Open Access

Open Access

CASE REPORT

A case report of epithelioid renal angiomyolipoma with inferior vena cava extension: robotic surgical management and literature review of rare presentation

Department of Urology, Montefiore Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY 10461, USA

* Corresponding Authors: Dimindra Karki. Email: ; Ahmed Aboumohamed. Email:

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(5), 501-507. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.063294

Received 10 January 2025; Accepted 11 June 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

Background: Epithelioid angiomyolipoma (EAML) is an uncommon renal tumor variant with histologic and radiologic features that can mimic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) on imaging due to the paucity of fat compared to the classic AML. EAML may exhibit aggressive behavior, including local invasion, recurrence, and distant metastases to the liver, lungs, and lymph nodes. Although recent reports suggest that up to one-third of EAML cases may behave malignantly, variability in diagnostic criteria and limited case series contribute to uncertainty regarding its true clinical course. Case Description: This case report describes a 19-year-old female presenting with an 11.9 cm right renal EAML with a tumor thrombus extending into the inferior vena cava (IVC). She underwent a robotic radical nephrectomy with IVC thrombectomy and lymph node dissection. The final pathology revealed EAML with negative margins. Follow-up computed tomography (CT) imaging demonstrated no recurrence of disease/metastasis. The rarity of this presentation and the lack of consensus on management highlight the importance of reporting such cases. Conclusions: This rare case of EAML with IVC tumor thrombus demonstrates that timely robotic surgical intervention with appropriate follow-up is critical for the appropriate management of renal EAML.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileEpithelioid angiomyolipoma (EAML) is a rare variant of angiomyolipoma (AML) accounting for fewer than 5% of cases. It can occur either sporadically or in association with tuberous sclerosis (TSC) and can sometimes be mistaken for RCC. Unlike classic AML with its generally benign course, EAML can sometimes behave aggressively through local invasion, recurrence and even metastasis.1 Given the potential for malignant behavior, better reporting and characterization of EAML can help delineate appropriate surveillance and treatment protocols.

We report a rare case of EAML with IVC tumor thrombus in a healthy 19-year-old woman, managed successfully with robotic-assisted radical nephrectomy and IVC thrombectomy. We also review the current literature to contextualize this presentation and summarize existing approaches to management and prognosis.

A 19-year-old woman with no significant medical history or family history of malignancy presented with right lower quadrant pain. She was a non-smoker with a body mass index (BMI) of 24.5 and no history of tuberous sclerosis. She had no urinary symptoms such as gross hematuria or dysuria, though urinalysis revealed microscopic hematuria (3–10 Red blood cells (RBCs), 0–5 White blood cells (WBCs), trace leukocytes and negative nitrites).

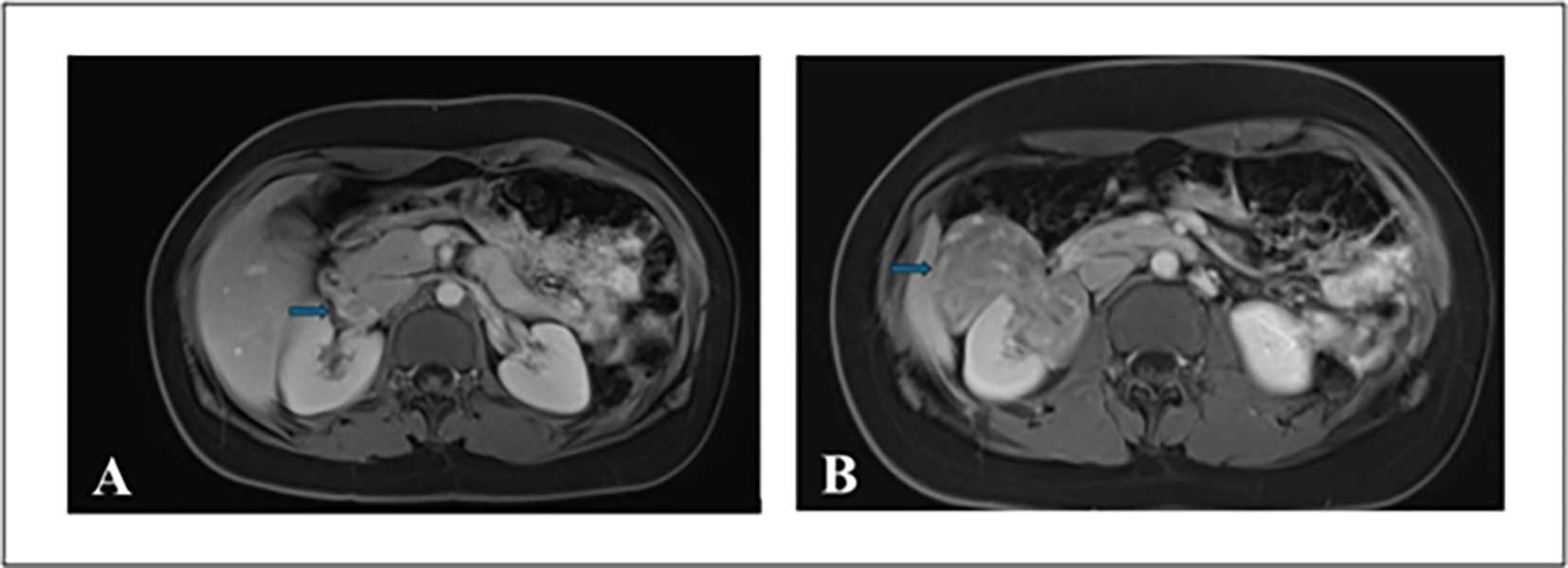

A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated a heterogenous 11.5 cm partially enhancing mass at the right lower pole of the kidney with mild right hydronephrosis. Follow-up magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed two weeks later revealed a solid 11.9 cm exophytic mid/lower pole renal mass with evidence of tumor thrombus extending into the right renal vein and the infrahepatic portion of the IVC (Figure 1). Heterogeneous nodular enhancement with hypointense T2 signal suggested RCC. There was no evidence of lymphadenopathy or pulmonary metastases on imaging. The physical examination and metabolic workup were unremarkable.

FIGURE 1. Multiplanar multi-sequence MRI of abdomen and pelvis with gadolinium enhancement. (A) Axial image showing a right renal mass with the arrow indicating tumor thrombus in the right renal vein. (B) Axial image with the arrow demonstrating an exophytic mass in the right kidney

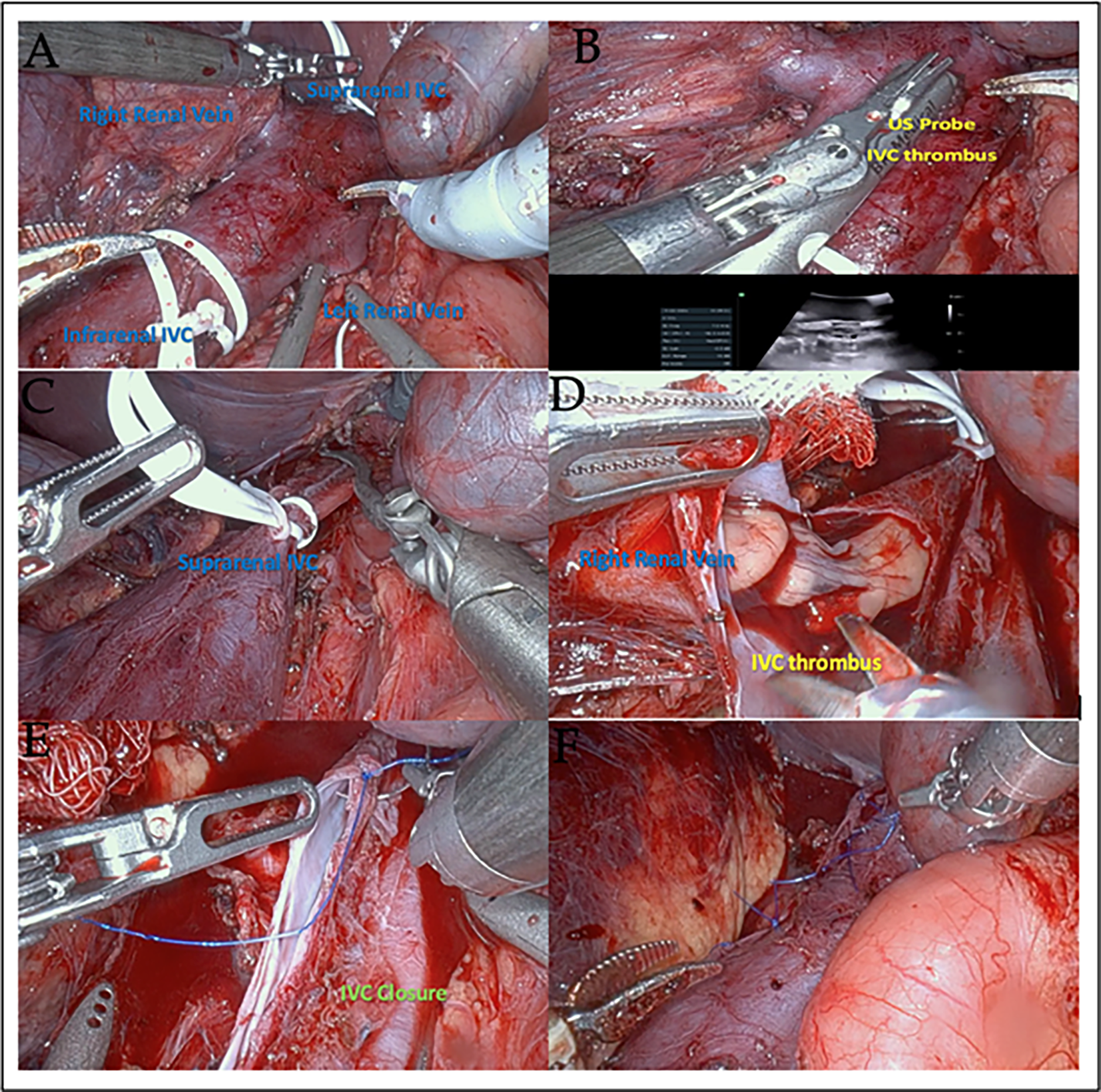

The patient underwent a robotic-assisted right radical nephrectomy with IVC thrombectomy and limited retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. Robotic-assisted right radical nephrectomy with IVC thrombectomy. (A) Vessel loops securing the infrarenal and suprarenal IVC for vascular control. (B) Ultrasound-guided identification of IVC thrombus extending less than 2 cm above the renal vein. (C) IVC is secured with Weck clips around vessel loops and a Scanlan clamp across the left renal vein. (D) IVC opened with retraction of the tumor thrombus into the right renal vein. (E) 4-0 Prolene running suture was used to close the IVC, with the vessel IVC unclamped at 28 min. (F) Hemostasis and inspection of the surgical bed following IVC repair

Follow-up CT imaging four months after resection demonstrated no recurrence of disease and no evidence of metastasis.

Surgical Technique:

Position: Modified flank position with the right flank elevated to 30 degrees.

Port placement: Access was gained to the abdomen using a Veress needle and insufflating it to 15 mmHg. Three 8 mm robotic ports were placed—the first port was placed at the lateral border of the right rectus muscle at the level of the umbilicus; the second and third ports were placed superiorly and inferiorly along the mid clavicular line—with a fourth 8 mm port placed laterally between the middle and inferior ports. Two 12 mm assistant ports were placed midline between the superior and middle ports, as well as between the middle and inferior ports. A final 5 mm port for liver retraction was placed midline above the superior assistant port.

Exposure:

Renal exposure was carried out in the standard fashion, including the medial reflection of the colon, duodenal Kocherization, and dissection of the ureter, followed by upward traction of the lower pole of the kidney, followed by exposure of the hilum and IVC to the level of the left renal vein.

Vascular control:

The right renal artery and an accessory renal artery were identified and stapled separately using a 45 mm Ethicon power stapler. The right gonadal veins and the short hepatic vein were stapled. Lumbar veins near the dissection were clipped. The adrenal vein was stapled using a 35 mm Ethicon power stapler.

Two vessel loops were applied around the IVC and clipped in order to aid with retraction (Figure 2A). Intraoperative ultrasound of the IVC delineated the extent of the thrombus to less than 2 cm above the right renal vein ostium into the IVC (Figure 2B).

The IVC was clamped by the vessel loops with a clip, in addition to Scanlan clamps above and below the thrombus (Figure 2C). The left renal vein was clamped with a Scanlan clamp.

The IVC was opened at the level of the right renal vein with robotic scissors, and the tumor thrombus was removed (Figure 2D), excising the right renal vein, and avoiding any spillage. The field was then irrigated. The IVC was closed in a running fashion with 4-0 Prolene (Figure 2E).

The vessel loops and Scanlan clamps were removed, and the anastomosis was examined carefully to confirm hemostasis (Figure 2F). The total clamp time was 28 min.

Paracaval and interaortocaval lymphadenectomy was performed. All specimens were removed via an Endocatch bag by extending the lowermost 12 mm port incision. A Jackson-Pratt (JP) drain was placed, and the ports were closed with 0-Vicryl figure-of-eight sutures.

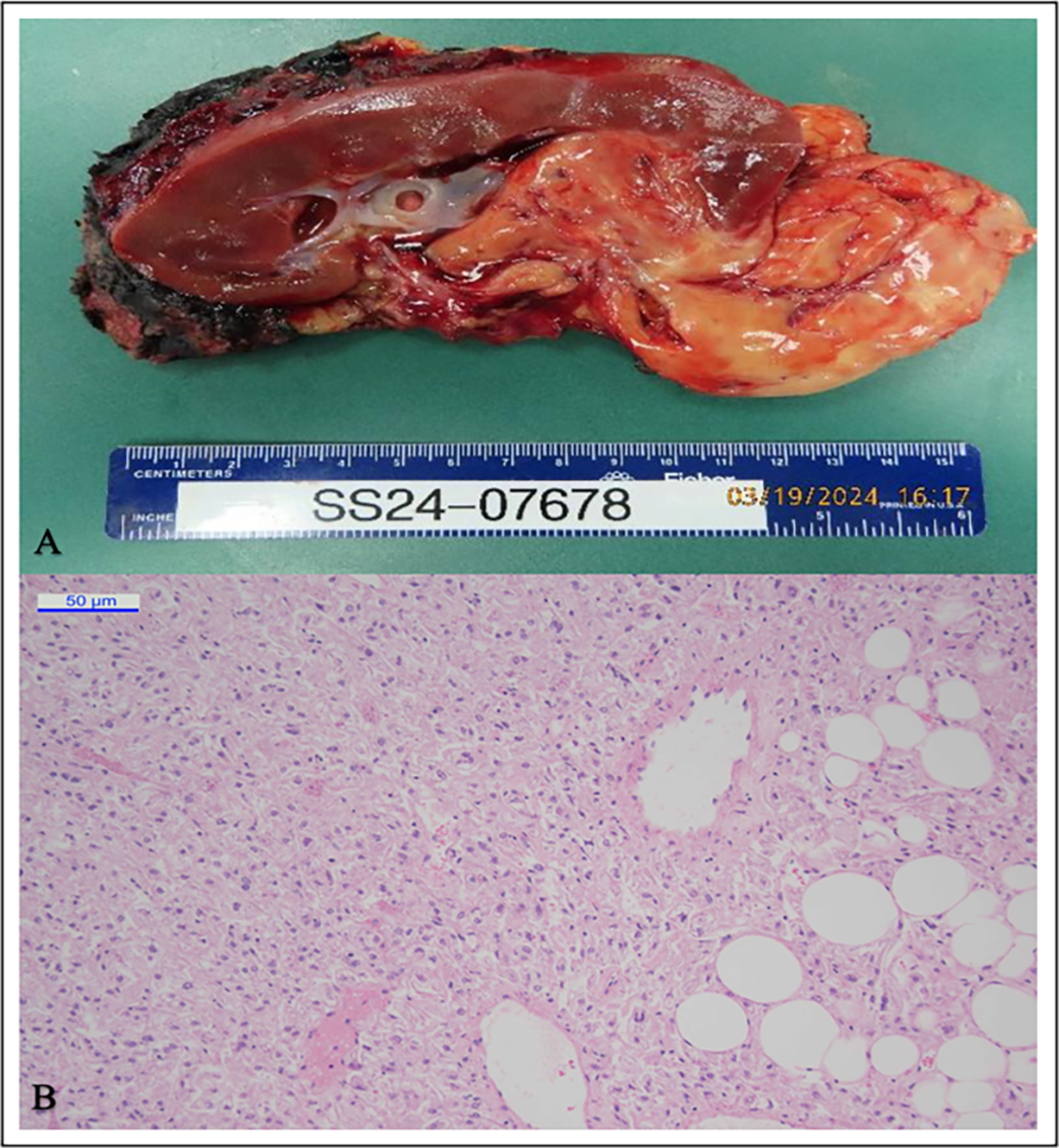

The nephrectomy specimen weighed 309 g with intact perinephric fat. It was bivalved through the hilum, revealing a well-delineated mass measuring 12 × 6 × 2 cm arising from the pelvicalyceal system, involving the lower pole, and significantly extending beyond the kidney. The cut surface was yellow with a soft, fleshy texture (Figure 3A). Microscopy showed a tumor composed of a diffuse sheet of pink eosinophilic cells, mixed with lobules of adipocytes (fat cells) and prominent vessels (Figure 3B). The eosinophilic cells were all large and rounded with granular cytoplasm, features considered “epithelioid” in appearance. All sampled tissue showed the tumor cells with this appearance, meeting the WHO criteria of >80% of tumor cells being epithelioid to be considered an epithelioid angiomyolipoma. Moderate to marked nuclear atypia was present. No necrosis or increased mitotic activity was observed.

FIGURE 3. Gross Specimen and Histopathology of the tumor. (A) The gross appearance of the nephrectomy specimen. (B) The microscopic features of the tumor

Final pathology demonstrated a 12.5 cm epithelioid angiomyolipoma with negative surgical margins. Immunohistochemical staining was positive for smooth muscle antigen (SMA), KIT and the melanocytic markers HMB45. Lymph nodes demonstrated no HMB45 staining and were deemed negative for tumor involvement. The staining pattern is highly valuable in confirming the diagnosis of angiomyolipoma.

One of the earliest reports of EAML was first described in a 1996 case report of a 40-year-old man who underwent resection of a 15 cm renal mass. Pathology demonstrated sheets of epithelioid cells, with neoplastic cells containing granular eosinophilic cytoplasm, and a relative lack of adipose tissue compared to the previously described classic AML.2

Classic AML is characterized by thick-walled blood vessels, smooth muscle, and adipose tissue. EAML can share histologic appearance with RCC, including necrosis and nuclear atypia. This Similarity extends to cross-sectional imaging, with heterogeneity and a relative lack of fat often challenging the differentiation. However, immunostaining with HMB-45 signifies epithelioid cells among smooth muscle, suggestive of AML.2

Both AML and EAML are generally positive for melanocytic markers, though individual markers may not be universally positive. Therefore, it is recommended to use a panel of melanocytic markers (HMB45, MelanA, tyrosinase, MITF) rather than relying on a single marker. Some findings have also suggested that estrogen receptors, bcl-2, and PR expression are higher in EAML, suggesting a possible predilection for presentation in female patients.3 Like classic AML, EAML has been associated with TSC, and missed diagnosis has been suggested as a factor in the slightly higher incidence of RCC detected in patients with TSC.

In contrast to AML, EAML can behave aggressively with local extension, recurrence, distant metastases, and death. Our patient’s presentation with IVC extension exemplifies this aggressive potential. While recent literature suggests malignant potential in up to one-third of patients, heterogeneity in diagnosis among small case series creates uncertainty about the exact incidence.1

Nese et al.1 described prognostic predictors of adverse outcomes for EAML, like concurrent diagnosis with TSC (or concurrent angiomyolipomas), tumor size > 7 cm, extrarenal extension and/or involvement of the renal vein, necrosis, and carcinoma-like histopathology were all considered negative prognostic indicators for survival in distinct risk-stratified categories. The patient cohort used to describe this stratification by the authors included 13 patients, plus 14 described previously in the literature, who had extrarenal extension (including perinephric fat) and/or renal vein involvement as a single subgroup. Involvement of the IVC was not independently described in the review.

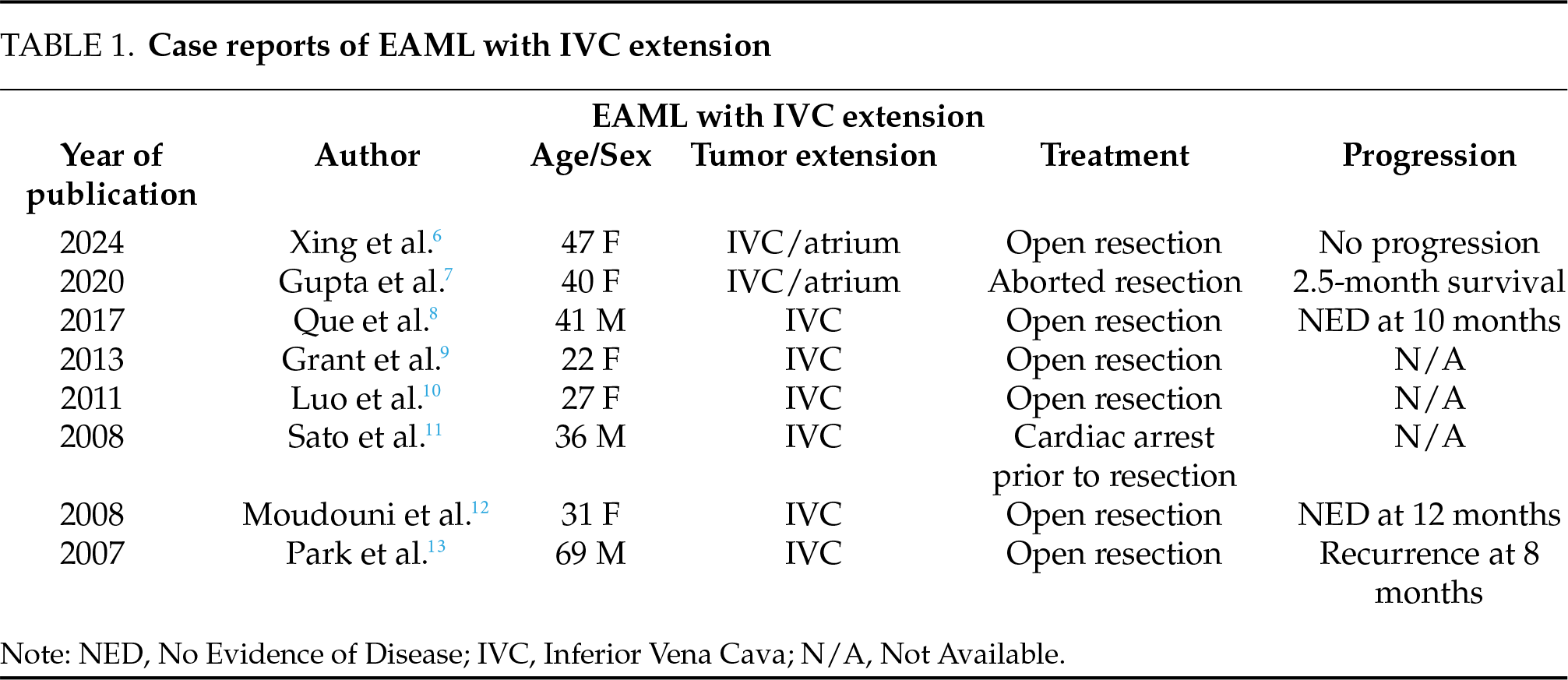

A small number of case reports describing EAML with IVC extension demonstrate mixed outcomes at follow-up (Table 1). While rare, IVC extension has been reported in both classic and epithelioid AML. However, recurrence or distant metastases have only been characterized in patients with EAML. For metastatic disease, doxorubicin and mTOR inhibitors have shown regression in EAML metastasis.4

Due to the radiographic similarities between EAML and RCC, surgical resection remains the initial treatment for non-metastatic disease. However, once the pathologic diagnosis of EAML is confirmed, the appropriate follow-up schedule is unclear. In pediatric patients, initial follow-up every three months with a physical exam and ultrasound or cross-sectional imaging has been suggested,5 though pediatric cohorts have a higher incidence of TSC, a known prognostic predictor.1 For adults diagnosed with EAML, post-operative surveillance and treatment remain unclear, thus emphasizing the importance of continuing to report cases of EAML, particularly those exhibiting aggressive features such as IVC extension. Our current case report highlights the management of a young adult patient presenting with EAML with an IVC thrombus extension successfully treated with a robotic-assisted approach to radical nephrectomy, IVC thrombectomy, and retroperitoneal lymph node dissection.

EAML is a rare form of AML that closely resembles RCC. As it has a high risk of recurrence and metastasis, close follow-up is warranted. However, due to the rarity of the disease, there are no standardized guidelines for further treatment (adjuvant therapy) and further surveillance in cases of EAML. The ongoing reporting of such rare disease presentations and their management, particularly in otherwise young, healthy individuals, is an important initial effort toward establishing standardized care for conditions outside of our current treatment guidelines.

Acknowledgement

The authors sincerely thank the multidisciplinary and cross-institutional team for their commitment to delivering exceptional patient care and fostering collaborative efforts. We are particularly thankful to the patient and their family for their trust, participation, and support. Their contribution to this work has been invaluable and is deeply appreciated.

Funding Statement

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Dimindra Karki: Contributed to conceptualization, data collection, data interpretation, manuscript drafting and revision, and had full access to the data. Ghizlane Yaakoubi: Contributed to conceptualization, data collection, manuscript drafting and revision, and had full access to the data. Beth Edelbute: Contributed to conceptualization, data collection, data interpretation, manuscript drafting and revision, and had full access to the data. Ahmed Aboumohamed: Contributed to conceptualization, data collection, data interpretation, manuscript drafting and revision, and had full access to the data. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

All data and materials related to this case report are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval

All procedures were conducted in accordance with institutional policies and ethical guidelines. According to the policy of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, case reports involving three or fewer patients do not require Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, provided that proper authorization is obtained from the patient.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient and their family prior to inclusion.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials

The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/cju.2025.063294/s1.

References

1. Nese N, Martignoni G, Fletcher CDM et al. Pure epithelioid PEComas (So-Called Epithelioid Angiomyolipoma) of the kidney. Am J Surg Pathol 2011 Feb 1;35(2):161–176. doi:10.1097/pas.0b013e318206f2a9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Mai KT, Perkins DG, Collins JP. Epithelioid cell variant of Renal Angiomyolipoma. Histopathology 1996;28(3):277–280. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2559.1996.d01-421.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Cho NH, Shim HS, Choi YD, Kim DS. Estrogen receptor is significantly associated with the Epithelioid variants of Renal Angiomyolipoma: a Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 67 cases. Pathol Int 2004;54(7):510–515. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1827.2004.01658.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Cibas ES, Goss GA, Kulke MH, Demetri GD, Fletcher CD. Malignant epithelioid angiomyolipoma (‘Sarcoma ex Angiomyolipoma’) of the kidney: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25(1):121–126. doi:10.1097/00000478-200101000-00014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Mahajan D, Jain V, Agarwala S, Jana M, Ramteke PP. Renal epithelioid angiomyolipoma in children. J Kidney Cancer VHL 2021;8(2):20–26. doi:10.15586/jkcvhl.v8i2.178. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Xing L, Yilun Y, Ji Z, Wei C. Rare case of Renal Epithelioid Angiomyolipoma with tumor thrombus into the IVC and Right Atrium. Circulat: Cardiovas Imag 2024 Jan 30;17(3):e016083. doi:10.1161/circimaging.123.016083. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Gupta D, Vishwajeet V, Pandey H, Singh M, Sureka B, Elhence P. Epithelioid Angiomyolipoma with tumor thrombus in IVC and right atrium. Autopsy Case Rep 2020;10(4):e2020190. doi:10.4322/acr.2020.190. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Que X, Zhu Y, Ye C et al. Invasive epithelioid angiomyolipoma with tumor thrombus in the inferior vena cava: a case report and literature review. Urol Int 2015 Jul 3;98(1):120–124. doi:10.1159/000434648. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Grant C, Lacy JM, Strup SE. A 22-year-old female with invasive epithelioid angiomyolipoma and tumor thrombus into the inferior vena cava: case report and literature review. Case Rep Urol 2013 Jan 1;2013(3):1–3. doi:10.1155/2013/730369. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Luo D, Gou J, Yang L, Xu Y, Dong Q. Epithelioid Angiomyolipoma with involvement of Inferior vena cava as a tumor thrombus: a case report. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2011 Feb;27(2):72–75. doi:10.1016/j.kjms.2010.05.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Sato K, Ueda Y, Tachibana H et al. Malignant Epithelioid Angiomyolipoma of the kidney in a patient with Tuberous Sclerosis: an autopsy case report with p53 gene mutation analysis. Pathol Res Pract 2008 Oct 1;204(10):771–777. doi:10.1016/j.prp.2008.04.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Moudouni SM, Tligui M, Sibony M et al. Malignant Epithelioid Renal Angiomyolipoma involving the inferior vena cava in a patient with Tuberous Sclerosis. Urologi Internation 2008 Jan;80(1):102–104. doi:10.1159/000111739. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Park HK, Zhang S, Wong MK, Kim HL. Clinical presentation of Epithelioid Angiomyolipoma. Int J Urol 2007;14(1):21–25. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2042.2006.01665.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools