Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

National survey of radiotherapy and androgen deprivation therapy strategies with PSMA-PET/CT integration in intermediate-risk prostate cancer: TROD 09-007 study

1 Department of Radiation Oncology, Baskent University Faculty of Medicine, Ankara, 06490, Turkiye

2 Division of Radiation Oncology, Iskenderun Gelisim Hospital, Hatay, 31200, Turkiye

3 Department of Radiation Oncology, Prof. Dr. Cemil Tascioglu City Hospital, Istanbul, 34360, Turkiye

4 Department of Radiation Oncology, Baskent University, Adana Dr. Turgut Noyan Research and Treatment Center, Adana, 01250, Turkiye

5 Department of Radiation Oncology, Hacettepe University Faculty of Medicine, Ankara, 06100, Turkiye

* Corresponding Author: Cem Onal. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Molecular Imaging and Targeted Therapies for Prostate Cancer)

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(4), 243-254. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.066700

Received 15 April 2025; Accepted 15 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Background: Intermediate-risk prostate cancer (IR-PC) represents a heterogeneous group requiring nuanced treatment approaches, and recent advancements in radiotherapy (RT), androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), and prostate-specific membrane antigen positron emission tomography (PSMA-PET/CT) imaging have prompted growing interest in personalized, risk-adapted management strategies. This study by the Turkish Society for Radiation Oncology aims to examine radiation oncologists’ practices in managing IR-PC, focusing on RT and imaging modalities to identify trends for personalized treatments. Methods: A cross-sectional survey was conducted among Turkish radiation oncologists treating at least 50 prostate cancer (PC) cases annually. The 22-item questionnaire covered IR-PC management aspects such as risk stratification, imaging preferences, androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) use and duration, RT techniques, and treatment combinations. Anonymous responses were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Results: Thirty radiation oncologists participated, 57% with over 20 years of experience. The median annual number of PC cases treated was 130. For risk stratification, 43% followed the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, while 30% used the D’Amico classification. Imaging preferences revealed 47% favored PSMA-PET/CT. External beam RT was universally preferred, with 60% adopting ultra-hypofractionation. ADT was used by 97%, with 73% recommending it for unfavorable IR-PC cases. Short-term ADT (4–6 months) was the standard, administered concurrently with RT by 57%. Cardiovascular status influenced decisions for 97% of respondents, while 37% also considered patient age, preferences, and sexual health. Conclusions: This national survey demonstrates a shift toward personalized care in intermediate-risk prostate cancer in Turkey, marked by selective PSMA-PET/CT use, tailored ADT, and evolving radiotherapy practices. The findings underscore the importance of multidisciplinary collaboration—particularly between urologists and radiation oncologists—to optimize imaging integration and treatment outcomes.Keywords

Intermediate-risk prostate cancer (IR-PC) represents a highly heterogeneous category, posing unique challenges for treatment decision-making.1 Treatment options for IR-PC include radical prostatectomy, radiotherapy (RT), and active surveillance, each with specific benefits and limitations.2 However, the diverse characteristics of this patient population contribute to significant variation in treatment approaches, complicating clinical management. Defining IR-PC itself presents challenges due to differing risk stratification guidelines. Recently, IR-PC has been subdivided into favorable (FIR) and unfavorable (UIR) groups,3 highlighting the need for personalized treatment approaches. Although most IR-PC patients are treated with definitive RT, key factors such as radiation dose, fractionation schemes, and the use of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) remain subjects of ongoing debate.

Radiation dose escalation has been a focal point of recent research due to its ability to improve local and biochemical control in IR-PC.4–6 However, despite these benefits, a recent meta-analysis confirmed that dose escalation does not translate into improved overall survival outcomes.7 Hypofractionation, which involves delivering larger radiation doses over fewer sessions, has gained attention for its potential to improve accessibility and reduce costs. Large randomized trials have shown that hypofractionated RT is non-inferior to conventional fractionation for low- and IR-PC, with recent evidence such as the Prostate Cancer Study (PCS) 5 trial also supporting its application in high-risk cases.8 Despite this, the adoption of hypofractionation, especially in resource-limited settings, remains inconsistent and poorly understood.

ADT plays a crucial role in IR-PC, particularly for patients with unfavorable features. It enhances the efficacy of RT and improves biochemical and disease-specific outcomes.9,10 However, its use should be individualized, considering disease risk, comorbidities, and potential side effects. Although ADT is effective in specific scenarios, it is not universally indicated for all IR-PC patients due to its side effects, such as sexual dysfunction, cardiovascular (CV) risks, and metabolic changes, which can significantly affect the quality of life.11,12 Clinical practice reflects considerable variability in ADT use, influenced by risk stratification methods, physician preferences, and patient-specific factors.13 Therefore, a deeper understanding of current clinical decision-making trends is necessary to address this variability.

The integration of new imaging modalities, including prostate-specific membrane antigen positron emission tomography (PSMA-PET/CT), has revolutionized staging and treatment planning in PC. Its superior sensitivity and accuracy in detecting metastases enable more personalized treatment strategies, reducing overtreatment and improving outcomes.14–16 Despite its benefits and widespread use in clinical practice, the specific application of PSMA-PET/CT in IR-PC remains unclear, necessitating further investigation.

In response to these challenges, the Uro-oncology Subgroup of the Turkish Radiation Oncology Society (TROD) conducted a national survey to evaluate RT preferences for IR-PC, including radiation dose, fractionation schemes, treatment fields, and ADT usage. The survey also assessed the utilization of PSMA-PET/CT in IR-PC patients. By analyzing the survey data, this study aims to identify prevailing practices, highlight variations in treatment and imaging approaches, and provide insights to support the development of consensus guidelines and inform clinical practice.

This study employed a cross-sectional design, capturing data from radiation oncologists at a single point in time to assess contemporary clinical practices in the management of intermediate-risk prostate cancer. The survey was conducted via a one-time electronic questionnaire without any follow-up, consistent with the methodology of cross-sectional studies. Participants were identified through the registry of the TROD. The survey was developed by the Uro-oncology Subgroup of TROD, which currently consists of 129 members, to explore key aspects of IR-PC management, including risk stratification methods, imaging preferences, ADT usage and duration, RT techniques, fractionation schemes, and treatment combinations. The questionnaire was reviewed and validated by an expert panel composed of five senior radiation oncologists with at least 15 years of clinical experience. The selection criteria for expert panel members included academic rank, publication record in PC, and leadership roles in national guidelines. This process ensured the clarity, clinical relevance, and validity of the survey items.

The 22-question survey was distributed electronically via email, along with an invitation letter outlining its purpose. A translated version of the full questionnaire has been added as a supplementary file (Appendix A). Participation was voluntary and anonymous, with periodic reminders sent during the seven-day data collection period. Ethical approval was not required, as the survey involved anonymized professional data without patient involvement. Completion of the survey implied informed consent.

The survey comprised single-choice, multiple-choice, and open-ended questions organized into four key sections. The first section, ‘Demographics and Professional Information’, gathered data on participants’ experience in radiation oncology, the type of institutions where they worked, and their annual PC case volume. The second section, ‘Risk Stratification and Imaging Preferences’, focused on the use of classification systems such as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), European Association of Urology (EAU), and D’Amico, along with imaging tools like magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and PSMA-PET/CT for staging and treatment planning. The third section explored criteria for ADT usage, including timing, duration, and patient-specific factors influencing treatment decisions. The final section examined preferences for RT methods, such as external beam RT (EBRT) and brachytherapy, along with fractionation schedules (conventional, moderate hypofractionation, and ultra-hypofractionation), radiation doses, and treatment fields.

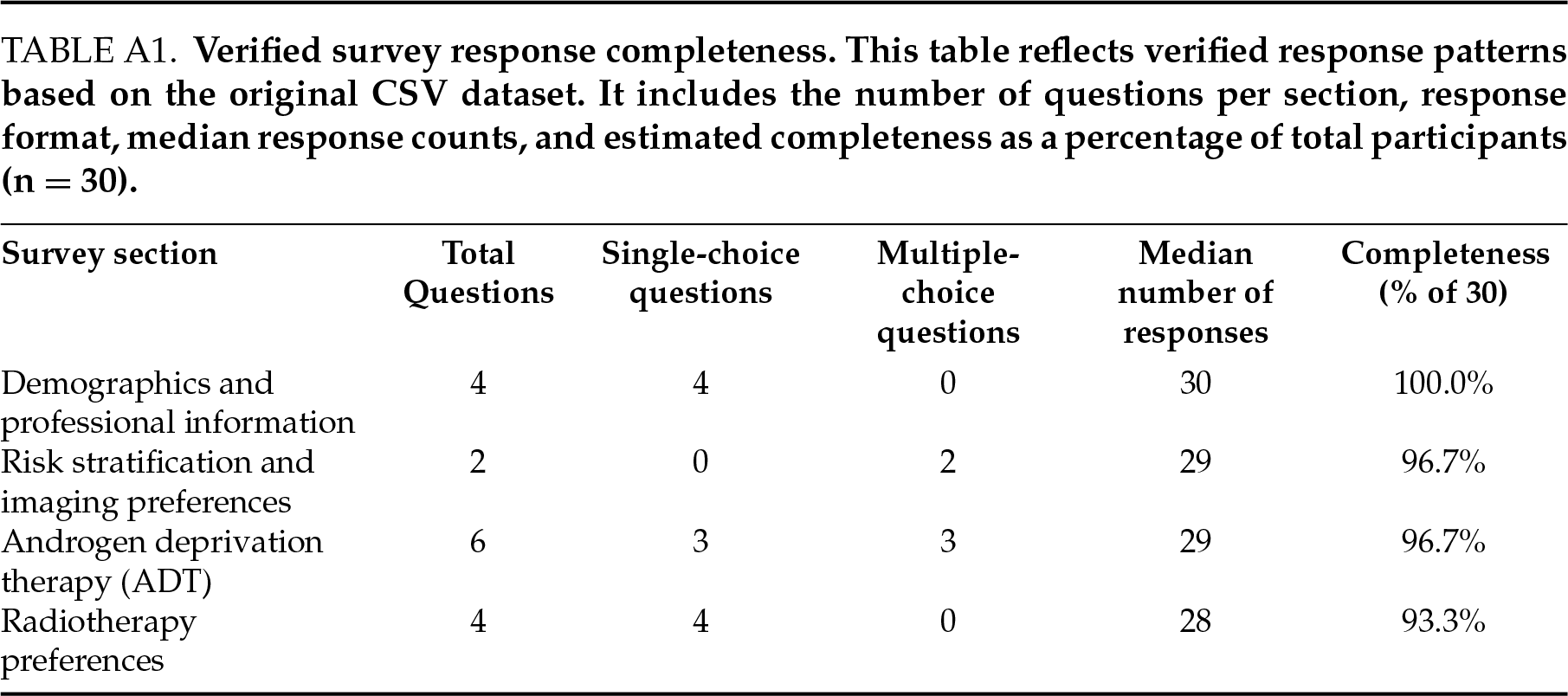

Some survey items allowed multiple responses, and not all participants completed every question. As a result, total response counts vary between questions. A detailed summary of the number and format of responses per section is provided in Table A1.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Responses were collected anonymously and analyzed using descriptive statistics. Frequencies and percentages were calculated for categorical variables, while means were used for numerical data. No inferential statistical tests were conducted, as the primary aim was to summarize and interpret practice patterns rather than establish causal relationships.

Demographics and professional information

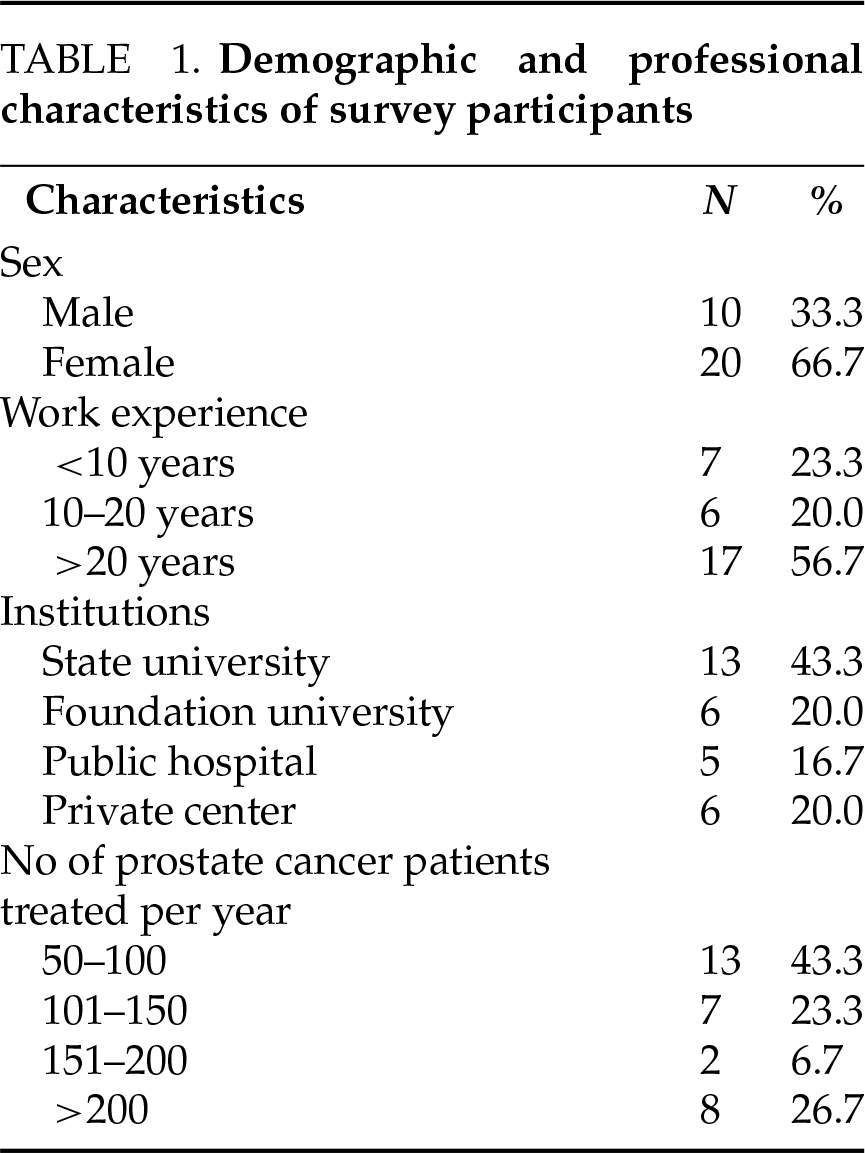

The characteristics of the 30 radiation oncologists who participated in the survey are summarized in Table 1. The majority of participants were female (66.7%), and more than half (56.7%) had over 20 years of experience in radiation oncology. Most participants (63.3%) were affiliated with university hospitals, including 43.3% at public universities and 20% at foundation universities.

The median annual number of PC patients treated at the participants’ centers was 130 (range: 50–300). The median distribution of patients which were treated in these centers across risk categories was as follows: low-risk (LR), 20% (range: 5–50%); intermediate-risk (IR), 30% (range: 10–45%); high-risk (HR), 30% (range: 20–70%); and metastatic cases, including oligometastatic disease, 20% (range: 5–60%).

Risk stratification and imaging preferences

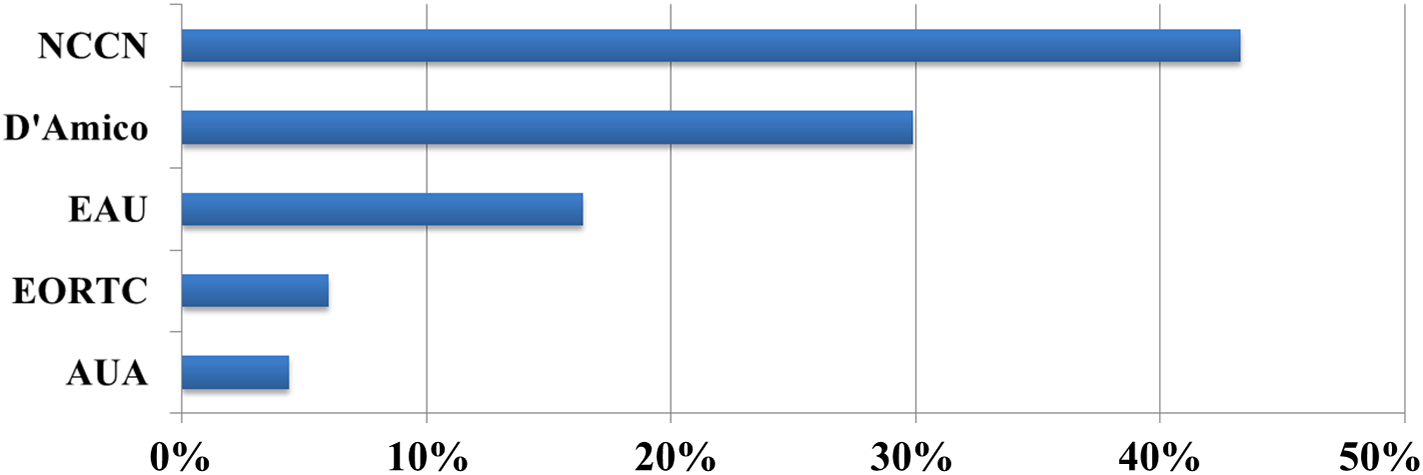

Although several expert consensus statements have been published by the Turkish Radiation Oncology Society Uro-Oncology Subgroup Survey: Intermediate-Risk Prostate Cancer Management (Appendix A), there is no officially endorsed national prostate cancer guideline in Turkey. Consequently, Turkish radiation oncologists primarily rely on internationally recognized guidelines, such as NCCN, D’Amico, and EAU.1,2,17 For risk stratification and treatment planning, 67 responses were received to a multiple-choice question on guideline preferences. The NCCN guidelines were the most commonly used, selected by 43% of respondents, followed by the D’Amico classification system, chosen by 30% (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Bar chart showing the guidelines referenced in making prostate cancer treatment decisions. NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; EAU, European Association of Urology; EORTC, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer; AUA, American Urological Association

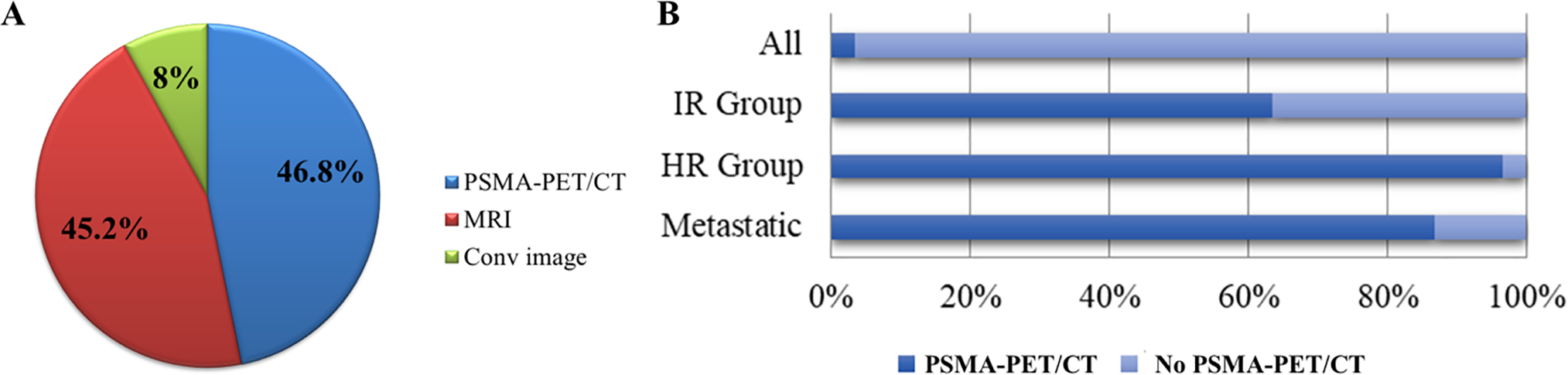

The question regarding imaging modality preference asked participants to indicate their routine approach for initial staging across all prostate cancer risk groups. The term ‘Conventional Imaging’ included both computed tomography (CT) and technetium-99m (Tc-99m) bone scans. For staging, 62 responses were analyzed. PSMA-PET/CT emerged as the most preferred imaging modality (46.8%), followed by MRI (45.2%) and conventional imaging (8%) (Figure 2A). Further analysis of PSMA-PET/CT usage, based on 75 responses, revealed its preference across different risk categories: 63% of participants preferred it for intermediate-risk (IR) patients, 97% for high-risk (HR) patients, and 87% for metastatic cases (Figure 2B).

Figure 2: Preferences and utilization of imaging modalities for prostate cancer staging among radiation oncologists. (A) Distribution of preferred imaging modalities for initial staging across all prostate cancer risk groups (‘Conventional Imaging’ [Conv image] includes CT and Tc-99m bone scan). (B) Bar chart illustrating the utilization of PSMA PET/CT across different risk groups. PSMA-PET/CT, prostate-specific membrane antigen positron emission tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; IR, intermediate-risk; HR, high-risk

Most participants (93%) supported dividing IR-PC into favorable and unfavorable subgroups. Among them, 44% preferred PSMA-PET/CT for all IR-PC cases, while 56% limited its use to unfavorable IR-PC patients only (Figure 3A). No participants preferred using PSMA-PET/CT for favorable IR-PC patients. Regarding the utilization of PSMA-PET/CT in IR patients, 90% of respondents cited staging as a key indication, 87% for RT planning, and 63% for evaluating treatment response. In addition to staging and RT planning, 43% of respondents reported using PSMA-PET/CT to inform the decision to proceed with definitive radiotherapy (i.e., assessing eligibility based on imaging findings such as nodal involvement or extent of disease), while 63% used it for evaluating treatment response (Figure 3B).

Figure 3: Utilization patterns and clinical indications for PSMA-PET/CT in intermediate-risk prostate cancer. (A) Percentage of radiation oncologists recommending PSMA-PET/CT for all intermediate-risk (IR) patients versus only unfavorable IR cases. (B) Clinical indications for PSMA-PET/CT use (‘RT decision’ refers to the role of PET findings in confirming the suitability of radiotherapy as a definitive treatment approach). PSMA-PET/CT, prostate-specific membrane antigen positron emission tomography; RT, radiotherapy.

Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT)

Regarding the use of ADT in IR-PC, only one respondent (3%) did not recommend its use. Among those who did, 27% preferred ADT for all IR-PC patients, while 73% limited its use to the unfavorable subset (Figure 4A). All respondents who utilized ADT opted for short-term treatment (4–6 months).

Figure 4: Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) preferences and factors influencing treatment decisions in intermediate-risk prostate cancer. (A) Pie chart representing the proportion of radiation oncologists recommending ADT for intermediate-risk prostate cancer. (B) Bar chart showing factors influencing ADT decisions. IR, intermediate-risk

In terms of timing, 57% administered ADT concurrently with RT, while 43% initiated it in the neoadjuvant setting. Nearly all participants (97%) combined ADT with both a Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) agonist and an anti-androgen. Furthermore, 87% (n = 26) preferred limiting anti-androgen use to a short duration rather than extending it throughout the entire course of GnRH agonist therapy.

CV status was deemed a critical factor in ADT decision-making by 97% of respondents (Figure 4B). Additionally, 37% reported considering other factors such as patient age, preferences, and sexual health in their treatment plans.

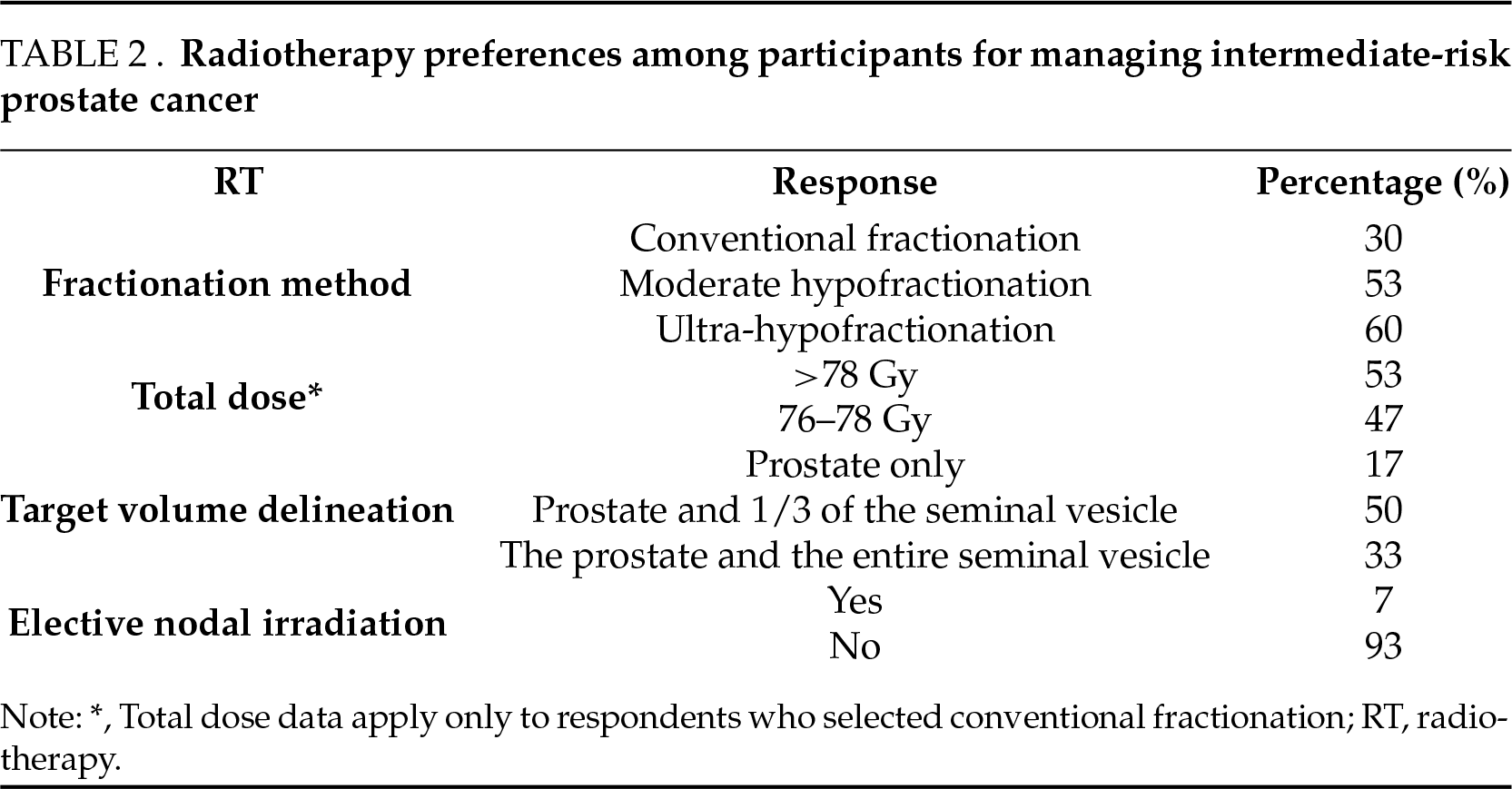

For the definitive treatment of IR-PC, all respondents preferred EBRT. Ultra-hypofractionation was the most commonly utilized fractionation method (60%), followed by conventional fractionation (30%). Among respondents who used conventional fractionation (30%), 53% preferred total doses exceeding 78 Gy, while the remainder used doses between 76–78 Gy (Table 2).

Target volume delineation practices varied: 50% included the prostate and proximal seminal vesicles, 33% included the prostate and the entire seminal vesicles, and 17% treated the prostate alone. Elective nodal irradiation was rarely favored, with 93% avoiding it and only 7% incorporating it into their practice.

This survey offers a preliminary insight into current radiotherapy practices and PSMA-PET/CT utilization in the management of IR-PC among selected high-volume radiation oncologists in Turkiye. The findings reveal important insights into clinical decision-making trends, particularly regarding risk stratification, ADT application, and imaging integration.

Current guidelines classify IR-PC as clinical T2b-c, Gleason score 7, or PSA levels of 10–20 ng/mL, recognizing its heterogeneity in outcomes.3,17 To address this variability, IR-PC is often stratified into favorable and unfavorable subgroups.3 The primary challenge with treatment intensification lies in determining the benefit-to-risk ratio, particularly for unfavorable IR patients—those with Gleason score 4 + 3, >50% positive biopsies, or >2 IR factors—treated with EBRT.3,5,7 In this study, most participants adhered to established guidelines such as the NCCN and D’Amico classifications and favored stratifying IR-PC into favorable and unfavorable subgroups to guide the use of PSMA-PET/CT and treatment decisions. This evidence-based approach ensures consistency in clinical practice while emphasizing the need for regular updates to guidelines to incorporate advancements in imaging modalities and hypofractionation, keeping them aligned with current evidence and innovations.

PSMA-PET/CT has emerged as a valuable imaging tool in PC, particularly for staging and treatment planning.15,16,18 Recent studies have demonstrated its feasibility for staging, RT planning, and response evaluation in IR-PC, with a growing body of literature supporting these findings.18–20 Current guidelines reflect differing approaches to advanced imaging in IR-PC. The NCCN recommends advanced imaging for unfavorable IR-PC, citing evidence of higher metastatic risk in this subgroup.21 In contrast, the American Urological Association (AUA)/American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) guidelines do not differentiate between favorable and unfavorable IR-PC, potentially underutilizing supplemental imaging in unfavorable cases.22 In our study, PSMA-PET/CT was identified as the preferred imaging modality for 47% of participants, with 90% using it for staging and 63% applying it specifically to IR-PC cases. A risk-adapted approach was evident, with 56% of respondents limiting PSMA-PET/CT use to unfavorable IR-PC, while 44% extended its application to all IR-PC patients. Furthermore, 87% employed PSMA-PET/CT for RT planning, including target volume delineation and field adjustments, highlighting its growing role in enhancing RT strategies. These findings underscore the importance of PSMA-PET/CT in improving treatment precision and enabling individualized approaches to PC management. Its selective use for unfavorable IR-PC reflects a tailored strategy aimed at optimizing outcomes. Clinically, this highlights the need for broader access to PSMA-PET/CT and continued efforts to refine its role in staging and response evaluation to maximize therapeutic benefits.

The role of ADT in combination with RT for IR-PC has been studied in several randomized trials, particularly focusing on the distinction between favorable IR and unfavorable IR disease. Several randomized trials demonstrated the survival benefit of ADT in IR-PC patients, particularly for patients with unfavorable risk factors.23–25 In parallel with the literature, our survey demonstrates that 93% of radiation oncologists reported the use of short-term (4–6 months) ADT in IR-PC patients, with 73% reserving it for the unfavorable subcategory, indicating a preference for a more selective approach.

The optimal approach to ADT—whether to use a GnRH agonist alone or in combination with an antiandrogen—has not been definitively established through randomized trials. However, observational studies suggest potential benefits to combining a GnRH agonist with an antiandrogen.26 Current protocols, such as those from NRG/RTOG, recommend this combination during the initial four months of therapy, a practice widely reflected in clinical settings.27 In our survey, 97% of participants indicated they routinely initiate treatment with a combination of a GnRH agonist and an antiandrogen. Among these, 87% preferred limiting the antiandrogen component to the initial phase of therapy rather than continuing it throughout the entire course of GnRH agonist treatment.

The increased risk of toxicity associated with ADT has been a consistent concern across multiple studies. The risk of developing diabetes can increase by 44% with hormonal therapy, as reported in the literature.23,28 Additionally, large population-based studies have shown an elevated risk of CV events, with men who have pre-existing risk factors or a history of CV events being particularly susceptible to new fatal or non-fatal events.11,27 The Prostate Cancer Active Concomitant Therapy (PROACT) survey highlighted the importance of monitoring patient weight (80%), metabolic profile (70%), and CV status (77%) during hormonal therapy follow-up to mitigate these risks.24 Our survey highlights the critical role of cardiovascular status in deciding whether to initiate ADT, with 97% of respondents emphasizing its importance due to the heightened risk of cardiovascular complications. This underscores the need for careful patient selection to minimize ADT-related toxicities, particularly in IR-PC patients with diverse prognoses. Personalizing treatment is essential to ensure ADT is used selectively, prioritizing cases where the benefits outweigh the risks, especially in patients with comorbidities such as CV disease.

Evidence from randomized trials, including CHHiP and PROFIT, demonstrated that hypofractionated RT was as effective as conventional radiotherapy in managing IR-PC, achieving comparable biochemical progression-free survival and local control.25,29 Recent trials have further shown that ultra-hypofractionated RT (UHRT) is non-inferior to conventional and moderately hypofractionated regimens in terms of biochemical and clinical outcomes.6,8 Ongoing international studies (e.g., NCT01794403 and NCT03367702) aim to provide more definitive data on the comparative effectiveness and toxicity profiles of stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) versus other radiation approaches in IR-PC. Our survey found that 100% of respondents preferred EBRT for treating IR-PC, with 60% favoring UHRT and 30% conventional fractionation, reflecting the growing trend toward UHRT in clinical practice. However, the implementation of UHRT faces challenges, including the need for advanced equipment, precise imaging techniques, and clinician training to manage steep dose gradients safely. Barriers such as high costs, resource limitations, and a lack of standardized protocols, combined with concerns over acute toxicities and limited long-term data, further complicate its broader adoption. Addressing these issues through improved infrastructure, training, and robust clinical trials is essential for the wider implementation of UHRT in IR-PC management.

Comparative data from other countries offer valuable context. The French GETUG-PROACT survey similarly highlighted selective ADT use and rising interest in PSMA-PET/CT among radiation oncologists.25 In the United States, NCCN guidelines and NRG trials, including RTOG 0126 and RTOG 0415, have shaped risk-adapted therapy pathways.4,5 Canadian studies, including the CHHiP and PROFIT trials, demonstrated widespread acceptance of moderate hypofractionation, which aligns with the increasing UHRT use observed in this study.26,30

While novel biomarkers such as the Decipher genomic classifier and ArteraAI multimodal artificial intelligence (AI) platforms are gaining traction in guiding radiotherapy intensification, treatment de-escalation, and ADT duration decisions in the United States and parts of Europe, their use in Turkey remains negligible.30,31 This is largely due to economic barriers, the absence of insurance coverage, and the limited availability of molecular testing infrastructure. Decipher, a genomic classifier based on RNA expression profiles, has been shown to stratify risk beyond traditional clinical factors and influence decisions regarding the addition or omission of ADT in intermediate- and high-risk prostate cancer.32,33 Similarly, ArteraAI has demonstrated promising performance in integrating histopathology and clinical data to predict response to therapy and refine risk assessment.31 Despite their promise, the clinical utility of these tools in Turkey is currently theoretical. Broader implementation would require local validation, cost-effectiveness analyses, and health policy support. Nonetheless, they represent an opportunity to complement imaging-based personalization strategies such as PSMA-PET/CT and may help harmonize clinical practice with emerging global standards.

This study has several limitations. First, as a survey-based study targeting radiation oncologists in Turkey, the findings may not fully represent global practices. Although the survey provides valuable insight into real-world clinical practices, the relatively small sample size limits the generalizability of the findings. Nevertheless, the participants were selected from high-volume centers and represent experienced clinicians actively involved in prostate cancer care, lending relevance to the reported patterns. Larger surveys with broader representation across practice settings are needed to validate and expand upon these findings. Second, the cross-sectional design captures preferences and practices at a single point in time, potentially overlooking evolving trends or changes in clinical decision-making influenced by new evidence. Third, the survey relies on self-reported data, which may introduce recall or response biases, as participants might provide idealized rather than actual clinical practices.

Despite its limitations, this study provides valuable insights into current RT practices for IR-PC in a national context. It highlights significant variability in treatment approaches and imaging preferences, emphasizing the need for standardized protocols tailored to patient subgroups, particularly favorable and unfavorable IR-PC. The survey effectively captures the integration of advanced imaging modalities, such as PSMA-PET/CT, in staging and radiotherapy planning, showcasing their growing clinical relevance. Furthermore, the study sheds light on the prevalent use of ADT and evolving fractionation techniques, such as hypofractionated and UHRT, reflecting contemporary advancements in PC management. By identifying barriers to implementing UHRT, including resource constraints and training needs, the study lays the groundwork for addressing these challenges through strategic investments and education, ultimately contributing to improved care quality.

In conclusion, this national survey highlights the evolving practices and challenges in the management of IR-PC among radiation oncologists in Turkey. The findings emphasize the growing preference for stratifying IR-PC into favorable and unfavorable subgroups to guide personalized treatment approaches. Advanced imaging modalities, particularly PSMA-PET/CT, are increasingly integrated into staging and RT planning, improving precision and enabling risk-adapted strategies. The adoption of hypofractionated RT and UHRT reflects alignment with contemporary evidence supporting their efficacy and convenience. However, barriers such as resource limitations, high costs, and the need for clinician training hinder broader implementation, particularly for UHRT. These results underscore the necessity of addressing these challenges through improved infrastructure, training, and standardized protocols while encouraging further research to refine treatment strategies and optimize outcomes for IR-PC patients. Future research should also validate these approaches in diverse patient populations to ensure equitable and effective care delivery.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the Uro-Oncology Subgroup of the Turkish Radiation Oncology Society for their administrative support and assistance in the dissemination of the survey. No other in-kind contributions or external assistance were received.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Aysenur Elmali, Birhan Demirhan, Caglayan Selenge Beduk Esen, Ozan Cem Guler, Pervin Hurmuz, Cem Onal. Data collection: Aysenur Elmali, Birhan Demirhan, Caglayan Selenge Beduk Esen. Analysis and interpretation of results: Aysenur Elmali, Cem Onal. Draft manuscript preparation: Aysenur Elmali, Ozan Cem Guler, Pervin Hurmuz, Cem Onal. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval

As the study did not involve identifiable human data or interventions, formal ethical approval was not required. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, with periodic reminders sent during the seven-day data collection period. Ethical approval was not required, as the survey involved anonymized professional data without patient involvement. Completion of the survey implied informed consent.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Turkish Radiation Oncology Society Uro-Oncology Subgroup Survey: Intermediate-Risk Prostate Cancer Management

1. How many years have you been practicing in the field of radiation oncology?

• Less than 10 years

• 10–20 years

• More than 20 years

2. What type of institution are you currently affiliated with?

• Public university hospital

• Private university hospital

• Public state hospital

• Private healthcare facility

• Other: ______

3. Approximately how many prostate cancer patients receive radiotherapy annually at your center?

• Your answer: ______

4. Estimated distribution of prostate cancer patients by risk category (%)

• Low-risk: ______

• Intermediate-risk: ______

• High-risk: ______

• Metastatic (oligometastatic/widespread): ______

5. Which guideline(s) do you follow for prostate cancer risk classification? (Select all that apply)

• D’Amico Risk Stratification

• NCCN

• EAU

• AUA

• EORTC

• Other: ______

6. Which imaging modality/modalities do you typically use for staging? (Select all that apply)

• Conventional imaging (CT/bone scan)

• Prostate MRI

• PSMA-PET/CT

• Other: ______

7. In which patient groups do you utilize PSMA-PET/CT? (Select all that apply)

• I do not use PSMA-PET/CT

• All patients

• Intermediate-risk group

• High-risk group

• Metastatic patients

• Other: ______

8. Do you stratify intermediate-risk patients into favorable and unfavorable subgroups?

• Yes

• No

9. What is your preferred first-line treatment for intermediate-risk prostate cancer?

• Surgery

• Radiotherapy

• Combined surgery and radiotherapy

• Active surveillance

• Other: ______

10. For which intermediate-risk patients do you prefer using PSMA-PET/CT?

• I do not use it

• All intermediate-risk patients

• Favorable subgroup only

• Unfavorable subgroup only

11. For what purpose(s) do you perform PSMA-PET/CT prior to radiotherapy? (Select all that apply)

• Staging

• Radiotherapy decision-making

• Radiotherapy planning

• Treatment response evaluation

• Other: ______

12. Which radiotherapy approach do you prefer for intermediate-risk patients?

• External beam radiotherapy (EBRT) only

• EBRT combined with brachytherapy

• Brachytherapy only

• Other: ______

13. Which fractionation scheme(s) do you typically use? (Select all that apply)

• Conventional fractionation (>35 fractions)

• Moderate hypofractionation (20–30 fractions)

• Ultra-hypofractionation (≤5 fractions)

• Other: ______

14. What is your preferred total dose when using conventional fractionation?

• 76–78 Gy

• >78 Gy

• Other: ______

15. What is your standard primary treatment volume?

• Prostate only

• Prostate and proximal seminal vesicles

• Prostate and entire seminal vesicles

• Other: ______

16. Do you perform elective pelvic lymph node irradiation in intermediate-risk patients?

• Yes

• No

• Other: ______

17. Do you routinely combine androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) with radiotherapy?

• Yes

• No

• Other: ______

18. In which intermediate-risk patients do you administer ADT?

• I do not use ADT

• All intermediate-risk patients

• Favorable subgroup only

• Unfavorable subgroup only

19. What is your preferred ADT duration?

• Short-term (4–6 months)

• Long-term (12–24 months)

• Other: ______

20. When do you typically initiate ADT in relation to radiotherapy?

• Neoadjuvant only

• Neoadjuvant + concurrent + adjuvant

• Concurrent + adjuvant

• I do not use ADT

• Other: ______

21. Do you add an antiandrogen to LHRH agonist/antagonist therapy?

• Yes, short-term use only

• Yes, throughout the course of ADT

• No

• I use antiandrogen monotherapy without LHRH agents

• Other: ______

22. Which additional factors influence your ADT selection? (Select all that apply)

• Patient’s age

• Cardiovascular comorbidities

• Patient preference

• Sexual function considerations

• Other: ______

Appendix B

References

1. Schaeffer EM, Srinivas S, Adra N et al. Prostate cancer, Version 4. 2023, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2023;21(10):1067–1096. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2023.0050. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Mottet N, van den Bergh RCN, Briers E, Van den Broeck T, Cumberbatch MG, De Santis M et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer-2020 update. Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent. Eur Urol 2021;79(2):243–262. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2020.09.042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Zumsteg ZS, Spratt DE, Pei X et al. Short-term androgen-deprivation therapy improves prostate cancer-specific mortality in intermediate-risk prostate cancer patients undergoing dose-escalated external beam radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2013;85(4):1012–1017. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.07.2374. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Atun R, Jaffray DA, Barton MB et al. Expanding global access to radiotherapy. Lancet Oncol 2015;16(10):1153–1186. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(15)00222-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Michalski JM, Moughan J, Purdy J et al. Effect of standard vs dose-escalated radiation therapy for patients with intermediate-risk prostate cancer: the NRG oncology RTOG, 0126 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2018;4(6):e180039. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0039. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. van As N, Griffin C, Tree A et al. Phase 3 trial of stereotactic body radiotherapy in localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2024;391(15):1413–1425. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2403365. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Patel KR, Spratt DE, Tran PT, Krauss DJ, D’Amico AV, Nguyen PL. The benefit of short-term androgen deprivation therapy with radiation therapy for intermediate-risk prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2025;122(2):407–415. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2025.01.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Niazi T, Nabid A, Malagon T et al. Hypofractionated dose escalation radiotherapy for high-risk prostate cancer: the survival analysis of the prostate cancer study-5 (PCS-5a GROUQ-led phase III trial. Eur Urol 2025;87(3):314–323. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2024.08.032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Nabid A, Carrier N, Vigneault E et al. Androgen deprivation therapy and radiotherapy in intermediate-risk prostate cancer: a randomised phase III trial. Eur J Cancer 2021;143(11):64–74. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2020.10.023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Onal C, Guler OC, Erbay G, Elmali A. The effect of dose-escalation radiotherapy with simultaneous-integrated-boost on the use of short-term androgen deprivation therapy in patients with intermediate risk prostate cancer. Prostate 2024;84(8):763–771. doi:10.1002/pros.24693. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Alibhai SM, Breunis H, Timilshina N et al. Impact of androgen-deprivation therapy on physical function and quality of life in men with nonmetastatic prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010;28(34):5038–5045. doi:10.1200/jco.2010.29.8091. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Nguyen PL, Alibhai SM, Basaria S et al. Adverse effects of androgen deprivation therapy and strategies to mitigate them. Eur Urol 2015;67(5):825–836. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2014.07.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Dykstra MP, Regan SN, Yin H et al. Variation in androgen deprivation therapy use among men with intermediate-risk prostate cancer: results from a statewide radiation oncology quality consortium. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2024;120(4):999–1007. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2024.05.026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Hofman MS, Lawrentschuk N, Francis RJ et al. Prostate-specific membrane antigen PET-CT in patients with high-risk prostate cancer before curative-intent surgery or radiotherapy (proPSMAa prospective, randomised, multicentre study. Lancet 2020;395(10231):1208–1216. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30314-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Onal C, Ozyigit G, Guler OC et al. Role of 68-Ga-PSMA-PET/CT in pelvic radiotherapy field definitions for lymph node coverage in prostate cancer patients. Radiother Oncol 2020;151:222–227. doi:10.1016/j.radonc.2020.08.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Onal C, Torun N, Akyol F et al. Integration of 68Ga-PSMA-PET/CT in radiotherapy planning for prostate cancer patients. Clin Nucl Med 2019;44(9):e510–e516. doi:10.1097/rlu.0000000000002691. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. D’Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB et al. Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA 1998;280(11):969–974. doi:10.1001/jama.280.11.969. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Hagens MJ, Luining WI, Boevé LMS et al. The appropriateness of PSMA PET/CT in newly diagnosed unfavorable intermediate-risk prostate cancer patients-towards a tumor volume-based risk stratification. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2024. doi:10.1038/s41391-024-00899-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Hofman MS, Kasivisvanathan V, Link E et al. Baseline nodal status on 68Ga-PSMA-11 positron emission tomography/computed tomography in men with intermediate- to high-risk prostate cancer is prognostic for treatment failure: follow-up of the proPSMA trial. Eur Urol Oncol 2024;395:1208. doi:10.1016/j.euo.2024.11.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Onal C, Guler OC, Torun N et al. Impact of definitive radiotherapy on metabolic response measured with 68Ga-PSMA-PET/CT in patients with intermediate-risk prostate cancer. Prostate 2024;84(15):1366–1374. doi:10.1002/pros.24775. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Zumsteg ZS, Spratt DE, Daskivich TJ et al. Effect of androgen deprivation on long-term outcomes of intermediate-risk prostate cancer stratified as favorable or unfavorable: a secondary analysis of the RTOG, 9408 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3(9):e2015083. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.15083. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Sanda MG, Cadeddu JA, Kirkby E et al. Clinically localized prostate cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO guideline. Part I: risk stratification, shared decision making, and care options. J Urol 2018;199(3):683–690. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2017.11.095. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Alibhai SM, Duong-Hua M, Sutradhar R et al. Impact of androgen deprivation therapy on cardiovascular disease and diabetes. J Clin Oncol 2009;27(21):3452–3458. doi:10.1200/jco.2008.20.0923. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Belkacemi Y, Latorzeff I, Hasbini A et al. Patterns of practice of androgen deprivation therapy combined to radiotherapy in favorable and unfavorable intermediate risk prostate cancer. Results of The PROACT Survey from the French GETUG Radiation Oncology group. Cancer/Radiothérapie 2020;24(8):892–897. doi:10.1016/j.canrad.2020.03.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Dearnaley D, Syndikus I, Mossop H et al. Conventional versus hypofractionated high-dose intensity-modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer: 5-year outcomes of the randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 CHHiP trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17(8):1047–1060. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(16)30102-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Nanda A, Chen MH, Moran BJ et al. Total androgen blockade versus a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist alone in men with high-risk prostate cancer treated with radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010;76(5):1439–1444. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.03.034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Saigal CS, Gore JL, Krupski TL, Hanley J, Schonlau M, Litwin MS. Androgen deprivation therapy increases cardiovascular morbidity in men with prostate cancer. Cancer 2007;110(7):1493–1500. doi:10.1002/cncr.22933. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Keating NL, O’Malley A, Freedland SJ, Smith MR. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease during androgen deprivation therapy: observational study of veterans with prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2007;104(19):1518–1523. doi:10.1093/jnci/djs376. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Catton CN, Lukka H, Gu CS et al. Randomized trial of a hypofractionated radiation regimen for the treatment of localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2017;35(17):1884–1890. doi:10.1200/jco.2016.71.7397. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Spratt DE, Zhang J, Santiago-Jiménez M et al. Development and validation of a novel integrated clinical-genomic risk group classification for localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2018;36(6):581–590. doi:10.1200/jco.2017.74.2940. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Wang JH, Deek MP, Mendes AA et al. Validation of an artificial intelligence-based prognostic biomarker in patients with oligometastatic Castration-Sensitive prostate cancer. Radiother Oncol 2025;202:110618. doi:10.1016/j.radonc.2024.110618. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Morgan TM, Daignault-Newton S, Spratt DE et al. Impact of gene expression classifier testing on adjuvant treatment following radical prostatectomy: the G-MINOR prospective randomized cluster-crossover trial. Eur Urol 2025;87(2):228–237. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2024.09.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Leapman MS, Ho J, Liu Y et al. Association between the decipher genomic classifier and prostate cancer outcome in the real-world setting. Eur Urol Oncol 2025;163(6_suppl):1011. doi:10.1016/j.euo.2024.07.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools