Open Access

Open Access

CASE REPORT

Teapot ureterocystoplasty in posterior urethral valve and chronic kidney disease: a case report

Department of Surgery, Division of Urology, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON L8S 4L8, Canada

* Corresponding Authors: Geemitha Ratnayake. Email: ; Luis Henrique Braga. Email:

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(3), 209-212. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.064122

Received 06 February 2025; Accepted 15 May 2025; Issue published 27 June 2025

Abstract

Background: Bladder augmentation is often necessary to address poorly compliant and low-capacity bladders which can result from Posterior Urethral Valve. Traditional techniques are limited by complications from using bowel tissue, thus in the setting of a megaureter, ureterocystoplasty is favorable. Methods: We present a case of Teapot ureterocystoplasty, which improves vascular protection of the ureter by leaving the distal 3 cm of the ureter tubularized. Cystograms demonstrated bladder capacity improvement from 50 mL to 180 mL post-operatively. Additionally, creatinine stabilized after a peak of 250 µmol/L. Result and Conclusion: This patient is doing well at 4.5-year surveillance and has avoided renal transplant, a common fate for these children.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileBladder augmentation is a surgical technique to address poorly compliant and low-capacity bladders as a result of posterior urethral valve (PUV), neurogenic bladder, and bladder exstrophy, among other causes. Traditional techniques utilize bowel, but are plagued by excess mucus production, urolithiasis, urinary tract infection (UTI), and metabolic abnormalities. Ureterocystoplasty is an alternative technique that makes use of a dilated ureter as the source of augmenting tissue, eliminating the disadvantages of using bowel.1

Unfortunately, the indications for ureterocystoplasty are limited as it relies on the presence of a pathologically dilated ureter and often requires a non-functioning or poor-functioning kidney to make full use of the ipsilateral tortuous ureter and renal pelvis for augmentation.1 With limited tissue, maximizing ureteral blood supply to prevent ischemic contraction of the ureter is paramount. The Teapot ureterocystoplasty was developed to address this issue by protecting ureteral blood supply.2

Herein, we present a case of a boy with small bladder capacity secondary to PUV, for whom we performed a Teapot ureterocystoplasty and followed for 3 years.

Our case involved a boy born prematurely at 25 weeks gestational age with PUV. He was initially treated with an intrauterine vesicoamniotic shunt and a vesicostomy shortly after birth. This was reversed and the PUV was ablated. A MAG3 renal scan showed a non-functioning right kidney and his workup confirmed Stage IV Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) with baseline creatinine in the 130–140 umol/L range. His renal function continued to deteriorate slowly over the years until age of 5 years, when he was hospitalized with a febrile UTI and Acute on Chronic Kidney Disease with a creatinine of 250 umol/L. Urodynamic Studies (UDS) were attempted but could not be completed due to lack of cooperation from the child. As such, non-invasive UDS including detailed voiding diaries, Voiding Cystourethrogram (VCUG), uroflowmetry, post-void residuals and renal ultrasound were performed. According to the Koff formula, bladder capacity for children >1 year in age is estimated as:

Capacity (mL) = (2 + age (years)) × 303

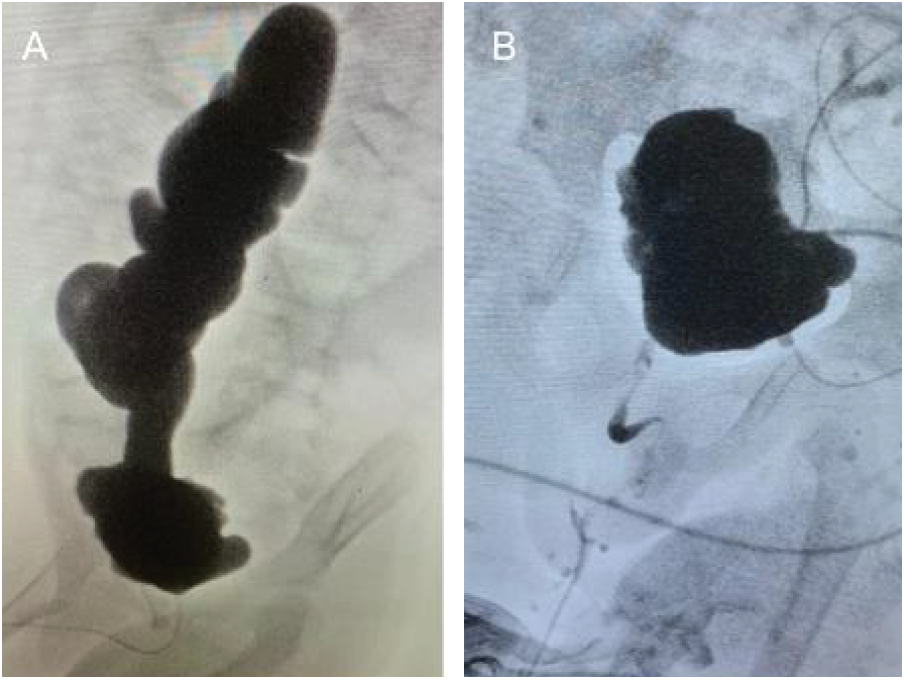

For our 5-year-old patient, expected bladder capacity was 210 mL. VCUG showed a bladder capacity of 50 mL and severe (grade V) right sided vesicoureteric reflux (VUR) (Figure 1A). His ultrasound indicated bilateral hydroureteronephrosis with parenchymal thinning. Due to low bladder capacity and VUR noted on diagnostic testing, right nephrectomy, ureterocystoplasty and Mitrofanoff procedure were performed.

FIGURE 1. A) preoperative cystogram showing small bladder and refluxing ureter that is severely dilated and tortuous. B) postoperative cystogram showing improved capacity and no reflux

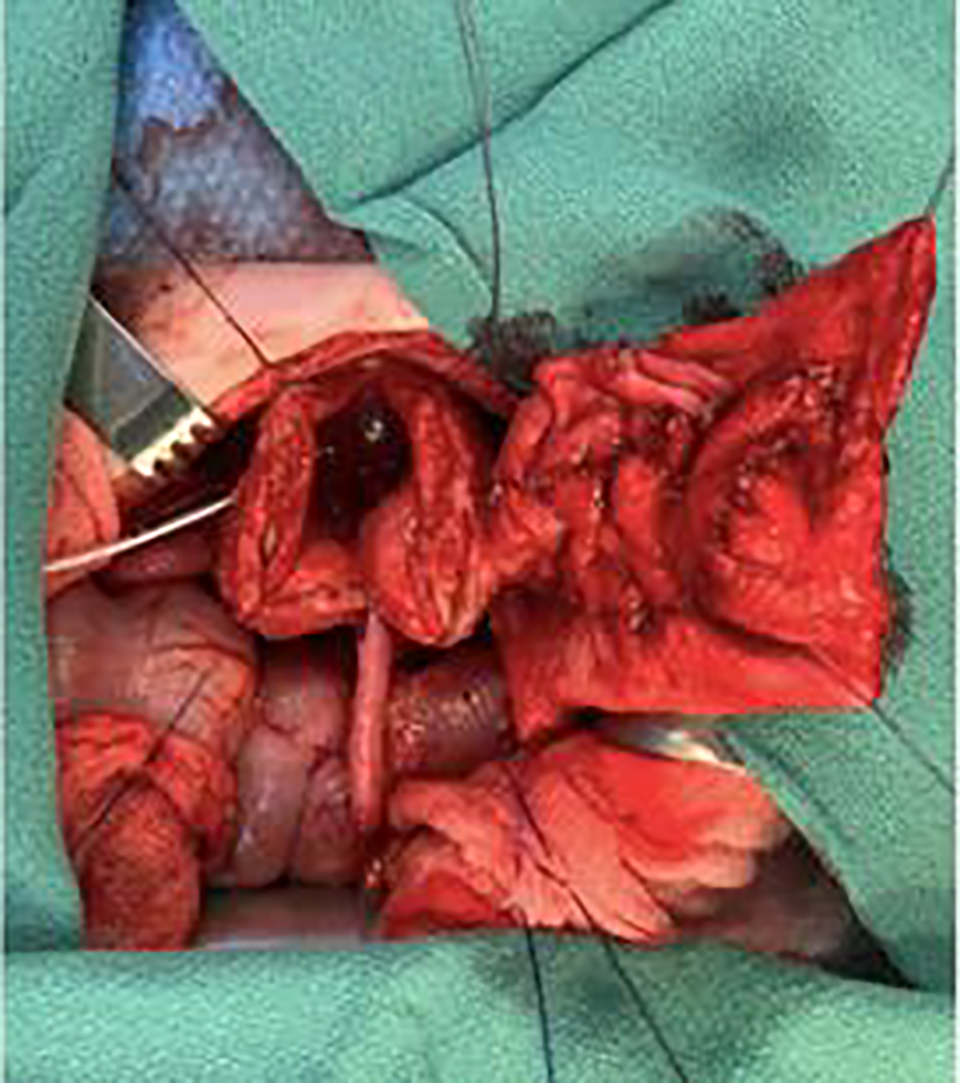

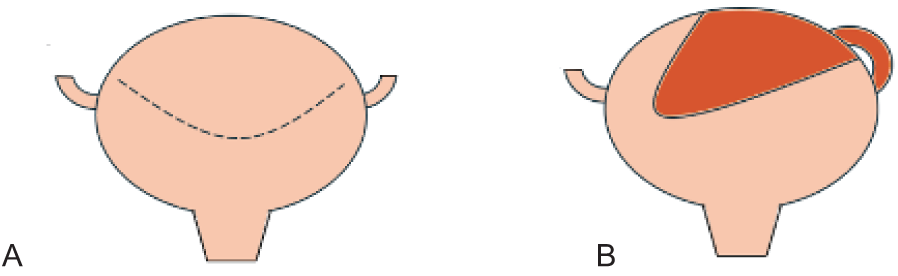

A midline lower abdominal wall laparotomy was chosen, allowing for a right nephrectomy and augmentation to be performed through the same incision. The renal pelvis was dissected out to be used as additional tissue as part of the augment. The ureter was dissected away from the retroperitoneum, with care taken to sweep adventitia and periureteral tissue from the peritoneum towards the ureter. The right ureter was then opened from the renal pelvis distally, starting laterally to avoid the proximal medial blood supply. The ureter was opened up to 3 cm from the ureteral orifice. This distal ureter was left untouched to work as a pedicle and decrease the risk of ureteral ischemia. The detubularized segment was then sutured together in an M configuration using a running absorbable suture. This is demonstrated in Figure 2. The bladder was opened horizontally demonstrated in Figure 3. A and the Mitrofanoff procedure was performed by creating a submucosal tunnel along the midline of the bladder, adhering to the 3:1 ratio of detrusor length to ureteral diameter. The final anastomosis of the detubularized segment to the bladder is demonstrated in Figure 3B. This forms a teapot configuration as seen. The postoperative course was uncomplicated, and the child was discharged home after 6 days with no adverse events.

FIGURE 2. Anastomosis of the M shaped ureteral flap to the bladder

FIGURE 3. A) horizontal cystotomy incision, B) ureteral flap is sewn to the bladder with the distal ureter remaining tubularized and undisturbed. This forms a teapot appearance

Cystogram done one month postoperatively showed no leaks and a bladder capacity of 180 mL (Figure 1B). Post-operative creatinine came down to 141 umol/L and ultrasound showed significantly improved hydroureteronephrosis. Clean intermittent catheterization (CIC) was started every 4 h during the day and continuously overnight and he was started on an anticholinergic agent. He has done well for the past 4.5 years. Creatinine stabilized at 191 umol/L however in the last 6 months, it has started climbing to around 260 umol/L. VCUG shows 370 mL bladder capacity. This is aligned with expected bladder capacity of a 9-year-old of 330 mL as per the Koff formula.3 UDS were completed at the 3-year mark and shows no reflux and compliance of 11.4 mL/cmH2O. This child has avoided renal transplant thus far because of this procedure.

Ureterocystoplasty is an alternative to traditional bladder augmentation that avoids pitfalls of using bowel. The main disadvantage of the technique is the requirement of a dilated ureter to provide enough tissue to increase bladder capacity in a clinically significant manner.1

When the technique was first described by Eckstein and Martin4 in 1973, and later in the 1990s,5 it was exclusively used in patients with a nonfunctioning kidney. This allowed for the use of the entire ipsilateral renal pelvis in addition to the dilated ureter.

When there are two functioning kidneys, some have done tapered reimplants with the remaining ureteric tissue.6 The literature is conflicting on whether using the distal ureter as a source of augmentation tissue allows for adequate increase in the bladder capacity. Husmann et al., in a large multicenter study, reported 92% of cases that used the distal ureter required re-augmentation,7 while Johal et al. reported that using the distal ureter still successfully increased compliance and capacity of the bladder.8 Regardless, these methods require very dilated ureters. Also, ureterocystoplasty techniques described detubularizing the entire ureter, including the ureteric orifice, disrupting ureteral blood supply. Good augmentation requires prevention of ischemic contraction. Adams et al. developed a technique in 1998 to protect ureteral blood supply.2 This was later called Teapot ureterocystoplasty in 2010.8 The Teapot technique called for the distal 3 cm of the ureter to be left tubularized, the ureteric orifice to be preserved, and the vas deferens to be undisturbed, protecting blood supply from the internal iliac, the superior vesical, and the gonadal artery, respectively.2,6

In this case report, we described a successful case of a patient who had Teapot ureterocystoplasty to treat a low capacity, high pressure bladder secondary to PUV. This patient’s bladder capacity increased from 50 mL preoperatively to 180 mL postoperatively, allowing decompression of the upper urinary tracts and limiting renal damage, hoping to postpone renal transplantation to an older age.

Ureterocystoplasty is limited by the need for a pathologically dilated ureter. The most common indication for bladder augmentation is neurogenic bladder, where hydroureteronephrosis can be avoided with good care and patient compliance to treatment protocols.1 Thus, the majority of neurogenic bladder patients are not good candidates for ureterocystoplasty. This is reinforced by Husmann et al.’s study where 46 of 64 patients had neurogenic bladder and 47 of 64 patients required re-augmentation.7 In Johal et al.’s study where only 2 of 17 patients had neurogenic bladder, 76% of patients did not need re-augmentation. As pointed out by Johal, patients with PUV tend to have better outcomes after ureterocystoplasty.8 PUV represents the best patient population for ureterocystoplasty as hypertrophic and hyperplastic changes to the detrusor results in a hyper-contractile, low compliance and small capacity bladder. This is frequently associated with severe hydroureteronephrosis and VUR. Obstructive uropathy results in kidney dysfunction and failure to concentrate urine, causing polyuria. High volumes of urine cause deterioration of renal and bladder functions even after timely PUV ablation. Patients are left with a largely dilated ureter and nonfunctioning kidney, giving ample tissue to augment the poorly compliant and small bladder.9

In this case report, we describe a recent successful application of the Teapot ureterocystoplasty technique. This technique of maintaining the distal ureter has been described few times but is valuable to preserve the blood supply to the ureteric tissue acting as an augment. While ureterocystoplasty does avoid the complications of using bowel with traditional enterocystoplasty, it has limited indications and PUV patients with small capacity, high pressure bladders appear to be the ideal candidates for this procedure.

Additionally, in this case report, we sought the perspective of the family who expressed their gratitude for “saving their son’s life”. They also highlighted the multidisciplinary care they received from Urologists, Nephrologists, other physicians and allied health providers and the length of follow up over many years as vital aspects of their child’s care. This study obtained informed consent from the patient’s parent, which is documented and available in the supplementary materials.

Acknowledgement

The authors sincerely acknowledge McMaster University clinical staff.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Luis Henrique Braga, Bruno Leslie, Yaqoub Jafar, Geemitha Ratnayake; data collection: Luis Henrique Braga, Yaqoub Jafar; analysis and draft manuscript: Luis Henrique Braga, Geemitha Ratnayake, Yaqoub Jafar. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

The authors confirm that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

Ethics Approval

This is not applicable. The Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board confirmed that specific ethics approval was not needed for this project. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of anonymized patient information in this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials

The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/cju.2025.064122/s1.

References

1. González R, Ludwikowski BM. Alternatives to conventional enterocystoplasty in children: a critical review of urodynamic outcomes. Front Pediatr 2013;1:25. [Google Scholar]

2. Adams MC, Brock JW, Pope JC et al. Ureterocystoplasty: is it necessary to detubularize the distal ureter? J Urol 1998;160(Pt 1):851–853. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

3. Koff SA. Estimating bladder capacity in children. Urology 1983;21(3):248. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

4. Eckstein H, Martin M. Uretero-cystoplastik. Aktuel Urol 1973;4:255–257. [Google Scholar]

5. Bellinger M. Ureterocystoplasty: a unique method for vesical augmentation in children. J Urol 1993;149(4):811–813. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

6. Kajbafzadeh AM, Farrokhi-Khajeh-Pasha Y, Ostovaneh MR et al. Teapot ureterocystoplasty and ureteral Mitrofanoff channel for bilateral megaureters: technical points and surgical results of neurogenic bladder. J Urol 2010;183(3):1168–1176. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

7. Husmann DA, Snodgrass WT, Koyle MA et al. Ureterocystoplasty: indications for a successful augmentation. J Urol 2004;171(1):376–380. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000100800.69333.4d. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Johal NS, Hamid R, Aslam Z et al. Ureterocystoplasty: long-term functional results. J Urol 2008;179(6):2373–2376. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

9. Baka-Ostrowska M. Bladder augmentation and continent urinary diversion in boys with posterior urethral valves. Cent European J Urol 2011;64(4):237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools