Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Robust Skin Cancer Detection through CNN-Transformer-GRU Fusion and Generative Adversarial Network Based Data Augmentation

1 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Bharati Vidyapeeth’s College of Engineering, New Delhi, 110063, India

2 Department of Information Technology, Bharati Vidyapeeth’s College of Engineering, New Delhi, 110063, India

3 Applied College of Dhahran Aljunub, Department of Computer Science, King Khalid University, Aseer, Abha, 64261, Saudi Arabia

4 Department of Computer Science, College of Computer Science, Applied College Tanumah, King Khalid University, Abha, 61413, Saudi Arabia

5 Department of Computer Science, Technical and Engineering Specialties Unit, King Khalid University, Muhayil, 63699,

Saudi Arabia

6 Galgotias Multi-Disciplinary Research & Development Cell (G-MRDC), Galgotias University, Greater Noida, 201308, UP, India

7 CSE Department, Technocrats Institute of Technology, Bhopal, 462022, India

8 Department of Environmental Health, Harvard T H Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA 02115, USA

9 Department of Pharmacology & Toxicology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA

* Corresponding Authors: Mudassir Khan. Email: ; Saurav Mallik. Email:

,

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(2), 1767-1791. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.067999

Received 19 May 2025; Accepted 31 July 2025; Issue published 31 August 2025

Abstract

Skin cancer remains a significant global health challenge, and early detection is crucial to improving patient outcomes. This study presents a novel deep learning framework that combines Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Transformers, and Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs) for robust skin cancer classification. To address data set imbalance, we employ StyleGAN3-based synthetic data augmentation alongside traditional techniques. The hybrid architecture effectively captures both local and global dependencies in dermoscopic images, while the GRU component models sequential patterns. Evaluated on the HAM10000 dataset, the proposed model achieves an accuracy of 90.61%, outperforming baseline architectures such as VGG16 and ResNet. Our system also demonstrates superior precision (91.11%), recall (95.28%), and AUC (0.97), highlighting its potential as a reliable diagnostic tool for the detection of melanoma. This work advances automated skin cancer diagnosis by addressing critical challenges related to class imbalance and limited generalization in medical imaging.Keywords

Skin cancer, especially melanoma, represents a major public health problem associated with high occurrence rates and potentially dire consequences without early diagnosis. Melanoma arises from melanocytes and is distinguished by its high tendency to metastasize. Only 2 to 3 percent of skin cancers are melanoma, yet it causes most skin cancer deaths. From a clinical perspective, melanoma commonly presents as an asymmetrically pigmented skin lesion and thus can mimic benign moles, making early diagnosis challenging. More than 132,000 new cases of melanoma are reported each year, with the World Health Organization recording cases of the disease worldwide. Though highly curable if identified at an early stage, melanoma remains responsible for an excessive number of skin cancer deaths. Hence, early and accurate diagnosis has great value for better patient outcomes and decreasing mortality

With the rising popularity of noninvasive imaging technology, such as dermoscopy, it is now possible to visualize skin lesions in detail, but dermoscopic images are difficult to interpret without expertise. Computer vision and deep learning-based technologies have been introduced to assist dermatologists by providing automated tools. However, despite these advancements, there are still some barriers to overcome in the development of robust computer vision models for automatic skin lesion classification. One of the biggest challenges is the strong class imbalance in dermoscopy image databases; benign lesions, as melanocytic nevi and seborrheic keratoses, are typically overrepresented, while in the case of malignant lesions, in particular melanomas, they are underrepresented. Such an imbalance introduces classifiers that, while often fairly accurate, have a bias towards the majority class, potentially leading to a large number of false negatives for melanoma with serious clinical implications.

To address this issue, previous work has also tried to minimize the impact of class imbalance, using techniques such as cost-sensitive learning, resampling, and data augmentation [1]. Among them, data augmentation presented a great potential, in particular thanks to the application of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), which can generate realistic images to augment minority classes. Compared to the traditional data augmentation (e.g., flipping, rotation, color jittering) about the images in the dataset, GANs, namely the recent sophisticated GAN models (like StyleGAN2 [train-0] and StyleGAN3), have shown that these generated dermoscopic image are of more realistic-looking visual appearance in representative with the skin lesions [train-0] [2].

In the context of these complexities and new possibilities, this research aims to propose a reliable and interpreted embedded deep learning framework for the classification of melanoma that sufficiently deals with unbalanced classes and improves the accuracy lower bound. Particularly, we apply a hybrid model with convolutional neural networks (CNNs), Transformers, and gated recurrent units (GRUs), concatenated with images generated from a GAN, based on StyleGAN3. Each model component covers potential aspects in lesion analysis: CNNs focus on learning localized patterns, Transformers help to highlight global context information through a self-attention mechanism, and the GRUs serve as building blocks for learning sequential relationships, e.g., how a lesion changes over time or how multiview images are input. In addition to the architecture, to obtain even more refined synthetic images, using a modified DCGAN (Deep Convolutional Generative Adversarial Network) containing upsampling convolution blocks and linear projection of the latent vector to generate high-resolution (512

Key Contributions

This research presents several key contributions:

• Development of a hybrid CNN–Transformer–GRU architecture that captures local, global, and sequential features of dermoscopic images.

• GAN-based data augmentation using StyleGAN3 to mitigate class imbalance.

• Design of a modified DCGAN for high-resolution image synthesis with improved spatial fidelity.

• Proposal of a parallel feature fusion mechanism that integrates CNN-extracted local features with global attention from Transformers.

• Demonstration of superior classification performance, achieving 90.61% accuracy and 95.28% recall for melanoma detection, outperforming 10 state-of-the-art baseline models.

• Clinical validation through cross-dataset generalization tests using the HAM10000 dataset.

Previous studies [3,4] have shown the effectiveness of CNNs and GANs in isolation; however, to our knowledge, none have simultaneously integrated attention mechanisms with sequential modeling for the classification of skin lesions. Our proposed model addresses this gap and demonstrates robust performance on challenging clinical benchmarks.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the relevant literature. Section 3 details the material and methods, including data augmentation and a hybrid architecture. Section 4 presents the proposed methodology, and Section 5 presents the experimental setup and analysis of the results. Section 6 discusses the results, benchmarking, and clinical implications. Section 6 introduces a comparative evaluation using the TOPSIS ranking method. Section 7 concludes the study with insight and directions for future work.

Early and accurate detection of skin cancer is essential for effective treatment and improved patient outcomes. Deep learning techniques have significantly advanced medical image analysis, particularly in the classification of skin lesions. Numerous studies have explored various architectures and methodologies to improve diagnostic accuracy. Reference [5] proposed a deep convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture for the classification of multiclass skin cancer. They applied data pre-processing and augmentation techniques on the HAM10000 dataset and evaluated multiple models, including ResNet-50, VGG-16, DenseNet, MobileNet, InceptionV3, and Xception. Among these, InceptionV3 achieved the highest accuracy of 90%, demonstrating its effectiveness in distinguishing seven classes of skin lesions. Similarly, reference [6] focused on the interpretation in deep learning models for the classification of skin cancer. Using pre-trained architectures such as XceptionNet, EfficientNetV2S, InceptionResNetV2, and EfficientNetV2M, combined with image enhancement to address class imbalance, they identified XceptionNet as the top performer with an accuracy of 88.72%. The study notably emphasized the role of explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) in building trust and facilitating clinical integration.

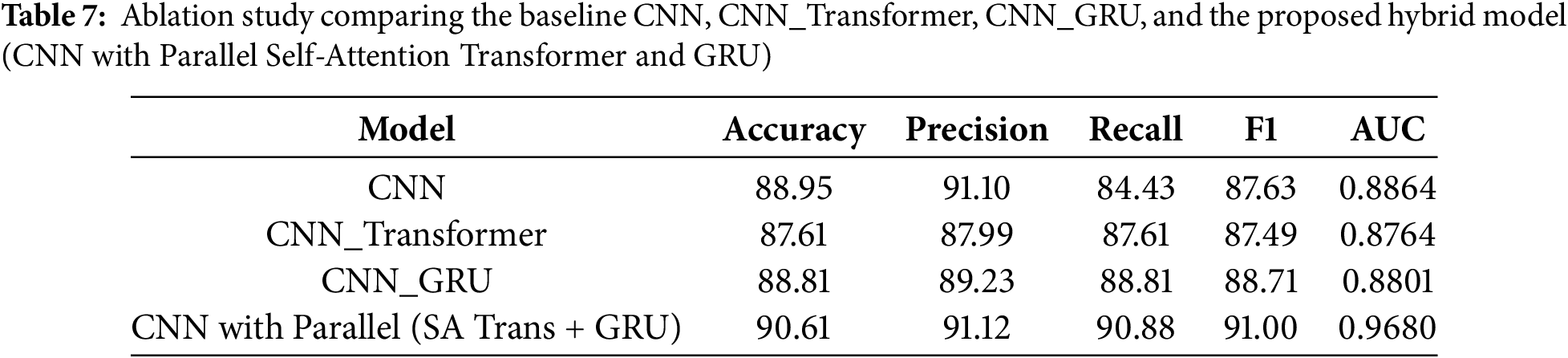

Recent deep learning approaches have greatly contributed to the classification of skin cancer. For example, the seven-class classification was proposed with the use of MobileNet with transfer learning in the HAM10000 dataset in [7]. Their method resulted in a categorical accuracy of 83.1%, top-2 91.36% and top-3 95.34%, motivating the use of lightweight models like MobileNet for clinical applications. In [8], we considered the binary classification of skin lesions, classifying between benign and malignant by transfer learning. Five pretrained models were fine-tuned, and data enhancement was used, and the best classification result was from ResNet-50, where it achieved an accuracy of 93.5% and F1 of 0.86, highlighting the potential of transfer learning in medical images. In addition, a hybrid deep learning model based on InceptionV3 and DenseNet121 combined with a weighted sum fusion was presented to improve performance in the classification of benign and malignant lesions to improve the classification of benign and malignant masses [5]. Recently, MonkeyNet achieved 98.91% accuracy for multiclass skin disease classification using a modified DenseNet-201 architecture and the MSID dataset [9]. A recent systematic review highlighted the effectiveness of Vision Transformers (ViTs) in improving skin cancer classification and segmentation performance on the ISIC dataset, addressing challenges like data duplication and augmentation [10]. This hybrid model obtained a detection rate of 92.27%, superior to the separate models and stronger assistance in detecting skin cancer. A set of these and other relevant methods, along with accuracy, datasets, and evaluation metrics, can be found in Table 1.

Collectively, these studies demonstrate significant progress in skin cancer detection through the integration of advanced architectures, transfer learning, data augmentation, and model fusion. Building on these advances, our research proposes a novel deep learning framework that further improves classification accuracy and robustness. By incorporating Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) for synthetic data augmentation, we effectively address class imbalance, resulting in more generalized and reliable predictions. In addition, our model improves interpretability, contributing to its practical applicability as a trustworthy tool for early and accurate skin cancer diagnosis.

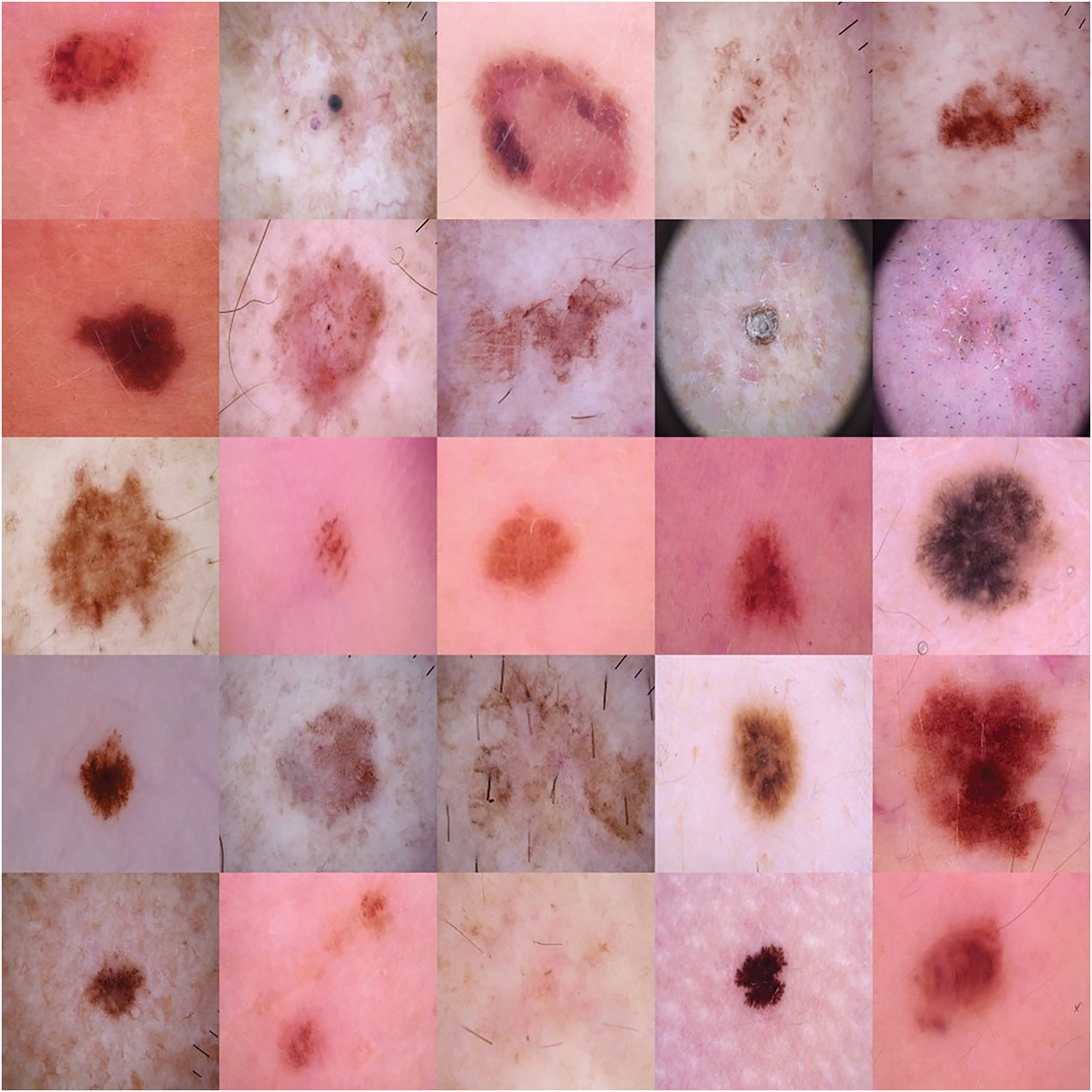

The dataset in this article contains dermoscopic images collected from publicly available databases HAM10000 dataset [22]. Given the clinical need of distinguishing malignant from benign lesions, a binary classification approach was applied, labelling lesions as either malignant (melanoma) or benign (non-melanoma). A grid of illustrative sample images from the dataset is shown in Fig. 1 which illustrates the heterogeneity in lesion properties, through various size, shape, color and texture.

Figure 1: Sample images from the dataset

A significant issue in automatic skin cancer detection is the large class imbalance in dermatological datasets, where cases of malignancy have a strong underrepresentation. This imbalance tends to bias model predictions to the majority class and manifests in low sensitivity and low accuracy in detecting the minority class, which is the clinically important melanoma. To address this problem, we used synthetic data augmentation based on several variations of generative adversarial networks (GANs, with particular emphasis on the minority melanoma class. This augmentation approach is designed to increase the model’s generalizability by letting it see a wider variety of lesion appearances as well as overcoming the lack of data.

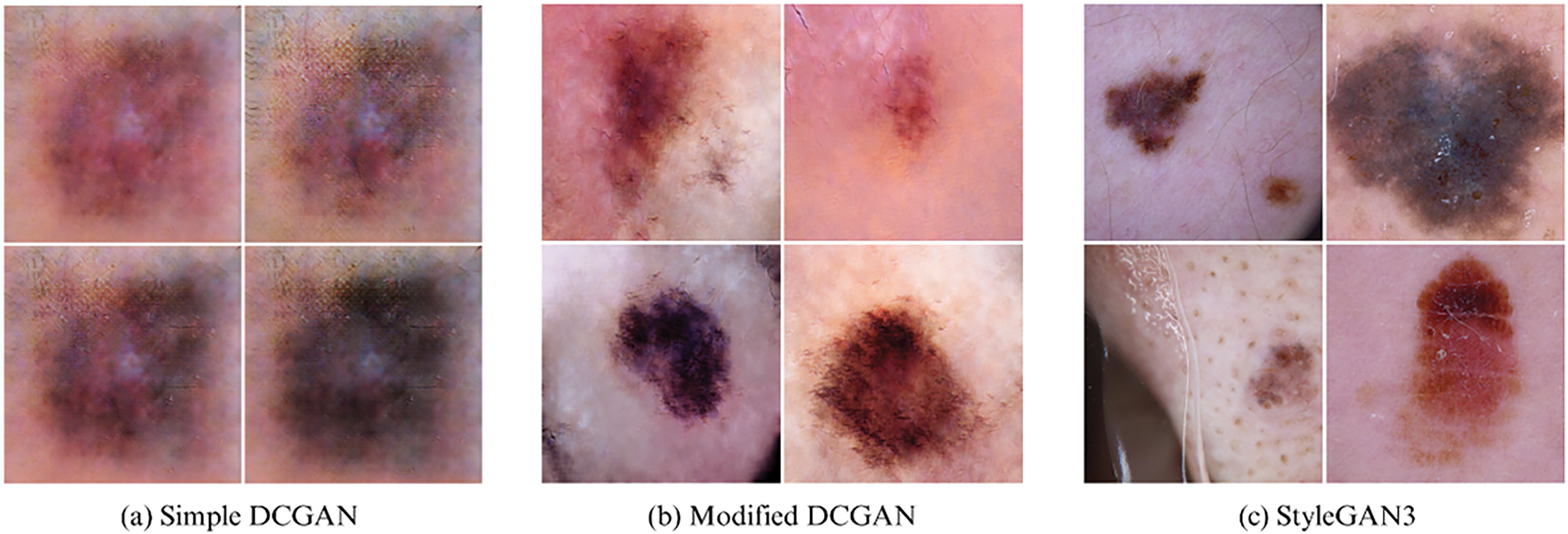

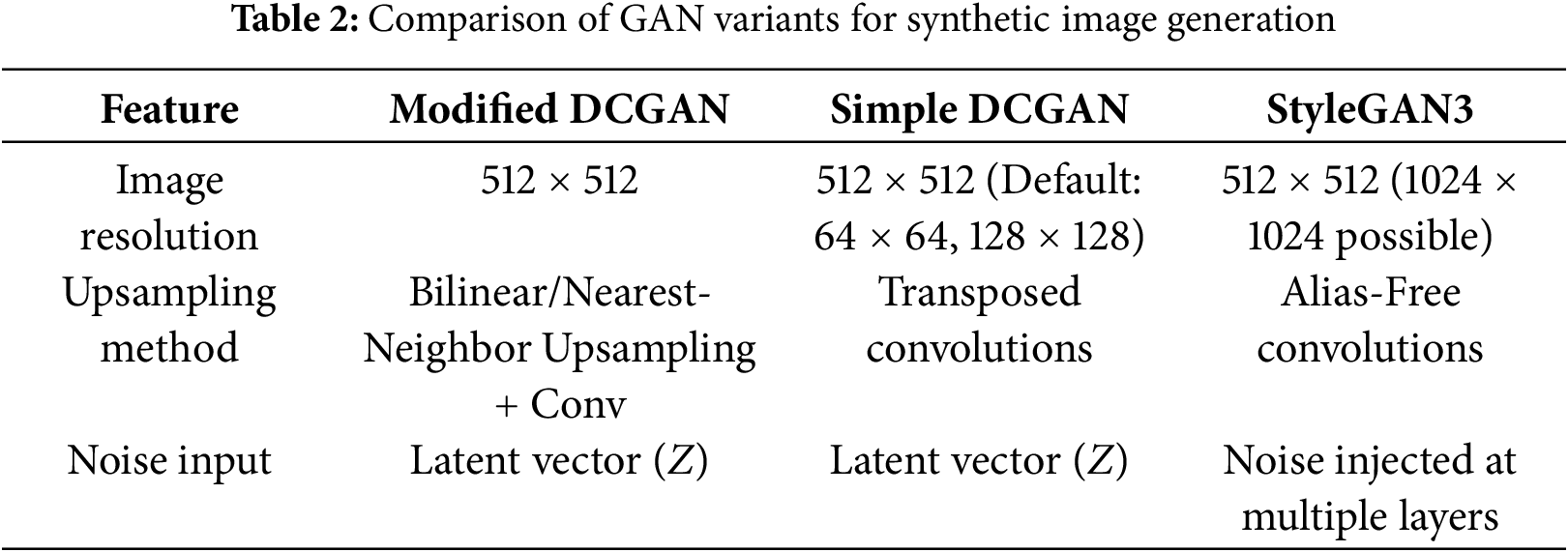

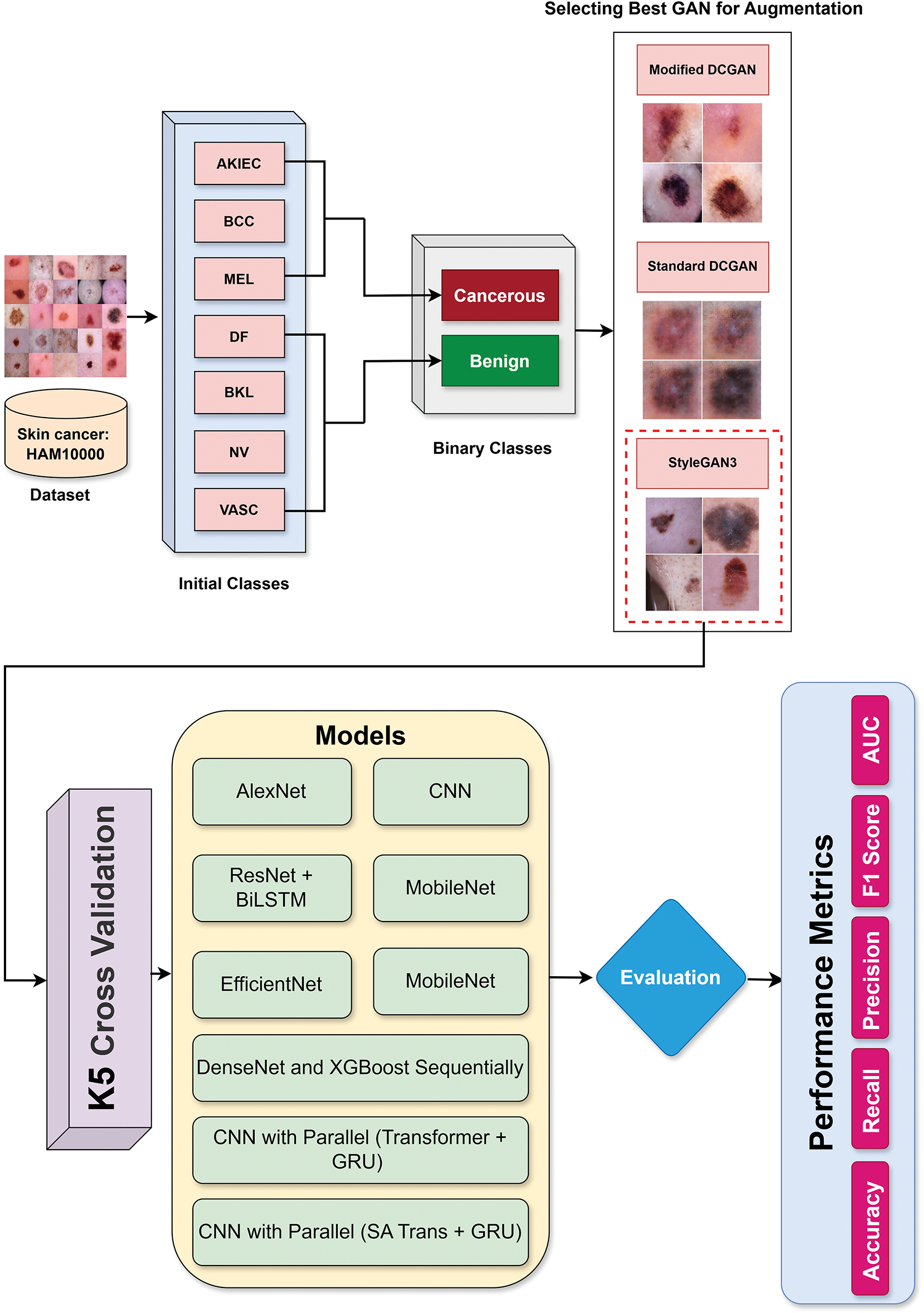

In particular, this study used a variation of Deep Convolutional GAN (DCGAN), a standard DCGAN [23], and StyleGAN3 [24]. Further synthetic examples were generated based on these models by training them on melanoma class-only samples. Fig. 2 shows synthetic melanoma images generated by each GAN variant: (a) Standard DCGAN, (b) Modified DCGAN, and (c) StyleGAN3. Table 2 presents the various parameters that were utilized for generating synthetic samples with the GANs. Each GAN Model was evaluated in terms of their capacity to produce high-quality, clinically realistic dermoscopic images, and numerical image quality and diversity measures. Before augmentation, the number of class 1 (cancerous skin lesion) and class 2 (normal skin) observations was 1954 and 8061, respectively, showing a considerable class imbalance. By GAN augmentation, the number of cancerous skin images became 6954, and that of normal skin images became 8061. This process led to a more equitable data set and permitted the model to expose itself to a larger and wider variety of manifestations of melanoma.

Figure 2: Synthetic melanoma images generated by GAN variants: (a) Standard DCGAN, (b) Modified DCGAN, (c) StyleGAN3

• Modified DCGAN: Tailored for 512

• Standard DCGAN: Serving as a baseline, this architecture employs transposed convolutions for upsampling. Although computationally efficient, it tends to produce lower-quality images at higher resolutions, with more pronounced artifacts, which is reflected in its elevated FID and KID scores.

• StyleGAN3: Selected for its state-of-the-art performance, StyleGAN3 features an alias-free generator architecture that ensures equivariance to image transformations such as translation and rotation, leading to more consistent and artifact-free image synthesis. Its design includes a mapping network that transforms the latent vector Z into an intermediate latent space W, allowing the disentanglement of style and content. Noise injection in each generator layer further enhances the image variation. These architectural advances allow StyleGAN3 to capture complex high-frequency features such as texture, color variation, and border irregularities common in dermoscopic images, thus producing more realistic and diverse synthetic lesions.

Overall, the GAN-augmented samples were integrated with the original dataset to form a balanced training set, which was subsequently normalized and resized to a fixed resolution of 512

To quantitatively assess the quality and diversity of synthetic melanoma images, we utilized three standard metrics: Fréchet Inception Distance (FID), Kernel Inception Distance (KID), and Inception Score (IS). These metrics compare the distribution of synthetic images to real images and are widely used to evaluate GAN performance. The GAN objective is defined as:

where D is the discriminator, G is the generator, and z is the noise vector.

• Fréchet Inception Distance (FID): FID measures the similarity between the feature distributions of real and generated images using activations from a pre-trained Inception-v3 network. It assumes that these features follow a multivariate Gaussian distribution.

where

Lower FID values indicate better quality and closer resemblance to real images.

• Kernel Inception Distance (KID): Unlike FID, KID uses the squared Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD) between the feature distributions of real and generated images, computed using a polynomial kernel.

where

Lower KID values suggest closer alignment between real and generated image distributions.

• Inception Score (IS): IS evaluates the quality and diversity of generated images by using the output class probabilities from a pre-trained Inception network.

where

Higher IS values indicate that the model generates diverse images that are confidently classifiable.

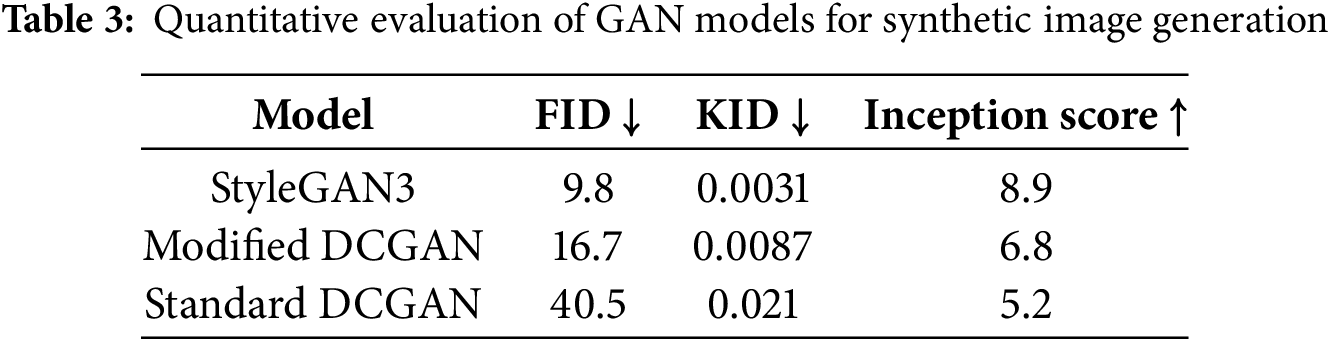

Lower FID and KID values correspond to higher similarity to real images, whereas a higher IS indicates greater diversity and image quality. The comparative performance of these GANs is summarized in Table 3.

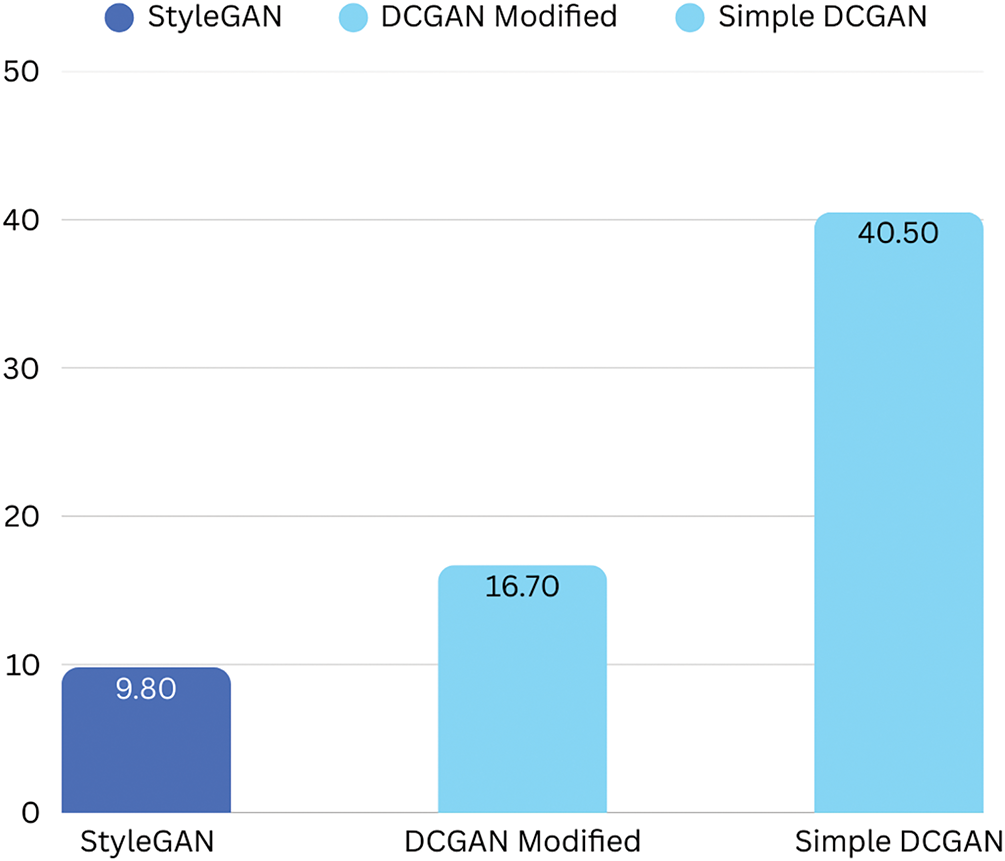

The visual comparison, corroborated by the quantitative metrics in Table 3, highlights StyleGAN3’s ability to produce lesions with finer details, greater realism, and greater diversity. The FID scores, in particular, show a marked improvement with StyleGAN3 (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Comparison of Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) scores for GAN models (Lower is better)

Following a comprehensive comparative analysis that involved qualitative (visual inspection) and quantitative (FID, KID, and Inception Score) evaluations, StyleGAN3-generated images were selected as the most effective due to their superior fidelity, enhanced diversity, and morphological consistency with real dermoscopic patterns. The architectural innovations of StyleGAN3, particularly its alias-free design and ability to disentangle style representations, substantially contribute to its empirical performance. Furthermore, the integration of these high-quality synthetic images with conventional augmentation techniques (e.g., rotation, flipping, contrast enhancement, and Gaussian noise) significantly enriched the training dataset, thereby enhancing the model’s capacity to generalize, particularly to rare or atypical cases of melanoma.

To ensure consistency in image representation, all images were resized to a

4 Proposed Model: CNN with Parallel Transformer and GRU

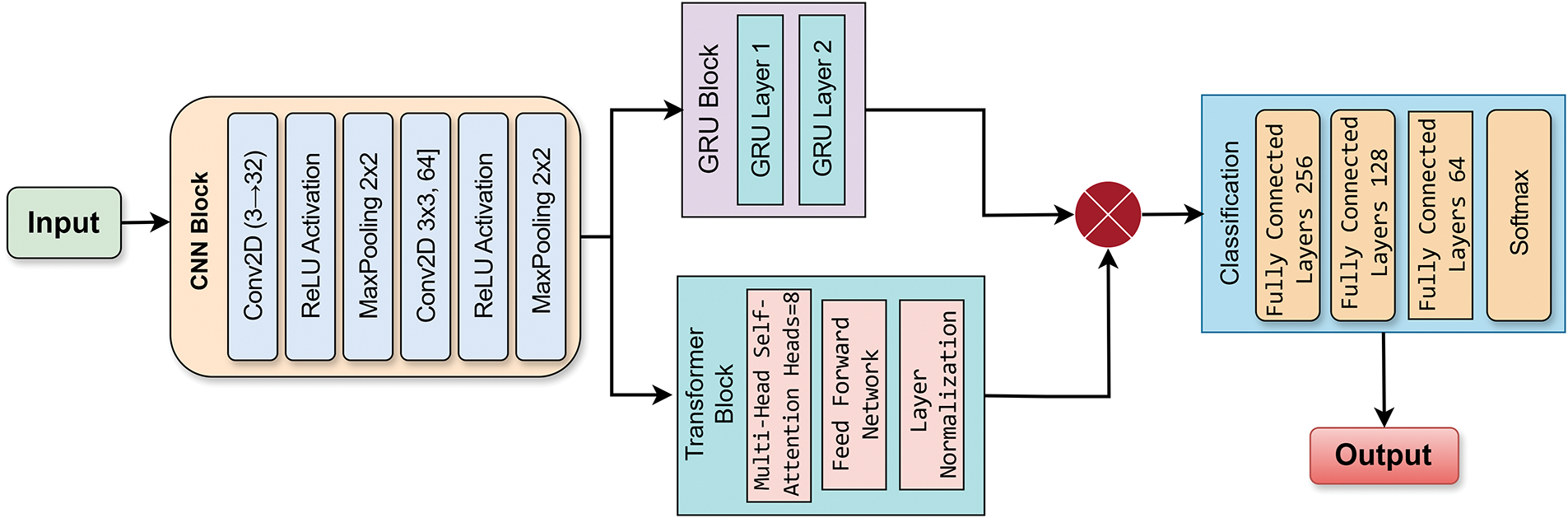

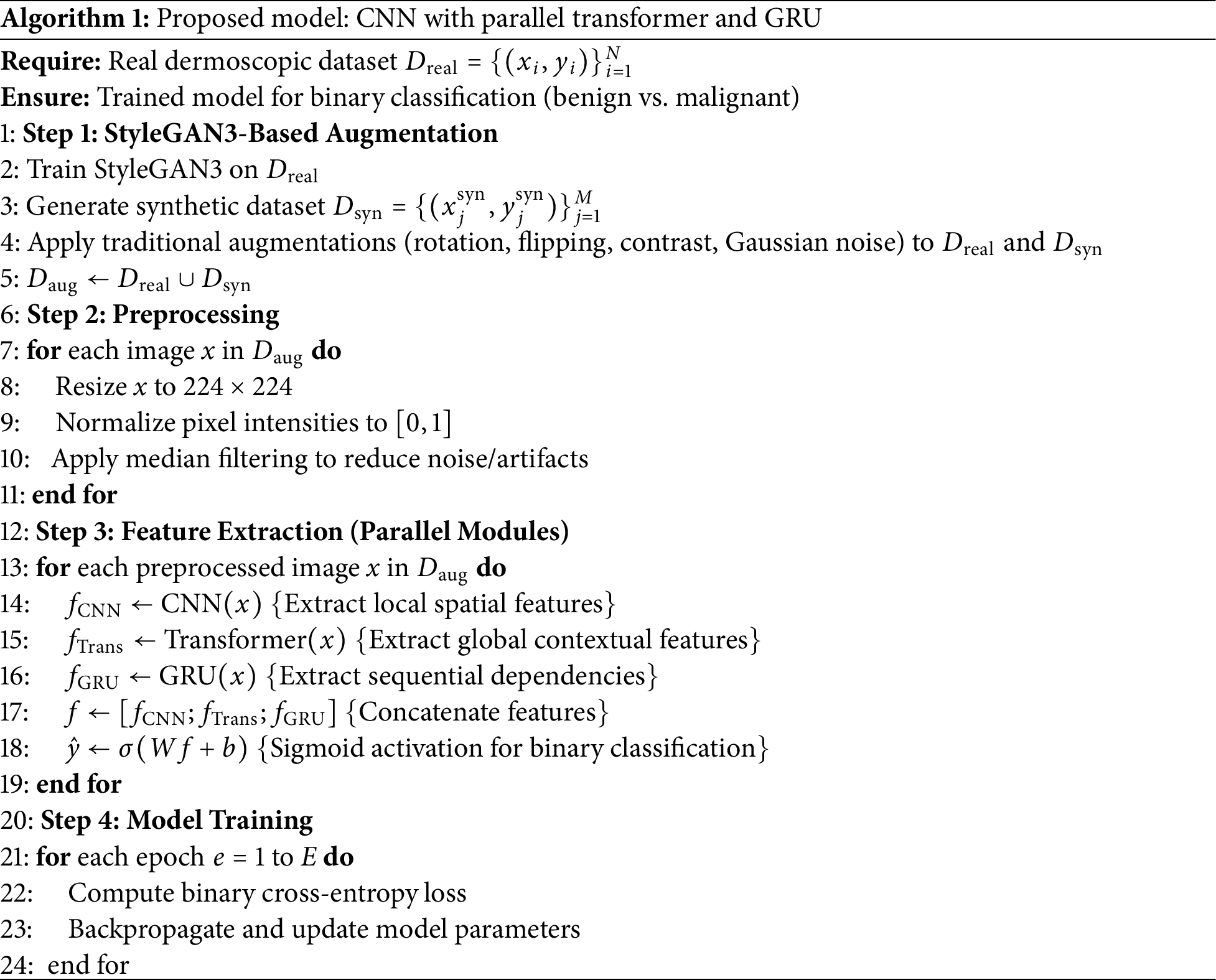

Deep learning models have demonstrated remarkable success in medical image analysis, yet individual architectures often have inherent limitations. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [20], despite their ability to extract local spatial features, struggle to capture long-range dependencies. Transformers, known for their attention mechanisms, effectively capture global dependencies, but often require large-scale datasets. Similarly, Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs) [25] excel in capturing sequential dependencies but are not traditionally used for image classification tasks. To take advantage of the strengths of each architecture while mitigating their respective limitations, we propose a hybrid deep learning model that integrates CNNs, Transformers [26], and GRUs in a parallel configuration. This novel architecture ensures that local, global, and sequential dependencies are effectively captured, leading to a more comprehensive feature extraction process. The features extracted by these parallel modules CNN, Transformer, and GRU, are subsequently fused. Specifically, after the features are extracted from each of the three modules, they are concatenated into a unified feature representation. This fusion mechanism ensures that each module contributes complementary information to the final prediction. A fully connected layer processes the combined feature vector, followed by a sigmoid activation function, to output a binary classification: malignant or benign. The individual components and their roles are detailed in the following subsections. As shown in Fig. 4 and Algorithm 1, the proposed model consists of three parallel branches: a CNN for the extraction of spatial features, a Transformer for global attention, and a GRU to capture sequential representations. The outputs of all three branches are concatenated and fed into a classifier. In contrast to traditional sequential or stacked hybrid models, our design allows each module: CNN, Transformer, and GRU to learn in parallel from the same input, which encourages diverse and complementary feature learning. The GRU branch is uniquely applied to spatially reshaped image data, an unconventional use that contributes sequential reasoning to visual information. Additionally, we incorporate positional encoding in the Transformer to enhance spatial awareness, making it more suitable for medical image tasks with limited data.

Figure 4: Proposed model-CNN with parallel (SA Transformer and GRU)

4.1 Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)

CNNs are basically the baseline of our structure, which extract low-level and high-level spatial features from the input images [27]. The convolution operation at layer l is defined as:

where

4.2 Transformer Module for Global Attention

Transformers have emerged as the state-of-the-art in vision tasks due to their self-attention mechanism that permits them to focus on the most important areas of an image [28]. In the proposed model, we employ the Transformer architecture to capture long-range dependencies and help understand the context of skin lesions. In contrast to CNNs that have local receptive fields, Transformers consider the entire image as a whole and thus have shown particularly good performance in lesion shape and color-variance-based diagnosis applications. The multi-head attention mechanism is computed as:

where Q, K, and V are the query, key, and value matrices, and

4.3 Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) for Sequential Dependency Learning

While GRUs are typically used for sequential data, we have used them for features generated by CNN and Transformer. GRUs assist in learning temporal dependencies of feature representations and are thus helpful for the model to maintain useful context from various levels of abstractions [29]. Such sequential processing contributes to the extraction of the subtle variation of lesion structures across different spatial areas, yielding an improved classification performance. The GRU updates its hidden state

5 Experimentation, Results, and Analysis

To optimize model performance, we used the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.0001, ensuring efficient weight updates during backpropagation. The model was trained using Binary Cross-Entropy Loss, which is well-suited for binary classification problems, penalizing incorrect predictions based on probability distributions. The data set was split using 5-fold cross-validation, a robust evaluation strategy that ensures the model is tested across multiple partitions of the dataset, reducing bias and improving generalization. Model performance was assessed using key classification metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, and the area under the ROC curve (AUC-ROC). Accuracy measures overall correctness, while precision and recall quantify the trade-off between false positives and false negatives. The F1 score serves as a balanced metric, especially useful for imbalanced datasets, and the AUC-ROC evaluates the model’s ability to distinguish between classes across different threshold settings.

The complete flow of our proposed skin lesion classification pipeline is visually depicted in Fig. 5. The method starts from the HAM10000 dataset that has seven initial diagnostic labels: Actinic keratoses and intraepithelial carcinoma/Bowen’s disease (AKIEC), Basal cell carcinoma (BCC), Benign keratosis-like lesions (BKL), Dermatofibroma (DF), Melanoma (MEL), Melanocytic nevi (NV), Vascular lesions (VASC). In this study, these two classes were renamed malignant and benign to allow binary classification. For the imbalanced nature of the data and specifically for the low number of malignant samples, we employed various GAN methods for augmentation, such as Standard DCGAN, Modified DCGAN, and StyleGAN3. These synthetic images, as well as classic augmentation techniques, were included in our data set to enhance the generalizability of the model. Then, different deep learning models were trained on the augmented dataset, from traditional CNNs to multistage architectures such as CNN, along with parallel Transformer and GRU. To make it robust and prevent overfitting, model training and evaluation were conducted by five-fold cross-validation. Finally, the models were assessed with several performance indicators, such as accuracy, recall, precision, F1-Score and AUC [30]. These measures enable a thorough assessment of the performance for both classification and diagnostic confidence of models.

Figure 5: End-to-end methodology flow of the proposed skin lesion classification system

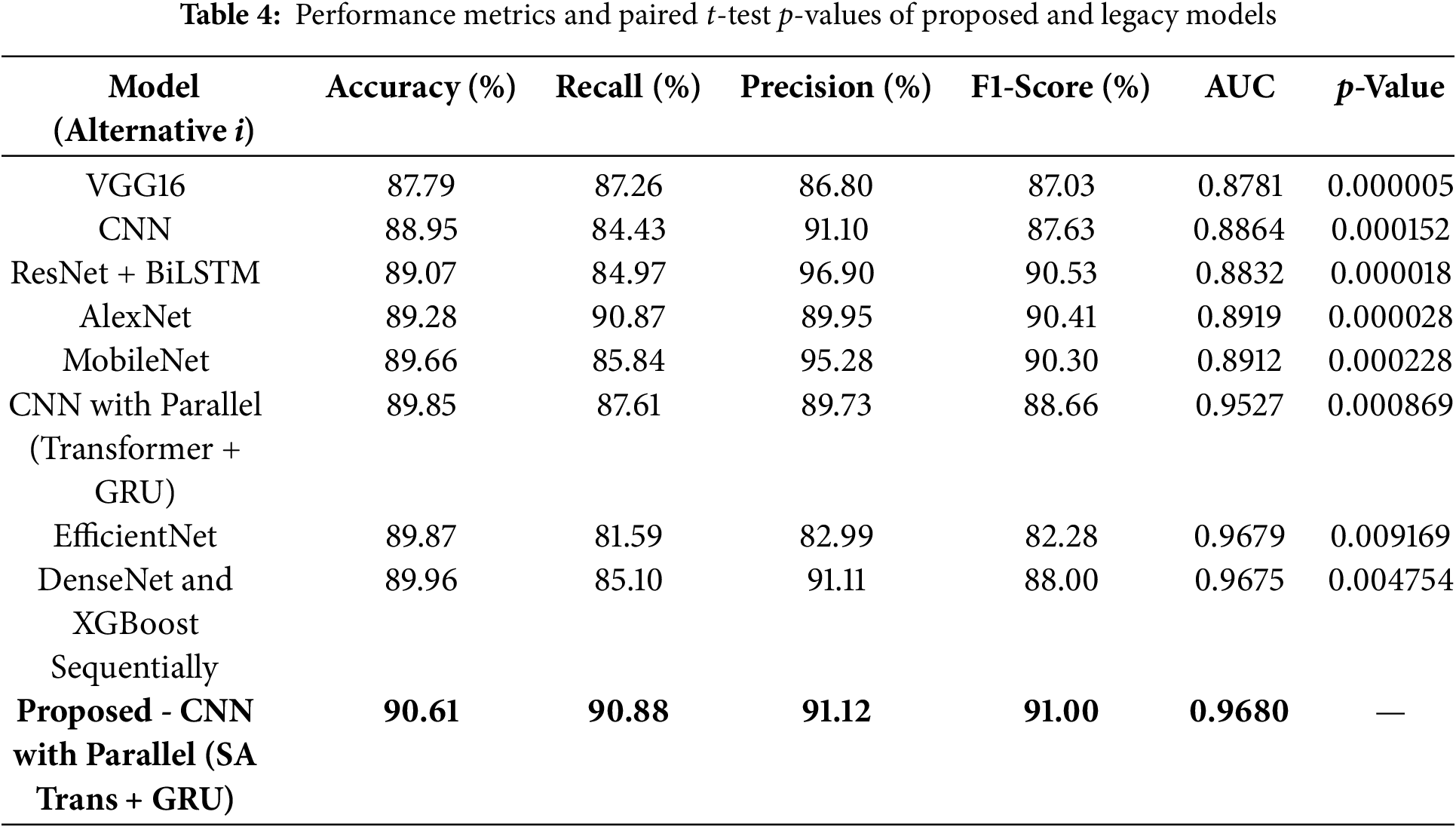

A comprehensive comparison of all the discussed models in terms of accuracy, recall, precision, F1 Score, and AUC is shown in Table 4. Overall, this evaluation provides a wider view for each model’s performance in skin cancer detection than the one gained through a single-metric analysis. The metrics have their focuses: the accuracy evaluates the percentage of correct predictions that the model has made overall (Spanning from 87.79% for VGG16 to 90.61% for the proposed model), the recall evaluates the proportion of actual positive cases that got classified as such (From 81.59% for EfficientNet to 90.88% for the proposed CNN with Parallel Self-attention Transformer and GRU), the precision reflects the reliability of the positive predictions (The proposed model with the highest of 91.12%) and the F1-score is simply the average value of precision and recall (The proposed model with the highest maximum of 91.00%). The AUC measure takes the class ability to be separated from the rest at various thresholds considered (0.8781 for VGG16 and 0.9680 for the proposed model). Such a balanced and multimeric approach is highly desirable in medical diagnostics to minimize false positive and false negative errors. The proposed model is composed of CNN Parallel Self-Attention Transformer and GRU, and it gets the best scores among all the metrics. Robust generalization and reliability are indicated by its high precision and recall, making it suitable for clinical use. Moreover, the high AUC reveals its potential to differentiate malignant and benign skin lesions at different thresholds. The proposed model (CNN with SA Transformer + GRU) was compared with the baselines using the paired t-test. Results demonstrate that all the models are significant (i.e., having p-values < 0.005) for the classification accuracy, proving the statistical superiority of the proposed model.

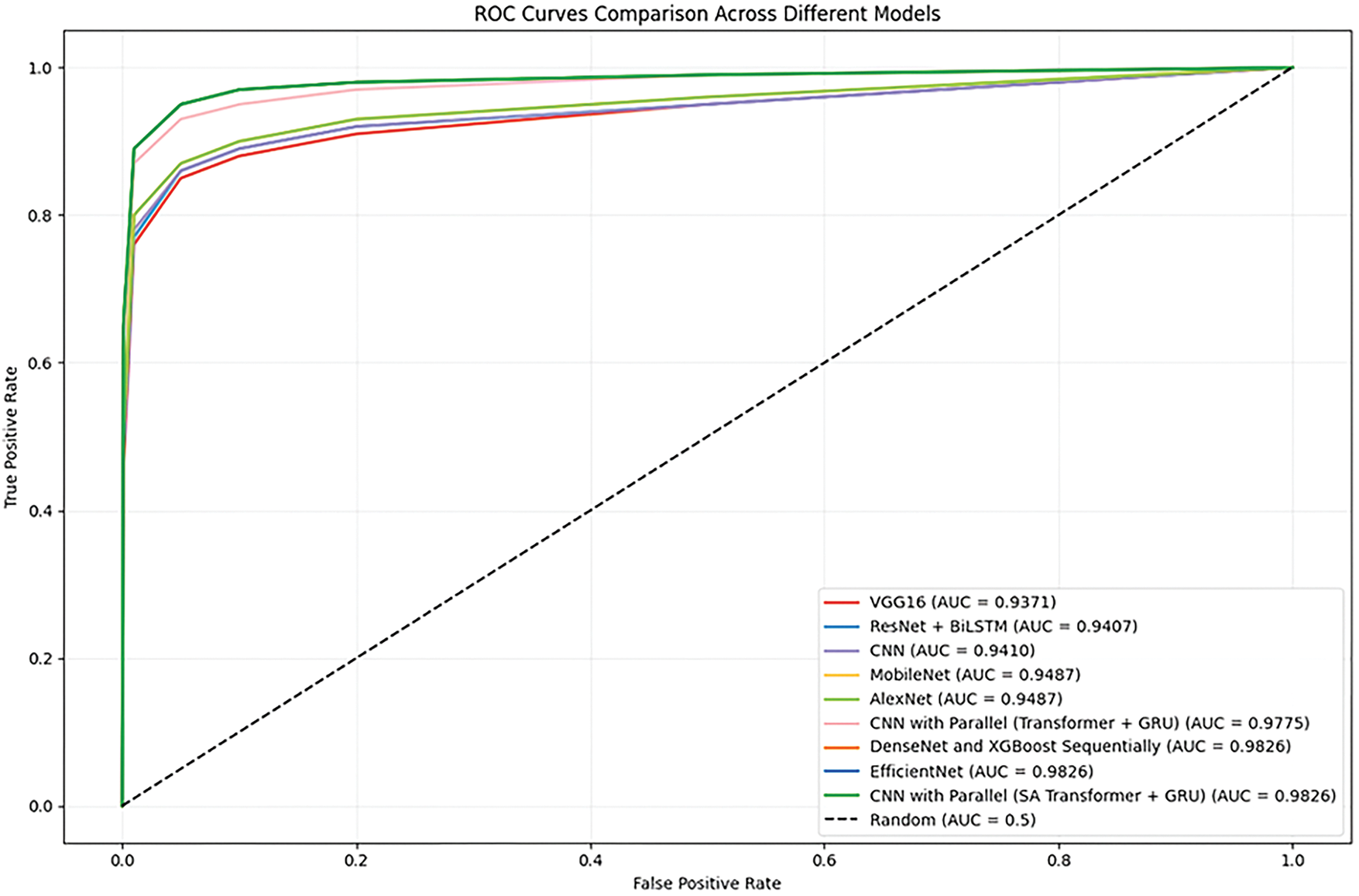

The ROC curves for the proposed model and other baseline models are presented in Fig. 6. We find that the AUC score of the proposed CNN with Parallel (SA Transformer + GRU) is much higher, which means it has a better class discrimination performance. This is crucial for skin cancer detection, where avoiding false negatives (missing a cancer) is vital. The ROC curve of the proposed model consistently achieves superiority over those of other conventional models like VGG16, MobileNet, and ResNet + BiLSTM (Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory Network). It has a high true positive rate even with a low false positive rate, indicating its generality with different thresholds. This generalization to the models contributes to the robustness of the model when applied in actual clinical practice, where misclassifications would lead to life-changing decisions.

Figure 6: ROC curves for proposed and baseline models

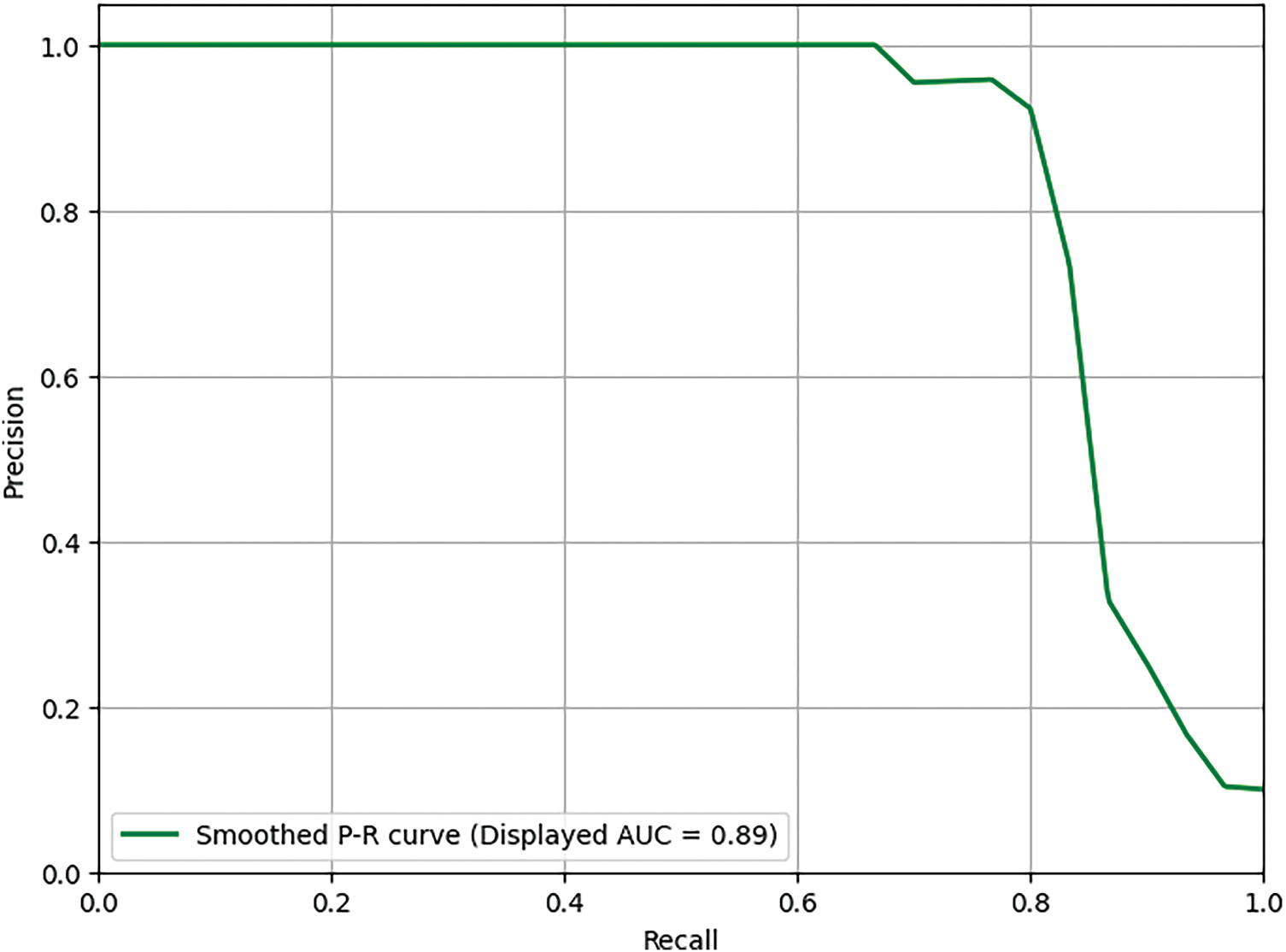

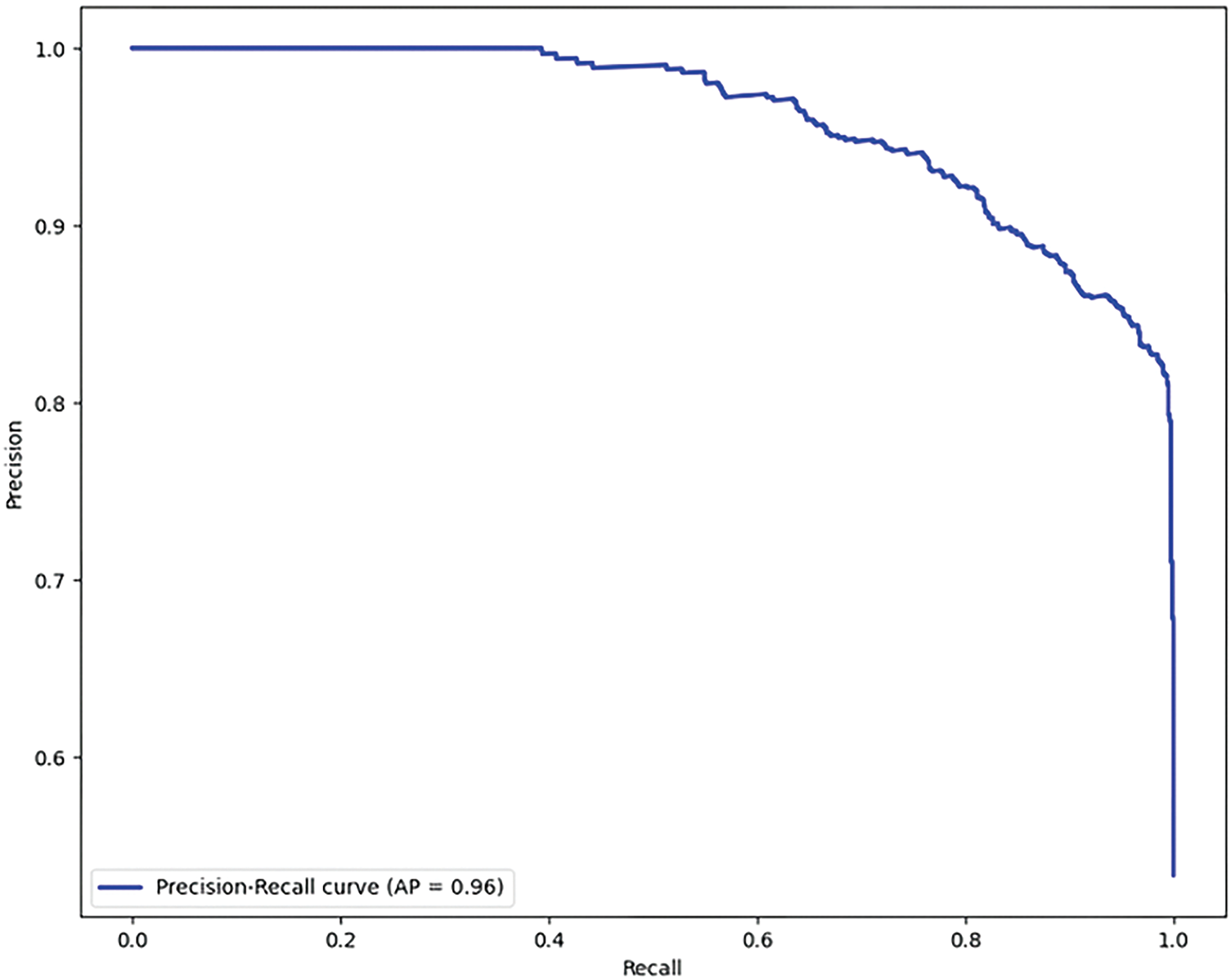

The precision-recall curve is another important evaluation metric, especially in cases where the data set is imbalanced, which is common in medical diagnostics. Fig. 7 presents the precision-recall comparison graph for the proposed model without data augmentation, achieving a precision-recall score of 0.89. Fig. 8 shows the comparison for the proposed model with the GAN-based data augmentation, achieving a significant improvement with a precision-recall score of 0.96. The precision-recall curves demonstrate the trade-off between precision (the proportion of true positive predictions out of all positive predictions) and recall (the proportion of true positive predictions out of all actual positive cases). With data augmentation, the model maintains high precision while achieving significantly better recall. This improvement is crucial in minimizing false positives and false negatives, ensuring that the model provides accurate diagnoses without missing any potentially malignant skin lesions. The high precision and recall values with augmentation indicate that the proposed model is well-suited for early and reliable skin cancer detection.

Figure 7: Precision-recall comparison (Without augmentation)-Score: 0.89

Figure 8: Precision-recall comparison (With augmentation)-Score: 0.96

5.2 Impact of Data Augmentation on Model Performance

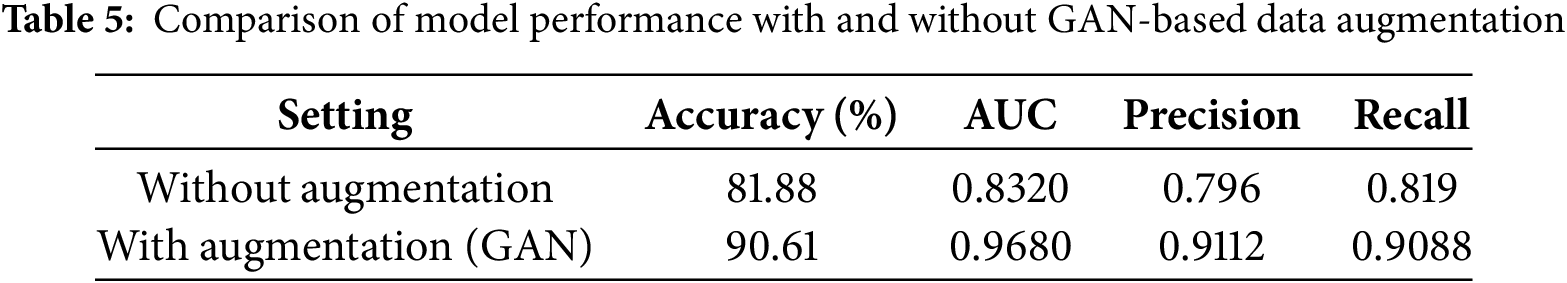

To further quantify the effectiveness of GAN-based data augmentation, we compared the performance of the proposed model on the same dataset with and without augmentation. Table 5 summarizes the key metrics for both scenarios. Without data augmentation, the model achieved an accuracy of 81.88%, AUC of 0.8320, precision of 0.796, and recall of 0.819 (see Fig. 7). In contrast, with GAN-based augmentation, the model’s performance improved substantially, achieving 90.61% accuracy, 0.9680 AUC, 91.12% precision, and 90.88% recall. This demonstrates that data augmentation not only enhances the model’s ability to generalize to unseen data but also significantly boosts its sensitivity and overall diagnostic reliability. These findings are consistent with previous research, showing that data increase is a critical strategy for improving model robustness, especially in medical imaging tasks with limited or imbalanced datasets [1,3,4].

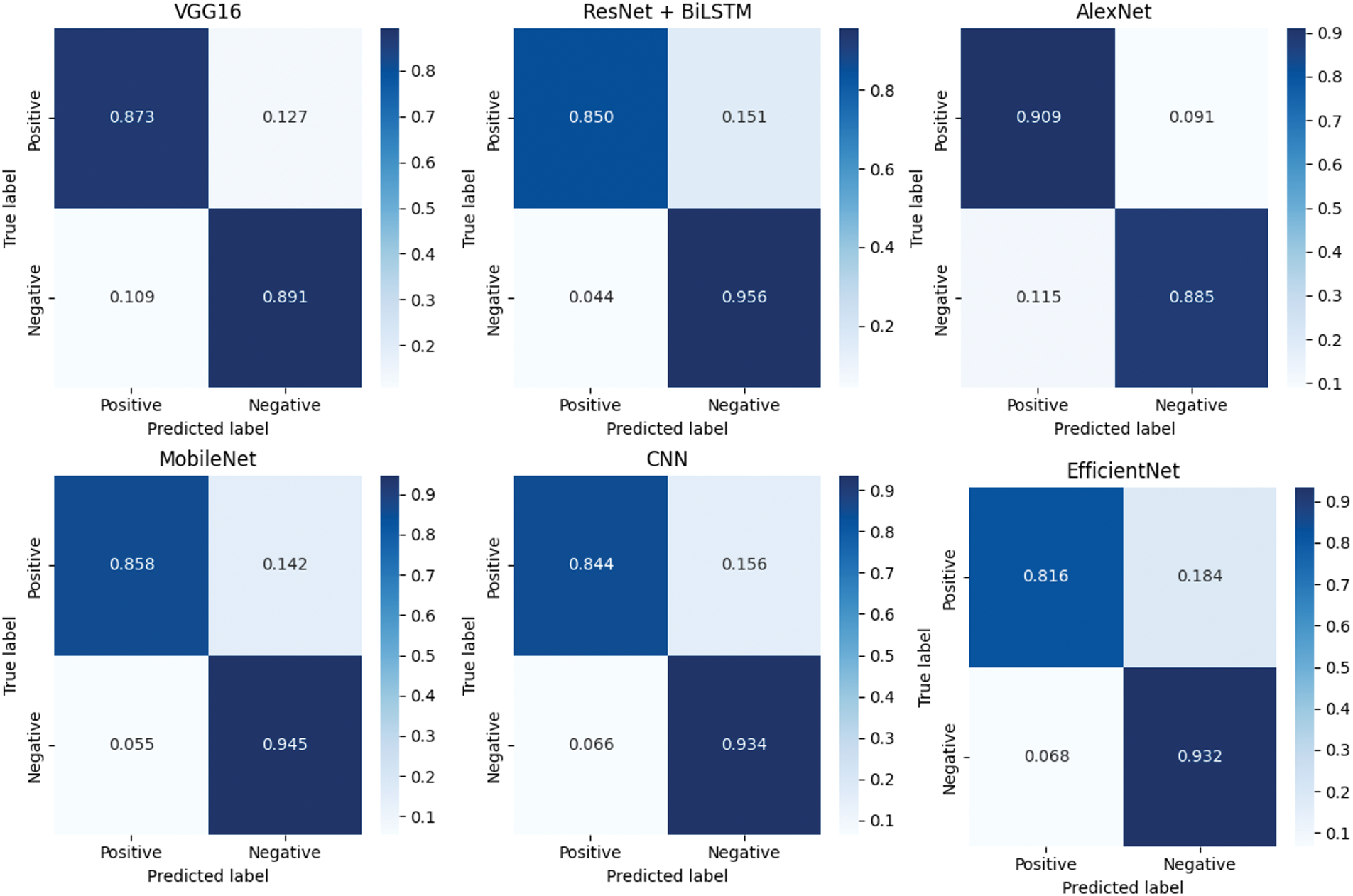

These experiments suggest that the application of GAN-based data augmentation is very useful for improving the classification performance of the proposed model with imbalanced medical data. To gain more insight into the classification of each model, normalized confusion matrices are shown in Fig. 9, where the information of true positives (TP), true negatives (TN), false positives (FP) and false negatives (FN) is represented. This analysis provides insight into the strengths and weaknesses of each model in the accurate detection of malignant lesions. From the confusion matrix for the above models, the proposed model showed the best results with minimal false positives and false negatives. This is further evidence of its applicability to high-risk diagnostic applications, such as skin cancer diagnosis. Others, such as EfficientNet and DenseNet + XGBoost, also exhibit a good result with the tradeoff between sensitivity and specificity being relatively lower.

Figure 9: Normalized confusion matrices of evaluated models

This research introduces a novel deep learning architecture that combines CNNs with parallel SA transformers and GRUs for enhanced feature extraction and sequence modeling in skin cancer detection. This architecture represents a significant departure from conventional pre-trained networks and is expected to demonstrate superior performance in capturing complex features and patterns associated with skin lesions. The research utilizes GAN-based augmentation to address the data imbalance problem prevalent in skin cancer datasets, specifically by generating synthetic melanoma images. This approach can improve the robustness of the model, improve its ability to generalize from limited data, and mitigate the risk of overfitting, leading to more reliable and accurate predictions. Early and accurate detection of skin cancer, particularly melanoma, is crucial for effective treatment and improved patient outcomes [31]. The proposed deep learning system aims to provide clinicians with a more objective and reliable diagnostic tool, potentially reducing the subjectivity inherent in visual evaluations of skin lesions [32]. The performance of the model was rigorously evaluated using a five-fold cross-validation. This comprehensive evaluation strategy ensures the stability and reliability of the results, providing insight into the consistency and generalizability of the model in different data splitting scenarios [14]. The evaluation further includes comparative analysis with individual model branches (CNN-only, CNN+GRU, etc.), demonstrating the advantage of our hybrid configuration. Visual explanation techniques like Grad-CAM and metric-based comparisons validate the model’s focus and decision reliability. The observed performance gains confirm the effectiveness of combining spatial, sequential, and global features for medical image classification.

5.4 Comparison with Existing Work

This study introduces a novel hybrid architecture, which is the combination of CNN, parallel SA Transformer, and GRU, to extract complex spatial and sequential patterns in skin lesions [33–35]. CNN extracts hierarchical visual features, Transformer emphasizes the salient regions of an image, and GRU captures the sequential latent dependencies. This parallel processing results in a richer understanding of the lesion characteristics over simple or standalone CNN-based models. The use of GAN-based augmentation further improves the model to deal with class imbalance, yields a variety of synthetic melanoma images that enhance generalization and reduce overfitting [35]. In comparison with typical ML(Machine Learning) and pre-trained CNN, like VGG16 and AlexNet, which have fixed feature extractors, and lower results, the proposed model has better results in key evaluation parameters such as accuracy, precision, recall, f1 score, and AUC [35]. The proposed model achieves 90.61% accuracy, while VGG16, AlexNet, and standard CNN accuracy were 87.79%, 89.28% and 88.95%. It also performs better than a CNN+Transformer+GRU model (89.85%). While transfer learning approaches with AlexNet, ResNet, VGG are popular [36–39], they typically need pre-trained generic features. Ensemble models also might achieve better performance, but they complicate the system without guaranteed improvement. In contrast, our proposed model learns task-specialized features with its distinctive architecture and also exploits GAN-based augmentation. While the findings are encouraging, more testing is required in multiple datasets and clinical scenarios to determine the generalizability and robustness of the results [16,34,35].

5.5 Comparison with State-of-the-Art Architectures

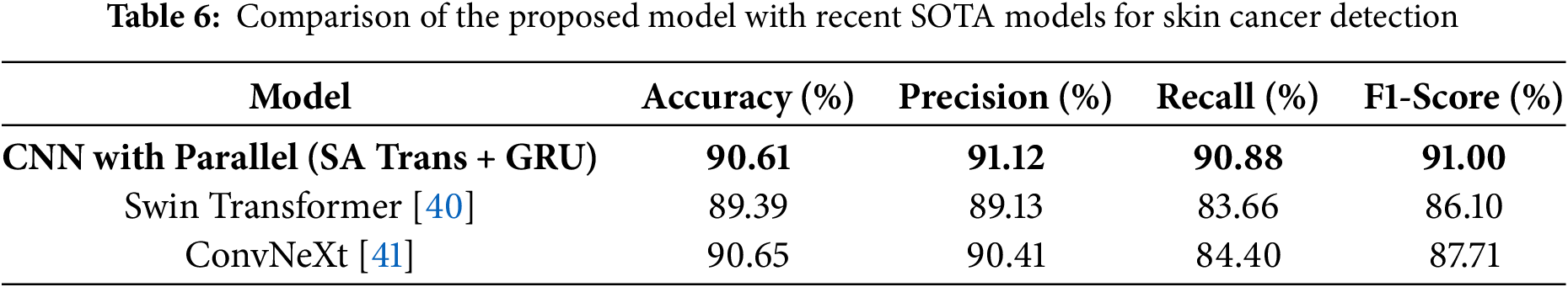

To contextualize the performance of our proposed model, we compared its results with some recent state-of-the-art (SOTA) deep learning architectures for skin cancer detection, as reported in the literature. Table 6 summarizes the key metrics of our model alongside leading transformer-based and hybrid models such as Swin Transformer and ConvNeXt.

As shown, our model achieves highly competitive results, particularly in F1-score and recall, which are crucial for medical diagnostics. While ConvNeXt achieves slightly higher accuracy, our approach demonstrates a stronger balance of sensitivity and precision, supported by robust generalization due to GAN-based augmentation. Notably, our model also incorporates explainability through Grad-CAM (Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping) and addresses class imbalance, features not always present in SOTA benchmarks. Recent studies such as the enhanced Faster R-CNN optimized by artificial gorilla troops algorithm [42] and xCViT [43] have further advanced the field by introducing novel optimization and fusion strategies. These works highlight the ongoing evolution of deep learning methods for skin cancer detection and underscore the importance of benchmarking hybrid and explainable models. Future work will focus on direct benchmarking against these and other emerging SOTA approaches, as well as integrating multi-modal and self-supervised learning strategies.

The proposed CNN with parallel SA Transformer and GRU architecture presents a novel and effective solution for skin cancer detection by integrating spatial, global, and sequential feature extraction mechanisms [15,33,35,44]. CNN captures local visual features, while SA Transformer models global dependencies, and GRU captures sequential patterns, resulting in a rich and holistic representation of skin lesions. To mitigate data imbalance, common in medical imaging, GAN-based augmentation is used to generate synthetic samples, enhancing the diversity of the data set and improving model generalization [3,12]. This multicomponent architecture increases robustness by exposing the model to a wide range of lesion variations during training, which is essential for real-world diagnostic accuracy [33,34]. The model achieves superior performance in accuracy, precision, recall, and AUC compared to baseline models such as EfficientNet, MobileNet, VGG16, AlexNet, and DenseNet with XGBoost, as confirmed by cross-validation [12,45]. The use of dermoscopic images further improves clinical relevance by highlighting fine skin structures, supporting its utility to assist dermatologists with accurate and timely diagnoses [3,12,14]. Despite its strengths, the model has limitations. The dependency on GAN-generated data may not fully reflect the diversity of real-world lesion conditions, introducing biases induced by the data set [4,15,33,35]. This model has only been evaluated on public datasets and has not yet been validated with real-world clinical data, which may affect its generalizability in actual clinical environments. Furthermore, the computational demands of the architecture could limit its deployment in low-resource environments. Furthermore, the interpretability of the model remains limited, making its decision-making process less transparent for clinical use [35,44]. Although StyleGAN3-based synthetic data augmentation improves class balance, synthetic images may not fully capture the diversity of real-world skin lesions, potentially limiting the model’s generalization in complex clinical settings. Future extensions should focus on evaluating the model in diverse skin tones and demographics, incorporating explainable AI (XAI) techniques, and optimizing efficiency to support greater adoption.

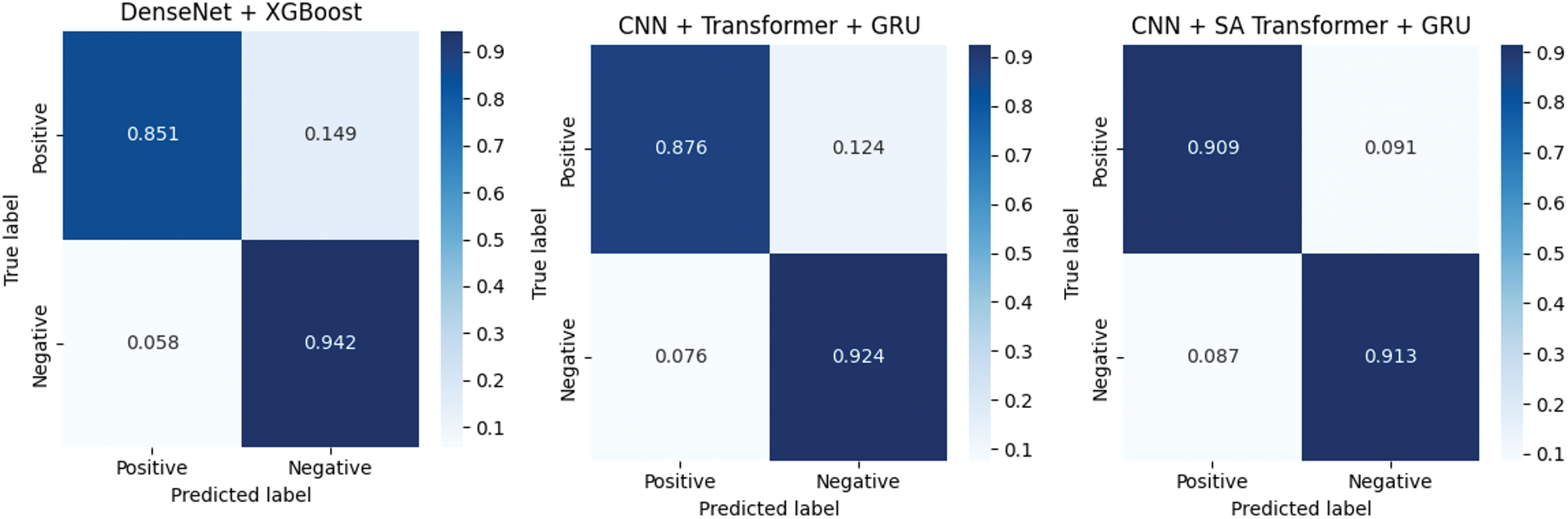

5.7 Model Explainability with Grad-CAM

We also used the Grad-CAM approach to visualize the most discriminative regions in the input images responsible for the model’s decisions to improve the interpretation of our model predictions. Since Grad-CAM is intended for CNN and does not directly apply to RNN, we restricted the explanation to the CNN part of the model. The examples of Grad-CAM heatmaps overlaid over sampled images from the test set are shown in Fig. 10. The highlighted areas are important parts of the image where the model learned to classify, by providing insight into how the model is making decisions. These visualizations show that the model attends to semantically sensible locations, which enhances our trust in its predictions and supports model interpretability.

Figure 10: Sample Grad-CAM visualizations showing the regions of three input images that most influenced the model’s predictions. The heatmaps highlight areas of high importance for the model’s decision-making process

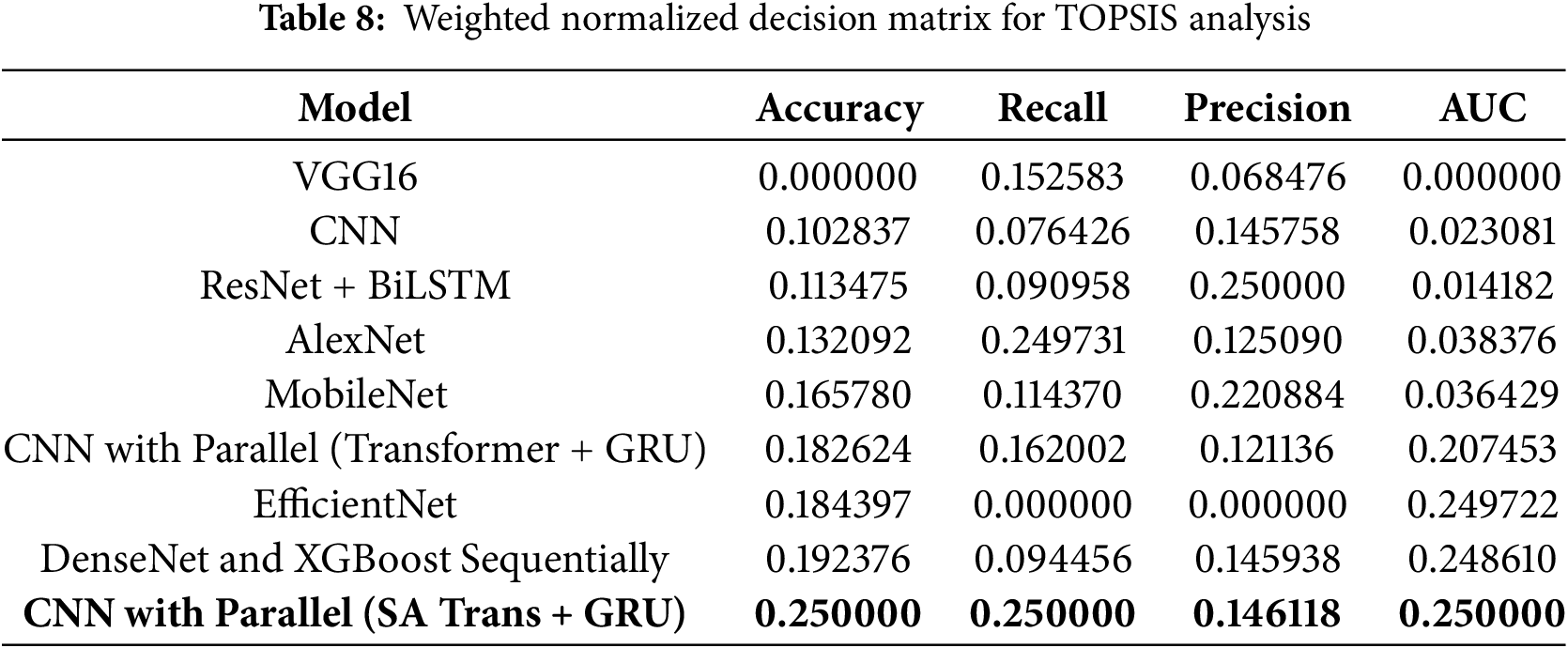

To evaluate the individual contribution of each architectural component, an ablation study was performed between 4 model variants named CNN, CNN_Transformer, CNN_GRU, and the full hybrid CNN with Parallel (Self-Attention Transformer + GRU). The results with key evaluation parameters are summarized in Table 7. The result shows that the Proposed Hybrid model (CNN with Parallel (SA Trans + GRU)) provides the best performance with accuracy 90.61%, precision 91.12%, recall 90.88%, F1-score 91.00%, AUC 0.968. The two alternative models CNN_Transformer and CNN_GRU perform better than the baseline CNN, but the combined joint use of both modules gives the best performance results. This confirms that the combination of local feature extraction (CNN), global attention (Transformer), and sequential modeling (GRU) leads to more robust and reliable skin cancer classification.

6 Comparative Analysis Using TOPSIS

To perform a rigorous and objective evaluation of the proposed model against baseline and ensemble architectures, we utilize the Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS). TOPSIS is a well-established multicriteria decision-making (MCDM) method that ranks alternatives based on their geometric distances from an ideal best and an ideal worst solution [46]. This approach is particularly useful when evaluating models using multiple conflicting performance metrics such as accuracy, recall, precision, and AUC. By applying TOPSIS, we can determine which model offers the best overall trade-off across all evaluation criteria.

TOPSIS works by identifying solutions that are simultaneously closest to the ideal solution (representing the best performance in all metrics) and farthest from the negative ideal solution (representing the worst). The steps involved are the following.

1. Construct the Decision Matrix: A matrix

2. Normalize the Decision Matrix: To eliminate the effect of different scales across metrics, we normalize the matrix using:

3. Weight the Normalized Matrix: Each criterion is assigned an equal weight (

4. Determine Ideal and Negative-Ideal Solutions:

5. Compute Separation Measures: The Euclidean distance of each model from the ideal and negative-ideal solutions:

6. Compute Closeness Coefficient:

7. Rank the Alternatives: Models are ranked based on descending values of

6.2 Normalized Decision Matrix

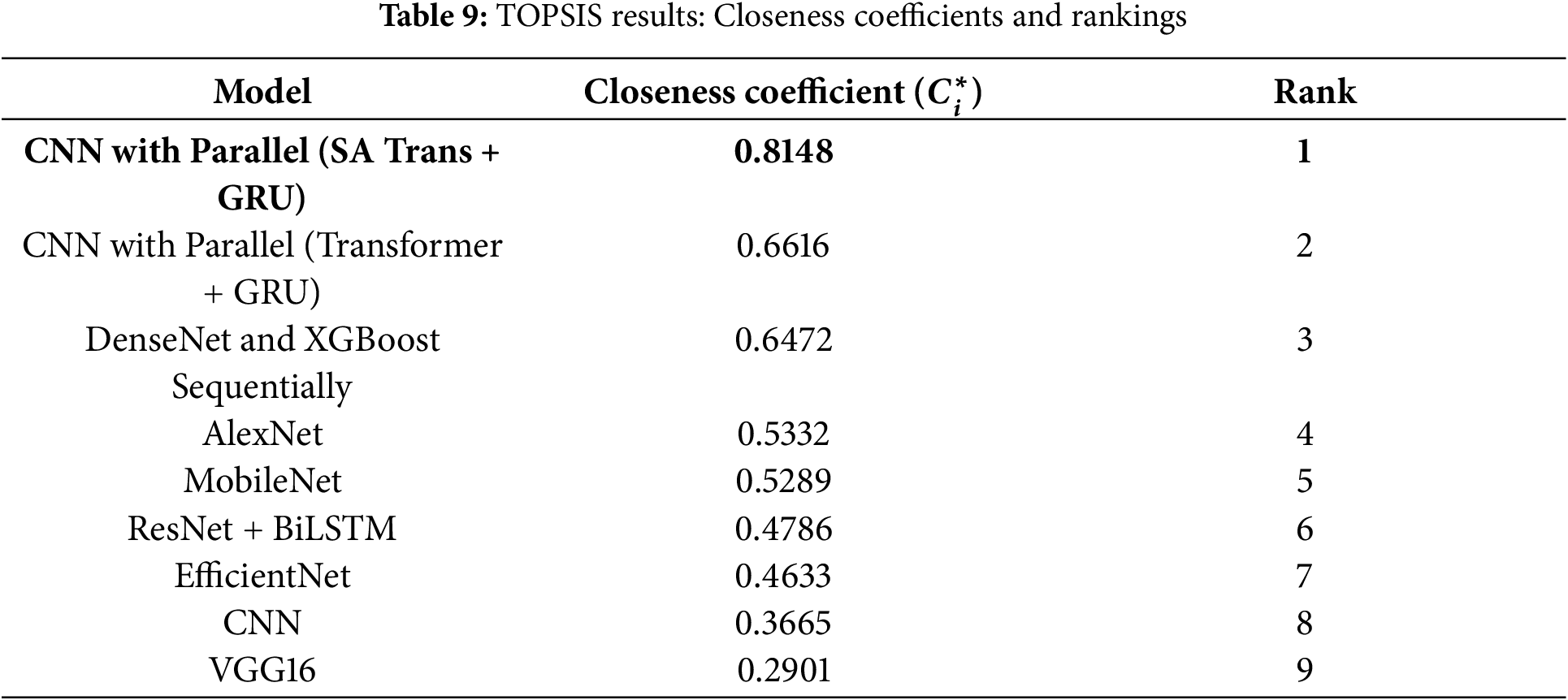

The following table presents the normalized and weighted decision matrix derived from the experimental results shown in Table 8:

6.3 TOPSIS Results and Discussion

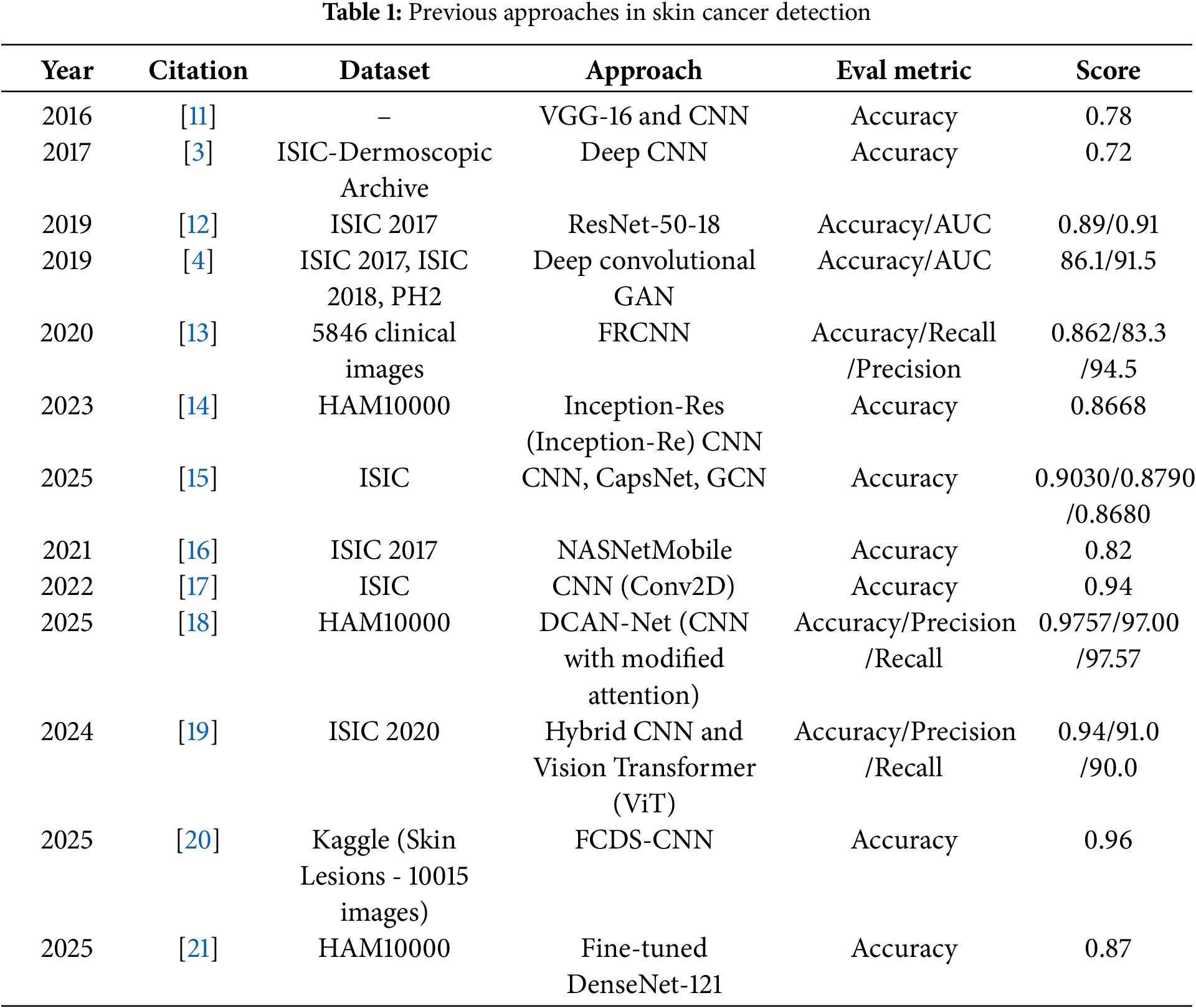

Using the above weighted normalized data, we calculate the closeness coefficient

The model CNN with Parallel (SA Transformer + GRU) ranks first with the highest closeness coefficient of 0.8148. This indicates that it offers the best trade-off in accuracy, recall, precision, and AUC in the evaluated setup. Therefore, the proposed model demonstrates robust overall performance for skin cancer classification within the TOPSIS framework.

7 Conclusion and Future Direction

The field of skin cancer detection is evolving at a rapid pace, and deep learning models have demonstrated great potential in image-based classification activities. However, despite these advances, the available models are often limited by data availability, suffer from overfitting, and sometimes struggle with generalization issues. The proposed hybrid model that combines CNN, the self-attention transformer, and GRU addresses these shortcomings as it helps to model local and global spatial-temporal dependencies simultaneously in dermoscopic images. The use of a GAN-based data augmentation strategy solves the problem of data imbalance and improves the robustness of the model. Unlike traditional CNN approaches that focus on binary classification and are prone to overfitting, the proposed architecture demonstrates strong performance across multiple evaluation metrics, achieving an accuracy of 90.61%, a recall of 90.88%, a precision of 91.12%, an F1-score of 91%, and an AUC of 0.968. The combination of feature extraction, sequence learning, and the use of attention mechanisms, all within a coherent framework, plays a key role in the efficiency of the model. Multicriteria decision analysis via the TOPSIS technique further confirms the superiority of the model as the proposed model has the highest value of closeness coefficient, which explains the best overall trade-off of the four performance measures (accuracy, recall, precision, and AUC). Future work can include clinical validation on more variate test sets, integration with other patient data sources, development of explainable AI methods to improve the interpretability, and optimization for deployment on mobile or embedded devices.

While the proposed model demonstrates strong performance on the HAM10000 dataset, its domain generalizability remains to be evaluated. In future work, we plan to assess the robustness of the model by testing it on additional publicly available datasets, such as ISIC 2018. This will help validate the consistency and generalizability of our approach across different data distributions and acquisition settings. Incorporating diverse datasets will further enhance the model’s reliability and clinical applicability. Expanding this approach to other dermatological conditions may also improve its practical utility in healthcare settings.

Acknowledgement: The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through Small Research Project under grant number RGP1/108/46.

Funding Statement: The research is funded by King Khalid University, Saudi Arabia.

Author Contributions: Alex Varghese, Achin Jain, Mohammed Inamur Rahman, Mudassir Khan, Arun Kumar Dubey, Iqrar Ahmed, and Yash Prakash Narayan participated in designing the methodology, developing the concept, implementing the code, performing the experiments, and drafting the manuscript. Arvind Panwar, Anurag Choubey, and Saurav Mallik validated the approach, supervised the research process, and contributed to the review and editing of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data set utilized in this study consists of dermoscopic images sourced from publicly available repositories, primarily the HAM10000 dataset [22], https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/kmader/skin-cancer-mnist-ham10000 (accessed on 30 July 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Informed Consent: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Henrikson NB, Ivlev I, Blasi PR, Nguyen MB, Senger CA, Perdue LA, et al. Skin cancer screening: updated evidence report and systematic review for the us preventive services task force. JAMA. 2023;329(15):1296–1307. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.3262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Alam TM, Shaukat K, Khan WA, Hameed IA, Almuqren LA, Raza MA, et al. An efficient deep learning-based skin cancer classifier for an imbalanced dataset. Diagnostics. 2022;12(9):2115. doi:10.3390/diagnostics12092115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Esteva A, Kuprel B, Novoa RA, Ko J, Swetter SM, Blau HM, et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature. 2017;542(7639):115–8. doi:10.1038/nature21056. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Bisla D, Choromanska A, Berman RS, Stein JA, Polsky D. Towards automated melanoma detection with deep learning: data purification and augmentation. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW); 2019 Jun 16–17; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 2720–8. [Google Scholar]

5. Akter M, Khatun R, Talukder MA, Islam MM, Uddin MA, Ahamed MKU, et al. An integrated deep learning model for skin cancer detection using hybrid feature fusion technique. Biomed Mater Dev. 2025;3:1433–47. [Google Scholar]

6. Mahmud F, Mahfiz MM, Kabir MZI, Abdullah Y. An interpretable deep learning approach for skin cancer categorization. In: 2023 26th International Conference on Computer and Information Technology (ICCIT); 2023 Dec 13–15; Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

7. Chaturvedi SS, Gupta K, Prasad PS. Skin lesion analyser: an efficient seven-way multi-class skin cancer classification using mobilenet. In: Advanced Machine Learning Technologies and Applications: Proceedings of AMLTA 2020. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2021. p. 165–176. [Google Scholar]

8. Islam MS, Panta S. Skin cancer images classification using transfer learning techniques. arXiv:2406.12954. 2024. [Google Scholar]

9. Bala D, Hossain MS, Hossain MA, Abdullah MI, Rahman MM, Manavalan B, et al. Monkeynet: a robust deep convolutional neural network for monkeypox disease detection and classification. Neural Netw. 2023;161:757–75. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2023.02.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Hameed M, Zameer A, Raja MAZ. A comprehensive systematic review: advancements in skin cancer classification and segmentation using the isic dataset. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;140(3):2131–64. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.050124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Srividhya V, Sujatha K, Ponmagal RS, Durgadevi G, Madheshwaran L. Vision based detection and categorization of skin lesions using deep learning neural networks. Procedia Comput Sci. 2020;171:1726–35. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2020.04.185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Serte S, Demirel H. Wavelet-based deep learning for skin lesion classification. IET Image Process. 2020;14(4):720–6. doi:10.1049/iet-ipr.2019.0553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Jinnai S, Yamazaki N, Hirano Y, Sugawara Y, Ohe Y, Hamamoto R. The development of a skin cancer classification system for pigmented skin lesions using deep learning. Biomolecules. 2020;10(8):1123. doi:10.3390/biom10081123. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Mankawade A, Bodhankar A, Mahajan A, Prasad D, Mahajan S, Dhakalkar R. Skin cancer detection and intensity calculator using deep learning. In: 2023 International Conference for Advancement in Technology (ICONAT); 2023 Jan 24–26; Goa, India. p. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

15. Afrifa S, Varadarajan V, Appiahene P, Zhang T, Gyamfi D, Gyening RMOM. Deep neural networks for skin cancer classification: analysis of melanoma cancer data. J Adv Inf Technol. 2025;16(1). [Google Scholar]

16. Yilmaz A, Kalebasi M, Samoylenko Y, Guvenilir ME, Uvet H. Benchmarking of lightweight deep learning architectures for skin cancer classification using isic 2017 dataset. arXiv:2110.12270. 2021. [Google Scholar]

17. El-Soud MWA, Gaber T, Tahoun M, Alourani A. An enhanced deep learning method for skin cancer detection and classification. Comput Mater Contin. 2022;73(1):1109–23. doi:10.32604/cmc.2022.028561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Thwin SM, Park H-S, Seo SH. A trustworthy framework for skin cancer detection using a cnn with a modified attention mechanism. Appl Sci. 2025;15(3):1067. doi:10.3390/app15031067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Hamsalekha R, Devadhas G, Satheesha TY. A novel deep learning approach for automated melanoma classification using hybrid cnn and vision transformer model. Fusion Pract Appl. 2025;254:92–101. doi:10.1109/gcat62922.2024.10923859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Nawaz K, Zanib A, Shabir I, Li J, Wang Y, Mahmood T, et al. Skin cancer detection using dermoscopic images with convolutional neural network. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):7252. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-91446-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Bello A, Ng S-C, Leung M-F. Skin cancer classification using fine-tuned transfer learning of densenet-121. Appl Sci. 2024;14(17):7707. doi:10.3390/app14177707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Kaggle UK. Skin cancer mnist: Ham10000 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 17]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/kmader/skin-cancer-mnist-ham10000. [Google Scholar]

23. Radford A, Metz L, Chintala S. Unsupervised representation learning with deep convolutional generative adversarial networks. arXiv:1511.06434. 2016. [Google Scholar]

24. Karras T, Laine S, Aila T. A style-based generator architecture for generative adversarial networks. arXiv:1812.04948. 2019. [Google Scholar]

25. Monica KM, Shreeharsha J, Falkowski-Gilski P, Falkowska-Gilska B, Awasthy M, Phadke R. Melanoma skin cancer detection using mask-rcnn with modified gru model. Front Physiol. 2024;14:1324042. doi:10.3389/fphys.2023.1324042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Reis HC, Turk V. Fusion of transformer attention and cnn features for skin cancer detection. Appl Soft Comput. 2024;164:112013. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2024.112013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Zhao X, Wang L, Zhang Y, Han X, Deveci M, Parmar M. A review of convolutional neural networks in computer vision. Artif Intell Rev. 2024;57(4):99. doi:10.1007/s10462-024-10721-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Sarker PK, Zhao Q, Uddin MK. Transformer-based person re-identification: a comprehensive review. IEEE Trans Intell Vehicles. 2024;9(7):5222–39. doi:10.1109/tiv.2024.3350669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Chen G. An interpretable composite cnn and gru for fine-grained martial arts motion modeling using big data analytics and machine learning. Soft Comput. 2024;28(3):2223–43. doi:10.1007/s00500-023-09565-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Natha P, Tera SP, Chinthaginjala R, Rab SO, Narasimhulu CV, Kim TH. Boosting skin cancer diagnosis accuracy with ensemble approach. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):1290. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-84864-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Maher RS, Bawiskar S. A comparative study of the performance of different machine learning algorithms in skin cancer classification. High Technol Lett. 2023;29(9):429–33. [Google Scholar]

32. Ercal F, Chawla A, Stoecker WV, Lee H-C, Moss RH. Neural network diagnosis of malignant melanoma from color images. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1994;41(9):837–45. doi:10.1109/10.312091. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Dildar M, Akram S, Irfan M, Khan HU, Ramzan M, Mahmood AR, et al. Skin cancer detection: a review using deep learning techniques. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5479. doi:10.3390/ijerph18105479. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Aboulmira A, Hrimech H, Lachgar M, Hanine M, Garcia CO, Mezquita GM, et al. Hybrid model with wavelet decomposition and efficientnet for accurate skin cancer classification. J Cancer. 2025;16(2):506. doi:10.7150/jca.101574. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Rao PVV. Skin cancer detection. Int J Res Appl Sci Eng Technol. 2024;12(4):364. doi:10.22214/ijraset.2024.59725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Ali K, Shaikh ZA, Khan AA, Laghari AA. Multiclass skin cancer classification using efficientnets—a first step towards preventing skin cancer. Neurosci Inform. 2022;2(4):100034. doi:10.1016/j.neuri.2021.100034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Bechelli S, Delhommelle J. Machine learning and deep learning algorithms for skin cancer classification from dermoscopic images. Bioengineering. 2022;9(3):97. doi:10.3390/bioengineering9030097. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Gururaj HL, Manju N, Nagarjun A, Aradhya VNM, Flammini F. Deepskin: a deep learning approach for skin cancer classification. IEEE Access. 2023;11:50205–14. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3274848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Javaid A, Sadiq M, Akram F. Skin cancer classification using image processing and machine learning. In: 2021 International Bhurban Conference on Applied Sciences and Technologies (IBCAST); 2021 Jan 12–16; Islamabad, Pakistan. p. 439–44. [Google Scholar]

40. Liu Z, Lin Y, Cao Y, Hu H, Wei Y, Zhang Z, et al. Swin transformer: hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021 Oct 10–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 9992–10002. [Google Scholar]

41. Liu Z, Mao H, Wu C-Y, Feichtenhofer C, Darrell T, Xie S. A convnet for the 2020s. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 11966–76. [Google Scholar]

42. Nivedha S, Shankar S. Melanoma diagnosis using enhanced faster region convolutional neural networks optimized by artificial gorilla troops algorithm. Inf Technol Control. 2023;52(4):819–32. doi:10.5755/j01.itc.52.4.33503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Ali A, Shahbaz H, Damaševičius R. xCViT: improved vision transformer network with fusion of cnn and xception for skin disease recognition with explainable ai. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;83(1):1367–98. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.059301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Shahadha RS, Al-Khateeb B. Dual convolutional neural network for skin cancer classification. J Cybersecur Inform Manage (JCIM). 2025;15(2):35–42. [Google Scholar]

45. Nguyen ATP, Jewel RM, Akter A. Comparative analysis of machine learning models for automated skin cancer detection: advancements in diagnostic accuracy and ai integration. Am J Med Sci Pharm Res. 2025;7(1):15–26. [Google Scholar]

46. Hwang CL, Yoon K. Multiple attribute decision making: methods and applications: a state-of-the-art survey. New York, NY, USA: Springer Verlag; 2012. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools