Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

How Does Physical Activity Shape Adolescents’ Coping Skills? Unveiling the Chain Mediation of Friendship Quality and Psychological Resilience

1 School of Physical Education and Sports Science, Soochow University, Suzhou, 215021, China

2 School of Foreign Languages, Shandong University of Political Science and Law, Jinan, 250014, China

3 College of Education Sciences, The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (Guangzhou), Guangzhou, 511355, China

* Corresponding Author: Songjian Du. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to be the co-first authors

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Active Living, Active Minds: Promoting Mental Health through Physical Activity)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(3), 333-345. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.062297

Received 15 December 2024; Accepted 28 February 2025; Issue published 31 March 2025

Abstract

Background: Adolescents face increasing academic and social pressures, which significantly impact their mental well-being and coping strategies. Physical activity (PA) has been recognized as crucial in promoting psychological resilience and social development. This study investigates the relationship between PA and adolescents’ coping styles, with a particular focus on the mediating roles of friendship quality and psychological resilience. By examining these associations, the study aims to provide insights into how PA contributes to adolescents’ ability to navigate challenges and develop adaptive coping mechanisms. Methods: This study employed a cross-sectional design and was conducted in Suzhou, Jiangsu Province, China. A total of 2288 high school students aged 15–18 were recruited using a convenience sampling approach. Data were collected through validated self-report questionnaires measuring PA, friendship quality, psychological resilience, and coping styles. Pearson correlation analysis and structural equation modelling (SEM) were applied to examine the relationships between variables and assess the mediating effects of friendship quality and psychological resilience in the association between PA and coping styles. Results: Significant positive correlations among variables: PA positively correlated with friendship quality (r = 0.29, p < 0.01), psychological resilience (r = 0.26, p < 0.01), and coping styles (r = 0.26, p < 0.01). Friendship quality and psychological resilience mediated the relationship between PA and coping styles, with direct effects accounting for 47.85% of the total effect. Indirect effects were distributed among three pathways: via friendship quality (15.38%), psychological resilience (27.56%), and a chain mediation of both (11.22%). Conclusion: The findings highlight the significant role of PA in enhancing adolescents’ coping styles, with friendship quality and psychological resilience as key mediators. These results underscore the importance of promoting PA to strengthen social bonds, build resilience, and improve adaptive coping mechanisms among adolescents. Future research should explore additional mediating factors and employ longitudinal or experimental designs to establish causal relationships.Keywords

With the improvement of the living conditions of contemporary teenagers, the pressures and challenges they face are also diversified, including the academic pressure from the family’s expectations [1]. In particular, the rise in the rate of depression among adolescents due to increased academic demands has become a concern, and adolescents are expected by both school and family [2]. For example, cyberbullying is more likely to be impulsive and immature for teenagers, which has become the focus of youth protection organizations. It can be seen that adolescents’ stress comes from family dynamics and external factors in society [3]. Therefore, participation in physical activity (PA) is essential for adolescents, as regular PA has a strong positive association with improved adolescent mental health [4]. In addition, sports participation provides opportunities for social interaction, which enhances opportunities for adolescents to participate in society [5]. This underscores the need for a multifaceted approach to addressing adolescent stress, with PA being just one part of the solution.

PA is the satisfaction of people’s self-selection according to their physical needs through various physical means, including the combined application of natural forces and hygiene measures [4]. On the one hand, its goal is to develop quality and regulate the spirit; on the other hand, it also helps to optimize the structure of leisure time. PA is a structured movement-based activity in which the body functions as an integrated unit [6]. For adolescents, exercise ranges from organized team sports to individual pursuits such as jogging, swimming, basketball, and other forms of physical exertion [6]. The primary forms of youth sports include school-based courses and extracurricular clubs. Sports play an indispensable role in education by fostering teamwork and communication skills [7,8]. Additionally, PA stimulates students’ creativity and nurtures innovative thinking and problem-solving abilities [9,10].

First, when discussing the effect of PA on the quality of adolescent friendship, the early quality of sports friendship was developed in psychology, which believed that the strength of individual sports ability was positively correlated with peer friendship [11]. Team participation in PA increases the frequency of social interaction and team cooperation among adolescents [12]. Through intimate experience with different groups, adolescents can gain experience maintaining friendship quality. Similarly, team sports serve as a problem-solving process that requires cooperation and trust, can foster mutual support among peers, and is a manifestation of strengthened emotional bonds [13]. In addition, adolescents who participate in sports often develop friendships based on shared interests and common goals, providing more of a bond for friendship development [12]. At the same time, the quality of friendship also inversely promotes PA, especially for adolescents, and peer acceptance and recognition can encourage adolescents to participate in physical activities and persist actively. In addition, Sarkar and Fletcher’s [14] research also confirmed that individuals with higher emotional security have higher motivation to participate in sports and have a more positive attitude when seeking external support.

Taking part in PA is also an effective measure to shape the mental resilience of teenagers. The higher the exercise motivation, the more significant the correlation of PA on mental resilience, reflected in adolescents’ goal focus and positive cognitive dimension [15]. The reason for the positive correlation between sports motivation and adolescents’ mental resilience may be that adolescents with subjectively “participative” motivation have better mental resilience than those with subjectively “avoidant” motivation [5,16]. Whisman et al. [17] analyzed that PA promotes the mental resilience of adolescents by instilling perseverance and coping skills to learn to overcome challenges and resolve failures. In addition, PA is biologically designed to stimulate the release of endorphins, which directly increase mood and reduce stress [18]. Related brain science research has also found that the brain’s executive function can be stimulated by sports, which not only promotes the cultivation of brain activity on the concentration of teenagers but also reduces the symptoms of depression to the greatest extent [19]. It can be seen that PA can comprehensively improve teenagers’ psychological state and significantly enhance their life anti-pressure ability and interpersonal relationships [20].

In particular, it should be noted that there is a strong relationship between the quality of friendship and the psychological resilience of adolescents [21]. Adolescents who have friendships are associated with a stronger sense of belonging and are more likely to have better mental health as adults [22]. This means that adolescents who lack friendship can suffer psychological damage, possibly social anxiety and a low sense of self-worth, in the same way that physical pain stimulates the brain. Adolescents who engage in PA tend to experience higher-quality friendships, which in turn contributes to greater mental resilience [23]. Strong friendships provide a support network during times of stress and improve adolescents’ ability to cope with adversity [24]. In addition, the shared experiences and challenges of sports participation strengthen bonds among peers and foster resilience through social support [25].

In general, PA plays a vital role in promoting the health and development of adolescents. Providing adolescents with a foundation of valuable skills and resources can also cultivate friendship qualities and enhance mental resilience, enabling them to successfully cope with adolescence’s challenges. Recognizing the multifaceted benefits of PA, policymakers, educators, and parents should prioritize and support opportunities for youth to participate in PA. Therefore, the current study intends to explore the correlation between youth PA on their coping styles and its internal role mechanism, comprehensively considering the independent mediating role and chain mediating role of friendship quality and psychological resilience in the relationship between adolescent PA and coping styles. We hypothesize that physical activity positively correlates with coping styles (Hypothesis 1) and that friendship quality and psychological resilience mediate this relationship (Hypothesis 2).

2.1 Study Design and Participants

This study primarily utilized a correlational design as its research method. We conducted a large-scale survey in Suzhou, Jiangsu Province, China, between August and September 2024. Five public and three private high schools were invited to participate using a convenience sampling method. One to three classes were randomly selected for each school, and a designated contact person was assigned to coordinate the process. Once a school expressed interest in joining the study, the first author contacted school representatives, such as the principal or administrative staff, via email, phone, or Zoom to provide a comprehensive overview of the study’s objectives, requirements, and procedures. The administration of self-report scales was conducted on-site by school personnel, including teachers or the headmaster, who facilitated distributing and completing the paper-based questionnaires. The study recruited an initial cohort of 2607 adolescents and children aged 15 to 18 through this process.

Participants who provided complete and relevant information on the variables of interest were included in this study. Conversely, individuals who did not report data on any of the required variables (e.g., independent variables, outcome measures, or covariates) were excluded from the initial sample. Ultimately, a total of 2288 participants, representing a response rate of 87.7%, were retained for this study and subsequent analyses, as they submitted valid and comprehensive data for the variables under investigation. Permission to conduct this study was secured from the teachers and principals of the participating schools. The adolescents involved and their parents or guardians were informed about the study, and participation was voluntary. All participants signed the informed consent in this study. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Soochow University (Approval No. SUDA20240626H06). The procedures followed were in accordance with the National Research Committee guidelines and the 1964 Helsinki Declaration, including its later amendments or comparable ethical standards [26]. Data was collected and analyzed anonymously.

PA was investigated with the Physical Activity Rating Scale (PAR-SC) that used to evaluate PA intensity, frequency, and duration in the past month using three questions. Light-to-vigorous intensity refers to PA that is performed in different sports. The duration of the questionnaire is measured in minutes, and the activity frequency is days. The PA participants’ exercise and sports participation levels were calculated using the formula of “physical activity amount = weekly activity frequency score * (each activity time score-1) * activity intensity score”. The judgment criteria are a low sports participation level of 19 points, a middle sports participation level of 20–42 points, and a high sports participation level of 43 points [27]. The higher the scale scores, the higher the individual exercise levels. The reliability test of PAR-SC is 0.89.

Shi et al. compiled the Youth Sports Friendship Quality Scale (YSFQ-SC), which combined 25 items suitable for Chinese youth students [28]. The scale has six dimensions, which are respectively sports support (3 items), common ground and communication (9 items), increased self-esteem (3 items), positive personal quality (3 items), accompanying and sports pleasure (4 items), conflict resolution (3 items). This scale uses a five-point Likert scale from strongly disagreeing to strongly agreeing. The reliability test of YSFQ-SC is 0.87. The score is the sum of the numbers between 25 and 125. A higher score implies better FQ.

Chen et al. developed the Psychological Resilience Scale (PR-SC), comprising 27 items specifically designed for Chinese youth students. The scale is structured into five dimensions: target focus (5 items), emotional control (6 items), positive cognition (4 items), family support (6 items), and interpersonal assistance (6 items). The first three dimensions assess individual internal factors, while the latter two evaluate external support factors. Responses are measured on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree,” providing a comprehensive evaluation of psychological resilience. The score is the sum of the numbers between 27 and 135 [29]. A higher score implies better PR.

Li et al. compiled the Coping Styles Scale (CS-SC), which combines 30 items suitable for Chinese middle school students. The scale has six dimensions: problem-solving (8 items), asking for help (7 items), patience (3 items), fantasy (3 items), venting (4 items), and retreat (5 items). The first two dimensions measure positive coping styles and the last four measure negative coping styles. This scale uses a five-point Likert scale from never to always. The reliability test of CS-SC is 0.78 [30].

Several important demographic information such as age, subjective family socioeconomic status (a 10-rung ladder with higher scores indicating better SES [31]), sex (male/female), location (urban/rural), siblings (only child/non-only child), grade (grade 10/grade 11/grade 12), ethnicity (Han/minority), parental education level (Junior middle school or below/High school or equivalent/Bachelor or equivalent/Master or above) were collected and recorded with a standard survey form.

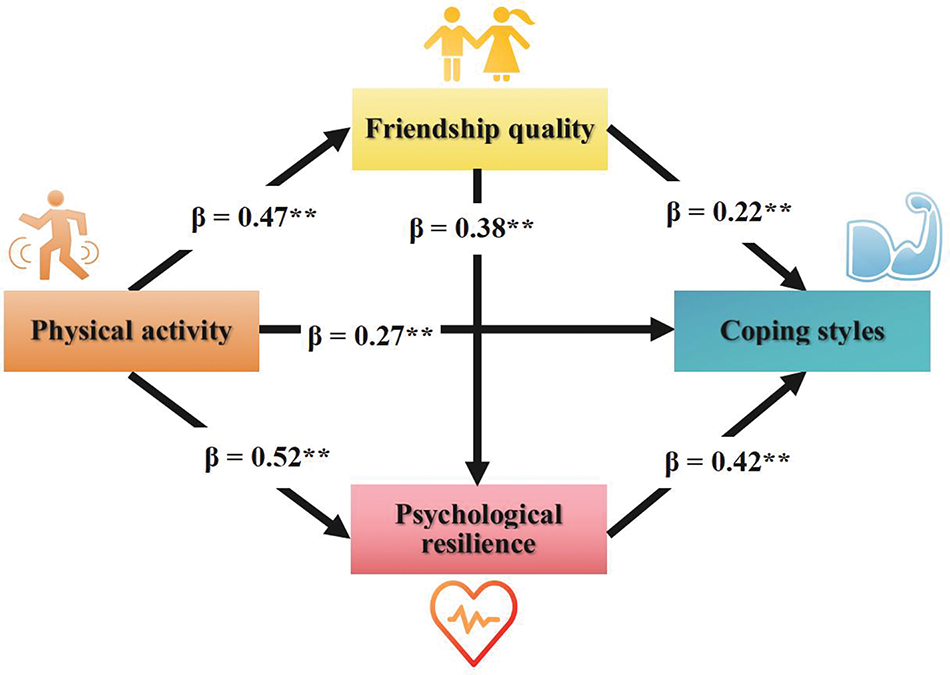

The theoretical framework establishes physical activity (PA) as the independent variable, coping style (CS) as the dependent variable, and friendship quality (FQ) and psychological resilience (PR) as mediating variables. According to this model, PA is hypothesized to positively correlate CS, with FQ and PR acting as intermediary mechanisms mediating this relationship (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: The mediating effect of friendship quality and psychological resilience on physical activity and coping styles. Note: **p < 0.01

Some questionnaire data were excluded due to unreasonable or missing values. Consequently, 2288 participants provided complete data for inclusion in the study’s final analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Initially, the assumption of data normality was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, ensuring that p-values exceeded 0.05 to confirm normal distribution. Subsequently, Pearson correlation analysis and linear regression were employed to examine the relationships among the variables. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was applied to further investigate the hypothesized chain mediation effects, as it allows for the modeling of latent variables and provides a more rigorous test of the proposed mediation pathways, enabling the assessment of both direct and indirect pathways through which PA correlates CS via FQ and PR [32,33]. The total effect of PA on CS was calculated as the sum of its direct and mediated effects. A two-tailed p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

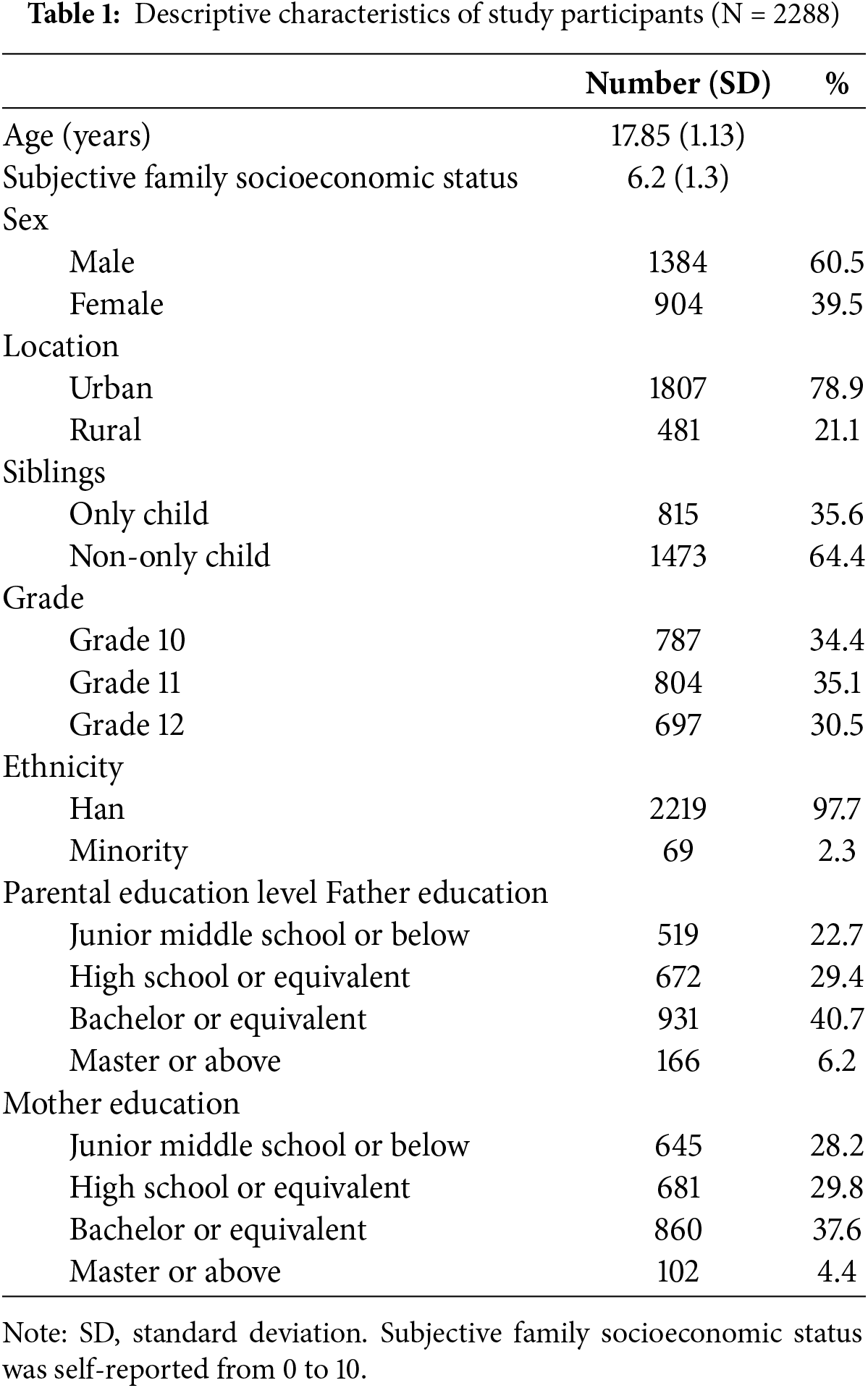

The study included 2288 valid participants with a mean age of 17.85 years (standard deviation [SD] = 1.13). Subjective family socioeconomic status, self-reported on a scale of 0 to 10, averaged 6.2 (SD = 1.3). The sample comprised 60.5% males and 39.5% females, with 78.9% residing in urban areas and 21.1% in rural areas. Regarding sibling status, 35.6% were only children, and 64.4% had siblings. Participants were distributed across grades, with 34.4% in Grade 10, 35.1% in Grade 11, and 30.5% in Grade 12. Most participants (97.7%) identified as Han, with 2.3% from minority groups. Parental education levels varied: 40.7% of fathers and 37.6% of mothers held a bachelor’s degree or equivalent, while 6.2% of fathers and 4.4% of mothers had attained a master’s degree or higher. Approximately 22.7% of fathers and 28.2% of mothers had education at or below junior middle school level, more information can be found in Table 1.

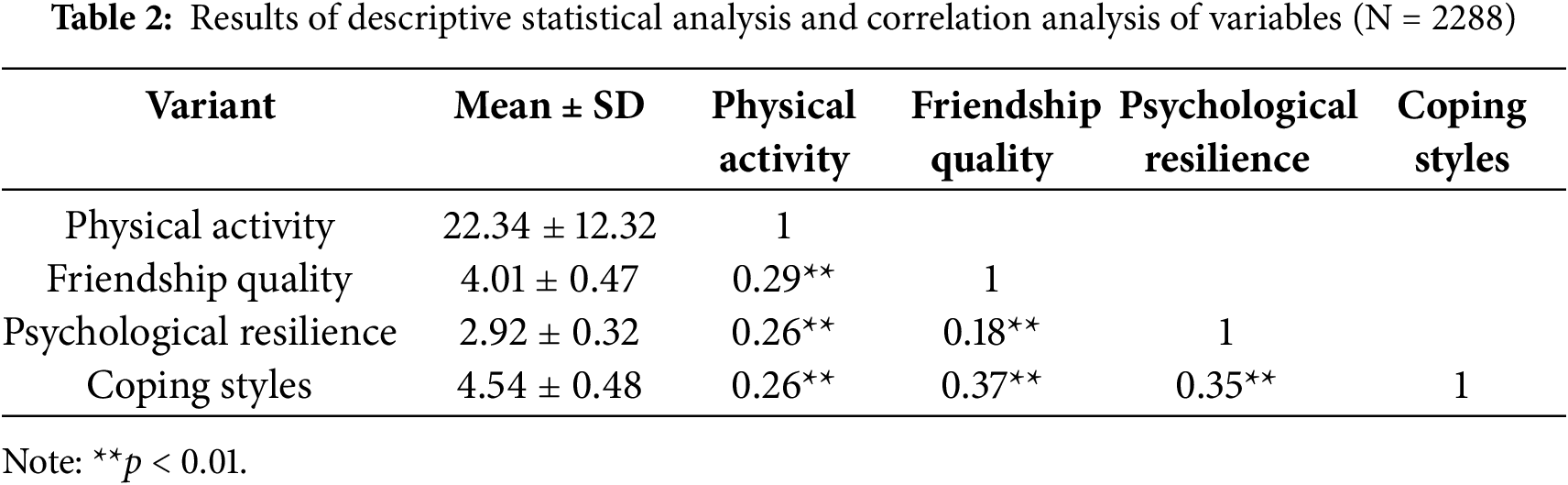

Descriptive statistical analysis revealed the following mean scores and standard deviations for various metrics: PA (Mean = 22.34, SD = 12.32), friendship quality (Mean = 4.01, SD = 0.47), psychological resilience (Mean = 2.92, SD = 0.32), and coping styles (Mean = 4.54, SD = 0.48). Correlation analysis showed significant relationships between these variables: PA positively correlates with friendship quality (r = 0.29, p < 0.01), psychological resilience (r = 0.26, p < 0.01), and coping styles (r = 0.26, p < 0.01). Friendship quality is positively correlated with psychological resilience (r = 0.18, p < 0.01) and coping styles (r = 0.37, p < 0.01), while psychological resilience also correlates positively with coping styles (r = 0.35, p < 0.01) (Table 2).

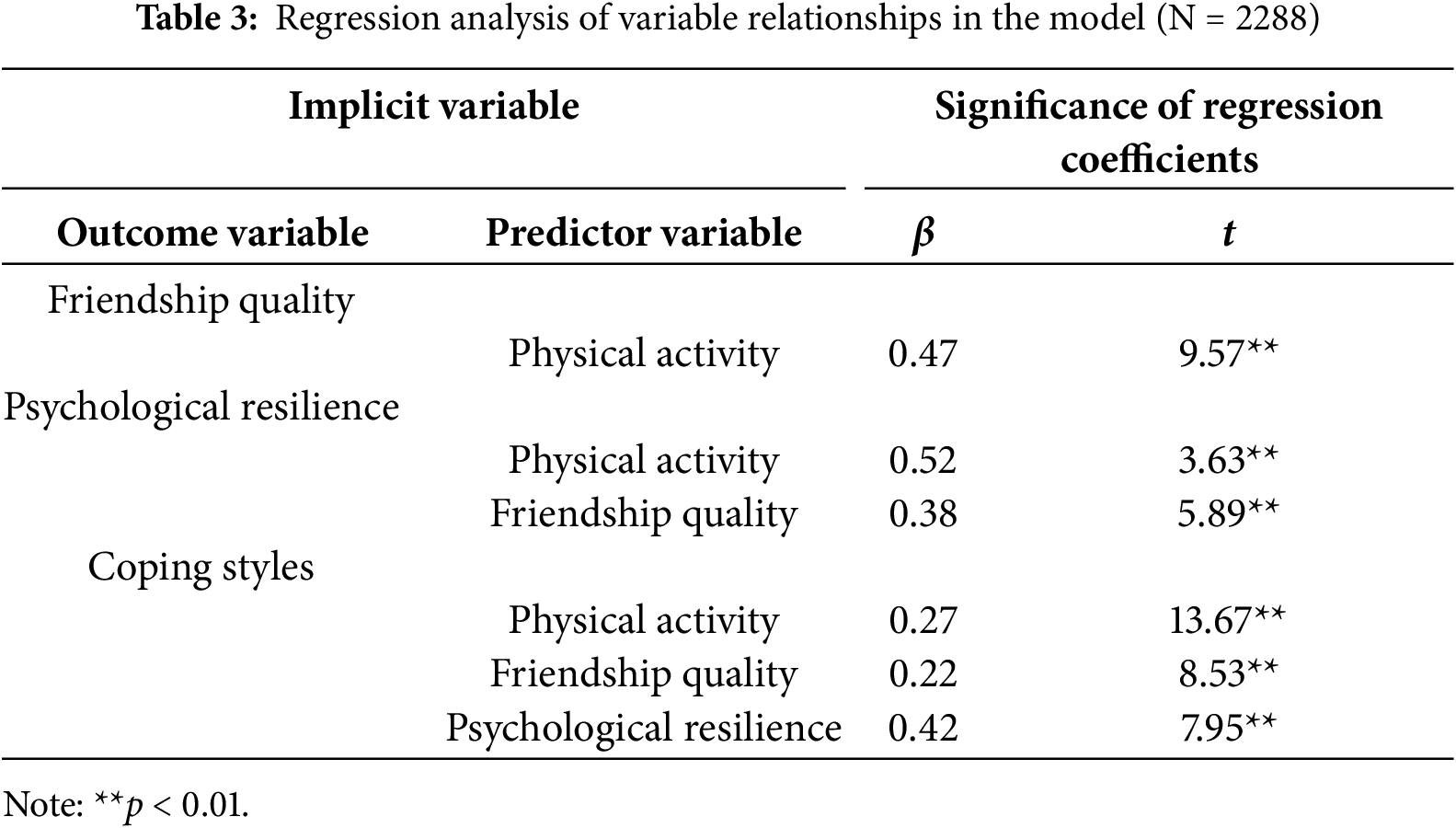

Regression analysis indicated that PA is significantly associated with friendship quality (β = 0.47, p < 0.01), psychological resilience (β = 0.52, p < 0.01), and coping styles (β = 0.27, p < 0.01). Friendship quality and psychological resilience were significantly associated with coping styles (β = 0.38, p < 0.01; β = 0.42, p < 0.01), as illustrated in Table 3 and Fig. 1. Additionally, descriptive statistical analysis examined the relationships between key demographic factors (e.g., gender, age, socioeconomic status) and the study variables. For instance, gender differences revealed that males reported higher levels of PA (Mean = 24.1, SD = 12.5) compared to females (Mean = 19.7, SD = 11.2), t (2288) = 6.45, p < 0.01. Age was positively correlated with psychological resilience (r = 0.15, p < 0.05), while socioeconomic status was significantly associated with friendship quality (r = 0.18, p < 0.01). To ensure the validity of the findings, demographic variables (e.g., gender, age, and socioeconomic status) were included as covariates in the mediation models. Results indicated that the mediation effects of friendship quality and psychological resilience remained significant even after controlling for these factors, suggesting robust relationships between PA and coping styles.

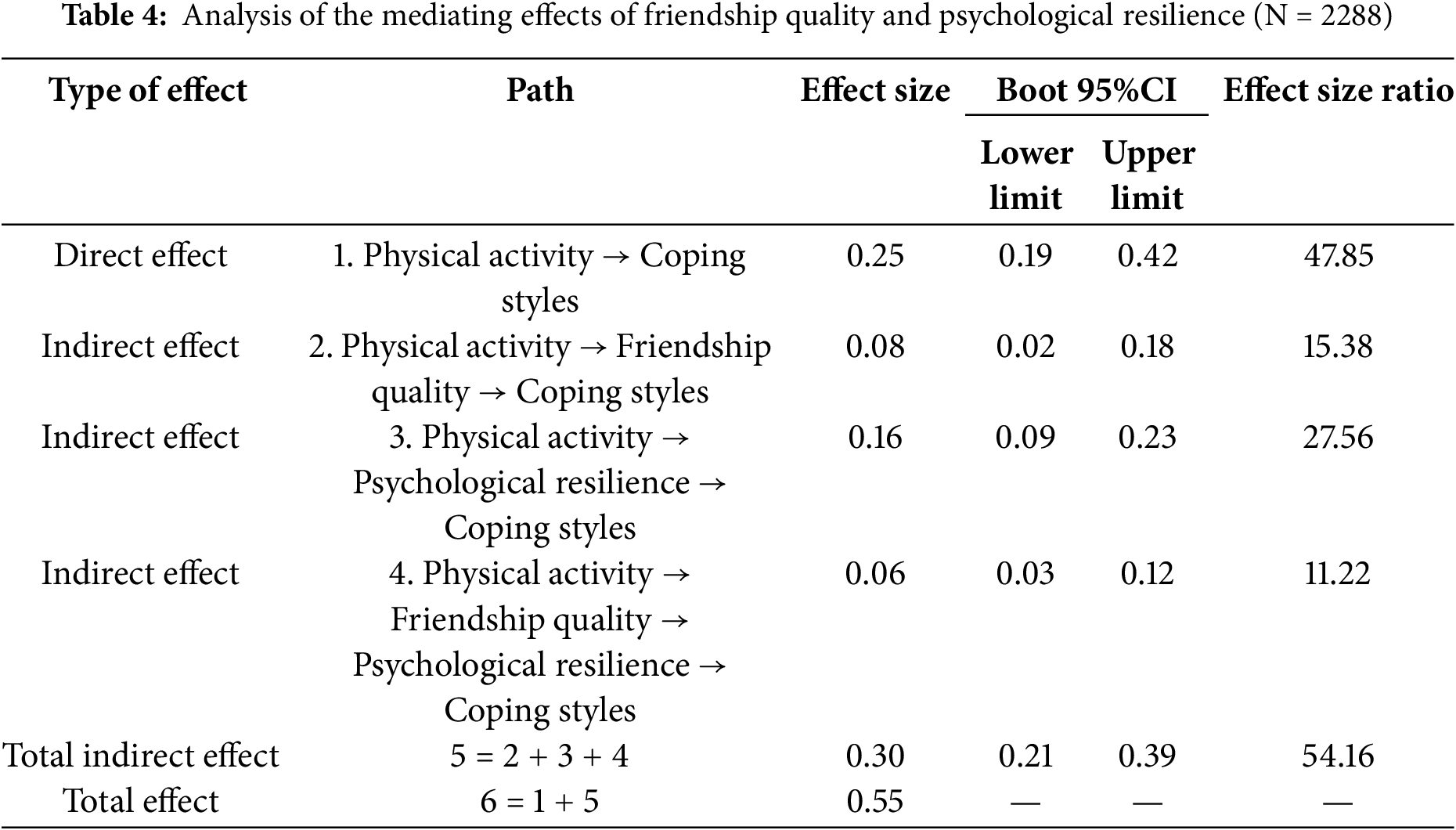

Table 4 analyzes the mediating effects of friendship quality and psychological resilience on the relationship between PA and coping styles. The direct effect of PA on coping styles is significant, with an effect size of 0.25 (95% CI = [0.19, 0.42]), accounting for 47.85% of the total effect. The indirect effects are also significant, with three pathways identified: PA to coping styles via friendship quality (effect size = 0.08, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.18], effect size ratio = 15.38%), PA to coping styles via psychological resilience (effect size = 0.16, 95% CI = [0.09, 0.23], effect size ratio = 27.56%), and PA to coping styles via both friendship quality and psychological resilience (effect size = 0.06, 95% CI = [0.03, 0.12], effect size ratio = 11.22%).

Fig. 1 illustrates the mediating effects of friendship quality and psychological resilience on the relationship between PA and coping styles. The figure shows how PA correlates coping styles directly and indirectly through the mediators’ friendship quality and psychological resilience. It visualizes the pathways and the strength of these relationships, emphasizing the significant roles of friendship quality and psychological resilience in enhancing coping styles through PA.

This study explored the psychological mechanisms linking the coping styles of Chinese adolescents from the perspectives of PA, friendship quality, and psychological resilience. We identified the direct effect of PA, friendship quality, and psychological resilience on coping styles in Chinese adolescents. In addition, our findings also provided evidence for the mediating effects of friendship quality and psychological resilience in the association of PA with coping styles. These results are consistent with our hypothesis and provide valuable insights into the underlying mechanisms by which physical activity correlates with adolescent well-being.

At present, there needs to be research on the relationship between PA and the coping styles of adolescents in China. Existing studies mainly focus on college or junior high school students to explore the correlation between PA on their coping styles. They believe that students who participate in PA have more positive coping styles when facing pressure and problems [34]. The experimental research on college students shows that changing the time and intensity of PA can significantly improve their coping styles [35,36]. Taking high school students as the research object, only Wu et al. [37] confirmed the relationship between PA, general self-efficacy, and coping styles by establishing a mediation model. Based on the coping styles chosen in the face of difficulties or pressures, this study further explores the relationship between PA and the coping styles of adolescents in combination with their growth and development characteristics. Correlation analysis showed a significant positive correlation between PA and coping styles; the higher the level of PA, the better the coping styles and performance of adolescents were. Further regression analysis showed that PA had a significant positive predictive effect on coping styles. This suggests that when adolescents are more involved in PA in physical education classes and extracurricular activities and show higher levels of exercise, their coping styles are more favorable. These results confirm the research on the correlation between PA and individual performance behavior and verify the correlation between PA and the coping styles of adolescents. Given this, when young people participate in PA, schools should provide them with more diversified sports items and exercise forms according to their psychological development characteristics, innovate exercise concepts, and cultivate students’ more robust sense of exercise participation. In addition, to create a comfortable and good PA atmosphere, according to young people’s hobbies, choose the projects they can participate in, increase their sense of achievement, and enhance their self-confidence. At the same time, it correctly guides teenagers’ cognition of coping styles, encourages them to promote physical health, improve social ability, resist frustration and pressure through PA, and choose more positive coping methods to face and solve problems.

The results show that PA is significantly associated with friendship quality, psychological resilience, and coping styles, indicating potential links between PA and peer relationships, psychological quality, and behavioral ability. The results of further mediation effect analysis show that PA can not only directly link the coping styles of adolescents but also indirectly associate the coping styles through the mediating effects of friendship quality and psychological resilience, including three mediating paths, namely, the mediating path through friendship quality, the mediating path through psychological resilience and the chain mediating path through friendship quality and psychological resilience.

First, this study explores the associations between PA and the coping styles of adolescents. PA is associated with coping styles and may also correlate them indirectly through the mediating role of friendship quality. The bidirectional association between PA and friendship quality underscores the complexity of their interplay, as both variables may mutually reinforce each other over time. Additionally, the inclusion of demographic variables in the analysis highlights the importance of considering individual differences, such as gender and socioeconomic status, in understanding these relationships. While significant associations were observed, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to infer causality. Teenagers are at a critical stage of life transition and must face the pressure from various aspects such as family, life, and study. Different handling choices will create different lives for them, and the level of PA has become a key factor linking their coping styles. Previous studies have confirmed the relationship between PA and high school students’ support, self-esteem, and quality, and the correlation of sports support, self-esteem enhancement, and positive quality on high school students’ coping styles [38]. Individuals with high levels of PA are likelier to show subjective emotional experiences such as exercise support, self-esteem enhancement, and positive qualities during exercise, thus forming stable friendship qualities. Adolescents with better friendships are likely to establish good interpersonal relationships with peers, enhance self-esteem, develop positive personal qualities when participating in PA, and show more positive coping styles in the face of pressure and difficulties. As a particular group in the critical period of individual personality shaping, the quality of friendship established between adolescents and their peers during sports is mainly reflected in trust and adaptability. The friendship established in sports can encourage individuals to participate in PA actively, stabilize the quality of friendship, and then use positive coping methods to face different situations [39,40].

Secondly, this study also found that PA can positively link adolescents’ coping styles through the independent mediating effect of psychological resilience and the chain mediating effect of friendship quality and psychological resilience [37,41]. This result is consistent with the previous research on the relationship between PA and students’ psychological resilience and the relationship between psychological resilience and coping styles. Further, it shows that adolescents’ psychological resilience and the accompanying positive adaptive traits can be the key factors linking coping styles. According to the compensation model of psychological resilience, when individuals face stressful environments, their personal traits and other protective mechanisms can positively reduce the negative correlation of adverse factors [42,43]. Psychological resilience includes the comprehensive effect of positive protective factors and negative risk factors [42,44], which is jointly associated the development of individuals. Students with high levels of PA tend to have a better sense of interpersonal communication efficacy. Participating in sports can strengthen interpersonal communication, increase friendship, and stabilize friendship quality. At the same time, they quickly show the excellent psychological quality of individual perseverance in problem-solving, interpersonal communication, emotion control, and other aspects, and they show better psychological resilience characteristics. Coping resources are the key factors influencing the choice of coping styles, including physiological resources (such as PA to promote health), psychological resources (such as mental resilience traits and interpersonal skills), and environmental resources (such as school support), which interact and jointly determine an individual’s cognitive and behavioral ability. The chain mediating effect of friendship quality and psychological resilience further explains the mechanism of the association of PA with coping styles. It expands the research field and direction of psychological resilience.

Strengths and Limitations

This study offers several strengths, including a comprehensive examination of PA’s correlation with adolescents’ physical health, friendship quality, and psychological resilience. Utilizing robust measurement tools and a large sample size of 2288 students, the study provides reliable, generalizable insights into the adolescent population in Jiangsu, China. However, limitations include the inability to establish causality due to the cross-sectional design and potential response bias from self-reported questionnaires. Additionally, the study does not explore other potential mediators between PA and coping styles. Given this, future research should explore the nature of these associations using longitudinal or experimental designs to better understand potential causal relationships. Additionally, the potential association of unexamined demographic variables should be further investigated to ensure comprehensive insights into the relationships among PA, coping styles, and their mediators.

Practical Implications

This study has further enriched the mechanism of PA and coping styles, provided correct inspiration for the choice of coping styles of contemporary adolescents, and provided theoretical support for shaping the tenacious will quality of adolescents. Teenagers are in a critical period of growth, development, and quality training. A closed teaching environment, heavy academic work, and worries about future uncertainty make them face more psychological pressure and life challenges. Cognitive level, interpersonal relationship, and personality determine how to cope with setbacks and challenges, and positive coping ways can help them face difficulties and relieve pressure. The degree of participation in PA, the quality of interpersonal relationships, and the tenacity of will quality become the essential components influencing their coping styles. Furthermore, our study effect sizes emphasize that PA interventions, even at moderate levels, could substantially improve adolescents’ coping styles and psychological resilience. This underscores the importance of integrating physical activity into school curriculums and community programs. Economically, fostering resilience and effective coping through physical activity could reduce long-term expenditures on mental health services, as proactive measures may mitigate the need for reactive treatments.

The effects of friendship quality and psychological functioning are often intertwined with unobserved family-level background factors [45], such as parenting styles, socioeconomic status, and household dynamics. Parenting styles significantly influence adolescents’ emotional regulation and social skills, shaping their ability to build and maintain high-quality friendships. Similarly, family SES impacts access to resources that facilitate social interaction and psychological development, with higher SES often providing more opportunities for positive growth. Household stability also plays a role, as consistent emotional support in stable family structures fosters resilience and healthy peer relationships, while fragmented households may contribute to emotional distress. By doing so, researchers can reduce bias and enhance the validity of findings. Moreover, interventions targeting adolescent mental health and social skills should involve family engagement, as supportive family environments can significantly amplify the benefits of such programs. Recognizing these dynamics ensures a more holistic understanding of the interplay between friendship quality, psychological functioning, and broader developmental outcomes.

This study highlights the significant correlations between PA, friendship quality, psychological resilience, and adolescent coping styles among adolescents. The mediating roles of friendship quality and psychological resilience demonstrate the broader psychosocial benefits of PA, emphasizing its critical role in shaping adaptive coping mechanisms. These findings have important implications for educational policies and intervention programs, suggesting that schools, policymakers, and families should actively promote PA to enhance adolescents’ emotional well-being and social competence. Future research should explore additional mediating factors and adopt longitudinal or experimental designs to establish causal relationships, further advancing the understanding of PA’s role in adolescent development.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to appreciate the youth who actively participated in the study.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by Jiangsu Province Education Science “14th Five-Year Plan” Project (No. C/2024/01/99).

Author Contributions: Jin Yan, Liu Yang: Writing—original draft, review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Project administration; Dongye Lyu, Jin Yan, Songjian Du: Writing—review & editing, Formal analysis, Methodology; Jin Yan: Writing—review & editing, Formal analysis, Methodology; Songjian Du: Writing—review, Conceptualization, Project administration. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to protect the students’ privacy, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Soochow University (SUDA20240626H06). All participants signed the informed consent in this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Crosnoe R, Cavanagh SE. Families with children and adolescents: a review, critique, and future agenda. J Marriage Family. 2010;72(3):594–611. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00720.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Deng Y, Cherian J, Khan NUN, Kumari K, Sial MS, Comite U, et al. Family and academic stress and their impact on students’ depression level and academic performance. Front Psychiat. 2022;13:869337. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.869337. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Sigfusdottir ID, Kristjansson AL, Thorlindsson T, Allegrante JP. Stress and adolescent well-being: the need for an interdisciplinary framework. Health Promot Int. 2017;32(6):1081–90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

4. Li H, Zhang W, Yan J. Physical activity and sedentary behavior among school-going adolescents in low- and middle-income countries: insights from the global school-based health survey. PeerJ. 2024;12(11):e17097. doi:10.7717/peerj.17097. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Liu T, Li D, Yang H, Chi X, Yan J. Associations of sport participation with subjective well-being: a study consisting of a sample of Chinese school-attending students. Front Public Health. 2023;11:84. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1199782. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Goguen Carpenter J, Bélanger M, O’Loughlin J, Xhignesse M, Ward S, Caissie I, et al. Association between physical activity motives and type of physical activity in children. Int J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2017;15(3):306–20. doi:10.1080/1612197X.2015.1095779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Bessa C, Hastie P, Araújo R, Mesquita I. What do we know about the development of personal and social skills within the sport education model: a systematic review. J Sports Sci Med. 2019;18(4):812. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

8. Yan J, Morgan PJ, Smith JJ, Chen S, Leahy AA, Eather N. Pilot randomized controlled trial of a game-based intervention for teaching basketball in Chinese primary school physical education. J Sports Sci. 2024;42(1):25–37. doi:10.1080/02640414.2024.2319457. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Welch R, Alfrey L, Harris A. Creativity in Australian health and physical education curriculum and pedagogy. Sport, Educ Soc. 2021;26(5):471–85. doi:10.1080/13573322.2020.1763943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Yan J, Jones B, Smith JJ, Morgan P, Eather N. A systematic review investigating the effects of implementing game-based approaches in school-based physical education among primary school children. J Teach Phys Educ. 2023;42(3):573–86. doi:10.1123/jtpe.2021-0279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Moran MM, Weiss MR. Peer leadership in sport: links with friendship, peer acceptance, psychological characteristics, and athletic ability. J Appl Sport Psychol. 2006;18(2):97–113. doi:10.1080/10413200600653501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Eime RM, Young JA, Harvey JT, Charity MJ, Payne WR. A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for children and adolescents: informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. Int J Beh Nutrit Phys Act. 2013;10(1):1–21. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-10-135. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Opstoel K, Chapelle L, Prins FJ, De Meester A, Haerens L, Van Tartwijk J, et al. Personal and social development in physical education and sports: a review study. Eur Phys Educ Rev. 2020;26(4):797–813. doi:10.1177/1356336X19882054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Sarkar M, Fletcher D. Psychological resilience in sport performers: a review of stressors and protective factors. J Sports Sci. 2014;32(15):1419–34. doi:10.1080/02640414.2014.901551. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Ramirez-Granizo IA, Sánchez-Zafra M, Zurita-Ortega F, Puertas-Molero P, González-Valero G, Ubago-Jiménez JL. Multidimensional self-concept depending on levels of resilience and the motivational climate directed towards sport in schoolchildren. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(2):534. doi:10.3390/ijerph17020534. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Gucciardi DF, Jackson B, Hanton S, Reid M. Motivational correlates of mentally tough behaviours in tennis. J Sci Med Sport. 2015;18(1):67–71. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2013.11.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Whisman MA, Sbarra DA, Beach SR. Intimate relationships and depression: searching for causation in the sea of association. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2021;17(1):233–58. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-081219-103323. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Pilozzi A, Carro C, Huang X. Roles of β-endorphin in stress, behavior, neuroinflammation, and brain energy metabolism. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;22(1):338. doi:10.3390/ijms22010338. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Fletcher D, Sarkar M. Psychological resilience. Eur Psychol. 2013. doi:10.1027/1016-9040/a000124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Guo H, Zhang Y, Tian Y, Zheng W, Ying L. Exploring psychological resilience of entrepreneurial college students for post-pandemic pedagogy: the mediating role of self-efficacy. Front Psychol. 2022;13:1001110. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1001110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Van Harmelen A-L, Kievit R, Ioannidis K, Neufeld S, Jones P, Bullmore E, et al. Adolescent friendships predict later resilient functioning across psychosocial domains in a healthy community cohort. Psychol Med. 2017;47(13):2312–22. doi:10.1017/S0033291717000836. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Arslan G. School belongingness, well-being, and mental health among adolescents: exploring the role of loneliness. Austral J Psychol. 2021;73(1):70–80. doi:10.1080/00049530.2021.1904499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Martins J, Rodrigues A, Marques A, Cale L, Carreiro da Costa F. Adolescents’ experiences and perspectives on physical activity and friend influences over time. Res Quart Exerc Sport. 2021;92(3):399–410. doi:10.1080/02701367.2020.1739607. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. van Harmelen A-L, Gibson JL, St Clair MC, Owens M, Brodbeck J, Dunn V, et al. Friendships and family support reduce subsequent depressive symptoms in at-risk adolescents. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0153715. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0153715. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Morgan PB, Fletcher D, Sarkar M. Developing team resilience: a season-long study of psychosocial enablers and strategies in a high-level sports team. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2019;45(1):101543. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.101543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Ashcroft RE. The declaration of Helsinki. In: The Oxford textbook of clinical research ethics; 2008. p. 141–8. [Google Scholar]

27. Yang G, Li Y, Liu S, Liu C, Jia C, Wang S. Physical activity influences the mobile phone addiction among Chinese undergraduates: the moderating effect of exercise type. J Beh Add. 2021;10(3):799–810. doi:10.1556/2006.2021.00059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Shi R, Wang KT, Xie Z, Zhang R, Liu C. The mediating role of friendship quality in the relationship between anger coping styles and mental health in Chinese adolescents. J Soc Pers Relat. 2019;36(11–12):3796–813. doi:10.1177/0265407519839146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Chen W, Xie E, Tian X, Zhang G. Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the Resilience Scale (RS-14preliminary results. PLoS One. 2020;15(10):e0241606. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0241606. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Li C, Liu Q, Hu T, Jin X. Adapting the short form of the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations into Chinese. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;1669–75. doi:10.2147/NDT. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Cundiff JM, Smith TW, Uchino BN, Berg CA. Subjective social status: construct validity and associations with psychosocial vulnerability and self-rated health. Int J Beh Med. 2013;20(1):148–58. doi:10.1007/s12529-011-9206-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res. 1981 Feb;18(1):39–50. doi:10.1177/002224378101800104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Beh Res Methods, Inst, Comput. 2004;36(4):717–31. doi:10.3758/BF03206553. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Xu T, Li Y, Chen X, Wang J, Zhang G. Effect of physical activity volume on active coping style among martial arts practicing adolescents: the mediating role of self-efficacy and positive affect. Arch Budo. 2020;16(1):315–24. [Google Scholar]

35. Blevins CE, Rapoport MA, Battle CL, Stein MD, Abrantes AM. Changes in coping, autonomous motivation, and beliefs about exercise among women in early recovery from alcohol participating in a lifestyle physical activity intervention. Mental Health Phys Act. 2017;13(3):137–42. doi:10.1016/j.mhpa.2017.09.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Heszen I. Temperament and coping activity under stress of changing intensity over time. Eur Psychol. 2012. doi:10.1027/1016-9040/a000121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Wu X, Liang J, Chen J, Dong W, Lu C. Physical activity and school adaptation among Chinese junior high school students: chain mediation of resilience and coping styles. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1376233. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1376233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Chen Z, Chi G, Wang L, Chen S, Yan J, Li S. The combinations of physical activity, screen time, and sleep, and their associations with self-reported physical fitness in children and adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(10):5783. doi:10.3390/ijerph19105783. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Ahmed MD, Ho WKY, Al-Haramlah A, Mataruna-Dos-Santos LJ. Motivation to participate in physical activity and sports: age transition and gender differences among India’s adolescents. Cogent Psychol. 2020;7(1):1798633. doi:10.1080/23311908.2020.1798633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Martín-Rodríguez A, Gostian-Ropotin LA, Beltrán-Velasco AI, Belando-Pedreño N, Simón JA, López-Mora C, et al. Sporting mind: the interplay of physical activity and psychological health. Sports. 2024;12(1):37. doi:10.3390/sports12010037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Zhang Y, Hu Y, Yang M. The relationship between family communication and family resilience in Chinese parents of depressed adolescents: a serial multiple mediation of social support and psychological resilience. BMC Psychol. 2024;12(1):33. doi:10.1186/s40359-023-01514-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Ellis BJ, Bianchi J, Griskevicius V, Frankenhuis WE. Beyond risk and protective factors: an adaptation-based approach to resilience. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2017;12(4):561–87. doi:10.1177/1745691617693054. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Hou X-L, Wang H-Z, Guo C, Gaskin J, Rost DH, Wang J-L. Psychological resilience can help combat the effect of stress on problematic social networking site usage. Personal Ind Diff. 2017;109:61–6. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2016.12.048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Hamby S, Grych J, Banyard V. Resilience portfolios and poly-strengths: identifying protective factors associated with thriving after adversity. Psychol Violence. 2018;8(2):172. doi:10.1037/vio0000135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Kim J. The quality of social relationships in schools and adult health: differential effects of student-student versus student-teacher relationships. School Psychol. 2021;36(1):6. doi:10.1037/spq0000373. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools