Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Partial Suppression of the Proline Dehydrogenase Gene Mitigates the Impact of Drought on the Photosynthetic Apparatus and Productivity in Winter Wheat

1 Institute of Plant Physiology and Genetics, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Vasylkivska St., 31/17, Kyiv, 03022, Ukraine

2 Mykhailo Kotsyubynskyi Vinnytsia State Pedagogical University, Ostrozhskogo St., 32, Vinnytsia, 21000, Ukraine

* Corresponding Author: Oleg O. Stasik. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Plant Responses to Abiotic Stress Mechanisms)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2026, 95(1), 6 https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2026.075371

Received 30 October 2025; Accepted 16 December 2025; Issue published 30 January 2026

Abstract

Water scarcity severely constrains the genetic potential of wheat yield worldwide. Proline is among the most versatile stress-related metabolites in plants, and targeting genes involved in proline synthesis and degradation represents a promising strategy for developing drought-tolerant wheat genotypes. This study evaluates the performance of the photosynthetic apparatus in transgenic wheat line with RNAi-mediated suppression of proline dehydrogenase (ProDH) and in the original (wild-type) genotype, under both drought and recovery conditions. Drought was induced at the flowering stage by lowering soil moisture to 30% field capacity for 7 days, compared with 70% field capacity in control plants. Measurements were taken at the onset and end of drought period and 7 days after subsequent recovery. The results demonstrated that drought-treated transgenic plants exhibited improved responses to both the short-term and prolonged effects of stress. Relative water content and chlorophyll levels in the leaves of the transgenic plants changed to a significantly lesser extent. The CO2 assimilation rate in the leaves of transgenic plants was significantly higher than in the wild type under both drought stress and recovery. The transgenic plants also showed superior water-use efficiency during photosynthesis under both conditions. While superoxide dismutase and ascorbate peroxidase activities in leaf chloroplasts increased similarly in both genotypes under drought, they returned to control levels more rapidly in the transgenic plants during recovery. Drought-induced productivity reduction was also significantly lower in the transgenic plants. These findings suggest that RNAi-mediated suppression of ProDH improved photosynthetic performance and grain yield in wheat under drought conditions.Keywords

Water deficit is one of the most widespread abiotic environmental factors that significantly limit the genetic potential of crop productivity in many regions of the world [1,2]. This issue is particularly critical for wheat—the leading cereal crop—since large areas of its cultivation are located in regions with high agricultural risk [3], resulting in substantial yield losses during dry years. Global climate change, characterized by rising temperatures and increasingly uneven precipitation patterns, both geographically and throughout the growing season, further exacerbates these risks [4,5,6].

Inhibition of photosynthetic processes and disruption of reproductive development under drought conditions are the primary factors contributing to grain yield losses, which may range from 25% to 70%, depending on the plant’s developmental stage, as well as on the severity and duration of the stress [7]. The most vulnerable stage in terms of drought impact on wheat productivity is the earing–flowering period [8,9]. Drought during this stage significantly reduces the number of grains per ear, leading to substantial crop losses [10]. Additionally, drought during the grain-filling period compromises grain weight and quality, further diminishing yield [11]. Therefore, the genetic improvement of drought resistance is of critical importance in wheat breeding.

Genetic engineering represents leading strategies for developing new agricultural crop varieties, including wheat, with enhanced resistance to biotic and abiotic stressors. The application of these techniques substantially improves the efficiency of generating drought-tolerant genotypes [12,13]. In recent years, significant progress has been achieved in identifying key regulatory components of drought tolerance in wheat [14], and transgenic lines with modified expression of drought-related genes have been produced using a range of transformation methods [15].

Proline is among the most multifunctional stress-associated metabolites in plants. Its accumulation is a well-documented physiological response to osmotic stress induced by salinity, drought, and other abiotic factors [16,17]. The relative contribution of proline’s diverse biological functions to stress tolerance varies with the stage of the adaptive response, the plant’s developmental phase, and the nature, intensity, and duration of the stressor. In addition to its established role as a compatible osmolyte, proline fulfills several interrelated functions under stress conditions: it stabilizes cellular membranes, exhibits molecular chaperone and antioxidant properties, participates in gene-expression regulation, and serves as a reservoir of energy, nitrogen, and carbon [18,19,20,21]. Proline is also thought to modulate cytosolic pH, maintain the NAD+/NADH redox balance, support the photochemical activity of photosystem II within thylakoid membranes, and reduce lipid peroxidation. Both enhanced endogenous synthesis and exogenous application of proline have been shown to increase the nonspecific resistance of plants to abiotic stresses by protecting cellular membranes, macromolecules, and other structural components [22,23].

One of the most promising strategies for developing drought-resistant wheat genotypes involves manipulating genes that regulate proline biosynthesis and catabolism [15]. In several cases, increased proline accumulation has been correlated with enhanced stress tolerance in transgenic plants [24]. Elevation of free proline levels in plant tissues can be achieved either by enhancing its synthesis or by reducing its rate of degradation. Two principal genetic approaches are commonly employed: (1) the introduction of additional cDNA copies of genes encoding key enzymes of proline biosynthesis, such as P5CS or OAT; and (2) the partial suppression of endogenous genes involved in proline catabolism, particularly proline dehydrogenase (ProDH), which catalyzes the initial step of proline degradation [25]. The latter approach is of particular practical significance, as targeted downregulation of ProDH expression can increase free proline content and thereby enhance plant tolerance to abiotic stressors [24]. Therefore, studying the physiological characteristics of genetically transformed wheat plants with elevated proline content, particularly the response of their photosynthetic apparatus to soil drought, is highly appropriate for assessing their potential application in breeding programs aimed at developing drought-resistant varieties.

The aim of this study was to compare the responses of the photosynthetic apparatus in transgenic wheat plants carrying a double-stranded RNA suppressor of the proline dehydrogenase gene and in the original (wild-type) genotype during drought and post-stress recovery period. Furthermore, the impact of drought stress on plant productivity was evaluated.

The experimental material consisted of a new, promising breeding line of winter bread wheat, UK 322/17 (wild type), and the T3 generation of transgenic wheat plants with RNAi-mediated suppression of ProDH derived from this line. Both genotypes were developed at the Institute of Plant Physiology and Genetics, NAS of Ukraine. The plants were transformed using the binary vector pBi2E, which contains a heterologous double-stranded RNA suppressor of the Arabidopsis proline dehydrogenase gene (ProDH1), as well as the neomycin phosphotransferase II selective gene (nptII) from Escherichia coli. Agrobacterium-mediated in planta transformation [26] was performed under pot experiment conditions by inoculating castrated inflorescences. T1 transformants were obtained, from which the T3 seed generation was subsequently derived. Integration of vector construct elements was confirmed by PCR, targeting fragments of both the exon and intron of the Arabidopsis gene ProDH1, as well as the nptII selective gene.

Pot experiment was conducted outdoors at the Institute of Plant Physiology and Genetics of National Academy of Science of Ukraine (50°24′54″N, 30°30′54″E). Seeds were sown on 28 September 2023. Plants were grown in pots containing 10 kg of fertilized soil located under the roof made of transparent polyethylene film, at natural light and temperature conditions. Each pot contained 15 plants. Fertilizers were applied twice in equal amounts (N80P80K80 + N80P80K80 mg·kg−1 of soil): once at pot filling with soil and again at the mid stem elongation stage (BBCH 35). The plants were harvested at fully ripe stage (BBCH 89) on 16 July 2024.

For the control (well-watered) plants, soil moisture was maintained at optimal 70% of field capacity (FC) throughout the entire growing season. At the beginning of the flowering stage (BBCH 59, 20 May 2024), irrigation was stopped for half of the plants, reducing soil moisture to 30% FC over 3 days. This level was maintained for the following 7 days. Thereafter (30 May 2024), watering of the drought-treated plants was resumed to the control level (70% FC) and continued until the end of the growing season. Soil moisture in the pots was monitored gravimetrically twice daily. During the water shortage period, the average daily temperature varied between 19.2 and 22.0°C and the photoperiod was approximately 15 h and 30 min.

Measurements of relative water content, photosynthetic pigment content, free proline content, gas exchange rate, and chloroplast antioxidant enzyme activity in the flag leaves of both control and treated plants were conducted on the first and seventh days of exposure to 30% field capacity (FC), as well as one week after soil moisture was restored to the control level. Grain productivity components were assessed at full grain maturity by weighing air-dry plant material.

2.3.2 Determination of Relative Water, Total Chlorophyll, and Proline Contents

Relative water content (RWC) in the leaves was determined using the standard method [27]. Freshly collected leaves were immediately weighed to determine their fresh weight (FW). The leaves were incubated in distilled water in darkness at 4°C for 24 h until fully turgid to determine the turgid weight (TW). Subsequently, the fully turgid leaves were oven-dried at 105°C to a constant mass to get the dry weight (DW). The RWC was calculated by the following formula:

RWC (%) = [(FW − DW)/(TW − DW)] × 100.Total chlorophyll (a + b) content in the leaves was measured spectrophotometrically [28] after extraction from fresh material using dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and results were expressed per unit of dry weight. The free proline content was determined by a method based on the formation of a colored product of the interaction between L-proline and ninhydrin [29].

2.3.3 Gas Exchange Rate Measurement

The photosynthetic rate was quantified under controlled environmental conditions using an open gas-exchange system equipped with an infrared gas analyzer (GIAM-5M) operating in differential mode. The central segments of two intact flag leaves from the main shoot were placed in a temperature-regulated chamber (25°C) and illuminated with a TA-11 50 W LED spotlight (color temperature: 5200 K). The photon flux density at the chamber level was 1500 μmol·m−2·s−1) of photosynthetically active radiation.

Conditioned atmospheric air with an absolute humidity of 9.5–10.0 mbar was supplied to the chamber at a flow rate of 1 L min−1. Transpiration rate was determined using a gas analyzer (EGM-5, PP Systems, Amesbury, MA, USA) based on the difference in water vapor concentration between the inlet and outlet air streams. The same instrument was used to record CO2 concentration at the chamber inlet. Gas-exchange parameters—including net CO2 assimilation rate, transpiration rate, stomatal conductance, and water-use efficiency—were calculated according to the methods described in [30].

2.3.4 Determination of Chloroplast Antioxidant Enzyme Activity

For the determination of antioxidant enzyme activities, chloroplasts were isolated mechanically at 0–4°C. Average samples (2 g) of flag leaves collected from five plants were homogenized in seven volumes of extraction buffer containing 0.33 M sorbitol, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 4 mM ascorbic acid, and 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). The homogenate was filtered through two layers of nylon mesh and centrifuged at 80× g for 5 min at 0–4°C (K-24D centrifuge) to remove coarse debris. The supernatant was transferred to pre-cooled tubes and centrifuged at 2000× g for 10 min to obtain the chloroplast fraction. The resulting pellet was resuspended in an isotonic medium containing 4 mM ascorbic acid and 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) to a final volume of 2 mL. This chloroplast suspension was subsequently used for the assay of superoxide dismutase and ascorbate peroxidase activities.

Superoxide dismutase (SOD; EC 1.15.1.1) activity was estimated spectrophotometrically at 560 nm using nitro blue tetrazolium, following the procedure described by Giannopolitis and Ries [31]. Ascorbate peroxidase (APX; EC 1.11.1.11) activity was measured at 290 nm in the ultraviolet range according to the method of Chen and Asada [32].

Each treatment included five replicate pots. Relative water content measurements were repeated five times using different plants. Chlorophyll content, proline content, and antioxidant enzyme activities were determined analytically four times using combined leaf samples from five individual plants. Gas exchange parameters and antioxidant enzyme activities were measured in four replicates. Grain productivity components for each treatment were calculated as the average of 20 plants.

The data were organized using Microsoft Excel 2019 software and statistically analyzed using ANOVA (STATISTICA ver. 7.0). Significant differences between means were assessed using Tukey’s test. In the figures and table, results are presented as mean ± standard error (m ± SE). Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

3.1 Proline Content in Leaves of Wild-Type and Transgenic Plants

Biochemical analysis revealed that the transgenic plants exhibited increased proline content in their leaves compared to wild-type plants, both under normal conditions and during drought stress. The free proline content in the leaves of wild-type plants under optimal watering conditions was 303 ± 23 μg·g−1 FW, and in transgenic plants it was 1.9 times higher—573 ± 32 μg·g−1 FW. Under drought conditions, the content of this amino acid increased in both wild-type (up to 880 ± 79 μg·g−1) and transgenic plants (2607 ± 138 μg·g−1), i.e., in the leaves of wild-type plants this index increased by 2.9 times, compared to the control, while in transformants it increased by 4.5 times.

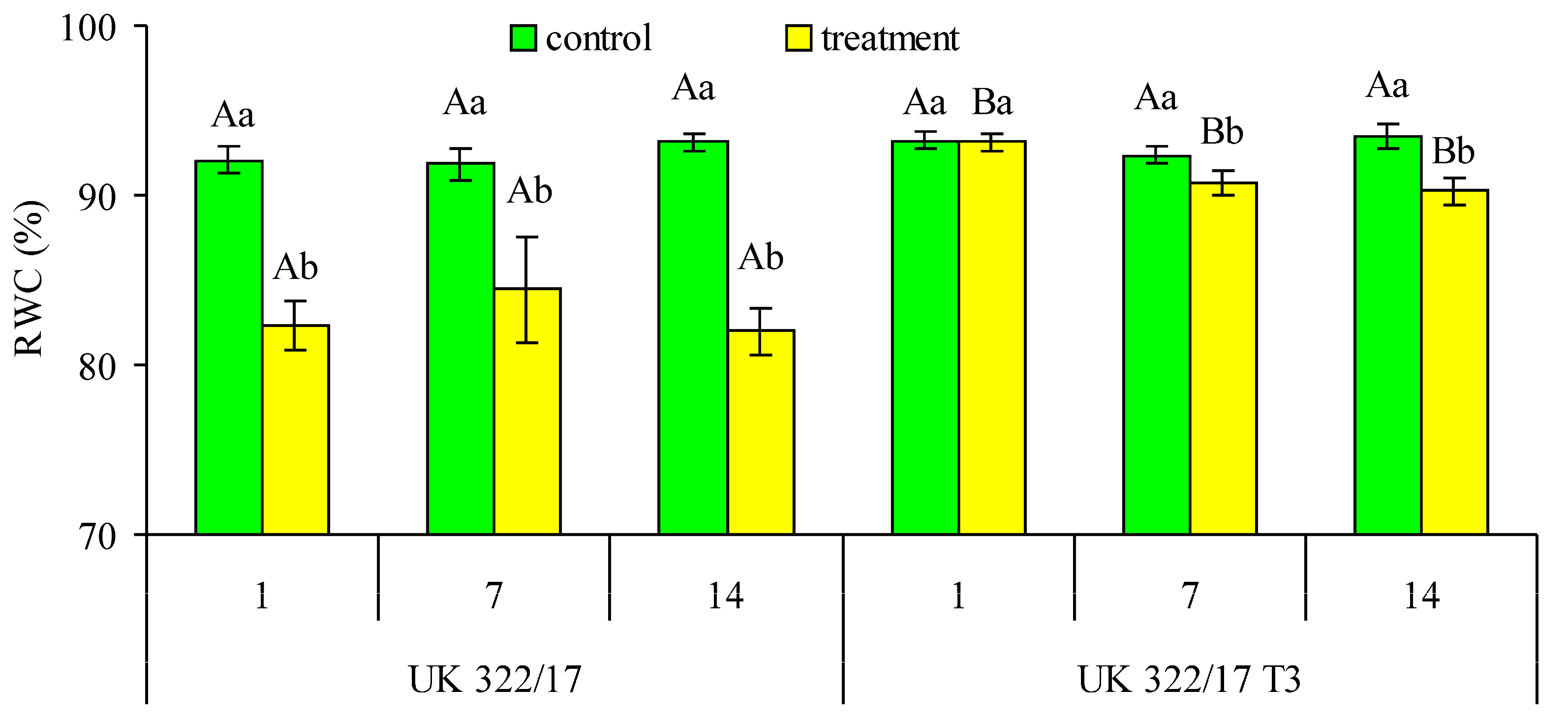

3.2 Effect of Drought on the Relative Water Content

At all measurement points, drought-treated wild-type plants exhibited significantly lower values of RWC in the flag leaves compared to the transgenic plants (Fig. 1). In control plants, RWC values for both wild-type and transgenic lines were similar, ranging between 92–93%. On the first day of drought stress, RWC in the drought-treated transgenic plants remained at control level. However, by the end of the stress period, RWC in these plants showed a tendency to decrease relative to the control. One week after the restoration of optimal soil moisture in the pots, the RWC in the leaves of transgenic plants was significantly lower than in the control. However, this difference was primarily due to a slight increase in RWC in the control plants compared to the first week of the experiment. When comparing RWC in the transgenic plants at the end of the drought and during the recovery period, the difference was not significant. In drought-treated wild-type plants, RWC was lower than in the control by 9.8% on the first day of drought, by 7.4% on the seventh day of stress, and by 11.2% during the recovery period. In transgenic plants, the corresponding differences were only 0.05%, 1.63%, and 3.28%, respectively.

Figure 1: Effect of drought on relative water content (RWC) in flag leaves of wild-type (UK 322/17) and transgenic (UK 322/17 T3) wheat plants with RNAi-mediated suppression of ProDH on the first (1) and seventh (7) days of exposure to 30% FC, and one week after soil moisture was restored to the control level (14). Each bar represents the mean ± SE (n = 5 replicates). Different uppercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between genotypes (р < 0.05); different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between control and drought-treated plants of the same genotype (р < 0.05).

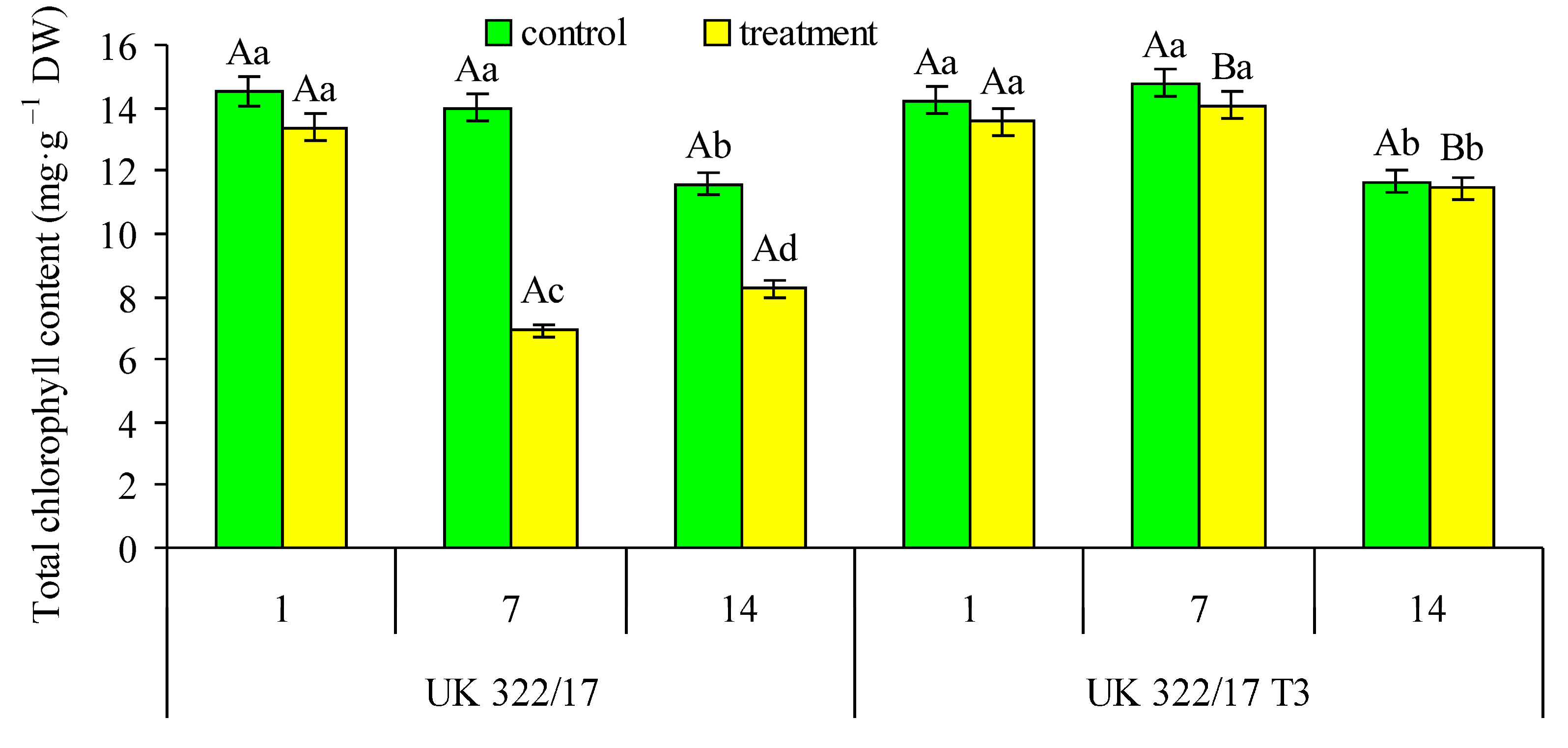

3.3 Effect of Drought on the Chlorophyll Content

The total chlorophyll content in the leaves of control plants of both genotypes was nearly identical, showing a slight decrease toward the end of the measurement period (Fig. 2). On the first day of drought, a tendency to decline in chlorophyll content was observed in the treated plants, although no differences were detected between genotypes. By the seventh day of drought, the chlorophyll content in the leaves of transgenic plants remained comparable to that of the control, whereas in wild-type plants it had decreased by approximately 50%. During the recovery period, a similar trend persisted: chlorophyll content in drought-treated wild-type plants slightly increased but remained 28% lower than in the control.

Figure 2: Effect of drought on the total chlorophyll content in flag leaves of wild-type (UK 322/17) and transgenic (UK 322/17 T3) wheat plants with RNAi-mediated suppression of ProDH on the first (1) and seventh (7) days of exposure to 30% FC, and one week after soil moisture was restored to the control level (14). Each bar represents the mean ± SE (n = 4 replicates). Different uppercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between genotypes (р < 0.05); different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between control and drought-treated plants of the same genotype (р < 0.05).

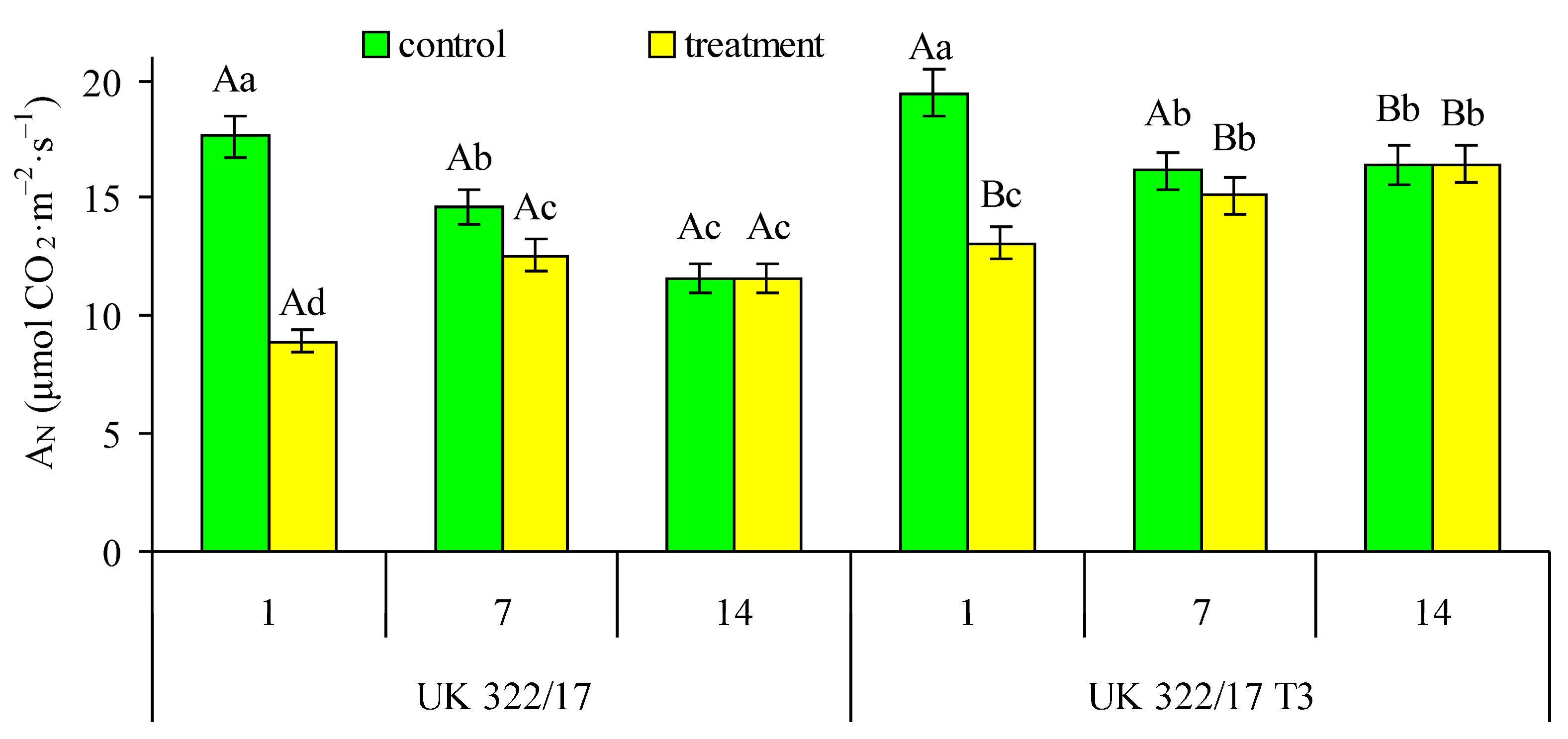

3.4 Net CO2 Assimilation Rate in Leaves under Drought and after the Restoration of Optimal Watering

At the beginning of the measurement period, the net CO2 assimilation rate (AN) in the flag leaves of well-watered (control) wild-type plants and transformants did not differ significantly. After one week, AN in leaves of control plants decreased by 17% in both genotypes. In the following week, this value continued to decline in wild-type plants, reaching 66% of the initial level, while in the transformants it remained stable. In drought-treated plants, AN significantly decreased on the first day after soil moisture reached 30% FC compared to the control (Fig. 3). Specifically, AN decreased by 49.3% in wild-type plants and by 32.8% in transformants. After 7 days of drought exposure, AN in treated plants significantly increased relative to the first day of stress. At this period, the difference with control was 14.0% in wild-type plants and 6.6% in transformants. One week after the restoration of optimal watering, AN in both wild-type and transgenic plants returned to control levels.

Figure 3: Effect of drought on the net CO2 assimilation rate (AN) in flag leaves of wild-type (UK 322/17) and transgenic (UK 322/17 T3) wheat plants with RNAi-mediated suppression of ProDH on the first (1) and seventh (7) days of exposure to 30% FC, and one week after soil moisture was restored to the control level (14). Each bar represents the mean ± SE (n = 4 replicates). Different uppercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between genotypes (р < 0.05); different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between control and drought-treated plants of the same genotype (р < 0.05).

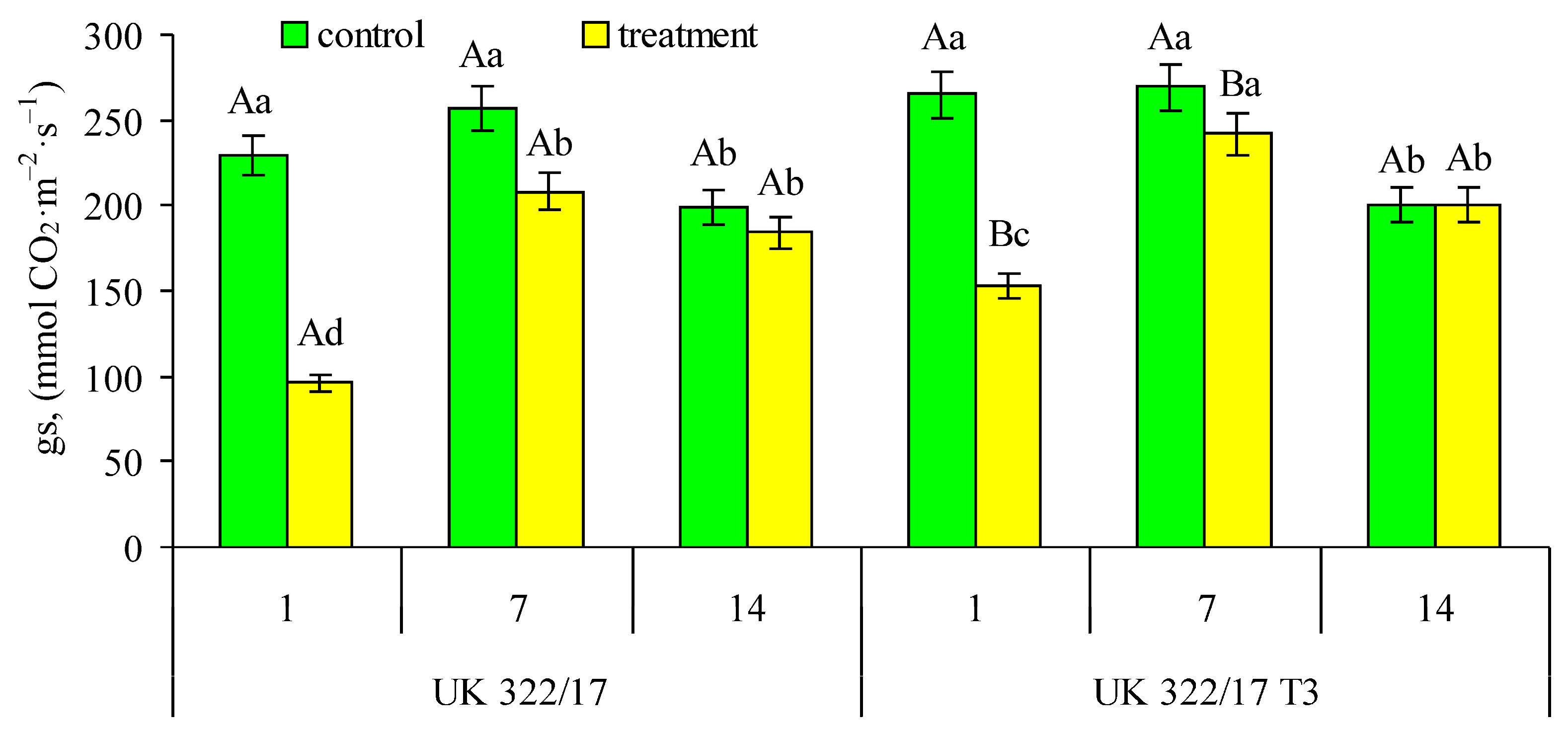

3.5 Stomatal Conductance in Leaves under Drought and after the Restoration of Optimal Watering

Somewhat different patterns were observed in the dynamics of stomatal CO2 conductance (gs) (Fig. 4). On the first and seventh days of the experiment, gs values in the control plants of both genotypes were nearly identical. A decrease of 23–26% in gs was observed only on the 14th day of the experiment, with no significant differences between the wild type and the transformants. In drought-treated wild-type plants, gs decreased by 58% compared to the control on the first day of drought, by 18.9% on the seventh day, and by 7.5% one week after the restoration of optimal soil moisture. In transformed plants, the reductions were smaller—42.4%, 10.3%, and 0.2%, respectively. It is worth noting that, although gs in the treated wild-type plants did not fully recover to control levels during the recovery period (unlike that was observed for the net CO2 assimilation rate), the difference between treated and well-watered plants was not statistically significant.

Figure 4: Effect of drought on the stomatal conductance (gs) in flag leaves of wild-type (UK 322/17) and transgenic (UK 322/17 T3) wheat plants with RNAi-mediated suppression of ProDH on the first (1) and seventh (7) days of exposure to 30% FC, and one week after soil moisture was restored to the control level (14). Each bar represents the mean ± SE (n = 4 replicates). Different uppercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between genotypes (р < 0.05); different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between control and drought-treated plants of the same genotype (р < 0.05).

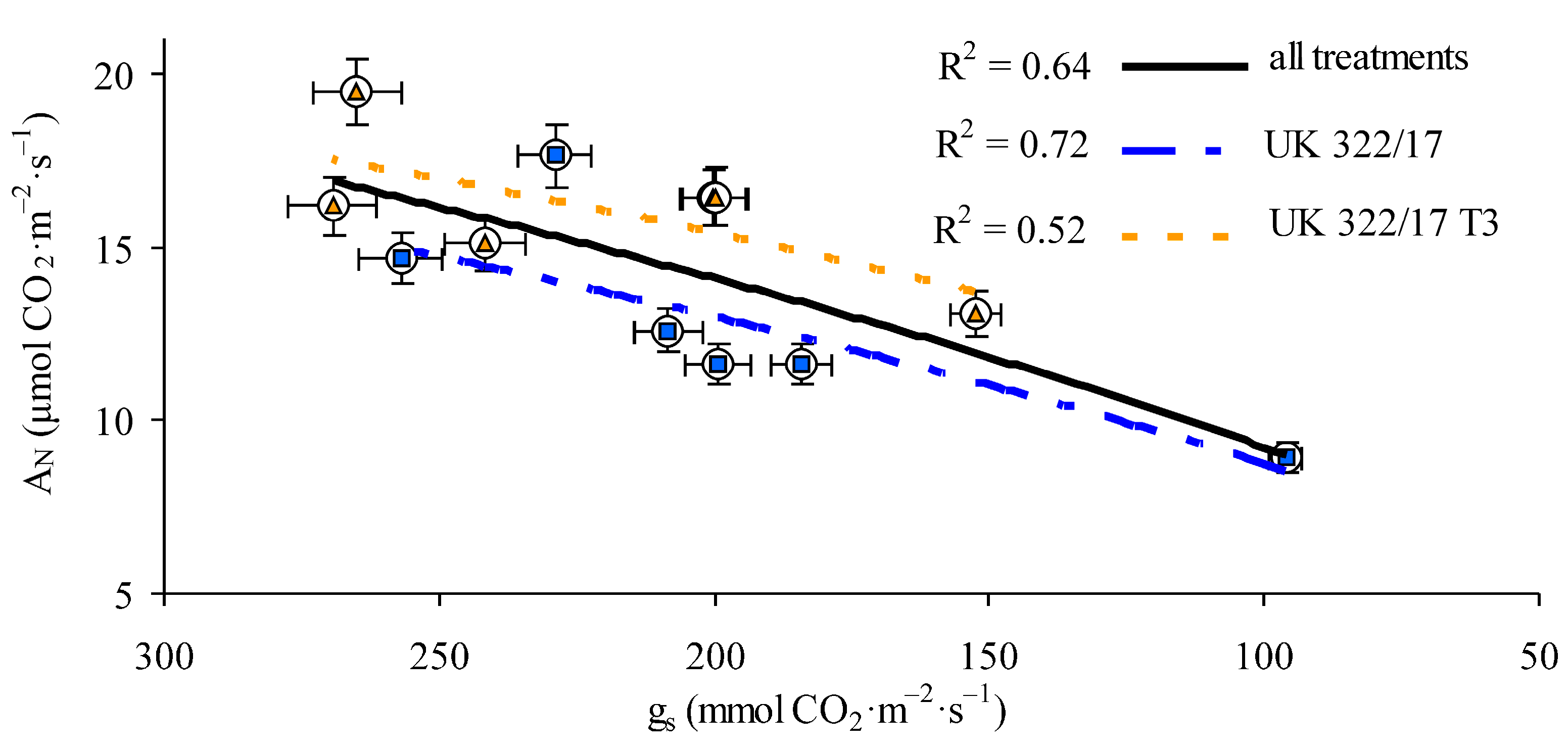

3.6 Correlation Analysis of gs and AN

A fairly strong positive correlation between gs and AN was observed in our experiment (Fig. 5). When considering all control and treated plants of both genotypes across all measurement periods, the correlation coefficient was r = 0.80 (p < 0.05). In addition, we plotted separate regression relationships for the wild-type and transformed plants including both control and treated groups. The trend lines for these groups were positioned on opposite sides of the overall regression line: the line for wild-type plants was lower, while that for the transformants was higher. The correlation coefficients were r = 0.85 (p < 0.01) for the wild type and r = 0.72 (p < 0.05) for the transformants.

Figure 5: Relationship between stomatal conductance (gs) and photosynthesis rate in flag leaves of winter wheat plants of the original line UK 322/17 and its transformants UK 322/17 T3 with RNAi-mediated suppression of ProDH.

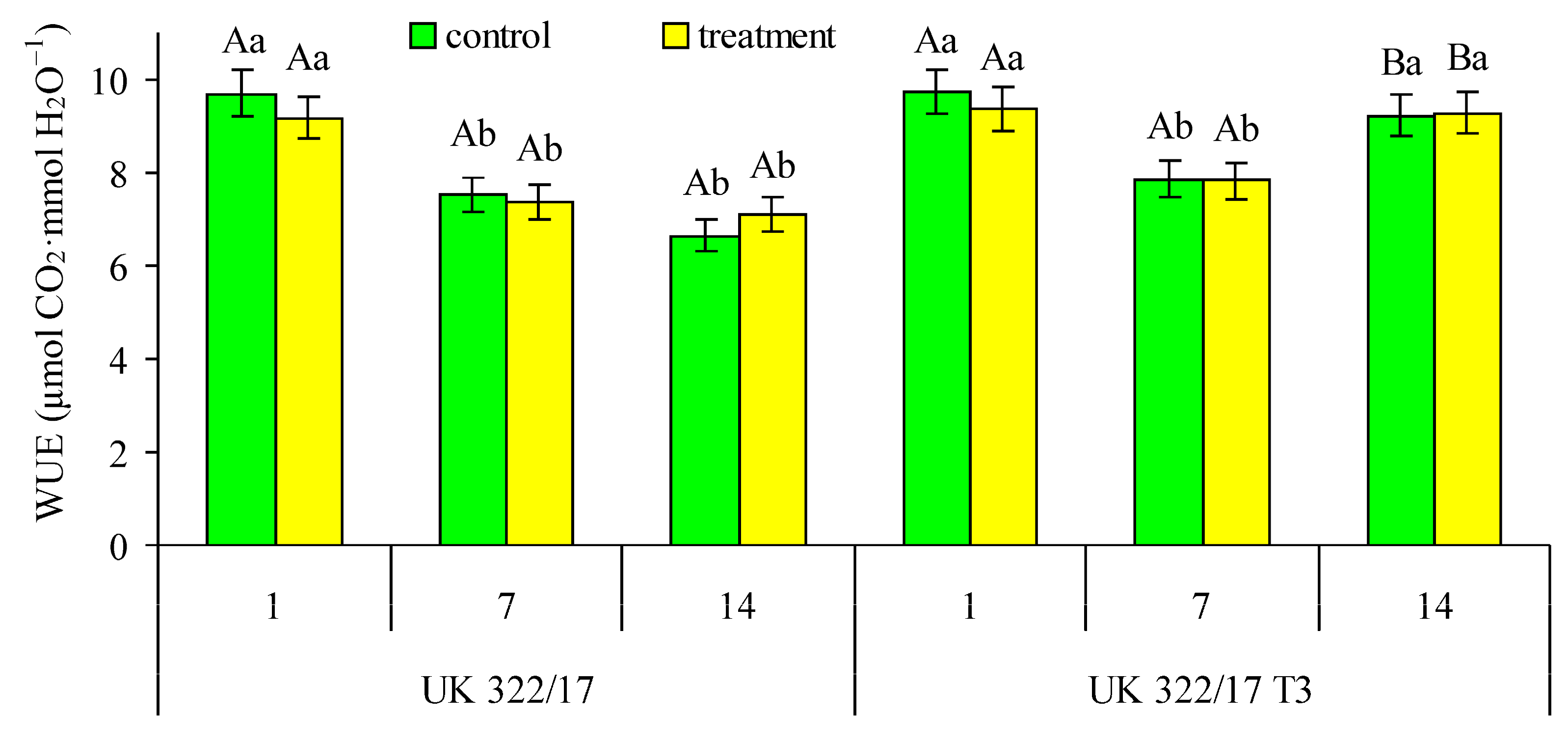

3.7 Water Use Efficiency in Leaves under Drought and after the Restoration of Optimal Watering

The genotypic difference in the ratio of AN to gs in the leaves of wild-type plants and their transformants reflected distinction in an important physiological parameter—water use efficiency (WUE) during photosynthesis. We calculated WUE as ratio of CO2 assimilation rate (AN) to transpiration rate in the flag leaves of control and drought-treated wild-type and transformed plants (Fig. 6). This parameter is referred to as instantaneous WUE (WUEi). The results showed that, in both genotypes, the differences in WUE between control and treated plants during drought period were not statistically significant. Yet, certain genotypic differences in WUE were observed. On the first day of drought, transformed plants showed only a slight tendency toward higher WUE compared to the wild type. By the seventh day of drought, this difference became more noticeable, although still not statistically significant. The advantage of the transformants became clearly evident during the recovery period, when their WUE exceeded that of the wild type by 31%.

Figure 6: Effect of drought on the water use efficiency (WUE) during photosynthesis in flag leaves of wild-type (UK 322/17) and transgenic (UK 322/17 T3) wheat plants with RNAi-mediated suppression of ProDH on the first (1) and seventh (7) days of exposure to 30% FC, and one week after soil moisture was restored to the control level (14). Each bar represents the mean ± SE (n = 4 replicates). Different uppercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between genotypes (р < 0.05); different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between control and drought-treated plants of the same genotype (р < 0.05).

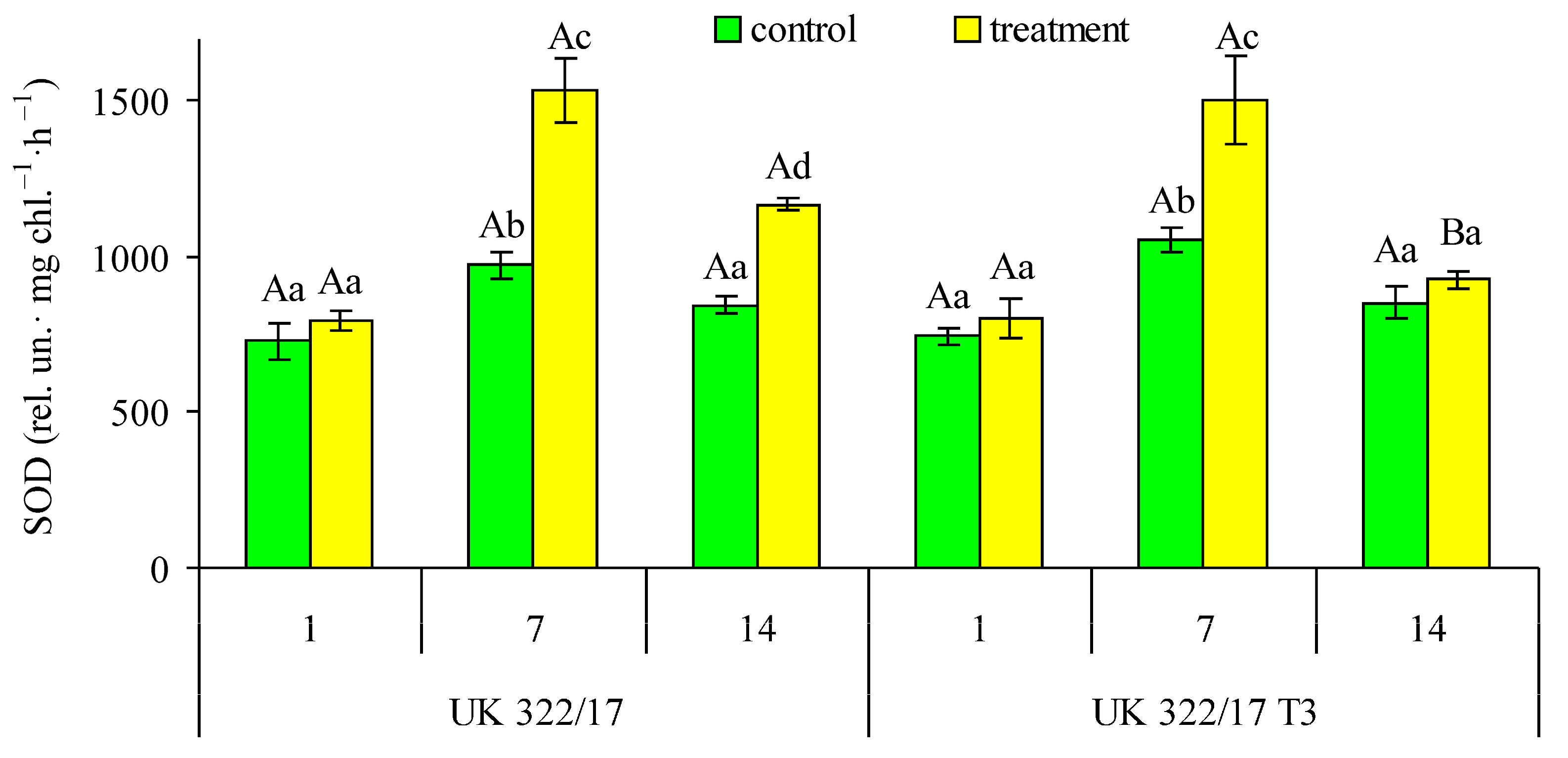

3.8 Effect of Drought on Chloroplast SOD Activity

It was found that SOD activity the in flag leaf chloroplasts in control plants of both genotypes did not differ significantly (Fig. 7). On the first day of drought, SOD activity in the leaves of treated plants showed only a slight, non-significant increase compared to the control. By the seventh day of drought, a significant increase in SOD activity was observed in treated plants compared to the control, with no notable genotypic differences. One week after the restoration of optimal soil moisture in pots with previously drought-treated plants, SOD activity in the transformants had decreased almost to control levels. In wild-type plants, SOD activity also declined compared to the seventh day of drought but remained significantly higher than in the control.

Figure 7: Effect of drought on the superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity in flag leaf chloroplasts of wild-type (UK 322/17) and transgenic (UK 322/17 T3) wheat plants with RNAi-mediated suppression of ProDH on the first (1) and seventh (7) days of exposure to 30% FC, and one week after soil moisture was restored to the control level (14). Each bar represents the mean ± SE (n = 4 replicates). Different uppercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between genotypes (р < 0.05); different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between control and drought-treated plants of the same genotype (р < 0.05).

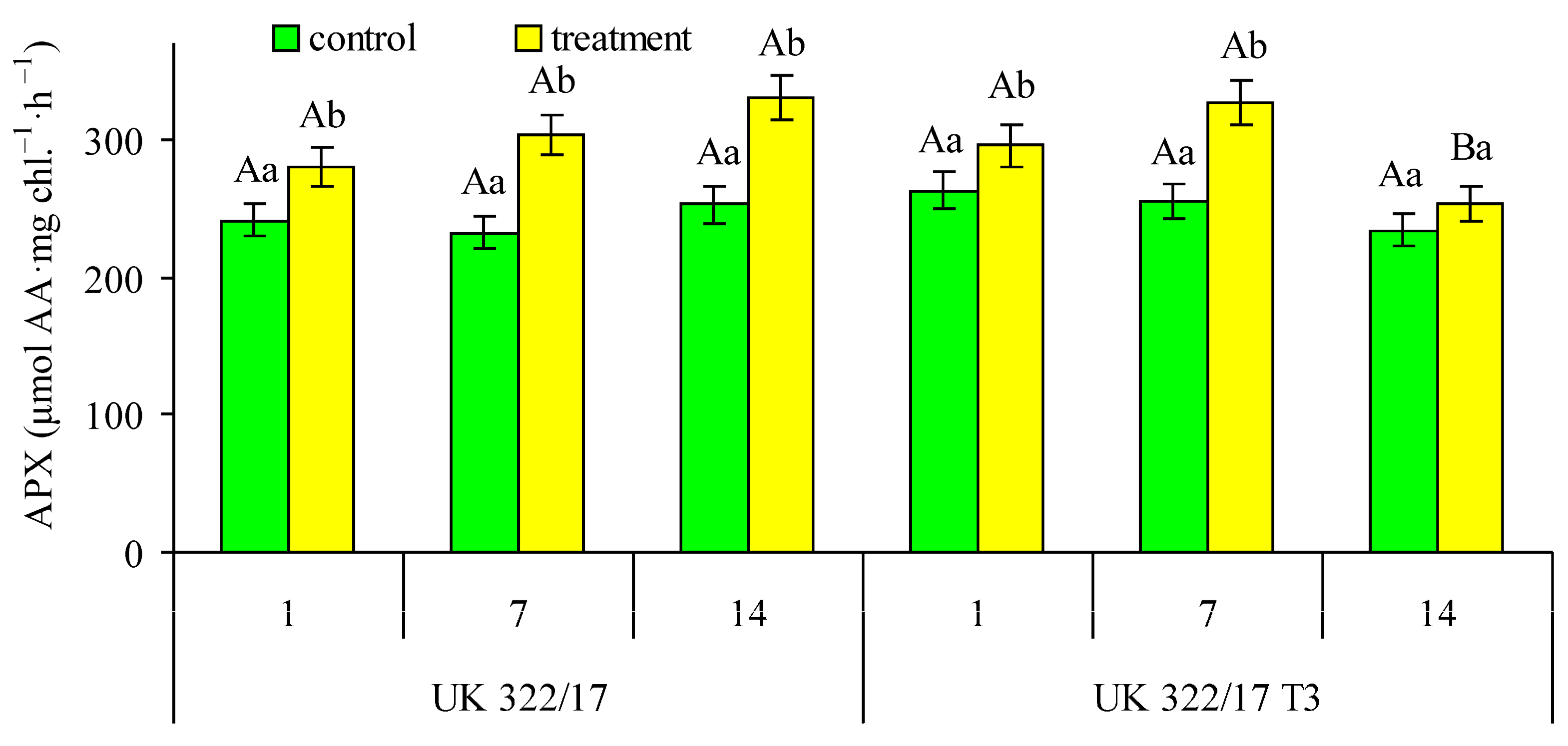

3.9 Effect of Drought on Chloroplast APX Activity

The dynamics of APX activity in chloroplasts generally followed a pattern similar to that of SOD (Fig. 8). Throughout the measurement period, the difference in APX activity between the control plants of both genotypes was insignificant. On the first day of drought, a slight increase in APX activity was observed in the leaves of treated plants compared to the control for both genotypes. By the seventh day of drought, the difference with the control had increased, and the treated transformants showed a tendency toward higher APX activity than the wild-type plants, although this difference was not statistically significant. During the recovery period, APX activity in the chloroplasts of drought-treated transformants decreased almost to control levels, whereas in the treated wild-type plants, it remained significantly elevated compared to the control.

Figure 8: Effect of drought on the ascorbate peroxidase (APX) activity in flag leaf chloroplasts of wild-type (UK 322/17) and transgenic (UK 322/17 T3) wheat plants with RNAi-mediated suppression of ProDH on the first (1) and seventh (7) days of exposure to 30% FC, and one week after soil moisture was restored to the control level (14). Each bar represents the mean ± SE (n = 4 replicates). Different uppercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between genotypes (р < 0.05); different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between control and drought-treated plants of the same genotype (р < 0.05). (AA—ascorbic acid).

3.10 Effect of Drought on Plant Productivity

A seven-day drought during the critical flowering period in wheat negatively affected plant productivity at full maturity. However, the severity of this effect was significantly lower in the transformants compared to the wild-type plants (Table 1). Specifically, the above-ground biomass of drought-treated wild-type plants was 21.2% lower than in the control, while in the transformants, the reduction was only 10.7%. Grain weight decreased by 29.5% in wild-type plants and by 15.3% in transformants. Interestingly, the number of grains per plant decreased to a similar extent in both genotypes—by 28.3% in wild-type plants and 27.3% in transformants. Notably, the 1000-grain weight increased under drought conditions—by 5.6% in wild-type plants and by 15.0% in transformants compared to their respective controls. The harvest index decreased by 10.2% in wild-type plants and by 6.1% in transformants. The number of productive shoots in drought-treated plants also declined—by 27.6% in wild-type plants, and 16.3% in transformants. In wild-type, the difference between control and drought-treated plants was significant for grain weight per plant, grain number, and the number of productive shoots. In transformed plants, significant differences were observed for grain weight per plant, grain number, 1000-grain weight, harvest index, and number of productive shoots. The comparison between drought-treated plants of different genotypes revealed significant differences in above-ground biomass, grain weight per plant, and grain number.

Table 1: The components of the whole plant productivity of control (70% FC) and seven-day drought-exposed during the flowering period (30% FC, treatment) plants of the wild type line UK 322/17 and transformants UK 322/17 T3 with RNAi-mediated suppression of ProDH (x ± SE, n = 20).

| Genotype | Treatment | Above-Ground Part Weight, g | Grain Weight, g | Grain Number, pcs. | 1000 Grains Weight, g | Harvest Index | Productive Shoots Number, pcs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK 322/17 (wild type) | Control | 7.69 ± 0.65Aa | 3.76 ± 0.35Aa | 108.0 ± 10.4Aa | 35.4 ± 1.3Aa | 0.49 ± 0.01Aa | 2.61 ± 0.34Aa |

| Drought | 6.06 ± 0.45Aa | 2.65 ± 0.22Ab | 77.4 ± 8.1Ab | 37.4 ± 3.3Aa | 0.44 ± 0.02Ab | 1.89 ± 0.20Ab | |

| UK 322/17 Т3 | Control | 8.29 ± 0.50Aa | 4.04 ± 0.23Aa | 124.5 ± 8.6Aa | 33.3 ± 1.2Aa | 0.49 ± 0.01Aa | 2.27 ± 0.19Aa |

| Drought | 7.40 ± 0.49Ba | 3.42 ± 0.26Bb | 90.5 ± 6.5Bb | 38.3 ± 1.9Ab | 0.46 ± 0.01Ab | 1.90 ± 0.14Ab |

Thus, the presence of the double-stranded RNA suppressor of the ProDH gene in transgenic plants leads to an increase in proline content in their tissues both under optimal watering conditions and under soil drought. Apparently, this contributed to maintaining a higher RWC in the leaves of transformants during drought conditions and the post-stress recovery period, compared to wild-type plants (Fig. 1). On one hand, elevated proline levels enhanced the water-holding capacity of the leaves. On the other hand, it can be assumed that increased proline accumulation in plant tissues, including the roots, improved their water-absorbing ability, thereby contributing to the overall optimization of the plant’s water status under soil moisture deficiency.

The total chlorophyll content in the leaves of transformants remained more stable under drought conditions and during the recovery period compared to wild-type plants (Fig. 2). This stability was likely due to both the improved water status of the plants, as discussed above, and the protective role of proline as an antioxidant. It is well established that drought stress leads to a sharp increase in the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in plant tissues, causing oxidative stress and damage to various cellular structures, including membranes and chlorophyll-protein complexes in chloroplasts [33]. In such conditions, the antioxidant and chaperone functions of proline become particularly important and are clearly evident in the transformed plants.

It should be noted that while the direct antioxidant (radical-scavenging) activity of proline is not its primary function, it does exhibit significant antioxidant properties by reducing ROS levels within the cell [34]. Free proline, as well as its terminal groups within polypeptides, can directly react with hydrogen peroxide and singlet oxygen, forming stable free radicals, specifically, adducts of proline and hydroxyproline derivatives [35]. The antioxidant properties of proline are evidenced by its ability to eliminate H2O2-induced DNA fragmentation and to prevent programmed cell death by reducing ROS levels [36]. Proline’s antioxidant effect is also linked to its capacity to protect membrane protein-lipid complexes and to indirectly reduce lipid peroxidation by inactivating hydroxyl radicals and other ROS [37]. Alongside classical antioxidants such as glutathione and ascorbic acid, proline plays a role in cellular redox signaling and redox regulation [38]. An additional antioxidant function of proline is its ability to chelate transition metal ions, thereby limiting non-enzymatic free radical formation [35,39]. Furthermore, due to its molecular chaperone properties, proline prevents protein aggregation and denaturation and helps stabilize the structure of antioxidant enzymes [19,35].

While the net CO2 assimilation rates were similar in the leaves of wild-type plants and transformants under optimal soil moisture, the drought-induced decrease in this parameter was less pronounced in the transformants than in the wild type (Fig. 3). As a result, the CO2 assimilation rate in the flag leaves of drought-treated transformants was significantly higher than that of the treated wild-type plants, both during the drought and at the post-stress recovery period. At the same time, the apparent recovery of AN to control levels in drought-treated wild-type and transformed plants one week after the restoration of optimal watering was, to some extent, facilitated by a gradual decline in AN in the control plants over the study period, particularly in the wild type. This decline can be attributed to the onset of leaf senescence associated with the transition to reproductive development, which involves the degradation of photosynthetic apparatus proteins and the remobilization of nitrogen-containing compounds to the developing ear [40].

It is also noteworthy that the adaptation of the photosynthetic apparatus to drought, reflected in the reduced degree of photosynthesis inhibition on the seventh day compared to the first day under 30% FC soil moisture, was more effective in the transformed plants than in the wild type. Specifically, the degree of AN inhibition in wild-type plants decreased 3.5-fold, while in the transformed plants it decreased nearly 5-fold. This suggests that the increased proline content, resulting from the inhibition of its catabolism, contributed to greater resistance of the photosynthetic apparatus to drought stress. The dual role of proline as an osmotically active compound and an antioxidant likely contributes to the preservation of structural and enzymatic integrity in mesophyll cells in general, and in chloroplasts in particular, under conditions of limited water availability.

Stomatal conductance (gs) is one of the key parameters of photosynthetic gas exchange regulation in leaves under the influence of abiotic stresses [41]. In our experiments, transformed wheat plants with RNAi-mediated suppression of ProDH exhibited a smaller reduction in gs under drought conditions compared to wild-type plants (similar to the trend observed for AN) (Fig. 4). It is well known that the primary function of stomata is to optimize the balance between CO2 influx into the leaf and water vapor loss to the atmosphere [42]. On one hand, stomata maintain the CO2 concentration in the intercellular spaces necessary for efficient photosynthesis; on the other hand, they help limit unproductive water loss by the plant. It is possible that at the onset of drought, the sharp increase in the concentration of abscisic acid (ABA), the primary stress hormone in plant tissues, plays a dominant role in reducing AN, as ABA is known to induce stomatal closure [43]. Under these conditions, the limitation of CO2 influx into the leaf is likely the main cause of the reduced CO2 assimilation rate. However, drought stress induces acclimation processes in photosynthetic apparatus making it more stress-tolerant. The rate of carbon dioxide assimilation increases relative to the early stages of stress, prompting a partial reopening of stomata, even in the presence of elevated ABA levels.

This is supported by our data on gs in the leaves of control and treated plants (Fig. 4). On the seventh day of drought, gs in treated plants both genotypes were significantly higher than on the first day. Notably, on the first day of drought, gs in transformed plants was more than 1.5 times higher than in wild-type plants; however, by the seventh day, this difference had narrowed to just 16%. One week after the restoration of optimal soil moisture, gs in treated transformed plants returned to control levels, whereas in wild-type plants it remained slightly lower, though not significantly.

The fact that the trend lines representing the relationships between gs and AN for separate genotypes (Fig. 5) lie on opposite sides of the general regression line—lower for wild-type plants and higher for transformants—indicates that, at the same stomatal conductance, the AN in leaves of transformed plants was higher than in wild-type plants under both stress and non-stress conditions. In the first case, this is clearly attributable to the protective role of proline discussed earlier. In the second case, it can be assumed that the chaperone and antioxidant properties of proline also have relevance under normal conditions, as the proper functioning of the photosynthetic apparatus in mesophyll cells is continually associated with the ROS formation and photodamage to proteins in the light-harvesting complexes, particularly under high light intensity [44].

The study of water use efficiency (WUE) is relevant in the context of increasing aridification due to climate change, as it is influenced by numerous factors, including phenotype, genotype, and environmental conditions [45]. At the crop level, WUE can be defined as the ratio of biomass or yield produced to the amount of water evaporated by plants during the growing season. At the leaf level, instantaneous water use efficiency (WUEi) is expressed as the ratio of AN to transpiration, that is, the amount of CO2 assimilated per unit of water evaporated over time. This parameter integrates stomatal and intracellular (metabolic) components of photosynthesis regulation and indicates the stability of the photosynthetic apparatus at the cellular level and its adaptive capacity under stress conditions [46].

In our experiments, the advantage of transformants over wild-type plants in WUEi (Fig. 6) was primarily due to the maintenance of a higher AN in the leaves of transformed plants both during the period of drought stress and after its cessation (Fig. 3). This was observed in both treated and control transformed plants. In the latter, WUEi remained at a high level as a result of the previously mentioned delay in the senescence of the photosynthetic apparatus during the reproductive stage, compared to wild-type plants. It can be assumed that this effect was facilitated by the antioxidant properties of proline, as it is well established that the aging process is both triggered and accompanied by increased ROS production [44,47].

However, it should be noted that the obtained WUEi values do not reflect its dynamics throughout the entire life cycle of the crop. WUE is highly variable both during the day and over the course of the growing season, depending on genotypic characteristics [48]. Nevertheless, in our experiments, measurements of leaf gas exchange were conducted under controlled light and temperature conditions. The observed differences in AN and transpiration rates resulted solely from variations in soil moisture. Therefore, the identified genotypic differences in WUEi can be considered representative and reliable under the given experimental conditions.

It is shown that at high concentrations, endogenous proline can also function as a signaling molecule, capable of modulating the expression of stress-related genes, including an increase in the transcription of cytosolic APX and chloroplast Cu/Zn SOD isoforms [49]. Exogenous application of proline has been shown to enhance the activity of antioxidant enzymes (specifically SOD, APX, catalase, and peroxidase) under ionic and oxidative stress in certain plant species [19,20].

Even under normal conditions, the functioning of the photosynthetic apparatus is accompanied by the ROS formation, which must be neutralized to prevent cellular damage. In particular, during the operation of the electron transport chain (ETC) in chloroplasts, some electrons can be transferred directly to molecular oxygen, resulting in the formation of the superoxide anion radical via the Mehler reaction [50]. This radical is a highly reactive and harmful ROS, and its detoxification is carried out by superoxide dismutase (SOD). Under stress conditions, such as drought, when the utilization of ETC products (ATP and NADPH) in the Calvin–Benson cycle is reduced, the Mehler reaction is significantly intensified. This is typically accompanied by an increase in SOD activity [51]. The reaction catalyzed by SOD produces hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which is itself a ROS. In chloroplasts, ascorbate peroxidase (APX) is responsible for detoxifying H2O2 by reducing it to water. Thus, SOD and APX function cooperatively, which explains the similarity in their activity dynamics in our experiment (Fig. 7 and Fig. 8).

Under stressful conditions, an increase in the activity of antioxidant enzymes is a typical response, as it is necessary to eliminate the excess amounts of ROS that are produced [39]. In our experiments, drought significantly increased the key antioxidant enzyme activity in leaf chloroplasts, which protect the photosynthetic apparatus from excessive ROS accumulation. Therefore, this response can be considered beneficial, functioning as a form of priming that prepares plants to better withstand adverse environmental conditions. Notably, although the levels of antioxidant enzyme activity under drought conditions were nearly identical in plants of both studied genotypes, at the recovery period their activity in transformed plants returned to control levels more quickly than in wild-type plants.

This leads to at least two conclusions. First, the increase in proline content in transformed plants did not interfere with the functioning of other defense mechanisms under stress conditions. Second, it contributed to more effective homeostatic regulation of antioxidant systems following the cessation of the stressor. It can be assumed that in transformants, the antioxidant and chaperone effects of elevated proline levels facilitated the faster normalization of antioxidant enzyme activity to levels characteristic of non-treated plants. In contrast, drought caused more severe metabolic and structural damage in wild-type plants (as indirectly indicated by their significantly lower AN values (Fig. 3)) necessitating the sustained activity of antioxidant enzymes during the recovery period for effective repair.

The activity of SOD and APX enzymes in chloroplasts is also considered a part of an alternative electron transport pathway in the chloroplast ETC—the so-called water–water cycle (WWC), or Asada–Halliwell cycle—which serves regulatory and protective functions [52]. Similar to cyclic electron transport, the WWC helps protect photosystems from photodamage and increases the ATP synthesis rate relative to NADPH production. It is generally believed that under steady-state light condition, WWC activity remains low compared to the primary linear electron flow, even under stress conditions [53]. However, the relative activity and physiological significance of the WWC increase substantially under fluctuating light conditions, particularly during transitions from darkness or shade to bright light, when the rate of electron transport can temporarily exceed the demand for CO2 assimilation due to differences in induction kinetics [54]. Activation of the WWC during the transition from shading to bright light accelerates ATP synthesis, which in turn promotes increased activity of Rubisco activase and the synthesis of phosphorylated sugar intermediates in the Calvin–Benson cycle. Significant differences in the rate of light-induced photosynthesis during transitions from darkness to bright light have been observed among wheat varieties, under both optimal and stressful conditions [55]. Given that the plants in our experiments were grown under natural light and temperature conditions, it can be assumed that the drought-induced increase in SOD and APX activity in chloroplasts enhanced the induction of photosynthesis under fluctuating light and improved energy balance regulation within the chloroplasts.

A seven-day drought during the critical flowering period in wheat negatively affected the productivity of both genotypes. However, due to the aforementioned advantages of the photosynthetic apparatus in the leaves of the transformants, the impact was significantly less severe compared to the wild type (Table 1). Overall, the well-watered transformed plants showed a tendency to surpass the wild type in most productivity indices, although the differences were not always statistically significant. Nevertheless, this trend is noteworthy, given that in our pot experiment only mineral nutrition and soil moisture were controlled, while other important growth factors—such as light, air humidity, and especially temperature—were natural and not always optimal during the summer. It can be assumed that the greater stress tolerance of the transformed plants also contributed to this observed trend.

As previously noted, all indices of productivity per whole plant of the treated plants were lower than those of the control, except for the 1000-grain weight. This can be explained by a sharp decrease in grain number under drought conditions, largely due to a reduction in the number of productive shoots. Consequently, during the grain filling period—after the drought had ceased and the photosynthetic apparatus had recovered—the reduced number of grains per plant allowed for a better supply of assimilates to each grain, resulting in an increase in individual grain weight. Ultimately, the grain weight in transformed plants subjected to a seven-day drought during the flowering period was 29.1% higher than that in the treated wild-type plants.

Thus, it was established that drought significantly affected the physiological parameters of wheat flag leaves: relative water content, chlorophyll content, CO2 assimilation rate, and stomatal conductance all decreased, while the proline content and activity of antioxidant enzymes increased. At the same time, drought-treated transformed plants with RNAi-mediated suppression of ProDH exhibited improved responses to both the stressor and its after-effects across all studied parameters compared to the wild type. In particular, the relative water and chlorophyll contents in their leaves were affected to a much lesser extent. Although the photosynthetic rate under optimal soil moisture was nearly identical between the control wild-type and transformed plants, the reduction in this index under drought conditions was smaller in the transformants. As a result, the CO2 assimilation rate in the flag leaves of treated transformed plants was significantly higher than that of treated wild-type plants, both during drought and throughout the recovery period.

In transformed plants, the decrease in stomatal conductance at the onset of drought was significantly smaller relative to the control than in wild-type plants. Moreover, at the same level of stomatal conductance, the photosynthetic rate in the leaves of the transformants was higher than in the wild type. Consequently, the transformants exhibited greater water-use efficiency during photosynthesis under both drought conditions and during the recovery period following the restoration of optimal soil moisture.

At comparable levels of chloroplast antioxidant enzyme activity (SOD and APX) in both genotypes under stress conditions, the activity in the leaves of transformants returned to control values faster during the recovery period than in wild-type plants. This indicates that elevated proline content in the transformed plants contributed to more effective homeostatic regulation of antioxidant systems after the stressor was removed. The combined action of proline as an osmotically active substance and antioxidant promotes maintaining the functionality of structural and enzymatic systems in mesophyll cells under conditions of limited water availability.

A seven-day drought during the critical wheat flowering period negatively affected the productivity of plants in both genotypes. However, due to the enhanced stress tolerance of the photosynthetic apparatus in the leaves of transformed plants, the degree of this effect was significantly lower than in the wild type. The grain weight per plant in the drought-treated transformed plants was almost one-third higher than in the wild type.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The present study was conducted within the framework of the state budget research topic “Development of the scientific principles of creating high-productive varieties of cultivated plants with increased adaptive potential to adverse environmental conditions” No. 6541030 funded by the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Oleg O. Stasik, Dmytro A. Kiriziy and Oksana V. Dubrovna; data collection: Dmytro A. Kiriziy, Oleg O. Stasik, Oksana V. Dubrovna, Oksana G. Sokolovska-Sergiienko, Alina S. Holoboroda and Victor V. Rohach; analysis and interpretation of results: Dmytro A. Kiriziy, Oleg O. Stasik and Oksana V. Dubrovna; writing—original draft: Dmytro A. Kiriziy; writing—review & editing: Oleg O. Stasik. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: This research was conducted in accordance with the Law of Ukraine of 31 May 2007, No. 1103, “On the State Biosafety System for the Creation, Testing, Transportation, and Use of Genetically Modified Organisms”. The article does not contain any results of studies involving the use of animals as objects of study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Farooq M, Wahid A, Zahra N, Hafeez MB, Siddique KHM. Recent advances in plant drought tolerance. J Plant Growth Regul. 2024;43(10):3337–69. doi:10.1007/s00344-024-11351-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Kompas T, Che TN, Grafton RQ. Global impacts of heat and water stress on food production and severe food insecurity. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):14398. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-65274-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Neupane D, Adhikari P, Bhattarai D, Rana B, Ahmed Z, Sharma U, et al. Does climate change affect the yield of the top three cereals and food security in the world? Earth. 2022;3(1):45–71. doi:10.3390/earth3010004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Pequeno DNL, Hernández-Ochoa IM, Reynolds M, Sonder K, MoleroMilan A, Robertson RD, et al. Climate impact and adaptation to heat and drought stress of regional and global wheat production. Environ Res Lett. 2021;16(5):054070. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/abd970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Kiriziy D, Kedruk A, Stasik O. Effects of drought, high temperature and their combinations on the photosynthetic apparatus and plant productivity. In: Yastreb TO, Kolupaev YE, Yemets AI, Blume YB, editors. Regulation of adaptive responses in plants. Hauppauge, NY, USA: Nova Science Publishers; 2024. p. 1–33. doi:10.52305/TXQB2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Mehmood M, Khan ZA, Mehmood A, Zaynab M, ur Rahman MA, Al-Sadoon MK, et al. Impact of drought, salinity, and waterlogging on wheat: physiological, biochemical responses, and yield implications. Phyton. 2025;94(4):1111–35. doi:10.32604/phyton.2025.059812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Bapela T, Shimelis H, Tsilo TJ, Mathew I. Genetic improvement of wheat for drought tolerance: progress, challenges and opportunities. Plants. 2022;11(10):1331. doi:10.3390/plants11101331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Morgun VV, Stasik OO, Kiriziy DA, Sokolovska-Sergiienko OG, Makharynska NM. Effects of drought at different periods of wheat development on the leaf photosynthetic apparatus and productivity. Regul Mech Biosyst. 2020;10(4):406–14. doi:10.15421/021961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Senapati N, Stratonovitch P, Paul MJ, Semenov MA. Drought tolerance during reproductive development is important for increasing wheat yield potential under climate change in Europe. J Exp Bot. 2019;70(9):2549–60. doi:10.1093/jxb/ery226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Sadras VO, Richards RA. Improvement of crop yield in dry environments: benchmarks, levels of organisation and the role of nitrogen. J Exp Bot. 2014;65(8):1981–95. doi:10.1093/jxb/eru061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wasaya A, Manzoor S, Ahmad Yasir T, Sarwar N, Mubeen K, Ismail IA, et al. Evaluation of fourteen bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genotypes by observing gas exchange parameters, relative water and chlorophyll content, and yield attributes under drought stress. Sustainability. 2021;13(9):4799. doi:10.3390/su13094799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Khan S, Anwar S, Yu S, Sun M, Yang Z, Gao ZQ. Development of drought-tolerant transgenic wheat: achievements and limitations. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(13):3350. doi:10.3390/ijms20133350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. El-Mouhamady A, El-Hawary M, Habouh M. Transgenic wheat for drought stress tolerance: a review. Middle East J Agric Res. 2023;12(1):77–94. doi:10.36632/mejar/2023.12.1.7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Adel S, Carels N. Plant tolerance to drought stress with emphasis on wheat. Plants. 2023;12(11):2170. doi:10.3390/plants12112170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Dubrovna OV, Mykhalska SI, Komisarenko AG. Genetic modification of wheat to increase its drought tolerance. Cytol Genet. 2025;59(3):289–306. doi:10.3103/S009545272503003X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Alsamman AM, Bousba R, Baum M, Hamwieh A, Fouad N. Comprehensive analysis of the gene expression profile of wheat at the crossroads of heat, drought and combined stress. Highlights BioScience. 2021;4:1–14. doi:10.36462/H.BioSci.202104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Alagoz SM, Lajayer BA, Ghorbanpour M. Proline and soluble carbohydrates biosynthesis and their roles in plants under abiotic stresses. In: Plant stress mitigators. Cambridge, MA, USA: Academic Press; 2023. p. 169–85. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-89871-3.00027-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Jogawat A. Osmolytes and their role in abiotic stress tolerance in plants. In: Roychoudhury A, Tripathi D, editors. Molecular plant abiotic stress: biology and biotechnology. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2019. p. 91–104. doi:10.1002/9781119463665.ch5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Hossain A, Garai S, Mondal M, Hamed Abdel Latef AA. The key roles of proline against heat, drought and salinity-induced oxidative stress in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). In: Organic solutes, oxidative stress, and antioxidant enzymes under abiotic stressors. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2021. p. 171–90. doi:10.1201/9781003022879-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Meena M, Divyanshu K, Kumar S, Swapnil P, Zehra A, Shukla V, et al. Regulation of L-proline biosynthesis, signal transduction, transport, accumulation and its vital role in plants during variable environmental conditions. Heliyon. 2019;5(12):e02952. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Forlani G, Trovato M, Funck D, Signorelli S. Regulation of proline accumulation and its molecular and physiological functions in stress defence. In: Osmoprotectant-mediated abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2019. p. 73–97. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-27423-8_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Hosseinifard M, Stefaniak S, Ghorbani Javid M, Soltani E, Wojtyla Ł, Garnczarska M. Contribution of exogenous proline to abiotic stresses tolerance in plants: a review. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(9):5186. doi:10.3390/ijms23095186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ghosh UK, Islam MN, Siddiqui MN, Cao X, Khan MAR. Proline, a multifaceted signalling molecule in plant responses to abiotic stress: understanding the physiological mechanisms. Plant Biol. 2022;24(2):227–39. doi:10.1111/plb.13363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Dubrovna OV, Priadkina GO, Mykhalska SI, Komisarenko AG. Drought-tolerance of transgenic winter wheat with partial suppression of the proline dehydrogenase gene. Regul Mech Biosyst. 2022;13(4):385–92. doi:10.15421/022251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Dubrovna OV, Mykhalska SI, Komisarenko AG. Using proline metabolism genes in plant genetic engineering. Cytol Genet. 2022;56(4):361–78. doi:10.3103/S009545272204003X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Slivka LV, Dubrovna OV. Genetic transformation of promising genotypes of winter bread wheat by in planta method. Fakt Eksp Evol Org. 2021;28:106–11. doi:10.7124/FEEO.v28.1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. González L, González-Vilar M. Determination of relative water content. In: Handbook of plant ecophysiology techniques. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2006. p. 207–12. doi:10.1007/0-306-48057-3_14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Wellburn AR. The spectral determination of chlorophylls a and b, as well as total carotenoids, using various solvents with spectrophotometers of different resolution. J Plant Physiol. 1994;144(3):307–13. doi:10.1016/S0176-1617(11)81192-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Bates LS, Waldren RP, Teare ID. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil. 1973;39(1):205–7. doi:10.1007/BF00018060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Busch FA, Ainsworth EA, Amtmann A, Cavanagh AP, Driever SM, Ferguson JN, et al. A guide to photosynthetic gas exchange measurements: fundamental principles, best practice and potential pitfalls. Plant Cell Environ. 2024;47(9):3344–64. doi:10.1111/pce.14815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Giannopolitis CN, Ries SK. Superoxide dismutases: I. occurrence in higher plants. Plant Physiol. 1977;59(2):309–14. doi:10.1104/pp.59.2.309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Chen GX, Asada K. Ascorbate peroxidase in tea leaves: occurrence of two isozymes and the differences in their and molecular properties. Plant Cell Physiol. 1989;30(7):987–98. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a077844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Kolupaev YE, Yastreb TO, Ryabchun NI, Kokorev AI, Kolomatska VP, Dmitriev AP. Redox homeostasis of cereals during acclimation to drought. Theor Exp Plant Physiol. 2023;35(2):133–68. doi:10.1007/s40626-023-00271-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zulfiqar F, Ashraf M. Proline alleviates abiotic stress induced oxidative stress in plants. J Plant Growth Regul. 2023;42(8):4629–51. doi:10.1007/s00344-022-10839-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Liang X, Zhang L, Natarajan SK, Becker DF. Proline mechanisms of stress survival. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19(9):998–1011. doi:10.1089/ars.2012.5074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Qamar A, Mysore KS, Senthil-Kumar M. Role of proline and pyrroline-5-carboxylate metabolism in plant defense against invading pathogens. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:503. doi:10.3389/fpls.2015.00503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Kolupaev YE, Karpets YV, Kabashnikova LF. Antioxidative system of plants: cellular compartmentalization, protective and signaling functions, mechanisms of regulation (review). Appl Biochem Microbiol. 2019;55(5):441–59. doi:10.1134/S0003683819050089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Arora D, Jain P, Singh N, Kaur H, Bhatla SC. Mechanisms of nitric oxide crosstalk with reactive oxygen species scavenging enzymes during abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Free Radic Res. 2016;50(3):291–303. doi:10.3109/10715762.2015.1118473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Kolupaev YE, Karpets YV, Yastreb TO, Shemet SA, Bhardwaj R. Antioxidant system and plant cross-adaptation against metal excess and other environmental stressors. In: Landi M, Shemet SA, Fedenko VS, editors. Metal toxicity in higher plants. Hauppauge, NY, USA: Nova Science Publishers; 2020. p. 21–66. [Google Scholar]

40. Stasik OO, Kiriziy DA, Sokolovska-Sergiienko OG, Bondarenko OYu. Influence of drought on the photosynthetic apparatus activity, senescence rate, and productivity in wheat plants. Fiziol Rast Genet. 2020;52(5):371–87. doi:10.15407/frg2020.05.371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Wang Y, Wang Y, Tang Y, Zhu XG. Stomata conductance as a goalkeeper for increased photosynthetic efficiency. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2022;70:102310. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2022.102310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Nunes TDG, Zhang D, Raissig MT. Form, development and function of grass stomata. Plant J. 2020;101(4):780–99. doi:10.1111/tpj.14552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Lawson T, Matthews J. Guard cell metabolism and stomatal function. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2020;71:273–302. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-050718-100251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Pyo L, Kim C. Photosynthetic ROS and retrograde signaling pathways. New Phytol. 2024;244(4):1183–98. doi:10.1111/nph.20134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Condon AG. Drying times: plant traits to improve crop water use efficiency and yield. J Exp Bot. 2020;71(7):2239–52. doi:10.1093/jxb/eraa002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Bertolino LT, Caine RS, Gray JE. Impact of stomatal density and morphology on water-use efficiency in a changing world. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:225. doi:10.3389/fpls.2019.00225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Isgandarova TY, Rustamova SM, Aliyeva DR, Rzayev FH, Gasimov EK, Huseynova IM. Antioxidant and ultrastructural alterations in wheat during drought-induced leaf senescence. Agronomy. 2024;14(12):2924. doi:10.3390/agronomy14122924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Lopez MA, Xavier A, Rainey KM. Phenotypic variation and genetic architecture for photosynthesis and water use efficiency in soybean (Glycine max L. merr). Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:680. doi:10.3389/fpls.2019.00680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. de Carvalho K, de Campos MKF, Domingues DS, Pereira LFP, Vieira LGE. The accumulation of endogenous proline induces changes in gene expression of several antioxidant enzymes in leaves of transgenic Swingle citrumelo. Mol Biol Rep. 2013;40(4):3269–79. doi:10.1007/s11033-012-2402-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Foyer CH, Hanke G. ROS production and signalling in chloroplasts: cornerstones and evolving concepts. Plant J. 2022;111(3):642–61. doi:10.1111/tpj.15856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Morgun VV, Stasik OO, Kiriziy DA, Sokolovska-Sergiienko OG. Effect of drought on photosynthetic apparatus, activity of antioxidant enzymes, and productivity of modern winter wheat varieties. Regul Mech Biosyst. 2019;10(1):16–25. doi:10.15421/021903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Endo T, Asada K. Photosystem I and photoprotection: cyclic electron flow and water-water cycle. In: Photoprotection, photoinhibition, gene regulation, and environment. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer Netherlands; 2008. p. 205–21. doi:10.1007/1-4020-3579-9_14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Walker BJ, Kramer DM, Fisher N, Fu X. Flexibility in the energy balancing network of photosynthesis enables safe operation under changing environmental conditions. Plants. 2020;9(3):301. doi:10.3390/plants9030301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Sun H, Yang YJ, Huang W. The water-water cycle is more effective in regulating redox state of photosystem I under fluctuating light than cyclic electron transport. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2020;1861(9):148235. doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2020.148235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Kedruk АS, Kiriziy DA, Stasik OO, Sokolovska-Sergiienko ОG, Tarasiuk MV. Effects of drought on photosynthetic induction in leaves of different wheat genotypes under dark-to-light transition. Regul Mech Biosyst. 2024;15(3):504–13. doi:10.15421/022471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools