Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Effect of Virtual Reality Combined with Forest Therapy on Psychological Resilience of Submarine Personnel with Insomnia Symptoms

1 Xingcheng Special Duty Sanatorium of PLA Joint Logistic Force, Huludao, 125105, China

2 Department of Military Psychology, Army Medical University, Chongqing, 400038, China

* Corresponding Authors: Muyu Chen. Email: ; Liang Zhang. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Emotional Regulation, Wellbeing, and Happiness)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2026, 28(1), 9 https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.072327

Received 24 August 2025; Accepted 29 October 2025; Issue published 28 January 2026

Abstract

Background: Submarine personnel often experience insomnia and reduced psychological resilience due to extended deployments in confined, high-stress environments. Effective non-pharmacological interventions are needed to improve sleep quality and resilience in this population. This study aimed to investigate the effect of virtual reality (VR) combined with forest therapy interventions on psychological resilience and sleep quality among submarine personnel with insomnia symptoms. Methods: Using convenience sampling, 92 submarine personnel with insomnia symptoms undergoing recuperation at a PLA sanatorium between July 2023 and May 2025 were randomly allocated to experimental and control groups (n = 46 each). The control group received forest therapy intervention, while the intervention group received combined VR and forest therapy interventions. Pre- and post-intervention assessments were conducted using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Results: There is no significant differences between two groups before the intervention on sleep or psychological resilience. Both groups showed significant pre- to post-intervention improvements in sleep and resilience; however, mixed-ANOVA results showed that the intervention (VR + forest therapy) group achieved significantly better outcomes than the control group at post-intervention after Bonferroni correction, including lower PSQI total and key component scores (subjective sleep quality, sleep efficiency, daytime dysfunction) and higher CD-RISC resilience scores. Conclusions: The integration of virtual reality and forest therapy effectively improved sleep quality and psychological resilience among submarine personnel with insomnia symptoms. This combined intervention shows promise as a non-pharmacological approach in military healthcare settings; however, further studies are needed to validate and generalize these findings.Keywords

Submarines, as strategic platforms that independently execute missions underwater for extended periods, place their personnel in enclosed, isolated, and high-pressure special environments for long durations. This unique environment poses severe challenges to the physiological and psychological health of personnel, among which sleep problems and psychological resilience are two core factors affecting their combat effectiveness and well-being. Many submarines adopt an 18-h work cycle of “6 h on duty, 12 h rest”, which severely conflicts with humans’ endogenous circadian rhythms of approximately 24 h [1]. This chronobiological misalignment precipitates substantial circadian rhythm dysregulation, resulting in persistent physiological desynchronization among submarine personnel. The consequent sleep architecture disruption manifests as impaired sleep onset latency, compromised sleep maintenance, and decreased total sleep duration. Concurrently, psychological resilience emerges as a critical adaptive mechanism—functioning analogously to a “psychological immune system”—that is essential for maintaining psychological homeostasis and preserving operational effectiveness among personnel exposed to chronic high-stress submarine environments.

Psychological resilience is operationally defined as an individual’s adaptive capacity to successfully navigate, accommodate, and recover from exposure to adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats, or other significant psychosocial stressors while maintaining functional competence [2]. Adequate sleep duration and quality constitute fundamental prerequisites for optimal cognitive functioning, emotional homeostasis, and stress regulatory capacity [3]. Chronic sleep deprivation or compromised sleep architecture results in prefrontal cortical dysfunction, characterized by impaired emotional regulation, increased behavioral impulsivity, and dysregulated hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activation with consequent elevation of stress hormones, particularly cortisol. These neurobiological alterations collectively compromise individual psychological resilience capacity [4]. Conversely, individuals characterized by enhanced psychological resilience demonstrate superior adaptive coping repertoires and maintain more resilient cognitive-emotional frameworks, facilitating more effective stress processing across occupational and personal domains, thereby attenuating stress-mediated sleep architecture disruption [5]. Consequently, psychological resilience may function as a critical protective factor that moderates the deleterious effects of extreme environmental stressors on sleep quality parameters, serving as a buffer against stress-induced sleep deterioration in high-risk occupational populations.

In countries like China, submarine personnel typically receive structured recuperation services following extended deployment missions, involving rest and recovery at officially designated facilities [6]. Traditional recuperative approaches commonly employ therapeutic modalities such as seawater bathing, thermal spring therapy, and forest-based interventions to promote psychophysiological relaxation [7]. Recently, virtual reality (VR) technology has emerged as a promising non-pharmacological intervention modality in the field of rehabilitation [8] and military [9], attracting increasing research attention. Mounting evidence indicates that nature-based interventions and VR can alleviate stress and improve mental health outcomes. For instance, a meta-analysis reported that forest therapy significantly reduces depression and anxiety [10], highlighting the psychological benefits of nature exposure. Meanwhile, VR-based relaxation techniques have demonstrated efficacy in lowering perceived stress and enhancing subjective sleep quality [11]. These findings suggest that integrating VR with traditional forest therapy might yield synergistic benefits. Therefore, this study seeks to leverage the existing strengths of a specialized military recuperation facility (forest therapy) while incorporating VR technology, in order to examine their combined therapeutic effects on submarine personnel’s sleep quality and psychological resilience. The goal is to provide empirical evidence to inform future research and potential implementation of such interventions.

Using convenience sampling (means participants were recruited based on their availability at the recuperation center rather than random selection from the entire population), male submarine personnel who came to Xingcheng Special Duty Sanatorium of the Joint Logistics Support Force for recuperation from July 2023 to May 2025 and whose admission physical examination indicated insomnia symptoms were selected as research subjects. They were divided into experimental and control groups using the random number table method, with 46 people in each group. There were no statistically significant differences in basic information such as job composition, marital status, and education level between the two groups (p > 0.05). Details shown in Table 1. All subjects signed written informed consent forms. This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Xingcheng Special Duty Sanatorium of the Joint Logistics Support Force, PLA (Approval number: XLLL2301).

Table 1: Sociodemographic information of participants.

| Item | Intervention Group (n = 46) | Control Group (n = 46) | χ2 or t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soldier/Officer | 27/19 | 28/18 | 0.05 | 0.83 |

| Marriage (Y/N) | 24/22 | 26/20 | 0.17 | 0.68 |

| Education (Bachelor’s degree or not) | 26/20 | 24/22 | 0.17 | 0.68 |

| Smoking (Y/N) | 32/14 | 35/11 | 0.49 | 0.48 |

| Age (mean ± standard deviation) | 28.02 ± 5.03 | 26.98 ± 5.05 | 0.32 | 0.94 |

Submarine personnel underwent standardized forest therapy interventions comprising forest accommodation, thermal spring therapy, guided forest walks, and forest-based aerobic activities. The intervention protocol consisted of 1-month treatment cycles with sessions conducted 5 times weekly for 1.5 h each (9:00–10:30 a.m.). Combined dynamic and static therapeutic activities were implemented along designated forest health pathways, following a structured sequence: warm-up stretching → forest brisk walking → vocal expression activities → Baduanjin exercises → relaxation training. Under physician supervision, sessions commenced with stretching exercises in open areas, followed by 20-min brisk walks along forest trails targeting moderate exertion levels (light perspiration with conversational capacity but limited vocal range). Interactive components, including singing, vocal expression, and photography, were conducted at scenic forest overlooks to enhance engagement. Sessions concluded with 20-min Baduanjin traditional exercise routines at designated fitness platforms.

Intervention group participants received adjunctive VR therapeutic sessions integrated with the same standard forest therapy protocol as the control group. The intervention schedule was identical to the control group (4-week duration, 5 sessions per week, 90 min each session from 3:00–4:30 p.m.). VR interventions were administered in a controlled therapeutic environment (a dedicated sunroom at the fitness trail rest area), immediately after the completion of the Baduanjin exercise. The treatment environment was systematically optimized with ergonomic reclining furniture, hydration provisions, and climate control maintained at 24°C to ensure optimal participant comfort and treatment adherence. Certified therapists (each holding Chinese national certification in psychological counseling and over five years of clinical experience) conducted brief structured pre-intervention consultations (~10 min per session) to assess each participant’s current psychological state, therapeutic needs, personal preferences, and suitability for various VR scenarios. Based on this assessment and the participant’s input, the therapist and participant collaboratively selected personalized VR content for that session. Selection criteria were guided by individual needs: for example, participants with pronounced insomnia symptoms were guided toward the forest-based sleep-enhancement VR module, whereas those with higher stress or anxiety levels engaged in the progressive relaxation or cognitive stress-reduction modules. Despite personalization, all participants received the same total VR exposure per session (two modules of ~8 min each, ~16 min total) to maintain a consistent “dose” of VR intervention. During VR sessions, participants wore HTC Vive CONC head-mounted displays (HTC, Shanghai, China), and trained therapists facilitated immersive therapeutic experiences using a library of validated VR content. Four evidence-based therapeutic VR scenarios were available: (1) progressive muscle relaxation, (2) cognitive stress reduction, (3) guided meditative visualization, and (4) forest-based sleep enhancement, each approximately 8 min in duration. Each session incorporated 2 of these scenarios (selected as described above) for about 16 min of VR exposure per session. Structured post-session debriefings were conducted to evaluate each participant’s subjective responses and therapeutic feedback, which were documented to inform minor individual adjustments in subsequent sessions while adhering to the standardized protocol.

2.3.1 Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)

The scale was developed by Buysse et al. [12]. The PSQI comprises 19 self-rated items and 5 clinician-rated items, organized into 7 component domains: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medications, and daytime dysfunction. Each component is scored on a 0–3 scale, yielding a total possible score of 21, with higher scores reflecting worse sleep quality. The established cutoff score of ≥7 is widely used in China to identify clinically significant sleep quality impairment in adults. The internal consistency reliability of the scale in this study was satisfactory (Cronbach’s α = 0.83).

2.3.2 Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC)

The scale was developed by Connor et al. [13] and comprises 25 items across three dimensions: Tenacity (13 items), Strength (8 items), and Optimism (4 items). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0–4), yielding a maximum total score of 100, with higher scores reflecting greater psychological resilience and adaptive capacity in response to stressful situations. We used the Chinese version of the CD-RISC, which has shown high reliability in Chinese samples (Cronbach’s α~0.91) [14] and it demonstrated excellent internal consistency reliability in this study (Cronbach’s α = 0.94).

Participants in both groups completed baseline assessments during the psychological evaluation component of their admission medical screening (T0) and underwent follow-up testing upon completion of all interventions (T1). All evaluations were administered using paper format.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), with graphical representations generated using GraphPad Prism version 8.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). We evaluated the normality of continuous data using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Given the relatively small sample size per group, which reduces the power of normality tests, we also inspected Q-Q plots; no major deviations from normal distribution were observed, supporting the use of parametric tests. A 2 (time: baseline [T0] vs. post-intervention [T1]) × 2 (group: control vs. intervention) mixed-design repeated measures analysis of variance was conducted to evaluate within-subject changes over time, between-group differences, and time × group interaction effects. Main effects for time and group factors, as well as simple effects analyses, were examined to determine the source of significant interactions. Statistical significance was established at α = 0.05 for all analyses. To address multiple comparisons across outcomes, we adjusted the significance threshold for primary outcomes using a Bonferroni correction (for two primary outcomes, adjusted α = 0.025). Violations of sphericity assumptions were addressed using Greenhouse-Geisser epsilon correction factors. Categorical demographic and clinical variables were analyzed using Pearson chi-square tests of independence.

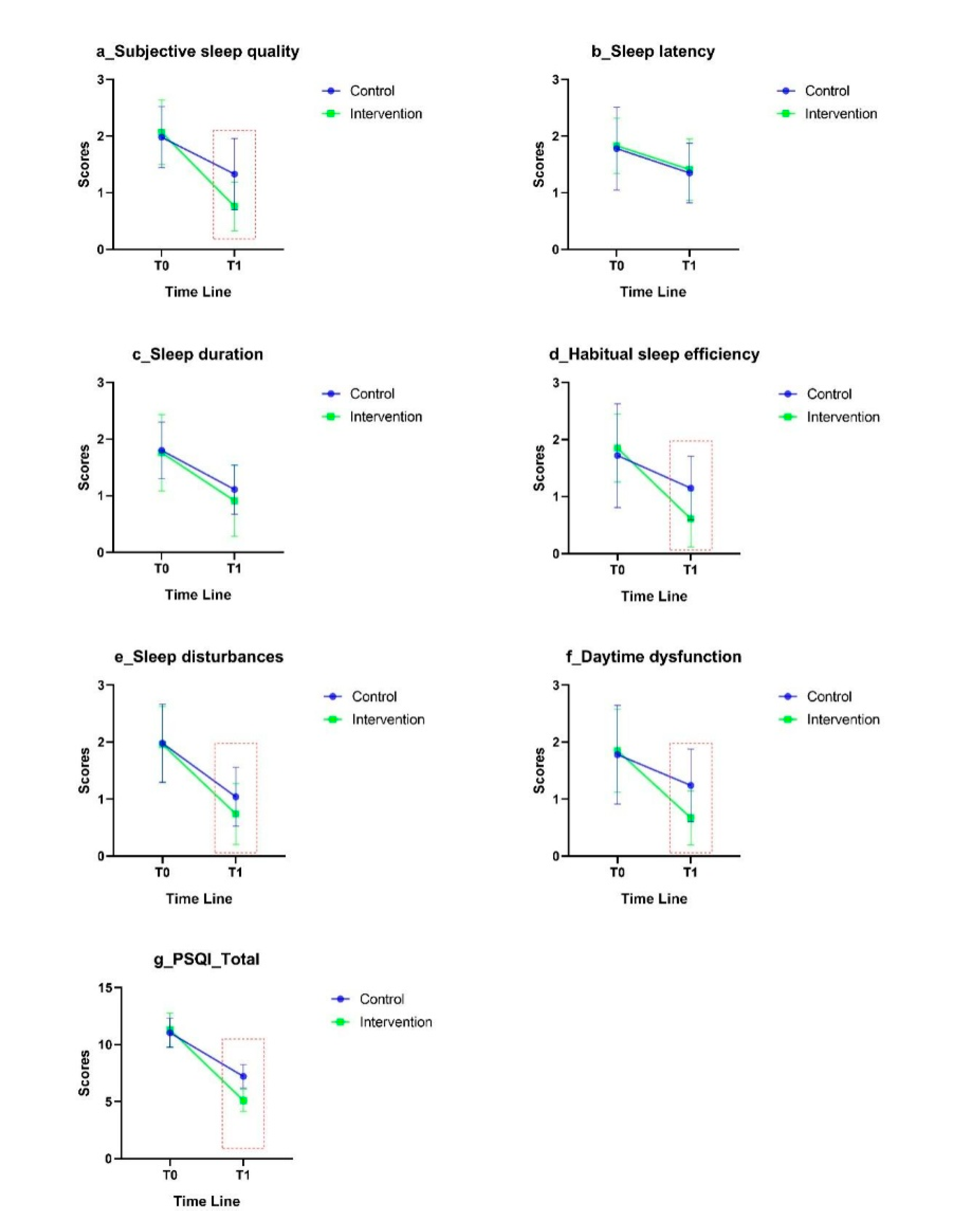

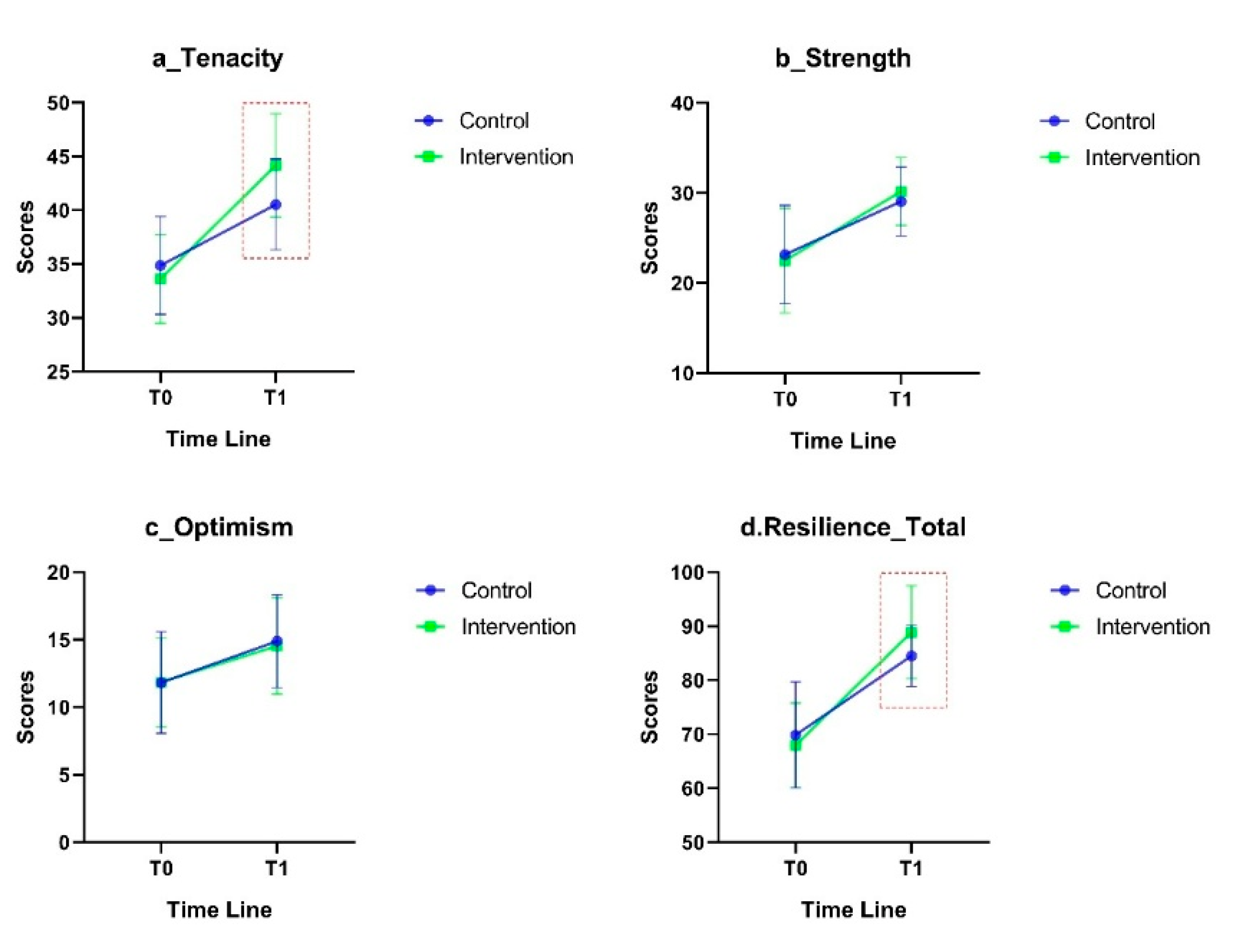

The mixed-design ANOVA showed significant Time × Group interaction effects for several outcomes, including CD-RISC total score, PSQI total score, CD-RISC Tenacity subscale, PSQI sleep duration, subjective sleep quality, habitual sleep efficiency, and daytime dysfunction components (interaction Fs significant at p < 0.05). There were significant main effects of Time for all outcome measures, indicating overall improvements from T0 to T1 in both groups. Simple effects analyses revealed that at post-intervention (T1), the intervention group had significantly higher resilience scores (CD-RISC total and Tenacity) than the control group, and significantly lower scores (better outcomes) on the PSQI total and key PSQI components (sleep duration, subjective sleep quality, habitual sleep efficiency, and daytime dysfunction) (all adj-Ps < 0.05). These between-group differences were not significant at baseline (T0). Detailed results are presented in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 and Table 2 and Table 3.

Figure 1: Comparison of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) between different groups. (a) Subjective sleep quality; (b) Sleep latency; (c) Sleep duration; (d) Habitual sleep efficiency; (e) Sleep disturbances; (f) Daytime dysfunction; (g) Total.

Figure 2: Comparison of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) between different groups. (a) Tenacity; (b) Strength; (c) Optimism; (d) Total.

Table 2: Comparison of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) between different groups.

| Items | Time | Intervention Group (n = 46) | Control Group (n = 46) | t | F | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interaction | Time | Group | |||||

| PSQI_F1 | T0 | 2.07 ± 0.57 | 1.98 ± 0.54 | 0.75 | 15.67*** | 141.06*** | 9.04*** |

| T1 | 0.76 ± 0.43 | 1.33 ± 0.63 | −4.99*** | ||||

| PSQI_F2 | T0 | 1.83 ± 0.48 | 1.78 ± 0.72 | 0.33 | 0.04 | 56.24*** | 0.26 |

| T1 | 1.41 ± 0.54 | 1.35 ± 0.52 | 0.58 | ||||

| PSQI_F3 | T0 | 1.76 ± 0.67 | 1.78 ± 0.50 | −0.35 | 1.62 | 166.18*** | 1.38 |

| T1 | 0.91 ± 0.62 | 1.11 ± 0.43 | −1.74 | ||||

| PSQI_F4 | T0 | 1.85 ± 0.59 | 1.72 ± 0.91 | 0.81 | 12.10*** | 86.78*** | 4.49* |

| T1 | 0.61 ± 0.49 | 1.15 ± 0.55 | −4.95*** | ||||

| PSQI_F5 | T0 | 1.96 ± 0.66 | 1.98 ± 0.68 | −0.15 | 2.82 | 163.53*** | 3.03 |

| T1 | 0.74 ± 0.53 | 1.04 ± 0.51 | −2.78** | ||||

| PSQI_F7 | T0 | 1.85 ± 0.72 | 1.78 ± 0.86 | 0.39 | 15.82*** | 117.36*** | 4.30* |

| T1 | 0.67 ± 0.47 | 1.24 ± 0.63 | −4.81*** | ||||

| PSQI_Total | T0 | 11.30 ± 1.48 | 11.04 ± 1.28 | 0.90 | 50.13*** | 896.71*** | 23.88*** |

| T1 | 5.11 ± 0.97 | 7.22 ± 1.03 | −10.09*** | ||||

Table 3: Comparison of Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) between different groups.

| Items | Time | Intervention Group (n = 46) | Control Group (n = 46) | t | F | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interaction | Time | Group | |||||

| Resilience_Tenacity | T0 | 33.61 ± 4.13 | 34.87 ± 4.55 | −1.39 | 14.80*** | 163.08*** | 3.12 |

| T1 | 44.17 ± 4.80 | 40.54 ± 4.22 | 3.85*** | ||||

| Resilience_Strength | T0 | 22.50 ± 5.82 | 23.17 ± 5.47 | −0.57 | 1.66 | 96.33*** | 0.09 |

| T1 | 30.17 ± 3.77 | 29.07 ± 3.83 | 1.40 | ||||

| Resilience_Optimism | T0 | 11.85 ± 3.31 | 11.83 ± 3.75 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 29.55*** | 0.10 |

| T1 | 14.54 ± 3.55 | 14.89 ± 3.44 | −0.48 | ||||

| Resilience_Total | T0 | 67.96 ± 7.81 | 69.87 ± 9.82 | −1.03 | 8.46** | 269.33*** | 0.91 |

| T1 | 88.89 ± 8.61 | 84.50 ± 5.66 | 2.89** | ||||

The present investigation demonstrates that while both treatment groups exhibited significant improvements in sleep quality parameters and psychological resilience measures following structured recuperative interventions, participants receiving the combined forest therapy and virtual reality training protocol demonstrated significantly superior therapeutic outcomes compared to those receiving forest therapy alone. These findings not only corroborate the established therapeutic efficacy of forest-based interventions for enhancing mental health outcomes among naval submarine personnel, but more importantly, provide compelling evidence for the synergistic therapeutic potential of integrating virtual reality technology as an adjunctive modality to optimize psychological health promotion strategies in high-stress military occupational environments.

4.1 Mechanisms of VR Therapy Effects on Insomnia

Our findings showed that adding VR sessions to forest therapy led to greater improvements in sleep quality for submarine personnel with insomnia symptoms. Prior research suggests that VR technology can ameliorate insomnia by modulating psychophysiological arousal [15]. VR-based guided breathing and relaxation exercises have been shown to increase parasympathetic (vagal) activity [16], resulting in reduced heart rate and increased high-frequency heart rate variability [17], thereby counteracting the hyperarousal state underlying chronic insomnia. In addition, immersive virtual natural environments help redirect attention away from pre-sleep rumination and anxiety, which alleviates bedtime cognitive arousal and performance anxiety [18]. Consistent with these mechanisms, a recent study reported that VR relaxation training significantly increased alpha brain-wave activity in individuals with chronic insomnia, indicating an enhanced cortical relaxation state conducive to sleep onset [19]. Although we did not directly measure physiological responses in this study, such evidence provides a plausible explanation for the improved subjective sleep quality observed in the intervention group.

4.2 Impact of VR on Psychological Resilience

The combined VR and forest therapy intervention also resulted in greater improvements in psychological resilience compared to forest therapy alone. VR interventions may enhance psychological resilience through neurobiological and physiological pathways. Studies have found that VR-based stress management training can induce neuroplastic changes in stress-related brain circuits. For example, VR exposure therapy has been associated with reduced activation in the amygdala-hippocampal-prefrontal circuit during stress, suggesting improved regulation of emotional responses. Additionally, immersive VR relaxation experiences can improve autonomic balance (e.g., increase heart rate variability) and normalize HPA-axis function (e.g., reduce excessive cortisol levels), indicating a reduction in physiological stress reactivity. Over time, these adaptations may translate into a greater capacity to withstand and recover from stress—i.e., increased resilience. While we did not measure neural activity or hormone levels in this study, the greater post-intervention resilience gains in the VR group align with these proposed mechanisms.

In the present study, forest therapy served as the foundational intervention for both groups, with the VR component added in the intervention group. The results demonstrated that both groups showed significant improvements from pre- to post-intervention in PSQI scores (total and components such as subjective sleep quality, sleep efficiency, and daytime dysfunction), but the intervention group achieved superior improvements than the control group. These findings align with previous research by Davenport et al. [20] and Imran et al. [21], supporting the efficacy of VR interventions for enhancing sleep quality among military populations, including submarine personnel. The greater post-intervention psychological resilience observed in our VR + forest group further demonstrates the potential of integrating VR technology into military recuperation programs to enhance service members’ resilience. Future applications could involve incorporating VR as a component of comprehensive stress management and resilience training protocols for military personnel.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to specifically examine submarine personnel as a population and to evaluate the synergistic effects of combined VR and forest therapy on sleep and resilience outcomes. The findings provide preliminary evidence supporting the therapeutic potential of integrating VR technology into military recuperation programs. However, several methodological limitations warrant consideration. First, the sample size was relatively small (n = 92), which may limit statistical power and the generalizability of the findings to the broader submarine personnel population. Second, this was a single-center study: all participants were from one recuperation facility, so results may not generalize to other settings or units. Third, there was an absence of objective physiological measures: we relied on self-report questionnaires without incorporating objective assessments such as polysomnography, actigraphy, heart rate variability monitoring, cortisol assays, or neuroimaging biomarkers. This is a significant limitation that restricts our ability to understand the biological mechanisms of the intervention and to validate the self-reported improvements. Furthermore, because participants were aware of their group assignments and all outcomes were self-reported, there is a risk of expectancy effects or self-report biases (e.g., placebo effects or social desirability bias) influencing the results. Future studies should include objective sleep and stress measures and consider blinding where feasible to strengthen the evidence and reduce measurement bias. Fourth, no long-term follow-up: we did not collect data beyond the immediate post-intervention period, so the durability of the improvements in sleep and resilience remains unknown. Fifth, the use of a convenience sample (as opposed to a random sample of all submarine personnel) may introduce selection bias and limit the external validity of the findings. Consequently, caution is advised when generalizing these results to all submarine force members.

Our study demonstrates that integrating forest-based therapy with VR technology during a recuperation program can produce beneficial effects on the sleep quality and psychological resilience of submarine personnel with insomnia symptoms. However, given the modest sample size and specific study context, these findings should be considered preliminary. The combined VR and forest therapy approach shows promise as a novel non-pharmacological strategy in military medical settings, but further validation in larger, more diverse military populations is required before recommending broad implementation. Future investigations should also aim to elucidate the underlying physiological and psychological mechanisms driving the observed benefits, which would help optimize the intervention protocol and inform effective deployment in practice.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Yang Deng, Muyu Chen, Liang Zhang; Methodology: Yang Deng, Muyu Chen; Software: Tong Su, Muyu Chen; Validation: Liang Zhang, Li Peng; Formal analysis: Yang Deng, Tong Su; Investigation: Yang Deng, Bin Wu; Resources: Tong Su; Data Curation: Muyu Chen; Writing—Original Draft: Yang Deng, Muyu Chen; Writing—Review & Editing: Liang Zhang, Li Peng; Visualization: Muyu Chen; Supervision: Liang Zhang; Project Administration: Liang Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author (Muyu Chen), upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Xingcheng Special Duty Sanatorium of the Joint Logistics Support Force, PLA (Approval number: XLLL2301). All subjects signed written informed consent forms.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Guo JH , Ma XH , Ma H , Zhang Y , Tian ZQ , Wang X , et al. Circadian misalignment on submarines and other non-24-h environments—from research to application. Mil Med Res. 2020; 7( 1): 39. doi:10.1186/s40779-020-00268-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Troy AS , Willroth EC , Shallcross AJ , Giuliani NR , Gross JJ , Mauss IB . Psychological resilience: an affect-regulation framework. Annu Rev Psychol. 2023; 74: 547– 76. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-020122-041854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zhu Y , Zhang Y , Zhuang M , Ye M , Wang Y , Zheng N , et al. Association between sleep duration and psychological resilience in a population-based survey: a cross-sectional study. J Educ Health Promot. 2024; 13: 43. doi:10.4103/jehp.jehp_832_23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Hughes JM , Ulmer CS , Hastings SN , Gierisch JM , Workgroup MVM , Howard MO . Sleep, resilience, and psychological distress in United States military Veterans. Mil Psychol. 2018; 30( 5): 404– 14. doi:10.1080/08995605.2018.1478551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Sher L . Sleep, resilience and suicide. Sleep Med. 2020; 66: 284– 5. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2019.08.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zhang WB . Special duty recuperation. Beijing, China: People’s Military Medical Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

7. Chen JJ , Luo ZY , Zhang H , Xiong B , Wang L , Xu H . Correlation of sleep quality with depression, anxiety and stress among special service convalescents. J Navy Med. 2025; 4: 327– 30. [Google Scholar]

8. Freeman D , Reeve S , Robinson A , Ehlers A , Clark D , Spanlang B , et al. Virtual reality in the assessment, understanding, and treatment of mental health disorders. Psychol Med. 2017; 47( 14): 2393– 400. doi:10.1017/s003329171700040x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. MacKenzie CF , Harris TE , Shipper AG , Elster E , Bowyer MW . Virtual reality and haptic interfaces for civilian and military open trauma surgery training: a systematic review. Injury. 2022; 53( 11): 3575– 85. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2022.08.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Yeon PS , Jeon JY , Jung MS , Min GM , Kim GY , Han KM , et al. Effect of forest therapy on depression and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 18( 23): 12685. doi:10.3390/ijerph182312685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Ahn J , Kim J , Park Y , Kim R , Choi H . Nature-based virtual reality relaxation to improve mental health and sleep in undergraduate students: a randomized controlled trial. Digit Health. 2025; 11: 20552076251365140. doi:10.1177/20552076251365140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Buysse DJ , Reynolds CF III , Monk TH , Berman SR , Kupfer DJ . The pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989; 28( 2): 193– 213. doi:10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Connor KM , Davidson JRT . Development of a new resilience scale: the connor-davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003; 18( 2): 76– 82. doi:10.1002/da.10113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Yu X , Zhang J . Factor analysis and psychometric evaluation of the connor-davidson resilience scale (cd-risc) with Chinese people. Soc Behav Pers. 2007; 35( 1): 19– 30. doi:10.2224/sbp.2007.35.1.19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Schöne B , Kisker J , Lange L , Gruber T , Sylvester S , Osinsky R . The reality of virtual reality. Front Psychol. 2023; 14: 1093014. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1093014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Yang AHX , Khwaounjoo P , Cakmak YO . Directional effects of whole-body spinning and visual flow in virtual reality on vagal neuromodulation. J Vestib Res. 2021; 31( 6): 479– 94. doi:10.3233/VES-201574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Aganov S , Nayshtetik E , Nagibin V , Lebed Y . Pure purr virtual reality technology: measuring heart rate variability and anxiety levels in healthy volunteers affected by moderate stress. Arch Med Sci. 2020; 18( 2): 336– 43. doi:10.5114/aoms.2020.93239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zhou H , Chen C , Liu J , Fan C . Acute augmented effect of virtual reality (VR)-integrated relaxation and mindfulness exercising on anxiety and insomnia symptoms: a retrospective analysis of 103 anxiety disorder patients with prominent insomnia. Brain Behav. 2024; 14( 10): e70060. doi:10.1002/brb3.70060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Wan Y , Gao H , Zhou K , Zhang X , Xue R , Zhang N . Virtual reality improves sleep quality and associated symptoms in patients with chronic insomnia. Sleep Med. 2024; 122: 230– 6. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2024.08.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Davenport ND , Werner JK . A randomized sham-controlled clinical trial of a novel wearable intervention for trauma-related nightmares in military veterans. J Clin Sleep Med. 2023; 19( 2): 361– 9. doi:10.5664/jcsm.10338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Imran MADB , Goh CSY , Nisha V , Shanmugham M , Kuddoos H , Leo CH , et al. A virtual reality game-based intervention to enhance stress mindset and performance among firefighting trainees from the Singapore civil defence force (SCDF). Virtual Worlds. 2024; 3( 3): 256– 69. doi:10.3390/virtualworlds3030013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools