Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Negotiable Fate Belief and Suicidal Ideation among Left-Behind Children: The Mediating Role of Coping Self-Efficacy and Gender Differences

1 Department of Education, Shiyuan College of Nanning Normal University, Nanning, 530226, China

2 School of Education, Guangxi Science & Technology Normal University, Laibin, 546199, China

* Corresponding Author: Jun Qin. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(8), 1203-1220. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.066297

Received 04 April 2025; Accepted 22 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Objectives: Suicidal ideation is a strong predictor of suicide deaths, which refers to the consideration or desire to give up one’s own life. Left-behind children in rural China are more vulnerable to psychological problems and suicidal ideation compared to their non-left-behind peers. The aim of the current study was to examine two potential protective factors, negotiable fate belief and coping self-efficacy, and to test the mediating role of coping self-efficacy in the relationship between negotiable fate belief and suicidal ideation. We also analyzed gender differences in this mediation model. Methods: A cross-sectional survey was conducted in rural areas of China. A sample of 526 left-behind children (285 males, 54.18%; 241 females, 45.82%; Meanage = 13.29 years, SD = 0.97 years) was recruited to complete the Negotiable Fate Belief Scale, Coping Self-Efficacy Scale, and the Positive and Negative Suicide Ideation Inventory-Negative Scale. We used structural equation modeling to test the mediation model and multigroup analysis to test the moderation effect of gender. Results: Negotiable fate belief is negatively correlated with suicidal ideation (r = −0.13, p < 0.01). Moreover, coping self-efficacy mediates the relationship between negotiable fate belief and suicidal ideation (β = −0.06, 95% confidence interval (CI) [−0.12, −0.02]), accounting for 35.29% of the total effect. Finally, the mediating effect of coping self-efficacy was found to be significant only for female left-behind children (male: 95% CI [−0.09, 0.07]; female: 95% CI [−0.16, −0.01]). For female left-behind children, the mediating effect was complete, with a coefficient of −0.06, accounting for 85.71% of the total effect. Conclusions: The relationship between negotiable fate belief and suicidal ideation among rural left-behind children is mediated by coping self-efficacy, and this mediation effect was moderated by gender. This study provides a theoretical explanation for how cultivating the belief in negotiable fate and coping self-efficacy is effective for reducing suicidal ideation of rural left-behind children.Keywords

Since China’s reform and opening up policy in 1978, industrialization and urbanization have led to a large number of rural workers migrating to urban areas for employment [1]. Most of these workers have a low level of education and earn their income through manual labor. They face long hours, low wages, poor living conditions, and the constraints of the household registration system [2]. As a result, they often have to leave their children behind in rural residences under the care of relatives or friends. This has given rise to a distinct subpopulation, known as left-behind children: minors who have been left alone in their hometown and cared for by someone other than parents for over six months [3].

Left-behind children have been found to suffer from adverse psychological outcomes [4–6]. Meta-analytic findings indicate that the prevalence of suicidal ideation among these children is 18.7% (95% CI: 15.4–21.9) [7]. Notably, they exhibit a significantly higher risk of suicidal ideation compared to their non-left-behind peers, with an odds ratio of 1.26 (95% CI: 1.11–1.43, I2 = 65.3%), indicating a notable disparity that achieves statistical significance [7].

However, not all left-behind children are equally vulnerable to suicidal thoughts. While this phenomenon may be triggered by the lack of parental care and support [8,9], some left-behind children may exhibit resilience and cope well with stress. A possible explanation for this difference is the presence of protective factors that mitigate the adverse effects of parental migration [10,11]. These factors may involve the beliefs that individuals hold about their lives (such as negotiable fate belief) and their capacities to cope with stress (such as coping self-efficacy). In this study, we focus on two factors: negotiable fate belief and coping self-efficacy. We propose that these two factors may have a protective effect against suicidal ideation among left-behind children. We test this hypothesis by examining the mediating role of coping self-efficacy and the moderating role of gender in the relationship between negotiable fate belief and suicidal ideation.

1.1 Negotiable Fate Belief and Suicidal Ideation

Suicidal ideation is the consideration or desire to end one’s own life [12]. It is a strong predictor of suicide deaths [13]. Left-behind children who often face challenges such as lack of parental care, social support, educational opportunities, and personal development [8] may have their basic psychological needs undermined and feel hopeless, worthless, and isolated [14], ultimately increasing the risk of suicidal ideation and behavior. However, some accept their plight, overcome maladaptive responses, and engage in agentic actions when facing environmental challenges and pressures [15], despite experiencing constraints.

The belief in negotiable fate is the acknowledgment of fate’s authority, but still engaging in active coping [16]. This concept is deeply embedded in traditional Chinese thought, reflecting a nuanced approach to perceived control that differs from purely individualistic Western views [16,17]. Negotiable fate belief allows for the acceptance of inherent limitations while still valuing personal effort and adaptation, a balance often reflected in Chinese folk wisdom (e.g., “Man proposes, Heaven disposes”). Further cross-cultural studies support its cultural prevalence, which indicate that negotiable fate belief is more common in China than in America [18]. The finding is consistent with the broader understanding that Chinese culture emphasizes a social orientation where individual needs often conform to interpersonal, familial, and societal demands [19], making negotiable fate belief more prominent among Chinese individuals. This cultural perspective provides an adaptive cognitive framework for maintaining psychological well-being despite perceived restrictions.

Negotiable fate belief is a protective factor that may help overcome suicidal thoughts. According to the model of negotiable fate, the belief in negotiable fate enables individuals to negotiate with fate for control and maintain mental health [16]. As an adaptive belief, negotiable fate belief is psychologically beneficial: it allows negotiable fate subscribers to have an adaptive cognitive style that enables them to accept unexpected outcomes more easily [17], relates to positive emotions [20], increases life satisfaction and well-being [21], and reduces the likelihood of engaging in suicidal behavior [22]. Therefore, we expect that the belief in negotiable fate should protect left-behind children from negative affect and reduce suicidal ideation.

Emerging empirical research has begun to investigate the direct role of negotiable fate belief in relation to suicidal ideation and suicide risk. For instance, studies have shown its moderating effect on the relationship between variables such as social adversity perception [22,24], psychache [22], sleep quality [23], and employment pressure [25] on suicidal ideation among university students. It has also been explored as a moderator in the link between bullying victimization and psychological distress [26], and in the association between mindfulness and psychological distress [27]. However, despite these important contributions, there remains a specific gap in understanding how negotiable fate belief subscribers associate with less suicidal thoughts within the context of rural left-behind children.

1.2 Coping Self-Efficacy, Negotiable Fate Belief and Suicidal Ideation

Coping self-efficacy may mediate the relationship between negotiable fate belief and suicidal ideation. Coping self-efficacy refers to people’s beliefs about their capabilities to cope with stress [28] and their abilities to control events in their lives [29]. It is a specific domain of self-efficacy that reflects the individual’s unique style of dealing with challenges [30]. It also involves the confidence that one can cope successfully, such as the evaluation of one’s coping ability, which is different from the general self-efficacy.

To our knowledge, there is limited existing literature that directly discusses the association between negotiable fate belief and coping self-efficacy. This association may be explained by the transactional theory of stress and coping [31,32]. According to this theory, people continuously appraise the stimuli in their environment. The appraisal process is influenced by both beliefs and situational factors, which determine whether the stimuli are perceived as harm/loss, threat, or challenge [32,33]. Coping self-efficacy is a form of coping appraisal that refers to the evaluation of one’s ability and resources to cope with a stressful situation [32]. For left-behind children who hold the belief in negotiable fate, it may play a role in their coping appraisal process. The negotiable fate belief provides a positive interpretation of their situation as a temporary and manageable challenge [16], which enables them to use active coping strategies and thus increase the likelihood of successful coping efforts [34]. Therefore, the negotiable fate belief may also increase their coping self-efficacy by providing them with positive feedback or encouragement about their performance or potential.

Coping self-efficacy is an intra-personal factor that protects against suicidal ideation [35]. According to the cognitive model of suicidal behavior [36], the activation of a person’s suicide schema may increase the likelihood of experiencing state hopelessness, which may induce suicidal ideation as a means of escaping intolerable pain. Coping self-efficacy represents one’s confidence and perceived ability to cope when facing life challenges [37]. When encountering a stressful life event, individuals who have high coping self-efficacy are able to use adaptive coping strategies, which are helpful in reducing emotional distress [38,39] and enhancing a sense of hope and control. Thus, increased coping self-efficacy can be related to decreased suicidal thoughts by reducing the likelihood of activating the suicide schema and enhancing the ability to cope with stressful life events, emotions, and adaptive ways.

Consistent with the theoretical perspective, existing empirical studies have supported the protective role of coping self-efficacy against suicidal ideation. For example, research on individuals with multiple sclerosis found that higher coping self-efficacy dimensions were significantly associated with lower suicidal ideation [40]. Similarly, a study on veterans utilizing a mobile application demonstrated that increased coping self-efficacy was associated with a reduction in suicidal ideation severity [35]. While these studies highlighted the general importance of coping self-efficacy in specific clinical or general adolescent populations, its protective role within the unique population of vulnerable left-behind children remains less explored.

1.3 The Moderating Role of Gender

Gender may be an important moderating variable in the hypothesized model of coping self-efficacy mediating the relationship between negotiable fate belief and suicidal ideation. There is some evidence that the prevalence of suicidal ideation in adolescence is influenced by gender, with suicidal ideation being more common among females than males [13]. For example, a meta-analytic review of 16 articles on left-behind children found that female left-behind children had a higher risk of suicidal ideation than male left-behind children [7].

Regarding coping self-efficacy, gender differences have been explored extensively by prior studies, but the results are mixed. Some studies have suggested that women have higher coping self-efficacy than men [41], while others have indicated the opposite [42]. However, the studies that investigated gender as a moderator of coping self-efficacy did not find any significant differences between men and women [43,44]. These mixed findings in coping self-efficacy can be illuminated by considering how gender role socialization affects coping styles. Socialization theory posits that individuals are taught gender-specific coping patterns from an early age [45]. According to this theory, girls are commonly taught to express their emotions more openly and to adopt more passive or accommodative strategies. Conversely, boys are taught to approach situations in a more active, problem-focused, and instrumental manner [46]. This implies that gender differences in coping strategy use would be found across various situations and social roles, which contributes to the varied outcomes observed in studies on gender differences in coping.

Regarding negotiable fate belief, previous studies have not examined gender differences and have only treated gender as a control variable. However, we can draw some reasonable inferences from the literature on secondary control and culture. Secondary control and negotiable fate belief are similar in that they both involve adjusting oneself to the environment or the situation, rather than changing the environment or the situation itself [18]. According to cultural psychology, secondary control is more prevalent and adaptive in collectivistic cultures, such as China, than in individualistic cultures, such as the United States [47]. Women used secondary control strategies more often and more diversely than men, and secondary control can be beneficial for them [48]. We propose that gender may also influence the endorsement of negotiable fate belief, depending on the cultural and situational factors that shape gender roles and expectations.

In this paper, we aim to explore whether gender moderates the mediating effect of coping self-efficacy on the relationship between negotiable fate belief and suicidal ideation among left-behind children in rural China.

In the current study, we examine the mediating role of coping self-efficacy in the association between negotiable fate belief and suicidal ideation among left-behind children. Based on the aforementioned literature, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Left-behind children who believe in a negotiable fate will be associated with less suicidal ideation.

Hypothesis 2: Coping self-efficacy will mediate the association between negotiable fate belief and suicidal ideation among left-behind children.

Hypothesis 3: The mediation model will differ between male left-behind children and female left-behind children.

We conducted a cross-sectional survey in July 2023 in rural areas of Hunan Province and Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China. Prior to data collection, a priori power analysis was conducted using G*Power 3.1 to determine the adequate sample size for detecting the hypothesized mediation effects [49]. The results showed that an estimated minimum sample size of 68 was required to achieve 80% power for detecting a medium effect size (f2 = 0.15) at a significance level of α = 0.05. We randomly sampled six middle schools from the school roster and used a cluster-sampling method to select the classes as the sampling units. From 1200 invited middle school students, 1142 completed the questionnaires. We excluded the questionnaires that had irregular response patterns (such as S-shaped responses) and retained 1098 valid data, resulting in an effective response rate of 91.5%. Among the participants, 526 students met the criteria for being left-behind children: (1) residing in a rural area at the time of the survey; (2) having at least one parent who was a migrant worker; and (3) having parents who migrated for work for more than 6 months.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of School of Education Science at Guangxi Science & Technology Normal University (Reg. No. JK2023002), following the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. The relevant school boards, principals, and teachers also approved the study. We trained postgraduate students with a psychology background to conduct data collection. They administered a set of validated questionnaires that measured various aspects of mental health. We reviewed and approved the research protocol with each school before the data collection. We informed the participants and their parents about the purpose and procedures of the study and obtained their written informed consent and assent to participate. We also assured them that their participation was voluntary and confidential, and that they could opt out or withdraw at any time. The participants completed a set of paper-and-pencil questionnaires in about 20 min during school hours, under the supervision of the researchers, who collected the questionnaires right after they were done. Since some of the survey items could cause psychological distress, we offered group psychological counseling sessions and free local mental health hotlines to the participants and their parents on the consent form.

Using the negotiable fate view scale developed by Chaturvedi et al., 2009 [15], Chang adapted and revised it to a Chinese version with six items [20]. The scale included items such as “When fate does not give you the most favorable situations, you need to make the best of the situations you given” and “Through my actions, I can negotiate with fate and materialize my dreams”. The participants rated their agreement with each item on a 6-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). A higher average score indicated a stronger belief in negotiable fate. In Chang’s study, the scale demonstrated acceptable internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.77. The scale had a Cronbach’s α of 0.71 for the current sample.

Coping self-efficacy was assessed with the coping self-efficacy scale developed by Tone 2005 [50]. The scale consisted of 17 items that reflected three aspects of coping efficacy: cognitive level, self-confidence degree, and competence perception. An example item is “I have the confidence to overcome any difficulties”. The participants indicated how much each item described them on a 4-point scale, from 1 (not at all like me) to 4 (totally like me). A higher average score signifies a higher belief in their coping efficacy. The Cronbach’s α coefficient is 0.86, split-half reliability is 0.79, and it has been widely used in China [44,51]. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for the current sample was 0.91.

Suicidal ideation was assessed using the Chinese version of the negative suicidal ideation scale revised by Wang et al. 2011 [52], derived from the positive and negative suicidal ideation scale (PANSI) developed by Osman et al. 1988 [53]. The revised PANSI-Negative scale consists of 8 items that capture negative thoughts about suicide, with higher scores on the PANSI–Negative scale suggesting a higher frequency of suicidal ideation. Participants indicated the frequency of each type of thought on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (none of the time) to 5 (most of the time). The Chinese version of the negative suicidal ideation scale was revised for 850 middle school students with a Cronbach’s α of 0.95. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for the current sample was 0.93.

We applied the mean imputation method to address the issue of missing values, which affected less than 3% of the data. Mean imputation involves replacing the missing scores with the mean score of the available data [54]. This method is appropriate when the proportion of missing data is negligible, as it produces similar results to other missing data processing methods. We followed this conventional and effective method that has been used by previous studies [55] for handling missing data.

We performed the following data analysis to test our hypotheses. First, we used SPSS software, version 26.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA), to conduct descriptive statistical analysis and correlation analysis of the variables in our study. Additionally, a student’s t-test was conducted to examine the relative prevalence of suicidal ideation among male and female participants.

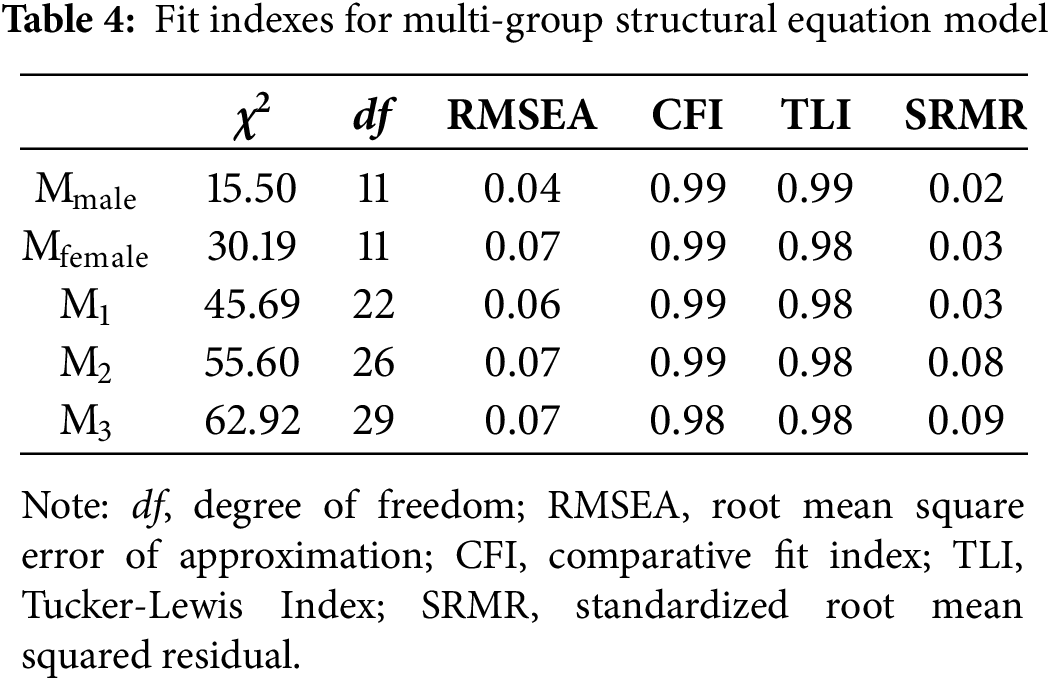

Next, we employed Mplus Version 8.3 statistical software (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA, USA) [56] to perform structural equation modeling (SEM), which is a statistical technique that allows us to test the relationships among latent variables that are not directly observable [57]. We used SEM to test a mediation model in which negotiable fate belief predicted left-behind children’s suicidal ideation both directly and indirectly through their coping self-efficacy. Prior to modeling, negotiable fate belief (6 items) was divided into two random parcels (3 items each), and suicidal ideation (8 items) was divided into two random parcels (4 items each). This parceling strategy was employed to clarify relationships among constructs [58]. We assessed the SEM model on the basis of the fit indices of the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI); Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR), and χ2. The model is acceptable when the model fitting indices meet the following criteria: CFI and TLI > 0.90, RMSEA < 0.08 [59], SRMR < 0.10 [60]. We examined the total, indirect, and direct effects of each predictor variable on suicidal ideation using bias-corrected bootstrapped estimates [61,62] based on 5000 bootstrapped samples. If the 95% bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals do not contain zero, it indicates statistical significance.

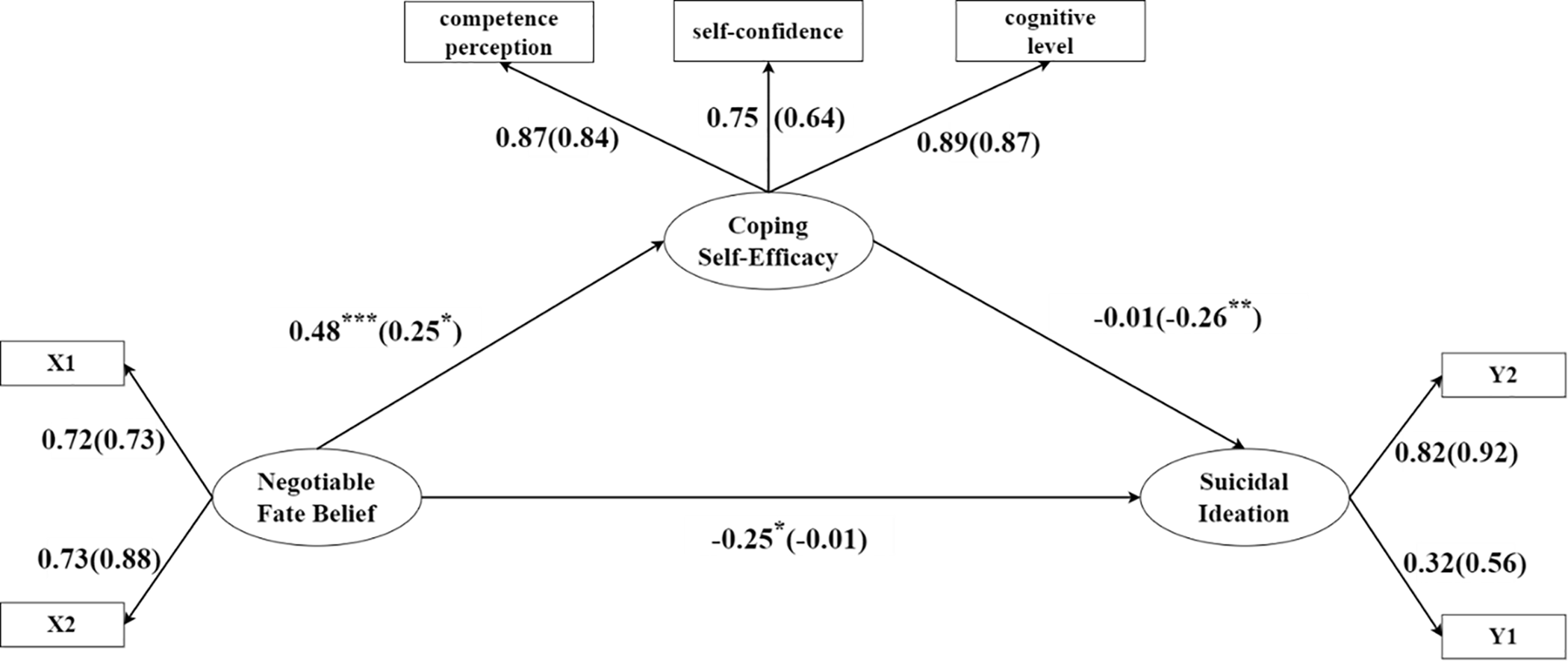

Finally, to examine whether gender moderated the mediation model, we conducted a multi-group analysis [63]. As a preliminary step, we tested the mediator (coping self-efficacy) and outcome variable (suicidal ideation) for male and female left-behind children groups separately to justify the multi-group analysis. We then constructed a series of nested models: an unconstrained model (M1) where all parameters were freely estimated for each group, a Model 2 (M2) testing the invariance of factor loadings across groups (based on M1), and a Model 3 (M3) assessing structural path invariance with equal path coefficients (based on M2). We also utilized the bootstrap method (with 5000 resamples) to test the mediating effect of coping self-efficacy within each gender group.

We assessed the potential common method variance by performing Harman single factor analysis in this study, as we used self-report measures for multiple variables [64]. In the exploratory factor analysis, the first factor explained only 26.02% of the variance, which was lower than the recognized 40% threshold, indicating that the common method bias was not severe.

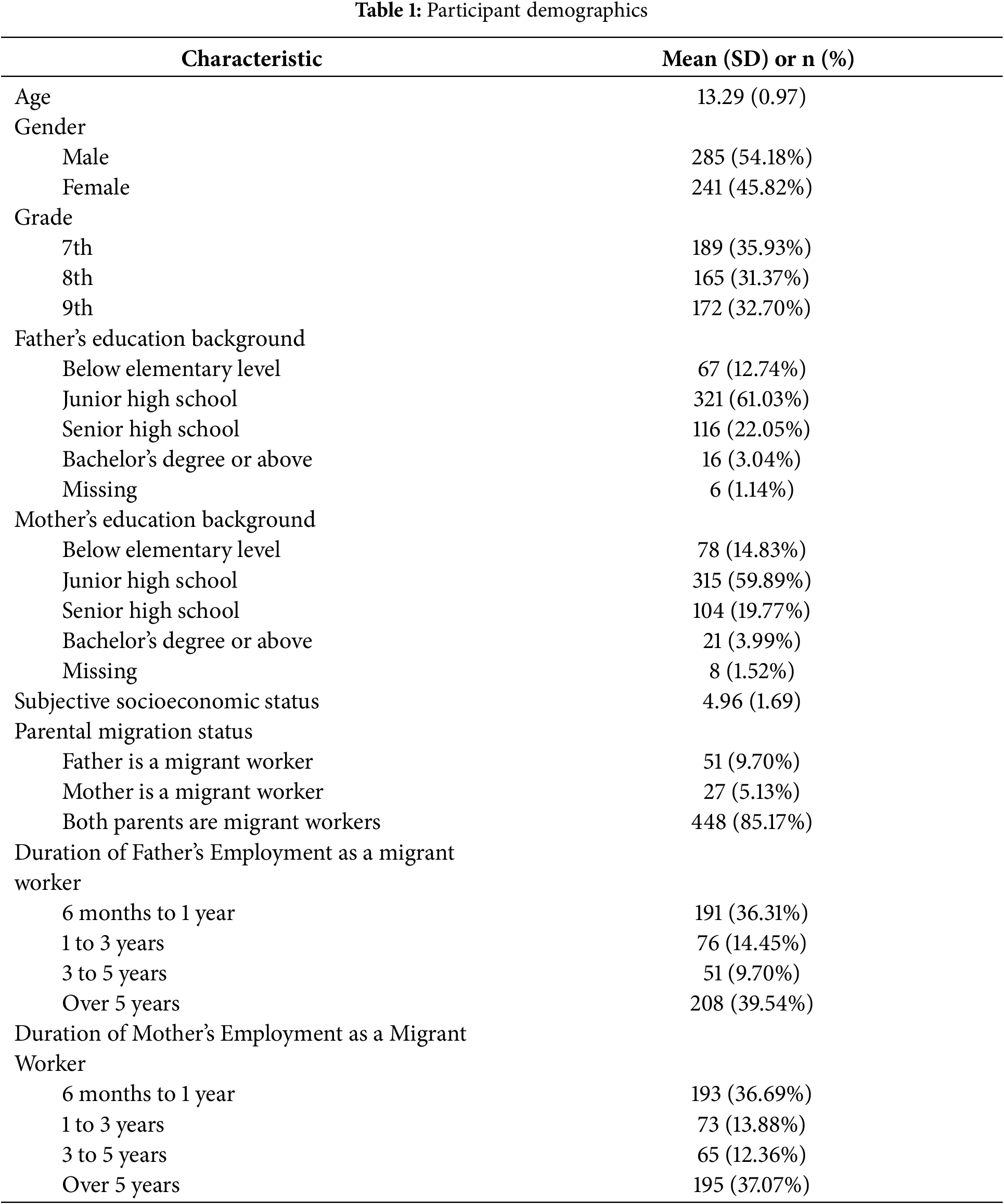

A total of 1098 valid questionnaires were retained for analysis, and the effective response rate is 91.5%. The mean age of the participants was 13.29 years (SD = 0.97). The sample consisted of 45.82% female students and 54.18% male students. Among the participants, 526 students met the criteria for being left-behind children. Participants’ demographic characteristics, including age, gender, grade, parental educational background, subjective socioeconomic status, and duration of parents’ employment as migrant workers, are shown in Table 1.

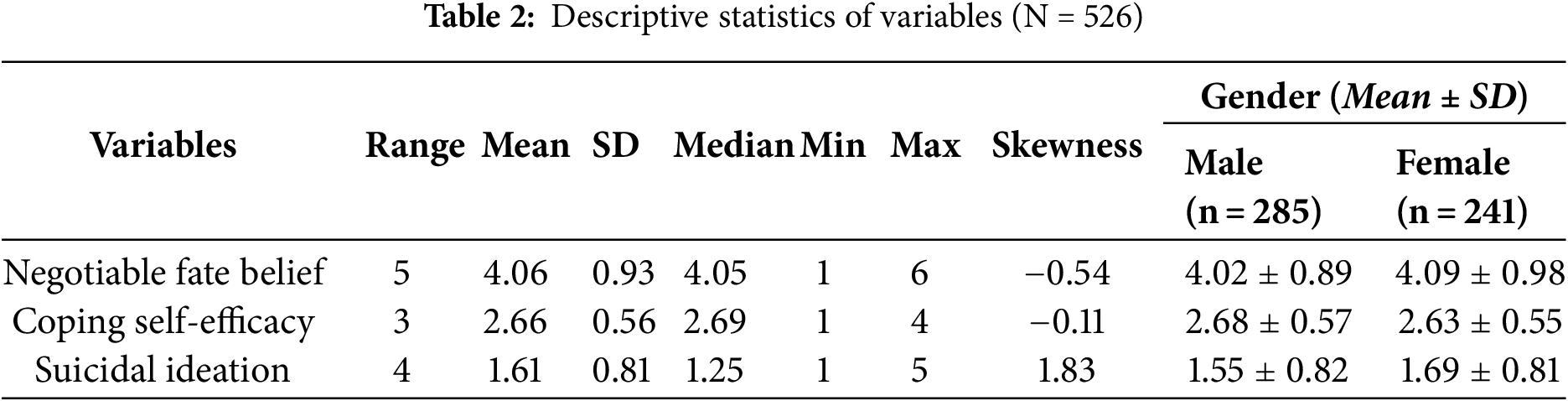

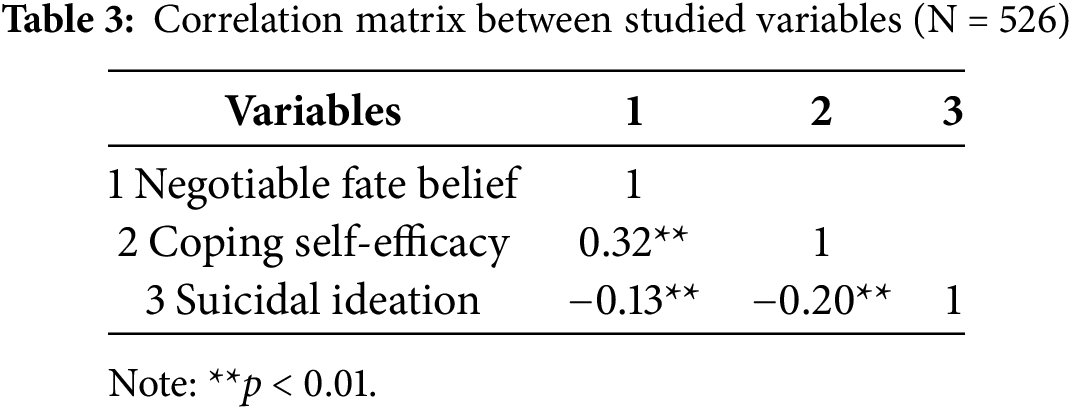

3.2 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Descriptive statistics of the variables are shown in Table 2. Negotiable fate belief had a mean of 4.06 and a standard deviation of 0.93, coping self-efficacy had a mean of 2.26 and a standard deviation of 0.56, and suicidal ideation had a mean of 1.61 and a standard deviation of 0.81.

The correlation analysis (see Table 3) revealed that negotiable fate belief was positively correlated with coping self-efficacy (r = 0.32, p < 0.01) and negatively correlated with suicidal ideation (r = −0.13, p < 0.01), while coping self-efficacy was negatively correlated with suicidal ideation (r = −0.20, p < 0.01).

To assess whether coping self-efficacy mediated the effect of negotiable fate belief on suicidal ideation, we first constructed a non-mediation model. The results indicated that the model fit well (χ2/df = 1.19, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.02, SRMR = 0.004). Negotiable fate belief significantly negatively predicted suicidal ideation (β = −0.17, SE = 0.05, t = −3.14, p < 0.001).

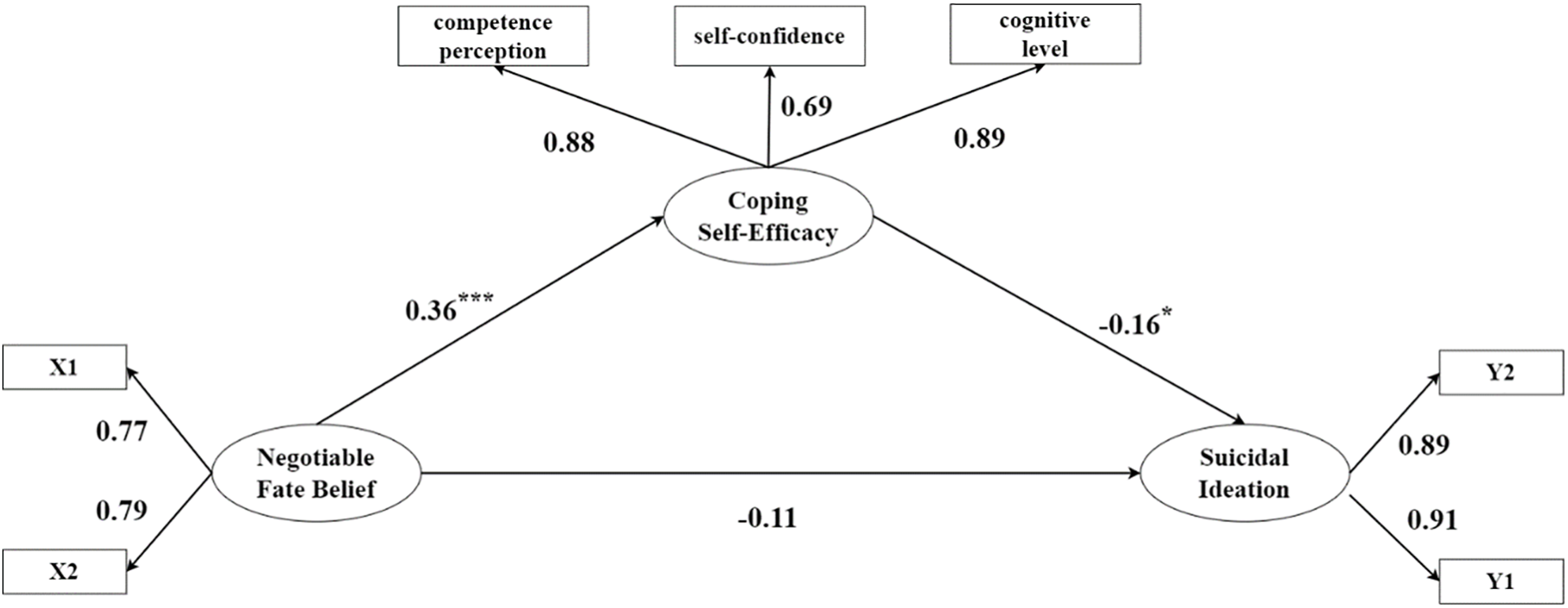

Subsequently, we added coping self-efficacy to construct a mediation model. We calculated confidence intervals for the mediation effects using the percentile bootstrap (bias correction) method with 5000 resamples. The results indicated that the model fit well (χ2/df = 2.37, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.02). Fig. 1 shows the mediation model with standardized coefficients.

Figure 1: Mediating model of coping self-efficacy. Note: The constructs X1 and X2 represent two parcels of a 6-item negotiable fate belief scale, each containing 3 items. Similarly, Y1 and Y2 are two parcels of an 8-item Positive and Negative Suicide Ideation Inventory-Negative Scale, each containing 4 items. Items were randomly assigned to subsets. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001

As shown in Fig. 1, negotiable fate belief significantly positively predicted coping self-efficacy (β = 0.36, SE = 0.06, t = 5.67, p < 0.001). However, it did not significantly predict suicidal ideation (β = −0.11, SE = 0.07, t = −1.61, p > 0.05). Coping self-efficacy significantly negatively predicted suicidal ideation (β = −0.16, SE = 0.06, t = −2.47, p < 0.05). The standardized direct effect of negotiable fate belief on suicidal ideation was −0.11 [95% CI = −0.24, 0.03], the standardized indirect effect through coping self-efficacy was −0.06 [95% CI = −0.12, −0.02], and the standardized total effect was −0.17 [95% CI = −0.30, −0.02]. The ratio of indirect to total effect was 35.29%, indicating that coping self-efficacy mediated the relationship between negotiable fate belief and suicidal ideation.

3.4 Multi-Group Analysis by Gender

Prior to conducting the multi-group analysis, Student’s t-tests were performed to compare the means of the negotiable fate belief, coping self-efficacy, and suicidal ideation among male and female participants. The results indicated a significant difference (t = −2.10, p < 0.05, Cohen’s d = −0.18), with female left-behind children exhibiting higher levels of suicidal ideation compared to male left-behind children. However, no significant gender differences were found for negotiable fate belief (t = −0.95, p = 0.34) or coping self-efficacy (t = 0.99, p = 0.32).

To examine whether gender moderated the mediation model, a multi-group analysis was conducted. Preliminary separate analyses of the mediator (coping self-efficacy) and outcome variable (suicidal ideation) for male and female left-behind children groups (detailed in Table 4) supported the appropriateness of multi-group analysis. We constructed a series of nested models to compare the mediation model across genders. Table 4 presents the fit indices of each model. Model 1 (M1), the unconstrained model, showed good fit. Comparison between M1 and Model 2 (M2, testing invariance of factor loadings) revealed a significant difference (Δχ2 = 9.91, Δdf = 4, p < 0.05), indicating that factor loadings were not invariant across genders. No significant difference was found between M2 and Model 3 (M3, testing equal path coefficients) (Δχ2 = 7.32, Δdf = 3, p > 0.05). However, a significant difference was observed between M1 and M3 (Δχ2 = 17.23, Δdf = 7, p < 0.05). The results of model comparison indicated that M1 was the best-fitting model, suggesting that the mediation model was significantly moderated by gender.

We further analyzed the path coefficients of the mediation model for male and female left-behind children (see Fig. 2). The results indicated that negotiable fate belief significantly predicted coping self-efficacy for both genders (male: β = 0.48, t = 6.07, p < 0.001; female: β = 0.25, t = 2.43, p < 0.05). Coping self-efficacy significantly predicted suicidal ideation for female students (β = −0.26, t = −2.97, p < 0.01), but did not significantly predict suicidal ideation for male students (β = −0.01, t = −0.13, p > 0.05). However, negotiable fate belief significantly predicted suicidal ideation only for male left-behind children (β = −0.25, t = −2.28, p < 0.05), but not for female left-behind children (β = −0.01, t = −0.14, p > 0.05). Utilizing the bootstrap method (with 5000 resamples), we tested the mediating effect of coping self-efficacy and found it to be significant only for female left-behind children (male: 95% CI [−0.09, 0.07]; female: 95% CI [−0.16, −0.01]). Coping self-efficacy completely mediated the relationship between negotiable fate and suicidal ideation in female left-behind children, with a coefficient of −0.06 (accounting for 85.71% of the total effect).

Figure 2: Mediating models of coping self-efficacy in different gender groups. Note: coefficients inside parentheses are for female left-behind children. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

The current study contributes to our understanding of the predictors of suicidal ideation among left-behind children in rural areas: we tested the mediating role of coping self-efficacy in the relationship between negotiable fate belief and suicidal ideation from a gender perspective.

4.1 The Relationship between Negotiable Fate Belief and Suicidal Ideation

We found that negotiable fate belief negatively predicted suicidal ideation among left-behind children in rural China. This means that left-behind children who believed that they could change their future to some extent within the limits of fate had lower levels of suicidal thoughts than those who completely believed in fate. The finding is consistent with the model of negotiable fate [17], which suggests that individuals who hold this belief may be able to cope with unexpected outcomes and preserve mental well-being. Negotiable fate subscribers firmly believe that “When Heaven is about to confer a great responsibility on man, it will first fill his heart with suffering”. For left-behind children with a stronger belief in negotiable fate, this may reduce their sense of despair and helplessness. Conversely, left-behind children with a low belief in negotiable fate may be more vulnerable to feelings of hopelessness and the perception that adversity is uncontrollable. This could potentially increase their susceptibility to adverse mental health outcomes, including suicidal ideation [65]. In summary, our study suggests that negotiable fate belief is negatively associated with suicidal ideation among left-behind children, thus supporting Hypothesis 1.

4.2 The Mediating Role of Coping Self-Efficacy

Consistent with our Hypothesis 2, coping self-efficacy played a key role in linking negotiable fate belief and suicidal ideation. The mediation effect was significant and accounted for 35.29% of the total effect. This suggests that negotiable fate belief reduced rural left-behind children’s suicidal thoughts indirectly through their belief in their ability to cope with stress.

Here are possible explanations for this mediation effect based on the existing literature. First, negotiable fate belief may enhance coping appraisal by determining how left-behind children perceive their situation. According to the transactional theory of stress and coping [32], coping appraisal is the evaluation of one’s resources and options for dealing with a stressful event. Left-behind children who believe that fate is negotiable acknowledge the limitations of fate, but they respond actively and persist in their set goals despite the constraints of fate and the negative feedback they receive. This may be related to the Chinese traditional style of thinking [34], which is more likely to endorse the self-increment theory (i.e., individual ability development is malleable) than Westerners (such as Americans). Therefore, negotiable fate belief may increase left-behind children’s confidence in their coping abilities.

Second, coping self-efficacy may reduce suicidal ideation by preventing the activation of suicidal schema. Consistent with previous research results [35], we found that coping self-efficacy was a significant negative predictor of suicidal ideation. This indicates that left-behind children with higher coping self-efficacy had lower levels of suicidal thoughts. In line with the cognitive model of suicidal behavior [36], the higher confidence in one’s ability to solve problems in life stress prevents the activation of suicidal thoughts. Left-behind children with high coping self-efficacy have the confidence to face all kinds of challenges and maintain a good state of adaptation in the face of adversity. They will not easily resort to more extreme ways to avoid adverse events.

Our study suggests that negotiable fate belief and coping self-efficacy offer a new theoretical perspective for explaining the mechanism of suicidal ideation. From this perspective, left-behind children who believe in negotiable fate pay more attention to giving full play to their subjective initiative. When the outcome of an event does not live up to expectations, they will not dwell on it or become obsessed with it, thus causing the aggravation of rumination. Instead, they respond positively with all available resources and maintain a positive self-view in the face of limitations until they achieve their goal, so as to experience more meaning of life [34], and suicidal thoughts will diminish accordingly.

4.3 The Moderating Role of Gender

The current study supports Hypothesis 3, that gender would moderate the effect of negotiable fate belief on suicidal ideation among left-behind children. Our findings supported this hypothesis, indicating that gender differences indeed moderated the mediation model. Specifically, for male left-behind children, negotiable fate belief was directly associated with suicidal ideation. However, contrary to our expectations, coping self-efficacy did not significantly mediate this relationship. In contrast, for female left-behind children, the relationship between negotiable fate belief and suicidal ideation was significantly mediated by coping self-efficacy, suggesting that this coping mechanism plays a more pivotal role in influencing suicidal thoughts among females.

One possible explanation for the lack of a significant mediating effect of coping self-efficacy among males may relate to the socialization of gender roles. Boys, often encouraged to be independent [66], may cultivate coping strategies that focus on problem-solving and autonomy. These strategies, reflecting their independent upbringing, might not be thoroughly evaluated by traditional measures of coping self-efficacy. Additionally, within rural Chinese culture, where sons are traditionally raised for old-age support and surname continuation [67], boys may receive more direct support from their parents. This support, which can include financial assistance or encouragement for future endeavors, may lessen the necessity for boys to develop self-reliant coping strategies, consequently diminishing the role of coping self-efficacy in mitigating suicidal ideation.

Another possible explanation could be related to gender bias in parental attitudes. In traditional Chinese culture, especially in rural left-behind families with limited economic resources, there is a tendency to invest more in boys, who are expected to become ‘masters’ and elevate the family’s social status. Girls, often considered ‘married daughters’, may not receive the same level of support, leading them to rely more on their own coping self-efficacy to deal with life’s challenges.

These factors may explain why coping self-efficacy did not significantly mediate the effect of negotiable fate belief on suicidal ideation for male left-behind children, while it completely mediated this effect for female left-behind children. However, these explanations are speculative and require further investigation through studies with more rigorous designs and measures.

Our findings provide robust support for a moderated mediation model in understanding suicidal ideation among left-behind children. Consistent with our comprehensive theoretical framework, negotiable fate belief acts as a significant predictor of suicidal ideation, with coping self-efficacy serving as a crucial explanatory mechanism in this relationship. Importantly, our results reveal that the proposed mediation pathway is not universally applicable but is significantly moderated by gender, demonstrating distinct mechanisms at play for male and female left-behind children. This integrated model not only contributes to the theoretical discourse in this field but also has significant implications for the prevention and intervention strategies targeting adolescent suicide.

Given the influence of negotiable fate belief, which emphasizes the anticipated efficacy of an individual’s capacity to optimize benefits and mitigate losses within the constraints and opportunities presented by fate, interventions such as growth mindset programs [68] can be implemented. These programs, designed to enhance the perceived value of effort, can be effectively embedded within existing school psychology programs or mental health initiatives. They advocate that educators should assist left-behind children in comprehending that while life encompasses external constraints, they should nonetheless not be deterred by setbacks, as they can still strive towards their goals through their own endeavors. It is proposed that educators undergo training to encourage students to appreciate the significance and value of effort, reorient attributions to controllable effort, and persistently cultivate a mindset of maximizing the circumstances dictated by fate.

In light of the findings regarding the mediating role of coping self-efficacy, interventions to enhance coping self-efficacy are recommended. Coping self-efficacy beliefs can be strengthened by providing individuals with opportunities to try new behaviors (mastery experiences), learn from others (vicarious experiences), receive verbal persuasion about their capabilities, and learn to control or reinterpret their anxiety before attempting new tasks (affective and somatic states) [29].

Interventions fostering mastery experiences, which represent the most influential source of efficacy information [29], could be disseminated by educational institutions in the form of printed or digital interventions and self-help guides [69]. These resources, such as brochures or online textual interventions encompassing active coping strategies, aim to stimulate experiential learning among left-behind children. Alternatively, face-to-face programs, either through individual sessions or group counseling facilitated by a psychological educator, could gradually introduce active coping behavior.

Building upon the concept of coping self-efficacy, coping effectiveness training has demonstrated significant potential in reducing stress and enhancing coping self-efficacy [70]. This training, often conducted within small group contexts, emphasizes the accurate assessment of life stressors, the judicious application of problem and emotion-focused coping strategies, and the maximization of social supports to alleviate stress and enhance coping efforts [70]. Furthermore, the study found a complete mediating effect for female left-behind children. This suggests that educators should pay particular attention to girls and develop programs specifically designed to help girls acquire coping skills. To ensure the effectiveness and optimize future iterations of these interventions, rigorous evaluation methods, including pre- and post-intervention assessments of negotiable fate belief, coping self-efficacy, and suicidal ideation, as well as process evaluations, are essential.

In terms of policy implications, it is crucial to advocate for policies that enhance access to mental health services in rural areas. This includes providing comprehensive training for educators and school counselors to effectively recognize and respond to signs of distress in left-behind children. Additionally, policies should be in place to support and encourage research into the specific mental health needs of this population. These measures could significantly contribute to improving the psychological well-being of left-behind children.

4.5 Limitations and Future Direction

In summary, our study suggests that negotiable fate belief is a predictor of suicidal ideation among left-behind children in rural areas. This finding has important implications for suicide prevention and intervention programs for this vulnerable population. We recommend that such programs should aim to enhance the belief in negotiable fate among left-behind children, as well as their coping self-efficacy and other psychological resources. However, our study also has some limitations that should be addressed in future research.

One limitation is that our study relied on cross-sectional data analyses, which limited our ability to make causal inferences. Future studies should use longitudinal or experimental designs to establish the causal relationships among negotiable fate belief, coping self-efficacy, and suicidal ideation.

Second, our study only included participants from rural China, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other cultural contexts. Previous studies have suggested that national cultures may influence the believe in negotiable fate [16]. Future research could compare participants from different countries to examine the cross-cultural variations in the effects of negotiable fate belief on suicidal ideation.

A final limitation is that our study did not include other relevant variables that may affect suicidal ideation among left-behind children, such as parental attachment [8], teacher-student relationship [71,72], peer support, academic stress, or mental health problems [1]. Future studies should explore the role of these variables in the model of negotiable fate belief and suicidal ideation, and test whether they mediate or moderate the effects of negotiable fate belief on suicidal ideation.

In the present research, we gained a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanism of negotiable fate belief and suicidal ideation among left-behind children. We proposed that coping self-efficacy mediates the relationship between negotiable fate belief and suicidal ideation, and that this mediation effect varies by gender. Our findings confirmed our hypotheses, revealing that coping self-efficacy acts as a significant explanatory mechanism in the relationship between negotiable fate belief and suicidal ideation. Importantly, this mediation effect was found to be significant only among female left-behind children. These results advance our knowledge of how negotiable fate belief shapes suicidal thoughts among this at-risk group and imply that interventions should target coping self-efficacy among left-behind children.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank all participants for the time that they kindly dedicated.

Funding Statement: This work was funded by the 2023 Laibin City Philosophy and Social Science Research Project (No. 2023LBZS035), 2024 Guangxi Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program Project (No. S202411546046X), and 2025 Research Project of Guangxi Science & Technology Normal University (No. GXKS2025YB020).

Author Contributions: Xiao Hu and Biao Li contributed equally to this work. Xiao Hu collected the data and wrote the original draft of the manuscript. Biao Li reviewed and edited the manuscript and performed statistical analysis. Jun Qin supervised the study and reviewed the final manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data used and analyzed in this study are not publicly accessible because of ethical limitations. The corresponding author can provide the dataset that supports the findings upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committees of School of Education Science at Guangxi Science & Technology Normal University, following the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki (Reg. No. JK2023002). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and their parents prior to their participation in the study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| PANSI | Positive and Negative Suicide Ideation Inventory |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| TLI | Tucker-Lewis Index |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| M1 | Model 1 |

| M2 | Model 2 |

| M3 | Model 3 |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| SE | Standard Error |

References

1. Zhou C, Sylvia S, Zhang L, Luo R, Yi H, Liu C, et al. China’s left-behind children: impact of parental migration on health, nutrition, and educational outcomes. Health Aff. 2015;34(11):1964–71. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Jingzhong Y, Lu P. Differentiated childhoods: impacts of rural labor migration on left-behind children in China. J Peasant Stud. 2011;38(2):355–77. doi:10.1080/03066150.2011.559012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Gao Y, Li LP, Kim JH, Congdon N, Lau J, Griffiths S. The impact of parental migration on health status and health behaviours among left behind adolescent school children in China. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):56. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Yang G. To assess and compare the mental health of current-left-behind children, previous-left-behind children with never-left-behind children. Front Public Health. 2022;10:997716. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.997716. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Lin K, Mak L, Cai J, Jiang S, Fayyaz N, Broadley S, et al. Urbanisation and mental health in left-behind children: systematic review and meta-analysis using resilience framework. Pediatr Res. 2025;103:1–20. doi:10.1038/s41390-025-03894-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Liu C, Xu Y, Sun H, Yuan Y, Lu J, Jiang J, et al. Associations between left-behind children’s characteristics and psychological symptoms: a cross-sectional study from China. BMC Psychiatry. 2024;24(1):510. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-3503814/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Qu G, Shu L, Zhang J, Wu Y, Ma S, Han T, et al. Suicide ideation, suicide plan, and suicide attempt among left-behind children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2021;51(3):515–27. doi:10.1111/sltb.12731. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Wen M, Lin D. Child development in rural China: children left behind by their migrant parents and children of nonmigrant families. Child Dev. 2012;83(1):120–36. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01698.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Liu Y, Wang L, Zhao J. Developmental trajectory of depressive symptoms among left-behind adolescents: the effects of parent-adolescent separation and parent-adolescent cohesion. J Adolesc. 2024;96(5):1102–15. doi:10.1002/jad.12320. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Wang X, Lu Z, Dong C. Suicide resilience: a concept analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:984922. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

11. Xiong J, Xie W, Zhang T. Cumulative risk and mental health of left-behind children in China: a moderated mediation model. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(2):1105. doi:10.3390/ijerph20021105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Cha CB, Franz PJM, Guzmán E, Glenn CR, Kleiman EM, Nock MK. Annual research review: suicide among youth—epidemiology, (potential) etiology, and treatment. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;59(4):460–82. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12831. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Klonsky ED, May AM, Saffer BY. Suicide, suicide attempts, and suicidal ideation. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2016;12(1):307–30. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Hill RM, Pettit JW. The role of autonomy needs in suicidal ideation: integrating the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide and self-determination theory. Arch Suicide Res. 2013;17(3):288–301. doi:10.1080/13811118.2013.777001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Chaturvedi A, Chiu CY, Viswanathan M. Literacy, negotiable fate, and thinking style among low income women in India. J Cross-Cult Psychol. 2009;40(5):880–93. doi:10.1177/0022022109339391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Au EWM, Chiu CY, Zhang ZX, Mallorie L, Chaturvedi A, Viswanathan M, et al. Negotiable fate: social ecological foundation and psychological functions. J Cross-Cult Psychol. 2012;43(6):931–42. doi:10.1177/0022022111421632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Au EWM, Chiu CY, Chaturvedi A, Mallorie L, Viswanathan M, Zhang ZX, et al. Maintaining faith in agency under immutable constraints: cognitive consequences of believing in negotiable fate. Int J Psychol. 2011;46(6):463–74. doi:10.1080/00207594.2011.578138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Au EWM. Negotiable fate: the belief, potential antecedents and possible consequences [dissertation]. Urbana, IL, USA: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; 2008. [Google Scholar]

19. Chui RCF, Li H, Chan CK, Siu NYF, Cheung RWL, Li WO, et al. Prosocial behaviour, individualism, and future orientation of Chinese youth: the role of identity status as a moderator. Behav Sci. 2025;15(2):193. doi:10.3390/bs15020193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Chang B, Bai B, Zhong N. Effect of negotiable fate on subjective well-being: the mediating role of meaning in life. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2017;25(4):724–30. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

21. Li Y, Zhu D. The relationship between negotiable fate and life satisfaction: the serial mediation by self-esteem and positive psychological capital. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2024;17:1625–33. doi:10.2147/prbm.s450973. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Liu H, Hao X, Kong D, Wang W, Yang J. Influences of perceived chronic social adversity, psychache and negotiable fate on suicidal risk: a moderated mediation model. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2022;30(4):954–8. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

23. Qin P, Chen J. Sleep quality and suicidal ideation in college students: a moderated mediation model. Psychol Mon. 2024;19(8):73–6. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

24. Gao J, Jin T, Tena WY. The influence of social adversity perception on suicidal ideation in college students: the mediating role of psychological torsion and the moderating role of negotiable destiny view. J Inn Mong Norm Univ. 2023;52(5):476–81. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

25. Chen M, Zheng M. Longitudinal association between employment pressure and suicidal ideation among recent graduates during the COVID-19 pandemic: a moderated mediation model. Iran J Public Health. 2024;53(12):2779–88. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-3961745/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhang Y, Jia X. When fate hands you lemons: a moderated moderation model of bullying victimization and psychological distress among Chinese adolescents during floods and the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1010408. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1010408. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Zhang Y, Wang C, An Y, Jiang X. When mindfulness is insufficient: the moderated moderating effects of self-harm and negotiable fate beliefs on the association between mindfulness and adolescent psychological distress in disasters. Sch Psychol Int. 2024;45(2):149–71. doi:10.1177/01430343231187108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Bandura A. Self-efficacy conception of anxiety. Anxiety Res. 1988;1(2):77–98. doi:10.1080/10615808808248222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York, NY, USA: Macmillan; 1997. [Google Scholar]

30. Sandler IN, Tein JY, Mehta P, Wolchik S, Ayers T. Coping efficacy and psychological problems of children of divorce. Child Dev. 2000;71:1099–118. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00212. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Biggs A, Brough P, Drummond S. Lazarus and Folkman’s psychological stress and coping theory. In: The handbook of stress and health: a guide to research and practice. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley Blackwell; 2017. p. 351–64. [Google Scholar]

32. Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

33. Tomaka J, Blascovich J. Effects of justice beliefs on cognitive appraisal of and subjective physiological, and behavioral responses to potential stress. J Personal Soc Psychol. 1994;67(4):732–40. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.67.4.732. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Au EWM, Savani K. Are there advantages to believing in fate? the belief in negotiating with fate when faced with constraints. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2354. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02354. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Denneson LM, Smolenski DJ, Bauer BW, Dobscha SK, Bush NE. The mediating role of coping self-efficacy in hope box use and suicidal ideation severity. Arch Suicide Res. 2019;23(2):234–46. doi:10.1080/13811118.2018.1456383. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Wenzel A, Beck AT. A cognitive model of suicidal behavior: theory and treatment. Appl Prev Psychol. 2008;12(4):189–201. doi:10.1016/j.appsy.2008.05.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Chesney MA, Neilands TB, Chambers DB, Taylor JM, Folkman S. A validity and reliability study of the coping self-efficacy scale. Br J Health Psychol. 2006;11(3):421–37. doi:10.1348/135910705x53155. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Mosher C, Prelow H. Active and avoidant coping and coping efficacy as mediators of the relation of maternal involvement to depressive symptoms among urban adolescents. J Child Fam Stud. 2007;16(6):876–87. doi:10.1007/s10826-007-9132-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Timkova V, Nagyova I, Reijneveld SA, Tkacova R, van Dijk JP, Bültmann U. Psychological distress in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea: the role of hostility and coping self-efficacy. J Health Psychol. 2020;25(13–14):2244–59. doi:10.1177/1359105318792080. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Mikula P, Timkova V, Vitkova M, Szilasiova J, Nagyova I. Suicidal ideation in people with multiple sclerosis and its association with coping self-efficacy. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2024;87:105677. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2024.105677. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Zhou Q, Wang Y, Deng X, Eisenberg N, Wolchik SA, Tein J. Relations of parenting and temperament to Chinese children’s experience of negative life events, coping efficacy, and externalizing problems. Child Dev. 2008;79(3):493–513. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01139.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Wu Y. Assessing regulatory emotional self-efficacy within overseas Chinese university students. Curr Psychol. 2022;41(7):4789–801. doi:10.1007/s12144-020-00987-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Ju C, Wu R, Zhang B, You X, Luo Y. Parenting style, coping efficacy, and risk-taking behavior in Chinese young adults. J Pac Rim Psychol. 2020;14:e3. doi:10.1017/prp.2019.24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Pan Q, Hao Z. Chinese college students’ help-seeking behavior: an application of the modified theory of planned behavior. PsyCh J. 2023;12(1):119–27. doi:10.1002/pchj.605. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Rosario M, Shinn M, Mørch H, Huckabee CB. Gender differences in coping and social supports: testing socialization and role constraint theories. J Community Psychol. 1988;16(1):55–69. [Google Scholar]

46. Sigmon ST, Stanton AL, Snyder CR. Gender differences in coping: a further test of socialization and role constraint theories. Sex Roles. 1995;33(9):565–87 doi: 10.1007/bf01547718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Morling B, Evered S. Secondary control reviewed and defined. Psychol Bull. 2006;132:269–96. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

48. Chipperfield JG, Perry RP, Bailis DS, Ruthig JC, Loring PC. Gender differences in use of primary and secondary control strategies in older adults with major health problem. Psychol Health. 2007;22:83–105 doi: 10.1080/14768320500537563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41(4):1149–60 doi: 10.3758/brm.41.4.1149. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Tone H. Designing of coping efficacy questionnaire and the construction of theory model. Acta Psychol Sin. 2005;37:413–9. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

51. Xu F, Huang L. Impacts of stress and risk perception on mental health of college students during the COVID-19 Pandemic: the mediating role of coping efficacy. Front Psychiatry. 2022;12:767189. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.767189. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Wang XZ, Gong HL, Kang XR, Liu WW, Dong XJ, Ma YF. Reliability and validity of Chinese revision of positive and negative suicide ideation in high school students. China J Health Psychol. 2011;19(8):964–6. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

53. Osman A, Gutierrez PM, Kopper BA, Barrios FX, Chiros CE. The positive and negative suicide ideation inventory: development and validation. Psychol Rep. 1998;82:783–93. doi:10.2466/pr0.1998.82.3.783. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Eekhout I, de Vet HC, Twisk JW, Brand JP, de Boer MR. Missing data in a multi-item instrument were best handled by multiple imputation at the item score level. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(3):335–42. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.09.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Liu A, Wang W, Wu X, Xu B. Relationship between self-compassion and nonsuicidal self-injury in middle school students after earthquake: gender differences in the mediating effects of gratitude and posttraumatic growth. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2023;15(7):1203–13. doi:10.1037/tra0001423. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Muthen L, Muthen B. Mplus user’s guide. 7th ed. Los Angeles, CA, USA: Muthen & Muthen; 2012. [Google Scholar]

57. Hair Jr JF, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM, Gudergan SP. Advanced issues in partial least squares structural equation modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: SAGE Publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

58. Little TD, Cunningham WA, Shahar G, Widaman KF. To parcel or not to parcel: exploring the question, weighing the merits. Struct Equ Model. 2002;9(2):151–73. doi:10.1207/s15328007sem0902_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 4th ed. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

61. Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(3):879–91. doi:10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An introduction to the bootstrap. New York, NY, USA: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 1994. [Google Scholar]

63. Byrne BM. Multigroup comparisons: testing for measurement, structural, and latent mean equivalence. In: The ITC international handbook of testing and assessment. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press; 2016. p. 377–94. [Google Scholar]

64. Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88:879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Liu RT, Lawrence HR, Burke TA, Sanzari CM, Levin RY, Maitlin C, et al. Passive and active suicidal ideation among left-behind children in rural China: an evaluation of intrapersonal and interpersonal vulnerability and resilience. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2021;51(6):1213–23. doi:10.1111/sltb.12802. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Bussey K, Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of gender development and functioning. In: The psychology of gender. 2nd ed. New York, NY, USA: The Guilford Press; 2004. p. 92–119. [Google Scholar]

67. Yu X, Sun S, Liu X, Cheng X. Son preference, family control and family member selection bias: evidence from Chinese listed family firms. Singap Econ Rev. 2025;70(1):251–79. doi:10.1142/s0217590824500188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Yeager DS, Dweck CS. Mindsets and adolescent mental health. Nat Ment Health. 2023;1(2):79–81. doi:10.1038/s44220-022-00009-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Fernández-González L, Calvete E, Sánchez-Álvarez N. Efficacy of a brief intervention based on an incremental theory of personality in the prevention of adolescent dating violence: a randomized controlled trial. Psychosoc Interv. 2020;29(1):9–18. [Google Scholar]

70. Heckman TG, Miller J, Kochman A, Kalichman SC, Carlson B, Silverthorn M. Thoughts of suicide among HIV-infected rural persons enrolled in a telephone-delivered mental health intervention. Ann Behav Med. 2002;24(2):141–8. doi:10.1207/s15324796abm2402_11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Guo J, Ren X, Wang X, Qu Z, Zhou Q, Ran C, et al. Depression among migrant and left-behind children in China in relation to the quality of parent-child and teacher-child relationships. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0145606. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0145606. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Li J, Wang J, Li JY, Qian S, Ling RZ, Jia RX, et al. Family socioeconomic status and mental health in Chinese adolescents: the multiple mediating role of social relationships. J Public Health. 2022;44(4):823–33. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdab280. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools