Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Auxin-Mediated Redox Control of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System: A Key Mechanism for Plant Growth and Development

1 Instituto de Investigaciones Biológicas (IIB-CONICET-UNMDP), Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata, Funes 3250, Mar del Plata, 7600, Argentina

2 Instituto de Fisiología, Biología Molecular y Neurociencias (IFIBYNE-UBA-CONICET) and Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Ciudad Universitaria, Buenos Aires, C1428EGA, Argentina

* Corresponding Authors: María Cecilia Terrile. Email: ; María José Iglesias. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Unraveling the Complexity of Ubiquitin E3 Ligases: Implications for Cellular Regulation and Disease)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(10), 1913-1928. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.067833

Received 13 May 2025; Accepted 26 August 2025; Issue published 22 October 2025

Abstract

In plants, the ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS) plays a central role in hormonal regulation, including the action of the phytohormone auxin, which orchestrates numerous aspects of growth and development. Auxin modulates redox metabolism and promotes the accumulation of nitric oxide (NO) in various tissues and physiological contexts. NO functions as a redox signaling molecule, exerting its effects in part through the reversible oxidation of cysteine residues via a post-translational modification known as S-nitrosylation. Recent findings highlight a dynamic interplay between S-nitrosylation and the ubiquitination machinery, shaping critical aspects of auxin-mediated plant responses. In this review, we summarize current knowledge on redox regulation of UPS components involved in auxin-mediated pathways and propose new perspectives on the integration of hormonal and redox signaling in plants. We describe and discuss the complexity of the latest evidence supporting the role of NO as a second messenger in auxin signaling, with S-nitrosylation acting as a regulatory mechanism that fine-tunes the UPS to control developmental outcomes. We focused on the direct effects of NO that include S-nitrosylation of specific cysteine residues of substrates, adaptors, and substrate receptors belonging to different CULLIN1- and CULLIN4-based E3 ubiquitin ligase complexes.Keywords

Plant growth and development depend on the ability to precisely regulate protein abundance in response to both internal signals and environmental cues. The ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS) is a central mechanism for targeted protein degradation, enabling plants to dynamically reshape their proteome with high specificity and temporal control [1]. Genome-wide analyses have revealed that plants encode a significantly larger number of UPS components than other eukaryotic organisms. In Arabidopsis thaliana, nearly 6% of the proteome encodes components of the UPS, underscoring its central role in plant biology and its extensive diversification during evolution [2].

This remarkable complexity is likely associated with the sessile lifestyle of plants, which must continuously adjust their physiology to a fluctuating environment. Importantly, the UPS not only contributes to general protein turnover but also plays a key role in the synthesis, perception, and signal transduction of multiple plant hormones, including auxin, jasmonic acid, gibberellins, ethylene, abscisic acid, strigolactones, cytokinins, and brassinosteroids [3].

Among these, the phytohormone auxin stands out as a master regulator of plant development, influencing a wide array of processes from embryogenesis and organogenesis to tropic responses and senescence. The canonical auxin signaling pathway involves the perception of the hormone by the SCFTIR1/AFB E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, which targets transcriptional repressors of the Aux/IAA (AUXIN/INDOLE-3-ACETIC ACID) family for proteasomal degradation [4]. This auxin-triggered proteolysis enables the activation of auxin-responsive genes, allowing for rapid and reversible modulation of transcriptional programs. In addition, auxin has also been shown to modulate redox metabolism, particularly by promoting the production of nitric oxide (NO), a reactive nitrogen species with signaling functions. NO exerts many of its regulatory effects through S-nitrosylation, a reversible oxidative post-translational modification of cysteine residues. Emerging evidence suggests that S-nitrosylation can influence not only transcription factors and signaling proteins but also components of the UPS, including E3 ligases, their adaptors, and substrates, establishing a novel link between auxin signaling, redox regulation, and proteasome-mediated control [5].

In this review, we explore how auxin-mediated redox signals, particularly those involving NO and S-nitrosylation, modulate the activity of E3 ubiquitin ligases and the broader UPS network. We discuss how this redox–hormonal crosstalk contributes to fine-tuning plant developmental programs, and highlight the potential of NO as a second messenger in auxin signaling pathways.

2 Ubiquitination in Plants: Multimeric E3 Ligases as Central Hubs in Plant Biology

The UPS mediates selective protein degradation through a conserved enzymatic cascade that ensures specificity and regulatory control. The process begins with the covalent attachment of multiple ubiquitin moieties (a highly conserved protein among eukaryotes) to a target protein, marking it for recognition and degradation by the 26S proteasome [6,7]. This ubiquitination process involves a sequential reaction catalyzed by three classes of enzymes: ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), and ubiquitin ligases (E3) [1,2]. While plants typically express one or two E1s and a moderate number of E2s (often regulated in a tissue- or stage-specific manner), the E3 ligases represent the most diverse group within the UPS, with thousands of predicted members in plant genomes.

E3 ligases are categorized into four main types based on their mechanism and structural composition. HECT (Homology to E6-AP C-Terminus)-type ligases form a covalent intermediate with ubiquitin before transferring it to the substrate. In contrast, RING (Really Interesting New Gene) and U-box ligases promote direct ubiquitin transfer from the E2 to the substrate without forming an intermediate. Still, they differ in how they stabilize the E2–E2-ubiquitin complex. Cullin–RING ligases (CRLs) are multisubunit complexes composed of a cullin scaffold (CUL1, CUL3, CUL4, or APC2-Anaphase-Promoting Complex), a RING-finger protein (RBX1 or APC11), and variable substrate recognition modules, such as F-box, BTB (Bric-a-Brac–Tramtrack–Broad Complex), or DWD (DNA Damage-Binding) proteins. Among these, CRLs E3 ligases exhibit the greatest diversity in plants [2].

A prominent subgroup of CRLs is the SCF complex (SKP1–CUL1–F-box), composed of SKP1 (S-phase kinase-associated protein 1), which links the complex to substrate receptors; CUL1, serving as a scaffold; an F-box protein that determines substrate specificity by binding targets directly; and a RING-domain protein (RBX1) that recruits the E2 enzyme for ubiquitination. The wide variety of F-box proteins enables SCF ligases to regulate numerous biological processes. SCF complexes play a key role in signaling pathways of major phytohormones, including auxin, gibberellins, jasmonates, and strigolactones, thereby integrating hormonal signals with plant growth and stress responses [8,9]. Other CRLs, such as CUL3–BTB and CUL4–DDB1–DWD (CRL4) complexes, also rely on interchangeable adaptors to determine substrate recognition. The relevance and mechanistic versatility of plant E3 ligases have been extensively discussed in recent reviews, which highlight their diverse functions across development and environmental responses [10,11].

3 Auxin Signaling and Redox Regulation

Auxins, which are central regulators of plant growth and development, are best exemplified by indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), the main natural auxin and key endogenous molecule involved in auxin signaling [4]. In parallel with their classical roles in growth regulation, auxins also exert profound control over cellular redox homeostasis—partly by modulating reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels and, importantly, by inducing NO biosynthesis. NO constitutes a gaseous signaling molecule that acts as a secondary messenger in auxin-mediated pathways [12,13]. In plants, NO is enzymatically produced mainly through nitrate reductase (NR) activity and by nitric oxide synthase (NOS)-like enzymes, although the precise identity and mechanisms of plant NOS-like sources remain under investigation [14,15]. Auxin-mediated NO production was described across species, organs, and physiological contexts. For instance, auxin stimulates NO accumulation in A. thaliana root tips during gravitropism, in stems under simulated shade, and in lateral root primordia during organogenesis [16–18]. Auxin-mediated NO accumulation was also described in tomato, rice, and sunflower plants [19–21]. In parallel, auxin also regulates the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), often mediated by NADPH oxidases of the Respiratory Burst Oxidase Homolog (RBOH) family, which play critical roles in redox signaling during developmental and stress-related processes [22,23]. By integrating auxin-triggered NO and ROS synthesis with redox-sensitive post-translational modifications (PTMs), plants achieve fine-tuned control over developmental and adaptive programs. This interplay highlights the versatility of auxins not only as growth regulators but also as orchestrators of redox homeostasis, with NO and ROS serving as critical mediators linking hormonal cues to protein-level modifications [13,24].

4 NO Action through S-Nitrosylation

NO exerts its regulatory effects primarily through redox-based PTMs. Among these, S-nitrosylation is one of the most prominent mechanisms described in plants. It consists of the covalent addition of a NO group to the thiol side chain of specific cysteine residues, resulting in the formation of S-nitrosothiols (SNOs). This reaction tends to occur on cysteines with low pKa and high nucleophilicity, often located within particular protein microenvironments that favor electron delocalization or interaction with metal cofactors [25].

The formation of protein-SNOs can take place through multiple pathways. S-nitrosylation may occur via trans-nitrosylation, where the NO group is transferred from a low-molecular-weight S-nitrosothiol donor, most commonly S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO), to a target protein. The rate and selectivity of these reactions are influenced by factors such as thiol accessibility, pH, and the redox status of the cellular environment, which collectively determine whether a cysteine exists in its reactive thiolate (RS−) form [25].

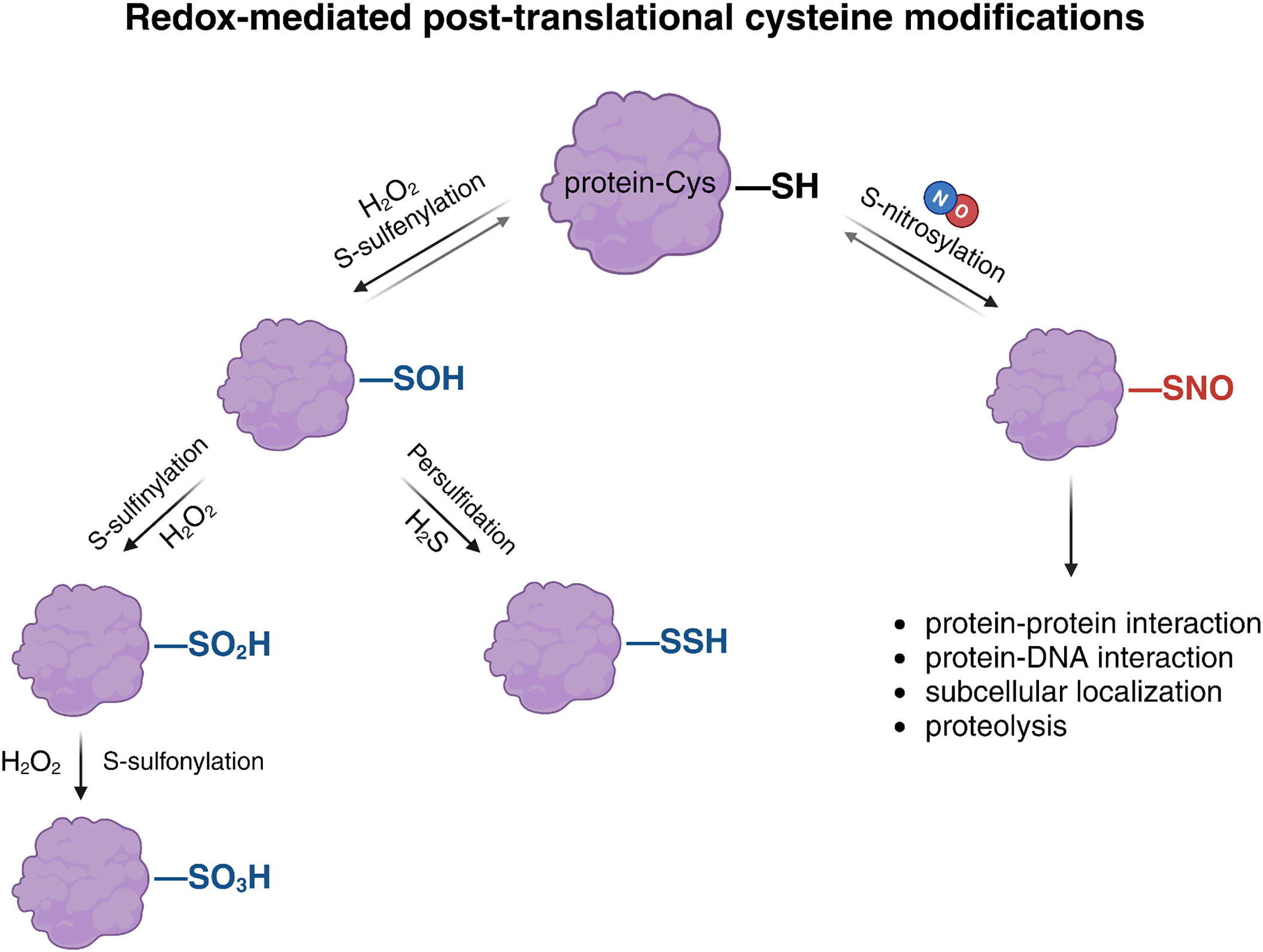

S-nitrosylation is a reversible and highly regulated modification that can modulate protein function in multiple ways (Fig. 1). It has been shown to influence protein conformation, catalytic activity, subcellular localization, protein–protein interactions, and susceptibility to proteolytic degradation. Depending on the target and the physiological context, this modification can either enhance or inhibit protein function. Its transient and specific nature makes it particularly well-suited for dynamic signaling events, including those related to hormonal responses and environmental adaptation [26].

Figure 1: Redox-mediated post-translational modifications (PTMs) of cysteine residues in proteins. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) promote diverse oxidative modifications of protein thiols. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) induces sulfenylation (–SOH), a reversible modification that can be further oxidized to sulfinylation (–SO2H) or sulfonylation (–SO3H), both considered irreversible. Sulfenylated cysteines can also undergo persulfidation (–SSH) in the presence of hydrogen sulfide (H2S). NO induces S-nitrosylation by covalently modifying the thiol group (–SH) of cysteine residues to form S-nitrosothiols (–SNO). This reversible modification regulates key processes such as protein–protein and protein–DNA interactions, subcellular localization, and proteolysis. Created with BioRender.com

Importantly, protein S-nitrosylation is balanced by active denitrosylation systems that restore the thiol state and ensure signaling flexibility. In plants, this process is mainly mediated by two enzymatic systems: the glutathione-dependent GSNOR pathway, which degrades GSNO, and the NADPH-dependent thioredoxin (Trx) system, which directly reduces protein-SNOs. Together, these systems maintain redox homeostasis and modulate the intensity and duration of NO-based signals [27].

Overall, S-nitrosylation constitutes a key mechanism through which NO integrates developmental and environmental signals into the protein regulatory network. By acting as a reversible redox switch, it enables rapid and localized control over protein function, contributing to the fine-tuning of physiological processes in plants. In contrast, tyrosine nitration—a less reversible PTM mediated by peroxynitrite (ONOO−) has not been linked to auxin signaling regulation, and is often associated with a degradation mark triggered by oxidative stress [28].

Beyond S-nitrosylation, thiol-based oxidative PTMs also include S-sulfenylation, persulfidation, and S-glutathionylation, primarily triggered by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hydrogen sulfide (H2S), and GSH/GSNO, respectively (Fig. 1). These reactive electrophilic species can reversibly modify redox-sensitive proteins, resulting in both beneficial and detrimental effects on plant growth, development, and responses to environmental stress. Notably, H2O2 can also induce irreversible oxidative modifications, often linked to protein degradation. It has been proposed that persulfidation and S-nitrosylation modifications in plants act as regulatory mechanisms to prevent the overoxidation of cysteine residues by ROS, which would otherwise lead to modifications such as carbonylation or sulfenylation, resulting in irreversible inactivation and subsequent degradation of proteins [29,30]. Focusing on the specificity of redox signals, the analysis of Aroca et al. (2017) reveals that 70% of S-nitrosylated proteins described in A. thaliana, were also targets of persulfidation, although both signals could be affecting the same or different Cys residues [31]. The functional impact of cysteine modifications by NO on protein targets has been more extensively studied in relation to diverse physiological processes, whereas research on S-sulfenylation and persulfidation is comparatively recent and still emerging [32].

5 Regulation of Auxin Response through Multi-Level Interactions between S-Nitrosylation and Ubiquitination

Recent studies have revealed that NO-mediated S-nitrosylation interacts in complex ways with other PTMs, including redox modification as persulfidation but also phosphorylation, SUMOylation, glutathionylation, and ubiquitination, thereby expanding the extensive repertoire of cellular signaling pathways it regulates [33]. Among these interactions, S-nitrosylation and ubiquitination converge to dynamically modulate protein stability, activity, and interactions, enabling plants to rapidly reconfigure transcriptional programs in response to auxin cues. The interplay between S-nitrosylation and ubiquitination underscores a sophisticated regulatory layer in auxin signaling. In this review, we propose that part of the auxin signaling response involves the tight regulation of NO levels, which, in turn, influence the ubiquitination process since several components of E3 ligases (or their substrates) act as redox-sensitive proteins [34]. This regulation affects the stability and degradation of transcriptional activators or repressors, thereby contributing to the auxin-mediated reprogramming of the plant transcriptome and proteome. In the following sections, we present several paradigmatic examples of this regulatory mechanism as proof of concept supporting our proposed mechanism.

5.1 S-Nitrosylation Acts as a Dynamic Redox Switch Modulator of Key Components of the SCFTIR1 E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Complex

Auxin drives transcriptional reprogramming primarily through its well-established canonical nuclear signaling pathway. Central to this process is the SCFTIR1/AFB complex, where TIR1/AFB F-box proteins and their Aux/IAA substrates function as hormone co-receptors [35,36]. In A. thaliana, the TIR1/AFB co-receptor family comprises six members (TIR1 and AFB1 through AFB5) each containing conserved F-box and LRR domains. Genetic studies have shown that while they largely function redundantly in mediating auxin perception, individual paralogs like AFB1 have evolved specialized roles, emphasizing both overlapping and distinct contributions to auxin signaling [37–39]. Upon auxin binding, the interaction between TIR1/AFB and Aux/IAA proteins is stabilized, enabling the SCFTIR1 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex to catalyze the polyubiquitination of Aux/IAA proteins and target them for degradation by the 26S proteasome. Aux/IAAs function as transcriptional repressors by inhibiting AUXIN RESPONSE FACTORs (ARFs), which are the transcription factors responsible for regulating auxin-responsive gene expression. Therefore, auxin-mediated degradation of Aux/IAAs results in ARF activation and subsequent transcription of auxin-inducible genes [40,41]. Molecularly, the SCFTIR1 complex recognizes a specific region in the Aux/IAA proteins (domain II), which contains a conserved degron motif essential for TIR1 binding. Auxin acts as a molecular glue, enhancing the affinity between TIR1 and the degron [42]. Recent structural and biochemical studies have further revealed that intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) flanking domain II play a critical role in orienting the substrate for optimal ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation [43]. This sequence- and structure-dependent recognition ensures the specificity and responsiveness of the auxin signaling pathway.

Terrile et al. (2012) have revealed that NO adds a redox-based regulatory layer to the canonical auxin signaling pathway through S-nitrosylation of key receptor proteins [44]. In A. thaliana, auxin promotes NO accumulation (dependent on NR-activity), which in turn triggers the S-nitrosylation of conserved cysteine residues in TIR1 (Cys140 and Cys480) and AFB2 (Cys135 and Cys511), enhancing their affinity for Aux/IAA substrates and accelerating their proteasomal degradation [23,44]. These PTMs significantly enhance auxin signaling outputs, such as primary root elongation and lateral root initiation. Conversely, mutation of these cysteines diminishes Aux/IAA binding, confirming the functional relevance of these redox-sensitive residues in modulating receptor activity [44]. This redox control mechanism not only adds complexity to the classical model of auxin signaling but also establishes NO as an integral signaling molecule in plant development.

Recently, Lu et al. (2024) have elucidated how redox-based modulation via NO and reactive oxygen species (ROS) orchestrates the spatial dynamics of auxin signaling components during root hair development [23]. In A. thaliana, auxin triggers a nitroso-oxidative burst mediated by the FERONIA (FER) receptor-like kinase and NADPH oxidase. This burst induces S-nitrosylation and oxidation of conserved cysteine residues in TIR1 (Cys140, Cys516) and AFB2 (Cys135, Cys511), promoting their nuclear accumulation in root hair and trichoblast cells. The nuclear translocation of these co-receptors facilitates SCF complex assembly within the nucleus, accelerates local Aux/IAA ubiquitination and degradation, and amplifies transcriptional responses essential for root hair formation. This study demonstrated that in fer mutants (deficient in FER signaling), TIR1 and AFB2 exhibit reduced oxidative modification and remain largely cytoplasmic, leading to diminished SCF assembly and impaired auxin responsiveness in root hairs. These findings underscore that NO and ROS not only regulate the biochemical receptor–substrate interaction but also govern the subcellular distribution of the SCFTIR1/AFB complex, thus reinforcing auxin-driven morphogenesis at the cellular level.

Interestingly, S-nitrosylation also targets Aux/IAA repressors themselves, adding another regulatory layer to the auxin signaling network. IAA17 is S-nitrosylated at Cys70, a modification that reduces its binding to TIR1 and delays its proteasomal degradation [45]. This contrasts with the previously reported effect of S-nitrosylation on TIR1 and AFB2, where modification of conserved cysteine residues enhances receptor–substrate interactions and accelerates Aux/IAA turnover [23,44]. Together, these findings suggest a dual-level regulation whereby NO enhances receptor activity while transiently stabilizing specific substrates, contributing to a fine-tuned control of auxin responses. Such a mechanism could allow the plant to modulate the intensity and duration of the auxin signal depending on developmental stage or environmental inputs. Given that A. thaliana encodes 29 Aux/IAA proteins with diverse expression patterns and functional roles, it remains an open question how widespread S-nitrosylation is across this family and whether it selectively modulates particular Aux/IAA members under specific physiological contexts.

In addition to modulating auxin receptors (TIR1/AFBs) and their substrates (Aux/IAAs), NO also targets ASK1 (Arabidopsis SKP1-like 1), the adaptor protein that bridges TIR1/AFBs with the CUL1 scaffold within the SCFTIR1/AFB E3 ubiquitin ligase complex. S-nitrosylation of ASK1 at Cys37 and Cys118 enhances its interaction with TIR1, AFB2, and CUL1, thereby promoting efficient SCF complex assembly. Functional analyses using plants expressing a non-nitrosylatable ASK1 mutant (C37A/C118A) display reduced auxin sensitivity and delayed Aux/IAA turnover, resulting in impaired root development [46]. These observations indicate that ASK1 functions as a redox-sensitive hub within the SCFTIR1/AFB complex, tuning its activity in response to NO signals.

Importantly, ASK1 is not exclusive to the auxin pathway: it serves as a shared adaptor in various SCF-type E3 ligases. Since substrate specificity is dictated by the F-box protein, redox regulation of ASK1 by S-nitrosylation may broadly influence the assembly and function of multiple SCF complexes. Supporting this, S-nitrosylation of ASK1 at Cys118 also enhances its interaction with COI1, the F-box protein of the SCFCOI1 complex, which mediates jasmonate signaling [5]. Consistently, plants overexpressing a non-nitrosylatable ASK1 variant exhibit disrupted JA-responsive gene expression, highlighting the functional relevance of this redox-based regulation beyond the auxin pathway [5]. These findings suggest that auxin-induced NO may exert broader regulatory effects through redox control of ASK1, potentially influencing the dynamics of multiple SCF complexes and mediating hormone crosstalk. Given the coexistence of multiple SCF complexes within the same cellular environment, S-nitrosylation of ASK1 may act as a molecular switch coordinating interactions between hormonal responses, fine-tuning plant development, and stress adaptation.

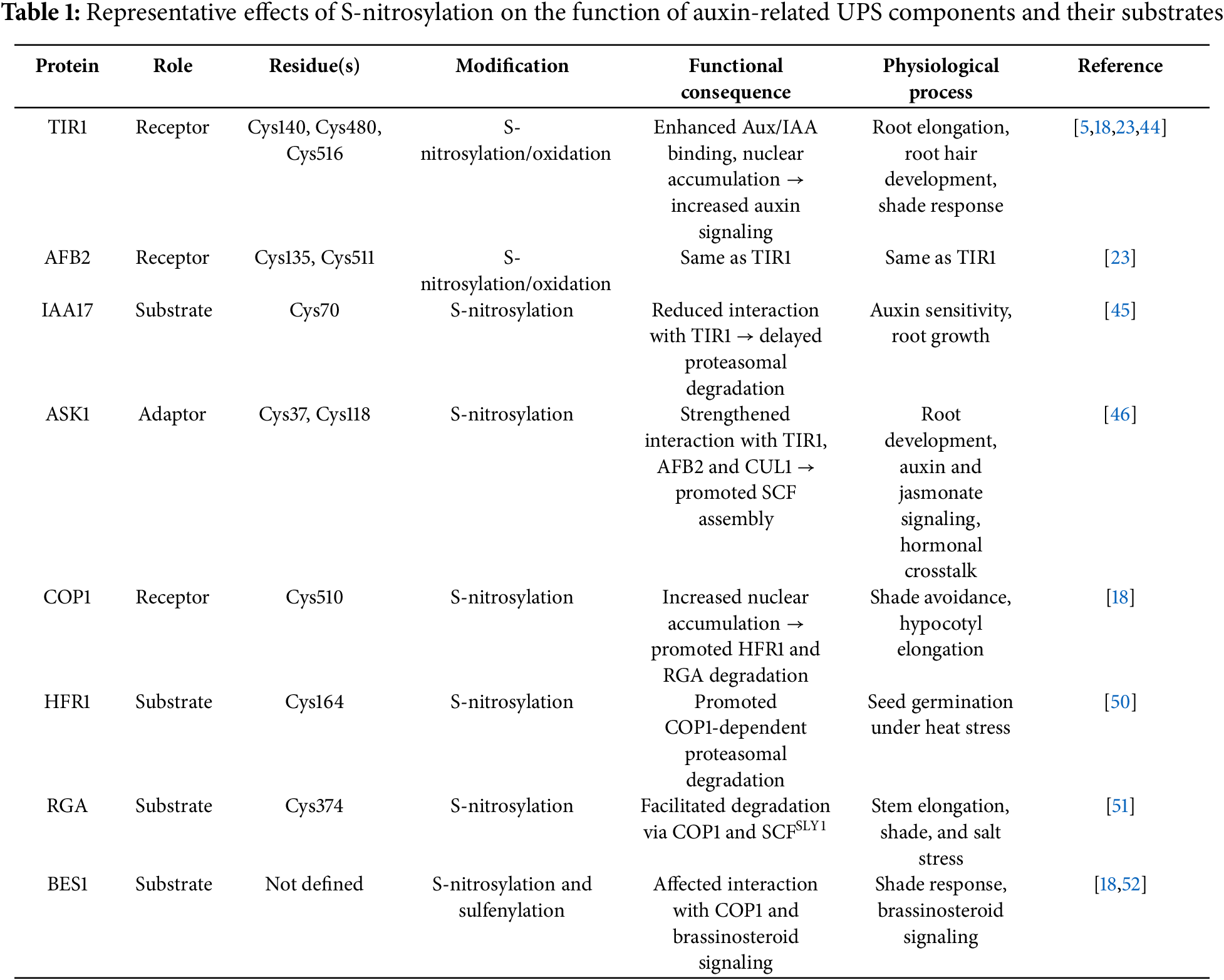

Meanwhile, the overlapping S-nitrosylation control of different SCF E3 ligase components and their substrates (Table 1) provides phytohormones with a dynamic mechanism to fine-tune transcriptional outputs, either by amplification or attenuation. By coupling NO-mediated redox signaling with UPS activity, plants achieve precise spatiotemporal control over development and stress adaptation, reshaping the transcriptome to align with environmental and hormonal cues. In addition to promoting NO accumulation and driving the S-nitrosylation of key signaling proteins, auxin also contributes to a redox-based negative feedback loop that modulates the extent and duration of this modification. Elevated NO levels stimulate the activity of the NADPH-dependent thioredoxin reductase (NTR)–thioredoxin (Trx) system, which selectively removes S-nitrosyl groups from target proteins, thereby preventing signal overamplification and contributing to redox homeostasis [47,48]. Notably, recent findings indicate that Trx family members also regulate the activity of deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), suggesting that NO-dependent redox signals not only modulate protein activity via S-nitrosylation but also influence protein stability through the ubiquitin–proteasome system [49]. This redox–UPS interface may represent a key convergence point for integrating multiple hormonal and environmental cues.

However, how plants orchestrate the dynamic assembly and specificity of distinct SCF complexes under fluctuating redox and hormonal conditions remains largely unexplored, highlighting a critical frontier in our understanding of plant signaling plasticity.

5.2 COP1/SPA-CUL4 E3 Ligase Complex in the Regulation of Light Signaling

Plants exhibit developmental plasticity, and light is an environmental cue that conveys information on day length, spatial orientation, and neighboring vegetation. Light is perceived by several photoreceptors that modulate gene expression through interactions with transcription factors and regulators such as CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENIC 1 (COP1) [53]. COP1 is the substrate-recognition subunit of the CRL4COP1/SPA E3 ligase complex, which is composed of the scaffold protein CUL4, the adaptor DDB1, the RING-finger protein RBX1, and the regulatory subunits COP1 and SUPPRESSOR OF PHYA-105 (SPA). COP1 and SPA together define the substrate specificity and modulate the activity of the complex [54]. In A. thaliana, COP1, together with the SPA, regulates photomorphogenesis. COP1 contains an N-terminal RING domain that interacts with E2 conjugating enzymes, a coiled-coil domain that mediates homodimerization and SPA binding, and a C-terminal WD40 domain that recognizes target proteins and photoreceptors. By degrading its substrates, the COP1/SPA complex controls light-regulated processes such as hypocotyl elongation, anthocyanin biosynthesis, shade avoidance, flowering time, stomatal patterning, and hormone signaling [55]. Co-expression analysis shows a correlation between COP1/SPA and PHYTOCHROME B (PHYB) expression across various tissues and conditions [56]. PHYB acts as both a photo- and thermo-sensor, modulating the activity of several transcriptional regulators through direct or indirect physical interactions with other proteins. Thus, the co-expression of COP1/SPA and PHYB strongly suggests that PHYB regulates COP1 activity [57–59].

In darkness, A. thaliana seedlings rely on cotyledon reserves to promote hypocotyl elongation, increasing the chance of emerging from the soil. After light perception, hypocotyl elongation slows, cotyledons unfold, and chlorophyll synthesis begins, a transition termed de-etiolation. COP1, first characterized in this transition, represses light responses in darkness by targeting photoreceptors (phyA, cry2) and the transcription factor ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL 5 (HY5) for degradation [60]. COP1 also regulates shade avoidance and integrates light and temperature cues [57,61]. More recently, COP1 has emerged as a key regulator of shade avoidance and as an integrator of conflicting seasonal light and thermal cues in A. thaliana plants [57,61]. In response to changes in light conditions caused by nearby vegetation, shade-avoiding plants adjust their growth and development to improve light capture including stem growth, leaf development, and flowering transitions. Shade avoidance responses, observed in many crop species as soybean, wheat, and sunflower, play a significant role in agricultural productivity [61]. Under shade conditions, COP1 accumulates in the nucleus [62] and facilitates the degradation of LONG HYPOCOTYL IN FARRED 1 (HFR1), the DELLA protein REPRESSOR OF ga13 (RGA), and BRI1EMSSUPPRESSOR 1/BRASSINAZOLERESISTANT 1 (BES1/BZR1), which are negative regulators of shade-induced responses [63–65]. Removal of these repressors enables PHYTOCHROME-INTERACTING FACTOR (PIF) transcription factors to induce auxin-biosynthetic genes, thereby promoting auxin-mediated hypocotyl elongation [66,67].

5.3 NO Regulation of COP1/SPA-CUL4 E3 LIGASE Complex through S-Nitrosylation Events

Neighbor-mediated changes in light quality are sensed primarily by PHYB, inducing auxin biosynthesis in cotyledons or leaves, which is transported to hypocotyl, stems, or petiole of leaves in order to coordinate adaptive growth [68,69]. Recent findings indicate that auxin triggers a transient rise in NO levels in the hypocotyl of A. thaliana and canola seedlings, a process required for promoting cell elongation under shade conditions [18]. TIR1 has also been validated as a target of auxin-induced NO in the regulation of hypocotyl elongation under shade conditions, as plants expressing a TIR1 variant mutated at Cys140 (the S-nitrosylation site) exhibit a reduced cell elongation response compared to wild-type plants [18].

In addition, shade-mediated transient accumulation of NO in an oxidative environment that also involves increased ROS levels leads to S-nitrosylation of COP1 at Cys510. At the physiological level, NO-mediated S-nitrosylation of COP1 regulates hypocotyl elongation, as plants expressing a non-nitrosylatable version of COP1 mutated at Cys510 exhibit impaired shade-avoidance responses. Disruption of this COP1 S-nitrosylation event also results in transverse asymmetries in hypocotyl growth, indicating defective cellular coordination and causing random bending of the hypocotyl, which likely reduces the plant’s competitive ability against neighboring vegetation. At the molecular level, COP1 S-nitrosylation enhances E3 ligase activity by reducing COP1 proteasomal degradation [18], a process likely mediated by an as-yet unidentified E3 ligase [70]. As a result, COP1 accumulates in the nucleus, where it facilitates the degradation of different substrates such as the transcription factor HFR1 and the DELLA transcriptional repressor, RGA. Consistently, mutations in Cys510 or treatment with NO scavengers result in stabilization of COP1 targets.

UV-light also induces NO accumulation in the hypocotyl [71], and UV RESISTANCE LOCUS 8 (UVR8) constitutes an interactor of COP1 E3 ligase during UV-B responses [72,73]. However, several differences can be observed between NO induced by shade and that triggered by UV-B light treatment. Shade-mediated accumulation of NO depends on auxin biosynthesis and is primarily mediated by NR activity, while UV-B promotes an auxin-independent increase in NO through NOS-like activity [18,71]. Shade primarily promotes COP1 accumulation in the nucleus, whereas UV-B favors its retention in the cytosol [63,74]. More importantly, under UV-B exposure, UVR8 inhibits COP1’s ubiquitin ligase activity, leading to the stabilization of key transcriptional regulators such as HY5 [75,76], while shade-induced COP1 S-nitrosylation promotes COP1 E3 ligase activity. Surprisingly, mutations in COP1 Cys510 or surrounding Cys509 did not alter its interaction with UVR8, suggesting a degree of specificity in the redox regulation of COP1’s interactome [18,77]. Recent evidence suggests that the COP1/SPA–UVR8 interaction depends on the oligomerization and phosphorylation states of UVR8 [78], adding another layer of regulation to COP1 activity.

Interestingly, the regulation of NO accumulation in terms of concentration and duration of this signal is not trivial to promote cell elongation and hypocotyl growth. The regulation of S-nitrosylation and denitrosylation is finely controlled by core components; for instance, phyB not only promotes auxin-mediated NO biosynthesis (enhancing S-nitrosylation) but also modulates denitrosylation by influencing GSNOR activity [50]. Therefore, results that seem to be controversial with NO promoting or inhibiting plant cell elongation should be considered in terms of a balance of NO redox signal, where COP1 regulation is a paradigmatic example. While shade-induced NO promotes S-nitrosylation of COP1 at Cys510, enhancing its E3 ligase activity, prolonged exposure to high concentrations of NO donors leads to alternative S-nitrosylation at Cys425 and Cys607, which negatively affects COP1 function [18,79]. In addition, TRXh3 and TRXh5, which act as selective protein-SNO reductases, have been identified among COP1 interactors, reinforcing the hypothesis of a tightly regulated balance of COP1 S-nitrosylation status [79].

Additional evidence indicates that NO has a broader role in regulating COP1 E3 ligase activity by modulating the stability of its substrates. As it was previously described for the SCF E3 ligase complex, S-nitrosylation is a common regulatory mechanism on E3 ligases and substrates (Table 1). CRL4COP1/SPA target BES1 (BRI1 EMS Suppressor 1) was also found to be S-nitrosylated in vivo in A. thaliana seedlings [18]. In addition, the transcription factor HFR1 is S-nitrosylated under high-temperature stress, promoting its COP1-dependent ubiquitination and degradation, thereby delaying seed germination [50]. The non-nitrosylatable version, HFR1-C164S, avoids degradation, underscoring the redox sensitivity of this regulatory node. Similarly, the DELLA protein RGA is regulated by NO through S-nitrosylation at Cys374, which facilitates its degradation via the UPS and promotes stem elongation [51]. Under shade conditions, RGA is also a substrate of COP1, whose S-nitrosylation enhances RGA degradation [18]. Additionally, RGA is targeted by the SCFSLY complex, where the F-box protein SLEEPY1 (SLY1) mediates its degradation. Intriguingly, in vitro data suggest that S-nitrosylation in RGA disrupts its interaction with SLY1, delaying degradation under salt stress [51]. Given that RGA undergoes both S-nitrosylation and ubiquitination by different E3 ligases, whose activities are themselves influenced by NO-mediated redox regulation, further studies are needed to dissect how these interconnected PTMs coordinate plant responses in a context-dependent manner.

6 Crosstalk with Alternative Cys Oxidative PTMs

In the last decade, increasing number of publications were focused on how NO and H2S orchestrate the modulation of ROS levels in the regulation of root development and architecture, including massive proteomic data revealing that auxin metabolism and signaling is a category enriched in redox PTM, including S-nitrosylation, persulfidation, and sulfenylation [32,80]. However, the role of H2S and H2O2 as possible signals regulating the synergistic or opposite ubiquitination of substrates mediated by SCFTIR1 has not been clarified yet, and will shed light on the redox regulation of auxin signaling at a physiological level.

In the context of light regulation of developmental programs, COP1 has been shown to interact with BES1, promoting its degradation in cotyledons while stabilizing it in the hypocotyl [65]. This organ-specific regulation raises important questions about redox modulation of the COP1–BES1 node, and how the redox PTMs influence protein stability and signaling outcomes. The transcription factors BES1 and BZR1, key components of brassinosteroid signaling, are both regulated by S-nitrosylation and S-sulfenylation [18,52,81]. H2O2 mediates oxidation of BES1 at specific Cys, affecting its activity and interaction with protein partners [52]. The specific residues and functional effects of S-nitrosylation in BES1 have not been studied; therefore, it remains an open question whether the redox signals NO and H2O2 target the same or distinct cysteine residues. In addition, although COP1 S-nitrosylation at Cys510 affects BES1 stability, it remains unclear how oxidative modifications on BES1 itself affect its interaction with COP1. Altogether, these findings position COP1 as a redox-sensitive hub to study how redox signals integrate environmental and hormonal cues. Since auxin is known to induce both NO and H2O2 in the regulation of physiological processes where COP1 and BES1 are involved, a deeper understanding of how COP1 and its substrates respond to auxin and NO under diverse environmental conditions and developmental contexts is essential to advance current knowledge of redox-regulated ubiquitin signaling in plant biology.

7 Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

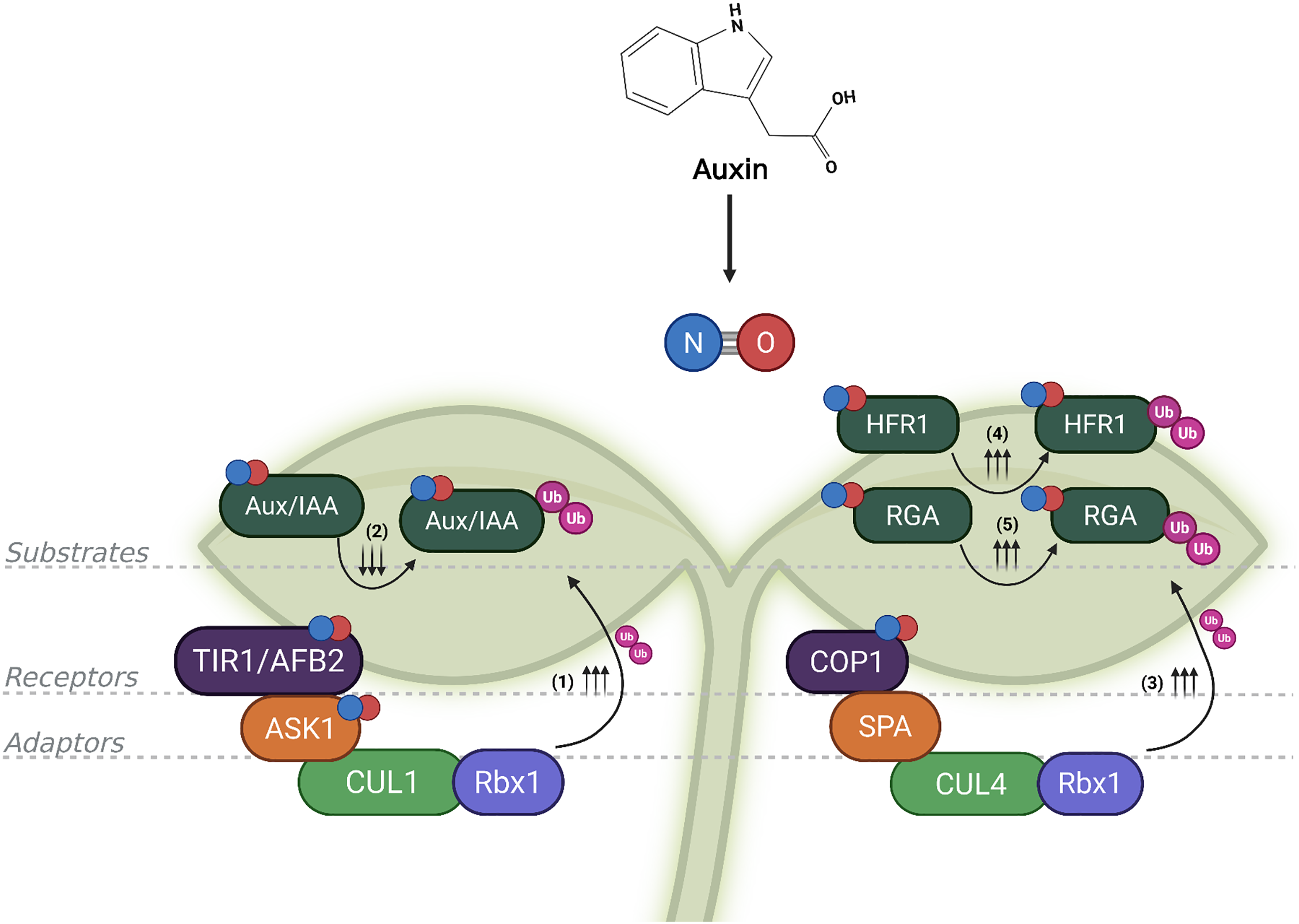

This review highlights the emerging role of NO-mediated redox signaling as a central modulator of the ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS) in auxin-regulated plant development. Through reversible post-translational modifications such as S-nitrosylation, NO dynamically regulates the activity, stability, and subcellular localization of key components of multimeric E3 ligase complexes, notably SCFTIR1/AFBs and CRL4COP1. These redox modifications govern the timely degradation of transcriptional repressors and signaling intermediates, ultimately shaping auxin outputs in diverse developmental and environmental contexts (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: The convergence of S-nitrosylation and ubiquitination creates a dynamic regulatory circuit in auxin signaling. Auxin-induced nitric oxide (NO) modulates E3 ubiquitin ligase complexes and their substrates via S-nitrosylation. On the left, in the SCFTIR1/AFB complex, S-nitrosylation of F-box proteins such as TIR1/AFB2 (TRANSPORT INHIBITOR RESPONSE 1/AUXIN SIGNALING F-BOX 2) and ASK1 (ARABIDOPSIS SKP1-LIKE 1), enhances the degradation of Aux/IAA (AUXIN/INDOLE-3-ACETIC ACID) repressors via increased ubiquitination (Ub; depicted by ↑↑↑), promoting auxin-responsive gene expression. In contrast, S-nitrosylation of certain Aux/IAA proteins (e.g., IAA17) can impair their recognition by the SCF complex, reducing their ubiquitination and temporarily stabilizing them (indicated by ↓↓↓), acting as negative feedback. On the right, NO also modifies the CUL4-COP1-SPA complex (comprising CULLIN4, the E3 ligase COP1, CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENIC, and the cofactor SPA, SUPPRESSOR OF PHYA-105), increasing the degradation of substrates such as HFR1 (LONG HYPOCOTYL IN FAR-RED 1) and RGA (REPRESSOR OF GA1-3), depicted by ↑↑↑. By targeting both E3 ligases and their substrates, NO ensures precise spatiotemporal control over auxin signaling, exemplifying the sophistication of post-translational modifications regulatory networks in plants. References: (1) [5,18,23,44]; (2) [45]; (3) [18]; (4) [50]; (5) [51]. Created with BioRender.com

Auxin not only stimulates NO biosynthesis but also modulates denitrosylation through the NADPH-dependent thioredoxin (Trx) system, creating a self-regulating feedback loop that maintains redox homeostasis and ensures signaling precision. Trx proteins may also influence deubiquitinating enzyme activity, hinting at a broader role in the dynamic remodeling of the plant proteome and cross-regulation between redox and hormonal pathways.

Looking ahead, the integration of redox biology with auxin signaling raises provocative questions and opens unexplored territory. Does a ‘redox code’ exist that defines UPS substrate selectivity and timing in response to auxin and NO? Can we decode spatially resolved redox networks that coordinate hormone signaling across tissues? Do E3 ligases act as redox sensors, integrating metabolic status with proteostasis decisions? Could NO-mediated S-nitrosylation switch E3 ligases from one substrate to another, enabling flexible reprogramming of signaling networks under stress or development? And fundamentally, can we engineer redox-sensitive protein switches to reprogram plant development and stress responses with synthetic precision?

Together, these findings underscore a sophisticated level of cross-regulation between hormonal and redox pathways, with NO positioned as a versatile second messenger capable of rewiring ubiquitin-dependent processes. This conceptual framework sets the stage for future research into how redox-dependent PTMs orchestrate the specificity, plasticity, and robustness of hormone signaling in plants. Such knowledge provides a critical foundation for the targeted editing through CRISPR/Cas or other precise mutagenesis of native cysteine residues in target proteins. The resulting plants would carry proteins engineered to change activity, localization, or interactions in response to specific redox cues. Such strategies could yield crops with enhanced resilience to temperature fluctuations, salinity, or pathogen attacks by reinforcing or bypassing natural regulatory circuits.

Finally, as interest in PROTAC (PROteolysis TArgeting Chimera) technologies and engineered E3 ligases grows across biomedical fields, plant-based insights into SCF systems offer foundational knowledge with far-reaching implications. Plant E3 ligases serve as powerful models for understanding targeted protein degradation and redox regulation. Their study is paving the way for the design of synthetic ligases with programmable specificity. When integrated with environmental sensors or optogenetic modules, redox-sensitive protein circuits could drive next-generation synthetic gene networks tailored for climate-resilient crops. Crucially, the discovery of redox control in E3 ligases positions plants at the forefront of cross-kingdom innovation, where principles of plant proteostasis may soon guide both agricultural advancement and therapeutic design.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This work has been supported by grants from CONICET (PIP 0237 to MCT), Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (ANPCYT, grant PICT-2020-0178 to MJI) and Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata (EXA 1217/24 and 1179/24 to MCT).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: María José Iglesias, María Cecilia Terrile; data collection: María José Iglesias, María Cecilia Terrile; analysis and interpretation of data: Nuria Malena Tebez, María Cecilia Terrile, María Elisa Picco, María José Iglesias; draft manuscript preparation: Nuria Malena Tebez, María Cecilia Terrile, María Elisa Picco, María José Iglesias. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Hershko A, Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin system. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67(1):425–79. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Vierstra RD. The ubiquitin-26S proteasome system at the nexus of plant biology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009 Jun;10(6):385–97. doi:10.1038/nrm2688. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Iglesias MJ, Casalongué CA, Terrile MC. Ubiquitin-proteasome system as part of nitric oxide sensing in plants. In: Nitric oxide in plant biology. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2022. p. 653–87 doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-818797-5.00002-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Cohen JD, Strader LC. An auxin research odyssey: 1989–2023. Plant Cell. 2024 Feb 21;36(5):1410–28. [Google Scholar]

5. Terrile MC, Tebez NM, Colman SL, Mateos JL, Morato-López E, Sánchez-López N, et al. S-nitrosation of E3 ubiquitin ligase complex components regulates hormonal signalings in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci. 2022;12:794582. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.794582. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Callis J. Regulation of protein degradation. Plant Cell. 1995 Jul;7(7):845–57. [Google Scholar]

7. Doroodian P, Hua Z. The ubiquitin switch in plant stress response. Plants. 2021 Feb;10(2):246. doi:10.3390/plants10020246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Cardozo T, Pagano M. The SCF ubiquitin ligase: insights into a molecular machine. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004 Sep;5(9):739–51. doi:10.1038/nrm1471. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Rusnac DV, Zheng N. Overview of protein degradation in plant hormone signaling. In: Hejátko J, Hakoshima T, editors. Plant structural biology: hormonal regulations. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 11–30 doi:10.1007/978-3-319-91352-0_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Serrano I, Campos L, Rivas S. Roles of E3 ubiquitin-ligases in nuclear protein homeostasis during plant stress responses. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:139. doi:10.3389/fpls.2018.00139. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Al-Saharin R, Hellmann H, Mooney S. Plant E3 ligases and their role in abiotic stress response. Cells. 2022 Jan;11(5):890. doi:10.3390/cells11050890. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Lamattina L, García-Mata C, Graziano M, Pagnussat G. Nitric oxide: the versatility of an extensive signal molecule. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2003;54(1):109–36. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.54.031902.134752. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Parveen N, Kandhol N, Sharma S, Singh VP, Chauhan DK, Ludwig-Müller J, et al. Auxin crosstalk with reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in plant development and abiotic stress. Plant Cell Physiol. 2022 Dec 1;63(12):1814–25. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcac138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Costa-Broseta Á, Castillo M, León J. Nitrite reductase 1 is a target of nitric oxide-mediated post-translational modifications and controls nitrogen flux and growth in Arabidopsis. IJMS. 2020 Oct 1;21(19):7270. doi:10.3390/ijms21197270. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Jeandroz S, Wipf D, Stuehr DJ, Lamattina L, Melkonian M, Tian Z, et al. Occurrence, structure, and evolution of nitric oxide synthase-like proteins in the plant kingdom. Sci Signal. 2016 Mar;9(417):re2. doi:10.1126/scisignal.aad4403. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Correa-Aragunde N, París R, Foresi N, Terrile C, Casalongué C, Lamattina L. The auxin-nitric oxide highway: a right direction in determining the plant root system. In: Lamattina L, García-Mata C, editors. Gasotransmitters in plants: the rise of a new paradigm in cell signaling. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016. p. 117–36. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-40713-5_6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. París R, Vazquez MM, Graziano M, Terrile MC, Miller ND, Spalding EP, et al. Distribution of endogenous NO regulates early gravitropic response and PIN2 localization in Arabidopsis roots. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:495. doi:10.3389/fpls.2018.00495. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Iglesias MJ, Costigliolo Rojas C, Bianchimano L, Legris M, Schön J, Gergoff Grozeff GE, et al. Shade-induced ROS/NO reinforce COP1-mediated diffuse cell growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024 Oct 15;121(42):e2320187121. doi:10.1073/pnas.2320187121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Correa-Aragunde N, Graziano M, Lamattina L. Nitric oxide plays a central role in determining lateral root development in tomato. Planta. 2004 Apr 1;218(6):900–5. doi:10.1007/s00425-003-1172-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Huang J, Wu Q, Jing HK, Shen RF, Zhu XF. Auxin facilitates cell wall phosphorus reutilization in a nitric oxide-ethylene dependent manner in phosphorus deficient rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Sci. 2022 Sep 1;322(2003):111371. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2022.111371. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Yadav S, David A, Bhatla SC. Nitric oxide accumulation and actin distribution during auxin-induced adventitious root development in sunflower. Sci Hortic. 2011 May 25;129(1):159–66. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2011.03.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. León J, Costa-Broseta Á. Present knowledge and controversies, deficiencies, and misconceptions on nitric oxide synthesis, sensing, and signaling in plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2020;43(1):1–15. [Google Scholar]

23. Lu B, Wang S, Feng H, Wang J, Zhang K, Li Y, et al. FERONIA-mediated TIR1/AFB2 oxidation stimulates auxin signaling in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant. 2024 May;17(5):772–87. doi:10.1016/j.molp.2024.04.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Martí-Guillén JM, Pardo-Hernández M, Martínez-Lorente SE, Almagro L, Rivero RM. Redox post-translational modifications and their interplay in plant abiotic stress tolerance. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:1027730. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.1027730. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Massa CM, Liu Z, Taylor S, Pettit AP, Stakheyeva MN, Korotkova E, et al. Biological mechanisms of S-nitrosothiol formation and degradation: how is specificity of s-nitrosylation achieved? Antioxidants. 2021; 10(7):1111. [Google Scholar]

26. Liu Y, Liu Z, Wu X, Fang H, Huang D, Pan X, et al. Role of protein S-nitrosylation in plant growth and development. Plant Cell Rep. 2024 Jul 30;43(8):204. doi:10.1007/s00299-024-03290-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Treffon P, Vierling E. Focus on nitric oxide homeostasis: direct and indirect enzymatic regulation of protein denitrosation reactions in plants. Antioxidants. 2022 Jul;11(7):1411. doi:10.3390/antiox11071411. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. León J. Protein tyrosine nitration in plant nitric oxide signaling. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:859374. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.859374. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Tanou G, Molassiotis A, Diamantidis G. Hydrogen peroxide- and nitric oxide-induced systemic antioxidant prime-like activity under NaCl-stress and stress-free conditions in citrus plants. J Plant Physiol. 2009 Nov 15;166(17):1904–13. doi:10.1016/j.jplph.2009.06.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Gotor C, García I, Aroca Á, Laureano-Marín AM, Arenas-Alfonseca L, Jurado-Flores A, et al. Signaling by hydrogen sulfide and cyanide through post-translational modification. J Exp Bot. 2019 Aug 19;70:4251–65. doi:10.1093/jxb/erz225. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Aroca A, Benito JM, Gotor C, Romero LC. Persulfidation proteome reveals the regulation of protein function by hydrogen sulfide in diverse biological processes in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2017 Oct 13;68(17):4915–27. doi:10.1093/jxb/erx294. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Mukherjee S, Corpas FJ. H2O2, NO, and H2S networks during root development and signalling under physiological and challenging environments: beneficial or toxic? Plant Cell Environ. 2023;46(3):688–717. [Google Scholar]

33. Gupta KJ, Mur LAJ, Wany A, Kumari A, Fernie AR, Ratcliffe RG. The role of nitrite and nitric oxide under low oxygen conditions in plants. New Phytol. 2020;225(3):1143–51. doi:10.1111/nph.15969. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Lin W, Shang JX, Li XY, Zhou XF, Zhao LQ. Nitric oxide regulates multiple signal pathways in plants via protein S-nitrosylation. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2025 Jun;47(6):407. doi:10.3390/cimb47060407. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Dharmasiri N, Dharmasiri S, Estelle M. The F-box protein TIR1 is an auxin receptor. Nature. 2005 May;435(7041):441–5. doi:10.1038/nature03543. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Kepinski S, Leyser O. The Arabidopsis F-box protein TIR1 is an auxin receptor. Nature. 2005 May;435(7041):446–51. doi:10.1038/nature03542. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Prigge MJ, Platre M, Kadakia N, Zhang Y, Greenham K, Szutu W, et al. Genetic analysis of the Arabidopsis TIR1/AFB auxin receptors reveals both overlapping and specialized functions. eLife. 2020 Feb 18;9:e54740. [Google Scholar]

38. Dubey SM, Han S, Stutzman N, Prigge MJ, Medvecká E, Platre MP, et al. The AFB1 auxin receptor controls the cytoplasmic auxin response pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Plant. 2023 Jul;16(7):1120–30. doi:10.1016/j.molp.2023.06.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Chen H, Li L, Zou M, Qi L, Friml J. Distinct functions of TIR1 and AFB1 receptors in auxin signaling. Mol Plant. 2023 Jul 3;16(7):1117–9. doi:10.1016/j.molp.2023.06.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Gray WM, Kepinski S, Rouse D, Leyser O, Estelle M. Auxin regulates SCFTIR1-dependent degradation of AUX/IAA proteins. Nature. 2001;414(6861):271–6. doi:10.1038/35104500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Vanneste S, Pei Y, Friml J. Mechanisms of auxin action in plant growth and development. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2025 Sep;26(9):648–66. doi:10.1038/s41580-025-00851-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Tan X, Calderon-Villalobos LIA, Sharon M, Zheng C, Robinson CV, Estelle M, et al. Mechanism of auxin perception by the TIR1 ubiquitin ligase. Nature. 2007 Apr;446(7136):640–5. doi:10.1038/nature05731. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Niemeyer M, Moreno Castillo E, Ihling CH, Iacobucci C, Wilde V, Hellmuth A, et al. Flexibility of intrinsically disordered degrons in AUX/IAA proteins reinforces auxin co-receptor assemblies. Nat Commun. 2020 May 8;11(1):2277. doi:10.1101/787770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Terrile MC, París R, Calderón-Villalobos LIA, Iglesias MJ, Lamattina L, Estelle M, et al. Nitric oxide influences auxin signaling through S-nitrosylation of the Arabidopsis TRANSPORT INHIBITOR RESPONSE 1 auxin receptor. Plant J. 2012;70(3):492–500. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313x.2011.04885.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Jing H, Yang X, Emenecker RJ, Feng J, Zhang J, Figueiredo MRAD, et al. Nitric oxide-mediated S-nitrosylation of IAA17 protein in intrinsically disordered region represses auxin signaling. J Genet Genom. 2023 Jul;50(7):473–85. doi:10.1016/j.jgg.2023.05.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Iglesias MJ, Terrile MC, Correa-Aragunde N, Colman SL, Izquierdo-Álvarez A, Fiol DF, et al. Regulation of SCFTIR1/AFBs E3 ligase assembly by S-nitrosylation of Arabidopsis SKP1-like1 impacts on auxin signaling. Redox Biol. 2018 Sep 1;18(702–710):200–10. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2018.07.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Correa-Aragunde N, Cejudo FJ, Lamattina L. Nitric oxide is required for the auxin-induced activation of NADPH-dependent thioredoxin reductase and protein denitrosylation during root growth responses in Arabidopsis. Ann Bot. 2015 Sep;116(4):695–702. doi:10.1093/aob/mcv116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Correa-Aragunde N, Foresi N, Lamattina L. Nitric oxide is a ubiquitous signal for maintaining redox balance in plant cells: regulation of ascorbate peroxidase as a case study. J Exp Bot. 2015 May 1;66(10):2913–21. doi:10.1093/jxb/erv073. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Bleau JR. Thioredoxins enable selective and reversible redox signalling in plants [Internet]; 2023. [cited 2025 Jul 16]. Available from: https://era.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/39749. [Google Scholar]

50. Ying S, Yang W, Li P, Hu Y, Lu S, Zhou Y, et al. Phytochrome B enhances seed germination tolerance to high temperature by reducing S-nitrosylation of HFR1. EMBO Rep. 2022 Oct 6;23(10):e54371. doi:10.15252/embr.202154371. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Chen L, Sun S, Song CP, Zhou JM, Li J, Zuo J. Nitric oxide negatively regulates gibberellin signaling to coordinate growth and salt tolerance in Arabidopsis. J Genet Genom. 2022 Aug 1;49(8):756–65. doi:10.1016/j.jgg.2022.02.023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Tian Y, Fan M, Qin Z, Lv H, Wang M, Zhang Z, et al. Hydrogen peroxide positively regulates brassinosteroid signaling through oxidation of the BRASSINAZOLE-RESISTANT1 transcription factor. Nat Commun. 2018 Mar 14;9(1):1063. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-03463-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Legris M, Nieto C, Sellaro R, Prat S, Casal JJ. Perception and signalling of light and temperature cues in plants. Plant J. 2017;90(4):683–97. doi:10.1111/tpj.13467. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Kerner K, Nagano S, Lübbe A, Hoecker U. Functional comparison of the WD-repeat domains of SPA1 and COP1 in suppression of photomorphogenesis. Plant Cell Environ. 2021;44(10):3273–82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

55. Ponnu J, Hoecker U. Illuminating the COP1/SPA ubiquitin ligase: fresh insights into its structure and functions during plant photomorphogenesis [Internet]; 2021. [cited 2025 Jul 16]. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/plant-science/articles/10.3389/fpls.2021.662793/full. [Google Scholar]

56. Hernando CE, Murcia MG, Pereyra ME, Sellaro R, Casal JJ. Phytochrome B links the environment to transcription. J Exp Bot. 2021 May 18;72:4068–84. [Google Scholar]

57. Nieto C, Catalán P, Luengo LM, Legris M, López-Salmerón V, Davière JM, et al. COP1 dynamics integrate conflicting seasonal light and thermal cues in the control of Arabidopsis elongation. Sci Adv. 2022;8(33):eabp8412. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abp8412. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Sheerin DJ, Menon C, zur Oven-Krockhaus S, Enderle B, Zhu L, Johnen P, et al. Light-activated phytochrome A and B interact with members of the SPA family to promote photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis by reorganizing the COP1/SPA complex. Plant Cell. 2015 Jan 1;27(1):189–201. doi:10.1105/tpc.114.134775. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Kwon Y, Kim C, Choi G. Phytochrome B photobody components. New Phytol. 2024;242(3):909–15. doi:10.1111/nph.19675. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Yi C, Deng XW. COP1—from plant photomorphogenesis to mammalian tumorigenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 2005 Nov 1;15(11):618–25. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2005.09.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Casal JJ, Fankhauser C. Shade avoidance in the context of climate change. Plant Physiol. 2023 Mar 17;191(3):1475–91. [Google Scholar]

62. Pacín M, Legris M, Casal JJ. COP1 re-accumulates in the nucleus under shade. Plant J. 2013;75(4):631–41. doi:10.1111/tpj.12226. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Pacín M, Semmoloni M, Legris M, Finlayson SA, Casal JJ. Convergence of CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENESIS 1 and PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR signalling during shade avoidance. New Phytol. 2016;211(3):967–79. doi:10.1111/nph.13965. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Blanco-Touriñán N, Legris M, Minguet EG, Costigliolo-Rojas C, Nohales MA, Iniesto E, et al. COP1 destabilizes DELLA proteins in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020 Jun 16;117(24):13792–9. doi:10.1101/2020.01.09.897157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Rojas CC, Bianchimano L, Oh J, Montepaone SR, Tarkowská D, Minguet EG, et al. Organ-specific COP1 control of BES1 stability adjusts plant growth patterns under shade or warmth. Dev Cell. 2022 Aug 22;57(16):2009–25.e6. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2022.07.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Kohnen MV, Schmid-Siegert E, Trevisan M, Petrolati LA, Sénéchal F, Müller-Moulé P, et al. Neighbor detection induces organ-specific transcriptomes, revealing patterns underlying hypocotyl-specific growth. Plant Cell. 2016 Dec;28(12):2889–904. doi:10.1105/tpc.16.00463. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Lin F, Cao J, Yuan J, Liang Y, Li J. Integration of light and brassinosteroid signaling during seedling establishment. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Jan;22(23):12971. doi:10.3390/ijms222312971. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Martinez-Garcia JF, Rodriguez-Concepcion M. Molecular mechanisms of shade tolerance in plants. New Phytol. 2023;239(4):1190–202. doi:10.1111/nph.19047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Han R, Ma L, Terzaghi W, Guo Y, Li J. Molecular mechanisms underlying coordinated responses of plants to shade and environmental stresses. Plant J. 2024;117(6):1893–913. doi:10.1111/tpj.16653. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Casal JJ. Seedling signalling: ubiquitin ligases acting in tandem. Nat Plants. 2016 Feb 3;2(2):16001. doi:10.1038/nplants.2016.1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Latorre L, Fernández MB, Cassia R. Nitric oxide is a key part of the UV-B-induced photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Environ Exp Bot. 2023 Dec 1;216(5):105538. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2023.105538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Favory JJ, Stec A, Gruber H, Rizzini L, Oravecz A, Funk M, et al. Interaction of COP1 and UVR8 regulates UV-B-induced photomorphogenesis and stress acclimation in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 2009 Mar 4;28(5):591–601. doi:10.1038/emboj.2009.4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Huang X, Ouyang X, Yang P, Lau OS, Chen L, Wei N, et al. Conversion from CUL4-based COP1–SPA E3 apparatus to UVR8–COP1–SPA complexes underlies a distinct biochemical function of COP1 under UV-B. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 Oct 8;110:16669–74. doi:10.1073/pnas.1316622110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Fang F, Lin L, Zhang Q, Lu M, Skvortsova MY, Podolec R, et al. Mechanisms of UV-B light-induced photoreceptor UVR8 nuclear localization dynamics. New Phytol. 2022;236(5):1824–37. doi:10.1111/nph.18468. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Brown BA, Jenkins GI. UV-B signaling pathways with different fluence-rate response profiles are distinguished in mature Arabidopsis leaf tissue by requirement for UVR8, HY5, and HYH. Plant Physiol. 2008 Feb;146(2):576–88. doi:10.1104/pp.107.108456. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Ulm R, Baumann A, Oravecz A, Máté Z, Ádám É, Oakeley EJ, et al. Genome-wide analysis of gene expression reveals function of the bZIP transcription factor HY5 in the UV-B response of Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Feb 3;101:1397–402. [Google Scholar]

77. Zhang Q, Lin L, Fang F, Cui B, Zhu C, Luo S, et al. Dissecting the functions of COP1 in the UVR8 pathway with a COP1 variant in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2023;113(3):478–92. doi:10.1111/tpj.16059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Liu W, Jenkins GI. Recent advances in UV-B signalling: interaction of proteins with the UVR8 photoreceptor. J Exp Bot. 2025 Feb 7;76(3):873–81. doi:10.1093/jxb/erae132. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Zhang Q, Cai X, Wu B, Tong B, Xu D, Wang J, et al. S-nitrosylation may inhibit the activity of COP1 in plant photomorphogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2024 Jul 30;719:150096. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2024.150096. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Corpas FJ, González-Gordo S, Rodríguez-Ruiz M, Muñoz-Vargas MA, Palma JM. Thiol-based oxidative posttranslational modifications (OxiPTMs) of plant proteins. Plant Cell Physiol. 2022 Jul 1;63(7):889–900. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcac036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Zhou H, Huang J, Willems P, Breusegem FV, Xie Y. Cysteine thiol-based post-translational modification: what do we know about transcription factors? Trends Plant Sci. 2023 Apr 1;28(4):415–28. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2022.11.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools