Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Novel Analysis of SiO2 + ZnO + MWCNT-Ternary Hybrid Nanofluid Flow in Electromagnetic Squeezing Systems

1 Department of Mathematics, Government College University Faisalabad, Faisalabad, 38000, Pakistan

2 KMUTT Fixed Point Research Laboratory, Room SCL 802, Fixed Point Laboratory, Science Laboratory Building, Departments of Mathematics, Faculty of Science, King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi (KMUTT), 126 Pracha-Uthit Road, Bang Mod, Thung Khru, Bangkok, 10140, Thailand

3 Drug Exploration and Development Chair (DEDC), Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, College of Pharmacy, King Saud University, Riyadh, 11451, Saudi Arabia

4 Department of Mathematics, Saveetha School of Engineering, SIMATS, Saveetha University, Chennai, 602105, India

5 College of Engineering and Architecture, Gulf University for Science and Technology, Mishref, 32093, Kuwait

6 Applied Science Research Center, Applied Science Private University, Amman, 11931, Jordan

7 Department of Medical Research, China Medical University Hospital, China Medical University, Taichung, 40402, Taiwan

8 University College, Korea University, Seoul, 02841, Republic of Korea

9 Department of Mathematical Sciences, College of Science, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, P.O. Box 84428, Riyadh, 11671, Saudi Arabia

10 Mechanical Engineering Department, College of Engineering and Computer Science, Jazan University, P.O. Box 706, Jazan, 45142, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Authors: Muhammad Ramzan. Email: ; Ibrahim Mahariq. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Applications of Modelling and Simulation in Nanofluids)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2026, 146(1), 19 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.070435

Received 16 July 2025; Accepted 27 August 2025; Issue published 29 January 2026

Abstract

The present investigation inspects the unsteady, incompressible MHD-induced flow of a ternary hybrid nanofluid made ofKeywords

Energy usage has been identified as the demanding problem confronting humans, particularly over the next 50–70 years, particularly the global warming and monitoring carbon emissions [1]. Most wealthy countries now prioritise the security of renewable energy. Primarily, energy conversion and transmission occur at the atomic level; nanotechnology is anticipated to play a key role in invigorating current energy industries and boosting emerging renewable sectors. More than 80% of the energy we use today is generated or consumed in the form of heating. Several manufacturing procedures require the movement of heat to either input or remove energy from the system. Given the enormous increase in global energy consumption, improving heat transfer and reducing energy loss caused by inefficient use have become essential priorities [2]. Heat extraction and regulation are challenging tasks in many high-heat-flux networks, including microchemical processes, nuclear fission, fusion, and process intensification.

Nanofluids are a revolutionary form of nanotechnology-based heat transfer fluid generated by dispersing and stabilizing nanoparticles with typical lengths ranging from

A hybrid substance is a material that integrates the physicochemical characteristics of many substances at the same time and delivers these properties in a cohesive aspect. The physical and chemical characteristics of fabricated hybrid nanostructures are extraordinary since they do not exist in separate components [13]. Muneeshwaran et al. [14] presented hybrid nanofluids in a diversity of heat transport applications. The characteristics, preparation, and stability of hybrid nanofluids were scrutinized by Eshgarf et al. [15]. Additionally, a few correlations and models for forecasting the features of hybrid nanofluids were provided. Sharma et al. [16] inspected how a unique

Ternary nanofluids have been shown to significantly improve heat transport properties of base fluids when compared to conventional fluids, nanomaterials-induced fluids, and hybrid materials-based fluids. As predicted, these are useful in energy control, cooling, and further applications requiring efficient heat transmission. Mahabaleshwar et al. [19] focused on ternary nanofluid flow with heat transfer over the Riga plates, taking into account the Newtonian heating effect. The current framework discovered that in the presence of a Newtonian heating effect, the temperature profile performs better thermally than in the absence of the heating effect. Farooq et al. [20] studied the mixed convection at the stagnation point of ternary hybrid nanofluids approaching an upright Riga plate. Further, note that Silicon dioxide

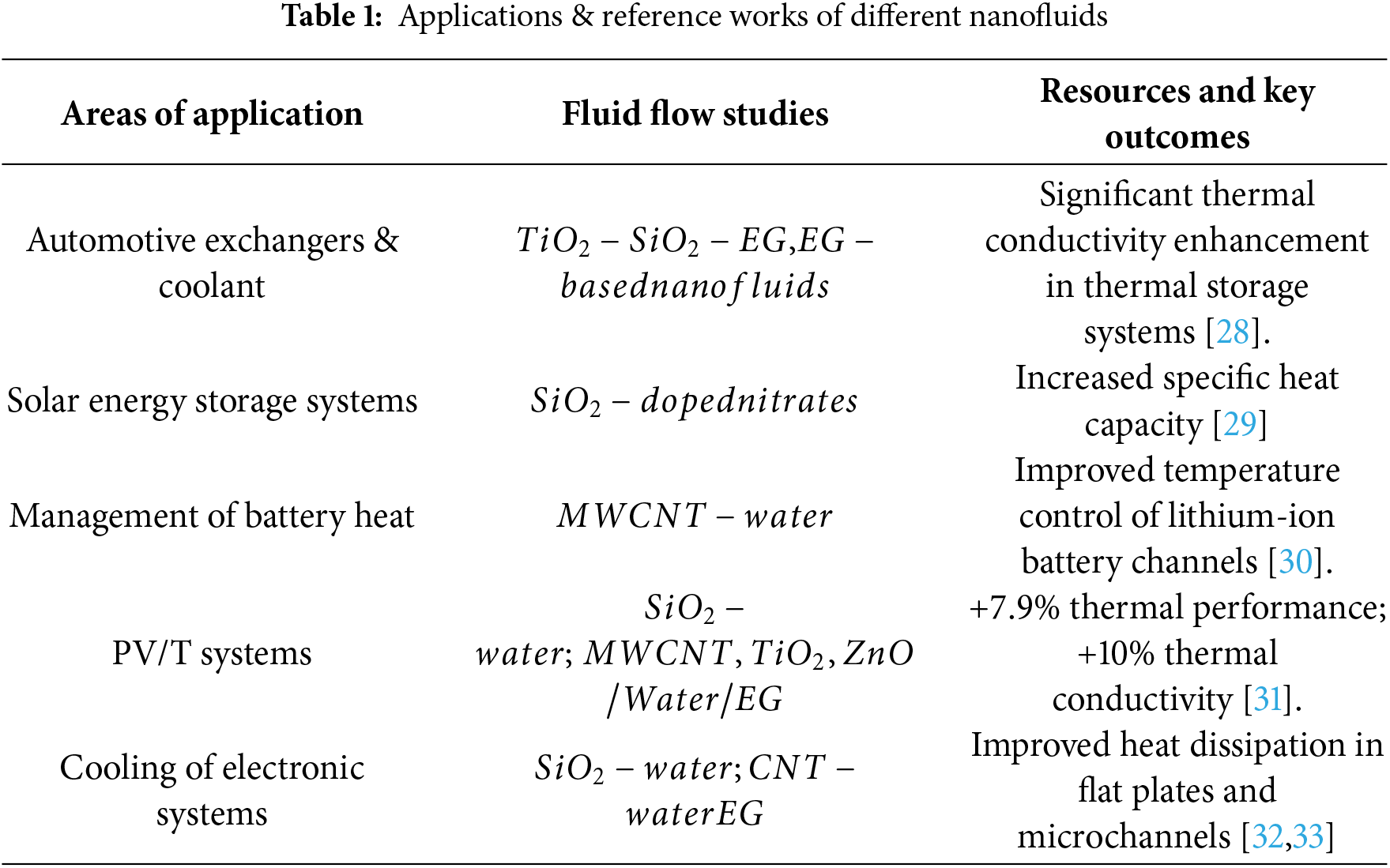

Table 1 discusses the applications and reference works of various nanofluids.

The results suggest a need for further investigation into pierced ternary nanofluids. This framework provides a novel investigation of the following points:

• A ternary hybrid nanofluid consisting of silicon dioxide

• This work is unique because it synergistically combines three different nanoparticles, each of which contributes complementary thermal and physical properties:

• A more accurate and flexible framework than conventional shooting or finite difference approaches is offered by the numerical solution of the highly nonlinear transformed boundary layer equations using MATLAB’s BVP4C method.

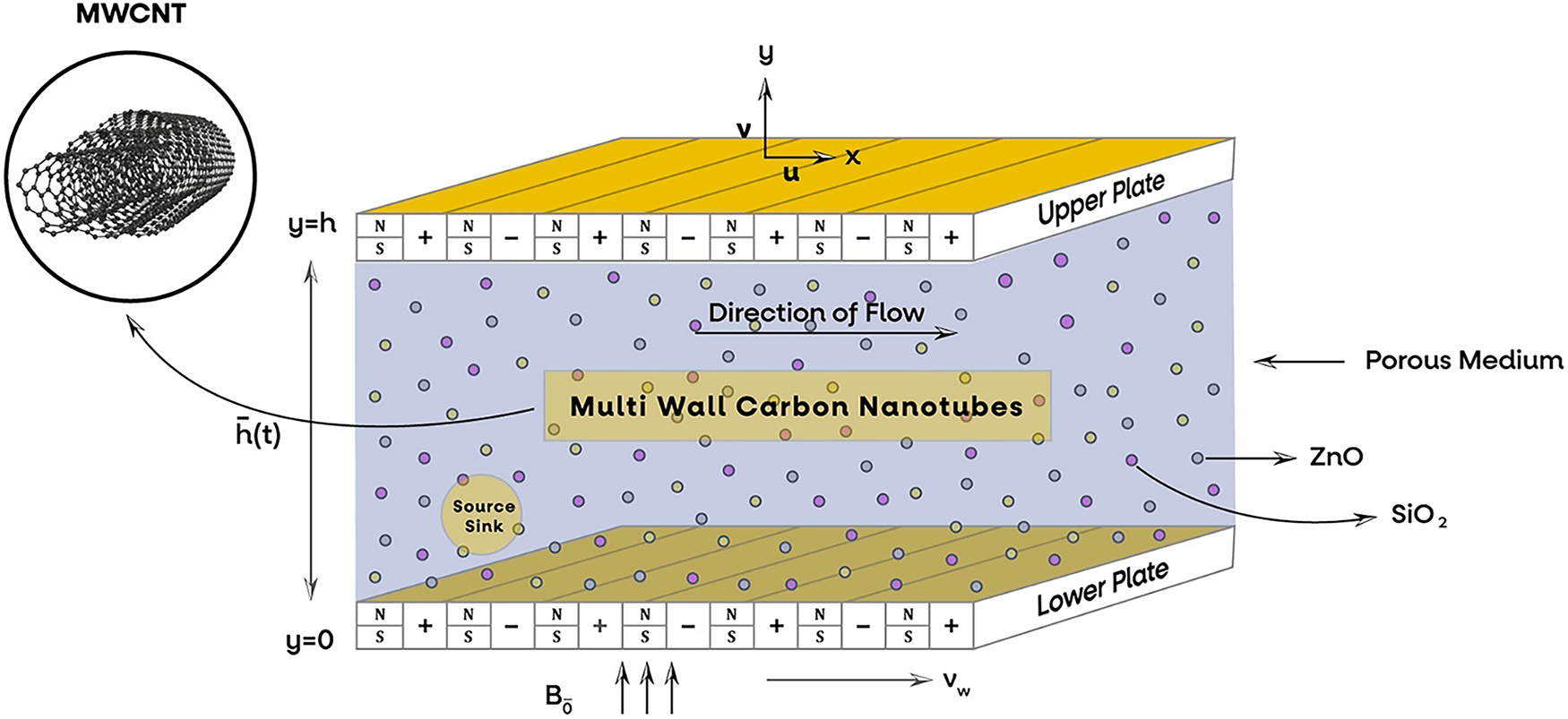

2.1 Physical Layout of the Model

This study examines the unsteady convective squeezing flow of a viscous, tri-hybrid nanomaterial fluid through two perforated Riga plates. This flow regime occurs between the compressed infinitely parallel Riga plates and is influenced by thermal radiation, varying thermal conductivity, magnetic fields, and viscous dissipation. The top plate moves with velocity toward the lower plate, generating a squeezing motion.

The symbol

The proposed model is structured utilizing the

Figure 1: Physical arrangement of the flow model

The following are the governing continuity equation (principle of conservation of mass), Navier-Stokes equation (principle of conservation of momentum), and temperature equation (principle of conservation of energy). Based on the literature [34–36].

2.2 Mathematical Modeling of the Problem

Continuity Equation:

Momentum Equation:

Energy Equation:

where the Rosseland approximation yields a radiative unidirectional heat flux (

It is anticipated that the fluid temperature corresponds to

The current model considers the following boundary conditions (BCs):

In Eq. (7), when

Role and Modelling of Porosity and Permeability

In the current study, the porous medium is modelled using Darcy’s law, which introduces a resistance force proportional to the fluid velocity. This is captured in the momentum equation through the term:

Here,

While permeability directly enters the governing equations, porosity is inherently embedded in the effective thermophysical properties of the ternary hybrid nanofluid. It influences how heat and momentum are transported through the medium by altering the apparent density, heat capacity, and viscosity. These effects are considered in the definitions of

The combined effect of porosity and permeability controls the extent of momentum suppression and heat dispersion within the porous region, which is crucial for realistic modelling of nanofluid behaviour in engineered materials and biological tissues.

Similarity Variables:

Suitable similarity variables are proposed to solve the gained nonlinear coupled boundary value problem numerically. The stated equations are converted into a nondimensional form employing the dimensionless similarity variables. They were added in order to make the equations simpler and facilitate analysis. Eq. (8), which represents these dimensionless variables, is based on a related work by Muhammad et al. [36]. Using these scaling modifications, a nonlinear ordinary differential model is created using the 2D, unstable TNF flow Eqs. (2)–(4) and the boundary conditions given by Eq. (7).

when Eq. (8) is applied to Eqs. (2)–(4) and (7), they are modified as follows.

Furthermore, Eq. (11) incorporates the boundary constraints from Eq. (7):

where,

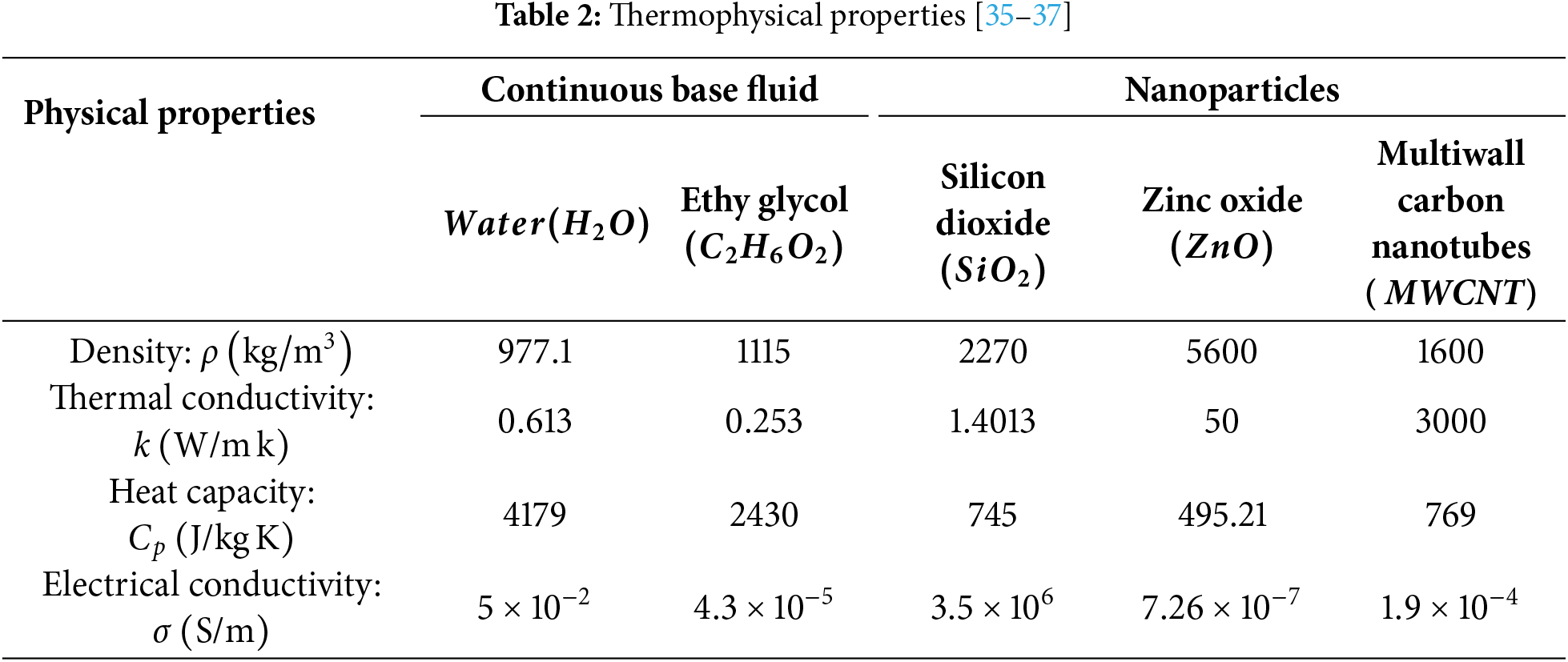

Based on the similarity transformation, the parameters shown in Eq. (12) are taken into consideration. Using TNF correlation, Table 2 lists the values for

Engineering Parameters

Engineering quantities such as skin friction coefficient

when

So,

when examining the behavior of fluid flow and heat transfer at boundaries, Eq. (14) is important. It provides the information required to assess and predict the thermal and momentum characteristics of a system. Where the local Reynolds number is defined as

Thermophysical Characteristics:

As thermophysical characteristics are extremely important since they allow us to more accurately calculate efficiency. According to the literature, heat transfer characteristics are dependent on the formulation, whereas viscosity is temperature-dependent and thermal conductivity is concentration-dependent.

Density

Viscosity

Thermal conductivity

where,

Thermal expansion coefficient

The system of coupled ordinary differential equations ODEs that forms the boundary value problem (BVP) is defined by using a MATLAB solver. After that, functions are developed for the ODEs along with the boundary conditions, and the boundary constraints are given for the interval’s ends. The numerical solver has an option called collocation that uses these functions in addition to an initial guess for the answer. The behavior of the system may be further analyzed and visualised by extracting the solution from the returning structure. Convergence requires adjusting the tolerance and iteration settings, which also offers a reliable method for resolving BVPs via collocation with the solver. A system of nonlinear, differential equations, Eqs. (9) and (10), with matching boundary constraints, Eq. (11), is solved using this approach. The following is how equations are converted into first-order ODEs:

Let

The system is defined by the initial conditions listed below:

We tackled the boundary value problem using MATLAB’s BVP4C solver, which utilizes a collocation method that keeps an eye on errors based on the residuals of the differential equations. Instead of directly managing the error of the true solution, this solver focuses on making sure the norm of the residual stays within certain limits, dictated by both relative and absolute tolerances. By default, these tolerances are set to

Figure 2: Flow chart of numerical scheme

The fluid behaviour in this study is illustrated by the graphical illustrations of temperature and momentum profiles for the tri-hybrid nanofluid

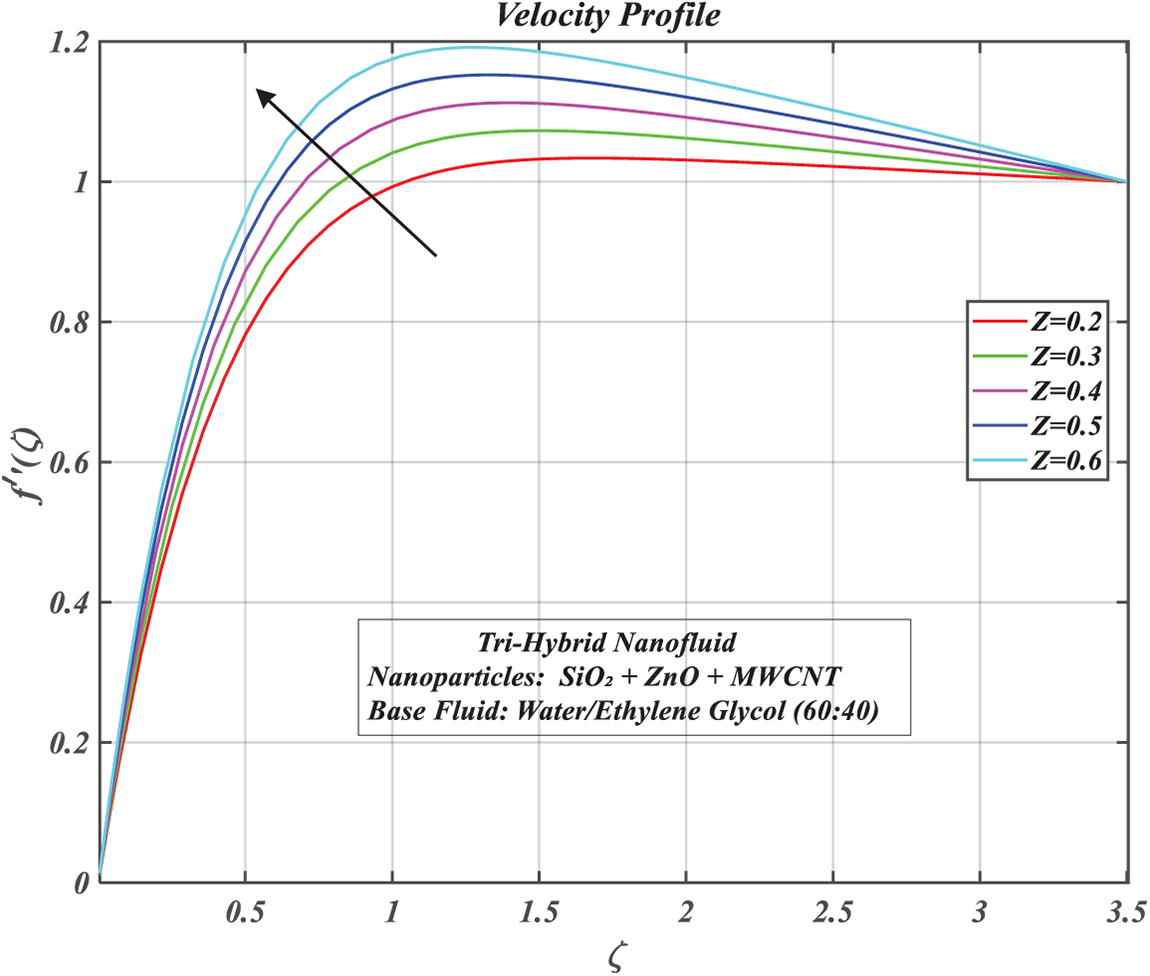

Figure 3: Consequences of hertman number on

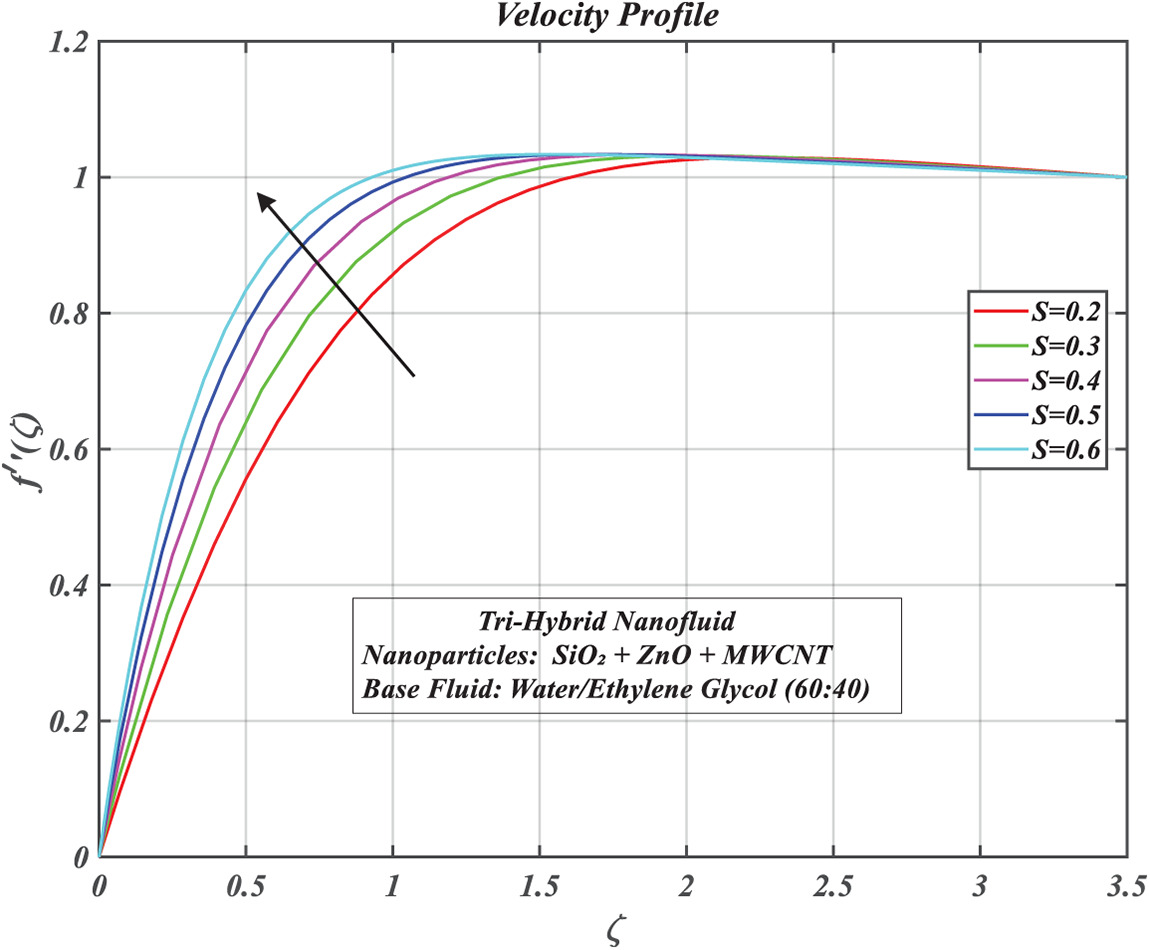

Figure 4: Consequences of suction on

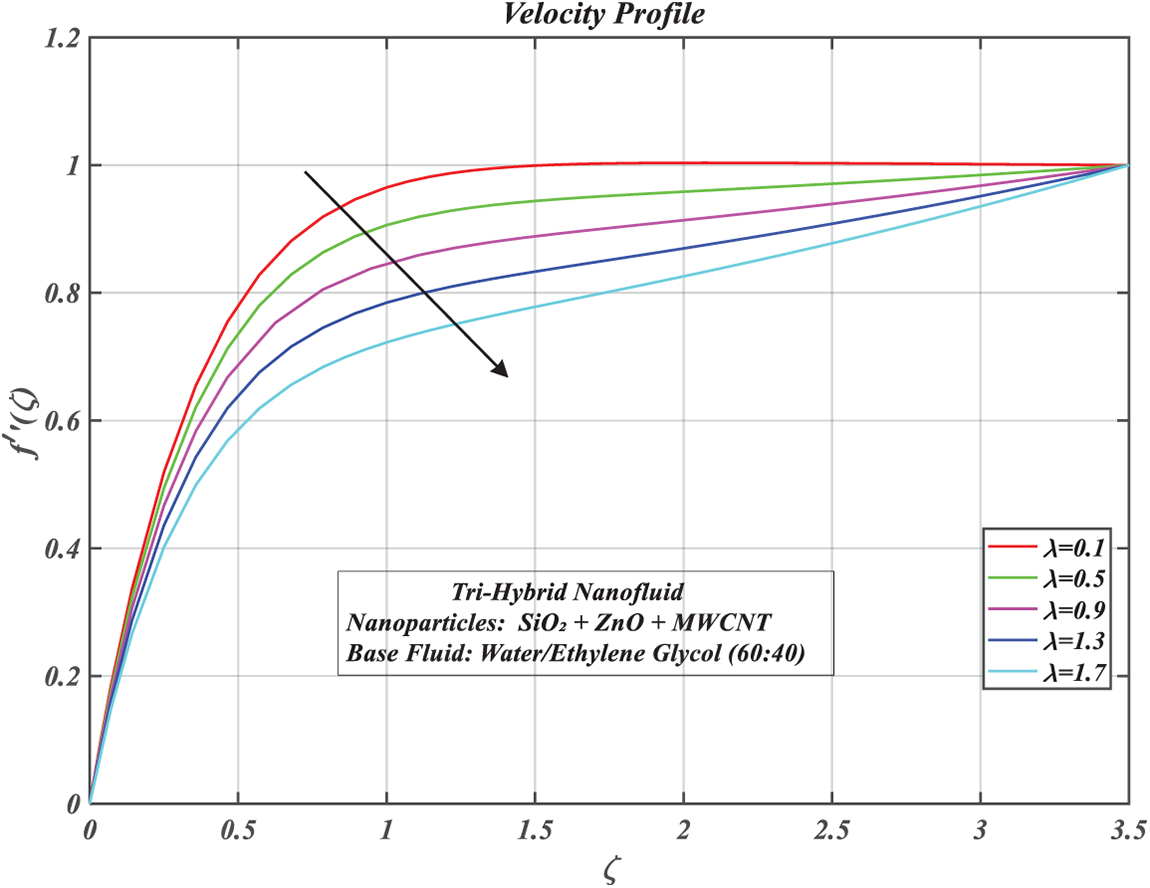

Figure 5: Consequences of porous parameter on

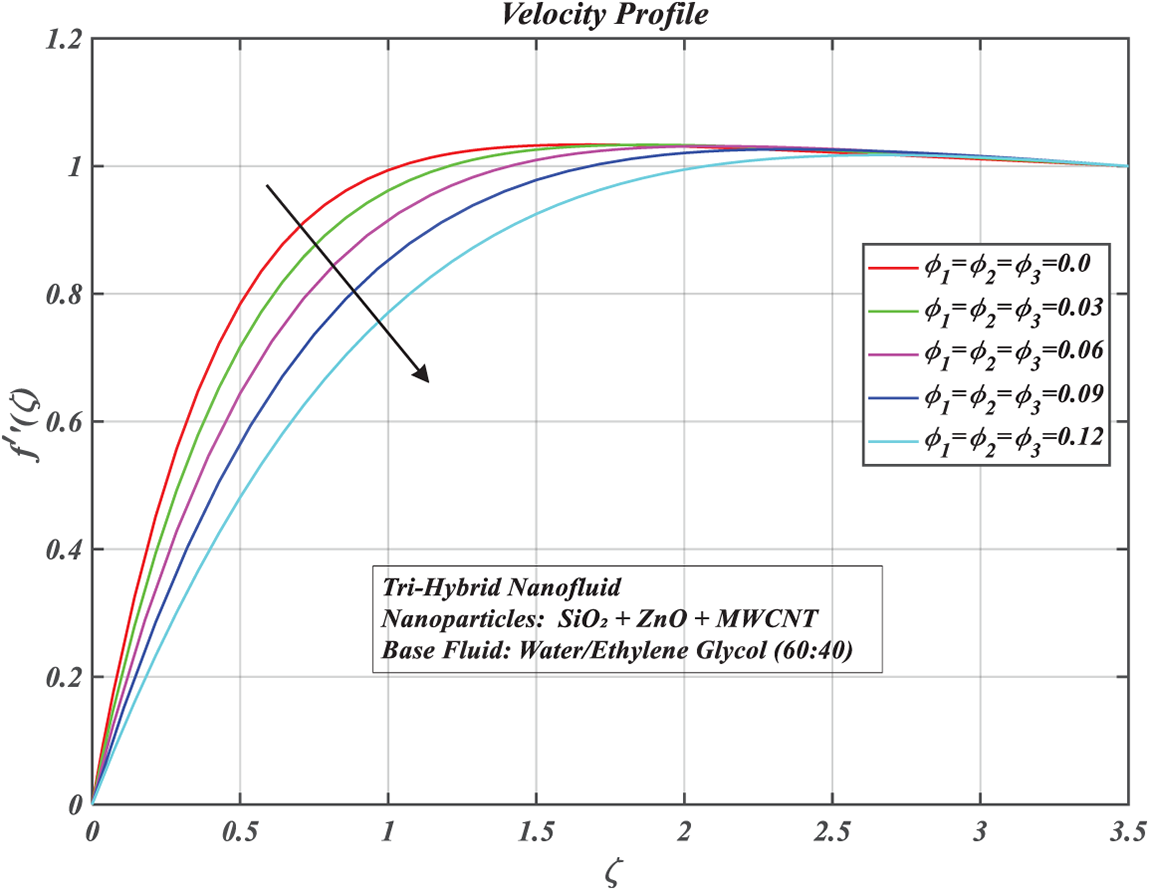

Figure 6: Consequences of volume fractions of nanoparticles on

Figure 7: Consequences of suction parameter on

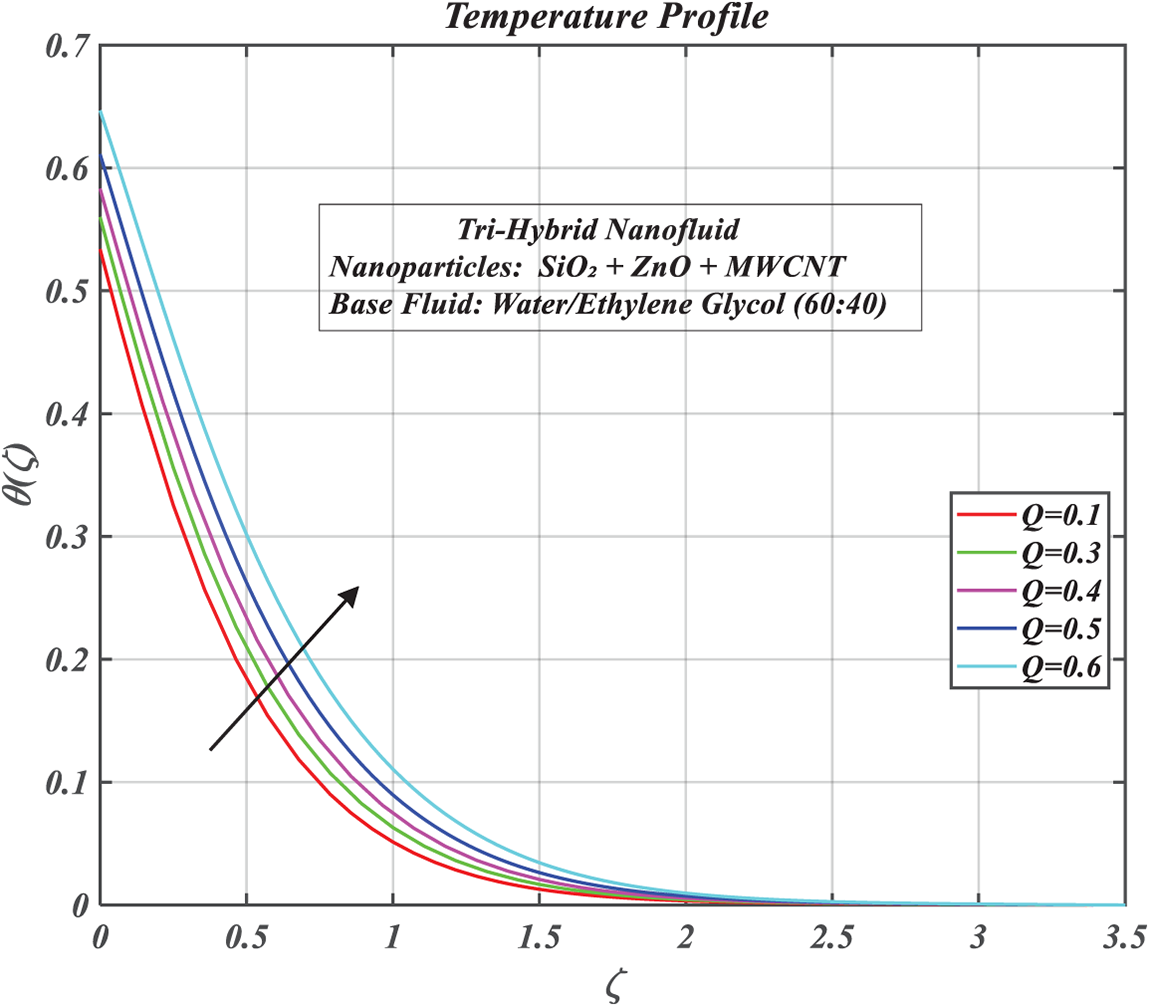

Figure 8: Consequences of thermal radiation on

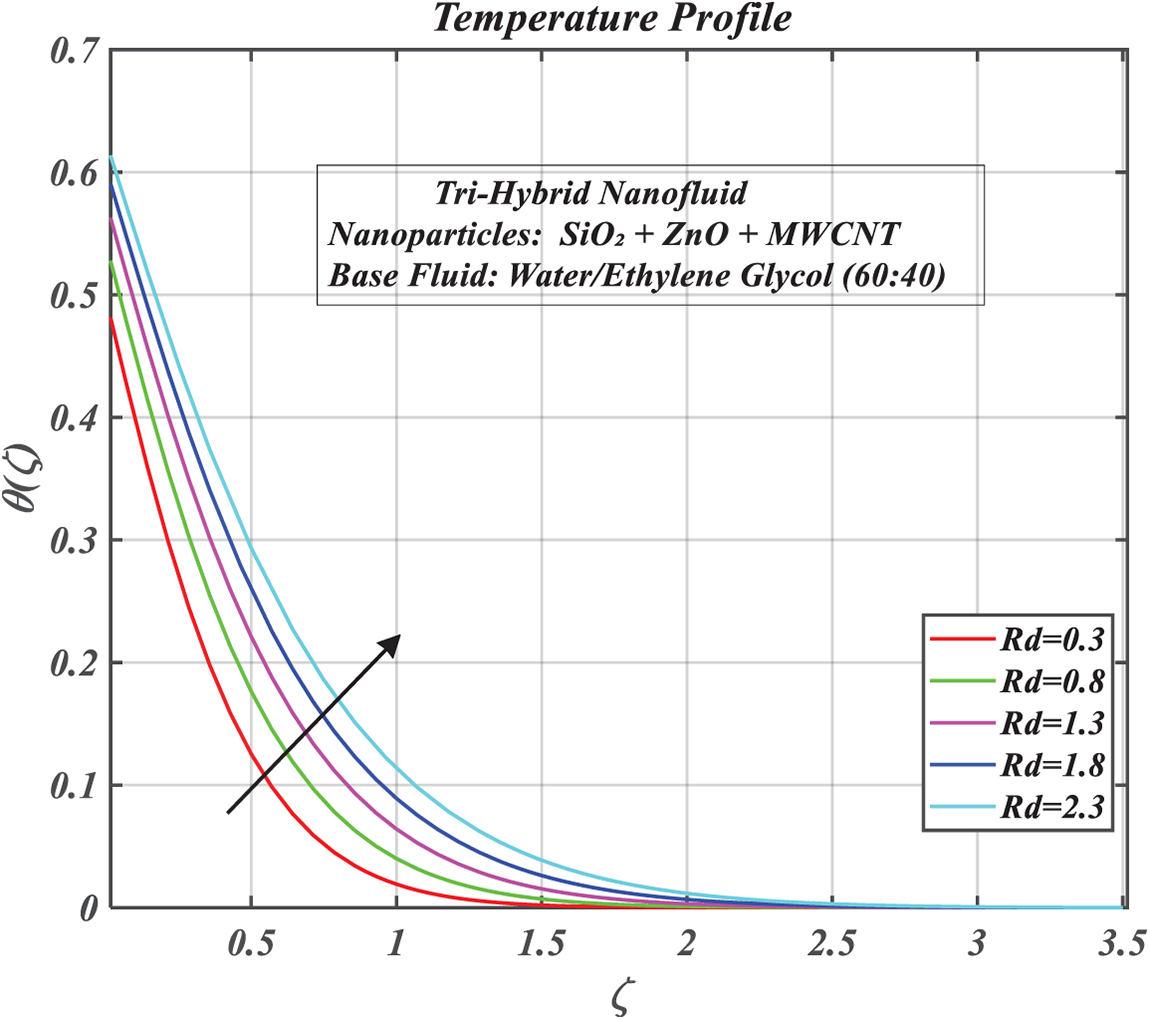

Figure 9: Consequences of Biot number on

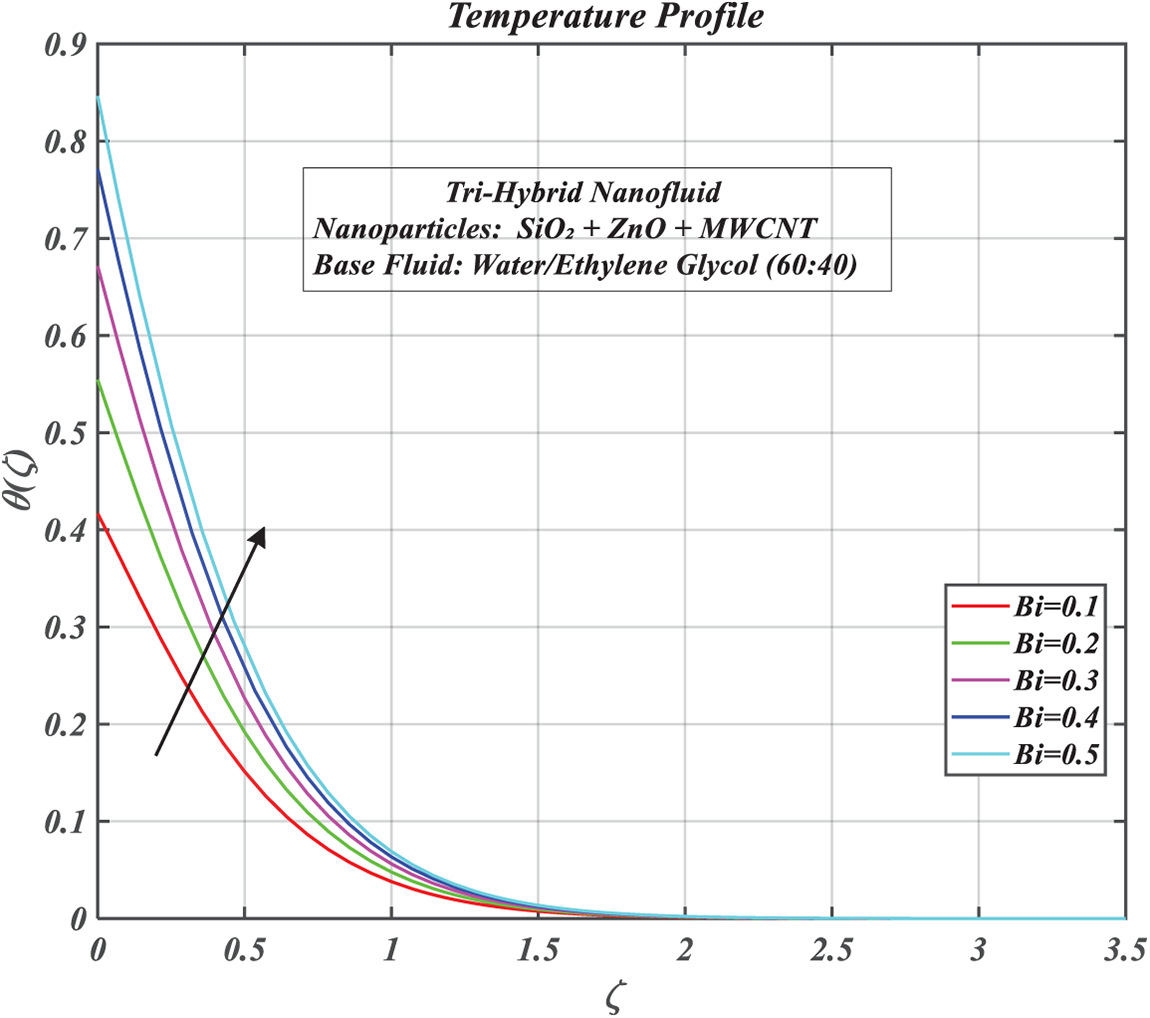

Figure 10: Consequences of Eckert number on

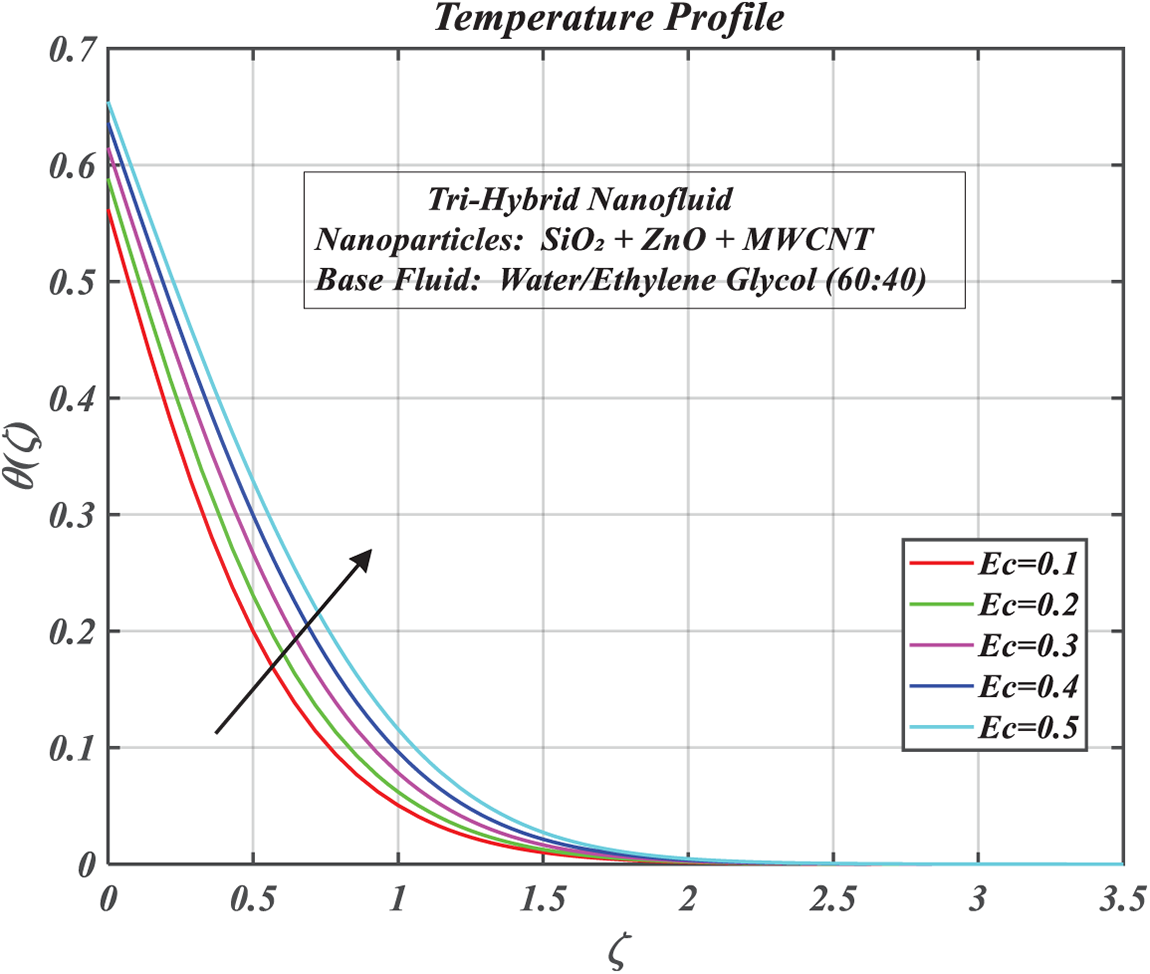

Figure 11: Consequences of thermal conductivity on

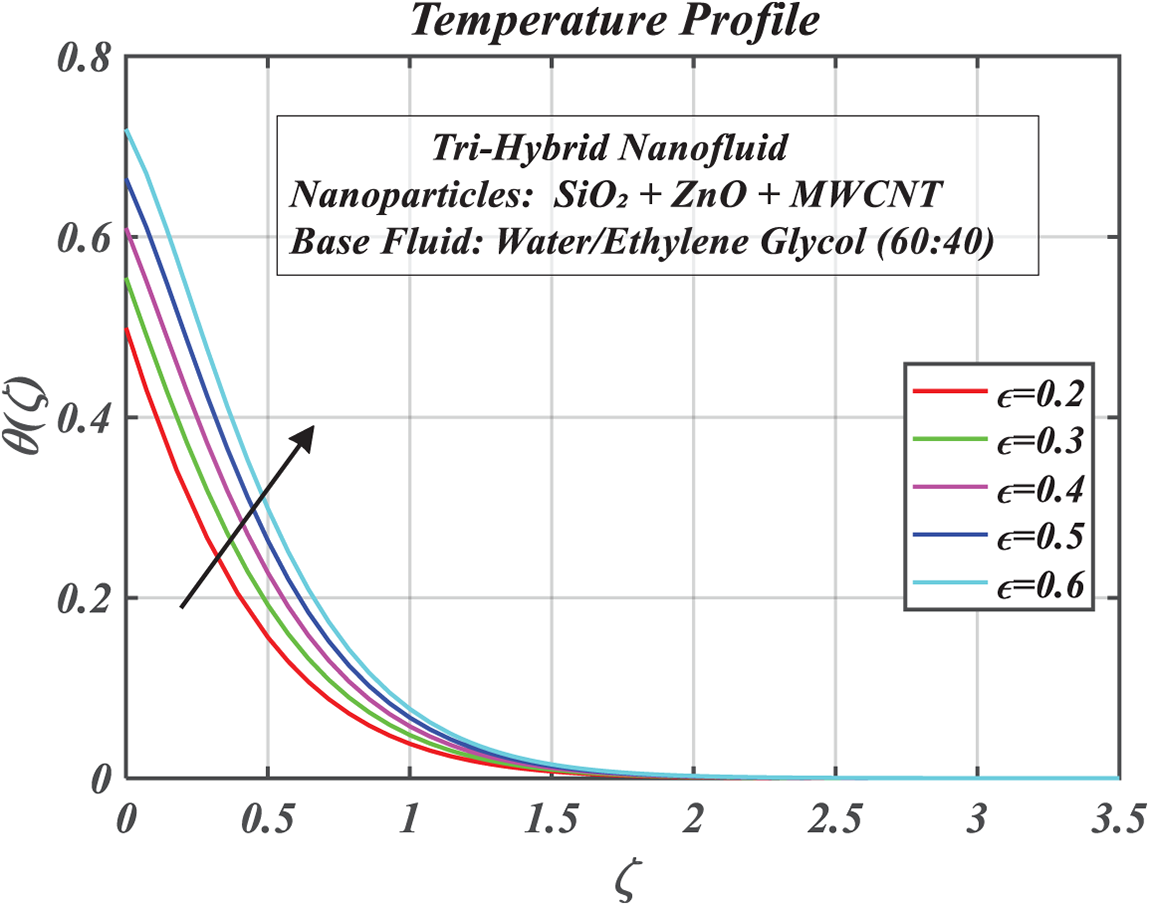

Figure 12: Consequences of Prandtl number on

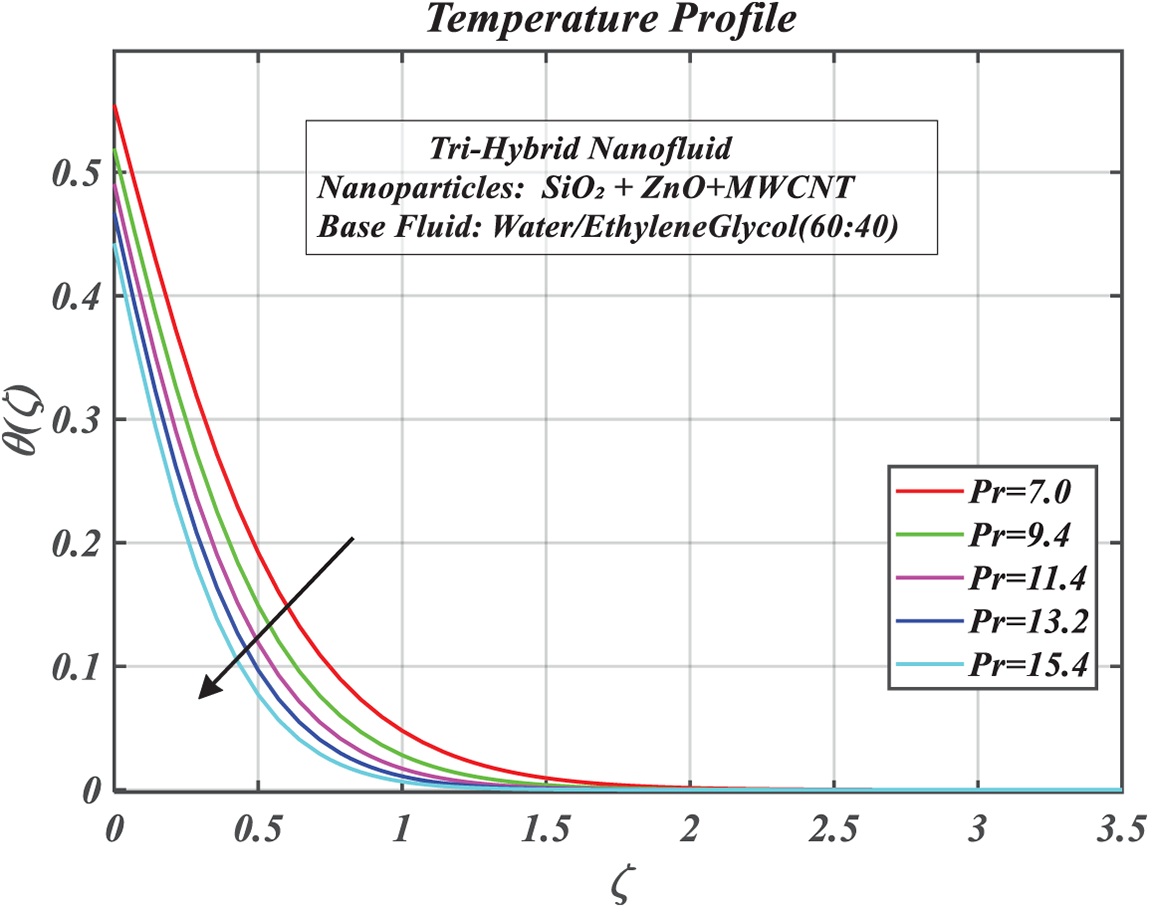

Figure 13: Consequences of the sSuction parameter on

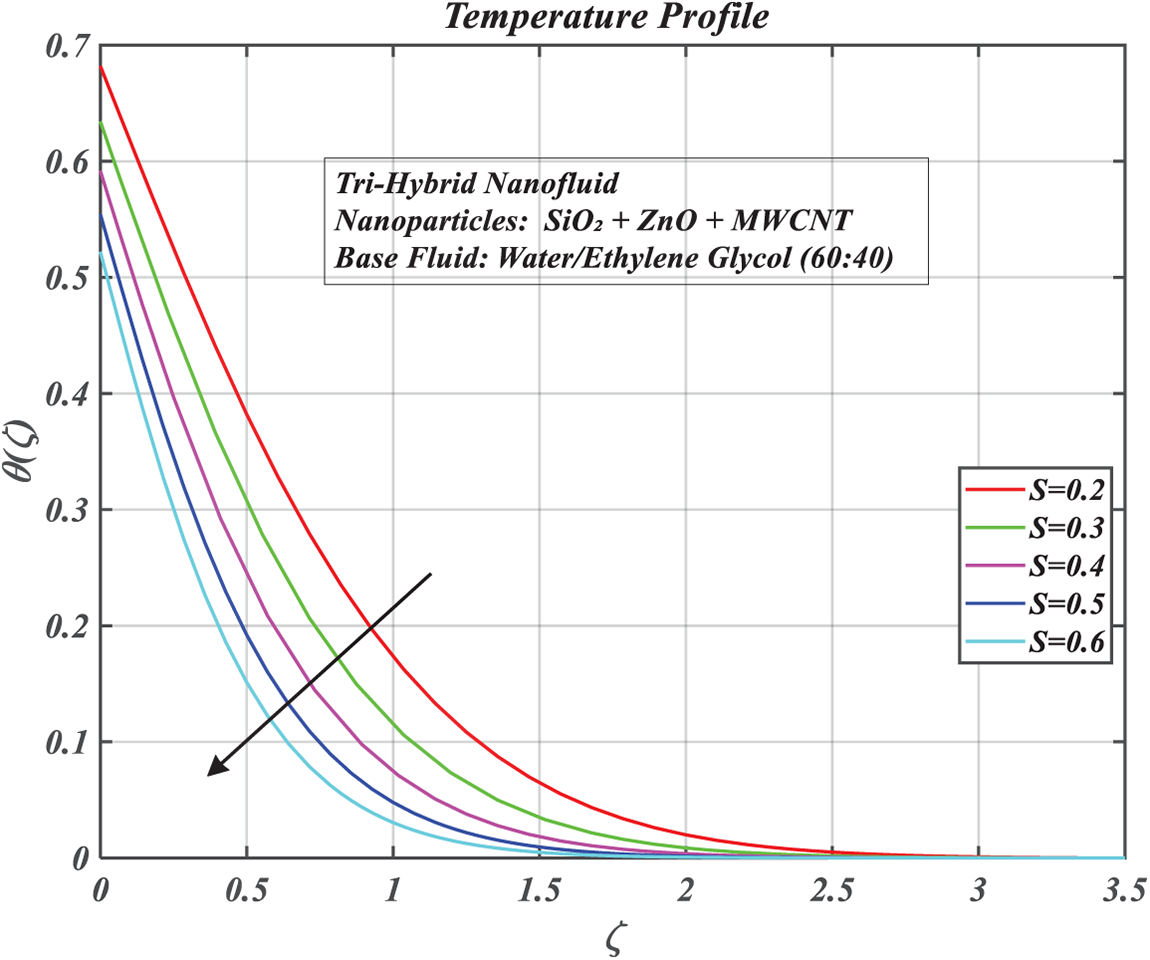

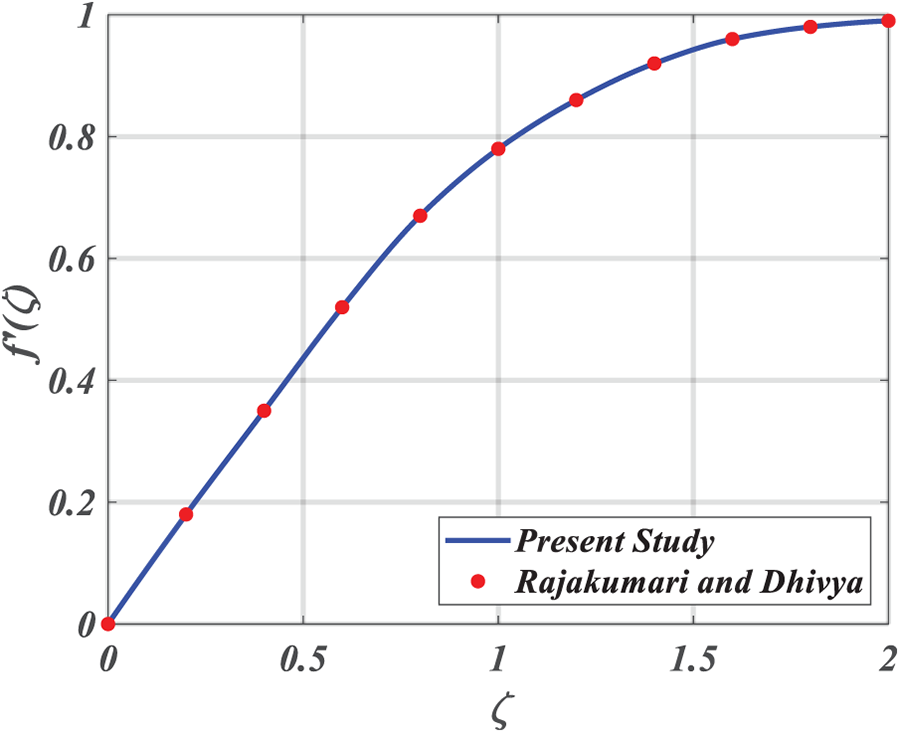

Figure 14: Velocity profile comparison between the present study and the benchmark results by Rammoorthi and Mohanavel

4.1 Influence of Various Parameters on the Velocity Profile

The impact of

The effect of the suction parameter

The impact of a porous parameter

The volume fraction

4.2 Influence of Various Parameters on the Temperature Profile

The effect of the heat source parameter on the thermal field

The effect of the thermal radiation parameter,

The impact of thermal Biot number,

Fig. 10 demonstrates the impact of the Eckert number

The transport of heat to the fluid is influenced by varied thermal conductivity

The inspiration of the Prandtl number

The inspection of suction parameter,

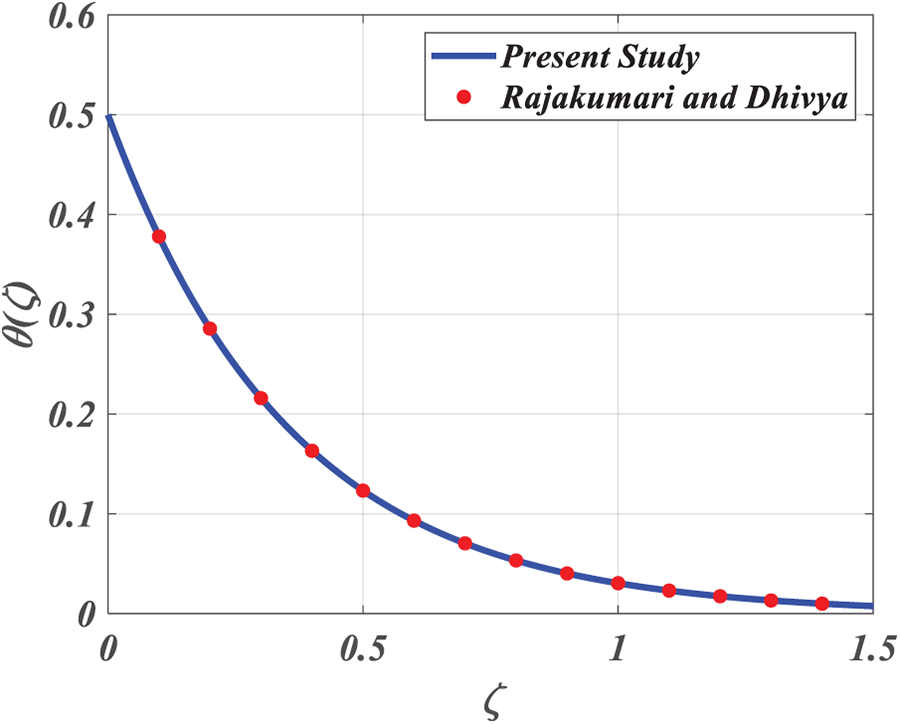

The present analysis is benchmarked against the study by Rammoorthi and Mohanavel [27] by employing parameter values consistent with their work. The reliability of the results is validated through the graphical comparisons presented in Figs. 14 and 15. As shown in Table 2, the skin friction coefficient and Nusselt number exhibit sensitivity to various dimensionless parameters. Specifically, both

Figure 15: Temperature profile comparison between the present study and the benchmark results by Rammoorthi and Mohanavel

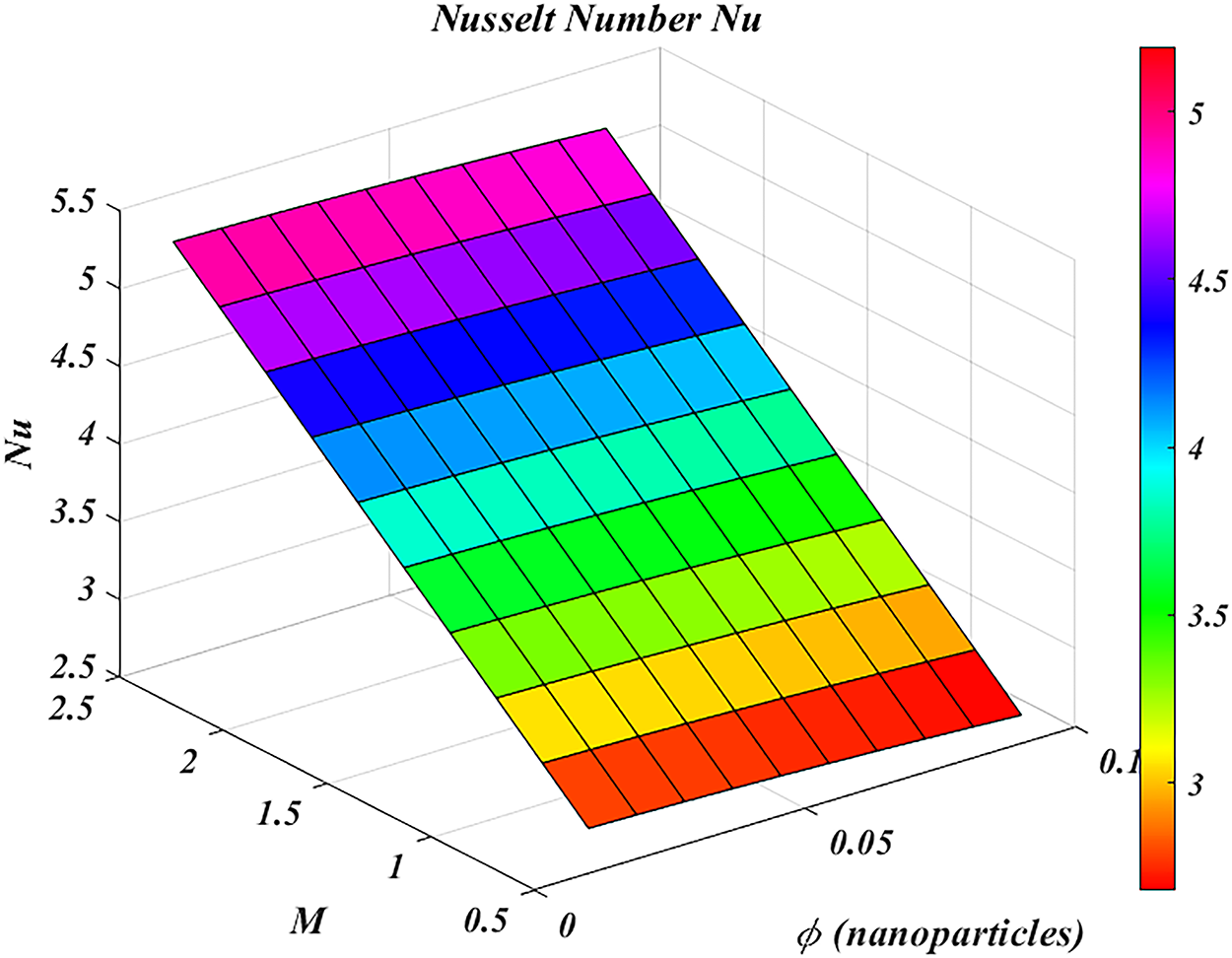

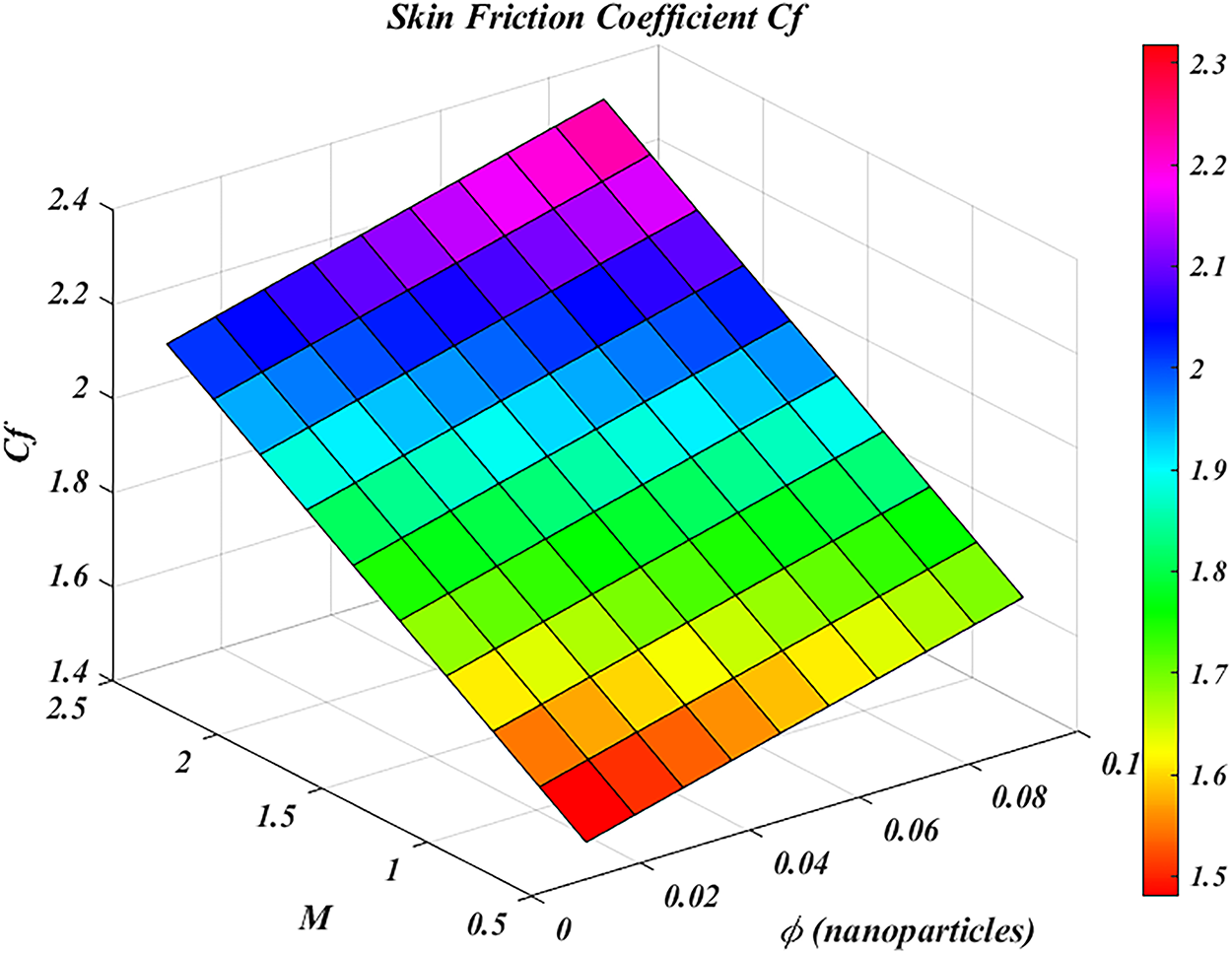

In this section, 3D surface plots against various flow factors are illustrated in Figs. 16 and 17. The following 3D surface plots show how in a magnetohydrodynamic tri-hybrid nanofluid flow system, the local Nusselt number

Figure 16: 3D surface plots of

Figure 17: 3D surface plots of

The fluid transport and thermal properties of nanofluids between horizontal, parallel Riga plates are examined in this work, when magnetic fields and radiative impacts are present. A scrutiny of a time-dependent(unsteady), squeezing flow of tri-hybrid nanofluid

• The enrichment of Hartmann number (

• Raising the suction parameter enhances the flow field but reduces the temperature profile of the used tri-hybrid nanofluid.

• Water-Ethyl Glycol

• Higher values of

• A combined investigation through streamline plots reveals quantifiable changes in

This work offers a new numerical investigation of ternary hybrid nanofluid flow in a Riga plate-based squeezing system, although it has certain drawbacks. Only two-dimensional, laminar, and incompressible flow with simplified boundary conditions is included in the study; turbulence, surface roughness, and geometric imperfections are not taken into account. The impacts of temperature variations, nanoparticle clumping, and interparticle forces are also ignored, as it is assumed that the thermophysical characteristics of the nanofluid stay constant. Furthermore, a streamlined Riga plate configuration with homogeneous fields is used to model the electromagnetic effects, which may not fully represent actual situations.

Furthermore, the lack of experimental validation means that the findings remain speculative. These simplifications, while required for tractability, limit the findings’ direct application to complicated practical systems. Future research could address these constraints by expanding the model to include three-dimensional geometries, experimental benchmarks, and non-ideal effects like slip conditions, temperature-dependent characteristics, and turbulence modelling.

Acknowledgement: The authors are grateful to King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for funding this work through the Ongoing Research Funding program—Research Chairs (ORF-RC-2025-0127). Furthermore, this study is supported via Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R443), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, through the Ongoing Research Funding program—Research Chairs (ORF-RC-2025-0127). Furthermore, this research was funded via Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R443).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Muhammad Hamzah and Muhammad Ramzan; methodology, Muhammad Ramzan; software, Muhammad Hamzah; validation, Muhammad Hamzah, Muhammad Ramzan, Abdulrahman A. Almehizia, and Ibrahim Mahariq; formal analysis, Laila A. AL-Essa; investigation, Ahmed S. Hassan; resources, Abdulrahman A. Almehizia and Ahmed S. Hassan; data curation, Ibrahim Mahariq and Laila A. AL-Essa; writing—original draft preparation, Muhammad Hamzah and Muhammad Ramzan; writing—review and editing, Muhammad Hamzah and Muhammad Ramzan; visualization, Laila A. AL-Essa; supervision, Ahmed S. Hassan. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

1. Smalley RE. Future global energy prosperity: the terawatt challenge. Mrs Bull. 2005;30(6):412–7. doi:10.1557/mrs2005.124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Wen D, Lin G, Vafaei S, Zhang K. Review of nanofluids for heat transfer applications. Particuology. 2009;7(2):141–50. doi:10.1016/j.partic.2009.01.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Huminic G, Huminic A. Hybrid nanofluids for heat transfer applications-a state-of-the-art review. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2018;125:82–103. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2018.04.059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Sidik NAC, Adamu IM, Jamil MM, Kefayati GHR, Mamat R, Najafi G. Recent progress on hybrid nanofluids in heat transfer applications: a comprehensive review. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2016;78(1):68–79. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2016.08.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Sajid MU, Ali HM. Thermal conductivity of hybrid nanofluids: a critical review. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2018;126:211–34. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2018.05.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Raja M, Vijayan R, Dineshkumar P, Venkatesan M. Review on nanofluids characterization, heat transfer characteristics and applications. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2016;64(6):163–73. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2016.05.079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Jensen MK, Bergles AE, Shome B. The literature on enhancement of convective heat and mass transfer. J Enhanc Heat Transf. 1997;4(1):1–6. doi:10.1615/jenhheattransf.v4.i1.10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Manglik RM. Heat transfer enhancement. In: Heat transfer handbook. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley, Inc.; 2003. p. 1029–130. [Google Scholar]

9. Alam T, Kim MH. A comprehensive review on single phase heat transfer enhancement techniques in heat exchanger applications. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2018;81:813–39. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2017.08.060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Xuan Y, Li Q. Heat transfer enhancement of nanofluids. Int J Heat Fluid Flow. 2000;21(1):58–64. doi:10.1016/s0142-727x(99)00067-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Guo ZY, Li DY, Wang BX. A novel concept for convective heat transfer enhancement. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 1998;41(14):2221–5. doi:10.1016/s0017-9310(97)00272-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Kakaç S, Bergles AE, Mayinger F, Yüncü H, editors. Heat transfer enhancement of heat exchangers. Vol. 355. New York, NY, USA: Springer Science & Business Media; 2013. [Google Scholar]

13. Sundar LS, Sharma KV, Singh MK, Sousa ACM. Hybrid nanofluids preparation, thermal properties, heat transfer and friction factor—a review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2017;68(3):185–98. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2016.09.108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Muneeshwaran M, Srinivasan G, Muthukumar P, Wang CC. Role of hybrid-nanofluid in heat transfer enhancement-a review. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2021;125(8):105341. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2021.105341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Eshgarf H, Kalbasi R, Maleki A, Shadloo MS. A review on the properties, preparation, models and stability of hybrid nanofluids to optimize energy consumption. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2021;144(5):1959–83. doi:10.1007/s10973-020-09998-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Sharma PO, Barewar SD, Chougule SS. Experimental investigation of heat transfer enhancement in pool boiling using novel Ag/ZnO hybrid nanofluids. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2021;143(2):1051–61. doi:10.1007/s10973-020-09922-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Prashar P, Ojjela O. Numerical investigation of ZnO-MWCNTs/ethylene glycol hybrid nanofluid flow with activation energy. Indian J Phys. 2022;96(7):2079–92. doi:10.1007/s12648-021-02132-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ekiciler R. Performing SiO2-MWCNT/water hybrid nanofluid with differently shaped nanoparticles to enhance first-and second-law features of flow by considering a two-phase approach. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2024;149(4):1725–44. doi:10.1007/s10973-024-12885-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Mahabaleshwar US, Nihaal KM, Pérez LM, Oztop HF. An analysis of heat and mass transfer of ternary nanofluid flow over a Riga plate: newtonian heating. Numer Heat Transf Part B Fundam. 2025;86(2):310–25. doi:10.1080/10407790.2023.2282165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Farooq U, Bibi A, Abbasi JN, Jan A, Hussain M. Nonsimilar mixed convection analysis of ternary hybrid nanofluid flow near stagnation point over vertical Riga plate. Multidiscip Model Mater Struct. 2024;20(2):261–78. doi:10.1108/mmms-09-2023-0301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Abbas Z, Mahmood I, Batool S, Shah SAA, Ragab AE. Evaluation of thermal radiation and flow dynamics mechanisms in the Prandtl ternary nanofluid flow over a Riga plate using artificial neural networks: a modified Buongiorno model approach. Chaos Soliton Fract. 2025;193(2):116083. doi:10.1016/j.chaos.2025.116083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Ramzan M, Ali F, Akkurt N, Saeed A, Kumam P, Galal AM. Computational assesment of Carreau ternary hybrid nanofluid influenced by MHD flow for entropy generation. J Magn Magn Mater. 2023;567(1):170353. doi:10.1016/j.jmmm.2023.170353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Gangadhar K, Sangeetha Rani M, Wakif A. Improved slip mechanism and convective heat impact for ternary nanofluidic flowing past a riga surface. Int J Mod PhysB. 2025;39(8):2550064. doi:10.1142/s021797922550064x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Karthikeyan S, Ali F, Loganathan K, Thamaraikannan N. An implication of entropy generation in Maxwell fluid containing engine oil based ternary hybrid nanofluid over a riga plate. J Taibah Univ Sci. 2024;18(1):2387925. doi:10.1080/16583655.2024.2387925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Sharif H, Ali B, Siddique I, Saman I, Jaradat MM, Sallah M. Numerical investigation of dusty tri-hybrid Ellis rotating nanofluid flow and thermal transportation over a stretchable Riga plate. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):14272. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-41141-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Thakur A, Sood S. Tri-hybrid nanofluid flow towards convectively heated stretching Riga plate with variable thickness. J Nanofluids. 2023;12(4):1129–40. doi:10.1166/jon.2023.1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Rammoorthi R, Mohanavel D. Numerical investigation and sensitivity analysis of MHD ternary nanofluid flow between perforated squeezed Riga plates under the surveillance of microcantilever sensor. AIP Adv. 2024;14(9):95020. doi:10.1063/5.0218608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Algehyne EA, Alduais FS, Saeed A, Dawar A, Ramzan M, Kumam P. Framing the hydrothermal significance of water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over a revolving disk. Int J Nonlinear Sci Numer Simul. 2024;24(8):3133–48. doi:10.1515/ijnsns-2022-0137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Chung SY, Brinza DE, Minton TK, Liang RH. BMDO materials testing in the EOIM-3 experiment. In: NASA Conference Publication. Washington, DC, USA: NASA; 1993. [Google Scholar]

30. Rana S, Zahid H, Kumar R, Bharj RS, Rathore PKS, Ali HM. Lithium-ion battery thermal management system using MWCNT-based nanofluid flowing through parallel distributed channels: an experimental investigation. J Energy Storage. 2024;81(2023):110372. doi:10.1016/j.est.2023.110372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Sreekumar S. Performance enhancement of photovoltaic/thermal system using hybrid nanofluid [dissertation]. Northern Ireland, UK: Ulster University; 2023. [Google Scholar]

32. Moita A, Moreira A, Pereira J. Nanofluids for the next generation thermal management of electronics: a review. Symmetry. 2021;13(8):1362. doi:10.3390/sym13081362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Wciślik S. The influence of nusselt correlation on exergy efficiency of a plate heat exchanger operating with TiO2: SiO2/EG:DI hybrid nanofluid. Inventions. 2024;9(1):11. doi:10.3390/inventions9010011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Khaled AR, Vafai K. Hydromagnetic squeezed flow and heat transfer over a sensor surface. Int J Eng Sci. 2004;42(5–6):509–19. doi:10.1016/j.ijengsci.2003.08.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Elsebaee FAA, Bilal M, Mahmoud SR, Balubaid M, Shuaib M, Asamoah JKK, et al. Motile micro-organism based trihybrid nanofluid flow with an application of magnetic effect across a slender stretching sheet: numerical approach. AIP Adv. 2023;13(3):35237. doi:10.1063/5.0144191/2881329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Muhammed RK, Basha H, Reddy GJ, Shankar U, Bég OA. Influence of variable thermal conductivity and dissipation on magnetic Carreau fluid flow along a micro-cantilever sensor in a squeezing regime. In: Waves in random and complex media. London, UK: Taylor & Francis; 2022. p. 1–30 doi:10.1080/17455030.2022.2139013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Venkateswarlu B, Chavan S, Woo Joo S, Kim SC. Entropy analysis in squeezing flow of CoFe2O4+TiO2+MgO/H2O trihybrid nanofluid between parallel plates with viscous dissipation and chemical reaction: a numerical approach. In: Numerical heat transfer, part A: applications. London, UK: Taylor & Francis; 2024. p. 1–30 doi:10.1080/10407782.2024.2375634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Loganathan K, Thamaraikannan N, Eswaramoorthi S, Jain R. Entropy framework of the bioconvective Williamson nanofluid flow over a Riga plate with radiation, triple stratification and swimming microorganisms. Int J Thermofluids. 2025;25(5):101000. doi:10.1016/j.ijft.2024.101000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Eswaramoorthi S, Loganathan K, Choudhary P, Senthilvadivu K, Ahlawat A, Sivakumar M. Computational analysis of sutterby nanofluid with heat and mass convective conditions: a comparative study of Riga plate and stationary plate. Discov Appl Sci. 2025;7(3):1–24. doi:10.1007/s42452-025-06508-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Akindele AO, Ogunsola AW, Zhiri AB, Ohaegbue AD, Obalalu AM, Salawu SO. Significance of Solar radiation and Cattaneo-Chistov heat flux on Maxwall tri-component hybrid nanofluid flow with heat generation and entropy analysis: application in drone technology. Hybrid Adv. 2025;11(6):100524. doi:10.1016/j.hybadv.2025.100524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Adebisi O, Ajala OA, Akindele AO, Okunade IO, Ohaegbue AD, Yahaya AA. Investigation of heat transfer in a radiative Casson triple particle nanofluid flow with Riga plate and variable thermo-physical characteristics. Nano-Struct Nano-Objects. 2025;42(8):101486. doi:10.1016/j.nanoso.2025.101486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools