Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Cross-Site Map-Free Indoor Localization for 6G ISAC Systems Using Low-Frequency Radio and Transformer Networks

1 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Kanagawa University, Yokohama, Kanagawa, 221-8686, Japan

2 Department of Electrical Engineering, Ming Chi University of Technology, New Taipei City, 24301, Taiwan

3 Department of Electronic Engineering, Ming Chi University of Technology, New Taipei City, 24301, Taiwan

4 Research Center for Intelligent Medical Devices, Ming Chi University of Technology, New Taipei City, 24301, Taiwan

* Corresponding Author: En-Cheng Liou. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Artificial Intelligence for 6G Wireless Networks)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(2), 2551-2571. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.072471

Received 27 August 2025; Accepted 03 November 2025; Issue published 26 November 2025

Abstract

Indoor localization is a fundamental requirement for future 6G Intelligent Sensing and Communication (ISAC) systems, enabling precise navigation in environments where Global Positioning System (GPS) signals are unavailable. Existing methods, such as map-based navigation or site-specific fingerprinting, often require intensive data collection and lack generalization capability across different buildings, thereby limiting scalability. This study proposes a cross-site, map-free indoor localization framework that uses low-frequency sub-1 GHz radio signals and a Transformer-based neural network for robust positioning without prior environmental knowledge. The Transformer’s self-attention mechanisms allow it to capture spatial correlations among anchor nodes, facilitating accurate localization in unseen environments. Evaluation across two validation sites demonstrates the framework’s effectiveness. In cross-site testing (Site-A), the Transformer achieved a mean localization error of 9.44 m, outperforming the Deep Neural Network (DNN) (10.76 m) and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) (12.02 m) baselines. In a real-time deployment (Site-B) spanning three floors, the Transformer maintained an overall mean error of 9.81 m, compared with 13.45 m for DNN, 12.88 m for CNN, and 53.08 m for conventional trilateration. For vertical positioning, the Transformer delivered a mean error of 4.52 m, exceeding the performance of DNN (4.59 m), CNN (4.87 m), and trilateration (>45 m). The results confirm that the Transformer-based framework generalizes across heterogeneous indoor environments without requiring site-specific calibration, providing stable, sub-12 m horizontal accuracy and reliable vertical estimation. This capability makes the framework suitable for real-time applications in smart buildings, emergency response, and autonomous systems. By utilizing multipath reflections as an informative structure rather than treating them as noise, this work advances artificial intelligence (AI)-native indoor localization as a scalable and efficient component of future 6G ISAC networks.Keywords

Indoor positioning has emerged as a fundamental enabler for a wide range of applications, including emergency response, healthcare management, industrial automation, and intelligent transportation systems [1]. However, the maturity of outdoor Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) does not extend effectively to indoor environments, as their signals are severely degraded by attenuation, multipath propagation, and non-line-of-sight (NLOS) conditions. This has led to the development of numerous alternative techniques to achieve reliable indoor localization, ranging from map-based navigation methods to fingerprinting approaches using common radio signals like Wi-Fi, Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE), or Ultra-Wideband (UWB) [1–4].

Despite demonstrating utility in controlled settings, these traditional solutions are heavily dependent on prior knowledge of the environment, extensive site-specific calibration, or dense infrastructure, which significantly constrains their scalability and practicality. In particular, fingerprinting techniques, while capable of delivering meter-level accuracy, require labor-intensive data collection and continuous recalibration to adapt to environmental changes like renovations and changes in human occupancy [1,5]. Similarly, map-based methods rely on accurate building floor plans, which are often incomplete or unavailable in critical situations like disaster relief or operations in older buildings, severely limiting their usability [6]. Geometry-based methods, including trilateration, also lack robustness under multipath and obstruction, frequently leading to errors that exceed acceptable thresholds for practical deployment [3]. These limitations highlight a persistent gap between laboratory-validated methods and deployable indoor localization systems for dynamic and resource-constrained environments.

Motivated by these challenges, recent research has increasingly turned to machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) approaches for indoor localization [7–11]. While Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) have shown promising results in single-site experiments, a critical limitation persists: their transferability across sites is severely limited [9,12]. These models tend to overfit environment-specific propagation patterns, leading to substantial performance degradation when applied to unseen environments, thereby undermining their viability for scalable and rapid deployment. Therefore, a new framework is required that eliminates dependence on pre-existing maps or site-specific fingerprints while maintaining robust accuracy across heterogeneous environments and supporting real-time adaptability [7,8,13].

Despite progress in wireless and AI-driven positioning, a significant research gap remains in developing a deployable framework that can operate without prior maps or extensive site-specific measurements, while sustaining real-time adaptability across multiple environments [7,8,13]. Current approaches rely heavily on pre-collected fingerprints or experience severe accuracy loss in unseen deployment sites [9,10,12]. To address this gap, this paper proposes and validates a map-free indoor localization framework that integrates low-frequency radio signals with Transformer-based neural networks [12,14,15]. Through systematic cross-site validation and real-time deployment across different buildings, this work demonstrates the feasibility of achieving robust, transferable indoor positioning, meeting the operational requirements of emergency response, healthcare, and other environments where rapid deployment and reliability are essential [16–18].

The primary objective of this research is to develop and validate a deployable, map-free indoor localization framework capable of achieving reliable, real-time performance across diverse indoor environments. By conducting systematic cross-site and real-time experiments, this research aims to establish a scalable solution that directly addresses the practical requirements of rapid setup, adaptability, and accuracy. The key contributions of this work are as follows:

• Deployable, map-free framework: Establishes a localization system that functions without pre-existing maps or site-specific fingerprints, addressing a major barrier to real-world deployment in dynamic and resource-limited environments [7,8,13].

• Low-frequency physical layer foundation: Validates the effectiveness of low-frequency carriers as a robust foundation for indoor positioning, highlighting their superior penetration and resilience against obstructions compared to traditional signals [19–22].

• Transformer-based modeling for improved generalization: Introduces a Transformer encoder into indoor localization, demonstrating that its self-attention mechanism effectively models inter-anchor dependencies, enabling reliable cross-site transfer and mitigating the limitations of CNNs and DNNs in unseen environments [12,14,15].

• Comprehensive cross-site and real-time validation: Evaluate the framework across multiple buildings with different layouts, demonstrating its ability to consistently achieve sub-10 m horizontal and sub-5 m vertical accuracy under dynamic conditions [17,23].

• System-level implications for 6G: Positions indoor localization as a native capability of 6G Integrated Sensing and Communication (ISAC) networks rather than an auxiliary overlay, providing a pathway for seamless integration into next-generation wireless systems [16,18,24,25]. The advent of 6G wireless networks presents new avenues to address the limitations of current localization systems [26,27]. A prominent paradigm in 6G is ISAC, which combines communication and radar-like sensing into a unified framework [28]. Recent works have demonstrated that the ISAC paradigm holds significant promise for seamless indoor positioning, with studies showing its potential to address the scalability and practical challenges of widespread, multi-site deployments [29–31]. By facilitating simultaneous data transmission and high-accuracy localization, ISAC enables seamless and robust indoor positioning.

2.1 Traditional and Fingerprinting Approach

Indoor positioning has been a key area of research, with existing solutions typically categorized according to their dependence on pre-existing spatial knowledge. Map-based navigation methods rely on detailed floor plans and environmental information to guide users and infer position [6]. These techniques, which sometimes fuse data from Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) and Wi-Fi [32], are highly effective in environments where structural information is accurate and static. However, their major drawback lies in their strong dependence on complete and up-to-date building layouts, which are rarely available in scenarios involving renovations, structural changes, or emergency situations such as natural disasters.

In contrast, fingerprinting-based approaches construct a radio map by collecting signal measurements, such as Received Signal Strength Indicator (RSSI) or Channel State Information (CSI), at predefined locations [4]. User positions are then determined by matching real-time measurements to this pre-collected database [1]. These methods exhibit superior robustness to multipath and NLOS effects compared to geometric trilateration [1]. However, their effectiveness comes at the cost of substantial manual effort required for the initial site survey and continuous recalibration to account for dynamic environmental changes, such as moving furniture or human mobility [5]. This dependency on labor-intensive data collection severely constrains their portability and cross-domain adaptability [7].

Multiple wireless technologies serve as the backbone for these approaches. Wi-Fi-based localization is widely studied due to the ubiquity of access points, often achieving meter-level accuracy in controlled conditions. However, its performance is highly sensitive to environmental changes and requires frequent recalibration [1,5]. BLE offers a low-cost, low-energy alternative suitable for short-range applications, such as in healthcare or retail [2]. For high-precision use cases, UWB technology remains a leading choice, leveraging its wide bandwidth to achieve decimeter-level accuracy and strong resilience to multipath interference [3]. Yet, UWB’s reliance on dedicated hardware and higher installation costs limits its widespread adoption.

2.2 DL for Indoor Localization

To overcome the limitations of traditional methods, the field has increasingly turned to data-driven and AI-based solutions. DL approaches have proven capable of learning complex, non-linear relationships between wireless signal features and user positions, which is particularly useful in environments plagued by multipath propagation and dynamic interference.

DNNs have been successfully employed to model the intricate relationship between received signal distributions and spatial coordinates, thereby reducing reliance on handcrafted features and improving performance under environmental variations [1,23]. Similarly, CNNs have been applied to localization by treating signal data (e.g., CSI) as a structured image, effectively capturing local spatial correlations [9]. These DL methods have significantly improved accuracy and mitigated some limitations of traditional fingerprinting [10], but they still require large-scale labeled datasets for training and often struggle to generalize across different physical environments without extensive retraining [9,12]. This limitation underscores a persistent challenge in developing a truly universal localization model. Furthermore, the calibration and confidence estimation of these DL systems remain critical for achieving reliable deployment in real-world scenarios [33].

Recent research has focused on improving adaptability and reducing data dependency. Semi-supervised learning approaches, such as those based on variational autoencoders (VAEs), have shown promise in minimizing the need for labeled data [11]. Transfer learning frameworks have further enhanced cross-environment generalization by adapting pre-trained models using limited new samples [7,8]. Additionally, federated learning paradigms have been proposed to mitigate privacy concerns and reduce centralized data collection, allowing distributed model training across multiple devices while preserving local data ownership [13].

2.3 Low-Frequency Radio and Transformer Architecture

A key trend in next-generation wireless systems is the exploration of alternative spectrum bands and advanced AI architectures to address the remaining challenges of indoor localization. Low-frequency spectrum bands, such as 600 MHz, have recently gained attention for their superior propagation characteristics in challenging environments. Compared with higher frequency bands used in Wi-Fi and 5G, these signals exhibit lower attenuation and greater resilience to walls and obstacles [20]. Their propagation characteristics are well understood through established channel models [19], and their deployment aligns with standardized base station specifications [21,34]. This makes them particularly suitable for robust positioning in environments where the line of sight is frequently broken, such as in emergency and disaster response scenarios.

Building on the strengths of DL, Transformer architectures have recently gained traction in indoor positioning because of their unique self-attention mechanism [12,14,15]. Unlike CNNs, which focus on local features, Transformers excel at capturing long-range dependencies and contextual relationships among multiple data points. In localization, this allows a Transformer to learn how a signal from one anchor is influenced by conditions affecting other anchors, such as partial obstructions or multipath. This capability enhances the model’s generalization across different environments by learning a transferable relationship between signals and spatial positions [12]. The integration of Transformers with emerging 6G time-domain features and distributed sensor networks further highlights their potential for future localization systems [17]. This evolution toward Integrated ISAC represents a paradigm shift in which wireless networks simultaneously provide communication and sensing capabilities [16,18,24,25].

2.4 Limitations of the Existing Method

Despite significant progress in wireless and AI-driven indoor positioning, a critical gap remains that hinders scalability and real-world deployment. The main limitations of existing methods can be summarized into three key categories, which directly motivate the framework proposed in this study.

First, reliance on environmental knowledge restricts the portability and scalability of current solutions. Map-based approaches assume access to accurate and static floor plans [1], while fingerprinting techniques depend on densely deployed, manually calibrated infrastructure [2]. This reliance on fixed environmental information increases deployment costs and renders systems vulnerable to structural changes, human mobility, or hardware failures [1,2].

Second, a major challenge is the lack of robust cross-domain transferability and real-time adaptability. Traditional fingerprinting and even advanced DL models often perform well only in controlled or static environments [7,8]. Their performance degrades when deployed in unseen locations without extensive recalibration, highlighting the absence of effective mechanisms for cross-site generalization [5]. Achieving seamless portability of localization models across heterogeneous environments thus remains a major obstacle [9,12].

Third, existing systems exhibit instability under dynamic conditions. In real-world environments with human movement, mobile objects, and temporal variations, signal fluctuations can significantly degrade the reliability of RSSI or CSI-based fingerprints. Although some attention mechanisms have been introduced to mitigate NLOS effects [9,14], maintaining consistent performance in highly dynamic public spaces remains difficult. This instability compromises the system’s reliability, which is essential for safety-critical applications.

In summary, the dependence on environmental knowledge, lack of cross-domain transfer, and instability under dynamic conditions highlight the gap between academic prototypes and practical, large-scale solutions. The proposed research directly addresses this gap by integrating an adaptive AI model with a robust low-frequency physical layer foundation, designed for resilience and portability. This approach aims to bridge the divide between theoretical advancements and the practical demands of mission-critical deployments.

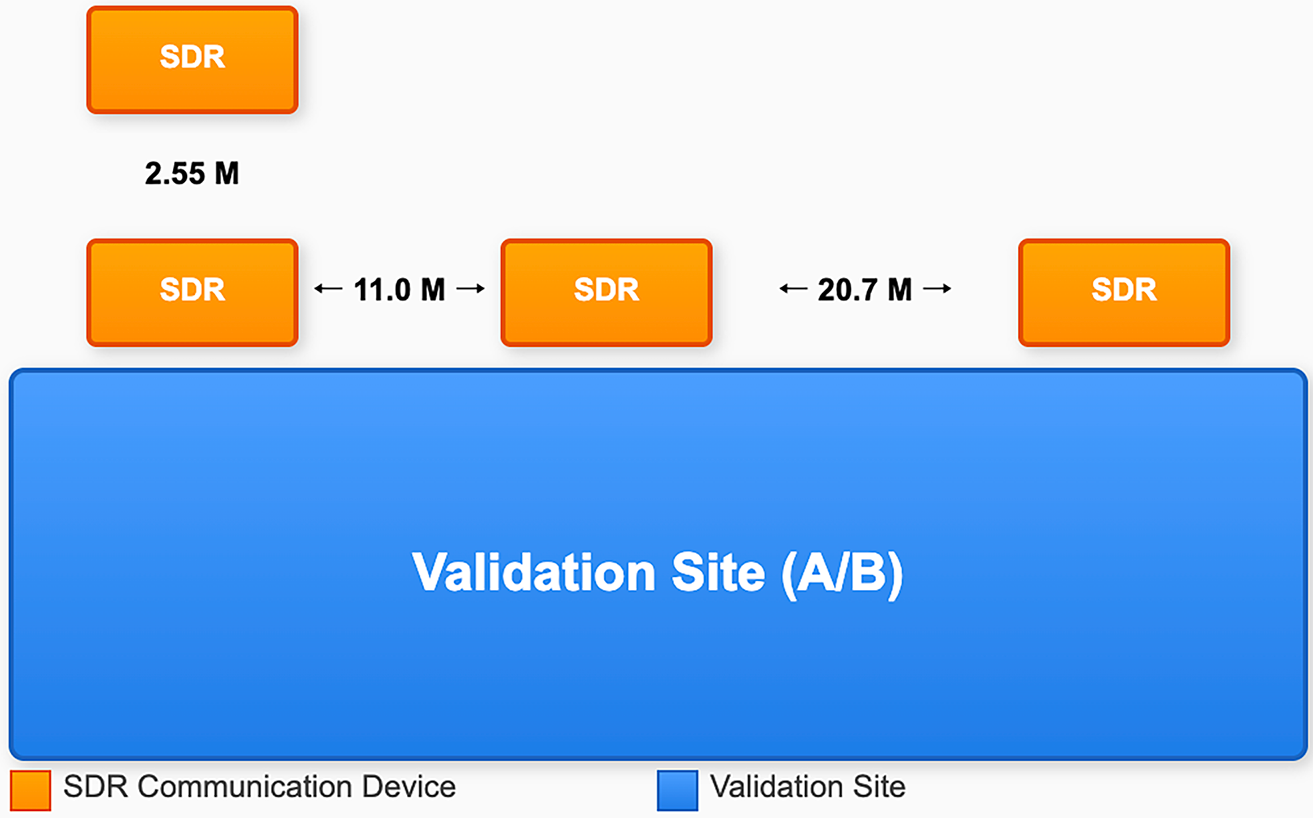

The proposed system is a map-free indoor localization framework designed for rapid and resilient deployment in dynamic environments. The core architecture consists of a wireless transceiver network utilizing software-defined radio (SDR) transceivers, configured in a “four outdoor anchors + one indoor mobile receiver” topology. This configuration was specifically chosen to emulate rapid emergency deployment scenarios and to mitigate common signal distortions caused by pedestrian movement, vehicular obstruction, and ground reflections. By positioning the four anchors at a uniform elevation of 2.55 m on the building’s exterior, the system ensures reliable signal reception across multiple floors and establishes a stable geometric baseline for three-dimensional positioning. This topology is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Deployment topology for map-free indoor localization using SDR anchors

Because the anchors were mounted outside the building while the receiver operated indoors, all communication links necessarily traversed exterior walls. To address this, Line-of-Sight (LOS) and NLOS conditions were explicitly defined during data acquisition. (LOS) was assigned when the signal path involved only a single-wall penetration without major additional obstructions, whereas NLOS was defined for signals that traversed multiple structural barriers such as interior walls, partitions, or closed doors. This clear labeling ensured that both unobstructed and obstructed propagation conditions were consistently represented in the dataset, reflecting realistic deployment challenges where indoor receivers rarely maintain a fully unobstructed path to anchors. The system’s design reflects a balance between theoretical assumptions and practical feasibility. From a geometric perspective, four anchors provide the minimum configuration necessary for robust three-dimensional multilateration, while the coplanar placement allows investigation into whether Transformer-based learning can recover height information from subtle signal variations. From a practical perspective, an outdoor anchor arrangement reduces the need for invasive indoor installation and reflects the operational requirements of disaster recovery or temporary infrastructure deployment, where building interiors may be inaccessible or unsafe. The experimental evaluation was conducted across three distinct sites to ensure a rigorous evaluation: the Ming-Chi Innovation Building (training site), the Ming-Chi Electrical Engineering Building (cross-site validation, Site-A), and a multi-story office building outside the campus for real-time deployment (Site-B). This multi-site design systematically evaluates the framework’s generalization and adaptability to different environmental contexts.

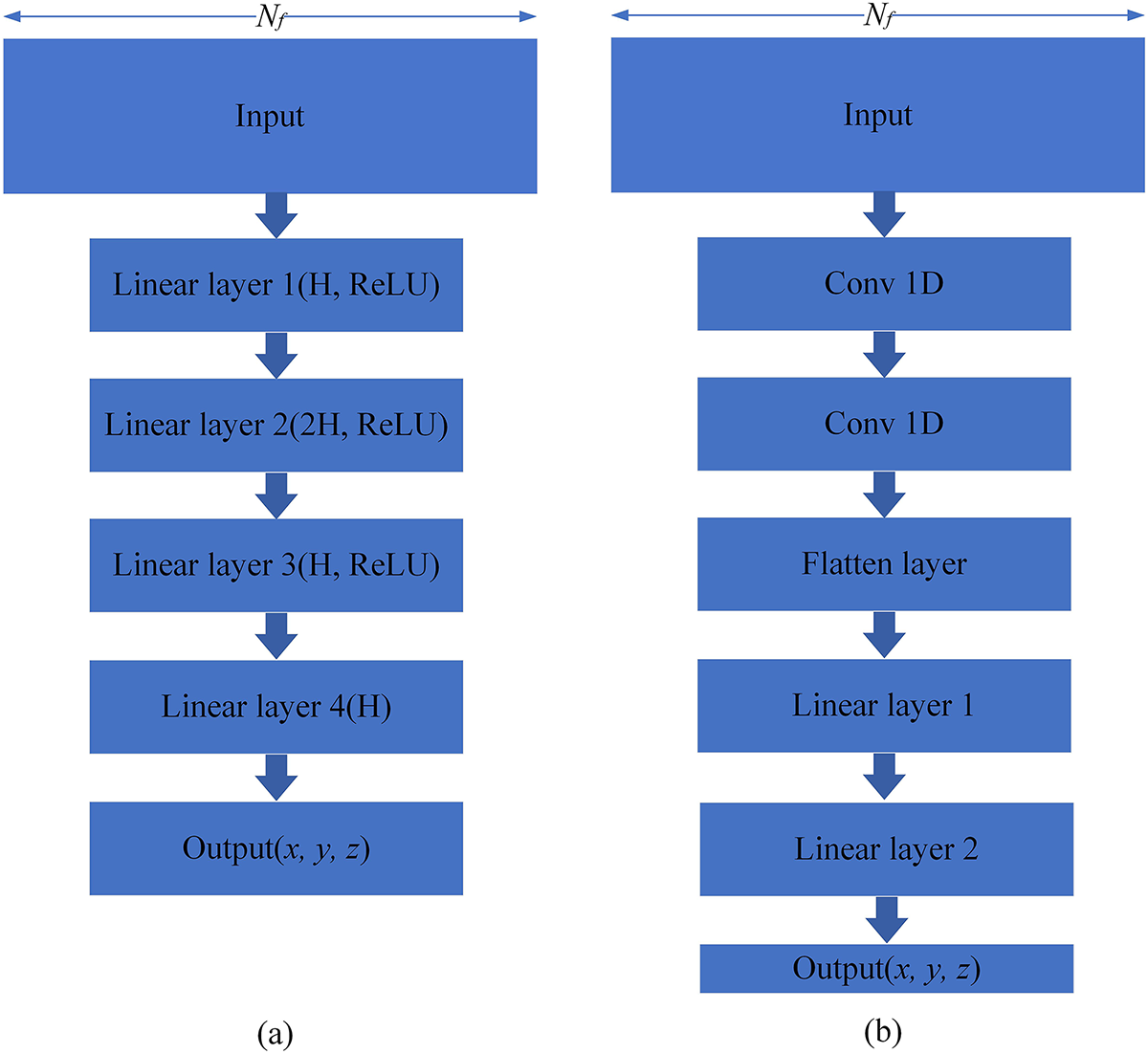

3.2 Hardware and Computational Environment

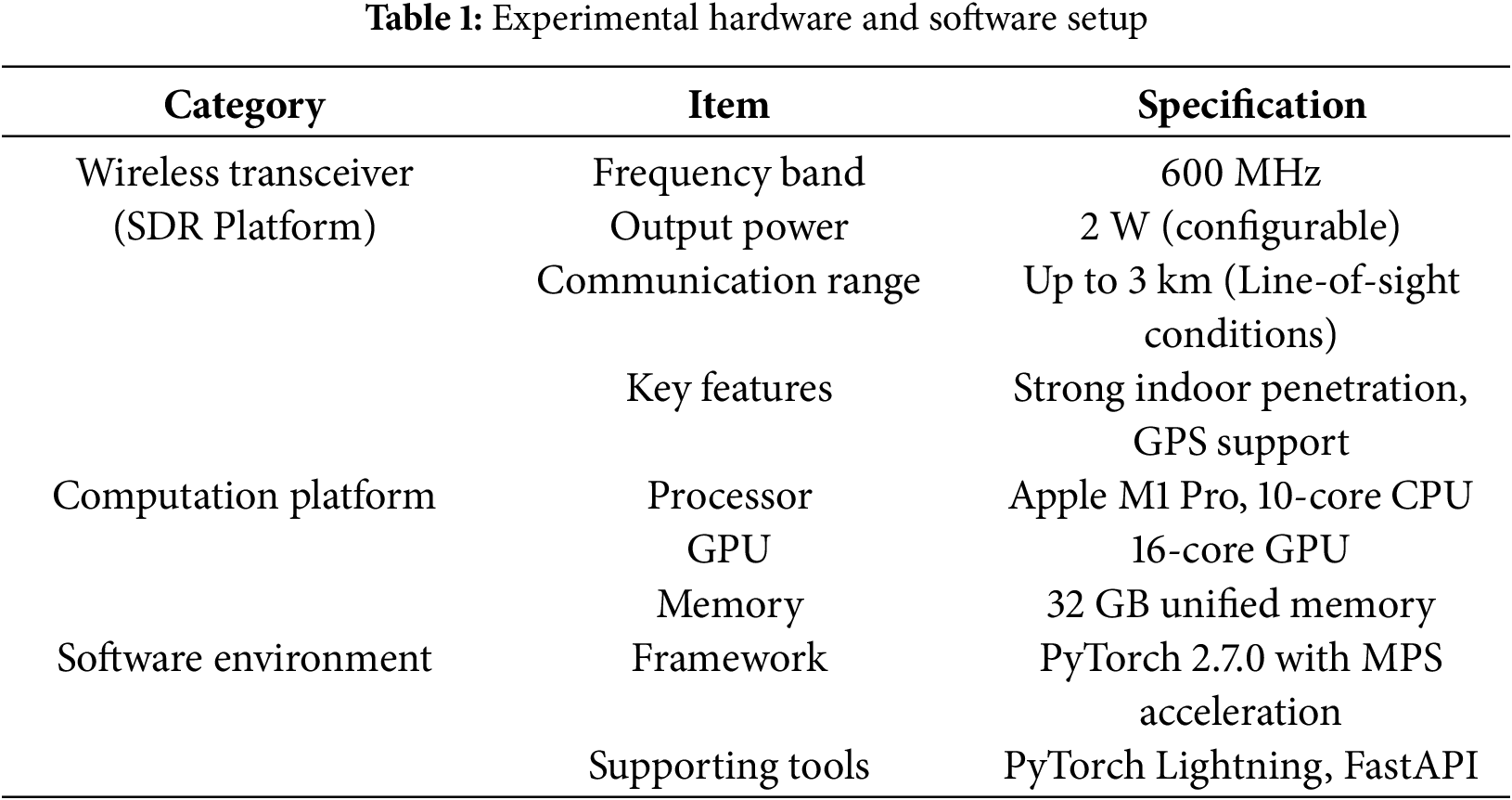

The wireless front-end was implemented using an SDR platform operating in the 600 MHz band. This frequency was chosen to leverage the advantages of sub-1 GHz carriers, which are increasingly recognized in the context of 6G research for their superior penetration, extended coverage, and resilience to obstruction. These characteristics provide a more robust foundation for positioning in complex indoor environments where LOS is frequently unavailable. In the experimental setup, the mobile receiver was implemented by directly interfacing the SDR platform with a laptop (MacBook Pro, M1 Pro), which acted as the receiving client during all data acquisition sessions. This laptop-based receiver configuration allowed flexible movement, real-time data collection, and high-fidelity baseband signal recording for subsequent processing. The system was supported by a high-performance computing platform, a MacBook Pro with an Apple M1 Pro chip, selected for its high-performance CPU and integrated GPU acceleration. The software environment was built around PyTorch as the core DL framework, supplemented by PyTorch Lightning for structured model training and FastAPI to create a robust and low-latency API for real-time localization inference. The detailed hardware and software specifications are summarized in Table 1.

The data acquisition process was structured to ensure both representativeness and robustness. At the training site, measurements were conducted using a grid-based sampling scheme, distributing 114 points across four floors with approximately three meters spacing. This design captured a diverse range of propagation conditions, including both LOS and NLOS links, while emphasizing corridors and common areas where pedestrian mobility typically induces dynamic multipath. By prioritizing regions of high human traffic, the dataset incorporated variability often absent in static fingerprinting databases, thereby enhancing generalizability for real-world deployment. The specific floor plan and grid-based layout for the training site are shown in Fig. 2. The Ming-Chi Innovation building was chosen as the training site due to its structured and regular layout, which facilitated systematic and repeatable data collection.

Figure 2: Training site and data collection setup. (a) A view of the Ming-Chi Innovation building. (b) The four exterior SDR anchors (A, B, C, D). (c) The indoor grid-based layout for data acquisition across different floors

The data collection was performed manually by a single operator to ensure consistency in measurement conditions. The receiver was held at a constant height of 1.5 m above the floor throughout the experiment. At each of the 114 predetermined points, continuous measurements were recorded for five minutes to average out short-term fluctuations and capture a robust representation of the signal environment. Data was collected in a single systematic pass through each floor to minimize temporal variation across sessions.

Ground truth coordinates for each measurement point were established with high precision. A combination of architectural floor plans and a laser distance meter was used to determine the three-dimensional coordinates (x, y, z). The x- and y-coordinates were measured relative to a fixed origin at the lower-left corner of the first floor, while the z-coordinate (height) was measured relative to the floor using the same laser distance meter. This technique provided ground truth accuracy of approximately ±10 cm, ensuring the reliability of the reported localization error metrics.

3.4 Model Training and Architecture

The localization problem was formulated as a regression task, mapping received wireless signal features directly to three-dimensional coordinates (x, y, z). Each input sample consisted of a sixteen-dimensional feature vector derived from RSSI and Signal to Noise Ratio (SNR) values measured across the four anchors.

To prepare the data, we applied max-scaling for normalization, which stabilizes training and ensures balanced gradient updates. A group-wise data split was used at the measurement point level instead of conventional random splits. This approach preserved the spatial structure of the environment, preventing overly optimistic estimates of generalization performance and providing a more rigorous assessment of model robustness. The models were trained using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 1 × 10−3, a batch size of 64, and for 60 epochs. These hyperparameters were selected to balance convergence stability, training efficiency, and generalization performance. The learning rate avoided divergence while maintaining sufficient gradient signal; the batch size stabilized variance during optimization without excessive memory overhead; and the number of epochs was chosen to ensure convergence while preventing overfitting.

The primary architecture was the Transformer Encoder, selected for its ability to capture relational dependencies among anchors through its self-attention mechanism. This is a key advantage because signal distortions from multipath or partial obstructions are not independent across anchors but manifest as structured correlations. The Transformer learns to assign context-dependent weights to anchors, providing a channel-aware representation that better reflects the underlying propagation dynamics. For a comparative evaluation, CNN and DNN baselines were trained under identical conditions. These models served two purposes: to empirically benchmark the Transformer’s superiority in cross-site generalization and to contextualize the proposed framework within prior AI-based localization studies.

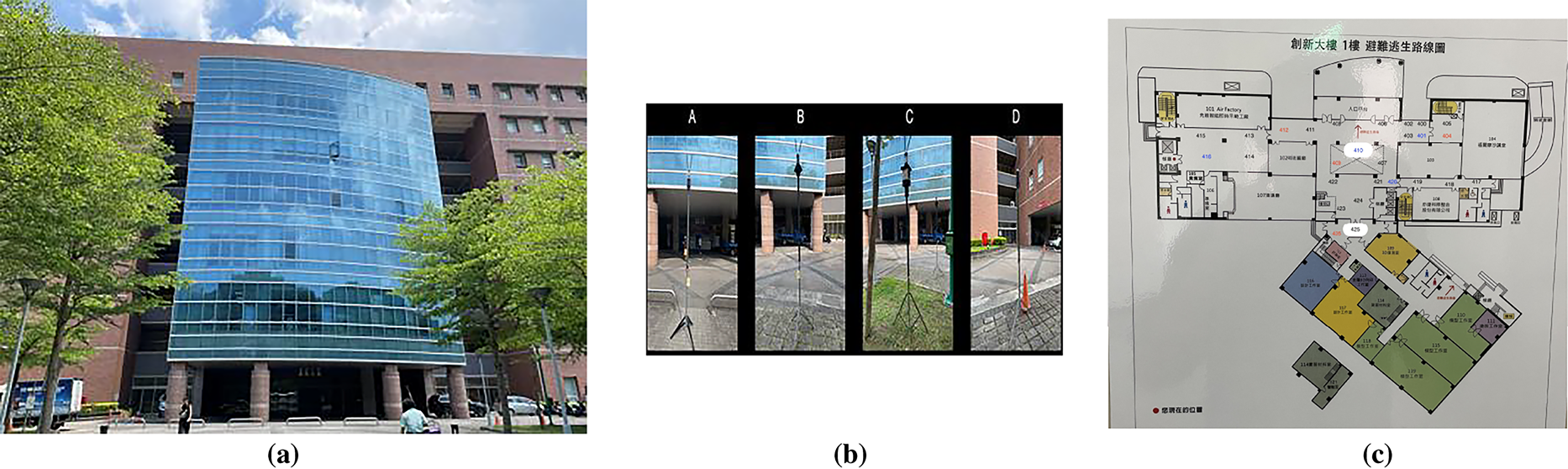

A. DNN

The DNN architecture is a standard fully-connected network used as a baseline for performance evaluation. It processes input features as a single, flat vector. The architecture of the DNN is shown in Fig. 3a and its layer details are given as:

Figure 3: The neural network architectures used for regression. (a) The architecture of the Simple DNN, a standard fully-connected network. (b) The architecture of the CNN utilizes 1D convolutional layers

• Input Layer: An input tensor of shape (

• Linear Layer 1: Maps the

• Linear Layer 2: This layer takes the H neurons from the previous layer and maps them to 2 × H neurons, followed by another ReLU activation.

• Linear Layer 3: The network then narrows the representation, mapping the 2 × H neurons back to H neurons, with a final ReLU activation.

• Output Layer: The final layer maps the H neurons to the three-dimensional coordinate output (x, y, z), producing an output tensor of shape (

B. CNN

The CNN architecture is designed to capture local correlations within the input feature vector. The raw input was first reshaped to a 1D sequence to enable convolutional processing. The architecture of the CNN is shown in Fig. 3b. The layer details are given as:

• Input Layer: The input tensor of shape (

• Conv1D Layer 1: This layer applies a 1D convolution with a kernel size of 3 and padding of 1. It transforms the single input channel to 32 output channels, resulting in a tensor of shape (

• Conv1D Layer 2: A second 1D convolution layer with a kernel size of 3 and padding of 1, transforming the 32 channels to 64. The output tensor has a shape of (

• Flatten Layer: The output of the convolutional layers is reshaped into a flat vector. The output tensor shape becomes (

• Linear Layer 1: Maps the 1024 flattened features to a hidden layer of size H=256, followed by a ReLU activation.

• Output Layer: This layer maps the H neurons to the 3-dimensional coordinate output (x, y, z), producing an output tensor with a shape of (

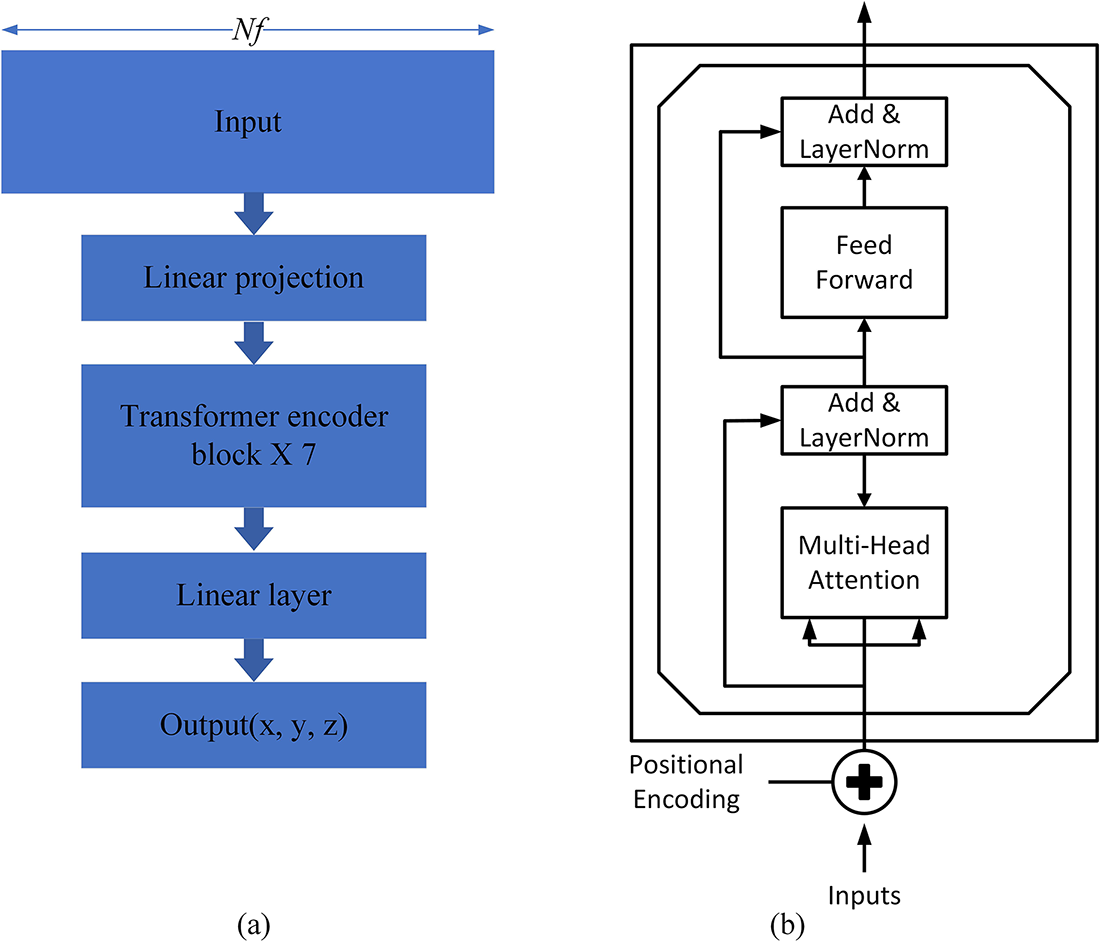

C. Transformer Model

The Transformer architecture is designed to model complex relationships within a sequence of data points using self-attention. This model treats the input features as a single sequence of 16 numeric values to learn global dependencies. The architecture of the Transformer model is shown in Fig. 4a. The layer details are given as:

Figure 4: Transformer model architecture. (a) The full architecture of the Transformer model. (b) The detailed architecture of a single Transformer encoder block

• Input and projection: The 16-dimensional numeric features are first projected into a higher-dimensional embedding space via a linear layer Linear (16, H = 256).

• Transformer encoder blocks: The projected sequence is passed through seven encoder blocks. Each of these blocks is composed of a multi-head self-attention sublayer followed by a feed-forward sublayer, with residual connections and layer normalization applied to stabilize training. The self-attention mechanism enables the model to assess the importance of all input features, thereby capturing long-range dependencies across the entire sequence. The architecture of a Transformer encoder is given in Fig. 4b.

• Output head: The final output from the last encoder block is passed through a linear layer, Linear (H, 3), serving as the regression head that maps the learned H-dimensional representation to the final 3D coordinate output (x, y, z). The final output of the network is a tensor with the shape of (

3.5 Conventional Trilateration Method

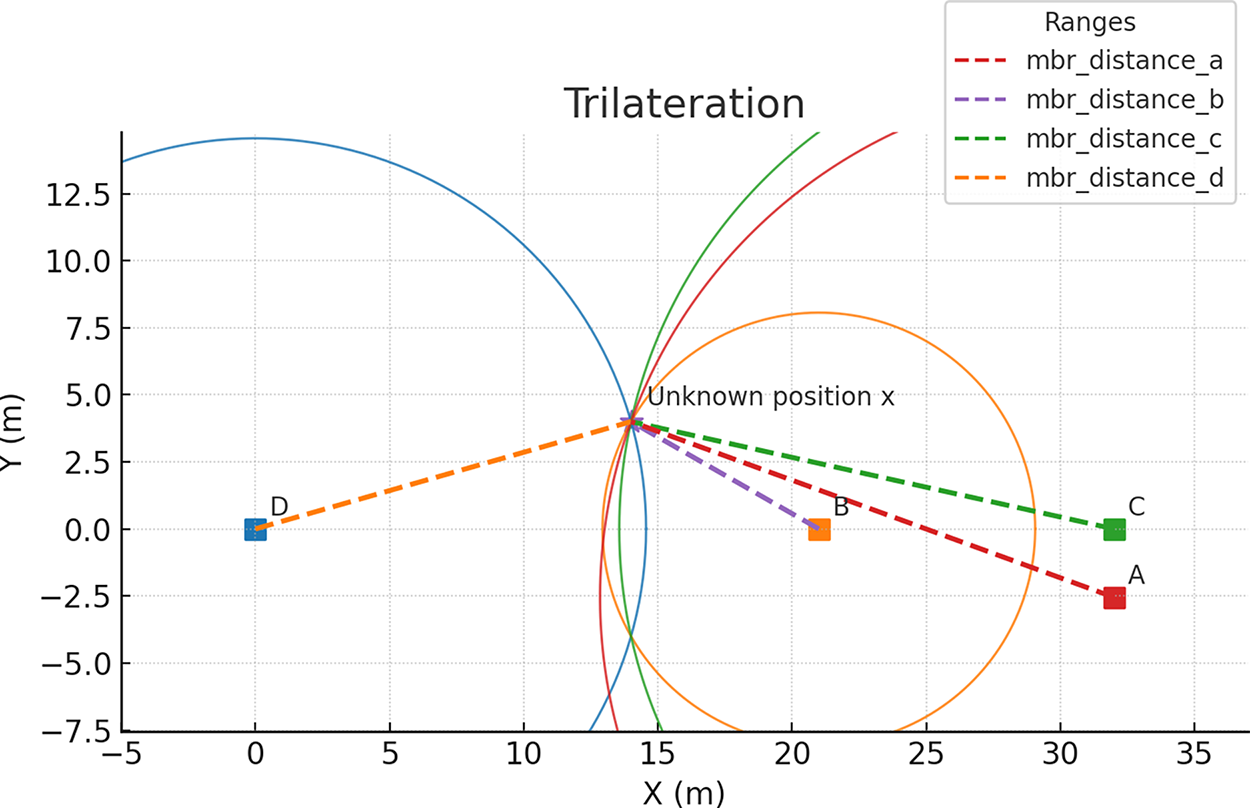

To establish a comprehensive baseline, this study compares the proposed Transformer-based framework with a conventional trilateration algorithm. A distance-based multilateration method was implemented using the Gauss-Newton method for non-linear least-squares estimation, adapted from the work of Yan et al. [35]. As illustrated in Fig. 5, this method establishes an indoor coordinate system with reference point D as the origin (shifted 8 m north) and iteratively calculates the target’s estimated position by minimizing the sum of squared errors from the known anchor coordinates and measured distances (mbr_distance).

Figure 5: Schematic representation of the conventional trilateration method

The error function,

where

The Gauss-Newton method iteratively refines the estimated position by applying incremental corrections until convergence, yielding the final three-dimensional coordinates of the target. This approach is well-suited for indoor positioning with multiple reference points and inherent measurement noise, as it finds the optimal location that minimizes the sum of squared distance residuals. However, a significant limitation of this method is its dependency on the accurate definition of the relative distances to the anchors and the mbr_distance values. If the signal is severely attenuated or distorted by walls or other obstacles, the mbr_distance can be inaccurate, which can significantly compromise the final positioning accuracy. To mitigate potential numerical instability during Gauss-Newton iterations, the solver was initialized using the centroid of the anchor positions and constrained by convergence thresholds, preventing divergence under noisy or obstructed measurement conditions. This addition explicitly documents our approach to ensuring numerical stability when using Gauss-Newton under multipath and obstruction.

3.6 Cross-Site Validation and Real-Time Deployment

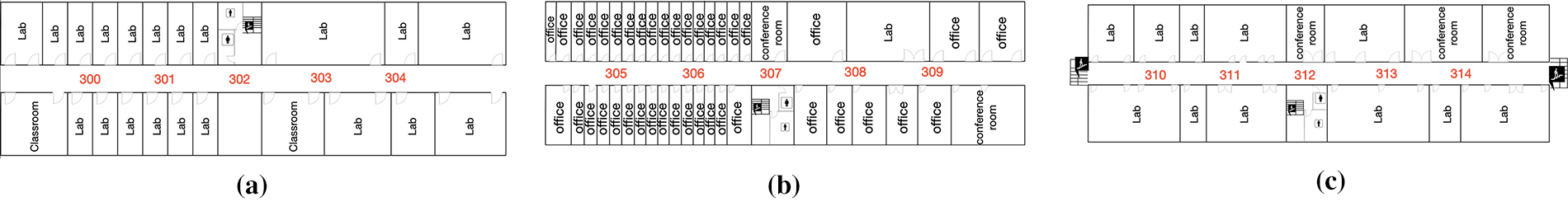

Following model training, cross-site validation was conducted at the Ming-Chi Electrical Engineering Building (Site-A). This site was specifically chosen because, while it shared a similar geometric layout to our training site, it differs substantially in construction materials and signal propagation characteristics. This controlled variation allowed for a direct and stringent evaluation of the model’s ability to transfer without site-specific calibration. The floor plans for validation Site-A are presented in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Floor plans of the Ming-Chi Electrical Engineering building. The three diagrams show the layouts of different floors at the validation site. (a) Layout of the first floor. (b) Layout of the second floor. (c) Layout of the third floor

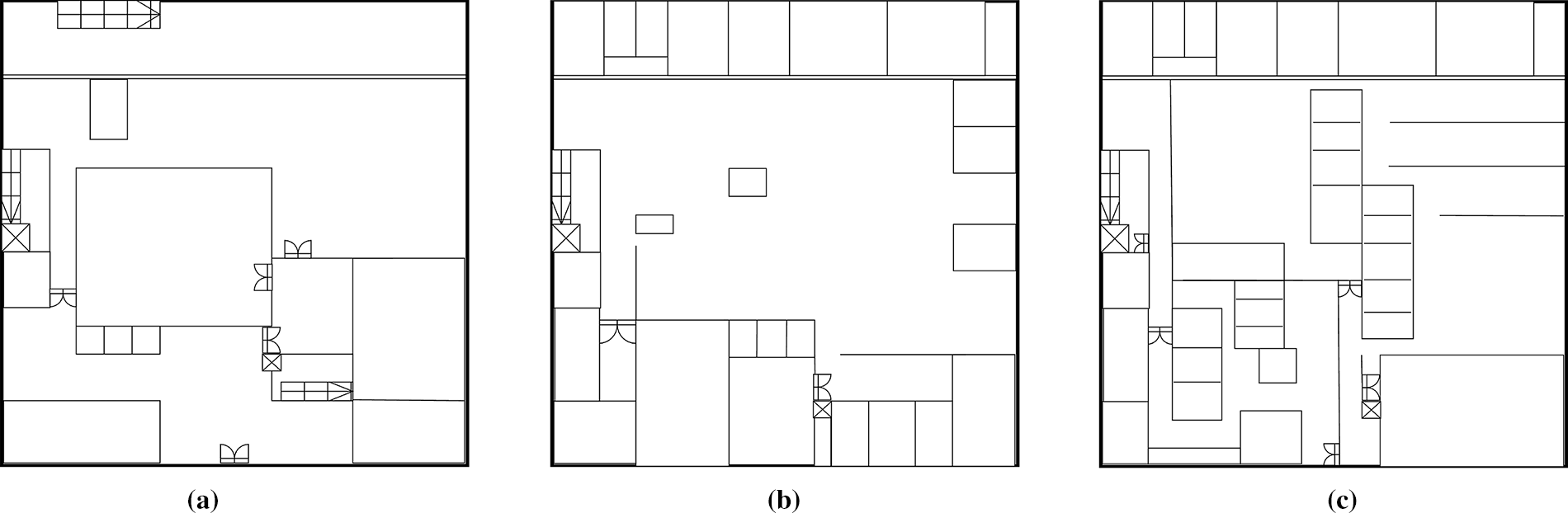

The best-performing Transformer model was then deployed at Site-B for a final real-time test. This site, characterized by its denser pedestrian flow and frequent transient obstructions, served as a stringent benchmark for the framework’s adaptability and robustness in a complex, dynamic environment. The floor plan for this deployment site is shown in Fig. 7. The live system used FastAPI to process real-time RSSI/SNR data from the SDR platform, providing low-latency coordinate predictions to a front-end interface.

Figure 7: Floor plans of the Site-B building. The three diagrams show the layouts of different floors at the real-time deployment site. (a) Layout of the first floor. (b) Layout of the second floor. (c) Layout of the third floor

The evaluation framework was designed to capture not only the absolute accuracy of the proposed system but also its robustness and reliability, which are critical for mission-critical applications. To achieve this, three complementary metrics were employed.

The Mean Localization Error (

where:

•

•

•

•

To complement the mean error, the Median Localization Error (

Finally, the Standard Deviation (

where

By combining

The evaluation of the proposed framework was conducted across multiple sites to validate its generalization capability and real-time applicability. The analysis was structured in three stages: cross-site validation using an unseen environment (validation Site-A), real-time deployment in a dynamic scenario (validation Site-B), and three-dimensional positioning performance, including the vertical axis. The results are presented in comparison with baseline AI models and conventional trilateration to highlight the methodological contributions.

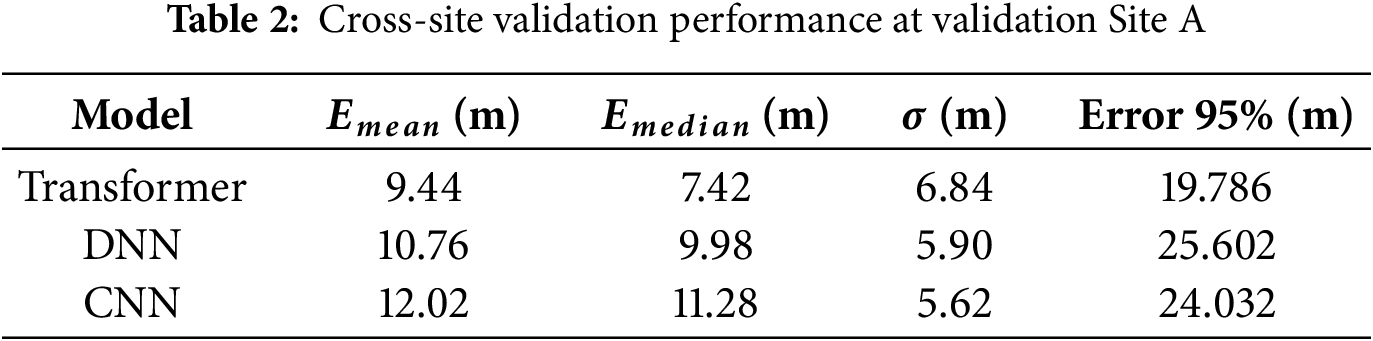

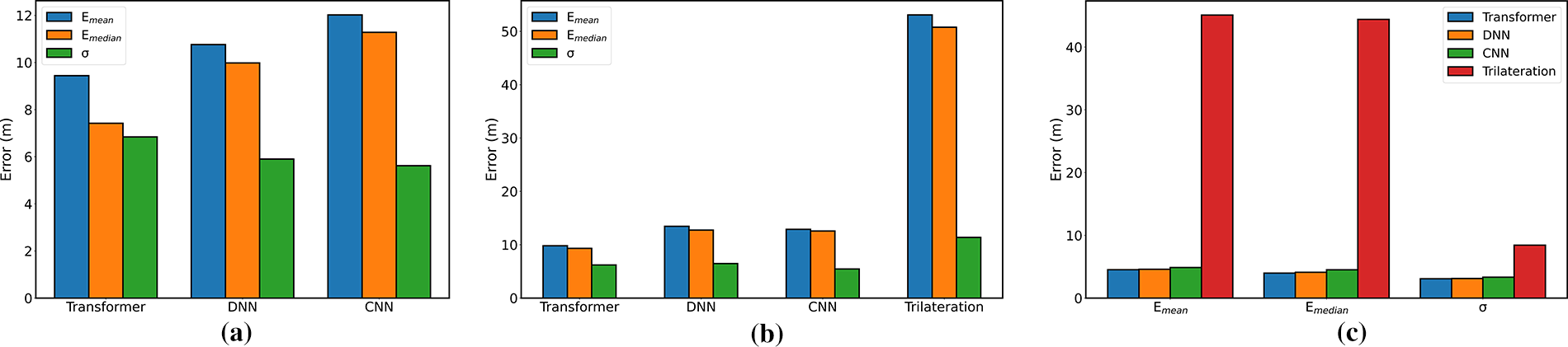

Cross-site validation was conducted at validation Site-A, which was selected to provide structural similarity to the training site in terms of geometry while differing in material composition and environmental conditions. The results, summarized in Table 2, indicate that the Transformer model achieved a mean localization error of 9.44 m (7.42 m median, σ = 6.84 m), outperforming both the DNN (10.76 m mean, 9.98 m median, σ = 5.90 m) and CNN (12.02 m mean, 11.28 m median, σ = 5.62 m). Although the Transformer exhibited slightly higher error dispersion than the DNN and CNN, the overall distribution remained stable and within acceptable limits. These findings confirm the Transformer’s ability to generalize beyond the training environment, particularly under NLOS conditions.

4.2 Real-Time Deployment Analysis

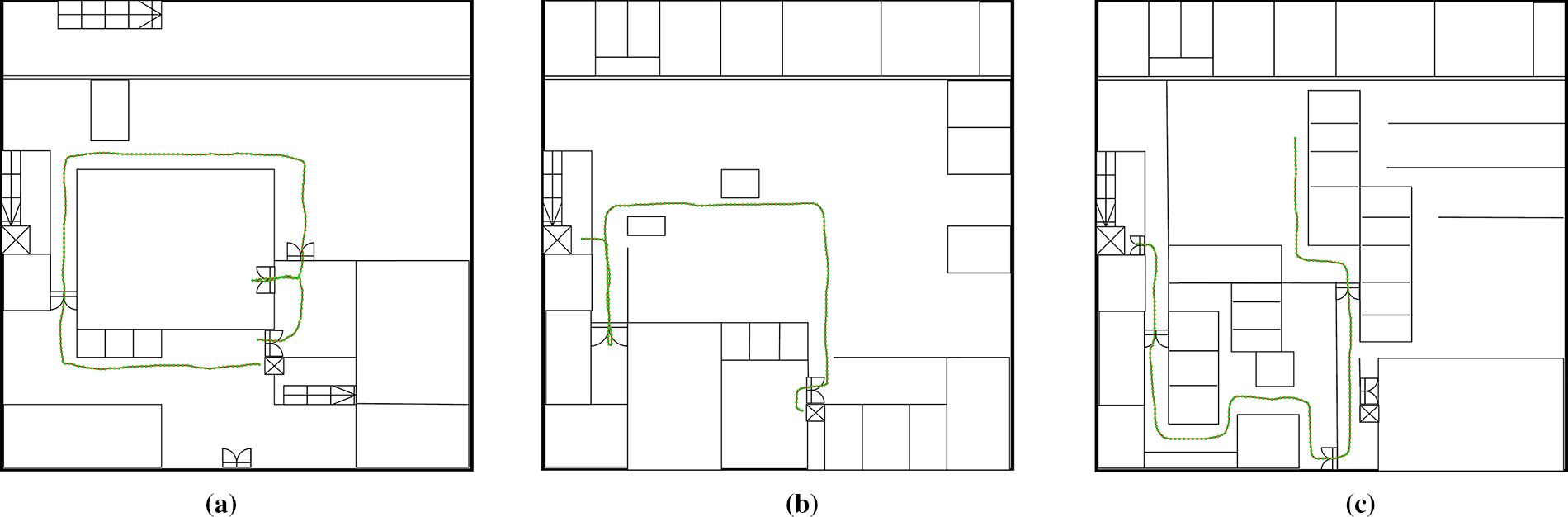

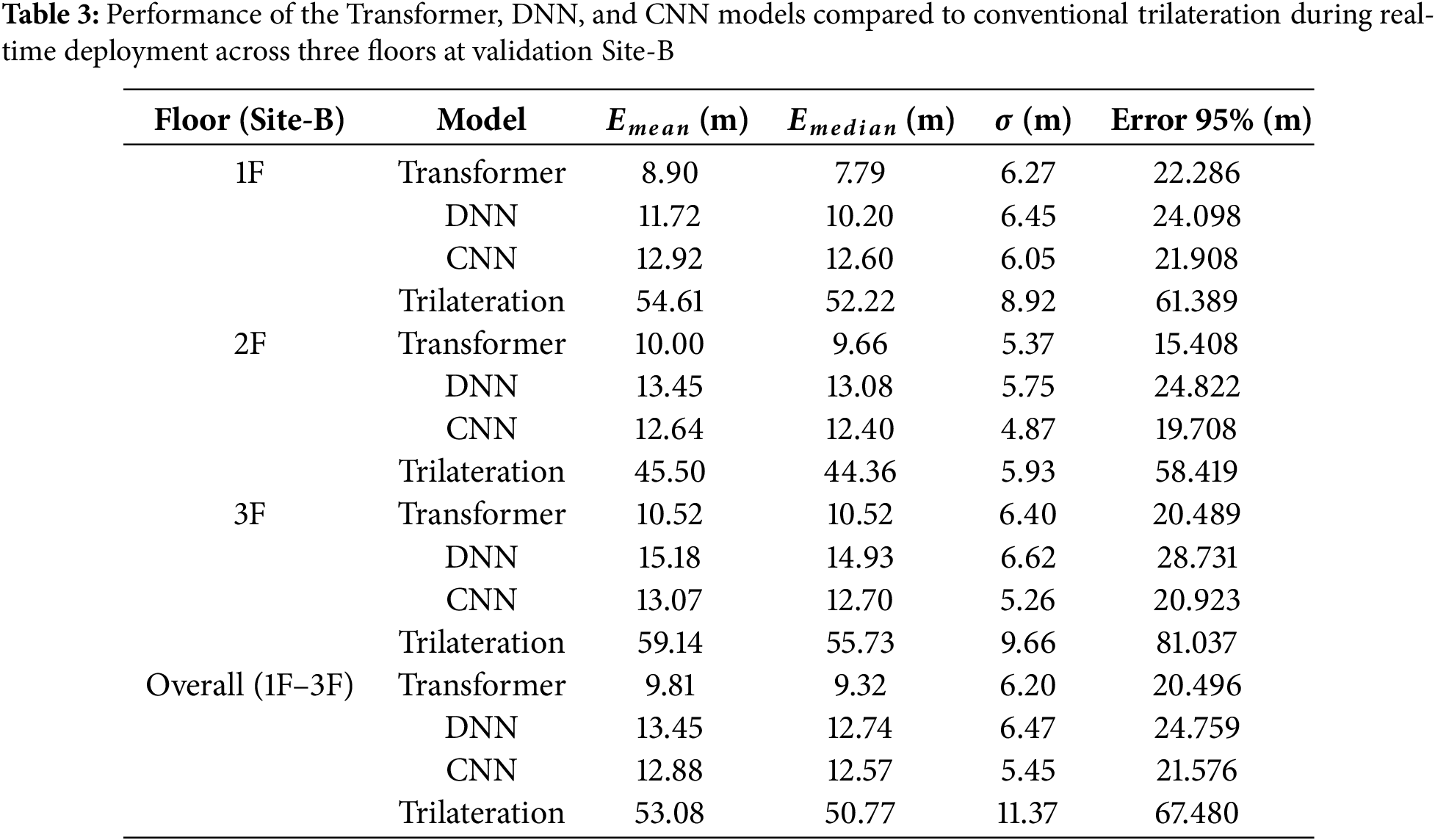

The universal Transformer model was subsequently deployed in validation Site-B, an environment characterized by dense pedestrian flow, dynamic obstacles, and heterogeneous floor layouts. The site layout and the representative path of the mobile receiver are presented in Fig. 8. The localization accuracy of the Transformer, CNN, DNN, and conventional trilateration methods across three floors of Site-B is summarized in Table 3. Across all floors, the Transformer consistently achieved the best performance. On the first floor, it reached a mean error of 8.90 m (7.79 m median, σ = 6.27 m), outperforming the DNN yielded 11.72 m (10.20 m, σ = 6.45 m), while the CNN recorded 12.92 m (12.60 m, σ = 6.05 m). Trilateration performed the worst with 54.61 m (52.22 m, σ = 8.92 m). On the second floor, the Transformer again led with 10.00 m (9.66 m, σ = 5.37 m), outperforming both the CNN achieved 12.64 m (12.40 m, σ = 4.87 m), while the DNN followed with 13.45 m (13.08 m, σ = 5.75 m). Trilateration once more lagged far behind, with 45.50 m (44.36 m, σ = 5.93 m). Similarly, on the third floor, the Transformer sustained strong performance with 10.52 m (10.52 m, σ = 6.40 m). In contrast, the CNN produced 13.07 m (12.70 m, σ = 5.26 m), while the DNN had the highest errors among the neural models at 15.18 m (14.93 m, σ = 6.62 m). Trilateration again showed poor results, with 59.14 m (55.73 m, σ = 9.66 m).

Figure 8: Real-time deployment site and mobile receiver path at validation Site-B. The three floor plans show the representative paths taken by the mobile receiver during the real-time test on each floor of the Site-B Building. (a) First floor. (b) Second floor. (c) Third floor

When aggregated across all three floors, the Transformer achieved an overall mean localization error of 9.81 m (9.32 m, σ = 6.20 m) clearly outperforming the CNN 12.88 m (12.57 m, σ = 5.45 m) and DNN 13.45 m (12.74 m, σ = 6.47 m), while conventional trilateration remained the least effective at 53.08 m (50.77 m, σ = 11.37 m). These comprehensive findings confirm the proposed framework’s sub-12 m localization accuracy and robust generalization capability across dynamic, multi-story indoor environments, demonstrating reliable performance without site-specific calibration.

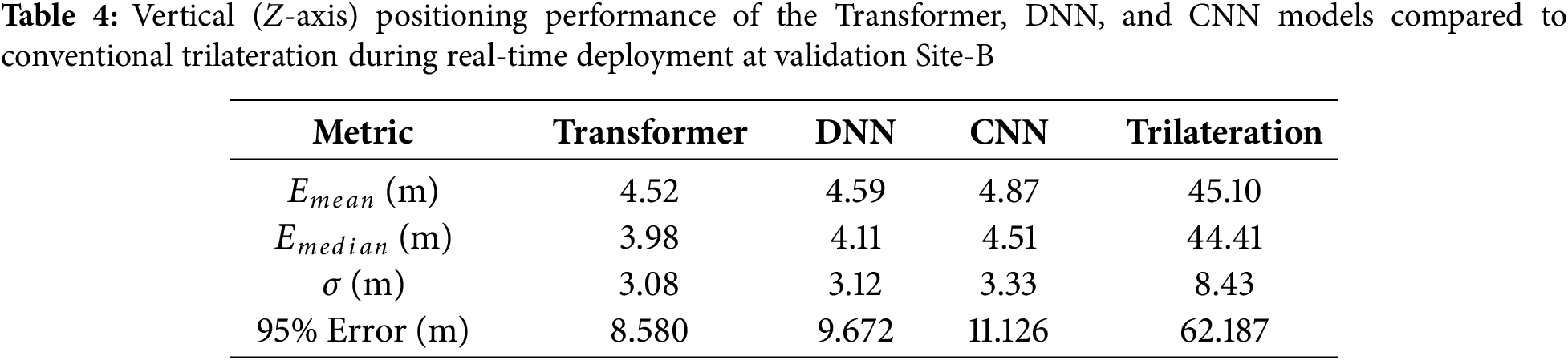

The vertical positioning results at validation Site-B demonstrate the feasibility of accurate height estimation even with all four anchors deployed on a common horizontal plane. As reported in Table 4, the Transformer achieved a mean vertical error of 4.52 m (median = 3.98, σ = 3.08), surpassing the DNN (4.59 m; median = 4.10, σ = 3.12) and CNN (4.87 m; median = 4.35, σ = 3.33). In contrast, trilateration failed to provide reliable height estimation, with errors exceeding 45 m (median = 44.60, σ = 8.43). These results confirm that Transformer’s self-attention mechanism can extract implicit height cues from subtle cross-floor variations in signal statistics, effectively converting multipath from a source of error into informative structure for three-dimensional positioning.

The experimental results collectively demonstrate that the Transformer-based framework achieves robust cross-site performance while maintaining predictable error characteristics in both static and dynamic environments. Fig. 9 shows an overall summary of these findings, comparing the performance of the Transformer model with CNN, DNN, and Trilateration. At validation Site-A, the model attained lower mean and median errors than the CNN and DNN baselines (9.44 m/7.42 m vs. 12.02 m/11.28 m and 10.76 m/9.98 m, respectively), confirming its ability to generalize under moderate shifts in building materials and environmental conditions (Fig. 9a). At the more demanding Site-B, the Transformer preserved a decisive advantage over conventional trilateration, which exhibited mean errors above 53 m, while the proposed model maintained accuracy near 10 m (Fig. 9b). These results confirm that the framework can be deployed across heterogeneous sites without site-specific calibration, addressing a fundamental gap in existing indoor localization methods.

Figure 9: Overall summary of the results by comparing the performance of the Transformer model with CNN, DNN, and Trilateration models. (a) Cross-site validation performance at Site A, (b) Real-time deployment performance at Site B (overall), and (c) Vertical positioning performance at Site B

From a signal processing perspective, the self-attention mechanism functions as a dynamic reweighting of anchor contributions, allowing the model to downscale distorted inputs produced by NLOS conditions, partial blockages, or strong reflections. This channel-aware inductive bias is particularly well-suited to indoor environments, where multipath effects are not merely noise but a dominant structural feature of the propagation channel. The resulting learned representation offers greater resilience to environmental variability compared with CNNs, which emphasize local correlations, and DNNs, which lack relational structure.

The evaluation metrics further illustrate this advantage. While mean error provides an overall indicator of accuracy, the consistently lower medians achieved by the Transformer suggest superior user-perceived quality under typical deployment conditions. Moreover, the narrower dispersion observed relative to trilateration (6.20 m vs. 11.37 m, Fig. 9a) indicates more stable outcomes, a property essential for mission-critical applications where predictability is prioritized over occasional best-case performance. In vertical positioning, the model achieved sub-5 m accuracy despite coplanar anchor deployment, demonstrating that learned attention patterns can extract implicit height cues from subtle cross-floor variations in signal statistics (Fig. 9c). This capability effectively converts multipath, traditionally treated as a source of error, into an informative structure for three-dimensional positioning.

Importantly, the achieved sub-12 m horizontal accuracy (~10 m) should be understood as the outcome of a deliberate design trade-off. While this level of accuracy does not meet the sub-meter precision required for specialized applications such as surgical tracking or autonomous robotics, it directly addresses the key barriers to real-world deployment. The framework is map-free, eliminating the costly and time-consuming recalibration associated with fingerprinting and UWB-based DL systems [7,8,13]. By operating in the sub-1 GHz band, it leverages superior penetration and resilience to walls and obstructions, ensuring stable performance in diverse indoor environments [19–22]. This makes ~10 m accuracy not only acceptable but also practical for a wide range of applications where scalability and reliability outweigh the need for centimeter-level precision. For instance, the performance significantly exceeds the U.S. FCC’s 50 m benchmark for indoor E-911 calls [36], enabling reliable floor-level determination and first-responder situational awareness. In addition, 5–10 m accuracy is operationally sufficient for wide-area asset tracking, occupancy monitoring, and in-building wayfinding in large, complex facilities [37,38]. Taken together, the Transformer-based architecture and successful cross-site validation [12,14,15] demonstrate a highly practical solution for generalized, large-scale deployment that aligns with emerging 6G ISAC architectures [16,18,24,25].

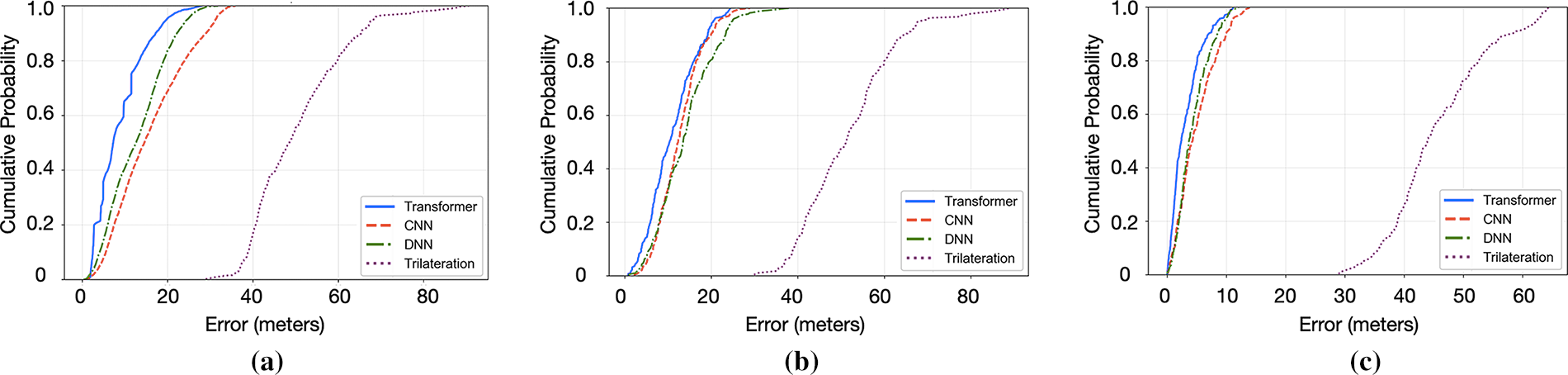

Complementary visualizations further reinforce these findings. Fig. 10 presents cumulative distribution functions (CDFs), which provide deeper insight into error distributions and worst-case scenarios. In cross-site validation (Fig. 10a), the Transformer demonstrated slightly higher overall performance, particularly in the 5–10 m error range, compared with CNN, DNN, and the conventional trilateration method. For real-time deployment (Fig. 10b), the Transformer performed well and was closely followed by CNN, which, in turn, outperformed DNN, while conventional trilateration completely failed in complex environments. In vertical positioning (Fig. 10c), the Transformer maintained a consistent advantage, highlighting its unique ability to recover height information effectively from signal statistics.

Figure 10: Cumulative distribution of localization errors comparing the Transformer, CNN, DNN, and Trilateration models. (a) Cross-site validation at Site A, (b) Real-time deployment at Site B (overall), and (c) Vertical positioning at Site B

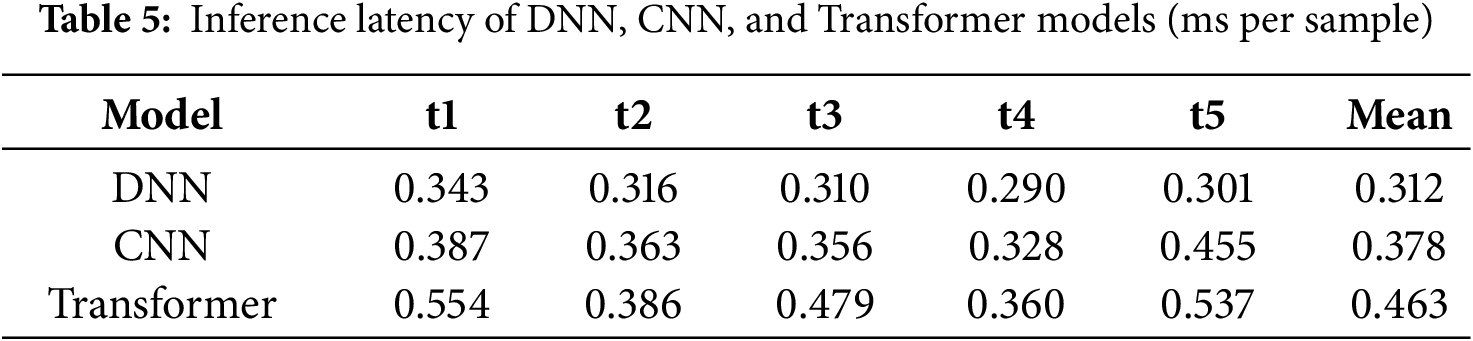

While accuracy is critical, practical deployment also depends on computational efficiency and scalability to mobile or embedded platforms. To this end, inference latency was measured on a MacBook Pro (M1 Pro, 16 GB RAM). Table 5 summarizes the results for the three architectures. All models achieved inference within 1 ms per sample, confirming their suitability for real-time deployment. As expected, the DNN was fastest due to its lightweight fully connected design, while the Transformer incurred slightly higher latency owing to self-attention layers. However, the Transformer remained well within real-time thresholds, with average latency below 0.5 ms per sample. This computational profile suggests that deployment on smartphones, IoT devices, or embedded platforms is feasible, provided modest hardware acceleration (e.g., mobile GPUs or NPUs). Furthermore, energy efficiency is aided by the fact that inference is far less demanding than data acquisition and wireless communication, which dominate system-level power consumption.

Overall, the findings support the treatment of indoor localization as a native capability of communication networks rather than as an auxiliary service. By demonstrating that low-frequency bands can provide reliable sensing when integrated with AI native models, this study points toward a design paradigm in which coverage-oriented spectrum and Transformer-based localization jointly enable scalable, real-time spatial awareness within future 6G ISAC systems.

Before outlining the broader limitations, it is important to acknowledge the validity considerations addressed in this study. On the internal validity side, potential measurement biases were minimized through a consistent acquisition protocol (single operator, fixed receiver height of 1.5 m, and 5-min averaging per location), while ground-truth coordinates were established with ±10 cm accuracy using architectural plans and a laser distance meter. Numerical stability was also ensured through input normalization during Transformer training and convergence thresholding for the Gauss–Newton solver in the trilateration baseline. On the external validity side, the evaluation was limited to institutional buildings with coplanar anchor placement and research-grade SDR platforms, which restricts immediate generalization to other typologies and commodity devices.

Two primary limitations should be acknowledged when interpreting these results. First, the anchor geometry was optimized for rapid field deployment rather than inference accuracy; further improvements are expected with modest height diversity or additional anchors, which may enhance sub-5 m vertical positioning accuracy. Second, although the framework demonstrated strong generalization across two distinct building typologies, a university campus and a multi-story office building, broader validation is required to confirm long-term stability across diverse settings such as residential, commercial, and industrial facilities.

Building on these findings, future work will focus on three key directions. The first is system portability and achieving higher accuracy. The current framework relies on research-grade SDR platforms, and future adaptations must demonstrate feasibility with commodity hardware such as smartphones and Wi-Fi access points. It is important to acknowledge that the present ~10 m horizontal accuracy, while sufficient for applications such as floor-level determination, asset tracking, occupancy monitoring, or in-building wayfinding, does not meet the sub-meter precision required by use cases like AR/VR, surgical tracking, or autonomous robotics. To address this gap, future research will investigate multiband fusion and hybrid modalities (e.g., combining BLE, UWB, and IMU data) to leverage the framework’s robust generalized position for short-range refinement. Evaluation under device heterogeneity and multi-band interference from coexisting wireless systems will also be conducted. The second direction is model interpretability. To build trust in safety-critical contexts, we will analyze the Transformer’s attention patterns against measurable channel attributes, thereby offering deeper insight into the model’s decision-making process. The third direction involves practical deployment implications. Future work will investigate latency–accuracy trade-offs at different beaconing rates, conduct larger-scale and longer-horizon trials, and evaluate interoperability with existing infrastructure. These steps will enable a deeper understanding of scalability, energy efficiency, and operational costs when extending the system beyond a single campus environment. Ultimately, these steps will enable a deeper understanding of how the proposed framework can be fully integrated into emerging 6G ISAC standards, advancing the vision of indoor localization as a native network capability rather than an auxiliary service.

The findings support the treatment of indoor localization as a native capability of communication networks rather than as an auxiliary service. By demonstrating that low-frequency bands can provide reliable sensing when integrated with AI native models, this study highlights a design paradigm in which coverage-oriented spectrum and Transformer-based localization jointly enable scalable, real-time spatial awareness with future 6G ISAC systems.

This work establishes a deployable map-free indoor localization framework that couples low-frequency radio (600 MHz) with a Transformer encoder, eliminating the need for prior maps or extensive site-specific measurements while preserving real-time operation across heterogeneous buildings. The approach specifically targets environments where reliability and rapid setup are paramount practical constraints.

Evidence from controlled cross-site evaluation and live deployment confirms the robustness of the proposed framework. At validation Site-A, the Transformer achieved 9.44 m mean and 7.42 m median localization error, outperforming CNN and DNN baselines under material and environmental shifts that typically degrade model transferability. In a more dynamic setting (validation Site-B), the overall mean error was approximately 10 m (median 9.32 m), and the Transformer reduced absolute error by more than 40 m compared to trilateration, revealing the practical advantage of learned relational models over purely geometric methods in multipath-rich environments. Vertical positioning under coplanar anchors remained sub-5 m on average (4.52 m mean; 3.98 m median), indicating that learned attention can partially compensate for limited height diversity in anchor placement.

These outcomes arise from the model’s self-attention mechanism, which reweights anchor contributions based on observed signal dependencies, thereby transforming multipath, traditionally a source of error, into an informative structure for position inference. This inductive bias is better aligned with the sequential and relational nature of RSSI/SNR than architectures that either emphasize local spatial features (CNN) or rely on unconstrained mappings (DNN). The use of sub-1 GHz spectrum further sustains performance by improving penetration and obstruction tolerance, which matches the operational needs of rapid deployment and mission-critical coverage.

Beyond model performance, the findings have broader implications for 6G ISAC system design. The results show that coverage-oriented low-frequency bands can serve as resilient sensing resources when combined with AI native localization, enabling a single infrastructure to support communication, environmental awareness, and positioning within one stack. Treating localization as a first-class network capability rather than an auxiliary service aligns with the emerging ISAC vision and simplifies integration at the SMO or edge runtime.

Taken together, these results advocate for redefining indoor localization as an intrinsic function of 6G networks. Embedding the learned Transformer-based module alongside communication functions will allow future systems to expose spatial position with the predictability demanded by real propagation rather than by idealized geometric assumptions, thereby advancing ISAC from concept to practice.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan, under grant number MOST 114-2224-E-A49-002, and was received by En-Cheng Liou.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Bin Zhang, En-Cheng Liou, and Muhammad Usman; Methodology, Bin Zhang and En-Cheng Liou; Software, Bin Zhang; Validation, Bin Zhang, En-Cheng Liou, and Yi-Chih Tung; Formal Analysis, Bin Zhang and Chao-Shun Yang; Investigation, Bin Zhang, Yi-Chih Tung, and Chiung-An Chen; Resources, En-Cheng Liou; Data Curation, Bin Zhang, Muhammad Usman, and Chiung-An Chen; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Bin Zhang, Yi-Chih Tung, and Muhammad Usman; Writing—Review and Editing, Bin Zhang, En-Cheng Liou, Muhammad Usman, and Chiung-An Chen; Visualization, Yi-Chih Tung and Chiung-An Chen; Supervision, En-Cheng Liou and Chao-Shun Yang; Project Administration, En-Cheng Liou and Muhammad Usman; Funding Acquisition, En-Cheng Liou. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, En-Cheng Liou, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Singh N, Choe S, Punmiya R. Machine learning based indoor localization using Wi-Fi RSSI fingerprints: an overview. IEEE Access. 2021;9:127150–74. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3111083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Wang H, Ganesh G, Zon M, Ghosh O, Siu H, Fang Q. A BLE based turnkey indoor positioning system for mobility assessment in aging-in-place settings. PLOS Digit Health. 2025;4(4):e0000774. doi:10.1371/journal.pdig.0000774. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Barbieri L, Brambilla M, Pitic R, Trabattoni A, Mervic S, Nicoli M, editors. UWB real-time location systems for smart factory: augmentation methods and experiments. In: Proceedings of the 31st Annual IEEE International Symposium on Personal, Indoor and Mobile Radio Communications (IEEE PIMRC); 2020 Aug 31–Sep 3; London, UK. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2020. [Google Scholar]

4. Salamah AH, Tamazin M, Sharkas MA, Khedr M. An enhanced WiFi indoor localization system based on machine learning. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation (IPIN); 2016 Oct 4–7; Madrid, Spain. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2016. [Google Scholar]

5. Fahama HS, Kavian YS, Asl KA, Soorki MN. Indoor localization using RSSI based supervised machine learning approaches. In: Proceedings of the 2025 Fifth National and the First International Conference on Applied Research in Electrical Engineering (AREE); 2025 Feb 4–5; Ahvaz, Iran. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2025. [Google Scholar]

6. Herath S, Irandoust S, Chen BW, Qian YM, Kim P, Furukawa Y. Fusion-DHL: WiFi, IMU, and floorplan fusion for dense history of locations in indoor environments. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 2021 May 30–Jun 5; Xi’an, China. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2021. [Google Scholar]

7. AlHajri MI, Shubair RM, Chafii M. Indoor localization under limited measurements: a cross-environment joint semi-supervised and transfer learning approach. In: Proceedings of the 22nd IEEE International Workshop on Signal Processing Advances in Wireless Communications (IEEE SPAWC); 2021 Sep 27–30; Lucca, Italy. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2021. [Google Scholar]

8. Pan SJ, Zheng VW, Yang Q, Hu DH. Transfer learning for wifi-based indoor localization. Chicago, IL, USA: The Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence Palo Alto; 2008. [Google Scholar]

9. Zhang BW, Sifaou H, Li GY. CSI-fingerprinting indoor localization via attention-augmented residual convolutional neural network. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. 2023;22(8):5583–97. doi:10.1109/twc.2023.3235449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang MX, Fan ZP, Shibasaki R, Song X. Domain adversarial graph convolutional network based on RSSI and crowdsensing for indoor localization. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023;10(15):13662–72. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3262740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Chidlovskii B, Antsfeld L, editors. Semi-supervised variational autoencoder for WiFi indoor localization. In: Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation (IPIN); 2019 Sep 30–Oct 3; Pisa, Italy. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2019. [Google Scholar]

12. Nguyen SM, Le DV, Havinga PJM. Seeing the world from its words: all-embracing Transformers for fingerprint-based indoor localization. Pervasive Mob Comput. 2024;100(3):16. doi:10.1016/j.pmcj.2024.101912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Nagia N, Rahman MT, Valaee S, editors. Federated learning for WiFi fingerprinting. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC); 2022 May 16–20; Seoul, Republic of Korea. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2022. [Google Scholar]

14. Masrur S, Khamesi AR, Guvenc I. Transforming indoor localization: advanced transformer architecture for NLOS dominated wireless environments with distributed sensors. arXiv:2501.07774. 2025. [Google Scholar]

15. Ott J, Pirkl J, Stahlke M, Feigl T, Mutschler C. Radio foundation models: pre-training transformers for 5G-based indoor localization. In: Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation; 2024 Oct 14–17; Hong Kong, China. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2024. [Google Scholar]

16. 3GPP. Feasibility study on integrated sensing and communication (Release 193rd generation partnership project (3GPP); 2023 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.3gpp.org. [Google Scholar]

17. Chiu CC, Wu HY, Chen PH, Chao CE, Lim EH. Indoor localization using 6G time-domain feature and deep learning. Electronics. 2025;14(9):13. doi:10.3390/electronics14091870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Liu F, Cui YH, Masouros C, Xu J, Han TX, Eldar YC, et al. Integrated sensing and communications: toward dual-functional wireless networks for 6G and beyond. IEEE J Sel Areas Commun. 2022;40(6):1728–67. doi:10.1109/jsac.2022.3156632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. 3GPP. Study on channel model for frequencies from 0.5 to 100 GHz. 3GPP TR 38.901 V16.1.0. Sophia Antipolis, France: ETSI; 2020 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.etsi.org/deliver/etsi_tr/138900_138999/138901/16.01.00_60/tr_138901v160100p.pdf. [Google Scholar]

20. GSMA. Low-band spectrum for 5G; London, UK: GSMA; 2022 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.gsma.com/spectrum/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Low-band-Spectrum-for-5G.pdf. [Google Scholar]

21. ITU-R. Recommendation ITU-R P.2109-2: prediction of building entry loss. Geneva, Switzerland: ITU-R; 2023. [Google Scholar]

22. Obiri NM, Van Laerhoven K. EnviKal-Loc: sub-10m indoor LoRaWAN localization using an environmental-aware path loss and adaptive RSSI smoothing. arXiv:2505.01185. 2025. [Google Scholar]

23. Deebalakshmi R, Markkandan S, Arjunan VK. Performance evaluation on extended neural network localization algorithm on 5 g new radio technology. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):26. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-96673-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. ISC EI. Integrated sensing and communications (ISAC); use cases and deployment scenarios. ETSI GR ISC 001 V1.1.1. Sophia Antipolis, France: ETSI; 2025 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.etsi.org/deliver/etsi_gr/isc/001_099/001/01.01.01_60/gr_isc001v010101p.pdf. [Google Scholar]

25. MEC EI. Multi-access edge computing (MEC); framework and reference architecture. In: ETSI GS MEC 003 V4.1.1. Sophia Antipolis. France: ETSI; 2025. [Google Scholar]

26. Chen H, Keskin MF, Sakhnini A, Decarli N, Pollin S, Dardari D, et al. 6G localization and sensing in the near field: features, opportunities, and challenges. IEEE Wirel Commun. 2024;31(4):260–7. doi:10.1109/mwc.011.2300359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. De Lima C, Belot D, Berkvens R, Bourdoux A, Dardari D, Guillaud M, et al. Convergent communication, sensing and localization in 6G systems: an overview of technologies, opportunities and challenges. IEEE Access. 2021;9:26902–25. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3053486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhu XQ, Liu JQ, Lu LY, Zhang T, Qiu T, Wang CP, et al. Enabling intelligent connectivity: a survey of secure ISAC in 6G nNetworks. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2025;27(2):748–81. [Google Scholar]

29. Aldirmaz-Colak S, Namdar M, Basgumus A, Özyurt S, Kulac S, Calik N, et al. A comprehensive review on ISAC for 6G: enabling technologies, security, and AI/ML perspectives. IEEE Access. 2025;13(2):97152–93. doi:10.1109/access.2025.3573371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Chopra G, Ahmed S. Ris-assisted integrated sensing and communication: applications, challenges and usecase scenario. Discov Appl Sci. 2025;7(7):650. doi:10.1007/s42452-025-07098-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Salem H, Sadia H, Quamar MM, Magad A, Elrashidy M, Saeed N, et al. Data-driven integrated sensing and communication: recent advances, challenges, and future prospects. ICT Express. 2025;11(4):790–808. doi:10.1016/j.icte.2025.06.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Zhang MY, Jia J, Chen J, Deng YS, Wang XW, Aghvami AH. Indoor localization fusing WiFi with smartphone inertial sensors using LSTM networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;8(17):13608–23. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3067515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Guo CA, Pleiss G, Sun Y, Weinberger KQ. On calibration of modern neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2017 Aug 6–11; Sydney, Australia. San Diego, CA, USA: Jmlr-Journal Machine Learning Research; 2017. [Google Scholar]

34. NR G. Base station (BS) radio transmission and reception. 3GPP TS 38.104 (Rel-17/18). Sophia Antipolis, France: ETSI; 2022–2024 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.etsi.org/deliver/etsi_ts/138100_138199/138104/17.18.00_60/ts_138104v171800p.pdf. [Google Scholar]

35. Yan JL, Tiberius C, Bellusci G, Janssen G. Feasibility of Gauss-Newton method for indoor positioning. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/ON Position, Location and Navigation Symposium; 2008 May 5–8; Monterey, CA, USA. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 200810.1109/plans.2008.4569986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Federal Communications Commission. Indoor location accuracy timeline and live call data reporting template: federal communications commission; 2021 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.fcc.gov/public-safety-and-homeland-security/policy-and-licensing-division/911-services/general/location-accuracy-indoor-benchmarks. [Google Scholar]

37. Ahmad NS. Recent advances in WSN-based indoor localization: a systematic review of emerging technologies, methods, challenges, and trends. IEEE Access. 2024;12:180674–714. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3509516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Obeidat H, Shuaieb W, Obeidat O, Abd-Alhameed R. A review of indoor localization techniques and wireless technologies. Wirel Pers Commun. 2021;119(1):289–327. doi:10.1007/s11277-021-08209-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools