Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Relationship between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Health Risk Behaviors of Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Executive Function Deficits

Developmental and Educational Psychology, School of Psychology, Northeast Normal University, Changchun, 130024, China

* Corresponding Author: Xiaosong Gai. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Healthy Lifestyle Behaviours and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(6), 787-807. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.065065

Received 03 March 2025; Accepted 28 May 2025; Issue published 30 June 2025

Abstract

Background: Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are a significant issue in adolescent health due to their robust correlation with deficits in executive functions (EF) and health risk behaviors (HRBs). This study aimed to examine the association between ACEs and a range of HRBs, including substance use, sexual risk behavior, suicidal ideation, physical inactivity, and violence. Methods: This cross-sectional study used self-administered questionnaire and cluster sampling in seven junior high schools in Samarinda, Indonesia, with a sample size of 534 students. Data analysis using descriptive statistics, the Chi-square test, the independent t-test, ANOVA, binary logistic regression, and mediation analysis with macro-PROCESS. Results: The most common ACEs were community violence (68.0%), physical neglect (52.8%), psychological/emotional abuse (52.6%), physical abuse (50.4%), and peer bullying (45.9%). Adolescents with more than five ACEs showed significantly higher involvement in smoking/vaping (67.9%), suicidal ideation (75.2%), sexual risk behavior (57.7%), bullying (64.3%), and physical fighting (59.7%) (p < 0.001). ACEs were significantly correlated with EF deficits (r = 0.471, p < 0.01) and HRB (r = 0.578, p < 0.01). Regression analysis confirmed that ACEs predicted EF deficits (β = 0.466, p < 0.001) and HRB (β = 0.469, p < 0.001), with EF deficits partially mediating this relationship (β = 0.107, 95% CI [0.045, 0.094]). In addition, two subdomains of EF deficits, self-motivation (β = 0.042) and self-regulation of emotion (β = 0.032), significantly mediated the relationship between ACEs and HRBs. Conclusion: These findings suggest an important role for EF deficits in linking childhood adversity to engagement in risky behaviors. Addressing ACEs and EF deficits (self-motivation and self-regulation of emotion) through early intervention may be important in reducing long-term health risks among Indonesian adolescents.Keywords

Many individuals have faced adverse or traumatic experiences during their childhood. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that at least one in six adults encountered five or more types of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) during adolescence [1]. Prior research highlights that exposure to adversity during childhood and adolescence significantly shapes adult health outcomes through various psychosocial mechanisms, elevating the risk of long-term health complications [2]. In specific regions, particularly in Southeast Asia, studies involving students from ASEAN countries such as Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, Vietnam, and Myanmar have demonstrated that exposure to violence increases the likelihood of mental health issues, engagement in risky behaviors, and addiction in adulthood. ACEs are highly prevalent among adolescents and young adults in Southeast Asia and have a strong dose-response relationship with increased risk of various health risk behaviors, such as risky sexual behavior, physical inactivity, substance use, and suicide risk [3,4]. Additionally, data from Indonesia’s Ministry of Women’s Empowerment and Child Protection reveals that nearly half of boys (47.7%) and 18% of girls aged 13–17 experienced physical or psychological abuse in 2013 [5]. The previous study found that nearly 80% of adolescents in Indonesia experienced at least one traumatic event, with depression symptoms similarly prevalent in both boys and girls [6]. Despite the prevalence of child violence, research on ACEs in Indonesia remains scarce [7], though it is critically linked to future health risk behaviors among adolescents.

Extensive research has established a robust link between ACEs and adverse health outcomes. Prior studies underscore the significant correlation between ACE exposure and the increased likelihood of developing physical health issues [8]. Even minimal exposure to ACEs has been shown to negatively impact an individual’s health condition and behaviors [9,10]. The importance of ACEs lies not only in their immediate effects but also in their long-term consequences on health outcomes and behaviors [11]. ACEs are very common among adolescents and have a significant impact on physical, mental health, and risk behavior, especially when the number of ACEs is high. However, in addition to the number, the specific pattern or combination of ACEs also determines the level, type, and combination of negative impacts experienced [12], especially on aspects of emotion, personality, behaviors, and executive functions (EF) [9,13,14]. ACEs have been associated with various risky behaviors, including smoking, alcohol abuse, promiscuity, obesity, drug use, and poor self-rated health [15]. Individuals with four or more ACEs face elevated risks of behavioral health problems, ranging from sedentary lifestyles and obesity to more severe issues like substance abuse and mental health disorders [16]. They also had increased risks for smoking, severe obesity, physical inactivity, sexually transmitted diseases, unintended pregnancies, and a higher prevalence of diseases like ischemic heart disease, neoplasia, chronic pulmonary illness, skeletal fractures, and hepatic [10,17]. Covariate variables, such as age, sex, and minority status, have been investigated as potential factors influencing the relationship between ACEs and these behaviors [18]. The connection between ACEs and health risk behaviors in adolescents remains a key focus of this research, as evidence suggests that exposure to ACEs increases the likelihood of engaging in behaviors that compromise health, underscoring the necessity for targeted interventions to mitigate these risks [19]. Moreover, ACEs have been associated with delinquency, substance use initiation, and emotional distress in high-risk adolescents, highlighting the critical need for early intervention and support for these vulnerable groups [20]. A deeper understanding of the link between ACEs and adolescent behavioral issues can offer valuable insights into the complex effects of childhood adversity on multiple dimensions of well-being [21].

Previous research has identified a correlation between ACEs and impairments in executive function domains, including problem-solving abilities and reasoning skills [22,23]. EF deficits linked to ACEs also play a role in elevating the risk of adolescents participating in health risk behaviors. Research indicates that impaired skills in planning, problem-solving, and decision-making, associated with EF deficits, can forecast involvement in risky activities such as substance abuse, unsafe sexual practices, and aggression. Adolescents exhibiting these EF deficits are often less inclined to weigh the long-term repercussions of their actions [24,25]. The scope of EF such as cognitive abilities such as higher EF, including attention, perseverance, goal orientation, planning, problem solving, and working memory [26,27]. These mechanisms enable adolescents to manage and adjust their behavior in order to reach their goals [28].

The association between EF deficits and risk-taking behaviors is particularly pronounced in adolescents and young adults, given that their frontal systems are still undergoing development. This research further elucidates that the elevated susceptibility to risk-taking during adolescence can be attributed to a stronger inclination towards immediate rewards and an underdeveloped ability to manage impulses, which are characteristic of this developmental stage [29]. Evidence links ACEs to reduced EF and increased health risk behaviors, but the exact mechanisms affecting short-term and long-term memory remain unclear [16,30]. Another gap that needs to be studied is to see the interaction of mediating factors, such as EF, in a specific domain of goal-directed behavior [31], which can affect the relationship between ACEs and health risk behaviors. Previous studies provide consideration of psychosocial factors in viewing the development of adolescents with ACEs and need to develop interventions that can reduce the impact of ACEs later in life, especially related to direct health behavior impacts [32,33].

In this study, we examined EF deficits as a key mediator, consisting of five primary components: self-management of time, self-organization/problem-solving, self-restraint, self-motivation, and self-regulation of emotion [34–36]. EF deficits were chosen as a mediator because development is significantly influenced by ACEs and can affect the potential for engaging in risky health behaviors during adolescence and adulthood [34]. Other studies have shown that EF deficits, which are often linked to early-life adversities, can impair one’s ability to regulate behaviors and emotions, leading to greater susceptibility to health-risk behaviors (HRBs), such as substance use and risky sexual activities [37,38]. These cognitive deficits are associated with a range of negative outcomes, including poorer mental health and lower educational achievement, emphasizing the critical role of EF in mitigating the long-term impacts of childhood adversity [39,40].

The extant literature suggests that negative childhood experiences affect EF [34] and health risk behavior among adolescents [19,41]. Despite previous cross-sectional studies on ACEs and risky health behaviors [42,43], studies that focus on various components of EF deficits among Asian adolescents are still limited, especially bridging the relationship between ACEs and HRBs. In addition, existing studies in Indonesia tend to observe trauma [44,45], lack of literacy related to the impacts of complex health risk behaviors such as substance use, low nutritional intake, lack of physical activity, suicidal ideation, risky sexual behavior, bullying experiences, and physical fights. Addressing this gap is essential to develop more effective interventions aimed at reducing long-term health risks and mapping potential health risk behaviors that are in accordance with the characteristics of Asian adolescents in Indonesia. The objectives of this study are (1) to identify the prevalence of ACEs based on gender and sociodemographic factors; (2) to examine the relationship between ACEs, EF deficits, and HRBs; (3) to determine the predictive power of ACEs on HRBs; (4) to investigate the mediating role of EF deficits in the link between ACEs and HRBs.

A total of 534 junior high school students from 7 schools across 6 districts in Samarinda, East Kalimantan, Indonesia, participated in the current study. All of which are categorized as urban or semi-urban districts based on the administrative zoning of the location [46]. The sample comprised 293 females (54.9%) and 241 males (45.1%), with participants ranging in age from 11 to 17 years (Mean = 13.50, standard deviation [SD] = 0.93). The culture tribe of participants, 29.0% identified as Javanese, 21.2% as Bugis, and 20.6% as Banjar, and the remaining 29.2% of participants identified as “other”, representing over 15 different ethnic groups across Indonesia. Exclusion criteria included adolescents who were unable to read or had special needs. Participants were selected through a cluster sampling method. To ensure geographical diversity, six school districts in Samarinda were initially chosen. One public high school was randomly selected from each district, with one district contributing two schools due to a higher student population, resulting in a total of seven schools. Within each selected school, two classes from grades 10 and 11 were randomly chosen as clusters. All students in these selected classes who met the inclusion criteria were invited to participate. This study was approved by the Academic Ethics Committee of the School of Psychology, Northeast Normal University, China, and by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Mulawarman University, Indonesia. Formal approval for the study was obtained from the school authorities, and the study also received permission from the Department of Education, Samarinda. After receiving approval, the school authorities communicated study details to the eligible students and their parents. Informed consent was obtained from both participants and their parents. Students who agreed to participate were given printed questionnaires, which were completed in person during class time.

2.2.1 Socioeconomic and Family Background

The demographic characteristics measured in this study included gender (1 = male, 2 = female), grade level (1st grade = 1, 2nd grade = 2, and 3rd grade = 3), and religion (Islam = 1, Protestant = 2, Catholic = 3, Hinduism = 4, Buddhism = 5, and Confucianism = 6). Additionally, weight (kg) and height (cm) were directly measured using a digital scale and a stature meter. Respondents were also asked to self-evaluate their academic achievement, with response options ranging from high = 1, above average = 2, average = 3, below average = 4, and low = 5. Furthermore, respondents provided information on their ethnicity, which was determined based on paternal lineage.

Family background adapted by GEAS-Indonesia Baseline [47] was assessed based on several factors, including parental marital status, which was categorized as (1 = intact family, 2 = non-intact family). The composition of caregivers was identified as (1 = both parents, 2 = single mother, 3 = single father, 4 = grandparents, 5 = others). Current residence status was also evaluated, with options including (1 = self-owned house, 2 = rented house, 3 = boarding house/dormitory/orphanage). Additionally, family income was classified as (1 = high, 2 = medium, 3 = low). Other identified factors included parental education levels and the number of siblings, categorized as (1 = no siblings, 2 = 1–2 siblings, 3 = 3–5 siblings, and 4 = more than 6 siblings).

2.2.2 Adverse Childhood Experiences

The questionnaire used in this study is the Adverse Childhood Experience International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ), developed by the World Health Organization [48]. This instrument assesses how frequently adolescents experienced 13 types of adversity during childhood up to the present [49]. The questionnaire addresses 13 categories of adversity, including family dysfunction; physical, sexual, and emotional abuse or neglect by parents or caregivers; peer violence; witnessing community violence; and exposure to collective violence. The instrument was modified to align with the language and contextual meanings understood by Indonesian participants [7,47]. The ACE score is calculated by summing the total number of adverse experiences reported for each time period. The ACE-IQ offers two coding methods: binary and frequency-based [48]. This study uses the binary coding approach, where the final score represents the total number of ACE events, regardless of their frequency. In contrast, the frequency-based coding method represents the sum of events occurring at a specific frequency, this method helps to indicate the severity of ACEs in adolescents [41,50,51]. The response options for participants were “never = 1”, “occasionally = 2”, “sometimes = 3”, and “often or always = 4”. Responses were subsequently categorized as “no = 0” if the answer was “never” and “yes = 1” for all other options. For specific items such as parental or family alcohol or substance abuse; parental or family history of major depression, mental illness, or suicide; parental or guardian imprisonment; and parental or guardian divorce or death, the response choices were limited to “yes = 1” or “no = 0”. The Cronbach’s alpha for the questionnaire was 0.731. The total ACE score was based on 13 items, with categories of ACEs classified as 0, 1–2 ACEs, 3–4 ACEs, and >5 ACEs [19].

2.2.3 Executive Function Deficits

In this study, the Barkley Deficits in Executive Functioning Scale—Short Form: Self-Report (BDEFS-SF) was utilized, consisting of a 20-item questionnaire designed to assess difficulties in executive functioning in daily life. The scale evaluates five sub-scales [52], this encompasses self-management of time (efficiently planning and utilizing time), self-organization/problem-solving (structuring tasks and devising solutions), self-restraint (controlling impulses and resisting temptation), self-motivation (initiating and persisting in tasks autonomously), and self-regulation of emotion (managing emotional responses in various situations) among adolescents, with each subscale comprising four question items [36]. The Barkley Deficits in Executive Functioning Scale (BDEFS) short form is a 20-item self-report tool developed to evaluate executive functioning difficulties in everyday life [31]. Respondents are asked to rate their experiences based on a four-point Likert scale, with response options ranging from “never or rarely = 1,” indicating minimal occurrence of the behavior, to “very often = 4” representing frequent occurrence. The Cronbach’s alpha for the questionnaire was 0.903. The diverse response options allow for a nuanced understanding of how often individuals face difficulties related to executive functioning in various aspects of their daily routines.

2.2.4 Health Risk Behaviors (HRBs)

HRB variables in this study will broadly adapt the Youth Risk Behavior Surveys (YRBS) instrument, and in several sub-indicators of HRB, the analysis items will be adjusted to the prevalence of the most dominant HRB among adolescents in this study area [19,53]. The Cronbach’s alpha for the questionnaire was 0.627, with here is a detailed explanation.

Smoking and vaping behavior. This study focused on the following survey items: “How many cigarettes have you smoked in the past 30 days?” and “On how many days have you used an electronic cigarette in the last 30 days?” In this scale, 1 represents none, 2 = 1–2 days, 3 = 3–5 days, 4 = 6–9 days, 5 = 10–19 days, 6 = 20–29 days, and 7 = daily. Responses were then classified into a dichotomous indicator, with 0 = none and 1 = any other option as “yes”, to reflect smoking or vaping behaviors among adolescents.

Substance use. This sub-indicator identified adolescents’ self-reported alcohol use through the question, “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you have at least one drink of alcohol?” Responses were coded as 1 = never, 2 = 1–2 days, 3 = 3–5 days, 4 = 6–9 days, 5 = 10–19 days, 6 = 20–29 days, and 7 = every day. Lifetime use of substances such as inhaled glue and aerosol was assessed with the question, “Throughout your life, how many times have you inhaled glue, aerosol, or paint to get high?” Lifetime drug use was similarly assessed with the question, “Throughout your life, how many times have you used drugs?” These items were coded as 1 = never, 2 = 1–2 times, 3 = 3–9 times, 4 = 10–19 times, 5 = 20–39 times, and 6 = more than 40 times. All questions were then recoded into dichotomous variables, where 0 = never and 1 = any other response, indicating substance use behaviors.

Low nutritional intake. We assessed daily nutritional intake through a series of questions focused on specific food and drink items. Participants were asked, “During the past 7 days, how many times did you drink 100% fruit juice, eat fruit, eat green vegetables, or consume other vegetables?” with response options ranging from 1 = none, 2 = 1–3 times, 3 = 4–6 times, 4 = once per day, 5 = twice per day, 6 = 3 times per day, to more than 4 times per day. These responses were dichotomized, with ≥4 times categorized as “yes” and <3 times as “no”. Similarly, participants were asked, “How many times did you drink soda or a sweetened beverage?” with <3 times categorized as “no” and ≥4 times as “yes”. Fast food intake was assessed by asking, “How many times did you eat fast food in the last week?” “with response options of 1 = none, 2 = 1–2 times, 3 = 3–4 times, and 4 = 5 times or more, and dichotomized as <2 times categorized as ‘no’ and ≥2 as ‘yes’. Lastly, breakfast frequency was assessed with the question, ‘During the past 7 days, how many days did you have breakfast?’ with response options from 1 = 0 days to 8 = every day, and dichotomized as ≥5 days categorized as ‘yes’ and <5 days as ‘no’. Lack of physical activity, for lack of physical activity was assessed using two items. Participants were asked, ‘During the past 7 days, how many days did you exercise for at least 60 min?’ and ‘How many days did you attend physical education classes?’ Responses were recorded on a scale ranging from 1 = 0 days to 8 = every day. For analysis purposes, these responses were dichotomized, with ≥3 days categorized as ‘no’ and <3 days categorized as ‘yes’”.

Suicidal ideation. This aspect was identified based on three items referring to the Youth Risk Behavior Survey [53]. The first question asked, ‘In the past year, have you ever seriously considered attempting suicide?’ The second question was, ‘In the past year, have you made a plan for attempting suicide?’ The third asked, ‘How many times have you actually attempted suicide?’ Each of these questions had four response options: 1 = never; 2 = once; 3 = 2–3 times; 4 = 4 times or more. Responses of ‘never’ were coded as 0 (no), and those indicating one or more attempts were coded as 1 (yes). Sexual behavior, there were seven items assessing risky sexual behaviors, which included accessing pornographic content, spending time with a romantic partner without parental or guardian supervision, touching a partner’s body, mutual genital touching, kissing, sending sexually explicit photos, and engaging in sexual intercourse without condoms. Response options were 1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = often. The variables were then dichotomized, with ‘never’ coded as 0 (no), and all other responses coded as 1 (yes).

Bullying and physical fight. The bullying-related questions focused on two items: ‘In the past 12 months, have you ever experienced bullying at school?’ and ‘In the past 12 months, have you experienced electronic bullying through messages or other social media?’ Response options were 1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = often. The variables were then dichotomized, with ‘never’ coded as 0 (no), and all other responses coded as 1 (yes). Regarding physical fights, two items were asked: ‘In the past 12 months, how many times have you been involved in a physical fight?’ and ‘How many times have you been involved in a physical fight at school?’ Responses were 1 = never, 2 = 1 time, 3 = 2–3 times, 4 = 4–5 times, 5 = 6–7 times, 6 = 8–9 times, 7 = 10–11 times, and 8 = more than 12 times. The variables were then dichotomized, with ‘never’ coded as 0 (no), and all other responses coded as 1 (yes).

To address the research objectives, data analysis was conducted in several stages. Missing data were reviewed immediately after questionnaire completion by enumerators and re-checked prior to analysis. As the proportion of missing data was low (<5%) and showed no systematic pattern, listwise deletion was applied to ensure consistency across analytic models. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the prevalence of ACEs and participants’ demographic characteristics. Group differences in ACEs were examined using Chi-square tests (χ2), depending on assumption fulfillment. For continuous variables, independent t-tests and one-way ANOVA were used to compare mean differences between groups. To explore relationships between ACEs, EF deficits (total and each sub-scale), and HRBs, Spearman’s rank correlation was applied based on normality test results (Shapiro-Wilk test). The association between ACE categories (0, 1–2, 3–4, >5) and HRBs, such as smoking, alcohol use, risky sexual behaviors, and others, was analyzed using Chi-square tests. Additionally, binary logistic regression was performed to examine whether ACEs predicted HRBs after controlling for demographic variables such as gender, grade level, self-academic evaluation, parental marital status, caregiver composition, and number of siblings.

In this study, multicollinearity was assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF) and Tolerance values for all predictor variables, including continuous categorical variables and dummy-coded categorical variables. VIF < 2 and Tolerance > 0.1 were used as thresholds to indicate the absence of multicollinearity. In the fourth purpose of this study, mediation analysis is more focused on understanding how ACEs influence HRBs through EF deficits as a mediator (without or with covariates) by the PROCESS macro (version 4.0; [54]) in SPSS 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) by identifying bootstrapping and confidence interval (CI). The regression and mediation analyses, Cohen’s f 2 was calculated to estimate the effect size of the mediator (EF deficits) by comparing the R2 values of the reduced and full regression models. In addition, a parallel mediation model included five EF subscales as simultaneous mediators to identify their specific indirect effects on the ACEs-HRBs relationship. These subscales were: self-management of time (M1), self-organization/problem solving (M2), self-control (M3), self-motivation (M4), and emotion regulation (M5).

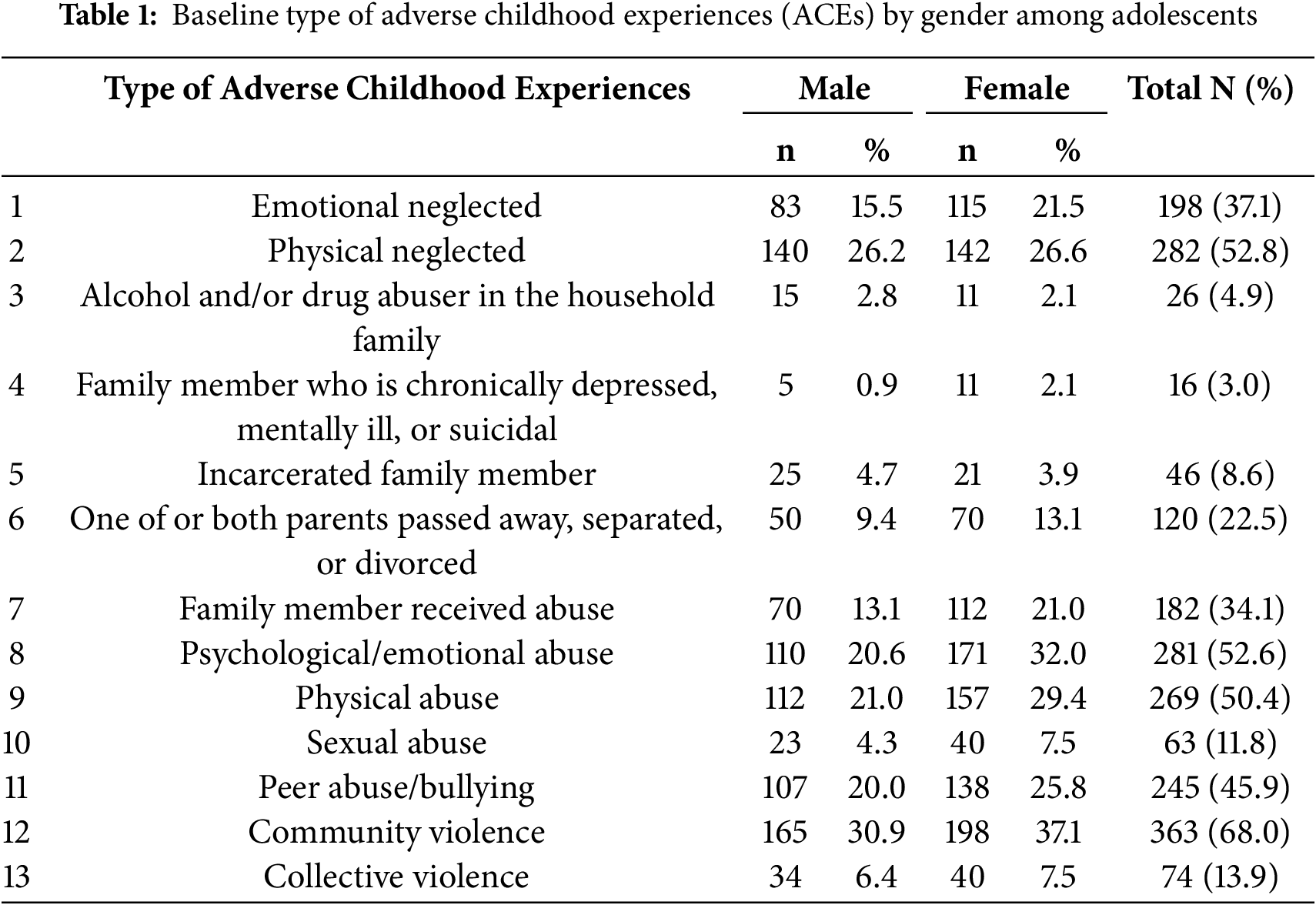

3.1 Baseline Results of ACEs to HRBs Based on Gender

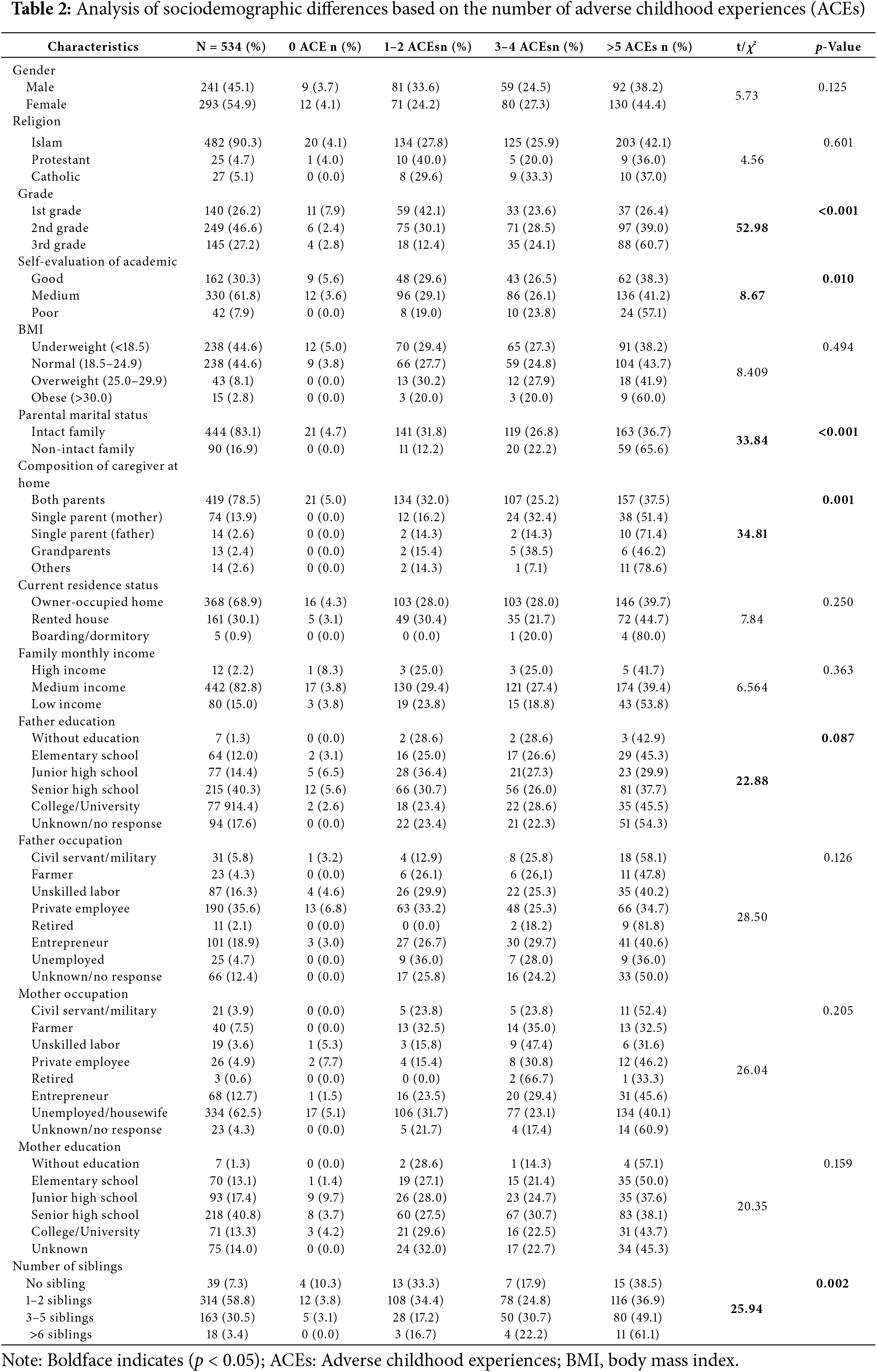

Based on the analysis of demographic characteristics and their relationship with ACEs, several important findings emerged among 534 study respondents (Tables 1 and 2). The five types of ACEs with the highest prevalence were community violence (68.0%), physical neglect (52.8%), psychological/emotional abuse (52.6%), physical abuse (50.4%), and peer bullying (45.9%), indicating high exposure of respondents to various forms of violence and neglect in the family and social.

There were no significant differences observed (Table 2) concerning gender (p = 0.125) or religion (p = 0.601), indicating that ACE exposure is evenly distributed among males and females and across different religious affiliations, grade levels showed a significant relationship with ACE scores (p < 0.001).

Specifically, ninth-grade students had a higher prevalence of >5 ACEs (60.7%) compared to their peers in seventh and eighth grades. Self-assessment of academic performance was statistically related to ACE exposure (p = 0.010), with those rating their performance as poor having the highest percentage of >5 ACEs (57.1%). Furthermore, parental marital status emerged as a significant factor (p < 0.001), with non-intact family reporting a higher proportion of >5 ACEs (65.6%). Caregiver composition also reflected a significant disparity (p = 0.001), where children raised in single-parent households showed increased ACE scores.

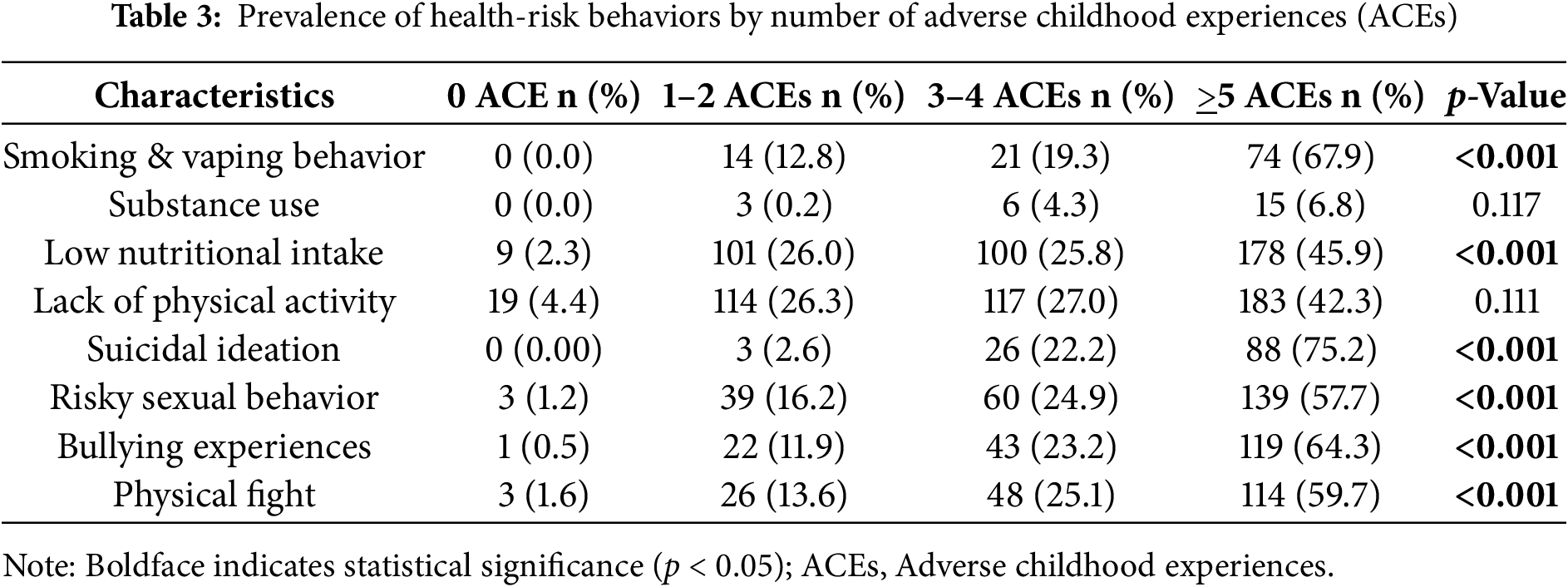

The findings reveal a link between higher ACE exposure to an increased prevalence of HRBs (Table 3). Adolescents with more than five ACEs were significantly more likely to engage in smoking and vaping (67.9%), risky sexual behavior (57.7%), suicidal ideation (75.2%), bullying (64.3%), and physical fights (59.7%) compared to those with fewer ACEs (p < 0.001). Notably, no participants with zero ACEs reported smoking, vaping, substance use, or suicidal ideation. While substance use and physical inactivity were more frequent among those with higher ACEs, their associations were not statistically significant. In addition, suicidal ideation was strongly linked to ACEs, with 75.2% of those with more than 5 ACEs reporting such thoughts (p < 0.001). Risky sexual behavior was similarly prevalent, with 57.7% of those engaging in it having high ACE exposure (p < 0.001). Bullying and involvement in physical fights also correlated strongly with ACE exposure, with 64.3% and 59.7% of participants, respectively, reporting these behaviors in the group with more than 5 ACEs (p < 0.001).

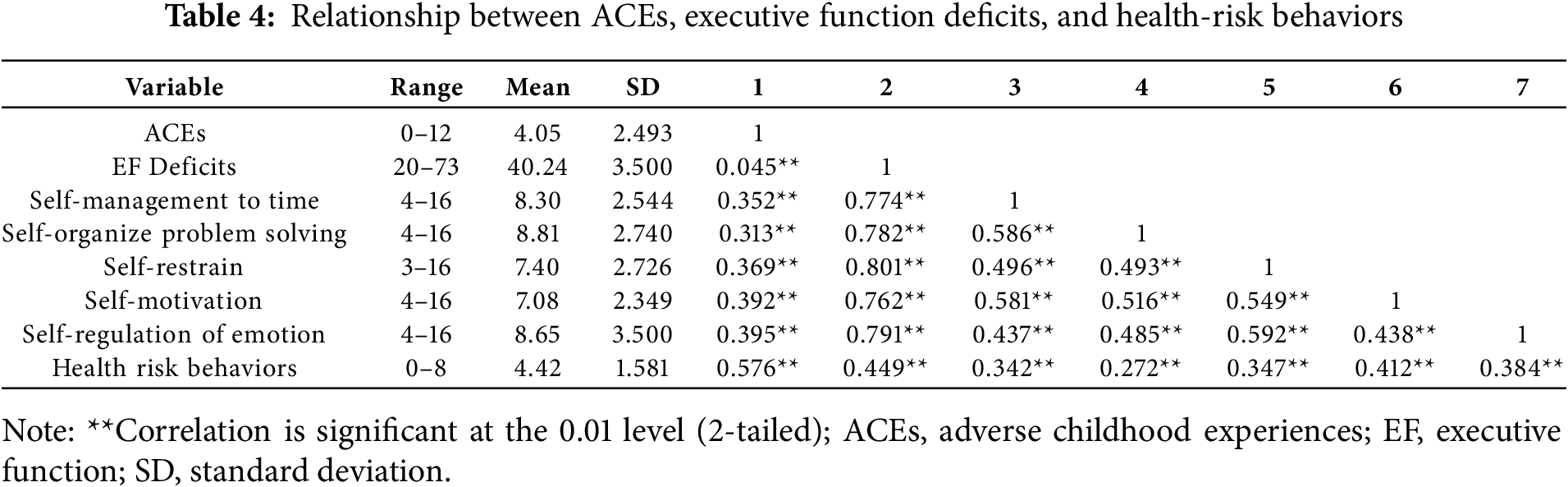

3.2 The Relationships between ACEs and HRBs

As shown in Table 4, there is a substantial positive link between ACEs and both EF deficits (r = 0.471, p < 0.01) and HRBs (r = 0.578, p < 0.01). Additionally, EF deficits are significantly correlated with HRBs (r = 0.469, p < 0.01). Higher exposure to childhood adversity is associated with higher EF deficits. Additionally, adolescents with more adverse experiences are more likely to engage in risky behaviors. EF deficits further contribute to this link, suggesting their mediating role in the relationship between childhood adversity and HRBs.

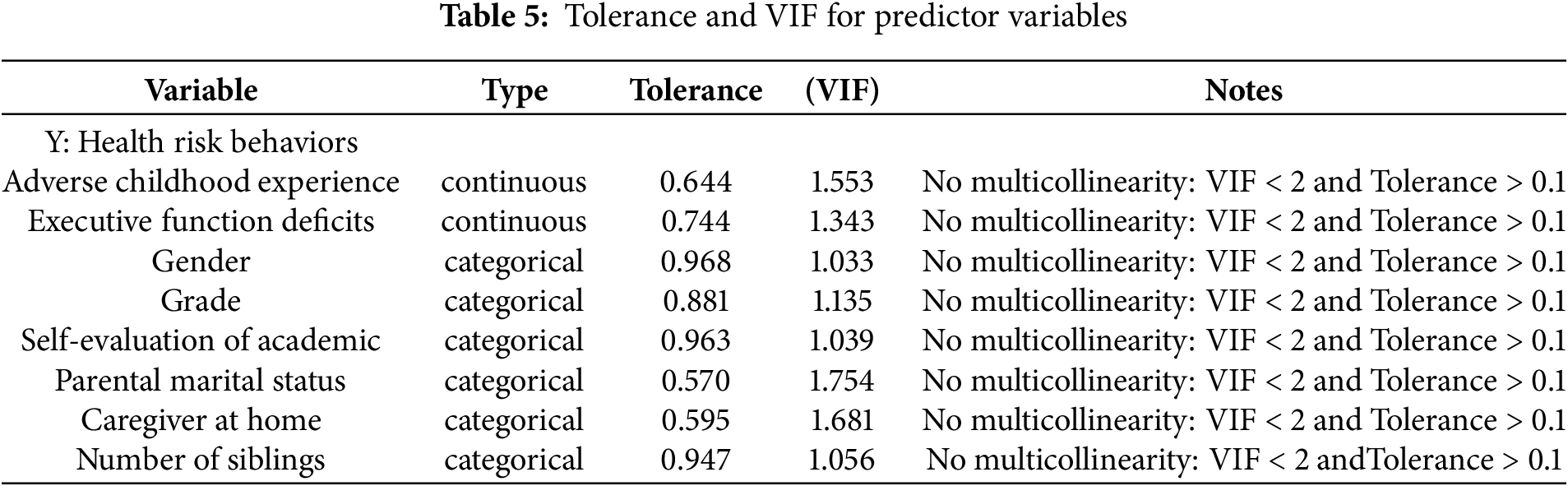

All five EF subscales were significantly positively correlated with ACEs (r ranging from 0.313 to 0.395, p < 0.01). Self-regulation of emotion (r = 0.395, p < 0.01) and self-motivation (r = 0.392, p < 0.01) exhibited the strongest associations with ACEs. This suggests that individuals with higher ACE exposure are more likely to experience difficulties in regulating emotional responses and initiating goal-directed behavior without external incentives. Regarding HRBs, all EF subscales also showed significant positive correlations (r ranging from 0.272 to 0.412, p < 0.01). The highest correlation was observed for self-motivation (r = 0.412, p < 0.01), followed by self-regulation of emotion (r = 0.384, p < 0.01), indicating that lower capacity for intrinsic motivation and emotional regulation may be particularly linked to increased engagement in health-compromising behaviors. The VIF and tolerance values indicated no multicollinearity among the predictor variables (VIF range: 1.033–1.754; Tolerance range: 0.570–0.968). These results support the robustness of the regression model and confirm that the independent variables—ACEs, EF deficits, and sociodemographic factors—do not exhibit redundancy, allowing for reliable interpretation of their effects on HRBs (Table 5).

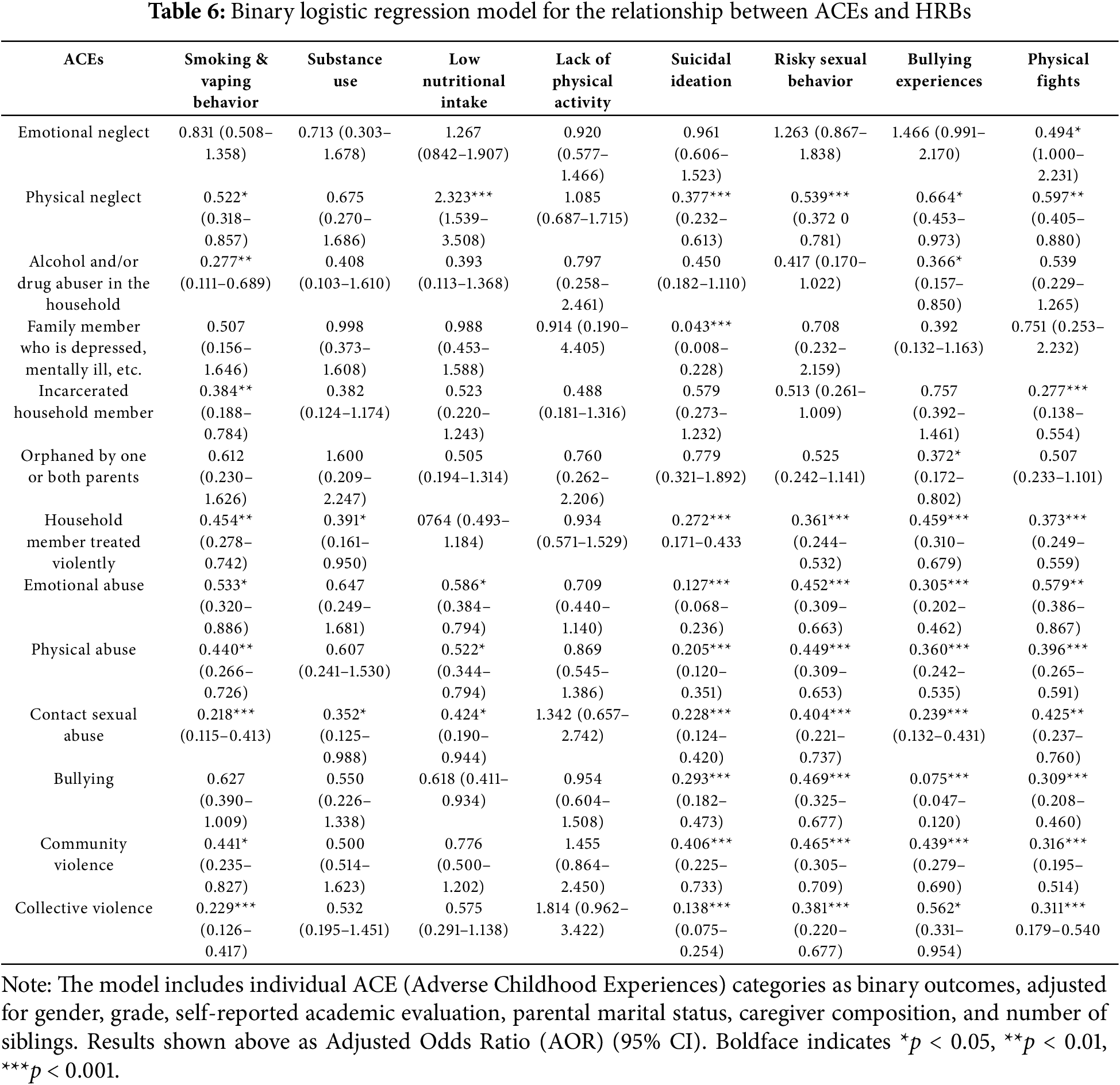

The logistic regression analysis (Table 6) revealed that multiple forms of ACEs were significantly associated with increased engagement in HRBs. Emotional and physical neglect significantly predicted low nutritional intake (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 2.323, p < 0.001) and suicidal ideation (AOR = 0.377, p < 0.001). Household violence, emotional abuse, and physical abuse show strong associations with suicidal ideation, risky sexual behavior, bullying, and physical fights (p < 0.001). Contact sexual abuse emerges as a particularly strong predictor of smoking, suicidal ideation, and bullying (p < 0.001). The findings provide an overview of the role of childhood adversity in the occurrence of maladaptive adolescent HRBs that need further treatment for adolescents with ACEs.

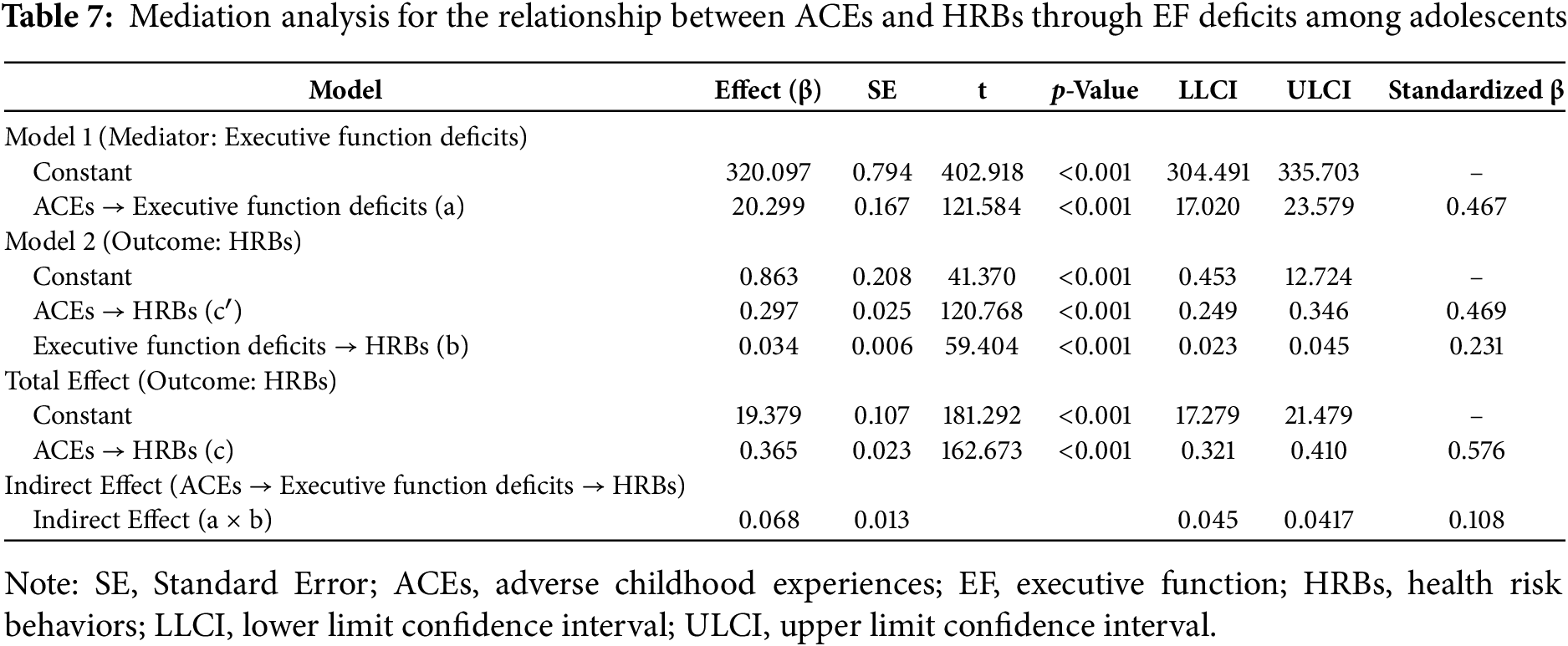

3.3 EF Deficits as a Mediator between ACEs and HRBs

The mediation analysis indicates that ACEs significantly predict both EF deficits and HRBs (Table 7). EF deficits partially mediate the relationship between ACEs and HRBs, with an indirect effect. While ACEs have a direct impact on HRBs, the presence of EF deficits further contributes to increased HRBs, highlighting their mediating role in this relationship.

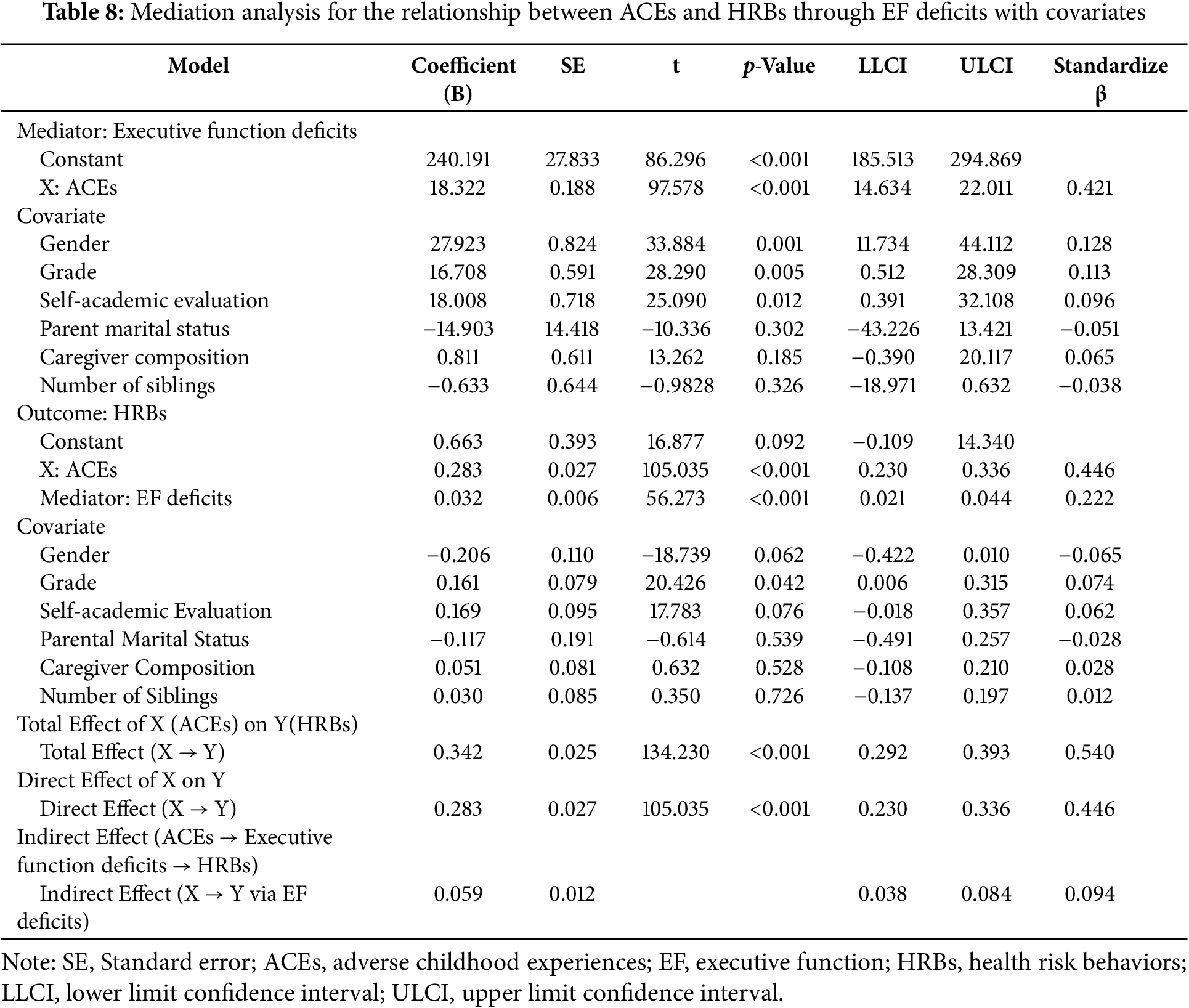

The mediation analysis involving covariate variables (Table 8), such as gender, grade, and self-academic evaluation, also influences EF deficits, but their impact is smaller compared to ACEs. This finding underscores the central role of ACEs as a major contributor to EF deficits, highlighting their importance in understanding the psychological consequences of early adverse experiences. Moreover, ACEs exhibit both direct and indirect effects on HRBs (Btotal = 0.342, β = 0.540), with a portion of this relationship mediated by EF deficits (Bindirect = 0.059, 95% CI [0.038, 0.084]). EF deficits significantly increase HRBs (B = 0.032, p < 0.001, β = 0.222), but ACEs remain the primary predictor of HRBs.

To further assess the contribution of EF deficits as a mediator, Cohen’s f 2 was calculated to estimate the effect size of its inclusion in the regression model predicting HRBs. The R2 of the reduced model (without EF deficits) was 0.353, and the R2 of the full model (with EF deficits) was 0.389. The resulting Cohen’s f 2 = 0.059, indicating a small to moderate effect size. This suggests that EF deficits meaningfully, though modestly, enhance the model’s explanatory power for predicting HRBs among adolescents.

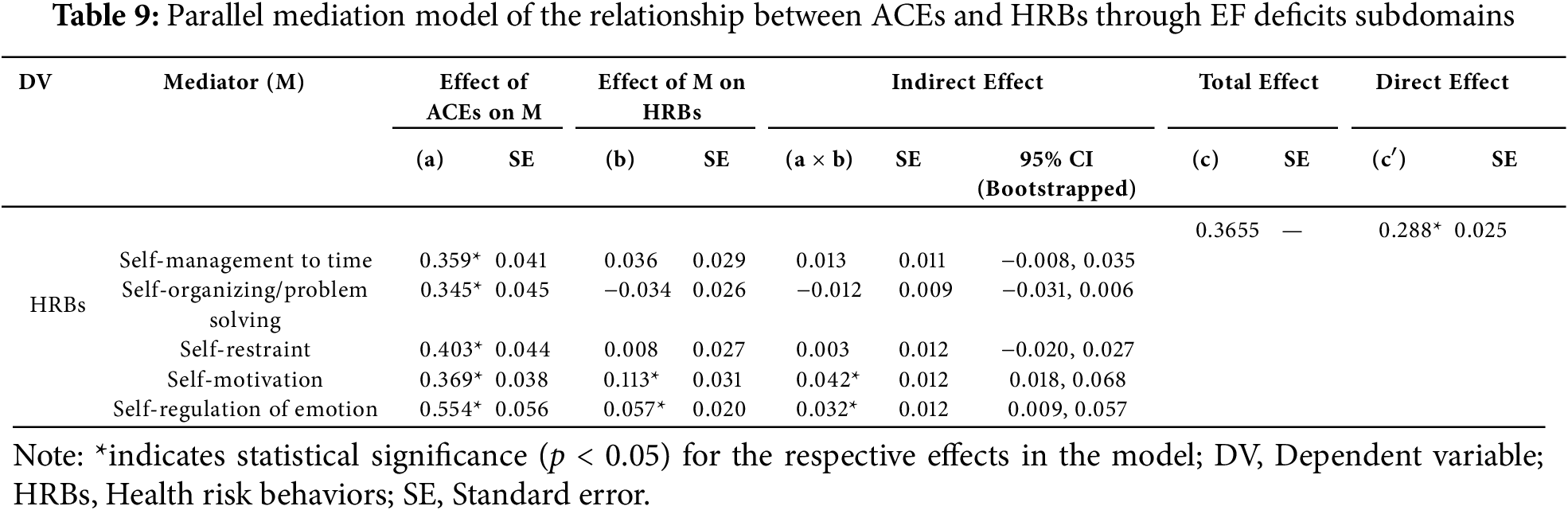

In the next analysis, a parallel mediation analysis tested whether EF deficits mediate the relationship between ACEs and HRBs (Table 9). Five EF deficits subdomains were included as mediators, only self-motivation (B = 0.042, 95% CI [0.018, 0.068]) and self-regulation of emotion (B = 0.032, 95% CI [0.009, 0.057]) showed significant indirect effects. The direct effect of ACEs on HRBs remained significant (B = 0.2877, p < 0.001), suggesting partial mediation (S9). These results highlight the specific role of motivational and emotional regulation deficits in linking childhood adversity to risky health behaviors.

Community violence, physical neglect, emotional abuse, physical violence, and peer bullying showed the highest exposure in the families and social settings of respondents in this study. Previous research showed that individuals who experience community violence tend to develop maladaptive behaviors as coping mechanisms, including aggressive behavior and substance abuse [10]. Community violence can create an unsafe environment, negatively affecting adolescents’ social and emotional development [55]. Findings of physical neglect can lead to the development of mental health disorders such as anxiety and depression, while also potentially raising the likelihood of risky behaviors, such as drug use and criminal behavior among adolescents [56,57]. Psychological or emotional abuse includes actions such as insults, threats, or denial of affection. A study showed that children or teens who experience emotional abuse are at higher risk for developing mental health problems, risky behaviors, or sexual violence [58]. In addition, the young people who are victims of physical violence often have difficulty managing their emotions, possibly diverting their emotional pain through risky behaviors such as alcohol or drug use [55]. Further, bullying can have direct negative impacts on individuals [59]. The level of victimization varies, whether direct, verbal, or non-verbal, and electronic bullying is associated with almost every HRB and condition studied [60].

In this study, community violence had a significant relationship with suicidal ideation. This result in line shows by Lambert SF [61] that exposure to violence in the surrounding environment can increase risks, including depression and anxiety, that contribute to suicidal ideation. Physical neglect also showed strong associations with low nutritional intake. The previous study highlights that children who experience physical neglect tend to have poor eating patterns [62], and this can have a significant relationship with risky sexual behavior and bullying experiences. Evidence indicates a causal association between nonsexual child maltreatment and various mental disorders, substance usage, suicide attempts, sexually transmitted illnesses, and high-risk sexual conduct [63]. This neglect is often due to a lack of support from caregivers, who play a critical role in a child’s social and emotional development. Exposure to domestic violence was strongly associated with suicidal, risky sexual behavior, and physical violence. This study is in line with the study [64,65], which showed that children who witness domestic violence and stressful family situations often experience profound psychological trauma, which can significantly affect their mental health and risky behaviors [66]. These impacts indicate the need for comprehensive intervention approaches to address domestic violence as a major risk factor for adolescent health.

The present study suggests that the mediator of EF deficits played a significant role as a pathway connecting ACEs to HRBs, indicating that this deficit has an important contribution to the relationship. The total effect of ACEs on HRBs was greater than its direct effect, confirming the role of the mediator. EF focuses on the cognitive skills adolescents need to manage behavior and emotions, and to plan and make both positive and negative decisions [26]. The findings of this investigation are in accordance with those of prior studies that exposure to ACEs, such as violence and neglect, is consistently associated with EF deficits in adolescents, including difficulties in emotion regulation [67] and self-motivation [40]. This study also confirms previous research findings that EF contributes to variance in risky behaviors [68]. Previous research has also indicated that EF deficits increase the probability of healthy young adults engaging in potentially hazardous health-risky behaviors [69]. This study also supports previous studies’ mention that there is a need to examine the impact of ACEs and the roles that they may play in shaping these impacts [70]. The results of the practical study of EF deficits as a mediator were further examined through effect size estimation. The analysis showed a small to moderate contribution of EF deficits in explaining the relationship between ACEs and HRBs. This is in line with previous studies [38,71], which showed that EF deficits significantly mediate the relationship between environmental risk factors (including traumatic experiences) and adolescent involvement in risky behaviors such as substance abuse, with a moderate contribution of EF as a mediator.

Several covariate factors, such as gender, academic self-evaluation, and grade level, also showed significant effects on EF deficits and high-risk behaviors, while other factors, such as parental marital status, caregiver composition, and number of siblings, did not show significant effects. Previous research has shown that social support factors and resilience capacity also have the potential to mediator the negative impact of ACEs on HRBs [72]. Previous research showed that individuals who have strong adaptability or social support tend to be better able to overcome the impact of ACEs as they grow up [73].

This study has several limitations that should be considered. First, this study used self-report instruments to measure ACEs, HRBs, and other sociodemographic components, which could potentially introduce recall bias or self-report bias. For example, the data on monthly household income were based on adolescents’ self-reports rather than obtained directly from their parents. Previous research has shown that self-report methods are often influenced by individuals’ desire to provide more socially acceptable answers, or memory limitations in recalling traumatic experiences, and it is also expected that there will be a cross-check of supporting data by parents or other significant persons [74]. Covariates used in the study, such as gender, grade level, parental marital status, and number of siblings, provide additional insights but do not fully capture all relevant socioeconomic and environmental contexts. For example, the quality of relationships with caregivers or access to mental health services were not analyzed, even though these factors may have significant impacts on EF and HRBs. An important consideration in developing an effective tiered intervention strategy is the limited number of mental health workers in Indonesia, especially for adolescent health services that focus on childhood trauma [75,76]. This also highlights the potential for training non-specialist personnel, such as teachers, as frontline mental health responders to bridge the service gap and reduce stigma associated with adolescents experiencing ACEs and potentially engaging in HRBs. Future research can expand the exploration by adding variables such as resilience, specific family support, and mental well-being, all of which have been shown to play an important role in mitigating the adverse effects of ACEs [42]. The role of family function can mitigate the negative impact of accumulated ACEs on adolescents’ health and emotional well-being [65]. Adolescents with higher ACE scores tended to report worse physical and emotional outcomes compared to adolescents with lower ACE scores, after controlling for demographic and socioeconomic factors [77].

In the cultural aspect, the sample size for each ethnic group was not sufficient to conduct a robust moderation analysis, as the participants represented more than 15 culturally diverse ethnicities. It is recommended to explore this aspect using qualitative or mixed-method approaches for deeper cultural insights in future studies. Although this study provides good insight into a specific population, such as Samarinda, Indonesia, generalization of the results to a wider population should be approached with caution [16]. Emphasized the importance of diversifying samples based on specific ethnicity, and a deeper family background, including the family’s economic status and living conditions that can all influence how individuals respond to traumatic experiences related to EF and HRBs. Considering the cultural variability in how ACEs influence HRBs, it is essential for future studies to develop culturally informed norms, values, prevention, and intervention strategies that cater to the distinctive requirements and protective factors of diverse communities [78,79]. In addition, future research needs to use longitudinal methods to track how ACEs impact HRBs across life stages, this is to determine critical time frames for early preventive interventions and identify specific developmental periods during which interventions may be most effective in reducing the long-term risk of ACEs. Understanding these phase trajectories will allow for more targeted and timely interventions to break the cycle of adverse outcomes associated with ACEs. A comprehensive overview is also needed regarding policies and regulations related to the prevention of ACEs and HRBs in groups of children and adolescents. Future interventions should consider targeting specific domains of EF that mediate the relationship between ACEs and health-risk behavior [80]. For example, increasing intrinsic motivation in adolescents exposed to certain types of traumas may promote adaptive, goal-directed behaviors [81]. To reduce emotion dysregulation, school-based programs (adapted to the religious context of the student’s educational level) that incorporate multisensory emotion regulation training may effectively enhance adolescents’ self-regulatory abilities, consequently, negative childhood experiences have less of an impact on hazardous conduct [82].

This study has addressed the relationship between ACEs on HRBs among adolescents, particularly in the context of junior high school students in Samarinda, Indonesia. The study findings provide an overview that higher exposure to ACEs is strongly associated with increased engagement in a range of HRBs, including substance use, risky sexual behavior, suicidal ideation, physical inactivity, and violence. Notably, adolescents with more than five ACEs exhibited alarming rates of smoking or vaping, risky sexual practices, and suicidal ideation, underscoring the urgent need for interventions in both school and family settings.

Mediation analysis also suggested that EF deficits have played a role in this association, serving as a pathway through which ACEs influence HRBs. This suggests that improving executive function skills may mitigate some of the negative effects associated with ACEs exposure. Therefore, it is imperative for policymakers and educators to implement early intervention programs that not only address the impacts of ACEs but also include targeted strategies to enhance specific EF (particularly self-motivation and emotional regulation) for Indonesian adolescents, as highlighted in this study. This study contributes to a growing body of literature emphasizing the importance of a holistic approach to promoting adolescent mental health to address the challenges posed by ACEs. These initiatives can be embedded within school-based mental health and social-emotional learning programs through the integration of emotional regulation curricula (e.g., mindfulness training) in junior high schools, such as Islamic schools, to conduct ACEs screening and psychological counseling, which are more familiar within the Indonesian context, engagement of community leaders (e.g., village heads) in culturally appropriate prevention campaigns, and to bypass reliance on family self-reporting. The tiered strategy trains teachers as frontline responders (especially in areas with limited mental health services) to promote students’ motivation and healthy life decision-making.

Furthermore, family welfare policies should support parenting programs and home-based interventions that build these executive skills from early childhood, ensuring that parents and caregivers are equipped with the tools and strategies to foster these essential skills. Such initiatives can help create a strong foundation for children’s cognitive, emotional, and social development, ultimately improving long-term outcomes and reducing the risk of harmful behaviors later in life.

Acknowledgement: We extend our gratitude and appreciation to everyone participants for their time and experience, as well as the parents who have given permission for their children to participate in this research. We would also like to express our gratitude to all members of the school community, especially the principal and student subject teachers, for their technical support during the data collection process. In addition, our appreciation extends to the field researchers and support team for their support and assistance in this study.

Funding Statement: This study has been supported by the STI 2030—Major Projects (2021ZD0200500).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Riza Hayati Ifroh; data collection: Riza Hayati Ifroh; analysis and interpretation of results: Riza Hayati Ifroh, Xiaosong Gai; draft manuscript preparation: Riza Hayati Ifroh; supervision and funding acquisition: Xiaosong Gai. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author by Xiaosong Gai, Email: gaixs669@nenu.edu.cn upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: We received ethical approval for this study from Academic Ethics Committee of School of Psychology, Northeast Normal University, Changchun, China (Approval Number: 2024020), and the research ethics approval based on the study location were approved by the Commission of Ethical Research for Health Medical Faculty of Mulawarman University, Samarinda, Indonesia (Approval Number: 228/KEPK-FK/IX/2024). Formal approval was obtained from the school authorities and the Samarinda Department of Education (Permit No. 500.10.30/2636/100.01). Informed consent was obtained from both participants and their parents.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing adverse childhood experiences (ACEsleveraging the best available evidence. Atlanta, GA, USA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention; 2019. 40 p. [Google Scholar]

2. Lei MK, Berg MT, Simons RL, Beach SRH. Specifying the psychosocial pathways whereby child and adolescent adversity shape adult health outcomes. Psychol Med. 2023;53(13):6027–36. doi:10.1017/S003329172200318X. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Majid M, Rahman AA, Taib F. Adverse childhood experiences and health risk behaviours among the undergraduate health campus students. Malays J Med Sci. 2023;30(1):152–61. doi:10.21315/mjms2023.30.1.13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Luan PT, Pham QL, Tan DD, Linh NT, Long NT, Oanh KT, et al. Suicide risk among young people who use drugs in Hanoi, Vietnam: prevalence and related factors. J Paediatr Child Health. 2024;60(11):654–9. doi:10.1111/jpc.16648. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Patunru AA, Kusumaningrum S. Inequalities and children in Indonesia. In: Child Poverty and Social Protection Conference; 2013 Sep 11–13; Jakarta, Indonesia. p. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

6. Ramaiya A, Choiriyyah I, Heise L, Pulerwitz J, Blum RW, Levtov R, et al. Understanding the relationship between adverse childhood experiences, peer-violence perpetration, and gender norms among very young adolescents in Indonesia: a cross-sectional study. J Adolesc Health. 2021;69(1S):S56–63. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.01.025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Rahapsari S, Puri VGS, Putri AK. An Indonesian adaptation of the World Health Organization adverse childhood experiences international questionnaire (WHO ACE-IQ) as a screening instrument for adults. Gadjah Mada J Psychol. 2021;7(1):99. doi:10.22146/gamajop.64996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Webster EM. The impact of adverse childhood experiences on health and development in young children. Glob Pediatr Health. 2022;9:1–11. doi:10.1177/2333794X221078708. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Swedo EA, Pampati S, Anderson KN, Thorne E, McKinnon II, Brener ND, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and health conditions and risk behaviors among high school students—youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2023. MMWR Suppl. 2024;73(4):39–50. doi:10.15585/mmwr.su7304a5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, et al. Household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults the adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(6):245–58. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2019.04.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Espeleta HC, Bakula DM, Delozier AM, Perez MN, Sharkey CM, Mullins LL. Transition readiness: the linkage between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and health-related quality of life. Transl Behav Med. 2019;9(3):533–40. doi:10.1093/tbm/iby130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Agrawal J, Lei Y, Shah V, Bui AL, Halfon N, Schickedanz A. Young adult mental health problem incidence varies by specific combinations of adverse childhood experiences. Adversity Resil Sci. 2025;6(1):19–32. doi:10.1007/s42844-024-00140-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Tzouvara V, Kupdere P, Wilson K, Matthews L, Simpson A, Foye U. Adverse childhood experiences, mental health, and social functioning: a scoping review of the literature. Child Abuse Negl. 2023;139(11):106092. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2023.106092. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Xu H, Cai J, Li M, Yuan Y, Qin H, Liu J, et al. Beyond cumulative scores: distinct patterns of adverse childhood experiences and their differential impact on emotion, borderline personality traits, and executive function. Stress Health. 2025;41(2):e3511. doi:10.1002/smi.3511. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Larkin H, Shields JJ, Anda RF. The health and social consequences of adverse childhood experiences (ACE) across the lifespan: an introduction to prevention and intervention in the community. J Prev Interv Commun. 2012;40(4):263–70. doi:10.1080/10852352.2012.707439. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, Sethi D, Butchart A, Mikton C, et al. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(8):e356–66. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Wiehn J, Hornberg C, Fischer F. How adverse childhood experiences relate to single and multiple health risk behaviours in German public university students: a cross-sectional analysis. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1005. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5926-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Garrido EF, Weiler LM, Taussig HN. Adverse childhood experiences and health-risk behaviors in vulnerable early adolescents. Physiol Behav. 2017;176:139–48. doi:10.1177/0272431616687671. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Xu H, Zhang X, Wang J, Xie Y, Zhang Y, Xu S, et al. Exploring associations of adverse childhood experiences with patterns of 11 health risk behaviors in Chinese adolescents: focus on gender differences. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2023;17(1):26. doi:10.1186/s13034-023-00575-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Gajos JM, Leban L, Weymouth BB, Cropsey KL. Sex differences in the relationship between early adverse childhood experiences, delinquency, and substance use initiation in high-risk adolescents. J Interpers Violence. 2023;38(1–2):NP311–35. doi:10.1177/08862605221081927. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Qu G, Liu H, Han T, Zhang H, Ma S, Sun L, et al. Association between adverse childhood experiences and sleep quality, emotional and behavioral problems and academic achievement of children and adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2024;33(2):527–38. doi:10.1007/s00787-023-02185-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Spilková J, Pikhart H, Dzúrová D. Multilevel analysis of health risk behaviour in Czech teenagers. Auc Geogr. 2015;50(1):91–100. doi:10.14712/23361980.2015.89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Danese A, McEwen BS. Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiol Behav. 2012;106(1):29–39. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.08.019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. León JC, Carmona J, García P. Health-risk behaviors in adolescents as indicators of unconventional lifestyles. J Adolesc. 2010;33(5):663–71. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.11.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Kwan M. Health promotion and chronic disease prevention in Canada research. Policy Pract. 2016;163:163–70. [Google Scholar]

26. Jurado MB, Rosselli M. The elusive nature of executive functions: a review of our current understanding. Neuropsychol Rev. 2007;17(3):213–33. doi:10.1007/s11065-007-9040-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Tekin S, Cummings JL. Frontal-subcortical neuronal circuits and clinical neuropsychiatry: an update. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(2):647–54. doi:10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00428-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Banich MT. Executive function: the search for an integrated account. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2009;18(2):89–94. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01615.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Steinberg L, Albert D, Cauffman E, Banich M, Graham S, Woolard J. Age differences in sensation seeking and impulsivity as indexed by behavior and self-report: evidence for a dual systems model. Dev Psychol. 2008;44(6):1764–78. doi:10.1037/a0012955. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. McCrory EJ, Viding E. The theory of latent vulnerability: reconceptualizing the link between childhood maltreatment and psychiatric disorder. Dev Psychopathol. 2015;27(2):493–505. doi:10.1017/S0954579415000115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Clauss K, Witte TK, Bardeen JR. Examining the factor structure and incremental validity of the Barkley deficits in executive functioning scale—short form in a community sample. J Pers Assess. 2021;103(6):777–85. doi:10.1080/00223891.2021.1887879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Belsky D, Dickson N, Hancox RJ, Harrington H, et al. A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(7):2693–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.1010076108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Evans GW, Kim P. Childhood poverty, chronic stress, self-regulation, and coping. Child Dev Perspect. 2013;7(1):43–8. doi:10.1111/cdep.12013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Trossman R, Spence SL, Mielke JG, McAuley T. How do adverse childhood experiences impact health? Exploring the mediating role of executive functions. Psychol Trauma. 2021;13(2):206–13. doi:10.1037/tra0000965. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Goldstein S, Editors JAN. Executive functioning. In: Encyclopedia of human development. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: SAGE Publications; 2013. [Google Scholar]

36. Kamradt JM, Nikolas MA, Burns GL, Garner AA, Jarrett MA, Luebbe AM, et al. Barkley deficits in executive functioning scale (BDEFSvalidation in a large multisite college sample. Assess. 2021;28(3):964–76. doi:10.1177/1073191119869823. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Crockett LJ, Raffaelli M, Shen YL. Linking self-regulation and risk proneness to risky sexual behavior: pathways through peer pressure and early substance use. J Res Adolesc. 2006;16(4):503–25. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00505.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Claro A, Dostaler G, Shaw SR. Clarifying the relationship between executive function and risky behavior engagement in adolescents. Contemp Sch Psychol. 2022;26(2):164–72. doi:10.1007/s40688-020-00287-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Williams PG, Tinajero R, Suchy Y. Executive functioning and health. In: Oxford handbook topics in psychology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press (OUP); 2017. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935291.013.75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Lund JI, Boles K, Radford A, Toombs E, Mushquash CJ. A systematic review of childhood adversity and executive functions outcomes among adults. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2022;37(6):1118–32. doi:10.1093/arclin/acac013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Siva Prasad MS, Joseph JK, Vardhanan YS. Exploration of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and health risk behaviors (HRBs) in male recidivist violent offenders: Indian scenario. J Child Adolesc Trauma. 2022;15(3):639–52. doi:10.1007/s40653-021-00434-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Bellis MA, Hughes K, Leckenby N, Perkins C, Lowey H. National household survey of adverse childhood experiences and their relationship with resilience to health-harming behaviors in England. BMC Med. 2014;12(1):72. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-12-72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Stoltenborgh M, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Alink LRA, van IJzendoorn MH. The prevalence of child maltreatment across the globe: review of a series of meta-analyses. Child Abuse Rev. 2015;24(1):37–50. doi:10.1002/car.2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Mustikaningtyas M, Pinandari AW, Setiyawati D, Wilopo SA. Are adverse childhood experiences associated with depression in early adolescence? An ecological analysis approach using GEAS baseline data 2018 in Indonesia. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2022;10(E):1844–51. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2022.8210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Pinandari AW, Page A, Oktavitie IT, Herawati E, Prastowo FR, Wilopo SA, et al. Early adolescents’ voices in Indonesia: a qualitative exploration of results from the global early adolescent study [Internet]. [cited 2025 May 30]. Available from: https://rutgers.international/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/YVR2-ENG.pdf. [Google Scholar]

46. Fitriangga A, Albilardo G, Pramulya M. Distribution and spatial pattern analysis on malnutrition cases: a case study in Pontianak city. Malays J Public Health Med. 2020;20(2):56–64. doi:10.37268/mjphm/vol.20/no.2/art.477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Center for Reproductive Health UGM Faculty of Medicine Public Health and Nursing. Early adolescents’ health in Indonesia: evidence base from GEAS-Indonesia baseline 2019. Yogyakarta, Indonesia: UGM Center for Reproductive Health; 2019. [Google Scholar]

48. World Health Organization. Adverse childhood experiences international questionnaire (ACE-IQ). Retrieved online World Heal World Heal Organ [Internet]. [cited 2025 May 30]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/adverse-childhood-experiences-international-questionnaire-(ace-iq). [Google Scholar]

49. Camille L, Christine R, Elise E, Charles MK, Marion T, Cyril T. Psychometric validation of the French version of the adverse childhood experiences international questionnaire (ACE-IQ). Child Youth Serv Rev. 2023;150(3):107007. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2023.107007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Kidman R, Smith D, Piccolo LR, Kohler HP. Psychometric evaluation of the adverse childhood experience international questionnaire (ACE-IQ) in Malawian adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 2019;92(2):139–45. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.03.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. World Health Organization. Adverse childhood experiences international questionnaire (ACE-IQ)—section D: guidance for analysing ACE-IQ. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

52. Lace JW, McGrath A, Merz ZC. A factor analytic investigation of the Barkley deficits in executive functioning scale, short form. Curr Psychol. 2022;41(4):2297–305. doi:10.1007/s12144-020-00756-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. CDC. 2023 state and local youth risk behavior survey [Internet]. [cited 2025 May 30]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/yrbs/questionnaires/index.html. [Google Scholar]

54. Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach [Internet]. [cited 2025 May 30]. Available from: https://www.guilford.com/books/Introduction-to-Mediation-Moderation-and-Conditional-Process-Analysis/Andrew-Hayes/9781462549030?srsltid=AfmBOoq4h8YdvkGe3kIC8a5eJIOau-sypvEwRcT5KwODccQQxRPfquYm. [Google Scholar]

55. Madigan S, Deneault AA, Racine N, Park J, Thiemann R, Zhu J, et al. Adverse childhood experiences: a meta-analysis of prevalence and moderators among half a million adults in 206 studies. World Psychiatry. 2023;22(3):463–71. doi:10.1002/wps.21122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Xu P, Liu Z, Xu Y, Li T, Xu G, Xu X, et al. The prevalence and profiles of adverse childhood experiences and their associations with adult mental health outcomes in China: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2024;53(6):101253. doi:10.1016/j.lanwpc.2024.101253. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Novais M, Henriques T, Vidal-Alves MJ, Magalhães T. When problems only get bigger: the impact of adverse childhood experience on adult health. Front Psychol. 2021;12:693420. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.693420. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Francis L, Pearson D. The recognition of emotional abuse: adolescents’ responses to warning signs in romantic relationships. J Interpers Violence. 2021;36(17–18):8289–313. doi:10.1177/0886260519850537. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Hikmat R, Suryani S, Yosep I, Jeharsae R. KiVa anti-bullying program: preventing bullying and reducing bulling behavior among students—a scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):2923. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-20086-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Hertz MF, Everett Jones S, Barrios L, David-Ferdon C, Holt M. Association between bullying victimization and health risk behaviors among high school students in the United States. J Sch Health. 2015;85(12):833–42. doi:10.1111/josh.12339. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Lambert SF, Copeland-Linder N, Ialongo NS. Longitudinal associations between community violence exposure and suicidality. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43(4):380–6. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.02.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Geiker NW, Astrup A, Hjorth MF, Sjödin A, Pijls L, Markus CR. Does stress influence sleep patterns, food intake, weight gain, abdominal obesity and weight loss interventions and vice versa? Obes Rev. 2018;19(1):81–97. doi:10.1111/obr.12603. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9(11):e1001349. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Odgers CL, Russell MA. Violence exposure is associated with adolescents’ same- and next-day mental health symptoms. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2017;58(12):1310–8. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12763. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Kedzior SGE, Barrett S, Muir C, Lynch R, Kaner E, Forman JR, et al. They had clothes on their back and they had food in their stomach, but they didn’t have me: the contribution of parental mental health problems, substance use, and domestic violence and abuse on young people and parents. Child Abus Negl. 2024;149(7):106609. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2023.106609. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Yu Y, Chotipanvithayakul R, Kuang H, Wichaidit W, Wan C. Associations between mental health outcomes and adverse childhood experiences and character strengths among university students in Southern China. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2023;25(12):1343–51. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2023.043446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Trossman R, Mielke JG, McAuley T. Global executive dysfunction, not core executive skills, mediate the relationship between adversity exposure and later health in undergraduate students. Appl Neuropsychol Adult. 2022;29(3):405–11. doi:10.1080/23279095.2020.1764561. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Romer D, Betancourt LM, Brodsky NL, Giannetta JM. Does adolescent risk taking imply weak executive function? Dev Sci. 2012;14:1119–33. [Google Scholar]

69. Reynolds BW, Basso MR, Miller AK, Whiteside DM, Combs D. Executive function, impulsivity, and risky behaviors in young adults. Neuropsychol. 2019;33(2):212–21. doi:10.1037/neu0000510. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Park E, Lee J, Han J. The association between adverse childhood experiences and young adult outcomes: a scoping study. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2021;123(1):105916. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Gray-Burrows K, Taylor N, O’Connor D, Sutherland E, Stoet G, Conner M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the executive function-health behaviour relationship. Health Psychol Behav Med. 2019;7(1):253–68. doi:10.1080/21642850.2019.1637740. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Bethell C, Jones J, Gombojav N, Linkenbach J, Sege R. Positive childhood experiences and adult mental and relational health in a statewide sample: associations across adverse childhood experiences levels. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(11):e193007. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.3007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Luthar SS, Cicchetti D. The construct of resilience: implications for interventions and social policies. Dev Psychopathol. 2000;12(4):857–85. doi:10.1017/s0954579400004156. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Hardt J, Rutter M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: review of the evidence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45(2):260–73. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Munira L, Liamputtong P, Viwattanakulvanid P. Barriers and facilitators to access mental health services among people with mental disorders in Indonesia: a qualitative study. Belitung Nurs J. 2023;9(2):110–7. doi:10.33546/bnj.2521. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Basrowi RW, Wiguna T, Samah K, Djuwita F, Moeloek N, Soetrisno M, et al. Exploring mental health issues and priorities in Indonesia through qualitative expert consensus. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2024;20(1):e17450179331951. doi:10.2174/0117450179331951241022175443. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Balistreri KS, Alvira-Hammond M. Adverse childhood experiences, family functioning and adolescent health and emotional well-being. Public Health. 2016;132(12):72–8. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2015.10.034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Assini-Meytin LC, Fix RL, Green KM, Nair R, Letourneau EJ. Adverse childhood experiences, mental health, and risk behaviors in adulthood: exploring sex, racial, and ethnic group differences in a nationally representative sample. J Child Adolesc Trauma. 2021;15(3):833–45. doi:10.1007/s40653-021-00424-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Liu J, Abdin E, Vaingankar JA, Verma S, Tang C, Subramaniam M. Profiles of adverse childhood experiences and protective resources on high-risk behaviors and physical and mental disorders: findings from a national survey. J Affect Disord. 2022;303(4):24–30. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2022.01.112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Berthelsen D, Hayes N, White SLJ, Williams KE. Executive function in adolescence: associations with child and family risk factors and self-regulation in early childhood. Front Psychol. 2017;8:903. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00903. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Mclean S. Developmental differences in children who have experienced adversity: emotional dysregulation. Southbank, VIC, Australia: Child Family Community Australia; 2018. [Google Scholar]

82. Song W, Qian X. Adverse childhood experiences and teen sexual behaviors: the role of self-regulation and school-related factors. J Sch Health. 2020;90(11):830–41. doi:10.1111/josh.12947. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools