Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Anime Generation through Diffusion and Language Models: A Comprehensive Survey of Techniques and Trends

1 School of Computer Science, Jiangsu University of Science and Technology, Zhenjiang, 212003, China

2 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV 89154, USA

* Corresponding Author: Xing Deng. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(3), 2709-2778. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.066647

Received 14 April 2025; Accepted 25 August 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

The application of generative artificial intelligence (AI) is bringing about notable changes in anime creation. This paper surveys recent advancements and applications of diffusion and language models in anime generation, focusing on their demonstrated potential to enhance production efficiency through automation and personalization. Despite these benefits, it is crucial to acknowledge the substantial initial computational investments required for training and deploying these models. We conduct an in-depth survey of cutting-edge generative AI technologies, encompassing models such as Stable Diffusion and GPT, and appraise pivotal large-scale datasets alongside quantifiable evaluation metrics. Review of the surveyed literature indicates the achievement of considerable maturity in the capacity of AI models to synthesize high-quality, aesthetically compelling anime visual images from textual prompts, alongside discernible progress in the generation of coherent narratives. However, achieving perfect long-form consistency, mitigating artifacts like flickering in video sequences, and enabling fine-grained artistic control remain critical ongoing challenges. Building upon these advancements, research efforts have increasingly pivoted towards the synthesis of higher-dimensional content, such as video and three-dimensional assets, with recent studies demonstrating significant progress in this burgeoning field. Nevertheless, formidable challenges endure amidst these advancements. Foremost among these are the substantial computational exigencies requisite for training and deploying these sophisticated models, particularly pronounced in the realm of high-dimensional generation such as video synthesis. Additional persistent hurdles include maintaining spatial-temporal consistency across complex scenes and mitigating ethical considerations surrounding bias and the preservation of human creative autonomy. This research underscores the transformative potential and inherent complexities of AI-driven synergy within the creative industries. We posit that future research should be dedicated to the synergistic fusion of diffusion and autoregressive models, the integration of multimodal inputs, and the balanced consideration of ethical implications, particularly regarding bias and the preservation of human creative autonomy, thereby establishing a robust foundation for the advancement of anime creation and the broader landscape of AI-driven content generation.Keywords

At the forefront of this transformation are diffusion models and language models, two classes of generative AI designed to bridge textual and visual domains. These powerful models are significantly impacting certain creative sectors like anime generation and are increasingly relevant across diverse scientific and engineering fields [1]. Diffusion models have demonstrated strong capabilities in synthesizing high-quality images and videos [2,3]. Studies have shown that these models have improved performance improved performance compared to traditional generative adversarial networks (GANs) in image synthesis in terms of general quality, diversity, and specific metrics like FID [4–6]. Meanwhile, Language models such as BERT and GPT have significantly advanced the field of natural language processing [7,8]. The integration of these technologies has enabled systems to interpret textual prompts and generate corresponding anime-style visuals with notable fidelity, a capability demonstrated by models like Stable Diffusion [3].

This survey focuses on pivotal diffusion and language models that have demonstrated substantial impact and are directly relevant to anime content generation. Specifically, this comprehensive review addresses the pivotal question: How are diffusion and language models currently advancing and transforming the landscape of anime content generation, and what are the key challenges and future directions in effectively leveraging these technologies? Our selection criteria prioritize models with demonstrated efficacy in synthesizing anime-style visuals, coherent narratives, and related creative assets, alongside their technical innovation and prominence within the generative AI landscape.

This study investigates the application of these models across key anime production domains: narrative and graphic novel genesis, illustrative and keyframe synthesis, and episodic and interactive media expansion. For instance, language models can automate script generation and dialogue creation, while diffusion models synthesize anime-stylized imagery and sequential frames [9,10]. The integration of these technologies addresses enduring challenges in creative efficiency, content personalization, and fiscal optimization. While necessitating significant computational resources and capital outlay for high-performance infrastructure, these technologies can streamline certain manual workflows, potentially leading to time savings and reduced labor-intensive operational costs in anime production. This shift has led to notable advancements by streamlining complex processes and accelerating content generation in specific areas [11]. The use of large-scale datasets like LAION-5B enhances the multilingual and stylistic capabilities of these models [12], broadening their applicability. Furthermore, a synergistic analysis employing automated (e.g., Fréchet Inception Distance, CLIP Score) metrics alongside human-centered evaluation provides a comprehensive paradigm for appraising the efficacy of sophisticated diffusion and language models. This approach elucidates their technical viability and observed capacity to foster creative innovation within animation production [13,14], thereby elucidating both their technical viability and their capacity to foster creative innovation within animation production.

Despite their promise, these technologies face significant hurdles. Technical challenges include maintaining consistency across multi-frame sequences and multi-character scenes. Ethical considerations, such as originality, copyright, and the potential diminishment of human creativity, also loom large [15].

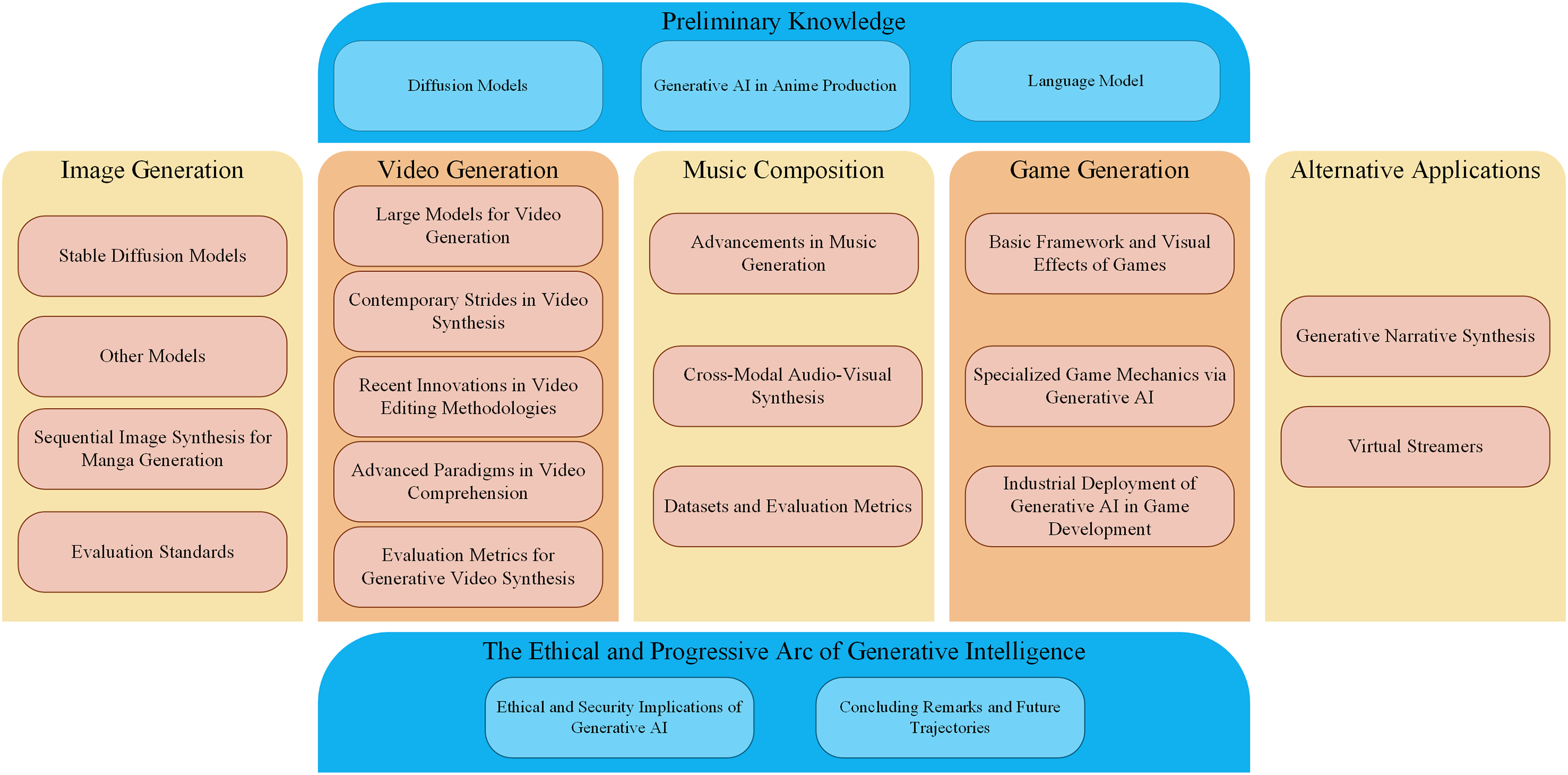

The overall structure of this study is depicted in Fig. 1: Section 2 offers a comprehensive background on diffusion models and language models, detailing their theoretical foundations and development history. Section 3 explores image generation methodologies, focusing on Stable Diffusion and its ecosystem for anime-style synthesis. Section 4 examines video generation, addressing advancements in temporal consistency and character animation. Section 5 delves into music composition, while Section 6 investigates game generation, extending the application of these models to interactive media. Section 7 covers alternative applications, such as narrative synthesis and virtual streamers. Section 8 discusses the ethical implications and reviews the progress and foundational challenges of generative AI. Section 9 concludes the paper by synthesizing the key findings and proposing directions for further research.

Figure 1: The generative intelligence framework: a structural overview

2.1 Generative AI in Anime Production

The anime industry is undergoing notable changes precipitated by the growing emergence of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GAI). The synergistic integration of Natural Language Processing (NLP), Computer Vision (CV), and cross-modal synthesis offers a potential pathway to automate certain conventional manual workflows. While these advanced models incur high computational overhead, their ability to reduce human effort and accelerate content iteration can represent a strategic shift towards more efficient and cost-effective production paradigms. Language Models (LMs) and Diffusion Models have emerged as pivotal instruments, providing the field with enhanced content comprehension and generative capabilities. This significant influence of AI in creative industries necessitates a judicious equilibrium between technological innovation and the preservation of human ingenuity. While AI automates repetitive tasks across numerous sectors, within creative domains like anime, it functions as a collaborative instrument, enabling novel creative avenues, optimizing workflows, and enhancing creative processes [15]. Nevertheless, maintaining the human element and inherent authenticity that define the output of creative industries remains paramount [15].

This significant evolution is impacting various echelons of anime production, from the foundational literary and visual substrates to certain culminating deliverables. Specifically, the following critical domains are undergoing notable developments:

Narrative and Graphic Novel Genesis: Literary works, serving as rich repositories of imaginative narratives, frequently constitute the genesis for anime adaptations, while graphic novels (manga) represent a sophisticated synthesis of visual and textual storytelling. AI’s role encompasses facilitating script generation and potentially influencing narrative architectures.

Illustrative and Keyframe Synthesis: Illustrations, conveying nuanced emotional expression and visual narratives, and key animation, defining pivotal movement frames, are critical constituents of the animation process. AI is being leveraged to expedite the colorization of anime line drawings [9], synthesize anime-stylized imagery (Yang) [10], and even contribute to character conceptualization (Tang and Chen) [16].

Episodic and Interactive Media Expansion: Anime television series, a cornerstone of the industry and a primary revenue stream, and interactive media, notably role-playing games (RPGs), amplify the influence of anime narratives through immersive engagement. AI contributes to enhanced efficiency across various stages of animation production, including pre-production, asset creation, animation production, and post-production [17].

The confluence of sophisticated LMs, such as GPT and BERT, which exhibit aptitude in generating coherent scripts and dialogues, with advanced Diffusion Models, adept at synthesizing anime-stylized visuals, offers potential solutions to enduring challenges pertaining to creative efficiency, content personalization, and fiscal optimization. This synergistic integration aims to bridge textual narratives with visual content, contributing to a period of notable advancement in certain aspects of the anime creation paradigm. This integration is facilitating some aspects of industrial upgrading, fostering innovation, and augmenting productivity within parts of the digital creative industry (Wagan and Sidra) [11].

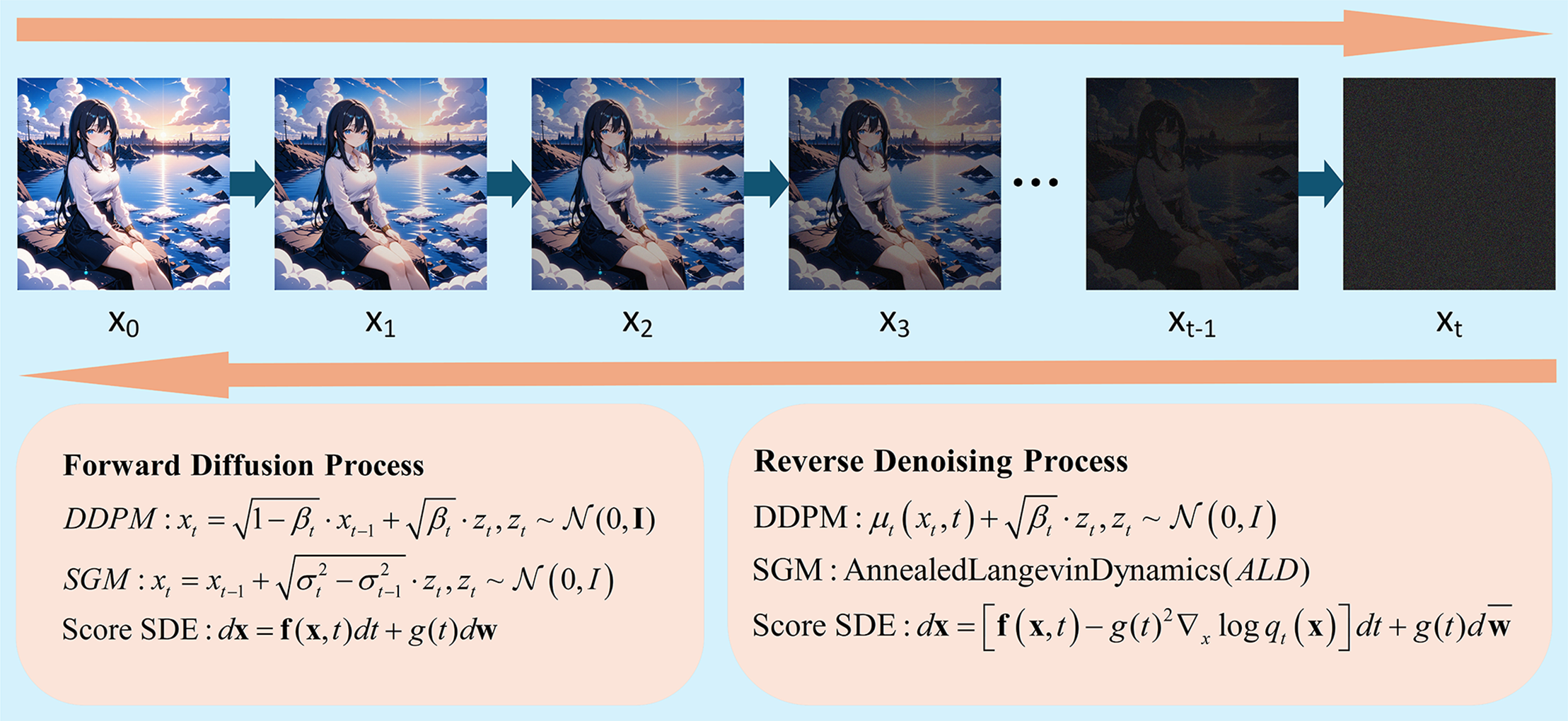

Diffusion models [3], a class of generative models, leverage the principle of stochastic reverse diffusion to synthesize images from latent noise. The core mechanistic paradigm involves a forward diffusion process, iteratively corrupting data with Gaussian noise, followed by a reverse denoising process, reconstructing the image from the noise distribution. In essence, these models learn to invert the progressive degradation of data structure, enabling the recovery of high-fidelity images. This process is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Overview of diffusion models (DDPM, SGM, and Score SDE diffusion and denoising processes)

2.2.1 Mathematical Formalization of Diffusion Processes

Diffusion models operate on the principle of incrementally transforming data through a forward diffusion process and subsequently reversing this transformation via a denoising process to generate novel samples.

The forward process systematically introduces Gaussian noise into an initial image x0 across T discrete timesteps, progressively corrupting it until it approximates a pure noise distribution xT. This controlled degradation is governed by a predetermined noise schedule.

Conversely, the reverse denoising process endeavors to iteratively reconstruct the original image from noise. This is achieved by training a neural network to predict the subtle noise component at each timestep, effectively learning to reverse the corruption introduced by the forward process. The core objective during training is to parameterize this denoising network, enabling it to accurately approximate the conditional probability distribution of a slightly less noisy image given its noisy counterpart.

Generative sampling leverages this trained denoising network. It commences with a random sample drawn from a Gaussian noise distribution, analogous to xT. The network then iteratively refines this noisy input through successive denoising steps, gradually transforming the pure noise into a coherent, synthesized image x0.

The optimization of diffusion models primarily involves minimizing the Evidence Lower Bound (ELBO). This objective function quantifies the discrepancy between the forward diffusion process and the model’s learned reverse denoising capabilities, effectively guiding the network to accurately reverse the noise corruption.

For readers seeking a comprehensive mathematical treatment of these processes, we refer to the foundational works cited in the original text [18–21].

2.2.2 Development History of Diffusion Models

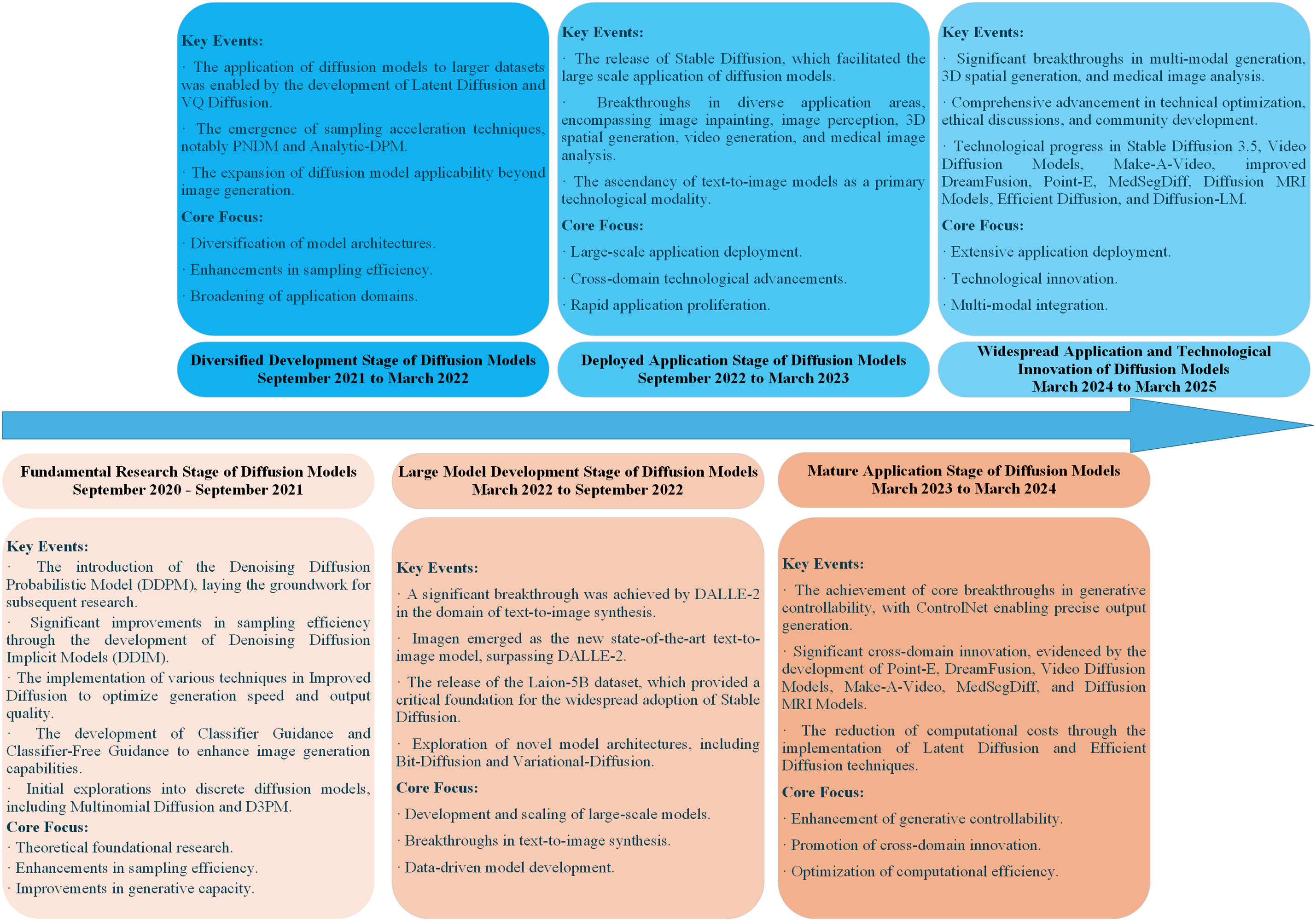

Fig. 3 shows the historical development of diffusion models. The trajectory of diffusion models has been marked by distinct phases, each characterized by pivotal advancements that have collectively propelled their capabilities from theoretical constructs to increasingly powerful generative tools, influencing fields like anime generation.

Figure 3: Historical development of diffusion models

The initial phase, ignited by the advent of Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPMs), focused on solidifying theoretical foundations [2]. Key innovations like Denoising Diffusion Implicit Models (DDIMs) significantly enhanced sampling efficiency, substantially reducing the steps required for high-fidelity generation [22]. Concurrently, Classifier Guidance and its successor, Classifier-Free Guidance, markedly improved conditional image synthesis, laying the groundwork for the sophisticated text-to-image models that followed [5,23]. Theoretical explorations into discrete diffusion models, exemplified by Multinomial Diffusion and D3PM, also contributed to this foundational period [23,24].

Subsequent developments centered on diversifying applications and enhancing scalability. Techniques such as Latent Diffusion and VQ Diffusion were instrumental in applying diffusion models to large-scale datasets, making them amenable to real-world applications [3,25]. This period also saw significant strides in sampling acceleration, with methods like PNDM and Analytic-DPM that further reduced computational overhead while maintaining generative quality [26,27]. The observed versatility of these models has extended their utility beyond mere image generation to tasks like semantic segmentation and advanced image editing.

The focus then shifted toward the creation of large-scale models, particularly in the text-to-image domain. Influential models like DALLE-2 and Imagen showcased impressive capabilities in synthesizing images from textual prompts, leveraging vast datasets [28,29]. The release of open-source initiatives like Stable Diffusion, alongside accompanying massive datasets such as Laion-5B, has made these powerful generative tools widely accessible [3,12]. This has led to significant and rapid adoption within research communities, among individual creators, and in agile development environments, fostering experimentation and innovation in AI-driven content generation.

This widespread adoption in research and creative exploration has rapidly led to a phase of deployed applications and domain expansion, manifesting primarily in specialized tools, academic prototypes, and niche creative workflows, rather than comprehensive industry-wide overhauls. Stable Diffusion, in particular, became a cornerstone for diverse applications [3], including image inpainting (e.g., Equilibrium Diffusion, Shadow Diffusion) [30,31], image perception, 3D generation (e.g., DreamFusion, Magic3D) [32,33], video generation (e.g., Latent Video Diffusion) [34], and medical imaging (e.g., MedSegDiff) [35]. This marked a crucial transition from academic research to practical utility.

The most recent phase emphasizes controllability and cross-domain innovation. Tools like ControlNet have enabled precise manipulation of generated images through explicit conditions (e.g., edge maps, depth maps), offering enhanced creative control. Advancements in text-to-3D generation (e.g., Point-E, DreamFusion), and text-driven video synthesis (e.g., Video Diffusion Models, Make-A-Video) further extended their capabilities [32,36–38]. Concurrently, ongoing research into computational efficiency (e.g., Latent Diffusion [3], Efficient Diffusion) and multi-modal fusion (e.g., Diffusion-LM) continues to explore and enhance the capabilities of diffusion models, integrating disparate data types for more complex and nuanced generative tasks, including their observed impact on anime generation through specialized applications and stylistic control [39,40].

2.2.3 Datasets for Diffusion Model Training

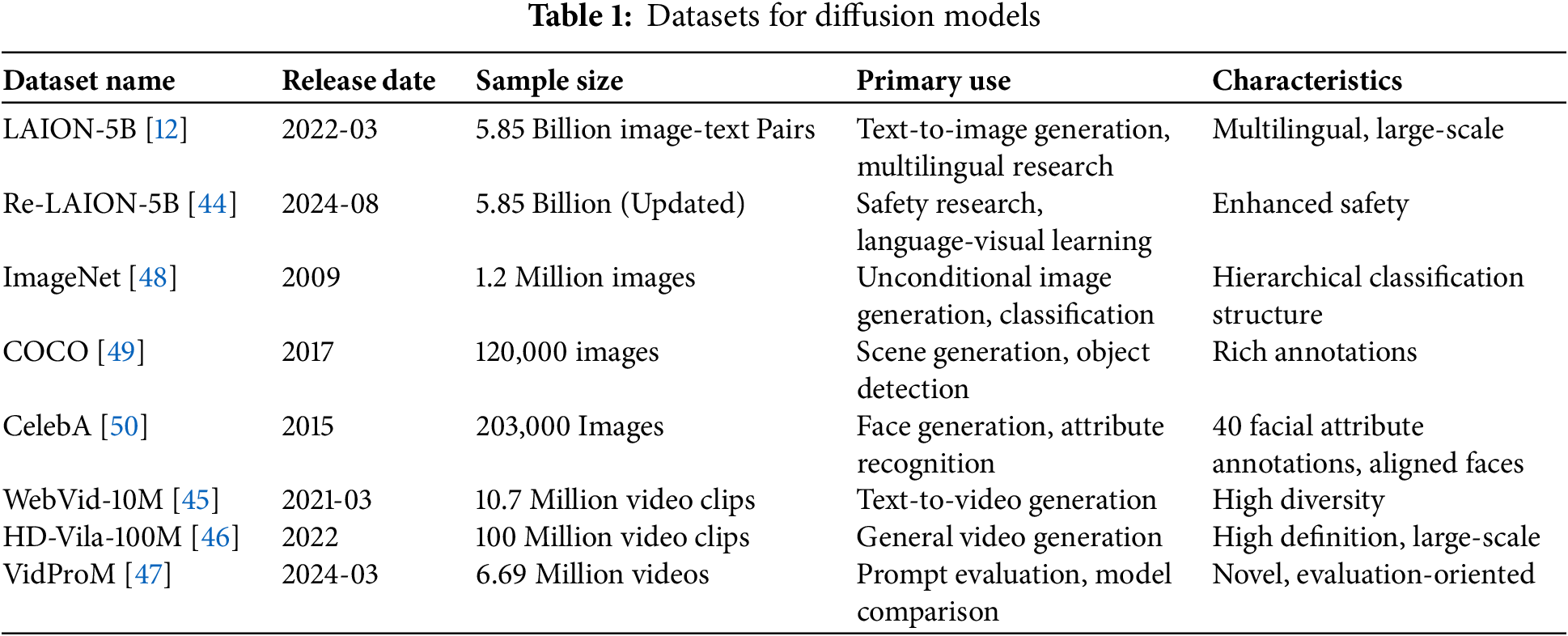

The training of diffusion models, irrespective of modality (image, video, audio), necessitates large-scale, high-fidelity datasets [41]. Optimal datasets are characterized by: Extensive Cardinality: Datasets comprising hundreds of millions to billions of paired data samples (e.g., image-text) are requisite for capturing the inherent diversity and complexity of the data manifold [42]. Comprehensive Heterogeneity: Datasets must encompass a broad spectrum of scenes, styles, and linguistic representations to ensure robust generalization of generated outputs [43]. Precise Annotation Fidelity: Particularly for conditional generative tasks, the semantic coherence between textual and visual/temporal data is paramount. Exemplary datasets are summarized in Table 1.

Exemplary Datasets for Diffusion Model Training:

LAION-5B (March 2022) [12]: A corpus of 5.85 billion image-text pairs, curated via CLIP-based filtering, exhibiting multilingual scope. This dataset has facilitated the training of models such as Stable Diffusion, enhancing generative fidelity and zero-shot capabilities.

Re-LAION-5B (August 2024) [44]: An augmented iteration of LAION-5B, incorporating stringent filtering to mitigate illicit content and providing academically compliant subsets, thereby addressing ethical and legal considerations.

WebVid-10M (March 2021) [45]: A video dataset comprising 10.7 million video clips (52,000 h) with alt-text annotations, contributing to improved temporal consistency and zero-shot video generation.

HD-Vila-100M (2022) [46]: A large-scale video dataset consisting of 100 million high-definition videos (371,000 h) with automatically transcribed textual data, supporting generalized video synthesis tasks.

VidProM (March 2024) [47]: A synthetic video dataset featuring 6.69 million generated video clips (1.6-3 s each), synthesized using multiple generative models, and augmented with NSFW detection and prompt embeddings, designed to facilitate model evaluation and prompt engineering research.

2.2.4 Architectural Advantages

The architectural design of Diffusion Models offers several advantages in generative tasks, notably in latent space operation, flexibility and tractability, neural network adaptability, conditional generation capabilities, and scalability. Many Diffusion Models, such as Stable Diffusion, employ a two-stage training paradigm that first compresses high-dimensional image data into a lower-dimensional latent space via an autoencoder [44]. This approach not only substantially reduces computational complexity but also enhances model scalability, particularly for high-resolution image synthesis. By conducting diffusion and reverse diffusion within this latent space, models like Latent Diffusion Models (LDMs) can efficiently process intricate data while often preserving high-quality generative outcomes [3]. Diffusion Models can effectively balance the analytical tractability of simpler distributions (e.g., Gaussian) with the expressive power of complex models (e.g., GANs), enabling them to model sophisticated data distributions with notable training stability and sampling efficiency, and have often outperformed traditional generative models as evidenced by their superiority over GANs in image synthesis [51]. The reverse diffusion process is typically orchestrated by flexible neural network architectures, including U-Net or Transformer variants, allowing for task-specific customization; for instance, Stable Diffusion leverages U-Net with cross-attention, while Stable Diffusion 3 employs a Diffusion Transformer (DiT), showcasing this architectural versatility [52,53]. Furthermore, Diffusion Models excel in conditional generation through mechanisms like cross-attention or dedicated conditioning modules (e.g., text encoders), enabling models such as Stable Diffusion and DALL-E 2 to synthesize imagery from textual prompts, thereby broadening their applicability to tasks like text-to-image and layout-to-image generation [28]. Their inherent scalability, facilitated by latent space representations and efficient architectures, allows them to manage high-dimensional data, balancing generative quality with computational expediency; Cascade Diffusion Models, for example, have demonstrated enhanced high-resolution image generation through multi-stage diffusion processes [54].

The training regimen for Diffusion Models encompasses several critical steps, primarily involving the forward and reverse diffusion processes, the strategic selection of variance schedules, and the application of advanced optimization techniques. The training commences with the forward diffusion process, wherein original data is progressively corrupted by Gaussian noise, transitioning from the data distribution to a pure noise distribution. This process, governed by a predefined variance schedule (typically linear or cosine), functions as a Markov chain, incrementally introducing noise. The judicious choice of variance scheduling significantly impacts training stability and generative quality. Subsequently, the reverse diffusion process trains a neural network to invert this corruption, iteratively denoising from pure noise to reconstruct the original data. The neural network typically predicts the noise or the denoised data at each step, optimizing through the minimization of a simple mean squared error (MSE) based loss function. Variance schedules, which dictate the rate of noise addition, are paramount, with linear and cosine schedules being common choices. Advanced training techniques, such as DDIM (Denoising Diffusion Implicit Models), have markedly accelerated sampling by reducing the number of necessary steps. Progressive Distillation further refines model performance using a teacher-student framework, and Consistency Models enhance generative quality by enforcing specific consistency constraints [2].

2.3.1 Foundational Architectures of Transformer-Based Language Models

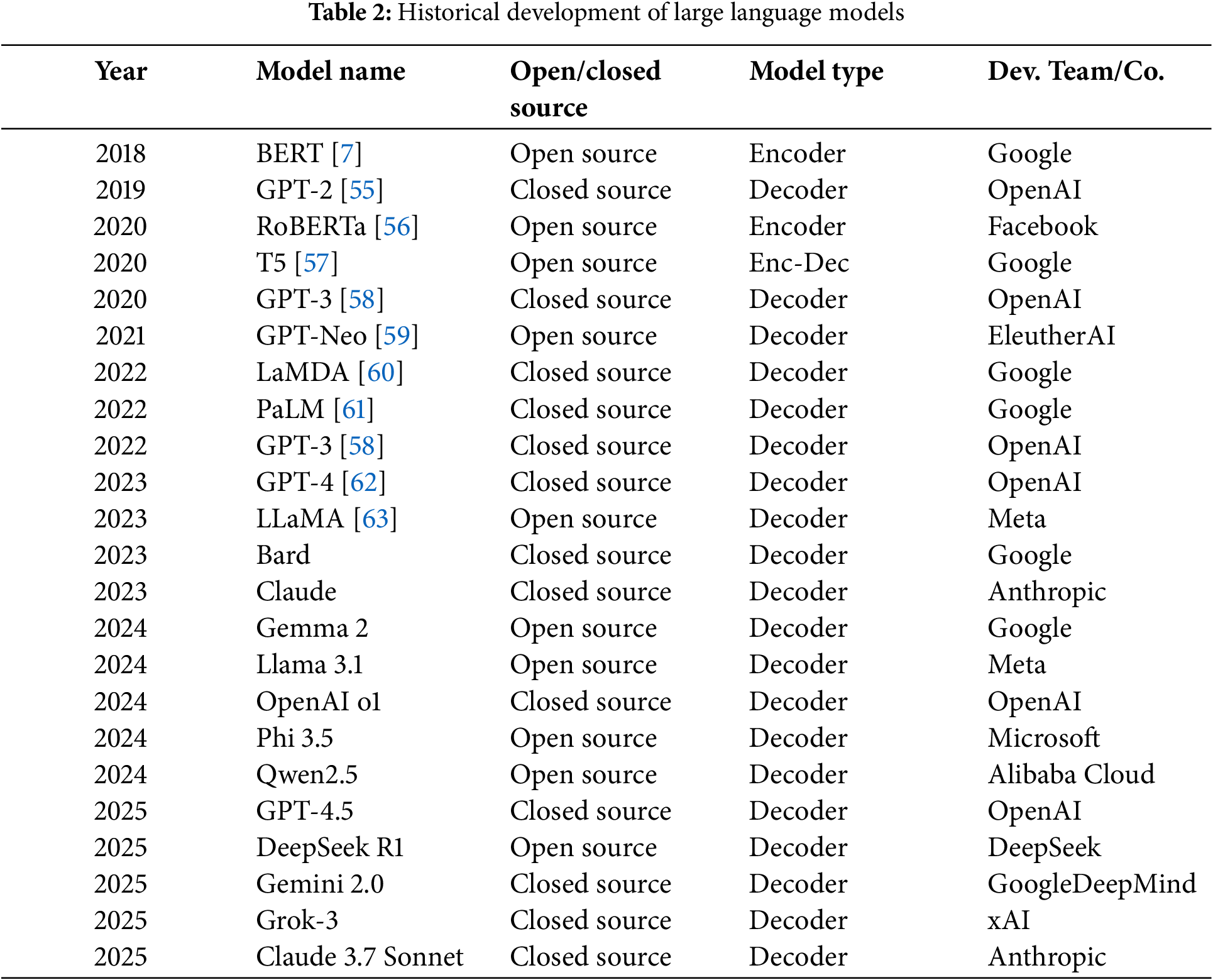

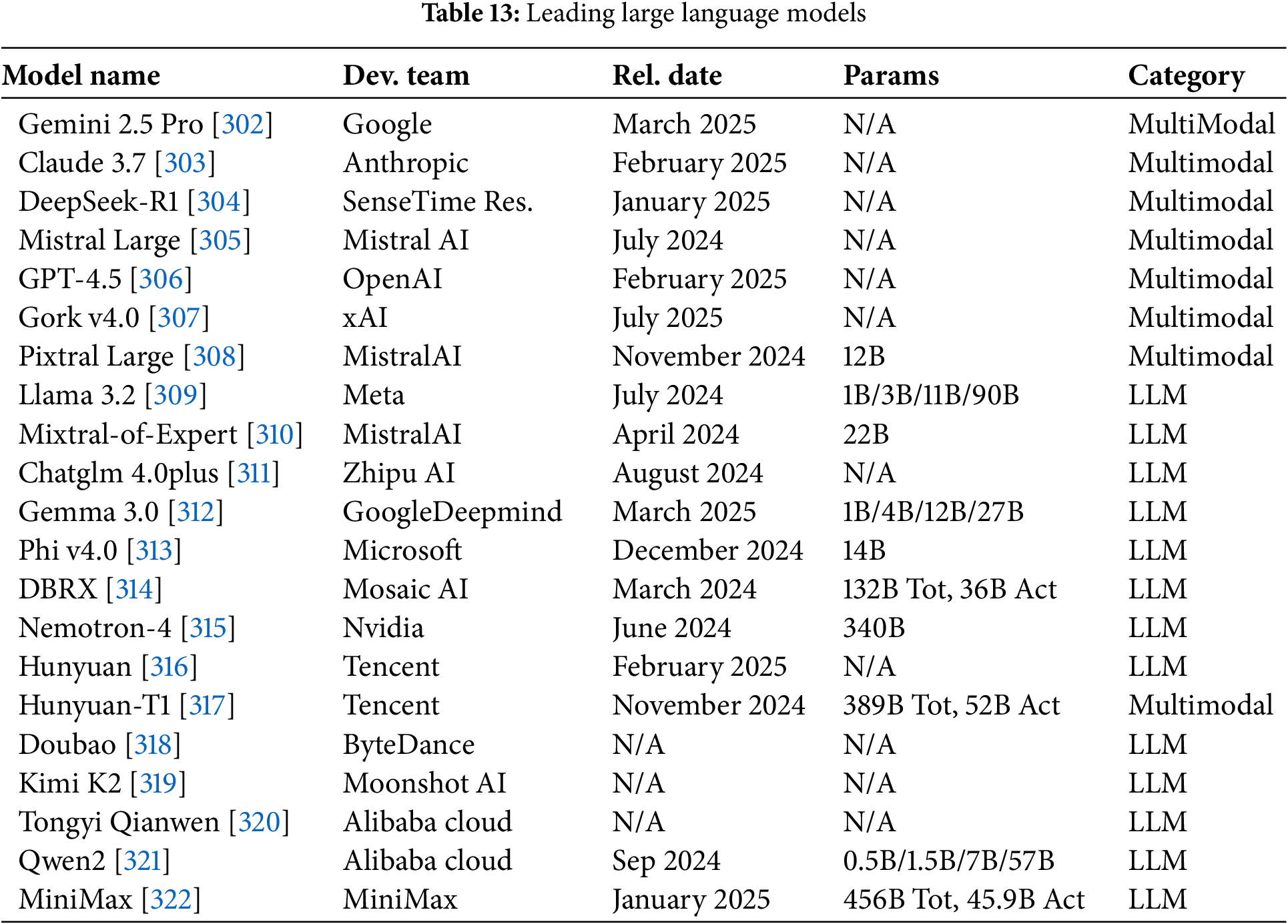

The historical development of these models is summarized in Table 2. Transformer-based language models, fundamental to advancements in natural language processing, are broadly categorized into three core architectural paradigms, each optimized for distinct linguistic tasks [64]:

Encoder-Centric Models: Exemplified by models such as BERT, these architectures are primarily designed for comprehension-oriented tasks [7]. They excel at understanding the intricate semantic relationships within input text by learning deep contextual representations. This makes them highly effective for applications like text classification, named entity recognition, and reading comprehension, where the goal is to extract meaning from existing text.

Encoder-Decoder Hybrid Models: Represented by models like T5, these architectures combine the strengths of both encoders and decoders [57,65]. The encoder processes the input sequence, capturing its semantic essence, while the decoder then uses this understanding to synthesize an output sequence. This dual mechanism makes them highly adept at sequence transduction tasks, such as machine translation and text summarization, where one sequence is transformed into another.

Decoder-Dominant Models: Typified by the GPT series (e.g., GPT-4, LLaMA), these models are built for generative tasks [62,63]. Operating autoregressively, they predict subsequent tokens based on preceding ones, enabling them to produce fluent and contextually coherent text. Their inherent design makes them ideal for applications requiring creative text generation, dialogue systems, and content creation, including potential applications in anime script and narrative generation.

2.3.2 Encoder-Centric Models: Contextual Representation Learning

Encoder-centric models, notably BERT [7], are specifically engineered to grasp contextual information within text. Their pre-training focuses on learning deep relationships between words in a given context, making them highly effective at tasks that require understanding existing text, such as text classification or question-answering. However, their architecture, being primarily focused on comprehension, inherently limits their direct application in generating novel text or dialogues.

2.3.3 Encoder-Decoder Hybrid Models: Sequence Transduction

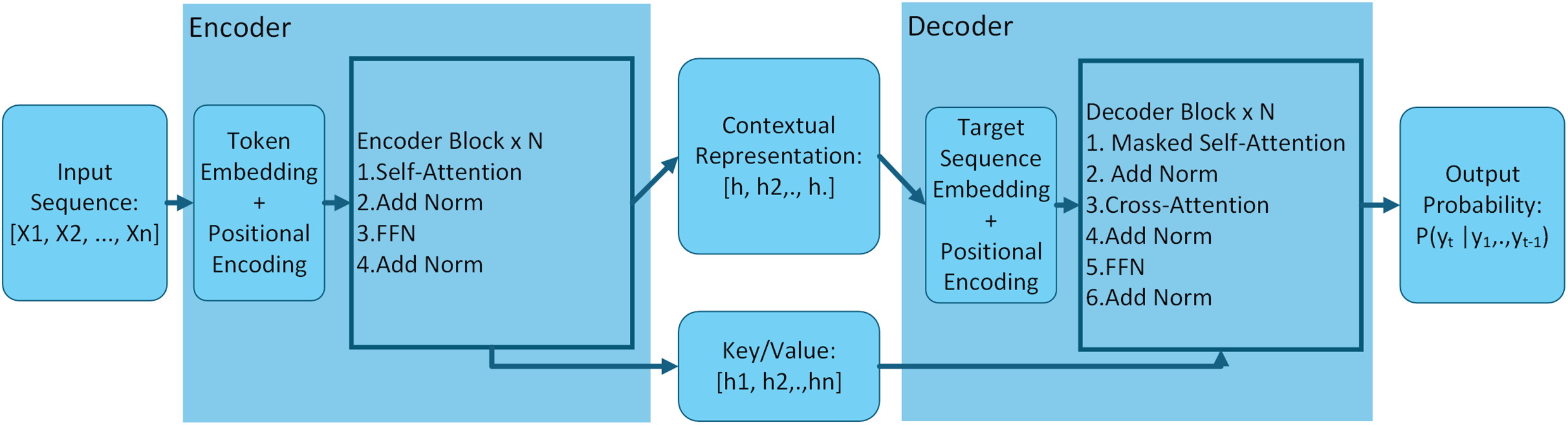

The architecture of an encoder-decoder model is shown in Fig. 4. Encoder-decoder models facilitate sequence transduction by employing a two-part system. An encoder first processes an input sequence to distill its underlying meaning into a rich contextual representation. This representation is then passed to a decoder, which uses this understanding to construct a new, coherent output sequence. This architecture is highly effective for tasks where the input needs to be transformed into a different output format, such as translating a script from one language to another or summarizing a long narrative into a concise synopsis, which could be valuable for managing anime production content [57,65].

Figure 4: Encoder-decoder model architecture diagram

2.3.4 Decoder-Dominant Models: Autoregressive Sequence Generation

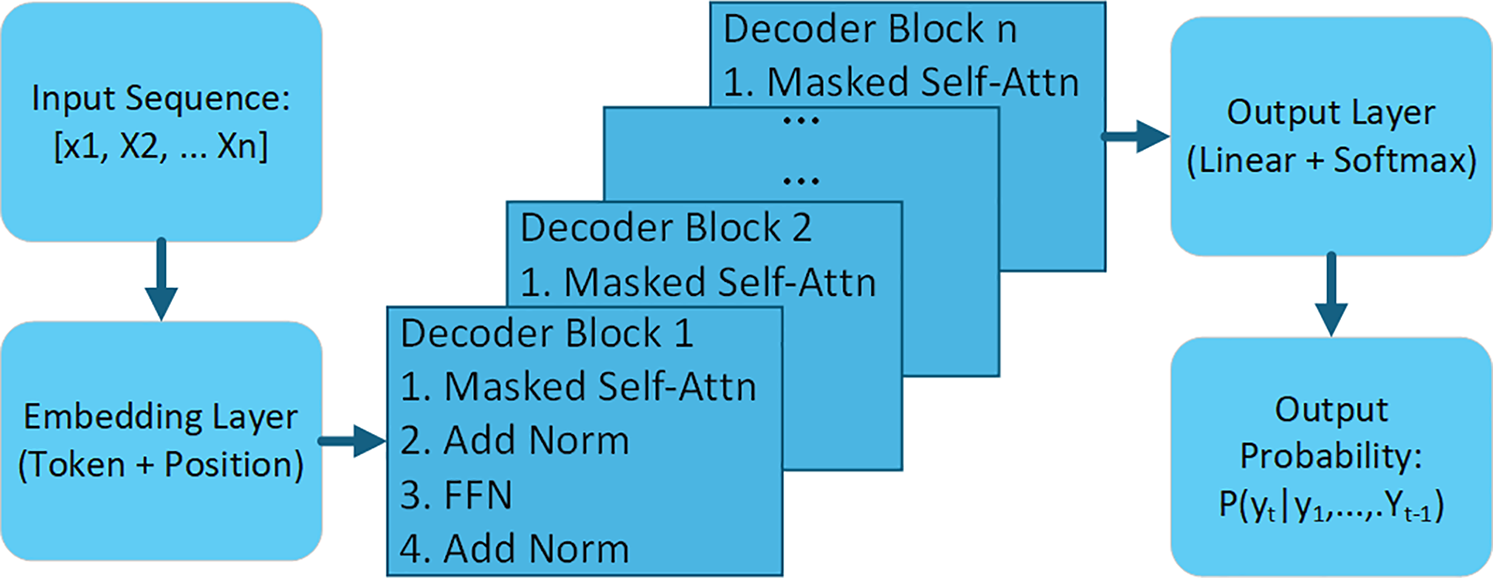

The schematic for a decoder-only model is depicted in Fig. 5. Decoder-dominant models operate autoregressively, generating sequences token-by-token, conditioned on preceding tokens. Input sequences are embedded and processed through stacked decoder blocks, each comprising masked self-attention, add-and-norm, and FFN layers. The output is a probability distribution over subsequent tokens.

Figure 5: Decoder-only model architecture schematic

The GPT and LLaMA series are representative decoder-dominant models [62,63]. GPT models demonstrate strong generative capabilities, with GPT-4 extending to multimodal content. LLaMA models offer scalable architectures for diverse applications.

2.3.5 Architectural Advantages

The Transformer architecture derives its notable generative capabilities from several key innovations, including the self-attention mechanism, inherent parallelizability, scalability, the absence of recurrent structures, multi-head attention, positional encodings, and a continuous evolution of efficient variants. The self-attention mechanism, a cornerstone of the Transformer, dynamically allocates attention weights based on the relevance of input sequence elements, thereby capturing long-range dependencies without relying on sequential processing, a significant advancement over traditional models in complex tasks like machine translation and text generation [64]. Unlike recurrent neural networks (RNNs), Transformers inherently support parallel processing of entire input sequences, dramatically accelerating training and inference, particularly on GPUs [64]. This parallelization, combined with the ability to handle arbitrary sequence lengths, provides Transformers with high scalability across diverse tasks, enabling models such as BERT and GPT to adapt from text classification to generation via pre-training and fine-tuning [7,66]. The elimination of recurrent structures mitigates the vanishing gradient problem, facilitating the training of deeper, more stable, and efficient networks for long sequences. Multi-head attention further augments representational capacity by allowing the model to concurrently attend to distinct subspaces within the input sequence, instrumental in capturing bidirectional context (e.g., BERT) or facilitating autoregressive generation (e.g., GPT) [7,66]. Given the inherent order-agnostic nature of self-attention, Transformers incorporate positional encodings, such as sinusoidal functions, to convey token position; recent innovations like Rotary Positional Embeddings (RoPE) and ALiBi optimize for relative positional dependencies and enable fine-tuning on longer sequences after pre-training on shorter ones [67,68]. To address the computational demands of the Transformer, numerous efficient variants have emerged, including Reformer, which leverages locality-sensitive hashing (LSH) to reduce attention complexity from O(N2) to O(NlogN), and BigBird, achieving O(N) complexity via small-world networks [69,70]. Furthermore, FlashAttention and FlashAttention-2 have dramatically accelerated attention computations, reaching speeds up to 230 TFLOPs/s on A100 GPUs [71]. Contemporary trends in Transformer architecture, as of 2025, focus on sparsity through sparse attention mechanisms for reduced computation and improved memory efficiency, Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models to enhance scalability and efficiency by partitioning the network into specialized modules, and adaptive computation techniques that dynamically adjust computational resources based on input complexity to optimize performance.

Transformer training typically unfolds in a two-stage paradigm: pre-training and fine-tuning. Initial pre-training occurs on vast corpora (e.g., Wikipedia) using self-supervised objectives such as masked language modeling (BERT) or auto-regressive language modeling (GPT). This is followed by fine-tuning on smaller, task-specific datasets to adapt the model for particular applications, a methodology that significantly curtails training costs and enhances generalization. The standard Transformer architecture comprises an encoder and a decoder. The encoder processes input sequences via multi-head self-attention to generate contextual representations, while the decoder, employing masked self-attention and encoder-decoder attention, produces output sequences auto-regressively. Attention mechanisms are pivotal in training: encoder self-attention captures intra-input relationships; decoder masked self-attention ensures predictions are solely based on preceding tokens; and encoder-decoder attention integrates the encoder’s output into the decoder, thereby enhancing generative quality. Layer Normalization and Residual Connections, applied after each sub-layer, are crucial for mitigating the vanishing gradient problem and facilitating the training of deeper networks. Optimization for Transformer training typically employs the Adam optimizer coupled with learning rate schedules (e.g., warmup and decay) to improve convergence, while regularization techniques like Dropout prevent overfitting, especially in models with extensive parameter counts. Recent advancements in training methodology include efficient inference techniques such as Key-Value Caching to obviate redundant computations of key and value vectors, speculative decoding, and multi-token prediction to balance accuracy and speed in real-time applications. Pre-layer normalization (Pre-LN) has been introduced to enhance training stability. Moreover, the Transformer architecture has been extended for multimodal training, exemplified by models like DALL-E, which jointly process complex datasets encompassing both text and images [64].

2.4 Model Fine-Tuning Techniques and Anime-Related Datasets

2.4.1 Model Fine-Tuning Techniques

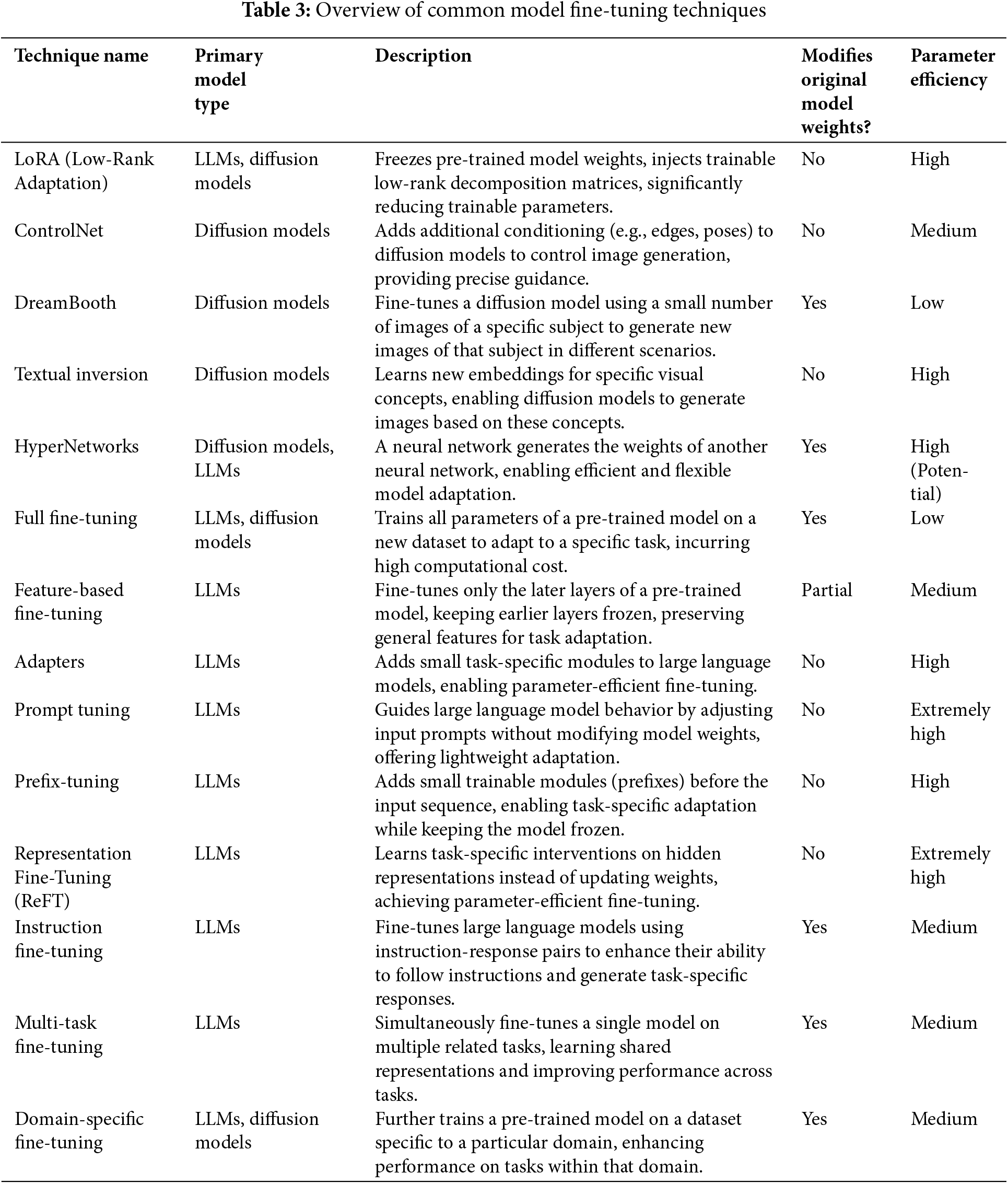

An overview of common fine-tuning techniques is provided in Table 3. Full Fine-Tuning, the most direct method, updates all model parameters. While offering maximal adaptation potential for a specific style, it incurs high computational expense, requires substantial data, and exhibits limited generalizability to diverse, unseen anime styles, risking overfitting on limited datasets [72].

To mitigate these costs, Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) methods update only a small subset of parameters or introduce minimal new ones. LoRA injects low-rank matrices, achieving high efficiency but struggling with blending or switching between vastly different styles [73]. Adapters insert small modules, offering modularity and efficiency at the cost of potential inference latency and configuration complexity; combining style-specific Adapters for generalization is challenging [74]. Prompt Tuning and Prefix-Tuning manipulate input embeddings for extreme efficiency but provide limited control over complex stylistic details [75,76]. Representation Fine-Tuning (ReFT) intervenes on latent representations, offering low cost and non-invasiveness, though its efficacy for complex anime style generalization is under investigation [77].

Diffusion-specific techniques provide conditional control. ControlNet adds spatial conditioning (e.g., edges), potent for structure but relying on the base model’s style aptitude [78]. DreamBooth specializes models on specific subjects from few images, achieving high fidelity but overfitting and limiting subject generalization across varied anime styles [79]. Textual Inversion learns new embeddings for concepts, offering efficiency but limited capacity for intricate style representation [80]. HyperNetworks dynamically generate model parameters, promising flexibility but facing training instability and potentially yielding lower quality outputs than direct fine-tuning [81]. Feature-Based Fine-Tuning updates only later layers, computationally lighter but potentially insufficient for style changes requiring lower-level feature modification and bounded in its generalization to diverse styles [82].

Finally, Instruction Fine-Tuning, Multi-Task Fine-Tuning, and Domain-Specific Fine-Tuning enhance task-specific or domain-confined performance. While improving utility within a prescribed scope (e.g., sci-fi anime), they face constraints in achieving comprehensive generalization or synthesizing novel anime styles due to dataset limitations, task interference, and inherent model capacity [83].

While fine-tuning is crucial for anime style acquisition, achieving seamless, high-fidelity generalization across the diverse spectrum of anime aesthetics remains a significant research challenge.

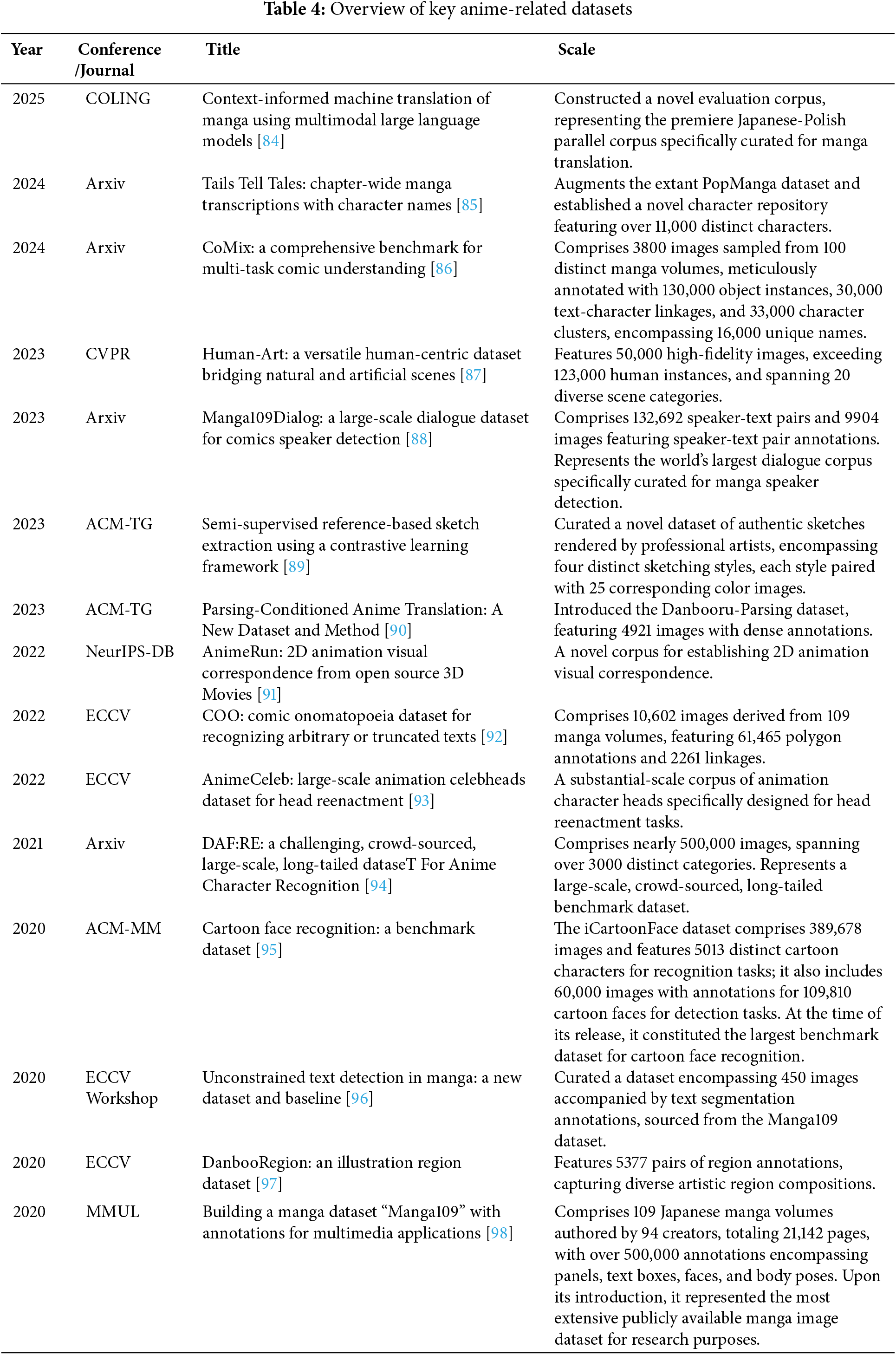

Table 4 provides an overview of key anime-related datasets. Despite advancements, current anime/manga datasets face notable limitations impeding sophisticated model development. Prominent among these is pervasive stylistic heterogeneity without granular annotation, hindering style-specific mastery or seamless generalization across diverse aesthetics [99,100]. This often results in dataset bias, overrepresenting popular styles and diminishing performance on less common ones, exacerbated by long-tailed character distributions.

Furthermore, the landscape is characterized by fragmentation, with datasets often task-specific and lacking comprehensive multi-modal integration of visual, textual, and structural elements crucial for holistic understanding [101]. Annotation quality and consistency remain concerns, prone to human error and complexity, particularly for intricate tasks [102]. Finally, the static nature of most datasets fails to capture the domain’s dynamic evolution, limiting their enduring relevance for cutting-edge research. These constraints collectively underscore the pressing need for more nuanced, integrated, and continuously evolving data resources.

This section elucidates the current state of generative image synthesis models, focusing on prominent architectures particularly relevant to anime content creation, a domain where artificial intelligence is increasingly employed as an artistic tool. Our selection encompasses architectures distinguished by their efficacy in generating high-fidelity anime-style visuals, their impact on the field, and the depth of available research and practical applications. We focus on Stable Diffusion [3], related mainstream models, manga synthesis methodologies, and evaluation metrics.

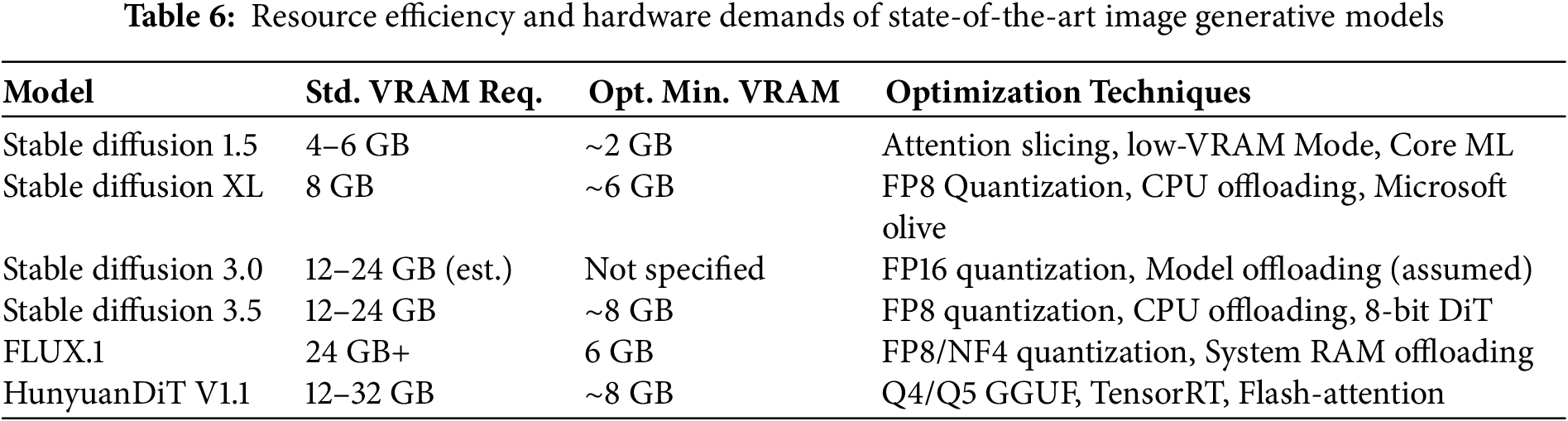

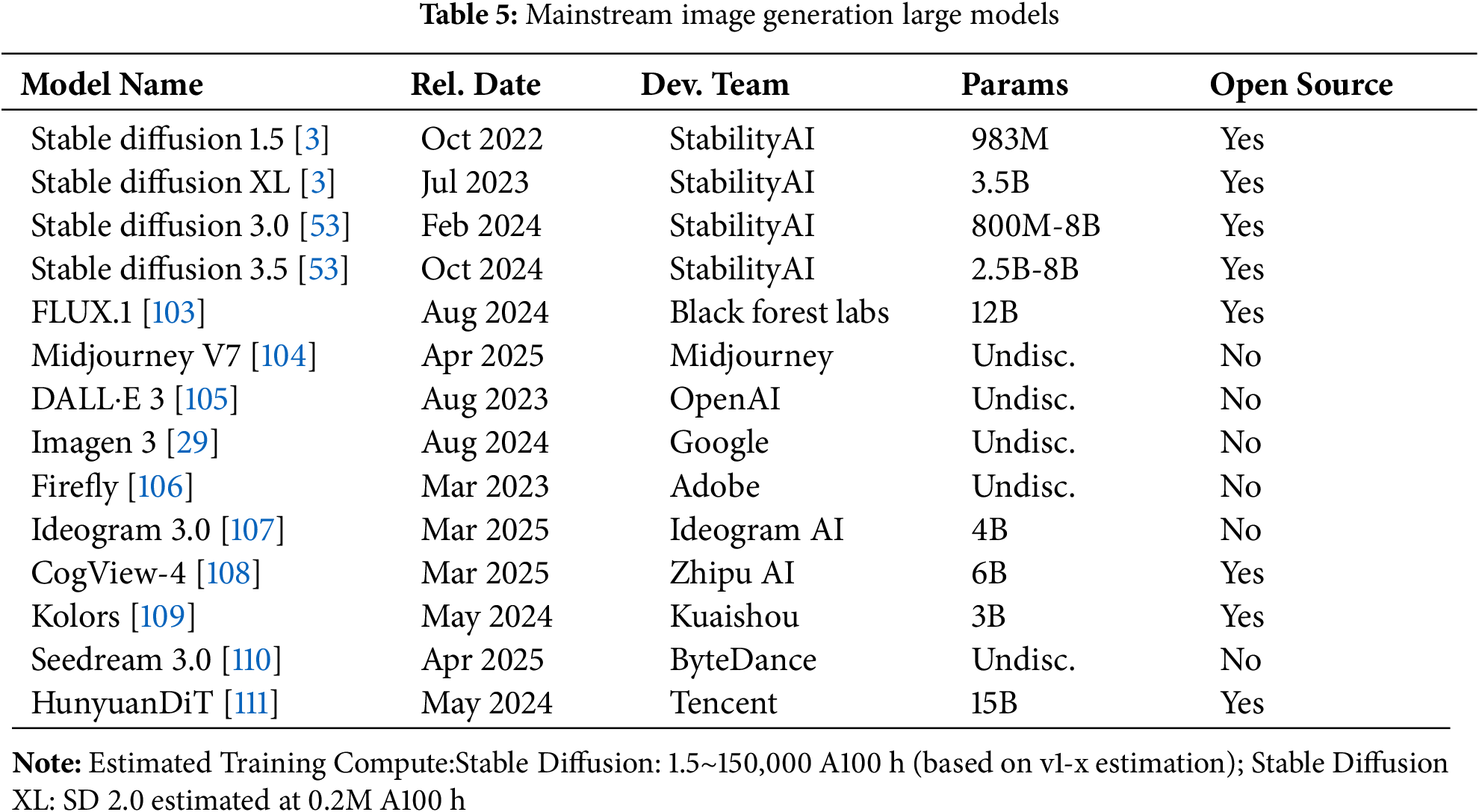

While the substantial parameters, training compute, and VRAM requirements detailed in Tables 5 and 6 underscore the significant computational investment in these models, these costs are often offset by significant gains in creative efficiency and reduced manual labor. Moreover, ongoing research into architectural efficiencies and optimization techniques actively seeks to enhance their accessibility and integration into practical creative pipelines, continuously lowering the effective cost of deployment relative to the benefits derived.

3.1.1 Image Synthesis via Stable Diffusion Models

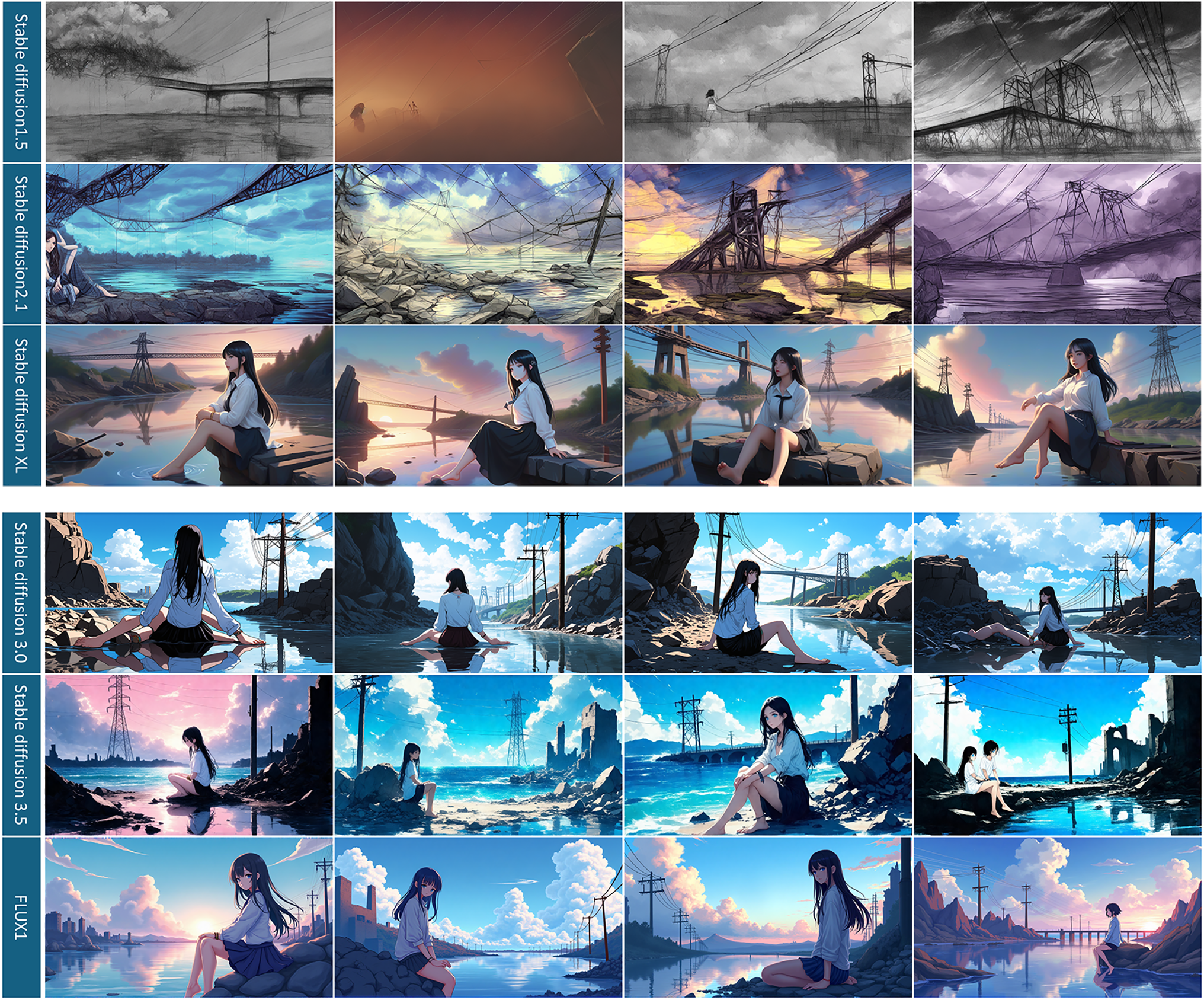

Stable Diffusion, a prominent tool in anime image synthesis, leverages latent diffusion to generate high-fidelity images through iterative denoising in latent space. Developed by StabilityAI, CompVis, and Runway, its initial release in October 2022 marked a significant advancement. Subsequent iterations, including Stable Diffusion XL 1.0 (July 2023), Stable Diffusion 3.0 (February 2024), and Stable Diffusion 3.5 (October 2024), have progressively enhanced resolution, text alignment, and overall generative performance. Notably, the FLUX model (August 2024) [112], by Black Forest Labs, presents a competitive alternative, demonstrating superior image quality. Fig. 6 illustrates the evolution of image generation quality across Stable Diffusion versions.

Figure 6: Evolution of Stable Diffusion Models demonstrated via images generated under consistent input conditions. See Appendix A

3.1.2 Ancillary Technologies in Stable Diffusion Ecosystems

The open-source nature of Stable Diffusion has fostered a diverse ecosystem of ancillary technologies, enhancing its applicability in artistic creation.

Controllable Image Synthesis: ControlNet (February 2023) enables precise pose and detail manipulation through trainable copies conditioned on edge and contour maps [78], As demonstrated in Fig. 7. T2I-adapter (February 2023) provides analogous functionality with a lightweight architecture [113]. MaskDiffusion (March 2024) refines textual controllability [114].

Figure 7: ControlNet controls the generation of images by adding constraints

Model Fine-Tuning and Optimization: LoRA (June 2021) achieves efficient fine-tuning by reducing trainable parameters [73]. Latent Consistency Models (LCMs) (October 2023) accelerate fine-tuning by learning latent space mappings [115].

User Interface and Workflow Management: stable-diffusion-webui provides a user-friendly web interface for text-to-image synthesis [116]. ComfyUI offers a node-based interface for advanced customization and pipeline construction [117].

Advanced Image Manipulation: PaintsUndo (August 2024) simulates painting brushstrokes and enables sketch extraction and anime-style transformations [118]. Its generation process is detailed in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: PaintsUndo model generation process

3.2 Other Models and Related Technological Landscape

3.2.1 Notable High-Impact Models

While these models collectively push the boundaries of generative capabilities, the landscape of text-to-image synthesis, beyond established open-source models like Stable Diffusion, is populated by a diverse array of other high-performing architectures.

ImagenFX (Google Labs), leveraging Imagen 2 and 3 [29,119], provides global users with high-fidelity visual content generation through an intuitive interface and robust semantic interpretation. Its integration with Gemini enhances multilingual support and complex scene rendering. Lumina-Image 2.0 (Alpha-VLLM) employs a 2.6B-parameter DiT architecture and a Gemma-2B text encoder [120], demonstrating superior text-following performance in DPG and GenEval benchmarks [121–123], particularly for Sino-Anglic prompts. CogView3 (Zhipu AI) utilizes a cascaded diffusion framework and relay diffusion techniques [124], achieving accelerated inference and enhanced generative quality via a three-stage generation strategy and diffusion distillation optimization. Adobe Firefly [106], integrated within Adobe Creative Cloud and powered by Adobe Sensei, offers comprehensive image, video, and audio synthesis, trained on commercially compliant datasets, excelling in 1080p video generation. DALL·E 3 [62,125], through its integration with GPT, enhances intelligent image generation and editing, improving user interaction naturalness and editing precision. Ideogram focuses on generating images with legible textual elements, addressing a critical limitation in existing generative AI tools [107]. Its rapid synthesis and diverse stylistic options facilitate the creation of high-quality visuals for logo, poster, and graphic design.

Illustrious (OnomaAI Research) [126], built upon the SDXL architecture and leveraging Danbooru tags and multi-level captions, specializes in high-fidelity anime and illustration synthesis, excelling in resolution, color gamut, and anatomical accuracy. Pony Diffusion [127], an SDXL-derived anime model, has garnered significant acclaim on Civitai, recognized for its exceptional stylistic adaptation and high-resolution synthesis.

HunyuanDiT (Tencent) employs a DiT architecture with multi-resolution training and a dual-encoder system [52,111], demonstrating superior text-image consistency, subject clarity, and aesthetic fidelity, particularly for Chinese prompts.

These architectures, through continuous innovation, collectively propel the evolution of text-to-image synthesis. Regarding their specific relevance to anime generation, many proprietary models primarily leverage their robust general prior knowledge to infer and render anime aesthetics. In contrast, models such as Illustrious and Pony Diffusion exemplify targeted specialization, having been comprehensively fine-tuned on anime-specific datasets to significantly enhance the anime generation capabilities of their Stable Diffusion base, achieving remarkable stylistic adaptation and fidelity. It is also noteworthy that HunyuanDiT, an open-source model from Tencent built on the Diffusion Transformer (DiT) architecture, represents a convergence of language model and diffusion model strengths. However, as a comparatively recent entrant to the open-source domain, its subsequent development has often involved the adaptation and integration of techniques originating from the more established Stable Diffusion ecosystem. Fig. 9 compares images generated by various models under consistent conditions.

Figure 9: Depictions generated by various contemporary large-scale generative models using a consistent textual prompt and parameters. See Appendix A

3.2.2 Related Technological Developments

Recent advancements significantly enhance anime generation by reducing costs, boosting efficiency, and refining control. “Stretching Each Dollar” democratizes high-quality generation through resource-frugal training [128], effective delayed patch masking, and synthetic data incorporation. While democratizing access, it struggles with precise text rendering and granular object control, particularly at high masking rates. SANA excels in high-resolution synthesis (up to 4K) via innovations like the deep compression autoencoder (AE-F32) and Linear DiT, improving prompt adherence with complex instructions through a decoder-only LLM [129]. Its speed and consumer hardware deployability lower entry barriers, but challenges remain in guaranteed content safety, controllability, and artifact handling in complex areas like faces and hands, showing a trade-off with raw reconstruction quality. Both accelerate rapid iteration in concept design and storyboarding; “Stretching Each Dollar” aids smaller studios, while SANA provides high-resolution assets and precise text-to-image alignment for diverse anime aesthetics.

ThinkDiff and DREAM ENGINE advance multimodal information fusion [130,131]. ThinkDiff integrates VLM outputs with diffusion processes for in-context reasoning, enabling complex instruction interpretation and generation based on inferred relationships. Despite being lightweight and robust, it currently lacks high image fidelity and mastery of the full spectrum of complex reasoning tasks. DREAM ENGINE offers efficient text-image interleaved control through a versatile multimodal encoder and a two-stage training regimen, excelling in object-driven generation, complex composition, and free-form image editing. These capabilities are transformative for animation: ThinkDiff could automate storyboarding and character development, while DREAM ENGINE provides precise control for detailed scenes, character refinement, and visual consistency.

For fine-grained control and targeted outputs, MangaNinja and PhotoDoodle are pivotal [132,133]. MangaNinja provides user-controllable diffusion-based manga line-art colorization, handling discrepancies between references and line art with a dual-branch structure and point-driven control. It enhances color consistency and detail, robust for complex scenarios, yet semantic ambiguity can arise with intricate line art, and a dependency on reference imagery persists. PhotoDoodle introduces an instruction-guided framework for learning artistic image editing from few-shot examples using an EditLoRA module. This enables efficient style capture from minimal data (30-50 examples) for seamless integration and mask-free instruction-based editing, though paired dataset collection and training are practical considerations. These tools significantly streamline labor-intensive processes: MangaNinja improves colorization efficiency and character consistency, while PhotoDoodle offers powerful stylistic application and precise, text-prompted modifications.

FluxSR optimizes image generation for practical applications like super-resolution via efficient single-step inference through Flow Trajectory Distillation (FTD) [134]. Built on powerful pre-trained text-to-image diffusion, it achieves superior perceptual quality and fidelity in recovering high-frequency details. Despite its high computational cost from a large parameter count and residual periodic artifacts, FluxSR offers transformative potential for enhancing low-resolution anime assets. This investment is justified by its ability to significantly streamline production through efficient upscaling of intermediate frames, ultimately contributing to a more rapid and less labor-intensive workflow.

Finally, CSD-MT reduces reliance on large labeled datasets through unsupervised content-style decoupling for facial content and makeup style manipulation [135]. Its efficiency, minimal parameters, and rapid inference offer flexible controls, yet extreme makeup styles can challenge accurate boundary rendering. CSD-MT’s generalization to unseen anime makeup styles presents a pertinent avenue for efficiently designing and transferring makeup styles onto anime characters, streamlining visual development and creative exploration.

3.3 Sequential Image Synthesis for Manga Generation

Diffusion models [3], renowned for their efficacy in single-image synthesis, are demonstrating progress in generating coherent image sequences, which is a critical aspect of manga production.

Reference-Guided Synthesis: IP-Adapter (August 2023) guides diffusion processes using reference images, though with reduced textual prompt controllability [136].

Identity Preservation and Control: InstantID (January 2024) integrates facial and landmark images with textual prompts [137], imposing semantic and spatial constraints for identity consistency. PhotoMaker (December 2023) encodes multiple identity images into a unified embedding [138], preserving identity information while accommodating diverse identity integration. However, both models exhibit limitations in maintaining clothing and scene consistency across sequences.

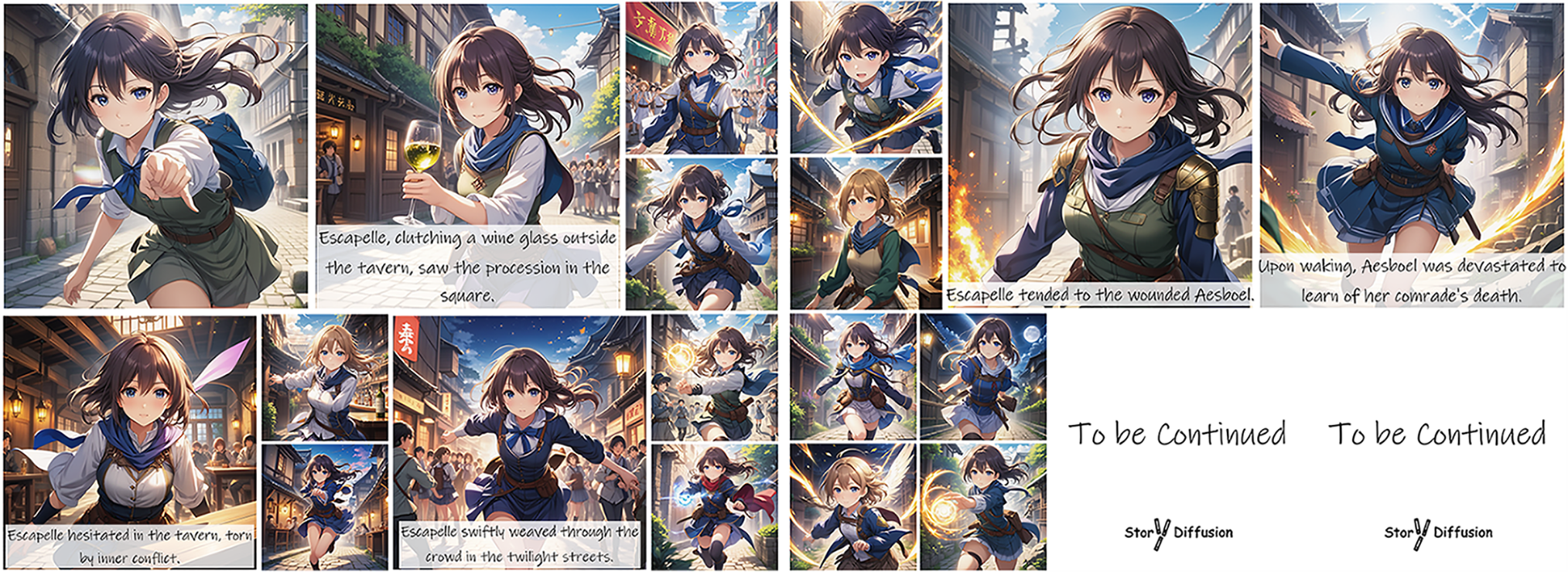

Thematic Consistency Across Sequences: StoryDiffusion (May 2024) achieves thematic coherence within image batches by incorporating consistent self-attention into Stable Diffusion [139], facilitating manga-style narrative sequencing. The sequential narrative imagery synthesized by StoryDiffusion is shown in Fig. 10. Nevertheless, minor inconsistencies in character details persist in multi-character scenes.

Figure 10: Sequential narrative imagery synthesized via Storydiffusion

Multimodal Integration and Layout Control: DiffSensei (December 2024) integrates diffusion-based image generation with multimodal large language models (MLLMs) [140], employing masked cross-attention for seamless character feature incorporation and precise layout control. The MLLM-based adapter enables flexible character expression, pose, and action modifications aligned with textual prompts.

High-Fidelity Personalization: AnyStory (January 2025) utilizes an “encoding-routing” approach [141], employing ReferenceNet and an instance-aware subject router, to achieve high-fidelity personalization for single and multiple subjects in text-to-image generation. This approach enhances subject detail preservation and textual alignment.

While models like InstantID, PhotoMaker, and StoryDiffusion have shown promising advancements in generating consistent characters across scenes, minor inconsistencies in character details and clothing still persist in multi-character or long-form sequences, highlighting an area for continued research.

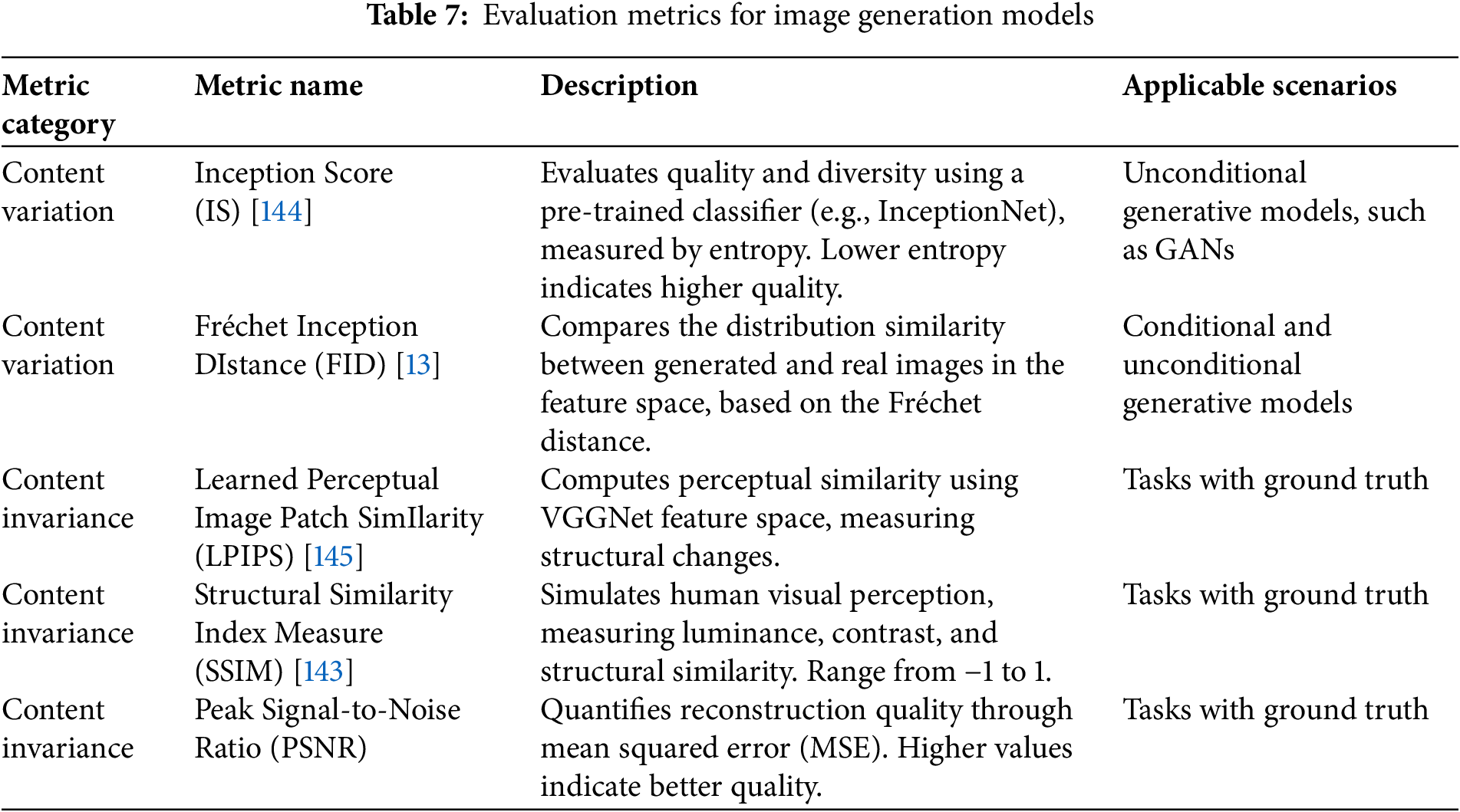

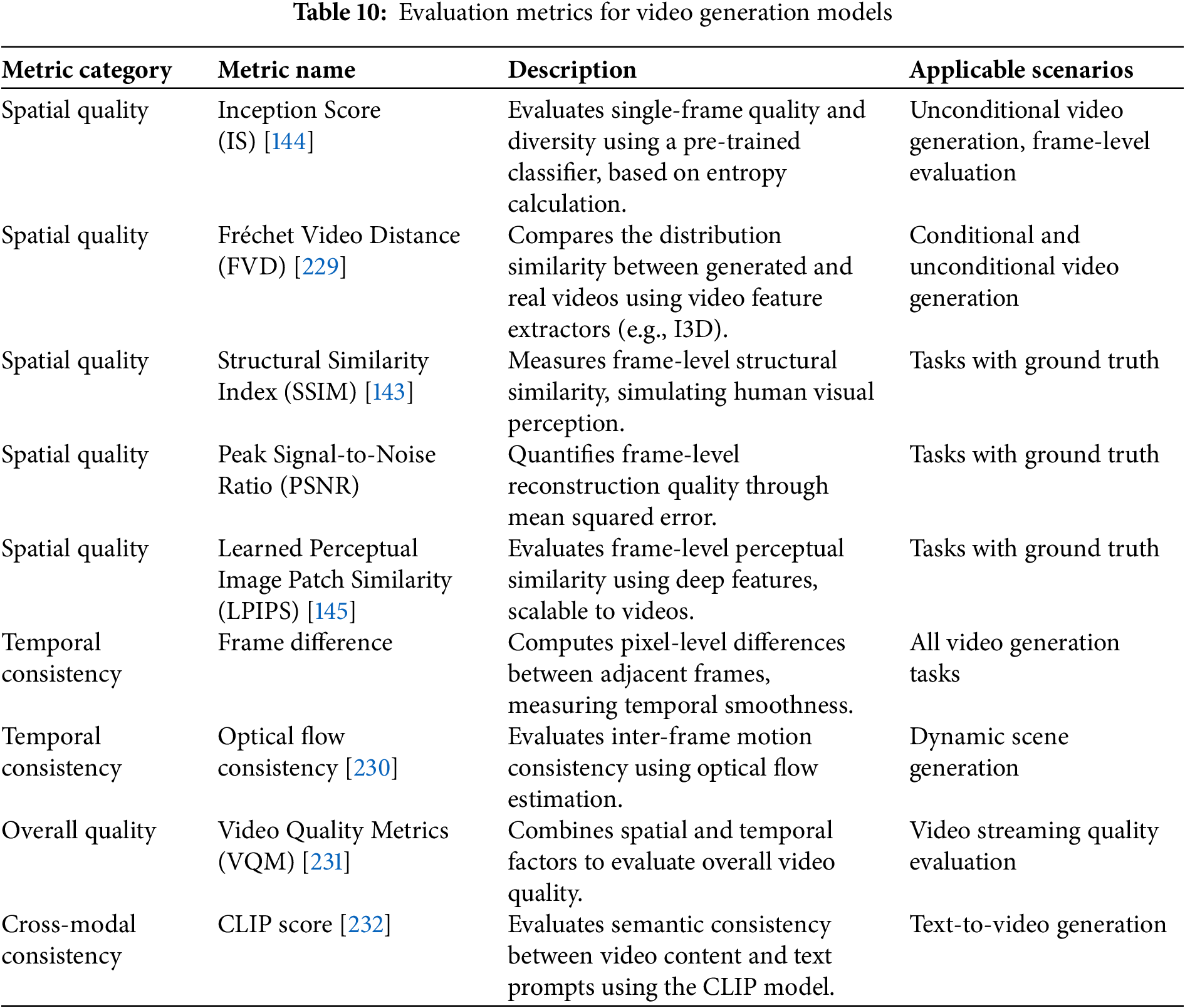

Evaluation of generative image synthesis models bifurcates into automated and human-centric paradigms [142]. Automated metrics further diverge into content-invariant and content-variant assessments, tailored to scenarios with and without ground truth, respectively [143]. Table 7 delineates the principal metrics and their salient characteristics.

Beyond these foundational metrics, several nuanced evaluations merit consideration: Precision and Recall quantify the fidelity and completeness of generated samples; the F1 Score harmonizes these measures; Kernel Inception Distance (KID) [146] offers a robust alternative to FID using Maximum Mean Discrepancy; and the CLIP Score [14] evaluates semantic alignment between generated images and text prompts using pre-trained CLIP models, critical for text-to-image frameworks.

The discussion of generative models, particularly those fine-tuned or designed for specific aesthetics like anime, remains crucial. While empirical benchmarks are valuable, it’s pertinent to acknowledge that standard metrics, such as the FID calculated with a general pre-trained Inception model, may not perfectly capture the perceptual nuances highly valued within specialized artistic styles. This underscores the im-portance of qualitative assessments and human-centric evaluations in understanding a model’s true per-formance and aesthetic appeal, especially for complex and subjective domains like anime image synthesis. Further insights can be gained from analyzing representative sets of samples generated from diverse prompts, which can highlight models’ varying strengths across multiple evaluation axes and demonstrate progress in producing perceptually appealing and contextually relevant imagery.

The proliferation of generative models, notably Stable Diffusion and Flux, alongside community-driven plugins, has significantly expedited anime creation. Current creative paradigms primarily manifest in: (1) the rapid generation of evocative imagery within non-realistic domains, such as post-apocalyptic punk and steampunk, to aid creative ideation; (2) the meticulous refinement of model parameters to instantiate personalized stylistic generators, followed by iterative enhancement of initial outputs, encompassing aesthetic optimization, granular detail augmentation, structural anomaly rectification, and ambient modulation; and (3) the utilization of synthesized images as texture mapping repositories. However, if the complexities of AI-generated content copyright are effectively navigated, and the synthesis process is judiciously controlled, iteratively refined, and finalized by human artists with keen aesthetic sensibility, the output of AI models can meet commercial production requirements. Furthermore, ancillary technologies facilitating the decomposition of image painting processes offer pedagogical utilities for education and novice practitioners.

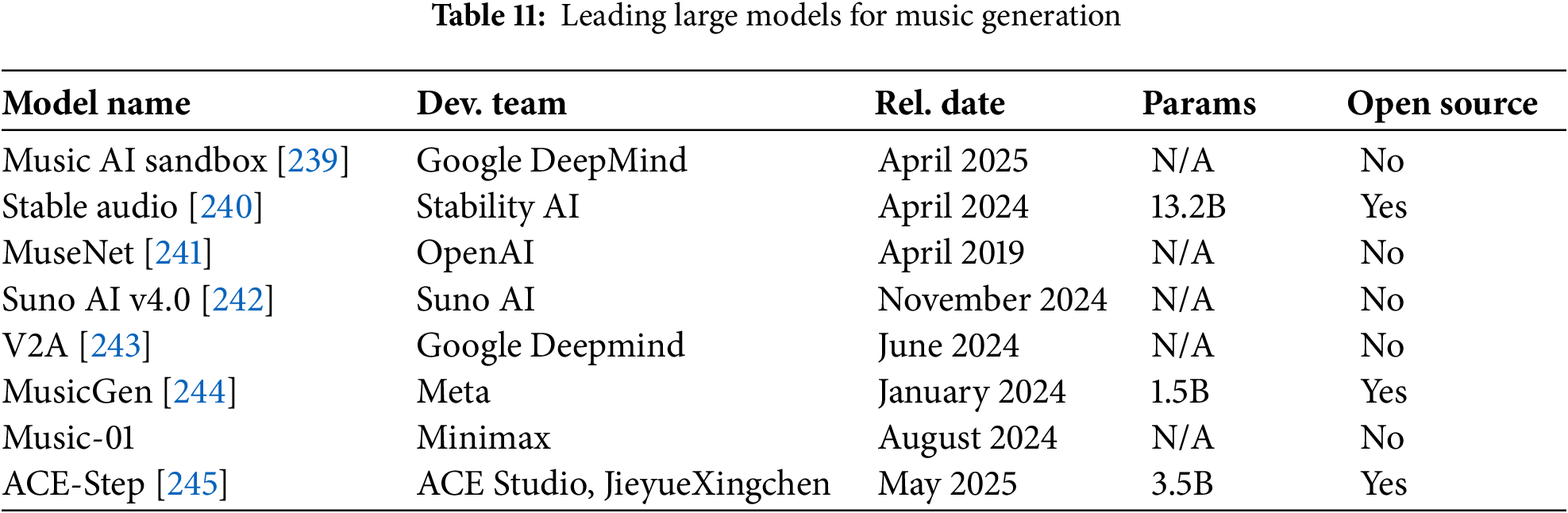

The year 2024 marked a watershed moment in video synthesis, propelled by augmented computational resources and the refined capacity of generative models to process intricate spatiotemporal data. While still in a nascent stage compared to static image generation, this sub-field is rapidly transforming at the research and developmental frontiers. The advent of sophisticated open-source models has pushed the boundaries of fidelity, duration, and controllability. This section delves into prominent generative video synthesis models, reflecting the field’s dynamic, albeit nascent, trajectory. Model selection emphasizes recent breakthroughs, novel architectural paradigms addressing core challenges like temporal coherence and computational efficiency, and demonstrable potential for application within anime production workflows. Notable exemplars, including Google’s Gemini 2.0, OpenAI’s DALL-E and Sora, Midjourney, and Meta’s Make-A-Video, underscore the burgeoning technological sophistication within this domain [36,147].

4.1 Large Models for Video Generation

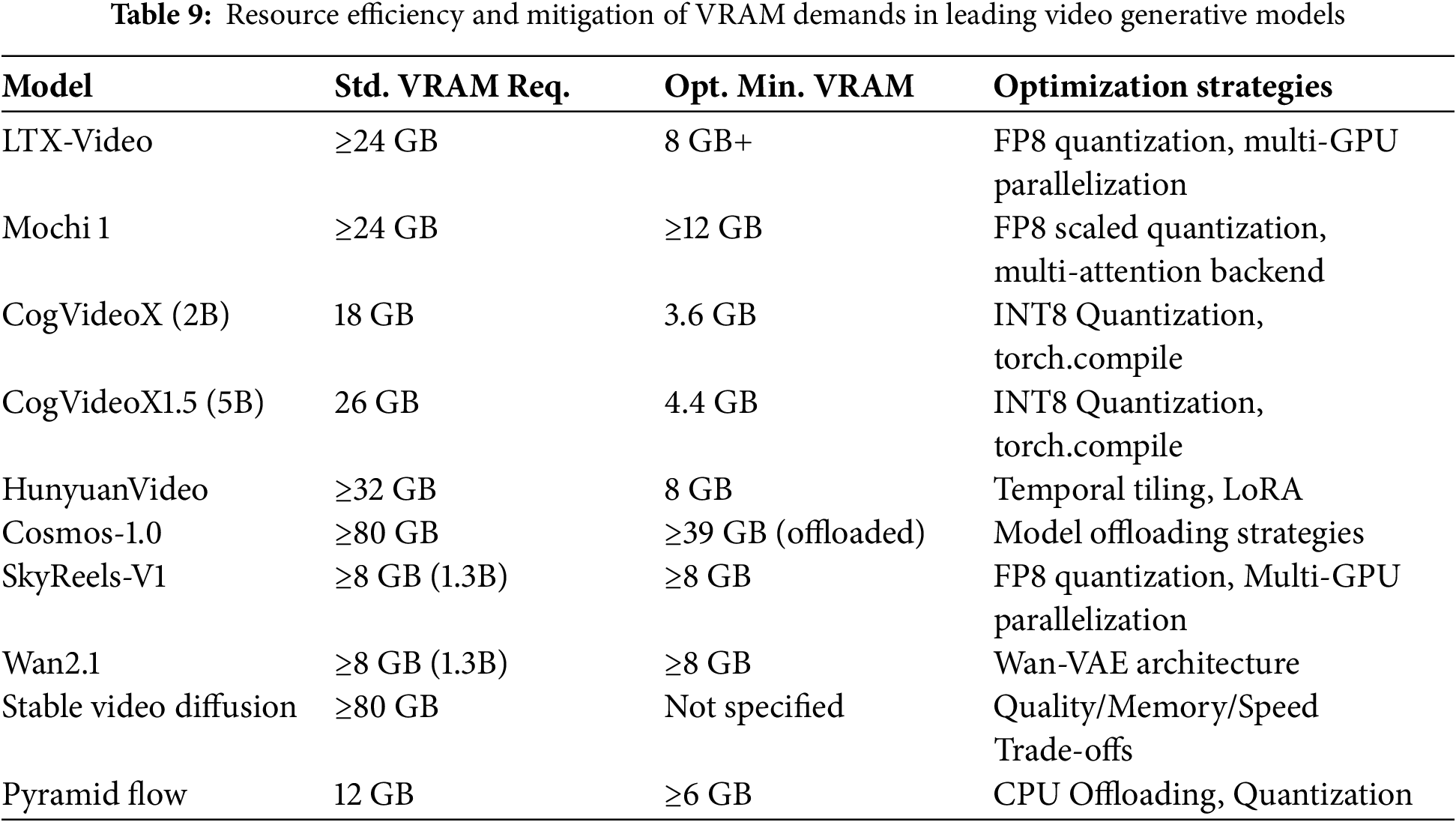

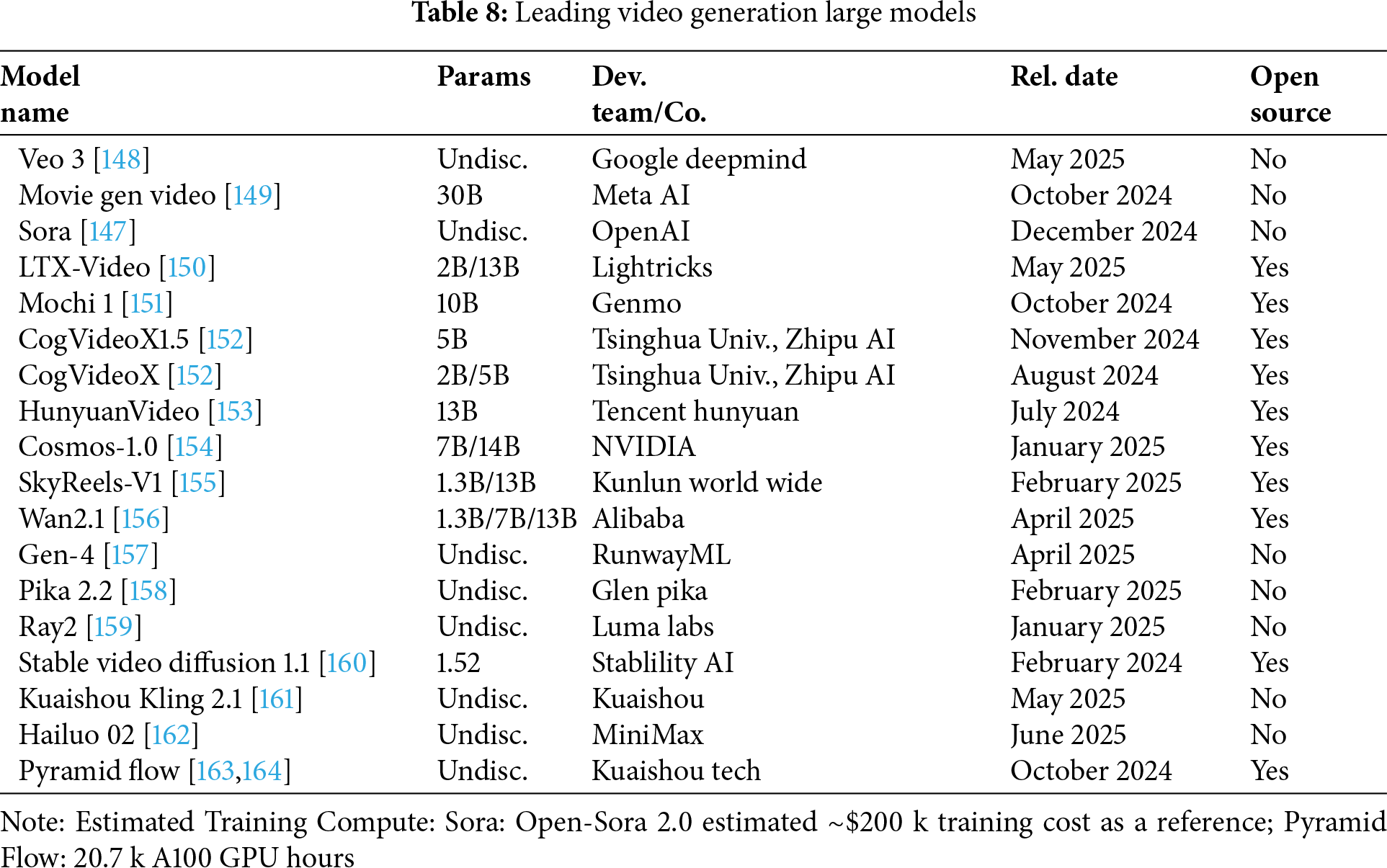

As Tables 8 and 9 illustrate, state-of-the-art video generation models involve even greater computational exigencies compared to their image counterparts, demanding substantial parameters, training resources, and VRAM. Addressing these considerable resource requirements is paramount for wider adoption, with ongoing research focusing on developing more efficient architectures and sophisticated optimization strategies to mitigate hardware demands and facilitate integration into complex animation workflows.

4.1.1 Capabilities and Challenges of Open-Source Generators

The advent of sophisticated open-source models has rapidly transformed video synthesis, pushing the boundaries of fidelity, duration, and controllability. A critical assessment of these advancements reveals diverse architectural strategies and performance profiles.

The WAN model leverages a dual image-video training paradigm to achieve broad synthesis capabilities, balancing efficiency and scale through its 1.3 and 14B variants. Its innovative spatiotemporal mechanisms facilitate the capture of complex dynamics, with the Streamer method enabling extended video generation at enhanced speeds. Nonetheless, challenges persist in preserving fine details during substantial motion and managing the computational cost associated with larger models.

Hunyuan Video, the largest open-source model evaluated at over 13 billion parameters, presents a comprehensive framework integrating advanced data curation and scalable training [153]. It excels in generating high-quality videos with precise text-video alignment and robust conceptual generalization. Its capabilities extend to coherent action sequences and localized text generation, partly attributed to large language model integration. While the original text doesn’t explicitly detail disadvantages, challenges include the significant computational resources required and difficulties in maintaining perfect consistency in intricate scenarios. Artefacts from tiling during VAE inference require further refinement.

Stable Video Diffusion (SVD) marks a significant advancement in high-resolution latent video diffusion, underpinned by a systematic data management pipeline that elevates performance through pre-training [160]. SVD demonstrates a strong command of motion and 3D understanding, serving as a potent 3D prior for multi-view synthesis. Its modularity supports fine-tuning for downstream tasks like image-to-video generation and camera control. However, its efficacy is primarily limited to short videos, struggling with extended sequences, and inherent diffusion model characteristics result in slower sampling and high memory demands.

The Pyramidal Flow Matching approach enhances video generative modeling efficiency through a unified algorithm that reduces training tokens via temporal pyramids and integrates trajectories into a single Diffusion Transformer. This method supports high-quality video generation up to 10 s but can introduce subtle subject inconsistencies in longer videos. Current limitations include a lack of support for keyframe or video interpolation and an opportunity for improved fidelity to intricate prompts.

LTX-Video focuses on realtime video latent diffusion by optimizing a Transformer-based model with a high-compression Video-VAE [150]. This enables efficient spatiotemporal attention and high-resolution output directly in pixel space, achieving faster-than-realtime generation speeds. Yet, the high compression inherently limits fine detail representation, and performance can be sensitive to prompt clarity. The model currently focuses on short videos, with domain-specific adaptability remaining largely unexplored.

CogVideoX employs an expert Transformer within its diffusion model to generate continuous videos up to 10 s with strong text alignment and coherent actions [152]. It utilizes a 3D VAE for improved compression and fidelity, addressing the persistent challenge of flickering in generated video sequences. While scalable, aggressive compression can hinder convergence, and high-quality fine-tuning might slightly diminish semantic capabilities. Achieving long-term consistency with dynamic narratives is a persistent challenge. SkyReels-A1 is specifically designed for expressive portrait animation using a video diffusion Transformer framework [155]. It excels at transferring expressions and movements while preserving identity, producing realistic animations adaptable to various proportions. The model handles subtle expressions effectively. Nonetheless, identity distortion, background instability, and unrealistic facial dynamics remain challenges, particularly with extreme pose variations.

Finally, the Cosmos World Foundation Model Platform provides a framework for building world models for physical AI, generating high-quality 3D consistent videos with accurate physical attributes through diffusion and autoregressive methods. Its open-source nature promotes accessibility. However, these models are in an early stage of development, exhibiting limitations as reliable physical simulators regarding object permanence, contact dynamics, and instruction following. Evaluating physical fidelity is also a significant challenge.

In summation, the open-source video generative landscape is marked by diverse, powerful models. Ongoing research is essential to address current limitations in fidelity, efficiency, and controllability, paving the way for broader applications and continued innovation.

4.1.2 Performance Evaluation and Anime Potential

Recent advancements in open-source video generative models have demonstrated notable superiority over established baselines and various contemporary models in rigorous paper evaluations. The WAN model, for instance, has consistently surpassed existing open-source and sophisticated commercial solutions across a spectrum of internal and external benchmarks, exhibiting a decisive performance advantage, notably outperforming models such as Sora, Hunyuan, and various CN-Top variants in weighted scores and human preference studies. Despite these impressive gains in fidelity and text alignment, challenges persist, particularly in achieving perfect consistency in long-form narratives, maintaining fine detail during significant motion, and fully meeting the high standards for stylistic precision and emotional depth inherent in complex anime productions. Similarly, Hunyuan Video has been shown to exceed the performance of prior state-of-the-art models, including Runway Gen-3 and Luma 1.6, alongside several prominent domestic models, particularly excelling in text alignment, motion quality, and visual fidelity assessments [153]. Stable Video Diffusion (SVD) has proven superior to models like GEN-2 and PikaLabs in image-to-video generation quality and significantly outperformed models such as CogVideo, Make-A-Video, and Video LDM in zero-shot text-to-video generation metrics [160]. The PyramidFlow model has distinguished itself by surpassing all evaluated open-source video generation models on comprehensive benchmarks like VBench and EvalCrafter, achieving parity with commercial counterparts such as Kling and Gen-3 Alpha using exclusively public datasets. LTX-Video has demonstrated a considerable lead over models including Open-Sora Plan, CogVideoX (2B), and PyramidFlow in user preference studies for both text-to-video and image-to-video tasks [144]. CogVideoX-5B has shown dominance over a range of models including T2V-Turbo, AnimateDiff, and VideoCrafter-2.0 in automated evaluations and outperformed the closed-source Kling in human assessments. Furthermore, SkyReels-A1 has exhibited superior generative fidelity and motion accuracy compared to diffusion and non-diffusion models like Follow-Your-Emoji and LivePortrait, also achieving higher image quality than most existing methods [155]. Lastly, the Cosmos World Foundation Model Platform’s components have showcased remarkable performance improvements, with its Tokenizer outperforming existing tokenizers like CogVideoX-Tokenizer and Omni-Tokenizer in key metrics, and its World Foundation Models demonstrating significant advantages over VideoLDM and CamCo in 3D consistency, view synthesis, camera control, and instruction-based video prediction [152]. These findings collectively underscore the rapid progress and increasing competitive edge of open-source initiatives in the video generation domain.

Capitalizing on their recent performance breakthroughs, these sophisticated video generative models constitute a significant development for anime production, and can augment the creative and technical palette available to animators. These models demonstrate capabilities ranging from generating diverse artistic styles and handling multi-language text integration to exhibiting robust generalization in avatar animation tasks, including anime and CGI characters, with precise control over pose and expression. The capacity for high-resolution, temporally consistent video generation from text or images provides valuable tools for preliminary concept visualization, storyboarding, and generating certain complex scenes or effects. This can augment workflow efficiency and reduce production overheads. Furthermore, specialized models excelling in expressive portrait animation with accurate facial and body motion transfer, adaptable to varied anatomies and scene contexts, directly address the nuanced demands of character animation in anime. While challenges persist in achieving perfect consistency in long-form narratives, maintaining fine detail during significant motion, and fully meeting the high standards for stylistic precision and emotional depth inherent in anime, the open availability and progressive capabilities of these models offer a fertile ground for developing next-generation animation techniques and tools. Their foundational strengths in high-quality video synthesis, 3D consistency, and increasing controllability suggest a potential for streamlining pipelines, fostering creative exploration, and contributing to the visual lexicon of anime.

Comparative video generation results from various large models, obtained on identical hardware using a uniform text prompt, are presented in Figs. 11–18.

Figure 11: CogVideoX 1.5 (5B Parameters). See Appendix A

Figure 12: Cosmos-1.0 (7B Parameters)

Figure 13: HunyuanVideo

Figure 14: LTX-Video (2B Parameters)

Figure 15: Mochi 1 (10B Parameters)

Figure 16: Pyramid-Flow

Figure 17: SkyReels-V1

Figure 18: WAN2.1

4.2 Contemporary Strides in Video Synthesis

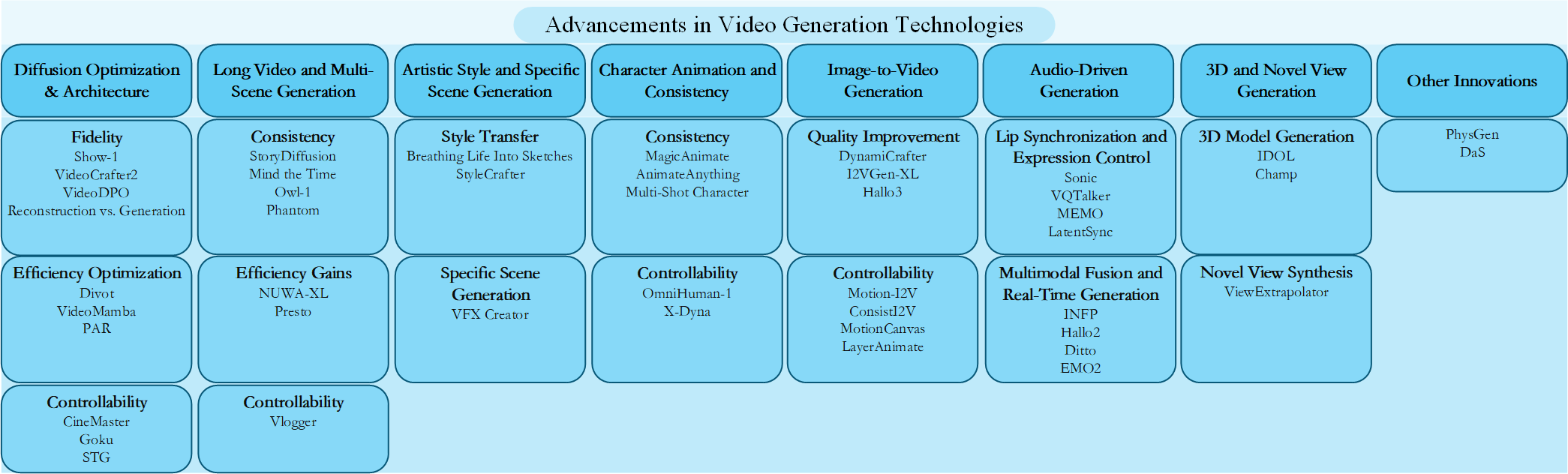

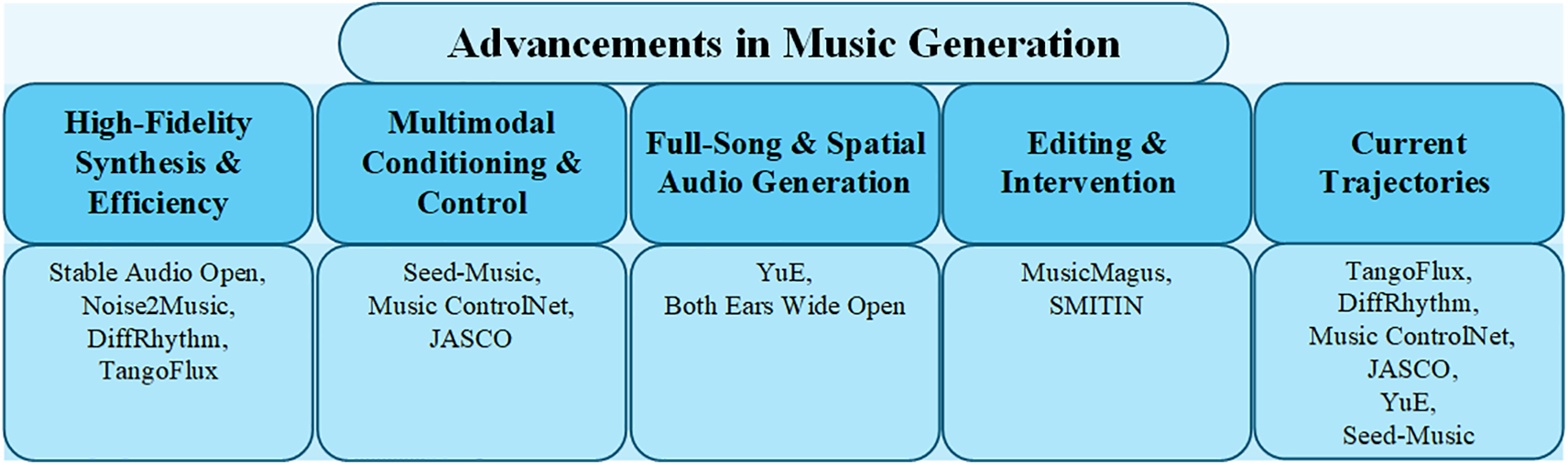

Drawing upon recent breakthroughs in generative AI, particularly within diffusion and language models, the landscape of anime video synthesis is rapidly advancing. A critical challenge in this domain lies in effectively generating extended, multi-scene narratives with both temporal and character consistency, while simultaneously addressing the exponential increase in computational demands Contemporary research endeavors are addressing this complex challenge through innovative architectural designs and optimization strategies. Techniques such as global-local diffusion cascades and segmented cross-attention mechanisms are being developed to enhance efficiency in processing long video sequences. Alongside these architectural improvements, optimization strategies like temporal tiling and parameter-efficient fine-tuning (e.g., LoRA) are crucial for managing computational resources, particularly VRAM. Furthermore, significant strides are being made in explicitly improving temporal coherence through methods like consistent self-attention, temporal-aware positional encoding, and latent state variable-based modeling. Concurrently, advancements in character animation are focusing on maintaining consistent appearances across frames and scenes via appearance encoders, multi-scale feature fusion networks, and query injection mechanisms. While challenges persist, the convergence of these architectural, algorithmic, and optimization-focused innovations is contributing to progress towards more efficient and consistent generation of long-form anime video content. A overview of these advancements is presented in Fig. 19.

Figure 19: Overview of advancements in video generation technologies

Key advancements can be categorized into four interconnected areas, with particular emphasis on their implications for anime:

Diffusion Model Optimization and Architectural Innovations: Foundational to high-fidelity video generation, this area focuses on refining diffusion models for enhanced quality, efficiency, and controllability. Core contributions include hybrid pixel-latent diffusion frameworks (e.g., Show-1), high-fidelity image fine-tuning (e.g., VideoCrafter2), and human preference alignment [165–167]. For anime, these improvements directly translate to sharper visuals and more aesthetically pleasing outputs. Efficiency gains, such as parallel generation strategies (e.g., PAR), are crucial for scaling up anime production, which often involves numerous frames [39].

Long Video and Multi-Scene Generation: This domain tackles the critical challenge of maintaining temporal coherence and content consistency across extended narratives, a paramount concern for anime series and films. Pivotal methods include consistent self-attention and semantic motion predictors (e.g., StoryDiffusion), temporal-aware positional encoding, and latent state variable-based modeling (e.g., Owl-1) [139,168,169]. These innovations are directly applicable to ensuring narrative flow and visual continuity in multi-episode anime productions. Efficiency techniques like global-local diffusion cascades (e.g., NUWA-XL) and segmented cross-attention mechanisms (e.g., Presto) are vital for generating long anime sequences without prohibitive computational costs [170,171].

Character Animation and Consistency: Maintaining consistent character appearances and actions across frames and scenes is indispensable for compelling anime. Research here centers on achieving temporal coherence and visual realism. Seminal works utilize video diffusion models with appearance encoders (e.g., MagicAnimate), multi-scale feature fusion networks, and query injection for cross-shot consistency [172–174]. These advancements are directly responsible for preserving character identity and fluidity of motion throughout anime narratives.

Artistic Style and Specific Scene Generation: This area is particularly relevant to anime, which relies heavily on distinctive artistic styles. It focuses on achieving stylistic diversity and scene-specific content. Key methodologies involve T2V priors and deformation techniques and reference image-driven style adapters (e.g., StyleCrafter) [175,176]. These enable precise control over the aesthetic qualities of generated anime, allowing for the replication of diverse artistic styles and the creation of highly customized visual content.

4.2.1 Diffusion Model Optimization and Architectural Innovations

The adaptation of diffusion models to video generation, while promising, necessitates addressing inherent complexities related to temporal dynamics, computational efficiency, and user controllability. Current research endeavors are strategically focused on enhancing generation fidelity, optimizing computational throughput, and augmenting user-directed manipulation.

Regarding fidelity, seminal works have introduced hybrid pixel-latent diffusion frameworks (Show-1, October 2023) to balance quality and efficiency [166], refined spatial modules via high-fidelity image fine-tuning (VideoCrafter2, January 2024) [167], and leveraged human preference alignment through novel metrics (VideoDPO, December 2024) [165]. Furthermore, the reconciliation of reconstruction and generation objectives via VA-VAE and LightningDiT (Reconstruction vs. Generation, March 2025) has shown improvements in image quality and training efficiency [177].

For efficiency optimization, PAR (December 2024) introduces a parallel generation strategy by discerning dependencies among visual tokens [39], with the aim of augmenting the efficiency of image and video generation while maintaining the quality of autoregressive models.

Controllability has been enhanced through frameworks that enable cinema-level control over objects and cameras (CineMaster, February 2025) [178], rectified flow transformers achieving benchmark performance (Goku, February 2025), and transformer-based diffusion models that improve sample quality (STG, November 2024) [179].

These advancements collectively propel diffusion models towards a synergistic enhancement of quality, efficiency, and controllability, expanding technological frontiers through multimodal integration, spatial-temporal decoupling, and efficient architectural paradigms.

4.2.2 Long Video and Multi-Scene Generation

The generation of long-form and multi-scene videos poses significant challenges related to temporal coherence, content consistency, and computational scalability. Innovations in this domain emphasize consistency preservation, efficiency augmentation, and user-directed control.

Consistency is addressed via consistent self-attention and semantic motion predictors (StoryDiffusion, May 2024) [139], temporal-aware positional encoding (Mind the Time, December 2024) [169], latent state variable-based world evolution modeling (Owl-1, December 2024) [168], and thematic element extraction through cross-modal alignment (Phantom, February 2025) [180].

Efficiency gains are realized through global-local diffusion cascades (NUWA-XL, March 2023) and segmented cross-attention mechanisms (Presto, December 2024) [170,171], enabling the generation of extended video segments with reduced computational overhead.

Controllability is enhanced through LLM-driven multi-scene script generation pipelines (Vlogger, March 2024; VideoStudio, January 2024) [181,182], facilitating complex narrative construction and user-directed content creation.

Despite these advancements, challenges remain in maintaining long-term consistency, mitigating computational demands, and ensuring seamless multi-scene transitions.

4.2.3 Artistic Style and Specific Scene Generation

This domain focuses on achieving stylistic diversity and scene-specific content generation, catering to artistic creation and personalized customization. Research avenues encompass style transfer and generation, and specific scene synthesis.

Style transfer is facilitated by T2V priors and deformation techniques (Breathing Life Into Sketches, November 2023) and reference image-driven style adapters (StyleCrafter, September 2024) [175,176], decoupling content and style through pre-training and fine-tuning.

Specific scene generation is enabled by controllable diffusion transformers (VFX Creator, February 2025) [183], allowing for user-directed animated visual effects synthesis.

These methodologies expand the creative potential of video generation through innovative architectural designs and multimodal fusion.

4.2.4 Character Animation and Consistency

Character animation research centers on generating temporally coherent and visually realistic animations. Key objectives include consistency enhancement and controllability augmentation.

Consistency is addressed via video diffusion models and appearance encoders (MagicAnimate, November 2023) [173], multi-scale feature fusion networks and frequency domain stabilization (AnimateAnything, November 2024) [174], and query injection for cross-shot consistency (Multi-Shot Character, December 2024) [172].

Controllability is enhanced through diffusion Transformer-based frameworks (OmniHuman-1, February 2025) and zero-shot, diffusion-based pipelines with dynamic adapters (X-Dyna, January 2025), enabling realistic and contextually rich animations.

Future research aims to address consistency in complex motion and multi-character scenarios and optimize computational efficiency.

4.2.5 Image-to-Video Generation

I2V generation focuses on synthesizing dynamic videos from static images, addressing challenges related to motion inference and content consistency. Research is bifurcated into quality improvement and controllability enhancement.

Quality is improved through text-aligned image context projection and noise connection (DynamiCrafter, November 2023) [184], cascaded models with hierarchical encoders (I2VGen-XL, November 2023) [185], and identity reference networks (Hallo3, March 2025) [186].

Controllability is enhanced via motion field predictors and temporal attention (Motion-I2V, January 2024), spatio-temporal attention and noise initialization (ConsistI2V, July 2024), user-driven cinematic shot design (MotionCanvas, February 2025), and layer-specific control mechanisms (LayerAnimate).

These advancements propel I2V technology towards enhanced realism and user-directed control, though challenges remain in complex scene consistency and computational efficiency.

Audio-driven generation synchronizes video content with audio, addressing challenges related to lip synchronization, facial expression control, and multimodal integration. Research is segmented into lip synchronization and expression control, and multimodal fusion and real-time generation.

Lip synchronization is improved via global audio perception and motion decoupled control (Sonic, November 2024), facial motion tokenization (VQTalker, December 2024) [187], memory-guided temporal and emotion-aware audio modules (MEMO, December 2024) [188], and audio-conditional latent diffusion models (LatentSync, December 2024) [189].

Multimodal fusion is enhanced through dual-aspect audio driving (INFP, December 2024) [190], improved patch deletion and noise enhancement (Hallo2, October 2024) [191], explicit motion space and streaming inference (Ditto, June 2024), and two-stage audio-driven virtual avatar generation (EMO2, January 2025) [192].

These technologies advance audio-driven generation towards enhanced realism, multimodal integration, and real-time applicability.

4.2.7 3D and Novel View Generation

This domain focuses on generating 3D models and novel views from 2D inputs, addressing challenges related to 3D structure inference and spatial consistency. Research encompasses 3D model generation and novel view synthesis.

3D model generation is facilitated by bi-modal U-Nets and motion consistency loss (IDOL, December 2024) and SMPL model-guided depth [193], normal, and semantic map fusion (Champ, June 2024) [194].

Novel view synthesis is enhanced by optimized SVD denoising (ViewExtrapolator, November 2024) [195].

These advancements drive the integration of 3D and novel view generation in creative applications.

Innovations such as physical modeling integration (PhysGen, September 2024) and 3D tracking video-driven diffusion (DaS, January 2025) expand the boundaries of video generation by incorporating domain-specific knowledge [196,197].

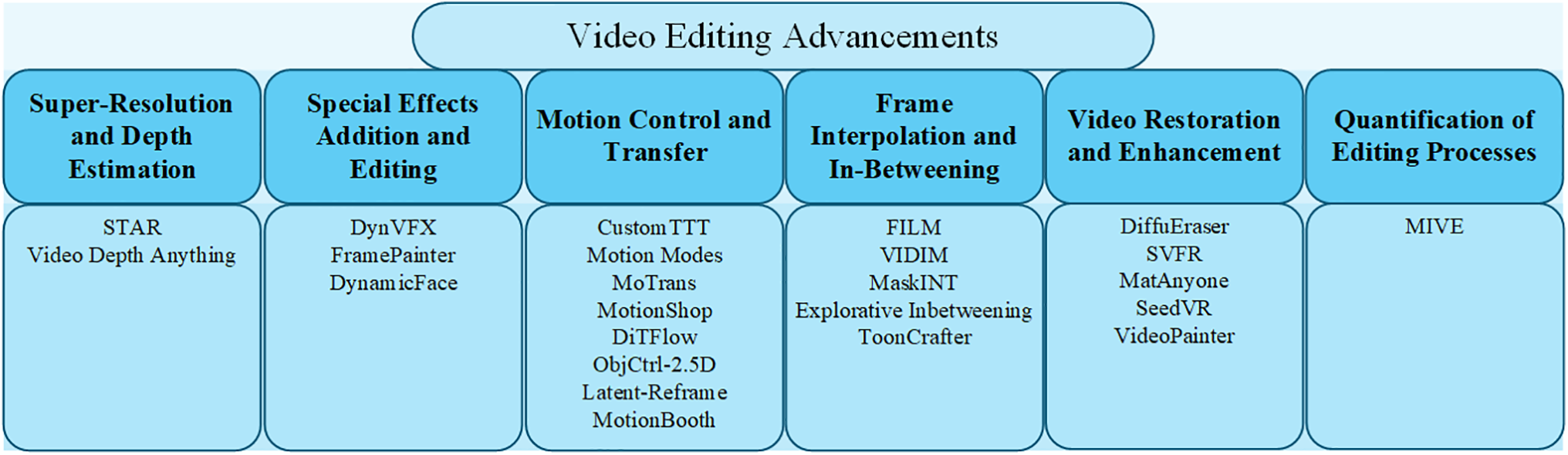

4.3 Recent Innovations in Video Editing Methodologies

Fig. 20 provides an overview of recent advancements in video editing.

Figure 20: Overview of advancements in video editing technologies

4.3.1 Super-Resolution and Depth Estimation

Innovations in video editing are significantly propelled by advancements in super-resolution and depth estimation. STAR (January 2025) leverages a local information enhancement module and dynamic frequency loss [198], coupled with a text-to-video model, to achieve spatio-temporal enhancement in real-world video super-resolution, thereby improving detail fidelity and temporal coherence. Video Depth Anything (January 2025) introduces an efficient spatio-temporal processing head and concise temporal consistency loss [199], enabling high-quality, temporally consistent depth estimation for ultra-long videos, achieving state-of-the-art zero-shot performance.

These methodologies advance video processing by enhancing visual fidelity and geometric perception. STAR balances detail and consistency through multimodal guidance and frequency domain constraints, while Video Depth Anything (January 2025) achieves zero-shot depth estimation with architectural efficiency [199]. Future research must address real-time performance and complex scene adaptability, critical for applications in film production and autonomous driving.

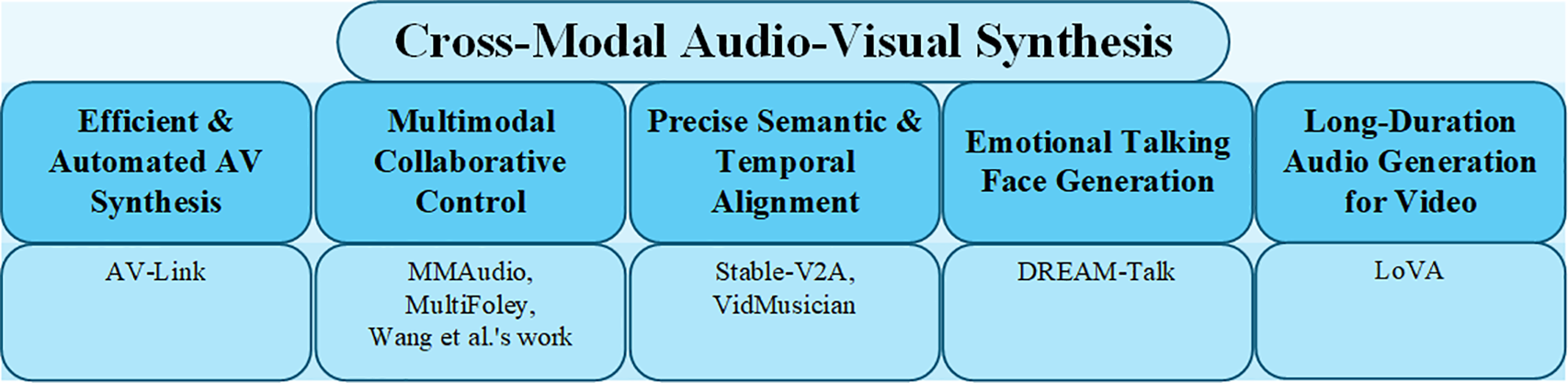

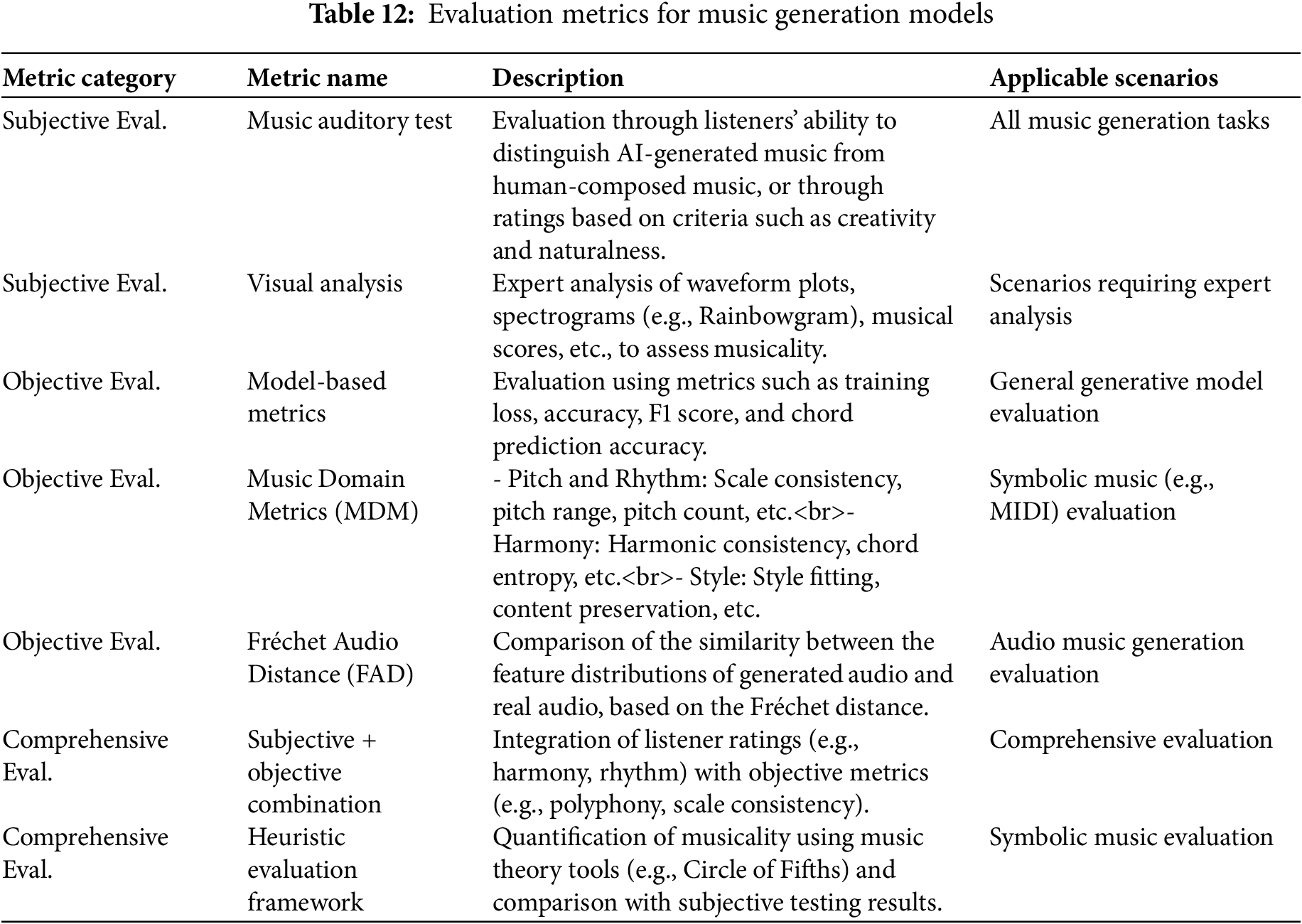

4.3.2 Special Effects Addition and Editing