Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Impact of Virtual Reality Environment Design on Emotional Recovery: Exploring Factors and Mechanisms

1 School of Art & Design, Wuhan Institute of Technology, Wuhan, 430205, China

2 Village Culture and Human Settlements Research Center, Wuhan Institute of Technology, Wuhan, 430205, China

3 School of Arts and Communication, China University of Geosciences (Wuhan), Wuhan, 430074, China

4 Department of Cardio-Psychiatry Liaison Consultation, Beijing Chao-Yang Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, 100020, China

5 Graduate School of Journalism, Columbia University, New York, NY 10027, USA

6 School of Education, China University of Geosciences (Wuhan), Wuhan, 430074, China

* Corresponding Author: Lin Li. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Emotional Regulation, Wellbeing, and Happiness)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(7), 1051-1069. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.066369

Received 07 April 2025; Accepted 11 July 2025; Issue published 31 July 2025

Abstract

Objectives: Emotional stress is a significant public health challenge. Virtual reality (VR) offers the potential for aiding emotional recovery. This study explores the impact of VR environment design factors on emotional recovery, examining underlying mechanisms through physiological indicators and behavioral responses. Methods: Two experiments were conducted. Experiment 1 employed a 4 [Scene Type: real environment (RE), virtual scenes that restore the RE (VR), virtual scenes that incorporate natural window view design (VR-W), and a no-scene control condition (CTL)] × 3 (Experimental Phase: baseline, emotion arousal, recovery) mixed design (N = 33). Participants viewed a 4-min anxiety-inducing video followed by a 3-min scene exposure. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-State Form (STAI-S), galvanic skin response (GSR), and blood-volume pulse (BVP) frequency were analyzed with linear mixed-effects models. Experiment 2 used a 3 (Motion-control mode: Unnatural, Semi-natural, Natural) × 2 (Sound form: Spatial positioning, Surround) × 3 (Experimental Phase: baseline, emotion arousal, recovery) mixed design (N = 42). Presence was analyzed with the Scheirer–Ray–Hare test; phase efficacy was verified with Friedman tests. Results: Experiment 1 showed significant Scene Type × Experimental Phase interactions for GSR (F = 8.006, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.624) and BVP frequency (F = 11.491, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.704). VR-W produced the largest recovery (ΔGSR = –1.26; ΔBVP = –5.80; Hedges g ≥ 0.83) vs. RE and VR. STAI-S returned to baseline across all Scene Types. Experiment 2 revealed main effects of Motion-control mode (F = 8.55, p = 0.001, η2p = 0.32) and Sound form (F = 4.35, p = 0.044, η2p = 0.11) on Presence (Semi-natural + Spatial positioning highest). The greatest physiological recovery occurred with the Unnatural Motion-control mode (GSR H = 20.17, p < 0.001, ε2 = 0.49; BVP H = 7.92, p = 0.019), amplified by Spatial positioning Sound form only in this mode. Design factors did not influence STAI-S change. Conclusions: VR scenes are as restorative as RE; embedding VR-W accelerates recovery. Maximal Presence is not essential: Unnatural Motion-control mode induced the largest physiological recovery, especially combined with Spatial positioning Sound form.Keywords

Emotional well-being is a crucial aspect of overall public and psychological health, with its significance increasingly acknowledged on a global scale [1]. Mental health issues associated with emotional well-being, such as anxiety and depression, are becoming more prevalent across various populations and geographic regions [2–4]. A systematic review and meta-analysis conducted in 2021 indicated that the global average prevalence of anxiety and depression is 26.9% [5]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 264 million people worldwide suffer from depression, which has become the leading cause of disability globally [6]. Similarly, anxiety disorders affect around 284 million individuals, making it the most widespread mental health condition worldwide [7]. Research consistently shows that untreated emotional disorders contribute to decreased productivity, cognitive impairment, and strained interpersonal relationships [8,9].

Given these challenges, identifying effective methods for regulating emotions has emerged as a critical focus within the public health sector. Among the various approaches, digital media-based interventions, particularly those utilizing virtual reality (VR) technology, have demonstrated promise in enhancing emotional experiences and improving mental health outcomes [10,11]. VR offers users an immersive experience that significantly exceeds the engagement levels of traditional media, such as images or videos. Numerous studies have underscored the potential of VR environments to elicit and regulate emotions, especially in individuals with psychological disorders [12–14]. Felnhofer et al. investigated the emotional responses elicited by five distinct VR scenarios, discovering that each situation effectively triggered corresponding emotional reactions [15]. Furthermore, VR has been effectively employed in treating successfully employed in the treatment of phobias, where patients are gradually exposed to realistic, fear-inducing virtual environments within a controlled therapeutic setting, resulting in substantial improvements [16]. In comparison to traditional treatment methods, the emotional memory retention rate for VR interventions is as high as 68%, whereas the traditional method achieves only 42% [17]. In clinical treatment, Chiesa and Serretti integrated VR into relaxation therapy for individuals experiencing anxiety and depression, reporting significant advancements in emotional regulation [18]. In addition, VR has also been employed to train and enhance emotional regulation skills [19].

Despite the promise of VR environments in clinical settings, relatively little attention has been paid to their potential to aid emotional recovery in the general population. It is critical to explore the specific design factors that contribute to effective emotional recovery within VR systems in order to optimize their use and improve accessibility in public health settings. Previous research by Bohil has identified two primary factors influencing emotional responses in VR settings: the content of the virtual scenes and the user’s presence within the environment [20]. Design, as a goal-oriented creative activity that enables precise quantification of the content of a virtual scene, is centered on the systematic translation of ideas into visual solutions for solving a specific problem or realizing an ideal state through the medium of images, models, or language [21]. Chirico et al. found that the introduction of controlled fear or awe stimuli in VR enables comparative analyses of how different content affects emotional intensity and duration, providing empirical evidence for the selection of design elements [22]. VR has also been used to create restorative environments (combining natural landscapes and interactive activities) to alleviate emotional problems such as anxiety and depression [23]. Therefore, the impact on emotional recovery can be explored by designing VR scenario content that incorporates elements of natural landscapes.

Presence is a combination of sensory immersion and cognitive engagement that determines whether a virtual scene is “real” enough to trigger an emotional response [24]. It is not only a core indicator of VR experience, but also a necessary mediator to drive real emotional responses [23]. A high degree of presence can enhance the user’s engagement and emotional involvement, and deepen his/her psychological connection with the virtual environment, thus improving emotional recovery [25]. However, different design elements have different effects on the presence, such as spatially localized sound can enhance the sense of space and presence more than ordinary stereo sound, thus enhancing the immersion degree and emotional adjustment effect [26]. On the one hand, as a function of emotional arousal, presence needs to reach a certain level in order to elicit emotions; on the other hand, manipulation of emotions through scene content will elicit more presence [27]. For this reason, we start from the design of virtual scene content, and quantitatively analyze the law of its influence on the presence and emotion recovery by focusing on a variety of design elements, such as natural landscape, spatial positioning sound, and so on. Through systematic experimental evaluation and data analysis, this paper aims to propose actionable design strategies to provide theoretical and methodological guidance for the grounded practice of emotional recovery-oriented VR systems in public health and daily health management.

The present study aimed to elucidate the effects of specific design factors in VR environments on emotional recovery and their mechanisms of action. Experiment 1 compared the differences in emotional recovery between virtual environments based on real scene restoration and traditional static environments, and assessed the facilitating effect of scene design incorporating natural landscape elements on emotional recovery; based on this, Experiment 2 further examined the impact of key design elements that constitute presence on the emotional recovery of a VR scene, exploring which combination of design elements is more effective for emotional recovery in terms of both motion control modes and sound forms. These findings not only have the potential to expand research perspectives on emotional recovery but may also offer new insights into the optimized application of immersive technologies in everyday emotional regulation scenarios, further driving design innovations in VR to promote individual psychological resilience and positive emotional experiences.

2.1 Emotional Elicitation and Emotional Recovery

Emotional elicitation methods can be categorized into two primary types: emotional material elicitation methods and emotional situational elicitation methods [28]. Emotional material elicitation involves presenting participants with stimuli, such as images, videos, or other forms of content, specifically designed to evoke particular emotions. For instance, Philippot developed a collection of film materials capable of inducing six predetermined emotions in individuals [29].

Emotional recovery in individuals refers to their capacity to sustain a positive emotional state in the face of negative emotional stimuli or to rapidly shift from a negative emotional response to a more positive one. This ability reflects the individual’s resilience in bouncing back emotionally and regaining a positive outlook after experiencing adverse emotional events [30]. Research indicates that negative emotions generally diminish in intensity relatively quickly, often returning to baseline levels within approximately five minutes. In contrast, positive emotions tend to increase in intensity over a short duration. This upward trajectory of positive emotions may be attributed to psychological facilitation, which enhances an individual’s overall mood and well-being [31]. Consequently, the onset and recovery processes of negative emotions are often more pronounced and manageable than those of positive emotions, providing a clearer understanding of how individuals respond to emotional experiences.

The mechanism by which the content of VR scenes influences emotional recovery is linked to the concept of restorative environments. Restorative environment theory, introduced by Kaplan and Talbot, refers to environments that promote recovery from mental fatigue and alleviate negative emotions associated with stress. In the context of VR, the content of the scenes plays a crucial role in creating a restorative environment that supports emotional recovery [32]. It is well established that humans have aesthetic preferences for natural elements, which has led to significant research on the restorative effects of natural environments [33–35]. Studies have demonstrated that exposure to restorative environments featuring natural landscapes can result in significant reductions in blood pressure and heart rate [36]. Furthermore, such exposure has been shown to enhance mood and improve attention and focus [37]. Herzog was among the first researchers to highlight the importance of indoor environments in facilitating individual emotional recovery. Specifically, he conducted a study investigating the restorative potential of churches as regular environments frequented by American college students [38]. The evidence strongly supports the idea that both suitable indoor environments and natural settings have the potential to enhance users’ moods [39].

The restorative nature of the environment aligns with Ulrich’s theory of psychological evolution. According to this theory, human responses to the environment are universal and instinctive, occurring rapidly and without the necessity for conscious cognitive involvement [40]. When specific features are present within the environment, individuals typically exhibit a primary response characterized by a shift toward positive affect. This rapid and positive affective response serves to reduce arousal levels and alleviate stress. The preference for these restorative environments, combined with distancing from threatening stimuli, triggers physiological and psychological changes that initiate a recovery process, facilitating the restoration of emotional equilibrium [41]. The natural environment contains a greater abundance of the aforementioned structural features and elements. Therefore, incorporating natural elements into the design can potentially provide enhanced support for users’ emotional regulation [42]. By integrating natural elements into the design of indoor or virtual environments, designers can create spaces that are more conducive to promoting emotional well-being and facilitating effective emotional regulation for users.

Hypothesis H1: VR scenes incorporating natural elements have better emotional recovery effects.

2.3 VR Presence Experience Design

Presence is a crucial factor in assessing the efficacy of virtual environment systems [43]. It is commonly regarded as a mental state, representing the subjective experience of being present in a place or environment. This experience is generated through automatic or controlled mental processes and may not necessarily correspond to the actual physical environment in which the individual is physically situated [44]. Draper argued that the attainment of a presence is a consequence of attentional focus. Specifically, when individuals are exposed to a novel and distinct virtual environment, it captures their attention and directs their focus toward a broad range of stimuli within that environment [45]. Witmer et al. proposed that while the novel features of a virtual environment may indeed capture individuals’ attention, they primarily serve as facilitating conditions. According to their argument, the acquisition of a presence is primarily dependent on the extent to which individuals receive and transmit stimulus information within the virtual environment. In other words, the immersive and interactive aspects of the virtual environment play a crucial role in fostering a strong presence [24].

From a design standpoint, factors related to the experience of presence in VR can be categorized into control design factors and audiovisual-touch multisensory design factors. Control design factors pertain to the naturalness of user interaction and movement within the VR environment. They can be classified into three mainstream types based on the naturalness of operation: unnatural movement control, natural movement control, and semi-natural movement control. These types reflect the different approaches and techniques used to enable users to navigate and interact with the VR environment in a manner that aligns with their expectations and real-world experiences [46]. Unnatural movement control involves using the controller exclusively to move and adjust the direction of the field of view while remaining stationary in a fixed position. Walking or movement is controlled through buttons or other input mechanisms. Users have the freedom to navigate within the virtual environment using this control method. Natural movement control utilizes locational tracking technology to accurately detect users’ spatial positioning within a designated range. Users can move within the virtual environment in a manner that closely resembles real-world movement. Semi-natural movement control combines elements of both unnatural and natural movement control modes. It typically incorporates a combination of control methods to provide users with a more versatile and adaptable means of interacting and navigating within the virtual environment.

Hypothesis H2: There are differences in the emotional recovery effects of different movement control modes in the VR system.

In the context of visual-auditory-touch multisensory design, various sensory channels, including visual, auditory, and tactile, serve as avenues for individuals to acquire attentional cues. Different forms of perceptual information can significantly influence an individual’s experience of presence. Effective sound design is crucial for enhancing the presence in VR systems. Depending on its presentation, sound can evoke distinct impressions and emotions, exhibiting cross-cultural consistency [47]. The primary modalities of VR sound design include surround sound and spatial positioning sound. Surround sound envelops the user, rotating around their head, while spatial positioning sound accurately conveys the location of sound sources within the virtual environment [48]. Spatial positioning sound associates the sound source with a specific object, whereas surround sound immerses the user in audio from multiple directions. These two sound modalities offer varied user experiences.

Hypothesis H3: Different sound information designs have an impact on the emotional recovery effects of virtual reality systems.

3 Experiment 1: Emotional Restorative Study of VR Environment Scenes

To ensure the validity and reliability of the experimental results, participants were rigorously screened prior to the experiment. All participants were healthy individuals with normal vision (no correction required) and the ability to adapt to an immersive VR environment. Considering the possibility of motion sickness, the screening criteria included: no significant 3D motion sickness reaction (mild discomfort is acceptable) when wearing an immersive VR headset with visual display functionality for five consecutive minutes, and normal psychological and physiological responses to experimental stimuli, with the ability to cooperate in completing physiological data collection tasks. Ultimately, 33 college students aged 22 to 26 (14 males and 19 females) passed the screening and voluntarily participated in the experiment. All participants had normal mental health and cognitive function, with no history of mental illness or family history. Participants were randomly assigned to three experimental groups (six participants each) and one control group (15 participants). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the study, and each participant received a compensation of 30 RMB after the experiment. The study was approved by Wuhan University of Technology Ethics committee at the Wuhan University of Technology (IRB number: A2024002). All participants signed the informed consent in this study.

1. Experimental equipment

Hardware: HTC Vive kit (HTC Corporation, Taoyuan, Taiwan, China), BioNeuro biofeedback instrument (Thought Technology Ltd., Montreal, QC, Canada), and high-performance computer (CPU: Intel® Core™ i7-11850H; GPU: NVIDIA RTX™ A2000 Laptop GPU, HP Inc., 1501 Page Mill Road, Palo Alto, CA 94304, USA).

Software: Unity 2021.3 LTS (Long Term Support), 3ds Max 2022, and V-Ray 5 for 3ds Max, Update 2.

2. Materials

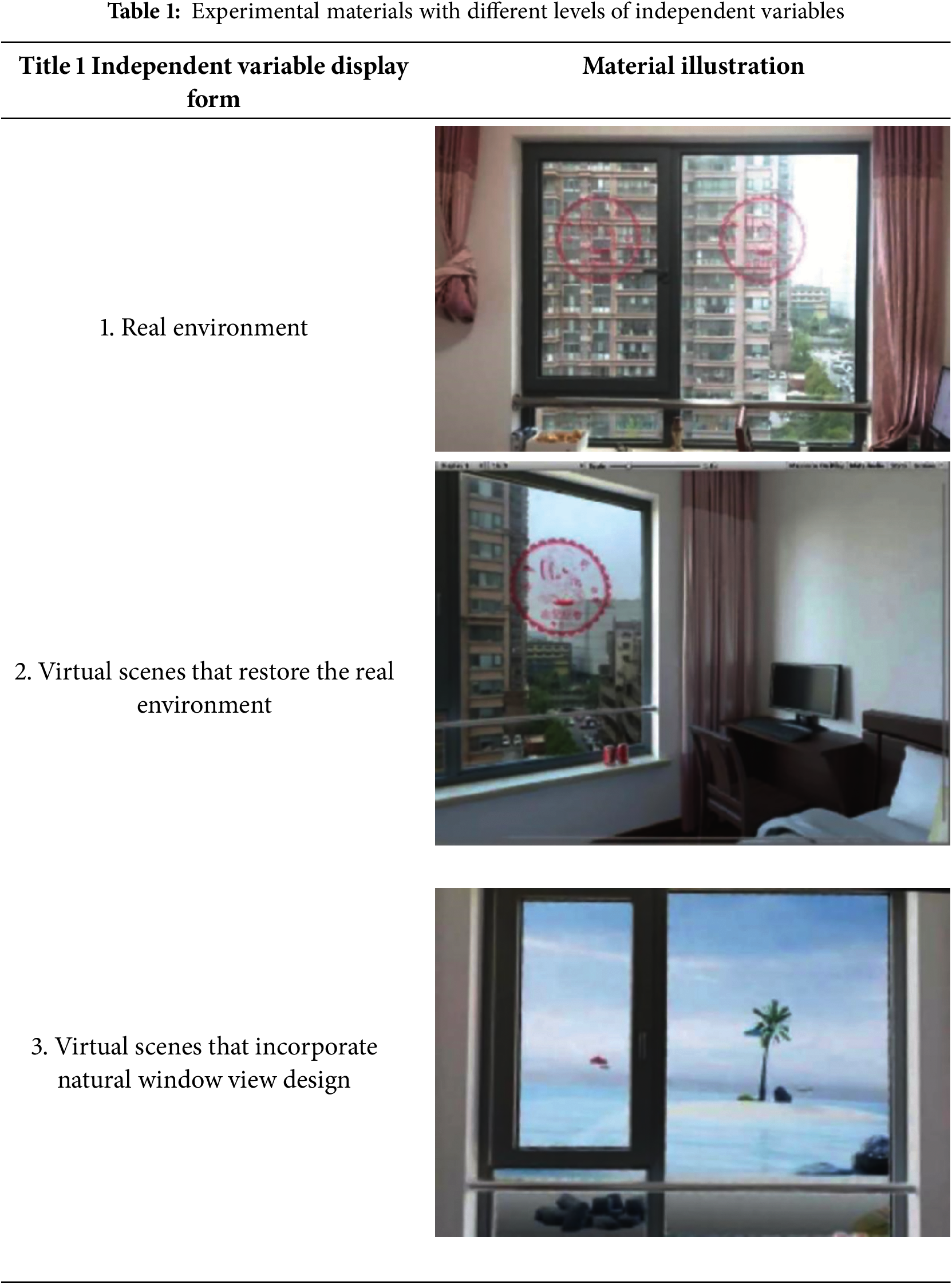

a. Three types of scenes. A representative real living room environment was selected and a 1:1 virtual environment was constructed as the experimental material, as shown in Table 1.

b. Emotion-eliciting material. We began by referring to previous literature to identify videos that trigger anxiety by searching for the following terms: ‘sad videos that make you cry after watching them’, ‘shocking and scary highway moments caught on camera’, and “Top 10 videos that make you feel sad” and selected 10 anxiety-related videos from these [49]. Then, with the help of 30 students (who were not part of the formal experiment), after watching each video, their emotions were rated using a Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 8 (very strongly). This rating process was designed to assess the emotional arousal effect of the material. Subsequently, the 4-min video clips with the highest emotional ratings were selected as experimental material for the formal experiment.

c. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-State Form (STAI-S). To assess users’ psychological state, we adopted the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), a widely recognized psychological measurement tool. The STAI was developed by Charles D. Spielberger et al. in 1970 and translated into Chinese in 1988. It is a 40-item scale. The scale can be used to measure trait anxiety (the degree of anxiety an individual experiences across different times and contexts) and state anxiety (the degree of anxiety an individual experiences at a specific moment), as it includes two independent subscales: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-Trait Form (STAI-T) and STAI-S, each containing 20 items [50]. This study utilized the STAI-S subscale. The scale is rated on a 1–4 scale, with 1 indicating the lowest level and 4 indicating the highest level of anxiety [51]. Some questions are reverse-scored. State anxiety scores were calculated individually, with higher scores indicating greater levels of anxiety.

A 4 × 3 mixed-factor design was used. The between-participants factor was Scene Type with four levels: (1) a real environment (RE), (2) a virtual scenes that restore the RE (VR), (3) a virtual scenes that incorporate natural window view design (VR-W), and (4) a no-scene control condition (CTL). The within-participants factor was Experimental Phase with three levels: baseline, emotion arousal, and emotion recovery.

The dependent variable was emotional response, indexed by both psychological and physiological measures. Psychological reactions were assessed using STAI-S. Physiological indices comprised Blood-Volume Pulse (BVP) frequency and amplitude, galvanic skin response (GSR), and peripheral skin temperature (ST). BVP and GSR, which are regulated by sympathetic nerves, are sensitive physiological indicators of emotional arousal, and are particularly suitable for detecting short-term mood changes [52]. Skin temperature, on the other hand, is affected by peripheral vasoconstriction/diastole, and its level can reflect changes in mood [53].

In the pre-experiment phase, 10 participants were recruited to establish a reference for the specific duration of the experiment and to verify the positive effect of the indoor environment on emotional recovery. Each experiment lasted approximately 30 min, with a stress-relieving phase of 250 s (determined by the longest recovery time of the electrodermal index) as the environment-free recovery experience.

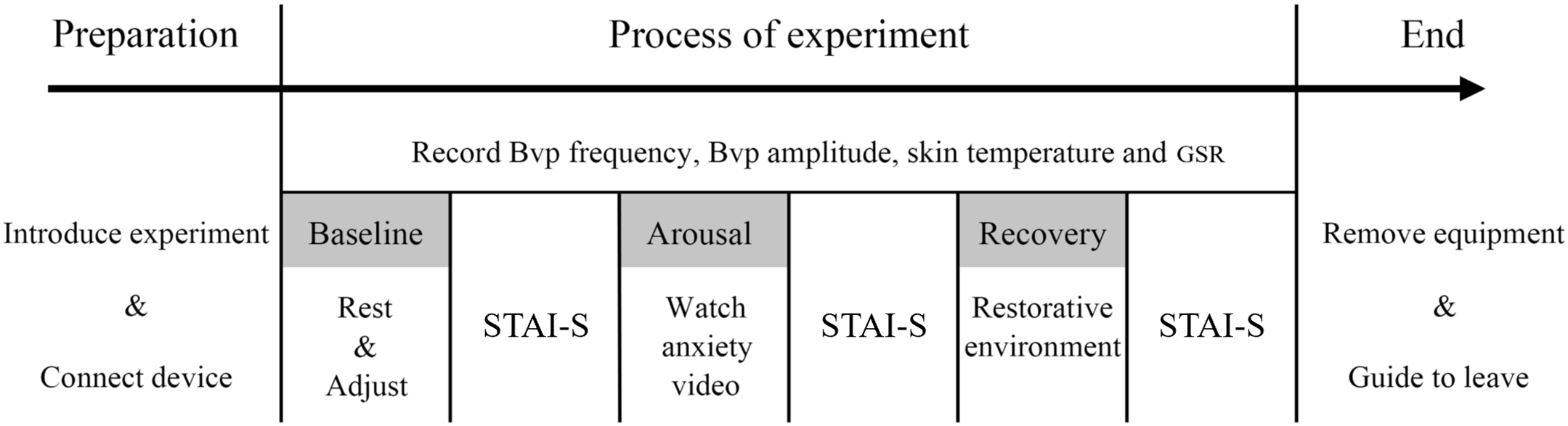

Throughout the formal experiment, changes in physiological indicators were recorded. The experiment consisted of three phases: baseline phase, arousal phase, and recovery phase.

During the baseline phase, participants were instructed to calm down upon arrival at the laboratory and complete the first state anxiety measure.

In the arousal phase, participants watched a 4-min anxiety-inducing video clip and immediately filled out the second anxiety state questionnaire to assess their anxiety levels.

In the recovery phase, the three groups of participants entered either the living room or the laboratory to experience the three different environments in groups. Each environmental experience lasted for 3 min, after which participants completed the state anxiety questionnaire again. The experimental setup is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Flow chart of Experiment 1

Prior to inferential testing, all psychophysiological signals were processed to minimise artefacts: GSR traces were baseline-corrected, low-pass filtered and motion artefacts rejected through accelerometer cross-checks, while BVP data were cleaned for ectopic beats and converted to R-R-interval series to derive heart-rate variability; for each phase, the mean of the final 30 s was retained as the analysis value.

Descriptive statistics (mean ± SE) were computed for STAI-S scores and four physiological indices (BVP frequency, BVP amplitude, GSR, peripheral skin temperature). Phase-dependent and scene-dependent changes in the physiological indices were examined with 4 (Scene Type: RE, VR, VR-W, CTL) × 3 (Experimental Phase: Baseline, Arousal, Recovery) linear mixed-effects models, specifying a random intercept for Participant and an unstructured covariance matrix; models were fitted by restricted maximum-likelihood (REML) and Satterthwaite corrections were applied to denominator degrees of freedom. Significant interactions were decomposed with simple-effects analyses, and Hedges g was reported for pairwise contrasts.

State-anxiety scores were analyzed with a 4 × 3 mixed-design ANOVA (SPSS Statistics 25, Type III sums of squares); when Mauchly’s test indicated violation of sphericity, Greenhouse–Geisser adjustments were applied. Two-tailed p < 0.05 denoted statistical significance, and η2p (or Hedges g) quantified effect size.

In each phase of the experiment, the values of each physiological index were calculated as the mean value of the corresponding data collected during the last 30 s of the phase. This approach allowed for a focused analysis of the physiological responses during the baseline, arousal, and recovery phases. During GSR data preprocessing, baseline correction was performed and combined with accelerometer data to detect motion artifacts and reject abnormal skin conductance response (SCR), followed by removal of high-frequency noise with a low-pass filter, and then smoothing of the signal [54]. BVP data preprocessing was performed and combined with accelerometer data to detect motion-induced disturbances and reject abnormal heartbeat cycles, and the time difference between consecutive R-R intervals was calculated to obtain the heart rate variability time series [55].

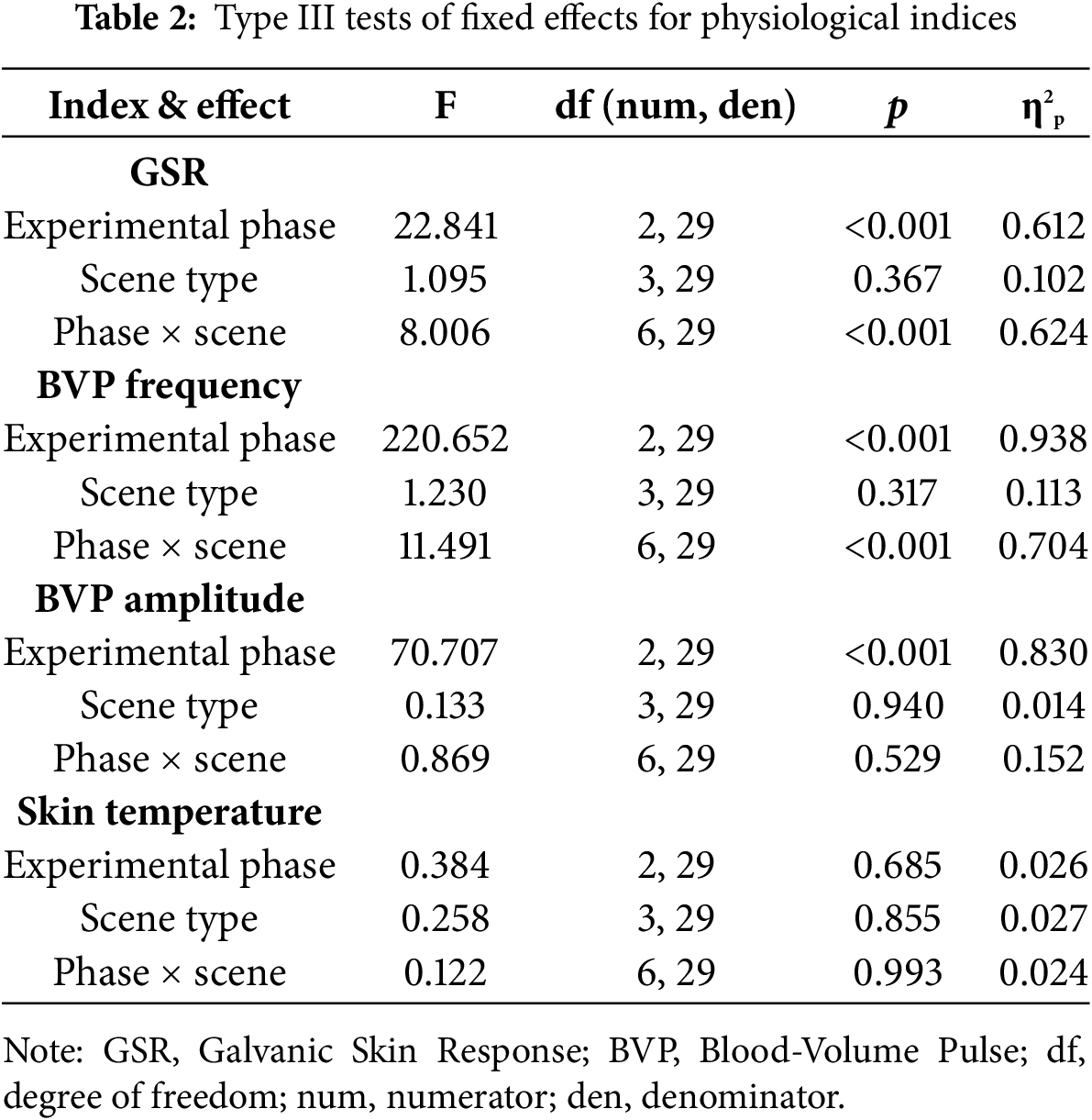

Linear mixed-effects models with random intercepts for participants and an unstructured covariance matrix were fitted with Scene Type (RE, VR, VR-W, CTL) and Experimental Phase (baseline, arousal, recovery) as fixed factors. REML estimation and Satterthwaite degrees of freedom were used. Model fit was adequate (e.g., GSR: –2 log-likelihood = 210.04, Akaike information criterion (AIC) = 222.04). Complete test statistics appear in Table 2.

1. GSR

The Phase × Scene interaction was significant, F (6, 29) = 8.006, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.624 [95% CI = 0.38, 0.75].

Simple contrasts. During arousal, VR (Mean = 4.26) and VR-W (Mean = 4.11) exceeded CTL (Mean = 2.78), p < 0.001. From arousal to recovery, the VR-W scene produced the largest drop (Δ = –1.26, SE = 0.32, Hedges g = 0.83), significantly greater than RE (Δ = –0.69, p = 0.006) and marginally greater than VR (Δ = –0.74, p = 0.051).

2. BVP Frequency

Phase × Scene interaction: F (6, 29) = 11.491, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.704.

VR-W again showed the largest recovery (Δ = –5.80 bpm, SE = 1.00, Hedges g = 1.05), exceeding VR (–3.76 bpm) and RE (–3.09 bpm), Holm-adjusted p < 0.05. The main effect of Phase was highly significant, F (2, 29) = 220.652, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.938.

3. BVP Amplitude

A robust main effect of Phase emerged, F (2, 29) = 70.707, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.830.

Amplitude increased from baseline (Mean = 3.31) to arousal (Mean = 3.88) and partially returned at recovery (Mean = 3.59). Neither the Scene main effect nor the interaction reached significance (p = 0.529).

4. Skin Temperature

No fixed effects were significant (largest F = 0.384, p = 0.685). The mean change from arousal to recovery was –0.10 (95% CI = –0.44 to 0.24), indicating thermoregulatory inertia under the present stressor.

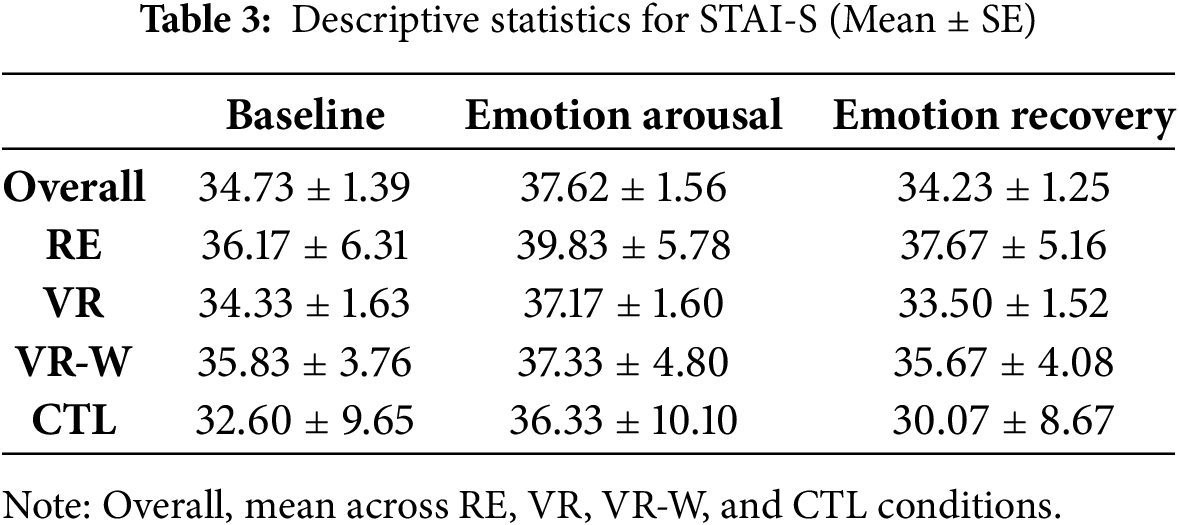

Scores on the STAI-S were analyzed with a 4 (Scene Type) × 3 (Experimental Phase) mixed-design ANOVA, implemented in SPSS 25’s General Linear Model (GLM) procedure (Type III sums of squares). When Mauchly’s test indicated a violation of sphericity, Greenhouse–Geisser corrections were applied to the degrees of freedom and p values.

Mauchly’s test indicated that the assumption of sphericity was violated for the main effect of Experimental Phase, χ2 (2) = 6.84, p = 0.03. Therefore, Greenhouse-Geisser corrections were applied (ε = 0.82).

The mixed-model GLM revealed a significant main effect of Experimental Phase, F (1.64, 47.67) = 7.20, p = 0.005, η2p = 0.20, but no significant main effect of Scene Type, F (3, 29) = 0.87, p = 0.47, η2p = 0.08. The Experimental Phase × Scene Type interaction was not significant, F (4.93, 50.00) = 0.91, p = 0.48, η2p = 0.09.

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 3. Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise comparisons showed a marginal rise in anxiety from baseline (Mean = 34.73, SE = 1.39) to emotion arousal (Mean = 37.62, SE = 1.56), p = 0.057. Anxiety then dropped significantly to emotion recovery (Mean = 34.23, SE = 1.25), p = 0.002, with baseline and emotion recovery indistinguishable (p > 0.99), confirming full return to baseline levels.

Furthermore, there were no significant group differences in state anxiety scores, indicating that subjective reporting of state anxiety reflected the participants’ emotional changes but was not sensitive enough to detect differences in different emotionally restorative environments.

4 Experiment 2: Design Study of Emotional Recovery Based on the Presence of VR

By recruiting advertisements selected 42 college students to participate in the research, 21 males and 21 females, aged 22–25 years old, were selected to participate in this study according to the same requirements of Experiment 1. The participants were randomly divided into six groups of seven each. The participants were those who had participated in Experiment 1 or other similar experiments. The study was approved by Wuhan University of Technology Ethics committee at the Wuhan University of Technology (IRB number: A2024002). All participants signed the informed consent in this study.

1. Measurement equipment

Same as Experiment 1.

2. Measurement tools

STAI-S. Same as Experiment 1.

Presence Questionnaire. This study used the Presence Questionnaire developed by Witmer and Singer. This questionnaire contains 24 items in 7 dimensions, with higher scores indicating a greater presence. The seven dimensions are: Realism, Possibility to Act, Quality of Interface, Possibility to Examine, Self-Evaluation of Performance, Sounds, and Haptic [24]. “Possibility to Examine” refers to the possibility that the user can closely observe objects in the virtual world, and “Self-Evaluation of Performance” is the user’s performance self-assessment” is the user’s self-assessment of performance in VR. Since the effect of haptic perception was not used in this study, the relevant questions were removed.

3. Experimental materials

Emotion-eliciting material. Same as Experiment 1.

VR scenes. Based on the virtual living room environment in Experiment 1, the VR scenes were designed according to different levels of independent variables, with each virtual scene being a combination of movement control modes and sound forms, as well as scenes without movement control and sound information.

A 3 × 2 × 3 mixed experimental design was used, with the independent variables being the mode of movement control (between-participants variable, divided into unnatural movement control, semi-natural movement control, and natural movement control), the form of sound (between-participants variable, divided into spatial positioning sound and surround sound), and the experimental phase (within-participants variable, divided into baseline phase, arousal phase, and recovery phase), which constitute the presence in the design of the VR Experience. Motion control modes are categorized with reference to VR interaction: unnatural motion control (based on joystick controllers), semi-natural motion control (based on indoor system roaming approach) and natural motion control (based on HTC Vive headset suite of devices) [46]. The maximum movement speed of the joystick controllers is controlled to be equal to the average walking speed in real walking and only supports natural movement of about 8 square meters. In the HTC Vive technology, the participant’s movement within the HTC Vive is directly mapped (directionally and proportionally) to a point-of-view transformation in the virtual environment, with the direction of viewing decoupled from the direction of walking. The virtual environment is displayed to the participant via a head-mounted display, and the viewpoint is controlled by a vertical bar. The dependent variables were presence and emotional response, where the psychological indicator of emotional response was anxiety and the physiological indicators were specifically BVP frequency and GSR.

The specific procedure in this experiment was the same as that in Experiment 1. After completing the third state anxiety assessment, participants were also required to complete a presence questionnaire.

Presence was evaluated with a 3 (Motion-Control Mode: unnatural, semi-natural, natural) × 2 (Sound Form: spatial-positioning, surround) Scheirer–Ray–Hare extension of the Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise comparisons when warranted. The efficacy of the base-line–arousal–recovery manipulation was confirmed with Friedman tests on GSR, BVP frequency and SAI, with stage-wise Wilcoxon tests for post-hoc contrasts (Bonferroni corrected).

Recovery magnitude for each dependent variable was expressed as the change score d = Recovery − Arousal; effects of design factors on these d values were tested with Kruskal-Wallis tests and a Scheirer-Ray-Hare model. ε2 or η2p provided effect-size estimates. Statistical decisions were based on two-sided tests with p < 0.05.

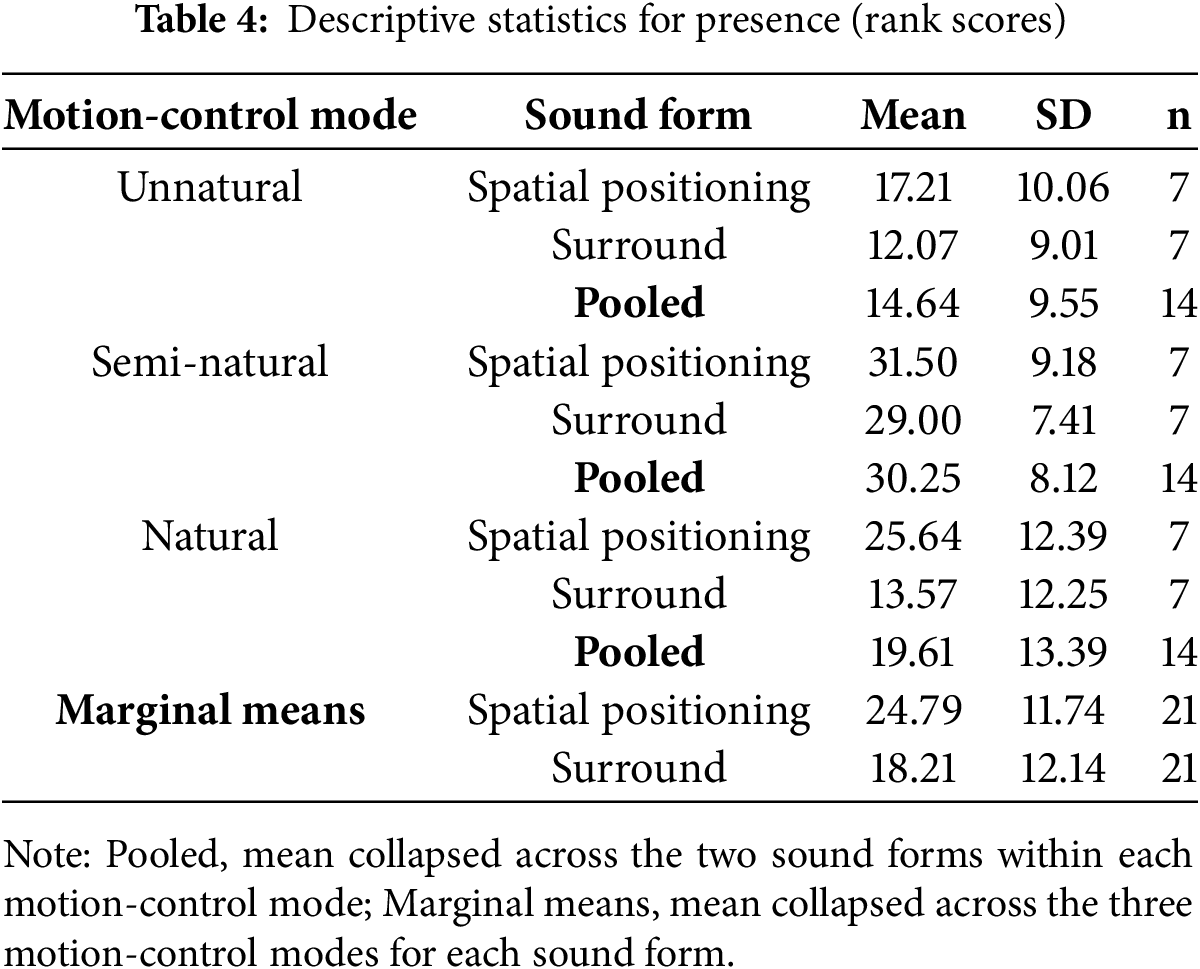

Descriptive statistics for each condition are provided in Table 4. A two-way Scheirer-Ray-Hare (SRH) test on the rank-transformed presence scores revealed a robust main effect of Motion-Control Mode, H (2) = 8.55, p = 0.001, η2p = 0.32, and a smaller but significant main effect of Sound Form, H (1) = 4.35, p = 0.044, η2p = 0.11. The interaction was non-significant, H (2) = 0.82, p = 0.45.

Bonferroni contrasts showed that the semi-natural mode elicited higher presence than both the unnatural mode (Δrank = 15.61, p = 0.001, r = 0.58) and the natural mode (Δrank = 10.64, p = 0.027, r = 0.41); the latter two did not differ. Across modes, spatial-positioning sound produced higher presence ranks (Mean = 24.79) than surround sound (Mean = 18.21, Δrank = 6.57, p = 0.044).

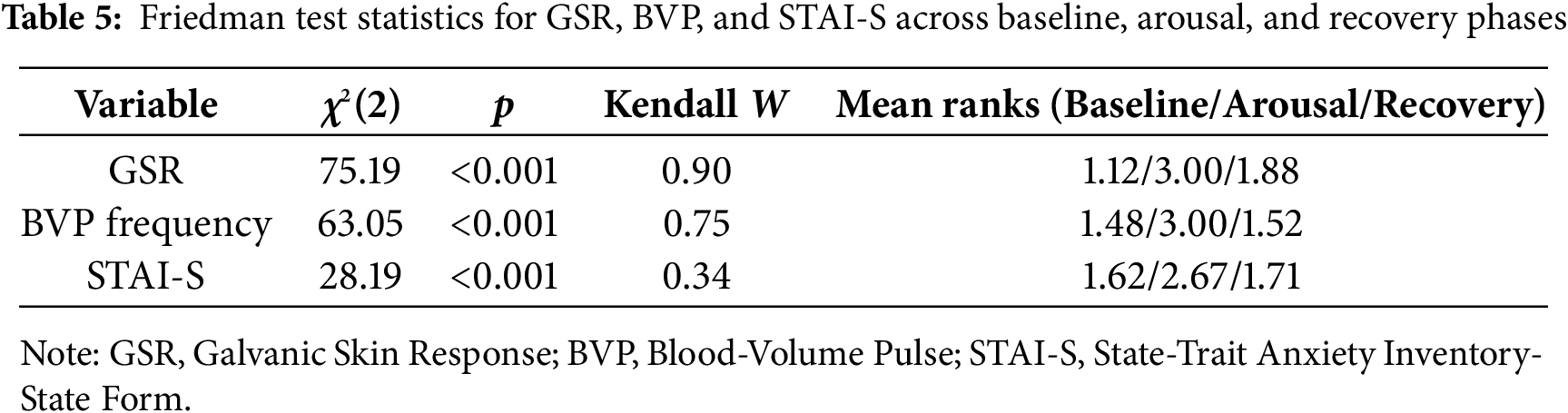

4.2.2 Manipulation Check: Arousal–Recovery Trajectory

Friedman tests confirmed successful induction and partial recovery (Table 5). Stage-wise Wilcoxon tests (Bonferroni-adjusted) were all significant (all p < 0.001).

4.2.3 Design Factors and Recovery Magnitude

Recovery magnitude was indexed by change scores (d = Recovery

1. GSR recovery (d_GSR)

Motion-control mode: Kruskal-Wallis H (2) = 20.17, p < 0.001, ε2 = 0.49 (large). unnatural produced the greatest recovery (mean rank = 33.4), followed by natural (17.1) and semi-natural (14.0).

Sound form: H (1) = 0.34, p = 0.56.

A Scheirer–Ray–Hare test on ranks confirmed a large main effect of Motion-control mode, H (2) = 23.68, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.568, and a moderate Motion-control mode × Sound form interaction, H (2) = 6.05, p = 0.005, η2p = 0.252. Under Spatial positioning sound, unnatural control (Mean = 37.93) was superior to semi-natural (8.14) and natural (15.14); the pattern attenuated under surround sound.

2. BVP frequency recovery (d_BVP)

Motion-control mode: H (2) = 7.92, p = 0.019, ε2 = 0.19; SRH H (2) = 4.53, p = 0.018, η2p = 0.201. unnatural > semi-natural (Bonferroni p = 0.016).

Sound form and the interaction were not significant (η2p = 0.044).

3. STAI-S recovery (d_STAI-S)

No significant effects of Motion-control mode, Sound form, or their interaction (all p > 0.42; η2p ≤ 0.04).

In Experiment 1, Hypothesis 1 was validated, demonstrating that VR scenes incorporating natural elements exhibit superior emotional recovery effects. However, no significant difference was observed between the virtual scenes that recreated the RE and the actual environment regarding their emotional recovery effects. This lack of distinction may be attributed to the highly realistic visual effects of the virtual scenes in replicating the real environment. However, when examining both GSR and BVP frequency, the virtual scene featuring a natural window view demonstrated a superior recovery effect compared to the virtual scenes representing urban landscapes and the actual urban environment [56]. Previous research has indicated that exposure to nature is more effective in reducing cognitive fatigue and promoting emotional recovery than exposure to man-made environments [57]. Thus, the virtual natural-window-view scene may have harnessed the benefits of natural landscapes, resulting in enhanced emotional recovery compared to real environments.

Consistent with our Hypothesis 1, the GSR indicator did differentiate the scenes: VR-W produced the largest drop from arousal to recovery, supporting the notion that electrodermal activity is highly sensitive to rapidly changing restorative cues [58]. Together with the parallel pattern in BVP frequency, this finding suggests that multi-modal autonomic measures converge in highlighting the restorative value of virtual nature. Neither BVP amplitude nor ST differentiated the scenes, indicating that these indices reflect more sluggish or homeostatic processes that were less responsive to the relatively brief VR exposure.

Interestingly, the state anxiety score failed to consistently reflect differences in emotional arousal and emotional recovery functions across the different environments, as observed in the physiological indicators. This discrepancy may be partly attributed to the fact that physiological changes can more subtly and objectively represent autonomic responses to emotional affect [59]. Additionally, physiological indicators provide real-time recordings of emotional changes, whereas state anxiety scores reported afterward reflect participants’ emotional states following the experimental manipulation.

The results of Experiment 2 validated Hypothesis 2, which states that different motion control modes in VR systems have different emotional recovery effects, and further revealed a more complex relationship between immersion and emotional recovery: although the semi-natural movement-control mode combined with spatial-positioning sound yielded the highest presence scores, the greatest physiological recovery (d_GSR and d_BVP) emerged in the unnatural movement-control condition. This uncoupling suggests that maximal presence is not a prerequisite for effective down-regulation of stress.

Unexpectedly, virtual scenes that utilized unnatural movement control produced the most pronounced physiological recovery. One possible explanation is that joystick-based locomotion imposes minimal proprioceptive load, thereby reducing vestibular–visual conflict and allowing the autonomic system to settle more quickly during recovery [60]. In contrast, semi-natural and natural movement controls, while increasing ecological validity, may also introduce mild postural or navigational effort that delays full autonomic relaxation.

The influence of sound form [61,62] on the emotional recovery effects of virtual scenes is contingent upon the movement control mode employed. Therefore, this study integrates the original Hypothesis 2 and Hypothesis 3 in Experiment 2 and explores whether different sound information designs under different motion control modes have different emotional recovery effects. Experimental results indicate that the regulatory effects primarily manifest in non-natural control modes: spatial-positioning sound combined with joystick locomotion amplified GSR recovery relative to surround sound, whereas sound form had little influence in the semi- and natural-control modes. These findings further validate Hypothesis 3, and both GSR and BVP frequency capture these design-dependent differences, indicating that heart rate variability is as sensitive as skin conductance activity when movement demands change. It is important to highlight that the effects of different sound forms on emotional recovery in VR are primarily evidenced by GSR, while changes in BVP frequency were not significantly different. This discrepancy may arise from the fact that BVP frequency serves as a more stable overall measure of emotional state, whereas GSR indicators are more responsive to variations in stimuli [63,64].

It is interesting to note that neither the movement control mode nor the sound form showed significant differences in subjective anxiety indicators. Some researchers have suggested that the differences in recovery effects produced by VR design may not be sufficient to directly influence subjective emotional feelings related to anxiety. Instead, physiological changes and autonomic responses to emotional affect can provide more subtle insights into the emotional state of individuals, which aligns with the findings of this study [59].

However, other researchers have explored the effects of sound quality, sound information, and sound localization on users’ subjective emotional evaluations. They have found that behaviorally relevant ecological sounds can have a more significant impact on users’ subjective emotions [63,64]. Therefore, when designing the sound form in VR experiences, it may be beneficial to incorporate ecological sound information that can generate feedback sound effects such as footsteps and door-closing sounds. Additionally, in cases where sound sources cannot be precisely positioned, surround sound can be employed to allow users to perceive environmental sounds from any position, thus enhancing the emotional atmosphere of the VR environment.

Our findings provide valuable insights into how VR technology can effectively aid individuals in their journey toward emotional well-being and resilience. By understanding the impact of VR design elements (e.g., natural landscapes and spatially-located sounds) on emotional recovery, it was validated that individuals can benefit from immersive virtual environments that promote relaxation and rejuvenation [65]. Furthermore, our study sheds light on the specific mechanisms underlying emotional recovery within VR environments, paving the way for the development of targeted interventions and experiences. Individuals who face emotional stress and seek solace can find practical guidance in utilizing VR systems that prioritize effective design factors. This research fosters a greater understanding of the interplay between VR design elements, user experiences, and emotional regulation, offering a roadmap for the advancement and refinement of VR technology in the domain of emotional well-being.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the subjects in this study were primarily college students whose preferences for the content of VR scenarios may be group-specific, limiting the generalizability of the findings; future research should expand the diversity of the participant group to enhance the external validity of the findings. Secondly, existing VR scenes mostly rely on visual and auditory stimuli, while sensory feedback technologies such as touch, smell, and temperature and humidity are not yet mature, and these factors may weaken the presence and emotion regulation effects, and more factors can be further explored in the future to investigate the effects on emotion recovery. Furthermore, public perceptions and understandings of risks are important [66], and subsequent studies could investigate how the VR system might be leveraged to reduce anxiety among the public when confronted with risks. Finally, the dissociation we observed between physiological recovery and self-reported anxiety underscores a measurement limitation: subjective scales may lack sensitivity to subtle design manipulations. Future work should incorporate finer-grained affective reports or ecological momentary assessment to bridge this gap.

Currently, many individuals are struggling with negative emotions that significantly affect their well-being. Our research seeks to identify tools that promote emotional recovery by integrating VR with restorative environments. Additionally, we explore the design elements and mechanisms of VR environments that contribute to emotional recovery. This study has the potential to improve the effectiveness of emotional recovery strategies for individuals facing mental health challenges.

In summary, this study shows that highly realistic VR scenes can evoke an emotional recovery effect comparable to that of their real-world counterparts and that incorporating natural features such as sky, trees, and water further enhances recovery—especially when presented as a window-view inside otherwise urban settings. Presence remains a useful predictor of emotional recovery, but our data reveal that maximal presence is not strictly required for the greatest physiological benefit. Movement-control mode proved critical: contrary to our initial hypothesis, the unnatural (joystick-based) control yielded the largest GSR and BVP recovery, whereas semi-natural and natural controls produced smaller—but still significant—benefits. Sound information also shaped outcomes, but its influence was mainly evident when joystick control was used; spatial-positioning sound in that context amplified recovery compared with surround sound, while sound form had little effect in more embodied control modes. Taken together, these findings highlight that design factors affecting sensorimotor load (locomotion, spatial audio) interact with scene content to determine how quickly the autonomic system returns to baseline. Designers should therefore tailor control schemes and audio rendering to the intended restorative goal rather than assuming that the most “natural” option always produces the strongest benefit.

Acknowledgement: The authors gratefully acknowledge the Human Factors Engineering Experimental Platform at Southwest Forestry University for providing access to experimental facilities and technical support during the supplementary experiments. We also extend our sincere appreciation to Qinling Dai, Jilin Li, Ying Ran, and fellow students for their valuable contributions to the execution of this study.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the General Project of the National Social Science Fund (NSSF) of China in Art (Project No. 23BG133), the Scientific Research Foundation of Wuhan Institute of Technology (Project No. K2023064), the Open Fund of Key Research Base of Humanities and Social Sciences in Hubei Province—Research Center for College Students’ Development and Innovation Education: “VR Healing Intervention for College Students’ Academic Anxiety—VR Healing Based on Intention Dialogue” (Project No. DXS2023017), the Research Project of China Youth and Children Research Society (Project No. 2025B11), and the Major Strategic Consulting Projects of the Chinese Academy of Engineering between Academy and Local Regions (Project No. 2024-DFZD-41).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Hao Fang; methodology, Hongyun Guo; software, Yinchao Chen; validation, Hui Shi; formal analysis, Lin Li; investigation, Yihan Gan; resources, Lin Li; data curation, Yinchao Chen; visualization, Hui Shi; supervision, Hongyun Guo; project administration, Hao Fang; funding acquisition, Hao Fang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data will be provided upon request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: The study was approved by Wuhan University of Technology Ethics committee at the Wuhan University of Technology (IRB number: A2024002). All participants signed the informed consent in this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Penno J, Hetrick S, Christie G. Goals give you hope: an exploration of goal setting in young people experiencing mental health challenges. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2022;24(5):771–81. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2022.020090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Javaid SF, Hashim IJ, Hashim MJ, Stip E, Samad MA, Ahbabi AA. Epidemiology of anxiety disorders: global burden and sociodemographic associations. Middle East Curr Psychiatry. 2023;30(1):44. doi:10.1186/s43045-023-00315-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Shen SH, Hu YK, Ran XG, Zhu ZH, Liu HB, Wang JL, et al. Investigation on psychosomatic status of entry quarantine personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic. Food Sci Technol. 2022;42(09):e57521. doi:10.1590/fst.57521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Chen Y, Chen Z, Wang S, Hang Y, Guo J. How emotion nurtures mentality: the influencing mechanism of social-emotional competency on the mental health of university students. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2024;26(4):303–15. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2024.046863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Nochaiwong S, Ruengorn C, Thavorn K, Hutton B, Awiphan R, Phosuya C, et al. Global prevalence of mental health issues among the general population during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):10173. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-89700-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. World Health Organization. Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2017 [cited 2025 Jun 26]. Available from: https://coilink.org/20.500.12592/thw4fb. [Google Scholar]

7. Baxter AJ, Scott KM, Vos T, Whiteford HA. Global prevalence of anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-regression. Psychol Med. 2013;43(5):897–910. doi:10.1017/S003329171200147X. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Smit F, Willemse G, Koopmanschap M, Onrust S, Cuijpers P, Beekman A. Cost-effectiveness of preventing depression in primary care patients: randomised trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188(4):330–6. doi:10.1192/bjp.188.4.330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Knapp M, McDaid D, Parsonage M. Mental health promotion and mental illness prevention: the economic case [Internet]. London, UK: Department of Health; 2011 [cited 2025 Jul 4]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/mental-health-promotion-and-mental-illness-prevention-the-economic-case. [Google Scholar]

10. Zhu L. Optimization of digital media product interface design based on multidimensional heterogeneous emotion analysis of users. Math Probl Eng. 2022;2022(12):944909. doi:10.1155/2022/6944909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Peters D, Calvo RA, Ryan RM. Designing for motivation, engagement and wellbeing in digital experience. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:797. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00797. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Dehghan B, Saeidimehr S, Sayyah M, Rahim F. The effect of virtual reality on emotional response and symptoms provocation in patients with OCD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2022;12:733584. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.733584. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Zhang Y, Zhang L, Hua H, Jin J, Zhu L, Shu L, et al. Relaxation degree analysis using frontal electroencephalogram under virtual reality relaxation scenes. Front Neurosci. 2021;15:719869. doi:10.3389/fnins.2021.719869. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Veling W, Lestestuiver B, Jongma M, Hoenders HJR, van Driel C. Virtual reality relaxation for patients with a psychiatric disorder: crossover randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(1):e17233. doi:10.2196/17233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Felnhofer A, Kothgassner OD, Schmidt M, Heinzle AK, Beutl L, Hlavacs H, et al. Is virtual reality emotionally arousing? Investigating five emotion inducing virtual park scenarios. Int J Human Computer Stud. 2015;82(4):48–56. doi:10.1016/j.ijhcs.2015.05.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Krijn M, Emmelkamp PMG, Olafsson RP, Biemond R. Virtual reality exposure therapy of anxiety disorders: a review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24(3):259–81. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2004.04.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Montana JI, Matamala-gomez M, Maisto M, Mavrodiev PA, Cavalera CM, Diana B, et al. The benefits of emotion regulation interventions in virtual reality for the improvement of wellbeing in adults and older adults: a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2020;9(2):500. doi:10.3390/jcm9020500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Chiesa A, Serretti A. A systematic review of neurobiological and clinical features of mindfulness meditations. Psychol Med. 2010;40(8):1239–52. doi:10.1017/S0033291709991747. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Saiz-Gonzalez P, McDonough DJ, Liu W, Gao Z. Acute effects of virtual reality exercise on young adults’ blood pressure and feelings. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2023;25(5):711–9. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2023.027530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Bohil CJ, Alicea B, Biocca FA. Virtual reality in neuroscience research and therapy. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12(12):752–62. doi:10.1038/nrn3122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Cooper A, Reimann R, Cronin D, Noessel C. About face: the essentials of interaction design. 4th ed. Indianapolis, IN, USA: John Wiley & Sons; 2014. 720 p. [Google Scholar]

22. Chirico A, Cyberpsychology A. When virtual feels real: comparing emotional responses and presence in virtual and natural environments. Cyberpsychol Behav Social Netw. 2019;22(3):220–6. doi:10.1089/CYBER.2018.0393. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Wang Z, Li Y, An J, Dong W, Li H, Ma H, et al. Effects of restorative environment and presence on anxiety and depression based on interactive virtual reality scenarios. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(13):7878. doi:10.3390/ijerph19137878. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Witmer BG, Singer MJ. Measuring presence in virtual environments: a presence questionnaire. Pres Teleoperato Virtual Environ. 1998;7(3):225–40. doi:10.1162/105474698565686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Faragó Z. Analyzing virtual reality gaming through theoretical frameworks [bachelor’s thesis]. Jyväskylä: Jamk University of Applied Sciences; 2024. [Google Scholar]

26. He Z, Zhu F, Perlin K, Ma X. Manifest the invisible: design for situational awareness of physical environments in virtual reality. arXiv:1809.05837. 2018. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1809.05837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Pavic K, Chaby L, Gricourt T, Vergilino-Perez D. Feeling virtually present makes me happier: the influence of immersion, sense of presence, and video contents on positive emotion induction. Cyberpsychol Behavd Social Netw. 2023;26(4):238–45. doi:10.1089/CYBER.2022.0245. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Pu Z, Cong-Hui L, Guo-Liang Y. An overview of mood-induction methods. Adv Psychol Sci. 2012;20:45. (In Chinese). doi:10.3724/sp.j.1042.2012.00045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Philippot P. Inducing and assessing differentiated emotion-feeling states in the laboratory. Cogn Emot. 1993;7(2):171–93. doi:10.1080/02699939308409183. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Li G, Fang P, Jiang Y. The advance of the temporal dynamics of affective responding. Adv Psychol Sci. 2008;16:290. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

31. Freemantle AWJ, Stafford LD, Wagstaff CRD, Akehurst L. The relationship between olfactory function and emotional contagion. Chemosens Percept. 2022;15(2):49–59. doi:10.1007/s12078-021-09293-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Hunter MR, Gillespie BW, Chen SY-P. Urban nature experiences reduce stress in the context of daily life based on salivary biomarkers. Front Psychol. 2019;10:413490. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00722. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Joye Y, van den Berg A. Is love for green in our genes? A critical analysis of evolutionary assumptions in restorative environments research. Urban For Urban Green. 2011;10(4):261–8. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2011.07.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Ode Å, Fry G, Tveit MS, Messager P, Miller D. Indicators of perceived naturalness as drivers of landscape preference. J Environ Manage. 2009;90(1):375–83. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2007.10.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Frumkin H, Bratman GN, Breslow SJ, Cochran B, Kahn PH, Lawler JJ, et al. Nature contact and human health: a research agenda. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125(7):3. doi:10.1289/EHP1663. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Mao G, Cao Y, Lan X, He Z, Chen ZM, Wang YZ, et al. Therapeutic effect of forest bathing on human hypertension in the elderly. J Cardiol. 2012;60(6):495–502. doi:10.1016/j.jjcc.2012.08.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Bowler DE, Buyung-Ali LM, Knight TM, Pullin AS. A systematic review of evidence for the added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):456. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-456. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Herzog TR, Ouellette P, Rolens JR, Koenigs AM. Houses of worship as restorative environments. Environ Behav. 2010;42(4):395–419. doi:10.1177/0013916508328610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. White MP, Alcock I, Grellier J, Wheeler BW, Hartig T, Warber SL, et al. Spending at least 120 minutes a week in nature is associated with good health and wellbeing. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):7730. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-44097-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Ulrich RS. Aesthetic and affective response to natural environment. In: Altman I, Wohlwill JF, editors. Behavior and the natural environment. Boston, MA, USA: Springer; 1983. p. 85–125. doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-3539-9_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. SU Q, XIN Z-Q. The research on restorative environments: theories, methods and advances. Adv Psychol Sci. 2010;18:177. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

42. Browning MHEM, Mimnaugh KJ, van Riper CJ, Laurent HK, LaValle SM. Can simulated nature support mental health? comparing short, single-doses of 360-degree nature videos in virtual reality with the outdoors. Front Psychol. 2020;10:2667. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02667. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Cummings JJ, Bailenson JN. How immersive is enough? a meta-analysis of the effect of immersive technology on user presence. Media Psychol. 2016;19(2):272–309. doi:10.1080/15213269.2015.1015740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Zhou R, Zhang K. Presence and measuring presencein virtual environment. Adv Psychol Sci. 2004;12:201. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

45. Draper JV, Kaber DB, Usher JM. Telepresence. Hum Factors. 1998;40(3):354–75. doi:10.1518/001872098779591386. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Nabiyouni M, Saktheeswaran A, Bowman DA, Karanth A. Comparing the performance of natural, semi-natural, and non-natural locomotion techniques in virtual reality. In: 2015 IEEE Symposium on 3D User Interfaces (3DUI). Arles, France; 2015. p. 3–10. doi:10.1109/3DUI.2015.7131717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Nishimura A, Unoki M, Kondo K, Ogihara A. Objective evaluation of sound quality for attacks on robust audio watermarking. Proc Meet Acous. 2013;19:030052. doi:10.1121/1.4799661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Chaurasia HK, Majhi M. Sound design for cinematic virtual reality: a state-of-the-art review. In: International Conference of the Indian Society of Ergonomics. Springer; 2021. p. 357–68. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-94277-9_31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Elgendi M, Galli V, Ahmadizadeh C, Menon C. Dataset of psychological scales and physiological signals collected for anxiety assessment using a portable device. Data. 2022;7(9):132. doi:10.3390/data7090132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Newham JJ, Westwood M, Aplin JD, Wittkowski A. State-trait anxiety inventory (STAI) scores during pregnancy following intervention with complementary therapies. J Affect Disord. 2012;142:22–30. doi:10.1016/J.JAD.2012.04.027. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Hedberg AG. Review of state-trait anxiety inventory [review of the book state-Trait anxiety inventory, by C. D. Spielberger, R. L. Gorsuch & R. E. Lushere]. Prof Psychol. 1972;3(4):389–90. doi:10.1037/h0020743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Zhang QY, Lu JM. The moderating effect of preconceptions on emotional contagion: a case study of teaching activities. Acta Psychol Sin. 2015;47(6):797. (In Chinese). doi:10.3724/sp.j.1041.2015.00797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Conroy J, Perryman K, Robinson S, Rana R, Blisard P, Gray M. The coregulatory effects of emotionally focused therapy. J Counsel Develop. 2023;101(1):46–55. doi:10.1002/JCAD.12453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Consoli E. A modular wearable device for vital signs monitoring in heavy industries [master’s thesis]. Torino: Politecnico di Torino; 2020. [Google Scholar]

55. Qiao D, Ayesha AH, Zulkernine F, Jaffar N, Masroor R. ReViSe: remote vital signs measurement using smartphone camera. IEEE Access. 2022;10:131656–70. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3229977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Shin S, Browning MHEM, Dzhambov AM. Window access to nature restores: a virtual reality experiment with greenspace views, sounds, and smells. Ecopsychology. 2022;14(4):253–65. doi:10.1089/ECO.2021.0032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Chen X, Wang B, Zhang B. Far from the madding crowd: the positive effects of nature, theories and applications. Adv Psychol Sci. 2016;24:270. (In Chinese). doi:10.3724/sp.j.1042.2016.00270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Kuhne C, Kecelioglu ED, Maltby S, Hood RJ, Knott B, Ditton E, et al. Direct comparison of virtual reality and 2D delivery on sense of presence, emotional and physiological outcome measures. Front Virtual Real. 2023;4:1211001. doi:10.3389/FRVIR.2023.1211001/BIBTEX. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Mauss IB, McCarter L, Levenson RW, Wilhelm FH, Gross JJ. The tie that binds? Coherence among emotion experience, behavior, and physiology. Emotion. 2005;5(2):175–90. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.5.2.175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Nishiike S, Okazaki S, Watanabe H, Akizuki H, Imai T, Uno A, et al. The effect of visual-vestibulosomatosensory conflict induced by virtual reality on postural stability in humans. J Med Investig. 2013;60(3.4):236–9. doi:10.2152/JMI.60.236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Lee J, Yoo SK. Recognition of negative emotion using long short-term memory with bio-signal feature compression. Sensors. 2020;20(2):573. doi:10.3390/s20020573. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Yin J, Zhu S, MacNaughton P, Allen JG, Spengler JD. Physiological and cognitive performance of exposure to biophilic indoor environment. Build Environ. 2018;132(6):255–62. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2018.01.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Li Z, Xing Y, Pi Y, Jiang M, Zhang L. A novel physiological feature selection method for emotional stress assessment based on emotional state transition. Front Neurosci. 2023;17:1138091. doi:10.3389/fnins.2023.1138091. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Wang Z, Yu Z, Zhao B, Guo B, Chen C, Yu Z. Emotionsense: an adaptive emotion recognition system based on wearable smart devices. ACM Trans Comput Healthc. 2020;1(4):1–17. doi:10.1145/3384394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. McGarry S, Brown A, Gardner M, Plowright C, Skou R, Thompson C. Immersive virtual reality: an effective strategy for reducing stress in young adults. Br J Occup Ther. 2023;86(8):560–7. doi:10.1177/03080226231165644. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Cao Y, Zhang N, Zhang X, Zhang J. Warning dissemination and public response in China’s new warning system: evidence from a strong convective event in Qingdao City. J Risk Res. 2022;25(1):67–91. doi:10.1080/13669877.2021.1905694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools