Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Bridging the Gap in Recycled Aggregate Concrete (RAC) Prediction: State-of-the-Art Data-Driven Framework, Model Benchmarking, and Future AI Integration

1 Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, 50603, Malaysia

2 National Water and Energy Centre, United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain, 15551, United Arab Emirates

* Corresponding Authors: Soon Poh Yap. Email: ; Ahmed El-Shafie. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(1), 17-65. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.070880

Received 26 July 2025; Accepted 25 September 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

Data-driven research on recycled aggregate concrete (RAC) has long faced the challenge of lacking a unified testing standard dataset, hindering accurate model evaluation and trust in predictive outcomes. This paper reviews critical parameters influencing mechanical properties in 35 RAC studies, compiles four datasets encompassing these parameters, and compiles the performance and key findings of 77 published data-driven models. Baseline capability tests are conducted on the nine most used models. The paper also outlines advanced methodological frameworks for future RAC research, examining the principles and challenges of physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) and generative adversarial networks (GANs), and employs SHAP and PDP tools to interpret model behaviour and enhance transparency. Findings indicate a clear trend toward integrated systems, hybrid models, and advanced optimization strategies, with integrated tree-based models showing superior performance across various prediction tasks. Based on this comprehensive review, we offer a recommendation for future research on how AI can be effectively oriented in RAC studies to support practical deployment and build confidence in data-driven approaches.Keywords

Recycled Aggregate Concrete (RAC) is a type of concrete that incorporates recycled aggregates from Construction and Demolition Waste (CDW) as a partial or full replacement for natural aggregates. It has received a great deal of attention due to its potential to reduce the environmental impact of construction activities [1]. RAC aims to address growing concerns about the depletion of natural resources and the increasing volume of construction waste. Using recycled aggregates, RAC not only helps conserve natural aggregate resources but also minimises demand for landfill space, contributing to a more sustainable built environment [2,3].

The advantages of RAC in terms of sustainability and environmental friendliness are numerous. Firstly, the use of recycled aggregates reduces the demand for the extraction of virgin aggregates, thus reducing associated environmental degradation and energy costs [4]. Secondly, RAC contributes to more efficient management of construction waste, alleviating the burden on landfills and mitigating environmental pollution caused by waste disposal [5]. Furthermore, RAC production can reduce carbon emissions, as it generally consumes less energy compared to the extraction and processing of natural aggregates [6,7]. In general, RAC plays a crucial role in promoting sustainable practices and enhancing the eco-efficiency of concrete [7]. Regrettably, the optimistic expectations surrounding the eco-friendliness of RAC often fall short of reality’s demands. A study assessing the life-cycle environmental impacts of RAC found that statistical differences across various environmental indicators could be as high as 7%, and that transportation assumptions introduced significant variability in the results [8]. These shortcomings have led to a fragmented and inconsistent body of research, leaving substantial gaps in our understanding of the life-cycle environmental impacts of RAC. Moreover, the challenges in this domain extend far beyond the intricate design compositions required for synthesising high-performance RACs. Given that RACs possess parameter-sensitive non-linear mechanical properties, even when dissecting these challenges into individual components, countless factors of influence persist to complicate the picture [9]. A prevalent issue is the noticeable variability in the quality of recycled aggregates, which contributes significantly to the uncertainties plaguing the mechanical properties of RAC [10]. Due to the intrinsic heterogeneity of recycled materials [11,12], It remains a significant challenge for simple models to accurately characterize the performance of RAC, which includes compressive strength, flexural strength, splitting tensile strength and elastic modulus.

In reviewing related research on machine learning modelling, numerous techniques have been employed to address the aforementioned challenges arising from complex nonlinearities and intricate causal structures. Traditional machine learning models such as neural networks and tree-based methods have often been used. However, shallow neural network models may perform poorly in certain data sets. To address this issue, many studies have introduced the concept of fuzzy sets [13–15] into traditional models including artificial neural network. The incorporation of fuzzy logic into artificial neural networks seeks to augment their capability to manage data uncertainty, bolster robustness, and diminish errors in RAC predictions.

In another aspect, traditional machine learning models frequently encounter difficulties when dealing with sparse datasets, this is due to the limited amount of data which cannot meet the generalisation needs [16], violating the basic assumption of data intensity [17]. Certain studies that employ tree-based models have attempted to enhance model complexity and utilize ensemble methods to account for nonlinearity within the data [18–20]. Nevertheless, this enhances the ability to capture the nonlinearity of the data, the amount and diversity of the data have not improved [21]. A considerable number of data-driven investigations find it challenging to conduct benchmarks on a unified dataset. Unlike fields such as computer vision or multimodal research, which have widely recognized datasets like ‘MNIST’ and ‘Caltech 101’, the intricate nature of the various components of RAC and their interactions poses a challenge in establishing a large and standardized dataset, even with the establishment of unified datasets, the target labels of the datasets may neither be objective nor represent reality [22]. Consequently, many researchers tend to focus solely on data of a similar nature rather than adopting a global perspective. In a sense, these data subsets are interconnected at a local level, yet they appear fragmented on a global scale. Using only a limited set of evaluation metrics often leads to insufficient assessment of model effectiveness, particularly when applied to practical RAC scenarios [23].

Given the current trends in AI development, the contradiction between the high data requirements of intelligent algorithms and the desire in engineering experiments to reduce data dependency is likely to persist. Advancing small-sample machine learning will remain a key direction in materials science [24]. Enhancing generalisation capabilities in conditions of limited data [25,26] and minimising experimental costs continue to be significant challenges in the field.

This study presents three key novelties to advance the application of machine learning in RAC. First, critical input parameters were systematically extracted from 35 studies, resulting in the compilation of four datasets with broader coverage to support unified model evaluation. Second, 77 data-driven studies on RAC were reviewed to investigate model optimization strategies, including hybrid model, and to benchmark the baseline performance of nine widely used machine learning models, revealing significant gaps compared to originally reported results. Third, future research directions were explored, highlighting the potential of advanced data-driven methods such as generative adversarial networks for data augmentation and physics-informed neural networks for improving generalization under limited data conditions. These novelties address major challenges in the field, including inconsistent parameter definitions, lack of standardized datasets, and limited model interpretability.

This section of the article highlights the differences in experimental sample sizes across various testing standards and introduces the integrated RAC data sources compiled for this study. Through a critical review of the relevant literature, it examines the key factors influencing RAC and provides a comprehensive overview of the background related to its mechanical properties.

2.1 Dataset of RAC Mechanical Properties

Before conducting data-driven research, it is usually necessary to establish a high-quality dataset, which is often multi-sourced. This requires the data set to have a unified method of parameter measurement and units. However, due to different testing standards, specimens come in various sizes. The compressive strength and the split tensile strength tested under different standards must be converted and unified for effective use; otherwise, unnecessary noise may be introduced, or the model may learn relationships not inherent in the data set.

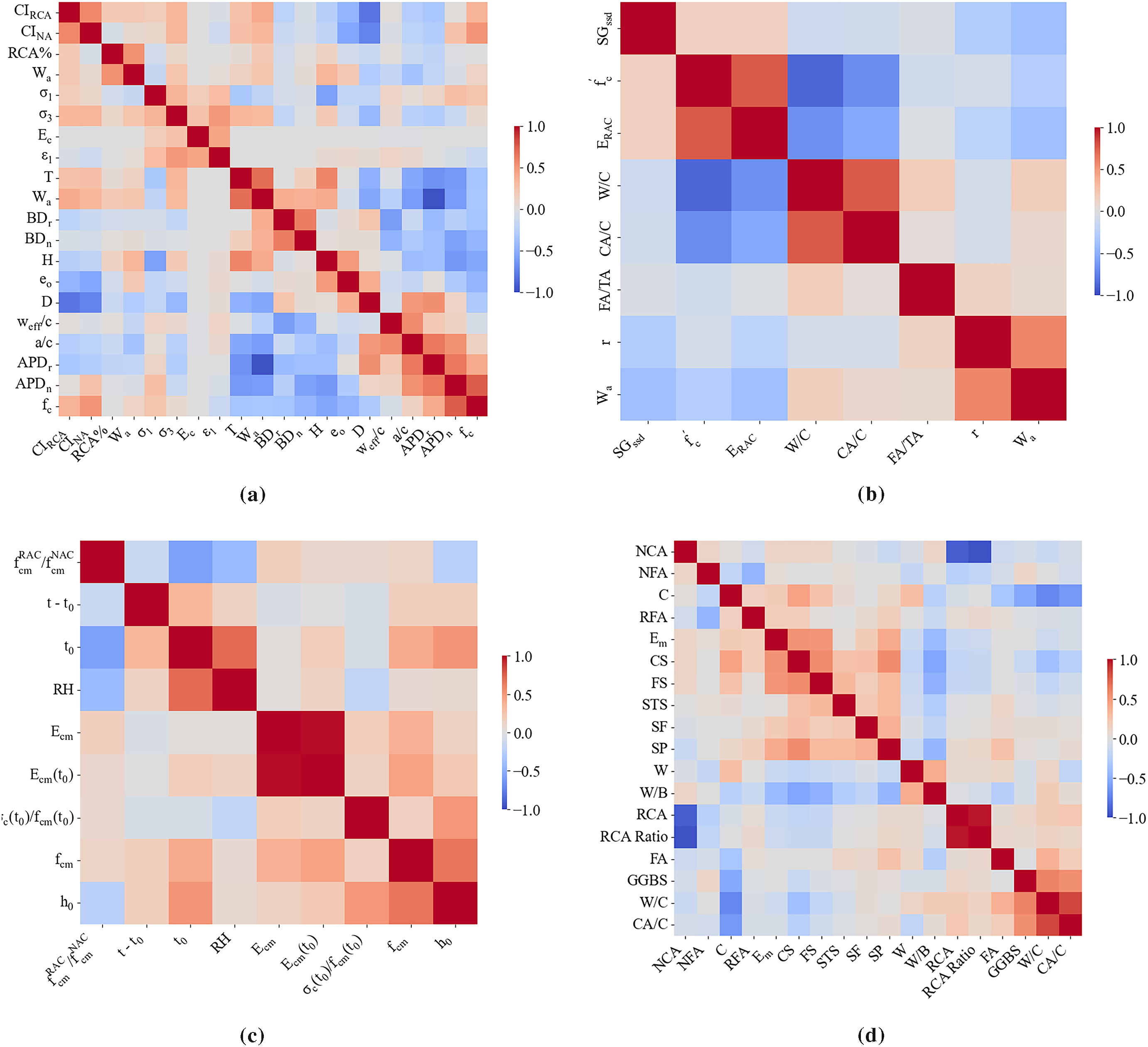

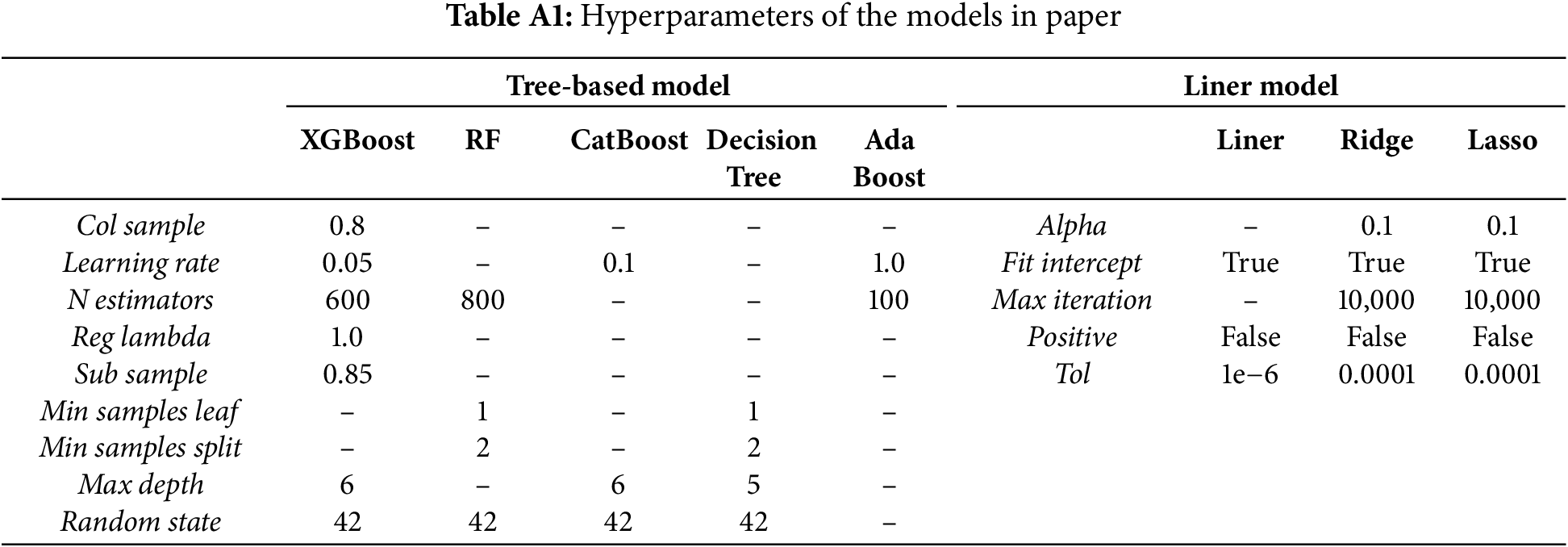

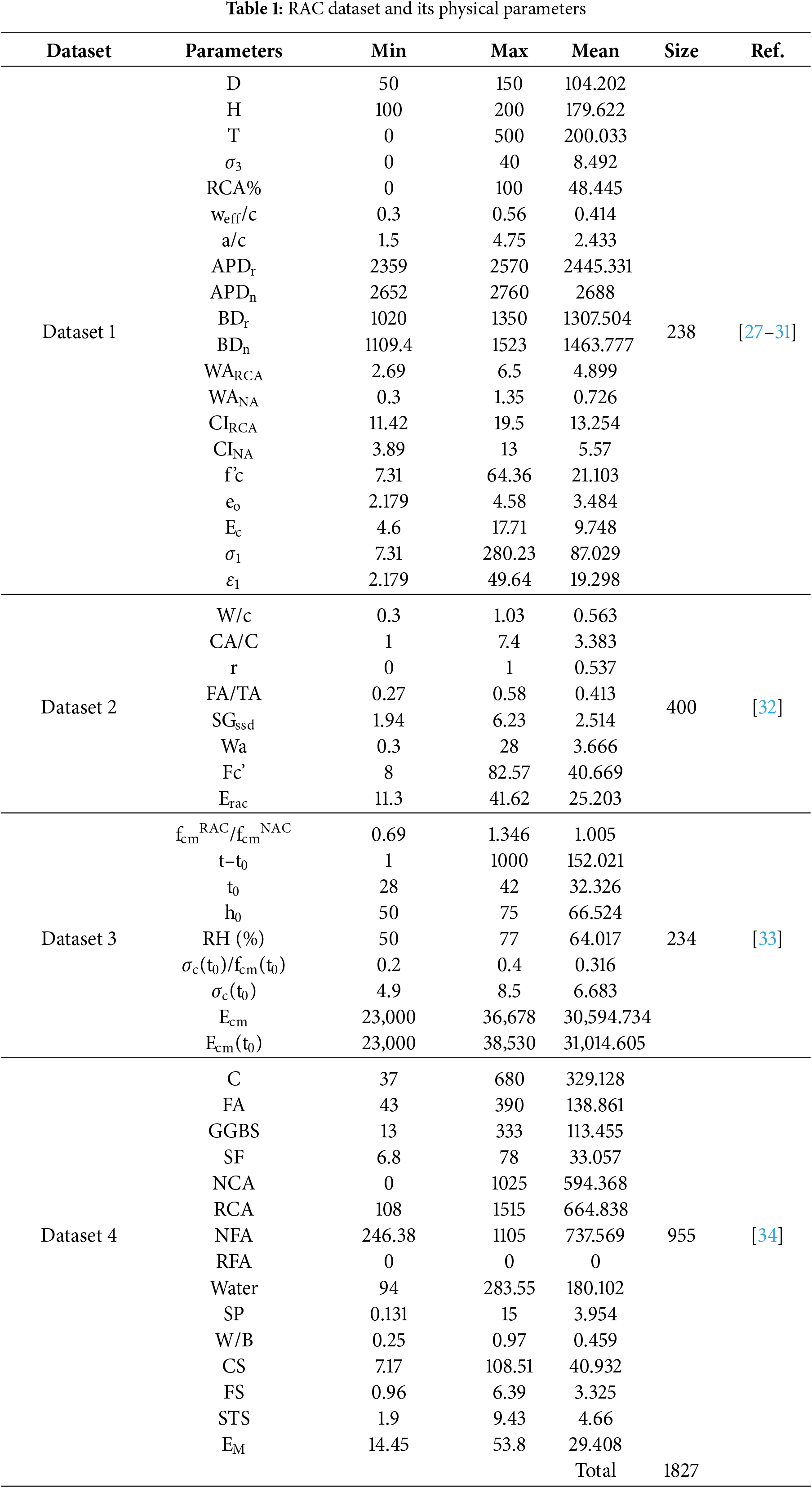

To examine the correlation between variables of various RAC mix designs and responses such as ultimate mechanical strength (including compressive strength, flexural strength, and tensile strength of splitting) and elastic modulus, we have compiled data sets that have been used in RAC data-driven research. These data sets will also be used to uniformly validate the model benchmark performance on external data. Some databases compiled in this article include these mechanical properties shown in Fig. 1 and Table 1, Fig. 1 was prepared by the authors using data obtained from the literature: Fig. 1a corresponds to Dataset 1 [27–31], Fig. 1b to Dataset 2 [32], Fig. 1c to Dataset 3 [33], and Fig. 1d to Dataset 4.

Figure 1: Clustering heatmap of the RAC dataset and its physical properties. (a) Dataset 1: RCA Properties Dataset (Crushing index of recycled coarse aggregate, crushing index of natural aggregate, replacement percentage of recycled coarse aggregate, water absorption, axial stress (σ1), confining pressure (σ3), elastic modulus of concrete, axial strain (ε1), temperature, bulk density of recycled aggregate, bulk density of natural aggregate, specimen height, void ratio, specimen diameter, effective water-to-cement ratio, aggregate-to-cement ratio, apparent density of recycled aggregate, apparent density of natural aggregate, and compressive strength.); (b) Dataset 2: RAC Mechanical Properties Dataset (Saturated surface-dry specific gravity, Compressive strength, Elastic modulus of RAC, Water-to-cement ratio, Coarse aggregate-to-cement ratio, Fine aggregate-to-total aggregate ratio, Replacement rate, Water absorption.); (c) Dataset 3: RAC Time-Dependent Performance Dataset (Compressive strength ratio of RAC to NAC, age difference (t − t0), initial curing age (t0), relative humidity (RH), elastic modulus, elastic modulus at t0, initial compressive strength ratio, mean compressive strength, and initial specimen height (h0)); (d) Dataset 4: RAC Mixture Design and Performance Dataset (Natural coarse aggregate, natural fine aggregate, cement, recycled fine aggregate, elastic modulus, compressive strength, flexural strength, splitting tensile strength, silica fume, superplasticizer, water content, water-to-binder ratio, recycled coarse aggregate, recycled coarse-to-natural aggregate ratio, fly ash, ground granulated blast furnace slag, water-to-cement ratio, and coarse aggregate-to-cement ratio)

This review compiled four structured datasets encompassing a total of over 1800 samples and 55 key parameters related to RAC, with each dataset tailored to a distinct research focus. Dataset 1, comprising 238 samples, is designed to facilitate the analysis of RAC under triaxial shear and complex stress conditions, and is employed in Section 2 to investigate the impact of RCA on RAC behavior. Dataset 2 contains 400 samples focusing on the mechanical and material properties of RAC, and Dataset 3 includes 234 samples examining the time and environment-dependent development of mechanical properties under different curing conditions. Both datasets are used in Section 2.2 to identify key factors affecting the mechanical performance of RAC. Dataset 4 is the most important dataset, containing 955 samples on the mixture design of RAC, and forms the basis for the unified testing presented in Section 3.6. For all datasets, missing values in the additive dosage of each substance were imputed as 0 to denote “not added,” thereby ensuring that the loaded samples contain no missing data.

The heatmap in Fig. 1 illustrates the clustering of the RAC dataset along with its physical properties, including compressive strength, RAC elastic modulus, recycled aggregate elastic modulus, splitting tensile strength, and flexural strength. The results reveal several meaningful groupings: W/C, CA/C, and FA/TA form a cluster that is negatively correlated with compressive strength indicators.

2.2 Key Parameters Affecting Mechanical Performance of RAC

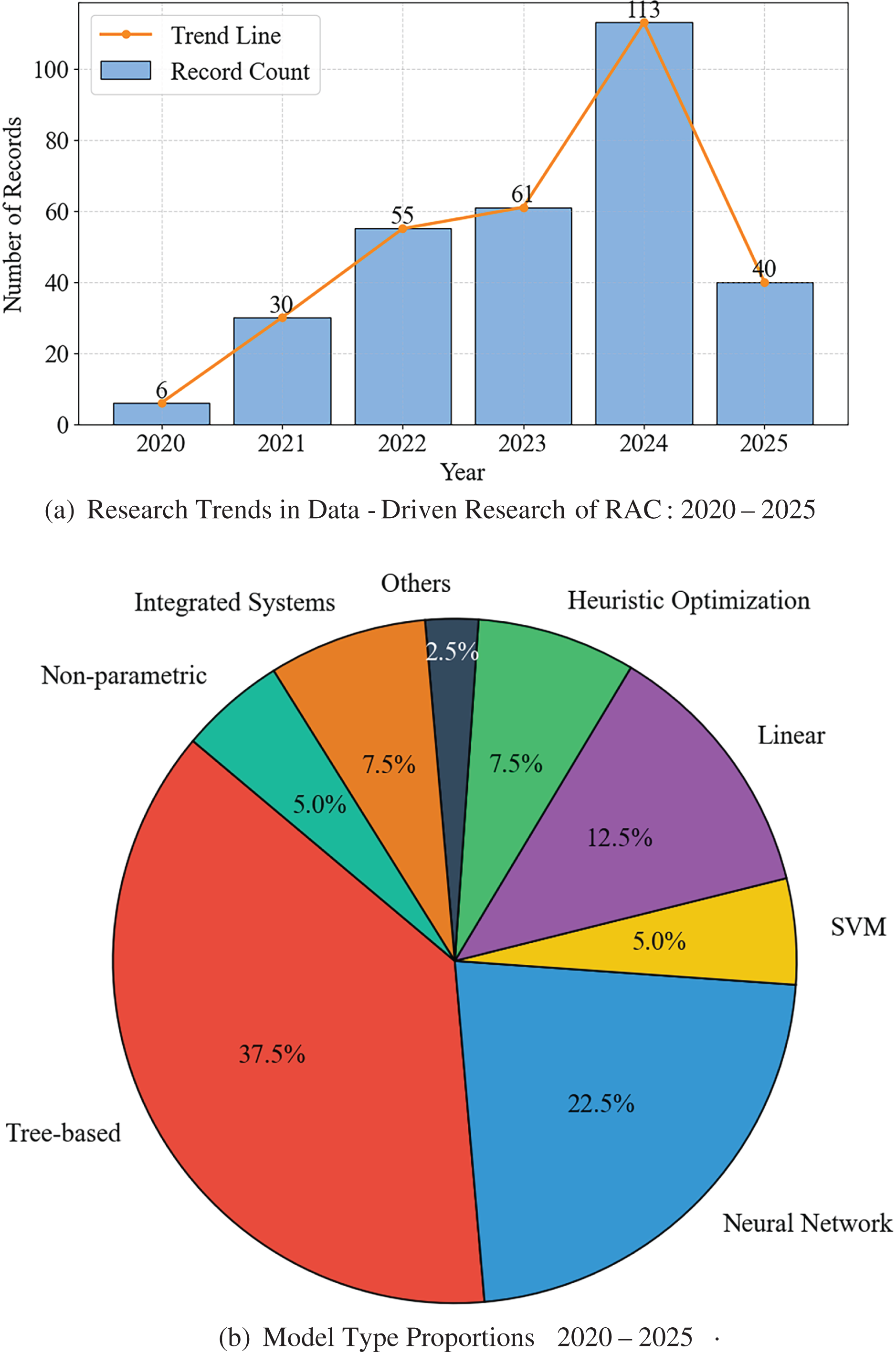

This section examines the primary factors influencing the mechanical properties of RAC and synthesizes the pertinent research findings and observed phenomena in Table 2. Recycled coarse aggregates (RCAs) demonstrate a general performance trend in the strength evaluation as outlined in Table 3.

In Table 3, the classification of recycled coarse aggregates [67] is based on four key performance parameters. Aggregates classified as Grade I generally correspond to better concrete performance, which may suggest a consistent advantage across these parameters that contributes to improved overall mechanical properties.

3 RAC Data-Driven Research Methods

In this section, we synthesize the primary data-driven approaches applied to RAC within the PRISMA framework (Appendix Fig. A1), providing a comparative assessment of their capabilities and demonstrating baseline performance under unified testing protocols.

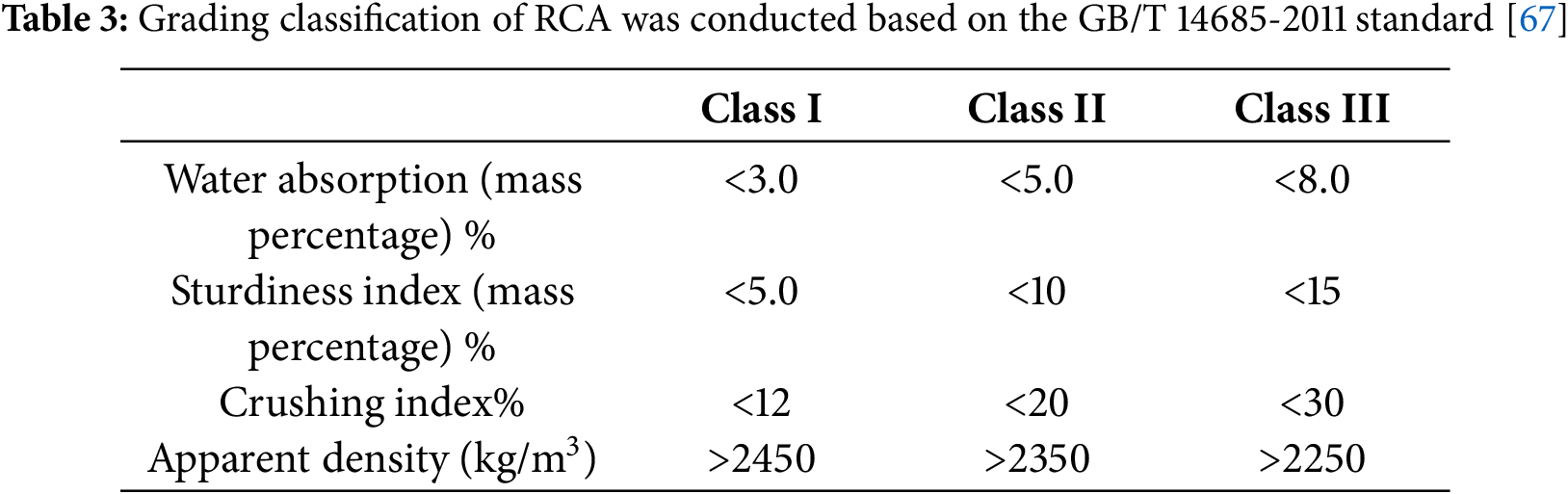

3.1 Data-Driven Research Paradigm & Trend

According to WoS data [68], from 2020 to 2025, data-driven research on RAC has exhibited a rapid growth trend, as shown in Fig. 2a. During 2020–2021, the number of related studies accounted for only 11.8% of the total. However, since 2022, research activity has risen significantly, with 18.0% and 20.0% of the publications in 2022 and 2023, respectively. Notably, in 2024, the number of publications experienced explosive growth, reaching 37.0%, making it the most active year. Even within the first four months of 2025, the publication volume has already reached 13.1%, suggesting that this field is expected to maintain its strong upward momentum in the future.

Figure 2: Data-driven research trends and bibliometric analysis of RAC

Regarding data-driven models, Fig. 2b presents the distribution of model types used in publications from 2020 to 2025. Based on their underlying principles, the models were classified into eight categories. Tree-based models, such as XGBoost, Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosted Regression Trees (GBRT), Gradient Boosting (GB), Decision Tree (DT), LightGBM, and CatBoost, were the most frequently used, accounting for 37.5% of all cases, reflecting their strong nonlinear modelling capabilities and wide applicability. Neural networks, including ANN, BPNN, CNN-LSTM, RNN, and DNN, made up 22.5%, highlighting the growing adoption of deep learning techniques. Linear models (Linear Regression, Ridge and Lasso Regression) constituted 12.5%, valued for their simplicity and computational efficiency. Heuristic optimization methods, such as PSO, GA, NSGA-II, and GEP, and integrated systems, including AutoML tools and Type-2 Fuzzy Inference Systems (IT2FIS), each accounted for 7.5%. Notably, both categories exceeded the usage of SVM models (SVM, SVR-PSO, MLS-SVR) and non-parametric models (KNN, GPR, MARS), suggesting that recent studies are increasingly favouring optimization techniques and model integration over traditional machine learning approaches. Models not covered by these categories were classified as Others. This distribution reveals a trend toward the use of more integrated, complex, and interpretable modelling approaches in data-driven research on RAC.

Early studies applied machine learning algorithms such as artificial neural networks [69,70] and support vector regression [71,72] to predict compressive strength, elastic modulus and other mechanical properties of RAC, achieving better estimation results than traditional empirical formulas.

As the demand for enhanced model accuracy intensifies, the integration of multiple models has demonstrated superior generalisation capabilities and yielded more accurate predictions compared to individual models. Nunez et al. [73] developed a hybrid predictive framework by integrating multiple models, including Gaussian regression, recurrent neural networks, and gradient regression. This ensemble approach significantly enhanced predictive accuracy, increasing the R² from 0.84 to 0.919 and reducing the prediction error from 7.087 to 5.076 MPa. Gholampour et al. [74] employed various data-driven models such as LSSVR, MARS, and M5Tree to estimate the mechanical properties of RAC, achieving a minimum prediction error of 7.7 MPa for compressive strength tests. Zhang et al. [75] introduced a hybrid machine learning model combining backpropagation neural networks (BPNN) and random forest (RF), attaining an R² value of 0.91 while decreasing the prediction error to 6.639 MPa. These findings collectively underscore the efficacy of hybrid modelling approaches in improving the predictive performance for concrete property estimation. Many current data-driven studies improve base model performance by optimising hyperparameters. In particular, the rise of metaheuristic algorithms, based on biological survival, foraging, and movement strategies in nature, has offered significant advantages over traditional optimisation methods. Mohammadi Golafshani et al. [15] proposed a fuzzy inference model based on a novel metaheuristic optimisation algorithm to predict the compressive strength of RAC. Ulucan et al. [76] aimed to improve the interpretability of the model by adapting the sunflower algorithm, based on metaheuristic mechanisms, to an interpretable predictive algorithm to optimise RAC mix design problems. However, these machine learning models are heavily based on data integrity and struggle to model data sets with many missing or null values. Fuzzy strategies can address such issues [15], but there is still a research gap in interpretability. Ensemble models currently offer a promising solution to this problem.

Ensemble models have been a research focus in recent years due to their excellent interpretability, reliable and robust performance, compatibility with sparse data, and superior control over overfitting. They are poised to elevate the interdisciplinary field of machine learning and engineering materials to the forefront of advanced data-driven research. Some ensemble models [77] have already been applied in the RAC domain [78,79] to predict the elastic modulus and compressive strength, reducing experimental dependence and lowering unit costs. Ensemble models constitute a significant branch of machine learning.

In general, several trends have emerged in the design of the experiment mixture and data-driven research related to RAC. The parameters considered in the experiment have shifted from merely adjusting the proportions to a deeper explanation of the reasons, aiming to meet the strength requirements while also tending to satisfy more environmental constraints. The handling technology of the mixture and the curing environment tend to become more complex. Prediction algorithms have evolved from single models to more complex systems, optimisation methods have shifted from simple fixed parameter searches to more diverse and intelligent strategies, and model functionality has transitioned from single “black box” predictions to interpretable and more transparent approaches. In addition, data requirements are increasingly leaning toward better compatibility and integration. As research progresses, the complexity of the system may force data-driven methods to become more important in research.

3.2 Recycled Aggregate Concrete Mixture Design & Optimisation Techniques

Early RAC research focused on replacing natural aggregates with recycled ones and evaluating strength and durability, showing that performance is governed by RCA properties [80]. This drove efforts to enhance RCA and a subsequent shift toward mixture design. ACI and DOE procedures were adapted to RCA characteristics, and the equivalent mortar volume method (EMV) [81] achieves higher RAC performance with reduced cement compared with traditional designs.

To achieve the desired target strength, another approach modifies the design parameters of the mixture without the need for extensive experimentation [82], which is essentially a single-objective optimisation. With the advancement of research, more sophisticated optimisation techniques have been employed to enhance the performance of RAC.

Multi-objective optimisation (MOO) strategies [83,84] and the technique for the preference of orders similar to the ideal solution (TOPSIS) have been used to integrate mechanical, environmental, and economic sustainability indicators to select optimal mix proportions. These methods consider RAC performance while sustainably choosing admixtures, reducing carbon footprint, and lowering costs. Metaheuristic algorithms in hybrid intelligent systems [73,85] have also been designed for multi-objective optimisation to find the optimal proportions of the RAC mix.

Pareto frontier is widely used in RAC mixture design multi-objective optimization. Wang et al. [84] illustrated the mix ratios of RAC and associated costs (including environmental) by applying constraints on LCA indicators like GWP and EI. The Pareto frontiers of Qc, EI, and LCC are negatively correlated, suggesting that improving chloride ion resistance in RAC increases EI and LCC. TOPSIS results prioritize chloride ion resistance over EI and LCC. EI and LCC are linearly related, and their objective functions are linear in the MOO model.

The two-stage mixing approach (TSMA) [86] is another method to optimise the design of the RAC mix. Enhance stiffness and strength by addressing the high porosity of RCA. TSMA can achieve optimal performance at RA replacement rates of 20%–40% and 50%–70%.

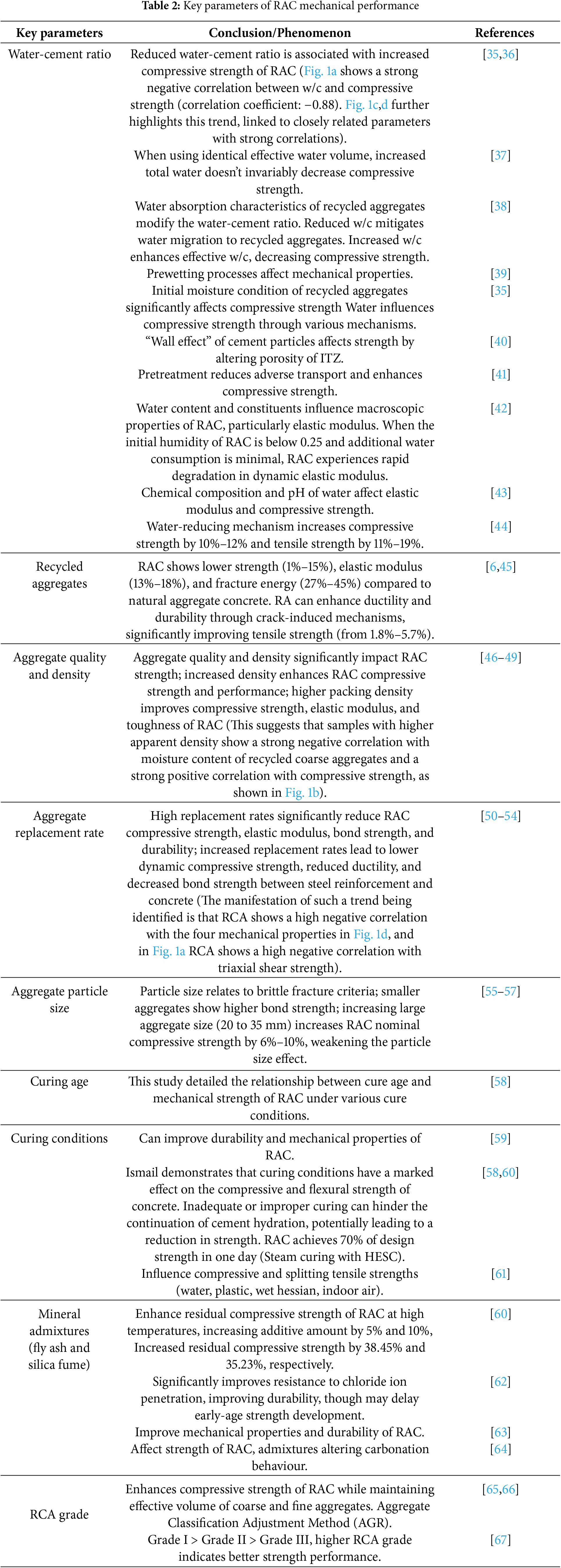

3.3 Data-Driven Approaches in Prior RAC Research

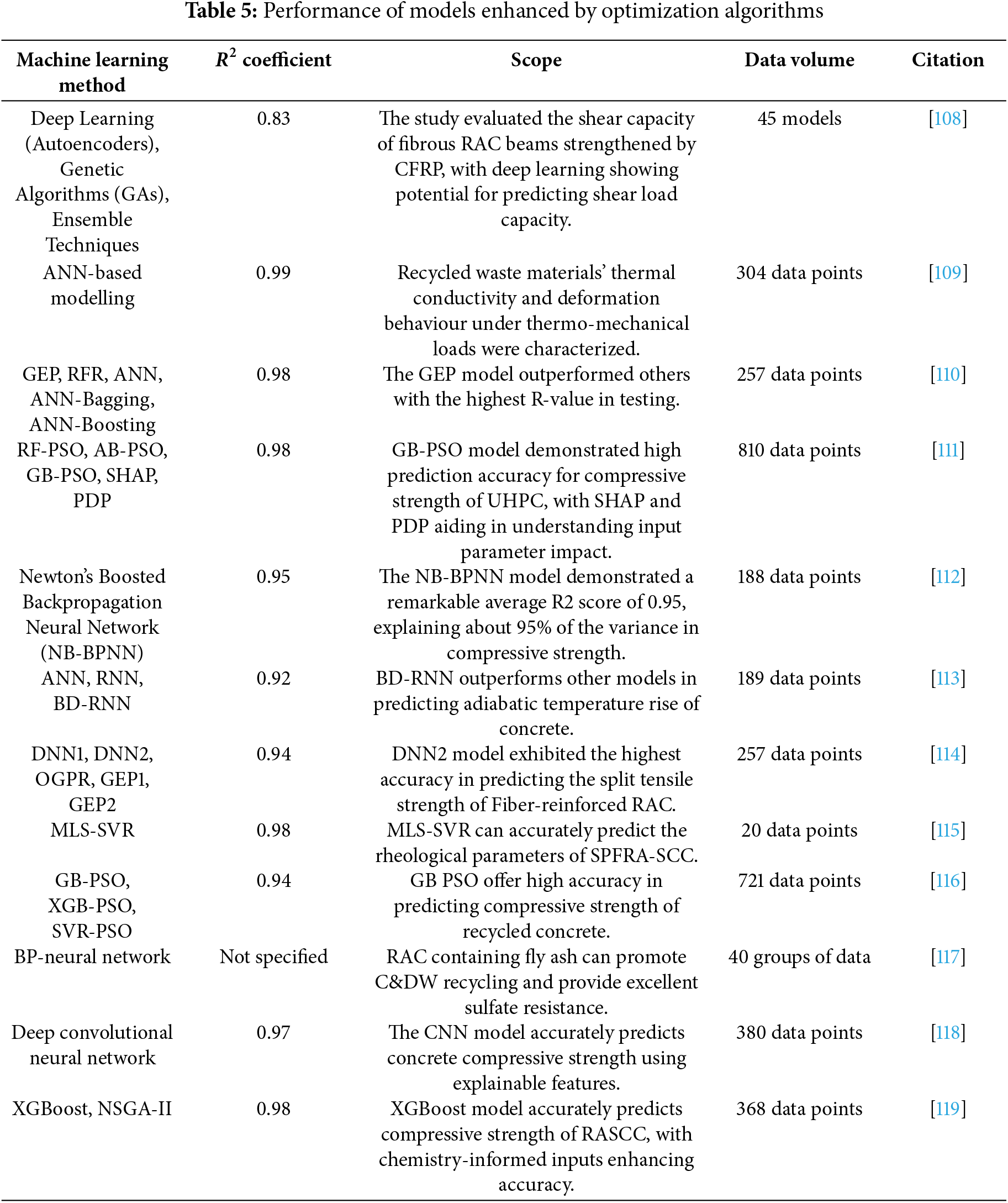

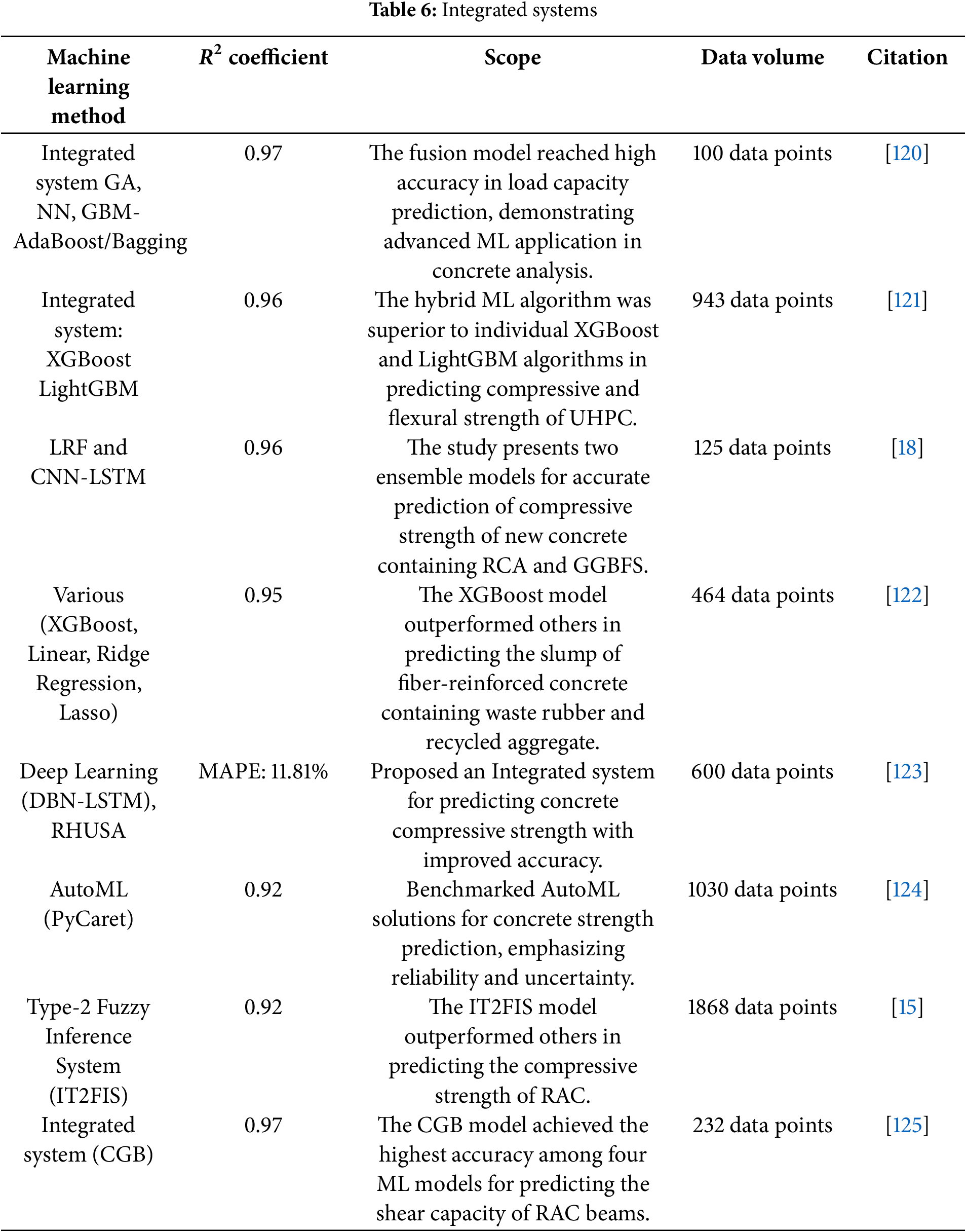

To provide a clearer overview of recent data-driven approaches for predicting the properties of RAC, Table 4 presents traditional machine learning models applied under limited data conditions, highlighting their baseline performance in RAC prediction tasks. Table 5 summarizes the performance of models enhanced by optimization algorithms, including Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Genetic Algorithms (GA), and their impact on improving model accuracy. Table 6 outlines the application of integrated systems, showcasing recent efforts to enhance prediction accuracy and generalization capability. Each table includes details on dataset size, experimental results, and the main contributions of the respective studies, aiming to facilitate more targeted data collection and modelling efforts for future research.

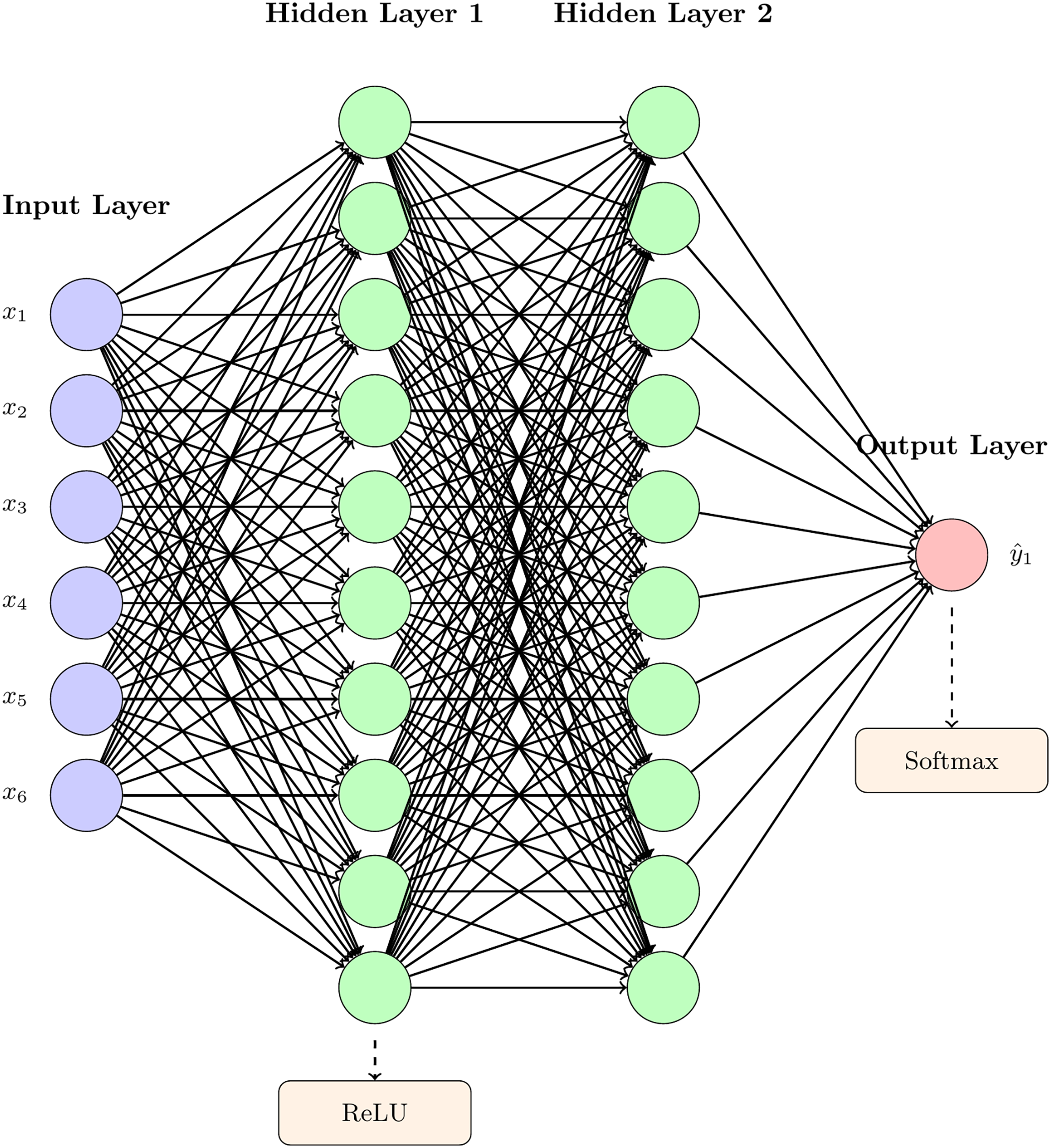

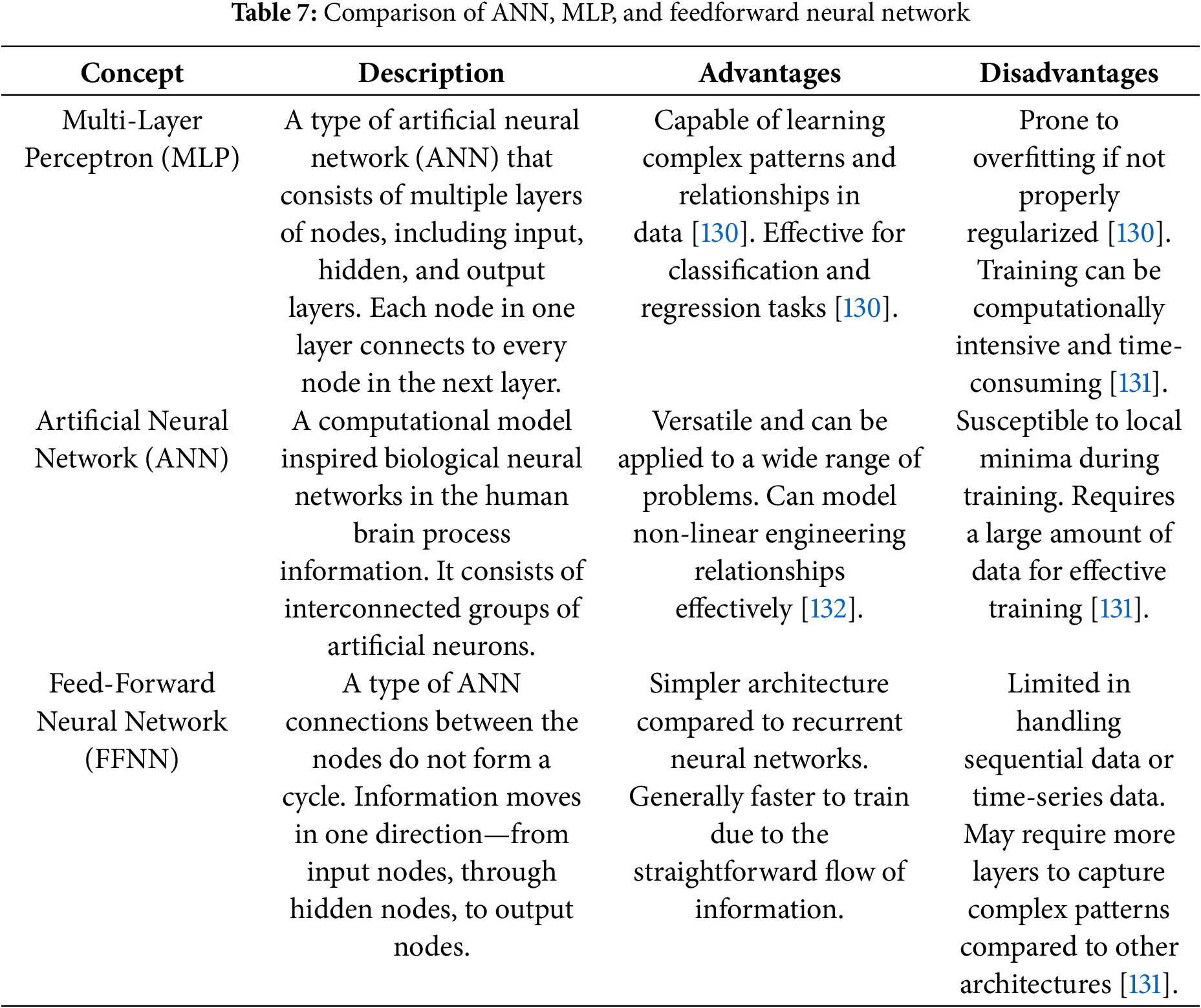

Neural network methods are computational approaches to supervised learning inspired by the functioning of biological neurones [126]. Subsequently, the development of backpropagation-based neural networks (BP-NN) [127] and feedforward neural networks with universal approximation capabilities [128] demonstrated the uniform density of function clusters formed by neural networks in continuous spaces, known as the Universal Approximation Theorem, a comparison of the model listed in Table 7. Since then, neural networks have been widely employed in engineering disciplines [87,129].

Fig. 3 illustrates an example of an artificial neural network (ANN) architecture commonly used in RAC-related prediction tasks. This model adopts a 6–10–10–1 structure, where the input layer receives mix design variables and the output layer predicts the compressive strength of concrete. ReLU activation is applied in the hidden layers, and Softmax in the output layer. While this configuration is not universal, it reflects a typical approach for capturing nonlinear relationships in concrete strength prediction using ANN.

Figure 3: An artificial neural network (ANN) with A 6–10–10–1 architecture

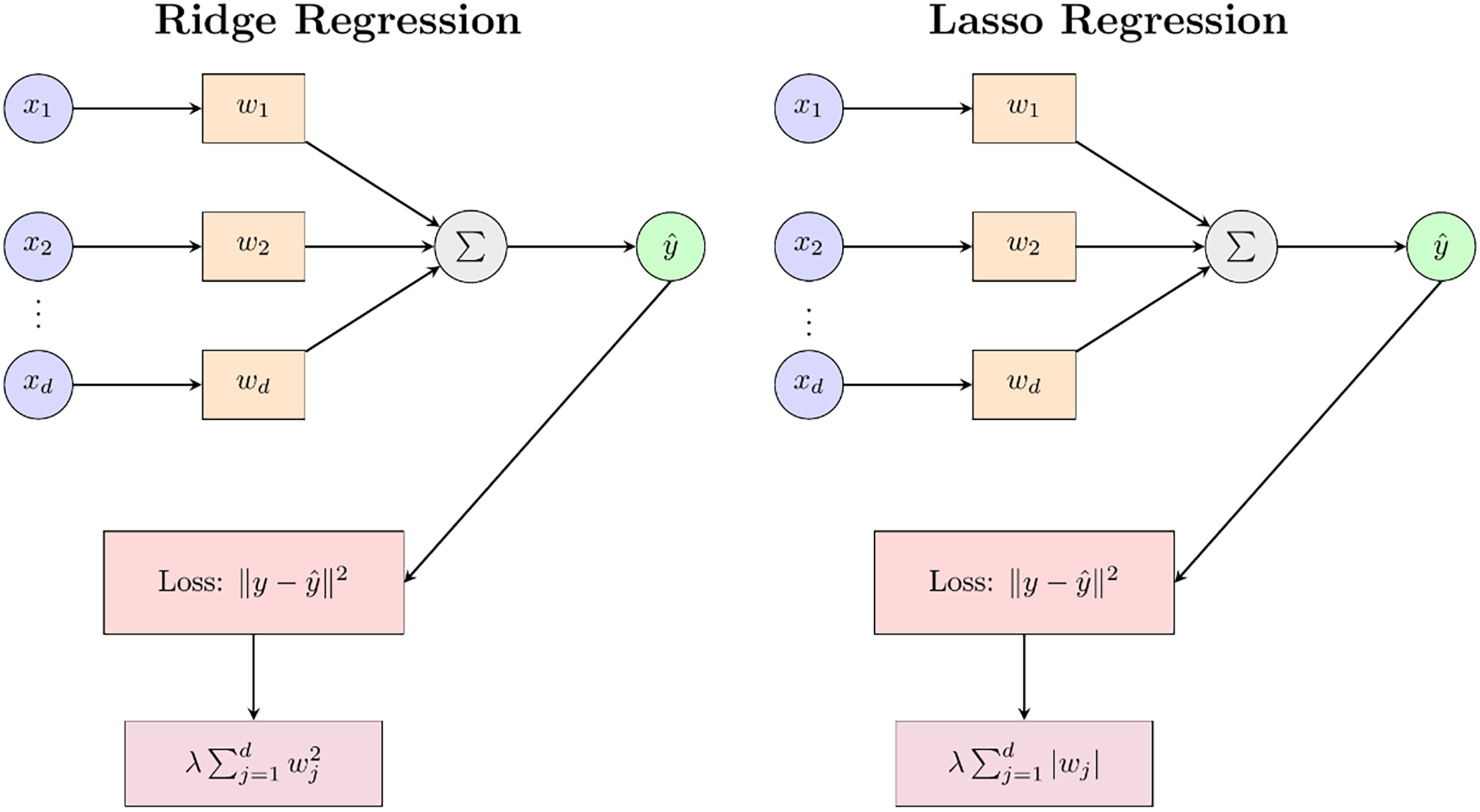

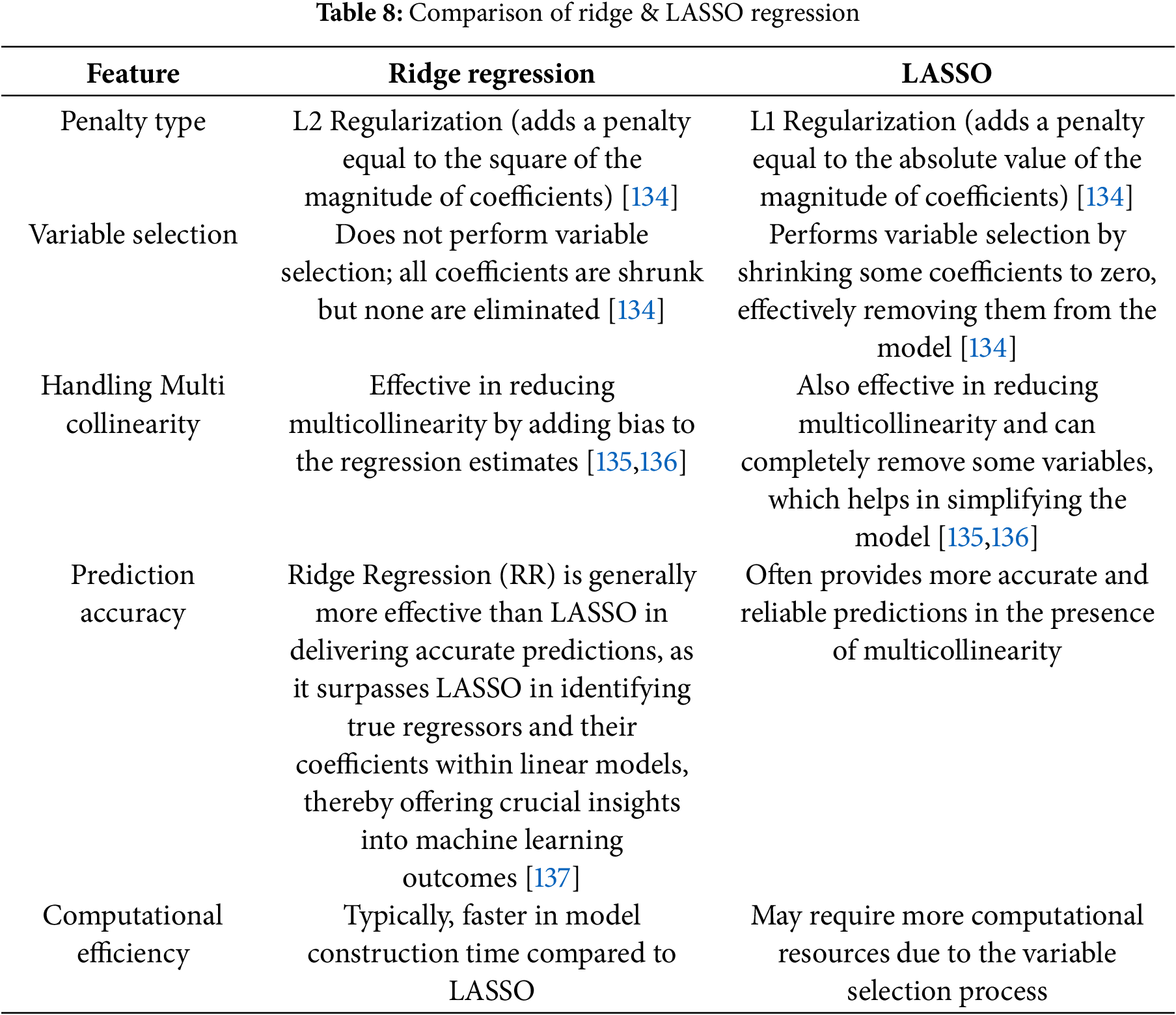

3.5 Ridge and Lasso Regression

Ridge and Lasso regression models in Fig. 4 are important regularisation techniques widely used in machine learning and inverse problems. When their regression parameters are assumed to have Gaussian (normal) and independent Laplace (double exponential) priors, respectively, they can be interpreted as Bayesian posterior estimates [133]. Ridge regression applies L2 regularisation to linear regression models to reduce the risk of overfitting. Both methods can be described using the following Eqs. (1) and (2):

Figure 4: Model structures of ridge regression and lasso regression

It introduces a penalty term λ to limit the magnitude of the regression coefficients, aiding in achieving a compromise between the model’s explanatory capacity and its complexity. The differences between the ridge regression model and the lasso regression model are listed in Table 8.

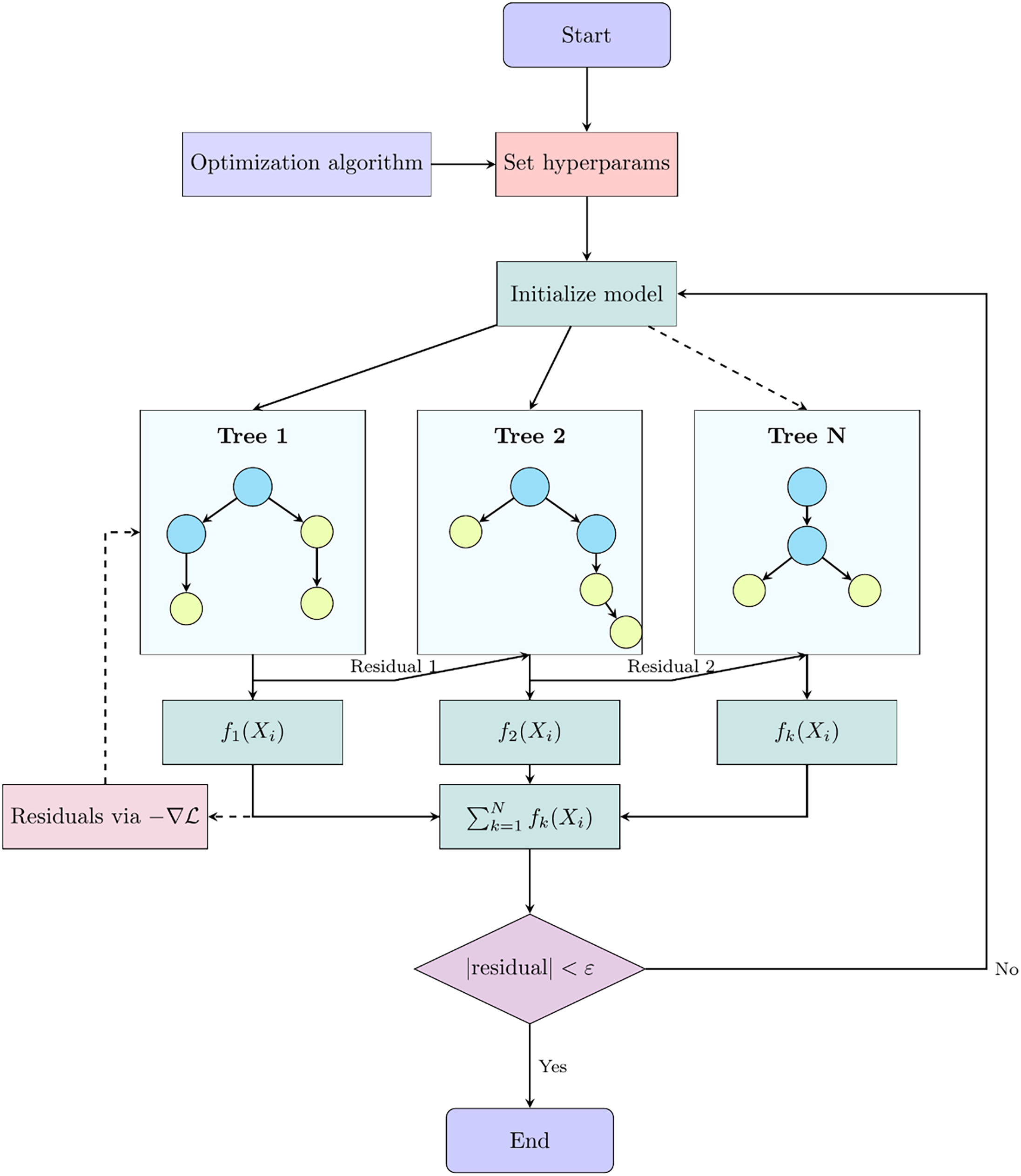

Tree-based algorithms, such as decision trees, gradient boosting, and gradient boosting regression trees (GBRT), are fundamental methods in machine learning. Ensemble models like Random Forest (RF) [129,138], Gradient Boosting (GB), GBRT [99], XGBoost [116], AdaBoost, and CatBoost further enhance predictive power by building weak learners, optimising gradient boosting efficiency, and reducing overfitting. Fig. 5 illustrates the basic structure of the tree-based model.

Figure 5: Flow diagram of the decision tree-based model

These models are particularly advantageous for handling missing values and sparse data, making them highly suitable for engineering data sets. Their robustness and versatility suggest that they will play a significant role in the future of data-driven development in the fields of engineering and materials science.

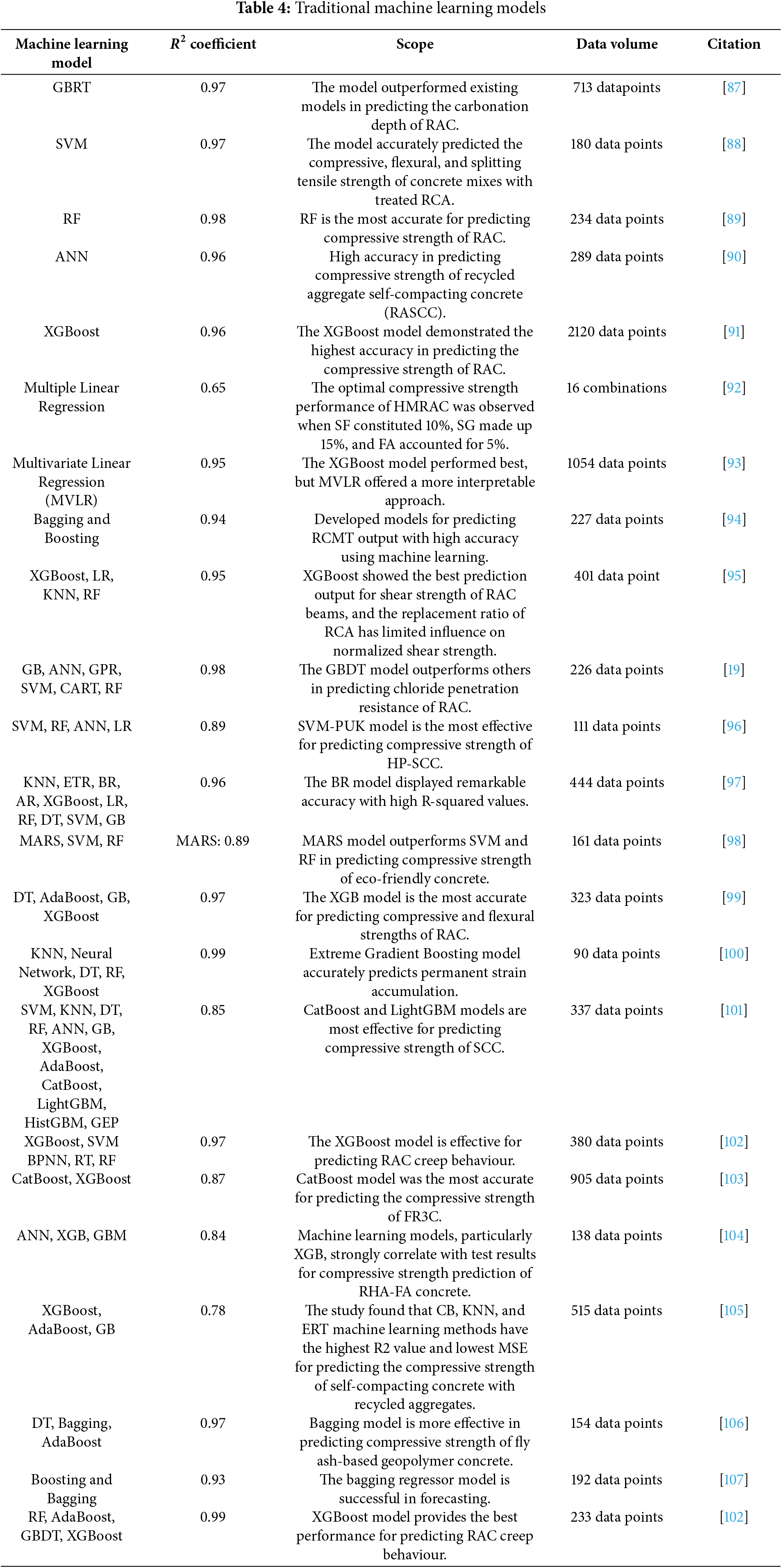

3.7 Benchmark Performance Comparison & Validation of Machine Learning Algorithms

Here separately performed baseline capability tests on external datasets for the nine models frequently used in previous studies LR, LASSO, Ridge [122], SVM [19,139,140], RF, GB [19,116], AdaBoost, DT [99], XGBoost [19,95]. However, we did not test the backpropagation neural network (BPNN) supported by optimisation algorithms. Although these models may achieve accurate predictions, the original paper did not provide the model optimisation steps or hyperparameter settings. Therefore, we cannot select a model as a representative of the baseline capability for comparison.

In the realm of RAC data-driven research, various metrics are employed to assess the efficacy of the model, such as RMSE (Root Mean Squared Error), R2 (R-squared or coefficient of determination), MAPE (Mean Absolute Percentage Error), STD (Standard Deviation of Errors) and MAE (Mean Absolute Error).

3.8 Comparative Analysis of ML Models under a Unified RAC Benchmark

Testing on a Unified Dataset

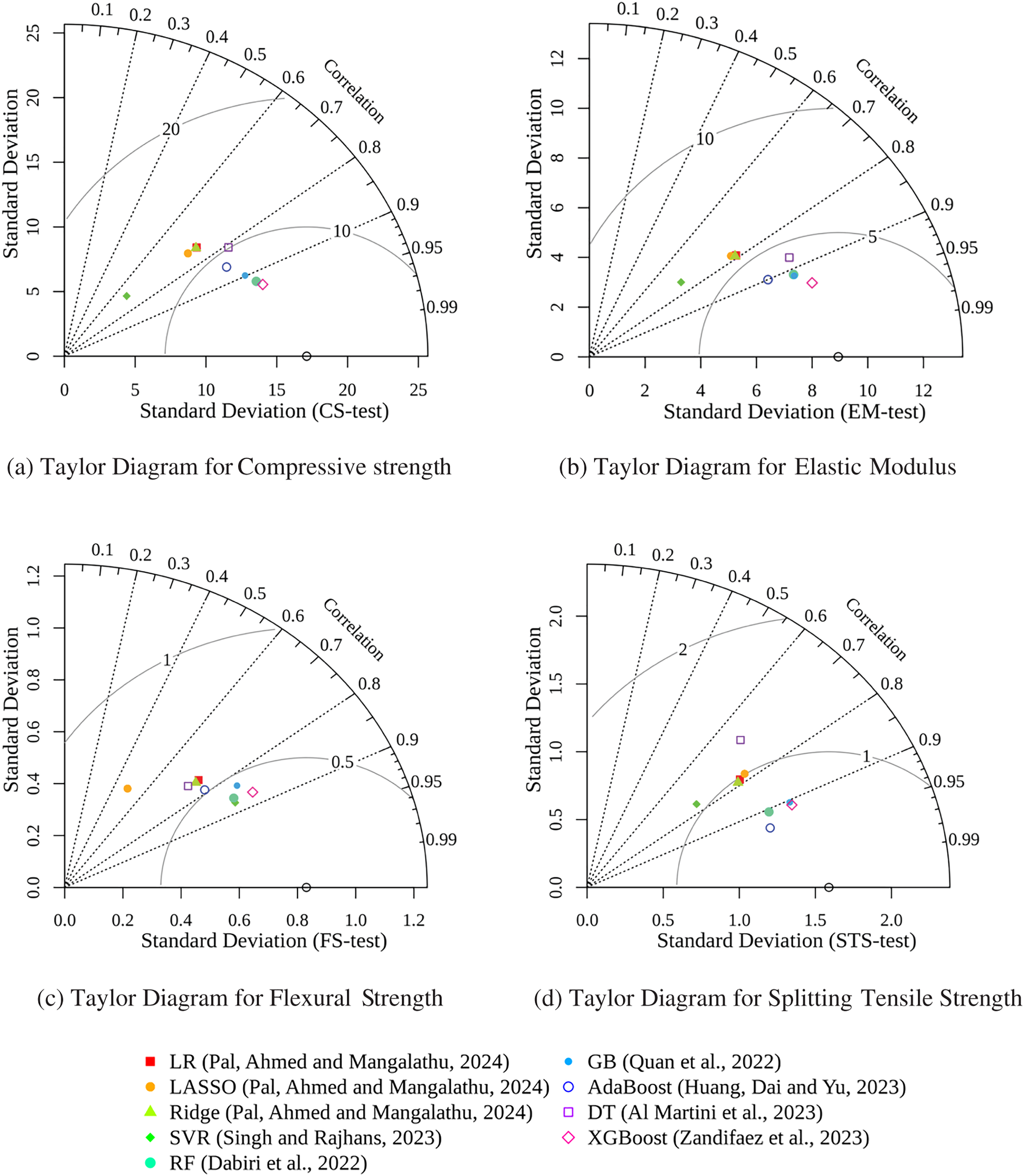

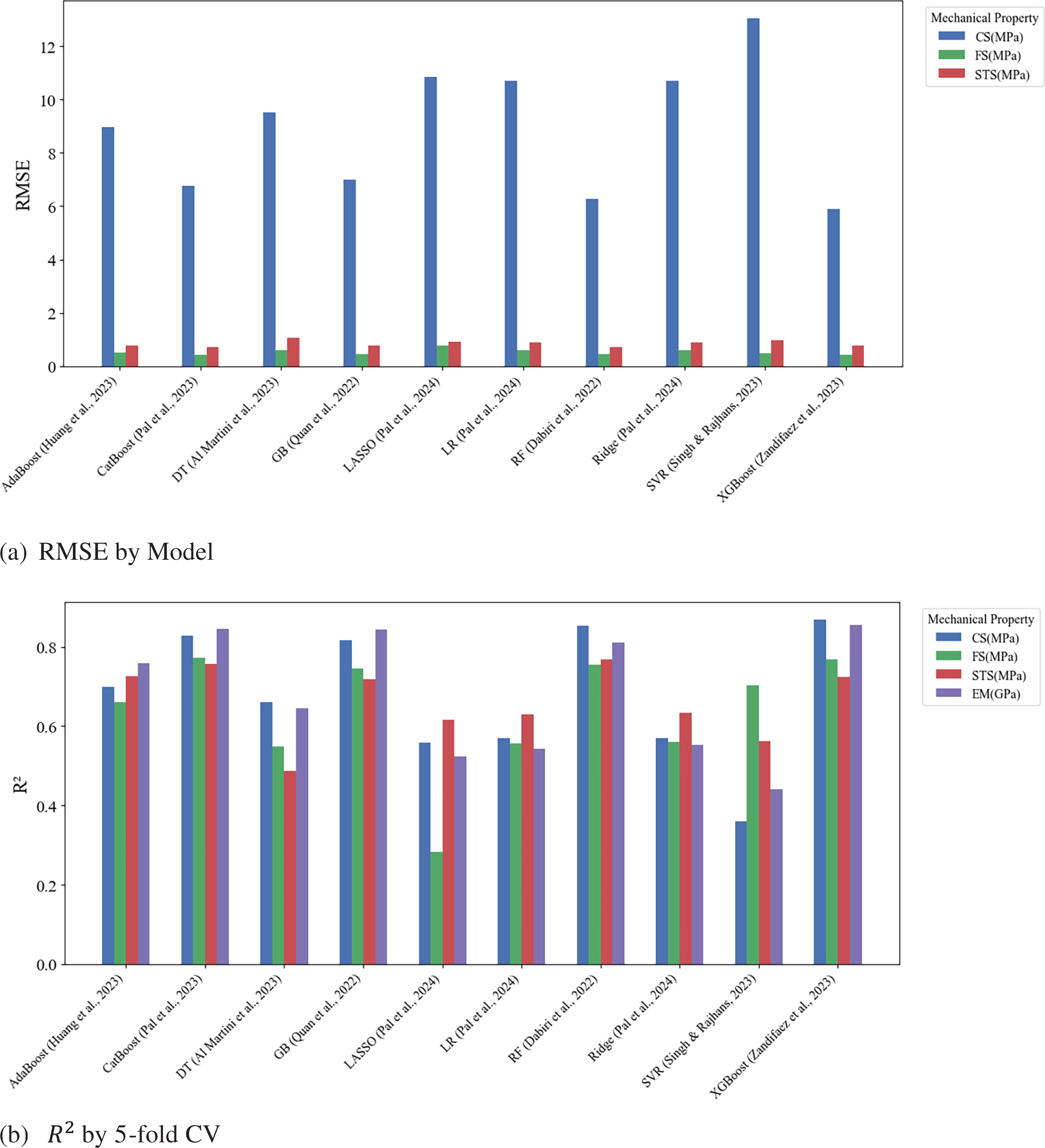

To ensure consistency in performance comparison, the studies reviewed commonly adopt standard data partitioning strategies, such as an 80:20 split between training and testing subsets. In this context, Fig. 6 presents a comparative evaluation of various machine learning models including LR, LASSO, Ridge, SVR, RF, GB, DT, XGBoost, and AdaBoost across key mechanical properties of RAC: compressive strength (Fig. 6a), elastic modulus (Fig. 6b), flexural strength (Fig. 6c), and splitting tensile strength (Fig. 6d). The Taylor diagrams shown in Fig. 6 a concise visualization of model performance by simultaneously displaying correlation, standard deviation, and root mean square error.

Figure 6: Comparison of Taylor diagrams for different metrics (testing)

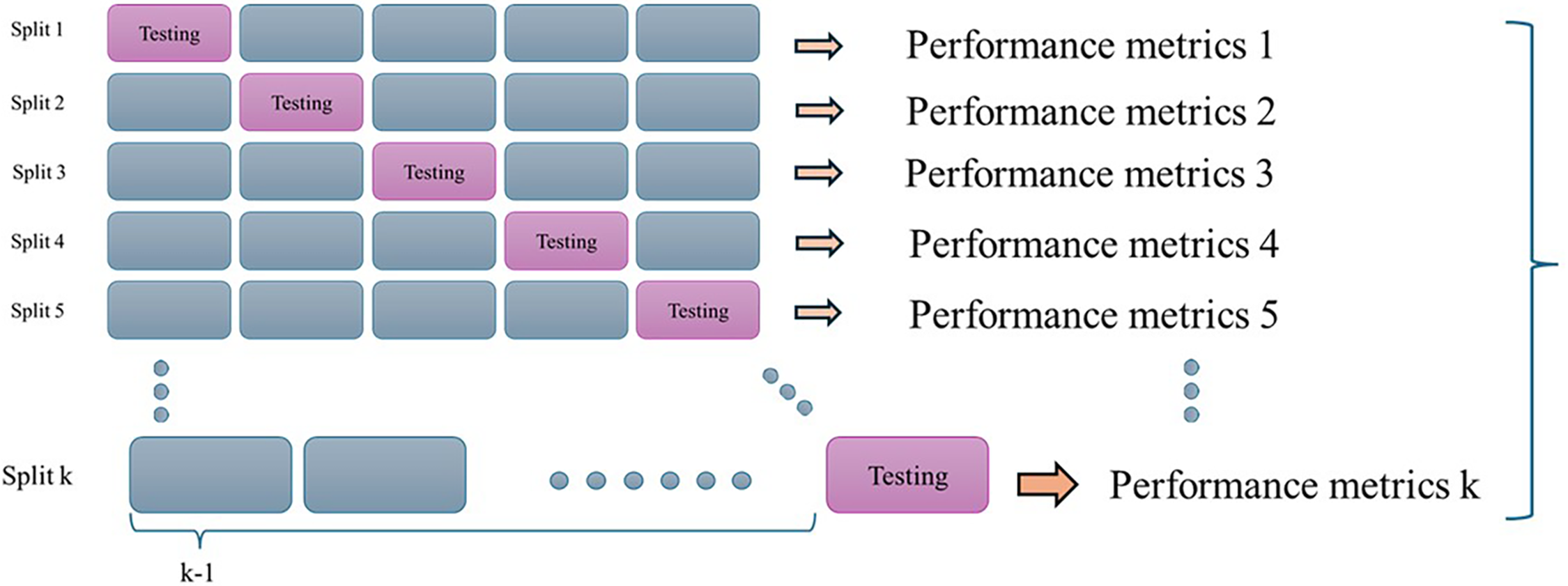

K-Fold-Cross Validation

The five-fold validation represent prevalent approaches to cross validation to evaluate the efficacy of machine learning models of concrete properties [141,142]. In the five-fold validation, the data set is segmented into five equal sections in Fig. 7; one segment serves as the validation set, with the other four used for training. This procedure is conducted five times, upon which the average performance is regarded as the conclusive outcome.

Figure 7: 5-Fold to K-fold cross validation

The performance outcomes of the five-fold validations RMSE and R square for models are illustrated in Fig. 8a,b, respectively. There is no discernible difference between the five-fold and ten-fold validations across all models, with XGBoost demonstrating the most robust baseline capability for predicting compressive strength.

Figure 8: 5-fold CV result on unified data set

By evaluating the performance of mainstream machine learning models for predicting the compressive strength (CS) of RAC using a unified dataset, a general decline in predictive accuracy was observed compared to the results reported in previous studies. For instance, the R² value of XGBoost, which reached up to 0.963 in the literature, was reduced to 0.861 in this study, representing a 10.55% decrease. CatBoost demonstrated relatively stable performance with a 4.83% decline, while Decision Tree and Random Forest models exhibited more substantial drops of 32.67% and 14.13%, respectively. These variations underscore the influence of data characteristics, sample distribution, feature selection, and preprocessing approaches on model generalizability across studies.

XGBoost consistently delivered the best predictive accuracy for compressive strength, with the lowest MSE and RMSE values, and an R² of 0.8614, confirming both high precision and strong model fit. In contrast, linear models such as Linear Regression, Lasso, and Ridge exhibited moderate performance, characterized by similar error levels and lower goodness-of-fit. Support Vector Regression (SVR), however, consistently underperformed across all tasks, showing high errors and weak predictive capability.

For splitting tensile strength and flexural strength predictions, gradient boosting models (particularly XGBoost and CatBoost) again showed superior performance, with XGBoost achieving an R² of 0.7550 and maintaining low error metrics. Although Random Forest slightly lagged behind the gradient boosting models, it still outperformed the remaining methods. Overall, ensemble-based models, including XGBoost, CatBoost, and Random Forest, proved more effective than linear models and SVR, especially in capturing complex, nonlinear relationships within the data. Linear models performed adequately in simpler scenarios but struggled with intricate patterns, while SVR consistently delivered the weakest results, indicating its unsuitability for such predictive tasks.

Furthermore, the robustness of these observations was confirmed through consistent outcomes across five-fold cross-validation, reinforcing the reliability of the performance rankings. This unified dataset, therefore, provides a fair and consistent platform for benchmarking different machine learning approaches, offering valuable insights into their adaptability and robustness in practical applications. These findings serve as a critical reference for future research in model selection and data integration strategies for RAC property prediction.

Despite the observed performance gap of 4.83% to 32.67% compared to results reported in previous studies, a notable consistency remains: tree-based ensemble methods, particularly XGBoost, continued to demonstrate strong predictive capabilities under the unified dataset. This aligns with prior research, where XGBoost has consistently outperformed traditional small-sample machine learning models across various RAC prediction tasks. Its stability and high accuracy, even under more complex and heterogeneous data conditions, further confirms its effectiveness as a preferred model for RAC mechanical property prediction.

XGBoost performed best for CS, FS, and EM, while RF and AdaBoost were more effective for STS. Regularized tree-based models generally outperformed others because zero values in Dataset 4 could deactivate neural networks and cause instability. Lasso also showed that regularization helps with sparse data. The hyperparameters of all models are provided in Appendix Table A1. For RAC applications, however, model robustness should be judged by dataset characteristics and feature interpretability.

The interpretability of a model involves the capacity to comprehend and articulate the reasoning behind machine learning models’ predictions [143]. This is vital for maintaining transparency and trust in machine learning models. This section presents explanation tools such as SHAP and PDP, which are grounded in game theory and are predominantly utilised in the RAC domain.

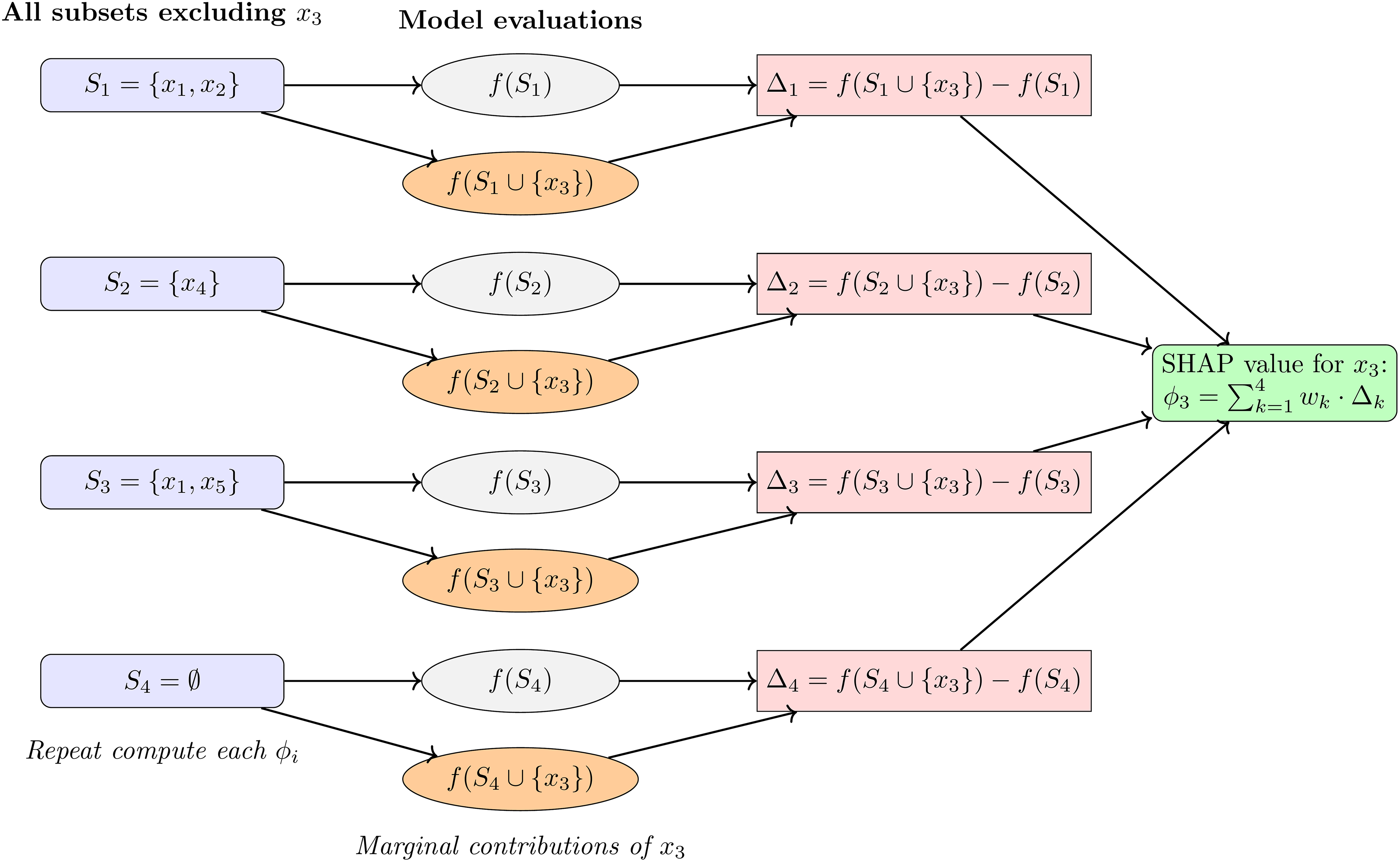

4.1 SHapley Additive Explanations (SHAP)

SHapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) is a method to interpret machine learning models. SHapley values, originally used to allocate gains among players in cooperative game theory, are adapted by SHAP to attribute contributions of individual features to model predictions. Fig. 9a illustrates how the contribution of a single feature is calculated. This approach calculates the marginal contribution of each feature [111], assigning weights according to the definition of SHapley values. The method of calculation of SHAP values is shown in Eq. (8) and various visualisation techniques are then employed to illustrate the SHAP values, allowing the interpretation of the model’s behaviour [144].

Figure 9: An example of the SHAP computation process for compressive strength

Karim et al. [104] and Gao et al. [145] respectively identified curing age and coarse-aggregate content as the dominant predictors of RAC compressive strength. In Karim’s analysis, curing age exhibited an average SHAP value of 5.33, indicating that the progressive generation of C–S–H gel over time enhances structural densification. By contrast, coarse-aggregate content showed a negative correlation: increasing its proportion markedly reduced strength, consistent with SEM observations of interfacial microcracks and insufficient paste coating. Similarly, in recycled steel slag concrete mix-design study, curing age yielded the highest SHAP value among all features, with an average of 20.6 and local values exceeding 40, underscoring its dominant role in compressive strength. This finding aligns with the physical mechanism of continued hydration and sustained C–S–H gel formation. The high SHAP value of silica fume further reflects its pozzolanic reactivity with calcium hydroxide, leading to secondary C–S–H formation and improved microstructural compactness [111]. Conversely, the negative SHAP values for aggregate content highlight its potential to disrupt paste continuity and induce interfacial microcracks, thereby reducing overall strength. Section 2.1 and aligns with Section 2.2’s identification of RA and its replacement ratio as key factors.

4.2 Partial Dependence Plots (PDP)

Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs) serve the purpose of interpreting machine learning models by showing the connection between a feature and the predicted result, with other features held constant. Within the RAC machine learning model [146,147], PDPs are instrumental in clarifying how various input variables affect the mechanical characteristics of concrete. In Das and Kashem [121], PDP shows that recycled steel slag concrete compressive strength rises roughly linearly with age from 25.04 MPa at 7 days to 39.33 MPa at 28 days, consistent with increased C–S–H gel formation; SEM images at 28 days reveal a more uniform C–S–H distribution. Raising coarse aggregate from 1200 to 2000 kg/m³ reduces strength by 27.8% because excess aggregate limits paste coating, weakens the ITZ, and concentrates microcracks and pores as in SEM. Increasing cement content from 350 to 600 kg/m³ boosts strength by 12% due to more hydration products Ca(OH)2 and C–S–H and a denser matrix. XRF also indicates high CaO content in the cement [104].

Regarding the influence of the W/C, it was found through PDP that a lower W/C obtained by increasing cement content and reducing moisture enhances strength and compactness [116]. Reduced water absorption in RCA affects the reliability of cement by yielding smaller pores. The impact of sand is minimal. An increased proportion of natural aggregates improves the load bearing capacity of the cement; this effect is more pronounced with less RCA. Changes in substitution rates heavily affect strength. Cement and moisture are crucial for the compressive strength of RAC [116]. Wang et al. [84] explored how key design parameters impact the resistance of RAC to chloride ions by PDP, found that the electric charge passed increases as the W/C ratio increases but decreases significantly with higher values of sand and CA. This trend occurs because a higher W/C ratio reduces concrete density while enhancing its ability to bind chloride ions; accordingly, the total charge passed declines as S and CA increase. These results suggest that the hydration-accelerating process consumes free ions more rapidly.

5 Gaps and Limitations in Existing RAC Data-Driven Research

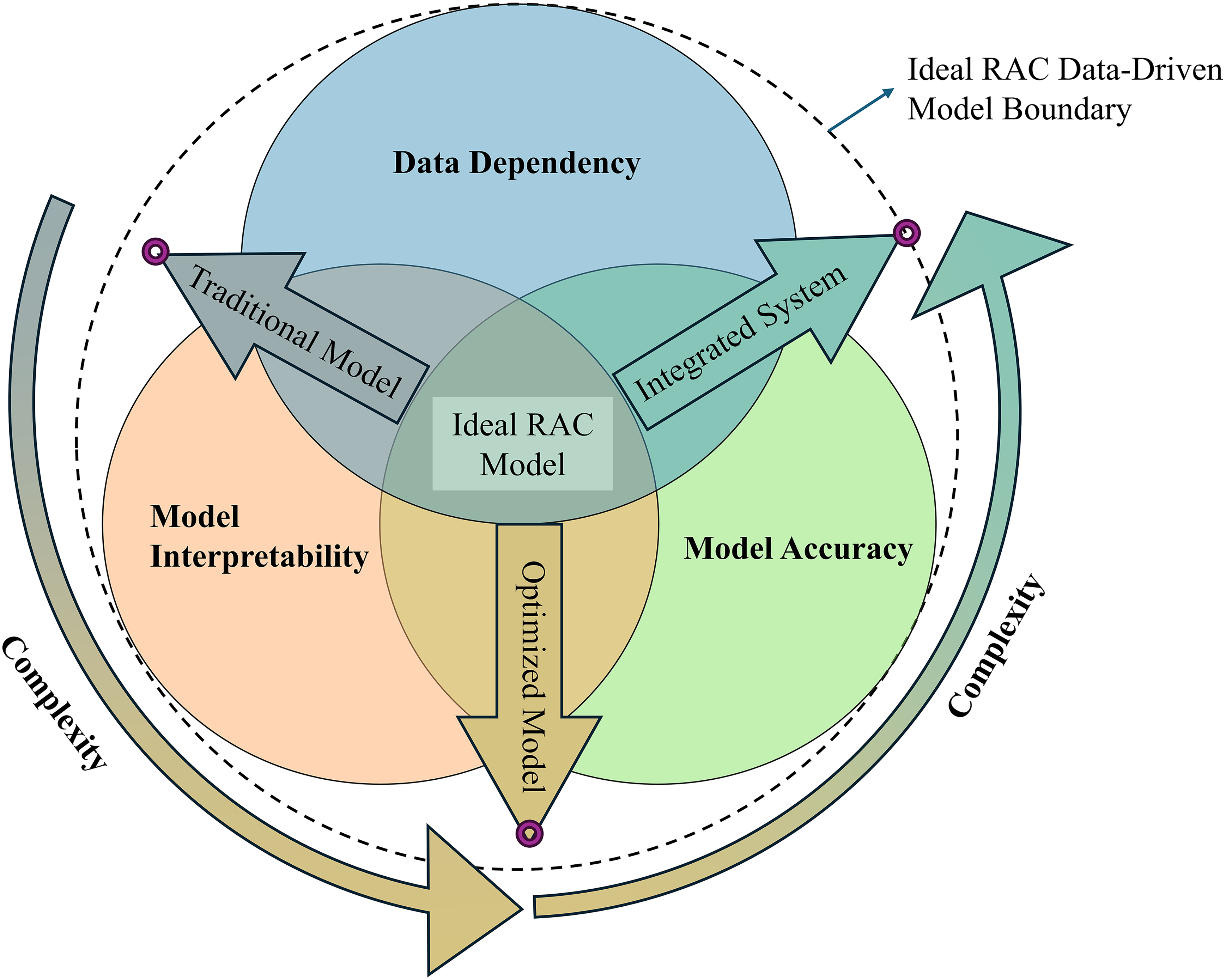

By reviewing the literature summarised in Tables 3–5, three major research gaps are identified: data dependency, model interpretability, and model accuracy. An ideal model should strike a balance among these three aspects, as illustrated in Fig. 10, by minimizing reliance on large datasets while achieving both strong interpretability and high predictive performance. XGBoost [20,78,148] currently comes closest to meeting these criteria, however, it still falls short in fully addressing the trade-offs, particularly in terms of interpretability and generalizability across diverse datasets.

Figure 10: Major gaps in current data-driven research on RAC systems

In terms of data dependence, Gao et al. [145] found that even On the same RAC dataset, altering only the train/test split produced material shifts in CatBoost performance: R² increased by 2.78%, RMSE decreased by 22.7%, and MAE decreased by 15.1%, SHAP feature importances also shifted.

Model interpretability [110] is not only challenged by the increasing complexity of the models themselves, but also by the rising complexity of optimization algorithms such as PSO [116] and GA [108], which further weakens interpretability. On top of this, ensemble systems are even more complex and often regarded as “black boxes.” Methods like SHAP and PDP provide only posterior explanations for RAC parameters, and their effectiveness largely depends on the type of RAC and the composition of the dataset. Therefore, the interpretability of features may lack generalisability.

The issue of model accuracy degradation has already been discussed in Section 3. In addition to the decline in model performance on different datasets, current RAC data-driven approaches primarily focus on learning from high-dimensional data using techniques such as Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [149] and Genetic Algorithms (GA) [150], while overlooking the potential of discovering patterns within low-dimensional manifolds. This limitation results in marginal accuracy improvements at the cost of significantly increased computational complexity. According to the manifold hypothesis, high-dimensional RAC data are likely to lie on low-dimensional manifolds embedded within high-dimensional spaces [151]. Therefore, there should exist simpler and more accurate representations in the latent space. In the following sections, this paper will introduce several promising advanced methodological frameworks aimed at bridging these gaps and will provide recommendations for their application.

6 Potential Applications for Advanced Method Framework

This section discusses coupling generative adversarial networks (GANs) with physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) as a promising framework for RAC applications. If GANs outputs are constrained to a dimensionally consistent space, the generator suppresses samples that violate unit-consistency assumptions. The PINN can then use this GAN-augmented, denser RAC sample set as inputs, improving its ability to capture RAC priors and the underlying physics.

6.1 Physics-Informed Neural Networks

Traditional finite element (FE) methods are widely adopted numerical techniques in current computational engineering mechanics. The primary approach of FEM involves embedding transfer properties of elements, material parameters, and other relevant factors, followed by modelling and discretization of the mesh, and subsequently performing computations. However, the finite element method is excessively dependent on prerequisites, and traditional FEM exhibits the following drawbacks:

Dependence on High-Quality Meshes. FEM requires the creation of a mesh to discretise the domain, which can be computationally expensive and complex, especially for irregular geometries or fine features such as voids and crack domains. Obtaining high-quality meshes in these cases is nearly infeasible [152,153].

Difficulty in Handling Complex Boundary Conditions and Non-Smooth Features: FEM may encounter challenges with complex boundary and internal conditions, as well as interface settings. These complexities often adversely affect the convergence of results [154].

Excessive Computational Resource Consumption and High Costs: The necessity for fine meshes and the resultant increase in degrees of freedom can render FEM computationally intractable for large-scale simulations. Although the generalised finite element method (GFEM) proposed by Strouboulis et al. [152] mitigates some of the computational resource challenges associated with complex calculations, overall resource demands remain substantial.

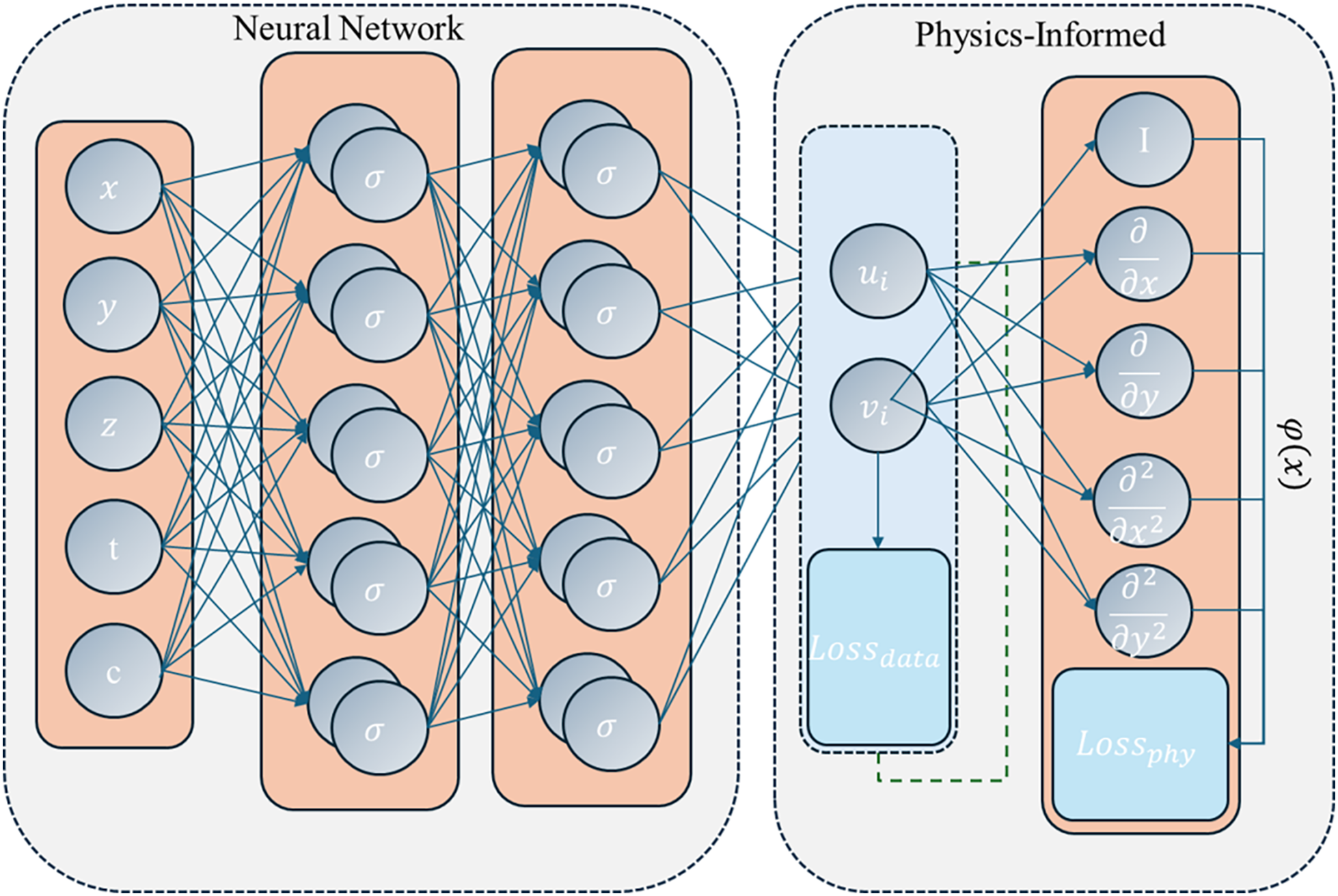

Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) in Fig. 11 represent an extremely promising advanced methodology with the potential to replace traditional finite element methods. Rezaei et al. [155] used spatial gradients and energy forms from finite element methods, demonstrating that PINNs can effectively address engineering problems in heterogeneous domains with performance superior to that of finite elements. In numerous classical computational mechanics problems, such as maximisation of the shear modulus in two-dimensional metamaterials and minimisation of compliance under various geometric configurations, PINNs have achieved results comparable to methods of finite elements [156]. Furthermore, research by Pantidis and Mobasher [157] indicates that PINNs can alleviate computational resource consumption, accelerate the resolution of non-linear computational mechanics problems, provide mesh-independent results, and diffuse non-local strain and damage curves while maintaining computational efficiency. Deng et al. [158] states that the modelling of heterogeneous material deformation using PINN is more promising than traditional methods. Furthermore, PINNs have been applied in fluid mechanics to solve Reynolds boundary value problems [159] and in solid mechanics to directly predict elastoplastic behaviour and stress-strain distributions [160].

Figure 11: The basic architecture of a physics-informed neural network

6.2 Applications and Prospects of Physics-Informed Neural Networks

PINNs have demonstrated remarkable application prospects when employed to solve the pressure fields of the two-dimensional Navier-Stokes equations by minimising the Mean Squared Error (MSE). In the study [161], the residual minimisation of Burgers’ equation was used as a physical constraint to progressively approximate the solution of this partial differential equation. For the one-dimensional nonlinear Schrödinger equation, we express the residual in the complex domain and train a complex valued neural network to minimise it, driving convergence to the true solution. In engineering practice, equations derived from experimental fitting are usually not PDEs, so high dimensional nonlinear behaviour is handled by machine learning models that are often treated as black boxes. Although such models often outperform traditional formulas, their reliability, robustness, interpretability, and potential social risks remain in question [162,163]. This has led to increased research efforts focused on interpretability, particularly in the form of post hoc interpretability studies [164] and surrogate models that approximate black-box models [165]. PINNs are effective in approximating solutions to both forward and inverse problems [161]. This is particularly advantageous for data-driven inverse problems in engineering, where PINNs can efficiently and rapidly validate the plausibility and applicability of models by integrating data with empirical formulas or existing published equations. This capability opens numerous possibilities for data-driven approaches in the future of engineering fields. The Fig. 12 illustrates several applications of PINNs and potential future case studies. The forward problem case refer to [166] and are used to illustrate the stress distribution of a 3D spherical cavity problem calculated using a PINN model. The inverse case from [161] and is used to demonstrate the inference of properties such as viscosity and density of a liquid material for a 2D cylinder flow through a PINN model.

Figure 12: Forward and inverse problems and the application framework of the PINN model

6.3 The Impact of Error Metric Functions on PINNs

Optimisation of the loss function is of paramount importance in establishing the convergence potential of PINNs, thereby affecting their learning efficiency. Ill-posed differential operators present a substantial challenge to the application of PINNs. “Ill-posed” refers to problems that do not satisfy any of the Hadamard criteria: the existence, continuity, or uniqueness of the solution [167]. Krishnapriyan et al.’s investigation [168] into a one-dimensional convection-diffusion problem illustrated that the failure modes of PINNs are attributable not to the representational capacity of the neural network but rather to the optimisation challenges arising from the formulation of the loss function.

The most prevalent error metrics include the least squares method and the mean squared error (MSE) [169,170]. The squared error component accentuates the impact of errors, producing elevated numerical values that facilitate accelerated convergence. However, this approach exhibits substantial sensitivity to discrete data points, thereby compromising its stability in convergence and dependence on the assumption of normality of the residuals.

The computation of the least squares method only requires solving the gradient of the sum of squared residuals, expressed as follows:

The residual of the partial differential equation can be expressed using the least squares method as:

The gradient of the least squares loss has an analytical form, allowing for rapid computation during the training of PINNs, which significantly reduces computation time and naturally aligns with gradient descent methods such as SGD. On this basis, incorporating L1 and L2 regularization transforms it into Lasso and Ridge regression, respectively.

By adding a minimum error term to the least squares method and setting a threshold, this approach guides the use of squared errors for small residuals and absolute errors for larger residuals. This makes the method insensitive to outliers while ensuring responsiveness to small errors, enabling a smooth transition and providing strong robustness. In this case, the equation evolves into the Huber loss:

Huber loss combines the characteristics of MAE and MSE [171], being less sensitive to outliers compared to MSE while still penalising larger errors more effectively than MAE [172]. This makes it a versatile choice for PINNs, particularly in scenarios where data may contain noise or outliers. The Huber loss provides a good balance between robustness and sensitivity to large errors [173,174].

Similarly, the Log-Cosh Loss uses the hyperbolic cosine function to describe the loss, effectively combining the characteristics of the MSE and MAE equations. Its formulation is as follows.

where cosh(x) is the hyperbolic cosine function, defined by the equation:

When the error is small, the equation degenerated as MSE approximation:

Conversely, it approximates MAE when the error is large.

Compared to MSE and SSE, MAE is less sensitive to outliers as it calculates the absolute differences between predicted and actual values [175]. This makes it useful in scenarios requiring robustness to outliers. However, MAE is less effective at penalizing larger errors.

Log-Cosh Loss, with its smooth nature, elegantly unifies piecewise capabilities and offers greater stability than simple MSE optimisation. It performs better than MSE in scenarios with outliers and high uncertainty [155].

Several improved versions of the least squares method have been developed to balance the stability of the training process and the convergence speed of PINNs, addressing singular perturbation problems. These methods have been shown to achieve more accurate solutions in a faster time than traditional gradient descent. For example, the Marquardt-Levenberg method [176] enhances nonlinear capabilities by combining gradient descent with the Newton method for rapid convergence. However, this approach introduces higher computational complexity, increasing the computational overhead of PINNs. Parallel processing techniques can be used to mitigate computation time [177].

From a probabilistic perspective, the loss function can also be represented by the Kullback-Leibler divergence:

The Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence equation quantifies the divergence between two probability distributions, P and Q, with respect to a common variable, x. Each component in the summation assesses the additional information required when the distribution Q is employed to approximate the true distribution P, rather than utilizing P itself. It is commonly used to measure the difference between the data distribution and the original data. An important improvement, the Wasserstein distance, will be discussed in detail in the section on adversarial neural networks.

6.4 Engineering Practice Challenges of the PINN Method and Enhanced Alternatives

In the forward PINN method case presented in this paper, the setting of boundary conditions is highly dependent on the loss function. A “correctly” configured loss function facilitates fast convergence of computations and reduces the consumption of computational resources. However, determining a standard for setting the “correct” loss function is challenging. When applying it to more complex solid mechanics computations, issues such as excessive boundary conditions in the loss function that prevent convergence, and the complexity of multiphase models making loss function setup difficult arise. These challenges are significant and require further algorithmic research and better solutions.

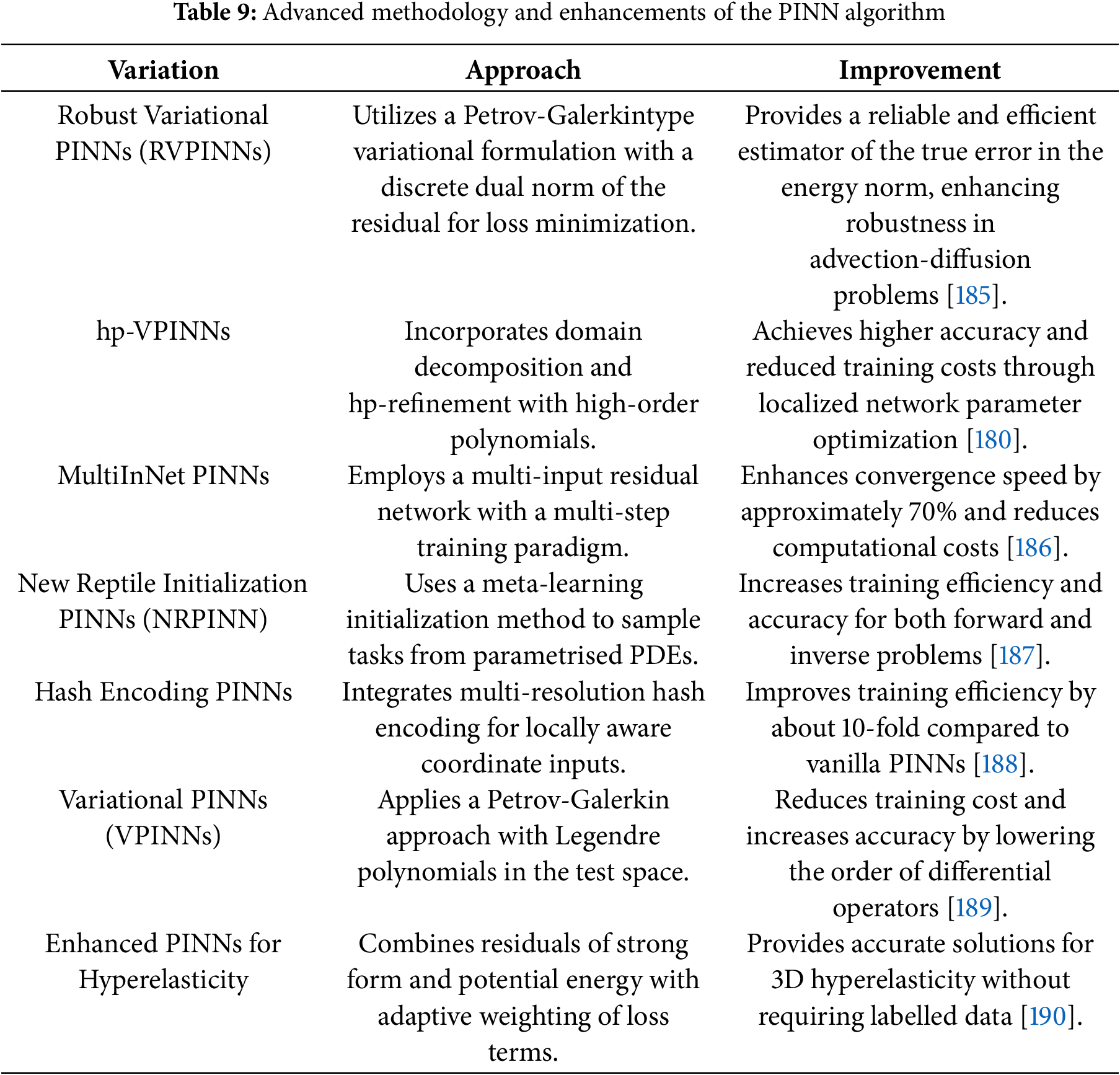

To overcome issues including convergence challenges, the necessity for a precisely configured loss function, and computational inefficiencies, several variants of the PINN algorithm have been devised. These advancements predominantly aim to optimise the training process by minimising the loss function, thereby improving efficiency, convergence capabilities, and the algorithm’s receptive field. In addition, encoding strategies have been introduced to further enhance training efficiency. A summary of several key variants of PINN is provided in Table 9.

In addition to these advances, there have been developments in the crafting of loss functions. The least squares method [178] serves as a fundamental and effective example, enhancing convergence, while residual terms [179] improve the model’s accuracy through better representation capabilities. To date, many methods used in the literature are forward approaches, predominantly used for scenarios requiring precise solutions for differential equations. This results in high computational costs, especially since the order of differential operators significantly influences the computational load [180]. Fortunately, by applying strict constraints derived from low-dimensional physical principles, the network retains interpretability and reliability, helping to discover implicit associations in high-dimensional spaces, and consequently increasing the accuracy of the model.

For future studies on RAC, to overcome the aforementioned challenges, we believe that beyond the fundamental improvements to the loss function discussed earlier, the application of PINN methods to RAC should consider the following enhancements:

• Since the performance of RAC exhibits strong age dependence, explicit temporal causal constraints can be incorporated [181]. By refining the residual loss function to address multi-scale evolution, this approach may help reduce prediction error.

• Through dimensional analysis, methods such as autoencoders and the Buckingham π theorem [182–184] can be employed to compress the feature space of existing RAC data samples. This would improve dimensional consistency in RAC mixture design data and mitigate the sparsity issue.

• Given that RAC mixture design involves numerous microscopic chemical reactions [119], prior constraints based on chemical information can be incorporated, building upon existing theories of concrete hydration.

6.5 Advanced Data-Driven Methods to Mitigate Data Dependency: Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

Generative adversarial networks (GANs) [191] in Fig. 13 have emerged as a groundbreaking approach in the field of artificial intelligence and machine learning. Introduced by Ian Goodfellow and his colleagues in 2014, GANs have made substantial advances in disciplines such as image processing [192], signal processing, and medical applications [193]. Chen et al. [194] used GAN to augment a dataset of concrete incorporating industrial waste, expanding the original 1030 samples to 50,208 and raising the predictive accuracy of a 1D CNN from 0.83 to 0.96, which corresponds to a relative gain of about 15.7%. Liu et al. [195] applied a GAN to FRP specimens, increasing the dataset from 287 to 576 samples and improving prediction accuracy by 1.3%. Zhang et al. [196] used a GAN to augment a dataset of rectangular concrete filled steel tube specimens from 1003 to 51,003 samples, achieving a 17.1% increase in predictive accuracy. These successful applications indicate that GAN methods are promising for various types of RACs. As reported in [197], the mean experimental sample size per RAC study was 36, with a minimum of 2 samples, whereas specific RAC’s data remain exceedingly scarce.

Figure 13: Standard GAN data augmentation framework

In a standard GAN model, the discriminator D optimises the Jensen-Shannon divergence, and the objective function is as follows:

Achieved through optimising the Jensen-Shannon (JS) divergence, the process involves the following:

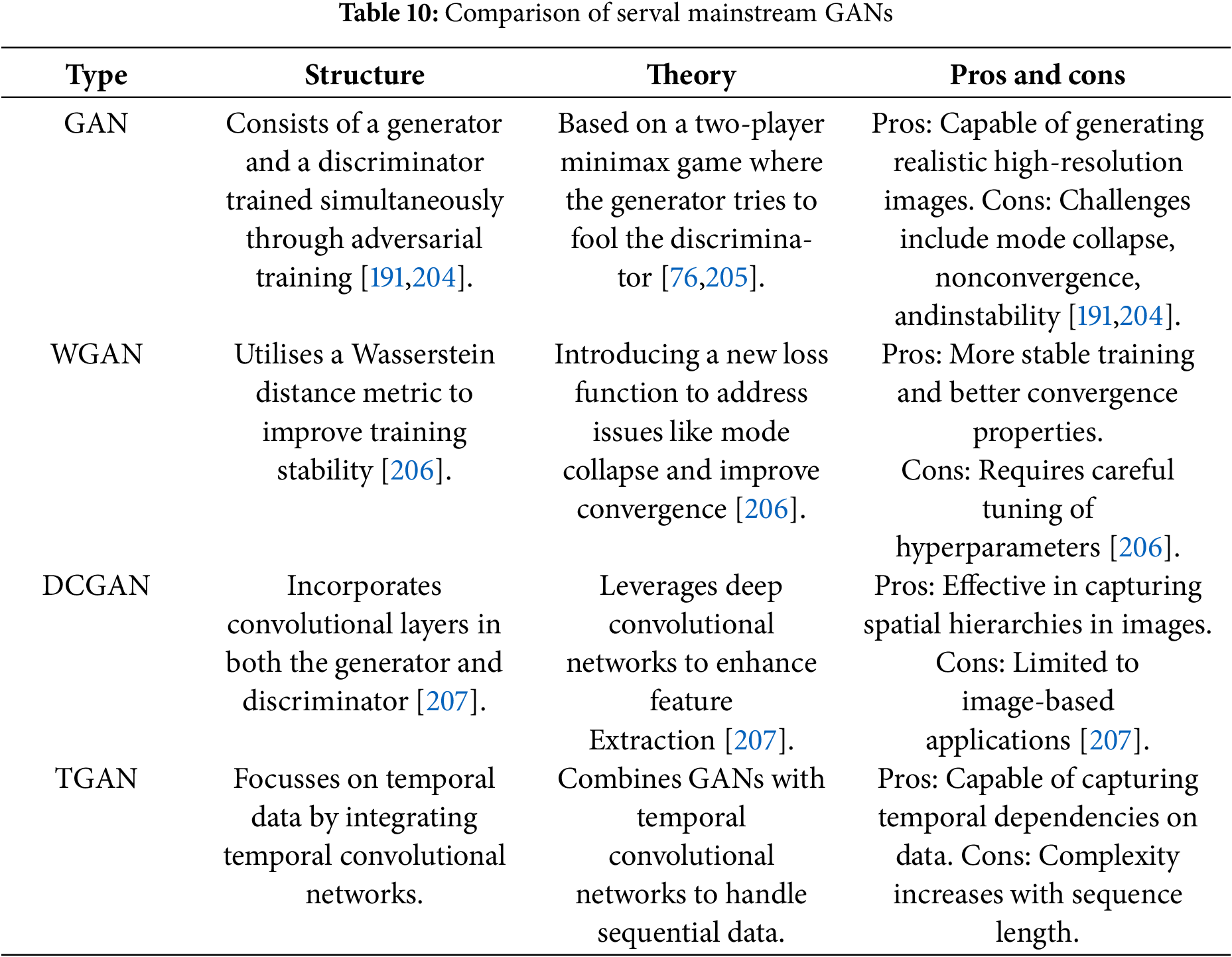

GANs fundamentally consist of two main components: a generator and a discriminator. The generator’s objective is to produce data indistinguishable from real data, while the discriminator’s role is to differentiate between real data and generated data. These two neural network modules compete against each other until the discriminator can no longer distinguish between real and generated data [198]. This Fig. 13 illustrates the process of generating new data for RAC using a standard GAN framework. In this setup, random seeds serve as noise inputs to the generator, which continuously outputs generated data to the discriminator. The discriminator then evaluates the data, identifying discrepancies between generated and real RAC data. The process iterates until the discriminator can no longer distinguish between real and generated data, at which point synthetic data samples are output. Different models for the generator and discriminator result in various GAN variants. Among these, some of the most widely recognized and accepted derivative models include TGAN, WGAN, and DGAN.

6.5.1 Temporal Generative Adversarial Network (TGAN)

TGAN is a type of GAN model specifically designed to handle time-series data [199]. It integrates Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCN) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) to effectively capture patterns and dependencies within time-based data. However, TGAN has high computational resource requirements and may encounter difficulties in capturing complex patterns during training.

The Wasserstein distance is used to measure the difference between real and generated data:

WGAN uses the Wasserstein distance [200] as a replacement for the Jensen Shannon (JS) divergence to measure the gap between generated data and real data, thus improving the stability problems commonly observed in traditional GAN training [201]. This approach helps to reduce the problem of vanishing gradients during training and enhances the quality of the generated samples. The optimisation objective for WGAN is expressed as follows:

6.5.3 Deep Convolutional GAN (DCGAN)

DCGAN (Deep Convolutional GAN) improves image generation quality by incorporating convolutional and deconvolutional layers and introducing conditional vectors to generate images under specific conditions. It shows excellent performance in image generation tasks [202] and is well suited for conditional image generation. However, DCGAN is prone to mode collapse, where the generator produces limited types of output and fails to capture the diversity of the data distribution.

GAN models approximate the original data distribution in a broader way, making data generated from these models more effective for training with improved generalisation performance and enhanced sample diversity [203]. Such methods, combined with appropriate experimental designs, can reduce the need for creating physical experimental samples, thereby lowering experimental costs and carbon emissions.

In Table 10, we present a summary comparison and schematic illustrations of the model architectures for various main adversarial neural networks.

6.6 Analysing the Development and Optimisation of GANs from Network Architecture, Training Differences, and Mode Collapse

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), introduced as a core technology for generative modelling, achieve data generation through an adversarial process between a generator and a discriminator. However, standard GANs face numerous training challenges, including selection of network architectures, disparities in optimisation methods, and the problem of mode collapse [208]. As GANs have evolved, various improved models [208] have been proposed to address these issues from different angles, resulting in more stable and efficient generation performance. The following discussion focusses on the optimisation strategies of GAN and its variants (WGAN, LSGAN) from three perspectives: network architecture, training differences, and mode collapse.

6.6.1 Improvements and Optimisation in Network Architecture

The standard GAN architecture typically uses simple fully connected layers for both the generator and the discriminator. Although this basic structure can be applied to various tasks, it becomes limited when dealing with complex data distributions, particularly for high-dimensional image data, where gradient vanishing often occurs [204]. Improved models such as DCGAN incorporate convolutional layers, in conjunction with techniques such as residual connections and batch normalisation, to better capture local features in both the generator and the discriminator, significantly improving the quality of generated samples [207].

Likewise, WGAN refines the discriminator structure by replacing it with a ‘critic’ and adopting a weight-clipping or gradient penalty to constrain the output range [200], thus measuring the divergence between data distributions more effectively. In addition, LSGAN focusses on minimising the mean-squared error between generated data and real data, enabling the generator to produce a broader distribution of outputs more smoothly. From the perspective of network design, the adjustment of the number of layers, activation functions, and regularisation methods according to specific tasks remains a crucial direction for optimising GAN models.

6.6.2 Training Differences and Optimisation Effects

At its core, GAN training involves adversarial optimisation between the generator and the discriminator. Standard GANs are based on cross-entropy loss, which can quickly saturate the discriminator loss if the generator does not capture the real data distribution in an early stage, causing vanishing gradient. By introducing the Wasserstein distance instead of the Jensen–Shannon divergence [200], WGAN provides stable gradient signals, allowing effective optimisation even when the generator is undertrained. Furthermore, the gradient penalty technique in WGAN-GP further stabilises the training by imposing constraints on the gradient of the critic.

In contrast, LSGAN employs the least squares loss that reduces the discriminator’s binary ’true/false’ extremes, helping mitigate common oscillation issues during training through smoother loss feedback. In practical applications, adjusting the learning rate and optimiser parameters, combined with increasing data diversity, can all contribute to more stable GAN training outcomes. Some studies [209,210] have demonstrated that minimising Pearson divergence exhibits more robust performance compared to standard GANs, particularly when penalty terms (GP) are introduced. This approach performs better in mitigating the disappearance of the gradient during the training phase [210].

LSGAN in [209] demonstrates low FID scores of 21.55 and 14.28 for LSUN and Cat datasets, showing superior performance on low-complexity datasets. It uses mean squared error to reduce gradient oscillations, aiding generator learning. However, LSGAN−110 struggles with high-complexity datasets like ImageNet, with a higher FID score of 68.95 compared to WGANs-GP’s 62.05. WGANs-GP excels in complex datasets like ImageNet and CIFAR10, with FID scores of 62.05 and 40.83, due to Wasserstein distance optimization for stable gradients. Conversely, NS-GANs show high FID scores across datasets, with 28.04 on LSUN and 74.15 on ImageNet [210].

Standard GANs often produce low-quality samples and unstable training, particularly with complex or imbalanced data, due to vanishing gradients and mode collapse. Dataset complexity largely determines which variant performs better. LSGAN performs well on simpler datasets such as LSUN and Cat because its least-squares loss smooths training. WGAN-GP is preferable for complex datasets such as ImageNet and CIFAR-10 because the Wasserstein objective handles intricate distributions more effectively. As a rule of thumb, choose LSGAN for low complexity and WGAN-GP for high complexity. Future work could combine their strengths by adding a Wasserstein term to the LSGAN loss and by using data augmentation and self-supervised learning to improve LSGAN on complex data.

6.6.3 The Mode Collapse Problem

Mode collapse is a well-known issue in GAN training, wherein the generator produces only a single mode (or a few modes) of output, failing to adequately cover the true data distribution. This issue is particularly salient when applied to datasets such as RAC. In standard GANs, mode collapse often arises from the complexity of the data distribution and the imbalanced training between the generator and the discriminator. A straightforward but crude solution is to reinitialize network weights, which, however, discards valuable training information. By providing continuous feedback based on the Wasserstein distance, WGAN can substantially reduce the occurrence of mode collapse [200,206]. Meanwhile, LSGAN addresses this challenge by modifying the loss function to encourage the generator to produce more diverse samples. Other strategies, such as increasing the diversity of training data, introducing regularisation techniques (L1 & L2) [134], and designing task-specific network architectures, can also alleviate mode collapse to varying degrees.

7 Recommendations for Future Research

• Unified baseline integrating physical, chemical, and dimensional constraints. Set this workflow before training and evaluation. In PINNs, enforce dimensional homogeneity for dosage variables and apply π-theorem–based analysis to keep variables and loss terms physically consistent [182–184].

• Mechanistic priors with white box models. Use RAC microchemical priors to strengthen chemical constraints [119,211]. Embed white box physical models as differentiable priors in the PINN loss as shown in Fig. 14 from tree based regularization, symbolic regression, and sparse regression, and optimize a mechanism term plus a data residual to improve interpretability and transferability [102,110,212].

• Physically consistent data and augmentation. For GAN-based augmentation, improve generator and discriminator and enforce unit consistency across all variables as in Fig. 14. Use GANs to strengthen latent representations, reduce data dependence, and enhance smoothness and robustness. Emphasize experiments and develop a unified reproducible large scale RAC dataset to raise generalization and comparability.

• Causal and residual oriented objectives and evaluation. Add causal relations and residual terms to the loss and tailor it to the empirical distribution. Begin modeling after the above preparations so the model extracts faithful physical patterns on low dimensional manifolds, relies less on post hoc tools such as SHAP and PDP, and gains practical value for engineering use.

Figure 14: Recommendations for future RAC data-driven research

The article reviews key parameters of data-driven models in 35 publicly published studies on RAC, compiles four datasets containing these parameters, reviews 77 data-driven models in related fields, and conducts baseline capability tests on the nine most commonly used models. Combining existing research trends, it discusses a potential advanced method framework for the future in this field, discusses in detail the advantages and existing issues of advanced technologies including multi-objective optimization, physics-informed neural networks, and adversarial neural networks in future applications of data-driven research on RAC, and examines tools for interpreting model parameters, aiming to enhance researchers’ trust in data-driven models and provide valuable insights. The following conclusions can be drawn:

• The key parameters of RAC significantly impact its mechanical properties such as compressive and flexural strength.

• To meet sustainability and environmental needs while ensuring good performance, complex multi-objective optimization methods have been developed, and key influencing factors have been improved during aggregate manufacturing.

• The data-driven model of RAC is moving from single-model predictions of mechanical properties towards more robust, sparse data-tolerant, and more accurate integrated system and hybrid models.

• Tree-based models, particularly XGBoost, have demonstrated superior performance compared to other models under standardized baseline testing and cross-validation.

• Generative adversarial neural networks and physics-informed neural methodologies possess substantial potential for application in the simulation and verification of optimal mix design models and in addressing various inverse problems associated with RAC, especially in scenarios characterized by data insufficiency.

• Numerous advancements in GAN architectures have led to enhanced performance. In the pursuit of data-driven research on RAC, it is imperative to employ these methodologies selectively, contingent upon the dataset available.

• Empirical investigations concerning RAC have elucidated principal parameters impacting RAC through the application of SHAP and PDP methodologies, thereby augmenting the comprehensibility of variables.

While this study proposes a prospective data-driven framework for RAC, heterogeneity across data sources and potential discrepancies in RAC testing standards remain. Given the absence of a large single-laboratory dataset in this field, expanding the experimental dataset will be necessary to develop more robust data-driven RAC models in the future.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Haoyun Fan: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Methodology, Visualization, Validation. Soon Poh Yap: Conceptualization, Visualization, Methodology, Writing—review & editing, Supervision. Shengkang Zhang: Resource, Data curation. Ahmed El-Shafie: Writing—review & editing, Visualization, Methodology, Supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in [Mendeley data] at [https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/wc898ff5pj/1] (accessed on 24 September 2025). The code that support the findings of this study are openly available in [Google Colab] at [https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1TfxpRMOlps1wp6PqDfBRmXFJMGOz8nuy?usp=sharing;] (accessed on 24 September 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Figure A1: PRISMA flow diagram

References

1. Zhang P, Sun X, Wang F, Wang J. Mechanical properties and durability of geopolymer recycled aggregate concrete: a review. Polymers. 2023;15(3):615. doi:10.3390/polym15030615. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Silva RV, de Brito J, Dhir RK. Establishing a relationship between modulus of elasticity and compressive strength of recycled aggregate concrete. J Clean Prod. 2016;112:2171–86. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.10.064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wang B, Yan L, Fu Q, Kasal B. A comprehensive review on recycled aggregate and recycled aggregate concrete. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2021;171(5):105565. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Corinaldesi V, Moriconi G. Influence of mineral additions on the performance of 100% recycled aggregate concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2009;23(8):2869–76. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2009.02.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Tayeh BA, Al Saffar DM, Alyousef R. The utilization of recycled aggregate in high performance concrete: a review. J Mater Res Technol. 2020;9(4):8469–81. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2020.05.126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Casuccio M, Torrijos MC, Giaccio G, Zerbino R. Failure mechanism of recycled aggregate concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2008;22(7):1500–6. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2007.03.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Revilla-Cuesta V, Skaf M, Faleschini F, Manso JM, Ortega-López V. Self-compacting concrete manufactured with recycled concrete aggregate: an overview. J Clean Prod. 2020;262:121362. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Xing W, Tam VW, Le KN, Hao JL, Wang J. Life cycle assessment of recycled aggregate concrete on its environmental impacts: a critical review. Constr Build Mater. 2022;317:125950. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.125950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Ren Q, Pacheco J, de Brito J. Mesoscale modelling of recycled aggregate concrete: a parametric analysis of properties of mesoscopic phases of RAC. J Clean Prod. 2024;478:143967. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.143967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Pacheco J, de Brito J, Chastre C, Evangelista L. Experimental investigation on the variability of the main mechanical properties of concrete produced with coarse recycled concrete aggregates. Constr Build Mater. 2019;201:110–20. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.12.200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Omary S, Ghorbel E, Wardeh G. Relationships between recycled concrete aggregates characteristics and recycled aggregates concretes properties. Constr Build Mater. 2016;108:163–74. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.01.042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Bui NK, Satomi T, Takahashi H. Improvement of mechanical properties of recycled aggregate concrete basing on a new combination method between recycled aggregate and natural aggregate. Constr Build Mater. 2017;148:376–85. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.05.084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Cheng MY, Chou JS, Roy AFV, Wu YW. High-performance concrete compressive strength prediction using time-weighted evolutionary fuzzy support vector machines inference model. Autom Constr. 2012;28:106–15. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2012.07.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Khan MA, Zafar A, Farooq F, Javed MF, Alyousef R, Alabduljabbar H, et al. Geopolymer concrete compressive strength via artificial neural network, adaptive neuro fuzzy interface system, and gene expression programming with K-fold cross validation. Front Mater. 2021;8:621163. doi:10.3389/fmats.2021.621163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Mohammadi Golafshani E, Behnood A, Hosseinikebria SS, Arashpour M. Novel metaheuristic-based type-2 fuzzy inference system for predicting the compressive strength of recycled aggregate concrete. J Clean Prod. 2021;320:128771. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Arantes RB, Vogiatzis G, Faria DR. Learning an augmentation strategy for sparse datasets. Image Vis Comput. 2022;117:104338. doi:10.1016/j.imavis.2021.104338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Ning Z, Jiang Z, Zhang D. Sparse projection infinite selection ensemble for imbalanced classification. Knowl Based Syst. 2023;262:110246. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2022.110246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Imran H, Ibrahim M, Al-Shoukry S, Rustam F, Ashraf I. Latest concrete materials dataset and ensemble prediction model for concrete compressive strength containing RCA and GGBFS materials. Constr Build Mater. 2022;325:126525. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.126525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Liu KH, Zheng JK, Pacheco-Torgal F, Zhao XY. Innovative modeling framework of chloride resistance of recycled aggregate concrete using ensemble-machine-learning methods. Constr Build Mater. 2022;337:127613. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.127613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Golafshani EM, Behnood A, Kim T, Ngo T, Kashani A. Metaheuristic optimization based- ensemble learners for the carbonation assessment of recycled aggregate concrete. Appl Soft Comput. 2024;159:111661. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2024.111661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Kern C, Klausch T, Kreuter F. Tree-based machine learning methods for survey research. Survey Research Methods. 2019;13(1):73–93. doi:10.18148/srm/2019.v1i1.7395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Paullada A, Raji ID, Bender EM, Denton E, Hanna A. Data and its (dis)contents: a survey of dataset development and use in machine learning research. Patterns. 2021;2(11):100336. doi:10.1016/j.patter.2021.100336. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Mortaz E. Imbalance accuracy metric for model selection in multi-class imbalance classification problems. Knowl Based Syst. 2020;210:106490. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2020.106490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Xu P, Ji X, Li M, Lu W. Small data machine learning in materials science. npj Comput Mater. 2023;9:42. doi:10.1038/s41524-023-01000-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhang Y, Ling C. A strategy to apply machine learning to small datasets in materials science. npj Comput Mater. 2018;4:25. doi:10.1038/s41524-018-0081-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Jain A. Machine learning in materials research: developments over the last decade and challenges for the future. Curr Opin Solid State Mater Sci. 2024;33:101189. doi:10.1016/j.cossms.2024.101189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Folino P, Xargay H. Recycled aggregate concrete-Mechanical behavior under uniaxial and triaxial compression. Constr Build Mater. 2014;56:21–31. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.01.073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. He ZJ, Zhang JX. Strength characteristics and failure criterion of plain recycled aggregate concrete under triaxial stress states. Constr Build Mater. 2014;54:354–62. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.12.075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Deng Z, Wang Y, Sheng J, Hu X. Strength and deformation of recycled aggregate concrete under triaxial compression. Constr Build Mater. 2017;156:1043–52. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.08.189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Meng E, Yu Y, Yuan J, Qiao K, Su Y. Triaxial compressive strength experiment study of recycled aggregate concrete after high temperatures. Constr Build Mater. 2017;155:542–9. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.08.101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Xu J, Chen Y, Xie T, Zhao X, Xiong B, Chen Z. Prediction of triaxial behavior of recycled aggregate concrete using multivariable regression and artificial neural network techniques. Constr Build Mater. 2019;226:534–54. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.07.155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Golafshani EM, Behnood A. Automatic regression methods for formulation of elastic modulus of recycled aggregate concrete. Appl Soft Comput. 2018;64:377–400. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2017.12.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Miao X, Zhu JX, Zhu WB, Wang Y, Peng L, Dong HL, et al. Intelligent prediction of comprehensive mechanical properties of recycled aggregate concrete with supplementary cementitious materials using hybrid machine learning algorithms. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2024;21:e03708. doi:10.1016/j.cscm.2024.e03708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Fan H, Zhang S. Design of mechanical strength, creep, and triaxial shear of recycled aggregate concrete—data-driven method database. Mendeley Data. 2024;V1. doi:10.17632/wc898ff5pj.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Koenders EAB, Pepe M, Martinelli E. Compressive strength and hydration processes of concrete with recycled aggregates. Cem Concr Res. 2014;56:203–12. doi:10.1016/j.cemconres.2013.11.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Zhu L, Zhao C, Dai J. Prediction of compressive strength of recycled aggregate concrete based on gray correlation analysis. Constr Build Mater. 2021;273:121750. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]