Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Associations of systemic immune-inflammation index, product of platelet, and neutrophil count, with the pathological grade of bladder cancer

1 North Sichuan Medical College, Nanchong, 637000, China

2 Department of Urology, Mianyang 404 Hospital, Mianyang, 621000, China

3 Department of Urology, Mianyang Maternal and Child Health Hospital, Mianyang, 621000, China

* Corresponding Author: Jiabing Li. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Personalized Medicine in Urology: The Role of Inflammatory Bio-Markers in Urothelial Carcinoma)

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(5), 457-468. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.067364

Received 01 May 2025; Accepted 27 August 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

Background: Studies have indicated an association between inflammatory factors (IFs) in the blood and the development of bladder cancer (BC). This study aimed to explore the correlation and clinical significance of IFs with the pathological grading of BC. Methods: A retrospective analysis was conducted on the preoperative blood routine results, postoperative pathological findings, and baseline information of 163 patients. Patients were divided into high-grade and low-grade groups based on pathological grading. Group comparisons and logistic regression analyses were performed using R software version 4.1.3 to explore the relationships between IFs and BC pathological grading. Results: The results indicated that platelet count, lymphocyte count, neutrophil count, body mass index (BMI), smoking, drinking, and hypertension (all p < 0.05) were associated with BC pathological grading. The logistic regression model revealed that higher levels of IFs in the blood were associated with a higher probability of high-grade BC tumors (ln-SII, odds ratio [OR]: 2.95, 95% CI: 1.43, 6.38, p = 0.004; ln-PPN, OR: 16.02, 95% CI: 6.37, 47.02, p < 0.001), suggesting a correlation between IFs in the blood and BC pathological grading. Additionally, group comparisons showed that the values of systemic immune inflammation index (SII) and product of platelet and neutrophil count (PPN) were significantly higher in the high-grade BC group than in the low-grade BC group (p < 0.05). Conclusions: IFs have predictive value for BC pathological grading, providing a theoretical basis for clinical diagnosis and treatment.Keywords

Bladder cancer (BC) ranks among the ten most common malignancies worldwide. Its high incidence and mortality rates represent a significant threat to public health and remain a major obstacle to the advancement of global health initiatives.1 According to the statistical data from 2020, approximately 573,000 new cases of BC were diagnosed globally, with over 212,000 deaths attributed to this disease.2 Data from the National Cancer Center of China (2022) indicated that there were about 82,300 new BC cases in China, and approximately 33,700 deaths.3

Currently, cystoscopy with biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosing BC.4 However, as an invasive procedure, cystoscopy is not only technically demanding but may also cause considerable discomfort to patients.5 Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop an effective, non-invasive, repeatable, and cost-efficient screening method for BC. Given the non-invasive nature, reproducibility, and affordability of routine hematological testing, we further explored the clinical utility of blood-derived inflammatory markers. These routinely accessible and minimally invasive biomarkers may provide valuable insights into tumor biology and support clinical decision-making in BC.6

In 1863, German pathologist Virchow first observed the infiltration of white blood cells (WBC) into cancerous tissues, proposing the hypothesis that inflammatory responses are associated with the occurrence and development of tumors.7 A growing body of recent evidence has demonstrated a strong link between chronic inflammation and tumorigenesis, underscoring the pivotal role of inflammatory microenvironments in cancer initiation and progression.8 A study reported that shows variable expression patterns among different histological types of BC prior to treatment, and that these patterns affect prognosis.9 Some studies have demonstrated the associations between routine blood parameters and cancer, including systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) and the product of platelet and neutrophil counts (PPN).10–12 Studies have shown that, at the cellular level, blood-based inflammatory markers represent promising biomarkers that can complement traditional pathological assessments in BC.13 At the genetic level, the loss of the Y chromosome has also been implicated in the progression of urogenital malignancies. Together, these findings may support the development of more personalized treatment strategies.14 Current research suggests that higher levels of IFs are associated with higher pathological grades of BC, supporting the role of inflammatory responses in tumor development.15 Several studies have also confirmed the diagnostic value of IFs in BC pathology.16,17 However, significant research gaps remain regarding the relationship between BC pathology and inflammatory factors on a global scale. Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the associations between SII, PPN, and the pathological grade of bladder cancer, and to explore whether these indicators could serve as potential predictors of tumor aggressiveness.

This study retrospectively included and analyzed 163 BC patients who completed routine blood tests before treatment at a tertiary hospital in Mianyang City, Sichuan Province, from May 2019 to May 2024. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Mianyang 404 Hospital (IRB No. 2024-028) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2013 revision). This study is a retrospective analysis and, therefore, was not assigned a clinical trial registration number. Data collection and processing followed strict anonymization protocols, with encrypted storage on password-protected servers accessible only to the research team. No personally identifiable information is included in this publication.

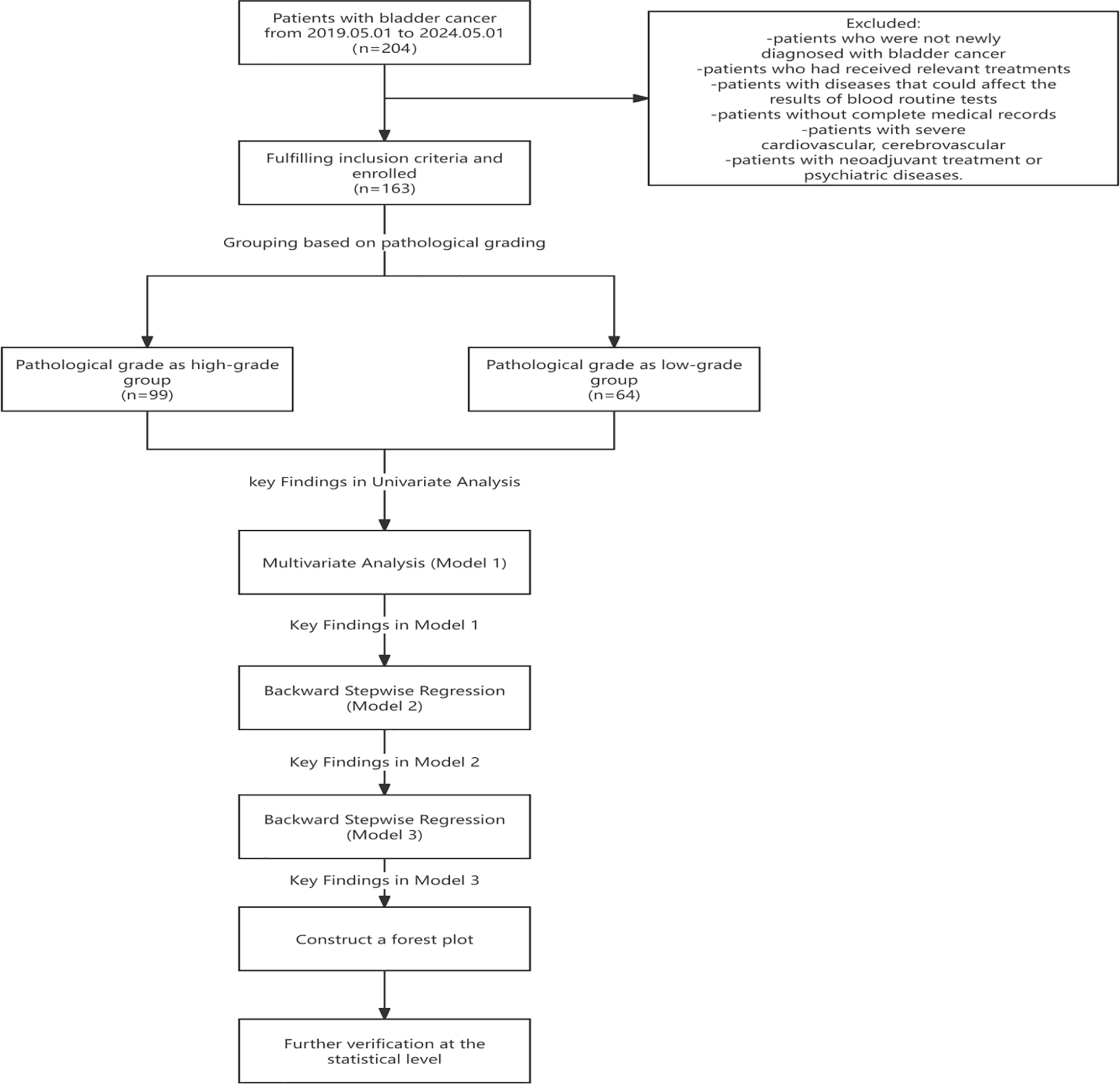

Among the 163 BC patients included in the treatment analysis, therapeutic interventions were distributed as follows: Transurethral resection of bladder tumor in 118 cases (72.4%), partial cystectomy in 12 cases (7.4%), radical cystectomy with urinary diversion in 25 cases (15.3%), and palliative care accompanied by diagnostic biopsy in 8 cases (4.9%). The inclusion criteria were: (1) patients with the ability to independently sign the informed consent form; (2) all cases were confirmed by both routine blood tests and pathological examination, with complete pathological grading information; (3) patients with complete medical records and pathological data. The exclusion criteria were: (1) patients who were not newly diagnosed with BC; (2) patients who had received relevant treatments (chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy, etc.); (3) patients with diseases that could affect the results of blood routine tests (recent or past 3-month acute/chronic infections, acute/chronic renal failure, acute/chronic liver disease, malignant tumors other than BC, immune-related diseases, or acute/chronic blood diseases, whether current or resolved); (4) patients without complete medical records; (5) patients with severe cardiovascular, cerebrovascular; (6) patients with neoadjuvant treatment or psychiatric diseases. The patient selection process was depicted in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1. Flowchart depicting the patient selection process. A retrospective cohort study was conducted, including 204 bladder cancer patients treated between 1 May 2019, and 1 May 2024. Following the application of inclusion and exclusion criteria, 163 patients qualified for enrollment. Participants were stratified into two groups according to pathological grading of bladder cancer: the high-grade group (n = 99) and the low-grade group (n = 64). The analytical workflow comprised the following components: univariate analysis, multivariate logistic regression (Model 1), backward stepwise regression (Models 2 and 3), and forest plot visualization

Data collection and hematological test methods

Peripheral venous blood samples (5 mL) were collected from all enrolled patients either on the day of hospital admission or the following morning, prior to any surgical intervention. Blood collection was performed under fasting conditions, defined as a minimum of 10 h without food or drink. Samples were drawn from the antecubital vein using standardized vacuum tubes containing anticoagulant and promptly transported to the central laboratory for analysis. All samples were obtained before any preoperative treatment to ensure consistency in baseline inflammatory marker assessment. All blood test data were obtained from the electronic medical record system data platform. By accessing the hospitalization records of all BC patients from the past five years through the medical records department and querying these IDs in the system, we finally obtained information on preoperative blood routine results, postoperative pathological examination results, and baseline characteristics of 163 BC patients who met the inclusion criteria.

Definition of outcome variables

Tumor grade was determined based on the 2016 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of urothelial tumors. According to this system, bladder cancers are categorized as either low-grade or high-grade urothelial carcinoma, depending on the degree of architectural and cytological atypia.18 Low-grade tumors exhibit mild to moderate nuclear atypia with relatively organized architecture, while high-grade tumors display marked pleomorphism, increased mitotic activity, and disorganized tissue architecture.

Definition of covariates (other variables)

In this study, the selected covariates included sex, age, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, alcohol consumption, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, unintentional weight loss, bladder area tenderness, red blood cell count, hemoglobin level, monocyte count, platelet count, neutrophil count, and lymphocyte count. Demographic and behavioral variables were defined as follows: Sex was categorized as male or female. Age was treated as a continuous variable. BMI was calculated by dividing body weight in kilograms by the square of height in meters (kg/m2), and categorized according to the WHO criteria: underweight (<18.5), normal (18.5–24.9), overweight (25.0–29.9), and obese (≥30.0).19 Smoking status was defined as having smoked at least 100 cigarettes in one’s lifetime and currently smoking either daily or occasionally, in accordance with CDC guidelines.20 Alcohol consumption was defined as any self-reported intake of alcoholic beverages within the past 12 months, based on WHO definitions.21 Clinical comorbidities included: Hypertension, defined as a systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg, or the use of antihypertensive medications22; Diabetes mellitus, defined according to the American Diabetes Association (ADA) criteria: fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL, hemoglobin A1c ≥ 6.5%, or current use of antidiabetic medications.23 Symptom-related variables included: Unintentional weight loss, defined as a loss of more than 5% of body weight over the past six months without intentional dietary restriction24; Bladder area tenderness, recorded as a binary variable (present/absent) based on physical examination findings. Laboratory indicators were derived from pre-treatment routine blood tests, including red blood cells, hemoglobin, monocytes, platelets, neutrophils, and lymphocytes. All measurements were conducted using standardized automated analyzers in the hospital laboratory, following institutional reference ranges.

Data were entered using Excel 2020 and analyzed statistically using R 4.1.3 software. The main R packages used included “dplyr” for data manipulation, “compareGroups” for baseline comparisons, and “forestmodel” for visualization of multivariable regression results. Descriptive statistics were employed for general data analysis. Continuous variables of measurement data conforming to a normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (x̅± SD), and comparisons between groups were performed using the t-test. For non-normally distributed continuous variables, the median (M) or interquartile range (Q1, Q3) was used, and comparisons between groups were conducted using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were represented by frequencies and percentages, and comparisons between groups were made using the Chi-square test. A multifactorial logistic regression model was utilized for analyzing the association between independent and dependent variables using the odds ratio (OR). The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to determine the range of OR values. The significance level was set at α = 0.05, and a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Univariate logistic regression analyses were initially conducted to identify variables significantly associated with the pathological grade of bladder cancer, using a threshold of p < 0.05. The variables identified were then included in multivariate logistic regression analyses. Model 1 was constructed using all significant variables from the univariate analysis. A backward stepwise regression was subsequently applied to remove less significant variables, first eliminating lymphocyte count to form Model 2. A second round of backward elimination excluded smoking status, resulting in Model 3, which included the most strongly associated predictors. To assess model performance and select the optimal model, the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) was calculated for each model. The model with the lowest AIC—Model 3—was deemed the best fitting. The variables retained in this optimal model were then used to generate a forest plot, visually displaying the strength and direction of associations with pathological grade.

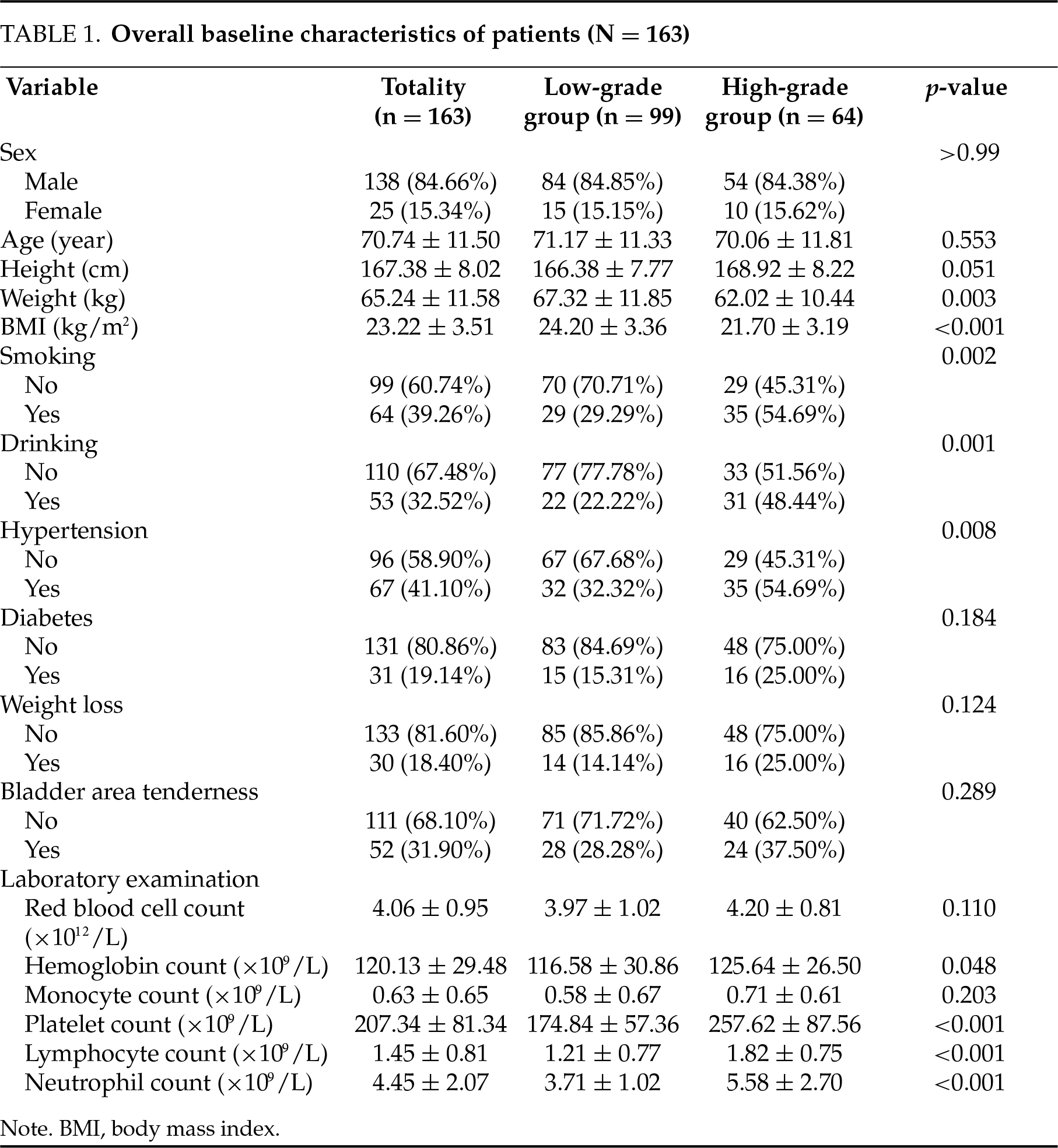

Overall, 163 BC patients were enrolled, of whom 99 (60.74%) were classified into the low-grade group and 64 (39.26%) into the high-grade group. BMI (p < 0.001), smoking (p = 0.002), drinking (p = 0.001), hypertension (p = 0.008), hemoglobin count (p = 0.048), platelet count (p < 0.001), lymphocyte count (p < 0.001) and neutrophil count (p < 0.001) were statistically significant between low-grade and high-grade groups. Detailed information about the patients in the study cohort was presented in Table 1.

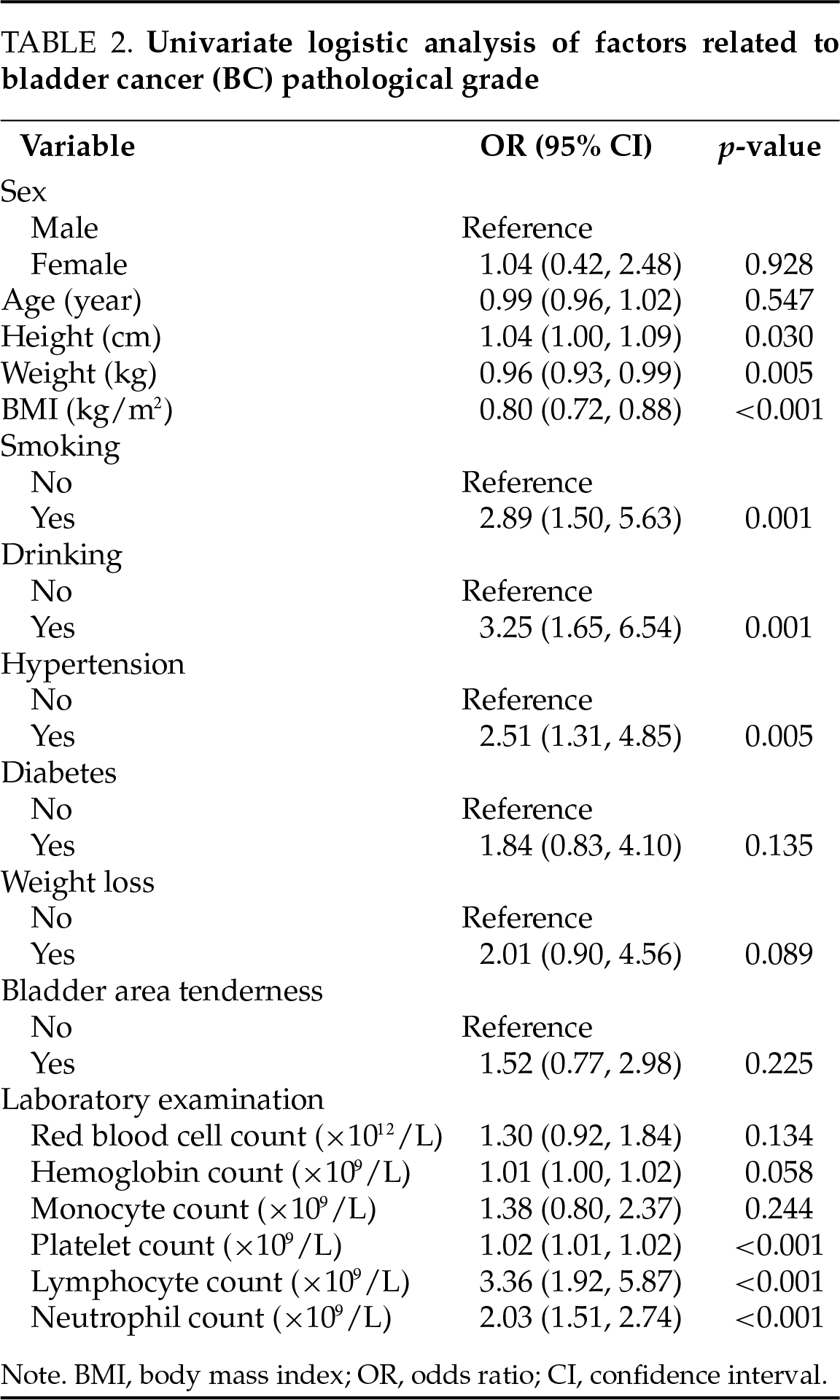

Univariate logistic regression for high-grade BC

The results of univariate logistic regression analysis (Table 2) indicated that platelet count, lymphocyte count, neutrophil count, smoking, drinking, hypertension, and BMI were relevant factors influencing the pathological grading of BC (all p < 0.05).

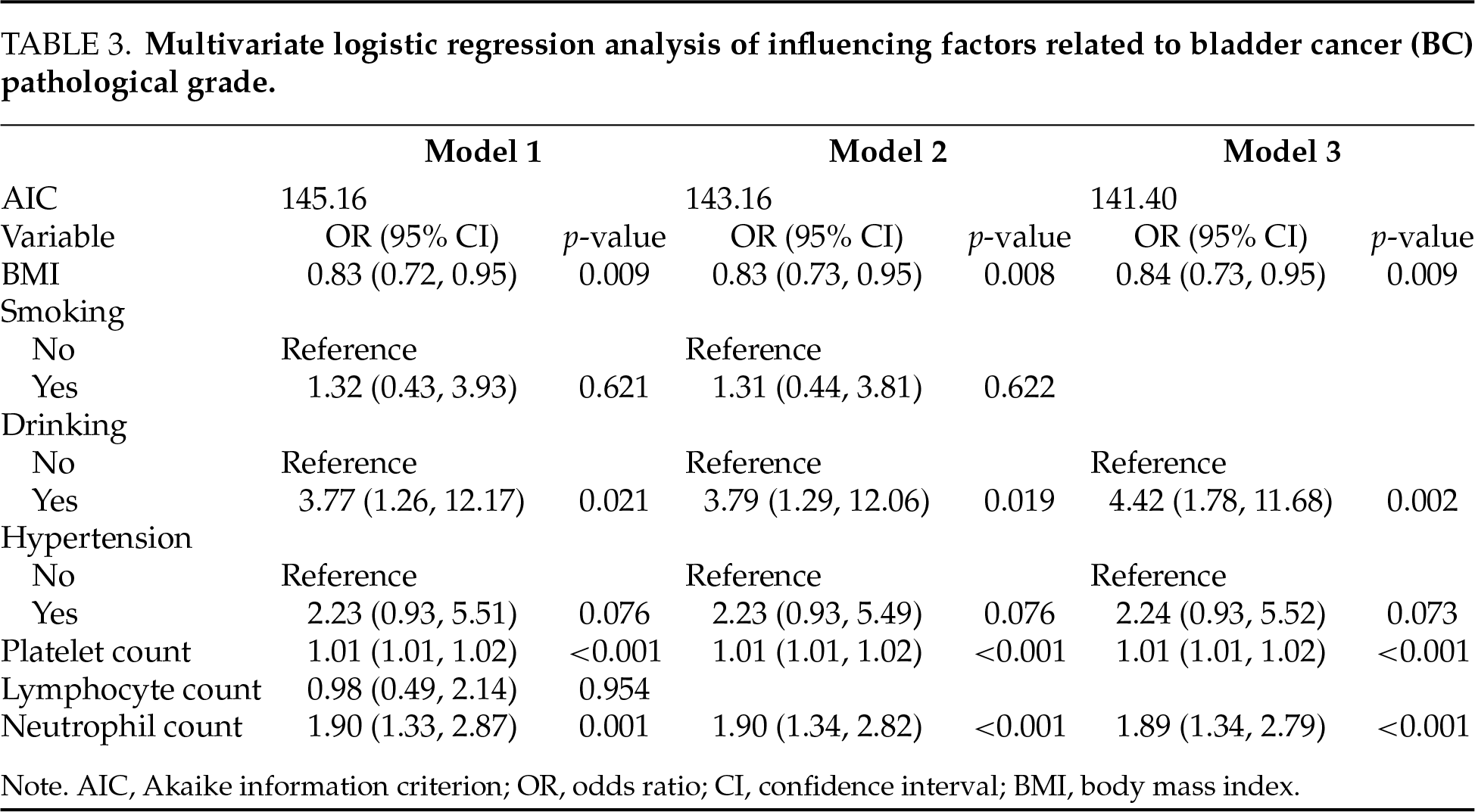

Multivariate logistic regression for high-grade BC

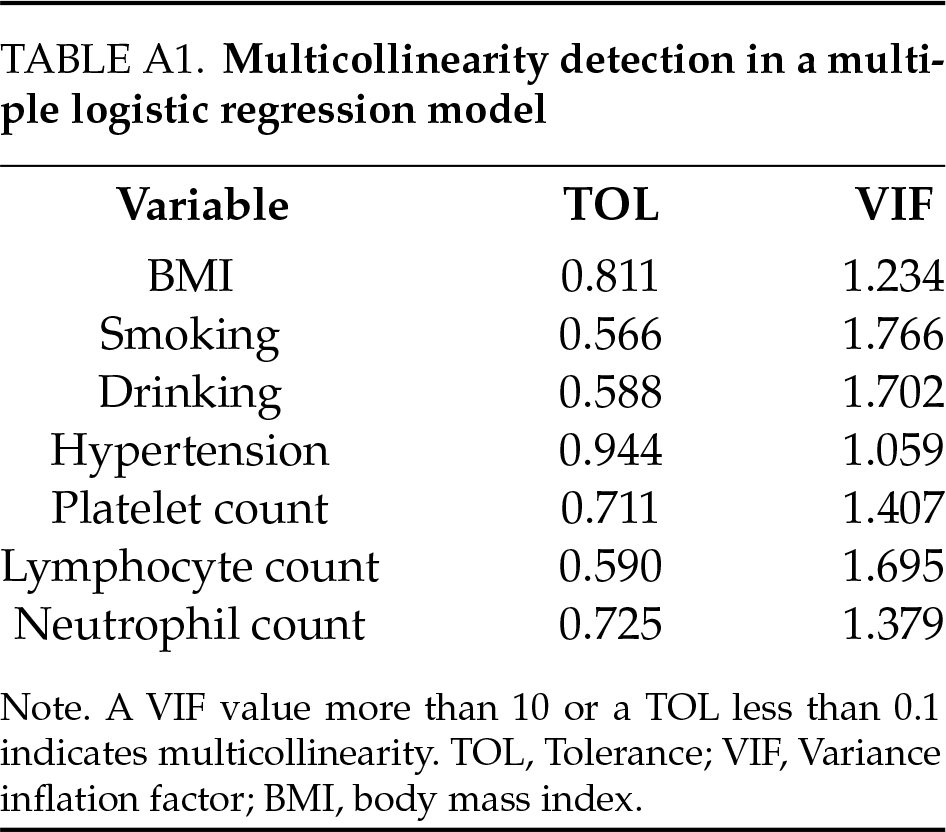

In this study, we constructed a logistic regression model using BC pathological grading (low-grade and high-grade) as the dependent variable, and the results are shown in Table 3. The models (model 1, model 2, and model 3) likelihood ratio chi-square values were 145.16, 143.16, and 141.40, respectively, and the model fits were successful (all p < 0.05). Multiple collinearity diagnosis was shown in Table A1; the results show that there was no collinearity between the variables. The smallest AIC value for Model 3 indicated that it achieved a better balance between model fit and complexity. Model 3 indicated that BMI (OR: 0.84, 95% CI: 0.73–0.95, p = 0.009), drinking (OR: 4.42, 95% CI: 1.78–11.68, p = 0.002), hypertension (OR: 2.24, 95% CI: 0.93–5.52, p = 0.073), platelet count (OR: 1.01, 95% CI: 1.01–1.02, p < 0.001) and neutrophil count (OR: 1.89, 95% CI: 1.34–2.79, p < 0.001).

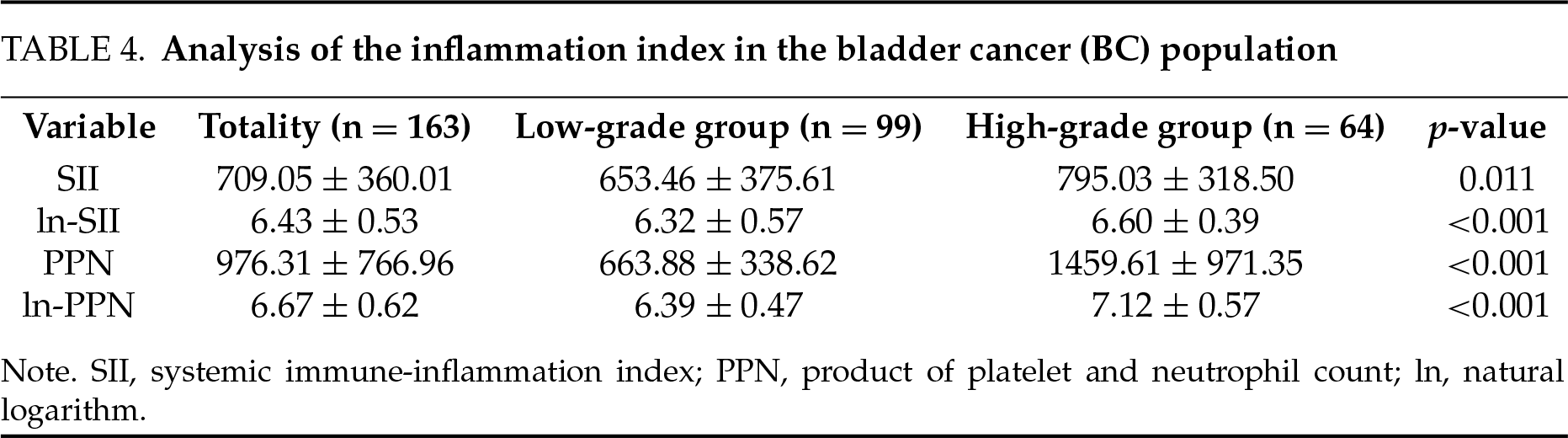

Analysis of SII and PPN expression levels between different grades of BC

In addition, this study further analyzed SII and PPN expression levels between different grades of BC. To reduce the impact of skewed distributions, we applied natural logarithm transformations to SII and PPN, obtaining ln-SII and ln-PPN (Table 4). The results show that the expression levels of SII, In-SII, PPN, and In-PPN in the high-grade group were significantly higher than those in the low-grade group (all p < 0.05). This suggests a correlation between the immune-inflammatory load in the body and the pathological grading of BC.

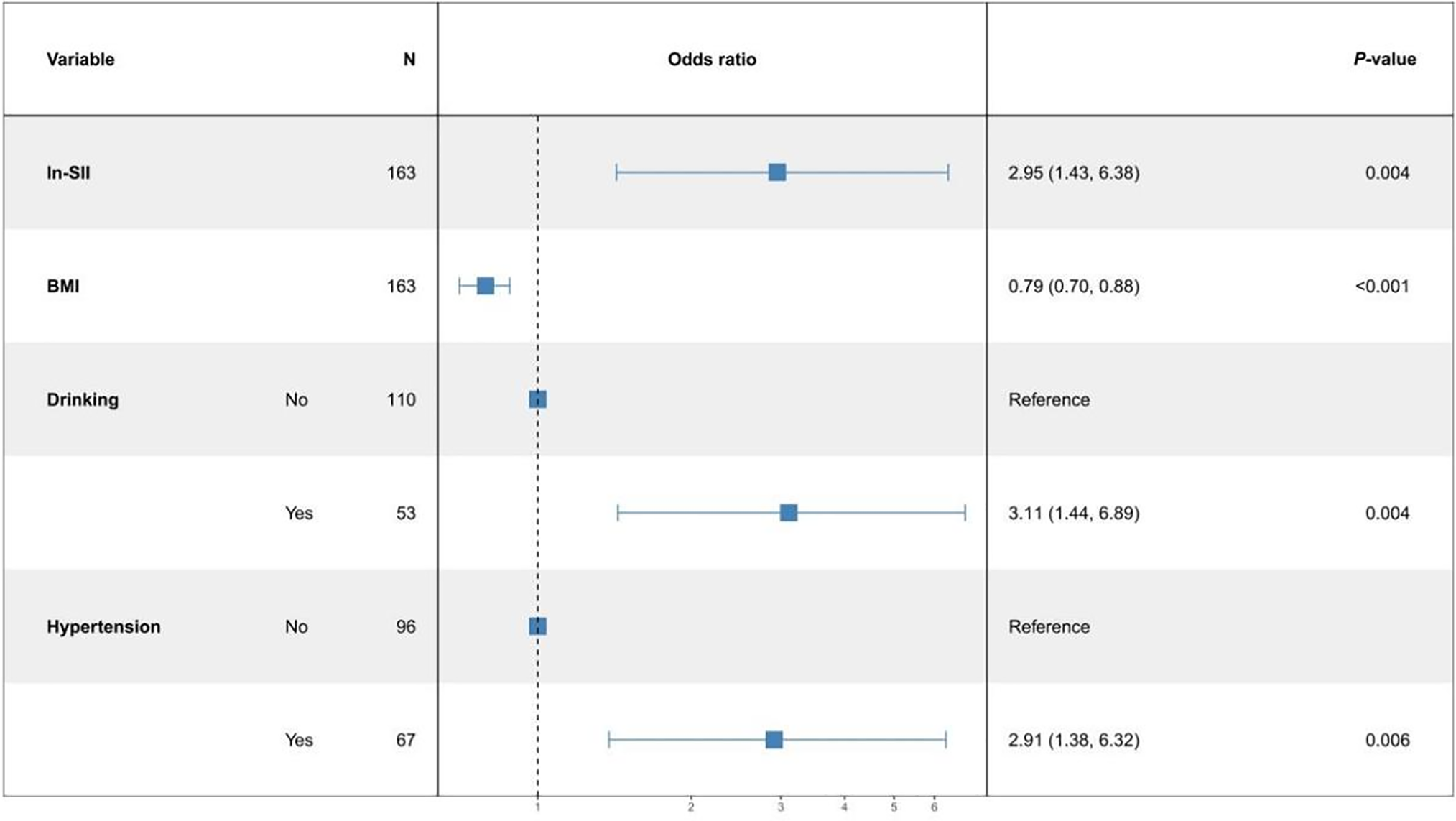

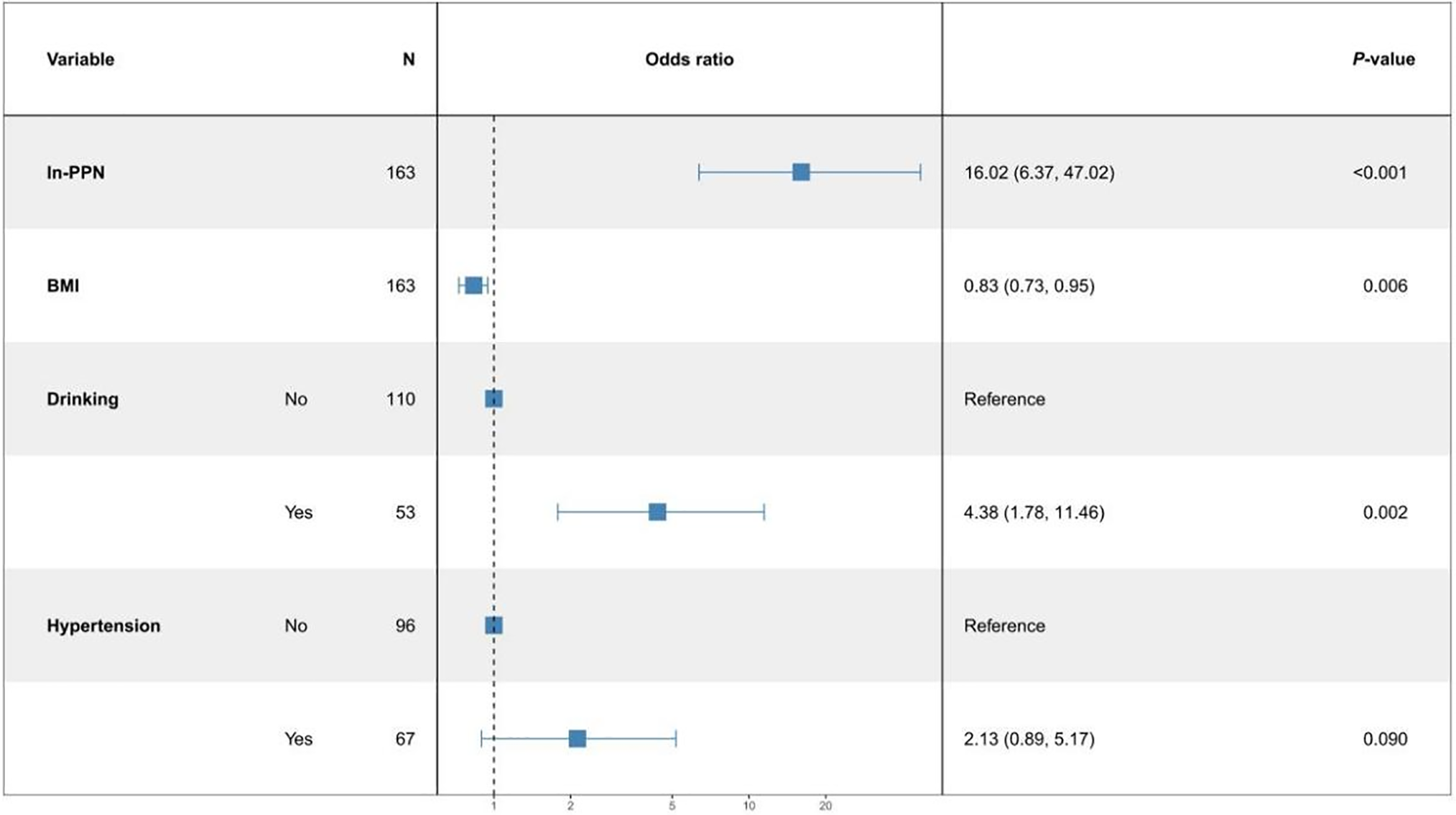

Logistic regression analysis to correlate between SII and PPN, and BC

Pathological grade of BC was used as the dependent variable, SII or PPN, and baseline information was used as the independent variables to build two logistic regression models. Figure 2 shows that for every 1-unit increase in ln-SII, the probability of BC being in the high-grade group increased 2.95 times (95% CI: 1.43, 6.38). Figure 3 showed every 1-unit increase in ln-PPN, the probability of BC being in the high-grade group was 16.02 times (95% CI: 6.37, 47.02).

FIGURE 2. Multifactor logistic regression model of ln-SII (systemic immune-inflammation index)

FIGURE 3. Multifactor logistic regression model of ln-PPN (product of platelet and neutrophil count)

BC is among the most common malignancies of the urinary system, often associated with poor prognosis and reduction in quality of life.1,25 However, patients frequently experience discomfort during the procedure and various complications such as pain, persistent hematuria, urinary tract infections, and urethral damage may occur.4,26 It is imperative to develop novel detection techniques.27 Liquid biopsy, particularly using blood, represents a highly feasible and noninvasive approach for BC diagnosis that is well-accepted by patients.28 IFs can be easily derived from standard blood test results through simple calculations. In recent years, IFS has been widely used in clinical practice.29,30 IFs had yielded meaningful results in tumors such as gastric cancer, colon cancer, and breast cancer.31–33

Firstly, this study found that neutrophil count was significantly higher in the high-grade group compared to the low-grade group (p < 0.001). Studies had indicated that bladder tumor cells can produce granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, which can stimulate the body to produce more neutrophils.34 Neutrophils can accelerate tumor cell growth and metastasis by releasing elastase.35 Secondly, platelet count was also higher in the high-grade group. Platelets affect tumor metastasis and spread, primarily by aggregating around tumor cells entering the bloodstream and encapsulating tumor cells, reducing immunogenicity. It helps tumor cells evade immune system detection and clearance, facilitating tumor growth and spread.36,37 In addition, the reduction of lymphocytes in tumor tissue leads to local immunosuppression and weakened immune inhibition of the tumor.38

Furthermore, logistic regression analysis showed that BMI is a significant factor affecting BC pathological grading, with a negative correlation. High-grade tumors are more likely to cause weight loss during progression, possibly due to the release of various cytokines by immune cells and hypermetabolism of some cells in the body. These factors can lead to increased resting energy expenditure (REE)39,40 and induce anorexia,41,42 which have been considered possible contributors to BMI reduction in cancer.43 Another contributing mechanism involves tumor-derived lipid mobilizing factors (LMFs), including IL-6 family cytokines such as leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) and oncostatin M, which activate the JAK/STAT3 pathway in adipose tissue to induce lipolysis via ATGL/CGI-58 transcriptional upregulation. At the muscular level, IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signaling promotes proteolysis through activation of atrophy-related ubiquitin ligases (e.g., Atrogin-1, MuRF1), leading to skeletal muscle wasting.44,45 Simultaneously, the results indicated a positive correlation between drinking and BC pathological grading. This suggests a relationship between drinking and tumor spread and progression. Some researchers attribute the carcinogenicity of alcohol to the accumulation of its metabolite, acetaldehyde (ACE).46,47 Although the age difference between the two groups in this study was not statistically significant, related studies have also reported the impact of age on the prognostic value of biomarkers (such as C-reactive protein [CRP], Hemoglobin [Hb]), platelets, and leukocytes in patients with high-grade BC. The results indicate that the absolute levels of Hb, platelets, and leukocytes significantly decrease with age, suggesting that these biomarkers hold predictive value for survival in high-grade BC patients.48 Analysis also revealed that hypertension and tumor progression had a positive correlation. Indirect reasons may be related to long-term antihypertensive drug use by hypertensive patients.49 There were more smokers in the high-grade group compared to the low-grade group (54.69% vs. 29.29%, p = 0.002). Smoking patients are more likely to present with high-grade tumors with detrusor muscle invasion at their initial visit.50 This study also found that SII and PPN were significantly higher in the high-grade group compared to the low-grade group, suggesting a correlation between BC pathological grading and blood IFs. Studies by Wang et al.17 and Prijovic et al.29 have shown that IFs play an important role in the pathological diagnosis of BC. Recent studies have underscored the prognostic significance of inflammatory markers in bladder cancer. Notably, a study specifically investigating patients undergoing radical cystectomy found that elevated preoperative systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) was significantly associated with poorer recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS), thereby reinforcing its prognostic relevance in curative surgical settings.51 Furthermore, a meta-analysis involving over 14,000 cases of urothelial carcinoma demonstrated that high pre-treatment SII correlated with worse OS, cancer-specific survival (CSS), and RFS, with hazard ratios ranging from 1.37 to 1.87 (all p < 0.05).52 A separate bladder cancer–focused review also revealed that elevated SII predicted shorter biochemical recurrence-free survival, OS, and CSS.53 Collectively, these findings support the notion that systemic inflammation—reflected by indices such as SII and PPN—can serve as reliable indicators of tumor aggressiveness and unfavorable prognosis. In addition to their prognostic relevance, SII and PPN may also be linked to postoperative complications. Although direct data on SII/PPN and complication rates remain limited, Russo et al. (2023) evaluated preoperative SII in bladder cancer patients undergoing radical cystectomy and observed that high SII was independently associated with poorer RFS and OS (HR ≈ 2.15 for RFS, HR ≈ 1.72 for OS), along with more aggressive pathological characteristics.54 These findings suggest that elevated preoperative inflammatory indices may reflect an adverse systemic state that predisposes patients to suboptimal postoperative recovery and an increased risk of complications following major surgery. Our study aligns with these observations, indicating that higher preoperative SII and PPN levels may not only reflect worse pathological grade but also serve as markers of heightened postoperative risk. Incorporating these inflammatory markers into preoperative risk stratification models and clinical decision-making may improve personalized treatment strategies. Prospective studies are warranted to validate these associations and to explore their integration into routine clinical workflows.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the relatively small sample size may have reduced the statistical power of our analyses, potentially obscuring true associations. Second, a limited cohort size restricts the generalizability of our findings to broader patient populations. Third, the retrospective and single-center design of the study may have introduced multiple sources of bias. Patient inclusion was not randomized, and variations in clinical decision-making and follow-up protocols may exist within the institution, increasing the likelihood of selection bias. Fourth, reliance on pre-existing medical records may have led to incomplete or missing clinical and pathological data, resulting in information bias and limiting the comprehensiveness of the analysis, which may compromise internal validity and further reduce the external applicability of the results. Fifth, this study did not include external validation using an independent patient cohort. Without replication of the findings in other populations, the reproducibility and clinical utility of our conclusions remain uncertain. In addition, potential confounding factors were not fully accounted for in this study. Although we excluded patients with certain comorbidities during cohort selection, other relevant factors (such as concurrent medication use, additional underlying diseases not specified in the exclusion criteria, and socioeconomic status) were not included in the analysis. These variables may influence systemic inflammation, nutritional status, treatment choices, and ultimately, patient prognosis. Finally, several key tumor-related pathological characteristics (such as tumor multifocality, pathological stage) were not consistently documented in the available medical records. The lack of standardized and complete recording of these variables limited our ability to include them in the analysis. As these features are known to influence disease behavior, treatment decisions, and outcomes, their omission may have affected the depth of our findings and potentially introduced uncontrolled confounding.

To address the limitations of the present study, future research will focus on incorporating multicenter data and enrolling larger, more diverse patient cohorts to improve the robustness and external validity of the findings. We emphasize the need for well-designed prospective studies to validate our results, strengthen the evidence base, and further explore the observed associations. Moreover, future studies should aim to capture a broader range of clinical data through more standardized and comprehensive data collection strategies. Incorporating these additional factors may enhance the predictive accuracy and clinical applicability of inflammation-based prognostic models in bladder cancer.

This study indicated a certain positive correlation between IFs (SII, PPN) and the pathological grading of BC. Additionally, BMI, drinking, and hypertension history are also associated with the pathological grading of BC. These findings provide a theoretical basis for clinicians to utilize IFs in the diagnosis and treatment of BC tumors.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Mianyang 404 Hospital for the support of this research.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions

Lihao Zhang: conceived and designed this research; wrote the paper. Jiabing Li: find a research direction; design research. Lin Cao and Lige Huang: study conceptualization; collect and organize data; analyze data individually; writing—review and editing. Jie Wang: performed this research, collect and organize data, analyzed and interpreted the data. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mianyang 404 Hospital (Approval No. IRB-2024-028).

Informed Consent

The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the use of anonymized retrospective data. This study utilized de-identified patient data. The ethics committee waived the requirement for informed consent due to the retrospective and anonymized nature of the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A

References

1. Dyrskjøt L, Hansel DE, Efstathiou JA et al. Bladder cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2023;9(1):58. doi:10.1038/s41572-023-00468-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Jubber I, Ong S, Bukavina L et al. Epidemiology of bladder cancer in 2023: a systematic review of risk factors. Eur Urol 2023;84(2):176–190. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2023.03.029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Zheng R, Zhang S, Zeng H et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2016. J National Cancer Cent 2022;2(1):1–9. doi:10.1016/j.jncc.2022.02.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Babjuk M, Burger M, Capoun O et al. European association of urology guidelines on non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (Ta, T1, and carcinoma in situ). Eur Urol 2022;81(1):75–94. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2021.08.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Tam J, MacDonald E, Sparks DA et al. Creating an extraordinary experience for women undergoing cystoscopy: a patient-centered approach to process improvement. Urology 2023;174:23–27. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2023.01.039. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Salari A, Ghahari M, Bitaraf M et al. Prognostic value of NLR, PLR, SII, and dNLR in urothelial bladder cancer following radical cystectomy. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2024;22(5):102144. doi:10.1016/j.clgc.2024.102144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature 2008;454(7203):436–444. doi:10.1038/nature07205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Nishida A, Andoh A. The role of inflammation in cancer: mechanisms of tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis. Cells 2025;14(7):488. doi:10.3390/cells14070488. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Rodler S, Buchner A, Ledderose ST et al. Prognostic value of pretreatment inflammatory markers in variant histologies of the bladder: is inflammation linked to survival after radical cystectomy? World J Urol 2021;39(7):2537–2543. doi:10.1007/s00345-020-03482-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. He Q, Wei C, Cao L, Zhang P, Zhuang W, Cai F. Blood cell indices and inflammation-related markers with kidney cancer risk: a large-population prospective analysis in UK Biobank. Front Oncol 2024;14:1366449. doi:10.3389/fonc.2024.1366449. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Du D, Zhang G, Xu D et al. Association between systemic inflammatory markers and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population-based study. Heliyon 2024;10(10):e31524. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e31524. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Chen Y, Xu H, Yan J et al. Inflammatory markers are associated with infertility prevalence: a cross-sectional analysis of the NHANES 2013-2020. BMC Public Health 2024;24(1):221. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-17699-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Russo P, Foschi N, Palermo G et al. SIRI as a biomarker for bladder neoplasm: utilizing decision curve analysis to evaluate clinical net benefit. Urolog Oncol: Sem Orig Investigat 2025;43(6):393.e1–393.e8. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2025.01.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Russo P, Bizzarri FP, Filomena GB et al. Relationship between loss of Y chromosome and urologic cancers: new future perspectives. Cancers 2024;16(22):3766. doi:10.3390/cancers16223766. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Batur AF, Aydogan MF, Kilic O et al. Comparison of De Ritis Ratio and other systemic inflammatory parameters for the prediction of prognosis of patients with transitional cell bladder cancer. Int J Clin Pract 2021;75(4):e13743. doi:10.1111/ijcp.13743. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Tang X, Cao Y, Liu J, Wang S, Yang Y, Du P. Diagnostic value of inflammatory factors in pathology of bladder cancer patients. Front Mol Biosci 2020;7:575483. doi:10.3389/fmolb.2020.575483. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Wang Y, Hao X, Li G. Prognostic and clinical pathological significance of the systemic immune-inflammation index in urothelial carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol 2024;14:1322897. doi:10.3389/fonc.2024.1322897. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Humphrey PA, Moch H, Cubilla AL, Ulbright TM, Reuter VE. The 2016 WHO classification of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs—part B: prostate and bladder tumours. Eur Urol 2016;70(1):106–119. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2016.02.028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. WHO Consultation on Obesity (1999: Geneva, Switzerland) & World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic: Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

20. Cornelius ME, Loretan CG, Jamal A et al. Tobacco product use among adults-United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023;72(18):475–483. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7218a1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. Geneva: WHO; 2018. [Google Scholar]

22. Unger T, Borghi C, Charchar F et al. International Society of Hypertension global hypertension practice guidelines. J Hypertension 2020;38(6):982–1004. doi:10.1097/hjh.0000000000002453. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care 2024;47(Suppl 1):S1–S210. doi:10.2337/dc21-s014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Perera LAM, Chopra A, Shaw AL. Approach to patients with unintentional weight loss. Med Clin North Am 2021;105(1):175–186. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2020.08.019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clinicians 2021;71(1):7–33. doi:10.3322/caac.21654. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Alfred Witjes J, Max Bruins H, Carrión A et al. European association of urology guidelines on muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer: summary of the 2023 guidelines. Eur Urol 2024;85(1):17–31. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2020.08.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Crocetto F, Barone B, Ferro M et al. Liquid biopsy in bladder cancer: state of the art and future perspectives. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2022;170(3):103577. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2022.103577. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Li S, Xin K, Pan S et al. Blood-based liquid biopsy: insights into early detection, prediction, and treatment monitoring of bladder cancer. Cell Mol Biol Lett 2023;28(1):28. doi:10.1186/s11658-023-00442-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Prijovic N, Acimovic M, Santric V et al. Predictive value of inflammatory and nutritional indexes in the pathology of bladder cancer patients treated with radical cystectomy. Curr Oncol 2023;30(3):2582–2597. doi:10.3390/curroncol30030197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Luo Z, Yan Y, Jiao B et al. Prognostic value of the systemic immune-inflammation index in patients with upper tract urothelial carcinoma after radical nephroureterectomy. World J Surg Oncol 2023;21(1):337. doi:10.1186/s12957-023-03225-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. He K, Si L, Pan X et al. Preoperative systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) as a superior predictor of long-term survival outcome in patients with stage I–II gastric cancer after radical surgery. Front Oncol 2022;12:829689. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.829689. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Cheng HW, Wang T, Yu GC, Xie LY, Shi B. Prognostic role of the systemic immune-inflammation index and pan-immune inflammation value for outcomes of breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2024;28(1):180–190. doi:10.26355/eurrev_202401_34903. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Tan Y, Hu BE, Li Q, Cao W. Prognostic value and clinicopathological significance of pre-and post-treatment systemic immune-inflammation index in colorectal cancer patients: a meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol 2025;23(1):11. doi:10.1186/s12957-025-03662-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Jing W, Wang G, Cui Z et al. Tumor-neutrophil cross talk orchestrates the tumor microenvironment to determine the bladder cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024;121(20):e2312855121. doi:10.1073/pnas.2312855121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Okamoto M, Mizuno R, Kawada K et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps promote metastases of colorectal cancers through activation of ERK signaling by releasing neutrophil elastase. Int J Molecul Sci 2023;24(2):1118. doi:10.3390/ijms24021118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Zhao J, Huang A, Zeller J, Peter K, McFadyen JD. Decoding the role of platelets in tumour metastasis: enigmatic accomplices and intricate targets for anticancer treatments. Front Immunol 2023;14:1256129. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1256129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Schlesinger M. Role of platelets and platelet receptors in cancer metastasis. J Hematol Oncol 2018;11(1):125. doi:10.1186/s13045-018-0669-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Damen PJJ, Lin SH, van Rossum PSN. Editorial: updates on radiation-induced lymphopenia. Front Oncol 2024;14:1448658. doi:10.3389/fonc.2024.1448658. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Satari S, Mota INR, Silva ACL et al. Hallmarks of cancer Cachexia: sexual dimorphism in related pathways. Int J Mol Sci 2025;26(9):3952. doi:10.3390/ijms26093952. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Eunbyul Y, Kweon Y. Understanding the molecular basis of anorexia and tissue wasting in cancer Cachexia. Exp Mol Med 2022;54(4):426–432. doi:10.1038/s12276-022-00752-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Talbert EE, Guttridge DC. Emerging signaling mediators in the anorexia-Cachexia syndrome of cancer. Trends Cancer 2022;8(5):397–403. doi:10.1016/j.trecan.2022.01.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Laird BJ, McMillan D, Skipworth RJE et al. The emerging role of interleukin 1β (IL-1β) in cancer Cachexia. Inflammation 2021;44(4):1223–1228. doi:10.1007/s10753-021-01429-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Sato R, da Fonseca GWP, das Neves W, von Haehling S. Mechanisms and pharmacotherapy of cancer cachexia associated-anorexia. Pharmacol Res Perspect 2025;13(1):e70031. doi:10.1002/prp2.70031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Gandhi AY, Yu J, Gupta A, Guo T, Iyengar P, Infante RE. Cytokine-mediated STAT3 transcription supports ATGL/CGI-58-dependent adipocyte lipolysis in cancer Cachexia. Front Oncol 2022;12:841758. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.841758. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Martin A, Gallot YS, Freyssenet D. Molecular mechanisms of cancer cachexia-related loss of skeletal muscle mass: data analysis from preclinical and clinical studies. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023;14(3):1150–1167. doi:10.1002/jcsm.13073. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Rumgay H, Murphy N, Ferrari P, Soerjomataram I. Alcohol and cancer: epidemiology and biological mechanisms. Nutrients 2021;13(9):3173. doi:10.3390/nu13093173. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Thomas LA, Hopkinson RJ. The biochemistry of the carcinogenic alcohol metabolite acetaldehyde. DNA Repair 2024;144(80):103782. doi:10.1016/j.dnarep.2024.103782. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Volz Y, Pfitzinger PL, Eismann L et al. Prognostic value of pretreatment inflammatory markers in patients receiving radical cystectomy for urothelial bladder cancer: does age matter? Urol Int 2022;106(8):832–839. doi:10.1159/000521829. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Xie Y, Xu P, Wang M et al. Antihypertensive medications are associated with the risk of kidney and bladder cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging 2020;12(2):1545–1562. doi:10.18632/aging.102699. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Pietzak EJ, Mucksavage P, Guzzo TJ, Malkowicz SB. Heavy cigarette smoking and aggressive bladder cancer at initial presentation. Urology 2015;86(5):968–972. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2015.05.040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Zhang S, Du J, Zhong X et al. The prognostic value of the systemic immune-inflammation index for patients with bladder cancer after radical cystectomy. Front Immunol 2022;13:1072433. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.1072433. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Zheng L, Wang Z, Li Y et al. Prognostic significance of systemic immune inflammation index in patients with urothelial carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol 2024;14:1469444. doi:10.3389/fonc.2024.1469444. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Yu Z, Xiong Z, Ma J et al. Prognostic and clinicopathological significance of systemic immune-inflammation index in upper tract urothelial carcinoma: a meta-analysis of 3911 patients. Front Oncol 2024;14:1342996. doi:10.3389/fonc.2024.1342996. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Russo P, Palermo G, Iacovelli R et al. Comparison of PIV and other immune inflammation markers of oncological and survival outcomes in patients undergoing radical cystectomy. Cancers 2024;16(3):651. doi:10.3390/cancers16030651. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools