Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Tranexamic acid and hematuria outcomes following aquablation for benign prostatic hyperplasia

1 Department of Urology, The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX 75390, USA

2 Department of Urology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC 27710, USA

* Corresponding Author: Ramy Goueli. Email:

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(5), 491-499. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.068150

Received 22 May 2025; Accepted 24 July 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

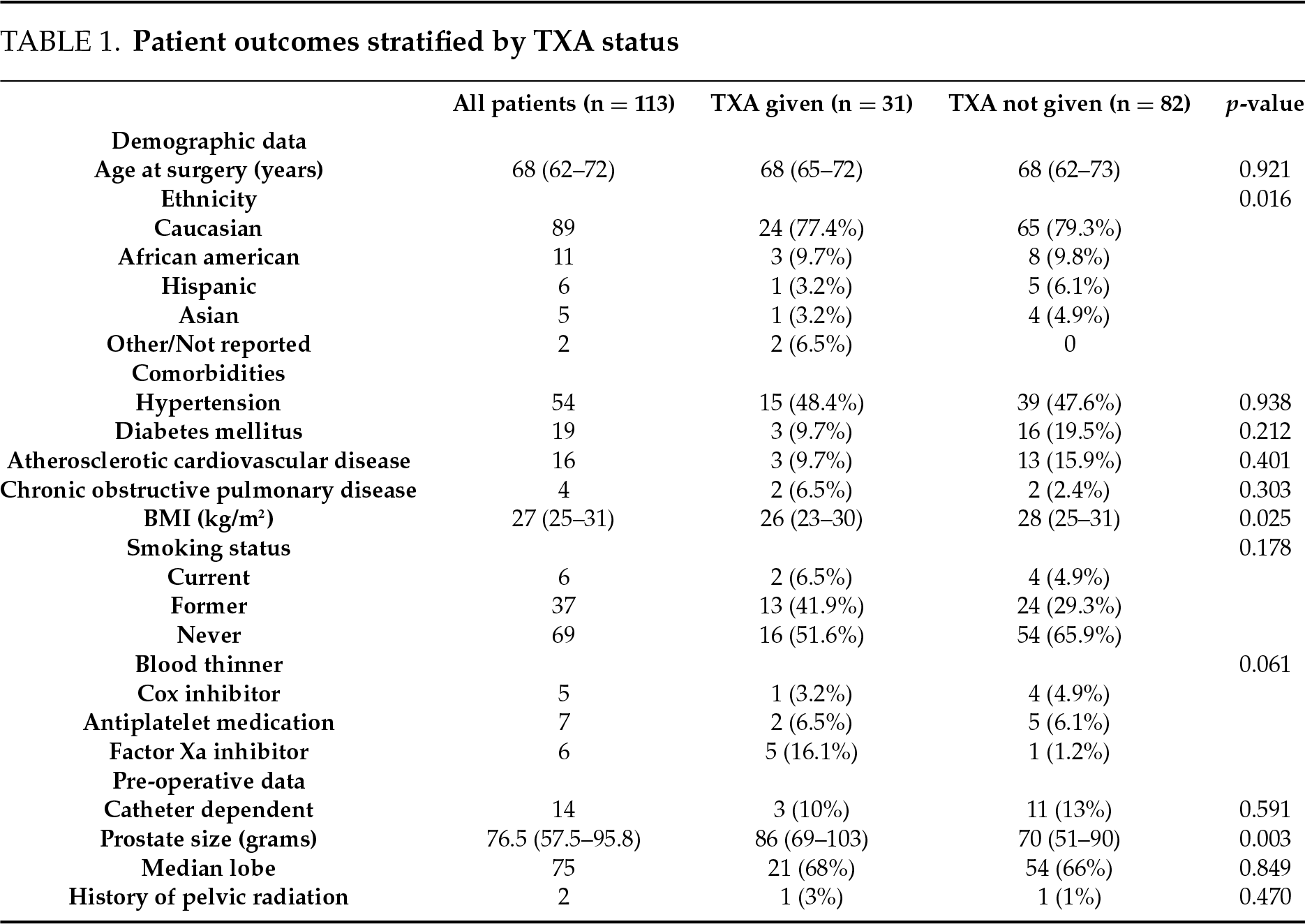

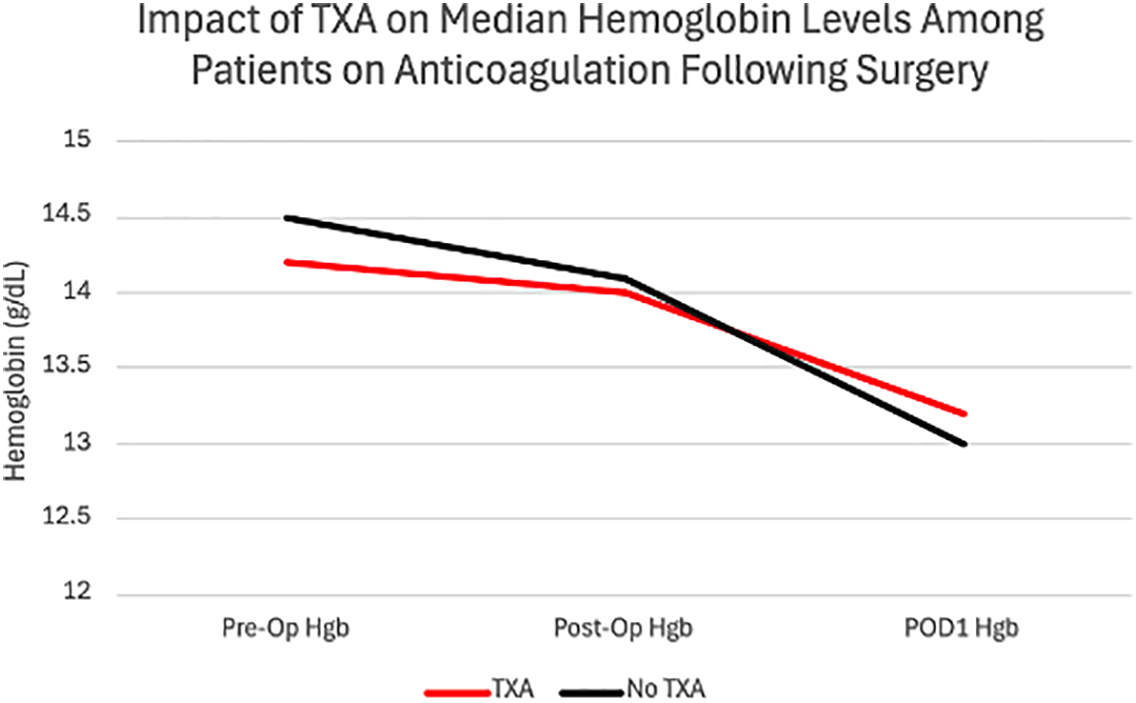

Background: Aquablation is a robotic-assisted, water jet-based transurethral therapy for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Concerns about postoperative hematuria led to the practice of limited transurethral resection (TUR) with cauterization. This study aimed to assess the impact of tranexamic acid (TXA) on hematuria outcomes when combined with limited TUR after Aquablation. Methods: We retrospectively analyzed men undergoing Aquablation at our institution (October 2020–July 2024). Demographic, prostate, surgical, and hematuria outcomes were extracted from electronic medical records. Kruskal-Wallis test compared medians. Results: Of 131 patients, 113 (86%) had limited TUR; 31 (27%) received 1 g TXA perioperatively. TXA patients had larger prostates (86 g vs. 70 g, p = 0.003). No TUR patients, with or without TXA, required transfusion. Among TUR patients, TXA did not significantly affect preoperative, postoperative, or postoperative day-one hemoglobin. Patient-initiated communications and emergency visits for hematuria were minimal and similar between groups. Hematuria outcomes were independent of prostate size, TUR volume, or TUR-to-prostate ratio. Subgroup analysis (<80 g vs. ≥80 g) showed no TXA effect. No TXA recipient had a thromboembolic event within 30 days. At one month, median urinary flow increased by 12.8 mL/sec interquartile range [IQR]: 8.7–18.8, and median International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) decreased by 7 (IQR: 3–12). Conclusions: Limited TUR during Aquablation provides effective hemostasis. TXA had minimal impact on bleeding and was not associated with thromboembolic events. Routine TXA use should be reconsidered when limited TUR is performed.Keywords

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a leading cause of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in aging men, significantly impacting quality of life and often necessitating surgical intervention when medical management fails.1

Aquablation, a robotic-assisted waterjet ablation technology, has emerged as a minimally invasive treatment option for BPH. Using real-time ultrasound guidance and precise tissue targeting, Aquablation reduces operator dependence while preserving functional outcomes.2 Unlike transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) and other thermal-based procedures, it minimizes the risk of thermal injury to surrounding structures, resulting in lower rates of ejaculatory dysfunction—an important consideration for many patients.2,3 Comparative studies, such as the WATER trial, have shown that Aquablation provides symptom relief and urinary flow improvement comparable to TURP but with a more favorable side effect profile.3,4 These advantages, along with standardized procedural outcomes, make Aquablation an appealing option for men seeking effective symptom management with fewer functional side effects.

Postoperative hematuria remains one of the most common complications following surgical BPH interventions,1 with potential downstream effects on catheter duration,5 hospital stay,6 and patient anxiety.7 Even when clinically insignificant, visible bleeding often triggers patient-initiated communications and emergency department visits. In resource-constrained settings, this can result in unnecessary testing, catheter reinsertion, and increased healthcare utilization.8 Therefore, strategies to proactively minimize hematuria—even if transfusion is not required—remain a key target for quality improvement.

Since its inception, post-operative bleeding following Aquablation for enlarged prostate has significantly decreased with the adoption of standardized techniques, particularly routine focal bladder neck cautery in addition to limited transurethral resection (TUR) with adjunctive cauterization is often applied to improve hemostasis.9 While larger prostates still carry a higher bleeding risk, improved hemostasis techniques have substantially mitigated this concern. Antifibrinolytic agents, including aprotinin, tranexamic acid (TXA), and epsilon aminocaproic acid (EACA), have been proposed for use in complex surgeries to minimize bleeding.10 Tranexamic acid (TXA) is the most extensively studied antifibrinolytic agent and the most widely used worldwide.

TXA is a synthetic lysine derivative which inhibits plasminogen activation, stabilizing fibrin clots. Intravenous TXA has been demonstrated to improve surgical outcomes by reducing intraoperative bleeding and subsequently decreasing postoperative irrigation volume, catheterization time, and length of hospital stay.11–13 However, TXA’s role in Aquablation has not been reported.

This study evaluates the impact of TXA on hematuria outcomes in Aquablation with limited TUR, comparing patients with and without antithrombotic therapy to provide further guidance on bleeding management in this setting. Antithrombotic therapy status was included due to prior work demonstrating that the use of oral antiplatelet and anticoagulation (APAC) may have an independent effect on increasing morbidity among patients who received TURP, even if APAC was held prior to surgery.14 We hypothesized that patients who received TXA perioperatively would have decreased postoperative blood loss and decreased need for blood transfusion.

Study design and data collection

Four surgeons performed all Aquablation procedures at UT Southwestern Medical Center. Surgeons A–D performed 6, 8, 25, and 74 surgeries, respectively. Preoperative management for patients on anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy (APAC) involved discontinuing medication based on type: Cyclooxygenase (Cox) inhibitors and antiplatelet agents were held for 7 days prior to surgery, while factor Xa inhibitors were held for 3 days. Surgeons A and B did not administer TXA to any of their patients, while Surgeon C and Surgeon D administered TXA to 8 of 25 patients (32%) and 23 of 74 patients (21%), respectively. When TXA was administered, 1 g of intravenous TXA was given perioperatively. Upon completion of surgery, hemostasis was verified by cystoscopic inspection of the bladder neck and prostatic fossa following limited TUR and selective cauterization before catheter placement. All patients received a 22 Fr three-way catheter with a 30 mL balloon placed in the bladder and initiated on continuous bladder irrigation. Antithrombotic agents were held based on current perioperative guidelines. Patients were admitted for overnight observation.

A retrospective analysis was conducted on men who underwent Aquablation from October 2020 to July 2024 at UT Southwestern Medical Center. Data on demographics (age at surgery, body mass index [BMI], medical comorbidities, American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification System [ASA]) score, antithrombosis status), prostate characteristics (prior prostate surgeries for BPH, catheter dependent urinary retention status, prior pelvic radiation, prostate size, presence of median lobe, preoperative and post-operative International Prostate Symptom Score [IPSS]), operative details (pre-operative Hemoglobin, pre-operative noninvasive urodynamics, number of Aquablation passes, total Aquablation time, transurethral resection volume, estimated blood loss, TXA administration), and postoperative outcomes were extracted from electronic medical record (EMR) system. Postoperative data that was queried was postoperative hemoglobin obtained several hours after surgery, postoperative day one hemoglobin, need for blood transfusion, number of post-operative patient-initiated communications (either messages via patient EMR portal or calls to the clinic) and emergency department presentations regarding hematuria and other post-surgical concerns within 30 days of surgery. We also collected data on post-operative noninvasive urodynamics and IPSS scores, which were typically assessed at the first post-operative clinic visit, typically between 4 and 6 weeks after surgery.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (STU-2024-0834). Informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the entire cohort, with subgroup analyses based on TXA administration and antithrombotic status. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used for comparison of medians, a two-tailed t-test to compare averages, and univariate regression analyses were employed to assess relationships between continuous variables. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Data analysis was done with Version 25 of the IBM SPSS Statistics software package (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

A total of 113 patients underwent Aquablation followed by limited transurethral resection (TUR) at the end of the procedure to promote hemostasis. The median age at surgery was 68 years (interquartile range [IQR] 62–72), and the median BMI was 27 kg/m2 (IQR 25–31). Most patients (79%) were Caucasian. Comorbidities included hypertension in 48%, diabetes in 17%, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in 14%, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in 4% of patients.

Patients who received TXA had a median prostate size of 86 g (IQR 69–103 g) compared to 70 g (IQR 51–90 g) in those not receiving TXA (p = 0.003, Table 1), but no significant differences were observed in estimated blood loss (median 25 mL in both groups, IQR 20–30 mL, p = 0.847), transfusion rates, or hematuria-related emergency department visits. Subgroup analysis of patients with prostate volume <80 g and ≥80 g was only significant for a smaller transurethral resection volume (4 g, IQR 3–8) obtained from the patients with prostates <80 g who did not receive TXA (n = 53) compared to those who did receive TXA (n = 11) (9.4 g, IQR 6–11) (p = 0.026). Across all patients, TXA recipients had a median Aquablation procedure time of 9.53 min compared to 7.66 min in those who did not receive TXA (p = 0.002) and required three Aquablation passes in 6 out of 31 TXA patients compared to 9 out of 82 non-TXA patients (p = 0.027). Median hemoglobin change from baseline to post-op day one was −1.55 g/dL (IQR −2.25–−0.85 g/dL) in the TXA group and −1.5 g/dL (IQR −2.25–−0.75 g/dL) in the non-TXA group (p > 0.05). No thromboembolic events were reported in any patient receiving TXA within 30 days of surgery.

On postoperative day one, 47 of 113 patients (42%) underwent a void trial, of which 40 (85%) successfully voided and were discharged without a catheter. The remaining 66 patients were discharged with a catheter and a scheduled outpatient void trial. One month after Aquablation, functional outcomes improved in all patients. The median urinary flow rate was 12.8 mL/sec (IQR 8.7–18.8 mL/sec), and the median International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) was 7 points (IQR 3–12). Patients receiving TXA demonstrated a lower median post-operative IPSS score of 4 (IQR 2–6), while those not receiving TXA had a median score of 8 (IQR 3–13) (p = 0.006). There was no significant postoperative change in median urinary flow rates between groups.

Patient-initiated communication

Patient-initiated communications (e.g., EMR messages or clinic calls) and emergency department (ED) visits for hematuria-related concerns remained low in both TXA and non-TXA groups. Hematuria-related communications occurred in 14 out of 31 patients (45%) in the TXA group, compared to 28 out of 82 patients (34%) in the non-TXA group (p = 0.405).

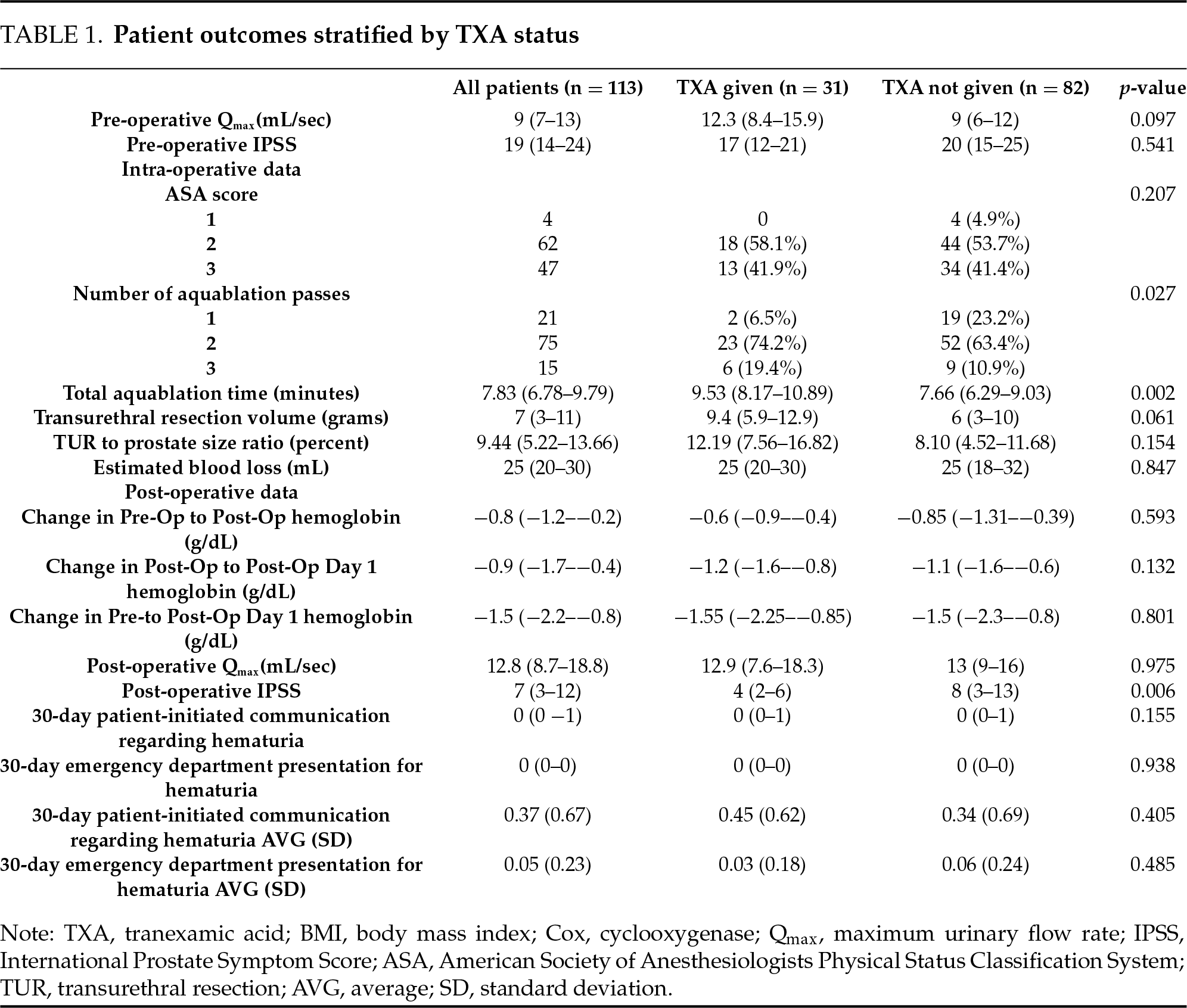

Stratification by prior antiplatelet or anticoagulant use

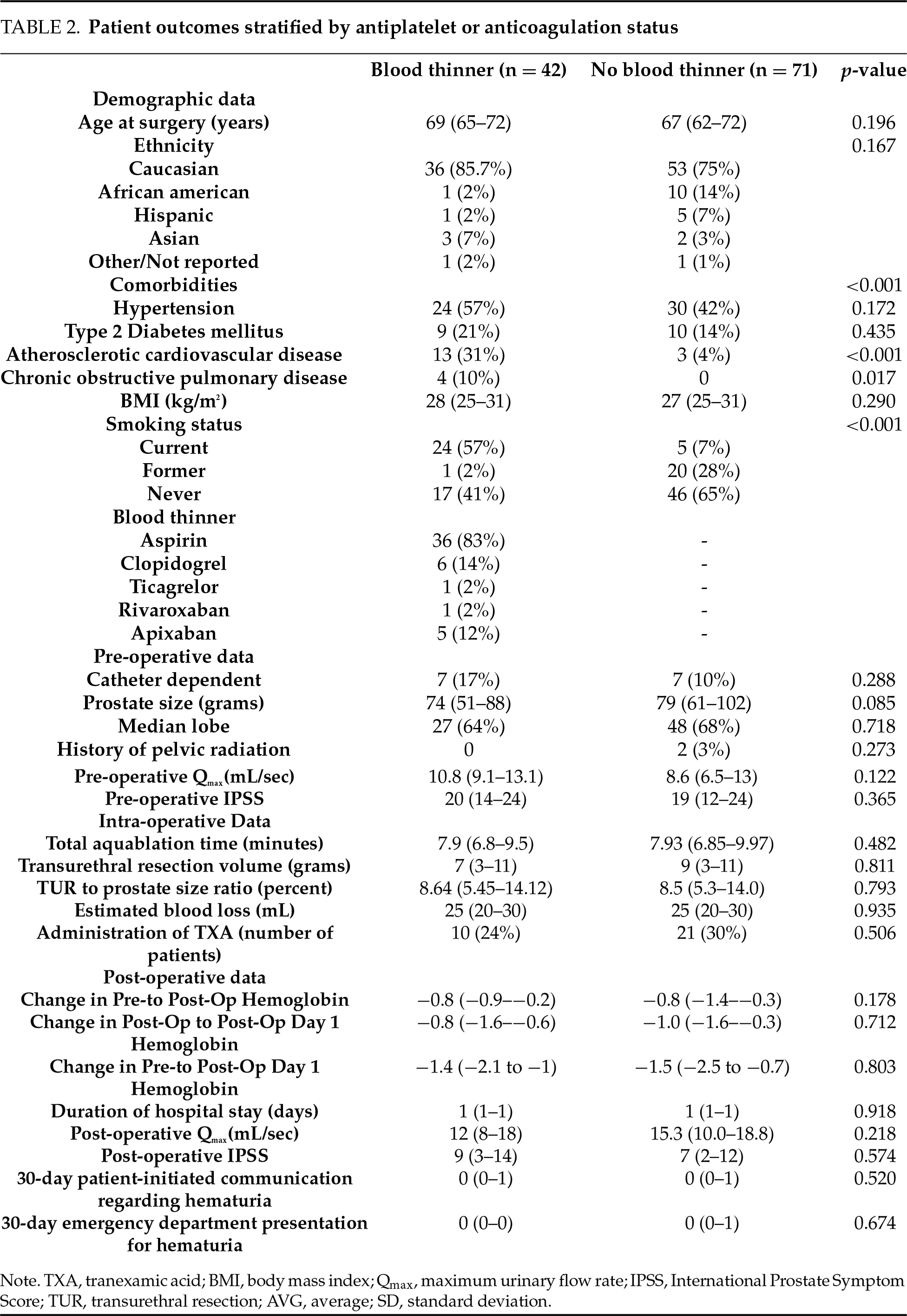

42 patients were on antiplatelet or anticoagulation therapy prior to surgery. TXA was administered to 10 of 42 (23.8%) on blood thinners and 21 of 71 (29.6%) patients not on blood thinners (p = 0.506). Among patients on anticoagulation therapy, no significant differences were observed in postoperative hematuria, hemoglobin changes, or estimated blood loss (Table 2). Median estimated blood loss was 25 mL in both anticoagulation and non-anticoagulation groups (p = 0.935), transfusion rates (0% in both groups), or emergency department visits related to hematuria. Patients on anticoagulation had similar postoperative hemoglobin regardless of TXA administration (−1.4 g/dL vs. −1.5 g/dL, p = 0.801, Figure 1). When patients on 81 mg aspirin were excluded from the blood thinner group in a separate subgroup analysis, there were similarly no significant differences observed in post-operative hematuria, hemoglobin changes, or estimated blood loss.

FIGURE 1. Impact of tranexamic acid (TXA) on median hemoglobin levels among patients on anticoagulation following Aquablation (p = 0.801)

The role of TXA in reducing blood loss during TURP is well documented; however, its application in Aquablation is less extensively reported. Aquablation has been associated with a 10% risk of bleeding15 and a 6% transfusion rate.16 Several methods, including traction and selective cautery, have been developed to mitigate perioperative bleeding risks.9,16 In our study, Aquablation combined with limited TUR provided adequate bleeding control, even among patients on antithrombotic agents. The addition of TXA in cases with increased bleeding did not significantly impact bleeding outcomes.

Our surgeons favored TXA use in patients with larger prostates, likely due to an increased transfusion risk among these patients when undergoing TURP.17 However, the subgroup analysis shows that prostate size did not significantly affect postoperative hematuria outcomes. Beyond prostate size, neither TUR volume nor TUR-to-prostate size ratio influenced postoperative hematuria outcomes, regardless of TXA administration. These findings align with a systematic review outlining TXA’s limited effect in altering hemostatic parameters including transfusion rates, postoperative hemoglobin, operative time, and length of stay among patients undergoing transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP).18,19

In contrast, patients undergoing percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) demonstrated improvement in all hemostatic parameters after receiving TXA.20 This may be explained by the innate difference in bleeding risk between TURP and PCNL procedures. TURP, having a lower baseline risk of bleeding and complications when compared to PCNL, may achieve adequate hemostasis without additional agents such as TXA.16,17 This discrepancy may support why our findings yielded little effect of TXA on hemostatic outcomes in Aquablation patients, as Aquablation has been shown to have further decreased bleeding risk than TURP five years after surgery.21

However, given that there were significantly fewer patients on antithrombotic agents that received TXA compared to those that did not, the lack of TXA’s benefit in reducing postoperative bleeding in this population may be underestimated. Patients on anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents are at an inherently higher risk of perioperative bleeding, even when these medications are temporarily held before surgery. Current guidelines recommend holding aspirin for at least 5 to 7 days,22 clopidogrel for 5 days, and ticagrelor for 3 to 5 days before surgery.23 Direct oral anticoagulants such as apixaban and rivaroxaban are typically held for 24 to 48 h, depending on renal function, while warfarin requires 5 days for full reversal.24 Despite these precautions, residual anticoagulant effects can still contribute to increased bleeding risk. While TXA could theoretically provide additional hemostatic support in these patients, our findings suggest that Aquablation with limited TUR provides effective bleeding control even among those on blood thinners.

The lack of venous thromboembolic events (VTE) among TXA recipients in our cohort aligns with a large-scale systematic review concerning prostate procedures that reported no VTE in either TXA or control groups.19 However, this may be due to lower baseline rates of VTE associated with shorter endoscopic urologic procedures (<2 h) when compared to more complex urologic surgeries such as radical cystectomy, prostatectomy, or oncologic procedures, which typically have longer operative times and higher VTE risk.25–27 Despite concern for postoperative hematuria among patients on anticoagulation, patient-initiated communication and emergency department visits related to bleeding remained low and were not mitigated by TXA administration. Most patient inquiries were related to routine postoperative concerns. Common topics included guidance on continuing BPH medications and symptoms such as urinary urgency, dysuria, bladder spasms, and rectal bleeding—typically attributed to the ultrasound probe used during surgery. These concerns could be more effectively addressed through improved discharge instructions and preoperative education, ensuring patients are informed about expected postoperative side effects during their recovery.

This study has several limitations. It is a retrospective, single-center study with a predominantly healthy population, where the most common comorbidity was hypertension (48%) and no patients had significant medical conditions that prevented discontinuation of anticoagulation. TXA administration was subjective and based on the surgeon’s assessment of bleeding, with no correlation between higher estimated blood loss (EBL) and TXA use. Additionally, TXA was administered intraoperatively to patients who were thought to have increased blood loss, introducing selection bias. Hematuria outcomes were only assessed within 30 days, and longer-term outcomes were not evaluated. Additionally, data on volume of post-operative continuous bladder irrigation (CBI) use and catheter irrigation due to hematuria were unavailable.

This study demonstrates that Aquablation with limited TUR is a safe and effective treatment for BPH, minimizing reliance on TXA for hemostasis, even among patients who take blood thinners or those with larger prostates. Further prospective studies could enhance understanding of these findings, specifically focusing on identifying patient characteristics that may predict the need for TXA.

Acknowledgement

We thank the nursing, surgical, and administrative staff for their support in the care and coordination of Aquablation patients.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Rohit R. Badia, Ramy Goueli, Ryan J. Mauck, Jennifer Tse, Jeffrey Gahan, Claus G. Roehrborn; data collection: Phillip Taboada, Dhillon Advano, Rohit R. Badia, Andrew Murphy; analysis and interpretation of results: Phillip Taboada, Rohit R. Badia, Dhillon Advano, Andrew Murphy; draft manuscript preparation: Phillip Taboada, Rohit R. Badia, Dhillon Advano, Christina Sze, Jennifer Tse. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Ramy Goueli, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval

This study included human subjects from whom informed consent was obtained. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (Approval number: STU-2024-0834).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Sandhu JS, Bixler BR, Dahm P et al. Management of lower urinary tract symptoms attributed to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPHAUA Guideline amendment 2023. J Urol 2023;10:11–19. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000003698. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Gilling P, Reuther R, Kahokehr A, Fraundorfer M. Aquablation—image-guided robot-assisted waterjet ablation of the prostate: initial clinical experience. BJU Int 2016;117(6):923–929. doi:10.1111/bju.13358. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Gilling P, Barber N, Bidair M et al. WATER: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial of aquablation® vs transurethral resection of the prostate in benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol 2018;199(5):1252–1261. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2017.12.065. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Kasivisvanathan V, Hussain M. Aquablation versus transurethral resection of the prostate: 1 year United States-cohort outcomes. Can J Urol 2018;25(3):9317–9322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

5. Skolarus TA, Dauw CA, Fowler KE, Mann JD, Bernstein SJ, Meddings J. Catheter management after benign transurethral prostate surgery: RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Criteria. Am J Manag Care 2019;25(12):e366–e372. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

6. Zorn KC, Chakraborty A, Chughtai B et al. Safety and efficacy of same day discharge for men undergoing contemporary robotic-assisted aquablation prostate surgery in an ambulatory surgery center setting-first global experience. Urology 2025;195(S2):132–138. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2024.08.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Gaur AS, Mandal S, Pandey A, Das MK, Nayak P. Efficacy of PCNL in the resolution of symptoms of nephrolithiasis. Urolithiasis 2022;50(4):487–491. doi:10.1007/s00240-022-01334-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Kerdegari N, Varma R, Ippoliti S et al. A systematic review of outcomes associated with patients admitted to hospital with emergency haematuria. BJUI Compass 2025;6(2):e497. doi:10.1002/bco2.497. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Gloger S, Schueller L, Paulics L, Bach T, Ubrig B. Aquablation with subsequent selective bipolar cauterization versus holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP) with regard to perioperative bleeding. Can J Urol 2021;28(3):10685–10690. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

10. Munoz JJ, Birkmeyer NJ, Birkmeyer JD, O’Connor GT, Dacey LJ. Is epsilon-aminocaproic acid as effective as aprotinin in reducing bleeding with cardiac surgery?: a meta-analysis. Circulation 1999;99(1):81–89. doi:10.1161/01.cir.99.1.81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Kumsar Ş, Dirim A, Toksöz S, Sağlam HS, Adsan Ö. Tranexamic acid decreases blood loss during transurethral resection of the prostate (TUR-P). Cent Eur J Urol 2011;64(3):156–158. doi:10.5173/ceju.2011.03.art13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Vanderbruggen W, Brits T, Tilborghs S, Derickx K, De Wachter S. The effect of tranexamic acid on perioperative blood loss in transurethral resection of the prostate: a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Prostate 2023;83(16):1584–1590. doi:10.1002/pros.24616. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Tawfick A, Mousa W, El-Zhary AF, Saafan AM. Can tranexamic acid in irrigation fluid reduce blood loss during monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate? A randomised controlled trial. Arab J Urol 2022;20(2):94–99. doi:10.1080/2090598X.2022.2026011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Descazeaud A, Robert G, Lebdai S et al. Impact of oral anticoagulation on morbidity of transurethral resection of the prostate. World J Urol 2011;29(2):211–216. doi:10.1007/s00345-010-0561-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Ghiraldi E, Higgins AM, Sterious S. Initial experience performing “cautery-free waterjet ablation of the prostate”. J Endourol 2022;36(9):1237–1242. doi:10.1089/end.2022.0062. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Elterman D, Bach T, Rijo E et al. Transfusion rates after 800 Aquablation procedures using various haemostasis methods. BJU Int. 2020;125(4):568–572. doi:10.1111/bju.14990. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Lynch M, Sriprasad S, Subramonian K, Thompson P. Postoperative haemorrhage following transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) and photoselective vaporisation of the prostate (PVP). Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2010;92(7):555–558. doi:10.1308/003588410X12699663903557a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Abdullah A, Javed A. Does topical tranexamic acid reduce post turp hematuria; a double blind randomized control trial. J Urol 2012;187(4S):e816. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2012.02.2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Kim J, Alrumaih A, Donnelly C, Uy M, Hoogenes J, Matsumoto ED. The impact of tranexamic acid on perioperative outcomes in urological surgeries a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can Urol Assoc J. 2023;17(6):205–216. doi:10.5489/cuaj.8254. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Cleveland B, Norling B, Wang H et al. Tranexamic acid for percutaneous nephrolithotomy: an abridged Cochrane review. BJU Int 2024;133(3):259–272. doi:10.1111/bju.16244. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Gilling PJ, Barber N, Bidair M et al. Five-year outcomes for aquablation therapy compared to TURP: results from a double-blind, randomized trial in men with LUTS due to BPH. Can J Urol 2022;29(1):10960–10968. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

22. Halvorsen S, Mehilli J, Geisler T. Continue or discontinue aspirin before non-cardiac surgery? Eur Heart J 2023 Jul 7;44(26):2410. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehad246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. O’Riordan JM, Margey RJ, Blake G, O’Connell PR. Antiplatelet agents in the perioperative period. Arch Surg 2009;144(1):69–76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

24. Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC. Perioperative management of patients taking direct oral anticoagulants: a review. JAMA 2024;332(10):825–834. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

25. Rice KR, Brassell SA, McLeod DG. Venous thromboembolism in urologic surgery: prophylaxis, diagnosis, and treatment. Rev. Urol. 2010;12(2–3):e111–e124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

26. Clement C, Rossi P, Aissi K et al. Incidence, risk profile and morphological pattern of lower extremity venous thromboembolism after urological cancer surgery. J Urol 2011;186(6):2293–2297. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

27. Hammond J, Kozma C, Hart JC et al. Rates of venous thromboembolism among patients with major surgery for cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2011;18(12):3240–3247. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools