Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Crosstalk between mitochondrial dysfunction and benign prostatic hyperplasia: unraveling the intrinsic mechanisms

1 Department of Urology, Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan, 430071, China

2 Department of Urology, Xijing Hospital of Fourth Military Medical University, Xi’an, 710000, China

* Corresponding Author: Xinhua Zhang. Email:

# These authors have contributed equally to this work

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(4), 255-269. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.066523

Received 10 April 2025; Accepted 13 June 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) represents a prevalent etiology of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in the male population, clinically defined by a non-malignant proliferation of prostatic tissue. While BPH exhibits a high prevalence among older male populations globally, the precise underlying mechanisms contributing to its development remain incompletely elucidated. Mitochondria, essential organelles within eukaryotic cells, are critical for cellular bioenergetics, the regulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, and the modulation of cell death pathways. The maintenance of mitochondrial homeostasis involves a complex interplay of processes. By synthesizing previous literature, this review discusses mitochondrial homeostasis in prostate glands and the role of mitochondrial dysfunction in the context of BPH. Furthermore, the review delved into each dimension of mitochondrial dysfunction in the specific etiology of BPH, highlighting its impact on cell survival, apoptosis, ferroptosis, oxidative stress and androgen receptor (AR). Overall, this review aims to unveil the crosstalk between mitochondrial dysfunction and BPH and identify intrinsic mechanisms.Keywords

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), a ubiquitous age-associated nonmalignant condition in males, is characterized by a cascade of troublesome lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), such as urinary obstruction and voiding difficulties, adversely affecting male health and quality of life.1 The incidence of BPH rises with age,2 with histological prevalence increasing to over 70% in those aged 60–69, and exceeding 80–90% in men above 80.3 LUTS, as a common consequence of BPH, bothered 44% of individuals aged 40–59 and 70% of those over 80.4,5 Furthermore, the global burden of BPH has shown a noticeable increase, with reported cases rising from 5.48 million in 1990 to 11.26 million in 2019.6 Current mechanistic studies substantiate that unbounded epithelial and stromal cellular proliferation, concomitant with dysregulated programmed cell death pathways, constitutes a fundamental role in the development of BPH/LUTS.7 Additionally, the imbalanced ratio of androgen and estrogen,8 aberrant epithelial-stromal interaction,9 chronic inflammation,10 and oxidative stress (OS)11 have been implicated in BPH progression. Nevertheless, no definitive consensus has been established regarding the intrinsic mechanisms underlying the etiopathogenesis of BPH.

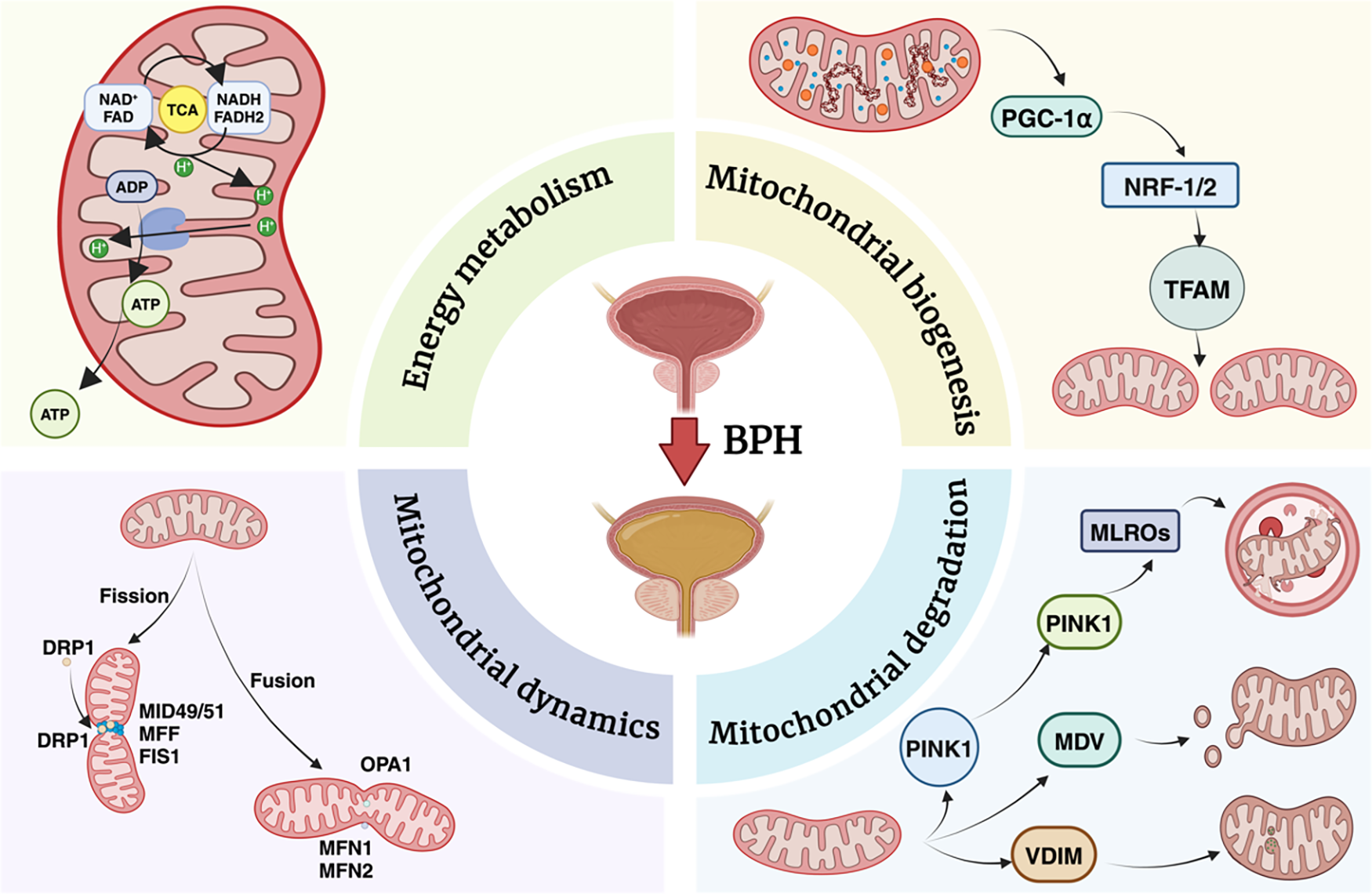

Mitochondrial homeostasis plays a critical role in sustaining various physiological processes, including mitochondrial energy metabolism, mitochondrial biogenesis, mitochondrial dynamics, as well as mitochondrial degradation.12 Emerging evidence underscores mitochondrial dysfunction as a central driver in diverse pathologies, with distinct mechanisms linked to structural and regulatory defects.13 Notably, in Parkinson’s disease, impaired PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1)/Parkin-mediated mitophagy drives toxic mitochondrial accumulation, precipitating dopaminergic neurodegeneration.14 In addition, cardiovascular pathologies such as heart failure are exacerbated by dysregulated mitochondrial dynamics, specifically dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1) hyperactivation, which induces excessive fission and cardiomyocyte apoptosis.15,16 Meanwhile, metabolic disorders like type 2 diabetes are linked to oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) failure due to ROS overproduction and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α) suppression, promoting systemic insulin resistance.17 Similarly, cancer progression involves oncogene-driven mitochondrial metabolic rewiring, particularly electron transport chain (etc) complex I dysfunction, which enhances glycolysis and chemoresistance.18 In parallel, Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis correlates with optic atrophy 1 (OPA1)-dependent cristae destabilization, accelerating neuronal death via unregulated cytochrome c (Cyt-c) release.19 Furthermore, autoimmune conditions such as lupus arise from compromised outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) integrity, enabling mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) leakage and cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)-stimulator of interferon genes (STING)-mediated inflammation.20 These findings highlight the critical role of mitochondrial dysregulation across diseases, emphasizing therapeutic targeting of mitochondrial quality control, dynamics, and redox balance.

The diverse outcomes of mitochondrial dysfunction have been widely implicated in BPH progression. It was found that decreased mitophagy aggravated BPH in aged mouse models via inducing DRP1 and estrogen receptor.21 In addition, our recent study unraveled that the NELL2 knockdown might trigger mitochondria-dependent apoptosis via extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK1/2) in prostatic cells.22 Furthermore, we revealed that glutathione peroxidase 3 (GPX3) could induce mitochondria-mediated apoptosis and resist autophagy-related ferroptosis in hyperplastic prostate.23 Collectively, this review delves profoundly into the physiological functions of mitochondria in the prostate and elaborates on how mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to the onset and progression of BPH. These insights may pave the way for innovative treatments to mitigate BPH/LUTS.

Overview of Mitochondrial Homeostasis

Basic structure of mitochondria

Dating back to 1857, Rudolf Albert von Kölliker discovered a granular structure in muscle cells, and in 1898, Carle Benda named this granular structure “mitochondria”. Mitochondria are essential intracellular organelles characterized by intricate structural organization and multifunctional metabolic capabilities.24 Structurally, mitochondria are compartmentalized into four distinct domains: the OMM, mitochondrial inner membrane (IMM), intermembrane space (IMS), and matrix.25 The OMM contains abundant mitochondrial porins, such as mitofusin 1 (MFN1) and mitofusin 2 (MFN2). The IMM undergoes invagination to form cristae, which serve as the structural platform for the etc enzyme complexes and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthase-mediated oxidative phosphorylation. The IMS is situated between the IMM and OMM, and houses critical mitophagy regulators, metabolic enzymes, and apoptosis-related factors, including but not limited to: PINK1, OPA1, Cyt-c, and adenine nucleotide translocase (ANT).26

Mitochondrial energy metabolism

Mitochondria, serving as the primary bioenergetic organelles within eukaryotic cells, facilitate the synthesis of approximately 90% of cellular ATP through the process of OXPHOS.27 Succinctly, energy substrates undergo active transport into the mitochondrial matrix, in which these substrates are subsequently metabolized within the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle to yield electron carriers, specifically nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) alongside flavin adenine dinucleotide (FADH2). Subsequently, these electron carriers donate electrons to etc, inducing proton pumps to translocate protons from the matrix to the IMS, thereby generating an electrochemical gradient, also referred to as the mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm).28 ATP synthase utilizes the proton gradient to catalyze the phosphorylation of ADP into ATP. In the terminal oxidative step, cytochrome c oxidase IV (COX IV) catalyzes the four-electron reduction of molecular oxygen to water, coupling electron transfer from reduced Cyt-c with the consumption of matrix-derived protons.29

The homeostatic regulation of mitochondrial bioenergetics is essential for normal physiologic function of the prostate. Prostatic luminal cells, the predominant epithelial subtype, exhibit specialized mitochondrial bioenergetics that uniquely support seminal fluid biosynthesis. A notable characteristic of prostatic luminal cells is their capacity to accumulate elevated concentrations of zinc ions.30 This intracellular zinc enrichment is hypothesized to exert an inhibitory influence on the activity of mitochondrial aconitase, a TCA cycle enzyme catalyzing citrate isomerization to isocitrate. The suppression of aconitase activity leads to the accumulation of citrate within luminal cells, thereby permitting its subsequent efflux into the prostatic fluid. Nevertheless, this metabolic adaptation is associated with certain cellular trade-offs.31 The TCA cycle truncation compromises OXPHOS efficiency, forcing a compensatory shift toward aerobic glycolysis.32 It was found that overexpression of anoctamin 7 (ANO7) resulted in the downregulation of OXPHOS activity in both prostate tissue and normal prostate epithelial cell lines (RWPE1), which highlighted the critical role of mitochondrial bioenergetics in prostatic physiology.33

In addition to energy metabolism, mitochondrial homeostasis relies on mechanisms such as mitochondrial biogenesis.

Mitochondrial biogenesis, critical for cellular mitochondrial renewal, necessitates coordinated nuclear-mitochondrial crosstalk through synchronized expression of nuclear-encoded genes and mtDNA-dependent transcription/translation machinery.34 Fundamentally, mtDNA expression is subject to modulation by specific nuclear transcription factors, notably nuclear respiratory factor 1/2 (Nrf1/2), alongside nuclear co-activators such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α).35 Nrf1 and Nrf2 exert transcriptional control over nuclear genes that encode subunits of the mitochondrial respiratory chain and mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM).36 TFAM exhibits binding affinity for multiple sites on mtDNA, thereby coordinating both the maintenance of the mitochondrial genome and the initiation of transcription.37 PGC-1α, functioning as a transcriptional co-activator lacking direct DNA-binding capability, is recruited to chromatin through interactions with nuclear receptors and transcription factors, consequently promoting the process of mitochondrial biogenesis.38,39 Beyond transcriptional regulators, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), key metabolic sensors governing mitochondrial biogenesis, coordinately activate PGC-1α via phosphorylation of AMPK and deacetylation of SIRT1 under energy stress, thereby linking cellular energy status to mitochondrial homeostasis.40

Mitochondrial biogenesis is indispensable for sustaining cellular bioenergetic homeostasis and function, with its dysregulation being pathophysiologically implicated in prostatic diseases, particularly BPH. However, the predisposition of mitochondrial biogenesis remained controversial in BPH. A study analyzed the copy numbers of mtDNA in 32 patients with BPH, revealing that the amount in the BPH group was significantly greater in contrast to normal controls.41 On the other hand, previous research in rat models demonstrated decreased SIRT3 expression in the prostate tissues of BPH rats. SIRT3 overexpression restored mitochondrial ultrastructural integrity in prostate tissues of BPH rats. Mechanistically, SIRT3 significantly activated the AMPK-PGC-1α signaling pathway, stabilizing ΔΨm and mitochondrial structure. This pathway ameliorated BPH progression by preserving mitochondrial bioenergetic competence.42

Apart from mitochondrial biogenesis, mitochondrial dynamics were also implicated in the regulation of mitochondrial homeostasis.

Mitochondrial reticular formation is a dynamically regulated system governed by fusion-fission dynamics, which modulate mitochondrial morphology, distribution, and abundance.43 The process of mitochondrial fusion necessitates the coordinated action of several proteins, prominently including MFN1 and MFN2, which mediate OMM fusion, and OPA1, responsible for IMM fusion.44,45 Within mammalian cells, MFN1 and MFN2 proteins interact to form either homodimers or heterodimers, leading to the formation of inter-mitochondrial bridging structures between adjacent organelles. These mitochondrial fusion proteins possess a GTPase catalytic domain capable of enzymatically hydrolyzing guanosine triphosphate (GTP), thereby inducing conformational alterations in the OMM and facilitating its fusion.45 DRP1, the principal regulator of mitochondrial fission, is a cytosolic GTPase characterized by the presence of three functional domains: an amino-terminal GTPase domain, a carboxyl-terminal GTPase effector domain, and an intermediate helix domain. Following activation mediated by specific receptors for DRP1, such as mitochondrial fission factor (MFF), mitochondrial fission protein 1 (FIS1), and mitochondrial dynamics proteins of 49 and 51 kDa (MID49/51), GTP hydrolysis-driven conformational changes generate mechanical force to sever mitochondrial membranes, executing fission.46 Thus, mitochondrial fission serves as a critical regulatory mechanism for eliminating dysfunctional mitochondria and ensuring the dynamic equilibrium of the mitochondrial reticulum through quality control processes.

Dysregulated mitochondrial fission-fusion dynamics are implicated in the progression of BPH. It was observed that the phosphorylation of DRP1 (p-DRP1, serine 637) was significantly decreased in BPH rats in comparison to the normal group. By utilizing the Korean red ginseng (KRG), p-DRP1 was dramatically elevated in contrast with that in the BPH group. Mechanically, this upregulation of p-DRP1 inhibited mitochondrial fission, thus resulting in mitochondrial elongation.47 In addition, ellagic acid treatment upregulated mitochondrial fusion-associated protein MFN1 and fission-associated dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1/DNM1L) in testosterone propionate (TP)-induced BPH rat models along with RWPE-1 cells, thereby attenuating BPH progression.48

Along with the function mechanisms above, mitochondrial integrity relies on degradation mechanisms such as mitophagy.

A multitude of specialized mechanisms exist to selectively eliminate or degrade distinct mitochondrial constituents, segments of mitochondria, or entire mitochondrial organelles. Specific OMM proteins targeted for degradation undergo selective ubiquitination and subsequent processing by the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS).49 Conversely, the degradation of IMM proteins relies on AAA ATPase family proteases that traverse the IMM to facilitate the removal of misfolded substrates within both the mitochondrial matrix and IMS.50 Contemporary research has elucidated a previously undescribed phenomenon, designated as vesicle derived from the inner mitochondrial membrane (VDIM), which functions to selectively remove compromised regions of the IMM and is hypothesized to preserve the structural integrity of intact mitochondrial cristae, thereby potentially protecting mitochondria from localized damage.51 Mitochondria-derived vesicles (MDVs) bud from mitochondrial compartments as a quality control mechanism, mediating the selective transport of oxidative proteins to either lysosomes or peroxisomes, ultimately leading to proteolytic degradation.52 Completely non-functional mitochondria undergo selective encapsulation within microvesicles or migrasomes, followed by secretion via extracellular vesicles through mechanisms encompassing mitocytosis and the autophagic secretion of mitochondria.53,54 Moreover, compromised mitochondria undergo selective elimination through mitophagy, a process wherein autophagosomes sequester mitochondria and subsequently fuse with lysosomes for degradation, or via direct lysosome-mediated micromitophagy. Mitophagy is a canonical selective autophagy process in which excess or dysfunctional mitochondria are selectively removed via autophagosomes. Canonical mitophagy operates through ubiquitination-mediated PINK1-Parkin axis or receptor-mediated pathways.55 Emerging studies reveal that under specific physiological or pathological conditions, mitochondria are capable of undergoing adaptive structural reorganization, leading to the formation of mitochondrial spheroids or mitochondria-lysosome-related organelles (MLROs), characterized by the acquisition of lysosomal markers, potentially targeting them for degradation. Within murine embryonic fibroblasts, mitochondria exhibiting depolarization adopt annular or C-shaped morphologies, eventually culminating in the formation of spherical structures with an internal lumen, delimited by membranes enclosing cytosolic constituents.56 MLROs arise from MDVs that undergo fusion with lysosomes to facilitate proteolytic clearance, a process under negative regulation by transcription factor EB (TFEB) and mechanistically associated with mitochondrial proteostasis.57 In contrast to VDIM, MLROs exhibit a comprehensive degradative capacity for all mitochondrial constituents, encompassing the OMM, IMM, and matrix proteins.58

The alteration of mitophagy was broadly reported in the studies regarding BPH. In aging mice, specifically those aged 12 and 24 months, a reduction in Parkin phosphorylation levels was observed in comparison to young controls aged 8 weeks. In addition, the number of MLROs appeared to be significantly decreased under the electron microscopy analysis, revealing reduced mitophagy.21 Moreover, a novel study utilized the prostate organoid to explore the mitochondrial dysfunction in BPH. The results demonstrated a reduction of PINK1 and Parkin in lipopolysaccharide (LPS) treated BPH organoid, resulting in the accumulation of damaged mitochondria. Nevertheless, the application of Kaempferol, a flavonoid present in diverse plants including broccoli and spinach, mitophagy was dramatically restored and confronted the development of BPH.59

In summary, the dynamic network consisting of these intricate actions collaborates to maintain mitochondrial homeostasis under conditions of energy deprivation or in the context of mitochondrial perturbation. Figure 1 demonstrates the regulation of mitochondrial homeostasis, which is implicated in the pathogenesis of BPH. Figure 1 was created by BioRender software (www.biorender.com).

Figure 1: Schematic overview of the key mitochondrial processes implicated in BPH

Energy metabolism within the mitochondria is driven by the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and oxidative phosphorylation, resulting in ATP generation. Mitochondrial biogenesis is regulated by transcriptional coactivators and factors, including PGC-1α, Nrf-1/2, and TFAM, which coordinate the replication and transcription of mitochondrial DNA. Mitochondrial dynamics involve fission (mediated by DRP1, MID49/51) and fusion (controlled by MFN1, MFN2, and OPA1), maintaining organelle morphology, distribution, and quality control. Damaged or dysfunctional mitochondria undergo selective degradation via PINK1-Parkin mediated pathways, which can involve mitochondrial-derived vesicles (MDVs), vesicular interactions with lysosomes (VDIM), and mitochondrial-lysosomal repair organelles (MLROs). Collectively, these interconnected processes maintain mitochondrial integrity, bioenergetics, and turnover in the context of BPH, underscoring their potential as therapeutic targets.

Core Dimensions of Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Etiology of BPH

Mitochondrial dysfunction and cell viability, proliferation

Histopathologically, BPH is characterized by prostatic hyperplasia, denoting an increase in cellular number as opposed to cellular hypertrophy, which signifies an augmentation in cell size. The pathogenesis of BPH involves the excessive proliferation of both epithelial and stromal cell populations during the pathological phase of the condition.60 Plenty of studies have unraveled the vital role of cell viability or cell proliferation in BPH. Our previous study first revealed that smoothened (SMO), the key regulatory component of hedgehog signaling pathways, exhibited upregulation within BPH tissues and demonstrated localization within both the stromal and epithelium compartments of human prostate tissues. Moreover, the suppression of smoothened could result in decreased cell proliferation, thereby attenuating the process of BPH.61 Additionally, bone morphogenetic protein 5 (BMP5) was found upregulated in human BPH tissues, which enhanced cell viability in both prostatic epithelial and stromal cells.62

Existing evidence also emphasized the impact of various dimensions of mitochondrial dysfunction on cell viability. Excessive mitochondrial energy metabolism was reported to motivate cell proliferation.63 In colorectal cancer cells (CRC), the researchers found that overexpression of testis-specific protease 50 could significantly elevate the activity of mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes, ATP levels, and ΔΨm via PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, thereby enhancing the migration, invasion and viability of the tumor.64 Translocase of Inner Mitochondrial Membrane 23 (TIMM23) is a fundamental constituent of the mitochondrial protein import machinery, facilitating the translocation of precursor proteins across the inner mitochondrial membrane into the mitochondrial matrix. In the context of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines, the genetic perturbation of TIMM23 expression via shRNA-mediated silencing or CRISPR/Cas9-mediated ablation resulted in compromised mitochondrial function, characterized by diminished complex I activity, ATP depletion, dissipation of ΔΨm, augmented oxidative stress, and lipid peroxidation. These observed mitochondrial dysfunctions correlated with a reduction in cellular viability, proliferative potential, and migratory capacity.65 Recent studies indicated that mitochondrial biogenesis was essential for cell viability, and the AMPK/SIRT1/PGC-1α axis constituted a significant regulatory signaling cascade governing the process of mitochondrial biogenesis. In a study of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), SLC25A35 was identified to promote the proliferation and metastasis of HCC cells via facilitating mitochondrial biogenesis. Mechanistically, PGC-1α was upregulated by SLC25A35 via increasing acetyl-CoA-mediated acetylation of PGC-1α.66 Apart from studies on cancers, the dysfunction of mitochondrial biogenesis was also implicated in sarcopenia. Activation of NAD+ functioned to restore the suppression of the SIRT1/PGC-1α axis, stimulating mitochondrial biogenesis and promoting satellite cell proliferation, ultimately improving muscle function.67 The reduction of cell viability also stemmed from the impairment of mitochondrial dynamics. As a key regulator of mitochondrial fission, DRP1 was extensively studied in diverse scenarios. A recent investigation revealed that downregulation of PINCH-1 suppressed mitochondrial fission through the attenuation of DRP1 expression levels. Moreover, the suppression of mitochondrial fission has the potential to impede the proliferative capacity and metastatic potential of head and neck squamous carcinoma cells.68 Moreover, a detailed analysis utilizing machine learning-enhanced transmission electron microscopy was conducted on 7141 mitochondria isolated from 54 glioma patients following surgical resection. This investigation unequivocally demonstrated an inhibitory role for the DNM1L/DRP1-FIS1 axis in the proliferation of high-grade glioma cells.69 As mentioned above, PINK1-Parkin-dependent mitophagy played a dominant role in mitochondrial degradation. The effect of mitophagy on cell proliferation was controversial in diverse scenarios. In breast cancer, the combination of fasting and sorafenib induced mitophagy, characterized by mitochondrial dysfunction and activation of the PINK1-Parkin pathway. Consequently, increased mitophagy inhibited the cancer cell proliferation.70 In contrast, an additional investigation identified 16 genes associated with mitophagy through a screening process to develop a resilient prognostic model demonstrating notable predictive accuracy for patient outcomes in bladder cancer. The findings indicated that DARS2 promoted cellular proliferation via the upregulation of PINK1, consequently enhancing PINK1-mediated mitophagy.71

Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Apoptosis

Apoptosis is generally recognized as the most renowned form of programmed cell death, which functions to maintain homeostasis of growth in normal cells.72 An imbalance in the processes of prostatic cell proliferation and apoptosis has been identified as a critical pathogenic mechanism underlying the development of BPH.73 Importantly, the deprivation of apoptosis in the progression of BPH was uncovered in numerous studies. S100 calcium-binding protein A4 (S100A4) was found to be mainly localized in human prostatic stroma. The upregulation of S100A4 inhibited cell apoptosis through the ERK pathway in both the human prostate stromal cell line (WPMY-1) and rat prostate tissues.74 In addition, our recent research suggested that the six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of prostate 4 (STEAP4) could strongly reduce the apoptosis in BPH.75 Moreover, Li et al. indicated that the balance between epithelial proliferation and apoptosis could be disrupted by the METTL3/YTHDF2/PTEN axis, accelerating BPH development.76

Apoptosis encompasses two principal signaling pathways: the intrinsic and the extrinsic. Mitochondria assume a pivotal function within the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, also designated as the mitochondrial pathway.77 Notably, abnormalities in mitochondrial function contributed to cell apoptosis based on mounting evidence. Creatine kinase mitochondrial isoform 1 (CKMT1), an enzyme that regulates cellular energy homeostasis, was investigated in the context of ulcerative colitis (UC) pathogenesis. Given its role as a kinase that catalyzes the production of mitochondrial ATP through oxidative phosphorylation, CKMT1 exhibited a direct functional association with the etc. Furthermore, the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) was implicated in CKMT1-mediated apoptosis.78 Similarly, the research focused on esophageal cancer (EC) indicated that angiotensin II receptor type 1 (AGTR1) was upregulated in EC cells, further elevating intracellular Ca2+ levels, reducing ATP levels and ΔΨm, which was accompanied by enhanced mitochondrial pathway apoptosis.79 Also, a great number of publications unveiled the interplay between mitochondrial biogenesis and cell apoptosis. In peripheral lens epithelial cells (LECs), overexpression of ATM is demonstrated to functionally repair damaged mtDNA to enhance mitochondrial biogenesis, consequently, preventing LECs apoptosis.80 In addition, inhibition of TRIM63 in rat models resulted in significant upregulation of the PPARα and PGC-1α expression levels. This alteration robustly enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis, which finally reduced the apoptosis level of rat diaphragmatic tissue.81 Furthermore, numerous investigations shed light on the role of mitochondrial dynamic-related regulators in the modulation of apoptosis. As reported, Kirenol, a bioactive diterpene derived from traditional herbal medicine, functioned to improve neurological outcomes and augmented OPA1 expression. This improvement of mitochondrial fusion effectively restored apoptotic-related protein markers in rats with middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO).82 Mitochondrial caseinolytic peptidase P (ClpP), an ATP-dependent protease, resided within the mitochondrial matrix. The knockdown of ClpP resulted in a significant augmentation of mitochondrial fission, accompanied by a reduction in the ratio of phosphorylated DRP1 at serine 616 (p-DRP1S616) to total DRP1 and a decrease in the expression levels of MFN1, MFN2, and Opa1. This cascade of events led to an increase in the levels of caspase 9, cleaved caspase 3, and Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax), alongside a decrease in the levels of Bcl-2 in cardiomyocytes when compared to normal control cells.83 Moreover, cell apoptosis could also result from dysregulated mitochondrial degradation. Impaired mitophagy induced by amyloid-beta (Aβ) was associated with neuronal dysfunction and neurodegenerative processes in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). A recent investigation demonstrated that protein phosphatase Mn2+/Mg2+-dependent 1D (PPM1D) promoted autophagosome formation and subsequent lysosomal degradation of dysfunctional mitochondria in the murine hippocampus. Analogous effects of PPM1D on neuronal apoptosis and mitophagy were observed in neuronal cell lines, and these effects were abrogated by the mitophagy inhibitor cyclosporine A.84 In addition, the inhibition of the PINK1/Parkin pathway was shown to increase the apoptosis rate in cognitive impairments related to methylmalonic acidemia (MMA).85

Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Ferroptosis

Ferroptosis, a recently elucidated modality of non-apoptotic regulated cell death, is defined by the iron-dependent accumulation of lipid peroxides and has garnered considerable attention since its initial description in 2012.86 This distinct form of cell death exhibits both morphological and biochemical characteristics that differentiate it from established cell death mechanisms, including apoptosis, necrosis, and autophagy.87 Specifically, ultrastructural analysis via electron microscopy reveals a prominent morphological alteration in ferroptotic cells, characterized by shrunken mitochondria with elevated membrane density.88 The principal biochemical hallmarks of ferroptosis include elevated levels of intracellular labile iron, increased ROS production, diminished glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) activity, and the accumulation of lipid metabolites.89 The execution of ferroptosis involves excessive oxidative damage to cellular membrane lipids. This process is frequently associated with the upregulation of intracellular labile iron, transferrin, and malondialdehyde (MDA), alongside the downregulation of glutathione (GSH) and anti-ferroptotic defense mechanisms.90 While the involvement of ferroptosis has been extensively investigated in various malignancies, including prostate cancer,91 its role in benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) remains largely unexplored. Significantly, recent studies have elucidated the presence of autophagy-related ferroptosis in the progression of BPH.23,92 Li et al. indicate that GPX3 is expressed in both the stromal and epithelial compartments of the prostate and exhibits reduced expression in BPH specimens. Furthermore, the overexpression of GPX3 demonstrated an inhibitory effect on autophagy by modulating the AMPK/mTOR pathway and upregulating the Nrf2/GPX4 axis, thereby counteracting autophagy-related ferroptosis in hyperplastic prostatic tissue.23 Additionally, by performing RNA sequencing, Zhan et al. screened out an upregulated long noncoding RNA (lncRNA), taurine-upregulated gene 1 (TUG1), in BPH tissues. As a result, induced TUG1 was found to competitively bind with miR-188-3p and facilitate the expression of GPX4, thereby diminishing intracellular ROS levels and impeding ferroptosis in prostate luminal cells.93 As aforementioned, we could speculate that ferroptosis might act as a critical contributor to BPH.

Considering the pivotal role of mitochondria in modulating cell death pathways, investigators have posited a potential involvement of mitochondria in the regulation of ferroptosis. Emerging evidence indicates that the involvement of mitochondria in ferroptosis is context-specific. The mitochondrial protein pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (PDK4) acts as an inhibitor of ferroptosis via a mechanism dependent on acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), by hindering pyruvate dehydrogenase-dependent pyruvate oxidation and the ensuing production of citric acid and fatty acids in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) cells, thereby suppressing glucose-dependent ferroptosis.87 Mitochondrial NADP+-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH2) catalyzes the initial oxidative decarboxylation reaction within the TCA cycle. The downregulation of IDH2 increased the susceptibility of tumor cells to ferroptosis via depleting the mitochondrial NADPH pool, a key location for mitochondrial glutathione (GSH) metabolism.94 In head and neck cancer cells, the occurrence of lipid peroxidation and cystine deprivation-induced ferroptosis was mitigated via a mechanism involving glutaminolysis. Consequently, the maintenance of mitochondrial energy metabolism might contribute to ferroptosis by modulating glucose metabolism pathways, such as the TCA cycle or glutaminolysis.95 Furthermore, an association between mitochondrial biogenesis and ferroptosis has been implicated. It was demonstrated that the degradation of TFAM triggered mtDNA stress as well as ferroptosis in a macroautophagy/autophagy-dependent manner within human pancreatic carcinoma cells.96 Indeed, Nrf2 served as a vital nexus in the orchestration of mitochondrial-dependent ferroptosis. Conflicting evidence exists regarding the precise role of the Nrf2/heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) signaling pathway in modulating ferroptosis within CRC cells.97 While one study demonstrated that the Nrf2-dependent transcriptional upregulation of HO-1 promoted ferroptotic cell death, a contrasting investigation indicated that suppression of the Nrf2/HO-1 cascade augmented ferroptosis specifically within KRAS-mutant CRC cells.98 The divergent observations above underscore the ongoing debate surrounding the involvement of Nrf2 in mitochondrial biogenesis as it pertains to ferroptosis susceptibility.

The regulation of mitochondrial dynamics is notably intertwined with the process of ferroptosis. Specifically, the knockdown of DRP1 resulted in mitochondrial filamentation, a mitigation of impaired mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), and a reduction in both basal and maximal mitochondrial respiration. These alterations collectively conferred protection against ferroptosis by maintaining mitochondrial structural integrity and preserving cellular redox homeostasis.99 Furthermore, deficiency in OPA1 conferred resistance to ferroptosis through the attenuation of mtROS production and the induction of the activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4)-dependent upregulation of the xCT-GSH-GPX4 antioxidant pathway as an element of the integrated stress response.100 Mitophagy plays a critical role in the restoration of cellular homeostasis under both physiological and stress conditions by restraining the accumulation of mtROS. Given the function of mitophagy in mitigating elevated mtROS levels, it is plausible to hypothesize that this process confers protection against ferroptosis. In contrast, research conducted by Basit et al. showed that inhibition of complex I led to an increase in mtROS levels, which subsequently triggered mitophagy and initiated a mitophagy-dependent elevation in overall ROS production, ultimately culminating in ferroptotic cell death.101 Furthermore, defects in mitophagy mediated by BNIP3 and NIP3-like protein X (NIX) elevated mtROS levels, thereby synergistically enhancing the susceptibility of HeLa cells to ferroptosis in the context of compromised Nrf2-driven antioxidant enzyme systems.102

Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress, a recognized predisposing factor in BPH, is characterized by an imbalance in the equilibrium between the generation and scavenging of oxidants, encompassing ROS among others.103 This state of oxidative stress arises from either an excessive production of oxidants, diminished antioxidant capacity, or a combination thereof, and has been shown to induce DNA damage, including mutations, deletions, and rearrangements, while concurrently impairing DNA repair mechanisms. Consequently, the hyperplastic prostate experiences oxidative stress due to both the overgeneration of oxidants and the compromised antioxidant defense, ultimately stimulating compensatory cellular proliferation and prostatic enlargement.11 Elevated levels of oxidants and their byproducts, such as inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), reactive nitrogen species,104 nitric oxide (NO),105 and plasma peroxides,106 have been detected in individuals with BPH compared to control subjects. Inflammatory cells are widely acknowledged as a primary source of ROS during the progression of BPH. Conversely, a compromised antioxidant defense mechanism exhibits diminished capacity in the attenuation of oxidative stress, consequently amplifying reactive ROS-mediated injury to prostatic tissues. Research by Olinski and colleagues indicated that a significant proportion of BPH tissue samples exhibited comparatively reduced the functional ability of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT).107 However, in contrast with previous studies, our recently published evidence underlined the fundamental role of heat shock protein family members, including glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78)108 and heat shock protein family A member 1A (HSPA1A)109 in attenuating oxidative stress in prostatic cells or testosterone-induced BPH (T-BPH) rat models, thus resulting in the occurrence of BPH. Therefore, the accurate underlying mechanism of oxidative stress in BPH deserves further exploration.

In terms of the mechanism of oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction presented an indispensable link. ROS, byproducts of oxygen consumption and cellular metabolism, primarily originate from mitochondria and NADPH oxidase.110 Within the myocardium, where mitochondria constitute roughly 30% of the cellular volume, a diminution in OXPHOS occurred during ischemia, leading to ATP depletion, structural alterations, and the accumulation of succinate within the TCA cycle. Subsequently, during reperfusion, the rapid oxidation of succinate drives reverse electron transport at mitochondrial complex I, generating a burst of ROS that induces damage to lipids, proteins, and mtDNA.111 Another study carried on in CT26 and HT29 CRC cell lines also indicated that lauric acid could induce mitochondrial oxidative stress by inhibiting mitochondrial OXPHOS.112 As for mitochondrial biogenesis, astaxanthin was found to enhance the expression of p-AMPK and PGC-1α in mouse preantral follicles as well as NRF1 and TFAM, which are crucial for mitochondrial biogenesis, ultimately protecting the oocytes against oxidative stress.113 Moreover, activation of the AMPK/PGC1-α/NRF-1/TFAM signaling pathway was confirmed to promote mitochondrial biogenesis, thus reducing oxidative stress in a zinc-deficient mouse model.114 The functional interaction between mitochondrial dynamics and oxidative stress has been covered in thousands of research studies. As reported, Zinc transporter 6 (ZnT6), a key modulator of mitochondrial dynamics and function within cardiomyocytes, played a role in the disruption of zinc ion (Zn2+) homeostasis by inducing excessive mitochondrial fission mediated by DRP1, which caused overproduction of ROS and apoptotic cell death.115 In a study concerning asthma, gene ABCG2 was identified to reduce DRP1-mediated mitochondrial fission while enhancing MFN2-mediated fusion. This functional mechanism led to an improvement of antioxidant capacity by mitigating mtROS.116

Mitophagy, a central part of mitochondrial degradation, was also involved in the adjustment of oxidative stress. A contemporary study revealed that ataxia-telangiectasia and Rad3-related (ATR) kinase and PINK1 are localized to the mitochondrial translocase of the outer and inner membrane (TOM/TIM) complex, wherein ATR directly interacts with and consequently stabilizes PINK1. The ablation of ATR inhibited the initiation of mitophagy, thereby perturbing OXPHOS functionality, leading to the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that compromise cytosolic macromolecules in both cellular and brain tissue contexts.117 In addition, G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 4 (GRK4) was investigated in ischemic brain injury. It was proved that the overexpression of GRK4 resulted in the impairment of mitophagy, as evidenced by the altered expression levels of key proteins involved in mitophagy, including Beclin-1, PINK1, and p62, thereby contributing to mitochondrial dysfunction and elevated oxidative stress levels.118

Mitochondrial dysfunction and androgen receptor

It is widely established that androgen receptor (AR) signaling plays a pivotal role in the initiation and progression of BPH,119 and the inhibition of this signaling pathway has demonstrated the potential to reduce prostatic volume and alleviate LUTS associated with BPH.120 Early investigations in the 1980s reported comparatively elevated levels of nuclear AR in hyperplastic prostatic tissue.121,122 Classified within the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily, AR has been consistently observed within the nuclear compartment of prostatic cells, a finding substantiated by evidence derived from both normal and hyperplastic prostatic tissues.123 Contemporary investigations have delineated the regulatory influence of AR on the cellular proliferation of both stromal and epithelial cell populations, in addition to its participation in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) process.9,124 In vivo, studies utilizing AR knockout models have demonstrated that the absence of stromal AR resulted in a diminution of the proliferative activity of prostatic cells and a concomitant reduction in the volume of the anterior prostate lobes.125,126 Furthermore, stromal AR was shown to promote the viability of stromal cells through the recruitment of infiltrated macrophages.127 Conversely, the abrogation of AR signaling within luminal cells resulted in an increased rate of proliferation.128 These findings indicated a notable divergence in the mode of AR action between epithelial and stromal cells.

It is broadly accepted that androgen administration enhances AR activity within epithelial cells while simultaneously diminishing its function in stromal cells. Indeed, chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) data on AR binding regions revealed distinct target gene profiles in epithelial and stromal cells, providing further evidence for the differential modes of action between epithelial and stromal AR.129 Moreover, epithelial AR promoted BPH development in a manner of macrophage-mediated EMT, suggesting that AR in BPH-1 and mPrE cells possessed the capacity to recruit macrophages and enhance the EMT process.130 Collectively, the evidence suggested that AR, whether expressed in epithelial or stromal cells, played a significant role in the pathogenesis of BPH. Nevertheless, further mechanistic investigations are warranted to fully elucidate the intricate relationship between AR expression and the etiology of BPH.

There is still a lack of studies regarding the precise correlation between AR and mitochondrial dysfunction. Prostate cancer (PCa) is a well-known androgen-dependent malignancy. Yin et al. indicated that TOMM20, a mitochondrial outer translocase protein, functioned to stabilize AR and augment its transcriptional activity, whereas its knockdown facilitated AR degradation via the SKP2-mediated ubiquitin-proteasome pathway.131 In androgenetic alopecia (AGA), a hereditary disease, researchers found that MitoQ, a mitochondrially targeted antioxidant, could prevent dihydrotestosterone (DHT)-induced hair loss via modulating mitochondrial dysfunction. However, this effect might not be direct since mRNA and protein expression of AR remained unchanged in human dermal papilla cells (DPCs) treated with MitoQ.126

Mitochondrial dysfunction has been identified as a pivotal element in the pathogenesis of BPH, influencing cellular survival, apoptosis, ferroptosis, oxidative stress, and AR signaling. This review synthesizes the existing insights regarding mechanisms driving mitochondrial dysfunction in its etiological role, encompassing mitochondrial energy metabolism, mitochondrial biogenesis, mitochondrial dynamics, and mitochondrial degradation. A comprehensive understanding of the complex mechanisms of mitochondrial dysfunction across various pathophysiological states unequivocally presents novel opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Future investigations centered on mitochondrial-targeted therapies may yield innovative strategies to enhance the prevention and management of BPH, with the aim of improving clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgement

The assistance of the workforce in Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University in accomplishing this study is greatly acknowledged.

Funding Statement

This research received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Huan Liu and Yan Li; writing—original draft preparation: Huan Liu, Yan Li and Jizhang Qiu; figure construction: Junchao Zhang and Huan Lai; writing—review and editing: Huan Liu and Xinhua Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Xinhua Zhang, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Chughtai B, Forde JC, Thomas DDM et al. Benign prostatic hyperplasia. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016;2(1):16031. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2016.31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Robert G, De La Taille A, Descazeaud A. Epidemiology of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Prog Urol 2018;28(15):803–812. doi:10.1016/j.purol.2018.08.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Launer BM, McVary KT, Ricke WA, Lloyd GL. The rising worldwide impact of benign prostatic hyperplasia. BJU Int 2021;127(6):722–728. doi:10.1111/bju.15286. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Lin L, Wang W, Shao Y, Li X, Zhou L. National prevalence and incidence of benign prostatic hyperplasia/lower urinary tract symptoms and validated risk factors pattern. Aging Male 2025;28(1):2478875. doi:10.1080/13685538.2025.2478875. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Wei H, Zhu C, Huang Q et al. Global, regional, and national burden of benign prostatic hyperplasia from 1990 to 2021 and projection to 2035. BMC Urol 2025;25(1):34. doi:10.1186/s12894-025-01715-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. GBD 2019 Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Collaborators. The global, regional, and national burden of benign prostatic hyperplasia in 204 countries and territories from 2000 to 2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Healthy Longev 2022;3(11):e754–e776. [Google Scholar]

7. Tamalunas A, Sauckel C, Ciotkowska A et al. Inhibition of human prostate stromal cell growth and smooth muscle contraction by thalidomide: a novel remedy in LUTS? Prostate 2021;81(7):377–389. doi:10.1002/pros.24114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Devlin CM, Simms MS, Maitland NJ. Benign prostatic hyperplasia—what do we know? BJU Int 2021;127(4):389–399. doi:10.1111/bju.15229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Alonso-Magdalena P, Brössner C, Reiner A et al. A role for epithelial-mesenchymal transition in the etiology of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106(8):2859–2863. doi:10.1073/pnas.0812666106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Liedtke V, Stöckle M, Junker K, Roggenbuck D. Benign prostatic hyperplasia—A novel autoimmune disease with a potential therapy consequence? Autoimmun Rev 2024;23(3):103511. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2023.103511. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Udensi UK, Tchounwou PB. Oxidative stress in prostate hyperplasia and carcinogenesis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2016;35(1):139. doi:10.1186/s13046-016-0418-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Larson-Casey JL, He C, Carter AB. Mitochondrial quality control in pulmonary fibrosis. Redox Biol 2020;33:101426. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2020.101426. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Vazquez-Calvo C, Suhm T, Büttner S, Ott M. The basic machineries for mitochondrial protein quality control. Mitochondrion 2020;50(7):121–131. doi:10.1016/j.mito.2019.10.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Antico O, Thompson PW, Hertz NT, Muqit MMK, Parton LE. Targeting mitophagy in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2025;46(4):816–828. doi:10.1038/s41573-024-01105-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Lesnefsky EJ, Chen Q, Hoppel CL. Mitochondrial metabolism in aging heart. Circ Res 2016;118(10):1593–1611. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.307505. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Zhou B, Tian R. Mitochondrial dysfunction in pathophysiology of heart failure. J Clin Invest 2018;128(9):3716–3726. doi:10.1172/JCI120849. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Liu C, Lin JD. PGC-1 coactivators in the control of energy metabolism. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin 2011;43(4):248–257. doi:10.1093/abbs/gmr007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Uslu C, Kapan E, Lyakhovich A. Cancer resistance and metastasis are maintained through oxidative phosphorylation. Cancer Lett 2024;587(6):216705. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2024.216705. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Ahmed ME, Selvakumar GP, Kempuraj D et al. Synergy in disruption of mitochondrial dynamics by Aβ (1-42) and glia maturation factor (GMF) in SH-SY5Y cells is mediated through alterations in fission and fusion proteins. Mol Neurobiol 2019;56(10):6964–6975. doi:10.1007/s12035-019-1544-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Barrera M-J, Aguilera S, Castro I et al. Dysfunctional mitochondria as critical players in the inflammation of autoimmune diseases: potential role in Sjögren’s syndrome. Autoimmun Rev 2021;20(8):102867. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2021.102867. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Hong G-L, Kim K-H, Kim Y-J, Lee H-J, Kim H-T, Jung J-Y. Decreased mitophagy aggravates benign prostatic hyperplasia in aged mice through DRP1 and estrogen receptor α. Life Sci 2022;309(3):120980. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2022.120980. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Liu J, Liu D, Zhang X et al. NELL2 modulates cell proliferation and apoptosis via ERK pathway in the development of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Clin Sci 2021;135(13):1591–1608. doi:10.1042/CS20210476. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Li Y, Zhou Y, Liu D et al. Glutathione peroxidase 3 induced mitochondria-mediated apoptosis via AMPK/ERK1/2 pathway and resisted autophagy-related ferroptosis via AMPK/mTOR pathway in hyperplastic prostate. J Transl Med 2023;21(1):575. doi:10.1186/s12967-023-04432-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Green DE. Mitochondria–structure, function, and replication. N Engl J Med 1983;309(3):182–183. doi:10.1056/NEJM198307213090311. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Nunnari J, Suomalainen A. Mitochondria: in sickness and in health. Cell 2012;148(6):1145–1159. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Klecker T, Westermann B. Pathways shaping the mitochondrial inner membrane. Open Biol 2021;11(12):210238. doi:10.1098/rsob.210238. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Holmström KM, Finkel T. Cellular mechanisms and physiological consequences of redox-dependent signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014;15(6):411–421. [Google Scholar]

28. Vercellino I, Sazanov LA. The assembly, regulation and function of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2022;23(2):141–161. doi:10.1038/s41580-021-00415-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Vakifahmetoglu-Norberg H, Ouchida AT, Norberg E. The role of mitochondria in metabolism and cell death. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2017;482(3):426–431. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.11.088. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Lo S-T, Parrott D, Jordan MVC et al. The roles of ZnT1 and ZnT4 in glucose-stimulated zinc secretion in prostate epithelial cells. Mol Imaging Biol 2021;23(2):230–240. doi:10.1007/s11307-020-01557-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Frégeau-Proulx L, Lacouture A, Berthiaume L et al. Multiple metabolic pathways fuel the truncated tricarboxylic acid cycle of the prostate to sustain constant citrate production and secretion. Mol Metab 2022;62(1):101516. doi:10.1016/j.molmet.2022.101516. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Costello LC, Franklin RB. Prostate epithelial cells utilize glucose and aspartate as the carbon sources for net citrate production. Prostate 1989;15(4):335–342. doi:10.1002/pros.2990150406. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Löf C, Sultana N, Goel N et al. ANO7 expression in the prostate modulates mitochondrial function and lipid metabolism. Cell Commun Signal 2025;23(1):71. doi:10.1186/s12964-025-02081-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Pfanner N, Warscheid B, Wiedemann N. Mitochondrial proteins: from biogenesis to functional networks. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2019;20(5):267–284. doi:10.1038/s41580-018-0092-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Li PA, Hou X, Hao S. Mitochondrial biogenesis in neurodegeneration. J Neurosci Res 2017;95(10):2025–2029. doi:10.1002/jnr.24042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Klinge CM. Estrogenic control of mitochondrial function. Redox Biol 2020;31(Part 3):101435. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2020.101435. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Picca A, Lezza AMS. Regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis through TFAM-mitochondrial DNA interactions: useful insights from aging and calorie restriction studies. Mitochondrion 2015;25(28):67–75. doi:10.1016/j.mito.2015.10.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Liu L, Li Y, Wang J et al. Mitophagy receptor FUNDC1 is regulated by PGC-1α/NRF1 to fine tune mitochondrial homeostasis. EMBO Rep 2021;22(3):e50629. doi:10.15252/embr.202050629. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Dominy JE, Puigserver P. Mitochondrial biogenesis through activation of nuclear signaling proteins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2013;5(7):a015008. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a015008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Lumpuy-Castillo J, Amador-Martínez I, Díaz-Rojas M et al. Role of mitochondria in reno-cardiac diseases: a study of bioenergetics, biogenesis, and GSH signaling in disease transition. Redox Biol 2024;76:103340. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2024.103340. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Zole E, Baumanis E, Freimane L et al. Changes in TP53 gene, telomere length, and mitochondrial DNA in benign prostatic hyperplasia patients. Biomedicines 2024;12(10):2349. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2024.103340. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Li Y, Wang Q, Li J, Shi B, Liu Y, Wang P. SIRT3 affects mitochondrial metabolic reprogramming via the AMPK-PGC-1α axis in the development of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Prostate 2021;81(15):1135–1148. doi:10.1002/pros.24208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Meng K, Jia H, Hou X et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases: mechanisms and corresponding therapeutic strategies. Biomedicines 2025;13(2):327. doi:10.3390/biomedicines13020327. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Chen H, Detmer SA, Ewald AJ, Griffin EE, Fraser SE, Chan DC. Mitofusins Mfn1 and Mfn2 coordinately regulate mitochondrial fusion and are essential for embryonic development. J Cell Biol 2003;160(2):189–200. doi:10.1083/jcb.200211046. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Cao Y-L, Meng S, Chen Y et al. MFN1 structures reveal nucleotide-triggered dimerization critical for mitochondrial fusion. Nature 2017;542(7641):372–376. doi:10.1038/nature21077. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Szabadkai G, Simoni AM, Chami M, Wieckowski MR, Youle RJ, Rizzuto R. Drp-1-dependent division of the mitochondrial network blocks intraorganellar Ca2+ waves and protects against Ca2+-mediated apoptosis. Mol Cell 2004;16(1):59–68. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Hong G-L, Kim K-H, Cho S-P, Lee H-J, Kim Y-J, Jung J-Y. Korean red ginseng alleviates benign prostatic hyperplasia by dysregulating androgen receptor signaling and inhibiting DRP1-mediated mitochondrial fission. Chin J Nat Med 2024;22(7):599–607. doi:10.1016/S1875-5364(24)60671-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Park WY, Song G, Park JY et al. Ellagic acid improves benign prostate hyperplasia by regulating androgen signaling and STAT3. Cell Death Dis 2022;13(6):554. doi:10.1038/s41419-022-04995-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Karbowski M, Youle RJ. Regulating mitochondrial outer membrane proteins by ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2011;23(4):476–482. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2011.05.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Leonhard K, Guiard B, Pellecchia G, Tzagoloff A, Neupert W, Langer T. Membrane protein degradation by AAA proteases in mitochondria: extraction of substrates from either membrane surface. Mol Cell 2000;5(4):629–638. doi:10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80242-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Prashar A, Bussi C, Fearns A et al. Lysosomes drive the piecemeal removal of mitochondrial inner membrane. Nature 2024;632(8027):1110–1117. doi:10.1038/s41586-024-07835-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Soubannier V, McLelland G-L, Zunino R et al. A vesicular transport pathway shuttles cargo from mitochondria to lysosomes. Curr Biol 2012;22(2):135–141. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.11.057. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Jiao H, Jiang D, Hu X et al. Mitocytosis, a migrasome-mediated mitochondrial quality-control process. Cell 2021;184(11):2896–2910. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.027. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Tan HWS, Lu G, Dong H et al. A degradative to secretory autophagy switch mediates mitochondria clearance in the absence of the mATG8-conjugation machinery. Nat Commun 2022;13(1):3720. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-31213-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Narendra DP, Youle RJ. The role of PINK1-Parkin in mitochondrial quality control. Nat Cell Biol 2024;26(10):1639–1651. doi:10.1038/s41556-024-01513-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Ding W-X, Li M, Biazik JM et al. Electron microscopic analysis of a spherical mitochondrial structure. J Biol Chem 2012;287(50):42373–42378. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.413674. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Ma X, Manley S, Qian H et al. Mitochondria-lysosome-related organelles mediate mitochondrial clearance during cellular dedifferentiation. Cell Rep 2023;42(10):113291. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2023.113291. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Ma X, Ding W-X. Quality control of mitochondria involves lysosomes in multiple definitive ways. Autophagy 2024;20(12):2599–2601. doi:10.1080/15548627.2024.2408712. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Lee MJ, Cho Y, Hwang Y et al. Kaempferol alleviates mitochondrial damage by reducing mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production in lipopolysaccharide-induced prostate organoids. Foods 2023;12(20):3836. doi:10.3390/foods12203836. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Schuster GA, Schuster TG. The relative amount of epithelium, muscle, connective tissue and lumen in prostatic hyperplasia as a function of the mass of tissue resected. J Urol 1999;161(4):1168–1173. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)61620-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Liu J, Yin J, Chen P et al. Smoothened inhibition leads to decreased cell proliferation and suppressed tissue fibrosis in the development of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Cell Death Discov 2021;7(1):115. doi:10.1038/s41420-021-00501-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Liu D, Liu J, Li Y et al. Upregulated bone morphogenetic protein 5 enhances proliferation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition process in benign prostatic hyperplasia via BMP/smad signaling pathway. Prostate 2021;81(16):1435–1449. doi:10.1002/pros.24241. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Lu J, Tan M, Cai Q. The Warburg effect in tumor progression: mitochondrial oxidative metabolism as an anti-metastasis mechanism. Cancer Lett 2015;356(2 Pt A):156–164. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2014.04.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Gao F, Liu S, Sun Y et al. Testes-specific protease 50 heightens stem-like properties and improves mitochondrial function in colorectal cancer. Life Sci 2025;370(Pt 3):123560. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2025.123560. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Zha J, Li J, Yin H, Shen M, Xia Y. TIMM23 overexpression drives NSCLC cell growth and survival by enhancing mitochondrial function. Cell Death Dis 2025;16(1):174. doi:10.1038/s41419-025-07505-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Yu H-C, Bai L, Jin L, Zhang Y-J, Xi Z-H, Wang D-S. SLC25A35 enhances fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial biogenesis to promote the carcinogenesis and progression of hepatocellular carcinoma by upregulating PGC-1α. Cell Commun Signal 2025;23(1):130. doi:10.1186/s12964-025-02109-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Zhang Z, Guo Q, Yang Z et al. Bifidobacterium adolescentis-derived nicotinic acid improves host skeletal muscle mitochondrial function to ameliorate sarcopenia. Cell Rep 2025;44(2):115265. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2025.115265. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Tian R, Song H, Li J et al. PINCH-1 promotes tumor growth and metastasis by enhancing DRP1-mediated mitochondrial fission in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Biol Ther 2025;26(1):2477365. doi:10.1080/15384047.2025.2477365. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Li X, Tie J, Sun Y et al. Targeting DNM1L/DRP1-FIS1 axis inhibits high-grade glioma progression by impeding mitochondrial respiratory cristae remodeling. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2024;43(1):273. doi:10.1186/s13046-024-03194-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Li R, Ma Y, He A et al. Fasting enhances the efficacy of Sorafenib in breast cancer via mitophagy mediated ROS-driven p53 pathway. Free Radic Biol Med 2025;229(2):350–363. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2025.01.047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Li D, Su H, Deng X et al. DARS2 promotes bladder cancer progression by enhancing PINK1-mediated mitophagy. Int J Biol Sci 2025;21(4):1530–1544. doi:10.7150/ijbs.107632. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Hengartner MO. The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature 2000;407(6805):770–776. doi:10.1038/35037710. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. McConnell JD. Medical management of benign prostatic hyperplasia with androgen suppression. Prostate Suppl 1990;3:49–59. doi:10.1002/pros.2990170506. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Yang L, Liu J, Yin J et al. S100A4 modulates cell proliferation, apoptosis and fibrosis in the hyperplastic prostate. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2024;169:106551. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2024.106551. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Liu J, Zhou W, Yang L et al. STEAP4 modulates cell proliferation and oxidative stress in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Cell Signal 2024;113:110933. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2023.110933. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Li J, Yao H, Huang J et al. METTL3 promotes prostatic hyperplasia by regulating PTEN expression in an m6A-YTHDF2-dependent manner. Cell Death Dis 2022;13(8):723. doi:10.1038/s41419-022-05162-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Tian X, Srinivasan PR, Tajiknia V et al. Targeting apoptotic pathways for cancer therapy. J Clin Invest 2024;134(14):e179570. doi:10.1172/JCI179570. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Wang Z, Wu H, Chang X et al. CKMT1 deficiency contributes to mitochondrial dysfunction and promotes intestinal epithelial cell apoptosis via reverse electron transfer-derived ROS in colitis. Cell Death Dis 2025;16(1):177. doi:10.1038/s41419-025-07504-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Liu K, Bie J, Zhang R et al. AGTR1 potentiates the chemotherapeutic efficacy of cisplatin in esophageal carcinoma through elevation of intracellular Ca2+ and induction of apoptosis. Int J Oncol 2025;66(4):1–17. doi:10.3892/ijo.2025.5738. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Wang C, Wang S, Zhang G et al. HUWE1-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of oxidative damage repair gene ATM maintains mitochondrial quality control system in lens epithelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2025;1871(5):167796. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2025.167796. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Liu J, Chen Y, Han D, Huang M. Inhibition of the expression of TRIM63 alleviates ventilator-induced diaphragmatic dysfunction by modulating the PPARα/PGC-1α pathway. Mitochondrion 2025;83(5):102025. doi:10.1016/j.mito.2025.102025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Zhang Y, Ye Y, Feng Y et al. Kirenol alleviates cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury by reducing oxidative stress and ameliorating mitochondrial dysfunction via activating the CK2/AKT pathway. Free Radic Biol Med 2025;232(2):353–366. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2025.03.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Li H, Wang G, Tang Y, Wang L, Jiang Z, Liu J. Rhein alleviates diabetic cardiomyopathy by inhibiting mitochondrial dynamics disorder, apoptosis and hypertrophy in cardiomyocytes. Cell Signal 2025;131:111734. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2025.111734. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Wang A, Zhang F, Zhang W, Gong J, Sun X. PPM1D ameliorates Alzheimer’s disease by promoting mitophagy. Exp Neurol 2025;388:115218. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2025.115218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Lu X, Zheng H, Bai H, Wang Y, Li L, Ma B. Costunolide Ameliorates the methylmalonic acidemia Via the PINK1/Parkin pathway. Neurochem Res 2025;50(2):115. doi:10.1007/s11064-025-04364-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR et al. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 2012;149(5):1060–1072. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Aaronson SA et al. Molecular mechanisms of cell death: recommendations of the nomenclature committee on cell death 2018. Cell Death Differ 2018;25(3):486–541. doi:10.1038/s41418-017-0012-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Gan B. Mitochondrial regulation of ferroptosis. J Cell Biol 2021;220(9):e202105043. doi:10.1083/jcb.202105043. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Li J, Cao F, Yin H-L et al. Ferroptosis: past, present and future. Cell Death Dis 2020;11(2):88. doi:10.1038/s41419-020-2298-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Tang D, Chen X, Kang R, Kroemer G. Ferroptosis: molecular mechanisms and health implications. Cell Res 2021;31(2):107–125. doi:10.1038/s41422-020-00441-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Ghoochani A, Hsu E-C, Aslan M et al. Ferroptosis inducers are a novel therapeutic approach for advanced prostate cancer. Cancer Res 2021;81(6):1583–1594. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-3477. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Zhou X-Z, Huang P, Wu Y-K, Yu J-B, Sun J. Autophagy in benign prostatic hyperplasia: insights and therapeutic potential. BMC Urol 2024;24(1):198. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

93. Zhan M, Xu H, Yu G et al. Androgen receptor deficiency-induced TUG1 in suppressing ferroptosis to promote benign prostatic hyperplasia through the miR-188-3p/GPX4 signal pathway. Redox Biol 2024;75(4):103298. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

94. Kim H, Lee JH, Park J-W. Down-regulation of IDH2 sensitizes cancer cells to erastin-induced ferroptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2020;525(2):366–371. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.02.093. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Shin D, Lee J, You JH, Kim D, Roh J-L. Dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase regulates cystine deprivation-induced ferroptosis in head and neck cancer. Redox Biol 2020;30(6):101418. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2019.101418. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Li C, Zhang Y, Liu J, Kang R, Klionsky DJ, Tang D. Mitochondrial DNA stress triggers autophagy-dependent ferroptotic death. Autophagy 2021;17(4):948–960. doi:10.1080/15548627.2020.1739447. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Wei R, Zhao Y, Wang J et al. Tagitinin C induces ferroptosis through PERK-Nrf2-HO-1 signaling pathway in colorectal cancer cells. Int J Biol Sci 2021;17(11):2703–2717. doi:10.7150/ijbs.59404. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Yang J, Mo J, Dai J et al. Cetuximab promotes RSL3-induced ferroptosis by suppressing the Nrf2/HO-1 signalling pathway in KRAS mutant colorectal cancer. Cell Death Dis 2021;12(11):1079. doi:10.1038/s41419-021-04367-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Tang S, Fuß A, Fattahi Z, Culmsee C. Drp1 depletion protects against ferroptotic cell death by preserving mitochondrial integrity and redox homeostasis. Cell Death Dis 2024;15(8):626. doi:10.1038/s41419-024-07015-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Liang FG, Zandkarimi F, Lee J et al. OPA1 promotes ferroptosis by augmenting mitochondrial ROS and suppressing an integrated stress response. Mol Cell 2024;84(16):3098–3114. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2024.07.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Basit F, van Oppen LM, Schöckel L et al. Mitochondrial complex I inhibition triggers a mitophagy-dependent ROS increase leading to necroptosis and ferroptosis in melanoma cells. Cell Death Dis 2017;8(3):e2716. doi:10.1038/cddis.2017.133. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Yamashita S-I, Sugiura Y, Matsuoka Y et al. Mitophagy mediated by BNIP3 and NIX protects against ferroptosis by downregulating mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Cell Death Differ 2024;31(5):651–661. doi:10.1038/s41418-024-01280-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Minciullo PL, Inferrera A, Navarra M, Calapai G, Magno C, Gangemi S. Oxidative stress in benign prostatic hyperplasia: a systematic review. Urol Int 2015;94(3):249–254. doi:10.1159/000366210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. Baltaci S, Orhan D, Gögüs C, Türkölmez K, Tulunay O, Gögüs O. Inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in benign prostatic hyperplasia, low- and high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and prostatic carcinoma. BJU Int 2001;88(1):100–103. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.02231.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Gradini R, Realacci M, Ginepri A et al. Nitric oxide synthases in normal and benign hyperplastic human prostate: immunohistochemistry and molecular biology. J Pathol 1999;189(2):224–229. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199910)189:𠀼224::AID-PATH422𠀾3.0.CO;2-K. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

106. Pace G, Di Massimo C, De Amicis D et al. Oxidative stress in benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer. Urol Int 2010;85(3):328–333. doi:10.1159/000315064. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

107. Olinski R, Zastawny TH, Foksinski M, Barecki A, Dizdaroglu M. DNA base modifications and antioxidant enzyme activities in human benign prostatic hyperplasia. Free Radic Biol Med 1995;18(4):807–813. doi:10.1016/0891-5849(94)00171-f. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

108. Fu X, Liu J, Liu D et al. Glucose-regulated protein 78 modulates cell growth, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and oxidative stress in the hyperplastic prostate. Cell Death Dis 2022;13(1):78. doi:10.1038/s41419-022-04522-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

109. Liu H, Zhou Y, Wang Z et al. Heat shock protein family a member 1A attenuates apoptosis and oxidative stress via ERK/JNK pathway in hyperplastic prostate. MedComm 2025;6(3):e70129. doi:10.1002/mco2.70129. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

110. Yang S, Lian G. ROS and diseases: role in metabolism and energy supply. Mol Cell Biochem 2020;467:1–12. doi:10.1007/s11010-019-03667-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

111. Kuznetsov AV, Javadov S, Margreiter R, Grimm M, Hagenbuchner J, Ausserlechner MJ. The role of mitochondria in the mechanisms of cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury. Antioxidants 2019;8(10):454. doi:10.3390/antiox8100454. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

112. Mori S, Fujiwara-Tani R, Ogata R et al. Anti-cancer and pro-immune effects of lauric acid on colorectal cancer cells. Int J Mol Sci 2025;26(5):1953. doi:10.3390/ijms26051953. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

113. He J, Zhong Y, Li Y, Liu S, Pan X. Astaxanthin alleviates oxidative stress in mouse preantral follicles and enhances follicular development through the AMPK signaling pathway. Int J Mol Sci 2025;26(5):2241. doi:10.3390/ijms26052241. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

114. Yang X, Wang S, Liu H, Zhang T, Cheng S, Du M. A dual absorption pathway of novel oyster-derived peptide-zinc complex enhances zinc bioavailability and restores mitochondrial function. J Adv Res 2025;46:64. doi:10.1016/j.jare.2025.02.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

115. Tuncay E, Olgar Y, Aryan L, Şık S, Billur D, Turan B. ZnT6-mediated Zn2+ redistribution: impact on mitochondrial fission and autophagy in H9c2 cells. Mol Cell Biochem 2025;9:2111. doi:10.1007/s11010-025-05247-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

116. Ding N, Bai Q, Wang Z et al. Artemetin targets the ABCG2/RAB7A axis to inhibit mitochondrial dysfunction in asthma. Phytomedicine 2025;140(3):156600. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2025.156600. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

117. Marx C, Qing X, Gong Y et al. DNA damage response regulator ATR licenses PINK1-mediated mitophagy. Nucleic Acids Res 2025;53(5):gkaf178. doi:10.1093/nar/gkaf178. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

118. Wang J, Gu D, Jin K, Shen H, Qian Y. The role of G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 4 in modulating mitophagy and oxidative stress in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Neuromolecular Med 2025;27(1):21. doi:10.1007/s12017-025-08843-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

119. Joseph DB, Henry GH, Malewska A et al. 5-Alpha reductase inhibitors induce a prostate luminal to club cell transition in human benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Pathol 2022;256(4):427–441. doi:10.1002/path.5857. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

120. Gormley GJ, Stoner E, Bruskewitz RC et al. The effect of finasteride in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. the finasteride study group. N Engl J Med 1992;327(17):1185–1191. doi:10.1056/NEJM199210223271701. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

121. Barrack ER, Bujnovszky P, Walsh PC. Subcellular distribution of androgen receptors in human normal, benign hyperplastic, and malignant prostatic tissues: characterization of nuclear salt-resistant receptors. Cancer Res 1983;43(3):1107–1116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

122. Rennie PS, Bruchovsky N, Goldenberg SL. Relationship of androgen receptors to the growth and regression of the prostate. Am J Clin Oncol 1988;11 Suppl 2:S13–S17. doi:10.1097/00000421-198801102-00004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

123. Ratajczak W, Lubkowski M, Lubkowska A. Heat shock proteins in benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23(2):897. doi:10.3390/ijms23020897. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

124. Bierhoff E, Vogel J, Benz M, Giefer T, Wernert N, Pfeifer U. Stromal nodules in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Eur Urol 1996;29(3):345–354. doi:10.1159/000473774. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

125. Yu S, Yeh C-R, Niu Y et al. Altered prostate epithelial development in mice lacking the androgen receptor in stromal fibroblasts. Prostate 2012;72(4):437–449. doi:10.1002/pros.21445. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

126. Yu S, Zhang C, Lin C-C et al. Altered prostate epithelial development and IGF-1 signal in mice lacking the androgen receptor in stromal smooth muscle cells. Prostate 2011;71(5):517–524. doi:10.1002/pros.21264. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

127. Wang X, Lin W-J, Izumi K et al. Increased infiltrated macrophages in benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPHrole of stromal androgen receptor in macrophage-induced prostate stromal cell proliferation. J Biol Chem 2012;287(22):18376–18385. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.355164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

128. Singh M, Jha R, Melamed J, Shapiro E, Hayward SW, Lee P. Stromal androgen receptor in prostate development and cancer. Am J Pathol 2014;184(10):2598–2607. doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.06.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

129. Nash C, Boufaied N, Mills IG, Franco OE, Hayward SW, Thomson AA. Genome-wide analysis of AR binding and comparison with transcript expression in primary human fetal prostate fibroblasts and cancer associated fibroblasts. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2018;471(23):1–14. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2017.05.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

130. Lu T, Lin W-J, Izumi K et al. Targeting androgen receptor to suppress macrophage-induced EMT and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) development. Mol Endocrinol 2012;26(10):1707–1715. doi:10.1210/me.2012-1079. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

131. Yin L, Dai Y, Wang Y et al. A mitochondrial outer membrane protein TOMM20 maintains protein stability of androgen receptor and regulates AR transcriptional activity in prostate cancer cells. Oncogene 2025;44(21):1567–1577. doi:10.1038/s41388-025-03328-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools