Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Spikelet Filling Characteristics in Early-Season Rice Experiencing High Temperatures during Ripening

1 Rice and Product Ecophysiology, Key Laboratory of Ministry of Education for Crop Physiology and Molecular Biology, Hunan Agricultural University, Changsha, 410128, China

2 Yuelushan Laboratory, Changsha, 410128, China

3 Jiangxi Institute of Red Soil and Germplasm Resources, Nanchang, 331717, China

4 National Engineering Research Center of Rice, Changsha, 410128, China

* Corresponding Author: Min Huang. Email:

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2026, 95(1), 15 https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.075255

Received 28 October 2025; Accepted 16 December 2025; Issue published 30 January 2026

Abstract

Spikelet filling characteristics in early-season rice in southern China may be distinctive due to its exposure to high temperatures during the ripening period. However, limited information is currently available on these characteristics. This study aimed to characterize spikelet filling in early-season rice and identify the key factors contributing to its improvement. Field experiments were conducted over two years (2021 and 2022) to mainly investigate the proportions of fully-filled, partially-filled, and empty spikelets, along with the biomass-fertilized spikelet ratio and harvest index, in 11 early-season rice varieties. The results revealed significant varietal variation in spikelet filling, with the proportion of fully-filled spikelets ranging from 60.6% to 81.1% in 2021 and from 66.3% to 79.2% in 2022. Among the 11 varieties, Liangyou 42, Lingliangyou 942, and Liangyou 287 exhibited relatively superior performance in spikelet filling. Linear regression revealed that, although a significant negative relationship existed between the proportion of fully-filled spikelets and both partially-filled and empty spikelets, the relationship with partially-filled spikelets was stronger. Additionally, the proportion of fully-filled spikelets showed a significant positive relationship with the harvest index but not with the biomass-fertilized spikelet ratio. These findings indicate that increasing the harvest index and reducing the occurrence of partially-filled grains are essential strategies for improving spikelet filling in early-season rice.Keywords

Rice serves as the staple food for approximately 65% of China’s population [1]. To produce sufficient rice grains to meet domestic food demand, double-season rice cropping systems—where early- and late-season rice are grown consecutively from March to November within a single year—has become common in southern China, leveraging the region’s abundant hydrothermal resources [2]. According to the latest national statistics [3], early- and late-season rice were planted on 4.76 and 5.11 million hectares, yielding 28.12 and 30.72 million tons of grains, respectively, in 2022. These figures represent about 16% and 17% of China’s total rice planting area (29.45 million hectares) and 13% and 15% of the country’s total rice production (208.49 million tons).

In double-season rice cropping systems, early-season rice includes many varieties with high amylose content, making them ideal for rice noodle production [4]. Rice noodles are a popular food product across East and Southeast Asia—including China, Thailand, and Vietnam—and have gained global market presence due to their nutritional value and appealing flavor [5]. In recent years, early-season rice suitable for noodle production has shown strong market competitiveness, commanding higher prices. Therefore, enhancing the grain yield of early-season rice is critical not only for ensuring national food security but also for supporting the growth of the rice industry.

The grain yield of rice is determined by four key components: the number of panicles per unit area, the number of spikelets per panicle, the spikelet filling percentage, and the weight of the grains [6]. While increasing any one of these four components can enhance grain yield, previous research has indicated that a specific component is critical for achieving high grain yield in early-season rice [7,8,9]. However, different studies have highlighted various components as being crucial, leading to a lack of consensus on the most significant factor.

The formation of all yield components in rice is closely related to environmental factors [10]. Early-season rice typically encounters low temperatures during the vegetative period and high temperatures during the ripening period. The formation of either more panicles or larger panicles in early-season rice is challenging due to limited vegetative growth, which is partially linked to the low temperatures experienced during the vegetative growth period [7,11]. The high temperature during the ripening period can enhance the grain filling rate, ultimately resulting in reduced grain weight for early-season rice [12]. In comparison to the other three yield components, the spikelet filling percentage has received relatively less attention in early-season rice research. This characteristic may be distinctive for early-season rice, considering that it is exposed to high temperatures during the ripening period.

Spikelets on rice panicles can be categorized into three types based on their filling conditions: fully-filled, partially-filled, and empty spikelets. A study by Meng et al. [13] identified the proportion of partially-filled spikelets as a critical factor affecting spikelet filling in rice. However, this research concentrated on large-panicle single-season rice varieties. In contrast, early-season rice generally has smaller panicle sizes than single-season rice due to shorter vegetative growth duration and lower temperatures during the vegetative period. It remains unclear whether the finding from large-panicle single-season rice varieties is applicable to early-season rice with relatively smaller panicles.

The spikelet filling percentage is influenced by source capacity and the translocation of assimilates into fertilized spikelets [14]. Huang et al. [15] reported a significant positive relationship between the spikelet filling percentage and the harvest index in rice, suggesting that spikelet filling percentage is driven by assimilate translocation. However, this finding was derived from single-season rice, and its applicability to early-season rice remains uncertain. In addition, high temperatures during the ripening period have contrasting effects on source capacity and assimilate translocation in early-season rice. Specifically, they can accelerate plant senescence, which may reduce biomass production while enhancing the translocation of biomass into fertilized spikelets [14]. These underscore the necessity to determine whether source capacity or assimilate translocation is more closely associated with spikelet filling in early-season rice.

Overall, the current information remains insufficient to draw definitive conclusions about the spikelet filling characteristics and the key factors influencing them in early-season rice. Therefore, in this study, we examined the proportions of fully-filled, partially-filled, and empty spikelets, along with source capacity and harvest index, in 11 early-season rice varieties grown over two years. Our objectives were (i) to characterize spikelet filling in early-season rice and (ii) to identify the key factors that contribute to improving spikelet filling in early-season rice.

Field experiments were carried out in Yongan, a site situated in southern China with a latitude of 28°09′ N and a longitude of 113°37′ E, during the early rice-growing seasons of 2021 and 2022. The experimental site has a subtropical monsoon humid climate. Before the experiment began in 2021, the soil of the experimental field contained 112 mg kg−1 of available nitrogen (N), 23.2 mg kg−1 of available phosphorus, and 80.0 mg kg−1 of available potassium in the top 20 cm layer. The experiment included 11 early-season rice varieties: Ezao 18, Jiyou 421, Liangyou 287, Liangyou 42, Lingliangyou 179, Lingliangyou 268, Lingliangyou 674, Lingliangyou 942, Tanliangyou 83, Zhuliangyou 4024, and Zhuliangyou 819. These varieties were chosen due to their widespread adoption by rice farmers in the study area and neighboring regions. Table 1 provides information about each variety, including type, female and male parents, and year of release. The experimental design utilized a completely randomized block layout with three replicates and a plot size of 20 m2.

Table 1: Information about varieties used in the study.

| Variety | Type | Female Parent | Male Parent | Year of Release |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ezao 18 | Indica inbred | Zhongyouzao 81 | Jiazao 935 | 2003 |

| Jiyou 421 | Indica three-line hybrid | Jifeng A | R421 | 2019 |

| Liangyou 287 | Indica two-line hybrid | HD9802S | R287 | 2005 |

| Liangyou 42 | Indica two-line hybrid | HD9802S | R42 | 2006 |

| Lingliangyou 179 | Indica two-line hybrid | Xiangling 628S | Zhong 09-179 | 2017 |

| Lingliangyou 268 | Indica two-line hybrid | Xiangling 628S | Hua 268 | 2008 |

| Lingliangyou 674 | Indica two-line hybrid | Xiangling 628S | Hua 674 | 2011 |

| Lingliangyou 942 | Indica two-line hybrid | Xiangling 628S | Huai 94-2 | 2010 |

| Tanliangyou 83 | Indica two-line hybrid | Tannong S | Tanzao 183 | 2010 |

| Zhuliangyou 4024 | Indica two-line hybrid | Zhu 1S | 4024 | 2009 |

| Zhuliangyou 819 | Indica two-line hybrid | Zhu 1S | Hua 819 | 2005 |

Seeds were sown in rice seedling trays (length × width × depth = 58.0 cm × 22.5 cm × 2.5 cm) on March 25 at a rate of 80 g per tray. The seedlings were transplanted on April 25 with a hill spacing of 25 cm × 12 cm and about 4–5 seedlings per hill, using a rice transplanter (2ZGQ-7D25, Yanmar Agricultural Equipment Co., Ltd., Wuxi, China). Basal fertilizers, including 75 kg N ha−1, 75 kg P2O5 ha−1, and 75 kg K2O ha−1, were applied one day prior to transplanting. Additional topdressing fertilizers were applied seven days after transplanting (45 kg N ha−1) and again at the panicle initiation stage (30 kg N ha−1 and 75 kg K2O ha−1). A floodwater level of 5–10 cm was maintained in all plots from transplanting to seven days before maturity, at which point the plots were drained for harvesting. Diseases, insects, and weeds were controlled by chemicals according to the recommendations of the local agricultural technology department. Specifically, rice sheath blight and false smut were controlled by applying 5% validamycin aqueous solution at 2625 mL ha−1. Striped rice borer, planthopper, and leaf roller were managed using 20% triazophos emulsion concentrate at 750 mL ha−1, 25% buprofezin wettable powder at 750 g ha−1, and 45% phoxim emulsion concentrate at 900 mL ha−1, respectively. Weed control was achieved by applying 25 mg penoxsulam mL−1 suspension concentrate at 900 mL ha−1.

An automatic weather station (Vantage Pro2, Davis Instruments Corp., Hayward, USA) was set up adjacent to the experimental field to monitor and log daily maximum, minimum, and mean temperatures throughout the ripening period. Three heat-stress indices—accumulated days of heat stress, heat-stress intensity, and heat degree-days—were calculated following the method of Shi et al. [16], using a daily maximum temperature of 35°C as the threshold for defining heat stress.

Twelve hills of rice plants were sampled from each plot at maturity. The sampled plants were hand threshed after counting the number of panicles, and all spikelets were submerged in tap water. Spikelets that sank were classified as fully filled, while those that floated were sun-dried and then separated into partially filled and empty categories, first by winnowing and then manually checked. The counts of fully-filled, partially-filled, and empty spikelets were recorded, and all were then oven-dried at 70°C until a constant weight was achieved. The straw was also dried in the oven at the same temperature. Total biomass production was the sum of dry weights of straw and fully-filled, partially-filled, and empty spikelets. Panicle number per m2, spikelet number per panicle, the proportions of fully-filled, partially-filled, and empty spikelets, and grain weight were calculated, along with the biomass-fertilized spikelet ratio (total biomass production/total number of fully-filled and partially filled spikelets) and harvest index (fully-filled spikelet weight/total biomass production × 100). Grain yield was determined from a 5 m2 area in each plot at maturity and adjusted to a moisture content of 0.135 g H2O g−1.

Variations in grain yield and yield components (panicle number per m2, spikelet number per panicle, the proportion of fully-filled pikelets, and grain weight) were evaluated using the coefficient of variance. Analysis of variance was conducted separately for each year on the proportions of fully-filled, partially-filled, and empty spikelets, as well as on the biomass-fertilized spikelet ratio and harvest index. Varietal means were compared using the least significant difference (LSD) test at the 0.05 probability level. Linear regression and path analysis was employed to assess the relationships among the proportions of fully-filled, partially-filled, and empty spikelets, as well as the relationships between the proportion of fully-filled spikelets with the biomass-fertilized spikelet ratio and harvest index, across 11 rice varieties over two years. All statistical analysis were performed using DPS 18.10 software (Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China).

3.1 Temperature Conditions during Ripening of Early-Season Rice

Average daily maximum, minimum, and mean temperatures during the ripening period across 11 early-season rice varieties were 32.9, 26.1, and 29.2°C in 2021, and 33.7, 26.2, and 29.5°C in 2022, showing with overall averages of 33.3, 26.2, and 29.4°C across the two years, respectively (Table 2). These temperatures are close to those reported in earlier studies conducted at the same location over several years [17,18,19]. Notably, the average daily mean temperatures exceeded the upper limit of the optimum temperature range for rice ripening (20–25°C) [20] by more than 4°C, indicating that early-season rice is typically exposed to high temperatures during the ripening period.

Table 2: Average daily temperature and heat stress indices during the ripening period of early-season rice in 2021 and 2022.

| Temperature Parameter | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| Average daily temperature (°C) | ||

| Maximum | 32.9 ± 0.4 | 33.7 ± 0.5 |

| Minimum | 26.1 ± 0.3 | 26.2 ± 0.2 |

| Mean | 29.2 ± 0.3 | 29.5 ± 0.4 |

| Heat stress index | ||

| Accumulated days of heat stress (d) | 7.9 ± 1.3 | 11.9 ± 1.3 |

| Heat-stress intensity (°C) | 36.8 ± 0.1 | 35.8 ± 0.1 |

| Heat degree-days (°C·d) | 14.1 ± 1.8 | 10.2 ± 2.4 |

In addition, the average accumulated days of heat stress, heat-stress intensity, and heat degree-days during the ripening period across 11 early-season rice varieties were 7.9 d, 36.8°C, and 14.1°C·d in 2021, and 11.9 d, 35.8°C, and 10.2°C·d in 2022, with overall averages of 9.9 d, 36.3°C, and 12.2°C·d across the two years, respectively (Table 2). These values are comparable to those reported by Shi et al. [16] for early-season rice in the southern Middle and Lower Reaches of the Yangtze River—one of the regions most affected by heat stress—which showed average accumulated days of heat stress, heat-stress intensity, and heat degree-days during the ripening period of 10.4 d, 36.4°C, and 14.5°C·d between 1981 and 2010. This further supports that early-season rice is routinely exposed to high temperatures during the ripening period.

3.2 Grain Yield, Yield Components, and Spikelet Filling Characteristics in Early-Season Rice

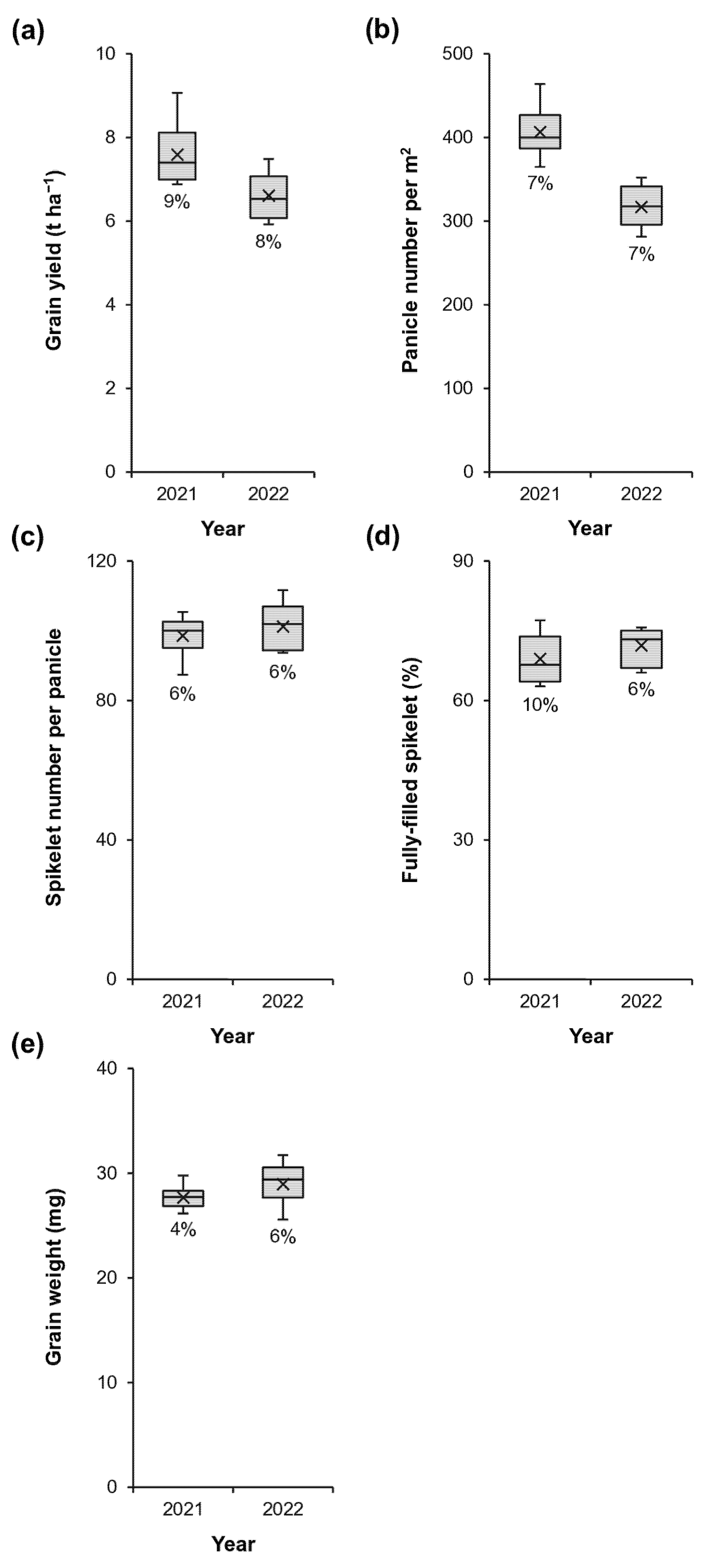

Among grain yield and yield components in 2021, the highest coefficient of variance was observed for the proportion of fully-filled spikelets (Fig. 1a–e). In 2022, the variation in coefficients of variance for grain yield and its components was relatively small. These results indicate that the proportion of fully-filled spikelets is the most variable yield component in early-season rice.

Figure 1: Variations in grain yield (a) and yield components (b–e) among 11 early-season rice varieties grown in 2021 and 2022. The box-and-whisker plots show the 50% interquartile range (box), the mean (cross within the box), the median (horizontal line within the box), and the minimum and maximum values (end of the whiskers). Percentage values within each panel represent the coefficients of variance.

In 2021, the proportion of fully-filled spikelets across the 11 varieties ranged from 60.6% to 81.1%, with an average of 68.9%. In 2022, this range varied from 66.3% to 79.2%, yielding a mean of 71.9% (Table 3). These values are comparable to those from previous studies at the same site [17,18,19]. In 2021, Lingliangyou 942 exhibited the highest proportion of fully-filled spikelets, which was not significantly different from Liangyou 42, Liangyou 287, and Lingliangyou 268 but was 15%–34% higher than the other seven varieties. In 2022, Liangyou 42 recorded the highest proportion, similar to Tanliangyou 83, Liangyou 287, Lingliangyou 674, Lingliangyou 268, and Lingliangyou 942, yet 15%–19% higher than the other five varieties.

Table 3: Proportions of fully-filled, partially-filled, and empty spikelets in 11 early-season rice varieties grown in 2021 and 2022.

| Variety | Fully-Filled Spikelets (%) | Partially-Filled Spikelets (%) | Empty Spikelets (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | |||

| Ezao 18 | 67.7 ± 2.1 | 16.3 ± 0.5 | 16.0 ± 1.8 |

| Jiyou 421 | 62.8 ± 3.3 | 25.9 ± 2.0 | 11.3 ± 1.4 |

| Liangyou 287 | 73.8 ± 5.1 | 13.5 ± 2.7 | 12.7 ± 2.8 |

| Liangyou 42 | 78.2 ± 2.2 | 11.1 ± 1.1 | 10.7 ± 1.1 |

| Lingliangyou 179 | 64.4 ± 1.6 | 17.4 ± 0.3 | 18.2 ± 1.3 |

| Lingliangyou 268 | 70.7 ± 6.8 | 15.5 ± 5.0 | 13.8 ± 1.9 |

| Lingliangyou 674 | 64.6 ± 2.6 | 17.3 ± 1.7 | 18.1 ± 1.5 |

| Lingliangyou 942 | 81.1 ± 1.9 | 10.7 ± 0.9 | 8.2 ± 1.0 |

| Tanliangyou 83 | 70.4 ± 2.1 | 18.9 ± 0.9 | 10.7 ± 1.2 |

| Zhuliangyou 4024 | 60.6 ± 2.3 | 24.0 ± 2.1 | 15.4 ± 0.7 |

| Zhuliangyou 819 | 64.1 ± 4.9 | 18.5 ± 2.5 | 17.4 ± 2.7 |

| Mean | 68.9 | 17.2 | 13.9 |

| LSD (0.05) | 10.6 | 6.5 | 5.2 |

| 2022 | |||

| Ezao 18 | 69.0 ± 4.0 | 17.8 ± 3.7 | 13.1 ± 0.6 |

| Jiyou 421 | 67.0 ± 2.2 | 18.4 ± 1.2 | 14.6 ± 1.0 |

| Liangyou 287 | 75.1 ± 1.2 | 9.0 ± 0.5 | 15.9 ± 1.6 |

| Liangyou 42 | 79.2 ± 0.6 | 10.3 ± 0.2 | 10.5 ± 0.6 |

| Lingliangyou 179 | 66.5 ± 1.3 | 14.0 ± 0.3 | 19.5 ± 1.6 |

| Lingliangyou 268 | 74.3 ± 3.6 | 14.0 ± 1.5 | 11.7 ± 2.6 |

| Lingliangyou 674 | 74.7 ± 5.4 | 14.2 ± 1.7 | 11.2 ± 4.4 |

| Lingliangyou 942 | 73.2 ± 3.8 | 11.2 ± 0.6 | 15.6 ± 3.2 |

| Tanliangyou 83 | 76.5 ± 3.4 | 11.8 ± 0.5 | 11.7 ± 3.0 |

| Zhuliangyou 4024 | 66.3 ± 2.7 | 14.4 ± 0.4 | 19.2 ± 2.4 |

| Zhuliangyou 819 | 68.7 ± 3.3 | 13.7 ± 1.4 | 17.6 ± 2.9 |

| Mean | 71.9 | 13.5 | 14.6 |

| LSD (0.05) | 7.9 | 3.8 | 6.6 |

The proportion of partially filled spikelets among the 11 varieties ranged from 10.7% to 25.9% in 2021 and from 9.0% to 18.4% in 2022, with means of 17.2% and 13.5%, respectively (Table 3). In 2021, Lingliangyou 942 had the lowest proportion of partially filled spikelets, comparable to Liangyou 42, Liangyou 287, Lingliangyou 268, and Ezao 18, but 38%–59% lower than the other six varieties. In 2022, Liangyou 287 recorded the lowest proportion of partially filled spikelets, similar to Liangyou 42, Lingliangyou 942, and Tanliangyou 83, yet 34%–51% lower than the remaining seven varieties.

In 2021, the proportion of empty spikelets across the 11 varieties varied from 8.2% to 18.2%, averaging 13.9%. In 2022, this proportion ranged from 10.5% to 19.5%, with a mean of 14.6% (Table 3). In 2021, Lingliangyou 942 showed the lowest proportion of empty spikelets, comparable to Tanliangyou 83, Liangyou 42, Jiyou 421, and Lingliangyou 287, yet 41%–55% lower than the other six varieties. In 2022, Liangyou 42 had the lowest proportion of empty spikelets, similar to Lingliangyou 674, Tanliangyou 83, Lingliangyou 268, Ezao 18, Jiyou 421, Lingliangyou 942, and Liangyou 287, but 40%–46% lower than the other three varieties.

Considering results from two years, it was found that Liangyou 42, Lingliangyou 942, and Liangyou 287 consistently performed well in spikelet filling, evidenced by a high proportion of fully-filled spikelets and a low proportion of partially-filled and empty spikelets (Table 3). In contrast, Zhuliangyou 4024, Lingliangyou 179, and Zhuliangyou 819 exhibited the opposite trend. This suggests that Liangyou 42, Lingliangyou 942, and Liangyou 287 possess greater tolerance to high temperatures during the ripening period compared to the latter varieties. The findings highlight the effectiveness of developing heat-tolerant varieties to enhance spikelet filling in early-season rice under high-temperature conditions. This aligns with recent research by Wakatsuki et al. [21], which emphasized the advantages of breeding heat-tolerant rice varieties in maintaining grain quality amid high temperatures during ripening.

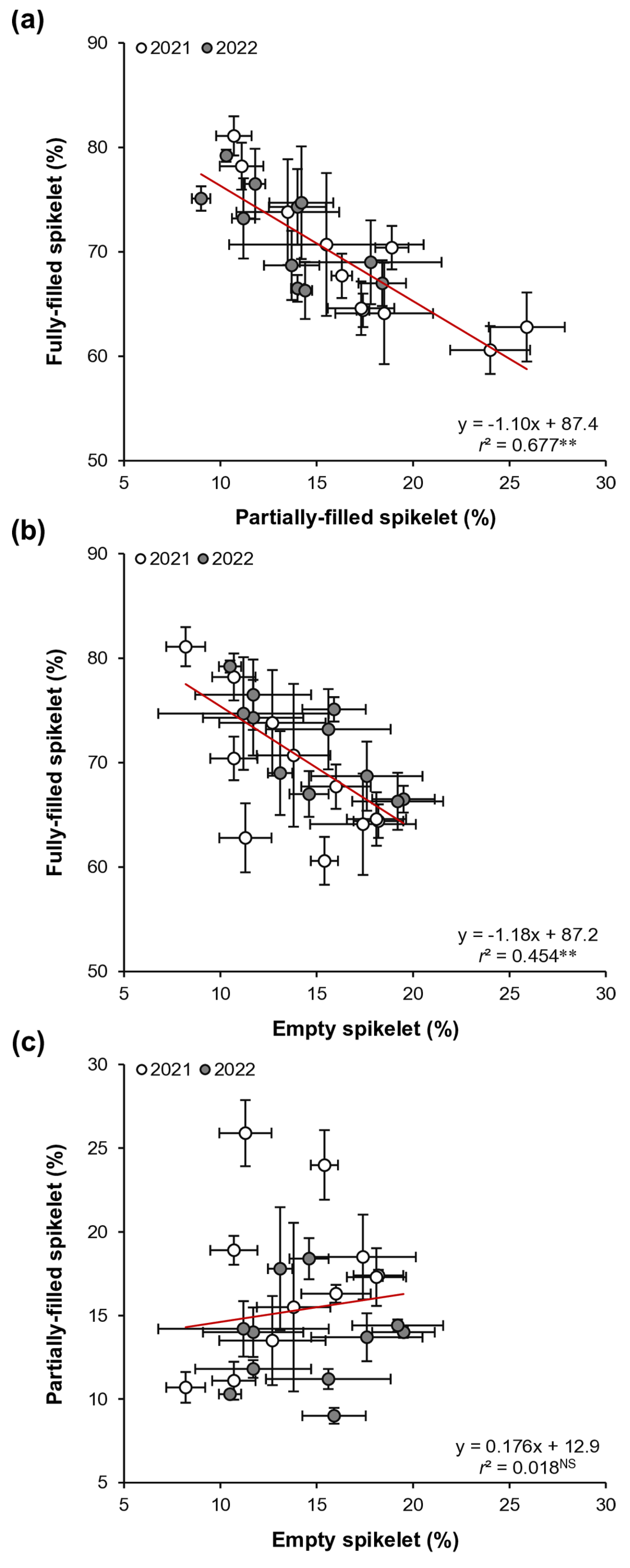

Linear regression analysis revealed a significant negative relationship between the proportion of fully-filled spikelets and the proportions of both partially-filled and empty spikelets (Fig. 2a,b). Notably, the relationship between fully-filled and partially-filled spikelets was stronger than that between fully-filled and empty spikelets. The variation in fully-filled spikelets was explained by 68% from partially-filled and 45% from empty spikelets. Consistently, the path analysis indicated that the proportion of partially filled spikelets had a stronger association with the proportion of fully filled spikelets than did the proportion of empty spikelets (Table 4). No significant relationship was found between the proportions of partially-filled and empty spikelets (Fig. 2c).

These results indicate the importance of reducing the incidence of partially-filled spikelets to enhance spikelet filling in early-season rice. This finding aligns with that of Meng et al. [13], who identified the proportion of partially-filled spikelets as a key factor influencing spikelet filling in rice. However, the study by Meng et al. [13] focused on large-panicle single-season rice varieties, which had spikelets per panicle exceeding 350. In contrast, early-season rice typically exhibits smaller panicle sizes than single-season rice due to shorter vegetative growth periods and lower temperatures during the vegetative period [7,11]. In this study, the 11 early-season rice varieties had spikelets per panicle ranging from 92 to 108 (data not shown), which is less than one-third the panicle size of the single-season varieties used by Meng et al. [13]. This study offers valuable insights for enhancing spikelet filling in early-season rice with relatively small panicle sizes.

3.3 The Biomass-Fertilized Spikelet Ratio and Its Relationship with Spikelet Filling in Early-Season Rice

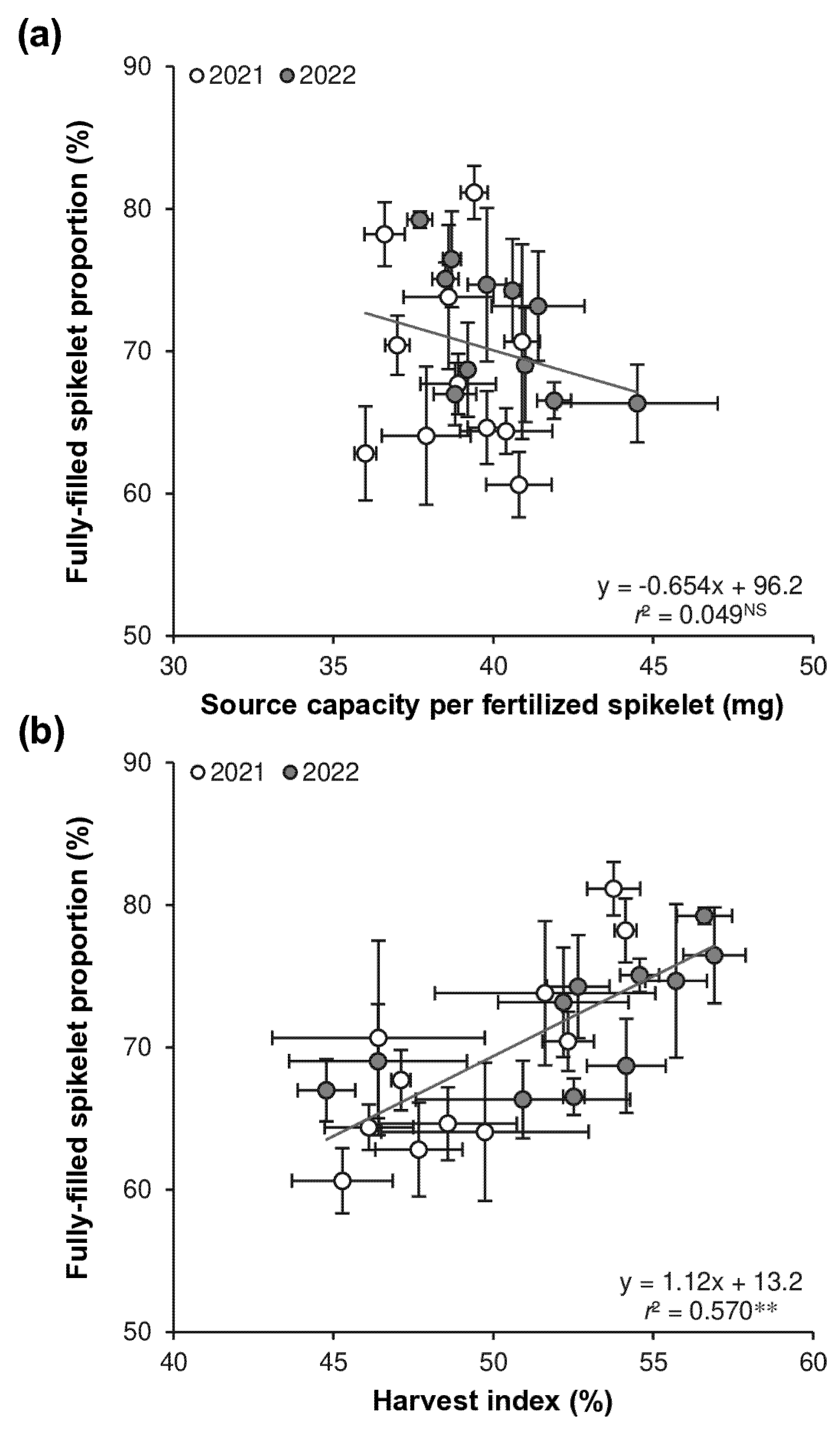

The biomass-fertilized spikelet ratio of the 11 varieties ranged from 36.0 to 40.9 mg spikelet−1, with a mean of 38.8 mg spikelet−1 in 2021, and from 37.7 to 44.5 mg spikelet−1, with a mean of 40.2 mg spikelet−1 in 2022 (Table 5). In 2021, Lingliangyou 268 exhibited the highest biomass-fertilized spikelet ratio, which was not significantly different from that of Zhuliangyou 4024, Lingliangyou 179, Lingliangyou 674, Lingliangyou 942, Ezao 18, and Liangyou 287, but was 8%–14% higher than that of the other four varieties. In 2022, Zhuliangyou 4024 had the highest biomass-fertilized spikelet ratio, which was not significantly different from that of Lingliangyou 179, but was 8%–18% higher than those of the other nine varieties. Collectively, both years showed that Zhuliangyou 4024 and Lingliangyou 179 consistently had high biomass-fertilized spikelet ratio, whereas Liangyou 42, Jiyou 421, Tanliangyou 83, and Zhuliangyou 819 consistently exhibited low biomass-fertilized spikelet ratio. This varietal performance in the biomass-fertilized spikelet ratio differed markedly from that observed in the proportion of fully-filled spikelets (Table 3 and Table 5). As a consequence, there was no significant relationship between the proportion of fully-filled spikelets and the biomass-fertilized spikelet ratio (Fig. 3a).

These results suggest that the biomass-fertilized spikelet ratio is not a limiting factor for improving spikelet filling in early-season rice. This finding is consistent with Huang et al. [15], who reported no significant difference in biomass production between two single-season rice varieties with differing spikelet filling. However, it contradicts the finding of Meng et al. [13], who argued that high source capacity (e.g., leaf area, leaf photosynthetic capacity, and biomass accumulation) was critical for achieving high spikelet filling in single-season rice. This discrepancy might be partially attributed to the much smaller panicle sizes of the 11 early-season rice varieties used in this study compared to the four single-season varieties examined by Meng et al. [13]. It also highlights the specificity of physiological traits related to spikelet filling in early-season rice with relatively small panicle sizes.

Figure 2: Relationships between proportions of fully-filled and partially-filled spikelets (a), between proportions of fully-filled and empty spikelets (b), and between proportions of partially-filled and empty spikelets (c) across 11 early-season rice varieties over 2021 and 2022. Data are the mean ± SE of three replicates. ** denotes a significant relationship at p < 0.01. NS denotes a non-significant relationship at p < 0.05.

Table 4: Path analysis among proportions fully-filled, partially-filled (X1), and empty spikelets (X2) across 11 early-season rice varieties over 2021 and 2022.

| Variable | Direct | Indirect | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trough X1 | Trough X2 | ||

| X1 | −0.746 | −0.077 | |

| X2 | −0.573 | −0.100 | |

Table 5: The biomass-fertilized spikelet ratio and harvest index in 11 early-season rice varieties in 2021 and 2022.

| Variety | Biomass-Fertilized Spikelet Ratio (mg spikelet−1) | Harvest Index (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 2021 | ||

| Ezao 18 | 38.9 ± 1.2 | 47.1 ± 0.3 |

| Jiyou 421 | 36.0 ± 0.3 | 47.7 ± 1.4 |

| Liangyou 287 | 38.6 ± 1.4 | 51.6 ± 3.4 |

| Liangyou 42 | 36.6 ± 0.6 | 54.1 ± 0.3 |

| Lingliangyou 179 | 40.4 ± 1.4 | 46.1 ± 1.4 |

| Lingliangyou 268 | 40.9 ± 0.6 | 46.4 ± 3.3 |

| Lingliangyou 674 | 39.8 ± 0.6 | 48.6 ± 2.2 |

| Lingliangyou 942 | 39.4 ± 0.4 | 53.8 ± 0.8 |

| Tanliangyou 83 | 37.0 ± 0.4 | 52.3 ± 0.8 |

| Zhuliangyou 4024 | 40.8 ± 1.0 | 45.3 ± 1.6 |

| Zhuliangyou 819 | 37.9 ± 1.4 | 49.7 ± 3.2 |

| Mean | 38.8 | 49.3 |

| LSD (0.05) | 2.9 | 6.2 |

| 2022 | ||

| Ezao 18 | 41.0 ± 0.2 | 46.4 ± 2.8 |

| Jiyou 421 | 38.8 ± 0.7 | 44.8 ± 0.9 |

| Liangyou 287 | 38.5 ± 0.4 | 54.6 ± 0.6 |

| Liangyou 42 | 37.7 ± 0.4 | 56.6 ± 0.9 |

| Lingliangyou 179 | 41.9 ± 0.5 | 52.5 ± 0.3 |

| Lingliangyou 268 | 40.6 ± 0.2 | 52.7 ± 1.0 |

| Lingliangyou 674 | 39.8 ± 0.6 | 55.7 ± 1.0 |

| Lingliangyou 942 | 41.4 ± 1.5 | 52.2 ± 2.0 |

| Tanliangyou 83 | 38.7 ± 0.3 | 56.9 ± 1.0 |

| Zhuliangyou 4024 | 44.5 ± 2.5 | 50.9 ± 3.4 |

| Zhuliangyou 819 | 39.2 ± 0.1 | 54.2 ± 1.2 |

| Mean | 40.2 | 52.5 |

| LSD (0.05) | 2.9 | 4.6 |

3.4 Harvest Index and Its Relationship with Spikelet Filling in Early-Season Rice

The harvest index of the 11 varieties ranged from 45.3% to 54.1% in 2021 and from 44.8% to 56.9% in 2022, with means of 49.3% and 52.5%, respectively (Table 5). In 2021, Liangyou 42 recorded the highest harvest index, which was not significantly different from those of Lingliangyou 942, Tanliangyou 83, Liangyou 287, Zhuliangyou 4024, and Lingliangyou 674, but was 9%–27% higher than the other five varieties. In 2022, Tanliangyou 83 achieved the highest harvest index, similar to Liangyou 42, Lingliangyou 674, Liangyou 287, Zhuliangyou 819, Lingliangyou 268, and Lingliangyou 179, but 13%–19% higher than the other four varieties. Overall, Liangyou 42, Tanliangyou 83, Liangyou 287, Lingliangyou 674, and Zhuliangyou 819 consistently exhibited high harvest indices, while Jiyou 421, Ezao 18, and Zhuliangyou 4024 showed consistently low harvest indices. This performance in harvest index was partially similar to that in the proportion of fully-filled spikelets (Table 3 and Table 5). Consequently, a significant positive relationship was observed between the proportion of fully-filled spikelets and harvest index, with approximately 60% of the variation in fully-filled spikelets explained by harvest index (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3: Relationships between the proportion of fully-filled spikelets with the biomass-fertilized spikelet ratio (a) and harvest index (b) across 11 early-season rice varieties over 2021 and 2022. Data are the mean ± SE of three replicates. NS denotes a non-significant relationship at p < 0.05. ** denotes a significant relationship at p < 0.01.

These results suggest that enhancing harvest index is a viable approach to improving spikelet filling in early-season rice. This finding is consistent with observations in single-season rice by Huang et al. [15], who reported a significant positive relationship between spikelet filling percentage (i.e., the proportion of fully-filled spikelets) and harvest index. They also found that a higher harvest index was associated with increased biomass production during the ripening period. However, additional research is needed to confirm whether this relationship accounts for the varietal difference in harvest index in early-season rice, given the distinct varietal traits and climatic conditions between early- and single-season rice. In particular, early-season rice generally experiences shorter vegetative growth durations and lower temperatures during the vegetative period [11], potentially resulting in lower biomass production and reduced non-structural carbohydrate accumulation in stems and sheaths. The remobilization of these carbohydrates to developing grains is closely related to spikelet filling [22,23]. Moreover, the translocation of carbohydrates can be affected by temperatures during the ripening period. Although high temperatures accelerate the translocation of carbohydrates to the grains, the capacity of grains to accept these carbohydrates may not match the increased translocation rate. Consequently, grain ripening efficiency may decline, resulting in incomplete ripening and leaving carbohydrates in vegetative organs [24]. Furthermore, high temperatures during ripening can affect sink activity. On one hand, they may reduce the expression of starch-synthase enzymes in the grain, thereby limiting starch synthesis [25]. On the other hand, they can decrease abscisic acid (ABA) content by suppressing ABA biosynthesis and enhancing ABA catabolism, while simultaneously increasing gibberellin (GA) content by promoting GA biosynthesis. These hormonal changes can further stimulate the expression of α-amylase, leading to the breakdown of synthesized starch into sugars that are subsequently consumed within the grain [26,27,28,29,30]. These findings emphasize the need for further research into source-sink relationships to better understand the physiological and molecular mechanisms underlying the harvest index in early-season rice.

Along with selecting varieties with high spikelet filling performance, developing optimal agronomic practices is essential for increasing the harvest index and reducing the proportion of partially-filled spikelets in rice. Research has shown that improving water and nitrogen management practices plays a crucial role in enhancing the harvest index [30]. Additionally, exogenous applications of plant growth regulators—such as ascorbic acid, alpha-tocopherol, methyl jasmonates, and brassinosteroids—have been found effective in alleviating high-temperature stress in rice [31]. Moreover, incorporating biochar into soils can improve the root-zone environment and mitigate the adverse effects of high temperatures on rice plants [32]. These findings provide valuable insights for developing optimal agronomic practices to improve spikelet filling in early-season rice.

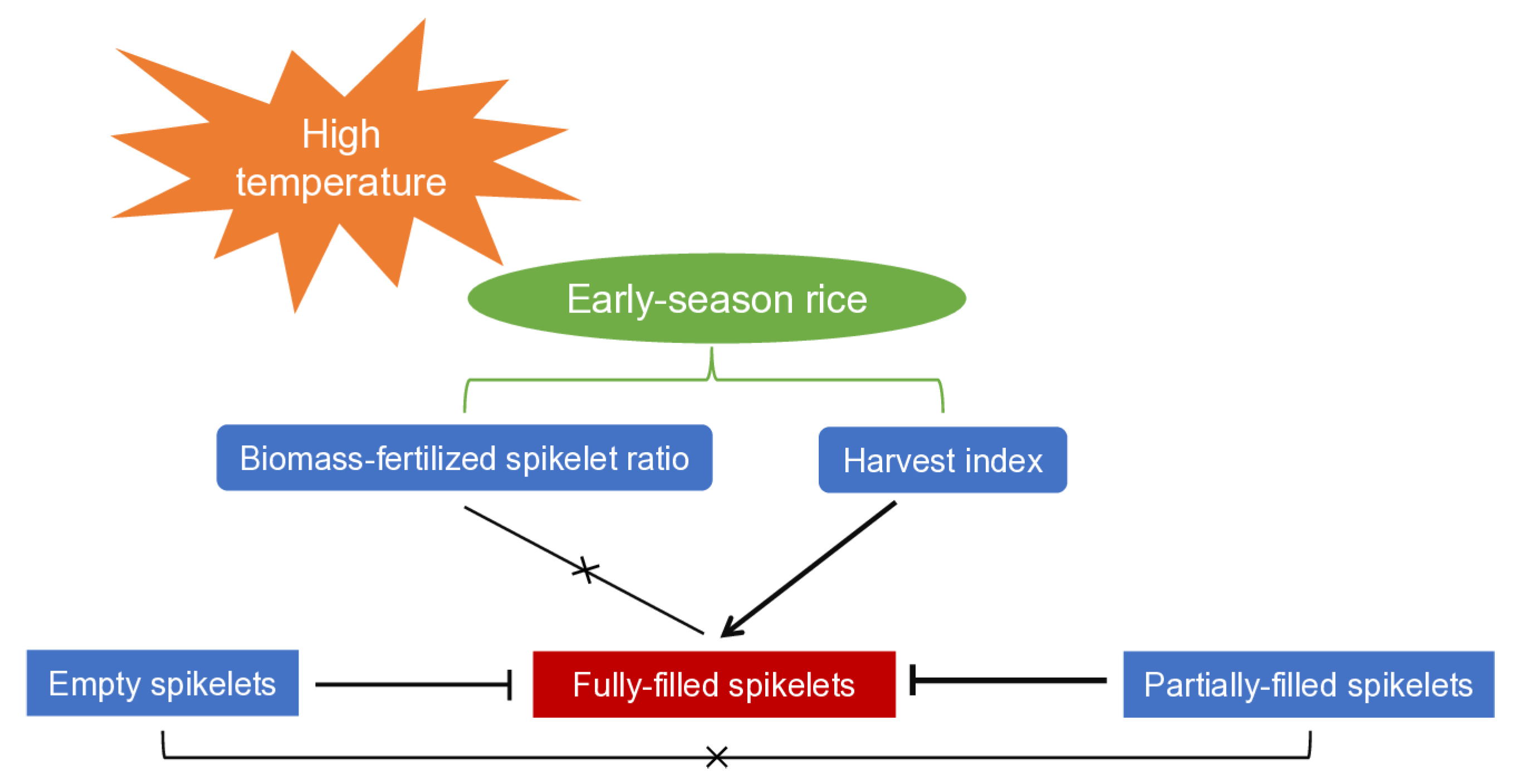

Varietal differences in spikelet filling are evident in early-season rice that experiences high temperatures during the ripening period. Liangyou 42, Lingliangyou 942, and Liangyou 287 are early-season rice varieties that demonstrate relatively high performance in spikelet filling, characterized by a high proportion of fully-filled spikelets and low proportions of partially-filled and empty spikelets. To enhance spikelet filling in early-season rice, it is crucial to increase the harvest index and to minimize the occurrence of partially-filled spikelets (Fig. 4). Further research is needed to uncover the physiological and molecular mechanisms regulating harvest index and spikelet filling, as well as to develop optimal agronomic practices for improving spikelet filling in early-season rice.

Figure 4: Schematic diagram illustrating spikelet-filling characteristics in early-season rice exposed to high temperatures during the ripening period.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Earmarked Fund for China Agriculture Research System, grant number CARS-01-33.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Min Huang; formal analysis, Jiazhou Li; investigation, Mingyu Zhang, Xing Li, Fangbo Cao; writing—original draft preparation, Jiazhou Li, Min Huang; supervision, Jiana Chen, Weiqin Wang, Huabin Zheng, Min Huang; funding acquisition, Min Huang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, [Min Huang], upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Nie L , Peng S . Rice production in China. In: Chauhan BS , Jabran K , Mahajan G , editors. Rice production worldwide. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2017. p. 33– 52. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-47516-5_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zou Y . Development of cultivation technology for double cropping rice along the Changjiang River valley. Sci Agr Sin. 2011; 44: 254– 62. doi:10.3864/j.issn.0578-1752.2011.02.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. National Bureau of Statistics . National Data [ cited 2025 Oct 21]. Available from: https://data.stats.gov.cn. [Google Scholar]

4. Wei P , Fang F , Liu G , Zhang Y , Wei L , Zhou K , et al. Effects of composition, thermal, and theological properties of rice raw material on rice noodle quality. Front Nutr. 2022; 9: 1003657. doi:10.3389/fnut.2022.1003657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Li C , You Y , Chen D , Gu Z , Zhang Y , Holler TP , et al. A systematic review of rice noodles: Raw material, processing method and quality improvement. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2021; 107: 389– 400. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2020.11.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Xiong D , Flexas J , Huang J , Cui K , Wang F , Douthe C , et al. Why high yield QTLs failed in preventing yield stagnation in rice? Crop Environ. 2022; 1: 103– 7. doi:10.1016/j.crope.2022.05.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Chen J , Cao F , Shan S , Yin X , Huang M , Zou Y . Grain filling of early-season rice cultivars grown under mechanical transplanting. PLoS One. 2019; 14: e0224935. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0224935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Huang G , Guo L , Zeng Y , Huang S , Zeng Y , Xie X . Changes in the grain yield and quality of early indica rice from 2000 to 2020 in southern China. Agronomy. 2024; 14: 295. doi:10.3390/agronomy14020295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Wu W , Nie L , Liao Y , Shah F , Cui K , Wang Q , et al. Toward yield improvement of early-season rice: Other options under double rice-cropping system in central China. Eur J Agron. 2013; 45: 75– 86. doi:10.1016/j.eja.2012.10.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Shrestha S , Asch F , Dusserre J , Ramanantsoanirina A , Brueck H . Climate effects on yield components as affected by genotypic responses to variable environmental conditions in upland rice systems at different altitudes. Field Crops Res. 2013; 134: 216– 28. doi:10.1016/j.fcr.2012.06.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Huang M , Fan L , Zou Y . Contrasting responses of grain yield to reducing nitrogen application rate in double- and single-season rice. Sci Rep. 2019; 9: 92. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-36572-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Duan L , Guo R , Cai Z , Yang J , Gong Q , Zhang C . Effects of high temperature on grain filling and yield of early season rice under different sowing dates in Jiangxi. Chin J Agrometeorol. 2024; 45: 584– 93. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1000-6362.2024.06.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Meng T , Wei H , Li C , Dai Q , Xu K , Huo Z , et al. Morphological and physiological traits of large-panicle rice varieties with high filled-grain percentage. J Integr Agr. 2016; 15: 1751– 62. doi:10.1016/S2095-3119(15)61215-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Yang J , Zhang J . Grain-filling problem in ‘super’ rice. J Exp Bot. 2009; 61: 1– 5. doi:10.1093/jxb/erp348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Huang M , Cao J , Zhang R , Chen J , Cao F , Fang S , et al. Late-stage vigor contributes to high grain yield in high-quality hybrid rice. Crop Environ. 2022; 1: 115– 8. doi:10.1016/j.crope.2022.05.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Shi P , Tang L , Wang L , Sun T , Liu L , Cao W , et al. Post-heading heat stress in rice of south China during 1981–2010. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0130642. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0130642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Chen J , Zhang R , Cao F , Yin X , Liang T , Huang M , et al. Critical yield factors for achieving high grain yield in early-season rice grown under mechanical transplanting conditions. Phyton-Int J Exp Bot. 2020; 89: 1043– 57. doi:10.32604/phyton.2020.011361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Huang M , Chen J , Cao F , Zou Y . Increased hill density can compensate for yield loss from reduced nitrogen input in machine-transplanted double-cropped rice. Field Crops Res. 2018; 221: 333– 8. doi:10.1016/j.fcr.2017.06.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Shan S , Jiang P , Fang S , Cao F , Zhang H , Chen J , et al. Printed sowing improves grain yield with reduced seed rate in machine-transplanted hybrid rice. Field Crops Res. 2020; 245: 107676. doi:10.1016/j.fcr.2019.107676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Yoshida S . Fundamentals of rice crop science. Los Baños, The Philippines: International Rice Research Institute; 1981. p. 72. [Google Scholar]

21. Wakatsuki H , Takimoto T , Ishigooka Y , Nishimori M , Sakata M , Saida N , et al. Effectiveness of heat tolerance rice cultivars in preserving grain appearance quality under high temperatures in Japan—a meta-analysis. Field Crops Res. 2024; 310: 109303. doi:10.1016/j.fcr.2024.109303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Li G , Pan J , Cui K , Yuan M , Hu Q , Wang W , et al. Limitation of unloading in the developing grains is a possible cause responsible for low stem non-structural carbohydrate translocation and poor grain yield formation in rice through verification of recombinant inbred lines. Front Plant Sci. 2017; 8: 1369. doi:10.3389/fpls.2017.01369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Pan J , Cui K , Wei D , Huang J , Xiang J , Nie L . Relationships of non-structural carbohydrates accumulation and translocation with yield formation in rice recombinant inbred lines under two nitrogen levels. Physiol Plant. 2011; 141: 321– 31. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3054.2010.01441.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Sun T , Liu B , Hasegawa T , Liao Z , Tang L , Liu L , et al. Sink-source unbalance leads to abnormal partitioning of biomass and nitrogen in rice under extreme heat stress: An experimental and modeling study. Eur J Agron. 2023; 142: 126678. doi:10.1016/j.eja.2022.126678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhou R , Hu Q , Meng X , Zhang Y , Shuai X , Gu Y , et al. Effects of high temperature on grain quality and enzyme activity in heat-sensitive versus heat-tolerant rice cultivars. J Sci Food Agr. 2024; 104: 9729– 41. doi:10.1002/jsfa.13797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Sun X , Bian X , Wang J , Chen S , Yang R , Li R , et al. Loss of RSR1 function increases the abscisic acid content and improves rice quality performance at high temperature. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024; 256: 128426. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Suriyasak C , Harano K , Tanamachi K , Matsuo K , Tamada A , Iwaya-Inoue M , et al. Reactive oxygen species induced by heat stress during grain filling of rice (Oryza sativa L.) are involved in occurrence of grain chalkiness. J Plant Physiol. 2017; 216: 52– 7. doi:10.1016/j.jplph.2017.05.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Riaz A , Thomas J , Ali HH , Zaheer MS , Ahmad N , Pereira A . High night temperature stress on rice (Oryza sativa)—insights from phenomics to physiology. A review. Funct Plant Biol. 2024; 51: FP24057. doi:10.1071/FP24057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Nakata M , Fukamatsu Y , Miyashita T , Hakata M , Kimura R , Nakata Y , et al. High temperature-induced expression of rice α-amylases in developing endosperm produces chalky grains. Front Plant Sci. 2017; 8: 2089. doi:10.3389/fpls.2017.02089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Yang J , Zhang J . Simultaneously improving grain yield and water and nutrient use efficiencies by enhancing the harvest index in rice. Crop Environ. 2023; 2: 157– 64. doi:10.1016/j.crope.2023.07.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Fahad S , Hussain S , Saud S , Hassan S , Ihsan Z , Shah AN , et al. Exogenously applied plant growth regulators enhance the morpho-physiological growth and yield of rice under high temperature. Front Plant Sci. 2016; 7: 1250. doi:10.3389/fpls.2016.01250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Huang M , Yin X , Chen J , Cao F . Biochar application mitigates the effect of heat stress on rice (Oryza sativa L.) by regulating the root-zone environment. Front Plant Sci. 2021; 12: 711725. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.711725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools