Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Impact of SWMF Features on the Performance of Random Forest, LSTM and Neural Network Classifiers for Detecting Trojans

College of Professional Studies, Northeastern University, Vancouver, BC V6B 1Z3, Canada

* Corresponding Author: Fatemeh Ahmadi Abkenari. Email:

Journal of Cyber Security 2026, 8, 93-109. https://doi.org/10.32604/jcs.2026.074197

Received 05 October 2025; Accepted 16 December 2025; Issue published 20 January 2026

Abstract

Nowadays, cyberattacks are considered a significant threat not only to the reputation of organizations through the theft of customers’ data or reducing operational throughput, but also to their data ownership and the safety and security of their operations. In recent decades, machine learning techniques have been widely employed in cybersecurity research to detect various types of cyberattacks. In the domain of cybersecurity data, and especially in Trojan detection datasets, it is common for datasets to record multiple statistical measures for a single concept. We referred to them as SWMF features in this paper, which include metrics such as standard deviation, minimum, maximum, total, variance, … for a single feature. The primary question this paper aims to address is the effectiveness of SWMF features in the performance of three widely used classifiers—Random Forest, Neural Network, and the LSTM deep learning method—in detecting Trojan cyberattacks. Our implementations on Trojan detection dataset demonstrate that while considering SWMF features enhance the performance of the Random Forest model in terms of accuracy from 0.82251855 to 0.992487558, and Kappa from 0.646722 to 0.985278422, the absence of SWMFs tends to either have no effect or slightly improve the performance of the neural network and LSTM classifiers in terms of loss, and prediction accuracy from 0.99291 to one for Neural network from 0.999981219 to 0.999981218893792 for LSTM. As a result, these features could be eliminated from the input for neural network–based classifiers.Keywords

Trojan malware is a type of threat that appears to be legitimate software, enticing users to take actions such as downloading or attempting to install it. Once executed, the payload provides the attacker with the opportunity to carry out further malicious activities, such as installing additional malware, monitoring user behavior, or stealing data. Trojan threats can cause significant reputational damage to companies and lead to widespread customer churn. The nature of a Trojan can vary widely. It may function as a backdoor, ransomware, spyware, part of a botnet, a rootkit, a fake antivirus, or take on other malicious forms.

There are also hardware trojans (HTs) that are malicious attack vectors concealed within ICs, causing a security threat that monitors device operations secretly. When the payloads of HT are activated, the malicious action will start. The variety of the supply chains of ICs makes developing a consistent detection approach very difficult [1].

Given access to a dataset containing all recorded Trojan events, various statistical and analytical methods can be employed to distinguish between Trojan and non-Trojan behaviors. This paper aims to apply machine learning and deep learning techniques to effectively detect and classify Trojan threats.

One common structure of cybersecurity datasets is to represent statistical measures for a single concept, which are then used to generate various features. In this research, we refer to these features as SWMF. Statistical Wise Measure Features (SWMF) refers to the existence of multiple statistical measures for one single metric, such as standard deviation, mean, minimum, maximum, and/or variance, per a single concept, such as flow-IAT in a cybersecurity-based dataset. For example, in the Trojan1 dataset, there are multiple SWMF, such as Flow.IAT Max, Flow.IAT Min, Flow.IAT Mean, and Flow.IAT Std represents a single concept of flow-IAT, which refers to flow inter-arrival time observations in network monitoring. This phenomenon is common in other cybersecurity datasets, such as CSE-CIC-IDS20182 for intrusion detection.

In this paper, our goal is to investigate whether SWMFs are truly effective for the task of Trojan detection in machine learning and cybersecurity paradigms. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first research study that specifically focuses on this concept.

The contributions of this paper are as follows:

• We compare the performance of the Random Forest model, neural network-based model, and the LSTM deep learning classifier on the binary classification task of Trojan detection.

• We investigate the effectiveness of SWMF features in the context of cybersecurity data, specifically in relation to the Trojan detection problem, using Random Forest, neural network classifiers, and an LSTM model. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore this research question.

The paper is organized as follows: first, we review previous work on attack detection, and we focus on the research on Trojan detection conducted by researchers. Then, we detail our methodology. Initially, we use Decision Tree, Random Forest, and XGBoost algorithms to assess feature importances. Following that, we apply the aforementioned models to evaluate performance in two settings: with SWMF features and without them. This allows us to measure the impact of including SWMF on model effectiveness.

Ahmadi et al. (2023) measured model overfitting through utilizing various overfitting combating techniques in machine learning, such as LASSO, XGBoost classifier and dropout mechanism in a deep neural network for the intrusion detection problem. They proved and illustrated the effectiveness of the Decision Tree classifier with the least amount of overfitting on the reduced sets of features constructed from Auto Encoders [2].

Laghrissi et al. (2021) implemented three classifiers as LSTM3, LSTM-PCA4 and LSTM-MI5 for feature selection and reduction and for attack detection on the KDD996 dataset. The results show the outperformance of the LSTM-PCA approach for attack detection. The results of the experiments were compared to improved CNN, LSTM-RNN, and pruning VELM7 [3].

Ruth Ramya et al. (2024) proposed a framework for detecting Trojans in which a dataset containing both benign and malicious samples was first collected. Following comprehensive preprocessing and feature engineering, Random Forest, Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), and Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) models were employed. To further improve performance, a hybrid fusion of machine learning and deep learning techniques was applied, which outperformed the individual models [4].

After putting the AE-IDS in place, RMSE8 is used as the judgment metric to distinguish the normal traffic from the abnormal ones. The CSE-CIC-IDS9 2018 AWS dataset is used in this paper. The dataset includes seven types of attacks, including Brute-force (Brute-force-Web, Brute-force XSS, FTP Brute-force, SSH Brute-force), Bot, DoS (DoS attack Hulk, DoS SlowHTTPTest), DDoS (DDoS attack HOIC, DDoS attack LOIC-UDP), SQL Injection, and infiltration, including many features representing system logs and network traffic from which 83 features are selected. The time efficiency of this model is compared to KitNet10 and the results show a faster detection time in AE-IDS than KitNet [5].

Leevy and Khoshgoftaar (2020) implemented different classifiers such as CNN, Auto Encoders, LSTM, AdaBoost, Random Forest, Decision Tree, XGBoost, … on CIC201811 dataset. They reached a high accuracy rate in some classifiers while they suffer from overfitting. They investigated the lack of addressing class imbalance, detailed report on the data preprocessing, and transfer learning in the research they reviewed [6].

Choo et al. (2020) utilized machine learning approaches in order to detect hardware-level and Register Transfer Level (RTL) injected Trojans. The employed classification approaches were decision tree, logistic regression, Support Vector Machine (SVM), and K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) with an average True Positive Rate (TPR) of 93.72% on four branching circuit features. Since the dataset was artificially made through the Adaptive Synthetic Sampling (ADASYN) algorithm, the result may not reflect the real scenarios [7].

Wijitrisnanto et al. (2021) investigated the Trojan detection problem on multiple data sources, considering AES, RS232, and WB-Conmax benchmarks on a single branch feature called the Rbit feature. The implemented model was Logistic Regression and Neural Network via a training time of 300 and 894 ms, respectively, with an accuracy of 92%. However, the model did not perform well regarding the F1 measure evaluation metric [8].

Kuang et al. (2025) proposed a Hardware Trojans (HT) detection approach based on large pre-trained models utilizing a novel natural language processing model called NtNDet, which encompasses an approach called Netlist-to-Natural-Language (NtN) for transforming gate-level netlists to a natural language format suitable for Natural Language Processing (NLP) models. They also applied a self-attention mechanism within the Transformer to model Netlist dependencies. They utilized Trust-Hub, TRIT-TC, and TRIT-TS benchmarks with increased precision by 5.27%, increased True Positive Rate (TPR) by 3.06%, increased True Negative Rate (TNR) by 0.01%, and increased F1 measure score by 3.17% over the existing HT detection approaches [1].

Ghimire et al. (2023), proposed a new unsupervised approach for Hardware Trojan detection for small and short-triggered Trojans that leads to an improvement in trustworthiness of semiconductor IC supply chains. The unsupervised learning techniques show a better False Positive Rate (FPR) and close accuracy in comparison to the KNN, SVM, and Gaussian classifiers and resulting in an accuracy of 93% [9].

Das, and Ghosh (2023), investigated the impact of Trojan insertion on quantum circuits via utilizing a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model, called TrojanNet. They generated 12 datasets by considering a variation in Trojan gate types, the number of gates, insertion locations, and compiler backends via the Qiskit framework. Then the TrojanNet model has been trained and evaluated on these datasets. The average accuracy of 98.80% and an average F1 measure of 98.53% have been achieved by the TrojanNet model [10].

Bajcsy et al. (2021) simulated nine types of Trojan attacks and designed an interactive web-based Trojan simulator in neural network-based models. They measured and visualized neural network-based models’ states by calculating KL divergence. They also developed the mathematical foundation for designing Trojan detectors. The results show that the complexities of Trojan problems have a direct relationship to factors such as the size of the input data space, characteristics of Trojan embedding, the number of classes in the target, and the number and selection of provided training data points for each class [11].

Liu et al. (2018) tried to issue Trojan attacks against a neural network structure following the research on poisoning attacks on machine learning models. Through utilizing reverse engineering, they generated a Trojan trigger by inverting the process and then retraining the model in order to inject malicious behaviors while stamped as the Trojan in the dataset. They used five different applications to trigger attacks, and the results show that the attacks were effective [12].

Azizi et al. developed a deep neural network-based model termed T-miner that implemented a sequence-to-sequence generative model to produce textual data that likely includes Trojan triggers. T-miner does not need to be trained on any training data upon using a generative model that produced synthetic text input. They tried to detect Trojan and backdoor cyberattacks based on T-miner. The authors reported 98.75% overall accuracy while achieving a low false positive rate [13].

Deep neural network structures, either in a single or in a hybrid mode, have been widely used in detecting various forms of cyberattacks. Gueriani investigated the effectiveness of a hybrid attention-based LSTM and CNN deep neural network in the structure of an IDS12 for detecting Industrial IoT–related attacks using the Edge-IIoTset dataset. They first applied the SMOTE13 to balance the dataset and then evaluated multiple classifiers, where the hybrid attention-based LSTM-CNN model demonstrated the best performance [14].

Gueriani et al. developed a transformer-based IDS, called BiGAT-ID, in order to detect cyberattacks in Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) and the Industrial IIoT. To this aim, they employed a bidirectional gated recurrent unit (BiGRU), LSTM networks, and multi-head attention (MHA) in the structure of an IDS. They conducted the experiments on two datasets as CICIoMT2024 medical IoT and EdgeIIoTset industrial IoT. They reported the detection accuracies of 99.13 percent and 99.34 percent, respectively [15].

Xu et al. developed Malbert, a malware detection system for Windows software-based malware detection. Malbert learns API sequences by pre-training, and then implements malware detection on data with malware and benign labels by fine-tuning. They evaluated Malbert on two datasets, the Ki dataset (44,262 samples) and the Catak dataset (7207 samples). Malbert reaches a 99.9% detection rate on both datasets and a detection rate exceeding 98% [16].

The Trojan detection dataset14 represents a collection of network flow data designed to simulate realistic cybersecurity scenarios where malicious software attempts to infiltrate systems through seemingly normal network communications. Sourced from Kaggle’s cybersecurity repository, this dataset provides researchers with a robust foundation for developing and evaluating machine learning-based intrusion detection systems.

The dataset encompasses 177,482 individual network flow records, each representing a distinct communication session between source and destination endpoints. These records span approximately 18 days of network activity, captured from 30 June 2017 to 17 July 2017, providing temporal depth that enables analysis of attack patterns across different time periods. The data collection methodology appears to follow controlled laboratory conditions, where Trojan behaviors were systematically injected into monitored network environments to generate labelled training data that mirrors real-world attack scenarios.

Each network flow record contains 86 distinct features that comprehensively characterize communication patterns, including fundamental identifiers (flow ID, source IP, destination IP, source port, destination port), temporal measurements (timestamps, flow duration, inter-arrival times), traffic volume metrics (packet counts, byte transfers, total length of forward packets, total length of backward packets, …), and protocol-specific indicators (TCP flags, URG flag count, CWE flag15 count, ECE flag16 count, PSH flag count, SYN flag count, RST flag count, ACK flag count, FIN flag count, window size). This dataset, like many other cybersecurity datasets, defines a single character in terms of different statistical measures. For example, packet length is represented with mean, standard deviation, variance, minimum and maximum. Such observations happen for different metrics with four or five statistical measures. The multidimensional feature space captures both the quantitative aspects of network traffic and the subtle behavioral signatures that distinguish malicious from benign communications, which appears in the target column called Class which making the problem a binary classification problem.

The dataset maintains class balance, with 90,683 Trojan instances (51.09%) and 86,799 Benign flows (48.91%). This near-perfect equilibrium eliminates the common machine learning challenge of class imbalance, ensuring that trained models develop unbiased decision boundaries and perform reliably across both attack and normal traffic scenarios.

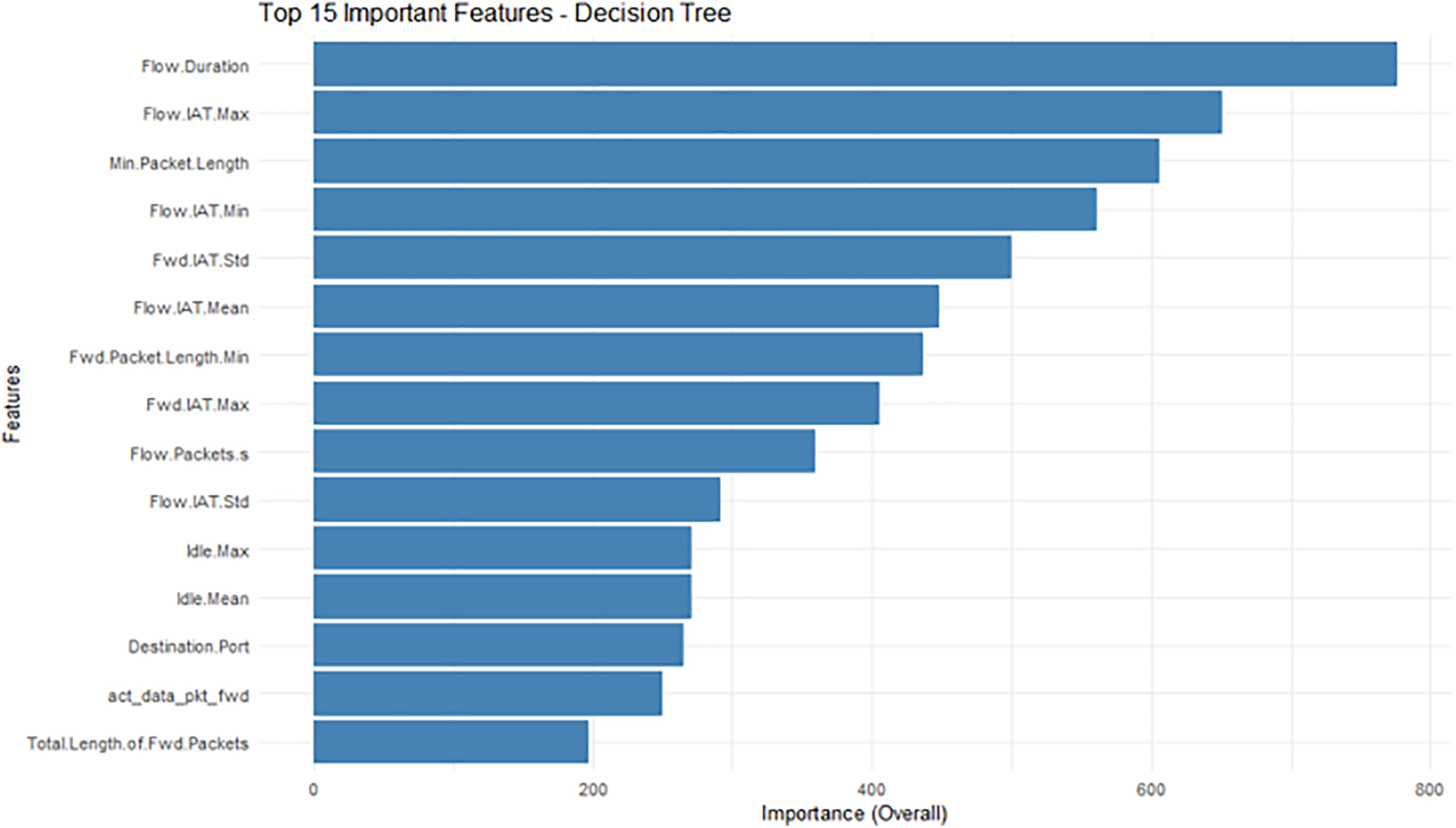

Since feature engineering plays a vital role before classification and modelling attempts, first we employed Decision Tree, Random Forest and XGBoost approaches to investigate the importance of the existing features. The results are depicted in Figs. 1–3. As we can see in these figures, in multiple cases, Statistical Wise Measure Features (SWMF) has a place in this list. For example, we can see Flow.IAT Max, Flow.IAT Min, Flow.IAT Mean, and Flow.IAT Std for flow inter-arrival time observations17, Fwd.IAT Std and Fwd.IAT Max for forward inter-arrival time observations, Idle Mean and Idle Max, for idle time observations in the list of top 15 most important features created by the Decision Tree, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Top 15 important features based on decision tree approach

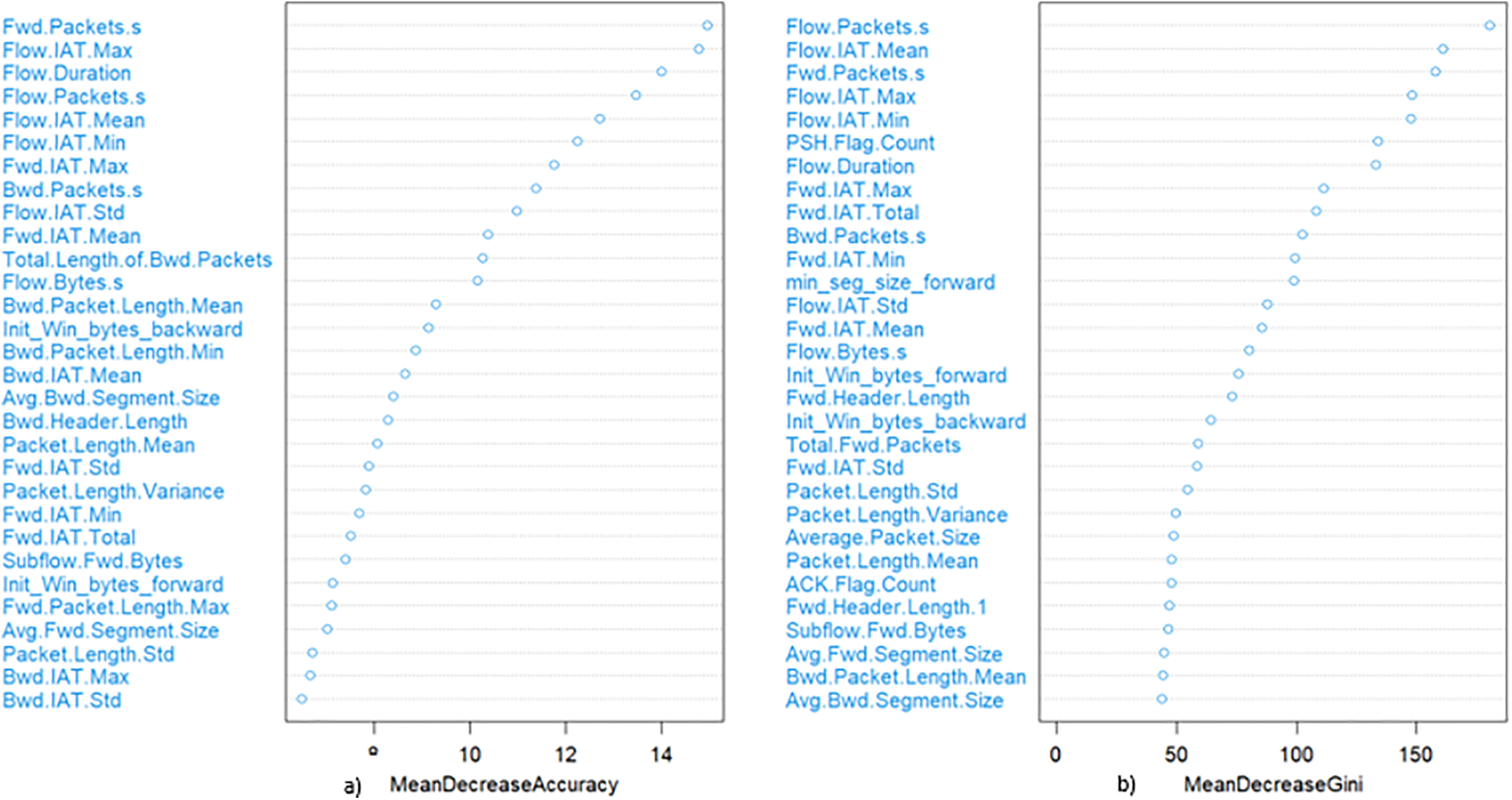

Figure 2: Most important features based on the random forest approach according to (a) mean decreased accuracy and (b) Mean decreased gini

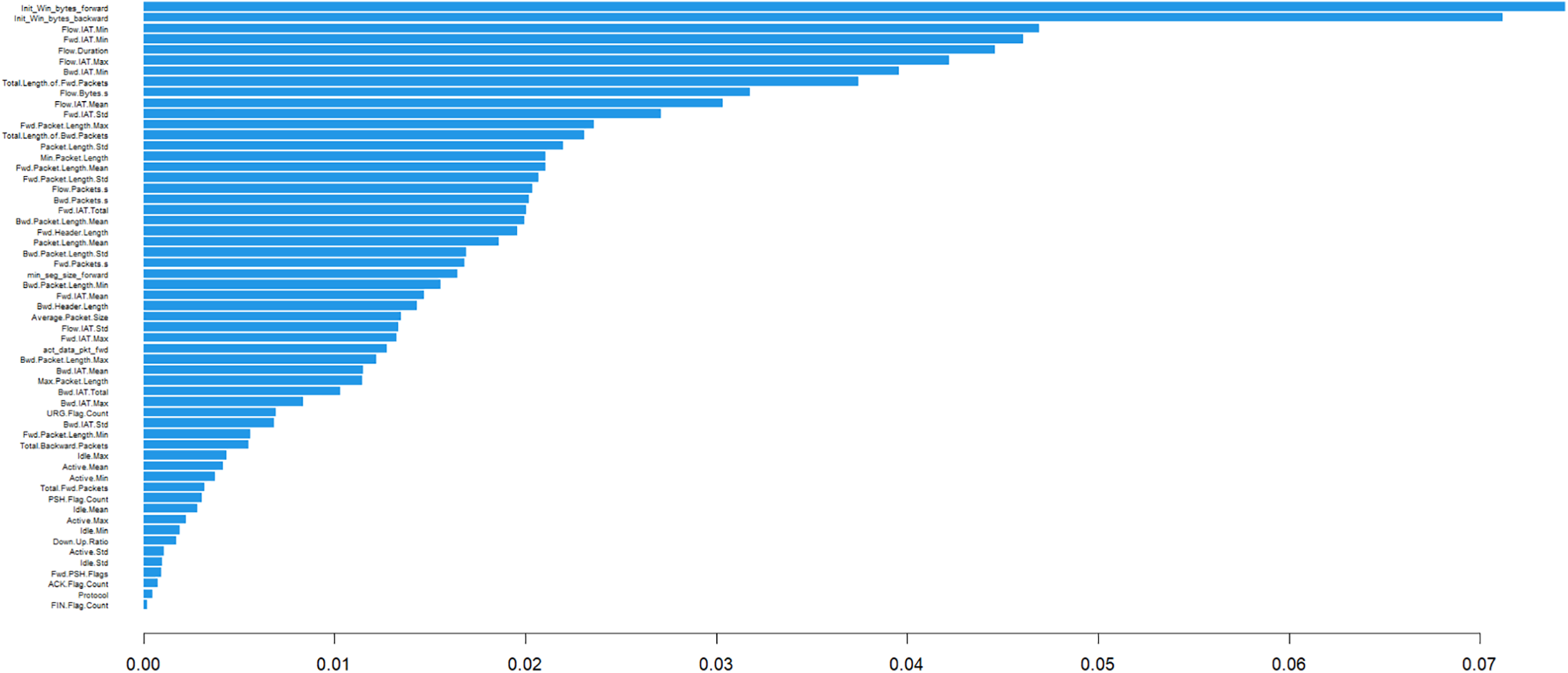

Figure 3: Most important features based on the XGBoost approach

Fig. 2 illustrates the important features extracted by the Random Forest approach. Fwd.IAT Min, Fwd.IAT Total, Fwd.IAT Std, Fwd.IAT Mean and Fwd.IAT Max for forward inter-arrival time observation, Bwd.IAT Max, Bwd.IAT Std, and Bwd.IAT Mean for backward inter-arrival time observations and Flow.IAT.Max, Flow.IAT.Min, Flow.IAT.Mean, and Flow.IAT.Std for flow inter-arrival time observation based on Mean Decreased Accuracy metrics are among the SWMF features. While we can also see some of them in the list of most important features based on Mean Decreased Gini metric.

Fig. 3 illustrates the important features using the XGBoost approach. In this list, Flow.IAT Min, Flow.IAT Mean, Flow.IAT Max and Fwd.IAT Std, Fwd.IAT Min and Fwd.IAT Total are all SWMF feature among the most important features.

Next, we investigate the effectiveness of the existing SWMF on the performance of various classification approaches.

As mentioned in the previous section, the Trojan dataset contains 86 columns, including the target column labelled Class. The dataset is balanced, and the target column consists of two classes: Benign and Trojan samples. There are eight features with SWMF extra related features present in the dataset: Flow.IAT, Fwd.IAT, Bwd.IAT, Idle, Active, Packet Length, Bwd Packet Length, and Fwd Packet Length. Each of these features is represented with multiple statistical measures such as minimum, maximum, standard deviation, mean, and in some cases, variance and/or total.

We classify the dataset into two modes:

1. SWMF Mode: In this mode, we retain all SWMF-related columns and build our models using the full set of statistical features.

2. Non-SWMF Mode: In this mode, we keep only one representative feature for each SWMF type and remove the rest. For example, to represent the concept of flow inter-arrival time, we keep Flow.IAT.Mean and discard the Flow.IAT.Min, Flow.IAT.Max, Flow.IAT.Std, and Flow.IAT.Total.

First, the Spearman-based correlation among all features has been computed, and obviously, the correlation among the SWMF features belonging to the same concept was high. After scaling, we build classification models for both modes and analyze the impact of including or excluding the set of SWMF features on model accuracy.

For both modes, during the preprocessing step, we removed the Flow ID, Source IP, and Destination IP features. We also extracted date and time components from the Timestamp column, and then removed the month, minute, second and year.

For modelling, we implemented Random Forest (with 50, 80, 150, 300, and 500 trees as the number of estimators), a neural network, and an LSTM-based deep neural network model. The implementation environment included RStudio and Python within Jupyter Notebook. The version of scikit-learn used in the Anaconda Python environment was 1.2.0, while the version of XGBoost in RStudio was 1.7.5.1.

We computed various performance metrics for the neural network and LSTM, including training accuracy, validation accuracy, prediction accuracy, loss, and validation loss. Additionally, for the Random Forest models, we calculated Kappa, accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity.

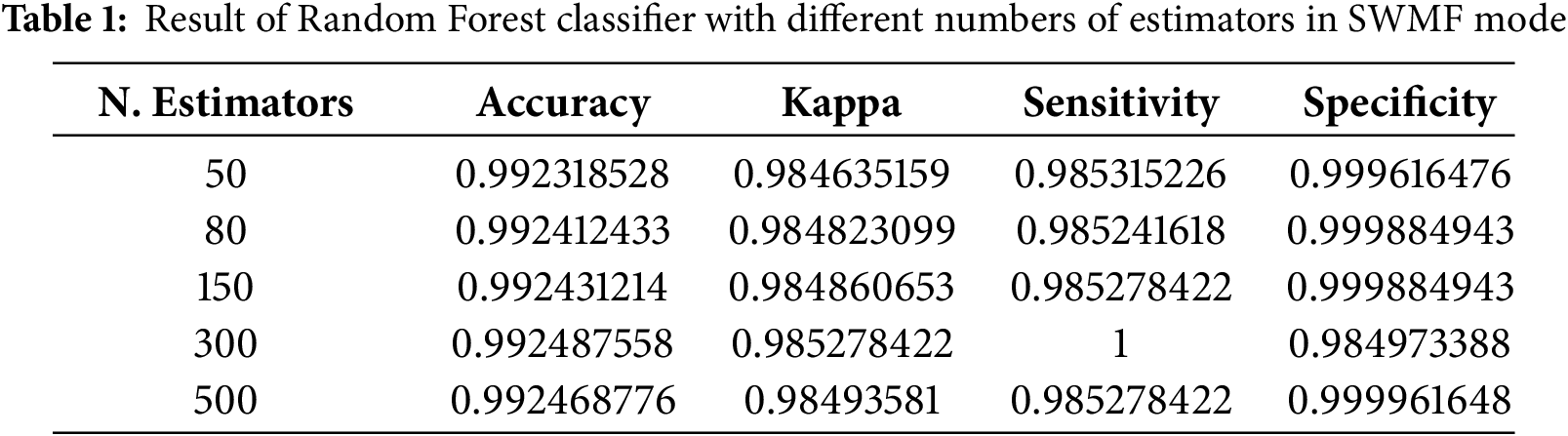

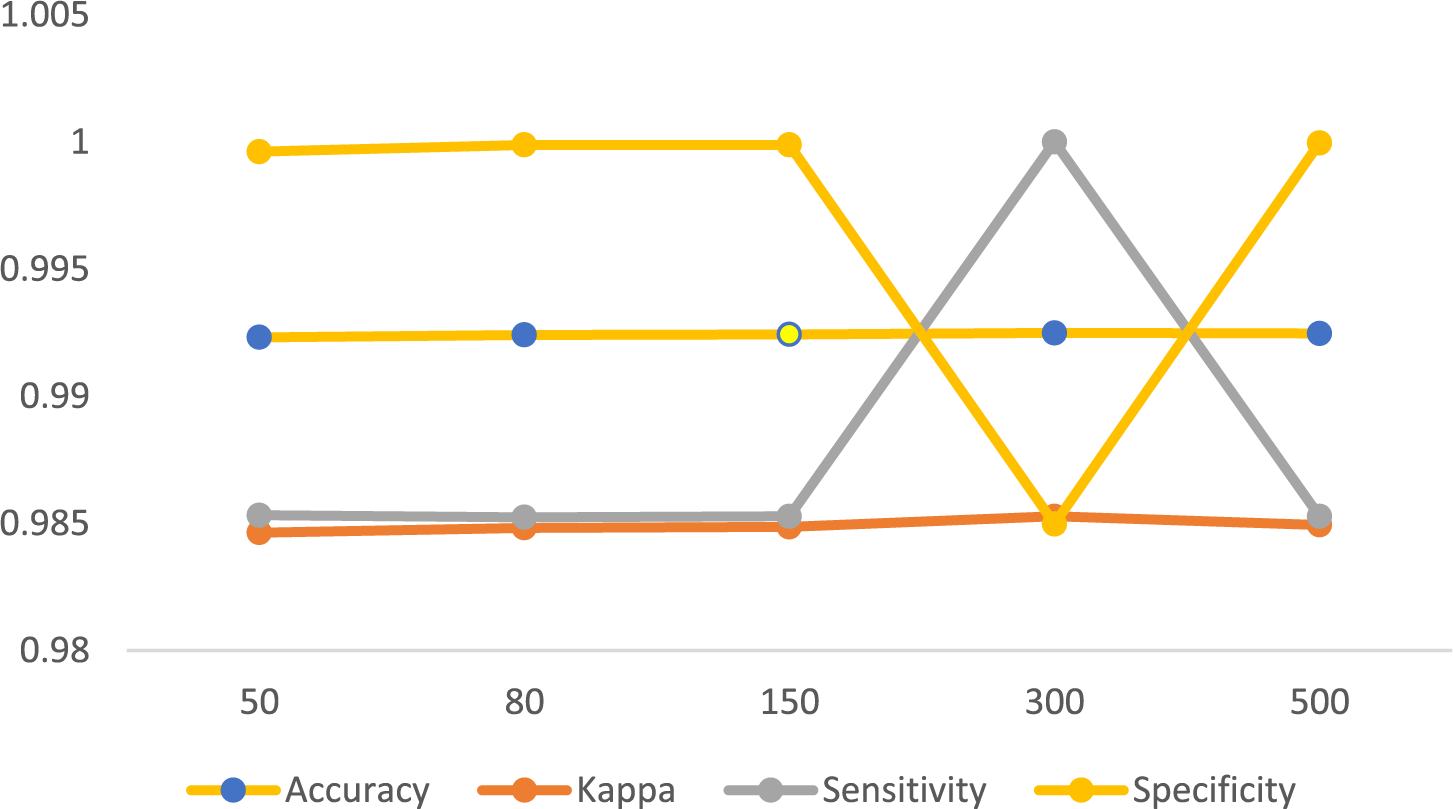

Table 1 and Fig. 4 present the results of the Random Forest classification approach in Python, using all SWMF features. As the number of estimators increases, we observe an improvement in the accuracy. The highest accuracy and Kappa are achieved with 300 estimators.

Figure 4: Result of Random Forest classifier with different number of estimators in SMWF mode

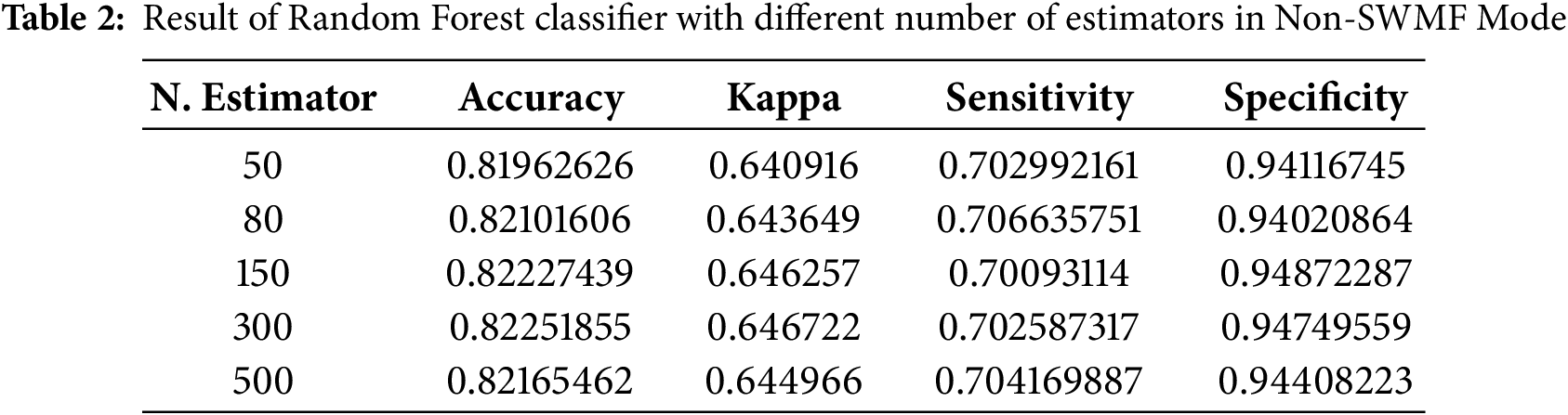

Table 2 and Fig. 5 show the results of the Random Forest classifier in Python under the Non-SWMF Mode. In this mode, a noticeable decrease in both accuracy and Kappa is observed due to the removal of statistical measures. The highest accuracy is obtained with 150 trees, while the best Kappa is achieved with 300 trees.

Figure 5: Result of Random Forest classifier with different numbers of estimators in Non-SMWF mode

The results show that evaluation metrics such as accuracy, Kappa, sensitivity, and specificity of the Random Forest model were significantly affected by the absence of SWMF features.

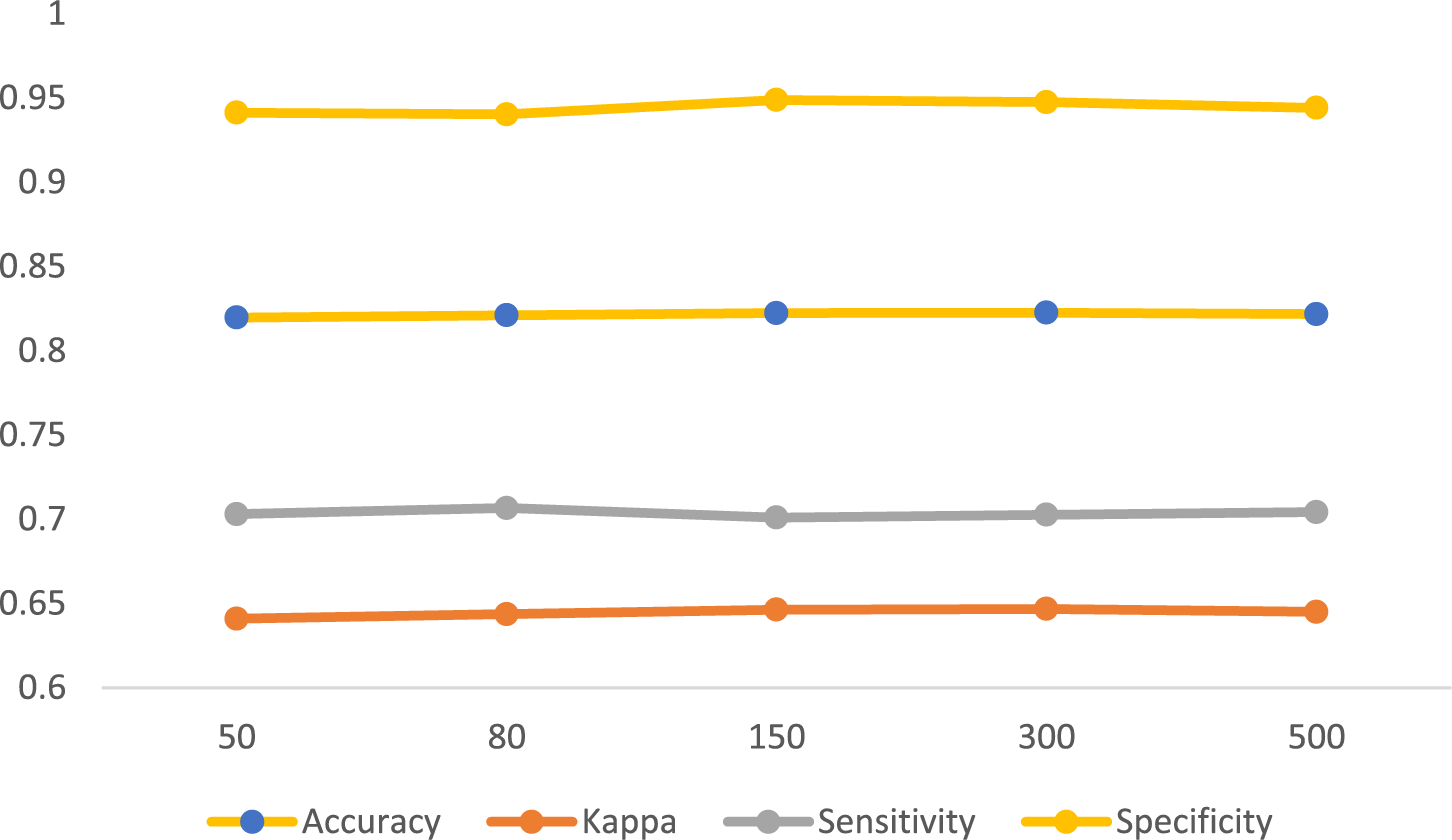

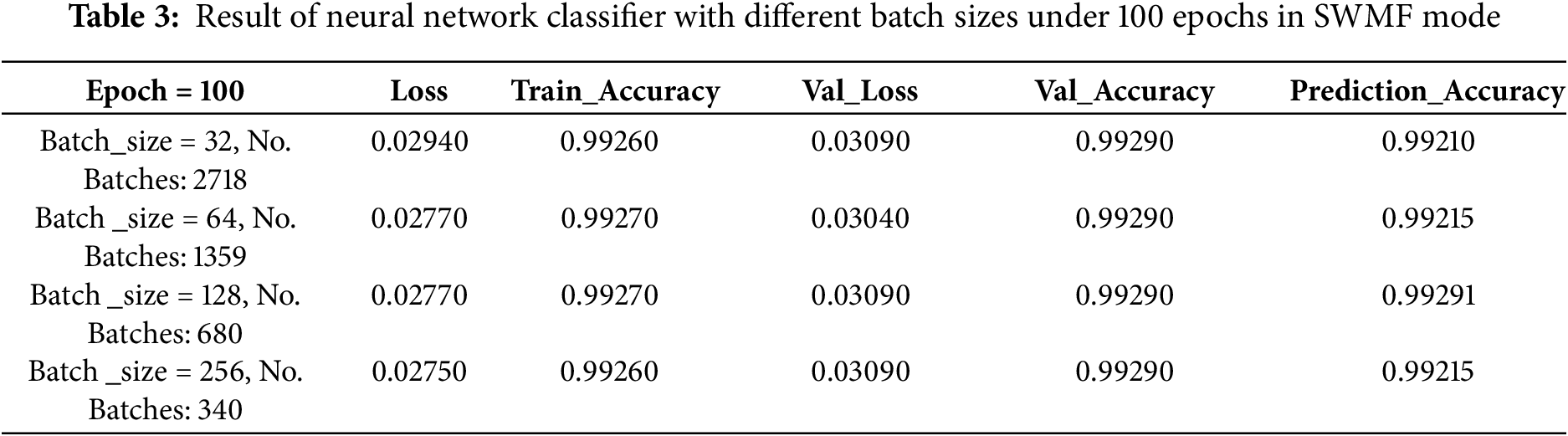

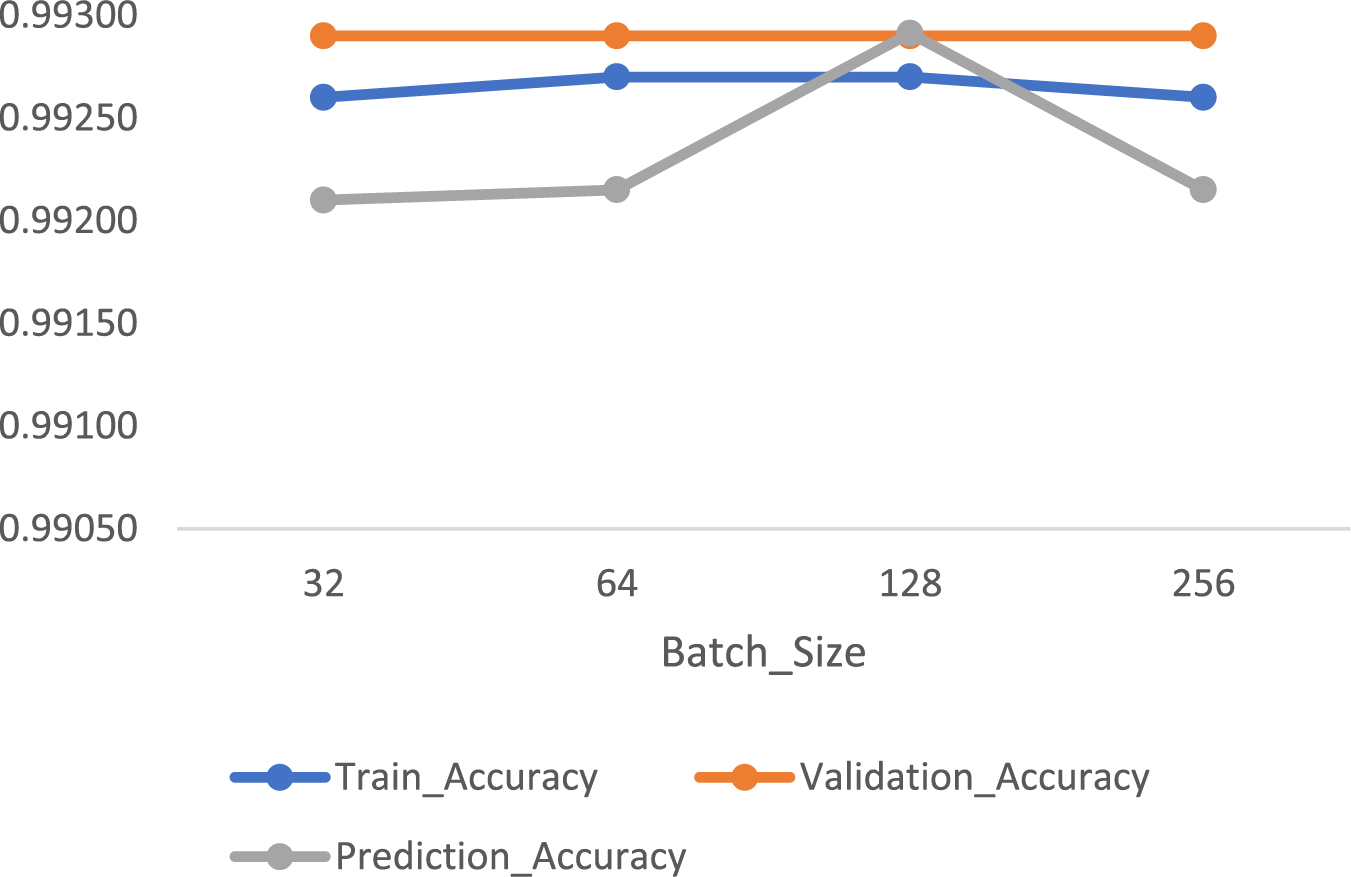

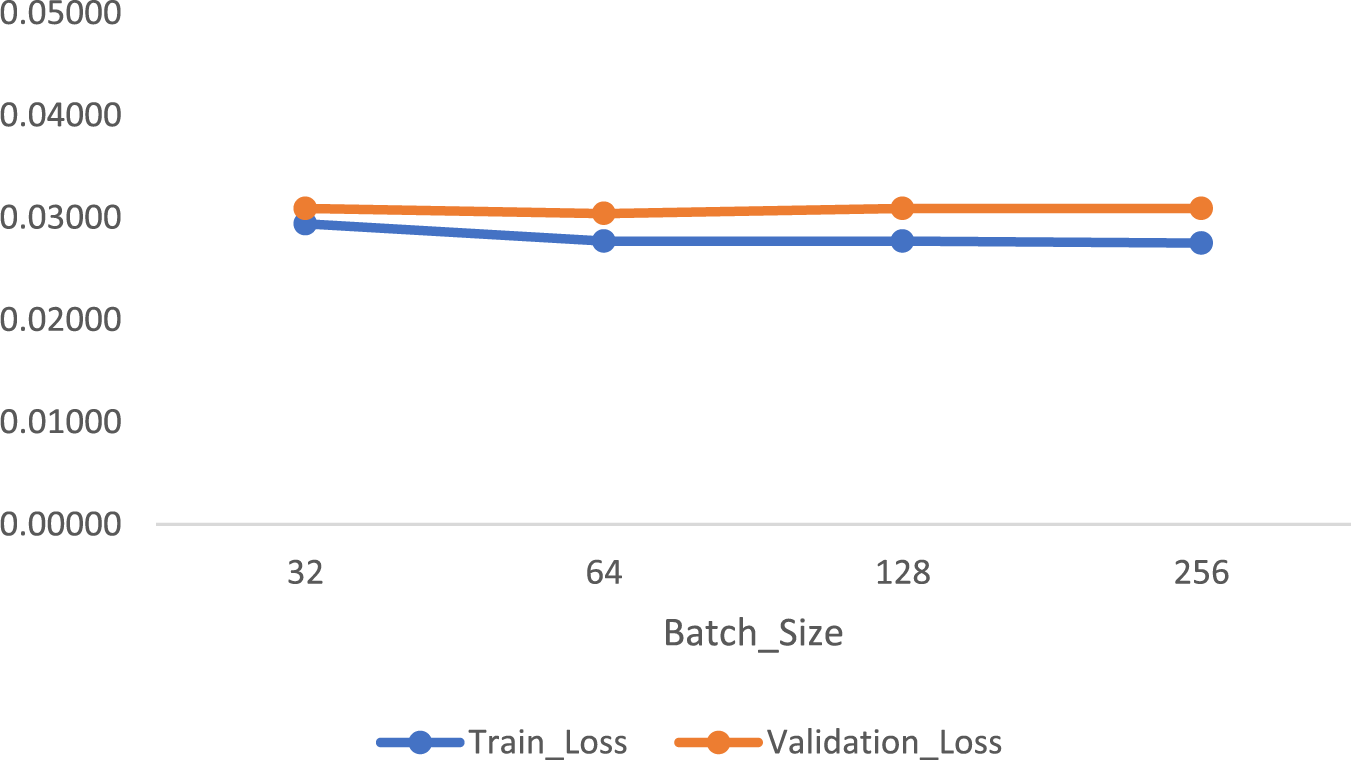

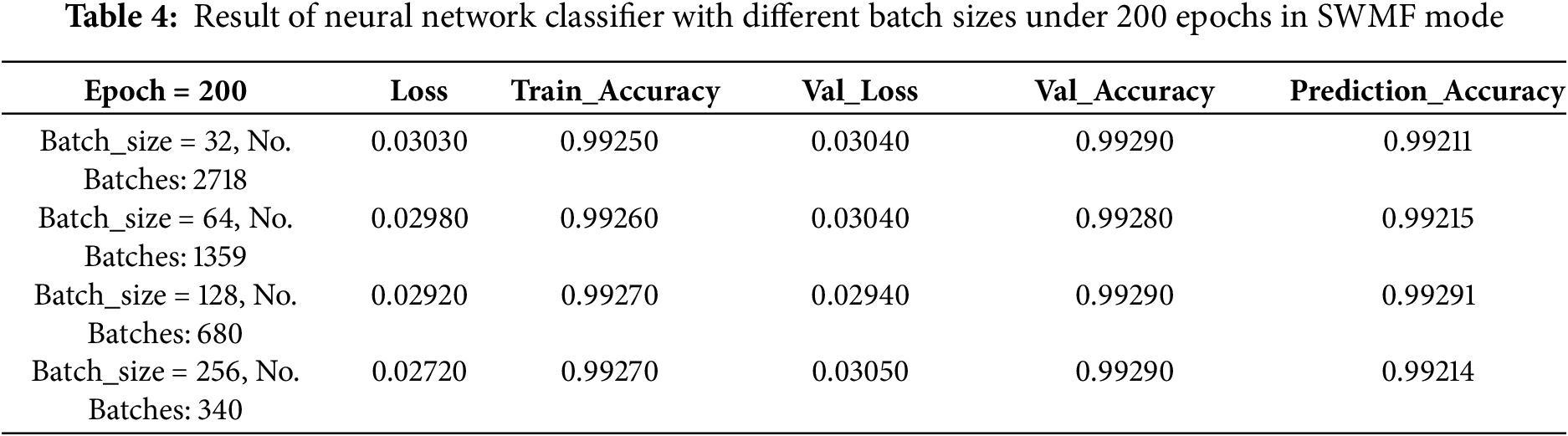

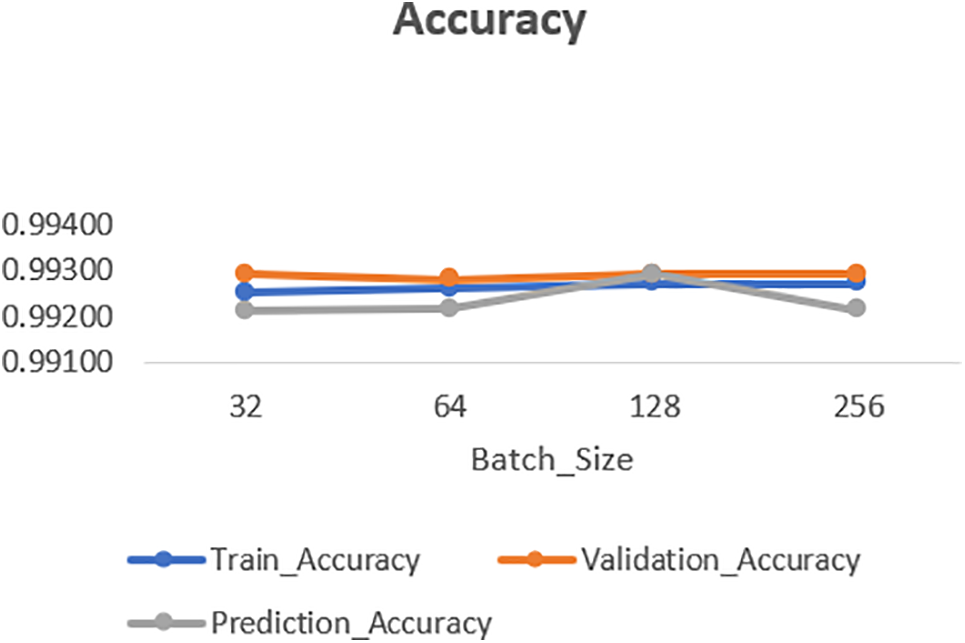

Then we implemented a neural network structure in Python in SWMF Mode and ran it first up to 100 epochs and then 200 epochs under different batch sizes of 32, 64, 128 and 256 with the mentioned number of batches under each implementation. The structure of our neural network includes four layers with one Dropout layer to turn off 50 percent of nodes. The activation function for the three layers is RELU, and for the last layer is Sigmoid. The best result achieved by batch_size = 64 encompassed 1359 batches under 100 epochs as shown in Table 3 and Figs. 6 and 7. The results of running the same classifier under 200 epochs have been depicted in Table 4 and Figs. 8 and 9.

Figure 6: Accuracy of neural network classifier with different batch sizes under 100 epochs in SMWF mode

Figure 7: Loss of neural network classifier with different batch sizes under 100 epochs in SMWF mode

Figure 8: Accuracy of neural network classifier with different batch sizes under 200 epochs in SMWF mode

Figure 9: Loss of neural network classifier with different batch sizes under 200 epochs in SMWF mode

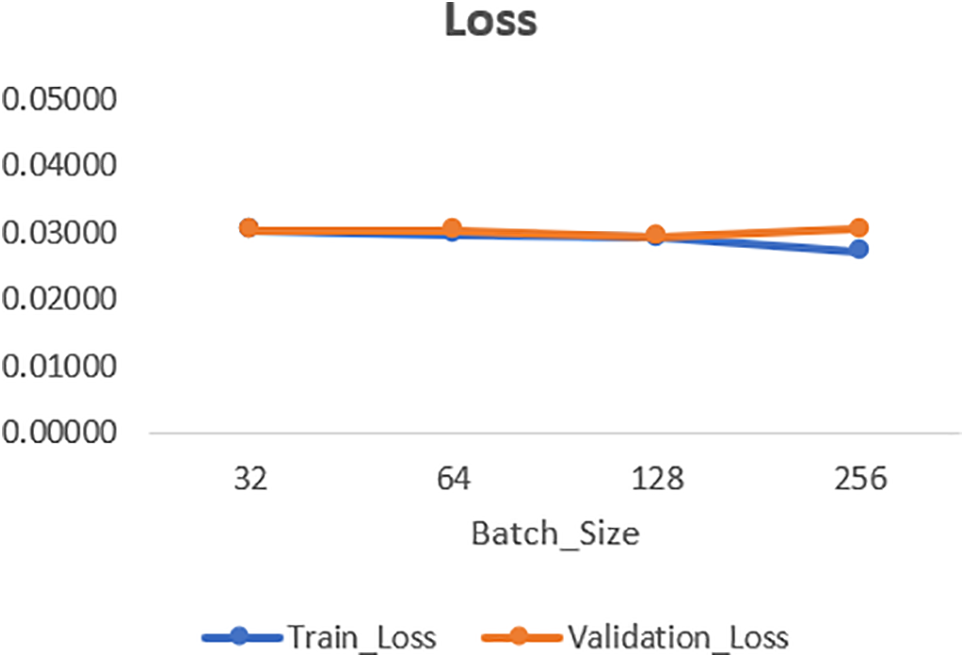

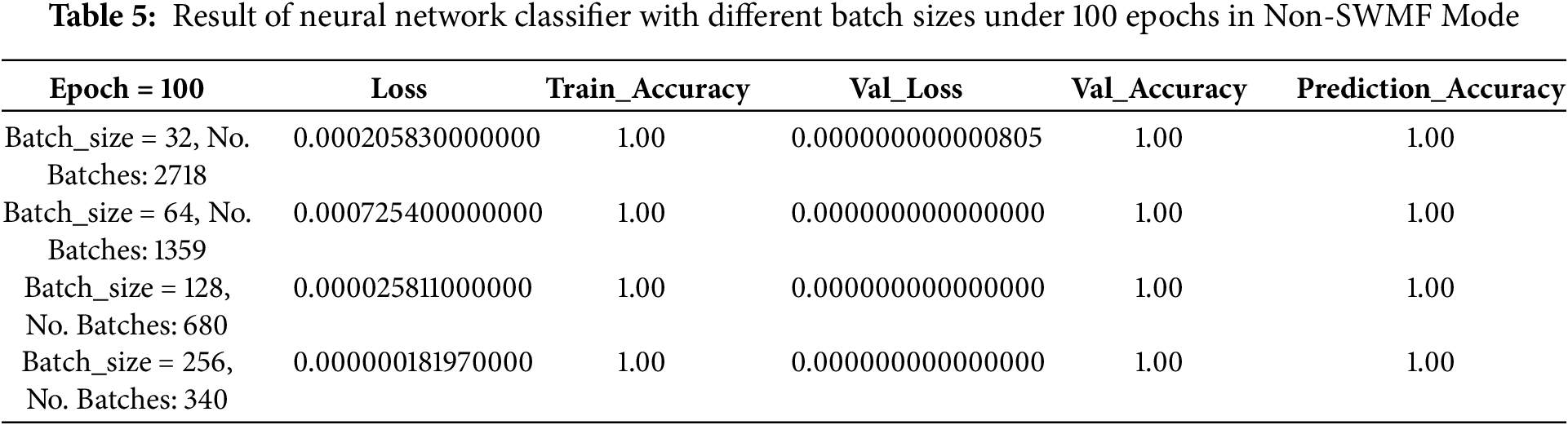

Next, we implemented the neural network classifier using the same structure as described earlier, applied to the Non-SWMF Mode, with 100 epochs, as shown in Table 5 and Fig. 10. We did not include an accuracy plot, as the model consistently achieved 100% accuracy across all configurations. Furthermore, since maximum accuracy was already reached, we did not extend the training process to 200 epochs. Among all configurations, the lowest loss was achieved with a batch size of 256, although all other values remained the same.

Figure 10: Loss of neural network classification with different batch sizes under 100 epochs in Non-SWMF Mode

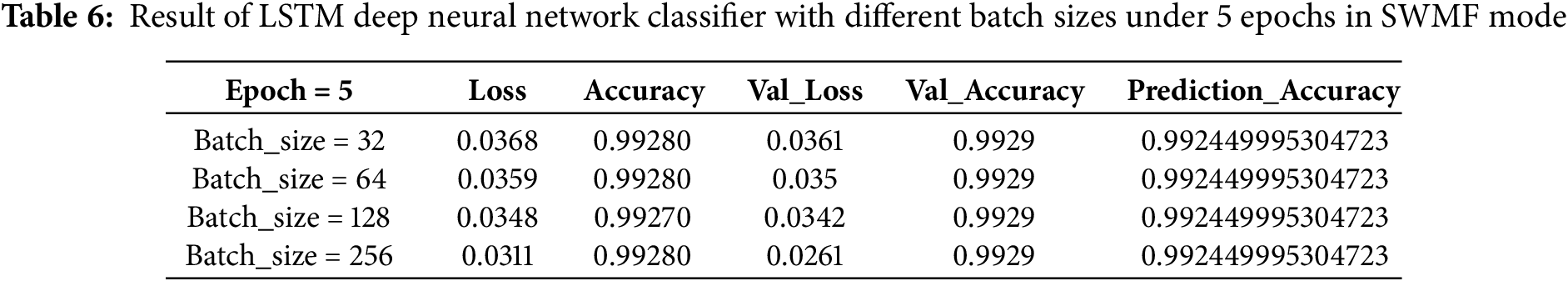

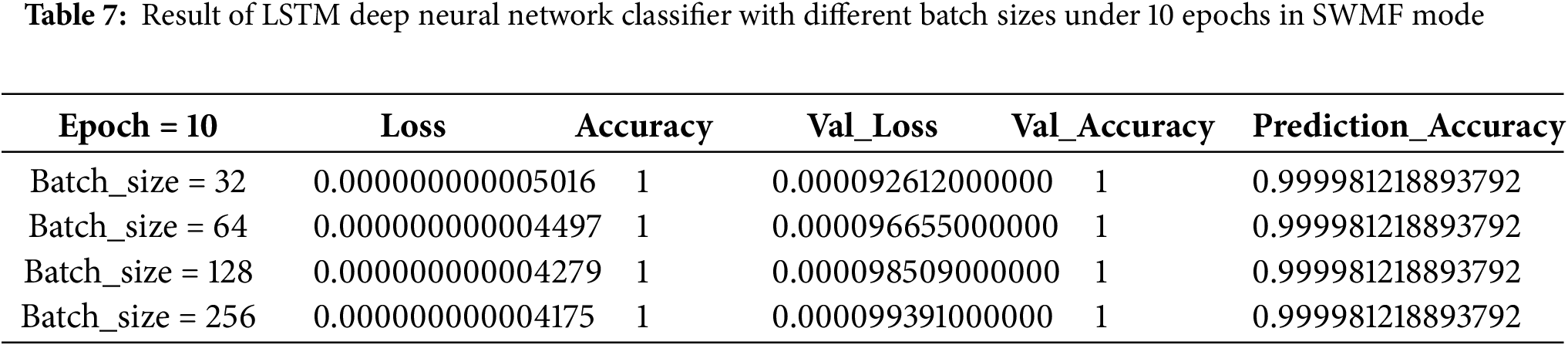

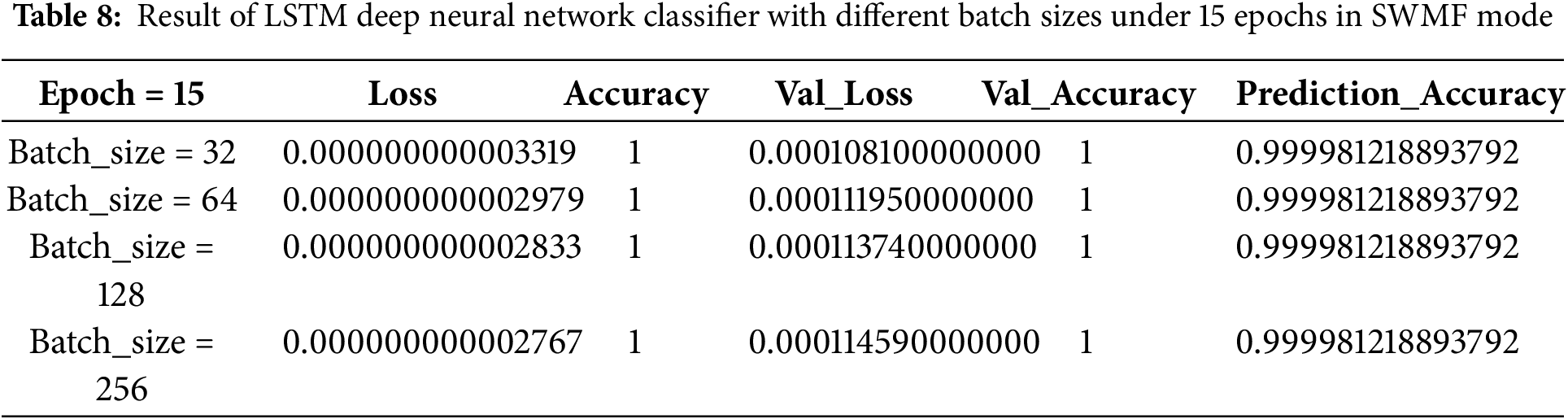

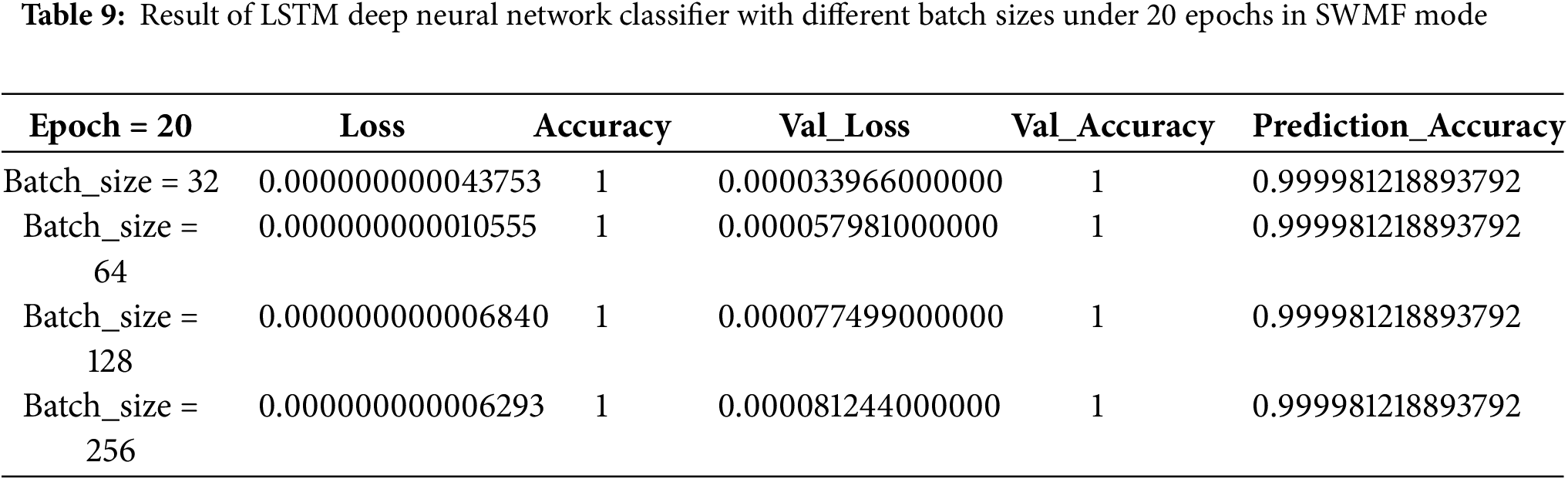

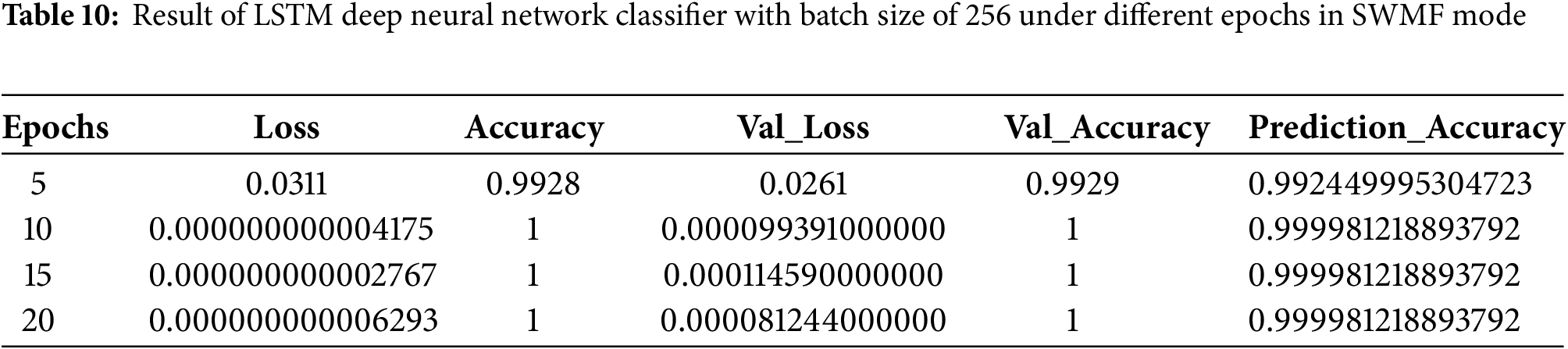

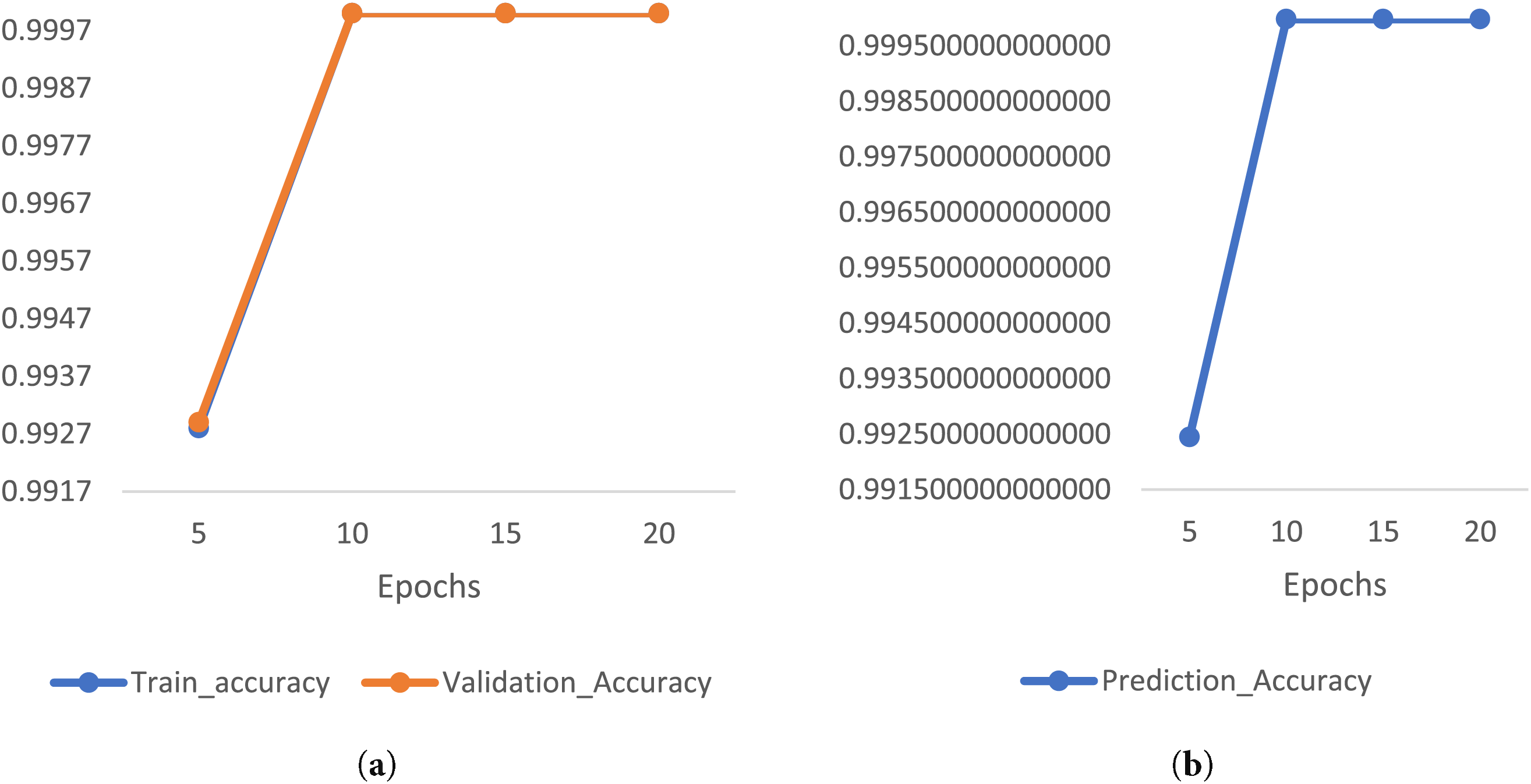

As the final model, we implemented an LSTM-based deep neural network classifier, first in SWMF Mode, using 5, 10, 15, and 20 epochs, and varying the batch size among 32, 64, 128, and 256. In the LSTM architecture, we used Binary Cross-Entropy as the loss function and Adam as the optimizer. The results are presented in Tables 6–9, while Table 10 summarizes the results for a batch size of 256 across the four epoch settings. The lowest loss was achieved at 15 epochs, while the prediction accuracy remained consistent for 10, 15, and 20 epochs.

Fig. 11a shows the training and validation accuracy, and Fig. 11b illustrates the prediction accuracy of the LSTM classifier with a batch size of 256 across different epoch settings in SWMF Mode. Fig. 12 displays the training loss and validation loss under the same conditions.

Figure 11: (a) Train accuracy and validation accuracy (b) Prediction accuracy of LSTM classifier under batch size = 256 with different epochs in SWMF mode

Figure 12: Train loss and validation loss of LSTM classifier under batch size = 256 with different epochs in SWMF mode

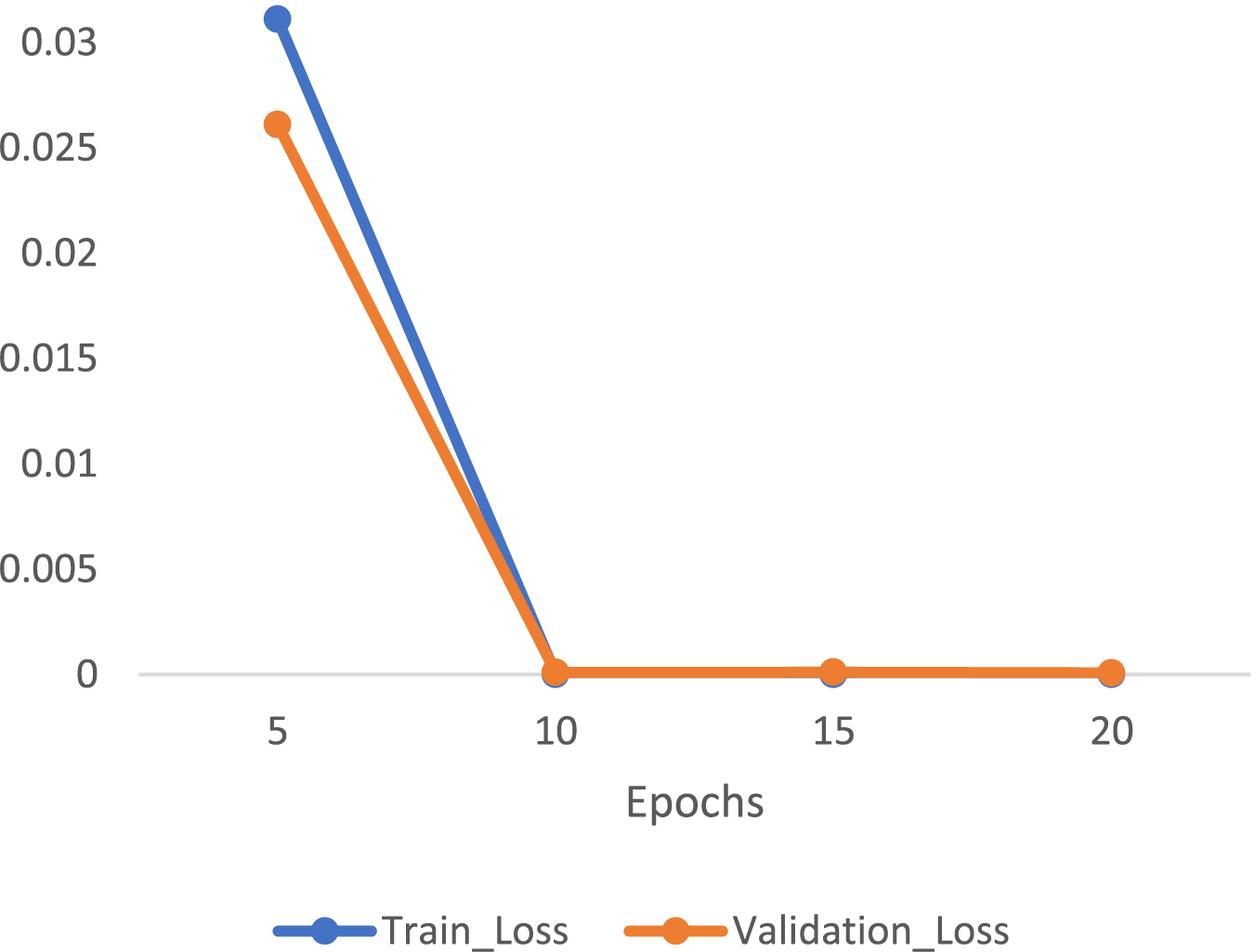

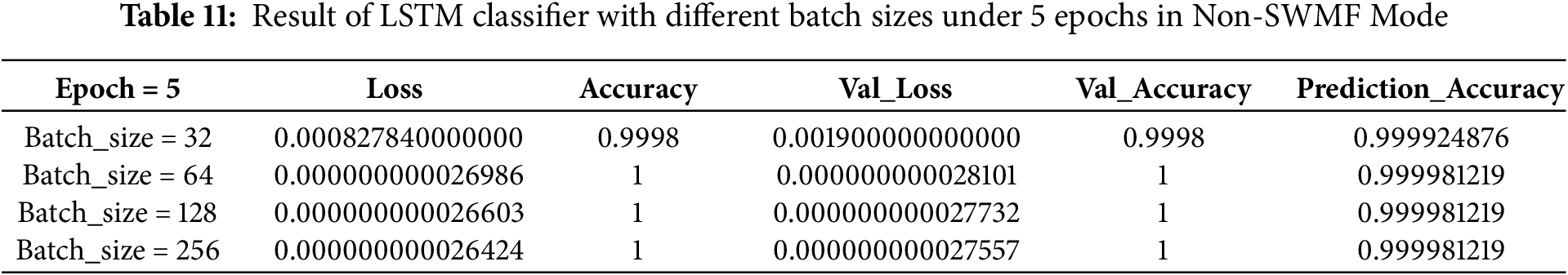

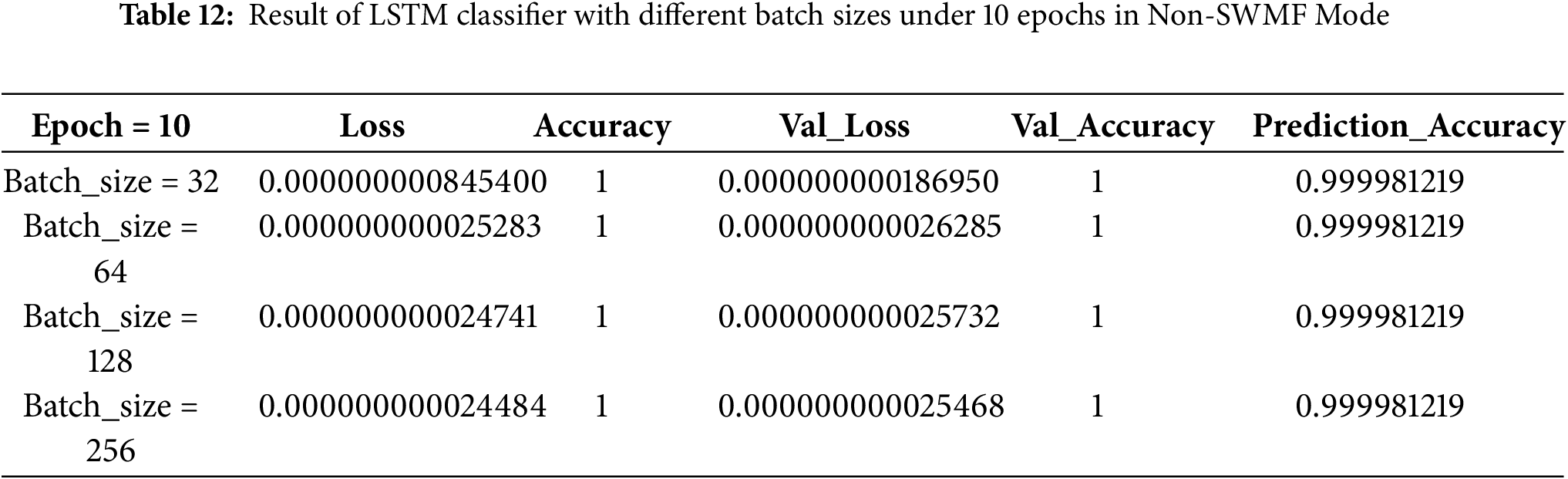

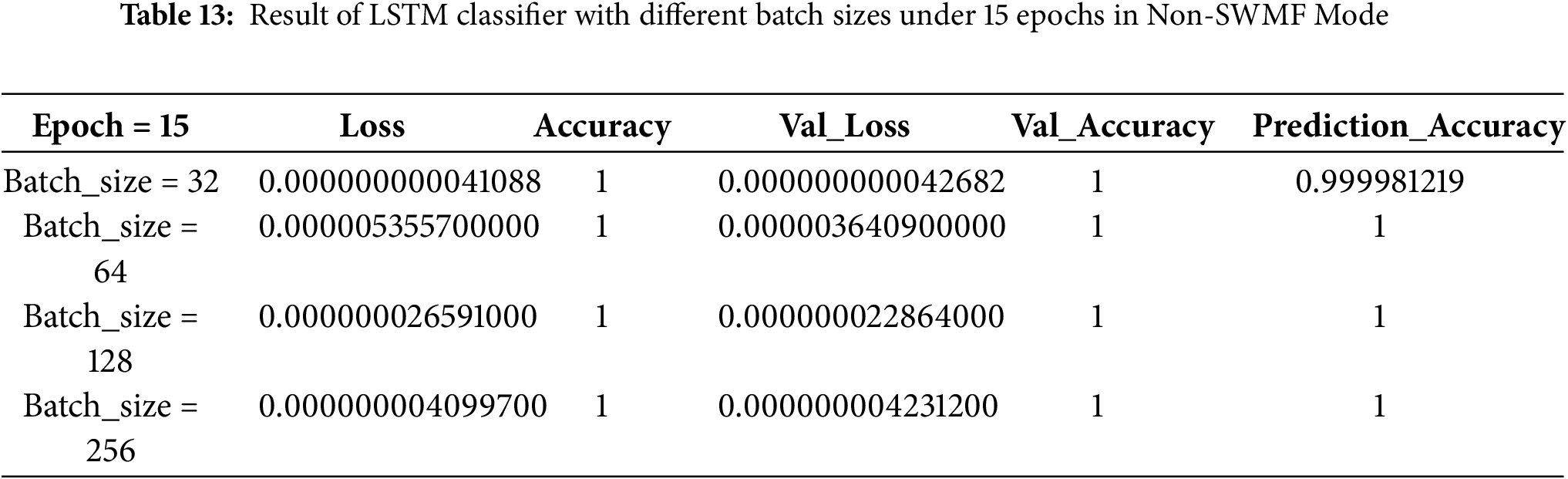

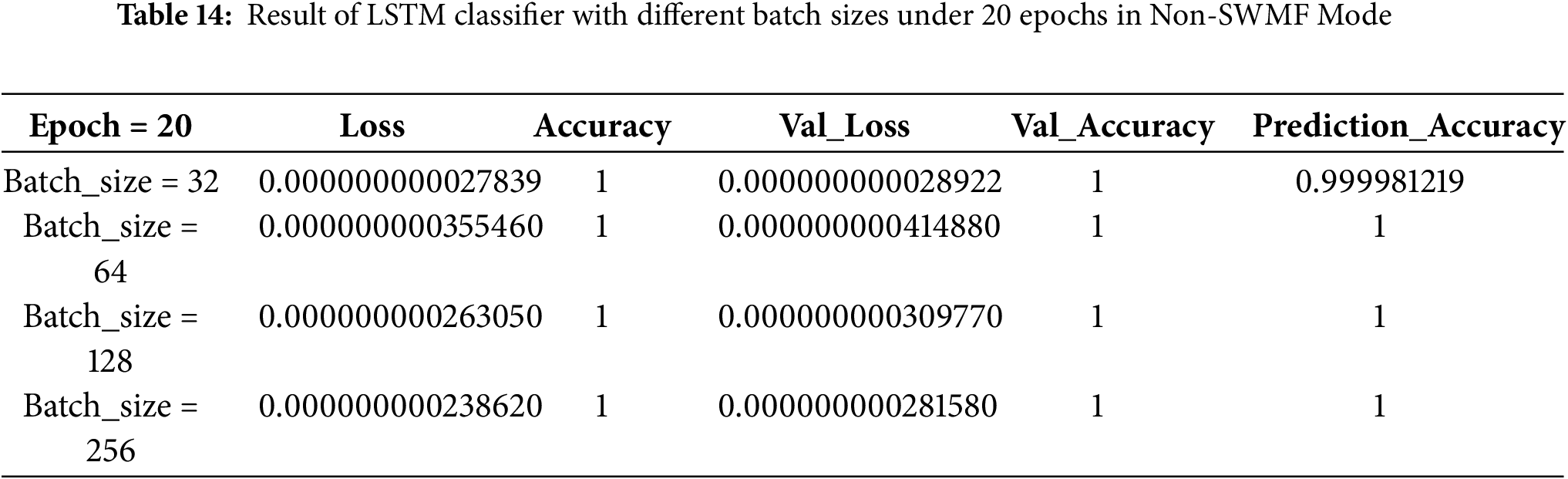

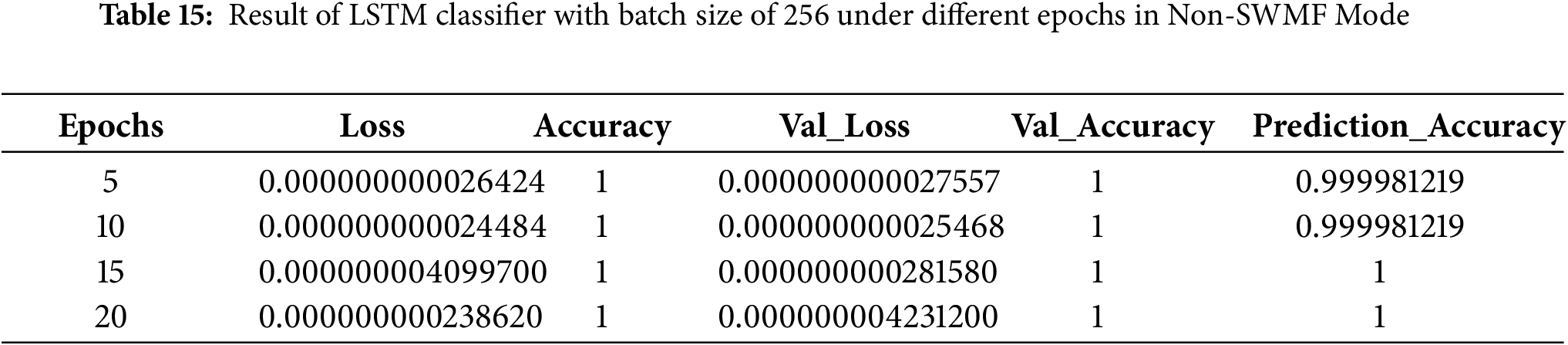

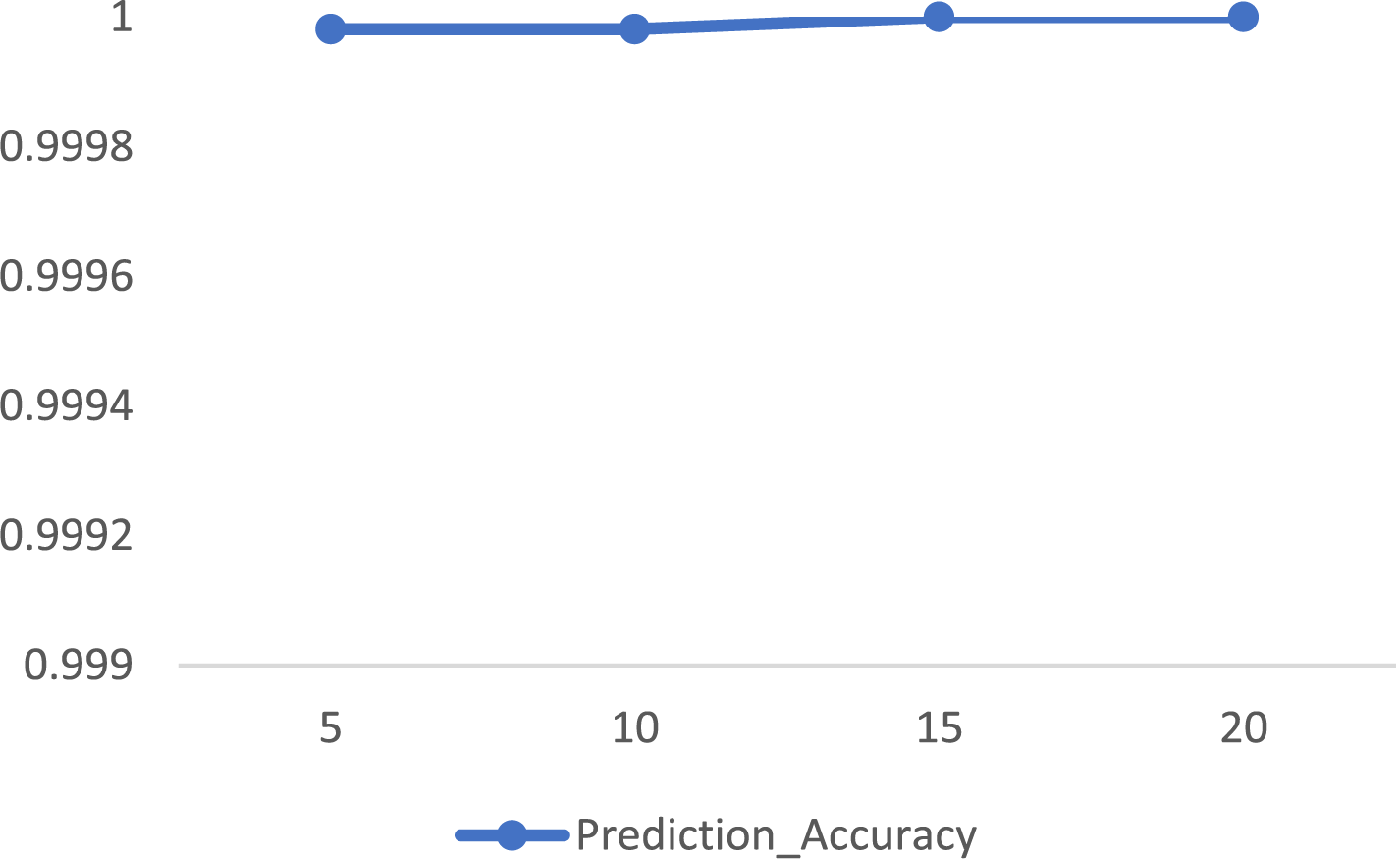

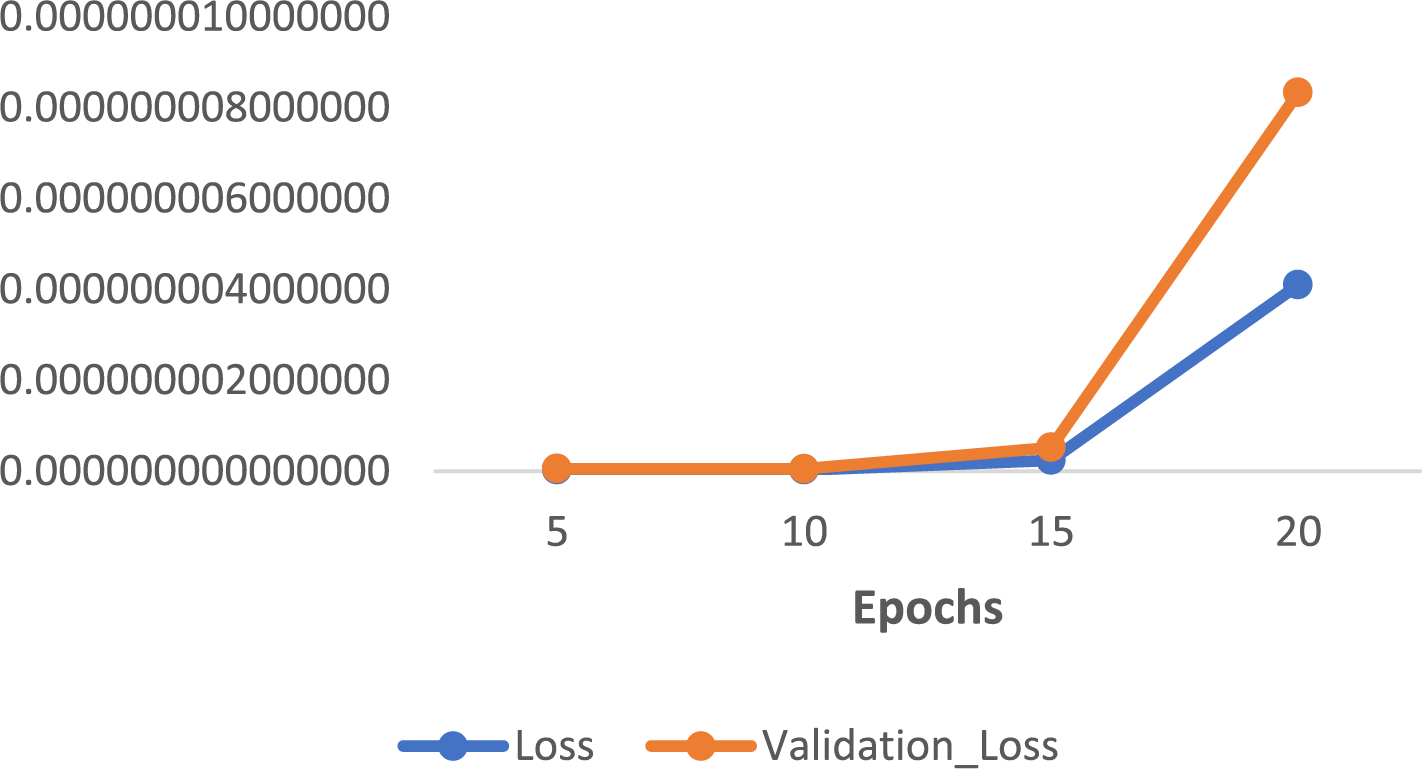

Then, we implemented the same LSTM-based deep neural network classifier in Non-SWMF Mode, using 5, 10, 15, and 20 epochs, and varying the batch size among 32, 64, 128, and 256. The results have been illustrated in Tables 11–14, while Table 15 summarizes these results for a batch size of 256 across the four epoch settings. The lowest loss was achieved at 15 epochs, while the prediction accuracy remained consistent for 15 and 20 epochs. Fig. 13 depicts the prediction accuracy of the LSTM classifier under batch size = 256 with different epochs in Non-SWMF Mode. Fig. 14 shows the train loss and validation loss of the LSTM classifier under batch size = 256 with different epochs in Non-SWMF Mode. The results of running the neural network classifier showed improvements in metrics, including loss, validation loss, training accuracy, validation accuracy, and prediction accuracy, when SWMF features were removed.

Figure 13: Prediction accuracy of LSTM Classifier under batch size = 256 with different epochs in Non-SWMF Mode

Figure 14: Train loss and validation loss of LSTM Classifier under batch size = 256 with different epochs in Non-SWMF Mode

The result of LSTM model implementations shows a slight improvement in evaluation metrics in the absence of SWMF features.

The result of training three classifiers with hyperparameter tuning in order to model the Trojan classification problem shows that evaluation metrics—such as accuracy, Kappa, sensitivity, and specificity—of the Random Forest model were positively affected by the presence of SWMF features. In contrast, employing a neural network classifier showed improvements in metrics, including loss, validation loss, training accuracy, validation accuracy, and prediction accuracy, when SWMF features were removed. A similar trend was observed in the LSTM model, where a slight improvement in evaluation metrics was noted in the absence of SWMF features.

Random Forest classifier with 300 estimators in Non-SWMF mode yields the highest accuracy of 0.82251855 and the highest Kappa of 0.646722. Random Forest classifier with 300 estimators in SWMF mode yields the highest accuracy of 0.992487558 and the highest Kappa of 0.985278422. This result proved that SWMF features are effective in boosting the performance of a Random Forest classifier.

With a neural network under the mentioned structure in Non-SWMF mode with 100 epochs and a batch size of 256, the minimum loss value of 0.000000181970000 was achieved, while the prediction accuracy was 100 percent and was the same under different batch sizes. With a neural network in SWMF mode with 100 epochs and a batch size of 128, the best prediction accuracy was achieved as 0.99291, while the loss value of 0.02770 was the same under different batch sizes. According to these results, taking SWMF features into account is not effective in boosting the model’s performance.

Under the LSTM classifier with a batch size of 256 under 10 epochs in Non-SWMF mode, we reached the prediction accuracy of 0.999981219 and the loss of 0.000000000024484. Although with more epochs, the accuracy reached 100 percent but the loss value also increased. Under an LSTM classifier with a batch size of 256 under 15 epochs in SWMF mode, we reached the prediction accuracy of 0.999981218893792 and the loss value of 0.000000000002767. Modelling a dataset including SWMF features has a higher computation time in comparison to a model based on the same dataset without the SWMF features, and these features increase the size of the dataset. From these results, it is clear that including the SWMF features—despite the added input burden—does not significantly improve the performance of the LSTM classifier.

In this study, we removed multiple non-SWMF features, such as Subflow Fwd Packets, Subflow Fwd Bytes, Subflow Bwd Packets, Subflow Bwd Bytes, Init_Win_bytes_forward and Init_Win_bytes_backward in order to investigate their impact on the overall performance of the classifiers. The experiments show that they have a relatively similar impact on the performance of all three classifiers. Therefore, for the experiments presented in this paper, we kept all of them in our feature set.

In this paper, we investigated modelling the Trojan binary classification problem using Random Forest, neural network, and LSTM approaches. To this end, we employed these models on a Trojan dataset in two configurations: with and without SWMF features. The aim is to assess the impact of SWMF features on models’ performance. SWMF features are commonly found in cybersecurity datasets. To identify important features, we used XGBoost, Random Forest, and Decision Tree models for feature importance analysis. Among the top-selected features, multiple SWMF-related attributes were identified, including several that represent similar concepts.

From the findings, we conclude that although some of the SWMF features are rated high as the most important features, their presence is important for enhancing the performance of the Random Forest model. On the other side of the spectrum, SWMF features are not essential for achieving competitive performance in neural network and LSTM classifiers. The limitation of this study is the lack of access to other Trojan-centric databases that include SWMF features and were truly built on Trojan attack observations.

In future work, we plan to extend this research by applying dimensionality reduction techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Autoencoder-based deep neural networks for feature reduction. We aim to investigate and compare their effects on the performance of various models for the Trojan identification problem.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The corresponding author designed the study and responsible for the conception and the methodology, and all authors contributed equally to the experiments, analysis, and writing of this manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used and/or analyzed during this study are available online at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/subhajournal/trojan-detection.

Ethics Approval: This research did not involve human participants or animals.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/subhajournal/trojan-detection

2https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/solarmainframe/ids-intrusion-csv

3Long-Short Term Memory

4Principal Component Analysis

5Mutual Information

6https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/toobajamal/kdd99-dataset

7Shen Y, Zheng K, Wu C, Zhang M, Niu X, Yang Y. An ensemble method based on selection using bat algorithm for intrusion detection. Comput J. 2018;61(4):526–38.

8Root Mean Squared Error

9The Communications Security Establishment (CSE) and the Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity (CIC)

10Mirsky, Y., Doitshman, T., Elovici, Y., Shabtai, A., 2018. Kitsune: An Ensemble of Autoencoders for Online Network Intrusion Detection. Proceedings of NDSS. Internet Society. doi: 10.14722/ndss.2018.23211.

11https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/ids-2018.html

12Intrusion Detection Systems

13Synthetic Minority Over-Sampling Technique

14https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/subhajournal/trojan-detection

15CWE: Common Weakness Enumeration helps identify patterns that, if unaddressed, could lead to security vulnerabilities.

16ECE: Explicit Congestion Notification Echo for network congestion management is a signal that congestion was encountered in the network on its path to the destination.

17Flow.IAT refers to the time difference between consecutive packets or flows within a network.

References

1. Kuang S, Quan Z, Xie G, Cai X, Chen X, Li K. NtNDet: hardware Trojan detection based on pre-trained language models. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;271(4):126666. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2025.126666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Ahmadi Abkenari F, Milani Fard A, Khanchi S. Hybrid machine learning-based approaches for feature and overfitting reduction to model intrusion patterns. J Cybersecur Priv. 2023;3(3):544–57. doi:10.3390/jcp3030026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Laghrissi F, Douzi S, Douzi K, Hssina B. Intrusion detection systems using long short-term memory (LSTM). J Big Data. 2021;8(1):65. doi:10.1186/s40537-021-00448-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. RuthRamya K, Jayadheer NS, Sravani V, Vamsi D, SarathSrinivas M. Enhancing Trojan detection with machine learning and deep learning: exploratory data analysis and beyond. Int J Adv Eng Manag. 2024;6(4):572–9. [Google Scholar]

5. Li X, Chen W, Zhang Q, Wu L. Building auto-encoder intrusion detection system based on random forest feature selection. Comput Secur. 2020;95(1):101851. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2020.101851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Leevy JL, Khoshgoftaar TM. A survey and analysis of intrusion detection models based on CSE-CIC-IDS2018 big data. J Big Data. 2020;7(1):104. doi:10.1186/s40537-020-00382-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Choo HS, Ooi CY, Inoue M, Ismail N, Moghbel M, Kok CH. Register-transfer-level features for machine-learning-based hardware Trojan detection. IEICE Trans Fundam. 2020;103(2):502–9. doi:10.1587/transfun.2019eap1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wijitrisnanto F, Sutikno S, Putra SD. Efficient machine learning model for hardware Trojan detection on register transfer level. In: Proceedings of the 2021 4th International Conference on Signal Processing and Information Security (ICSPIS); 2021 Nov 24–25; Dubai, United Arab Emirates. p. 37–40. doi:10.1109/icspis53734.2021.9652443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Ghimire A, Amsaad F, Hoque T, Hopkinson K, Rahman MT. Unsupervised IC security with machine learning for Trojan detection. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 66th International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems (MWSCAS); 2023 Aug 6–9; Tempe, AZ, USA. p. 20–4. doi:10.1109/mwscas57524.2023.10406045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Das S, Ghosh S. TrojanNet: detecting Trojans in quantum circuits using machine learning. arXiv:2306.16701. 2023. [Google Scholar]

11. Bajcsy P, Schaub NJ, Majurski M. Designing Trojan detectors in neural networks using interactive simulations. Appl Sci. 2021;11(4):1865. doi:10.3390/app11041865.doi:. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Liu Y, Ma S, Aafer Y, Lee WC, Zhai J, Wang W, et al. Trojaning attack on neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 2018 Annual Network and Distributed System Security Symposium; 2018 Feb 18–21; San Diego, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

13. Azizi A, Tahmid IA, Waheed A, Mangaokar N, Pu J, Javed M, et al. T-miner: a generative approach to defend against Trojan attacks on DNN-based text classification. In: Proceedings of the 30th USENIX Security Symposium; 2021 Aug 11–13; Virtual. [Google Scholar]

14. Gueriani A, Kheddar H, Mazari AC. Adaptive cyber-attack detection in IIoT using attention-based LSTM-CNN models. arXiv:2501.13962. 2025. [Google Scholar]

15. Gueriani A, Kheddar H, Mazari AC, Ghanem MC. A robust cross-domain IDS using BiGRU-LSTM-attention for medical and industrial IoT security. arXiv:2508.12470. 2025. [Google Scholar]

16. Xu Z, Fang X, Yang G. Malbert: a novel pre-training method for malware detection. Comput Secur. 2021;111(2):102458. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2021.102458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools