Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

AI-Powered Digital Twin Frameworks for Smart Grid Optimization and Real-Time Energy Management in Smart Buildings: A Survey

1 Department of Civil Engineering, University of Texas at Arlington, Arlington, TX 76019, USA

2 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Houston, Houston, TX 77004, USA

3 College of Arts and Letters, School of Art, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, FL 33431, USA

4 Faculty of Industrial Engineering, Urmia University of Technology, Urmia, 57169-31557, Iran

5 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Florida International University, Miami, FL 33174, USA

6 Department of Electrical and Computer Science, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, FL 33431, USA

* Corresponding Author: Mohsen Ahmadi. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Innovative Computational Models for Smart Cities)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(2), 1259-1301. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.070528

Received 18 July 2025; Accepted 30 September 2025; Issue published 26 November 2025

Abstract

The growing energy demand of buildings, driven by rapid urbanization, poses significant challenges for sustainable urban development. As buildings account for over 40% of global energy consumption, innovative solutions are needed to improve efficiency, resilience, and environmental performance. This paper reviews the integration of Digital Twin (DT) technologies and Machine Learning (ML) for optimizing energy management in smart buildings connected to smart grids. A key enabler of this integration is the Internet of Things (IoT), which provides the sensor networks and real-time data streams that fee/d DT–ML frameworks, enabling accurate monitoring, forecasting, and adaptive control. Through this synergy, DT–ML systems enhance energy prediction, occupant comfort, and automated fault detection, while also supporting broader sustainability goals. The review examines recent advances in DT–ML energy systems, with attention to enabling technologies such as IoT sensor networks, building energy management systems, edge–cloud computing, and advanced analytics. Key challenges including data interoperability, cybersecurity, scalability, and the need for standardized frameworks are critically discussed, along with emerging solutions such as federated learning and blockchain. Special focus is given to human-centric digital twin frameworks that integrate user comfort and behavioral adaptation into energy optimization strategies. The findings suggest that DT–ML integration, enabled by IoT sensor networks, has the potential to significantly reduce energy consumption, lower operational costs, and improve resilience in urban infrastructures. The paper concludes by outlining future research priorities, including decentralized learning models, universal data standards, enhanced privacy protocols, and expanding digital twin applications for distributed renewable energy resources.Keywords

The increasing trend of urbanization, with forecasts suggesting that by 2050, 70% of the world population would inhabit urban areas, highlights the critical necessity for sustainable and efficient energy systems in cities [1]. Buildings, encompassing residential, commercial, and industrial structures, are significant contributors to urban energy consumption, constituting over 40% of overall energy consumption and a significant portion of greenhouse gas. This substantial energy footprint necessitates innovative approaches to optimize energy usage, enhance occupant comfort, and contribute to environmental sustainability [2,3]. Recent breakthroughs in digital technologies have brought Digital Twin (DT) virtual counterparts of physical items that enable real-time monitoring, modeling, and optimization of systems [4,5]. In the realm of smart buildings, DTs facilitate the amalgamation of Internet of Things (IoT) sensors, Building Energy Management Systems (BEMS), and data analytics to formulate dynamic models that represent the building’s operational condition. These models provide a basis for educated decision-making, predictive maintenance, and energy optimization methods [6,7]. Simultaneously, Machine Learning (ML) methodologies have arisen as potent instruments for scrutinizing intricate datasets, discerning patterns, and generating predictions. In the context of building energy systems, Algorithms can analyze data from diverse sources, including occupancy sensors, weather forecasts, and energy meters, to enhance the efficiency of heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) operations, lighting, and other energy-consuming processes [8–12]. The integration of DTs and ML in smart buildings presents a significant opportunity for attaining energy efficiency and environmental objectives [13,14]. Data trees offer the structural foundation for data integration and system modeling, whereas ML techniques augment analytical skills, facilitating adaptive and predictive control mechanisms [15]. This collaboration enables the creation of sophisticated energy management systems that can react to real-time conditions, predict future demands, and enhance resource efficiency [16–18]. While the prospective advantages, the incorporation of DTs and ML in intelligent edifices poses numerous problems. Issues related to data interoperability, cyber-security, scalability, and the need for standardized frameworks hinder the widespread adoption of these technologies. Addressing these challenges requires a multidisciplinary approach, encompassing technological innovation, policy development, and stakeholder collaboration [19–23].

In addition to the role of DT and ML in enhancing building energy efficiency, these technologies are increasingly viewed as integral components of smart grid ecosystems, enabling bi-directional energy flows and the integration of renewable resources. Addressing challenges such as interoperability, cybersecurity, and privacy is critical, and emerging approaches such as federated learning, blockchain, and edge computing are beginning to offer promising solutions. This review paper provides a thorough examination of the combination of ML and DT technologies in smart grid systems to enhance energy consumption efficiency in smart buildings. The major contributions of this study are as follows:

• This study identify specific challenges in smart grids including energy distribution inefficiencies, grid stability issues, and renewable energy integration and discusses how DT and ML can provide concrete solutions for improving efficiency and reliability. Unlike prior reviews, we emphasize the role of decentralized learning and edge-based decision-making as emerging strategies to tackle these challenges.

• The progression of smart grid and DT technologies is traced, highlighting their development from simple monitoring tools to intelligent, real-time optimization platforms. This evolution is framed as a foundation for the future integration of AI-powered DT frameworks in urban energy systems.

• Critical enabling technologies such as IoT sensor networks, advanced metering, and communication systems are examined, with a conceptual mapping that shows how these technologies can be integrated with ML techniques to optimize energy use and enhance building automation. This mapping offers a systematic perspective that has not been explicitly synthesized in prior works.

• A structured framework is introduced to demonstrate how DTs and ML jointly support real-time monitoring, predictive maintenance, energy forecasting, and optimization across both grid and building systems, with an emphasis on extending these capabilities through human-centric frameworks that address occupant comfort and behavioral adaptation.

• Beyond the synthesis of existing studies, underexplored gaps are identified in data interoperability, cybersecurity, scalability, and privacy protocols. Targeted future research directions are proposed, including the development of universal data standards, federated and decentralized learning models, and adaptive frameworks for managing distributed renewable energy resources.

• Beyond summarizing existing studies, this review contributes original insights by identifying underexplored gaps in data interoperability, cybersecurity, scalability, and privacy protocols, and by proposing targeted future research directions such as universal data standards, federated and decentralized learning models, and adaptive frameworks for managing distributed renewable energy resources.

Through these contributions, this review aims to provide a holistic understanding of the intersection between Machine Learning, DT technologies, and smart grid systems, offering valuable insights for researchers, practitioners, and policymakers in advancing energy optimization strategies in smart buildings.

The combination of DT technology and ML has emerged as a pivotal study domain in enhancing energy management in smart buildings. Several studies have explored the potential of DTs in enhancing energy forecasting and decision-making processes, particularly in the context of demand response. Xie et al. [24] identified that while DTs hold promise for real-time monitoring and energy optimization, current work in this area remains exploratory, with many applications still in early stages. Similarly, the use of DTs in the energy sector has been shown to significantly enhance real-time energy management and decision-making by improving visualization and monitoring [25]. This ability to visualize energy consumption patterns in real time provides a valuable tool for optimizing energy usage and supporting demand response initiatives.

In line with this, the use of ML models, particularly back-propagation neural networks, has been highlighted as highly effective in forecasting energy consumption within buildings. Muniandi et al. [26] demonstrated that these models, when incorporated into a DT framework, can accurately predict power usage, thereby facilitating more efficient energy management. The efficacy of the back-propagation network in forecasting power consumption of campus buildings highlights the increasing significance of ML in optimizing building energy usage. Furthermore, studies by Abed Almoussawi et al. [27] emphasize AI-driven energy management systems that use predictive analytics for energy forecasting and participation in demand response programs. These AI systems can enhance the sustainability of buildings by anticipating energy demands, reducing reliance on non-renewable energy sources, and ensuring smoother energy distribution during peak demand periods. The forecasting of energy demand has also benefited from advanced techniques such as the Heap Based Optimization with Deep Learning-Based Energy Forecasting (HBODL-EFSG) model, which has been shown to outperform traditional forecasting [28]. This deep learning-based approach offers superior accuracy in predicting energy consumption and can be used to optimize energy distribution and scheduling, improving overall grid stability and reducing energy costs. Similarly, El Husseini et al. [29] applied deep learning models, specifically the Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System with Interval Type-2 Fuzzy Logic (ANFIS-IC), in commercial buildings to forecast energy demand and optimize demand-side management. Their results demonstrated a 33.14% reduction in energy consumption and a 39.22% decrease in energy costs, which illustrates the tangible benefits of using advanced ML models for energy optimization in smart buildings.

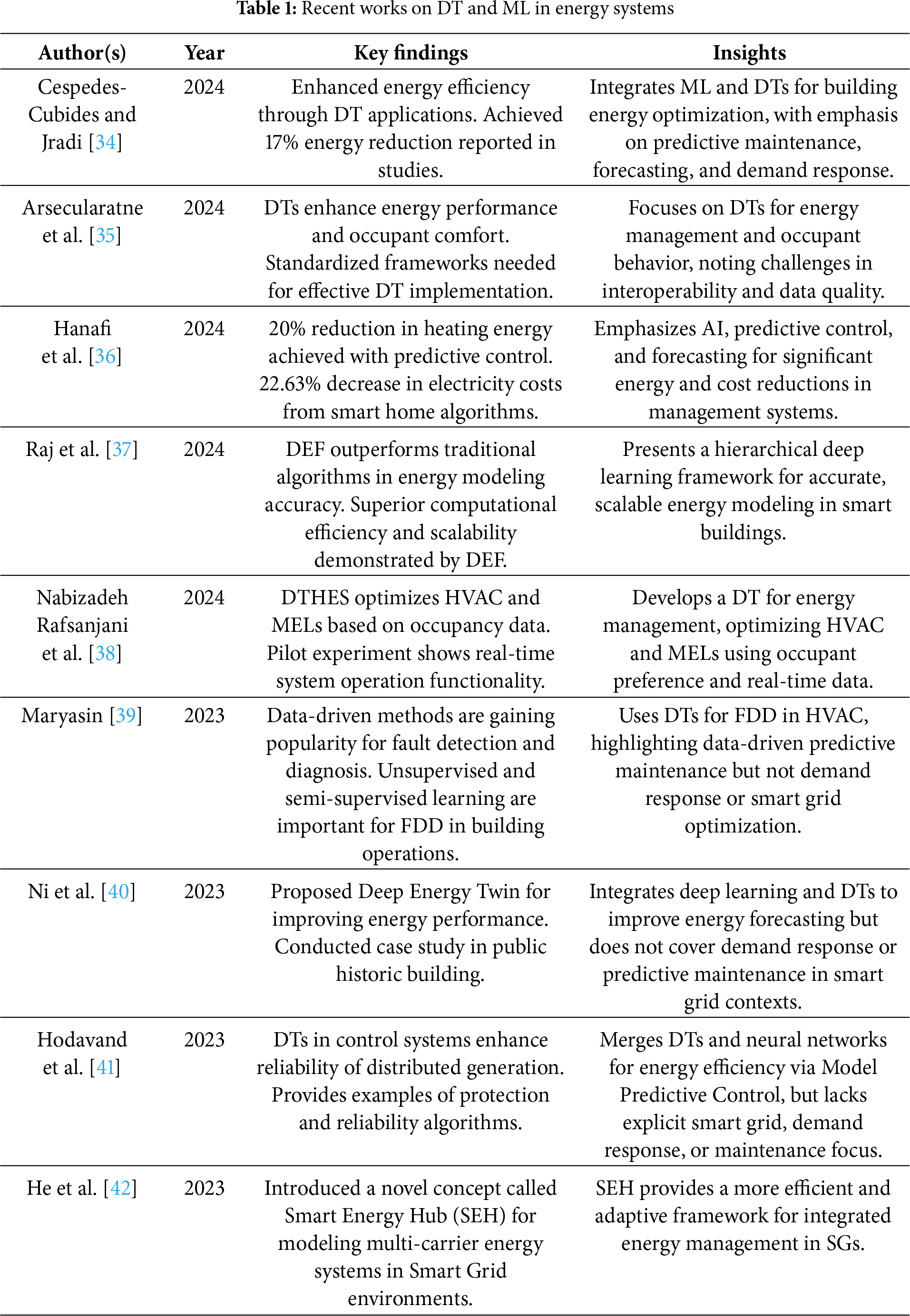

Renganayagalu et al. [30] emphasized the significance of ML in advancing Energy Management Systems (EMS) through improved load forecasting, energy optimization, and predictive maintenance. These systems support demand response and help ensure the efficient use of energy by predicting equipment failures and optimizing operational performance before issues arise. However, challenges such as the integration of various systems, data quality, and ensuring the scalability of these technologies remain significant barriers to full adoption, as noted by several authors. The incorporation of IoT sensors with DT technology has been another key development in optimizing energy performance in buildings. A recent study presented an energy management system for smart grids integrating photovoltaic and battery storage, demonstrating that optimized dynamic control can maintain grid stability and voltage levels within the required range during fluctuations in solar power and storage charge. A study in [31] presented an energy management system for smart grids integrating photovoltaic and battery storage, demonstrating that optimized dynamic control can maintain grid stability and voltage levels within the required range during fluctuations in solar power and storage charge. In addition, the use of multivariate deep neural networks (DNN) has proven effective in integrating heterogeneous IoT data sources for energy forecasting, as illustrated by Antonesi et al. [32]. Their model successfully integrated multiple data points from various IoT sensors in different building types, improving the accuracy of energy consumption predictions. This study illustrates the significance of integrating varied data sources in intelligent building energy systems to improve predictive accuracy and optimize energy use. Meanwhile, Zou et al. [33] showed that Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, a type of recurrent neural network, significantly improve prediction accuracy for energy consumption by capturing long-term dependencies in energy usage patterns. The findings highlight the potential of LSTM networks in handling complex, time-series energy data for more accurate forecasting. Other related studies are provided the Table 1.

Abdelalim et al. [43] demonstrate how combining AI, DT, and Building Information Modeling (BIM) improves facilities management in mega-facilities, reducing energy consumption and maintenance costs while increasing predictive accuracy. Together, these studies illustrate how AI–DT integration benefits both grid-level and building-level management. Building on these insights, the present work reviews DT–ML convergence for smart grid–enabled buildings, focusing on energy optimization, occupant comfort, and sustainable urban development. Jia et al. [44] applied Temporal Graph Convolutional Networks (T-GCN) for short-term PV prediction, capturing spatial and temporal factors with greater accuracy than traditional models. This approach highlights the value of spatiotemporal learning for renewable forecasting in smart grid and DT systems. Zhang et al. [45] proposed a county-level PV day-ahead prediction method combining grey correlation analysis with a Transformer–Graph Convolutional Attention Network (Transformer-GCAN). The model captures both spatial and temporal dependencies among distributed PV stations and showed significant error reduction compared to baseline models, with RMSE improvements of up to 19.6% under varying weather conditions. This approach highlights the value of hybrid deep learning frameworks for large-scale renewable energy forecasting in smart grid applications.

Xin et al. [46] proposed an enhanced temporal convolutional network (TCN) with spatial and attention modules for ultra short-term wind power forecasting. The model outperformed existing methods in accuracy and adaptability, showing the potential of deep learning to improve renewable energy prediction and support reliable grid management. Ge et al. [47] proposed STGATN, a wind speed forecasting method that incorporates geospatial dependency to address randomness and spatial heterogeneity in complex environments. By combining spatiotemporal graph attention networks with self-attention mechanisms, the model effectively captured both spatial and temporal patterns, achieving higher accuracy than conventional single or hybrid models. This approach highlights the potential of spatially informed deep learning methods for improving renewable energy forecasting in diverse geographical conditions. Wang et al. (2025) [48] proposed an improved Differential Mutation Aquila Optimizer (DMAO) for dispatching in hybrid energy ship power systems (HESPS). Their strategy integrates waste heat recovery and thermal energy storage to enhance efficiency while minimizing costs and emissions. Simulation results demonstrated reductions of over 11% in operating costs and nearly 21% in greenhouse gas emissions, showing superior stability and reliability compared to conventional optimization methods. This work illustrates the effectiveness of advanced metaheuristic algorithms in optimizing multi-energy systems for sustainable maritime applications.

All of these studies underscore the transformative potential of integrating DT technology with ML to optimize energy management within smart buildings. The ability to predict energy consumption, optimize energy usage, and manage demand response effectively positions these technologies as critical components of future energy systems. The incorporation of IoT sensors, AI, and specialized ML algorithms demonstrates significant potential; nevertheless, further study is required to tackle current issues concerning data integration, scalability, and real-time decision-making. As these technologies advance, they possess the capacity to markedly enhance the sustainability and efficiency of smart buildings and their energy systems.

3 Progress in Energy Systems with ML and DT Technologies

The integration of ML and DT technologies has sparked significant advancements in energy systems, offering improvements in performance, efficiency, and management across various domains [44–47]. Below, we summarize the key progress made in energy systems leveraging these technologies.

3.1 Enhanced Battery Management in Cyber-Physical Energy Systems (CPES)

An important development in energy systems is the utilization of Temporal Convolutional Neural Networks (TCN) for forecasting battery behavior in CPES. TCNs employ causal and dilated convolutions that enable the model to capture long-term dependencies in time-series data while maintaining stable gradients during training, unlike recurrent neural networks that often suffer from vanishing gradient issues [48]. The use of TCN models allows for more precise predictions regarding battery responses to power setpoint instructions, which is crucial for the effective operation and stability of energy systems. This model improves upon traditional methods, such as relying on historical averages of battery behavior, by utilizing larger time windows to capture relevant patterns. These advancements in predictive modeling not only improve the precision and recall of battery management but also reduce the dependency on detailed battery data, such as type or age, which might otherwise be difficult or sensitive to obtain. As highlighted in recent studies [49–52], TCNs have demonstrated robust forecasting performance in scenarios involving complex charge–discharge cycles, variable load profiles, and fluctuating grid demands. The innovation suggests that a deep understanding of temporal data trends is vital to optimizing battery performance and integrating batteries more efficiently into smart energy systems.

Nevertheless, the deployment of TCNs in real-world energy infrastructures faces several challenges. Large volumes of high-quality data are necessary to ensure generalizable models, and data availability remains inconsistent across different systems. Computational requirements, although lower than some deep recurrent models, can still be demanding for real-time applications if not paired with edge or cloud computing solutions. Furthermore, the adaptability of TCN-based models to heterogeneous battery chemistry, operating conditions, and degradation patterns remains limited. Addressing these issues may require hybrid approaches that combine TCNs with physics-informed constraints or transfer learning techniques, thereby enhancing both robustness and interpretability.

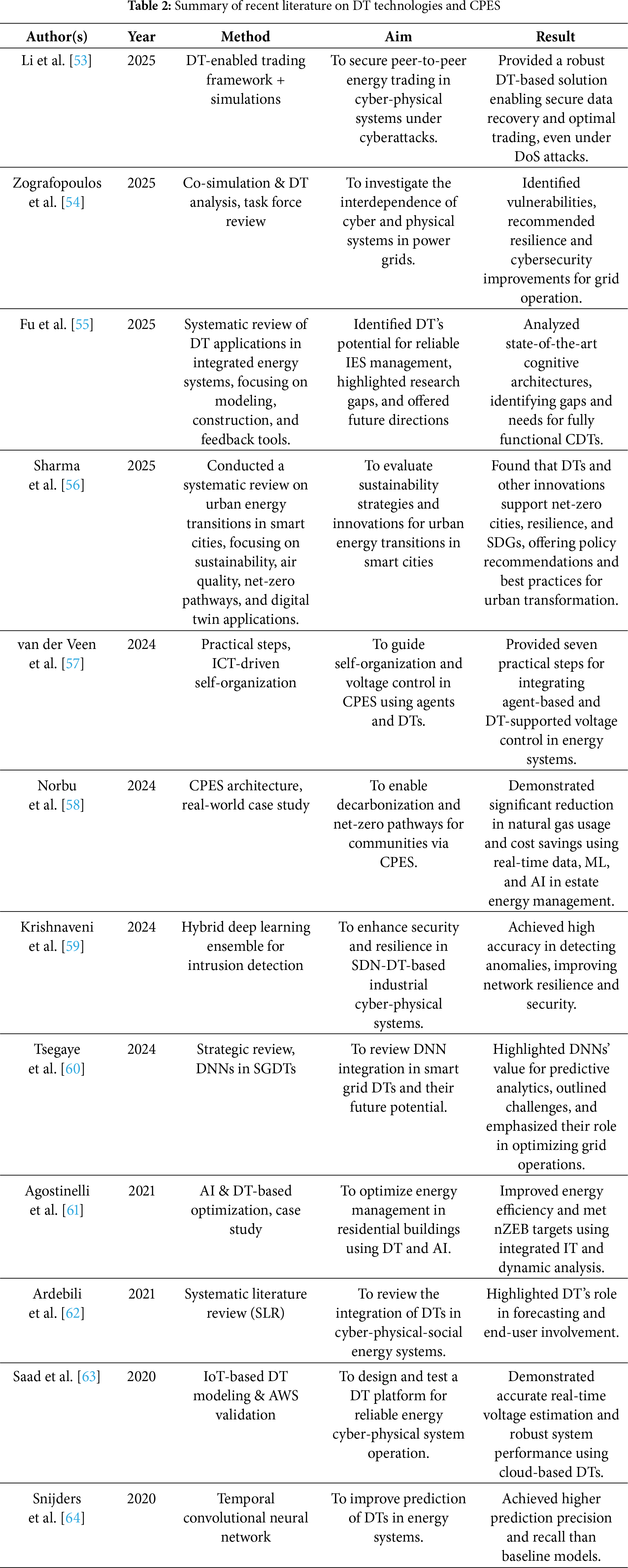

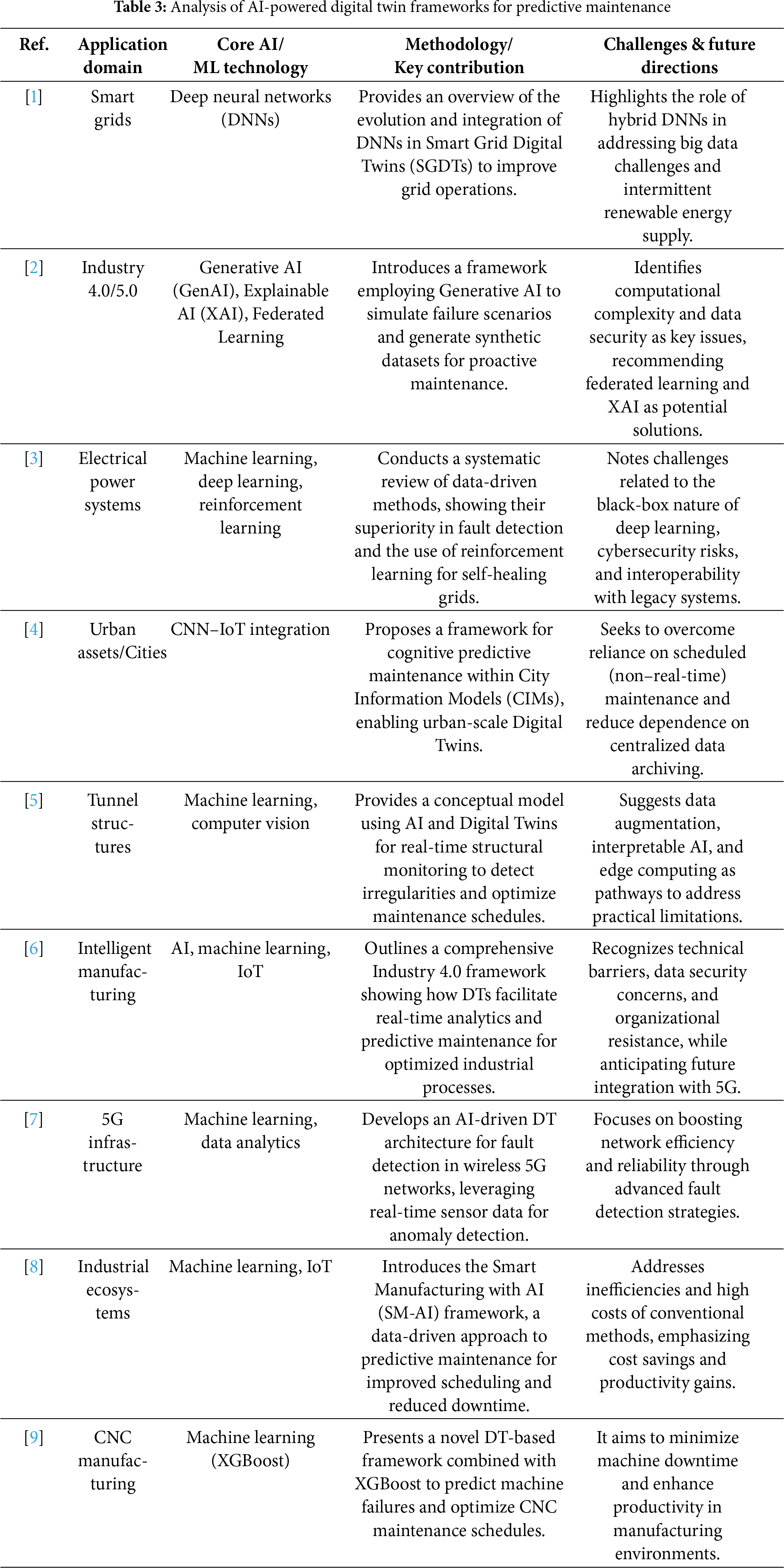

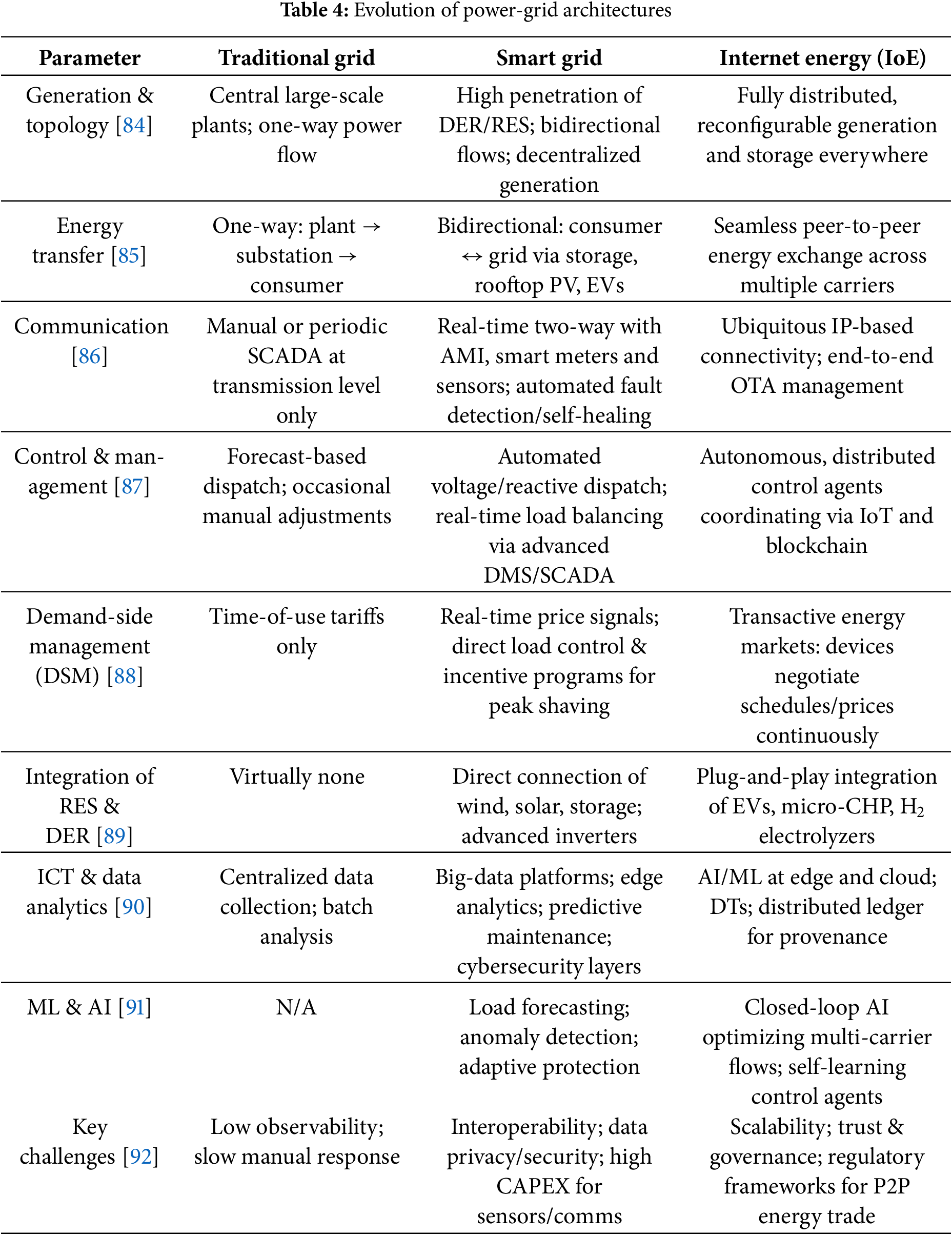

This Table 2 summarizes recent research on DTs and CPES, highlighting each study’s methods, goals, and main findings. The entries show advancements in prediction, security, management, and decarbonization of energy systems using DTs, AI, and related technologies across various applications.

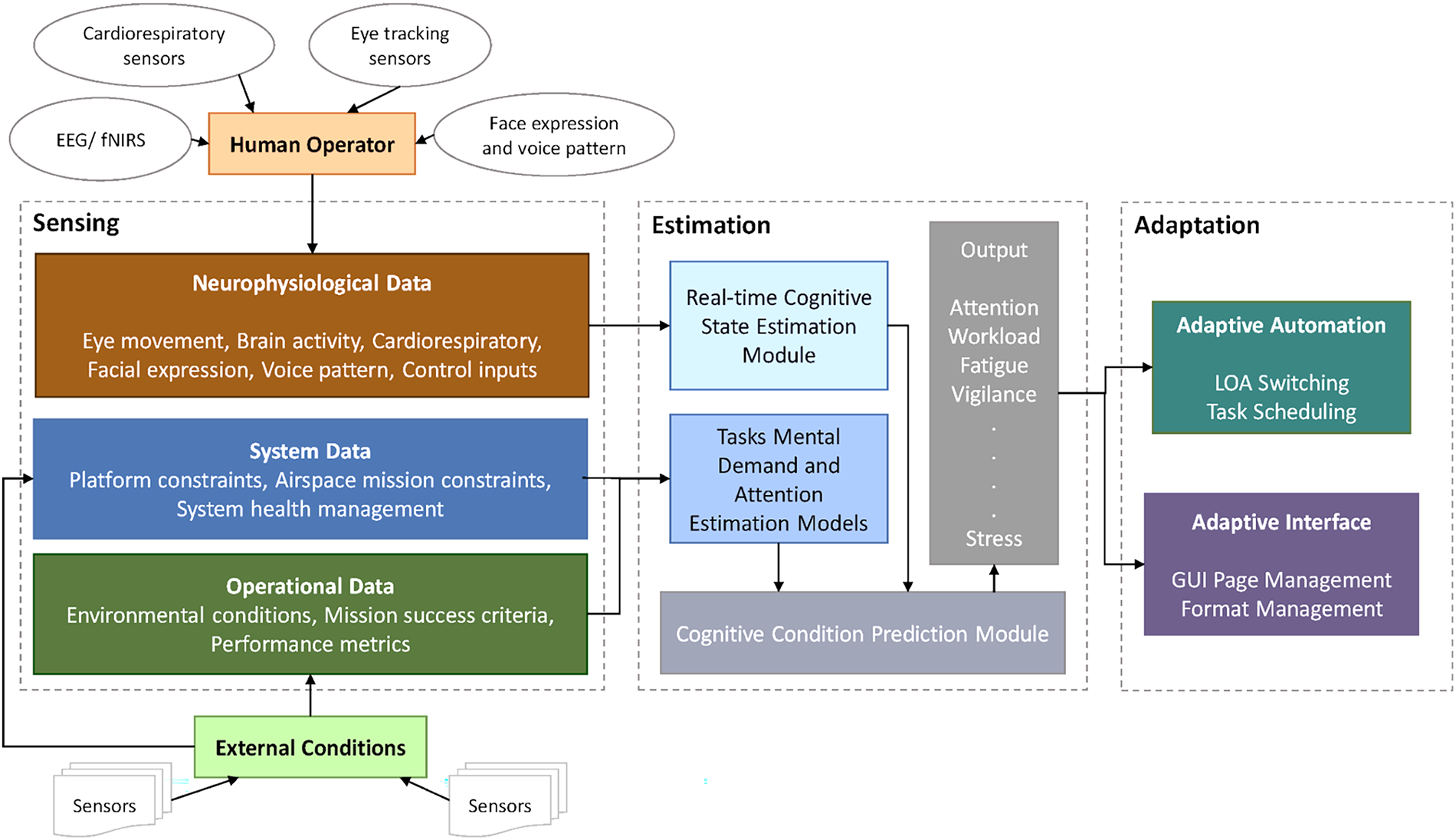

Fig. 1 presents a cognitive adaptation framework for human-machine systems, highlighting the flow from sensing to adaptation. The system begins with multi-modal sensors capturing neurophysiological, system, and operational data from the human operator and external environment. This data is processed in the estimation phase through cognitive state and mental demand models, resulting in real-time outputs such as attention, workload, fatigue, and stress. The adaptation phase utilizes these outputs to dynamically adjust automation levels and user interface features, optimizing system performance and operator support.

Figure 1: Cognitive adaptation system for human-machine interaction, illustrating the process from multi-modal data sensing and real-time cognitive state estimation to adaptive automation and user interface management

3.2 Real-Time Monitoring and Predictive Maintenance with AI and DT

DTs, when coupled with Artificial Intelligence (AI), enable real-time monitoring, predictive maintenance, and remote diagnostics within energy systems. These capabilities are essential for the management of Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) systems, where energy grids or buildings rely on the continuous monitoring of assets. The integration of AI with DT allows for rapid responses to potential issues by simulating the behavior of physical systems in real time, predicting maintenance needs, and preventing failures before they occur [53,54]. By ensuring that the energy systems are constantly optimized, this integration leads to more reliable, sustainable, and cost-effective energy management. The ability to perform predictive maintenance also enhances system longevity and reduces operational costs by addressing potential failures before they escalate into more significant problems.

Table 3 provides a comparative overview of recent research on AI-powered Digital Twin frameworks across diverse application domains, including smart grids, urban infrastructure, intelligent manufacturing, and 5G networks. Each study is categorized by its primary application area, the core AI/ML technologies applied, the methodology or key contributions, and the identified challenges along with proposed future research directions. The table highlights the breadth of AI methods employed ranging from deep neural networks and reinforcement learning to generative AI and explainable AI and shows how these approaches are being leveraged to enable predictive maintenance, real-time fault detection, and system optimization. Collectively, the works summarized in the table underscore both the opportunities of AI-integrated Digital Twins in achieving efficiency, resilience, and scalability, as well as the persistent issues of computational complexity, interoperability, cybersecurity, and organizational adoption that remain open for future investigation.

3.3 Smart Grid Optimization and Demand Response

The application of DTs within smart grids has shown considerable progress in energy distribution and optimization. Through real-time data modeling, DTs provide a virtual image of the physical energy system, facilitating enhanced grid management via sophisticated forecasting and simulation. ML algorithms are integrated into these models to predict and manage energy demand more effectively, reducing grid instability and optimizing energy use. The predictive power of ML allows for better demand response mechanisms, adjusting energy distribution based on predicted consumption patterns. This synergy between DTs and ML in smart grids helps balance energy supply and demand, ensuring efficient energy use while minimizing wastage and grid overloads.

3.4 Energy Management in Smart Buildings

Energy management in smart buildings has undergone significant improvement with the integration of DTs and Machine Learning. These technologies enable the creation of virtual models that simulate the building’s energy consumption and environmental conditions in real time [63–65]. By collecting data from various IoT devices and incorporating advanced forecasting techniques, these models allow for optimized energy usage, occupant behavior modeling, and automation. ML algorithms optimize this process by forecasting energy usage using real-time data, thereby modifying heating, cooling, lighting, and other systems to maximize comfort and energy efficiency. The incorporation of digital technology and ML guarantees that intelligent buildings are both energy-efficient and responsive to tenant requirements, thereby optimizing energy consumption while preserving a comfortable atmosphere [66,67].

3.5 Challenges and Future Directions in DT and ML Integration

Despite the significant advancements made in integrating ML with DT technologies, several challenges remain. The complexity of integrating these systems across heterogeneous energy infrastructures and the scalability of DT models are key areas requiring further research. Additionally, while DTs can provide accurate simulations, the integration with IoT devices and ensuring real-time synchronization of data remains a complex task.

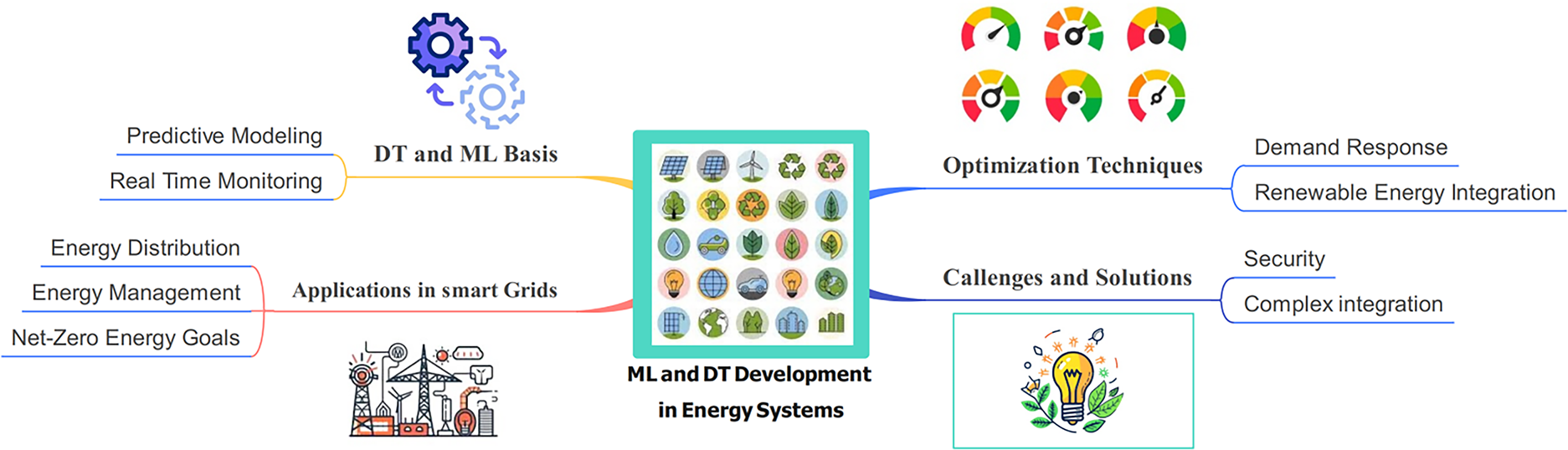

The research underscores the need for ongoing development in data security, ensuring that sensitive energy consumption data is protected while enabling the effective use of real-time information [68–71]. Moving forward, the continued evolution of ML and DT in energy systems must focus on overcoming these challenges, improving the scalability and accuracy of these models, and ensuring that the benefits of these technologies are fully realized in large-scale energy systems (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Different types of progress in energy systems with ML and DT

4 Comprehensive Review of Smart Grids: Challenges and Opportunities

The rapid growth of urban populations and the increasing demand for energy have necessitated significant advancements in electrical grid systems [72]. Traditional grids, designed for unidirectional power flow, are being transformed into smart grids that are more intelligent, responsive, and capable of accommodating the dynamic needs of modern consumers. A fundamental component of this transformation is the integration of IoT, which enables real-time data collection and communication across various grid elements. However, the proliferation of IoT devices introduces substantial security concerns [72,73]. Each connected device represents a potential entry point for cyber-attacks, and the interconnected nature of smart grids means that a breach in one area can have cascading effects throughout the system. The vulnerability of critical infrastructures to cyber threats underscores the importance of implementing robust cyber-security measures. Advanced solutions, such as blockchain-based secure data transmission systems, are being explored to enhance the resilience of smart grids against cyber-physical attacks [74–76].

In parallel with security challenges, the evolution of smart grids presents numerous opportunities to enhance energy management and efficiency. The incorporation of ML and artificial intelligence (AI) into grid operations facilitates predictive maintenance, demand forecasting, and optimization of energy distribution [77,78]. These technologies enable the grid to adapt to real-time conditions, improving reliability and reducing operational costs. Furthermore, the integration of renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind, is more feasible within smart grid frameworks due to their ability to manage variable power inputs effectively [79,80]. However, the successful implementation of smart grids requires overcoming challenges related to interoperability, data standardization, and consumer engagement. Incentive mechanisms, including dynamic pricing and rewards for energy conservation, are essential to encourage active participation from consumers. Facing these obstacles and utilizing the opportunities offered by smart grids can result in more sustainable and efficient energy systems [81–83].

Table 4 highlights the transformation of power-grid architectures from traditional grids to smart grids and finally to the Internet of Energy (IoE). Traditional grids relied on centralized plants, one-way flows, and limited integration of renewables. Smart grids introduced distributed resources, bidirectional flows, real-time communication, and automated control. The IoE envisions a fully decentralized, intelligent, and reconfigurable energy ecosystem enabled by AI, IoT, and blockchain.

5 Introduction and Conceptual Development of DTs

DTs have evolved as revolutionary technology that connects the physical and digital realms, offering a virtual replica of actual systems. The notion of DTs was initially presented as a virtual equivalent to tangible products, enabling real-time data surveillance and analysis for enhanced performance. Over the years, DT technology has advanced and become essential across numerous industries, especially within the context of Industry 4.0, where it is pivotal in the design, development, operation, and maintenance of complex systems [93–95]. A DT is a dynamic virtual model that mirrors a physical asset, system, or process, continuously updated with real-time data from its physical counterpart [96,97]. This bidirectional data exchange allows the virtual model to simulate the behavior of the physical entity, enabling better decision-making, predictive maintenance, and performance optimization. Initially, DTs were primarily used in aerospace and manufacturing industries for system monitoring and maintenance. However, their applications have expanded across sectors such as healthcare, agriculture, intelligent transportation systems, and smart cities, where they contribute significantly to operational efficiency, resource optimization, and predictive insights [98,99].

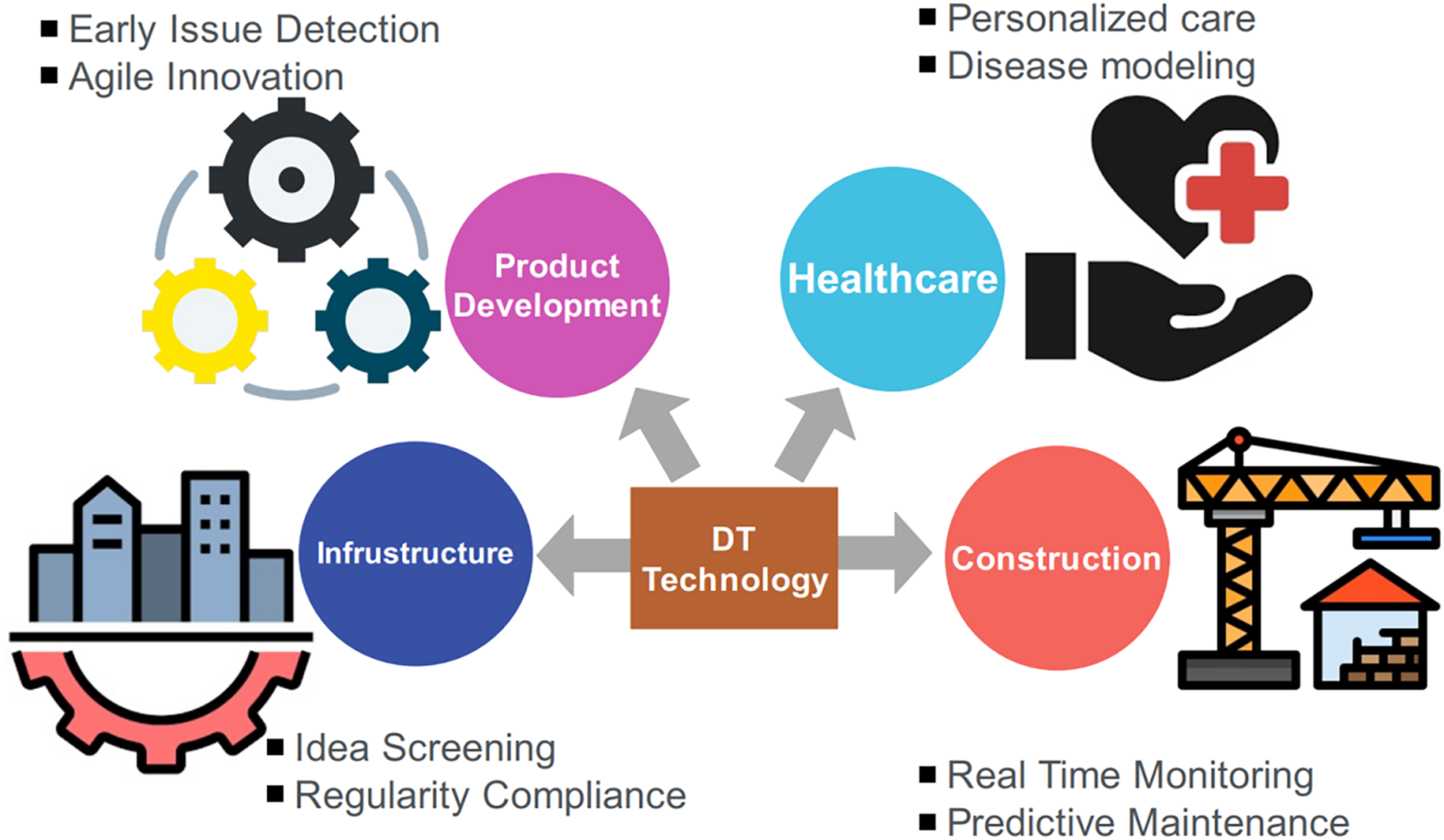

The conceptual development of DTs involves integrating multiple technologies, including the IoT, Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS), and Big Data Analytics, to enable seamless data collection, processing, and decision-making. IoT devices, sensors, and smart systems collect data from the physical environment, which is then fed into the DT model to create real-time virtual representation. The integration of ML and artificial intelligence (AI) further enhances the capabilities of DTs, enabling predictive analytics, optimization, and automation of complex processes [100–102]. The utilization of DTs encompasses the entire lifecycle of products and systems, commencing with the design phase and continuing through real-time operation and maintenance. In the design process, DTs provide virtual testing, design validation, and performance forecasting using real data, enabling the identification of optimal design options. In manufacturing, DTs enhance production processes, resource management, and quality control through continuous monitoring and real-time feedback. DTs facilitate predictive maintenance by evaluating data from physical systems to identify potential faults prior to breakdowns, hence minimizing downtime and maintenance expenses [103–105]. Despite their promise, the full integration of DTs into operational environments faces several challenges, including issues of interoperability, data standardization, and security [106,107]. Fig. 3 visually demonstrates the diverse applications and evolution of DT Technology across four major sectors: product development, healthcare, construction, and infrastructure.

Figure 3: The evolution and application of DT technology

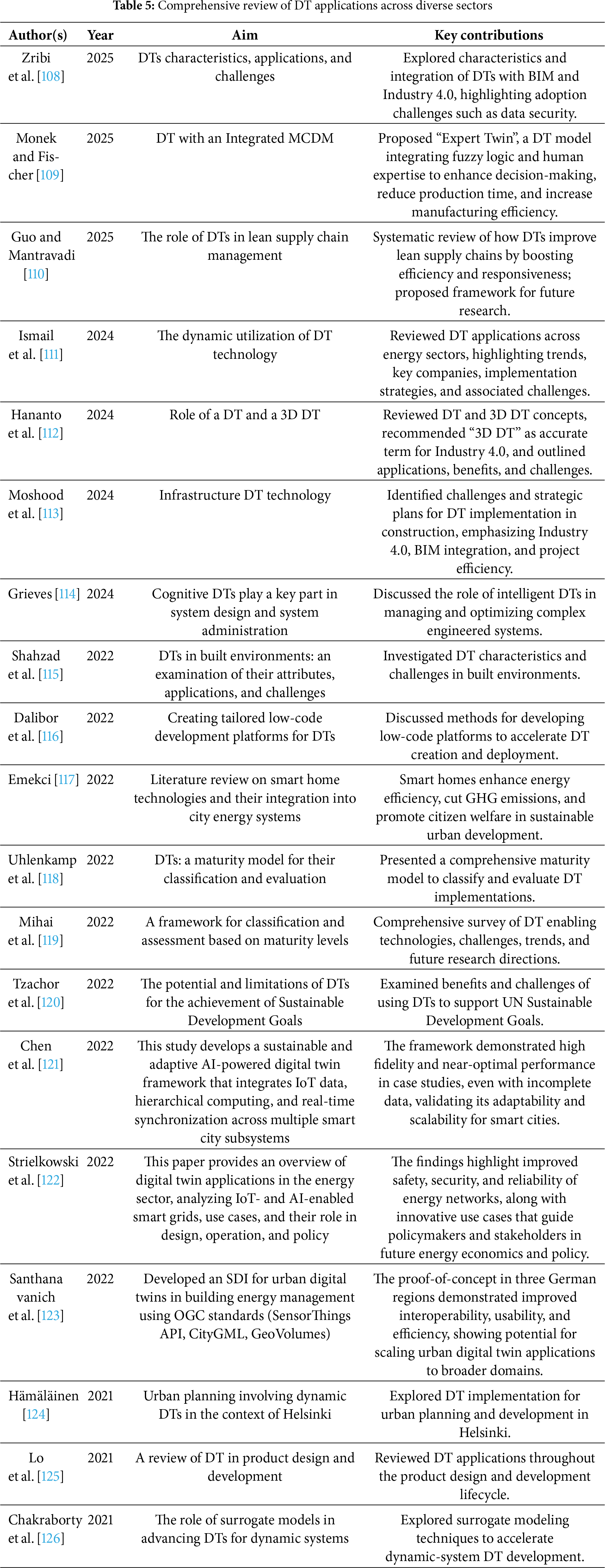

As more industries adopt DTs, the need for scalable, secure, and standardized solutions becomes critical. Table 5 summarizes the main points of studies in DTs. Ongoing research aims to address these challenges by developing frameworks for data integration, improving the accuracy of predictive models, and ensuring secure communication channels between the physical and digital systems. The future of DT technology holds vast potential for advancing not only manufacturing and industrial operations but also various other fields, enhancing sustainability, efficiency, and innovation across sectors.

6 Emergence and Growth of ML in Energy Systems

The application of ML in energy systems has experienced rapid evolution, driven by increasing complexity and demand for more efficient, sustainable, and resilient energy infrastructures. As the energy sector faces growing challenges such as integrating renewable energy sources, managing fluctuating energy demands, and ensuring grid reliability, traditional approaches often struggle to keep up. In this context, ML techniques have become indispensable tools for addressing these challenges, providing solutions that enhance decision-making processes, optimize energy production, and improve overall grid management [127,128].

Over the past decade, the emergence of advanced ML models has led to transformative changes in energy systems. One of the key factors propelling this growth is the increasing availability of large-scale data generated by smart meters, sensors, and advanced monitoring technologies deployed across energy grids. This wealth of data, when analyzed using ML algorithms, can uncover patterns and trends that were previously difficult or impossible to detect. By leveraging historical data and real-time inputs, ML models are now capable of making accurate predictions about energy demand, renewable energy generation, and even equipment failure, which was once a major challenge for energy operators [129,130].

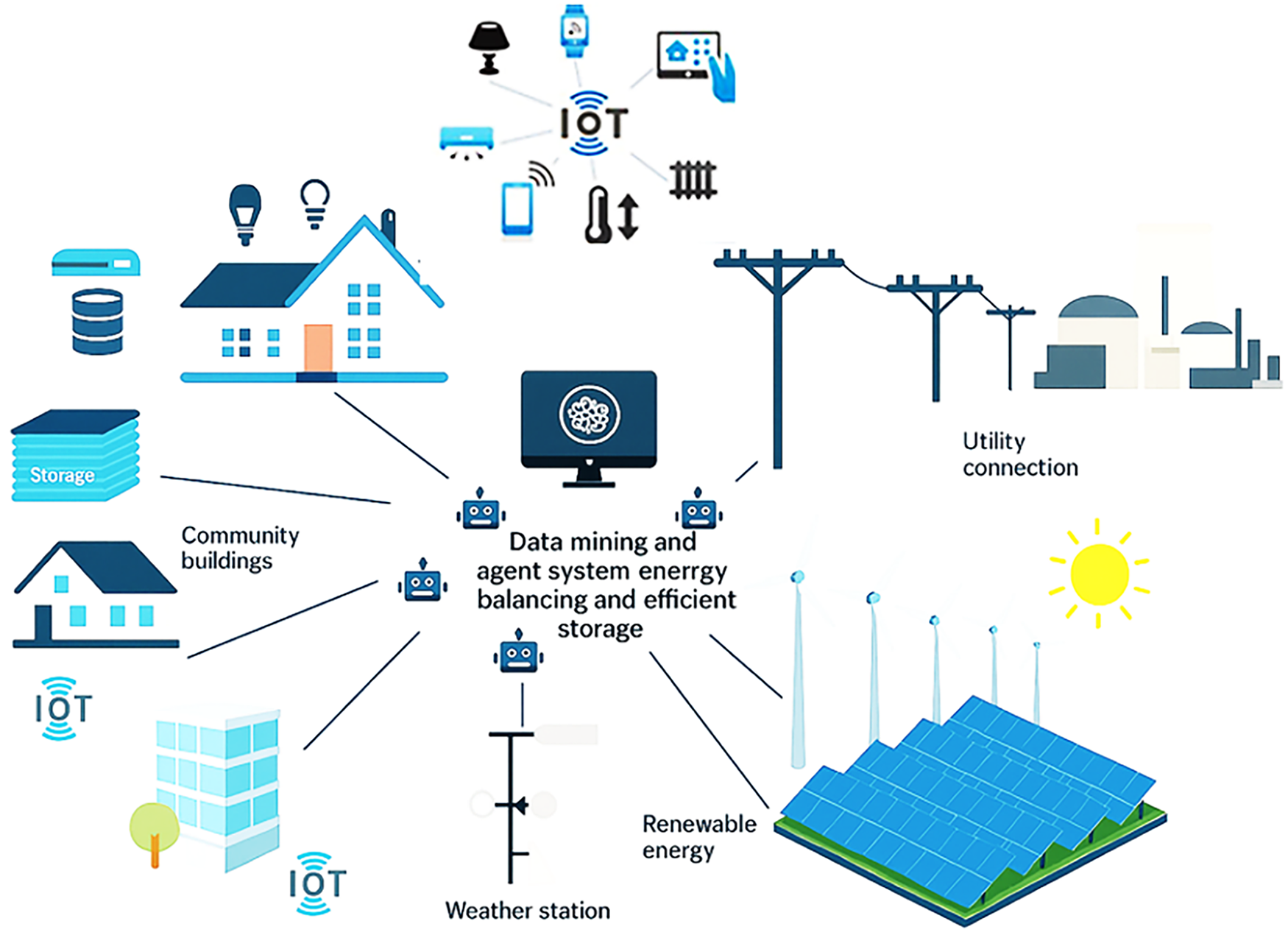

Fig. 4 illustrates a modern smart energy ecosystem where data mining and intelligent agent systems enable energy balancing and efficient storage across diverse community assets. The diagram highlights interconnected community buildings, renewable energy resources (solar and wind), utility connections, weather stations, and storage units, all linked through IoT technology. Real-time data from these sources is collected and processed by a central intelligent system, supporting advanced monitoring, optimization, and decision-making for energy management. Additionally, the incorporation of renewable energy sources, including solar and wind, and hydro has added layers of unpredictability to power generation, making grid management more complicated. Traditional forecasting methods struggled to keep up with the intermittency and variability inherent in renewable generation. However, ML has revolutionized energy forecasting by using complex models that can process vast amounts of environmental, historical, and operational data to predict energy production from renewable sources with much higher accuracy. This not only aids in better grid integration but also improves the efficiency of energy storage and dispatch systems [131–133].

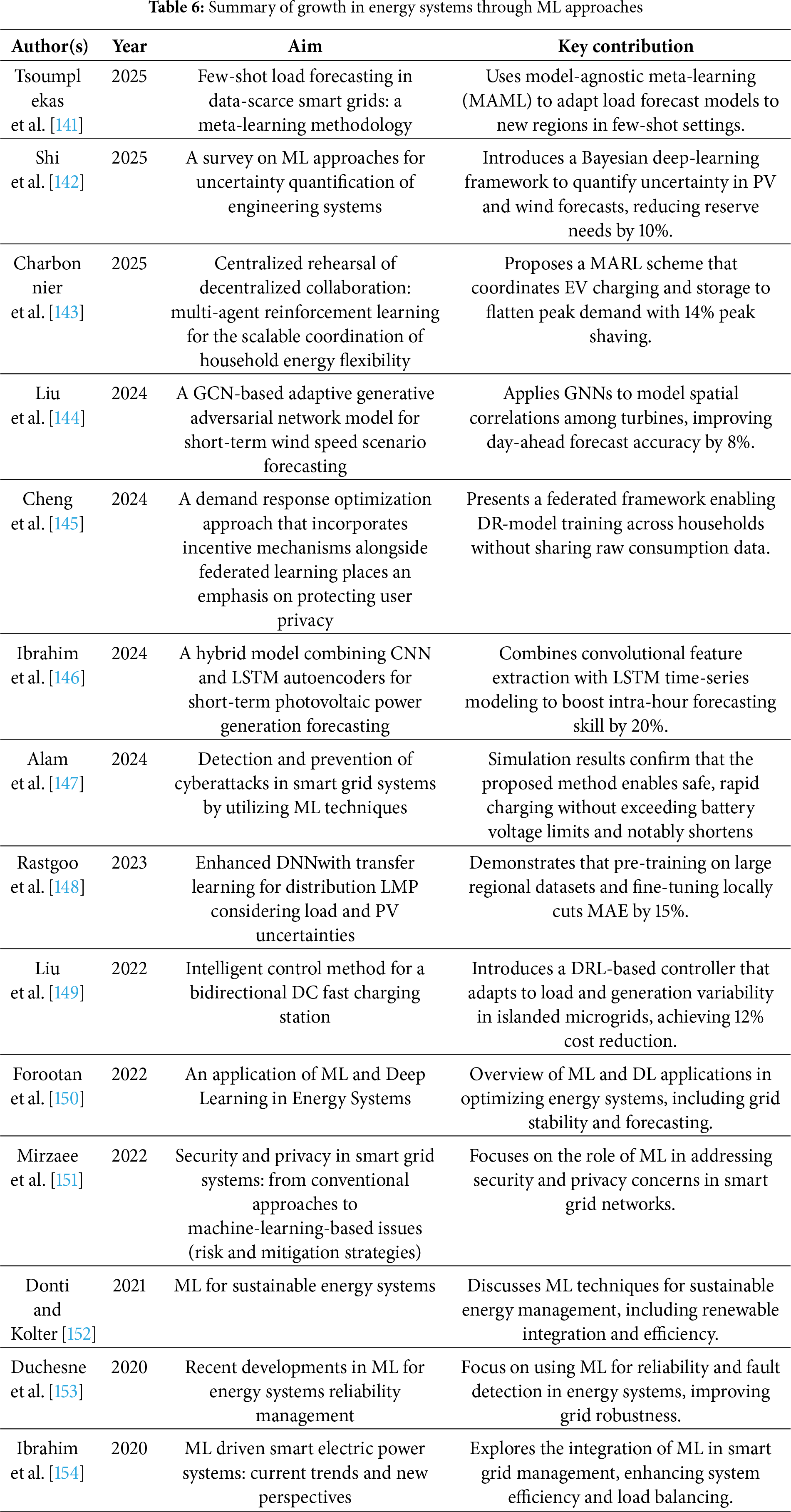

Figure 4: Schematic of a smart energy management system integrating data mining, intelligent agents, IoT devices, and renewable energy for real-time energy balancing and storage

In parallel, as the energy sector pivots toward sustainability, ML technologies are playing a critical role in optimizing energy consumption and reducing carbon footprints. By using machine learning, utilities can tailor energy usage patterns to reduce waste, balance loads, and even predict the need for preventive maintenance in real-time, resulting in operational cost savings and improved system reliability [134,135]. Energy management systems powered by ML are increasingly used to automatically adjust energy consumption based on predictive models, further promoting energy conservation and minimizing environmental impact. The rapid expansion of ML in the energy sector is also evident in the rise of smart grids and their ability to autonomously respond to changing conditions [136]. These grids depend on real-time data from multiple sources, including distributed energy resources and sensors, and employ ML to forecast future energy consumption, identify abnormalities, and enhance resource allocation [137]. Moreover, reinforcement learning, a branch of machine learning, has demonstrated notable efficacy in dynamic energy systems by allowing them to constantly learn from real-time operations and adjust their control techniques accordingly. Machine learning’s growth in energy systems is also supported by the emergence of new tools and models that combine different techniques, such as deep learning for predictive analytics, genetic algorithms for optimization, and reinforcement learning for real-time decision-making. As these technologies mature, they continue to expand the range of applications in the energy sector, offering promising solutions for optimizing grid operations, improving energy storage systems, and reducing energy losses (See Table 6). The integration of ML with IoT and the use of AI-driven analytics are enhancing the capability of energy systems to operate autonomously, providing both economic and environmental benefits [138–142].

Looking forward, the convergence of AI, big data, and advanced ML algorithms is set to drive the next wave of innovation in the energy sector, empowering stakeholders to create smarter, more efficient, and sustainable energy systems. The continued development of these technologies is expected to unlock new levels of efficiency, system reliability, and carbon footprint reduction, ushering in a new era for the global energy industry

7 Emerging Solutions to Cybersecurity and Data Privacy Challenges

The integration of DT and ML into smart grids and smart buildings presents substantial opportunities, but it also brings forward critical challenges concerning interoperability, data protection, and cybersecurity. Recent innovation in edge intelligence and secure computation provides promising strategies for addressing these risks. Blockchain has also been named an enabling technology for trust and data integrity for the energy sector. By providing tamper-proof, decentralized ledgers, blockchain ensures that data between DTs, IoT devices, and grid management cannot be falsified or manipulated. Smart contracts also ensure automated enforcement for safety protocols, thus permitting safe demand management and peer-to-peer energy trading. Blockchain-enabled microgrids, for example, have demonstrated resilience to cyberattacks by verifying each transaction over an eliminated single point of failure with a distributed network. Scalability challenges as well as the high-power demand for the consensus mechanism, however, remain the major challenges yet to be optimized.

Federated learning (FL) provides an alternative solution by facilitating collaborative ML without the need for centralizing sensitive data. Instead of sending raw energy consumption or occupant behavior data, only the updates to models are exchanged between participating nodes, thus lowering the risk of privacy violations. This distributed solution is especially useful in human-centered DT configurations where data on occupant comfort, behavior, or wellness needs to remain secret. Recent research has further indicated that FL may be combined with methods like differential privacy and homomorphic encryption for the purpose of adding additional protection, even though balancing the need for high accuracy with the need for strong protection remains an issue. Edge computing also complements DT and ML configurations by enabling data to be processed nearer its respective source so as to lower latency and increase security [155]. By restricting the transmission of raw data through centralized servers, edge devices reduce the exposure of sensitive data to would-be attackers. Edge-based anomaly detection mechanisms may also, in real-time, indicate attempted intrusions or manipulation of data, thereby bolstering the resilience of both smart building and grid systems. Collectively, blockchain, federated learning, and edge computing comprise an orthogonal set of solutions to the pressing concern for cybersecurity as well as data protection in smart energy systems. Their incorporation into cohesive architecture will constitute an indispensable requirement for the achievement of scalability, the protection of data by the user, and the establishment of confidence by the stakeholder for the wide deployment of unified AI-powered DT configurations [156].

8 Evolution of Smart Buildings and Energy Automation

The evolution of smart buildings and energy automation has been driven by rapid advancements in technology, especially the integration of IoT, machine learning, and artificial intelligence (AI). These advancements have enabled a paradigm shift in how buildings operate, focusing not just on energy efficiency, but also on improving occupant comfort, safety, and overall building management. Historically, buildings have been energy-consuming structures, with a focus on basic functions such as heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC). However, as energy demands and sustainability grew, so did the need for more efficient systems [157,158].

A vital advancement in the progression of smart buildings has been the incorporation of IoT devices, facilitating the transformation of buildings into networked ecosystems. Devices like sensors, thermostats, and smart meters gather extensive real-time data on temperature, humidity, occupancy, and energy consumption. The data is subsequently processed and analyzed utilizing sophisticated ML algorithms to enhance energy usage, augment HVAC system efficiency, and forecast maintenance requirements. This transition to data-driven decision-making has facilitated enhanced management of energy resources and a more efficient distribution of building systems [159,160]. Moreover, smart buildings are no longer perceived merely as energy consumers. As renewable energy sources, including solar panels and wind turbines, become increasingly prevalent, numerous buildings are becoming active contributors within the energy ecosystem. They can now optimize their energy consumption while simultaneously contributing to the grid by providing supplementary services or generating excess energy. This trend has been further enhanced by the emergence of the smart grid, in which buildings are crucial for controlling energy flows and reacting to real-time pricing signals. A notable advancement is the application of ML to automate energy management and building control. AI-driven systems may now modify lighting and HVAC systems using real-time data and predictive models, hence improving energy efficiency and user comfort. This includes predicting and adapting to changes in occupancy patterns or external weather conditions. The automation capabilities of these systems have reduced the need for manual intervention and have made building management more dynamic and responsive [161,162].

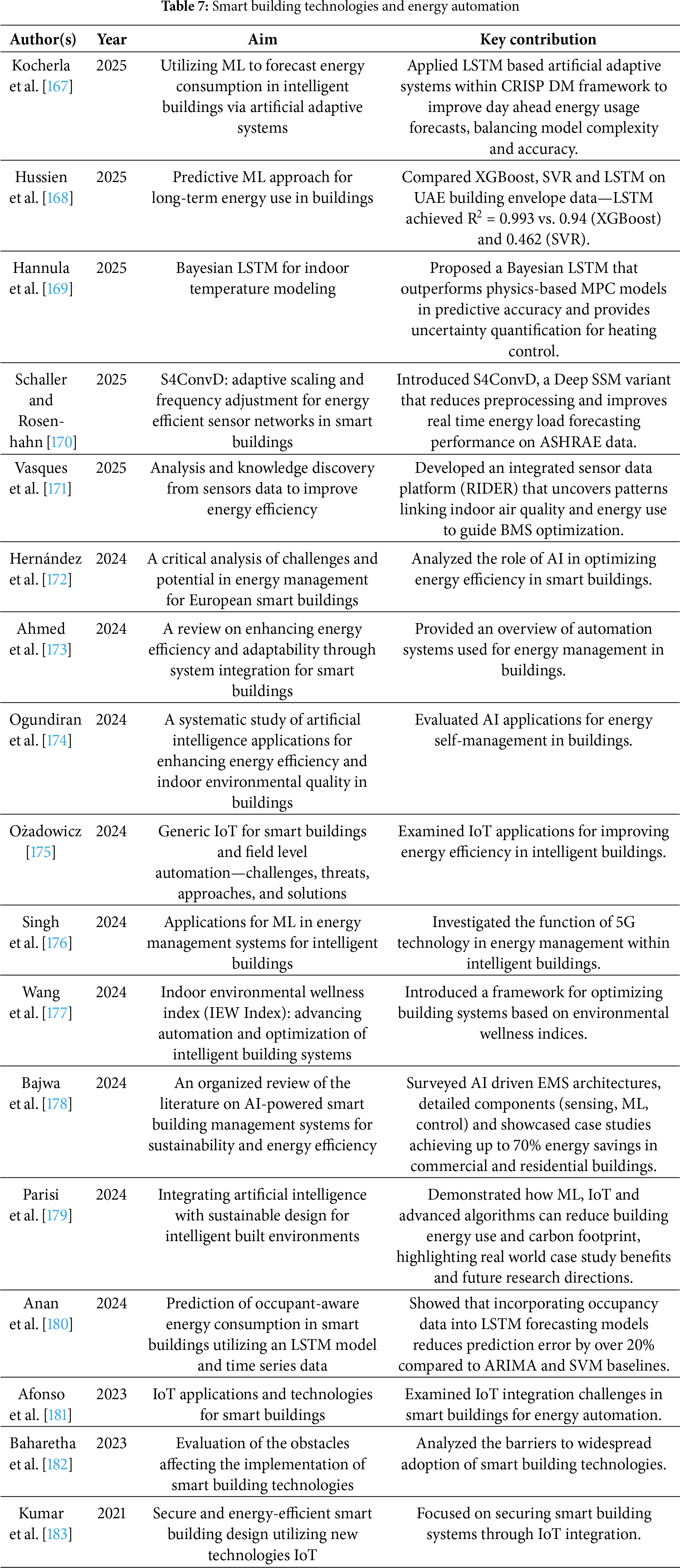

As smart building technologies evolve, their scope is expanding beyond basic energy management. Systems now integrate additional functions such as security, fire safety, and emergency response. AI and IoT play a critical role in this expansion, allowing for advanced monitoring and faster decision-making in critical situations. For instance, in residential settings, IoT sensors can detect abnormal behavior or emergencies, such as a potential fire or a medical issue, and trigger automated responses, which can range from alerting emergency services to notifying family members or healthcare providers [163,164]. The future of smart buildings lies in their ability to seamlessly integrate with urban infrastructure. The concept of smart cities relies heavily on the interoperability between smart buildings, energy grids, and other city systems. Smart buildings will continue to evolve into hubs of advanced automation and connectivity, allowing for greater energy savings, enhanced sustainability, and improved quality of life for inhabitants. With advancements in AI, cloud computing, and edge computing, the potential for intelligent, energy-efficient buildings will only grow, providing new opportunities for building owners, residents, and city planners to achieve a more sustainable and connected future [165,166]. In Table 7, the development of smart buildings and energy management has substantially advanced in recent years, pushed by the integration of ML, IoT, and other developing technologies. A multitude of studies, notably from 2021 to 2025, show the growing importance of these technologies in optimizing energy usage, boosting energy efficiency, and enabling real-time adaptive systems in smart buildings.

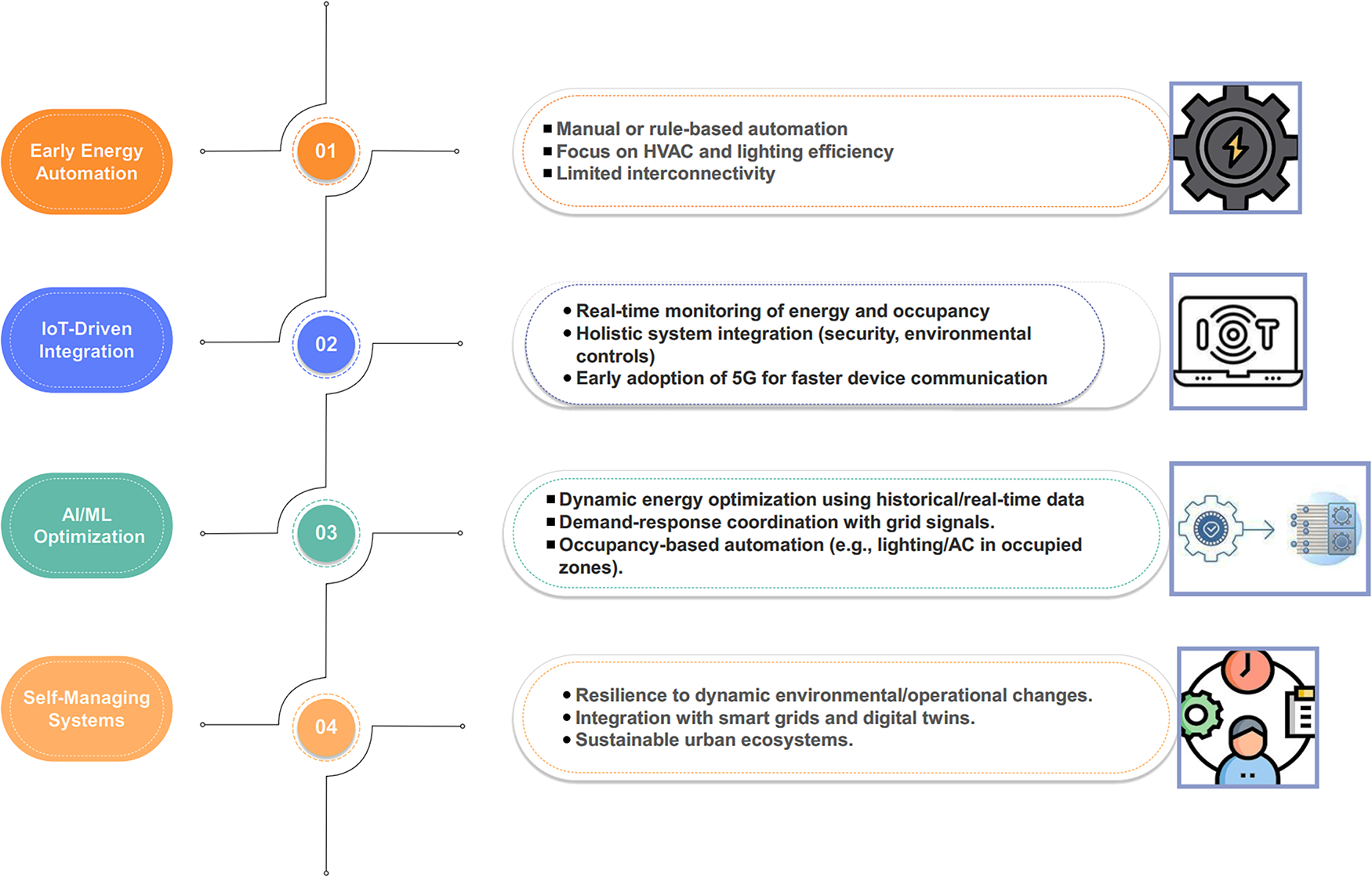

Fig. 5 depicts evolution of smart building and energy automation, from original rule-based to adaptive, AI-enabled environments. IoT and AI/ML enabling techs enable real-time optimization, while self-sustaining systems, combined with innovation from renewables integration, take energy independence to a higher level. There are underlying issues in each stage throughout (cyber-security, interoperability).

Figure 5: Harnessing AI and IoT for energy efficiency in smart buildings

9 Human-Centric and Adaptive DT Frameworks in Smart Buildings

The application of human-centric and occupant-aware DTs is particularly salient in environments where occupant experience and productivity are closely tied to building performance. In modern office settings, for example, real-time monitoring of thermal sensation and work engagement has been shown to enhance room allocation strategies, leading to improvements in comfort and satisfaction. Occupants can be assigned to rooms or zones that best fit their preferences and needs, while newcomers benefit from generalized models until personalized data is available. Similarly, pilot projects in public-use buildings have demonstrated that occupant-aware frameworks can drive energy savings without compromising comfort. By transforming passive building assets into interactive, context-aware devices, such systems provide real-time feedback, adapt device operation, and promote eco-friendly behavior. Results from these deployments indicate that energy efficiency and occupant satisfaction can be improved simultaneously, supporting broader organizational goals for sustainability and well-being. In recent years, human-centric and occupant-aware frameworks have rapidly advanced in both smart buildings and industry, largely driven by innovations in DT technology, IoT, and artificial intelligence. While early DT systems mainly targeted efficiency, maintenance, and large-scale optimization, newer research increasingly integrates the unique needs and experiences of users and workers, in line with the values of Industry 5.0 and the rise of intelligent environments.

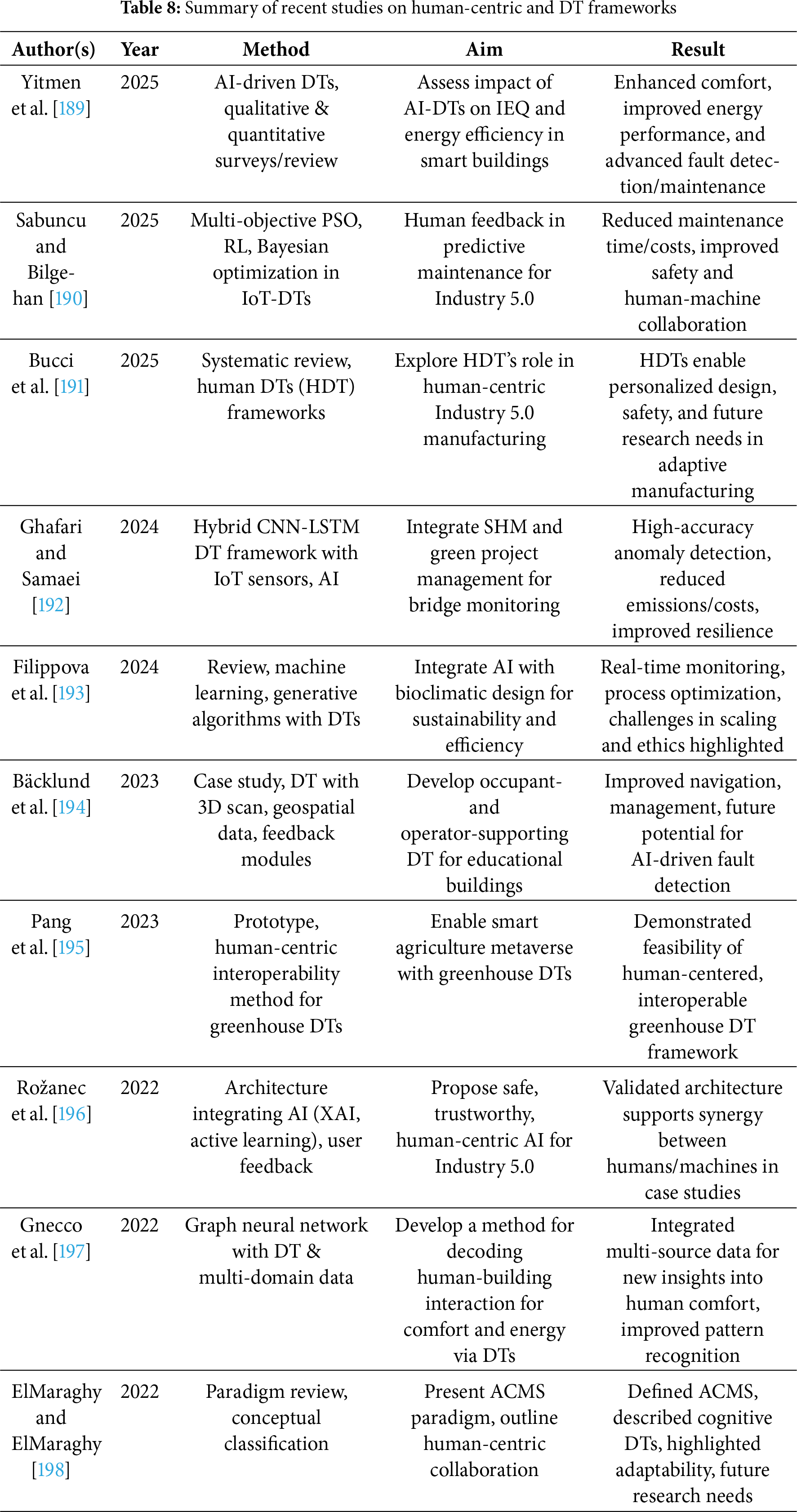

Modoni and Sacco [184] proposed a DT framework for manufacturing that brings workers and their virtual counterparts together, enhancing collaboration and simulation accuracy. Likewise, Asad et al. [185] reviewed technologies enabling human-centric DTs, highlighting the role of sensors, ergonomics, and visualization in adapting to modern industry needs. In the context of smart buildings, Deng et al. [186] introduced a Digital ID framework that uses real-time occupant data and predictive models to improve comfort and environmental control, demonstrating its value through practical case studies. Casado-Mansilla et al. [187] further contributed with the GreenSoul project, transforming building assets into interactive, energy-efficient systems that adapt to user behavior and reduce waste. Additionally, Khan and Lucas [188] systematically reviewed how human-centric design can be embedded in building systems to boost comfort and well-being, stressing the need for interdisciplinary collaboration. Collectively, these works signal a shift toward prioritizing user experience and participation within DT frameworks. However, ongoing challenges such as data privacy, behavioral modeling, scalability, and ethical standards highlight the need for continued research, particularly in developing standardized protocols and leveraging immersive technologies to further enrich user and worker experiences. Ultimately, the successful deployment of human-centric and occupant-aware DT systems will depend on multidisciplinary collaboration among engineers, behavioral scientists, data privacy experts, and building stakeholders. By placing human experience at the center of smart building innovation, these frameworks offer a pathway to more sustainable, healthy, and responsive urban environments (see Table 8).

Despite the promise of human-centric DT frameworks, several technical and practical challenges persist. First and foremost are concerns regarding privacy, data protection, and ethical use of occupant information. Robust protocols are required to ensure user consent, secure storage, and transparent use of personal data. Anonymization and encryption techniques are essential for safeguarding sensitive information. Another significant challenge is the accurate modeling of occupant behavior and comfort. Human preferences are complex, context-dependent, and may vary over time or across populations. Developing predictive models that account for this variability requires large, high-quality datasets and advanced analytics. ML models must also be interpretable and generalizable, avoiding overfitting specific user groups or scenarios. Furthermore, integrating real-time user feedback with automated building control systems demands a careful balance between system autonomy and user empowerment. Excessive automation may reduce user agency and satisfaction, while insufficient automation can fail to realize the benefits of adaptive optimization. Scalability and interoperability also pose technical obstacles, particularly in large or heterogeneous building environments. Ensuring that human-centric DT systems can be seamlessly deployed across different building types, device platforms, and organizational contexts remains an open area for future research. Emerging trends in the field suggest that the integration of human-centric design with DT technology will continue to gain momentum. Advances in artificial intelligence, federated learning, and edge computing are expected to further enhance the capabilities of occupant-aware systems.

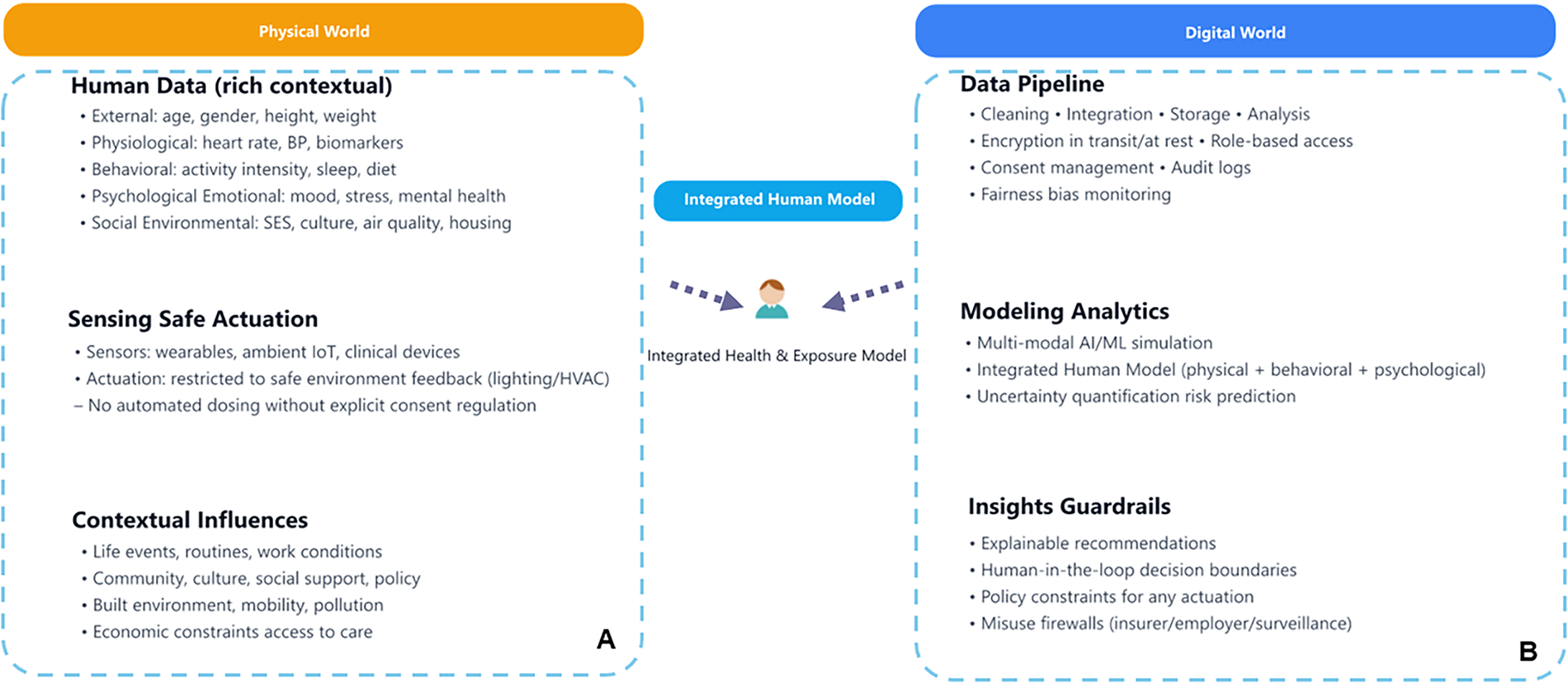

The adoption of immersive technologies, such as augmented and virtual reality, may provide new modalities for user interaction and feedback, strengthening the participatory aspect of smart building management. Research efforts are increasingly focused on developing standardized frameworks for privacy, data governance, and interoperability, which are critical for scaling human-centric DT solutions. Additionally, expanding the range of occupant metrics such as incorporating mental well-being, stress levels, or social interaction will enrich the potential applications of these frameworks. Fig. 6 illustrates the core technologies and architectural components that enable Human-Centric DT systems within the context of Industry 5.0. The diagram showcases how various data sources such as biological sensors, visual and motion sensors, and direct user input are integrated through computational intelligence to provide rich inputs for human DTs. These DTs interact with the physical environment, autonomous robots, and robotic intelligence to enable seamless collaboration, real-time feedback, and adaptive task execution. The framework also highlights key features like VR/AR functionality, physics simulation, and photorealistic rendering, as well as the essential tools that support their operation, including robot operating systems, simulation platforms, and advanced analytics software. This integrated approach emphasizes the fusion of human, machine, and environmental data to drive resilience, adaptability, and human-centric innovation in next-generation industrial systems.

Figure 6: Core technologies and architecture of human-centric DT Systems

10 Modern Scheduling Techniques in Smart Grids and Cloud Environments

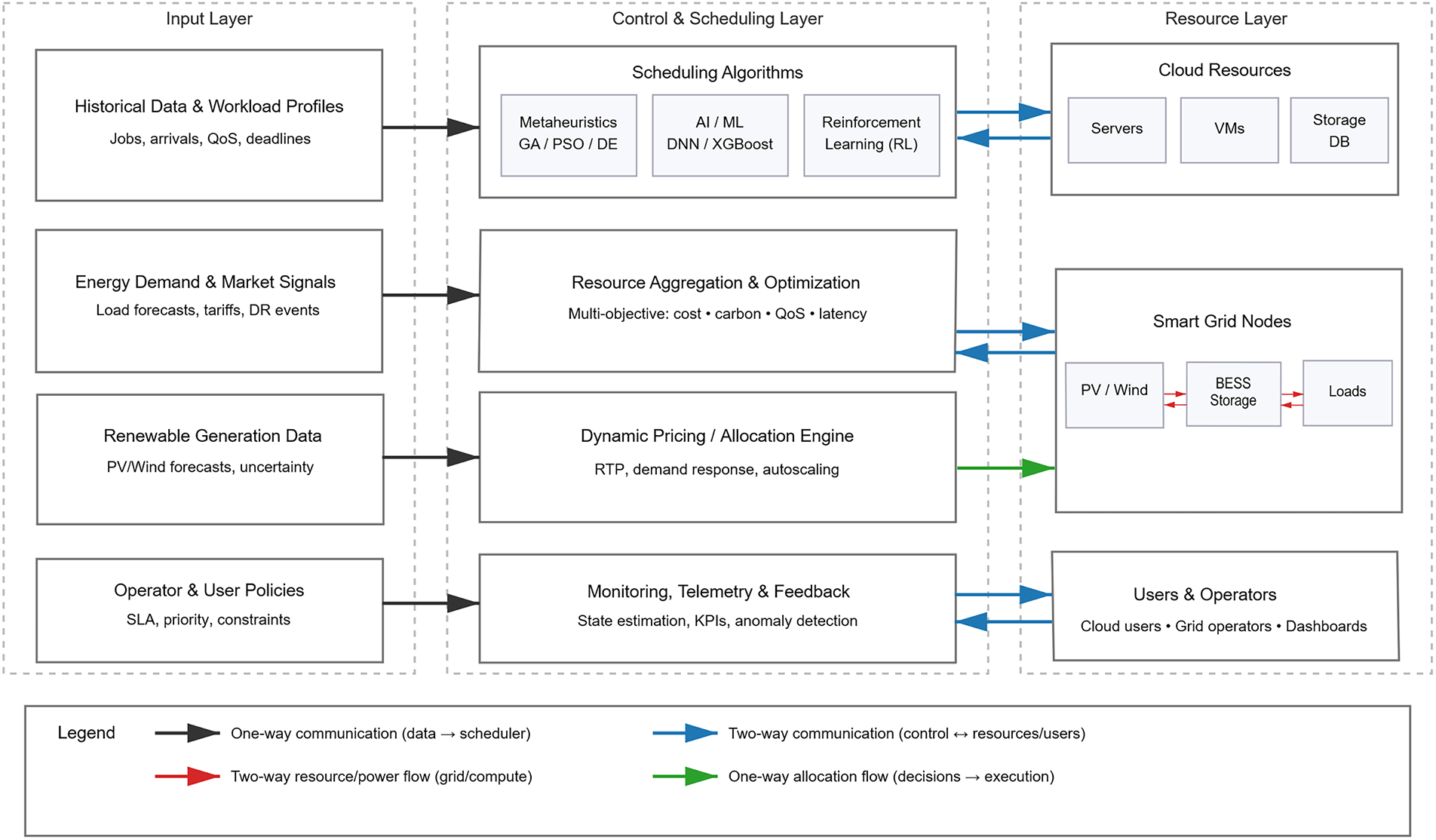

Traditional scheduling heuristics such as Round Robin (RR), First-Come-First-Served (FCFS), and greedy algorithms have been used on clouds and grids because of the ease of implementation and minimal computational overhead. Rule-based techniques such as these, however, typically consider just optimizing throughput, or cost, with no care given to energy consumption, nor system variability. These thus fare poorly where the workload is variable, and/or where service-level agreements (SLAs) call for adaptive service. In response to these challenges, AI and ML methods have become strong contenders, offering adaptive, data-based scheduling solutions. Reinforcement learning (RL) has been adapted to dynamic task scheduling, so that systems can learn the optimum allocation policy by interacting with the environment and refining decisions on the fly. Fig. 7 illustrates a conceptual framework for applying modern scheduling techniques to optimize performance in smart grids and cloud environments. The Input Layer aggregates data from multiple sources, including historical workload profiles, energy demand and market signals, renewable energy generation forecasts, and operator/user-defined constraints.

Figure 7: Modern scheduling techniques in smart grids and cloud environments. The framework comprises three layers: (1) Input, collecting workload, demand, renewable, and policy data; (2) Control & Scheduling, applying algorithms, optimization, and pricing engines; and (3) Resource, including cloud resources, smart grid nodes, and users. Arrows indicate communication and resource flows

This information feeds into the Control & Scheduling Layer, which hosts diverse scheduling approaches such as metaheuristics, machine learning, and reinforcement learning. These algorithms operate in tandem with resource aggregation and optimization modules to balance multi-objective trade-offs including cost, carbon emissions, quality of service (QoS), and latency. A dynamic pricing and allocation engine manages real-time pricing (RTP), demand response, and autoscaling strategies. Monitoring, telemetry, and feedback loops ensure continuous state estimation, anomaly detection, and performance tracking. Finally, the Resource Layer captures the operational infrastructure: cloud resources (servers, virtual machines, and storage systems), smart grid nodes (renewable energy generation units, battery energy storage systems, and consumer loads), and end users or operators. Directional arrows highlight different flows one-way communication, two-way communication, resource/power exchanges, and allocation decisionsmaking explicit the interaction between computational and energy systems.

Deep learning-based models, such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks and convolution-based architectures, have been adopted for successful predictive load balancing, by which the scheduler can predict incoming fluctuations of demand and assign resources ahead of time. Compositions of metaheuristics (e.g., Particle Swarm Optimization, Genetic Algorithms) and ML further enhance the performance of the scheduling system, optimally balancing energy effectiveness, cost saving, and task completion time. Recent works have offered strong evidence of the benefits of learning-based scheduling. For instance, a study conducted in 2025 attempted a workload scheduler that employed DRL with a Deep Q-Network to assign resources depending on the task-execution time, CPU, and memory requirements. The DRL scheduler offered average latency of ~15 ms, throughput of ~500 tasks/s, and load-balancing effectiveness of 92%, with the improvement of resource usage to 95% and quality of service to 97% dramatically surpassing those of RR, FCFS, and heuristic strategies. In the same vein, the meta-reinforcement learning-based MRLCC algorithm adjusts to novel environments more quickly than the conventional and DRL baselines. The experiments proved that it attained the smallest makespan and highest server utilization of all the algorithms that were compared, with high utilization retaining after just some gradient updates. With the use of a meta-learning loop, MRLCC generalizes over the sets of workload scenarios to decrease the time of retraining and sample demands alike, remaining effective at optimizing the usage of resources. These developments reflect that the current scheduling research tends to develop adaptive, learning-oriented approaches that can accommodate the dynamic and diverse environments of intelligent grids and cloud-based energy systems. Notably, they also outline the prospectives of energy-aware scheduling for smart grid applications. For instance, integrating federated RL with edge–cloud computing can allow several buildings to learn scheduling policies cooperatively without revealing precious information, accommodating both scalability and privacy of large-scale digital twin platforms.

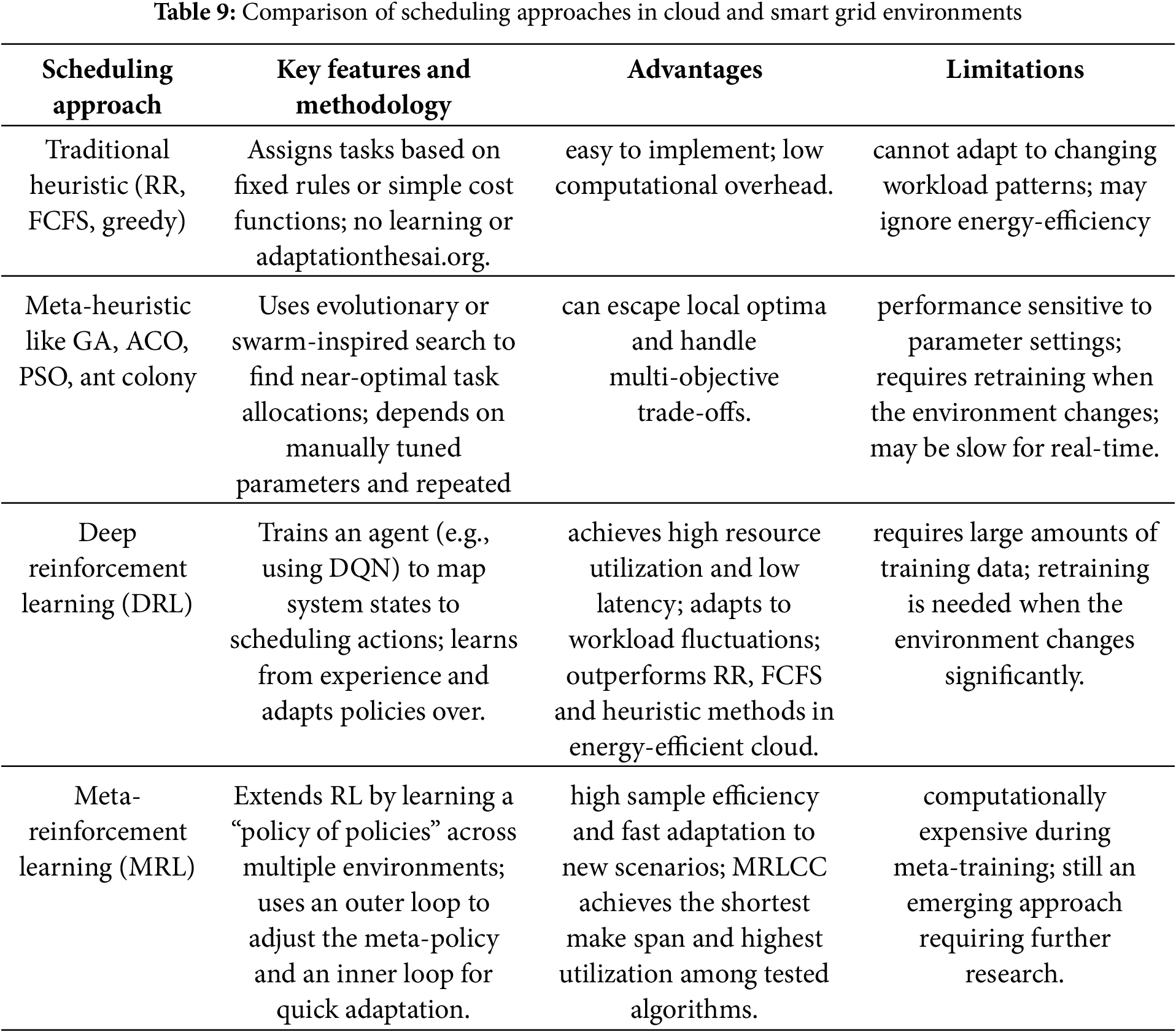

Table 9 summarizes four major categories of scheduling techniques: traditional heuristics, meta-heuristics, DRL and meta-reinforcement learning (MRL). Each row lists the core characteristics, benefits and drawbacks of the approach. Traditional heuristics such as Round-Robin and FCFS are simple and computationally light but cannot adapt to changing workloads and often ignore energy efficiency. Meta-heuristic methods (e.g., genetic algorithms or particle swarm optimization) offer better optimization across multiple objectives but require manual tuning and retraining when conditions change. DRL-based schedulers, exemplified by Deep Q-Network models, dynamically allocate resources based on task features and have shown higher throughput and energy efficiency than conventional methods. MRL approaches build on DRL by training a meta-policy that quickly adapts to new scenarios, achieving shorter make span and higher resource utilization with minimal retraining. The comparison highlights a clear progression from static rule-based scheduling to adaptive, learning-based algorithms that better handle dynamic and energy-constrained environments.

The results of the review underscore the revolutionary promise of DT and ML technologies to improve energy efficiency, predictive maintenance, and occupant comfort in intelligent buildings and intelligent grids. Through the development of dynamic, data-based models, DTs facilitate continuous monitoring and adaptive control, and the ML algorithms improve predictive abilities of energy forecasting, fault detection, and demand-management response. Collectively, the technologies offer the basis of intelligent and sustainable energy infrastructures. Despite these benefits, some key challenges constrain their broader implementation. Data interoperability is the foremost one, since diverse IoT platforms and energy management systems of buildings usually do not have standardized protocols to facilitate smooth interoperability. Cybersecurity and privacy issues stand next, since occupant and energy usage information that is highly confidential will be susceptible to cyber-attacks if not safeguarded by advanced defense mechanisms. Scalability presents further issues: pilot installations show promise, but scaling DT–ML frameworks to the high-volume, multisite or city-scale applications incurs immense computation and dependable communication infrastructure requirements.

A particularly important bottleneck lies in achieving real-time synchronization between digital twins and their physical counterparts. Effective synchronization requires continuous and low-latency data exchange; however, limitations in communication infrastructure, sensor accuracy, and edge–cloud coordination can introduce delays and discrepancies. Such misalignments reduce the reliability of DT-based predictions and may compromise critical energy management decisions. Overcoming these bottlenecks will require investment in ultra-low-latency networks such as 5G/6G, adaptive data sampling strategies, and distributed computing frameworks that balance processing tasks between edge and cloud resources. The other limitation is the human aspect of intelligent building management. Whereas energy optimization technical frameworks have come of age, the incorporation of user comfort, behavioral response, and social acceptability into DT–ML systems are weak at present. Human-oriented digital twins that integrate occupants’ preferences and instantaneous feedback into predictive simulations will probably become central to balancing technological effectiveness and user satisfaction.

To the future, DT-ML integration will need to move forward with decentralized and federated learning architectures that honor privacy but facilitate cross-building and cross-grid interoperability. Prospective solutions like blockchain to safely exchange data, federated learning to anonymously deploy analytics, and edge computing to achieve real-time responsiveness offer promising avenues to overcome present-day chokepoints. By combining these strategies with standardized interoperability protocols, the DT-ML architectures of the future might realize the resilience, scalability, and flexibility needed to accommodate sustainable cities’ energy systems.

12 Conclusions and Future Directions

The integration of DT and ML technologies in smart buildings and smart grids represents a transformative step toward intelligent energy management and sustainable urban development. By enabling real-time monitoring, adaptive forecasting, and predictive maintenance, these technologies can reduce energy consumption, lower operational costs, and enhance occupant comfort, making them essential tools for addressing the growing complexity of urban energy systems. Despite this potential, challenges related to data interoperability, cybersecurity, scalability, and privacy continue to hinder large-scale deployment. Addressing these barriers will require not only technological innovation but also collaboration across disciplines and stakeholders. Looking ahead, future research should explore decentralized and federated learning models that enable collaboration without compromising privacy, develop universal standards for data interoperability, and design lightweight edge-computing solutions for real-time decision-making. Robust AI-based defense mechanisms are also necessary to secure smart grids against evolving cyber threats. Moreover, advancing human-centric DTs that integrate occupant behavior and comfort preferences, alongside the expansion of applications to distributed renewable resources, storage systems, and peer-to-peer energy trading, will be vital for building resilient, adaptive, and sustainable energy infrastructures.

Future research on DT and ML integration should focus on practical solutions for deployment in smart grids and buildings. Decentralized and federated learning models are needed to enable collaborative optimization across multiple buildings or microgrids without compromising privacy, ensuring that raw consumption or behavioral data does not need to be shared. Standardized frameworks for data interoperability across heterogeneous IoT platforms must also be established to ensure scalability, allowing devices and systems from different vendors to communicate seamlessly and avoiding fragmentation in large-scale deployments. Advancing edge computing will be essential for achieving real-time control, particularly in applications such as demand response, fault detection, and grid stabilization, where latency must be minimized to milliseconds. Research should investigate lightweight ML models optimized for edge devices and explore hybrid edge–cloud architectures that balance computational load with security and responsiveness. At the same time, stronger AI-based cybersecurity mechanisms are required to safeguard against evolving threats, including spoofing, denial-of-service attacks, and data manipulation. Integrating blockchain-secured data exchanges with anomaly detection models represents one promising direction for building resilient defenses.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The funding sources were not involved in any aspect of the study or manuscript preparation.

Author Contributions: Saeed Asadi: Conceptualization, Writing—Original Draft, Investigation. Hajar Kazemi Naeini, Delaram Hassanlou, Abolhassan Pishahang, Saeid Aghasoleymani Najafabadi: Resources, Investigation, Visualization, Writing—Review & Editing. Abbas Sharifi: Writing—Original Draft, Visualization. Mohsen Ahmadi: Writing—Original Draft, Supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Singh M, Arora V, Kulshreshta K. Towards sustainable cities: exploring the fundamentals of urban sustainability. In: AI applications for clean energy and sustainability. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global; 2024. p. 212–33. [Google Scholar]

2. Ghanim I. A systematic literature review on energy efficiency in buildings energy management systems. Int Innov J Appl Sci. 2024;1(2). [Google Scholar]

3. Cirrincione L, Geropanta V, Peri G, Scaccianoce G. Enhance urban energy management and decarbonization through an EC-based approach. In: 2023 IEEE International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering and 2023 IEEE Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe (EEEIC/I&CPS Europe). IEEE; 2024 Jun. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

4. Sharifi A, Ahmadi M, Ala A. The impact of artificial intelligence and digital style on industry and energy post-COVID-19 pandemic. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2021;28(34):46964–84. [Google Scholar]

5. Ferrigno E, Barsola GA. 3D real time digital twin. In: SPE Latin America and Caribbean Petroleum Engineering Conference. SPE; 2024 Jun. D021S010R006. [Google Scholar]

6. Mateev M. Digital twins concept for energy-efficient smart buildings. Годишник на Стопанския факултет на СУ „Св. Климент Охридски. 2024;23(1):187–98. [Google Scholar]

7. Nie J, Xu WS, Cheng DZ, Yu YL. Digital twin-based smart building management and control framework. Comput Sci Eng. 2019. doi:10.12783/dtcse/icaic2019/29395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhang W, Wu Y, Calautit JK. A review on occupancy prediction through machine learning for enhancing energy efficiency, air quality and thermal comfort in the built environment. Renew Sustain Energ Rev. 2022;167:112704. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2022.112704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Ardabili S, Abdolalizadeh L, Mako C, Torok B, Mosavi A. Systematic review of deep learning and machine learning for building energy. Front Energy Res. 2022;10:786027. [Google Scholar]

10. Villano F, Mauro GM, Pedace A. A review on machine/deep learning techniques applied to building energy simulation, optimization and management. Thermo. 2024;4(1):100–39. [Google Scholar]

11. Mahdavi Z, Lombardi AJ, Imtiaz MH, Boolani A. IMU-based automatic prediction of energy and fatigue in a single-task walking gait. In: Mathematics Conference and Competition of Northern New York; 2024. [Google Scholar]

12. Krajčík M, Arıcı M, Ma Z. Trends in research of heating, ventilation and air conditioning and hot water systems in building retrofits: integration of review studies. J Build Eng. 2023;76:107426. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2023.107426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Khaleel M, Yusupov Z, Alfalh B, Guneser MT, Nassar Y, El-Khozondar H. Impact of smart grid technologies on sustainable urban development. Int J Electr Eng and Sustain. 2024:62–82. [Google Scholar]

14. Sghiri A, Gallab M, Merzouk S, Assoul S. Leveraging digital twins for enhancing building energy efficiency: a literature review of applications, technologies, and challenges. Buildings. 2025;15(3):498. doi:10.3390/buildings15030498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Noori N, Hoppe T, Van der Werf I, Janssen M. A framework to analyze inclusion in smart energy city development: the case of smart city amsterdam. Cities. 2025;158:105710. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2025.105710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Abilesh KS, Naresh B, Maithili P. Revolutionizing energy management system with machine learning based energy demand prediction and theft detection. In: 2024 10th International Conference on Advanced Computing and Communication Systems (ICACCS). IEEE; 2024 Mar. Vol. 1, p. 765–70. [Google Scholar]

17. Segun-Falade OD, Osundare OS, Kedi WE, Okeleke PA, Ijomah TI, Abdul-Azeez OY. Developing innovative software solutions for effective energy management systems in industry. Eng Sci Technol J. 2024;5(8):2649–69. [Google Scholar]

18. Manoharan G, Ashtikar SP, Nivedha M. Unveiling the critical role of artificial intelligence in energy management. In: AI applications for clean energy and sustainability. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global; 2024. p. 234–53. [Google Scholar]

19. Mousavi Y, Gharineiat Z, Karimi AA, McDougall K, Rossi A, Gonizzi Barsanti S. Digital twin technology in built environment: a review of applications, capabilities and challenges. Smart Cities. 2024;7(5):2594–615. [Google Scholar]

20. Sharifi A, Beris AT, Javidi AS, Nouri M, Lonbar AG, Ahmadi M. Application of artificial intelligence in digital twin models for stormwater infrastructure systems in smart cities. Adv Eng Inform. 2024;61:102485. [Google Scholar]

21. Omrany H, Al-Obaidi KM, Husain A, Ghaffarianhoseini A. Digital twins in the construction industry: a comprehensive review of current implementations, enabling technologies, and future directions. Sustainability. 2023;15(14):10908. doi:10.3390/su151410908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Sadri H, Yitmen I, Tagliabue LC, Westphal F, Tezel A, Taheri A, et al. Integration of blockchain and digital twins in the smart built environment adopting disruptive technologies—a systematic review. Sustainability. 2023;15(4):3713. doi:10.3390/su15043713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Lachvajderová L, Trebuňa M, Kádárová J. Unlocking industry potential: the evolution and impact of digital twins. Acta Mech Slovaca. 2024;28(1):46–51. [Google Scholar]

24. Xie Y, Fang Z, Korolija I, Rovas D. Review of digital twins–enabled applications for demand response. Proc Ins Civil Eng-Smart Infrastruc Constr. 2024;1–9. [Google Scholar]

25. Han F, Du F, Jiao S, Zou K. Predictive analysis of a building’s power consumption based on digital twin platforms. Energies. 2024;17(15):19961073. [Google Scholar]

26. Muniandi B, Maurya PK, Bhavani CH, Kulkarni S, Yellu RR, Chauhan N. AI-driven energy management systems for smart buildings. Power Syst Technol. 2024;48(1):322–37. [Google Scholar]

27. Abed Almoussawi Z, Khaleel BM, Kurdi WHM, AL-Attabi K, Sabah HA, Alazzai WK. Heap based optimization with deep learning based energy forecasting in smart grid with consideration of demand response. In: 2023 6th International Conference on Engineering Technology and Its Applications (IICETA). IEEE; 2023 Jul. p. 440–6. [Google Scholar]

28. Erten MY, İnanç N. Forecasting electricity consumption for accurate energy management in commercial buildings with deep learning models to facilitate demand response programs. Elect Power Compon Syst. 2024;52(9):1636–51. doi:10.1080/15325008.2024.2317353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. El Husseini F, Noura H, Vernier F. Machine-learning-based smart energy management systems: a review. In: 2024 International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing (IWCMC); 2024. p. 1296–302. [Google Scholar]

30. Renganayagalu SK, Bodal T, Bryntesen TR, Kvalvik P. Optimising energy performance of buildings through digital twins and machine learning: lessons learnt and future directions. In: 2024 4th International Conference on Applied Artificial Intelligence (ICAPAI). IEEE; 2024 Apr. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

31. Kermani A, Jamshidi AM, Mahdavi Z, Dashtaki AA, Zand M, Nasab MA, et al. Energy management system for smart grid in the presence of energy storage and photovoltaic systems. Int J Photoenergy. 2023;2023(1):5749756. [Google Scholar]

32. Antonesi G, Cioara T, Anghel I, Salomie I, Bertoncini M. An energy consumption forecasting tool for buildings based on multivariate deep neural network model. In: 2024 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Living Environment (MetroLivEnv). IEEE; 2024 Jun. p. 337–42. [Google Scholar]

33. Zou S, Luo X, Yang Z. Energy consumption forecasting in buildings based on long-term and short-term memory networks. In: 2024 2nd International Conference on Mechatronics, IoT and Industrial Informatics (ICMIII). IEEE; 2024 Jun. p. 831–5. [Google Scholar]

34. Cespedes-Cubides AS, Jradi M. A review of building digital twins to improve energy efficiency in the building operational stage. Energy Inf. 2024;7(1):11. [Google Scholar]

35. Arsecularatne B, Rodrigo N, Chang R. Digital twins for reducing energy consumption in buildings. A Rev Sustain. 2024;16(21):9275. [Google Scholar]

36. Hanafi AM, Moawed MA, Abdellatif OE. Advancing sustainable energy management: a comprehensive review of artificial intelligence techniques in building. Eng Res J (Shoubra). 2024;53(2):26–46. [Google Scholar]

37. Raj JRF, Nikshya JE, Vinothini S, Umesh R, Krishnan RS, Gopikumar S. Hierarchical deep learning framework for multi-scale energy modeling in smart building environments. In: 2024 International Conference on Inventive Computation Technologies (ICICT). IEEE; 2024 Apr. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

38. Nabizadeh Rafsanjani H, Nabizadeh AH, Momeni M. Digital twin energy management system for human-centered hvac and mels optimization in commercial buildings. SSRN. 2024. doi:10.2139/ssrn.4837416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Maryasin OY. Optimal energy consumption control in a multi-zone building based on a hybrid digital twin. In: 2023 International Russian Smart Industry Conference (SmartIndustryCon). IEEE; 2023 Mar. p. 118–23. [Google Scholar]

40. Ni Z, Zhang C, Karlsson M, Gong S. Leveraging deep learning and digital twins to improve energy performance of buildings. In: 2023 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Industrial Electronics for Sustainable Energy Systems (IESES). IEEE; 2023 Jul. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

41. Hodavand F, Ramaji IJ, Sadeghi N. Digital twin for fault detection and diagnosis of building operations: a systematic review. Buildings. 2023;13(6):1426. [Google Scholar]

42. He Q, Wu M, Liu C, Jin D, Zhao M. Management and real-time monitoring of interconnected energy hubs using digital twin: machine learning based approach. Sol Energy. 2023;250(12):173–81. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2022.12.041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Abdelalim AM, Essawy A, Sherif A, Salem M, Al-Adwani M, Abdullah MS. Optimizing facilities management through artificial intelligence and digital twin technology in mega-facilities. Sustainability. 2025;17(5):1826. doi:10.3390/su17051826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Jia W, Liang X, Xiong L, Hu X. Short-term distributed photovoltaic prediction: leveraging T-GCN to mine spatiotemporal features. In: 2025 4th International Conference on Energy, Power and Electrical Technology (ICEPET). IEEE; 2025 Apr. p. 321–4. [Google Scholar]

45. Zhang P, Zhang B, Yin J, Shi J. County-level distributed PV day-ahead power prediction based on grey correlation analysis and transformer-GCAN model. IEEE Trans Sustain Energy. 2025;1–10. doi:10.1109/tste.2025.3584976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Xin Z, Chi W, Zhang H, Liu X, Zheng G, Sun N, et al. Ultra short-term wind power prediction based on an improved temporal convolutional network. Int J Green Energy. 2025;1–21. [Google Scholar]

47. Ge X, Peng L, Yang Y, Qin C, Chen J, Liu H, et al. STGATN: a wind speed forecasting method based on geospatial dependency. Int J Digit Earth. 2025;18(1):2496794. [Google Scholar]

48. Wang X, Li R, Luo X, Guan X. Improved differential mutation aquila optimizer-based optimization dispatching strategy for hybrid energy ship power system. IEEE Trans Transp Electrification. 2025;11(5):12667–83. doi:10.1109/TTE.2025.3593366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Bhambri P, Rani S, Khang A. AI-driven digital twin and resource optimization in industry 4.0 ecosystem. Intell Techn Predictive Data Anal. 2024;47–69. [Google Scholar]

50. Kabir MR, Halder D, Ray S. Digital twins for IoT-driven energy systems: a survey. IEEE Access. 2024. [Google Scholar]

51. Aivaliotis P, Georgoulias K, Chryssolouris G. The use of Digital Twin for predictive maintenance in manufacturing. Int J Comput Integr Manuf. 2019;32(11):1067–80. [Google Scholar]

52. Vijayan DS, Devarajan P, Mohanavel V, Sankaran N, Kannan S, Ahsan MS. A review of sustainable implications of energy-efficient buildings in the environment. Adv Civil Eng. 2025;2025(1):9584777. [Google Scholar]

53. Li Y, Guan P, Li T, Larsen KG, Aiello M, Pedersen TB, et al. Digital twin for secure peer-to-peer trading in cyber-physical energy systems. IEEE Trans Netw Sci Eng. 2024;12(2):669–83. doi:10.1109/TNSE.2024.3507956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Zografopoulos I, Srivastava A, Konstantinou C, Zhao J, Jahromi AA, Chawla A, et al. Cyber-physical interdependence for power system operation and control. IEEE Trans Smart Grid. 2025;16(3):2554–73. doi:10.1109/TSG.2025.3538012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Fu K, Mohapatra A, Häger U, Tonkoski R, Hamacher T. Application-oriented digital twin for integrated energy system: a review. SSRN. 2025. doi:10.2139/ssrn.5230556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Sharma A, Singh SN, Serratos MM, Sahu D, Strezov V. Urban energy transition in smart cities: a comprehensive review of sustainability and innovation. Sustain Futures. 2025;100940. [Google Scholar]

57. van der Veen A, van Leeuwen C, Helmholt KA. Self-organization in cyberphysical energy systems: seven practical steps to agent-based and digital twin-supported voltage control. IEEE Power Energy Mag. 2024;22(1):43–51. doi:10.1109/mpe.2023.3327065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Norbu S, Couraud B, Challinor J, Flynn D, Gibbons G, Andoni M, et al. Cyber-physical energy systems: enabling tailored decarbonization and net-zero pathways for communities. In: IET Powering Net Zero (PNZ 2024). Birmingham, UK: IET; 2024 Dec. p. 28–34. [Google Scholar]

59. Krishnaveni S, Sivamohan S, Jothi B, Chen TM, Sathiyanarayanan M. TwinSec-IDS: an enhanced intrusion detection system in SDN-digital-twin-based industrial cyber-physical systems. Concurr Comput. 2025;37(3):e8334. doi:10.1002/cpe.8334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Tsegaye S, Heyi KG, Endaylalu MT, Melaku ZA, Turufi KT. Deep neural networks in smart grid digital twins: evolution, challenges, and future outlooks. IEEE Access. 2025. doi:10.1109/access.2025.3585967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Agostinelli S, Cumo F, Guidi G, Tomazzoli C. Cyber-physical systems improving building energy management: digital twin and artificial intelligence. Energies. 2021;14(8):2338. [Google Scholar]