Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Selection of Conservation Practices in Different Vineyards Impacts Soil, Vines and Grapes Quality Attributes

1 Department of Agricultural Sciences, Biotechnology and Food Science, Cyprus University of Technology, Limassol, 3036, Cyprus

2 Malia Winery-KEO, Limassol, 4777, Cyprus

* Corresponding Authors: Antonios Chrysargyris. Email: ; Nikolaos Tzortzakis. Email:

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2026, 95(1), 1 https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2026.076565

Received 22 November 2025; Accepted 25 December 2025; Issue published 30 January 2026

Abstract

Cyprus has an extensive record in grape production and winemaking. Grapevine is essential for the economic and environmental sustainability of the agricultural sector, as it is in other Mediterranean regions. Intensive agriculture can overuse and exhaust natural resources, including soil and water. The current study evaluated how conservation strategies, including no tillage and semi-tillage (as a variation of strip tillage), affected grapevine growth and grape quality when compared to conventional tillage application. Two cultivars were used: Chardonnay and Maratheftiko (indigenous). Soil pH decreased, and EC increased after tillage applications, in both vineyards. Tillage lowered soil N levels through mineralization, but the vineyard with Maratheftiko cultivar had higher soil N and K levels than the vineyard with Chardonnay cultivar. No tillage reduced yield in Chardonnay; however, semi-tillage enhanced yield in Maratheftiko. There were no major changes in plant physiology, even though Maratheftiko had less variation in stomatal conductance values under the various tillage practices than Chardonnay. Tillage enhanced N and K content in Chardonnay vines during flowering, and increased N in Maratheftiko. Total phenols and antioxidant status of leaves varied, with tillage stimulating them, especially at the harvest stage. Furthermore, tillage raised grape juice total soluble solids, pH, and total phenols in both cultivars, while anthocyanins and tannins content were increased in Maratheftiko under no tillage. The results of this study may aid in the development of cultivation strategies to enable viticulture to address various environmental challenges due to climate change.Keywords

One of the most valuable natural resources is soil; therefore, protecting it is crucial as climate change progresses [1,2]. An estimated 12% of European soils are subjected to significant water erosion and soil deterioration resulting from intensive agriculture [3]. Soil losses due to erosion greatly exceed the natural rate of soil formation [4]. Conservation agriculture is one of the most effective systems recently adopted to combat soil erosion and desertification, with sustainable, cost-effective and water-saving management practices [5,6] and biological resources combined with external inputs [7]. It has been reported that soil and water conservation techniques can reduce runoff by 50–70% and soil losses by 70–95%, depending on the specific practices and environmental conditions [8,9]. According to the Conservation Tillage Information Center (CTIC) [10], conservation tillage is defined as any tillage strategy that leaves at least 30% of the soil surface covered with crop residue after planting, thereby reducing water erosion. However, it does not always provide sufficient protection against soil erosion and waste conservation [7]. Conservation tillage, as opposed to traditional tillage, is a farming practice that reduces soil disturbance and promotes soil health [11,12]. Conservation tillage includes practices such as reduced tillage, ridge-tillage, strip tillage, mulching, and no tillage with various advantages and limitations [3,13]. According to Kertész and Madarasz [14], conservation tillage was practiced on 22.7 million hectares (26% of arable lands) in Europe in 2010, while Kassam et al. [5] stated that it has been expanded to nearly 200 million hectares globally.

Several studies have demonstrated the advantages of no tillage or reduced tillage in reducing soil erosion and alleviating soil compaction compared to conventional tillage [3,15,16]. Other studies under conservation tillage have highlighted its efficacy in terms of crop yield [17,18], improvement of soil organic carbon (C) and nitrogen (N) [6,19] and enhancement of soil water retention capacity and water use efficiency [20].

Strip tillage is a common conservation practice that minimizes soil disturbance within the sowing strip while leaving the inter-row areas of the field undisturbed [13]. Additionally, this method can reduce tillage costs by up to 43% and 47% [21]. A variation of the strip tillage might include the application of tillage in every second row, by reducing the tillage area up to 50%. This application is often called semi-tillage. However, the impact on crop yield and soil health varies depending on the area, cultivation practices, tested cultivars, and relies on soil and climate conditions, in comparison to conventional and no tillage [13]. In Cyprus, conservation agriculture has been documented only recently (post 2016) and occupies approximately 270 ha [5]. Indeed, there is a growing interest in sustainable and environmentally friendly agricultural practices across the island.

Grapevine is one of the most cultivated fruit crops globally, grown in dry or semi-arid settings. Due to climate change constraints, conservation tillage practices are important to be explored and applied to vineyards, to promote soil health and conserve natural resources. Sustainable cropping systems, cultivation techniques and management using various soil tillage methods in semi-arid vineyards are being investigated to reduce production costs and energy consumption, while also influencing soil water availability. Reduced (semi-tillage or decreased applications) and soil conservation tillage (no tillage) have gained popularity as alternatives to traditional soil tillage [22]. No tillage systems in vineyards have become more widespread recently due to their effectiveness in reducing soil erosion [2], minimizing dust formation [23], managing soil greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [24], and supporting biological control management [25].

According to Pérez-Bermúdez et al. [26], tillage affects the distribution of soil pores and the availability of water and oxygen for roots and microbes, factors that contribute to organic matter degradation and soil fertility. Conversely, tillage and irrigation are necessary for vines to absorb nutrients [27]. Early spring tillage at a greater depth (e.g., 0.25 m) reduces soil water availability for the vines by increasing evaporation losses as soil from deeper parts is exposed to the sun. In contrast, tillage in low depth (<0.10 m) may impact the micropores in warmer months, affecting water movements [28].

Native cultivars, which are well-adapted to local environmental conditions, have evolved stress-resistance mechanisms that are often linked to hormonal changes such as abscisic acid production [29]. These mechanisms serve as the primary signalling channel in drought-stressed plants, controlling stomatal closure [30]. Recent research suggests that stomatal conductance is primarily influenced by hydraulic signals, abscisic acid, and/or their interplay with regards to drought stress [31,32]. Tillage is the primary agricultural practice in Cypriot vineyards, with 2–3 applications each year to eliminate ground weed cover and decrease any antagonism for water and minerals by the weeds and the main crop. More recently, growers have allowed natural vegetation to grow between rows as an effort to reduce cultivation costs and to adopt more environmentally friendly practices.

The current research aimed to examine the impacts of conservation (no tillage or semi-tillage) versus tillage cultivation practice on two commercial vineyards with Chardonnay (international) and Maratheftiko (indigenous) cultivars, and compare the effects of the applied cultivation practices. The study included evaluation of soil physicochemical characteristics, vine growth, yield and grape quality during the cultivation period. The present research is related to a specific region and climate in Cyprus.

2.1 Experiment Layout and Cultivars

The experiment was conducted at the Malia winery commercial vineyards (34°48′58.08″ Ν, 32°46′17.18″ Ε and 645 m a.s.l. elevation) in Limassol, Cyprus. The experiment began in late January 2020 with vine pruning and concluded in September, when the grapes were harvested, and soil samples were collected. Two self-rooted grapevine cultivars were used, Chardonnay and Maratheftiko. Chardonnay is an international white grape cultivar, sensitive to water shortage [33]. The Chardonnay plants were 23-year-old own-rooted grapevines, and the vineyard was 0.69 ha. Maratheftiko is the most prominent Cypriot indigenous red cultivar marketed in the island, known for its drought resistance. However, it lacks hermaphrodite flowers and requires co-planting with other varieties (i.e., Spourtiko-white variety) to achieve fruit set and development [34]. Maratheftiko plants were 14-year-old own-rooted grapevines, and the vineyard was roughly 0.62 ha.

The cultivars were selected based on their popularity in Cyprus and the proximity of the commercial fields. The two vineyards were located only 0.7 km apart, and experienced similar environmental conditions (from May till September; dry climate with mean rainfall 15.9 mm, average min, mid and max temperatures of 16.02°C, 23.4°C, and 40.7°C; mean relative humidity 43.8%). Considering the soil texture, it was a clay soil in Chardonnay with 48.56% clay, 32.39% sand and 19.05% silt, and a clay-loam soil in Maratheftiko with 39.08% clay, 41.34% sand and 19.58% silt. Standard cultivation practices in these commercial vineyards include the application of tillage two-to-three times per year, application of synthetic fertilizer (15-15-15 for N, P and K needs), irrigation two times during the summer period to manage heat stress and water shortage, and common pest management practices (sulphur and insecticides with 3–4 applications yearly). The vines were trained as a traditional bilateral ‘royat’ system, having two horizontal arms with spurs growing from each arm, as described previously [34]. Plant density was 2600 plants/ha, with 1.5 m in rows oriented north-south and 2.5 m in between. However, in the present research, vines were drip-irrigated from the end of May, every 15–20 days, and irrigation events were based on soil water content measures with a field-scout TDR300 with 0.2 m rods (Spectrum Technologies Inc., Aurora, IL, USA), targeting to a volumetric water content-VWC of 20–30%, as reported in prior studies [34].

Before starting the experiment, the soil was tilled following standard practice from the previous year, as is common in commercial vineyards. Three cultivation practices were examined, as (i) no tillage—NTi, (ii) semi-tillage—STi and (iii) tillage-Ti with four replicate plots for each treatment and each cultivar. Each treatment consisted of four plots distributed across two distinct rows (2 individual plots in each row, with 5 vines in each plot, for a total of 20 vines in each treatment). A single guard row was placed between treatments to prevent treatment interference. In the case of Chardonnay, the guard row consisted of Chardonnay cultivar, whereas in case of Maratheftiko the guard row was Spourtiko cultivar, which is necessary for flower fertilization. The guard rows were not included in any measurements. In the no tillage treatments, natural vegetation was allowed to develop throughout the entire growing season. In the semi-tillage treatment, soil was tilled in every second vine row. In tillage treatment, soil in each row was tilled, and tillage (depth 0.15–0.20 m) took place two times (early March and end of May) during the growing period, eliminating all natural vegetation.

In May, samples of natural vegetation were taken. Using four samples per treatment, all vegetative soil cover biomass inside a 1 m2 square quadrat (one quadrat per plot) was eliminated. Squares were chosen at random. Natural vegetation fresh and dry weight (kg), total nitrogen (g/kg), organic matter (%), and the percentage of land covered by natural vegetation per m2 were all determined.

2.3 Soil Physicochemical Characteristics

Soil physicochemical characteristics were determined during the three plant developmental stages (flowering-May, veraison-July and harvesting-September) for both vineyards. Soil samples (four soil cores per plot, were bulked and considered as a replicate) were collected from four replicate plots per treatment and cultivar, with sampling to be 0.15–0.2 m distance from the plants and 0.2 m in depth. Samples were air-dried, sieved (2 mm), and analyzed. Calcium carbonate (CaCO3) was determined with the use of the Bernard calcimetry method, and results were expressed as a percentage. The Walkley-Black technique was used to assess organic matter, and the findings were reported as a percentage [35]. The paste method was used to measure pH and electrical conductivity (EC). After extraction, phosphorus (P) was determined using the Olsen sodium bicarbonate method spectrophotometrically, and potassium (K) and sodium (Na) content were measured by employing a flame photometer (Lasany Model 1832, Lasany International, Pachkula, India). Mineral content was expressed as grams per kilogram of dry weight (g/kg DW). Nitrogen (N) content was determined by the Kjeldahl method (BUCHI, Digest automat K-439 and Distillation Kjelflex K-360, Switzerland). The soil texture (percentage of sand, silt and clay) was determined only once with a hydrometer (Bouyoucus methods), at flowering stage in each vineyard, since this parameter is not expected to change within couple of months, during the experimental implementation.

2.4 Plant Growth, Yield and Physiological Attributes

Plant physiology and photosynthesis attributes were determined at the three phenological phases (flowering, veraison and harvesting) with four replicates per treatment. Leaf stomatal conductance was measured on the 5th sun-exposed leaf from the top of the plant (2 measures per leaf) with a ΔT-Porometer AP4 (Delta-T Devices-Cambridge, UK) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. In the same leaves used for stomatal conductance measurements, chlorophyll fluorescence was measured (highest Fv/Fm photochemical quantum yield of PSII) with an OptiSci OS-30p Chlorophyll Fluorometer (Opti-Sciences). Moreover, leaf samples (four replications/treatment) were used for chlorophyll extraction with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Photosynthetic pigments, such as chlorophyll a (Chl a), chlorophyll b (Chl b) and total chlorophyll (total Chl) contents were computed as previously reported [36] and the ratio of Chl a:Chl b was computed.

During harvesting (late-August for Chardonnay, mid-September for Maratheftiko), the number of clusters per plant, the cluster fresh weight (g) and the yield (ton/ha) were measured in four replicates (each replicate had three plants) per treatment for each cultivar.

2.5 Total Phenols Content and Antioxidant Capacity in Leaves

Total phenols and antioxidant activity in leaves (six replications; each replication was a poll of three to four leaves) were measured throughout flowering, veraison and harvesting phases, as described previously [37]. The total phenols content was assayed with the Folin–Ciocalteu method at 755 nm [37]. The antioxidant capacity assayed with the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) and 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) (ABTS) methods.

The nutrient content of petiols was measured at flowering and at veraison phases. Minerals were extracted from around 100 leaf stems (four replicates per treatment) that were dried at 65°C [37]. Nitrogen, K, Na and P determined [37], while magnesium (Mg) determined by an atomic absorption spectrophotometer (PG Instruments AA500FG, Leicestershire, UK).

2.7 Berries Qualitative Characteristics

When the sugar content reached about 24 oBrix, berries were collected according to their ripening stage. To avoid dehydration in the field, the collected berries −100 from each of the four plots/treatments- were transported to the lab in less than 40 min. Berries from every treatment were weighed in the lab before being frozen and kept at −20°C until analysis or utilized for measurements.

Total soluble solids-TSS, titratable acidity-TA and pH were determined based on the International Organization of Vine and Wine method [38] and ascorbic acid (AA), total phenols, total anthocyanins and tannins based on Chrysargyris et al. [34] study.

Results were statistically analysed with the IBM SPSS version 29, performing one way-ANOVA and Duncan’s multiple range tests for comparing treatments at p < 0.05, for each cultivar. Four to six biological replicates/treatment (each replicate was a pool of three individual measures/samples) were measured. The pairwise metabolite effect correlations were calculated by Pearson’s correlation test using the R program (R version 3.6.2; 11 December 2019).

3.1 Vineyards Soil Physicochemical Properties

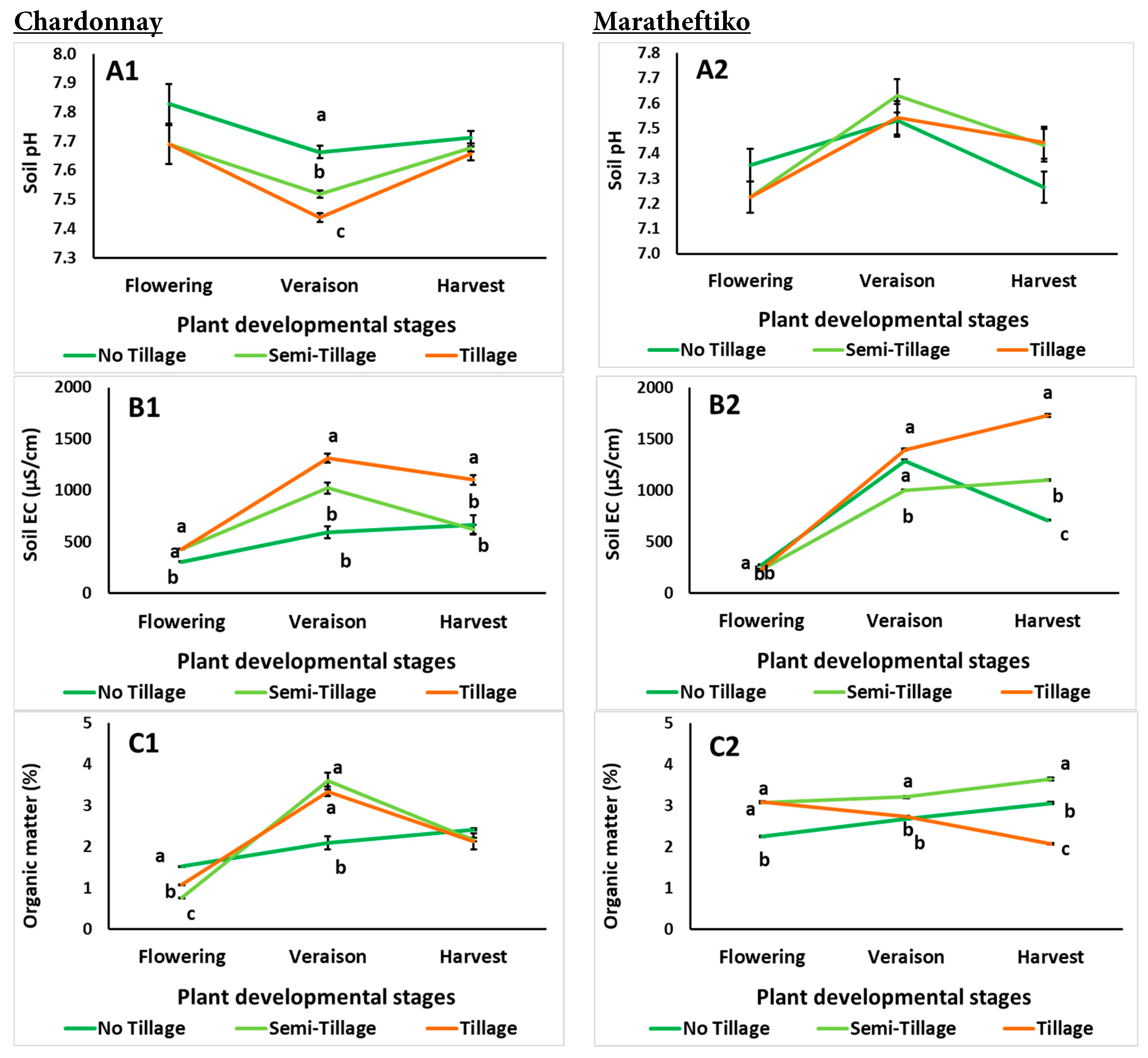

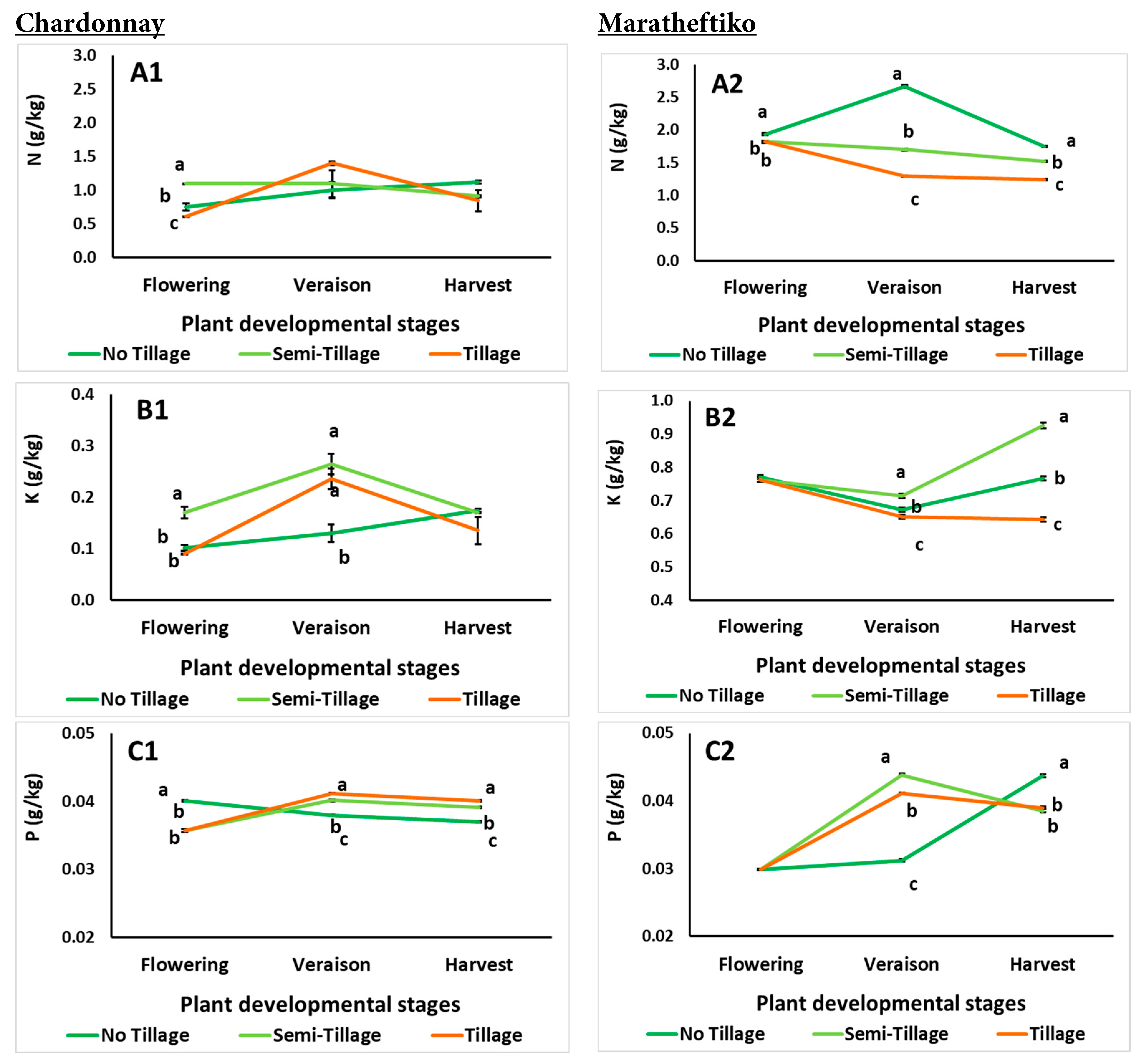

Soil physicochemical properties from the Chardonnay and Maratheftiko commercial vineyards were examined during the three main plant developmental stages—flowering, veraison and harvesting. For Chardonnay vineyard, analysis indicated that soil pH and total CaCO3 were significantly higher following no tillage practice compared to the ones obtained with semi tillage and tillage, at the veraison stage (Fig. 1(A1,D1)). Soil EC was increased with the application of tillage as it was evidenced from the flowering (up to 39.3%) to veraison (up to 120%), and harvesting (up to 65.7%) stages (Fig. 1(B1)). Tillage and semi-tillage practices resulted in increased organic matter content (up to 72.6%) in soil at the veraison stage (Fig. 1(C1)).

In the case of Maratheftiko, tillage increased (up to 143%) the soil EC during the plant growing period (Fig. 1(B2)) while no differences were found in soil pH averaged in 7.40 among the treatments (Fig. 1(A2)). Increased organic matter content (up to 75% and 47.1%) was found after the semi-tillage application, followed by no tillage application, respectively, at harvesting period (Fig. 1(C2)), while decreased total CaCO3 content was found in semi-tillage treated soils (Fig. 1(D2)).

Figure 1: Effects of cultivation practice (no-tillage, semi-tillage and tillage) on soil physicochemical characteristics on Chardonnay and Maratheftiko vineyards. (A1,A2) soil pH, (B1,B2) soil electrical conductivity (EC: μS/cm), (C1,C2) organic matter content (%) and (D1,D2) total CaCO3 (%). Measurements were made during the three plant developmental stages (flowering, veraison and harvesting). Significant differences (p < 0.05) among treatments are presented with different letters for each stage, based on Duncan’s multiple range tests. Error bars show SE (n = 4). No lettering indicating not significant.

Long term no tillage application, has been shown that can improve the organic carbon storage in soil [39]. However, such changes could not be observed in the present study, due to the short duration growing period, as organic C (derived from organic matter) did not accumulate in soil at the no tillage applications. Increased organic matter content can preserve soil erosion and improve soil fertility [26]. Previous reports have indicated that conservation tillage can decrease soil pH [40], an effect attributed to increased NH4+-N release in soil. However, the pH decrease was not evidenced in the present study for the tested vineyards at no tillage application, most probably due to different soil textures, duration of the research and/or examined plant species among the different studies. Busari et al. [41] reported that tillage may not have a direct impact on soil pH; rather, its impacts will vary depending on soil’s type, management practices, and current climate. Indeed, the pH fluctuation during the growing period was varied in Chardonnay and in Maratheftiko vineyards, and this can also be attributed to their specific soil microbiome profile [42]. In a previous report by the authors, it has been proven the negative correlation of soil pH with Maratheftiko cultivar under water shortage conditions [42].

The EC reflects the capacity of soil water to conduct electrical current. Thus, EC may be used to quantify soil salinity. Soil EC increased over the growing season likely due to elevated evaporation during the hot, dry summer in Cyprus, causing salt accumulation in the soil’s top layers [43]. Soils with natural vegetation seem to preserve the increase of EC, but the final effects are also depended on the grapevine cultivar and mineral needs. This aspect should be considered to minimize saline issues in soils, and a portion of the irrigation dosage should be utilized to remove salt from the soil’s deeper levels.

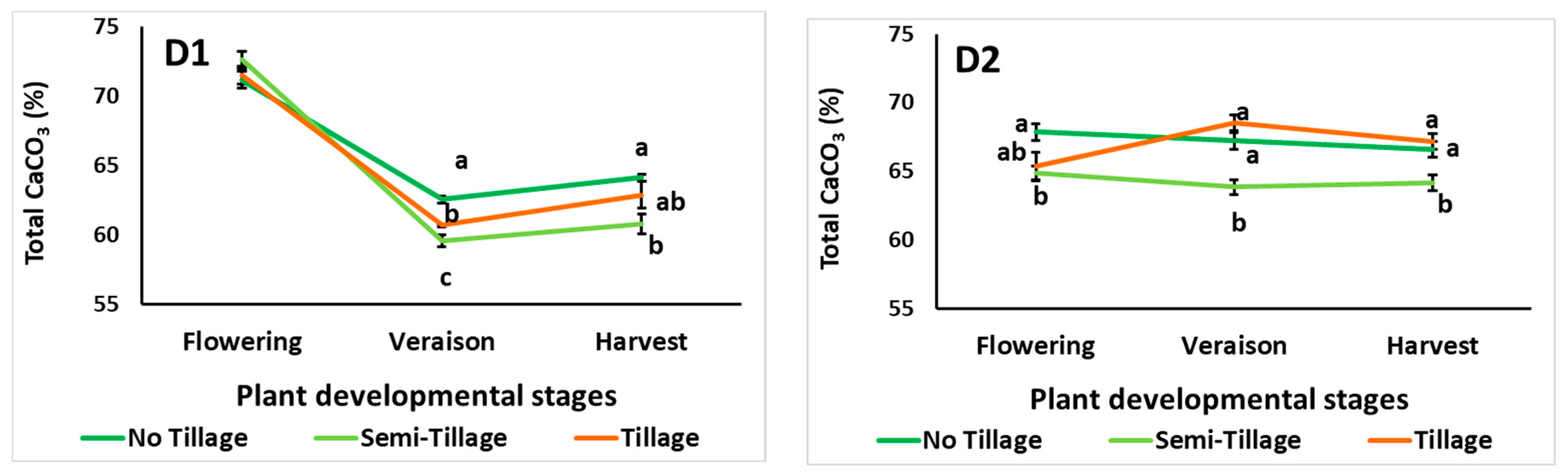

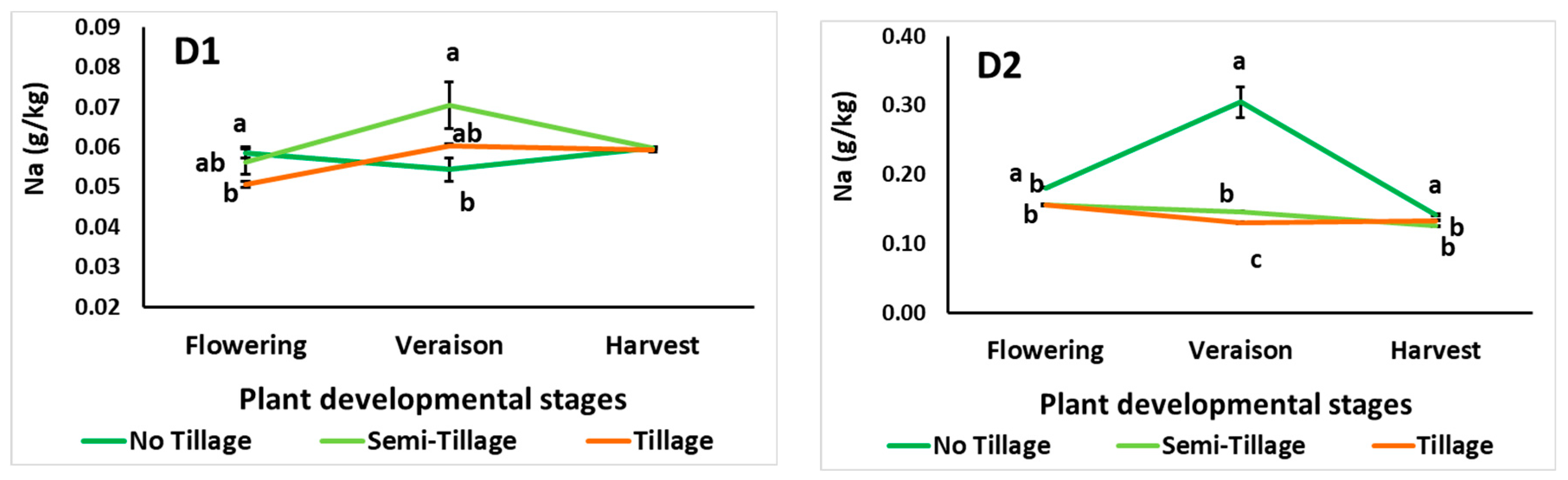

Mineral content in soil affected by the cultivation practices, cultivar and growing period for both Chardonnay and Maratheftiko (Fig. 2). In Chardonnay, N content was high in semi-tilled soil at the flowering stage (Fig. 2(A1)), K content was increased in semi-tilled and tilled soils during the flowering and veraison stages (Fig. 2(B1)). Phosphorus content was initially higher at no-tilled soil at the flowering stage but decreased at veraison and harvesting stages when compared to semi-tilled and tilled soils (Fig. 2(C1)). Sodium fluctuated among the treatments with not clear tendency/effect (Fig. 2(D1)). For Maratheftiko, no tillage practice resulted in higher N and Na content in soil compared to semi-tillage and tillage applications (Fig. 2(A2,D2)), whereas soil K content was increased after the semi-tillage application (Fig. 2(B2)). Decreased P levels were found in no-tilled soils at the veraison stage compared to semi-tilled and tilled soils, however, this was reversed at the harvesting stage (Fig. 2(C2)).

Soil tillage impacts the breakdown and mineralization of nitrogen from crop residues and existing sources, affecting the inorganic N pool accessible to grapevines [44]. This can possibly justify the decreased N levels obtained in soil after the tillage application, which is in accordance with prior reports on spring wheat when subjected to different conservation tillage strategies [40]. In a previous report by the authors, it has been proven the increased content of N and K in Maratheftiko compared to other indigenous (Xynisteri) or international (Chardonnay) cultivars [42]. Furthermore, the quantity of K and N in the soil accessible for absorption rises throughout the growing season, although P levels often stay steady [45]. Considering the K and N levels in soil, both of them are more prevalent in clay soils than the P, and this is related to their greater mobility in soil [46]. Overall, soil management, cultivation period, and phenological phase were affected the soil chemical properties [47].

Figure 2: Effects of cultivation practice (no-tillage, semi-tillage and tillage) on soil mineral content on Chardonnay and Maratheftiko vineyards. (A1,A2) nitrogen-N, (B1,B2) potassium-K, (C1,C2) phosphorus-P, (D1,D2) sodium-Na content (g/kg). Measurements were made during the three plant developmental stages (flowering, veraison and harvesting). Significant differences (p < 0.05) among treatments are presented by different letters for each stage, based on Duncan’s multiple range tests. Error bars show SE (n = 4). No lettering indicating not significant.

For Chardonnay vineyard, the natural vegetation occupied the 48.1% of soil surface, with the main species identified were Poaceae (Avena sp., Bromus sp. and Lolium sp.), Malvaceae (Malva sp.), Asteraceae (Sonchus sp.), Fabaceae (Medicago sp.), Papaveraceae (Papaver sp.), and Brassicaceae (Hirschfeldia incana). Total biomass weight was 0.78 kg/m2 for the no-tilled soils having 40.3% dry matter content. The organic matter and total N content were 90.95% and 12.05 g/kg, respectively. In the Maratheftiko vineyard, the natural vegetation occupied 57.6% of the surface soil, and the main species were Poaceae (Aegilops sp., Bromus sp.), Brassicaceae (H. incana, Capsella bursa-pastoris), Malvaceae (Malva sp.), Asteraceae (Sonchus sp.), and Fabaceae (Medicago sp.). Total biomass weight was 0.813 kg/m2 for the no-tilled soils having 40.5% dry matter content. The organic matter and total N content were 92.38% and 11.89 g/kg, respectively. The increased dry matter content observed from the harvested biomass was related to some woody species involved in the sampling plots. Overall, in both vineyards, the organic matter levels and total N were in similar levels that could contribute to the additional mineral input in a long-term time, after decomposition of the organic matter. The observed plant species in the present study are frequently appear in vineyards and olive-groves and constitute a multispecies natural vegetation [48]. It is also important to consider that natural vegetation might compete the main crop (i.e., grapevines) with minerals and water, and possible additional fertilization and irrigation efforts might be needed, in order to avoid any antagonistic evidence among grapevines and natural vegetation.

3.3 Plant Growth and Physiology

Cultivation practices affected mainly the grapevine yield rather than the cluster number produced and their relevant fresh weight (Table 1). In Chardonnay, plant yield increased up to 54% with tillage compared to no tillage application, while increased tendency for cluster fresh weight and number was evidenced for the tillage treatment. In Maratheftiko, the tillage application increased yield (up to 44.7%) in semi-tillage treatment compared to the no tillage application (Table 1).

The number of cluster and mean fresh weight were in similar levels after tillage and no tillage application in two cultivars [49], being in agreement with the current results. Similar observations were reported for the Portuguese native grapevine Trincadeira cultivar, following tillage, no tillage and cover crop practices [50]. Additionally, in the same study it was mentioned that cluster number and yield can vary within different years. The impact of cover crops in vineyards varies. It has been reported that cover crops may decrease vegetation with more profound yield losses in warmer areas, with indirect negative impacts on grape quality [49]. Other reports showed no effect [51] or even increased yield when grapevines were intercropped with annual species [52,53]. In the present research, plant yield was increased with soil tillage in Chardonnay or with soil semi-tillage in Maratheftiko. However, these impacts on yield might change after a multiyear application of natural vegetation or cover crops, as their rooting system can interact with the vines roots.

Short-term no tillage application decreased maize yield and this economic losses render no tillage less popular to be adapted by the farmers [54], while strip tillage application increased maize yield [55]. Therefore, intermediate solutions such as semi-tillage might be more favorable and economically efficient, combining the advantages of the no tillage and tillage practices. In the present study, semi-tillage applications resulted in similar (in case of Chardonnay) or higher (in case of Maratheftiko) yield than no tillage, depending on the cultivar examined and its adaptation to the semi-arid conditions. This is in line with the adaptation of Maratheftiko to semi-arid climatic conditions with increased heat stress evidence and impacts plant physiological performance [42]. Prior reports indicated that in mature vineyards, the cover crop presence or no tillage (natural vegetation) application did not affect grapevine yield due to less competition among the crops and the well-established root system of the grapevines [47]. This could be a cultivation strategies of introduction cover crops in mature vineyards to maintain yield and grape quality [49].

Table 1: Effects of cultivation practice (no-tillage, semi-tillage and tillage) on Chardonnay and Maratheftiko cultivars on the number of clusters per plant, cluster fresh weight (FW; g) and yield (ton/ha).

| Clusters Number | Clusters FW | Yield | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chardonnay | No tillage | 18.97 ± 1.84 | 144.97 ± 12.53 | 7.05 ± 0.77b |

| Semi-tillage | 20.04 ± 1.68 | 164.77 ± 9.24 | 8.77 ± 1.04ab | |

| Tillage | 23.80 ± 1.06 | 177.45 ± 15.73 | 10.86 ± 1.20a | |

| Maratheftiko | No tillage | 27.98 ± 3.43 | 133.94 ± 15.59 | 9.68 ± 1.21b |

| Semi-tillage | 34.07 ± 3.22 | 169.74 ± 2.39 | 14.01 ± 1.14a | |

| Tillage | 26.36 ± 3.17 | 164.44 ± 20.51 | 10.51 ± 1.71b |

In Chardonnay, leaf stomatal conductance decreased after tillage practice at flowering and veraison stages, but increased at harvesting stage (Fig. 3(A1)). Chlorophyll fluorescence was not affected by the cultivation practice and plant growth stage, as averaged in Fv/Fm 0.71 (Fig. 3(B1)). In Maratheftiko, both leaf stomatal conductance and chlorophyll fluorescence were decreased at harvesting stage in vines grown in tilled soil (Fig. 3(A2,B2)). A few studies have looked at the effects of soil tillage on grapevine physiology when natural vegetation is present. It has been reported that soil tillage might have little effect on grapevine stomatal conductance and net photosynthesis [41], being in accordance to the present observations, as stomatal conductance was decreased at flowering and veraison stages but recovered at the harvesting stage for Chardonnay or had mimic effects on Maratheftiko. Several studies reported negligible effects of tillage on leaf gas exchange [49,56], highlighting the leaf photosynthetic performance, as it was observed with the negligible or not differences on the Fv/Fm values in Chardonnay and in most cases in Maratheftiko. However, more insights can be observed when the cultivars are evaluated for their potential genetic, morphological and root system differences. Prior report in Chardonnay and in Maratheftiko soil microbiome profile support the differences among the cultivars and their adaptation to semi-arid climate [42].

Figure 3: Effects of cultivation practice (no-tillage, semi-tillage and tillage) on Chardonnay and Maratheftiko cultivars on (A1,A2) leaf stomatal conductance (mmol/m2/s) and (B1,B2) leaf chlorophyll fluorescence (Fv/Fm). Evaluation was made in three plant developmental stages (flowering, veraison and harvesting). Significant differences (p < 0.05) among treatments are presented with different lettering, based on Duncan’s multiple range tests. Error bars show SE (n = 6). ns: not significant.

Chlorophylls content was mainly affected during flowering and veraison stages for Chardonnay (Fig. 4(A1–D1)) or throughout the whole growing period for Maratheftiko (Fig. 4(A2–D2)). In Chardonnay, chlorophylls were increased at semi-tillage application at flowering stage and at no tillage at the veraison stage (Fig. 4(A1–C1)). Increased Chl a:Chl b ratio was found with semi-tillage and tillage applications at the veraison stage (Fig. 4(D1)). In Maratheftiko, chlorophylls content ranged among the examined treatments, with no clear trend (Fig. 4(A2–C2)), while increased Chl a:Chl b ratio was found with tillage applications at harvesting stage (Fig. 4(D2)). Chl b is converted to Chl a by the degradation of chlorophylls [57]; which can explain the lower chlorophyll content and higher Chl a:Chl b ratios observed in plants subjected in tillage. Plants that are less stressed can devote more resources to chlorophyll synthesis rather than stress responses, resulting in greater chlorophyll content [58].

Figure 4: Effects of cultivation practice (no-tillage, semi-tillage and tillage) on Chardonnay and Maratheftiko cultivars on (A1,A2) Chlorophyll a (Chl a; mg/g FW), (B1,B2) Chlorophyll b (Chl b; mg/g FW), (C1,C2) total chlorophylls (total Chl; mg/g FW) and (D1,D2) Chl a:Chl b ratio. Evaluation was made in three plant developmental stages (flowering, veraison and harvesting). Significant differences (p < 0.05) among treatments are presented with different lettering, based on Duncan’s multiple range tests. Error bars show SE (n = 6). ns: not significant.

3.4 Total Leaf Phenols and Antioxidant Activity

In Chardonnay, total leaf phenols and antioxidant activity as assayed by DPPH, FRAP and ABTS method, revealed reduced levels in plants subjected to semi-tillage application (Fig. 5(A1–D1)). In Maratheftiko total phenols increased in plants at veraison stage (up to 21.9%) after soil tillage and at harvesting stage (up to 7.7%) after soil no tillage (Fig. 5(A2)). Additionally, increased antioxidant capacity was evidenced in plants grown in tilled soil at veraison (as shown by DPPH; Fig. 5(B2)) and harvesting (as shown by DPPH, FRAP, ABTS; Fig. 5(B2–D2)) stage. Total phenols and antioxidant mechanisms of plants increased under the challenges of both abiotic and biotic stressors [59,60]. It seems that semi-tillage caused less oxidative damage which was mirrored to the less phenolics and antioxidant capacity of the grapevine’s leaves. Interestingly, Maratheftiko leaves had higher levels of phenols and antioxidants at harvesting stage compared to Chardonnay, which is of importance as several grapevine cultivars’ leaves are collected and used as edible leaves in Mediterranean countries [61]. In Galicia, Spain, differences between local and international grape varieties were found in the polyphenols content and antioxidant activity of wine samples [62], supporting further the present observations.

Figure 5: Effects of cultivation practice (no-tillage, semi-tillage and tillage) on Chardonnay and Maratheftiko cultivars on (A1,A2) total phenols (mg GA/g), and antioxidant activity (B1,B2) DPPH (mg Trolox/g), (C1,C2) FRAP (mg Trolox/g), and (D1,D2) ABTS (mg Trolox/g). Evaluation was made in three plant developmental stages (flowering, veraison and harvesting). Significant differences (p < 0.05) among treatments are presented with different lettering, based on Duncan’s multiple range tests. Error bars show SE (n = 6). ns: not significant.

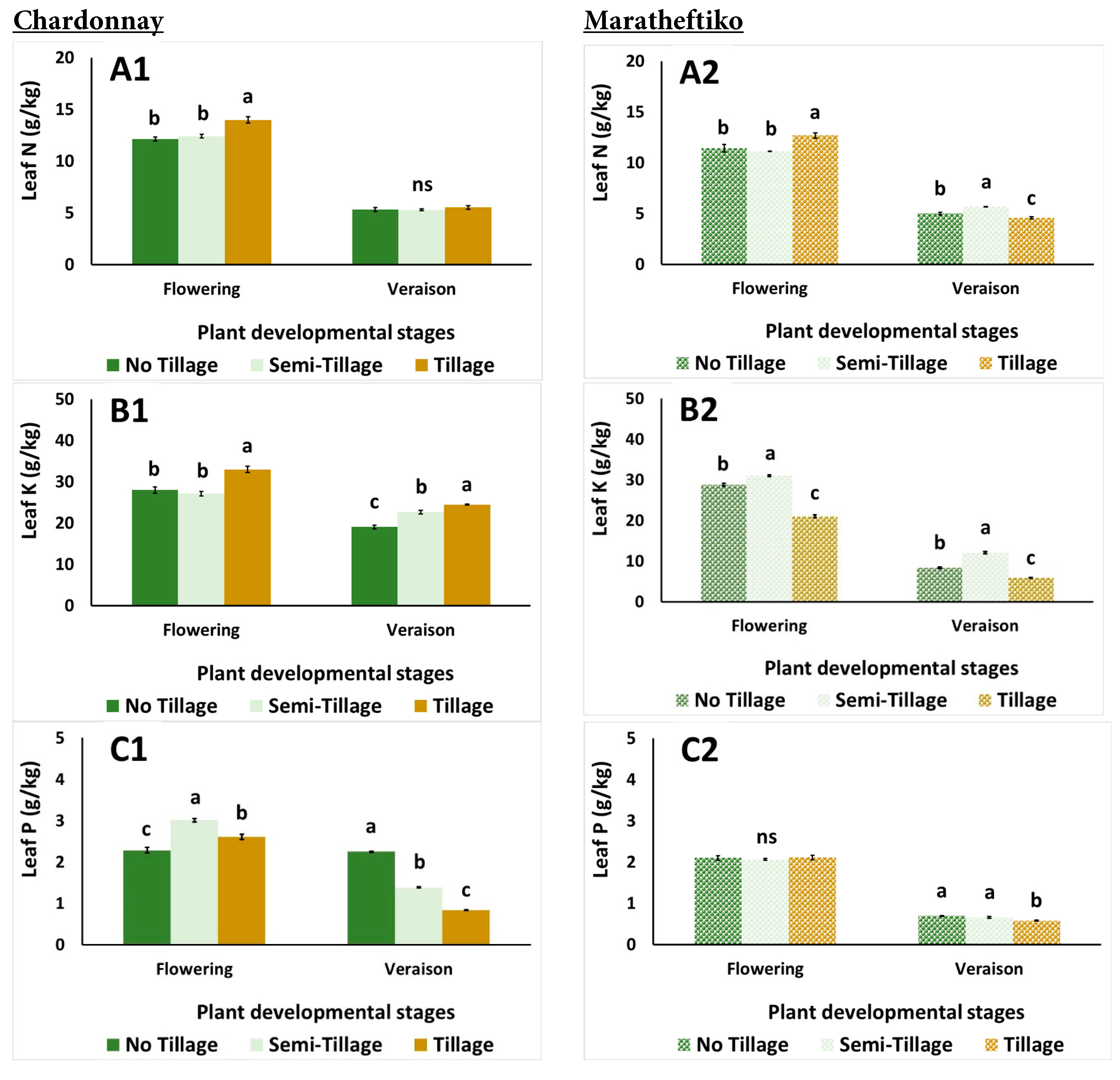

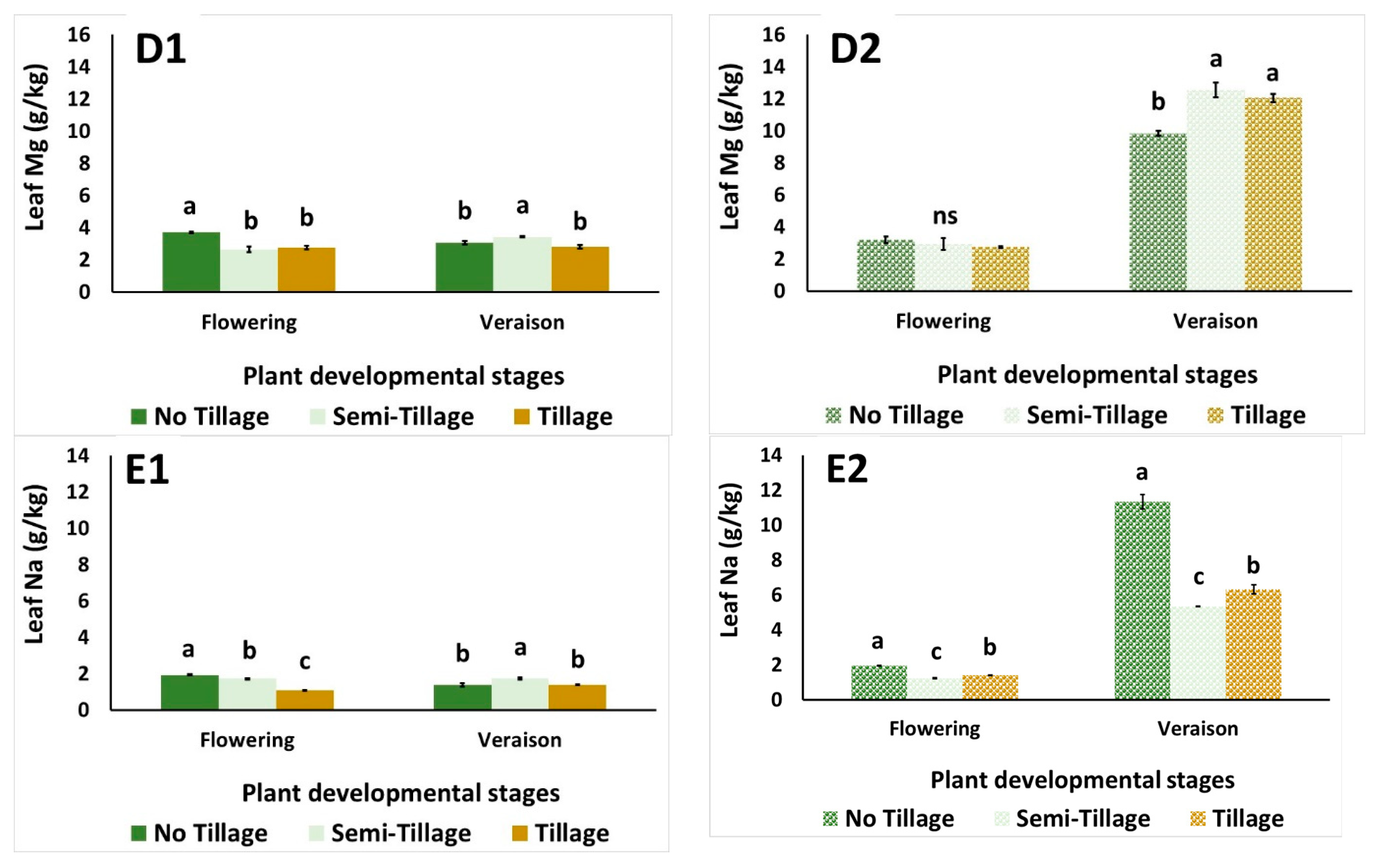

Mineral content in petiols were evaluated at flowering and veraison stages, whereas highly active leaf metabolism was taken place. In Chardonnay, tillage increased N (up to 15.3%) and K (up to 17.9%) content during flowering and this was also evidenced during veraison for K (up to 28.5%) (Fig. 6(A1,B1)). At flowering, increased P content was found in plants grown in semi-tilled soil while at veraison stage, the greatest P content was observed in plants grown in no-tilled soil compared to the plants grown to soils with semi-tillage and tillage (Fig. 6(C1)). The Mg and Na content was increased in plants at flowering stage after no tillage in soil and at veraison stage after soil semi-tillage (Fig. 6(D1,E1)). In Maratheftiko, increased N, K and P levels were found during flowering stage compared with the veraison stage while the opposite was evidenced for Mg and Na content that were increased at the veraison stage (Fig. 6(A2–E2)). In details, at flowering stage, plants N content was increased after soil tillage, plants K content was increased after semi-tillage in soil and plant Na content was increased in no-tilled soil. At the veraison stage, plants N and K were higher at semi-tilled soil (Fig. 6(A2,B2)), plant Na increased at no-tilled soil (Fig. 6(E2)), plant P increased at no-tilled and semi-tilled soils (Fig. 6(C2)), and plant Mg increased at semi-tilled and tilled soils (Fig. 6(D2)), in comparison to the other applied treatments.

In previous studies, N content in leaves was lower in no tillage compared to tillage applications in grapevine [49], where the cover crop might increase the competition for nutrients, especially N [63]. Moreover, tillage stimulated the decomposition and mineralization of N from plant leftovers and make available N to be up taken by the grapevines roots [44]. The differences in nutrient accumulation under different cultivation practices indicate competition of nutrient uptake with the natural vegetation in vineyards under arid conditions. Moreover, the increased N and K levels in petiols found in vines after soil tillage are mirrored to the decreased mineral levels in soil for the adequate plant phenological stages. These shifts might reflect different nutrient leaching, microbial activity, or cultivar-specific uptake. Leaf P content increased at veraison stage from plant grown to soil with no tillage or semi-tillage compared to tillage, being in accordance with table grapes vineyard in Italy whereas both P and S increased in cover-cropped vineyards [64]. However, other studies showed that cover crops and no tillage applications on regulated deficit irrigation grapevines for three years, had little or no effects on mineral accumulation in plant tissue, suggesting that conservation tillage practices may be applied in irrigated vineyards with very little direct impacts on plant development in mature vineyards [27].

Figure 6: Effects of cultivation practice (no-tillage, semi-tillage and tillage) on Chardonnay and Maratheftiko cultivars on (A1,A2) nitrogen-N, (B1,B2) potassium-K, (C1,C2) phosphorus-P, (D1,D2) magnesium-Mg, and (E1,E2) sodium-Na content (g/kg). Evaluation was made in two plant developmental stages (flowering and veraison). Significant differences (p < 0.05) among treatments are presented with different lettering, based on Duncan’s multiple range tests. Error bars show SE (n = 4). ns: not significant.

3.6 Grape Quality Characteristics

The effect of cultivation practices on grape quality characteristics for Chardonnay and Maratheftiko cultivars is presented in Table 2. In Chardonnay, soil tillage increased TSS, pH, total phenols, anthocyanins and tannins content but decreased TA in grapes. Similar to tillage, semi-tillage also resulted in increased pH in grape juice compared to the no tillage application. No changes were evidenced in ascorbic acid content. In Maratheftiko, tillage increased TSS, pH, AA, total phenols but decreased anthocyanins and tannins content. The highest TA and anthocyanins levels were found in grapes from vines grown in semi-tilled soil, while the highest tannins were found in grapes from vines grown in no-tilled soil.

Previous studies indicated that tillage application resulted in decreased juice pH of grapes, compared to the no tillage treatment [49], which is in contrast to the present findings, whereas the juice pH was increased with tillage. This variation might be related to the different experimental set up, cultivars and environmental conditions, among the different studies. The TA was significantly increased in grapes from vines grown in till-treated soil compared to no-tilled ones [63], which is in contrast with the present findings. However, tillage could boost the TSS levels and promote the ripening process of grapes compared to the vines grown in no-tilled soil, as also presented previously [29]. In other studies, TSS was not affected [49] or decreased [22] by the tillage application. These differences could be related to the fact that mature grapevines can be more resistive to the cover crops adoption because of the well-established root system that can withstand the competition with cover crop [47].

Table 2: Effects of cultivation practice (no-tillage, semi-tillage and tillage) on Chardonnay and Maratheftiko cultivars on grape total soluble solids (TSS: %), titratable acidity (TA: % tartaric acid), pH, ascorbic acid (AA: mg/100 mL grape juice), total phenols (gallic acid equivalent: GAE/100 g FW), anthocyanins (mg cyn-3-glu/100 g FW) and tannins (mg/100 mL grape juice).

| TSS | TA | pH | AA | Phenols | Anthocyanins | Tannins | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chardonnay | No tillage | 19.71 ± 0.33c | 0.81 ± 0.03a | 3.24 ± 0.05b | 0.81 ± 0.12 | 2.65 ± 0.07c | 0.26 ± 0.03ab | 0.21 ± 0.04b |

| Semi-tillage | 20.65 ± 0.16b | 0.68 ± 0.01b | 3.39 ± 0.01a | 0.76 ± 0.02 | 3.10 ± 0.09b | 0.16 ± 0.02b | 0.24 ± 0.04ab | |

| Tillage | 21.53 ± 0.19a | 0.61 ± 0.01c | 3.34 ± 0.01a | 0.77 ± 0.03 | 4.43 ± 0.07a | 0.42 ± 0.09a | 0.34 ± 0.04a | |

| Maratheftiko | No tillage | 20.43 ± 0.13b | 0.64 ± 0.04b | 3.04 ± 0.03b | 1.01 ± 0.21ab | 4.08 ± 0.07c | 61.80 ± 1.77b | 0.66 ± 0.04a |

| Semi-tillage | 21.57 ± 0.44b | 0.73 ± 0.03a | 3.05 ± 0.01b | 0.56 ± 0.13b | 4.74 ± 0.07b | 67.42 ± 2.58a | 0.40 ± 0.07b | |

| Tillage | 22.77 ± 0.31a | 0.66 ± 0.02ab | 3.16 ± 0.01a | 1.26 ± 0.11a | 5.91 ± 0.12a | 47.37 ± 0.27c | 0.19 ± 0.03c |

Red grapevines cultivars and wines are associated with increased anthocyanins and tannins levels compared to the white cultivars [65]. Anthocyanins and tannins are interconnected, with the former to contribute to grapes colors whereas the latter contribute to grapes and wines tactile characteristics and color stability [66]. In red cultivars (such as Maratheftiko), one of the most noticeable aspects of fruit ripening is anthocyanins accumulation or red pigments, in the grape skin during veraison. Grape anthocyanin accumulation may follows a trend of sugar accumulation, while regional variations and cultural management practices can significantly alter this pattern [67]. In accordance with the findings of Cataldo et al. [68,69] grapes with higher °Brix values tended to show increased anthocyanin levels, suggesting that sugar accumulation may promote phenolic synthesis under favorable ripening conditions. In the present study, Maratheftiko anthocyanins levels did not follow up the TSS levels, most possibly due to the very little variation on TSS by the tillage applications. Tannins are complex molecules of polymers that contribute to many sensorial characteristics of wine, especially red wines. Additionally, they act as antioxidants, shielding the wine from quality degradation [70]. The content of these chemicals in grapes can alter in regards to tillage methods [71], but it can be cultivar depended. In the present study, tannins increased with tillage in Chardonnay but decreased in Maratheftiko cultivar. Moreover, tillage boosted the phenolics levels in grape, which consumers may find quite appealing.

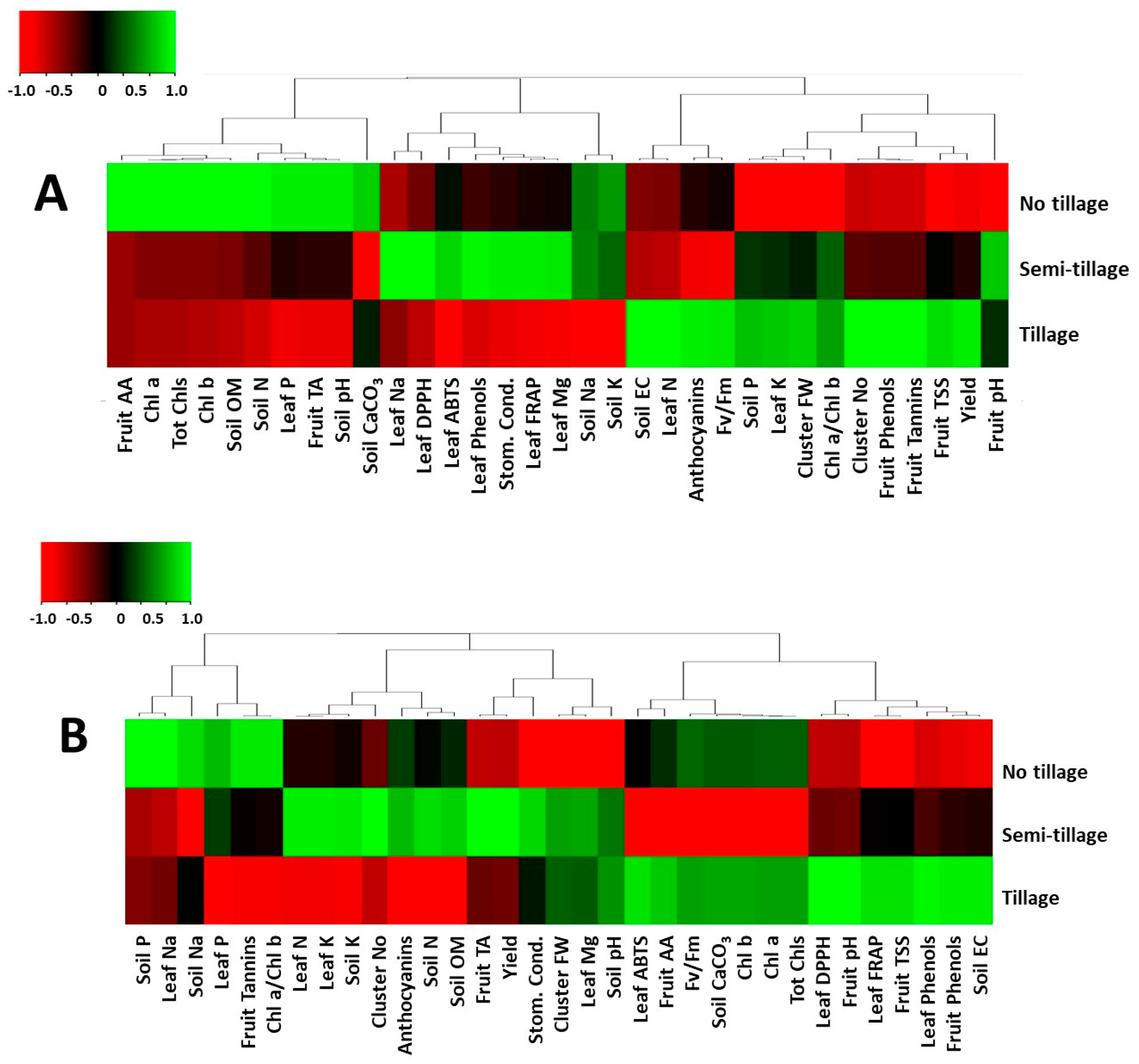

Heat maps (Fig. 7A,B) according to the relative expressions of soil characteristics, plant growth, minerals, physiological and fruit quality traits of the Chardonnay and Maratheftiko demonstrated a differential in responses among the treatments. In Chardonnay, tillage stimulated soil EC and P; chlorophyll fluorescence and leaf N and K; cluster weight, number produced and yield, fruit phenols, tannin, TSS, and pH, whereas no tillage promotes the accumulation of organic matter content and N, as well as increases soil pH; Chlorophylls content; leaf P; fruit AA and TA levels (Fig. 7A). Interestingly, semi-tillage stimulated antioxidant capacity of plants and stomatal conductance (Fig. 7A).

In Maratheftiko, tillage stimulated total phenols in leaves and fruits, leaf antioxidant activity (DPPH, FRAP), fruit pH and TSS and soil EC. No tillage application allows the buildup of soil P and Na, leaf P and Na, fruit tannins and Chl a:Chl b ratio (Fig. 7B). Semi-tillage promoted the accumulation of soil organic matter content, soil (N, K) and leaf (N, K, Mg) minerals, and increased leaf stomatal conductance, cluster number, fresh weight and yield (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7: Metabolite changes in grapevines. Heat map indicating relative expressions of growth and physiological traits elicited in grapevines (at veraison) and soil properties (at harvesting) (A) Chardonnay and (B) Maratheftiko when subjected to semi-tillage and tillage as compared with the no tillage treatment.

Previous studies have indicated that no tillage, which minimizes soil disturbance, promotes the buildup of organic matter and soil N [72]. This effect was more pronounced in the Chardonnay vineyard than in the Maratheftiko vineyard. In contrast, tillage accelerated the decomposition of soil organic matter and mineralization processes, which can potentially influence plant growth, yield and quality attributes. However, tillage may also increase the risk of long-term productivity losses, by depleting soil organic matter and reducing microbial biodiversity [17]. Semi-tillage application resulted in intermediate outcomes compared to tillage and no tillage treatments, as similar findings and increased yields have been reported when strip tillage was applied in maize fields [13,55].

Agriculture’s environmental impact and climate change present additional challenges. Agriculture accounts for approximately 30% of global greenhouse gas emissions (GGE), including carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide and methane, and is directly influenced by climate change [5]. Therefore, practices that reduce GGE and promote sustainable food production represent critical challenges for the coming decades. Busari et al. [41] reviewed that conservation tillage enhances crop resilience, enabling plants to better withstand various stress events compared to those under conventional tillage. The reduced tillage (up to 67%) application (from three times to one time per year] and application of locally produced animal manure in Cyprus may contribute to decrease carbon footprint by 40–67% [73]. Although carbon footprint was not directly evaluated in the present study, both no tillage and semi-tillage practices are expected to contribute positively in this regard compared to the conventional tillage practice. Conservation tillage techniques are therefore more crucial than ever for producing food sustainably while minimizing potential negative impacts on the soil health and atmosphere.

In the present research, the impacts of conservation tillage treatments on the soil physicochemical profile, and the vine’s growth, yield and grape quality were evaluated in Chardonnay and in the indigenous Maratheftiko cultivars. Tillage decreased soil N levels through mineralization. Interestingly, the soil in the Maratheftiko vineyard had increased N and K levels compared to the soil in the Chardonnay vineyard. No tillage practice in the soil decreased yield in Chardonnay, while increased yield was found in Maratheftiko following the soil semi-tillage. No great effects were found on plant physiology, even though Maratheftiko vines revealed more stable leaf stomatal conductance levels under the different cultivation practices, compared to Chardonnay. In Chardonnay, the tillage increased the plants N and K content during flowering. In Maratheftiko, N and K content increased at plants after soil tillage and soil semi-tillage, respectively. Moreover, soil tillage increased grape juice TSS, pH and total phenols for both cultivars and increased tannin content only in Chardonnay. Additional research will determine the impact of tillage on other cultivars in Cyprus, particularly the local varieties that might be utilized to adapt Cypriot viticulture to climate change. The present research is related to a specific region and climate, and broader research is needed to define the outputs of the present study in other regions. Furthermore, these trials must be repeated for multiple years and in other soil textures to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the impacts of tillage on grapevines' physiology and yield quality. Organic matter enrichment in soil could also support soil health and improve its fertility.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The present work was financed by PRIMA (MiDiVine project), the European Union (ERA-NET Cofound FACCE SURPLUS Call of Horizon 2020-FACCE JPI, “VitiSmart” project), a programme supported by the European Union with co-funding by the Funding Agencies RIF—Cyprus.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Nikolaos Tzortzakis; methodology: Antonios Chrysargyris, Timos Boyias and Nikolaos Tzortzakis; software: Antonios Chrysargyris; validation: Antonios Chrysargyris and Nikolaos Tzortzakis; formal analysis: Antonios Chrysargyris, Demetris Antoniou and Nikolaos Tzortzakis; investigation: Antonios Chrysargyris, Timos Boyias, Demetris Antoniou and Nikolaos Tzortzakis; resources: Timos Boyias and Nikolaos Tzortzakis; data curation: Antonios Chrysargyris, Demetris Antoniou and Nikolaos Tzortzakis; writing—original draft preparation: Antonios Chrysargyris and Nikolaos Tzortzakis; writing—review and editing: Antonios Chrysargyris and Nikolaos Tzortzakis; visualization: Antonios Chrysargyris; supervision: Nikolaos Tzortzakis; project administration: Nikolaos Tzortzakis; funding acquisition: Nikolaos Tzortzakis. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Yuan X , Li S , Chen J , Yu H , Yang T , Wang C , et al. Impacts of global climate change on agricultural production: a comprehensive review. Agronomy. 2024; 14( 7): 1360. doi:10.3390/agronomy14071360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Eekhout JPC , de Vente J . Global impact of climate change on soil erosion and potential for adaptation through soil conservation. Earth Sci Rev. 2022; 226: 103921. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2022.103921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Madarász B , Jakab G , Szalai Z , Juhos K , Kotroczó Z , Tóth A , et al. Long-term effects of conservation tillage on soil erosion in Central Europe: a random forest-based approach. Soil Tillage Res. 2021; 209: 104959. doi:10.1016/j.still.2021.104959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Novara A , Gristina L , Saladino SS , Santoro A , Cerdà A . Soil erosion assessment on tillage and alternative soil managements in a Sicilian vineyard. Soil Tillage Res. 2011; 117: 140– 7. doi:10.1016/j.still.2011.09.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Kassam A , Friedrich T , Derpsch R . Global spread of conservation agriculture. Int J Environ Stud. 2019; 76( 1): 29– 51. doi:10.1080/00207233.2018.1494927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Chen N , Zhao X , Dou S , Deng A , Zheng C , Cao T , et al. The tradeoff between maintaining maize (Zea mays L.) productivity and improving soil quality under conservation tillage practice in semi-arid region of Northeast China. Agriculture. 2023; 13( 2): 508. doi:10.3390/agriculture13020508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Reicosky DC . Conservation tillage is not conservation agriculture. J Soil Water Conserv. 2015; 70( 5): 103A– 8A. doi:10.2489/jswc.70.5.103A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Xiong M , Sun R , Chen L . Effects of soil conservation techniques on water erosion control: a global analysis. Sci Total Environ. 2018; 645: 753– 60. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.07.124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhao J , Yang Z , Govers G . Soil and water conservation measures reduce soil and water losses in China but not down to background levels: evidence from erosion plot data. Geoderma. 2019; 337: 729– 41. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2018.10.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Conservation Tillage Information Center (CTIC) MR . National Crop Residue Management Survey [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 24]. Available from: https://www.ctic.org/resource_display/?id=255&title=crop+residue+management+survey. [Google Scholar]

11. Singh B , Singh AP , Havale DS , Singh NK , Rashmi M , Anbarasan S , et al. Role of conservation tillage practices in sustainable agricultural systems. J Exp Agric Int. 2024; 46( 8): 833– 42. doi:10.9734/jeai/2024/v46i82766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Bezboruah M , Sharma SK , Laxman T , Ramesh S , Sampathkumar T , Gulaiya S , et al. Conservation tillage practices and their role in sustainable farming systems. J Exp Agric Int. 2024; 46( 9): 946– 59. doi:10.9734/jeai/2024/v46i92892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Dou S , Wang Z , Tong J , Shang Z , Deng A , Song Z , et al. Strip tillage promotes crop yield in comparison with no tillage based on a meta-analysis. Soil Tillage Res. 2024; 240: 106085. doi:10.1016/j.still.2024.106085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Kertész Á , Madarász B . Conservation agriculture in Europe. Int Soil Water Conserv Res. 2014; 2( 1): 91– 6. doi:10.1016/S2095-6339(15)30016-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Gao L , Wang B , Li S , Wu H , Wu X , Liang G , et al. Soil wet aggregate distribution and pore size distribution under different tillage systems after 16 years in the Loess Plateau of China. Catena. 2019; 173: 38– 47. doi:10.1016/j.catena.2018.09.043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Seitz S , Goebes P , Puerta VL , Pereira EIP , Wittwer R , Six J , et al. Conservation tillage and organic farming reduce soil erosion. Agron Sustain Dev. 2018; 39( 1): 4. doi:10.1007/s13593-018-0545-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Dekemati I , Simon B , Vinogradov S , Birkás M . The effects of various tillage treatments on soil physical properties, earthworm abundance and crop yield in Hungary. Soil Tillage Res. 2019; 194: 104334. doi:10.1016/j.still.2019.104334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Trevini M , Benincasa P , Guiducci M . Strip tillage effect on seedbed tilth and maize production in Northern Italy as case-study for the Southern Europe environment. Eur J Agron. 2013; 48: 50– 6. doi:10.1016/j.eja.2013.02.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Jakab G , Filep T , Király C , Madarász B , Zacháry D , Ringer M , et al. Differences in mineral phase associated soil organic matter composition due to varying tillage intensity. Agronomy. 2019; 9( 11): 700. doi:10.3390/agronomy9110700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Brunel-Saldias N , Seguel O , Ovalle C , Acevedo E , Martínez I . Tillage effects on the soil water balance and the use of water by oats and wheat in a Mediterranean climate. Soil Tillage Res. 2018; 184: 68– 77. doi:10.1016/j.still.2018.07.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Luna JM , Staben ML . Strip tillage for sweet corn production: yield and economic return. HortScience. 2002; 37( 7): 1040– 4. doi:10.21273/HORTSCI.37.7.1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Bahar E , Yasain AS . The yield and berry quality under different soil tillage and clusters thinning treatments in grape (Vitis vinifera L.) cv. Cabernet-Sauvignon. Afr J Agric Res. 2010; 5( 21): 2986– 93. [Google Scholar]

23. Thapa B , Dura R . A review on tillage system and no-till agriculture and its impact on soil health. Arch Agric Environ Sci. 2024; 9( 3): 612– 7. doi:10.26832/24566632.2024.0903028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wolff MW , Alsina MM , Stockert CM , Khalsa SDS , Smart DR . Minimum tillage of a cover crop lowers net GWP and sequesters soil carbon in a California vineyard. Soil Tillage Res. 2018; 175: 244– 54. doi:10.1016/j.still.2017.06.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Daane KM , Hogg BN , Wilson H , Yokota GY . Native grass ground covers provide multiple ecosystem services in Californian vineyards. J Appl Ecol. 2018; 55( 5): 2473– 83. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.13145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Pérez-Bermúdez P , Olmo M , Gil J , García-Férriz L , Olmo C , Boluda R , et al. Cover crops and pruning in Bobal and Tempranillo vineyards have little influence on grapevine nutrition. Sci Agric. 2016; 73( 3): 260– 5. doi:10.1590/0103-9016-2015-0027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Steenwerth KL , McElrone AJ , Calderón-Orellana A , Hanifin RC , Storm C , Collatz W , et al. Cover crops and tillage in a mature merlot vineyard show few effects on grapevines. Am J Enol Vitic. 2013; 64( 4): 515– 21. doi:10.5344/ajev.2013.12119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Beis A , Patakas A . Differential physiological and biochemical responses to drought in grapevines subjected to partial root drying and deficit irrigation. Eur J Agron. 2015; 62: 90– 7. doi:10.1016/j.eja.2014.10.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Chrysargyris A , Xylia P , Litskas V , Stavrinides M , Heyman L , Demeestere K , et al. Assessing the impact of drought stress and soil cultivation in chardonnay and xynisteri grape cultivars. Agronomy. 2020; 10( 5): 670. doi:10.3390/agronomy10050670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Tombesi S , Nardini A , Frioni T , Soccolini M , Zadra C , Farinelli D , et al. Stomatal closure is induced by hydraulic signals and maintained by ABA in drought-stressed grapevine. Sci Rep. 2015; 5: 12449. doi:10.1038/srep12449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. McAdam SAM , Brodribb TJ . Hormonal dynamics contributes to divergence in seasonal stomatal behaviour in a monsoonal plant community. Plant Cell Environ. 2015; 38( 3): 423– 32. doi:10.1111/pce.12398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Vishwakarma K , Upadhyay N , Kumar N , Yadav G , Singh J , Mishra RK , et al. Abscisic acid signaling and abiotic stress tolerance in plants: a review on current knowledge and future prospects. Front Plant Sci. 2017; 8: 161. doi:10.3389/fpls.2017.00161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Hatmi S , Gruau C , Trotel-Aziz P , Villaume S , Rabenoelina F , Baillieul F , et al. Drought stress tolerance in grapevine involves activation of polyamine oxidation contributing to improved immune response and low susceptibility to Botrytis cinerea. J Exp Bot. 2015; 66( 3): 775– 87. doi:10.1093/jxb/eru436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Chrysargyris A , Xylia P , Litskas V , Mandoulaki A , Antoniou D , Boyias T , et al. Drought stress and soil management practices in grapevines in Cyprus under the threat of climate change. J Water Clim Chang. 2018; 9( 4): 703– 12. doi:10.2166/wcc.2018.135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Chrysargyris A , Stavrinides M , Moustakas K , Tzortzakis N . Utilization of paper waste as growing media for potted ornamental plants. Clean Technol Environ Policy. 2019; 21( 10): 1937– 48. doi:10.1007/s10098-018-1647-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Chrysargyris A , Tzortzakis N . Iron and zinc foliar spraying affected Sideritis cypria post. growth, mineral content and antioxidant properties. Plants. 2025; 14( 6): 840. doi:10.3390/plants14060840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Chrysargyris A , Tzortzakis N . Optimizing nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium requirements to improve Origanum dubium Boiss. growth, nutrient and water use efficiency, essential oil yield and composition. Ind Crops Prod. 2025; 224: 120291. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2024.120291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. OIV-MA-AS1-11 . Compendium of international methods of analysis of wines and musts. Paris, France: Organisation Internationale de la Vigne et du Vin (OIV); 2012. [Google Scholar]

39. Li J , Wang YK , Guo Z , Li JB , Tian C , Hua DW , et al. Effects of conservation tillage on soil physicochemical properties and crop yield in an arid Loess Plateau, China. Sci Rep. 2020; 10( 1): 4716. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-61650-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Yuan J , Yan L , Li G , Sadiq M , Rahim N , Wu J , et al. Effects of conservation tillage strategies on soil physicochemical indicators and N(2)O emission under spring wheat monocropping system conditions. Sci Rep. 2022; 12( 1): 7066. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-11391-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Busari MA , Kukal SS , Kaur A , Bhatt R , Dulazi AA . Conservation tillage impacts on soil, crop and the environment. Int Soil Water Conserv Res. 2015; 3( 2): 119– 29. doi:10.1016/j.iswcr.2015.05.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Vink SN , Chrysargyris A , Tzortzakis N , Salles JF . Bacterial community dynamics varies with soil management and irrigation practices in grapevines (Vitis vinifera L.). Appl Soil Ecol. 2021; 158: 103807. doi:10.1016/j.apsoil.2020.103807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Wichelns D , Qadir M . Achieving sustainable irrigation requires effective management of salts, soil salinity, and shallow groundwater. Agric Water Manag. 2015; 157: 31– 8. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2014.08.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Guerra B , Steenwerth K . Influence of floor management technique on grapevine growth, disease pressure, and juice and wine composition: a review. Am J Enol Vitic. 2012; 63( 2): 149– 64. doi:10.5344/ajev.2011.10001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Marschner P , Rengel Z . Nutrient availability in soils. In: Marschner’s mineral nutrition of higher plants. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2012. p. 315– 30. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-384905-2.00012-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Yahaya SM , Ahmad Mahmud A , Abdullahi M , Haruna A . Recent advances in the chemistry of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium as fertilizers in soil: a review. Pedosphere. 2023; 33( 3): 385– 406. doi:10.1016/j.pedsph.2022.07.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Gattullo CE , Mezzapesa GN , Stellacci AM , Ferrara G , Occhiogrosso G , Petrelli G , et al. Cover crop for a sustainable viticulture: effects on soil properties and table grape production. Agronomy. 2020; 10( 9): 1334. doi:10.3390/agronomy10091334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Gómez JA , Llewellyn C , Basch G , Sutton PB , Dyson JS , Jones CA . The effects of cover crops and conventional tillage on soil and runoff loss in vineyards and olive groves in several Mediterranean countries. Soil Use Manag. 2011; 27( 4): 502– 14. doi:10.1111/j.1475-2743.2011.00367.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Zumkeller M , Torres N , Marigliano LE , Zaccaria D , Tanner JD , Kaan Kurtural S . Cover crops and No-tillage show negligible effects on grapevine physiology in Mediterranean vineyard agroecosystems. OENO One. 2023; 57( 2): 375– 92. doi:10.20870/oeno-one.2023.57.2.7136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Barroso JM , Pombeiro L , Rato AE . Impacts of crop level, soil and irrigation management in grape berries of cv ‘Trincadeira’ (Vitis vinifera L.). J Wine Res. 2017; 28( 1): 1– 12. doi:10.1080/09571264.2016.1238350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Jordan LM , Björkman T , Vanden Heuvel JE . Annual under-vine cover crops did not impact vine growth or fruit composition of mature cool-climate ‘Riesling’ grapevines. HortTechnology. 2016; 26( 1): 36– 45. doi:10.21273/HORTTECH.26.1.36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Messiga AJ , Gallant KS , Sharifi M , Hammermeister A , Fuller K , Tango M , et al. Grape yield and quality response to cover crops and amendments in a vineyard in nova Scotia, Canada. Am J Enol Vitic. 2016; 67( 1): 77– 85. doi:10.5344/ajev.2015.15013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Fourie JC . Soil management in the breede river valley wine grape region, South Africa. 3. grapevine performance. S Afr N J Enol Vitic. 2016; 32( 1): 60– 70. doi:10.21548/32-1-1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Chen Y , Liu S , Li H , Li XF , Song CY , Cruse RM , et al. Effects of conservation tillage on corn and soybean yield in the humid continental climate region of Northeast China. Soil Tillage Res. 2011; 115: 56– 61. doi:10.1016/j.still.2011.06.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Chen Q , Zhang X , Sun L , Ren J , Yuan Y , Zang S . Influence of tillage on the mollisols physicochemical properties, seed emergence and yield of maize in Northeast China. Agriculture. 2021; 11( 10): 939. doi:10.3390/agriculture11100939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Hatch TA , Hickey CC , Wolf TK . Cover crop, rootstock, and root restriction regulate vegetative growth of cabernet sauvignon in a humid environment. Am J Enol Vitic. 2011; 62( 3): 298– 311. doi:10.5344/ajev.2011.11001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Lin YP , Charng YY . Chlorophyll dephytylation in chlorophyll metabolism: a simple reaction catalyzed by various enzymes. Plant Sci. 2021; 302: 110682. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2020.110682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Dubey T , Mishra DS . Effect of rooting media and different polythene wrappers on air layering of pomegranate (Punica granatum) cv. Bhagwa. Int J Adv Biochem Res. 2024; 8( 8S): 401– 6. doi:10.33545/26174693.2024.v8.i8Sf.1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Valifard M , Mohsenzadeh S , Kholdebarin B , Rowshan V . Effects of salt stress on volatile compounds, total phenolic content and antioxidant activities of Salvia mirzayanii. S Afr N J Bot. 2014; 93: 92– 7. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2014.04.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Heyman L , Chrysargyris A , Demeestere K , Tzortzakis N , Höfte M . Responses to drought stress modulate the susceptibility to Plasmopara viticola in Vitis vinifera self-rooted cuttings. Plants. 2021; 10( 2): 273. doi:10.3390/plants10020273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Pintać D , Četojević-Simin D , Berežni S , Orčić D , Mimica-Dukić N , Lesjak M . Investigation of the chemical composition and biological activity of edible grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) leaf varieties. Food Chem. 2019; 286: 686– 95. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.02.049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Alvarez-Casas M , Pajaro M , Lores M , Garcia-Jares C . Polyphenolic composition and antioxidant activity of Galician monovarietal wines from native and experimental non-native white grape varieties. Int J Food Prop. 2016; 19( 10): 2307– 21. doi:10.1080/10942912.2015.1126723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Reeve AL , Skinkis PA , Vance AJ , Lee J , Tarara JM . Vineyard floor management influences ‘pinot noir’ vine growth and productivity more than cluster thinning. HortScience. 2016; 51( 10): 1233– 44. doi:10.21273/HORTSCI10998-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Tarantino A , Mazzeo A , Lopriore G , Disciglio G , Gagliardi A , Nuzzo V , et al. Nutrients in clusters and leaves of Italian table grapes are affected by the use of cover crops in the vineyard. J Berry Res. 2020; 10( 2): 157– 73. doi:10.3233/JBR-190428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Bucchetti B , Matthews MA , Falginella L , Peterlunger E , Castellarin SD . Effect of water deficit on Merlot grape tannins and anthocyanins across four seasons. Sci Hortic. 2011; 128( 3): 297– 305. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2011.02.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Bautista-Ortín AB , Martínez-Hernández A , Ruiz-García Y , Gil-Muñoz R , Gómez-Plaza E . Anthocyanins influence tannin-cell wall interactions. Food Chem. 2016; 206: 239– 48. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.03.045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Mira de Orduña R . Climate change associated effects on grape and wine quality and production. Food Res Int. 2010; 43( 7): 1844– 55. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2010.05.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Cataldo E , Fucile M , Manzi D , Peruzzi E , Mattii GB . Effects of Zeowine and compost on leaf functionality and berry composition in Sangiovese grapevines. J Agric Sci. 2023; 161( 3): 412– 27. doi:10.1017/S002185962300028X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Cataldo E , Fucile M , Manzi D , Masini CM , Doni S , Mattii GB . Sustainable soil management: effects of clinoptilolite and organic compost soil application on eco-physiology, quercitin, and hydroxylated, methoxylated anthocyanins on Vitis vinifera. Plants. 2023; 12( 4): 708. doi:10.3390/plants12040708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Deis L , Cavagnaro JB . Effect of water stress in grape berries Cabernet Sauvignon (Mendoza, Argentina) during four years consecutives. J Life Sci. 2013; 7( 9): 993– 1001. [Google Scholar]

71. Trigo-Córdoba E , Bouzas-Cid Y , Orriols-Fernández I , Mirás-Avalos JM . Effects of deficit irrigation on the performance of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) cv. ‘Godello’ and ‘Treixadura’ in Ribeiro, NW Spain. Agric Water Manag. 2015; 161: 20– 30. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2015.07.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Szostek M , Szpunar-Krok E , Pawlak R , Stanek-Tarkowska J , Ilek A . Effect of different tillage systems on soil organic carbon and enzymatic activity. Agronomy. 2022; 12( 1): 208. doi:10.3390/agronomy12010208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Litskas VD , Irakleous T , Tzortzakis N , Stavrinides MC . Determining the carbon footprint of indigenous and introduced grape varieties through life cycle assessment using the island of cyprus as a case study. J Clean Prod. 2017; 156: 418– 25. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.04.057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools