Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

A Review of Computational Fluid Dynamics Techniques and Methodologies in Vertical Axis Wind Turbine Development

1 Solar Energy Research Institute (SERI), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi, 43600, Selangor, Malaysia

2 Power and Energy Research Laboratories (PERL), Faculty of Engineering, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Jalan UMS, Kota Kinabalu, 88400, Sabah, Malaysia

* Corresponding Author: Ahmad Fazlizan. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(2), 1371-1437. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.067854

Received 14 May 2025; Accepted 12 August 2025; Issue published 31 August 2025

Abstract

This review provides a comprehensive and systematic examination of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) techniques and methodologies applied to the development of Vertical Axis Wind Turbines (VAWTs). Although VAWTs offer significant advantages for urban wind applications, such as omnidirectional wind capture and a compact, ground-accessible design, they face substantial aerodynamic challenges, including dynamic stall, blade–wake interactions, and continuously varying angles of attack throughout their rotation. The review critically evaluates how CFD has been leveraged to address these challenges, detailing the modelling frameworks, simulation setups, mesh strategies, turbulence models, and boundary condition treatments adopted in the literature. Special attention is given to the comparative performance of 2-D vs. 3-D simulations, static and dynamic meshing techniques (sliding, overset, morphing), and the impact of near-wall resolution on prediction fidelity. Moreover, this review maps the evolution of CFD tools in capturing key performance indicators including power coefficient, torque, flow separation, and wake dynamics, while highlighting both achievements and current limitations. The synthesis of studies reveals best practices, identifies gaps in simulation fidelity and validation strategies, and outlines critical directions for future research, particularly in high-fidelity modelling and cost-effective simulation of urban-scale VAWTs. By synthesizing insights from over a hundred referenced studies, this review serves as a consolidated resource to advance VAWT design and performance optimization through CFD. These include studies on various aspects such as blade geometry refinement, turbulence modeling, wake interaction mitigation, tip-loss reduction, dynamic stall control, and other aerodynamic and structural improvements. This, in turn, supports their broader integration into sustainable energy systems.Keywords

1.1 Background on Vertical Axis Wind Turbines

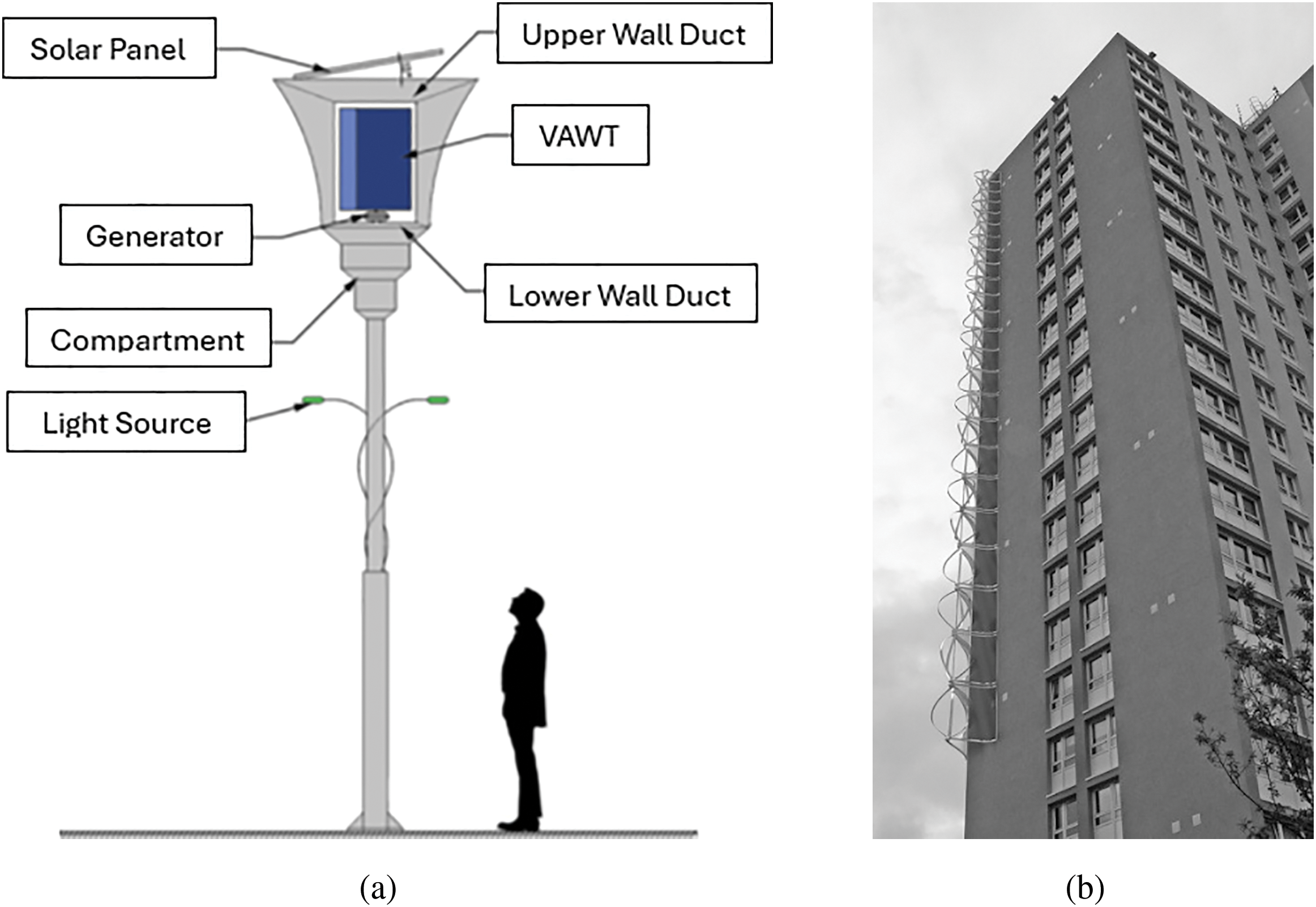

Vertical axis wind turbines (VAWTs) offer a compelling alternative to the dominant horizontal axis wind turbines (HAWTs), especially in urban environments where wind conditions are highly turbulent and unpredictable. Unlike HAWTs, which require constant reorientation to face the wind, VAWTs operate efficiently regardless of wind direction, eliminating the need for complex yaw mechanisms and reducing mechanical wear. Their design thrives in the chaotic airflow of cities, where HAWTs often underperform, and their compact, visually distinct form fits better within dense urban settings. Though typically less efficient at converting wind energy, VAWTs trade raw performance for adaptability, lower noise, aesthetic compatibility, and simpler integration into existing infrastructure [1–3]. Additionally, VAWTs can be designed with visually appealing shapes, such as helical or spiral blades, allowing them to blend into architectural designs rather than standing out as industrial intrusions. And therefore, unlike HAWTs, which require tall towers and large rotor diameters, VAWTs can be incorporated into streetlights [4–6] installed on rooftops, along highways, or even integrated into building facades [7–11] (examples are as shown in Fig. 1).

Figure 1: (a) Eco-Greenergy™ hybrid wind-solar energy generation system design and general arrangement [6], (b) Crossflex wind turbine blended into a corner of a building [11]

VAWTs are omnidirectional, meaning they can capture wind from any direction without needing complex yaw systems, making them well-suited for the changing wind conditions in urban areas [7,12,13]. Recent CFD-based works have demonstrated the urban viability of VAWTs. Yu et al. (2025) analyzed gusty inflow effects typical of street-level environments using transient CFD [14]. Saleh et al. (2025) employed ANSYS Fluent to assess helical and IceWind turbines mounted on residential buildings, quantifying both aerodynamic and energy-saving benefits [15]. Their vertical orientation means they occupy less space while still harnessing wind energy effectively. Maintenance becomes easier and safer because their generators and gearboxes are typically located at ground level, which is an essential consideration in densely populated urban areas. Furthermore, VAWTs can operate at lower wind speeds, making them viable even in areas where conventional turbines would be ineffective. Recent advancements in design, such as helical and hybrid models, have improved their efficiency by up to 30% in such environments [12,16]. In other studies, VAWTs arranged in clusters have been shown to have enhanced power output, a promising development that underscores their potential in urban settings [17]. This configuration allows for efficient operation even in turbulent wind conditions typical in urban areas.

Despite their advantages, VAWTs face challenges such as optimising start-up performance and reducing production costs. The future of vertical axis wind turbines (VAWTs) hinges on advancing computational fluid dynamics (CFD) to optimise rotor design, mitigate aerodynamic inefficiencies like dynamic stall, and enhance performance in turbulent urban flows. CFD plays a crucial role in VAWT development by enabling precise simulation of complex blade-wind interactions, allowing for innovations such as helical blades and flow control devices to reduce torque fluctuations and noise [18,19]. However, challenges persist in scaling CFD models from 2-D to 3-D analyses to capture real-world effects like blade tip vortices and structural fatigue, requiring high-fidelity simulations and validation against experimental data [20,21]. While AI-assisted design and hybrid configurations show promise for efficiency gains, standardised methodologies and cost-effective computational frameworks remain critical to overcoming VAWTs’ lower efficiency and durability concerns, particularly in large-scale applications [18,19].

1.2 Fundamentals of Computational Fluid Dynamics

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) is a branch of fluid mechanics that uses numerical methods and computational algorithms to simulate and predict fluid flow behaviour, including properties such as velocity, pressure, temperature, density, and viscosity under defined conditions [22] Acting as a virtual laboratory, CFD allows researchers and engineers to mathematically model fluid dynamics by solving complex governing equations, often replacing or complementing physical experiments [22]. It is widely applied across industries such as aerospace, automotive, energy, environmental, and biomedical engineering—for example, predicting aircraft aerodynamics to reduce wind tunnel testing or improving electric vehicle cooling systems [23]. The foundation of CFD lies in the conservation laws of physics, mathematically expressed through partial differential equations like the Navier-Stokes equations [24], which are typically too complex and non-linear to solve analytically for real-world problems. This complexity necessitates the use of numerical approximation techniques and substantial computing power to generate practical solutions [25,26].

The cornerstone of CFD simulations lies in the mathematical representation of fundamental physical principles governing fluid motion. These principles, universally applied, ensure the conservation of mass, momentum, and energy within a fluid system [24]. The conservation of mass (continuity equation) dictates that the mass within a defined fluid volume must remain constant over time unless there is a net flow of mass across the volume’s boundaries. Mathematically, it relates the rate of change of fluid density (

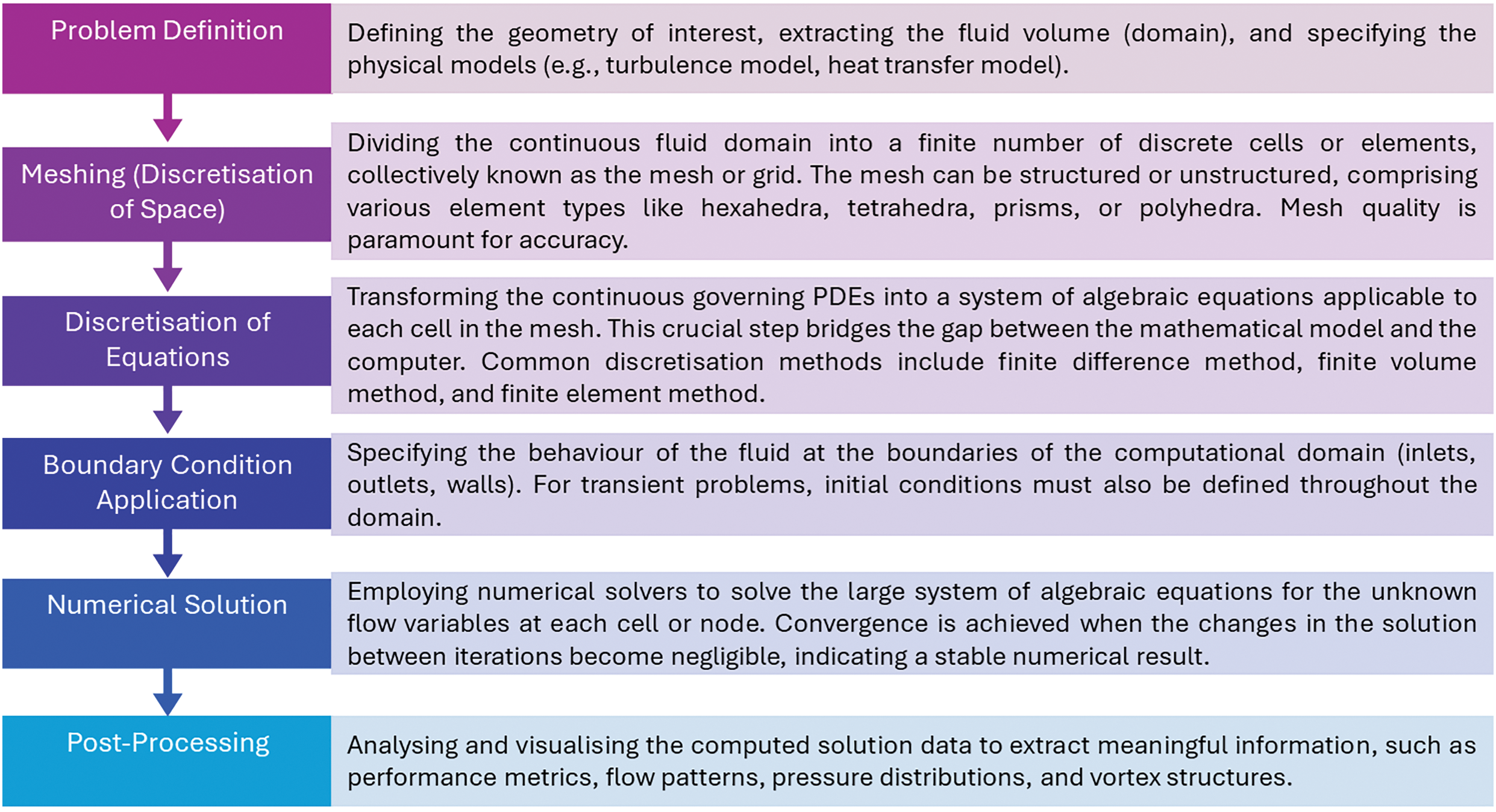

The development of CFD has closely followed the progress of high-performance computing (HPC). Early CFD work in the mid-20th century relied on simplified equations, but digital computing enabled basic simulations using methods from pioneers like Richardson and Harlow [28–32]. As computer power grew, more advanced techniques and commercial CFD software emerged. Despite these advances, CFD remains computationally intensive, particularly for the complex, three-dimensional turbulent flows that characterize VAWTs [33]. Future advancements, such as widespread use of Direct Numerical Simulation (DNS), will continue to rely on HPC progress [34]. It is crucial to recognise that CFD is fundamentally a modelling process where each step introduces assumptions and potential errors [25,35]. The results are approximations of reality, necessitating a rigorous process of verification and validation against experimental data to build confidence and understand their limitations. As shown in Fig. 2, the practical application of CFD systematically translates a physical fluid problem into a solvable numerical framework through six key stages: problem definition, meshing, equation discretisation, boundary condition application, numerical solution, and post-processing [25].

Figure 2: A typical numerical framework consists of problem definition, meshing, discretisation of equations, boundary condition application, numerical solution and finally post-processing

1.3 Contribution of the Current Review

The current review aims to map the evolution and current state of CFD analysis in the context of vertical axis wind turbines, which involves a critical comparison of the different computational approaches applied to VAWT analysis to synthesise insights from the review to highlight areas that may or may not require further exploration. Therefore, the review’s objectives are to identify key studies and trends in CFD analysis of VAWTs, and to analyse the effectiveness of various CFD models and methods.

• To identify key studies and trends in CFD analysis of VAWTs.

• To analyse the effectiveness of various CFD models and methods.

• To identify gaps and future research directions.

2 Vertical Axis Wind Turbines: Designs and Aerodynamic Complexities

Vertical axis wind turbines are characterised by their main rotor shaft being oriented vertically, perpendicular to the ground [36,37]. This fundamental design distinguishes them from the more common Horizontal Axis Wind Turbines (HAWTs) and endows them with inherent advantages.

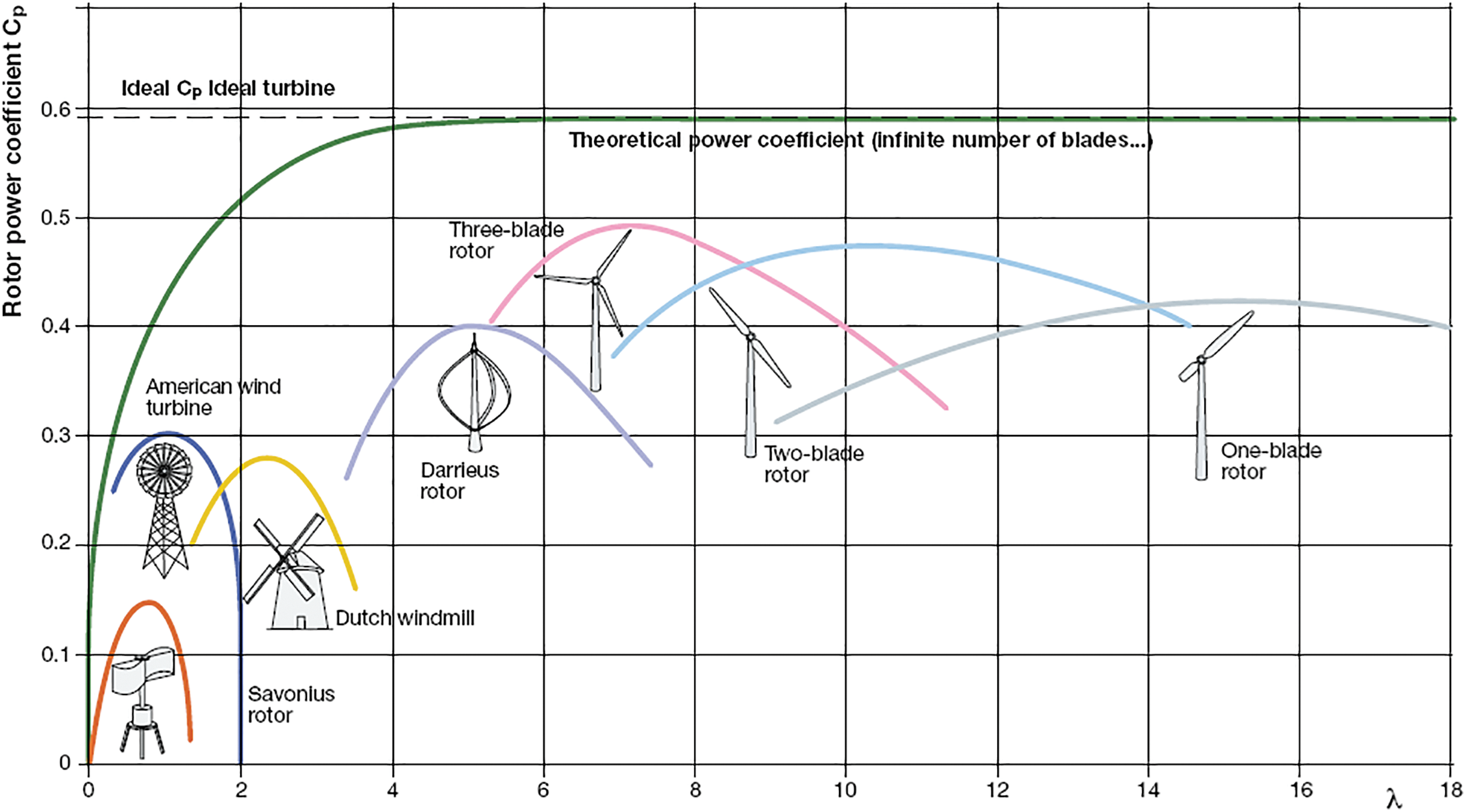

Although the efficiency of horizontal axis turbines is better than that of vertical axis turbines in wind power extraction (as shown in Fig. 3), there are still a lot of significant benefits in deploying vertical axis wind turbines as part of a renewable energy generation strategy [38]. A primary benefit of the vertical axis wind turbine (VAWT) configuration is its omnidirectional capability, allowing it to capture wind from any direction without requiring complex yaw mechanisms to align the rotor with the wind [39,40]. This simplifies the design and control systems, making VAWTs particularly suitable for environments with variable wind directions, such as urban areas or offshore locations [41–44]. Other advantages include placing heavy components at ground level, like the generator and gearbox, facilitating easier installation and maintenance [36]. Additionally, VAWTs are often perceived as producing lower noise emissions because they typically operate at lower tip speeds compared to horizontal axis wind turbines (HAWTs) of similar size, and they may have a reduced visual impact [45]. Furthermore, studies suggest that VAWTs can allow for denser arrangements in wind farms due to faster wake recovery than HAWTs, potentially resulting in higher power output per unit of land area [39]. For detailed information on different VAWT installations and configurations, readers may refer to other excellent reviews, such as the works by [46,47].

Figure 3: Various wind turbine types and their general power coefficient vs. tip speed ratio characteristic curves [38]

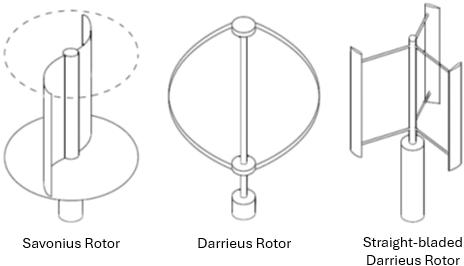

VAWT designs (some examples are shown in Fig. 4) are broadly categorised based on the primary aerodynamic principle they employ [48]:

Figure 4: From left to right—Savonius rotor, Darrieus rotor, H-rotor Darrieus (images from [48])

• Lift-Based (Darrieus Type): Named after Georges Darrieus, these turbines utilise airfoil-shaped blades designed to generate aerodynamic lift as the primary driving force for rotation [42]. The lift force acts predominantly perpendicular to the relative airflow experienced by the blade. Common Darrieus configurations include the original “egg-beater” design with curved blades attached at the top and bottom of the shaft, and the H-rotor (or H-Darrieus) design featuring straight, vertical blades attached to the central shaft via support arms or struts [36,41]. Darrieus turbines can achieve relatively high aerodynamic efficiencies. While large-scale HAWTs can exceed power coefficient, Cp values of 0.45, well-designed research VAWTs typically achieve maximum power coefficients in the 0.35 to 0.42 range [47]. CFD analysis is critical for the blade and rotor optimisation required to reach these higher efficiencies. However, a significant drawback is their typically poor self-starting capability; they often require an external impulse or operate at very low torque at low wind speeds, making it difficult for them to begin rotating from a standstill without assistance [36]. Nonetheless, over the years, research into VAWT has produced a particular novel design based on the Darrieus concept called the cross-axis wind turbine that has improved on the self-starting capabilities of the VAWT [2,49]. Another novel design utilising a vented airfoil based on the NACA0012 profile has been developed to improve torque generation at low tip-speed ratios (TSRs or λ), enhancing self-starting capabilities without significantly affecting performance at high TSRs [50]. Varying the solidity of the Darrieus-type VAWT has also been shown to enhance self-starting. By adjusting solidity, the turbine can self-start in under 30 s at wind speeds of 7.9 m/s, with improved power generation efficiency [51].

• Drag-Based (Savonius Type): Invented by Sigurd Savonius, these turbines primarily rely on aerodynamic drag forces to generate torque [45]. They typically consist of two or more curved, scoop-like vanes (often resembling an “S” shape in cross-section) [43]. The difference in drag experienced by the advancing (concave) side vs. the returning (convex) side creates a net rotational torque [41]. Savonius turbines are known for their simplicity, robustness, and excellent self-starting characteristics, even at low wind speeds [40]. Their main limitation is significantly lower aerodynamic efficiency compared to Darrieus or HAWT designs [39], where the returning blade generates a counter-acting drag force, limiting the maximum achievable TSR to around unity (λ ≤ 1) and thus capping the potential power extraction [41].

• Hybrid Designs: Attempts have been made to combine the strengths of both types, most commonly by integrating a Savonius rotor within a Darrieus rotor [40]. The Savonius component intends to provide the necessary starting torque at low speeds, while the Darrieus component delivers higher efficiency at operational speeds. However, the aerodynamic interactions between the two rotor types are complex. The wake shed by the inner Savonius rotor can negatively impact the performance of the outer Darrieus blades, potentially leading to transient load fluctuations and a lower overall peak efficiency compared to an equivalent standalone Darrieus turbine [52].

2.2 Inherent Aerodynamic Challenges of VAWTs

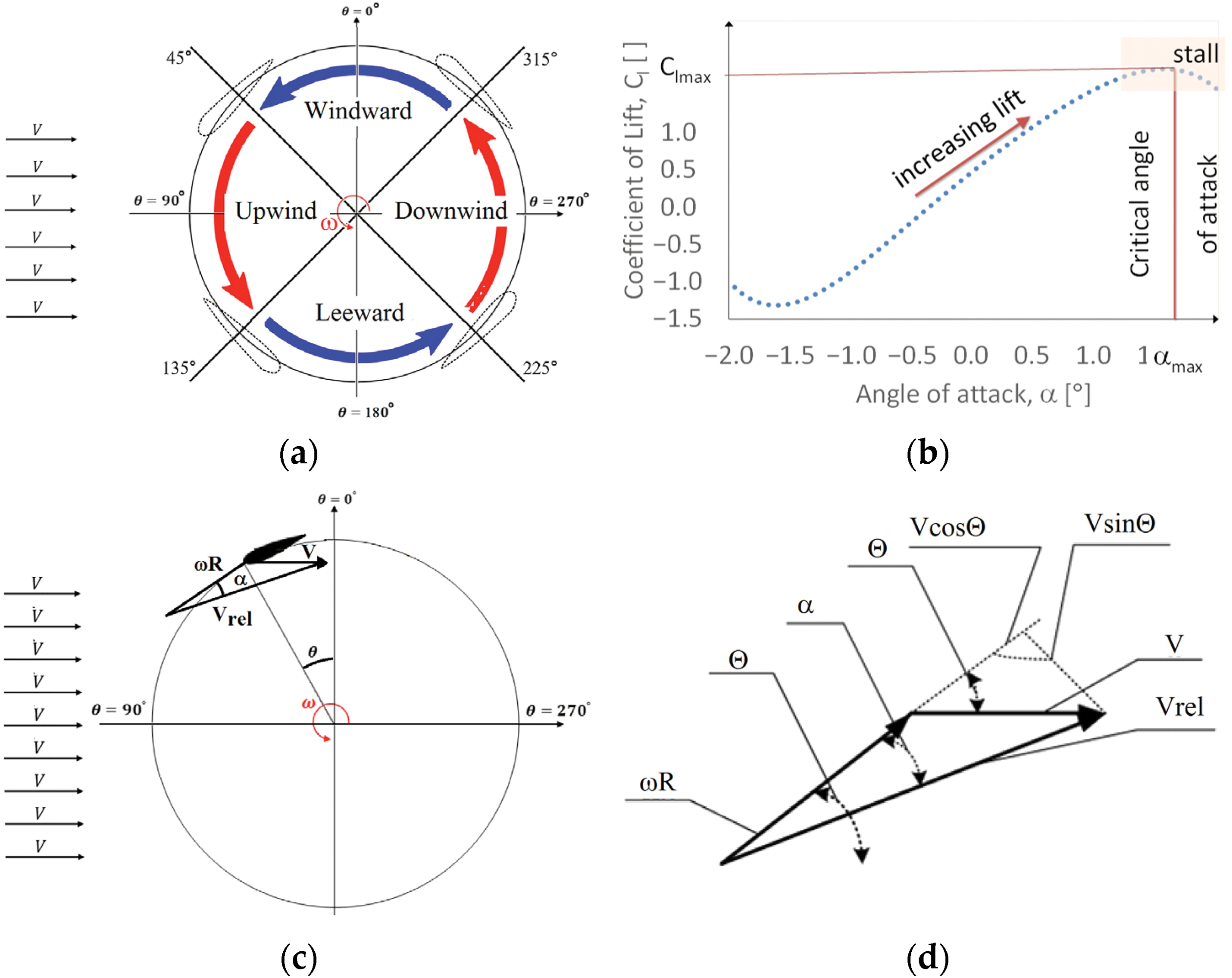

The operation of VAWTs, particularly the lift-driven Darrieus type, involves highly complex and inherently unsteady aerodynamic phenomena [39,42,53]. As a blade traverses its circular path (i.e., the azimuthal angle), the interaction between the freestream wind velocity (U∞ or V) and the blade’s rotational velocity (ωR) causes both the angle of attack (AoA or α)—the angle between the blade chord line and the incoming relative wind—and the magnitude of the relative wind velocity (UT or Vrel) continuously vary throughout each revolution [39,54]. Fig. 5 illustrates this principle. The turbine’s rotation is typically analysed by dividing it into an upwind region (where the blade moves against the incoming wind) and a downwind region (where the blade moves with the wind), as shown in Fig. 5a. As indicated by the velocity triangles in Fig. 5c,d, the changing vector sum of V and ωR, lead to significant variations in α, which in turn influence the lift (or drag) coefficient in the blades (as shown in Fig. 5b). This cyclic variation is the root cause of several significant aerodynamic challenges that complicate analysis and can limit performance.

Figure 5: Schematic representation of a vertical axis wind turbine: (a) segmentation of a wind turbine path, (b) lift coefficient,

• Dynamic Stall: This is arguably the most critical aerodynamic challenge for VAWTs, especially when operating at low Tip Speed Ratios (TSRs), typically below λ ≈ 4 or 5 [39]. Dynamic stall occurs when the blade experiences a rapid change in AoA that significantly exceeds the angle at which stall occurs under steady (static) conditions [42]. Under these dynamic conditions, flow separation is delayed, allowing lift to increase beyond the static maximum for a short period [56]. However, this is followed by the abrupt formation and shedding of large-scale, energetic vortices, primarily the Dynamic Stall Vortex (DSV), often originating near the leading edge [39,42,57,58]. The shedding of the DSV causes an abrupt loss of lift and a sharp increase in drag. This event is directly responsible for the significant torque ripple observed in VAWTs, where the instantaneous torque can fluctuate by over 100% of the mean torque throughout a single revolution [59]. These fluctuations not only reduce the average power output but also induce damaging fatigue loads on the drivetrain and support structure, which can be 2 to 4 times greater than the mean aerodynamic loads [41]. As a result, the overall efficiency and reliability of the turbine are compromised, highlighting the importance of accurate stall prediction and control for advancing VAWT performance [39].

• Blade-Wake Interactions: As VAWT blades rotate, they inevitably pass through the turbulent wakes generated by the preceding blades and interact with their wake shed during the previous revolution [41,42,60]. This interaction occurs primarily in the downstream half of the rotor’s rotation (leeward side). The blades encounter lower velocity, higher turbulence, and potentially structured vortices within these wakes [58]. This complex interaction further modifies the instantaneous AoA and relative velocity experienced by the blades, impacting their aerodynamic loads and contributing to torque fluctuations and reduced energy extraction in the downstream pass [61]. Current turbulence models used in simulations often struggle to accurately predict the wake characteristics of VAWTs, which can lead to suboptimal design and placement of turbines. Improvements in these models are necessary to better understand and mitigate the effects of blade-wake interactions on efficiency [62]. However, advanced simulation methods have been developed to better capture complex vortex dynamics and wake interactions, which more accurate predictions of wake behaviour and its impact on turbine efficiency [63]

• Other Complexities: Additional factors contribute to the complex aerodynamics, including the curvature of the flow path experienced by the blades [42], the generation of tip vortices at the blade ends in three-dimensional flows (which influence loads and wake development) [19,64], the effects of operating in skewed or highly turbulent inflow conditions, often found in urban or offshore environments [65], and potentially significant Reynolds number effects, especially for smaller turbines or specific parts of the blade operating at lower relative speeds [66].

Historically, the aerodynamic complexities associated with VAWTs, particularly dynamic stall and wake interactions, have presented significant barriers to their analysis using simpler theoretical models and contributed to their slower commercial development than HAWTs [53,67]. While VAWTs possess attractive characteristics for specific applications, realising their potential hinges on overcoming these aerodynamic challenges. This requires sophisticated analysis tools to capture the unsteady, separated, and vortical flow features inherent to their operation. Advanced computational methods like CFD and targeted experimental validation provide the necessary capabilities to unravel these complexities and guide the development of more efficient and robust VAWT designs [68].

3 An Overview of Setting up CFD Simulations for VAWT Analysis

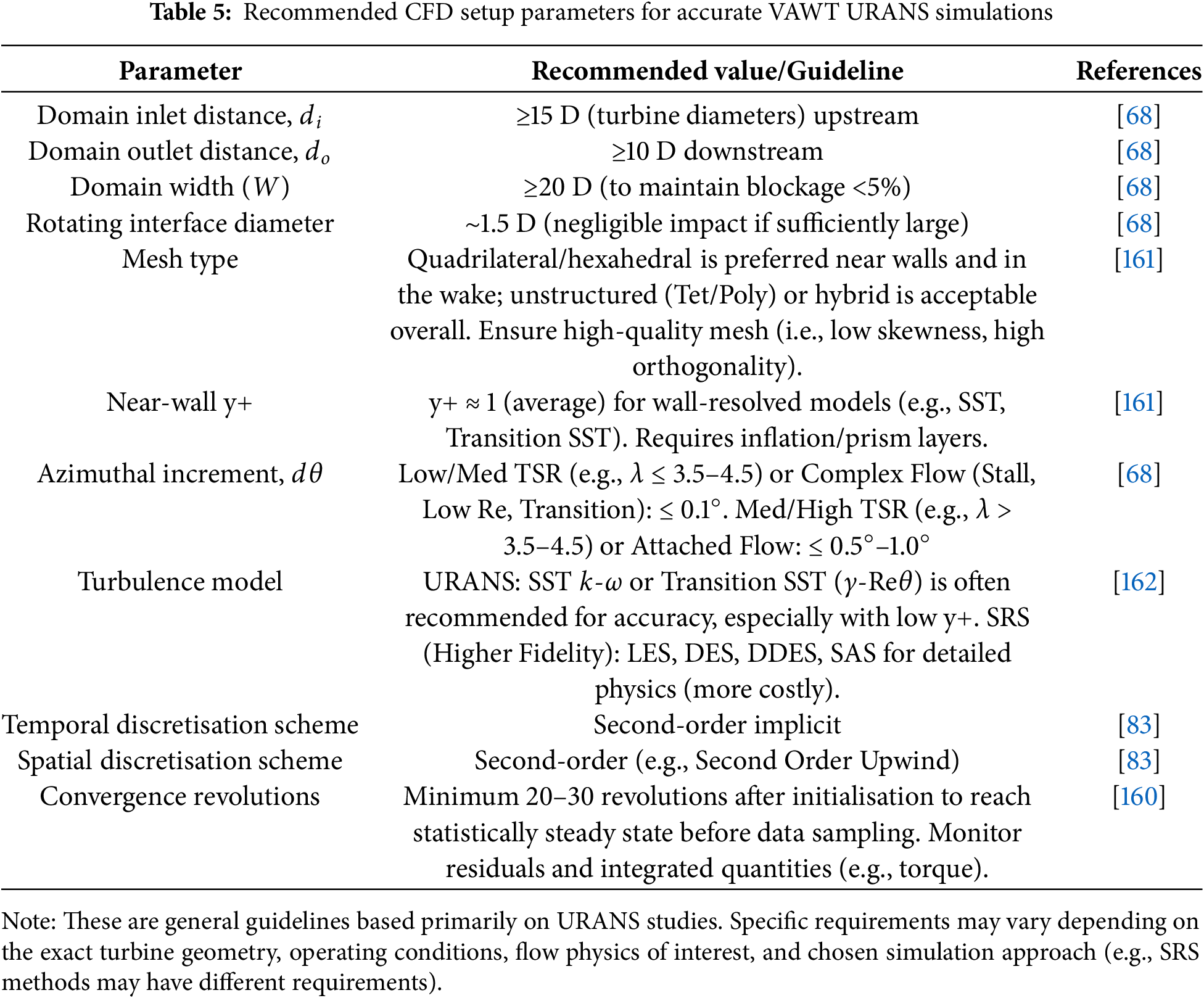

Conducting meaningful CFD analysis of VAWTs requires careful consideration of the simulation setup, including the computational domain, boundary conditions, mesh generation strategy, turbulence modelling, and solver configuration. These choices significantly impact the simulation’s accuracy, stability, and computational cost.

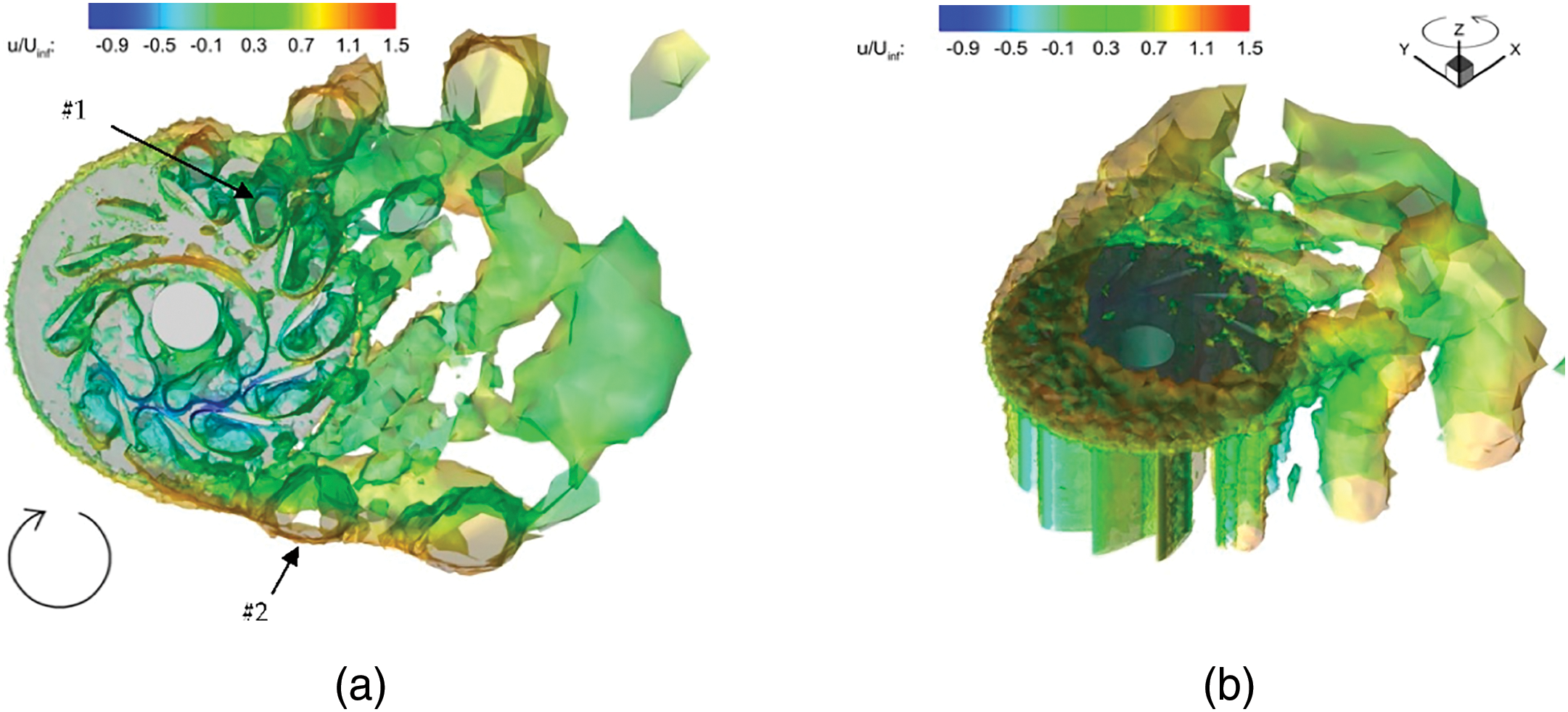

3.1 Significance of 2-D vs. 3-D Modelling in VAWT CFD Simulations and Analysis

Simulation dimensionality is critical when evaluating turbulence model performance in VAWT CFD applications. Two-dimensional (2-D) simulations have been extensively employed, particularly in earlier research and parametric analysis studies, primarily due to their reduced computational requirements [69–73]. This approach provides a reasonable computational cost while delivering an accurate estimation of turbine performance [73]. However, empirical evidence demonstrates that 2-D simulations inherently fail to capture essential three-dimensional (3-D) flow phenomena that substantially impact VAWT aerodynamic performance and behaviour, especially for configurations with low aspect ratios that characterise numerous contemporary designs [69]. These 3-D effects encompass blade tip vortices, spanwise flow divergence, structural element interference, and associated aerodynamic losses [73,74]. The neglect of these phenomena in 2-D simulations results in a systematic overestimation of VAWT performance metrics. Specifically, by ignoring tip losses and the parasitic drag from support struts, 2-D models can overpredict the peak power coefficient by 30% to 50% compared to validated 3-D simulations and experimental data. This makes 3-D analysis essential for any performance prediction intended for real-world application [69,72,75].

While quantitatively accurate performance predictions generally necessitate 3-D simulations, 2-D analyses may retain utility for qualitative trend identification or preliminary design comparative assessments, provided their inherent limitations are appropriately acknowledged and considered [19,72,73,76]. It should also be noted that with recent advancements in computational resources, an increasing number of 3-D studies have been published, enabling more accurate representation of complex flow physics generated by VAWTs. These 3-D CFD simulations can effectively capture detailed flow characteristics through appropriate turbulence modelling, with the Spalart-Allmaras (S-A) turbulence model demonstrating a favourable compromise between model fidelity and computational requirements [19].

3.2 Computational Domain and Boundary Conditions

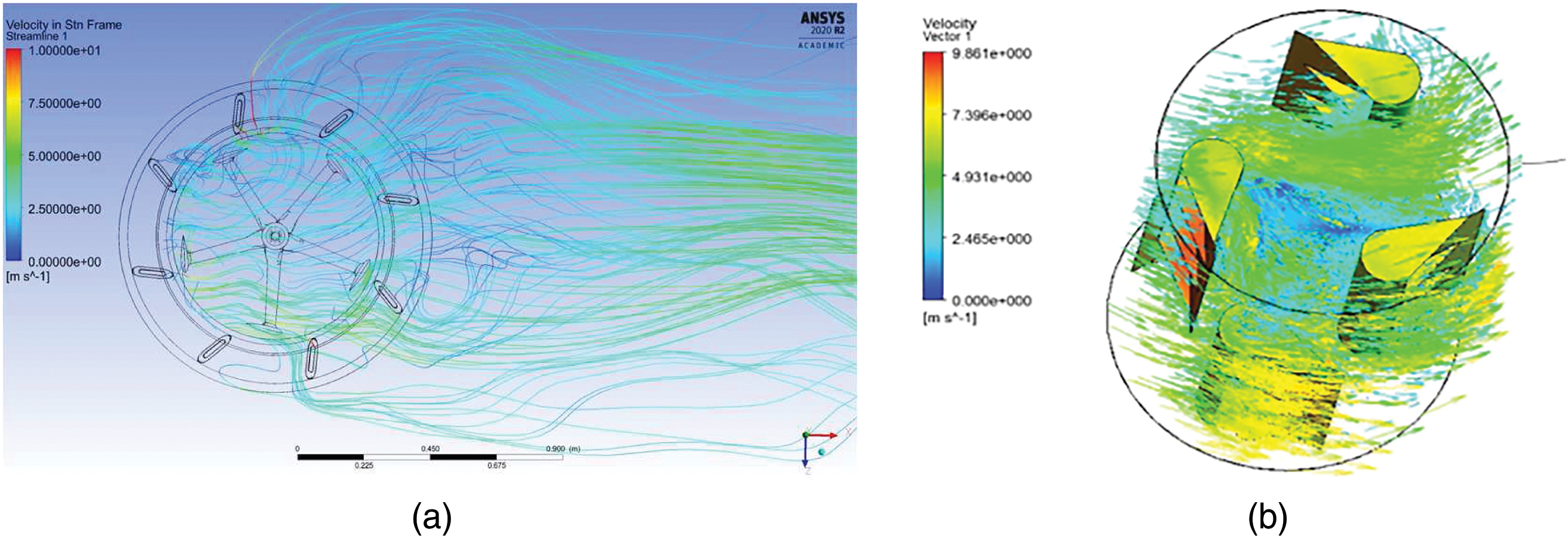

The first step in simulation involves defining the computational domain, the region of fluid flow to be simulated, which typically encompasses the VAWT and a significant portion of its surrounding environment. Fig. 6a,b shows the common overall computational domain for 2-D and 3-D simulations, respectively. The geometry is usually imported from CAD software. To handle the turbine’s rotation, the domain is commonly divided into at least two zones: an inner, rotating sub-domain that encloses the turbine blades and shaft, and an outer, stationary sub-domain representing the far-field flow [68].

Figure 6: (Left) Schematic of the computational domain, where

The size of the outer domain is critical to minimise the influence of artificial boundaries on the flow around the turbine and its wake development [68]. Inadequate domain size can lead to unrealistic flow acceleration or blockage, affecting performance predictions. Based on systematic sensitivity studies, recommended minimum distances from the turbine centre (or axis) to the domain boundaries are:

• Upstream Inlet

• Downstream Outlet

• Domain Width

• Domain Height (for 3-D): Sufficient height is needed to avoid boundary influence; for example, 2.5D was used in one large-scale VAWT study [19].

Boundary conditions (BCs) define the fluid behaviour at the edges of this computational domain. For typical VAWT simulations, these include [79]:

• Inlet: Specifies the incoming flow conditions. This can be a uniform velocity (

• Outlet: Usually defined as a pressure outlet condition, often set to zero-gauge pressure, allowing flow to exit the domain naturally. Another possibility is an outflow condition (imposing zero gradient for flow variables).

• Side Boundaries (and Top/Bottom in 3-D): Depending on the simulation setup, these can be defined as symmetry planes (or walls) (if the flow is expected to be symmetric, reducing computational cost), slip walls (zero shear stress, representing inviscid far-field boundaries), or periodic boundaries (for simulating infinite arrays).

• Turbine Surfaces (Blades, Shaft): A no-slip wall condition is applied, meaning the fluid velocity at the surface is equal to the surface velocity (zero for stationary parts relative to the frame, non-zero tangential velocity for rotating parts).

• Interfaces: Special boundary conditions are required at the interface between the rotating and stationary sub-domains. Sliding mesh interfaces (or sometimes overlapping/overset interfaces) allow for transferring flow information between the moving and fixed mesh zones while accommodating the relative motion.

3.3 Mesh Generation Strategies for Rotating Systems

Dividing the computational domain into discrete cells (i.e., meshing) is fundamental to CFD. The quality and resolution of the mesh directly impact solution accuracy and stability [68]. The governing equations of fluid dynamics (i.e., Navier-Stokes equations) are then solved numerically within each cell [81]. For VAWTs, CFD aims to predict [82,83]:

• Aerodynamic forces (lift and drag) on the blades.

• Torque and power generation.

• Flow patterns, including wake structures and blade-wake interactions.

• Effects of design changes (airfoil shape, solidity, number of blades, and others).

• Dynamic stall phenomena.

Many researchers employ strategies that suit their requirements and objectives to predict the many inherent characteristics of a VAWT in CFD. An overview of the strategy is discussed as follows:

3.3.1 Mesh Types and Strategies for VAWT

The choice of mesh topology is a critical decision in VAWT simulations, balancing geometric complexity, solution accuracy, and computational cost. The main strategies are structured, unstructured, and hybrid meshing, as follows:

• Structured mesh: Structured meshes are characterized by a regular grid pattern (quadrilaterals in 2-D, hexahedra in 3-D), which offer high computational efficiency and allow for precise control of cell quality. This makes them ideal for resolving the critical boundary layer region around VAWT airfoils, where high orthogonality and smooth cell transitions are paramount for accuracy [69]. However, generating structured meshes for complex geometries like a complete VAWT system with curved blades and support struts can be difficult and time-consuming [84,85]. Fig. 7 illustrates the variation of structured mesh for the 2-D and 3-D simulation of VAWT.

Figure 7: (a) 2-D structured mesh near a blade, (b) structured mesh of the whole domain, where the mesh is clustered around the rotor and in the wake region, (c) 3-D mesh around the blade and the adjacent arm, and (d) the 3-D mesh of the surrounding subdomain at the symmetric plane [69]

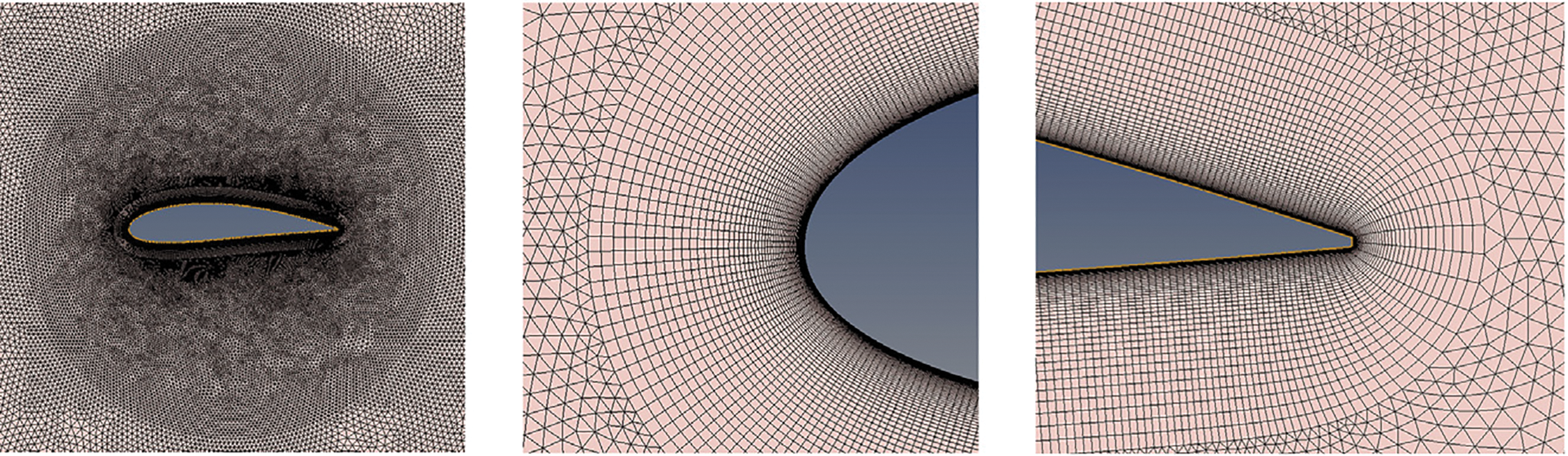

• Unstructured mesh: Unstructred meshes typically use triangles (2-D) or tetrahedra (3-D) to provide significant flexibility to handle the complex and irregular geometries of VAWTs with ease [86]. Their generation can be highly automated, and they are well-suited for local mesh refinement. The trade-off is that they may be more memory-intensive and can produce lower-quality cells (e.g., high skewness) if not generated carefully, which can impact solver convergence and solution accuracy [87]. Fig. 8 shows an example of unstructured mesh on a Savonius turbine simulation.

Figure 8: The unstructured meshing of the Savonius turbine [88]

• Hybrid mesh: Hybrid meshes represent the most common and effective strategy in modern VAWT CFD, combining the strengths of the other two approaches [89]. This strategy typically employs a structured mesh with thin inflation layers directly around the blade surfaces to accurately capture the boundary layer, while using a flexible unstructured mesh for the rest of the rotating and stationary domains. This hybrid approach provides an optimal balance, ensuring high-fidelity results in critical flow regions while efficiently handling complex geometries, and is now standard practice in high-fidelity aerodynamic studies of VAWTs [90–92]. Fig. 9 depicts an example of structured and unstructured mesh combination.

Figure 9: The hybrid mesh strategy, where the structured grids are used near the airfoil walls, and unstructured grids elsewhere in the domain [93]

3.3.2 Mesh Refinement and Independence

Beyond topology, the mesh density must be sufficient to capture high-gradient flow regions. This is achieved through mesh refinement, a process that is defined before the simulation begins (static refinement) and remains fixed. Refinement is targeted at areas where significant flow changes are anticipated, such as near blade surfaces, leading and trailing edges, and in the expected path of the wake. A critical verification step is to perform a mesh independence study, where simulations are run on a series of progressively finer meshes (e.g., coarse, medium, fine) to ensure that the solution (e.g., the power coefficient) no longer changes significantly with further refinement. This process is vital for quantifying the discretization error in the simulation. Several formal methods are used to assess this convergence:

• General Richardson Extrapolation (GRE): GRE is a numerical method used to improve the accuracy of numerical solutions by combining results from solutions with different discretisation sizes. It effectively removes leading-order error terms, leading to higher-order accuracy [94]. In a study by [95], the GRE was applied to a regime of 2-D CFD simulations of VAWTs to monitor the power coefficient across different mesh resolutions. The technique provided a reliable measure of mesh convergence and helped identify flow phenomena such as vortex shedding and viscous losses, which are critical to turbine performance evaluation. In another study, GRE offered encouraging results for determining mesh-independent power coefficients in simulations of straight-blade VAWTs. Compared to exhaustive mesh refinement, GRE provided reliable results with lower computational cost [85]. Additionally, the GRE was successfully used to confirm mesh independence in dynamic stall simulations of a straight-blade VAWT. The study emphasised the importance of transition models for accurately capturing laminar separation bubbles, which significantly affect stall behaviour and turbine torque prediction [85].

• Grid Convergence Index (GCI): GCI is a method used in CFD to estimate the accuracy of numerical results and assess their sensitivity to mesh discretisation. It helps to determine how much uncertainty is present in a simulation due to the mesh used, and if the results are converging towards a stable solution [96]. One of the most detailed studies by Almohammadi et al. evaluated four mesh independency techniques, i.e., mesh refinement, General Richardson Extrapolation (GRE), GCI, and a fitting method for a straight-blade VAWT. They found that while GRE was promising, GCI often failed to yield consistent results due to oscillations in the power coefficient convergence, making it unreliable in this context [85]. Despite its limitations, some studies still use GCI for initial mesh sensitivity analysis. For example, Liu et al. used GCI in assessing mesh convergence before evaluating aerodynamic performance improvements from a novel movable Gurney flap design on a VAWT [97].

3.3.3 Boundary Layer Meshing (i.e., Near-Wall Mesh Resolution,

Accurately capturing the flow behaviour very close to the blade surfaces (the boundary layer) is critical for predicting forces (lift, drag, torque) and phenomena like separation and stall. This requires careful control of the mesh resolution perpendicular to the wall, often quantified by the non-dimensional wall distance,

where

where y is the distance from the wall to the first cell center, 𝜈 is the kinematic viscosity, and 𝜏w is the wall shear stress.

The value of

VAWT simulations, especially those involving dynamic stall have shown that accurate capture of boundary layer development and separation requires finer near-wall resolution (y+ ≈ 1) for reliable torque and Cp prediction [84,101]. This is because boundary layer separation, and its timing during the blade’s azimuthal cycle, has a direct impact on the onset and intensity of dynamic stall [102]. Generating meshes that satisfy the stringent

As discussed, VAWTs operate in a complex aerodynamic environment, where the angle of attack on VAWT blades changes continuously throughout each rotation. Capturing the transient effects associated with VAWTs requires time-accurate CFD simulations where the turbine’s rotation is explicitly modelled [104]. One of the key parameters influencing the stability and accuracy of such unsteady simulations is the Courant–Friedrichs–Lewy (CFL) number, defined as:

where u is the local flow velocity, Δt is the time step, and Δx is the characteristic mesh length scale. In transient VAWT simulations, maintaining CFL ≤ 1 is typically recommended to ensure numerical stability, particularly when resolving sharp gradients near blade surfaces and wake regions. Lower CFL values (e.g., 0.1–0.5) are often necessary for accurate prediction of dynamic stall and vortex shedding phenomena, especially when using sliding mesh methods. This stability criterion is well established in CFD literature [105]. Numerical studies focusing on rotating and sliding mesh in VAWTs, such as the work by Trivellato and Raciti Castelli (2014), have emphasized the importance of strict CFL control at interface zones to ensure accurate torque and power coefficient estimation [106]. This is where moving mesh techniques come in. Three common mesh motion strategies used in simulating rotating components like wind turbine blades are sliding mesh, overset mesh, and morphing mesh, each offering distinct approaches to handling relative motion between rotating and stationary domains.

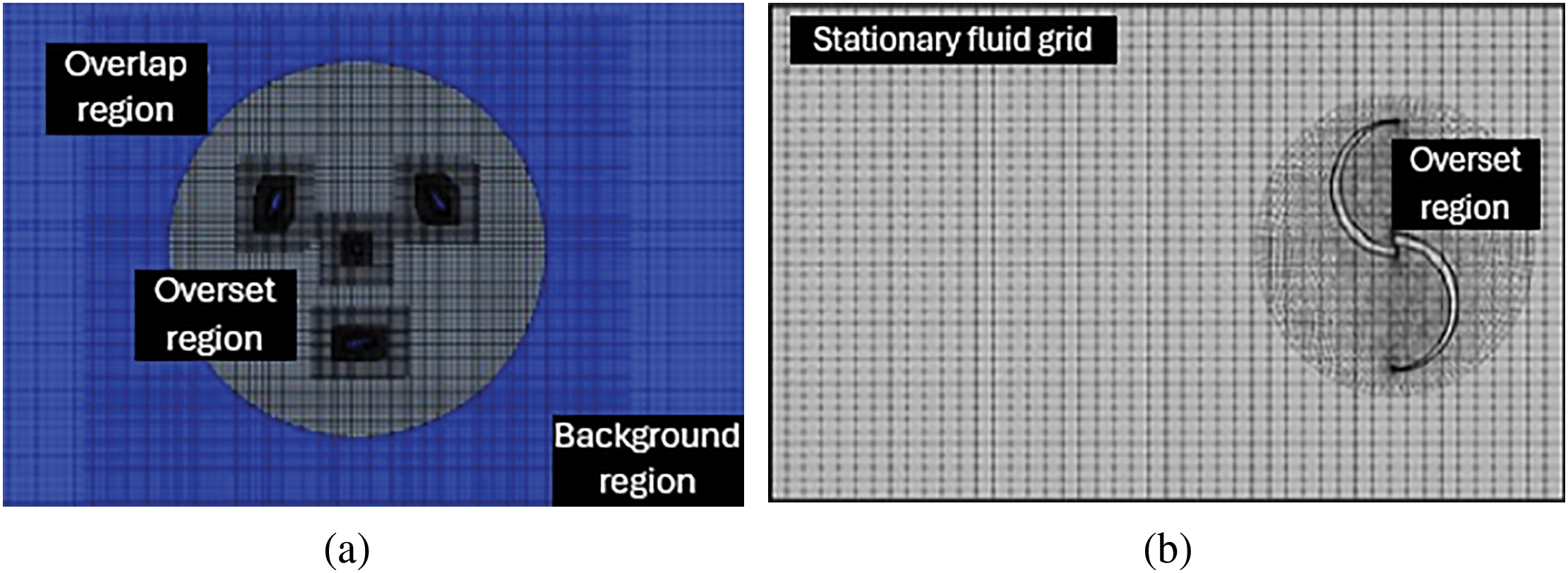

• Sliding mesh (or sliding grid): The most common technique for simulating rotating machinery is the sliding mesh approach [83]. This technique is designed to handle the relative motion between rotating and stationary components, making it highly suitable for VAWT simulations. The computational domain is explicitly divided into at least two cell zones: a rotating zone containing the turbine rotor and a stationary zone representing the surrounding environment (as shown in Figs. 6 and 7). These zones meet at one or more interface boundaries. The mesh within the rotating zone is physically rotated at the specified turbine speed relative to the stationary zone mesh at each time step. Specialised CFD algorithms are required to identify intersecting faces and accurately interpolate values between non-matching cells to compute mass, momentum, and energy fluxes across the interface at each time step [77,107]. The sliding mesh technique has proven effective for simulating VAWT rotation, showing good agreement with experiments in studies using models like the straight-bladed NACA0021, VAWT with flat plate deflectors [108], twin VAWT configurations validated against experiments [109] and variable blade pitching increasing performance by 81% at certain tip speed ratios [110] with satisfactory alignment with experimental data. Advanced applications of the sliding mesh technique include the integration of passive flow control mechanisms [111] and the effects of dielectric barrier discharge plasma actuators, which improved the power coefficient by 38% compared to conventional fixed-pitch VAWTs [112]. The sliding mesh technique offers several advantages for CFD simulations, including ease of implementation in most codes, natural handling of large rotational motions, and the ability to maintain good mesh quality within each rotating zone through rigid body motion [113]. However, it requires careful setup of interface boundaries, and interpolation across the non-conformal interface can introduce numerical errors, though these are generally minimal with adequate mesh resolution. Maintaining mesh quality near the interface is crucial, and since the method relies on an unsteady simulation framework with time-step interface calculations, it is more computationally demanding than steady-state approaches like the Multiple Reference Frame (MRF) method, which is less suited to the inherent unsteadiness of VAWTs [114].

• Overset mesh (or Chimaera mesh/overlapping grid): The overset mesh technique, also known as Chimaera grids, offers an alternative approach for handling relative motion and complex geometries. This technique uses multiple independent meshes that overlap geometrically. A “component” mesh containing the VAWT blades moves through a stationary “background” mesh representing the far-field. Cells in the overlapping regions communicate via interpolation (graphically shown in Fig. 10). Special algorithms identify active cells, inactive cells within the background mesh covered by the component mesh, and interpolation cells at the overlap boundary [115]. The overset mesh technique is prominently used to simulate the dynamic motion of floating vertical axis wind turbines (OF-VAWTs) under various degrees of freedom. This approach helps in understanding how surge motion affects the aerodynamic performance and stability of the turbines [116]. The overset mesh allows for capturing complex flow interactions around the rotor blades, which are crucial for optimising turbine design and performance under varying wave loads [117]. In the context of Savonius wind turbines, the overset mesh framework has been used to simulate wind-driven rotation and assess modifications in blade design. This approach has demonstrated potential improvements in power efficiency by 10%–28% [118]. While sliding mesh is often more efficient in simpler cases, overset mesh handles more complex and flexible movements better [91]. It also simplifies meshing by allowing separate meshing of complex components like blades, independent of the background mesh, enabling non-traditional blade motion [119]. However, it requires careful setup of overlapping regions and interpolation schemes, with accuracy depending on mesh resolution in these areas. Poor overlap or resolution can cause significant errors or conservation issues, and robust algorithms are needed to manage potential orphan cells that lack interpolation data [120].

Figure 10: (a) Computational mesh topology showing the overset and overlap regions (image cropped from [116]), and (b) a structured background mesh overlapping with an unstructured but layered mesh around the turbine in the overset region (image cropped from [118])

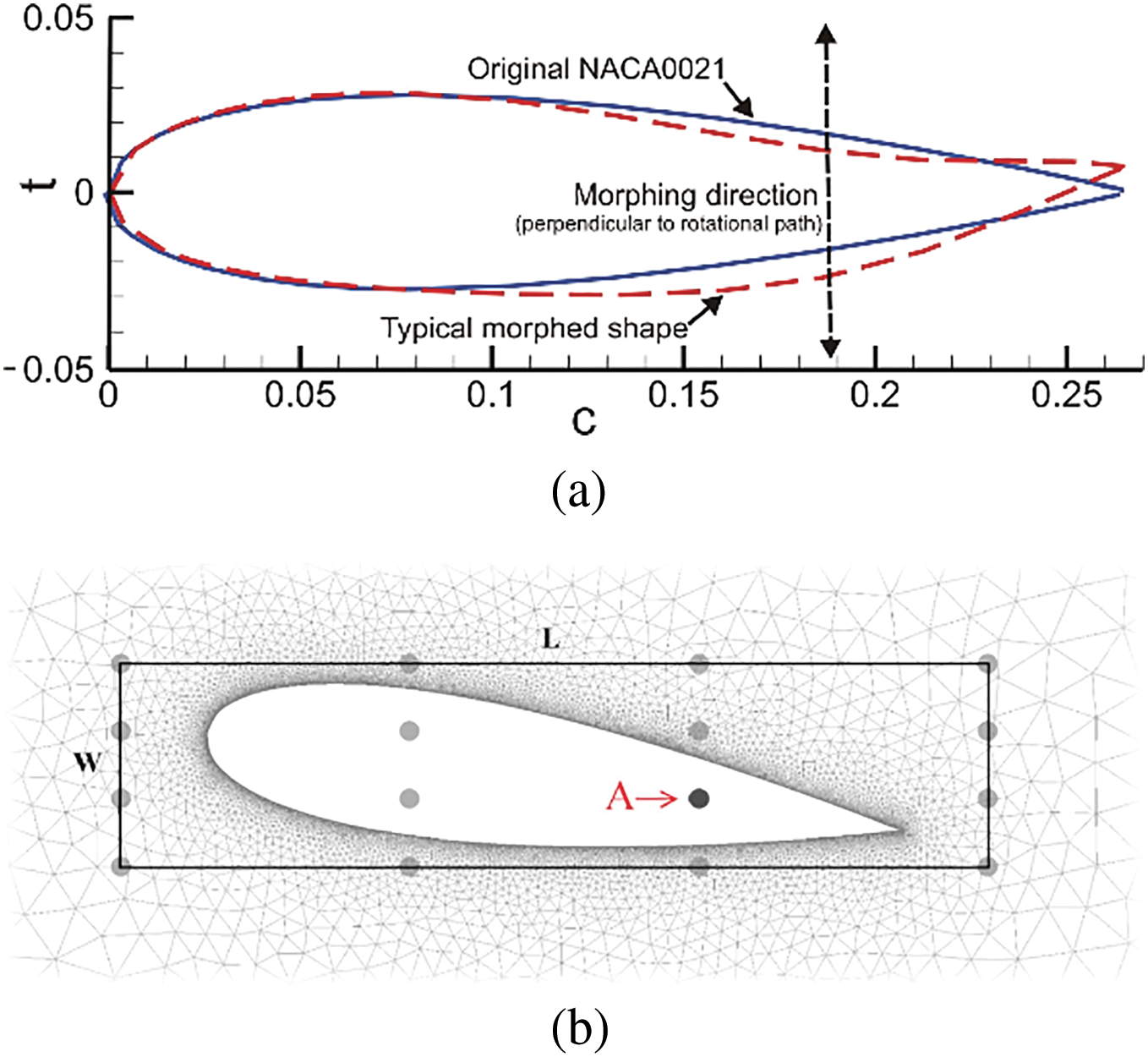

• Morphing mesh (or deforming mesh/dynamic mesh): This strategy involves adapting the mesh to accommodate boundary motion or deformation beyond the rigid body rotation handled by sliding or overset methods. They are particularly relevant for simulating Fluid-Structure Interaction (FSI) or turbines with actively deforming components like morphing blades [65,121–123]. The mesh connectivity (or the topology) of the morphing mesh technique remains constant during rotation of the blades, but the nodes of the mesh move to accommodate the boundary motion. The motion of the internal mesh nodes is typically calculated using algorithms like spring-based smoothing, diffusion-based smoothing, or remeshing techniques when distortion becomes too severe [123,124]. In a study that introduced a novel design for VAWTs that employs a blade morphing technique, the researchers dynamically adjust the blade shape based on azimuthal angle and TSR. This approach uses a Free-Form Deformation (FFD) algorithm combined with a mesh morpher and optimisation methods, leading to significant improvements in power output compared to fixed-blade designs [125]. As shown in Fig. 11, the researchers created control points to set the scale and direction of deformations. These points keep proper connectivity between deforming and non-deforming regions. The morphing mesh technique’s main advantage is that it preserves mesh topology, avoiding interpolation errors common in sliding or overset methods. It is especially well-suited for modelling structural deformations and fluid–structure interaction (FSI) problems where boundary movements are small relative to cell size [65,121]. However, it is not suitable for large, rigid body motions like full VAWT rotation, as this can severely distort the mesh and degrade quality. It also requires strong algorithms to move internal nodes without creating invalid cells, and frequent remeshing to correct distortion can be both computationally costly and prone to interpolation errors [65,124,126].

Figure 11: (a) NACA0021 unaltered shape profile vs. (a) NACA0021 morphed shape profile, and box encasement for the blade showing the control points [125]

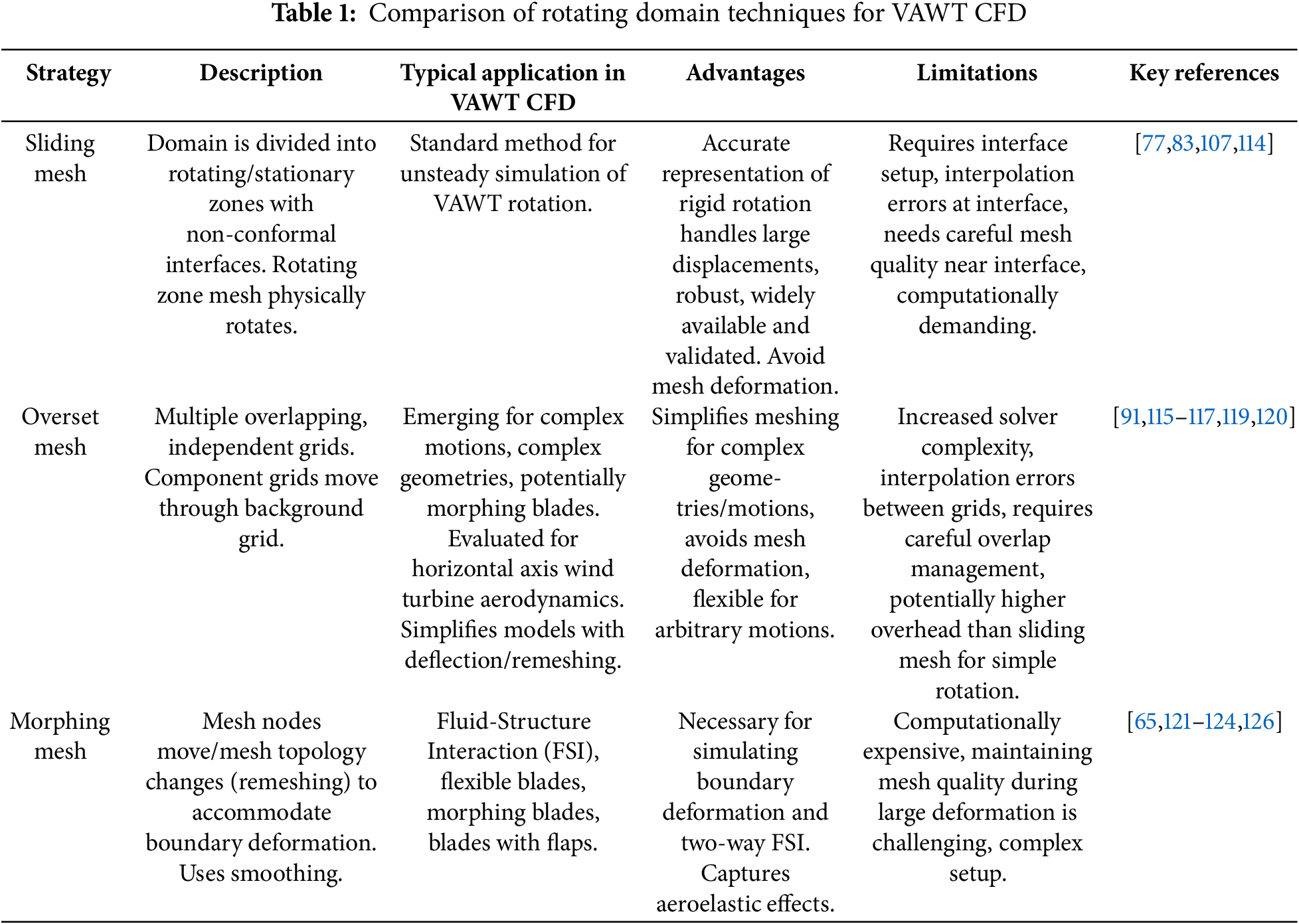

Table 1 provides a comparison of sliding mesh, overset mesh, and morphing mesh strategies, highlighting their descriptions, advantages, and disadvantages in the context of simulating rotating systems.

Beyond mesh density and near-wall resolution, the overall quality of the mesh elements significantly impacts simulation stability, convergence speed, and solution accuracy. Poorly shaped cells can introduce large discretisation errors [77,127]. Key metrics used to assess mesh quality include:

• Skewness: Measures the deviation of a cell from its ideal shape (e.g., equilateral triangle, square, regular tetrahedron/hexahedron). High skewness is generally undesirable. A maximum skewness target might be set during meshing [77].

• Aspect ratio: The ratio of the longest edge or dimension of a cell to its shortest. High aspect ratios are acceptable and often necessary in boundary layers (where cells are stretched parallel to the wall) but can be problematic in isotropic flow regions.

• Orthogonality: Measures the angle between cell faces and the vectors connecting cell centroids. Low orthogonality (high non-orthogonality) can degrade accuracy, especially for pressure-velocity coupling schemes.

• Smoothness/growth rate: Refers to the rate at which cell size changes between adjacent cells. Abrupt changes in cell size can lead to numerical errors. A gradual transition is preferred [128].

• Mesh size: The total number of cells can vary widely depending on the dimensionality (2-D vs. 3-D), geometric complexity, required resolution, and simulation type (Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes, or RANS vs. SRS). There is no standard for determining the most optimal mesh size for a VAWT CFD, since every numerical model will differ. Examples range from hundreds of thousands for 2-D Unsteady-RANS 36 to over 10 million for detailed 3-D RANS/SRS simulations [83]. Farm simulations involving multiple turbines naturally require even larger meshes [76].

CFD software packages typically provide tools to diagnose mesh quality based on these metrics. It is standard practice to check and improve mesh quality during the generation process to ensure it meets acceptable standards before proceeding with the simulation. The selection of domain size, mesh topology, near-wall resolution strategy, and turbulence model is intrinsically linked. For example, opting for a low-Re turbulence model necessitates achieving

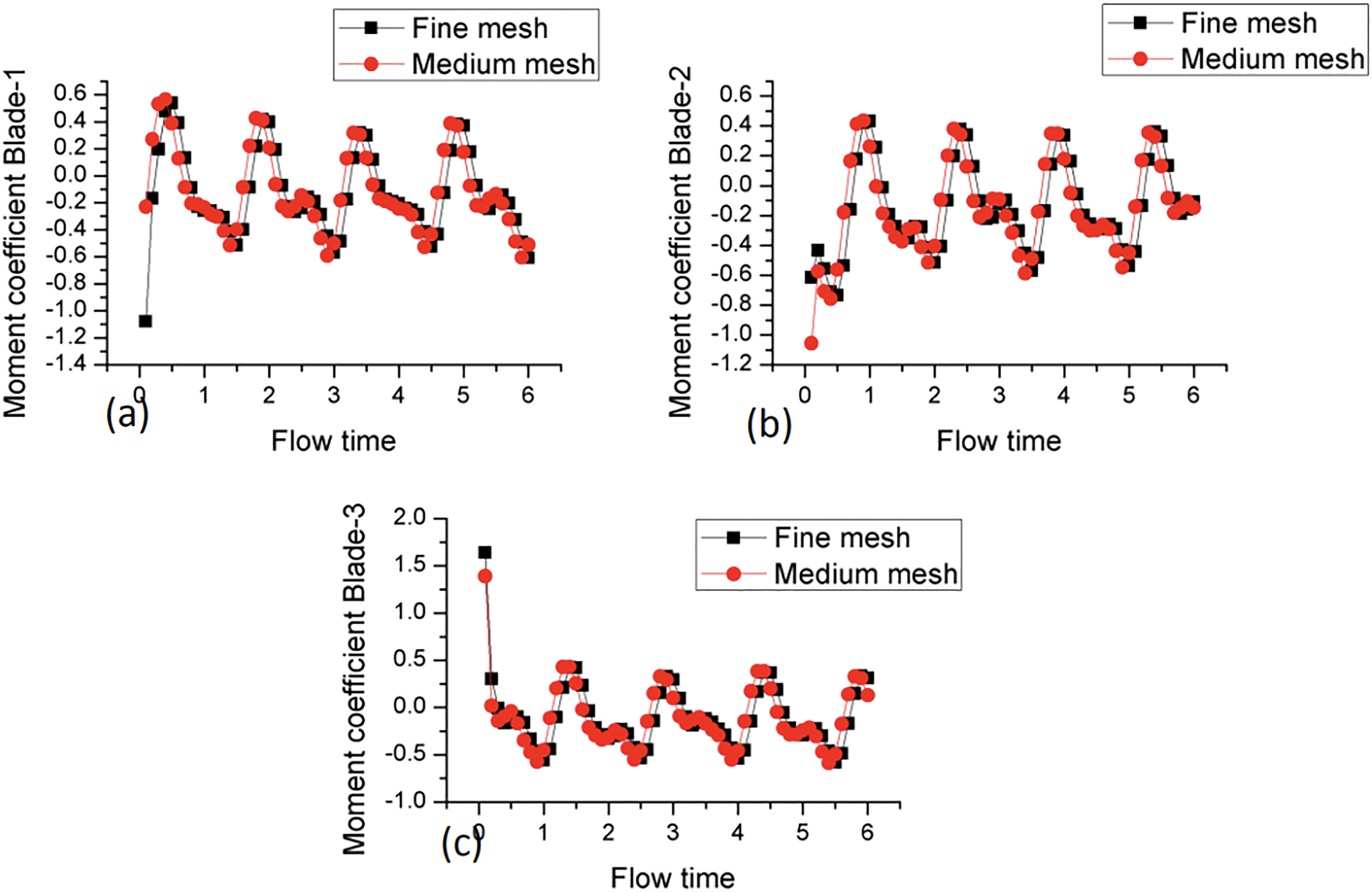

Consequently, sensitivity studies examining the impact of these parameters remain crucial for ensuring the reliability of VAWT CFD simulations. To further illustrate mesh sensitivity, Fig. 12 presents the variation of the moment coefficient (Cm) over one turbine revolution, comparing medium and fine mesh resolutions at a fixed time step of 0.0002 s. The figure is taken from Naidu et al. (2019), demonstrate that both mesh levels yield consistent aerodynamic behavior, with the fine mesh producing a smoother Cm profile [129]. This supports the mesh convergence assumption and confirms that medium mesh resolution is sufficient for capturing key unsteady flow features in 2-D VAWT simulations.

Figure 12: Instantaneous moment coefficient (Cm) of Blade 1 plotted over one full rotation (azimuth angle θ), comparing medium and fine mesh resolutions at a time step of 0.0002 s [129]

3.4 Turbulence Modelling Approaches in CFD and Their Applications in VAWT Analysis

3.4.1 The Nature of Turbulence in VAWT Flows

Turbulence represents a pervasive phenomenon within fluid dynamics, characterised by chaotic, irregular, and stochastic fluid motion occurring across diverse spatial and temporal scales [130]. Within the operational context of VAWTs, turbulence manifests through multiple mechanisms. The ambient atmospheric wind frequently exhibits turbulent properties, particularly in urban environments or complex topographical settings where VAWTs are commonly deployed [65,69]. This upstream turbulence subsequently interacts with the turbine rotor structure. Furthermore, the fluid flow surrounding the rotating blades develops turbulent characteristics as boundary layers form, potentially separate, and undergo transition from laminar to turbulent regimes [70,131]. The wakes generated by the blades, structural components, and the complete rotor assembly inherently display turbulent properties, containing complex vortical structures [68,71].

A fundamental attribute of turbulent flows is the energy cascade mechanism: large-scale eddies, which contain the majority of kinetic energy, progressively fragment into smaller eddies, facilitating energy transfer across scales until reaching the Kolmogorov microscales, where viscous dissipation transforms kinetic energy into thermal energy [132]. The principal challenge in Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) turbulence modelling accurately represents the effects of this multi-scale phenomenon on mean flow properties, including velocity distributions, pressure fields, and aerodynamic force coefficients [133]. Although Direct Numerical Simulation (DNS), which resolves all turbulent scales to the Kolmogorov scale, provides a comprehensive characterisation of turbulent flow behaviour, its computational requirements increase prohibitively with Reynolds number, rendering it impractical for applied engineering applications such as VAWT simulation [95]. Consequently, alternative modelling methodologies are implemented to render turbulent flow simulations computationally feasible.

The transition from laminar to turbulent flow can be predicted through analysis of the dimensionless Reynolds number (Re), which quantifies the ratio between inertial and viscous forces within a fluid (i.e.,

3.4.2 Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS/URANS)

The most widely used approach for industrial CFD simulations is based on the Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) equations, as shown in Eq. (4). This method decomposes the instantaneous flow variables into a mean (time-averaged or ensemble-averaged) component and a fluctuating component. Substituting these into the Navier-Stokes equations and averaging leads to equations for the mean flow that resemble the original equations but contain an additional term known as the Reynolds stress tensor [135,136]. This tensor represents the effects of turbulent fluctuations on the mean flow.

The core task of RANS turbulence modelling is to provide a mathematical model for the unknown Reynolds stresses to close the system of mean flow equations. The most common approach relies on the Boussinesq hypothesis, which relates the Reynolds stresses to the mean velocity gradients via an eddy or turbulent viscosity [135]. Models that use this hypothesis are called eddy viscosity models. Among these, two-equation models are prevalent, which solve transport equations for two turbulence quantities to determine the eddy viscosity. The most common pairs are

A fundamental limitation of the RANS/URANS approach is that it models the effect of all turbulent scales on the mean flow. It does not resolve any part of the turbulence spectrum directly. This time- or ensemble-averaging process can inherently smear out large-scale, unsteady turbulent structures that might be physically important, particularly in flows with massive separation or strong vortex shedding, such as those encountered during dynamic stall on VAWT blades [70,140]. While computationally efficient, this limitation can compromise the accuracy of RANS/URANS models for flows where the dynamics of large turbulent eddies play a dominant role. This section delves into the performance and applicability of specific RANS/URANS turbulence models commonly encountered in VAWT CFD simulations, evaluating them based on findings from the literature.

•

Turbulent kinetic energy (k) equation:

Turbulent dissipation rate (ε) equation:

Despite this computational convenience, it is generally regarded as unsuitable for accurately simulating VAWT aerodynamics due to poor performance in flows with strong adverse pressure gradients, inaccurate prediction of flow separation, and the limitations of standard wall functions [62,95,135]. Extensive comparative studies consistently show that it fails to reproduce VAWT performance metrics accurately [137,141]. While the model is computationally efficient, it provides low accuracy in the context of VAWT applications.

• RNG

• Realisable k-ϵ model: The model introduces a modified transport equation for

•

Turbulent kinetic energy (k) equation:

Specific dissipation rate (ε) equation:

• SST k-ω model: The model introduced by Menter [145], is a highly popular and effective two-equation model that blends the strengths of k-ω and

• Spalart-Allmaras (SA): The SA model is a one-equation turbulence model that solves a single transport equation for a modified turbulent kinematic viscosity (

where fv1 is a viscous damping function,and defined as:

where ν is a molecular kinematic viscosity, and

where the constants

The SA model is significantly more computationally efficient than two-equation models. This efficiency has led to its occasional use in vertical axis wind turbine (VAWT) simulations, where some studies have reported reasonable agreement in capturing dynamic stall behavior despite the model’s simplicity [83]. However, its overall performance in VAWT applications is limited. Validation studies consistently show that the SA model performs poorly in predicting key aerodynamic outputs such as power and torque coefficients (Cp, Ct) and wake development [95,135,137]. It is generally less accurate than more advanced two-equation models like SST k-ω, particularly in resolving flow separation [135]. Overall, it offers very low computational cost but at the expense of low predictive accuracy for VAWT performance [95,137].

• Transitional models (focusing on SST variants): Boundary layer transition plays a critical role in the aerodynamics of small to medium-sized VAWTs, especially at low tip speed ratios (TSRs), where local Reynolds numbers typically range from 105 to 106 [131,137,142]. In this regime, much of the blade surface may remain laminar before transitioning to turbulence, influencing separation, dynamic stall, and aerodynamic performance. Standard RANS models like k-ϵ and SST

A related approach, SST

The literature evidence indicates that the Transition Shear Stress Transport (TSST) model and its variants demonstrate enhanced predictive capability compared to conventional Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) models for Vertical Axis Wind Turbine (VAWT) simulations [78,137]. Phenomena like dynamic stall, which significantly influence VAWT torque production, involve complex boundary layer dynamics where the state of the boundary layer prior to separation plays a crucial role. By assuming fully turbulent flow, Standard RANS models inherently miss this critical piece of physics. The TSST model, by explicitly modelling intermittency and transition onset, provides a more physically realistic representation of the boundary layer development, leading to improved predictions of stall onset, vortex shedding dynamics, and overall turbine performance [78,137,142,151,152].

3.4.3 Scale-Resolving Simulation (SRS) Models

Scale-Resolving Simulation (SRS) models offer a higher-fidelity approach. Unlike RANS, which models the effect of all turbulent scales on the mean flow, SRS models aim to directly resolve the larger, energy-containing turbulent eddies while modelling only the smaller, more universal scales. This category includes Large Eddy Simulation (LES), Detached Eddy Simulation (DES), and related hybrid RANS-LES approaches like Scale-Adaptive Simulation (SAS), Improved Delayed DES (IDDES), and Stress-Blended Eddy Simulation (SBES).

• Large Eddy Simulation (LES): LES offers a higher-fidelity approach than RANS/URANS. The fundamental idea behind LES is to directly resolve the large, energy-containing turbulent eddies in the flow field while modelling the effects of the smaller, more universal sub-grid scale (SGS) eddies [70,83,95,138,139]. This is achieved by applying a spatial filter to the Navier-Stokes equations, which separates the large, resolved scales from the small, unresolved (sub-grid) scales [153]. The main advantage of LES is its potential to capture the unsteady dynamics of large turbulent structures much more accurately than RANS/URANS [70]. This is particularly relevant for VAWTs, where dynamic stall vortex shedding and wake evolution involve large, coherent turbulent structures. However, this increased fidelity comes at a significantly higher computational cost [70,138,139]. LES requires much finer computational meshes than RANS/URANS to resolve a sufficient range of turbulent scales. Additionally, LES simulations must be run as unsteady calculations with small time steps to capture the temporal evolution of the resolved eddies [154]. Due to these high costs, pure LES is often restricted to fundamental research, benchmarking studies, or simulations of relatively simple geometries or low-Re flows [70,140].

• Hybrid RANS-LES models: Hybrid RANS-LES models have emerged as a pragmatic approach seeking to bridge the gap between the computational efficiency of RANS/URANS and the high fidelity of LES [95,138–140,155]. The core idea is to combine the strengths of both methods: use the computationally cheaper RANS approach to model the flow in regions where it performs adequately (typically attached boundary layers near walls, where LES is most expensive) and switch to an LES-like approach to resolve the large, unsteady turbulent structures in regions where RANS struggles (typically separated flow regions, wakes, and free shear layers) [138–140]. Several hybrid strategies have been developed, i.e., Detached Eddy Simulation (DES) [95,140], Delayed DES (DDES) and Improved DDES (IDDES) DES [64,82,137,139,140,155], Scale-Adaptive Simulation (SAS) [95], and Stress-Blended Eddy Simulation (SBES) [138,139]. This aims to provide a more robust and rapid transition between the RANS and LES zones compared to DES-type switching mechanisms. These models aim to efficiently capture complex, separated turbulent flows typical in VAWTs, where standard RANS lacks fidelity and LES is often too costly [70,140]. The evolution from DES to SBES reflects ongoing efforts to balance accuracy and computational cost while resolving key unsteady features like dynamic stall and wake dynamics [95,138,140].

3.4.4 Summary and Recommendations

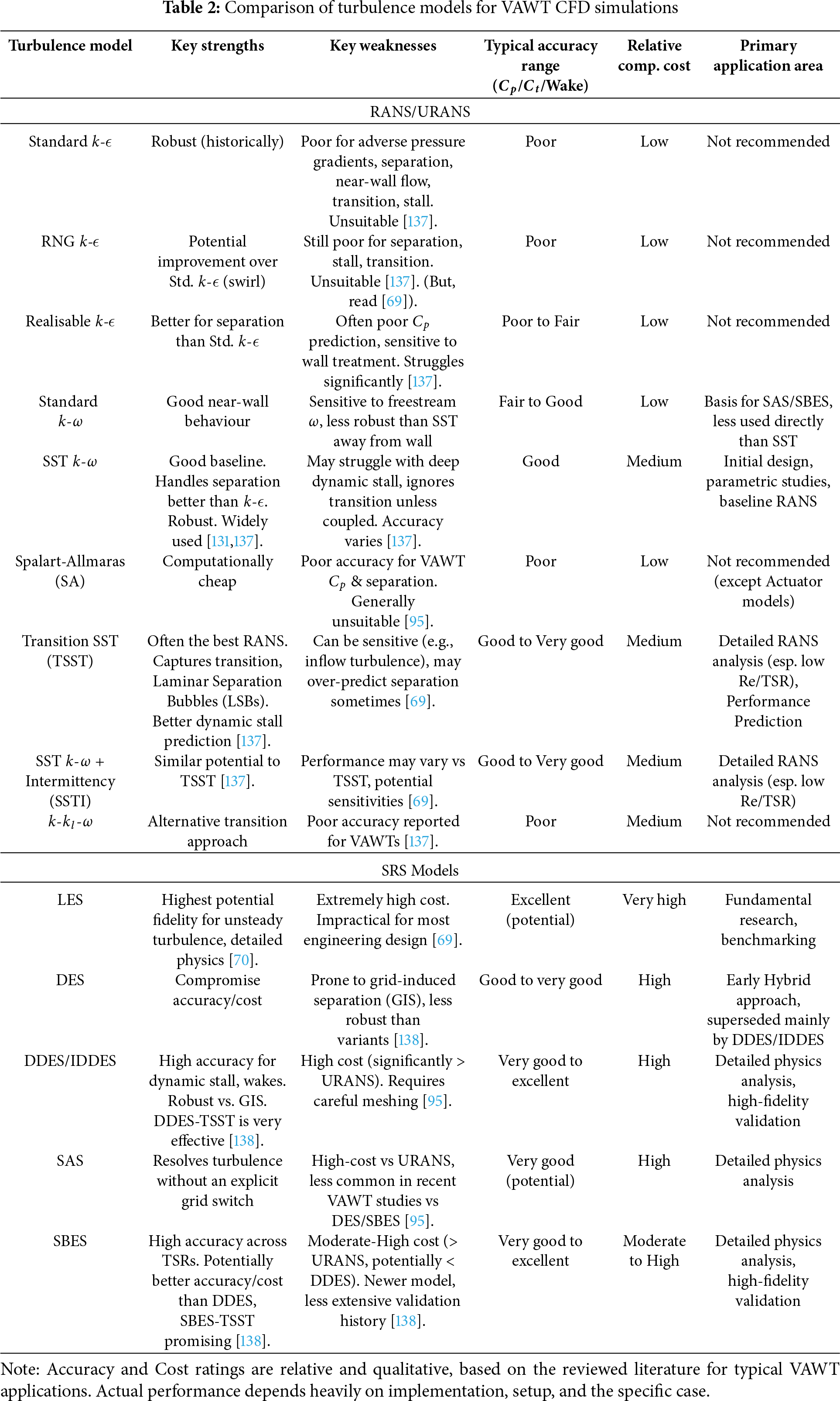

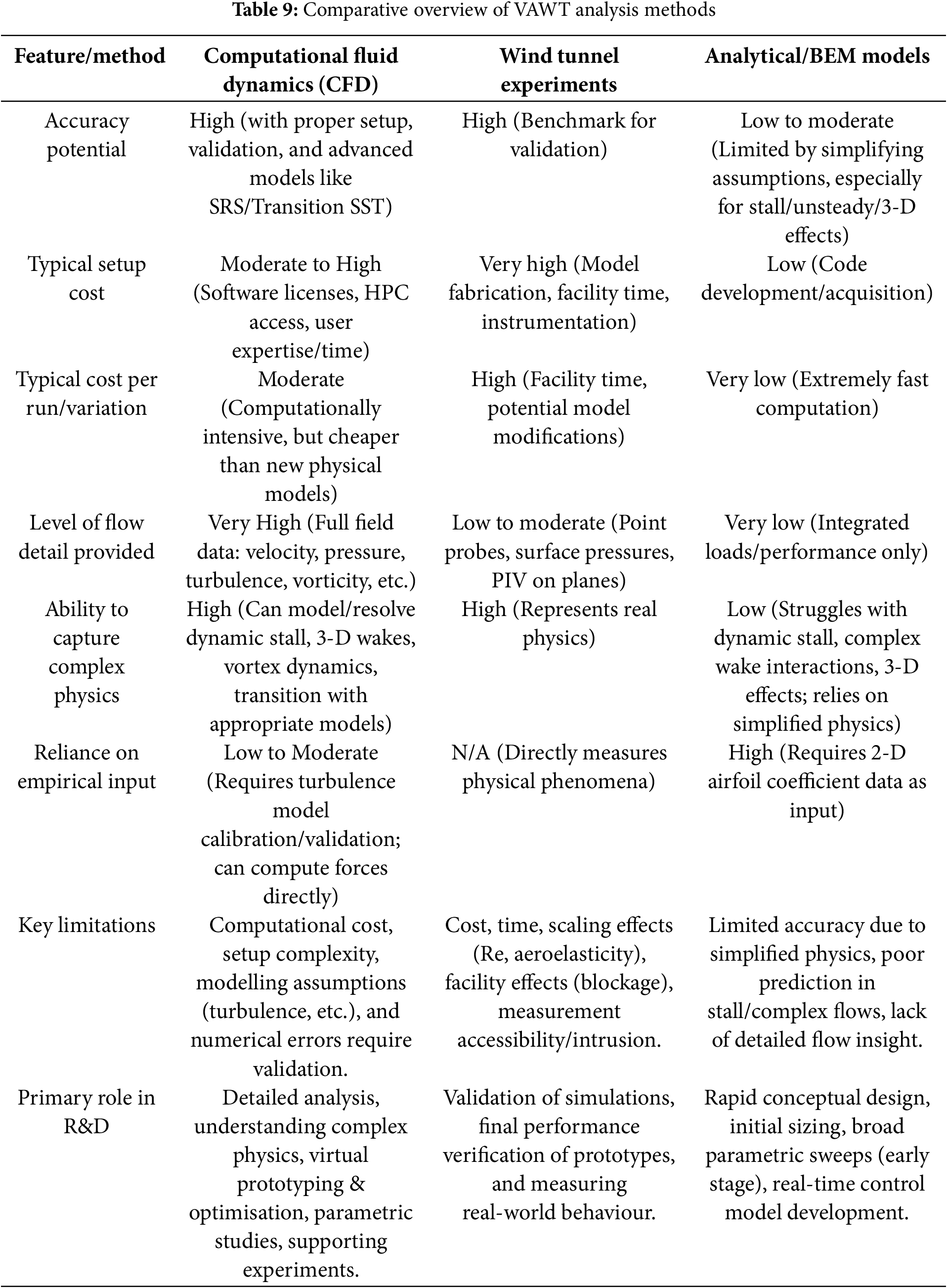

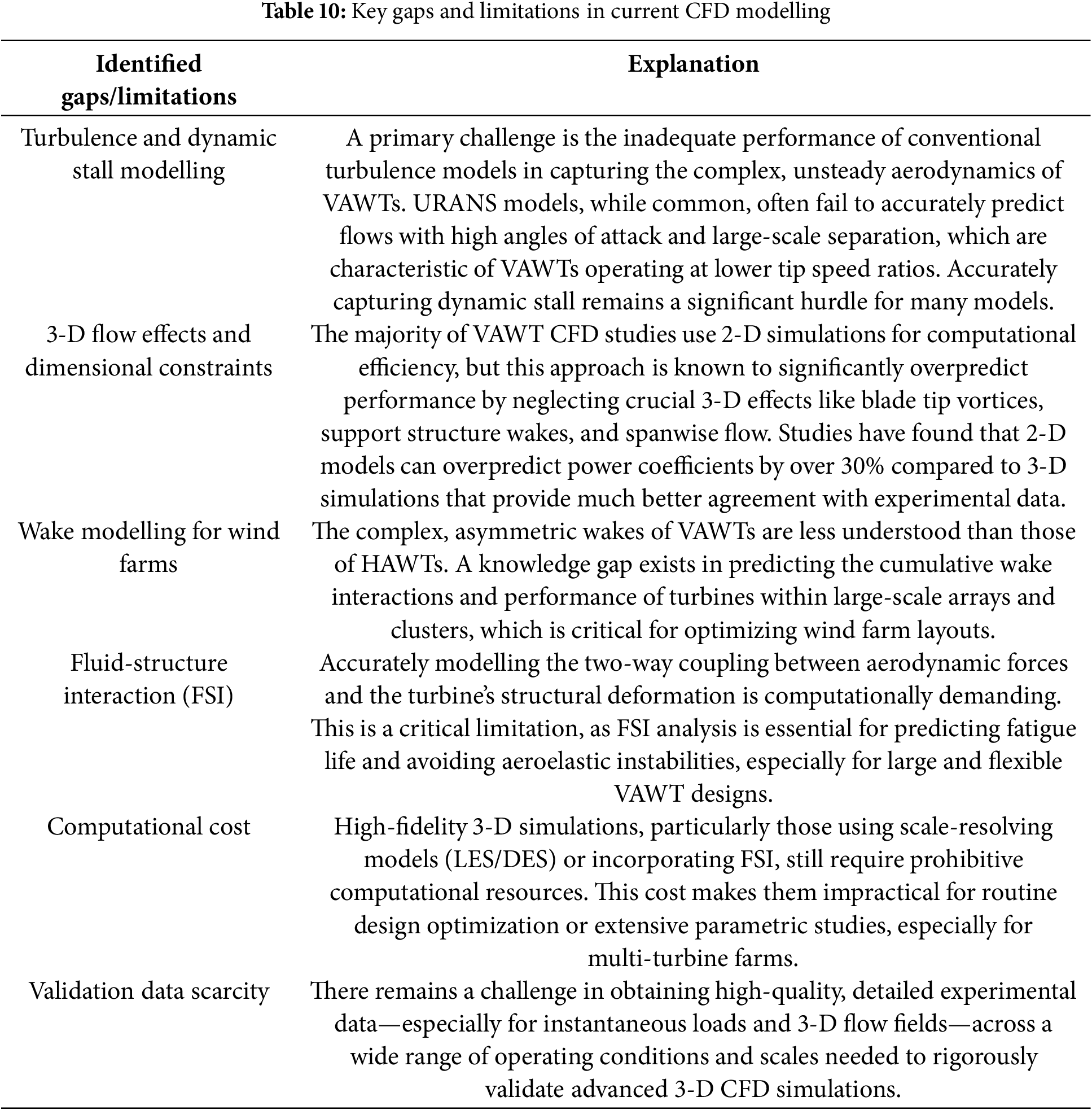

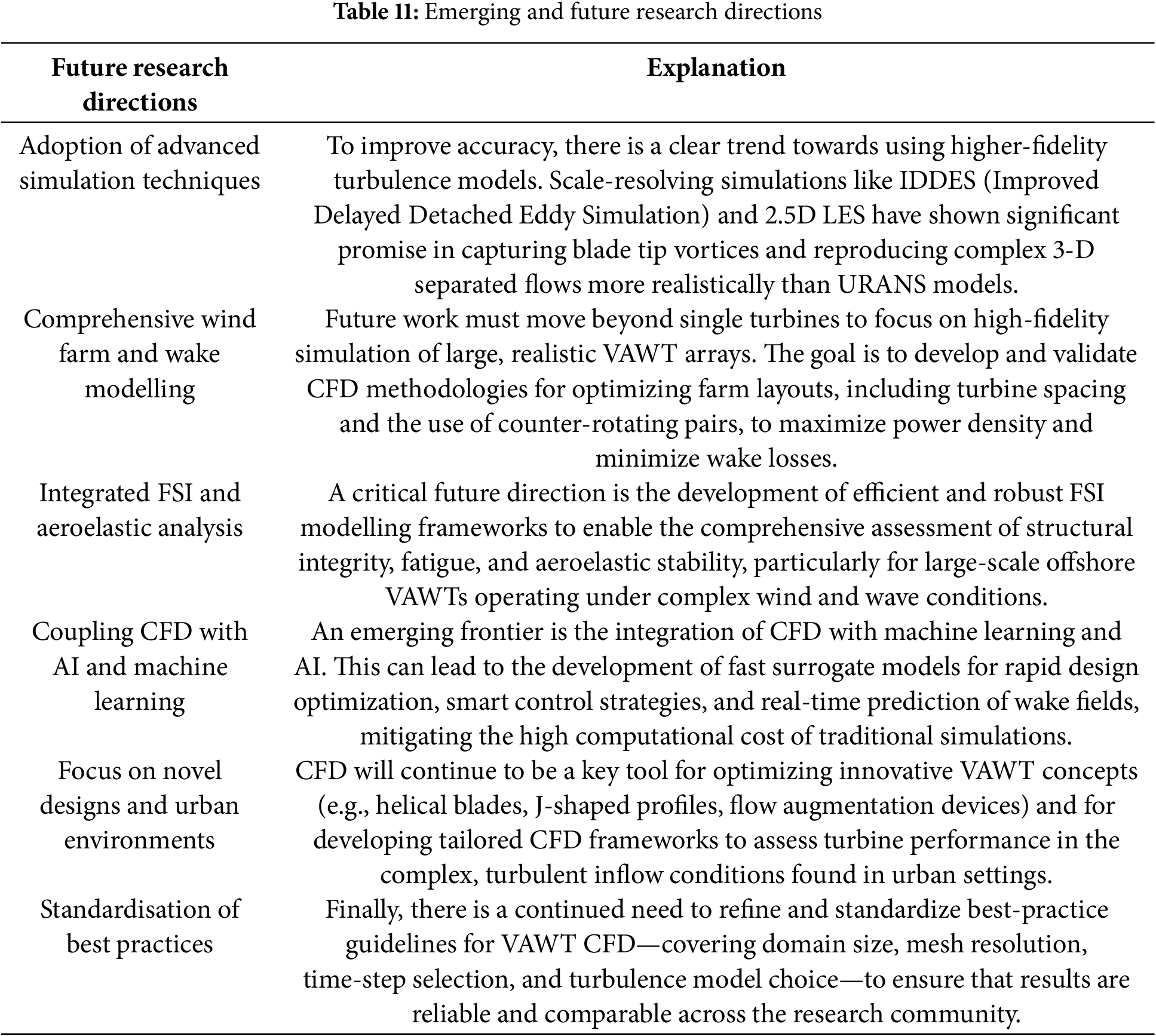

This section synthesises the findings of the previous analyses, directly comparing the turbulence models and offering guidance for model selection based on specific simulation objectives and constraints. Table 2 summarises the turbulence models discussed, evaluating them against key criteria relevant to VAWT CFD simulations. Accuracy ratings are qualitative (Poor, Fair, Good, Very Good, Excellent) based on the consensus from the reviewed literature for predicting overall performance (

The selection of a turbulence model for VAWT CFD invariably involves a trade-off between the desired level of predictive accuracy and the available computational resources (time and hardware). Fig. 13 illustrates this relationship conceptually. At the lower end of the cost spectrum lie the standard RANS/URANS models. While computationally inexpensive, models like the

Figure 13: Conceptual illustration of the Accuracy vs. Computational Cost trade-off for turbulence models in VAWT CFD

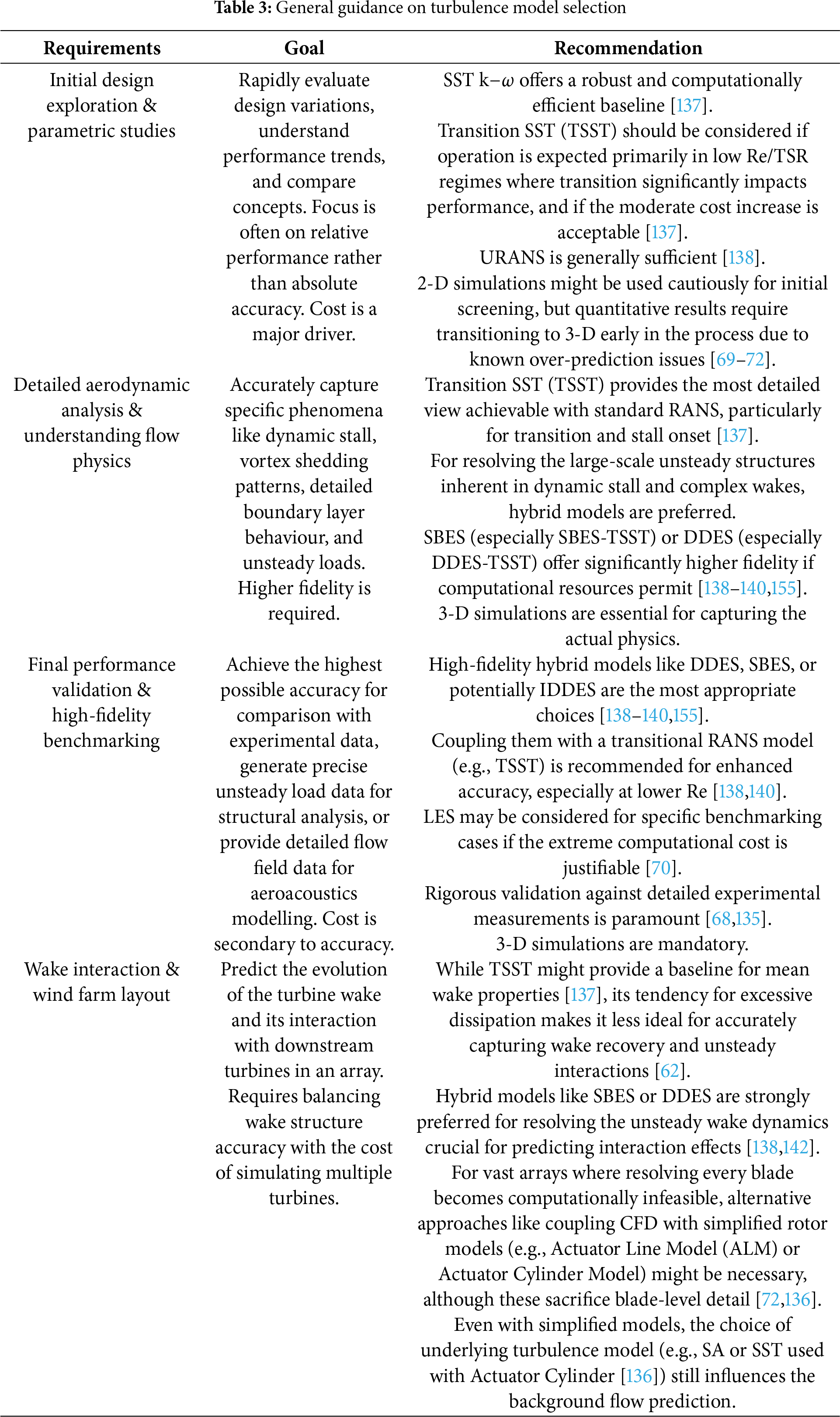

Different turbulence models exhibit varying capabilities in capturing the specific aerodynamic phenomena crucial to VAWT operation, e.g., dynamic stall, flow separation, tip vortices and 3-D effects, wake characteristics and transitional flow. The optimal choice of turbulence model depends heavily on the CFD simulation’s specific goals, the required accuracy level, and the available computational resources. The following Table 3 encapsulates the general guidance on turbulence model selection.

3.5 Solver Configuration and Convergence Practices

Appropriate solver settings are crucial for obtaining stable and accurate transient solutions for VAWTs.

• Solver Type: For the relatively low Mach numbers typical of wind turbine applications, pressure-based solvers are commonly employed [82].

• Discretisation Schemes: Using at least second-order accurate schemes for both spatial and temporal discretisation is generally recommended to minimise numerical diffusion and accurately capture transient phenomena [68,83].

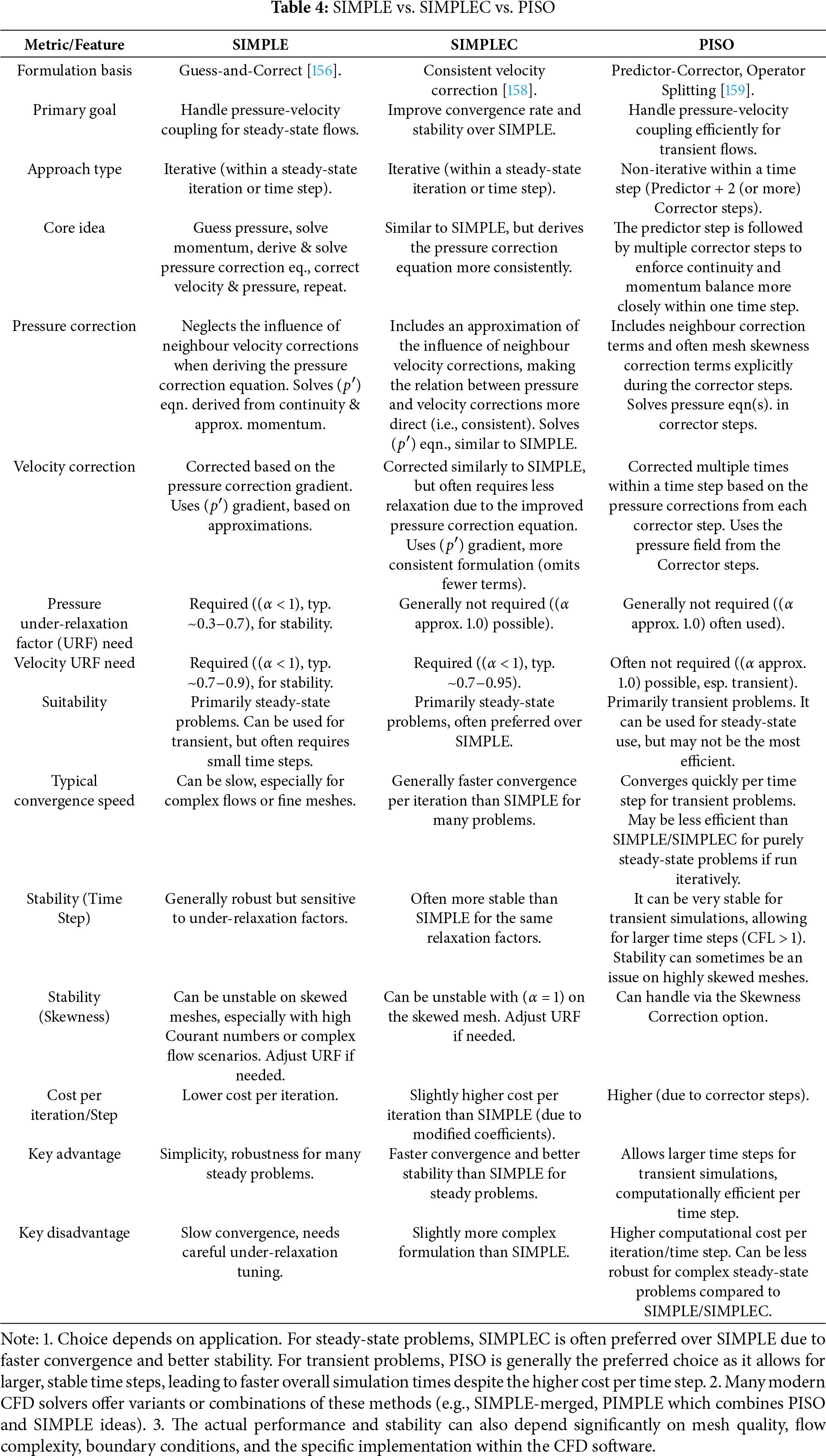

• Pressure-Velocity Coupling: Algorithms like SIMPLE (Semi-Implicit Method for Pressure Linked Equations) [156,157], SIMPLEC (SIMPLE-Consistent) [158], or PISO (Pressure-Implicit with Splitting of Operators) [159] are used to handle the interdependence of pressure and velocity in the governing equations [68,83]. Table 4 summarises the key characteristics and comparative aspects between these algorithms.

• Time Stepping: Transient simulations are required since VAWT flow is inherently unsteady. The time step size (

The required

• ○ Within each time step, multiple inner iterations (e.g., 10–50) are typically needed to converge the nonlinear algebraic equations before advancing to the next time step [68,83].

Initialisation and Convergence: Transient simulations are often initialised using a converged steady-state RANS solution to provide a reasonable starting flow field and potentially reduce the time needed to reach a periodic state [68]. The simulation must then be run sufficiently long to allow initial transients to dissipate. Monitoring key performance indicators like blade torque or overall power coefficient over successive revolutions is crucial. A statistically steady (periodic) state is typically considered reached when these metrics exhibit consistent cycle-to-cycle behaviour [68]. Studies suggest that 20 to 30 complete turbine revolutions may be required to achieve this state before meaningful time-averaged performance data can be extracted [160], with convergence criteria of between 10−4 to 10−5 [137].

Achieving reliable CFD results for VAWTs demands a careful, integrated approach. The choices of turbulence model, mesh resolution (particularly

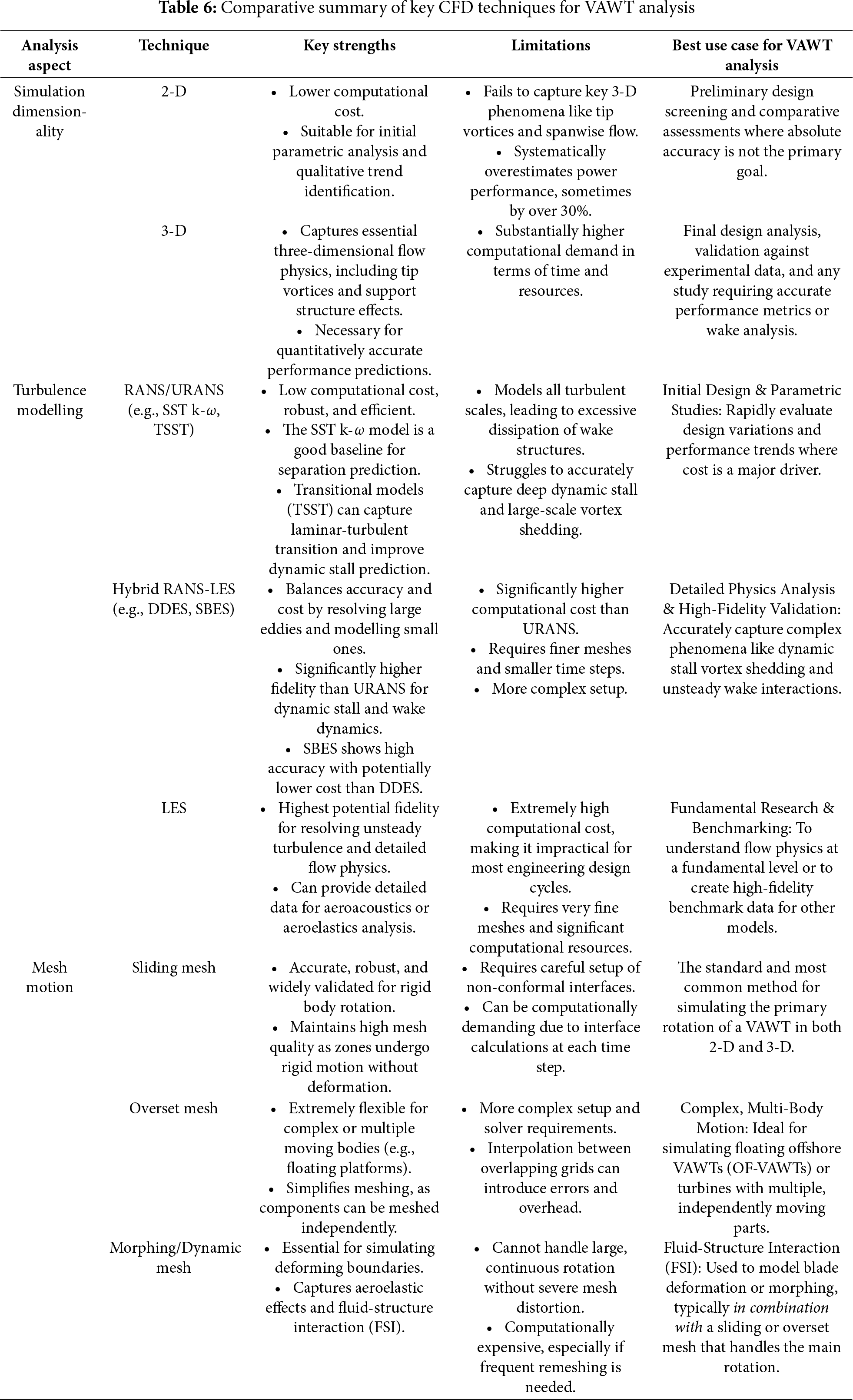

3.6 Summary of Methodological Choices

The selection of an appropriate CFD methodology for VAWT analysis involves a series of critical decisions, each with a trade-off between computational cost, setup complexity, and physical fidelity. Table 6 provides a consolidated overview of the primary techniques discussed in this review, comparing their relative advantages, disadvantages, and most suitable applications for VAWT research and development.

4 Predicting and Analysing VAWT Aerodynamic Performance via CFD

A primary application of CFD in VAWT research is the prediction and detailed analysis of aerodynamic performance under various conditions. CFD simulations provide access to key metrics characterising the turbine’s efficiency and loading.

4.1 Key Performance Metrics–Important Parameters for VAWT Analysis in CFD

CFD solvers calculate the forces and moments acting on the turbine blades by integrating the pressure and viscous shear stress distributions over the blade surfaces [163]. From these fundamental quantities, several critical performance metrics are derived:

• Torque (T): The rotational moment generated by the aerodynamic forces on the blades around the turbine’s axis of rotation. Due to the constantly changing AoA and phenomena like dynamic stall, the instantaneous torque produced by a VAWT blade varies significantly throughout each revolution [42]. CFD calculates both the instantaneous torque and, by averaging over one or more full cycles (after reaching a periodic state), the mean torque, which is essential for power calculation [68]. Torque is often non-dimensionalised into a Torque Coefficient (

• Power (P): The rate at which the turbine extracts kinetic energy from the wind and converts it into mechanical rotational energy. It is calculated directly from the mean torque (

• Aerodynamic Forces: CFD calculates the fundamental aerodynamic forces acting on the blades. These can be resolved into components parallel and perpendicular to the relative wind (Lift,

• Tip Speed Ratio (TSR or λ): This dimensionless parameter relates the speed of the blade tips (

The ability of CFD to provide not just average performance metrics like

4.2 Parametric Analysis—What Can Be Expected from the Obtained CFD Data

CFD enables the virtual testing of numerous geometric modifications, such as solidity, which is the ratio of blade area to the rotor’s swept area. CFD-based parametric studies show that increasing solidity generally increases the maximum power coefficient but shifts the optimal performance to a lower TSR. For example, one study found that increasing the rotor solidity from 0.24 to 0.48 increased the peak Cp by approximately 15%, but the TSR at which this peak occurred dropped from 3.1 to 2.5 [60]. This type of analysis is critical for tuning a turbine’s design to match the expected wind conditions of a specific site.

• Effect of Tip Speed Ratio (TSR): By running simulations at various rotational speeds (

• Effect of Wind Conditions: CFD allows analysis under varying freestream wind speeds (

• Effect of Design Parameters: CFD enables the virtual testing of numerous geometric modifications:

○Solidity: Investigating the impact of changing the number of blades (

Blade Pitch Angle: Assessing the effect of fixed pitch angles or evaluating the potential benefits of complex variable pitch schedules.

○Airfoil Profile: Comparing the performance of different standard airfoil shapes (e.g., NACA series) or evaluating novel, custom-designed profiles [36].

○Aspect Ratio (Height/Diameter): Studying its influence on performance and flow structures [67].

○Other Geometric Features: Analysing the impact of support strut design, tower presence, blade endplates, or helical twist [56].

The performance of a VAWT is sensitive to a complex interplay of these parameters. For example, the optimal TSR often changes with solidity, and the effectiveness of a particular airfoil shape can depend on the Reynolds number and TSR range [53]. Exploring this multi-dimensional design space experimentally would be highly costly and time-consuming [165]. CFD provides a uniquely powerful and cost-effective means to perform these extensive parametric sweeps, identify key sensitivities, and guide the design towards optimal configurations for specific applications [162].

4.2.1 Performance Enhancement via Blade Modifications: Some Case Studies of CFD Application

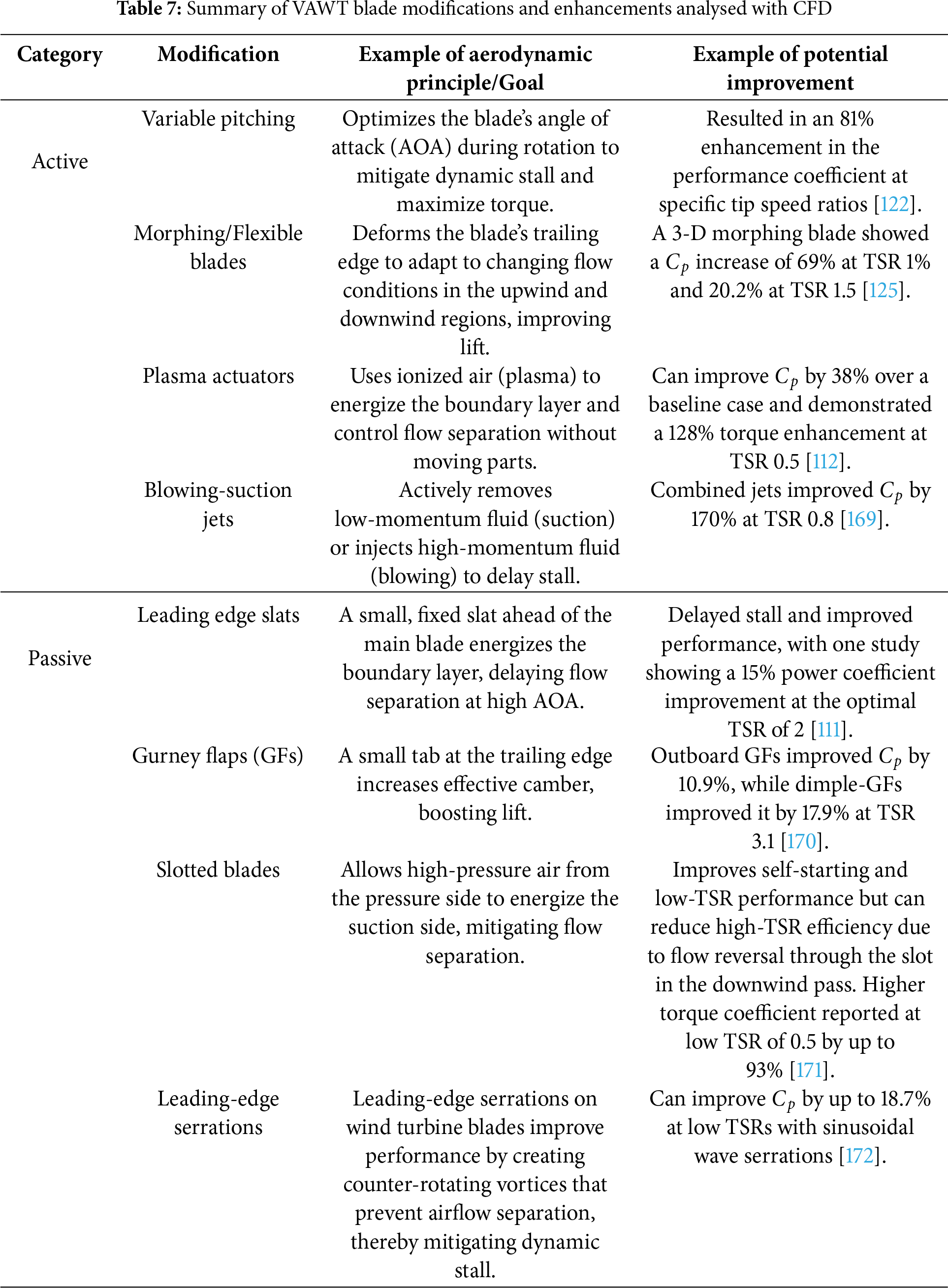

A primary application of CFD in VAWT development is to investigate and optimize blade modifications designed to improve aerodynamic performance by addressing issues like poor self-starting and dynamic stall. As categorized by recent reviews, these solutions can be broadly classified as either passive or active techniques.

• Passive techniques involve geometric modifications that do not require external energy. They alter the flow based on their fixed shape and include features like slats, winglets, dimples, and leading-edge serrations [97,111,166].

• Active techniques require external energy and control systems to dynamically manipulate the flow. Examples include variable-pitch systems, morphing blades, and plasma actuators [112,167,168].

CFD is instrumental in quantifying the effectiveness of both types of modifications. Table 7 provides a summary of various advancements, categorized as active or passive, and highlights their principles and reported outcomes from numerical and experimental studies.

As the findings in Table 7 indicate (coupled with the discussions found in Section 3 and Table 1), there is often a trade-off between performance and practicality. Active solutions like variable pitching and morphing blades the highest potential performance gains by adapting to the flow, but at the cost of increased complexity, maintenance, and system cost. Passive solutions are simpler and more robust, but their benefits are often confined to specific operating ranges, sometimes leading to performance penalties at off-design conditions. The ongoing challenge, which CFD is uniquely suited to address, is the development of solutions that bridge this gap, offering significant aerodynamic improvement without compromising practical viability. For additional work on blade modifications—beyond CFD-focused studies—see [41].

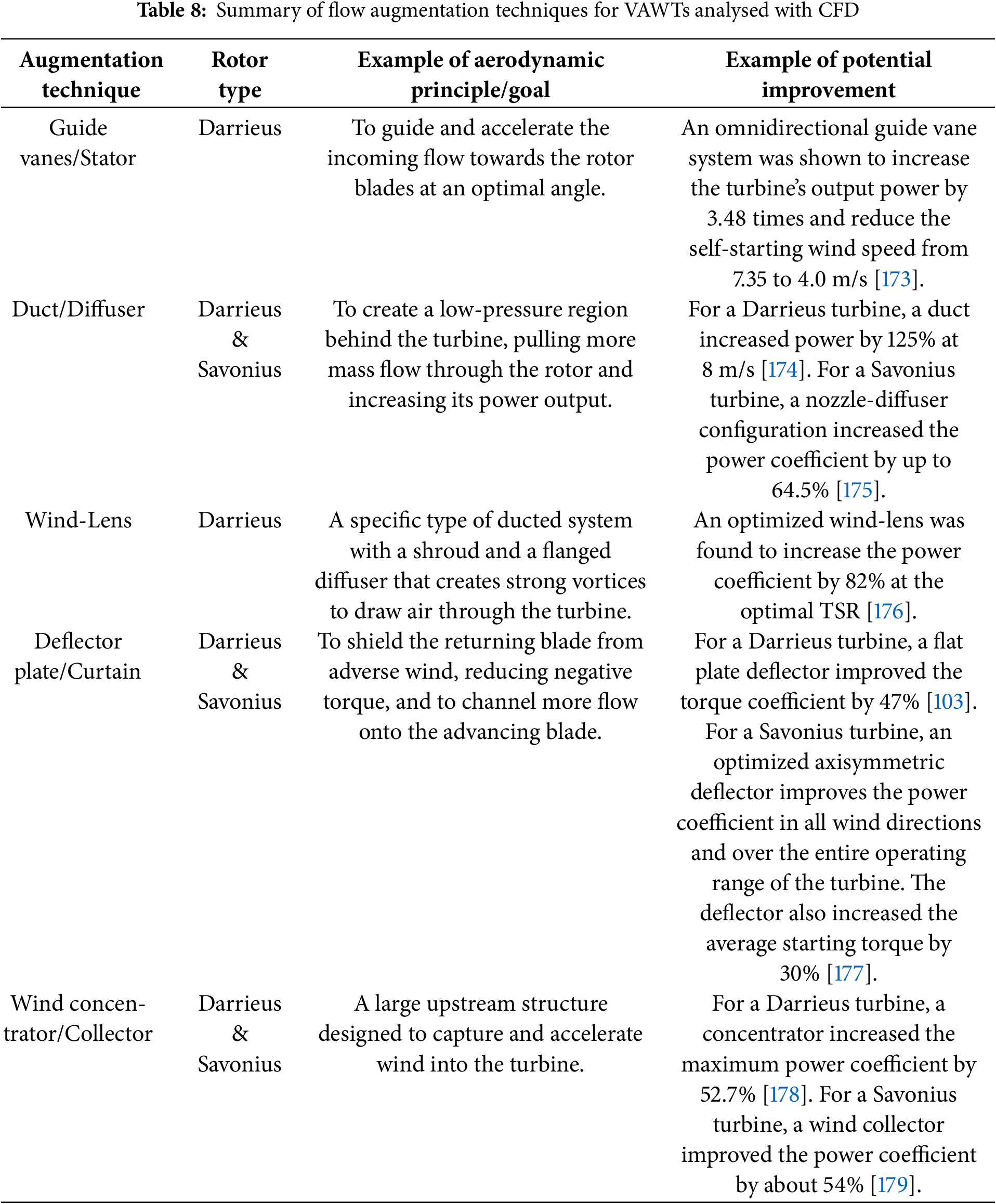

4.2.2 Performance Enhancement via Flow Augmentation Systems: Some Case Studies of CFD Application

Beyond modifying the turbine blades themselves, a significant area of VAWT research involves using external structures to augment the flow entering the rotor. These flow augmentation techniques aim to increase the local wind velocity, guide the flow onto the blades at more favorable angles, and shield the returning blades from negative torque. Because these systems create complex aerodynamic interactions between the stationary structure and the rotating turbine, CFD is the primary tool for their design and analysis.

CFD simulations are essential for modelling the flow acceleration through ducts or nozzles, the pressure changes induced by diffusers, and the shielding effects of deflectors. Such analyses allow for the optimization of the augmentation device’s geometry and its placement relative to the rotor to maximize power output. Table 8 summarizes several common flow augmentation techniques for both Darrieus and Savonius rotors that have been evaluated using CFD.

4.3 Post-Processing for Performance Evaluation

Once a CFD simulation has converged and run for a sufficient number of cycles, specialised post-processing tools within the CFD software are used to extract and analyse the performance data [80].

• Calculating Forces and Torque: The solver directly computes the net forces (e.g., lift, drag) and moments (torque) acting on specified surfaces (like the turbine blades) by integrating the pressure and viscous shear stress distributions over the mesh faces defining those surfaces [163]. The underlying calculation involves summing the contributions from each face element, considering both pressure forces (pressure * area * moment arm) and viscous forces (shear stress * area * moment arm) [163].

• Calculating Coefficients: To obtain non-dimensional coefficients like

• Averaging: For unsteady (URANS or SRS) simulations, the instantaneous torque and power values fluctuate over a rotation cycle. To obtain the mean performance metrics (average

• Validation: A critical step in post-processing is comparing the CFD-predicted performance characteristics (e.g., the

4.4 CFD Analysis of Self-Starting Capability of VAWTs

A significant historical and ongoing challenge for Darrieus-type VAWTs is their inherently poor self-starting capability. At low rotational speeds (or from a standstill), the blades experience very high angles of attack, leading to massive flow separation and dynamic stall. This often produces negative torque over parts of the rotation, preventing the turbine from accelerating on its own. CFD is an indispensable tool for diagnosing the root causes of this issue and for evaluating the effectiveness of strategies designed to overcome it [41,180,181].

4.4.1 Diagnosing Starting Problems with CFD: Performance Curves and Flow Visualisation

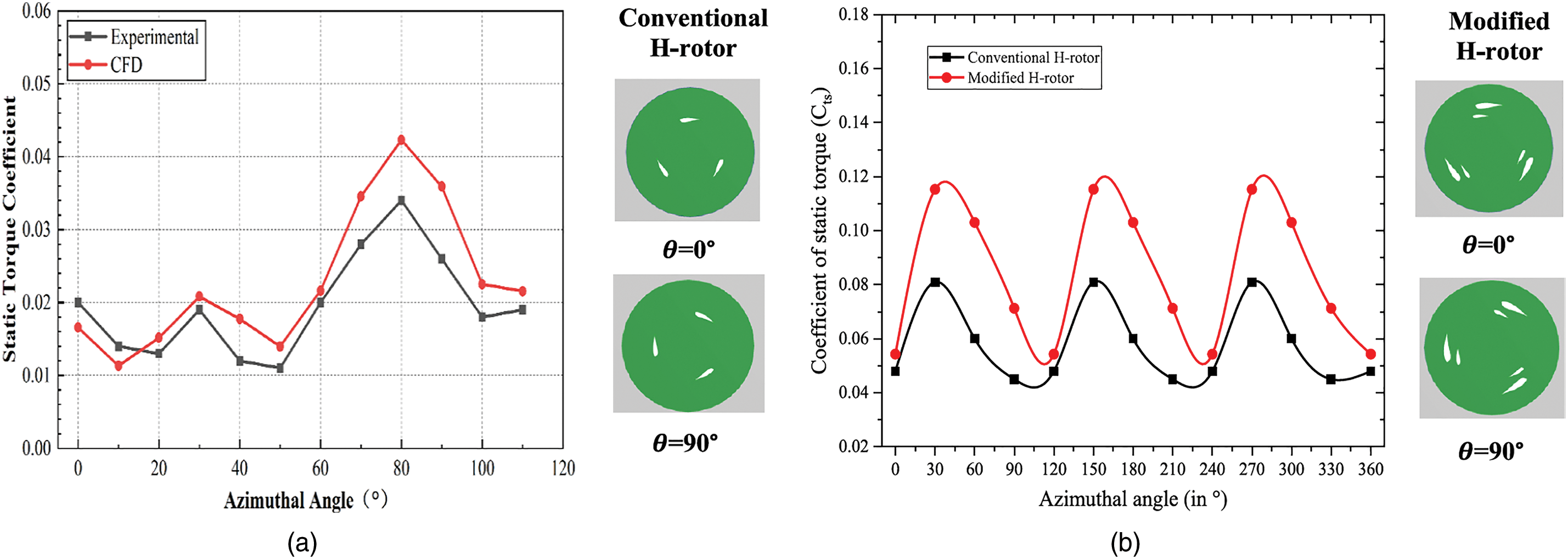

To understand the self-starting problem, a combination of quantitative performance curves and detailed flow visualization is required. A static CFD analysis can generate a static torque coefficient (CTS, or Cts, or Cms) vs. azimuthal angle curve (examples are as shown in Fig. 14a,b). The static torque performance of a VAWT refers to the amount of torque produced by the rotor when it is stationary and wind is blowing. In CFD, to obtain the static torque of the rotor, one could run a numerical simulation at steady state (i.e., rotor is fixed) at different rotor azimuthal positions. A turbine is considered to have starting potential only if the average static torque is positive, allowing it to overcome initial bearing friction and begin to turn. This method is helpful for a preliminary assessment. For instance, Uma Reddy et al. [182] used static torque curves to show that adding auxiliary blades increased the maximum static torque by 84%, indicating a significantly stronger initial turning force.

Figure 14: Illustrating the relationship between the static torque coefficient and the azimuthal angle. In general, the higher the static torque coefficient, the better the self-start characteristic of the rotor is. Figures are obtained from studies of (a) Xu et al. [180] and (b) Uma Reddy et al. [182]

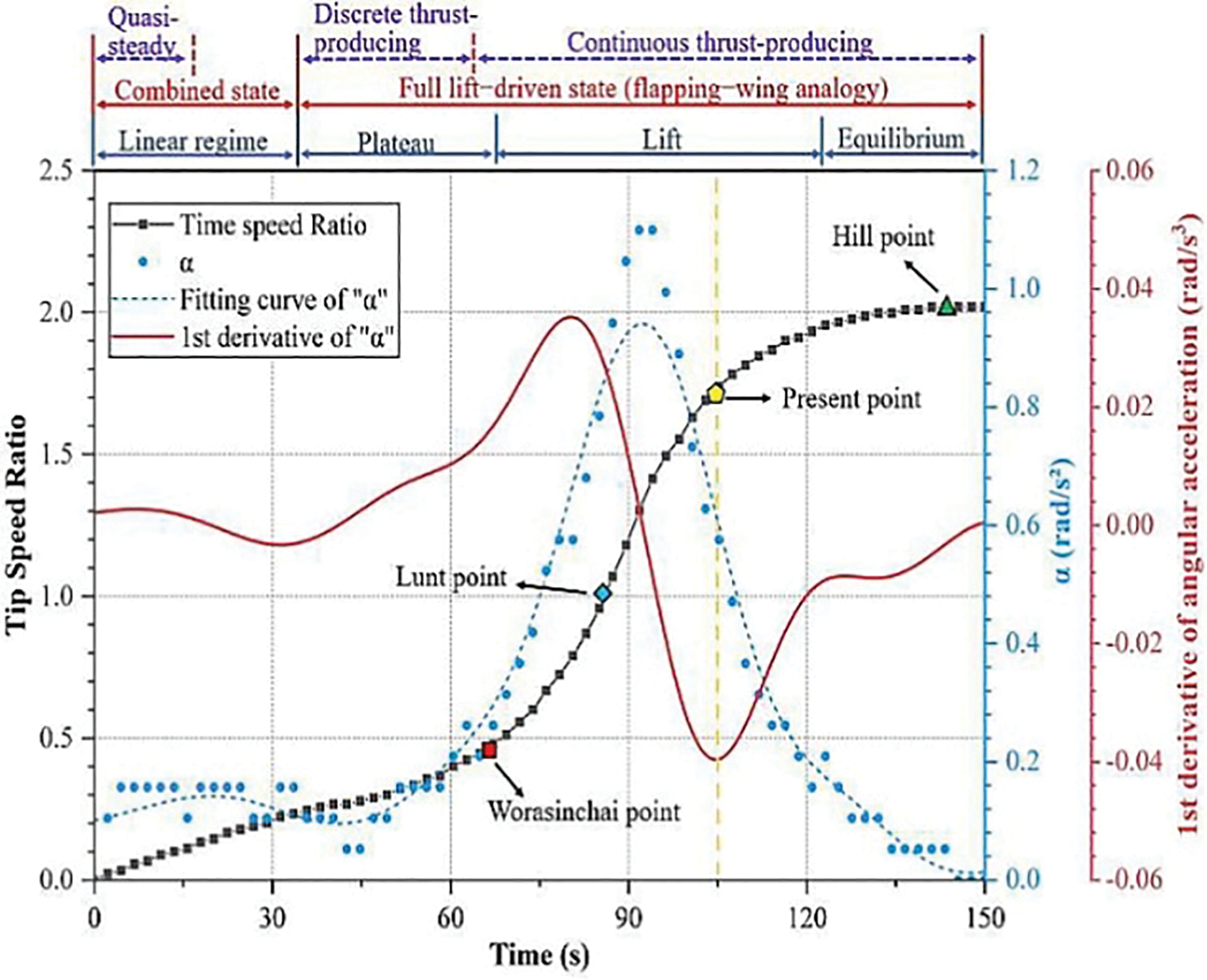

While a high static torque coefficient is necessary for initial rotation, studies show it is not a sufficient predictor of dynamic self-starting success. A key finding, demonstrated by Xu et al. [180], is that a high initial static torque does not guarantee a successful or fast start-up. Their study showed that a turbine starting at an angle with maximum static torque took longer to accelerate through the initial phase than one starting from an angle with minimum static torque. This is because the static analysis cannot capture the complex, unsteady aerodynamic effects that occur once the rotor begins to move, particularly as it enters the low-TSR “dead band” or “plateau state” where dynamic stall and blade-wake interactions can generate significant negative torque and stall the acceleration. Furthermore, reference [180] shows that a dynamic start-up analysis via TSR vs. time curve, which visualises the entire journey of the turbine from rest (TSR = 0) to its final operational speed, would be a better choice of analysis tool. This curve clearly reveals the initial rotation (which is often a slow rotation), the critical plateau state (or “dead band”, where acceleration may stagnate), and whether the turbine successfully accelerates to its final operating speed (i.e., lift acceleration state towards stable operating TSR, where the aerodynamic torque balances any resistive loads). For example, to better showcase the self-starting characteristics of a VAWT rotor, Fig. 15 was developed by [180] based on the insights into the self-starting characteristics of VAWT rotors from [183,184]. Worasinchai et al. [183] divide the self-starting process into a “combined state” and a “full lift-driven state”. The “full lift-driven state” is further divided into two thrust generation states: “discrete” and “continuous”. They considered reaching the “continuous thrust-producing state” to be the completion of the self-starting process, as indicated by the red dot in the figure. In a similar study, Hill et al. [184] divided the self-starting process into four states: a “linear regime”, a “plateau” state, a “lift” state, and an “equilibrium” state. Celik et al. [185] came to a similar conclusion to [184], in which they considered the wind turbine reaching a stable condition as the completion of the self-starting process, as indicated by the green dot in Fig. 15. The Lunt point (i.e., blue dot) refers to the conclusion made by Lunt [186] in which they adopted a TSR of 1 as the self-starting point.

Figure 15: A self-starting process of a NACA2418 VAWT [180]

CFD contour plots are essential for visualising the underlying physics that performance curves cannot show alone. They allow researchers to diagnose the precise causes of poor torque generation. (Note: General discussions of different visualisation tools are discussed in Section 5).

• Vorticity Contours: These are used to track the evolution of the flow from a complex, separated state to an organised one. For example, Celik et al. [185] used vorticity contours to demonstrate that during the initial start-up phase (TSR < 1), the flow is characterised by large, complex vortices and separated flow. As the turbine successfully accelerates to its operational speed, the same contours indicate that the blade vortices become smaller, more organised, and the flow becomes more attached, which is essential for generating the higher lift force required for efficient operation.

• Pressure Contours: These plots diagnose the sources of positive and negative torque at specific blade positions. Xu et al. [180] used static pressure contours to analyse why a turbine failed to start at 5.5 m/s but succeeded at 6 m/s. The contours revealed that at lower wind speeds, the pressure distribution on the blades at azimuthal angles between 60° and 120° generated a significant negative torque that offset any positive torque gained elsewhere. This level of detailed, localised diagnostic information is only possible through CFD.

• Streamline Plots: Streamlines are highly effective for visualising flow separation and the efficacy of flow control devices. For instance, Uma Reddy et al. [182] used streamline plots to compare a conventional H-rotor with one modified with auxiliary blades. The visualisations clearly showed significant flow separation near the trailing edge of the conventional blade. In contrast, for the modified rotor, the streamlines remained “more attached to the surface of the main blade”. This directly illustrates the physical mechanism by which the auxiliary blades improve performance.

4.4.2 Aerodynamic Factors and Improvement Strategies

While Darrieus turbines are lift-driven at operational speeds, CFD analysis has revealed that in the critical start-up region (TSR < 1), the drag force can have a significant positive contribution to the overall torque. Numerous strategies, both passive and active, leverage CFD for their design and aim to optimise the torque profile at low TSRs. Some examples are discussed below:

• Passive Flow Control Devices: The effect of modifying blade surfaces to enhance VAWT performance has been explored through various design strategies. One such approach involves adding cavities to the blade surface, as demonstrated by Yousefi Roshan et al. [187], who used CFD to show that strategically placed cavities can trap vortices and significantly boost performance. A single cavity located on the upper surface near the trailing edge was found to increase the static torque coefficient by 5 to 7 times compared to a smooth blade at certain angles, greatly improving the self-starting potential. Another strategy involves the addition of fixed auxiliary blades positioned ahead of the main blades. In this approach, Uma Reddy et al. [182] showed that the auxiliary blades act as passive flow control devices, reducing separation on the main blade. Their experimental and numerical results indicated that this configuration enhanced the maximum static torque coefficient by 84% compared to a conventional H-rotor.

• Blade and Rotor Modifications: The selection of airfoil type and pitch angle plays a crucial role in determining a VAWT’s self-starting capability. CFD simulations have shown that cambered airfoils, such as the NACA2418, outperform symmetric profiles like the NACA0018 in terms of starting performance. In particular, Xu et al. [180] demonstrated that increasing the pitch angle of a NACA2418 blade to 10° reduced its start-up time by 20% compared to a 0° pitch angle. Another innovative design involves the use of J-shaped blades, which feature a concave profile to harness drag more effectively and generate a stronger starting torque. Farzadi and Bazargan [188], using 3-D CFD analysis, found that at a wind speed of 5 m/s, J-type blades increased the average self-starting torque by 37.6% compared to traditional straight blades, highlighting their potential for use in low-wind environments.

• Turbine Pair and Farm Optimisation: The self-starting of a VAWT is further complicated when it is part of an array. Fatahian et al. [181] used a CFD-Taguchi optimisation method to study the start-up of VAWT pairs. They found that the angle between adjacent rotors was the most significant factor affecting start-up and that a downstream rotor in an optimised layout could benefit from the wake of the upstream rotor, starting faster and at a lower TSR.

4.5 Advanced CFD Optimisation Using Design of Experiments (DoE) and Surrogate Models