Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Parental Phubbing and Parenting Styles’ Effect on Adolescent Bullying Involvement Depending on Their Attachments to Significant Adults

1 Department of Criminal Justice and Criminology, Salve Regina University, Newport, RI 02840, USA

2 Department of Sociology, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA 24061, USA

3 Department of Social, Developmental and Educational Psychology, University of Huelva, Huelva, 21007, Spain

4 Department of Psychology, Metropolitan State University Denver, Denver, CO 80217, USA

5 Department of Psychology, Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, MA 02325, USA

* Corresponding Author: Diego Gomez-Baya. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Adolescent and Youth Mental Health: Toxic and Friendly Environments)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2026, 28(1), 2 https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.072605

Received 30 August 2025; Accepted 12 December 2025; Issue published 28 January 2026

Abstract

Background: Bullying is a current social and educational problem with detrimental consequences in adolescence and later life stages. Previous research has explored the risk or protective factor at different socio-ecological levels, but further integration is needed to examine the relationships of family characteristics. This study examines how parenting style and attachment relate to adolescents’ bullying and cyberbullying, and whether parental phubbing mediates these links. Methods: Grounded in social bonding theory, we surveyed a cross-sectional convenience sample of U.S. college students (N = 545; Meanage = 19.60, SD = 1.41) who retrospectively reported middle/high-school experiences from Massachusetts, Colorado, and Virginia. Measures followed established traditions of bullying involvement, parenting style, and partner phubbing). Linear regressions tested associations among parenting style, attachment to parents/teachers, parental phubbing, and bullying/cyberbullying offending and victimization. Results: Stronger parental attachment and democratic (authoritative) parenting were associated with lower bullying victimization, and teacher attachment was protective for offline and overall offending. Critically, parents’ excessive personal technology use (phubbing) mediated the link between democratic parenting and bullying outcomes: high parental device use attenuated or nullified the protective association of democratic parenting. Conclusion: Findings reaffirm the value of nurturing, boundary-setting parenting and close parent–child/teacher bonds, while highlighting a contemporary risk—parental device-related inattention. Despite rapid technological change, the core need for stable human connection remains central to reducing bullying involvement.Keywords

Bullying is repeated, intentional aggression directed at a peer who struggles to defend themselves—combining negative action, repetition, and power imbalance [1]. Cyberbullying is not merely a digital translation of the same phenomenon; its affordances—persistence, searchability, scalability, and perceived anonymity—alter how harm is enacted and experienced across email, social media, and messaging platforms [2,3]. Recent figures remain sobering: roughly half of students report lifetime cybervictimization, with more than a quarter reporting incidents in the prior month [4]. Involvement—whether as victim, perpetrator, or both—coincides with poorer psychological, physical, and academic outcomes [5] and elevates risk for substance use, suicidality and problematic technology use, including social media patterns that themselves predict cyber-victimization [6,7,8,9]. Scholars consequently frame (cyber) bullying as deviance—a patterned violation of social norms that clusters with other forms of misconduct [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18].

We approach these patterns through a multilevel developmental lens. Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory reminds us that adolescents navigate nested contexts—family and school microsystems, peer networks and media in the mesosystem/exosystem, and broader cultural and policy macrosystems—that jointly shape risk and protection [19]. Within the microsystem, attachment processes are pivotal: secure parental bonds scaffold emotion regulation and social competence [20], whereas insecure relationships undermine those competencies and increase reliance on dysregulated or status-seeking behavior [21]. These vulnerabilities are not sealed inside the home; peers and media can normalize or reward aggression, including its online variants [22]. In short, cyberbullying risk is unlikely to be explained by “the internet” alone; it is produced where everyday family practices meet platform affordances.

Attachment theory clarifies why these early bonds matter. Secure attachment cultivates trust and effective regulation; insecure patterns (avoidant, ambivalent, disorganized) are linked to difficulties with empathy, conflict management, and help-seeking [23,24]. By adolescence, these difficulties are visible as susceptibility to peer pressure, risk-taking, and deviant coping [25,26], a trajectory corroborated across studies that connect insecure attachment with behavioral problems and substance use [27]. Social control perspectives specify the external side of this story: social bonding theory argues that attachment, commitment, involvement, and belief tie youth to conventional others and institutions, thereby constraining delinquency [28]. When those ties weaken—through poor family functioning or ineffective childrearing—risk rises [29,30,31]. Yet control alone is not the mechanism; social learning theory explains how behaviors are acquired: adolescents observe models, infer contingencies, and adopt behaviors that appear tolerated or rewarded—especially when modeled by parents and peers to whom they are strongly attached [32]. Put simply, what parents are to youth (warmth, responsiveness, structure) and what parents do (the everyday, modeled practices around conflict, technology, and attention) jointly shape bullying involvement.

This theoretical integration helps explain several empirical puzzles in the current literature. Strong parent–child bonds protect against in-person offending and victimization [10,11,12], yet the same bonds show inconsistent effects online [10,11]. One reason is that many supervisory strategies were designed for co-located risks; being “in the same room” offers limited protection when aggression flows through asynchronous, networked channels. Indeed, some forms of close supervision correlate with higher cyber-victimization among boys, with null effects for girls [13,14,15], implying that undifferentiated “monitoring” can backfire or that boys and girls experience (and interpret) oversight differently. A second puzzle concerns gendered pathways: parental control can weigh more heavily for males under authoritarian styles [16], and scholars call for attention to mediators and moderators—for example, adolescents’ fear or experiences of parental rejection—that may convert parenting style into bullying risk [16,17].

We propose that one underexamined but theoretically central mechanism is parental phubbing—parents’ phone-preoccupied disengagement during parent–child interaction [18]. Phubbing is ecologically situated (a microsystem practice that occurs in daily routines) and theoretically consequential: it erodes attachment (control perspective) by signaling unavailability, models divided attention and digital norm-violations (learning perspective), and alters emotion-regulation opportunities (attachment perspective) precisely at moments when adolescents seek connection or guidance. In the online domain, this combination plausibly weakens the very ties that would constrain aggression while simultaneously modeling the attentional habits that normalize distracted, impulsive, or performative conduct in peer-facing digital spaces.

Three gaps motivate the present study. First, we lack clarity on which parental practices—beyond broad style labels—actually relate to youth involvement in bullying and cyberbullying, and why those links appear inconsistent across online and offline contexts [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Second, potential mediators that translate parenting style into behavior remain understudied; calls to examine rejection and related experiences point to everyday interactional dynamics rather than abstract styles [16,17]. Third, scholarship rarely centers parental phubbing as a theoretically coherent mediator positioned at the intersection of ecological context, attachment quality, social bonding, and social learning [18,19,20,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32].

This study advances the field by testing a theory-driven mediation model in which parenting style predicts adolescents’ bullying and cyberbullying involvement through parental phubbing, with attention to gendered patterns and the distinct affordances of online settings. Our aim is not to adjudicate between attachment, control, and learning theories, but to braid them: if parenting style sets the emotional climate (attachment/control) and daily phone-preoccupation supplies the modeled script (learning), then the combination should forecast bullying outcomes more powerfully—and more plausibly for cyber contexts—than style alone. Clarifying these pathways can guide practical, modifiable targets (e.g., reducing phubbing during key routines; aligning monitoring with warm, autonomy-supportive practices) and inform prevention that meets youth where they now live: at the interface of family life and networked media.

1.1 Attachment, Parental Phubbing, and Bullying Involvement

A multitude of studies show that weak parent-child bonding is linked to youth problem behavior, including problematic internet use [33,34]. Weaker social bonds are observed among bully victims [35] who are more aggressive [36], have more insecure attachments to parents [37], and display more problem behaviors, depressive symptoms, and conflicts with parents compared to bullies and victims [38]. Both traditional bullies and victims perceive less support from their parents compared to non-involved adolescents [39,40]. Ybarra and Mitchell [41,42] found that perpetrators of cyberbullying had poorer emotional bonds with parents than those not involved in bullying. Longitudinal findings show parental support protects against cyberbullying and victimization [43], while Bayraktar et al. [44] found that cyberbully-victims had the poorest parental attachment.

Research also shows that weak social bonds predict antisocial behavior [29,30,45]. Students who are well-integrated are more likely to follow rules [46,47], while strong attachment, commitment, and belief inhibit misbehavior [29,30]. Bullying victimization is linked to lower school attachment [38,48] and to delinquent outcomes such as dropout, drug use, and later criminality [49,50]. Popp and Peguero [48] also found that school violence reduced attachment.

Building on this broader attachment perspective, “phubbing” (a portmanteau of “phone” and “snubbing”) is defined as a form of social exclusion and neglect caused by mobile phone use [18]. Unlike chronic parental neglect, phubbing represents situational but recurring relational neglect, where parents prioritize devices over interaction. Despite being momentary, it repeatedly signals to adolescents that parental attention is secondary, undermining security and belonging in distinct ways. This subtle, everyday rejection has been linked to problem behaviors, including bullying involvement. Although many studies documented negative effects of parental phubbing on parent-child relationships, few address its impact on adolescent deviance [51]. A recent review indicated that parental use of mobile phones during parent-child interactions decreases the quality of interactions and increases the child’s injury [52]. Individuals who are phubbed experience social rejection or exclusion by a loved one who is using handheld technology excessively. Consequently, they may turn to social media to compensate for their needs [53], a need tied to heavy phone use [54], and internet addiction [55]. Similar to phubbing, technoference, the habitual interruption and disruption of face-to-face interaction [56], predicts deviant behaviors such as aggression [57,58]. McDaniel’s review [59] identified technoference as a strong antecedent of youth problem behaviors, while Dixon et al. [17] found adolescent perceptions of parents’ technoference were negatively associated with mental health and positively with violent behavior. Technoference also impairs parent-child interactions [60] and parenting quality [61].

Most existing research has focused on younger children (<12 years) [52,59,62,63,64], while studies of adolescents are few and mainly from China [65,66,67]. These studies consistently show parental phubbing predicts adolescent cyberbullying perpetration [66,67]. Mechanisms include: (1) social learning—adolescents imitate parents’ problematic phone use [32,58,68]; (2) parental hostility when interrupted during device use [52]; and (3) adolescents’ perception of exclusion, which fosters rejection, frustration, and displaced aggression such as cyberbullying [69,70,71], consistent with frustration-aggression theory [72].

1.2 Parenting Style, Gender and Bullying Involvement

The impact of parenting style on adolescent deviance reveals significant differences in outcomes associated with authoritative versus authoritarian parenting styles. Authoritative (or democratic) parenting—high warmth and support with clear, fair limits—predicts better self-regulation and social competence and, correspondingly, lower involvement in deviance and bullying [73,74]. By contrast, authoritarian parenting—high control with low warmth—erodes communication and trust and is associated with aggression and other antisocial outcomes [75,76]. Early work on bullying already reflected this gradient: parents of bullies tended to be conflicted, low in warmth, and power-assertive, sometimes employing physical punishment [1,77], whereas authoritative parenting reduced the odds of bully-victim status [78]. Traditional bullying is reported most frequently among youth from authoritarian homes [16,79,80], while permissiveness is a stronger predictor of victimization than perpetration [77,81,82].

Findings are less uniform for indulgent/overprotective approaches. Some studies link indulgent or overcontrolling parenting to the highest likelihood of victimization, others to the lowest, and still others to no association [79,82,83]. A plausible mechanism is “helicopter” oversight—close supervision without warmth or autonomy support—eliciting frustration and anxiety that may spill into online aggression [84]. In this vein, scholars have called for direct tests of how parental overcontrol relates to problematic internet use among adolescents [13]. Overprotection has also been tied to victimization more generally: intense parental emotion and guarding can foster no assertiveness and anxiety, increasing vulnerability to peer aggression [81,85,86].

Modality qualifies these associations. Several studies report that global parenting style labels are not directly associated with offline bullying roles, yet lax rule-setting and low demandingness are associated with cyber involvement [87]. Results for parental monitoring are mixed [88], and one review concludes that style may not meaningfully shape traditional bullying [89]. For cyberbullying, evidence points in both directions: authoritarian style has been reported as a risk factor for offending [90,91] and for victimization [79,83,90], while other work finds no style effect on perpetration [79]. Taken together, these discrepancies suggest that, online, the operative ingredients are the specific practices around devices, rules, and everyday attention rather than style labels alone.

Gender further conditions these dynamics. Strong parent–child bonds are protective for all adolescents, but the salient tie differs: mother–child attachment appears especially consequential for boys’ delinquency (emphasizing emotional closeness and communication) [92], whereas girls’ deviance is more tightly linked to monitoring and the father–daughter relationship [93]. In cyber contexts, supervision plays different roles by gender—more important at the onset of experience for boys and more useful for resisting involvement among girls [94]. These patterns align with broader tendencies for girls to internalize distress and boys to externalize it [95], and with evidence that parental control carries particular weight for males in authoritarian homes [16].

Threading across these literatures is a relatively stable mechanism: attachment. Higher warmth and stronger bonds are associated with lower odds of both perpetration and victimization online [91] and with reduced online harassment of others [42]; weaker bonds predict greater involvement on both sides [43]. Accordingly, the protective edge of authoritative parenting likely operates through relationship quality and everyday contingencies—signals of availability, clear but reasonable limits, and modeled attention/conflict practices—rather than through style labels in isolation.

While previous research examined the relationships between adolescent bullying/cyberbullying involvement and attachment to significant adults (such as parents and teachers), parenting styles’ mitigating effects on child bullying behavior and victimization, and even parental phubbing’s impacts on children’s behavior, further research is needed to integrate the above factors and examine their effects on adolescent bullying. In addition, previous studies only concentrated on examining the relationship between parental phubbing and early childhood problematic behavior, but studies neglected to examine adolescent groups. Thus, the current study contributes to research on youth bullying involvement within the above theoretical frameworks. Besides advancing theory by integrating attachment, bonding, and social learning perspectives in a single empirical model, the study fills an age-group gap by testing parental phubbing in adolescence, identifies a mechanism through which parental device use can undermine otherwise protective parenting, and sharpens practice by directing prevention toward parent–teen relationships and adult digital conduct, not only student behavior.

Therefore, the present research aimed to examine the mediating impact of parental attachment and phubbing on the relationship between parental style and bullying/cyberbullying. We hypothesized that parental style had direct effects on both parental bonding and phubbing, while these variables were related to bullying and cyberbullying experiences. Specifically, (Hypothesis 1) an authoritative style was expected to be related to more parental attachment and less phubbing. Moreover, (Hypothesis 2) higher parental attachment was expected to be associated with less phubbing. Finally, (Hypothesis 3) higher parental attachment and less phubbing were hypothesized to be associated with fewer bullying/cyberbullying experiences.

We recruited survey participants in three large public universities in the U.S.: Bridgewater State University, Metropolitan State University Denver, and Virginia Tech during the academic year of 2022/23. Undergraduate students were eligible to participate in the one-time online survey, either for course credit or for entering a drawing for a gift card. Participation was voluntary and confidential. For those who were offered course credits, an alternative assignment was provided to ensure voluntariness. The research was approved by all three participating universities’ Institutional Review Boards: The Institutional Review Board of Bridgewater State University (IRB approval code 2025126), the Institutional Review Board of Metropolitan State University Denver (IRB approval code 2025126), and the Institutional Review Board of Virginia Tech (IRB approval code 20-647). Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Altogether, 630 students participated in the survey. To concentrate on undergraduate college students born between 2000 and 2005, we excluded those younger than 18 and older than 23 years of age (n = 85) at the time of the survey participation. As a result, the sample consisted of 545 participants (119 males, 401 females, 25 non-binary) in total from the three universities. The mean age of the sample was 19.60 years (SD = 1.41), ranging from 18 and 23. Sample demographics are reported in Table 1.

Table 1: Sample demographics.

| Variable | Categories | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 119 | 21.8 |

| Female | 401 | 73.6 | |

| Other | 25 | 4.6 | |

| Age | 18 | 141 | 25.9 |

| 19 | 159 | 29.2 | |

| 20 | 113 | 20.7 | |

| 21 | 67 | 12.3 | |

| 22 | 40 | 7.3 | |

| 23 | 25 | 4.6 | |

| Ethnicity | White | 248 | 45.5 |

| Black | 49 | 9.0 | |

| Native | 10 | 1.9 | |

| Asian | 19 | 3.5 | |

| Hispanic | 163 | 29.9 | |

| Mixed/Other | 56 | 10.2 | |

| School type | Public | 507 | 93.0 |

| Private | 36 | 6.6 | |

| Home-schooled | 2 | 0.4 |

The survey included demographic questions, retrospective questions about bullying and cyberbullying experiences in middle and high school, and attachment to parents and teachers. Studies show sensitive questions, including deviant behavior, are most likely answered when asked retrospectively. Therefore, retrospective style questions are anticipated to increase response reliability.

Bullying involvement. We used items from the revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire [96,97] to measure bullying victimization and offending. In inquiring about bullying victimization, we asked about three different deviant activities, such as “Someone called me names;” “I was physically hit or harmed;” “I was threatened of stalked (followed around);” or “None of these happened to me.” Similar questions were asked to measure bullying offending by changing the above questions to offending, respectively. Answer options were binary (0 No, 1 Yes), and participants could select multiple options. Utilizing the Massachusetts Aggression Reduction Center Questionnaire [98], we used additional items to examine bullying perpetration: “Because you were angry, possibly, or for any reason, during high school, did you ever: 1. spread a rumor about someone; 2. call someone names; 3. stare at someone in a mean way; 4. ignore someone; 5. try to get others to stop liking someone; 6. or just be mean to someone deliberately?” (0 No, 1 Yes), and an additional variable to measure bullying victimization in elementary, middle, and high school, respectively: “A kid was repeatedly mean to me, and it really bothered me” (0 No, 1 Yes). A factor was created for bullying victimization including the six indicators (i.e., “Someone called me names;” “I was physically hit or harmed;” “I was threatened of stalked (followed around)”; bullying victimization in elementary, middle, and high school, respectively: “A kid was repeatedly mean to me, and it really bothered me”), with an eigenvalue of 2.14 (35.59% of variance) and Ω = 0.64.

Cyberbullying involvement. To assess different forms of cyberbullying involvement, we used one item, again, from the Massachusetts Aggression Reduction Center Questionnaire on online bullying [98,99]: “Cyberbullying can appear in various forms. Based on your answers above, how would you define your role in cyberbullying before/during the pandemic? (Select all that are true).” 1. Witnessed cyberbullying (0 No, 1 Yes), 2. Victimized by cyberbullying (0 No, 1 Yes), 3. Exhibited cyberbullying behavior (0 No, 1 Yes), 4. None of the above (0 No, 1 Yes). Additionally, we took concrete variables from the Massachusetts Aggression Reduction Questionnaire [98] to measure cyberbullying by the level of impact: “Have you been the target of some moderately mean actions online? For example, people spreading rumor about you, or (on purpose) posting pics of an event you weren’t invited to.” (emphasis in original; 0 False, 1 True, but this only happened to me once, 2 True, this happened to me more than once), and “Have you ever experienced pretty severe acts of meanness online? For example: people posting vicious rumors about me, or doctoring a photo of me in a really bad way, or passing around a pic I didn’t want distributed” (emphasis in original; 0 False, 1 True, but it was only one incident, 2 True, but this was several repeated incidents or one incident repeated more than twice). Given the repeated or ongoing nature of cyberbullying [2], we only used answer options three to measure both moderate and severe levels of cyberbullying victimization. A cyberbullying victimization factor was created with the three indicators (i.e., “Victimized by cyberbullying”, “Have you been the target of some moderately mean actions online?”, and “Have you ever experienced pretty severe acts of meanness online?”), with an eigenvalue of 1.92 (64.02% of variance), with saturations of 0.73, 0.82, and 0.85, respectively, and Ω = 0.74. Furthermore, two factors were created for overall victimization, including both bullying and cyberbullying victimization factors (eigenvalue of 1.48, 74.03% of variance, and saturations of 0.86), and for overall offending, including the two indicators of bullying and cyberbullying perpetration (eigenvalue = 1.09, 54.33%, saturations of 0.74).

Family characteristics. Three items were used to assess parenting style, attachment, and phubbing. To measure parenting style, we used four distinct parenting styles [76,87,100]. Maccoby and Martin [76] built upon Baumrind’s [101] seminal typology of parenting by using the demandingness and responsiveness dimensions comprising four distinct parenting styles [102]. According to their typology, authoritative parents are demanding and responsive—these parents are child-centered but have clear and consistent expectations for their children within a warm and nurturing environment. Authoritarian parents are demanding but unresponsive—they are strict rule setters who punish non-compliance, but they do not demonstrate much warmth or affection toward their children. Indulgent or “helicopter” parents [84] are overprotective, set few rules but demonstrate considerable affection, and often wish to be friends with their children first and foremost. Finally, neglectful parents are neither demanding nor responsive. Utilizing the above four categories, we evaluated parenting style with the question “How would you describe your parents (or guardians)?” and four response options were presented: Neglectful: (1) “Not very involved; they let me do what I wanted, mostly.” Authoritarian: (2) “Not very warm, but very strict, and they enforce rules.” Helicopter/indulgent/overprotective: (3) “Loving but too “hovering” and too involved.” And Authoritative/democratic: (4) “Warm and loving; they also had firm rules, but not usually excessively strict.”

Parental attachment was assessed with measuring parent-child communication intensity by asking “How would you characterize your interactions with your parents, while in high school?” with three response options: (0) “I did not have an active relationship with either parent.” (1) “I had an active relationship with one parent, but not the other.” (2) “I had an active relationship with both parents.” We used these measures based on the findings of Popp and Peguero [48], who, on a national sample of 10,440 U.S. youth, found that students from a two-parent/guardian household report a higher level of commitment than students from a single-parent/guardian household. According to their results, as parental involvement increases, the students’ commitment and involvement increase, which decreases the risks of victimization and offending [48].

Teacher attachment was measured utilizing the Massachusetts Aggression Reduction Questionnaire’s teacher attachment perception question [98] asking “Did you feel that you really liked and/or connected with any of your teachers?” with three answer options that we coded high level of attachment (“Yes, definitely—at least one teacher each year”; 0 No, 1 Yes), moderate level of attachment (“Yes, but not every year”; 0 No, 1 Yes) and low level of attachment (“No, I didn’t really connect with my teachers”; 0 No, 1 Yes).

Finally, a question taken from the Partner Phubbing Scale developed by Roberts and David [18], adapted to adolescents by Hong et al. [103] was administered to examine the frequency of parental phubbing, “Before high school, did you remember feeling like you wanted your parents’ attention but they were distracted by their own technology (laptop, phone, etc.)?” with three response options: (1) rarely or never, (2) sometimes, now and then, (3) regularly, often. An additional variable was used to measure parental distraction from the Massachusetts Aggression Reduction Questionnaire [98]: “Did your parents ever get so involved online with a game or an app that they didn’t pay you enough attention?” (0 No, 1 Yes). A factor was created based on these two indicators, which had an eigenvalue of 1.42 (71.16% of variance) and saturations of 0.84 for each indicator.

Demographics. Some items were used to collect information about gender (What is your gender identity? 1. Male, 2. female, 3. transitioning to male, 4. transitioning to female, 5. gender fluid or intersex, or 6. other; Birth year (What year were you born?); Ethnicity (What is your ethnic group? 1. White, 2. Black, or African American, 3. American Indian or Alaska Native, 4. Asian, 5. Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander, 6. Hispanic, 7. Mixed/other), and school type (What kind of school did you attend for high school? 1. I went to a public (or charter) high school, 2. I went to a parochial or private school for high school, 3. I was home-schooled).

First, descriptive statistics were examined by presenting frequency and percentage distribution in all the separate indicators of bullying, cyberbullying, and family relationships (parenting style, attachment, and phubbing). Five factors of phubbing, bullying victimization, cyberbullying victimization, overall victimization, and overall offending were calculated to be used in the correlation, regression, mediation, and structural equation analyses. These factors were created by conducting exploratory factor analyses with the respective indicators to save factorial scores as variables using the regression method in SPSS 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The variables were non-normally distributed, as shown by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (p < 0.001), and non-parametric and robust analyses were conducted. Second, bivariate Spearman correlations were calculated between all study variables. Third, robust hierarchical regression analyses were conducted, using the RLM macro, which applies Davidson-MacKinnon (HC3) heteroskedasticity-consistent estimator for robust standard errors and calculates the Shrunken R2. These analyses were conducted to explain the bullying and cyberbullying in the cases of both victimization and offending, based on the indicators of teacher attachment, parental attachment, parental phubbing, and parenting styles, and controlling for demographics. In the first step, gender, age, ethnicity, and school type were included, and in the second step, teacher attachment, parental attachment, parental phubbing, and parenting styles were added to the regression equation. Fourth, a multiple partial mediation model was tested, to examine the partial mediation of parental bonding (Mediator 1, M1) and phubbing (Mediator 2, M2) in the relationship between parenting style (Independent variable, X) and bullying/cyberbullying factor (Dependent variable, Y). PROCESS macro for SPSS was used to design the mediational model number 6 [104]. This model tested the mediation of two interrelated mediators (M1 → M2) in the relationship between X and Y. Thus, this model included: (a) the effects by parenting styles (X) on parental bonding (M1), parental phubbing (M2) and the factor of bullying/cyberbullying (Y); (b) the effects by parental bonding (M1) on parental phubbing (M2) and the factor of bullying/cyberbullying (Y); (c) the effect by parental phubbing (M2) on the factor of bullying/cyberbullying (Y). Davidson-MacKinnon (HC3) heteroskedasticity-consistent estimator and covariance matrix estimator were used. 5000 bootstrap samples were used for percentile bootstrap confidence intervals. Standardized coefficients were also reported for total, direct and indirect effects. Fifth, gender moderation in the relationships between family variables and bullying/cyberbullying was examined, using model 1 in macro PROCESS, with robust estimator and showing Johnson-Neyman output. Standardized coefficients were reported. All the previous analyses were conducted with statistical package SPSS 21.0 [105]. Finally, based on the previous results a structural equation model was tested with program EQS 6.1 (Multivariate Software, Inc., Encino, CA, USA) also using robust fit indicators, such as Satorra-Bentler (SB) χ2, Bentler-Bonnet Non-Normed fit index (BBNNFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA).

Table 2 and Table 3 show the frequency and percentage distribution of study variables. According to Table 2, most participants reported a high level of attachment to parents and teachers, and a democratic parenting style. Around 14% of the sample indicated a frequent parental phubbing.

Table 2: Descriptive statistics of variables of teachers’ and parental attachment, parenting style, and phubbing.

| Variable | Categories | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Attachment to teachers | Low | 33 (6.1) |

| Moderate | 188 (34.5) | |

| High | 324 (59.4) | |

| Parental attachment | Low | 44 (8.1) |

| Moderate | 198 (36.3) | |

| High | 303 (55.6) | |

| Parenting style | Neglectful | 58 (10.6) |

| Authoritarian | 55 (10.1) | |

| Overprotective | 73 (13.4) | |

| Democratic | 359 (65.9) | |

| Phubbing experience | No | 466 (85.5) |

| Yes | 79 (14.5) | |

| Phubbing frequency | Never | 285 (52.3) |

| Sometimes | 184 (33.8) | |

| Often | 76 (13.9) |

In Table 3, a quarter of the participants indicated cyberbullying victimization, around 7% of the sample acknowledged being a cyberbullying offender, and most of the participants indicated that they observed bullying of others (bystanders). Concerning the frequency and intensity of cyberbullying victimization, 18.8% of the sample indicated frequent moderate victimization, and 7.5% reported frequent severe victimization. Furthermore, the experience of offline bullying victimization increased from elementary to middle school (from percentages of a quarter of the sample to almost a third of the sample) but plummeted in high school (around 13%). More than half of the respondents indicated that someone called them names, and a quarter acknowledged being threatened by others. Around 14% reported physical bullying victimization, and a third of the sample indicated bullying perpetration (of any type).

Table 3: Descriptive statistics of cyberbullying and bullying variables.

| Variable | Categories | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyberbullying | Bystander | No | 227 (41.7) |

| Yes | 318 (58.3) | ||

| Victim | No | 406 (74.5) | |

| Yes | 139 (25.5) | ||

| Offender | No | 506 (92.8) | |

| Yes | 39 (7.2) | ||

| None | No | 364 (66.8) | |

| Yes | 181 (33.2) | ||

| Moderate cyberbullying victimization | Never | 268 (49.5) | |

| Once | 172 (31.7) | ||

| More than once | 102 (18.8) | ||

| Severe cyberbullying victimization | Never | 399 (73.2) | |

| Once | 105 (19.3) | ||

| More than once | 41 (7.5) | ||

| Bullying | Victimization in Elementary School | No | 401 (73.6) |

| Yes | 144 (26.4) | ||

| Victimization in Middle School | No | 387 (71.0) | |

| Yes | 158 (29.0) | ||

| Victimization in High School | No | 476 (87.3) | |

| Yes | 69 (12.7) | ||

| Called me names | No | 265 (48.6) | |

| Yes | 280 (51.4) | ||

| Been physically hit | No | 468 (85.9) | |

| Yes | 77 (14.1) | ||

| Been threatened | No | 409 (75.0) | |

| Yes | 136 (25.0) | ||

| None | No | 322 (59.1) | |

| Yes | 223 (40.9) | ||

| Offender | No | 360 (66.1) | |

| Yes | 185 (33.9) | ||

3.2 Correlation and Linear Regression Analyses

Factors were calculated for parental phubbing (composed of the indicators of phubbing experience and phubbing frequency), cyberbullying victimization (composed of indicators of being victim of cyberbullying, moderate cyberbullying and severe cyberbullying), bullying victimization (with the indicators of having been bullied in elementary, middle and high school and the indicators of having been called names, physically hit and threatened), victimization (by integrating cyberbullying and bullying victimization factors), and offending (composed of the separate indicators of cyberbullying offender and bullying offender). These factors were created by applying factor analyses, which we used for creating variables based on regression. After calculating these variables, correlations and regression analyses were conducted.

Table 4 presents bivariate correlations between study variables. Results show that stronger parental attachment and more democratic parenting styles were associated with less parental phubbing and less adolescent victimization, in both cyberbullying and bullying. Parenting style and parental attachment showed a positive correlation. Furthermore, attachment to teachers had a negative effect on bullying perpetration. More parental phubbing was associated with more adolescent victimization and perpetration, in both online and offline bullying. In addition, positive correlations were observed between victimization and offending.

Table 4: Bivariate Spearman correlations between study variables.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Attachment to teachers | 1 | |||||||||

| 2. Parental attachment | 0.13** | 1 | ||||||||

| 3. Parenting styles | 0.06 | 0.36*** | 1 | |||||||

| 4. Phubbing | −0.04 | −0.18*** | −0.23*** | 1 | ||||||

| 5. Cyberbullying victimization | −0.02 | −0.15** | −0.06 | 0.20*** | 1 | |||||

| 6. Bullying victimization | −0.04 | −0.21*** | −0.20*** | 0.23*** | 0.48*** | 1 | ||||

| 7. Overall Victimization | −0.03 | −0.21*** | −0.15*** | 0.25*** | 0.86*** | 0.86*** | 1 | |||

| 8. Cyberbullying offending | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.12** | 0.18*** | 0.05 | 0.13** | 1 | ||

| 9. Bullying offending | −0.11** | −0.07 | −0.02 | 0.09* | 0.29*** | 0.26*** | 0.31*** | 0.09* | 1 | |

| 10. Overall Offending | −0.10* | −0.05 | −0.02 | 0.14** | 0.31*** | 0.21*** | 0.30*** | 0.74*** | 0.74*** | 1 |

Table 5 presents the results of three linear regression analyses to explain cyberbullying victimization, bullying victimization, and overall victimization, based on demographics, attachment, parenting styles, and parental phubbing. Results showed a positive effect of parental phubbing and a negative effect of parental attachment on both cyberbullying and bullying victimization. Moreover, a democratic parenting style had a negative effect on only bullying victimization, while teachers’ attachment had no significant effects. School type and gender had significant effects on cyberbullying victimization, so that more victimization was reported in females and non-binary students and those enrolled in private schools. The size of explained variance was small in all three analyses.

Table 5: Linear regression analysis to explain victimization, based on demographics, attachment, parenting styles, and phubbing.

| Variable | Cyberbullying Victimization | Bullying Victimization | Overall Victimization | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F/R2 | β | F/R2 | β | F/R2 | β | |

| Step 1 | 5.07***/0.02 | 2.08/0.01 | 3.88**/0.02 | |||

| Gender | 0.08*** | 0.06* | 0.08*** | |||

| Age | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.01 | |||

| Ethnicity | −0.03 | −0.02 | −0.03 | |||

| School type | 0.31* | −0.10 | 0.12 | |||

| Step 2 | 5.95***/0.05 | 6.27***/0.08 | 7.31***/0.08 | |||

| Gender | 0.07** | 0.03 | 0.06* | |||

| Age | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | |||

| Ethnicity | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.03 | |||

| School type | 0.31* | −0.09 | 0.12 | |||

| Teachers’ attachment | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.02 | |||

| Parental attachment | −0.17* | −0.22** | −0.12** | |||

| Parenting styles | 0.03 | −0.11* | −0.05 | |||

| Parental phubbing | 0.17** | 0.16*** | 0.19*** | |||

Table 6 shows the results of linear regression analyses to explain overall offending, based on demographics, attachment, parenting styles, and parental phubbing. Results indicated that parental phubbing had a positive effect on offending, while teacher attachment had a negative effect. Female participants reported more offending. The Shrunken R2 value was low.

Table 6: Linear regression analysis to explain offending, based on demographics, attachment, parenting styles and phubbing.

| Variable | Overall Offending | |

|---|---|---|

| F/R2 | β | |

| Step 1 | 3.09*/0.01 | |

| Gender | 0.06* | |

| Age | −0.02 | |

| Ethnicity | −0.03* | |

| School type | −0.07 | |

| Step 2 | 3.30**/0.02 | |

| Gender | 0.05* | |

| Age | −0.01 | |

| Ethinicity | −0.03* | |

| School type | −0.06 | |

| Teachers’ attachment | −0.16* | |

| Parental attachment | −0.04 | |

| Parenting style | 0.03 | |

| Parental phubbing | 0.12* | |

3.3 Mediation and Moderation Analyses

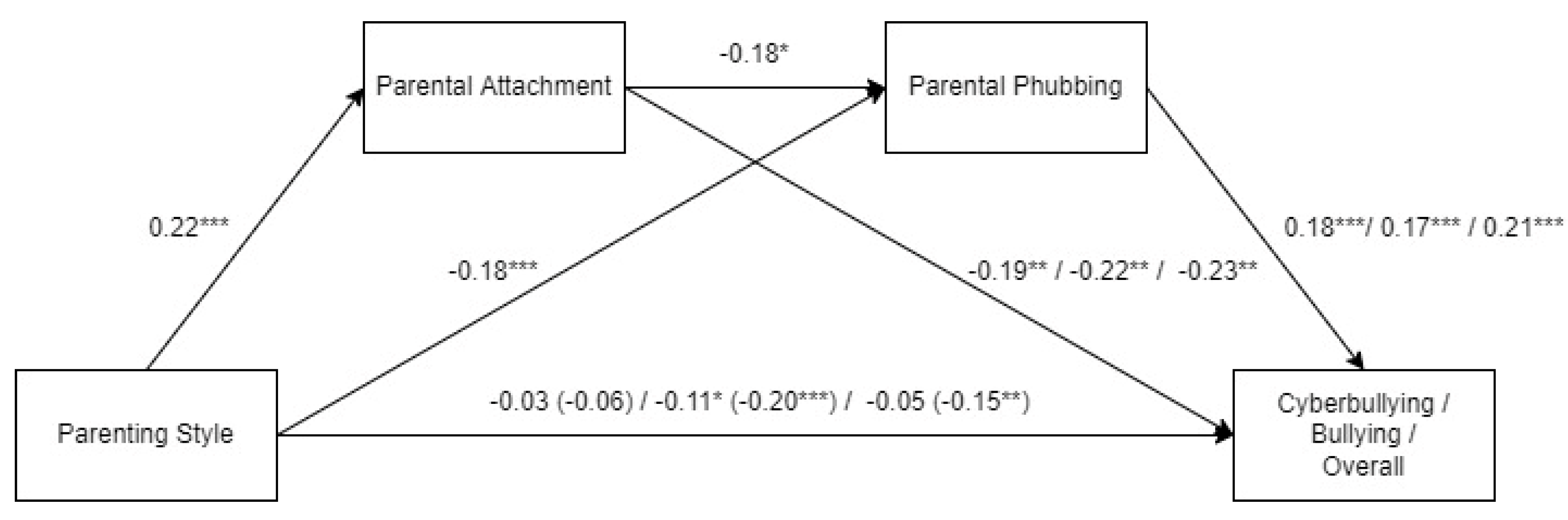

Based on the previous regression analyses, partial mediation analyses were performed to examine victimization. Fig. 1 shows a partial mediation model of parental attachment and parental phubbing in the relationship between parenting style and adolescent victimization variables (cyberbullying victimization, bullying victimization, and overall victimization). The model shows that a more democratic parenting style is associated with more parental attachment and less parental phubbing, what is consistent with Hypothesis 1. Moreover, more parental attachment was related toless phubbing, in line with Hypothesis 2. Furthermore, more parental attachment and less parental phubbing were associated with less adolescent victimization, in both cyberbullying and bullying, as expected in Hypothesis 3. Concerning mediational analysis, the results indicated: (a) a total mediation of parental attachment and phubbing in the relationship between parenting style and adolescent cyberbullying victimization; and (b) a partial mediation of parental attachment and phubbing in the relationship between parenting style and adolescent bullying victimization. In the case of overall victimization, the results showed a significant total effect by parenting, but it lost significance after including the mediators. Table 7 describes the indirect effects of parenting style on victimization through parental attachment and/or phubbing. Results point out that parenting style had significant indirect effects on adolescent cyberbullying and bullying victimization through its effects on parental attachment, on parental phubbing, and through its effects on both parental attachment and phubbing. Thus, democratic parenting was associated with less adolescent victimization through its associations with more attachment and less phubbing. In the case of offline bullying, parenting style maintained a negative relationship with victimization after adding the mediators.

Figure 1: Partial mediation of parental attachment and phubbing in the relationship between parenting style and adolescent victimization (separating cyberbullying, bullying, or overall types). Note: ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. Dependent Variable: Cyberbullying victimization factor: F = 9.54, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.05; Bullying victimization factor: F = 15.75, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.09; Overall victimization factor: F = 15.60, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.09.

Table 7: Indirect effects of the partial mediation of parental attachment and phubbing in the relationship between parenting style and victimization (separating cyberbullying, bullying, or overall types).

| Victimization Type | Cyberbullying | Bullying | Overall | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Boot 95% CI | β | Boot 95% CI | β | Boot 95% CI | |

| Indirect 1: Parenting Style → Attachment → Victimization | −0.04 | −0.08, −0.01 | −0.05 | −0.09, −0.02 | −0.05 | −0.09, −0.02 |

| Indirect 2: Parenting Style → Phubbing → Victimization | −0.03 | −0.06, −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.06, −0.01 | −0.04 | −0.07, −0.01 |

| Indirect 3: Parenting Style → Attachment → Phubbing → Victimization | −0.01 | −0.02, −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.02, −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.02, −0.01 |

| Indirect 1–Indirect 2 | −0.01 | −0.05, 0.04 | −0.02 | −0.06, 0.03 | −0.02 | −0.06, 0.03 |

| Indirect 1–Indirect 3 | −0.04 | −0.07, −0.01 | −0.04 | −0.08, −0.01 | −0.04 | −0.08, −0.01 |

| Indirect 2–Indirect 3 | −0.03 | −0.06, −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.05, −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.06, −0.01 |

Finally, gender moderations in the effects of victimization by parental attachment, phubbing, and parenting styles were examined. Table 8 describes the results of these moderation analyses, showing that: a) gender did not moderate the effects of neither parenting style nor phubbing on any adolescent victimization or offending; and b) gender moderated the relationship between parental attachment and adolescent cyberbullying victimization, so that a significant negative effect was only observed in females (β = −0.26, p < 0.001; not significant in males: β = 0.13, p = 0.282).

Table 8: Gender moderation analyses of the relationships of family indicators with victimization and offending variables.

| Variable | Cyberbullying Victimization | Bullying Victimization | Victimization | Offending | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | β | F | β | F | β | F | β | |

| Parenting Style × Gender | 4.67** | −0.03 | 8.55*** | −0.01 | 7.43*** | −0.03 | 2.38 | −0.02 |

| Attachment × Gender | 8.14*** | −0.10** | 9.36*** | −0.03 | 10.73*** | −0.07* | 2.55 | −0.02 |

| Phubbing × Gender | 11.71*** | −0.01 | 10.36*** | 0.01 | 14.16*** | 0.01 | 4.92** | 0.01 |

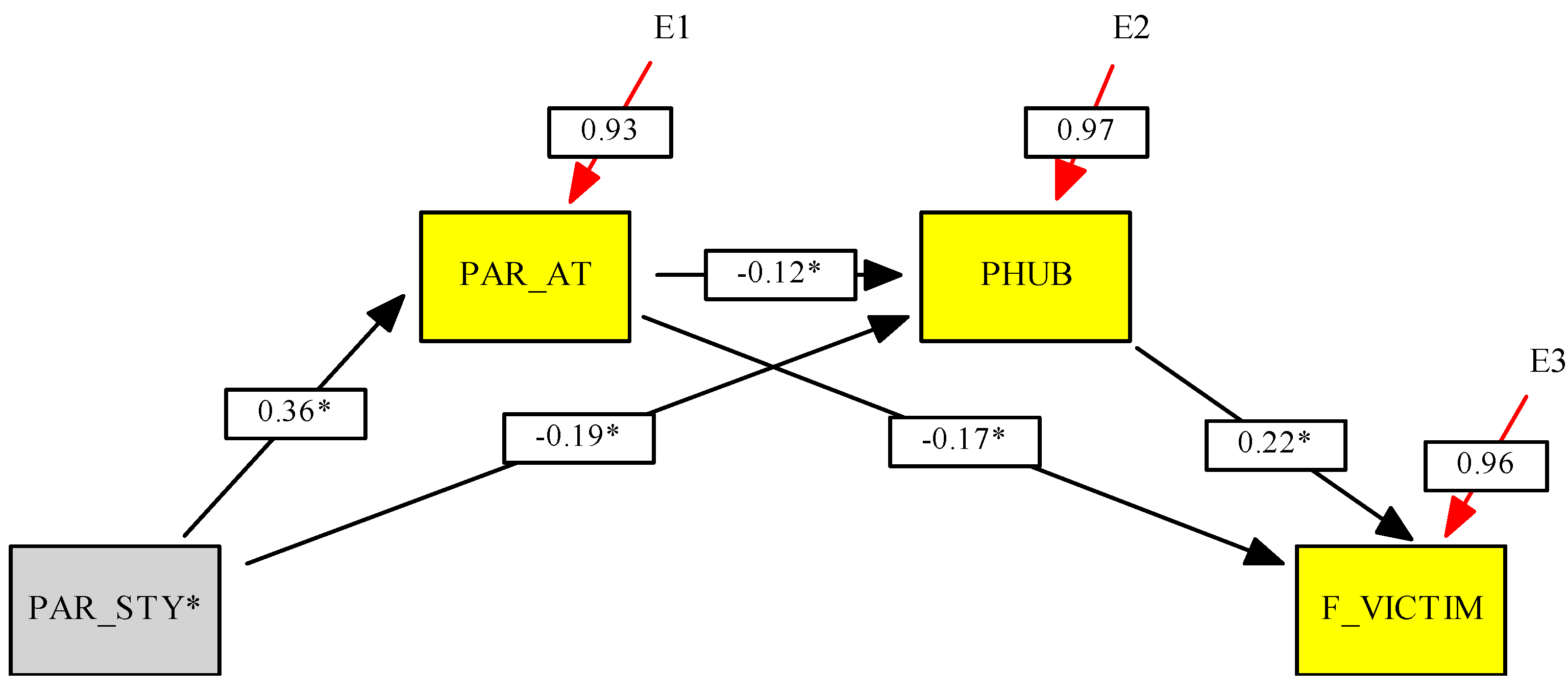

Finally, a structural equation model was tested to explain overall victimization by integrating the results observed in the mediational analyses (Fig. 2). The model corroborated the previous results. The model reached a good data fit, SB χ2 = 1.27, p = 0.259, BBNNFI = 0.988, CFI = 0.998, RMSEA = 0.022, and all measurement equations were significant. In this model, parental attachment and phubbing were total mediators between parenting styles and overall victimization.

Figure 2: Structural equation model to explain victimization. Note. PAR_STY = Parenting style; PAR_AT_ Parental attachment; PHUB: Parental phubbing factor; F_VICTIM: Overall Victimization factor. *p < 0.05.

The current study enhances understanding of patterns and associations between attachment, parental style, parental phubbing, and youth bullying involvement among American college students. It contributes to the growing bullying research by integrating theoretical propositions from several individual-level risk and protective factors. While previous empirical studies in the field of criminology have tested existing theories to explain cyberbullying perpetration, most have focused on a single theoretical proposition [106,107]. In addition, previous research only examined the relationships between adolescent bullying/cyberbullying involvement and either attachment to significant adults (such as parents and teachers), parenting styles’ mitigating effects on child bullying and victimization, or parental phubbing’s impacts on children’s behavior. This study is unique in integrating the above factors and examining their moderating and mediating effects on adolescent bullying and cyberbullying involvement. The analysis also provides a comprehensive picture of the possible indirect effects of parenting styles on adolescent bullying and cyberbullying involvement by specifically examining the moderating effects of parental attachment and parental phubbing on an age group of students whose attachment to parents is less crucial than in childhood, yet their relationship with parents still can be formative to online behaviors and deterministic to online victimization. We executed our analysis on a sample of American college students who answered retrospective questions about bullying offending and victimization in their adolescent years. Our study finds that problematic internet-related behavior in parents can indeed significantly increase adolescent risk factors in online spaces. Specifically, the analyses corroborated the negative association between strong positive (secure) parental attachment and democratic parenting styles and cyberbullying and bullying victimization of children [35,36,38,39,41,42,78,79], and the positive relationship between parental technoference (phubbing) and both cyberbullying and bullying victimization and offending behaviors [17,57,58,59]. These results were consistent with our Hypotheses 1–3.

In our sample, teacher attachment only showed meaningful effects on making offline (visible) bullying offending decline (although causality could not be established), therefore, this relationship was deemed insignificant compared to previous research advocating for stronger teacher and school attachment to mitigate the risks of students’ bullying involvement [46,47]. Perhaps this is due to peer influence becoming stronger than that of teachers during adolescence. According to Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory [19], the peer microsystem gains prominence as adolescents increasingly spend more time with friends than with teachers, altering the balance of influence. Bandura’s social learning theory [32] further explains that adolescents tend to imitate behaviors they observe in peers, especially when those behaviors receive approval, which can encourage engagement in risky activities. Collectively, these developmental theories underscore why adolescents’ behaviors frequently reflect the values of their peer groups more than the expectations of their teachers. Additionally, this finding may be due to the simplified measures we applied. Therefore, we propose to repeat the study with refined attachment measures. Female and non-binary students, as well as private school students, reported more cyber and traditional bullying victimization.

We also found that the relationship between parenting style and victimization was strongly mediated by parental attachment and phubbing when it came to cyberbullying victimization and partially mediated by offline bullying victimization. However, looking in-depth into these relationships, we identified parenting styles’ significant indirect effect on both online and offline victimization, through parental attachment and phubbing. In particular, we found democratic/authoritative parenting’s strong association with less victimization because this parenting style was related to stronger parental attachment and, at the same time, less parental phubbing. Gender moderated the relationship between parental attachment and cyber victimization (not offending) in that females who experienced a firm but warm (democratic) parenting style at home were more likely to be strongly attached to their parents, and less likely to be victimized online. While this pattern aligns with prior evidence suggesting that parenting practices affect boys and girls differently—such as findings that parental supervision is more protective for boys against offline antisocial behaviors [13], while authoritarian control tends to affect girls more negatively [16,17] and may even provoke resistance or defiance [94]—our results should be interpreted with caution. Given the severe gender imbalance in our sample (73.6% female), these moderation effects cannot be considered definitive and may be partially driven by the predominance of female respondents. Thus, rather than drawing strong conclusions about gendered mechanisms, we view this result as a preliminary indication that democratic, conversational parenting may play a particularly protective role for girls in the online context, warranting further investigation in studies with more balanced gender distributions.

At the same time, the current analysis only considers gender as a moderator. Other potentially influential dimensions—such as parents’ educational level, whether parents accompany their children, whether children reside in boarding schools, and the extent of children’s own use of electronic products—may also differentially shape bullying and victimization outcomes, and future studies should extend the model to incorporate these variables.

The study contributes to the existing literature by further deciphering the connections between democratic parenting style and adolescent behavioral problems that often lead to cyberbullying and bullying victimization and offending. Concerning parental attachment, theorized by Bronfenbrenner [51], Bandura [32], Hirschi [28], and Bowlby [23], we found that its relationship with adolescent delinquency is much more complicated, and therefore it should be studied taking into consideration the complexities of different factors influencing the parent-child relationships. One factor is parenting style, which, according to our study, can indeed be mediated by technology-related parental dysfunctions such as parents’ excessive use of technology. Parenting style plays a critical role in shaping the likelihood of adolescent victimization, both online and offline, through its influence on parental attachment and behaviors such as phubbing, which children can imitate and learn from parents at home. The findings also underscore the moderating role of gender, showing that girls who experience democratic parenting tend to form stronger attachments to parents, thereby reducing their vulnerability to online victimization. This suggests that girls, in particular, benefit from a nurturing and balanced parenting approach, which fosters resilience against cyber threats. Future research must seek a more nuanced understanding of how parenting styles and parents’ own digital habits affect adolescent outcomes, including victimization and delinquency. However, the current analyses remain limited by insufficient consideration of socioeconomic and other family factors (e.g., number of siblings, parental employment status) that may shape these dynamics. Extending the variables along with the above would provide a more holistic view of how the family environment and technology intersect in shaping youth behavior and risks. In addition, adolescent bullying involvement must be studied in light of how adolescents interact with broader systems; for instance, peers and media, as suggested by Bronfenbrenner’s exosystem. Thus, we should acknowledge that the validity of our conclusions is limited. Another limitation is our convenience sample. Although convenience samples of college students are not rare [108], this renders the findings not generalizable to other populations, particularly since existing studies on phubbing and bullying come primarily from non-Western contexts like China [65,66,67]. Nevertheless, our results are in line with international studies: parental phubbing is strongly associated with greater child bullying involvement. This convergence suggests a likely cross-cultural effect, though replication in more diverse global samples is needed.

The retrospective and the self-reporting nature of the questions might have further compromised data reliability. All these attributes make the findings challenging to compare with random samples and multi-informant studies collecting data from various sources (e.g., peer groups, teachers, parents, etc.) and bear the possibility of under- or overreporting [109]. However, we tried to minimize the effect of recall bias by not telling participants the specific exposure of interest so they would not unconsciously emphasize or downplay it. Future studies should also triangulate using data from different sources, such as parent and teacher reports and observations. Furthermore, the determination of bully/cyberbully and victim roles depended on dichotomous variables, and the results might change with more precise measurements, particularly those that account for the intensity and frequency of such behaviors. Thus, these limitations of our instruments suggest a cautious interpretation of the results.

Although according to research, each element (attachment, commitment, involvement, and belief) of the social bonding theory independently influences the adolescent’s propensity toward criminal behavior [48], the four elements are highly interconnected, and their combined effect is supposed to be greater than the individual effects [28]. However, our study utilized a simplified scale to measure parenting style, as well as parental and teacher attachment. This gap needs to be addressed, particularly through future research employing richer, multidimensional measures of teacher–student attachment. Additionally, Kinoshita M [29] studied the impact of personal and familial characteristics on attachments and found that gender had a direct effect on deviant and criminal behavior. We looked at some of the personal characteristics and parenting styles and found that these characteristics only had indirect effects, which were mediated by social attachments. This shows that gender was indicative of the strengths of the adolescents’ social attachments, but what remains unclear is what mediating processes link these demographic characteristics and parenting styles to social attachments.

Some studies have suggested that the causal direction between school attachment or engagement and delinquency might be reversed, or the relationship might be reciprocal [110,111]. In this conceptualization, a youth’s prior delinquent behavior in school might lead to poor treatment in school, which results in a lower level of attachment to teachers and to school in general, contributing to further delinquent behavior. It is also possible that underlying characteristics of individuals, such as self-control, are causally prior to both early delinquent behavior and attachment to school [13,112,113]. Additionally, the statistical effect size in the regression is quite small (Shrunken R² < 10%), thus limiting the model’s predictive power. Importantly, statistical significance in our models still indicates non-random associations worth further exploration. Future studies must conceptualize the link between attachment and deviance more comprehensively, including more individual and structural/contextual factors.

Our study applied measures of parental phubbing to decipher connections between social attachments and bullying involvement. Although our analytical strategy indicated the control measures’ mediating effect in relation between social attachments and bullying involvement, Rabbani and Pusch [13] suggest including additional attitudinal and behavioral measures (e.g., low self-control, substance use, risky driving) to examine social attachments and whether these measures can predict cyberbullying. Future studies must further extend the list of control measures and investigate their effects on adolescent bullying involvement. We also recommend replication of the analysis using validated multi-item instruments such as the Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire [114]. The use of single-item instruments limits the construct validity of our measures, and consequently, of our conclusions.

Based on these findings, bullying prevention strategies that teach parents to correct unwanted behavior [13] and involve parent training interventions might be more effective [115,116] than strictly school-based programs. Multi-modal programs that intervene simultaneously in the home and school are suggested to be more influential in reducing bullying [91] than programs concentrating on schools. Consequently, it is vital to conduct future research seeking to identify more variables for increasing parental attachment mechanisms in the family so school and criminal justice practitioners could be better prepared to address the issue of bullying within the adolescent population. Given our modest explanatory power, we recommend universal or selective (not determinate, individual-risk) approaches: schools and community partners should adopt whole-school climate programs paired with parent components rather than using parenting variables to “screen” or label individual students.

Educating parents about the potentially harmful effects of excessive digital device use on children’s behavior is essential for fostering healthy development. Prolonged screen time can lead to reduced attention span, reduced self-esteem, sleep disturbances, and social withdrawal, both in adults [117] and children [118,119]. Excessive parental use of technology can, indeed, be imitated and learned by children, exacerbating children’s feelings of neglect and being outcast from the family. As our results suggest, children can interpret parental phubbing as a sign of neglect and dominance, which can lead to diminished self-esteem and, consequently, more vulnerability to peer bullying. It also could encourage children to apply similar, excluding or even hostile behavior towards peers, to show dominance or improve rank in the social hierarchy. On the other hand, non-conversational, oppressive parenting is inadequate in preparing children for addressing peer conflicts peacefully and respectfully. Accordingly, practitioner guidance should emphasize low-cost, low-risk practices (e.g., device-free family routines, responsive communication) that are justified even when effect sizes and model fit are modest.

It is equally important to guide parents on the impact of different parenting styles. Authoritative parenting, which combines warmth with clear boundaries, tends to lead to positive behavioral outcomes, while overly permissive or authoritarian approaches may foster negative consequences such as low self-esteem [120,121] or aggression toward others [122]. By raising awareness of these issues, parents can adopt more balanced strategies to nurture their children’s emotional and social well-being and lower their risk of being victimized at school or online.

Parent-involved programs indeed show that integrating parental digital literacy and screen-time education is feasible and effective. Modules that target parental phubbing via implementation intentions reduce phubbing (“If it’s dinner, the phone is parked away”) [123], while family screen-reduction challenges and mindful-parenting practices such as attentive listening, single-tasking during child interactions, improve parent–child synchrony and lower child externalizing [124,125]. Such educative elements are embedded in the Positive Parenting Program (Triple P), a multi-level system offering seminars, groups, and individualized coaching that strengthens authoritative warmth, clear expectations, and consistent follow-through, paired with co-created family media plans and device-attention routines [126]. At school, adding an “adult digital habits” session to parent-involved, whole-school anti-bullying efforts such as Media Heroes (Medienhelden), a cyberbullying curriculum with structured classroom lessons and parent outreach [127], and the Friendly Schools Friendly Families program, which builds home-school communication and parent/teacher competencies through coordinated activities and workshops, are proven effective in preventing and reducing bullying [128].

This study contributes to the growing bullying research by further investigating the mediating impacts of parental attachments and parental phubbing on the link between parenting style and adolescents’ bullying involvement. However, because our regression models showed modest explanatory power, these associations should inform broad prevention priorities rather than individual-level prediction. In practical terms, two facts argue for action even with modest model fit: the high prevalence of cybervictimization in our sample (25.5%) and the frequent bystander role (58.3%). Findings reaffirm the value of nurturing, boundary-setting parenting and close parent–child/teacher bonds, while highlighting a contemporary risk—parental device-related inattention. Despite rapid technological change, the core need for stable human connection remains central to reducing bullying involvement.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Myunghoon Roh, Katalin Parti, Diego Gomez-Baya, Cheryl E. Sanders and Elizabeth K. Englander; methodology, Katalin Parti, Cheryl E. Sanders and Elizabeth K. Englander: formal analysis, Myunghoon Roh, Katalin Parti, and Diego Gomez-Baya; data curation, Katalin Parti, Cheryl E. Sanders and Elizabeth K. Englander; writing—original draft preparation, Myunghoon Roh, Katalin Parti, Diego Gomez-Baya, Cheryl E. Sanders and Elizabeth K. Englander; writing—review and editing, Myunghoon Roh, Katalin Parti, Diego Gomez-Baya, Cheryl E. Sanders and Elizabeth K. Englander; project administration, Katalin Parti, Cheryl E. Sanders and Elizabeth K. Englander. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from Diego Gomez-Baya, DGB, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: All participants provided written informed consent. The research was approved by all three participating universities’ Institutional Review Boards: The Institutional Review Board of Bridgewater State University (IRB approval code 2025126), the Institutional Review Board of Metropolitan State University Denver (IRB approval code 2025126), and the Institutional Review Board of Virginia Tech (IRB approval code 20-647).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Olweus D . Bullying at school: basic facts and effects of a school based intervention program. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1994; 35( 7): 1171– 90. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01229.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Englander E , Donnerstein E , Kowalski R , Lin CA , Parti K . Defining cyberbullying. Pediatrics. 2017; 140( Suppl 2): S148– 51. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-1758U. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Smith PK , Mahdavi J , Carvalho M , Fisher S , Russell S , Tippett N . Cyberbullying: its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008; 49( 4): 376– 85. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01846.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Patchin JW . 2023 cyberbullying data [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Dec 1]. Available from: https://cyberbullying.org/2023-cyberbullying-data [Google Scholar]

5. Kowalski RM , Limber SP . Psychological, physical, and academic correlates of cyberbullying and traditional bullying. J Adolesc Health. 2013; 53( 1 Suppl): S13– 20. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Bansal S , Garg N , Singh J , Van Der Walt F . Cyberbullying and mental health: past, present and future. Front Psychol. 2024; 14: 1279234. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1279234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Litwiller BJ , Brausch AM . Cyber bullying and physical bullying in adolescent suicide: the role of violent behavior and substance use. J Youth Adolesc. 2013; 42( 5): 675– 84. doi:10.1007/s10964-013-9925-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Gámez-Guadix M , Orue I , Smith PK , Calvete E . Longitudinal and reciprocal relations of cyberbullying with depression, substance use, and problematic Internet use among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2013; 53( 4): 446– 52. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.03.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Marengo N , Borraccino A , Charrier L , Berchialla P , Dalmasso P , Caputo M , et al. Cyberbullying and problematic social media use: an insight into the positive role of social support in adolescents-data from the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children study in Italy. Public Health. 2021; 199: 46– 50. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2021.08.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Chiang CJ , Chen YC , Wei HS , Jonson-Reid M . Social bonds and profiles of delinquency among adolescents: Differential effects by gender and age. Children and Youth Services Review. 2020; 110: 104751. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Pusch N . Protective factors for violent victimization in schools: a gendered analysis. J Sch Violence. 2019; 18( 4): 597– 612. doi:10.1080/15388220.2019.1640706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Pusch N , Holtfreter K . Sex-based differences in criminal victimization of adolescents: a meta-analysis. J Youth Adolesc. 2021; 50( 1): 4– 28. doi:10.1007/s10964-020-01321-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Rabbani MG , Pusch N . Explaining the victim-offender overlap of cyberbullying using low self-control and parental bonds. Crime Delinquency. 2025; 71( 10): 3219– 43. doi:10.1177/00111287231218690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Baldry AC , Sorrentino A , Farrington DP . Cyberbullying and cybervictimization versus parental supervision, monitoring and control of adolescents’ online activities. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2019; 96: 302– 7. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.11.058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Wright MF . Parental mediation, cyberbullying, and cybertrolling: the role of gender. Comput Hum Behav. 2017; 71: 189– 95. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.01.059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Georgiou SN , Ioannou M , Stavrinides P . Parenting styles and bullying at school: the mediating role of locus of control. Int J Sch Educ Psychol. 2017; 5( 4): 226– 42. doi:10.1080/21683603.2016.1225237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Dixon D , Sharp CA , Hughes K , Hughes JC . Parental technoference and adolescents’ mental health and violent behaviour: a scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2023; 23( 1): 2053. doi:10.1186/s12889-023-16850-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Roberts JA , David ME . My life has become a major distraction from my cell phone: partner phubbing and relationship satisfaction among romantic partners. Comput Hum Behav. 2016; 54: 134– 41. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Bronfenbrenner U . The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press; 1979. doi:10.4159/9780674028845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Sroufe L , Egeland B , Carlson E , Collins W . The development of the person: the Minnesota study of risk and adaptation from birth to adulthood. New York, NY, USA: Guilford; 2005. [Google Scholar]

21. Bowlby J . A secure base: parent-child attachment and healthy human development. New York, NY, USA: Basic Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

22. Dishion TJ , McCord J , Poulin F . When interventions harm: peer groups and problem behavior. Am Psychol. 1999; 54( 9): 755– 64. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.54.9.755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Bowlby J . Attachment and loss. Vol. 1, Attachment. New York, NY, USA: Basic Books; 1969. [Google Scholar]

24. Ainsworth MDS , Blehar MC , Waters E , Wall S . Patterns of attachment: a psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, NJ, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1978. [Google Scholar]

25. Allen JP , Land D . Attachment in adolescence. Dev Psychol. 1999; 35( 5): 1236– 45. [Google Scholar]

26. Dishion TJ , Patterson GR . The development and ecology of antisocial behavior. In: Cicchetti D , Cohen DJ , editors. Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 3. Risk, disorder, and adaptation. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley; 2006. p. 503– 41. doi:10.1002/9780470939406.ch13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. van Ijzendoorn MH , Schuengel C , Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ . Disorganized attachment in early childhood: meta-analysis of precursors, concomitants, and sequelae. Dev Psychopathol. 1999; 11( 2): 225– 49. doi:10.1017/s0954579499002035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Hirschi T . Causes of delinquency. London, UK: Routledge; 2017. doi:10.4324/9781315081649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Kinoshita M , Kawabata Y , Onishi A . The longitudinal association between school bonding and delinquency among adolescents. Current Psychology. 2024; 43: 28416– 28. doi:10.1007/s12144-024-06483-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Demanet J , Van Houtte M . School belonging and school misconduct: the differing role of teacher and peer attachment. J Youth Adolescence. 2012; 41( 4): 499– 514. doi:10.1007/s10964-011-9674-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Kapetanovic S , Boele S , Skoog T . Parent-adolescent communication and adolescent delinquency: Unraveling within-family processes from between-family differences. J Youth Adolesc. 2019; 48: 1707– 23. doi:10.1007/s10964-019-01043-w [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Bandura A . Social learning theory. Morristown, NJ, USA: General Learning Press; 1971. [Google Scholar]

33. Boniel-Nissim M , Sasson H . Bullying victimization and poor relationships with parents as risk factors of problematic Internet use in adolescence. Comput Hum Behav. 2018; 88: 176– 83. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2018.05.041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Wang M , Qi W . Harsh parenting and problematic Internet use in Chinese adolescents: child emotional dysregulation as mediator and child forgiveness as moderator. Comput Hum Behav. 2017; 77: 211– 9. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.09.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Unnever JD . Bullies, aggressive victims, and victims: are they distinct groups? Aggress Behav. 2005; 31( 2): 153– 71. doi:10.1002/ab.20083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Salmivalli C , Nieminen E . Proactive and reactive aggression among school bullies, victims, and bully-victims. Aggress Behav. 2002; 28( 1): 30– 44. doi:10.1002/ab.90004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Boulton MJ , Smith PK . Bully/victim problems in middle-school children: stability, self-perceived competence, peer perceptions and peer acceptance. Br J Dev Psychol. 1994; 12( 3): 315– 29. doi:10.1111/j.2044-835X.1994.tb00637.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Haynie DL , Nansel T , Eitel P , Crump AD , Saylor K , Yu K , et al. Bullies, victims, and bully/victims. J Early Adolesc. 2001; 21( 1): 29– 49. doi:10.1177/0272431601021001002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Demaray MK , Malecki CK . Perceptions of the frequency and importance of social support by students classified as victims, bullies, and bully/victims in an urban middle school. Sch Psychol Rev. 2003; 32( 3): 471– 89. doi:10.1080/02796015.2003.12086213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Cutrona CE , Cole V , Colangelo N , Assouline SG , Russell DW . Perceived parental social support and academic achievement: an attachment theory perspective. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994; 66( 2): 369– 78. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.66.2.369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Ybarra ML , Mitchell KJ . Online aggressor/targets, aggressors, and targets: a comparison of associated youth characteristics. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004; 45( 7): 1308– 16. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00328.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Ybarra ML , Mitchell KJ . Youth engaging in online harassment: associations with caregiver-child relationships, Internet use, and personal characteristics. J Adolesc. 2004; 27( 3): 319– 36. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.03.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Fanti KA , Demetriou AG , Hawa VV . A longitudinal study of cyberbullying: examining riskand protective factors. Eur J Dev Psychol. 2012; 9( 2): 168– 81. doi:10.1080/17405629.2011.643169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Bayraktar F , Machackova H , Dedkova L , Cerna A , Ševčíková A . Cyberbullying: the discriminant factors among cyberbullies, cybervictims, and cyberbully-victims in a Czech adolescent sample. J Interpers Violence. 2015; 30( 18): 3192– 216. doi:10.1177/0886260514555006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Gottfredson DC . Schools and delinquency. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

46. Peguero AA , Bondy JM , Hong JS . Social bonds across immigrant generations. Youth Soc. 2017; 49( 6): 733– 54. doi:10.1177/0044118x14560335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Peguero AA , Popp AM , Latimore TL , Shekarkhar Z , Koo DJ . Social control theory and school misbehavior: examining the role of race and ethnicity. Youth Violence Juv Justice. 2011; 9( 3): 259– 75. doi:10.1177/1541204010389197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Popp AM , Peguero AA . Social bonds and the role of school-based victimization. J Interpers Violence. 2012; 27( 17): 3366– 88. doi:10.1177/0886260512445386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Finkelhor D , Hashima P . The victimization of children & youth: a comprehensive overview. In: White SO, editor. Law and social science perspectives on youth and justice. New York, NY, USA: Plenum; 2001. p. 49– 78. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-1289-9_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Hazler RJ . When victims turn aggressors: Factors in the development of deadly school violence. Prof Sch Couns. 2000; 4: 105– 12. [Google Scholar]

51. Bronfenbrenner U . Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am Psychol. 1977; 32( 7): 513– 31. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.32.7.513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Kildare CA , Middlemiss W . Impact of parents mobile device use on parent-child interaction: a literature review. Comput Hum Behav. 2017; 75: 579– 93. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.06.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. David ME , Roberts JA . Phubbed and alone: phone snubbing, social exclusion, and attachment to social media. J Assoc Consum Res. 2017; 2( 2): 155– 63. doi:10.1086/690940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Walsh SP , White KM , Cox S , Young RM . Keeping in constant touch: the predictors of young Australians’ mobile phone involvement. Comput Hum Behav. 2011; 27( 1): 333– 42. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2010.08.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Chen C , Leung L . Are you addicted to Candy Crush Saga? An exploratory study linking psychological factors to mobile social game addiction. Telematics Inform. 2016; 33( 4): 1155– 66. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2015.11.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. McDaniel BT , Radesky JS . Technoference: longitudinal associations between parent technology use, parenting stress, and child behavior problems. Pediatr Res. 2018; 84( 2): 210– 8. doi:10.1038/s41390-018-0052-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]