:10.1128/spectrum.02333-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Xiong R , He X , Gao N , Li Q , Qiu Z , Hou Y , et al. Soil pH amendment alters the abundance, diversity, and composition of microbial communities in two contrasting agricultural soils. Microbiol Spectr. 2024; 12( 8): e04165– 23. doi:10.1128/spectrum.04165-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Singh B . Are nitrogen fertilizers deleterious to soil health? Agronomy. 2018; 8( 4): 48. doi:10.3390/agronomy8040048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Li R , Tao R , Ling N , Chu G . Chemical, organic and bio-fertilizer management practices effect on soil physicochemical property and antagonistic bacteria abundance of a cotton field: implications for soil biological quality. Soil Tillage Res. 2017; 167: 30– 8. doi:10.1016/j.still.2016.11.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Zhang L , Tan C , Li W , Lin L , Liao T , Fan X , et al. Phosphorus-, potassium-, and silicon-solubilizing bacteria from forest soils can mobilize soil minerals to promote the growth of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Chem Biol Technol Agric. 2024; 11( 1): 103. doi:10.1186/s40538-024-00622-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Pang F , Li Q , Solanki MK , Wang Z , Xing YX , Dong DF . Soil phosphorus transformation and plant uptake driven by phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms. Front Microbiol. 2024; 15: 1383813. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2024.1383813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Wang Y , Zhang MH , Zhao XL . Effects of organic amendments on microbial biomass carbon and nitrogen uptake by corn seedlings grown in two purple soils. Huan Jing Ke Xue. 2019; 40( 8): 3808– 15. doi:10.13227/j.hjkx.201901022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Madhupriyaa D , Baskar M , Sherene Jenita Rajammal T , Kuppusamy S , Rathika S , Umamaheswari T , et al. Efficacy of chelated micronutrients in plant nutrition. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal. 2024; 55( 22): 3609– 37. doi:10.1080/00103624.2024.2397019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Caires EF , Joris HAW , Churka S . Long-term effects of lime and gypsum additions on no-till corn and soybean yield and soil chemical properties in southern Brazil. Soil Use Manag. 2011; 27( 1): 45– 53. doi:10.1111/j.1475-2743.2010.00310.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Barrow NJ . The effects of pH on phosphate uptake from the soil. Plant Soil. 2017; 410( 1): 401– 10. doi:10.1007/s11104-016-3008-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Cao W , Sun H , Shao C , Wang Y , Zhu J , Long H , et al. Metabolomics combined with physiology and transcriptomics reveals key metabolic pathway responses in ginseng roots to nitrogen and potassium deficiency. Plant Stress. 2025; 18: 101107. doi:10.1016/j.stress.2025.101107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Liu C , Xia R , Tang M , Chen X , Zhong B , Liu X , et al. Improved ginseng production under continuous cropping through soil health reinforcement and rhizosphere microbial manipulation with biochar: a field study of Panax ginseng from Northeast China. Hortic Res. 2022; 9: uhac108. doi:10.1093/hr/uhac108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Liu L , Huang X , Zhang J , Cai Z , Jiang K , Chang Y . Deciphering the relative importance of soil and plant traits on the development of rhizosphere microbial communities. Soil Biol Biochem. 2020; 148: 107909. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2020.107909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Huang M , Jiang L , Zou Y , Xu S , Deng G . Changes in soil microbial properties with no-tillage in Chinese cropping systems. Biol Fertil Soils. 2013; 49( 4): 373– 7. doi:10.1007/s00374-013-0778-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Wei D , Yang Q , Zhang JZ , Wang S , Chen XL , Zhang XL , et al. Bacterial community structure and diversity in a black soil as affected by long-term fertilization. Pedosphere. 2008; 18( 5): 582– 92. doi:10.1016/S1002-0160(08)60052-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Shu X , He J , Zhou Z , Xia L , Hu Y , Zhang Y , et al. Organic amendments enhance soil microbial diversity, microbial functionality and crop yields: a meta-analysis. Sci Total Environ. 2022; 829: 154627. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.154627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Gougoulias C , Clark JM , Shaw LJ . The role of soil microbes in the global carbon cycle: tracking the below-ground microbial processing of plant-derived carbon for manipulating carbon dynamics in agricultural systems. J Sci Food Agric. 2014; 94( 12): 2362– 71. doi:10.1002/jsfa.6577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Kang Y , Shen M , Wang H , Zhao Q . A possible mechanism of action of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) strain Bacillus pumilus WP8 via regulation of soil bacterial community structure. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 2013; 59( 4): 267– 77. doi:10.2323/jgam.59.267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Liu H , Du X , Li Y , Han X , Li B , Zhang X , et al. Organic substitutions improve soil quality and maize yield through increasing soil microbial diversity. J Clean Prod. 2022; 347: 131323. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.131323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Shi Y , Li Y , Yang T , Chu H . Threshold effects of soil pH on microbial co-occurrence structure in acidic and alkaline arable lands. Sci Total Environ. 2021; 800: 149592. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Tan C , Luo Y , Fu T . Soil microbial community responses to the application of a combined amendment in a historical zinc smelting area. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2022; 29( 9): 13056– 70. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-16631-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Vessey JK . Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria as biofertilizers. Plant Soil. 2003; 255( 2): 571– 86. doi:10.1023/A:1026037216893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Ahsan T , Tian PC , Gao J , Wang C , Liu C , Huang YQ . Effects of microbial agent and microbial fertilizer input on soil microbial community structure and diversity in a peanut continuous cropping system. J Adv Res. 2024; 64: 1– 13. doi:10.1016/j.jare.2023.11.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Berendsen RL , Pieterse CMJ , Bakker PAHM . The rhizosphere microbiome and plant health. Trends Plant Sci. 2012; 17( 8): 478– 86. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2012.04.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Sorokin DY , Lücker S , Vejmelkova D , Kostrikina NA , Kleerebezem R , Rijpstra WIC , et al. Nitrification expanded: discovery, physiology and genomics of a nitrite-oxidizing bacterium from the phylum Chloroflexi. ISME J. 2012; 6( 12): 2245– 56. doi:10.1038/ismej.2012.70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. De Castro VHL , Schroeder LF , Quirino BF , Kruger RH , Barreto CC . Acidobacteria from oligotrophic soil from the Cerrado can grow in a wide range of carbon source concentrations. Can J Microbiol. 2013; 59( 11): 746– 53. doi:10.1139/cjm-2013-0331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Bastida F , Selevsek N , Torres IF , Hernández T , García C . Soil restoration with organic amendments: linking cellular functionality and ecosystem processes. Sci Rep. 2015; 5: 15550. doi:10.1038/srep15550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Wang CY , Zhou X , Guo D , Zhao JH , Yan L , Feng GZ , et al. Soil pH is the primary factor driving the distribution and function of microorganisms in farmland soils in northeastern China. Ann Microbiol. 2019; 69( 13): 1461– 73. doi:10.1007/s13213-019-01529-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. DeBruyn JM , Nixon LT , Fawaz MN , Johnson AM , Radosevich M . Global biogeography and quantitative seasonal dynamics of Gemmatimonadetes in soil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011; 77( 17): 6295– 300. doi:10.1128/AEM.05005-11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Farh ME , Kim YJ , Abbai R , Singh P , Jung KH , Kim YJ , et al. Pathogenesis strategies and regulation of ginsenosides by two species of Ilyonectria in Panax ginseng: power of speciation. J Ginseng Res. 2020; 44( 2): 332– 40. doi:10.1016/j.jgr.2019.02.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Tian GL , Bi YM , Jiao XL , Zhang XM , Li JF , Niu FB , et al. Application of vermicompost and biochar suppresses Fusarium root rot of replanted American ginseng. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2021; 105( 18): 6977– 91. doi:10.1007/s00253-021-11464-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Zhao F , Zhang Y , Dong W , Zhang Y , Zhang G , Sun Z , et al. Vermicompost can suppress Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici via generation of beneficial bacteria in a long-term tomato monoculture soil. Plant Soil. 2019; 440( 1): 491– 505. doi:10.1007/s11104-019-04104-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Schmidt MWI , Noack AG . Black carbon in soils and sediments: analysis, distribution, implications, and current challenges. Glob Biogeochem Cycles. 2000; 14( 3): 777– 93. doi:10.1029/1999GB001208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Gill JS , Sale PWG , Tang C . Amelioration of dense sodic subsoil using organic amendments increases wheat yield more than using gypsum in a high rainfall zone of southern Australia. Field Crops Res. 2008; 107( 3): 265– 75. doi:10.1016/j.fcr.2008.02.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. He Y , Liao H , Yan X . Localized supply of phosphorus induces root morphological and architectural changes of rice in split and stratified soil cultures. Plant Soil. 2003; 248( 1): 247– 56. doi:10.1023/A:1022351203545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Liu J , Li H , Yuan Z , Feng J , Chen S , Sun G , et al. Effects of microbial fertilizer and irrigation amount on growth, physiology and water use efficiency of tomato in greenhouse. Sci Hortic. 2024; 323: 112553. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2023.112553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools