Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Influence of Psychological Factors Related with Body Image Perception on Resistance to Physical Activity amongst University Students in Southern Spain

1 Department of Corporal Expression, Faculty of Education Sciences, University of Granada, Granada, 18071, Spain

2 Department of Didactics of Social Sciences, Faculty of Education, International University of La Rioja, Logroño, 26006, Spain

3 Department of Behavioral Science Methodology, Faculty of Psychology, University of Granada, Granada, 18071, Spain

4 Mind, Brain and Behavior Research Center (CIMCYC), University of Granada, Granada, 18071, Spain

* Corresponding Author: Gracia Cristina Villodres. Email:

# Gracia Cristina Villodres and Rocío Vizcaíno-Cuenca are co-first authors

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Healthy Lifestyle Behaviours and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(7), 877-899. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.066137

Received 31 March 2025; Accepted 27 June 2025; Issue published 31 July 2025

Abstract

Background: University students face significant challenges in maintaining healthy physical activity (PA) and dietary habits, and they often fall short of global health recommendations. Psychological factors such as social physique anxiety, body image concerns, and self-objectification may act as barriers to PA engagement, influencing both mental and physical health. The present study constructed a structural equation model (SEM) to examine the relationship between body image-related psychological factors and resistance to PA in university students from southern Spain. Methods: A cross-sectional and correlational study was conducted with 519 university students (74% females, 26% males; Mean age = 21.14 ± 3.26 years) from universities in Granada and Malaga (Spain). Data were collected between May and October 2024 via online questionnaires that assessed PA engagement, Mediterranean diet adherence, eating disorder symptoms, body image-related psychological factors (social physique anxiety, appearance control beliefs, body surveillance, body shame, and self-esteem), and sociodemographic characteristics. SEM was performed to analyze relationships and sex-based differences. Results: Social physique anxiety was positively associated with body shame, body surveillance, and eating disorders, and negatively associated with self-esteem, PA engagement, and appearance control beliefs (all p < 0.001). Appearance control beliefs were positively related to self-esteem, body surveillance, and PA (all p < 0.05). Body surveillance was negatively linked to PA and positively linked to body shame. Mediterranean diet adherence and eating disorders were positively associated with PA (all p < 0.001). Sex-based differences were observed in the model. Conclusion: Body image-related psychological factors may act as barriers to PA among university students. Interventions should integrate mental health promotion and consider sex differences.Keywords

Over the past few decades, researchers have focused their attention on the physical and mental health of the university population [1]. In fact, the World Health Organization (WHO) has produced a global action plan on physical activity (PA), reducing sedentary behaviour and promoting general health [2]. This arose due to the concerning fact that one in five adults and four in five adolescents worldwide do not perform enough PA, thereby increasing the risk of non-communicable diseases, which cause 71% of deaths worldwide in the over-30s [2].

Despite the creation of clear protocols and recommendations targeted towards the promotion of PA and the reduction of sedentary behaviour [3], alongside the broad dissemination of information regarding the benefits of PA and the risks of inactivity [4]. Recent studies suggest that more than 90% of Spanish university students do not comply with the PA recommendations proposed by the WHO [5]. Thus, despite the scientific community manifesting concern for this issue and tailoring interventions towards this population to promote healthy habits, such as PA engagement or following a healthy diet, such interventions have thus far been ineffective, with even innovative methodologies and new technologies failing to bring about desired improvements [6,7]. Likewise, Spanish university students exhibit poor adherence to healthy diets, such as the Mediterranean diet (MD) [8]. It is worth noting that Castro-Cuesta et al. [8] observed that Spanish university students who were more prone towards low MD adherence led more sedentary lives.

While it is true that external barriers such as a lack of time, energy, and sports facilities in which to engage in PA [9], and socioeconomic resources [10] have been documented in university students. Psychological and emotional factors as barriers to the adoption of healthy habits have been less thoroughly considered despite the fact that they, too, may drive decisions around the adoption of healthy habits such as PA engagement. For example, social appearance anxiety [11] and factors related to objectified body consciousness (e.g., body shame) [12] are related to lower PA engagement. Likewise, factors such as self-esteem and body image have a mediating effect on exercise performance [13].

In addition, classical behavioural theories such as the Theory of Planned Behaviour proposed by Fishbein and Ajzen [14] and the Protection Motivation Theory conceived by Rogers [15] provide a standpoint from which to understand PA engagement. From this perspective, constructs like social norms and perceived behavioural control may be closely related to body image variables such as appearance control beliefs (ACB) and social physique anxiety (SPA). This provides a complementary lens through which to interpret the emotional and cognitive mechanisms that underlie PA engagement.

In this sense, the present study draws upon two complementary theoretical frameworks to better understand these psychological dynamics. First, the Objectification Theory proposed by Fredrickson and Roberts [16] offers a useful lens for understanding the way in which appearance-focused environments, such as those created by social media, lead individuals, especially women, to internalize an observer’s perspective of their bodies. This internalization results in chronic self-monitoring, appearance anxiety, and feelings of body shame, all of which have been shown to negatively affect motivation and engagement in health-oriented behaviors like PA. Second, the Sociocultural Model of Body Image and Disordered Eating [17,18] helps explain the influence of media, peers, and family when shaping body dissatisfaction and maladaptive behaviors. According to this model, the internalization of appearance ideals and appearance-based social comparisons acts as a mediator to buffer the impact of sociocultural pressures on negative body image outcomes, such as disordered eating or PA behaviors driven by aesthetic goals rather than health.

In this sense, one should not dismiss the importance of the social pressures (family, peers, media) exerted on university students, specifically with regards to their academic performance, self-esteem [19] and body image [20], all of which negatively affect mental health and decision-making [21]. It is especially true in this population that social media has become the main means of communication, with Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook being the most commonly used platforms by young Spaniards [22]. In relation to such platforms and exercise, university students may come across information about trends (e.g., fitspiration) that aim to promote healthy lifestyles through exercise and healthy eating [23]. However, although the well-being focus taken by this trend initially seems positive, content analyses of fitspiration posts consistently reveal that idealized and sexualized bodies are continuously encouraged through restricted eating and excessive exercise engagement [24].

Such dynamics can lead to emotional problems (e.g., appearance-related anxiety, low self-esteem), cognitive problems (e.g., body surveillance), and behavioral disorders (e.g., eating disorders [EDs] and dysfunctional exercise) [25–27]. Consequently, the pursuit of healthy habits not oriented towards health, but, instead, towards appearance, is encouraged, which creates a direct pathological relationship between exercise and eating behaviors, respectively, and the aim of achieving unrealistic ideals of thinness (women) or muscularity (men) [28]. This supersedes the role of these behaviors in terms of well-being and a means of improving physical and mental health.

All of that discussed above can lead university students to perceive idealised bodies as the only body type that is suitable for healthy practices, which generates feelings of inadequacy and demotivation towards PA. Thus, the present study constructed a structural equation model (SEM) with the aim of examining the relationship between body image-related psychological factors and resistance to PA engagement in university students from southern Spain.

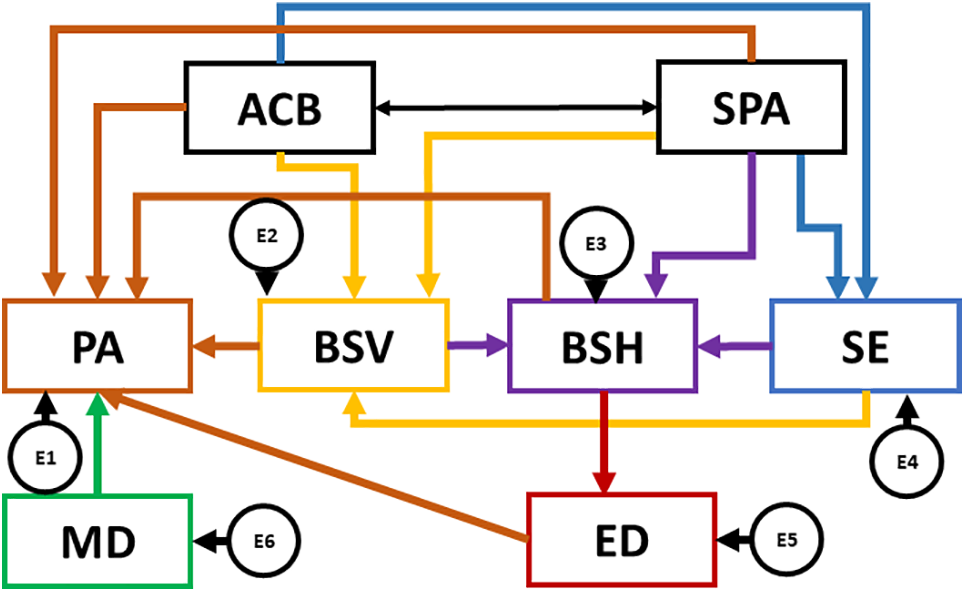

Based on the theoretical framework presented above, an SEM was constructed in which the first level considered SPA and ACB, with both being subjected to the influence of factors such as social networks, social pressures, and self-confidence [29,30]. In the present study, SPA was characterized by concern about the way in which others perceive their physical appearance [31], whilst ACB referred to the extent to which individuals believe themselves to be responsible for their physical appearance [32]. Both of these constructs were placed at the first level of the hierarchical model since they have been identified as having a negative influence on other psychological aspects subsequently located at the second level. Second-level factors included self-esteem and the self-objectification behaviors of shame and body surveillance [33]. These constructs are key within the framework of Objectification Theory and the Sociocultural Model, as they represent internalized sociocultural pressures and are known to function as mediators between external appearance demands and behavioral responses. All of these aforementioned emotional and cognitive problems have been found to act as facilitators of or barriers to PA engagement [11–13] and so they were positioned to the far left of the second level. Finally, the third level considered eating behaviors (EDs and MD), given that MD adherence has been found to be associated with adequate PA engagement from an early age [34], whilst self-objectifying behaviors such as body shame appear to be associated with EDs [35], and EDs, in turn, are associated with excessive, compensatory and dysfunctional PA engagement [36].

Likewise, the decision was made to conduct a sex-stratified analysis due to well-documented differences between men and women with regards to body image concerns, internalization of appearance ideals, and related PA and eating behaviors. Women tend to exhibit higher levels of body dissatisfaction and engage more in self-objectification behaviors such as body surveillance and shame, whereas men are more influenced by sociocultural pressures emphasizing muscularity and strength. These differences lead to the configuration of different patterns regarding body image and health-related behaviors [23]. Accounting for these sex-specific differences would allow for a more precise understanding of the psychological factors affecting PA engagement and healthy habits in each group.

Despite extensive literature highlighting the benefits of PA and healthy eating, as well as the psychological barriers associated with these behaviors, there remains a notable gap in understanding the complex interrelationships between psychological variables, body image-related constructs, eating behaviors and PA engagement, particularly among university students in southern Europe. Existing studies have tended to analyse these variables in isolation or using linear models, which fail to capture the multifactorial nature of resistance to PA. Additionally, while social media has been identified as a source of pressure that influences body image, its indirect effects through emotional and cognitive indirect pathways remain understudied in this population.

The present study seeks to address these limitations by developing and testing an SEM that integrates a range of psychological and behavioural variables related to PA resistance. By doing so, the present research provides a more holistic understanding of the psychological mechanisms underpinning PA drop-out and maladaptive eating behaviors among Spanish university students.

The main objective of the present study is to explore the psychological mechanisms that link body image related factors to resistance to PA engagement. Specifically, the model examines the way in which SPA and ACB influence self-esteem, body shame, and body surveillance, whilst also evaluating the relationships between these psychological variables and eating behaviors (e.g., EDs) and PA engagement.

Additionally, a descriptive exploratory analysis was conducted to examine the reasons reported by participants for engaging or not engaging in PA in order to provide contextual insight into motivational profiles and potential barriers. This complementary analysis supports the multifactorial perspective of the study and will help to interpret the behavioural patterns observed in the model.

Accordingly, the research question guiding the present study is as follows: How do body image related psychological factors and eating behaviors interact to influence PA engagement among Spanish university students?

Based on the theoretical framework and existing evidence, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): The SEM will reveal significant relationships between SPA, ACB, self-esteem, self-objectification behaviors (shame and body surveillance), eating behaviors and PA engagement.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): The patterns of these relationships will differ between men and women, with women expected to exhibit higher SPA, body shame and dysfunctional eating behaviors. Further, the subsequent effect of this on PA engagement will be stronger in women than in men.

Through this approach, the study aims to advance understanding of the interconnected roles of emotional, cognitive, and behavioural variables in the adoption or rejection of healthy habits, thereby offering new insights for more tailored and psychologically informed health promotion strategies.

A cross-sectional, comparative, and correlational study was conducted with a final sample of 519 university students, comprising 384 women (74%) and 135 men (26%), with a mean age of 21.14 (SD = 3.26) years. All participants were enrolled at one of two universities in Granada and Malaga (Spain). This sex distribution broadly reflects the sex distribution of enrolment at the participating universities, where female students are more prevalent, particularly in certain fields of study. However, it is acknowledged that this imbalance may affect the interpretation of sex differences in the SEM model due to lower statistical power for male subgroup analyses. With regards to socioeconomic status (SES), 8.3% had a low SES, 65.3% a medium SES and 26.4% a high SES. In terms of PA engagement, 66% regularly engaged in PA, whilst 33.3% did not. Further, 27.2% exhibited low MD adherence, 53.6% exhibited a need to improve their MD adherence and 19.3% exhibited optimal MD adherence. These percentages are presented solely to describe the characteristics of the final sample and were not used as inclusion criteria or quota-based parameters during the recruitment process.

A non-random and convenience method was employed for sampling due to the accessibility of distribution lists for both universities. In addition to institutional electronic mail, questionnaires were also distributed via social media, with the main inclusion criteria being outlined: (a) being enrolled as a student at the University of Malaga or the University of Granada; (b) full voluntary completion of the questionnaire. A total of 915 students responded to the questionnaires through the various channels employed. Of these, 396 were excluded due to not meeting at least one inclusion criterion.

The present study was conducted between May and October 2024. This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid out in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Granada, Spain (Approval No.: 4260/CEIH/2024, date of approval: 21 May 2024). All participants provided written informed con-sent to participate in the study. Prior to data collection, permission was obtained from the University of Granada and the University of Malaga to use the student distribution lists. Questionnaires were distributed via email, using the Qualtrics platform, accompanied by full study details and an informed consent form. As a means of encouraging participation, students were offered the opportunity to enter a €50 raffle, which was funded by the ‘Projects for UGR PhD students’ program (Ref: PPJIB2023-084).

Firstly, participants completed an ad hoc PA questionnaire that was designed to estimate the average number of hours they engaged in PA per day during a typical week. This measure was developed to provide a simple and direct assessment tailored to the present sample and online format. Although standardized tools such as the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) are commonly used, this scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency (α = 0.96), which suggests that it is reliable. Final scores were calculated as the average number of hours of PA engaged in each week.

In addition, participants were asked to report their reasons for engaging or not engaging in PA, depending on their current PA status. Three groups were identified based on participant responses: 1) those who currently engage in PA; 2) those who do not engage in PA but intend to do so; and 3) those who do not engage in PA and have no intention to do so. Each group was presented with a tailored multiple-choice question. Participants who engaged in PA were asked “Why do you engage in PA?” to which possible valid responses were ‘to improve health’, ‘to improve body composition’ and ‘enjoyment’. Those not currently active but willing to start were asked “Why would you engage in PA?” and presented with the same set of response options. Finally, participants who did not engage in PA and had no intention to start were asked, “Why not?” to which they could respond ‘I don’t have time’, ‘I’m ashamed of my body and my abilities’, or ‘Injury prevents me from doing so’. Responses were analyzed descriptively within each group to provide contextual insights into the motivational and psychological factors underlying PA engagement.

Further, the latest Spanish version of the Mediterranean Diet Quality Index (KIDMED) questionnaire was employed to evaluate MD adherence in teenagers [37]. Participants responded to 16 dichotomous (yes or no) response items. Total scores for this questionnaire range from –4 to 12. Positive responses were scored as 1, whilst negative responses were scored as 0, with the exception of the four negatively framed items included on the questionnaire, in which case positive responses were scored as –1. The Cronbach alpha estimated for this scale was acceptable (α = 0.60).

Finally, the abbreviated version of the Eating Disorder Examination Self-Report Questionnaire (EDE-Q-S) conceived by Fairburn and Beglin [38] was administered to evaluate the presence of an ED. This tool consists of 12 items which are rated along a four-point Likert scale, in which responses for the first 10 items range from ‘on no days’ to ‘on 6–7 days’, whilst responses to the last two items range from ‘not at all’ to ‘markedly’. This tool assesses beliefs and behaviors that are typical of EDs (e.g., binge eating, fear of weight gain, dietary restrictions, concerns about body image, weight, and eating habits). Mean scores are computed with higher scores indicating a higher incidence of EDs (maximum of 36). The Cronbach alpha produced for this scale indicates adequate reliability (α = 0.91).

Firstly, the Spanish adaptation of the Objectified Body Consciousness Scale (OBCS) [32] was administered to gather data on 24 items pertaining to the study variables of body surveillance (items 1, 3, 7, 9, 14, 16, 18 and 20), body shame (items 2, 5, 8, 11, 13, 15, 17 and 22) and ACB (items 4, 6, 10, 12, 19, 21, 23 and 24). Respondents responded along a seven-point Likert scale that ranged from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’. Negatively framed items were recoded prior to final scoring in order to preserve consistency. Mean scores were computed with higher factor scores indicating higher body surveillance, body shame, and ACB, respectively. The Cronbach alpha calculated for this scale indicates good reliability (α = 0.73).

Further, in order to evaluate SPA, a version of the Social Physique Anxiety Scale (SPAS) adapted for use with the adolescent Spanish population [39] was administered. Participants respond to the seven items comprising this tool along a five-point Likert scale that ranges from ‘never’ to ‘always’. Items describe scenarios in which physical appearance-related social anxiety may be induced (e.g., I would feel uncomfortable if I knew others were evaluating my physique). Mean scores are computed with higher scores indicating higher levels of SPA. The Cronbach alpha calculated indicates adequate reliability (α = 0.88).

Moreover, a version of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) adapted for use with Spanish university students was employed to evaluate self-esteem [40]. This tool comprises 10 items with participants expressing their agreement with each item via a four-point Likert scale that ranges from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’. Of the 10 included items, five are positively framed and five are negatively framed. Total scores range from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating greater self-esteem. Item scores are summed to produce overall scores with higher scores indicating higher self-esteem. The Cronbach alpha produced for this scale indicates acceptable reliability (α = 0.60).

2.3.3 Sociodemographic Characteristics

Finally, an ad-hoc questionnaire was developed to enable participants to report certain sociodemographic information (age, sex, and SES). In terms of SES, participants answered the question: “Where would you place yourself according to your SES or that of your closest relative? Please indicate from 0 to 100 where you would place yourself according to your SES, where 0 represents the most poverty-stricken and 10 represents the most affluent.” Responses were given by moving a mobile line along a continuum to the desired position.

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS 21.0 statistical software (Armonk, NY, USA). Categorical data, such as reasons for PA engagement, are represented as percentages. Means and standard deviations are presented for numerical data. Sample distribution was analyzed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Upon confirming that the data did not follow a normal distribution, the Mann-Whitney U test was employed to compare two independent groups. Correlations were performed according to Spearman, with significance being set at p = 0.05.

Next, SEM was performed using IBM AMOS® 24.0 software (Armonk, NY, USA). SEM facilitates the establishment of connections between variables specified in a theoretical model (Fig. 1). The model constructed in the present study comprised eight observed variables. Of these, five variables were endogenous (self-esteem, body shame, body surveillance, PA, Eds, and MD adherence) and two were exogenous (SPA and ACB). Endogenous variables are represented within the developed model alongside their associated error terms, which are illustrated with a circle, whilst exogenous variables do not have associated error terms and are depicted via two-way arrows. SEM was employed to determine existing relationships between the variables included in the theoretical model as a function of sex (men/women).

Figure 1: Structural equation model. Note: ACB, appearance control beliefs; SPA, social physique anxiety; PA, physical activity; SE, self-esteem; BSH, body shame; BSV, body surveillance; MD, Mediterranean diet; ED, eating disorder; E1-E6, error terms

In order to evaluate the extent to which the SEM fits the observed data, multiple fit indices were analysed. The chi-square statistic serves as a primary indicator of model fit, with non-significant p-values suggesting good fit. However, it has been highlighted that this statistic can be highly sensitive to sample size [41], which makes it necessary to consider additional measures. Consequently, several fit indices were computed, including the comparative fit index (CFI), incremental fit index (IFI), normed fit index (NFI), and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI). For the model to be considered adequately fitted, all indices should exceed 0.90, whilst values above 0.95 would indicate an excellent fit. Additionally, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was assessed, with values below 0.08 representing acceptable fit and those under 0.05 denoting superior fit.

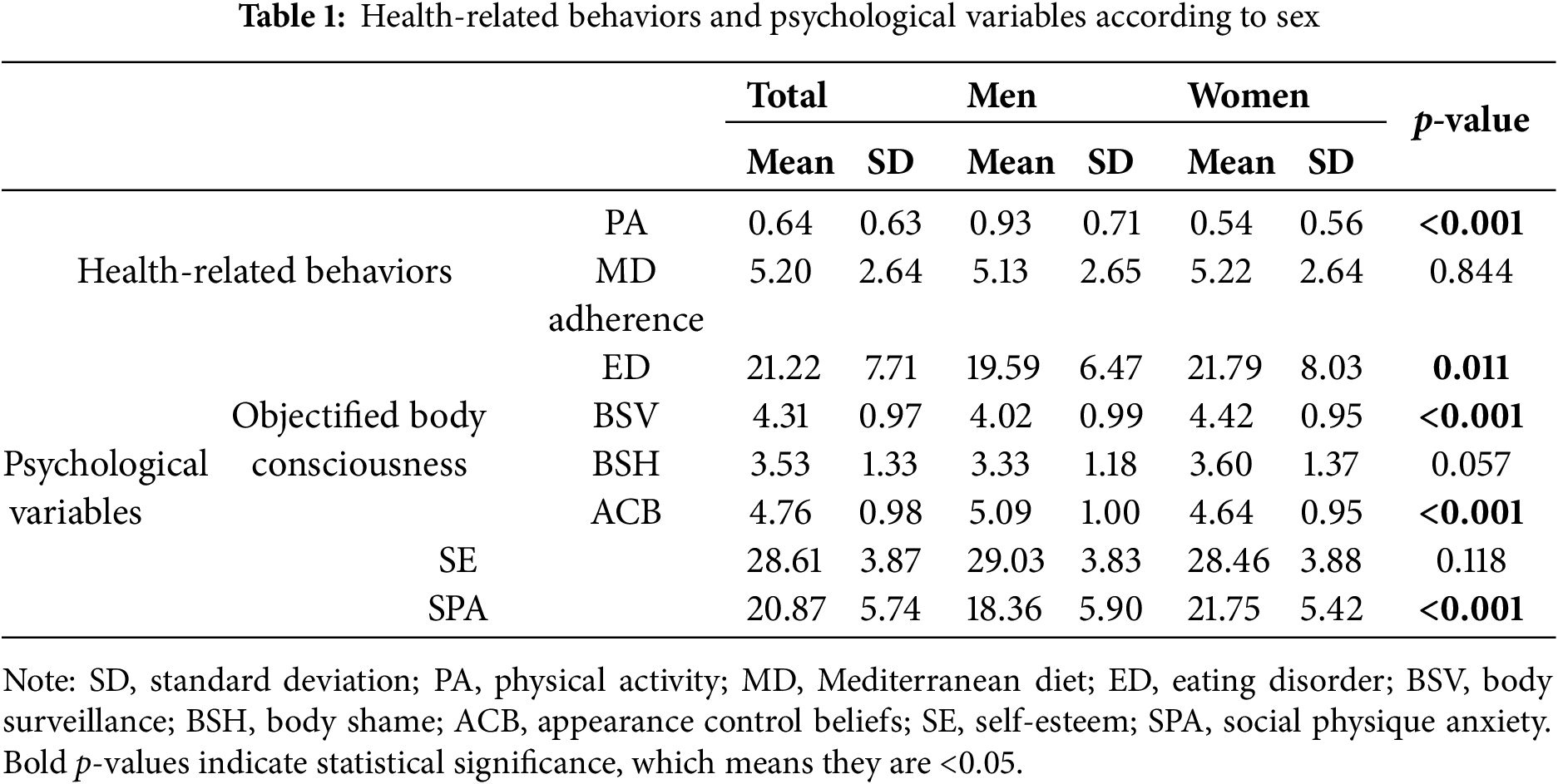

Table 1 presents descriptive characteristics pertaining to the study sample. With regards to sex, men reported higher PA engagement (0.93 ± 0.71 vs. 0.54 ± 0.56; p < 0.001) and higher ACB (5.09 ± 1.00 vs. 4.64 ± 0.95; p < 0.001) than women. At the same time, women reported more EDs (21.79 ± 8.03 vs. 19.59 ± 6.47; p < 0.001), higher body surveillance (4.02 ± 0.99 vs. 4.42 ± 0.95; p < 0.001) and higher SPA (21.75 ± 5.42 vs. 18.36 ± 5.90; p < 0.001) than men. No significant differences were found with regard to MD, body shame, and self-esteem.

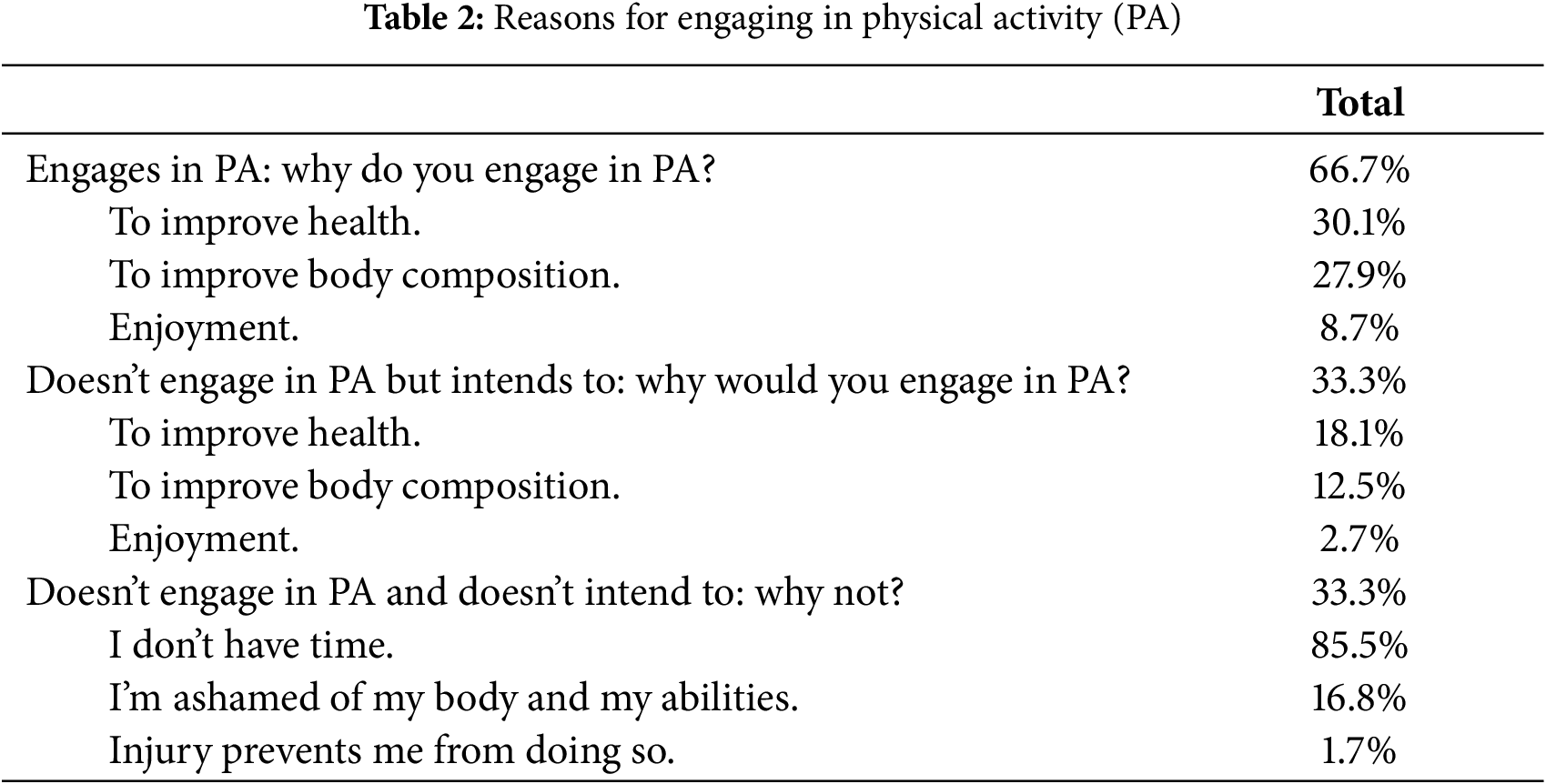

Table 2 presents the reasons stated by participants for engaging or not engaging in PA. The sample was divided into three groups describing those who engage in PA, those who don’t engage in PA but would be willing to do so, and those who don’t engage in any PA at all and have no intention to do so. Firstly, 66.7% of respondents reported engaging in PA. Within this group, the main reason for doing so was for health improvement, with this motive accounting for 30.1% of respondents, followed by 27.9% who outlined improving their body composition as the main motive for PA. Notably, only 8.7% reported engaging in PA for enjoyment. Secondly, 33.3% of respondents stated that they did not engage in PA at the time of the study but that they would be willing to do so in the future. Within this group, the main motivation should they decide to initiate PA was to improve their health, with this being reported by 18.1% of this group. This was followed by 12.5% who indicated that they would initiate PA engagement to improve their body composition, and only 2.7% would do so for enjoyment. Finally, 33.3% of respondents reported they didn’t exercise and had no intention to do so. Within this group, the most common reason for not engaging in PA was lack of time, which accounted for 85.5% of responses. Another 16.8% stated that they avoided PA because they felt ashamed of their body or their abilities, followed by 1.7% who mentioned that injury prevented them from exercising.

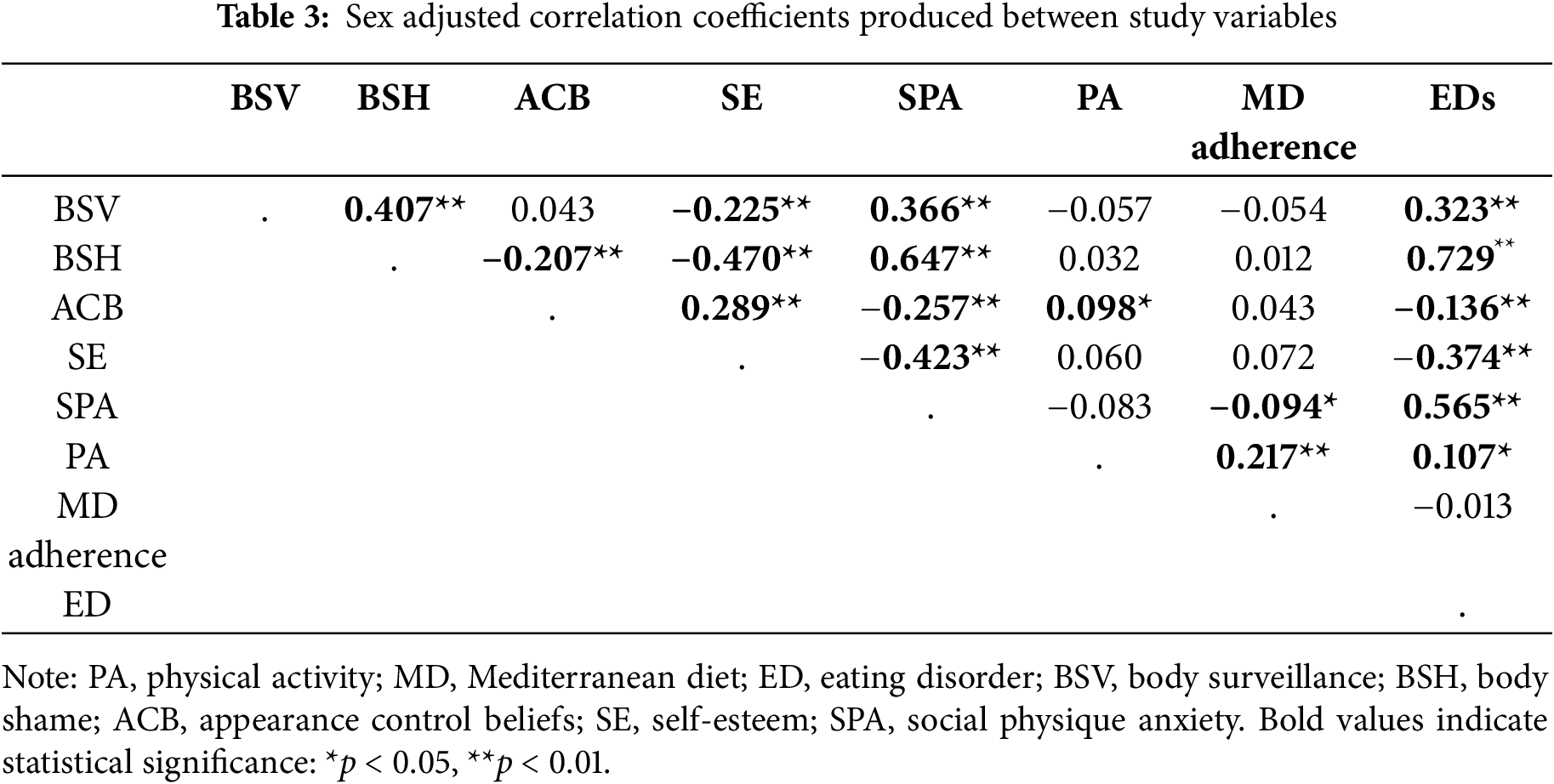

Table 3 presents the correlation coefficients produced between study variables. SPA was positively associated with body surveillance (r = 0.366; p < 0.01), body shame (r = 0.647; p < 0.01) and EDs (r = 0.565; p < 0.01), and inversely associated with ACB (r = −0.257; p < 0.01), self-esteem (r = −0.423; p < 0.01) and MD adherence (r = −0.094; p = 0.032). Further, ACB was positively associated with self-esteem (r = 0.289; p < 0.01) and PA engagement (r = 0.098; p = 0.026), and inversely associated with body shame (r = −0.207; p < 0.01) and EDs (r = −0.136; p = 0.002). Also, self-esteem was inversely associated with body surveillance (r = −225; p < 0.01), body shame (r = −0.470; p < 0.01) and EDs (r = −0.374; p < 0.01). At the same time, EDs were positively associated with body surveillance (r = 0.323; p < 0.01), body shame (r = 0.729; p < 0.01), and PA (r = 0.107; p = 0.015). Finally, PA was positively associated with MD adherence (r = 0.217; p < 0.01), whilst body shame was positively associated with body surveillance (r = 0.407; p < 0.01).

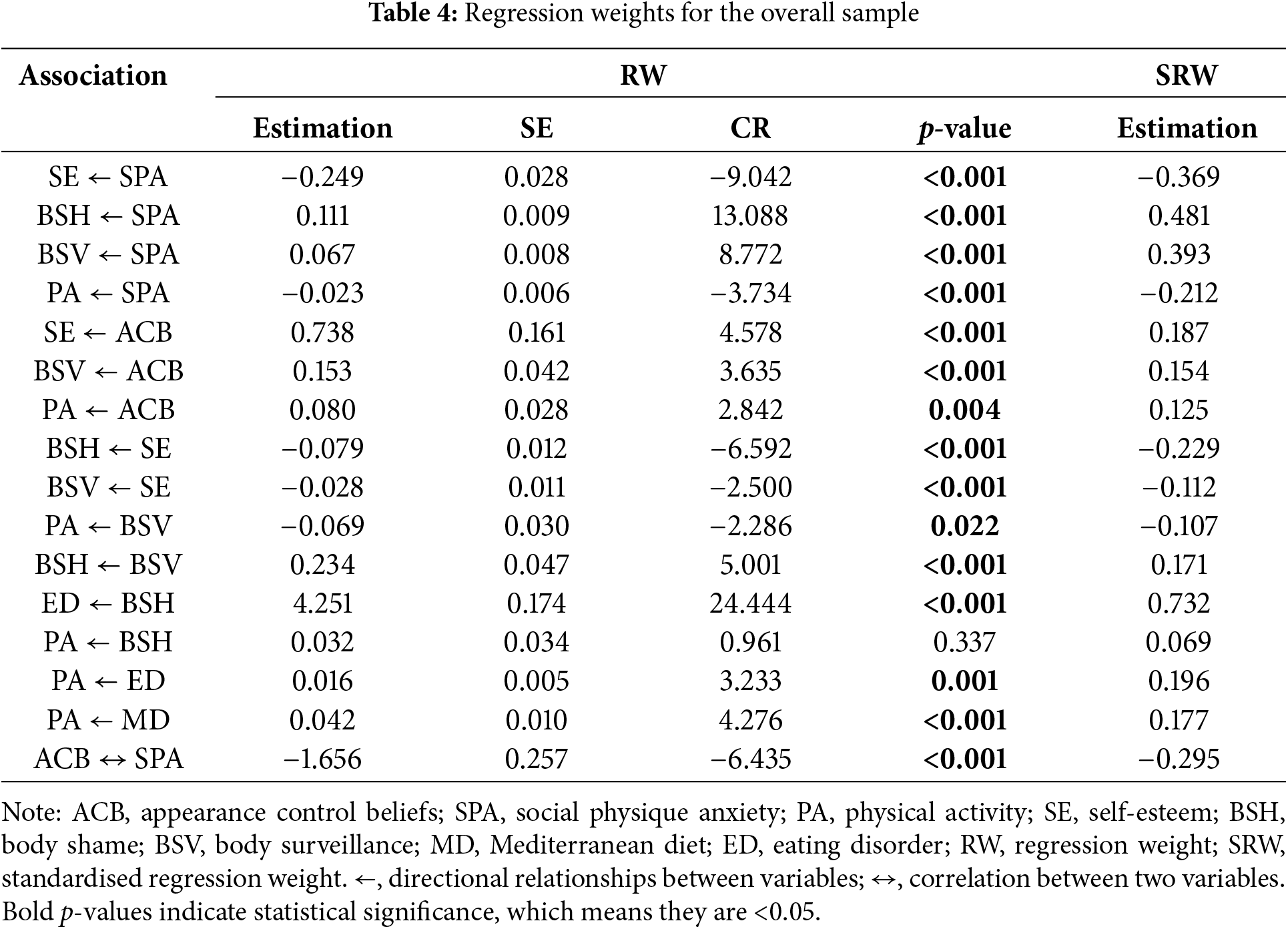

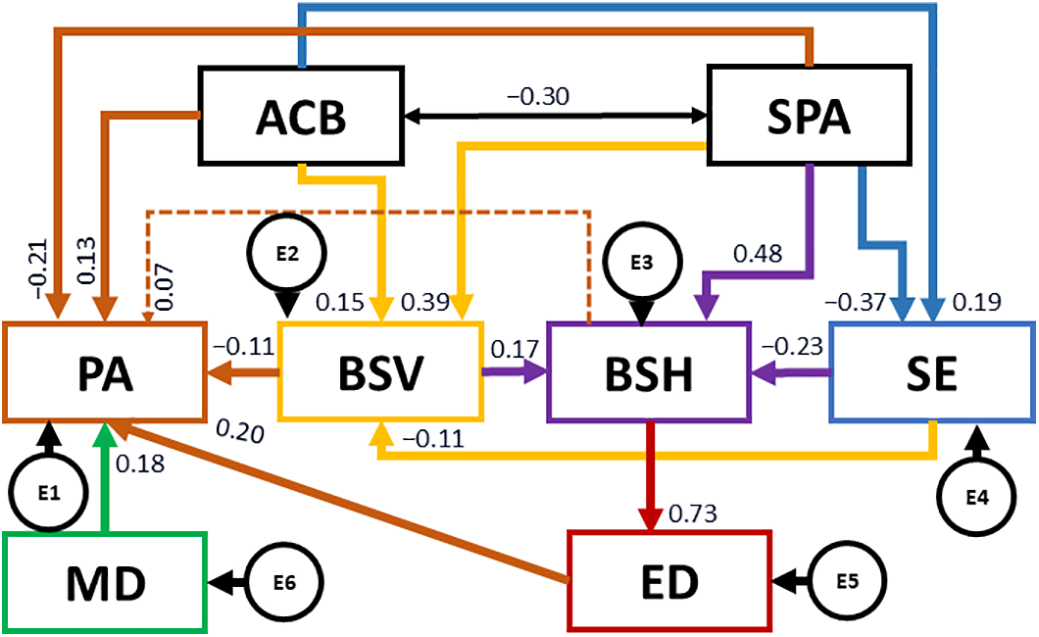

Table 4 and Fig. 2 present regression weights and standardized regression weights pertaining to the SEM constructed for the overall sample. The chi-square statistic was significant (χ2 = 33.8; df = 12; p = 0.001), which led to the null hypothesis being rejected. For this reason, other standardized fit indices were consulted that are less sensitive to sample size [41]. In this sense, an acceptable RFI of 0.929 was produced. Further, NFI, IFI, TLI, and CFI were all excellent, being 0.970, 0.980, 0.953, and 0.980, respectively. At the same time, an acceptable RMSEA value of 0.059 was produced.

Figure 2: Structural equation model for the overall sample. Note: ACB, appearance control beliefs; SPA, social physique anxiety; PA, physical activity; SE, self-esteem; BSH, body shame; BSV, body surveillance; MD, Mediterranean diet; ED, eating disorder; E1-E6, error terms

The revised model explained 21.2% of total variance for self-esteem, 18.2% for body surveillance, 49% for body shame, 53.6% for EDs, and 11.2% for PA.

The SEM model shows different indirect pathways that influence PA. On the one hand, SPA negatively predicted self-esteem (b = −0.369; p < 0.001), and positively predicted body shaming (b = 0.481; p < 0.001) and body surveillance (b = 0.393; p < 0.001). Further, SPA negatively predicted PA (b = −0.212; p < 0.001). Also, SPA is negatively associated with ACB (b = −0.295; p < 0.001), whilst ACB are positively associated with self-esteem (b = 0.187; p < 0.001) and body surveillance (b = 0.154; p < 0.001). Further, ACB positively predict PA (b = 0.125; p = 0.004).

At the same time, self-esteem is negatively associated with body shame (b = −0.229; p < 0.001) and body surveillance (b = −0.112; p < 0.001), whilst body surveillance is also positively associated with body shame (b = 0.171; p < 0.001). Further, body surveillance negatively predicts PA (b = −0.107; p = 0.022). Finally, body shame positively predicts EDs (b = 0.732; p < 0.001) and, in turn, EDs positively predicts PA (b = 0.196; p = 0.001). Finally, MD adherence is positively associated with PA (b = 0.177; p < 0.001).

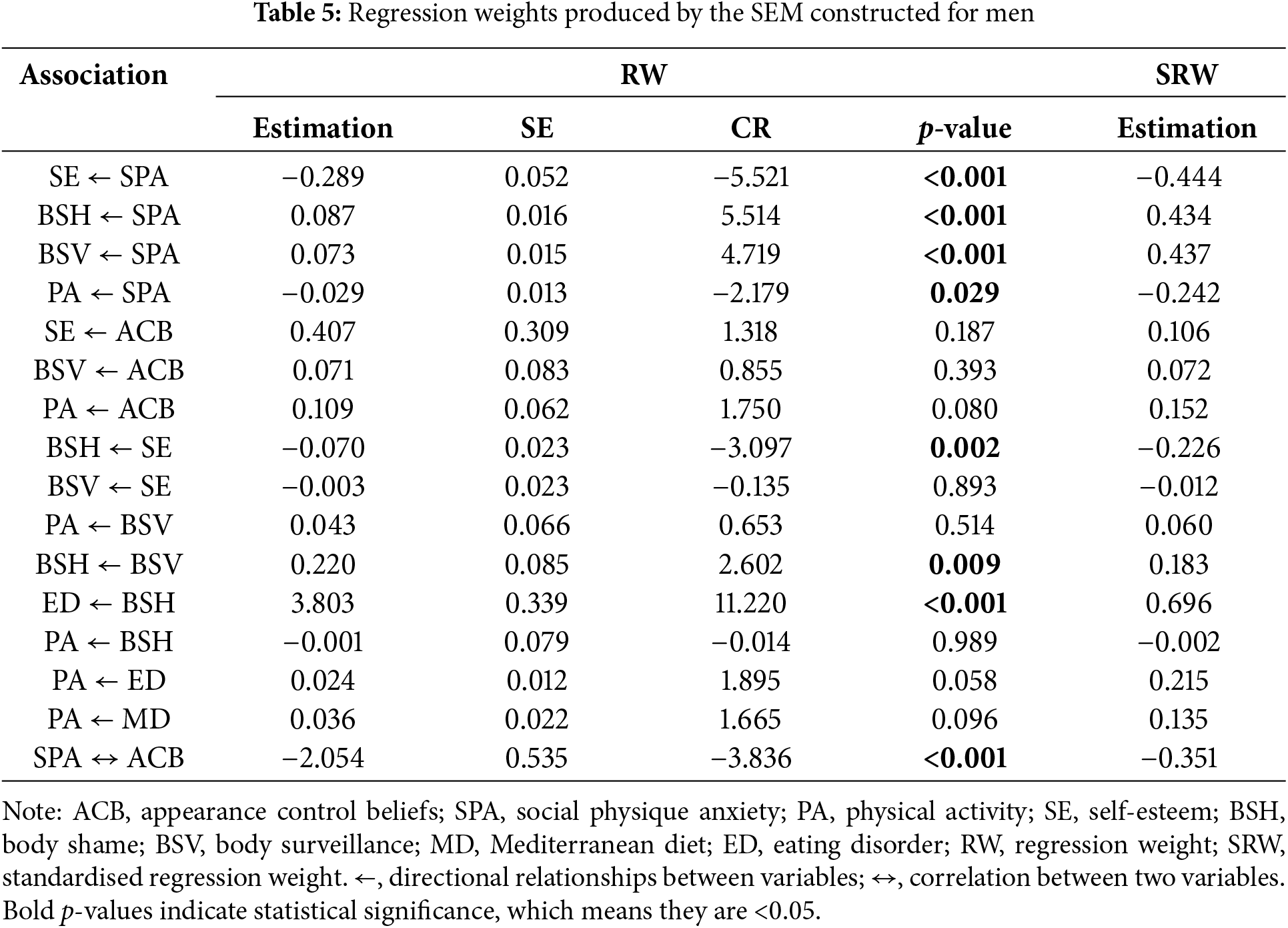

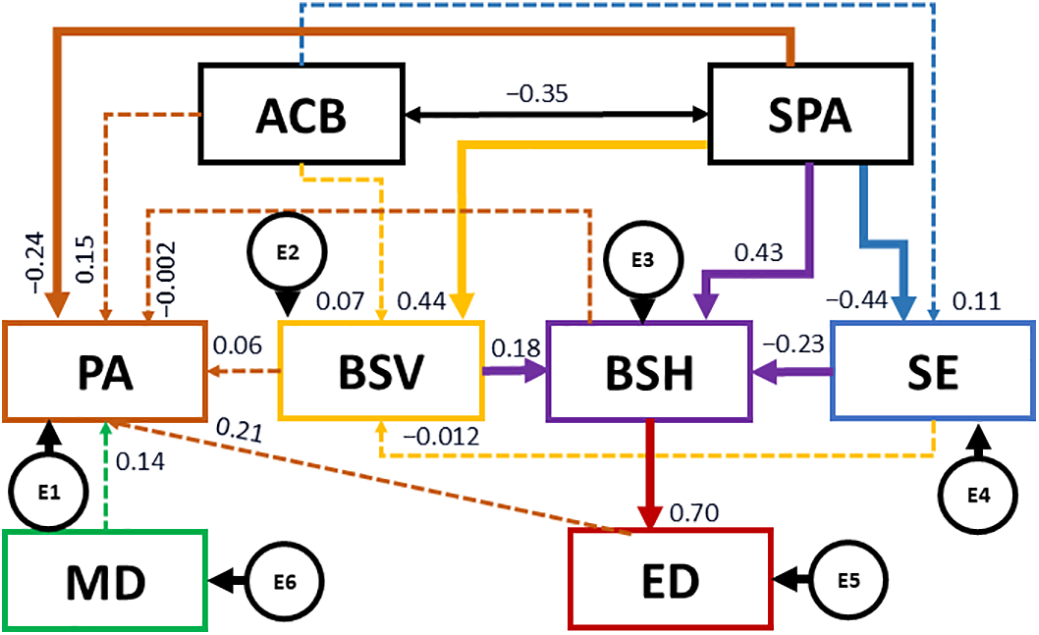

Table 5 and Fig. 3 present regression weights and standardised regression weights pertaining to male participants. The chi-square statistic was non-significant (χ2 = 15.7; df = 12; p = 0.204), which suggests that the model provides a good fit to the data. The model could also be concluded to be homogeneous. Furthermore, NFI and RFI values were acceptable, being 0.944 and 0.906, respectively. Further, IFI, TLI, and CFI were excellent, being 0.986, 0.966, and 0.985, respectively. At the same time, an excellent RMSEA value of 0.048 was produced.

Figure 3: Structural equation model for men. Note: ACB, appearance control beliefs; SPA, social physique anxiety; PA, physical activity; SE, self-esteem; BSH, body shame; BSV, body surveillance; MD, Mediterranean diet; ED, eating disorder; E1-E6, error terms

The revised model explained 24.1% of total variance for self-esteem, 17.9% for body surveillance, 45.1% for body shame, 48.4% for EDs, and 11.4% for PA.

The SEM model reveals a key indirect pathway that influences PA. In this sense, SPA negatively predicted self-esteem (b = −0.444; p < 0.001), and positively predicted body shaming (b = 0.434; p < 0.001) and body surveillance (b = 0.437; p < 0.001). Further, SPA negatively predicts PA (b = −0.242; p = 0.029).

On the other hand, SPA is negatively associated with ACB (b = −0.351; p < 0.001). At the same time, self-esteem is negatively associated with body shame (b = −0.226; p = 0.002) and body surveillance (b = 0.183; p = 0.009). Finally, body shame positively predicts EDs (b = 0.696; p < 0.001).

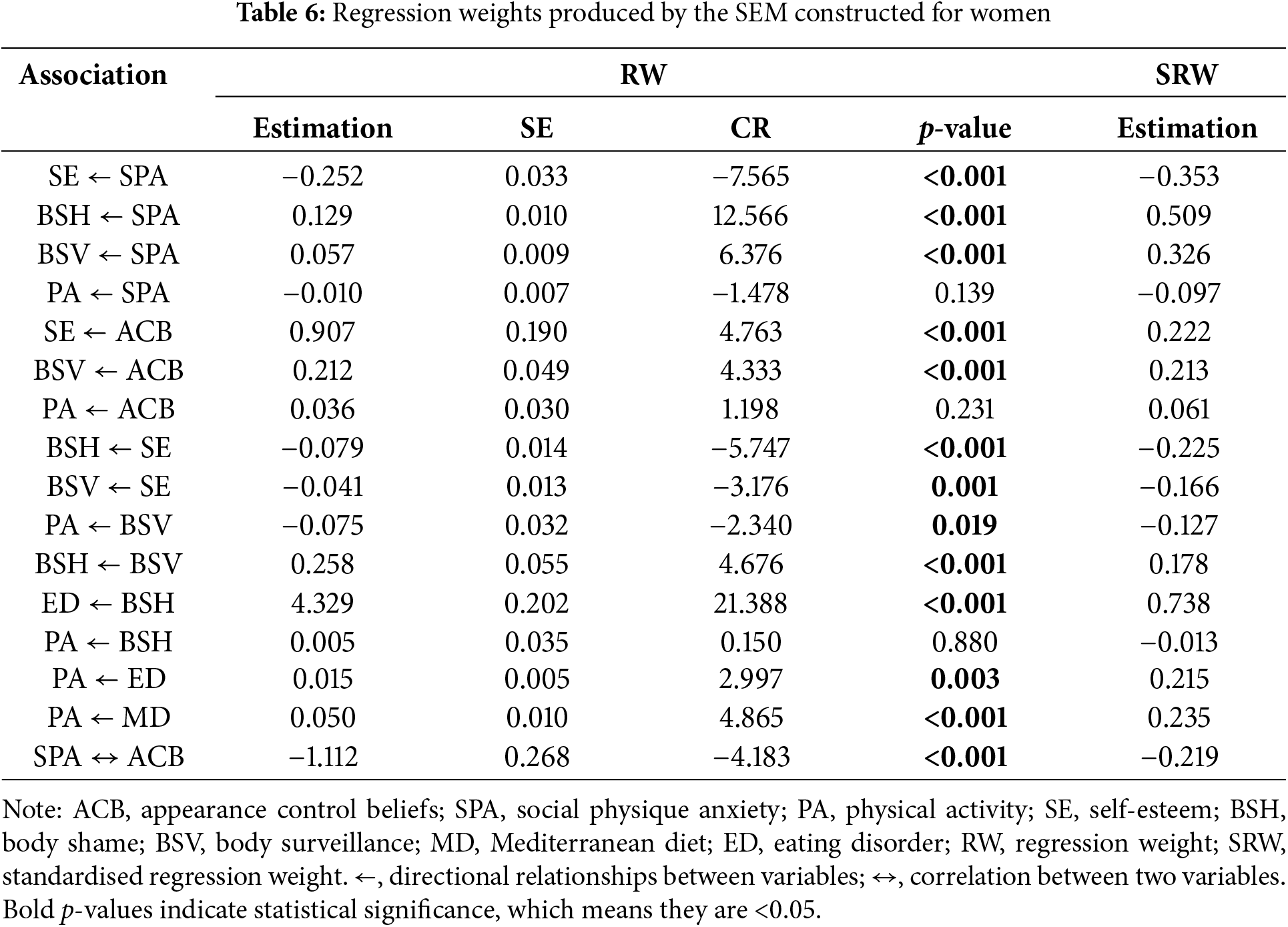

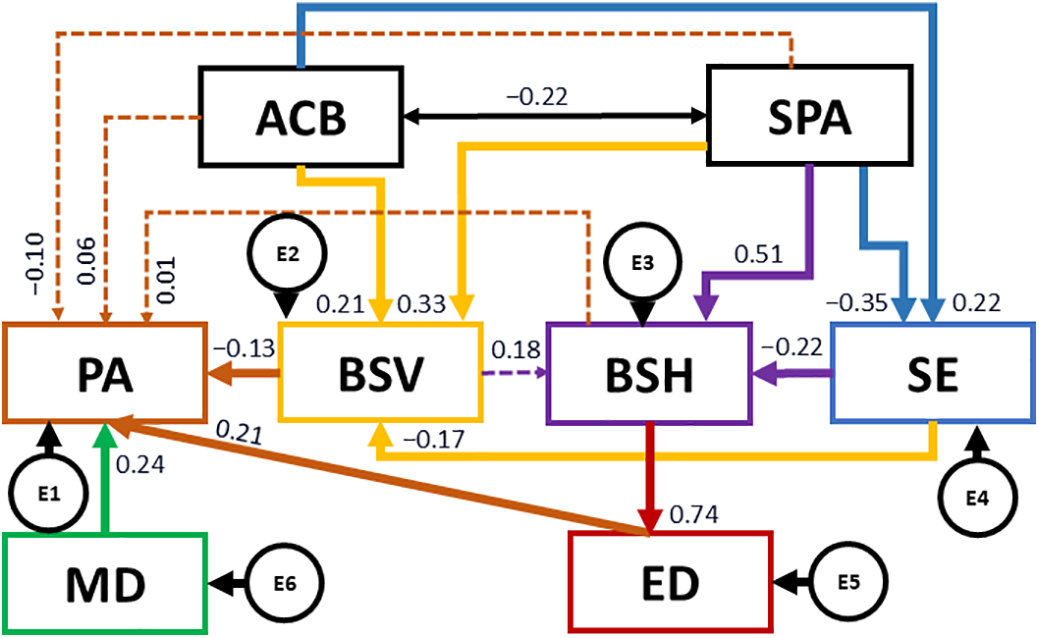

Table 6 and Fig. 4 present regression weights and standardized regression weights pertaining to participating women. The chi-square statistic was significant (χ2 = 33.2; df = 12; p = 0.001), which led to the rejection of the null hypothesis. Thus, other standardized fit indices were consulted that are less sensitive to sample size. In this sense, RFI and TLI values were acceptable, being 0.907 and 0.939, respectively. Further, NFI, IFI, and CFI were excellent, being 0.960, 0.974, and 0.974, respectively. At the same time, an acceptable RMSEA value of 0.068 was produced.

Figure 4: Structural equation model for women. Note: ACB, appearance control beliefs; SPA, social physique anxiety; PA, physical activity; SE, self-esteem; BSH, body shame; BSV, body surveillance; MD, Mediterranean diet; ED, eating disorder; E1-E6, error terms

The revised model explained 20.8% of total variance for self-esteem, 17.1% for body surveillance, 51.5% for body shame, 54.4% for EDs, and 10.2% for PA.

The SEM model shows different indirect pathways that influence PA. On the one hand, SPA negatively predicts self-esteem (b = −0.353; p < 0.001), and positively predicts body shaming (b = 0.509; p < 0.001) and body surveillance (b = 0.326; p < 0.001). Likewise, SPA is negatively associated with ACB (b = −0.219; p < 0.001), whilst ACB positively predict self-esteem (b = 0.222; p < 0.001) and body surveillance (b = 0.213; p < 0.001). At the same time, self-esteem is negatively associated with body shame (b = −0.225; p < 0.001) and body surveillance (b = −0.166; p = 0.001), whilst body surveillance is positively associated with body shame (b = 0.178; p < 0.001). Further, body surveillance negatively predicts PA (b = −0.127; p = 0.022).

Finally, body shame positively predicts EDs (b = 0.738; p < 0.001) and, in turn, EDs positively predict PA (b = 0.215; p = 0.003). Finally, MD adherence is positively associated with PA (b = 0.235; p < 0.001).

The present research reveals important connections between psychological factors related to body image perceptions and PA engagement amongst university students in southern Spain, revealing differential outcomes as a function of sex.

4.1 Motivations and Barriers Pertaining to PA in University Students

Although the analysis of participants’ motivations and barriers for engaging or not engaging in PA was exploratory and descriptive in nature, it provides valuable contextual insights that complement the main SEM findings. Most notably, findings reflect the worrying reality that PA is not primarily viewed by the university population as a source of enjoyment, despite scientific evidence indicating that fun is a key factor for ensuring adherence and securing exercise benefits, whether in children [42], university students [43] and adults [44]. Of the university population participating in the present study, only 8.7% of those who engage in PA do so for fun, whilst, in those who are not active but plan to be so, this percentage drops to 2.7% (see Table 2). This suggests that PA continues to be perceived as an obligation or a means to achieve other ends, rather than a pleasurable activity in itself. This lack of intrinsic motivation, which has been shown to be associated with lower sitting time and higher PA engagement [45], may explain why many people fail to maintain long-term active habits. Another striking finding is that a large proportion of participating university students engage in PA for aesthetic reasons. Specifically, 27.9% of active students engaged in PA as a means of improving their body composition, far outnumbering those who did so for enjoyment (8.7%) (see Table 2). This reinforces the idea that social pressure and beauty standards strongly influence decisions regarding exercise, especially amongst women [46]. An even more concerning finding is that aesthetic motivations remain present amongst those who do not engage in PA but would be willing to (12.5%), once again superseding enjoyment as the main reason underlying PA engagement (2.7%) (see Table 2). The fact that aesthetic reasons outweigh enjoyment invites reflection on the messages promoted by society about exercise, which tend to be more oriented towards appearance than other wellness purposes. For example, multiple verified profiles exist on Instagram, one of the most used social media platforms as a means of communication for young people between 16 and 24 years old [47], as “professional accounts” that motivate users to adopt healthy lifestyles through exercise and eating habits, as well as creating trends through hashtags (e.g., #fitspo) [48]. However, the opportunity offered by this appears to be being wasted with #fitspo posts being more oriented towards appearance and acting as conduits to objectification rather than promoting health or enjoyment. Likewise, 33.3% of participants who do not engage in PA identify lack of time as the main barrier (85.5%) (see Table 2). This suggests that exercise is one of the first activities to be dropped when university students feel pressured by academic or work demands and social responsibilities [49]. This gives rise to a paradox in which physical exercise, rather than being considered a necessity for well-being, is perceived as an unnecessary burden. This outlook contributes towards the perpetuation of sedentary lifestyle habits with subsequent serious long-term consequences, such as increased chronic disease risk and lower quality of life [50].

Finally, 16.8% of participants mentioned that the experience of shame about their body or abilities acted as an impediment to PA engagement (see Table 2). This reinforces the idea that body shame can negatively affect PA engagement in university students [51]. Finally, a small percentage (1.7%) mentioned injury as a reason for not engaging in PA (see Table 2), which indicates that physical limitations are not a major barrier.

4.2 SPA, Self-Objectification and PA Engagement

In another sense, according to the SEM model constructed with the entire study sample (see Table 4 and Fig. 2), participating university students with greater SPA engaged in less PA. Previously conducted research studies have concluded that individuals with greater SPA have the enduring belief that others judge them to be inadequate in terms of their body and that this belief stands in the way of them engaging in PA and exercise [52]. Similarly, Bevan et al. [53] observed that weight-related stigma and concerns about physical appearance in university students led to lower enjoyment and greater avoidance of PA. As can be deduced, such individuals tend to view themselves as objects, are always worried about being evaluated by others based on their body image, hold negative opinions of themselves, and even exhibit self-esteem defects [54]. The latter may help to explain the present finding that SPA was negatively correlated with self-esteem (see Table 4 and Fig. 2).

In this same SEM (see Table 4 and Fig. 2), self-esteem was found to be negatively correlated with shame and body surveillance, whilst SPA was discovered to be positively correlated with these same two constructs. Previously conducted research reports that self-objectifying behaviors are reasonable predictors of SPA [33]. In the same way that the present study reveals that higher body surveillance is associated with greater body shame and lower PA engagement (see Table 4 and Fig. 2), other studies demonstrate that greater body surveillance is linked with more negative affective appraisals regarding PA with this response being heightened during actual PA engagement. This could potentially compromise subsequent engagement in PA [55]. In this regard, previous research has shown that the presence of certain conditions or specific contexts increases the likelihood of body surveillance and PA avoidance (e.g., presence of mirrors, restrictive clothing, appearance-centred environments such as gyms) [56], whilst other contexts (e.g., being active outdoors) are negatively associated with self-objectification and positively associated with exercise engagement [57]. Other cues, such as feedback that directs attention to one’s physical appearance or focuses on weight, are strongly discouraged, as they directly increase body surveillance [58] and, therefore, aversion to PA.

4.3 ACB, Self-Esteem, EDs, MD Adherence and PA Engagement

In contrast, the present study reveals that social anxiety is negatively correlated with ACB, which, in turn, is positively correlated with self-esteem and PA engagement (see Table 4 and Fig. 2). This suggests that the conviction that one is capable of changing their appearance may be a motivating factor that drives exercise engagement. This finding is similar to that reported in other research, in which perceptions of self-efficacy and intrinsic motivation were found to be associated with greater PA adherence [59]. This being said, a problem arises when ACB leads to an increase in unhealthy body surveillance. This, in turn, is related to greater feelings of shame about one’s body and, subsequently, increases awareness of imperfections leading to an increase in EDs [35]. This latter assertion is supported by the positive correlation uncovered in the present study between body shame and EDs (see Table 4 and Fig. 2). In this sense, other studies have observed that, in addition to young people experiencing greater body shame due their more acute internalization of the thinness or muscular ideal, alongside their greater concerns regarding weight, body mass index, body size, etc. [60], the specific type of body shame associated with EDs may also be caused by unsolicited comments/opinions from peers, family members and, even, health professionals [61]. As revealed by young people on the receiving end, such comments are often derogatory regarding their physical appearance, especially those with a higher body weight [62], and attribute them with prejudicial stereotypical traits (e.g., laziness, lack of willpower or moral fibre, low intelligence and low attractiveness) [63]. Some of the studies mentioned call for urgent action to draw the attention of the scientific and non-scientific community (health professionals, researchers, physicians, educators, coaches, teachers and, parents) to the harmful effects of any form of weight-related prejudice and discrimination [61]. Indeed, the absence of information around the healthy and beneficial effects of maintaining a healthy weight status can harm the mental health of stigmatized young people [63].

All of the above can also give rise to negative attitudes towards engaging in PA. Such attitudes may take the form of total rejection or the notion that PA serves exclusively as a means to lose weight. The latter can lead to a scenario in which PA is performed compulsively or excessively with the sole objective of losing weight or controlling body shape. This type of behavior is inherent in many EDs [64], as borne out by the positive correlation revealed in the overall sample of the present study between EDs and PA (see Table 4 and Fig. 2). Nonetheless, engagement in PA is adapted to coincide with cognitive-behavioral therapy [65] designed to avoid dysfunctional exercise behaviors [66] and has been shown to be effective for the treatment of EDs. Such carefully designed PA is effective as it replaces the conception of pathological and appearance-related PA engagement with one that foregrounds health and wellness. According to Ouellet and Monthuy-Blanc [67], this type of PA intervention would further benefit from the inclusion of relaxed group PA and psycho-educational sessions that allow cognitive restructuring of the concept of exercise and attitudes towards engagement in order to promote a climate that is oriented towards health improvement as opposed to appearance. However, the SEM constructed in the present study for the overall sample (see Table 4 and Fig. 2) reveals that ACB (functional or dysfunctional PA) and EDs (dysfunctional PA) are, not only, positively related to PA engagement, but, also, to the adoption of healthy habits such as adequate MD adherence. This is far removed from the typical eating behaviors exhibited by individuals with EDs, which tend to involve binge eating or consumption of restrictive and low-calorie diets and are usually associated with dysfunctional exercise practices [36]. Notably, the adoption of healthy diets, specifically, in the present study, the MD, is usually linked to engagement in functional and health-oriented exercise from an early age [34].

4.4 Sex Differences in Psychological Factors and PA Engagement

Moving on, outcomes uncovered in the present study reveal marked differences between men and women. Correlations produced by the SEM constructed for men were typically more pronounced (see Table 5 and Fig. 3), with social anxiety being associated with lower self-esteem, greater body surveillance, and lower ACB only in men, together with lower PA engagement. This may be explained by the fact that when men feel insecure about their bodies in social contexts, they typically feel the burden of pressure exerted by peers and the media to comply with standards of masculinity, which promote a muscular and athletic physique [68]. Such pressures chip away at their conviction that they are capable of changing their appearance, which, in turn, reduces their self-esteem and leads them to avoid situations or environments in which their physique or competence is likely to be subjected to assessment [69]. This is the case despite the finding in the present study (see Table 1) that PA engagement is more normalized and accessible in men than in women, as has consistently been demonstrated by previous studies conducted in similar populations [70,71].

Similarly, in the present study, women reported higher SPA, body surveillance and EDs, and lower ACB than men (see Table 1). Furthermore, in the SEM constructed for female participants (see Table 6 and Fig. 4), social anxiety was more strongly linked to body shame than it was in men. In accordance with Objectification Theory conceived by Fredrickson and Roberts [16], this may be explained by the greater sociocultural pressures faced by women to conform to rigid and unrealistic beauty standards [72], which are currently widely promoted by the media and on social networks. In this sense, constant exposure to idealized body images leads to unhealthy behaviors, such as excessive image modification and a reluctance to display certain body parts, thus reinforcing said body shame [73]. In the present study, body shame was only positively associated with EDs in women. This suggests that, in women, body shame can act to trigger the development of EDs [35] and indicates that dissatisfaction with one’s own body does not merely generate emotional discomfort, but, beyond this, may also seriously affect current physical and mental health in women and drive them to suffer from the concomitant negative effects of this over the entire course of their lifetime [74].

It is also worth noting that, especially in women, a differentiation emerges between healthy and unhealthy PA engagement. On the one hand, it was observed that higher self-esteem is associated with lower body surveillance and that this, in turn, is related to higher PA engagement (see Table 6 and Fig. 4). Further, MD adherence was only associated with PA engagement in women (see Table 6 and Fig. 4). This finding suggests that, in some cases, PA engagement is motivated by the desire for better health and well-being, steering away from concerns about one’s appearance. On the other hand, the finding that EDs are associated with PA engagement only emerged in women (see Table 6 and Fig. 4). According to the Sociocultural Model of Body Image and Disordered Eating [17,18], this relationship may also be explained by the pressure to achieve beauty standards, especially when it comes to the female body, with such standards encouraging the pursuit of thinness through behaviors such as excessive exercise [75]. Furthermore, women tend to express higher weight-related concerns and are more likely to turn to PA as a compensation strategy in the context of EDs, which reinforces unhealthy dietary and activity patterns [76].

It is suggested that interventions aimed at promoting the adoption of healthy habits in university students, such as via PA or a healthy diet, emphasize a health-related orientation at the same time as ensuring pleasant experiences that encourage exercise adherence. To this end, it is urgent that such interventions begin to consider the influence of psychological factors such as SPA, self-esteem, shame, and body surveillance. Ensuring that such interventions offer a space to experience pleasure and boost well-being, as opposed to becoming another source of anxiety and discomfort, is essential for university students to be able to overcome psychological and social barriers to exercise. One such approach to this could be to tailor interventions towards the adolescent stage, at which concerns regarding body image [77] and other mental health issues first arise. Another approach should be to encourage critical considerations of information received through the media (e.g., social media), as well as highlighting the importance of adopting healthy habits focused on health rather than physical appearance. Such approaches will help prevent EDs and other mental health disorders that may arise from these issues (e.g., social anxiety disorder and body dysmorphia). The pleasant experiences likely to follow from this type of exercise intervention will be essential for boosting adherence. Furthermore, sex differences should be considered when designing interventions. Future studies are needed to conduct more in-depth research on the influence of beauty standards and other social pressures on psychological factors related with body perceptions, especially in women, as well as their influence on ED risk and their relationship with the adoption of health-related habits, whether compulsive (PA) or restrictive (healthy diet).

Turning attention to the findings of the present study, certain limitations must be considered. One key limitation pertains to the study’s reliance on self-reported data, which may introduce biases such as social desirability or memory recall errors. Future research could benefit from incorporating objective PA assessment measures and conducting more detailed dietary evaluations in order to enhance data accuracy. Specifically, the PA measure used was an ad hoc questionnaire designed to estimate average hours of PA per day during a typical week in the study sample. Although this measure showed excellent internal consistency (α = 0.96), it lacks the extensive validation of standardized tools such as the IPAQ. Future research could benefit from incorporating objective PA assessment measures and employing validated, standardized questionnaires to enhance data accuracy and construct validity.

Additionally, the use of a convenience sample may restrict the generalizability of findings to the broader university population. Expanding the sample to include students from diverse sociocultural backgrounds would help improve the representativeness of study findings. Furthermore, another limitation of the present study concerns the unequal sex distribution of the sample, with a predominance of women (74%) over men (26%). While this imbalance was not intentional, it reflects a natural outcome of the convenience-based recruitment strategy. The questionnaire was distributed broadly across both universities without filtering according to academic program or discipline. The majority of respondents were enrolled in education (64.2%) and social sciences-related courses, which are traditionally female-dominated. This disciplinary composition likely contributed to the overrepresentation of women in the sample. Nonetheless, the underrepresentation of male participants may limit the generalizability of findings and may have reduced statistical power for detecting sex-based differences in the SEM analyses. Future studies should consider employing more stratified or targeted sampling strategies to achieve a more balanced sex distribution and to enhance the robustness of sex-based comparisons.

In this sense, another methodological limitation concerns the decision not to perform a multigroup SEM to test for measurement or structural invariance by sex. While such an analysis would have provided valuable insight into whether relationships between constructs differ by sex, the male subsample recruited to the study was too small to meet the minimum case-to-parameter ratio recommended for reliable confirmatory factor analysis (i.e., 5–10 participants per estimated parameter) according to Bentler [78]. Given this constraint, model stability and interpretability was prioritized by not conducting invariance testing. Future studies with more balanced group sizes should consider applying multigroup SEM approaches to explore potential sex-based differences in the structural relationships.

Finally, the cross-sectional nature of the study prevents causal inferences from being made about the relationship between social media use, healthy habits and body image-related psychological factors. Longitudinal or experimental studies are called for to further explore these connections.

It is concluded that psychological factors related to body perceptions, specifically, higher scores in SPA, body shame and surveillance, and lower scores in ACB and self-esteem, as well as EDs may serve to act as barriers to healthy PA amongst university students in southern Spain.

In recent decades, researchers have sought to address the gap between recognition and acceptance of the benefits of exercise and a healthy diet on physical and mental health and the subsequent impact on rates of inactivity and unhealthy diet adoption, regardless of SES. The present study suggests that, despite established protocols and official dissemination channels being in place, such as through the WHO, interventions will continue to fall short if they fail to take an integrative approach towards both healthy lifestyle habits and the various mental health factors that act as barriers to intervention adoption. Although interventions may be effective in the short term, long-term maintenance is unlikely to be achieved in the absence of the more comprehensive approach referred to above. Likewise, gender differences must be considered during intervention design with specific interventions being urgently needed for women who are more vulnerable in terms of both mental health disorders and their greater risk of present and future physical illnesses due to physical inactivity.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank all students for their participation in this study. The authors would like to especially thank Emily Knox for her assistance in reviewing the English version.

Funding Statement: The present research was financially supported by the Vice-Rector’s Office for Research and Transfer at the University of Granada (Grant Ref. PPJIB2023-084), Spanish Ministry of Universities (Grants Ref. FPU20/02739 and FPU20/01987), María de Maeztu Excellence Unit Program funded by the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Ministry of Universities attached to the State Research Agency (Grant Ref. CEX2023-001312-M/AEI/10.13039/501100011033) and the Excellence Unit funded by the University of Granada (Grant Ref. UCE-PP2023-11/UGR.).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm that the following contributions were made to the paper: Conceptualization, Gracia Cristina Villodres and Rocío Vizcaíno-Cuenca; methodology, Gracia Cristina Villodres and Rocío Vizcaíno-Cuenca; software, Gracia Cristina Villodres and Rocío Vizcaíno-Cuenca; validation, Gracia Cristina Villodres, Federico Salvador-Pérez, José Joaquín Muros and Rocío Vizcaíno-Cuenca; formal analysis, Gracia Cristina Villodres; investigation, Gracia Cristina Villodres, Federico Salvador-Pérez, José Joaquín Muros and Rocío Vizcaíno-Cuenca; resources, Gracia Cristina Villodres and Rocío Vizcaíno-Cuenca; data curation, Gracia Cristina Villodres and Rocío Vizcaíno-Cuenca; writing—original draft preparation, Gracia Cristina Villodres; writing—review and editing, Gracia Cristina Villodres, José Joaquín Muros and Rocío Vizcaíno-Cuenca; visualization and supervision, José Joaquín Muros; project administration, Gracia Cristina Villodres and Rocío Vizcaíno-Cuenca; funding acquisition, Gracia Cristina Villodres and Rocío Vizcaíno-Cuenca. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid out in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Granada, Spain (Approval No.: 4260/CEIH/2024, date of approval: 21 May 2024). All participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| ACB | Appearance control beliefs |

| SPA | Social physique anxiety |

| PA | Physical activity |

| SE | Self-esteem |

| BSH | Body shame |

| BSV | Body surveillance |

| MD | Mediterranean diet |

| ED | Eating disorder |

References

1. García-Pérez L, Villodres GC, Muros JJ. Differences in healthy lifestyle habits in university students as a function of academic area. J Public Health. 2023 Jun 1;45(2):513–22. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdac120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. World Health Organization. WHO launches global action plan on physical activity [Internet]. 2018 Jun 4 [cited 2025 Mar 25]. Available from: https://www.who.int/es/news/item/04-06-2018-who-launches-global-action-plan-on-physical-activity. [Google Scholar]

3. World Health Organization. Recommendations. In: WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021 [cited 2025 Mar 25]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK581973/. [Google Scholar]

4. World Health Organization. Physical activity [Internet]. [cited 2025 Mar 25]. Available from: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity. [Google Scholar]

5. Moral Moreno L, Flores Ferro E, Maureira Cid F. Nivel de actividad física en estudiantes universitarios: un estudio comparativo España-Chile. Retos. 2024;56:188–99. (In Spanish). doi:10.47197/retos.v62.109757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Béjar LM, Mesa-Rodríguez P, Quintero-Flórez A, del Ramírez-Alvarado MM, García-Perea MD. Effectiveness of a smartphone app (e-12HR) in improving adherence to the mediterranean diet in spanish university students by age, gender, field of study, and body mass index: a randomized controlled trial. Nutrients. 2023 Jan;15(7):1688. doi:10.3390/nu15071688. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Lemola S, Gkiouleka A, Read B, Realo A, Walasek L, Tang NKY, et al. Can a ‘rewards-for-exercise app’ increase physical activity, subjective well-being and sleep quality? An open-label single-arm trial among university staff with low to moderate physical activity levels. BMC Public Health. 2021 Apr 23;21(1):782. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-10794-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Castro-Cuesta JY, Montoro-García S, Sánchez-Macarro M, Carmona Martínez M, Espinoza Marenco IC, Pérez-Camacho A, et al. Adherence to the mediterranean diet in first-year university students and its association with lifestyle-related factors: a cross-sectional study. Hipertensión Y Riesgo Vascular. 2023 Apr 1;40(2):65–74. (In Spanish). doi:10.1016/j.hipert.2022.09.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Olănescu M. Main factors that contribute to the reduction of participation in sports activities among university students. Stud Univ Babeş-Bolyai Educ Artis Gymnast. 2021 Mar 30;51–9. doi:10.24193/subbeag.66(1).05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Abakay H, Dere T, Akbayrak T. The relationship between the reasons for doing and not doing sports and sports awareness in university students: a cross-sectional study. Anatolian Clin. 2023 Sep 28;28(3):411–9. doi:10.21673/anadoluklin.1345701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Meyer S, Lang C, Ludyga S, Grob A, Gerber M. “What if others think I look like..” the moderating role of social physique anxiety and sex in the relationship between physical activity and life satisfaction in swiss adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Mar 2;20(5):4441. doi:10.3390/ijerph20054441. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Pila E, Gilchrist JD, Huellemann KL, Adam MEK, Sabiston CM. Body surveillance prospectively linked with physical activity via body shame in adolescent girls. Body Image. 2021 Mar;36(3):276–82. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.01.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Shang Y, Xie HD, Yang SY. The relationship between physical exercise and subjective well-being in college students: the mediating effect of body image and self-esteem. Front Psychol. 2021;12:658935. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.658935. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, Attitude, intention, and behavior: an introduction to theory and research. Reading (MAAddison-Wesley Publishing Company; 1975. 600 p. [Google Scholar]

15. Rogers RW. A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change1. J Psychol. 1975 Sep 1;91(1):93–114. doi:10.1080/00223980.1975.9915803. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Fredrickson BL, Roberts TA. Objectification theory: toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychol Women Q. 1997 Jun;21(2):173–206. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Thompson JK, Smolak L, editors. Body image, eating disorders, and obesity in youth: assessment, prevention, and treatment. Washington, DC, USA: American Psychological Association; 2001. doi:10.1037/10404-000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Stice E. Review of the evidence for a sociocultural model of bulimia nervosa and an exploration of the mechanisms of action. Clin Psychol Rev. 1994 Jan 1;14(7):633–61. doi:10.1016/0272-7358(94)90002-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Sultana I, Ditta AA, Atta A. Influence of family dynamics and peer pressure on academic performance: the mediating role of self-esteem in Pakistan. Contemp Issues Soc Sci Manag Pract. 2024 Aug 12;3(3):12–23. [Google Scholar]

20. da Silva WR, Marôco J, Campos JADB. Escala de Influência dos Três Fatores (TIS) aplicada a estudantes universitários: estudo de validação e aplicação. Cad Saúde Pública. 2019 Apr 8;35(3):e00179318. (In Portuguese). doi:10.1590/0102-311x00179318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Alaraj MM, Alotaibi YQ. The impact of outside pressure on Saudi university students decision making. Int J Humanit Soc Sci. 2019 Aug;9(8):7–14. [Google Scholar]

22. Candale CV. Las características de las redes sociales y las posibilidades de expresión abiertas por ellas. La comunicación de los jóvenes españoles en Facebook, Twitter e Instagram. Colindancias: Revista De La Red De Hispanistas De Europa Central. 2017;8(2):201–18. (In Spanish). doi:10.7195/ri14.v13i2.821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Vandenbosch L, Fardouly J, Tiggemann M. Social media and body image: recent trends and future directions. Curr Opin Psychol. 2022 Jun;45:101289. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.12.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Deighton-Smith N, Bell BT. Objectifying fitness: a content and thematic analysis of #fitspiration images on social media. Psychol Pop Media Cult. 2018;7(4):467–83. doi:10.1037/ppm0000143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Cohen R, Newton-John T, Slater A. The relationship between Facebook and Instagram appearance-focused activities and body image concerns in young women. Body Image. 2017 Dec;23:183–7. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.10.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Sicilia Á., Granero-Gallegos A, Alcaraz-Ibáñez M, Sánchez-Gallardo I, Medina-Casaubón J. Sociocultural pressures towards the thin and mesomorphic body ideals and their impact on the eating and exercise-related body change strategies of early adolescents: a longitudinal study. Curr Psychol. 2023;42(4):28925–36. doi:10.1007/s12144-022-03920-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Saiphoo AN, Vahedi Z. A meta-analytic review of the relationship between social media use and body image disturbance. Comput Hum Behav. 2019;101(1):259–75. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2019.07.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Carrotte ER, Prichard I, Lim MSC. Fitspiration on social media: a content analysis of gendered images. J Med Internet Res. 2017 Mar 29;19(3):e6368. doi:10.2196/jmir.6368. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Pan Y. Analysis of the causes of appearance anxiety of contemporary college students and its countermeasures. J Med Health Stud. 2023 Jul 10;4(4):45–53. doi:10.32996/jmhs.2023.4.4.6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Boursier V, Gioia F, Griffiths MD. Objectified body consciousness, body image control in photos, and problematic social networking: the role of appearance control beliefs. Front Psychol. 2020 Feb 25;11:147. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Hart TA, Flora DB, Palyo SA, Fresco DM, Holle C, Heimberg RG. Development and examination of the social appearance anxiety scale. Assess. 2008 Mar;15(1):48–59. doi:10.1177/1073191107306673. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Moya Garófano A, López Megías J, Rodríguez Bailón RM, Moya Morales MC. Spanish version of the objectified body consciousness scale (OBCSresults from two samples of female university students. Int J Soc Psychol Rev Psicol Soc. 2017;32(2):377–94. doi:10.1080/02134748.2017.1292700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Naqi S, Iqbal N, Gull A. Self-objectification and body shame: a study about appearance anxiety among Pakistani students participating in sports. Sky Int J Phys Educ Sports Sci. 2022 Dec 14;6:30–46. doi:10.51846/the-sky.v6i0.1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Muros JJ, Cofre-Bolados C, Arriscado D, Zurita F, Knox E. Mediterranean diet adherence is associated with lifestyle, physical fitness, and mental wellness among 10-y-olds in Chile. Nutrition. 2017 Mar;35:87–92. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2016.11.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Nechita DM, Bud S, David D. Shame and eating disorders symptoms: a meta-analysis. Int J Eat Disord. 2021;54(11):1899–945. doi:10.1002/eat.23583. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Martin SJ, Schell SE, Srivastav A, Racine SE. Dimensions of unhealthy exercise and their associations with restrictive eating and binge eating. Eat Behav. 2020 Dec 1;39(5):101436. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2020.101436. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Altavilla C, Comeche JM, Comino IC, Pérez PC. El índice de calidad de la dieta mediterránea en la infancia y la adolescencia (KIDMED). Propuesta de actualización para países hispano hablantes. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2020 Jun 19;94(1):8. (In Spanish). doi:10.5209/poso.56119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Eating disorder examination-questionnaire (EDE-Q 6.0). In: Fairburn CG, editor. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. p. 309–13. [Google Scholar]

39. Sáenz-Alvarez P, Sicilia Á., González-Cutre D, Ferriz R. Psychometric properties of the social physique anxiety scale (SPAS-7) in Spanish adolescents. Span J Psychol. 2013;16:E86. doi:10.1017/sjp.2013.86. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Martín-Albo J, Núñiez JL, Navarro JG, Grijalvo F. The rosenberg self-esteem scale: translation and validation in university students. Span J Psychol. 2007;10(2):458–67. doi:10.1017/s1138741600006727. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with Mplus: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. New York: Routledge; 2013. [Google Scholar]

42. Nally S, Ridgers ND, Gallagher AM, Murphy MH, Salmon J, Carlin A. ‘When you move you have fun’: perceived barriers, and facilitators of physical activity from a child’s perspective. Front Sports Act Living. 2022;4:789259. doi:10.3389/fspor.2022.789259. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Ribeiro Nunes Lages SM, Ferreira Emygdio R, Sampaio Irene Monte A, Alchieri JC. Motivation and self-esteem in university students’ adherence to physical activity. Rev Salud Publica. 2015 Oct;17(5):677–88. doi:10.15446/rsap.v17n5.33252. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Lewis BA, Williams DM, Frayeh A, Marcus BH. Self-efficacy versus perceived enjoyment as predictors of physical activity behaviour. Psychol Health. 2016;31(4):456–69. doi:10.1080/08870446.2015.1111372. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Esmaeilzadeh S, Rodriquez-Negro J, Pesola AJ. A greater intrinsic, but not external, motivation toward physical activity is associated with a lower sitting time. Front Psychol. 2022;13:888758. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.888758. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. D’Alonzo KT, Fischetti N. Cultural beliefs and attitudes of Black and Hispanic college-age women toward exercise. J Transcult Nurs. 2008 Apr;19(2):175–83. doi:10.1177/1043659607313074. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. DataReportal—Global Digital Insights. Digital 2023: Global Overview Report [Internet]. Global Overview Report [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Mar 24]. Available from: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2023-global-overview-report. [Google Scholar]

48. Santarossa S, Coyne P, Lisinski C, Woodruff SJ. #fitspo on Instagram: a mixed-methods approach using Netlytic and photo analysis, uncovering the online discussion and author/image characteristics. J Health Psychol. 2019 Mar 1;24(3):376–85. doi:10.1177/1359105316676334. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Hilger-Kolb J, Loerbroks A, Diehl K. When I have time pressure, sport is the first thing that is cancelled’: a mixed-methods study on barriers to physical activity among university students in Germany. J Sports Sci. 2020;38(21):2479–88. doi:10.1080/02640414.2020.1792159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Singh C, Bandre G, Gajbe U, Shrivastava S, Tiwade Y, Bankar N, et al. Sedentary habits and their detrimental impact on global health: a viewpoint. Nat J Community Med. 2024 Feb 1;15(2):154–60. doi:10.55489/njcm.150220243590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Gu M, Huang X, Ye X, Zhang S. The relations between physical exercise and body shame among college students in China. Atlantis Press; 2021. p. 1051–5. [cited 2025 Mar 23]. Available from: https://www.atlantis-press.com/proceedings/isemss-21/125959676. [Google Scholar]

52. Zartaloudi A, Christopoulos D. Social physique anxiety and physical activity. Eur Psychiatry. 2021 Apr;64(S1):S759. doi:10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Bevan N, O’Brien KS, Lin CY, Latner JD, Vandenberg B, Jeanes R, et al. The relationship between weight stigma, physical appearance concerns, and enjoyment and tendency to avoid physical activity and sport. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Sep 22;18(19):9957. doi:10.3390/ijerph18199957. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Bagherinia H, Saghebi SA. Study on the mediator role of self-esteem in the relationship between female self-objectification and social physique anxiety. J Educ Health Promot. 2023;12(1):385. doi:10.4103/jehp.jehp_597_22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Gilchrist JD, Pila E, Lucibello KM, Sabiston CM, Conroy DE. Body surveillance and affective judgments of physical activity in daily life. Body Image. 2021 Mar 1;36(4):127–33. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.11.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Prichard I, Tiggemann M. Objectification in fitness centers: self-objectification, body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating in aerobic instructors and aerobic participants. Sex Roles. 2005 Jul 1;53(1):19–28. doi:10.1007/s11199-005-4270-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Melbye L, Tenenbaum G, Eklund R. Self-objectification and exercise behaviors: the mediating role of social physique anxiety. J Appl Biobehav Res. 2007;12(3–4):196–220. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9861.2008.00021.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Calogero RM, Herbozo S, Thompson JK. Complimentary weightism: the potential costs of appearance-related commentary for women’s self-objectification. Psychol Women Q. 2009 Mar 1;33(1):120–32. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.01479.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Chu IH, Chen YL, Wu PT, Wu WL, Guo LY. The associations between self-determined motivation, multidimensional self-efficacy, and device-measured physical activity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Jul 29;18(15):8002. doi:10.3390/ijerph18158002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Hoffmann S, Warschburger P. Prospective relations among internalization of beauty ideals, body image concerns, and body change behaviors: considering thinness and muscularity. Body Image. 2019 Mar 1;28:159–67. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.01.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Cerolini S, Vacca M, Zegretti A, Zagaria A, Lombardo C. Body shaming and internalized weight bias as potential precursors of eating disorders in adolescents. Front Psychol. 2024 Feb 6;15:1356647. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1356647. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Puhl RM, Lessard LM. Weight stigma in youth: prevalence, consequences, and considerations for clinical practice. Curr Obes Rep. 2020 Dec;9(4):402–11. doi:10.1007/s13679-020-00408-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Tanas R, Gil B, Marsella M, Nowicka P, Pezzoli V, Phelan SM, et al. Addressing weight stigma and weight-based discrimination in children: preparing pediatricians to meet the challenge. J Pediatr. 2022 Sep;248:135–136.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2022.06.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Arslan M, Yabancı Ayhan N, Sarıyer ET, Çolak H, Çevik E. The effect of bigorexia nervosa on eating attitudes and physical activity: a study on university students. Int J Clin Pract. 2022;2022(4):6325860–11. doi:10.1155/2022/6325860. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Galasso L, Montaruli A, Jankowski KS, Bruno E, Castelli L, Mulè A, et al. Binge eating disorder: what is the role of physical activity associated with dietary and psychological treatment? Nutrients. 2020 Nov 25;12(12):3622. doi:10.3390/nu12123622. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Mathisen TF, Hay P, Bratland-Sanda S. How to address physical activity and exercise during treatment from eating disorders: a scoping review. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2023 Nov 1;36(6):427–37. doi:10.1097/yco.0000000000000892. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Ouellet M, Monthuy-Blanc J. Quand bouger n’est plus synonyme de santé: une recension des traitements de l’exercice physique pathologique en troubles des conduites alimentaires. Ann Méd Psychol. 2022 Nov 1;180(9):862–74. doi:10.1016/j.amp.2022.01.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Yeung NCY, Massar K, Jonas K. “Who pushes you to be bigger?”: psychosocial correlates of muscle dissatisfaction among Chinese male college students in Hong Kong. Psychol Men Masc. 2021;22(1):177–88. doi:10.1037/men0000283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Wilson OWA, Colinear C, Guthrie D, Bopp M. Gender differences in college student physical activity, and campus recreational facility use, and comfort. J Am Coll Health. 2022 Jul;70(5):1315–20. doi:10.1080/07448481.2020.1804388. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Frederick GM, Williams ER, Castillo-Hernández IM, Evans EM. Physical activity and perceived benefits, but not barriers, to exercise differ by sex and school year among college students. J Am Coll Health. 2022 Jun 22;70(5):1426–33. doi:10.1080/07448481.2020.1800711. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Wilson OWA, Bopp CM, Papalia Z, Duffey M, Bopp M. Freshman physical activity constraints are related to the current health behaviors and outcomes of college upperclassmen. J Am Coll Health. 2022 May 19;70(4):1112–8. doi:10.1080/07448481.2020.1785475. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Ramati-Ziber L, Shnabel N, Glick P. The beauty myth: prescriptive beauty norms for women reflect hierarchy-enhancing motivations leading to discriminatory employment practices. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2020;119(2):317–43. doi:10.1037/pspi0000209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Lee-Won RJ, Joo YK, Baek YM, Hu D, Park SG. “Obsessed with retouching your selfies? Check your mindset!”: female Instagram users with a fixed mindset are at greater risk of disordered eating. Pers Individ Dif. 2020 Dec 1;167(1):110223. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2020.110223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Allison S, Wade T, Warin M, Long R, Bastiampillai T, Looi JCL. Tertiary eating disorder services: is it time to integrate specialty care across the life span? Australas Psychiatry. 2021 Oct;29(5):516–8. doi:10.1177/10398562211010802. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Cunningham ML, Pinkus RT, Lavender JM, Rodgers RF, Mitchison D, Trompeter N, et al. The ‘not-so-healthy’ appearance pursuit? Disentangling unique associations of female drive for toned muscularity with disordered eating and compulsive exercise. Body Image. 2022 Sep 1;42:276–86. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2022.06.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Tabri N, Murray HB, Thomas JJ, Franko DL, Herzog DB, Eddy KT. Overvaluation of body shape/weight and engagement in non-compensatory weight-control behaviors in eating disorders: is there a reciprocal relationship? Psychol Med. 2015 Oct;45(14):2951–8. doi:10.1017/S0033291715000896. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Wang SB, Haynos AF, Wall MM, Chen C, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D. Fifteen-year prevalence, trajectories, and predictors of body dissatisfaction from adolescence to middle adulthood. Clin Psychol Sci. 2019 Nov 1;7(6):1403–15. doi:10.1177/2167702619859331. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull. 1990 Mar;107(2):238–46. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text