Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

The Transparency Revolution in Geohazard Science: A Systematic Review and Research Roadmap for Explainable Artificial Intelligence

1 Department of Irrigation and Reclamation Engineering, College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of Tehran, Karaj, 31587-77871, Iran

2 Center of Excellence in Hydroinformatics, Faculty of Civil Engineering, University of Tabriz, 29 Bahman Ave, Tabriz, 51666-16471, Iran

3 Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and Architecture, World Peace University, Sht. Kemal Ali Omer St. No:22, Yenisehir, Nicosia/TRNC, Mersin 10, Türkiye

4 Department of Civil Engineering, Lübeck University of Applied Sciences, Lübeck, 23562, Germany

5 Department of Civil Engineering, Ilia State University, Tbilisi, 0162, Georgia

6 School of Civil, Environmental and Architectural Engineering, Korea University, Seoul, 02841, Republic of Korea

7 Key Laboratory of Water Cycle and Related Land Surface Processes, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, 100101, China

8 Disaster Prevention Research Institute (DPRI), Kyoto University, Kyoto, 611-0011, Japan

9 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA

10 Department of Soil Science and Geomorphology, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, 72076, Germany

11 College of Environmental Science and Engineering/Sino-Canada Joint R&D Centre for Water and Environmental Safety, Nankai University, Tianjin, 300071, China

* Corresponding Author: Moein Tosan. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Emerging Artificial Intelligence Technologies and Applications-II)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2026, 146(1), 3 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.074768

Received 17 October 2025; Accepted 16 December 2025; Issue published 29 January 2026

Abstract

The integration of machine learning (ML) into geohazard assessment has successfully instigated a paradigm shift, leading to the production of models that possess a level of predictive accuracy previously considered unattainable. However, the black-box nature of these systems presents a significant barrier, hindering their operational adoption, regulatory approval, and full scientific validation. This paper provides a systematic review and synthesis of the emerging field of explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) as applied to geohazard science (GeoXAI), a domain that aims to resolve the long-standing trade-off between model performance and interpretability. A rigorous synthesis of 87 foundational studies is used to map the intellectual and methodological contours of this rapidly expanding field. The analysis reveals that current research efforts are concentrated predominantly on landslide and flood assessment. Methodologically, tree-based ensembles and deep learning models dominate the literature, with SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) frequently adopted as the principal post-hoc explanation technique. More importantly, the review further documents how the role of XAI has shifted: rather than being used solely as a tool for interpreting models after training, it is increasingly integrated into the modeling cycle itself. Recent applications include its use in feature selection, adaptive sampling strategies, and model evaluation. The evidence also shows that GeoXAI extends beyond producing feature rankings. It reveals nonlinear thresholds and interaction effects that generate deeper mechanistic insights into hazard processes and mechanisms. Nevertheless, several key challenges remain unresolved within the field. These persistent issues are especially pronounced when considering the crucial necessity for interpretation stability, the demanding scholarly task of reliably distinguishing correlation from causation, and the development of appropriate methods for the treatment of complex spatio-temporal dynamics.Keywords

Geohazards, spanning from landslides and floods to wildfires and earthquakes, represent a mounting threat to human populations and critical infrastructure. This complex problem is being significantly intensified by the dual pressures of global climate change and rapid urbanization [1]. Consequently, the capacity to accurately predict where and when these destructive events might occur is not just beneficial but critical for establishing effective risk management strategies [2], informing strategic land-use planning decisions [3], and operating reliable early warning systems [4]. For decades, the field has tackled this challenge using two main approaches; mechanistic models and data-driven statistical models [5]. Physics-based models, built on the principles of geomechanics and hydrology, give valuable insight into how hazards form and their underlying processes [6]. However, these models often face significant limitations when applied at a regional scale. Specifically, such regional modeling necessitates immense demands on computational power and requires a high quality and depth of detailed geotechnical input data which is rarely available in practice.

To circumvent these traditional limitations, data-driven methodologies, particularly those based on machine learning (ML), have emerged as a major paradigm shift in the field of geohazard susceptibility mapping and forecasting [7,8]. By effectively utilizing vast geospatial datasets, these ML models have provided a considerable advancement in predictive capability [9]. This progress encompasses a diverse array of techniques, ranging from powerful ensemble models—such as random forest (RF) [10] and eXtreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) [11–13]—to more sophisticated deep learning (DL) architectures, including convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [14,15], long short-term memory (LSTM) networks [16,17], and graph neural networks (GNNs) [18]. However, this undeniable success is accompanied by a fundamental challenge: the well-known black-box problem [19,20]. The very complexity that grants these models their predictive strength simultaneously obstructs an understanding of their underlying mechanisms and internal decision-making processes. This lack of transparency remains as a major obstacle to their practical implementation, especially in high-stakes, mission-critical scenarios [21]. When it comes to high-stakes decisions, such as those made by policymakers, stakeholders, or civil protection agencies, simply receiving a prediction isn’t sufficient; they must be able to comprehend, validate and ultimately justify the rationale behind the model’s recommendation [22].

Building on this critical need for justified decision-making, explainable AI (XAI) has emerged precisely to address the transparency challenge in geohazard prediction systems [23]. Essentially, XAI provides researchers and practitioners with an extensive toolkit of methods, all specifically engineered to take the complex predictions and often-opaque internal logic of advanced predictive models and make them intelligible to human domain experts [24,25]. In the context of earth sciences, the utilization of geohazard explainable artificial intelligence (GeoXAI) has recently seen a rapid expansion [26,27]. Its function has matured well beyond simple, passive post-hoc interpretation—such as merely ranking the importance of input features [28]. Instead, GeoXAI now actively influences the modeling process itself [29]. Currently, researchers employ GeoXAI for strategic tasks like intelligent feature selection [30], targeted model simplification [31], and rigorously validating a model’s underlying logic against established physical principles [32]. At the vanguard of this field, XAI is even being employed as a tool for scientific discovery, helping scholars uncover latent physical parameters [33], pinpoint novel hazard precursors, and fundamentally connect the physics-based and data-driven modeling domains.

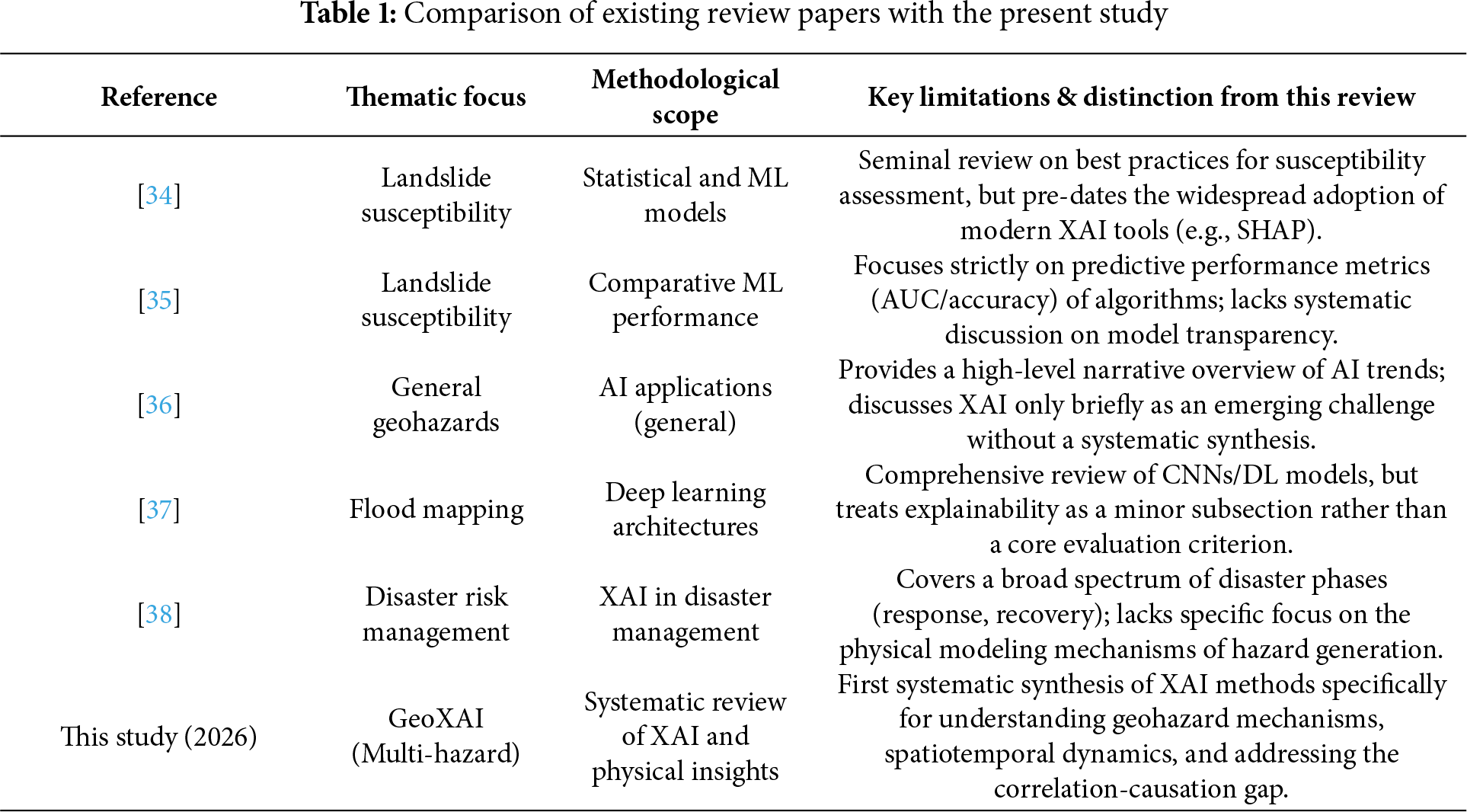

While GeoXAI has advanced rapidly, a genuinely comprehensive synthesis of the field is still absent in the current literature. Most existing review papers focus narrowly on a few particular hazards or methodological tools (see Table 1). Therefore, there is a recognized and critical need for the community to consolidate this dispersed knowledge more holistically and, crucially, to establish a clear, unified agenda for future research efforts. This systematic review is designed to address that gap. First, it maps out the intellectual and thematic structure of GeoXAI by using quantitative and thematic analyses. Building from there, the review synthesizes the mechanistic insights into hazard processes that XAI has produced, such as identifying thresholds, interactions, and the spatio-temporal dynamics of hazards. This paper then traces the evolution of XAI, following its development from a passive post-hoc explanation tool into a more active component within the modeling lifecycle. Finally, the review outlines the frontier challenges—which include uncertainty quantification, causal inference, and merging physics-based with data-driven approaches—to propose a research roadmap aimed at developing robust, transparent, and operational geospatial artificial intelligence (GeoAI) systems. By bringing together these state-of-the-art advances, this work aims to give researchers and practitioners a solid foundation and a forward-looking perspective for advancing trustworthy AI in geohazard science and risk management. Accordingly, this study aims to provide a comprehensive and systematic synthesis of explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) applications in geohazard science, identify their methodological evolution, and establish a research roadmap to guide future GeoXAI development.

To ensure a comprehensive and unbiased synthesis, the review followed the PRISMA 2020 protocol, providing a transparent and standardized approach for systematic literature analysis. This ensures that the final set of selected articles accurately reflects the contemporary research landscape and satisfies the core objectives of this review. The methodology was guided by closely following the Preferred Reporting Items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) framework [39,40]. This approach was explicitly engineered to be transparent, fully reproducible, and rigorously thorough, thereby ensuring that the final set of selected articles accurately reflects the contemporary research landscape and completely satisfies the core objectives of this review.

2.1 Search Strategy and Database Selection

The web of science (WoS) core collection was chosen as the primary database for this work. The selection of this database was based on several critical factors: its stringent curation process, complete citation tracking capabilities [41,42], and its strong reputation for consistently indexing high-impact, peer-reviewed articles [43,44]. Consequently, this choice aligns strongly with the study’s primary objective: to effectively synthesize the most influential and methodologically sound research specifically within the GeoXAI field. To ensure the successful retrieval of a body of studies that was simultaneously comprehensive and precisely focused, a detailed search string was subsequently developed and meticulously fine-tuned by the researchers. The final query was structured around three essential core pillars: the geohazard context, the underlying ML methodology, and the explainability component. A typical search string is shown below:

TS = (“landslide” OR “flood” OR “wildfire” OR “earthquake” OR “drought” OR “geohazard*”) AND (“machine learning” OR “artificial intelligence” OR “deep learning” OR “ensemble learning”) AND (“explainable AI” OR “XAI” OR “interpretability” OR “SHAP” OR “LIME” OR “Grad-CAM” OR “causal inference” OR “physics-informed”).

The search was deliberately restricted to articles published between 01 January 2021, and September 2025. This precise temporal constraint constitutes a strategic choice, implemented to capture the modern paradigm of algorithmic explainability effectively. Before the main review, a preliminary scoping analysis decisively revealed that the first significant wave of studies applying contemporary XAI frameworks (e.g., SHAP) to geohazard assessment began to proliferate quite notably in 2021. Consequently, this focus ensures that the review analyzes a coherent body of cutting-edge literature that is actively shaping the future direction of the field, thereby avoiding a broad overview of older, conceptually distinct research focused merely on general model interpretation.

2.2 Screening and Selection Process

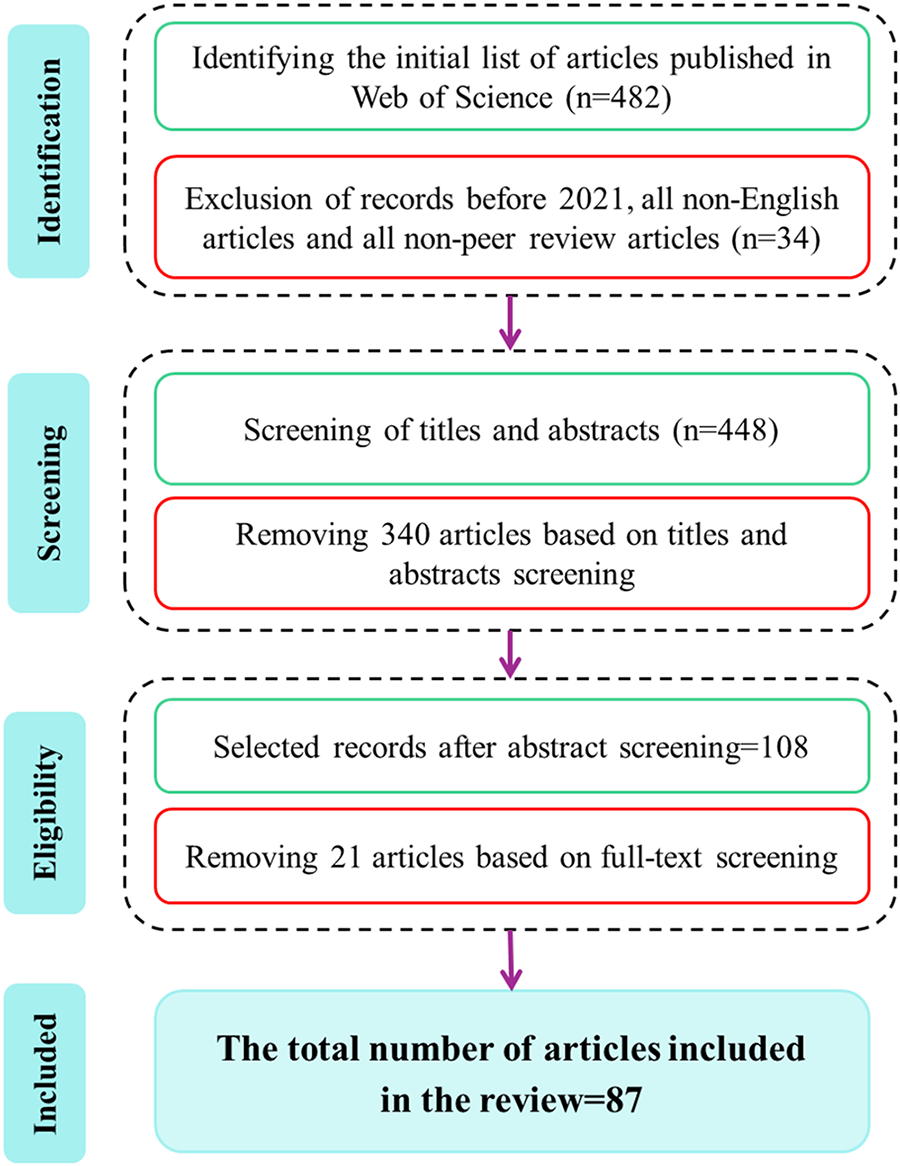

To ensure a systematic and unbiased review, the article selection process rigorously followed the four-stage PRISMA protocol (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: PRISMA-based workflow showing the four-step process (identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion) used for selecting the 87 studies analyzed in this GeoXAI systematic review. This ensures transparency and reproducibility of the literature selection process

Identification: Executing the optimized search string on the WoS database initially yielded 482 articles, from which 34 records were removed after initial filters.

Screening: Following identification, the titles and abstracts of all 448 articles were independently screened by two separate reviewers. The reviewers’ role was to meticulously assess relevance against the established core inclusion criteria. This step proved critical: articles were primarily excluded if they clearly fell outside the thematic scope. Examples of such exclusions include studies where XAI was applied only to medical imaging, where ML was used solely for mineral exploration, or, importantly, geohazard studies that completely lacked an XAI component. This initial screening successfully resulted in a substantial reduction of the pool, moving us toward the set of potentially eligible papers.

Eligibility: The full text of all remaining articles (108) was subsequently retrieved for a detailed eligibility assessment. During this more rigorous review phase, articles were systematically excluded if they failed to meet the necessary methodological depth (for instance, if the application of XAI was superficial or limited solely to a standard feature importance plot without any deeper analysis), were not original peer-reviewed research (e.g., conference papers, existing reviews, or book chapters), or failed to satisfy other specific inclusion criteria.

Inclusion: Following the full-text review, a final consensus was reached on 87 articles that fully met all established criteria. This highly curated collection of studies serves as the foundation for quantitative mapping, thematic synthesis, and critical analysis presented in the subsequent sections of this paper. Fig. 1 summarizes this entire process using the PRISMA flow diagram. With the final corpus of 87 studies established, the following section synthesizes their collective findings—mapping how XAI has been adopted, adapted, and advanced within geohazard modeling over the past five years.

2.3 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To effectively maintain both the required focus and requisite academic rigor of this review, the following explicit criteria were consistently applied throughout the entire screening process:

– The studies selected had to explicitly apply one or more XAI techniques to either the modeling or assessment of a geohazard (e.g., landslides, floods, wildfires, erosion, earthquakes, subsidence).

– Importantly, the paper needed to implement a recognized post-hoc XAI framework (such as SHAP, LIME, or Grad-CAM) or utilize an intrinsically interpretable (glass-box) model [45]. Studies reporting only standard, model-internal feature importance metrics were generally considered insufficient for inclusion. Such papers were ruled out unless they demonstrated a genuine engagement with the broader XAI literature and provided analysis beyond these basic measures. This criterion was central to distinguishing genuine GeoXAI research from broader ML applications.

– The publication must be a peer-reviewed, original research article in a scientific journal.

– The article must be published in English between 01 January 2021, and September 2025.

– Studies using ML for geohazards but lacking any explicit explainability component.

– Studies focused on XAI applications in non-geospatial or non-environmental domains.

– Review articles, meta-analyses, book chapters, conference proceedings, and pre-prints.

– Methodological papers that develop new XAI techniques without applying them to a concrete—geohazard case study.

3.1 The Emerging Landscape: A Quantitative and Thematic Analysis

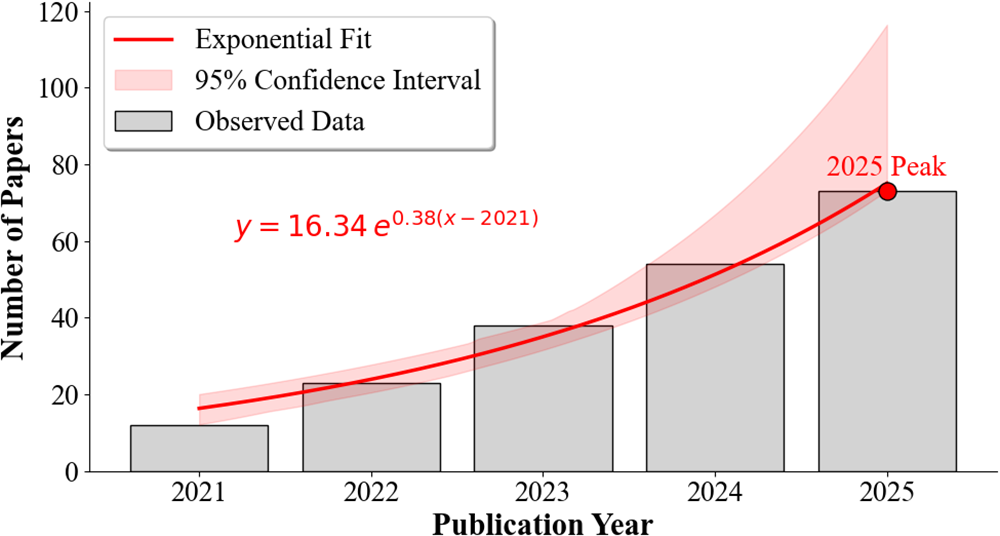

This section provides a comprehensive statistical and thematic overview of the GeoXAI research landscape, mapping its main application areas, dominant methodologies, and key geographical research centers. The field where XAI meets geohazard assessment; a domain termed GeoXAI; is no longer just a theoretical idea but has become a rapidly expanding and vibrant area of scientific research [46,47]. A statistical analysis of the papers foundational to this review reveals a clear and accelerating growth pattern. The field has seen an exponential jump in publications, especially since 2022, a surge that points to a critical shift within the geoscientific community (Fig. 2). There is a clear move away from simply accepting ML models as high-performing black-boxes and a growing demand for transparency, trustworthiness, and deeper mechanistic insight.

Figure 2: Temporal distribution of the reviewed GeoXAI publications (2021–2025), illustrating the exponential growth of the research field

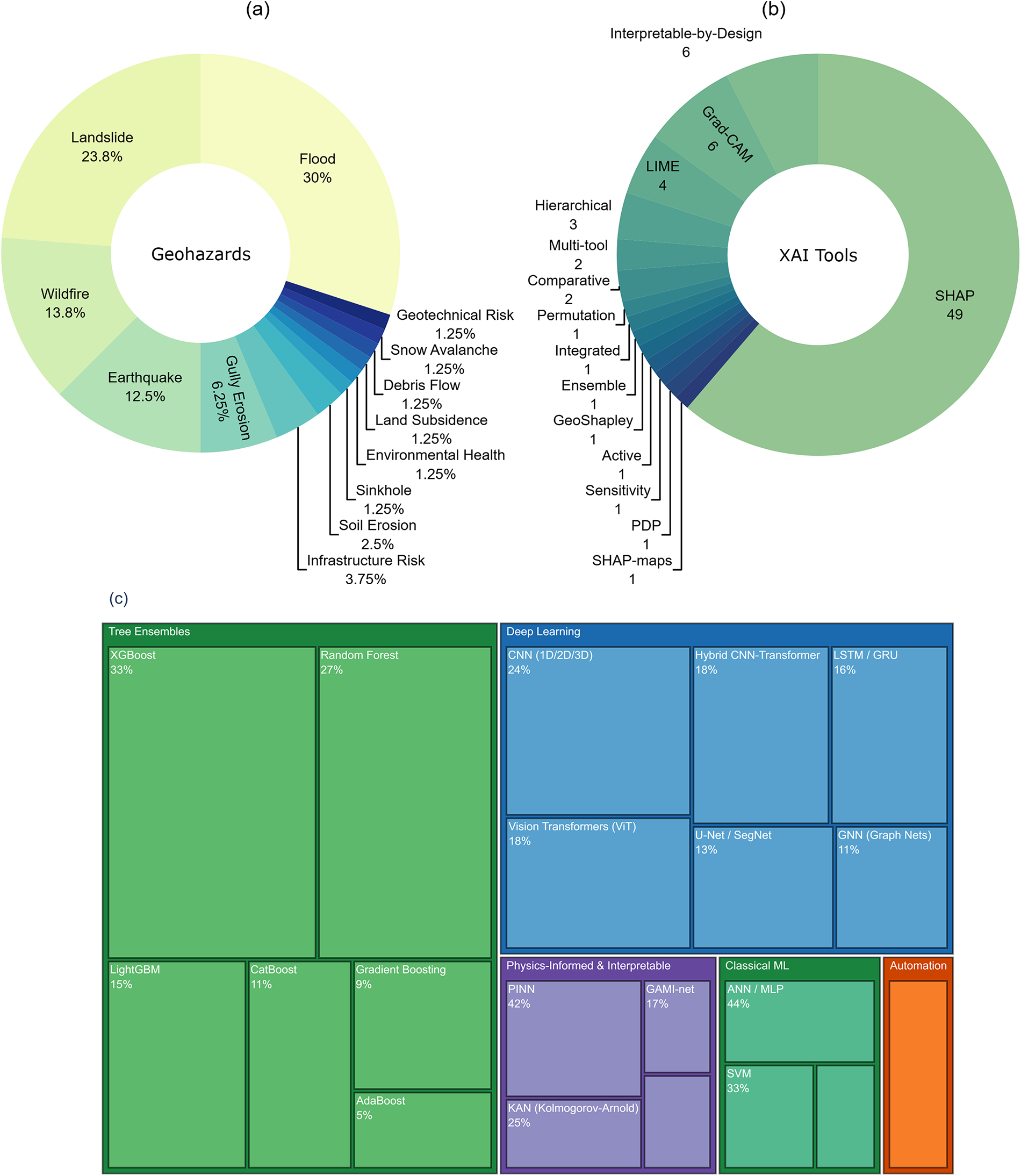

As summarized in Fig. 3, the thematic landscape of GeoXAI shows a field with both focused depth and expanding breadth. Landslides and various forms of flooding (e.g., pluvial, fluvial, flash) have become the dominant testbeds for this research, accounting for a large majority of applications. There is a logical reason for this focus. These hazards are typically backed by large historical inventories and well-defined conditioning factors, which offer a solid basis for building and testing complex models. At the same time, the field is quickly broadening to cover other geohazards, now including wildfires, various forms of erosion (gully, soil), and earthquake-related risks. The growing flexibility and adoption of this methodology across the Earth sciences is highlighted by more specialized applications, such as studies on sinkhole susceptibility [48], land subsidence [49], and even failures in geotechnical infrastructure [50].

Figure 3: Thematic landscape of the reviewed GeoXAI studies showing (a) distribution of research by hazard type, (b) frequency of explainability methods, and (c) hierarchy of ML/DL models. The figure highlights landslides and floods as dominant applications and SHAP as the prevailing interpretation tool

The methodological core of the entire GeoXAI toolkit rests decisively on the performance ceiling of its chosen ML algorithms. In this area, tree-based ensemble methods are clearly the primary methods. Algorithms like RF, XGBoost, and Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM) are deployed extensively, mainly because of their well-established reputation for exceptional robustness and consistent high predictive accuracy across various geohazard datasets. Moving past these standard ensembles, researchers are increasingly leveraging sophisticated DL architectures for more advanced predictive modeling, particularly when intricate data types are involved [12]. For instance, CNNs are remarkably effective when it comes to processing gridded spatial information, while researchers typically utilize LSTM networks for detailed time-series data analysis. Additionally, the field’s advanced toolkit has recently expanded its capacity with GNNs, a class of models uniquely engineered to capture and learn directly from the intrinsic spatial relationships embedded within complex geographic data structures [51]. A significant development parallel to these modeling advancements is the rise of automated ML (AutoML). The synthesis reveals that AutoML is shifting from a mere efficiency tool to a critical component of the GeoXAI workflow. Frameworks such as AutoGluon [52], tree-based pipeline optimization tool (TPOT) [53], and Bayesian optimization engines like Optuna [54,55] are now being employed to democratize high-performance modeling. For instance, [52] demonstrated that an AutoML framework could generate a state-of-the-art landslide susceptibility model in just 156 s, a task that typically requires weeks of manual tuning. Crucially, within the GeoXAI paradigm, AutoML does not just automate prediction; it enhances process transparency. Studies like [53] utilize the visualization tools inherent in these frameworks (e.g., hyperparameter importance plots) to explain how the model reached its optimal architecture, thereby adding a layer of interpretability to the optimization process itself.

In the domain of interpretability, the research community has shown an overwhelming consensus, effectively converging on SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) as the de facto standard for post-hoc explanation. This consensus exists because of the method’s rigorous game-theoretic foundation, which has firmly established SHAP as the premier analytical tool available. This robust theoretical underpinning is what enables researchers to meticulously dissect and precisely quantify the individual, specific contribution of every conditioning factor to the final prediction outcome. Other methods, however, play important complementary roles. local interpretable model-agnostic explanations (LIME) is often employed for instance-specific diagnoses [56,57], while gradient-weighted class activation mapping (Grad-CAM) is the preferred technique for visualizing the spatial focus of CNNs in image-based tasks [58,59]. The increasing adoption of a multi-tool approach—where the insights derived from several distinct XAI techniques are strategically fused—is a compelling indicator of the growing methodological sophistication and maturity now characterizing the geohazard modeling community [60,61].

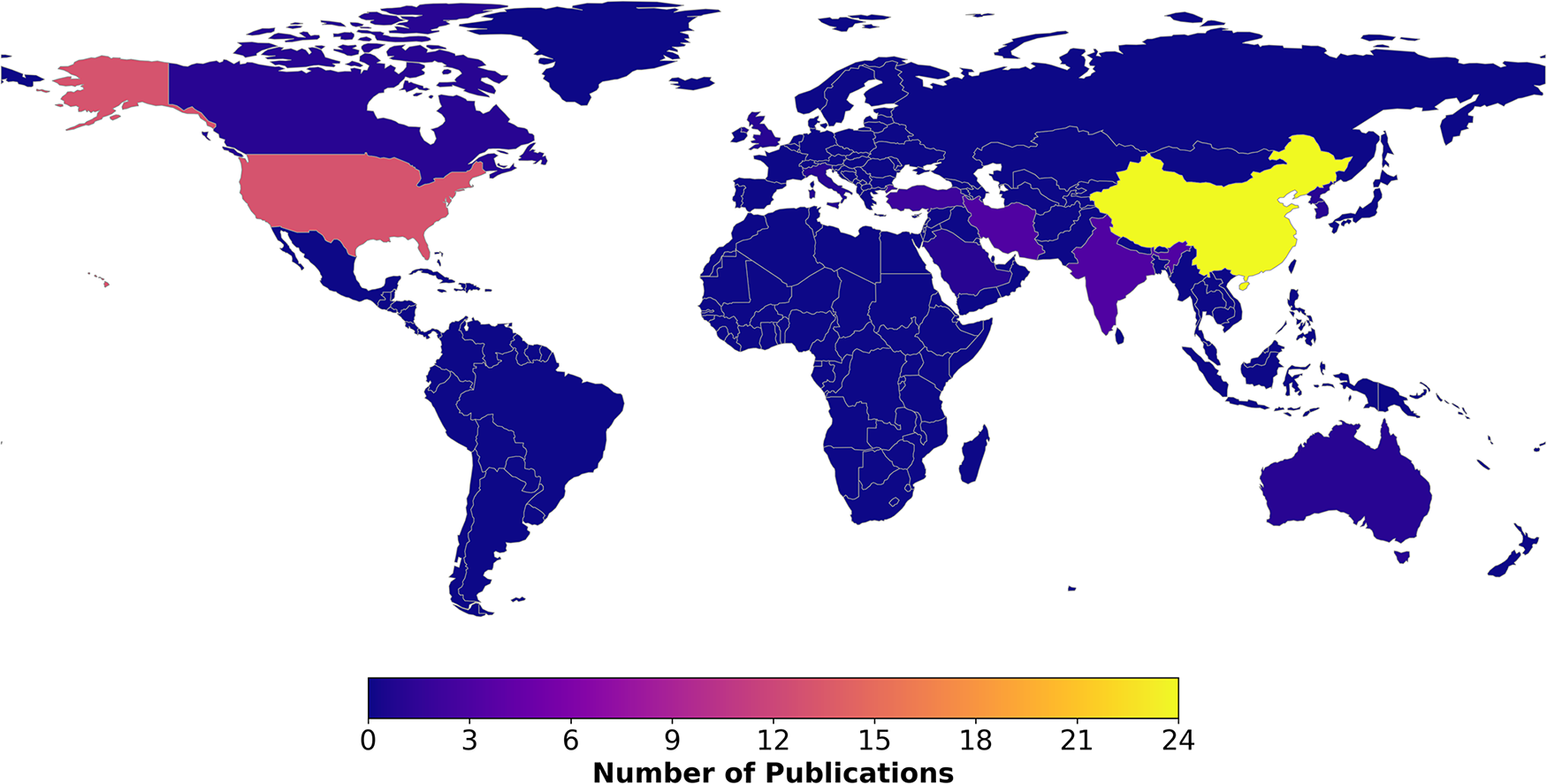

Finally, the geographic distribution of GeoXAI research highlights its global relevance (Fig. 4). While China is a leader in producing a high volume of impactful studies, research groups from Europe, the United States, Iran, and Türkiye are also making significant contributions. The widespread nature of this work points to a shared international agreement: tackling the common challenges of geohazards requires transparent and trustworthy AI. In essence, this quantitative overview shows a field defined by its rapid growth. It has a diversifying range of applications, an increasingly sophisticated toolkit, and a truly global research community.

Figure 4: Geographic distribution of GeoXAI research based on the affiliations of the primary authors, highlighting the global research hubs and collaborative landscape

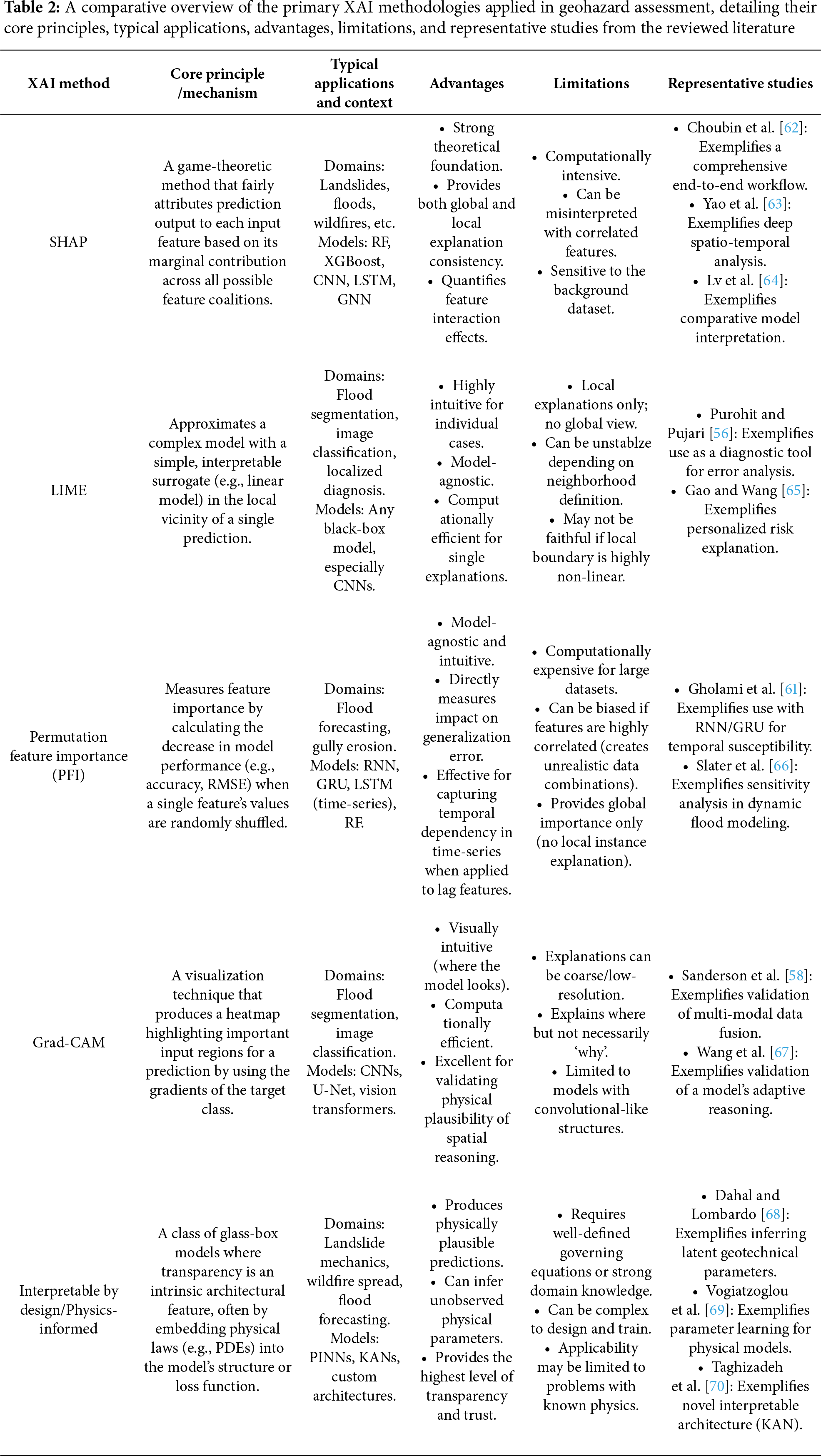

To provide a systematic and more detailed understanding of the methodological toolkit that underpins GeoXAI, we comparatively summarize the principal explainability frameworks found in the literature. Table 2 offers a structured overview of these different methods. The comparison itself is structured around several key aspects for each framework: its core principles, how it’s typically implemented, the predictive models it’s often paired with, and specific examples of its application to geohazards.

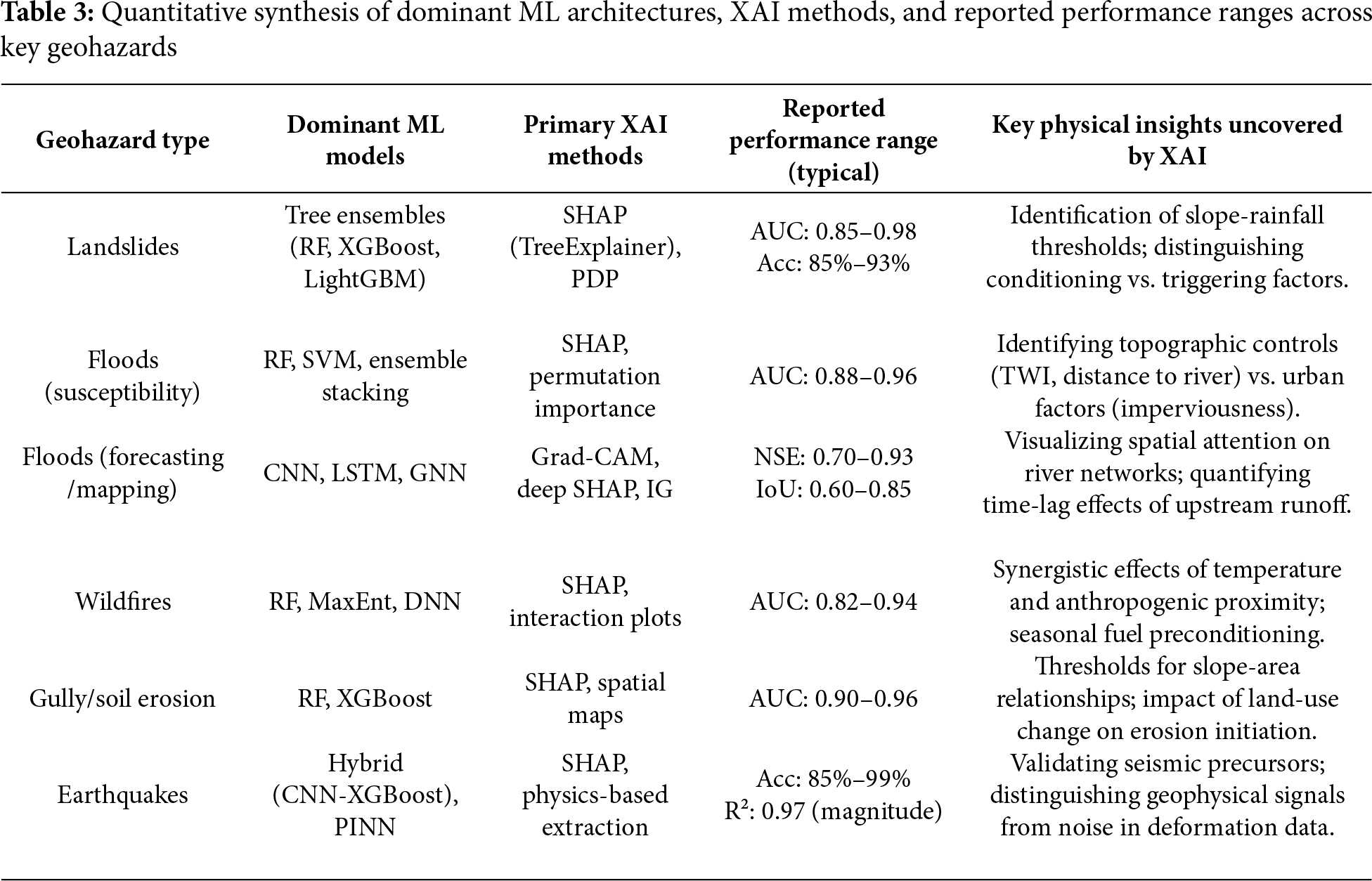

To address the need for a quantitative synthesis beyond thematic mapping, we analyzed the reported performance metrics and XAI efficacy across the reviewed studies (summarized in Table 3). This synthesis reveals distinct methodological patterns tailored to specific hazard types. For Landslide susceptibility, tree-based ensembles (RF, XGBoost) paired with SHAP are the dominant standard, consistently delivering high predictive performance (Mean AUC

3.2 Unpacking the Black-Box: Core Insights from XAI Applications

The true value of integrating XAI into geohazard modeling lies in its capacity to transform a model’s outputs from opaque predictions into a authentic source of new scientific knowledge and actionable intelligence [71]. By systematically unpacking the black-box, researchers are empowered to move decisively beyond simply knowing what a model predicts, allowing them instead to fully understand why it arrives at certain decisions [49]. Critically, this essential process of inquiry unfolds across two distinct, yet complementary, scales: the global and the local.

3.2.1 Global vs. Local Interpretability: From General Drivers to Site-Specific Diagnosis

A fundamental duality exists in model interpretation. Global interpretability aims to elucidate the model’s behavior in its entirety, specifically by identifying the average influence of each conditioning factor across the whole study area [72,73]. Essentially, it answers the strategic question: What are the most important drivers of this hazard in this region? Local interpretability, in sharp contrast, involves dissecting a single, specific prediction for an individual data point, such as an isolated pixel, a distinct slope unit, or a single structure. It answers the tactical question: Why was this specific location assigned to this particular risk level? While both global and local interpretations are essential, the synthesis reveals that it is the power of local interpretation that most effectively bridges the gap between high-performance predictive modeling and crucial operational decision-making.

At the global scale, interpretation provides the crucial first step of understanding broad hazard mechanisms. It provides a crucial initial step, often achieved through analyzing SHAP summary plots or reviewing feature importance rankings. These global interpretation methods are instrumental in two primary areas: first, they confirm established domain knowledge, and second, they reliably pinpoint the dominant predisposing and triggering factors across a macro scale. Such global interpretations, for example, have been successfully used in various studies to identify key drivers. Reference [74] found the Fire Weather Index to be the dominant factor driving wildfire risk throughout Italy. Similarly, these techniques consistently validate that elements like distance to streams and topographic wetness are critical in assessing flood susceptibility [62]. Moreover, research has clearly demonstrated that specific seismological parameters are paramount for accurately assessing earthquake probability [75]. Notably, this level of analysis effectively provides the broad, essential scientific context required for effective regional planning and informed policy development. However, integrating spatiotemporal analysis into these large-scale predictions remains a frontier challenge. In continental-scale assessments, treating space and time as static features can obscure critical regional variances. Recent applications address this by integrating dynamic inputs directly into the XAI framework. For instance, in a pan-European wildfire study, [76] utilized Spatio-temporal SHAP Maps to demonstrate that the drivers of fire risk shift from solar radiation in Southern Europe to precipitation deficits in Northern Europe, and that these drivers have distinct seasonal time-lags. This demonstrates that for large-scale modeling to be operationally valid, XAI must move beyond global averages to reveal the heterogeneous spatiotemporal mechanisms driving the hazard.

Crucially, local interpretations do more than just illustrate global trends on a smaller scale; they often reveal that site-specific mechanisms can deviate significantly from the regional average. A compelling example is found in Teke and Kavzoglu [57]. A global landslide model identified slope and elevation as the dominant regional drivers. However, when researchers conducted a local analysis of three distinct landslides in that same area, they found that a completely different factor was the primary cause for each one. This finding is profound because it shows that a one-size-fits-all mitigation strategy based only on global drivers would be fundamentally flawed. As noted in Ibrahim et al. [50], the local context—whether it’s a unique geological feature or a human influence—can often override the general trend.

Ultimately, the most mature GeoXAI frameworks leverage a synergistic workflow between the two scales. Peng et al. [60] offers a clear example of this synergy. The study first used global SHAP to understand network-wide trends in flood-induced pavement damage. It then employed local LIME to diagnose the specific impact of a flood on an individual road segment. This ability to shift from the general trend (what matters everywhere) to the specific cause (why it mattered here) is the hallmark of an effective explainable system. While global interpretability provides the scientific foundation, it is the local explanation that makes AI operational. The capacity to deliver a specific diagnosis for a single hillslope, building, or asset is what turns a prediction into actionable knowledge and builds the trust required for real-world adoption.

Despite the utility of global and local interpretations, it is crucial to distinguish between explaining a model’s internal logic and establishing true physical causality. This review highlights that post-hoc tools like SHAP explain the model, not necessarily the physical reality. A critical comparative study by [64] demonstrated that different high-performance models (e.g., XGBoost vs. DenseNet) can yield contradictory feature attributions for the same landslide inventory, revealing that explanations are often model-dependent rather than physically absolute. Furthermore, standard XAI frameworks face significant challenges with time-variant features. As noted by [75], algorithms like SHAP were primarily designed for static tabular data; consequently, applying them to dynamic, time-series geohazard data often requires simplified aggregations that may obscure the temporal evolution of risk triggers, such as the changing lag-effects of rainfall.

3.2.2 Beyond Linear Importance: Uncovering Thresholds and Complex Interactions

Global feature importance rankings provide a valuable overview, but the most significant scientific insights from XAI are found when the analysis moves beyond simple linear attribution. The real value comes from exploring the non-linear, conditional, and interdependent relationships that drive complex Earth systems. High-performance ML models are particularly good at learning these nuanced patterns from data. In turn, XAI tools like SHAP dependence plots and interaction analyses provide a way to make these learned mechanisms transparent and open to interpretation. The synthesis of the literature conducted effectively reveals two critical capabilities within this domain: (1) The identification of quantitative, physically meaningful thresholds that translate a model’s continuous predictions into actionable rules, and (2) The discovery of complex interaction effects that reveal the synergistic recipes for geohazards.

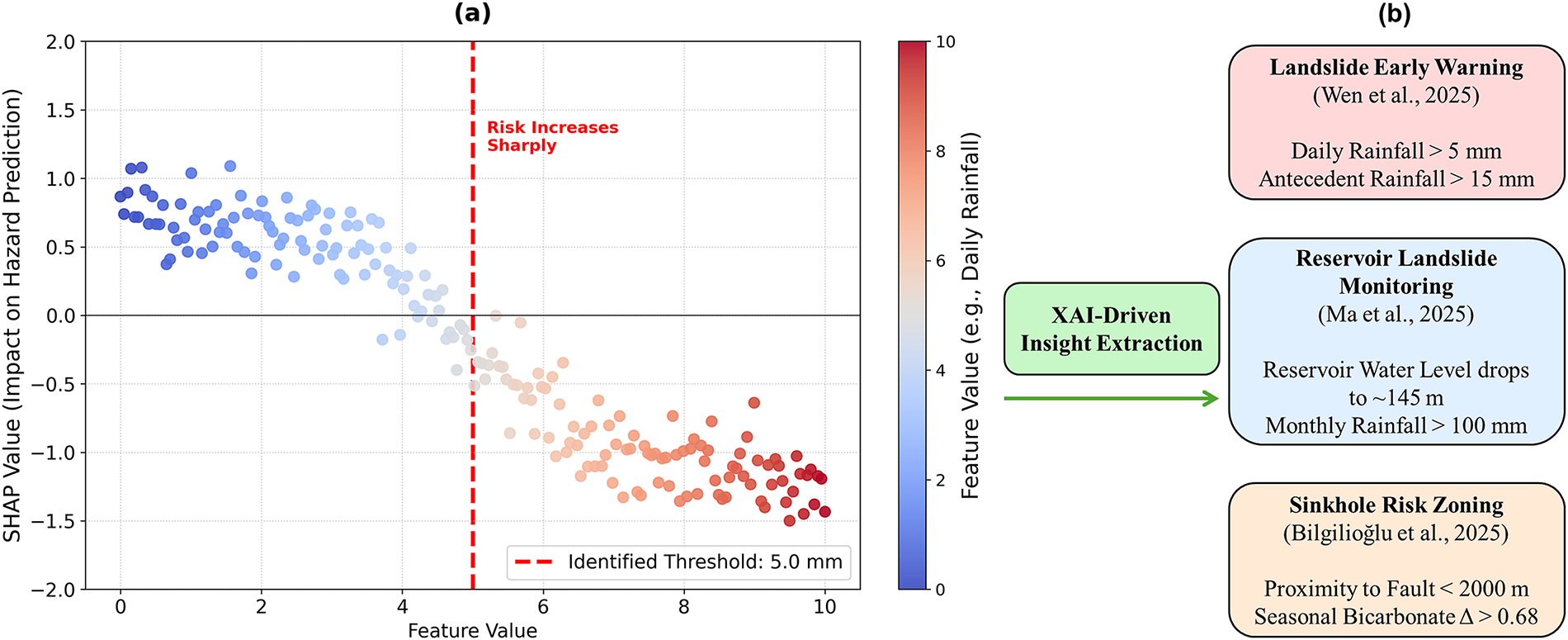

A key function of XAI is to demystify the complicated decision boundaries hidden inside any black-box model. Tools like SHAP dependence plots, for example, are highly effective at visualizing the intricate relationship between a specific feature’s value and its isolated, marginal impact on the final model prediction. Significantly, this unique capability successfully reveals critical tipping points where the inherent geohazard susceptibility dramatically changes. This specific capability has been leveraged powerfully and successfully to accelerate the operationalization of predictive models, demonstrating particular utility for deployment within critical early warning systems [77]. For example, several specific studies [78,79] successfully utilized their XAI frameworks to directly extract the precise numerical parameters needed to trigger alerts. This led to the identification of clear thresholds—such as daily rainfall (>5 mm), antecedent moisture (>15 mm), and reservoir water level (∼145 m)—which definitively signify a sharp increase in landslide risk.

This approach extends beyond dynamic triggers to static predisposing conditions, providing an evidence-based foundation for land management and zoning policies. The work on sinkhole susceptibility in Bilgilioğlu et al. [48] serves as a clear practical example. Instead of producing just a complex risk map, the model’s internal logic was translated into a set of simple, testable rules for planners. For instance, the analysis established a straightforward geological rule: sinkhole risk increases substantially within 2000 m of a fault line. It also produced a novel hydrochemical rule, showing that risk also goes up when the seasonal bicarbonate difference exceeds 0.68. This ability to convert the complex reasoning of an AI model into a short list of practical, quantitative rules is what bridges the gap between an abstract prediction and an actionable, on-the-ground risk management strategy. As Fig. 5 illustrates, advanced AI can be translated into practical, on-the-ground risk management strategies.

Figure 5: Conceptual workflow illustrating the translation of black-box model logic into actionable knowledge. This process is exemplified with studies that used XAI to derive quantitative thresholds for landslide early warning [78], reservoir monitoring [79], and sinkhole risk zoning [48]

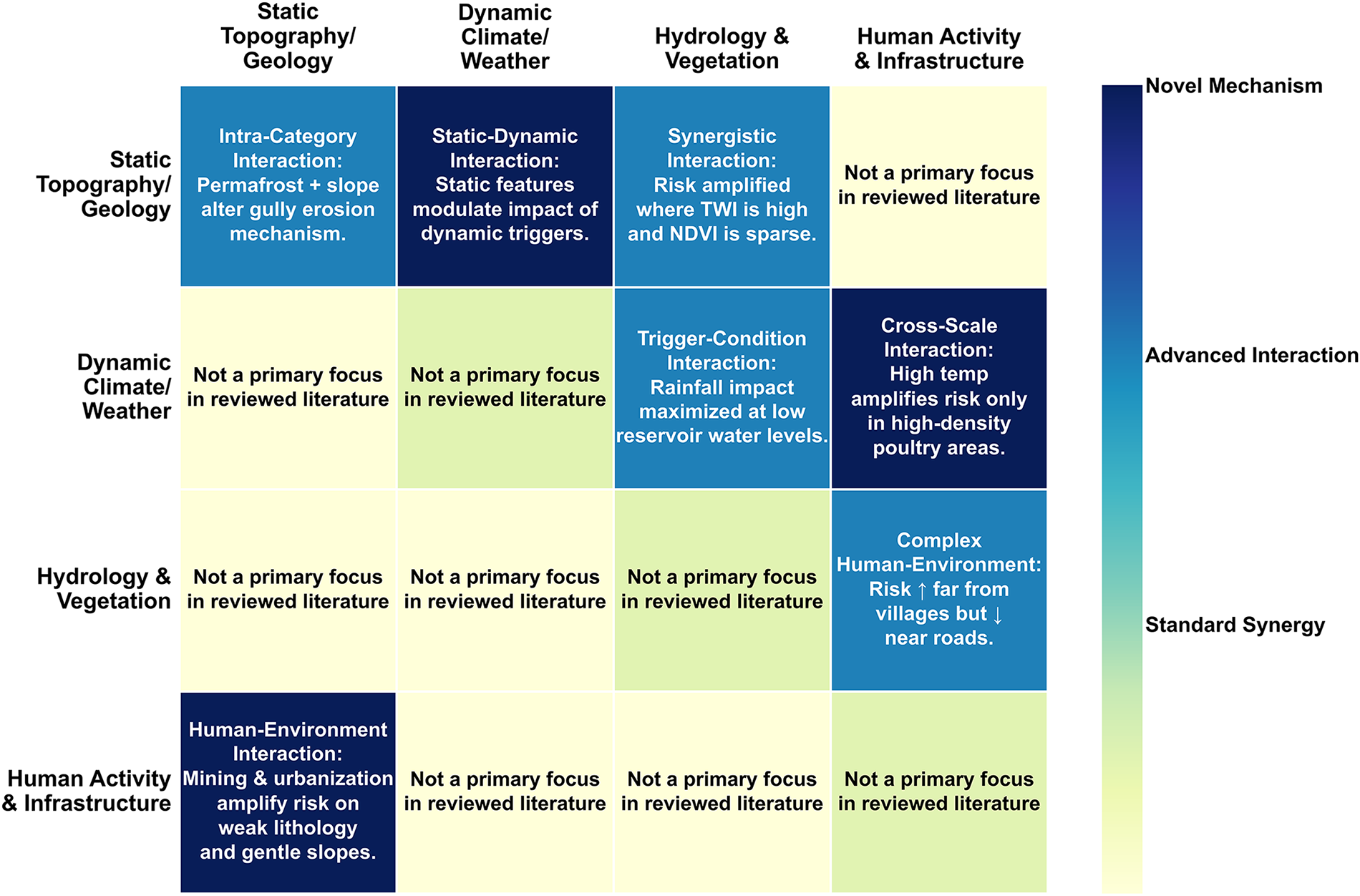

Geohazards rarely stem from a single cause; instead, they typically arise from the complex interaction of multiple factors. A significant strength of XAI is its ability to look beyond the main effects of individual variables and quantify how they work together, whether they amplify (synergy) or reduce (antagonism) risk. The literature reviewed here reveals several classes of these complex interactions, deepening the mechanistic understanding of hazard processes (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: Synthesis of multi-factor interaction classes uncovered by XAI, exemplified by studies on static-dynamic coupling (Wang et al. [80], Slater and Coxon [66]), cross-scale environmental interactions (Wang et al. [81], Choubin et al. [62], Zhang et al. [82]), and the interplay between natural triggers and human activity (Ma et al. [79], Fang et al. [83], Nam et al. [53], Iban Aksu [84])

One important class is the cross-scale interaction, where a large-scale context alters the impact of a local-scale trigger. For instance, a study on avian influenza [81] found that high temperatures (>30°C)—normally considered low-risk—become a significant risk amplifier when they occur within a macro-scale context of high poultry density. Another critical category is the static-dynamic interaction, where a dynamic event changes the importance of a static landscape feature. Research in Wang et al. [80] found that the dynamic forces of a typhoon significantly amplified the role of static features like vegetation. This proves that the vulnerability of a landscape is not fixed but changes based on interacting events.

Crucially, XAI’s utility extends beyond mere model validation; it has also proven essential for accurately quantifying complex human-environment interactions. For example, a notable investigation utilized an interpretable-by-design model to find that the combined effect of local mining activities and rainfall was a considerably more potent predictor of landslides in a Karst region than if those factors were assessed individually [83]. The key takeaway is this: when a predisposing anthropogenic stressor intersects with a natural trigger, the resultant risk of failure is powerfully elevated, often to a disproportionately high degree.

This ability to dissect a model’s logic elevates XAI from a simple interpretation tool to a computational laboratory. It allows researchers to probe the inner workings of a trained model to generate new, data-driven, and often non-intuitive hypotheses about the complex, conditional, and synergistic mechanisms that drive geohazards. While these interpretive analyses deepen scientific understanding, the next step in GeoXAI’s evolution is its integration into the modeling workflow itself—where explainability no longer follows modeling, but actively guides it.

3.3 XAI as an Active Agent: Enhancing the Geohazard Modeling Workflow

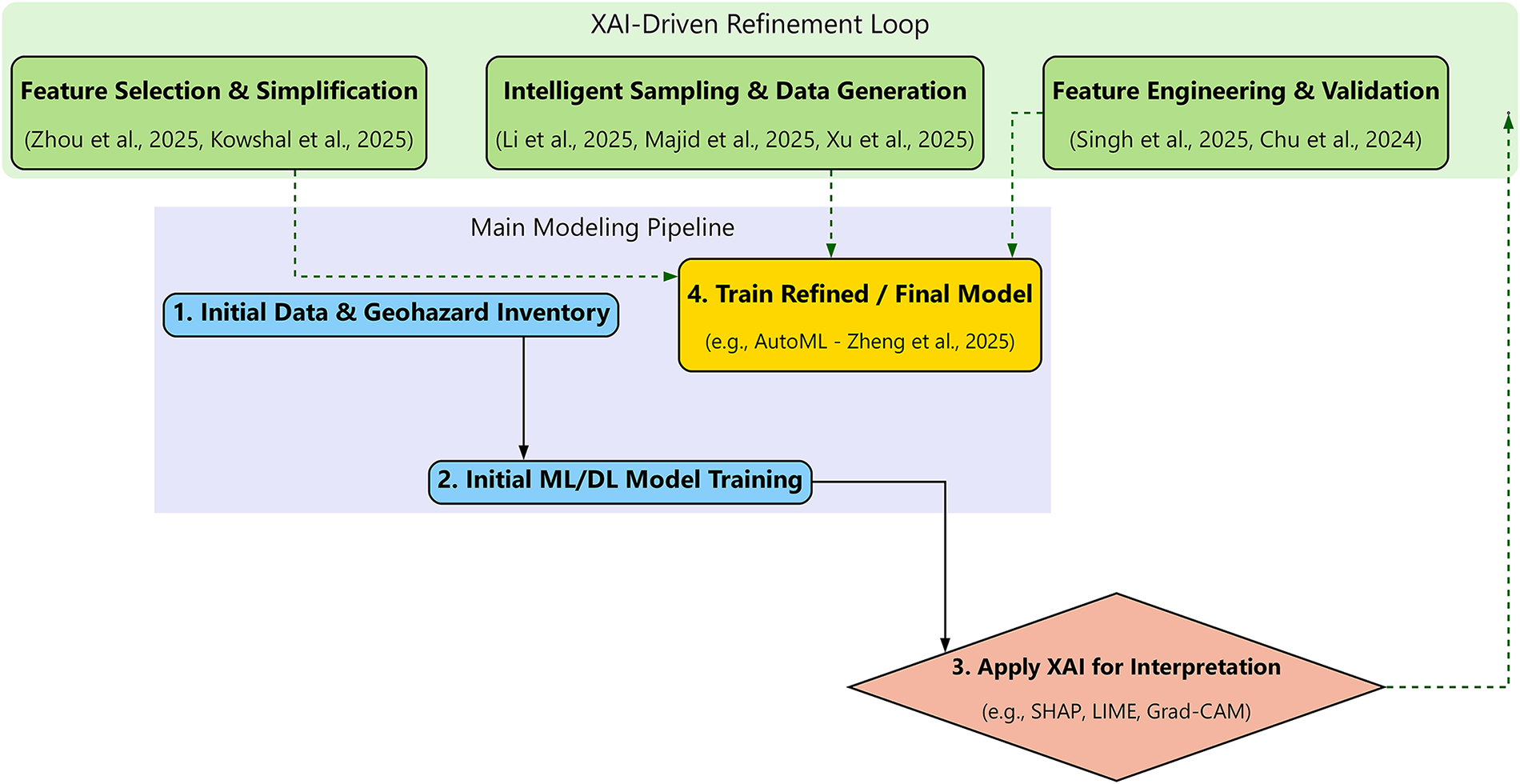

A significant paradigm shift has occurred in how XAI is used in geohazard science. It began as a post-hoc tool, something used simply to interpret a model after it was already built. Now, however, it is emerging as an active component that is integrated directly into the modeling workflow itself. This new paradigm is built around a core iterative feedback loop: Model → Explain → Refine → Final Model. In this in-the-loop approach, an explanation is not treated as a final report card after the fact. It becomes an active blueprint for making the model better. Researchers use these insights to guide and refine the entire modeling route—from how the data is prepared and features are engineered, all the way to the final optimization. The systems that come out of this process are more than just transparent; they are measurably more robust, efficient, and physically plausible.

3.3.1 Data-Driven Refinement: XAI for Feature Engineering and Sampling Strategies

The most notable application where XAI functions as an active agent involves the data-driven optimization of the complete modeling pipeline. This all-encompassing procedure spans every stage, from the critical initial steps of feature selection and engineering right through to the systematic generation of the necessary training data itself (Fig. 7).

Figure 7: The GeoXAI active modeling workflow, illustrating the use of XAI as an in-loop agent for model refinement. This is exemplified by studies that leverage XAI insights for feature selection and simplification (Zhou et al. [85], Kowshal et al. [86]), intelligent sampling and data generation (Li and Tian [87], Majid et al. [88], Xu et al. [89]), and feature engineering and validation (Singh and Roy [90], Chu et al. [91])

One fundamental and practical aim of the in-the-loop methodology is the development of models that are both simpler and more efficient, a goal typically accomplished through strategic feature selection followed by thorough model simplification. XAI makes this possible by providing a quantitative ranking of predictor importance. This allows researchers to create a more focused (parsimonious) model by keeping only the most impactful features. A case study on post-fire gully erosion [85] shows this process in action. An initial, complex model used 21 different factors. After a consensus-based SHAP analysis across four different models, the researchers identified the eight most dominant factors. They subsequently trained a new, highly simplified model utilizing only those eight identified predictors. The outcome was striking: the much simpler model performed almost identically to its complex predecessor. The performance trade-off was minimal; the model’s area under the curve (AUC) only dropped from 0.989 to 0.973. This provides powerful evidence that XAI can be used to reduce a model’s complexity without a major sacrifice in predictive performance. This same technique—using SHAP to distill a complex research model into a more practical tool with fewer inputs—has also been effectively applied to ice-jam flooding [86]. Several other studies have similarly confirmed the tangible value of XAI when applied to rigorous feature selection [61,80,92].

More innovatively, XAI is being used to guide intelligent data generation and sampling. A groundbreaking workflow developed by Li and Tian (2025) [87] demonstrates a powerful feedback loop for landslide susceptibility: (1) an initial model is trained; (2) SHAP is used to identify a rule for landscape stability (NDVI > 0.8); and (3) this rule is then used to filter the original random negative samples and replace them with a more physically plausible, higher-quality set. The implementation of this specific XAI-driven sampling methodology led to a dramatic enhancement in model performance, with the AUC soaring from 0.914 to an impressive 0.986. The principle of using data-driven insights to guide data generation, as exemplified by the XAI-driven workflow, is also central to other sophisticated methods such as hybrid modeling. These frameworks frequently leverage physics-based models (such as RIVICE, RUSLE, or TRIGRS) to effectively create large, synthetic, and physically consistent training datasets—a critical technique where observational data are naturally scarce [86,88,89]. Furthermore, utilizing unsupervised clustering strategically to engineer a more robust target variable out of raw historical data constitutes yet another sophisticated technique within the realm of data refinement [93].

XAI also serves as a critical validation tool for physics-informed feature engineering. In this workflow, domain knowledge is used to create new, powerful predictors, and XAI is then used to confirm their efficacy. For earthquake magnitude prediction [90], new features were engineered based on seismological principles; a subsequent SHAP analysis provided definitive proof of their value by showing that the new energy variable had become the single most dominant predictor in the model. A similar approach was used to validate engineered spatiotemporal features for urban flood forecasting, where SHAP confirmed the new features contributed significantly (approx. 14%) to the model’s output [91].

The most advanced expression of this active refinement paradigm is AutoML, where the AI system itself takes on the role of refinement. An AutoML framework built for landslide susceptibility Zheng et al. [52] offers a clear example. It automates the entire modeling pipeline, from algorithm selection and hyperparameter tuning to the final ensembling. The system was able to produce a state-of-the-art model (AUC = 0.90) in only 156 s. This result showcases the immense potential of AutoML to accelerate the development of objective, high-performance, and reproducible geohazard models.

3.3.2 Building Confidence: XAI for Model Comparison and Validation

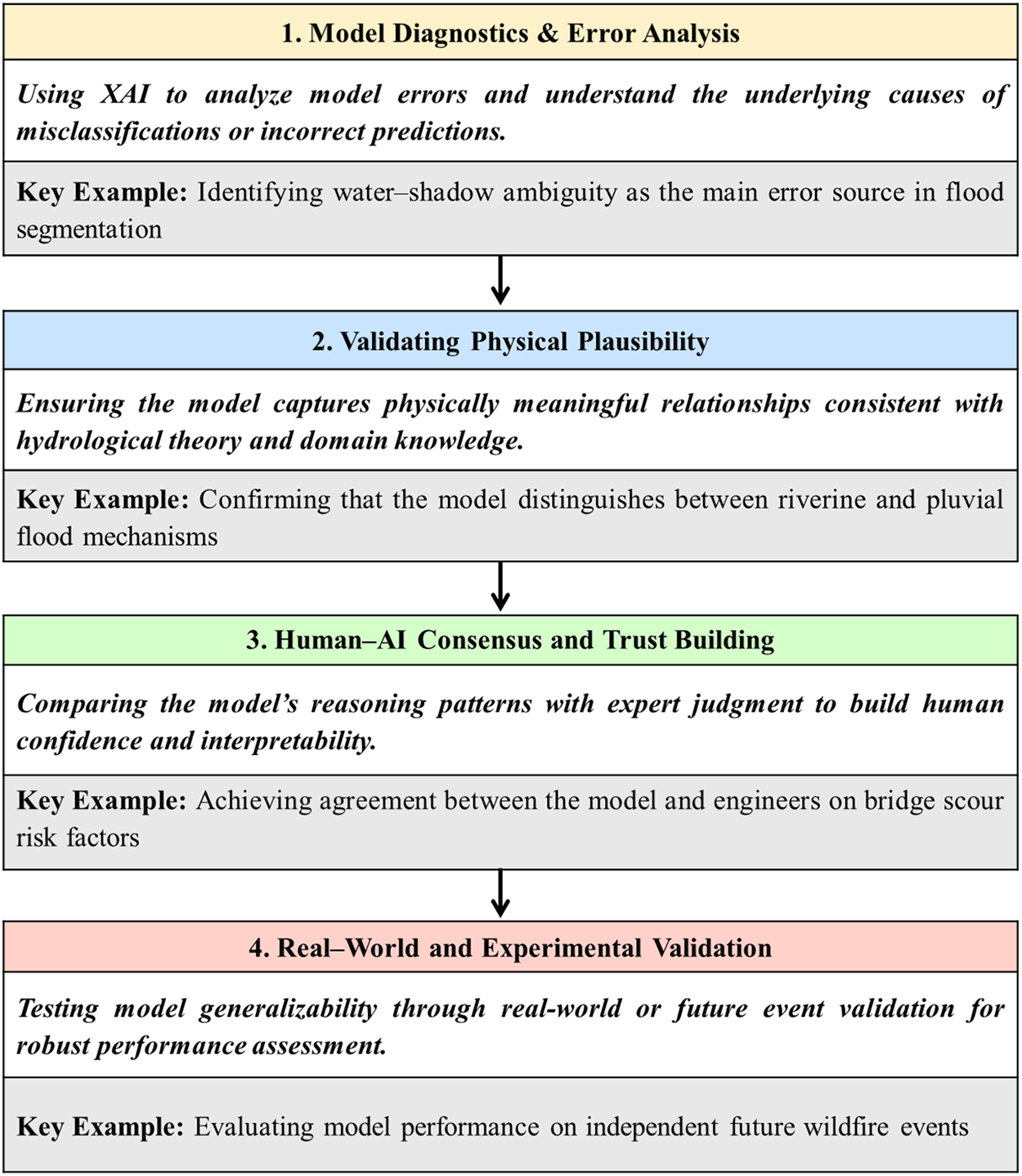

While continuous refinement efforts generate high-performing models, it is crucial to acknowledge that strong metric scores don’t inherently equate to trustworthiness [94,95]. In fact, conventional validation—which often relies solely on a single measure, such as the AUC—is frequently a poor indicator of genuine reliability in real-world scenarios [96]. A model might achieve outstanding performance benchmarks yet rely on spurious correlations or physically implausible reasoning. Such hidden dependencies make the system brittle and untrustworthy, especially in mission-critical contexts [97]. The literature reviewed for this paper strongly suggests, therefore, that XAI offers the essential framework for a much deeper, multi-faceted validation. As vividly shown in Fig. 8, this XAI-driven methodology pushes beyond simple performance statistics, focusing instead on establishing confidence in a model’s internal logic, its underlying robustness, and its concrete practical utility.

Figure 8: A spectrum of XAI-driven validation methods that build model trustworthiness, exemplified by studies on: (1) diagnostics and error analysis [56], (2) validation of physical plausibility [67], (3) establishing human-AI consensus [98], and (4) validation against independent, real-world events [99]

One of the most valuable and readily available applications of XAI is its use in model diagnostics and detailed error analysis. It’s vital to recognize that the actual utility of XAI goes significantly beyond simply spotting that a model produced an error; critically, it offers researchers the unique ability to precisely pinpoint and fully understand the specific mechanism that caused the mistake [100,101]. A premier illustration of this diagnostic capability, for example, is the utilization of LIME for analyzing a state-of-the-art flood segmentation model [56]. XAI essentially offers a post-mortem analysis, allowing us to diagnose exactly why a model fails, even when its overall quantitative metrics are otherwise excellent. Take, for instance, a flood model that initially posted high overall accuracy scores: researchers utilized LIME heatmaps to carefully investigate the specific regions it had misclassified. The resulting heatmaps proved highly instrumental, revealing that the model’s core failure mode was rooted in water-shadow ambiguity. To be specific, the model consistently mistook dark shadows for actual floodwater, a clear problem arising from their similar visual textures. This kind of specific, diagnostic insight is critical; crucially, you can’t get it solely from an aggregate accuracy score. Pinpointing the exact underlying reason for the failure provides a clear, direct pathway for targeted improvements—a necessary effort that forms a fundamental step toward developing any truly robust predictive system. This same potent diagnostic capability, notably, was instrumental in explaining the catastrophic failure of an optical satellite model that struggled with cloudy conditions. The failure stemmed from the fact that the system had erroneously concentrated its analysis on the clouds themselves, entirely neglecting the underlying ground features it was initially engineered to observe [58].

Significantly, XAI moves beyond mere error diagnosis; it is, in fact, vital for validating the physical plausibility of a model’s underlying reasoning [102]. This concept fundamentally involves using explainability tools as a necessary sanity check, which ensures the model has, in fact, learned scientifically sensible relationships instead of spurious ones [103]. A compelling illustration of this comes from research on a hydrology-aware DL model: validating it with Grad-CAM clearly demonstrated that the model had, in fact, acquired a sophisticated, adaptive reasoning strategy. Specifically, for riverine flood prediction, the model correctly focused its attention on the river network; however, it then smartly shifted its focus to local topography when dealing with pluvial floods occurring further away from the main channel [67]. Similarly, SHAP analysis was effectively used to confirm that a complex forecasting model had learned a physically sound heuristic by primarily relying on the most recent downstream data. This finding built confidence that the model’s high accuracy was not just a result of spurious or non-physical patterns [104]. Ultimately, when an XAI-derived explanation aligns perfectly with known physical principles, such as the confirmed impact of a large dam on river dynamics [105], it provides powerful validation of the model’s learned representation of the entire system.

Perhaps the most advanced form of validation is building trust through human-AI consensus. A deeper form of validation goes beyond data and physics to the epistemological level, where a model’s logic is compared directly to the reasoning of human domain experts. A study on bridge scour risk [98] provides a powerful example. Confidence in the model was established not just through a high AUC, but by showing that both the model and a group of 26 field engineers came to the same conclusion: they were in unanimous agreement on the most important risk factor. This consensus between the AI’s feature ranking and the experts’ collective judgment is a far more convincing validation of the model’s core logic than any statistical metric alone. A similar approach was used to validate a landslide model. In that case, the SHAP-based explanation for a specific event was shown to align with the findings of an independent, in-situ geotechnical investigation [106].

XAI is a key component of more rigorous validation frameworks for both experimental and real-world settings. The ultimate test of a model’s generalizability is its performance on an entirely independent, future event. This gold standard approach was employed in one study by validating a wildfire damage model on the major 2025 Southern California wildfires. This test provided exceptional confidence in the model’s actual utility for real-world scenarios [99]. Furthermore, moving past simple accuracy metrics, XAI enables a deep comparative validation process, allowing researchers to diagnose not merely whether one model outperforms another, but fundamentally why. As an example, a SHAP analysis was successfully used to reveal that a comparatively weaker support vector machine (SVM) model had learned relationships for key variables that were both physically implausible and often contradictory, particularly when assessed against a much more accurate RF model. This analytic step thus validated the superior physical logic and logical consistency inherent in the better-performing algorithm [107]. Such advanced validation strategies, fully empowered by XAI, are essential. They are actively helping the field transition from simply developing models that are accurate toward engineering systems that are demonstrably robust, physically plausible, and entirely trustworthy.

3.4 The Spatiotemporal Frontier: Challenges and Opportunities in GeoXAI

Despite the significant progress in applying XAI to geohazard assessment, a critical review of the literature points to a fundamental limitation [108]. The majority of current applications, while analyzing geographic phenomena, use ML and interpretation methods that are inherently aspatial and static [109]. In practice, most frameworks treat geographic data as a simple feature-based representation [75]. This approach ignores cornerstone principles of geography, such as spatial autocorrelation (the idea that nearby things are more related than distant things), spatial heterogeneity (the fact that relationships can change across a landscape), and the fundamental concept of scale [110]. This aspatial assumption—that a single, global model can capture the processes driving a hazard uniformly across a diverse landscape—is often invalid and can lead to models that are not only less accurate but whose explanations are incomplete or even misleading [111].

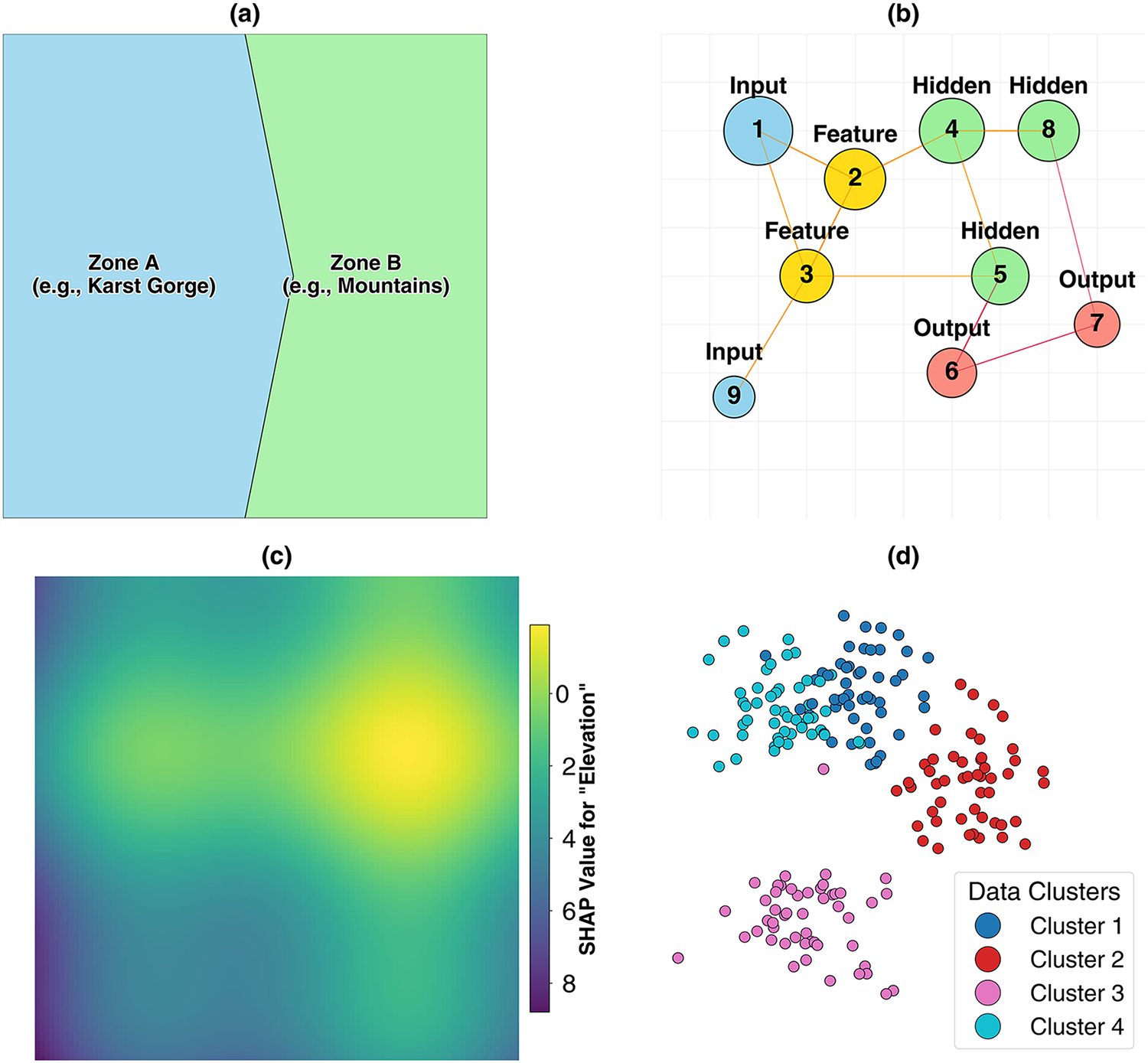

Adopting this spatial viewpoint immediately brings the major challenge of spatial heterogeneity (or non-stationarity) into focus. This describes the core phenomenon where the drivers of a geohazard, along with their relative levels of importance, change fundamentally from one location to another [112]. Given this fundamental challenge, a considerable portion of the research community is now deliberately transitioning away from traditional global, one-size-fits-all modeling strategies [113]. Therefore, the overarching objective has shifted toward creating far more sophisticated frameworks: those designed specifically to effectively capture and provide clear explanations for these critical spatial variations within the drivers of geohazards [114]. Broadly, these emerging solutions for effectively handling spatial heterogeneity can be sorted into three clear, distinct methodological approaches (Fig. 9). The first approach is defined as knowledge-driven stratification: this involves researchers applying deep domain expertise to logically partition the larger study area into smaller, more homogeneous and physically meaningful sub-regions. This necessary step occurs prior to initiating the primary modeling process. By building and interpreting separate models for distinct geomorphological zones or areas with different triggering mechanisms, studies have quantitatively proven that the dominant drivers of landslides are fundamentally context-dependent and vary significantly between these zones [64,115].

Figure 9: A comparison of four methodological approaches for analyzing spatial heterogeneity in GeoXAI. (a) Knowledge-driven Stratification, where the study area is pre-divided into homogeneous zones. (b) Geo-algorithmic approach, using inherently spatial models like GNNs. (c) GeoXAI-Native Interpretation, using spatially explicit explanation techniques like SHAP maps. (d) Data-driven discovery, using unsupervised clustering to automatically identify zones of similar behavior

A second, more sophisticated approach employs geo-algorithmic models engineered specifically for inherent spatial awareness. A key example is the geographical RF (GRF), a technique that operates by iteratively fitting localized models within a moving spatial window. This localized adaptation is critical because it allows the GRF to account for particular regional conditions, consequently yielding significantly more realistic risk patterns. This methodology has been empirically shown to drastically outperform conventional aspatial models that ignore geographic context [116]. In a similar vein, the recent adoption of GNNs is noteworthy because these networks are fundamentally designed to learn from the topological relationships established among spatial units. The result is the production of geographically much more coherent and plausible regionalization outcomes [51]. The third, and arguably the cutting-edge, strategy is the development of GeoXAI-native frameworks. This strategy ensures that both the core predictive model and its accompanying interpretation methodology are developed from first principles to inherently handle spatial data intrinsically. From this area, key innovations are emerging, including GeoMLR (which explicitly incorporates geographic coordinates directly as modeling features) and the novel GeoShapley interpretation method. These tools are explicitly designed to quantitatively measure and, isolate purely spatial effects from other concurrent environmental factors [28]. A key output from these frameworks is the SHAP map, which visualizes how a feature’s impact is distributed across space. This turns the abstract idea of feature importance into a tangible geographic pattern, offering a unique view into the model’s spatial reasoning [117].

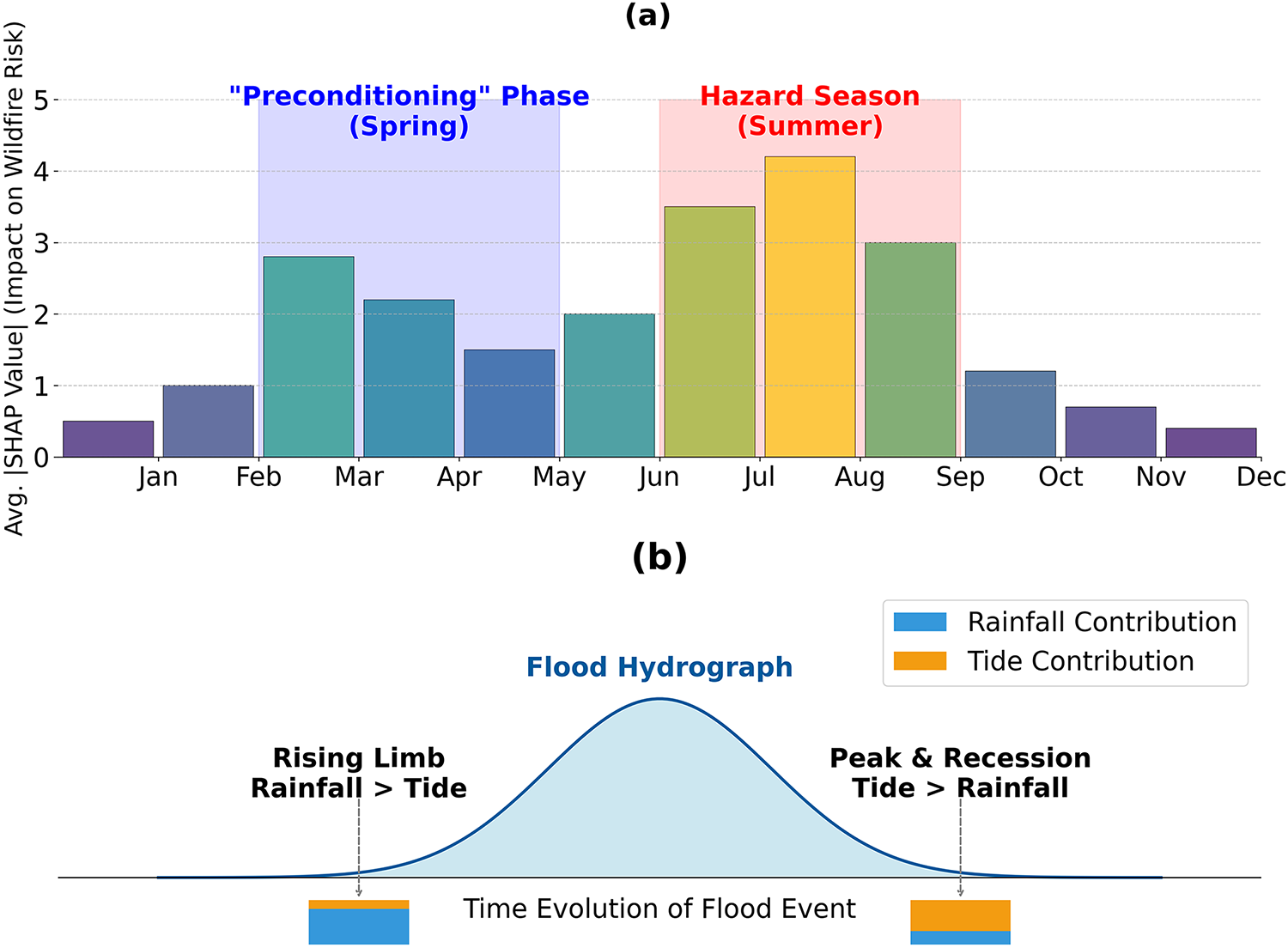

Beyond the spatial frontier lies the temporal frontier. The vast majority of GeoXAI studies produce static susceptibility maps, which represent a long-term average probability but ignore the dynamic of geohazards. However, geohazards are dynamic processes [118,119]. A growing body of work is now using XAI to dissect these temporal dynamics (Fig. 10). This includes analyzing long-term dynamics and time-lag effects, moving beyond immediate triggers to understand how hazards are preconditioned over time. A landmark study using an LSTM-SHAP framework on wildfire data discovered that the risk of a summer fire was significantly influenced not just by summer weather, but also by the climate conditions of the preceding spring, which governed the growth of fuel [76]. Other research is tackling temporal non-stationarity by systematically evaluating how model interpretations change when trained on different chronological datasets [90].

Figure 10: Visualization of two distinct types of spatio-temporal dynamics analyzed with XAI. (a) Uncovering long-term, time-lag effects, where antecedent conditions (the preconditioning phase such as spring climate) have a delayed but critical impact on a future hazard season (summer wildfire risk) [76]. (b) Dissecting intra-event dynamics, showing how the relative importance of different triggering factors (rainfall vs. tide) evolves during the course of a single compound flood event [120]

Analyzing the intra-event spatio-temporal dynamics is perhaps the most sophisticated application currently available. This methodology is unique because it specifically reveals how the drivers of a singular hazard event evolve across both spatial extent and temporal duration. Consider, for example, the dynamics of compound flooding: a time-dependent SHAP analysis distinctly illustrated the shifting hierarchy among the influential drivers throughout the event. Rainfall was found to be the most critical factor during the initial onset, yet high tides ultimately gained the dominant influence precisely when the flood reached its maximum peak [120]. Similarly, a parallel methodological approach was successfully employed to dissect the complex, internal kinematics of an active landslide. This specific analysis demonstrated how the relative impact of rainfall compared to reservoir levels fluctuated, not only across distinct segments of the landslide mass but also notably varied over the total duration of the event [63]. These pioneering investigations strongly indicate the trajectory for future GeoXAI work: a notable movement toward formulating and employing genuinely spatio-temporal models. Such models must be capable of capturing, and subsequently explaining, the complete, dynamic complexity intrinsically tied to geohazard processes.

To capture this dynamic nature, recent studies have moved beyond static mappings to employ specialized spatiotemporal architectures. The review highlights the adoption of LSTM networks for capturing temporal dependencies in flood runoff [105] and hybrid architectures like LSTM-MHA (multi-head attention) for modeling compound flood dynamics [120]. Furthermore, GNNs, such as the HydroGraphNet employed by [70], represent a significant leap, allowing for the modeling of flood propagation on unstructured meshes. However, these architectures present unique XAI challenges. Standard SHAP implementations often struggle to attribute importance to specific time-steps in recurrent layers. To address this, recent works have utilized time-dependent SHAP visualizations to track how feature influence evolves during an event [76], revealing that drivers like antecedent soil moisture may be critical only in specific pre-event windows.

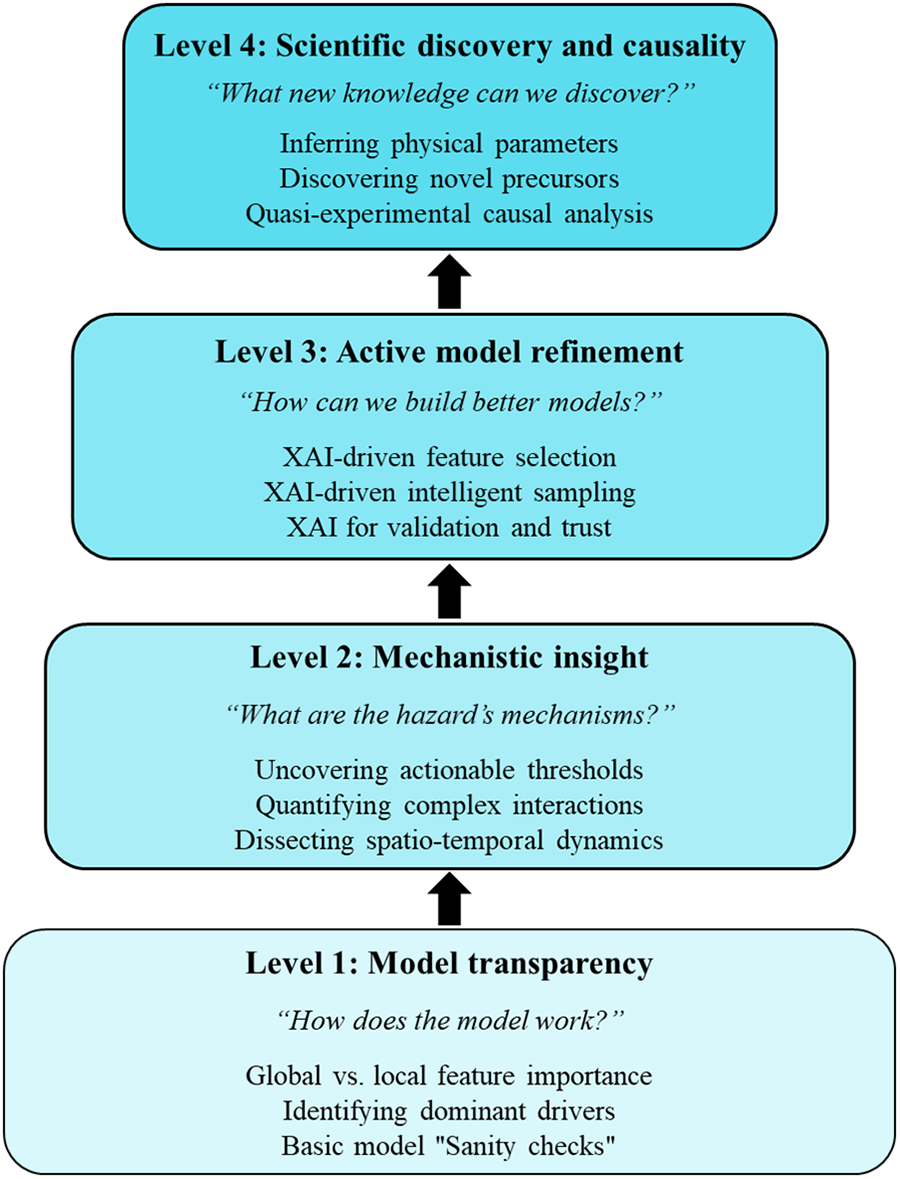

This final synthesis, which spans from the initial thematic mappings to the dissection of complex spatio-temporal dynamics, lays out a clear evolutionary trajectory for GeoXAI [87,121]. The function of explainability has fundamentally transitioned [122]; it has moved beyond its foundational role as a post-hoc tool for model transparency and has become a sophisticated framework for generating new scientific knowledge [123]. To capture this evolution, we propose a conceptual model—the hierarchy of GeoXAI Insights—which organizes the state-of-the-art into a four-tiered hierarchy (Fig. 11). The framework’s foundation is Model Transparency (Section 3.2.1), which is essential for building the trust required for real-world use. Building upon this, the next level is Mechanistic Insight (Section 3.2.2), where XAI is used to find non-linear thresholds and complex interactions. These insights then enable Active Model Refinement and Validation (Section 3.3), where XAI is integrated straightway within the modeling workflow to improve robustness and physical plausibility. The hierarchy culminates in the frontier of scientific discovery and causal inference (Section 3.4), where advanced GeoXAI is used not just to predict but to infer physical parameters, but also to discover novel hazard precursors, and dissect complex causal chains. This framework serves a dual function: it acts as a structured summary of the field’s current capabilities and as a conceptual bridge connecting this review of the state-of-the-art to the future challenges in developing trustworthy GeoAI. Having now established the methodological and spatio-temporal frontiers of GeoXAI, the subsequent section will critically examine the unresolved challenges that must be addressed to ensure the reliability, robustness, and real-world deployment of these emerging systems.

Figure 11: The GeoXAI hierarchy of insights, a conceptual model illustrating the hierarchical progression of knowledge gained from XAI applications. The framework progresses from foundational model transparency (Matin and Pradhan [124], Pradhan et al. [113], Choubin et al. [62]), to deriving mechanistic insight (Wen et al. [78], Ma et al. [79], Wang et al. [81]), to enabling active model refinement (Zhou et al. [85], Li and Tian [87], Wang et al. [98]), and culminating in the research frontier of scientific discovery and causality (Dahal et al. [68], Graciosa et al. [125], Wei et al. [105])

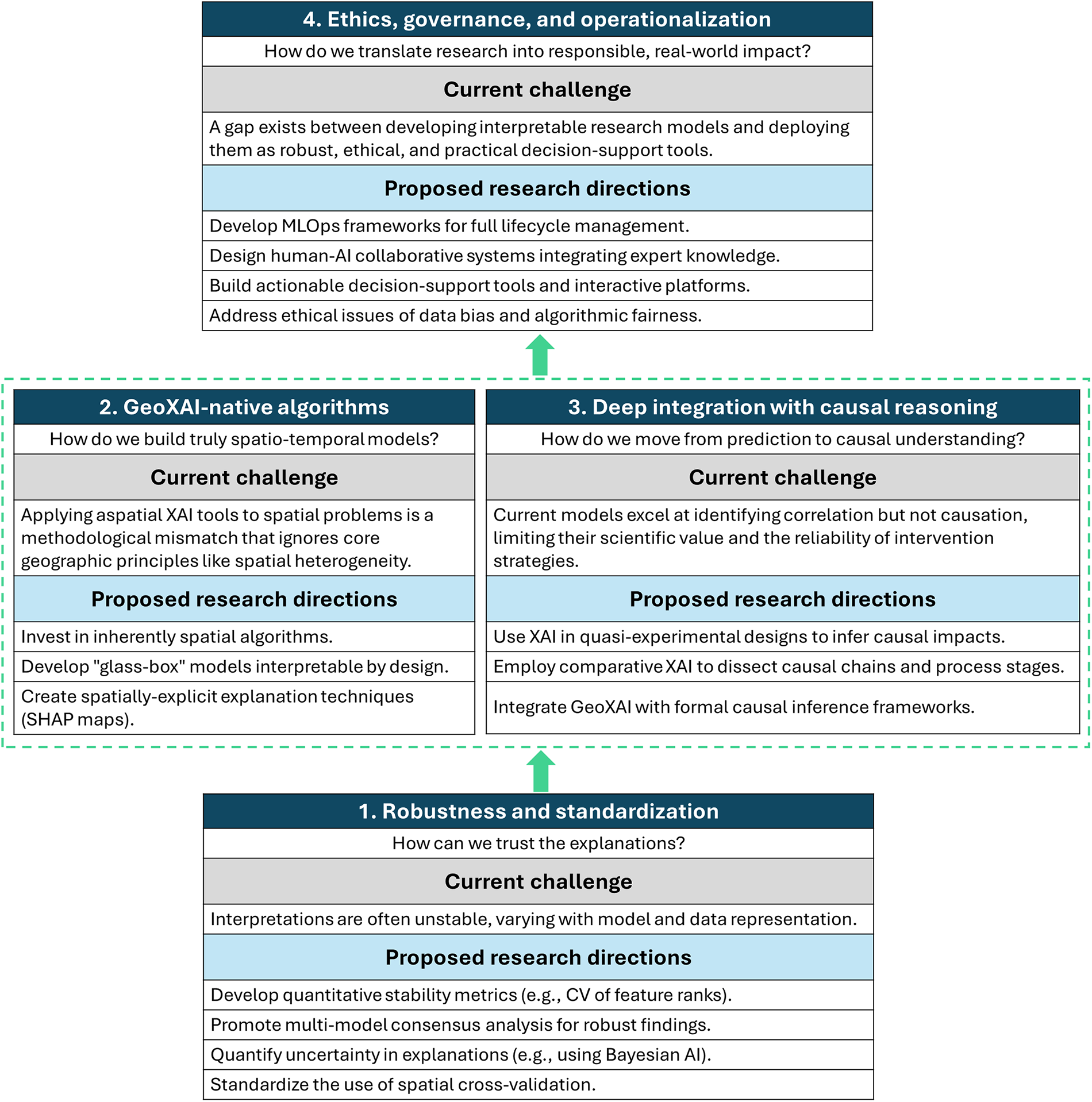

4 Critical Challenges and Frontier Themes: Moving towards Trustworthy AI

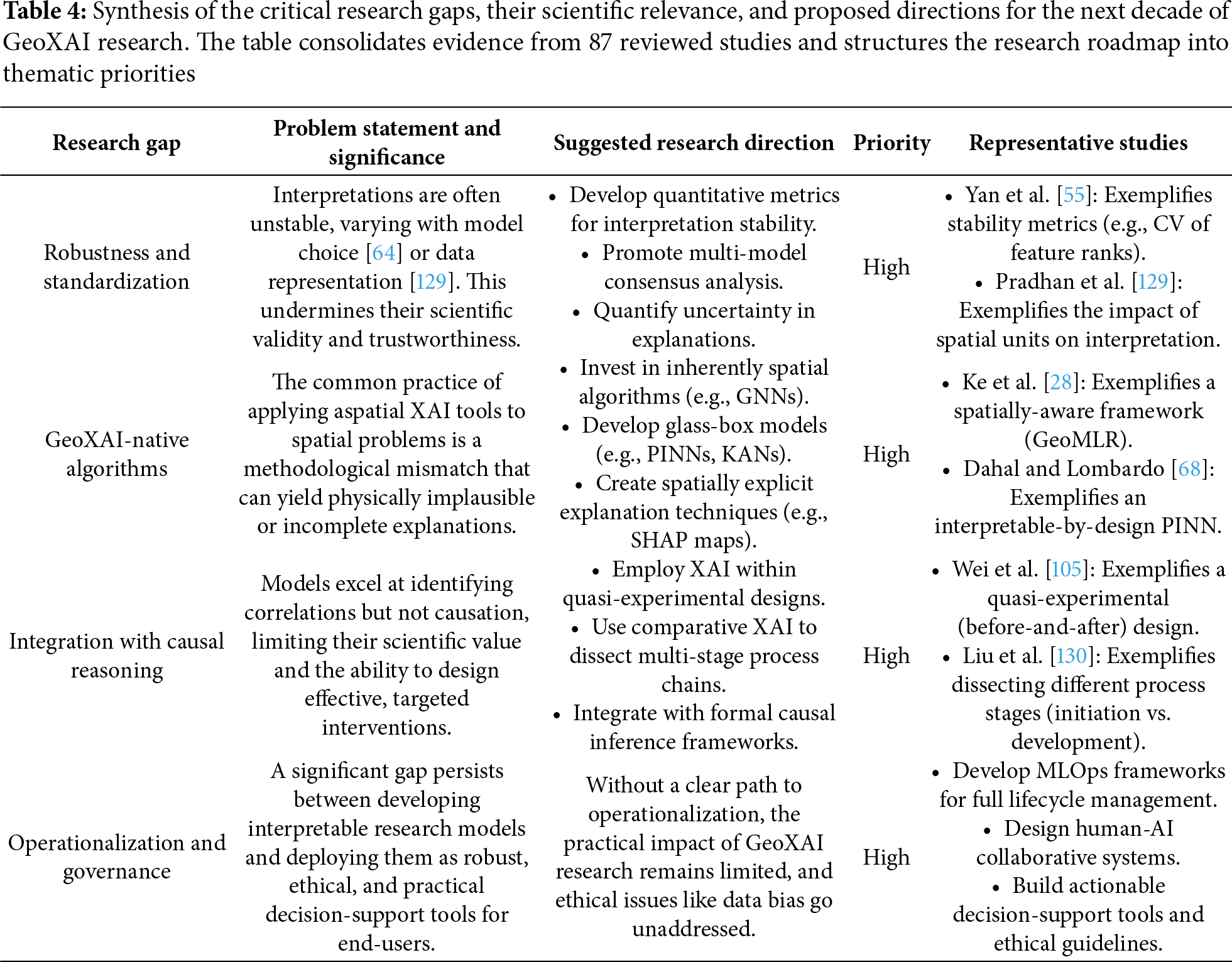

The successful deployment of XAI across a varied spectrum of geohazards certainly represents a major stride forward for the field [126]. Yet, effectively moving these systems from promising laboratory results toward achieving truly reliable operational status fundamentally demands that the community successfully tackle a more complex array of interwoven challenges [127]. Interestingly, the very quest for transparency has brought a new issue into focus: even when the black-box is opened, the resulting explanations are not consistently stable, unique, or genuine reflections of the underlying physical reality [128]. Consequently, this section undertakes a critical review of the frontier themes poised to define the next ten years of GeoXAI research. The primary research themes center squarely on three critical areas: effectively managing the inherent uncertainty found in the explanations derived, successfully pushing the analysis past simple correlation toward genuine causation, and working toward a more rigorous, deeper integration of data-driven and physics-based models. To organize these key challenges and future-looking themes effectively, this review brings them together into a concise, forward-looking summary. Table 4 fulfills this specific function: it offers a systematic breakdown of the most vital research gaps identified, clearly clarifies the fundamental importance of these gaps for the broader discipline, and subsequently proposes prioritized trajectories for future investigation. This essential tabular framework, in turn, provides the direct basis for the comprehensive research roadmap detailed in the final section of this manuscript.

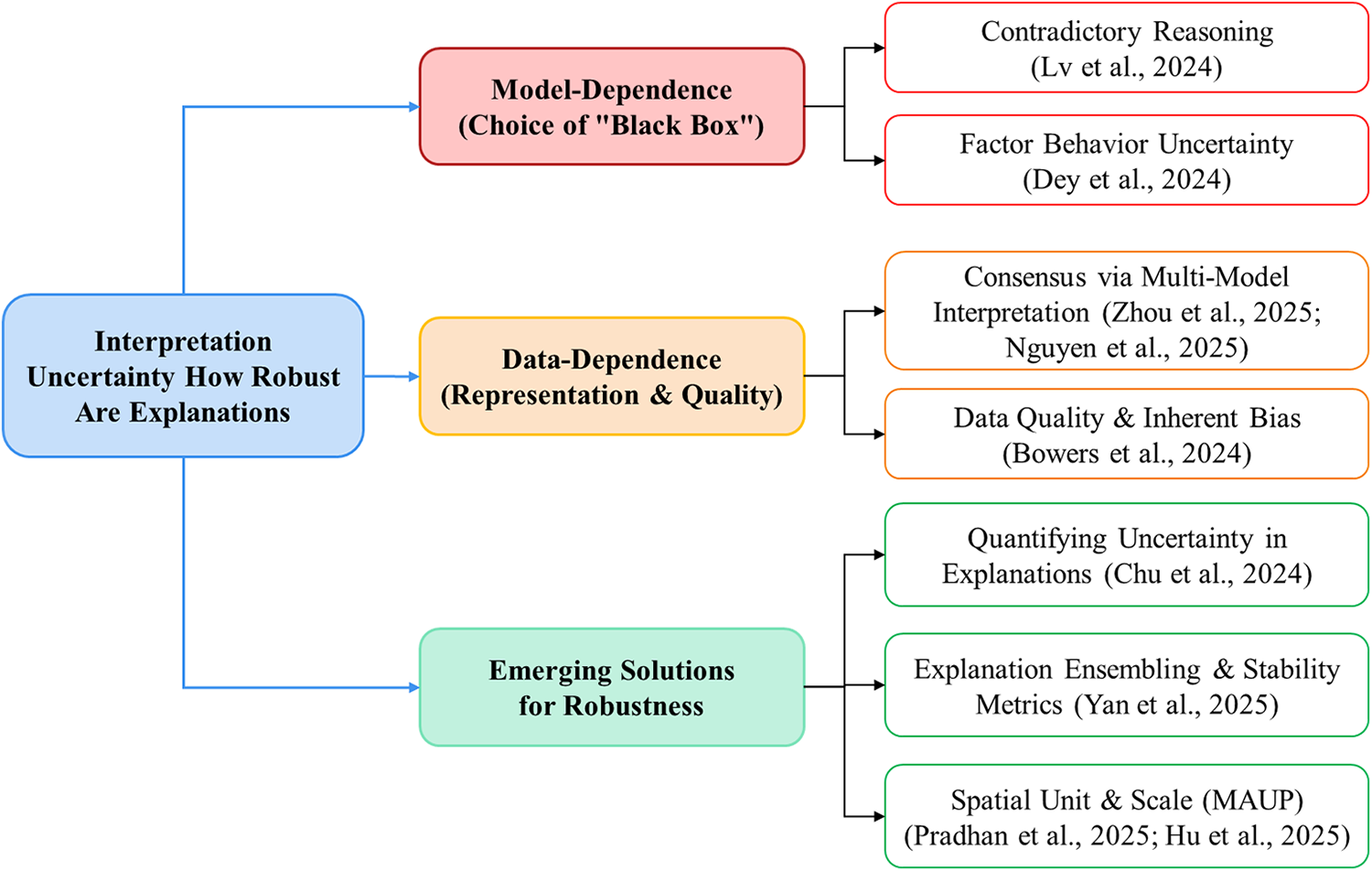

4.1 The Uncertainty of Explanations: How Robust Are Interpretations?

A core, often unstated, assumption in many XAI applications is that the generated explanation represents a singular, robust truth. The reality, however, is more complex [131]. An explanation is not a direct measurement of a natural process, but rather an artifact of a specific modeling pipeline [132]. As such, it is susceptible to significant uncertainty stemming from the choices made during that process (Fig. 12).

Figure 12: Conceptual mind map of the challenges and solutions related to the robustness of GeoXAI explanations. The analysis highlights key challenges such as model-dependence (Lv et al. [64], Dey, et al. [133]) and data-dependence (Pradhan et al. [129], Hu et al. [134], Bowers et al. [135]), along with emerging solutions like multi-model consensus (Zhou et al. [85], Nguyen Van et al. [136]), the use of stability metrics [55], and quantifying explanation uncertainty [91]

A primary source of this uncertainty comes from model dependence. This synthesis shows compelling evidence that different black-box models, even when they are equally accurate, can learn fundamentally different; and sometimes contradictory; mechanisms to solve the same problem. A critical investigation by Lv et al. [64], for instance, found that while both an XGBoost and a DenseNet model accurately predicted landslide susceptibility, their SHAP-based interpretations were at odds for key factors; XGBoost learned a negative correlation with relief, while the DenseNet model learned a positive one. This phenomenon, which Dey, Das and Roy [133] have termed factor behavior uncertainty, demonstrates that an explanation is a property of the model’s learned solution, not necessarily a fixed law of the geohazard system. This is further backed up by studies on stacking ensembles. These show that individual base models might prioritize entirely different sets of features (e.g., topographic vs. climatic) but still contribute to a highly accurate final prediction [137]. The implication is that refering to the interpretation from a single, arbitrarily chosen model architecture can be a unreliable and potentially misleading approach.

A second, equally critical source of uncertainty is data-dependence. A model’s interpretation of the world can be fundamentally altered by how geospatial data is represented, scaled, and sampled. The most profound challenge in this context is the modifiable areal unit problem (MAUP). A foundational study by [129] provided a stark example of this; they found that simply changing the spatial unit of analysis from slope units to hydrological response units didn’t just change the model’s accuracy—it completely inverted the feature importance hierarchy, swapping elevation and slope as the top-ranked landslide driver. The choice of spatial scale has also been shown to have a significant impact on both model performance and interpretation stability [134]. In addition, the quality and inherent biases within the data itself can lead to robust explanations of an inaccurate reality. A crucial cautionary study by [135] represented how socioeconomic biases in flood insurance data led to a physically counter-intuitive explanation. It’s a critical lesson: XAI will faithfully explain any bias a model learns from the data it is fed.

An efficient and highly effective strategy involves achieving a consensus-based interpretation by systematically applying XAI techniques across a diverse ensemble of models. Notably, research teams analyzing four [85] and six [136] distinct model architectures discovered a striking agreement on the most dominant geohazard drivers. To expand upon this encouraging conceptual basis, a more structured approach elevates the process: it involves actively combining the explanations themselves and then setting up specific quantitative metrics intended to measure their inherent stability. As an illustration, one pioneering work [55] put forward a novel hybrid framework specifically engineered to average the SHAP values derived from multiple models. Crucially, they introduced the coefficient of variation (CV) of feature ranks as a metric, proving that this ensemble explanation was substantially more stable than any single model’s interpretation alone. The most advanced frontier, however, is the direct quantification of uncertainty in these explanations. By applying SHAP to probabilistic models, such as Bayesian neural networks (BNNs), researchers can generate a complete distribution of SHAP values for each feature. This capability then permits the clear calculation and visualization of confidence intervals (CI) surrounding an interpretation [91]. This clear evolution, which transitions from simply supplying an explanation, to rigorously ensuring its robustness, and ultimately to directly quantifying its inherent uncertainty, is indeed a truly critical step toward building genuinely trustworthy AI systems for comprehensive geohazard assessment.

4.2 From Correlation to Causation: The Next Frontier in Interpretability

A fundamental limitation currently affecting virtually all applications of ML within the geosciences stems from their inherently correlational nature. Indeed, even when leveraging the transparency provided by XAI, what is ultimately being explained remains the model’s discovered association between patterns within the input data, rather than a definitively demonstrated causal mechanism [138]. A model may discover, for example, that Factor A is a robust predictor of Hazard B, yet it remains completely agnostic about whether A causes B, B causes A, or if some unobserved confounding factor C influences both. This crucial distinction isn’t merely theoretical; it actually forms the bedrock of effective intervention. It follows, therefore, that attempting to mitigate a factor which is only correlated and lacks a true causal link proves to be a largely futile endeavor; however, focused intervention along a genuine causal pathway holds the authentic potential to genuinely avert catastrophic disasters [139]. Consequently, the single greatest challenge; and, simultaneously, the most significant opportunity; for the next decade of GeoXAI research lies in taking the difficult, yet essential, leap from merely explaining correlations to reliably inferring causality.

While the robust formal integration of causal inference frameworks remains in a unequivocally nascent state, this review nonetheless succeeds in highlighting key pioneering research already utilizing XAI to achieve substantially more causally informed insights. These researchers are moving past basic feature importance metrics to effectively disentangle the complex web of geohazard drivers. A key emerging strategy, for instance, uses XAI to cleanly differentiate predisposing conditions where from proximate triggers when. In short-term landslide forecasting, for example, a SHAP analysis showed that static factors like slope correlate strongly with the long-term spatial distribution of landslides, yet it is the dynamic trigger variables, specifically recent rainfall, that actually contain the predictive power for an imminent event [140]. This vital separation is inherently critical, as it truly represents the first major step required to achieve a causal understanding of how hazard initiation processes unfold.

A more sophisticated approach involves using comparative XAI to dissect the drivers of different stages within a causal chain. A novel framework for gully erosion [130] accomplished this by building and interpreting two separate models: one for the potential for gully formation and another for the risk of further development. The comparative SHAP analysis yielded a profound mechanistic insight: gully initiation was primarily driven by climatic factors, whereas the subsequent development was governed by a more complex interplay of topography, climate, and human activities. This demonstrates how XAI can be used to understand the evolving causal recipe of a multi-stage geomorphic process.

Perhaps the most powerful current approach for inferring causal impact involves using XAI to analyze quasi-experimental scenarios or natural experiments. A key study on riverine flooding [105] demonstrates this by using a before-and-after framework to quantify the impact of a massive intervention: the construction of the Three Gorges Dam. The comparative XAI analysis provided direct, compelling evidence that the system’s causal structure had shifted. Before the dam’s construction, downstream flooding was primarily driven by upstream runoff. After the dam was built, the analysis showed that the primary driver had changed to local precipitation. This use of XAI to illuminate the mechanistic changes resulting from a major intervention represents a significant step forward. It helps in the development of geohazard models that are more causally robust and scientifically powerful.

These studies are the vanguard of a critical new frontier. The future of GeoXAI will not be defined by simply building more accurate correlational models, but by integrating them with formal causal inference frameworks (e.g., structural causal models, do-calculus). In this new paradigm, XAI is used to generate testable causal hypotheses. The subsequent validation for these derived hypotheses would then need to be secured through other established methods, such as physics-based modeling, highly targeted field experiments, or rigorous quasi-experimental studies. This entire, crucial process marks a deliberate pivot away from mere simple pattern recognition and toward the dedicated discovery of underlying physical mechanisms. This necessary shift in focus is precisely what will change the primary function of GeoXAI; instead of remaining merely a powerful engineering tool for prediction, it successfully becomes an instrument for fundamentally advancing the scientific understanding of complex Earth systems.

4.3 Bridging Data and Physics: The Role of XAI in Hybrid and Physics-Informed Models

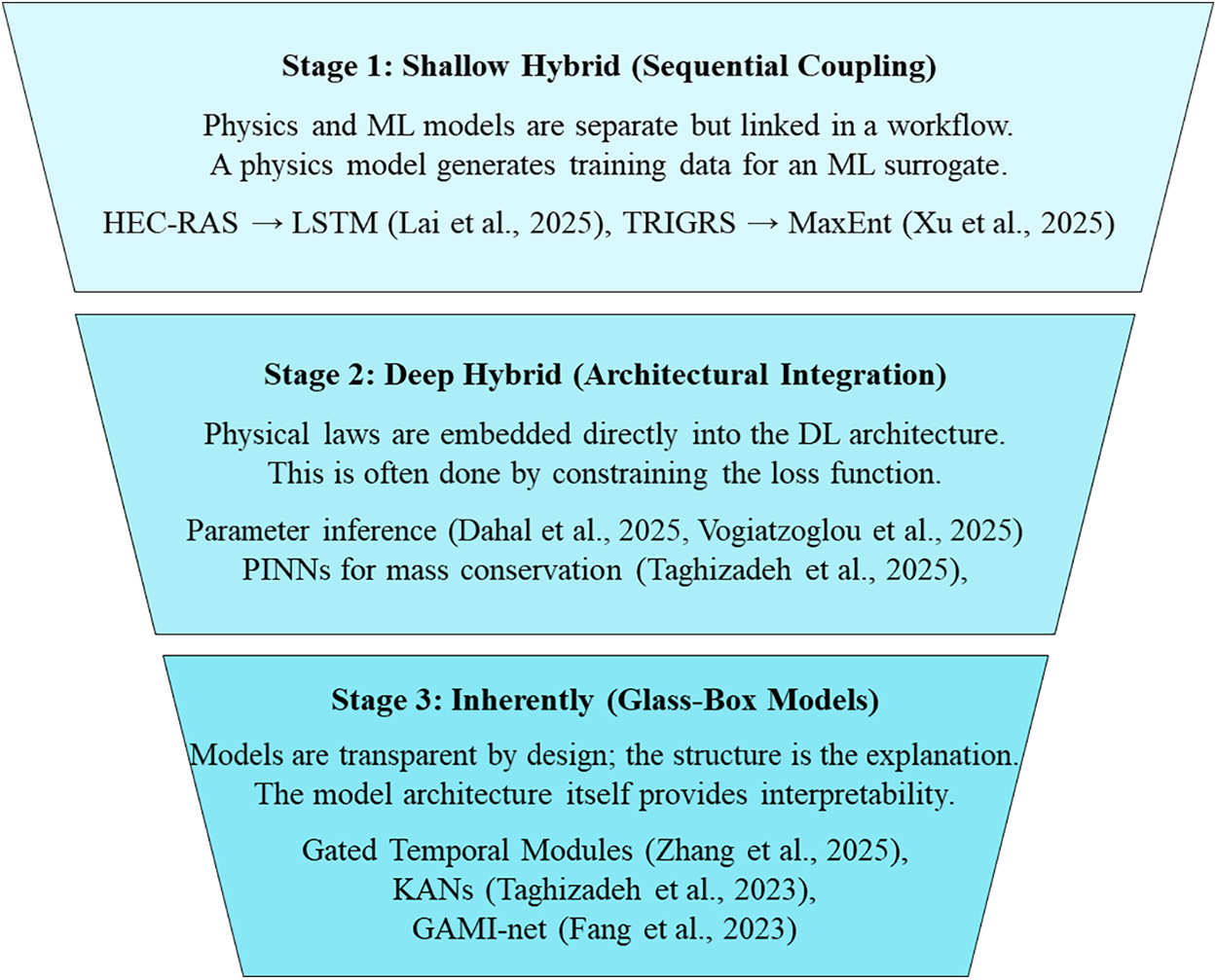

A fundamentally sound critique frequently directed at purely data-driven models centers on their inherent physics-agnostic nature. It is, in fact, quite true that when these computational frameworks operate entirely without the guidance of relevant physical constraints, even those models that attain excellent statistical accuracy run a substantial risk of learning spurious or inherently implausible correlations [141]. Consequently, this critical deficiency severely compromises their overall reliability, especially when they are tasked with critical operations such as extrapolation or, more broadly, with generating authentic scientific insight [142]. Consequently, this challenge has long created a visible great divide: highly flexible, though potentially error-prone, data-driven methods occupy one side, facing off against robust, yet frequently computationally intractable, physics-based models on the other [143]. The leading edge for designing truly trustworthy AI systems, especially those addressing geohazards, is now undeniably focused on successfully closing this methodological gap [144]. This unification is typically achieved by developing and deploying hybrid models, which are critical because they effectively merge the core strengths of both data-driven and physics-based paradigms [145]. This reviewed literature examined here, consequently, clearly charts an evolutionary trajectory pointing toward these more sophisticated, integrated hybrid architectures. Notably, as Fig. 13 vividly illustrates, XAI assumes an absolutely pivotal role in this progression, supplying the essential tools required to rigorously validate and illuminate the often-complex internal functions of these integrated systems.

Figure 13: The evolutionary spectrum of data-physics integration in GeoAI, illustrating the progression from shallow hybrid models that sequentially couple physics and ML (Lai et al. [120], Xu et al. [89], Kowshal et al. [86]), to Deep Hybrid models with architectural integration of physical laws (Taghizadeh et al. [70], Dahal and Lombardo [68], Vogiatzoglou et al. [69]), and culminating in inherently interpretable glass-box systems (Zhang et al. [146], Fang et al. [83], Taghizadeh et al. [70])

The most established approach is shallow or sequential hybridization, where physics-based and ML models operate as distinct but connected components in a workflow. A dominant strategy is using physics to inform data generation, where a trusted, albeit computationally expensive, mechanistic model is used to create a large, physically plausible synthetic dataset. This dataset then serves to train a highly efficient ML surrogate model suitable for real-time applications. For the specific challenge of compound flooding, a hydrodynamic model (HEC-RAS) was utilized to train a DL surrogate; this model proved to be significantly faster—216 times faster, in fact. Furthermore, the crucial validation step involved SHAP analysis, which was instrumental in confirming that the surrogate had genuinely and successfully learned the correct underlying physical dynamics [120]. This approach has also been used to generate high-quality training data for landslide susceptibility by first identifying physically unstable slopes with a slope stability model (TRIGRS) [89].

A more profound integration is found in deep hybridization, where physical principles are embedded directly into the architecture of a DL model. This is the domain of Physics-informed neural networks (PINNs). In this setup, the model’s loss function is importantly augmented by including a term that directly penalizes any violation of the system’s known governing equations; this could be, for example, the foundational laws of mass or energy conservation. This vital mechanism forces the network to find solutions that not only line up statistically with available observational data, but also inherently adhere to fundamental physics. Crucially, evidence consistently demonstrates that this approach notably lowers prediction errors in especially critical applications, such as in flood forecasting [70]. Furthermore, a genuinely transformative use of this framework appears when solving inverse problems: here, researchers have cleverly designed PINNs to infer previously unobserved, spatially-varying physical parameters—for instance, wildfire heat transfer coefficients [69] or certain geotechnical properties like the soil friction angle —simply by leveraging more accessible proxy environmental data [147]. Significantly, this successfully shifts the role of AI; it moves the system beyond being a mere passive predictor, establishing it instead as an active engine for scientific discovery.

The development of inherently interpretable, or glass-box models, clearly represents the logical culmination of this established evolutionary trend. In these advanced architectures, high predictive performance and essential transparency are not separated; rather, they are co-designed from the outset, entirely avoiding the pitfalls of clumsy or inefficient post-hoc retrofitting. This critical difference highlights a needed, fundamental shift: instead of just applying an explanatory tool like SHAP to an inherently opaque black-box, the next wave of models should be thoughtfully built using components that are intelligible by design. Several truly innovative architectures already demonstrate the viability of this movement. Several truly innovative architectures already illustrate this movement’s direction. For instance, some models incorporate custom gated modules where the weights derived during the training process inherently function as the explanation [146]. Furthermore, important frameworks like GAMI-net are specifically built to isolate main effects from their corresponding interaction effects cleanly [83]. The emerging Kolmogorov-Arnold networks (KANs) likely represent the most promising development in this area. This methodology is potentially groundbreaking precisely because it employs activation functions that are both highly visualizable and, more importantly, remarkably learnable splines [70]. Importantly, these interpretable-by-design frameworks are frequently shown to reach state-of-the-art performance, effectively offering a genuine fusion of data-driven modeling power and physical domain understanding. Notably, they resolve the historical trade-off between accuracy and interpretability, clearly signaling a future where the most powerful geohazard models are also, by their very nature, the most transparent.

4.4 The Computational Tax of Interpretability