Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Physics-Informed Neural Networks for Multiaxial Fatigue Life Prediction of Aluminum Alloy

1 Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, University of Tabriz, Tabriz, 51666-16471, Iran

2 Department of Computer Science, Faculty of Mathematics, Statistics, and Computer Science, University of Tabriz, Tabriz, 51666-16471, Iran

3 Doctoral School of Applied Informatics and Applied Mathematics, John von Neumann Faculty of Informatics, Obuda University, Budapest, 1034, Hungary

4 Institute of the Information Society, Ludovika University of Public Service, Budapest, 1083, Hungary

5 Faculty of Innovative Technologies, Abylkas Saginov Karaganda Technical University, Karaganda, 100000, Kazakhstan

6 Faculty of Economics and Informatics, Univerzita J. Selyeho, Komarno, 945 01, Slovakia

* Corresponding Author: Hamed Tabrizchi. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(1), 305-325. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.068581

Received 01 June 2025; Accepted 22 July 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

The ability to predict multiaxial fatigue life of Al-Alloy 7075-T6 under complex loading conditions is critical to assessing its durability under complex loading conditions, particularly in aerospace, automotive, and structural applications. This paper presents a physical-informed neural network (PINN) model to predict the fatigue life of Al-Alloy 7075-T6 over a variety of multiaxial stresses. The model integrates the principles of the Geometric Multiaxial Fatigue Life (GMFL) approach, which is a novel fatigue life prediction approach to estimating fatigue life by combining multiple fatigue criteria. The proposed model aims to estimate fatigue damage accumulation by the GMFL method. The proposed GMFL-PINN combines this physics-based approach with data-driven neural networks. Experimental validation demonstrates that GMFL-PINN outperforms FS, Smith–Watson–Topper (SWT) and Li–Zhang (LZH) fatigue life prediction methods which provides a reliable and scalable solution for structural health assessment and fatigue analysis.Keywords

Fatigue life prediction is essential in the safety and reliability of engineering components, particularly in aerospace and automotive industries. Modeling and analysis of the fatigue life prediction has more necessity for lightweight materials such as aluminum alloys. Aluminum 7075-T6, a high-strength alloy known for its excellent mechanical properties, is a popular choice in various applications due to its superior strength-to-weight ratio and corrosion resistance [1]. However, accurate prediction of the fatigue life under multiaxial loading conditions remains a challenge due to the complex interactions between stress states, loading paths, and material microstructure [2]. The literature includes several multiaxial fatigues to consider various materials and loads scenarios. The modeling criteria are generally grouped into three main approaches, i.e., stress-based, strain-based, and energy-based formulations. For instance, Findley [1] and McDiarmid [2] are representative of stress-based methods. Strain-based models include those proposed by Kandil et al. [3], Fatemi et al. [4], Li et al. [5], and Wang et al. [6]. In contrast, energy-based approaches often involve the interaction of stress and strain which are exemplified by the criteria of Smith et al. [7], Glinka et al. [8], and Varani-Farahani [9]. A recent study [10] evaluated eight multiaxial fatigue criteria using a detailed 3D model of the Polcevera railway bridge under realistic traffic conditions. It found that criteria based on axial stress tended to overestimate fatigue life compared to those that also account for shear stress components. Another way to classify multiaxial fatigue models is based on whether or not they incorporate the critical plane concept. This approach involves identifying a specific plane, commonly where shear strain reaches its maximum value, as critical, and computing the relevant fatigue parameters on that plane. Recent advancements in machine learning, particularly deep learning techniques, have opened new avenues to improve fatigue life prediction models. Among these techniques, Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) have gained popularity for their ability to incorporate governing physical laws into the training process, which ensures the predictions are consistent with established scientific principles. Unlike traditional black-box neural networks, PINNs partial differential equations (PDEs) to impose physical constraints, which is particularly advantageous in materials science problems where data may be sparse or costly to obtain. The application of machine learning models in fatigue life prediction is becoming more important, such as the prediction of fatigue crack length [11–13], crack growth [14–16] or fatigue life [17–19]. Several applications have been developed for fatigue life prediction, such as predicting the number of cycles to failure [20–22] and probabilistic fatigue S-N curve estimation which both mean and variance of the fatigue life can be learned [23–25]. In the field of fatigue lifetime prediction, artificial neural networks are clearly the most commonly used machine learning models. This type of data-driven model is unable to predict outside of the training dataset effectively [26]. Thus, Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) were developed [27]. Physics-based deep learning approaches have emerged as powerful tools for modeling systems governed by physical laws typically expressed through partial differential equations (PDEs). Among these, the PINNs models integrate physical principles directly into the architecture of neural networks by embedding the governing equations as part of the learning process. In the learning process, PINN incorporates mathematical laws expressed through physical equations, enhancing predictability. A recent and comprehensive review by Yang et al. [28] examines the very high-cycle fatigue (VHCF) behavior of steels in hydrogen environments and identifies Physics-Informed Machine Learning (PIML) as a promising approach to address limitations in conventional fatigue life prediction models. Complementing this, Zhu et al. [29] provide a broader perspective on the use of PIML in structural integrity assessment and outline key research challenges. Several studies further demonstrate ML’s growing role in hydrogen-related degradation: Zhang et al. [30] combined finite element method (FEM) and neural networks to study pipeline failure and Zhang et al. [31] applied ensemble learning with physical features to predict fracture toughness. These advances highlight the potential of hybrid and physics-informed ML methods in accurately modeling hydrogen-assisted failure mechanisms. According to Chen et al. [32], Walker mean stress model parameters and Basquin S-N were computed using the concept of PINN in a fully connected neural networks (FCNN). In an attempt to predict the length of fatigue cracks on aircraft wings, Nascimento and Viana [13] incorporated the Paris law into a recurrent neural network (RNN) cell called the cumulative damage cell. As well, Dourado and Viana [33] modeled corrosion-induced fatigue crack propagation using PINN models based on cumulative damage cells. For the analysis of main bearing fatigue, Viana et al. [34] applied physical differential equations to neural networks. A data-driven component was incorporated to capture the aspects of the physical model that remain partially understood. To address the fatigue crack growth problem and estimate model parameters, Nascimento et al. [35] employed recurrent neural networks (RNNs) within a Python-based model to solve the governing ordinary differential equations (ODEs).

This research work aims to propose a PINN-based approach for predicting Aluminum 7075-T6 multiaxial fatigue life under various loading conditions. The model integrates the Fatemi Socie (FS), Smith–Watson–Topper (SWT) and Li–Zhang (LZH) prediction models including the proposed geometric mean method [36] into the loss function of a neural network. This allows it to capture multiaxial fatigue’s complex nonlinear behavior. It also validates and trains the model based on the results of numerical stress and strain analyses together with experimental fatigue life testing for 7075-T6 aluminum. The key contributions of this study are as follows. Firstly, a new PINN model has been built to predict the fatigue life of Aluminum 7075-T6 under multiaxial loads. Secondly, it uses test data from open-holed specimens exposed to different loading conditions and blends in several fatigue criteria for better accuracy. Thirdly, by mixing deep learning with physics rules, the model works well even when data is limited. Overall, it’s a practical and reliable tool for understanding complex fatigue behavior and helping engineers make better life predictions.

2 Predictive Modeling of Fatigue Life Using Multiaxial Criteria

2.1 Multiaxial Fatigue Criteria

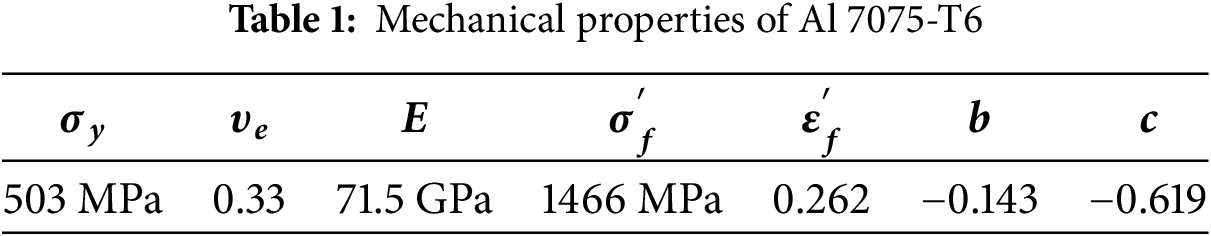

To predict the fatigue behavior of open-hole test specimens, this research employed a comparative analysis of three distinct multiaxial fatigue life prediction models. The material-specific parameters associated with each model, essential for accurate calculations, are documented in Table 1. Which is adapted from [37]. An overview of each criterion’s formulation is presented below.

Fatemi and Socie [4] introduced a shear-based fracture metric, conceptually related to the Kandil-Brown-Miller (KBM) parameter. However, their approach diverges by incorporating the maximum normal stress experienced on the critical plane, rather than normal strain. This substitution enables the model to explicitly account for hardening and mean stress influences via the normal stress component.

here,

Specifically designed for tensile fracture modes, this criterion utilizes the product of principal stress and principal strain range. However, variations of the SWT approach exist that extend beyond solely normal fracture assessments. Notably, the inclusion of both

In this equation,

This is a strain-based criterion that designates the plane experiencing the maximum shear strain as the critical plane. It further incorporates both the normal stress and the normal strain range evaluated on this plane [5].

The computation of

2.5 Geometric Multiaxial Fatigue Life

The Geometric Multiaxial Fatigue Life (GMFL) prediction method is a novel approach to estimating fatigue life by combining multiple fatigue criteria. This method overcomes the limitations of relying on a single fatigue criterion by taking the geometric mean of estimated fatigue lives. This approach leads to more balanced and reliable predictions. The GMFL method combines results from well-known multiaxial fatigue models, e.g., FS, LZH, and SWT. These individual models often either underestimate or overestimate fatigue life. The GMFL integrate their predictions using a geometric mean, and helps to reduce errors and provides a more accurate and robust estimate of fatigue life.

A detailed explanation of the methodology is provided in this section.

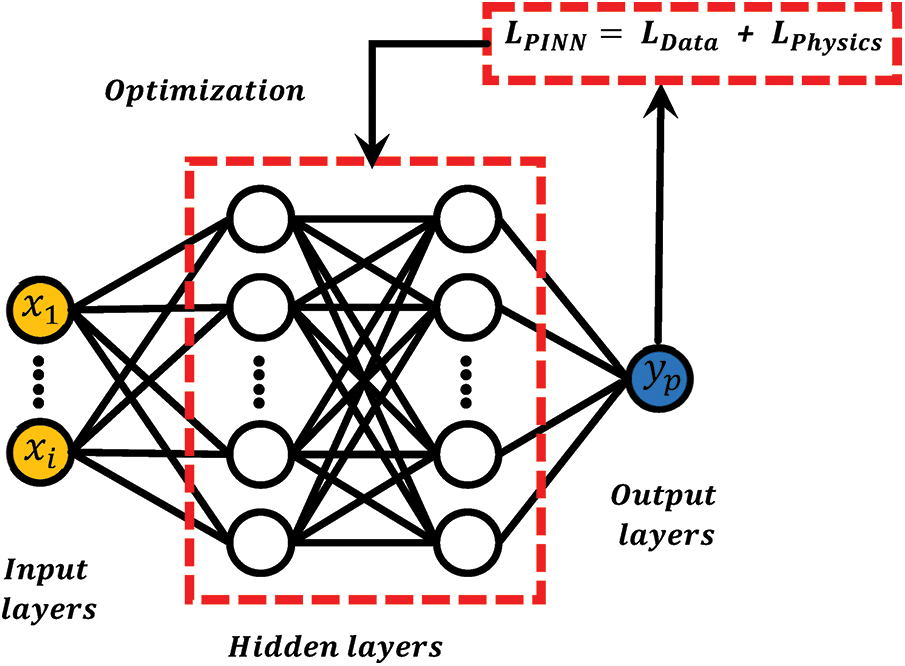

3.1 Physics-Informed Neural Network

Hybrid models are a novel approach to overcome data-driven neural network models, abbreviated PINN. The primary motivation for merging physical information, foundational physical knowledge, and physics-based models with deep learning architectures comes from a desire to address critical limitations inherent in purely data-driven approaches. This integration aims to produce physically consistent models capable of accurately assessing complex structures and nonlinear behaviors, thereby enhancing prediction reliability. By incorporating established physical principles, network training data demands can be significantly reduced, leading to more precise predictions even with limited datasets. Moreover, this synergy substantially improves models’ extrapolation capabilities, enabling robust predictions beyond the training domain. Physical constraints also bolster model robustness by mitigating noisy or erroneous training data. Finally, integrating physical knowledge enhances model interpretability, clarifying the underlying interaction relationships between inputs and outputs. This is crucial for understanding and validating model predictions. In this type of network architecture, by adding physical information to machine learning models, a unified approach is created. For investigation and analysis in the fields of materials engineering analysis, physical information is available in various forms. These include experimental and semi-empirical models, differential equations, simulation results, and probabilistic relationships. The general schematic of the PINN network architecture is shown in Fig. 1. Therefore, it is necessary to create different PINN architectures to guide machine learning model training on specific engineering problems and types of physical information. When machine learning models are used for evaluation, it is necessary to establish an optimal nonlinear mapping relationship between the output and the input of the machine learning models. Therefore, during the training process, an error function is used to reduce the optimal prediction error in the machine learning model. Thus, during the training process, an error function is used to reduce the optimal prediction error. For regression problems, the data-driven error function (

where

Figure 1: General schematic of the PINN

The error function in the physics-based neural network, as the most common strategy for building PINN, embeds physical information as physics-based regularization in the machine learning network. The error function in the physics-based fusion network is as follows:

where

This study utilizes experimental datasets containing stress and strain components alongside fatigue life test data for Aluminum 7075-T6. The data is preprocessed to ensure consistency and reliability before being fed into the PINN. Although only 16 distinct experimental load cases are shown in the fatigue life plots, the actual training dataset was significantly larger. For each load case, we extracted stress–strain states from several nodes near the critical hole region (see Section 4.2), generating a total of approximately 800 input–output data pairs. These samples included full tensorial stress and strain features, paired with fatigue life targets based on the experimental failure cycles of each specimen.

Stress Components (

Strain Components (

Fatigue Life (Life-Test): The experimentally obtained fatigue life values. The output is the predicted fatigue life

3.3.1 Handling Missing and Infinite Values

Missing values are addressed using linear interpolation. Infinite values are replaced with zero to maintain numerical stability.

3.3.2 Normalization (Min-Max Scaling)

All input features are normalized using Min-Max scaling to ensure values are within the range of 0 to 1, preventing scale-related biases in training.

3.3.3 Splitting Data into Training and Testing Sets

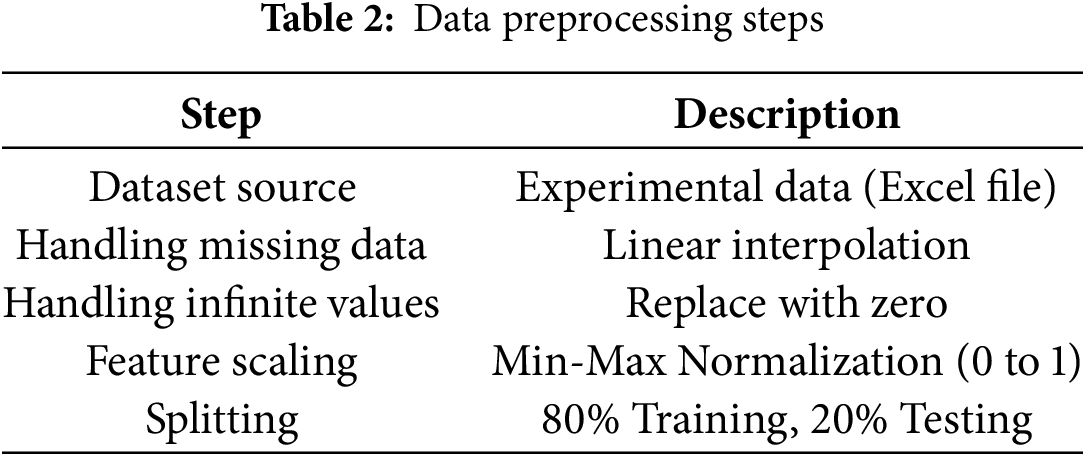

The dataset is randomly split into 80% training and 20% testing for model validation. Table 2 illustrates the steps involved in data preprocessing. This setup enabled robust learning while allowing for independent evaluation of model performance. To further enhance generalization, we applied dropout regularization (30%), feature normalization, and adaptive loss weighting between physics-informed and data-driven components during training.

The proposed GMFL-PINN model is a deep learning-based regression model which incorporates physics constraints for fatigue life prediction.

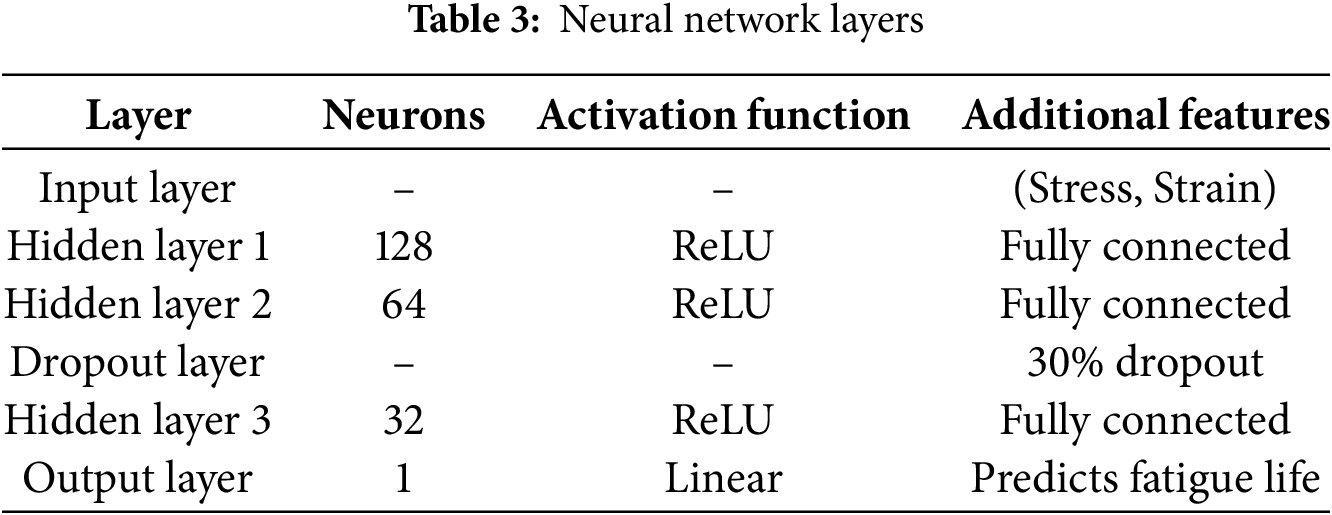

The neural network model consists of several layers structured to predict fatigue life based on input features. The input layer accepts stress and strain components as input variables. This is followed by three fully connected hidden layers, each utilizing the rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation function to introduce non-linearity and improve learning capacity. To enhance the model’s generalization and prevent overfitting, a dropout layer with a dropout rate of 30% is applied. Finally, the output layer comprises a single neuron with a linear activation function designed to output the predicted fatigue life. The detailed configuration of the neural network layers is presented in Table 3.

3.4.2 Key Features of GMFL-PINN

Deep Learning-Based Regression: Predicts fatigue life from stress and strain features.

Physics-Informed Loss: Integrates fatigue life equations for enhanced prediction accuracy.

Adaptive Loss Balancing: Dynamically adjusts weight factors (

Dropout Regularization: Prevents overfitting, improving model generalization.

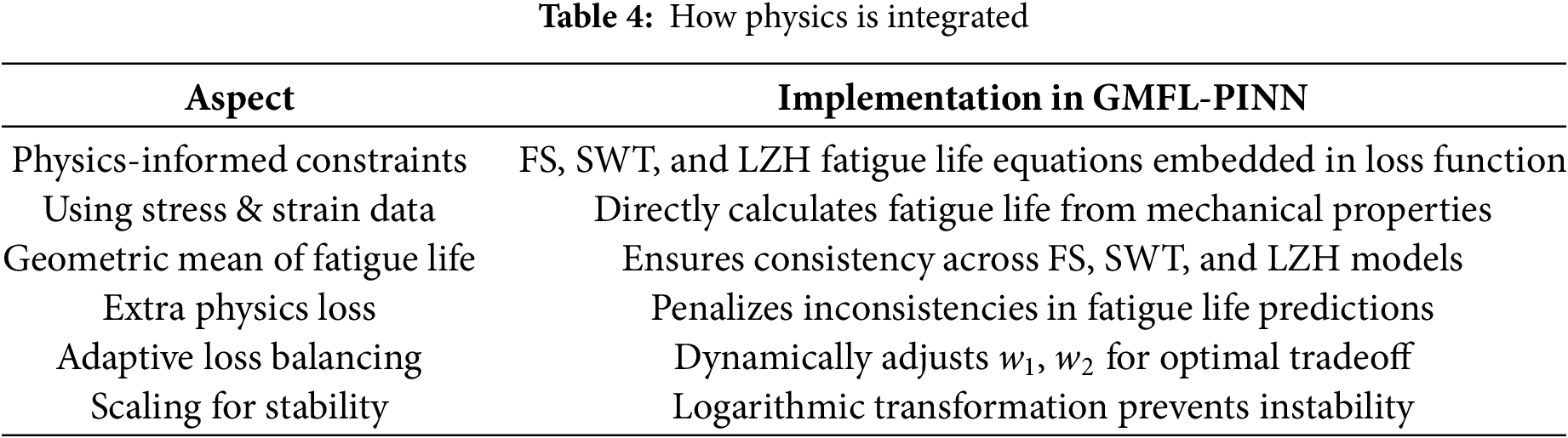

3.4.3 Physics-Based Constraints

The PINN method is employed to integrate fundamental mechanical principles into the learning process. The model uses three fatigue life prediction criteria, i.e., Fatemi-Socie (FS) Criterion, Smith–Watson–Topper (SWT) Criterion, Li–Zhang (LZH) Criterion. These physically derived estimates are aggregated using the geometric mean to ensure consistency. A physics-informed loss function is designed to penalize inconsistencies between data-driven predictions and physics-based constraints. The specific implementation of these mechanisms, including adaptive loss balancing, scaling for stability, and direct use of stress-strain data, is detailed in Table 4.

3.5.1 Loss Function Incorporating Physics-Based Constraints

The total loss function is defined as:

• Data-Driven Loss

• Physics-Based Loss

• Logarithmic Scaling: Prevents physics loss from dominating training.

The total loss is a weighted sum of data and physics losses:

where

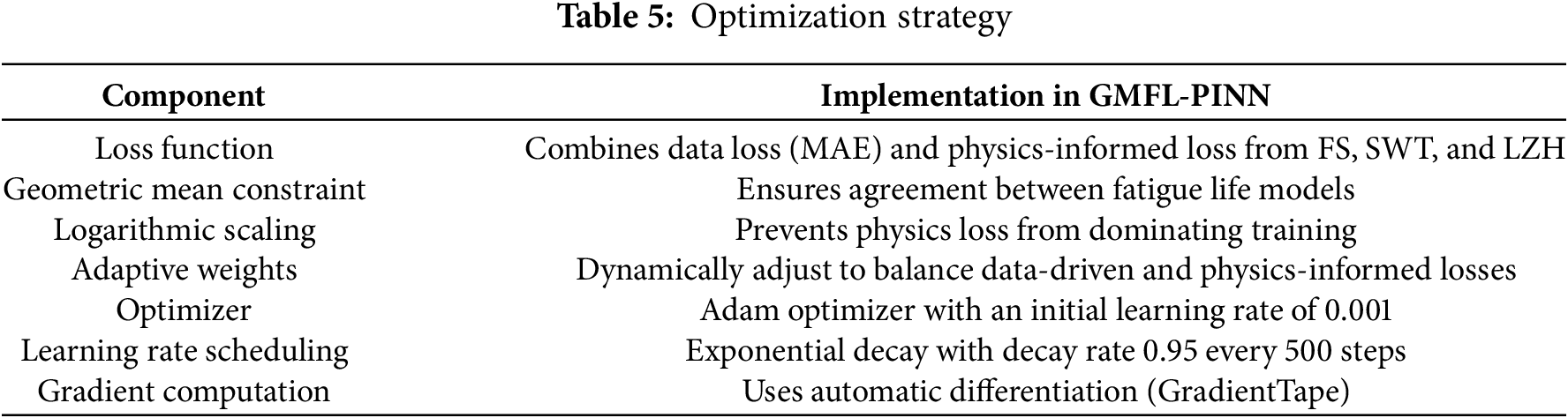

To ensure stable and reliable training under complex and noisy data conditions, a comprehensive optimization strategy was developed. Robustness against noise and outliers was enhanced through multiple techniques during the training process. These included physics-informed loss embedding, adaptive weighting between data and physics losses, dropout regularization (30%), and logarithmic scaling of fatigue life terms. Input features were normalized using Min–Max scaling, and data artifacts (e.g., infinite values) were cleaned systematically. These measures collectively enhanced model stability and performance under uncertain data conditions. An overview of the full optimization strategy, including key components such as loss function design, adaptive weights, and geometric constraints, is summarized in Table 5.

• Optimizer: Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.001.

• Learning Rate Scheduling: Exponential decay with a rate of 0.95 every 500 steps.

• Gradient Computation: Utilizes automatic differentiation (Gradient Tape) for efficient gradient updates.

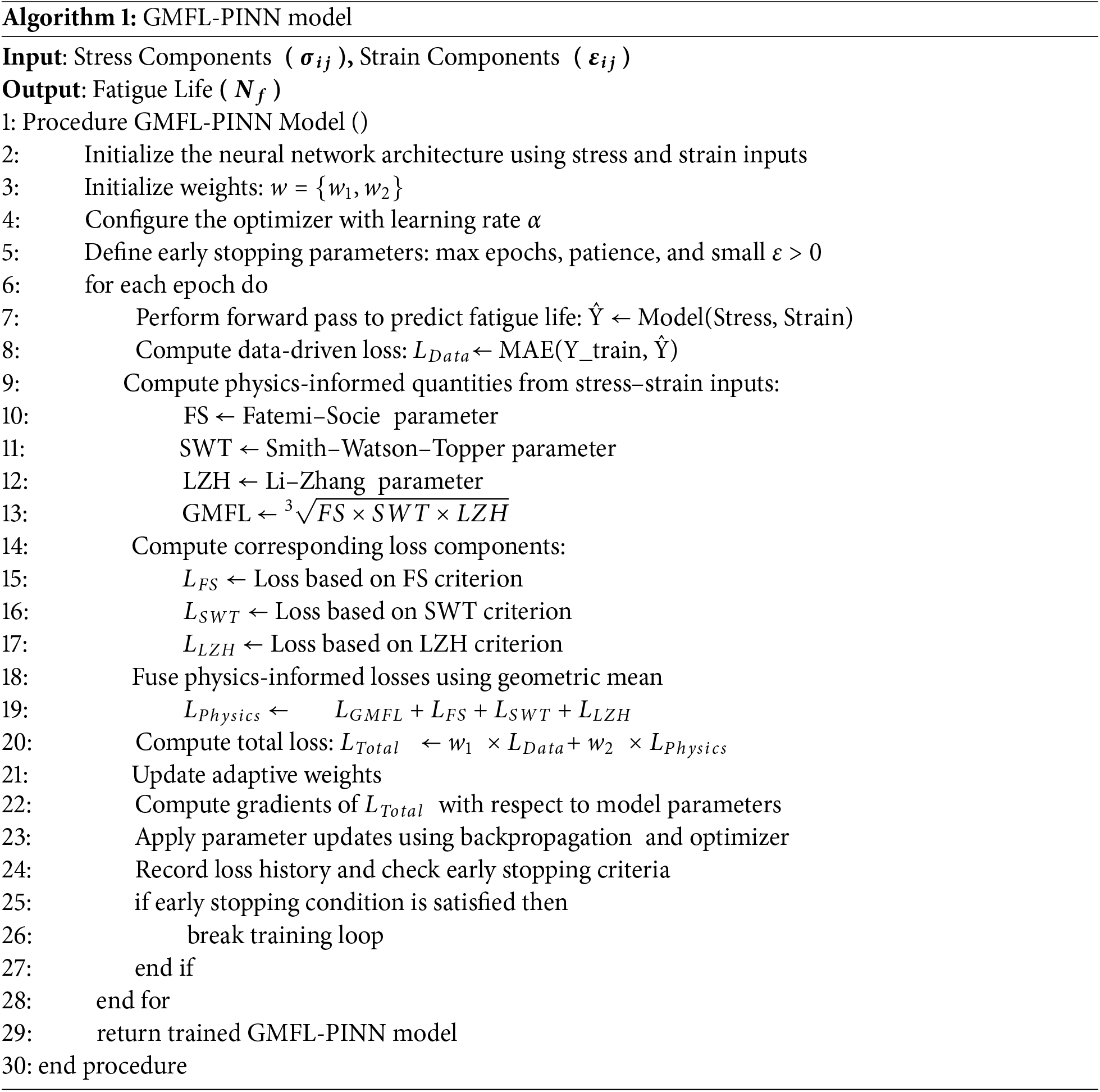

The GMFL-PINN model presents a novel approach to multiaxial fatigue life prediction by integrating domain knowledge into deep learning. It preprocesses stress-strain data through normalization and missing value handling, ensuring data quality before training. The model utilizes a deep neural network with embedded physics constraints to enhance prediction accuracy while employing adaptive loss balancing and logarithmic scaling for stable convergence. A physics-informed loss function incorporating the FS, SWT, and LZH criteria ensures physical consistency, while an optimized training process, leveraging the Adam optimizer and learning rate scheduling, refines model performance. This hybrid model enables the model to generalize effectively across different loading conditions while maintaining alignment with established mechanical principles. In the following, Algorithm 1 shows GMFL-PINN model.

Unlike conventional PINNs where fatigue criteria are pre-computed and fed as auxiliary inputs, the proposed method dynamically computes FS, SWT, and LZH directly from stress–strain states during training. These physics-based parameters are further fused through a geometric mean (GMFL) to form a unified indicator, enabling a more holistic representation of multiaxial fatigue behavior. This approach enhances physical interpretability, improves predictive robustness, and reduces dependency on preprocessing.

3.6 Discussion on Our Proposed Method (GMFL-PINN)

The Geometric Multiaxial Fatigue Life prediction with Physics-Informed Neural Networks (GMFL-PINN) method combines the robust predictive capabilities of the GMFL approach with the computational power of PINNs. In the PINN framework, the appropriate selection of functions used in the loss function plays a key role in the network’s ability. If the selected life prediction model lacks sufficient accuracy for the given material, incorporating it into the neural network’s loss function may adversely affect the network’s predictive performance. Conversely, employing a reliable prediction model such as the GMFL, which demonstrates good predictive capability for this material as part of the loss formulation, can enhance the overall accuracy of the neural network. This hybrid method enhances fatigue life estimation by integrating physics-based principles with machine learning techniques, offering improved accuracy and generalizability. The GMFL-PINN model incorporates the geometric mean of multiple fatigue criteria, such as FS, LZH and SWT, while leveraging PINNs to embed domain knowledge directly into the neural network’s structure. This ensures that predictions adhere to physical laws and empirical fatigue data. The PINN component effectively captures complex relationships between multiaxial loading conditions, material properties, and fatigue life. This makes it particularly suitable for other challenging cases such as cold-expanded specimens or non-standard geometries. Experimental validation demonstrates that GMFL-PINN achieves superior accuracy than traditional methods, consistently reducing prediction error and confining results within acceptable limits. This method represents a significant advancement in fatigue life prediction, combining GMFL reliability with machine learning adaptability and efficiency.

The results of our experiment are presented in this section.

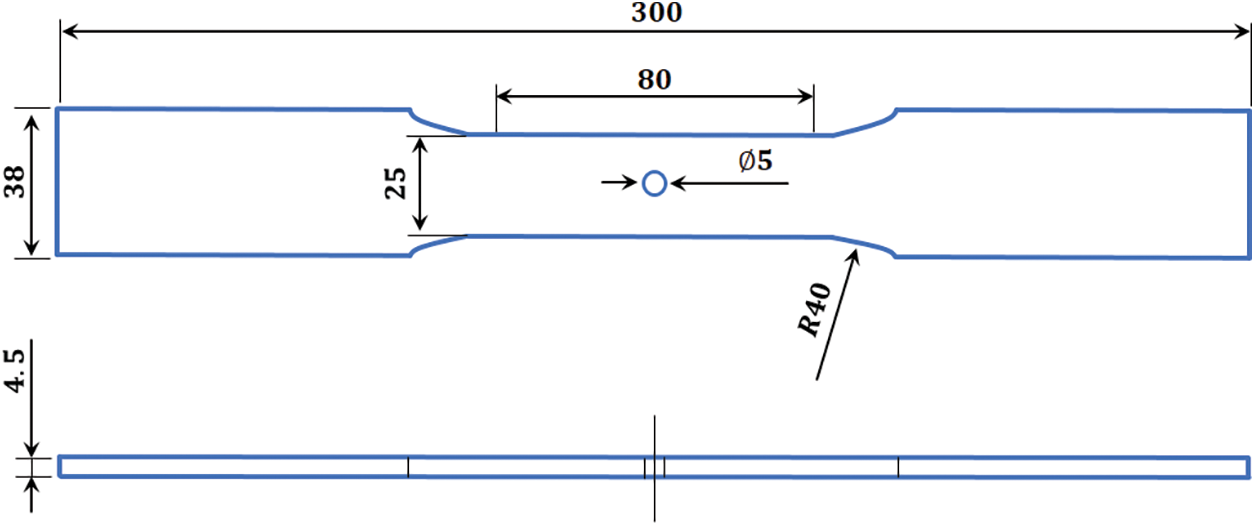

Comprehensive details of the experimental procedures can be found in [38,39]. For context, a brief summary is provided here. The fatigue test specimens were made from 7075-T6 aluminum alloy sheets with a thickness of 4.50 mm. Each specimen featured a centrally located circular hole with a diameter of 5 mm, created through drilling followed by reaming. Fig. 2 illustrates the geometric specifications of a standard open-hole specimen, based on the configuration presented in [38], with necessary modifications to suit the present study.

Figure 2: Dimensions of open hole fatigue specimens

Fatigue tests were carried out using an electro-hydraulic servo-controlled pull–push fatigue testing machine of Zwick/Roell Amsler HA250 on the specimens using sinusoidal cyclic loads of constant amplitude with a load ratio of zero at a frequency of 12 Hz. These tests were performed at load levels from 29 to 41 kN.

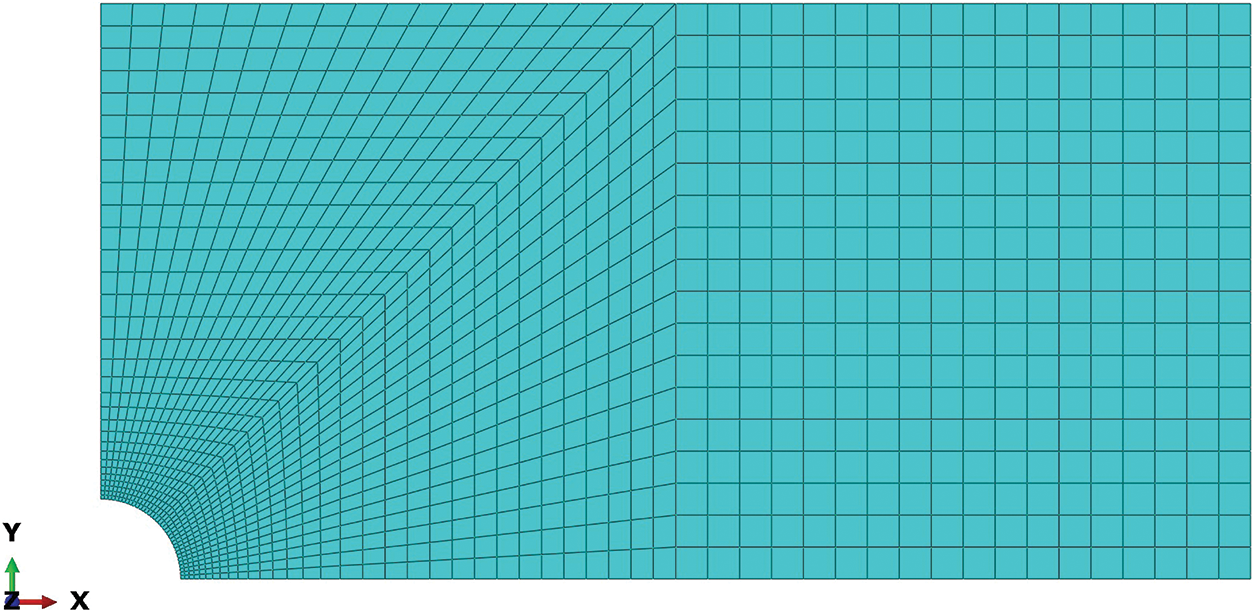

To estimate the fatigue life of specimens using multiaxial fatigue criteria, it is essential to understand how stress and strain are distributed, particularly around stress concentrators like holes. Because the behavior is nonlinear and complex, analytical solutions are difficult to achieve. Instead, finite element results from earlier research were used. The open-hole specimens are symmetric in both geometry and loading with respect to the Cartesian coordinate planes. This symmetry made it possible to model only a quarter of the plate, reducing computational effort. The simulation was performed using Abaqus, as shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Meshed finite element model for simulation of specimens

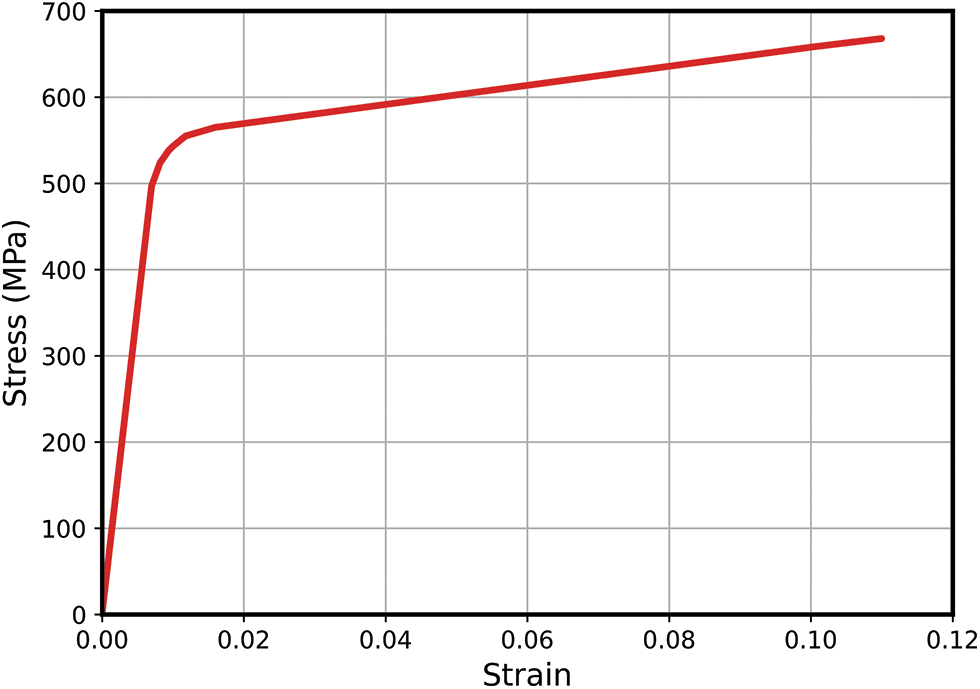

As in ABAQUS, 2D structural solid elements (CPS4R) were employed to mesh the specimen geometry due to their computational efficiency and suitability for plane stress conditions under multiaxial loading. The element size was refined through a mesh convergence study, in which multiple levels of mesh density were analyzed to ensure solution accuracy and eliminate mesh dependency in the final results. The optimal mesh size was selected based on a balance between computational cost and the accuracy of the stress and strain fields. This was done with the criterion of achieving element size-independent results in the regions of stress concentration and damage initiation. In the numerical simulations, an elastic–plastic multilinear kinematic hardening material model was adopted to accurately represent the cyclic deformation behavior of the Al-Alloy 7075-T6 alloy under fatigue loading. This material model captures both initial yield behavior and subsequent strain hardening characteristics. This makes it particularly well-suited to modeling ratcheting and cyclic plasticity effects encountered in multiaxial fatigue conditions. The material behavior was calibrated using monotonic tensile tests conducted along the rolling direction, as shown in Fig. 4 and the mechanical properties were measured to be an elastic modulus of E = 71.5 GPa and a Poisson’s ratio of υ = 0.33 [38]. The finite element (FE) models provided detailed distributions of stress and strain throughout the specimen, including critical locations where fatigue damage is expected to initiate. These outputs serve as the basis for coupling with fatigue life prediction models. They also serve as the basis for validating stress-strain histories used in both mechanical and PINN-based fatigue life estimation approaches. The combination of accurate material modeling, mesh refinement, and advanced constitutive behavior representation ensures that the FE analysis produces high-fidelity data, essential for evaluating fatigue performance under complex loading.

Figure 4: Stress-strain curve of Al 7075-T6

Regarding the fact that fatigue cracks initiate and propagate around the hole, the required numerical data, such as principal stresses and strains, were recorded from the nodes of the region near the hole, at exactly the hole edge and away from it. The data from FE models were then manipulated to be used in multiaxial fatigue criteria.

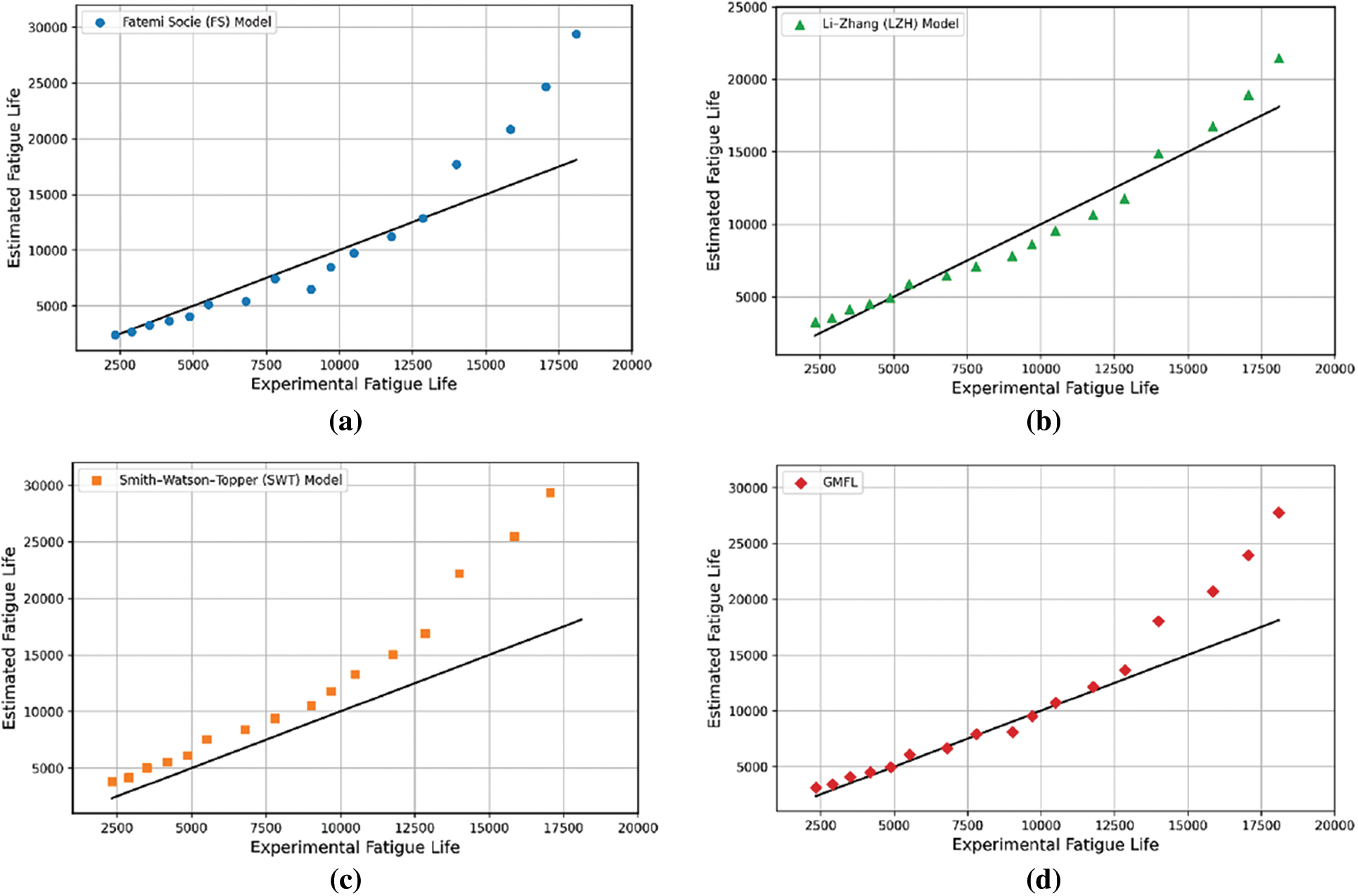

4.3 Comparison with Prediction Models

Fig. 5a illustrates the comparison of fatigue life predictions using the Fatemi-Socie (FS) model against experimental fatigue life data. The solid black line represents a correlation between predictions and experimental results, while the scattered data points indicate the model’s predictive performance. This figure shows the estimated fatigue lives based on Fatemi-Socie (FS) multiaxial fatigue criteria vs. experimental fatigue tests results for open hole specimens subjected to various remote stresses of the experimental fatigue tests. There is a hole in such specimens that causes stress and strain concentration, resulting in fatigue cracks. Fig. 5b shows the comparison of fatigue life predictions using the Li–Zhang (LZH) model against experimental fatigue life data. Fig. 5c illustrates the comparison of fatigue life predictions using the Smith–Watson–Topper (SWT) model against experimental fatigue life data. Fatigue life is overestimated in most SWT model predictions. As shown in Fig. 5d, the comparison of fatigue life predictions using the GMFL model against experimental fatigue life data. According to the results (Fig. 5a–c), FS, SWT, and LZH criterion underestimate fatigue lives. Consequently, a combination of these criteria as a geometric mean of estimated fatigue lives as mentioned in the previous section (GMFL) can be used to estimate fatigue life, see Fig. 5d. The results shown in Fig. 5d are only a mathematical combination of the results of other criteria and therefore they have no special physical concepts.

Figure 5: The comparison of fatigue life predictions using the mechanical models: (a) Fatemi–Socie (FS), (b) Li–Zhang (LZH), (c) Smith–Watson–Topper (SWT), and (d) Geometric Mean Fatigue Life (GMFL), against experimental fatigue life data

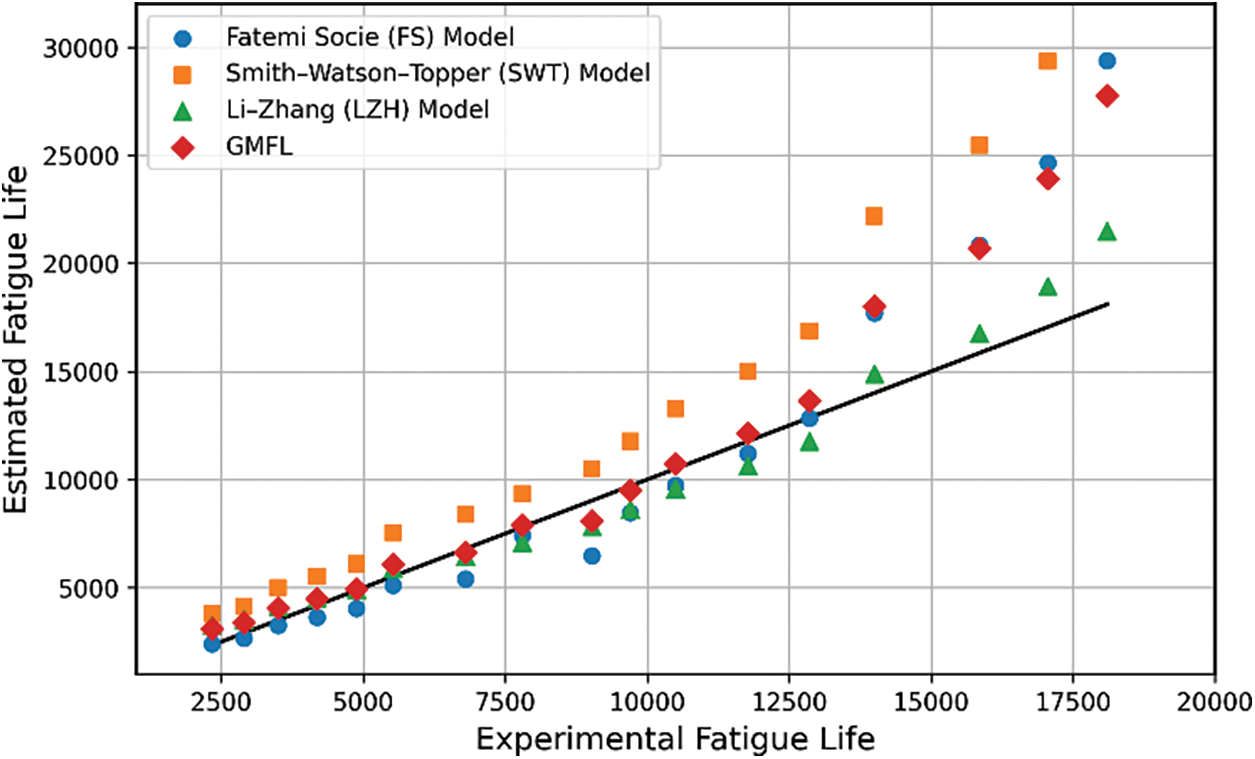

Figure 6: The comparison of fatigue life predictions using the mechanical models against experimental fatigue life data

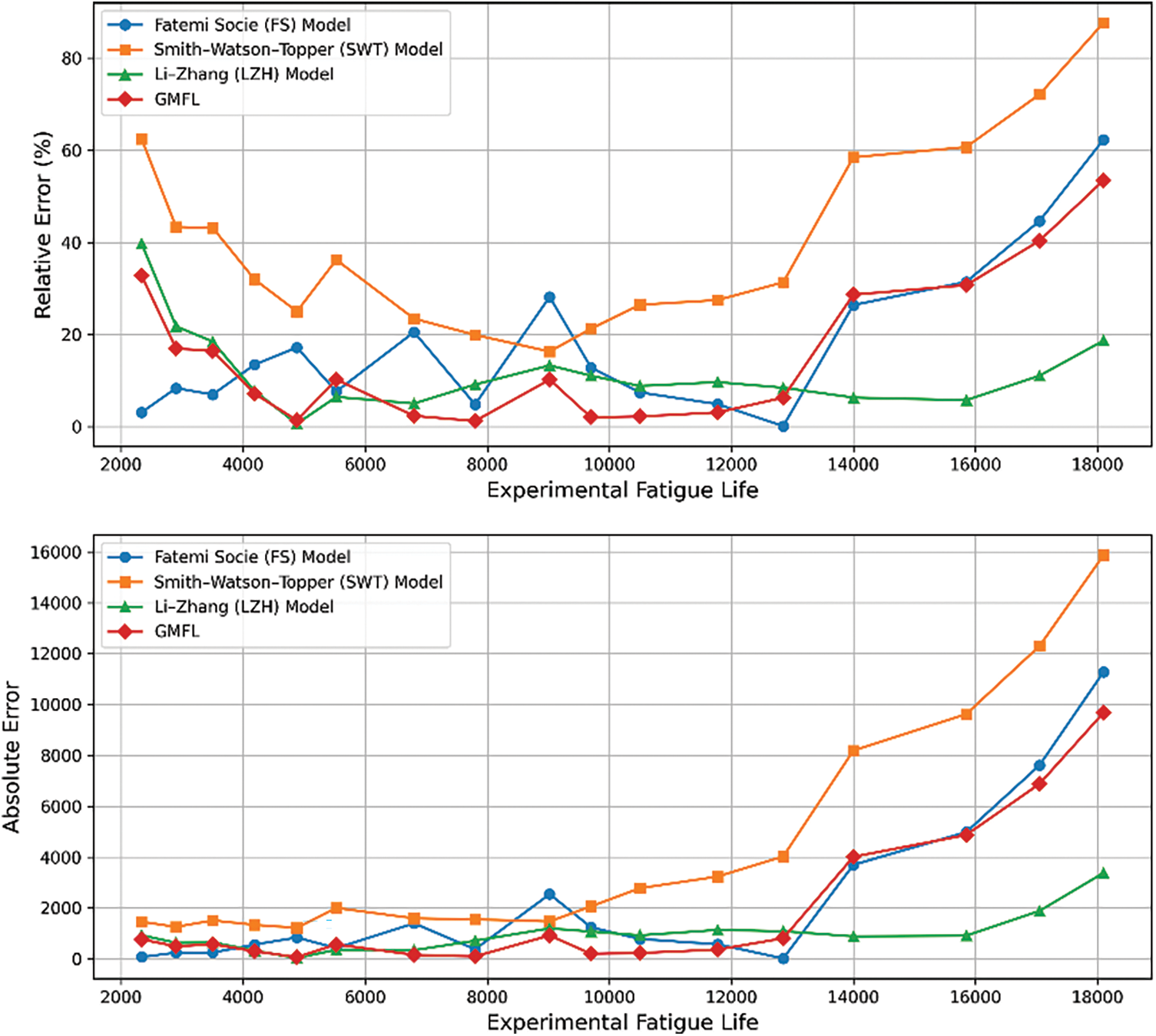

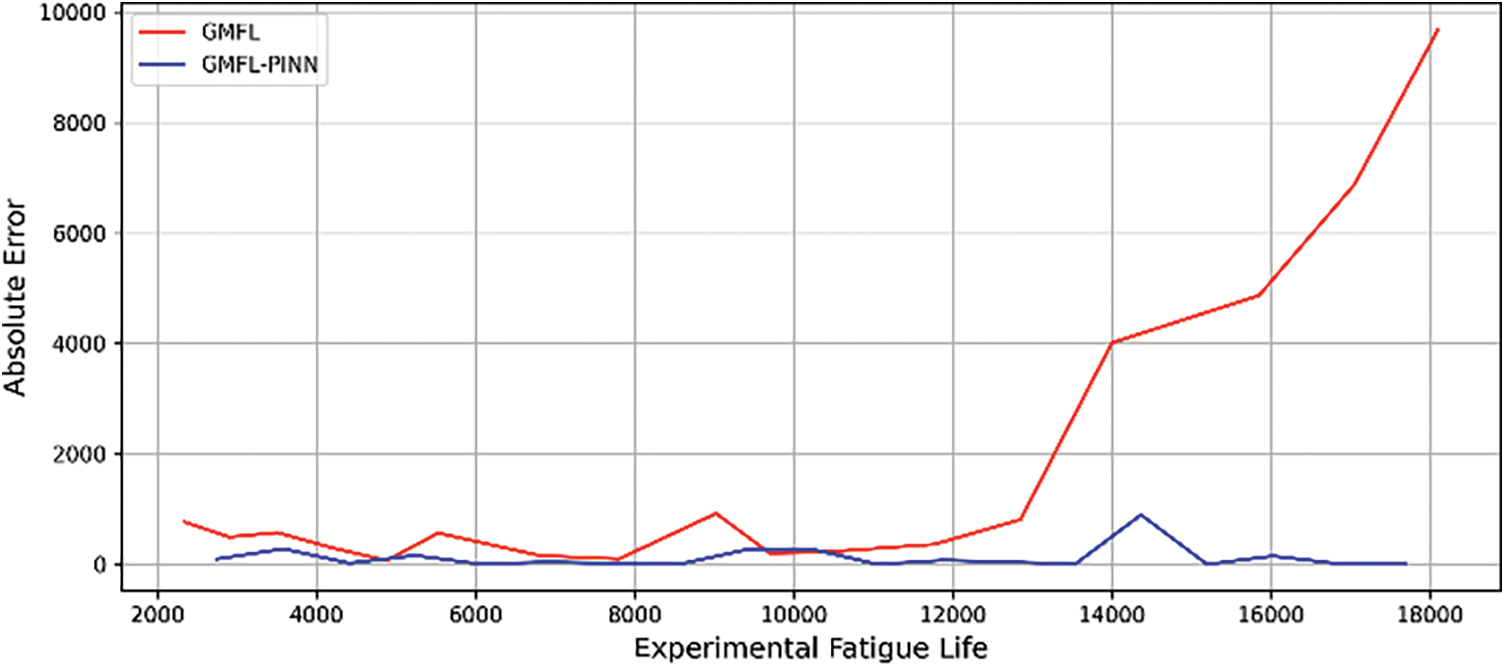

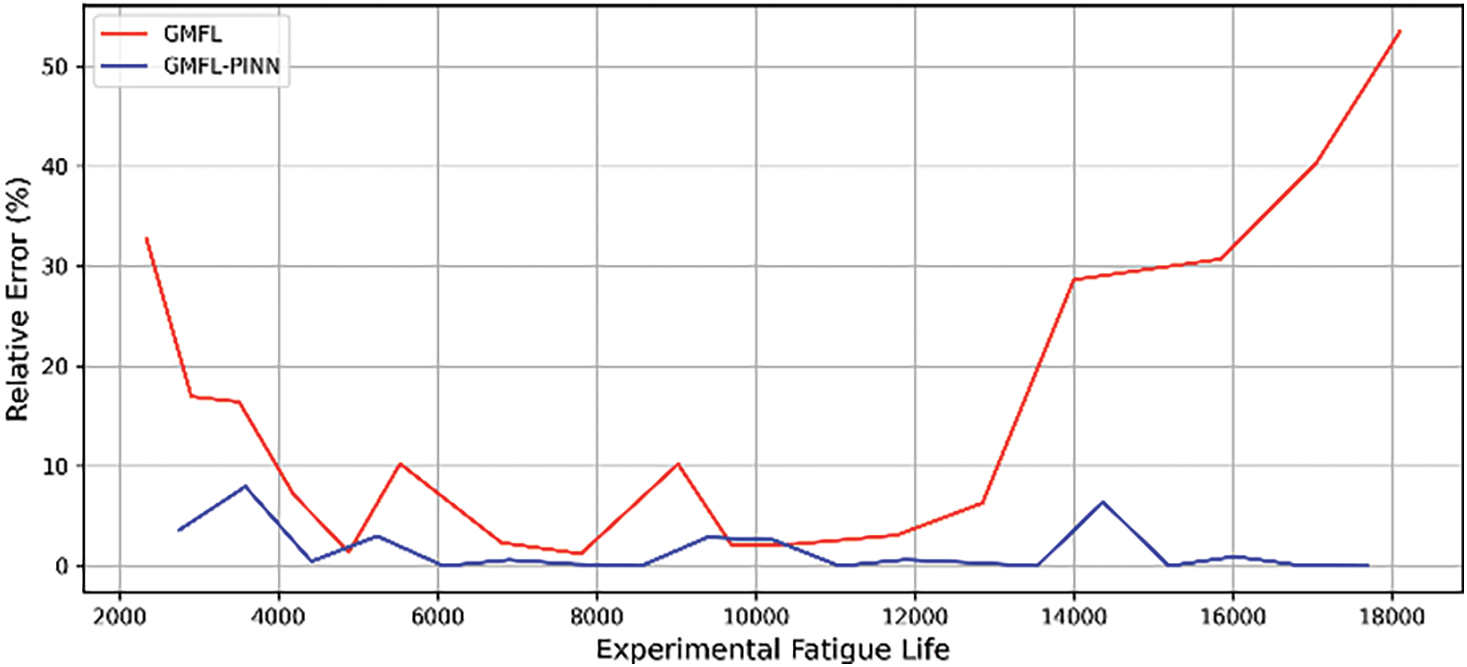

To facilitate a more intuitive comparison of the prediction performance of these models, the prediction results are shown in Fig. 6. The advantage of the proposed equation (GMFL) is the capability of predicting the fatigue life of specimens with a rather good accuracy whereas the calculated errors are almost the same and acceptable, as shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: The comparison of absolute and relative error of predictive models

This figure, Fig. 7, shows a comparison of absolute and relative error of predictive models. A typical fatigue life prediction comparison plot shows experimental fatigue life data on the x-axis against absolute error values, and relative error on the y-axis. The second plot features multiple curves representing different predictive models, where each curve illustrates how absolute error changes across various experimental life cycles. Higher absolute error values indicate a larger deviation from experimental results, while lower values suggest more accurate predictions. This visualization helps identify which models perform better across different fatigue life ranges. It can reveal whether certain models are more reliable for specific life ranges. At higher cycle counts, the curves often exhibit increased scatter or error magnitude, reflecting greater uncertainty in long-term predictions.

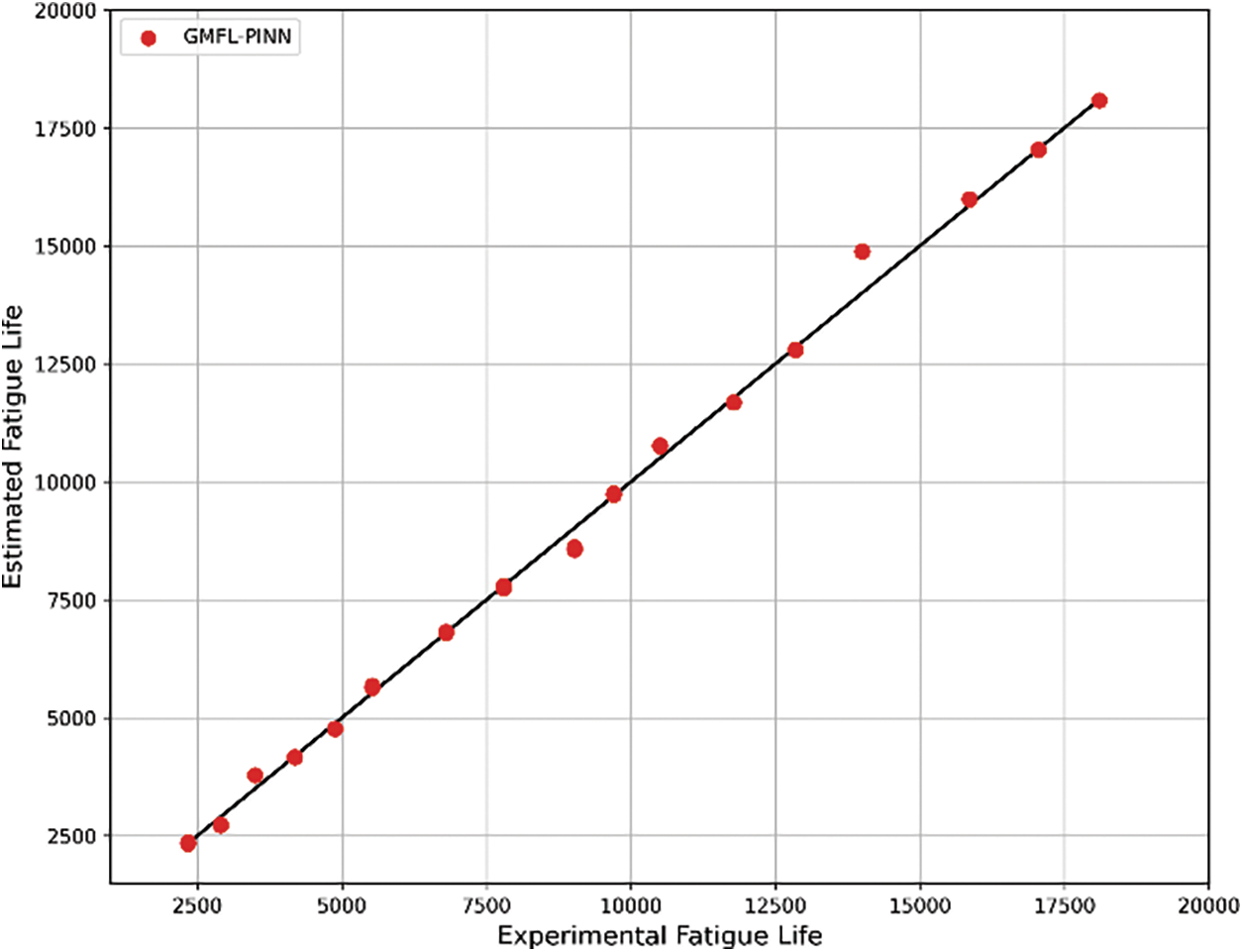

Fig. 8 illustrates the comparison between the predicted fatigue life values obtained using the GMFL-PINN model and the corresponding experimental data across a range of multiaxial loading conditions. The results clearly demonstrate that the GMFL-PINN model exhibits a significantly improved correlation with experimental observations compared to previous modeling approaches. This enhanced predictive capability can be attributed to the incorporation of a physics-informed loss function, in which a multiaxial fatigue life prediction model is explicitly embedded as a governing constraint during network training. By directly enforcing the underlying fatigue damage mechanisms within the learning process, the GMFL-PINN effectively captures the complex stress–strain path dependencies and cyclic damage evolution, leading to higher life estimation accuracy.

Figure 8: The comparison of fatigue life predictions using the GMFL-PINN model against experimental fatigue life data

The improved agreement between predicted and experimental fatigue life highlights the robustness and accuracy of the GMFL-PINN approach. As a result, it has been demonstrated to be a reliable tool for assessing fatigue in multiaxially loaded structural components.

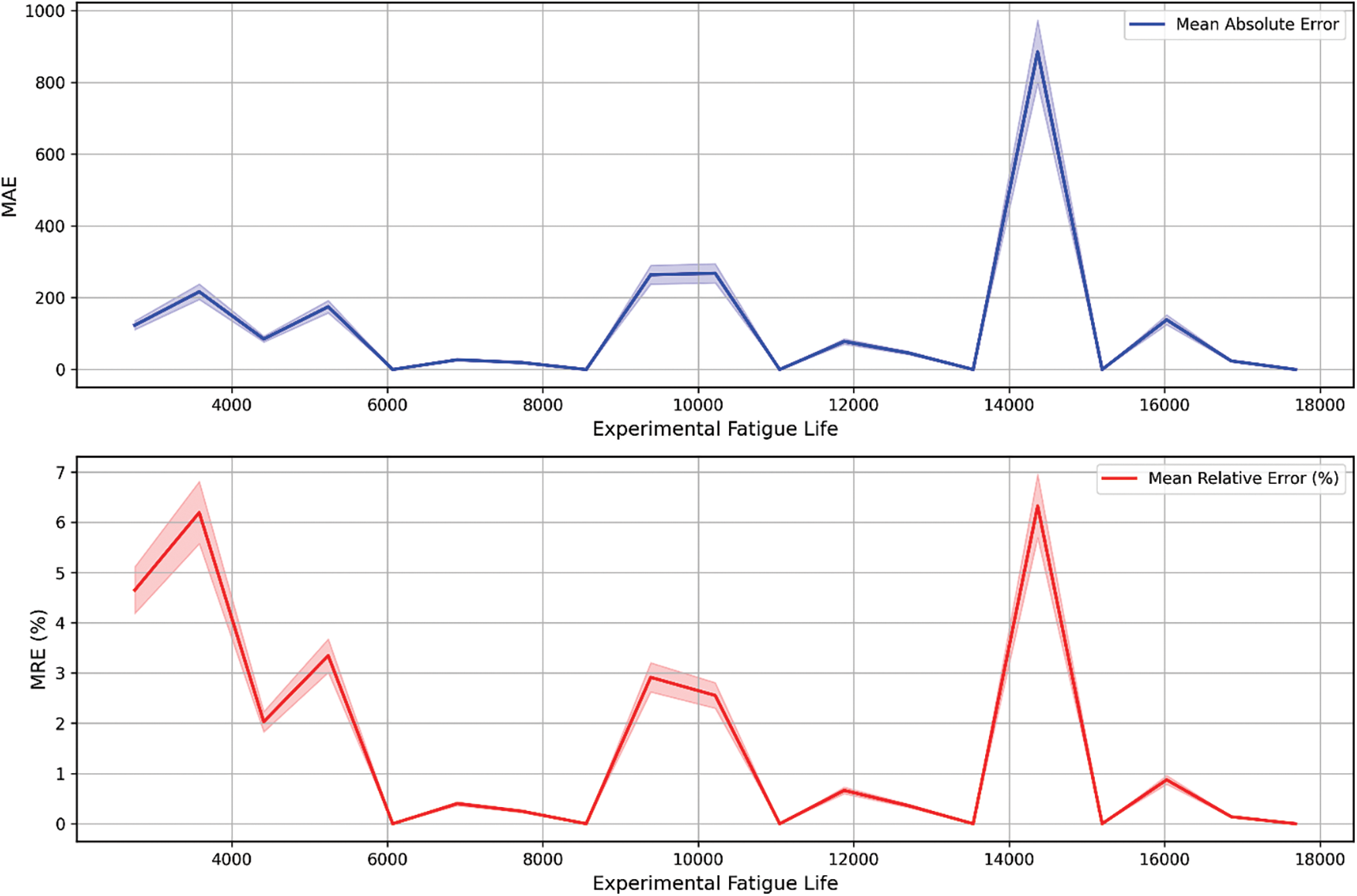

To further quantify the predictive performance and robustness of the proposed GMFL-PINN model, Fig. 9 presents the statistical evaluation in terms of Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Mean Relative Error (MRE) across a comprehensive set of multiaxial fatigue test cases. These metrics serve as critical indicators of the model’s accuracy in estimating fatigue life, both in absolute terms and relative to true experimental values. The MAE reflects the average magnitude of errors between predicted and actual fatigue life values, regardless of their direction. A lower MAE value, as observed in the GMFL-PINN results, indicates that the model consistently produces predictions that are closely aligned with the experimental data, even under complex loading conditions. This demonstrates the network’s ability to capture nonlinear fatigue damage progression and stress–strain path effects with high fidelity. The MRE, on the other hand, provides a normalized perspective of prediction error. This is done by accounting for the relative magnitude of each prediction in proportion to the actual fatigue life. This is particularly important in fatigue life modeling, where life values can span several orders of magnitude depending on loading amplitude and phase. The low MRE values observed in the GMFL-PINN model confirm that prediction accuracy is acceptable across fatigue life prediction, avoiding underestimation in critical short-life regions and overestimation in long-life regions. Collectively, the low MAE and MRE values indicate that the New-PINN model not only minimizes prediction errors on average but also maintains uniform predictive accuracy across the entire fatigue life spectrum. This consistent performance demonstrates a significant advancement over traditional empirical models, which often suffer from local overfitting and poor generalization across different loading spectra. Moreover, these findings further substantiate the value of embedding physics-based constraints in neural network training, leading to more stable, reliable, and physically interpretable fatigue life predictions.

Figure 9: MRE and MAE for GMFL-PINN

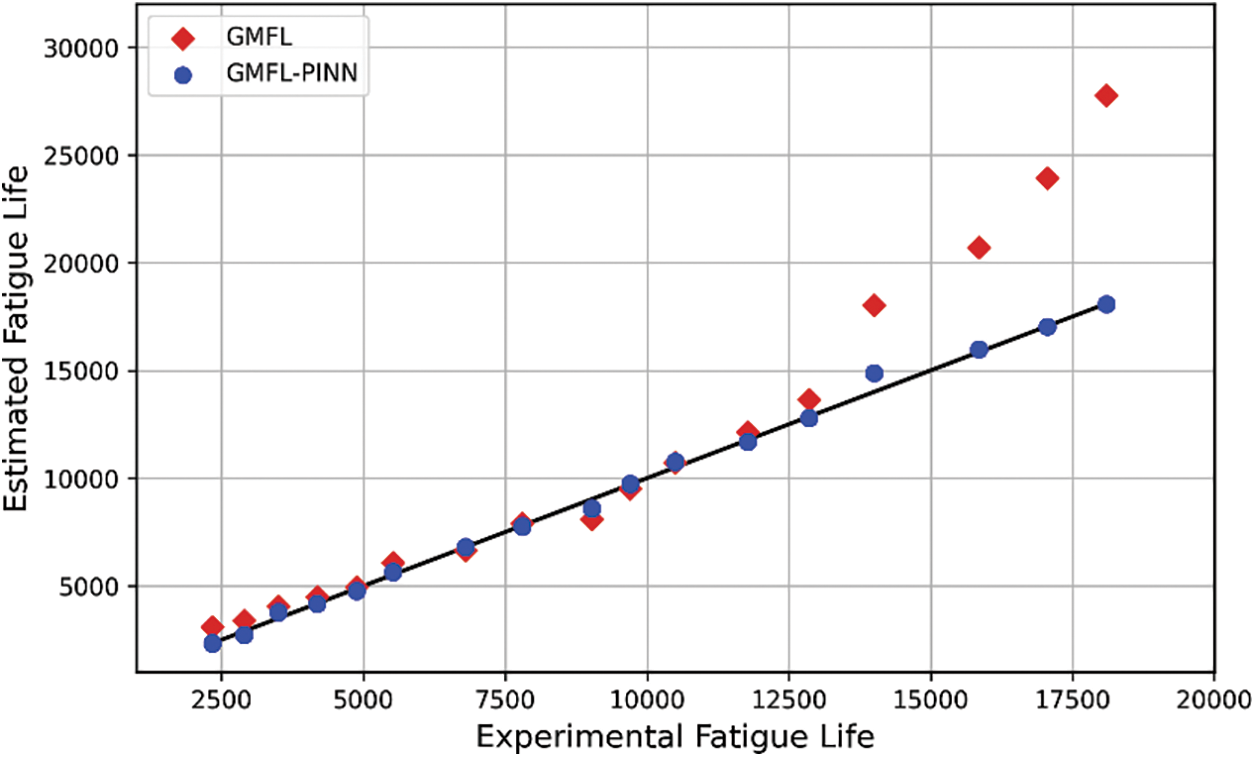

Fig. 10 illustrates a comparative analysis of the predicted fatigue life between the GMFL (purely mechanical model) and the GMFL-PINN model under various multiaxial loading conditions. As evident from Fig. 10, the GMFL-PINN model demonstrates a marked improvement in prediction accuracy, closely aligned with the experimental fatigue life data across the full spectrum of load cases. This enhancement can be attributed to the integration of physics-informed constraints within the neural network architecture, which effectively guides the learning process toward physically consistent solutions. Unlike the purely mechanical model (GMFL), which relies solely on classical fatigue theories and deterministic formulations, the GMFL-PINN model incorporates governing fatigue mechanisms directly into the training process. The figure clearly reflects this advancement, as the GMFL-PINN consistently reduces the deviation between predicted and actual fatigue life values. Furthermore, Fig. 10 provides clear visual evidence of enhanced predictive consistency in the GMFL-PINN model, not only through lower prediction errors but also via a noticeable reduction in output variability across different loading cases. As a result of improved stability and reliability, predicted values are more tightly clustered around experimental fatigue life data. This outcome emphasizes the strength of integrating domain-specific physical laws into the neural network framework, which constrains the solution space and promotes physically coherent predictions. Such integration enables the model to better capture intrinsic fatigue behavior under complex multiaxial loading, thereby delivering more dependable and application-ready fatigue life estimations.

Figure 10: The comparison of fatigue life predictions using the GMFL model against GMFL-PINN

The comparative analysis of prediction accuracy between the proposed GMFL-PINN model and the GMFL is illustrated in Fig. 11, which present the distribution of Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Mean Relative Error (MRE) for each model across the multiaxial fatigue dataset. These figures clearly demonstrate the superior performance of the GMFL-PINN model in both absolute and relative error metrics. When compared to the purely GMFL, the GMFL-PINN model exhibits significantly lower MAE and MRE values. As well, visual examinations of the error distribution reveal a reduced variance and enhanced prediction stability, which indicates better generalization capabilities. This is attributed to the physics-informed regularization embedded in the model, which constrains learning to physically admissible solutions, even under sparse or noisy data conditions. This performance enhancement can be attributed to the PINN architecture’s ability to capture complex fatigue behavior. This is done by embedding governing fatigue damage laws and stress–strain evolution equations directly into the learning process. In contrast, the purely GMFL exhibits higher error dispersion and limited adaptability under complex loading scenarios. Overall, the integration of physical laws with data-driven learning in the GMFL-PINN model establishes a robust, scalable, and generalizable approach to fatigue life prediction, with strong potential for deployment in advanced structural health monitoring and digital twin systems across the aerospace, automotive, and structural engineering domains.

Figure 11: The comparison of fatigue life prediction accuracy between the GMFL-PINN and GMFL model

4.4 Discussion of Discrepancies

While the GMFL-PINN model demonstrates strong agreement with experimental fatigue life data, some discrepancies between predicted and actual results are observed, which merit further analysis. These deviations can be attributed to several potential sources of error. Material variability, including microstructural heterogeneities, surface finish effects, and residual stresses, can introduce inherent uncertainty in experimental fatigue life. This uncertainty is not explicitly captured by the model. Additionally, limitations of the fatigue damage model embedded within the PINN, such as assumptions in the constitutive equations or simplifications, may restrict the model’s ability to fully represent complex, real-world fatigue mechanisms. Some prediction discrepancies may arise from noise in the experimental labels or uncertainties in the stress–strain fields derived from FE simulations. The GMFL-PINN addresses these challenges by incorporating physical constraints, which dynamically balances the loss function, and applies regularization techniques. Even so, when we conduct a more explicit robust analysis, such as sensitivity tests or uncertainty quantification, would further enhance the model’s credibility. We suggest this as an important direction for future work. Although the PINN offers improved accuracy and generalization, the interpretability of machine learning models remains an open area of research. Future work could explore alternative approaches such as symbolic regression or physics-guided Gaussian processes, which may provide more transparent predictive structures while still incorporating physical knowledge. Moreover, experimental uncertainties, including load application inaccuracies, measurement noise, and specimen misalignments, may contribute to deviations in fatigue life. Finally, model simplifications, such as assuming ideal boundary conditions, homogeneous material behavior, or neglecting environmental factors, can further impact prediction accuracy. These factors collectively highlight the need for continuous refinement of both the physical modeling components and the experimental validation process. This can further improve the predictive robustness and generalizability of the GMFL-PINN model. For future research considering other materials and alloys and also various shape memory alloys, e.g., [40] with the proposed method is suggested.

A physics-informed neural network is proposed to predict the multiaxial fatigue life of Al-Alloy 7075-T6, i.e., GMFL-PINN. Unlike conventional data-driven methods, which often operate as black-box models and lack interpretability, the PINN architecture embeds fundamental physical laws directly into the training process through physics-constrained loss functions. The hybrid modeling approach allows more accurate estimation of fatigue under complex loading conditions. In comparison to FS, SWT, and LZH models, GMFL-PINN results in better performance. The model demonstrates generalization capabilities with relatively sparse training data as a result of the physics-guided learning process, which reduces the model’s overfit. The scalability and reliability make the PINN approach particularly attractive for integration into digital twin environments, probabilistic life assessment, and real-time structural health monitoring systems. The results demonstrate the potential of PINN-based fatigue modeling as a possible tool for the next generation fatigue life prediction in various engineering applications. As a future direction, more comparative analysis is required for a deep understanding of the PINN potential. In addition, we aim to further study the function of the GMFL methodology by incorporating additional multiaxial fatigue criteria to improve generalizability across a broader range of material behaviors. One may also study the model’s robustness to noise and uncertainty through sensitivity analyses, probabilistic modeling approaches such as Bayesian PINNs, and the adoption of robust loss functions to better manage experimental and numerical analysis.

Acknowledgement: After the preparation of the first draft to enhance and remove the typos, and later during the preparation of revised versions, we used LLM to improve the readability and language of the manuscript. Finally, we carefully reviewed and edited the content as needed and took full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Ehsan Akbari: Methodology, Conceptualization, Investigation, Visualization, Analysis, Software, Writing—original draft, review & editing. Tajbakhsh Navid Chakherlou: Supervision, Validation, Writing—review & editing. Hamed Tabrizchi: Consultation, Validation, Writing—original draft, review & editing. Amir Mosavi: Consultation, Validation, Writing—review & editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data can be available through the corresponding author upon reasonable requests for the academic purposes to relevant professors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Findley WN. A theory for the effect of mean stress on fatigue of metals under combined torsion and axial load or bending. J Eng Ind. 1959;81(4):301–5. doi:10.1115/1.4008327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. McDiarmid DL. A shear stress based critical-plane criterion of multiaxial fatigue failure for design and life prediction. Fatigue Fract Eng Mater Struct. 1994;17(12):1475–84. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2695.1994.tb00789.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Kandil FA, Brown MW, Miller KJ. Biaxial low-cycle fatigue failure of 316 stainless steel at elevated temperatures. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Mechanical Behaviour and Nuclear Applications of Stainless Steel at Elevated Temperatures; 1981 May 20–22; Varese, Italy. [Google Scholar]

4. Fatemi A, Socie DF. A critical plane approach to multiaxial fatigue damage including out-of-phase loading. Fatigue Fract Eng Mater Struct. 1988;11(3):149–65. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2695.1988.tb01169.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Li J, Zhang ZP, Sun Q, Li CW, Qiao YJ. A new multiaxial fatigue damage model for various metallic materials under the combination of tension and torsion loadings. Int J Fatigue. 2009;31(4):776–81. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2008.03.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wang YY, Yao WX. A multiaxial fatigue criterion for various metallic materials under proportional and nonproportional loading. Int J Fatigue. 2006;28(4):401–8. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2005.07.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Smith KN. A stress-strain function for the fatigue of metals. J Mater. 1970;5:767–78. [Google Scholar]

8. Glinka G, Wang G, Plumtree A. Mean stress effects in multiaxial fatigue. Fatigue Fract Eng Mater Struct. 1995;18(7–8):755–64. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2695.1995.tb00901.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Varvani-Farahani A. A new energy-critical plane parameter for fatigue life assessment of various metallic materials subjected to in-phase and out-of-phase multiaxial fatigue loading conditions. Int J Fatigue. 2000;22(4):295–305. doi:10.1016/S0142-1123(00)00002-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Maiorana E, Aloisio A, Tasse V, Briseghella B. Prediction of fatigue life of a bolted joint in railway steel arch bridge using multiaxial fatigue criteria. Eng Fail Anal. 2024;166(7):108908. doi:10.1016/j.engfailanal.2024.108908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Li D, Wang W, Ismail F. Enhanced fuzzy-filtered neural networks for material fatigue prognosis. Appl Soft Comput. 2013;13(1):283–91. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2012.08.031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Hambli R, Hattab N. Application of neural network and finite element method for multiscale prediction of bone fatigue crack growth in cancellous bone. In: Gefen A, editor. Multiscale computer modeling in biomechanics and biomedical engineering. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2012. p. 3–30. doi:10.1007/8415_2012_146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Nascimento RG, Viana FAC. Fleet prognosis with physics-informed recurrent neural networks. In: Chang FK, Kopsaftopoulos F, editors. Structural health monitoring 2019. Lancaster, PA, USA: DEStech Publications Inc.; 2019. p. 1740–7. doi: 10.12783/shm2019/32301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Haque ME, Sudhakar KV. ANN based prediction model for fatigue crack growth in DP steel. Fatigue Fract Eng Mater Struct. 2001;24(1):63–8. doi:10.1046/j.1460-2695.2001.00361.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Haque ME, Sudhakar KV. Prediction of corrosion-fatigue behavior of DP steel through artificial neural network. Int J Fatigue. 2001;23(1):1–4. doi:10.1016/S0142-1123(00)00074-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Fotovati A, Goswami T. Prediction of elevated temperature fatigue crack growth rates in TI-6AL-4V alloy-neural network approach. Mater Des. 2004;25(7):547–54. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2004.03.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang XC, Gong JG, Xuan FZ. A deep learning based life prediction method for components under creep, fatigue and creep-fatigue conditions. Int J Fatigue. 2021;148(5):106236. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2021.106236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Wang J, Fan D, Cai CS. Application and feasibility analysis of knowledge-based machine learning in predicting fatigue performance of stainless steel. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2025;22(1):e04090. doi:10.1016/j.cscm.2024.e04090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhan Z, Li H. A novel approach based on the elastoplastic fatigue damage and machine learning models for life prediction of aerospace alloy parts fabricated by additive manufacturing. Int J Fatigue. 2021;145(2):106089. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2020.106089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Bao H, Wu S, Wu Z, Kang G, Peng X, Withers PJ. A machine-learning fatigue life prediction approach of additively manufactured metals. Eng Fract Mech. 2021;242(10):107508. doi:10.1016/j.engfracmech.2020.107508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Maleki E, Unal O, Reza Kashyzadeh K. Fatigue behavior prediction and analysis of shot peened mild carbon steels. Int J Fatigue. 2018;116:48–67. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2018.06.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wei X, Zhang C, Han S, Jia Z, Wang C, Xu W. High cycle fatigue S-N curve prediction of steels based on transfer learning guided long short term memory network. Int J Fatigue. 2022;163(5):107050. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2022.107050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Barbosa JF, Correia JAFO, Júnior RCSF, De Jesus AMP. Fatigue life prediction of metallic materials considering mean stress effects by means of an artificial neural network. Int J Fatigue. 2020;135:105527. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2020.105527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Chen J, Liu Y. Probabilistic physics-guided machine learning for fatigue data analysis. Expert Syst Appl. 2021;168:114316. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2020.114316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Chen J, Liu Y. Fatigue property prediction of additively manufactured Ti-6Al-4V using probabilistic physics-guided learning. Addit Manuf. 2021;39:101876. doi:10.1016/j.addma.2021.101876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. da Silva IN, Hernane Spatti D, Andrade Flauzino R, Liboni LHB, dos Reis Alves SF. Artificial neural network architectures and training processes. In: Artificial neural networks. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2016. p. 21–8. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-43162-8_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Raissi M, Perdikaris P, Karniadakis GE. Physics-informed neural networks: a deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. J Comput Phys. 2019;378:686–707. doi:10.1016/j.jcp.2018.10.045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Yang S, De Jesus AMP, Meng D, Nie P, Darabi R, Azinpour E, et al. Very high-cycle fatigue behavior of steel in hydrogen environment: state of the art review and challenges. Eng Fail Anal. 2024;166(1):108898. doi:10.1016/j.engfailanal.2024.108898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zhu SP, Wang L, Luo C, Correia JAFO, De Jesus AMP, Berto F, et al. Physics-informed machine learning and its structural integrity applications: state of the art. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2023;381(2260):20220406. doi:10.1098/rsta.2022.0406. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Zhang H, Tian Z. Failure analysis of corroded high-strength pipeline subject to hydrogen damage based on FEM and GA-BP neural network. Int J Hydrog Energy. 2022;47(7):4741–58. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.11.082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhang Y, Ai Y, Zhang W. Physics informed ensemble learning used for interval prediction of fracture toughness of pipeline steels in hydrogen environments. Theor Appl Fract Mech. 2024;130(43):104302. doi:10.1016/j.tafmec.2024.104302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Chen D, Li Y, Liu K, Li Y. A physics-informed neural network approach to fatigue life prediction using small quantity of samples. Int J Fatigue. 2023;166(14):107270. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2022.107270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Dourado AD, Viana F. Physics-informed neural networks for bias compensation in corrosion-fatigue. In: AIAA Scitech 2020 Forum; 2020 Jan 6–10; Orlando, FL, USA. doi:10.2514/6.2020-1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Viana FAC, Nascimento RG, Dourado A, Yucesan YA. Estimating model inadequacy in ordinary differential equations with physics-informed neural networks. Comput Struct. 2021;245:106458. doi:10.1016/j.compstruc.2020.106458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Nascimento RG, Fricke K, Viana FAC. A tutorial on solving ordinary differential equations using Python and hybrid physics-informed neural network. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2020;96(153):103996. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2020.103996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Chakherlou TN, Abazadeh B. Estimation of fatigue life for plates including pre-treated fastener holes using different multiaxial fatigue criteria. Int J Fatigue. 2011;33(3):343–53. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2010.09.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. André Meyers M. Mechanical behavior of materials (2nd ed.). Aircr Eng Aerosp Technol Int J. 2009;81(2). doi:10.1108/aeat.2009.12781bae.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Chakherlou TN, Oskouei RH, Vogwell J. Experimental and numerical investigation of the effect of clamping force on the fatigue behaviour of bolted plates. Eng Fail Anal. 2008;15(5):563–74. doi:10.1016/j.engfailanal.2007.04.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Chakherlou TN, Aghdam AB. An experimental investigation on the effect of short time exposure to elevated temperature on fatigue life of cold expanded fastener holes. Mater Des. 2008;29(8):1504–11. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2008.03.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Alhilfi AH, Ruszinkó E. Effect of ultrasound on the austenite transformation of shape memory alloys. Acta Polytech Hung. 2023;20(4):85–101. doi:10.12700/aph.20.4.2023.4.5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools