Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Exploring Adolescents’ Social Anxiety, Physical Activity, and Core Self-Evaluation: A Latent Profile and Mediation Approach

1 Science and Technology College, Nanchang Hangkong University, Nanchang, 330000, China

2 School of Physical Education, Jiangxi Normal University, Nanchang, 330031, China

* Corresponding Author: Chang Hu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Latent Profile Analysis in Mental Health Research: Exploring Heterogeneity through Person Centric Approach)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(10), 1611-1626. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.070457

Received 16 July 2025; Accepted 16 September 2025; Issue published 31 October 2025

Abstract

Background: Social anxiety is prevalent among adolescents and severely impacts their mental health and social functioning. This study aims to explore the underlying mechanisms and subgroup differences in adolescent social anxiety to provide a theoretical basis for targeted interventions. Methods: 3025 Chinese adolescents (Meanage = 13.91 ± 1.60 years; 47% male) completed self-report measures of physical activity, core self-evaluation, and social anxiety. Variable-centered analyses employed PROCESS Model 4 with 5000 bootstrap samples; covariates were gender, grade, and place of residence. Person-centered analyses used latent profile analysis in Mplus 8.3 to identify subgroups based on social anxiety item profiles. Results: Variable-centered analyses showed that physical activity had a significant negative association with social anxiety (β = −0.224, p < 0.001) and a significant positive association with core self-evaluation (β = 0.471, p < 0.001); core self-evaluation partially mediated this relationship, accounting for 30% of the total effect. Person-centered analyses revealed an optimal two-profile solution: a low social anxiety profile (89.6%) and a high social anxiety profile (10.4%). The high social anxiety profile reported significantly lower physical activity and lower core self-evaluation than the low social anxiety profile. Conclusions: This study integrates variable-centered and person-centered evidence, identifies physical activity and core self-evaluation as key modifiable factors in reducing social anxiety, providing a theoretical basis for targeted and differentiated interventions.Keywords

Social anxiety refers to the tension, avoidance, and self-focus an individual experiences in social situations due to the fear of negative evaluation by others [1,2]. It has been widely recognized as one of the most common forms of anxiety [3–5]. A survey conducted across seven countries revealed that the prevalence of social anxiety among individuals aged 13–18 ranges from 23% to 58%. Among them, approximately 40% of middle-school students exhibit moderate-to-high-level symptoms of social anxiety during their academic years, and these symptoms tend to increase with age [6]. This type of anxiety not only directly hampers interpersonal expansion [7], academic engagement [8], and self-identity development [9], but also significantly co-occurs with depression, loneliness, mobile phone dependence, and substance abuse such as smoking and drinking [10–12]. Interestingly, despite the increasing popularity of mental health courses and the explosive growth of online social channels, social anxiety among adolescents has not decreased but instead increased [13]. In the information age, it seems to create a deeper sense of “collective loneliness.” To address this gap, the present study focuses on three key variables: physical activity, core self-evaluation, and social anxiety. Physical activity is a modifiable behavior with known benefits for mental health [14], while core self-evaluation represents a fundamental appraisal of one’s worth and capability [15]. Our primary objective is to explore the relationships among these variables to better understand the mechanisms that may contribute to or protect against social anxiety in adolescents. Doing so aims to provide a more comprehensive framework for addressing this pressing issue.

1.1 Physical Activity and Social Anxiety

In recent years, physical activity has drawn wide scholarly interest as a low-cost, highly effective health-behavior intervention [16–18]. It is recognized as an important way to reduce anxiety because it significantly benefits adolescents’ physical and mental health [19,20]. Physical activity refers to planned and organized sports activities that individuals engage in to enhance physical fitness and promote mental and physical health [21]. From the perspective of self-efficacy theory, physical activity can significantly enhance an individual’s self-efficacy [22]. When facing stressful stimuli, higher self-efficacy enables individuals to cope better, thereby reducing the level of anxiety [23]. From the perspective of cognitive control, Physical activity can effectively change individuals’ erroneous perceptions of external stimuli, thereby reducing the generation of anxiety [24,25]. In addition, a positive atmosphere for Physical activity can create harmonious interpersonal relationships and provide adolescents with a positive social environment, which can effectively reduce and alleviate social anxiety and help them maintain a healthy and positive psychological state [26,27]. Dimech and Seiler [28] found that participating in team sports can effectively alleviate social anxiety in adolescents. Panza et al. [29] also pointed out that regular physical activity in schools can significantly improve adolescents’ anxiety and depression. Longitudinal surveys have shown that physical activity can not only positively predict mental health levels years later but also negatively predict negative emotions in adolescents, including depression, stress, and other psychological problems, such as social anxiety [30–32]. However, although existing studies have revealed the association between Physical activity and social anxiety in adolescents, research on the underlying mechanisms by which Physical activity affects social anxiety is still relatively scarce.

1.2 The Mediating Role of Core Self-Evaluation

Core self-evaluation is likely to be an important mediating variable in the relationship between physical activity and social anxiety. To ground our hypothesis in a specific theoretical framework, we draw upon Hobfoll’s Conservation of Resources Theory (COR) [33]. This theory posits that psychological well-being depends on obtaining and protecting valued resources. Within this framework, core self-evaluation can be conceptualized as a critical personal resource. We propose that physical activity acts as a resource-building activity; fostering mastery and accomplishment enhances an adolescent’s reservoir of core self-evaluation [34]. According to the COR, social anxiety emerges from the perceived threat of resource loss in social settings. Adolescents with higher core self-evaluations possess greater personal resources, making them better equipped to manage social stressors and less vulnerable to anxiety [35]. Thus, COR theory provides a cohesive explanation for how physical activity builds the personal resource of core self-evaluation, which in turn functions as a buffer against social anxiety. In addition, some related studies also support this view. Judge [36] pointed out that core self-evaluation is an individual’s overall evaluation of their abilities and worth, which can significantly influence emotional and behavioral responses. In adolescents, Physical activity enhances physical fitness and improves self-efficacy and self-esteem, thereby improving core self-evaluation [37–39]. In addition, core self-evaluation has been regarded as a powerful motivational component in many studies, driving individuals to approach (or avoid) situations that enhance (or undermine) self-evaluation [40,41]. Preliminary research has shown that core self-evaluation is a key factor in coping with stress and anxiety [42]. Individuals with higher levels of core self-evaluation tend to exhibit greater psychological resilience and less anxiety [43,44]. However, the mechanisms by which Physical activity, core self-evaluation, and social anxiety interact are still unclear.

Previous studies have mostly been conducted from a variable-centered perspective. However, this variable-centered approach, which is based on the average level of all samples, fails to fully reveal the heterogeneity among individuals [45]. Analyzing different categories of individuals can help researchers gain a deeper understanding of the differences in Physical activity and core self-evaluation among different types of individuals and how these differences affect social anxiety [46]. Therefore, analyzing the potential categories of social anxiety from a person-centered perspective is particularly important. Latent profile analysis is a person-centered analytical technique that explains the associations among manifest indicators through latent continuous variables and uses latent categorical variables to explain the associations among manifest indicators [47]. In recent years, a few researchers have used this method to explore the potential categories of social anxiety. For example, Zhang et al. [48] found that social anxiety can be divided into three categories, while Yu et al. [49] believed that a four-category model is more appropriate. However, research on the potential categories of social anxiety is still limited, and different studies have yielded inconsistent classification results. This indicates that the potential categories and characteristics of social anxiety have not been fully verified and clearly defined. Given these inconsistencies, the current study aims to provide a more nuanced understanding of social anxiety profiles among adolescents. By identifying distinct profiles, we can better understand how different levels and types of social anxiety are associated with physical activity and core self-evaluation. This approach allows us to move beyond average trends and capture the heterogeneity within the sample, which is crucial for developing targeted interventions tailored to the specific needs of each subgroup.

Given the high prevalence of social anxiety and its wide-ranging impact on the physical and mental health of adolescents, this study aims to analyze the relationship between physical activity, core self-evaluation, and social anxiety from both variable-centered and person-centered perspectives to fully reveal their interrelationships and further verify the potential categories of social anxiety. Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed for this study: (Hypothesis 1) Physical activity is negatively correlated with social anxiety; (Hypothesis 2) Core self-evaluation plays a mediating role between Physical activity and social anxiety; (Hypothesis 3) There are different potential categories of social anxiety, and these categories show significant differences in Physical activity and core self-evaluation. By verifying the above hypotheses, this study expects to provide a new perspective for understanding the complex mechanisms of social anxiety in adolescents and to offer a theoretical basis for developing targeted mental health intervention measures.

To assess the required sample size from a statistical power perspective, we conducted a priori power analysis using G*Power 3.1 software based on the central hypothesis of this study (i.e., the mediation model). This analysis aimed to determine the minimum sample size required to test a complete multiple regression model. Following Cohen’s (1988) standards [50], we set the effect size to a smaller, more conservative value (effect size f2 = 0.02), statistical power to 0.95, and significance level α to 0.05. The model included five predictor variables: the independent variable (physical exercise), the mediator variable (core self-evaluation), and three covariates (gender, grade level, and place of residence). The results from G*Power indicated that at least 995 participants were needed to achieve the desired statistical power. The actual sample size of this study (N = 3025) far exceeds the minimum requirement calculated by G*Power, indicating that this study has sufficient statistical power to accurately test the mediating effect. Additionally, the sample size also far exceeds previous research on latent profile analysis, which has indicated a requirement for 300–500 participants [51,52], providing a solid foundation for the robustness of both analytical methods.

Between March and April 2025, this study adopted a convenience sampling method to conduct questionnaire surveys in ten middle schools in Jiangxi Province, central China. Before data collection, permission was obtained from each school’s administrators, and every participant provided written informed consent from their guardians and themselves. The study strictly followed the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Ethics Committee of the School of Science and Technology, Nanchang Hangkong University (IRB-NCHU-STC-20250103).

Because ninth-grade and twelfth-grade students faced examinations, only seventh-, eighth-, tenth-, and eleventh-grade students were included in the survey. The questionnaires were administered uniformly in classrooms, with 3412 questionnaires collected. To ensure the validity of the questionnaires, the following screening procedures were implemented: Firstly, two attention control items were inserted in the middle and at the end of the questionnaire, namely “Please select the value 1” and “Please select the value 3,” with options on a 1–5-point scale, to identify whether students had answered carefully. Those who answered either of these two questions incorrectly were excluded (179 participants were eliminated). Secondly, questionnaires where all items had the same answer were excluded by checking for uniformity in responses (110 participants were excluded). Finally, questionnaires with incomplete responses were removed (98 participants were excluded). A total of 3025 valid samples were obtained.

The participants ranged from 11 to 18 years, with a mean age of 13.91 ± 1.60 years. There were 1422 male students (47.0%) and 1603 female students (53.0%). Among them, 1698 were from urban areas (56.1%) and 1327 were from rural areas (43.9%). Specifically, there were 923 seventh-grade students (30.5%), 826 eighth-grade students (27.3%), 710 tenth-grade students (23.5%), and 566 eleventh-grade students (18.7%).

Physical activity was measured with a single question: “Over the past 7 days, how many days did you engage in at least 20 min of exercise or activity that made you sweat or breathe heavily?” Participants could respond with a number ranging from 0 to 7 days. This single-item question is a commonly used and validated method for assessing physical activity in large epidemiological studies, and its utility has been demonstrated in previous research with adolescent populations [53–56].

The Core Self-Evaluation Scale was developed by Judge et al. [57], was used in this study to measure the core self-evaluation level of the participants. This scale consists of 10 items, scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). Some items in the scale require reverse scoring. After calculating the mean scores of all items, a higher score indicates a higher level of core self-evaluation. The scale has been widely used among Chinese populations [58,59]. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient of the scale was 0.83, indicating good internal consistency reliability and suitability for the measurement purpose of this study.

The Short Form Social Interaction Anxiety Scale and the Short Form Social Phobia Scale, revised by Peters et al. [60], were used in this study to measure social anxiety levels. Each scale consists of 6 items, totaling 12 items, and employs a 5-point Likert scale for scoring, ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The total score of the items represents the level of social anxiety experienced by the participants, with higher scores indicating higher levels of social anxiety. The scale has been widely used among Chinese populations [61,62]. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient for the scale was 0.94, indicating good internal consistency, reliability, and suitability for the measurement purpose of this study.

Given that adolescent social anxiety may be influenced by various factors, particularly those related to individual characteristics [63,64], these individual characteristic variables include gender and place of residence. Therefore, this study includes student gender, grade, and place of residence as control variables in the analysis. They are coded as dummy variables: gender (0 = male, 1 = female) and place of residence (0 = urban, 1 = rural), and grade (1 = 7th, 2 = 8th, 3 = 10th, 4 = 11th).

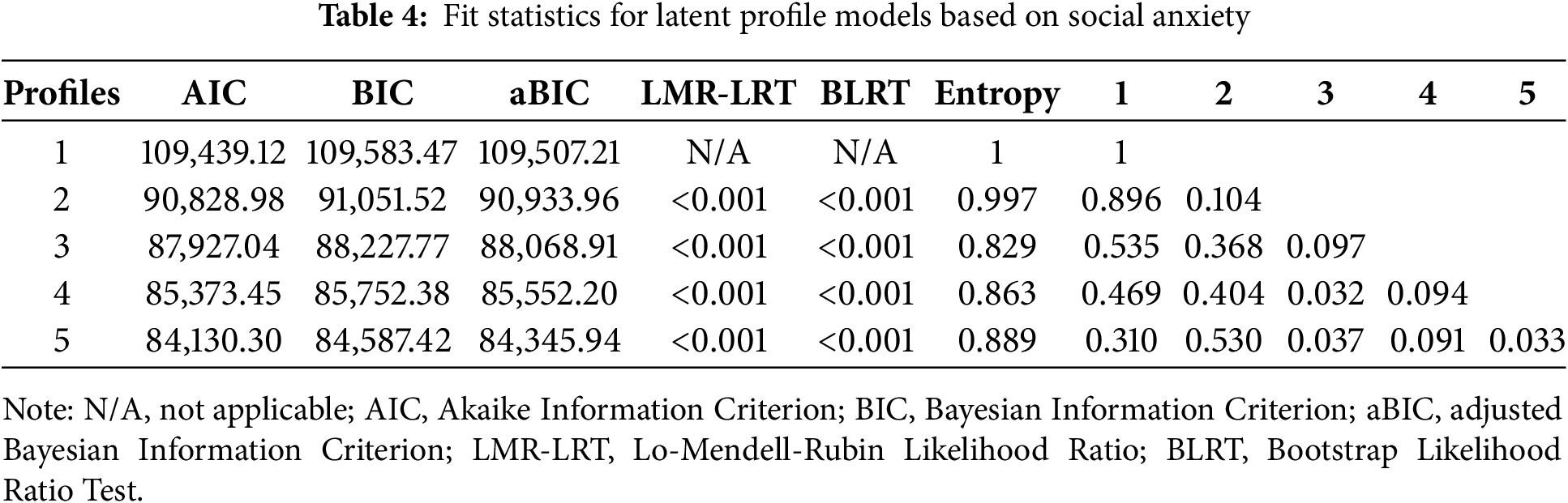

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and Mplus 8.3 (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA, USA). Descriptive statistics and correlation analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0. In the variable-centered analysis, we used Model 4 in the Process macro 3.5 to examine how physical activity influences social anxiety through core self-evaluation, with mediation effects estimated using 5000 bootstrap samples at a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) [65]. Next, an unconditional latent profile analysis model was constructed in Mplus 8.3 based on 12 items related to adolescent social anxiety. The number of latent profiles was determined using the following criteria: (1) each profile must include at least 5% of the total sample [51]; (2) model fit indices Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion (aBIC) were evaluated, with lower values indicating a better fitting model [66]; (3) p-values of the parametric Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (LMR-LRT), and the bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT) below 0.05 indicated that the model with k profiles was superior to the model with k minus one profiles [67]; (4) entropy values ranging from 0 to 1 were assessed, with higher values indicating better classification accuracy. Independent-samples t-tests were used to examine differences in physical activity and core self-evaluation between different social anxiety categories. Throughout the analyses, place of residence, grade, and gender were included as covariates, and all variables were standardized prior to analysis.

This study used Harman’s single-factor test to assess common method bias from adolescents’ self-reports. The first factor accounted for 35.571% of the variance, below the 40% threshold, indicating that common method bias was not a significant issue [68].

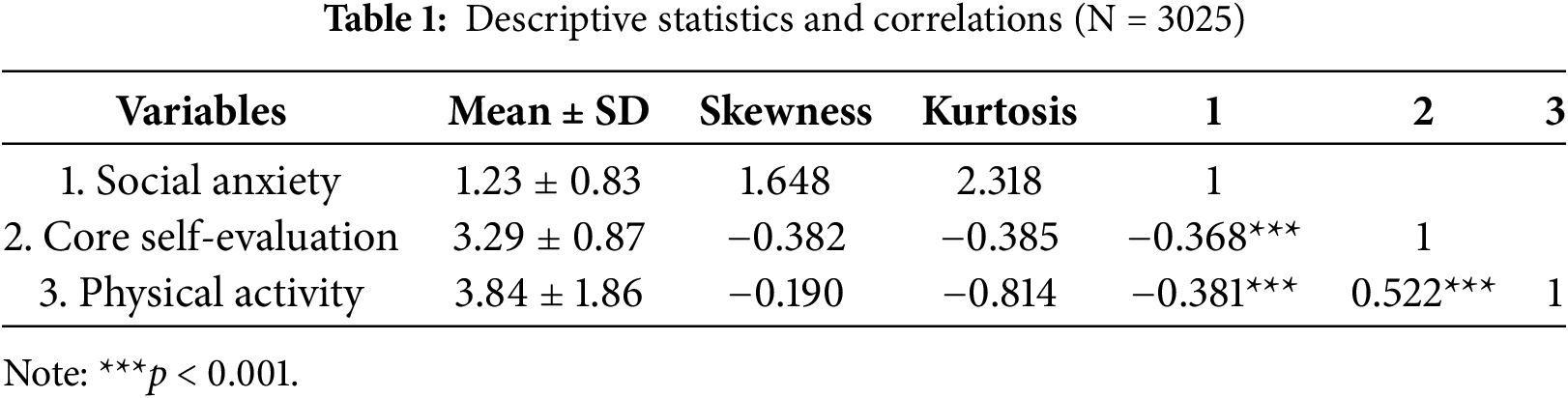

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and correlations for social anxiety, core self-evaluation, and physical activity. Social anxiety (Mean = 1.23, standard deviation [SD] = 0.83) showed significant negative correlations with both core self-evaluation (r = −0.368, p < 0.001) and physical activity (r = −0.381, p < 0.001). Core self-evaluation (Mean = 3.29, SD = 0.87) was positively correlated with physical activity (r = 0.522, p < 0.001).

3.2 Variable-Centered Analysis

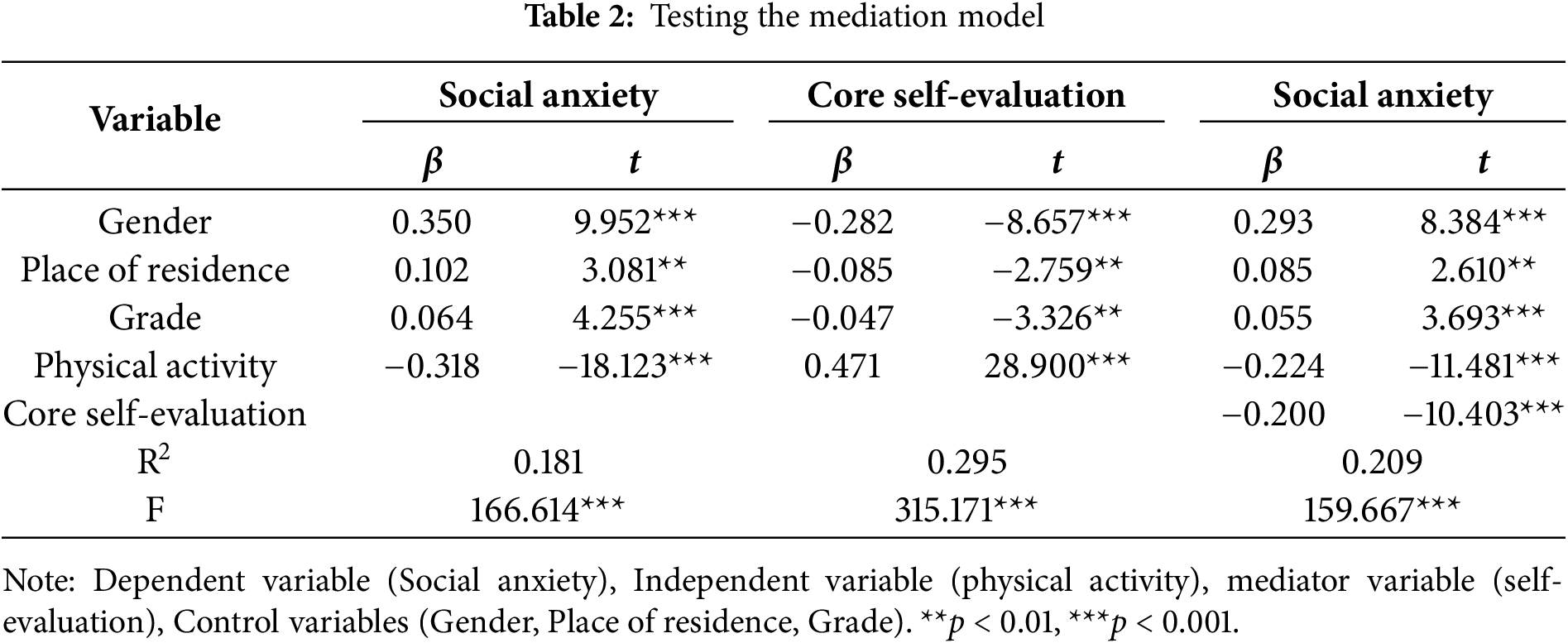

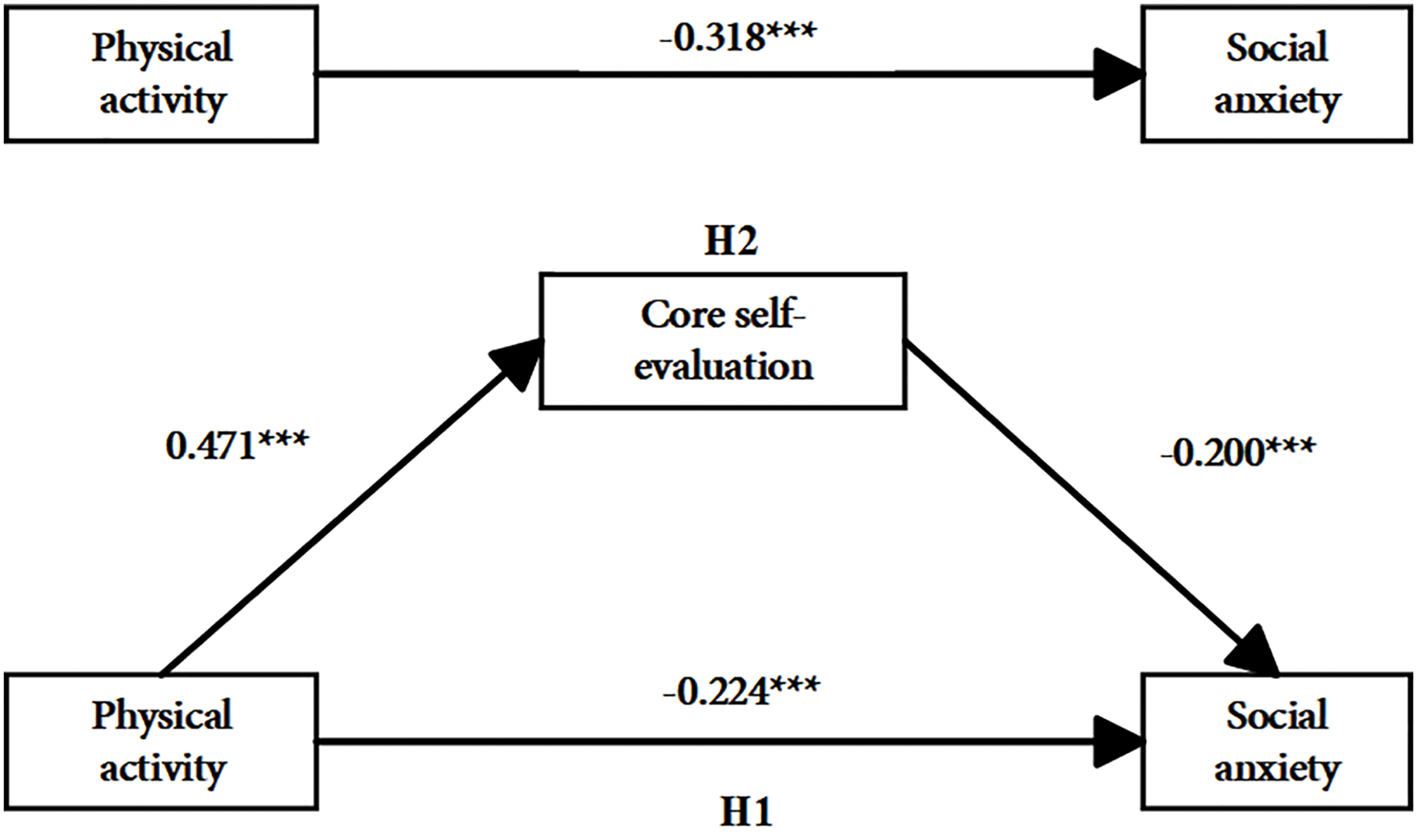

The relationship between physical activity, core self-evaluation, and social anxiety was examined from a variable-centered perspective, with core self-evaluation tested as a mediator. After standardizing all variables, social anxiety was set as the dependent variable, physical activity as the independent variable, and core self-evaluation as the mediator. Gender, grade, and place of residence were included as control variables, and the analysis was conducted using the PROCESS macro. The results showed that physical activity was significantly negatively associated with social anxiety (β = −0.318, p < 0.001) and a significant positive association with core self-evaluation (β = 0.471, p < 0.001). When both physical activity and core self-evaluation were included in the regression, Physical activity still had a significant negative association with social anxiety (β = −0.224, p < 0.001), and core self-evaluation had a significant negative association with social anxiety (β = −0.200, p < 0.001). Additionally, gender showed significant associations with social anxiety (β = 0.350, p < 0.001), core self-evaluation (β = −0.282, p < 0.001), with females reporting higher levels of social anxiety and lower levels of core self-evaluation compared to males. The results are presented in Table 2 and illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Mediation effect diagram. ***p < 0.001

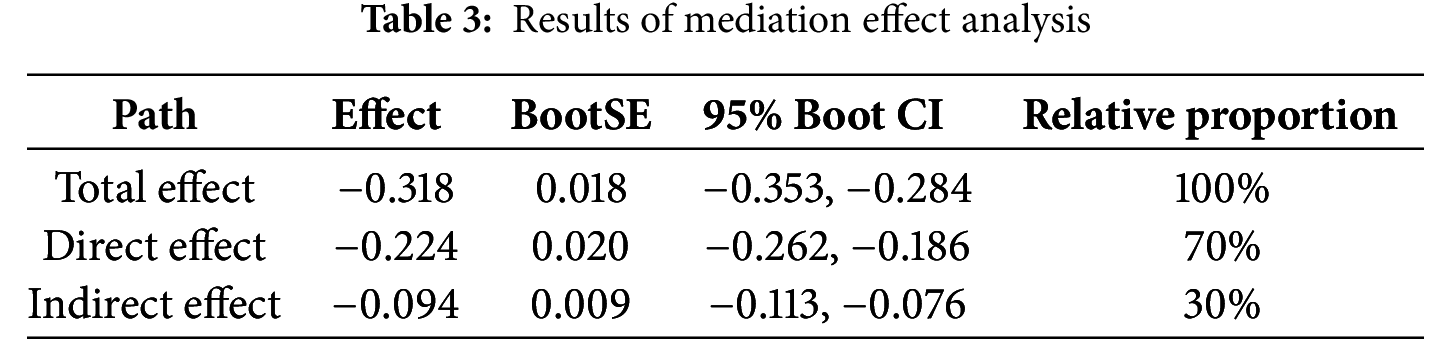

The mediating effect was further tested using the Bootstrap method with 5000 resamples. As shown in Table 3, the 95% CI did not include “0,” with an effect value of −0.09 accounting for 30% of the total effect [69]. Therefore, core self-evaluation has a mediating effect between physical activity and social anxiety.

The relationship between physical activity, core self-evaluation, and social anxiety was further examined from a person-centered perspective. First, based on the 12 adolescent social anxiety scale items, latent profile analysis was conducted using Mplus 8.3, testing models with 1 to 5 profiles. As shown in Table 4, the 2-profile model performed well, with an Entropy value as high as 0.997, indicating clear differentiation of the profiles. The LMR-LRT and BLRT were significant (p < 0.001), and the smallest profile accounted for more than 5% of the sample. Overall, the 2-profile model was the best-fitting model.

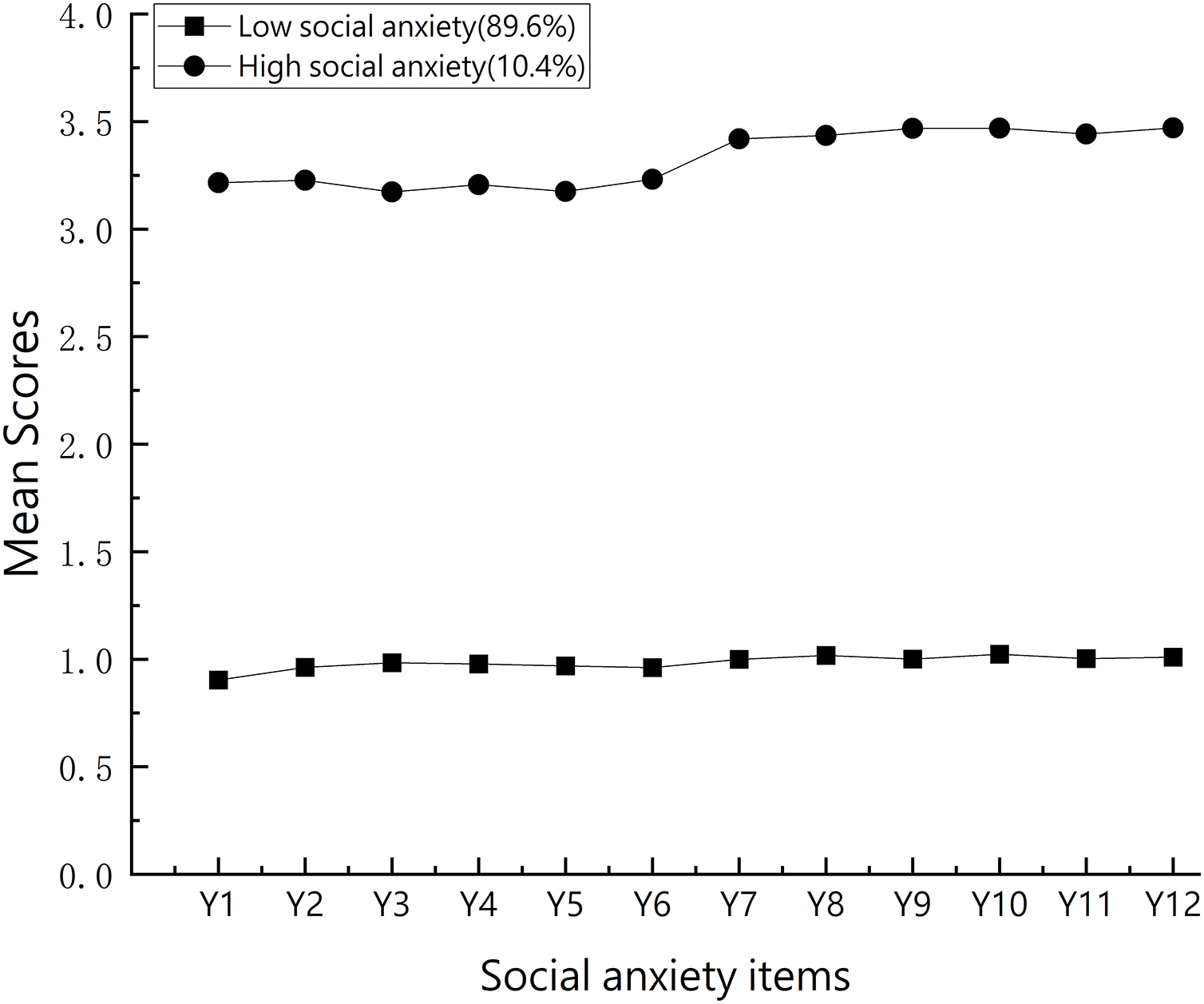

Fig. 2 shows the characteristics of the two identified profiles. Profile 1 (labeled as “low social anxiety profile,” n = 2709, 89.6%) was characterized by mean scores around 1 on all 12 items. Profile 2 (labeled as “high social anxiety profile,” n = 316, 10.4%) was characterized by mean scores all exceeding 3, with no overlap between the two profiles.

Figure 2: Scores and distribution of the two social anxiety profiles. Note: Y1–Y12 represent the 12 items for social anxiety

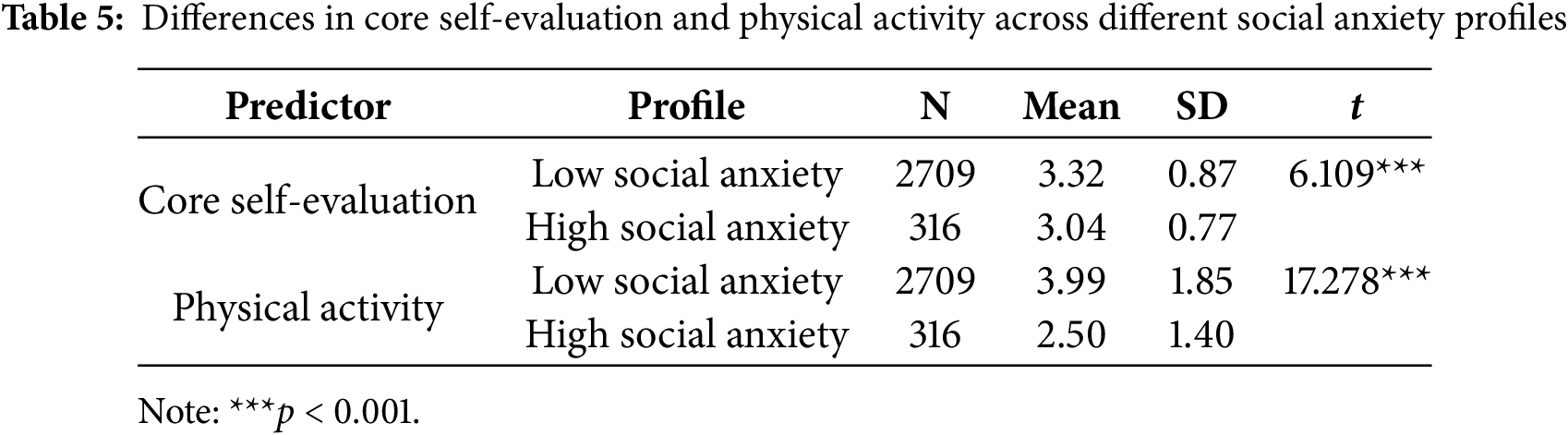

Table 5 shows the differences in core self-evaluation and physical activity across different social anxiety profiles. The high social anxiety profile had significantly lower scores on core self-evaluation and physical activity than the low social anxiety profile.

This study adopted both variable-centered and person-centered analytical approaches. It focused on the predictive role of physical activity in adolescent social anxiety and the mediating role of core self-evaluation. Furthermore, from a person-centered perspective, it identified latent profiles of social anxiety among adolescents and examined the differences in physical activity and core self-evaluation across these profiles. The results from these two approaches complement each other, providing a more in-depth exploration of the factors influencing adolescent social anxiety and offering theoretical support for effective prevention and intervention.

Our study found that physical activity has a negative association with adolescents’ level of social anxiety, thereby supporting Hypothesis 1, and this finding is consistent with previous research [19,31]. According to self-efficacy theory, Physical activity can significantly enhance an individual’s self-efficacy, enabling them to better cope with stressful situations and thereby reducing the level of anxiety [22,70]. Additionally, from the cognitive control perspective, physical activity can effectively change individuals’ erroneous perceptions of external stimuli, reducing anxiety caused by cognitive biases [20,24,25]. Through regular physical activity, adolescents can improve their physical fitness and enhance their social skills in team sports, creating a positive social environment that alleviates social anxiety [71,72]. Therefore, promoting their physical activity habits is one of the more effective approaches to reducing social anxiety in adolescents. Both school and family education should place greater emphasis on cultivating adolescents’ physical activity habits.

This study found that core self-evaluation mediates adolescents’ physical activity and social anxiety, confirming Hypothesis 2. Adolescents can build positive interpersonal interaction patterns through physical activity [73,74]. On this basis of positive interaction, they are more likely to perceive support, understanding, and affirmation from others, recognize their significance and value, and thus evaluate themselves more positively. Meanwhile, as an important psychological resource for individuals, core self-evaluation can enhance their sense of control in coping with stress and difficulties, prompting them to adopt more positive coping strategies to solve problems and face life with a more positive and optimistic attitude and stronger adaptability [75,76]. According to the perspective of self-efficacy theory, individuals with higher core self-evaluation have a stronger motivation to complete tasks. Adolescents with higher core self-evaluation are more confident in handling various matters in life, reducing social anxiety.

Our study also highlights the significant associations of gender with social anxiety, core self-evaluation, and physical activity. The pronounced association of gender with social anxiety, which is even more pronounced than the association with physical activity, suggests that gender differences should be taken into account in interventions aimed at reducing social anxiety. Therefore, families, schools, and society should all value the positive role of physical activity in adolescents’ physical and mental health development. They should guide adolescents to discover their strengths and values during physical activity to improve their core self-evaluation, reduce social anxiety, and develop positive mental health. Future research should further explore the underlying mechanisms of these gender differences and develop targeted interventions that address the specific needs of different genders.

Building on the variable-centered approach, this study introduced a person-centered research perspective. Through latent profile analysis, adolescents’ social anxiety was divided into two potential categories: lowsocial-anxiety type and high-social-anxiety type, thereby supporting Hypothesis 3. It is important to note that these categories were not determined by a median split. The results show that there are significant differences in physical activity habits and core self-evaluation among adolescents in different social anxiety categories. Specifically, adolescents in the low-social-anxiety category have significantly better physical activity habits and higher levels of core self-evaluation than those in the high-social-anxiety category. This result corroborates the variable-centered research findings: individuals with good physical activity habits tend to have higher core self-evaluation, predicting lower social anxiety levels.

On the other hand, looking at the scores of adolescents in each potential category on the relevant indicators, it can be seen that the overall level of physical activity habits and core self-evaluation among adolescents is in the lower-middle range, similar to previous research findings. According to the social ecological model [77], adolescent physical activity evolves gradually. Early adolescence is shaped mainly by family and school influences, and later by peers, community, and broader social and cultural factors, gradually stabilizing into lasting habits. The subjects of this study are in the middle adolescence stage, and their physical activity habits and core self-evaluation are still in the development stage. Meanwhile, studies have shown that restricted environments can affect the development of adolescents’ physical activity habits and core self-evaluation. For example, some adolescents may have fewer opportunities to participate in physical activity due to factors such as family economic conditions, insufficient school sports resources, or lack of peer support, thereby affecting the improvement of their core self-evaluation. These additional barriers and factors can exacerbate adolescents’ challenges, resulting in lower physical activity habits and core self-evaluation levels.

Furthermore, it is worth noting that adolescents in the high social anxiety category had significantly lower scores in physical activity habits and core self-evaluation than those in the other category. First, this pattern aligns with findings from previous studies and supports developmental contextual theory [78]. Developmental contextual theory proposes that physical activity habits begin in adolescence as a single, undifferentiated dimension and gradually evolve into a differentiated, multifactor structure as adolescents interact with expanding social and environmental contexts [79,80]. This change is related to cognitive functions and brain development [81]. Most of the subjects in this survey are in the middle adolescence stage, and the results show that this developmental change is also the case among adolescents. Second, developing physical activity habits involves multiple aspects, including individuals’ interest in sports activities, the frequency and intensity of their participation, and the sense of achievement they gain from sports activities [82]. The reason why adolescents in the high-social-anxiety category have lower core self-evaluation scores may be related to their lack of sufficient opportunities for physical activity during their growth.

This study integrates both variable-centered and person-centered perspectives. Based on self-efficacy theory and cognitive control theory, it explores the mediating mechanism of core self-evaluation in the relationship between physical activity and social anxiety. It also finds that adolescents can be divided into subgroups based on different physical activity habits and core self-evaluation combinations. This provides new ideas for future in-depth research on social anxiety and has important practical guiding significance for the prevention and intervention of social anxiety in adolescents.

To begin with, educators and parents should pay attention to cultivating adolescents’ physical activity habits and improving their core self-evaluation, and recognize the importance of physical activity and core self-evaluation for individual growth and development. Early adolescence is critical for developing physical activity habits, core self-evaluation, and forming stable values. Physical activity and core self-evaluation can help adolescents coordinate personal goals with the demands of the external environment, achieve harmonious development between the self and the environment, and promote positive autonomous development in adolescents.

Next, when guiding adolescents’ growth, educators and parents should focus on guiding them to set reasonable goals and provide beneficial environmental resources for their growth, for example, by understanding adolescents’ psychological needs and helping them clarify their growth goals and values according to external environmental requirements and their actual situations, especially in establishing a positive self-perception to achieve a higher level of core self-evaluation.

Lastly, educators and parents should pay attention to differences among groups. For adolescents with different levels of social anxiety, schools can conduct tiered psychological counseling and group activities. For example, small-group counseling can be conducted to help adolescents in the high-social-anxiety category gradually overcome social barriers and improve their social skills. Schools can also popularize knowledge about social anxiety through mental health education courses to help students correctly understand and cope with social anxiety.

This study has certain limitations. First, this study is a cross-sectional study. Physical activity and core self-evaluation are variables that change over time. Therefore, future research needs to supplement longitudinal studies to explore these variables’ dynamic development and changes. Second, the research on the mediating mechanism of core self-evaluation is still insufficient. Future research should introduce more third variables (such as family support, peer relationships, etc.) to explore the key factors influencing social anxiety. Third, our study utilized a convenience sampling method, drawing participants from ten middle schools in Jiangxi Province. This non-random sampling approach may limit the generalizability of our findings. While our sample size is large, the results may not be representative of all adolescents in China. Future research should aim to use more diverse and representative samples to confirm these findings. In addition, the measurement tools used in this study may have limitations. For example, the single-item measure of physical activity may not fully reflect an individual’s activity level, and the applicability of the core self-evaluation scale may be affected by cultural background. Future research should consider using more comprehensive measurement tools to improve the accuracy and reliability of the results. Finally, this study did not collect more relevant demographic variables (such as family economic status, parents’ education level, etc.), and the sample was mainly from urban areas. Future research should consider more control variables and require more samples to further verify the universality of the results.

Using a sample of 3025 Chinese adolescents, this study applied both variable-centered and person-centered approaches to examine the associations among physical activity, core self-evaluation, and social anxiety. Variable-centered analyses revealed that physical activity exerted a significant negative association with social anxiety and that core self-evaluation partially mediated this link, accounting for 30% of the total effect. Person-centered latent profile analysis identified an optimal two-profile solution: a low social-anxiety profile (89.6%) and a high social-anxiety profile (10.4%). The high-anxiety profile reported markedly lower levels of both physical activity and core self-evaluation than the low-anxiety profile. For the first time in an adolescent population, the findings integrate evidence from both analytical perspectives, establish physical activity and core self-evaluation as modifiable protective factors against social anxiety, and validate a two-profile structure of social anxiety. These results provide a theoretical foundation and practical guidance for tiered and targeted school-based mental-health interventions. Schools and families are encouraged to jointly promote adolescents’ engagement in physical activity and foster positive self-evaluations, while delivering specially tailored support for those at elevated risk.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank all the participants in the study and all the research team members who supported its completion.

Funding Statement: The Ministry of Education of China supported this work under the Humanities and Social Sciences Research Project for Young Scholars (Grant No. 20YJC890020).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Huazhe Wan and Wenying Huang; methodology, Huazhe Wan and Wen Zhang; formal analysis, Wen Zhang and Chang Hu; data curation, Chang Hu and Huazhe Wan; writing—original draft preparation, Huazhe Wan and Wenying Huang; writing—review and editing, Wenying Huang and Wen Zhang; funding acquisition, Wenying Huang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the Corresponding Author, Chang Hu, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Science and Technology, Nanchang Hangkong University (IRB-NCHU-STC-20250103).

Informed Consent: All participants and their legal guardians provided informed consent.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Leichsenring F, Leweke F. Social anxiety disorder. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(23):2255–64. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1614701. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Stein MB, Stein DJ. Social anxiety disorder. Lancet. 2008;371(9618):1115–25. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60488-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Akbari A, Torabizadeh C, Nick N, Setoodeh G, Ghaemmaghami P. The effects of training female students in emotion regulation techniques on their social problem-solving skills and social anxiety: a randomized controlled trial. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2025;19(1):3. doi:10.1186/s13034-025-00860-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Wu P, Cao K, Feng W, Lv S. Cross-lagged analysis of rumination and social anxiety among Chinese college students. BMC Psychol. 2024;12(1):28. doi:10.1186/s40359-023-01515-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Morrison AS, Goldin PR, Gross JJ. Fear of negative and positive evaluation as mediators and moderators of treatment outcome in social anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2024;104(2):102874. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2024.102874. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Jefferies P, Ungar M. Social anxiety in young people: a prevalence study in seven countries. PLoS One. 2020;15(9):e0239133. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0239133. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Zhao K, Liu Y, Shi Y, Bi D, Zhang C, Chen R, et al. Mobile phone addiction and interpersonal problems among Chinese young adults: the mediating roles of social anxiety and loneliness. BMC Psychol. 2025;13(1):372. doi:10.1186/s40359-025-02686-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Flotte E. Social anxiety, academic self-efficacy, and course performance in pre-nursing students enrolled in human anatomy and physiology I and II. Physiology. 2023;38(S1):5734653. doi:10.1152/physiol.2023.38.s1.5734653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Gilboa-Schechtman E, Keshet H, Peschard V, Azoulay R. Self and identity in social anxiety disorder. J Personal. 2020;88(1):106–21. doi:10.1111/jopy.12455. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Wu D, Liu M, Li D, Yin H. The longitudinal relationship between loneliness and both social anxiety and mobile phone addiction among rural left-behind children: a cross-lagged panel analysis. J Adolesc. 2024;96(5):969–82. doi:10.1002/jad.12309. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Oren-Yagoda R, Melamud-Ganani I, Aderka IM. All by myself: loneliness in social anxiety disorder. J Psychopathol Clin Sci. 2022;131(1):4–13. doi:10.1037/abn0000705. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. O’Day EB, Butler RM, Morrison AS, Goldin PR, Gross JJ, Heimberg RG. Reductions in social anxiety during treatment predict lower levels of loneliness during follow-up among individuals with social anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2021;78:102362. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102362. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Kerr B, Garimella A, Pillarisetti L, Charlly N, Sullivan K, Moreno MA. Associations between social media use and anxiety among adolescents: a systematic review study. J Adolesc Health. 2025;76(1):18–28. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2024.09.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Tandon PS, Zhou C, Johnson AM, Gonzalez ES, Kroshus E. Association of children’s physical activity and screen time with mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(10):e2127892. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.27892. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Chen W, Yang T, Luo J. Core self-evaluation and subjective wellbeing: a moderated mediation model. Front Public Health. 2022;10:1036017. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.1036071. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Wu J, Shao Y, Zang W, Hu J. The influence of leisure-time physical activity and peer relationships on cyberbullying among adolescents: a one-year longitudinal investigation. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2025;27(5):717–35. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2025.061576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Yu L, Li J, Zou L, Chen Y, Werneck AO, Herold F, et al. Associations of physical activity and sedentary behavior with internalizing problems among youth with chronic pain. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2025;27(2):97–110. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2025.061237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Lee YH, Park Y, Kim H. The effects of accumulated short bouts of mobile-based physical activity programs on depression, perceived stress, and negative affectivity among college students in South Korea: quasi-experimental study. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2024;26(7):569–78. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2024.051773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Wu J, Shao Y, Hu J, Zhao X. The impact of physical exercise on adolescent social anxiety: the serial mediating effects of sports self-efficacy and expressive suppression. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil. 2025;17(1):57. doi:10.1186/s13102-025-01107-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Aumer T, Vögele C. Anxiety reducing effects of physical activity in adolescents and young adults. Eur J Health Psychol. 2025;32(2):87. doi:10.1027/2512-8442/a000168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Biddle S. Physical activity and mental health: evidence is growing. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(2):176–7. doi:10.1002/wps.20331. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Bandura A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am Psychol. 1982;37(2):122–47. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ringeisen T, Lichtenfeld S, Becker S, Minkley N. Stress experience and performance during an oral exam: the role of self-efficacy, threat appraisals, anxiety, and cortisol. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2019;32(1):50–66. doi:10.1080/10615806.2018.1528528. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Sheng X, Wen X, Liu J, Zhou X, Li K. Effects of physical activity on anxiety levels in college students: mediating role of emotion regulation. PeerJ. 2024;12(2):e17961. doi:10.7717/peerj.17961. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Jones JD, Timblin H, Rahmani E, Garrett S, Bunch J, Beaver H, et al. Physical activity as a mediator of anxiety and cognitive functioning in Parkinson’s disease. Ment Health Phys Act. 2021;20(3):100382. doi:10.1016/J.MHPA.2021.100382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Anker EA, Bøe Sture SE, Hystad SW, Kodal A. The effect of physical activity on anxiety symptoms among children and adolescents with mental health disorders: a research brief. Front Psychiatry. 2024;15:1254050. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1254050. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Biddle SJH, Ciaccioni S, Thomas G, Vergeer I. Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: an updated review of reviews and an analysis of causality. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2019;42(4):146–55. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.08.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Dimech AS, Seiler R. The association between extra-curricular sport participation and social anxiety symptoms in children. J Clin Sport Psychol. 2010;4(3):191–203. doi:10.1123/JCSP.4.3.191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Panza MJ, Graupensperger S, Agans JP, Doré I, Vella SA, Evans MB. Adolescent sport participation and symptoms of anxiety and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2020;42(3):201–18. doi:10.1123/jsep.2019-0235. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Jetten J, Haslam C, Von Hippel C, Bentley SV, Cruwys T, Steffens NK, et al. Let’s get physical—or social: the role of physical activity versus social group memberships in predicting depression and anxiety over time. J Affect Disord. 2022;306(8):55–61. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2022.03.027. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Wu J, Shao Y, Zang W, Hu J. Is physical exercise associated with reduced adolescent social anxiety mediated by psychological resilience?: evidence from a longitudinal multi-wave study in China. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2025;19(1):17. doi:10.1186/s13034-025-00867-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Yan W, Wang Y, Yuan Y, Farid M, Zhang P, Peng K. Timing matters: a longitudinal study examining the effects of physical activity intensity and timing on adolescents’ mental health outcomes. J Youth Adolesc. 2024;53(10):2320–31. doi:10.1007/s10964-024-02011-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Hobfoll SE, Halbesleben J, Neveu J-P, Westman M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: the reality of resources and their consequences. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2018;5(1):103–28. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Liu M, Wu L, Ming Q. How does physical activity intervention improve self-esteem and self-concept in children and adolescents? Evidence from a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0134804. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0134804. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Zeb I, Khan A, Yan Z. Exploring the influence of core self-evaluation on students’ academic self-efficacy: a qualitative study considering anxiety and interpersonal responses. J Appl Res High Educ. 2025;17(1):526–41. doi:10.1108/jarhe-07-2024-0343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Judge TA. Core self-evaluations and work success. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2009;18(1):58–62. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01606.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Peng B, Chen W, Wang H, Yu T. How does physical exercise influence self-efficacy in adolescents? A study based on the mediating role of psychological resilience. BMC Psychol. 2025;13(1):1–17. doi:10.1186/s40359-025-02529-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Li X, Wang J, Yu H, Liu Y, Xu X, Lin J, et al. How does physical activity improve adolescent resilience? Serial indirect effects via self-efficacy and basic psychological needs. PeerJ. 2024;12(2):e17059. doi:10.7717/peerj.17059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Wallman-Jones A, Eigensatz M, Rubeli B, Schmidt M, Benzing V. The importance of body perception in the relationship between physical activity and self-esteem in adolescents. Int J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2024;14(1):1–23. doi:10.1080/1612197x.2024.2428194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Erez A, Judge TA. Relationship of core self-evaluations to goal setting, motivation, and performance. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86(6):1270–9. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.6.1270. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Chang C-H, Ferris DL, Johnson RE, Rosen CC, Tan JA. Core self-evaluations. J Manag. 2012;38(1):81–128. doi:10.1177/0149206311419661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Csibi S, Csibi M, Bognár J. Preventing health anxiety: the role of self-evaluation, sense of coherence, self-rated health and perceived social support. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2023;25(10):1081–8. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2023.029390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Yudes C, Chamizo-Nieto MT, Peláez-Fernández MA, Extremera N. Core self-evaluations and perceived classmate support: independent predictors of psychological adjustment. Scand J Psychol. 2025;66(1):150–7. doi:10.1111/sjop.13072. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Hosseini Z, Homayuni A. Personality and occupational correlates of anxiety and depression in nurses: the contribution of role conflict, core self-evaluations, negative affect and bullying. BMC Psychol. 2022;10(1):215. doi:10.1186/s40359-022-00921-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Howard MC, Hoffman M. Variable-centered, person-centered, and person-specific approaches. Organ Res Methods. 2018;21(4):846–76. doi:10.1177/1094428117744021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Feczko E, Miranda-Dominguez O, Marr M, Graham AM, Nigg JT, Fair DA. The heterogeneity problem: approaches to identify psychiatric subtypes. Trends Cogn Sci. 2019;23(7):584–601. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2019.03.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Spurk D, Hirschi A, Wang M, Valero D, Kauffeld S. Latent profile analysis: a review and how to guide of its application within vocational behavior research. J Vocat Behav. 2020;120(1):103445. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Zhang M, Zhang C, Jiang Z, Liu Y. A latent profile analysis of social anxiety among Chinese left-behind children and adolescents: associations with online parent-child communication and online social capital. Child Abus Negl. 2024;158(6):107102. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2024.107102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Yu M, Zhou H, Wang M, Tang X. The heterogeneity of social anxiety symptoms among Chinese adolescents: results of latent profile analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;274(1):935–42. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. New York, NY, USA: Routledge; 2013. doi:10.4324/9780203771587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Coelho SG, Keough MT, Hodgins DC, Shead NW, Parmar PK, Kim HS. Latent profile analyses of addiction and mental health problems in two large samples. Int J Ment Health Addct. 2025;23(1):70–92. doi:10.1007/s11469-022-01003-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Wang M-C, Deng Q, Bi X, Ye H, Yang W. Performance of the entropy as an index of classification accuracy in latent profile analysis: a monte carlo simulation study. Acta Psychol Sin. 2017;49(11):1473. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1041.2017.01473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Wang J, Xiao T, Liu Y, Guo Z, Yi Z. The relationship between physical activity and social network site addiction among adolescents: the chain mediating role of anxiety and ego-depletion. BMC Psychol. 2025;13(1):477. doi:10.1186/s40359-025-02785-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Uddin R, Salmon J, Islam SMS, Khan A. Physical education class participation is associated with physical activity among adolescents in 65 countries. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):22128. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-79100-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Roberts CJ, Ryan DJ, Campbell J, Hardwicke J. Self-reported physical activity and sedentary behaviour amongst UK university students: a cross-sectional case study. Crit Public Health. 2024;34(1):1–17. doi:10.1080/09581596.2024.2338182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Huang W, Chen B, Hu C. The latent profile structure of negative emotion in female college students and its impact on eating behavior: the mediating role of physical exercise. Front Public Health. 2025;13:1663474. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2025.1663474. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Judge TA, Erez A, Bono JE, Thoresen CJ. The core self-evaluations scale: development of a measure. Pers Psychol. 2003;56(2):303–31. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2003.tb00152.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Liu F, Zhu Z, Jiang B. The influence of Chinese college students’ physical exercise on life satisfaction: the chain mediation effect of core self-evaluation and positive emotion. Front Psychol. 2021;12:763046. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.763046. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Ma G, Han Z, Ma X. Core self-evaluation and innovative behavior: mediating effect of error orientation and self-efficacy of nurses. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1298986. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1298986. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Peters L, Sunderland M, Andrews G, Rapee RM, Mattick RP. Development of a short form social interaction anxiety (SIAS) and social phobia scale (SPS) using nonparametric item response theory: the SIAS-6 and the SPS-6. Psychol Assess. 2012;24(1):66–76. doi:10.1037/a0024544. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Li X, Liu Y, Rong F, Wang R, Li L, Wei R, et al. Physical activity and social anxiety symptoms among Chinese college students: a serial mediation model of psychological resilience and sleep problems. BMC Psychol. 2024;12(1):440. doi:10.1186/s40359-024-01937-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Chau AKC, So SH, Sun X, Zhu C, Chiu C-D, Chan RCK, et al. The co-occurrence of multidimensional loneliness with depression, social anxiety and paranoia in non-clinical young adults: a latent profile analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:931558. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.931558. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Shi Y, Kong F, Zhu M. How does social media usage intensity influence adolescents’ social anxiety: the chain mediating role of imaginary audience and appearance self-esteem. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2024;26(12):977–85. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2024.057596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Wang Y, Yan X, Liu L, Lu X, Luo L, Ding X. The influence of vulnerable narcissism on social anxiety among adolescents: the mediating role of self-concept clarity and self-esteem. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2024;26(6):429–38. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2024.050445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Hayes AF, Montoya AK, Rockwood NJ. The analysis of mechanisms and their contingencies: process versus structural equation modeling. Australas Mark J. 2017;25(1):76–81. doi:10.1016/j.ausmj.2017.02.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Vrieze SI. Model selection and psychological theory: a discussion of the differences between the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). Psychol Meth. 2012;17(2):228–43. doi:10.1037/a0027127. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Vermunt JK. The Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin test for latent class and latent profile analysis: a note on the different implementations in Mplus and LatentGOLD. Methodology. 2024;20(1):72–83. doi:10.5964/meth.12467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(3):879–91. doi:10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Deng J, Liu Y, Wang T, Li W. The association between physical activity and anxiety in college students: parallel mediation of life satisfaction and self-efficacy. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1453892. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2024.1453892. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Chen S, Jing L, Li C, Wang H. Exploring the Nexus between moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, self-disclosure, social anxiety, and adolescent social avoidance: insights from a cross-sectional study in central China. Children. 2023;11(1):56. doi:10.3390/children11010056. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Bell SL, Audrey S, Gunnell D, Cooper A, Campbell R. The relationship between physical activity, mental wellbeing and symptoms of mental health disorder in adolescents: a cohort study. Int J Behav Nutr Phy. 2019;16(1):138. doi:10.1186/s12966-019-0901-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Lin H, Wang B, Hu Y, Song X, Zhang D. Physical activity and interpersonal adaptation in Chinese adolescents after COVID-19: the mediating roles of self-esteem and psychological resilience. Psychol Rep. 2024;127(3):1156–74. doi:10.1177/00332941221137233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Yang S, Jing L, He Q, Wang H. Fostering emotional well-being in adolescents: the role of physical activity, emotional intelligence, and interpersonal forgiveness. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1408022. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1408022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Kammeyer-Mueller JD, Judge TA, Scott BA. The role of core self-evaluations in the coping process. J Appl Psychol. 2009;94(1):177–95. doi:10.1037/a0013214. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Wang Q, Duan R, Han F, Huang B, Wang W, Wang Q. The impact of core self-evaluation on school adaptation of high school students after their return to school during the COVID-19 pandemic: the parallel mediation of positive and negative coping styles. PeerJ. 2023;11(538):e15871. doi:10.7717/peerj.15871. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Maher JP, Villarreal A, Behler M, Hudgins BL, Murray E, Postlethwait EM, et al. A daily analysis of adolescent girls’ physical activity using a social ecological model lens. Women Sport Phys Act J. 2025;33(1):179. doi:10.1123/wspaj.2024-0124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Lerner RM, Kauffman MB. The concept of development in contextualism. Dev Rev. 1985;5(4):309–33. doi:10.1016/0273-2297(85)90016-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Avraham R, Simon-Tuval T, Van Dijk D. Determinants of physical activity habit formation: a theory-based qualitative study among young adults. Int J Qual Stud Heal. 2024;19(1):2341984. doi:10.1080/17482631.2024.2341984. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Hagger MS. Habit and physical activity: theoretical advances, practical implications, and agenda for future research. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2019;42:118–29. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.12.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Johnson M, Munakata Y. Processes of change in brain and cognitive development. Trends Cogn Sci. 2005;9(3):152–8. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2005.01.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Baretta D, Gillmann N, Edgren R, Inauen J. HabitWalk: a micro-randomized trial to understand and promote habit formation in physical activity. Appl Psychol Health Well-Being. 2025;17(1):e12605. doi:10.1111/aphw.12605. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools