Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Current and perceived optimal use of point-of-care ultrasound in urology

1 Department of Urology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA

2 Division of Urology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA 02215, USA

* Corresponding Author: Ryan L. Steinberg. Email:

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(6), 643-649. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.064818

Received 25 February 2025; Accepted 06 August 2025; Issue published 30 December 2025

Abstract

Introduction: Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is a valuable tool for clinicians, but little data exists regarding the perceptions of ideal POCUS utilization, as compared to actual use, amongst urologists. We aim to assess how perceptions align or diverge with actual practice. Methods: An institutional review board (IRB)-approved survey was developed and disseminated by email to 6 of 8 American Urologic Association Sections, program directors via the Society of Academic Urologists, and to 2 residency programs. The primary outcome was to assess differences in current and perceived optimal use. Data was collected via the University of Iowa RedCap system. Descriptive statistics and Chi-squared analyses were performed. Results: 184 non-trainees and 41 trainees completed the survey. Rates of current POCUS use were significantly lower than perceived optimal usage for renal (58% to 88%, p < 0.001), testis (37% to 74%, p < 0.001), and penile (19% to 37%, p < 0.001) application amongst the urologic organs. Current use was also lower than perceived optimal use with regard to utilization in the emergency room (16% to 39%, p < 0.001) and for diagnostic purposes (53% to 81%, p < 0.001), regardless of organ focus. Sub-analysis found that trainees, compared to non-trainees, identified the inpatient unit (54% to 18%, p < 0.001) and emergency room (81% to 35%, p < 0.001) as optimal locations for use. Conclusions: Perceptions of POCUS use differ between trainees and non-trainees, especially the location of use. These results help identify areas for which training could be focused, as well as highlight the need for further research on generational variation in desired POCUS use.Keywords

Ultrasound has long been a cornerstone of urologic organ imaging; yet, historically, only transrectal ultrasound has been performed by urologists. With advances in ultrasound technology and reduced equipment costs, the ability to perform point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) has expanded, but actual utilization in urology has remained limited. This is in spite of many well-established benefits, including real-time results.1,2

Our prior work has demonstrated that urologists have an overall favorable opinion of POCUS and a desire for further training in POCUS.3 While there is plentiful evidence supporting the merits of POCUS,4,5 there are no studies outlining contemporary opinions on the optimal use of POCUS in urology practice.

Given the limited scope of existing literature, the primary aim of this study was to describe contemporary practice patterns and perceived optimal POCUS utilization amongst practicing urologists. Our secondary objective was to assess differences in perceived optimal utilization of POCUS between trainees and non-trainees.

A survey3 was constructed which included questions regarding demographic and practice-related information, prior ultrasound education, current ultrasound use in practice (or training in the case of trainees), and perceived optimal POCUS utilization. Institutional review board (IRB) of the University of Iowa approval was obtained (IRB# 202103395) and was exempt from informed consent

The survey was sent to urology residency program directors (PDs) through the Society of Academic Urologists (SAU) listserv. In addition, all American Urological Association (AUA) sections were contacted regarding survey dissemination to their members. 6 of 8 sections chose to participate. We did not receive confirmation from all subsections on the exact number of email recipients; thus, the number is abstracted from total subsection memberships from that year. We estimated that 8300 urologists received an invitation to participate in the survey, including both trainees and non-trainees. Standalone emails requesting completion of the survey were sent to the membership, followed by a second email 1–2 weeks later. Two urology residency programs (University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics (UI) and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC)) were planned to undergo a novel ultrasound curriculum. The questions regarding current and perceived optimal use were distributed directly to these residents prior to the training and outside of the section emails.

Data were collected using the University of Iowa RedCap system (NIH CTSA UL1TR002537), and descriptive statistics were generated using SPSS 29 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and Microsoft Excel with a Chi-Squared with 0.05 as the level of significance.

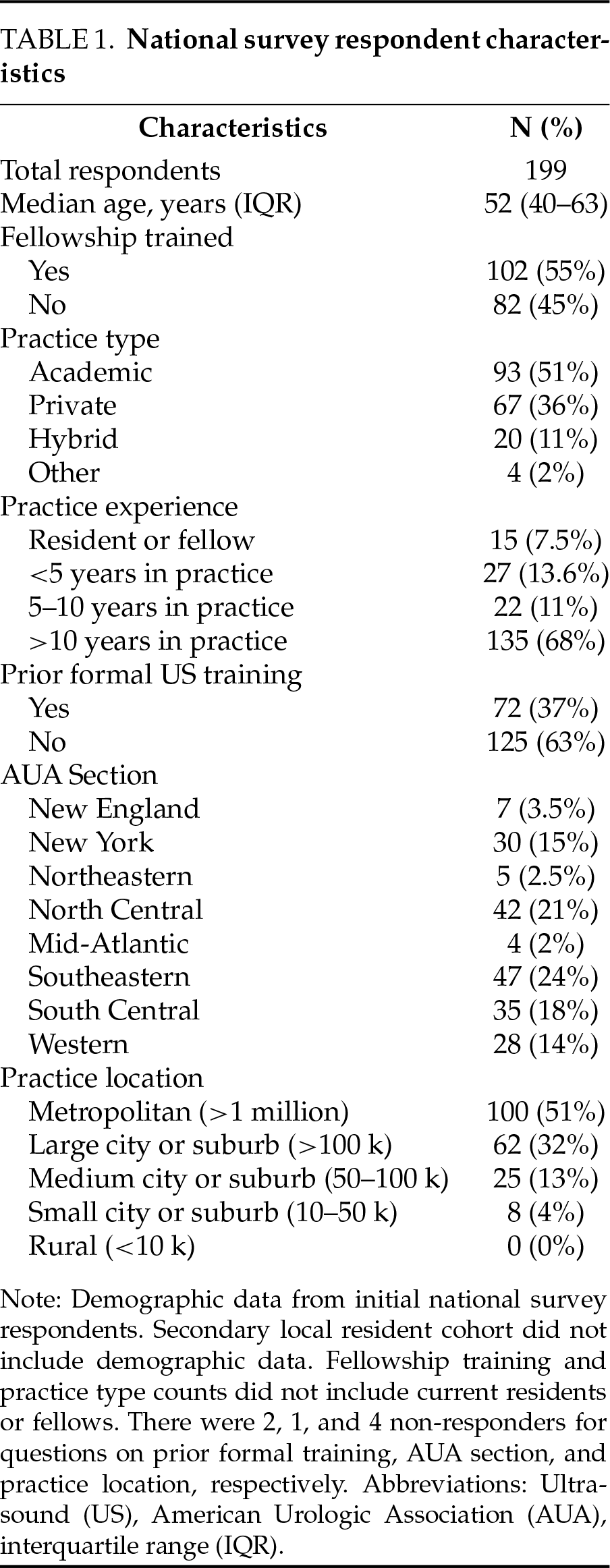

One hundred ninety-nine urologists completed the survey distributed by the SAU and AUA subsections emails, including 40 PDs, 144 non-PD practicing urologists, and 15 trainees. The response rate from AUA subsections was estimated at 2.0%, while 28% (40/143) of program directors completed the survey. The median age of respondents was 53 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 40–63), with 55%. Having completed a fellowship trained, and 51% practicing in an academic setting. Sixty three percent reported no prior formal ultrasound training. Table 1 summarizes the remainder of the cohort demographics. The secondary cohort, those at the two local residency programs, included 26 residents ranging from PGY-1 to PGY-6 training levels (9 from BIDMC, 17 from UI).

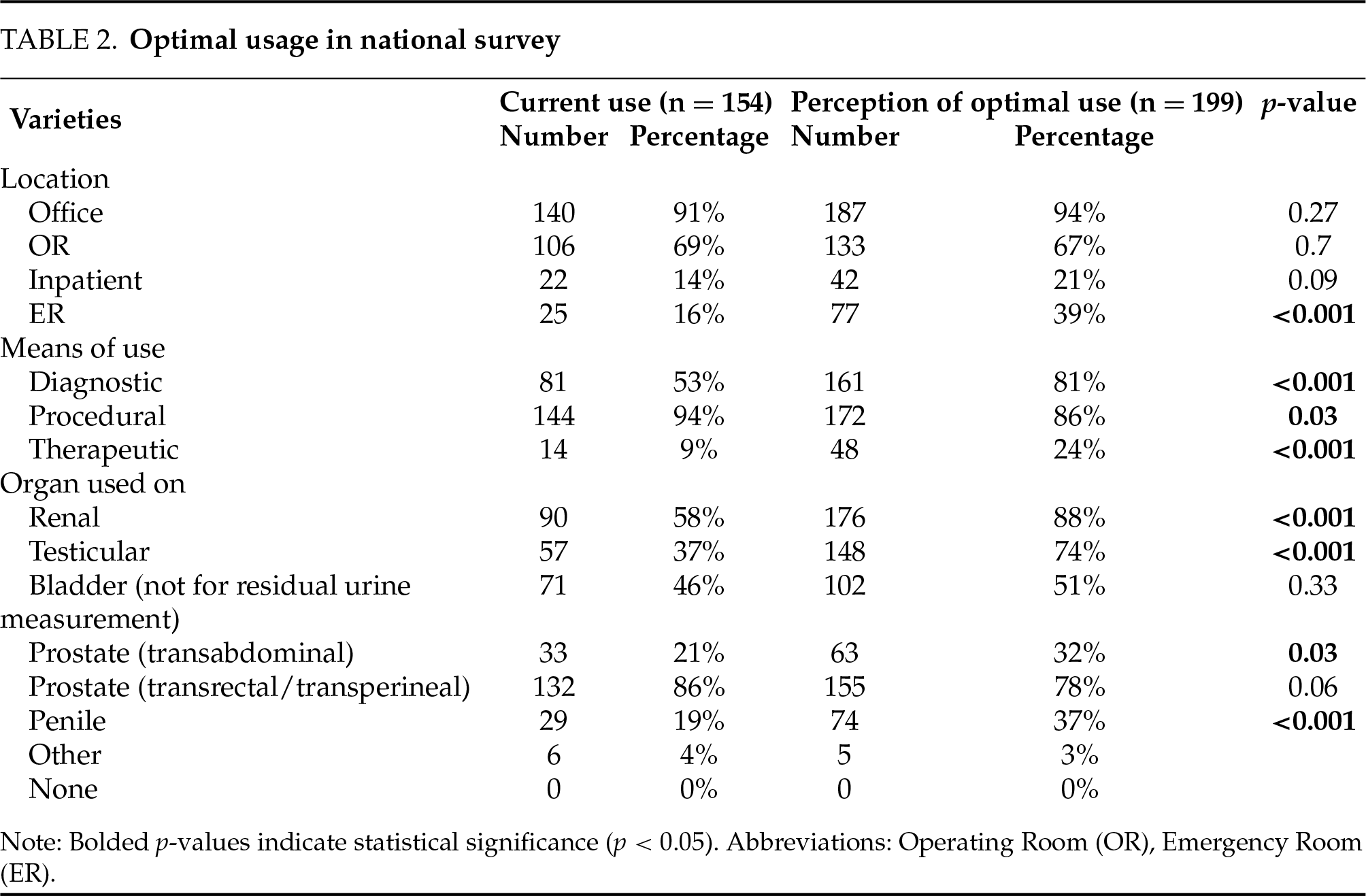

Of the national cohort of respondents, 154 of 199 (77%) urologists utilized POCUS in their practice (Table 2). The vast majority utilized POCUS as a procedural adjunct (94%), and most did perform some diagnostic POCUS (53%). The most common organ systems for current POCUS utilization were transrectal or transperineal prostatic (86%), renal (58%), and bladder (46%). The majority of respondents used POCUS in their office (91%) or in the operating room (OR) (69%). Only 16% of surveyed urologists utilized POCUS in the emergency department (ED).

When asked about the perceived optimal location of POCUS use, the majority felt that office (94%) and OR (67%) were ideal environments, similar to current rates of actual use (Table 2). However, 39% felt that the ED was an optimal location, significantly higher than actual current use (16%, p < 0.001). Regarding the purpose of POCUS use, most respondents (81%) indicated that POCUS was an optimal diagnostic tool, which was significantly higher than the current usage (53%, p < 0.001). Though therapeutic uses (described as “e.g., HIFU” in the prompt) were not common in the cohort (9%), nearly 1 in 4 (24%, p < 0.001) felt that this could be an optimal use of POCUS. The vast majority of respondents (94%) currently used POCUS procedurally, but the number reporting procedural use as optimal was significantly lower (86%, p = 0.03). When asked about the optimal organ systems for use, respondents indicated the highest perceived yield organ systems, as compared to current use, were renal (88% to 58%, p < 0.001), testis (74% to 37%, p < 0.001), and penile (37% to 19%, p < 0.001). To ensure that each of these differences were not purely driven by non-POCUS users, all analyses were replicated amongst current POCUS-users only; this confirmed rates of perceived optimal use and statistical significance in all cases.

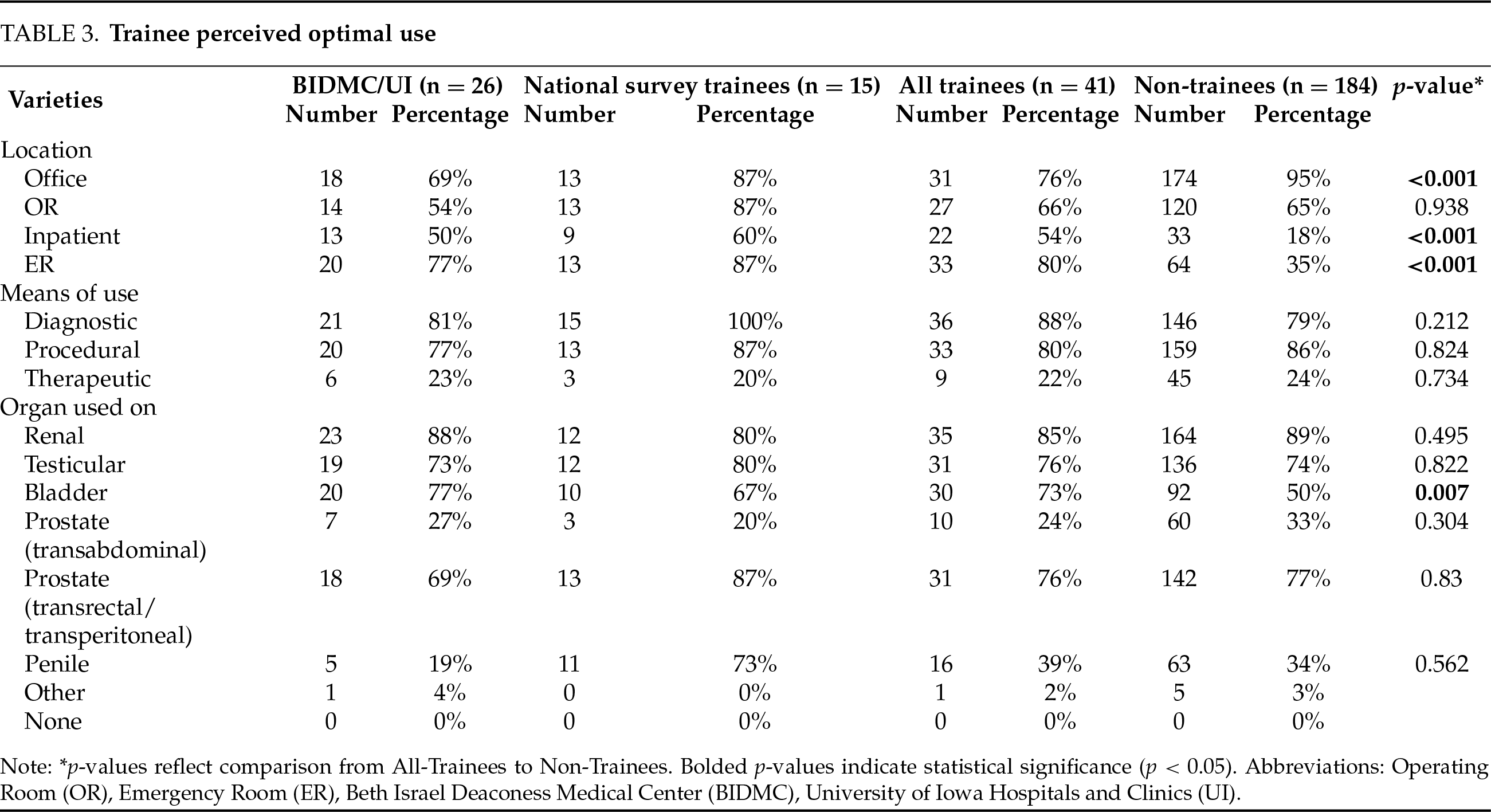

In the secondary cohort of trainees undergoing the novel POCUS curriculum, residents identified the inpatient unit (54%) and emergency room (80%) as optimal locations for use more than non-trainees (18% and 35%, respectively, both p < 0.001). Conversely, non-trainees considered the office an optimal location (95%) more than trainees (76%, p < 0.001). When considering optimal urologic organs for POCUS imaging, the bladder was the only difference noted between trainees (73%) and non-trainees (50%, p = 0.007). There were no differences identified between groups when considering the purpose for POCUS use (diagnostic, procedural adjunct, etc.) (Table 3).

The merits of POCUS are widely acknowledged, and yet, the uptake amongst urologists has been slow in light of multiple technologic advancements. Our prior work reported on utilization patterns and identified equipment procurement, imaging interpretation and medicolegal considerations as specific concerns for implementation.3 The current study builds upon this to better characterize how urologists view optimal use of POCUS in practice. The survey results demonstrated several aspects of potential underutilization in current practice, including several organ systems (renal, testicular, penile, and transabdominal prostate) and location (emergency room). Of note, the primary respondents to the survey were urologists in practice for >10 years; thus, these results likely serve as a guide with regards to best targeting future training for this cohort of urologists.

This report also augments the prior data with respect to trainee-related data. Trainees overwhelmingly felt that the emergency room and inpatient setting were ideal uses of POCUS, relative to those already in practice. While this may indicate a bias due to hospital-based training efforts and current resident practice patterns, it still indicates that trainees would value POCUS skills in these areas. Relative to non-trainees (50%), most trainees (73%) identified bladder ultrasound as a potentially useful areas for POCUS. This discordance could be impacted by different practice types and environments. Further sub-analysis was limited by the moderate sample size, but the results may illustrate interest and willingness to use POCUS as a procedural adjunct (such as suprapubic tube placement), as well as for diagnostic purposes (such as evaluation of clot burden after hand irrigation). Overall, the study demonstrated that there are differing goals and beliefs in ideal POCUS utilization amongst trainees relative to those that are more established in practice. Training efforts going forward will need to consider the needs of both of these populations and be tailored to each in order to achieve broad adoption of this skill.

Given the survey results, namely that there is a clear gap between optimal and current use patterns and strong support for dedicated training during residency,3 our group has developed a formal urology-focused POCUS curriculum. We are currently completing the initial year of implementation at our respective institutions as part of the residency training programs. Our hope is that this curriculum can be disseminated and adopted by other urology residency programs as standard practice to ensure competency in ultrasound use before entering clinical practice. Though, there are a number of hurdles that must be overcome, as indicated in the data, including equipment procurement and system integration, the need for expert instructors, and procurement of training models (either by purchase or creation). While this list appears overwhelming, this is not substantially different than any number of other curricula employed in urology over the past several decades (e.g., laparoscopy and robotics). Moving forward, we aim to identify local champions of POCUS at other institutions and provide adequate training for expertise (if needed) to allow for local implementation of this curriculum.

Beyond trainees, providing adequate opportunity for skill acquisition amongst urologists already in practice will be necessary, as well. Depending on the success of our curriculum amongst trainees, a similar structured approach could be undertaken amongst those already in practice but adjusted to account for the differences seen in our data above. Ultimately, support from the AUA, as has been done by other national medical organizations, such as Emergency Medicine,6,7 will be necessary to truly see dissemination of information and democratization of these skills.

As we better understand the current perspectives of POCUS and structure methods to teach these skills, there remain some who question whether the adoption of urologic POCUS is truly necessary. The authors fervently believe that it is. With improved technology and decreased cost, nearly every hospital and emergency room will have an ultrasound machine. But the availability of sonographers can vary. Depending on the level of rurality, there may not be an ultrasonographer or the hours that they work can be limited. In such resource-strained environments, POCUS provides physicians with autonomy and results in real time. This may lead to improved patient satisfaction.8 POCUS has also allowed certain procedures, such as renal mass biopsy, to be performed in the office, providing greater convenience to patients.9 Further, POCUS provides significant cost- and time-savings to patients during follow-up clinic visits.10 Finally, multiple new technologies for treatment of urologic conditions, including high intensity focused ultrasound11 and burst wave lithotripsy,12 are ultrasound-based. As such, if we do not invest in the necessary training to optimally utilize these devices, we risk ceding such modalities to other specialties, such as radiology or emergency medicine.

This study has several limitations. First, there was an overall low response rate to the survey, which is known to happen with dissemination through organizational email lists in general and within urology specifically.13–15 Next, our survey included the definition of POCUS, given that the principles are translatable to other broader uses of POCUS. However, we recognize this may have influenced the responses from some of the cohort. While our survey was not comprehensive in reviewing every use of urologic ultrasound, it demonstrates several key areas of POCUS use and highlights disparities amongst those at different levels of practice/training. Our results on current and perceived optimal POCUS use provide important feedback to educational programs and urologic societies regarding areas of further research and educational investment. This study could be used as a framework in the future to specifically direct POCUS training based on the desired and/or needed areas of improvement of the learner.

Current rates of POCUS use are much lower in several organ systems, practice locations, and purposes of use relative to perceived optimal rates of use, indicating underutilization in urology practice. Perceptions on optimal POCUS use differ between trainees and non-trainees, especially the location of use. These insights can serve to better curate training for POCUS amongst urologists and urology trainees.

Acknowledgement

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

The study was conducted with funding from an institutional grant from the University of Iowa Graduate Medical Education Office. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR002537.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Vignesh T. Packiam, Chad R. Tracy, Elizabeth B. Takacs, Ruslan Korets, Ryan L. Steinberg, data collection: Ryan L. Steinberg, analysis and interpretation of results: Charles H. Schlaepfer, Zubin Shetty, Ryan L. Steinberg, draft manuscript preparation: Charles H. Schlaepfer, Zubin Shetty, Chad R. Tracy, Elizabeth B. Takacs, Ryan L. Steinberg. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, RLS, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval

This study had Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Iowa approval (# 202103395) and was exempt from informed consent.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Chawla TP, Cresswell M, Dhillon S et al. Canadian association of radiologists position statement on point-of-care ultrasound. Can Assoc Radiol J 2019;70(3):219–225. doi:10.1016/j.carj.2019.06.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Moore CL, Copel JA. Point-of-care ultrasonography. N Engl J Med 2011;364(8):749–757. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

3. Schlaepfer CH, Packiam VT, Tracy CR, Takacs EB, Steinberg RL. Current utilization and perceptions of formal education of point-of-care ultrasound in urology. Urology 2024;184:8–14. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2023.11.025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Chu C, Masic S, Usawachintachit M et al. Ultrasound-guided renal access for percutaneous nephrolithotomy: a description of three novel ultrasound-guided needle techniques. J Endourol 2016;30(2):153–158. doi:10.1089/end.2015.0185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Rowley KJ, Liss MA. Systematic review of current ultrasound use in education and simulation in the field of urology. Curr Urol Rep 2020;21(6):23. doi:10.1007/s11934-020-00976-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Boulger C, Adams DZ, Hughes D, Bahner DP, King A. Longitudinal ultrasound education track curriculum implemented within an emergency medicine residency program. J Ultrasound Med 2017;36(6):1245–1250. doi:10.7863/ultra.16.08005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Chen W-L, Hsu C-P, Wu P-H, Chen J-H, Huang C-C, Chung J-Y. Comprehensive residency-based point-of-care ultrasound training program increases ultrasound utilization in the emergency department. Medicine 2021;100(5):e24644. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000024644. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Howard ZD, Noble VE, Marill KA et al. Bedside ultrasound maximizes patient satisfaction. J Emerg Med 2014 Jan 1;46(1):46–53. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.05.044. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Dave CN, Seifman B, Chennamsetty A et al. Office-based ultrasound-guided renal core biopsy is safe and efficacious in the management of small renal masses. Urology 2017 Apr 1;102:26–30. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2016.12.026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Villanueva J, Pifer B, Colaco M et al. Point-of-care ultrasound is an accurate, time-saving, and cost-effective modality for post-operative imaging after pyeloplasty. J Pediatr Urol 2020 Aug 1;16(4):472.e1–472.e6. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2020.05.156. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Ter Haar G. HIFU tissue ablation: concept and devices. Therap Ultras 2016 Jan;1(4):3–20. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-22536-4_1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Harper JD, Dunmire B, Thiel J et al. Facilitated clearance of small, asymptomatic renal stones with burst wave lithotripsy and ultrasonic propulsion. J Urol 2025 Mar;17(1):10–97. doi:10.1097/ju.0000000000004533. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Barnhart BJ, Reddy SG, Arnold GK. Remind me again: physician response to web surveys: the effect of email reminders across 11 opinion survey efforts at the american board of internal medicine from 2017 to 2019. Eval Health Prof 2021;44(3):245–259. doi:10.1177/01632787211019445. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Dubin JM, Greer AB, Patel P et al. Global survey of the roles and attitudes toward social media platforms amongst urology trainees. Urology 2021;147(3):64–67. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2020.09.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Connor J, Zheng Y, Houle K, Cox L. Adopting telehealth during the COVID-19 era: the urologist’s perspective. Urology 2021;156:289–295. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2021.03.051. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools