Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

AI-based detection of MRI-invisible prostate cancer with nnU-Net

1 Department of Urology, Beijing Friendship Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, 100050, China

2 Institute of Urology, Beijing Municipal Health Commission, Beijing, 100050, China

* Corresponding Author: Jian Song. Email:

# Jingcheng Lyu and Ruiyu Yue are co-first authors

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advancing Early Detection of Prostate Cancer: Innovations, Challenges, and Future Directions)

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(5), 445-456. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.068853

Received 08 June 2025; Accepted 15 August 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

Objectives: This study aimed to develop an artificial intelligence (AI)-based image recognition system using the nnU-Net adaptive neural network to assist clinicians in detecting magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-invisible prostate cancer. The motivation stems from the diagnostic challenges, especially when MRI findings are inconclusive (Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System [PI-RADS] score ≤ 3). Methods: We retrospectively included 150 patients who underwent systematic prostate biopsy at Beijing Friendship Hospital between January 2013 and January 2023. All were pathologically confirmed to have clinically significant prostate cancer, despite negative findings on preoperative MRI. A total of 1475 MRI images, including T2-weighted imaging (T2WI), diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) sequences, were collected. The nnU-Net was employed as the initial segmentation framework to delineate tumor regions in MRI images, based on histopathologically confirmed prostate cancer sites. A convolutional neural network-based deep learning model was subsequently designed and trained. Its performance was evaluated using five-fold cross-validation. Results: Among 150 patients with clinically significant prostate cancer diagnosed, all with PI-RADS ≤ 3 on MRI, the median age was 67 years (IQR: 62–72), and 105 patients (70.0%) had a Gleason score ≥ 7. A total of 1475 multiparametric MRI images were analyzed. Using five-fold cross-validation, the AI-based image recognition system achieved a mean Dice similarity coefficient of 55.0% (range: 51.6–56.5%), with a mean sensitivity of 50.5% and a mean specificity of 96.9%. The corresponding mean false-positive and false-negative rates were 3.1% and 49.5%, respectively. Conclusion: We successfully developed an AI-based image recognition system utilizing the nnU-Net adaptive neural network, demonstrating promising diagnostic performance in detecting MRI-invisible prostate cancer. This system has the potential to enhance early detection and management of prostate cancer.Keywords

Prostate cancer is one of the most common malignant tumors in men and remains the second most frequently diagnosed cancer among men worldwide, according to the latest Global Burden of Disease study. It poses a major threat to men’s health globally, with considerable incidence and mortality disparities across different regions.1 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is among the most effective diagnostic tools for prostate cancer, offering clinicians detailed information on tumor size, shape, and extent of invasion.2 However, interpreting MRI images demands specialized expertise and extensive experience. Notably, approximately 11% of prostate cancers remain undetectable on MRI, which called as MRI-invisible prostate cancer.3,4 This may be attributed to the human eye’s limited ability to distinguish subtle differences between images. Additionally, the inherent low resolution of prostate MRI and limited understanding of its imaging characteristics may contribute to false-negative interpretations.

In recent years, advances in big data technology have driven significant progress in the application of artificial intelligence (AI) in medicine. Compared to traditional manual diagnostic methods, AI systems demonstrate superior capability in processing image features such as brightness contrast and sharpness, often surpassing human visual perception.5 Leveraging large-scale computing and deep learning, AI systems can detect subtle differences between images that may be imperceptible to human observers. Additionally, AI reduces the risk of misdiagnosis associated with subjective factors such as physician experience, skill level, and fatigue. However, most prior studies on AI in prostate cancer imaging have focused on machine learning techniques that assist clinicians in identifying visually apparent tumors on MRI. Accurate detection of prostate cancer lesions that are invisible to the naked eye remains a significant challenge.

nnU-Net is an adaptive neural network architecture specifically designed for medical image segmentation. It has won multiple international competitions and demonstrates superior performance and versatility compared to other AI frameworks.6,7 It can automatically configure its network architecture based on input data characteristics such as size and spacing. This adaptability facilitates its application across diverse medical imaging datasets. Previous studies have explored the use of deep learning to construct reference segmentation models for prostate cancer. In similar studies, various U-Net-based algorithms have demonstrated accurate segmentation of visible intraprostatic tumors. For instance, Singla et al.8 and Duran et al.9 included MRI datasets graded by Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System (PI-RADS) scores, particularly those with scores of 4 and 5, which yielded good recognition and segmentation results. However, in patients with PI-RADS scores ≤ 3, prostate cancer lesions are often imperceptible to the naked eye. To date, no studies have specifically focused on applying AI to segment suspicious regions in MRI-refractory prostate cancer. Therefore, employing AI to highlight potential tumor regions on seemingly normal prostate MRI scans and alert clinicians to these areas could have substantial clinical value in reducing diagnostic oversight. In this study, we used the nnU-Net adaptive neural network to develop an AI system for identifying MRI-invisible prostate cancer. This system is expected to facilitate earlier diagnosis and treatment, thereby reducing misdiagnosis rates and improving patient survival and quality of life.

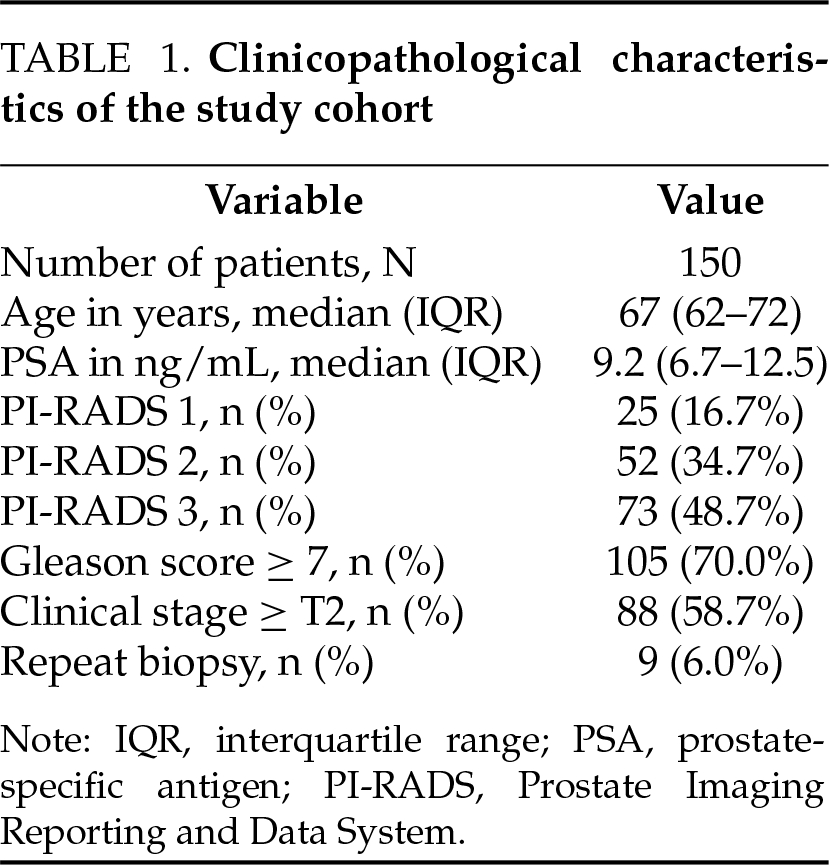

This retrospective study included 150 patients diagnosed with clinically significant prostate cancer by systematic prostate biopsy at Beijing Friendship Hospital between January 2013 and January 2023. All patients had negative or equivocal findings on preoperative MRI, with PI-RADS scores of ≤3. A total of 1475 images of prostate MRI T2-weighted imaging (T2WI), diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) sequences were collected for analysis. The clinicopathological characteristics of the 150 enrolled patients are summarized in Table 1. This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and is approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Beijing Friendship Hospital, Capital Medical University (Approval No. 2024-P2-153).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria: (i) patients with biopsy-proved PCa between January 2013 and January 2023, (ii) have done mpMRI (including T2-w, DW, ADC parameters MR images at least) before biopsy within 1 month in Beijing Friendship Hospital, (iii) PI-RADS score from 1 to 3.

Exclusion criteria: (i) undergone any prior treatment, such as transurethral resection of prostate, androgen deprivation, etc. (ii) without systematic biopsy, (iii) incomplete MRI without DWI or ADC, (iv) poor images quality that made physicians unable to outline the prostate.

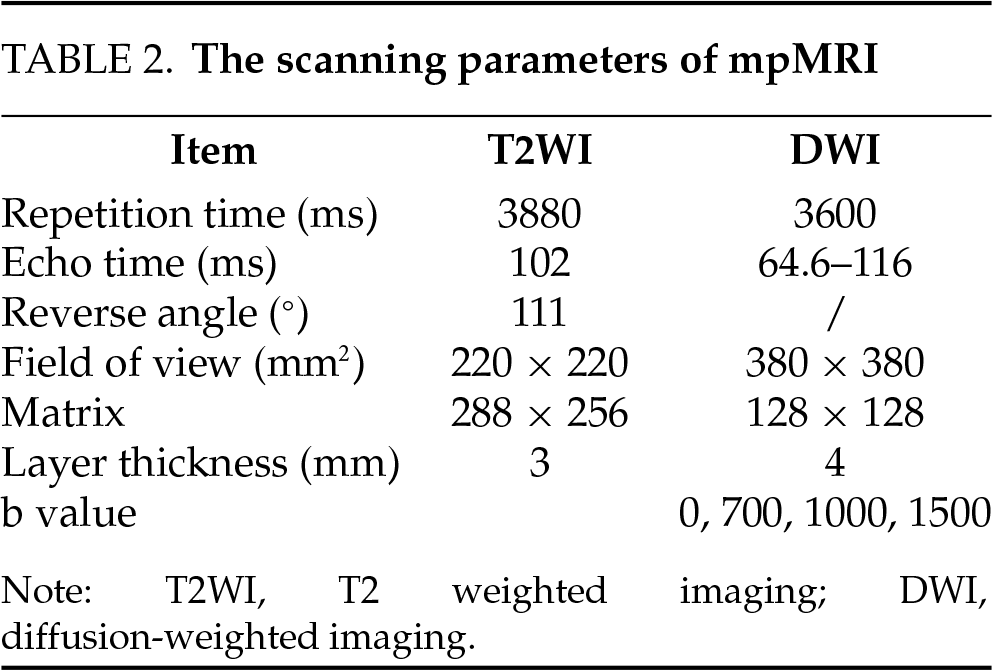

The scanning parameters for the multiparametric MRI (mpMRI) used in this study are presented in Table 2. All MRI scans in this study were acquired using a DiscoveryTM MR750 3.0 T scanner (GE HealthCare, Chicago, IL, USA). The Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System version 2 (PI-RADS v2)10 was used to assess the likelihood of prostate cancer.

After gotten all those mpMR images, including T2-WI, DWI and ADC, two radiologist (reader 1 and 2) with more than 5 years of experience would read the images layer-by-layer and scored the PI-RADS separately without knowing any clinical information and pathological results. In cases of disagreement, a third radiologist (reader 3) with over 10 years of experience reviewed the images and made the final decision. Patients with final MRI results scored PI-RADS ≥ 4 were excluded from the study.

Histopathological specimen and tumor location acquisition

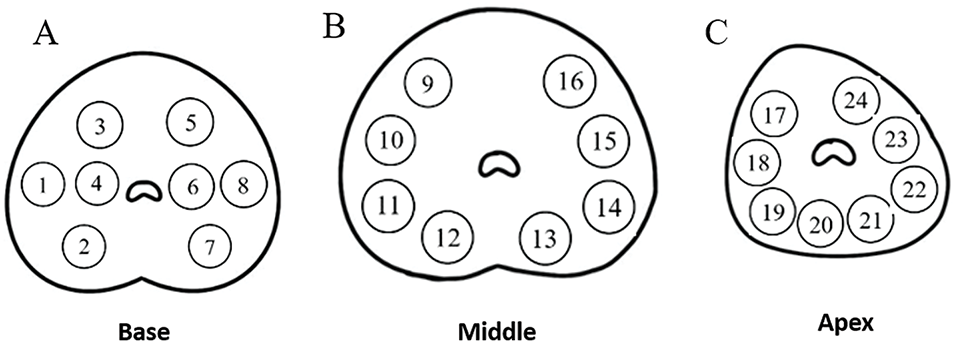

All patients in this study have undergone transrectal ultrasound guided transperineal prostate systematic biopsy (the biopsy site is shown in Figure 1) in order to ensure every core could be restricted in a certain scope and easy to relocate on MR images relatively. The disposable core biopsy instrument we used was produced by Max-CoreTM (Catalogue Number: MC1825; BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) with 1.8 cm the length of sample notch and 22 mm of penetration depth.

FIGURE 1. Schematic diagram of 24-core transperineal prostate biopsy sites. (A) Base; (B) Middle; (C) Apex

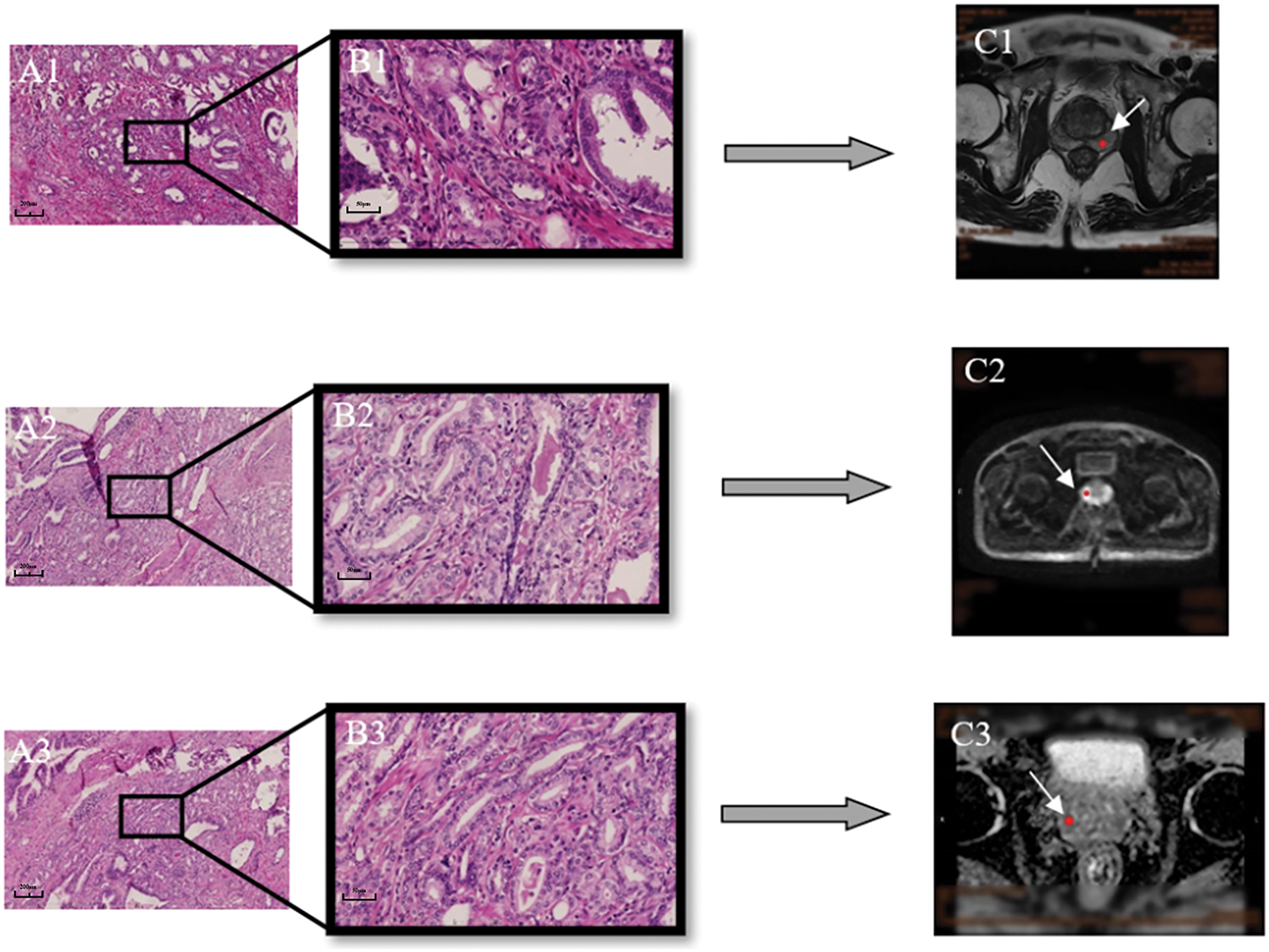

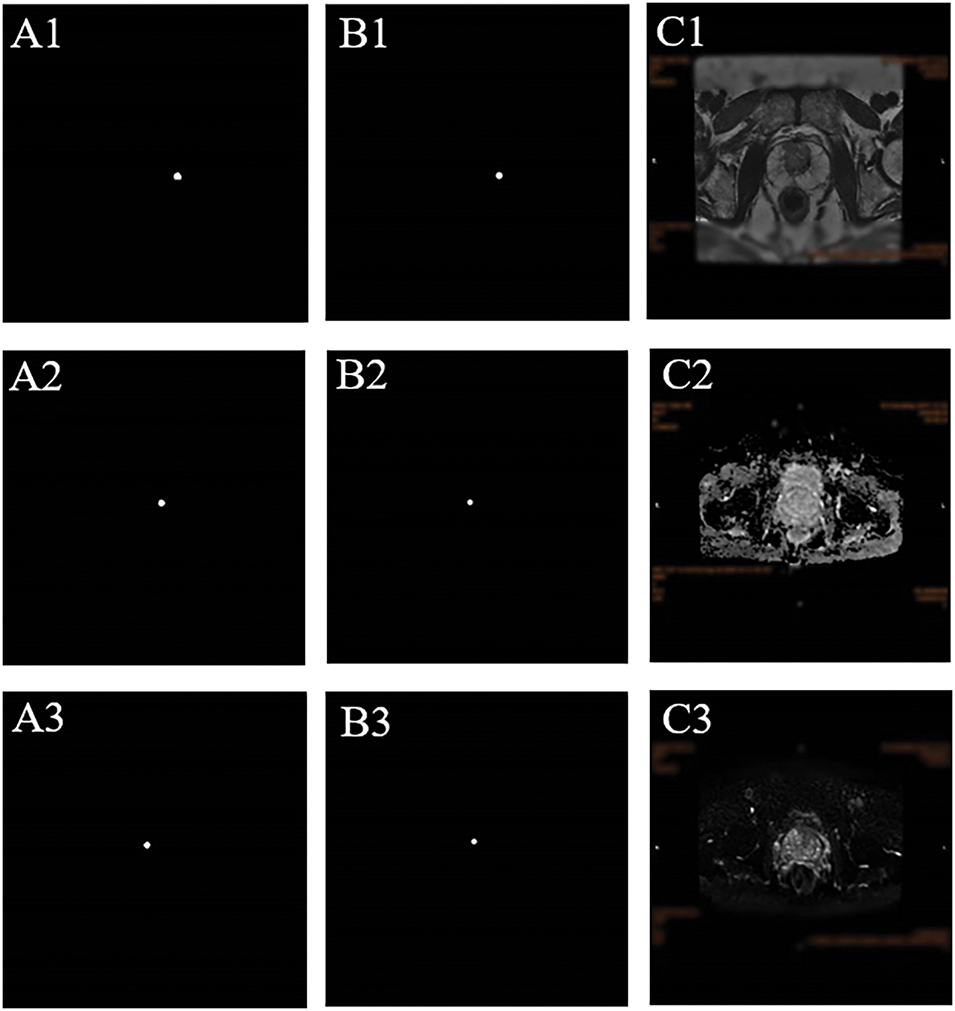

Each histopathological specimen included in this study has been re-read by another full-experienced pathologist, and the pathologically confirmed tumor puncture sites were located on the MR images (Figure 2). Among the 150 patients, 9 (6%) underwent repeat transperineal biopsy during follow-up.

FIGURE 2. The position of prostate cancer in MRI was determined according to pathological findings. (A1–3) Pathological images of prostate cancer (10×). (B1–3) 40×. (C) The white arrow indicates the location of the prostate cancer in the MRI pictures (C1: T2 weighted imaging [T2WI]; C2: diffusion-weighted imaging, [DWI]; C3: apparent diffusion coefficient, [ADC])

Artificial intelligence model construction

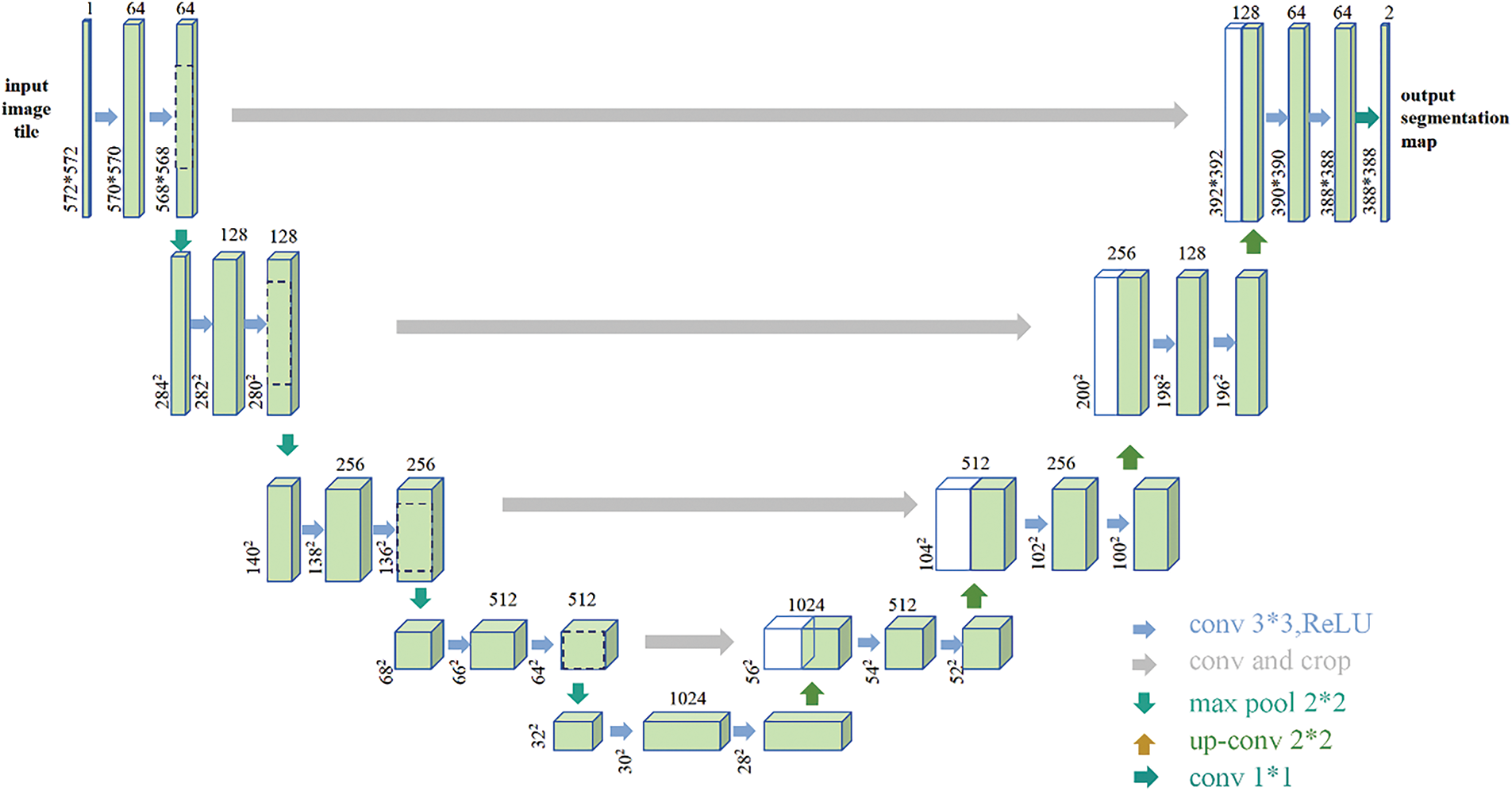

nnU-Net is an adaptive neural network architecture specifically designed for medical image segmentation. Developed by Fabian Isensee et al., nnU-Net has clinched multiple international medical image segmentation competition titles, demonstrating its superior performance and versatility. In this study, the dataset comprises two-dimensional image data, and the 2D U-Net architecture of nnU-Net is employed for model training.

The U-Net architecture exhibits a “U” shape, comprising a contracting (downsampling) path and an expansive (upsampling) path. Contracting Path includes multiple convolutional layers followed by max pooling layers. Each convolutional layer typically consists of two consecutive convolution operations, followed by a ReLU activation function. Max pooling operations are used for downsampling, halving the dimension of the feature maps while doubling the number of feature channels. In image segmentation tasks, the contracting path helps the network understand the objects and their context within the image by extracting increasingly abstract and complex features layer by layer.

The expansive path gradually increases the size of the feature maps through upsampling and convolution operations. After upsampling, the feature maps are concatenated with the corresponding feature maps from the contracting path (skip connections) to restore positional information. After each upsampling step, the number of feature channels is halved. In image segmentation tasks, the role of the expansive path is to combine the deep, abstract features extracted from the contracting path with spatial information to generate precise segmentation maps. The expansive path aids the network in precisely locating and segmenting target areas within the image by gradually restoring spatial details and context.

The network concludes with a 1 × 1 convolution that transforms the feature map into the final segmentation map (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. U-Net structure diagram. The left side of the network is the contracting path and the right side is the expansive path. The jump connection is used between the contraction path and the expansive path (the jump connection directly transfers the output of the shallow layer in the network to the deeper layer). The jump connection can alleviate the gradient disappearance, allow the network to reuse the shallow layer features in the deep layer, improve the information flow of the entire network, and improve the performance of the network and the stability of training. The final network has 23 convolutional layers

nnU-Net establishes an adaptive network architecture that automatically configures itself based on the characteristics of the input data, such as size and spacing. This adaptability makes it easier to apply to different types of medical image datasets. nnU-Net offers four architectures: 2D U-Net, 3D U-Net, 3D U-Net Cascade, and 3D Full Resolution U-Net, covering the vast majority of medical imaging data.

2D U-Net: Suitable for processing two-dimensional image slices, this architecture is specifically designed for 2D image data.

3D U-Net: Appropriate for three-dimensional volumetric data, this architecture captures contextual information in three dimensions, ideal for scenarios where inter-layer differences are minimal or three-dimensional context is necessary.

3D U-Net Cascade: This cascade approach processes 3D image data by first segmenting with a coarse resolution 3D U-Net and then using the result as input for a high-resolution 3D U-Net. This architecture leverages the advantages of different resolutions to effectively improve segmentation quality.

3D Full Resolution U-Net: Focused on processing images at full resolution, this architecture is suitable for high-resolution 3D images where detail is crucial.

Enhanced data preprocessing and model optimization

nnU-Net employs more sophisticated data preprocessing steps, including normalization and data augmentation, to improve the model’s generalization ability. Data augmentation techniques used include random rotations, scaling, elastic deformations, gamma correction enhancements, and mirroring.

nnU-Net utilizes an adaptive loss function that combines Dice loss and cross-entropy loss to optimize the accuracy of segmentation boundaries and classification consistency.

The activation function has been modified to use leaky ReLUs instead of ReLUs. Leaky ReLU allows a non-zero gradient to pass even when input values are negative, avoiding the “dead neuron” problem that can occur with ReLU, where some neurons may never activate. With a small positive slope (e.g., 0.01), Leaky ReLU maintains a flow of gradients even when inputs are negative, aiding in the stability and improved convergence of the network during training.

Epochs: 1000. This refers to the number of times all training samples are used completely by the model during the training process. An epoch of 1000 means the data is fully trained 1000 times.

Iterations per epoch: 250. This value indicates how many iterations are needed in one epoch to update the model’s weights using the entire training set. In training neural networks, it is common to iterate through multiple epochs, each containing several iterations, until the desired training volume or stopping criteria is reached.

Learning rate: 0.01, decreasing by 0.00001 per epoch. This controls the step size of the model’s parameter updates along the gradient direction.

Weight decay coefficient: 0.00003. This uses regularization techniques to reduce the complexity of the model to prevent overfitting. Increasing weight decay helps prevent overfitting, but if too high, it can limit the model’s ability to learn effective features, thus reducing the model’s complexity. Adjustments may be needed to find the optimal setting.

The dataset used in this study consists of prostate MRI scan slice images from 150 patients in medical practice, totaling 1475 MRI scan slice images. Each image is accompanied by a binary grayscale image label indicating tumor locations. All personal information in the dataset has been anonymized to protect patient privacy. The dataset is divided into a training set and a validation set in an 8:2 ratio, with 1180 images from 120 patients for training and 295 images from the other 30 patients for validation. To ensure that the model can fully learn features and more accurately segment the target areas, a five-fold cross-validation training method was adopted. This method effectively enhances the model’s generalization ability and ensures good performance across different data subsets. By using this approach, the model is trained and validated on different data sets in each training round, reducing the risk of overfitting and increasing its reliability and accuracy in practical applications (The setting of parameters is mentioned in Section Enhanced data preprocessing and model optimization).

The Dice coefficient is a metric used to measure the similarity between two sets, and the formula is as follows:

where TP represents true positives (the number of pixels predicted as positive and actually positive), FP represents false positives (the number of pixels predicted as positive but actually negative), and FN represents false negatives (the number of pixels predicted as negative but actually positive).

In this context, |X∩Y| represents the intersection between X and Y, which can be seen as the size of the overlap between the predicted results and the correct results. |X| and |Y| respectively represent the number of elements in X and Y, which can be viewed as the combined size of the predicted and correct results. The coefficient of 2 in the numerator is because the denominator counts the common elements between X and Y twice. The larger this value, the greater the overlap between the predicted results and the correct results.

Mean Validation Dice refers to a performance evaluation metric used in tasks such as medical image segmentation. It represents the average Dice coefficient across the validation set.

SPSS 25.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all statistical analyses in this study. In this study, all continuous variables conforming to normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD); Continuous variables that do not conform to the normal distribution were expressed as median (IQR). The categorical variables were represented by the number of cases.

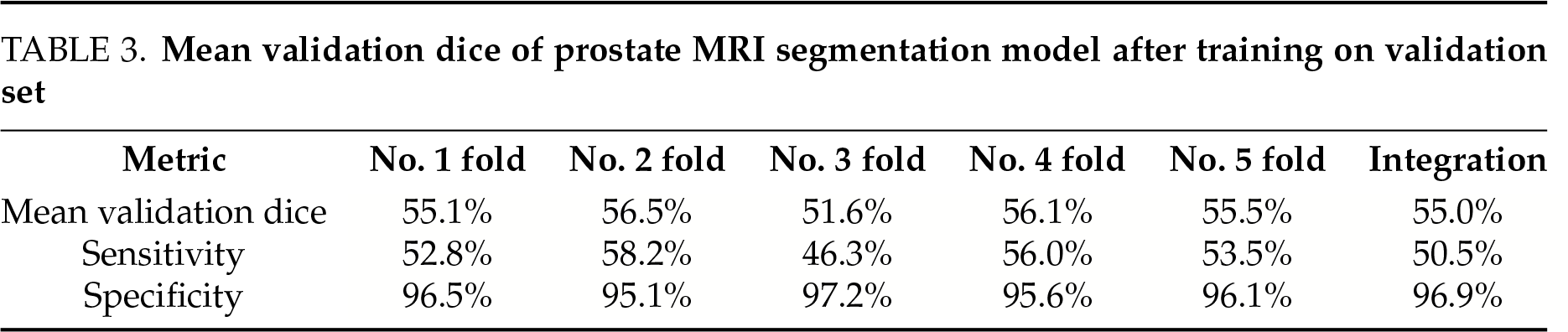

The artificial intelligence image recognition system developed using nnU-Net effectively identified MRI-invisible prostate cancer, which is often undetectable by clinicians through conventional imaging. The mean validation Dice scores, derived from five-fold cross-validation, are summarized in Table 3. In addition to the Dice coefficient, we also calculated sensitivity and specificity. The mean sensitivity was 50.5%, and the mean specificity was 96.9%. Based on our results, the model achieved a mean false-positive rate of approximately 3.1% and a mean false-negative rate of approximately 49.5%, consistent with the sensitivity and specificity reported.

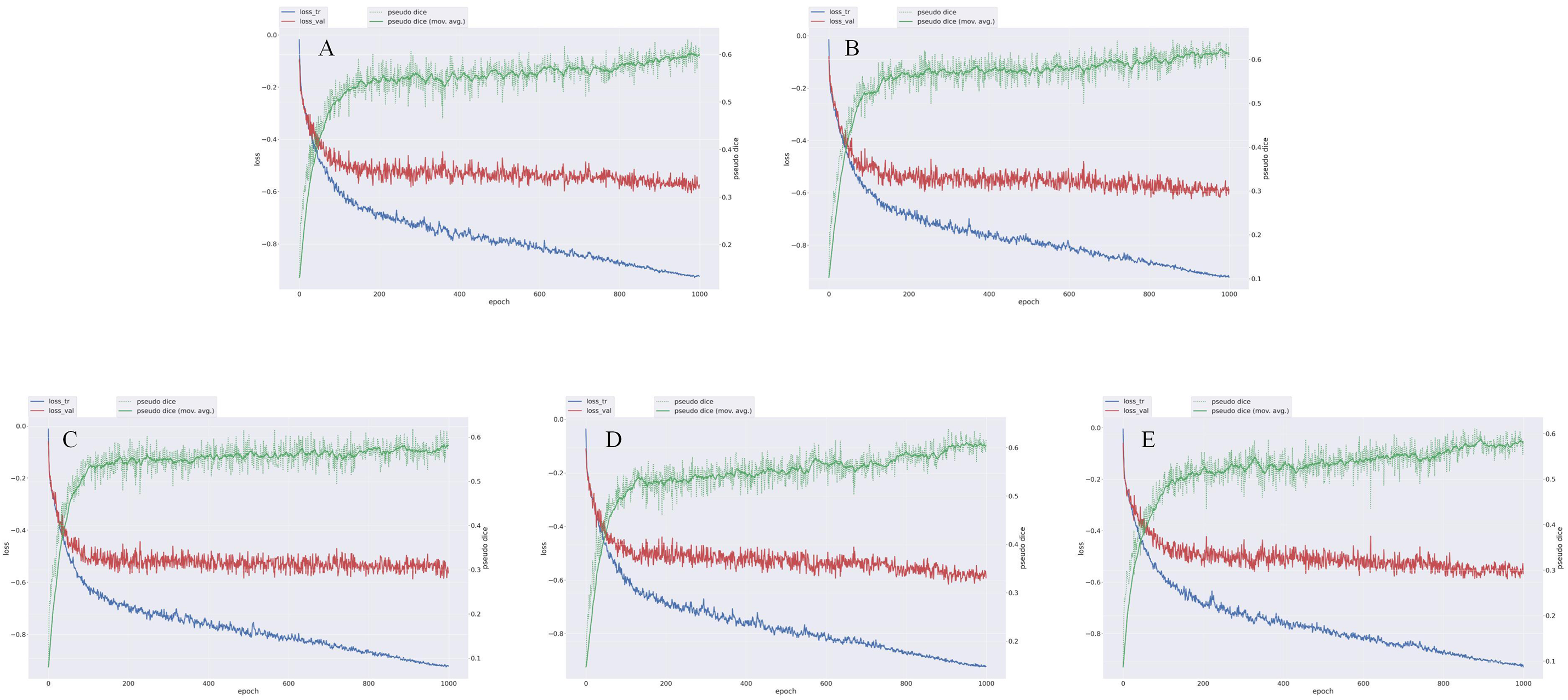

During model training, the optimal epoch was recorded. Minor overfitting observed in the later training stages did not significantly affect the final performance (Figure 4). The loss in both the training and validation sets decreased with increasing epochs, while segmentation accuracy progressively improved throughout training (Figure 5).

FIGURE 4. Loss variation map of nnU-Net model trained with five-fold cross-validation for prostate cancer. Each graph represents the result of each fold. loss_tr represents the loss on the training set, with values closer to −1 indicating better model fit on the training data. loss_val represents the loss on the validation set, with values closer to −1 indicating better model fit on the validation data. Pseudo Dice is a variant of the Dice coefficient, which assigns a higher weight to the positive class to balance the contribution between positive and negative classes. Pseudo Dice (mov.avg.) is a smoothed version of Pseudo Dice that shows the overall trend. (A) The loss change graph of the nnU-Net model after No. 1 fold in the diagnosis of prostate cancer; (B) The loss change graph of the nnU-Net model after No. 2 fold in the diagnosis of prostate cancer; (C) The loss change graph of the nnU-Net model after No. 3 fold in the diagnosis of prostate cancer; (D) The loss change graph of the nnU-Net model after No. 4 fold in the diagnosis of prostate cancer; (E) The loss change graph of the nnU-Net model after No. 5 fold in the diagnosis of prostate cancer

FIGURE 5. Representative segmentation results of the AI model using nnU-Net for MRI-invisible prostate cancer. (A) Pathological confirmation of tumor location obtained from systematic biopsy, serving as the reference standard. (B) Predicted tumor region generated by the AI segmentation model. The delineation reflects the model’s interpretation of the suspected lesion location, shape, and extent. (C) Corresponding MRI slices across three sequences—(C1) T2WI, (C2) DWI, and (C3) ADC—highlighting the tumor region as predicted by the model. These images demonstrate that the lesion was not visually apparent to radiologists but was identified by the AI model based on subtle imaging features

Globally, prostate cancer is the most frequently diagnosed malignancy in men.1 In imaging-based diagnosis of prostate cancer, mpMRI is widely regarded as the gold standard. The PI-RADS, based on mpMRI, is used for prostate lesion localization, diagnosis, and risk stratification. Although the incidence of prostate cancer is low among patients with PI-RADS scores ≤ 3, studies have reported that approximately 7.8%–19.8% of such patients are diagnosed with clinically significant prostate cancer (csPCa) following biopsy, a condition referred to as MRI(-)PCa.2–4 This may be attributed to variability in radiologists’ experience and the presence of subtle image features that are difficult to recognize, potentially leading to underestimation of the PI-RADS score, delayed diagnosis, and poorer prognosis. In addition, previous studies have indicated that variant histological subtypes and aberrant glandular architectures contribute to inconclusive or negative mpMRI findings in some patients with clinically significant prostate cancer. These variants often exhibit less conspicuous imaging features and challenge radiological detection.11 AI, using machine learning and deep learning techniques, can extract morphological, texture, and intensity features from MRI images. It enables accurate discrimination of normal and abnormal prostate tissues, assists in identifying potential tumor regions, and helps distinguish benign from malignant lesions.5 nnU-Net is a semi-automated neural network architecture based on the U-Net design, specifically tailored for medical image analysis. With high accuracy and robustness, nnU-Net has demonstrated excellent performance in medical image segmentation and is widely recognized as one of the leading architectures in biomedical imaging.6,7 However, most applications of nnU-Net have focused on image recognition in diseases such as lung and liver cancer, with few studies addressing its use in prostate MRI. To date, no research has reported its application in detecting or segmenting MRI(-) prostate cancer. Most previous studies have focused on using large sample-sized machine learning to assist clinicians in identifying tumors that can be discerned by the naked eye, aiming to improve the efficiency of manual image reading and reduce the time cost for clinicians. However, although the artificial intelligence systems in these studies have shown significantly higher tumor detection rates and accuracy than clinicians, a large part of this reason is that clinicians are prone to fatigue or mental confusion during intense and long working periods, which leads to missed diagnoses. If all imaging images were interpreted by a physician who is always energetic and highly experienced, then he could definitely identify these tumors and avoid missed diagnoses. However, this is obviously impossible in actual work.

We believe that for the current lesions that clinicians cannot identify with the naked eye, no matter how experienced a physician is or how energetic he is, they will never be able to recognize them as tumor lesions because this is limited by the imaging principle of magnetic resonance images, and also due to the lack of development of different imaging sequences or the incomplete understanding of the multi-dimensional imaging biomarker characteristics of tumors. Therefore, how to discover and accurately identify tumors that are invisible to the naked eye has become one of the urgent problems in clinical practice. The emergence of artificial intelligence has well compensated for this deficiency. Artificial intelligence can efficiently and accurately identify many imaging biomarker features that the naked eye cannot distinguish, such as the texture features of local tissues, pixel features, intensity features, etc. These may currently only be summarized as “magnetic resonance signal intensity” by medicine, but this is obviously too general. Therefore, we want to develop such an artificial intelligence system to initially establish a theoretical framework in the field of prostate cancer magnetic resonance imaging, providing a research basis for the future combination of artificial intelligence image recognition with more tumor types or disease types. Most previous studies have focused on using large sample-sized machine learning to assist clinicians in identifying tumors that can be discerned by the naked eye, aiming to improve the efficiency of manual image reading and reduce the time cost for clinicians. However, although the artificial intelligence systems in these studies have shown significantly higher tumor detection rates and accuracy than clinicians, a large part of this reason is that clinicians are prone to fatigue or mental confusion during intense and long working periods, which leads to missed diagnoses. If all images were interpreted by a physician who is always energetic and highly experienced, then he could definitely identify these tumors and avoid missed diagnoses. However, this is obviously impossible in actual work. We believe that for the current lesions that clinicians cannot identify with the naked eye, no matter how experienced a physician is or how energetic he is, they will never be able to recognize them as tumor lesions because this is limited by the imaging principle of magnetic resonance images, and also due to the lack of development of different imaging sequences or the incomplete understanding of the multi-dimensional imaging biomarker characteristics of tumors. Therefore, how to discover and accurately identify tumors that are invisible to the naked eye has become one of the urgent problems in clinical practice. The emergence of artificial intelligence has well compensated for this deficiency. Artificial intelligence can efficiently and accurately identify many imaging biomarker features that the naked eye cannot distinguish, such as the texture features of local tissues, pixel features, intensity features, etc. These may currently only be summarized as “magnetic resonance signal intensity” by clinical medicine, but this is obviously too general. Therefore, we want to develop such an artificial intelligence system to initially establish a theoretical framework in the field of prostate cancer magnetic resonance imaging, providing a research basis for the future combination of artificial intelligence image recognition with more tumor types or disease types. So, in this study, nnU-Net was used to construct an artificial intelligence system to identify MRI-invisible prostate cancer, in order to reduce the missed diagnosis rate of clinical prostate cancer and improve the prognosis of patients.

Biparametric magnetic resonance imaging (bpMRI) is a faster and more economical scanning approach. Numerous studies have explored automatic segmentation algorithms for prostate cancer based on bpMRI. In a study involving 262 patients, Dai et al.12 developed a deep learning-based segmentation model for csPCa using combined T2WI and ADC sequences, achieving a Dice coefficient of 0.52. In another study, the ProstateX-2 challenge training set included 99 patients and 112 lesions, and the test set included 63 patients and 70 lesions. Vente et al.13 developed a csPCa segmentation model with a Dice coefficient of 0.37. Our results are slightly higher than those of the above studies. Both bpMRI and mpMRI offer considerable diagnostic accuracy when interpreted manually.14,15 However, we speculate that incorporating more multi-dimensional imaging data may improve the performance of AI-assisted csPCa segmentation models. Moreover, biopsy-related architectural distortion, including fibrosis and inflammation, may also alter MRI appearance and impact AI performance. In our cohort, 6% of patients underwent repeat transperineal biopsy during follow-up. Prior studies have shown that transperineal biopsy is associated with a significantly lower re-biopsy rate compared to the transrectal route, likely due to more comprehensive and anterior zone sampling.16,17 These findings support the use of transperineal biopsy as a preferred diagnostic approach, while also highlighting the need to consider post-biopsy changes when developing and validating AI models.

In our study, 5 fold cross-validation was adopted to demonstrate the accuracy of this model for finding and segmenting MRI(-) prostate cancer. Although the mean Dice coefficient of 55.0% achieved by our model is reasonable given the challenge of detecting MRI-invisible prostate cancer, it remains below the commonly desired threshold of 70% for clinical application. This modest performance may be partially attributed to the high resolution (670 × 470) and large size of the MRI images, which increases the difficulty of precise voxel-level segmentation. Nevertheless, this also highlights the need for further optimization. In future work, incorporating larger and more diverse training datasets, exploring advanced network architectures (such as attention mechanisms or transformer-based models), and applying more sophisticated post-processing techniques may help improve segmentation accuracy and enhance clinical applicability. In addition to the Dice coefficient, we also calculated sensitivity and specificity to better characterize the diagnostic performance of the model. The mean sensitivity was 50.5%, and the mean specificity was 96.9%, indicating the model’s ability to correctly identify true tumor regions while minimizing false positives. Importantly, the computational burden of our model is low, and once trained, it can operate efficiently on standard clinical workstations without the need for specialized hardware. Inference for each patient case can be completed within a few seconds, enabling real-time feedback to clinicians during routine diagnostic workflows. Such efficiency and practicality lower the barrier to adoption and integration into existing clinical infrastructure.

The nnU-Net system constructed in this study, behind the surface numerical value of 54.95% Dice coefficient, embodies a methodological breakthrough in the collaborative interpretation of the physical essence and biological characteristics of medical images. Previous studies on visible lesions (such as PI-RADS 4-5 grades) often relied on macroscopic features such as organ structure deformation or obvious signal interruption, and their segmentation essence was “locating known abnormal areas”. However, this study faced lesions that presented nearly normal anatomical structures in conventional sequences (T2/DWI/ADC)—this means that the model needs to identify malignant signals from the microscopic texture heterogeneity, which is comparable to finding the specific morphological differences of sand grains in a desert. Compared to the relatively lower Dice coefficients in previous studies (including mixed data containing macroscopic lesions), the performance of this model on pure microscopic lesions actually demonstrates higher technical value. At the same time, the biological decoding of radiomics features is another important contribution of this study. The model operates through a three-level feature engine: the primary convolution layer captures pixel intensity gradients (such as microsecond-level diffusion differences in ADC values), the intermediate network parses sub-millimeter texture features (such as the tissue homogeneity disruption represented by Markov random fields), and the high-order network integrates spatial topological relationships (such as the fiber bundle orientation distortion caused by the “pushing effect” of the stroma around the cancer).18–20 These features may correspond to relevant carcinogenic mechanisms in molecular imaging studies: abnormal calcium ion channels leading to local water molecule diffusion limitation (ADC feature), collagen fiber cross-linking rupture (texture feature), and mechanical stress transmission at the tumor-stroma interface (topological feature). This also explains why experienced physicians still miss diagnoses—the human eye’s resolution limit for single pixel gray level is 2%, while the model can identify 0.5% differences in ADC values; more importantly, the human brain cannot decouple the quantization noise of the DWI sequence from the real biological signal, while nnU-Net achieves noise removal through frequency-domain wavelet transformation.

Another core clinical value of this system lies in the redefinition of the “MRI-negative” medical term. The traditional PI-RADS standard describes lesions with a score of 3 as “extremely low probability of malignancy”, which actually artificially sets the sensitivity threshold of imaging examinations at approximately 80 μm (the current highest resolution of MRI). However, pathological studies have shown that over 35% of micro-diseases in prostate cancer (<3 mm) can achieve distant metastasis through perineural invasion (PNI). The hidden lesions identified by this research model include some with a Gleason score of 4 + 3 = 7. This suggests that the “negative” nature of imaging is a technical blind spot rather than a biological static state. This leads to a revolutionary diagnostic and therapeutic approach: for patients with clinical PI-RADS scores of ≤3, the suspicious areas labeled by the system can guide targeted-saturating combined puncture schemes—additional puncture biopsies can be supplemented in the AI-identified areas, which may increase the puncture positive rate while avoiding unnecessary extensive punctures. The more profound significance of this study lies in promoting a fundamental transformation in the definition of tumor presence. Traditional medicine relies on the cognitive model of “visible with the naked eye = existence”, but this study has confirmed that malignant tumors still have active biological behaviors below the imaging visibility threshold. This is cross-modally corroborated with the discovery in liquid biopsy that ctDNA “signals precede lesions”, jointly pointing to the tumor occurrence pattern of “molecular abnormalities precede structural abnormalities”. Some of the micro-diseases identified by the system present a characteristic “galaxy-like” distribution—core area ADC values decrease accompanied by ring-shaped texture disorder bands, which are confirmed by pathology as central catheter cancer and peripheral stroma remodeling areas. This area, which appears as “uniform gray scale” in human vision, is actually a potential lesion for multi-strain tumor evolution. Just as PET-CT changed the perception of “all or nothing” for metastatic foci, this system may reconstruct the continuous map of spatial heterogeneity of prostate cancer.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, this study is limited by its single-center dataset of 150 patients, which may affect generalizability. External multi-center validation is planned to enhance robustness. Future studies will address these aspects. Secondly, tumor localization in this study was retrospectively inferred by mapping biopsy-confirmed sites onto pre-biopsy MRI scans. This indirect method introduces a certain degree of spatial uncertainty, as the precise correspondence between biopsy needle trajectory and MRI imaging plane is inherently limited. Additionally, operator-dependent interpretation during localization may introduce bias. Unlike whole-mount pathology from prostatectomy specimens, this approach lacks histological spatial precision, which may influence the ground truth used for training the AI model and potentially affect segmentation accuracy. Future studies incorporating MRI-ultrasound fusion-guided biopsy data or post-prostatectomy histopathology could enhance spatial fidelity and reduce such biases. Finally, this study did not perform an ablation analysis to compare nnU-Net with other architectures, such as Transformer-based models. Future work should include comparative studies to justify model selection.

This study developed an AI-based image recognition system using the nnU-Net adaptive neural network to detect MRI-invisible prostate cancer, often missed by conventional imaging. A cohort of 150 patients with clinically significant prostate cancer (PI-RADS ≤ 3 on MRI) was analyzed, and the model achieved a Dice coefficient of 55.0% through five-fold cross-validation.

These findings demonstrate the potential of AI to enhance diagnostic accuracy, reduce missed diagnoses, and improve patient outcomes. However, external multi-center validation and more precise tumor localization post-biopsy are needed to support clinical translation. Overall, the integration of AI into prostate cancer diagnostics may significantly advance early detection and personalized treatment strategies.

Acknowledgement

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

This research was not supported by any fundings.

Author Contributions

Jingcheng Lyu was responsible for collecting and analyzing data, designing the research, visualizing and drafting the article. Ruiyu Yue was responsible for collecting data, designing the research, visualizing and drafting the article. Boyu Yang was responsible for collecting data and drafting the article. Xuanhao Li and Jian Song were responsible for revising the paper and designing the research. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committees and with the Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for ethical approval and informed consent was waived by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Beijing Friendship Hospital, Capital Medical University (Approval No. 2024-P2-153), as the study involved retrospective analysis of anonymized clinical data without any direct patient intervention or identifiable private information.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Chu F, Chen L, Guan Q et al. Global burden of prostate cancer: age-period-cohort analysis from 1990 to 2021 and projections until 2040. World J Surg Oncol 2025;23(1):98. doi:10.1186/s12957-025-03733-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Radtke JP, Kuru TH, Boxler S et al. Comparative analysis of transperineal template saturation prostate biopsy versus magnetic resonance imaging targeted biopsy with magnetic resonance imaging-ultrasound fusion guidance. J Urol 2015;193(1):87–94. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2014.07.098. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Wang R, Wang H, Zhao C et al. Evaluation of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging in detection and prediction of prostate cancer. PLoS One 2015;10(6):e0130207. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0130207. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Wysock JS, Mendhiratta N, Zattoni F et al. Predictive value of negative 3T multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging of the prostate on 12-core biopsy results. BJU Int 2016;118(4):515–520. doi:10.1111/bju.13427. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Twilt JJ, van Leeuwen KG, Huisman HJ, Fütterer JJ, de Rooij M. Artificial intelligence based algorithms for prostate cancer classification and detection on magnetic resonance imaging: a narrative review. Diagnostics. 2021;11(6):959. doi:10.3390/diagnostics11060959. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Isensee F, Jaeger PF, Kohl SAA, Petersen J, Maier-Hein KH. nnU-Net: a self-configuring method for deep learning-based biomedical image segmentation. Nat Methods 2021;18(2):203–211. doi:10.1038/s41592-020-01008-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Bhandary S, Kuhn D, Babaiee Z et al. Investigation and benchmarking of U-Nets on prostate segmentation tasks. Comput Med Imaging Graph 2023;107(1):102241. doi:10.1016/j.compmedimag.2023.102241. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Singla D, Cimen F, Narasimhulu CA. Novel artificial intelligent transformer U-NET for better identification and management of prostate cancer. Mol Cell Biochem 2023;478(7):1439–1445. doi:10.1007/s11010-022-04600-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Duran A, Dussert G, Rouvière O, Jaouen T, Jodoin PM, Lartizien C. ProstAttention-Net: a deep attention model for prostate cancer segmentation by aggressiveness in MRI scans. Med Image Anal 2022;77(10071):102347. doi:10.1016/j.media.2021.102347. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Weinreb JC, Barentsz JO, Choyke PL et al. PI-RADS prostate imaging-reporting and data system: 2015, version 2. Eur Urol 2016;69(1):16–40. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2015.08.052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Marra G, van Leenders GJLH, David G et al. Assessment of the reporting and incidence of prostate cancer unconventional histologies in tertiary referral institutions: an under-reported but exploding phenomenon? Eur Urol Oncol 2025;S2588–9311(25):00126–9. doi:10.1016/j.euo.2025.05.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Dai Z, Jambor I, Taimen P et al. Prostate cancer detection and segmentation on MRI using non-local mask R-CNN with histopathological ground truth. Med Phys 2023;50(12):7748–7763. doi:10.1002/mp.16557. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Vente C, Vos P, Hosseinzadeh M, Pluim J, Veta M. Deep learning regression for prostate cancer detection and grading in bi-parametric MRI. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2021;68(2):374–383. doi:10.1109/TBME.2020.2993528. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Thestrup KC, Logager V, Baslev I, Møller JM, Hansen RH, Thomsen HS. Biparametric versus multiparametric MRI in the diagnosis of prostate cancer. Acta Radiol Open 2016;5(8):2058460116663046. doi:10.1177/2058460116663046. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Stanzione A, Imbriaco M, Cocozza S et al. Biparametric 3T magnetic resonance imaging for prostatic cancer detection in a biopsy-naïve patient population: a further improvement of PI-RADS v2? Eur J Radiol 2016;85(12):2269–2274. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2016.10.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Marenco Jimenez JL, Claps F, Ramón-Borja JC et al. Rebiopsy rate after transperineal or transrectal prostate biopsy. Prostate Int 2021;9(2):78–81. doi:10.1016/j.prnil.2020.10.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Abdulmajed MI, Hughes D, Shergill IS. The role of transperineal template biopsies of the prostate in the diagnosis of prostate cancer: a review. Expert Rev Med Devices 2015;12(2):175–182. doi:10.1586/17434440.2015.990376. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Haustrate A, Shapovalov G, Spriet C et al. TRPV6 calcium channel targeting by antibodies raised against extracellular epitopes induces prostate cancer cell apoptosis. Cancers 2023;15(6):1825. doi:10.3390/cancers15061825. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Zadvornyi T, Lukianova N, Mushii O, Pavlova A, Voronina O, Chekhun V. Benign and malignant prostate neoplasms show different spatial organization of collagen. Croat Med J. 2023;64(6):413–420. doi:10.3325/cmj.2023.64.413. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Rao Z, Zhang M, Huang S et al. Cancer driver topologically associated domains identify oncogenic and tumor-suppressive lncRNAs. Genome Res 2025;35(8):1842–1858. doi:10.1101/gr.280235.124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools