Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Association of urinary tract infection and low albumin/globulin ratio with chemoresistance to gemcitabine-cisplatin in advanced urothelial carcinoma

1 Department of Urology, Capital Medical University, Beijing Friendship Hospital, Beijing, 100050, China

2 Institute of Urology, Beijing Municipal Health Commission, Beijing, 100050, China

* Corresponding Authors: Ye Tian. Email: ; Xinyi Hu. Email:

# These two authors contributed equally to this work

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(5), 411-422. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.066758

Received 16 April 2025; Accepted 14 July 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

Objective: Urothelial carcinoma (UC) remains a prevalent malignancy with high recurrence and chemoresistance rates despite gemcitabine-cisplatin (GC) chemotherapy. The study aimed to identify clinical risk factors for chemoresistance in advanced UC patients and develop a predictive model. Method: A retrospective analysis was conducted on 375 UC patients who received postoperative GC chemotherapy between 2013 and 2024. Patients were categorized into chemotherapy-resistant (CR, n = 91) and non-chemotherapy resistant (NCR, n = 284) groups based on tumor progression. Clinical, pathological, and laboratory variables were compared using t-tests and chi-square tests. Kaplan-Meier assessed overall survival (OS), and binary logistic regression identified independent predictors of chemoresistance. Result: Overall survival (OS) was significantly lower in the CR group than in the NCR group urinary tract infection (OR: 54.60; 95% CI: [21.19, 140.67]) and low A/G (OR: 0.18;95% CI: [0.03, 0.94]). The prediction model was: Logit(P)=−3.69+0.96×multifocal tumor+1.05×Tstage+4.00×long-termurinary tract infection(UTI)−1.73×A/G. Conclusion: Multifocality, high T stage, persistent UTI, and low A/G ratio are significantly associated with chemoresistance to GC in UC. These routine clinical indicators may support early identification of high-risk patients and guide treatment decisions.Keywords

Urinary tract tumors, including bladder, kidney, and prostate cancers, are placing an increasing burden on global health systems. A recent study reported that both the incidence and disability-adjusted life-year (DALY) rates of these malignancies have risen steadily worldwide from 1990 to 2021, with continued growth projected through 2046, particularly in aging populations and countries with a high Socio-demographic Index (SDI).1 These trends highlight the pressing need for improved diagnostic and treatment strategies. In recent years, with the gradual aging of the population, the incidence of urothelial carcinoma (UC) has also gradually increased. However, fortunately, the initial clinical manifestations of UC are mostly painless hematuria, which is more likely to attract patients’ discovery and attention. Meanwhile, with the popularity of regular physical examination, more patients still have relatively early-stage tumors at the time of discovery.2 Unfortunately, due to the multi-centrality of UC in time and space, many UC patients still suffer from recurrent tumors after surgery, and even the malignancy of tumors will gradually increase, which also causes the incidence of advanced UC to remain high.3,4 For patients with advanced UC, systemic maintenance or postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy combined with gemcitabine and cisplatin (GC) is often used clinically.5 However, there are still a part of patients who develop chemoresistance during the GC regimen chemotherapy, resulting in local tumor progression, recurrence or even distant metastasis.6 For UC patients with chemoresistance, although immunotherapy and other methods can be used, the therapeutic effect and prognosis of the patients are significantly poorer than those without chemoresistance.7 Before chemoresistance occurs in UC patients, combination therapy such as immune checkpoint inhibitors can improve the prognosis of these patients and extend the overall survival time.8 Most previous studies were aimed at exploring the molecular mechanism of GC chemoresistance in UC patients, and few studies discussed the correlation between clinical information and chemoresistance in UC patients.9

In this study, we conducted a statistical analysis of the epidemiological characteristics, tumor burden, and blood and urine laboratory test results of UC patients undergoing gemcitabine-cisplatin (GC) chemotherapy. The objective was to identify potential clinical factors associated with chemoresistance and to construct a predictive model that may support individualized treatment decisions in advanced UC.

This study included a total of 375 patients who visited Beijing Friendship Hospital from January 2013 to June 2024 and were pathologically diagnosed as UC combined with GC chemotherapy after the surgery. All patients were divided into the Chemotherapy Resistant (CR) group (91 patients) and the Non-Chemotherapy Resistant (NCR) group (284 patients) according to whether they had radiographic recurrence, local progression, or distant metastasis of the tumor during chemotherapy. Chemoresistance in this study was defined based on the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) 1.1 criteria. Specifically, patients who developed progressive disease (PD) during GC chemotherapy.10,11 This study follows the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Friendship Hospital. All subjects have signed informed consent, and the approval number is: BFHHZS20240170.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria: (1) Patients admitted to Beijing Friendship Hospital and confirmed as UC by postoperative pathology; (2) Patients who received GC chemotherapy in Beijing Friendship Hospital. Exclusion criteria: (1) Patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy before surgery; (2) Combination therapy with GC regimen and other drugs, such as Pembrolizumab, Tislelizumab, etc.; (3) Patients with malignant tumors of other organs; (4) Patients who need urinary system surgery due to other urinary system diseases (such as urinary calculi, urinary system malformations, etc.); (5) Patients who need long-term indwelling catheters or ureteral stents; (6) Patients with incomplete clinical data.

No age restriction was applied during patient selection. All eligible patients who met the diagnostic and treatment criteria were included, regardless of age.

All patients in this study underwent radical tumor resection prior to GC chemotherapy. Specifically, patients diagnosed with upper tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC) received standard radical nephroureterectomy with bladder cuff excision, while those with bladder carcinoma (BCa) underwent radical cystectomy with urinary diversion (including ileal conduit or orthotopic neobladder reconstruction depending on the patient’s condition and preference). All surgeries were performed by experienced urologists following standard oncologic principles and guidelines.12

In this study, all patients received postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy rather than neoadjuvant therapy. This was primarily due to the retrospective nature of the cohort and the real-world clinical practice pattern in our center during the study period (2013–2024), where neoadjuvant chemotherapy was not routinely applied for UC patients, especially for those with high surgical urgency, renal dysfunction, or uncertain staging before surgery. Therefore, all included patients received standard GC chemotherapy within 1–2 months following radical tumor resection. Specific drug usage and dosage are as follows: The strategy consists of a chemotherapy cycle of 21 days, in which gemcitabine was administered on day 1, day 8 and day 15, with a dose of 1280 mg/m2 mixed with 500 mL normal saline, and intravenous infusion was completed within 2 h. On day 2, cisplatin was administered at a dose of 75 mg/m2 mixed with 500 mL 5% glucose solution, and the intravenous infusion was completed within 2 h without light. Before and after cisplatin infusion, 20% mannitol and 5% glucose and sodium chloride solution were used for hydration. At the same time, 5 mg of dexamethasone sodium phosphate was administered before cisplatin, and 20 mg of furosemide was used for diuresis after cisplatin. In the course of chemotherapy, blood routine, liver and kidney function, protein level and other indicators were detected on the first day after each medication, and the rest of the time were detected once or twice every week, while urine routine and urine bacterial culture were reviewed. If the patient has bone marrow suppression, such as leukopenia and thrombocytopenia, gastrointestinal reactions, such as nausea and vomiting, or other complications, such as severe rash during chemotherapy, symptomatic treatment will be taken, and the next cycle of chemotherapy will be postponed accordingly. All patients were re-examined with chest and abdominal pelvic computed tomography (CT) after every 2–3 cycles of chemotherapy to monitor tumor treatment.

This study retrospectively collected the pre-chemotherapy epidemiological data of all patients, such as age, sex, body mass index (BMI), whether they had hypertension, diabetes mellites (DM), coronary heart disease (CHD), hyperlipidemia, whether they had undergone kidney transplantation, and personal history such as smoking and drinking. Data on the patient’s tumor burden, such as tumor origin, whether it was multifocal, maximum diameter, TNM stage, postoperative pathological type, number of recurrences before chemotherapy, and mean time interval for recurrence, were collected. The overall survival (OS) of all patients during the follow-up period was also collected.

In terms of laboratory test results, we collected and analyzed the urine routine results, urinary bacterial culture count, bacterial species, blood coagulation, neutrophil, lymphocyte, monocyte, granulocyte count and platelet count, albumin and globulin levels, etc. of patients during chemotherapy, and calculated systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) (equation1) and A/G (equation2).

In this study, the postoperative pathological type of all patients was mainly occupied by urothelial carcinoma, and some patients may have mixed adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma. For patients with available urine culture results, the diagnosis of urinary tract infection (UTI) was based on a positive culture (≥105 CFU/mL of a single organism). In patients without culture results, UTI was defined by pyuria in urinalysis, specifically > 10 white blood cells per high-power field (HPF) in a clean-catch midstream sample. Clinical symptoms such as fever or dysuria were considered supportive but not required for classification. In other blood laboratory tests, if the patient showed chemoresistance, the results of 3 times before drug resistance were selected and averaged; If the patient did not develop drug resistance, the results of 3 times during chemotherapy were randomly selected and the average value was calculated.

SPSS 25.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all statistical analyses in this study. In this study, all continuous variables conforming to normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and the t-test was applied; Continuous variables that do not conform to the normal distribution are tested by non-parametric tests. The categorical variables were represented by the number of cases, and the chi-square test was used.

To explore clinical factors associated with chemoresistance, we used binary logistic regression analysis on the entire cohort without pre-matching and included tumor T, N, and M stages as covariates. The dependent variable was defined as chemoresistance (CR group = 1, NCR group = 0). Variables that were statistically significant in univariate analysis were further evaluated using multivariable logistic regression analysis to identify independent predictors. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported for each variable. The Pearson and Spearman correlation tests were also used to analyze the association between these risk factors and the time to onset of tumor resistance. The null hypothesis (H0) for each variable tested was that there is no association between the predictor and GC chemoresistance (i.e., OR = 1). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

To compare OS between CR and NCR groups while controlling for tumor stage, we conducted 1:1 propensity score matching based on TNM staging, resulting in 69 matched pairs with simple urothelial carcinoma. Kaplan–Meier (KM) survival analysis and Cox proportional hazards models were used to compare OS between groups, and to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals. Risk tables were added under KM plots to show patients at risk over time.

The OS of UC patients without chemoresistance was higher than patients with chemoresistance

A total of 375 patients with a pathological diagnosis of UC were included in this study, including 91 in the CR group and 284 in the NCR group. In the entire cohort, the median follow-up time was 96.00 months (95% CI: 73.11, 118.89). The median OS in the CR group was 52.00 months (95% CI: 39.12, 62.88), lower than 106.00 months (95% CI: 88.22, 123.78) in the NCR group, and the hazard ratio (HR) was 1.70 [95% CI: 1.01, 2.86], the difference was statistically significant (p = 0.048) (Figure 1). To control for tumor malignancy and histological subtype, TNM-based propensity score matching identified 69 patients with simple urothelial carcinoma in each group. Post-matching, median OS in the CR group was 60.00 months (95% CI: 52.24, 67.76); in the NCR group, it was not reached due to >50% of patients being alive at follow-up. The hazard ratio was 2.03 (95% CI: 1.02, 4.03; p = 0.044) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the overall cohort. Note: CR, chemotherapy resistant; NCR, non-chemotherapy resistant.

FIGURE 2. Kaplan-Meier survival curves after TNM-based propensity score matching. Note: CR, chemotherapy resistant; NCR, non-chemotherapy resistant.

The risk factors leading to GC chemoresistance in UC patients

The mean age of patients in the CR group was 65.9 ± 8.99 years, which was significantly lower than that in the NCR group (68.9 ± 9.87 years). Meanwhile, long-term smoking may also be a risk factor for GC chemotherapy in UC patients (Table 1). In terms of tumor load, the T stage (p < 0.001) and N stage (p < 0.001) in the CR group were also significantly higher than those in the NCR group, but there was no significant difference in M stage (p = 0.702). Moreover, if the tumor is multifocal at the time of the initial surgery (this is mainly for BCa), these patients are also more likely to be resistant to GC chemotherapy (p < 0.001). More than 70% of the patients in the two groups were pathologically indicated as simple urothelial carcinoma, 17 patients in the CR group were found to have mixed partial squamous cell carcinoma and 8 patients were found to have mixed partial adenocarcinoma. In the NCR group, there were only 3 cases of mixed squamous cell carcinoma and 2 cases of mixed adenocarcinoma (p < 0.001). This difference in postoperative pathological classification also has a guiding role in predicting whether UC patients may develop GC chemoresistance in the future. The mean maximum tumor diameter of the CR group was 2.7 ± 1.53 cm, which was significantly higher than that of the NCR group (2.2 ± 1.59 cm), indicating that patients with larger tumors were more likely to develop chemoresistance. At the same time, the median number of tumor recurrence before chemotherapy in CR group and NCR group was 1 (0, 2.0) and 0 (0, 1.0), respectively, and the difference was also statistically significant (p < 0.001), while there was no statistical difference in the average time interval of tumor recurrence between the two groups (Table 2).

In terms of laboratory examination, 82 patients (90.1%) in the CR group had urinary tract infection, which was significantly more than that in the NCR group (22 patients, 7.7%) (p < 0.001). However, there was no significant difference between groups in Gram staining and species identification (p = 0.520) (Table 3). At the same time, the mean granulocyte count (GRA) (p = 0.011) and SII (p < 0.001) in the CR group were significantly higher than those in the NCR group, but there was no significant difference in coagulation function and absolute values for other types of blood cells. The average albumin level in the CR group and NCR group was 33.7 ± 4.33 and 39.7 ± 4.36 g/L, respectively, with statistical significance (p < 0.001), but there was no statistical difference in globulin level between groups (p = 0.555). This also indicates that when the nutritional status of UC patients continues to be poor during chemotherapy, the occurrence of chemoresistance should be vigilant (Table 4).

Multifocal tumor, later t stage, long-term urinary tract infection during chemotherapy, and persistently low A/G are independent risk factors for GC chemoresistance in UC patients

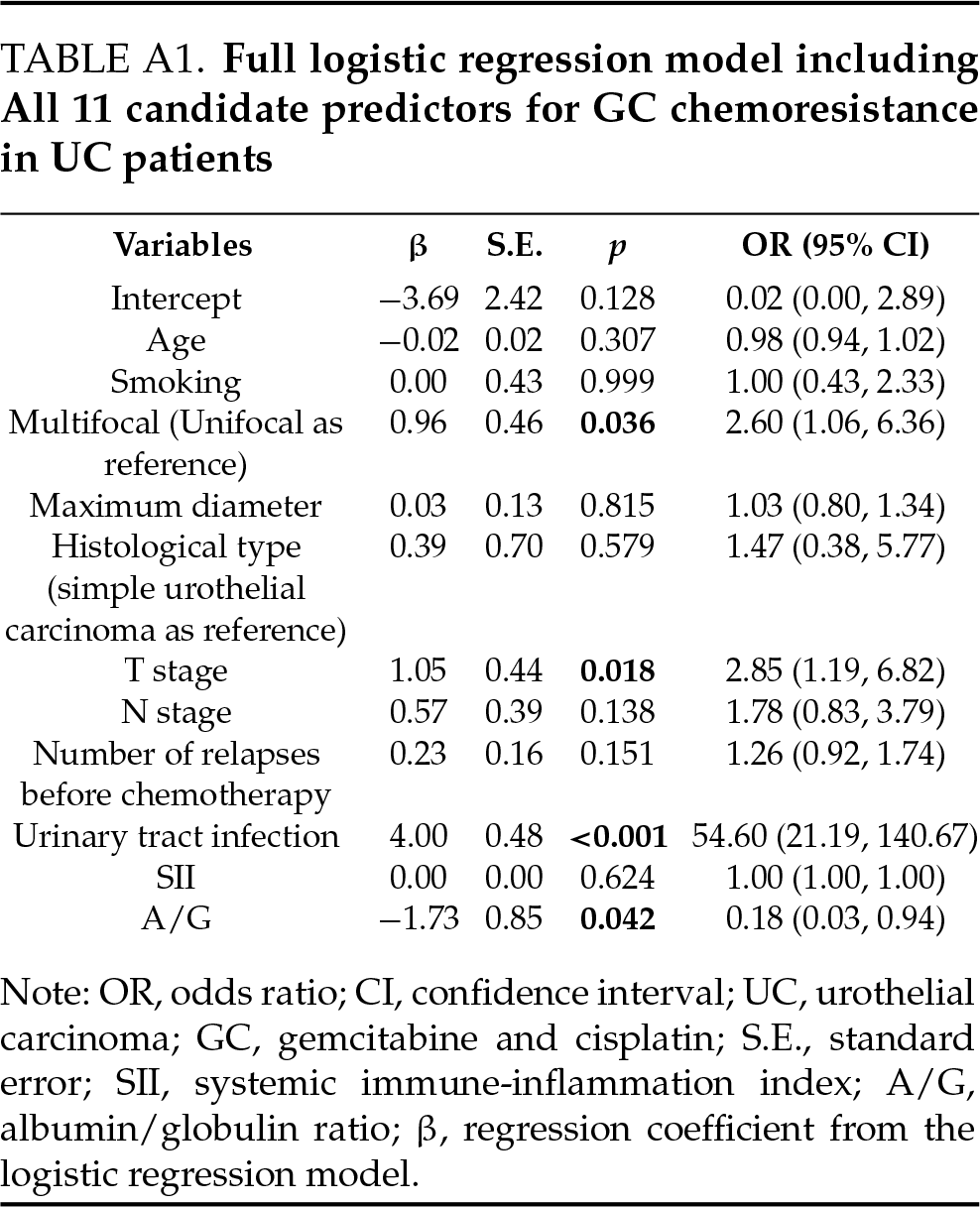

Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate the association between clinical variables and GC chemoresistance. Variables that remained significant in the multivariate model included multifocal tumor (OR = 2.60, 95% CI: 1.06, 6.36, p = 0.036), T stage (OR = 2.85, 95% CI: 1.19, 6.82, p = 0.018), presence of long-term urinary tract infection (OR = 54.60, 95% CI: 21.19, 140.67, p < 0.001), and lower A/G ratio (OR = 0.18, 95% CI: 0.03, 0.94, p = 0.042). Further, we obtained the following prediction model about the incidence of GC chemoresistance in UC patients: Logit (P) = −3.69 + 0.96 × multifocal tumor + 1.05 × T stage + 4.00 × long-term UTI – 1.73 × A/G (Table 5). The full regression model, including all candidate variables, is provided in Table A1.

Factors related to the occurrence time of GC chemoresistance

All of the above risk factors that may lead to GC chemoresistance in UC patients are related to the duration of chemoresistance. It is worth noting that the younger the patient, the earlier the onset of chemoresistance may occur (p = 0.033). At the same time, if the serum albumin level is persistently low, which means poor nutritional status, it may also lead to the onset of chemoresistance earlier (p < 0.001). The other factors were proportional to the time of drug resistance (Table 6).

Intravenous systemic chemotherapy with gemcitabine combined with cisplatin is currently the first-line treatment for advanced UC. For patients with GC chemoresistance, although other strategies such as combined immunotherapy can be adopted clinically, the prognosis of patients is poor.7 On the basis of avoiding excessive medical treatment, if these patients with a high possibility of chemoresistance are identified early after surgery, clinicians can add Tislelizumab or other immunotherapy drugs on the basis of GC chemotherapy in a more timely and accurate manner to improve the prognosis of patients.13 The purpose of this study was to explore the risk factors leading to GC chemoresistance in UC patients and to obtain the corresponding prediction model, in order to play a certain guiding role in clinical treatment decisions.

Previous studies have studied the molecular mechanism of GC chemoresistance in urothelial carcinoma, but there is no conclusion. Shi et al.14 recognized that the expression of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein U (HNRNPU) was associated with the cisplatin sensitivity of UC, and inhibiting the expression of HNRNPU could regulate the DNA damage repair process, then the sensitivity of UC to cisplatin was enhanced. In addition, the study also found that HNRNPU can modulate the chemotherapy sensitivity of UC by affecting the expression of neurofibromin 1. Metabolomics analysis indicated that gemcitabine resistance in urothelial cancer cells may be related to metabolic reprogramming of the cells themselves.15–17 By increasing the metabolism of aerobic glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway, the synthesis of pyrimidine can be promoted, and then the production of deoxycytidine triphosphate can be increased, so that it can competitively bind to related receptors with gemcitabine, thereby reducing the tumor therapeutic effect of gemcitabine. In addition, isocitrate dehydrogenase 2 can also promote the metabolism of aerobic glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway by inducing reduced glutamine metabolism, leading to the generation of gemcitabine resistance in UC cells. Although the above studies have explained the possible mechanism of GC chemoresistance in UC patients at the molecular level, they are mostly aimed at finding molecular targets of UC chemoresistance and then developing new drugs to avoid GC chemoresistance. Due to the lack of a large number of clinical trials and the high cost of genetic testing, etc. At present, it is still impossible to predict the possibility of chemoresistance in UC patients after surgery. Therefore, this study conducted statistical analysis based on existing and easily accessible clinical data, and predicted whether or not GC chemoresistance would occur in UC patients after surgery and the time of occurrence of drug resistance, so that high-risk patients with chemoresistance could be identified earlier and more accurately in clinic, and combined chemotherapy and immunity treatment could be taken in time.

Current studies generally believe that smoking is an independent risk factor for UC.18 On this basis, our study also found that long-term smoking may be a risk factor for GC chemotherapy resistance in UC patients, but its mechanism remains to be further studied. Due to the limitations of the retrospective study method, although we could not further collect the specific smoking years, smoking quantity, frequency and other parameters of patients, this also suggests that we should be particularly vigilant about the occurrence of GC chemotherapy resistance in UC patients who smoke for a long time.

In terms of tumor load, we found that whether it is UTUC or BCa, the higher the T and N stages of patients, the more recurrence times before chemotherapy, the more complex histological types, and the multiple primary tumors are all risk factors leading to GC chemotherapy resistance. All these indicate that the higher the degree of malignancy of UC, the more likely it is to lead to the emergence of chemotherapy resistance. In recent years, more and more studies have suggested that the generation of GC chemotherapy resistance is related to UC cell death processes such as apoptosis and autophagy.19 In the initial stage of tumor development, autophagy can maintain the integrity of the tumor genome and prevent tumor proliferation, thus playing a role in tumor inhibition. However, in the process of further tumor progression and recurrence and metastasis, UC cells can use protective autophagy to resist stress damage, which also enables cancer cells to resist the killing effect of chemotherapy.20 Yin et al.21 found that Nucleosome-localized sirtuin 4 (SIRT4) plays a crucial role in the regulation of autophagy of tumor cells. However, the expression level of SIRT4 protein in BCa is significantly lower than that in normal tissues, and the reduction of SIRT4 level is correlated with larger tumor size and late T stage, which is an independent risk factor affecting the prognosis of BCa patients. Overexpression of SIRT4 significantly inhibited the proliferation, migration and invasion of BCa cells, while interference with SIRT4 did the opposite. Mechanically, SIRT4 can inhibit the growth of BCa by inhibiting autophagy. This also indirectly indicates that with the progression of urothelial carcinoma, its autophagy level changes, and then develops resistance to GC chemotherapy.

This study also found that long-term urinary tract infection during chemotherapy in UC patients may lead to GC chemotherapy resistance, but further bacterial culture and species identification found that there may be no significant difference between Gram-negative (G-) and Gram-positive (G+) bacteria in the role of leading to chemotherapy resistance. The relationship between bacterial infection and tumor and chemotherapy resistance of the tumor has been more involved in previous studies. For example, Helicobacter pylori infection in the digestive tract can lead to gastric cancer22 and cisplatin combined gemcitabine chemotherapy resistance23 through the NF-κB pathway, and Clostridium nuclear infection may lead to oxaliplatin chemotherapy resistance in colon cancer and docetaxel and other chemotherapy drugs resistance in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.24 However, as is known to us, no studies have been reported on the relationship between urinary tract infection and UC chemotherapy resistance. Only a 2016 study by Lee et al.25 found that latent Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpes virus in BCa cells may lead to BCa resistance by reducing reactive oxygen species. Although this study did not further study what bacterial infection may cause the emergence of chemotherapy resistance in UC patients, nor did it explore the specific mechanism, it still proposed the research direction for the first time in terms of urinary system infection and urinary system tumor chemotherapy resistance. Meanwhile, previous studies have suggested that urinary E. coli infection can inhibit the NF-κB pathway by secreting multifunctional virulence factor toll-interacting protein of E. coli C-type (TcpC), thereby inhibiting M1 and promoting the polarization of M2 macrophages.26 However, some previous studies have suggested that changes in the NF-κB pathway and polarization of macrophages towards the M2 phenotype are important mechanisms leading to chemotherapy resistance in malignant tumors.27,28 Therefore, it also indirectly confirmed that urinary tract bacterial infection during chemotherapy in UC patients may promote chemotherapy resistance of tumor cells through the above pathways, although this still needs to be verified by experiments at the cellular and molecular levels. It should be noted that in patients without urine culture results, the diagnosis of UTI was based solely on urinalysis findings (i.e., pyuria), which may not always distinguish true bacterial infections from tumor-related inflammatory responses. This potential misclassification is a limitation of the retrospective design and should be addressed in future prospective studies with standardized diagnostic protocols.

In solid tumors, the systemic inflammatory status of patients is closely related to chemotherapy resistance and the prognosis of tumors.29 The SII is a parameter derived from a complete blood count that measures a patient’s systemic inflammatory status. In urinary system diseases, it can not only reflect the infection of the urinary system, but also effectively reflect the activation of the patient’s systemic immune-inflammatory system. Due to the use of platinum drugs in the course of chemotherapy, many patients will have varying degrees of myelosuppression, which can be specifically expressed as a decrease in the count of white blood cells, platelets, or red blood cells in peripheral blood. In this case, SII is more accurate than the simple count of white blood cells in the assessment of immunoinflammatory status.30 At the same time, our study showed similar results to previous studies. Long-term chronic inflammation during chemotherapy may lead to the emergence of chemotherapy drug resistance.31,32 This may also be related to changes in various signaling pathways of tumor cells under inflammatory conditions.33

This study also found that lower A/G may be associated with the development of chemotherapy resistance. A previous meta-analysis summarized A total of 12 relevant studies, including 5727 UC patients, and found that the tumor relapse-free survival, specific survival and overall survival of patients with low A/G were significantly lower than those with high A/G.34 Although the study did not conduct further subgroup analysis of UC patients who developed chemotherapy resistance, the reason for this difference in survival was somewhat related to chemotherapy resistance. At the same time, patients with low A/G often have poor systemic nutritional status, which also promotes the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in tumor cells, and a large number of studies have confirmed that ROS accumulation is one of the important mechanisms leading to chemotherapy resistance in tumor cells.35,36 This also explains why patients with lower A/G may be more susceptible to chemotherapy resistance.

Although this study focused on clinical indicators, the underlying mechanisms linking UTI and low A/G ratio to chemoresistance merit discussion. Recurrent urinary tract infections can induce chronic inflammation, creating a tumor-supportive microenvironment that promotes chemoresistance. Recent evidence highlights the central role of the IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway in this process. Persistent inflammatory stimuli may activate STAT3, which in turn facilitates epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), inhibits apoptosis, and supports immune evasion. These changes enable tumor cell survival under chemotherapy stress and contribute to resistance. Moreover, malnutrition reflected by a low A/G ratio may further compromise immune function and reinforce this inflammatory axis.37 These molecular insights support our clinical observations and suggest that targeting inflammation-related pathways may offer a therapeutic avenue to overcome chemoresistance.

This study has several limitations. First, its retrospective design and small sample size may introduce selection bias and limit generalizability; multicenter studies with larger cohorts are needed for validation. Second, resistance to gemcitabine and cisplatin was analyzed as a combined GC regimen, without distinguishing drug-specific effects. Third, while an association between urinary tract infection and GC chemoresistance was identified, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear and warrant further investigation through cellular and molecular studies. Incomplete progression data precluded progression-free-survival (PFS) analysis; logistic regression and correlation analyses were used as exploratory alternatives. Lastly, although the HR was statistically significant, the narrow confidence interval (95% CI: 1.01, 2.86) suggests limited robustness and should be interpreted cautiously.

For patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma, the high degree of malignancy of the tumor, and patients who suffer a persistently urinary tract infection or low A/G during GC chemotherapy, clinicians should be alert to the emergence of tumor chemoresistance and the possibility of further progression.

Acknowledgement

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Jingcheng Lyu was responsible for collecting and analyzing data and drafting the article. Ruiyu Yue was responsible for designing the research and revising the paper. Yichen Zhu and Ye Tian were responsible for designing the research. Xinyi Hu was responsible for designing the paper and supervising. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Beijing Friendship Hospital, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Beijing Friendship Hospital.

Ethics Approval

This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and is approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Friendship Hospital.

Informed Consent

All subjects have signed informed consent, and the batch number is: BFHHZS20240170.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| UTI | Urinary Tract Infection |

| A/G | Albumin/Globulin Ratio |

| UC | Urothelial Carcinoma |

| GC | Gemcitabine and Cisplatin |

| UTUC | Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma |

| BCa | Bladder Carcinoma |

| CR | Chemotherapy Resistant |

| NCR | Non-Chemotherapy Resistant |

| OS | Overall Survival |

| SII | Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| DM | Diabetes Mellitus |

| CHD | Coronary Heart Disease |

| Fbg | Fibrinogen |

| INR | International Normalized Ratio |

| PLT | Platelet Count |

| GRA | Granulocyte Count |

| LYM | Lymphocyte Count |

| MO | Monocyte Count |

| S.E | Standard Error |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| HNRNPU | Heterogeneous Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein U |

| SIRT4 | Sirtuin 4 |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa B |

| JAK | Janus Kinase |

| STAT3 | Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor Beta |

Appendix A

References

1. Feng DC, Li DX, Wu RC et al. Global burden and cross-country inequalities in urinary tumors from 1990 to 2021 and predicted incidence changes to 2046. Mil Med Res 2025;12(1):12. doi:10.1186/s40779-025-00599-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Stormoen DR, Rohrberg KS, Mouw KW et al. Similar genetic profile in early and late stage urothelial tract cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2024 Jul 8;150(7):339. doi:10.1007/s00432-024-05850-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Rac G, Patel HD, James C et al. Urinary comprehensive genomic profiling predicts urothelial carcinoma recurrence and identifies responders to intravesical therapy. Mol Oncol 2024 Feb;18(2):291–304. doi:10.1002/1878-0261.13530. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Chen CY, Chang CH, Yang CR et al. Prognostic factors of intravesical recurrence after radical nephroureterectomy for upper tract urothelial carcinoma. World J Urol 2024 Jan 10;42(1):22. doi:10.1007/s00345-023-04700-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Shinohara M, Hata S, Inoue T et al. Simple predictors for the completion of scheduled gemcitabine-cisplatin regimens based on real-world urothelial cancer data. Mol Clin Oncol 2024 Apr 1;20(5):37. doi:10.3892/mco.2024.2735. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Msaouel P, Sweis RF, Bupathi M et al. A Phase 2 study of sitravatinib in combination with nivolumab in patients with advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Eur Urol Oncol 2024 Aug;7(4):933–943. doi:10.1016/j.euo.2023.12.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Sridhar SS, Powles T, Climent Durán MÁ. et al. Avelumab first-line maintenance for advanced urothelial carcinoma: analysis from JAVELIN bladder 100 by duration of first-line chemotherapy and interval before maintenance. Eur Urol 2024 Feb;85(2):154–163. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2023.08.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Powles T, Valderrama BP, Gupta S et al. Enfortumab vedotin and pembrolizumab in untreated advanced urothelial cancer. N Engl J Med 2024 Mar 7;390(10):875–888. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2312117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Ye J, Zhang M, Bao Y. Discordance in HER2 expression in primary and recurrent/metastatic lesions of upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Asian J Surg 2024 Sep;47(9):3928–3929. doi:10.1016/j.asjsur.2024.04.161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Schwartz LH, Seymour L, Litière S et al. RECIST 1.1—Standardisation and disease-specific adaptations: perspectives from the RECIST Working Group. Eur J Cancer 2016;62(3):138–145. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2016.03.082. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Ren J, Wu S, Su T et al. Analysis of chemoresistance characteristics and prognostic relevance of postoperative gemcitabine adjuvant chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Med 2024;13(9):e7229. doi:10.1002/cam4.7229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Rouprêt M, Seisen T, Birtle AJ et al. European association of urology guidelines on upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma: 2023 update. Eur Urol 2023;84(1):49–64. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2023.03.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Gao Z, Qi N, Qin X et al. The addition of tislelizumab to gemcitabine and cisplatin chemotherapy increases thrombocytopenia in patients with urothelial carcinoma: a single-center study based on propensity score matching. Cancer Med 2023 Dec;12(24):22071–22080. doi:10.1002/cam4.6807. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Shi ZD, Hao L, Han XX et al. Targeting HNRNPU to overcome cisplatin resistance in bladder cancer. Mol Cancer 2022 Feb 7;21(1):37. doi:10.1186/s12943-022-01517-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Shigeta K, Hasegawa M, Hishiki T et al. IDH2 stabilizes HIF-1α-induced metabolic reprogramming and promotes chemoresistance in urothelial cancer. EMBO J 2023 Feb 15;42(4):e110620. doi:10.15252/embj.2022110620. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Ai Z, Lu Y, Qiu S, Fan Z. Overcoming cisplatin resistance of ovarian cancer cells by targeting HIF-1-regulated cancer metabolism. Cancer Lett 2016 Apr 1;373(1):36–44. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2016.01.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. De Santis M, Bellmunt J, Mead G et al. Randomized phase II/III trial assessing gemcitabine/carboplatin and methotrexate/carboplatin/vinblastine in patients with advanced urothelial cancer who are unfit for cisplatin-based chemotherapy: EORTC study 30986. J Clin Oncol 2012 Jan 10;30(2):191–199. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.37.3571. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Kanai Y. Molecular pathological approach to cancer epigenomics and its clinical application. Pathol Int 2024 Apr;74(4):167–186. doi:10.1111/pin.13418. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Berning L, Schlütermann D, Friedrich A et al. Prodigiosin sensitizes sensitive and resistant urothelial carcinoma cells to cisplatin treatment. Molecules 2021 Feb 27;26(5):1294. doi:10.3390/molecules26051294. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Gupta P, Kumar N, Garg M. Emerging roles of autophagy in the development and treatment of urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2021 Sep;25(9):787–797. doi:10.1080/14728222.2021.1992384. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Yin J, Cai G, Wang H et al. SIRT4 is an independent prognostic factor in bladder cancer and inhibits bladder cancer growth by suppressing autophagy. Cell Div 2023 Jun 10;18(1):9. doi:10.1186/s13008-023-00091-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Cao L, Zhu S, Lu H et al. Helicobacter pylori-induced RASAL2 through activation of nuclear factor-κB promotes gastric tumorigenesis via β-catenin signaling axis. Gastroenterology 2022 May;162(6):1716–1731.e17. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.01.046. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Song H, Yao X, Zheng Y, Zhou L. Helicobacter pylori infection induces POU5F1 upregulation and SPP1 activation to promote chemoresistance and T cell inactivation in gastric cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol 2024 Jul;225(1):116253. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2024.116253. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Chen L, Zhao R, Kang Z et al. Delivery of short chain fatty acid butyrate to overcome Fusobacterium nucleatum-induced chemoresistance. J Control Release 2023 Nov;363:43–56. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2023.09.028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Lee S, Jang J, Jeon H et al. Latent Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection in bladder cancer cells promotes drug resistance by reducing reactive oxygen species. J Microbiol 2016 Nov;54(11):782–788. doi:10.1007/s12275-016-6388-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Fang J, Ou Q, Wu B et al. TcpC inhibits M1 but promotes M2 macrophage polarization via regulation of the MAPK/NF-κB and Akt/STAT6 pathways in urinary tract infection. Cells 2022 Aug 28;11(17):2674. doi:10.3390/cells11172674. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Frerichs LM, Frerichs B, Petzsch P et al. Tumorigenic effects of human mesenchymal stromal cells and fibroblasts on bladder cancer cells. Front Oncol 2023 Sep 13;13:1228185. doi:10.3389/fonc.2023.1228185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Li H, Luo F, Jiang X et al. CircITGB6 promotes ovarian cancer cisplatin resistance by resetting tumor-associated macrophage polarization toward the M2 phenotype. J Immunother Cancer 2022 Mar;10(3):e004029. doi:10.1136/jitc-2021-004029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Demircan NC, Atcı MM, Demir M, Işık S, Akagündüz B. Dynamic changes in systemic immune-inflammation index predict pathological tumor response and overall survival in patients with gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2023 Feb;19(1):104–112. doi:10.1111/ajco.13784. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Yumioka T, Honda M, Nishikawa R et al. Sarcopenia as a significant predictive factor of neutropenia and overall survival in urothelial carcinoma patients underwent gemcitabine and cisplatin or carboplatin. Int J Clin Oncol 2020 Jan;25(1):158–164. doi:10.1007/s10147-019-01544-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Özkan A, Stolley DL, Cressman ENK, McMillin M, Yankeelov TE, Rylander MN. Vascularized hepatocellular carcinoma on a chip to control chemoresistance through cirrhosis, inflammation and metabolic activity. Small Struct 2023 Sep;4(9):2200403. doi:10.1002/sstr.202200403. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Stevens LE, Peluffo G, Qiu X et al. JAK-STAT signaling in inflammatory breast cancer enables chemotherapy-resistant cell states. Cancer Res 2023 Jan 18;83(2):264–284. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-22-0423. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Mousset A, Lecorgne E, Bourget I et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps formed during chemotherapy confer treatment resistance via TGF-β activation. Cancer Cell 2023 Apr 10;41(4):757–775.e10. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2023.03.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Xia Z, Fu X, Li J et al. Prognostic value of pretreatment serum albumin-globulin ratio in urothelial carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol 2022 Aug 16;12:992118. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.992118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Tsang CK, Chen M, Cheng X et al. SOD1 phosphorylation by mTORC1 couples nutrient sensing and redox regulation. Mol Cell 2018 May 3;70(3):502–515.e8. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2018.03.029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Zhou X, An B, Lin Y et al. Molecular mechanisms of ROS-modulated cancer chemoresistance and therapeutic strategies. Biomed Pharmacother 2023 Sep;165(5):115036. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Tuo Z, Zhang Y, Li D et al. Relationship between clonal evolution and drug resistance in bladder cancer: a genomic research review. Pharmacol Res 2024;206:107302. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2024.107302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools