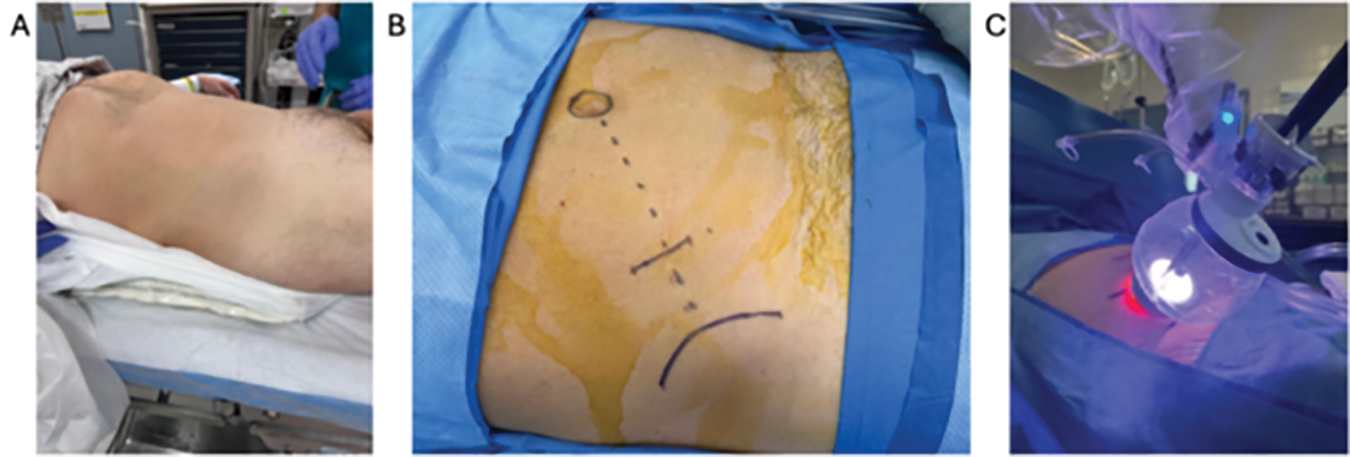

Open Access

Open Access

HOW I DO IT

Single port robotic partial nephrectomy via a retroperitoneal approach

1 Department of Urology, Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA 19107, USA

2 Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA

3Division of Urology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA 02215, USA

4 Scott Department of Urology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX 77030, USA

* Corresponding Author: Joon Yau Leong. Email:

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(5), 469-475. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.066348

Received 06 April 2025; Accepted 18 August 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

In recent years, the introduction of the Da Vinci Single Port (SP) robotic platform has opened new doors for the treatment of localized renal masses. This technology, particularly when utilized via a regionalized retroperitoneal (RP) approach, offers several distinct advantages that may improve patient recovery. These advantages include easier access to both anterior and posterior renal tumors, avoidance of the peritoneal cavity with complicating adhesions, and simplified supine positioning, potentially reducing the risk of musculoskeletal or nerve injuries. Yet, the learning curve for RP surgery remains steep due to the unfamiliarity of many surgeons with the RP endoscopic perspective and ergonomic challenges of the SP robot. Given this relatively new technology and its growing availability in many institutions, most surgeons remain early in their evolution of performing SP partial nephrectomy (PN). Herein, we discuss our technique for performing SP PN via an RP approach, including port access, anatomic considerations, and operative techniques. Our hope is to familiarize readers with this powerful approach and smooth out early pitfalls during the learning curve.Keywords

The adoption of single port (SP) robotic partial nephrectomy (PN) represents a transformative approach in managing localized renal tumors. The da Vinci SP system (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), equipped with three articulating instruments and a camera, allows for improved access to the retroperitoneum through a single incision. This technology, particularly when utilizing the regionalized retroperitoneal (RP) approach, appears to offer some distinct advantages that enhance both surgical efficacy and patient recovery.1

Yet, the learning curve for RP surgery remains steep due to the unfamiliarity with the endoscopic RP perspective. One of the game changers for this approach has been the use of low anterior RP access, which provides a viewpoint climbing toward the kidney along the axis of the ureter. This perspective can be disorienting for new surgeons, even if they are relatively experienced with traditional multiport posterior flank access. There also exist the challenges in camera maneuverability, lack of a large working space, arm clashes, and decreased grip and arm strength of the robot. Taken together, these disadvantages create an ergonomic challenge that the experienced multiport robotic surgeon is unaccustomed to. The advantage of the SP, however, lies in its ability to insinuate into surgical planes, using one small incision. A feat heretofore not possible with the Xi robot. Therein lies the true promise of this platform. Below, we discuss our technique for performing SP PN via an RP approach and we include port access, anatomic considerations, and operative techniques. Our goal is to familiarize readers with the power of this technique and to smooth out potential pitfalls they may encounter during their initial learning curve.

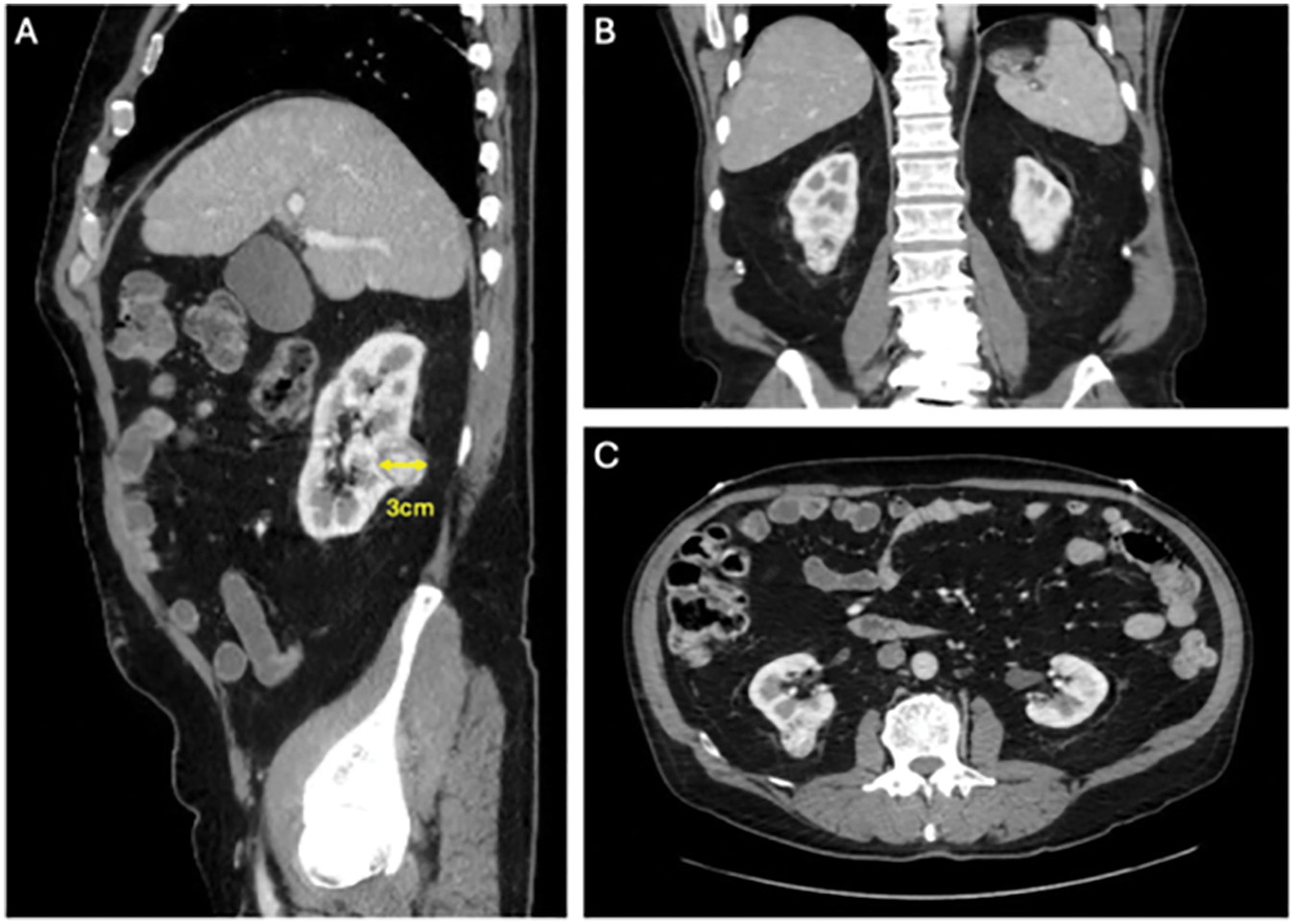

Patient presentation and tumor characteristics

The nature of this “How I Do It” article was IRB exempt. Informed consent was not obtained as no patient identifiable information was included within our manuscript. Index patient number 1 is a 66-year-old man with a body mass index (BMI) of 27.8 kg/m2 who was found to have an enhancing, exophytic, 3 cm right posterior lower pole renal mass. Cross-sectional imaging is shown in Figure 1. Nephrometry score was 4P. The patient underwent a successful right SP PN via an RP approach. Total operative time was 147 min, warm ischemia time was 25 min, estimated blood loss was 200 mL, and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) immediately post-operatively remained stable at 75 mL/min/1.73 m2. The patient was discharged the same day without narcotics and did not have any 30-day complications. Final pathology demonstrated pT1aNx clear cell renal cell carcinoma with negative surgical margins. Additionally, we present a total of five patients in Table 1 who underwent SP PN via an RP approach to highlight a case series.

FIGURE 1. Abdomen computed tomography (CT) demonstrating a 3 cm exophytic, posterior, right lower pole renal mass

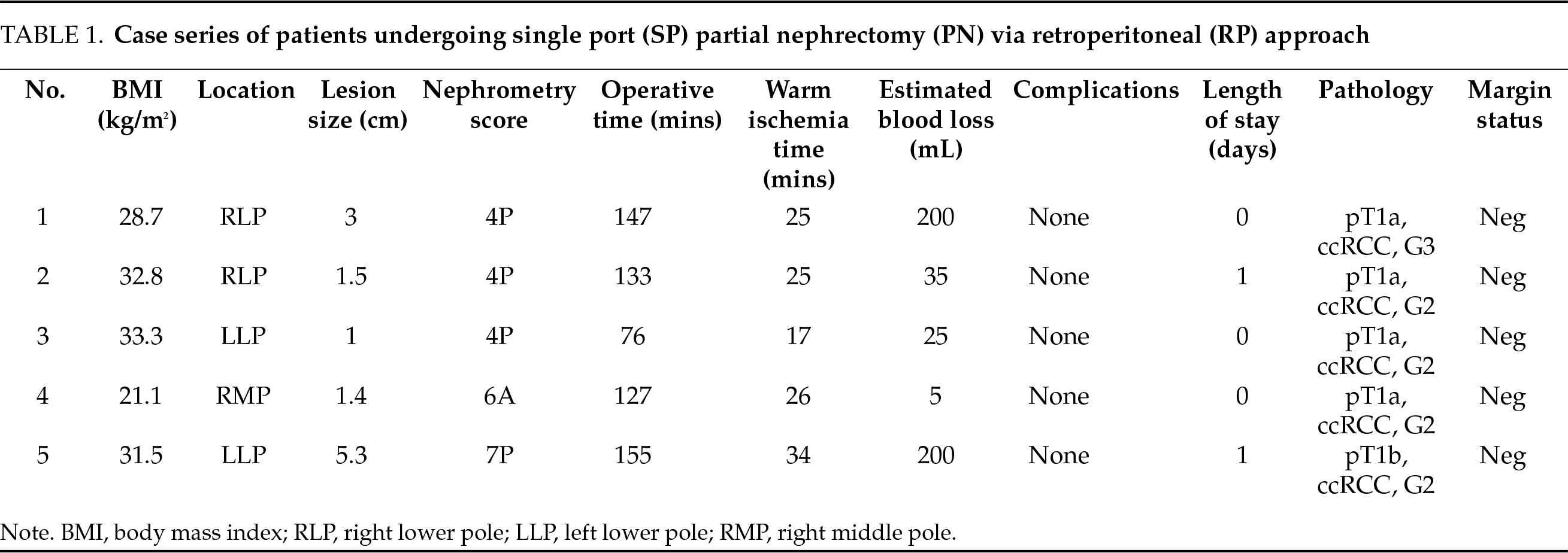

Bilateral sequential compression devices are placed, and a Foley catheter is inserted per urethra in sterile fashion and placed to gravity drainage. The patient is placed in the supine position with a small gel bump to the ipsilateral side (Figure 2A). Tilting the table slightly towards the contralateral side can sometimes aid in having the bowel and peritoneum fall away from the surgical site. The patient’s arms are placed out perpendicular to the axis of the table with appropriate support and padding to all pressure points. The patient is then shaved, prepped, and draped in sterile fashion.

FIGURE 2. Patient positioning. (A) Patient positioned supine with a slight lateral bump on the ipsilateral side. (B) Access is obtained via the supine anterior retroperitoneal access (SARA) approach. (C) The robot is docked through the balloon floating dock into the surgical incision

We utilize the low or supine anterior retroperitoneal access (SARA) technique.2 An approximately 3 cm skin incision is created in a mini-Gibson style, two fingerbreadths medial to the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) and towards the umbilicus. Alternatively, the incision can be placed 2 fingerbreadths superior to the ASIS, which can help avoid entry into the peritoneum (Figure 2B). Dissection is carried down through Camper’s and Scarpa’s fascia to the external oblique fascia. The fascial layer is incised in line with its fibers, and blunt dissection is used to separate the external and internal oblique muscles and finally the transversalis muscles to enter the retroperitoneum using a relatively lateral trajectory. The fascial incision can be made slightly longer than 3 cm and slightly more superior to the skin incision. The fascia is aggressively stretched with a blunt clamp to avoid creating a limiting keyhole-shaped entry into the retroperitoneum. Using a finger sweeping motion, blunt dissection is used to develop the retroperitoneal space by pushing the retroperitoneal contents medially until the quadratus lumborum and psoas muscles are palpated deeply. This is best achieved by guiding the finger and palpating the underside of the pelvic bone inferiorly and then gently sweeping all the peritoneal contents medially. Care should be taken to avoid peritoneal entry, the risk of which is increased by excessive sweeping medially. Inadvertent peritonotomies should be immediately closed primarily when recognized to avoid insufflation of the peritoneum when docking the robot, as this can limit the working space within the retroperitoneum.

A dilating balloon is not required. We then insert the SP inner ring into the developed space, and the balloon floating dock is attached to the outer external ring and oriented towards the contralateral shoulder. Visual confirmation of the psoas muscle belly deep in our incision, or at least retroperitoneal fat after placement of the access port, confirms appropriate access. Insufflation is activated using the AirSeal device via an 8 mm AirSeal (ConMed Corp., Largo, FL, USA) assistant port into the balloon floating dock at a pressure of 8–10 mmHg and a flow rate of 2.0 mL/min under pediatric mode. Additional assistant ports are not typically necessary, however can be used, especially early in the learning curve. The SP robotic system is subsequently docked accordingly, taking care to center the incision within the camera view. We have found that docking the robot such that the camera points towards the contralateral shoulder will orient things properly towards the psoas muscle. The robotic camera and instruments are introduced respectively. We typically favor the placement of the SP robotic camera at the 6 o’clock position, which provides ideal lifting exposure to access the renal hilum. The monopolar scissors, Cadiere forceps, and fenestrated bipolar forceps are in the 3, 12, and 9 o’clock positions, respectively. A Remotely Operated Suction Irrigation (ROSI) device is inserted into the surgical field via the balloon port and can be handled manually by the operating surgeon. Additionally, the controlled remote center (CRC) technology, once set, allows the operating surgeon to manipulate all instruments around a fixed point, providing dexterity and control within the surgical site, despite operating through a limited access point.

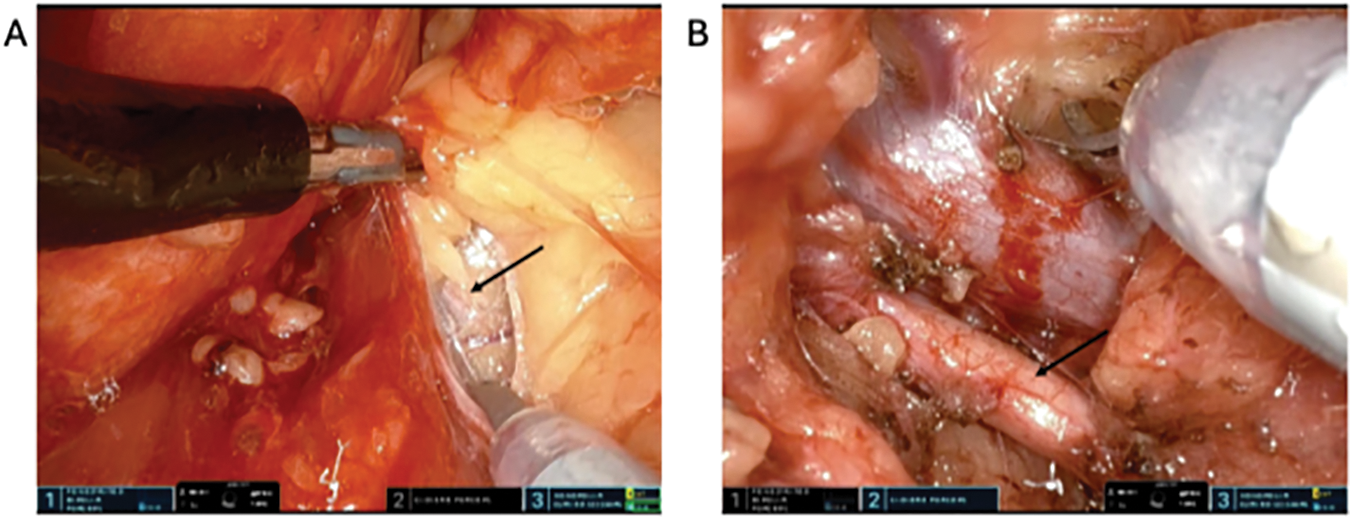

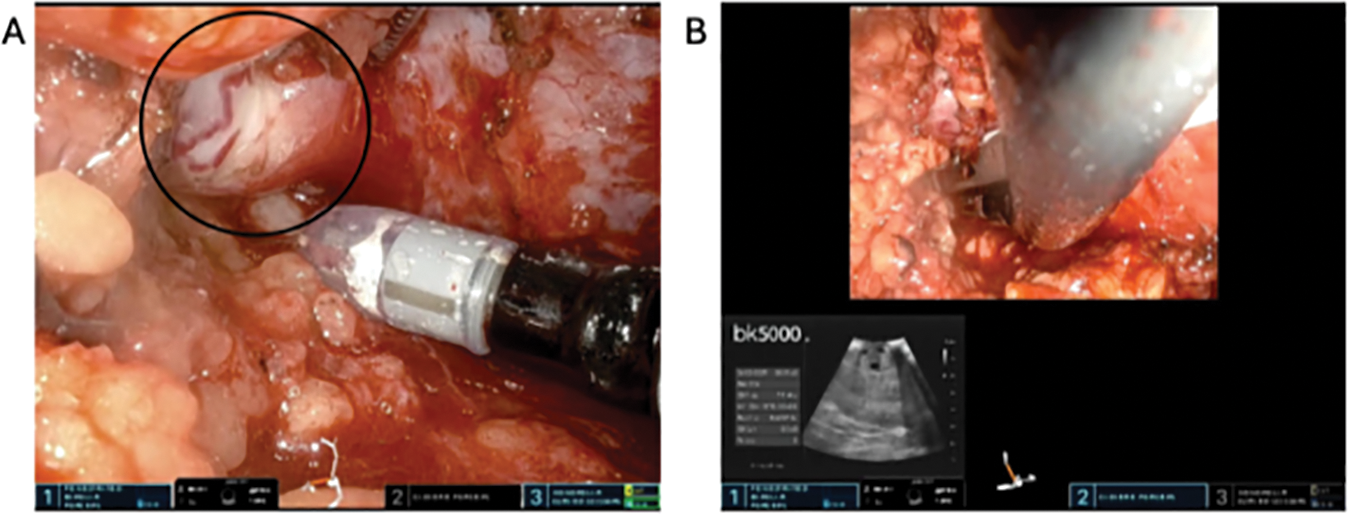

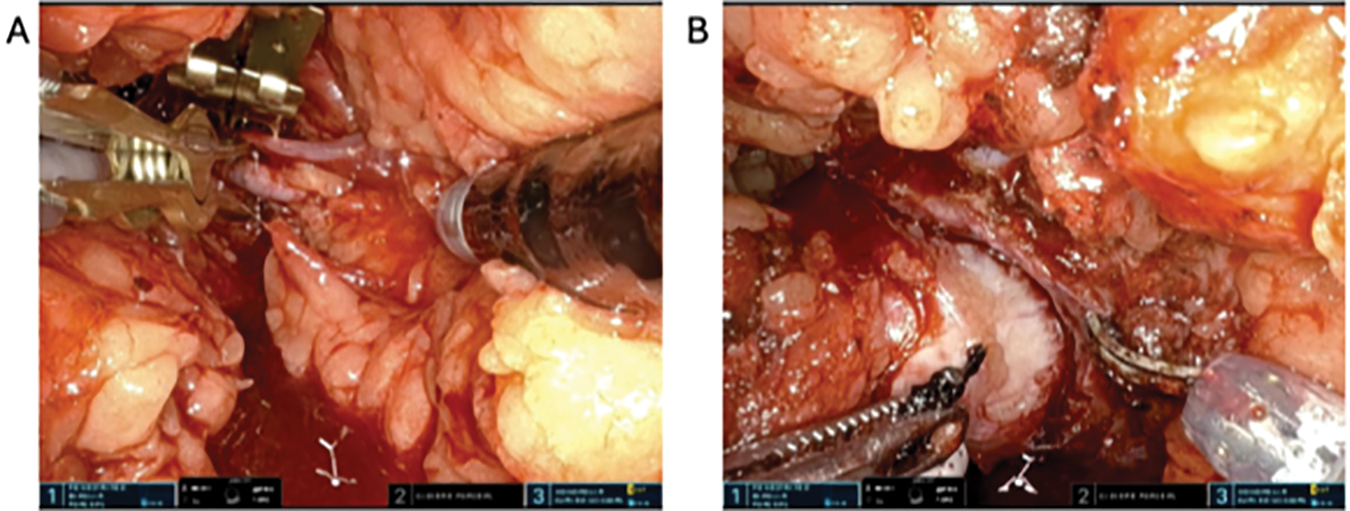

Firstly, we mobilize the posterior retroperitoneal adipose tissue off the psoas muscle, identifying the psoas tendon. This is often challenging, and care must be taken to avoid mistaking the lateral quadratus lumborum muscle for the psoas. The psoas is often more medial than expected and we find it helpful to verify that the robot is pointing towards the contralateral shoulder. Additionally, there is a layer of posterior Gerota’s fascia that requires incising, a “leap of faith” that is rewarded with identification of the psoas. This posterior Gerota’s can be confused for peritoneum so care must be taken to make sure the dissection is sufficiently posterior. Cadiere forceps are used to apply blunt traction superiorly on the kidney and Gerota’s fascia. Dissection along the psoas muscle will reveal the ureter medially (Figure 3A). Dissection is continued cranially until the renal hilum is encountered. One method of identifying the hilum is by first identifying the horizontal fibers of posterior diaphragm as these fibers insinuate with the psoas superiorly. It is at this level that the renal hilum lies in most cases. The renal vasculature is circumferentially dissected, and hilar dissection is considered satisfactory when Bulldog clamps can be safely applied (Figure 3B). We typically dissect only the renal artery (ies). Occasionally, in patients with significant volumes of retroperitoneal fat, a vessel loop can be applied circumferentially around the renal vasculature to allow for easier identification and efficient return to the hilum later in the case. Next, the kidney is mobilized by incising Gerota’s fascia and dissecting off perirenal fat to appropriately visualize and resect the tumor and perform the renorrhaphy (Figure 4A). In many cases, temporarily placing gauze into the retroperitoneal space to adjust kidney position is very advantageous. At this point, an ultrasound probe may be placed into the surgical field via the assistant port of the balloon floating dock for intraoperative delineation of the tumor (Figure 4B). One of the challenges of this procedure is the lack of space, preventing easy access for the ultrasound probe. A small newer generation flexible “drop in” probe is a significant advantage here.

FIGURE 3. Hilar dissection. (A) Dissection over the psoas muscle cranially revealing the ureter (arrow) medially. (B) Renal artery (arrow) and vein dissection

FIGURE 4. Mass identification using ultrasound. (A) Dissecting perinephric fat to reveal the tumor (circle). (B) Intraoperative ultrasound using a drop-in probe to delineate the tumor along the renal capsule

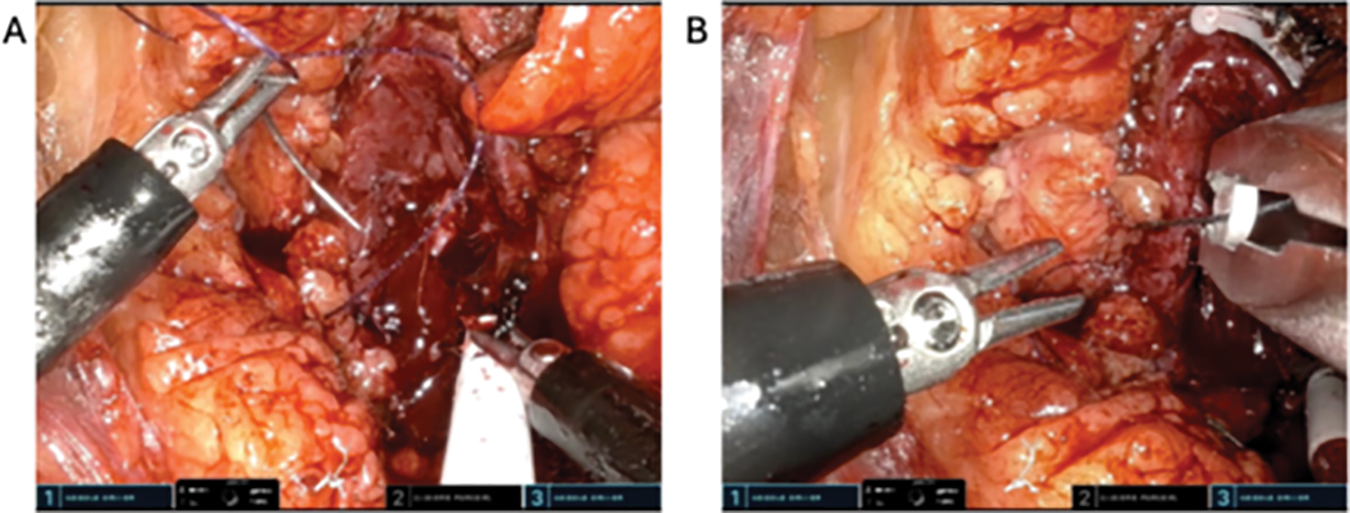

Prior to bulldog application, confirm that the sheath on the Cadiere and bipolar instruments is applied far enough back so that the writing “IS” is visible. If the sheath is covering the marking, application of the bulldog will be compromised. Once we apply our golden Scanlan® Reliance Bulldog Light Pressure (LP) clamps (Scanlan International, Saint Paul, MN, USA) to the renal artery, the timer for warm ischemia time is initiated (Figure 5A). Important to note here is that these specific light-pressure bulldog clamps are designed for application on the SP system due to its lower tensile pressure needed to handle and apply onto the renal arteries. As a result, it also has a lower clamping pressure and provides approximately 205 g of pressure on initial use compared to regular vascular bulldogs, which can apply up to 350 g of pressure. As such, we typically apply at least two low-pressure bulldogs onto the renal artery, although some of our authors routinely use only one of these clamps with success. A renal vein bulldog clamp is not routinely applied. Using sharp instruments and minimal cautery, we gently excise the tumor lesion in its entirety, careful to keep an adequate margin outside the tumor pseudocapsule plane. Alternatively, an enucleation technique can also be applied and is left to surgeon discretion. Maximizing the utilization of all three working arms during tumor resection is advantageous. A visually appreciated negative margin is typically achieved throughout the entirety of the mass (Figure 5B). Liberal use of high-power bipolar cautery during deep resection allows for control of end-arteries, particularly in hilar tumors or those tumors adjacent to the renal sinus. The lesion is either immediately removed and placed into the dock or set aside within the retroperitoneum for later extraction.

FIGURE 5. Arterial clamping and tumor dissection. (A) Application of Bulldog clamps to the renal artery. (B) Tumor dissection and enucleation

Renorrhaphy techniques vary amongst surgeon preferences. In this case, we performed our renorrhaphy in two layers. The inner layer is completed with a running 3-0 V-LocTM suture (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) with clips on either end at the level of the renal capsule (Figure 6A). All bleeding vessel lumens are closed within this layer. If there are additional collecting system defects, these are individually closed with 3-0 Vicryl sutures in an interrupted fashion. We then remove the bulldog clamps on the renal artery and observe for any additional uncontrolled bleeding vessels, which are repaired as needed. The warm ischemia time is noted. Next, a second renorrhaphy layer is performed using a 2-0 V-locTM suture in a running horizontal mattress fashion, with clips placed on either side of the defect. This layer is tightened with a sliding clip technique. If the tumor is in a favorable location, the individual Hem-o-lok® clips (Teleflex, Wayne, PA, USA) may be applied by the bedside assistant (Figure 6B). More frequently, the robotic clip applier is used. Each time a clip is utilized, the robotic clip applier has to be removed, loaded, and reinserted into the surgical field. Depending on the size of the defect and surgeon preference, additional hemostatic agents may be administered. Note that, depending on the tumor location, the administration of these additional products may be difficult for the bedside assistant and may need to be applied by the console surgeon.

FIGURE 6. Renorrhaphy. (A) Two-layer renorrhaphy performed using absorbable barbed sutures. (B) Absorbable clips individually applied manually by the bedside assistant using a clip applier

If the renal mass is less than 3 cm, it can be extracted via the port carefully under direct vision and left in the access port balloon. If the mass is larger than the incision, a specimen extraction bag can be used for safe retrieval. All needles, Bulldog clamps, and vessel loops are removed. The SP robot is undocked, and the ring is removed. The internal and external oblique muscles can be reapproximated with 2-0 Vicryl suture. The external oblique fascia is closed in a running fashion with a 0 PDS suture, and the skin is closed in a running subcuticular fashion with a 4-0 Monocryl suture. Dermabond skin glue is applied to the incision after the patient is washed and dried.

The regionalized RP approach has many potential advantages when compared to the more traditional transperitoneal (TP) approach for PN. However, adoption amongst robotic surgeons in the USA has been surprisingly limited to date. The RP approach facilitates direct early identification of the renal hilum and eliminates the need for colonic mobilization and minimizes the risk of gastrointestinal injuries and postoperative ileus, potentially leading to a smoother postoperative course. This is particularly useful for patients with a complex surgical history where the abdominal cavity might be fraught with significant adhesive disease.3 Additionally, RP access provides improved visualization of posterior tumors, particularly those immediately posterior to the hilum, avoiding the need for kidney rotation during a transperitoneal approach.4 The innovation of low anterior access with the SP system now allows easy access to tumors located almost anywhere in the kidney. A meta-analysis by Zhou et al. demonstrated superior perioperative outcomes for the RP approach with regards to hospital stays, estimated blood loss, and operative times, while maintaining similar oncologic outcomes and complication rates when compared to a TP approach, supporting the safety and feasibility of RP robotic PN.5

In well-selected patients, SP PN via an RP approach offers several significant benefits regarding operative efficiency and patient safety, without compromising oncologic outcomes.6 The ability to approach both anterior and posterior tumors while avoiding the peritoneal cavity altogether makes the RP approach an attractive option for managing localized renal masses. Moreover, patients can be positioned supine with a slight bump, which may reduce the risk of peripheral nerve injuries that occur when patients are positioned in a prolonged flank position. This synergy between SP robotics and the low anterior RP approach presents an optimal path forward for PN. Early in the SP RP learning curve, ideal patient selection criteria should include patients with lower pole tumors and modest volumes of retroperitoneal fat, irrespective of abdominal surgical history. Higher BMI male patients with large Gerota’s fat envelopes and upper pole tumors may pose a challenge and should be reserved for cases further along the learning curve.

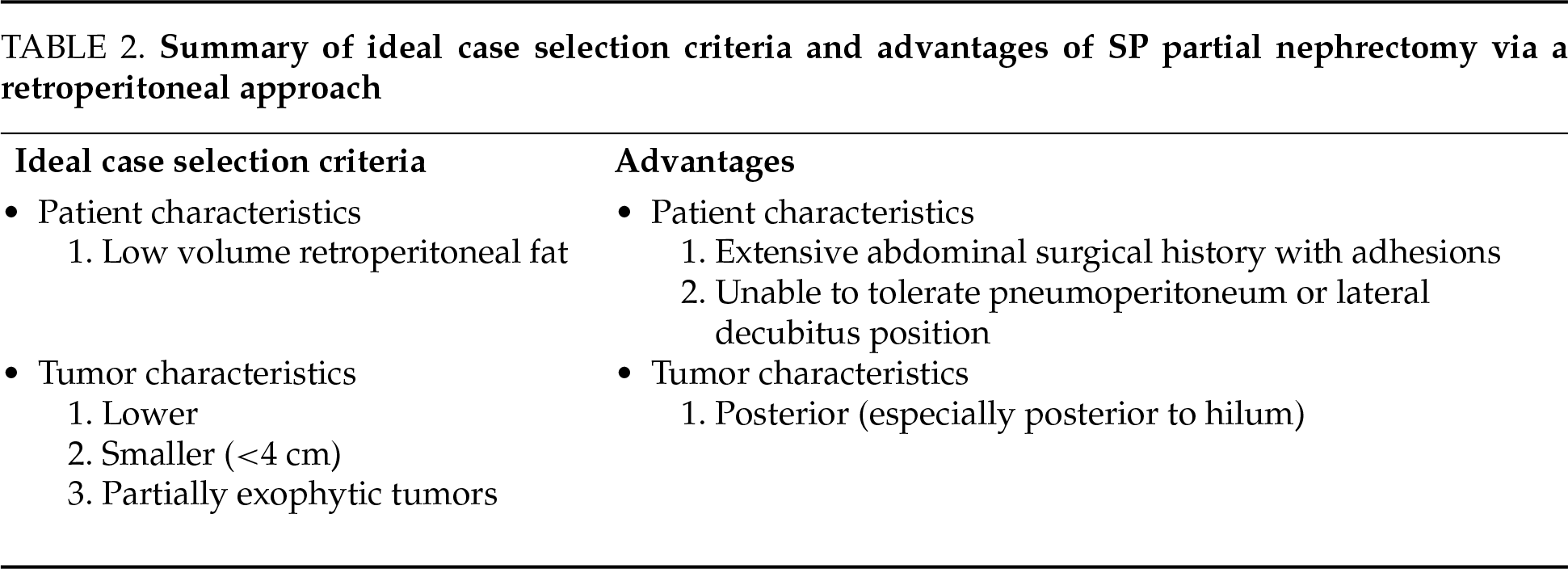

The SP robot has distinct disadvantages in ergonomics and instrument grasping strength. These issues create a challenge even for very experienced robotic surgeons. Thus, early in one’s experience, the ideal patient selection criteria should include smaller (<4 cm) lower pole tumors that are at least partially exophytic and in patients with relatively low retroperitoneal fat content, irrespective of abdominal surgical history. Table 2 summarizes the overall ideal case selection criteria and advantages of performing SP PN via an RP approach.

Future research could focus on prospective comparisons of both clinical outcomes and quality of life between SP and multi-port robotic patients. Expanding research to include more diverse patient populations and tumor characteristics would be advantageous to define the spectrum of clinical cases best approach with the regionalized SP RP approach. Moreover, an evaluation of the true learning curve of this procedure is warranted in addition to determining which surgeons/programs are able to successfully overcome this learning curve for PN.

Acknowledgement

None.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Joon Yau Leong, Andrew A. Wagner, Richard E. Link, Mihir S. Shah; Data collection: Joon Yau Leong, Mihir S. Shah; Analysis and interpretation of results: Joon Yau Leong, Vignesh Prasad, Carlos J. Perez Kerkvliet; Draft manuscript preparation: All authors. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Joon Yau Leong, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval

The nature of this “How I Do It” article was IRB exempt.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was not obtained as no patient identifiable information was included within our manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

REL is a Member of the Scientific Advisory Board and Proctor for Intuitive Surgical. All other authors declare no conflicts of interests to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Lasorsa F, Orsini A, Bignante G et al. Predictors of delayed hospital discharge after robot-assisted partial nephrectomy: the impact of single-port robotic surgery. World J Urol 2024;43(1):30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

2. Pellegrino AA, Chen G, Morgantini L, Calvo RS, Crivellaro S. Simplifying retroperitoneal robotic single-port surgery: novel supine anterior retroperitoneal access. Eur Urol 2023;84(2):223–228. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

3. Soputro NA, Okhawere KE, Ramos-Carpinteyro R et al. Development of patient-specific nomogram to assist in clinical decision-making for single port versus multi-port robotic partial nephrectomy: a report from the single port advanced robotic consortium. J Endourol 2025;39(3):252–260. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

4. Strauss DM, Lee R, Maffucci F, Abbott D, Masic S, Kutikov A. The future of Retro robotic partial nephrectomy. Transl Androl Urol 2021;10(5):2199–2208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

5. Zhou J, Liu ZH, Cao DH et al. Retroperitoneal or transperitoneal approach in robot-assisted partial nephrectomy, which one is better? Cancer Med 2021;10(10):3299–3308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

6. Raver M, Ahmed M, Okhawere KE et al. Adoption of single-port robotic partial nephrectomy increases utilization of the retroperitoneal approach: a report from the single-port advanced research consortium. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2025;35(2):131–137. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools