Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Identification of inflammatory markers as indicators for disease progression in primary Sjögren syndrome

1

Department of Rheumatology and Clinical Immunology, the First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University, School of Medicine,

Xiamen University, Xiamen, 361000, China

2

Xiamen Municipal Clinical Research Center for Immune Diseases, Xiamen, 361000, China

3

Xiamen Key Laboratory of Rheumatology and Clinical Immunology, Xiamen, 361000, China

4

Department of Dermatology, Xiang’an Hospital of Xiamen University, School of Medicine, Xiamen University, Xiamen, China

5

School of Chinese Medicine, LKS Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

#*

These authors contributed equally to this article

* Corresponding Author: Guixiu Shi,

European Cytokine Network 2024, 35(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1684/ecn.2024.0496

Accepted 06 February 2024;

Abstract

Primary Sjögren syndrome (pSS) is a systemic autoimmune disorder that affects various systems in the body, resulting in symptoms such as dry eyes and mouth, pain, and fatigue. Inflammation plays a critical role in pSS and its associated complications, with chronic inflammation being a common occurrence in patients with pSS. This review of the literature highlights inflammatory markers that could serve as indicators to predict disease progression in pSS. Results: Laboratory markers are frequently and significantly increased in pSS patients, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, complement proteins, S100 proteins, cytokines (IFNs, CD40 ligand, soluble CD25, rheumatoid factors, interleukins, and TNF-α), and chemokines (CXCL13, CXCL10, CCL2, CXCL11, and CCL25). These inflammatory markers can be used as prognostic indicators for disease progression in pSS. Conclusion: In conclusion, the results from the studies reported in this review indicate that high levels of inflammatory markers may serve as markers for disease progression of pSS, which, in turn, may be valuable in predicting disease outcome.Keywords

Primary Sjögren syndrome (pSS) is a systemic rheumatic disease characterized by disorders of the external exocrine glands, multiorgan involvement and autoantibody generation and autoimmune epithelitis [1]. Patients with pSS exhibit increased glandular disorder and xerostomia, as well as xerophthalmia, which are attributed to infiltrating lymphocytes and autoimmune damage of the salivary gland and lacrimal gland [2]. More than half of pSS patients suffer from systemic autoimmune diseases and approximately 5% develop lymphoma [3]. Distinguishing pSS from other autoimmune disorders is challenging because many pSS patients have symptoms similar to those associated with autoimmune diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [4]. Despite emerging studies on pSS diagnosis and treatment, currently available therapies are ineffective in maintaining salivary function and reducing disease activity [5]. Therefore, pSS remains a severe rheumatic disease, and there is a need to explore novel potential biomarkers to aid in the management of pSS.

Various studies have demonstrated that immune abnormalities in pSS cause T and B cell dysfunction based on animal models and studies on peripheral blood of patients [6]. Inflammation plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of pSS. In this respect, inflammatory cytokines have been suggested to interact with the epithelial cells of the salivary gland, contributing to the pathology of pSS [7]. Patients with pSS often exhibit chronic inflammation, with laboratory indices, such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), complement proteins, S100 proteins, and cytokines and chemokines, being markedly elevated. These markers are often used to indicate pSS disease development and activity [8]. Hence, in this review, we summarize the function of several inflammatory markers, such as ESR, CRP, complement proteins, S100 proteins, cytokines (interferons [IFNs], cluster of differentiation [CD] 40 ligand, soluble CD25, rheumatoid factors, interleukins, and tumour necrosis factor-alpha [TNF-α]), and chemokines (chemokine [C-X-C motif] ligand [CXCL] 13, CXCL10, CCL2, CXCL11, and CXCL25), related to the occurrence and development of pSS. Based on our findings, we suggest that inflammatory markers can be used as prognostic indicators of progression of pSS.

– Primary Sjögren syndrome (pSS) is an autoimmune disorder affecting multiple systems in the body.

– Chronic inflammation is a common occurrence in pSS and plays a critical role in disease progression.

– Laboratory markers are frequently and significantly increased in pSS patients, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, complement proteins, and cytokines.

– These inflammatory markers can be used as prognostic indicators of disease progression in pSS.

pSS is characterized by dry mouth and eyes, fatigue, pain, and systematic damage throughout the body. These clinical manifestations are caused primarily by exocrine gland lymphocyte infiltration and B cell malfunction [1]. Although pSS is recognized as a significant component of autoimmune diseases, its exact cause has yet to be fully elucidated. A multitude of factors, such as environmental (infectious, hormonal, and stress-related), genetic, and immune factors, have been identified to contribute to the development of pSS through the use of innovative technologies and tools [9]. pSS affects approximately 0.1% to 0.6% of the general population, with a higher prevalence in women than men.

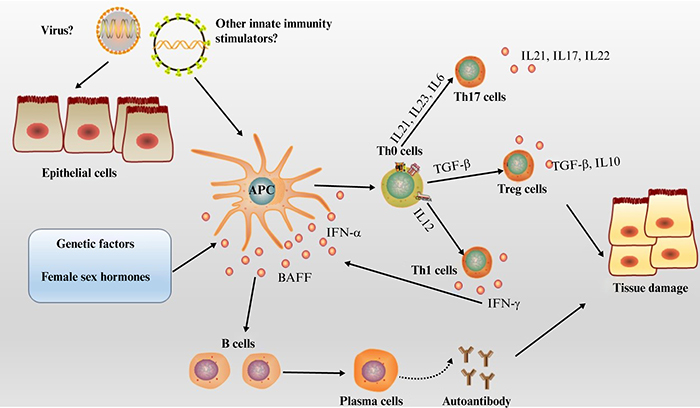

Age at onset is typically between 40 and 60 years old. The occurrence of pSS is influenced by a hereditary predisposition, and variations in both HLA and non-HLA genes have been associated with the condition. Environmental factors, such as viral infections, hormonal changes, and stress, can also contribute to the development of pSS. Xerostomia and xerophthalmia are early and prevalent symptoms of pSS, while a growing number of studies have recently been conducted on complications involving diverse systems; for instance, cerebrovascular inflammation, transverse myelitis, or demyelinating lesions in the central nervous, respiratory, and urinary systems [1]. Studies reveal that the alleles, DRB1*03:01, DQA1*05:01, DQB1*02:01, and DRB1*03, are suspected risk factors for pSS. DQA1*02:01, DQA1*03:01, and DQB1*05:01, on the other hand, are protective factors for pSS [10]. Furthermore, pSS has been linked to viral infections, including Epstein-Barr virus, hepatitis C virus, and hepatitis G virus [11]. The current understanding of pSS pathogenesis is summarized in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the pathogenesis of primary Sjögren syndrome.

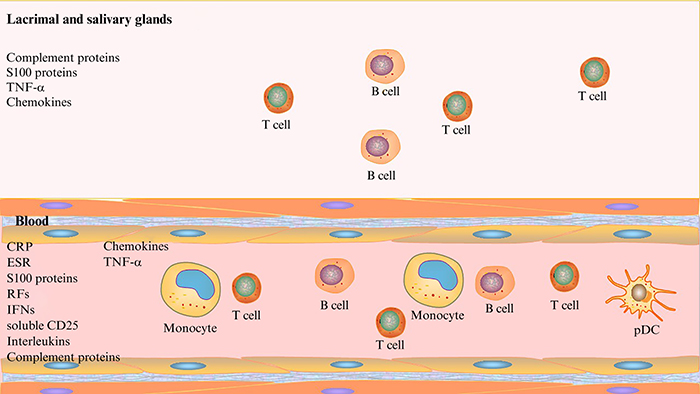

Figure 2.

Inflammation-related prognostic markers in primary Sjogren syndrome.

Fortunately, pSS has a relatively favourable prognosis, and with appropriate medical treatment, most individuals can experience relief [12]. Treatment guidelines for pSS include alternatives to eye drops and saliva products, such as pilocarpine or simefrine, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, immunosuppressants, and biologics such as rituximab [6].

Common inflammatory markers in the blood

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is an indicator of disease and inflammation in patients with pSS [13]. Serum immunoglobulin level is associated with the disease activity index of the European League Against Rheumatism, and is a key factor leading to elevated ESR. Extra-glandular symptoms of pSS are associated with hypergammaglobulinaemia (mainly cutaneous vasculitis and joint, pulmonary and renal related conditions) [14]. In addition, hypergammaglobulinaemia leads to an increased ESR level and inflammatory activity in pSS patients [15, 16]. However, contrary to this, studies have shown that pSS patients usually exhibit low levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) [17].

The role of complement proteins in pSS has not been widely studied. However, recent research highlights the importance of the classic complement pathway in pSS. One study revealed that decreased levels of C3 and C4 complement proteins are linked to higher disease activity and tissue injury in pSS patients [18]. Low levels of C3 and C4 are common in pSS patients and may contribute to lymphoma progression [19, 20]. Additionally, lower expression of complement proteins is linked to immunological indicators (e.g., cryoglobulinemia, rheumatoid factors [RFs]) and extraglandular symptoms (e.g., fever, joint and skin involvement, vasculitis, and peripheral neuropathy) [20]. Studies have shown that patients with pSS have lower serum C3 and C4 compared to healthy individuals [21], while C3 levels in the labial gland are higher in pSS patients [22]. Hypocomplementaemia is associated with poor prognosis in pSS due to an increased risk of lymphomas and mortality. Moreover, decreased expression of C4 is significantly associated with aberrant lymphocyte proliferation and an increased risk of death [20, 21, 23].

The classic complement activation pathway is initiated by complement component 1q (Clq). A study showed that levels of C1q and membrane attack complex (MAC) were lower in the labial salivary glands of pSS patients compared to controls. This indicates that autoimmune processes in pSS are not related to complement activation pathways, including classic, alternative, and lectin activation pathways [22]. Moreover, the absence of C1q and MAC in salivary glands of pSS patients suggests that MAC-induced cytolytic mechanisms cannot be responsible for complement activation and glandular tissue damage [24]. As a result, the expression of complement regulatory protein is altered in pSS, non-specific sialadenitis, as well as healthy salivary glands, indicating that alternative activities of these regulatory proteins may be more significant in pSS [24].

Complement regulators, including protectin (CD59), decay accelerating factor (CD55), membrane cofactor protein (CD46), and clusterin, were found in the saliva of pSS patients and were shown to be highly expressed in inflamed salivary gland tissue due to the inflammatory response, and were linked to pSS self-reactive exocrinopathy [25]. Additionally, the concentration of salivary gland protectin (CD59) varied in pSS patients [24]. According to immunohistochemical (IHC) data, CD59 expression on acinar cell membranes in pSS salivary glands varied in intensity from negative to slightly positive, despite the luminal surface. Non-specific sialadenitis samples exhibited positive/moderately positive intensity on the entire surface of acinar cells. Non-affected control salivary glands showed predominantly highly positive intensity on the entire surface of acinar and ductal epithelial cells [24]. These results suggest that CD59 may reduce the proinflammatory effect in pSS.

The homologous C4 genes, C4A and C4B, were found to have a significant impact on the risk of developing pSS among cohorts with common C4 alleles, with C4B associated with a higher risk compared to C4A. A recent study also showed that a low copy number of C4A closely correlated with pSS [26]. Additionally, C4 serum levels were considerably lower in pSS patients compared to healthy individuals, and there was no statistical difference in c4d concentration between the two groups. However, the anti-SSA/SSB-seropositive pSS group had significantly lower expression of C4d than both the healthy and anti-SSA/SSB-seronegative pSS groups, and the concentration of C4d inversely correlated with ESSPRI [21, 27]. Overall, the presence of C4d in the serum of pSS patients may serve as a promising predictor of immunological response and complement overactivation in the development of pSS [28].

S100 proteins have been implicated in various pathologies such as autoimmune, inflammatory, and cancerous conditions as well as in brain and cardiovascular dysfunction [29]. These proteins are known to participate in the immune response, and act as ligands for the receptor for advanced glycation end product (RAGE), damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP), and toll-like receptor-4 (TLR-4), which can lead to cell and immune aberrations, resulting in inflammatory damage [30].

Studies have shown that S100A6, S100A7and S100A8 are upregulated in patients with pSS compared to healthy individuals [31]. Another study found that S100A7, S100A8, S100A9, S100A11 and S100A12 were the most differentially expressed proteins related to neutrophil degranulation between pSS and normal groups, and S100A8 and S100A9 were shown to be related to IL-12 signalling pathways [32]. Furthermore, S100A protein was found to be highly expressed in salivary inflammatory sites, and levels increased in a stage-specific manner related to pSS phenotype [33]. S100A9, a member of the S100A8/S100A9 complex in the salivary gland, was shown to be significantly increased in pSS individuals prone to lymphoma [34]. Elevated serum levels of S100A8 and S100A9 in pSS individuals were associated with enhanced levels of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, IL-10, IL-17A, IL-22, TNF and IFN), mainly in polymorphonuclear neutrophils and macrophages. Therefore, S100A8 and S100A9, along with certain cytokines, may play a role in the development of pSS [35].

A recent study demonstrated markedly increased levels of S100A8, S100A9, and S100A12 in 141 pSS patients compared to healthy controls (HCs) [36]. Furthermore, pSS individuals exhibited significantly higher levels of faecal S100A8 and S100A9 compared to HCs, and this increase was associated with the EULAR Sjögren syndrome disease activity index (ESSDAI) [37]. Tear samples collected from the ocular surface showed upregulation of S100A8, S100A9, S100A4, and S100A11. Additionally, salivary levels of S100A8 and S100A9 were also found to be useful in differentiating between pSS, disease controls, and normal controls, particularly in pSS patients with lymphoma or at high risk of lymphoma [38]. Recently, S100A8 and S100A9 were identified as new endogenous ligands for TLR-4 that promote systemic endotoxin-induced shock and inflamed arthritis, making them crucial components of innate immunity. Under inflammatory conditions, S100A8 and S100A9 expression is observed in infiltrated monocytes and neutrophils, but not in macrophages or lymphocytes in healthy tissues [39]. Based on a comparison between pSS patients and healthy and disease-control subjects, levels of S100A8 and S100A9 were significantly altered in parotid saliva but not in whole saliva [39]. Additionally, preliminary proteomic analyses of parotid saliva indicated that S100A8 and S100A9 levels were different between pSS, with or without a risk of lymphoma, and control groups. In summary, S100A8 and S100A9 are promising predictors for the development of lymphoma in pSS patients [34].

Rheumatoid factors (RFs) are an important prognostic factor in patients with pSS and are associated with some serious conditions, related to a poor Schirmer test, elevated ESSDAI score, leucopenia, increased concentration of gammaglobulins, anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-SSA antibodies, anti-SSB auto-antibodies, and increased B cell activity [40]. RFs are immunoglobulins that can be classified into different isotypes (IgA, IgG, IgM, IgE, and IgD), with IgM being the predominant isotype [41, 42]. As an immune disease, pSS is closely related to RFs and RF-IgM is a key predictor of outcome and disease activity [43]. Patients with pSS are more likely to have high levels of RF-IgM in their serum (70-90%) [44], and RF-IgA concentrations in the saliva and serum of pSS patients also increase significantly [45]. In addition, RF-IgA and RF-IgG immunoglobulin family members have been identified as promising markers for the diagnosis of pSS patients [46].

Interferons (IFNs) are proinflammatory cytokines that play an important role in the pathology of pSS, with systemic elevation observed in 57% of patients [47]. The increased expression of IFN-related genes in salivary glands, isolated monocytes, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), and B cells is a direct result of this increase in systemic IFNs [48, 49]. Both type I and II IFNs have been implicated in pSS progression. Type I IFNs (IFN-α and IFN-β) are secreted by nearly all mammalian cells and bind to a common receptor, while, type II IFN (IFN-γ) only binds to a specific receptor and can be released by innate and adaptive immune cells, such as CD4+ Th1 cells, CD8+ T cells, NK cells, B cells, and classic antigen-presenting cells [50]. In the early stages of innate immunity, the expression of type I IFN is increased in glandular tissue and serum [51], while type I and type II IFN produced by T and B cells are involved in the later stages of disease progression [52]. This process can be enhanced by B cell activating factor of the TNF family (BAFF) [53]. BAFF is produced by dendritic cells (DCs) and monocytes, and is essential for the proliferation, differentiation and survival of B cells [54].

Moreover, activated plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) have been shown to exhibit elevated IFN-α in pSS salivary tissue [55, 56]. IFN-related genes have also been found to be increased in pSS biopsy tissue [57]. TLRs and cytosolic sensors of nucleic acid stimulation, which are specifically expressed in pDCs and responsible for activating the initial factors in the type I IFN response, are both increased in pSS. Additionally, retinoic acid inducible gene 1 (RIG1), melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (MDA5), and retinoic acid inducible receptors (RLRs), which are involved in the type I IFN signature in pSS, activate these receptors to initiate intracellular pathways, that result in the generation of type I IFN [58].

Historically, IFNα was believed to be a significant factor in the pathogenesis of pSS. However, recent studies have revealed that some effects leading to type I IFN signalling may also result in the activation of the type II pathway, as IFN-γ can stimulate a variety of specific genes increased by IFN-α [59]. Therefore, studies have shown both activated type I and type II IFN signalling in pSS patients [59]. In particular, pSS is linked to genetic polymorphisms and mRNA expression which are indicators of excessive innate and type I IFN immune responses. Additionally, the overexpression of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) caused by type I IFN is called the “type I IFN signature” [60]. Significant overexpression of type I IFN is known to be a hallmark of pSS and is thought to be critical in the disease’s disordered immune response. Type I ISGs are significantly expressed in PBMCs, pDCs, B cells and salivary glands of pSS patients [61], and approximately 50–80% of pSS patients exhibit a positive type I IFN signature [62].

IFN-γ contributes to the loss of goblet cell and epithelial apoptosis. Elevated levels of proteins and mRNAs have been observed in tears, saliva, conjunctiva, the submandibular gland, the lacrimal gland, and blood, making them recognized biomarkers for xerophthalmia in pSS [63]. Genetic analysis has revealed polymorphisms in STAT4, a transcription factor responsible for IFN synthesis in Th1 cells and macrophages in pSS patients [64, 65]. IFN-γ guides apoptosis in human salivary gland cells, and early IFN-γ-induced glandular apoptosis is a precursor to pSS development [66]. Therefore, IFN-γ is crucial for the initiation of pSS in mouse models and is relevant to human diseases. One study suggested that several cytokines generated by immunocompetent cells, such as IFN-γ and IL-17, are elevated, and auto-reactive T cells and B cells are activated via IFN as part of the immune aetiology of pSS exocrine glands [67]. Recently, type II IFN function has been demonstrated, and only 7% of individuals with pSS have this specific IFN signature, which is typically linked to a stronger type I IFN signature [62]. CD14+ monocytes and DCs are the principal source of type I IFN, and during the development of pSS, IFN-γ helps to activate Th1 cells, upregulate MHC class II antigen-presenting or epithelial cells, produce IFN-γ-inducible proteins, and activate a variety of immune cells that express the IFN-γ receptor [68]. IFN-γ has been confirmed to be one of the factors involved in the pathogenesis of pSS, leading to an increased ESSDAI score and elevated concentration of IFN-γ [69].

The production of high levels of type III IFN is dependent on STAT1 and STAT2 heterodimers in pDCs, which transduce intracellular signals to control the expression of ISGs by binding to IFN-enhanced response elements. Type III IFN has a variety of biological effects as it interacts with different receptors expressed on various cell surfaces. Notably, the expression of type III IFN receptors (IFN-λ receptors: IFNLR and IL-10 receptors) has been observed in epithelial cells [70]. Increased concentrations of IFN-λ1/IL-29 were detected in pSS patients with minor salivary gland (MSG) damage, and the expression of IFN-λ2/IL-28A was also elevated in MSGs. Moreover, although there was no constitutive release of type III IFNs from long-term cultured salivary gland epithelial cells, these were easily generated upon TLR3 stimulation, indicating that the level of type III IFNs is reliant on on-and-off signals of innate immunity, similar to type I IFNs [71]. A recent study suggests that type III IFNs play a role in regulating the local autoimmune response in pSS. Although type III IFNs were expressed similarly between pSS and control groups, the elevated expression of IFN-λR1/IL-28Ra receptor in pDC-infiltrated MSGs of pSS patients suggests that epithelial type III expression could regulate pDC activation in pSS autoimmune injuries. pDCs have been implicated in pSS and are thought to be critical in pSS inflammatory responses via generating IFN-α [56, 72].

The concentration of serum soluble CD25 (sCD25) is associated with T-cell activation and is considered a promising indicator of disease activity in autoimmune diseases [73]. In comparison to HCs, patients with pSS had significantly elevated levels of serum sCD25. The levels of sCD25 were positively correlated with ESSDAI score, particularly the haematological domain, ESR, CRP, IgG, and γ-globulin levels [74]. The expression of plasma sIL-2R (CD25+) in pSS patients was significantly higher than in HCs. Recent studies have shown that patients with a more severe phenotype, as evaluated by pathologically low salivary flow, had the highest levels of sIL-2R, and the levels of plasma sIL-2R were inversely correlated to salivary flow [75].

Salivary IL-6 expression was shown to be higher in pSS patients compared to both HCs and individuals with other systemic autoimmune disorders without salivary gland dysfunction. Increased salivary IL-6 concentration in pSS was indicative of local exocrine involvement and may serve as a sensitive indicator of disease activity [76]. Another study showed that circulating IL-6 expression was increased in pSS and significantly associated with systemic inflammation markers, such as ESSDAI, ESR, CRP, and IgG [77].

Serum IL-7 concentration was found to correlate with several Th cell cytokines including IL-4, IL-9, IL-10, IL-17, and IFNs. IL-7 was reported to be closely correlated with pSS activity, more so than other cytokines [78], suggesting that it may be an important mediator in the complex cytokine network involved in pSS immunopathology. The IL-7/IL-7R signalling pathway may be a potential treatment target for pSS individuals [78]. Elevated IL-7 expression has also been detected in isolated PBMCs of patients with pSS [79]. Additionally, a recent study demonstrated that during the early stage of pSS, stimulation with IL-7 upregulated the expression of IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-17 and IL-21 by CCR9+ Th cells despite their inability to sustain homeostatic proliferation responses to IL-7 [80].

In pSS, IL-33 is released from damaged salivary cells due to proinflammatory stimuli and epithelial barrier dysfunction [81]. This leads to significantly elevated levels of IL-33 in the serum and tears of pSS patients, where it functions with IL-12 and IL-23 to activate NK and NKT cells and promote the production of IFN-γ, thereby inducing inflammation [82]. The IL-33/ST2 signalling pathway can be activated by TNF-α, IL-1β and IFN-γ, creating a vicious circle of inflammation that exacerbates disease progression [82].

IL-17, on the other hand, has been shown to disrupt the integrity of salivary tight junctions and serves an important role in salivary gland dysfunction [83]. In SS-non-susceptible mice, IL-17A has also been shown to cause pathological alterations resembling SS-like diseases [84]. Lin et al. [85] reported that the level of circulating Th17, which secrete IL-17, positively correlates with the duration of pSS, indicating a potential role in disease progression [86].

Gene chip analysis revealed that IL-11 expression levels were decreased in lacrimal glands of individuals with pSS [87]. Another study also reported a significant decrease in IL-11 mRNA levels in lacrimal glands of pSS patients compared to HCs. IL-11 levels in pSS patients were positively correlated with CRP levels and negatively correlated with RF levels, suggesting that IL-11 is strongly associated with disease activity and could be a diagnostic predictor of pSS [88].

The levels of IL-34 in serum and inflamed salivary glands of pSS patients were shown to be elevated compared to HCs [89]. Additionally, the anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB-positive groups of pSS patients had higher IL-34 expression than the anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB-negative groups. Serum IL-34 concentration was also associated with RF, IgG and γ-G and may play a role in B cell activation and antibody production. These findings suggest that IL-34 may be a significant regulator of the systemic immunoregulatory mechanism of pSS [90].

TNF-α, a pro-inflammatory cytokine, is associated with inflammation and apoptosis, which can lead to the activation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and result in salivary gland dysfunction [91]. Previous research has shown that endogenous TNF-α is involved in the aetiology of pSS in non-obese diabetic mice [92]. A recent clinical study reported elevated salivary TNF-α concentrations in pSS patients compared to HCs [93]. However, Moriyama et al. [94] found no statistically significant difference in salivary TNF-α levels between pSS and HC groups. Another study indicated that salivary TNF-α levels were elevated in patients with pSS compared to HCs, but this difference was not statistically significant. Targeting TNF-α with an anti-TNF monoclonal antibody (mAb) showed a curative effect based on an in vitro study [95], however, a clinical study did not reveal any evidence of the curative effect of infliximab (a type of anti-TNF mAb) in pSS patients [96]. Therefore, the effects of TNF-α on the aetiology of pSS need to be further clarified and investigated.

CD40L, a type II transmembrane glycoprotein, is a member of the TNF family and is primarily expressed in activated CD4+ T lymphocytes. A case-control study showed significant overexpression of CD40L in activated CD4+ T cells in females with pSS, but not HCs [97]. About half of pSS patients will develop systemic symptoms, and the inflammatory infiltration of the salivary glands in pSS primarily comprises activated CD40-CD40L bearing lymphocytes and B cells [98]. CD40-CD40L signalling might be related to the appearance of ectopic GCs in salivary glands in patients with pSS and the thyroid gland in patients with Graves disease, as well as the production of antibody-producing plasma cells [99, 100]. Activation of salivary epithelia via CD40 by CD40L-expressing T cells in inflammatory lesions in patients with pSS may be detrimental to epithelial tissue renewal and repair [101]. Furthermore, soluble CD40L (sCD40L) has been shown to increase ICAM-1 expression in pSS salivary gland cells by activating NF-kB p50 [102], and higher serum sCD40L levels and higher CD40L transcript levels in the CD4+ T cell compartment were detected in patients with pSS in recent studies [103]. Downregulation of CD40 pathway-related genes, a reduction in lymphocytic infiltration and autoantibody production, and prevention of ectopic lymphoid structure development with CD40L blockade have been reported based on a specific murine pSS model [104].

BAFF (also known as B cell enhancer) belongs to the TNF superfamily of proteins and promotes B lymphocyte survival and proliferation. It is produced as both membrane-bound and soluble proteins [105]. The expression levels of BAFF may be used as a criterion for the filtering naive B lymphocytes because autoreactive B lymphocytes rely more heavily on BAFF than naive mature B lymphocytes. Data show that elevated expression of BAFF in lymphoid tissue is related to the proliferation of mature B cells and may be involved in the pathological process of pSS [105].

OX40L (CD252, TNFSF4) and other tumour necrosis factor ligands, such as type II transmembrane proteins, participate in the costimulation and differentiation of T lymphocytes, and act as a positive signal in immune responses [106]. Studies have shown that serum soluble OX40L (sOX40L) in healthy donors increases with age, and the levels of sOX40L are also elevated in some autoimmune disorders [106]. In patients with pSS, the elevated expression of OX40 and OX40L in peripheral blood lymphocytes significantly correlated with clinical outcome and treatment response. The levels of OX40 and OX40L on peripheral lymphocytes were upregulated in the pSS cohort and their expression levels significantly positively correlated with clinical prognosis and curative responses in patients with pSS. These results suggest that circulating sOX40L in human serum could play a key role in the pathogenesis of pSS [107].

Chemokines are often produced in response to cytokines and play a crucial role in recruiting more inflammatory cells to participate in the inflammatory response. Several studies have demonstrated a relationship between chemokines and disease activity. CXCL13 is an essential biomarker of pSS disease activity, and clinical indicators, such as RF, κ-to-λ free light chain ratio, β2-microglobulin, γ-globulins, anti-Ro/SSA, anti-La/SSB, and ESR, have been shown to be significantly associated with elevated concentrations of serum CXCL13 in pSS patients. Serum CXCL13 concentration is also strongly correlated with a risk of lymphoma in patients [108, 109]. In addition, elevated CXCL13 concentrations have also been detected in saliva [110], salivary gland tissues [111], and the salivary gland secretome [112] of pSS patients. Moreover, serum levels of CXCL13 were strongly correlated with a risk and occurrence of lymphoma in patients with pSS [108, 109]. CXCL13 levels are also reported to be correlated with ectopic lymphoid-like structures (ELSs), a core player in pSS pathogenesis [113]. In addition, serum CXCL13 levels were shown to be related to increased lymphocytic infiltration, disease activity, lymphatic tissues, and the occurrence of ectopic GCs in salivary glands from patients [114]. Furthermore, CXCL13 levels were positively correlated with Tfh cell counts in the salivary glands of pSS patients [115]. Mechanistically, CXCL13 may mediate pSS progression by recruiting CXCR5+ B cells and Tfh cells into inflammatory salivary glands [111]. Based on pSS preclinical studies, administration of anti-CXCL13 neutralizing antibody markedly decreased the inflammatory response and CD19 concentrations in submandibular gland tissue [110]. Furthermore, increased CXCL13 expression in pSS patients was accompanied by hypocomplementemia, elevated RFs, and an increased probability of lymphoma [116]. These results suggest that CXCL13 may serve as a promising indicator for predicting the progression and clinical outcome of pSS.

CXCL10 was found to be increased in patients with preclinical pSS, suggesting its involvement in early pSS pathogenesis [117]. Administration of a CXCL10 antagonist to MRL/lpr mice resulted in decreased Th1 CXCR3+ infiltration and parenchymal destruction in sialadenitis, leading to lower IFN-γ production [118]. However, another study reported lower concentrations of CXCL10 and CCL2 in tears from pSS cohorts, which were associated with worse ophthalmic symptoms and positive ocular target test results, respectively [119].

CXCL9 levels are elevated in whole salivary glands and SGECs in patients with pSS, which is mediated by IFN-γ expression [120]. In pSS, most periductal lymphocytes infiltering salivary gland tissue are CXCR3+, suggesting that CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 may play a role in the progression of pSS [121]. CXCL11 is located within the ductal epithelium adjacent to lymphatic infiltration in pSS, but not in salivary glands from control subjects [122]. When paired with low concentrations of sCD163, serum CXCL11 has been shown to be a reliable indicator of pSS [123]. CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 are also detected in the gland tissue, tear film, and ocular surface in pSS patients [124]. CCL2 levels were shown to be increased in salivary gland tissue, serum, and saliva of pSS patients compared with HCs [117, 125], and SS patients with salivary gland germinal centres were shown to express increased concentrations of CCL2 compared with those without [126, 127]. Similar to CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11, CCL2 is observed in ductal structures, and its levels are enhanced in vitro when SGECs are stimulated with IFN-γ [128]. Furthermore, epidemiological studies of pSS indicate that the expression of CCL2 is linked to female preponderance and perimenopausal disease initiation. Recent research on aromatase knockout mice suggests that postmenopausal status modulates sialadenitis and CCL2 expression in pSS [129].

CCL25 mRNA expression was shown to be considerably higher in the salivary glands of pSS patients than in those of non-pSS individuals [80]. CCR9+ CD4 T cell counts were higher in patients with pSS, both in the peripheral circulation and in the salivary glands, compared to controls, and they produced more IL-21, IL-4, and IFN-γ than CXCR5+ CD4 T cells [80, 130]. Similarly, CCL25, the ligand for CCR9, was shown to be increased in salivary glands of pSS patients [80], but was undetectable in salivary glands of HCs [131]. In individuals with pSS, primary type I IFN-producing cells, called pDCs, were shown to express a higher level of CCR5 compared to HCs [132]. Additionally, both CCL5 and CCR5 levels were elevated in salivary glands of the pSS group [94]. Their increase was also observed in the inflammatory glands of a mouse model of an SS-like condition, in which inhibition of CCL5 reduced disease [133].

Discussion

pSS is a chronic autoimmune disorder that causes inflammation in exocrine glands, resulting in dysfunction of the salivary and lacrimal gland, and systemic signs that can affect almost all systems. Therefore, there is a crucial need for sensitive and specific inflammatory markers in pSS. Advances in our understanding of the pathophysiology of pSS have made it possible to identify potential markers for the diagnosis and monitoring of disease activity. However, the validity of several of the inflammatory indicators needs to be confirmed through larger clinical investigations. This review summarizes the latest progress in identifying inflammatory markers of pSS to guide clinical work.

Laboratory indicators, such as ESR, CRP, complement proteins, S100 proteins, some cytokines, and chemokines, are frequently elevated in pSS individuals compared to HCs. However, increased production of CRP and ESR can also be observed in concurrent infections. While ESR, CRP and complement proteins remain crude parameters, immunoglobulin may also change not only in the autoimmune condition but also in the inflammatory stage. Multiple studies have focused on the use of omic analyses in pSS patients and healthy individuals, but the results have yet to be validated using well established techniques. Some of the candidate biomarkers based on omics analyses have the potential to enter this field in the near future.

For pSS, salivary gland ultrasound (SGUS) is used to score glandular parenchyma using several scoring systems [134]. Developments in artificial intelligence (AI) and computerized software tools may predict progress in salivary gland screening based on SGUS, which could reduce screening times and reliance on experts [135]. However, automatized tools for segmentation and reconstruction of salivary glands based on SGUS are not yet commonly used in the clinic for pSS management [135]. So far, such tools for SGUS assessment have performed at a level similar to that by humans, indicating that AI methods might lead to the use of novel methods for the diagnosis of pSS in the future.

In conclusion, a wide range of conventional and innovative inflammatory markers have been presented for pSS over the years. Recent breakthroughs in multi-omics and molecular technologies have yielded a slew of novel possible histological targets in sera, tears, and saliva that might help improve the management of patients with pSS.

| pSS | Primary Sjögren syndrome |

| SLE | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| ESR | Erythrocyte sedimentation rate |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| MAC | Membrane attack complex |

| sCD163 | Soluble cluster of differentiation 163 cells |

| SSA | Sjogren syndrome A |

| SSB | Sjogren syndrome B |

| DAMP | Damage-associated molecular pattern |

| RAGE | Receptor for advanced glycation end product |

| TLRs | Toll-like receptors |

| IL | Interleukins |

| IL-1 | Interleukin-1 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| IL-11 | Interleukin-11 |

| IL-12 | Interleukin-12 |

| IL-17 | Interleukin-17 |

| IL-17A | Interleukin-1A |

| IL-22 | Interleukin-22 |

| IL-23 | Interleukin-23 |

| IL-33 | Interleukin-33 |

| IL-34 | Interleukin-34 |

| TNF | Tumour necrosis factor |

| IFN | Interferons |

| ESSDAI | Sjögren syndrome disease activity index |

| RFs | Rheumatoid factors |

| IgA | Immunoglobin A |

| IgG | Immunoglobin G |

| IgM | Immunoglobin M |

| IgE | Immunoglobin E |

| IgD | Immunoglobin D |

| ANA | Anti-nuclear antibodies |

| PBMCs | peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| Th cells | T helper cells |

| NK cells | Natural Killer cell |

| NKT cells | Natural killer T cells |

| DCs | Dendritic cells |

| pDCs | Plasmacytoid dendritic cells |

| BAFF | B cell activating factor of the TNF family |

| RIG1 | Retinoic acid inducible gene 1 |

| MDA5 | Melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 |

| RLRs | Retinoic acid inducible receptors |

| ISGs | Interferon-stimulated genes |

| STAT | Signal transducers and activators of transcription |

| MHC | Major histocompatibility complex |

| IFNLR | Interferon lambda receptor |

| sCD25 | Serum soluble CD25 |

| MSG | Minor salivary gland |

| HCs | Healthy controls |

| sIL-2R | Soluble interleukin-2 receptor |

| CCR9 | C-C chemokine receptor 9 |

| mAb | Monoclonal antibody |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1 |

| OX40L (TNFSF4) | Tumour necrosis factor superfamily, member 4 |

| sOX40L | Soluble OX40L |

| ELSs | Ectopic lymphoid-like structures |

| CXCR5 | C-X-C chemokine receptor type 5 |

| CCR5 | C-C chemokine receptor type 5 |

| CXCL9 | C-X-C motif chemokine 9 |

| CXCL10 | C-X-C motif chemokine 10 |

| CXCL11 | C-X-C motif chemokine 11 |

| CXCL13 | C-X-C motif chemokine 13 |

| CCL2 | C–C motif chemokine ligand 2 |

| CCL5 | C–C motif chemokine ligand 5 |

| CCL25 | C–C motif chemokine ligand 25 |

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely appreciate the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Scientific and Technological Projects of Xiamen City for financially supporting this research.

Disclosure: Financial support: This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82171779, 81971536), and Scientific and Technological Projects of Xiamen City (3502Z20209004) to GS. Conflicts of interest: none.

Credit authorship contribution statement: Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, resources, writing the original draft preparation, writing the review and editing: Yan Li., Jimin Zhang., Xiaoyan Liu., Kumar Ganesan and Guixiu Shi. Supervision, project administration: Guixiu Shi. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

1. Mariette X, Criswell LA. Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome. N Eng J Med 2018;378:931-9. [Google Scholar]

2. Mavragani CP, Moutsopoulos HM. Sjögren’s syndrome. Ann Rev Pathol 2014;9:273-85. [Google Scholar]

3. Brito-Zerón P, Baldini C, Bootsma H et al. Sjögren syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Prim 2016;2:16047. [Google Scholar]

4. Goldblatt F, O’Neill SG. Clinical aspects of autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Lancet (London, England) 2013;382:797-808. [Google Scholar]

5. Seror R, Nocturne G, Mariette X. Current and future therapies for primary Sjögren syndrome. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2021;17:475-86. [Google Scholar]

6. Mavragani CP, Moutsopoulos HM. Sjögren’s syndrome: Old and new therapeutic targets. J Autoimmun 2020;110:102364. [Google Scholar]

7. Roescher N, Tak PP, Illei GG. Cytokines in Sjögren’s syndrome. Oral Dis 2009;15:519-26. [Google Scholar]

8. Shiboski CH, Shiboski SC, Seror R et al. 2016 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism classification criteria for primary Sjögren’s syndrome: A consensus and data-driven methodology involving three international patient cohorts. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:9-16. [Google Scholar]

9. Bautista-Vargas M, Vivas AJ, Tobón GJ. Minor salivary gland biopsy: Its role in the classification and prognosis of Sjögren’s syndrome. Autoimmun Rev 2020;19:102690. [Google Scholar]

10. Cruz-Tapias P, Rojas-Villarraga A, Maier-Moore S, Anaya JM. HLA and Sjögren’s syndrome susceptibility. A meta-analysis of worldwide studies. Autoimmun Rev 2012;11:281-7. [Google Scholar]

11. Maślińska M. The role of Epstein-Barr virus infection in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2019;31:475-83. [Google Scholar]

12. Fox RI, Fox CM, Gottenberg JE, Dörner T. Treatment of Sjögren’s syndrome: current therapy and future directions. Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 2021;60:2066-74. [Google Scholar]

13. Bray C, Bell LN, Liang H et al. Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate and C-reactive Protein Measurements and Their Relevance in Clinical Medicine. WMJ 2016;115:317-21. [Google Scholar]

14. Martel C, Gondran G, Launay D et al. Active immunological profile is associated with systemic Sjögren’s syndrome. J Clin Immunol 2011;31:840-7. [Google Scholar]

15. Ramos-Casals M, Font J, Garcia-Carrasco M et al. Primary Sjögren syndrome: hematologic patterns of disease expression. Medicine 2002;81:281-92. [Google Scholar]

16. Quartuccio L, Isola M, Baldini C et al. Clinical and biological differences between cryoglobulinaemic and hypergammaglobulinaemic purpura in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: results of a large multicentre study. Scand J Rheumatol 2015;44:36-41. [Google Scholar]

17. Pertovaara M, Jylhävä J, Uusitalo H, Pukander J, Helin H, Hurme M. Serum amyloid A and C-reactive protein concentrations are differently associated with markers of autoimmunity in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. J Rheumatol 2009;36:2487-90. [Google Scholar]

18. Jordán-González P, Gago-Piñero R, Varela-Rosario N, Pérez-Ríos N, Vilá LM. Characterization of a subset of patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome initially presenting with C3 or C4 hypocomplementemia. Eur J Rheumatol 2020;7:112-7. [Google Scholar]

19. Carubbi F, Alunno A, Cipriani P et al. A retrospective, multicenter study evaluating the prognostic value of minor salivary gland histology in a large cohort of patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Lupus 2015;24:315-20. [Google Scholar]

20. Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, Yagüe J et al. Hypocomplementaemia as an immunological marker of morbidity and mortality in patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2005;44:89-94. [Google Scholar]

21. Theander E, Manthorpe R, Jacobsson LT. Mortality and causes of death in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:1262-9. [Google Scholar]

22. Sun W, Zhang N, Zhang Y, Shao Z, Gong L, Wei W. Immunophenotypes and clinical features of lymphocytes in the labial gland of primary Sjogren’s syndrome patients. Journal of clinical laboratory analysis. 2018;32:e22585. [Google Scholar]

23. Ioannidis JP, Vassiliou VA, Moutsopoulos HM. Long-term risk of mortality and lymphoproliferative disease and predictive classification of primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:741-7. [Google Scholar]

24. Legatowicz-Koprowska M, Nitek S, Czerwińska J. The complement system in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: the expression of certain cascade and regulatory proteins in labial salivary glands - observational study. Reumatologia 2020;58:357-66. [Google Scholar]

25. Cuida M, Legler DW, Eidsheim M, Jonsson R. Complement regulatory proteins in the salivary glands and saliva of Sjögren’s syndrome patients and healthy subjects. Clin Exp Rheumatol 1997;15:615-23. [Google Scholar]

26. Kamitaki N, Sekar A, Handsaker RE et al. Complement genes contribute sex-biased vulnerability in diverse disorders. Nature 2020;582:577-81. [Google Scholar]

27. Gottenberg JE, Seror R, Miceli-Richard C et al. Serum levels of beta2-microglobulin and free light chains of immunoglobulins are associated with systemic disease activity in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Data at enrollment in the prospective ASSESS cohort. PloS one 2013;8:e59868. [Google Scholar]

28. Sudzius G, Mieliauskaite D, Siaurys A et al. Could the complement component C4 or its fragment C4d be a marker of the more severe conditions in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome? Rheumatol Int 2014;34:235-41. [Google Scholar]

29. Simon MA, Bartus É, Mag B et al. Promiscuity mapping of the S100 protein family using a high-throughput holdup assay. Sci Rep 2022;12:5904. [Google Scholar]

30. Kozlyuk N, Monteith AJ, Garcia V, Damo SM, Skaar EP, Chazin WJ. S100 Proteins in the Innate Immune Response to Pathogens. Methods Mol Biol (Clifton, NJ) 2019;1929:275-90. [Google Scholar]

31. Hynne H, Aqrawi LA, Jensen JL et al. Proteomic Profiling of Saliva and Tears in Radiated Head and Neck Cancer Patients as Compared to Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome Patients. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23 [Google Scholar]

32. Finamore F, Cecchettini A, Ceccherini E et al. Characterization of Extracellular Vesicle Cargo in Sjögren’s Syndrome through a SWATH-MS Proteomics Approach. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22 [Google Scholar]

33. Cecchettini A, Finamore F, Ucciferri N et al. Phenotyping multiple subsets in Sjögren’s syndrome: a salivary proteomic SWATH-MS approach towards precision Medicine Clin. Proteomics 2019;16:26. [Google Scholar]

34. Jazzar AA, Shirlaw PJ, Carpenter GH, Challacombe SJ, Proctor GB. Salivary S100A8/A9 in Sjögren’s syndrome accompanied by lymphoma. J Oral Pathol Med 2018;47:900-6. [Google Scholar]

35. Nicaise C, Weichselbaum L, Schandene L et al. Phagocyte-specific S100A8/A9 is upregulated in primary Sjögren’s syndrome and triggers the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines in vitro. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2017;35:129-36. [Google Scholar]

36. Nordal HH, Brun JG, Halse AK, Madland TM, Fagerhol MK, Jonsson R. Calprotectin (S100A8/A9S100A12, and EDTA-resistant S100A12 complexes (ERAC) in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Scand J Rheumatol 2014;43:76-8. [Google Scholar]

37. Andréasson K, Saxne T, Scheja A, Bartosik I, Mandl T, Hesselstrand R. Faecal levels of calprotectin in systemic sclerosis are stable over time and are higher compared to primary Sjögren’s syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2014;16:R46. [Google Scholar]

38. Zhou L, Wei R, Zhao P, Koh SK, Beuerman RW, Ding C. Proteomic analysis revealed the altered tear protein profile in a rabbit model of Sjögren’s syndrome-associated dry eye. Proteomics 2013;13:2469-81. [Google Scholar]

39. Soyfoo MS, Roth J, Vogl T, Pochet R, Decaux G. Phagocyte-specific S100A8/A9 protein levels during disease exacerbations and infections in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 2009;36:2190-4. [Google Scholar]

40. Maślińska M, Mańczak M, Kwiatkowska B. Usefulness of rheumatoid factor as an immunological and prognostic marker in PSS patients. Clin Rheumatol 2019;38:1301-7. [Google Scholar]

41. Gioud-Paquet M, Auvinet M, Raffin T et al. IgM rheumatoid factor (RFIgA RF, IgE RF, and IgG RF detected by ELISA in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 1987;46:65-71. [Google Scholar]

42. Schroeder HWJr., Cavacini L. Structure and function of immunoglobulins. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;125:S41-52. [Google Scholar]

43. García-Carrasco M, Mendoza-Pinto C, Jiménez-Hernández C, Jiménez-Hernández M, Nava-Zavala Aand Riebeling C. Serologic features of primary Sjögren’s syndrome: clinical and prognostic correlation. Int J Clin Rheumatol 2012;7:651-9. [Google Scholar]

44. Malladi AS, Sack KE, Shiboski SC et al. Primary Sjögren’s syndrome as a systemic disease: a study of participants enrolled in an international Sjögren’s syndrome registry. Arthritis Care Res 2012;64:911-8. [Google Scholar]

45. Markusse HM, Otten HG, Vroom TM, Smeets TJ, Fokkens Nand Breedveld FC. Rheumatoid factor isotypes in serum and salivary fluid of patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 1993;66:26-32. [Google Scholar]

46. Meek B, Kelder JC, Claessen AME, van Houte AJ, Ter Borg EJ. Rheumatoid factor isotype and Ro epitope distribution in primary Sjögren syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis with keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Rheumatol Int 2018;38:1487-93. [Google Scholar]

47. Brkic Z, Maria NI, van Helden-Meeuwsen CG, et al. Prevalence of interferon type I signature in CD14 monocytes of patients with Sjogren’s syndrome and association with disease activity and BAFF gene expression. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:728-35. [Google Scholar]

48. Imgenberg-Kreuz J, Sandling JK, Almlöf JC et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis in multiple tissues in primary Sjögren’s syndrome reveals regulatory effects at interferon-induced genes. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:2029-36. [Google Scholar]

49. Wildenberg ME, van Helden-Meeuwsen CG, van de Merwe JP, Drexhage HA, Versnel MA. Systemic increase in type I interferon activity in Sjögren’s syndrome: a putative role for plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol 2008;38:2024-33. [Google Scholar]

50. Schroder K, Hertzog PJ, Ravasi T, Hume DA. Interferon-gamma: an overview of signals, mechanisms and functions. J Leuk Biol 2004;75:163-89. [Google Scholar]

51. Peck AB, Nguyen CQ. What can Sjögren’s syndrome-like disease in mice contribute to human Sjögren’s syndrome? Clin Immunol (Orlando, Fla) 2017;182:14-23. [Google Scholar]

52. Schoenborn JR, Wilson CB. Regulation of interferon-gamma during innate and adaptive immune responses. Adv Immunol 2007;96:41-101. [Google Scholar]

53. Nocturne G, Mariette X. Advances in understanding the pathogenesis of primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2013;9:544-56. [Google Scholar]

54. Yoshimoto K, Tanaka M, Kojima M et al. Regulatory mechanisms for the production of BAFF and IL-6 are impaired in monocytes of patients of primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Res Ther 2011;13:R170. [Google Scholar]

55. Båve U, Nordmark G, Lövgren T et al. Activation of the type I interferon system in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a possible etiopathogenic mechanism. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:1185-95. [Google Scholar]

56. Gottenberg JE, Cagnard N, Lucchesi C et al. Activation of IFN pathways and plasmacytoid dendritic cell recruitment in target organs of primary Sjögren’s syndrome. PNASS 2006;103:2770-5. [Google Scholar]

57. Hjelmervik TOPetersen K, Jonassen I, Jonsson R, Bolstad AI. Gene expression profiling of minor salivary glands clearly distinguishes primary Sjögren’s syndrome patients from healthy control subjects. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:1534-44. [Google Scholar]

58. Maria NI, Steenwijk EC, IJ AS et al. Contrasting expression pattern of RNA-sensing receptors TLR7, RIG-I and MDA5 in interferon-positive and interferon-negative patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:721-30. [Google Scholar]

59. Hall JC, Casciola-Rosen L, Berger AE et al. Precise probes of type II interferon activity define the origin of interferon signatures in target tissues in rheumatic diseases. PNASS 2012;109:17609-14. [Google Scholar]

60. Bodewes ILA, Björk A, Versnel MA, Wahren-Herlenius M. Innate immunity and interferons in the pathogenesis of Sjögren’s syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2019 [Google Scholar]

61. Fitzgerald-Bocarsly P, Dai J, Singh S. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells and type I IFN: 50 years of convergent history. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2008;19:3-19. [Google Scholar]

62. Bodewes ILA, Al-Ali S, van Helden-Meeuwsen CG, et al. Systemic interferon type I and type II signatures in primary Sjögren’s syndrome reveal differences in biological disease activity. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2018;57:921-30. [Google Scholar]

63. Ogawa Y, Shimizu E, Tsubota K. Interferons and Dry Eye in Sjögren’s Syndrome. Int J Mol Sci 2018;19 [Google Scholar]

64. Lessard CJ, Li H, Adrianto I et al. Variants at multiple loci implicated in both innate and adaptive immune responses are associated with Sjögren’s syndrome. Nat Gen 2013;45:1284-92. [Google Scholar]

65. Gestermann N, Mekinian A, Comets E et al. STAT4 is a confirmed genetic risk factor for Sjögren’s syndrome and could be involved in type 1 interferon pathway signaling. Genes Immun 2010;11:432-8. [Google Scholar]

66. Kulkarni K, Selesniemi K, Brown TL. Interferon-gamma sensitizes the human salivary gland cell line, HSG, to tumor necrosis factor-alpha induced activation of dual apoptotic pathways. Apoptosis 2006;11:2205-15. [Google Scholar]

67. Youinou P, Pers JO. Disturbance of cytokine networks in Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Res Ther 2011;13:227. [Google Scholar]

68. Yin H, Vosters JL, Roescher N et al. Location of immunization and interferon-γ are central to induction of salivary gland dysfunction in Ro60 peptide immunized model of Sjögren’s syndrome. PloS one 2011;6:e18003. [Google Scholar]

69. Sebastian A, Madej M, Sebastian M et al. The Clinical and Immunological Activity Depending on the Presence of Interferon γ in Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome-A Pilot Study. J Clin Med 202111. [Google Scholar]

70. Apostolou E, Kapsogeorgou EK, Konsta OD et al. Expression of type III interferons (IFNλs) and their receptor in Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol 2016;186:304-12. [Google Scholar]

71. Kyriakidis NC, Kapsogeorgou EK, Gourzi VC, Konsta OD, Baltatzis GE, Tzioufas AG. Toll-like receptor 3 stimulation promotes Ro52/TRIM21 synthesis and nuclear redistribution in salivary gland epithelial cells, partially via type I interferon pathway. Clin Exp Immunol 2014;178:548-60. [Google Scholar]

72. Nezos A, Gravani F, Tassidou A et al. Type I and II interferon signatures in Sjogren’s syndrome pathogenesis: Contributions in distinct clinical phenotypes and Sjogren’s related lymphomagenesis. J Autoimmun 2015;63:47-58. [Google Scholar]

73. Zhang RJ, Zhang X, Chen J et al. Serum soluble CD25 as a risk factor of renal impairment in systemic lupus erythematosus - a prospective cohort study. Lupus 2018;27:1100-6. [Google Scholar]

74. Chen J, Jin Y, Li C et al. Evaluation of soluble CD25 as a clinical and autoimmune biomarker in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2020;38(Suppl 126: 142-9. [Google Scholar]

75. Keindl M, Davies R, Bergum B et al. Impaired activation of STAT5 upon IL-2 stimulation in Tregs and elevated sIL-2R in Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Res Ther 2022;24:101. [Google Scholar]

76. Benchabane S, Boudjelida A, Toumi R, Belguendouz H, Youinou P, Touil-Boukoffa C. A case for IL-6, IL-17A, and nitric oxide in the pathophysiology of Sjögren’s syndrome. Int J Immunopathol Pharm 2016;29:386-97. [Google Scholar]

77. Chen C, Liang Y, Zhang Z, Zhang Z, Yang Z. Relationships between increased circulating YKL-40, IL-6 and TNF-α levels and phenotypes and disease activity of primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Int Immunopharmacol 2020;88:106878. [Google Scholar]

78. Liang Y, Zhang Z, Li J, Luo W, Jiang T, Yang Z. Association between IL-7 and primary Sjögren’s syndrome: A single-center study and a systematic scoping review. Int Immunopharmacol 2022;108:108758. [Google Scholar]

79. Bikker A, van Woerkom JM, Kruize AA et al. Increased expression of interleukin-7 in labial salivary glands of patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome correlates with increased inflammation. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:969-77. [Google Scholar]

80. Blokland SLM, Hillen MR, Kruize AA et al. Increased CCL25 and T Helper Cells Expressing CCR9 in the Salivary Glands of Patients With Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome: Potential New Axis in Lymphoid Neogenesis. Arthritis Rheumatol (Hoboken, NJ). 2017;69:2038-51. [Google Scholar]

81. Shakerian L, Kolahdooz H, Garousi M et al. IL-33/ST2 axis in autoimmune disease. Cytokine 2022;158:156015. [Google Scholar]

82. Soyfoo MS, Nicaise C. Pathophysiologic role of Interleukin-33/ST2 in Sjögren’s syndrome. Autoimmun Rev 2021;20:102756. [Google Scholar]

83. Zhang LW, Cong X, Zhang Y et al. Interleukin-17 Impairs Salivary Tight Junction Integrity in Sjögren’s Syndrome. J Dent Res 2016;95:784-92. [Google Scholar]

84. Nguyen CQ, Yin H, Lee BH, Carcamo WC, Chiorini JA, Peck AB. Pathogenic effect of interleukin-17A in induction of Sjögren’s syndrome-like disease using adenovirus-mediated gene transfer. Arthritis Res Ther 2010;12:R220. [Google Scholar]

85. Lin X, Rui K, Deng J et al. Th17 cells play a critical role in the development of experimental Sjögren’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1302-10. [Google Scholar]

86. Alunno A, Carubbi F, Bartoloni E et al. Unmasking the pathogenic role of IL-17 axis in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a new era for therapeutic targeting? Autoimmun Rev 2014;13:1167-73. [Google Scholar]

87. Shi H, Cao N, Pu Y, Xie L, Zheng L, Yu C. Long non-coding RNA expression profile in minor salivary gland of primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Res Ther 2016;18:109. [Google Scholar]

88. Ye L, Shi H, Wu S, Yu C, Wang B, Zheng L. Dysregulated interleukin 11 in primary Sjögren’s syndrome contributes to apoptosis of glandular epithelial cells. Cell Biol Int 2019 [Google Scholar]

89. Ciccia F, Alessandro R, Rodolico V et al. IL-34 is overexpressed in the inflamed salivary glands of patients with Sjogren’s syndrome and is associated with the local expansion of pro-inflammatory CD14(bright)CD16+ monocytes. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2013;52:1009-17. [Google Scholar]

90. Liu Y, Zhang B, Lei Y, Xia L, Lu J, Shen H. Serum levels of interleukin-34 and clinical correlation in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Int J Rheum Dis 2020;23:374-80. [Google Scholar]

91. Azuma M, Aota K, Tamatani T et al. Suppression of tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced matrix metalloproteinase 9 production in human salivary gland acinar cells by cepharanthine occurs via down-regulation of nuclear factor kappaB: a possible therapeutic agent for preventing the destruction of the acinar structure in the salivary glands of Sjögren’s syndrome patients. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:1585-94. [Google Scholar]

92. Zhou J, Kawai T, Yu Q. Pathogenic role of endogenous TNF-α in the development of Sjögren’s-like sialadenitis and secretory dysfunction in non-obese diabetic mice. Lab Invest 2017;97:458-67. [Google Scholar]

93. Kang EH, Lee YJ, Hyon JY, Yun PY, Song YW. Salivary cytokine profiles in primary Sjögren’s syndrome differ from those in non-Sjögren sicca in terms of TNF-α levels and Th-1/Th-2 ratios. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2011;29:970-6. [Google Scholar]

94. Moriyama M, Hayashida JN, Toyoshima T et al. Cytokine/chemokine profiles contribute to understanding the pathogenesis and diagnosis of primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol 2012;169:17-26. [Google Scholar]

95. Aota K, Azuma M. Targeting TNF-α suppresses the production of MMP-9 in human salivary gland cells. Arch Oral Biol 2013;58:1761-8. [Google Scholar]

96. Mariette X, Ravaud P, Steinfeld S et al. Inefficacy of infliximab in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: results of the randomized, controlled Trial of Remicade in Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome (TRIPSS). Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:1270-6. [Google Scholar]

97. Belkhir R, Gestermann N, Koutero M et al. Upregulation of membrane-bound CD40L on CD4+ T cells in women with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Scand J Immunol 2014;79:37-42. [Google Scholar]

98. Goules A, Tzioufas AG, Manousakis MN, Kirou KA, Crow MK, Routsias JG. Elevated levels of soluble CD40 ligand (sCD40L) in serum of patients with systemic autoimmune diseases. J Autoimmun 2006;26:165-71. [Google Scholar]

99. Corsiero E, Nerviani A, Bombardieri M, Pitzalis C. Ectopic Lymphoid Structures: Powerhouse of Autoimmunity. Front Immunol 2016;7:430. [Google Scholar]

100. Jonsson MV, Skarstein K, Jonsson R, Brun JG. Serological implications of germinal center-like structures in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. J Rheumatol 2007;34:2044-9. [Google Scholar]

101. Dimitriou ID, Kapsogeorgou EK, Moutsopoulos HM, Manoussakis MN. CD40 on salivary gland epithelial cells: high constitutive expression by cultured cells from Sjögren’s syndrome patients indicating their intrinsic activation. Clin Exp Immunol 2002;127:386-92. [Google Scholar]

102. Saito M, Ota Y, Ohashi H et al. CD40-CD40 ligand signal induces the intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression through nuclear factor-kappa B p50 in cultured salivary gland epithelial cells from patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. Mod Rheumatol 2007;17:45-53. [Google Scholar]

103. Jobling K, Ng WF. CD40 as a therapeutic target in Sjögren’s syndrome. Exp Rev Clin Immunol 2018;14:535-7. [Google Scholar]

104. Wieczorek G, Bigaud M, Pfister S et al. Blockade of CD40-CD154 pathway interactions suppresses ectopic lymphoid structures and inhibits pathology in the NOD/ShiLtJ mouse model of Sjögren’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis 2019;78:974-8. [Google Scholar]

105. Thompson N, Isenberg DA, Jury EC, Ciurtin C. Exploring BAFF: its expression, receptors and contribution to the immunopathogenesis of Sjögren’s syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2016;55:1548-55. [Google Scholar]

106. An J, Ding S, Hu X et al. Preparation, characterization and application of anti-human OX40 ligand (OX40L) monoclonal antibodies and establishment of a sandwich ELISA for autoimmune diseases detection. Int Immunopharmacol 2019;67:260-7. [Google Scholar]

107. Zhu R, Jiang J, Wang T et al. [Expressions and clinical significance of OX40 and OX40L in peripheral blood of patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome]. Chin. J Cell Mol Immunol 2013;29:862-5. [Google Scholar]

108. Nocturne G, Seror R, Fogel O et al. CXCL13 and CCL11 Serum Levels and Lymphoma and Disease Activity in Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol (Hoboken, NJ). 2015;67:3226-33. [Google Scholar]

109. Traianos EY, Locke J, Lendrem D et al. Serum CXCL13 levels are associated with lymphoma risk and lymphoma occurrence in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Rheumatol Int 2020;40:541-8. [Google Scholar]

110. Kramer JM, Klimatcheva E, Rothstein TL. CXCL13 is elevated in Sjögren’s syndrome in mice and humans and is implicated in disease pathogenesis. J Leuk Biol 2013;94:1079-89. [Google Scholar]

111. Amft N, Curnow SJ, Scheel-Toellner D et al. Ectopic expression of the B cell-attracting chemokine BCA-1 (CXCL13) on endothelial cells and within lymphoid follicles contributes to the establishment of germinal center-like structures in Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:2633-41. [Google Scholar]

112. Blokland SLM, Hillen MR, van Vliet-Moret FM, et al. Salivary gland secretome: a novel tool towards molecular stratification of patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome and non-autoimmune sicca. RMD open 2019;5:e000772. [Google Scholar]

113. Nocturne G, Mariette X. B cells in the pathogenesis of primary Sjögren syndrome. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2018;14:133-45. [Google Scholar]

114. Colafrancesco S, Priori R, Smith CG et al. CXCL13 as biomarker for histological involvement in Sjögren’s syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2020;59:165-70. [Google Scholar]

115. Blokland SLM, van Vliet-Moret FM, Hillen MR, et al. Epigenetically quantified immune cells in salivary glands of Sjögren’s syndrome patients: a novel tool that detects robust correlations of T follicular helper cells with immunopathology. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2020;59:335-43. [Google Scholar]

116. Chatzis L, Goules AV, Stergiou IE, Voulgarelis M, Tzioufas AG, Kapsogeorgou EK. Serum, but Not Saliva, CXCL13 Levels Associate With Infiltrating CXCL13+ Cells in the Minor Salivary Gland Lesions and Other Histologic Parameters in Patients With Sjögren’s Syndrome. Front Immunol 2021;12:705079. [Google Scholar]

117. Hernández-Molina G, Michel-Peregrina M, Hernández-Ramírez DF, Sánchez-Guerrero J, Llorente L. Chemokine saliva levels in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome, associated Sjögren’s syndrome, pre-clinical Sjögren’s syndrome and systemic autoimmune diseases. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2011;50:1288-92. [Google Scholar]

118. Hasegawa H, Inoue A, Kohno M et al. Antagonist of interferon-inducible protein 10/CXCL10 ameliorates the progression of autoimmune sialadenitis in MRL/lpr mice. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:1174-83. [Google Scholar]

119. Hernández-Molina G, Ruiz-Quintero N, Lima G et al. Chemokine tear levels in primary Sjögren’s syndrome and their relationship with symptoms. International ophthalmology. 2022;42:2355-61. [Google Scholar]

120. Aota K, Yamanoi T, Kani K, Nakashiro KI, Ishimaru N, Azuma M. Inverse correlation between the number of CXCR3(+) macrophages and the severity of inflammatory lesions in Sjögren’s syndrome salivary glands: A pilot study. J Oral Pathol Med 2018;47:710-8. [Google Scholar]

121. Ogawa N, Ping L, Zhenjun L, Takada Y, Sugai S. Involvement of the interferon-gamma-induced T cell-attracting chemokines, interferon-gamma-inducible 10-kd protein (CXCL10) and monokine induced by interferon-gamma (CXCL9in the salivary gland lesions of patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:2730-41. [Google Scholar]

122. Ogawa N, Kawanami T, Shimoyama K, Ping L, Sugai S. Expression of interferon-inducible T cell alpha chemoattractant (CXCL11) in the salivary glands of patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Immunol (Orlando, Fla) 2004;112:235-8. [Google Scholar]

123. Padern G, Duflos C, Ferreira R et al. Identification of a Novel Serum Proteomic Signature for Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome. Front Immunol 2021;12:631539. [Google Scholar]

124. Yoon KC, Park CS, You IC et al. Expression of CXCL9, -10, -11, and CXCR3 in the tear film and ocular surface of patients with dry eye syndrome. Invest Ophtalm Vis Sci 2010;51:643-50. [Google Scholar]

125. Aqrawi LA, Jensen JL, Øijordsbakken G et al. Signalling pathways identified in salivary glands from primary Sjögren’s syndrome patients reveal enhanced adipose tissue development. Autoimmunity. 2018;51:135-46. [Google Scholar]

126. Szodoray P, Alex P, Jonsson MV et al. Distinct profiles of Sjögren’s syndrome patients with ectopic salivary gland germinal centers revealed by serum cytokines and BAFF. Clin Immunol (Orlando, Fla) 2005;117:168-76. [Google Scholar]

127. Szodoray P, Alex P, Brun JG, Centola M, Jonsson R. Circulating cytokines in primary Sjögren’s syndrome determined by a multiplex cytokine array system. Scand J Immunol 2004;59:592-9. [Google Scholar]

128. Iwamoto N, Kawakami A, Arima K et al. Regulation of disease susceptibility and mononuclear cell infiltration into the labial salivary glands of Sjögren’s syndrome by monocyte chemotactic protein-1. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2010;49:1472-8. [Google Scholar]

129. Iwasa A, Arakaki R, Honma N et al. Aromatase controls Sjögren syndrome-like lesions through monocyte chemotactic protein-1 in target organ and adipose tissue-associated macrophages. Am J Pathol 2015;185:151-61. [Google Scholar]

130. McGuire HM, Vogelzang A, Ma CS et al. A subset of interleukin-21+ chemokine receptor CCR9+ T helper cells target accessory organs of the digestive system in autoimmunity. Immunity. 2011;34:602-15. [Google Scholar]

131. Kunkel EJ, Campbell JJ, Haraldsen G et al. Lymphocyte CC chemokine receptor 9 and epithelial thymus-expressed chemokine (TECK) expression distinguish the small intestinal immune compartment: Epithelial expression of tissue-specific chemokines as an organizing principle in regional immunity. J Ecp Med 2000;192:761-8. [Google Scholar]

132. Hillen MR, Pandit A, Blokland SLM et al. Plasmacytoid DCs From Patients With Sjögren’s Syndrome Are Transcriptionally Primed for Enhanced Pro-inflammatory Cytokine Production. Front Immunol 2019;10:2096. [Google Scholar]

133. Törnwall J, Lane TE, Fox RI, Fox HS. T cell attractant chemokine expression initiates lacrimal gland destruction in nonobese diabetic mice. Lab Invest 1999;79:1719-26. [Google Scholar]

134. Jousse-Joulin S, D’Agostino MA, Nicolas C et al. Video clip assessment of a salivary gland ultrasound scoring system in Sjögren’s syndrome using consensual definitions: an OMERACT ultrasound working group reliability exercise. Ann Rheum Dis 2019;78:967-73. [Google Scholar]

135. Devauchelle-Pensec V, Zabotti A, Carvajal-Alegria G, Filipovic N, Jousse-Joulin S, De Vita S. Salivary gland ultrasonography in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: opportunities and challenges. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2021;60:3522-7. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools